inbox and environment news: Issue 521

December 5 - 11, 2021: Issue 521

Sounds-Signs Of Summer: Birdland

Adult Crimson Rosellas (Platycercus elegans) have a single post-breeding moult each year, from December to May. This moult is complete except in some bids, mostly females, that defer moult of outer primaries until the following year. Birds fledge in juvenile plumage, pass into pre-adult plumage when two to six months old with a moult of the head and body feathers and pass into adult plumage when twelve to eighteen months old with a complete moult. Replacement of primaries starts with middle primaries and progresses inwards and outwards from this focus. Average duration of primary moult is 114 days

Edmund Wyndham, John Le Gay Brereton & Robert J.S. Beeton (1983) Moult and Plumages of Eastern Rosellas Platycercus Eximius, Emu - Austral Ornithology, 83:4, 242-246, DOI: 10.1071/MU9830242

Almost all rosellas are sedentary, although occasional populations are considered nomadic; no rosellas are migratory. Outside of the breeding season, crimson rosellas tend to congregate in pairs or small groups and feeding parties. The largest groups are usually composed of juveniles, who will gather in flocks of up to 20 individuals. When they forage, they are conspicuous and chatter noisily. Rosellas are monogamous, and during the breeding season, adult birds will not congregate in groups and will only forage with their mate.

Nesting sites are hollows greater than 1 metre (3.3 feet) deep in tree trunks, limbs, and stumps. These may be up to 30 metres (98 feet) above the ground. The nesting site is selected by the female. Once the site is selected, the pair will prepare it by lining it with wood debris made from the hollow itself by gnawing and shredding it with their beaks. They do not bring in material from outside the hollow. Only one pair will nest in a particular tree. A pair will guard their nest by perching near it and chattering at other rosellas that approach. They will also guard a buffer zone of several trees radius around their nest, preventing other pairs from nesting in that area.

The breeding season of the crimson rosella lasts from September through to February, and varies depending on the rainfall of each year; it starts earlier and lasts longer during wet years. The laying period is on average during mid- to late October. Clutch size ranges from 3–8 eggs, which are laid asynchronously at an average interval of 2.1 days; the eggs are white and slightly shiny and measure 28 by 23 millimetres (1+1⁄8 in × 7⁄8 in). The mean incubation period is 19.7 days, and ranges from 16–28 days. Only the mother incubates the eggs. The eggs hatch around mid-December; on average 3.6 eggs successfully hatch. There is a bias towards female nestlings, as 41.8% of young are male. For the first six days, only the mother feeds the nestlings. After this time, both parents feed them. The young become independent in February, after which they spend a few more weeks with their parents before departing to become part of a flock of juveniles. Juveniles reach maturity (gain adult plumage) at 16 months of age.

Channel Billed Cuckoo being harassed by miner birds

The channel-billed cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae) is a species of cuckoo in the family Cuculidae. It is monotypic within the genus Scythrops. The species is the largest brood parasite in the world, and the largest cuckoo. It is found in Australia, New Guinea and Indonesia.

The channel-billed cuckoo is often shy, remaining hidden in tree canopies feeding on fruit and most active in early morning and evening. Its loud raucous call makes it more often heard than seen. Other birds such as crows harass and chase it when they encounter it; Miner birds and crows and some other species also swoop them.

Channel-billed cuckoos are brood parasites; instead of raising their own young, they lay eggs in the nests of other birds. They are thought to form pair bonds for the duration of a breeding season.[20] Their mating behaviour has been described as involving calling and gift-giving, with the male presenting items of food such as insects to the female. Pairs also work together in order to aid the laying of eggs in host nests; the male will fly over the nest in order to provoke the nest occupants into a mobbing response, whereupon the female will slip into the nest and lay an egg. Alternatively the pair may work together by attacking an incubating bird, driving it off the nest and allowing the female to lay.

The host species varies depending on the location; the most commonly targeted hosts are ravens, currawongs, butcherbirds and Australian magpies. Several eggs can be laid in a single nest, sometimes by different females. Often resembling those of currawongs and magpies (but not ravens), the eggs vary in colour and pattern, measuring 48 x 32 mm. They can be a reddish- or yellowish-brown to dull white, with darker brown splotches. The incubation period for this species is unknown. Upon hatching the chicks are altricial, being blind and naked. Unlike many other cuckoos, the chicks of the channel-billed cuckoo do not eject the other host eggs upon hatching or kill the host's chicks, but these seldom survive as the cuckoo chick is able to monopolise the supply of food. The chicks are fully feathered within four weeks, and leave the nest to clamber about on the branches, although chicks are fed for a number of weeks by the host parents after fledging. - BirdLife Australia

Fledgling Butcher Bird being fed this week; our garden:

Photos by A J Guesdon, 2021.

White's Seahorse Signage At Palm Beach

White’s Seahorse, also known as the Sydney Seahorse, is a medium-sized seahorse that is endemic to the east coast of Australia. The species is named after John White, Surgeon General to the First Fleet, and is one of four species of seahorses known to occur in NSW waters. Favouring shallow-water estuarine habitats, it is currently known to occur in eight estuaries on the NSW Coast, but is most abundant in Port Stephens, Sydney Harbour and Port Hacking. Its northern limit is Hervey Bay in Queensland and it has been historically recorded as far south as St Georges Basin in NSW.

Some of the characteristics of the White’s Seahorse are:

- 17-18 dorsal-fin rays,

- 16 pectoral-fin rays

- 34-35 tail-rings

- coronet is tall arranged in five pointed star at apex

- spines are variable ranging from low to moderately developed and from round to quite sharp

- a long snout

They have a very small anal fin which is used for propulsion, however, they are known to be one of the slowest swimming fishes in the ocean.

The White’s Seahorse is considered to be endemic to the waters of southern Queensland (Hervey Bay) to Sussex Inlet NSW where it can be found occurring in coastal embayments and estuaries. It is known to occur from depths of 1 m to 18 m. Habitats that are considered important habitat for the White’s Seahorse include natural habitats such as sponge gardens, seagrass meadows and soft corals. It is also known to use artificial habitats such as protective swimming net enclosures and jetty pylons.

The primary cause for the decline in abundance of White’s Seahorse is the loss of natural habitats across their range in eastern Australia. The seahorses occur within coastal estuaries and embayments which are areas subject to population pressure.

Below: the signage at Palm Beach

Careel Creek: Dusky Moorhen + Chicks In Residence - Please Keep Your Dogs On Their Leads

Dusky Moorhen in Careel Creek, Saturday October 30, 2021 - photos by A J Guesdon

Dusky Moorhen in Careel Creek, Thursday November 30, 2021 - photos by A J Guesdon

Canopy Keepers Offer 100 Trees For Avalon Beach 100 Celebration

A group of local tree enthusiasts is inviting Avalon Beach residents to celebrate the suburb’s 100th anniversary by planting a tree.

Canopy Keepers convenor Deb Collins said Pittwater residents are surrounded by a unique urban tree canopy covering nearly 60 per cent of the area.

However, between 2009 and 2016 the Pittwater Local Government Area lost more canopy than any other in NSW - due to development and the removal of trees from residential land.

So to celebrate the naming of Avalon Beach 100 years ago, Canopy Keepers will plant at least 100 trees in the 2107 postcode in coming months, Ms Collins said.

Avalon Beach residents and others in the postcode area are therefore invited to apply for one of these trees at no cost, to plant and care for the next generation of canopy, she said.

“We are looking for 100 recipients - 100 new Canopy Keepers,” Ms Collins said.

“Will you help us grow the future and become a canopy keeper, so that we can ensure our children and grandchildren enjoy the benefits of our wonderful urban forest?” Ms Collins said.

“The radical changes to our environment are not just upsetting residents.

“Forty per cent of all wildlife relies on a connected canopy to nest, raise their young and travel between food and water sources.

“The simple removal of ‘just one tree’ can break a critical link in a canopy pathway and threaten the habitat of wildlife such as Squirrel gliders, Powerful owls, and of course the much loved Koala, now extinct from our area but remembered here by so many of us from our childhood.

“We can do much to prevent our wildlife and trees from suffering the same fate as the Koala.

“But it will take a noisy village to achieve this.

“Please join our growing community and ensure Avalon and Pittwater in 100 years are as beautiful as they are today.”

Residents are asked to fill in the following form before December 10 and Canopy Keepers will offer you a tree that is best suited to where you live.

https://forms.gle/hPAVdU5qYT4YzgAc6

Otherwise please email Canopy Keepers at 100trees@canopykeepers.org.au

Find Canopy Keepers at the Avalon car boot sale, on Sunday December 19, where registered tree recipients will be able to pick up their trees for planting.

Canopy keepers is a local group dedicated to the preservation and regeneration of tree canopy in our local area. We want to link arms with all our neighbours and bring to life the vision of homes amongst the trees not shrubs along the edge.

Find out more at: www.canopykeepers.org.au

Migratory Bird Season

Boobook Owl And Baby Possum Rescue; Sydney Wildlife Rescue Volunteer - Nesting Boxes Available - All Sales To Sydney Wildlife

Helen Pearce is one of our local Sydney Wildlife volunteers - last week she got a call for a raptor rescue.

Helen says; ''As a licensed wildlife rescuer, I get to deal with some pretty cool animals, but today was a beautiful privilege.

Sydney Wildlife Rescue had a call at about 8:30 this morning for an owl on the ground. Thinking it’d be a Tawny chick (who is not an owl, not even a nightjar, but has very recently been reclassified in its own classification order), but preparing for a Powerful Owl, I set out with all necessary equipment. When I arrived, I found the most gorgeous fledgling Boobook owl. What a cutey!

The parents were around and watching and rather concerned as to what we were going to do with their precious baby. Fluttering between Jo’s and Lisa Yost Palmer ‘s garden, I caught the petrified little fluffball of claws and sharp beak and we formulated a plan.

Having consulted with SWR’s experienced raptor coordinator, we made a make-shift nest and Jo and Lisa’s amazing husbands scaled a tree and started fixing the new ‘nest’ as high as we practically could and placed ‘Fluffy’ in.

This evening, mum and dad have tended to the chick and there’s a second chick still in the original nest!

I’d like to extend my massive thanks to all involved for the effort made to help these birds. It’s great to know there’s people like these guys who care so deeply about our wildlife. Chicks of all species are fledging at the moment and may need a little extra help from us humans.''

The other recent rescue Helen has attended is a baby possum. More and more of these are coming into care as their tree homes are cut down without any checking to see if they are already inhabited by our wildlife.

Helen says;

''It’s baby season! And I have a huge soft spot for brushtail possums.

The little guy in this photo is a 300g brushtail Joey. He was found all alone, in the middle of the day on a concrete slab by the side of a building. How he wasn’t already dead, I don’t know. Cats, dogs, birds, snakes, humans……hunger, dehydration, exposure to the sun, wind, cold……either way, he’s a very lucky boy. What happened to his mum is unknown.

He’s very scared. He doesn’t know what’s happened to him, who this strange thing is who’s trying to feed a funny-tasting milk to him, where his mum is. He cries at night, calling for his mum, but she doesn’t come.

He will settle in a day or two and get used to the new milk (which is a specialised marsupial milk, purely for his stage of development. Other various types of milks can kill him) and he’ll begin to trust me, but I can’t replace his mum.

If you find a Joey on its own, it needs help. If you find one, please try to contain it and keep it safe from predators and exposure and call either Sydney Wildlife (Sydney Metropolitan Wildlife Services) or WIRES. If you find a dead possum (ringtail or brushtail), please check the pouch for a Joey. Brushies generally have one but ringtails will have 2, sometimes three. If you are unable to, that’s ok, but please call it in to a wildlife organisation so someone can attend to it.

If you find a native animal in need, or if you have concerns, please call either

Sydney Wildlife Rescue - 02 9413 4300

Or WIRES - 1300 094 737

NB: Please do not attempt to handle a raptor, snake or other wild animals unless you are trained as you may cause injury to them or yourself.

Nesting Boxes Available

We are licensed wildlife rescuers with Sydney Wildlife Rescue and have been making more and more wildlife boxes, both for our releases and for members of the public.

As fewer nesting areas are available and tree hollows are becoming rarer, as development takes over, our native wildlife are struggling. We have decided to make more boxes and sell them to the community with all profits going back to Sydney Wildlife.

They can either be painted and sealed to make them weatherproof or unsealed for you to paint yourself as a fun activity for the family to add your own personal touch.

The possum boxes will all have an access branch on the front. The Kookaburra boxes have an access tunnel to mimic a tree hollow.

Please email me if you’d like to purchase one at helenjanepearce@yahoo.com

Photos: Helen Pearce

Dendrobium Coal Mine Declared State Significant Infrastructure

On Saturday December 4, 2021 Deputy Premier and Minister responsible for Resources Paul Toole said a proposal to extend Dendrobium coal mine had been declared State Significant Infrastructure (SSI) given its importance to Port Kembla steelworks and its thousands of employees.

“Dendrobium is a critical source of coking coal for the Port Kembla steelworks and the decision to declare the project SSI will provide thousands of workers with greater certainty on the future of their jobs,” Mr Toole said.

“This decision recognises the proposal’s potential economic benefits, with the mine already contributing $1.9 billion to the State’s economy each year, employing 4,500 workers and supporting another 10,000 jobs across the Illawarra.”

On February 5 of this year the Independent Planning Commission refused the company's proposed extension under the Sydney Water Catchment.

South32 wants to extract an additional 78 million tonnes of coal from its Dendrobium mine, west of Wollongong, through to 2048.

The company had received approval from the state Department of Planning for the $956 million project but was blocked by the IPC.

The state's planning authority found the impacts of the project outweighed the benefits.

In its reasons it said "the level of risk posed by the project has not been properly quantified and based on the potential for long-term and irreversible impacts — particularly on the integrity of a vital drinking water source for the Macarthur and Illawarra regions, the Wollondilly Shire and Metropolitan Sydney drinking water — it is not in the public interest".

The IPC also raised concerns about the longwall design, the degradation of watercourses and loss of swampland.

WaterNSW also "strongly opposed" the extension, finding it would cause significant environmental impact in watercourses and "would fundamentally change the hydrological and ecological functions" of upland swamps.

Then the proponents, South32, stated that as many as 2,000 jobs in the region were at risk if a reworked mine plan was not considered.

The company then commenced proceedings in the Land and Environment Court, seeking a judicial review of the IPC assessment of the Dendrobium mine.

Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Rob Stokes said Dendrobium mine’s proponent, South32, had taken into consideration concerns raised by the Independent Planning Commission.

“The decision to declare Dendrobium SSI followed support for a motion passed in the Legislative Council early this year. It will now go through a rigorous assessment process and the community will still have their say,” Mr Stokes said.

An SSI declaration does not change the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment’s rigorous assessment of the proposal to extend Dendrobium coal mine.

South32 can now request assessment requirements to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement which will then go on public exhibition for community feedback and detailed assessment.

Government Must Release Natural Resources Commission’s Forestry Report In Full

November 25, 2021

The NSW Government must explain why it ignored the advice of the independent Natural Resources Commission and kept logging forests in regions hit hardest by the 2019-20 Black Summer Bushfires.

The government has kept the Commission’s report secret since June 2020 but extracts have been published today by Guardian Australia. [1]

“It is now clear the government was advised it should suspend timber harvesting for at least three years in extreme risk zones, including Narooma, Nowra and Taree,” Nature Conservation Council Chief Executive Chris Gambian said.

“The leaked extracts from the NRC report validate what the conservation movement has said since day one – logging must stop in burnt native forests to give them a chance to recover.

“For some unknown reason, the government and its logging company, Forestry Corporation, chose to ignore the expert advice and put wildlife at extreme risk.

“It’s quite astonishing. If you were looking for a case study of environmental negligence, you wouldn’t need to look any further than this.

“The government must explain why it has kept this report secret for almost six months and also why it has not fully implemented the recommendations.”

[1] Extract from Advice on Coastal IFOA operations post-2019-20 wildfires, June 2020, NSW Natural Resources Commission. Published on The Guardian Australia.

Secret document urges native logging halt in NSW regions hit hard by black summer bushfires, 25-11-21, The Guardian Australia

Threatened Species Habitat At Risk From A Hotter Climate

October 12, 2021

New research released today has found climate change will expose larger areas of forest in coastal NSW to higher frequency and more intense fires, amplifying the changes to fire regimes brought about by the 2019/20 fires.

Leading researchers at the University of the Wollongong, a partner at the NSW Bushfire Research Hub, conducted the research using the latest data on behalf of the NSW Natural Resources Commission.

According to the lead researcher, Emeritus Professor Ross Bradstock, “The 2019/20 fires mean now only 10 percent of forested areas are currently within their recommended fire frequency thresholds. We found half of the state forest and national park area is now classified as ‘vulnerable’ in coastal NSW. This means the 2019/20 fires effectively doubled the extent of vulnerable forested vegetation on these tenures.”

The research also modelled what would happen to the habitat of 24 threatened species under a climate change scenario of hotter temperatures and little change in rainfall. Of the 24 species, seven species are predicted to have their habitat reduced by over 75% by 2070.

NSW Natural Resources Commissioner Professor Hugh Durrant-Whyte said. “This is an important report, one that highlights consequences of the 2019/20 bushfires and future climate for NSW's forests and provides guidance for future planning of our forests”.

The research team evaluated:

- the specific risks to achieving the Coastal IFOA objectives and outcomes as result of the legacy landscape scale impacts of the NSW 2019/20 wildfire season

- the broad implications of predicted changing fire regimes on the achievement of the Coastal IFOA’s objectives and outcomes options to mitigate risks.

The researchers found:

- The 2019/20 fires impacted about 3.6 million hectares of forests across all tenures within the mapped Coastal IFOA region.

- Around 60 percent of the total state forest and national park area within this region was burnt, almost half of which was subject to high or extreme fire severity.

- Previous timber harvesting did not increase the fire extent or severity of the 2019/20 fires. However, there is potential for cumulative impacts in harvested landscapes that are subject to fire.

- The 2019/20 fires mean now only 10 percent of forested areas are currently within their recommended fire frequency thresholds.

- Half of state forest and national park area is now classified as ‘vulnerable’, meaning the 2019/20 fires effectively doubled the extent of vulnerable forested vegetation on these tenures.

- Under the climate change scenario of hotter temperatures and little change in rainfall, of the 24 assessed threatened species, seven species are predicted to have their habitat reduced by over 75% by 2070.

However, there is potential for cumulative impacts in harvested landscapes that are subject to fire, particularly in the next 5 to 10 years.

This research supports the recommendations of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry, and through the implementation of those recommendations, the NSW Government can lead efforts to mitigate the impacts and risks from changing fire regimes and climate.

The ful University of Wollongong report is available here: ''Risks to the NSW Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approvals Posed by the 2019/2020 Fire Season and Beyond: A Report to the New South Wales Natural Resources Commission''

Draft Cycling Strategy For NSW's National Parks

The Draft Cycling Policy, Draft Cycling Strategy and Draft Cycling Strategy: Guidelines for Implementation is on public exhibition until 30 January 2022.

The scope of this new strategy is broad. It includes all types of cycling experiences in our parks. It is complemented with a more detailed set of guidelines for implementation and updates to our Cycling policy.

- The Draft Cycling policy builds upon our experience from previous versions and has been updated in parallel to the draft strategy. It identifies in a legislative framework where cycling is permissible in parks.

- The Draft Cycling Strategy outlines our vision, objectives and priorities for the provision of cycling experiences.

- The Draft Cycling Strategy: Guidelines for Implementation provides further details on the processes and procedures that National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) will apply to assess, approve, manage and monitor cycling opportunities within NPWS estate as detailed in the Cycling Strategy.

- The draft Cycling Strategy sets a precedent for managing the conservation of natural and cultural heritage values in our parks as a priority and then allows for the development of compatible cycling opportunities. Not all cycling activities will be suitable in all parts of parks.

- The draft Cycling Strategy details a clear framework for how we seek to provide for, and manage, cycling opportunities within parks. The processes for cyclists to work with National Parks and Wildlife Service are made clear. We intend to work collaboratively with stakeholders and other land managers to tackle key challenges including, unauthorised tracks, the safety and enjoyment of visitors on multi-use trails and the provision of park visitor facilities.

- The draft Guidelines for Implementation address the way we will deliver the Cycling Strategy, including the approval process for new tracks and networks, the rehabilitation of unauthorised tracks, how we will work with external parties (including volunteer groups) and our management of cycling experiences. These documents will replace the Sustainable Mountain Biking Strategy 2011.

Public online presentation

You are invited to an online public presentation on Wednesday, 1 December, 12:00 – 1:00pm. Please register to attend this presentation.

Your feedback on the draft Cycling Policy, strategy and implementation guideline documents is valued. Our response to your submission will be based on the merits of the ideas and issues you raise rather than just the quantity of submissions making similar points. For this reason, a submission that clearly explains the matters it raises will be the most effective way to influence the finalisation of the plan.

Submissions are most effective when we understand your ideas and the outcomes you want for park management. Some suggestions to help you write your submissions are:

- write clearly and be specific about the issues that are of concern to you

- note which part or section of the document your comments relate to

- give reasoning in support of your points - this makes it easier for us to consider your ideas and will help avoid misinterpretation

- tell us precisely what you agree/disagree with and why you agree or disagree

- suggest solutions or alternatives to managing the issue if you can.

Have your say by Thursday 30 January 2022.

There are three ways to provide feedback:

Formal submission: Address: Manager, NPWS Planning Evaluation and Assessment Locked Bag 5022 Parramatta NSW 2124

BASIX Higher Standards: Feedback Open

The NSW Government are improving BASIX standards to build more comfortable homes, cut energy costs and contribute to our target of net zero homes by 2050.

This is part of the Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings, a national plan that aims to achieve zero energy and carbon-ready buildings. The plan proposes increases to the energy efficiency provisions in the National Construction Code (NCC) for residential buildings from 2022.

What do the proposed new standards mean:

- Cheaper energy bills. You’ll use less electricity so your bills will be cheaper – saving as much as $980 a year on energy bills.

- More comfortable homes. Your home will be naturally cooler in summer, warmer in winter, which means you won’t be turning the heater or air conditioner on as often

- Fewer carbon emissions. This contributes towards our goal of net zero homes by 2050

The proposed higher standards

Te NSW Department of Planning welcome feedback on the proposed increases to BASIX standards. The proposed changes can be found in the Proposed BASIX Higher Standards document. This document shows a map of the climate zones in NSW.

The proposed thermal performance and energy standards vary according to climate zones.

The tables show the proposed maximum allowable thermal loads and the energy standards for the climate zones.

Technical information about the changes

The proposed BASIX thermal performance and energy standards vary depending on;

- location based on climate

- building type for apartment buildings

Standards for most new residential buildings are proposed to increase across NSW from late 2022. Exceptions include apartment buildings up to 5 storeys and properties in the NSW North Coast climate zone.

The North Coast climate zones where standards won’t be changed are climate zones 9, 10 and 11 defined by the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS). They are predominantly on the NSW North Coast but also include Port Stephens and Maitland.

Other documents

Proposed BASIX Higher Standards

Cost Benefit Analysis report

BASIX Higher standards FAQ

Have your say

The government welcome your feedback on the proposed BASIX higher standards from Wednesday, 17 November until January 17 2022. The BASIX higher standards exhibition aligns with the Design and Place SEPP exhibition.

The exhibitions will close on the same day, currently expected in January 2022.

Visit: www.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/draftplans/exhibition/basix-higher-standards

Home Design To Drive Energy Bills Down

November 22, 2021

New sustainability standards for homes will save residents up to $980 a year on energy bills and reduce the State’s carbon footprint as we move to net-zero emissions by 2050.

The Building Sustainability Index (BASIX) is a key assessment tool that ensures new homes are comfortable to live in regardless of the temperature, are more energy efficient and save water.

Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Rob Stokes said BASIX had prevented 12.3 million tonnes of greenhouse gas over the past 17 years – equivalent to taking 2.5 million cars off the road.

“These proposed increases in standards will see more energy-efficient homes from Double Bay to Dubbo and beyond, with better design, better insulation, more sunlight and more solar panels,” Mr Stokes said.

“We want to lift BASIX standards even higher to drive down emissions further, saving another 150,000 tonnes a year and helping to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

“Better design will keep your home naturally cooler in summer and warmer in winter, so you won’t be turning the heater or air conditioner on as often.

Energy bills are expected to reduce significantly as a result of the new BASIX standards:

- Savings of up to $190 each year for people living in high-rise apartments;

- Savings of up to $850 each year for people living in new Western Sydney houses; and

- Savings of up to $980 a year for people living in new houses in the regions.

“To showcase the benefits of these new measures, we’re inviting up to 10 builders to test the proposed BASIX requirements ahead of its official roll out next year,” Mr Stokes said.

These new targets complement work underway, such as planting one million trees and investing $4.8 million to make building materials more environmentally friendly.

The community is encouraged to provide feedback on the proposed BASIX changes by Monday 31 January, 2022 at planningportal.nsw.gov.au/BAS IX- standards

Draft Marine Park Management Plan Released

New Plans To Protect Sydney's Koalas

December 2, 2021

Sydney's largest, and one of the state’s healthiest, koala populations will be further protected under new measures being implemented as part of the Cumberland Plain Conservation Plan (CPCP).

Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Rob Stokes said the changes put the protection of one of Australia’s most iconic threatened species at the heart of planning in south-west Sydney.

“After seeking advice from the NSW Chief Scientist & Engineer on the draft Plan, I’m pleased to confirm we are adopting all 31 recommendations to protect our critical koala population,” Mr Stokes said.

“We have updated the Plan to protect additional areas of habitat and ensure that wildlife corridors are suitable for koala movement.

Member for Penrith and Minister for Western Sydney Stuart Ayres said the koala population of the Greater Macarthur region is one of healthiest colonies in the state and one which continues to grow.

“It’s important that we support the region’s koala population, while also managing a growing community in Sydney’s south-west,” Mr Ayres said.

“This area is also rich in significant Aboriginal culture and history, and we’re committed to working more closely with Local Aboriginal Land Councils and Traditional Custodians to preserve this in our planning for the community.”

Environment Minister Matt Kean said one of the leading threats to koala populations in the wild, is the loss and fragmentation of their habitat.

“South West Sydney is home to the only disease-free koala populations in the Sydney basin and it is one of the most important koala populations anywhere in the state,” Mr Kean said.

“This advice from the NSW Chief Scientist & Engineer is crucial in protecting koala habitat in the Campbelltown and Macarthur regions as we finalise the implementation of the CPCP.

“As this part of Sydney continues to grow these recommendations will guide future development in the area and ensure koala habitat and wildlife corridors are protected in perpetuity.”

The Greater Macarthur 2040 Plan is also being finalised which will work alongside the CPCP to create koala movement corridors, improve connections and allow koalas to travel more safely throughout the region.

The CPCP and Greater Macarthur 2040 Plan are expected to be finalised and released in 2022.

For more information on the CPCP visit the CPCP web page.

_________________________________

Koala Underpasses Must Be Built Before Development: Greens

December 2, 2021

Today’s commitment by the NSW Government to enact all 31 of the Chief Scientist & Engineer’s recommendations to protect Campbelltown’s Koalas is welcome news for the community and koalas, however underpasses must be built and koala corridors protected before Lendlease starts any development, says Cate Faehrmann Greens MP and spokesperson for Environment and Wildlife.

The new measures will form part of the Cumberland Plain Conservation Plan and include commitments to build koala underpasses on Appin road and protect the east-west koala corridors. The commitment comes after the NSW Legislative Council passed a Greens motion calling on the Government to ensure the underpasses are built and corridors protected prior to the development.

“This is a welcome news for local residents who have been working tirelessly to see Campbelltown’s koalas protected for years now. They’ve been demanding more be done to protect this vital koala population from development and they’re being heard,” said Ms Faehrmann.

“There is a serious desire to see Campbelltown’s koalas protected from the threats posed by development in the south west Sydney Growth centre.

“Just a few weeks ago, the NSW Upper House overwhelmingly supported my motion calling for Appin Rd koala underpasses and corridors to be in place before construction begins.

“This latest commitment by the government is welcome but there are still questions over when the corridors and crossings will be completed. The government has known about how deadly Appin Rd has been for koalas for years and have sat on their hands while koalas continue to be killed.

“If the necessary protections aren’t in place before development begins the koala population will be hugely impacted by construction activities.

“Lendlease should not be allowed to put a shovel in the ground until these underpasses are in place,” said Ms Faehrmann.

Novel Implants To Protect Australia’s Wildlife From Feral Cats

New technology developed by the University of South Australia may put an end to predatory cat behaviours in native environments and help control Australia’s feral felines.

Using polymer chemistry principles, researchers at UniSA’s Applied Chemistry and Translational Biomaterials Group have created novel Population Protecting Implants (PPIs) to provide a targeted method for controlling invasive and problem feral cats.

The rice-sized implants are injected just under the skin of native animals, where they remain inert, only activating when digested by a feral predator. The result is deadly.

UniSA PhD student and 2021 recipient of an Australian Wildlife Society research grant, Kyle Brewer, says the PPIs could save hundreds of native animals that have been decimated by feral cats.

“Feral cats present a catastrophic threat for Australia’s wildlife as they occur across more than 99 per cent of Australia’s land area and kill more than 815 million mammals each year, the majority of which are native species,” Brewer says.

“Smaller, ‘meal size’ mammals are most at risk, especially ground-dwellers such as the bilby, bettong and quoll.

“Efforts to remove feral cats from a native landscape have had limited success, making it near impossible to re-establish threatened native populations outside a fenced area. Invariably, when native mammal reintroduction schemes are activated, they’re swiftly wiped out by an incursive feral cat.

“By injecting native species with the PPI before they are reintroduced to their natural environment, we’re providing a protective buffer that aims to take out the feral invader in one stroke.

“If a feral cat successfully preys upon one of the PPI-injected mammals, it eats the implant, which activates in the cat’s gastric system causing poison release and death. Ultimately, this protects the remaining native animal population.”

The PPIs are covered by a protective coating and contain a toxin derived from a natural poison in native plants. They present no danger to tolerant native mammals but are deadly once the toxin is activated in the introduced predator’s stomach.

Brewer’s project is a collaborative effort, with researchers from local ecology groups, Ecological Horizons and Peacock Biosciences, and the University of Adelaide, already trialling PPIs in South Australia.

Currently, 30 bilbies have been implanted with PPIs at Arid Recovery, a 123 km2 wildlife reserve in South Australia’s north. Results from this trial are expected to demonstrate the effectiveness of the technology and lead to its commercialisation.

Feral cats threaten the survival of more than 100 native species in Australia and have caused the extinction of many ground-dwelling birds and small to medium-sized mammal species.

“We need to pounce on any opportunity to protect our native species. Nine lives no more for feral cats.”

More than 200 Australian birds are now threatened with extinction – and climate change is the biggest danger

Up to 216 Australian birds are now threatened – compared with 195 a decade ago – and climate change is now the main driver pushing threatened birds closer to extinction, landmark new research has found.

The Mukarrthippi grasswren is now Australia’s most threatened bird, down to as few as two or three pairs. But 23 Australian birds became less threatened over the past decade, showing conservation actions can work.

The findings are contained in a new action plan released today. Last released in 2011, the action plan examines the extinction risk facing the almost 1,300 birds in Australia and its territories. We edited the book, written by more than 300 ornithologists.

Without changes, many birds will continue to decline or be lost altogether. But when conservation action is well resourced and implemented, we can avoid these outcomes.

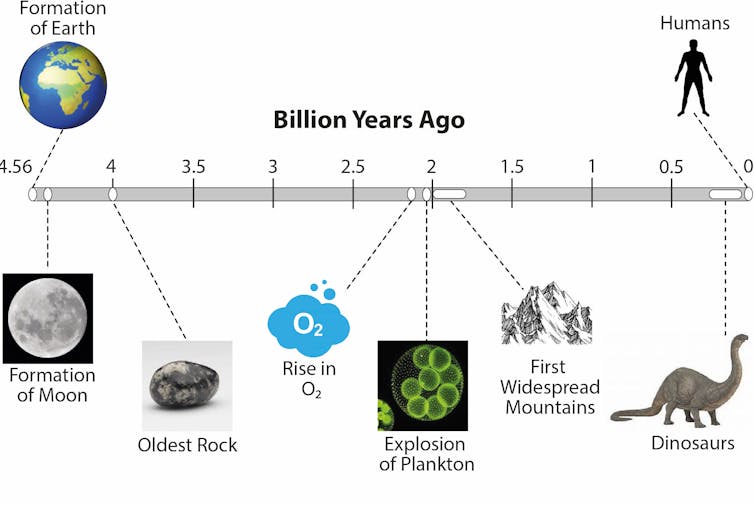

The Numbers Tell The Story

The 216 Australian birds now at risk of extinction comprise:

- 23 critically endangered

- 74 endangered

- 87 vulnerable

- 32 near-threatened.

This is up from 134 birds in 1990 and 195 a decade ago.

We assessed the risk of extinction according to the categories and criteria set by the International Union for Conservation of Nature in its Red List of threatened species.

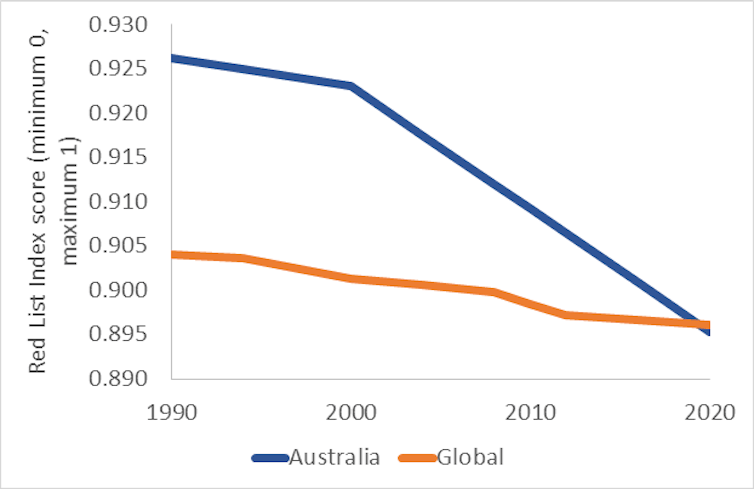

As the below graph shows, the picture of bird decline in Australia is not pretty – especially when compared to the global trend.

What Went Wrong?

Birds are easily harmed by changes in their ecosystems, including introduced species, habitat loss, disturbance to breeding sites and bushfires. Often, birds face danger on many fronts. The southeastern glossy black cockatoo, for example, faces no less than 20 threats.

Introduced cats and foxes kill millions of birds each year and are considered a substantial extinction threat to 37 birds.

Land clearing and overgrazing are a serious cause of declines for 55 birds, including the swift parrot and diamond firetail. And there is now strong evidence climate change is driving declines in many bird species.

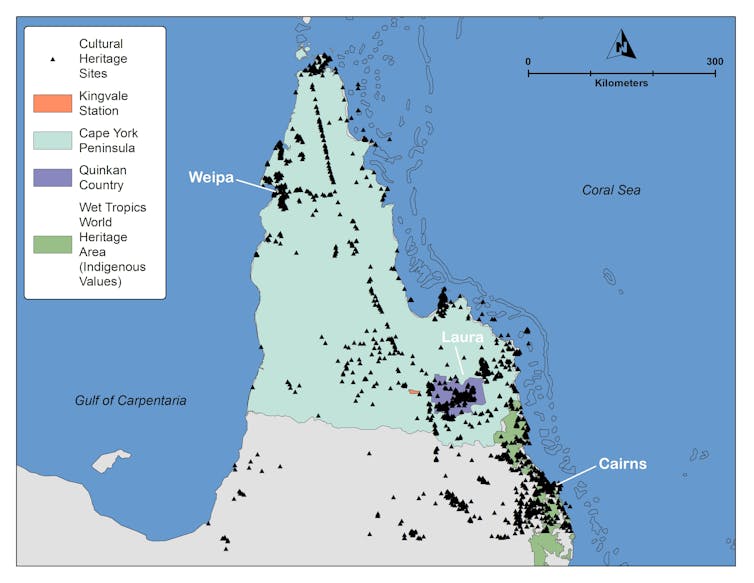

A good example is the Wet Tropics of far north Queensland. Monitoring at 1,970 sites over 17 years has shown the local populations of most mid- and high-elevation species has declined exactly as climate models predicted. Birds such as the fernwren and golden bowerbird are being eliminated from lower, cooler elevations as temperatures rise.

As a result, 17 upland rainforest birds are now listed as threatened – all due to climate change.

The Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20 – which were exacerbated by climate change – contributed to the listing of 27 birds as threatened.

We estimate that in just one day alone – January 6, 2020 – about half the population of all 16 bird species endemic or largely confined to Kangaroo Island were incinerated, including the tiny Kangaroo Island southern emu-wren.

Some 91 birds are threatened by droughts and heatwaves. They include what’s thought to be Australia’s rarest bird, the Mukarrthippi grasswren of central west New South Wales, where just two or three pairs survive.

Climate change is also pushing migratory shorebirds towards extinction. Of the 43 shorebirds that come to Australia after breeding in the Northern Hemisphere, 25 are now threatened. Coastal development in East Asia is contributing to the decline, destroying and degrading mudflat habitat where the birds stop to rest and eat.

But rising seas as a result of climate change are also consuming mudflats on the birds’ migration route, and the climate in the birds’ Arctic breeding grounds is changing faster than anywhere in the world.

The Good News

The research shows declines in extinction risk for 23 Australian bird species. The southern cassowary, for example, no longer meets the criteria for being threatened. Land clearing ceased after its rainforest habitat was placed on the World Heritage list in 1988 and the population is now stable.

Other birds represent conservation success stories. For example, the prospects for the Norfolk Island green parrot, Albert’s lyrebird and bulloo grey grasswren improved after efforts to reduce threats and protect crucial habitat in conservation reserves.

Intensive conservation efforts have also meant once-declining populations of several key species are now stabilising or increasing. They include the eastern hooded plover, Kangaroo Island glossy black-cockatoo and eastern bristlebird.

And on Macquarie Island, efforts to eradicate rabbits and rodents has led to a spectacular recovery in seabird numbers. The extinction risk of nine seabirds is now lower as a result.

There’s also been progress in reducing the bycatch of seabirds from fishing boats, although there is much work still to do.

Managing Threats

The research also examined the impact of each threat to birds – from which we can measure progress in conservation action. For 136 species, we are alarmingly ignorant about how to reduce the threats – especially climate change.

Some 63% of important threats are being managed to a very limited extent or not at all. And management is high quality for just 10% of “high impact” threats. For most threats, the major impediments to progress is technical – we don’t yet know what to do. But a lack of money also constrains progress on about half the threats.

What’s more, there’s no effective monitoring of 30% of the threatened birds, and high-quality monitoring for only 27%.

Nevertheless, much has been achieved since the last action plan in 2010. We hope the new plan, and the actions it recommends, will mean the next report in 2030 paints a more positive picture for Australian birds.![]()

Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University and Barry Baker, University associate, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photos from the field: leaving habitats unburnt for longer could help save little mammals in northern Australia

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

Native small mammals such as bandicoots, tree-rats and possums have been in dire decline across Northern Australia’s vast savannas for the last 30 years – and we’ve only just begun to understand why.

Feral cats, livestock, wildfires, and the complex ways these threats interact, have all played a crucial role. But, until now, scientists have struggled to pinpoint which factor was the biggest threat.

Our new research points to fire. In the most comprehensive study of small mammals and the threats they face in northern Australia, we found the length of time a habitat is left unburnt determines the number of different mammal species present, and their abundance.

This is important because Northern Australia’s tropical savanna is one of the most fire-prone regions on the planet. Our findings suggest we need to change the way we manage wildfires so we can help native wildlife come back from the brink.

The Last Mammal Stronghold

The remote and breathtakingly beautiful Northern Kimberley is the only place in mainland Australia where there have been no mammal extinctions. Instead, it’s a stronghold for species that are now extinct or in decline elsewhere in northern Australia, such as golden-backed tree-rats, brush-tailed rabbit-rats and northern quolls.

It’s also home to species found nowhere else in Australia, such as the monjon (the world’s smallest rock-wallaby), the hamster-like Kimberley rock rat, and the enigmatic scaly-tailed possum.

But wildfires are a significant threat to these small mammals, as well as many other plants and animals, with many officially listed as endangered or vulnerable.

Fire is a fundamental part of savanna ecology, and up to 50 million hectares burn each year. This means only a small proportion of the landscape remains unburnt for longer than four years.

This fire-proneness is driven by the monsoon climate. Wet season rainfall causes grass to grow rapidly, and a prolonged dry season causes these grasses to dry out, creating fuel. Lightning and other ignition sources from the mid to the end of the dry season from August to December result in frequent and massive high-intensity wildfires. Climate change may be exacerbating this threat.

Fire managers, largely led by Indigenous rangers as well as state government agencies and conservation organistations, use low intensity prescribed burning in the early dry season, when vegetation is moist and conditions are cooler. This produces patchy fire scars that limit the spread of the inevitable wildfires later in the dry season.

There’s ample evidence this approach is highly effective. And yet, mammals continue to decline, and scientists have been criticised for not having the answers.

What We Found

We’ve been studying small mammals in the Northern Kimberley for the last ten years, amassing the one of the largest datasets for any study in northern Australia.

Our work confirms the critical role of feral cats and livestock (such as buffaloes, horses, cattle and donkeys) in mammal declines. Sites with more cats and livestock had fewer native mammals.

However, the most vital factor was vegetation that remained unburnt for four or more years – whether from wildfires or prescribed burns. Sites with longer unburnt vegetation, including with fruiting shrubs and trees, had far more mammals.

We also tested an age-old debate in fire management: does pyrodiversity create greater wildlife diversity?

Pyrodiversity refers to the number of patches within a landscape, with different times since the last fire, and is something fire managers try to achieve.

However, we found pyrodiversity had a negative influence on mammals. Unburnt vegetation was the only attribute that explained the higher abundance and diversity of small mammal species.

What’s more, the benefits for small mammals increase with the size of the unburnt patch – bigger is better. These longer unburnt patches provide critical resources such as food from fruiting trees and shrubs, and shelter including tree hollows and hollow logs. They also help small mammals to evade feral cats.

A Conundrum For Fire Managers

Our findings present fire managers with a conundrum. While it’s vital to mammals, large unburnt patches are often targeted because they burn more easily and are often viewed as being risky.

We’re not suggesting there should be no prescribed burning or that current fire management has adverse effects on small mammals. In fact, we need around 25% of savannas to be burnt under milder fire-weather conditions each year to maintain longer unburnt vegetation and, therefore, achieve the best results for mammals.

However, our study does suggest fire management needs to be more nuanced than simply reducing wildfires. We mustn’t lose sight of the need to look at longer term fire patterns.

Fire management in northern Australia is already highly sophisticated. Advances in fire scar and landscape mapping mean we have tools at our disposal to take a more strategic approach.

For example, we can identify refuge areas for mammals, as well as areas that are naturally less fire prone. We can decrease the randomness of prescribed burning by focusing on recently burnt areas and landscape features, such as rivers and cliffs, that maximise the stopping power of strategic fire scars.

Indeed, ideas for more strategic fire management, with ecologically meaningful management targets, have been championed for some time, and are being further refined.

But monitoring and reporting on this needs to become more widespread, and coordinated across different fire-managed areas. New fire reporting tools, such as the Savanna Monitoring and Evaluation Reporting Framework, will help make this happen.

We realise achieving this across northern Australia’s vast and remote landscapes is a formidable and expensive undertaking. But it’s essential adequate and targeted monitoring is embedded within fire management programs, so we can better track wildlife responses. ![]()

Ben Corey, Adjunct Research Associate, Charles Darwin University; Ian Radford, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, Charles Darwin University, and Leigh-Ann Woolley, Adjunct Research Associate, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s Black Summer of fire was not normal – and we can prove it

Garry Cook, CSIRO; Andrew Dowdy, Australian Bureau of Meteorology; Juergen Knauer, CSIRO; Mick Meyer, CSIRO; Pep Canadell, CSIRO, and Peter Briggs, CSIROThe Black Summer forest fires of 2019–2020 burned more than 24 million hectares, directly causing 33 deaths and almost 450 more from smoke inhalation.

But were these fires unprecedented? You might remember sceptics questioning the idea that the Black Summer fires really were worse than conflagrations like the 1939 Black Friday fires in Victoria.

We can now confidently say that these fires were far from normal. Our new analysis of Australian forest fire trends just published in Nature Communications confirms for the first time the Black Summer fires are part of a clear trend of worsening fire weather and ever-larger forest areas burned by fires.

What Did We Find?

Our study found that the annual area burned by fire across Australia’s forests has been increasing by about 48,000 ha per year over the last three decades. After five years, that would be roughly the size of the entire Australian Capital Territory (235,000 hectares).

We found three out of four extreme forest fire years since states started keeping records 90 years ago have occurred since 2002.

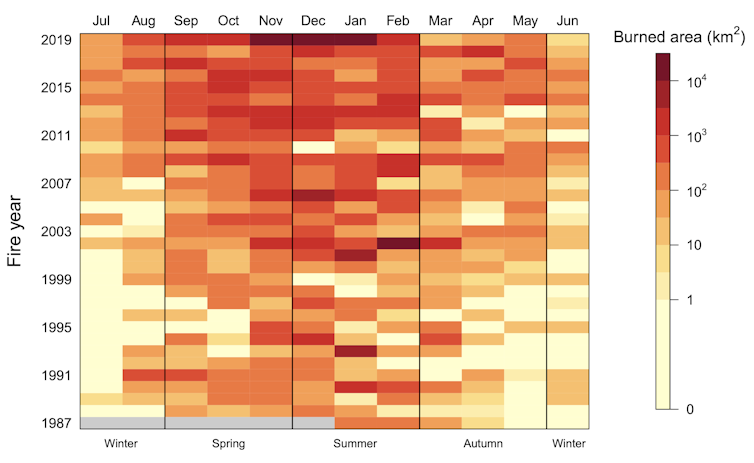

And we found that the fire season is growing, moving out of spring and summer into autumn and winter.

These trends are almost entirely due to Australia’s increasingly severe fire weather and are consistent with predicted human-induced climate change.

Our study is based on satellite and ground-based estimates of burnt forest area, and trends of nine wildfire risk factors and indices that relate to characteristics of fuel loads, fire weather, extreme fire behaviour, and ignition.

We have focused here only on the most dangerous forest fires, not the fires affecting Australia’s savanna across the tropical north.

Fire Burns Much More Land Than 25 Years Ago

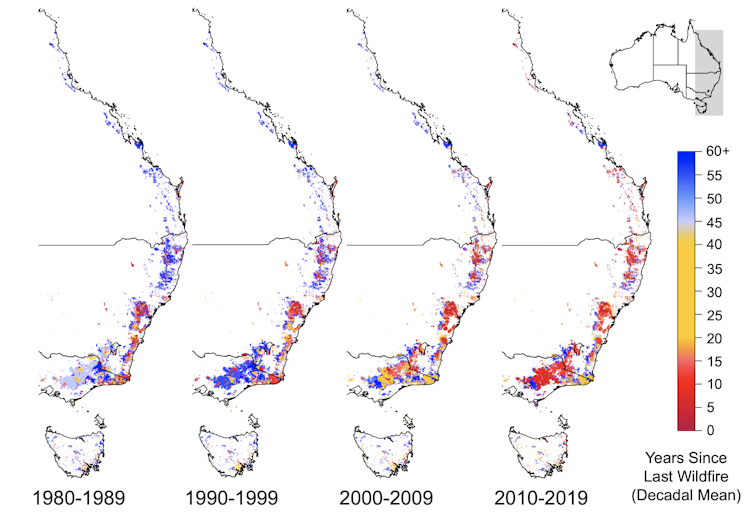

Before the 1990s, Australia’s forest fires were infrequent, though damaging. A given area would burn at an interval between 20 to over 100 years.

The exception were rare summers which would see severe and extensive fires, such as 1939. Overall, only a small fraction of the total forest area burned in any year.

This pattern of fire behaviour no longer exists.

Over the last 30 years, the areas affected by fire have grown enormously.

If we compare the satellite records from 1988–2001 to the period from 2002–2018, the annual average fire area has shot up by 350%.

If we include the 2019–20 Black Summer fires, that figure soars to 800% – an enormous leap.

We are seeing fires growing the most in areas once less likely to be affected by fire, such as cool wet Tasmanian forests unaccustomed to large fires as well as the warmest forests in Queensland previously kept safe from fire by rainfall and a humid microclimate. This includes ancient Gondwanan rainforests not adapted for fire.

More Extreme Fire Years And Longer Fire Seasons

Before 2002, there was just one megafire year in the 90 years Australian states have been keeping records – and that was 1939.

Since 2001, there have been three megafire years, defined as a year in which more than one million hectares burn.

Our fire seasons are also getting longer. Spring and summer used to be the time most forest fires would start. That’s no longer guaranteed.

Since 2001 winter fires have soared five-fold compared to 1988–2001 and autumn fires three-fold.

Overall, fires in the cooler months of March to August are growing exponentially at 14% a year.

What’s Driving These Changes?

Imagine a forest fire starts from a lightning strike in remote bushland. What are the factors which would make it grow, spread and intensify?

A fire will get larger and more dangerous if it has access to more fuel (dry grass, fallen limbs and bark), and if the fire starts when the weather is hotter, drier and windier. Topography also plays a role, with fire able to move much faster uphill.

To get a sense of the overall risk of forest fire, temperature, humidity, windspeed and soil moisture are combined into a single figure, the Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI).

As you might expect, this index has been steadily worsening over the past 40 years. The number of very high fire danger days in forest zones has been increasing by 1.6 days per decade.

So what does this mean for fire behaviour and spread?

In what we believe is a first, we have used 32 years of fire index data across Australia’s forest zones and compared the number of very high or severe fire danger days with areas subsequently burnt by fire.

We found a clear link, with a 300 to 500% increase in burnt area for every extra day of severe fire danger, and a 21% increase in burnt area for every extra day of very high fire danger.

Could fuel loads or prescribed burning be to blame? No. We looked for trends in these factors, and found nothing to explain the rise in burnt areas.

The main driver for the growing areas burnt by fire is Australia’s increasingly severe fire weather, accounting for 75% of the variation observed in the total annual area of forest fires. This is consistent with predictions from climate change scenarios that severe fire weather conditions will intensify due to increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Other fire weather risks are also growing. We’re seeing more higher atmospheric conditions which can lead to the formation of fire-generated thunderstorms (known as pyrocumulonimbus clouds).

These thunderstorms emerging out of fire plumes can spread burning embers further and whip up more dangerous winds for unpredictable fire behaviour on the ground, as well as generate lightning in the fire plume that can ignite new fires far ahead of the fire front.

Dry lightning is the primary natural cause of fire ignitions. Here too, the trends are worsening in southeast Australia. We are now seeing 50% more dry lightning in forest areas in recent decades (2000–2016) compared to the previous two (1980–1999).

Under most climate change scenarios, fire weather is predicted to keep on worsening.

Can We Predict Our Next Megafire?

So could we have predicted how bad and how widespread the Black Summer fires would have been, if we had examined fire danger index forecasts in mid-2019?

In short, yes.

The huge amount of bush that burned is entirely consistent with the 34 days of very high forest fire danger across the forest zones that summer. That’s in line with the long-range bushfire weather forecasts provided to fire agencies earlier in 2019.

This means that in future years, we will be able to broadly predict the area likely to burn each fire season by examining fire index forecasts.

We can also safely – and sadly – predict that more and more of Australia will burn in years to come, with increasing numbers of megafire years.

While many factors contribute to catastrophic fire events, our Black Summer was not an aberration.

Rather, it was the continuation of fire trends beginning more than two decades ago. It is now clear that human-induced climate change is creating ever more dangerous conditions for fires in Australia.

We need to be ready for more Black Summers – and worse.![]()

Garry Cook, Honorary Fellow, CSIRO; Andrew Dowdy, Principal Research Scientist, Australian Bureau of Meteorology; Juergen Knauer, Research fellow, CSIRO; Mick Meyer, Post Retirement Fellow, CSIRO; Pep Canadell, Chief research scientist, Climate Science Centre, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere; and Executive Director, Global Carbon Project, CSIRO, and Peter Briggs, Scientific Programmer and Data Analyst, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s biggest fossil fuel investment for a decade is in the works – and its greenhouse gas emissions will be horrifying

The controversial Scarborough gas project off Western Australia will cause a substantial rise in greenhouse gas emissions at a time when the world must rapidly decarbonise, new analysis released today shows.

The A$16 billion plan by Woodside Petroleum has been described as Australia’s biggest new fossil fuel investment in nearly a decade. The report, produced by Climate Analytics, a research organisation I help lead, is the first to examine the full climate impact of the entire expansion project.

The Morrison government has put the gas industry at the heart of its economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. But as the Scarborough example shows, such projects makes it less likely the world will meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The sheer scale of emissions from the expansion, and projects linked to it, will make achieving 2030 emissions targets much harder for Western Australia and, by extension, Australia and the world.

Emissions Worse Than We Thought

Woodside’s expansion proposal involves developing the Scarborough offshore gas field 375 kilometres off Australia’s northwest coast. It also includes a new pipeline to the company’s onshore Pluto processing facility on the Pilbara coast, and expansion of that facility.

Woodside last week announced it had approved the final investment decision on the developments. Chief executive Meg O'Neill said the project “supports the decarbonisation goals of our customers in Asia”.

Our study examines the full emissions implications of the expansion and associated projects, including domestic gas supply and a proposed project converting gas to hydrogen.

Estimates of the entire projects’ greenhouse gas implications are spread across several reports and documents. This report assembles these for the first time. The research was commissioned by the Conservation Council of Western Australia.

We examined the emissions from the gas facilities themselves, and emissions that will, or are likely to, occur as a result of the project. This second group of emissions includes locked-in domestic demand for natural gas and overseas export markets burning its product for energy.

We estimate that by 2055, the expansion and associated projects will emit 1.37 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases. Almost 20% is projected to be emitted in Western Australia and the rest would be emitted overseas where the exported gas will be burnt.

The total emissions we calculate is far more than the 878 million tonnes Woodside says the project will emit.

In a statement to The Conversation, a Woodside spokeswoman said its emissions figure was “correct and has been accepted by the federal regulator NOPSEMA”.

However the NOPSEMA report covers only the emissions that come from gas derived from the Scarborough gas field and not the emissions from the entire Pluto expansion. In contrast, Woodside’s greenhouse gas action plan is based on the entire Pluto expansion, including all aspects of the project we included in our calculations.

Woodside said Scarborough gas, used to generate electricity, could power ten cities the size of Perth for 30 years and the emissions would be around half those for the same electricity generated from coal.

However, we found that introducing Scarborough-Pluto gas into electricity grids of countries decarbonising in line with the Paris Agreement would raise greenhouse gas emissions by several hundred million tonnes between 2026 and 2040.

Questionable Emissions Reduction Plan

Woodside says its “greenhouse gas abatement program” shows how the company will offset a substantial amount of emissions. We believe that plan, approved by the WA government, is questionable on several counts.

For example, a Woodside project approved in 2006 at 12 million tonnes of LNG per year was later scaled down. However, Woodside’s plan for emissions reduction plan comes off the earlier high-emissions baseline.

Woodside proposes to reduce emissions reductions using carbon offsets (removing CO₂ from the atmosphere in one place to compensate for emissions made elsewhere). But there appears to be no guarantee these offsets would not have occurred as part of Woodside’s usual business operations.

Woodside says it plans to abate all emissions from the project by 2050. But most of this emissions reduction will not occur until after 2040, and depends on factors such as the availability of technology, government policy and the availability of carbon offsets for purchase.

Woodside has also not accounted for expected global increases in the price of carbon offsets. We calculate that by 2050, the cost of offsets could comprise between 21% and 71% of Woodside’s export revenue for liquified natural gas.

Bad News For Net-Zero

In May this year, the International Energy Agency said no new oil and gas fields can be developed if the world is to meet the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 and avert catastrophic global warming.

This, in our view, includes the Scarborough-Pluto expansion. Introducing gas from the project into electricity grids of importing nations would slow global decarbonisation efforts.

Big buyers of Australian gas, such as South Korea and Japan, are moving away from fossil fuels and towards green hydrogen and renewable energy. This suggests a softening, or even collapse, in demand for LNG this decade – a trend consistent with assessments by the International Energy Agency and Australia’s Reserve Bank.

For Woodside, the Scarborough-Pluto expansion is increasingly looking like a stranded asset. And the WA government’s support for the project, and the broader gas industry, means it’s missing out on massive, and growing, opportunities in renewable energy and green hydrogen exports.![]()

Bill Hare, Adjunct Professor, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Labor’s 2030 climate target betters the Morrison government, but Australia must go much further, much faster

Wesley Morgan, Griffith UniversityThe Labor opposition has pledged to reduce Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions by 43% this decade based on 2005 levels, claiming the plan will create jobs, cut power bills, boost renewables and provide business certainty.

Labor says the policy would create 604,000 jobs – mostly in regional areas – unlock A$52 billion in private sector investment in Australian industry, and cause electricity prices to fall by $275 per household by 2025.

Announcing the policy on Friday, Labor leader Anthony Albanese said the plan was backed by comprehensive modelling. He said Labor has produced a policy Australia can be proud of, while the Morrison government was “frozen in time while the world warms around it”.

Labor’s emissions-reduction goal is a significant step up on what the Morrison government has offered – 26-28% over the same time frame. And it’s a firm step to build on in coming years.

But it falls short of what experts say is needed for Australia to do its share on emissions reduction under the Paris Agreement, and is less ambitious than the targets adopted by Australia’s international peers.

What The Science Says Is Needed

While Labor’s 2030 target is higher than the Coalition’s, and provides a solid foundation on which to build, it still falls well below what the science says is necessary.

Earlier this year an independent Climate Targets Panel - made up of high-profile Australian climate scientists and experts - examined the action required by Australia if it’s to act consistently with the Paris Agreement goals.

To do its share in limiting global warming to below 1.5℃ this century, Australia must cut emissions by 75% below 2005 levels this decade. Limiting warming to well below 2℃ this century would require a 50% emissions reduction in the same time frame.

The last official government review of Australia’s climate targets was conducted by the Climate Change Authority, and updated in 2015. It found that to act in line with the 2℃ goal, Australia should aim for 45–65% emissions reduction by 2030, based on 2005 levels.

Notably, the Coalition government ignored this recommendation when it set Australia’s 2030 target of 26-28%. This recommendation is also more ambitious than the target announced by Labor today.

The Global Picture

The Glasgow Climate Pact, agreed to at COP26 last month, called on nations to bring a stronger 2030 target to the next United Nations conference in November 2022. It said limiting global warming to 1.5℃ would require global emissions reduction of at least 45% below 2010 levels by 2030.

To play their part, wealthy nations need to cut emissions by much more than 45% this decade. This particularly applies to Australia – a skilled, wealthy, developed nation blessed with sunshine and wind.

While the Glasgow pact uses a baseline year of 2010 rather than Australia’s 2005, our national emissions were similar in both years. So Labor’s new 43% commitment approaches, but still falls short of, the Glasgow pact.

Pacific island countries have called on Australia to cut emissions by at least 50% by 2030. So again, Labor’s target comes close but does not actually fulfil what island states want to see from Australia to help ensure their survival.

Labor’s 43% target also brings us closer to, but not into line with, our major allies. Over the same time frame, the United States is aiming for a 50-52% reduction, Japan 46% and New Zealand 50%. The United Kingdom plans to reduce emissions by 68% below 1990 levels, and the European Union 55%.

And special treatment afforded Australia under the Kyoto protocol – the precursor to the Paris Agreement – means the country is uniquely advantaged. We are allowed to count emissions from land use change in the base year from which emissions reduction is measured – something most countries don’t do.

Because of this, an Australian commitment to 43% below 2005 levels - a year when land use emissions were high - involves far less real-world emissions reduction than that of our international peers.

Building On The Work Of Others

Thanks to the head-start gifted by the states and territories, Australia could achieve emissions reduction far beyond the target set by Labor with just a modest amount of federal effort.

The Morrison government may claim Australia’s woeful 2030 target is “fixed”, but state and territory commitments made it redundant long ago.

The two most populous states – New South Wales and Victoria – both plan to halve their emissions over the same period. South Australia and the ACT intend to outperform even that, and Tasmania is already at net-zero emissions.

Even in Western Australian – where energy sector emissions have grown by two-thirds since 2005 as a result of unrestrained gas expansion – the state government announced yesterday it will establish a process to set emissions reductions targets in line with its net-zero goal.

Assuming state targets are only met and not exceeded, Australia’s emissions would fall by 34% from 2005 levels by 2030 with no effort from the federal government whatsoever.

In 2019, the Business Council of Australia loudly opposed Labor’s 2030 target of 45% below 2005 levels in 2030. In the context of increased state and territory ambition, it has now adopted this target as its own. Far from being “economy-wrecking” or other such hyperbole, such a target is in fact a humble but important additional effort that builds on existing state and territory action.

As has been shown time and again – most recently just yesterday in research the Climate Council commissioned from Deloitte Access Economics – good climate policy is good economic policy, and will drive job creation in regional areas.

Setting a stronger 2030 target is important for driving investment in the clean energy economy of the future. Australia is well-placed to take advantage of a world shifting toward net-zero emissions, and it makes no sense to delay the inevitable transition. This is especially so when Australia is so acutely vulnerable to climate impacts.

Go Further, Faster

Announcing the policy on Friday, Albanese said the planned emissions reduction was consistent with that of Canada, which has a comparable economy.

If Labor wins government at next year’s election, Australia could “go to international climate conferences and not be in the naughty corner”, Albanese said. “I wanted to make sure we have a policy that doesn’t leave people behind, that supports industry, supports jobs and gets the balance right.”

There’s no question that Labor’s target is inadequate. But it provides a solid framework for further action in the next decade.

Any federal government that implements meaningful policy to reduce emissions will quickly realise it’s in Australia’s interests to go further, faster. Doing so will leave households better off, grow jobs in regional Australia, and ensure we play a role in the global effort to avert climate catastrophe.![]()

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute and Climate Council researcher, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most Australian households are well-positioned for electric vehicles – and an emissions ceiling would help

Many people believe Australia’s shift to electric vehicles is stuck in the slow lane – another strollout, rather than a rollout. But while federal policies are still lacklustre, most Australians themselves are ready for the shift, according to our recent research.

We found most car-owning households will be able to charge their cars in their garage or driveway. Electric vehicles are also getting more attractive as purchase costs fall and battery range rises.

Australia’s world-beating solar uptake is another plus. Many of our three million solar households would be able to effectively charge their cars for free at daytime.

Surveys have found 56% of Australians would consider going electric with their next car purchase, while the share of consumers who would not purchase an electric car is declining quickly.

Will Electric Vehicles Come Suddenly Or Slowly?

The shift will not be sudden and disruptive but gradual, as people trade in their old petrol clunkers for sleek new electric vehicles. Many will buy an electric car for everyday driving, while holding onto a petrol or diesel SUV for longer trips. No weekends need be sacrificed.

About half of Australia’s car-owning households live in houses with off-street parking and own more than one car. These households will be the first to shift to electric cars.

Almost all owners charge their electric vehicles at home. For most houses with off-street parking, charging a vehicle is as simple as getting an electrician to check your wiring and install an outlet in your garage or near your driveway. In most cases installation isn’t expensive.

Some households will install a small charger on the wall of their garage to speed up the charging process, which will mean they can completely charge their electric vehicle overnight.

But what about range anxiety and sticker shock, two issues many consumers cite?

While surveys still show drivers worry about battery range for electric vehicles, the underlying technology is improving year by year. As batteries get better and cheaper, these issues will fade into memory. Technology isn’t standing still.

This year, for instance, electric vehicles came on market in Australia with a battery range of up to 650km, and on average 400km. That’s more than enough for common weekend round trips, such as Melbourne to Phillip Island (280km), Sydney to Kiama (260km), or Brisbane to Sunshine Coast (200km).

While everyone knows running an electric vehicle is cheaper than petrol or diesel – due to much cheaper energy and vastly reduced maintenance costs – the upfront cost has to date been a deterrent. That, too, is changing.

The cost of an electric car is falling. Price parity in many market segments should be reached by the mid 2020s. That means one-car households who currently rely on utes or 4WDs for weekend trips will be able to easily switch in time to contribute to our target of net-zero by 2050 target.

Not only that, but our research has found the number of public electric vehicle chargers has soared to more than 2500 standard chargers. There are now almost 500 fast chargers, which can get your electric vehicle back to 80% charged in under an hour.

How Can We Shift To Electric Vehicles Faster?

For us to reach net zero by 2050, we need electric vehicles to make up an increasing share of Australia’s cars. The federal government is belatedly embracing the technology as part of the new 2050 target.

While Australia is increasingly ready to shift, at present electric vehicles still make up less than 1% of new car sales. By contrast, Norway will sell its last fossil fuel-powered car next year if current trends hold.

At present, many manufacturers have skipped Australia entirely to focus on more attractive markets, leaving us with a limited range and older models.

So what needs to happen? As our report explains, the best way to bring down prices and increase the variety of electric vehicles is for the federal government to introduce an “emissions ceiling” on new vehicles.

This ceiling would limit the average emissions from vehicles and encourage manufacturers to bring Australia’s electric vehicle range up to par with the rest of the world.

Do these policies work? In a word, yes. Countries with emissions ceilings in place have a much wider range of electric vehicles for sale. Last year there were only 31 zero-emissions vehicles for sale in Australia, compared to more than 130 in the United Kingdom.

If we had an emissions ceiling in place, drivers would find it easier to switch to electric vehicles, as more choice brings cheaper cars and a wider range. Of course, no one would be forced to shift. Those who want to wait for an electric ute or SUV will be able to.

While people who own detached homes with off-street parking will find it easier to switch to electric cars, Australians who rent or live in apartments may find it harder or more expensive to get a charger installed at home.

Once homeowners with offstreet parking begin to shift to electric vehicles, charging will get easier for everyone else. Why? Because the increase in electric vehicles will prompt commercial operators to add more and more public chargers in accessible locations. The federal government’s Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy also has plans to close gaps in the network.

If you want a glimpse of the future, look at South Korea. There, companies are building ultra-fast charging stations as a replacement for petrol stations, offering recharging in under 20 minutes and a cafe to fill the time. In the near future we’ll use clean, fume-free charging stations like these in the same way we use petrol stations today.

As a bonus for switching, the air in our cities will become ever cleaner, and traffic noise will plummet.

Even if our leaders drag their feet on electric cars, we don’t need to. Australians are ready to swap petrol for electric. And we’ll never look back.![]()

Ingrid Burfurd, Senior Associate, Transport and Cities Program, Grattan Institute, Grattan Institute