inbox and environment news: Issue 523

January 23-29, 2022: Issue 523

Summer Babies 1: Butcher Bird + A 1953 Insight On These By Bill Grayden

"Do Try This Scorpion," Said The Butcher Bird

Summer Babies 2: Bluetongue Lizard

Avalon Dunes Bushcare

World Wetlands Day 2022

Birds Flock To Breed In North-West NSW Wetlands

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

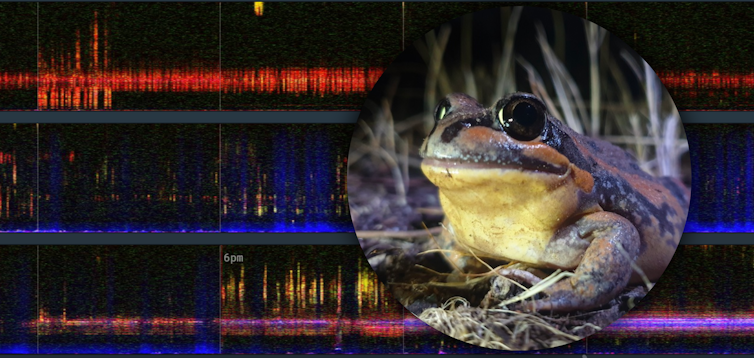

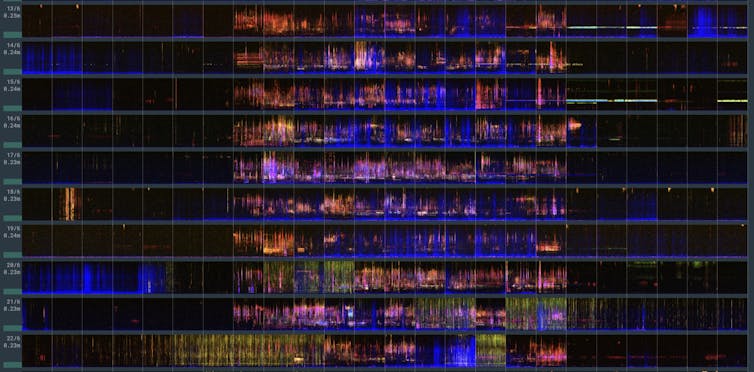

Citizen Scientists Needed To Help Record Impact Of Fires On Biodiversity

January 18, 2022

UNSW Sydney scientists are behind a citizen science event that will document the bushfire recovery of plants, animals and fungi across three bushfire affected regions in New South Wales.

UNSW Sydney scientists are behind a citizen science event that will document the bushfire recovery of plants, animals and fungi across three bushfire affected regions in New South Wales.

The Big Bushfire BioBlitz starting on February 25 is a series of weekend-long events which will generate new evidence on the impacts of large-scale fire on biodiversity.

The BioBlitzes will take place in the Gondwana Rainforests of Washpool National Park, the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, and Murramarang National Park on the south coast.

Thomas Mesaglio, iNaturalist curator and PhD candidate at the UNSW Evolution & Ecology Research Centre, said that the BioBlitzes will give people the opportunity to contribute meaningful biodiversity data that inform our understanding of how the environment recovers after large scale bushfires, and in turn contribute to research and conservation.

“A ‘bioblitz’ is a focused effort to record as many species as possible in a defined location within a limited period of time,” Mr Mesaglio said.

“Citizen science events such as bioblitzes provide an invaluable opportunity to maximise the amount of data collection, intensely focusing on particular areas, as well allowing people of all skill levels to be involved.

“Participants get to interact with and learn from experts, and also offer their own local expertise and insights to the experts, so it’s a fantastic two-way transfer of knowledge.

“These events are also great for motivating participants to become long-term contributors to citizen science platforms such as iNaturalist.”

Experts – including from one of the partner scientific organisations, the Australian Museum – will lead biodiversity events over the weekends.

Casey Kirchhoff, PhD candidate at the UNSW Centre for Ecosystem Science, founded the Environment Recovery Project on the iNaturalist website after the devastating Southern Highlands’ Morton bushfire destroyed her Wingello home in January 2020.

“Citizen scientists have been really motivated since the 2019-2020 bushfires,” Mrs Kircchoff said.

“We’ve already had over 17,500 observations of bushfire recovery submitted to the Environment Recovery Project.

“We’ve been delayed by COVID-19, but it’s great to finally have the opportunity to engage more directly with some of the bushfire impacted communities through citizen science at the bioblitzes.

“The more observations we can collect, the more we will know about the impact of the fires on our environment.”

While not everyone will be able to make it to an in-person bioblitz, everyone who can access a bushfire-impacted area right across Australia is encouraged to participate.

“The Big Bushfire BioBlitz iNaturalist project will be open to every citizen scientist keen to ‘bioblitz’ their own area, no matter if they’re in Western Australia or Kangaroo Island,” Mrs Kirchhoff said.

The iNaturalist community has more than 88 million biodiversity records and links to Australia’s leading open-access biodiversity data platform, the Atlas of Living Australia, where everybody from scientists and policymakers to the general public can access a wealth of biodiversity information.

The bioblitzes are supported through the Australian government’s Regional Bushfire Recovery Fund and UNSW’s Centre for Ecosystem Science, in partnership with the Atlas of Living Australia, Minderoo’s Fire and Flood Resilience Initiative and the Australian Citizen Science Association.

- BioBlitz 1: Blue Mountains, Friday 25 February – Sunday 27 February 2022

- BioBlitz 2: Washpool National Park, Friday 4 March – Sunday 6 March 2022

- BioBlitz 3: Murramarang National Park, Friday 11 March – Sunday 13 March 2022

Register for the Big Bushfire BioBlitz.

The Atlas of Living Australia is Australia’s national biodiversity data infrastructure funded by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) and hosted by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO. image; Scientists are hoping that people of all skill levels will get involved in the forthcoming 'bioblitzes' which will see citizen scientists record as many species as possible over three weekends. Photo: Dean Martin 2021 (CC-BY-NC).

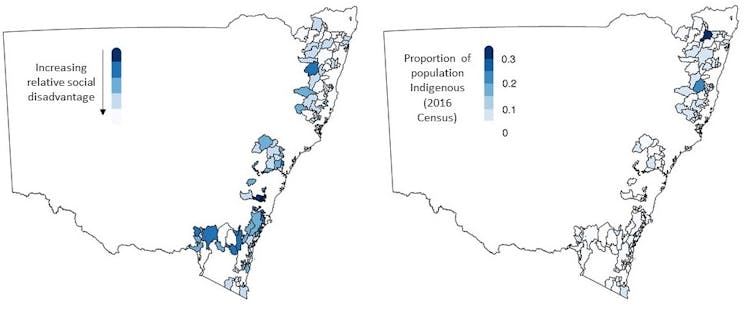

Aboriginal Land Claim Granted On Reserve At Naremburn

January 17, 2022

A total of 1.51 hectares of Crown land will be transferred to the ownership of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council after an Aboriginal land claim was approved over the Talus Street Reserve at Naremburn, on Sydney’s north shore.

A total of 1.51 hectares of Crown land will be transferred to the ownership of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council after an Aboriginal land claim was approved over the Talus Street Reserve at Naremburn, on Sydney’s north shore.

Talus Street Reserve, at the headwater of Flat Rock Creek, features bushland, walking tracks, picnic tables, eight tennis courts, a clubhouse and parking area.

The land claim by the NSW Aboriginal Land Council was granted after the land was found to be claimable on the date of the claim, after Willoughby City Council leases on the site had been ruled invalid by the Supreme Court.

Agreement will be sought from the land council to create easements to ensure continued public access on walking trails, and for site maintenance access when needed.

Sections of land will be retained for the essential public purposes of a public road, public access, maintenance, and stormwater.

Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council chair Allan Murray said the land will support social, cultural and economic benefits for the Aboriginal community, which in turn benefits the broader community.

“As the new owners, we look forward to moving ahead and undertaking the necessary due diligence of working with the community to understand who the stakeholders, users of the site and surrounding communities are,” Mr Murray said.

“Once we know this, and with our members’ support, Metropolitan LALC will be able to make an informed decision and plan for the site’s future. This is an exciting time for Metropolitan LALC and our membership.”

Willoughby City Council, which previously managed the reserve, welcomed the ‘momentous’ decision to transfer the land under the Aboriginal Lands Rights Act 2016.

“We respect and support the NSW Government’s decision to grant the claim made by the Land Council as the owners and custodians of this beautiful land. Willoughby Council is committed to working collaboratively and positively with the Land Council to ensure a smooth transition,” Willoughby Mayor Cr Tanya Taylor said.

“On behalf of the community, Council acknowledges the rich indigenous history of the Gammeraygal people in the area. The transfer will embed this significant indigenous heritage, drive cultural and social outcomes as it affirms Aboriginal Land Rights and supports reconciliation.”

Image: Talus Street Reserve

NSW Campaigns Clean-Up And Reduce Litter

January 19, 2022

An independent evaluation of the state’s Litter Prevention Program has shown litter has reduced by 43 per cent as part of the NSW Environment Protection Authority’s (EPA) successful Waste Less, Recycle More campaigns since 2012.

The EPA has received a positive evaluation of its nine-year Litter Prevention Program that shows the reductions in litter surpassed the former Premier’s Priority 2020 40 per cent target and has allowed us to set ambitious future litter reduction targets.

EPA Executive Director, Engagement, Education and Programs, Liesbet Spanjaard said this encouraging result has enabled the setting of a new target of reducing litter by a further 60 per cent by 2030, outlined in the Waste and Sustainable Materials Strategy 2041.

“Over-achieving on the former Premier’s Priority target and reducing litter by 43 per cent enables us to continue to expand on the successful path that the Waste Less Recycle More campaigns have laid out," Ms Spanjaard said.

“The independent evaluation demonstrates that the Litter Prevention Program is providing value for money. Evidence in the report indicates that the program provides a net economic benefit to the people of NSW both through direct savings on litter clean-up and through indirect effects of improved amenity in communities and reduced environmental harm.”

Highlights of the nine-year $50 million Litter Prevention Program include:

The introduction and success of Return and Earn, the NSW Container Deposit Scheme

Introduced in 2017 as an initiative to reduce beverage container litter, already over 6.5 billion containers have been returned through the scheme’s network of over 620 return points. Return and Earn has contributed to an overall 52 per cent reduction in the volume of drink container litter in NSW in the last four years and has provided over $28 million in fundraising revenue for charities and community groups.

An innovative marine litter campaign

To reduce the growth of litter in our waterways and oceans and its detrimental effect on marine life, we launched an exciting marine litter campaign in March 2021. The campaign features Rocky the Lobster and his band, Rage against the Polystyrene with the new smash hit Don’t be a Tosser song. The initiative builds on the successful Don’t be A Tosser Campaign.

Stand-out results from the world-leading Cigarette Butt Litter Prevention Trial

In 2018, the EPA led a collaborative behaviour change trial in partnership with 16 local councils to understand what strategies are effective in reducing cigarette butt littering behaviour. Outcomes show binning rates increased from 38 per cent to 58 per cent (a 53 per cent increase in binning behaviour). For some strategies a peak binning rate of 76 per cent was achieved (a 144 per cent increase in binning behaviour). For more information, see the report and supporting video.

The EPA will build on these achievements to meet the new 60 per cent reduction target outlined in the Waste and Sustainable Materials Strategy 2041. For details of the evaluation report, visit the EPA website.

Promise Delivered On Protecting Liverpool Plains Land

- certainty for local landholders and communities

- prime agricultural farmland to be preserved through the relinquishment of the Shenhua Watermark development consent and exploration licence, and the prohibition of future coal mining projects on this site

- the acquisition of more than 6000 hectares of high biodiversity land to be managed by Local Land Services including the protection of habitat for koalas and other endangered species

- protecting significant Indigenous cultural sites and artefacts

- ensuring that water that would have been taken by the mine can continue to be used for agriculture and other productive uses.

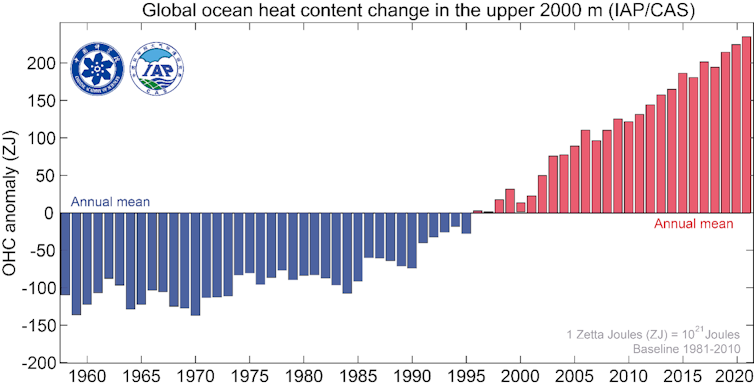

Past Eight Years Warmest Since Modern Recordkeeping Began

January 13, 2022

Earth's global average surface temperature in 2021 tied with 2018 as the sixth warmest on record, according to independent analyses done by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Continuing the planet's long-term warming trend, global temperatures in 2021 were 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit (0.85 degrees Celsius) above the average for NASA's baseline period, according to scientists at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in New York. NASA uses the period from 1951-1980 as a baseline to see how global temperature changes over time.

Collectively, the past eight years are the warmest years since modern recordkeeping began in 1880. This annual temperature data makes up the global temperature record -- which tells scientists the planet is warming.

According to NASA's temperature record, Earth in 2021 was about 1.9 degrees Fahrenheit (or about 1.1 degrees Celsius) warmer than the late 19th century average, the start of the industrial revolution.

"Science leaves no room for doubt: Climate change is the existential threat of our time," said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. "Eight of the top 10 warmest years on our planet occurred in the last decade, an indisputable fact that underscores the need for bold action to safeguard the future of our country -- and all of humanity. NASA's scientific research about how Earth is changing and getting warmer will guide communities throughout the world, helping humanity confront climate and mitigate its devastating effects."

This warming trend around the globe is due to human activities that have increased emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The planet is already seeing the effects of global warming: Arctic sea ice is declining, sea levels are rising, wildfires are becoming more severe and animal migration patterns are shifting. Understanding how the planet is changing -- and how rapidly that change occurs -- is crucial for humanity to prepare for and adapt to a warmer world.

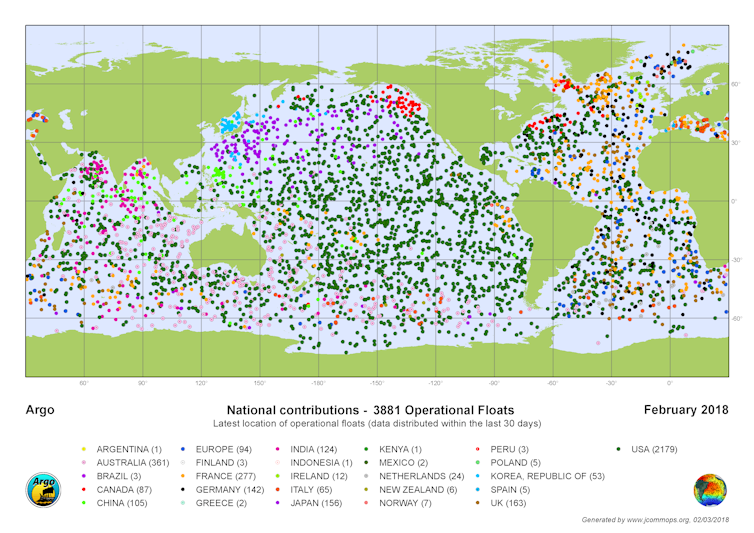

Weather stations, ships, and ocean buoys around the globe record the temperature at Earth's surface throughout the year. These ground-based measurements of surface temperature are validated with satellite data from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) on NASA's Aqua satellite. Scientists analyse these measurements using computer algorithms to deal with uncertainties in the data and quality control to calculate the global average surface temperature difference for every year. NASA compares that global mean temperature to its baseline period of 1951-1980. That baseline includes climate patterns and unusually hot or cold years due to other factors, ensuring that it encompasses natural variations in Earth's temperature.

Many factors affect the average temperature any given year, such as La Nina and El Nino climate patterns in the tropical Pacific. For example, 2021 was a La Nina year and NASA scientists estimate that it may have cooled global temperatures by about 0.06 degrees Fahrenheit (0.03 degrees Celsius) from what the average would have been.

A separate, independent analysis by NOAA also concluded that the global surface temperature for 2021 was the sixth highest since record keeping began in 1880. NOAA scientists use much of the same raw temperature data in their analysis and have a different baseline period (1901-2000) and methodology.

"The complexity of the various analyses doesn't matter because the signals are so strong," said Gavin Schmidt, director of GISS, NASA's leading center for climate modelling and climate change research. "The trends are all the same because the trends are so large."

NASA's full dataset of global surface temperatures for 2021, as well as details of how NASA scientists conducted the analysis, are publicly available from GISS (https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp).

GISS is a NASA laboratory managed by the Earth Sciences Division of the agency's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The laboratory is affiliated with Columbia University's Earth Institute and School of Engineering and Applied Science in New York.

For more information about NASA's Earth science missions, visit: https://www.nasa.gov/earth

Kurri Gas Plant Approval Gives Fresh Cabinet The Same Old Stink: Lock The Gate Alliance NSW - Climate Council

December 21, 2021

The state approval of the Kurri Kurri gas fired power station is a disappointing decision at a time when the world needs to embrace more renewable energy and zero carbon technology, not more polluting fossil fuel projects, states the Lock the Gate Alliance NSW .

On December 20th, 2021 the NSW Government’s Planning Portal issued a notification advising stakeholders the plant had been approved. The Planning Department then retracted that approval, before the approval was later uploaded to its website. The announcement came the same day new NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet announced his Cabinet, and just days after, on 12 December 2020, the Hunter Power Project (Kurri Kurri Gas-Fired Power Station) was declared as a critical State significant infrastructure project by order under Clause 12 of Schedule 5 of State Environmental Planning Policy (State and Regional Development) 2011.

The change to becoming a State significant infrastructure project was unannounced, unlike that change to a State significant infrastructure project for the Dendrobium Coal Mine Extension Project.

The Independent Planning Commissions of NSW refused consent for the development application Dendrobium Coal Mine Extension Project (SSD8294) in accordance with Part 4 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (the Act) on February 5th, 2021.

The state's planning authority found the impacts of the project outweighed the benefits.

In its reasons it said "the level of risk posed by the project has not been properly quantified and based on the potential for long-term and irreversible impacts — particularly on the integrity of a vital drinking water source for the Macarthur and Illawarra regions, the Wollondilly Shire and Metropolitan Sydney drinking water — it is not in the public interest".

The IPC also raised concerns about the longwall design, the degradation of watercourses and loss of swampland.

On Saturday December 4, 2021 Deputy Premier and Minister responsible for Resources Paul Toole said a proposal to extend Dendrobium coal mine had been declared State Significant Infrastructure (SSI) due to its importance to Port Kembla steelworks and its thousands of employees, signifying the current state government incumbents have no plans or no ideas how to shift this workforce to employment taht will not pollute the water they too will drink or save the significant environmental areas this project will impact, irreversibly.

The Kurri Kurri gas fired power station approval was signed by the then Minister for Environment and Planning, Pittwater MP Rob Stokes.

Lock the Gate Alliance NSW spokesperson Nic Clyde said it was the worst kind of Christmas present.

“The NSW Government has gifted the people of NSW not coal, but gas under the Christmas tree this year. We think most people would have preferred renewable energy, not more of the same old polluting fossil fuels," he said.

“This is a $610m white elephant that Australia doesn’t need, it will waste scarce public funding that is desperately needed elsewhere, and it will drive up energy prices, not bring them down.

“It’s anticipated it will only operate two percent of the time, but will be creating local and greenhouse pollution when it does.

“Worse still, the plant could incentivise Santos to proceed with its destructive Narrabri coal seam gasfield - so people in NSW can expect more damage to land and water and higher energy costs to boot.”

Australia's Climate Council states the May 2021 announcement by the Morrison Government it will commit up to $600 million of public funds to the new gas-fired power station at Kurri Kurri, in the New South Wales Hunter Valley, is utilising ‘sneaky,’ unallocated funding from the Federal Budget to put public money towards the 660 megawatt open cycle gas turbine, which will be built by the government-owned company Snowy Hydro Limited.

''Building a government-owned fossil fuel gas power station in the middle of a climate crisis is the equivalent of asking the Australian public to jump onto a sinking ship without a safety raft.'' the Climate Council stated

Victory For NT Community As Pitt’s Methodology Renders Empire Fracking Grants Void

December 23, 2021

Protect Country Alliance wholeheartedly congratulates the Environment Centre NT on its hard fought victory against Resource Minister Keith Pitt’s foolish decision to grant millions in public funds to fracking company Empire Energy’s subsidiary Imperial Energy.

With the Environmental Defenders Office, the ECNT took Mr Pitt to the Federal Court and argued that he had failed to make proper inquiries into a range of matters before granting Imperial Energy $21 million for its NT fracking program.

Today, the Court ruled in the ECNT’s favour, finding the government’s decision to enter into the contract with Empire Energy was legally unreasonable, because it occurred while legal proceedings were underway. The contracts are now considered void.

“This decision exposes the appalling and reckless behaviour of Mr Pitt, who arrogantly approved the grants despite an active legal case and thus breached common law model litigant obligations,” said Protect Country Alliance spokesperson Dan Robins.

“This reveals yet again that the Morrison Government’s rush to throw billions in public money at gas giants is blatant corporate welfare that undermines our democracy.

“This case also opens the door to a range of future legal challenges against government ministers who fail to act in accordance with the law when making decisions about fracking projects.

“Thanks to the tremendous hard work of the ECNT and Environmental Defenders Office, a line has been drawn in the sand.

“Keith Pitt’s decision to spend taxpayer money on the fracking industry was always questionable, and now, thanks to today’s ruling, we know he made a grave error in the eyes of the law.

“Territorians don’t want to see public money wasted on fracking projects that will threaten groundwater, that are opposed by Traditional Owners, and that will drive the climate crisis and ever more terrifying extreme weather events.”

Territory Frack Fest Free For All: Origin Exploration Plan A Terrifying Indicator Of What’s To Come

January 14, 2022

Origin Energy’s newly released Environment Management Plan for four exploratory frack wells in the Northern Territory provides a terrifying glimpse into the future and the water that will be required if full scale production goes ahead, according to Protect Country Alliance.

The EMP, which was published yesterday, concerns Origin’s Amungee and Velkerri projects, which will host two new wells each and are located southeast of Daly Waters. It brings the number of exploratory fracking wells owned by Origin in the area to six in total.

The plan reveals the company expects to use 525 million litres of water during the three year project, which it will access from the Gum Ridge formation - the equivalent of about 210 Olympic sized swimming pools.

The sheer volume of water required for the exploratory project prompted concern from local pastoralists and Traditional Owners, however these concerns were brushed aside by Origin in its EMP. Several pastoralist water bores surround Origin’s project which rely on the Gum Ridge formation.

The documents also reveal fracking the four wells will lead to the creation of about 56 million litres of salt-heavy wastewater.

PCA also has concerns about the use of phytotoxins in Origin’s fracking fluid concoction, owing to the presence of stygofauna (aquatic animals that live in groundwater) in aquifers beneath the drilling site that may be impacted.

As well, Origin plans to use chemicals described as “possible carcinogens” in its fracking fluid slurry.

PCA spokesperson Graeme Sawyer said the sheer amount of water required for just four wells offered a deeply concerning window into how much water would be lost if the fracking industry reached production phase in the Territory.

“The impact of Origin’s exploratory fracking wells on Territory groundwater aquifers is worrying enough, but this is really just the tip of the iceberg if the company decides to ramp up to full throttle production,” he said.

“Origin will be using vast quantities of groundwater to drill and frack and that will come at a huge cost to cultural values, other water users, and the environment.

"What's also worrying is the NT Gunner Government is still yet to implement a water allocation plan for the Beetaloo. It's paved the way for the thirsty frackers, but with no way to know how water will be safeguarded for communities.

“The experience in Queensland and the USA shows us that once commercial production begins, fracking wells multiply like pockmarks across the landscape, polluting waterways, and industrialising rural landscapes with a network of well pads, pipelines, and access roads.

“We can’t allow this destruction in the Territory and we certainly can’t afford the climate risks of these projects - Territory weather extremes are already severe and rapidly worsening.

“The use of toxins in fracking fluid that are harmful to stygofauna demonstrates the importance of Strategic Regional Environmental and Baseline Assessment (SREBA).

“Unfortunately this unfinished process has already been mired in controversy and accusations of government bias in favour of the fracking industry.”

Fracking Queensland’s Lake Eyre Basin Could Unleash 300 Million Tonnes Of GHG Each Year: New Report Findings

January 13, 2022

New expert analysis undertaken by Professor Ian Lowe reveals the shocking amount of greenhouse gas emissions that would be released if the fracking industry is allowed to develop gasfields in the Queensland Channel Country floodplains of the Lake Eyre Basin.

Professor Lowe’s report reveals that even under a “low development” scenario, fracking in the basin would make it nearly impossible for the Queensland Palaszczuk Government to meet its stated 2030 GHG emissions reduction targets.

Under a “high development” scenario, the fracking industry in the basin would be responsible for about 190 million tonnes per annum of fugitive and domestic emissions, and 300 million tonnes of emissions if the burning of the gas was taken into account. Australia’s annual domestic GHG emissions are roughly 500 million tonnes.

Professor Lowe’s report reveals the high emissions figures are because:

- The petroleum resources in the Lake Eyre Basin contain extremely high levels of carbon dioxide (around 30%), which would have to be vented or otherwise disposed of, making them some of the most polluting gasfields in Australia.

- Production of gas inevitably also results in direct methane leakage (known as fugitive emissions) and methane is a very potent greenhouse gas.

Professor Lowe said, “If we are serious about net zero emissions by 2050, then it is criminally irresponsible for governments to be approving new fossil fuel projects.

“Approving fracking in the Channel Country would ensure the Queensland Government fails to meet its stated emissions reduction target.”

The release of the report comes after the Palaszczuk Government was accused of conducting “sham consultation” with Traditional Owners and the wider community in the Channel Country, after it approved Origin Energy petroleum leases across more than 250,000 hectares near Windorah.

Lock the Gate Alliance Queensland spokesperson Ellie Smith urged the Palaszczuk Government to honour its past election promises and protect the floodplains of the Lake Eyre Basin from fracking.

She said Professor Lowe’s report showed sacrificing the floodplains to fracking would make the job of emissions reductions in every other sector of the state’s economy that much harder.

“This report confirms what we have long suspected - fracking this unique and spectacular part of Queensland will release a carbon bomb at a time when the world desperately needs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” she said.

“If the Lake Eyre Basin is opened up to fracking the Queensland Palaszczuk Government will need to find its planned emissions reductions elsewhere.

“That means manufacturing businesses, agriculture, the transport sector, and Queensland households will all have to make up for the extra emissions of between 16 and 40 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent every year on top of existing reduction commitments just so companies like Origin can rip through another precious part of our state for profit.

“Sacrificing Queensland’s Lake Eyre Basin rivers and floodplains to fracking will harm the communities and the world class organic beef industry of Far Western Queensland.

“It will threaten the Channel Country’s free flowing desert rivers, which are among the last desert rivers not seriously compromised by human activity on the planet.

“It would be a travesty to allow thousands of fracking gas wells, roads and pipelines to destroy these floodplains in order to build the dirtiest, most polluting gasfields in Australia.”

previously:

In 2020, a leaked document revealed the Queensland Government's own scientists deemed fracking the sensitive Channel Country floodplains of the Lake Eyre Basin too risky.

New Fracking Plan For The Kimberley

January 18, 2021

A new fracking project in the Great Sandy Desert area of WA’s Kimberley region that will require nearly 18 million litres of water is the thin edge of the wedge as the McGowan Government continues to roll out the red carpet to the oil and gas industry, states the WA Lock the Gate Alliance.

The WA Environmental Protection Authority today published Theia Energy’s proposal to drill two “exploration” wells on the company’s tenement south east of Broome, giving the public just six days to respond.

While the application is for one vertical and one horizontal well, with plans by Theia to frack the horizontal well, the company has previously flagged intentions to build thousands of wells across its tenements, by comparing the Kimberley’s resources to that of the Eagle Ford Shale in the USA, where 24,000 wells have been drilled since 2008.

Media has also reported previously that the company is targeting “as much as 57 billion barrels of oil in the desert location”. If such a plan was realised, it would make Theia Australia’s largest oil producer.

The company’s new plan also reveals the exploratory drilling project would result in the creation of nearly eight million litres of “flowback” or waste water from only two wells.

“This is typically what we expect from fracking companies - they start off with a handful of exploratory wells, and once production approval is granted, they build frack fields that spread like spider webs across the landscape,” said Lock the Gate Alliance WA spokesperson Claire McKinnon.

“It’s extremely concerning that for just one exploratory well, Theia plans to use 18 million litres of water from a local aquifer beneath a desert. The amount of water that would be required for a fully fledged fracking industry in the Kimberley is truly terrifying.

“Fracking projects leak massive plumes of climate-heating methane into the atmosphere. The fugitive emissions from Theia’s frack field will fuel the climate crisis even before the gas or oil is burnt.

“Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, and the place where Theia wants to frack is among the driest places in Australia. Water is so very precious here - it should not be sacrificed to dirty, polluting fracking companies.

“It is madness the McGowan Government is even considering these fracking projects. They must be rejected.”

Draft Cycling Strategy For NSW's National Parks

The Draft Cycling Policy, Draft Cycling Strategy and Draft Cycling Strategy: Guidelines for Implementation is on public exhibition until 30 January 2022.

The scope of this new strategy is broad. It includes all types of cycling experiences in our parks. It is complemented with a more detailed set of guidelines for implementation and updates to our Cycling policy.

- The Draft Cycling policy builds upon our experience from previous versions and has been updated in parallel to the draft strategy. It identifies in a legislative framework where cycling is permissible in parks.

- The Draft Cycling Strategy outlines our vision, objectives and priorities for the provision of cycling experiences.

- The Draft Cycling Strategy: Guidelines for Implementation provides further details on the processes and procedures that National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) will apply to assess, approve, manage and monitor cycling opportunities within NPWS estate as detailed in the Cycling Strategy.

- The draft Cycling Strategy sets a precedent for managing the conservation of natural and cultural heritage values in our parks as a priority and then allows for the development of compatible cycling opportunities. Not all cycling activities will be suitable in all parts of parks.

- The draft Cycling Strategy details a clear framework for how we seek to provide for, and manage, cycling opportunities within parks. The processes for cyclists to work with National Parks and Wildlife Service are made clear. We intend to work collaboratively with stakeholders and other land managers to tackle key challenges including, unauthorised tracks, the safety and enjoyment of visitors on multi-use trails and the provision of park visitor facilities.

- The draft Guidelines for Implementation address the way we will deliver the Cycling Strategy, including the approval process for new tracks and networks, the rehabilitation of unauthorised tracks, how we will work with external parties (including volunteer groups) and our management of cycling experiences. These documents will replace the Sustainable Mountain Biking Strategy 2011.

Public online presentation

You are invited to an online public presentation on Wednesday, 1 December, 12:00 – 1:00pm. Please register to attend this presentation.

Your feedback on the draft Cycling Policy, strategy and implementation guideline documents is valued. Our response to your submission will be based on the merits of the ideas and issues you raise rather than just the quantity of submissions making similar points. For this reason, a submission that clearly explains the matters it raises will be the most effective way to influence the finalisation of the plan.

Submissions are most effective when we understand your ideas and the outcomes you want for park management. Some suggestions to help you write your submissions are:

- write clearly and be specific about the issues that are of concern to you

- note which part or section of the document your comments relate to

- give reasoning in support of your points - this makes it easier for us to consider your ideas and will help avoid misinterpretation

- tell us precisely what you agree/disagree with and why you agree or disagree

- suggest solutions or alternatives to managing the issue if you can.

Have your say by Thursday 30 January 2022.

There are three ways to provide feedback:

Formal submission: Address: Manager, NPWS Planning Evaluation and Assessment Locked Bag 5022 Parramatta NSW 2124

Home Design To Drive Energy Bills Down

November 22, 2021

New sustainability standards for homes will save residents up to $980 a year on energy bills and reduce the State’s carbon footprint as we move to net-zero emissions by 2050.

The Building Sustainability Index (BASIX) is a key assessment tool that ensures new homes are comfortable to live in regardless of the temperature, are more energy efficient and save water.

Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Rob Stokes said BASIX had prevented 12.3 million tonnes of greenhouse gas over the past 17 years – equivalent to taking 2.5 million cars off the road.

“These proposed increases in standards will see more energy-efficient homes from Double Bay to Dubbo and beyond, with better design, better insulation, more sunlight and more solar panels,” Mr Stokes said.

“We want to lift BASIX standards even higher to drive down emissions further, saving another 150,000 tonnes a year and helping to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

“Better design will keep your home naturally cooler in summer and warmer in winter, so you won’t be turning the heater or air conditioner on as often.

Energy bills are expected to reduce significantly as a result of the new BASIX standards:

- Savings of up to $190 each year for people living in high-rise apartments;

- Savings of up to $850 each year for people living in new Western Sydney houses; and

- Savings of up to $980 a year for people living in new houses in the regions.

“To showcase the benefits of these new measures, we’re inviting up to 10 builders to test the proposed BASIX requirements ahead of its official roll out next year,” Mr Stokes said.

These new targets complement work underway, such as planting one million trees and investing $4.8 million to make building materials more environmentally friendly.

The community is encouraged to provide feedback on the proposed BASIX changes by Monday 31 January, 2022 at planningportal.nsw.gov.au/BAS IX- standards

New University Of QLD Conservation Tool Calculates The Optimal Time To Spend Researching A Habitat Before Protecting It

January 13, 2022

Deciding when to stop learning and take action is a common, but difficult decision in conservation. Using a new method, developed by researchers at The University of Queensland, The University of British Columbia and CSIRO (Australia's national science agency), this trade-off can be managed by determining the amount of time to spend on research at the outset. The findings are published in the British Ecological Society journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution.

The work provides guidelines on the effective allocation of resources between habitat identification and habitat protection, predicting the optimal time to spend learning even when relatively little is known about a species and its habitat. Determining the optimal timing for habitat protection is vital if we are to ensure effective, long-term protection.

Dr Abbey Camaclang, The University of Queensland and lead author of the study, said: "Habitat protection can be more effective when we know more about species and their habitat needs, but delaying protection to improve our knowledge can result in continued habitat loss and population declines."

Using a simple model, the new method calculates how long we should spend improving our knowledge of a species' habitat before deciding which areas to protect, based upon an estimated rate of habitat loss and speed of acquiring knowledge. The researchers tested the method on two threatened species, the koala and northern abalone (a sea snail). They found that optimal time to spend learning is short when the threats are high. When habitat loss is low, the species benefit from greater knowledge, leading to an increased proportion of the species' habitat being protected.

Dr Camaclang explained: "Delaying habitat protection to improve our knowledge may sometimes be beneficial, but it is often better to protect habitats immediately rather than wait for more information when rates of habitat loss are high."

Professor Possingham, one of the co-authors at The University of Queensland, added "All too often ecologists will delay action on the ground to seek more and more data, ignoring the fact that time and money are limited resources in conservation."

Protecting habitat is the most valuable action for conservation, but it requires understanding the habitat requirements for the species of interest. Timely decisions can save species from extinction, but acting too soon might lead to protecting the wrong habitat -- a costly decision that is often irreversible.

The optimal timing for habitat protection also depends on the amount of non-habitat we can afford to protect. Any land that is incorrectly identified as habitat and protected unnecessarily can lead to conflict with other land uses.

The new method developed in this study has potential to be used in other areas of conservation decision-making. For example, to minimize the impact of harvesting wild plants and animals or manage the detrimental effects of invasive species. The approach can also be built on further, to provide guidance on optimising on-the-ground surveys, thus enabling conservationists to use time and funds most efficiently.

Abbey E. Camaclang, Iadine Chadès, Tara G. Martin, Hugh P. Possingham. Predicting the optimal amount of time to spend learning before designating protected habitat for threatened species. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 2022; DOI: 10.1111/2041-210X.13770

The study investigates how long we should spend improving our knowledge of a species’ habitat before deciding which areas to protect, using the koala and northern abalone as examples

‘Disappointment and disbelief’ after Morrison government vetoes research into student climate activism’

Between 2019 and early 2021, we developed a research proposal asking for funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC). The project was to investigate the mass student climate action movement and its relationship to democracy.

A few weeks ago, on Christmas Eve, we learnt via Twitter that the ARC had recommended our research proposal for funding, but acting Education Minister Stuart Robert vetoed the recommendation.

Robert also vetoed five other humanities projects. He did so on the grounds they “do not demonstrate value for taxpayers’ money nor contribute to the national interest”.

This political intervention is a problem for many reasons. Chief among them, it breaches key principles of academic autonomy and – in our case, also silences research working with young people on a crucial policy issue.

‘Freedom In Research And Training’

Since 1988, almost 1,000 universities in 94 countries have signed the Magna Charta Universitatum, including ten from Australia. The charter affirms the deepest values of university traditions.

In practice, it means a university “must serve society as a whole” and that “to meet the needs of the world around it, its research and teaching must be intellectually independent of all political authority and economic power”.

Central to the charter is that “freedom in research and training is the fundamental principle of university life”.

The ARC administers the National Competitive Grants Program, which delivers around $800 million to Australian researchers each year.

The ARC grants process involves several rounds of rigorous review and assessment, by internationally leading scholars. The ARC then recommends to the education minister which proposals should be funded, and the budget. The minister makes the final funding decisions.

The Morrison government claims it wants to protect academic freedoms. And it commissioned a 2019 review of freedom of expression and intellectual inquiry in higher education.

However, Robert’s veto of the ARC’s decision to fund six projects is a clear breach of the core principle of academic freedom.

What’s more, it’s not the first time Morrison government education ministers have ridden roughshod over the funding processes of the ARC and university research.

In 2018-19, Simon Birmingham vetoed 11 research grants recommended by the ARC. In 2020, Dan Tehan vetoed five.

An Important New Phenomenon

The project we proposed for ARC funding was titled “New possibilities: student climate action and democratic renewal”. It involved working directly with young people to investigate a significant new phenomenon.

Since 2018, millions of students across the globe have worked hard as leaders, organisers and advocates for action on climate change. Their actions include the school strikes for climate and various legal actions. In Australia since 2018, we estimate at least 500,000 school students have participated in the movement, including coordinated school strike actions online and in the streets.

Our project was designed to document such actions and to establish:

why young people participate

what activities they undertake

what we can learn from the movement to address climate change and strengthen our democracy.

Our project would have led to vital new knowledge on a global phenomenon. It had the potential to help address falling trust in governments and dissatisfaction with democracy, and to give new insights on engaging with young people in learning about and responding to climate change.

It also provided jobs for early-career researchers already facing cripplingly precarious employment in the university sector.

Our proposal relied on a vast body of academic work and expertise, and previous scholarship by the research team. It was connected to a global research network exploring young people’s climate politics and broader possibilities for democracy.

Developing the proposal involved hundreds of hours of additional research, writing, editing and consultation with professional staff across five universities.

For the ARC to judge the project worthy of funding, it must have determined it passed the national interest test and that it was value for money.

Significantly, we have no formal right to appeal the decision.

‘Disappointment And Disbelief’

The minister’s intervention is a serious blow to Australia’s reputation for research excellence and its commitment to academic freedom.

The Morrison government has also sent a negative message to Australia’s young people – essentially saying research into their views on climate change is irrelevant.

We asked students who we work with to respond to the government’s veto, and they stand with us in disappointment and disbelief. Audrey, aged 10, who has participated in climate action, said:

“I personally think that the vetoing was to stop the research from public view to make the government look better, as they aren’t doing enough on climate change. Another main reason why the vetoing is so bad and unfair is that the government is sending the message that young people’s views aren’t important to both young people and the community.”

Urgent change is needed to ensure academic autonomy, freedom, and independence of process are not subject to political interference in future.

Addressing urgent and complex problems such as climate change involves research across the full spectrum of society – and that includes Australia’s young people. ![]()

Philippa Collin, Associate Professor, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University; Brendan Churchill, ARC Research Fellow and Lecturer in Sociology, The University of Melbourne; Faith Gordon, Associate Professor in Law, Australian National University; Judith Bessant, Professor in School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University; Michelle Catanzaro, Senior Lecturer in Design / Senior Research Fellow (YRRC), Western Sydney University; Rob Watts, Professor of Social Policy, RMIT University, and Stewart Jackson, Senior Lecturer, Department of Government and International Relations, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

(The most social) bird of the year: why superb fairy-wren societies may be as complex as our own

One mystery many biologists want to solve is how complexity develops in nature. And among the many social systems in the natural world, multilevel societies stand out for their complexity. Individuals first organise into families, which are members of bands, which are organised into clans.

At each level, associations between components (individuals, families and clans) are structured and stable. In other words, individuals within families usually stay together, and families usually interact with other specific families in a predictable way, to form stable clans.

Such social organisation has probably characterised much of human evolution (and is still common among many hunter-gatherer societies around the world).

In fact, multilevel societies likely played a fundamental role in human history, by accelerating our cultural evolution. Organising into distinct social groups would have reduced the transmission of cultures and allowed for multiple traditions to coexist.

In our research, published today in Ecology Letters, we studied social behaviours in a wild population of superb fairy-wrens. We found these birds also organise into multilevel societies – a level of complexity once thought to be exclusive to big-brained mammals.

Cooperatively Breeding Birds

Although we have ideas about the advantages of multilevel societies, we know relatively little about how and why they form in the first place.

Of the few species known to live in multilevel societies, there is one characteristic shared among all. That is, they live in stable groups, in environments where food availability is inconsistent and difficult to predict.

This is also true for many cooperatively breeding birds, including the superb fairy-wren – familiar across southeastern Australia’s parks and gardens. They breed in small family groups, with non-breeding helpers assisting a dominant breeding pair. And this social system is common among Australian bird species.

The superb fairy-wren is a well-studied species and is beloved by Australians, even being crowned bird of the year in this year’s Guardian/BirdLife Australia poll.

These birds are notorious for their polyamorous approach to sex, despite being socially monogamous. Breeding pairs form exclusive social bonds, yet each partner will still mate with other individuals.

Our work now reveals this complex arrangement during the breeding season is just the tip of the iceberg.

Associating By Choice

We tracked almost 200 birds over two years, by attaching different-coloured leg bands to each individual. We recorded the birds’ social associations and, from our observations, built a complex social network that let us determine the strength of each relationship.

We found that during the autumn and winter months, some breeding groups – (which include the breeding pair, one or more helpers and last summer’s offspring), stably associated with other breeding groups to form supergroups. And this was usually done with individuals they were genetically related with.

In turn, these supergroups associated with other supergroups and breeding groups on a daily basis, forming large communities. In the following spring, these communities split back into the original breeding groups inhabiting well-defined territories – only to join again next winter.

Just like humans, these little birds don’t associate with each other randomly during the long winter months. They have specific individuals and/or groups they choose to be with (but we’re currently not sure how they make this choice).

While it’s not yet clear why superb fairy-wrens form upper social units (supergroups and communities), we suspect this might allow individuals to exploit larger areas during winter, when food is scarce. It would also provide additional safety against predators, such as hawks and kookaburras.

This theory is supported by our literature study, which shows that multilevel societies are likely common among other Australian cooperatively breeding birds, such as the noisy and bell miners and striated thornbills.

Cooperative breeding is another strategy to deal with harsh condition such as food scarcity. So the conditions that favour cooperative breeding are the same as those that favour multilevel societies.

Multilevel Societies In Other Animals

There are several other species which seem to have a similar social organisation. They include primates such as baboons, and other large mammals that exhibit rich animal cultures, such as killer whales, sperm whales and elephants.

For a long time, researchers thought living in complex societies might be how humans evolved large brains. They also thought this characteristic may be exclusive to mammals with large brains, since keeping track of many different social relationships is not easy (or so the reasoning went).

Consequently, other animals with whom we are less closely related have mostly been excluded from this field of investigation.

This might reflect a bias that we, humans, have towards our own species and species which are similar to us.

As it turns, you don’t need to be a mammal with a big brain to evolve complex multilevel societies. Even small-brained birds such as the tiny superb fairy-wren can do this – as well as the vulturine guineafowl a chicken-like bird from northeast Africa.

We strongly suspect quite a few birds will join their ranks in the coming years as more research is done.

Acknowledgement: we would like to thank our colleagues Alexandra McQueen, Kaspar Delhey, Carly Cook, Sjouke Kingma and Damien Farine who are co-authors on this research.![]()

Ettore Camerlenghi, PhD student, Monash University and Anne Peters, Professor, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We’ve unveiled the waratah’s genetic secrets, helping preserve this Australian icon for the future

When the smoke cleared after the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20, the bush surrounding the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden Mount Tomah was charred. Among the casualties was a NSW waratah, Telopea speciosissima, that had recently become the first of its species to have its genome sequenced. We have published this genome in the journal Molecular Ecology Resources.

The waratah is the official floral emblem of New South Wales, and its spectacular red blooms have been adopted as the logos of state government agencies and sporting teams.

The genome sequence paves the way for the waratah to serve as a model for understanding how plant populations change over time and adapt to their environments, and particularly how this species bounces back after a bushfire.

Genome sequencing has come a long way in a short time. The first human genome, completed in 2003, cost around US$1 billion and took about 13 years to compile the roughly 3 billion “letters” of our genetic code. Today, sequencing a human genome would cost less than $1,000 and take just a few days.

With rapidly decreasing costs and advancing technology, the genomic era presents the opportunity to decode many plant genomes that we can then use as reference resources. In turn, this will help us understand and conserve Australian fauna for the long term.

What Is A Genome Anyway?

An organism’s genome is the complete set of genetic information it needs to develop, grow and survive. Plants, animals and many other living things are made of DNA, which consists of a string of four chemical “bases”, known as A, C, G and T.

Sequencing a genome involves determining the order of these bases. When we began our project, we knew from previous research the waratah genome would be quite long, at around a billion bases, that it was likely to be arranged into 11 large parcels called chromosomes, and that each plant would have two copies of the genome in each of its cells.

Cracking The Waratah Code

Generating the waratah reference genome first involved sampling young leaves from a plant growing naturally in the Blue Mountains. We extracted DNA from the leaves, and used three different sequencing technologies to piece together its genetic code. This approach generated many sequences, hundreds or thousands of bases long, which we then needed to assemble to determine the full genome.

Assembling the genome involved a range of different software tools, running on powerful computers. The result was a sequence of slightly less than a billion bases, mostly in 11 large sequences, as expected. The sequences appear to contain around 40,000 genes in total – roughly twice as many as humans have.

Why We Sequenced The Waratah

Previous sequencing efforts have focused on important crops and on “model organisms” such as Arabidopsis, which is widely studied by researchers and was the first plant to have its genome sequenced, back in 2000. But of course, there are many other types of species in the plant tree of life.

The NSW waratah is one of five waratah species in the genus Telopea, which grows throughout southeastern Australia, and one of around 1,700 species in the family Proteaceae. This family includes other iconic Australian plants such as banksias, grevilleas and macadamias. Yet despite this, very few Proteaceae genomes have so far been sequenced.

A collaborative effort between the Australian Institute of Botanical Science and UNSW Sydney, the waratah genome project was the first completed as part of the Genomics for Australian Plants (GAP) Initiative. A key aim of this initiative is to generate genomes to enable better conservation and understanding of Australia’s unique plant diversity.

Hope For The Future

For many Australians, Black Summer embodied the threat posed by climate change to our unique natural heritage. But waratahs evolved with fire, and can regenerate with the help of a modified stem called a lignotuber, from which masses of fresh shoots emerge after a bushfire. It offers a potent symbol of our hope for the future.

The waratah plant whose genome we sequenced has resprouted after being burned in the Black Summer fires, and has now been propagated at the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden Mount Tomah and will become part of the garden’s living collection.

A display inspired by this plant and its genome will also feature in the foyer of the new National Herbarium of NSW when it opens at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan next year.

The waratah’s genome sequence will provide a platform for future studies of its evolution and environmental adaption, ultimately informing breeding efforts and helping us better conserve this iconic species. By sequencing its DNA, we can uncover its evolutionary past and pave the way for its survival long into the future.![]()

Stephanie Chen, PhD Candidate, UNSW; Jason Bragg, Research Scientist, and Richard Edwards, Senior Lecturer in Genomics and Bioinformatics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Lost Birds And Mammals Spell Doom For Some Plants: Animal-Dispersed Plants' Ability To Keep Pace With Climate Change Reduced By 60%

January 13, 2022

In one of the first studies of its kind, researchers have gauged how biodiversity loss of birds and mammals will impact plants' chances of adapting to human-induced climate warming.

More than half of plant species rely on animals to disperse their seeds. In a study featured on the cover of this week's issue of Science, U.S. and Danish researchers showed the ability of animal-dispersed plants to keep pace with climate change has been reduced by 60% due to the loss of mammals and birds that help such plants adapt to environmental change.

Researchers from Rice University, the University of Maryland, Iowa State University and Aarhus University used machine learning and data from thousands of field studies to map the contributions of seed-dispersing birds and mammals worldwide. To understand the severity of the declines, the researchers compared maps of seed dispersal today with maps showing what dispersal would look like without human-caused extinctions or species range restrictions.

"Some plants live hundreds of years, and their only chance to move is during the short period when they're a seed moving across the landscape," said Rice ecologist Evan Fricke, the study's first author.

As climate changes, many plant species must move to a more suitable environment. Plants that rely on seed dispersers can face extinction if there are too few animals to move their seeds far enough to keep pace with changing conditions.

"If there are no animals available to eat their fruits or carry away their nuts, animal-dispersed plants aren't moving very far," he said.

And many plants people rely on, both economically and ecologically, are reliant on seed-dispersing birds and mammals, said Fricke, who conducted the research during a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Maryland's National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) in collaboration with co-authors Alejandro Ordonez and Jens-Christian Svenning of Aarhus and Haldre Rogers of Iowa State.

Fricke said the study is the first to quantify the scale of the seed-dispersal problem globally and to identify the regions most affected. The authors used data synthesized from field studies around the world to train a machine-learning model for seed dispersal, and then used the trained model to estimate the loss of climate-tracking dispersal caused by animal declines.

He said developing estimates of seed-dispersal losses required two significant technical advances.

"First, we needed a way to predict seed-dispersal interactions occurring between plants and animals at any location around the world," Fricke said.

Modelling data on networks of species interactions from over 400 field studies, the researchers found they could use data on plant and animal traits to accurately predict interactions between plants and seed dispersers.

"Second, we needed to model how each plant-animal interaction actually affected seed dispersal," he said. "For example, when an animal eats a fruit, it might destroy the seeds or it might disperse them a few meters away or several kilometres away."

The researchers used data from thousands of studies that addressed how many seeds specific species of birds and mammals disperse, how far they disperse them and how well those seeds germinate.

"In addition to the wake-up call that declines in animal species have vastly limited the ability of plants to adapt to climate change, this study beautifully demonstrates the power of complex analyses applied to huge, publicly available data," said Doug Levey, program director of the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Directorate for Biological Sciences, which partially funded the work.

The study showed seed-dispersal losses were especially severe in temperate regions across North America, Europe, South America and Australia. If endangered species go extinct, tropical regions in South America, Africa and Southeast Asia would be most affected.

"We found regions where climate-tracking seed dispersal declined by 95%, even though they'd lost only a few percent of their mammal and bird species," Fricke said.

Fricke said seed-disperser declines highlight an important intersection of the climate and biodiversity crises.

"Biodiversity of seed-dispersing animals is key for the climate resilience of plants, which includes their ability to continue storing carbon and feeding people," he said.

Ecosystem restoration to improve the connectivity of natural habitats can counteract some declines in seed dispersal, Fricke said.

"Large mammals and birds are particularly important as long-distance seed dispersers and have been widely lost from natural ecosystems," said Svenning, the study's senior author, a professor and director at Aarhus University's Center for Biodiversity Dynamics in a Changing World. "The research highlights the need to restore faunas to ensure effective dispersal in the face of rapid climate change."

Fricke said, "When we lose mammals and birds from ecosystems, we don't just lose species. Extinction and habitat loss damage complex ecological networks. This study shows animal declines can disrupt ecological networks in ways that threaten the climate resilience of entire ecosystems that people rely upon."

NSF's Levey said, "Through SESYNC and other NSF investments, we are enabling ecologists to forecast what will happen to plants when their disperser 'teammates' drop out of the picture in the same way we predict outcomes of sports games."

The research was supported by NSF (1639145), the Villum Foundation (16549) and the Aarhus University Research Foundation (AUFF-F-2018-7-8) and is published in Science, January 2022 edition.

Evan C. Fricke, Alejandro Ordonez, Haldre S. Rogers and Jens-Christian Svenning. The effects of defaunation on plants’ capacity to track climate change. Science, 2022 DOI: 10.1126/science.abk3510

Researchers Find Nonnative Species In Oahu Play Greater Role In Seed Dispersal

January 11, 2022

University of Wyoming researchers headed a study that shows nonnative birds in Oahu, Hawaii, have taken over the role of seed dispersal networks on the island, with most of the seeds coming from nonnative plants.

"Hawaii is one of the most altered ecosystems in the world, and we are lucky enough to examine how these nonnative-dominated communities alter important processes, such as seed dispersal," says Corey Tarwater, an assistant professor in the UW Department of Zoology and Physiology. "What we have found is that not only do nonnative species dominate species interactions, but that these nonnative species play a greater role in shaping the structure and stability of seed dispersal networks than native species. This means that loss of a nonnative species from the community will alter species interactions to a greater extent than loss of a native species."

Tarwater was the anchor author of a paper, titled "Ecological Correlates of Species' Roles in Highly Invaded Seed Dispersal Networks," which was published Jan. 11 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Jeferson Vizentin-Bugoni, a postdoctoral researcher at UW and the U.S. Army Research Laboratory at the time of the research, is the paper's lead author. He performed most analyses and conceptualized and outlined the first version of the manuscript.

Becky Wilcox, of Napa, Calif., a recent UW Ph.D. graduate and now a postdoctoral researcher, and Sam Case, of Eden Prairie, Minn., a UW Ph.D. student in the Program in Ecology as well as in zoology and physiology, worked with Tarwater. The two aided in field data collection, processing all of the footage from the game cameras, and assisted in writing the paper. Patrick Kelley, a UW assistant research scientist in zoology and physiology, and in the Honors College, helped with developing project ideas, data processing and management, and writing the paper.

Other researchers who contributed to the paper are from the University of Hawaii, University of Illinois, Northern Arizona University and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Champaign, Ill.

"This is one of the first studies showing that nonnative species can take over the most important roles in seed dispersal networks. This means that Oahu's ecosystems have been so affected by species extinctions and invasions that most of the seeds dispersed on the island belong to nonnative plants, and most of them are dispersed by nonnative birds," Vizentin-Bugoni says. "This forms what has been called 'ecological meltdown,' which is a process occurring when nonnative mutualistic partners benefit each other and put the system into a vortex of continuous modification."

Seed dispersal by animals and birds is one of the most crucial ecosystem functions. It is linked to plant population dynamics, community structure, biodiversity maintenance and regeneration of degraded ecosystems, according to the paper.

Before Hawaii became the extinction and species invasion capital of the world, its ecological communities were much more diverse. Experts estimate that, in the last 700 years, 77 species and subspecies of birds in the Hawaiian Archipelago have gone extinct, accounting for 15 percent of bird extinctions worldwide.

"The Hawaiian Islands have experienced major changes in flora and fauna and, while the structure of seed dispersal networks before human arrival to the islands is unknown, we know from some of our previous work, recently published in Functional Ecology, that the traits of historic seed dispersers differ from the traits of introduced ones," Case says. "For instance, some of the extinct dispersers were larger and could likely consume a greater range in seed sizes compared to the current assemblage of seed dispersers."

Because of the large number of invasive plants and the absence of large dispersers, the invasive dispersers are incompletely filling the role of extinct native dispersers, and many native plants are not being dispersed, Tarwater says. On the island of Oahu, 11.1 percent of bird species and 46.4 percent of plant species in the networks are native to the island. Ninety-three percent of all seed dispersal events are between introduced species, and no native species interact with each other, the paper says.

"Nonnative birds are a 'double-edged sword' for the ecosystem because, while they are the only dispersers of native plants at the present, most of the seeds dispersed on Oahu belong to nonnative plants," Vizentin-Bugoni says. "Many native plant species have large seeds resulting from coevolution with large birds. Such birds are now extinct, and the seeds cannot be swallowed and, thus, be dispersed by the small-billed passerines now common on Oahu."

Researchers compiled a dataset of 3,438 faecal samples from 24 bird species, and gathered 4,897 days of camera trappings on 58 fruiting species of plants. It was determined that 18 bird species were recorded dispersing plant species.

In contrast to predictions, the traits that influence the role of species in these novel networks are similar to those in native-dominated communities, Tarwater says.

"In particular, niche-based traits, such as degree of frugivory (animals that feed on fruit, nuts and seeds) and lipid content, rather than neutral-based traits, such as abundance, were more important in these nonnative-dominated networks," Tarwater says. "We can then use the niche-based traits of dispersers and plants to predict the roles species may play in networks, which is critical for deciding what species to target for management."

Tarwater adds that the roles of different species in Oahu's seed dispersal networks can be predicted by the species' ecological traits. For example, the research group found that bird species that consume a greater amount of fruit in their diets are more likely to disperse seeds from a greater number of plant species. Likewise, the team found that plants that fruit for extended periods of time have smaller seeds and have fruits rich in lipids, will get dispersed more frequently.

"Land managers can use these ecological traits to identify species that can be removed or added to a system to improve seed dispersal," Tarwater explains. "For example, removal of highly important nonnative plants or the addition of native plants with traits that increase their probability of dispersal, could aid in restoration efforts."

Kelley and Tarwater obtained funding for the project. The research was funded by a U.S. Department of Defense award, UW, University of Hawaii, University of New Hampshire and Northern Arizona University.

"This upcoming year, we will be experimentally removing one nonnative plant species that is incredibly important for network structure and examining how the seed dispersal network changes in response," Tarwater says. "The results of this experiment can inform land managers as to whether removal of a highly invasive plant will improve seed dispersal for the remaining native plants, or whether it does not."

Jeferson Vizentin-Bugoni, Jinelle H. Sperry, J. Patrick Kelley, Jason M. Gleditsch, Jeffrey T. Foster, Donald R. Drake, Amy M. Hruska, Rebecca C. Wilcox, Samuel B. Case, Corey E. Tarwater. Ecological correlates of species’ roles in highly invaded seed dispersal networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021; 118 (4): e2009532118 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2009532118

Regent honeyeaters were once kings of flowering gums. Now they’re on the edge of extinction. What happened?

Rob Heinsohn, Australian National University; Dejan Stojanovic, Australian National University, and Ross Crates, Australian National UniversityLess than 80 years ago, regent honeyeaters ruled Australia’s flowering gum forests, with huge raucous flocks roaming from Adelaide to Rockhampton.

Now, there are less than 300 birds left in the wild. Habitat loss has pushed the survivors into little pockets across their once vast range.

Sadly, our new research shows these birds are now heading for rapid extinction. Unless we urgently boost conservation efforts, the regent honeyeater will follow the passenger pigeon into oblivion within the next 20 years.

If we let the last few die, the regent honeyeater will be only the second bird extinction on the Australian mainland since European colonisation, following the paradise parrot.

How Did It Come To This?

With vivid yellow and black wings, embroidered body and warty faces, these honeyeaters are among Australia’s most spectacular birds.

John Gould, one of Australia’s earliest European naturalists, observed these birds in “immense flocks amongst the brushes of New South Wales”. He described the regent honeyeater as “the most pugnacious bird he ever saw”, noting they “reigned supreme in the largest, most heavily-flowering trees.” Their success in securing nectar supplies made them vital pollinators.

The world Gould saw is sadly a thing of the past. Regent honeyeater populations have plummeted, with the loss of over 90% of their preferred woodland habitats to farmland.

You might wonder how this could be, given there are still large tracts of forest in Australia. But these are invariably on poorer soils and hilltops. Our remaining forests do not yield the rich nectar regent honeyeaters require for breeding.

As their habitat has declined, the surviving regent honeyeaters have been forced to compete with larger species – without the safety of their huge flocks. The result? The once common species no longer reigns supreme.

Gone Within 20 Years

Unless conservation actions are urgently stepped up, our research shows these birds will be extinct within 20 years.

We’ve known about the decline of regent honeyeaters since the late 1970s. In response, a recovery team including BirdLife Australia and Taronga Conservation Society launched a long-term recovery effort to protect habitat, plant new trees and release zoo-bred birds. These efforts have slowed but not arrested the decline of these birds.

In 2015, we began a large-scale survey to better understand their population decline. Regent honeyeaters are a notoriously difficult bird to study in the wild. As nomads, they wander long distances throughout their vast range in search of nectar in their favoured tree species. Finding these birds is hard enough, let alone monitoring the population in detail.

After six years of intensive fieldwork, and with data from research in the 1990s and long term bird banding, we have finally gathered enough information to be able to understand the challenges for the few remaining wild birds. We now know their breeding success has declined because their nests are raided and the chicks killed by aggressive native species, with noisy miners a particular problem.

We also know the wild birds are losing their song culture because of a lack of older birds for fledglings to learn their songs.

Our fieldwork has given us accurate estimates of vital breeding data, such as how many young birds fledge for each adult female, how many birds are breeding and how well juveniles are surviving. We combined this with data from the decades of monitoring of zoo-bred and released birds to create population models, which allow us to predict the future for the wild population under different conservation scenarios.

Habitat Is King

What do the models show? That time is critical. To have any chance of getting the regent honeyeater back, we must build its numbers up enough for them to be able to roam in large flocks for protection.

How? First, we have to nearly double the nesting success rate for both wild and released zoo-bred birds. Too many young birds are dying early. That means we have to find nesting birds early in the breeding season and protect them from noisy miners, pied currawongs and even possums.

Next, we have to boost the numbers of zoo-bred birds released in the Blue Mountains, and maintain these numbers for at least twenty years. Staff at Taronga Conservation Society are preparing zoo-bred birds for the trials of the wild by exposing them to competition in flight aviaries, song tutoring young males and improving husbandry practices in zoos to increase survival in the wild.