inbox and environment news: Issue 526

February 13 - 19, 2022: Issue 526

Koalas Now Listed As Endangered

February 11, 2022

The Federal Government is boosting the level of protection for Koalas under National Environmental law, and will this week seek agreement from Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory on the National Recovery plan.

Minister for the Environment Sussan Ley said “We are taking unprecedented action to protect the koala, working with scientists, medical researchers, veterinarians, communities, states, local governments and Traditional Owners,” Minister Ley said.

“As part of our $200 million bushfire response, I asked the Threatened Species Scientific Committee to consider the status of the Koala.

“Today I am increasing the protection for koalas in NSW, the ACT and Queensland listing them as endangered rather than their previous designation of vulnerable.

“The impact of prolonged drought, followed by the black summer bushfires, and the cumulative impacts of disease, urbanisation and habitat loss over the past twenty years have led to the advice.

“Together we can ensure a healthy future for the koala and this decision, along with the total $74 million we have committed to koalas since 2019 will play a key role in that process.

“The new listing highlights the challenges the species is facing and ensures that all assessments under the Act will be considered not only in terms of their local impacts, but with regard to the wider koala population.

“The National plan developed through scientific advice and public consultation will now go to the relevant states for their final adoption and will help guide state and local government strategies.”

The decision follows a joint nomination by the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), Humane Society International (HSI) and WWF-Australia in April 2020 to Australia’s Threatened Species Scientific Committee.

Koalas in Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory will now be classified as Endangered under national legislation and will gain elevated protections. The decision also recognises the koala is one step further along the pathway to extinction.

“Koalas are an international and national icon, but they were living on a knife edge before the Black Summer bushfires with numbers in severe decline due to land-clearing, drought, disease, car strikes and dog attacks. The bushfires were the final straw, hitting at the heart of already struggling koala populations and critical habitat,” IFAW Oceania Regional Director Rebecca Keeble said.

“This decision is a double-edged sword. We should never have allowed things to get to the point where we are at risk of losing a national icon. It is a dark day for our nation. If we can’t protect an iconic species endemic to Australia, what chance do lesser known but no less important species have?

“This must be a wake-up call to Australia and the government to move much faster to protect critical habitat from development and land-clearing and seriously address the impacts of climate change.”

The nomination was submitted on the basis of two scientific reports which revealed Queensland’s koala population crashed by at least 50% since 2001 and up to 62% of the NSW koala population has been lost over the same period.

IFAW also welcomed the federal government’s recent $50AUD million pledge for koala recovery and habitat restoration.

“These actions are vital to ensure the survival of the species into the future, but without addressing the root cause of their decline which is habitat loss and climate change, we are just plugging holes in a sinking ship. We must do everything possible to implement the plan and save this iconic species,” Ms Keeble said.

In January 2022, the Australian Government announced an additional $50 million over 4 years to maintain and support the recovery and conservation of the Koala through monitoring, the protection of Koala habitats, and the improvement of Koala health and care in response to natural disasters such as bushfires and diseases including Chlamydia.

This funding injection builds upon the $18 million Koala conservation package announced in 2020, which includes $14 million in bushfire recovery funding, given the impact of the 2019-20 bushfires on the species and its habitats.

The additional $50 million Koala investment includes:

- $20 million in grants and procurements for larger projects led by Natural Resource Management groups, NGOs, and Indigenous groups, as well as state and territory governments to build on existing work, guided by the outcomes and findings of the National Koala Monitoring Program.

- $10 million to extend the National Koala Monitoring Program to fill critical knowledge gaps and increase the use of citizen scientists

- $10 million in grants for small-scale community projects and local activities such as habitat protection and restoration, managing threats, health and care facilities, and citizen science projects

- $2 million in grants to improve Koala health outcomes through applied research activities and the practical application of research outcomes to address fundamental health challenges such as Koala retrovirus, Koala herpes viruses and Chlamydia

- $1 million to expand the national training program in Koala care, treatment and triage

The $18 million Koala Conservation package (to June 2022) includes:

- $10 million to support habitat restoration and threat mitigation in bushfire-affected regions of New South Wales and south-east Queensland

- $2 million for Koala protection and recovery at additional sites identified from the Investment Framework for Environmental Resources (INFFER) workshops held in northern New South Wales (funded under the Environment Restoration Fund)

- $2 million for habitat restoration and threat mitigation in other non-bushfire affected regions of central and western New South Wales and central Queensland(funded under the Environment Restoration Fund)

- $2 million for a Koala Health Initiative to support coordination and delivery of more effective health research and to support Koala veterinary activities

- $2 million for a National Koala Monitoring Program to produce a robust estimate of the national Koala population and fill key data gaps identified through the Koala re-assessment and recovery plan development process.

In addition, Australian Government commitments to the Koala under the Environment Restoration Fund include:

- $3 million to support Koala hospitals in south east Queensland (announced in December 2019)

- $3 million to support habitat restoration in northern New South Wales and south east Queensland (announced in November 2019).

Long-Billed Corella: Birds In Your Backyard And Urban Street

The long-billed Corella or slender-billed corella (Cacatua tenuirostris) is a cockatoo native to Australia, which is similar in appearance to the little corella. This species is mostly white, with a reddish-pink face and forehead, and has a long, pale beak, which is used to dig for roots and seeds. It has reddish-pink feathers on the breast and belly.Long-billed corellas form monogamous pairs and both sexes share the task of building the nest, incubating the eggs, and caring for the young. Nests are made in decayed debris, the hollows of large old eucalypts, and occasionally in the cavities of loose gravely cliffs. Breeding generally takes place in Austral winter to spring (from July to November). 2–3 dull white, oval eggs are laid on a lining of decayed wood. The incubation period is around 24 days and chicks spend about 56 days in the nest.

The long-billed corella typically digs for roots, seeds, corms, and bulbs, especially from the weed onion grass. Native plants eaten include murnong Microseris lanceolata, but a substantial portion of the bird's diet now includes introduced plants.

The call of the long-billed corella is a quick, quavering, falsetto currup!, wulluk-wulluk, or cadillac-cadillac combined with harsh screeches.

The long-billed corella can be found in the wild in Victoria and south-eastern New South Wales. It has extended its range since the 1970s into Melbourne, Victoria and can now be found in Tasmania, South Australia and southeast Queensland.

Long-billed corellas are now popular as pets in many parts of Australia, although they were formerly uncommon, and their captive population has stabilised in the last decade. This may be due to their ability to mimic words and whole sentences to near perfection. The long-billed corella has been labelled the best "talker" of the Australian cockatoos, and possibly of all native Psittacines.

Photo: A J Guesdon

Sulphur-Crested Cockatoo (Cacatua Galerita) Swinging On Norfolk Pine Branch: Summer 'Larking' About

Like all parrots, cockatoos are zygodactyl (of a bird's feet; having two toes pointing forward and two backward). This, along with the use of their beak, gives them the ability to use their feet much like we use our hands and helps make them terrific climbers! Having the ability to climb is a necessity for birds that live and nest in thick forests. It’s hard to fly through dense, leafy branches, and even tougher to get to the fruit or nuts that are their primary foods, but because cockatoos can climb through tree branches so well, they can easily get to the treats they want. These birds are also able to hold their food in one foot while balancing on the other.

The Sulphur-crested Cockatoo's normal diet consists of berries, seeds, nuts and roots. It also takes handouts from humans. Feeding normally takes place in small to large groups, with one or more members of the group watching for danger from a nearby perch.

Cockatoos often “play” with each other, performing intricate aerial manoeuvres or crazy antics, such as hanging upside down while perched, just for the “fun” of it - as this one was this week! These activities serve as a form of exercise for the birds, and strengthen social bonds. - Info: BirdLife Astralia

When not feeding, these birds will bite off smaller branches and leaves from trees, an activity that may help to keep the bill trimmed and from growing too large. This one can also be seen cleaning out its toes after its 'swinging display':

Photos: A J Guesdon

Cicada 'Rain': Summer Of 2022

Although it's not as deafening under the Pittwater Spotted Gums in our yard in recent weeks, it has been VERY LOUD from early January as masses of Black Prince Cicadas (Psaltoda plaga) emerged to 'sing'. Only the male cicadas sing, gathering in large numbers in trees and make their calls using organs on either side of the body called tymbals, amplifying the sound by their hollow abdomen. Cicadas have been recorded 'singing at up to 96 decibels - 70 is around the noise made by your vacuum cleaner. There are two components of the call; a rhythmic revving, which is more prevalent when the weather is cooler, and a continuous call, more common in hot weather. They make this noise to attract females. When you hear an insect at night it's usually a cricket or katydid. Cicadas love the sun, so rain and cloudy skies will decrease the likelihood they will sing. Temperature also affects whether or not they will sing. If it is too cold they won't sing.

These cicadas have provided a feast for the birds that live here, including those born in this yard as shared so far this Summer; Summer Babies: Butcher Bird + A 1953 Insight On These By Bill Grayden and Summer Babies 2022: Channel-Billed Cuckoo Pair Being Fed By Currawong + Dollarbird Babies.

They are also food for noisy miners, blue-faced honeyeaters, little wattlebirds, grey and pied butcherbirds, magpie-larks, Torresian crows, white-faced herons and even the nocturnal tawny frogmouth, have all been reported as significant predators. At night we have had numerous flying foxes visiting to feed on them too.

Even our dog, Matilda Mae, has been feasting on them - going out to catch those that land before bringing them inside to eat them on the rug or chasing those that fly in at night, attracted by the lights on. She only eats the abdomen though, meaning we have to clean up the wings - a nice crunchy mess underfoot!

Cicadas constantly drink tree sap which makes for a 'cicada rain' as they urinate - when you have masses of cicadas in your trees you are likely to experience this. They drink tree fluid to cool down on warm days, which causes them to pee excessively. Cicada pee, like these insects, is harmless, and is even called 'honeydew' by some.

Some experts state they are peeing on you on purpose. Others say the cicadas squirt fluids at other males, animals and people as a defence mechanism.

We think they just have to urinate all that tree sap out as, as can be seen in this photo, they pee all day long even when no one and nothing else is around:

The cicada spends seven years underground in nymph form drinking sap from the roots of plants before emerging from the ground as an adult, although here we hear and see them every year. Species on which it feeds include weeping willow, river sheoak, rough-barked apple and various eucalypts. The adults, which live for four weeks, fly around, mate, and breed over the summer.

The colour of adult male black prince varies with age and locality. Around Sydney north to the Hunter River, it is very dark, predominantly black, with some brown markings; the abdomen black above and brown below. The eyes are brown. Further north from Brunswick Heads to Coolum Beach, the black prince exhibits more green markings instead of brown, and is lighter overall in coloration. The female is similar but slightly smaller than the male.

male and female inside at night at our place

Adult male

The black prince was originally described by German naturalist Ernst Friedrich Germar in 1834 as Cicada argentata, the species name derived from the Latin argentum "silver". Swedish entomologist Carl Stål defined the new genus Psaltoda in 1861 with three species, including the black prince as Psaltoda argentata. Francis Walker described Cicada plaga in 1850 as well as querying further specimens as Cicada argentata. He noted in 1858 that the binomial Cicada argentata had been used by a European species, and declared that Germar's cicada needed a new name. The older combination was ruled invalid as the binomial Cicada argentata had been originally used for a European cicada now known as Cicadetta argentata, and the black prince became Psaltoda plaga. The name black prince was in popular use by 1923.

Photos: A J Guesdon

Asparagus Fern Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Ned Kelly sculpture at entrance to Kimbriki Resource Recovery Centre - made from discarded metals. Photo: A J Guesdon.

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment - Next Forum

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew Next Clean Is At: Queenscliff: Sunday 27th Of February

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

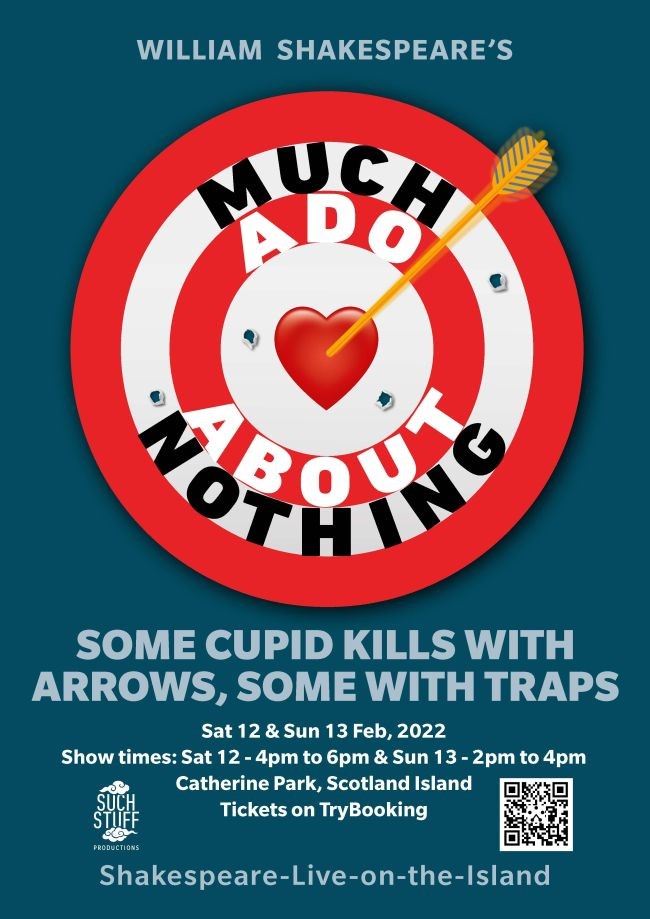

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

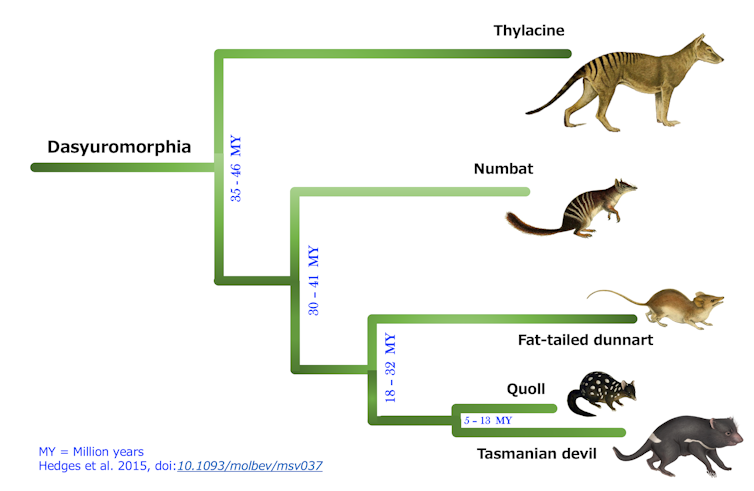

Back From The Brink: Bettongs, Numbats And Phascogales Flourish

February 9, 2022

A groundbreaking project helping mammals avoid extinction in NSW national parks is delivering great gains, with 150 animals since August released into a feral predator-free area.

On a visit to the Pilliga State Conservation Area site, Environment Minister James Griffin said the NSW Government-funded program removes feral cats and foxes from the landscape, creating safe refuges for endangered mammals.

The Pilliga and Mallee Cliffs National Park locations are just 2 of 7 feral-predator free areas already operational or being established, funded by the NSW Government and managed in partnership by the National Parks and Wildlife Service, Australian Wildlife Conservancy and Wild Deserts, led by UNSW.

'I can’t overstate how important this project is for protecting biodiversity – it’s one of the most ambitious mammal rewilding programs in Australia,' Mr Griffin said.

'Here at the Pilliga, we’ve seen the endangered bridled nailtail wallaby population double since it was reintroduced to this now feral-free area in August 2019, from 42 to about 90 at the latest estimate, including many females with joeys in pouches.

'This number is expected to eventually grow to more than 2000.'

In the Mallee Cliffs National Park, 60 vulnerable red-tailed phascogales were recently released back into the wild after an absence of almost 150 years.

red-tailed phascogale. Photo: Dr Laurence Berry / AWC

This population of tree-dwelling carnivores, which are related to the Tasmanian devil, is expected to grow to more than 1500 animals once established.

The phascogales were joined by 70 brush-tailed bettongs and another 20 numbats, the latter boosting a founding population established at Mallee Cliffs in 2020.

Numbat. Photo: Brad Leue / AWC;

Bettong. Photo: AWC

'The phascogale is the eighth mammal listed as extinct in New South Wales that has been returned to NSW national parks in the past 3 years,' Mr Griffin said.

'Within a few years, we hope to remove at least 10 mammals from the NSW extinct list – the first time that will have happened anywhere in the world.

'Many of these and other species already reintroduced to these feral-free areas have not been seen in our national parks for more than a century, largely because of foxes and feral cats. Feral cats kill over 1.5 billion native animals nationally every year.

'With these projects, we’re restoring ecosystems to health, giving locally extinct animals a second chance and, in time, offering the community the chance to see the bush at its best.'

Statewide there will soon be 65,000 hectares of feral predator-free areas on national park estate, including these 2 project sites. They’re being established as an essential part of the NSW Government’s conservation strategy, aiming to prevent extinction.

Photos: Red-tailed phascogale: Dr Laurence Berry / AWC; Numbat: Brad Leue / AWC; Bettong: AWC

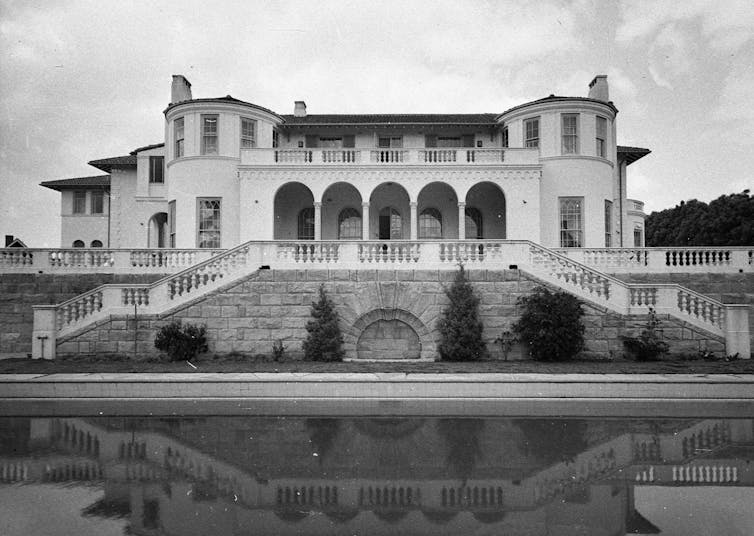

Billagoe Listed On State Heritage Register

February 10, 2022

The Billagoe (Mount Drysdale) Cultural Landscape has been listed on the NSW State Heritage Register, recognising its long and diverse history.

Heritage Minister James Griffin said he was proud to action the recommendation to list Billagoe Cultural Landscape, which is an outstanding example of a spiritual and cultural landscape.

"Billagoe (Mount Drysdale) has rich cultural significance to the Indigenous people of the Ngemba-Ngiyampaa-Wangaaybuwan-Wayilwan and Baiame, the ancestral creator of landscapes and resources," Mr Griffin said.

"It's important that we recognise and preserve the deep history of this site and I am pleased that my first listing as Heritage Minister is one that celebrates NSW's rich Aboriginal heritage.

"The site forms part of the Baiame cycle of creation stories and is linked to other significant places such as Cobar, Gundabooka National Park, Byrock Rockholes Aboriginal Place and the nationally and state listed Ngunnhu (Brewarrina Fishtraps)."

Billagoe (Mount Drysdale) Cultural Landscape is of state significance for its rare Aboriginal archaeology linked to ceremony, axe manufacturing, trade and social sites.

The site also includes examples of 19th-early 20th century gold mining infrastructure and Chinese market gardens, and a rare surviving example of a government caretaker's cottage, built in circa 1895.

As a multi-layered cultural landscape with shared history, it also has the ability to demonstrate the technology of water storage in an arid landscape, a theme that links the Indigenous, pastoral, mining and Chinese history.

"The listing of Billagoe (Mount Drysdale) Cultural Landscape celebrates and helps to protect unique and culturally important aspects of the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal history of NSW," Mr Griffin said.

Morrison government spends $50 million saving koalas while taking away their homes

Federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley is reportedly poised to decide whether some koala populations should be listed as endangered, as new research shows her government continues to approve land clearing in koala habitat.

Analysis released by the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) on Tuesday found that in the decade since koalas were declared vulnerable to extinction, the federal government had approved the clearing of 25,000 hectares of the species’ habitat.

It follows the Morrison government’s announcement last month of A$50 million to restore koala habitat, monitor populations and research the animals’ health.

But until the problems of habitat loss and land clearing are addressed, national koala populations will continue to dwindle. And as our recent research shows, much of the new funding is inadequate at the scale required.

Koala Cash-Splash

The Threatened Species Scientific Committee, which advises the federal government, has recommended the status of koalas in Queensland, New South Wales and the ACT be upgraded from vulnerable to endangered.

Ley is expected to respond to the recommendation by next month. Listing the koala as endangered would be a serious escalation in its threat status.

The federal government’s recent $50 million of koala funding supports various initiatives. They include:

$20 million for large habitat and health protection projects delivered by Indigenous groups, industry, state and territory governments and non-government organisations

$10 million for community-led habitat restoration, health and care facilities, and citizen science projects

$10 million to extend the National Koala Monitoring Program

$2 million to fund applied research in koala health

$1 million to fund vet staff and koala care, treatment and triage.

These are important investments. But we see two major issues with the federal government’s approach.

Habitat Loss: The Biggest Problem

Until koala habitat is protected, conservation efforts – largely funded by the taxpayer – will continue to be undermined.

Other recent federal koala funding includes $24 million after the Black Summer bushfires.

The NSW government wants to double the number of koalas in that state by 2050. To that end, it pledged $193 million over five years in the current budget. This followed the $44.7 million of koala funding it announced in 2018.

All this comes on top of the millions of dollars in international and national community donations for koala conservation efforts after the Black Summer bushfires.

But the primary driver of koala population decline is the clearing of its habitat. No amount of money can save koalas unless we tackle this.

The ACF research released on Tuesday confirmed the extent of the problem. The federal government approved the clearing of 25,000 hectares of koala habitat in the past decade, comprising 63 projects.

Most were mining projects, followed by land transport and housing developments.

Two recent federal decisions demonstrate this active undermining of koala conservation efforts:

approval to clear more than 75 hectares of critical koala habitat for housing west of Brisbane, reportedly in breach of the government’s own policy

approval of the Brandy Hill Quarry, which would clear 52 hectares of koala habitat to produce gravel and stone.

These projects were also approved by respective state governments, and were enabled by weak koala protections under both national and state environment laws.

Barely Scratches The Surface

Second, the federal funding for koala monitoring is inadequate.

We recently modelled the costs of conducting large-scale koala population surveys with methods that could be incorporated into the National Koala Monitoring Program.

We examined the cost of surveying 1.9 million hectares of fire-affected places in NSW considered “high and very high suitability” koala habitat.

We put the price tag at $9.5 million to $11.5 million for on-ground techniques, or about $7 million for efficient and cost-effective drone thermal imaging.

That’s just for one survey round. Even if the 1.9 million hectares was fairly distributed to key sampling areas, which is likely, the surveys must still be repeated at regular intervals to monitor koala populations over time.

The latest funding announcement for the National Koala Monitoring Program brings the total to $12 million since the initiative was announced in 2020. Given the vast extent of the koala’s range across five states and territories, this monitoring funding barely scratches the surface.

The Federal Government Must Step Up

Koala conservation is largely funded by the taxpayer and koalas receive far more funding than other threatened species.

So it’s only fair to expect this funding to deliver results. To protect the important public and community investment in koalas, the federal government must:

review current funding levels and provide adequate investment to support all Australia’s wildlife, including koalas

endorse the expert recommendation to list the koala as endangered in parts of Australia

finalise the Draft National Recovery Plan for the koala, which has been pending since 2012

enforce strong protections for koalas and other native wildlife, with independent oversight. The measures should follow the recommendations in Professor Graeme Samuel’s review of federal environment law.

In this, an election year, the Morrison government has the chance to show Australians it’s committed to saving our threatened wildlife. ![]()

Lachlan G. Howell, Research Fellow | Centre for Integrative Ecology, Deakin University; Ryan R. Witt, Postdoctoral Researcher and Honorary Lecturer | School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle, and Shelby A. Ryan, PhD Candidate | School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

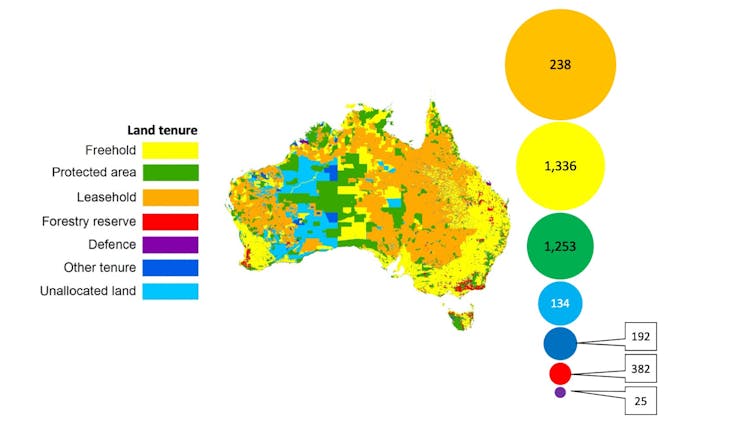

Native birds have vanished across the continent since colonisation. Now we know just how much we’ve lost

In the 250 years since Europeans colonised Australia, native birdlife has disappeared across the continent. Our new research has, for the first time, registered just how much Australia has actually lost – and our findings are astonishingly sad.

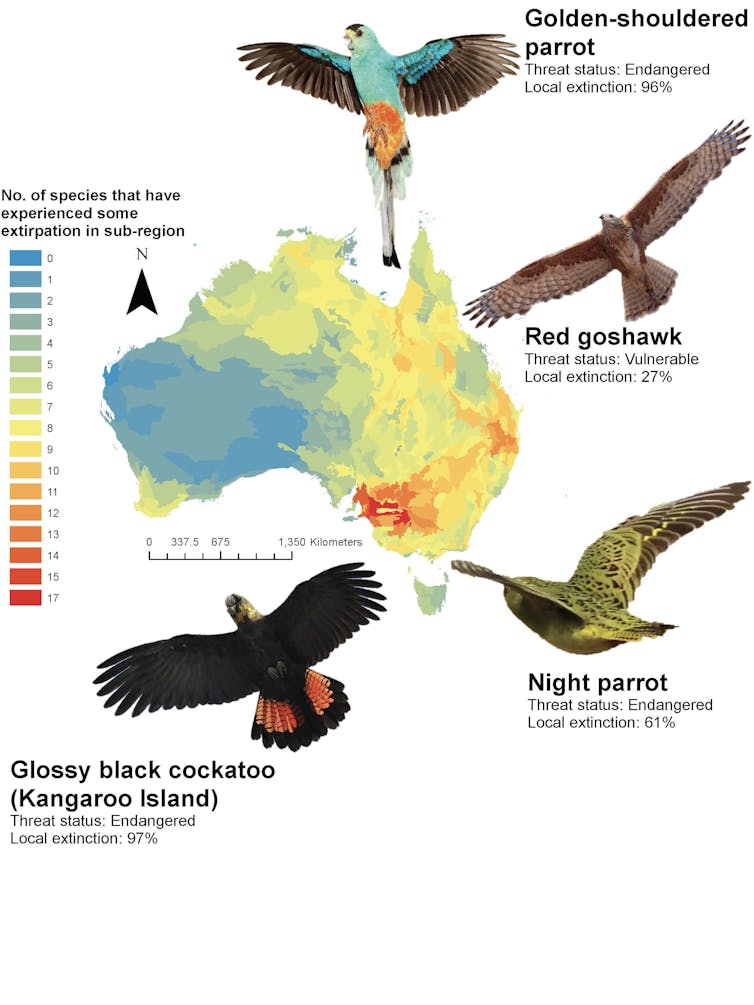

We focused on 72 species of birds faced with extinction today, including the Kangaroo Island glossy black cockatoo, regent honeyeater, and night parrot. We found 530 million hectares, or 69%, of Australia, has lost at least one bird species. In some parts of the country, we’ve lost up to 17 birds.

Land clearing, along with threats such as cat predation, have driven ten birds to disappear from over 99% of their historical habitat. Indeed, we show the last 250 years has seen more than 100 million hectares of now-threatened bird habitat cleared on mainland Australia – that’s 15% of Australia’s landmass.

For many of the species we examined, their remaining habitats occur in patches surrounded by farmland, towns and cities. To give birds and other animals a chance at survival, we need effective national leadership not only to protect existing habitats, but also to restore lost habitat and manage future habitat under climate change.

Lost, But Not Forgotten

In the last 250 years, 22 native birds have gone extinct. We found two more currently listed as threatened under Australia’s environmental legislation may also be now extinct.

One is the eastern star finch. This bird was once found from northern New South Wales to Queensland’s Burdekin River. A victim of overgrazing, it has not been seen since 1995. Surprisingly, this bird is only listed as “endangered” rather than “critically endangered” under [Australian law]

The other is the Tiwi Islands hooded robin, which has not been seen for 27 years. Changed fire patterns from European colonisation and invasive species such as cats and weeds have likely driven it to extinction.

Other species are on their last legs. The western ground parrot, for example, once swept across large parts of Western Australia, but are now in just two locations: Cape Arid National Park and Nuytsland Nature Reserve.

They’ve become locally extinct across more than 99% of their historical habitat because of habitat destruction, invasive species, and changed fire patterns. They’re at significant risk from isolated catastrophic events such as major bushfires. For example, the 2019-2020 fires alone destroyed 40% of the bird’s last remaining habitat.

The plight of the regent honeyeater is another tragic story of decline. Flocks of thousands once occurred from Adelaide to north of Brisbane, with the naturalist John Gould writing in 1865:

I met with it in great abundance among the brushes of New South Wales […] I have occasionally seen flocks of from fifty to a hundred in numbers, passing from tree to tree as if engaged in a partial migration from one part of the country to another, or in search of a more abundant supply of food.

Today, only 100 breeding pairs are left, and almost all breed in just three sites in NSW. The species has lost more than 86% of its historical habitat, with land clearing the main driver of decline. So few remain that young birds cannot learn to sing properly, so have trouble attracting a mate.

The Extinction Wave

Our research used a combination of historical field guides, reference books, research papers, government records, spatial data, and expert elicitation to create maps of past habitats, and compared those to current habitats.

We found certain areas across continental mainland Australia to be in worse shape than others.

For example, we revealed extinction hotspots in areas between Swan Hill in Victoria and Marmon Jabuk range in South Australia. In this region, up to 17 birds have gone extinct (red areas in map), such as the black-eared miner.

Likewise, over the last century, almost 10% of all known breeding land-based birds have vanished in SA’s Mount Lofty ranges. This includes the rufous fieldwren, bush stone-curlew, ground parrot, king quail, azure kingfisher, barking owl, regent honeyeater, and swift parrot.

The story of decline is not limited to only threatened species, with more common birds such as willie wagtails, brolgas, boobook owls, and even magpies now disappearing from many places they were once common.

Indeed, the loss of so many species is the canary in the coal mine of total ecosystem collapse. And total ecosystem collapse poses an existential threat to food systems, water quality and climate stability.

If we don’t make fundamental changes in the way we manage and use landscapes, the extinction wave will continue to inundate Australia.

What Can We Do About It?

We need federal leadership to curb the extinction crisis, and an important start is to implement promises we’ve already signed up to in, for example, the UN’s Aichi biodiversity targets.

At the ongoing international biodiversity conference – COP15 – a key ask is for countries to halt human-induced species extinctions from now onwards, to bring the overall risk of species extinctions to zero, and to bring population abundance of native species back to 1970s levels by 2050. This is a basic commitment to Australia’s heritage and culture.

Crucially, we need fundamental reform of Australia’s key environment legislation: the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

A major, independent review last year revealed that the EPBC Act has failed native wildlife. One of its key recommendations was to implement strong national environmental standards, such as not allowing any degradation of critical habitat.

These standards must be put in place as a matter of urgency. They must be legally enforceable, concise, specific, and focused on the conservation outcomes to properly protect Australian biodiversity and reverse the decline of our iconic places.

A huge thank you to all my wonderful co-authors, without which, this research would not be possible: James E.M. Watson, Hugh P. Possingham, Stephen T. Garnett, Martine Maron, Jonathan R. Rhodes, Chris MacColl, Richard Seaton, Nigel Jackett, April E. Reside, Patrick Webster, Jeremy S. Simmonds.![]()

Michelle Ward, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is the buff-breasted button-quail still alive? After years of searching, this century-old bird mystery has yet to be solved

In humid savanna on Cape York Peninsula, February 5, 1922, a man was on the hunt with a local Indigenous guide. They had just heard their quarry calling among the tall grass – a low “oomm, oomm, oomm” – before it burst into view with a flurry of wingbeats. A loud shotgun blast, and the bird dropped to the ground.

The bird was a buff-breasted button-quail, and the collector was Australian field naturalist William Rae McLennan. Later that evening he would have skinned and stuffed the bird, turning it into a museum specimen, before describing the encounter in his diary.

This skin was the last of the species ever collected. A century later, we have still yet to confirm any sightings of this mysterious, native bird.

I’ve spent four years searching for the buff-breasted button-quail, walking hundreds of kilometres and spending months scouring practically every locality where the species had ever been reported. All I’ve been able to find is its more common cousin: the painted button-quail.

Still, my ongoing research has brought us a step closer to solving this mystery and I remain hopeful the bird is still in existence. If it is, it urgently needs our help.

Searching For A Lost Species

McLennan’s diary from that wet season of 1921-1922 has remained the only detailed descriptions of the buff-breasted button-quail’s ecology. Some 60 years later in 1985, it was “rediscovered” just west of Cairns, and this launched dozens of new sightings by birdwatchers and several research projects over the next few decades.

Unfortunately, none of these reports or research endeavours produced anything more than brief sightings of the bird, typically only split-second views as it flew off from under their feet. No photos, no specimens, nor any other verifiable evidence has been produced.

For my doctoral project on the species, I joined the RARES research group at the University of Queensland in 2018. Our research team aimed to find a population, study its ecology, determine what threatening processes had led to its rarity, and learn how it could be conserved.

There were a few times in far north Queensland’s wet-season – supposedly the best time of year to see buff-breasted button-quail – when I saw birds fitting its widely accepted description: they were large, with sandy rufous (reddish brown) back and rumps, and contrasting dark primary feathers.

But whenever I thought I saw one on the ground, it turned out to be a painted button-quail. These differ by having a bright red eye and a grey breast.

Given there had been numerous reported sightings of buff-breasted button-quails from the region in the years prior, finding only painted button-quails was surprising, confusing and raised serious concerns.

Indeed, my research team and I became increasingly apprehensive about the status of the buff-breasted button-quail, and began questioning the features used to separate them from painted button-quail. This prompted a thorough investigation of all historical reports, and the reliability of characteristics used to identify the two birds in the field.

Has The Bird Been Misidentified?

To determine how best to separate these two species in the field, I examined over 100 button-quail skins in museum collections worldwide. I also caught and photographed painted button-quail throughout north Queensland. What I discovered was intriguing.

Several supposedly key characteristics of the buff-breasted button-quail either did not exist, or were actually features of the painted button-quail.

For instance, it was commonly reported that buff-breasted button-quail were much bigger than painted button-quail. My study of museum specimens, which is not yet published, showed the two are actually the same size.

I also discovered a previously undocumented colour variation in the plumage of painted button-quail. At the start of the wet season when they begin breeding, the female’s typical grey plumage is replaced by a much brighter rufous plumage. This brighter plumage is very similar to the sandy rufous colour expected of a buff-breasted button-quail.

This apparently breeding-related change in plumage was completely unknown, and its seasonal timing coincided with an increase in reports of the buff-breasted button-quail.

In short, with no hard evidence of the buff-breasted button-quail’s existence for 100 years, many of the most recent sightings of the species could actually have been the much more common painted button-quail.

This means the buff-breasted button-quail is likely far rarer than we could ever have ever feared.

What Does Its Future Hold?

When McLennan collected the last buff-breasted button-quail skin, the Tasmanian tiger roamed Tasmania’s forests, and the paradise parrot was still nesting in termite mounds in south east Queensland.

We realised too late that these unique species were in decline. Have we made the same mistake with the buff-breasted button-quail?

We already knew the bird was rare, but was our confidence in the species’ status misplaced, propped up by misidentifications of a more common species?

Aside from a clutch of eggs collected in 1924, there has been no incontrovertible proof the species continues to exist. Our extensive searches at sites where it was once found have failed.

We also know the bird communities of Cape York have been changing at a rapid rate, mostly due to the impact of changed fire patterns and cattle grazing. Other iconic Cape York species – such as the golden-shouldered parrot and red goshawk – have also declined over the past decades.

It seems likely the buff-breasted button-quail has suffered the same fate. It may not be extinct, but our research suggests it may only be hanging on by a thread, at best.

This 100-year anniversary is an opportunity to recognise the bird’s dire situation. Our new findings should prompt the federal and Queensland governments to act.

First, they should invoke the precautionary principle, which is to improve conservation actions for the species in light of its uncertain status. They should also immediately up-list the species to critically endangered, as right now it’s listed only as endangered.

Second, they should urgently provide the resources needed to re-evaluate the species’ conservation needs, as the status quo is not working.

We hope these efforts will prove the species is still in existence – perhaps living in a previously unsurveyed part of Cape York – and not another one that has disappeared on our watch.![]()

Patrick Webster, PhD candidate, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Time is their secret weapon’: the hidden grey army quietly advancing species discovery in Australia

Each year, many new species of Australian plants, animals and fungi are discovered and described. It’s detailed, time-consuming work, and much of it could not be done without the contribution of older Australians.

I’m an evolutionary botanist and I use DNA sequencing to better understand relationships between plant species – a field known as phylogenetics. My job involves collecting plant specimens in the furthest corners of Australia.

Time and again I’m helped by older, generally retired Australians with a passion for the plants I’m working on. In their own time and with their own resources, they take it upon themselves to explore and document a particular geographic area or group of plants.

Many have a professional scientific background, although not necessarily in the field they now contribute to. For these dedicated men and women, passion is their driver and time their secret weapon.

Without these older Australians, my research wouldn’t be where it is today. So let me introduce you to a few of them.

Bevan Buirchell, Ron Dadd And Russell Wait

From opposite sides of the country – Bevan and Ron in Western Australia and Russell in Victoria – these three collectors discover, sample and grow extensive collections of emu bush (Eremophila).

More than 200 species of emu bush have been described, and many are rare, threatened or endangered.

Emu bush is a culturally important plant for many Indigenous Australians, and recent research has revealed the genus contains many new chemical compounds of interest for medicinal use.

Each year, the trio spends weeks four-wheel driving in arid and remote parts of Australia where emu bush is thought to be found.

When the men come across something interesting, they record scientific details and collect a cutting for propagation in their own or each other’s gardens.

Between them, Bevan, Ron and Russell have collections of almost every described species of emu bush, and new species awaiting formal description. So far, Bevan has described 16 new species or subspecies.

In this way, their gardens are like living museums of species diversity. They’re a great resource for the inclusion of species in phylogenetic research.

Don Franklin

In the tablelands of Far North Queensland, retired ecologist Don Franklin spends his time expanding his knowledge of eucalypts.

A colleague put me in touch with Don when I was planning fieldwork to collect eucalypt species for my latest research project. Don was happy to help, assisting me with planning my collection route to ensure I sampled not just every species possible, but all the interesting variants he knows from different regions.

This on the ground experience is invaluable for my work, and impossible to gain from published literature alone.

Don is writing a comprehensive field study for eucalypt species spanning about 80,000 square kilometres. Over the past five years he’s travelled every road in the area, marking species distributions, morphological variants and regions of hybrid zones.

Don was my guide and assistant for a few weeks of field work, and my understanding of this group of plants benefited immeasurably.

Margaret Brookes

Margaret is a retired horticulturalist. For the past decade she’s volunteered at the National Herbarium of Victoria and the University of Melbourne Herbarium, where she helps curate the collections.

Over this period, Margaret’s work has included mounting thousands of new specimens submitted by researchers like me, and processing the backlog of old collections. Margaret has also transcribed historical field notes for plant collectors in decades and even centuries past.

Margaret’s work makes these plant collections accessible to researchers and the general public all over the world.

Continual advances in genetic sequencing technology mean we can increasingly access DNA from older and older dried specimens. In this way, the work done by Margaret and other herbarium volunteers becomes even more essential in discovering and classifying new species.

Combining Forces With Senior-Citizen Scientists

As an early career researcher I am bound by two to three year funding contracts. In that short time, samples must be collected and genetically sequenced, then analysed and the results interpreted.

And to come up with plausible hypotheses to understand species’ relationships, my expertise must be broad. I’ve got to be good in the lab, proficient at analysis and across the latest literature.

To produce high-quality work in such tight time frames, I rely on the hidden “grey army” of older people such as those described above.

And while I can only speak from personal experience, I daresay many fields of natural science also benefit from a dedicated older generation quietly contributing to the body of scientific knowledge.

We must recognise the invaluable contributions made by older volunteer researchers. And if we’re to have any chance of better understanding the estimated 70% of Australia’s biodiversity unknown to science, their continued involvement is imperative.

For those interested in volunteering or citizen science projects, try contacting your nearest herbaria. You could also check out the Atlas of Living Australia’s DigiVol volunteer portal or the Australian Citizen Science Association.![]()

Rachael Fowler, Post doctoral research fellow plant evolution, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The stunning recovery of a heavily polluted river in the heart of the Blue Mountains World Heritage area

For more than 40 years, an underground coal mine discharged poorly treated wastewater directly into the Wollangambe River, which flows through the heart of the Blue Mountains World Heritage area.

Much of this spectacular wild river was chronically polluted, with dangerously high levels of zinc and nickel. Few animals were able to survive there.

My colleagues and I had been calling for tougher regulations to clean-up the wastewater flow since 2014, after we first sampled the river for our research. Finally, with the Blue Mountains community rallying behind us, the New South Wales Environment Protection Agency (EPA) enforced stronger regulations in 2020.

Our latest research paper documents the Wollangambe River’s recovery since. Already we’ve seen a massive improvement to the water quality, with wildlife returning to formerly polluted sites in stunning numbers.

In fact, the long fight for the restoration of this globally significant river is the focus of a new documentary, Mining the Blue Mountains, released this week (and online in coming days).

But while the recovery so far is promising, it remains incomplete. Much more action is needed to return the river to its former health.

How Bad Was The River?

When the federal government nominated the Blue Mountains to be inscribed on the World Heritage list in 1998, it claimed “some coal mining operations occur nearby, but do not affect the water catchments that drain to the area”.

Our research has shown this not to be true, and the pollution of this river has generated international concern. In 2020, the International Union for Conservation of Nature – an official advisor to UNESCO – identified the coal mine as a major threat to the conservation values of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage area.

So, how bad was the pollution? Our previous survey conducted nine years ago investigated both water quality and river invertebrates – mostly aquatic insects.

Wastewater from the underground coal mine Clarence Colliery entered the Wollangambe River about 1.5 kilometres upstream of the World Heritage area boundary. The nature of the pollution was complex, but of most serious concern was the increased concentrations of nickel and zinc in the river.

These metals were unusually enriched for coal wastewater, with both at concentrations more than 10 times known safe levels. The pollution remained dangerous for more than 20km downstream, deep within the World Heritage area.

Compared to upstream and unaffected reference streams, we found the abundance of invertebrates in the Wollangambe fell by 90%, with the diversity of invertebrate families 65% lower below the mine waste outfall.

There was also a build-up of contaminants into the surrounding foodchain. For example, one of our studies detected metals accumulated in plants growing on the river bank. Another found a build-up in the tissue of aquatic beetles below the mine outfall.

Life Returns To The River

In 2014 we not only shared our published research findings with the NSW EPA, but also with the Blue Mountains community. This triggered a letter writing campaign from the Blue Mountains Conservation Society urging the EPA to take action.

After five long years, the EPA finally issued stringent regulations requiring Clarence Colliery to make enormous reductions in the release of pollutants, particularly zinc and nickel, in the colliery waste discharge.

And it worked! We collected samples 22km downstream of the river, and were very surprised at the speed and extent of ecological recovery. Not only has water quality improved, but animals are coming back, too.

The improved treatment resulted in a very significant reduction of zinc and nickel concentrations in the mine’s wastewater, which continues to be closely monitored and publicly reported by the colliery.

The most pollution-sensitive groups of invertebrates – mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies – had a steep increase (256%) in their abundance compared to when we conducted our earlier research in 2012 and 2013.

This could have positive implications for the surrounding plants and animals, as river invertebrates are a major food source for water birds, lizards, fish and platypus.

However, the road to recovery is a long one. River sediments remain contaminated by the build-up of four decades of zinc and nickel enrichment, up to 2km downstream of the mine outfall.

To help speed up the river’s recovery, contaminated sediment should be removed from the river below the mine outfall, similar to a 12-month clean-up operation conducted after a major spill from the mine in 2015.

Pollution Doesn’t Often End When Mines Do

Sadly, there are closed mines in the Blue Mountains that continue to release damaging pollution, such as Canyon Colliery and several in the Sunny Corner gold mine area, as the documentary explores.

Canyon Colliery closed in 1997, and contaminated groundwater continues to be discharged from its drainage shafts into the Grose River, which is part of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

Likewise, most Sunny Corner mines closed over a century ago, and yet severe pollution still seeps from the mines into waterways.

The pollution here is at extreme concentrations and includes arsenic, copper, lead and zinc. It’s dangerous to life in waterways, surrounding soil and contact with this pollution is hazardous to human health.

What Can We Learn From This?

Rehabilitating these closed mines are expensive, and often with limited success. But the Wollangambe River case study is an encouraging sign that clean-up is possible for even the most polluted environments.

Solid independent scientific research and community involvement are critical for these efforts. The community is the eyes and ears of the environment, and has an important role holding industry and government regulators to account.

The environmental regulators, such as NSW EPA, have enormous power to address pollution and trigger positive change. It’s important researchers and the community engages with them – and it helps to be patient as action can take years to happen.

And finally, we congratulate Centennial Coal, the owners of the Clarence Colliery, for making enormous improvements to their operation and complying with tough new environmental regulations.![]()

Ian Wright, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Science, Western Sydney University; Jason Reynolds, Senior Lecturer, Western Sydney University, and Leo Robba, Lecturer, Visual Communications / Social Design, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Just 16% of the world’s coastlines are in good shape – and many are so bad they can never fully recover

Only about 16% of the world’s coastal regions are in relatively good condition, according to our world-first research released today, and many are so degraded they can’t be restored to their original state.

Places where the land meets the sea are crucial for our planet to function. They support biodiversity and the livelihoods of billions of people. But to date, understanding of the overall state of Earth’s coastal regions has been poor.

Our research, involving an international team of experts, revealed an alarming story. Humanity is putting heavy pressure on almost half the world’s coastal regions, including a large proportion of protected areas.

All nations must ramp up efforts to preserve and restore their coastal regions – and the time to start is right now.

Our Coasts Are Vital – And Vulnerable

Coastal regions encompass some of the most diverse and unique ecosystems on Earth. They include coral reefs, kelp forests, seagrass, tidal flats, mangroves, estuaries, salt marshes, wetlands and coastal wooded habitat.

Many animal species, including those that migrate, rely on coastlines for breeding, foraging and protection. Coastal sites are also where rivers discharge, mangrove forests exchange nutrients with the ocean, and tidal flows are maintained.

Humans also need coastlines. Among other functions, they support our fisheries, protect us from storms and, importantly, store carbon to help mitigate climate change.

As much as 74% of the world’s population live within 50 kilometres of the coast, and humans put pressure on coastal environments in myriad ways.

In marine environments, these pressures include:

- fishing at various intensities

- land-based nutrient, organic chemical and light pollution

- direct human impacts such as via recreation

- ocean shipping

- climate change (and associated ocean acidification, sea-level rise and increased sea surface temperatures).

On land, human pressures on our coastlines include:

- built environments, such as coastal developments

- disturbance

- electricity and transport infrastructure

- cropping and pasture lands, which clears ecosystems and causes chemical and nutrient runoff into waterways.

To date, assessments of the world’s coastal regions have largely focused solely on either the land or ocean, rather than considering both realms together. Our research sought to address this.

A Troubling Picture

We integrated existing human impact maps for both land and ocean areas. This enabled us to assess the spectrum of human pressure across Earth’s coastal regions to identify those that are highly degraded and those intact.

Both maps use data up to the year 2013 – the most recent year for which cohesive data is available.

No coastal region was free from human influence. However, 15.5% of Earth’s coastal regions remained intact – in other words, humans had exerted only low pressure. Many of the intact coastal regions were in Canada, followed by Russia and Greenland.

Large expanses of intact coast were also found elsewhere including Australia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Chile, Brazil and the United States.

Troublingly, 47.9% of coastal regions have been exposed to very high levels of human pressure. And for 84% of countries, more than half their coastal regions were degraded.

What’s more, human pressures were high in about 43% of protected coastal regions – those regions purportedly managed to conserve nature.

Coastal regions containing sea grasses, savannah and coral reefs had the highest levels of human pressure compared to other coastal ecosystems. Some coastal regions may be so degraded they cannot be restored. Coastal ecosystems are highly complex and once lost, it is likely impossible to restore them to their original state.

So Where To Now?

It’s safe to say intact coastal regions are now rare. We urge governments to urgently conserve the coastal regions that remain in good condition, while restoring those that are degraded but can still be fixed.

To assist with this global task, we have made our dataset publicly available and free to use here.

Of course, the right conservation and restoration actions will vary from place to place. The actions might include, but are not limited to:

improving environmental governance and laws related to encroaching development

increasing well-resourced protected areas

mitigating land-use change to prevent increased pollution run-off

better community and local engagement

strengthening Indigenous involvement in managing coastal regions

effective management of fishing resources

addressing climate change

tackling geopolitical and socioeconomic drivers of damage to coastal environments.

In addition, there’s an urgent need for national and global policies and programs to effectively managing areas where the land and ocean converge.

Humanity’s impact on Earth’s coastal regions is already severe and widespread. Without urgent change, the implications for both coastal biodiversity and society will become even more profound.![]()

Brooke Williams, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Queensland; Amelia Wenger, Research fellow, The University of Queensland, and James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP26 Deal Sparks Hope For Positive Tipping Points

February 8, 2022

The Breakthrough Agenda agreed at COP26 could help trigger positive tipping points to tackle the climate crisis, researchers say. At the summit in Glasgow, leaders of countries covering 70% of world GDP pledged to "make clean technologies and sustainable solutions the most affordable, accessible and attractive option in each emitting sector globally before 2030."

This signals a key shift in thinking -- instead of focussing directly on emissions targets, it aims to tip economic sectors into a new state where the "green" option is cheapest and easiest.

A tipping point occurs when a small intervention sparks a rapid, often irreversible transformation -- and a new paper offers a "recipe" for finding and triggering positive tipping points.

"The only way we can get anywhere near our global targets on key issues like carbon emissions and biodiversity is through positive tipping points," said lead author Professor Tim Lenton, Director of the Global Systems Institute (GSI) at the University of Exeter.

"The challenges are enormous -- we need to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030, and reverse biodiversity loss to make our impact 'nature-positive'.

"The Breakthrough Agenda is the first time a large group of countries has agreed joint climate change goals in the form of economic tipping points.

"We argued for precisely this in a previous paper, and we are heartened to see world leaders adopting this approach.

"Our new paper shows a variety of ways that tipping points can be activated.

"Societies worldwide will need to put all of these into action to bring about low-carbon transitions at the pace and scale required to avoid dangerous climate change."

The paper examines the "enabling conditions" for a tipping point (such as the declining price of a green technology), and how the tipping point can be triggered (for example by coalitions of committed individuals).

Combinations of factors such as cost and public attitude have helped to trigger tipping points in electric vehicles and solar energy, and both are rapidly advancing around the world -- which in turn leads to feedbacks of technological improvements and lower costs.

Greta Thunberg's climate protest triggered a global surge of activism that continues to grow, with diverse impacts.

Asked about positive tipping points that could soon be triggered -- or might already be tipping -- Professor Lenton highlighted the growth and uptake of plant-based diets, including meat substitutes.

Co-author Scarlett Benson, from global sustainability consultancy SYSTEMIQ, said: "Policymakers have a critical role in triggering the shift away from meat-rich diets, for example by investing the trillions of dollars of public R&D spend into the development of plant-based and cell-based meat and dairy alternatives, and by directing the trillions of dollars of public procurement spend towards these products to stimulate demand and drive down costs."

Co-author Dr Tom Powell, from GSI, added: "In other cases, transformation can start with grassroots communities.

"For subsistence farmers facing land degradation and drought, regenerative farming methods can help rebuild the health of their soils and ecosystems, making them more resilient. A farmer-led scheme called TIST has spread to over 150,000 subsistence farmers in East Africa, because it supports farmers to share these practices and learn from one another.

"International voluntary carbon markets have enabled TIST members to collectively access payments for carbon sequestered in trees on their land, building in a further reinforcing feedback."

The researchers say positive tipping points can help to counter widespread feelings of disempowerment in the face of global challenges, and they stress that everyone can play a part in triggering positive tipping points.

"These changes often start with small groups of people with a big idea," said Professor Lenton.

"These can become networks of change that grow into large movements with a major impact.

"Public and private money is also important. Public money is often first, funding research and development, and private finance then comes to drive an idea at scale."

The paper notes the importance of equity when seeking to trigger tipping points. The authors write: "It is vital to consider what social safety nets can help ensure a just transformation."

The researchers say their framework for finding and triggering tipping points needs "testing and refining," adding: "There is no better way forward than to learn by doing.

"Continuing to delay action to accelerate a just transformation towards global sustainability will only accentuate the need to find and trigger even more dramatic positive tipping points in the future."

The paper, written by a team including researchers from Hamburg University and University College London and published in the journal Global Sustainability, is entitled: "Operationalising Positive Tipping Points towards Global Sustainability."

Timothy M. Lenton, Scarlett Benson, Talia Smith, Theodora Ewer, Victor Lanel, Elizabeth Petykowski, Thomas W. R. Powell, Jesse F. Abrams, Fenna Blomsma, Simon Sharpe. Operationalising positive tipping points towards global sustainability. Global Sustainability, 2022; 5 DOI: 10.1017/sus.2021.30

Lotus Effect: Self-Cleaning Bioplastics Repel Liquid And Dirt

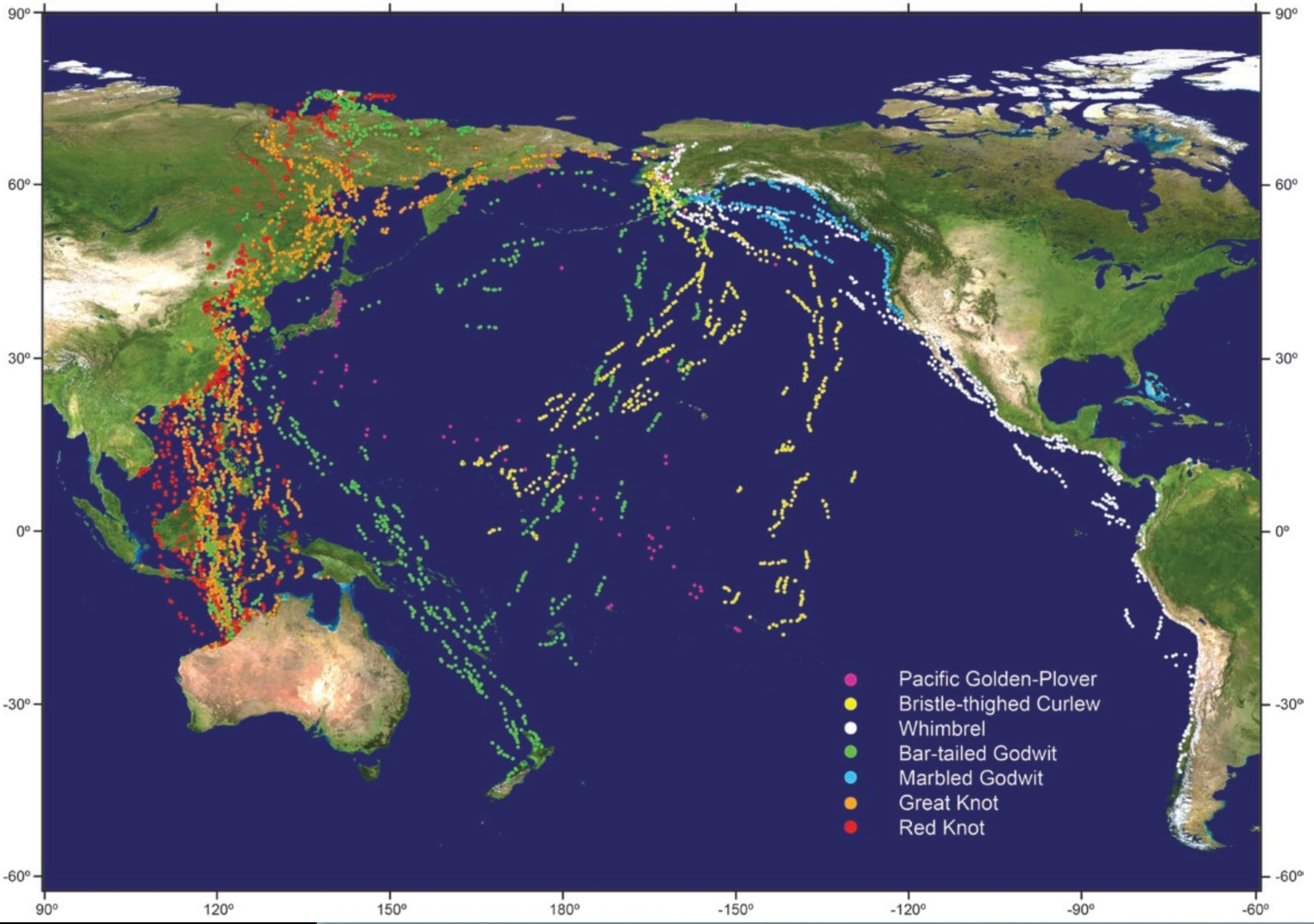

Pacific Ocean As The Greatest Theatre Of Bird Migration

Pink Pumice Key To Revealing Explosive Power Of Underwater Volcanic Eruptions

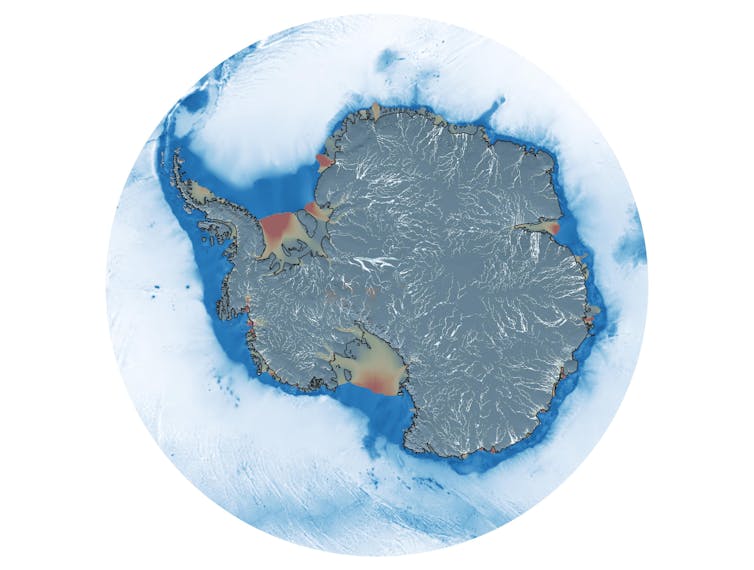

In research published in the Nature portfolio journal Communications Earth and Environment, the researchers including Professor Scott Bryan, Dr Michael Jones and PhD candidate Joseph Knafelc, were intrigued by the occurrence of pink pumice within the massive pumice raft that resulted from the Havre 2012 deep-sea eruption.

In research published in the Nature portfolio journal Communications Earth and Environment, the researchers including Professor Scott Bryan, Dr Michael Jones and PhD candidate Joseph Knafelc, were intrigued by the occurrence of pink pumice within the massive pumice raft that resulted from the Havre 2012 deep-sea eruption.

Unique Seagrass Nursery Aims To Help Florida's Starving Manatees

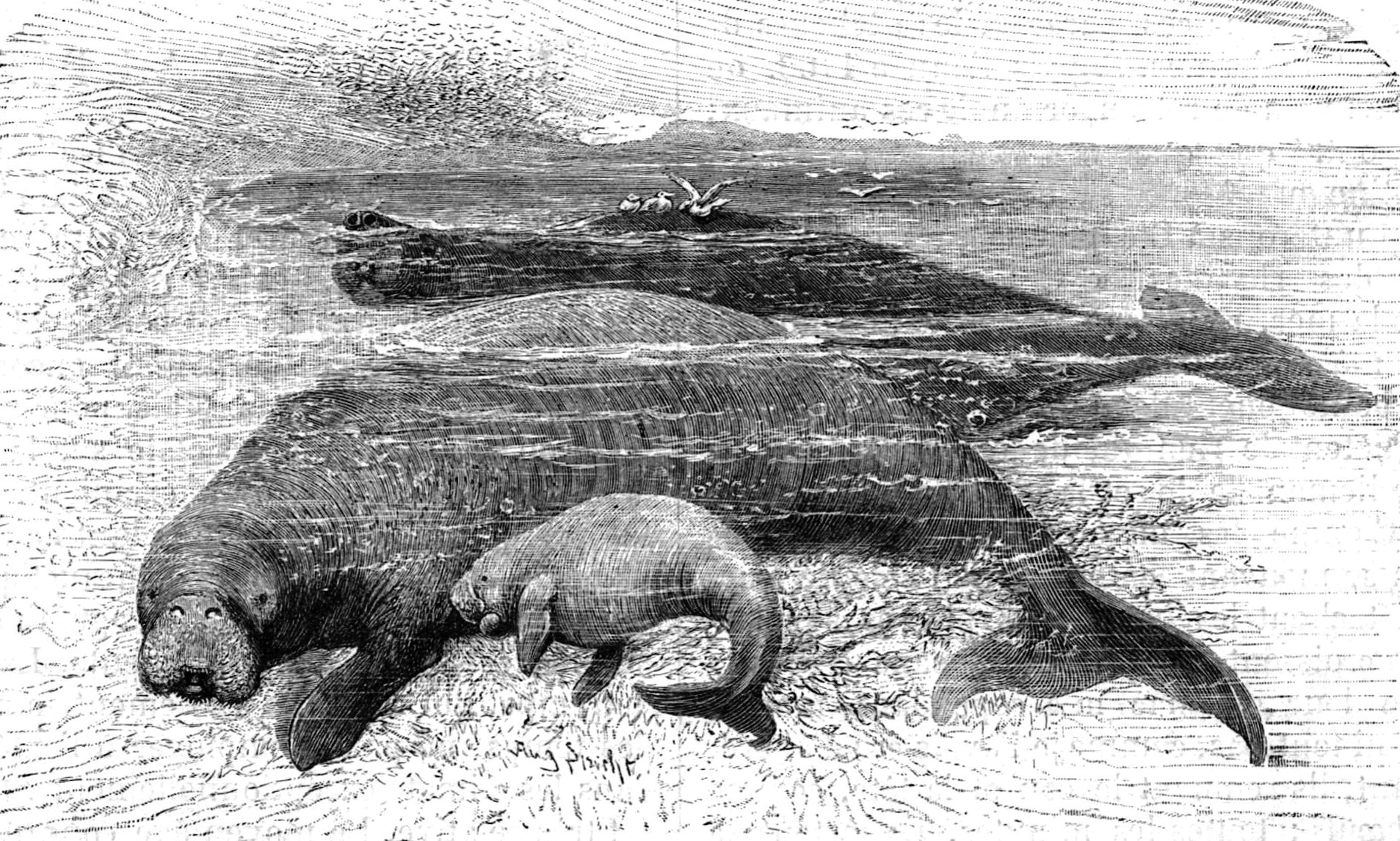

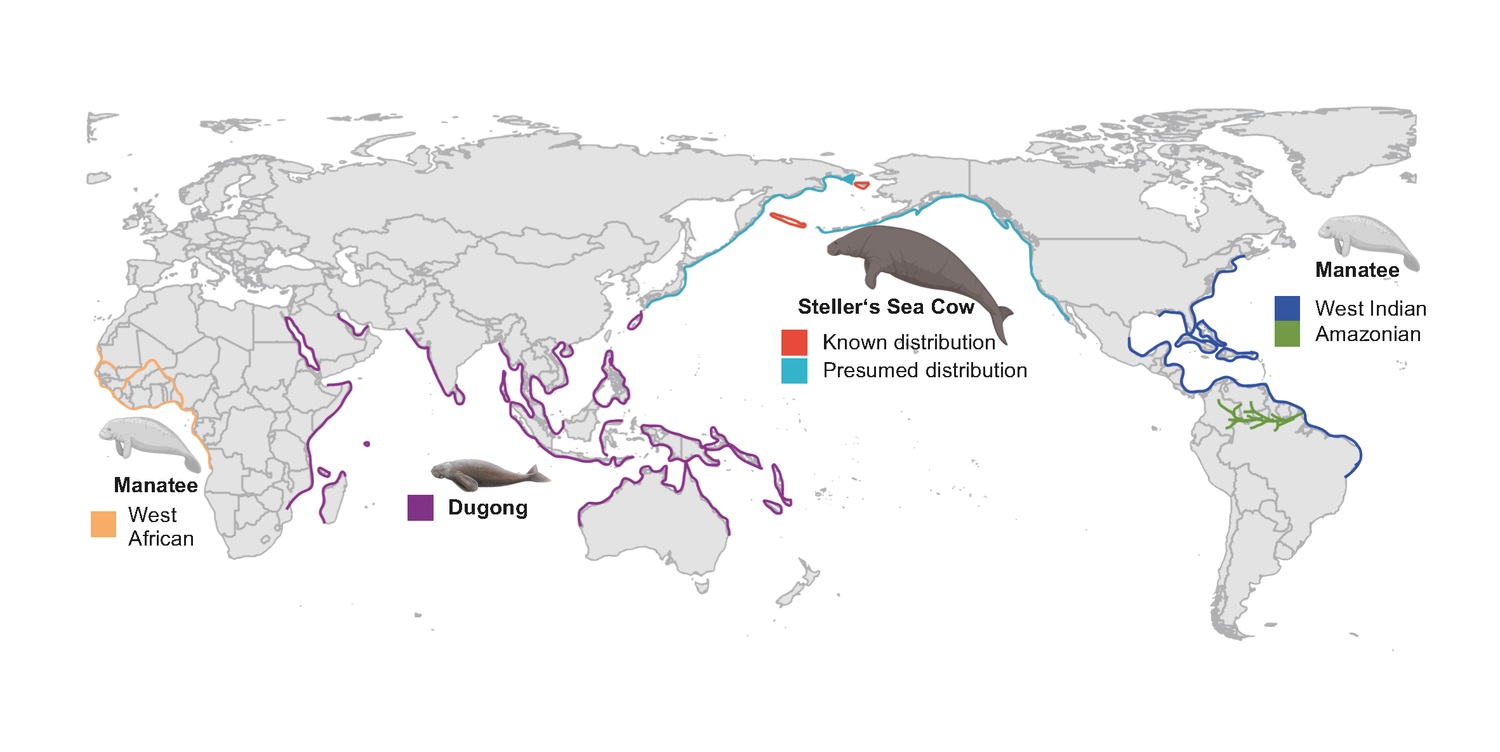

Genome Of Steller’s Sea Cow Decoded

February 8, 2022

During the Ice Age, giant mammals such as mammoths, sabre-toothed cats and woolly rhinoceroses once roamed Northern Europe and America. The cold oceans of the northern hemisphere were also home to giants like Steller's sea cow, which grew up to eight meters long and weighed up to ten tons, and has been extinct for around 250 years. Now an international research team has succeeded in deciphering the genome of this ice-age species from fossil bones. They also found an answer to the question of what the genome of this extinct species of sea cow reveals about present-day skin diseases.

1898 illustration of a Steller's sea cow family

The giant sea cow from the Ice Age was discovered in 1741 by Georg Wilhelm Steller and later named after him. The 18th-century naturalist was interested not only in the enormous size of this animal species but also in its unusual, bark-like skin. He described it as "a skin so thick that it is more like the bark of old oaks than the skin of an animal."

Such a bark-like structure of the epidermis is not found in related sirenians, which today live exclusively in tropical waters. In scientific circles, it was previously assumed that the bark-like epidermis was the result of parasite feeding, but also insulated heat and thus protected the sea cow well from the cold during the Ice Age and from injuries in the polar seas.

In the current study, the scientists led by Dr Diana Le Duc and Professor Torsten Schöneberg from Leipzig University, Professor Michael Hofreiter from the University of Potsdam and Professor Beth Shapiro from the University of California, show that the palaeogenomes of Steller's sea cow reveal functional changes. These changes were responsible for the bark-like skin and the adaptation to cold.

To find this out, an international research team from Germany and the US reconstructed the genome of this extinct species from fossil bone remains of a total of twelve different individuals.

"The most spectacular result of our investigations is that we have clarified why this giant of the sea had bark-like skin," said Diana Le Duc from the Institute of Human Genetics at Leipzig University Hospital. The scientists found inactivations of genes in the sea cow genome that are necessary for the normal structure of the outermost layer of the epidermis. These genes are also used in human skin.

"Hereditary defects in these so-called lipoxygenase genes lead to what is known as ichthyosis in humans. This is characterised by a thickening and hardening of the top layer of skin with large scales, and is sometimes also known as 'fish scale disease'," said Schöneberg from the Rudolph Schönheimer Institute of Biochemistry.

"The results of our research thus also sharpen our view of this clinical picture," explained the biochemist, adding: "Here may lie the key to new therapeutic approaches."

The scientists pinpointed the genetic defect by comparing the genome with that of the closest relative, the dugong. The researchers received support with their investigations from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, which contributed its bioinformatics expertise in the analysis of ancient DNA. As a result, they identified important evidence of genetic changes that may have contributed to adaptation to the cool North Pacific habitat.

"This is an impressive example of how gene defects can not only cause disease, but also have advantages depending on the habitat," said Hofreiter from the University of Potsdam. Furthermore, the genome data revealed a dramatic reduction in population size. This began 500,000 years before the species was discovered and may have contributed to its extinction.

Hofreiter summed it up as follows: "With today's molecular genetic clarification, our study closes the circle of an exact observation by a German naturalist in the early 18th century."

Distribution of sea cow species in the world’s oceans. Image: Diana Le Duc

Diana Le Duc, Akhil Velluva, Molly Cassatt-Johnstone, Remi-Andre Olsen, Sina Baleka, Chen-Ching Lin, Johannes R. Lemke, John R. Southon, Alexander Burdin, Ming-Shan Wang, Sonja Grunewald, Wilfried Rosendahl, Ulrich Joger, Sereina Rutschmann, Thomas B. Hildebrandt, Guido Fritsch, James A. Estes, Janet Kelso, Love Dalén, Michael Hofreiter, Beth Shapiro, Torsten Schöneberg. Genomic basis for skin phenotype and cold adaptation in the extinct Steller’s sea cow. Science Advances, 2022; 8 (5) DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abl6496

Gabon Provides Blueprint For Protecting Oceans

February 8, 2022

Gabon's network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) provides a blueprint that could be used in many other countries, experts say. Since announcing a new MPA network in 2014, Gabon has created 20 protected areas -- increasing protection of Gabonese waters from less than 1% to 26%.

The new paper -- by Gabonese policymakers, NGOs and researchers from the University of Exeter -- highlights the lessons from this work and its relevance elsewhere.

"A combination of factors made this MPA network possible, but a crucial first step was the creation by President Ali Bongo Ondimba of a government-led initiative called 'Gabon Bleu' in 2013," said Dr Kristian Metcalfe, of the Centre for Ecology and Conservation at Exeter's Penryn Campus in Cornwall.

"This sent out a clear signal that the Gabonese government wanted to develop an MPA network.

"That ensured all sectors -- from government agencies to ocean resource users -- were engaged in the planning process, and it gave confidence to external funders and the private sector to support the research that underpins the MPAs.

Dr Emma Stokes, Wildlife Conservation Society Regional Director for Central Africa & Gulf of Guinea, added: "This political will and long-term engagement was vital -- creating a 'tipping point' towards effective change.

"Collective action has accelerated progress, and the country has now committed to the 30x30 pledge to protect 30% of its oceans by 2030."

Global MPA coverage is still short of a 10% target set in 2010, partly due to limited progress in many low-income and middle-income countries.

However, a few of these countries -- including Gabon -- have met or exceeded international commitments on land and sea.

The MPAs are based on detailed evidence, resulting in an inter-connected network tailored to protect important habitats, as well as globally important populations of sea turtles and marine mammals, with protected zones extending from north to south, and from coastal waters to 200 nautical miles offshore.

The new paper argues that lessons from Gabon can be used to inform Post-2020 global biodiversity commitments and implementation.

It suggests a four-step approach for countries and donors:

- Governments must build and maintain their research and implementation capacity, ensuring scientific evidence underpins policy decisions.

- Countries should make public pledges on marine conservation targets, signalling their commitment to the international community and potential donors.

- The conservation community should respond by helping to create or strengthen the country's environmental agencies either directly or, if financial safeguards are weak, via international organisations.

- Each implementation agency should lead on developing national marine conservation frameworks, working with stakeholders and donors to produce plans that are ambitious but politically feasible, combining top-down initiatives with bottom-up approaches as much as possible.

In Gabon, crucial implementation work was led by the national parks agency, ANPN.

Professor Lee White, Gabon's Minister of Forests, Oceans, Environment and Climate Change and former Executive Secretary (head) of ANPN, said: "We learnt from the process that resulted in the creation of Gabon's terrestrial national parks by Omar Bongo in 2007 and were able to provide the scientific and legal framework to make President Ali Bongo Ondimba's vision for a sustainable blue economy a reality."

Professor Brendan Godley, of the University of Exeter, added: "By scaling conservation and fisheries management measures across the entirety of its EEZ, Gabon has made significant steps to ensure the long-term persistence of its marine biodiversity and fisheries resources, and should be celebrated as a global exemplar."

The University of Exeter's work was funded by the UK government's Darwin Initiative.

.JPG.png?timestamp=1644446248220)

Fisheries bycatch in Gabonese waters. Credit Tim Collins WCS

Kristian Metcalfe, Lee White, Michelle E. Lee, J. Michael Fay, Gaspard Abitsi, Richard J. Parnell, Robert J. Smith, Pierre Didier Agamboue, Jean Pierre Bayet, Jean Hervé Mve Beh, Serge Bongo, Francois Boussamba, Godefroy De Bruyne, Floriane Cardiec, Emmanuel Chartrain, Tim Collins, Philip D. Doherty, Angela Formia, Mark Gately, Micheline Schummer Gnandji, Innocent Ikoubou, Judicael Régis Kema Kema, Koumba Kombila, Pavlick Etoughe Kongo, Jean Churley Manfoumbi, Sara M. Maxwell, Georges H. Mba Asseko, Catherine M. McClellan, Gianna Minton, Samyra Orianne Ndjimbou, Guylène Nkoane Ndoutoume, Jean Noel Bibang Bi Nguema, Teddy Nkizogho, Jacob Nzegoue, Carmen Karen Kouerey Oliwina, Franck Mbeme Otsagha, Diane Savarit, Stephen K. Pikesley, Philippe du Plessis, Hugo Rainey, Lucienne Ariane Diapoma Kingbell Rockombeny, Howard C. Rosenbaum, Dan Segan, Guy‐Philippe Sounguet, Emma J. Stokes, Dominic Tilley, Raul Vilela, Wynand Viljoen, Sam B. Weber, Matthew J. Witt, Brendan J. Godley. Fulfilling global marine commitments; lessons learned from Gabon. Conservation Letters, 2022; DOI: 10.1111/conl.12872

Arctic Winter Warming Causes Cold Damage In The Subtropics Of East Asia

February 8, 2022

Due to climate change, Arctic winters are getting warmer. An international study by UZH researchers shows that Arctic warming causes temperature anomalies and cold damage thousands of kilometres away in East Asia. This in turn leads to reduced vegetation growth, later blossoming, smaller harvests and reduced CO2 absorption by the forests in the region.

During the past few days, the east coast of the United States experienced heavy snowfall and low temperatures as far south as Florida. Warmer Arctic winters are now also triggering extreme winter weather of this kind in East Asia, an international team of researchers from Switzerland, Korea, China, Japan and the United Kingdom has found.

The cooler southern winters reduce vegetation activity in the evergreen subtropics, and continue to negatively affect ecosystems in the spring, for example due to branches broken under heavy snowfall or frost-damaged leaves.

First author Jin-Soo Kim of the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Zurich says: "The cooler winters also reduce agricultural productivity of cereals, fruits, root vegetables, and legumes."

Melting ice on the islands of Severnaya Zemlya (Barents and Laptev Sea region). Image: Gabriela Schaepman-Strub, Arctic Century Expedition, 2021

Globally connected weather events

The scientists combined earth system modelling, satellite data and local observations for the study. They also analysed an index of sea surface temperatures from the Barents-Kara Sea and found that in years with higher than average Arctic temperatures, changes in atmospheric circulation resulted in an anomalous climate throughout East Asia.

In particularly cold years, the unfavourable conditions adversely affected vegetation growth and crop yields, and delayed blossoming. Moreover, the researchers estimated a decrease in carbon uptake capacity in the region of 65 megatons of carbon during winter and spring (by way of comparison, fossil fuel emissions in Switzerland are 8.8 megatons of carbon per year).

The reduction in carbon absorption capacity caused by climate change is thus another issue that must be taken into account when discussing carbon neutrality.

Climate change causes ecological and socioeconomic damage

The warming of the Arctic caused by human greenhouse gas emissions is causing social and economic harm to humans as far south as the subtropics.

Gabriela Schaepman-Strub, co-author of the study, says: "This study highlights how complex the effects of climate change are. While we observe strong warming in the Arctic system, especially over the Barents-Kara Sea, we have now discovered that this warming affects ecosystems thousands of kilometres away and over multiple weeks through climate teleconnections. Arctic warming is not only threatening the polar bear, but will affect us in many other ways."

The rapidly melting ice caps on the islands of Severnaya Zemlya leave behind landscapes like those on Mars. Image: Jón Björgvinsson © 2021 Swiss Polar Institute (CC BY 4.0), Arctic Century Expedition, 2021