inbox and environment news: Issue 527

February 20 - 26, 2022: Issue 527

PEP-11 Update

photo by A J Guesdon.

Australia’s Eucalypt Of The Year Voting Is Open For The 5th Year!

Clean Up Australia Day: Sunday March 6; 2022 - Local Sites List

- Committed to making a positive difference to the community and environment: activities should be inspiring, engaging and respectful of the local community.

- A volunteer movement: people cannot be charged to be involved in activities nor can activities be conducted for commercial or financial gain.

- Committed to the safety of volunteers: activities must be carried out in accordance with the local laws and regulations relevant to the activity.

- Uniting communities as part of a national campaign: participants must respect the presence and activities of other participants in their proximity.

- Welcoming to communities of all nations, cultures, races and faiths: participants and activities must respect political, cultural, and religious differences and beliefs

- Non-partisan: participants and activities must not imply endorsement of partisanship by Clean Up Australia.

Asparagus Fern Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Ned Kelly sculpture at entrance to Kimbriki Resource Recovery Centre - made from discarded metals. Photo: A J Guesdon.

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment - Next Forum

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew Next Clean Is At: Queenscliff: Sunday 27th Of February

Powerhouse Brookvale - Australia's First Urban Renewable Energy Zone: Launch February 28

Powerhouse Brookvale Launch

Mon 28th Feb 2022, 5:00 Pm - 6:00 Pm AEDT

Electrify! Saul Griffiths On The Big Switch

The Big Switch With Saul Griffith: Electrify Everything!

When: Wed, 23 March 2022; 6:30 PM – 8:00 PM

When: Wed, 23 March 2022; 6:30 PM – 8:00 PM Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

$100 Billion Of Investment Potential For Hunter-Central Coast Renewable Energy Zone

- 24 solar energy projects

- 13 onshore and seven offshore wind energy projects

- 35 large-scale batteries and

- eight pumped hydro projects.

Origin Proposes To Accelerate Exit From Coal-Fired Generation

NSW Government Response To The Closure Of The Eraring Power Station

Australia’s largest coal plant will close 7 years early – but there’s still no national plan for coal’s inevitable demise

In a major step forward for Australia’s clean energy transition, the country’s biggest coal-fired power station Eraring is set to close seven years early in 2025, Origin Energy announced this morning.

Eraring has been operating for 35 years in the central coast of New South Wales. Last year, it alone was responsible for around 2% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, based on calculations from electricity market and emissions data.

The fundamental reason for its early closure is the brutal impact the growth of renewable energy is having on the profitability of coal plants. Origin has announced it will be building a large, 700 megawatt battery on-site in its place to store renewable energy.

This announcement follows the acceleration of other major coal plant closures: Liddell power station is scheduled to close in 2023, Yallourn’s closure was brought forward to 2028, and only last week AGL Energy edged forwards the scheduled closure of two more coal plants.

This is a welcome step with transition planning by Origin – but also underlines the risks of Australia’s clean energy transition accelerating without a national plan for the exit of coal.

Why Is This Happening?

Old power stations are excellent sites for batteries due to their existing connections to transmission lines and lots of electricity capacity. This has also been announced for the closed Hazelwood and Wallerawang coal power stations.

Over the past 12 months, the market share of renewable energy has increased to over 30%. In particular, the rapid growth of rooftop solar and solar farms in the middle of the day has sent daytime wholesale electricity prices crashing.

To stay open, coal plants are using a variety of coping strategies. This includes cycling their output down on sunny days and ramping back up for higher prices as the sun sets and demand increases at the end of the day. However, this places stress on ageing plants and breakdowns are becoming more common.

Something has to give. Electricity market analysis last year found Eraring was the coal plant most exposed to the growth of renewable energy and likely to lose significant money by 2025 – so the writing was on the wall for Eraring.

As Origin CEO Frank Calabria, stated:

the reality is the economics of coal-fired power stations are being put under increasing, unsustainable pressure by cleaner and lower-cost generation, including solar, wind and batteries.

In announcing the closure, Origin also cited its commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050, and the recommendation of the International Energy Agency that advanced economies close coal plants by 2030.

What Will Happen To The Market And Workforce?

When the Hazelwood coal power station closed in 2017 with just a few months notice, power prices spiked for several years afterwards and many workers were unable to find alternative work.

Origin, however, has given three-years notice in accordance with electricity market rules brought in after the shockwaves from Hazelwood’s closure, and announced it will develop a transition plan for its workforce. This includes training, redeployment and prioritising site employees for long-term operational roles.

Origin presented figures showing the energy and capacity gap will be filled by a combination of new storage, Snowy 2.0, a new transmission line to move power between South Australia and NSW, and new renewable energy infrastructure scheduled for NSW.

Consequently, the impact on prices is likely to be modest compared to the Hazelwood closure.

Eraring’s closure may provide other coal plants some breathing space. Coal plant owners have effectively been playing a game of chicken, holding on and hoping another plant shuts to tighten supply and increase prices.

But as Origin’s figures illustrate, there’s a lot more renewable energy projects in the pipeline, and its figures don’t include the tremendous growth of rooftop solar, which last year saw over 3,000 megawatts installed.

So this is unlikely to be the last of the coal plant closures in our near future. Indeed, in the draft 2022 Integrated System Plan (a “roadmap” for the electricity system), the Australian Energy Market Operator projects as much as 60% of coal plant capacity could be gone by 2030.

We Still Don’t Have An Exit Plan For Coal

Even though coal plants are shutting up shop faster, Australia still doesn’t have an exit plan for coal. That’s unlikely to change, given neither major party is going to want to “own” the closures in an election year.

As a result, this pattern seems likely to continue: renewable energy will continue to grow as the cheapest form of electricity generation, governments will put in place policies to accelerate its growth, and it will be left to the market and asset owners to make decisions on closures without a policy framework. This is extremely risky.

Origin has done the right thing by giving three-years notice, committing to a transition plan for its workforce and investing in battery storage.

But energy market players don’t consider the penalties for not complying with notice requirements an effective deterrent, compared to the financial incentive to hang on and hope for a price uplift when other plants close.

This means we’re left relying on the owner’s goodwill, enlightened self-interest and fear of reputational damage to act responsibly.

Maybe Australia will muddle through like this. But without a plan, we’re at risk of a rush of closures in future years with disastrous impacts on electricity prices, regional economies and livelihoods in coal communities.

We Need Policy Commitments

A variety of models for an orderly exit from coal have been proposed and national agreements have been negotiated to phase out coal in other nations such as Germany and Spain.

While the Australian Energy Market Operator has noted there are technical challenges in the clean energy transition, it considers they can be addressed. There’s no lack of alternative generation and storage to fill the energy gap from retiring coal plants.

Just this week, the NSW government received expressions of interest from renewable energy and storage projects worth over A$100 billion. The government observed that this was equivalent to the electricity output of ten coal-fired power stations in the Hunter Valley Renewable Energy Zone.

Hopefully on the other side of the election there’ll be a political and policy commitment to an orderly exit from coal - a plan that can manage impacts on our electricity system and support coal power station workers through the inevitable transition.![]()

Chris Briggs, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How our album of birdsong recordings rocketed to #2 on the ARIA charts

Stephen Garnett, Charles Darwin University and Anthony Albrecht, Charles Darwin UniversityAustralia is losing its birds at an alarming rate – one in six species are now threatened with extinction, predominantly due to climate change, land clearing and worsening bushfires.

Last year, when we met in a Darwin cafe to discuss Anthony’s PhD on the impact of environmental art on conservation, we wondered if his project could contribute to saving threatened birds.

Could we, perhaps, harness the beauty of birdsong to help Australians care about what they were losing?

Throughout history, humans have been inspired by the complex melodies and rhythms of birdsong. It’s a natural, daily celebration of our biodiversity, and has shaped the evolution of human speech and song for millennia.

Our idea was to let the threatened birds speak directly to those who might help them.

Teaming up with renowned bird recordist David Stewart, we created a CD for the music charts consisting entirely of bird calls, titled Songs of Disappearance. For the title track, the Bowerbird Collective’s Simone Slattery arranged a fantasy dawn chorus of 53 threatened species.

As of February 18, the CD – now with a video by Senior Gooniyandi artist Mervyn Street and Bernadette Trench-Thiedeman – was sitting at No.2 on the charts.

Among The Stars

Launched on December 3, 2021, the album debuted at No.5 on the ARIA charts, in part because the conservation organisation BirdLife Australia alerted its supporter base to a wonderful Christmas present that would also help bird conservation.

Some calls on the CD are astonishing for their rarity. Night parrots, critically endangered with a bell-like call, were lost for a century before they were rediscovered in 2013. Regent honeyeaters are now so scarce that young birds lack models from which to learn their soft, warbling calls.

Others are poignant cries of a disappearing landscape - the creaking calls of gang-gangs, buzzing bowerbirds and the mournful cry of the far eastern curlew.

Some purchasers of the CD have written to say they have the 53 calls on loop.

Two weeks after its release, the CD reached number 3, ahead of such artists as Taylor Swift, Mariah Carey and Michael Bublé.

“I’m very happy to have birds flying above me!” Paul Kelly told us when Songs of Disappearance displaced his Christmas Train album.

Suddenly, retail giants wanted our album in their stores. Media requests flowed in from around the world. Our CDs are being manufactured and distributed for release in the United States.

Now it’s at number 2 on the ARIA charts – a pretty good result for threatened species from a project with a zero marketing budget. It may also be the first time, anywhere in the world, that a university research project has hit the music charts.

Will The Calls Be Answered?

In December last year, more than 300 of Australia’s leading ornithologists released the Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020. It found 216 Australian birds are now threatened with extinction, mainly due to climate change.

The devastating findings of the action plan are what spawned our idea. The resulting combination of research, conservation, and creativity told a story that has resonated globally, something the action plan alone would never have achieved.

But will it make a difference?

Certainly the profits, which go to BirdLife Australia, will be put to good use. However, the 200 Australian bird taxa identified in the action plan need far more assistance to survive than one CD can provide.

The question is, can art help change population trajectories? Or, as cultural policy expert Christiaan De Beukelaer writes, will these haunting bird calls just “naturalise the awful future it wishes to avert”, like other climate apocalyptic art?

The answer is that we do not know - hence our ongoing research. However, we do know that, 60 years ago this year, the fear of losing birdsong implied by conservationist Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring helped launch the environmental movement.

Where Will The Songs Lead Us?

Songs of Disappearance now presents a fascinating opportunity to understand whether it can catalyse some of the same impetus for change.

Those who purchased the album have been invited to complete a survey to help us understand whether this project and others like it can have a lasting effect on conservation outcomes.

We wish to know, for example, whether the CD has affected people emotionally. Conservation, like art, is a belief system driven by deep emotions. As 2020 research suggests, empathy for wildlife is strongly linked to a sense of moral justification for preventing extinctions.

So, has the CD changed behaviour? We know bird song, like music, boosts mental well-being. But can it turn intention into action? And if so, what sort of action? We also aim to learn lessons from this experience that might be transferred to other projects involving the arts and conservation.

The disappearance of Australian bird song is by no means inevitable. How wonderful if the songs of the birds themselves can help secure their future.![]()

Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University and Anthony Albrecht, PhD Candidate, Charles Darwin University | Co-founder, The Bowerbird Collective, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

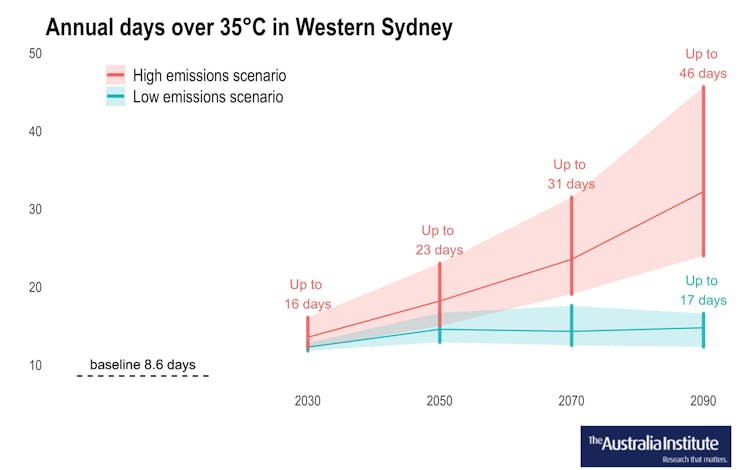

Western Sydney will swelter through 46 days per year over 35°C by 2090, unless emissions drop significantly

If emissions continue to accelerate, Western Sydney can expect to endure up to 46 days per year over 35℃ by 2090, a new analysis from the Australia Institute finds. This is a fivefold increase from the historical average of just under nine days of extreme heat per year.

Western Sydney, home to around 2.5 million people, is highly vulnerable to extreme heat and is 8-10℃ hotter than east Sydney during heatwaves. The region is too far inland to benefit from coastal breezes, and lacks the altitude of the neighbouring Blue Mountains.

The furthest inland suburbs, such as Penrith, are hottest. Indeed, in early January, 2020, Penrith was the hottest place on Earth, reaching a scorching high of 48.9℃.

However, such a dramatic rise in extreme heat days is not inevitable. If global warming is limited to 1.5℃ this century, in line with the Paris Agreement, Western Sydney will have fewer than 17 days of 35℃ per year by 2090. Emissions reduction and smart urban design are urgent measures to protect Western Sydney-siders from heat stress.

Heatwaves Are Deadly

In Australia, heat accounts for more deaths than all other natural disasters combined. If the power goes out, it’s much harder to mitigate the stress.

In January 2009, during the devastating heatwave that preceded the Black Saturday fires, Melbourne experienced a power outage on a 44℃ day, leaving some 500,000 people in the heat without electricity. The heatwave alone killed 374 people, and cost Melbourne an estimated A$800 million.

Heat also acutely affects worker productivity. The New South Wales treasury estimates that by 2061, the state could lose up to 2.7 million working days every year from reduced worker productivity in agriculture, construction, manufacturing and mining, due to heat.

However, under a low-emissions pathway, NSW estimates the loss in worker productivity could be limited to about 700,000 days. While this is still significant, it’s a quarter of cases compared to a high-emissions future.

To find out how climate change would affect Western Sydney, we analysed climate projections from the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO. We calculated temperature projections using a low-emissions scenario (where global warming is stopped at 1.5℃) and a high-emissions scenario (where global emissions continue unabated).

Examining 12 federal electorates that make up Western Sydney, we found the electorate of Lindsay, which includes the city of Penrith, will be most impacted. It can expect up to 58 days of 35℃ by 2090 under a high emissions scenario.

Who Is Impacted?

Western Sydney is uniquely prone to the “urban heat island” effect. The dense concrete and lack of green spaces absorbs and amplifies heat, raising temperatures to dangerous levels.

Residents without access to affordable air conditioning, with preexisting medical conditions or who work outdoors are most at risk of heat stress.

To understand the human impact of extreme heat, we partnered with extreme heat advocacy nonprofit Sweltering Cities. They conducted a targeted survey of Western Sydney in 2020, collecting insights from 682 respondents.

Gemma MacMillan is a single mum of a three-year-old boy, living in affordable housing in Ropes Cross. “In summer I have to keep my son Oliver inside as much as possible on hot days,” she says. “There’s no shade at all in my backyard.”

Gemma has lived in a house without air conditioning or ceiling fans. “In the past we’ve gone to stay with my ex-partner’s mum who has an air con, but now we’ve broken up and I worry about my son when it’s really hot.”

Even though retired chemist Rafael Perez has air conditioning, he says: “you’ve got to think of the cost. I’m not in a position to have it on all the time so I turn it off as soon as I can.”

In fact, despite Western Sydney having, on average, lower income levels, residents in areas such as Penrith are paying on average up to $100 per month more in electricity bills than those living closer to the coast.

Reflecting on his 22 years in the neighbourhood, Rafael says, “there used to be a lot more trees when I moved here, now there is a lot more concrete.”

What Needs To Change?

Reducing emissions is the difference between 1.5 months and 17 days of extreme heat per year in Western Sydney.

Thankfully, there is appetite for change. Earlier this month, for example, prominent cricketer Pat Cummins launched Cricketers for Climate in Penrith, a movement for Australian cricket clubs to achieve net-zero emissions over the next decade. The initiative highlights how the climate crisis threatens our ability to play sports, and positions athletes as advocates for climate action.

Additionally, the upcoming federal election could provide the policy window to increase climate ambition, as Western Sydney has a number of highly contested swing seats. According to the Sweltering Cities survey, 92.5% of Western Sydney residents say they want politicians and political parties to have policies on heat.

What do these policies look like? At the local level, we need to design our cities and homes to protect vulnerable members of the community. The NSW government recently announced a move to ban dark roofs. Lighter coloured roofs reflect heat, and can reduce indoor temperatures by 10℃ during heatwaves.

Increasing green spaces, ensuring bus stops and parks are adequately shaded, and providing affordable access to air conditioning are also crucial steps to making Western Sydney safe.

Most importantly, preventing extreme heat requires a significant emissions reduction. Australia’s national target of a 26-28% emissions reduction from 2005 is consistent with warming of 4℃, if all other countries were to follow a similar level of ambition. At the state level, instead of planning new coal mines, NSW should accelerate its transition to renewable energy.![]()

Hannah Melville-Rea, Research Fellow, New York University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Highly exaggerated’: experts debunk Morrison government claim of 53,000 fewer jobs from coal and gas ban

In an analysis recently released to News Limited newspapers, the Morrison government claims banning new coal and gas projects in Queensland would risk 53,000 jobs and A$85 billion in investment.

But we checked the job claims and found them highly exaggerated.

The government analysis, released by federal Resources Minister Keith Pitt, came in response to a call by the Greens for a six-month moratorium on new coal, oil and gas projects.

We analysed the most recent government data. We found even in an extreme scenario where all new coal and gas projects are banned, reductions in future Queensland jobs would be at most one-tenth of what the minister claims.

A Ban Won’t Affect Every Project

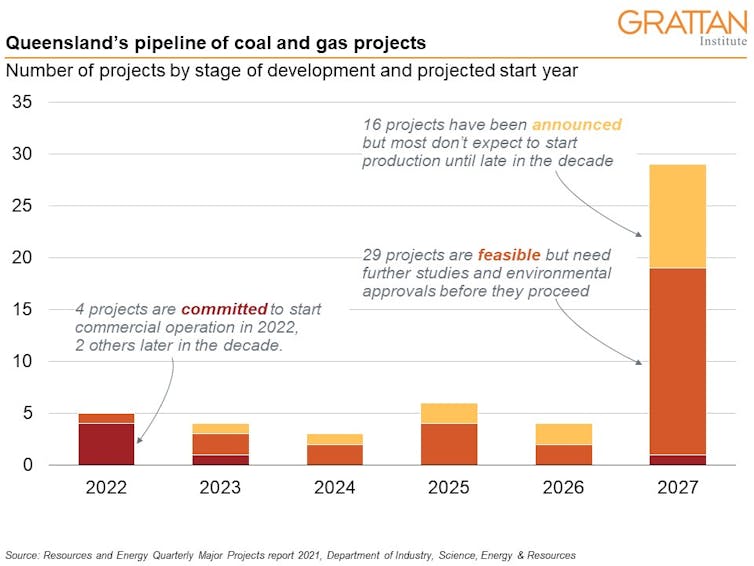

The most recent government dataset lists 44 coal projects and nine gas projects in Queensland. Two of the gas projects have already started production, so we discounted these from our analysis.

The rest of the dataset comprises the following projects:

six “committed” projects: those with environmental and planning approvals and a final investment decision

29 “feasible” projects: undergoing detailed analysis on their commercial viability, and awaiting environmental and planning approvals

16 “announced” projects with no detailed work behind them yet.

Committed projects wouldn’t be affected by a ban, because authorities have already approved them. That means associated jobs won’t be affected either. Some 2,700 construction jobs and 2,086 operational jobs are associated with these projects.

The ban would only affect projects not yet approved – the 45 projects classified “feasible” or “announced”. From now on we’ll refer to these projects as “uncommitted”.

If all 45 of these projects went ahead, it would create 26,853 additional construction jobs in Queensland and 19,131 operational jobs – or about 46,000 jobs in total.

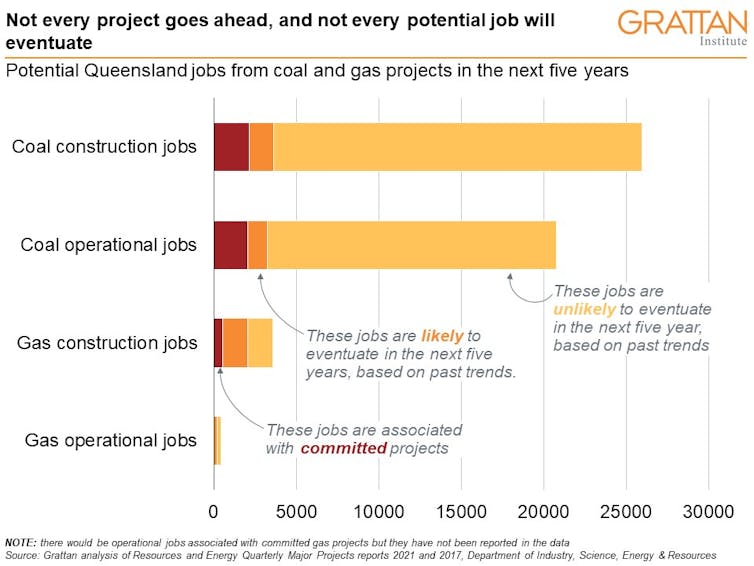

Not Every Project Will Be Developed

Most of these uncommitted projects will only ever exist on paper.

Official data reveals 29 of the 45 uncommitted projects have been on the books for five years or more without moving to “committed” status.

Of the projects that were uncommitted in 2017, only five were listed in 2021 as committed or operating. This progress rate is much worse for coal than gas. Half the gas projects on the books in 2017 are now committed or operating, compared to just 6% of coal projects.

If this trend is repeated over the next five years, just one in two Queensland gas projects and one in 16 Queensland coal projects would proceed. This would mean Queensland could expect 4,406 new coal and gas jobs, comprising:

- 3,013 additional jobs in construction (1,488 in coal and 1,525 in gas)

- 1,393 additional operational jobs (1,168 jobs in coal and 225 in gas).

It’s these 4,406 jobs that wouldn’t be created if there was a ban on new coal and gas projects – a far cry from the 53,000 estimated by the Morrison government.

Some 18 projects in the dataset don’t report job numbers, and our analysis doesn’t assume any jobs from these projects. Three of these are committed or complete (so there are more jobs locked in than our estimate of 4,786 suggests). Fifteen are uncommitted, meaning our estimate of the jobs impacted by a ban might be slightly low.

We also examined historic data for the small number of committed projects where job number estimates were provided. None created more jobs than their initial estimate, and some provided fewer.

In one case, Adani’s Carmichael mine, there were 975 fewer construction jobs and 2,270 fewer operational jobs in the 2021 data than estimated in 2017.

So, all this suggests even the more realistic job numbers we calculated aren’t guaranteed to come to fruition.

Bigger Worries For Regional Queensland

Overall, at least 4,786 jobs are locked in for Queensland from committed projects. A further 4,406 could be expected over the next five years if other projects go ahead.

Those 4,406 jobs, most in regional areas, are a lot to give up. In a small regional town, even an extra ten jobs can mean the local primary school retains all its teachers, the bank stays open and the pub remains viable. We shouldn’t dismiss the importance of this.

Queensland relies on coal and gas jobs more than some other states. But scaremongering and inflated claims about foregone jobs don’t help the debate – or help people who live in regional areas.

If the world is serious about achieving its collective goal of net-zero emissions, we can expect Australia’s coal exports to fall by 60% between 2020 and 2030.

It is this falling demand, not a moratorium or a ban, which will have the biggest effect on jobs and regional communities. And it is here that whichever party wins the 2022 election must focus its attention.![]()

Alison Reeve, Deputy Program Director, Energy and Climate Change, Grattan Institute and Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

World-first research confirms Australia’s forests became catastrophic fire risk after British invasion

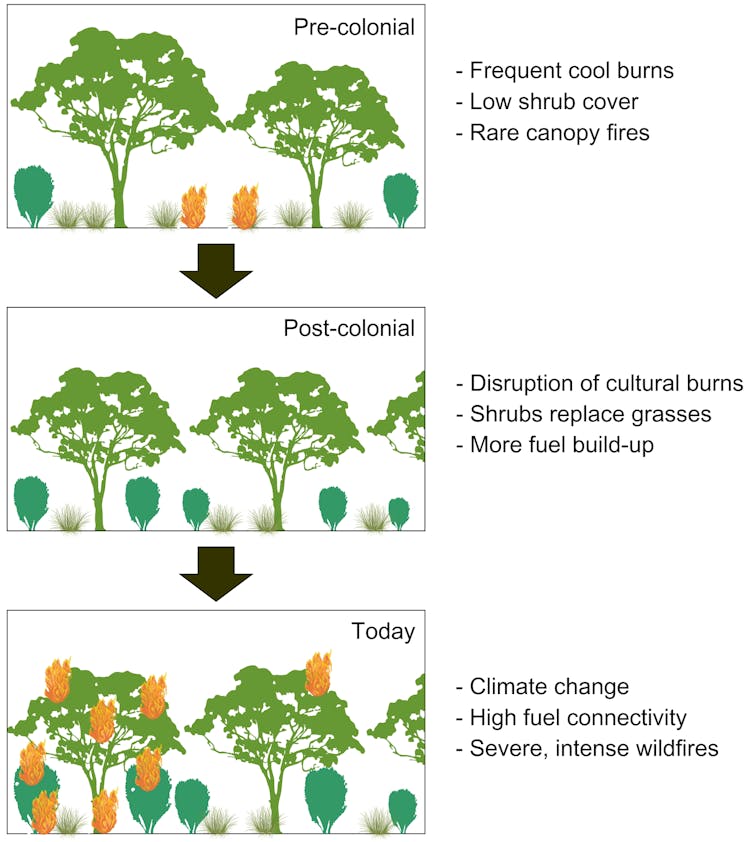

Michela Mariani, University of Nottingham; Michael-Shawn Fletcher, The University of Melbourne, and Simon Connor, Australian National UniversityAustralia’s forests now carry far more flammable fuel than before British invasion, our research shows, revealing the catastrophic risk created by non-Indigenous bushfire management approaches.

Contemporary approaches to forest management in Australia are based on suppression – extinguishing bushfires once they’ve started, or seeking to prevent them through hazard-reduction burning.

This differs from the approach of Indigenous Australians who’ve developed sophisticated relationships with fire over tens of thousands of years. They minimise bushfire risk through frequent low-intensity burning – in contrast to the current scenario of random, high-intensity fires.

Our research, released today, provides what we believe is the first quantitative evidence that forests and woodlands across southeast Australia contained fewer shrubs and more grass before colonisation. This suggests Indigenous fire management holds the key to a safer, more sustainable future on our flammable continent.

Not Just A Climate Story

Globally, climate change is causing catastrophic fire weather more often. In Australia, long-term drought and high temperatures were blamed for the Black Summer bushfires in the summer of 2019-20. This event burned 18 million hectares, an area almost twice the size of England.

The unusually high fire extent in forests prompted several important questions. Could these massive fires be explained by climate change alone? Or was the way we manage forests also affecting fire behaviour?

Recent catastrophic fires in Australia and North America prompted renewed scrutiny of how the disruption and exclusion of First Nations’ burning practices has affected forest fuel loads.

Fuel load refers to the amount of flammable organic matter in vegetation such as leaves, twigs, branches and trunks. Large fuel loads in the shrubby layers of vegetation enable flames to more easily reach tree canopies, causing intense and dangerous “crown” fires.

Long before British invasion of southeast Australia in 1788, Indigenous people managed Australia’s flammable vegetation with “cultural burning” practices. These involved frequent, low-intensity fires which led to a fine-grained vegetation mosaic comprising grassy areas and scattered trees.

Landscapes managed in this way were less prone to destructive fires.

But under colonial rule, Aboriginal people were dispossessed of their lands and often prevented from carrying out many important practices.

The colonisers suppressed Indigenous cultural burning – sometimes to protect fences – causing the land to become overgrown with shrubs.

Colonial vegetation management involved clear-cutting and intense intentional burning to create land on the plains for agriculture. Forests in rugged and less desirable terrain were left unmanaged or exploited through logging.

A fire-fighting mentality came to dominate fire management in Australia, in which fires are seen as a threat to be prevented, or stopped once they start. This thinking underlies mainstream fire and land management to this day.

Uncovering Past Landscapes

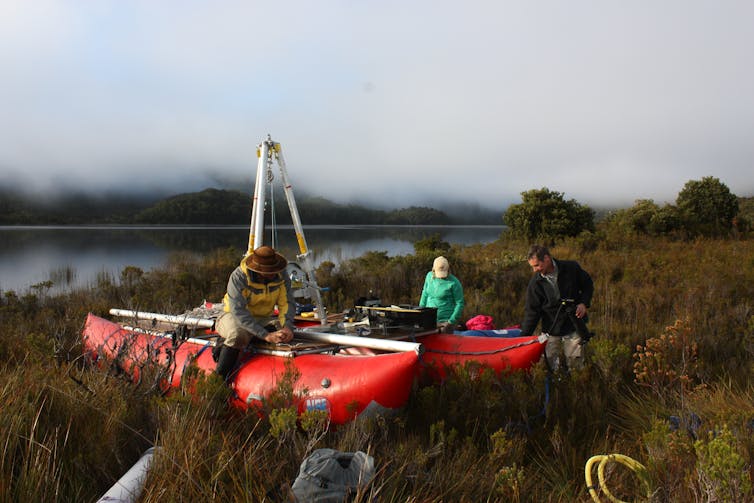

Our research set out to examine vegetation change at 52 sites across much of Australia’s southeast before and after colonisation in 1788. A large proportion of these are in forested areas of Victoria and New South Wales.

Scientists can develop a picture of past vegetation by extracting tiny fossilised grains of pollen from ancient sediment in wetlands and lake beds. Different plants produce pollen grains with different shapes, so by analysing them we can reconstruct past vegetation landscapes.

We also calibrated the amount of pollen to vegetation cover, to determine the past proportions of trees, shrubs, and grasses and herbs.

We did this using new modelling techniques that allow the conversion of pollen grain counts to plant cover across the landscape. These models have been widely applied in Europe, but our work represents a first in Australia.

We could then quantify vegetation changes before and after British invasion. We found forests in the southeast are now much denser, and more flammable, than before 1788.

We found grass and herb vegetation dominated the pre-colonial period, accounting for about half the vegetation across all sites. Trees and shrubs covered about 15% and 34% of the landscape, respectively.

After British invasion, shrubbiness in forests and woodlands in southeast Australia increased by up to 48% (with an average increase of 12%). Shrubs replaced grassy areas, while tree cover has remained stable overall.

Considering the vast area covered by our analysis, the shrub increase represents a massive accumulation of fuel loads.

More Than 200 Years Of Neglect

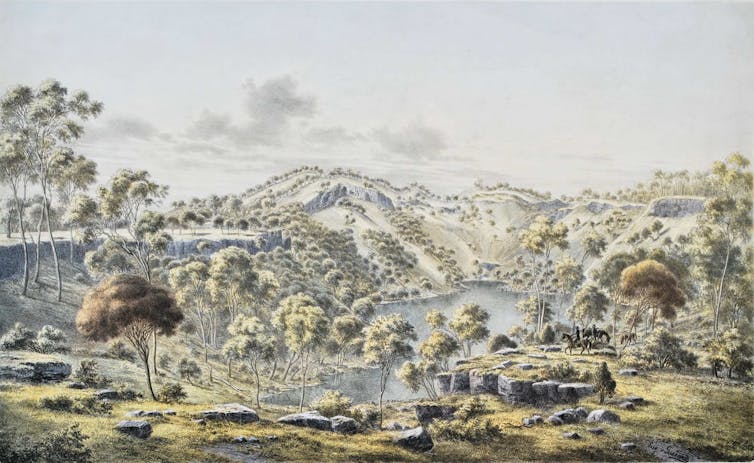

In 1770, natural history artist Sydney Parkinson described the landscape along Australia’s east coast as “free from underwood […] like a gentleman’s park”.

In 2011, historian Bill Gammage published a controversial book titled The Biggest Estate on Earth. It contained several paintings of early colonial Australia in which the landscapes resembled a savanna, with large gaps between trees and a grassy understorey.

Nowadays, many such areas are dense forest. Our research is the first region-wide analysis that gives scientific credence to these historical accounts of a landscape very different to what we see today.

The disposession of Indigenous Australians by British invaders has had a deep social and ecological impact. This includes neglect of the bush, the direct result of denying Aboriginal Australians the right to exercise their duty of care over Country, using fire.

Australia’s forests need fire, deployed by capable Indigenous hands. Without it, increased fuel loads, coupled with climate change, will create conditions for bushfires bigger and more ferocious than we’ve ever seen before.![]()

Michela Mariani, Assistant Professor in Physical Geography, University of Nottingham; Michael-Shawn Fletcher, Associate Professor in Biogeography, The University of Melbourne, and Simon Connor, Fellow in Natural History, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

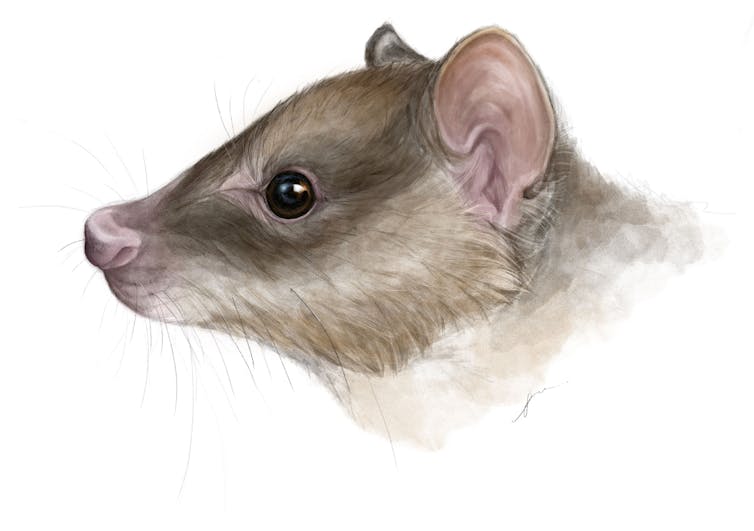

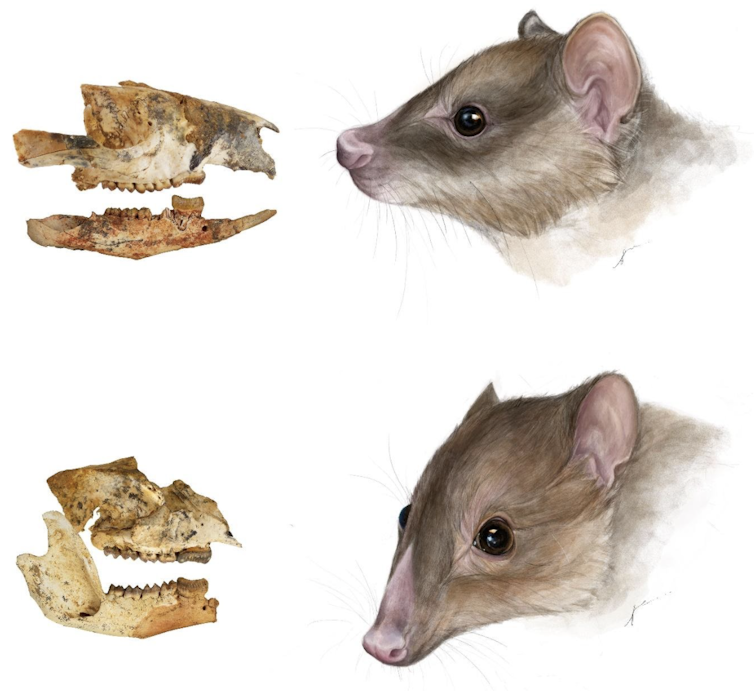

Microchips, 3D printers, augmented reality: the high-tech tools helping scientists save our wildlife

Around the world, Earth’s natural environments are being destroyed at a truly shocking scale. It means places animals need to shelter and breed, such as tree hollows, rock crevices and reefs, are disappearing.

The only long-term way to protect these animals is to stop destroying their homes. But political resistance, financial interests and other factors often work to prevent this. So scientists must get creative to try and hold off extinction in the short term.

One way they do this is to create artificial habitat structures. Our new research, released today, examines how ingenious, high-tech innovation is making some structures more effective.

But artificial habitats are not a silver bullet. Some can harm animals, and they can be used by developers to distract from the damage their projects cause.

What Are Artificial Habitat Structures?

Animals rely on specific environmental features to survive, grow, reproduce and sustain healthy populations. Artificial structures seek to replicate these habitats.

Some artificial homes provide habitat for just one species, while others benefit entire ecological communities.

They’ve been built for a huge variety of animals across the world, such as:

boxes which mimic tree hollows, for beetles

nests made of coconut husks, for seabirds

nests made from mud brick and aerated concrete for the shy albatross

“hotels” based on fish traps, for seahorses

ceramic poles that provide a surface for spotted handfish to lay eggs

textured tiles attached to seawalls that provide habitat for up to 85 marine species.

How Do New Technologies Help?

More recently, wildlife conservationists have partnered with engineers and designers to incorporate new and exciting technologies into artificial habitat design.

For example, researchers in Queensland recently installed microchip-automated doors on nest boxes for brushtail possums.

The doors opened only for microchipped possums as they came close, and most possums were trained to use them in about 11 days. Such technology may help to keep predators and other animals out of nest boxes provided for threatened species.

In New Zealand, small, native lizards hide from predatory house mice in the crevices of rock piles. Researchers used video game software to visualise these 3D spaces and create “Goldilocks” rock piles - those with crevices big enough to let lizards in, but small enough to exclude mice.

3D printing to create artificial habitats is also becoming increasingly common.

Scientists have used a combination of computer simulation, augmented reality and 3D-printing to create artificial owl nests that resemble termite mounds in trees.

And researchers and designers have created 3D-printed rock pools and reefs to provide habitat for sea life.

It’s Not All Good News

Collaboration between scientists and engineers has enabled amazing new homes for wildlife, but there’s still lots of room for improvement.

In some instances, artificial habitats may be detrimental to an animal’s health. For example, they may get too hot or be placed in areas with little food or lots of predators.

And artificial habitats can become ineffective if not monitored and maintained.

Artificial habitat structures can also be used to greenwash environmentally destructive projects, or to distract from taking serious action on climate change and habitat loss.

Further, artificial habitat structures are often only feasible at small scales, and can be expensive to build, deploy and maintain.

If the root causes of species decline - including habitat destruction and climate change - aren’t addressed, artificial habitat structures will do little to help wildlife in the long-term.

What Next?

It’s great that conservationists can create high-tech homes for wildlife – but it would be better if they didn’t have to.

Despite the dwindling numbers of countless species, environmental damage continues apace.

Native forests are cut down and rivers are dammed. Ocean shorelines are turned into marinas or seawalls and greenhouse gases are pumped into the atmosphere.

Such actions are the root cause of species decline.

We strongly encourage further collaboration between scientists and engineers to improve artificial habitat structures and help animal conservation. But as we help with one hand, we must stop destroying with the other.![]()

Darcy Watchorn, PhD Candidate, Deakin University; Mitchell Cowan, PhD Candidate, Charles Sturt University, and Tim Doherty, ARC DECRA Fellow, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In heatwave conditions, Tasmania’s tall eucalypt forests no longer absorb carbon

Southern Tasmania’s tall eucalyptus forests are exceptionally good at taking carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and converting it into wood.

For many years, we have believed these forests had a reasonable buffer of safety from climate change, due to the cool, moist environment.

Unfortunately, my research published today shows these forests are closer to the edge than we had hoped. I found during heatwaves, these forests switch from taking in carbon to pumping it back out.

That’s not good news, given heatwaves are only expected to increase as the world heats up. While we work to slash emissions, we need to explore ways to make these vital forests more resilient.

From Carbon Dioxide In To Carbon Out

It’s well established from forest sampling that moist, cool environments like southern Tasmania provide ideal growing conditions for tall eucalypt forests.

We had believed these types of forests would have a buffer against the worst effects of climate change to come, and perhaps even benefit from limited warming.

But this is no longer the case.

I monitored what happened to a messmate stringybark (Eucalyptus obliqua) forest during a three week heatwave in November 2017. Under these conditions, the forest became a net source of carbon dioxide, with each hectare releasing close to 10 tonnes of the greenhouse gas over that period.

A year earlier during more normal conditions, the forest was a net sink for carbon dioxide, taking in around 3.5 tonnes per hectare.

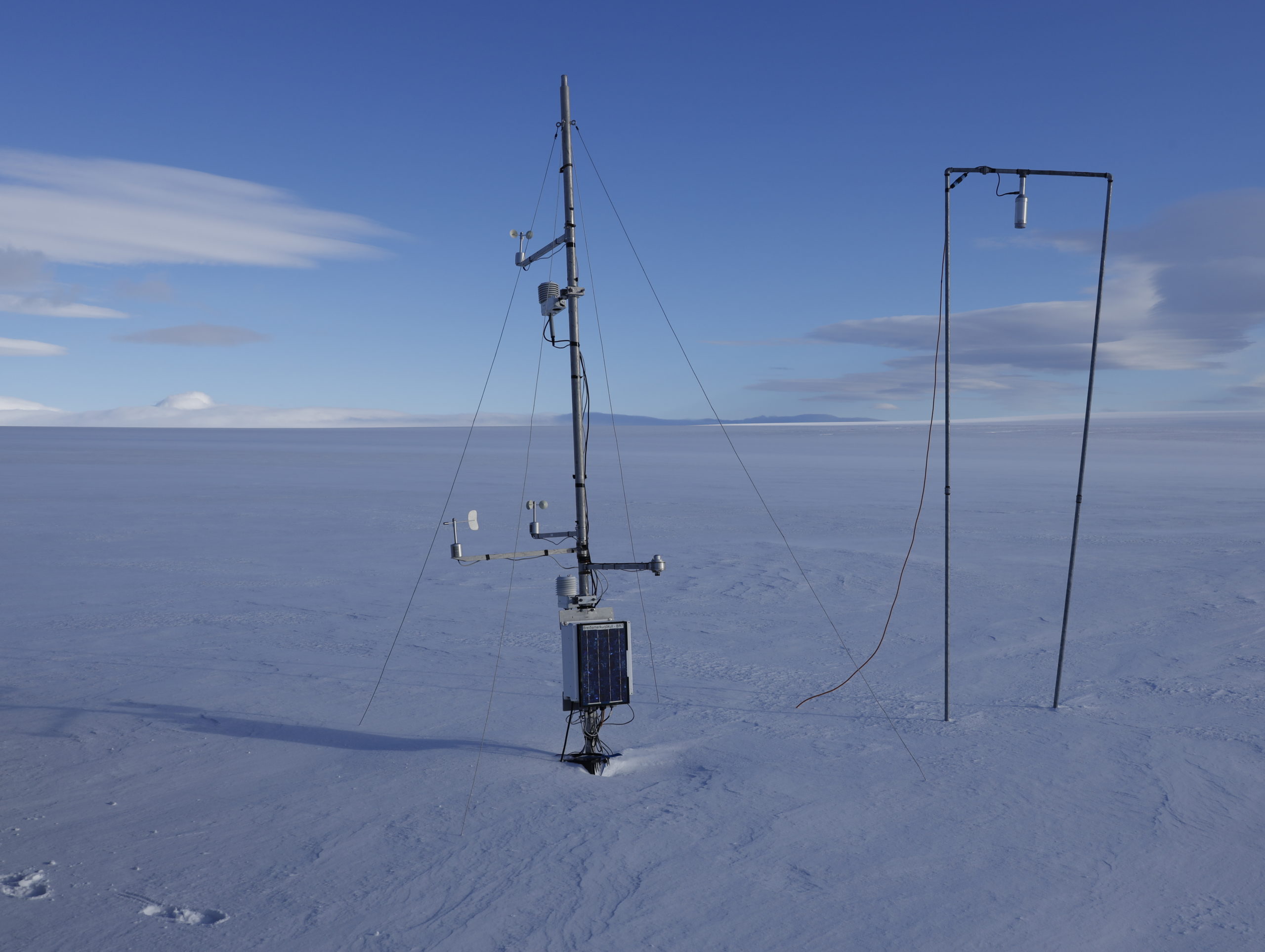

How can we know this? The forest I studied is at the Warra Supersite in the upper reaches of the Huon Valley, one of 16 intensive ecosystem monitoring field stations making up Australia’s Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network.

Instruments mounted on an 80-metre-tall tower at Warra give us great insight into how the forest is behaving. We can measure how much, and how quickly, carbon dioxide, water and energy shuttle between the forest and the atmosphere.

So what actually happened in the forest during the hot spell? Two crucial things.

The first was that the forest breathed out more carbon dioxide. This was expected, because living cells in all air-breathing lifeforms (yes, this includes trees) respire more as temperatures warm.

But the second was very unexpected. The forest’s ability to photosynthesise fell, meaning less solar energy was converted to sugars. This took place while the trees were transpiring (releasing water vapour) rapidly.

Until now, we’ve seen falls in photosynthesis output in heatwaves because the trees are trying to limit their water loss. They can do this by closing their pores on their leaves (stomata). When a tree closes its stomata, it makes it harder for carbon dioxide in air to enter the leaves and fuel the photosynthesis process.

By contrast, this heatwave saw trees releasing water and producing less food at the same time.

So what’s going on? In short, the temperatures were simply too hot for the forests in southern Tasmania. Every forest has an ideal temperature to get the best results from photosynthesis. We now know this temperature in Australia is linked to the historic climate of the local area.

That means the trees at Warra require lower temperatures to optimally feed themselves, compared to most other Australian forests.

During the 2017 heatwave, the temperatures soared well outside the forest’s comfort zone. In the hottest part of the day, the forest was no longer able to make enough food to feed itself.

Outside The Forest’s Comfort Zone

For now, the forest at Warra is still intact. After the heatwave, the messmate stringybark forest quickly recovered its ability to feed itself, and became a carbon sink again.

But as the world warms, these forests will be pushed outside their comfort zones more and more. They can only endure so many of these kinds of heatwaves. If they keep coming, there will be a tipping point beyond which the forest can no longer recover.

What then? We can see a disturbing glimpse when we look at Tasmania’s oceans, which are a marine heatwave hotspot. Fully 95% of Tasmania’s giant kelp forests are now gone, killed off by temperatures beyond their ability to tolerate.

It is no exaggeration to say that the rapid increase in temperatures are the most serious threat to the health of tall eucalypt forests I’ve encountered during 40 years of studying forest health and threats in Tasmania.

Unlike the kelp forests, our tall eucalyptus forests have not yet hit their tipping point. We still have time to lessen the risk global heating poses.

There is already work under way to test promising new methods for making future forests better able to cope with the new climate they find themselves in.

These techniques include climate adjusted provenancing, where forest managers sow seeds of local species collected from areas at the hotter end of their range. Another being tried for giant kelp is finding individual plants with better heat tolerance and breeding them.

Our eucalyptus forests will need our help, more and more. The better engaged and informed we are about the risks to forests we long thought were highly resilient, the likelier we will be to be able to preserve them.

One way we could do this is by making our monitoring data publicly accessible in real time, so we can grasp the strain our forests are under as the world warms.![]()

Tim Wardlaw, Research Associate, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

'Blue Blob' Near Iceland Could Slow Glacial Melting

Lichens Are In Danger Of Losing The Evolutionary Race With Climate Change

.jpg?timestamp=1644964737161)

Oceans are better at storing carbon than trees. In a warmer future, ocean carbon sinks could help stabilise our planet

We think of trees and soil as carbon sinks, but the world’s oceans hold far larger carbon stocks and are more effective at storing carbon permanently.

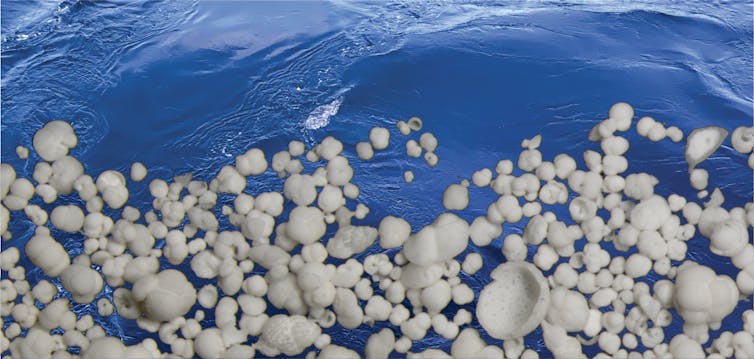

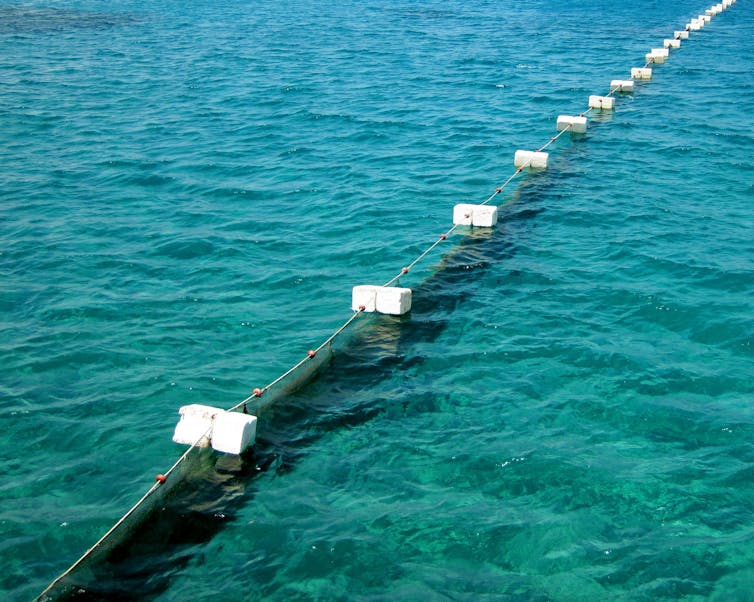

In new research published today, we investigate the long-term rate of permanent carbon removal by seashells of plankton in the ocean near New Zealand.

We show that seashells have drawn down about the same amount of carbon as regional emissions of carbon dioxide, and this process was even higher during ancient periods of climate warming.

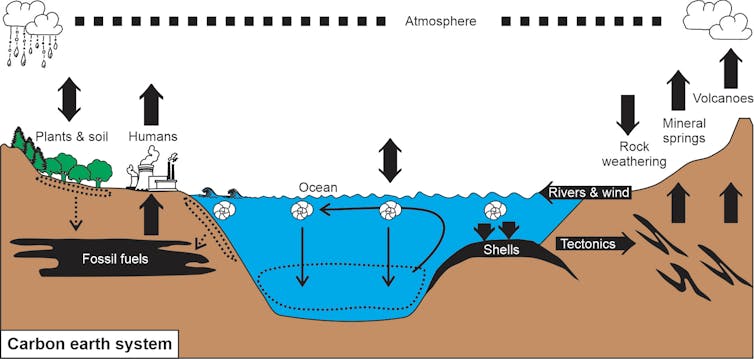

Humans are taking carbon out of the ground by burning fossil fuels deposited millions of years ago and putting it into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. The current rate of new fossil fuel formation is very low. Instead, the main geological (long-term) mechanism of carbon storage today is the formation of seashells that become preserved as sediment on the ocean floor.

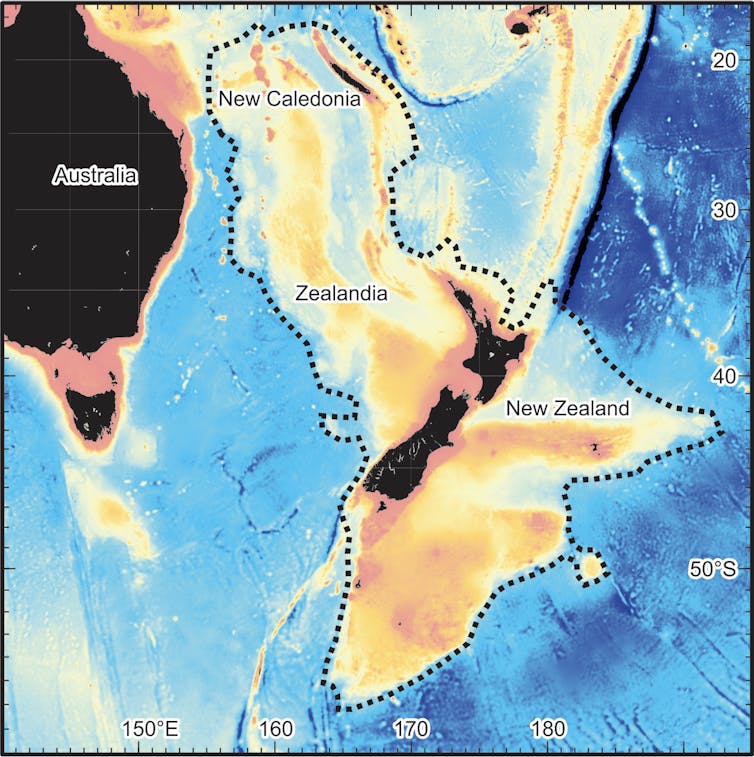

The continent of Zealandia is mostly submerged beneath the southwest Pacific Ocean but includes the islands of New Zealand and New Caledonia.

Carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels on the continent add up to about 45 million tonnes per year, which is 0.12% of the global total.

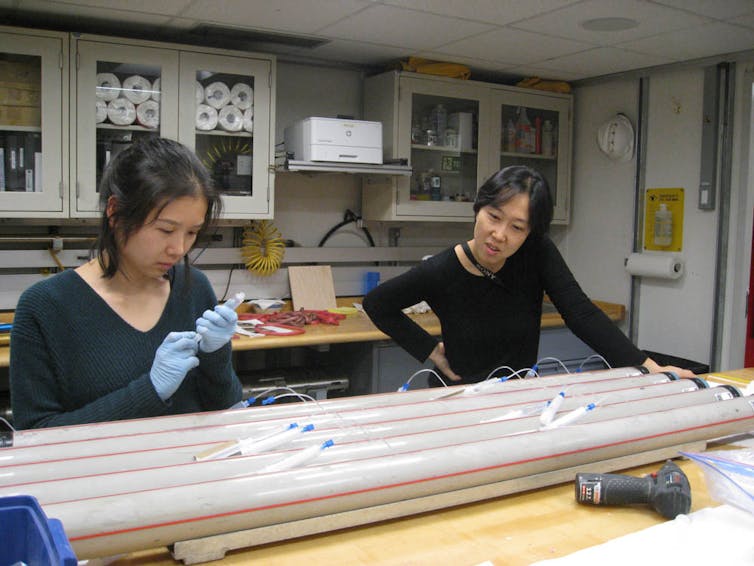

Our work documents a project that was part of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). Expedition 371 drilled into the seabed of Zealandia to investigate how the continent formed and to analyse ancient environmental changes recorded in its sediments.

Drawing Carbon To The Ocean Floor

Organic carbon in the form of dead plants, algae and animals is mostly eaten by other creatures, mainly bacteria, in both the ocean and in forest soils. Most organisms in the ocean are so small (less than 1mm in size) they remain invisible, but as they die and sink, they transport carbon to the deep ocean. Their shells can accumulate on the seabed to make vast deposits of chalk and limestone.

The sediments we cored were many hundreds of metres thick and formed during warmer climates that might resemble the decades and centuries to come. We know the past environments from analysis of fossils.

Seashells, which are made of calcium carbonate, sequester significant amounts of carbon. The accumulation rate of shells averaged over the last million years was about 20 tonnes per square kilometre per year.

The total area of the Zealandia continent is about 6 million square kilometres, so the average rate of calcium carbonate storage was about 120 million tonnes per year, which is equivalent to 53 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year.

This is about the same as emissions from burning fossil fuels on the continent today, within errors of calculation. However, a much larger area than just Zealandia is accumulating microscopic seashells.

The Planetary Carbon Cycle

Earth naturally expels carbon dioxide from mineral springs and volcanoes, as rocks are cooked at depth. This is unlikely to be affected by climate change. The Earth stores carbon dioxide when rocks are altered at the surface and as seashells accumulate on the seabed. Both these mechanisms might be affected by climate change.

The biosphere and oceans also hold significant carbon stocks that are sure to change. It is a complex system and many scientists are trying to understand how it will respond to human activities.

Different parts of the carbon system will respond in different ways and at different rates. Our work provides clues as to what might happen in the ocean.

About 4-8 million years ago, the climate was warmer, carbon dioxide levels were similar or even higher than today, and the ocean was more acidic. However, we found the average accumulation rate of seashells on Zealandia was more than double that of the most recent million years.

This is a pattern seen elsewhere around the world. Warmer climates during this period had oceans that produced more seashells, but these data are average accumulation rates over million-year time scales.

The mechanism by which these ancient warmer oceans produced more seashells remains a subject of ongoing research (including ours).

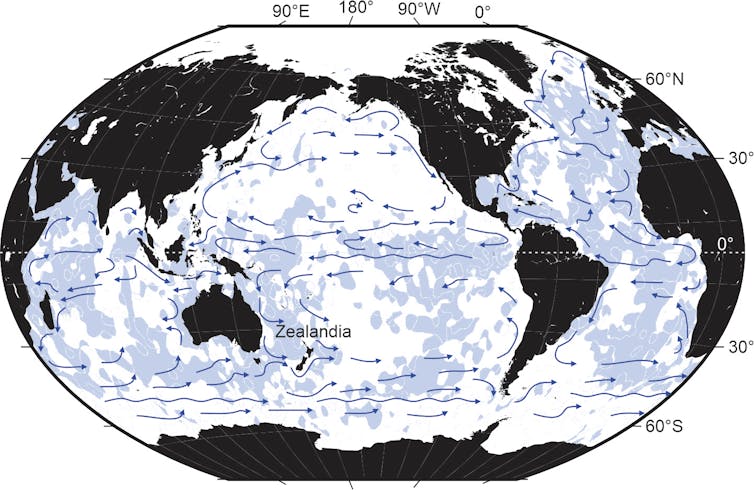

Rivers and the wind deliver nutrients to the ocean, especially during extreme weather events, and changes can occur over short time scales. At the other extreme, fully integrated climate models show that large-scale reorganisation of ocean currents to enhance the supply of nutrients from deep waters could take centuries or even millennia.

Our work highlights and quantifies the important role the ocean, and particularly the microscopic life within it, will eventually play in restoring balance to our planet. The rate at which dead plankton draw carbon to the deep ocean and small seashells permanently store it on the seabed is a significant proportion of human carbon dioxide emissions and it is likely to increase in the future.

Our work reveals that a warmer ocean may eventually produce more calcium carbonate shells than today’s ocean does, even though ocean acidification will almost certainly occur.

How quickly natural carbon sequestration in the ocean might change remains highly uncertain. It will take many centuries before we reach an ocean state similar to that found 4-8 million years ago.

More work is needed to understand how this transition might occur and whether it is possible and sensible to enhance biological productivity in our oceans to mitigate climate change and maintain or increase biodiversity.![]()

Rupert Sutherland, Professor of tectonics and geophysics, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington and Laia Alegret, Professor in Paleontology, Universidad de Zaragoza

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sydney shark attack triggers calls for a cull – but let’s take a deep breath and look at the evidence

Daryl McPhee, Bond UniversityThe fatal shark attack off Sydney on Wednesday left the city shocked, and triggered questions from a horrified public. Why would a shark just grab a man from the water? And will it strike again?

The incident – Sydney’s first fatal shark attack since 1963 – has prompted debate on what to do next. Some people even took to social media to call for sharks to be culled.

This is a common community response following unprovoked shark attacks. But killing sharks is highly controversial. And as my research has shown, there are many non-lethal alternatives to protect beachgoers from sharks.

As authorities grapple with the best way to respond to this tragedy, it’s worth remembering all shark mitigation measures come with both merits and drawbacks – and none is a silver bullet.

Killing Sharks Is Problematic

It’s unlikely authorities would ever be able to hunt down the individual shark involved in Wednesday’s fatality. As Macquarie University marine scientist Vanessa Pirotta has noted, sharks travel large distances and the animal is likely to be long gone.

Other times, members of the community call for an area-wide shark cull – and in rare cases a government will oblige.

In Western Australia in 2013, for example, the then Liberal government announced shark “kill zones” near beaches following a string of attacks. But the measure was scrapped after fierce opposition from the public and environment officials.

Any increased effort to kill sharks is likely to face public and political opposition, for several reasons.

First, sharks pose a low risk to humans. It’s true that globally, the frequency of unprovoked shark bites has increased, due to factors such as more water users and changes in shark distribution and behaviour.

But the probability of an unprovoked shark bite remains low.

Second, public perception towards sharks is changing. Many people now realise the intrinsic value of sharks and their important role in marine ecosystems.

Given all this, we must keep pursuing non-lethal methods to protect swimmers and surfers from sharks while avoiding environmental damage.

Let’s look at such approaches in more detail.

Aerial Surveys

Aerial surveys involve detecting sharks via a plane, helicopter or unmanned drone, or by people on land.

Their effectiveness can vary depending on how clear, calm or deep the water is, and on wind strength and shark behaviour.

An aircraft with human observers on board can survey a lot of coastline. But an aircraft can spend less than a minute on each beach, limiting the opportunity to locate a shark.

And research has shown even in reasonably clear water, overall rates of detection from planes and helicopters is low.

Drones cost less to operate than manned aircraft and are better for surveying a single location. However, battery constraints mean commercially available models can only stay airborne for a limited time.

In future, drones could be tethered to helium balloons or kites to allow for longer-term surveillance. But such technology is still at an early stage.

Surf patrol towers can help lifeguards detect sharks. But they must offer a vantage point more than 40 metres above sea level to be suitable for the task - a height well above that normally afforded by existing towers.

Nets And Drumlines

Sharks can be detected by capturing then releasing them. These methods include deploying either mesh nets or “drumlines” – baited hooks that lure sharks.

Shark nets operate at more than 50 NSW beaches in the warmer months. The program releases all live sharks caught in nets, but more than 80% of large “target” sharks caught in the nets die.

Traditional drumlines, used extensively in Queensland, also historically kill a significant proportion of sharks.

New “SMART” drumlines are designed to kill fewer captured animals. The device issues an alert when an animal is caught, and a contractor unhooks and relocates it.

Over three years of SMART drumline trials in NSW, high levels of live shark releases were reported. But the method requires extra labour expense to ensure rapid response to a capture.

Area-Based Deterrents

Electrical shark deterrents have been investigated over many years. Research shows substantial promise, and Australia is making progress in commercialising the technology.

Scientists have investigated using acoustic deterrents such as orca calls and novel sounds to deter sharks. But such methods do not work on all shark species, and the impacts on other animals needs to be considered.

Physical barriers to exclude sharks from a particular area is a longstanding approach to protect bathers. Permanent swimming enclosures have worked in areas protected from exposed ocean conditions, such as Sydney Harbour.

But on ocean beaches, physical barriers must be designed to withstand constant wave energy, including extreme conditions. Previous attempted trials on NSW surf beaches failed as the gear either could not be installed, or was destroyed by the surf.

No Quick Fix

Wednesday’s fatal shark attack has understandably shaken the community and prompted debate. In all this, of course, we must remember that a human life has been lost.

Right now, talk of preventing future attacks will be of little comfort to the victim’s family and friends, eyewitnesses and first responders.

Looking further ahead, no system will ever deter or detect 100% of sharks. But risks can be reduced with well-considered approaches, suited to local conditions.

More research is needed into non-lethal strategies. The cost of various approaches is also an important consideration.

And no matter what system is used to protect beachgoers, it should be accompanied by efforts to educate the public about shark safety.

Tips include avoiding swimming or surfing in low light levels, avoiding beaches near estuaries after heavy rain and flooding, and avoiding places where stranded marine mammals are present – as the sites may attract sharks.![]()

Daryl McPhee, Associate Professor of Environmental Science, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Environmental footprint calculators have one big flaw we need to talk about

Are you one of the increasingly large number of people seeking to minimise the environmental damage wrought when producing the food you eat? If so, you might use the common “environmental footprint” method to decide what to buy.

Environmental footprints measure the environmental damage caused by a product throughout its life. For food, this includes the impacts of growing crops and livestock, and manufacturing the inputs required such as fertilisers. It can also include packaging and transport.

But unfortunately, environmental footprints often don’t tell the full story. When consumers switch to a food seen as more environmentally friendly, its production expands at the expense of other products. This has consequences that environmental footprints don’t take into account.

Environmental footprint calculators may promise to help consumers lead a greener life. But they may in fact encourage choices that don’t benefit – and may even harm – the environment.

A Problematic Assumption

We are experts in assessing the effectiveness of climate change mitigation for agricultural systems. We regularly provide policy advice to governments, United Nations bodies and other organisations.

The design of environmental footprint calculators is guided by international standards organisations and policymakers, including the European Union. The tool is commonly found on the websites of environmental groups, government agencies, companies and other organisations.

The calculators aim to guide consumer choice, by assessing the impacts of current production on the environment. But this is a problem.

It assumes the footprint of a product calculated today remains constant as production is scaled up or down, but this often doesn’t hold true. When demand for a product changes, this has knock-on effects on nature. It might mean more agricultural land is required, or river water is used to irrigate different crops.

Below, we examine three ways environmental footprints can provide a misleading picture of a product’s true impacts.

1. Land Use

Agriculture makes a large contribution to greenhouse gas emissions – primarily due to animal belches but also the production and use of synthetic fertilisers.

Organic farming can help reduce agriculture emissions, primarily because it doesn’t use synthetic fertiliser. But some research suggests converting to organic farming production could also exacerbate greenhouse gas emissions.

One study in England and Wales examined what would happen if all food production was converted to organic. It found global greenhouse gas emissions from food production could increase by about 60%.

This was because organic systems produce lower yields, meaning more crop and livestock production would be needed overseas to make up the shortfall. Creating this agricultural land would mean clearing vegetation, which emits carbon dioxide when it decomposes.

And when grasslands are converted to cropland, soil organic carbon is also lost. Enhanced soil carbon storage from organic farming offsets only a small part of the higher overseas emissions.

When considering the consequences of switching from one food to another, the type of agricultural land used is also important.

In Australia, about 325 million hectares of land is used to raise cattle to produce red meat. This land often can’t be used to grow crops because it’s too dry, steep, vegetated or rocky.

If consumers switch from red meat to plant-based diets, more land suitable for growing crops would be needed, either in Australia or overseas, to produce alternative proteins such as legumes or plant-based meats.

In Australia, existing arable land is already being used to supply crops to domestic and global markets. So new land would have to be made suitable for crops, either by cultivating grazing land or clearing forest. Alternatively, crop production could be increased by using more fertiliser or other inputs.

The emissions associated with these shifts are not included in carbon footprints of plant-based protein production.

2. Water

It’s commonly assumed that choosing a product with a smaller water footprint will increase the water in rivers and lakes which replenishes the environment. However, in Australia, policy and markets determine how water is used.

Irrigation water can be traded between users. If a water-intensive crop such as rice is no longer grown, the farmer will almost always either use the water to grow a different crop or trade it with another farmer. In such a scenario, no water is returned to the environment.

Similarly, a fall in red meat production may not necessarily increase water for the environment.

Farmers whose land adjoins a river or other water body are allowed to take water for livestock to drink. Fewer livestock would leave more water available in rivers, but research in Australia suggests this water would be extracted for domestic uses, especially in dry years.

3. Goods Produced Together

Many agricultural products are produced in conjunction with others. For example, a cow slaughtered for red meat will also produce hide, meat meal and tallow. Likewise, a sheep can produce wool when alive, then other products when slaughtered.

So if consumers eschewed red meat due to its high carbon footprint, the associated products would also need to be replaced – and this would have environmental impacts.

If synthetic materials replace wool or hides, for example, demand for oil will likely increase. Or if wool is replaced with bio-based products such as cotton or hemp, demand for cropland will increase.

Increasing milk production per cow – and thus keeping fewer cows – has been considered as a way to reduce livestock emissions. But research suggests it may not have the intended result.

Fewer cows would produce fewer calves, which are used to produce veal. The research found less veal would require more red meat to be produced elsewhere, meaning no overall reduction in emissions.

It is realistic to assume that more red meat would be required. While per capita beef consumption is declining in some Western countries, global demand for beef is projected to increase to 2030 as wealth in developing countries increases and global population grows.

Towards A Healthier Planet

We and other experts are increasingly trying to raise awareness of the simplistic nature of environmental footprints.

It’s important to recognise the limitations of current methods and create tools that fully assess the consequences of consumers’ decisions.

Developing these tools will be challenging, due to the many uncertainties involved, and will require substantial research investment.

But it will lead to better environmental policy, fewer unintended consequences and a healthier planet. ![]()

Aaron Simmons, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, University of New England and Annette Cowie, Adjunct Professor, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Others

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham's Beach

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Australian First All-Female Surfing Series Launches: Challenge Her Team's Classic

Anne Dos Santos. Photo: Surfing NSW

Hunter Roberts. Photo: Surfing NSW

All In A Day's Work

Word Of The Week: Chortle

Military History Lesson On Offer For Students

Applications Now Open For NSW Youth Advisory Council 2022

Morning Of The Earth: 50th Anniversary Screening At Cremorne

Morning of the Earth 50th Anniversary screening with director Q&A Wed March 9 at the Hayden Orpheum Picture Palace, Cremorne. Beautifully remastered in 4K. One show only! Tickets: http://ow.ly/Rkhc30s774W

Deborah Harry - I Want That Man (HQ)

The International Space Station is set to come home in a fiery blaze – and Australia will likely have a front row seat

For more than two decades the International Space Station (ISS) has been the mainstay of human presence and research in space. More than 100 metres long, it’s the largest object ever placed in space, and its construction brought together the space agencies from the United States, Europe, Russia, Japan and Canada.

The ISS has hosted research that could not have been done anywhere else, in the fields of microgravity, space biology, human physiology and fundamental physics. It also provides a base for deep space exploration.

Now, the end of its life has been planned. According to NASA, the station is expected to be de-orbited by 2031 (an extension from the original plan to de-orbit by 2020). But if the ISS is so important, why is there an end-of-life plan at all?

In Short, The ISS Is Getting Old

The first components of the ISS were launched in the 1990s. And although many parts have been updated and replaced, it’s not feasible to replace everything.

In particular, the main structural components can’t be replaced. While they are checked, monitored and repaired, there are limits to this. The ISS was not designed to last forever.

It survives in a harsh environment, travelling at 27,500 kilometres per hour, with a day/night cycle every 90 minutes (the time it takes the ISS to orbit Earth).

The temperature differences experienced during each cycle put a small fatiguing load on the structure. Over a few years, this is not significant. But over the course of decades this can cause fatigue failures in the metal structure.

So there comes a time when the costs and risks of maintaining the ISS become too high, and this has been determined to be in 2030.

How Will The De-Orbiting Work?

As with all objects under the influence of gravity, given time the ISS would simply fall down to Earth. This is because, even at the orbital altitude of 400km, there is some drag due to small particles. In fact, the ISS currently requires a regular boost to lift its orbital altitude, which is slowly – but constantly – decreasing.

A natural re-entry would be a completely uncontrolled process, and there would be no way of predicting where this would take place. The responsible (and planned) approach is to use thrusters to slow the ISS down, causing the de-orbit to happen much faster and in a specific location decided in advance.

The slowing down will initially be done using thrusters on the station, and on support vehicles docked to the station. This process may take a few months and will slowly reduce the orbital altitude of the ISS, preparing it for the final re-entry phase.

In the final phase, the deceleration will be much more rapid, and will determine the ISS’s final re-entry trajectory. Although it hasn’t been decided exactly how the ISS will reach its final deceleration, the favoured option is to use three modified Russian Progress spacecraft.

The spacecraft will be docked to the ISS and fire their propulsion systems to achieve the required deceleration – controlling the trajectory of the re-entry and the re-entry location.

Artificial Fireballs

It will take a couple of minutes for the ISS to pass through the atmosphere. It’s likely the higher-altitude phase of this will take place near or above Australia.

The re-entry will be a visually spectacular event, resembling multiple large shooting stars. An increasing number of space debris breakup events have been observed and videoed over the last few years.

But these re-entries have been small objects, sized in the order of metres, such as the ATV-1 and Cygnus spacecrafts. Meanwhile, the ISS is about the size of a football field, and will be correspondingly more spectacular.

Crashing At Point Nemo