Inbox and Environment news: Issue 530

March 13 - 19, 2022: Issue 530

Weeds Strangling Trees At Governor Phillip Park Still Not Cleared; Banksias Now Dying

photo taken this week shows banksias are now submerged in weeds and beginning to die off - visit: $198,859 Allocated To Council For Weed Control - Governor Phillip Park Misses Out (and other much needed areas) - February 13, 2022

Avalon Beach 100 Years 100 Trees - Branching Out

Canopy Keepers is back with another 100 native tubestock to give away later this month as Avalon Beach Centenary celebrations continue - but this time the group is branching out to residents across Pittwater.

CK spokesperson Deb Collins said the group had been delighted with the response to its first offering of 100 trees at the opening of celebrations for the naming of Avalon Beach on December 4, with residents claiming more than 120 young plants.

“This time we're branching out, spreading the love wider, and inviting new Canopy Keepers from Narrabeen to Palm Beach, from The Basin to Scotland Island to join us in strengthening our precious canopy,” Ms Collins said.

“Did you know that for canopy trees and wildlife to thrive they need an understorey and ground cover and that eucalypts grow better with wattles nearby ?

“So whether you have room for a tall, mid storey or ground cover plant, please sign up, then come and meet us on this auspicious autumn day so you can take home a plant to support our canopy.”

Ms Collins asked those interested to please register online using the link below. The deadline for signing up for a tree is noon on March 12 - although some stock will be available on the day.

“Then find us at Dunbar Park to collect your tubestock on Saturday March 19 under our own canopy,” she said.

“We’ll have knowledgeable people on hand to help you with the best choice of tree for your location.”

Canopy Keepers thanks the Northern Beaches Council for its support of this initiative.

To sign up in advance for a tree please go to this link: https://forms.gle/McoPQYybHxXN9fQy6

To make enquiries please email 100trees@canopykeepers.org.au

To learn more about Canopy Keepers go to www.canopykeepers.org.au and sign up for our newsletter.

For general enquires about the March 19 program, please email Ros Marsh at asmallbizminder@bigpond.com

The Sydney Edible Garden Trail 2022

Peek inside some of Sydney’s private backyard fruit and veggie gardens this March, and discover their secrets to living sustainably.

Whether you’re a new or experienced gardener, the best way to learn how to grow juicy fruit and vegetables in your own backyard is to talk to a gardener who’s already doing it. Sydneysiders will have the opportunity to do this over the weekend of 26 & 27 March 2022 when over 50 suburban, community and school gardens will open for the Sydney Edible Garden Trail (SEGT).

Matthew Elphick, one of the garden hosts who participated last year, was inspired to reopen his garden again this year. He’s looking forward to the 2022 trail, saying “It was so wonderful to open last year and have people come through the garden and see how excited they are. You get to see the garden through their eyes, things that you don’t think much about, they find amazing. It’s such a great opportunity to meet like-minded people.”

With the motto “We don’t just grow food, we grow sustainable communities”, SEGT arranges for gardens to open to the public and allocates profits from ticket sales towards building stronger community and school gardens through a grants program with 8 gardens provided with grants in 2021.

This year the trail is extending to the wider Sydney metropolitan area with many new gardens included. Tickets are now on sale at https://sydneyediblegardentrail.com/tickets/

Those in our area listed so far for the 2022 edition of SEGT include:

Newport Community Garden

We are a membership based Community Garden of local neighbours who get together to learn about organic gardening, sustainable living, socialise and have a good time!

NCG has been running for over 8 years and from humble beginnings is now a vibrant, sustainable and inviting space with over 35 garden beds, compost bays, worms farms and native bee hive, green house, water tanks and garden shed.

We grow organic fruits, vegetable and herbs. We cultivate our compost, make our own natural pesticides and grow from seeds saved from our seasonal harvest.

It’s not just hard work, we are very social too and always finish the day with a cuppa and chat with local community members.

In November 2021 Newport Community Garden were announced as one of fifty SEGT GRANT RECIPIENTS 2021.

The grant will be used to attract local birdlife and bees by planting some native bush food plants and others native plants.

Newport Community Garden Profile of the Week

“The glory of gardening: hands in the dirt, head in the sun, heart with nature. To nurture a garden is to feed not just on the body, but the soul.” - Alfred Austin

Great reuse of an old boat in the Newport Community Garden

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: from Esther Andrews.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Australia’s Eucalypt Of The Year Voting Is Open For The 5th Year!

Asparagus Fern Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

$95 Million Clean Technology Funding To Drive Next Wave Of Net Zero Innovation

March 11, 2022

Scientists and start-ups can now apply for three new grant initiatives offering up to $95 million to foster a world-class innovation sector in NSW clean technologies.

Treasurer and Energy Minister Matt Kean said the grants will turbo charge the research, development and commercialisation of innovations needed to ensure New South Wales can achieve net zero by 2050.

'Boosting emerging innovations today will help establish NSW as a global leader in low-emissions products and services over the next decade,' Mr Kean said.

'These grants will support laboratories and entrepreneurs to help new business ideas get traction in both Australia and overseas, and grow the NSW economy.'

The three Clean Technology grant initiatives include:

- $45 million for infrastructure, such as world-leading innovation facilities, to accelerate research, development and commercialisation of clean technologies

- $10 million to help equip organisations such as start-ups and entrepreneurs with the necessary skills and resources to succeed commercially

- $40 million to drive the scaling up of clean technologies that will support the decarbonisation of high emitting and hard to abate sectors.

'We’re partnering with industry and researchers to target three key emissions areas that will drive a clean industrial revolution for future generations,' Mr Kean said.

'They include electrification and energy systems, land and primary industries, and power fuels including hydrogen.'

The Clean Technology Innovation stream is one of three focus areas within the $1.05 billion Net Zero Industry and Innovation Program, which in February was increased by $300 million to $1.05 billion to 2030.

For more information, visit the Clean technology innovation page on the Energy Saver website.

Opportunity To Obtain Water Access Licences

NSW Department of Planning & Environment

The opportunity to purchase water access licences across 55 different water sources within NSW will provide added water security to existing operations, allow additional water for new or expanding business and help improve the economies of regional towns and communities.

Chief Operating Officer, NSW Department of Planning and Environment, Graham Attenborough said the water access licences, which are spread across coastal and Murray-Darling Basin water sources, would be offered through a tender process.

“Interested parties will have the chance to buy access licences in some regulated river, unregulated river and groundwater sources not included in previous controlled allocations,” Mr Attenborough said. “The water offered in this controlled allocation comes from licences that were surrendered to the Minister for various reasons, for example where a licence holder gives up a licence because they no longer need it.”

This new controlled allocation order made on 4 March is the first controlled allocation order made in 2022 and separate from the controlled allocation order for groundwater in October 2021 that is currently being implemented.

A minimum price has been set for shares in each water source. The shares in these water sources will be offered in order of highest to lowest bids at or above the minimum price until all shares are exhausted or all bids are satisfied.

“Tenders for water access licences in previous controlled allocation processes have attracted diverse interest, ranging from various agricultural industries to mining companies,” Mr Attenborough said.

“The release of these shares will provide another opportunity for new or expanding businesses in regional and urban areas to buy water, which is important given that opportunities to buy water through the trading market are limited in many areas of NSW.”

Mr Attenborough continued, saying controlled allocations of groundwater began in 2009 and have continued to allow additional sustainable access to water for urban, regional and rural industries and communities.

This upcoming controlled allocation will also include surface water, providing more opportunities to meet the evolving needs of businesses and communities,” said Mr Attenborough.

The NSW Department of Planning and Environment invites interested parties to register their interest during the registration of interest period, which will run from 18 March to 18 April 2022.

Further information on the process, including details on how to register an expression of interest, can be found on the department’s website at: www.industry.nsw.gov.au/water/allocations-availability/controlled

The maps are available at: https://www.industry.nsw.gov.au/water/licensing-trade/licences/controlled/register-your-interest

The registration of interest period opens 18 March 2022 and closes at 5:00 pm on 18 April 2022. Late applications will not be accepted.

For more information visit the registration of interest timeline.

Using War To Call For Acland Coal Mine Expansion A New Low For Project’s Backers

March 8, 2022

Using Russia’s sickening invasion of Ukraine to call for the expansion of the New Acland coal mine is a new low for the project’s supporters, according to Oakey Coal Action Alliance and Lock the Gate Alliance.

If built, the New Acland Stage 3 expansion would destroy some of the best farming country in Queensland, put at risk the production of at least 10 million litres of milk each year from local dairies, and render many farming bores in the district useless.

It would require 3.5 million litres of water each day, resulting in a 47 metre water drawdown impacting over at least 1200 square kilometres of prime agricultural land.

Oakey Coal Action Alliance secretary Paul King said, “The short-sightedness from the likes of Keith Pitt who want to see this coal mine expansion built is breath-taking, even for politicians.

Mr. King's statement comes in response to a report in the Australian Financial Review where it is stated the Minister has ''slammed Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk for standing in the way of coal mines that could be helping desperate European nations wean themselves off Russian coal at a time of record high prices for Australian fossil fuels.'' and goes on to state Resources Minister Keith Pitt said ''the energy crisis unleashed by Russia’s “unacceptable” invasion of Ukraine should also be a wake-up for financiers who have blackballed Australia’s coal industry ...''

“South East Queensland is only just beginning to recover from record flooding that was almost certainly made worse due to the climate crises, which in turn is driven by humanity’s burning of fossil fuels.

“There has never been a better time to hasten the fair transition towards renewable energy.” Paul King stated

Lock the Gate Alliance Queensland spokesperson Ellie Smith said, “Darling Downs farmers must not be collateral damage in Keith Pitt’s pro-fossil fuel posturing.

“We sincerely hope the Queensland Palaszczuk Government recognises this for what it is - sickening war opportunism from the backers of New Acland.

“The Palaszczuk Government must keep its promise. The mine’s impacts on groundwater still need to be properly assessed and any proposed new conditions should be made public before a mining lease is issued. The independent assessment of this project must be allowed to proceed.

“New Acland coal mine shouldn’t be reopened. This area is amongst the best 1.5% of farmland in the state and it produces milk and beef to feed Australia.

“We'd like to see Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk protect the local community and reject the groundwater licence and the mining lease, and let locals move on with their lives.”

Assets Of Intergenerational Significance Conservation Action Plans Consultation

- 77 threatened plant species, including the previously declared Wollemi pine

- 30 threatened animal species

- 6 locally extinct mammals which have been reintroduced to 3 of the feral predator-free fenced areas

- 1 newly described species, the Wollumbin pouched frog recently discovered in Wollumbin National Park.

- the environmental and cultural values of the land

- key risks to those values

- management activities to address and mitigate the risks – such as dedicated feral animal control or fire management

- actions to measure and report on the health and condition of the declared value.

Endangered Species Live Alongside Hunter Gas Pipeline: Review Of Project Called For

March 9, 2022

Environment Minister Sussan Ley needs to give endangered animals along the Queensland-Hunter Gas Pipeline route a fighting chance and haul the project in for the highest assessment possible in light of new evidence, according to Lock the Gate Alliance.

Lock the Gate Alliance recently wrote a letter to Minister Ley, highlighting new evidence showing the presence of the critically endangered Regent Honeyeater, the endangered Booroolong Frog, and the threatened Spotted Tailed Quoll, among others, along the pipeline’s 620km NSW section.

Worryingly, these species weren’t even considered when a decision was made in late 2008 not to assess the project under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. What’s more, due to the nature of the Act, the now endangered koala, while present along the route, cannot be legally considered because it wasn’t a listed species when the original decision was made.

This week it has been reported that the Minister is re-considering the decision not to assess the project under the Act, and Lock the Gate Alliance spokesperson Georgina Woods said it was the bare minimum that needed to occur.

She said the same report that recently found evidence of the endangered species also found that if built, the pipeline would severely impact 31 Aboriginal Cultural Heritage sites along its route, and rip up some of the nation’s best cropping country.

“In a fair and just world, a project as destructive as the Hunter Gas Pipeline would never be permitted,” she said.

“Instead, we now find ourselves in a bizarre situation where a project approved 13 years ago, but not yet built, could go ahead without undergoing a thorough environmental assessment.

“With Santos recently receiving approval to build its polluting Narrabri gasfield, the threat of this pipeline being built is real.

“The Morrison Government must reassess the impacts of the Hunter Gas Pipeline, given it was approved 13 years ago and new information has emerged regarding its likely significant impact on iconic and threatened species like the Regent Honeyeater.

“Relying on an assessment that is now nearly a decade and a half old is a disgrace, and Minister Ley must step up and demand an Environmental Impact Statement is prepared that addresses all the threats the Hunter Gas Pipeline poses."

Federal Listing Of Yellow-Bellied Gliders As Threatened Is Another Reason To End Native Forest Logging In NSW

March 7, 2022

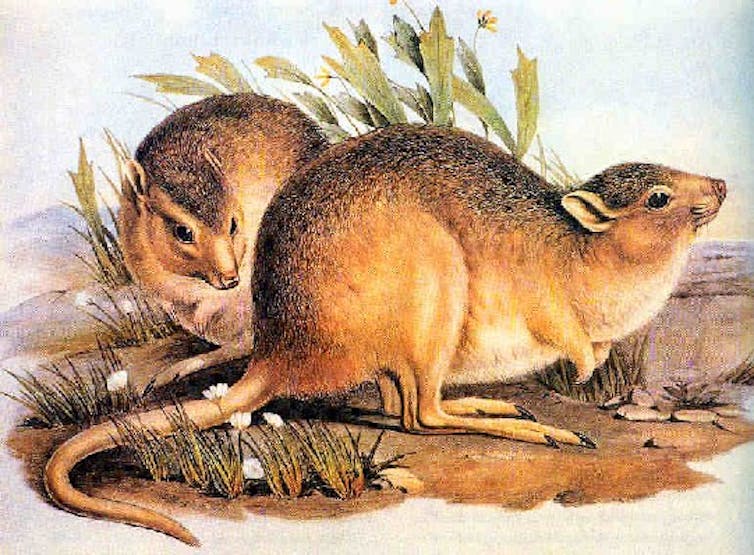

The listing of the yellow-bellied glider in southeast Australia as vulnerable to extinction [1] is another reason to end native forest logging in NSW.

Federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley has listed the iconic species as vulnerable on the advice of the Federal Threatened Species Scientific Committee.

The listing of the yellow-bellied glider comes just weeks after the minister increase the threatened status of the koalas in NSW and Queensland from “vulnerable” to “endangered”. [2]

“Thanks to decades of unsustainable logging and land clearing, we have pushed two of our most adorable forests species to the brink of extinction,” Nature Conservation Council Chief Executive Chris Gambian said.

“If we do not end native forest logging and land clearing now, we will lose these species for ever.”

The committee found the 2019-20 Black Summer bushfires, which destroyed more than 5 million hectares of forests, were a key factor that had increased risks to both species, along with land clearing, habitat fragmentation, and climate change.

“The NSW Government is still logging forests that were smashed by the Black Summer bushfires or forests that have become precious refuges for koalas and gliders that fled the flames,” Mr Gambian said.

“The native forest division of the NSW Government’s logging company, Forestry Corporation, lost $20 million last financial year.

"Effectively, taxpayers are subsidising the extinction of our koalas and gliders. It’s morally reprehensible.”

The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service says yellow-bellied gliders are an indicator species, and says protecting its habitat will protect a whole host of other species.

"Protection of the Yellow-bellied Glider can provide for conservation of a wider suite of forest values. Large home range requirements, naturally low densities, a sedentary habit and specialised foraging and denning requirements indicate that the species is sensitive to land use practices and management activities. This has led to the Yellow-bellied Glider being identified as a possible indicator or umbrella species for effective management of forest-dependent fauna (Milledge et al. 1991; Kavanagh 1991; Goldingay and Kavanagh 1993; Kavanagh and Bamkin 1995)." [4]

A yellow-bellied glider. Image credit: Matt Wright

References

- https://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=87600

- Koalas officially an endangered species in NSW, Queensland - February 2022

- Forestry Corp’s annual report for last year shows the native forest division lost $20m. See the table on page 13 of the report.

- See page 10. Approved Recovery Plan Yellow-bellied Glider, NPWS, 2003.

Secret Natural Resources Commission Review Of Native Forestry Codes Must Be Made Public

The Nature Conservation Council calls on NSW Government to release the Natural Resources Commission (NRC) review of draft private native forestry codes when it reports later this month.

It was revealed at Budget Estimates on Tuesday March 1st [1] the NRC was reviewing the proposed PNF codes at the centre of the Coalition’s koala wars last year. It was also revealed the government intends to keep the NRC report secret.

“The NSW Government must make the NRC review public — the people have a right to know what impact these codes will have on wildlife, carbon stores and water supplies,” Nature Conservation Council Chief Executive Chris Gambian said.

“This week’s UN report warned NSW forests face unprecedented threats from climate change [2] yet these forests also have a significant role to play in slowing and reversing climate change.

“This makes management of the total forest estate — public and private — a matter of vital public interest.”

Mr Gambian said the PNF codes would have a significant bearing on Australia’s ability to reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030, as it committed to do at last year’s climate conference, [3] and save koalas from extinction.

“The public must have confidence the proposed codes do not undermine the $193 million koala strategy the government is about to release,” he said.

“The people of NSW have a right to know if the new codes will see more koalas killed or fewer. It’s not much more complicated than that. Both scenarios have support within the government, so let’s see who has won.”

The government also revealed at Budget Estimates:

- The area of forest destroyed by private native forestry each year is not recorded.

- Less than 1% of properties with PNF plans were inspected by compliance officers in the past year (17 inspections out of 3,735 PNF plans). Those inspections resulted in 21 compliance notices being issued.

“That’s simply not good enough,” Mr Gambian said. “There are almost 9 million hectares of forest on private land in NSW, about 40 per cent of the total native forest estate. [4]

“The government clearly needs to boost resources for monitoring and compliance, especially as private native forestry looks set to increase significantly.

“As the amount of timber available from state forests continues to decline after decades of overharvesting and catastrophic bushfires, the government and industry both appear to be gearing up to intensify operations on private land.

“We must not repeat the mistakes we have made in public native forests by degrading millions of hectares of private forests with ecologically unsustainable practices.

“We call on the NSW Government to make the NRC review public when it reports its findings.”

REFERENCES

[1] See page 53, transcript of Budget Estimates hearing (Portfolio Committee No. 7 - Planning and Environment), Tuesday, 1 March 2022.

[2] Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, IPCC 2022.

[3] Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration On Forests And Land Use, November 2021

[4] See page 73, transcript of Budget Estimates hearing (Portfolio Committee No. 7 - Planning and Environment), Tuesday, 1 March 2022.

[5] See page 72, transcript of Budget Estimates hearing (Portfolio Committee No. 7 - Planning and Environment), Tuesday, 1 March 2022.

[5] Timber NSW, Private Native Forestry Review, 2021.

Federal Government Must Not Reward Illegal Land Clearers With Carbon Credits

The Federal Government must maintain carbon offset rules that exclude regrowth on illegally cleared land and the planting of weed species from the national carbon credit scheme the Nature Conservation Council states.

On March 3rd the government begun a public consultation asking stakeholders whether the exclusion applied to illegal and ecologically degrading processes should remain in place. [1]

The proposed changes to streamline the ERF scheme’s regulatory framework would remove the need for the Regulations.

The consultation closes March 17, 2022.

“It’s astonishing that the government even thinks this is a reasonable question to ask,” Nature Conservation Council Chief Executive Chris Gambian said.

“It speaks volumes about this government’s values and its approach to climate change and conservation.

“Energy Minister Angus Taylor must maintain these exclusions — to do otherwise would reward companies and individuals who are illegally clearing land and degrading our natural world.

"There are already serious questions about the integrity of Australia’s carbon credit scheme. Lifting these exclusions would make it a joke.”

The proposed amendments to the Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Rule 2015 come as the government announced another major change to the carbon market.

Minister Taylor has announced carbon traders will be allowed to re-sell credits already bought by the Commonwealth, a move that will significantly distort the carbon market and set back Australia’s emission reduction efforts by 112 million tonnes. [2]

“This reckless market intervention by Mr Taylor undermines the integrity of the carbon market in Australia and will slow the adoption of new emissions reduction measures,” Nature Conservation Council Chief Executive Chris Gambian said.

“This does nothing to reduce emissions or increase carbon sequestration – it is an accounting trick that will enrich carbon traders.”

“Today’s creative accounting by the Morrison Government is equivalent to almost the entire annual emissions of NSW. [3]

“If it was worried about carbon traders welching on contracts, the government had many options to enforce those contracts,” Mr Gambian said.

“Instead, the government has delivered a $2.6 billion windfall to carbon traders, at the expense of the integrity of the market and our emissions reduction goals.”

Background

[1] Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Rule 2015: proposed amendments to excluded offsets projects 3 March 2022 (link)

[2] Clean Energy Regulator, The evolving carbon market: transitional arrangements for Emissions Reduction Fund fixed delivery contracts 04 March 2022 (link) and PON Environment page Issue 529; ''Emissions Reduction Fund Contracts Changes''

Best Form Of Carbon Capture And Storage Is To Leave It In The Ground Opponents Tell WA Premier: $4 Billion Of Public Money Spent On CCS

March 9, 2022

Lock the Gate Alliance has criticised the WA McGowan Government after it announced it was drafting new laws to promote unproven, money wasting, carbon capture and storage technology for the benefit of greedy oil and gas companies.

“Despite decades of private and $4 billion in public spending on CCS since 2003 in Australia, it has not proven itself up to the task of reducing emissions in any meaningful way,” said Lock the Gate Alliance WA coordinator Claire McKinnon.

“Let’s be clear: CCS doesn’t work. It’s a smokescreen used by fossil fuel companies to justify continuing their polluting, climate wrecking projects.

“There are plans by companies like Theia Energy, and Black Mountain to drill many thousands of fracking wells in the Kimberley - what the industry coldly calls the ‘Canning Basin’. This announcement will encourage these companies further in their quest to industrialise this iconic part of our state.

“The gas industry’s flagship CCS project in Australia, located right here in WA and owned by Chevron, has completely failed to deliver on its promises. It received Federal Government handouts to the tune of $60M, but has only injected less than a third of its agreed CO2 target.

“The project failed to store any carbon at all for its first 3.5 years of operation, and the Gorgon plant pumped enough CO2 into the atmosphere just in 2017-18 to wipe out the emissions savings from all rooftop solar in Australia combined.

“CCS also does absolutely nothing to abate the vast amounts of fugitive emissions the gas industry is responsible for.

“It’s irresponsible of the McGowan Government to consider making it easier for oil and gas companies to pollute by giving even more time and public money to failed carbon capture and storage technology.

“Australia needs to urgently cut emissions right now, not waste more time waiting for this fossil fuel industry pipedream. With the climate crisis leading to more frequent and more severe weather disasters, we don’t have any more time to waste.”

Floodplain Development Manual Update: Feedback Until April 4

- Lessons learned from previous floods and the application of a flood risk management process and manual since 2005.

- A range of work on managing natural hazards across government, including relevant national and international frameworks, strategies, and best practice guidance.

- A Flood Risk Management Manual.

- A range of new flood risk management guides for the Flood Risk Management Toolkit.

Connecting To Country With Environmental Outcomes: POP Grants Open

The Big Switch With Saul Griffith: Electrify Everything!

When: Wed, 23 March 2022; 6:30 PM – 8:00 PM

When: Wed, 23 March 2022; 6:30 PM – 8:00 PM Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Under-resourced and undermined: as floods hit south-west Sydney, our research shows councils aren’t prepared

Nicky Morrison, Western Sydney University and Patrick Harris, UNSW SydneyThousands of people in south-western Sydney have been ordered to evacuate as extreme rain pummels the region and floodwaters rise rapidly. The downpour is expected to continue for days.

This region, particularly Western Sydney, is no stranger to climate-related disasters. Rain is falling on catchments already sodden from severe floods in March last year. Western Sydney is also vulnerable to extreme heat, and is 8-10℃ hotter than east Sydney during heatwaves.

Local councils are the level of government closest to communities and help determine how well regions withstand disasters like floods. But are councils prepared for the more frequent and intense disasters that climate change brings?

According to our new research on eight Western Sydney councils, the answer is no. We find it’s not easy to deliver action on the ground as these councils try to balance competing priorities in urban development, with limited resources and stretched budgets.

Balancing Responsibilities

When disasters such as floods strike, state and territory governments can declare a state of emergency and create evacuation orders.

But local councils are in a central position to increase community resilience and communicate directly with locals. This includes flood mapping, restricting certain developments near high-risk areas, and making evacuation routes known to residents.

Clearly distinguishing these responsibilities is crucial for Western Sydney, which is one of Australia’s fastest growing regionsand feels the destructive impacts of climate change intensely.

Western Sydney councils are currently dealing with back-to-back disasters in a continual crisis management cycle. At the same time, they’re tasked with pushing forward the NSW government’s housing and infrastructure development targets, which includes building almost 185,000 houses between 2016 and 2036.

Coupled with a lack of staff and funding, do they really have the capacity to cope with all this?

What We Found

We analysed 150 local government policies and planning documents, as well as local health district strategies. We also conducted 22 stakeholder interviews across the eight Western Sydney councils.

The good news is each council recognises the importance of addressing climate risk, and demonstrates a strong commitment to implementing sustainability, climate and resilience strategies. While action to mitigate climate change impacts on health and well-being is happening, the strategies are at very early stages.

According to our interviews, there’s a strong desire to do more, and all councils agree emergency preparedness and recovery work must take priority. While a NSW resilience program aims to address this, it doesn’t necessarily align with the unique risks each local community faces.

Acting quickly to move from planning to implementing strategies – such as redesigning buildings to match climate predictions – just isn’t in their capacity. And indeed, councils could not achieve this in time to mitigate the next climate crisis event.

Despite councils receiving money from the NSW government’s disaster assistance funding, they can struggle to pay for recovery from events like flooding. It can take weeks, months, or even years to get local communities back on their feet.

As the councils explained to us, this means already limited funds get pulled away from other work, such as long-term sustainability goals, or simply important day-to-day provisions.

Hawkesbury, Fairfield and Penrith city councils are especially challenged. They experienced the worst flooding in 50 years last March and now face even greater flood alert warnings at Hawkesbury-Nepean River.

State Government Undermines Local Decisions

Despite these difficulties, councils consistently told us that the biggest barrier to delivering sustainable, resilient, climate-ready development across Western Sydney was NSW state planning directives.

In the planning system, state policies override local plans and policies. This means local councils often struggle to implement their own strategies.

The result is that pressure from the state government to build more housing developments can undermine local councils’ policies to, for instance, preserve agricultural land and open spaces – measures that protect against flooding.

Indeed, this year’s floods have once again shown how problematic pro-growth agendas and “development for development’s sake” can be.

The recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes it clear flooding will increase in scale and frequency, and over-development (part of a problem termed “maladaptation”) will exacerbate the damage it inflicts.

So what needs to change? Our research presents a clear roadmap for local and state government agencies to better prepare.

This includes greater leadership and consistency from the state government, more collaboration between councils and in different levels of government, more capacity-building and more targeted funding.

What’s planned and built today must guarantee the safety, health and well-being of existing and new communities. Giving councils proper resources will help more of us survive in an uncertain future.![]()

Nicky Morrison, Professor of Planning, Western Sydney University and Patrick Harris, Senior Research Fellow, Deputy Director, CHETRE, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘The sad reality is many don’t survive’: how floods affect wildlife, and how you can help them

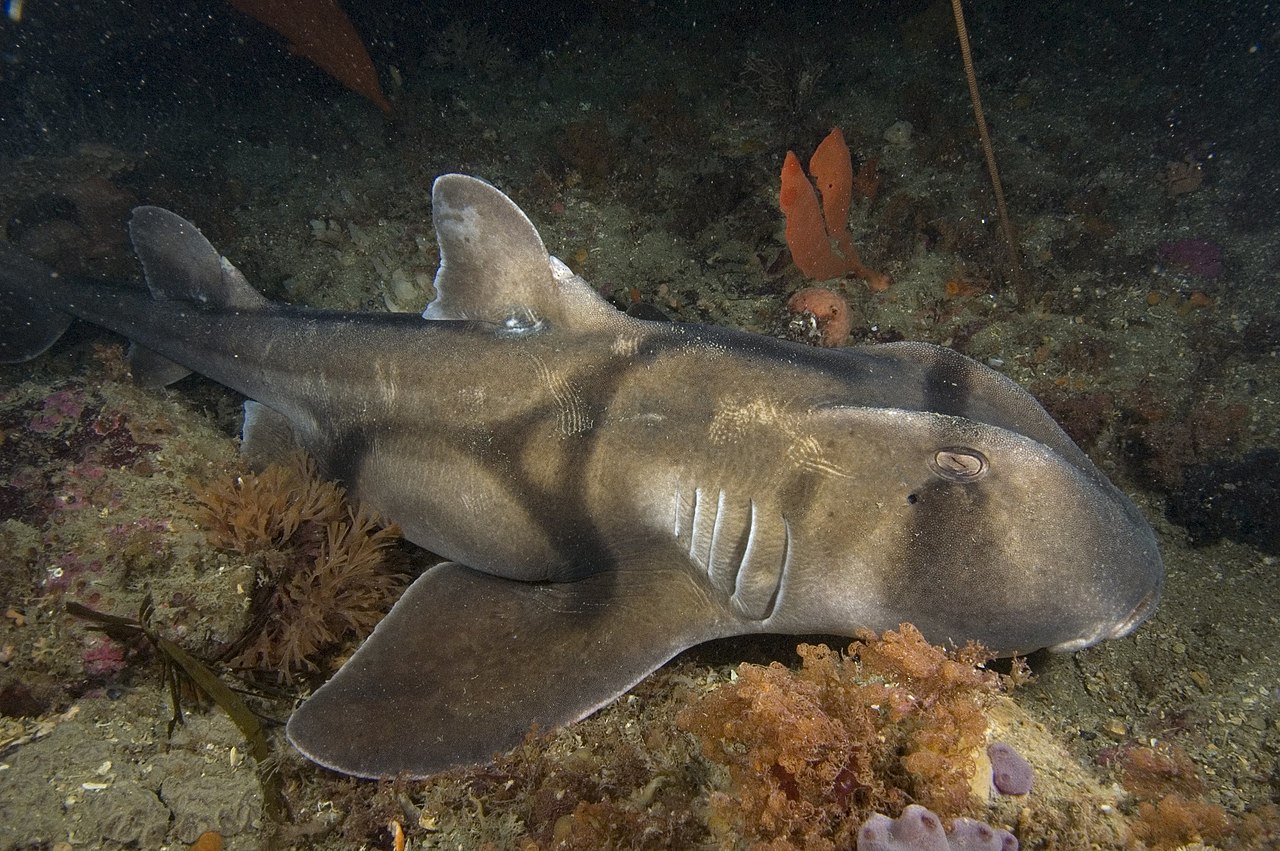

Euan Ritchie, Deakin University and Chris J Jolly, Macquarie UniversityFor over two decades, bull sharks have called a Brisbane golf course home after, it’s believed, a flood washed them into the course’s lake in 1996. Now, after severe floods connected their landlocked home back to the river system, these sharks have gone missing, perhaps attempting to seek larger water bodies.

This bizarre tale is one of many accounts illustrating how Australia’s wildlife respond to flooding. But the sad reality is many don’t survive. Those that do may find their homes destroyed or, like those bull sharks and others, find themselves displaced far from their original homes or suitable habitat.

The RSPCA and other wildlife care organisations have received hundreds of calls to help rescue and care for stranded animals. But the true toll on wildlife will remain unknown, in part because we know surprisingly little about the impacts of floods on wildlife.

Still, as many animals have amazing abilities to survive fire, so too do many possess the means to survive or even profit from floods. After all, Australia’s wildlife has evolved over millions of years to survive in this land of extremes.

How Wildlife Responds To Floods

Floods rapidly turn land habitats into underwater habitats, allowing aquatic animals to venture into places you wouldn’t expect. Flooding during northern Australia’s annual wet season, for example, sees crocodiles occasionally turn up in people’s backyard pools.

Land-dwelling animals typically don’t fare as well in floods. Some may be able to detect imminent inundation and head for higher, drier ground. Others simply don’t have the ability or opportunity to take evasive action in time. This can include animals with dependent young in burrows, such as wombats, platypus and echidnas.

The extent to which flooding affects animals will depend on their ability to sense what’s coming and how they’re able to respond. Unlike humans who must learn to swim, most animals are born with the ability.

Echidnas, for example, have been known to cover large areas of open water, but fast flowing, powerful floods pose a very different proposition.

Animals that can fly – such as many insects, bats and birds – may be able to escape. But their success will also partly depend on the scale and severity of weather systems causing floods.

Many birds, for example, couldn’t get away from the heavy rain and seek shelter, ending up waterlogged. If birds are exhausted and can’t fly, they may suffer from exposure and also be more vulnerable to predators, such as feral cats and foxes.

During floods, age old predator-prey relationships, forged through evolution, can break down. Animals are more focused on self preservation, rather than their next meal. This can result in strange, ceasefire congregations.

For example, a venomous eastern brown snake was filmed being an unintentional life raft for frogs and mice. Likewise, many snakes, lizards and frogs are expert climbers, and will seek safety in trees – with or without company.

Some spiders have ingenious ways of finding safety, including spinning balloon-like webs to initiate wind-driven lift-off: destination dry land. This is what happened when Victoria’s Gippsland region flooded last year.

One of the challenges of extreme events is it can make food hard to find. Some animals – including microbats, pygmy possums, and many reptiles – may reduce their energy requirements by essentially going to “sleep” for extended periods, commonly referred to as torpor. This includes echidnas and Antechinus (insect-eating marsupials), in response to bushfire.

Might they do the same during floods? We really don’t know, and it largely depends on an animal’s physiology. In general, invertebrates, frogs, fish and reptiles are far better at dealing with reduced access to food than birds and mammals.

What Happens When Floods Recede?

Flooding may provide a bounty for some species. Some predators such as cats, foxes, and birds of prey, may have access to exhausted prey with fewer places to hide. These same predators may scavenge the windfall of dead animals.

Fish, waterbirds, turtles and other aquatic or semi-aquatic life may benefit from an influx of nutrients, increasing foraging opportunities and even stimulating breeding events.

Other wildlife may face harsher realities. Some may become trapped far from their homes. Those that attempt to return home will have to run the gauntlet of different habitats, roads, cats, dogs and foxes, and other threats.

Even if they make it home, will their habitats be the same or destroyed? Fast and large volumes of water can destroy vegetation and other habitat structures (soils, rock piles) in minutes, but they may take many years or decades to return, if ever.

Floodwaters can also carry extremely high levels of pollution, leading to further tragic events such as fish kills and the poisoning of animals throughout food chains.

How Can You Help?

Seeing wildlife in distress is confronting, and many of us may feel compelled to want to rescue animals in floodwaters. However, great caution is required.

Wading into floodwaters can put yourself at significant risk. Currents can be swift. Water can carry submerged and dangerous obstacles, as well as chemicals, sewage and pathogens. And distressed animals may panic when approached, putting them and yourself at further risk.

For example, adult male eastern grey kangaroos regularly exceed 70 kilograms with long, razor sharp claws and toe nails, and powerful arms and legs. They’ve been known to deftly use these tools to drown hostile farm dogs in dams and other water bodies.

So unless you’re a trained wildlife expert or animal carer, we don’t recommend you try to save animals yourself. There is more advice online, such as here and here.

If you’d like to support the care and recovery of wildlife following the floods, a number of organisations are taking donations, including WWF Australia, WIRES and the RSPCA.

What Does The Future Hold?

While many Australian wildlife species are well adapted to dealing with periodic natural disasters, including floods, we and wildlife will face even more intense events in the future under climate change. Cutting greenhouse gas emissions can lessen this impact.

For common, widespread species such as kangaroos, the loss of individuals to infrequent, albeit severe, events is tragic but overall doesn’t pose a great problem. But if floods, fires and other extreme events become more regular, we could see some populations or species at increased risk of local or even total extinction.

This highlights how Earth’s two existential crises – climate change and biodiversity loss – are inextricably linked. We must combat them swiftly and substantially, together, if we’re to avoid a bleak future.![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University and Chris J Jolly, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The east coast rain seems endless. Where on Earth is all the water coming from?

At any one time, Earth’s atmosphere holds only about a week’s worth of rain. But rainfall and floods have devastated Australia’s eastern regions for weeks and more heavy rain is forecast. So where’s all this water coming from?

We recently investigated the physical processes driving rainfall in eastern Australia. By following moisture from the oceans to the land, we worked out exactly how three oceans feed water to the atmosphere, conspiring to deliver deluges of rain similar to what we’re seeing now.

Such research is important. A better understanding of how water moves through the atmosphere is vital to more accurately forecast severe weather and help communities prepare.

The task takes on greater urgency under climate change, when heavy rainfall and other weather extremes are expected to become more frequent and violent.

Big Actors Delivering Rain

The past few months in eastern Australia have been very wet, including the rainiest November on record.

Then in February, heavy rain fell on already saturated catchments. In fact, parts of Australia received more than triple the rain expected at this time of year.

So what’s going on?

In the theatre that is Australia’s rainfall, there are some big actors – the so-called climate oscillations. They’re officially known as:

El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO): this cycle comprises El Niño and its opposite, La Niña. ENSO involves temperature changes across the tropical Pacific Ocean, affecting weather patterns around the world

Southern Annular Mode (SAM): the north-south movement of strong westerly winds over the Southern Ocean

Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD): changes in ocean temperatures and winds across the tropical Indian Ocean.

Like swings in a character’s mood, each climate mode has positive, negative and neutral phases. Each affect Australia’s weather in different ways.

ENSO’s negative phase, La Niña, brings wetter conditions to eastern Australia. The IOD’s negative phase, and SAM’s positive phase, can also bring more rain.

Going Back In Time

We studied what happens to the moisture supplying eastern Australian rainfall when these climate drivers are in their wet and dry phases.

We used a sophisticated model to trace moisture backwards in time: from where it fell as rain, back through the atmosphere to where it evaporated from.

We did this for every wet winter and spring day between 1979 and 2013.

This research was part of a broader study into where Australia’s rain comes from, and what changes moisture supply during both drought and heavy rain.

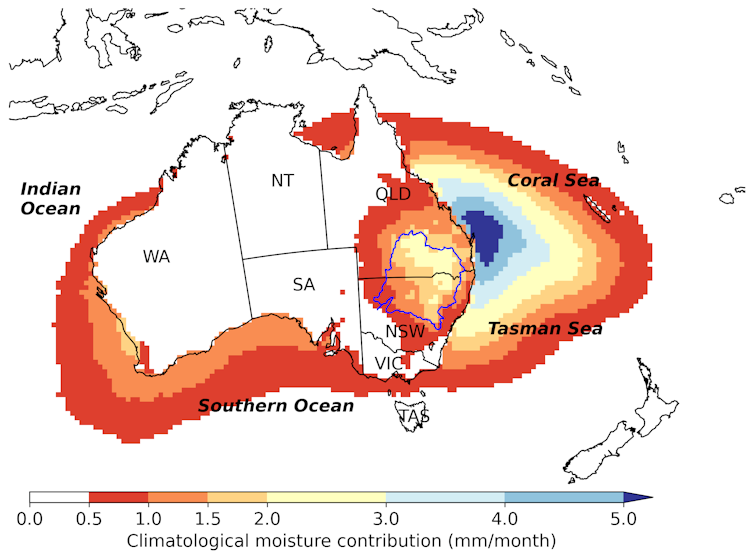

We found most rain that falls on eastern Australia comes from moisture evaporated from a nearby ocean. Typically, rain in eastern Australia comes from the Coral and Tasman seas. This is depicted in the strong blue colours in the figure below.

But interestingly, some water comes from as far as the Southern and Indian oceans, and some originates from nearby land areas, such as forests, bare soils, lakes and rivers.

Natural processes can alter the typical supply of moisture to the atmosphere, causing either droughts or floods.

Our research shows of all possible combinations of climate oscillations, a La Niña and a positive SAM phase occurring together has the biggest effect on eastern Australian rainfall. That combination is happening right now.

During La Niña, more moisture is transported from the ocean to the atmosphere over land and is more easily converted to rainfall when it arrives.

During the positive SAM, the usual westerly winds shift southward, allowing moisture-laden winds from the east to flow into eastern Australia.

Our research focused on winter and spring. However, we expect the current rainfall is the result of the same combined effect of the two climate oscillations.

The Indian Ocean Dipole is not active at this time of the year. But it was in a weak negative phase last spring, which tends to bring wetter-than-normal conditions.

Looking To Future Floods

Under climate change, extreme La Niña and El Niño events, and weather systems like those causing the current floods, are expected to worsen. So reducing greenhouse gas emissions is crucial.

The current La Niña event is past its peak and is predicted to dissipate in autumn. But because our catchments are so full of water, we still need to be on alert for extreme weather.

The current devastating floods are a sobering lesson for the future. They show the urgent need to understand and predict extreme events, so communities can get ready for them.![]()

Chiara Holgate, Hydroclimatologist, Australian National University; Agus Santoso, Senior Research Associate, UNSW Sydney, and Alex Sen Gupta, Senior Lecturer, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW is being hit by a one-two of east coast lows. But aren’t those a winter thing?

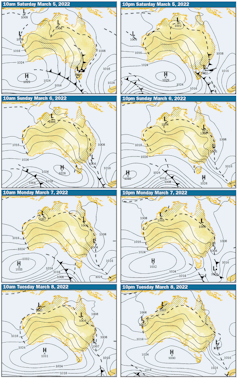

Milton Speer, University of Technology Sydney and Lance M Leslie, University of Technology SydneyIt was Western Sydney’s turn for a drenching this week, as the region was hit by an east coast low – the infamous storm systems that periodically bring heavy rainfall to the New South Wales coast.

This east coast low was created by the same persistent band of low atmospheric pressure that generated a series of thunderstorms that soaked Brisbane and Lismore during the preceding days, delivering daily rainfall totals greater than 250 millimetres to Southeast Queensland and the NSW Northern Rivers.

The east coast low then formed on Tuesday, dumping more than 100mm of rain on western Sydney and the nearby ranges.

And this low pressure trough isn’t done yet. It’s forecast to create a second east coast low that will develop over the weekend and affect the NSW south coast, bringing rain that could once again extend to the greater Sydney area and also to to the Hunter region.

The remarkable persistence and geographical spread of these rain systems prompts several questions. Why did the first east coast low form, even after so much rain had already fallen on Brisbane and Lismore? Why is a second east coast low poised to form further to the south? And why are these systems, more commonly thought of as a winter phenomenon, happening at the tail end of summer?

How And When Do East Coast Lows Form?

East coast lows typically form one at a time. But it’s not that unusual for a particularly large area of low atmospheric pressure to spawn several of these storm systems, either one after another, or sometimes even simultaneously.

As we’ve already described, the precursor to the formation of an east coast low is typically a low pressure trough, similar to the one that has been positioned near Brisbane and northern NSW for more than a week.

A low pressure trough is an elongated region of low atmospheric pressure, and on Australia’s east they typically run alongside the coast. They are often an indicator of coming clouds, showers or, given enough atmospheric moisture, very heavy showers or thunderstorms.

Combined with the high moisture content in the atmosphere over coastal eastern Australia, due partly to the influence of La Niña this summer, the resulting flood rainfall was focused close to the trough. The fact that the trough has remained almost stationary for an extended period of time has meant continuous rainfall for Southeast Queensland and the NSW Northern Rivers.

Eventually, the low pressure trough moved east on Tuesday and a weak low pressure centre developed well to the east of Brisbane, over the Tasman Sea. As the low pressure centre developed and moved slowly towards the NSW coast on Wednesday, the moist, southeast winds on the southern side of the low concentrated the rain onto the eastern side of the Great Dividing Range, north of Sydney.

The low pressure centre finally weakened on Thursday. But a second east coast low is forecast to form during Sunday near the southern half of the New South Wales coast, resulting in more coastal rain spreading as far north as the Hunter region.

Do They Eventually Move On?

These low pressure systems tend to dissipate in a matter of a day or two, unless other nearby atmospheric conditions prolong their survival. At this time of year, they need to be reinforced by cold fronts moving from west to east, immediately to Australia’s south.

Such frontal systems have been absent in recent months, enabling the very moist air to remain in place over most of eastern Australia.

A contrasting sequence of the persistent easterly airflow has been its impact on southwestern Australia. The easterly winds have shed their moisture during their passage over southern Australia. Hence, they reach southwestern Australia as a hot, dry air mass. It’s no coincidence that Perth has just smashed its record for the number of days above 40℃ in a summer.

Is This Normal For This Time Of Year?

East coast lows can form in any month of the year, although they tend to happen mostly in the cooler months of April to September. Some devastating east coast lows have formed during warmer months, including the one that hit the Sydney to Hobart Race in December 1998, claiming six lives and sinking five yachts.

It is hard to assess whether climate change has had an influence on the frequency of warm-season east coast lows. However, rising average sea surface temperatures could conceivably be a contributing factor to any change in their frequency.

For the more common cool-season east coast lows, however, we already know their development has shifted further south and east since the 1990s. This is consistent with the predictions of climate models that global warming will push mid-latitude westerly winds further towards the poles.

As this process continues, those east coast lows that develop in a westerly wind regime are likely to shift further poleward or become less frequent if conditions become less conducive to their formation, as suggested by recent research.

But these ferocious weather systems will nevertheless continue to be a threat to Australia’s east coast. Even if the rain doesn’t make landfall, east coast lows can generate large waves that disrupt otherwise benign sea conditions, such as in January 2021, when three people were tragically killed at Port Kembla.![]()

Milton Speer, Visiting Fellow, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney and Lance M Leslie, Professor, School of Mathematical And Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The floods have killed at least 21 Australians. Adapting to a harsher climate is now a life-or-death matter

Barbara Norman, University of CanberraThe devastating floods in Queensland and New South Wales highlight, yet again, Australia’s failure to plan for natural disasters. As we’re seeing now in heartbreaking detail, everyday Australians bear the enormous cost of this inaction.

It’s too soon to say whether the current floods are directly linked to climate change. But we know such disasters are becoming more frequent and severe as the climate heats up.

In 2019, Australia ranked last out of 54 nations on its strategy to cope with climate change.

Australia had a chance to lift its game when it released a new climate resilience and adaptation strategy late last year. But the plan was weak and contained no funding or detailed action.

At the time of writing, the current floods had killed at least 21 people across two states and left many thousands homeless. Sydney suburbs were being evacuated amid warnings of more intense rain.

Governments must urgently invest in measures to help communities cope with extreme weather events. As we’re seeing right now, Australian lives depend on it.

Right Here, Right Now

Last week’s report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was just one in a long line of warnings about the increasing risk of natural disasters as global warming worsens.

Australian governments are well aware of the problem. In fact, the federal government’s new National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy, launched at the Glasgow climate conference in November last year, stated:

As the global temperature rises and other changes to the climate increase, Australia will face more frequent and severe events, such as extreme weather, fires and floods, and slow-onset events, such as changing rainfall patterns, ocean acidification and sea level rise.

The measures it contained were a start – but communities across Australia need much more, right now.

The strategy contained no new budget commitments or specific programs. It also lacked detailed actions on how to help urban and regional communities prepare for the impacts of climate change.

I have extensive experience in the public sector at all levels of government, in areas such as coastal, urban and regional planning, and climate change adaptation.

I also have first-hand experience of natural disasters. In the 2019-20 Black Summer bushfires my family lost a much-loved holiday home at Mallacoota in Victoria, which we’d held for four generations. I’ve also worked on the ground helping councils and communities prepare for and recover from disasters.

I’m deeply concerned at how badly prepared Australia is for current and future damage from climate change. Australia lacks even the most basic policies and plans, including:

no national coastal plan for coastal erosion and inundation

no national urban policy for climate-resilient development

no national requirement for climate change to be considered in urban and regional land-use plans

no funded national support program for urban and regional communities to adapt to current and future climate risk.

Australia was once a leader in climate adaptation. But this momentum has been lost over the past decade, as the climate wars played out in federal parliament.

And last week, it emerged the federal government has spent just a fraction of the A$4.8 billion emergency fund despite the worsening flood crisis.

This does little to reassure the public that our leaders are focused on helping communities recover from and adapt to natural disasters.

The Plan Australians Deserve

So what must Australia do to get ready for the harsher future that awaits? Over many years, experts from a range of organisations and disciplines have put their minds to this question. These are some measures they’ve called for:

1. An integrated national climate action plan

This would involve funding and programs for state governments, local councils and industry, enabling them to work with communities to prepare for climate change.

2. A national coastal strategy

Coastal communities are especially vulnerable to storms, floods and bushfires which will worsen under climate change. Leading experts last year outlined the need for a climate change plan tailored to these communities. It would include a national agency to coordinate ocean and coastal governance across tiers of government.

3. Review urban planning legislation and city plans

Planning experts and others have called for climate change considered when making everyday decisions about the built environment. This would lead to more sustainable, pleasant and healthy urban and regional communities, as well as minimising disaster risks.

These decisions include where to locate new housing developments, as well as investing in green buildings and water-sensitive urban design.

And we also need to start conversations with communities at risk, such as those on floodplains or in bushfire-prone areas, to prepare city and town plans that incorporate future risks.

4. Stronger links between organisations

Greater cooperation is needed between emergency management, climate scientists and land-use planners, so they can effectively work together to prepare climate-resilient community plans. Better communication is also needed to ensure knowledge is shared and best-practice is maintained.

5. More money for research and community plans

Governments must fund the development of cutting-edge applied research to better understand and map climate risks. In addition, funding is needed for climate-resilient urban development and to support vulnerable communities through long-term adaptation plans.

Facing Hard Facts

In just a few years, many Australian communities have weathered a series of natural disasters overlaid by the COVID pandemic. They are exhausted, and deserve better.

Crucially, governments must be prepared to lead on emissions reduction to minimise, as much as we can, damage to Earth’s climate.

But we must also face the reality that natural disasters in Australia will get worse. Communities need practical, funded help now to ensure they survive and thrive as the climate warms. ![]()

Barbara Norman, Professor of Urban & Regional Planning; Chair of the Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience Research Network (CCARRN), University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Extinction crisis: native mammals are disappearing in Northern Australia, but few people are watching

At the time Australia was colonised by Europeans, an estimated 180 mammal species lived in the continent’s northern savannas. The landscape teemed with animals, from microbats to rock-wallabies and northern quolls. Many of these mammals were found nowhere else on Earth.

An unidentified account from the Normanton district of Northwest Queensland, dating back to 1897, told of the abundance:

“There were thousands of millions of those rats (Rattus villosissimus), and as most Gulf identities may remember, after them came a plague of native cats (the Northern Quoll).

These extended from 18 miles west of the Flinders (River) to within 40 miles of Normanton, and they cleaned up all our tucker.”

But tragically, in the years since, many of these mammals have disappeared. Four species have become extinct and nine face the same fate in the next two decades.

And we know relatively little about this homegrown crisis. Monitoring of these species has been lacking for many decades – and as mammal numbers have declined, the knowledge gaps have become worse.

A Precipitous Decline

Northern Australia savanna comprises the top half of Queensland and the Northern Territory and the top quarter of Western Australia. It covers 1.9 million square kilometres, or 26% of the Australian landmass.

Species already extinct in Northern Australia are:

- burrowing bettong

- Victoria River district nabarlek (possibly extinct)

- Capricornian rabbit-rat

- Bramble Cay melomys.

The Northern Australia species identified at risk of becoming extinct within 20 years are:

- northern hopping-mouse

- Carpentarian rock-rat

- black-footed tree rat (Kimberley and Top End)

- Top End nabarlek

- Kimberley brush-tailed phascogale

- brush-tailed rabbit-rat (Kimberley and Top End)

- northern brush-tailed phascogale

- Tiwi Islands brush-tail rabbit-rat

- northern bettong.

Many other mammal species have been added to the endangered list in recent years, including koalas, the northern spotted-tailed quoll and spectacled flying foxes.

So what’s driving the decline? For some animals, we don’t know the exact reasons. But for others they include global warming, pest species, changed fire regimes, grazing by introduced herbivores and diseases.

Monitoring Is Crucial

There’s no doubt some mammal species in Northern Australia are heading towards extinction. But information is limited because monitoring of these populations and their ecosystems is severely lacking.

Monitoring is crucial to species conservation. It enables scientists to protect an animal’s habitat, and understand the rate of decline and what processes are driving it.

Our research found most of Northern Australia lacks monitoring of species or ecosystems.

Monitoring mostly comprises long-term projects in three national parks in the Northern Territory. The trends for mammals across the region must be estimated from these few sites.

More recent monitoring sites have been established in Western Australia’s Kimberley. Very few fauna monitoring programs exist in Queensland savannas.

The lack of monitoring hampers conservation efforts. For example, researchers don’t know the status of the Queensland subspecies of black‐footed tree‐rat because the species is not monitored at all.

Research and monitoring efforts have declined significantly over the past couple of decades. Reasons for this include, but are not limited to:

a massive reduction in federal environment funding since 2013 and substantial reductions in some state and territory environment funding

reduced capacity of government-unded institutions devoted to ecosystem and species research

the existence of only two universities in northern Australia with an ecological research focus

a reliance on remote sensing and vegetation condition monitoring, which does not detect animal trends.

The Lesson Of The Bramble Cay Melomys

An avalanche of research shows increasing rates of decline in animal populations and extinctions. Australia has the worst mammal extinction rate of any country.

Yet governments in Australia have largely sat on their heels as the biodiversity crisis worsens.

A Senate committee was in 2018 charged with investigating Australia’s faunal extinctions. It has not yet produced its final report.

In September last year, the federal environment department announced 100 “priority species” would be selected to help focus recovery actions. But more than 1,800 species are listed as threatened in Australia. Prioritising just 100 is unlikely to help the rest.

The lack of threatened species monitoring in Australia creates a policy blindfold that prevents actions vital to preventing extinctions.

Nowhere is this more true than in the case of the Bramble Cay Melomys. The nocturnal rodent was confirmed extinct in 2016 due to flooding of its island home in the Torres Strait, caused by global warming.

The species had previously been acknowledged as one of the rarest mammals on Earth – yet a plan to recover its numbers was never properly implemented.

A Crisis On Our Watch

Conservation scientists and recovery teams are working across Northern Australia to help species and ecosystems recover. But they need resources, policies and long-term commitment from governments.

Indigenous custodians who work on the land can provide significant skills and resources to save species. If Traditional Owners could combine forces with non‐Indigenous researchers and conservation managers – and with adequate support and incentives – we could make substantial ground.

Indigenous Protected Areas, national parks and private conservation areas provide some protection, but this network needs expansion.

We propose establishing a network of monitoring sites by prioritising particular bioregions – large, geographically distinct areas of land with common characteristics.

Building a network of monitoring sites would not just help prevent extinctions, it would also support livelihoods in remote Northern Australia.

Policies determining research and monitoring investment need to be reset, and new approaches implemented urgently. Crucially, funding must be adequate for the task.

Without these measures, more species will become extinct on our watch.![]()

Noel D Preece, Adjunct Asssociate Professor, James Cook University and James Fitzsimons, Adjunct Professor in Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kelp won’t help: why seaweed may not be a silver bullet for carbon storage after all

Over the last few years, there’s been a lot of hope placed in seaweed as a way to tackle climate change.

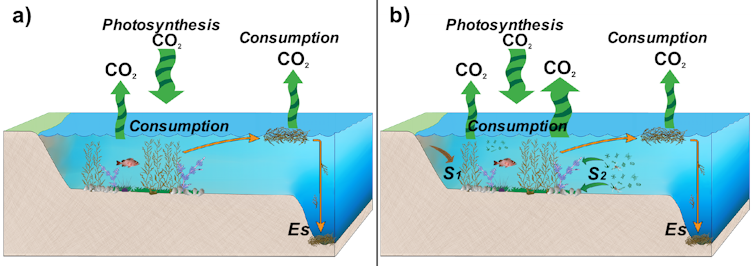

The excitement stemmed from studies suggesting seaweed could be scaled up to capture and store huge quantities of carbon dioxide, taking advantage of rapid growth rates, large areas, and long-term storage in the deep ocean.

At present it’s thought seaweed stores around 175 million tonnes annually of carbon, or 10% of the emissions from all the cars in the world. To many scientists, this suggested the possibility seaweed could join other blue carbon storage in mangroves and wetlands as a vital tool in the fight to stop climate change.

While we’re all ready for some good news on climate, there is nearly always a “but” in science. Our new research has identified a major overlooked issue. Is it significant? Unfortunately, yes. When we accounted for this, our calculations suggest on average seaweed ecosystems may not be a carbon sink after all, but a natural source of carbon.

How Can This Be?

There were good reasons to look to coastal seaweed as an important global carbon sink. Some species can grow as much as 60 centimetres per day. Seaweed covers around 3.4 million square kilometres of our oceans. And when wind and waves break off fronds and pieces of seaweed, some will escape being eaten and instead be whisked out to the deep ocean and deposited.

Once the seaweed is in deep waters or buried in sediments, the carbon it contains is safely locked away for several hundred years. That is to say, the time it takes ocean circulation to drive bottom waters towards the surface.

So what’s the issue?

As the surrounding coastal waters wash through the seaweed canopy, they bring in vast quantities of plankton and other organic material from further out at sea. This provides extra food for filter feeders like sea squirts, shellfish living amongst seaweed, and the bryozoan animals which end up coating many seaweed fronds.

As these creatures consume this extra food supply, they breathe out carbon dioxide additional to that produced by eating seaweed. Individually, the amount is tiny. But on an ecosystem scale, their numbers and ability to filter large amounts of water are enough to skew what researchers call the net ecosystem production – the balance between carbon dioxide inflows and outflows. And not just by a little, but potentially by a lot.

How did we figure this out? We collated global studies which directly measured or reported the key parts of net ecosystem production, ranging from polar regions to tropical.

Seaweed ecosystems, we found, were natural carbon sources, releasing on average around 20 tonnes per square kilometre every year.

But it could be much higher still. When we included estimates of how much carbon returned to the atmosphere from seaweed washed out towards the deep sea only to decompose or be eaten first, we found seaweed could be a much larger natural source.

We estimate it could be potentially as high as 150 tonnes emitted to the atmosphere per km² every year, in contrast to previous estimates that seaweed absorbs 50 tonnes per km². We must stress this figure has some uncertainty around it, given the difficulty of estimating the quantities involved.

Do We Give Up On Seaweed Carbon Storage?

In short, no. If we lose seaweed, what would replace it? It could be urchin barrens – large rocky outcrops dominated by sea urchins – or smaller seaweed species, or mussel beds. Climate change is already showing us in some places, with giant kelp dying en masse due to marine heatwaves and background warming in Tasmania and being replaced by urchin barrens.

To make a true accounting of what seaweed offers in carbon storage, we need to factor in what any replacement ecosystem would offer.

If a replacement ecosystem is an even greater carbon source or smaller carbon sink than the original seaweed ecosystem, it follows we should maintain or restore existing seaweed ecosystems to reduce further greenhouse gas emissions. However, to date, we have not found sufficient data to test whether all replacement ecosystems are in fact greater or lesser carbon sources.

What does this mean for efforts to tackle climate change? It means we should not look to seaweed as a silver bullet.

Any efforts to quantify seaweed carbon storage and mitigation for the protection, restoration or farming of seaweed must make a full accounting of carbon inputs and output to ensure we are not unwittingly making the problem worse rather than better.

As some carbon trading schemes look to include seaweed, we must not overestimate how good seaweed is at storing carbon.

If we get this wrong, we could see perverse outcomes where industries offset their emissions by funding the preservation or restoration of seaweeds – but in doing so, actually increase their emissions rather than zero them out.![]()

John Barry Gallagher, Associate Researcher, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Stunning New-To-Science Fairy Wrasse Is First-Ever Fish Described By A Maldivian Scientist

March 8, 2022

Though there are hundreds of species of fish found off the coast of the Maldives, a mesmerizing new addition is the first-ever to be formally described -- the scientific process an organism goes through to be recognized as a new species -- by a Maldivian researcher. The new-to-science Rose-Veiled Fairy Wrasse (Cirrhilabrus finifenmaa), described today in the journal ZooKeys, is also one of the first species to have its name derived from the local Dhivehi language, 'finifenmaa' meaning 'rose', a nod to both its pink hues and the island nation's national flower.

Scientists from the California Academy of Sciences, the University of Sydney, the Maldives Marine Research Institute (MMRI), and the Field Museum collaborated on the discovery as part of the Academy's Hope for Reefs initiative aimed at better understanding and protecting coral reefs around the world.

"It has always been foreign scientists who have described species found in the Maldives without much involvement from local scientists, even those that are endemic to the Maldives," says study co-author and Maldives Marine Research Institute biologist Ahmed Najeeb. "This time it is different and getting to be part of something for the first time has been really exciting, especially having the opportunity to work alongside top ichthyologists on such an elegant and beautiful species."

First collected by researchers in the 1990s, C. finifenmaa was originally thought to be the adult version of a different species, Cirrhilabrus rubrisquamis, which had been described based on a single juvenile specimen from the Chagos Archipelago, an island chain 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) south of the Maldives.

In this new study, however, the researchers took a more detailed look at both adults and juveniles of the multi-coloured marvel, measuring and counting various features, such as the color of adult males, the height of each spine supporting the fin on the fish's back and the number of scales found on various body regions. These data, along with genetic analyses, were then compared to the C. rubrisquamis specimen to confirm that C. finifenmaa is indeed a unique species.

Importantly, this revelation greatly reduces the known range of each wrasse, a crucial consideration when setting conservation priorities.

"What we previously thought was one widespread species of fish, is actually two different species, each with a potentially much more restricted distribution," says lead author and University of Sydney doctoral student Yi-Kai Tea. "This exemplifies why describing new species, and taxonomy in general, is important for conservation and biodiversity management."

Despite only just being described, the researchers say that the Rose-Veiled Fairy Wrasse is already being exploited through the aquarium hobbyist trade.

"Though the species is quite abundant and therefore not currently at a high risk of overexploitation, it's still unsettling when a fish is already being commercialized before it even has a scientific name," says senior author and Academy Curator of Ichthyology Luiz Rocha, PhD, who co-directs the Hope for Reefs initiative. "It speaks to how much biodiversity there is still left to be described from coral reef ecosystems."

Last month, Hope for Reefs researchers continued their collaboration with the MMRI by conducting the first surveys of the Maldives' 'twilight zone' reefs -- the virtually unexplored coral ecosystems found between 50- to 150-meters (160- to 500-feet) beneath the ocean's surface -- where they found new records of C. finifenmaa along with at least eight potentially new-to-science species yet to be described.

For the researchers, this kind of international partnership is pivotal to best understand and ensure a regenerative future for the Maldives' coral reefs.

"Nobody knows these waters better than the Maldivian people," Rocha says. "Our research is stronger when it's done in collaboration with local researchers and divers. I'm excited to continue our relationship with MMRI and the Ministry of Fisheries to learn about and protect the island nation's reefs together."

A vibrantly colored Rose-Veiled Fairy Wrasse. This new-to-science Rose-Veiled Fairy Wrasse is the first Maldivian fish to ever be described by a local researcher. (© Yi-Kai Tea)