Inbox and environment news: Issue 531

March 20 - 26, 2022: Issue 531

Newport SLSC Youngsters Take 3 For The Sea

Save Australia's Wildlife Group Make Whopping Donation Towards Saving Local Wallabies

Fauna Fences Down On Wakehurst Parkway: Please Drive Carefully Until They Are Restored

The Green Green Grass Of Des Creagh Reserve Avalon Beach

Weeds Strangling Trees At Governor Phillip Park Still Not Cleared; Banksias Now Dying

photo taken this week shows banksias are now submerged in weeds and beginning to die off - visit: $198,859 Allocated To Council For Weed Control - Governor Phillip Park Misses Out (and other much needed areas) - February 13, 2022

Careel Creek Still Flooded But Moorhens-Ducks Ok

Newport Pool Cliff Face Risk: New Film From John Illingsworth

Published March 15, 2022

John Illingsworth: Recent rain has further destabilised this cliff-collapse and landslide hotspot. When the beach is washed away like this, if you use the access track at the foot of the cliff your life may be at significant risk. Here is why.

NSW Landcare And Local Land Services Conference 2022 + 2021 NSW Landcare Awards Finalists And Winners

- Australian Government Individual Landcarer Award

- Australian Government Partnerships for Landcare Award

- Australian Government Landcare Farming Award

- Coastcare Award

- Landcare Community Group Award

- Woolworths Junior Landcare Team Award

- KPMG Indigenous Land Management Award

- Young Landcare Leadership Award.

- Julie Holstegge

- Marg Bull

- Winsome Lambkin

- Sydney Wildlife (Sydney Metropolitan Wildlife Services)

- Australian Association of Bush Regenerators-AABR

- The Protecting Little Llangothlin (RAMSAR) for Future Generation Project

- Martin Royds

- Stuart Austin

- Graham Strong

- Budgewoi Beach Dunecare

- Clean4shore

- Lennox Head Landcare

- Upper Lachlan Landcare Grazing Group

- Mulgoa Valley Landcare Inc.

- Upper Mooki Landcare Inc

- Bexhill Public School

- Ivanhoe Central School

- Grose View Public School

- Nari Nari Tribal Council

- Hunter Aboriginal Riverkeeper Team (H.A.R.T)

- Joel Orchard, Young Farmers Connect

- Gabrielle Stacey, Fern Creek Landcare

- Elisha Duxbury Macquarie University & Greater Sydney Landcare Network

- Brian Hilton

- Deb Tkachenko

- Louise Turner Western Landcare NSW

The Sydney Edible Garden Trail 2022: March 26-27 - Local Sites

Peek inside some of Sydney’s private backyard fruit and veggie gardens this March, and discover their secrets to living sustainably.

Whether you’re a new or experienced gardener, the best way to learn how to grow juicy fruit and vegetables in your own backyard is to talk to a gardener who’s already doing it. Sydneysiders will have the opportunity to do this over the weekend of 26 & 27 March 2022 when over 50 suburban, community and school gardens will open for the Sydney Edible Garden Trail (SEGT).

Matthew Elphick, one of the garden hosts who participated last year, was inspired to reopen his garden again this year. He’s looking forward to the 2022 trail, saying “It was so wonderful to open last year and have people come through the garden and see how excited they are. You get to see the garden through their eyes, things that you don’t think much about, they find amazing. It’s such a great opportunity to meet like-minded people.”

With the motto “We don’t just grow food, we grow sustainable communities”, SEGT arranges for gardens to open to the public and allocates profits from ticket sales towards building stronger community and school gardens through a grants program with 8 gardens provided with grants in 2021.

This year the trail is extending to the wider Sydney metropolitan area with many new gardens included. Tickets are now on sale at https://sydneyediblegardentrail.com/tickets/

Those in our area listed so far for the 2022 edition of SEGT include:

Newport Community Garden

We are a membership based Community Garden of local neighbours who get together to learn about organic gardening, sustainable living, socialise and have a good time!

NCG has been running for over 8 years and from humble beginnings is now a vibrant, sustainable and inviting space with over 35 garden beds, compost bays, worms farms and native bee hive, green house, water tanks and garden shed.

We grow organic fruits, vegetable and herbs. We cultivate our compost, make our own natural pesticides and grow from seeds saved from our seasonal harvest.

It’s not just hard work, we are very social too and always finish the day with a cuppa and chat with local community members.

In November 2021 Newport Community Garden were announced as one of fifty SEGT GRANT RECIPIENTS 2021.

The grant will be used to attract local birdlife and bees by planting some native bush food plants and others native plants.

Newport Community Garden Profile of the Week

“The glory of gardening: hands in the dirt, head in the sun, heart with nature. To nurture a garden is to feed not just on the body, but the soul.” - Alfred Austin

Great reuse of an old boat in the Newport Community Garden

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: from Esther Andrews.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Asparagus Fern Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Corroboree Frogs Return Home

After The Fires: Popular Blue Mountains Sites Reopen

Floodplain Development Manual Update: Feedback Until April 4

- Lessons learned from previous floods and the application of a flood risk management process and manual since 2005.

- A range of work on managing natural hazards across government, including relevant national and international frameworks, strategies, and best practice guidance.

- A Flood Risk Management Manual.

- A range of new flood risk management guides for the Flood Risk Management Toolkit.

The Big Switch With Saul Griffith: Electrify Everything!

When: Wed, 23 March 2022; 6:30 PM – 8:00 PM

When: Wed, 23 March 2022; 6:30 PM – 8:00 PM Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

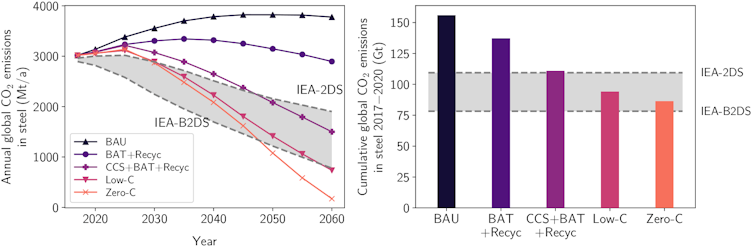

To really address climate change, Australia could make 27 times as much electricity and make it renewable

Australia’s electricity system is on the road to becoming 100% renewable as coal-fired power stations close and wind and solar takes their place.

But as a proportion of electricity consumed domestically, it’s on the road to more than 100% renewable. That’s because renewable power set to be produced in Australia’s north could be exported in ways such as via subsea cables.

And if we get really serious about bringing down global emissions we will be doing much, much more.

In a newly-published study carried out as part of a multi-disciplinary team under the Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia-Pacific project we analyse the potential for Australia to produce and export not only clean energy but also green value-added commodities, eliminating emissions that would have taken place elsewhere.

We find there is substantial scope for Australia to use its solar, wind and land endowments to become a major exporter of green electricity, green hydrogen, green ammonia, and green metals.

Australia’s Exports Are Emission-Intensive

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of coal and liquefied natural gas, mostly to countries in the Asia-Pacific. Each year, the emissions from overseas use of these fuels vastly exceed the total emissions from Australia itself.

Australia is also a major producer and exporter of other commodities that go on to be used in emissions-intensive ways in destination markets - among them iron ore, bauxite and alumina.

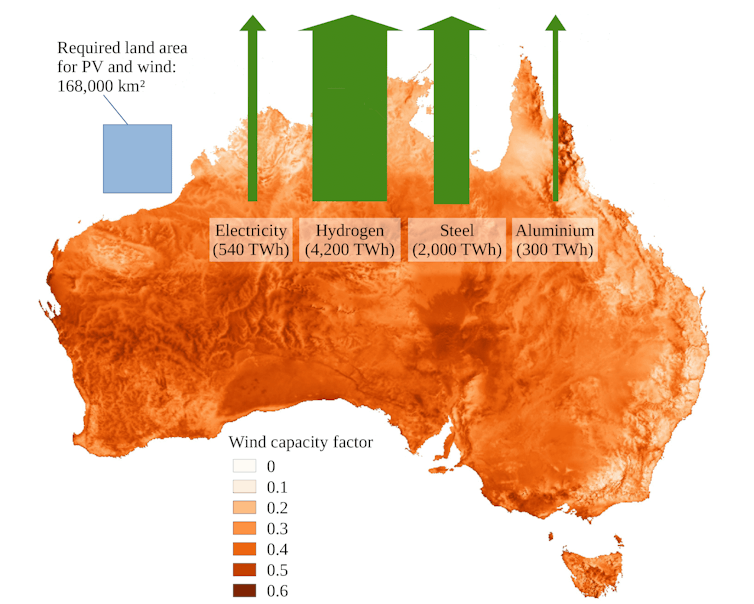

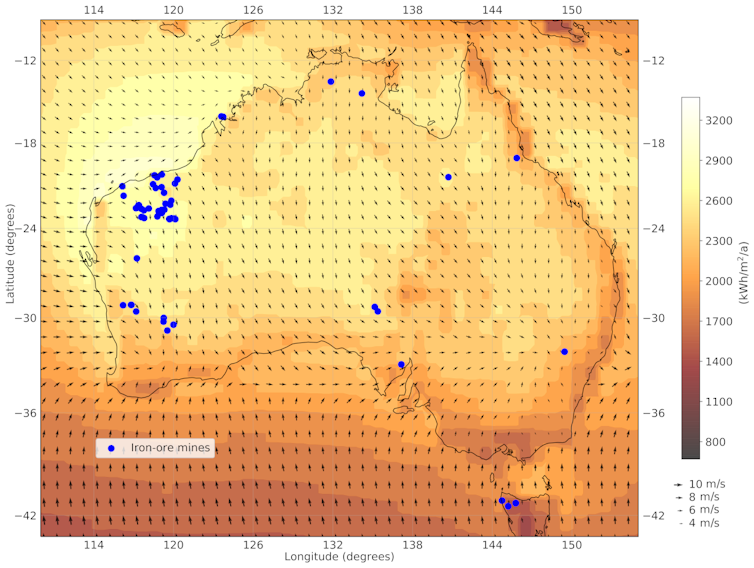

The figure below shows our calculations of the “consequential emissions” associated with Australia’s exports of several key commodities.

To avoid double counting, coking coal is not shown. Its emissions are instead included in the emissions tied to the overseas use of Australian iron ore.

The consequential emissions associated with the key commodity exports shown below account for about 8.6% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the Asia-Pacific and about 4% of global emissions.

While importing countries are certainly not absolved from responsibility for emissions from use of Australian exports, the calculations show just how important Australia’s upstream role is.

Australia Could Export Zero-Carbon Products And Energy

To get an indication of the production possibilities, we calculated the land area and energy requirements for an indicative scenario in which Australia:

exports the same quantity of energy in green electricity and hydrogen as it exports in thermal coal and liquefied natural gas.

processes currently-exported iron ore, bauxite, and alumina into green steel and green aluminium for value-added export.

Using 2018–2019 data, we calculate that about 2% of Australia’s land mass would be needed for solar and wind farms. This is a large area, although small relative to the area currently dedicated to livestock grazing and other agricultural activities.

The energy requirement would also be large, involving about 7,000 terawatt-hours of solar and wind generation per annum – about 27 times Australia’s current electricity output and use.

Water would be needed for electrolysis to produce hydrogen. This could be largely based on desalination of seawater, an activity that would involve minimal additional energy requirements.

The best locations for mega-scale solar and wind farms for export commodities are commonly in arid or semi-arid areas outside the most productive agricultural zones, so negative implications for food supply could be avoided.

Land and electricity requirements under a zero-carbon export scenario

Key priorities include ensuring that the sustainable development opportunities for Indigenous communities from these projects are harnessed and protecting the natural environment.

Reducing the need for new coal mines and other fossil fuel projects would be a major environmental benefit.

There’s Private Sector Interest

Australia is already a world-leader in the adoption of solar and wind power, and there is substantial private-sector interest in zero-carbon export opportunities.

Proposals for exports of solar electricity (Sun Cable), green hydrogen (including Fortescue Future Industries and the HyEnergy Project) and green ammonia (including the Asian Renewable Energy Hub, Western Green Energy Hub, and Yara Pilbara) are pointing the way.

The combined renewable electricity peak capacity for these projects alone (>100 GW) already exceeds Australia’s present electricity generating capacity by a considerable margin.

They Are Opportunities We Should Grab

Achieving the rates of investment required to realise our clean commodity export potential will require world-class policy.

In 2019 Australia released a National Hydrogen Strategy, and most states and territories have similar plans. The Technology Investment Roadmap, the Australian Renewable Energy Agency and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation are further examples of “green industrial policy” at work.

To facilitate access to premium markets, we need to ensure it is easy for new industries to prove that their production is clean. Australia is currently undertaking efforts to develop hydrogen certification.

International regulatory collaboration is essential. Negotiations for an Australia-Singapore Green Economy Agreement are a step in the right direction.

In October 2021 Australia announced a target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Our research finds domestic emissions are only part of the story. Australia has an opportunity to contribute to global net-zero emissions via clean exports.![]()

Paul Burke, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University; Emma Aisbett, Fellow, Australian National University, and Ken Baldwin, Inaugural Director, ANU Grand Challenge, Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia Pacific, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Surfing Towards Coastal Ecosystem Protection

March 14, 2022

Scientists at the University of Portsmouth believe a strategy used to protect popular surfing spots could now be more widely adopted to help preserve endangered coastal environments. A new research paper, published this week in Trends in Ecology & Evolution, says, 'wave reserves', initially aimed at protecting treasured surf spots, are also a way to ensure the conservation of ecologically valuable coastal areas.

The concept of wave reserves has gained popularity over the past few decades. The first wave reserve was established in Bells Beach, Australia in 1973 by surfers keen to defend their prized waves from damaging human activity. But it is especially since the beginning of the 2000s that the surfing community has established dozens of wave reserves around the world.

Waves can be affected by any number of factors such as the dredging of the seabed, building of dykes, changes in sediment regime and ocean acidification. The strategy has been so successful that in some locations there are now several large wave reserves being planned, with support from international NGOs such as Save The Waves.

The research from the University of Portsmouth finds this approach could help low and middle-income countries achieve global sustainability goals. Waves are not just important to surfers, they are also a vital part of the marine ecosystem. Waves play an active role in the gas exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere and in the movement of sediments. They also provide a favourable living environment for many aquatic species.

During the last 20 years the creation of wave reserves as a measure to preserve sports and recreational activities has aligned with initiatives to conserve the coastal environment. What is emerging is a win-win situation.

Academics believe a desire for corporations to put money behind surfing projects could also be a useful funding stream that benefits the coastal environment. The growing surf market, and its adoption as an Olympic sport could help generate significant revenues for conservation.

Gregoire Touron-Gardic, from the Centre for Blue Governance at the University of Portsmouth, says: "What is new and exciting -- in addition to seeing increasingly large reserves and with legal protection statuses -- is the private sector is now interested in wave reserve projects. We are now seeing sports, cosmetics and drinks brands finance international ocean conservation programs. Brands wish to be associated with responsible ecological and social projects, whilst benefiting from the image of surfing."

Touron-Gardic predicts wave reserves will become a popular tool of coastal conservation in countries recognised as surfing destinations, such as the Maldives, Indonesia, Costa Rica, Fiji and Chile. The reserves make it possible to combine preservation of the coastal environment, local economic prosperity and human well-being.

Professor Pierre Failler, Director of the Centre for Blue Governance, University of Portsmouth says, "The potential impact of wave reserves on the future of sustainable ocean management is huge. Wave reserves can become the foundation for an environmental approach to sport tourism. When large enough, wave reserves will allow low- and middle-income countries to increase their relatively weak area-based conservation systems at a lower cost, and therefore progress in achieving their international commitments such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Professor Failler, who is also UNESCO Chair in Ocean Governance, says: "It is achievable and accessible initiatives like these that will help improve the governance of the world's oceans. There are many challenges to overcome during the UN Decade of Ocean Sciences for Sustainable Development and collaboration is key to safeguarding the future of our oceans."

Grégoire Touron-Gardic, Pierre Failler. A bright future for wave reserves? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2022; DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2022.02.006

1.7 million foxes, 300 million native animals killed every year: now we know the damage foxes wreak

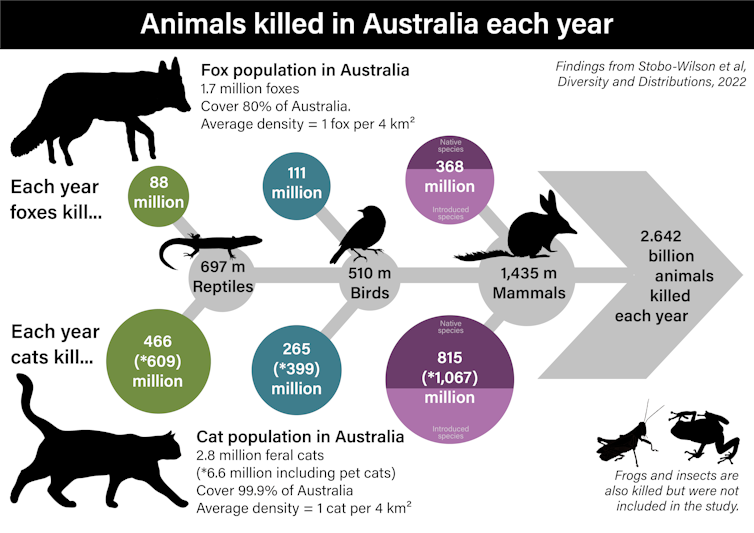

Foxes kill about 300 million native mammals, birds and reptiles each year, and can be found across 80% of mainland Australia, our devastating new research published today reveals.

This research, the first to quantify the national impact of foxes on Australian wildlife, also compares the results to similar studies on cats. And we found foxes and cats collectively kill 2.6 billion mammals, birds and reptiles every year.

This enormous death toll is one of the key reasons Australia’s biodiversity is suffering major declines. Cats and foxes, for example, have played a big role in most of Australia’s 34 mammal extinctions, including the desert rat-kangaroo which rapidly declined once foxes reached their region.

Australia must drastically scale up the management of both predators, to give native wildlife a fighting chance and to help prevent future extinctions.

Australia Is Home To 1.7 Million Foxes

European colonisers brought foxes (and cats) to Australia. From 1845, foxes were released into the wild in Victoria for the “sport” of hunting them on horseback with a pack of hounds.

Fox populations soon exploded, thanks to the deliberate introduction of rabbits and hares in the 1800s. Rabbits and hares are not only a food source for foxes, they also eat the vegetation that native animals need for food, habitat, and to hide from predators. They continue to boost fox numbers today.

Our study estimates there are now 1.7 million foxes in Australia, spread across 80% of the mainland and on 50 Australian islands. They’re largely absent from tropical northern Australia and Tasmania.

By comparison, cats occur over more than 99.9% of the country, including on far more islands.

Fox densities are highest in temperate mainland regions, including forests and farms, and near urban areas where food and shelter are abundant. The Victorian government estimates there are as many as 16 foxes per square kilometre in Melbourne.

What Are Foxes Eating?

The 300 million native animals that foxes kill every year consists of:

reptiles: foxes kill 88 million reptiles each year, and all are native. They’ve been recorded killing 108 different species – or 11% of all Australian reptile species – including the tjakura (great desert skink) and loggerhead turtle

birds: foxes kill 111 million birds each year, and 93% of these are native. They’ve been recorded killing 128 species – or 18% of all Australian bird species – including the mallee-fowl and little penguin

mammals: foxes kill 368 million mammals each year, and 29% of these are native. They’ve been recorded killing 114 species, or 40% of all land mammal species and half of all threatened mammal species. This includes the mankarr (greater bilby), quenda (southern brown bandicoot) and warru (black-footed rock-wallaby).

Foxes also kill another 259 million non-native invasive animals every year, predominately house mice and rabbits. They also kill livestock, such as lambs, piglets and chickens.

While rabbits and house mice form a major part of fox diets, there’s no evidence foxes (or cats) limit their numbers. Changes in rabbit and mice populations are largely driven by climate fluctuations.

Our findings are underpinned by modelling data assembled from almost 100 field studies. This included 49,458 fox poo and stomach samples, and fox density estimates at 437 locations.

Foxes are also known to eat bird and reptile eggs, and threaten the breeding success of many turtle species. However, we didn’t tally their impact on turtle eggs (or on fish, frogs or insects) because of insufficient data - they’re highly digestible and often hard to identify in fox poo.

Carrion (dead animals) account for an average of 10% of fox diets, but we excluded carrion in the estimated numbers of animals killed.

Foxes And Cats: A Deadly Combination

Although they eat many of the same species, foxes take larger prey than cats and have a bigger toll on kangaroos, wallabies and potoroos.

Cats eat smaller prey, so eat a lot more of them. Nationally, feral cats kill about five times more reptiles, two and a half times more birds and twice as many mammals than foxes.

In total, feral cats kill 1.5 billion animals every year (not including invertebrates and frogs). Pet cats kill another 500 million animals.

The impacts of both predators are concentrated in some regions more than others. And although cats kill more animals overall nationally, in some areas foxes take a greater toll.

This includes the Warren and Jarrah Forest in Western Australia, the Eyre and Yorke Penninsula in South Australia, across Victoria and in NSW’s Blue Mountains.

This is why foxes take a larger toll on forest animals such as possums and gliders, and kill over 1,000 animals per square kilometre each year in these areas.

To understand and manage these threats, it’s essential to take the cumulative impacts of both introduced predators into account. Many species fall prey to both cats and foxes.

Each day across Australia their combined death toll includes 1.9 million reptiles, 1.4 million birds and 3.9 million mammals.

So What Needs To Change?

The only way to stem these losses, and prevent the extinction of many vulnerable species, is to step up targeted and integrated cat and fox management.

Cat and fox eradication programs have had success in fenced areas and on islands. For example, cat eradication on Dirk Hartog Island is enabling many native animals to be reintroduced.

And long-term broad-scale management programs have enabled the recovery of threatened species in wider landscapes, such as the Bounceback Program helping yellow-footed rock wallabies and other wildlife in SA’s Flinders Ranges.

Our new research highlights the urgent need to increase investment for cat and fox management across Australia. Management will need to be large-scale and strategically coordinated as both species breed like rabbits, so to speak, and travel great distances.

This means patchy, or small-scale lethal programs can allow their numbers to quickly rebound.

We also need to protect and recover habitat for native animals. Evidence shows good habitat supports healthier native animal populations and gives them more places to hide from predators. ![]()

Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Alyson Stobo-Wilson, Postdoctoral Research Associate, Charles Darwin University; Brett Murphy, Associate Professor / ARC Future Fellow, Charles Darwin University; John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University; Sarah Legge, Professor, Australian National University, and Trish Fleming, Professor, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thinking of buying an electric vehicle for your next car? Here’s the market outlook and what to consider

As petrol prices soar and climate change impacts make themselves felt, many people are likely wondering if their next car should be a fully electric vehicle.

Yes, the upfront costs are generally higher – but what does the future hold? Will prices fall in coming years and what costs do you need to factor into your decision?

The unfortunate truth is unless policy settings in Australia change, we shouldn’t expect a significant increase in the number of electric vehicles (EVs) available to Australians over the coming years.

It’s important we all start to make the switch to this cleaner technology, but unfortunately that choice is not available to many Australian households and businesses due to a lack of local, supportive policy.

Costs To Consider

EVs in Australia are currently A$15,000-20,000 more expensive than petrol or diesel cars. But in some market segments – like some sub-premium sedans priced between $60,000 and $75,000 – they are already at parity.

Several manufacturers have promised to bring more supply to the Australian market in 2022 but many of these vehicles were meant to be here in 2021 (with their arrival pushed back).

If you’re thinking of making the switch to an EV, here’s what to consider:

don’t focus only on the price tag. With petrol prices now pushing past $2 per litre, many Australians will find themselves paying more than $2,000 in fuel each year for every car they own. Electric vehicles can be charged for the equivalent of around $0.20 per litre, or even cheaper when using your home solar. These savings add up, totalling more than $20,000 over the life of the vehicle.

EVs are cheaper to maintain, and in some cases have no servicing costs. This equates to thousands of dollars potentially saved over the life of the vehicle.

what about charging? Anywhere you have access to a standard power point you can charge an EV. With cars parked 90% of the time, and mainly driven fewer than 50 kilometres per day, a couple of hours’ charging is more than enough for most. If you want a quicker charge, you can install a wall charger in your garage. And if you park on the street you can use the growing list of public fast chargers across the country or ask your workplace to install a charger.

The reality, though, is that if there’s no change to policy settings, we can expect the EV market in Australia to stay much the same this year and for many years to come.

This means many Australians won’t have a choice but to continue to pay for expensive imported fuel, instead of using cheap Australian energy to power our vehicles.

Are All EVs Expensive?

There’s a vast range of EV models. It’s just that most of them aren’t sold in Australia.

One of Australia’s disadvantages is we are a market for right-hand-drive vehicles, and many European and American EVs just aren’t built that way. The UK is also a right-hand-drive market, where people have similar average incomes and quality of life compared to Australia. But the EV market there is very different with more than 160 EV models compared with around 50 in Australia.

The key difference is the UK has a (conservative) government that has embraced the technology and understands the broader economic benefits of making EVs easy for people to get and run.

Yes, Australia has boosted EV charging infrastructure but that’s not enough to encourage manufacturers to bring more models to this country (which would help get more affordable EVs on the market).

How would the Australian market look if we did have supportive policy? Well, there are about 80 million cars sold worldwide each year, around 1 million of which are sold in Australia. So we are about 1.3% of the global car market.

There were about 6.6 million EVs sold worldwide in 2021. So 6.6 million x 1.3% equals about 85,000 cars. That’s 85,000 EVs that should have been sold here last year if our market was in line with global trends.

But in fact, the number of EVs sold here was just over 21,000 in 2021. So we are about a quarter of the size we should be.

There’s plenty of demand for EVs in Australia, we just cannot get enough delivered because we haven’t got the right policy settings.

What Policies Could Help?

Policies that would help make EVs more affordable in Australia include:

incentives to bring down the upfront cost of EVs. Some people say this is subsidising rich people but clever policy would support jobs in the Australian energy market. It’s estimated we spend more than A$30 billion on foreign fuel for our cars every year. Redirecting that money to powering EVs would help keep those billions in the country, and support local Australian energy jobs.

we don’t have a fuel efficiency standard, putting us in poor company with Russia as two of the last remaining major economies without such standards. That’s why people say Australia is a dumping ground for vehicles that are illegal to sell overseas. The markets that have fuel efficiency standards are getting all of the EV supply.

having a clear target of EV sales for the next five to 15 years would support achieving net zero by 2050 – in other words, selling the last petrol or diesel car by the mid-2030s.

So What’s The Market Outlook?

Not much will change in Australia unless there’s a change in policy. We are competing with markets that have the right policies to stimulate EV sales. The manufacturers are, of course, going to prioritise supply there.

There will be small increases in EV sales in Australia every year. But it will take a number of years for the supply of these new vehicles to ramp up.

I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news. And I do hope your next vehicle purchase is an EV, after considering all of the costs over the life of the vehicle. It is the right thing to do for the climate and the long-term savings are attractive, especially if fuel prices continue to be so volatile.

Unfortunately, though, Australians should not expect EVs to suddenly become cheap and easy to buy here in the next couple of years – unless policy changes.![]()

Jake Whitehead, Tritum E-Mobility Fellow & Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It may not be cute, but here’s why the humble yabby deserves your love

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s series introducing you to Australia’s unloved animals that need our help.

For children growing up in rural areas, going “yabbying” in farm dams is a rite of passage. The common yabby (Cherax destructor) is the most widely distributed Australian crayfish, inhabiting rivers and wetlands across southeast Australia.

And although the humble yabby is not as cute and cuddly as some better-known Australian icons, from an ecosystem perspective, we argue they may be more important.

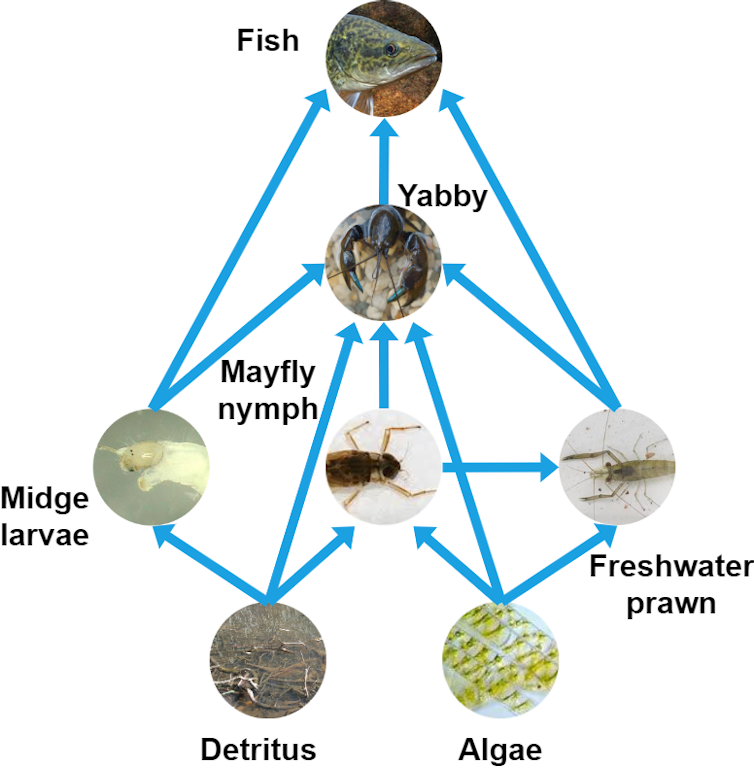

Yabbies are a staple food for platypus, many waterbird species, and fish such as Murray cod and golden perch. And yabbies’ diet is largely made up of algae, detritus (dead organic material) and small animals. This means they link energy from the very bottom of the food chain to apex predators at the top.

And yet, little is known how their diets influence their growth and alter their quality as a food source. Our recent research starts to fill this critical gap.

We found yabbies in wetlands are better food source for fish than those in rivers, because wetland yabbies eat more foods rich in high-quality fatty acids. While more research is needed, these results show how higher quality yabby diets can increase the total biomass of predators, such as Murray cod, that riverine ecosystems can support.

Untangling The Food Web

Food webs describe what eats what within ecological communities and provide a useful way to illustrate how energy moves through the environment.

But it’s more complex than big fish eats little fish. Within food webs, organisms can be lumped into two groups:

- autotrophs: organisms that obtain energy from the sun via photosynthesis, such as plants

- heterotrophs: organisms that obtain energy by eating other organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and animals.

Algae fall in to the first group, providing a high-quality energy pathway in food webs because they can synthesise so-called “long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids”: omega 3 and omega 6.

If you grew up in the 1980s you’re probably familiar with the term “polyunsaturated fatty acids” from its association with margarine (though few probably understood its relevance back then). Today, we more often hear the term around seafood.

We’re encouraged to eat oily fish because of the omega 3 and omega 6 they provide, which the body needs for brain function and cell growth. We source these fatty acids from fish thanks to algae, which underpins many aquatic food webs. Fatty acids are essential for the growth of all animals, including yabbies.

The other primary energy source in freshwater comes from detritus – organic debris and decomposing material. In wetlands and rivers, detritus accumulates from falling leaves and branches along banks, which can be washed into rivers during high flows.

But while detritus is often abundant, it’s considered poorer quality because it’s difficult to digest and has low concentrations of some important fatty acids. And in food webs, poor quality food provides less bounce for the ounce, so to speak.

The yabby is an omniovore - algae, detritus and other animals are its food, but we know little about how these different energy sources affect yabby growth and survival – or how it might affect animals that rely on yabbies for food.

You Are What You Eat

Our research investigated how different quality fatty acid diets affected yabby growth, and how this might influence other animals up the food chain.

We found yabbies fed poor quality diets in the laboratory, made up of only dead plant matter, barely grew at all. These yabbies also represented a poor-quality food resource for predators.

In contrast, yabbies fed mixed diets rich in high quality polyunsaturated fatty acids grew the most – more than doubling in mass over a 70-day trial. They also retained higher concentrations of these fatty acids in their body tissue, making them a good food resource for other animals.

Yabbies are tough. They’re well adapted to Australia’s extremes, capable of surviving dry conditions by lying dormant in burrows dug in dried waterways. During wetter periods, they can travel long distances in search of a new home – usually wetlands or rivers.

So how might their environment affect their diet? We found wild yabbies that live in wetland habitats ate foods with higher concentrations of these fatty acids compared to yabbies that live in rivers.

And as with our laboratory fed yabbies, wild wetland yabbies eating high quality foods also represented a better food option for fish than riverine yabbies. This is likely due to wetlands containing a higher proportion of diatoms (single-celled algae) and green algae, which both synthesise long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.

What Does This Mean For Freshwater Ecosystems?

Australia’s floodplain rivers are dynamic. Wet periods with high flows connect rivers to wetlands that lie on the floodplain. In dry periods with low flows, this connection is interrupted, leaving wetlands on floodplains isolated, sometimes even drying out completely.

Connectivity between rivers and their floodplain is important for many reasons. It provides habitat and breeding opportunities for birds and fish, revitalises plants, and an exchange of nutrients.

Water in the Murray-Darling Basin is shared between irrigators, municipal water supply and the environment, and is largley regulated with infrastructure such as dams and weirs.

Our research is an example of the many benefits that come with ensuring we have adequate water for the environment. Our work shows that an important aspect of connection is to allow riverine predators access to high quality food resources – yabbies – in floodplain wetlands.

If yabbies are thriving and passing essential fatty acids up the food chain, populations of popular recreational fish, such as Murray cod and golden perch, will benefit accordingly.

It’s critical we improve our understanding of these complex relationships. This includes recognising other drivers of riverine population success such as competition, habitat, life history traits and spawning cues, to ensure Australia’s riverine animals can thrive. ![]()

Paul McInerney, Research Scientist, CSIRO and Gavin Rees, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thanks to heavy rain, Australia’s environment scores a 7 out of 10 – but the future remains bleak

After the devastating floods, it’s hard to imagine only two years earlier many hard-hit communities suffered extreme heat, drought and unprecedented bushfires. Yet our report, released today, shows Australia’s environment has recovered dramatically since then.

Every year we use a supercomputer to analyse vast amounts of measurements from satellites and field stations to give the condition of Australia’s environment a score out of ten. For 2021, we score it 6.9 – four points higher than the year before.

The improvement is largely thanks to two years of plentiful rains that helped Australia’s forests, pastures and farmland recover well.

But as the rains only increased in 2022, inundating many parts of southeast Australia, you may well be wondering: can there be too much rain for our environment? And what might this all mean for the coming bushfire seasons?

First, Let’s Look Back At 2021

We assessed Australia’s environment using 15 key indicators, such as water availability, bushfire, population pressures and vegetation health. Combined, these help determine the overall “environmental condition score”.

On our website, you can also find regional scores for your state or territory, local government area, catchment and electorate. Unusually, scores improved almost everywhere.

We confirmed that rainfall was near or above average nearly everywhere, thanks to back-to-back La Niña events – a natural climate phenomenon over the Pacific Ocean associated with wetter weather.

What’s more, in the winter and spring of 2021, parts of Australia also felt the effects of a “negative Indian Ocean Dipole” – a little like the Indian Ocean’s version of La Niña that also brings rainier weather.

Here are a few ways all this rain benefited Australia’s environment:

it replenished parched soils that missed rainfall in 2020, and improved growing conditions in both natural and managed landscapes such as farms and plantation forests.

compared to 2020, drought conditions eased across previously drought-ravaged areas of inland northern Australia

river flows across Australia increased by 75% on 2020 figures, and urban water supplies increased for all capital cities

wetlands swelled to their greatest total extent since 2016 (although still 9% below the 20-year average), with no major algal blooms or fish kills

growth conditions in Australia’s cropping, grazing and irrigation lands were well above average and the best since 2000 in all major regions except South Australia and inland Western Australia.

Australia also experienced less population growth and carbon emissions in 2021, mainly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, translating to a slower increase of the pressure on our environment.

Dark Clouds On The Horizon

Unfortunately, some troubling trends did not get better in 2021. Biodiversity continued to decline. Twelve species were declared extinct, although ten of those probably went extinct more than 60 years ago. A more recent extinction was the Christmas Island pipistrelle, a tiny bat last seen in 2009.

Another 34 species were added to Australia’s list of threatened species, eight of which are birds from Kangaroo Island, which suffered extensive and severe bushfires in early 2020.

While the number of threatened species fluctuate with the condition of their habitat, their long-term decline continues unabated. This is largely driven by invasive species such as feral cats and foxes, logging, urban development, river water extraction and an increasingly hot climate.

For example, despite the good rains and increased wetland extent, researchers counted fewer birds in Eastern Australia than in the previous four years.

Favourable conditions in the Great Barrier Reef led to the rapid, but fragile, recovery of hard corals after three bleaching events in five years. However, a recent heatwave in northern Queensland means a fourth coral bleaching event is on the cards for 2022.

And of course, despite the relatively benign weather conditions in 2021, the spectre of climate change on a global level has not lifted.

World economies recovering from the pandemic saw atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration increase by 2.5 parts per million, 6% faster than in 2020 and 11% faster than the average growth rate since 2000.

Because of La Niña, more of the excess heat went into the Pacific Ocean in 2021 than normal, rather than into the atmosphere. So while the atmosphere was 0.14 degrees cooler than in 2021, it was still almost one degree above the 2000-20 average and the sixth-warmest year on record.

Can There Ever Be Too Much Rain?

Above-average rain already led to major flooding in Queensland and NSW in 2021, even before the more recent deluge. Indeed, the recent, record-breaking rains added more water to soils, catchments, rivers and dams already replenished in 2021.

Does Australia’s environment still benefit from so much rain? Mostly, it can.

Our ecosystems are generally better adapted to wild climate swings, shedding excess water efficiently and recovering quickly from damage.

In normally dry regions, more rain means more vegetation growth and uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere – although much of it will be released again during droughts or fires.

River flooding is a source of life in inland Australia, which may mitigate some of the damage done by the diversion and over-extraction of floodwaters.

The consequences of extreme rainfall for invasive plants and animals are poorly understood but probably very diverse. Invasive species less adapted to drought may spread faster.

But the biggest environmental impacts are where natural vegetation was cleared for farming, housing or mining. Unprotected, bare soil soaks up less excess rainfall, and the rain and runoff can loosen up more sediment.

This erosion degrades farmland, cuts away riverbanks and the washed-out sediment and nutrients end up in rivers and the sea, where it can smother marine life and encourages outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish that attack coral reefs.

What Does This Mean For Bushfires?

The Bureau of Meteorology expects that La Niña conditions reached their peak and rainfall conditions may normalise soon. Some of the excess heat stored in the ocean will be released, causing air temperatures to quickly resume their warming trend.

Combined with the booming growth of vegetation, the extent of bushfires will likely pick up again next fire season: more vegetation means more fuel for fire. And it only takes a few hot and dry weeks for these conditions to increase fire activity.

Unfortunately, the pressures of vegetation destruction, invasive species and climate change will degrade our agriculture and ecosystems for decades to come. Incisive reductions in carbon emissions and more careful ecosystem management can avoid these impacts worsening.

Both are within reach, but require the sort of consensus and resolve shown in response to COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion. Our environmental crisis is no less severe.![]()

Albert Van Dijk, Professor, Water and Landscape Dynamics, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University and Shoshana Rapley, Research assistant, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Trees: why they’re our greatest allies against floods – but also tragic victims

Gregory Moore, The University of MelbourneAs the floodwaters recede, mountains of debris are left behind – sheets of plaster, loose clothes, mattresses and, of course, trees. Some debris I’ve seen in floods includes massive tree trunks weighing 5 tonnes of more, bobbing along like corks in the rapidly flowing waters.

The trees that line our creeks, rivers and floodplains are on the front line when major flooding occurs, and bear the brunt of the flood’s mighty forces. But while they are often victims of floods, trees are also our greatest allies.

From stabilising river banks with the strong grip of their roots to changing the course of floodwater, here’s how trees influence floods – and how floods can kill them.

How Trees Influence Floods

The large and fine roots of trees, such as river red gums, bind and consolidate soil, stabilising river banks and reducing erosion. This reduces the amount of sediment entering waterways, and prevents waters down-stream becoming muddied and clogged with silt.

Large trees can also protect smaller plants such as shrubs by acting as a physical barrier, shielding other vegetation from the forceful momentum of floodwater. This is because the presence of trees slows the floodwaters’ speed, as their trunks, roots and branches block and deflect water, and change the direction of flow.

However, slowing floodwaters can also cause the flood front to widen, inundating areas further away from the usual river course. This is a major consideration when creek and river banks are being revegetated – we want to capture the benefits trees provide, but also ensure that if floodwaters slow down there’s no greater risk to property or life.

Another different but related role is that trees can prevent landslides or landslips. Indeed, landslides have occurred across flood-affected regions such as Illawarra and Kangaroo Valley in NSW, and continue to threaten people and homes.

On slopes, tree root systems consolidate soils and help prevent the movement of super saturated soil, which can flow like a liquid down hill. So it can be a problem when people remove trees from around their homes or along roads as a part of bushfire prevention programs, without thinking that cleared sites and roadside verges might be prone to landslides.

Sometimes a compromise might be a better management option. Rather than removing all trees on a slope or verge, leave some of those with large roots systems and plant trees that might slow fires or resist them. Also consider planting species that resprout after fires such as tree ferns, so their roots systems aren’t lost and the soil doesn’t erode.

Trees Are Also Flood Victims

Some trees won’t survive major floods as the water’s brute force undermines their root systems, bringing them down.

In other cases, the debris, including whole trees and large branches, acts as a battering ram on large trunks. Most big trees will survive this, but some will be repeatedly battered until the trunk, major branches or root systems fail.

These then become part of the debris that damages infrastructure, such as bridges and other trees downstream.

For most trees, floods are a fleeting event that lasts a few days or perhaps a couple of weeks. Many tree species cope well with this situation, but what happens to those that might be inundated for weeks or even months in the wake of floods?

Soils can remain very wet for a long time after flooding. Some trees, such as river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and swamp gum (Eucalyptus ovata), can tolerate inundation for many weeks. We’ve seen populations of river red gum, for example, cope with up to nine months of inundation.

Others may not do so well if they remain under water for long periods of time. This includes older and stressed trees, some fruit trees like citrus and stone fruit species, or some conifers.

Water-logged soils have low levels of oxygen, which means roots struggle to maintain their normal metabolism, health and function. This also affects the fungi associated with healthy roots. The longer low oxygen levels persist, the less suitable conditions are.

Low oxygen in soils lead to anaerobic respiration – when cells break down sugars to generate energy without oxygen, producing alcohol and lactic acid. Both alcohol and lactic acid are only mild poisons, but as their level rises, root and fungal cells can be killed.

Water-logged soils also mean roots are deprived of their usual sources of energy and die of starvation. And once the roots start to go, there’s a rapid downward spiral in the tree’s condition.

Trees can die very quickly, over a matter of days, and such rapid deaths are much more likely in older, stressed trees. Little can be done to help trees survive under these conditions.

Take Care Around Trees After Floods

When trees that survived the flood die in its aftermath, they can cause riverbanks to collapse. This creates a danger for those who approach at the wrong time.

And as roots die, the trees are less stable. This means if winds pick up speed, the compromised root system in soggy soil can lead to windthrow, which is where whole trees are blown over.

This can happen weeks or even months after a flood, so take care on these sites on windy days.

The major floods inundating NSW and Queensland are not the first – and will certainly not be the last – many of us will experience in our lifetimes.

For those of us who have been acutely aware of the prediction of major flooding events as part of climate change, these events haven’t come as a surprise. They were inevitable, just as fiercer bushfires and ferocious storms are inevitable.

In this land of extremes, trees have always been part of floods and flood prone ecosystems. Yet trees are disappearing at an alarming rate along many waterways.

While climate change poses new threats to trees, it also creates new opportunities for us to work with trees as allies in dealing with climate change and its consequences. We must not work against them. ![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Today’s disappointing federal court decision undoes 20 years of climate litigation progress in Australia

Jacqueline Peel, The University of Melbourne and Rebekkah Markey-Towler, The University of MelbourneThe federal court today unanimously decided Federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley does not have a duty of care to protect young people from the harms of climate change.

The ruling overturns a previous landmark win by eight high school students, who sought to stop Ley approving a coal mine expansion in New South Wales. While the judge did not prevent the mine expansion, he agreed the minister did indeed have a duty of care to children in the face of the climate crisis.

Ley’s successful appeal is disappointing. As legal scholars, we believe the judgment sets back the cause of climate litigation in Australia by two decades, at a time when we urgently need climate action to accelerate.

So why was Ley successful? The federal court’s 282-page judgment offers myriad reasons for why no duty should be imposed on the minister. But what emerges most clearly is the court’s view that it’s not their place to set policies on climate change. Instead, they say, it’s the job of our elected representatives in the federal government.

What Did The Judges Say?

In the original class action case filed in 2020, a single federal court judge decided Ley owed Australian children a common law duty of care when considering and approving the coal mine extension, under Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

This required the minister to take reasonable care when exercising her powers to avoid causing Australian children under 18 personal injury or death from carbon dioxide emissions.

Ley appealed this decision in July last year. She also approved the coal mine extension, arguing her decision wouldn’t contribute to global warming because even if the mine was refused, other sources would step in to meet the coal demand.

And today, in a live-streamed proceeding, the full bench of the federal court ruled in her favour: the stated duty should not be imposed on the minister. While the outcome was unanimous, the three judges had separate reasoning.

One judge saw climate change as a matter for government, not the courts, to address, saying the duty would be an issue “involving questions of policy (scientific, economic, social, industrial and political) […] unsuitable for the Judicial branch to resolve”.

Another said there was insufficient “closeness” and “directness” between the minister’s power to approve the coal mine and the effect this would have on the children. But he left open the possibility of a future claim if any of the children in the class action suffered damage.

The third judge had three main reasons. First, the EPBC Act doesn’t create a duty-of-care relationship between the minister and children. Second, establishing a standard of care isn’t feasible as it would result in “incoherence” between the duty and the minister’s functions. Third, it’s not currently foreseeable that approving the coal mine extension would cause the children personal injury, as the law is understood.

The Good News: Climate Science Remains Undisputed

In the original case, the judge made landmark rulings about the dangers of climate change, marking a significant moment in Australian climate litigation.

He found one million of today’s Australian children are expected to be hospitalised due to heat stress, they’ll experience substantial economic loss, and when they grow up the Great Barrier Reef and most eucalypt forests won’t exist.

According to the judge, this harm was “reasonably foreseeable”. This is important from a legal point of view, as courts have previously considered climate change to be speculative, and a future problem.

As part of her appeal, Sussan Ley argued that these findings, based on presented evidence, were incorrect and went beyond what was submitted to the court. Today, these arguments were unanimously rejected.

The federal court found all the minister’s criticisms on the evidence of climate change were unfounded and all of the primary judge’s findings were appropriate to be made. As Chief Justice Allsop concluded:

[B]y and large, the nature of the risks and the dangers from global warming, including the possible catastrophe that may engulf the world and humanity was not in dispute.

But while this reaffirms acceptance that climate science is unequivocal, it does nothing to prevent mounting climate change harms, most recently made clear by the devastating floods across NSW and Queensland.

Indeed, it only turns this responsibility back to the current federal government, which has policies increasingly at odds with what the science and concerned citizens say is needed.

Bucking The Trend

This was a test case in Australian law, as it explored a novel legal argument. Its failure will likely put a dampener on innovative climate litigation in Australia.

Today’s judgment asserts that the courts are limited in what they can do to address climate change. It goes against the trend of successful climate change court rulings overseas, and the widespread mobilisation across community groups, business and local governments for action.

Just last year, for example, we saw a court in The Hague order oil and gas giant Shell to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 45% by 2030, relative to 2019 levels, and a German court ruling that the government’s climate goals were not strong enough.

Today’s federal court finding that dealing with coal mine emissions is for governments alone seemingly reimposes barriers to climate litigation in Australia, carefully dismantled by the previous two decades of climate change cases.

We’ve seen a number of landmark climate cases in Australia. This includes the Rocky Hill verdict where a judge rejected a new coal mine on climate grounds, and the Bushfire Survivors case where the court found the NSW government had a legal obligation to take meaningful action on climate change.

These brought the glimmer of hope that where the federal government fails to act, the courts will step in. Today’s ruling suggests this is no longer the case.

In the lead up to the Australian federal election, the appeal outcome emphasises the importance of changing government policy if we’re going to get better outcomes on climate change in this country. Climate change certainly will not wait – the fight for a safe climate future continues.![]()

Jacqueline Peel, Director, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne and Rebekkah Markey-Towler, Research fellow, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

After the floods, the distressing but necessary case for managed retreat

Antonia Settle, The University of MelbourneFrom Brisbane to Sydney, many thousands of Australians have been reliving a devastating experience they hoped – in 2021, 2020, 2017, 2015, 2013, 2012 or 2010/11 – would never happen to them again.

For some suburbs built on the flood plains of the Nepean River in western Sydney, for example, these floods are their third in two years.

Flooding is a part of life in parts of Australia. But as climate change intensifies the frequency and severity of floods, fires and other disasters, and recovery costs soar, two big questions arise.

As a society, should we be setting up individuals and families for ruin by allowing them to build back in areas where they can’t afford insurance? And is it fair for taxpayers to carry the huge burden of paying for future rescue and relief costs?

Considering ‘Managed Retreat’

Doing something about escalating disaster risks require multiple responses. One is making insurance as cheap as possible. Another is investing in mitigation infrastructure, such as flood levees. Yet another is about making buildings more disaster-resistant.

The most controversial response is the policy of “managed retreat” – abandoning buildings in high-risk areas.

In Australia this policy has been mostly discussed as something to consider some time in the future, and mostly for coastal communities, for homes that can’t be saved from rising sea levels and storm surges.

It’s a sensitive subject because it uproots families, potentially hollows outs communities and also affects house prices – an unsettling prospect when economic security is tied to home ownership.

But managed retreat may also be better than the chaotic consequences of letting the market alone try to work out the risks to individuals and communities.

Grand Forks: A Case Study

The strategy is already being implemented in parts of western Europe and North America. An example from Canada is the town of Grand Forks, a community of about 4,000 people 300 kilometres east of Vancouver.

The town is located where two rivers meet. In May 2018 it experienced its worst flooding in seven decades, after days of extreme rain attributed to higher than normal winter snowfall melting quickly in hotter spring temperatures. Deforestation has been blamed for exacerbating the flood.

The flood damaged about 500 buildings in Grand Forks, with lowest-income neighbourhoods in low-lying areas the worst-affected.

In the aftermath the local council received C$53 million from the federal and provincial governments for flood mitigation. This included work to reinforce river banks and build dikes. About a quarter of the money was allocated to acquire about 80 homes in the most flood-prone areas.

The decision to demolish these homes – about 5% of the town’s housing – and return the area to flood plain has been contentious.

Some residents simply didn’t want to sell. Adding to the pain was owners being paid the post-flood market value of their homes (saving the council about C$6 million). There were also long delays, with residents stuck in limbo for more than year while authorities finalised transactions.

A Sensitive Subject

Grand Forks shares similarities to Lismore, the epicentre of the disaster affecting northern NSW and southern Queensland.

Lismore is also built on a flood plain where two rivers meet. Floods are a regular occurrence, with the last major disaster being in 2017. Insuring properties in town’s most flood-prone areas was already unaffordable for some. In the future it may be impossible.

Last week NSW premier Dominic Perrottet said about 2,000 of the town’s 19,000 homes would need to be demolished and rebuilt, a statement the local council general manager downplayed, saying in the majority of cases “people will not have to worry”.

For a community traumatised by loss, overwhelmed by the recovery effort and angry at the perceived tardiness of government relief efforts, discussing any form of managed retreat is naturally emotionally charged.

But there’s never an ideal time to talk about bulldozing homes and relocating households.

Uprooting Communities

Managed retreat has far-reaching financial ramifications. As in Grand Forks, the first questions are what homes are targeted, who pays, and how much.

Some residents may be grateful to sell up and move to safe ground. Others may not, disputing the valuation offered or being reluctant to leave at any price.

Managed retreat policies also affect many more than just those whose homes are being acquired. Demolishing a block or suburb can push down values in neighbouring areas, due to fears these homes may be next. Those households are also customers for local businesses. Their loss can potentially send a town economy into decline.

No wonder many people want no mention of managed retreat in their communities.

Pricing In Climate Change

Markets, however, are already starting to “price in” rising climate risks.

Insurance premiums are going up. The value of homes in high-risk areas will drop as buyers look elsewhere, particularly in the wake of increasingly frequent disasters.

The economic fallout, both for individual households and local communities, could be disastrous.

The Reserve Bank of Australia warned in September 2021 that climate-related disasters could rapidly drive house prices down, particularly in areas that have previously experienced rapid house price growth.

These disasters are also amplifying inequality, with poorer households more likely to live in high-risk locations and also to be uninsured.

In Lismore, for example, more than 80% of households flooded in 2017 were in the lowest 20% of incomes. These trends will intensify as growing climate risks translate into higher insurance premiums and lower house prices.

A deliberate strategy of managed retreat, though distressing and difficult, can help to minimise the upheaval in housing markets as climate risks become increasingly apparent.

We can do better than leaving the most socially and economically vulnerable households to live in high-risk areas, while those with enough money can move away to better, safer futures. Managed retreat can play a key role.![]()

Antonia Settle, Academic (McKenzie Postdoctoral Research Fellow), The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Permafrost Peatlands Approaching Tipping Point

March 14, 2022

Researchers warn that permafrost peatlands in Europe and Western Siberia are much closer to a climatic tipping point than previous believed. The frozen peatlands in these areas store up to 39 billion tons of carbon -- the equivalent to twice that stored in the whole of European forests.

Researchers warn that permafrost peatlands in Europe and Western Siberia are much closer to a climatic tipping point than previous believed. The frozen peatlands in these areas store up to 39 billion tons of carbon -- the equivalent to twice that stored in the whole of European forests.

A new study, led by the University of Leeds, used the latest generation of climate models to examine possible future climates of these regions and the likely impact on their permafrost peatlands.

The projections indicate that even with the strongest efforts to reduce global carbon emissions, and therefore limit global warming, by 2040 the climates of Northern Europe will no longer be cold and dry enough to sustain peat permafrost.

However, strong action to reduce emissions could help preserve suitable climates for permafrost peatlands in northern parts of Western Siberia, a landscape containing 13.9 billion tonnes of peat carbon.

The study, published in Nature Climate Change, emphasises the importance of socio-economic policies aimed at reducing emissions and mitigating climate change and their role in determining the rate and extent of permafrost peatland thaw.

Study lead author, Richard Fewster is a PhD researcher in the School of Geography at Leeds. He said: "We examined a range of future emission trajectories. This included strong climate-change mitigation scenario, which would see large-scale efforts to curb emissions across sectors, to no-mitigations scenarios and worse-case scenarios.

"Our modelling shows that these fragile ecosystems are on a precipice and even moderate mitigation leads to the widespread loss of suitable climates for peat permafrost by the end of the century.

"But that doesn't mean we should throw in the towel. The rate and extent to which suitable climate are lost could be limited, and even partially reversed, by strong climate-change mitigation policies."

Study co-author Dr Paul Morris, Associate Professor of Biogeoscience at Leeds, Said: "Huge stocks of peat carbon have been protected for millennia by frozen conditions but once those conditions become unsuitable all that stored carbon can be lost very quickly.

"The magnitude of twenty-first century climate change is likely to overwhelm any protection the insulating properties of peat soils could provide."

The large quantities of carbon stored in peatland permafrost soils are particularly threatened by rapid twenty-first-century climate change. When permafrost thaws the organic matter starts to decompose, releasing greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, which increase global temperatures and potentially accelerate global climate change.

Study co-author Dr Ruza Ivanovic, Associate Professor in Climatology at Leeds said: "Peatland permafrost responds differently to changing climates than mineral-soil permafrost due to the insulating properties of organic soils, but peatlands remain poorly represented in Earth system models.

"It is vitally important these ecosystems are understood and accounted for when considering the impact of climate change on the planet."

Study co-author Dr Chris Smith, from the School of Earth and Environment, said: "More work is needed to further understanding of these fragile ecosystems.

"Remote sensing and field campaigns can help improve maps of modern peat permafrost distribution in regions where observation data is lacking. This would enable future modelling studies to make hemispheric-scale projections."

Fewster, R.E., Morris, P.J., Ivanovic, R.F. et al. Imminent loss of climate space for permafrost peatlands in Europe and Western Siberia. Nat. Clim. Chang., 2022 DOI: 10.1038/s41558-022-01296-7

Restoring Tropical Peatlands Supports Bird Diversity And Does Not Affect Livelihoods Of Oil Palm Farmers

March 15, 2022

A new study has found that oil palm can be farmed more sustainably on peatlands by re-wetting the land -- conserving both biodiversity and livelihoods.

The research looked at tropical peatland restoration efforts in Indonesia, and investigates whether managing water levels on drained peatlands affects the viability of oil palm grown by farmers, as well as bird species diversity.

Tropical peatlands in Southeast Asia contain large below-ground carbon stocks, while peat swamp forests contain unique and threatened biodiversity. However, when peat forests are cleared and peatlands are drained for cultivation, it results in carbon emissions, biodiversity losses, and land subsidence. Drained peatlands are also prone to fire, which in the past has led to toxic haze, deaths, and health and economic damage.

Indonesia is estimated to contain 47% of global tropical peatlands, chiefly on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. Forests covered 76% of Sumatra's peatland in 1990, but by 2015, 66% was covered by smallholder agriculture or industrial plantations, primarily of oil palm.

Drainage is considered necessary to maintain oil palm yields because prolonged flooding reduces fruit production. However, peatland drainage means Sumatra is now a hotspot for peat fires.

The study found that re-wetting should have net positive effects for smallholders by reducing the risk of fires that can damage property, plantations, and human health, without having a detectable effect on oil palm yields.

A farmer collaborating on the project, Mr Udin, said: "Even if the farm flooded for a few days, the yield is not decreased."

The study, published in Journal of Applied Ecology, was led by the University of York and ZSL (Zoological Society of London), as well as colleagues from the Indonesian Center for Agricultural Land Resources Research and Development and Jambi University in Indonesia.

The study -- which focussed on Jambi province in Sumatra, Indonesia -- studied water table depths on oil palm farms managed by smallholder farmers, to assess impacts on oil palm yields and on bird species living on the farms.

Peat is a carbon-rich soil formed from partly decomposed vegetation in permanently wet conditions. Tropical peatlands are critically important for storing carbon in the ground, and also provide habitats for tropical wildlife, including tigers, gibbons, birds, and specially adapted plants, fish, and microbes.

Cultivating peatlands also supports people's livelihoods, such as small-scale farmers growing oil palm.

Peatland needs to be drained using canals to make the land suitable for farming, which can impact habitats and cause the peat to emit carbon. The dry land can also become prone to fire -- leading to increased carbon emissions, toxic haze, and a threat to the lives of both people and wildlife.

Restoring drained peatland involves a process of "rewetting" where canals draining water away are blocked or filled in, which makes it less likely that the peatlands will catch fire.

Ninety bird species were recorded in an area of peat swamp forest neighbouring the farms, but only 48 species were found in oil palm. The species living in the forest were also different, including 35 conservation-priority species, and tended to be larger-bodied species that play different ecological roles, meaning forest protection is critical for conserving biodiversity.

Reducing fire risk in the neighbouring oil palm farms by re-wetting should reduce the risk of forest burning and of further habitat loss for wildlife, while still supporting farmer production.

Dr. Eleanor Warren-Thomas, now at Bangor University and IIASA, and who led the study while a researcher at York, said: "Indonesia has been very successful in reducing deforestation and considerable effort has gone into peat restoration to avoid fires.

"But one of the big challenges is the trade-off between livelihoods of owners of small farms and ensuring biodiversity in these areas.

"What this new study shows is that retaining more water in oil palm farms to reduce fire risk seems to have no effect on yields, which is good news for farmers. In contrast to the concerns of some plantations, retaining water levels close to the surface (40cm or less) still enables oil palm cultivation."

Eleanor said: "By also surveying bird species in one of the remaining peat swamp forest areas nearby, we also showed the huge importance of protecting the remaining forest for bird conservation -- avoiding fires in the landscape is key to doing this.

"These unique birds can also act as seed dispersers -- crucial if in the longer-term forest restoration becomes an option.

"One of the conclusions of the study is that larger-scale industrial farming organisations would be able to help further studies in this area, if they are able to publish their data and share their knowledge to inform sustainable oil palm production strategies."

Eleanor Warren‐Thomas, Fahmuddin Agus, Panji Gusti Akbar, Merry Crowson, Keith C. Hamer, Bambang Hariyadi, Jenny A. Hodgson, Winda D. Kartika, Mailys Lopes, Jennifer M. Lucey, Dedy Mustaqim, Nathalie Pettorelli, Asmadi Saad, Widia Sari, Gita Sukma, Lindsay C. Stringer, Caroline Ward, Jane K. Hill. No evidence for trade‐offs between bird diversity, yield and water table depth on oil palm smallholdings: Implications for tropical peatland landscape restoration. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2022; DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.14135

Twenty-First Century Hydroclimate: A Continually Changing Baseline, With More Frequent Extremes

March 14, 2022

Maps of the American West have featured ever darker shades of red over the past two decades. The colours illustrate the unprecedented drought blighting the region. In some areas, conditions have blown past severe and extreme drought into exceptional drought. But rather than add more superlatives to our descriptions, one group of scientists believes it's time to reconsider the very definition of drought.

Researchers from half a dozen universities investigated what the future might hold in terms of rainfall and soil moisture, two measurements of drought. The team, led by UC Santa Barbara's Samantha Stevenson, found that many regions of the world will enter permanent dry or wet conditions in the coming decades, under modern definitions. The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveal the importance of rethinking how we classify these events as well as how we respond to them.

"Essentially, we need to stop thinking about returning to normal as a thing that is possible," said Stevenson, an assistant professor in the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. This idea affects both how we define drought and pluvial (abnormally wet) events and how we adapt to a changing environment.

A drought is when conditions are drier than expected. But this concept becomes vague when the baseline itself is in flux. Stevenson suggests that, for some applications, it's more productive to frame drought relative to this changing background state, rather than a region's historical range of water availability.

To predict future precipitation and soil moisture levels, Stevenson and her colleagues turned to a new collection of climate models from different research institutions. Researchers had run each model many times with slightly different initial conditions, in what scientists call an "ensemble." Since the climate is an inherently chaotic system, researchers use ensembles to account for some of this unpredictability.