Inbox and Environment News: Issue 532

March 27 - April 2, 2022: Issue 532

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Update On Wakehurst Parkway Wildlife

Wildlife are on the move and can be unpredictable. Please be careful driving in the area around Oxford Falls Road and Dreadnought Road.

Sadly one Swamp Wallaby has been hit and killed.

This death has been added to: https://wildlifemapping.org/

Happy to report that one echidna has been moved off the road to a safer location.

Find out more at: https://www.narrabeenlagoon.org.au/

Photo credit Margaret G Woods

Habitat Being Destroyed For Profit: Wildlife Leaping From Trees Being Cleared Under Them - Video

This is happening in Noosa at present - this is glossy cockatoo habitat and food trees and this is occurring during their breeding season.

At 1:39 you can see a mother ringtail leap from the tree that's being ripped out from under her to the machine. The wildlife 'spotters' were MIA or behind the machine - one later found the ringtail and one of the babies that was left, still clinging to mum's back.

It is ILLEGAL to do this in QLD; to hurt or endanger wildlife.

Furthermore, the Glossy Black-Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus lathami, are one of the more threatened species of cockatoo in Australia and are listed as vulnerable under QLD and NSW legislation.

Those sharing and bearing witness to this have asked Pittwater online to share a petition at: https://www.change.org/p/uniting-church-help-spencer-to-stop-the-church-to-save-our-glossies

Join The Fight Against Foxes On The Northern Beaches

Northern Beaches residents are invited to hear how they can join the fight against foxes in their area at a free online event on April 5th.

A joint initiative between NSW DPI, Greater Sydney Local Land Services and Northern Beaches Council, the webinar will feature a range of expert speakers and local information.

Greater Sydney LLS Senior Biosecurity officer Gareth Cleal said the event would give residents advice and information based on real life scenarios and experiences.

“There is no doubt foxes are becoming more and more prominent in urban areas of Sydney and the Northern Beaches is not immune,” he said.

“We regularly receive reports of fox sightings in the area and there are simple steps residents can take to help reduce their impact.”

Mr Cleal said foxes were attracted by food scraps and domestic pets like chickens and rabbits.

“Residents can help by ensuring compost bins are kept secure and properly closed, keeping household rubbish in a secure location, feeding domestic pets inside, ensuring food is not left outside and wherever possible, keeping pets inside overnight,” he said.

“Keeping yards in check by tidying gardens, weeding to reduce fox harbour and housing backyard chickens in secure, fox-proof enclosures rather than free ranging will also help.”

The webinar will feature presentations from local pest animal experts, and cover topics including:

- How to minimise impacts to your pets and native wildlife

- Recording/reporting foxes into FoxScan - https://www.foxscan.org.au/

- An update on local programs

The webinar will be held on Tuesday, 5 April 2022 from 7pm. RSVP via https://bit.ly/3qq5aIK or email feralscan@feralscan.org.au.

Synthetic Fields: Independent Review Report Due Mid Year

The Independent review into the design, use and impacts of synthetic turf in public open spaces by the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer has tabled its initial report in February 2022, with the final report due mid-year.

Pittwater Online News has been conducting research into the environmental impacts and feasibility of the planned introduction of more of these fields into our area, along with speaking to resident Julia Walsh over several months. Julia first brought the fragmentation of one of these fields to our attention in August 2021.

Julia has sent in a video update on one of the grassed areas for which synthetic fields is proposed, alongside Manly Creek, taken after the recent rains.

The February 2022 interim report may be accessed at: www.chiefscientist.nsw.gov.au/independent-reports/synthetic-turf-in-public-spaces

Melwood Oval at Forestville has had a synthetic field installed and during heavy rains Julia witnessed "pulverised rubber" washing off and down pathways.

"It's not just the plastics that you can see, it's the plastics you can't see," Julia stated in 2021.

"The biggest concern is that we're putting these fields in water catchment zones."

Melwood Oval - synthetic field fragmenting. Images: supplied.

Millers Reserve at Manly Vale is among seven greenspaces across the LGA that will be "upgraded" to a synthetic surface, with a $203,000 tender already awarded for the works. Millers Reserve is located beside Manly Creek, which flows to Manly Dam, and Ms Walsh is concerned about run-off there.

At their March 2021 council meeting, councillors Stuart Sprott and Roslyn Harrison called for council to halt approvals of synthetic fields pending a NSW Government investigation into sustainable alternatives, which was called for by Planning Minister Rob Stokes. Their response was not supported by other councillors.

Seven new synthetic ovals are planned for our area, including one being touted for Careel Bay, which floods during rain events with refuse carried into the wetlands alongside these. Careel Bay is a Wildlife Preservation Area (WPA) due to its importance to resident wildlife as well as migratory birds, many of which are endangered species.

Mitchelton football field No 2 in Everton Park Brisbane after rains there - February 28, 2022. The rest of their fields are grassed areas and these were quickly restored/cleaned to allow commencement of their Season in March. From the Mitchelton football Club Facebook page.

Mitchelton football field No 2 in Brisbane after rains there - February 28, 2022. From the Mitchelton football Club Facebook page.

Mitchelton football club - Fields 1, 3-4 in Brisbane after rains there, and perimiters - February 28, 2022. From the Mitchelton football Club Facebook page.

Millers Reserve submerged by water after the heavy rains, March 2022

Millers Reserve submerged by water after the heavy rains, March 2022

Millers Reserve submerged by water after the heavy rains, March 2022

More on this once the final report is released. Julia's latest video runs below.

Hawk Moth Caterpillars

These are Hawk Moth caterpillars on food plant Cayratia. Young ones camouflage by being green, older ones change to browns. Theretra indistincta has bright green spots on its spiracles where it takes in oxygen along its sides. Theretra latreillii’s spiracles just look like dots. Cayratia aka Native Grape grows madly in this weather but watch out for these lovely grubs before you clear it too energetically.

There are an estimated 850 species of Hawk Moth world wide, with the highest diversity occurring in wet tropical regions. Australia has 65 species and in the Sydney region 21 species are known.

The larvae (caterpillars) are large and often colourful, usually with a long horn near the end of the body. Many have lateral stripes and/or large eye spots on the thorax and abdominal segments. The colour patterns help to camouflage the caterpillars and the large eye spots may assist in warding off predators. The caterpillars don't bite or sting but may regurgitate green fluid (from a previous meal) if annoyed.

Adult Hawk Moths are medium to large in size. They are streamlined, robust flyers with an obvious head and large eyes. The forewings are long and narrow and much larger than the hind wings. When the moth is at rest the wings are tented over the body. The abdomen is large and has a tapered cigar-shape appearance. Hawk moths often have a long proboscis, coiled when not in use, which is used in nectar feeding. The adult moth hovers in front of flowers and inserts its proboscis to drink the nectar.

Theretra indistincta taken at Cooktown, QLD. Photo: Didier Descouens

Theretra latreillii, the pale brown hawk moth, taken at Mission Beach, QLD. Photo: Donald Hobern.

Theretra latreillii, the pale brown hawk moth, is a moth of the family Sphingidae described by William Sharp Macleay in 1826. Mr. Macleay emigrated to Australia in 1839, living briefly at the Colonial Secretary's House in Macquarie Place with his parents before moving in September of that year to the family's still unfinished Elizabeth Bay House. Mr. Macleay was interested in the natural history of Australia, the marine fauna around Port Jackson in particular. Later, he collected a large number of Australian insects; on his death, these were bequeathed to his cousin William John Macleay, whose interest in natural history he encouraged and who in 1888 transferred them to the Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, for which act he was knighted. He also encouraged the scientific interests of his brother George Macleay.

Common moths found in suburban gardens include the Impatiens Hawk Moth (Theretra oldenlandiae), Pale Brown Hawk Moth (T. latreilla), Bee Hawk Moth (Cephonodes kingii) and the Privet Hawk Moth (Psilogramma menephron). Adults are usually most active at dusk or at night but some, such as Bee Hawks, fly during the day.

The Sphingidae are a family of moths (Lepidoptera) called sphinx moths, also colloquially known as hawk moths, with many of their caterpillars known as “hornworms”; it includes about 1,450 species. It is best represented in the tropics, but species are found in every region. They are moderate to large in size and are distinguished among moths for their agile and sustained flying ability, similar enough to that of hummingbirds as to be reliably mistaken for them. Their narrow wings and streamlined abdomens are adaptations for rapid flight.

The family was named by French zoologist Pierre André Latreille in 1802. Sphingidae are named for their hovering, swift flight patterns - from New Latin, from Sphing-, Sphinx, type genus + -idae, New Latin, from Latin, from Greek -idai, suffix indicating offspring. Theretra is a genus of moths in the family Sphingidae. The genus was established by Jacob Hübner in 1819.

Cayratia is from Latin Cayratia, from the Annamese vernacular name, cay-rat, a vine + ia, forming nouns adopted unchanged from Latin or Greek (such as militia ), and modern Latin terms (such as utopia) forming names of genera and higher groups ("dahlia") and forming names of countries (Australia).The genus Cayratia consists of species of vine plants, typical of the tribe Cayratieae.

Some hawk moths, such as the hummingbird hawk-moth or the white-lined sphinx, hover in mid-air while they feed on nectar from flowers, so are sometimes mistaken for hummingbirds. This hovering capability is only known to have evolved four times in nectar feeders: in hummingbirds, certain bats, hoverflies, and these sphingids (an example of convergent evolution). Sphingids have been much studied for their flying ability, especially their ability to move rapidly from side to side while hovering, called "swing-hovering" or "side-slipping". This is thought to have evolved to deal with ambush predators that lie in wait in flowers.

Sphingids are some of the faster flying insects; some are capable of flying at over 5.3 m/s (19 km/h). They have wingspans from 4 cm (1+1⁄2 in) to over 10 cm (4 in).

_in_flight.jpg?timestamp=1648171091057)

The hummingbird hawk-moth (Macroglossum stellatarum) in flight, Yastrebets, Rila Mountains, Bulgaria. Photo: Charles J. Sharp photography, U.K.

Photos and information courtesy Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) and Australian Museum

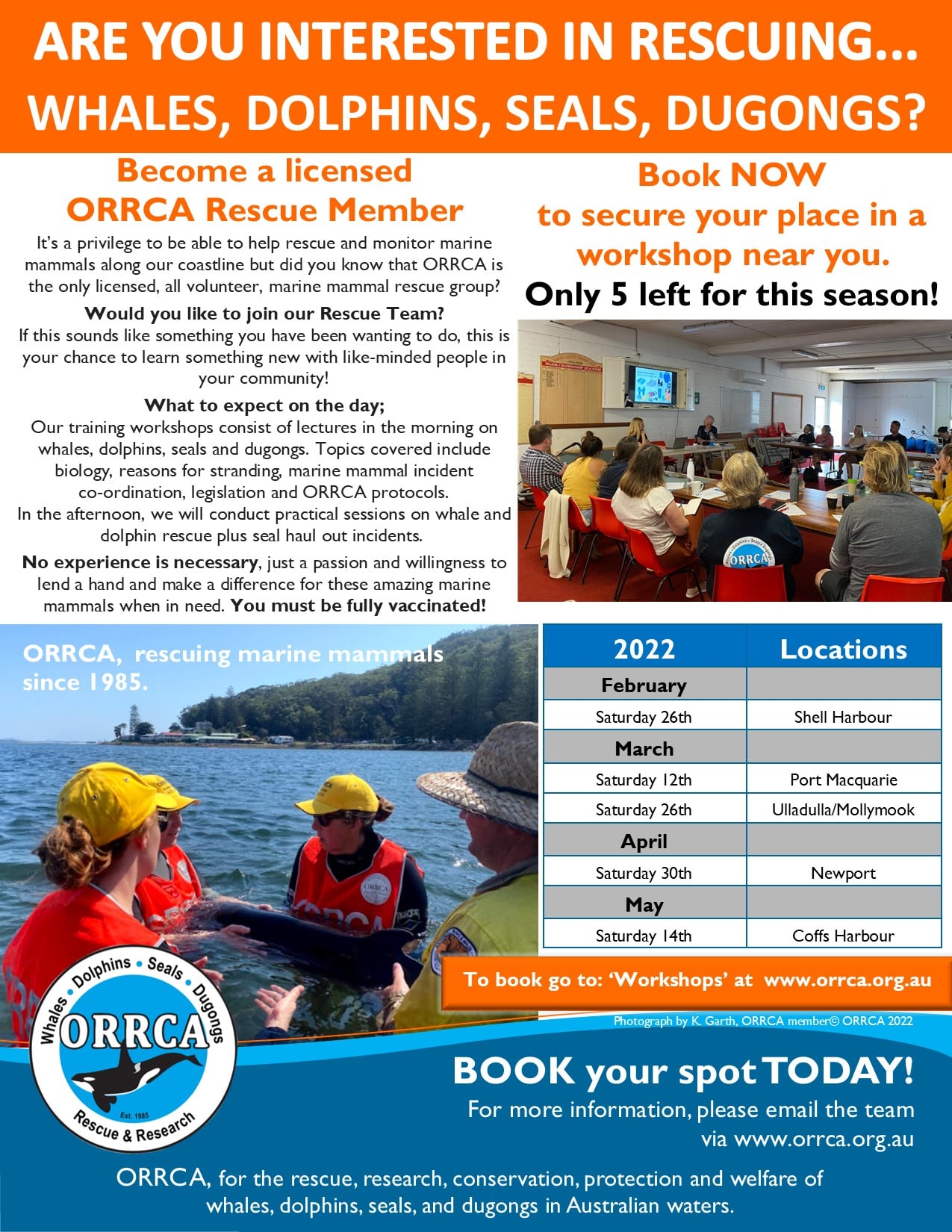

Australian Government Delists The Majestic Humpback Whale

On February 17th 2022 Federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley announced that Australia has delisted the Megaptera novaeangliae (Humpback Whale) from the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act’s Endangered Species listing.

Ms Ley cited numbers of around 40 thousand humpbacks mean it is no longer endangered.

This decision, Minister Ley outlines, is based on scientific research however ORRCA states it is shocked by this statement as are many other groups who have worked for the last 3 and a half decades to protect and save this species.

''When ORRCA was founded back in 1985, there were few Humpbacks observed passing our coasts. Thankfully, with the IWC enforcing a moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986, we have watched this species slowly recover year on year. This is one of humans’ conservation success stories, one that Australia can also be proud of for its role.'' a statement from the group says.

''ORRCA documented its strong conservation view in its submission to the Minister back in March of 2021. In general, there hasn’t been enough research done to support removing this whale from the Endangered Species list. As an organisation who has protected and rescued marine mammals for over well over three decades, we have been a part of and have seen the Humpback success story unfold. However, how stable are their numbers?''

''We believe that a reasonable concern for the whales’ future can be underpinned by science and that the process of their assessment should take this fully into account. Whilst we appreciate that the Humpback will be given protection in Australian waters under the EPBC Act, this isn’t enough for such an iconic species. Even under this Act there will be issues with responding to breaches, enforcing the Act and fining or reprimanding those who wilfully and continually break the law.'' an ORRCA spokesperson has stated

''Whaling nations such as Japan have previously expressed an interest in taking Humpbacks in the Southern Ocean, for scientific research, and has certainly taken many other species over the years. They could see this as a new opportunity and venture down into the Southern Ocean once again, exploiting these still vulnerable whales.

''While the threat of whaling is not an immediate issue, there are still many other issues that need to be considered. For example, the warming of the ocean impacts the routes these whales travel when migrating up and down our countries coastlines making monitoring and research difficult. The Humpback is faced with increasing human interaction, ship strike, pollution, a plastic and micro plastic epidemic, entanglement in fishing gear and shark nets, and then there is the increase in ocean noise or acoustic pollution which effects many whale species. Unless the Government gets serious about addressing the threats to marine mammals and marine life in general, our oceans will be faced with unrepairable and long-term impacts.

''Maintaining Humpback populations in sustainable balance is critical to maintaining biodiversity in the region, and as part of the marine ecology provides high economic and cultural value to the Australian economy through tourism activity.

''From an ORRCA perspective, the protection status, needs to be fully evaluated from not only a scientific perspective, but also an economic, cultural and community perspective to ensure that objective fact and decision making occurs for a species still recovering from critical threat, and in a rapidly changing environment.

''Australia has the highest rate of species facing extinction and following the black summer bush fires, we must do everything we can to stop any more species being lost. Without these important protections, the Humpback will potentially end up right back on the Endangered species list in the future!

''As long-lived, slow-breeding animals that live in cooperative family groups, Humpback populations are exceptionally vulnerable to depletion and will always be slow to recover whatever causes this depletion and this is one key reason why they continue to need the highest level of protection.

''ORRCA believes that the delisting of the Humpback at this time is premature. Our view would be to invest in more solid research of the species, climate change, and our oceans viability to sustain the Humpback before there was any revision of its status.''

The Sydney Edible Garden Trail 2022: March 26-27 - Local Sites

Peek inside some of Sydney’s private backyard fruit and veggie gardens this March, and discover their secrets to living sustainably.

Whether you’re a new or experienced gardener, the best way to learn how to grow juicy fruit and vegetables in your own backyard is to talk to a gardener who’s already doing it. Sydneysiders will have the opportunity to do this over the weekend of 26 & 27 March 2022 when over 50 suburban, community and school gardens will open for the Sydney Edible Garden Trail (SEGT).

Matthew Elphick, one of the garden hosts who participated last year, was inspired to reopen his garden again this year. He’s looking forward to the 2022 trail, saying “It was so wonderful to open last year and have people come through the garden and see how excited they are. You get to see the garden through their eyes, things that you don’t think much about, they find amazing. It’s such a great opportunity to meet like-minded people.”

With the motto “We don’t just grow food, we grow sustainable communities”, SEGT arranges for gardens to open to the public and allocates profits from ticket sales towards building stronger community and school gardens through a grants program with 8 gardens provided with grants in 2021.

This year the trail is extending to the wider Sydney metropolitan area with many new gardens included. Tickets are now on sale at https://sydneyediblegardentrail.com/tickets/

Those in our area listed so far for the 2022 edition of SEGT include:

Newport Community Garden

We are a membership based Community Garden of local neighbours who get together to learn about organic gardening, sustainable living, socialise and have a good time!

NCG has been running for over 8 years and from humble beginnings is now a vibrant, sustainable and inviting space with over 35 garden beds, compost bays, worms farms and native bee hive, green house, water tanks and garden shed.

We grow organic fruits, vegetable and herbs. We cultivate our compost, make our own natural pesticides and grow from seeds saved from our seasonal harvest.

It’s not just hard work, we are very social too and always finish the day with a cuppa and chat with local community members.

In November 2021 Newport Community Garden were announced as one of fifty SEGT GRANT RECIPIENTS 2021.

The grant will be used to attract local birdlife and bees by planting some native bush food plants and others native plants.

Newport Community Garden Profile of the Week

“The glory of gardening: hands in the dirt, head in the sun, heart with nature. To nurture a garden is to feed not just on the body, but the soul.” - Alfred Austin

Great reuse of an old boat in the Newport Community Garden

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: from Esther Andrews.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Asparagus Fern Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Tracking Paddles Of Platypuses In The Blue Mountains

March 23, 2022

Platypus DNA has been detected at 29 sites in the Blue Mountains due to a ground-breaking detection technique funded by the Australian and NSW Governments. Federal Minister for the Environment Sussan Ley has stated this week the use of environmental DNA tracking was vital in supporting the recovery of the elusive platypus after the Black Summer bushfires.

“If we want to best support the recovery of species like the platypus, we need coordinated action on the ground that includes monitoring and research across the entire the range of the animal,” Minister Ley said.

“Using cutting-edge eDNA technology will help us understand more about the platypus – simply locating this iconic native species will help remove one of biggest obstacles we have faced in supporting its recovery after the fires.

“It may be improving water quality by fixing soil erosion or removing sediment and debris from rivers to help them feed, but if we know where the platypus live, we can deliver the right support to the right location.”

The NSW Minister for Environment James Griffin said that until recently, tracking teams would need to spend hours beside waterways waiting for the elusive mammals to appear.

“What we’re doing now is using high-tech DNA science to build a snapshot of how platypuses are faring, particularly after the recent devastating bushfires in the Blue Mountains,” Mr Griffin said.

“So far, we’ve discovered platypus DNA at 29 of the 67 National Parks sites sampled, including in some waterways we didn’t previously know they lived in.”

As they swim, platypuses shed small traces of skin cells or body secretion into waterways, which can be detected via environmental DNA testing of water samples.

More sampling will take place in Autumn, when breeding females emerge from their burrows with their puggles and take to the water.

“These mammals can face threats of habitat loss, predation by feral animals and they can drown if they become tangled in fishing lines or yabby traps,” Mr Griffin said.

“I want to make sure we’re doing all we can to protect the species, which is why this research is so important. It’s helping us ensure precious platypus habitat is being conserved and protected now and into the future.”

So far, platypuses have been detected in the Blue Mountains, Wollemi, Kanangra-Boyd, Nattai, Mount Royal, Turon, Marrangaroo and Bangadilly National Parks and Upper Nepean State Conservation Area.

The project is being delivered by the NSW Government, supported by $23,000 from the Australian Government’s Bushfire Recovery for Wildlife and their Habitats fund.

Photo: NSW NP&WS/OEH

Photo: NSW NP&WS/OEH

Photo: NSW NP&WS/OEH

Summer Soaking Brings Superb Results For Endangered Orchid

March 23, 2022

The endangered superb midge orchid has continued its streak of record-breaking seasons, with a high number of plants found across the Southern Tablelands this summer, NP&WS reportr

The endangered superb midge orchid has continued its streak of record-breaking seasons, with a high number of plants found across the Southern Tablelands this summer, NP&WS reportr

Saving our Species ecologist Erika Roper said recent summer rains have prompted an explosion of these miniature raspberry-scented orchids in the bush near Nerriga and Braidwood.

'Before the fires there were only a handful of known plants and historical records, but since 2020 we have discovered more than 300 plants spread over 3 sites,' Ms Roper said.

'The number alone is impressive but even more so when you consider just how hard it is to find this plant.

'Like many orchids, midge orchids spend much of the year below ground as a tuber, before putting up a single narrow stem that develops a flower spike.

'The stem looks exactly like a chive, the kind you grow in the veggie garden, so even when you know exactly what you are looking for, it's still tricky surveying for this tiny plant.

'Fortunately, orchid-spotting is my superpower and I've found some emerging stems that are only around 1 centimetre high.

'We're into our third summer of soaking rains and we think that is why we are seeing such a response from this and other threatened and common midge orchid species in the area.

'The fires also reduced many of the threats to this species, such as grazing by herbivores, allowing the orchids to live up to their name and put on a superb show.

'Coloured varying shades of dark pink and purple with fringed 'petals', they are one of the prettiest orchids around, but most people have never seen or even heard of it.

'Last month's surveys also found new plants growing in unburnt areas, including along wombat tracks and roadsides, and we have installed temporary cages to protect these individuals from damage.

'It's just amazing to see these extremely rare and pretty unusual looking plants bouncing back.

'It really reconfirms the extraordinary and resilient biodiversity that can be found in this part of the world,' Ms Roper said.

The Saving Our Species program is investing almost $100,000 into orchid conservation in the Illawarra and surrounding regions. This funding supports ecologists like Erika to commit resources towards threat control, surveying and monitoring, all of which help secure species like the superb midge orchid into the future.

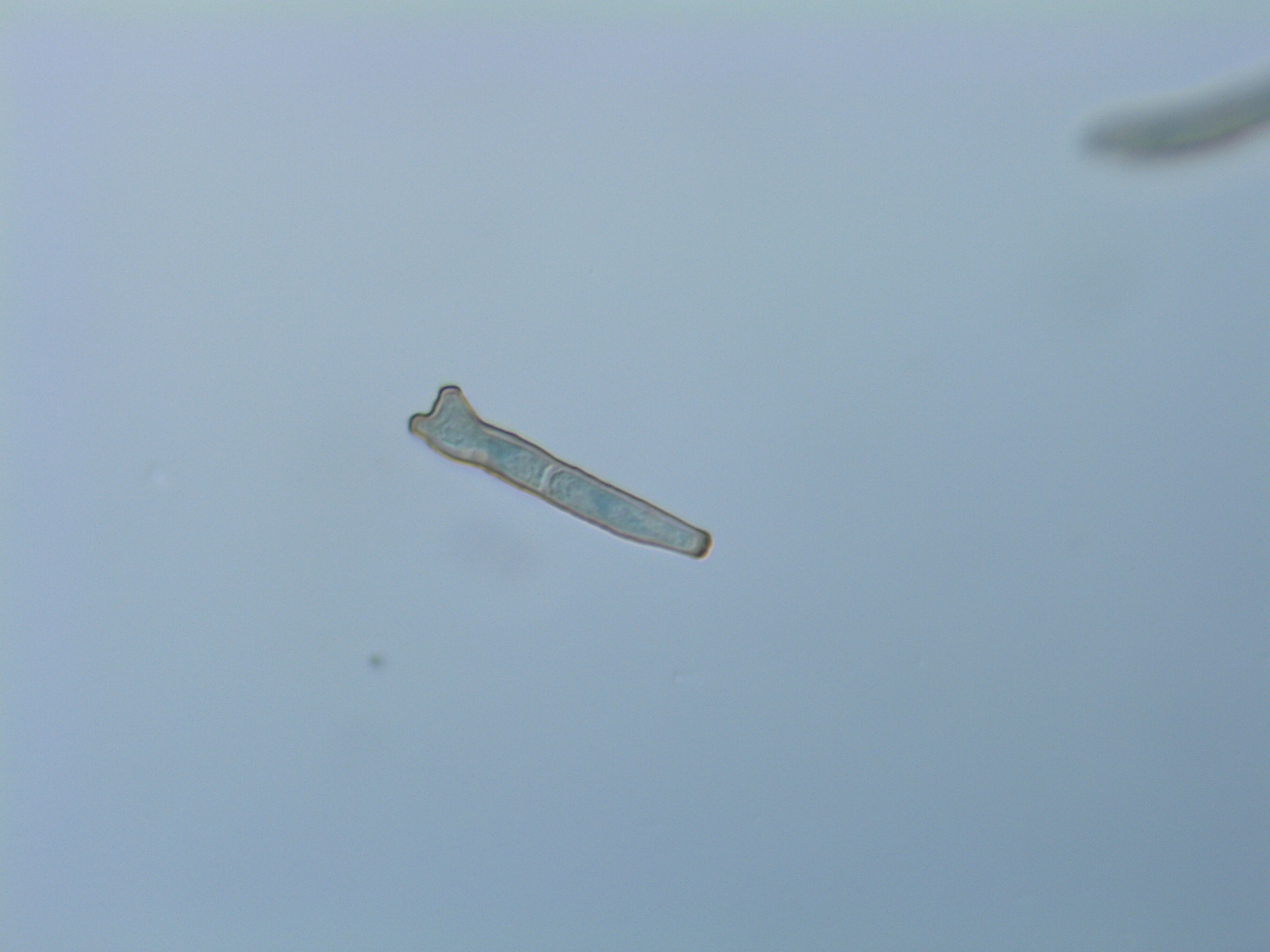

Superb midge orchid (Genoplesium superbum) Photo Credit: E Roper/DPE

NPWS Investigating Ongoing Vandalism At Greenfield Beach

March 24, 2022

Authorities are appealing for information following vandalism at the popular Greenfield Beach Picnic Area in Jervis Bay National Park. Nathan Cattell, Acting Area Manager with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) said that over recent months vandalism at this family-friendly picnic area has hit unprecedented levels, with regular reports of damage and anti-social behaviour.

'We are working with the NSW Police to try to control this behaviour that is stopping others from enjoying the site,' Mr Cattell said.

'Damage to visitor facilities, including destroying the toilet block and sinks not only costs thousands of dollars to repair but also leaves the area out of action while we clean up.

'Broken glass and smashed bottles are also littering the site which makes the area unsafe for people who are having a picnic or stopping off along their bushwalk.

'The time to repair vandalised facilities takes staff away from other critical jobs including maintenance of walking trails, other visitor facilities and conservation work.

'NPWS is working closely with the local Police and both agencies will be stepping up patrols to control this anti-social behaviour and find who is responsible.

'Local residents have been very helpful in providing information as part of this investigation and we ask anyone with information to please come forward.

'This is not a one off. There has been consistent vandalism at the site prompting NPWS to install remotely active CCTV cameras and other measures to curb this behaviour.

'Jervis Bay National Park is world renowned, attracting visitors from overseas and Australia and we want them to enjoy the area's natural beauty and not see broken, vandalised facilities,' Mr Cattell said.

This deliberate damage at Greenfield Beach is a criminal offence, attracting fines of between $500 and $10,000.

People with any information regarding the vandalism are urged to call NPWS at Ulladulla on 02 4454 9500, or Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.

Scientists Find Climate Main Factor Behind Dropping Water Levels At Thirlmere Lakes

March 24, 2022

An extensive research program into fluctuating water levels at Thirlmere Lakes has confirmed that climate variations were largely responsible for the ancient lake system's decline in water levels over the last decade. The 4-year study found no direct links between the drying of Thirlmere Lakes and the nearby coal mine but could not rule out a smaller (relative to climate) impact on water levels from mining.

The Thirlmere Lakes is a group of waterways in Wollondilly, south of Sydney, in the Thirlmere Lakes National Park that includes Lake Gandangarra, Lake Werri Berri, Lake Couridjah, Lake Baraba and Lake Nerrigorang.

The mystery of the drying of the lakes, which are thought to be 15 million years old, has been investigated for nearly a decade.

Dr Peter Scanes, Acting Director of Water, Wetlands and Coasts at the Department of Planning and Environment (DPE), said the research confirmed factors like rainfall and evaporation were responsible for most of the recent drying and water loss at the freshwater lakes.

'The drying has been increased by the recent droughts but our investigations of sediment cores taken from the lakes also found that the lakes have dried before,' Dr Scanes said.

'In fact, there was a major drying period around 12,000-21,000 years ago. The last 120 years of historical records also indicate that the Lakes have dried intermittently.

'Our scientists also looked at the underlying geology of the 5 lakes. Those studies found the lakes are like leaky bathtubs. They fill with water after rain and dry out on the surface from the sun but they can also leak into the groundwater.

'Understanding the dynamics of how the lakes work is important for both scientists and the local community, who have been very interested in what is behind the recent drop in water levels.'

The $1.9 million research program was funded by the NSW Government and included scientists from the department, the University of NSW, the University of Wollongong and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANTSO) with support from the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

The researchers looked at the lake system's sensitivity to external influences, the interaction between surface water and ground water, how water flows into and out of the lakes as well as its sediments and underlying geology.

Dr Scanes said researchers found no direct connection between Thirlmere Lakes and a nearby coal mine.

'Relative to climate, the impact of mining and groundwater extraction would be smaller, given climate factors are responsible for between 83 to 98% of water level fluctuations in recent times,' Dr Scanes explained.

'However mining impacts could not be ruled out as there was not enough data collected prior to mining occurring nearby. We therefore have no yardstick for comparison to conditions before mining took place.'

A 2012 Thirlmere Lakes Inquiry report by an Independent Committee speculated that the most recent changes in the water levels were due to climatic variations such as droughts and floods. However these earlier studies did not have access to the detailed data on surface water, groundwater, sediments and geology collected in the current program.

A review of those findings by the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer in 2013 agreed more research was needed into how the lake system works. This resulted in the $1.9 million Thirlmere Lakes Research Program launching in 2017.

The findings of the Thirlmere Lakes Research Program can be found online.

Following significant rainfall events in June 2016, February 2020, March 2021 and more recently, Thirlmere Lakes are potentially at their highest levels for the last decade.

Fast Facts

- Water into Thirlmere Lakes is primarily rainfall run-off

- The main cause of water loss from the lakes is evapotranspiration

- A smaller proportion of water is also lost from each lake to shallow groundwater.

- The groundwater loss is different for each lake.

- Thirlmere Lakes have had five major filling events due to rain over the last 6 years – June 2016, February 2020 and March 2021, January 2022, March 2022.

- It is likely the lakes will continue to swing between low and higher water levels depending on drought and major rainfall events.

In the longer term mining impacts on regional groundwater may affect lake water levels by reducing inflows to lakes and increasing the hydraulic gradient (water flow path) away from the lakes.

Thirlmere Lakes National Park is part of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

Hunter Diversification Panel No Place For A Coal Mining Lobbyist Environmentalists State

March 25, 2022

The appointment of a NSW Minerals Council representative to an expert panel that is meant to oversee the Hunter Region’s diversification beyond coal risks is undermining the work the group was established to do, according to Lock the Gate. The Alliance says the appointment of a member of the coal lobby interferes with the panel’s purpose and creates a risk that some of the transition funding may end up in the hands of multi-national coal mining companies.

The NSW Perrottet Government yesterday revealed the eight person interim expert panel that would guide spending from the $25 million per annum Royalties for Rejuvenation fund.

The Royalties for Rejuvenation interim Hunter Expert Panel members are;

- Amy Cooper, Hunter Valley Wine & Tourism Association

- Bob Hawes, Business Hunter

- Deb Barwick, NSW Indigenous Chamber of Commerce

- Ivan Waterfield, HunterNet

- James Barben, NSW Minerals Council

- Joe James, Hunter Joint Organisation

- Sarah Withell, Upper Hunter Mining Dialogue

- Warwick Jordan, Hunter Jobs Alliance

The fund was created to ensure coal mining communities have the support they need to develop other industries in the medium and long-term.

Legislation was introduced into the NSW Parliament this week to create the Fund and establish the Expert Panels - this will be made available through the Mining and Petroleum Legislation Amendment Bill 2022.

In an address given in parliament about the bill The Hon. Paul Toole stated;

The Royalties for Rejuvenation fund delivers on a key commitment to support the growth of new jobs and industries in traditional coalmining communities. That will not happen overnight but requires detailed, long-term planning to ensure the regions continue to have growth industries that offer skilled, well-paying jobs. The new section of the Act specifies the purpose of the fund:

… to alleviate economic impacts in affected coal mining regions caused by a move away from coal mining by supporting other economic diversification in those regions, including by the funding of infrastructure, services, programs and other activities.

Locals are best placed to understand their community's needs and develop emerging opportunities. That is why the bill provides for the Minister to establish expert panels to advise the Minister and make recommendations about the payments from the Royalties for Rejuvenation fund. That will ensure that regional communities and industries play a central role in shaping the fund's priorities through support and provision of comprehensive advice that will guide long-term decisions on the fund's investment. The bill establishes a requirement to review the fund after three years to consider whether the fund is meeting its policy objectives and whether the provisions in the bill remain appropriate. That review period will give the Government time to see how the fund is operating and provide an opportunity to make improvements or adjustments to the legislative framework if required.

However, a Lock the Gate Alliance spokesperson, Georgina Woods, has stated that a member of the Minerals Council on the panel would compromise its ability to make objective recommendations that diversified the Hunter’s economy.

“It makes no sense to appoint a coal mining lobbyist to a panel that is meant to advise on the best way to diversify the Hunter’s economy beyond coal,” she said.

“We are calling on NSW Deputy Premier Paul Toole to remove the NSW Minerals Council’s representative, and to promise that none of this $25 million will go to coal mining companies.

“We’re pleased the government is moving swiftly to get the Hunter on the road to renewal, but the coal mining industry already dominates the political and economic landscape in the Hunter. It doesn’t need any more influence. We need a panel that gives community, environment, Indigenous and local business groups space to plan for the diversification of the region beyond coal.

“The coal mining lobby is yet to acknowledge that expanding coal is completely at odds with global efforts to prevent catastrophic climate change.

“At this crucial moment, when we finally have funding to help diversify the Hunter’s economy, the NSW Perrottet Government must ensure industries and communities other than coal mining have space to grow and plan - without the coal lobby breathing down their necks.”

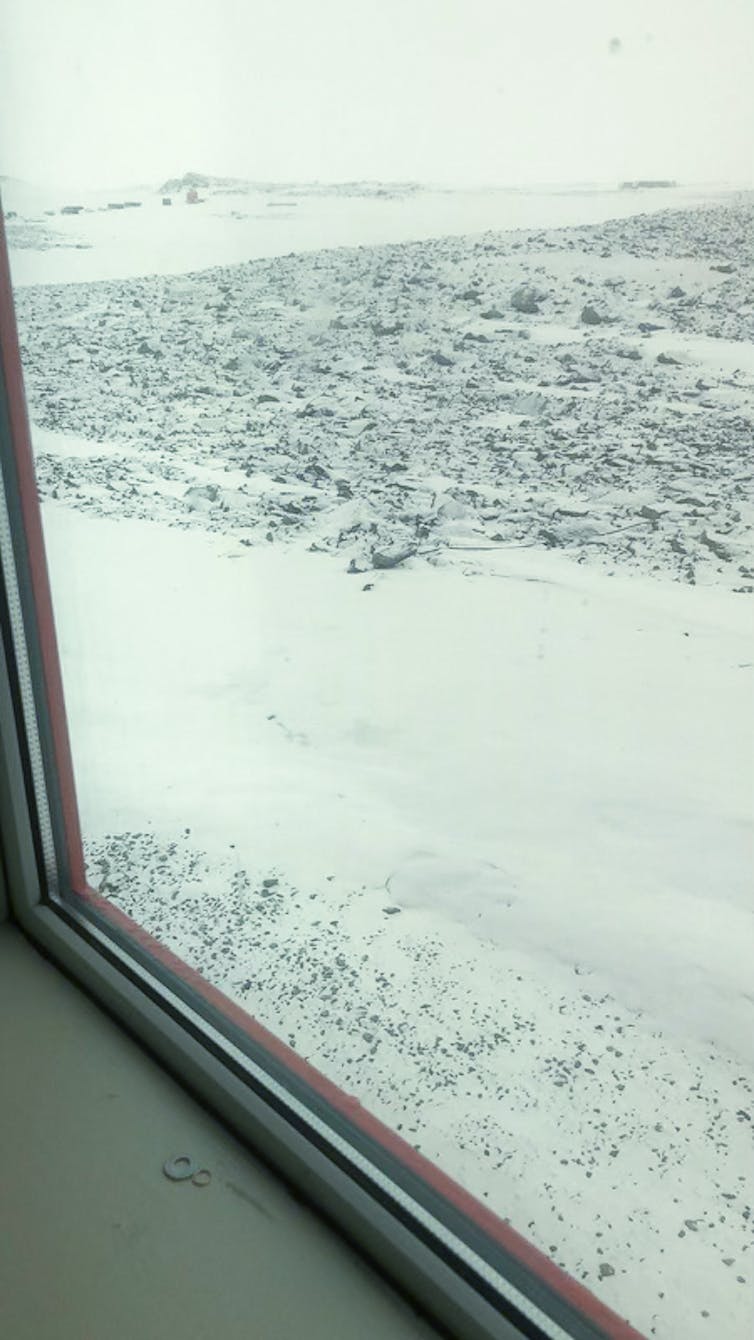

Director's Cut: What Happens On Nuyina

Published by the Australian Antarctic Division

Spectacular vision from Antarctica, in a light-hearted behind-the-scenes look at the first voyage south by Australia's new icebreaker RSV Nuyina.

Little Penguins To Benefit From CSIRO’s New Invasive Weed Solution

March 24, 2022

The CSIRO reports that Little penguins in Victoria will be among the native species to benefit from a new biocontrol solution to tackle the invasive coastal weed ‘sea spurge’, which will be released in Port Campbell National Park by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, and Parks Victoria today.

CSIRO researchers have found that the fungus, Venturia paralias, specifically attacks the invasive coastal weed called sea spurge (Euphorbia paralias), which threatens nesting sites of native species including little penguins (Edyptula minor), as well as impacting on the wider coastal ecosystem. Current control methods include removing the weed by hand or chemical sprays.

The fungus will be released by CSIRO and Parks Victoria at the world-renowned London Bridge, a natural offshore arch in Port Campbell National Park. The park is a popular tourist destination, with visitors coming to see the pristine coastline, Twelve Apostles and little penguins returning to their beach nests after fishing.

Little penguin chick, Port Campbell National Park. Photo: Parks Victoria

CSIRO scientist Dr Gavin Hunter said sea spurge is problematic for nesting shorebirds, including penguins, as the weed can alter sand dune structure and displace vegetation which could negatively impact nesting sites of shorebirds.

“The weed also has a sap which can cause irritation to animals as well as humans,” Dr Hunter said.

“Sea spurge grows along Australia’s southern coastline and is a concern for coastal ecosystems. We’re hopeful the biocontrol agent will help reduce the dense weed from penguin nesting sites at Port Campbell, and many other beaches along the coastline where the weed occurs.

“There are many challenges with current methods for removing sea spurge so finding a biocontrol agent for the weed was important to complement existing management strategies of hand pulling and chemical sprays that are very labour intensive, costly, and cannot easily be deployed in difficult-to-access beaches.”

CSIRO research technician Ms Caroline Delaisse will release the biocontrol agent at Port Campbell and said the fungus was originally found on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coast of France causing leaf and stem lesions on sea spurge plants.

“The fungus was isolated from these diseased plants and initial tests to explore its host range were performed in France. Following positive results from these tests, the fungus was imported to CSIRO’s quarantine facility in Canberra and studied extensively," Ms Delaisse said.

“Our research found that the fungus is highly specific towards sea spurge. Based on our results, the fungus was approved by the regulator for release in Australia.”

A fungus, Venturia paralias was found on the Atlantic coast of France. Photo: CSIRO

Infected sea spurge plants can topple. Photo: CSIRO

Sea splurge being sprayed with the mixture. Photo: CSIRO

Parks Victoria manages around 70 per cent of Victoria’s coast and is helping CSIRO release the fungus at several sites, in addition to Port Campbell National Park.

Parks Victoria Program Leader for Marine and Coasts Mr Mark Rodrigue assisted in the first releases of the fungus in Victoria and said this was an exciting advancement in weed control that would help protect the health of Victoria’s beautiful coast and native animals, such as little penguins and plants that depend on beach and dune habitats.

“If it successfully establishes, the biocontrol will be particularly important for managing this highly invasive weed in the more remote parts of the coast where access is very difficult for manual or chemical control,” Mr Rodrigue said.

“CSIRO has paved the way for land managers like Parks Victoria and volunteers to safely target areas of sea spurge infestation, with solid science and comprehensive guidelines developed to support us.”

A prolific seed producer, a mature sea spurge plant can produce up to 20,000 seeds per year and can grow anywhere on the beach above the high-water mark, taking over sand and dune vegetation.

Sea spurge can grow anywhere on the beach above the high-water mark. Photo: CSIRO

This project has been financially supported by the NSW Government as part of nearly $500,000 in funding targeting four weed species including sea spurge.

Sea spurge is an introduced plant from Europe that has invaded coastal ecosystems from Geraldton north of Perth in Western Australia through to the mid north coast of New South Wales and around Tasmania’s coastline.

CSIRO is calling for volunteers to help with the biocontrol release program on beaches infested with sea spurge in Victoria and Tasmania. To participate in community releases, seek approval from the land manager or owner in the first instance and then contact CSIRO scientists Gavin Hunter (gavin.hunter@csiro.au) or Caroline Delaisse (caroline.delaisse@csiro.au).

Sea spurge at Greens Beach in Tasmania. Photo: CSIRO

Sea spurge grows at Jervis Bay, NSW south coast. Photo: CSIRO

Port Campbell National Park is home to a little penguin colony. Photo: Parks Victoria

Roadmap Pinpoints Research Required For Smooth Transition To Renewables

March 25, 2022

Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO today released a Roadmap highlighting the research required to continue Australia’s transition to a more secure and affordable electricity system, showing that innovation can drive the integration of renewables.

Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO today released a Roadmap highlighting the research required to continue Australia’s transition to a more secure and affordable electricity system, showing that innovation can drive the integration of renewables.

The Roadmap was developed in collaboration with the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), and is based on input from leading Australian and international system operators and research agencies from the Global Power System Transformation (G-PST) Consortium.

The Consortium adapted key research questions to the Australian context, with the goal of supporting Australia’s energy transition in the long-term interests of consumers. The research areas they identified address the challenge of rapid change faced by Australia’s National Electricity Market and Wholesale Electricity Market.

Australia’s electricity systems face several key challenges, including ageing infrastructure, increasing complexity, and the need for investment in transmission and distribution.

The Roadmap summarises the outcomes of nine individual research plans, including their criticality to Australia’s energy transition, which research should be prioritised and how the research could form individual programs.

The key research topics are:

- Inverter design

- Stability tools and methods

- Control room of the future

- Planning

- Restoration and Black Start

- Services

- Architecture (Australian-specific)

- Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) (Australian-specific)

- DERs and Stability (Australian-specific)

CSIRO’s Energy Systems Research Director, Dr John Ward said the Roadmap could help forge a clear pathway to the integration of low emissions electricity.

“Across the energy system we are seeing a significant increase in renewable-generated electricity, combined with an increase in electricity requirements such as in transport, buildings, manufacturing and mining,” Dr Ward said.

“The cost of renewable energy is no longer the challenge – integrating renewable energy securely and efficiently into our electricity systems, and ensuring we have the right operational tools and capabilities in place, is what we need to solve.

“Australia has some of the world’s highest levels of rooftop solar, which means this integration challenge extends throughout our electricity system – from the largest generators through to efficiently integrating ‘distributed energy resources’ (such as solar and electric vehicles) into our homes and businesses.”

The Roadmap targets areas that will ensure ongoing energy security and reliability for Australian consumers, and an efficient and effective investment in infrastructure.

“The role of research throughout this transition is vitally important and Australia has the opportunity to lead the charge,” Dr Ward said.

Following industry consultation, CSIRO will use Roadmap priority areas to create technological steppingstones for further innovation while remaining adaptable to inevitable further change.

AEMO Executive General Manager Operations, Michael Gatt, said the research program targeted the increasing complexity facing power system operators with the rapid transition to inverter-based variable renewable generation.

“Australia is investing in renewable energy at a faster rate per capita than any other country. As Australia’s energy market operator, we’ve seen average renewable energy contribution increase to approximately 40 per cent of total or underlying demand, along with five-minute interval peaks above 60 per cent. In addition, consumer rooftop solar PV is pushing grid-scale generation out of the market under certain day-time conditions, setting minimum operational demand records across the country,” Mr Gatt said.

“The pace and scale of this transition is extraordinary. It demands new approaches to power system operations including tools, technologies, process and platforms, which complement network planning, and market and regulatory reforms.

“AEMO’s role is to design and operate a sustainable energy system that provides safe, reliable and affordable energy today, and to enable the energy transition for the benefit of all Australians. The CSIRO G-PST Research Roadmap, together with the AEMO Engineering Framework and upcoming Operations Technology Roadmap, is where the rubber hits the road in terms of providing a guide for government, industry and academia to work together to deliver a major step in achieving a net-zero emissions economy by 2050 – engineering net-zero energy systems.

“We need timely, multidisciplinary expertise and collaboration to identify and resolve the engineering and system issues involved in decarbonising Australia’s power systems. This is how we will keep the lights on for consumers while enabling an orderly transition to a safe, reliable and affordable net-zero energy future.”

The G-PST consortium intends the Roadmap to create a meaningful and holistic solution to the Australia’s energy transition.

CSIRO will soon be seeking input for phase 2 of this work.

Read the report Australia's Global Power System Transformation (G-PST) Research Roadmap

In 20 years of studying how ecosystems absorb carbon, here’s why we’re worried about a tipping point of collapse

From rainforests to savannas, ecosystems on land absorb almost 30% of the carbon dioxide human activities release into the atmosphere. These ecosystems are critical to stop the planet warming beyond 1.5℃ this century – but climate change may be weakening their capacity to offset global emissions.

This is a key issue that OzFlux, a research network from Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, has been investigating for the past 20 years. Over this time, we’ve identified which ecosystems absorb the most carbon, and have been learning how they respond to extreme weather and climate events such as drought, floods and bushfires.

The biggest absorbers of atmospheric carbon dioxide in Australia are savannas and temperate forests. But as the effects of climate change intensify, ecosystems such as these are at risk of reaching tipping points of collapse.

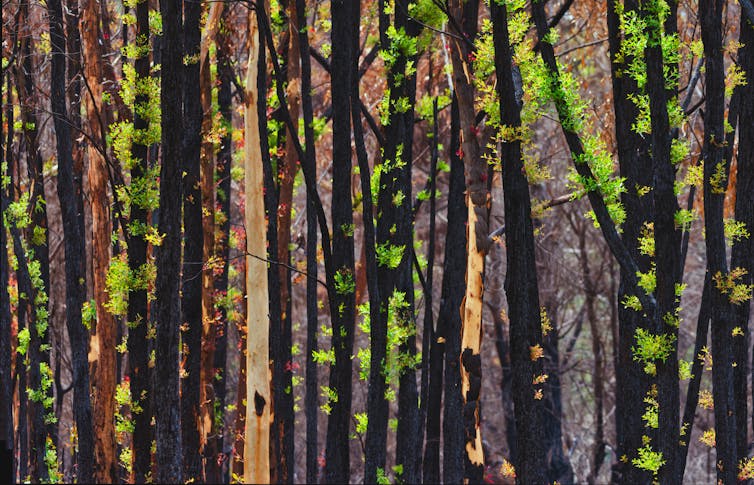

In our latest research paper, we look back at the two decades of OzFlux’s findings. So far, the ecosystems we studied are showing resilience by rapidly pivoting back to being carbon sinks after a disturbance. This can be seen, for example, in leaves growing back on trees soon after bushfire.

But how long will this resilience remain? As climate change pressures intensify, evidence suggests carbon sinks may lose their ability to bounce back from climate-related disasters. This reveals vital gaps in our knowledge.

Australian Ecosystems Absorb 150 Million Tonnes Of Carbon Each Year

Between 2011 and 2020, land-based ecosystems sequestered 11.2 billion tonnes (29%) of global CO₂ emissions. To put this into perspective, that’s roughly similar to the amount China emitted in 2021.

OzFlux has enabled the first comprehensive assessment of Australia’s carbon budget from 1990 to 2011. This found Australia’s land-based ecosystems accumulate some 150 million tonnes of CO₂ each year on average – helping to offset national fossil fuel emissions by around one third.

For example, every hectare of Australia’s temperate forests absorbs 3.9 tonnes of carbon in a year, according to OzFlux data. Likewise, every hectare of Australia’s savanna absorbs 3.4 tonnes of carbon. This is about 100 times larger than a hectare of Mediterranean woodland or shrubland.

But it’s important to note that the amount of carbon Australian ecosystems can sequester fluctuates widely from one year to the next. This is due to, for instance, the natural climate variability (such as in La Niña or El Niño years), and disturbances (such as fire and land use changes).

In any case, it’s clear these ecosystems will play an important role in Australia reaching its target of net-zero emissions by 2050. But how effective will they continue to be as the climate changes?

How Climate Change Weakens These Carbon Sinks

Extreme climate variability – flooding rains, droughts and heatwaves – along with bushfires and land clearing, can weaken these carbon sinks.

While many Australian ecosystems show resilience to these stresses, we found their recovery time may be shortening due to more frequent and extreme events, potentially compromising their long-term contribution towards offsetting emissions.

Take bushfire as an example. When it burns a forest, the carbon stored in the plants is released back into the atmosphere as smoke - so the ecosystem becomes a carbon source. Likewise, under drought or heatwave conditions, water available to the roots becomes depleted and limits photosynthesis, which can tip a forest’s carbon budget from being a sink to a carbon source.

If that drought or heatwave endures for a long time, or a bushfire returns before the forest has recovered, its ability to regain its carbon sink status is at risk.

Learning how carbon sinks may shift in Australia and New Zealand can have a global impact. Both countries are home to a broad range of climates – from the wet tropics, to the Mediterranean climate of southwest Australia, to the temperate climate in the southeast.

Our unique ecosystems have evolved to suit these diverse climates, which are underrepresented in the global network.

This means long-term ecosystem observatories – OzFlux, along with the Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network – provide a vital natural laboratory for understanding ecosystems in this era of accelerating climate change.

Over its 20 years, OzFlux has made crucial contributions to the international understanding of climate change. A few of its major findings include:

the 2011 La Niña event led to a greening of interior Australia, with ecosystems flourishing from increased water availability

heatwaves can negate the carbon sink strength of our ecosystems, and even lead to carbon emissions from plants

land clearing and the draining of peatland systems add to Australia’s and New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions

Critical Questions Remain

Plans in Australia and New Zealand to reach net zero emissions by 2050 strongly depend on the ongoing ability for ecosystems to sequester emissions from industry, agriculture, transport and the electricity sectors.

While some management and technological innovations are underway to address this, such as in the agricultural sector, we need long-term measurements of carbon cycling to truly understand the limits of ecosystems and their risk of collapse.

Indeed, we’re already in uncharted territory under climate change. Weather extremes from heatwaves to heavy rainfall are becoming more frequent and intense. And CO₂ levels are more than 50% higher than they were 200 years ago.

So while our ecosystems have remained a net sink over the last 20 years, it’s worth asking:

will they continue to do the heavy-lifting required to keep both countries on track to meet their climate targets?

how do we protect, restore and sustain the most vital, yet vulnerable, ecosystems, such as “coastal blue carbon” (including seagrasses and mangroves)? These are critical to nature-based solutions to climate change

how do we monitor and verify national carbon accounting schemes, such as Australia’s Emissions Reduction Fund?

Critical questions remain about how well Australia’s and New Zealand’s ecosystems can continue storing CO₂.![]()

Caitlin Moore, Research Fellow, The University of Western Australia; David Campbell, Associate Professor, University of Waikato; Helen Cleugh, Honorary Professor, Australian National University; Jamie Cleverly, Snr research fellow in environmental sciences, James Cook University; Jason Beringer, Professor, The University of Western Australia; Lindsay Hutley, Professor of Environmental Science, Charles Darwin University, and Mark Grant, Science Communication and Engagement Manager; Program Coordinator, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

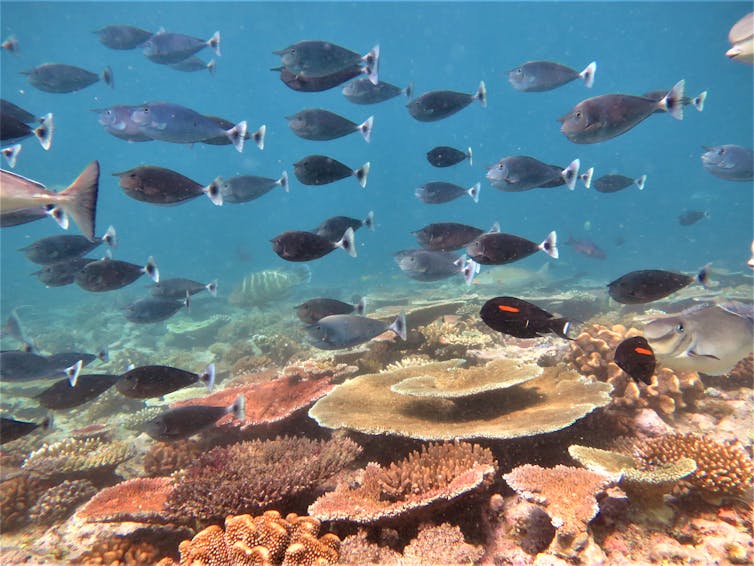

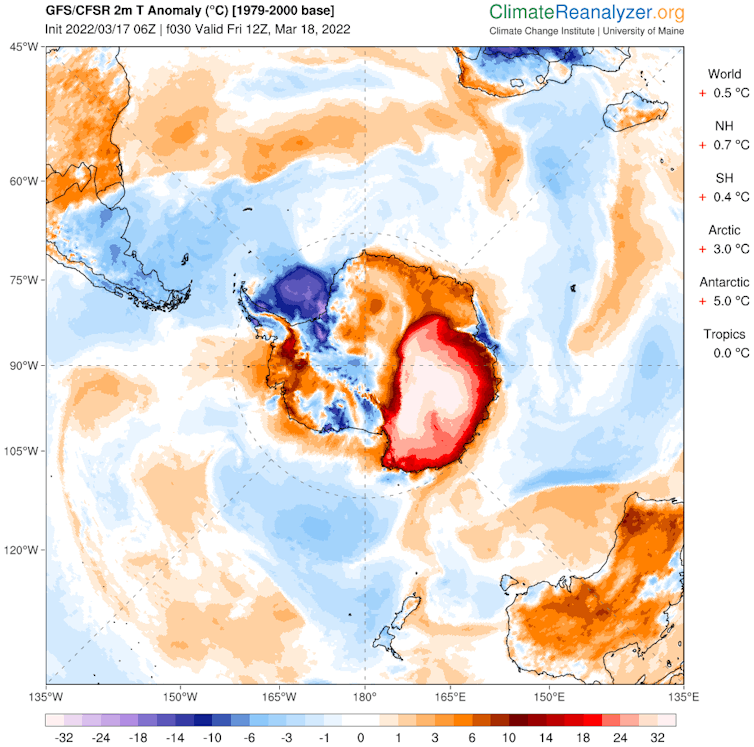

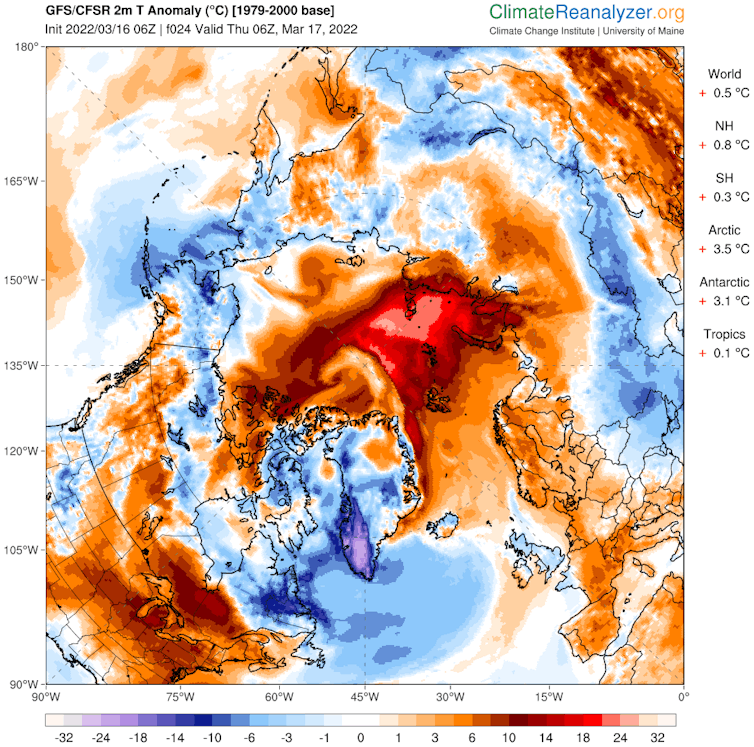

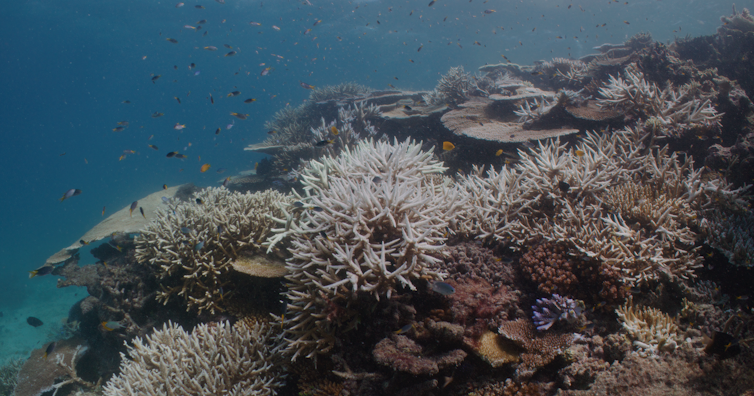

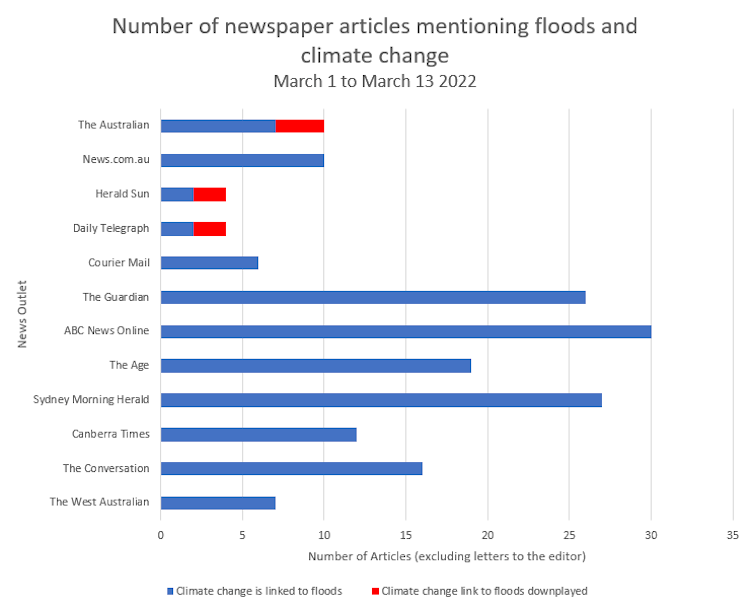

Saving the Great Barrier Reef: these recent research breakthroughs give us renewed hope for its survival

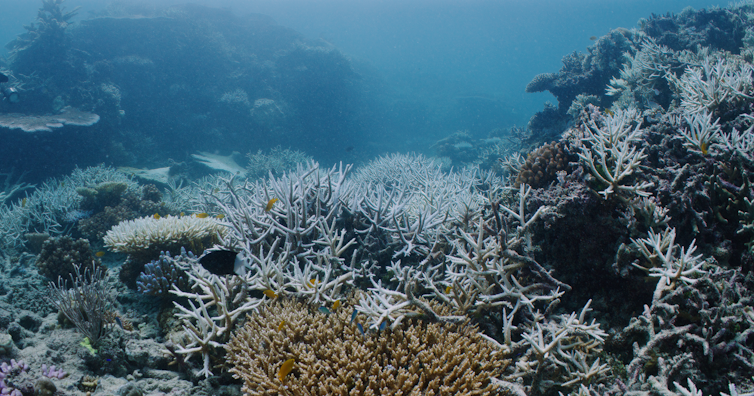

With yet another coral bleaching event underway on the Great Barrier Reef, we’re reminded of the tragic consequences of climate change.

Even if we manage to stop the planet warming beyond 1.5℃ this century, scientists predict up to 90% of tropical coral reefs will be severely damaged.

But we believe there’s a chance the Great Barrier Reef can still survive. What’s needed is ongoing, active management through scientific interventions, alongside rapid, enormous cuts to global greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2020, the federal government announced the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, which aims to help coral reefs adapt to the effects of warming oceans. It included research and development funding into 35 cutting-edge technologies that could be deployed at large scale, from cloud brightening to seeding reefs with heat-tolerant corals.

Now, two years into the effort, we’re seeing a number of breakthroughs that bring us renewed hope for the reef’s future.

Bleaching On The Reef

Aerial surveys of the entire reef are currently underway to determine the extent and severity of current bleaching. These should be complete before the end of March.

Meanwhile, United Nations’ reef monitoring delegates are visiting the Great Barrier Reef this week to determine whether its World Heritage status should be downgraded.

Early indications suggest bleaching is most severe in areas of greatest accumulated heat stress, particularly in the area around Townsville. In some places, water temperatures have reached 3℃ higher than normal.

Researchers involved in the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program are examining a wide range of interventions to repair coral reefs. Unlike current reef restoration efforts, which are done by hand on a few square metres of reef, these interventions are designed to be applied at tremendous scales – across thousands of square kilometres.

Major scientific, technological, process, communication and management breakthroughs are required to see this become successful. We’re pleased to report that we’re already seeing the first successes, with others becoming more likely as research and development continues.

Early Success Stories

One key family of possible interventions involves culturing and deploying millions of heat-tolerant corals onto selected reefs.

Over the last two years, the research team has accelerated the natural adaptation of several coral species to warmer temperatures, allowing them to survive up to an additional four weeks of 1℃ excess heat stress. We believe a total of eight weeks of 1℃ excess heat stress can be achieved.

This level of additional heat tolerance can make a real difference for reef survival if we can limit greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change.

We’ve also developed novel seeding devices, which allow mass delivery of juvenile corals to reefs in a way that enhances their survival, paving the way for larger field trials.

Seeding heat-tolerant corals onto the reef will require significant improvements in coral aquaculture – the process of raising healthy coral in an aquarium before transporting them to the Great Barrier Reef. While current methods are limited to producing and deploying a few thousand corals per year, new advanced methods are designed to produce tens of millions per year – faster and cheaper than ever before.

Another breakthrough relates to the ongoing development of new models and the data to calibrate them.

These are set to vastly improve our ability to predict where interventions are best deployed, and how well they’ll function. Early modelling results suggest even at a modest scale, well-targeted interventions could be enough to shift the state of individual reefs from terminal decline to survival over several decades.

4 Conditions For Lasting Benefit

For these early breakthroughs to bring lasting benefit at such tremendous scales, four key conditions must be met:

interventions will have to be readily scalable and affordable. That means methods and technologies now being trialled in labs and on small patches of reef will have to be automated, mass-produced, up-sized and delivered in ways not previously considered feasible. All of this will take significant investment

interventions must be safe and acceptable to regulators and the public

a range of people, especially Traditional Owners of reef sea-country, must be involved in the effort. This includes through consultation, in decision-making and design

most importantly, global emissions must be brought rapidly under control, ideally to keep warming to under 1.5℃ this century.

Over the coming months, the program will be conducting more trials on the reef. Alongside recent advances by other programs, such as approaches to control coral-eating crown of thorns starfish, there’s now real promise that a combined intervention at scale can be successful.

Saving The Reef

Imagine a world where coral reefs have largely disappeared from the world. The few remaining reefs are a shadow of what they once were: grey, broken, covered in weeds and devoid of colourful fish.

Millions of people who’ve depended on reefs must turn to other livelihoods, which may contribute to climate-related migration. Imagine, too, how we’d feel knowing it could have been prevented.

We are hopeful for an alternative vision for the future of the world’s reefs. It’s one in which the amazing beauty and diversity, and the huge global economic benefits, are intact and thriving well into the next century.

The difference between these two possible futures depends on choices we make right now. To save our reefs, we must simultaneously mitigate global warming and adapt to impacts already locked in. Neither alone will be enough. ![]()

Paul Hardisty, CEO, Australian Institute of Marine Science; David Mead, Executive Director of Strategic Development at Australian Institute of Marine Science, Australian Institute of Marine Science, and Rob Vertessy, Enterprise Professor in the School of Engineering, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tasmania’s forests are burning more as climate change dries them out. Our old tools can’t fight these new fires

David Bowman, University of Tasmania and Jenny Styger, University of TasmaniaThe summer of 2021-22 will be remembered for the extraordinarily destructive flooding across eastern Australia. At the same time, however, western Tasmania was experiencing extreme drought, with some areas receiving their lowest rainfall on record.

This drought fits an observed drying trend across the state, which will worsen due to climate change. This is very bad news for the ancient wilderness in the state’s World Heritage Area, where the lineage of some tree species stretch back 150 million years to the supercontinent Gondwana.

The drying trend has seen a steady increase in bushfires ignited by lightning, imperilling the survival of Tasmania’s Gondwanan legacy, and raising profound fire management challenges. Indeed, climate change means we’re on a learning curve, and the usual practices of managing fire are no longer necessarily fit for purpose.

There is increasing scientific recognition of the risk of the Gondanwan ecosystem collapsing from climate change driven fires. A new draft fire management plan outlines key steps to ensure these iconic forests survive for decades to come – and it must receive dedicated funding.

Tasmania’s Drought

Western Tasmania is one of Australia’s wettest regions, where average annual rainfall can exceed 3 metres. Cool temperatures, year-round rainfall, and complex topography have created fire refugia – landscapes naturally protected from fire. This is why western Tasmania is home to a suite of so-called “living fossils”, such as Huon pines and pencil pines.

The survival of these relic species hangs in a delicate balance. They occur in small patches surrounded by large areas of highly flammable Australian vegetation, such as eucalypts, tea-tree and, within in the World Heritage site, the ubiquitous buttongrass moorland.

The cool moist climate, combined with the skilful, intentional application of fire by Aboriginal people, have conserved ancient, unique trees for millennia. However, the changes in fire patterns following colonialism have caused some Gondwanan refugia to collapse.

Western Tasmania’s current drought is its worst in 40 years, despite the presence of La Niña – a natural climate phenomenon that brings cool, wet weather to parts of Australia. It has also been one Tasmania’s hottest summers on record.

Fortunately, the past summer has seen only a few bushfires ignited by lightning. Nonetheless, one of these fires was near the last remaining stand of unlogged Huon pine forest.

To understand the level of risk to Tasmania’s World Heritage Area, we can look to bushfires in 2016 and 2019 when massive dry lightning storms ignited fires in remote wilderness areas, threatening ecologically irreplaceable areas such as the Walls of Jerusalem and Mt Anne.

And let’s not forget, the largest fire in the 2019-20 bushfire crisis, which threatened many Blue Mountains towns, was ignited by a lightning strike in a remote and rugged area.

Likewise, the devastating 2003 Canberra bushfires was caused by lightning strikes in Kosciuszko and Namadgi National Parks.

There can be no doubt effective management of Tasmania’s wilderness will provide protection for nearby towns.

So What Does Sustainable Fire Management Look Like?

It’s widely accepted among Australian fire management agencies and conservation groups that aerial firefighting is key to controlling remote bushfires. But there are significant downsides to this approach.

The two most important are the very high costs of using aircraft, and the environmental impacts of firefighting chemicals. Some firefighting chemicals can, for instance, change soil chemistry so it favours weed invasion.

Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area needs a sustainable fire management approach which, crucially, employs and involves Aboriginal people. This would not only benefit the environment, but also enable Aboriginal people in Tasmania to reconnect with important cultural sites.

A sustainable approach is one that reduces the number of large bushfires while also intentionally applies fire to ecosystems and threatened species that require regular burning. For example, the critically endangered orange bellied parrot needs regularly burned buttongrass moorland as part of its habitat.

For this to work, we need to create carefully designed fuel breaks across the landscape – strips of land with less vegetation available to burn, which slows bushfires.

Naturally, such planned burning must consider biodiversity, ensuring fire sensitive plants that can’t bounce back – such as pencil pines and alpine vegetation – are protected. At the same time, we must continue to burn native plants that depend on fire to regenerate.

Protecting biodiversity can be achieved through carefully implementing a practice called “mosaic” burning. This is where small areas are regularly burnt to create a patchwork of habitats so wildlife has a diversity of resources and places to shelter in.

Ultimately, well-designed landscape management will give managers confidence to let some fires run free, rather than attempting costly aerial firefighting campaigns. By contrast, areas with internationally important natural and cultural values should be the focus of fire protection efforts when bushfires do occur, such as the innovative use of sprinklers to protect the shores of Lake Rhona.

More Fire In Our Future

The above fire management approaches are outlined in the current draft fire management plan for the World Heritage Area. Realising its objectives will require dedicated, recurrent funding, without which the plan’s goals will remain aspirational.

What’s more, any fire management evaluation going forward must be publicly transparent to see continual improvement. It will also ensure there’s a broader community understanding of the need to make difficult decisions to adapt to climate change-driven bushfires.

The 2019-20 bushfire crisis that shocked the world has been overwritten by many other subsequent crises, such as the pandemic, flooding, and geopolitical turmoil.

Indeed, the soggy summer in eastern Australia has no doubt engendered a widespread belief bushfires have gone away. They haven’t. The luxuriate growth from the La Niña is priming landscapes across eastern Australia to burn again.

We must keep focus on adapting to bushfires that are being turbo charged by climate change. With serious investment to protect Tasmania’s precious environment, the rest of Australia – and indeed other flammable wildernesses elsewhere in the world – can too learn how to sustainably manage increasingly devastating bushfires.![]()

David Bowman, Professor of Pyrogeography and Fire Science, University of Tasmania and Jenny Styger, Associate at The Fire Centre,, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If the UN wants to slash plastic waste, it must tackle soaring plastic production - and why we use so much of it

You pick up a piece of plastic litter from the beach, and get a small buzz. You’ve done something for the environment. But then you look around, and see plastic everywhere. It’s much more than you could pick up.

Earlier this month, the United Nations endorsed a new resolution on ending plastic pollution.

While that sounds positive, focusing on pollution is missing the elephant in the room: production. Why is more and more plastic being produced, with some ending up in forests, rivers and oceans near you?

Our research has shown that to actually make a difference to the ever-growing amount of plastics in our oceans, our soils and our bodies, we must focus on why our societies use and throw away ever more single use plastics.

The answer lies in our systems. If you’re a time-poor parent, stressed by juggling kids, work and the mortgage, it can be much easier and faster to reach for heavily packaged ready-made meals, or get dinner delivered in many layers of plastic.

It’s Time To Stop Focusing Just On Plastic Waste

Plastic pollution is out of control, with almost 80% of the 8.3 billion tonnes we have produced thrown away into landfill or the environment.

Why, then, is the UN focused only on the problem of waste, rather than production? We are producing more plastics than ever. Plastics are created from oil, and will account for one-fifth of all oil consumption by 2050. Not only this, but 40% of all the plastics we produce is used for packaging. Just over a third of these plastics are for food packaging.

Our research has shown mainstream approaches such as the UN resolution are ineffective and even counterproductive.

If we want to make a dent in the major problem of plastic pollution, we have to make systemic changes.

Why? Consider recycling and the notion of the circular economy, often held up as an answer to plastic waste. The issue here is that plastic degrades every time it is cycled through. Not only that, but recycling itself is often highly energy-intensive with its own set of environmental impacts.

Recycling only delays the final disposal of plastics. Similarly, the concept of a circular economy is only put into practice when profitable.

Could we switch en masse to alternative disposable materials, like bio-based packaging?

Alas not. This isn’t the solution either, as these products still have significant social and environmental impacts.

Both recycling and switching to bio-based packaging are drawn from the technocratic greenwashing playbook, in which we look to technology to let us keep living in an unsustainable way.

Why Do We Use And Throw Away So Much Plastic?

What we actually need is to consider how we can reduce how much plastic we make and consume, so we have a better chance of living within the planet’s ecological boundaries.

Our current capitalist system gives producers the incentive to make as much plastic as they can sell, and to create new market niches for their products. It’s no surprise the result is an avalanche of plastic.

Take food packaging. The use of plastics to cover food has increased dramatically since the 1960s, alongside the expansion of the globalised food market.

There is a link. As food production has gone global, it has displaced some local food production, manufacturing and consumption. Major corporations have profited from this shift, which requires longer and more complex supply chains. And longer supply chains means more packaging to keep food saleable.

To us, this suggests that the problem of plastic runs much deeper than how we prevent the waste entering our rivers and oceans. We believe the central issue stems from the growth-at-all-costs capitalist system.

Consider: packaged food is sold as “convenient”. Why do we need convenient ready-to-eat meals or those with minimal preparation, like frozen dinners, instant noodles and fast food? Because we are time-poor.

Why are we time-poor? Because in our fast-paced capitalist economies, people need to fit food preparation around their inflexible paid labour, which may often require long hours or fitting into a casualised system.

As a result, many of us get to the end of the day with little time and energy to shop in local stores, cook our meals from scratch using fresh ingredients, or grow our food.

It’s well established that time deprivation has increased how much processed packaged food we eat.

Waste Is Just A Symptom

We do not hold out great hopes for the new UN agreement on plastics, based not only on the failure to address the root causes but also the poor implementation of previous climate commitments and other international environmental agreements such as e-waste management.

Proposals to reduce plastic pollution which skim over the root causes will do very little to reduce our overall use of plastics and alleviate the significant damage they do to our societies and the environment.

If we are serious about reducing the damage, we must look at deeper solutions, One might be transitioning towards a degrowth society, which would help us re-localise food systems.

In a degrowth society, we would gradually shift back to local food production, which would reduce the globalisation of food and shorten supply chains. That, in turn, would slash the need for packaging.

Degrowth would also help us address time poverty by, for example, reducing working hours or introducing a work-sharing mechanism.

There would be more free time in a degrowth society, and local food systems would provide healthy, fresh, seasonal produce requiring minimum packaging.

Supporting local farmers or pursuing more free time for all might well be a more effective solution to the issue of plastic pollution rather than simply pushing for improved recycling schemes.

Is this just blue sky thinking? No. Consider how our society was able to react to the COVID pandemic and get organised differently.

The pandemic showed us we are capable of large-scale change if a problem is taken seriously. If we begin to prioritise our social and ecological well-being over company profits, we will see change.![]()

Sabrina Chakori, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland; Ammar Abdul Aziz, Lecturer, The University of Queensland; Martin Calisto Friant, PhD Researcher, Utrecht University, and Russell Richards, Lecturer, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The legacy of Lake Pedder: how the world’s first Green Party was born in Tasmania 50 years ago

Fifty years ago this week, the world’s first “green” political party was born in Tasmania after the state government purposefully flooded the magnificent Lake Pedder.

The flooding made way for a hydro-electricity scheme, transforming the nearly 10-square-kilometre lake into a reservoir spanning almost 250 square kilometres today. This damaged the surrounding wilderness – now recognised as part of Tasmania’s World Heritage Area – and greatly tarnished its natural beauty.

The controversial move sparked nationwide outcry. In an effort to save the lake, the United Tasmania Group was formed on March 23, 1972 by fielding candidates in the state election that year. The party was the forerunner to the Australian Greens and saw other green-oriented political parties soon follow worldwide, including New Zealand’s Values Party and Switzerland’s Popular Movement for the Environment.

Now, half a century later, environmentalists are upping their campaign to restore the lake to its former glory. It symbolises the broader contest between unsustainable industrialisation and a greener economy that addresses challenges such as climate change.

The Lake Was Once Beautiful