Inbox and Environment News: Issue 533

April 3 - 9, 2022: Issue 533

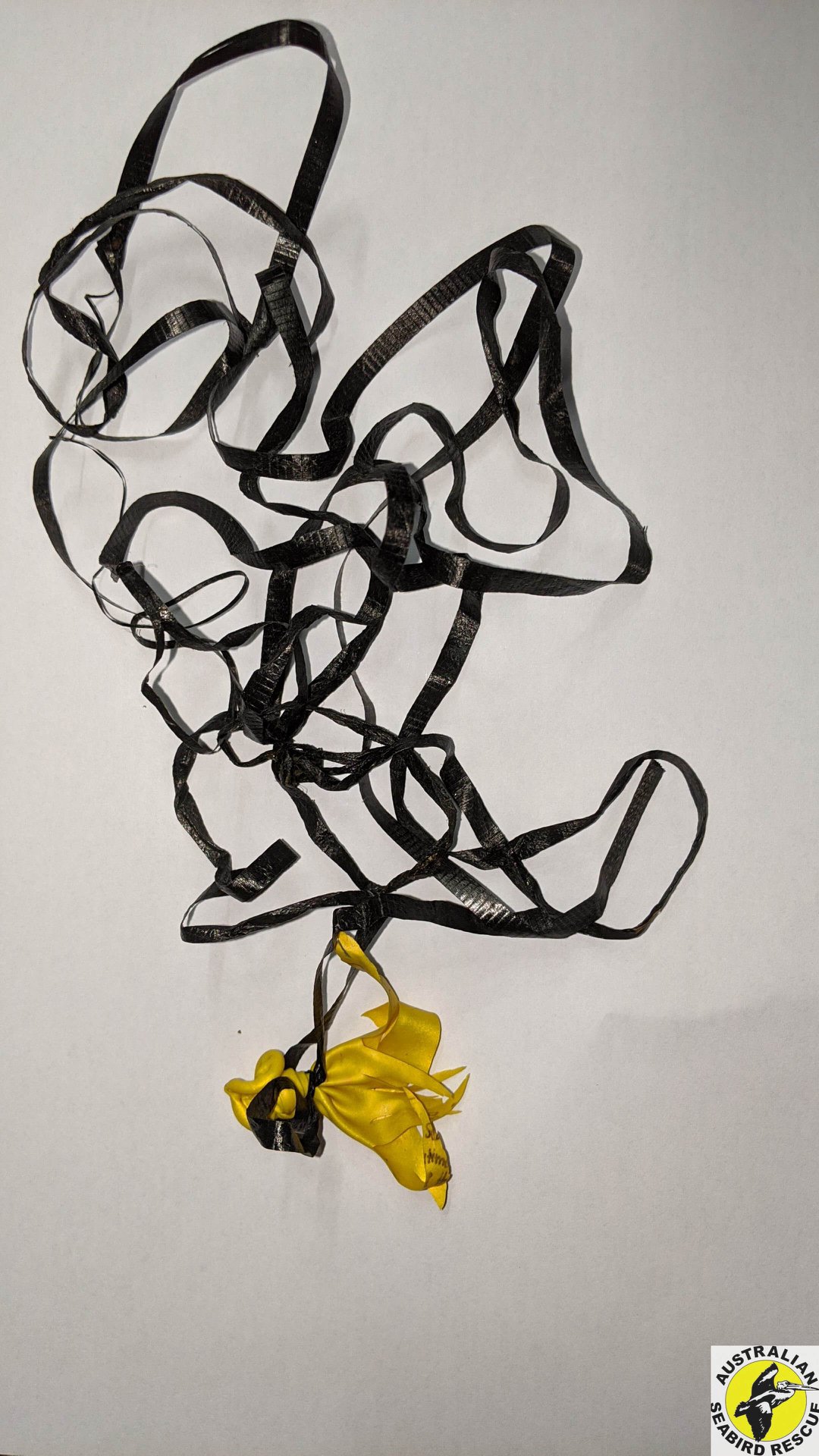

Ban The Release Of Balloons In NSW Petition

Ella: Green Turtle Rescued From Manly

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Join The Fight Against Foxes On The Northern Beaches

Northern Beaches residents are invited to hear how they can join the fight against foxes in their area at a free online event on April 5th.

A joint initiative between NSW DPI, Greater Sydney Local Land Services and Northern Beaches Council, the webinar will feature a range of expert speakers and local information.

Greater Sydney LLS Senior Biosecurity officer Gareth Cleal said the event would give residents advice and information based on real life scenarios and experiences.

“There is no doubt foxes are becoming more and more prominent in urban areas of Sydney and the Northern Beaches is not immune,” he said.

“We regularly receive reports of fox sightings in the area and there are simple steps residents can take to help reduce their impact.”

Mr Cleal said foxes were attracted by food scraps and domestic pets like chickens and rabbits.

“Residents can help by ensuring compost bins are kept secure and properly closed, keeping household rubbish in a secure location, feeding domestic pets inside, ensuring food is not left outside and wherever possible, keeping pets inside overnight,” he said.

“Keeping yards in check by tidying gardens, weeding to reduce fox harbour and housing backyard chickens in secure, fox-proof enclosures rather than free ranging will also help.”

The webinar will feature presentations from local pest animal experts, and cover topics including:

- How to minimise impacts to your pets and native wildlife

- Recording/reporting foxes into FoxScan - https://www.foxscan.org.au/

- An update on local programs

The webinar will be held on Tuesday, 5 April 2022 from 7pm. RSVP via https://bit.ly/3qq5aIK or email feralscan@feralscan.org.au.

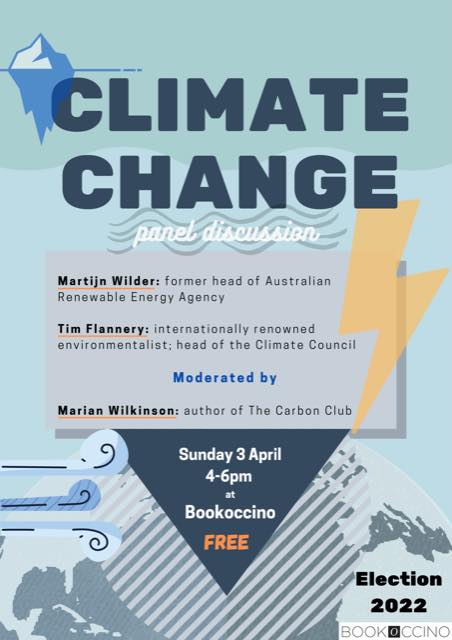

Bookoccino Discussion Events

Long Reef Fishcare Free Guided Walks

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Autumn 2022 Newsletter

Sulphur-Crested Cockatoo Mucking About

The Sulphur-crested Cockatoo's normal diet consists of berries, seeds, nuts and roots. It also takes handouts from humans. Feeding normally takes place in small to large groups, with one or more members of the group watching for danger from a nearby perch.

Cockatoos often “play” with each other, performing intricate aerial manoeuvres or crazy antics, such as hanging upside down while perched, just for the “fun” of it - as this one was this week! These activities serve as a form of exercise for the birds, and strengthen social bonds. - Info: BirdLife Astralia

.jpg?timestamp=1648774048876)

.jpg?timestamp=1648774149347)

.jpg?timestamp=1648774178595)

Photos: A J Guesdon, March 29, 2022

Long-Billed Corella

.jpg?timestamp=1648584010745)

.jpg?timestamp=1648584436823)

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Asparagus Fern Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

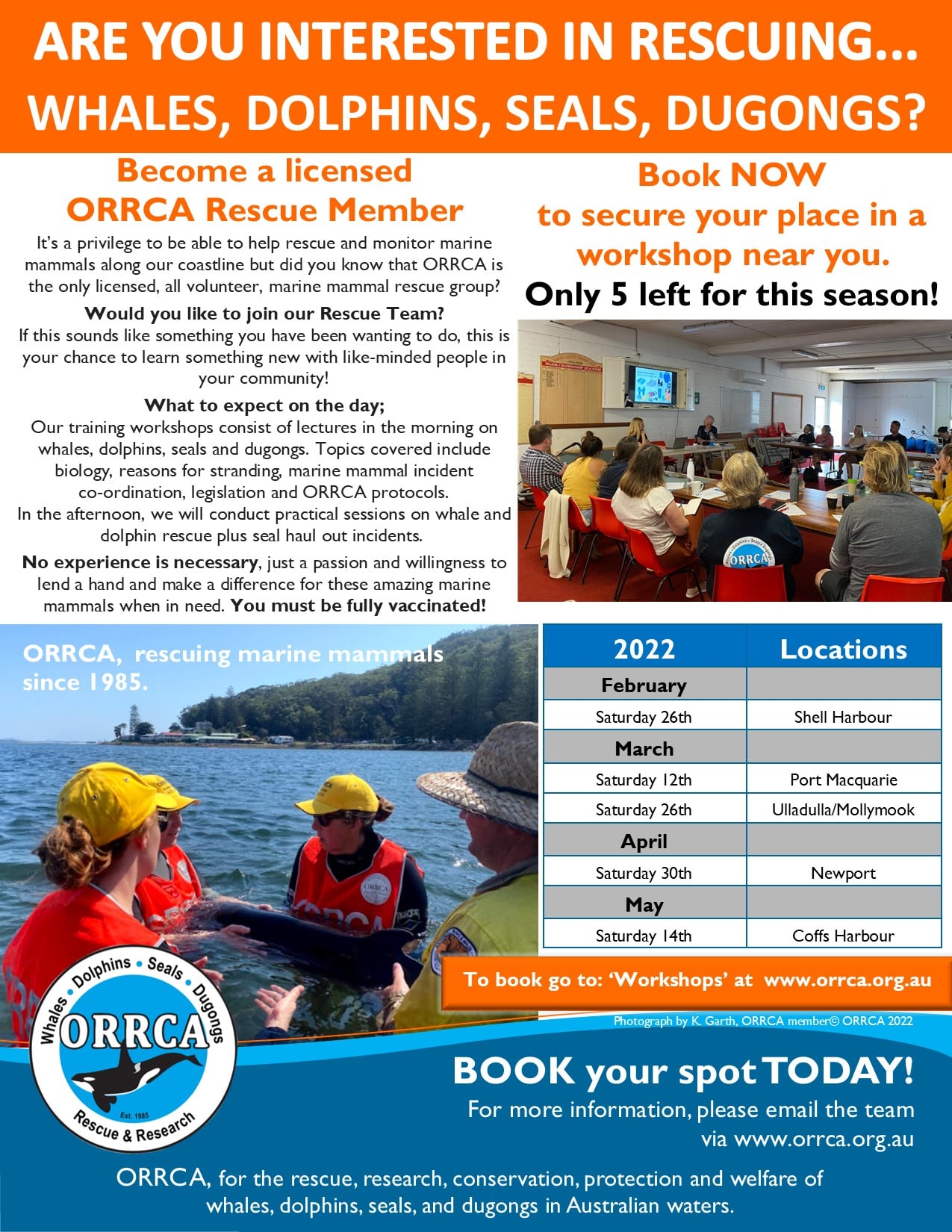

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Illegal Logging To Be Made Legal: New Powers Create Moving Goalposts On Logging Laws And Quash Community Rights To Consultation

- Legislation gives the power to Victorian senior bureaucrats or the Environment Minister to vary logging laws, without public consultation.

- By removing community rights to public consultation, the legislation is expected to undermine the ability of community groups and citizen scientists to hold government logging agency VicForests to account.

- The Victorian government intends to change an important legal principle known as the Precautionary Principle, this change is likely to impact several community court cases brought against VicForests for alleged breaches of logging laws.

New Hope’s Renewable Energy Shift Warmly Welcomed

Arrow’s Million Dollar Fine A Pittance For Its Owners But A Start For QLD

$4 Billion Industry Response To Hydrogen Hubs

Australia’s environment law doesn’t protect the environment – an alarming message from the recent duty-quashing climate case

Laura Schuijers, University of SydneyThe Federal Court recently quashed a duty of care owed by the environment minister to Australian children, to protect them from the harms of climate change.

The duty was attached to Australia’s federal environment law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. In reversing the decision that had established the duty, the new judgment shone a spotlight on the EPBC Act’s limitations. Or at least, it should have.

Much of the commentary around the judgment focused on lamenting the hands-off position the court took in its unwillingness to delve into so-called political territory.

Less attention was paid to a key take-home message: the EPBC Act gives the minister power to approve coal projects, even if they’ll have adverse effects.

It doesn’t, in a general sense, protect the environment from these effects. It doesn’t protect the public from consequent harm, even if deadly. And it doesn’t, actually, tackle climate change at all.

Alarmed? You should be.

Why The Duty Was Quashed

The appeal was heard by three judges, each with a different opinion on why there shouldn’t be a duty.

One key problem was that the class of victims won’t just include the children represented in the case. Currently unborn children will be affected too. The judges also found issues with the minister’s relationship with the children given the intervening steps that will lead to climate change, extreme weather events, and future harm.

To help resolve novel disputes, courts look to previous cases. One case that featured prominently was about protecting the public from contaminated oysters. In that case, a council wasn’t liable for failing to prevent water pollution that caused hepatitis infection. In another case, where there was no way of identifying the source of asbestos fibres that caused mesothelioma, it was found that whoever materially increased the risk of harm could be liable for it.

The fact these were considered the most relevant cases just goes to show how unprecedented the problem of climate change is. There was no case directly on point, which could help with the complex and cumulative cause-and-effects.

The Problem Of ‘Incoherence’

Another important problem for two of the three judges was that the duty wasn’t coherent – meaning consistent or compatible – with the EPBC Act. That’s because the EPBC Act doesn’t squarely address climate change or human safety, and yet the duty concerns precisely those two things.

For decades, it’s been recognised that humans depend on the environment for survival, and that a stable climate system is necessary for life as we know it.

The third judge thought the minister’s obligations, embedded in an environment protection framework, could therefore sit side by side with a duty of care. Our environment, he said, “is not just there to admire and objectify.”

But the other two were dissuaded by their view that the EPBC Act doesn’t in fact protect the environment in a general sense. Nor does it explicitly aim to mitigate climate change. It operates in a piecemeal way, rather than concerning ecosystems as a whole, or our dependency on them.

Can this really be how the EPBC Act operates in practice? Well, yes.

We heard this same message just recently via the ten-yearly, independent review of the legislation. It concluded that the EPBC Act is outdated, and not fit for the purpose of environment protection.

What Does The EPBC Act Do, Then?

For the most part, the EPBC Act is an impact assessment law. It’s triggered when specific environmental matters, like individual threatened species, are likely to be harmed by a proposed project (such as a coal mine). When it’s triggered, it sets in motion a procedural process that requires the minister to consider whether to approve the project given its impacts.

Year after year, nearly every single project that is put forward is approved. In fact, the coal mine that was the subject of the case was approved even before the appeal went to court. This explains why so many, including the independent review, feel the EPBC Act doesn’t really do enough to adequately safeguard against environmental loss.

The review recommended the introduction of science-backed environmental standards. If this happened, it may be easier for courts to judge ministerial decisions, with a legal reference point for what’s considered politically acceptable. It also recommended decision-making incorporate climate scenarios.

A Call To Action

Back in 2020, I wrote that whether the children win or lose, their case would make a difference.

Although not over yet (they have two more weeks to lodge an application to appeal to the High Court), it already has. It’s drawn attention to the fact that Australia doesn’t have a climate law to protect its children. That it has no law to protect against harmful floods and fire that have already manifest since the case began. And it’s forced the Federal Court to acknowledge the uncontested risks of climate change.

Let’s look at this case as a call to action. The Federal Court has essentially said it can’t act. Reading the judgment closely, there are hints to suggest the High Court might be able to, and that eventually, the law will have to evolve to manage complex causation.

But the decision certainly doesn’t mean the government can’t act. In fact, that’s exactly who the judges indicated must. ![]()

Laura Schuijers, Deputy Director, Australian Centre for Climate and Environmental Law and Lecturer in Law, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Poor policy and short-sightedness: how the budget treats climate change and energy in the wake of disasters

This year’s federal budget is characterised by an avalanche of immediate handouts in response to cost-of-living pressures, some sound initiatives and deferral of more fundamental decisions. This is precisely reflected in how the budget treats energy and climate change.

The A$1 billion to expand Australia’s low emission technology capabilities, such as green hydrogen, is welcome. But cuts to the fuel excise represent poor policy on fiscal and environmental grounds.

From the devastating bushfires of 2019-2020 to this year’s shocking floods, unprecedented climate-related disasters have wrought havoc across Australia.

It is deeply regretful that the budget and forward estimates do not specifically recognise the ongoing, and escalating, scale and the fiscal impact of these disasters.

Fuel Excise Is Poor Policy

For six months, the government will halve fuel excise to 22.1 cents per litre to offset soaring petrol prices. This short-term reduction will undoubtedly be welcomed by anyone with a petrol or diesel vehicle, and may provide the sort of political boost the government seeks ahead of the election.

Yet, it is poor fiscal policy. First, the outlook for global oil prices is as unpredictable as the outcome of the Ukraine war. That means the cut in fuel excise will quickly be either too strong a response or insufficient.

Second, restoring the level will not be politically simple. As a relief for households under financial stress, the measure is poorly targeted.

It is also a stark illustration of how motorists today would already be financially better off if Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was able to implement his proposed fuel efficiency standards in 2017, when he was the minister for energy and the environment.

At that time, the benefit to motorists was calculated to be more than $500 per year by 2025 – and that was based on prices below $1.50 per litre, well short of current levels above $2. And of course, we would have been making tangible progress on reducing emissions in the transport sector.

Funding Low-Emissions Technologies

Development and deployment of low-emission technologies – such as clean hydrogen, green steel and carbon capture and storage – will be critical to meeting Australia’s commitment to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

The government’s commitment of more than $1 billion to projects to support these technologies is welcome, as is the allocation of $84 million to support the development of microgrids.

These investments are generally aligned with the government’s technology investment roadmap, released in 2020. However, it would be better for these projects to be selected via an independent agency with criteria set by the government.

The government emphasises a “technology, not taxes” approach to bringing Australia’s emissions to net zero. But funding the net-zero transition from government coffers is not sustainable.

We need policies such as a price on carbon that encourage the market to deploy these technologies at scale. The recent history of such policies in Australia means this will be a big challenge for whoever is energy minister after the looming federal election.

Australia’s extensive renewable energy and critical minerals resources mean we could be a global leader in manufacturing, for instance, downstream processing or iron ore, copper, lithium and similar metals critical in a low emissions world.

So the $1 billion in the budget to boost our manufacturing capability is another step in the right direction.

But again, good governance should include a clear framework that determines which projects get selected. This process should be based primarily on Australia’s potential competitive advantage.

The primary source of such advantage lies in our renewable energy and minerals resources, while specific regions may also have advantages based on existing infrastructure such as ports and skilled workforces.

Investments in low-emission technologies and manufacturing is closely aligned with this budget’s focus on Australia’s regions.

Investment in new opportunities will be welcomed in the regions. It should be accompanied by an equally strong commitment to working with regional communities that may suffer job losses and other economic harms in the transition away from fossil fuel industries.

Short-Term Climate Thinking

Frydenberg’s budget acknowledged the devastation wrought in Australia by floods, drought and bushfires. Yet it failed to acknowledge the future cost of such disasters on the budget under climate change.

The budget includes measures to make regional Australia more resilient, to mitigate the impact of these disasters and support insurance coverage. But these are short-term commitments.

Even if we manage to stop global warming beyond 1.5℃ this century, the frequency and severity of natural disasters will only worsen. Australia is already feeling the damage.

The economic and fiscal consequences of these disasters will only increase. And there will be other risks from a changing climate such as rising health spending and reduced government revenues from key exports, including liquefied natural gas.

So What Should The Government Do Differently?

At the very least, the federal government should move to better understand and quantify the fiscal risks from climate change.

First, it should include some of the immediate risks of climate change in the budget’s “Statement of Risks”, which outlines the general fiscal risks that may affect the budget.

Second, it should adjust medium-term fiscal projection models to factor in declining revenue from fossil fuels, higher cost of debt, and higher expenditure on health and natural disaster supports.

Third, the longer-term impacts of climate change on the budget must be modelled. This should inform the next Intergenerational Report in 2025, which provides an economic outlook for Australia over coming decades.

Climate change ultimately challenges governments to reconsider their fiscal strategy. The many climate-related uncertainties make a strong case for preserving fiscal flexibility and firepower to cushion the direct impacts of climate change, including natural disasters.![]()

Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Morrison government’s $50 million gas handout undermines climate targets and does nothing to improve energy security

Samantha Hepburn, Deakin UniversityTuesday night’s federal budget confirmed the Morrison government will spend A$50.3 million on gas projects in the Northern Territory, South Australia and the east coast.

This decision, it says, will support the completion of seven new “priority” gas projects. Energy Minister Angus Taylor says the government strongly backs natural gas and accused the opposition of being “willing to risk Australia’s energy security and investment in regional Australia to appease gas activists.”

However, the development of new fossil fuel projects is completely inconsistent with the broader goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050 – and will not improve energy security.

Gas Extraction Drives Climate Change And Extreme Weather

Gas is a fossil fuel and a greenhouse gas. Emissions from the extraction, processing and export of gas contribute significantly to Australia’s carbon emissions.

Globally, there is growing recognition the energy sector must change. An International Energy Agency report last year made clear there can be no new oil, gas or coal development if the world is to have any chance of reaching net zero by 2050.

The methane found in natural gas is 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Funding new gas projects undermines Australia’s efforts to achieve an already unambitious climate target of 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Failing our climate target would breach the global goals of the Paris Agreement to limit the increase in global average temperatures to well below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels.

The consequences of global warming are catastrophic. Australia has had recent and profound experience of extreme climate events in the form of devastating bushfires and floods.

But What About Energy Security And Russian Gas?

The European Commission is phasing down two-thirds of Russian gas exports by the end of the year, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This will create a gas shortfall.

Russia supplies nearly 40% of the EU’s gas consumption via a fixed pipeline infrastructure.

To phase this supply out, the EU will this year require 500 terrawatt hours of additional imports of liquified natural gas (LNG).

This will be difficult. Global markets are tight and LNG tends to be sold on long-term contracts. Alleviating the EU shortfall will require record imports of LNG over the European spring and summer period and a rapid upgrade of gas infrastructure.

In a recent pact between Europe and the US, the EU will receive an additional 11 million tons of LNG by the end of 2022.

It’s unclear where this LNG will come from. Much may be sourced from non-contracted stock destined for Asia.

However it’s acquired, the price of LNG exports will continue to rise. Indeed, the delivered price for LNG in Northwest Europe rose 29% in a day after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced his special military operation. And spot prices for LNG in Asia are trading at near record levels.

Australia is one of the world’s largest exporters of LNG, with most going to China, Japan and South Korea.

Given the lock-in contracts, Australia has little existing capacity to assist the EU. Australian gas producers are, however, benefiting from the higher global prices for LNG exports caused by the EU shortfall.

Woodside, Santos and Oil Search have all registering significant gains in their share prices.

Complete Nonsense

Taylor says spending $50.3 million of public money for new gas projects will:

accelerate priority projects and ensure Australia does not experience the devastating impacts of a gas supply shortfall as seen in Europe.

This is complete nonsense.

Australia will never face a shortfall like Europe because it’s not import-dependent. We have plenty of gas.

The issue for Australia is regulating the export of gas to ensure a sufficient domestic supply.

If the federal government wanted to improve Australia’s energy security, it would force gas producers in the east coast market to reserve a percentage for domestic consumption.

And it would actually use the Australian Domestic Gas Security mechanism. The measure was introduced to ensure gas supplies meet forecast energy needs, but has never been triggered.

An Uncertain Future

Funding seven gas priority projects is also inconsistent with the conclusions of the 2022 Gas Statement of Opportunities, recently released by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO).

This statement argues the future path for the gas sector in Australia is uncertain because the pace and impact of a transforming energy sector upon the gas system remains unclear.

In the short term, this statement suggests funding new infrastructure will not alleviate domestic supply concerns because it won’t be running in time.

In the longer term, the statement forecasts a gradual decline in domestic gas demand as consumers inevitably shift from gas to electricity or zero-emission fuels.

Contrary To Australia’s Climate Targets

Funding seven new fossil fuel projects is fundamentally contrary to Australia’s climate targets.

These projects will not improve Australia’s energy security or assist the EU with its supply difficulties.

Nor do they cohere with AEMO’s longer term conclusions about the future of the gas sector.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has argued gas projects are needed to generate new dispatchable electricity which can be ramped up quickly when needed, making new gas projects integral to a national pandemic recovery plan.

But Kerry Schott, the former head of the Energy Security Board, disagrees. She’s made it clear there is an abundance of cheaper, cleaner alternatives.

Schott is right. This is where public money should be directed – to projects that represent the future, not the polluting past.![]()

Samantha Hepburn, Director of the Centre for Energy and Natural Resources Law, Deakin Law School, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Federal budget: $160 million for nature may deliver only pork and a fudge

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s cash-splash budget has a firm eye on the upcoming federal election. In the environment portfolio, two spending measures are worth scrutinising closely.

First is a A$100 million round of the Environment Restoration Fund – one of several grants programs awarded through ministerial discretion which has been found to favour marginal and at-risk electorates.

Second is $62 million for up to ten so-called “bioregional plans” in regions prioritised for development. Environment Minister Sussan Ley has presented the measure as environmental law reform, but I argue it’s a political play dressed as reform.

It’s been more than a year since Graeme Samuel’s independent review of Australia’s environment law confirmed nature on this continent is in deep trouble. It called for a comprehensive overhaul – not the politically motivated tinkering delivered on Tuesday night.

A Big Barrel Of Pork?

The Environment Restoration Fund gives money to community groups for activities such as protecting threatened and migratory species, addressing erosion and water quality, and cleaning up waste.

The first $100 million round was established before the 2019 election. In March 2020 it emerged in Senate Estimates that the vast majority had been pre-committed in election announcements. In other words, it was essentially a pork-barelling exercise.

The grants reportedly had no eligibility guidelines and were given largely to projects chosen and announced as campaign promises – and mostly in seats held or targeted by the Coalition.

Given this appalling precedent, the allocation of grants under the second round of the fund must be watched closely in the coming election campaign.

A Tricky Senate Bypass

Australia’s primary federal environment law is known as the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

Under provisions not used before, the need for EPBC Act approval of developments such as dams or mines can be switched off if the development complies with a so-called “bioregional plan”.

Bioregions are geographic areas that share landscape attributes, such as the semi-arid shrublands of the Pilbara.

In theory, bioregional plans deliver twin benefits. They remove the need for federal sign-off — a state approval will do the job – and so eliminate duplication. And national environmental interests are maintained, because state approvals must comply with the plans, which are backed by federal law.

But the government’s record strongly suggests it’s interested only in the first of these benefits.

Since the Samuel review was handed down, the government has largely sought only to remove so-called “green tape” – by streamlining environmental laws and reducing delays in project approvals.

Bills to advance these efforts have been stuck in the Senate. Now, the government has opted to fund bioregional plans which, as an existing mechanism, avoid Senate involvement.

Meanwhile, the government has barely acted on the myriad other problems Samuel identified in his review of the law, releasing only a detail-light “reform pathway”.

A Rod For The Government’s Back?

Ironically, bioregional plans may create more problems for the government than they solves.

First, the surveys needed to prepare the plans are likely to spotlight the regional manifestations of broad environmental problems, such as biodiversity loss.

And the EPBC Act invites the environment minister to respond to such problems in the resulting plans. This implies spelling out new investments or protections – challenging for the government given its low policy ambition.

The federal government would also need to find state or territory governments willing to align themselves with its environmental politics, as well as its policy.

Of the two Coalition state governments, New South Wales’ is significantly more green than the Morrison government, while Tasmania is not home to a major development push.

Western Australia’s Labor government has been keen to work with Morrison on streamlining approvals, but fudging environmental protections is another thing altogether. And Labor governments, with a traditionally more eco-conscious voter base, are particularly vulnerable to criticism from environment groups.

The government may fudge the bioregional plans so they look good on paper, but don’t pose too many hurdles for development. Such a fudge may be necessary to fulfil Morrison’s obligations to the Liberals’ coalition partner, the Nationals.

Tuesday’s budget contained more than $21 billion for regional development such as dams, roads and mines – presumably their reward for the Nationals’ support of the government’s net-zero target.

Bioregional plans containing strict environmental protections could constrain or even strangle some of these developments.

But on the other hand, the government may be vulnerable to court challenges if it seeks to push through bioregional plans containing only vague environmental protection.

For a government of limited environmental ambition bioregional plans represent more a political gamble than a reform.

Morrison has clearly rejected the safer option of asking Ley to bring forward a comprehensive response to the Samuel review, casting streamlining as part of a wider agenda.

Such a reform would have better Senate prospects and created room to negotiate.

Morrison could also have promised to reintroduce the streamlining bills after the election. But he must have concluded that the measure has no better chance of getting through the next Senate than this one.

What Price Fundamental Reform?

If the government successfully fudges bioregional plans, the result would be watered-down national environmental protections.

This would run completely counter to the key message of the Samuel review, that to shy away from fundamental law reforms:

“is to accept the continued decline of our iconic places and the extinction of our most threatened plants, animals and ecosystems”.

Clearly, good reform is too expensive — politically as well as fiscally — for this budget.![]()

Peter Burnett, Honorary Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

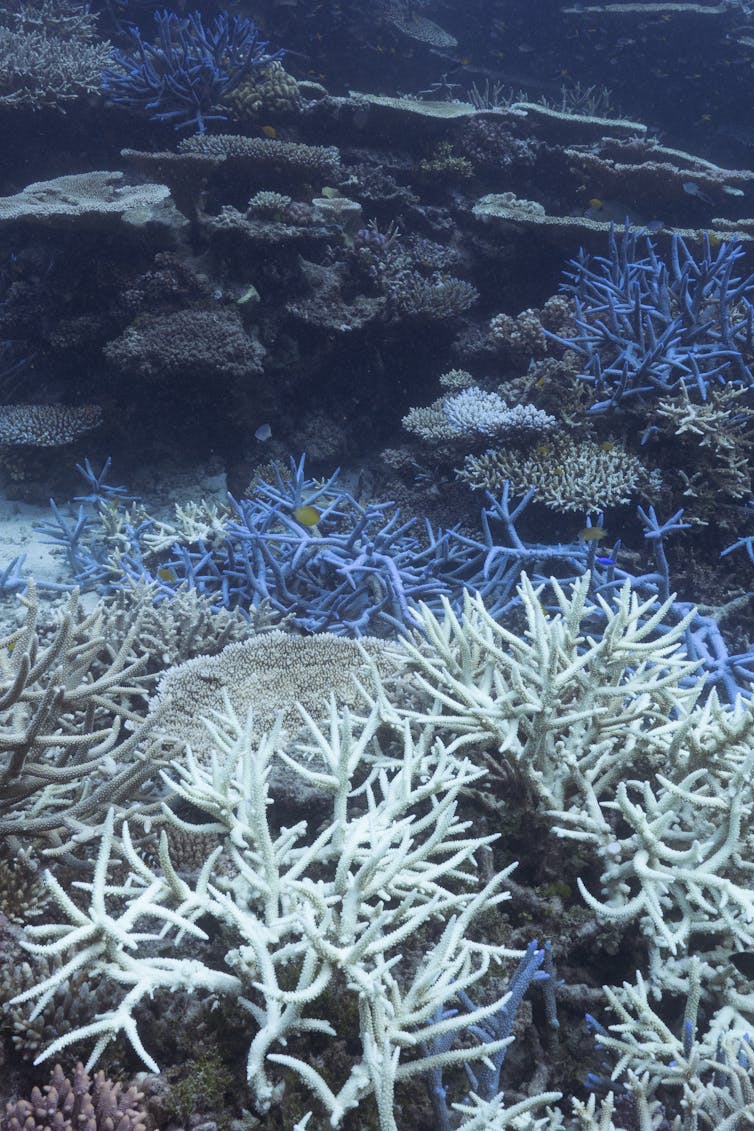

Another mass bleaching event is devastating the Great Barrier Reef. What will it take for coral to survive?

It’s official: the Great Barrier Reef is suffering its fourth mass bleaching event since 2016. We dived into the reef yesterday and saw the unfolding crisis firsthand.

Descending beneath the surface at John Brewer Reef near Townsville, our eyes were immediately drawn to the iridescent whites, blues and pinks of stressed corals among the deeper browns, reds and greens of healthier colonies.

It’s a depressing, but all-too-familiar feeling. A sense of: “here we go again”

This is the first time the reef has bleached under the cooling conditions of the natural La Niña weather pattern, which shows just how strong the long-term warming trend of climate change is. Despite the cooling conditions, 2021 was one of the hottest years on record.

When coral bleaches, it is not dead – yet. Coral reefs that suffer widespread bleaching can still recover if conditions improve, but it’s estimated to take up to 12 years. That is, if there’s no new disturbance in the meantime, such as a cyclone or another bleaching event.

So what conditions are needed for coral recovery? And under what conditions will coral die?

What It Takes For Coral To Die

Whether a coral can survive bleaching depends on how long conditions remain stressful, and to what level. What’s more, some species are more sensitive than others, such as branching acropora corals, especially if they’ve bleached previously.

If water remains too warm for too long, corals will eventually die. But if the water temperature drops and the ultraviolet light becomes less intense, then the coral may recover and survive.

While the average sea temperatures in the reef currently remain above average, they’ve shown signs of cooling to a more amenable average for coral survival.

Sea temperatures in Cleveland Bay, near Townsville, were above 31℃ in early March, but thankfully have now reduced to below 29℃. Similarly in the Whitsundays, Hardy Reef experienced temperatures as high as 30℃ but has receded to nearer 26℃ in the past few weeks.

If coral does survives a bleaching event, it is still impacted physiologically, as bleaching can slow growth rates and reduce reproductive capacity. Surviving colonies also become more susceptible to other challenges, such as disease.

Signs Of Stress

Survival also depends on each individual coral’s own resilience: its ability to cope with higher temperatures and increased ultraviolet stress.

For example, fast growing branching corals are the most susceptible to bleaching and are generally the first to die. Long-lived massive corals, such as porites, may be less susceptible to bleaching, show minimal effects of bleaching and recover quicker.

Corals can use fluorescent pigments to shield themselves from excessive ultraviolet radiation – a bit like sunscreen that lets coral manage, filter and attempt to regulate the incoming light.

To the casual observer, fluorescent corals look bright purple, pink, blue and yellow. For reef scientists, fluorescence is an obvious signal that corals are stressed and struggling to regulate their internal balance. As we’ve seen, white and fluorescent corals are currently a common sight on many reefs.

Most coral species have fluorescent pigments in their tissue. Some are always visible to humans, especially branching corals with bright blue or pink hues on the their branch tips.

Others are never visible, and some are visible only during times of heat stress when coral colonies boost these fluorescent pigments to fight the increasing ultraviolet intensity in warmer seas.

Coral Can’t Adapt Fast Enough

Scientists measure heat stress on corals using a metric called “degree heating weeks”.

One degree heating week is when the temperature at a given location is more than 1℃ over the historical maximum temperature. If the water is 2℃ above the historical maximum for one week, this would be considered two degree heating weeks.

Generally speaking, at four degree heating weeks, scientists expect to see signs of stress and coral bleaching. It usually takes eight degree heating weeks for coral to die.

According to Bureau of Meteorology data, many parts of the Great Barrier Reef, such as off Cairns and Port Douglas, currently remain in the window of between four and eight degree heating weeks. But some areas, near Townsville and the Whitsundays, are experiencing severe bleaching stress beyond eight degree heating weeks.

While we hope many coral reefs will recover from this round of bleaching, the long term implications cannot be understated.

When corals bleach, they eject their zooxanthellae – single-celled algae that gives coral colour and energy. Some corals may regain their zooxanthellae after the bleaching event is over, but this usually takes between three and six months.

To make matters worse, full reef recovery requires no new bleaching events or other disturbances in the years that follow. Given the reef has bleached six times since the late 1990s, alongside global climate trajectories, this would appear an unlikely scenario.

While some corals may learn to cope with these new conditions by potentially acquiring more heat-tolerant zooxanthellae, the reality is that change is happening too fast for coral to adapt via evolution.

The severe bleaching in previous years also means future events may appear less severe. But this is simply because most of the heat sensitive corals have already died, potentially resulting in a lower probability of widespread severe bleaching.

We Need Stronger Climate Policies And Action

Australia has the world’s best marine scientists and marine park managers. And yet, our policies are rated “highly insufficient”, according to the latest Climate Action Tracker.

If global emissions continue unabated, Australia may warm by 4℃ or more this century. Under this scenario, widespread coral bleaching is likely on the Great Barrier Reef every year from 2044 onward.

There has been some glimmers of hope in federal policy in recent years, such as statements recognising the existential threat climate change poses to coral reefs. Despite this recognition, substantial action is lacking, as any policy without action on climate change is ineffective.

If the federal government, reef businesses and individuals are to show leadership and maintain healthy reefs, we need to work together and take rapid, drastic action to reduce carbon emissions.

Committing to a stronger emissions target for 2030 and a carbon neutral footprint for all Great Barrier Reef businesses would go a long way to exhibiting the kind of change required if coral reefs, in their current form, are to survive into the future. ![]()

Adam Smith, Adjunct Associate Professor, James Cook University and Nathan Cook, Marine Scientist, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

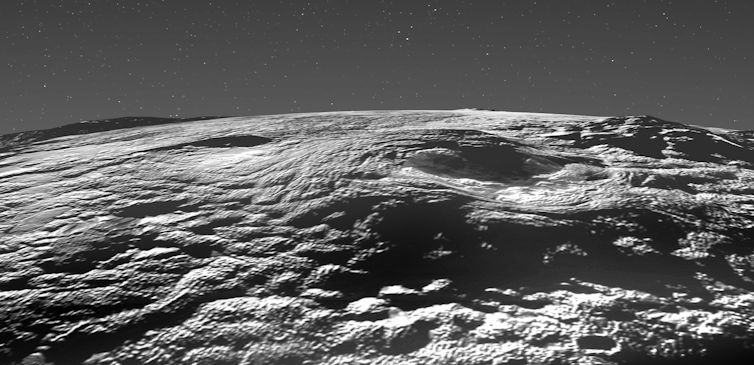

Conger ice shelf has collapsed: what you need to know, according to experts

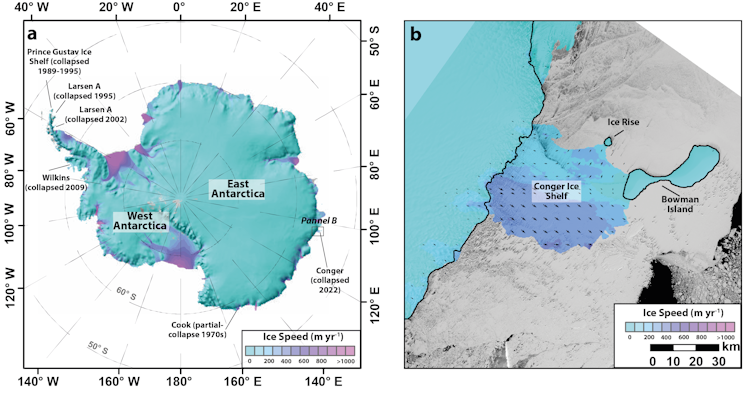

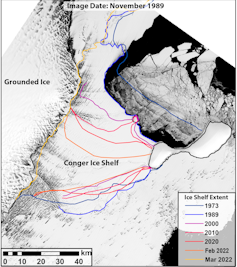

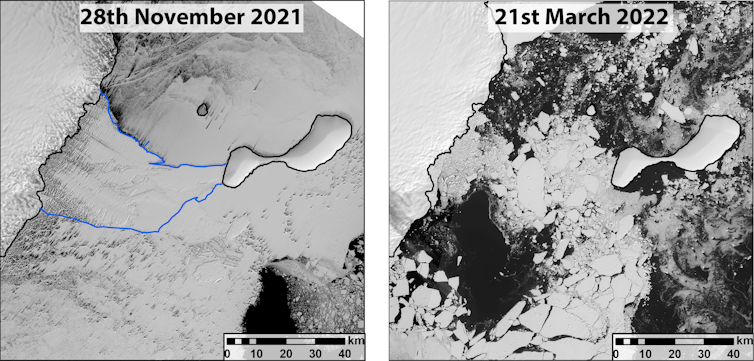

East Antarctica’s Conger ice shelf – a floating platform the size of Rome – broke off the continent on March 15, 2022. Since the beginning of satellite observations in the 1970s, the tip of the shelf had been disintegrating into icebergs in a series of what glaciologists call calving events.

Conger was already reduced to a 50km-long and 20km-wide strip attached to Antarctica’s vast continental ice sheet at one end and the ice-covered Bowman Island at the other. Two calving events on March 5 and 7 reduced it further, detaching it from Bowman and precipitating its final collapse a week later.

The world’s largest ice shelves fringe Antarctica, extending its ice sheet into the frigid Southern Ocean. Smaller ice shelves are found where continental ice meets the sea in Greenland, northern Canada and the Russian Arctic. By restraining how much the grounded ice flows upstream, they can control the loss of ice from the interior of the sheet into the ocean. When an ice shelf like Conger is lost, the grounded ice once kept behind the shelf may start to flow faster as the restraining force of the ice shelf is lost, resulting in more ice tumbling into the ocean.

What Caused The Collapse?

Ice shelves are sometimes referred to as the “safety band” of Antarctica because they buttress the upstream flow of ice from the bordering ice sheet. Little of the Antarctic ice sheet melts at its surface, where snow piles up. Instead, most of the continent loses ice through calving and melting along the underside of the floating ice shelves.

The breaking and detachment of parts of ice shelves is a natural process: ice shelves generally go through cycles of slow growth punctuated by isolated calving events. But in recent decades, scientists have seen several large ice shelves undergoing total disintegration.

Along the Antarctic Peninsula, the whip-like land mass which extends from the West Antarctic mainland, these include Prince Gustav ice shelf (from 1989 to 1995), Larsen A ice shelf (1995), Larsen B (2002), and Wilkins ice shelf (2008 to 2009). In East Antarctica, where Conger once was, Cook ice Shelf was partially lost in the 1970s. Taken together, this series of collapses suggests that some underlying environmental conditions, such as ocean and atmosphere temperatures, are changing.

It is too soon to say what triggered the collapse of the Conger ice shelf, but it appears unlikely to have been caused by melting at the surface – there are no indications of any ponds atop the ice shelf. The most recent sequence of events also preceded the record high air temperatures recorded in Antarctica on March 18.

What The Future Holds

As glaciologists, we see the impact of global warming on Antarctica in increasing ice loss with time. And what happens in Antarctica does not stay in Antarctica.

The consequences of the Conger ice shelf collapse are unlikely to be of global significance as the catchment area feeding ice into the former shelf is small. And due to its shape, the Conger ice shelf was most likely not a significant buttress to the flow of ice upstream.

But global warming is making events like this more likely. And as more and more ice shelves around Antarctica collapse, ice loss will increase, and with it global sea levels. There is enough ice in the West Antarctic ice sheet to raise sea levels by several meters, and if East Antarctica starts losing significant amounts of ice, the impact on sea levels could be measured in tens of meters.

Not everything that happens in nature is due to global warming alone. Antarctica loses mass through the discharge of icebergs and waxing and waning ice shelves as part of a natural cycle. But what we are seeing now, with the collapse of the Conger ice shelf and others, is the continuation of a worrying trend whereby Antarctic ice shelves undergo area-wide collapse one after another.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Hilmar Gudmundsson, Professor of Glaciology, Northumbria University, Newcastle; Adrian Jenkins, Professor of Ocean Science, Northumbria University, Newcastle, and Bertie Miles, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, Geosciences, University of Edinburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No, sunscreen chemicals are not bleaching the Great Barrier Reef

For the sixth time in the last 25 years, the Great Barrier Reef is bleaching. During bleaching events, people are quick to point the finger at different causes, including sunscreen.

Why sunscreen? Some active ingredients can wash off snorkelers and into the reef, contaminating the area. So could this be the cause of the Barrier Reef’s bleaching?

In a word, no. I reviewed the evidence for sunscreen as a risk to coral in my new research, and found that while chemicals in sunscreen pose a risk to corals under laboratory conditions, they are only found at very low levels in real world environments.

That means when coral bleaching does occur, it is more likely to be due to the marine heatwaves and increased water temperatures that have come with climate change, as well as land-based run-off.

Why Have We Been Concerned Over The Environmental Impact Of Sunscreens?

After we apply sunscreen, the active ingredients can leach from our skin into the water. When we shower after swimming, soaps and detergents can further strip the these sunscreen chemicals off and send them into our waste water systems. They pass through treatment facilities, which cannot effectively remove them, and end up in rivers and oceans.

It’s no surprise, then, that sunscreen contamination has been detected in freshwater and seas across the globe, from Switzerland to Brazil and Hong Kong. Contamination is highest in the summer months, consistent with when people are more likely to go swimming, and peaks in the hours after people have finished swimming.

Four years ago, the Pacific island nation of Palau made world headlines by announcing plans to ban all sunscreens that contain specific synthetic active ingredients due to concern over the risk they posed to corals. Similar bans have been announced by Hawaii, as well a number of other popular tourist areas in the Americas and Caribbean.

These bans are based on independent scientific studies and commissioned reports which have found contamination from specific active ingredients in sunscreen in the water at beaches, rivers and lakes.

Notably, the nations and regions which have banned these active ingredients, like Bonaire and Mexico, have local economies heavily reliant on summer tourism. For these areas, coral bleaching is not only an environmental catastrophe but an economic loss as well, if tourists choose to go elsewhere.

How Do We Know Sunscreen Isn’t The Issue?

So if contamination concerns over these active ingredients are warranted, how can we be sure they’re not the cause of the bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef?

Put simply, the concentrations of the chemicals are too low to cause the bleaching.

The synthetic ingredients used in most products are highly hydrophobic and lipophilic. That means they shun water and love fats, making them hard to dissolve in water. They’d much prefer to stay in the skin until they break down.

Because of this, the levels found in the environment are very low. How low? Think nanograms per litre (a nanogram is 0.000000001 grams) or micrograms per litre (a microgram is 0.00001 grams). Significantly higher levels are found only in waste water treatment sludge and some sediments, not in the water itself.

So how do we reconcile this with studies showing sunscreen can damage corals? Under laboratory conditions, many active ingredients in sunscreen have been found to damage corals as well as mussels, fish, small crustaceans, and plant-like organisms such as algae and phytoplankton.

The key phrase above is “under laboratory conditions”. While these studies would suggest sunscreens are a real threat to reefs, it’s important to know the context.

Studies like these are usually conducted under artificial conditions which can’t account for natural processes. They usually don’t account for the breakdown of the chemicals by sunlight or dilution through water flow and tides. These tests also use sunscreen concentrations up to thousands of times higher – milligrams per litre – compared to real world contamination levels found in collected samples.

In short, laboratory-only studies are not giving us a reliable indication of what happens to these chemicals in real world conditions.

If It’s Not Sunscreen, What Is It?

The greatest threats to the reef are climate change, coastal development, land-based run-off like pesticides, herbicides, and other pollutants, and direct human use like illegal fishing, according to a 2019 outlook report issued by the reef’s managing body.

Reefs get their striking colours from single-celled organisms called zooxanthellae which grow and live inside corals. Importantly, these organisms only grow under very specific conditions, including narrow bands of temperature and light levels. When conditions go outside the zooxanthellaes’ preferred zone, they die and the coral turns white.

As a result, the likeliest cause of this bleaching is climate change, which has increased ocean temperatures and acidity and resulted in more flooding, storms, and cyclones which block light and stir up the ocean floor.

So do you need to worry about the impact of your sunscreen on the environment? No. Sunscreen should remain a key part of our sun protection strategy, as a way to protect skin from UV damage, prevention skin cancers, and slow the visible signs of ageing. Our coral reefs face much bigger issues than sunscreen.![]()

Nial Wheate, Associate Professor of the Sydney Pharmacy School, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Roadside trees stitch the ecosystems of our nation together. Here’s why they’re in danger

You may know of marvellous tree-lined roads that lead into your favourite rural and regional towns. Sometimes they have an arched, church-like canopy, while others have narrow ribbons of remnant vegetation.

But have you noticed they’ve changed over the past decade? Some have gone, some have thinned and others are now declining. This is because in general, roads are not safe places for plants and their ecosystems.

There are the obvious dangers from collisions with cars. But there are also more subtle dangers from road construction and maintenance that increase the chances of plant (and animal) deaths, such as by altering the chemical and physical environment, which introduces weeds and segregates wildlife.

This network of vegetation reserves and corridors along Australian roads must be properly valued and better protected. They stitch the landscapes and ecosystems of our nation together and, as they diminish and disappear, will become an unrecognised part of road toll. We will all be the poorer for it.

Ecosystems Found On The Roadside

Roadside vegetation are often important corridors connecting wildlife to their habitats. In some cases, they are the last bastions of rare and endangered plant species. Indeed, some of the grass and smaller flowering species of Australia’s once extensive grassy plains only persist on roadside refuges in parts of Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia.

These corridors are also important habitats for smaller birds, mammals, insects and reptiles. They not only provide access to food and water sources, but allow breeding with a broader animal population.

For example, nine different mammal species have been recorded along the roadside of Victoria’s Strathbogie Ranges, including koalas, brushtail possums, gliders and phascogales.

Roads also increase water run-off and carry nutrients, which can allow a diversity of species to flourish on verges (nature strips). Plants that may not survive elsewhere get a toehold on edge of the bitumen using the precious extra resources it provides.

Australian road authorities often acknowledge the importance of these habitat corridors when roads are set to be upgraded or widened. But when it comes to the crunch, it’s the engineering and bottom line demands that generally win out – and plants invariably suffer.

This has an impact to cultural heritage, too. We saw this all too clearly in 2020 when a Djab Wurrung directions tree was bulldozed in Victoria for a new highway, despite valiant protest efforts.

Likewise, people rallied in Hong Kong to protect a significant banyan tree from removal from railway works. And the 300-year-old Bulleen river red gum, which won the National Trust’s Victorian Tree of the Year in 2019, awaits its fate in a major freeway project.

The Dangers Of Roads

Trees are supposed to be cleared according to codes of practice, such as the Australian Standard for Pruning Trees and the Australian Standard for Protecting Trees on Development Sites.

But based on my experiences over many years, when contractors breach one of these protections, there’s rarely enforcement or penalty.

For example, breaches can occur during powerline clearing across Australia, where old roadside trees can be decimated by losing much of their canopy. Trees may not survive such damage and if they do it will takes years for recovery.

Clearing roadside vegetation can occur on a monumental scale after bushfires. While burnt, dead trees may be dangerous and need to be removed or pruned, the clearing can far exceed the safety requirement.

Local communities have been left to lament the loss of their green and leafy road reserves from fires, as well as losses to the trees themselves from unnecessary clearing – it’s a double blow.

Herbicide is another very common, but rarely spoken of, cause of death for roadside trees and vegetation, with roadside verges routinely sprayed to reduce weeds encroaching onto the edges of roads and tarmac.

Herbicide spray can drift and kill non-target vegetation, such as crops on adjacent farms and even ancient remnant trees nearby. While such events have occurred in Australia, they are seldom reported and farmers are rarely successful in obtaining compensation for losses.

Vandalism is another major issue, with many local examples of street trees being poisoned, lopped or cut down, for instance, to secure prized coastal views.

This not only affects Australia. In 2012 thousands of roadside and rural trees were illegally poisoned or cut down in the United States by billboard advertisers. Similar advertising-related tree removals also occurred in India.

Love Your Trees

More of us should take stock of roadside trees: they are links to Australia’s past, refuges of once more widespread natural communities, and remain an important part of cultural heritage.

Importantly, they connect us to a future under climate change. We cannot possibly fight to mitigate global warming without urban trees. If we do not value them, it is inevitable that we will be lamenting an expanding list of endangered species and possible extinctions.![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Want to avoid a bluebottle sting? Here’s how to predict which beach they’ll land on

If you’re among the one in six Australians to experience the bitter pain of a marine stinger such as a bluebottle, you’ll know how quickly they can end a fun day at the beach.

We can’t stop the summer winds that deliver these creatures to our shores, but we can choose the safest spots to swim.

Our recent research provides the first evidence of what transports bluebottles to Australian beaches.

We found the direction a beach faces, relative to wind direction, largely determines how many bluebottles are pushed to shore. We hope these findings will help beachgoers safely plan where to take their next dip.

Delicate Ocean Drifters

The bluebottle is a jellyfish found mostly along Australia’s east coast.

Most bluebottle stings occur while swimming, and are the top reason people seek assistance from surf lifesavers.

Bluebottles aren’t a single animal. They’re a floating colony of individual organisms, each variously responsible for reproducing, capturing or digesting food and catching the wind.

The bluebottle’s long, trailing tentacles are designed to sting prey and creatures they feel threatened by, including humans.

Bluebottles do not swim, but drift on the ocean’s surface. Their inflated blue bladder is sensitive to aerodynamic forces and acts as a sail.

Currents drive a bluebottle’s long tentacles below the ocean’s surface and wind drives the sail above it.

The Bluebottle As A Sailboat

A bluebottle’s body, including the tentacles, is not aligned with its sail.

Some sails point to the left of the body, and others to the right. This quirk is thought to help populations survive.

If all bluebottle sails pointed the same way, an entire group might pick up a prevailing wind and be blown to shore. But when half the group has sails facing the other way, some individuals are blown in a different – and hopefully less perilous – direction.

Our previous research sought to shed light on bluebottle drift by examining physical equations that determine how sailboats respond to winds and currents.

That research found wind force can cause right-leaning bluebottles to drift around 50⁰ left of the downwind direction, while left-leaning individuals drift around 50⁰ to the right.

Choose Your Swimming Spot Wisely

Our latest research explored how winds and other environmental factors affect bluebottle beaching.

We analysed daily bluebottle numbers and stings at three Sydney beaches – Maroubra, Clovelly and Coogee – over four years. The project was led by Masters student Natacha Bourg.

Bluebottles numbers were highest during summer, peaking a few weeks before maximum ocean temperatures.

Cold temperatures have previously been thought to hinder bluebottle movements. But we recorded bluebottles on beaches in winter and spring, which suggests other factors are at play.

Our research found wind direction was the main factor driving bluebottles onshore. On Australia’s east coast, both northeast and southerly winds bring bluebottles towards the beach.

Crucially, we also found the shape of the coastline, and its orientation relative to prevailing winds, affects the rate of bluebottle arrivals.

Maroubra faces east and is the longest and most wind-exposed of the three beaches. We found a summer north-easterly wind at Maroubra led to a 24% chance of bluebottles the following day.

But at nearby Clovelly beach, the chance was just 4%. Clovelly faces south and sits relatively protected at the end of a narrow bay. However, after southerly winds, the chance of bluebottle encounter there increased to 12%.

Coogee faces south and is smaller than Maroubra. A small rocky outcrop limits exposure to the ocean and therefore exposure to bluebottles.

Overall, bluebottles were most likely to be found at Maroubra, followed by Coogee then Clovelly. This reflects their varying beach lengths and orientation with respect to prevailing winds.

Planning Your Day At The Beach

These conclusions can be applied beyond the beaches we studied. By checking beach orientation with wind direction, we can make an educated guess as to whether the chance of encountering bluebottles is high at any beach.

We know bluebottles are pushed around 50⁰ left or right of the wind direction. So a quick drawing in your head or on the sand may tell you which nearby beach is likely to be safest.

But there are exceptions to this rule. Strong ocean currents, for example, can influence bluebottle drift, especially when winds are weaker.

Rips and the circulation of water in surf zones are also linked to bluebottle beaching.

And bluebottles can extend and contract their sails and stinging tentacles which may change the direction of their drift.

So before entering the water, take plenty of precautions against bluebottles and other dangers. Surf Life Saving Australia urges all beachgoers to:

- stop and check your surroundings

- look for rips, large waves, rocks and other hazards

- plan to stay safe, including swimming at a patrolled location

- visit beachsafe.org.au.

Learning More

Further research is needed to better understand bluebottles, including how climate change, and subsequent warming oceans, will affect their drift.

Citizen science provides a powerful opportunity to learn about bluebottle distribution, size and arrival at our beaches.

Next time you see bluebottles at the beach, take photos and upload them to this project in the iNaturalist app.

In this way, you can help researchers discover more secrets of these beautiful marine creatures – which will hopefully lead to fewer painful bluebottle encounters.![]()

Amandine Schaeffer, Senior lecturer, UNSW Sydney and Jasmin C Lawes, Adjunct associate, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Indigenous peoples across the globe are uniquely equipped to deal with the climate crisis - so why are we being left out of these conversations?

Janine Mohamed; Pat Anderson, and Veronica Matthews, University of SydneyThe urgency of tackling climate change is even greater for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and other First Nation peoples across the globe. First Nations people will be disproportionately affected and are already experiencing existential threats from climate change.

The unfolding disaster in the Northern Rivers regions of New South Wales is no exception, with Aboriginal communities completely inundated or cut off from essential supplies.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have protected Country for millennia and have survived dramatic climatic shifts. We are intimately connected to Country, and our knowledge and cultural practices hold solutions to the climate crisis. Despite this, we continue to be excluded from leadership roles in climate solution discussions, such as the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report.

This continued exclusion is why investigation of the impacts of climate change on First Nations people is needed.

In October last year, the Lowitja Institute, in partnership with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander National Health Leadership Forum and the Climate and Health Alliance, brought together researchers, community members, young people and advocates from across the country at a round-table discussion.

Together, they put together the findings for the Discussion Paper Climate change and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health.

How Climate Change Impacts Indigenous Peoples

As the paper tells us, climate change threatens our social and cultural determinants of health, including access to Country, traditional foods, safe water, appropriate housing and health services.

Aboriginal health services are already struggling to operate in extreme weather, with increasing demands and a reduced workforce. All these forces combine to exacerbate already unacceptable levels of ill-health within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations and compound the historical and contemporary injustices of colonisation.

During the round table, we heard powerful and moving stories from communities on the front line of climate change.

Norman Frank Jupurrurla, a community leader from Tennant Creek, spoke of sacred waterholes drying up, ancient shade trees dying, temperatures rising, inadequate housing, power going out and spoiled essential food and medicines.

Vanessa Napaltjarri Davis, a Warlpiri/Northern Arrente woman and Senior Researcher at Tangentyere Council in Mparntwe/Alice Springs, spoke of changes to the availability of bush foods and medicines – essential to our health and well-being – due to changing temperatures and seasons.

For example, as Norman Frank Jupurrurla wrote:

…now the country is burning, getting destroyed, because of climate change. Already, I cannot see sand goannas any more.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples hold a deep and painful knowledge of the role dominant culture, racism and colonial power dynamics play within climate change. Although there have been many suggested solutions to climate change, access to these solutions is not equally or equitably available across Australia.

Norman Frank Jupurrurla demonstrated this when he shared the almost impossibly drawn-out process he has completed to become the first person to install solar panels on public housing in Tennant Creek, Northern Territory.

Indigenous Peoples’ Voices Excluded From Climate Change Conversations

Colonisation has ignored Indigenous ways of knowing, doing and being, right down to the weather. Colonisers insisted we live according to just four seasons, instead of the many seasons our people knew and respected.

This experience of marginalisation continues today where we have not been sufficiently included in national and international conversations about climate change, including being pushed to the sidelines at COP26.

The IPCC acknowledged this globally in its report last year. The report states that data and most reporting on climate change do not include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander or local knowledge in the assessment findings.

The IPCC’s most recent report looks to recognise this omission and focuses specifically on the importance of our role and knowledge in addressing the climate crisis and the need for climate justice.

The calls from our work are clear. We must elevate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices within climate change action and centre Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as leaders in protecting Country. In the words of Seed Mob, “We cannot have climate justice without First Nations justice.”

In seeking solutions, we must consider how colonial ideologies and practices around climate change can impact on our peoples. As Rhys Jones wrote, “It is not possible to understand and address climate-related health impacts for Indigenous peoples without examining this broader context of colonial oppression, marginalisation and dispossession.”

The Uluru Statement from the Heart, a gift to the Australian People, provides the road map for action:

We must correct power asymmetries and establish co-governance arrangements and become strong advocates of, not only our interests, but our capabilities to tackle climate change.

We must restore access to basic rights that will lay the groundwork for action that includes appropriate community participation/decision-making and incorporates cultural, environmental and sustainable design.

We must weave our knowledges and strengthen partnerships to ensure that our collective wisdom and knowledge as Australia’s First Nations is integrated into climate adaptation and mitigation planning, directly benefitting the whole nation.

Indigenous people know about this continent; we’ve looked after it for millennia.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart gives the opportunity to restore that ancient power – for the benefit of us all and the survival of the planet.![]()

Janine Mohamed, Distinguished Fellow and CEO; Pat Anderson, Chairperson, and Veronica Matthews, Senior Research Fellow, The University Centre for Rural Health, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

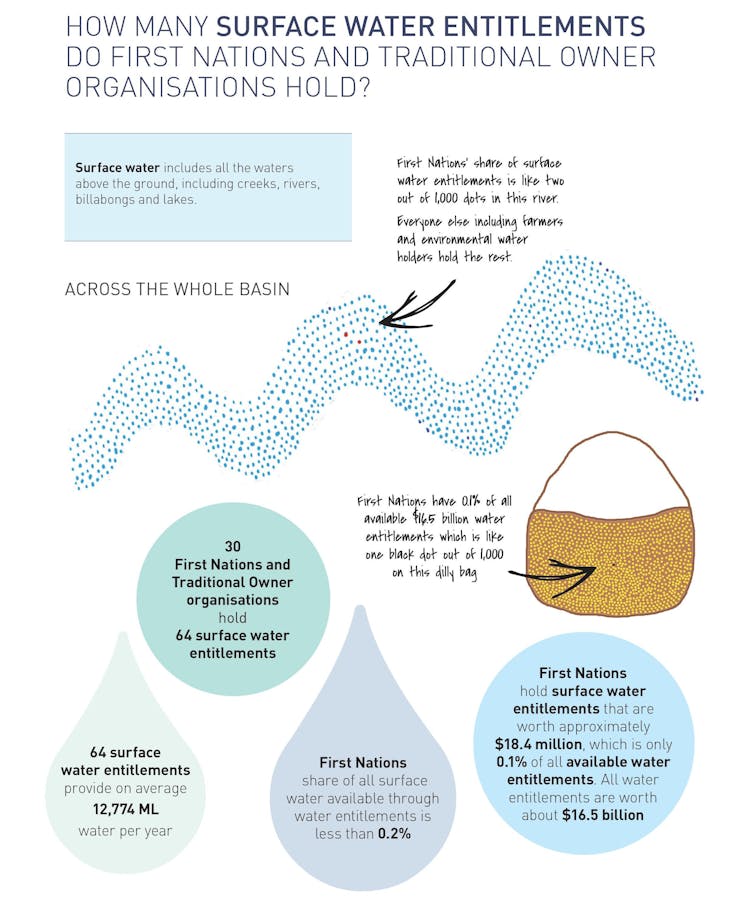

Terra nullius has been overturned. Now we must reverse aqua nullius and return water rights to First Nations people

Terra nullius has been overturned. Now we must reverse aqua nullius and return water rights to Traditional Owners.

In recent decades, important progress has been made on land rights for Traditional Owners, with more than 50% of Australia under some form of Indigenous title (including non-exclusive native title). But until now, we’ve had much less progress on water rights.

For millennia, Indigenous Australians maintained all water in Australia. After European colonisation, the rights to water were stolen. Almost none of it has come back. Where did the rest of the water go? Overwhelmingly, to settlers who used them to expand their agricultural interests.

Victoria has now begun to return water to Traditional Owners. Last week, the government returned 2.5 gigalitres (GL) to Gunditj Mirring in Victoria’s south-west. Earlier this year, 1.36GL was set aside for Traditional Owners in northern Victoria, and in late 2020, 2GL from the Mitchell River was returned to Gurnaikurnai in Gippsland. While welcome, this is only a start.

Victoria’s recent returns make it the leader in the eastern states, but competition is scarce. To date, there have been no tangible water handbacks in New South Wales and Queensland.

Why Are Water Rights So Important?

Water rights go well beyond commercial and economic gains. For First Nations people, water and the health of waterways are fundamental to health and well-being, including reviving cultural flows, improving physical health, restoring connection to spirit and culture, aiding self-determination, and making it possible to care for Country.

Land is important. But Australia is a dry country, and without water, there is no life. For instance, before colonisation, Gunditjmara in south-western Victoria created one of the world’s oldest and most extensive aquaculture systems to farm short-finned eels. The Budj Bim complex is now UNESCO-listed.

Most Australians are aware of terra nullius, the legal fiction that Australia belonged to no one before European settlement.

But very few know about aqua nullius, a similar fiction suggesting Traditional Owners had no rights to the water they had used for millennia.

To challenge this, First Nations people have long called for redistribution of water, particularly in the Murray-Darling Basin.

Since European colonisation, there have been vanishingly few opportunities for Indigenous communities in Australia to advance and strengthen their economies. It is vital that we recognise the central role played by aqua nullius and the long history of colonial resource rationing in stymieing Indigenous enterprise.

These first allocations are welcome. But they cannot be an afterthought. Without more, the Victorian government could recreate the water version of the rations regime of government-controlled food distribution Indigenous Australians lived with until the 1960s.

For decades, Indigenous Australians were not permitted to have a voice in how our nation’s water is allocated and used.

While these recent water returns in Victoria are vital first steps, the volumes of water are still too small to underpin the restorative justice approach needed for the environment and Aboriginal peoples.

Tinkering Around The Edges

In the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia’s most important agricultural catchment, just 0.2% of all surface water entitlements are owned by Aboriginal organisations, and 0.02% of all available groundwater.

Of this tiny fraction, the majority is low reliability. That means Aboriginal people are unlikely to get access to their water at all unless it has been a particularly wet year.

Four years ago, the federal government announced A$40 million to buy water rights for Traditional Owners in the Murray-Darling Basin. Not a dollar has been spent.

In New South Wales, unused water rights across 55 different sources have recently been listed for sale. Not one of these was returned to Traditional Owners.

In the Northern Territory, delays in water allocation planning processes continue to limit access to the Aboriginal Water Reserve – the policy that is supposed to provide Aboriginal people in the NT access to water resources and opportunities for economic development. New laws could make this problem even worse.

Handing Out Water Rights: A New Form Of Rations?

Colonisation of Australia resulted in Europeans gaining control over Aboriginal populations and the resources they relied on. This had a devastating effect on Aboriginal access to traditional resources. From the 19th century until the mid-20th century, Europeans introduced a regime of government distributed rations for Indigenous Australians.

As a result, First Nations peoples were rewritten, both in law and in society, as landless people trespassing on Country once their own.

Given this history, you can see why First Nations groups might be sceptical about these recent handbacks. While the announcements sound good, they represent a very small volume of overall water flows.

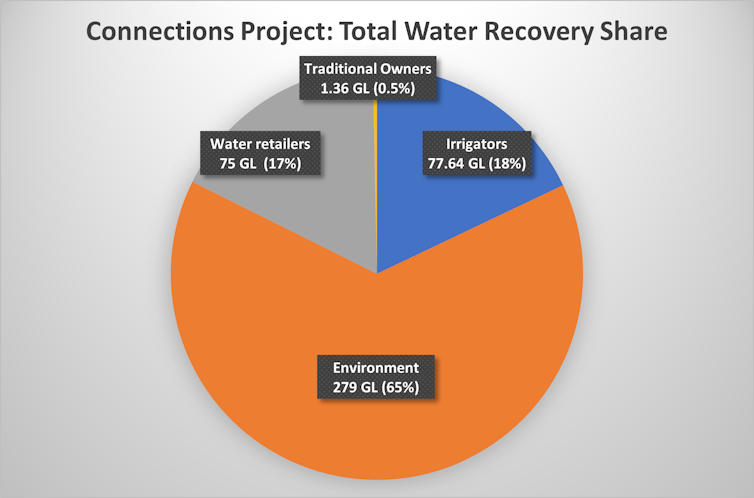

Take the recent announcement of 1.36GL set aside for Traditional Owners in Northern Victoria. Where did this water come from? From an extra 4GL of water recovered from the Connections irrigation modernisation project. While that sounds laudable, the allocation for Indigenous use represents just 0.5% of the total volume of water (433GL) recovered from this 12-year project.

What would real progress look like? Over in Western Australia, a major 2020 Indigenous land use agreement in the Geraldton region included rights to around 17% of the available water.

So while Victoria’s recent announcements are a step in the right direction, we cannot help but point out that they reinforce longstanding inequality by giving agricultural interests, who already hold vast land and water entitlements, even more water. By contrast, Victoria’s Aboriginal nations, who have barely any land and water, must divide up these miniscule offerings.

Overturning Aqua Nullius Requires Much More

We now have clear pathways for the return of water in ways which adequately tackle the staggering and ongoing injustice of aqua nullius.

To achieve water justice, we would have to see significant transfers of power and agency in water governance.

There are positive signs. The Victoria government is working with Traditional Owners on a new roadmap for Indigenous access to water. Advocacy groups are helping tailor the shift of water management functions to each Indigenous nation to match their capacity.

These recent handbacks are only the start of what’s needed. In the ongoing quest for self-determination, water is key. If governments are serious about tackling the harm caused by the forced takeover of Indigenous waters and lands, we need more significant transfers of power, agency, and water.![]()

Melissa Kennedy, Research Fellow - Participatory research and engagement, The University of Melbourne; Brendan Kennedy, Enterprise Principle Fellow in Cultural Economies and Sustainability, The University of Melbourne, and Sangeetha Chandrashekeran, Senior Research Fellow, Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Others

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham's Beach

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods