Inbox and environment news: Issue 534

April 10 - 23, 2022: Issue 534

Barrenjoey Headland Amenities Concept Plan

- the building will be set into the landscape, concealed by the landform and native heath

- screened walls to the front of the building will allow for natural light and ventilation

- timber screens will be left to grey with alternating painted battens to reference the colours of the surrounding natural landscape and heritage buildings

- unisex cubicles will be provided, including baby change facilities and a water refill station

- water supply and sewer infrastructure to service these amenities are already in place.

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek

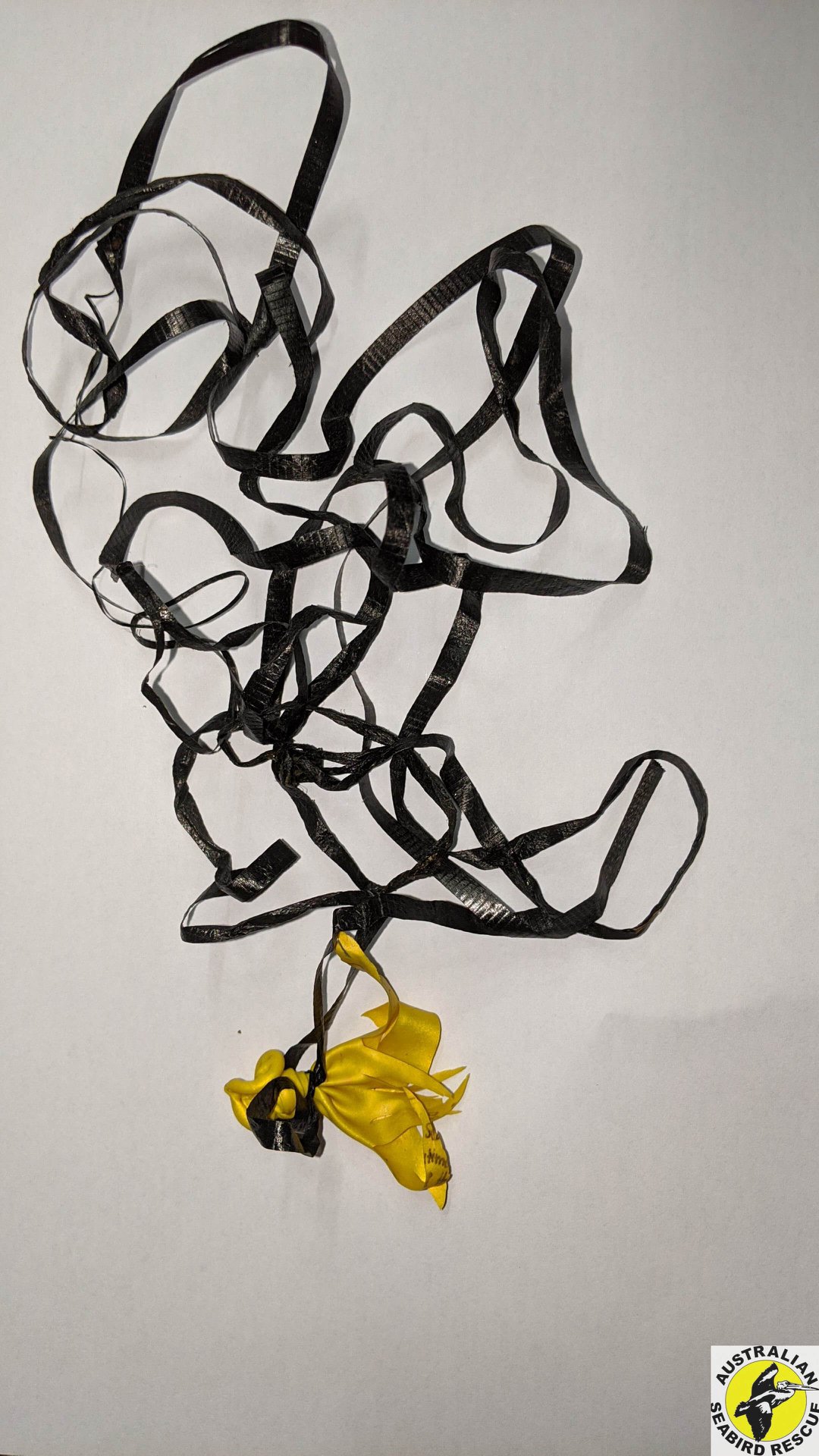

Ban The Release Of Balloons In NSW Petition

Ella: Green Turtle Rescued From Manly

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Long Reef Fishcare Free Guided Walks

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Autumn 2022 Newsletter

Cassia Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Rule Change For Emissions Reduction Fund: To Prevent Native Forest Regeneration Projects

- human-induced regeneration

- native forest from managed regrowth.

Proposed Changes To Rules For Generator Closures

Federal Coal Closure Changes No Substitute For Real Roadmap

Air Pollution Inches Lower As Clean Energy Begins To Replace Coal Power In NSW

- 101,000 tonnes of nitrogen oxides;

- 147,000 tonnes of sulphur dioxide;

- 543 tonnes of fine particles (PM2.5); and

- 184 kg of mercury.

Government Loan Enables Development Of Australia’s Rare Earths Refinery

- $239 million in loans to EcoGraf Ltd and Renascor Resources through the Critical Minerals Facility

- $243 million in grant funding to four critical minerals projects under the Modern Manufacturing Initiative

- the $200 million Accelerator Initiative grants program

- a $140 million loan to Hastings Technology Metals Ltd under the Northern Australian Infrastructure Facility

- $50 million for the establishment of a virtual National Critical Minerals Research and Development Centre.

Critical Minerals Accelerator Initiative Guidelines: Have Your Say

ARENA Board Appointments

Approvals Another Significant Step In Woodside's Scarborough Joint Venture

Production Licence Moves Santos Dorado Oil Project Forward

Gippsland Area Announced As Priority For Australia’s First Offshore Wind Assessment

- the environment, such as marine life and migratory birds

- existing maritime infrastructure and industries such as fishing shipping

- other marine stakeholders and local communities.

- serves to secure affordable energy

- creates jobs and investment

- increases economic growth of regional and coastal economies.

Tidal Wave Of Alarm For Tassie Oceans Amid Landmark Marine Law Review: Research

- More than three in four Braddon voters (76%) are concerned that Tasmania’s ocean is under pressure from climate change, pollution, and fishing and support the government taking action to make sure it stays healthy for future generations

- Majority of Braddon voters (63%) agree that the expansion of salmon farms around Tasmania should be suspended until current government inquiries are completed and their recommendations implemented

- Almost 7 in 10 (67%) agree the Federal Government should match Tasmania by setting a net-zero by 2030 emissions target

- Federal seat of Braddon 2PP: Labor 53%, Liberal 47%

- Eight out of 19 (42%) of Tasmania’s assessed commercial fish stocks are classified as having depleted or currently depleting stocks.

- Overfishing of rock lobsters allowed historic lows of less than 10% of natural levels in 2011-12. Stocks are now rebuilding and assessed as sustainable, despite some areas with less than 20% of their natural population levels at the latest stock assessment.

- The Act does not address climate change or include the precautionary principle, which prevents scientific uncertainty being used to delay environmental protection measures.

- Centrostephanus urchin barrens, which decimate rocky reefs, now cover over 15% of east coast reefs, impacting commercially and recreationally important habitats.

- Establishing an overarching legal framework for coordinated management that takes into account the needs of the environment to remain healthy. This includes consideration of current and future uses of Tasmania’s coastal waters for all uses, users and values.

- Use multi-sector marine spatial planning to implement this approach.

- Appropriate recognition of the rights of First Nations Tasmanians should be developed through direct engagement.

- An economic return should be paid to the community for the private use of public resources.

- Set precautionary fish stock targets to retain 48% of natural populations for Tasmanian fisheries.

National Koala Recovery Plan Released

$5 Million In Community Grants To Help Koalas

- improve the extent, quality and connectivity of Koala habitat and reduce local threats

- increase understanding and management of disease and injury affecting Koala health and lift capability in on-ground care, treatment and triage of koalas, and

- improve data and knowledge of Koala populations and health across their range, to support effective decision making and conservation action.

Devastating Floods Reinforce Need For Urgent Action On Climate Change AMA States

Another day, another flood: preparing for more climate disasters means taking more personal responsibility for risk

Celeste Young, Victoria University and Roger Jones, Victoria UniversitySydney is bracing for flash floods and landslides as the city yet again endures a disastrous downpour, with a month’s worth of rain falling in just 24 hours and evacuation orders issued. The rain is forecast to continue all week.

Communities in New South Wales have endured one disaster after another. As exhausted residents in Lismore began cleaning up from the record-breaking flood in late February, a second flood inundated the city. Indeed, some flood-damaged towns this year were previously in the path of the Black Summer bushfires.

Climate change is making disasters more frequent and severe, so how should we be preparing for these inevitable events?

As our latest research shows, a key aspect of pre-disaster preparation is that people accept and understand what risks they face and how they’ll be impacted. Stocking up on toilet paper in preparation for COVID lockdowns is an example of what happens when they don’t.

Meeting New Challenges

One of the lasting mantras in disaster risk management is “hope for the best, anticipate the worst”. But what happens when the worst-case scenario is realised – or even exceeded?

During the Black Summer bushfires in 2019, Rural Fire Service Commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons said:

We cannot guarantee a fire truck at every home. We cannot guarantee an aircraft will be overhead every time a fire is impacting on your property. We cannot guarantee that someone will knock on the door and give you a warning that there’s fires nearby.

What’s more, the recent NSW floods saw local communities instigate their own rescue operations, with boat or a jet ski owners pulling stranded survivors from inundated homes.

Being prepared at the individual, household and local community level is essential. Emergency management and support agencies such as hospitals are becoming overwhelmed by the unprecedented scales of recent disasters.

First, this is because many emergency workers who respond to earthquakes, cyclones, floods, fires, and storms are volunteers. Second, some events such as the pandemic are unbudgeted and exceptional, so agencies need additional resources.

Third, a disaster is, by definition, an event that exceeds the capacity to respond, making “disaster response” a paradox.

It is unreasonable to expect people to cope with all disasters – but it is reasonable to expect people to manage a certain level of risk. So how much responsibility should fall on the individual, and how much needs to be shared across governments, industry, agencies, and throughout the community?

72 Hours Are Crucial

For those directly affected, the 72 hours surrounding the event can be the most important. This spans the time between early warning, onset, and the immediate responses that may involve defence, evacuation or rescue.

In the United States, you’re encouraged to be prepared to cope for 72 hours in a disaster. We are beginning to see this encouraged in Australia along with greater acknowledgement of personal responsibility for risk.

Local disaster agencies in Australia are promoting lists of essentials to keep on hand, including first-aid kits, medications, and enough food and water for three days.

People are also encouraged to prepare psychologically, and rehearsing survival plans has been found to be especially useful with children. And emergency management agencies and community groups provide guidance for those with a disability, non-English speakers, and people with pets and other domestic animals.

Still, information does not always guarantee preparation. Our research surveyed bushfire-hit residents in East Gippsland following the Black Summer fires. We found people new to an area were less likely to be prepared or understand how to respond to risks.

They were also more likely to have unrealistic expectations about how long and demanding the recovery process was. Some people from non-English speaking backgrounds were isolated within their communities and did not know where to access information.

Owning Your Risk

Our Risk Ownership Framework allows communities and the public and private sector to unpack the complex connections of shared risk ownership. We explore the questions “who owns a risk?” and “how do they own it?”

We learned that if one area is unable to manage their risk, then it can increase or transfer to another person or entity.

For example, a homeowner may be responsible for home and contents insurance, while a community is responsible for maintaining social connectivity. Likewise, local government may own and maintain flood levees, while state government regulates the planning for them.

We also explored the concept of “unowned” risks – where roles and responsibilities in disasters are unallocated or unfulfilled. These can impact important community values such as liveability, local businesses (such as tourism) and natural resources.

Unowned risks raises difficult questions such as:

will the forests and wildlife recover and if so, how long will this take?

will displaced residents return to their communities, or will housing availability and affordability force them out?

will communities, such as Lismore, remain viable in the face of future disasters under climate change?

These questions often get passed over in favour of more immediate needs.

The escalation and breadth of disasters these last two years has left communities with barely enough time to recover before the next one arrives. We need to start negotiating how to prepare for the unexpected and what follows.

The mantra of community resilience and empowerment is now a central narrative, but recent events show there’s a pivotal role for government that cannot be neglected if we’re to survive future disasters.

We need a national conversation on what risk ownership for disaster means – personally and politically. ![]()

Celeste Young, Collaborative Research Fellow, Sustainable Industries and Liveable Cities (ISILC), Victoria University and Roger Jones, Professorial Research Fellow, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

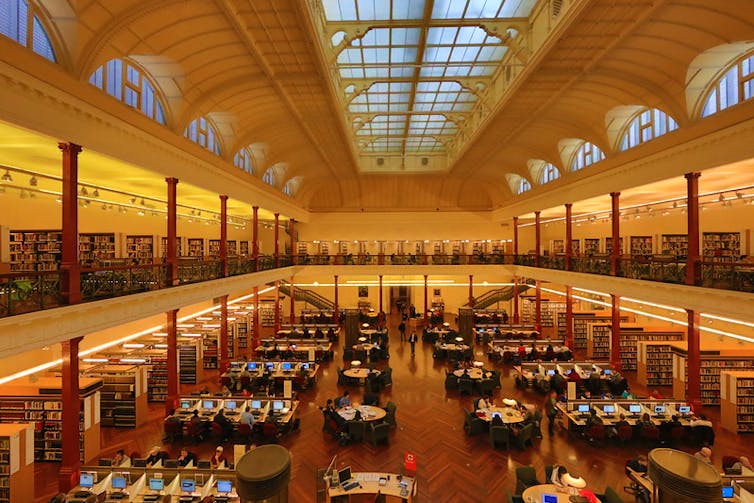

World-Class Herbarium Unveiled

In the midst of climate change, habitat loss and the extinction crisis, Australian scientists are more motivated than ever to ensure plant species are conserved, which is vital to all life that depends on them - ROB STOKES, MINISTER FOR INFRASTRUCTURE, CITIES AND ACTIVE TRANSPORT

Australia Has A Critical Role In Tackling Climate Change

On top of drastic emissions cuts, IPCC finds large-scale CO₂ removal from air will be “essential” to meeting targets

Large-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods is now “unavoidable” if the world is to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, according to this week’s report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The report, released on Monday, finds that in addition to rapid and deep reductions in greenhouse emissions, CO₂ removal is “an essential element of scenarios that limit warming to 1.5℃ or likely below 2℃ by 2100”.

CDR refers to a suite of activities that lower the concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere. This is done by removing CO₂ molecules and storing the carbon in plants, trees, soil, geological reservoirs, ocean reservoirs or products derived from CO₂.

As the IPCC notes, each mechanism is complex, and has advantages and pitfalls. Much work is needed to ensure CDR projects are rolled out responsibly.

How Does CDR Work?

CDR is distinct from “carbon capture”, which involves catching CO₂ at the source, such as a coal-fired power plant or steel mill, before it reaches the atmosphere.

There are several ways to remove CO₂ from the air. They include:

terrestrial solutions, such as planting trees and adopting regenerative soil practices, such as low or no-till agriculture and cover cropping, which limit soil disturbances that can oxidise soil carbon and release CO₂.

geochemical approaches that store CO₂ as a solid mineral carbonate in rocks. In a process known as “enhanced mineral weathering”, rocks such as limestone and olivine can be finely ground to increase their surface area and enhance a naturally occurring process whereby minerals rich in calcium and magnesium react with CO₂ to form a stable mineral carbonate.

chemical solutions such as direct air capture that use engineered filters to remove CO₂ molecules from air. The captured CO₂ can then be injected deep underground into saline aquifers and basaltic rock formations for durable sequestration.

ocean-based solutions, such as enhanced alkalinity. This involves directly adding alkaline materials to the environment, or electrochemically processing seawater. But these methods need to be further researched before being deployed.

Where Is It Being Used Right Now?

To date, US-based company Charm Industrial has delivered 5,000 tonnes of CDR, which is the the largest volume thus far. This is equivalent to the emissions produced by about 1,000 cars in a year.

There are also several plans for larger-scale direct air capture facilities. In September, 2021, Climeworks opened a facility in Iceland with a 4,000 tonne per annum capacity for CO₂ removal. And in the US, the Biden Administration has allocated US$3.5 billion to build four separate direct air capture hubs, each with the capacity to remove at least one million tonnes of CO₂ per year.

However, a previous IPCC report estimated that to limit global warming to 1.5℃, between 100 billion and one trillion tonnes of CO₂ must be removed from the atmosphere this century. So while these projects represent a massive scale-up, they are still a drop in the ocean compared with what is required.

In Australia, Southern Green Gas and Corporate Carbon are developing one of the country’s first direct air capture projects. This is being done in conjunction with University of Sydney researchers, ourselves included.

In this system, fans push atmospheric air over finely tuned filters made from molecular adsorbents, which can remove CO₂ molecules from the air. The captured CO₂ can then be injected deep underground, where it can remain for thousands of years.

Opportunities

It is important to stress CDR is not a replacement for emissions reductions. However, it can supplement these efforts. The IPCC has outlined three ways this might be done.

In the short term, CDR could help reduce net CO₂ emissions. This is crucial if we are to limit warming below critical temperature thresholds.

In the medium term, it could help balance out emissions from sectors such as agriculture, aviation, shipping and industrial manufacturing, where straightforward zero-emission alternatives don’t yet exist.

In the long term, CDR could potentially remove large amounts of historical emissions, stabilising atmospheric CO₂ and eventually bringing it back down to pre-industrial levels.

The IPCC’s latest report has estimated the technological readiness levels, costs, scale-up potential, risk and impacts, co-benefits and trade-offs for 12 different forms of CDR. This provides an updated perspective on several forms of CDR that were lesser explored in previous reports.

It estimates each tonne of CO₂ retrieved through direct air capture will cost US$84–386, and that there is the feasible potential to remove between 5 billion and 40 billion tonnes annually.

Concerns And Challenges

Each CDR method is complex and unique, and no solution is perfect. As deployment grows, a number of concerns must be addressed.

First, the IPCC notes scaling up CDR must not detract from efforts to dramatically reduce emissions. They write that “CDR cannot serve as a substitute for deep emissions reductions but can fulfil multiple complementary roles”.

If not done properly, CDR projects could potentially compete with agriculture for land or introduce non-native plants and trees. As the IPCC notes, care must be taken to ensure the technology does not negatively affect biodiversity, land-use or food security.

The IPCC also notes some CDR methods are energy-intensive, or could consume renewable energy needed to decarbonise other activities.

It expressed concern CDR might also exacerbate water scarcity and make Earth reflect less sunlight, such as in cases of large-scale reforestation.

Given the portfolio of required solutions, each form of CDR might work best in different locations. So being thoughtful about placement can ensure crops and trees are planted where they won’t dramatically alter the Earth’s reflectivity, or use too much water.

Direct air capture systems can be placed in remote locations that have easy access to off-grid renewable energy, and where they won’t compete with agriculture or forests.

Finally, deploying long-duration CDR solutions can be quite expensive – far more so than short-duration solutions such as planting trees and altering soil. This has hampered CDR’s commercial viability thus far.

But costs are likely to decline, as they have for many other technologies including solar, wind and lithium-ion batteries. The trajectory at which CDR costs decline will vary between the technologies.

Future Efforts

Looking forward, the IPCC recommends accelerated research, development and demonstration, and targeted incentives to increase the scale of CDR projects. It also emphasises the need for improved measurement, reporting and verification methods for carbon storage.

More work is needed to ensure CDR projects are deployed responsibly. CDR deployment must involve communities, policymakers, scientists and entrepreneurs to ensure it’s done in an environmentally, ethically and socially responsible way.![]()

Sam Wenger, PhD Student, University of Sydney and Deanna D'Alessandro, Professor & ARC Future Fellow, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Time’s up: why Australia has to quit stalling and wean itself off fossil fuels

If the world acts now, we can avoid the worst outcomes of climate change without any significant effect on standards of living. That’s a key message from the new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The key phrase here is “acts now”. Jim Skea, co-chair of the IPCC working group behind the report, said it’s “now or never” to keep global warming to 1.5℃. Action means cutting emissions from fossil fuel use rapidly and hard. Global emissions must peak within three years to have any chance of keeping warming below 1.5℃.

Unfortunately, Australia is not behaving as if the largest issue facing us is urgent – in fact, we’re doubling down on fossil fuels.

In recent years, Australia overtook Qatar to become the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG). We’re still the second-largest exporter of thermal coal, and the largest for metallurgical coal.

Time’s up, Australia. We have to talk about weaning ourselves off fossil fuels and exporting our wealth of clean alternatives.

Why Can’t Australia Keep Selling Fossil Fuels During The Transition?

You might think: “Sure, Australia needs to transition. But it will take decades for the world to rid itself of fossil fuels. Why can’t we keep selling gas and coal in the meantime?”

Because we’re out of time. As the report states, “if existing fossil fuel infrastructure … continue to be operated as historically, they would entail CO₂ emissions exceeding the carbon budget for 1.5°℃”.

And US climatologist Michael Mann recently pointed out, if you were going to pick the worst continent to live on as the climate changes, it would be Australia. We are “a poster child for what the rest of the world will be dealing with,” he said.

Urgent action is needed to avoid the devastation and vast expense of unchecked climate change, recently estimated at close to 40% of global GDP by 2100.

We need to accelerate the shift, with much faster greening of electricity supply, electrification of transport, improvement of industrial processes and management of land use and food production. Luckily, the technologies needed to achieve this goal have already been developed and are mostly already competitive with carbon-emitting alternatives.

The economic costs of the transition would be marginal. The required investment in clean energy would be around 2.5% of GDP. That’s far less than the costs of allowing global heating to continue, with costs further offset by clean energy’s zero fuel costs and lower operating costs.

What Are Australia’s Prospects For Weaning Off The Fossil Fuel Teat?

Are we seeing signs of the urgency of the situation? If you look at the election platforms of Australia’s major political parties, we are still falling far short.

After nine years in office, the Liberal government has reluctantly set a goal of net zero emissions by 2050, but has offered little more than wishful thinking as a policy response.

Last week’s budget projected funding cuts of as much as 35% for Australia’s clean energy finance and renewable energy initiatives.

By far the biggest shortcoming is the failure to plan for the transition. Despite calls for coal and gas workers to be given an honest assessment of their position, both Liberal and Labor sustain the illusion that coal and gas have a long-term future.

Labor has put forward worthwhile initiatives such as the Rewiring the Nation program aimed at supporting private investment to modernise the grid and make it ready for high levels of renewable energy.

But the opposition’s main concern has been to avoid any policy that leaves it open to attack from the Coalition and the Murdoch press. You can see this in Labor leader Anthony Albanese’s repeated declaration that “the climate wars are over”.

That means, in 2022, we are facing an election campaign in which neither major party has put up serious ideas to cut emissions. There’s no mention of a price on carbon or an emissions trading scheme, no real action on land clearing, and no expansion of the government’s safeguard mechanism, meant to provide incentives for large industries to cut emissions relative to a baseline.

Lagging On Transport

The plunging cost of renewable energy is one of the bright spots in the fight against climate change. Cost alone is driving out coal and gas from the power sector.

The pace of transition is much slower in areas such as transport, which the IPCC report notes had excellent prospects of cutting emissions.

“Electric vehicles powered by low-emissions electricity offer the largest decarbonisation potential for land-based transport,” the report says.

In Australia, our failures on transport are palpable. To reach net zero by 2050, we have to move to an all-electric vehicle fleet. Given cars last 20 years on average, almost all new vehicles must be electric by 2030.

By contrast to almost all developed countries, Australia doesn’t have a fuel efficiency target, or plans to end new sales of petrol vehicles. The government has no proposal to address this, while Labor offers a minor tax concession on electric vehicles and a fuel efficiency information website.

Bizarrely, these baby steps sit in stark contrast to the bipartisan rush to shield petrol users from rising prices in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine.

We’ve Stalled Long Enough

We’ve run out of time to deal with the problem of global heating. We cannot afford another three years of inaction.

What would it look like if Australia’s next government realises the urgency? It would begin by ending all new investment in fossil fuel production and electricity generation, as well as fossil-fuel reliant industrial plants such as blast furnaces for steel mills. It would accelerate investment in carbon-free replacements, and create pathways for fossil fuel workers to work in the green economy.

And our leaders would talk openly and clearly about the huge threat climate change poses to all of us here, and the benefits we stand to gain by quitting fossil fuels. We would go from laggards to leaders. Imagine that.![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

IPCC says the tools to stop catastrophic climate change are in our hands. Here’s how to use them

Humanity still has time to arrest catastrophic global warming – and has the tools to do so quickly and cheaply, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has found.

The latest IPCC assessment report, the world’s definitive stocktake of action to minimise climate change, shows a viable path to halving global emissions by 2030.

This outlook is much more favourable than in earlier assessments, made possible by tremendous reductions in the cost of clean energy technologies. But broad policy action is needed to make steep emissions reductions happen.

We each contributed expertise to the report. In this article, we highlight how the world can best reduce emissions this decade and discuss the potential implications for Australia.

All-In, Right Now

- Frank Jotzo, lead author on policies and institutions

The IPCC identifies clean electricity and agriculture/forestry/land use as the sectors where the greatest emissions reductions can be achieved, followed by industry and transport.

Further low-emissions opportunities exist in other areas of production, buildings and the urban sector, as well as shifts in consumer demand. Overall, half the options to cut emissions by 50% cost less than US$20 a tonne.

While the IPCC does not provide a country-level assessment, it is clear Australia has all these opportunities.

The transition to zero-emissions electricity is well underway. Decarbonising industry and transport is a next step. Emerging technologies such as green steel and hydrogen offer Australia new, clean export industries. Fossil fuel use in turn is destined to fall, with coal dropping off particularly quickly.

And Australia’s large land mass provides massive opportunities to remove CO₂ from the atmosphere through plants – and in future, perhaps also through chemical methods.

The IPCC says comprehensive policy packages are needed to make deep emissions cuts happen.

It finds carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes have been effective, alongside targeted regulation and other instruments – such as support for research and development, uptake of advanced technologies and removing fossil fuel subsidies.

The report also emphasises the need for continued technological innovation, and to greatly scale up finance for climate action.

It puts weight on the importance of equity, sustainable development and comprehensive engagement across society to avert unmanageable climate change.

That requires climate action to take centre stage in society, involving all manner of groups. Independent institutions such as Australia’s Climate Change Authority have a strong role to play, and business should be actively involved.

So what’s the IPCC’s overriding message? The world’s governments must go all-in on addressing climate change. The opportunities are there and the toolkit is ready.

Food For Thought

- Annette Cowie, lead author on cross-sectoral perspectives

To have our best shot at holding warming to 1.5℃, the world must hit net-zero emissions by mid-century.

Agriculture is a big contributor to global emissions. But the IPCC confirms the land also has a central role in getting to net-zero through measures that remove CO₂ from the atmosphere and store it, such as tree planting, soil carbon management and the use of biochar.

Benefits returned to farmers include improved soil fertility and income from carbon trading.

The way we produce and distribute food accounts for more than one-third of global emissions.

The report says one of the biggest individual contributions we can make to reducing emissions is adopting a sustainable, healthy diet and reducing food waste. Such a diet is rich in plant-based food, with moderate intake of meat and dairy.

We can also tackle direct emissions from food production. Manure can be made into biogas and feed additives offer promising ways to reduce livestock methane.

Moving The Dial On Transport

Peter Newman, coordinating lead author on transport

Jake Whitehead, lead author on transport

A set of technological solutions now exist to reduce emissions across energy, buildings, cities, transport and to a large extent, industry.

They include solar and wind-based power – now the cheapest form of electricity. They also include batteries and storage, electrified transport and “smart” technology that integrates these measures into zero-emissions solutions.

The IPCC report shows in the past decade, unit costs for solar have fallen by 85%, wind by 55% and batteries by 85%. Never before has the world had such an opportunity to decarbonise.

In recent decades, transport has been the laggard in emissions reduction. But, as the IPCC finds, technologies now exist to change the trajectory. Solar-powered electrification is rolling out for cars, bikes, scooters, buses and trucks.

Continuing advances in battery and charging technologies could enable the electrification of long-haul trucks, including electrified highways.

The IPCC assessed 60 actions individuals can take to reduce emissions. The largest contributions come from walking and cycling, using electrified transport, reducing air travel, as well as shifting towards plant-based diets.

This highlights how our individual choices matter.

Technology alone is not enough to reduce transport emissions. Cities must become more oriented toward public transport, walking and cycling. Effective new ways of doing this include on-demand shuttles, trackless trams and high speed rail.

Governments should provide incentives to supply and use electric scooters, bikes, cars, trucks and buses. This would ensure individuals and businesses who want to reduce their emissions have ways to do so.

The IPCC says cheap green hydrogen will be important to decarbonise aviation, shipping and parts of industry and agriculture. Much work is required in the next decade to bring this solution to fruition.

While government funding is vital to decarbonise transport, this transition also presents significant economic opportunities.

Australia could support transport decarbonisation globally through the mining of critical minerals, as well as the manufacturing, reuse and recycling of electric vehicles.

It’s Time To Act

Huge untapped potential exists to reduce global emissions quickly.

But the window of opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to safe levels is closing at an alarming rate. As the IPCC shows, fundamental change to both production and demand is required.

Clearly, business-as-usual is no longer tenable. The IPCC makes one thing patently evident: the time for action is well and truly upon us.

Arunima Malik, Glen Peters, Jacqueline Peel, Thomas Wiedmann and Xuemei Bai contributed to this article. See part one of the article here.![]()

Frank Jotzo, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy and Head of Energy, Institute for Climate Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University; Annette Cowie, Adjunct Professor, University of New England; Jake Whitehead, E-Mobility Research Fellow, The University of Queensland, and Peter Newman, Professor of Sustainability, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

IPCC finds the world has its best chance yet to slash emissions – if it seizes the opportunity

The world has its best chance yet to reduce greenhouse gas emissions quickly, but hard and fast cuts are needed across all sectors and nations to hold warming to safe levels, the global authority on climate change says.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, released today, says opportunities to affordably cut global emissions have risen sharply since the last assessment of this kind in 2014. But the need to act has also become far more urgent.

The report is the definitive assessment of how well the world is doing in finding solutions to rising temperatures. We each contributed expertise to the report.

Here, we explain key aspects of the findings and what it means for the world, including Australia.

Earth Remains On Red Alert

- Glen Peters, lead author on mitigation pathways compatible with long-term goals

The report finds the world has made progress on emissions reduction over the last decade. Growth in greenhouse gas emissions slowed to 1.3% per year in the 2010s, compared to 2.1% in the 2000s.

But global emissions remain at record highs. If policy ambition does not ramp up immediately, warming will shoot past 1.5℃ and be well on the way to 2℃ – failing to meet the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement.

Alarmingly, the world’s current policies put us on track for global warming of between 2.2℃ and 3.5℃ within 80 years. It’s far better than the 4℃ or more feared about a decade ago, but still far from consistent with the Paris Agreement.

To have a 50% chance of keeping global warming to 1.5℃ by century’s end, global CO₂ emissions must halve in a decade, reach net zero in the 2050s and go net negative thereafter.

Methane emissions would also have to halve by 2050 in these scenarios.

Halving global emissions by 2030 is viable and achievable, the IPCC says. But it requires an immediate step change in climate policy across all sectors, countries and levels of government.

Rich nations must make the most rapid emissions reductions. This includes Australia, where a plan for net zero emissions by 2050 falls short of the ambition needed and is not yet backed by policy.

More Than Technology

- Tommy Wiedmann, lead author on emissions trends and drivers

The report is a comprehensive catalogue of what can be done – but has mostly not yet been done – to avert devastating climate change.

Some trends are encouraging. Some 36 countries have successfully cut greenhouse gas emissions over more than a decade.

And opportunities to cut emissions affordably and cheaply have multiplied enormously since 2014, the report finds.

This is largely due to the plunging costs of renewables, which promises emissions reduction beyond the energy sector in areas such as manufacturing and heavy transport. We expand on the options here.

But change is not coming fast enough. The report confirms all energy efficiency gains in the last decade have been more than outpaced by economic and population growth.

Technology is not a silver bullet. To have a chance of halving global emissions by 2030, we must use fewer high-carbon products and adopt less emissions-intensive lifestyles. Like all other changes required, these cannot be incremental, the IPCC says.

Australia is blessed with a bounty of renewable energy resources. Used wisely, it could slash domestic emissions and help reduce other countries’ emissions, in the form of zero-emissions energy exports.

No-One Gets Left Behind

- Arunima Malik, lead author on introduction and framing

In 2016, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals – an action plan for people, planet and prosperity – came into effect.

Sustainable development meets the needs of the present without compromising future generations. And as the latest IPCC report emphasises, it cannot be achieved without effective climate action.

One Sustainable Development Goal explicitly focuses on tackling climate change. But climate action is linked to all other goals, including those relating to energy, cities, industry, land, water and people.

Emissions reduction policies must be inclusive and avoid unintended consequences such as exacerbating existing poverty and hunger. The transition to a low-carbon world should be equitable and leave no-one behind.

The IPCC report calls for both accelerated climate action and a just transition. This requires well-designed policies at all levels of government, and across all sectors. International co-operation is key.

Is The Paris Agreement Working?

- Jacqueline Peel, lead author on international cooperation

This report is the first to assess the Paris Agreement, which took effect from 2020. Under the agreement, countries submit and update pledges on emissions reduction and adapting to the changing climate.

For these pledges to be achieved globally, high-income countries must help other nations by providing finance, access to clean energy technologies, and other assistance and know-how.

The IPCC identified a shortfall in global climate finance. In particular, high-income countries missed their 2020 target to mobilise $US100 billion per year.

The Paris Agreement is a treaty but the pledges are voluntary. Countries set their own targets and can’t be forced to meet them. So, is it working?

According to this new report, it largely is – albeit slowly. For instance, it has encouraged nations such as Australia to make more ambitious emissions pledges.

It has also enhanced transparency, enabling outside groups, such as those in civil society, to assess countries’ progress.

Other international mechanisms, such as global business partnerships and youth climate protests, are also driving change.

But more must be done to halve emissions this decade.

Cities Are Central

- Xuemei Bai, lead author on urban systems and other settlements

The IPCC report found around 70% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions are produced in cities and urban areas. This offers both challenges and opportunities for emissions reduction.

To date, more than 1,000 cities worldwide have signed up to net-zero emission goals, including many in Australia.

To fulfil the Paris Agreement, more cities must step up and work towards goals such as 100% renewable energy, zero-carbon transport, decarbonising construction and improving waste management.

Developing countries are rapidly urbanising, which requires new housing and infrastructure. But doing so in a business-as-usual way could lead to substantial new emissions, the IPCC warns.

City leaders must embrace integrated planning and management to meet the climate challenge. This must be achieved while cities continue their important roles in maintaining social, economic and environmental well-being.

We need all hands on deck: businesses, communities, researchers and citizens.

Seize The Opportunity

This latest report shows how the choices we make now will determine the fate of generations to come – and all life on this planet.

Humanity has already missed so many opportunities to stabilise Earth’s climate. We now have the chance to right some of those past wrongs.

Only an urgent, concerted effort across all sectors and nations, starting today, will deliver the change needed.

Annette Cowie, Frank Jotzo, Jake Whitehead and Peter Newman contributed to this article. See part two of the article here.![]()

Thomas Wiedmann, Professor of Sustainability Research, UNSW Sydney; Arunima Malik, Senior Lecturer in Sustainability, University of Sydney; Glen Peters, Research Director, Center for International Climate and Environment Research - Oslo; Jacqueline Peel, Director, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne, and Xuemei Bai, Distinguished Professor, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Morrison government’s $50 million gas handout undermines climate targets and does nothing to improve energy security

Samantha Hepburn, Deakin UniversityTuesday night’s federal budget confirmed the Morrison government will spend A$50.3 million on gas projects in the Northern Territory, South Australia and the east coast.

This decision, it says, will support the completion of seven new “priority” gas projects. Energy Minister Angus Taylor says the government strongly backs natural gas and accused the opposition of being “willing to risk Australia’s energy security and investment in regional Australia to appease gas activists.”

However, the development of new fossil fuel projects is completely inconsistent with the broader goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050 – and will not improve energy security.

Gas Extraction Drives Climate Change And Extreme Weather

Gas is a fossil fuel and a greenhouse gas. Emissions from the extraction, processing and export of gas contribute significantly to Australia’s carbon emissions.

Globally, there is growing recognition the energy sector must change. An International Energy Agency report last year made clear there can be no new oil, gas or coal development if the world is to have any chance of reaching net zero by 2050.

The methane found in natural gas is 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Funding new gas projects undermines Australia’s efforts to achieve an already unambitious climate target of 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Failing our climate target would breach the global goals of the Paris Agreement to limit the increase in global average temperatures to well below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels.

The consequences of global warming are catastrophic. Australia has had recent and profound experience of extreme climate events in the form of devastating bushfires and floods.

But What About Energy Security And Russian Gas?

The European Commission is phasing down two-thirds of Russian gas exports by the end of the year, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This will create a gas shortfall.

Russia supplies nearly 40% of the EU’s gas consumption via a fixed pipeline infrastructure.

To phase this supply out, the EU will this year require 500 terrawatt hours of additional imports of liquified natural gas (LNG).

This will be difficult. Global markets are tight and LNG tends to be sold on long-term contracts. Alleviating the EU shortfall will require record imports of LNG over the European spring and summer period and a rapid upgrade of gas infrastructure.

In a recent pact between Europe and the US, the EU will receive an additional 11 million tons of LNG by the end of 2022.

It’s unclear where this LNG will come from. Much may be sourced from non-contracted stock destined for Asia.

However it’s acquired, the price of LNG exports will continue to rise. Indeed, the delivered price for LNG in Northwest Europe rose 29% in a day after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced his special military operation. And spot prices for LNG in Asia are trading at near record levels.

Australia is one of the world’s largest exporters of LNG, with most going to China, Japan and South Korea.

Given the lock-in contracts, Australia has little existing capacity to assist the EU. Australian gas producers are, however, benefiting from the higher global prices for LNG exports caused by the EU shortfall.

Woodside, Santos and Oil Search have all registering significant gains in their share prices.

Complete Nonsense

Taylor says spending $50.3 million of public money for new gas projects will:

accelerate priority projects and ensure Australia does not experience the devastating impacts of a gas supply shortfall as seen in Europe.

This is complete nonsense.

Australia will never face a shortfall like Europe because it’s not import-dependent. We have plenty of gas.

The issue for Australia is regulating the export of gas to ensure a sufficient domestic supply.

If the federal government wanted to improve Australia’s energy security, it would force gas producers in the east coast market to reserve a percentage for domestic consumption.

And it would actually use the Australian Domestic Gas Security mechanism. The measure was introduced to ensure gas supplies meet forecast energy needs, but has never been triggered.

An Uncertain Future

Funding seven gas priority projects is also inconsistent with the conclusions of the 2022 Gas Statement of Opportunities, recently released by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO).

This statement argues the future path for the gas sector in Australia is uncertain because the pace and impact of a transforming energy sector upon the gas system remains unclear.

In the short term, this statement suggests funding new infrastructure will not alleviate domestic supply concerns because it won’t be running in time.

In the longer term, the statement forecasts a gradual decline in domestic gas demand as consumers inevitably shift from gas to electricity or zero-emission fuels.

Contrary To Australia’s Climate Targets

Funding seven new fossil fuel projects is fundamentally contrary to Australia’s climate targets.

These projects will not improve Australia’s energy security or assist the EU with its supply difficulties.

Nor do they cohere with AEMO’s longer term conclusions about the future of the gas sector.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has argued gas projects are needed to generate new dispatchable electricity which can be ramped up quickly when needed, making new gas projects integral to a national pandemic recovery plan.

But Kerry Schott, the former head of the Energy Security Board, disagrees. She’s made it clear there is an abundance of cheaper, cleaner alternatives.

Schott is right. This is where public money should be directed – to projects that represent the future, not the polluting past.![]()

Samantha Hepburn, Director of the Centre for Energy and Natural Resources Law, Deakin Law School, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New research shows planting trees and shrubs brings woodland birds back to farms, from superb fairy wrens to spotted pardalotes

Rural landscapes are changing in southern Australia. Thanks to landholders, community volunteers and Landcare groups, farms are increasingly home to corridors of trees and shrubs along creeks, and paddocks bordered by trees.

Our research, published today, shows these efforts to revegetate farmland has made an important difference for woodland birds.

We surveyed and compared bird communities in farm landscapes with differing amounts of tree cover. We found when the amount of revegetation in open farmland increased, the number of woodland bird species did, too. For example, an increase in revegetation from 1% to 10% of the landscape doubled the number of woodland bird species.

This is important, because populations of woodland birds have been steeply declining in southern Australia, with species such as the southern whiteface, brown treecreeper and white-browed babbler now of conservation concern. The collective efforts of landholders can help reverse these declines by attracting species back into otherwise-cleared farmland.

Restoring Habitat For Woodland Birds

Look closely among native vegetation on farmland and you’ll find an array of birdlife, such as flame robins and superb fairy-wrens foraging for insects on the ground, and striated pardalotes and yellow thornbills feeding in canopy foliage.

Yet extensive habitat destruction, replaced by vast areas of intensive farmland, have caused the number of once-abundant woodland birds to decline greatly. Indeed, in many rural districts, such as in western and northern Victoria, more than 90% of native wooded vegetation has been cleared.

To help address this issue, the Morrison government last year announced an additional A$32.1 million for biodiversity stewardship on agricultural land.

A key activity under the stewardship scheme is revegetation. Our research clarifies how revegetation can help in the recovery of woodland birds.

How Does Revegetation Benefit Birds?

Most research on the value of revegetation looks at individual “patches”. Our approach differed, as we sampled entire landscapes. Each landscape was 8 square kilometres in size, spanning one to three farms in south-western Victoria.

We identified three groups of landscapes, each having 1-18% tree cover. In one group, the tree cover was from revegetation. A second group comprised remnant native vegetation (natural vegetation that remains after the land was cleared). And a third had a mix of both revegetation and remnants.

We investigated important questions such as:

does the number of woodland species increase if more of the landscape is revegetated?

does revegetation attract new species back into the landscape, or simply provide more habitat for common species already present?

is the bird community in revegetated landscapes similar to that in remnant landscapes?

In answer to the first two questions, we found the number of bird species in a landscape did increase with increasing wooded cover.

For example, in landscapes with only 1% revegetation cover, most birds were open-country species such as galah, red-rumped parrot and willie wagtail, with only 11 woodland species on average. On the other hand, landscapes with 15% revegetation cover had 25 woodland species, on average, as part of the bird community.

In response to the third question, we found that revegetated landscapes and those with remnant native vegetation don’t offer the same benefits. For a given amount of wooded vegetation, revegetated landscapes had fewer species in total and supported different types of woodland species.

For example, revegetation favours birds that forage in shrubby areas, such as the New Holland honeyeater and brown thornbill.

In contrast, those that depend on older trees were less likely to be found in revegetated landscapes. This includes the white-throated treecreeper and varied sitella which forage on tree trunks and large branches, and the spotted pardalote and white-naped honeyeater that feed within canopy foliage.

Where Will Revegetation Be Most Effective?

Our research shows revegetation has greatest value when it’s interspersed among remnant vegetation.

These mixed landscapes have similar numbers and types of woodland birds to the remnant landscapes, and provide complementary resources for feeding, nesting and refuge.

We also found individual patches of revegetation have the greatest value for birds when they include a diverse range of trees and shrubs, are close to or connected with native vegetation, and are older (meaning the plants have had longer to grow).

Another valuable feature for birds is scattered trees. These veteran trees act as stepping stones that help birds move, and provide foraging and nesting habitat for species such as the brown treecreeper, laughing kookaburra and eastern rosella.

Working Together

These results are encouraging, but there’s a long way to go to restore farmland environments. At least 11 of the 60 woodland species recorded in the study weren’t detected in revegetated landscapes, such as sacred kingfisher and black-chinned honeyeater. Others, such as jacky winter and eastern yellow robin were rare.

Increasing wooded vegetation to cover at least 10-30% of farmland is an important long-term goal to ensure sufficient habitat to sustain healthy populations of many species.

Of course, it’s not just for woodland birds – revegetating farms has a number of benefits. Planting along creeks helps stabilise stream banks and improve aquatic environments, trees store more carbon as they grow and age, and tree lines (shelterbelts) and shade benefit livestock and farm production.

In this United Nations Decade of Ecosystem Restoration, the actions we take now will benefit the lives of future generations.![]()

Andrew Bennett, Professor of Ecology, La Trobe University; Angie Haslem, Research Fellow, La Trobe University; Greg Holland, Associate Research Fellow, La Trobe University; Jim Radford, Principal Research Fellow, Research Centre for Future Landscapes, La Trobe University, and Rohan Clarke, Director, Monash Drone Discovery Platform, and Senior Lecturer in Ecology, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change, mental health services, a better education system: what marginalised young people told us needs to be fixed

In youth policy and service delivery the idea of youth voice and participation is an uncontested “good thing”. But which youth voices? Who is heard and who is left out?

Our recent research in Melbourne’s inner northern suburbs and in the Geelong region has grappled with this question.

We have interviewed more than 80 young people since the start of the pandemic, in an effort to better understand the concerns of many disengaged, marginalised and disadvantaged young people in these areas.

We wanted to find out:

what challenges have they faced?

why do some young people seem to be able to get a say, while others don’t?

how can these young people become active stakeholders in their own futures?

what might change these dynamics?

Crucially, we asked young people to share their views in a format they felt comfortable with – by speaking directly to their webcams or phone cameras. Common themes that emerged included:

the need for secure work now and in the future

the need for better mental health services

a sense of pressure around school

a sense of not being heard

concern about climate change and the future of the planet.

What We Did

Many of the young people we heard from live with health and well-being challenges, neuro-diversity, and disengagement from traditional education, training and employment pathways. Financial struggles were common.

We asked young people to speak directly to their communities, and to a wider audience by filming their contribution on their camera phone or on a webcam. This allowed for a more natural flow of ideas from our interviewees. We published many of the videos on YouTube and Instagram.

Our generous interviewees spoke openly about the connections between their health and well-being, and the hopes, aspirations and anxieties they feel about the future – around education, work, relationships, and the planet.

What Young People Told Us

Take, for example, Ruby, aged 16. She lives with her family in Geelong, is looking for work, and studies Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (an alternative to Year 11 and 12 at school) at her local TAFE. She told us:

[…] they kind of like just say, to people that have anxiety or depression, to like, ‘just breathe’. And I think for a lot of us that just doesn’t work. I think we just need some better listeners and I think we need some people who genuinely care.

Emilie, aged 24, lives in a sharehouse in Geelong. She studies social work and is uncertain about the future.

I want to be hopeful for the future, but honestly, I don’t know if I exactly am. In some ways, I feel that the government focuses on what the voters are gonna want to get them in for the next election.

Ruth, who was in Year 12 and living in the inner Melbourne suburb of Fitzroy, spoke about her life and her hopes for the future:

Dickheads in politics – less of them please.

I’d like to be in a relationship with someone who makes me really happy. Who treats me in a really genuinely wonderful way. And who brings me joy. And maybe cake as well.

During 2020, Astrid, now 20 years old, was living in social housing in Fitzroy with her mum and her kitten. She faces a number of challenges due to her dyslexia. She told us:

I hope, my biggest hope is that they figure out how to deal with climate change. Oh, no, I take that back. They know how to deal with climate change. I hope that they do it.

I also hope that the people who are running the community make note of the fact that young people want more involvement in it. And a place where they feel that they can be themselves.

Why Do Some Young People Seem To Be On The Margins?

Too often, the youth voices highlighted in public discourse and media narratives are the well-heeled, often privately educated beneficiaries of a system that serves wealthy people well while excluding those living with poverty or disability.

In an essay titled Can the Subaltern Speak? Indian scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak explores the legacies of colonialism in “postcolonial” states (such as India) and “settler colonies” (such as Australia), as well as the forms of disadvantage experienced by indigeneous peoples in these contexts.

The “subaltern” groups are those people facing often multiple forms of disadvantage, who are denied access to processes that shape their oppression. They have no voice.

Our discussion with these young, marginalised people harks back to these ideas, and calls for close consideration of what young people from the margins demand: “better listeners” among the adults who shape their lives, and a reason to hope for the future.

As young Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg put it:

We can no longer let the people in power decide what hope is. Hope is not blah, blah, blah. Hope is telling the truth. Hope is taking action. And hope always comes from the people.

Peter Kelly, Professor of Education, Deakin University; James Goring, Research Fellow, Deakin University, and Seth Brown, Lecturer in Education, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Do you toss biodegradable plastic in the compost bin? Here’s why it might not break down

Over one-fifth of all plastic produced worldwide is tossed into uncontrolled dumpsites, burned in open pits or leaked into the environment. In Australia, 1.1 million tonnes of plastic is placed in the market, yet just 16% (179,000 tonnes) is recovered.

To deal with this mounting issue, the Morrison government last week announced A$60 million to fund plastic recycling technologies. The goal is to boost plastic packaging recycling from 16% to 70% by 2025.

It comes after 176 countries, including Australia, last month endorsed a United Nation’s resolution to establish a legally binding treaty by 2024 to end plastic pollution.

This is a good start – more effective recycling and recovery of plastics will go a long way to solve the problem.

But some plastics, particularly agricultural plastics and heavily contaminated packaging, will remain difficult to recycle despite these new efforts. These plastics will end up being burnt or in landfill, or worse, leaking into the environment.

“Biodegradable” plastic is often touted as an environmentally friendly alternative. But depending on the type of plastic, this label can be very misleading and can lead environmentally conscious consumers astray.

What Are Biodegradable Plastics?

Biodegradable plastics are those that can completely break down in the environment, and are a source of carbon for microbes (such as bacteria).

These microbes degrade plastics into much smaller fragments before consuming them, which makes new biomass (cell growth), and releases water, carbon dioxide and, when oxygen is limited, methane.

However, this blanket description encompasses a wide range of products that biodegrade at very different rates and in different environments.

For example, some – such as the bacterially produced “polyhydroxyalkanoates”, used in, for instance, single-use cutlery – will fully biodegrade in natural environments such as seawater, soil and landfill within a few months to years.

Others, like polylactic acid used in coffee cup lids, require more engineered environments to break down, such as an industrial composting environment which has higher temperatures and is rich in microbes.

So while consumers may expect that “compostable” plastics will degrade quickly in their backyard compost bins, this may not be the case.

To add to this confusion, biodegradable plastics actually don’t have to be “bio-based”. This means they don’t have to be derived from renewable carbon sources such as plants.

Some, such as polycaprolactone used in controlled release drug delivery, are synthesised from petroleum-derived materials.

What’s more, bio-based plastics may not always be biodegradable. One example is polyethylene – the largest family of polymers produced globally, widely used in flexible film packaging such as plastic bags. It can be produced from ethanol that comes from cane sugar.

In all material respects, a plastic like this is identical to petroleum-derived polyethylene, including its inability to break down.

Confusion And Greenwashing

In 2018, we conducted a survey of 2,518 Australians, representative of the Australian population, with all demographics collected closely matching census data.

We found while there’s a lot of enthusiasm for biodegradable alternatives, there’s also a great deal of confusion over what constitutes a biodegradable plastic.

Consumers have also become increasingly concerned over the practice of “greenwashing” – marketing a product as biodegradable when, in reality, its rate of degradation and the environment in which it will decompose don’t match what the label implies.

So-called “oxo-degradable plastics” are an excellent example of why the issue is so complex and confusing. These plastics are commonly used in films, such as agricultural mulches, packaging and wrapping materials.

Chemically speaking, oxo-degradable plastics are often made from polyethylene or polypropylene, mixed with molecules that initiate degradation such as “metal stearates”.

These initiators cause these plastics to oxidise and break down under the influence of ultraviolet light, and/or heat and oxygen, eventually fragmenting into smaller pieces.

There is, however, some controversy surrounding their fate. Research indicates they can remain as microplastics for long periods, particularly if they’re buried or otherwise protected from the sun.

Indeed, evidence suggests oxo-degradable plastics aren’t suited for long-term reuse, recycling or even composting. For these reasons, oxo-degradable plastics have now been banned by the European Commission, through the European Single-Use Plastics Directive.

We Need Better Standards And Labels

The new government funding for plastic recycling technologies targets waste that’s notoriously difficult to deal with, such as bread bags and chip packets.

However, this still leaves a substantial stream of waste that’s even more challenging to address. This includes agricultural waste dispersed in the environment such as mulch films, which can be difficult to collect for recycling.

Biodegradable and bio-based plastics have great potential to replace such problematic plastics. But, as they continue to gain market share, the confusion and complexity around biodegradable plastics must be addressed.

For starters, a better understanding of how they impact the environment is needed. It’s also crucial to align consumer expectations with those of manufacturers and producers, and to ensure these plastics are appropriately disposed of and managed at the end of their life.

This is what we’re investigating as part of a new training centre for bioplastics and biocomposites. Our goal over the next five years is to improve knowledge for developing better standards and regulations for certifying, labelling and marketing “green” plastic products.

And with that comes greater opportunity for better education so both plastic producers and people who throw them away really understand these materials. We should be familiar with their strengths, weaknesses and how to dispose of them so we can minimise the damage they inflict on the environment.![]()

Bronwyn Laycock, Professor of Chemical Engineering, The University of Queensland; Paul Lant, Professor of Chemical Engineering, The University of Queensland, and Steven Pratt, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia plans to be a big green hydrogen exporter to Asian markets – but they don’t need it

In its latest budget, the federal government has promised hundreds of millions of dollars to expand Australia’s green hydrogen capabilities.

Green hydrogen is made by electrolysis of water, powered by solar and wind electricity, and it’s key to the government’s “technology not taxes” approach to meeting its climate target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

The government aims to create a major green hydrogen export industry, particularly to Japan, for which Australia signed an export deal in January. But as our latest research suggests, the likely scale may well be overstated.

We show Japan has more than enough solar and wind energy to be self-sufficient in energy, and does not need to import either fossil fuels or Australian green hydrogen. Indeed, Australia as a “renewable energy superpower” is far from a sure thing.

Japan Has Plenty Of Sun And Wind

“Green” hydrogen could be used to generate electricity and also to form chemicals such as ammonia and synthetic jet fuel.

In the federal budget, hydrogen fuel is among the low-emissions technologies that will share over A$1 billion. This includes $300 million for producing clean hydrogen, along with liquefied natural gas, in Darwin.

Australia plans to be a top-three exporter of hydrogen to Asian markets by 2030. The idea is that green hydrogen will help replace Australia’s declining coal and gas exports as countries make good on their promises to bring national greenhouse gas emissions down to zero.

Underlying much of this discussion is the notion that crowded jurisdictions such as Japan and Europe have insufficient solar and wind resources of their own, which is wrong.

Our recent study investigated the future role of renewable energy in Japan, and we modelled a hypothetical scenario where Japan had a 100% renewable electricity system.

We found Japan has 14 times more solar and offshore wind energy potential than needed to supply all its current electricity demand.

Electrifying nearly everything – transport, heating, industry and aviation – doubles or triples demand for electricity, but this still leaves Japan with five to seven times more solar and offshore wind energy potential than it needs.

After building enough solar and wind farms, Japan can get rid of fossil fuel imports without increasing energy costs. This removes three quarters of its greenhouse gas emissions and eliminates the security risks of depending on foreign energy suppliers.

Japanese Energy Is Cheaper, Too

Our study comprised an hourly energy balance model, using representative demand data and 40 years of historical hourly solar and wind meteorological data.

We found that the levelized cost of electricity from an energy system in Japan dominated by solar and wind is US$86-110 (A$115-147) per megawatt hour. Levelized cost is the standard method of costing electricity generation over a generator’s lifetime.

This is similar to Japan’s 2020 average spot market prices (US$102 per megawatt hour) – and it’s about half the cost of electricity generated in Japan using imported green hydrogen from Australia.

So why is it much more expensive to produce electricity from imported Australian hydrogen, compared to local solar and wind?

Essentially, it’s because 70% of the energy is lost by converting Australian solar and wind energy into hydrogen compounds, shipping it to Japan, and converting the hydrogen back into electricity or into motive power in cars.

Thus, hydrogen as an energy source is unlikely to develop into a major export industry.

What about exporting sustainable chemicals? Hydrogen atoms are required to produce synthetic aviation fuel, ammonia, plastics and other chemicals.

The main elements needed for such products are hydrogen, carbon, oxygen and nitrogen, all of which are available everywhere in unlimited quantities from water and air. Japan can readily make its own sustainable chemicals rather than importing hydrogen or finished chemicals.

However, the Japanese cost advantage is smaller for sustainable chemicals than energy, and so there may be export opportunities here.

What About Other Countries?

While large-scale fossil fuel deposits are found in only a few countries, most countries have plenty of solar and/or wind. The future decarbonised world will have far less trade in energy, because most countries can harvest it from their own resources.

Solar and wind comprise three quarters of the new power stations installed around the world each year because they produce cheaper energy than fossil fuels. About 250 gigawatts per annum of solar and wind is being installed globally, doubling every three to four years

Densely populated coastal areas – including Japan, Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam and northern Europe – have vast offshore wind resources to complement onshore solar and wind.

What’s more, densely populated Indonesia has sufficient calm tropical seas to power the entire world using floating solar panels.

Will international markets need Australian energy for when the sun isn’t shining, nor the wind blowing? Probably not. Most countries have the resources to reliably and continuously meet energy demand without importing Australian products.

This is because most countries, including Japan (and, for that matter, Australia) have vast capacity for off-river pumped hydro, which can store energy to balance out solar and wind at times when they’re not available. Batteries and stronger internal transmission networks also help.

Australia’s Prospects

Getting rid of fossil fuels and electrifying nearly everything with renewables reduces greenhouse emissions by three quarters, and lowers the threat of extreme climate change. It eliminates security risks from relying on other countries for energy, as illustrated by Europe’s dependence on Russian gas.

It will also bring down energy costs, and eliminates oil-related warfare, oil spills, cooling water use, open cut coal mines, ash dumps, coal mine fires, gas fracking and urban air pollution.

Australia’s coal and gas exports must decline to zero before mid-century to meet the global climate target, and solar and wind are doing most of the heavy lifting through renewable electrification of nearly everything.

But as our research makes clear, while Australian solar and wind is better than most, it may not be enough to overcome the extra costs and losses from exporting hydrogen for energy supply or chemical production.

One really large prospect for export of Australian renewable energy is export of iron, in which hydrogen produced from solar and wind might replace coking coal.

This allows Australia to export iron rather than iron ore. In this case the raw material (iron ore), solar and wind are all found in the same place: in the Pilbara.

While hydrogen will certainly be important in the future global clean economy, it will primarily be for chemicals rather than energy production. It’s important to keep perspective: electricity from solar and wind will continue to be far more important.![]()

Andrew Blakers, Professor of Engineering, Australian National University and Cheng Cheng, Research Officer, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

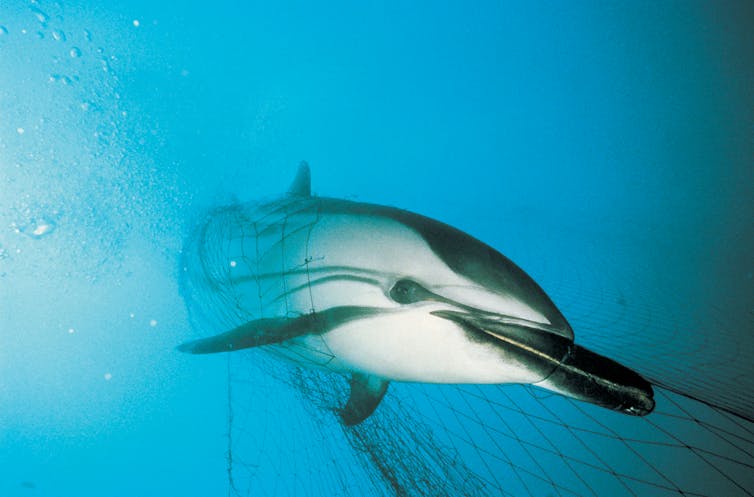

Dolphins, turtles and birds don’t have to die in fishing gear – skilled fishers can avoid it

In 1987, a biologist went undercover on a commercial tuna fishing vessel. One video he took made headlines around the world: hundreds of dolphins encircled in purse seine nets, drowning in distress.

Before that, few people had given much thought to bycatch – the fish and marine animals caught when trying to catch something else. It was out of sight, out of mind. But now, everyone could see the shocking footage.

In the decades since, some of the most confronting bycatch issues have been solved. Even so, bycatch remains one of the most difficult obstacles to making the world’s seafood more sustainable.

So if better nets and better rules aren’t the full answer, what is? Our new research suggests part of it is the human factor. The more skilled fishers are, the more likely they are to avoid accidental bycatch.

We Need More Than Technology And Top-Down Solutions

So far, the solutions for bycatch have tended to be technical or regulatory. Think of modified fishing gear so non-target animals can escape, or closing high bycatch areas to fishing during certain seasons or when bycatch exceeds a threshold.