inbox and environment news: Issue 535

April 24 - 30, 2022: Issue 535

Green Grants To Expand Urban Forest Allocates 50k To Council

- Northern Beaches Urban Tree Plan

- The Tiny Forest Project

- to improve our tree canopy and wildlife habitats;

- to create healthy and diverse landscaping in our streets and parks; and

- to contribute to the health and wellbeing of all that enjoy our area.

Barrenjoey Headland Amenities Concept Plan

- the building will be set into the landscape, concealed by the landform and native heath

- screened walls to the front of the building will allow for natural light and ventilation

- timber screens will be left to grey with alternating painted battens to reference the colours of the surrounding natural landscape and heritage buildings

- unisex cubicles will be provided, including baby change facilities and a water refill station

- water supply and sewer infrastructure to service these amenities are already in place.

The Story Of Narrabeen Lagoon: Part 1 (2011)

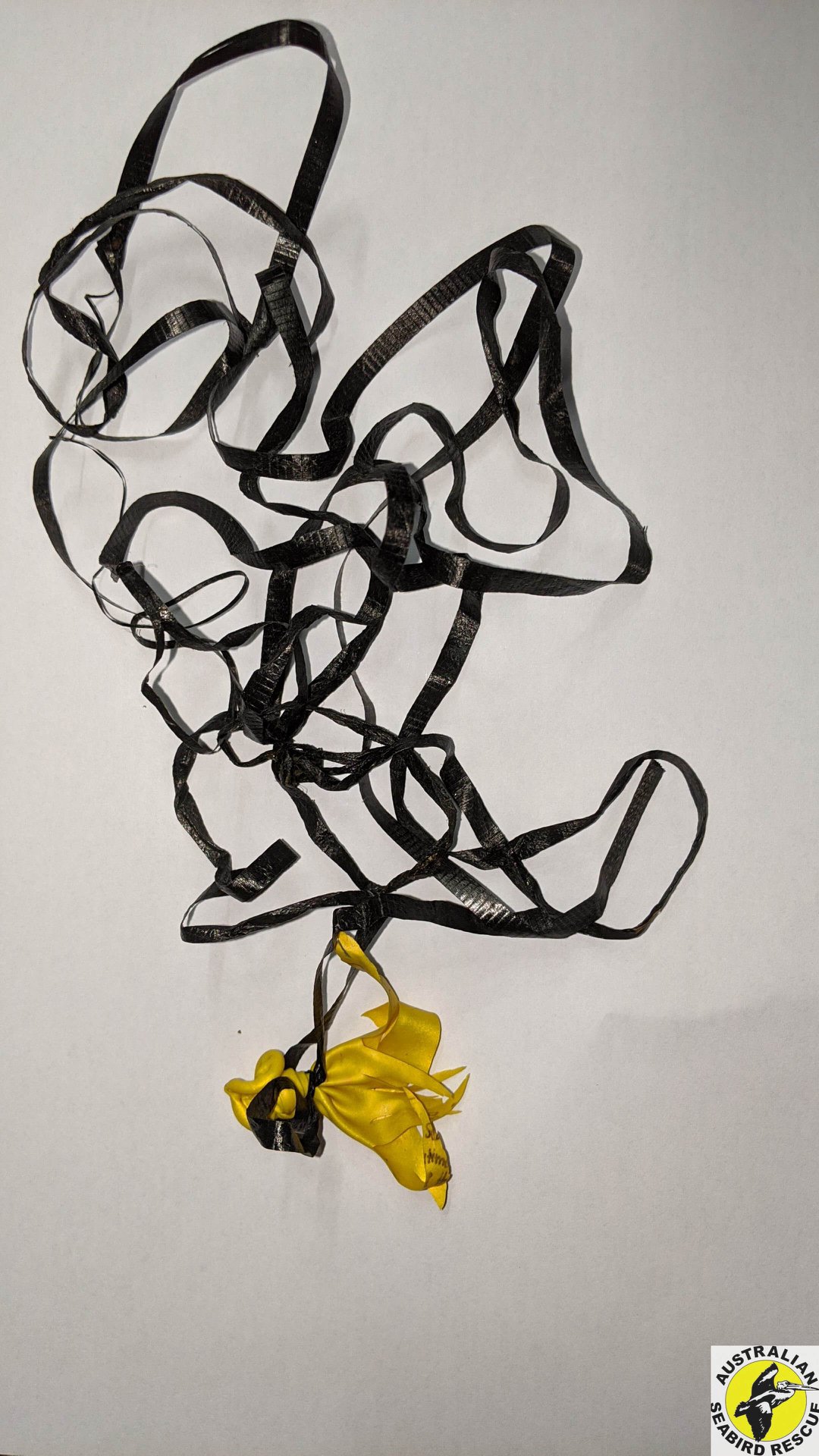

Ban The Release Of Balloons In NSW Petition

Ella: Green Turtle Rescued From Manly

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Mackellar Candidate Forum 2022: Managing The Big Issues Facing Our Community

- Christopher BALL - United Australia Party

- Paula GOODMAN - Australian Labor Party

- Ethan HRNJAK - The Greens

- Dr. Sophie SCAMPS - Independent

- Barry STEELE - TNL (formerly The New Liberals)

.jpg?timestamp=1650677177096)

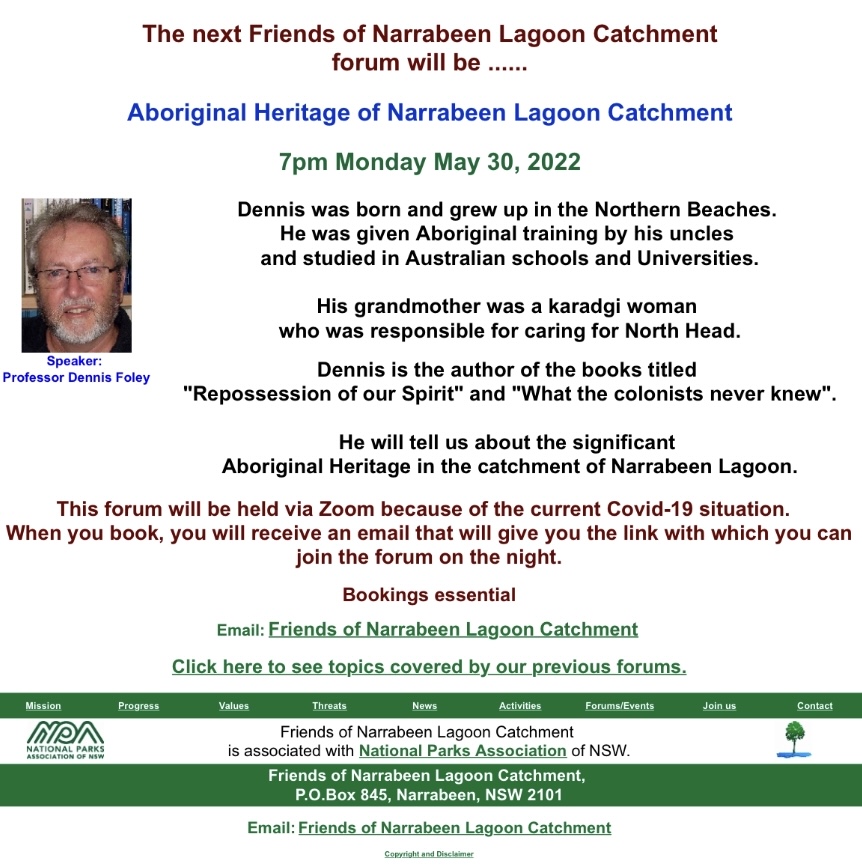

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Autumn 2022 Newsletter

Cassia Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Darkinjung Plans For 600 Homes On Central Coast's Lake Munmorah Now On Exhibition: Closes May 24

Perrottet Government Quietly Renews Massive Santos Gas Licences On Liverpool Plains Farmlands-Extends Piliga Range While Most Of The State On Holidays

- Is taking about 54 billion litres of water each year.

- Is expected to drain more than 700 water bores relied on for farming. Two hundred and thirty-three bores have already been impacted.

- Is causing groundwater levels to drop by more than 400 metres in some areas.

- Is expected to expand from 8,600 gas wells currently operating to about 22,000.

- Is causing farmland to sink due to depressurisation of coal seams beneath the surface.

Have Your Say On Key Environmental Legislation Reviews

EPA Statement On Recovered Soil Fines

- The need for record keeping, notification, quality control and quality assurance requirements.

- Setting out requirements for sampling and testing for a range of chemicals, including asbestos before they are approved for public use, which increases community safety.

Upper Hunter Community Wins 22 Year Battle Against Yancoal Mine Expansion

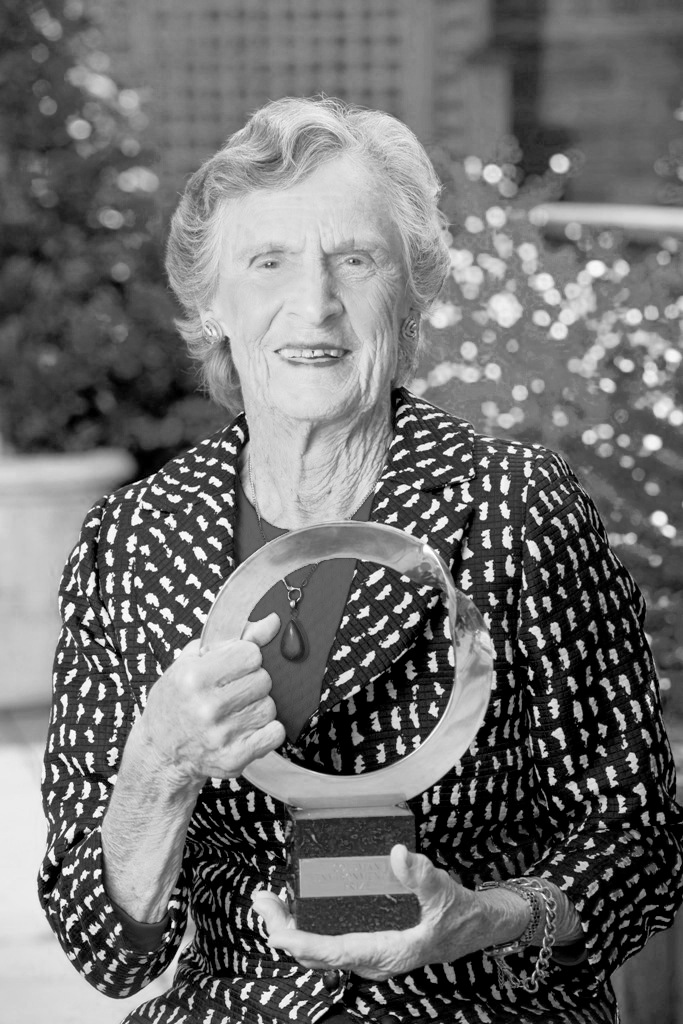

International Environmental Award For Hunter Valley Farmer Wendy Bowman Spotlights Coal Mining Damage

Wendy Bowman

2017 Goldman Prize Recipient

Islands And Island Nations

In the midst of an onslaught of coal development in Australia, octogenarian Wendy Bowman stopped a powerful multinational mining company from taking her family farm and protected her community in Hunter Valley from further pollution and environmental destruction.Islands of farms surrounded by coal mines

New South Wales (NSW), on Australia’s eastern coast, is a region with a rich agricultural history. Dairy farms, ranches, race horse farms, and vineyards dot the rural landscape in Hunter Valley, where descendants of some of the island’s earliest settlers have been working the land for generations. However, in recent years, the region’s farms have become islands surrounded by oceans of open-pit coal mines.

Under directives to prioritize economic growth above all else, government is issuing coal licenses with little regard to mining’s impact on local residents’ lives. Almost two-thirds of the Hunter Valley floor has been given away in coal concessions, producing 145 million tons of coal every year. Some of it is burned at nearby coal powered plants but the majority is shipped off to foreign markets, cementing Australia’s place as the world’s largest coal exporting country.

Coal mining has displaced many landowners in the valley. Those who remain live surrounded by around-the-clock blasting and heavy equipment operation. Coal dust settles onto houses, farmland, and water sources. When the wind blows, residents shut all doors and windows and stay inside. A survey by a local physician found that one in five children in the valley have lost some 20 percent of their lung capacity; asthma, heart disease, cancer, and mental health problems are on the rise.

Uprooted twice, now determined to stayWendy Bowman, 83, is one of the last residents left in Camberwell, a small village in Hunter Valley surrounded on three sides by coal mining. She married a farmer and took over the family business after her husband’s untimely death in 1984. She had to quickly learn how to manage a farm, and abruptly encountered the harsh reality of what coal development was doing to the local community.

Landowners were being forced to move off their property with little say or explanation of their rights. In fact, they often found out their land had been leased to mining companies by reading about it in the local newspaper, where the government posted notices. Coal companies created divisions within the community by offering huge sums of money to select landowners and imposing a gag order on the terms of the deal.

In 1988, just four years after losing her husband, Bowman’s crops suffered a devastating failure. A coal mine had tunneled under a creek that irrigated her farm, and the heavy metals in the water caused the crops to die. Around the same time, another mine broke ground on nearby land, causing constant noise and light pollution. Coal dust from the mine covered her fields, and the cows refused to eat. After a contentious four-year battle, Bowman convinced the mine to buy out her farm that had been destroyed by mining. In 2005, she was forced to relocate again when she was served an eviction notice—and given six weeks to move to make room for a coal mine. She eventually settled down in Rosedale, a small cattle farm in Camberwell. But her battle against coal was far from over.

In 2010, Chinese-owned Yancoal proposed to extend the Ashton South East Open Cut mine, which would bring mining operations onto Bowman’s grazing lands and the banks of one of Hunter River’s most important water tributaries. Bowman was determined to stay and protect the community’s health, land, and water from further destruction.

Protecting Rosedale and Hunter Valley’s healthThe Ashton mine expansion was initially opposed by the regional government agencies because of concerns about the mine’s air and water pollution. Yancoal appealed in 2012, and the planning committee approved the project. By early 2015, more than 87 percent of homeowners in the proposed mining area had sold their property.

As one of the few landowners left in the area, Bowman became a key plaintiff in a public interest lawsuit to fight back the mine expansion. Given that more than half of the coal for the proposed mine is under Bowman’s property, her refusal to sell was a significant factor in the case.

The Land and Environment Court issued its ruling in December 2014: The Ashton expansion could proceed, but only if Yancoal could get Bowman to sell them her land. It was the first time an Australian court placed this kind of restriction on a mining company. The New South Wales Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s decision, effectively stopping the mine expansion in its tracks.

Bowman has refused offers of millions from Yancoal, and is now working on a plan to have Rosedale protected in perpetuity. She continues to be an advocate for the community’s health and environment, and has worked with the local health department to place air monitors near coal mines. She has also recently installed solar panels on her property, and envisions an energy future where Hunter Valley is powered by its abundant sun and wind.

Join Wendy demand that Australian politicians stop mining companies from destroying rural Australian communities.

The Goldman Environmental Prize is the world's largest award honoring grassroots environmental activistsAbout the PrizeThe Goldman Environmental Prize honors grassroots environmental heroes from the world’s six inhabited continental regions: Africa, Asia, Europe, Islands & Island Nations, North America, and South & Central America. The Prize recognizes individuals for sustained and significant efforts to protect and enhance the natural environment, often at great personal risk. The Goldman Prize views “grassroots” leaders as those involved in local efforts, where positive change is created through community or citizen participation in the issues that affect them. Through recognizing these individual leaders, the Prize seeks to inspire other ordinary people to take extraordinary actions to protect the natural world.

The Prize RecipientsGoldman Prize recipients focus on protecting endangered ecosystems and species, combating destructive development projects, promoting sustainability, influencing environmental policies and striving for environmental justice. Prize recipients are often women and men from isolated villages or inner cities who choose to take great personal risks to safeguard the environment.

What the Goldman Prize ProvidesThe Goldman Prize amplifies the voices of these grassroots leaders and provides them with:- International recognition that enhances their credibility

- Worldwide visibility for the issues they champion

- Financial support to pursue their vision of a renewed and protected environment

Prize Selection and AnnouncementThe Goldman Environmental Prize recipients are selected by an international jury from confidential nominations submitted by a worldwide group of environmental organizations and individuals. The winners are announced every April to coincide with Earth Day. Prize recipients participate in a 10-day tour of San Francisco and Washington D.C.—highlighted by award ceremonies in San Francisco and Washington D.C.—including media interviews, funder briefings, and meetings with political and environmental leaders.

The OuroborosIn addition to a monetary prize, Goldman Prize winners each receive a bronze sculpture called the Ouroboros. Common to many cultures around the world, the Ouroboros, which depicts a serpent biting its tail, is a symbol of nature’s power of renewal.

- International recognition that enhances their credibility

- Worldwide visibility for the issues they champion

- Financial support to pursue their vision of a renewed and protected environment

Study Suggests Tree-Filled Spaces Are More Favourable To Child Development Than Paved Or Grassy Surfaces

Critically Endangered Spotted Tree Frogs Hop Back Into The Wild

NSW Releases Australia's Largest Investment In Koalas

- $107.1 million for koala habitat conservation, to fund the protection, restoration, and improved management of 47,000 hectares of koala habitat

- $19.6 million to supporting local communities to conserve koalas

- $23.2 million for improving the safety and health of koalas by removing threats, improving health and rehabilitation, and establishing a translocation program

- $43.4 million to support science and research to build our knowledge of koalas.

- Partnering with Taronga Conservation Society Australia to restore more than 5,000 hectares of Box Gum grassy woodlands around the Western Slopes of the Great Dividing Range. Koalas will be translocated to the site once the woodland is re-established.

- Partnering with World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Australia to protect 500 hectares of high quality koala habitat on private land under conservation agreements across the Northern Rivers region through the Biodiversity Conversation Trust.

- Working with volunteer wildlife rehabilitators, vets and other partner organisations to enhance co-ordination of emergency response for koalas and other wildlife due to bushfire or extreme weather events.

More Good News For Koalas

- In the state’s south, we have purchased 1,052 hectares adjoining Macanally State Conservation Area.

- Along the state’s north, we have purchased 752 hectares adjoining Bundjalung National Park and Bundjalung State Conservation Area.

- On the mid-north coast, 201 hectares of land will connect two separate sections of Killabakh Nature Reserve.

Humans Disrupting 66-Million-Year-Old Feature Of Ecosystems

Breakthrough In Estimating Fossil Fuel Carbon Dioxide Emissions

In a study published today they quantified regional fossil fuel CO2 emissions reductions during the Covid-19 lockdowns of 2020-2021, using atmospheric measurements of CO2 and oxygen (O2) from the Weybourne Atmospheric Observatory, on the north Norfolk coast in the UK.

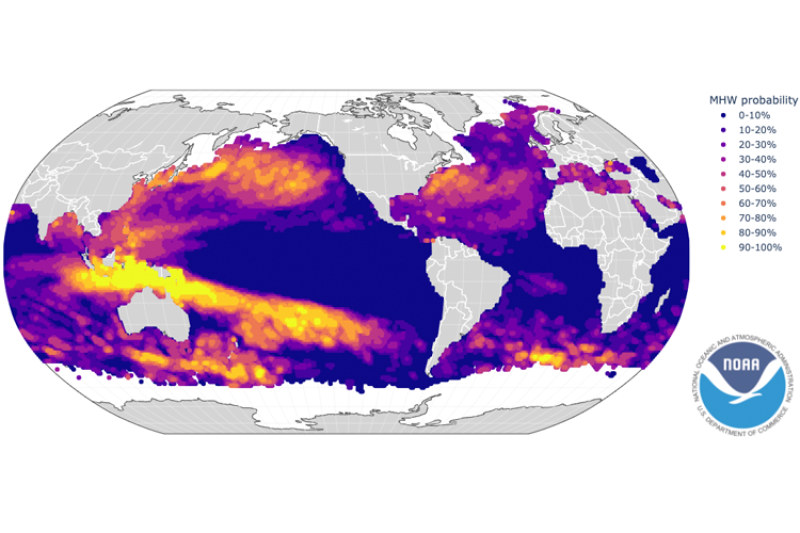

In a study published today they quantified regional fossil fuel CO2 emissions reductions during the Covid-19 lockdowns of 2020-2021, using atmospheric measurements of CO2 and oxygen (O2) from the Weybourne Atmospheric Observatory, on the north Norfolk coast in the UK.New Global Forecasts Of Marine Heatwaves Foretell Ecological And Economic Impacts

- Fish and shellfish declines that caused global fishery losses of hundreds of millions of dollars

- Shifting distributions of marine species that increased human-wildlife conflict and disputes about fishing rights

- Extremely warm waters that have caused bleaching and mass mortalities of corals

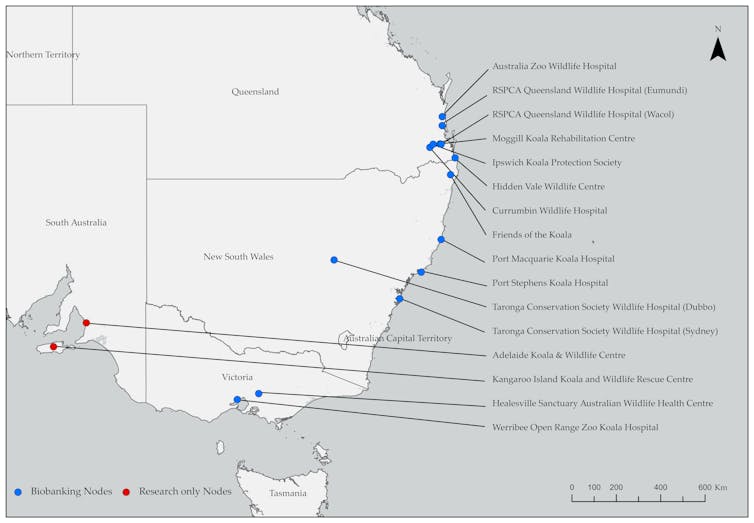

Frozen sperm and assisted reproduction: time to pull out all stops to save the endangered koala

Lachlan G. Howell, Deakin University and Ryan R. Witt, University of NewcastleAustralia’s wildlife was hit hard by the 2019-20 Black Summer megafires.

Amongst the casualties were our iconic tree-dwelling koalas, with an estimated 5000 dead in New South Wales alone. They are now officially endangered in three states and territories.

In response, researchers are ramping up captive breeding to prevent extinction. Unfortunately, captive breeding faces two major challenges: it’s expensive, and it can be hard to maintain genetic diversity.

To tackle both issues, our new modelling study backs the approach of biobanking (freezing koala sperm) and tailored assisted reproduction techniques. We found these techniques would result in a five-fold decrease in the costs of running captive breeding programs.

Despite their promise, these reproductive tools have not yet become widely used in conservation. With koalas facing an uncertain future, it’s time to explore their full potential. If we get this right, we could use the same tools to help other species in rapid decline.

What Are These Techniques?

In animals, biobanking refers to freezing and storing sperm, eggs and embryos, as well as other cells and tissues from the body. These techniques have long been used in agriculture to store valuable sperm from top breeding bulls and crops in seed banks.

Most people are aware of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), a common assisted reproductive technology, but other options exist such as artificial insemination and direct sperm injection into the egg. In humans, IVF and sperm injection have dramatically improved fertility while artificial insemination has revolutionised the breeding of livestock.

Models Show Huge Drop In Costs And Less Inbreeding

In our modelling, we set the goal of maintaining at least 90% of the genetic diversity in the captive population over a century.

We compared conventional natural breeding programs to programs mixing natural breeding with frozen koala sperm from wild animals delivered by artificial insemination or direct sperm injection.

We found supplementing captive breeding with frozen sperm would dramatically slow inbreeding rates, produce genetically healthier animals and require fewer animals to be held in breeding colonies.

To reach the genetic target, you would need 223 koalas in a conventional captive program. By contrast, adding assisted reproduction means you’d only have to keep 17 koalas.

These much smaller colony sizes are what drives down the cost. When you factor in the costs of assisted reproduction, including sperm freezing and performing artificial insemination or sperm injection, you still end up with a more than five-fold reduction in costs.

Let’s Put These Technologies To Work

While these technologies have proven their worth for us and for livestock, we largely haven’t put them to work in wildlife recovery. We believe this is a missed opportunity to cut costs and boost genetic diversity.

The few programs which have embraced these techniques have seen success. North America’s black-footed ferret is coming back from the edge of extinction, aided in part by assisted reproduction techniques. In the 1980s, the last remaining 18 black-footed ferrets were brought into a captive breeding program in America. Because the genetic diversity was so low, researchers used artificial insemination and frozen sperm to reintroduce lost genes and reduce the damage from inbreeding.

What Do We Need To Do?

In recent years, we’ve seen significant investment in frozen storage and genomic sequencing of tissue samples collected from wild koalas.

These technologies are useful to take stock of the genetic health of koala populations. But they can’t help us restore lost genetic diversity to wild populations because the frozen tissue samples cannot be turned into living animals.

While we’ve seen some progress in tailoring these technologies to koalas, there’s more to do. To date, 34 koala joeys have been born using artificial insemination in tame zoo koalas. These joeys, however, came from fresh or chilled sperm, not frozen. To use frozen sperm requires more research and technology development. Other procedures like embryo transfer and cryopreservation of sperm will also need more development.

If we perfect these techniques and technologies, we could see new possibilities for koala conservation.

These include:

- using genetic material from dead or sick koalas which would otherwise be lost

- preserving gene pools from genetically important koala populations at risk of extinction

- protecting the species against catastrophic events in the wild linked to climate change, disease and bushfire, which can cause major genetic loss

- reducing inbreeding in captive breeding programs and producing genetically fit koalas for release

- overcoming issues of separated populations and ensuring desirable breeding pairs can actually breed

- tackling relocation issues emerging from the varying diets of koalas across regions and risk of disease transfer.

We Already Have The Expertise

Australia already has a strong network of wildlife hospitals and zoos across the koala’s range in eastern Australia, as well as existing captive colonies and technical and husbandry expertise.

With a relatively small amount of funding (A$3-4 million to start, A$1 million annually), these sites could be equipped to collect and store koala sperm from wild populations and help perfect the technologies we need to make this a reality.

Longer term, we could adapt these technologies for other endangered marsupials. The potential is real. All we need now is attention from researchers and funding bodies.![]()

Lachlan G. Howell, Postdoctoral Research Fellow | Centre for Integrative Ecology, Deakin University and Ryan R. Witt, Postdoctoral Researcher and Honorary Lecturer | School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Listen to the Albert’s lyrebird: the best performer you’ve never heard of

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s series introducing you to Australia’s unloved animals that need our help.

Mention the superb lyrebird, and you’ll probably hear comments on their uncanny mimicry of human sounds, their presence on the 10 cent coin, and their stunning tail. Far less known – but equally, if not more, impressive – is the Albert’s lyrebird.

Like the superb lyrebird, the Albert’s lyrebird performs spectacular dance displays and, as our latest research shows, produces astounding mimicry of sounds from its environment. The Albert’s lyrebird is part of an ancient lineage of song birds, and even attracted the attention of Charles Darwin himself.

While the superb lyrebird is notoriously shy, the Albert’s lyrebird is more elusive still and is only found in a small region of subtropical rainforest hidden away in the mountainous areas of Bundjalung Country, on the border between New South Wales and Queensland.

Sadly, historical land clearing and recent bushfires have placed this species under threat, and a lack of information may be impeding its conservation. So let us introduce you to this shy performer and convince you that the Albert’s lyrebird is worthy of as much attention as its limelight-stealing sister species.

Impressive Displays

The Albert’s lyrebird (Menura alberti) is a large, ground-dwelling bird that forages by scratching up the soft, leaf-littered forest floor.

Both sexes have dark auburn-red feathers, and the male sports a showy tail made of silvery thread-like feathers that create a waterfall effect over his head during his courtship display. The display also reveals a bright, flame-like patch of orange feathers underneath his tail.

Like superb lyrebirds, male Albert’s lyrebirds hit the stage in midwinter. Hidden within the thick vegetation of the rainforest, they use clusters of vines or sticks as a platform to perform. The male Albert’s lyrebird then sings a remarkable song.

Impressively, they can accurately mimic up to 11 different species, including satin bowerbirds, Australian king-parrots, crimson rosellas and kookaburras, among others.

They also mimic multiple vocalisations from each species, as well as non-vocal sounds such as wingbeats. In fact, one lyrebird can mimic up to 37 different sounds!

Drama And ‘Whistle Songs’

In our latest research, we show each male arranges his mimicry into a particular order that’s repeated again and again throughout a performance. What’s more, all males within a location perform their mimicry in a similar order, suggesting this sequence is learnt from neighbouring males.

For example, lyrebirds at Binna Burra, in Lamington National Park, often mimic a kookaburra, followed by an eastern yellow robin, wingbeats, and the “tsit” of a green catbird. You can hear this shared sequence in the recordings below.

We’ve also discovered that males order their mimicry to place contrasting calls together within the sequence. This likely increases “drama”, and highlights the virtuosity of the male through the great diversity of sounds he can produce.

Lyrebirds not only mimic, but also sing their own songs, including their prominent whistle song – a striking melody we could hum or whistle along to, and during the dawn chorus the whistle songs of every lyrebird echo around the escarpments of their range.

These songs also vary from region to region, so each population has its unique set of whistle songs shared among the local males, which you can hear in the recordings below.

It’s not just the males that sing – female lyrebirds are shamefully underrated. Like female superb lyrebirds, female Albert’s lyrebirds sing both their own song and mimic the sounds of other birds.

They seem to often mimic alarm calls of eastern whipbirds, as well as grey goshawks, a fierce predator of lyrebirds.

While the Albert’s lyrebird may be most noticeable for its extravagant plumes and vocal virtuosity, they also likely play an important role in the local ecosystem.

Superb lyrebirds are “ecosystem engineers”, who turn over soil when foraging with their powerful claws, which can reduce bushfire fuel. Albert’s lyrebirds also rake the forest floor while foraging and are likely to have similar impacts.

A Threatened Species

Since European colonisation, Albert’s lyrebirds have endured a history of land clearing for agriculture, and were even once shot to put in pies!

As a result, they are listed nationally as “near threatened”, though this listing worsens to “vulnerable” in NSW, where the smallest population has an estimated 10 individuals.

The devastating 2019-2020 bushfires that engulfed Australia’s east coast burnt an estimated 32% of Albert’s lyrebirds habitat. As a result, Albert’s lyrebirds have now been listed as one of 13 priority bird species requiring urgent management after the fires.

Now, more than ever, it’s important to fully understand the behaviour and ecology of this species to ensure their survival.

What Can We Do?

The Albert’s lyrebird has escaped much public attention and has likely seen severe habitat loss after the fires. However, there is good news.

Citizen science initiatives in local council areas are helping to more accurately map Albert’s lyrebird occurrences, and improve habitat quality and connectivity by removing weeds.

Albert’s lyrebirds are not only important as an individual species, but also provide an entire soundscape through their diverse mimetic repertoires that they can perform for over an hour at a time.

They provide a soundtrack to our dwindling ancient rainforests, and are an important part of Australia’s natural and cultural history. Let’s ensure the next generation has the opportunity to meet this shy sister of the superb lyrebird.![]()

Fiona Backhouse, PhD Student in Behavioural Ecology, Western Sydney University; Anastasia Dalziell, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Wollongong; Justin A. Welbergen, Associate Professor in Animal Ecology, Western Sydney University, and Robert Magrath, Professor of Behavioural Ecology, Research School of Biology, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To make our wardrobes sustainable, we must cut how many new clothes we buy by 75%

If things don’t change fast, the fashion industry could use a quarter of the world’s remaining global carbon budget to keep warming under 2℃ by 2050, and use 35% more land to produce fibres by 2030.

While this seems incredible, it’s not. Over the past 15 years, clothing production has doubled while the length of time we actually wear these clothes has fallen by nearly 40%. In the EU, falling prices have seen people buying more clothing than ever before while spending less money in the process.

This is not sustainable. Something has to give. In our recent report, we propose the idea of a wellbeing wardrobe, a new way forward for fashion in which we favour human and environmental wellbeing over ever-growing consumption of throwaway fast-fashion.

What would that look like? It would mean each of us cutting how many new clothes we buy by as much as 75%, buying clothes designed to last, and recycling clothes at the end of their lifetime.

For the sector, it would mean tackling low incomes for the people who make the clothes, as well as support measures for workers who could lose jobs during a transition to a more sustainable industry.

Sustainability Efforts By Industry Are Simply Not Enough

Fashion is accelerating. Fast fashion is being replaced by ultra-fast fashion, releasing unprecedented volumes of new clothes into the market.

Since the start of the year, fast fashion giants H&M and Zara have launched around 11,000 new styles combined.

Over the same time, ultra-fast fashion brand Shein has released a staggering 314,877 styles. Shein is currently the most popular shopping app in Australia. As you’d expect, this acceleration is producing a tremendous amount of waste.

In response, the fashion industry has devised a raft of plans to tackle the issue. The problem is many sustainability initiatives still place economic opportunity and growth before environmental concerns.

Efforts such as switching to more sustainable fibres and textiles and offering ethically-conscious options are commendable. Unfortunately, they do very little to actually confront the sector’s rapidly increasing consumption of resources and waste generation.

On top of this, labour rights abuses of workers in the supply chain are rife.

Over the past five years, the industry’s issues of child labour, discrimination and forced labour have worsened globally. Major garment manufacturing countries including Myanmar, Cambodia, Bangladesh and Vietnam are considered an “extreme risk” for modern slavery.

Here’s what we can do to tackle the situation.

1. Limit Resource Use And Consumption

We need to have serious conversations between industry, consumers and governments about limiting resource use in the fashion industry. As a society, we need to talk about how much clothing is enough to live well.

On an individual level, it means buying fewer new clothes, as well as reconsidering where we get our clothes from. Buying secondhand clothes or using rental services are ways of changing your wardrobe with lower impact.

2. Expand The Slow Fashion Movement

The growing slow fashion movement focuses on the quality of garments over quantity, and favours classic styles over fleeting trends.

We must give renewed attention to repairing and caring for clothes we already own to extend their lifespan, such as by reviving sewing, mending and other long-lost skills.

3. New Systems Of Exchange

The wellbeing wardrobe would mean shifting away from existing fashion business models and embracing new systems of exchange, such as collaborative consumption models, co-operatives, not-for-profit social enterprises and B-corps.

What are these? Collaborative consumption models involve sharing or renting clothing, while social enterprises and B-corps are businesses with purposes beyond making a profit, such as ensuring living wages for workers and minimising or eliminating environmental impacts.

There are also methods that don’t rely on money, such as swapping or borrowing clothes with friends and altering or redesigning clothes in repair cafes and sewing circles.

4. Diversity In Clothing Cultures

Finally, as consumers we must nurture a diversity of clothing cultures, including incorporating the knowledge of Indigenous fashion design, which has respect for the environment at its core.

Communities of exchange should be encouraged to recognise the cultural value of clothing, and to rebuild emotional connections with garments and support long-term use and care.

What Now?

Shifting fashion from a perpetual growth model to a sustainable approach will not be easy. Moving to a post-growth fashion industry would require policymakers and the industry to bring in a wide range of reforms, and re-imagine roles and responsibilities in society.

You might think this is too hard. But the status quo of constant growth cannot last.

It’s better we act to shape the future of fashion and work towards a wardrobe good for people and planet – rather than let a tidal wave of wasted clothing soak up resources, energy and our very limited carbon budget.![]()

Samantha Sharpe, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney; Monique Retamal, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, and Taylor Brydges, Research Principal, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

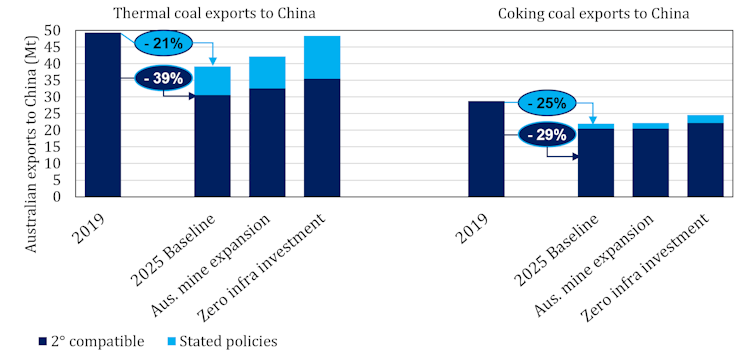

China’s demand for seaborne coal is set to drop fast and far. Australia should take note.

China’s plans to boost energy security and cut carbon emissions mean this year’s sudden boom for Australian coal exporters is just a blip.

Our new research explores the double pressures of China’s plans to bolster energy security in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine while aiming to hit net zero within 40 years.

Our model suggests that if China sticks to its current climate pledges, thermal coal imports will drop by a quarter within three years from 210 megatonnes (Mt) in 2019 to 155Mt by 2025. That means Australian exports could fall by 20% by 2025, while Australian coking coal exports could fall even more. This is in stark contrast to predictions of stable demand or even continued growth by the Australian government.

How could this happen so quickly, when coal prices have roughly tripled compared to the last decade? In short, better infrastructure. China has invested in major rail projects, including a direct rail line to a major coking coal mine in Mongolia, as well as increasing use in scrap steel.

Coal’s Wild Ride In The Volatile 2020s

The last few years have been a rollercoaster for coal producers. For Australia’s major coal exporters, it’s been a wild ride.

After falling for some years, coal prices fell sharply as the COVID pandemic and resulting lockdowns led to a sharp decline in energy consumption. Adding to the pressure, China banned the imports of coal from Australia.

Before the disruption of the 2020s, China bought roughly a quarter of Australia’s exports of thermal coal (burned in power stations) and a similar share of coking coal exports (used in steelmaking).

In 2021, coal consumption and emissions shot back up after an unexpectedly strong economic rebound. Coal supplies were also disrupted due to COVID-related restrictions and workforce shortages. Together, these factors tripled coal spot prices to US$300 a tonne for thermal coal and US$450 a tonne for coking coal.

In China, the sudden scarcity of coal led to Australian coal held at its ports rushed through customs clearance. While the import ban formally remains in place, government data shows Australia has managed to divert most of its coal exports to countries such as India, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Chinese Energy Security Means A Drop In Australian Seaborne Coal

We expect all of these issues to be fairly short-lived. The big picture is China’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2060, and its interim target to peak emissions before 2030.

How will it do that? By expanding renewable power generation, increasing coal power station efficiency while reducing dependence on coal power longer term, and increased use of steel scrap. Better steel recycling will reduce demand for new steel, which requires two of Australia’s key exports, iron ore and coking coal. Reduced demand will inevitably affect China’s need to import coal.

For the next few years, coal will remain vital to China’s industrial strength and ability to power its cities. That’s where energy security comes in. China has invested heavily in freight railway capacity, in order to bring its own coal to its power and steel plants more cheaply.

It has also built rail connections to Tavan Tolgoi in neighbouring Mongolia, one of the world’s largest and cheapest sources of high-quality coking coal. With the new railway capacity, coking coal can now travel 1,200 kilometres to China’s steelmaking heartland in Hebei province, near Beijing.

We took these factors into account in modelling different scenarios for Australian coal. We assume China will follow through on its existing climate policies.

In our scenarios, the largest losses would be borne by the biggest current suppliers of thermal coal to China. Number one exporter Indonesia could see its exports almost halved by 2025, falling from 125Mt in 2019 to as low as 65Mt.

Overall, China’s thermal coal imports should fall rapidly, dropping from 210Mt in 2019 to 155Mt by 2025. That means even if the embargo on Australian coal is lifted, our exports of thermal coal to China could still fall from 50Mt in 2019 to between 40 and 30 Mt in that timeframe, depending on China’s level of climate ambition. Coking coal exports could fall from 30Mt to as low as 20Mt.

If the embargo remains in place, the drop in Chinese demand for seaborne coal will mean China’s current suppliers will shift back to competing in the global market, and push out Australian suppliers. The net effect on Australian exports will likely be comparable.

We also explored the scenario in which all of Australia’s currently planned coal mine expansions actually go ahead. We found even in this scenario, there would be little impact on the loss of market share in China. By contrast, if Mongolian mines expand, our model predicts they would readily fill Chinese market demand at the expense of Australian coking coal imports.

To get these predictions, we ran a cost optimisation model with greatly improved representations of transport networks. The model finds the lowest cost at which different mines could supply all of China’s power and steel plants. We did not factor in political choices based on energy security or concerns about “just transitions”, such as, for instance, a Chinese push to limit the pain for its substantial coal mining and trucking workforce.

Overall, our model makes clear China’s demand for coal – expected to plateau or fall over the next few years – coupled with its expansion of domestic mine and transport capacity will reduce the role for Australian coal. The world’s top buyer of coal will increasingly be able to supply its power and steel plants with domestically mined coal at competitive costs.

In turn, that means it will be less costly for China to depend on what it considers to be volatile markets. It will also be easier to impose politically motivated import restrictions on suppliers from what it considers unfriendly countries.

China’s ability to cut seaborne coal imports will grow further if its government increases its decarbonisation ambitions. These plans will be a key influence on the the remaining demand for seaborne coal.

Australia’s government and investors would be wise to consider these macro-level changes and plans as they look ahead, rather than focusing on short term gains from current market volatility.

Alex Turnbull, fund manager at Keshik Capital, contributed to this article and was a co-author of the published research. He personally holds no coal stocks.![]()

Jorrit Gosens, Research Fellow, Australian National University and Frank Jotzo, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy and Head of Energy, Institute for Climate Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Others

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

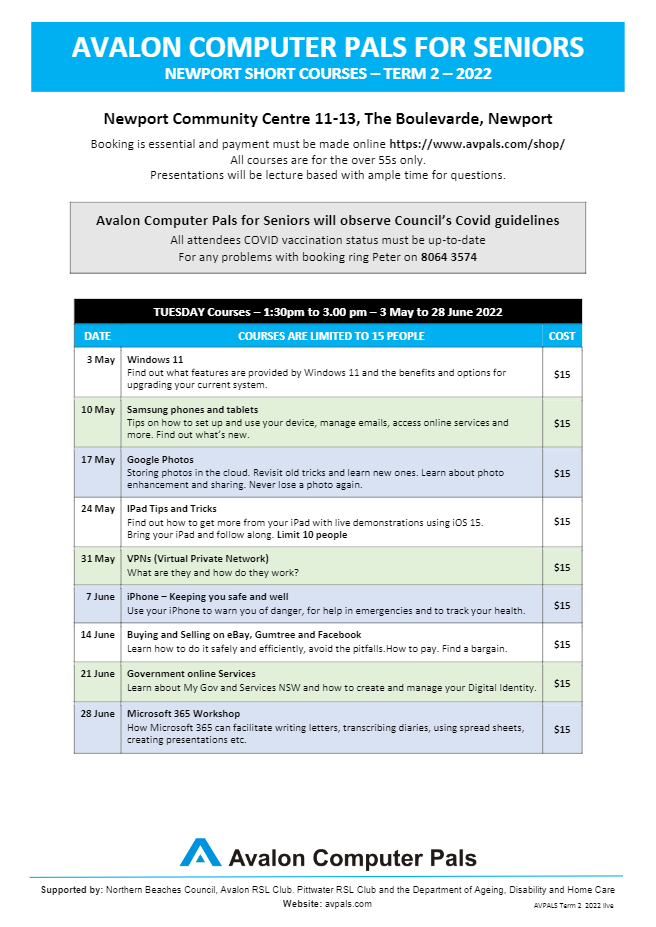

AvPals Newport Small Group Courses Return

Policy Recommendations For The 47th Parliament

Fake News, Retirement Taxes And What We Should Talk About

Election 2022: Information You Need To Know

- are outside the electorate where you are enrolled to vote

- are more than 8km from a polling place

- are travelling

- are unable to leave your workplace to vote

- are seriously ill, infirm, or due to give birth shortly (or caring for someone who is)

- are a patient in hospital and can't vote at the hospital

- have religious beliefs that prevent you from attending a polling place

- are in prison serving a sentence of less than three years or otherwise detained

- are a silent elector

- have a reasonable fear for your safety.

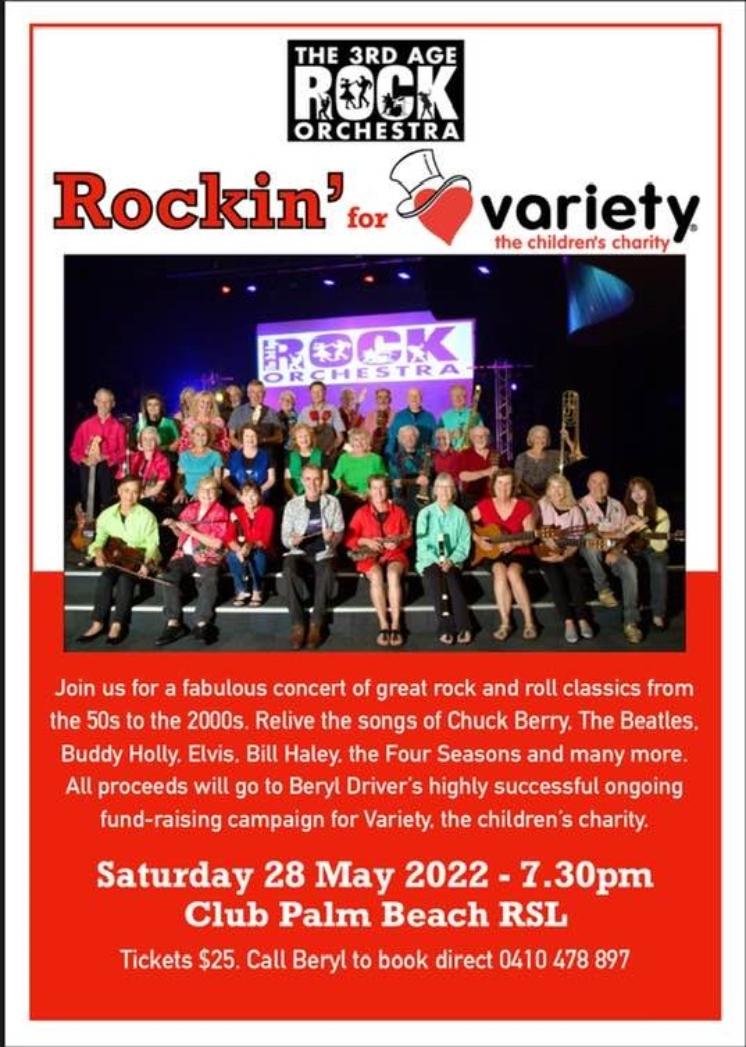

Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons - Who Loves You (Official Music Video)

Calming Overexcited Neurons May Protect Brain After Stroke

Older Australians on the tough choices they face as energy costs set to increase

Australian aged care policy and programs are increasingly focused on what’s known as “successful ageing” – helping people feel satisfied, happier and healthier as they age. The goal is not just living longer, but also living better.

An essential part of ageing successfully is having enough energy for cooking, heating, cooling, cleaning, and leisure activities.

Being able to use energy in these ways can help prevent ill health or premature death, manage illness and chronic disease, sustain social relations, and support positive mental health.

Recent research I led focused on the role domestic energy consumption plays in supporting successful ageing. Over several months, we met with and interviewed 39 householders aged over 60 living in the New South Wales Illawarra region, from varying economic, social and cultural backgrounds, and housing arrangements.

We found clear associations between energy consumption and health and well-being outcomes. Many people told us they avoid using energy – risking even their health and well-being – to reduce costs.

When You Can’t Use The Clothesline Anymore

Carl is a 97-year-old widower who survived the sinking of two battleships during WWII. He now lives alone after his wife died following a long illness.

He recently had a couple of bad falls, which means he can no longer manage to use his clothesline outside to dry his laundry. Carl explains:

I’ve stopped using the outside line because I felt awkward. I’d have to put my stick down and lift things up, then I’d go wobbly. I fell a couple of times […] I have a dryer for emergencies, but I try not to use it because of the electricity costs […] It dries in the kitchen anyway.

To save on energy costs, Carl uses a kitchen pulley system to dry his clothing.

While he is just about able to manage, is he ageing successfully?

Carl’s worries about the cost of energy have led him to risk his health instead of choosing the safer and easier option of the dryer.

Comfort Versus Cost

We found other participants were rarely putting the heating on. Danielle, a 72-year-old woman who lives with her husband, told us:

My daughter was here last night. She complained about being cold. I gave her a blanket. I offered to put the heater on; I gave her a blanket instead.

Zack, an 89-year-old widower, only offers to put the reverse cycle air conditioner on when he has visitors.

I put it on yesterday afternoon because I knew the daughter was coming. But at times I just got a couple of throw rugs and just sit here and watch the television with that on.

This inability to live at a comfortable temperature was also an issue for Georgie, a 72-year-old woman who lives alone in a small unit. Despite the cold mornings in winter, Georgie has so far avoided buying a reverse cycle air conditioner due to the cost:

It’s really quite cold in here in the winter. In the morning […] I get up really early. I’m up by 5:00 in the morning, and it’s cold. But it [reverse cycle air conditioning] would be expensive to run.

Energy Supports Health And Socialising

Participants also had to consider energy costs associated with essential medical devices such as CPAP machines, chairlifts, and blood pressure and blood sugar monitors.

As Daisy, a 72-year-old married woman explains, her husband Joe relies on energy for his CPAP machine:

Really, I mean, that has to come first, the fact that he needs to breathe.

Many older Australians face a difficult choice between using energy to manage their health or face high energy bills they can ill afford.

We also found energy supports well-being; hosting friends for a cup of tea or initiating social connections is tough without energy.

Genevieve, aged 89, explains how her computer helps her keep in touch with family:

There is a little bit of communication between them regularly every time we have a meeting and, you know, little things, so it’s continual. So, I’m doing emails and little reports and little things like that on it.

Energy Policy Must Consider The Needs Of Older People

Existing Australian energy policy focuses on marketisation, productivity, efficiency, security and the clean energy transition, offering little focus on health and well-being.

On the other hand, health policies pay scant attention to the role domestic energy consumption plays.

With energy prices set to increase later this year, billing anxiety lingering and fuel insecurity looming, there’s a risk the health and well-being needs of older Australians are neglected.

What Would Help?

Our findings underscore the need for health, energy, and housing policy to be integrated to better support older people to age successfully, in homes fit for purpose – without constant worries about high energy bills.

Policies and programs geared towards energy cost savings such as solar installations, insulation and efficient appliances would help. So too would promoting access to higher value energy rebates for those with chronic health conditions.

Health professionals can help by guiding eligible Australians towards their entitlements.

By recognising that energy is a basic human need, essential for health and well-being, we can better support successful ageing.![]()

Ross Gordon, Professor, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Word Of The Week: Family

Family Songs: A Mix

Listen to the Albert’s lyrebird: the best performer you’ve never heard of

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s series introducing you to Australia’s unloved animals that need our help.

Mention the superb lyrebird, and you’ll probably hear comments on their uncanny mimicry of human sounds, their presence on the 10 cent coin, and their stunning tail. Far less known – but equally, if not more, impressive – is the Albert’s lyrebird.

Like the superb lyrebird, the Albert’s lyrebird performs spectacular dance displays and, as our latest research shows, produces astounding mimicry of sounds from its environment. The Albert’s lyrebird is part of an ancient lineage of song birds, and even attracted the attention of Charles Darwin himself.

While the superb lyrebird is notoriously shy, the Albert’s lyrebird is more elusive still and is only found in a small region of subtropical rainforest hidden away in the mountainous areas of Bundjalung Country, on the border between New South Wales and Queensland.

Sadly, historical land clearing and recent bushfires have placed this species under threat, and a lack of information may be impeding its conservation. So let us introduce you to this shy performer and convince you that the Albert’s lyrebird is worthy of as much attention as its limelight-stealing sister species.

Impressive Displays

The Albert’s lyrebird (Menura alberti) is a large, ground-dwelling bird that forages by scratching up the soft, leaf-littered forest floor.

Both sexes have dark auburn-red feathers, and the male sports a showy tail made of silvery thread-like feathers that create a waterfall effect over his head during his courtship display. The display also reveals a bright, flame-like patch of orange feathers underneath his tail.

Like superb lyrebirds, male Albert’s lyrebirds hit the stage in midwinter. Hidden within the thick vegetation of the rainforest, they use clusters of vines or sticks as a platform to perform. The male Albert’s lyrebird then sings a remarkable song.

Impressively, they can accurately mimic up to 11 different species, including satin bowerbirds, Australian king-parrots, crimson rosellas and kookaburras, among others.

They also mimic multiple vocalisations from each species, as well as non-vocal sounds such as wingbeats. In fact, one lyrebird can mimic up to 37 different sounds!

Drama And ‘Whistle Songs’

In our latest research, we show each male arranges his mimicry into a particular order that’s repeated again and again throughout a performance. What’s more, all males within a location perform their mimicry in a similar order, suggesting this sequence is learnt from neighbouring males.

For example, lyrebirds at Binna Burra, in Lamington National Park, often mimic a kookaburra, followed by an eastern yellow robin, wingbeats, and the “tsit” of a green catbird. You can hear this shared sequence in the recordings below.

We’ve also discovered that males order their mimicry to place contrasting calls together within the sequence. This likely increases “drama”, and highlights the virtuosity of the male through the great diversity of sounds he can produce.

Lyrebirds not only mimic, but also sing their own songs, including their prominent whistle song – a striking melody we could hum or whistle along to, and during the dawn chorus the whistle songs of every lyrebird echo around the escarpments of their range.

These songs also vary from region to region, so each population has its unique set of whistle songs shared among the local males, which you can hear in the recordings below.

It’s not just the males that sing – female lyrebirds are shamefully underrated. Like female superb lyrebirds, female Albert’s lyrebirds sing both their own song and mimic the sounds of other birds.

They seem to often mimic alarm calls of eastern whipbirds, as well as grey goshawks, a fierce predator of lyrebirds.

While the Albert’s lyrebird may be most noticeable for its extravagant plumes and vocal virtuosity, they also likely play an important role in the local ecosystem.

Superb lyrebirds are “ecosystem engineers”, who turn over soil when foraging with their powerful claws, which can reduce bushfire fuel. Albert’s lyrebirds also rake the forest floor while foraging and are likely to have similar impacts.

A Threatened Species

Since European colonisation, Albert’s lyrebirds have endured a history of land clearing for agriculture, and were even once shot to put in pies!

As a result, they are listed nationally as “near threatened”, though this listing worsens to “vulnerable” in NSW, where the smallest population has an estimated 10 individuals.

The devastating 2019-2020 bushfires that engulfed Australia’s east coast burnt an estimated 32% of Albert’s lyrebirds habitat. As a result, Albert’s lyrebirds have now been listed as one of 13 priority bird species requiring urgent management after the fires.

Now, more than ever, it’s important to fully understand the behaviour and ecology of this species to ensure their survival.

What Can We Do?

The Albert’s lyrebird has escaped much public attention and has likely seen severe habitat loss after the fires. However, there is good news.

Citizen science initiatives in local council areas are helping to more accurately map Albert’s lyrebird occurrences, and improve habitat quality and connectivity by removing weeds.

Albert’s lyrebirds are not only important as an individual species, but also provide an entire soundscape through their diverse mimetic repertoires that they can perform for over an hour at a time.

They provide a soundtrack to our dwindling ancient rainforests, and are an important part of Australia’s natural and cultural history. Let’s ensure the next generation has the opportunity to meet this shy sister of the superb lyrebird.![]()

Fiona Backhouse, PhD Student in Behavioural Ecology, Western Sydney University; Anastasia Dalziell, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Wollongong; Justin A. Welbergen, Associate Professor in Animal Ecology, Western Sydney University, and Robert Magrath, Professor of Behavioural Ecology, Research School of Biology, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

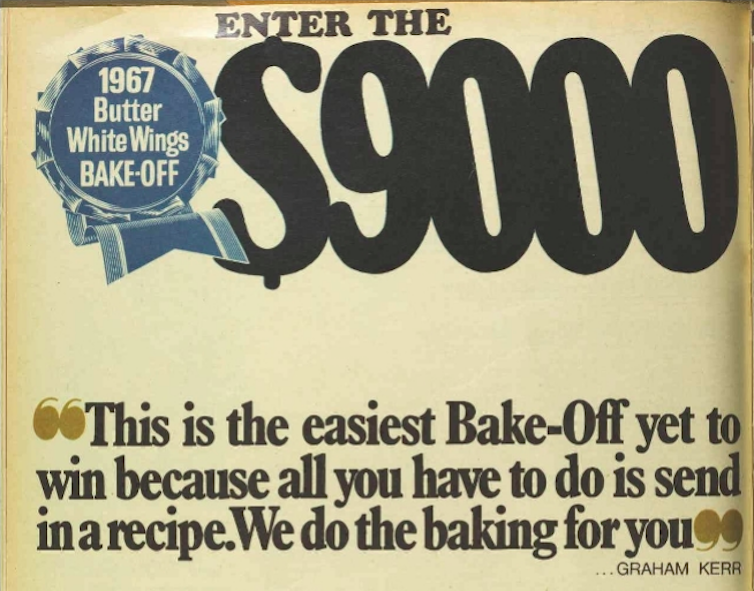

More than just MasterChef: a brief history of Australian cookery competitions

Australians were involved in competitive cookery long before MasterChef.

The earliest of Australia’s cooking competitions were at agricultural shows. In 1910, the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW hosted its first competition for “perishable foods” at the Royal Easter Show.

Along with pastry and pickles, competitors could also be judged on their calf’s foot jelly.

By the 1920s, the cookery category at the Easter Show had been firmly established. It was purely the preserve of women. Men were prohibited from entering and wouldn’t be allowed to enter until after the second world war.

Women living in NSW and the ACT also entered their wares in the Country Women’s Association’s The Land Cookery Competition. Starting in 1949, the competition judged women on their ability to bake classics such as fruit cake, butter cake and lamingtons, offering modest prize money to the winners. It is still running today.

These competitions are grounded in a history of cooking which saw women as “cooks” and men as “chefs”. Women were amateurs working in the home, while men worked in professional kitchens. This phenomenon continues today.

Cookery competitions allowed women to receive recognition for their often-overlooked hard work and skill. Contestants were encouraged to break out of their comfort zones, to be creative, innovate and impress.

Magazine Cookery Competitions

With women as their key demographic, it is little wonder that, by the 1960s, women’s magazines such as the Australian Women’s Weekly began hosting large-scale cookery competitions open to readers around the country.

Perhaps the most extravagant of these competitions was the Butter-White Wings Bake-Off, which ran from 1963 to 1970. The competition pitted Australia’s best home bakers against each other in a variety of categories, including cakes, desserts, main courses and “busy lady recipes”.

Entering their written recipes, contestants competed at state level for a chance to win a trip to the national final where they would cook for illustrious judges.

Thousands competed at the state level of these competitions, and one from each state and territory would go on to the final. These were held in either Sydney or Melbourne in front of live audiences, usually in the middle of a department store.

The 1970 final was televised, with the Weekly estimating two million viewers would watch the proceedings.

It was Australia’s first televised cooking competition.

Marketing And Celebrities

Just as MasterChef is sponsored by advertisers, the cookery competitions hosted in the Weekly proved to be lucrative marketing opportunities for a variety of sponsors. The prizes, provided by sponsors such as Breville and QANTAS, included cash, fur coats, appliances, cars and overseas holidays.

The choice of judges also offers us a glimpse of the glamour associated with the competitions as well as the continued gendered expectations surrounding cookery. A slew of early “celebrity chefs” were flown in from exotic, international destinations to judge the competition – including the Galloping Gourmet himself, Graham Kerr.

These celebrity chefs judged the main course section; the overtly feminine baking sections were judged primarily by women.

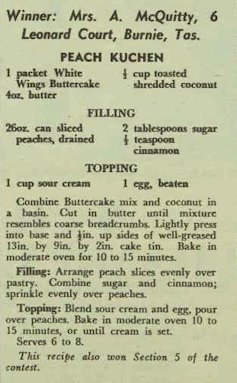

It was in the cake section that contestants really went above and beyond, both in the recipes themselves and in their names. In 1968, prize-winning recipes included “Golden Crown Dessert”, “Marshmallow-Cherry Cake”, “Chocolate Gold Layer Cake” and “Peach Kuchen”.

Peach Kuchen, which won the “Busy Lady” section, was made with a packet of White Wings cake mix, a tin of peaches and some sour cream. The Bake-Off helped to popularise (and sell!) boxed cake mixes: even the “busy woman” could create delicious cakes deserving of accolades.

A Dizzying Progression

The last Butter-White Wings Bake-Off was held in 1970, but the magazine kept hosting cooking competitions. In 1980, Elizabeth Love was crowned “Best Cook in Australia.”

Her prize-winning menu included oysters in pastry cases, ballotine of duckling with baby vegetables and a red wine jus, mango sorbet and almond petits fours.

In a recent interview, Love reflected that her menu drew on the concepts of nouvelle cuisine, which was popular at the time. It was an ambitious menu for a home cook – however Love declared that she didn’t think it would do very well if she went on MasterChef today.

Her menu demonstrates the dizzying progression of Australian food over the past 40 years.

Cookery competitions like those held in the Weekly gradually disappeared, replaced instead by competitions on television, which have grown in popularity over the last two decades.

Like the magazine cookery competitions of the past, where contestants were inventive and used new and exciting ingredients, television competitions have also proved important for introducing the Australian palate to innovative cooking techniques and exotic ingredients.

Our ongoing fascination with cooking competition shows such as MasterChef reflects the prestige still on offer for those ambitious contestants who enter them, as well as the cultural importance of food. ![]()

Lauren Samuelsson, Honorary Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Guide to the classics: Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the Everest of literature

Although I’m wary of declaring any literary work to be the greatest ever, Shakespeare’s Hamlet would be a frontrunner. It’s often proclaimed to be or voted Shakespeare’s best play (Google it). It has countless film adaptations, is widely referenced, and even gets a homage of sorts in The Simpsons.

Hamlet deserves such accolades because it offers the deepest of insights into the human condition; although this insight can be a little tricky to explain.

Let’s consider some of Shakespeare’s other popular, serious plays. Romeo and Juliet is a tale of forbidden love – the cliché drops effortlessly. Othello is about the horrors of jealousy. And Macbeth, with its Tarantino-grade account of regicide and its grim consequences, explores the dark side of ambition. So what about Hamlet?

Well … ah … It’s about when someone does something bad, and you’re pretty sure what they did wasn’t right, and you ought to do something about it, but you can’t find it within yourself to do this something, and your uncertainty and inaction cause you even more distress, but events roll on – as they always do – and everything ends up worse than if you’d done something in the first place. Maybe.

I’m being silly, but it’s my way of coping. For while I’m familiar with the woes associated with love, jealousy and ambition, my greatest grief is that time and again I did not act when the situation called for it. I was a coward. I’m certain that I’m far from alone in assessing my life this way. And this is why Hamlet, which depicts this state of inaction, is the Everest of literature.

An Overview Of The Play

Hamlet, the prince of Denmark, is a modern character. He attends the University of Wittenberg and is an intellectual. His father, the recently deceased king, also called Hamlet, was, in contrast to his son, a warrior.

In the play’s first scene, the ghost of old king Hamlet silently appears to Horatio, Hamlet’s friend. Upon seeing him, Horatio recalls the time when “in an angry parle [a battle], / He [the old king] smote the sledded Polacks on the ice.” This counterpoint to Hamlet’s famed inaction, like the ghost of the king itself, haunts the play.

We soon learn that the old king has only been dead two months and that Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, has hastily married the new king, Hamlet’s uncle Claudius.

The ghost of Hamlet’s father returns, this time telling his son he was murdered – poisoned – by Claudius (it was “murder most foul”) and urging Hamlet to avenge his death.

The scene finishes with young Hamlet revealing reluctance:

The time is out of joint: – O cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right!

But the ever more troubled prince is uncertain whether the ghost even spoke the truth. He gains proof when he asks a troupe of actors to reenact the poisoning before Claudius and Claudius reacts strongly.

Now Hamlet really must avenge his father. The opportunity arises when, on his way to meet his mother, he comes upon Claudius praying. But Hamlet is beset by doubts and cannot kill Claudius.

Hamlet goes on to confront his mother about her hasty marriage. While arguing with her, he stabs Polonius (the father of Ophelia, the woman he has been courting), who had been planted behind a curtain to spy on him.

Polonius’s son Laertes wants to avenge his father. He, unlike Hamlet, is willing to act.

Claudius, who now also wants Hamlet dead, arranges for Laertes to fight a duel with Hamlet with a poisoned rapier. They fight. Hamlet is cut by the rapier, and then Laertes is too. Meanwhile Hamlet’s mother accidentally consumes a poisoned drink intended for her son and dies.

Hamlet learns the truth of what has happened. He stabs Claudius, making him drink the poison too. Claudius dies, then Laertes dies, then finally, Hamlet dies. (South Park efficiently represents the final scene).

To Be Or Not To Be – Or Maybe Not

I had expected to illustrate Hamlet’s struggle to act with an analysis of the most famous speech in all of Shakespeare: ‘To be, or not to be’ (Act III Scene I). It begins with these oft-quoted lines:

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

But now I’m not so sure it’s a good idea. “To be, or not to be” is ambiguous. Also, Hamlet probably knows he is being watched by the king or others while he is speaking, and thus is not really speaking his mind.

Arguably, Hamlet’s definitive speech in the play comes just before this one, at the end of Act II. In this red-blooded soliloquy, he berates himself for his inaction, asking, “am I a coward?” and reflects that he lacks the gall, “To make oppression bitter”.

He says, ‘I should have fatted all the region kites / With this slave’s offal’; i.e. murdered Claudius and fed his guts to the carrion eaters.

He also mocks his proclivity to seek solace in words:

Why, what an ass am I! Ay, sure, this is most brave;

That I, the son of a dear father murder’d,

Prompted to my revenge by heaven and hell,

Must, like a whore, unpack my heart with my words…

The Refusal Of The Call To Adventure

Shakespeare’s play is notable because it tells of one who, to draw on Joseph Campbell’s enduring concept of the “hero’s journey”, refuses “the call to adventure”.

So many of the stories we consume involve some sort of heroic quest where a reluctant hero accepts this call. Observe Frodo in Lord of the Rings or Luke Skywalker’s ambivalence around the call in Star Wars. Both heroes end up defeating evil. And while they are changed by the experience (not entirely for the better), one senses that refusing the call would have led to worse outcomes.

Hamlet’s inaction – his refusal of the call – directly or indirectly causes eight deaths, including his own. If he had acted, then probably only Claudius would have died.

The moral of the story is that there is risk in action, but the greater risk lies in inaction. In short, action, in bad situations, is the lesser of two evils.

But maybe this isn’t the moral. Maybe the play is not exhorting the audience to act, but asking a deeper question. Namely, what does it mean for us to cross the threshold that separates reason from power? That is, what does it mean for us to abandon reason and strike back at the monster?

Reason appeals to principles. It appeals to the capacity for reason in others. It doesn’t take the law into its own hands. But what if it is sometimes reasonable to abandon reason and strike at power with power? Can reason survive such a decision?

The Endless Appeal Of Hamlet

Hamlet is not only successful because Hamlet himself embodies our own struggles. Hamlet is also staggeringly quotable – the quip is that there are too many quotations in it.

The play’s appeal also lies in the depth of the secondary characters, such as Ophelia, Polonius and the inseparable Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Hamlet’s friends from university).

And the play is seductively enigmatic. We are unsure whether Hamlet’s mother was in on the murder of the old king, whether Polonius is indeed a fool, whether Hamlet loses his mind, and so on. Where there are mysteries, there are detectives.

Hamlet turns up everywhere in Western culture – not just in The Simpsons and South Park.

Given all the trouble Hamlet has with his father and mother, it’s not surprising that Freud saw something Oedipal in the whole business.