inbox and environment news: Issue 536

May 1 - 7, 2022: Issue 536

Spotted Gums Are Blooming - Autumnul Food For Our Wildlife

Autum is the time our local spotted gums and swamp mahogany's flower - providing food for birds, possums and all other kinds of wildlife. These spotted gums in the trees here have been hosting a cacophony of birds during the day and been visited by the resident possums at night.

Grants Awarded To Local Schools For Sustainability Efforts

- The Beach School, Allambie Heights $2,000

- NBSC Freshwater Campus $1,550

- Balgowlah Heights Public School $1,927

- Maria Regina Primary School, Avalon $2,000

- Belrose Public School $1,098

- Killarney Heights High School $1,425

Barrenjoey Headland Amenities Concept Plan

- the building will be set into the landscape, concealed by the landform and native heath

- screened walls to the front of the building will allow for natural light and ventilation

- timber screens will be left to grey with alternating painted battens to reference the colours of the surrounding natural landscape and heritage buildings

- unisex cubicles will be provided, including baby change facilities and a water refill station

- water supply and sewer infrastructure to service these amenities are already in place.

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Mackellar Candidate Forum 2022: Managing The Big Issues Facing Our Community

- Christopher BALL - United Australia Party

- Paula GOODMAN - Australian Labor Party

- Ethan HRNJAK - The Greens

- Dr. Sophie SCAMPS - Independent

- Barry STEELE - TNL (formerly The New Liberals)

.jpg?timestamp=1650677177096)

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Autumn 2022 Newsletter

Cassia Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Darkinjung Plans For 600 Homes On Central Coast's Lake Munmorah Now On Exhibition: Closes May 24

Have Your Say On Key Environmental Legislation Reviews

Fail: our report card on the government’s handling of Australia’s extinction crisis

Australia is losing more biodiversity than any other developed nation. Already this year the charismatic and once abundant gang gang cockatoo has been added to our national threatened species list, the koala has been listed as endangered and the Great Barrier Reef suffered another mass bleaching event.

The Australian public consistently rates the loss of our unique plants and animals as a key concern. Indeed, in a recent poll of 10,000 readers of The Conversation, “the environment” was identified as the second-biggest issue affecting their lives, behind climate change at number one.

The Coalition has been in government since 2013. So what has it done about the biodiversity crisis? Unfortunately, the state of Australia’s plants, animals and ecological communities suggests the answer is - not nearly enough.

In fact, as the extinction crisis has escalated, protection and recovery for threatened species has declined. Poor decisions are contributing to the problem, rather than solving it.

The Sorry State Of Australia’s Biodiversity

Australia has formally acknowledged the extinction of 104 native species since European colonisation, but the true number is likely much higher.

Threatened bird, mammal and plant populations have, on average, halved or worse since 1985. Species recently thought to be safe – such as the bogong moth, gang gang cockatoos, and even the iconic koala – are being added to the global and national threatened species lists following drought, catastrophic fires and habitat destruction.

Today, 19 ecosystems show clear signs of collapse. This includes the Great Barrier Reef, savannas, mangroves, tropical rainforests, and tall mountain ash forests. These losses have profound ramifications for clean air and water, productive agriculture, pollination, and well-being.

Biodiversity is a crucial part of Australia’s national identity and Aboriginal culture. It delivers billions of dollars in tourism revenue and underpins most sectors of our economy.

It’s important for our health, too. COVID lockdowns recently brought the critical role of nature to our well-being into sharp focus, with thriving biodiversity shown to deliver avoided costs to the healthcare system.

Ignoring Key Recommendations

A 2018 Senate inquiry into the extinction crisis of Australian animals (fauna) concluded that native fauna was declining. It found biodiversity protection was under-resourced and failing, and Australia urgently needs an independent environmental regulator.

In 2022, the federal Auditor-General reviewed the government’s implementation of Australia’s threatened species legislation, finding:

limited evidence that desired outcomes are being achieved, due to the department’s lack of monitoring, reporting and support for the implementation of conservation advice, recovery plans.

The national Threatened Species Strategy focuses on 100 species and a few iconic places. But more than 1,800 species and ecosystems are threatened with extinction.

And economic analyses indicate we currently spend about around 7% of the targeted A$1.6 billion per year required to halt species loss and recover nationally listed threatened species.

These findings were reinforced in 2020 by a major independent review of Australia’s environment law – Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

The review by Professor Graeme Samuel made 38 recommendations, but almost none have been implemented. They include establishing an Environment Assurance Commissioner, rigorous national environmental standards and resourcing compliance and enforcement of environmental regulations.

Failure To Protect What We Have

Land clearing is a key threat to Australian wildlife, yet the government has not made meaningful progress to halt it.

The hectares cleared in New South Wales over the last decade have tripled, and a staggering 2.5 million hectares have been cleared in Queensland between 2000 and 2018.

Worryingly, more than 7.7 million hectares of threatened species habitat have been cleared since the EPBC Act came into force (between 2000 and 2017), including 1 million hectares of koala habitat.

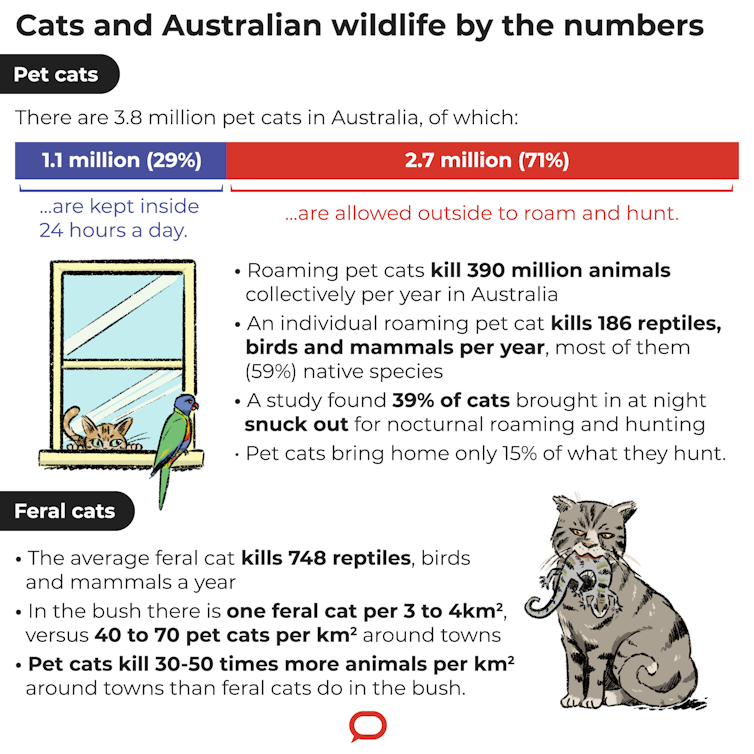

Invasive species – such as cats, foxes, rabbits, deer and buffel grass – continue to wreak havoc on many of our most endangered species.

Cats alone kill 1.7 billion native animals each year and threaten at least 120 species with extinction. While feral predator control has received some focus, the effort still falls well short of what’s required.

Lack Of Transparency And Accountability

Official reviews have consistently found the federal government’s approach to protecting biodiversity lacks transparency and accountability.

Questions have also been raised about the federal government’s delay in releasing its five-yearly State of the Environment Report ahead of the election.

And investigations have raised serious concerns about how the government handled decisions regarding grasslands illegally destroyed by a company part-owned by a government minister.

A key advisor to the government recently labelled a major scheme to promote forest restoration as carbon credits as environmental and taxpayer “fraud”.

A federal integrity commission, if it existed, could have explored these cases.

The government also continues to back activities that cause damage to biodiversity, including the fossil fuel and forestry industries.

On agriculture, the government is pursuing a “biodiversity stewardship” policy, to financially reward farmers for protecting wildlife.

But ongoing approval of unsustainable land management practices, particularly land clearing (of which agriculture is responsible for the lion’s share) will likely overshadow any stewardship gains.

So What’s Needed To Prevent Future Extinctions?

Labor has not yet revealed its full suite of environment policies. This week it told Guardian Australia it will release more details before the election, and has called on the government to release the State of the Environment report.

So what policies are needed to reverse the biodiversity crisis? The answer is: spend more and destroy less.

Just two days of Coalition election promises (estimated at $833 million per day) would fund recovery for Australia’s entire list of threatened species for a year.

Systems for protecting biodiversity need stronger legal mandates and less discretion for ministers to override decisions about project approvals, species listing and other matters.

Biodiversity should be integrated into key aspects of government practice. For example, it makes no sense to invest in protecting koalas while simultaneously approving koala habitat clearing.

And we need investment in every threatened species, not just a hand-picked few.

Finally, transformative policies are needed to support the substantial opportunities to enhance and restore biodiversity. This includes:

- using nature to help mitigate climate change

- green recovery of the economy post-COVID

- finding ways to farm profitably while enhancing biodiversity

- designing cities where people and nature can both flourish.

The fate of nature underpins our economy and health. Yet in the election campaign to date, there’s been a deafening silence about it.![]()

Sarah Bekessy, Professor in Sustainability and Urban Planning, Leader, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University and Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Ecology, School of Ecosystem and Forest Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Now we know the flaws of carbon offsets, it’s time to get real about climate change

Last month former carbon market watchdog Andrew MacIntosh blew the whistle on Australia’s carbon offset market. He described the scheme as a “rort” with up to 80% of carbon offsets “markedly low in integrity”.

While these allegations reignited debate over carbon offsets, the issues are not new. Integrity issues have plagued carbon trading schemes and offsets since they first emerged in the mid 1990s.

You might think this is a fairly major bug. In fact, it’s a feature. Polluting industries want low-cost compliance with climate laws – and poor quality offsets satisfy this demand. The key phrase there is “low cost”. That’s the reason free-market economists championed this kind of flexible compliance over direct regulation in the first place.

For polluters, it’s an easy win: buy offsets, appear to have done something, and keep on polluting. But bad quality offsets can actually make climate change worse.

Who loses? The rest of us. Questionable offsets and flexible compliance have slowed down the shift away from oil, gas and coal.

So should we abandon offsets entirely? Or do they have a place?

Carbon Offsets: A Failure In Market Experimentation

Carbon offsets have played a significant role in government and industry’s climate change response since emerging from early global climate negotiations. They have been popular because they do not require major change to the status quo.

Free market economists and their allies in industry have experimented with ways of paying for emission-reducing technology changes, avoiding deforestation, planting new trees, and building wind and solar farms. These methods have been packaged up as certificates and sold on market platforms created by both government and private actors as certified “emissions reductions”.

There are a number of problems with this.

First are the well-founded concerns over whether offset projects actually do reduce or soak up carbon. For instance, 85% of credits in the long-running United Nations carbon offset scheme did not actually reduce emissions as of 2017. That meant coal-fired power stations and industrial gas facilities owned by oil companies such as Shell were effectively subsidised while simultaneously increasing their emissions.

One of the world’s first regulatory carbon markets in NSW was similarly plagued by issues of “additionality” – that is, whether the offset activities would have happened anyway.

There are also questions about the governance of offsets. For offset schemes to be a real market, the buyers and sellers need to be separate, and the offsets need to independently verified. Australia’s offsets aren’t.

The Clean Energy Regulator creates, buys, sells and endorses the integrity of offsets.

Do Carbon Offsets Need Better Integrity?

Some experts have argued offsets and carbon markets can be fixed through better transparency, oversight, and more stringent baselines. This is appealing because it buys more time for sectors with no zero-emission technology substitute to develop one.

But this is too hopeful. Over the last 25 years, a clear pattern has emerged with each offsetting program: problems are visible, calls for improvements build, more transparency arrives, but industry pressure for low-cost compliance means almost nothing actually changes.

Some industries have benefited enormously from this soft regulation, especially fossil fuel extraction companies whose links to political parties have been concerning for many years.

Carbon offset markets won’t be fixed by calls for clear rules, especially while the Clean Energy Regulator is the buyer, seller and regulator of Australia’s offsets.

Moving Beyond Carbon Offsets

If offsets are broken by design, what should we do instead? In brief, we should switch from offsetting to a simple concept: keep fossil fuels in the ground.

To date, market-based approaches to environmental compliance have effectively given a huge windfall to the fossil fuel industry, emissions from which have only grown since offsetting approaches began. The industry has sponsored think tanks to support flexible compliance, attacked climate science and lobbied against international treaties trying to phase out out fossil fuels.

Rather than thinking of emissions by industries as something to offset, we must embrace the shift to a low-carbon society, free from fossil fuel combustion. We have to move past the magical thinking that carbon pricing and offsetting alone will lead to the technology shifts that will save us.

What does it mean for those of us buying high-quality carbon offsets for our flights? It might be a worthy act of charity, but it won’t undo the long-term damage done by carbon dioxide emissions.

Stopping new fossil fuel projects is the best way to avoid blowing through our shrinking carbon budgets into very dangerous levels of warming. Unlike offsets, phasing out fossil fuels can be easily monitored and verified. We know cutting fossil fuel use will make a difference as we work to check the worst ravages of climate change.![]()

Declan Kuch, Vice Chancellor's Research Fellow, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No, Mr Morrison – the safeguard mechanism is not a ‘sneaky carbon tax’

Prime Minister Scott Morrison this week claimed Labor was planning a “sneaky carbon tax” should it win power, and Nationals senator Matt Canavan declared the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 was “dead”.

We can expect both these concepts to be thrown around a fair bit during the federal election campaign, so it’s worth getting a few things straight right now.

The Safeguard Mechanism Is Not A Carbon Tax

The Coalition’s claims of a “sneaky carbon tax” are a reference to Labor’s plans to tighten an existing policy known as the safeguard mechanism.

The safeguard mechanism was introduced by the Abbott Coalition government in 2016 – and it is not a carbon tax.

The mechanism was supposed to “safeguard” gains achieved through the Coalition’s then-named Emissions Reduction Fund, by ensuring the emissions cuts were not offset by increases elsewhere in the economy.

The rule applies to about 200 large industrial polluters that directly emit more than 100,000 tonnes of greenhouse gases a year, in sectors such as electricity, mining, gas, manufacturing and transport.

Under the safeguard mechanism, these polluters must keep their emissions below historical levels, known as a baseline. If they exceed the baseline, polluters can either buy carbon credits to offset the excess pollution, or apply to the Clean Energy Regulator for the baseline to be adjusted.

Baseline adjustments were allowed because no overall cap was placed on the amount of emissions produced. Without a cap, the regulator has greater flexibility to make adjustments.

This flexibility has meant the safeguard mechanism is ineffectual. In fact, since its implementation, companies subject to the mechanism have actually increased their emissions by 7% overall.

So, Labor has promised to tighten the safeguard mechanism if it wins the election. This means large emitters will be less able to adjust their baselines, and gradually, their baselines will be reduced.

This approach coheres with the original purpose of the safeguard mechanism, and is supported by the Business Council of Australia and others.

Analysis suggests Labor’s policy could avoid a substantial 213 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions entering the atmosphere by 2030.

Labor has indicated that emissions-intensive industries, such as large coal and gas exporters, will not be forced to cut pollution in a way that makes them less competitive internationally.

Australia’s Never Had A Carbon Tax

Let’s be clear. No Australian government has implemented a carbon tax – and any suggestion to the contrary is inaccurate.

The spectre of a so-called “carbon tax” has haunted Labor ever since the 2010 election campaign, when then Prime Minister Julia Gillard ruled out implementing one.

Upon being returned to office, Gillard announced plans to legislate a carbon price, in the form of an emissions trading scheme.

Not all carbon pricing amounts to a carbon tax. But the Abbott-led Coalition nonetheless sought to conflate the two and accused Gillard of breaking a key election promise.

Greenhouse gas emissions, and associated climate change, come with costs. Extreme weather such as droughts and heatwaves damages crops and drives up demand for health care. Flooding, bushfires and sea level rise damages property.

Carbon pricing seeks to ensure those responsible for much of these costs – large polluters – either reduce their emissions or help pay for the social and environmental damage they cause.

Labor’s emissions trading scheme required polluters to report and pay for every tonne of carbon dioxide they produced, or face a financial penalty. The scheme was a success: compliance was high and emissions reduction targets were met.

The policy, however, was short-lived. The Abbott government repealed it in July 2014.

Net-Zero By 2050 Is Very Much Alive

So what of Senator Canavan’s claims this week that net-zero emissions targets were “dead” and should be scrapped?

Canavan this week told the ABC:

“[UK Prime Minister] Boris Johnson said he is pausing the net zero commitment, Germany is building coal and gas infrastructure, Italy’s reopening coal-fired power plants. It’s all over. It’s all over bar the shouting here”.

Late last year, Australia committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. That means cutting greenhouse gas emissions as far as possible, and then, for emissions that cannot be avoided, removing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere.

Net-zero emissions by 2050 is needed avert the worst impacts of climate change. Australia is also required to meet the target under its Paris Agreement obligations.

All Australian states and territories have committed to the net-zero goal. Victoria, the ACT and Tasmania have gone further and legislated net-zero as a target.

Australia may be a long way off achieving net-zero by 2050, particularly in the absence of a robust and credible carbon price. But Canavan is wrong to suggest the goal has been abandoned globally.

Some countries have already achieved net-zero. The UK has a legally binding net-zero target by 2050 and Germany has pledged to get there by 2045.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has left countries such as Germany worried about their reliance on Russian gas, and this may see a short-term increase in fossil fuel use in Europe.

But the world remains largely committed to the net-zero target.

Just a few days ago, German finance minister Christian Lindner outlined the importance of the low-carbon transition to the nation’s energy security, describing renewable energy as “freedom energy”.

So, contrary to Canavan’s suggestion, the world’s shift to clean energy is likely to accelerate in the longer term.![]()

Samantha Hepburn, Professor, Deakin Law School, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Net zero by 2050 will hit a major timing problem technology can’t solve. We need to talk about cutting consumption

Many climate activists, scientists, engineers and politicians are trying to reassure us the climate crisis can be solved rapidly without any changes to lifestyle, society or the economy.

To make the vast scale of change palatable, advocates suggest all we have to do is switch fossil fuels for renewable power, electric vehicles and energy efficiency technologies, add seaweed to livestock feed to cut methane and embrace green hydrogen for heavy industries such as steel-making.

There’s just one problem: time. We’re on a very tight timeline to halve emissions within eight years and hit net zero by 2050. While renewables are making major inroads, the world’s overall primary energy use keeps rising. That means renewables are chasing a retreating target.

My new research shows if the world’s energy consumption grows at the pre-COVID rate, technological change alone will not be enough to halve global CO₂ emissions by 2030. We will have to cut energy consumption 50-75% by 2050 while accelerating the renewable build. And that means lifestyle change driven by social policies.

The Limitations Of Technological Change

We must confront a hard fact: In the year 2000, fossil fuels supplied 80% of the world’s total primary energy consumption. In 2019, they provided 81%.

How is that possible, you ask, given the soaring growth rate of renewable electricity over that time period? Because world energy consumption has been growing rapidly, apart from a temporary pause in 2020. So far, most of the growth has been supplied by fossil fuels, especially for transportation and non-electrical heating. The 135% growth in renewable electricity over that time frame seems huge, but it started from a small base. That’s why it couldn’t catch fossil fuelled electricity’s smaller percentage increase from a large base.

As a renewable energy researcher, I have no doubt technological change is at the point where we can now affordably deploy it to get to net zero. But the transition is not going to be fast enough on its own. If we don’t hit our climate goals, it’s likely our planet will cross a climate tipping point and begin an irreversible descent into more heatwaves, droughts, floods and sea-level rise.

Our to-do list for a liveable climate is simple: convert essentially all transportation and heating to electricity while switching all electricity production to renewables. But to complete this within three decades is not simple.

Even at much higher rates of renewable growth, we will not be able to replace all fossil fuels by 2050. This is not the fault of renewable energy. Other low-carbon energy sources like nuclear would take much longer to build, and leave us even further behind.

Do we have other tools we can use to buy time? CO₂ capture is getting a great deal of attention, but it seems unlikely to make a significant contribution. The scenarios I explored in my research assume removing CO₂ from the atmosphere by carbon capture and storage or direct air capture does not occur on a large scale, because these technologies are speculative, risky and very expensive.

The only scenarios in which we succeed in replacing fossil fuels in time require something quite different. We can keep global warming under 2℃ if we slash global energy consumption by 50% to 75% by 2050 as well as greatly accelerating the transition to 100% renewables.

Individual Behaviour Change Is Useful, But Insufficient

Let’s be clear: individual behaviour change has some potential for mitigation, but it’s limited. The International Energy Agency recognises net zero by 2050 will require behavioural changes as well as technological changes. But the examples it gives are modest, such as washing clothes in cold water, drying them on clotheslines, and reducing speed limits on roads.

The 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on climate mitigation has taken a step further, acknowledging the importance of collectively reducing energy consumption with a chapter on “Demand, services and social aspects of mitigation”. To do this effectively, government policies are needed.

Rich people and rich countries are responsible for far and away the most greenhouse gas emissions. It follows that we have to reduce consumption in high-income countries while improving human well-being.

We’ll Need Policies Leading To Large Scale Consumption Changes

We all know the technologies in our climate change toolbox to tackle climate change: renewables, electrification, green hydrogen. But while these will help drive a rapid transition to clean energy, they are not designed to cut consumption.

These policies would actually cut consumption, while also smoothing the social transition:

- a carbon tax and additional environmental taxes

- wealth and inheritance taxes

- a shorter working week to share the work around

- a job guarantee at the basic wage for all adults who want to work and who can’t find a job in the formal economy

- non-coercive policies to end population growth, especially in high income countries

- boosting government spending on poverty reduction, green infrastructure and public services as part of a shift to Universal Basic Services.

You might look at this list and think it’s impossible. But just remember the federal government funded the economic response to the pandemic by creating money. We could fund these policies the same way. As long as spending is within the productive capacity of the nation, there is no risk of driving inflation.

Yes, these policies mean major change. But major disruptive change in the form of climate change is happening regardless. Let’s try to shape our civilisation to be resilient in the face of change.![]()

Mark Diesendorf, Honorary Associate Professor, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Finalists Announced In All Categories For 2022 Australian Surfing Awards Incorporating The Hall Of Fame

Young Writers’ Competition 2022

Young people across the Northern Beaches are encouraged to enter this year’s Young Writers’ Competition for their chance to be published.

Now in its 13th year, the annual competition is open to students from kindergarten to grade 12 who live or go to school on the Northern Beaches. The theme of this year’s competition is ‘rise’.

“The Northern Beaches is home to some very talented young writers, and I continue to be blown away by the creativity and skill of entrants in our annual Young Writers’ Competition,” Mayor Michael Regan said.

“It’s time for young writers to once again rise and shine and show us what they’ve got. More than 500 stories were submitted in last year’s competition, and we suspect this year will be just as competitive.”

Entrants can write on any topic or theme but must include a derivation of the word ‘rise’. Entries will be grouped by age and judged according to characterisation, originality, plot, and language.

Four finalists will be chosen in each age category and invited to a presentation night on Wednesday 10 August, where a winner, runner-up, and two highly commended prizes are awarded.

Finalists from each category will have their stories published in an eBook which is added to the Northern Beaches Council Library collection.

Entries close Tuesday 31 May 2022. Entrants must be members of the Northern Beaches Council Library Service.

Complete the online entry form and attach your story as a Word document. If your story is hand-written, then a clear, readable photo or scanned PDF can be submitted.

Not a member of the library? Don't worry, Council will use this form to create a membership for you. Just mark 'no' under the library member field in the online form. If you are a member and unsure of your library card number, just mark 'yes' in the library member field in the online form and Council will find your library membership number.

Entries are judged according to characterisation, originality, plot and use of language and arranged into six different age group categories.

Four finalists are chosen in each age category and invited to a presentation night where a winner, runner-up and two highly commended prizes are awarded. Finalists from each category will have their stories published in an eBook that will be added to Council's collection.

For more information visit Council's library.

Senior Australian Of The Year Backs The ‘Let Pensioners Work’ Campaign

Have You Heard Of Walking Netball?

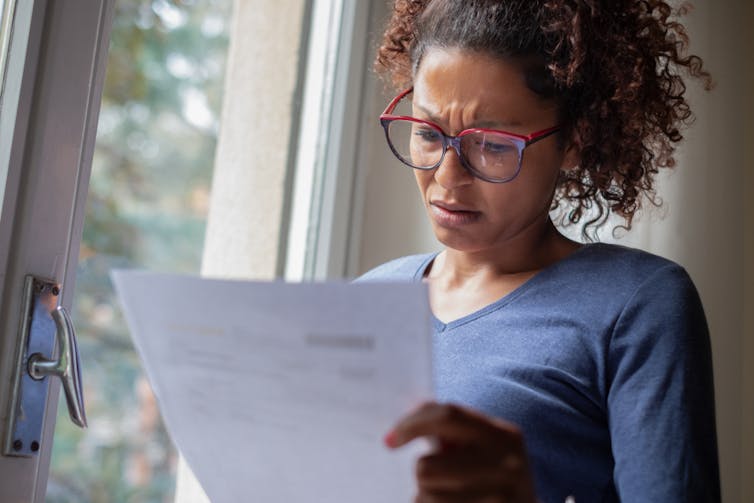

Rising out-of-pocket health costs are a worry. But the major parties have barely mentioned it

Rising out-of-pocket costs for health care is an important issue the major parties have not yet substantially addressed during the election campaign.

We heard just this week how health-care costs are rising faster than other costs of living pressures. Health-care costs are also rising faster than wages. The rising cost of specialists’ fees, in particular, are a concern. So, many Australian families are finding it increasingly difficult to keep up.

Earlier this year, a major consumer survey found 30% of people with chronic conditions were not confident they could afford needed health care if they became seriously ill; 14% could not pay for health care or medicine because of a shortage of money.

Out-Of-Pocket Costs Are Rising

Out-of-pocket health-care costs cover a range of expenses not covered by Medicare or private health insurance, such as doctors’ fees for consultations and surgery.

Only 35.1% of specialist consultations were bulk billed in 2020-21 compared with 88.8% of GP services.

For private (multi-day) hospital care in 2019-20, 43.7% of separations (hospital admissions that include procedures and operations) had no hospital or medical out-of-pocket cost.

Out-of-pocket costs are rising, Medicare statistics show.

There is ample evidence out-of-pocket costs reduce access to, and use of, health care. This more strongly affects people who need health care the most.

For instance, access to timely specialist care in Australia depends on your income and ability to pay.

Although richer people use more specialist care, on average, it is less-affluent people who have higher need for health care. Yet it is less-affluent people who have to wait to see a specialist in a public hospital.

High doctors’ fees have other consequences. They may provide skewed incentives to doctors, leading to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Doctors may also flock to high-earning specialties while we have a shortage of GPs (who are paid half as much as specialists).

What Do The Major Parties Promise?

Health policies announced by the major parties ahead of the federal election do not necessarily translate into lower out-of-pocket health costs, or focus on the most pressing issue.

The Coalition has promised to lower the safety net threshold for the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. This announcement, made in this year’s federal budget, would make medicines cheaper or free for people who need multiple scripts a year.

But this is an area where out-of-pocket costs have been falling for some time compared with other areas of spending. So any announcement may have been better targeted at areas where out-of-pocket costs are growing more quickly.

In any election there is always a focus on access to GPs and bulk billing. This includes Labor’s proposal for new urgent care centres, which would provide bulk billed services to take the pressure off emergency departments.

However, neither of the major parties are doing anything about the continuing and much larger increases in specialists’ out-of-pocket costs.

Can Informed Patients Make A Difference?

The Coalition introduced a price transparency website in 2019 that provides estimates of out-of-pocket costs for private hospital care, with plans for doctors to voluntarily upload their fees. Some private health insurers also have such websites.

However, these websites rely entirely on consumers doing the “leg work” by shopping around to reduce their out-of-pocket costs. The assumption is that by providing consumers with more information, they will make better choices. But this is too simplistic because information can difficult to get and understand, and these websites don’t include data on the quality of care.

Our review on price transparency websites in health care shows they may not work for consumers. Not all consumers can or want to use them. There’s also the risk doctors could use these websites to see what other doctors are charging and increase their fees.

It could be better if these websites were used by GPs when referring patients to specialists. Patients can also be encouraged to ask about the out-of-pocket cost when booking an appointment or during the visit.

But this does not help patients who are usually in a vulnerable position, who want care quickly, do not have the information or time to shop around, and might think the care they receive will be affected if they ask about cost.

Can Doctors Make A Difference?

Doctors set their own fees and many use the Australian Medical Association fee schedule as guidance. They decide what fee to charge, whether to bulk bill, or whether to use gap cover provided by private health insurers for private hospital care.

At the moment it would require a brave politician to directly control doctors’ fees given the constitutional protections they have and the way Medicare and private health insurance were designed to provide subsidies to patients, not to directly pay doctors.

However, something the major parties can address is “bill shock”. Patients don’t always know the doctor’s fee before they visit, and in some circumstances don’t know in advance how much a procedure will cost.

If care involves many tests, visits and procedures over time by different doctors, then there will be a bill for each. This shifts all the financial risk to patients, something private health insurance was designed to handle.

At a minimum, doctors’s fees and out-of-pocket costs need to be bundled together and published as an upfront quote or range for the expected course of care. This is something that could be addressed by one of the major parties.

What Next?

Addressing rising out-of-pocket health costs is a complex area linked closely to broader reform of the health-care system, which neither major party has promised to do anything about.

Without such reforms we’ll see Australians prioritising spending on food, housing and petrol over health care, in the current climate.

But Australia cannot afford to allow this to happen. As we have witnessed during the pandemic, an unhealthy population is not only bad for individuals, it’s bad for us all.![]()

Anthony Scott, Professor of health economics, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How the ‘Sydney School’ changed postwar Australian architecture

Australia’s architectural historians have struggled to explain the “Sydney School” of nature-responsive modern houses built after the second world war. As well as arguing about whether any “school” existed, they also overlooked some of the movement’s pioneering designers and residences.

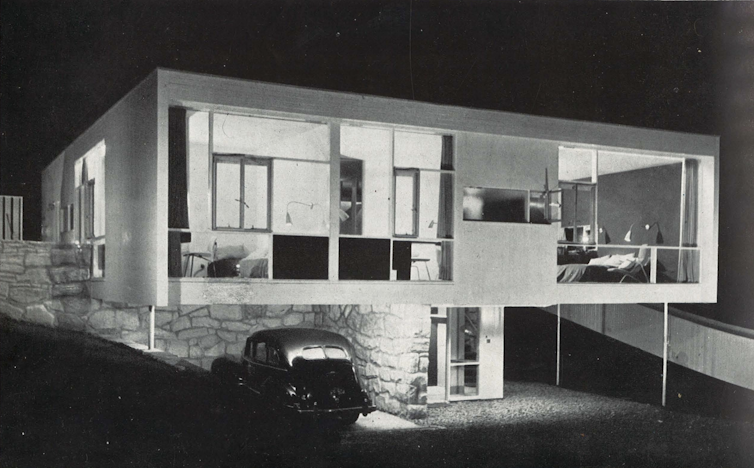

Studies of vintage Australian architecture and home publications suggest a hillside house at Church Point, built in 1948 by long-forgotten architect John Lander Browne, was Sydney’s first notable postwar interpretation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic (“natural”) principles for designing houses.

Rustic Materials Vs White Paint

Wright’s Prairie houses (1906-09) ignited one side of modernism’s “great dialogue” about designing buildings either to harmonise with their natural surroundings or to appear superior – like abstract sculptures glistening above manicured lawns. At first he avoided painting his exteriors — in contrast to 1920s European modernists (led by Bauhaus School professors Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe).

They pioneered the “international style” of whitewashed masonry and steel-framed glass houses.

Sydney School residences were labelled “nuts and berries” because they exposed rustic materials like brick, timber and stone. This differentiated them from modern Sydney houses that were painted.

The argument of Sydney’s postwar organic versus international style usually has been exemplified by Peter Muller’s brick and timber Audette House in Castlecrag (1954), in contrast to Harry Seidler’s pristine white Rose Seidler House at Wahroonga (1950).

Muller became the most internationally successful architect from the Sydney School. He transferred Wright’s principles and his own Asia-Buddhist experiences to produce supra-romantic village resorts in Indonesia.

And Seidler became Australia’s stellar modernist across all building types, especially the symbols of American capitalism: skyscrapers.

‘A New Eclecticism’

Most Sydney architects didn’t take sides in the style war as starkly as Muller and Seidler.

They copied new ideas from America, Britain, Scandinavia and Europe and combined these with traditional Mediterranean, South American, colonial and Oriental concepts that were introduced to Sydney before the war.

In a 1948 article for Britain’s Architectural Review (AR), visiting English architect Ryan Westwood “looked in vain for something that might be called an ‘Australian’ architecture”.

He noted:

inspiration has evidently sprung from Europe with latterly a crop of plagiarisms from California.

In AR’s September 1951 edition, Melbourne architect-critic Robin Boyd satirised the visual similarities of houses by Australian architects who were thought to be ideologically opposed. Boyd applauded signs of “a new eclecticism”.

Magazines show that in the late 1940s and early 1950s (pre-television) many Sydney architects were planning houses around prominent fireplaces and chimneys that were hand-built with rough-hewn sandstone blocks. And most avoided the modern concept of flat roofs, which often leaked and were usually opposed by local councils and neighbours.

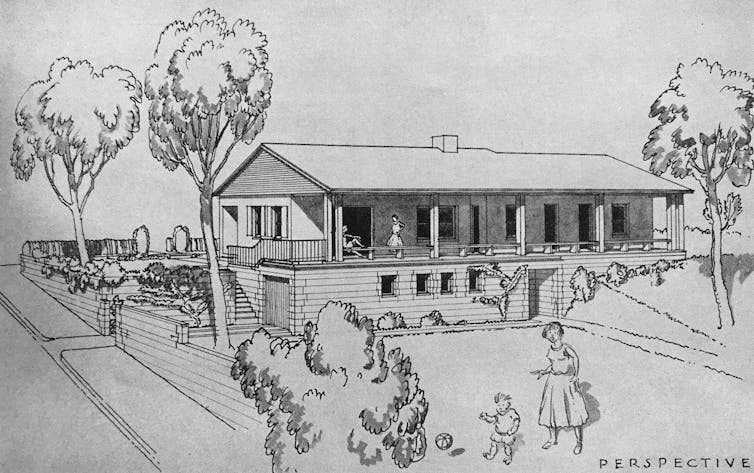

One Sydney architect, John D. Moore, included no flat roof among his 14 proposals for postwar modern houses, published in Home Again! Domestic Architecture for the Normal Australian (1944).

Mid-career practitioner Sydney Ancher won the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ 1945 Sulman Medal (best building in New South Wales) for a slate-gabled house. It was painted pale pink to suit the gum trees on his Killara site.

John Lander Browne’s organic house included one of Sydney’s first postwar flat roofs. Set high on a steep site, it was accessed via a garden path and sandstone steps leading up to large terrace. Both storeys were clad in dark-stained weatherboards, offset by white window frames. (This was a Swedish strategy that might have helped to refract Northern Europe’s faint sunlight indoors.)

The house featured in George Beiers’ 1948 book, Houses of Australia, and in Westwood’s AR article.

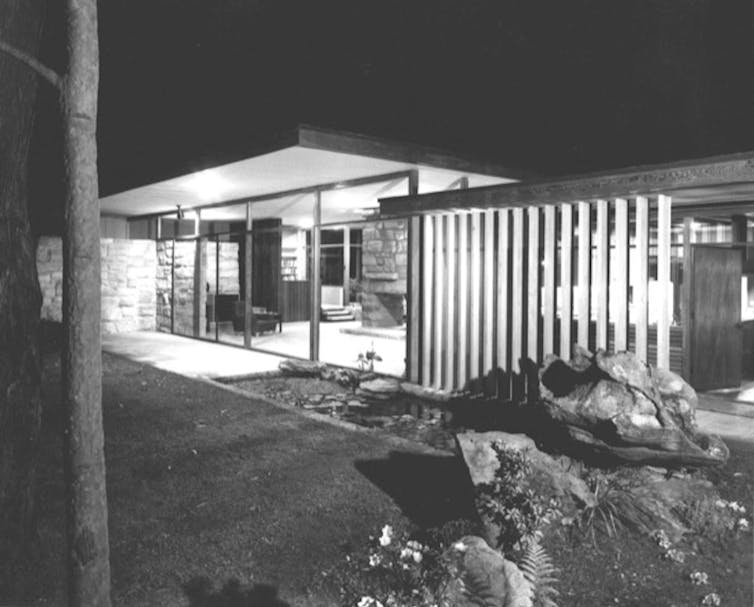

Wright’s organic approach also inspired England-born architect Douglas Snelling, who switched from commercial graphics and interior design after his second working visit to Los Angeles in 1948. He was overlooked in key articles about Sydney modernism — by Milo Dunphy (1962), Jennifer Taylor (1970s-1990s), Stanislaus Fung (1985) and other postmodernist historiographers who aim to retrospectively define Sydney modernism.

But Snelling’s brick, cedar and sandstone residences were strongly promoted in 1950s magazines. They deserve recognition now as pioneering contributions to the Sydney School.

Another English architect, Derek Wrigley, built two modest homes for himself on steep sites at Dee Why in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Today, he claims these reflected the Bauhaus teachings of his main design professor in Manchester. But old Sydney magazines show a Wright-style stone fireplace in Wrigley’s butterfly-roofed first house (OB1) and a California conical metal fireplace resting on a large rock projecting into the living room of his second residence (OB2).

Wrigley and Snelling both seem to have appreciated innovation, but they shared Wright’s basic alignment with nature.

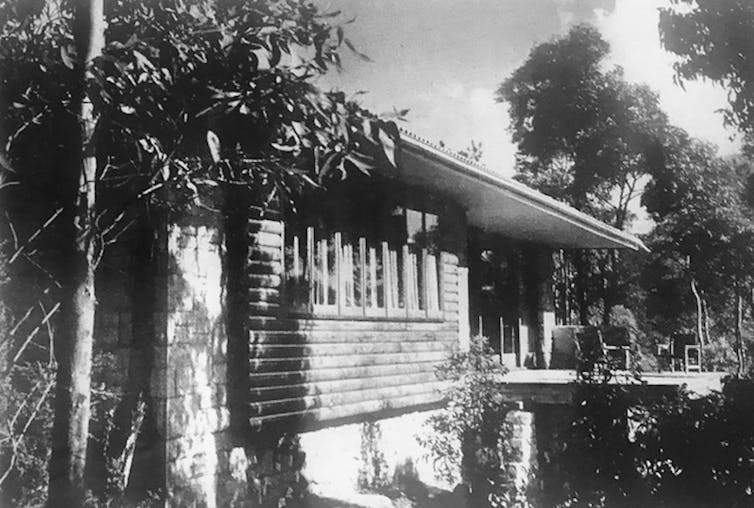

East Sydney Tech lecturer Phyllis Shillito’s 1954 book, 60 Beach and Holiday Homes, included a varnished weatherboard house in Hunters Hill by J. Lindsay Sever, another forgotten Sydney modern architect. This was influenced by Wright’s Taliesin West compound in the Arizona desert and deserves inclusion in future histories of the Sydney School.

Shillito’s book also includes classic white residences by Sydney Ancher and Arthur Baldwinson, and key European emigrés — Hugo Stossel, Aaron Bolot, Hans Peter Oser and Harry Divola — whose houses are excellent interpretations of the international style, built on remarkable coastal and bush sites in Sydney. But their works seem inconsistent with the basically Wrightian organic agenda that underpinned the Sydney School.

The heyday of the Sydney School was the mid-1950s to the early 1970s. During this time, younger Sydney architects were interpreting Wright’s followers in southern California and Scandinavia.

Wright died in 1959, causing the CIAM group leading the international style to disband. Then Wright’s greatest opponents, Le Corbusier, Gropius and Mies, died in the mid-to-late 1960s. And modernism moved on.

Sydney’s 1960s “humanists” (who followed Scandinavian architects in trying to synthesise European communist and American democratic/capitalist ideologies, and who were responsive to nature) included Ken Woolley, Peter Muller, Hugh Buhrich, Philip Cox, Neville Gruzman, Bruce Rickard, John Allen, Russell Jack, Ian McKay, Bryce Mortlock, Peter Johnson, John James, Ross Thorne and Don Gazzard.

Many favoured face brick and stained timber and replaced flat roofs with canopies raked at unusual angles. Some also introduced a cross-sectional strategy of central staircases and staggered floor levels. Their houses were intended not merely to harmonise with their sites but to dramatise Sydney’s extraordinary topography and vegetation.

Where Does Brutalism Fit In?

There is one major conundrum involved in classifying modern Sydney houses built after the second world war. Does Brutalism belong to the Sydney School?

Brutalism was a deliberately crude and visually aggressive style of building with rough-cast, unpainted cement. It was pioneered by Le Corbusier and artist Jean Dubuffet after their 1945 visit to Switzerland, gathering artworks by patients in mental asylums.

Dubuffet’s 1947 Art Brut manifesto celebrated primitive and psychotic creativity. Le Corbusier’s later housing complex, Unité d'habitation in Marseille (1947-52), physically expressed Dubuffet’s words with béton brut (raw concrete).

Because concrete is made with natural substances (cement and water), it could be interpreted as another strand of the Sydney School’s emphasis on earthy materials.

But Brutalist architecture, as interpreted in late 1940s-1950s Scandinavia and Britain — and by Australians John Andrews and Colin Madigan in the 1960s and 1970s — was mostly limited to government buildings for education, administration, health care and public housing (notably the Tao Gofers-designed Sirius building at Circular Quay).

Sydney School historian Jennifer Taylor identified only one residence, by Tony Moore at North Sydney (1959), as being brutalist in style. Heritage architects from Docomomo now contradict her because Moore’s house was a romantic composition of bricks, timber and tiles. (Although concrete also could appear romantic, as demonstrated in the 1920s by Wright’s protegés, Walter and Marion Griffin, with their Knitlock houses at Castlecrag.)

Today’s specialist on Sydney Brutalism, Glenn Harper, has listed the Harry and Penelope Seidler house in Killara (1966-67), the Hugh and Eva Buhrich House 2 in Castlecrag (1968–72), the Peter Johnson House in Chatswood (1963) and the Bill and Ruth Lucas House in Castlecrag (1957) as examples of Brutalism (although the steel and glass Lucas house and the brick, timber and tile Johnson house did not emphasise concrete, while several all-concrete “60s spaceship” houses by Stan Symonds are often ignored).

Intriguingly, most of the few Sydney houses that have been labelled Brutalist were designed by architects for their own occupation.

It was difficult to persuade aspirational clients to pay for architecture that British theorist Reyner Banham, in a 1955 AR article, recognised for “precisely its brutality – je-m’en foutisme, its bloody-mindedness”.![]()

Davina Jackson, Honorary Academic, School of Architecture, University of Kent

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Honeybees join humans as the only known animals that can tell the difference between odd and even numbers

“Two, four, six, eight; bog in, don’t wait”.

As children, we learn numbers can either be even or odd. And there are many ways to categorise numbers as even or odd.

We may memorise the rule that numbers ending in 1, 3, 5, 7, or 9 are odd while numbers ending in 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 are even. Or we may divide a number by 2 – where any whole number outcome means the number is even, otherwise it must be odd.

Similarly, when dealing with real-world objects we can use pairing. If we have an unpaired element left over, that means the number of objects was odd.

Until now odd and even categorisation, also called parity classification, had never been shown in non-human animals. In a new study, published today in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, we show honeybees can learn to do this.

Why Is Parity Categorisation Special?

Parity tasks (such as odd and even categorisation) are considered abstract and high-level numerical concepts in humans.

Interestingly, humans demonstrate accuracy, speed, language and spatial relationship biases when categorising numbers as odd or even. For example, we tend to respond faster to even numbers with actions performed by our right hand, and to odd numbers with actions performed by our left hand.

We are also faster, and more accurate, when categorising numbers as even compared to odd. And research has found children typically associate the word “even” with “right” and “odd” with “left”.

These studies suggest humans may have learnt biases and/or innate biases regarding odd and even numbers, which may have arisen either through evolution, cultural transmission, or a combination of both.

It isn’t obvious why parity might be important beyond its use in mathematics, so the origins of these biases remain unclear. Understanding if and how other animals can recognise (or can learn to recognise) odd and even numbers could tell us more about our own history with parity.

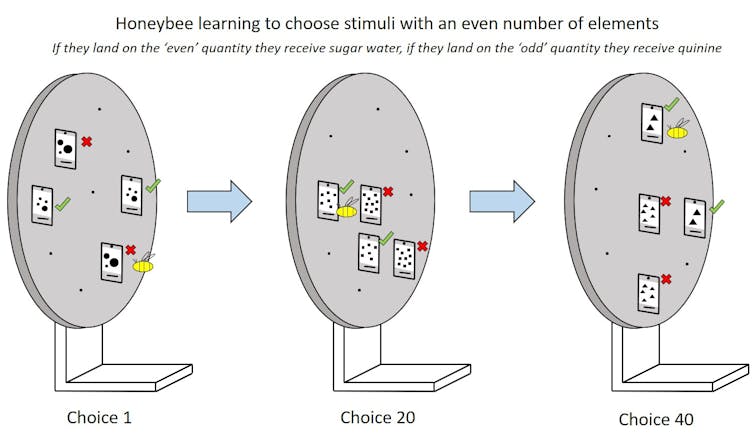

Training Bees To Learn Odd And Even

Studies have shown honeybees can learn to order quantities, perform simple addition and subtraction, match symbols with quantities and relate size and number concepts.

To teach bees a parity task, we separated individuals into two groups. One was trained to associate even numbers with sugar water and odd numbers with a bitter-tasting liquid (quinine). The other group was trained to associate odd numbers with sugar water, and even numbers with quinine.

We trained individual bees using comparisons of odd versus even numbers (with cards presenting 1-10 printed shapes) until they chose the correct answer with 80% accuracy.

Remarkably, the respective groups learnt at different rates. The bees trained to associate odd numbers with sugar water learnt quicker. Their learning bias towards odd numbers was the opposite of humans, who categorise even numbers more quickly.

We then tested each bee on new numbers not shown during the training. Impressively, they categorised the new numbers of 11 or 12 elements as odd or even with an accuracy of about 70%.

Our results showed the miniature brains of honeybees were able to understand the concepts of odd and even. So a large and complex human brain consisting of 86 billion neurons, and a miniature insect brain with about 960,000 neurons, could both categorise numbers by parity.

Does this mean the parity task was less complex than we’d previously thought? To find the answer, we turned to bio-inspired technology.

Creating A Simple Artificial Neural Network

Artificial neural networks were one of the first learning algorithms developed for machine learning. Inspired by biological neurons, these networks are scalable and can tackle complex recognition and classification tasks using propositional logic.

We constructed a simple artificial neural network with just five neurons to perform a parity test. We gave the network signals between 0 and 40 pulses, which it classified as either odd or even. Despite its simplicity, the neural network correctly categorised the pulse numbers as odd or even with 100% accuracy.

This showed us that in principle parity categorisation does not require a large and complex brain such as a human’s. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean the bees and the simple neural network used the same mechanism to solve the task.

Simple Or Complex?

We don’t yet know how the bees were able to perform the parity task. Explanations may include simple or complex processes. For example, the bees may have:

paired elements to find an unpaired element

performed division calculations – although division has not been previously demonstrated by bees

counted each element and then applied the odd/even categorisation rule to the total quantity.

By teaching other animal species to discriminate between odd and even numbers, and perform other abstract mathematics, we can learn more about how maths and abstract thought emerged in humans.

Is discovering maths an inevitable consequence of intelligence? Or is maths somehow linked to the human brain? Are the differences between humans and other animals less than we previously thought? Perhaps we can glean these intellectual insights, if only we listen properly. ![]()

Scarlett Howard, Lecturer, Monash University; Adrian Dyer, Associate Professor, RMIT University; Andrew Greentree, Professor of Quantum Physics and Australian Research Council Future Fellow, RMIT University, and Jair Garcia, Research fellow, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fern syrup, stewed eel and native currant jam: this 1843 recipe collection may be Australia’s earliest cookbook

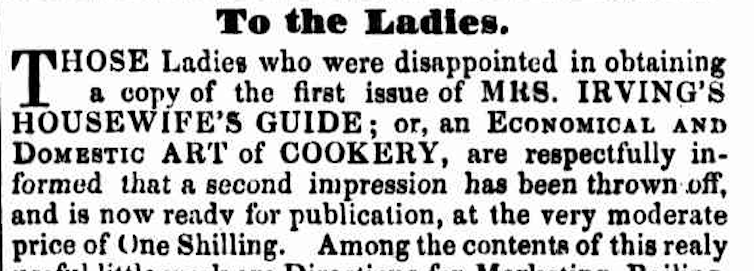

A chance find in a colonial newspaper from 1843 has us very excited: have we discovered evidence of Australia’s earliest cookbook?

Until now The English and Australian Cookery Book: Cookery for the Many, as well as the Upper Ten Thousand by Tasmanian-born Edward Abbott, published in London in 1864, have been credited with this honour.

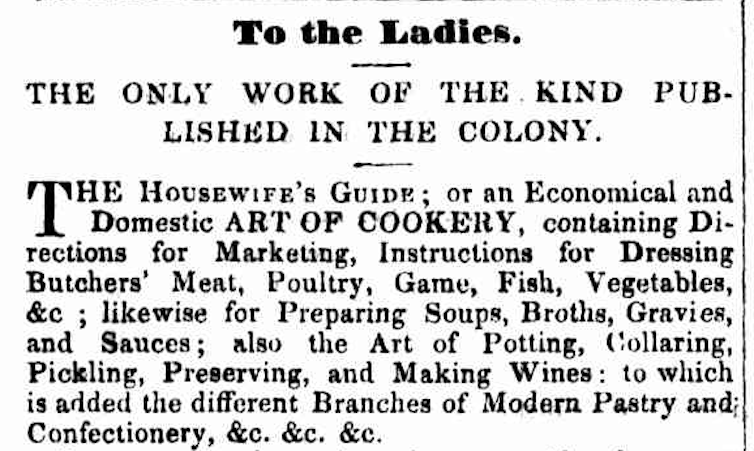

But when searching the National Library of Australia’s digital archive, our colleague Paul Van Reyk came across an advertisement in the December 30, 1843, Parramatta Chronicle and Cumberland General Advertiser for a cookbook none of us knew about: The Housewife’s Guide; or an Economical and Domestic Art of Cookery.

If this is indeed Australia’s earliest colonial cookbook, it would set the date back by 20 years.

A British Recipe Book

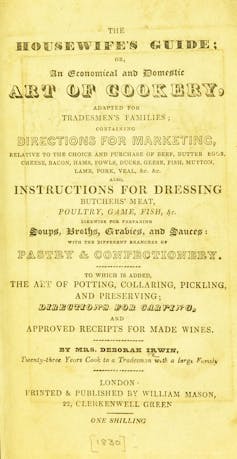

The Housewife’s Guide was published by Edmund Mason, who also published the Parramatta Chronicle.

The son of printer William Mason of Clerkenwell, London, Edmund arrived in Sydney in 1840 to work at the Sydney Morning Herald. He was employed there for two years before setting up his own printing business in Parramatta.

No author’s name is provided in the 1843 advertisement for The Housewife’s Guide, but a book with the identical title, written by Mrs Deborah Irwin, “23 years cook to a tradesman with a large family”, had been published in England by Mason’s father in 1830.

At the time, Australia’s cookery texts were generally imported from Britain, but Mason asserted this Housewife’s Guide was “the only work of the kind published in the colony”.

Perhaps through his father’s connections, Mason was printing Mrs Irwin’s text in downtown Parramatta.

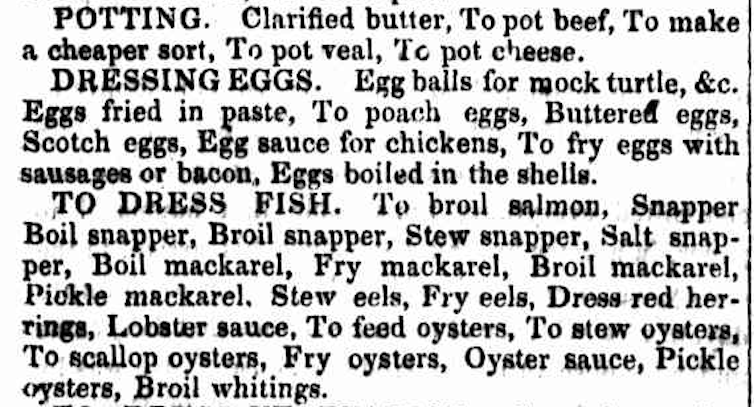

A locally reprinted text does not, to our minds, qualify as an Australian cookbook. But reading the list of contents given in Mason’s advertisement, “native currant jam” leapt off the page.

It is unlikely English Mrs Irwin would have had native currants in her repertoire.

Australian Ingredients

The 1830 edition of Mrs Irwin’s Housewife’s Guide has been digitised, allowing us to compare its contents more closely with the list provided in the Parramatta Chronicle. While there are clear similarities, with some sections possibly repeated verbatim, other significant differences convinced us this was a localised version of the original Irwin text.

Fish species common in Britain – sole, carp, haddock, grayling, trout, perch, tench and others – do not appear in the local listing. Varieties such as salmon, mackerel and eels, which are found in Australian waters, have been retained, and snapper has been added.

Irwin’s Housewife’s Guide contains several recipes for game – hare, partridge, pheasant – none of which are listed in the Australian edition. Recipes for rabbits and pigeons, on the other hand, are found in both.

The Parramatta edition also has sections not included in Irwin’s book. A section on preserved meat provides instructions for salting and smoking mutton and ham.

A new section on syrups includes two which may have been incorporated for their local appeal: capillaire made from maiden hair fern – several species of which are native to Australia, and “Pine apply” (presumably pineapple) syrup. Highly exotic in Britain, pineapples were grown in colonial gardens and sold at produce markets.

Clearly this publication was not simply a reprint of Mrs Irwin’s text, but an upgraded, localised edition. It could also be the first formally published cookbook with recipes using native ingredients.

New Mysteries

In July 1844 the Chronicle advised “a second impression has been thrown off and is ready for publication”.

This new round of advertising at last provided an author’s name, promoting the book as Mrs Irving’s Housewife’s Guide. The uncanny similarity between Irving and Irwin was impossible to ignore. Had Mason misspelled the name by accident or by intent? Was there indeed a Mrs Irving?

We have not identified a Mrs Irving in the colony at this time, and we are yet to find a physical copy of this early colonial cookbook. It does not appear in library catalogues and has not been referenced in any bibliography of Australian cookbooks.

It is quite probable that no copies have survived the 175-plus years since they were published.

We can confidently claim however, that Mrs Irving’s Housewife’s Guide published by Edmund Mason in Parramatta is the first locally produced Australian cookbook. The majority of recipes may have been British by nature and origin, but departures from the British text are clearly aimed at localising the book for produce available in colonial New South Wales.

Mrs Irving’s Housewife’s Guide indicates there was an appetite for local culinary knowledge, and the use of native ingredients – rather than relying on British authority – 20 years before Edward Abbott’s The English and Australian Cookery Book.![]()

Jacqueline Newling, Honorary Associate, History, University of Sydney and Alison Vincent, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Remaking history: using Ancient Egyptian techniques, I made delicious olive oil at home – and you can too

In this series, academics explain the ways they are recreating historical practices, and how this impacts their research today.

Olive oil was one of the major commodities in the ancient Mediterranean. Alongside wine, grain and perhaps also cheese in some regions, it enveloped and permeated Canaanite, Phoenician, Greek and Roman cultures, and was present in Egypt long before.

According to the Roman writer Pliny the Elder (1st century CE):

there are two liquids that are especially agreeable to the human body, wine inside and oil outside […] [the latter] being an absolute necessity.

Olive oil was used for a broad variety of purposes in antiquity: fuel for cooking, lighting and heating; personal hygiene; craft; and within the daily diet.

Large proportions of Greek, Roman and presumably Phoenician agricultural texts are devoted to the production of oil.

Authors like Columella, Palladius, Pliny and Cato the Elder, and the now-lost treatise of Mago the Carthaginian – the father of agriculture – debate what tools and equipment are needed, how and where to grow olive trees, what workers are required, and the array of olives and oils.

The detail within these texts is staggering. It extends to precise instructions for creating olive oil as well recipes for various types. Combined with surviving iconography and art that depicts these processes, as well as the archaeological remains of oileries and olive groves, we can attempt to reconstruct these ancient commodities.

This process is termed experimental archaeology. Experimental archaeology is often used to fill gaps in our knowledge and help us understand the practicalities of these production techniques – particularly for objects and processes that are rarely preserved.

This is particularly true for some types of oil presses, which were made almost entirely of organic materials and only survive in exceptional circumstances.

Recreating Ancient Egyptian Olive Oil

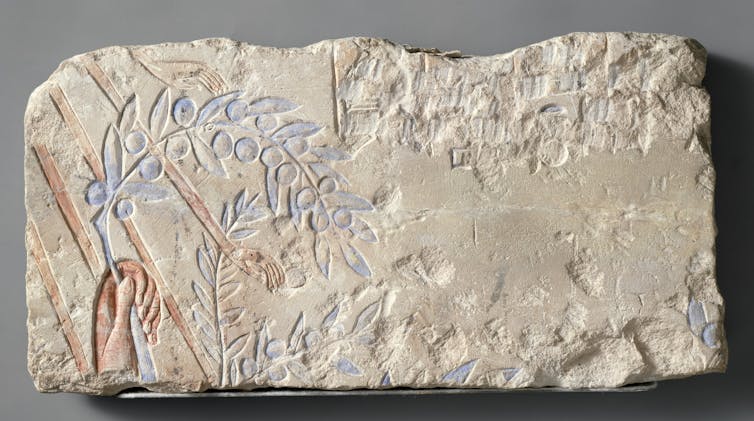

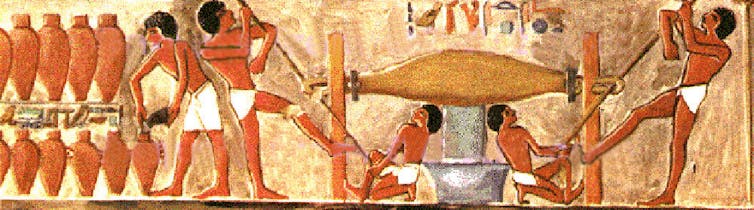

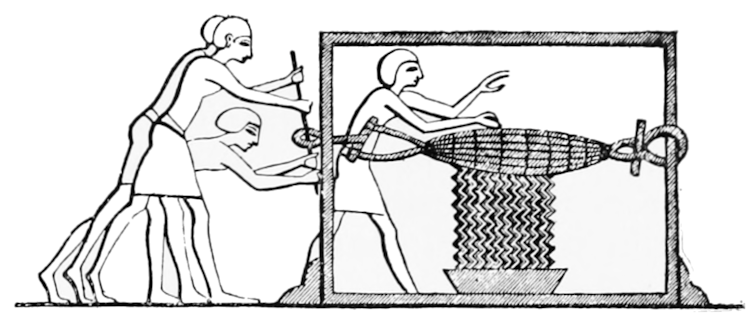

One of the earliest, if not the first, methods of pressing substances to produce a liquid such as wine or oil was by torsion.

This method involves filling a permeable bag with the crushed fruit, inserting sticks at either end of the bag before twisting them in opposite directions. This compresses the bag, and liquid filters out.

The torsion method is depicted on various Egyptian wall paintings, from the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms. The earliest known example is in the tomb of Nebemakhet from around 2600–2500 BCE.

This method lasted millennia. There is evidence for the use of the torsion bag method from pre-industrial Venice, Spain and Corsica, and it is illustrated in early 20th century Italy.

Egyptian depictions of the torsion press have often been assumed to be related to wine production, but we wanted to know: could it also be effectively used to make olive oil?

With a lack of written and structural archaeological evidence – unlike the later Graeco-Roman eras – depictions on wall paintings and in relief are some of our only clues in Egypt.

Accompanied by basic olive crushing methods, known since the Neolithic era and still used until recently, we aimed to use these processes to test how effective they were and what quality of oil was achievable.

It is difficult to determine exactly what cloth was used in antiquity for the bag, so we decided to use a simple cheesecloth.

A mix of green and black olives, still used by traditional Italian producers today to create high quality extra-virgin oil, were harvested in the late Australian autumn season of mid-May.

Following ancient recommendations, they were washed before processing.

Before the torsion occurs, crushing is necessary to tear the flesh of the olive. This allows for the release of oils under pressure. We used a basic mortar and pestle – a technique documented archaeologically since around 5000 BCE.

This was hard work, particularly on the less ripe green olives.

It is not surprising that advances through the Classical and Hellenistic Greek eras were made, including larger rotary mortars, called trapeta (or later, the slightly different mola olearia), allowing greater quantities to be processed with ease.

After crushing, the pulp was placed in a cheesecloth sack and a variety of torsion methods were tested: twisting on both ends; anchoring one end and twisting the other; and first soaking the fruit in hot water to release oils before twisting.

It was immediately noticeable that gentle pressure worked well, providing a slow but steady drip of liquid and minimising any solid materials being forced through the cloth. Multiple layers of cloth were required to prevent ripping, but this also made the filtration process slower and less permeable.

A Slow And Gentle Pressing

A compromise in the middle created the best results: a gentle, slow pressing, anchoring one end and twisting the other.

Some pressing methods separated the oil far quicker, with a fine yellow layer floating on the surface of the vegetable water in just minutes. Other methods did not separate even when left overnight and we were left with a thick brown mixture of vegetable water (the Roman amurca) and oils. Even Pliny noted “the very same olives can frequently give quite different results”.

The successful jars produced a delicious olive oil. Sharp, bitey and with hints of pepper – just like a nice fresh-pressed extra virgin oil.

Despite the fact that almost no archaeological evidence is known of actual olive oilry facilities in Pharaonic Egypt, with iconography providing the only real clues, this experiment clearly showed it is possible to press olives and produce oil using this frequently depicted method.

It is also an excellent (and relatively easy) method of making your own olive oil at home!![]()

Emlyn Dodd, Assistant Director of Archaeology, British School at Rome; Honorary Postdoctoral Fellow, Macquarie University; Research Affiliate, Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Regaining fitness after COVID infection can be hard. Here are 5 things to keep in mind before you start exercising again

Are you finding it difficult to get moving after having COVID? You are not alone. Even if you have mild symptoms, you may still experience difficulty in regaining your fitness.

Building back up to exercise is important, but so is taking it slowly.

In general, most people can start to return to exercise or sporting activity after experiencing no symptoms for at least seven days. If you still have symptoms two weeks post-diagnosis, you should seek medical advice.

It’s normal for your body to feel fatigued while you are fighting a viral infection, as your body uses up more energy during this period. But it’s also very easy to lose muscle strength with bed rest. A study of older adults in ICU found they could lose up to 40% of muscle strength in the first week of immobility.

Weaker muscles not only negatively impact your physical function but also your organ function and immune system, which are vital in regaining your strength after COVID-19.

You might consider doing some very gentle exercises (such as repeated sit to stands for a minute, marching on the spot or some light stretches) to keep your joints and muscles moving while you have COVID, especially if you are older, overweight, or have underlying chronic diseases.

Five Things To Keep In Mind About Exercising After COVID

If you do feel you are ready to return to exercise and have not experienced any COVID-related symptoms for at least seven days, here are five things to remember when resuming exercise.

1)Adopt a phased return to physical activity. Even if you used to be a marathon runner, start at a very low intensity. Low intensity activities include walking, stretching, yoga and gentle strengthening exercises.

2)Strengthening exercises are just as important as cardio. Strength training can trigger the production of hormones and cells that boost your immune system. Bodyweight exercises are a great starting point if you do not have access to weights or resistance bands. Simple bodyweight exercises can include free squats, calf raises and push-ups.

3)Don’t over-exert. Use the perceived exertion scale to guide how hard you should be working. For a start, aim to only exercise at a perceived exertion rate of two or three out of ten, for 10-15 minutes. During exercise, continue to rate your perceived level of exertion and do not push past fatigue or pain during this early stage as it can set your recovery back.

4)Listen to your body. Only progress the intensity of your exercise and lengthen your exercise duration if you do not experience any new or returning symptoms after exercise, and if you have fully recovered from the previous day’s exercise. Do not over-exert. You may also need to consider having a rest day between exercise sessions to allow time for recovery.

5)Look out for worrying symptoms. If you experience chest pain, dizziness or difficulty with breathing during exercise, stop immediately. Seek urgent medical advice if symptoms persist after exercise. And if you experience increased fatigue after exercise, talk to your GP.

Beware Post-Exertional Malaise

For most people, exercise will help you feel better after COVID-19 infection. But for some, exercise may actually make you feel worse by exacerbating your symptoms or bringing about new symptoms.

Post-exertional malaise can be experienced by people resuming exercise post-COVID infection. It occurs when an individual feels well at the start of the exercise but experiences severe fatigue immediately afterwards. In addition to fatigue, people with post-exertional malaise can also experience pain, emotional distress, anxiety and interrupted sleep after exercise.

If you believe you may have post-exertional malaise, you need to stop exercise immediately. Regular rest and spreading your activities throughout the day is needed to avoid triggering post-exertional malaise. Seek advice from your doctor or see a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist who can give you advice on how best to manage this condition.![]()

Clarice Tang, Senior lecturer in Physiotherapy, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How can more people be on unemployment benefits than before COVID, with fewer unemployed Australians? Here’s how

So low is Australia’s unemployment rate, the official count says there are now just 580,300 people unemployed – the least since 2009, when Australia’s population was one-sixth smaller than it is today. Compared to just before the start of the pandemic, 184,800 fewer Australians are now unemployed.

Yet surprisingly, the number of Australians on unemployment benefits (now known as JobSeeker and Youth Allowance Other) remains higher than at any point before the pandemic, at 935,300. This is 49,100 more than before COVID.

The apparent paradox has some people questioning the unemployment figures, while others are asking whether there are people getting benefits who should not.

We think we have worked out a lot of what’s happened, and – to jump straight to one of our important findings – it isn’t the unemployment figures that are at fault.

You might be surprised to discover that many Australians who are unemployed are not on unemployment benefits.

Prior to COVID, the Parliamentary Library found only about 30% of unemployed Australians were on benefits. It used the Bureau of Statistics survey of income and housing to estimate the overlap between benefits and unemployment.

Even odder, many of the Australians on those benefits (paid to those with the “capacity to work now or in the near future”) are not unemployed as defined by the Bureau of Statistics and international statistical agencies.