Inbox and environment news: Issue 537

May 8 - 14, 2022: Issue 537

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Autumn 2022 Newsletter

Cassia Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Darkinjung Plans For 600 Homes On Central Coast's Lake Munmorah Now On Exhibition: Closes May 24

Dendrobium Mine Extension Project: Have Your Say (Again)

Political Stitch Up Over Dendrobium Abandons Community, Climate, And Water, Favours Coal Mining Company Residents State

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Up Close With Gang-Gang Cockatoo Feeding On Conesticks – Blue Mountains

This Mother’s Day, let’s celebrate the brave, multi-tasking mums of the Australian bird world

In the human fascination with birds, it’s the flashy appearance and antics of males that get the most attention from researchers and the public.

From their colourful plumage to elaborate songs and courtship displays, male birds often steal the show. This has led to female birds routinely being overlooked by conservation planners.

First, let’s clear up a few misconceptions. At least 70% of female birds sing – a fact historically overlooked due to research and survey biases towards males. And while many female birds have more muted colours than males, there are numerous examples of females with brilliant plumage.

But the wonders of the female bird world go far deeper. The capacity of female birds to rear and protect their young is phenomenal. Somehow, they manage to hold their families together despite predators, harsh conditions and sometimes, a less-than-attentive partner.

Satin Bowerbirds: An Unequal Domestic Burden

The male bowerbird is one of the most over-the-top bachelors of the bird world.

Male satin bowerbirds have striking, iridescent blue plumage and violet-coloured eyes. Females, on the other hand, are green and brown to blend into their surroundings.

To attract a mate, the male dances in an exaggerated fashion and makes a decorated bower. Females visit various bowers and select their mate. After that, the female basically does everything.

She makes the nest – usually high in a tree to protect nestlings from predators such as goannas. She produces and incubates the eggs on her own. And once the chicks hatch, the mum alone feeds them and defends the nest.

Meanwhile, the male bowerbird fusses over his man-cave – or bower – throughout the year in the hope of attracting another mate.

Palm Cockatoos: The Female Bodyguard

Male palm cockatoos shot to fame a few years ago when new research identified their drumming abilities. The males make drumsticks from branches and bang them rhythmically against a tree for pair-bonding or sometimes to claim territory.

But once the palm cockatoos pair up, the female plays a crucial role in securing their territory for breeding. During many months of behavioural observations, we found the female sits sentinel (kind of like a bodyguard) on the tree hollow while the male goes inside, splintering sticks with his massive bill to make the nest.

If danger comes – perhaps a neighbouring cockatoo pair or predator – the female alerts her mate and chases away the intruder.

Virtuosic Lady Lyrebirds

The impressive repertoire of male superb lyrebirds is well-known. But it was only in recent years, when researchers turned their attention to the female, that her incredible singing ability was discovered.

Male lyrebirds don’t help with nest-building, incubation, brooding or feeding young.

Left alone to rear and protect her offspring, the female lyrebird has developed a cunning ability to confuse predators by mimicking the calls of at least 19 other bird species.

The female lyrebird is also remarkable for the length of time she cares for her young. Once fully feathered and able to fly, young lyrebirds remain dependent on their mothers and may stay in their care for more than a year.

Fairy-Wren Code-Makers

The Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoo does not build its own nest but instead lays its eggs in the nests of other birds such as fairy-wrens. This can leave the fairy-wren mother expending precious time and food raising another bird’s chicks.

But the female superb fairy-wren has developed a truly ingenious way to detect foreign nestlings once the eggs hatch.

She sings to her eggs – and includes in the song a specific “password”. Once her chicks hatch, they sing the password when begging for food.

It can be hard for the fairy-wren mum to differentiate her young in her dark, ball-shaped nest. But she can identify her offspring by their song. Cuckoo nestlings can’t learn or sing the password so are less likely to get fed.

Eclectus Parrot: The Ultimate Nest Defender

Even though nesting only takes a few months, female eclectus parrots guard their precious hollows for up to nine months.

This is why their plumage is red and their male counterparts are green.

The red serves as a beacon screaming “this hollow is taken!”, helping keep cockatoos away.

Here’s To All Mums

Female birds are just as worthy of our time and research effort as their male counterparts. Considering the behaviours and needs of female birds is especially vital from a conservation perspective.

What’s more, affirming the important role of females in any community – bird or human – is crucial to achieving more equitable and just societies. Never is that message more important than on Mother’s Day. ![]()

Ayesha Tulloch, ARC Future Fellow, Queensland University of Technology and Christina N. Zdenek, Lab Manager/Post-doc at the Venom Evolution Lab, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Global Big Day Bird Count Is Coming!!

- Get an eBird account: eBird is a worldwide bird checklist program used by millions of birders. It’s what allows us to compile everyone’s sightings into a single massive Global Big Day list—while at the same time collecting the data to help scientists better understand birds. Sign up here. It’s 100% free from start to finish.

- Watch birds on 14 May: It’s that simple. You don’t need to be a bird expert or go out all day long, even 10 minutes of birding from home counts. Global Big Day runs from midnight to midnight in your local time zone. You can report what you find from anywhere in the world.

- Enter what you see and hear in eBird: You can enter your sightings via our website or download the free eBird Mobile app to make submitting lists even easier. Please enter your checklists before 17 May to be included in our initial results announcement.

- Watch the sightings roll in: During the day, follow along with sightings from more than 170 countries in real-time on our Global Big Day page.

Mangrove or Striated Heron Butorides striata - Careel Creek - photo by A J Guesdon

Gardens Of Stone Officially Protected In Perpetuity: Draft Plan Of Management And Draft Master Plan - Have Your Say

- the ‘Lost City Adventure Experience’, which will be a key attraction of the park offering one of the longest zip-lines in Australia and exhilarating via ferrata (supported rock climbing) experiences.

- the ‘Wollemi Great Walk’ with eco-style accommodation and facilities, linking Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area to Wollemi National Park.

- an extensive network of purpose-built mountain bike tracks, catering for a range of abilities with connections to Lithgow township.

- all weather four-wheel drive designated touring routes

- family-friendly designated camping areas.

- State Mine Gully and Lost City Precinct

- Carne Creek and former Plantation Precinct

- Birds Rock Precinct

- Long Swamp Precinct.

- Environment and habitat

- Heritage and scenic amenity

- Visitation

- Vehicular access

- 4WD access

- Bush wallking experiences

- Mountain biking

- Adventure experiences and tourism

- Camping

- Services and Facilities

Central-West Orana Renewable Energy Zone Tender Shortlist Announced

- ACE Energy, comprising Acciona, Cobra and Endeavour Energy

- Network REZolution, comprising Pacific Partnerships, UGL, CPB Contractors and APA Group

- NewGen Networks, comprising Plenary Group, Elecnor, Essential Energy and SecureEnergy

Air Attack Training To Build Fire Fighting Strength

Ceremony Marks Return Of Bulagaranda To Aboriginal Owners

Scorched dystopia or liveable planet? Here’s where the climate policies of our political hopefuls will take us

The federal election campaign takes place against a background of flooding on Australia’s east coast, where some residents remain in temporary accommodation a month after the disaster. It’s just the latest reminder Australia is set to become a poster child for climate change harms.

Australia has warmed about 1.4℃ since 1910. With it has come extreme heat, bushfires, floods, drought and now, a sixth huge bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef.

Yet meaningful climate policy debate has largely been absent from this election campaign. So Climate Analytics, a research organisation I lead, has weighed up the policies of the Coalition, Labor, the Greens and the “teal” independents.

We analysed the global warming implications of each party’s or candidate’s target for 2030.

As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns, this timeframe is crucial if the world is to stay below the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels. Dramatic action by 2030 is also vital to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 or earlier.

Alarmingly, the Coalition’s climate policy is consistent with a very dangerous 3℃ of global warming. Labor’s policy is slightly better, but only policies by the Greens and the “teals” are consistent with keeping global warming at or below 1.5℃.

The Coalition

The Morrison government is pursing 26-28% emissions reduction by 2030, based on 2005 levels. If all other national governments took a similar level of action, Earth would reach at least 3℃ of warming, bordering on 4℃, our analysis shows.

That would mean the total destruction of all tropical reefs including Ningaloo and the Great Barrier Reef. And intense heatwaves over land that currently occur about once a decade could happen almost every other year.

At the United Nations climate conference in Glasgow last year, the Morrison government famously refused to increase its 2030 commitments. But the final pact from the meeting, which Australia signed, requires that by November this year, governments will strengthen their 2030 targets to align with the 1.5℃ goal.

Australia is under strong international pressure to meet this obligation, or face further global condemnation.

Labor

Labor’s target of a 43% emissions cut by 2030, from 2005 levels, is in line with 2℃ of global warming. That means it’s not consistent with the Paris Agreement.

Under 2℃ of warming, extreme heat events that currently happen once a decade could occur about every three to four years. And they would reach maximum temperatures about 1.7℃ hotter than heatwaves in recent decades.

Should Earth overshoot 1.5℃ warming and perhaps reach 2℃, some suggest this may be temporary and temperatures could be brought back down. This would require technologies that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But such technologies are uncertain and come with risks.

And the IPCC’s recent report warned even if 1.5℃ warming is exceeded temporarily, severe and potentially irreversible damage would result. The total loss of the Great Barrier Reef is just one example.

Under 2℃ of warming the most extreme heat events that occurred once in a decade in recent times could occur about every three to four years. The heatwaves would also reach a maximum temperature 1.7℃ hotter than those in recent decades.

‘Teal’ Independents

The “teals” are a group of pro-climate independent candidates.

Most prominent is Warringah MP Zali Steggall, whose climate change bill proposes a 2030 target of 60% below 2005 levels. Most climate policies of the “teals” are generally in line with the Steggall bill.

The target is also supported by industry.

We find this target consistent with 1.5℃ of warming, and so compatible with the Paris Agreement. However, it’s at the upper end of the emission levels consistent with the 1.5℃ pathway.

The Greens

Of all the climate policies on the table this election, the Greens target of a 74% cut by 2030, based on 2005 levels, is most comfortably consistent with keeping warming below 1.5℃.

That level of warming would still cause damage to Earth’s natural systems and our way of life. But it would avert significant devastation – for example, allowing parts of the Ningaloo and Great Barrier reefs to survive.

Under 1.5℃ global warming, the most extreme heat events that presently occur once a decade could be limited to about every five to six years.

The Land Sector Problem

Our calculations above do not paint a rosy picture. But they are, in fact, optimistic.

That’s because they include emission reductions from the land and forestry sector through such activities as tree planting and maintaining native vegetation. These so-called carbon sinks were recently described by a key insider as a “fraud”.

If the land and forest sector is excluded from the analysis, the various emissions reduction targets fall considerably: to between 11% and 13% for the Coalition, 31% for Labor, 50% for the teals and 67% for the Greens.

What’s more, even warming limited to 1.5℃ will reduce the capacity of the land sector to remove and store carbon.

Over To You

The scientific consensus is clear. Greenhouse gas emissions must peak by 2025 at the latest and plummet thereafter, to limit global warming to 1.5℃.

Unless policies are substantially strengthened, Earth is set to hit 1.5℃ warming in the 2030s, and a future of at least 3℃ warming awaits.

The onus is on the next parliament to protect Australians from climate catastrophe. On May 21, Australian voters have a chance to send a clear message about the kind of world we want to leave for future generations.![]()

Bill Hare, Adjunct Professor, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s next government must tackle our collapsing ecosystems and extinction crisis

Australia’s remarkable animals, plants and ecosystems are world-renowned, and rightly so.

Unfortunately, our famous ecosystems are not OK. Many are hurtling towards collapse, threatening even iconic species like the koala, platypus and the numbat. More and more species are going extinct, with over 100 since British colonisation. That means Australia has one of the worst conservation records in the world.

This represents a monumental government failure. Our leaders are failing in their duty of care to the environment. Yet so far, the election campaign has been unsettlingly silent on threatened species.

Here are five steps our next government should take.

1. Strengthen, Enforce And Align Policy And Laws

Australia’s environmental laws and policies are failing to safeguard our unique biodiversity from extinction. This has been established by a series of independent reviews, Auditor-General reports and Senate inquiries over the past decade.

The 2020 review of our main environmental protection laws offered 38 recommendations. To date, no major party has clearly committed to introducing and funding these recommendations.

To actually make a difference to the environment, it’s vital we achieve policy alignment. That means, for instance, ruling out new coal mines if we would like to keep the world’s largest coral reef system alive. Similarly, widespread land clearing in Queensland and New South Wales makes tree planting initiatives pointless on an emissions front.

Despite Australia’s wealth of species, our laws protecting biodiversity are much laxer than in other developed nations like the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. These nations have mandatory monitoring of all threatened species, which means they can detect species decline early and step in before it’s too late.

2. Invest In The Environment

How much do you think the federal government spends on helping our threatened species recover? The answer is shockingly low: Around $50 million per year across the entire country. That’s less than $2 a year per Australian. The government spent the same amount on supporting the business events industry through the pandemic.

Our overall environmental spending, too, is woefully inadequate. In an age of mounting environmental threats, federal funding has fallen sharply over the past nine years.

For conservationists, this means distressing decisions. With a tiny amount of funding, you can’t save every species. That means ongoing neglect and more extinctions looming.

This investment is far less than what is needed to recover threatened species or to reduce the very real financial risks from biodiversity loss. If the government doesn’t see the environment as a serious investment, why should the private sector?

The next government should fix this nature finance gap. It’s not as if there isn’t money. The estimated annual cost of recovering every one of Australia’s ~1,800 threatened species is roughly a mere 7% of the Coalition’s $23 billion of projects promised in the month since the budget was released in late March.

3. Tackle The Threats

We already have detailed knowledge of the major threats facing our species and ecosystems: the ongoing destruction or alteration of vital habitat, the damage done by invasive species like foxes, rabbits and cats, as well as pollution, disease and climate change. To protect our species from these threats requires laws and policies with teeth, as well as investment.

If we protect threatened species habitat by stopping clearing of native vegetation, mineral extraction, or changing fishing practices, we will not only get better outcomes for biodiversity but also save money in many cases. Why? Because it’s vastly cheaper to conserve ecosystems and species in good health than attempt recovery when they’re already in decline or flatlining.

Phasing out coal, oil and gas will also be vital to stem the damage done by climate change, as well as boosting support for green infrastructure and energy.

Any actions taken to protect our environment and recover species must be evidence-based and have robust monitoring in place, so we can figure out if these actions actually work in a cost-effective manner against specific objectives. This is done routinely in the US.

Salvaging our damaged environment is going to take time. That means in many cases, we’ll need firm, multi-partisan commitments to sustained actions, sometimes even across electoral cycles. Piecemeal, short-term or politicised conservation will not help Australia’s biodiversity long-term and do not represent best use of public money.

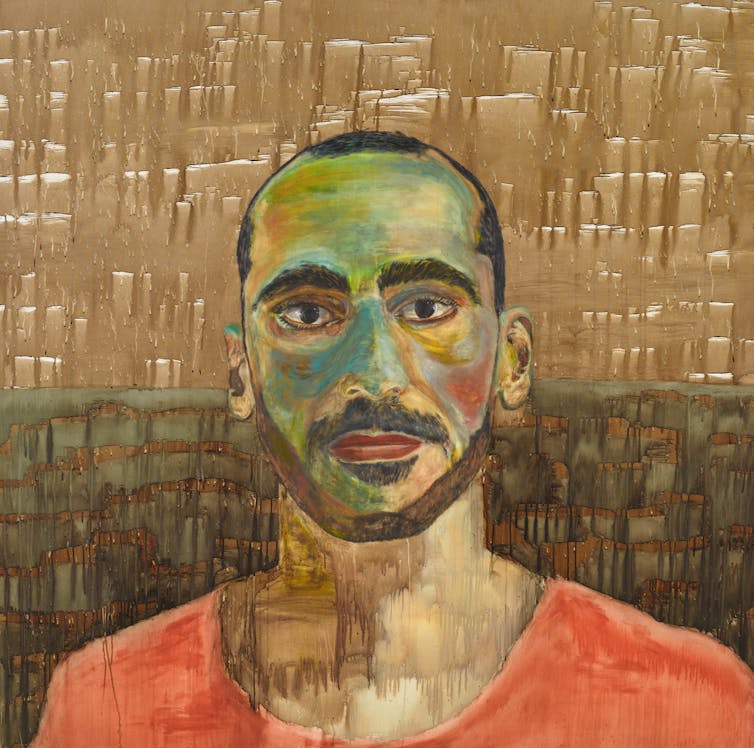

4.: Look To Indigenous Leadership To Heal Country

For millennia, First Nations people have cared for Australia’s species and shaped ecosystems.

In many areas, their forced displacement and disconnection with longstanding cultural practices is linked to further damage to the environment, such as more severe fires.

Focusing on Indigenous management of Country can deliver environmental, cultural and social benefits. This means increasing representation of Indigenous people and communities in ecosystem policy and management decisions.

5. Work With Communities And Across Boundaries

We must urgently engage and empower local communities and landowners to look after the species on their land. Almost half of Australia’s threatened species can be found on private land, including farms and pastoral properties. We already have good examples of what this can look like.

The next government should radically scale up investment in biodiversity on farms, through rebates and tax incentives for conservation covenants and sustainable agriculture. In many cases, caring for species can improve farming outcomes.

Conservation Is Good For Humans And All Other Species

To care for the environment and the other species we live alongside is good for us as people. Tending to nature in our cities makes people happier and healthier.

Protecting key plants and animals ensures key “services” like pollination and the cycling of soil nutrients continues.

We’re lucky to live in a land of such rich biodiversity, from the ancient Wollemi pine to remarkable Lord Howe island stick insects and striking corroboree frogs. But we are not looking after these species and their homes properly. The next government must take serious and swift action to save our species.![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University; Ayesha Tulloch, ARC Future Fellow, Queensland University of Technology, and Megan C Evans, Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

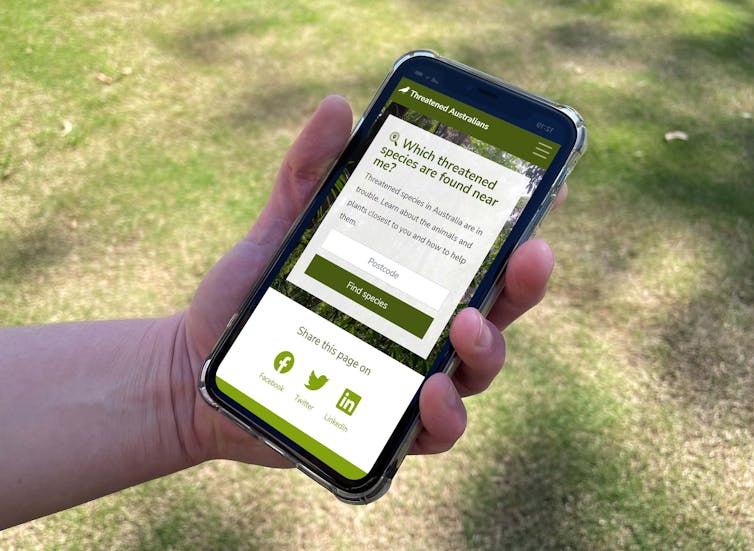

Find out what threatened plants and animals live in your electorate (and what your MP can do about it)

More than 1,800 Australian plants and animals are considered at-risk of extinction, and yet protecting threatened species is almost entirely absent from the current election campaign.

We’ve developed a web app, which launches today, that lets Australians learn which threatened plants and animals live in their federal electorate.

For example, we found the electorate with the most threatened species is Durack in Western Australia, held currently by the Liberal party’s Melissa Price. Some 61 threatened animals and 198 threatened plants live or used to live within its boundaries, such as the Numbat, Gouldian finch and the Western underground orchid.

Our goal is to help users engage with their elected representatives and put imperilled species on the political agenda this election and beyond. We urgently need to convince federal politicians to act, for they hold the keys to saving these species. So what can they do to help their plight?

Threatened Species In Your Neighbourhood

Our new app, called Threatened Australians, uses federal government data to introduce you to the threatened species living in your neighbourhood.

By entering a post code, users can learn what the species looks like, where they can be found (in relation to their electorate), and what’s threatening them. Importantly, users can learn about their incumbent elected representative, and the democratic actions that work towards making a difference.

For example, entering the postcode 2060 – the seat of North Sydney, held currently by the Liberal Party’s Trent Zimmerman – tells us there are 23 threatened animals and 14 threatened plants that live or used to live there.

This includes the koala which, among many others, have seen devastating losses in their populations in recent decades due to habitat destruction.

We’ve also put together data dividing the number of threatened species that live or used to live across each party’s electorates, as shown in the chart below. Labor-held seats are home to 775 of the 1,800-plus threatened species, while Liberal-held seats have 1,168.

A Seriously Neglected Issue

The good news is we know how to avert the extinction crisis. Innumerable reports and peer-reviewed studies have detailed why the crisis is occurring, including a major independent review of Australia’s environment laws which outlined the necessary federal reforms for changing this trajectory.

The bad news is these comprehensive reforms, like almost all the previous calls to action on the threatened species crisis, have been largely ignored.

Predictions show the situation will drastically worsen for threatened species over the next two decades if nothing changes.

Yet, environmental issues rarely play key roles in federal elections, despite the connection Australians share with the environment and our wildlife.

The health of the environment continually ranks among the top issues Australians care about, and nature tourists in Australia spend over $23 billion per year.

So how can we address this mismatch of widespread public desire for environmental action yet political candidates are focused on other issues?

What Can Local MPs Actually Do About It?

For change to occur, communities must effectively persuade elected representatives to act. There are a few ways they can exercise their democratic powers to make a difference.

Federal MPs often champion and advocate important issues such as developing new hospitals, schools and car parks in their electorate. By speaking out and advocating for their electorate in parliament and with the media, they can garner the support, such as funding and reform, to deliver change for their electorate.

Local MPs can help protect threatened species by instigating and voting for improved policy.

Let’s say, for instance, legislation for approving a new mine was before parliament, and the development overlapped with the habitat of a threatened animal. If protecting a certain plant or animal was on an MPs agenda thanks to the efforts of their community, it would help determine whether the MP votes for such legislation.

This has broader applications, too. Making the threatened species crisis a priority for an MP would determine the lengths they would go to for conservation in their electorate and Australia wide.

Threatened species desperately need the required funding alongside the appropriate policy and legislative reform. The current policies are responsible for the threats causing many species to go endangered in the first place.

Our app can help users engage with the current sitting MP in their electorate with the click of a button, as it helps users write an email to them. It’s time federal representatives were asked about their policies on threatened species and what they plan to do for them in their electoral backyards.

While climate change has, for decades, unfathomably been the subject of fierce debate in the Australian parliament, threatened species can be a cause of unity across the political divide.

We need an honest and urgent dialogue between local communities and their representatives about how to deal with the challenge these species face and what each prospective candidate intends to do about it. ![]()

Gareth Kindler, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland; James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland, and Nick Kelly, Senior Lecturer in Interaction Design, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Beyond electric cars: how electrifying trucks, buses, tractors and scooters will help tackle climate change

When you think of an electric vehicle, chances are you’ll picture a car. But there’s a quiet revolution going on in transport. It turns out electrification can work wonders for almost all of our transport options, from electric bikes to motorbikes to buses to freight trains and even to tractors and heavy trucks. There will soon be no need to burn petrol and diesel in an internal combustion engine.

This matters, because electric transport will be vital in our efforts to stem climate change. If all cars on the road became powered by renewable electricity, we’d cut almost one-fifth of our emissions. We’d also be much better placed to weather spikes in oil prices linked to war, and enjoy cleaner air and quieter cities.

It’s promising news that electric vehicles are shaping up as an election issue at last, with Labor promising a national EV charging network at its campaign launch, and the Greens promising rebates of up to $15,000 for EV purchases, while the Liberal Party last year reversed its previous scepticism and launched a smaller charging network policy.

But this is only the beginning of what’s required. Right now, all the focus is on electric cars. We will need new policy settings to encourage the electrification of all our transport options. And that means getting electric mobility on the radar of our political parties.

Why Electric And Why Now?

Electric vehicles have been around for more than 120 years. They accounted for a third of all cars on US roads in 1900, sought because they were clean and quiet. But their first dawn ended because of the high cost and weight of batteries, leaving internal combustion engines to rule the road.

So what changed? Two things: solar has become the cheapest form of power in human history, and lighter lithium-ion batteries have become vastly cheaper. These remarkable inventions have allowed electric vehicle manufacturers to become competitive. Cheap solar power funnels into the battery of the electric vehicle to provide running costs much lower than those of fossil fuel engines. The much simpler engines also mean vastly lower maintenance costs.

We’re also seeing major innovations brought across from electric public transport. Over the past two decades, there have been significant advances in smart technology in trains and trams, such as regenerative braking and sensors enabling active suspension. These breakthroughs have been taken up enthusiastically by electric vehicle manufacturers. All electric cars now have regenerative braking, which hugely increases energy efficiency, as well as smart sensors to aid steering, and active suspension, making the cars safer and the ride smoother.

We’re also seeing welcome cross-pollination in the form of trackless trams, which are upgraded buses that boast rail-like mobility. This is made possible based on technologies invented for high-speed rail.

In short, there’s no reason why solar and battery technology has to be limited to cars. All the world’s land-based internal combustion engine vehicles can now be replaced by electric equivalents.

Electric Mobility Is Arriving

You’ll already have seen signs of the potential of electric mobility. E-scooters are popping up in major cities, giving people a way to make short trips quickly and cheaply. E-bikes are surging ahead, popular among commuters and families choosing one over a second car. Even this is just the start.

Around the world, electric micromobility (scooters, skateboards and bikes) is growing at over 17% per year and expected to quadruple current sales of US$50 billion by 2030.

Even without much government assistance, Australians are shifting rapidly to all types of electric vehicle. But for Australia to embrace electric transport as fully as we can, we need the right policy settings. Cars, scooters, motorbikes, trackless trams, buses, trucks, freight trains and farm vehicles can all be part of the transition to the cheapest and highest-quality mobility the world has yet seen.

The policies on offer to date suggest no party has figured out the radical upheaval electrification will bring. Labor’s emission reductions policy of a 43% cut by 2030 gives electric cars only a tiny role, cutting emissions by less than 1%, or four million tonnes out of a total of 448 million tonnes. There’s no mention of other electric modes of transport. Even the Greens have little serious policy analysis of the broader EV options. The Liberals have no mention at all.

We Need Comprehensive, Broad Electric Vehicle Policy

Given we’re still at the starting line, what’s the best first step? Perhaps the simplest would be to enable Infrastructure Australia to work with the states on creating strategic directions for each electric transport mode. The ACT already has a plan like this for its bus network as part of its shift to a zero-carbon future.

Here’s what good EV policies would consider:

Electric micromobility: how to recharge and manage the explosion of electric scooters, skateboards and bikes with appropriate infrastructure, and how to enable the best public sharing systems

Electric public transit: how to electrify all buses, passenger trains and mid-tier transit (light rail, rapid transit buses and trackless trams), and how to link net zero urban developments and charging facilities

Electric trucks, freight trains and farm vehicles: how to create recharge highways and hubs in train stations, industrial precincts and standalone farm systems, and how to introduce these to the regions to enable net zero mining, agriculture and other processed products.

Each of these modes will also need the same targets, subsidies and regulations as electric cars do, to make possible a swift, clean transition away from petrol and diesel. If we focus only on electric cars, we could end up with cities still full of cars, even if they don’t pollute. By focusing on all transport modes, we will make our cities more equitable, safe and sustainable.![]()

Peter Newman, Professor of Sustainability, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How our bushfire-proof house design could help people flee rather than risk fighting the flames

By 2030, climate change will make one in 25 Australian homes “uninsurable” if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, with riverine flooding posing the greatest insurance risk, a new Climate Council analysis finds.

As a professor of architecture, I find this analysis grim, yet unsurprising. One reason is because Australian housing is largely unfit for the challenges of climate change.

In the past two years alone we’ve seen over 3,000 homes razed in the 2019-2020 megafires, and over 3,600 homes destroyed in New South Wales Northern Rivers region in the recent floods.

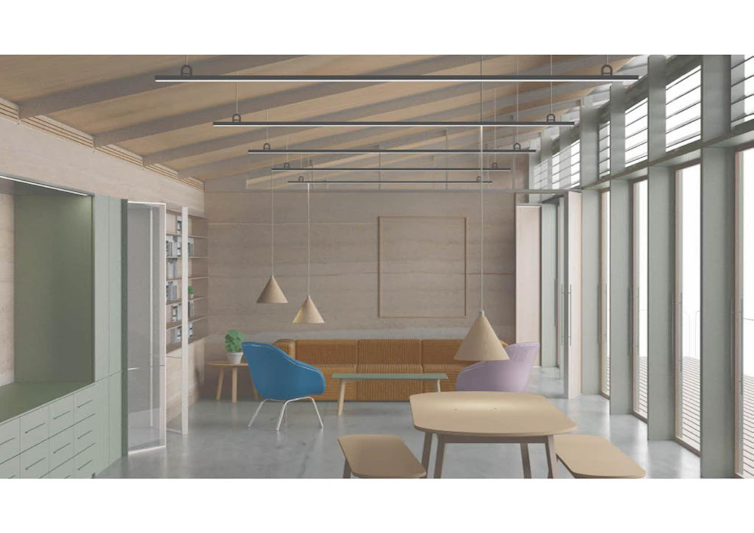

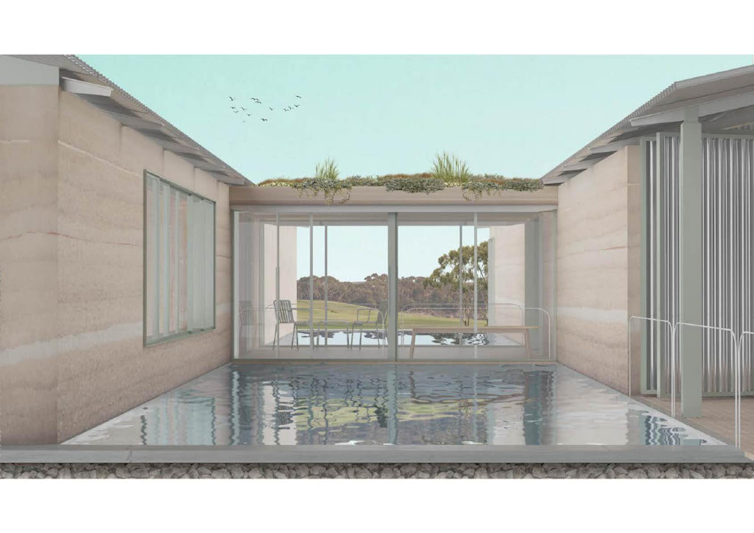

Building houses better at withstanding the impacts of climate change is one way we can protect ourselves in the face of future catastrophic conditions. I’m part of a research team that developed a novel, bushfire-resistant house design, which won an international award last month.

We hope its ability to withstand fires on its own will encourage owners – who would otherwise stay to defend their home – to flee when bushfires encroach. Let’s take a closer look at the risk of bushfires and why our housing design should one day become a new Australian norm.

Houses Today Are Easy To Burn

The Climate Council analysis reveals that across Australia’s 10 electorates most at risk of climate change impacts, one in seven houses will be uninsurable by 2030 under a high emissions scenario. This includes 25,801 properties (27%) in Victoria’s electorate of Nicholls, and 22,274 properties (20%) in Richmond, NSW.

Bushfires are among the worsening hazards causing homes to be uninsurable, and pose a particularly high risk to many thousands of homes across eastern Australia.

For example, the Climate Council found 55% of properties in the electorate of Macquarie, NSW, will be at risk of bushfires in 2030, if emissions do not fall. This jumps to 64% of properties by 2100.

The typical Australian house was not designed with bushfires in mind as most were built decades ago, before bushfire planning and construction regulations came into force.

This means they incorporate burnable materials, such as wood and plasterboard, and have features such as gutters which can trap embers.

What’s more, the gaps between building materials are often too large to keep embers out, which means spot fires can start on the inside of the house. And many houses are situated too close to fire-prone grasses and trees.

Indeed, at least 90% of houses currently in bushfire zones risk being destroyed in a bushfire.

How Our New Design Can Withstand Fire

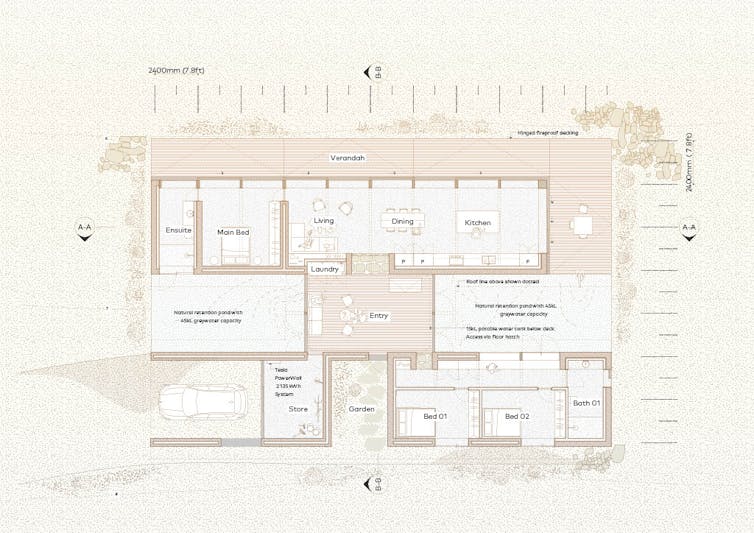

The prototypical bushfire resistant house we designed won first prize in the New Housing Division of the United States Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Solar Decathlon.

The house would be made from locally sourced, recycled steel frame. It would be mounted on reinforced concrete pilings to minimise its disturbance on the land, touching the ground only lightly. In this way, we help preserve the site’s biodiversity.

The primary building material is rammed earth – natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel – which is not combustible.

The roof and some cladding are made of fire-resistant corrugated metal. Its glass facades have fire shutters made of fibre cement sheeting, a material that’s non-combustible and can be closed to seal the house.

Importantly, the gaps between these construction materials are 2 millimetres or less.

The sloped roofs tilt inwards to capture rainwater. And as the roofs are made of corrugated metal, which has channels in it, the house does not require gutters.

These channels guide rainwater into two open retention ponds either side of the entry, and into protected tanks beneath the house. This also helps protect the house in a bushfire, as it means the fire can’t penetrate from beneath.

When bushfires strike, the risk to life is highest when people stay and defend their homes. A design that can resist fire on its own encourages its owners to leave.

But it’s worth noting that it’s not a bunker for people to shelter in. No matter how well designed a house is, it always will be too dangerous to stay when a fire comes through, and particularly in the catastrophic and extreme fire conditions we’re increasingly experiencing.

It’s Cost Effective, Too

The estimated cost of construction is between A$400,000 and $450,000. We deployed several strategies to keep costs down:

the house is designed to be energy and water independent, so will not need city utilities

it uses common construction techniques and is based on the construction industry standard for sheeting, so won’t require specialised builders and won’t waste any material

rammed earth is relatively inexpensive because it can be sourced in many locations, often for free. We also envision using recycled materials wherever possible.

Aesthetically speaking, the design also presents an elegant domestic space, one that’s flexible enough it can easily be adapted to almost any site.

The next stage is to build and test a prototype of the house so we can evaluate its performance and make improvements. We’re currently speaking to some potential funders to make this happen.

As climate change brings worsening disasters, Australia must brace for thousands more houses becoming destroyed. Innovative architecture like ours offers a chance for treasured homes and possessions to survive future catastrophes.![]()

Deborah Ascher Barnstone, Professor, Head of School, School of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

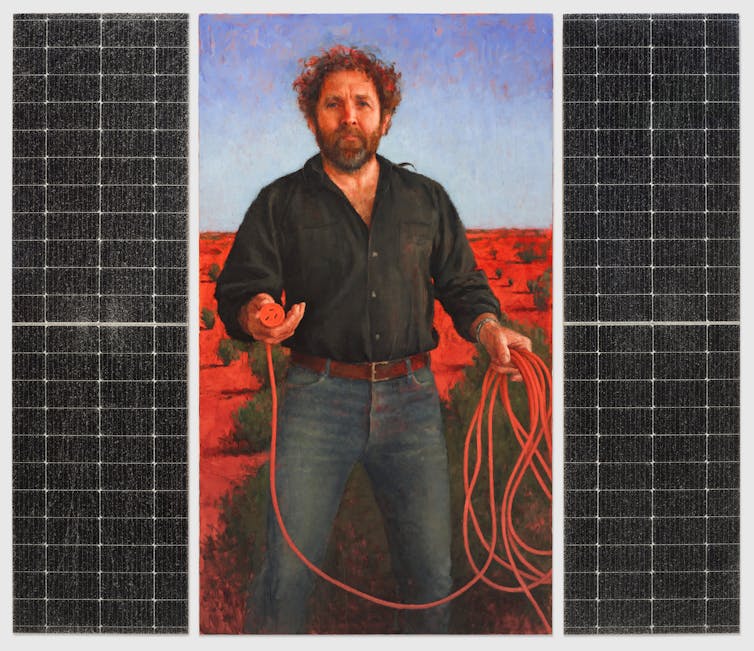

How can Aboriginal communities be part of the NSW renewable energy transition?

Heidi Norman, University of Technology Sydney and Chris Briggs, University of Technology SydneyThe New South Wales government’s roadmap to transition from coal-based electricity to renewable energy involves the creation of five “renewable energy zones” across the state.

These “modern-day power stations” will use solar, wind, batteries and new poles and wires to generate energy for the state. They’re part of a broader plan to meet a legislated target of 12 gigawatts of renewable energy and 2 gigawatts of storage by 2030.

These renewable energy zones include measures to deliver regional benefits such as engagement, jobs and benefit-sharing with local Aboriginal communities. This is a first for an Australian renewable energy program of this scale.

However, two things are needed to maximise this opportunity for Aboriginal people.

First, Aboriginal land councils need greater support and resources to participate effectively in delivery of the renewable energy zones.

Second, there should be a program to facilitate the development of renewable energy projects on Aboriginal-owned land.

Through these actions, the government can help develop partnerships that can deliver revenue and jobs for Aboriginal communities as the state transitions to clean energy.

Maximising Opportunities For First Nations Communities

There are some cases of renewable energy projects delivering for Aboriginal communities, such as solar farms engaging unemployed Aboriginal workers. But overall the benefits have been limited to date.

However, legislation requires the NSW government bodies and renewables projects in the renewable energy zones to comply with “First Nations Guidelines” currently under development.

The guidelines will require:

- regional reference groups

- an engagement framework for renewable energy projects, and

- a document reflecting community interests developed with the input of local Aboriginal organisations (land councils and Traditional Owners under Native Title) in each renewable energy zone.

Projects bidding for a “long-term energy supply agreement” from the NSW government - which will guarantee a minimum price for their output - have to comply with the Indigenous Procurement Policy. This includes ensuring a minimum 1.5% Aboriginal workforce and 1.5% of contract value to Aboriginal businesses.

These First Nations guidelines will form part of the tender evaluation, creating incentives for projects to increase benefits for First Nations communities.

The inclusion of these First Nations guidelines in the renewable energy projects is a first for Australian renewable energy. It’s likely to significantly improve economic outcomes for Aboriginal communities.

So far, so good.

However, there are also some missed opportunities.

First, if renewable energy projects and the First Nations guidelines are to work well, greater resourcing and capacity-building is needed for local Aboriginal land councils so they can participate effectively.

In addition, the NSW government should develop an Aboriginal-led local and regional level clean energy strategy so communities can identify what they want from this momentous change.

A study by the Indigenous Land and Justice Research Group, based at the University of Technology Sydney, revealed local Aboriginal land councils are eager for renewable energy. This would improve opportunities to live and work locally, boost energy security, lower costs, enable care of Country and create wealth.

However, the study found these communities had little or no knowledge about renewable energy options or how they could benefit.

Only one Local Aboriginal Land Council in the pilot renewable energy zone had prior dealings with renewable energy operators. All were uncertain about how their land assets could be mobilised.

More Opportunities Needed For Aboriginal-Owned Land In NSW

There are currently no measures to encourage and facilitate renewable energy projects on Aboriginal-owned land in NSW.

Work by Indigenous Energy Australia and the Institute for Sustainable Futures found the best outcomes often occur from “mid-sized” renewable energy projects on Indigenous-owned land.

Examples include:

the Ramahyuck Solar Farm (Longford, Victoria), which is wholly owned and operated by the Ramahyuck District Aboriginal Corporation. Following government funding, debt financing was secured for construction. The profit generated from the development will be redirected to Aboriginal education and health programs

the Tuaropaki Geothermal Power Station in New Zealand, which is 75% owned by the Māori, Tuaropaki Trust and 25% by Mercury Energy (a large energy company). The Tuaropaki Trust was developed through financial partnerships and government support. These developments produced long-term income for community programs and other commercial ventures

the Atlin Hydro Project in Canada, a 100% Indigenous owned and operated project. Government support was critical in establishing the project. Once established, revenues were distributed based on joint clan meetings for health programs and a land guardian program.

Developing projects on Aboriginal-owned land would take more time to identify a workable model, ensure there is support within the land council and local community and develop local capacity. But done well, it can deliver greater benefits for Aboriginal communities.

A government program developed in parallel with the roll out of the renewable energy zones could develop opportunities for renewable energy developments in partnership with local Aboriginal land councils.

Support for meaningful, Aboriginal-led renewable energy projects on Aboriginal land has the potential to make real progress towards the long hoped for benefits of land restitution for First Peoples in NSW.

The time for action is now.![]()

Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney and Chris Briggs, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

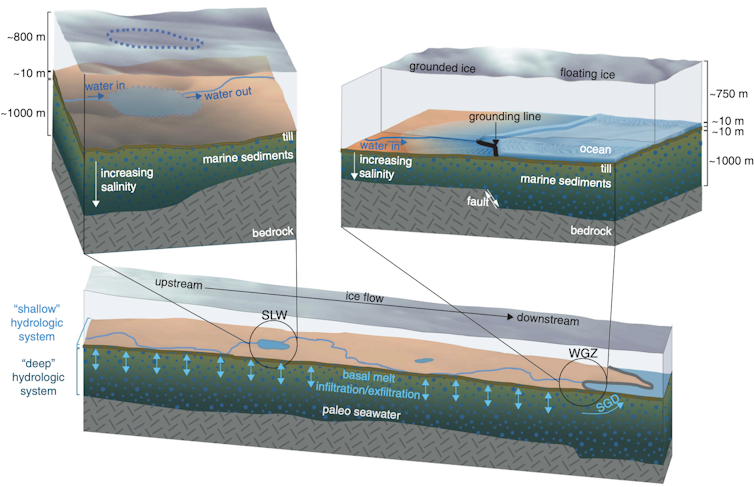

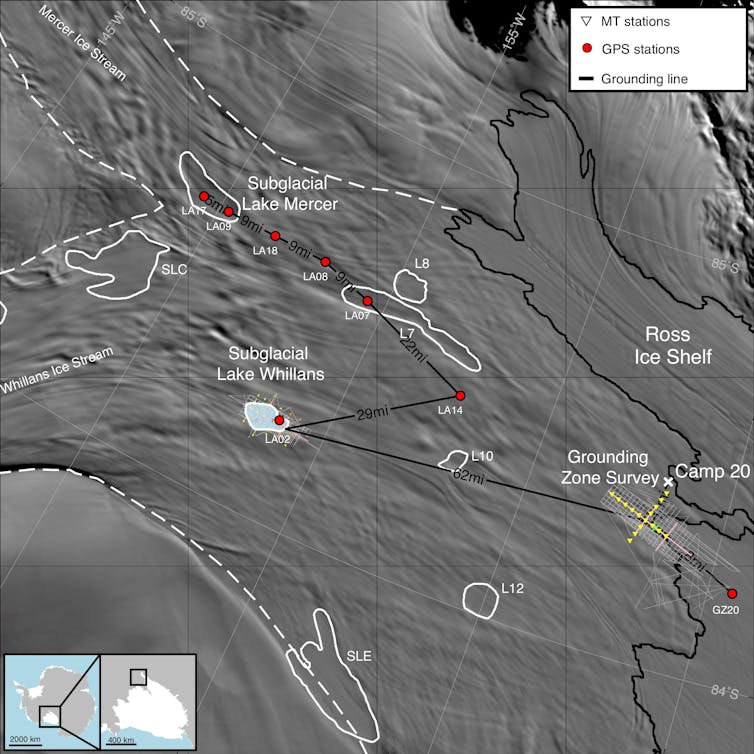

Scientists in Antarctica discover a vast, salty groundwater system under the ice sheet – with implications for sea level rise

A new discovery deep beneath one of Antarctica’s rivers of ice could change scientists’ understanding of how the ice flows, with important implications for estimating future sea level rise.

Glacier scientists Matthew Siegfried from Colorado School of Mines, Chloe Gustafson from Scripps Institution of Oceanography and their colleagues spent 61 days living in tents on an Antarctic ice stream to collect data about the land under half a mile of ice beneath their feet. They explain what the team discovered and what it says about the behavior of ice sheets in a warming world.

What Was The Big Takeaway From Your Research?

First, it helps to understand that West Antarctic was an ocean before it was an ice sheet. If it disappeared today, it would be an ocean again with a bunch of islands. So, we know that the bedrock below the ice sheet is covered with a thick layer of sediments – the particles that accumulate onto ocean floors.

What we didn’t know was what was in the tiny pore spaces among those sediments below the ice.

We expected to find meltwater coming from the ice stream above, a fast-moving channel of ice that flows from the center of the ice sheet toward the ocean. What we didn’t expect, but we found in this thick layer of sediments, was a huge amount of groundwater – including saltwater from the ocean.

Our findings suggest that this salty groundwater is the largest reservoir of liquid water below the ice stream we studied, and likely others, and it may be affecting how the ice flows on Antarctica.

Liquid water is incredibly important to how fast an ice stream moves. If there’s liquid water at the base of an ice stream, it flows fast. If that water freezes or the base dries out, the ice screeches to a stop.

Models of ice streams typically consider only whether ice at the base has reached the melting point or if water has flowed from upstream along the base of the ice. Scientists had never considered that more water was available under the ice sheet, let alone water that is much saltier, which keeps water from freezing at lower temperatures. (Think about why communities put salt on roads in winter.)

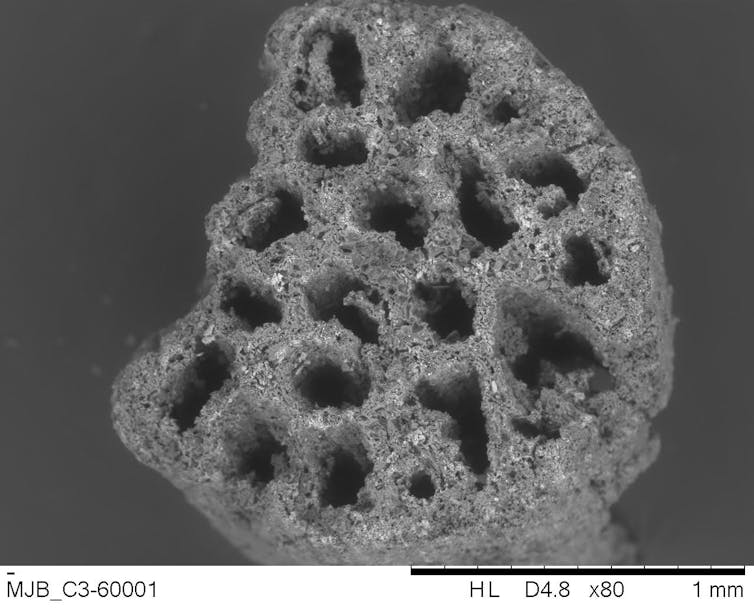

Our observations suggest there is so much water there, if you took the 500 to 1,900 meters (1,600 to 6,200 feet) or so of sediments below the ice stream and squeezed them like a sponge, you’d have a column of water about 220 to 820 meters (700 to 2,700 feet) deep.

This water can move through the pores in the subglacial groundwater system, just like groundwater elsewhere, but in Antarctica, there is a dynamic ice sheet on top. When the ice sheet gets thicker, it exerts more pressure on the sediment below, so it could drive meltwater from the base of the ice sheet deeper into the sediment. When the ice gets thinner, however, it could draw water, now a little saltier, out of the sediments. That saltier water could affect how fast the ice flows.

Knowing that there is a massive reservoir of water that may be linked to how fast-flowing regions of Antarctica behave means scientists need to rethink our understanding of ice streams.

What Does Finding Liquid Water In The Sediments Tell Scientists About Antarctica?

The salty groundwater was a clear sign of how far inland the boundary between the ice sheet and the ocean once reached.

This boundary, known as the grounding line, is incredibly important. When ice flows across the grounding line, it starts to float in the ocean. If you know how the grounding line is shifting, you have a good sense of how much ice is being contributed to the global ocean.

The fact that there were marine waters beneath our feet meant that the grounding line was upstream of us at some point, at least 70 miles (110 kilometers) from where it is today.

The next question is when it got there.

We argue in our paper that it can’t be too old. The groundwater is flowing, and fresh water is coming into the sediments from the glacier above. We estimate that most of this salty water arrived in the subglacial system within the past 10,000 years, based on how much radiocarbon has been found in the upper sediment in previous a study.

The ocean would have deposited that seawater when the ice sheet got smaller during warm periods in the past.

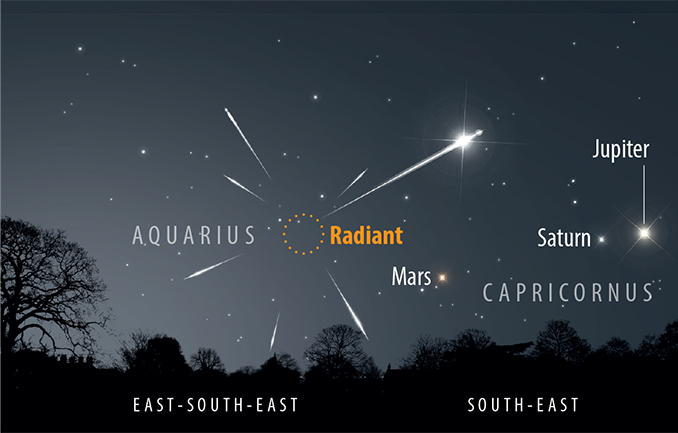

Whillans Ice Stream Is Pretty Remote. How Did You Determine What Was Happening A Mile Below You?

Our site is about a two-hour flight from McMurdo Station, Antarctica. The plane lands on skis and drops off everything you need to live. Then it takes off, and it’s you, your field team, and a couple pallets of cargo.

In all, we slept 61 days in a tent that season. Each day, we packed our snowmobiles, put in the coordinates for a site, and installed magnetotelluric stations.

Each station has three magnetometers – pointing east-west, north-south and vertical – and two pairs of electrodes – aligned east-west and north-south. These instruments can detect the electromagnetic signatures of different Earth materials in the subsurface.

Natural variations in the Earth’s magnetic and electric fields are created by events across the globe, such as solar wind interacting with the Earth’s ionosphere and lightning strikes. A change in the Earth’s magnetic and electric fields induces secondary electromagnetic fields in the subsurface, and the strength of those fields is related to how well the material there conducts electricity.

So, by measuring electric and magnetic fields on the ice surface, we can figure out the conductivity of the subsurface materials, including water. It’s the same method the oil and gas industry used to find fossil fuels.

We could see the groundwater, and since salt water has far greater conductivity than fresh water, we could estimate how salty it was.

What Else Might Be In The Groundwater?

Any time we’ve poked a hole through Antarctica, it’s been teeming with microbial life. There’s no reason to think microbes aren’t gnawing away at nutrients in the groundwater, too.

When you have microbial ecosystems that are cut off for extended periods of time – in this case, seawater was likely deposited there 5,000-10,000 years ago – you start to have a pretty good analog for how life might exist on other planetary bodies, locked in the subsurface and buried underneath thick ice.

Where there’s life, there is also the question of carbon.

We know that there are microbes in subglacial lakes and rivers at the top of the sediment that are consuming carbon and transforming it into greenhouse gases like methane and carbon dioxide. We know all of this carbon ultimately gets transferred to the Southern Ocean. But we still don’t have great measurements of any of this.

This is a new environment, and there’s a lot of research still to do. We have observations from one ice stream. It’s like sticking a straw in the groundwater system in Florida and saying, “Yeah, there’s something here” – but what does the rest of the continent look like?![]()

Matthew Siegfried, Assistant Professor of Geophysics and Hydrologic Science and Engineering, Colorado School of Mines and Chloe Gustafson, Postdoctoral Research Scientist in Geophysics, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

65,000 years of food scraps found at Kakadu tell a story of resilience amid changing climate, sea levels and vegetation

For 65,000 years, Bininj – the local Kundjeihmi word for Aboriginal people – have returned to Madjedbebe rock shelter on Mirarr Country in the Kakadu region (in the Northern Territory).

Over this immense span of time, the environment around the rock shelter has changed dramatically.

Our paper, published last week in Quaternary Science Reviews, uses ancient scraps of plant foods, once charred in the site’s fireplaces, to explore how Aboriginal communities camping at the site responded to these changes.

This cooking debris tells a story of resilience in the face of changing climate, sea levels and vegetation.

A Changing Environment

The 50-metre-long Madjedbebe rock shelter lies at the base of a huge sandstone outlier. The site has a dark, ashy floor from hundreds of past campfires and is littered with stone tools and grindstones.

The back wall is decorated with vibrant and colourful rock art. Some images – such as horsemen in broad-brimmed hats, ships, guns and decorated hands – are quite recent. Others are likely many thousands of years old.

Today, the site is situated on the edge of the Jabiluka wetlands. But 65,000 years ago, when sea levels were much lower, it sat on the edge of a vast savanna plain joining Australia and New Guinea in the supercontintent of Sahul.

At this time, the world was experiencing a glacial period (referred to as the Marine Isotope Stage 4, or MIS 4) . And while Kakadu would have been relatively well-watered compared with other parts of Australia, the monsoon vine forest vegetation, common at other points in time, would have retreated.

This glacial period would eventually ease, followed by an interglacial period, and then another glacial period, the Last Glacial Maximum (MIS 2).

Cut to the Holocene (10,000 years ago) and the weather became much warmer and wetter. Monsoon vine forest, open forest and woodland vegetation proliferated, and sea levels rose rapidly.

By 7,000 years ago, Australia and New Guinea were entirely severed from each other and the sea approached Madjedbebe to a high stand of just 5km away.

What followed was the rapid transformation of the Kakadu region. First the sea receded slightly, the river systems near the site became estuaries, and mangroves etched the lowlands.

By 4,000 years ago, these were partially replaced by patches of freshwater wetland. And by 2,000 years ago, the iconic Kakadu wetlands of today were formed.

Unlikely Treasure

Our research team, composed of archaeologists and Mirarr Traditional Owners, wanted to learn how people lived within this changing environment.

To do this, we sought an unlikely archaeological treasure: charcoal. It’s not something that comes to mind for the average camper, but when a fireplace is lit many of its components – such as twigs and leaves, or food thrown in – can later transform into charcoal.

Under the right conditions, these charred remains will survive long after campers have moved on. This happened many times in the past. Bininj living at Madjedbebe left a range of food scraps behind, including charred and fragmented fruit, nuts, palm stem, seeds, roots and tubers.

Using high-powered microscopes, we compared the anatomy of these charcoal pieces to plant foods still harvested from Mirarr Country today. By doing so, we learned about the foods past people ate, the places they gathered them from, and even the seasons in which they visited the site.

Ancient Anme

From the earliest days of camping at Madjedbebe, people gathered and ate a broad range of anme (the Kundjeihmi word for “plant foods”). This included plants such as pandanus nuts and palm heart, which require tools, labour and detailed traditional knowledge to collect and make edible.

The tools used included edge-ground axes and grinding stones. These were all found in the oldest layers at the site – making them the oldest axes and some of the earliest grinding stones in the world.

Our evidence shows that during the two drier glacial phases (MIS 4 and 2), communities at Madjedbebe relied more on these harder-to-process foods. As the climate was drier, and food was probably more dispersed and less abundant, people would have had to make do with foods that took longer to process.

Highly prized anme such as karrbarda (long yam, Dioscorea transvera) and annganj/ankanj (waterlily seeds, Nymphea spp.) were significant elements of the diet at times when the monsoon vine forest and freshwater vegetation got closer to Madjedbebe – such as during wetland formation in the last 4,000 years and earlier wet phases. But they were also sought from more distant places during drier times.

A Change Of Seasons

The biggest shift in the plant diet eaten at Madjedbebe occurred with the formation of freshwater wetlands. About 4,000 years ago, Bininj didn’t just start to include more freshwater plants in their diet, they also began to return to Madjedbebe during a different season.

Rather than coming to the rock shelter when local fruit trees such as andudjmi (green plum, Buchanania obovata) were fruiting, from Kurrung to Kunumeleng (September to December), they began visiting from Bangkerrang to Wurrkeng (March to August).

This is a time of year when resources found at the edge of the wetlands, now close to Madjedbebe, become available as floodwaters recede. With the emergence of patchy freshwater wetlands 4,000 years ago, communities changed their diet to make the best use of their environments.

Today, the wetlands are culturally and economically significant to the Mirarr and other Bininj. A range of seasonal animal and plant foods feature at dinner time, including magpie geese, turtles and waterlilies.

The Burning Question

It’s likely the First Australians not only responded to their environment but also shaped it. In the Kakadu region today, one of the main ways Bininj modify their landscape is through cultural burning.

Fire is a cultural tool with a multitude of functions – such as, hunting, generating vegetation growth, and cleaning up pathways and campsites.

One of its most important functions is the steady reduction of wet season biomass which, if left unchecked, becomes fuel for dangerous bushfires in Kurrung (September to October), at the end of the dry season.

Our data demonstrates the use of a range of plant foods at Madjedbebe during Kurrung, throughout most of the site’s occupation, from 65,000 to 4,000 years ago.

This points to an ongoing practice of cultural burning, as it suggests communities managed fire-sensitive plant varieties, and reduced the chance of high-intensity bushfires by practicing low-intensity cultural burns before the hottest time of the year.

Today, the Mirarr still return to Madjedbebe. Their knowledge of local anme is passed down to new generations, who continue to shape this incredible cultural legacy.

Acknowledgment: we would like to thank the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, the Mirrar, and especially our co-authors May Nango and Djaykuk Djandjomerr.![]()

Anna Florin, Research fellow, University of Cambridge; Andrew Fairbairn, Professor of Archaeology, The University of Queensland, and Chris Clarkson, Professor in Archaeology, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Toughness has limits: over 1,100 species live in Antarctica – but they’re at risk from human activity

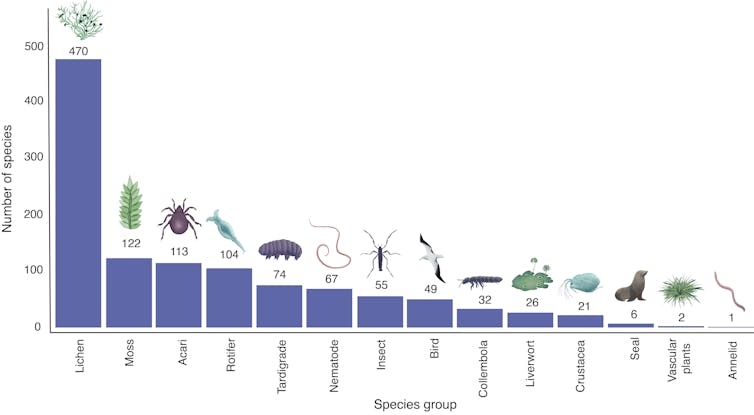

It’s hard to survive in bitterly cold Antarctica. But the ice continent is home to more than 1,100 species who have adapted to life on land and in its lakes.

Penguins are the most well known, but Antarctica’s diversity lies in its microbes and species like mosses, lichens and tardigrades (water bears). Most of these survive in the few ice-free areas on the continent.

Our new research provides a comprehensive inventory of Antarctic species. We believe it will help the 54 nations who are party to the Antarctic Treaty fulfil one of its major conservation goals – the continent-wide protection of Antarctic species.

Despite their toughness, climate change, introduced species and human activities pose growing threats for these species. We need rapid and widespread protection for Antarctica’s biodiversity if these species are to survive.

How Can So Many Species Live In Antarctica?

Our inventory found 1,142 land and lake-dwelling species currently known to live on the Antarctic continent. This list is dominated by extraordinarily resilient groups, such as lichens, mosses and invertebrates, which have evolved to thrive under extreme conditions.

These species have developed unique adaptations to live in this frozen desert, where sub-zero temperatures are the norm and life sustaining water is often locked up as ice.

Antarctic mosses have the incredible ability to freeze and almost completely dry out. They come back to life during the brief periods when it’s warm enough for ice to melt, and take advantage of liquid water to rehydrate and grow.

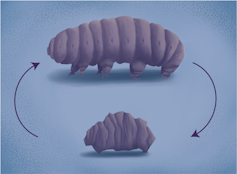

Tardigrades are, famously, masters of survival. During tough times, they can enter a frozen, inactive state very close to death. Some have remained frozen for over 30 years before recovering and resuming their normal lives as if nothing happened.

And then, of course, there are the penguins. Five of the world’s 18 species live in Antarctica, with another four species on sub-Antarctic islands. These birds are built for the cold with thick layers of insulating fat and feathers to keep warm.

Isn’t Antarctica Already Protected?

It’s a common belief that Antarctica is already highly protected. But, in practice, this is only true for specific areas.

In 1991, the nations party to the Antarctic Treaty agreed to conserve the unique continent through the Madrid Protocol. This agreement set the foundations for a network of 75 protected areas – those with outstanding environmental, scientific, historic, aesthetic and wilderness value.

This approach aided conservation, by restricting entry and limiting what people can do, safeguarding biodiversity from issues such as wildlife disturbance, pollution, and introduction of invasive species.

But there are still large gaps, leaving many species unprotected.

One solution is already outlined in the Madrid Protocol: protect the “type localities” of each species. This refers to the location where the very first specimen of a species was collected and described. These specimens are crucial for taxonomy, as they act as the point of reference to check against unknown or ambiguous specimens.

Importantly, protecting the type locality of a species ensures any species can be protected, even if we know little about their habitat or distribution. This is especially important for Antarctic species, because for many, the type locality is the only known location for that species.

To date, however, no Antarctic protected areas have been created specifically to conserve type localities. That’s where our research can help.

What Needs To Be Done?

The reason there are no protected areas of this kind is because we haven’t had a comprehensive list of Antarctic species and their type localities. That’s why we undertook this research.

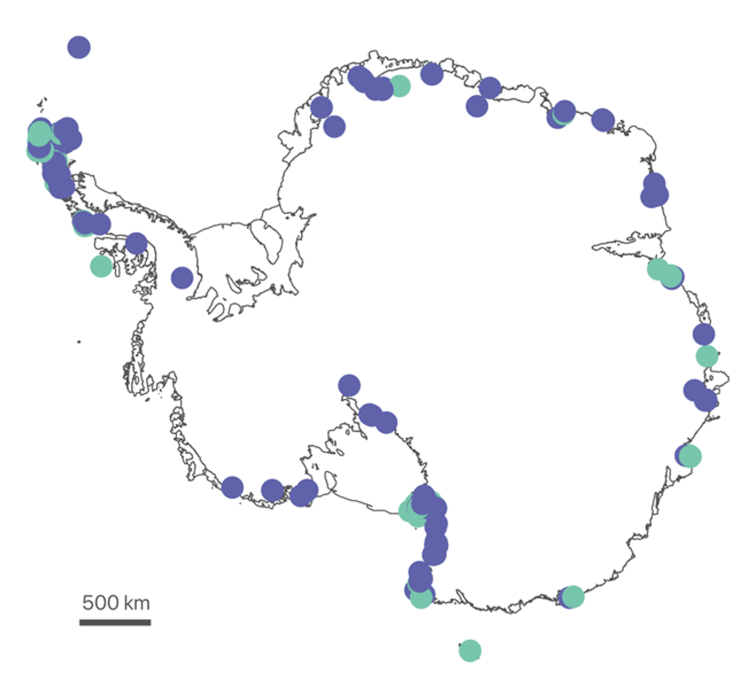

Once we had the list, we mapped the type localities across the continent to see how many of these sites are currently protected.

We found more than a quarter (28%) of all species already have their type localities protected for other reasons, such as scientific interest or wildlife colonies. That’s because they occur in the few and small ice free areas across the continent, where most of the existing protected areas have been created. The remaining 72% of the continent’s type localities are not protected in this way.

There is now a great opportunity to protect these localities. If we focus first on areas with multiple type localities, we could get many more species protected.

Over time, we could expand this network. We estimate another 105 new protected areas would cover all remaining type localities.

We would also need to update the plans for existing protected areas to ensure the value of type localities are taken into account.

Longer term, we will need to embrace a systematic conservation framework across Antarctica to ensure the world’s last great wilderness remains full of life.![]()

Laura Phillips, Antarctic Scientist, Monash University and Rachel Leihy, Ecologist, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.