inbox and environment news: Issue 538

May 15 - 21, 2022: Issue 538

Musk Lorikeets - Female King Parrot: Pittwater Spotted Gums Feasting

Dirt Runoff Stains Palm Beach

Reinstalled Synthetic Field At Cromer Costs 1.3 Million

Residents Warned Of Barmah Forest Virus Risk

- Always wear long, loose-fitting clothing to minimise skin exposure

- Choose and apply a repellent that contains either Diethyl Toluamide (DEET), Picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE)

- Be aware of peak mosquito times at dawn and dusk

- Keep your yard free of standing water like containers, birdbaths, kids toys and pot plant trays where the mosquitos can breed.

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Sydney Wildlife Rescue And Care Course: June 2022

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Autumn 2022 Newsletter

Cassia Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Darkinjung Plans For 600 Homes On Central Coast's Lake Munmorah Now On Exhibition: Closes May 24

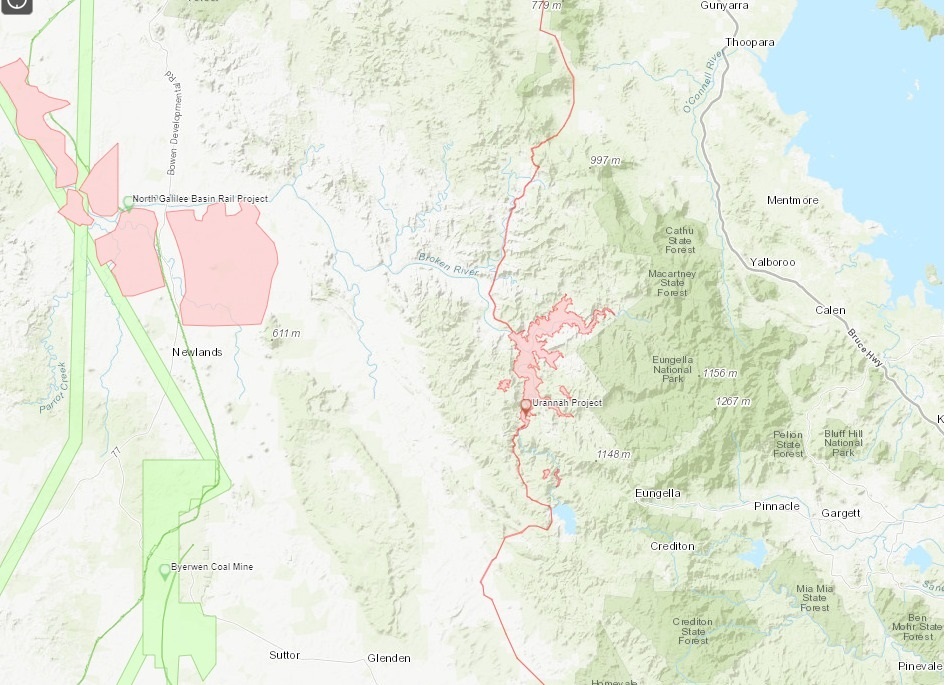

Dendrobium Mine Extension Project: Have Your Say (Again)

Political Stitch Up Over Dendrobium Abandons Community, Climate, And Water, Favours Coal Mining Company Residents State

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Great Barrier Reef Snapshot Of Summer 2021-22 Released: Over 90% Of Coral Reefs Impacted By Bleaching Event; 4th Mass Bleaching Event Since 2016 - New Coal Mine Proposed For 10k From Reef - UAP>LNP Preferences In 2022 Election

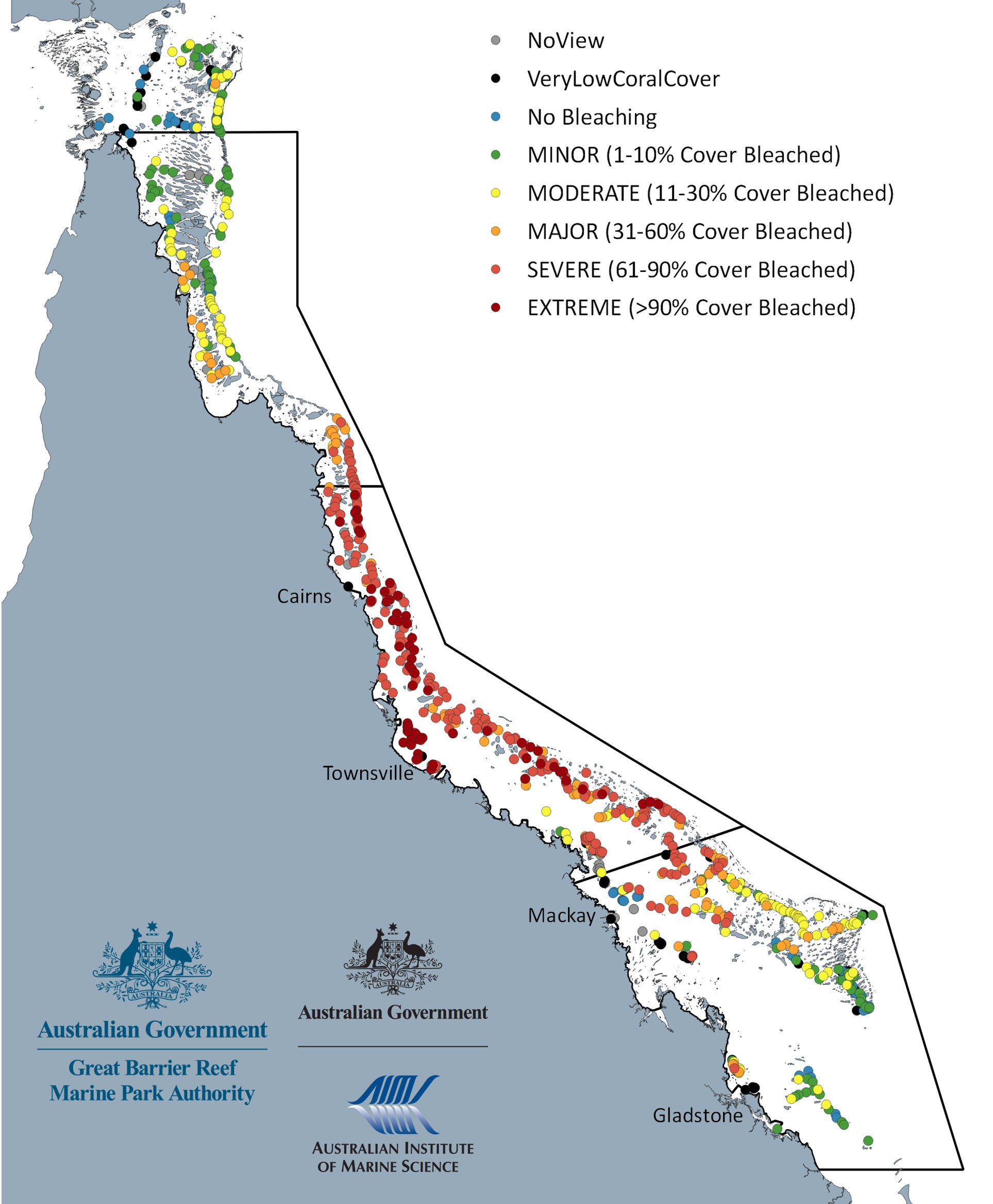

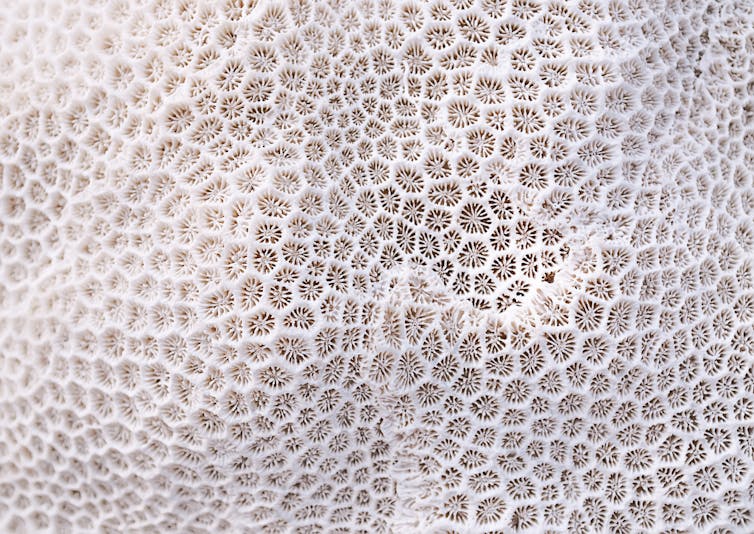

- A total of 719 reefs were surveyed from the air between the Torres Strait and the Capricorn Bunker Group in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

- Of these, 654 reefs (91 per cent) exhibited some bleaching. Coral bleaching observed from the air was largely consistent with the spatial distribution of heat stress accumulation, with a greater proportion of coral cover bleached on reefs that were exposed to the highest accumulated heat stress this summer.

- The 2022 Aerial Survey Map illustrates the variation in bleaching observed across the Reef in the latter half of March.

Northern region - includes coral reefs from the tip of Cape York down to Lizard Island and Cape Tribulation:

Northern region - includes coral reefs from the tip of Cape York down to Lizard Island and Cape Tribulation:

What the next Australian government must do to save the Great Barrier Reef

Widespread coral bleaching has now occurred on the Great Barrier Reef for the fourth time in seven years. As the world has heated up more and more, there’s less and less chance for corals to recover.

This year, the Morrison government announced a A$1 billion plan to help the reef. This plan tackles some of the problems the reef faces – like poor water quality from floods as well as agricultural and industrial runoff. But it makes no mention of the elephant in the room. The world’s largest living assemblage of organisms is facing collapse because of one major threat: climate change.

Our window of opportunity to act is narrowing. We and other scientists have warned about this for decades. Australia has doubled down on coal and gas exports with subsidies of $20 billion in the past two years. When these fossil fuels are burned, they produce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that trap more heat in the atmosphere that also warms the ocean.

If our next federal government wants to save the reef, it must tackle the main reason it is in trouble by phasing out fossil fuel use and exports as quickly as possible. Otherwise it’s like putting bandaids on an arterial wound. But to help the reef get through the next decades of warming we’ve already locked in, we will still need that $1 billion to help reduce other stressors.

Why Is This New Bleaching Event Such Bad News?

Past bleaching events have been linked to El Niño events. Stable atmospheric conditions can bring calm, cloud-free periods that heat up the water around the reef. That can bring extreme summer temperatures – and that is when corals bleach.

This year is a La Niña, which can bring warmer-than-usual temperatures but also tends to bring more clouds, rain, and storms that mix up the waters. These usually spread the heat to the deeper parts of the ocean and mean lower temperature for corals. Not this time.

Global warming means corals are already close to their bleaching threshold, and it doesn’t take much heat to tip the balance. Water temperatures across the reef have been several degrees hotter than the long-term average. And the corals are feeling the heat.

Four times in seven years means that bleaching events are accelerating. Predictions have suggested that bleaching will become an annual event in a little over two decades. It may not be that long.

You always remember the first time you see bleaching in real life. For co-author Jodie, that was in 2016, off Lizard Island, a previously pristine part of the reef far from human impacts or water quality issues. The water was shockingly warm. Looking at our dive computers, we saw that the temperatures we had been simulating in our laboratories for 2050 were already here.

For a week, the marine heatwave pushed the corals to their limits. When corals experience heat stress, some initially turn fluorescent while others go stark white. Then the water goes murky – that’s death in the water. It’s heartbreaking to see. Grief is common among marine scientists right now.

Corals can recover from bleaching if they get a recovery period. But annual bleaching means there is not enough time for proper recovery. Even the most robust corals can’t survive this year after year.

Some people hope the reef can adapt to hotter conditions – but there is little evidence it can happen fast enough to outpace warming. While some fish can move to cooler waters further south, corals face ocean acidification, yet another problem caused by carbon dioxide emissions. As CO₂ is absorbed by the ocean, the changed chemistry makes it harder for corals to build their skeleton (and for other marine organisms to form a shell). There’s no safe place for corals to go.

What Does The Next Government Need To Do?

The evidence is clear. We see it with our own eyes. We’re barrelling towards catastrophic levels of warming, and there’s not enough action.

As it stands, policies on offer by our two major parties will not save the reef, according to new research by Climate Analytics. Current Coalition emissions reduction targets of 26-28% by 2030 would lead to a 3℃ warmer world, which would be devastating for the Great Barrier Reef.

Labor’s policies of a 43% reduction by 2030 still lead to 2℃ of warming. The teal independents and the Greens have policies compatible with keeping warming to 1.5℃, though how to achieve those goals is unclear. What is clear is that every tenth of a degree matters.

We need leaders who are serious about climate action. Who can acknowledge the truth that the problem is real, that we’re causing it, and that it’s hurting us right now.

There are still a few people sceptical that humans can change the climate. But today the changes are apparent.

The words “unprecedented” and “record-breaking” are starting to lose relevance for natural disasters because they are used more and more. Australians faced the 2019/20 Black Summer of megafires. This year we’ve had major flooding. Marine heatwaves have killed off almost all of Tasmania’s giant kelp.

But climate impacts are also being seen around the world – extraordinary drought gripping California, fires in melting Siberia and events scientists consider to be “virtually impossible without the influence of human-caused climate change”. That includes the accelerating impacts on coral reefs worldwide.

We need government policies matching the scale and urgency of the threat. That means getting to net zero as soon as possible. It isn’t only about the reef – it’s about all land and sea natural systems vulnerable to climate change, and the people who rely on them.

No developed country has more to lose from inaction on climate than Australia. But no country has more to gain by shifting to clean energy, through new economic opportunities, new jobs, and better protection for our natural treasures.![]()

Jodie L. Rummer, Associate Professor & Principal Research Fellow, James Cook University and Scott F. Heron, Associate Professor in Physics, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Scorched dystopia or liveable planet? Here’s where the climate policies of our political hopefuls will take us

The federal election campaign takes place against a background of flooding on Australia’s east coast, where some residents remain in temporary accommodation a month after the disaster. It’s just the latest reminder Australia is set to become a poster child for climate change harms.

Australia has warmed about 1.4℃ since 1910. With it has come extreme heat, bushfires, floods, drought and now, a sixth huge bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef.

Yet meaningful climate policy debate has largely been absent from this election campaign. So Climate Analytics, a research organisation I lead, has weighed up the policies of the Coalition, Labor, the Greens and the “teal” independents.

We analysed the global warming implications of each party’s or candidate’s target for 2030.

As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns, this timeframe is crucial if the world is to stay below the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels. Dramatic action by 2030 is also vital to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 or earlier.

Alarmingly, the Coalition’s climate policy is consistent with a very dangerous 3℃ of global warming. Labor’s policy is slightly better, but only policies by the Greens and the “teals” are consistent with keeping global warming at or below 1.5℃.

The Coalition

The Morrison government is pursing 26-28% emissions reduction by 2030, based on 2005 levels. If all other national governments took a similar level of action, Earth would reach at least 3℃ of warming, bordering on 4℃, our analysis shows.

That would mean the total destruction of all tropical reefs including Ningaloo and the Great Barrier Reef. And intense heatwaves over land that currently occur about once a decade could happen almost every other year.

At the United Nations climate conference in Glasgow last year, the Morrison government famously refused to increase its 2030 commitments. But the final pact from the meeting, which Australia signed, requires that by November this year, governments will strengthen their 2030 targets to align with the 1.5℃ goal.

Australia is under strong international pressure to meet this obligation, or face further global condemnation.

Labor

Labor’s target of a 43% emissions cut by 2030, from 2005 levels, is in line with 2℃ of global warming. That means it’s not consistent with the Paris Agreement.

Under 2℃ of warming, extreme heat events that currently happen once a decade could occur about every three to four years. And they would reach maximum temperatures about 1.7℃ hotter than heatwaves in recent decades.

Should Earth overshoot 1.5℃ warming and perhaps reach 2℃, some suggest this may be temporary and temperatures could be brought back down. This would require technologies that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But such technologies are uncertain and come with risks.

And the IPCC’s recent report warned even if 1.5℃ warming is exceeded temporarily, severe and potentially irreversible damage would result. The total loss of the Great Barrier Reef is just one example.

Under 2℃ of warming the most extreme heat events that occurred once in a decade in recent times could occur about every three to four years. The heatwaves would also reach a maximum temperature 1.7℃ hotter than those in recent decades.

‘Teal’ Independents

The “teals” are a group of pro-climate independent candidates.

Most prominent is Warringah MP Zali Steggall, whose climate change bill proposes a 2030 target of 60% below 2005 levels. Most climate policies of the “teals” are generally in line with the Steggall bill.

The target is also supported by industry.

We find this target consistent with 1.5℃ of warming, and so compatible with the Paris Agreement. However, it’s at the upper end of the emission levels consistent with the 1.5℃ pathway.

The Greens

Of all the climate policies on the table this election, the Greens target of a 74% cut by 2030, based on 2005 levels, is most comfortably consistent with keeping warming below 1.5℃.

That level of warming would still cause damage to Earth’s natural systems and our way of life. But it would avert significant devastation – for example, allowing parts of the Ningaloo and Great Barrier reefs to survive.

Under 1.5℃ global warming, the most extreme heat events that presently occur once a decade could be limited to about every five to six years.

The Land Sector Problem

Our calculations above do not paint a rosy picture. But they are, in fact, optimistic.

That’s because they include emission reductions from the land and forestry sector through such activities as tree planting and maintaining native vegetation. These so-called carbon sinks were recently described by a key insider as a “fraud”.

If the land and forest sector is excluded from the analysis, the various emissions reduction targets fall considerably: to between 11% and 13% for the Coalition, 31% for Labor, 50% for the teals and 67% for the Greens.

What’s more, even warming limited to 1.5℃ will reduce the capacity of the land sector to remove and store carbon.

Over To You

The scientific consensus is clear. Greenhouse gas emissions must peak by 2025 at the latest and plummet thereafter, to limit global warming to 1.5℃.

Unless policies are substantially strengthened, Earth is set to hit 1.5℃ warming in the 2030s, and a future of at least 3℃ warming awaits.

The onus is on the next parliament to protect Australians from climate catastrophe. On May 21, Australian voters have a chance to send a clear message about the kind of world we want to leave for future generations.![]()

Bill Hare, Adjunct Professor, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Young voters will inherit a hotter, more dangerous world – but their climate interests are being ignored this election

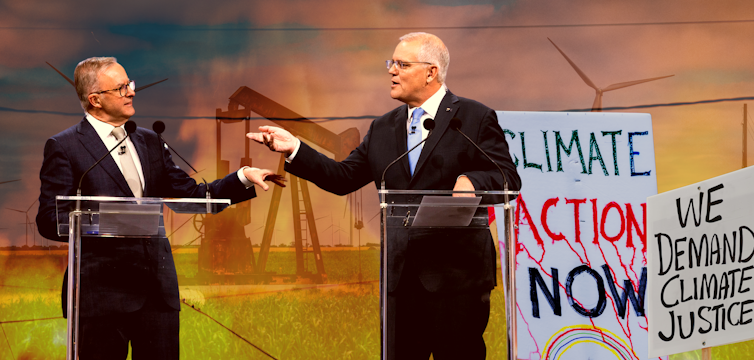

Hannah R. Feldman, Australian National UniversityWhile there was plenty of heat in Sunday’s night’s debate between Labor and Coalition leaders, one issue was barely mentioned: climate change. This raises a large red flag for Australia’s young voters.

In an election term marred by extreme bushfires, floods and heat waves, there was a conspicuous lack of climate change questioning during the debate. And when prompted on how young people will fare this election, both leaders quickly pivoted to housing reform and job security for all Australians.

For a generation that will face an extreme increase in environmental disasters in their lifetime, research consistently shows climate change represents one of the top challenges on the minds of young people. Students have recently been taking this message across the country, demanding greater climate action by political leaders ahead of the federal election on May 21.

So which party really has young interests at heart – and which doesn’t? Let’s look at where the major players stand on youth and climate change policy.

How Does Labor Rate?

According to vote compass data, more Australians have rated climate change as their top concern this election than any other issue. Climate change was also overwhelmingly rated as the top issue in The Conversation’s #SetTheAgenda poll.

But despite the long-term vision of voters, Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese was keen to focus squarely on immediate returns in Sunday’s debate, especially on issues related to “right now” – a phrase repeated nine times in his closing remarks.

Albanese took the campaign to classrooms this week, and pivoted to housing reform when directly asked about the future of youth lives in Australia.

Not only was this a missed opportunity to mention the newly announced funding for high-achievers to study teaching, but also to draw attention to the fact Labor also has an engagement plan to reconnect with young people in politics.

Youth voters often feel shut out of policy engagement exercises, finding consultation processes disingenuous and serving the agendas of people in power, rather than through genuine youth representation.

Labor policy looks to overcome some of these challenges by connecting government with youth voices in decision making. While this is still a very top-down approach, it could be a promising step towards meaningful integration of young people in politics.

With these foundations, it’s unfortunate that climate change and youth issues have not been openly championed by Albanese. Young people will have to go searching through buried policy to see whether they’ll be heard after May 21, but not before.

What About The Coalition?

Likewise, the Liberal National Party has been generally shying away from climate change discourse.

We saw this clearly in March, for example, when the federal court found Environment Minister Sussan Ley holds no duty of care towards young people facing the climate crisis. Ley had successfully appealed a previous ruling in a landmark case brought by eight students, setting a disappointing stage for the Coalition’s campaign trail.

The Liberal Party, however, do have policy support for communities and structures that surround young Australians, including funding for schools, parents, and getting young people into jobs, as Prime Minister Scott Morrison repeatedly highlighted in Sunday’s debate.

But Liberal Party youth policy also comes with a great irony: if elected, they promise large investments in youth mental health, despite climate change (and a lack of action) being a key source of anxiety and worry for young people.

Much research, including my own, has shown climate change presents an extreme burden on the mental health of young people, particularly teenagers. But while anxiety can be a source of disengagement from politics entirely, other young people can use it as motivation to engage with politics in ways they haven’t before.

This will likely be a driving force in School Strike 4 Climate events in the lead up to May 21 (and beyond), including planned action at Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s Kooyong electorate offices.

Overall, the Coalition’s hopes for an employed youth sector are not without merit, but failing to link the need for youth reform with the climate emergency seriously tarnishes any credibility they may have had on youth issues.

The Greens And Independents?

At the last election in 2019, Australian youth were overwhelmingly left-leaning, with the lowest Liberal vote on record for voters under 35. Indeed, 37% of 18-24 year olds were primarily voting for the Greens, and that number is likely to remain high on May 21.

The Greens are the only major player in the upcoming election to specifically mention youth and climate change together in their policies. They acknowledge the long term consequences of current climate action on future Australians, and also align strongly with the demands of the School Strike 4 Climate movement.

Much of the Greens climate policy is mirrored in some way by “teal” Independents. But the crossbench hopefuls are decidedly targeting different demographics in their contested seats: those trending Green are generally younger and on lower incomes than those in seats turning teal.

In key electorates such as Wentworth in New South Wales or Goldstein and Macnamara in Victoria, young people represent 16-18% of registered voters. Climate-aligned platforms may well be the deciding factor in seats moving away from the major parties.

The Verdict

While the near-sighted campaign trail might not care too much about youth voters, the long term consequences of their treatment will come with very real returns as they age.

Late teens and early-20s are critical ages for formulating political personas that only grow stronger into adulthood. Issues that matter to youth such as climate change are not going to diminish in their lifetimes.

Albanese may have won Sunday night’s debate by a hair according to The Conversation’s expert panel, but it was clear that Australia’s young people were not winners in the political shouting match.

The future of youth engagement and climate change may take a positive turn with a Labor government or a powerful crossbench, but the major parties are still too narrowly focused on the short term.![]()

Hannah R. Feldman, Research Fellow, Institute for Water Futures, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4 reasons why the Morrison government’s forestry cash splash is bad policy

This federal election campaign has involved very little discussion of environmental or natural resource policies, other than mining. An exception is a A$220 million Morrison government pledge for the forestry industry.

The money will be invested in new wood-processing technology and forest product research, and used to extend 11 so-called “regional forestry hubs”. Some $86 million will aid the establishment of new plantations.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison said he would not support “any shutdown of native forestry” and claimed the funding would secure 73,000 existing forestry jobs. The spending on native forests, however, is problematic. In 2019-20, 87% of logs harvested in Australia came from plantations, and more investment is needed to bring this to 100%.

Here, we show how directing public funds to native forest logging is bad for the economy, the climate and biodiversity, and will increase bushfire risk.

1. Economics

Native forest logging has long been a marginal economic prospect. The Western Australian government has recognised this, electing to halt the practice by the end of 2023. It will instead create sustainable forestry jobs by spending $350 million expanding softwood timber plantations.

The move followed Victoria’s promised end to native forest logging in 2030.

In Victoria, native forest logging has repeatedly incurred substantial losses across large parts of the state. Data from the state’s Parliamentary Budget Office in 2020 show Victoria would be more than $190 million better off without its native forest logging sector.

Native forest logging sustains far fewer jobs than the plantation sector, and does not produce substantial employment opportunities in any mainland Australian state.

For example, only about 300 direct and indirect jobs are sustained by native forest logging in southern NSW.

A recent economic analysis showed ceasing native forest harvesting in that region would bring $62 million in economic benefits – a result likely to be repeated in native forestry areas across Australia.

About 87% of sawn timber used in home construction is derived from plantations. The vast majority of native forest logged in Victoria and southern NSW goes into woodchips and paper pulp.

Victoria exports 75% of plantation-derived eucalypt pulp logs. A small percentage of this diverted for domestic use would readily replace native forest wood at Victoria’s biggest paper mill at Maryvale. The feasibility of this has been known for years.

2. Climate Change

Native forest logging in Australia generates around 38 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO₂) a year.

Victoria’s phase-out of native forest logging by 2030 will reduce emissions by 1.7 million tonnes of CO₂-equivalent gases each year for 25 years, equivalent to taking 730,000 motor vehicles off the road annually.

Ending native forest logging in southern NSW would likely be the biggest carbon abatement project in that state.

These benefits also bring economic value. Even under relatively low market prices for carbon, the value of not logging, in terms of reducing greenhouse gases, far exceeds the economic benefits of native forest logging.

3. Bushfire Risk

There’s now unequivocal evidence that logging native trees makes forests prone to more severe bushfires. Analysis of the 2019-20 Black Summer fires showed logged forests always burn more severely than intact ones.

Under moderate fire weather conditions during Black Summer, logged forests burned at higher severity than intact forests burning under extreme fire weather.

These logging-generated risks were particularly pronounced in southern and northern NSW. Importantly, they were also evident in Victoria’s 2009 Black Saturday fires in Victoria.

4. Biodiversity Conservation

Numerous studies have demonstrated the damage native forest logging causes to biodiversity. In Victoria, for example, a 2019 analysis of areas proposed for logging showed it would negatively affect 70 threatened forest-dependent species, such as the Leadbeater’s possum.

The bottom line is that ongoing logging will drive yet further declines of Australia’s threatened species and add to the nation’s sad record on biodiversity loss.

The Upshot

The empirical evidence points in one direction: ending native forest logging in Australia would bring substantial and multiple benefits to society and nature.

We welcome the Morrison government’s spending on supporting new plantations. To create the most positive return on taxpayer investment, however, the bulk of other industry funding should be directed to enhancing manufacturing and markets for high-value wood products from plantation timber.![]()

David Lindenmayer, Professor, The Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University; Brendan Mackey, Director, Griffith Climate Action Beacon, Griffith University, and Heather Keith, Senior Research Fellow in Ecology, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change hits low-income earners harder – and poor housing in hotter cities is a disastrous combination

Cost of living is a major focus in this election campaign, and yet political leaders have been unacceptably silent on the disproportionate impact of climate change on Australians with low incomes. This is particularly true for Western Sydney, home to around 2.5 million people.

Over the last half century, the balance of Sydney’s social housing has been pushed to the west, where it can be up to 10℃ hotter than the breeze-cooled coast. Meanwhile, rapid housing development reduces existing tree canopy daily, further intensifying heat.

This situation locks in cycles of disadvantage for decades and generations to come. Even if we limit global warming to 1.5℃ this century, Western Sydney will still experience fewer than 17 days of 35℃ per year by 2090.

Australia needs a more holistic, forward-thinking approach to the design of hot cities, one that’s up to the task of changing with the climate.

Living With Urban Heat Now

Low-income communities are more likely to live in poorly constructed, heat-affected rental accommodation and least able to afford air conditioning. What’s more, those living in community housing may be restricted from installing air conditioning units.

Our research from 2016 found residents expend a lot of mental and physical energy during summer just to keep their homes bearable, while worrying about how much cooling might be costing.

After interviewing vulnerable groups of people in Western Sydney – such as elderly citizens, disability carers and young mothers in social housing – we found people turn to lessons from their parents to find relief from heat.

This includes soaking sheets in water, directing fans to blow air over them and create cool pockets in the house, confine themselves to cooler rooms, and cover west-facing windows with blankets or aluminium foil.

This summer’s La Niña weather pattern may have spared Western Sydney from scorching daytime highs, but residents had to contend with hotter and more humid nights. Wet conditions and cloud cover inhibit the capacity of poorly designed houses to shed the heat, leading to sleeplessness.

Many Western Sydneysiders work from home, too. Community organisation Better Renting recently produced a report detailing the impact of poor housing on worker productivity during the pandemic. It found those working from home without the means or capacity to improve their environments said they were stressed, couldn’t focus, and needed to finish work early during summer.

Air-conditioning can provide relief and is critical for some residents, such as some people living with a disability who depend on cool homes and cars for survival. But air-conditioning displaces the indoor heat to the outside, contributing to a more hostile outdoor environment.

So while air-conditioning offers a short-term solution, it does nothing to address long-term disadvantage.

‘Solutions’ Don’t Go Far Enough

Social disadvantage underscores the limitations of well-meaning technical solutions, such as the New South Wales government’s program to plant five million trees by 2030, or City of Sydney’s project of committing to renewable-powered air conditioning.

These solutions don’t go anywhere near far enough to address the fundamental short-sightedness in how we design and plan our cities.

For example, young trees need far more care to reach maturity through extreme weather, unlike older trees, of which many have been cut down to make way for development. And solar-powered air conditioning will not undo the compounding impacts of urban heat, which research shows make us sedentary, passive and lonely and insecure because it keeps us indoors and isolated from each other.

Indeed, Western Sydney’s current trajectory of urban growth will see urban heat and its impacts worsen, particularly as the state government resists mandating lighter-coloured roof tiles as a perceived impediment to development. Lighter-coloured roof tiles are better at reflecting rather than absorbing heat, and are a low-hanging fruit for cooling homes.

This trajectory will subject future generations of Western Sydney residents to a city that may become ultimately uninhabitable for months at a time. These predictions may seem dire, but we cannot afford to ignore them.

One stark prospect is that even newer and more expensive homes being built in Western Sydney’s growth areas may become stranded assets in a future, when 50℃ summer days are a norm and the area is subject to regular flooding.

So What Do We Do?

Researchers and policy makers are turning their attention to making Australian cities more “climate-ready”.

While catastrophic for communities, the recent floods, fires and other disasters carry valuable lessons about design failures and community-led solutions that have ultimately kept people safe.

We’ve learnt “climate-readiness” cannot be done in a piecemeal way or achieved in the background of everyday life, like set-and-forget technologies. Instead, it means noticing how the natural and built environments interact, and the social practices that contribute to cooler, more liveable futures.

This might include enrolling communities in the care of young trees around their homes, maintaining breeze ways or shade through neighbourhoods, outdoor cooking during summer to reduce heat inside, or shifting the rhythms of social life to cooler night time hours.

This is encompassed in a process called “transition design”, which takes holistic, long-term view of urban planning to forge a sustainable future. This means starting with what residents want and know works – whether its creating cool pockets in the home or reaching out to neighbours when heat is on its way.

Planners, designers and policymakers should practically link these social solutions to designs that make these more accessible, manageable, engaging and safe.

Parts of everyday life will look very different in future as we grapple with managing energy and adapting homes to changing climates. But we must also recognise and hold on to what’s important, including reclaiming what we’ve lost to rampant development.

Long-term residents of Western Sydney may recall a more liveable city, with shaded pedestrian links between homes and shops, seating and facilities in parks and better access to public transport.

These basic amenities are a commonwealth that allow us to remain at home in an increasingly less hospitable world.![]()

Stephen Healy, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University and Abby Mellick Lopes, Associate Professor, Design Studies, Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The world doesn’t care about swings in marginal seats. Climate action must spearhead a new Australian foreign policy

Late last year, more than 100 former diplomats and officials called for a new Australian foreign policy — with climate action at the centre — to help cement Australia’s future in a world rapidly shifting to net-zero emissions.

Failure to act on climate change, they argued, would erode our national interests and international influence. Australia’s allies, partners and competitors would penalise us for not pulling our weight. Regardless of who wins the federal election, Australia’s next government must heed this advice.

There’s a saying that “all politics is local”. But Australian climate politics is dictated as much by the realities of a warming planet, and seismic shifts in global energy markets, as by marginal electorates in Queensland.

Managing the transition to a net-zero emissions economy must be a priority task for the next government. Our strategic and economic success depends on it.

How Did We Get Here?

In recent times, Australian foreign policy has promoted the nation as an energy superpower – a major supplier of coal and gas to Asia. Reducing emissions has been a secondary focus, as Australia’s diplomatic machinery is tasked with promoting fossil fuel exports.

This wasn’t always the case. When a scientific consensus on global warming emerged in the late 1980s, the Hawke Labor government appointed an ambassador for the environment to promote climate action, and supported ambitious national targets to cut emissions.

By the mid 1990s however — under the influence of a powerful fossil fuel lobby and following a national recession — the Keating government was increasingly concerned about potential economic costs of climate action. The subsequent Howard government decided taking serious climate action was not in Australia’s interests

The argument then, as it is now, was that Australia’s economy depends on fossil fuels, and cutting emissions would cost us relatively more than it would other countries.

So ever since, rather than act on climate change, Australia has sought to minimise obligations to cut emissions while expanding coal and gas exports.

Today, Australia has one of the weakest 2030 emissions targets in the developed world. At last year’s global climate talks in Glasgow, Australia refused to join other developed nations in strengthening its ambition.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres describes Australia as a holdout on climate action. He is right. Australia is among a small, isolated group of countries — including Russia and Saudi Arabia — resisting global efforts to cut emissions.

Not by coincidence Australia is also the world’s third-largest fossil fuel exporter, behind only Russia and Saudi Arabia.

The World Is Changing Around Us

When Prime Minister Scott Morrison last year sought support from his Nationals colleagues for a net-zero by 2050 target, he urged them to accept economic reality. The world is transitioning to net-zero. And climate action is now a key pillar of the Western alliance, and so key to Australia for national security reasons.

Morrison’s arguments show how the world has changed since he came to power in August 2018.

Australia’s most recent foreign policy white paper, released in 2017, forecast strong global growth in demand for fossil fuels. Those forecasts have proved wrong.

Instead, Australia’s key destination markets, such as Japan, China and South Korea, are phasing out fossil fuels. In the past two years alone, more than 100 countries, representing around 90% of the global economy, have committed to net-zero emissions.

This mega-trend has fundamentally altered Australia’s economic prospects.

Climate has also moved to the centre of global geopolitics. Major powers are integrating climate into defence and strategic planning, foreign policy, diplomacy and statecraft.

The European Union will next year start imposing border costs on imports from countries not doing enough to cut emissions, a move which could eventually shave A$12.5 billion from the Australian economy annually. G7 countries are planning a “climate club” to impose costs on countries that don’t meet shared standards for climate policy.

In the US, a new Indo-Pacific strategy signals an intention to pressure countries such as Australia to set a stronger 2030 target. This is partly so the US and allies might work together to press China to cut emissions.

Security Mismatch In The Pacific

The recent security deal between the Solomon Islands and China may demonstrate how Australia has yet to integrate climate action into its own statecraft.

For decades, Pacific island countries — including the Solomon Islands — have argued climate change is their first-order security threat, particularly for atoll island states who face inundation from rising seas.

But those concerns are not reflected in Australia’s current efforts to engage more closely with the Pacific. The recent Pacific Step Up strategy is largely driven by concern that China could leverage infrastructure lending to establish a military base in the region.

A former Australian intelligence chief, Nick Warner, says Australia’s position on climate has “undermined our standing in the Pacific” — a view echoed by former Australian High Commissioner to the Solomon Islands, Peter Hooton.

The lesson is clear. In a warming world climate policy is foreign policy.

Australia As A Clean Energy Superpower

Our foreign policy must be retooled to reposition Australia as a clean energy superpower, and to seize the economic opportunities that will flow.

As the sunniest and windiest inhabited continent on the planet, Australia has world-class renewable energy resources and enviable reserves of minerals needed for the electric vehicles, batteries and wind turbines of the future.

Australia is well-placed to export zero-emissions electricity to growing economies in Asia. Our renewable energy advantage also means we can competitively produce zero-carbon versions of the commodities the world urgently needs – steel, aluminium, hydrogen and fertilisers.

The Business Council of Australia estimates clean export opportunities could generate 395,000 jobs by 2040. With the right policy framework, Australia could grow a new clean energy export mix worth A$333 billion each year, almost triple the value of existing fossil fuel exports.

A Big Task For The Next Government

Whichever party wins the election on May 21 should reposition Australia as a global climate leader. This will require negotiation between domestic constituencies resisting change and an international context that’s changing regardless.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and Australia’s diplomatic network, should be tasked with promoting climate action. And a climate change ambassador should be appointed - separate from the existing ambassador for the environment.

Australia should also bid to host the annual UN climate summit and co-host the UN talks with Pacific island states.

Above all, the next government must strengthen Australia’s 2030 emissions reduction target before global climate talks in Egypt in November. We should at least match our key allies and commit to halving emissions this decade. Failure to do so will only bring increasing diplomatic and economic costs.![]()

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s next government must start talking about a ‘just transition’ from coal. Here’s where to begin

At last year’s Glasgow climate conference, countries lined up to increase their ambition to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Even Australia brought a new target of net-zero emissions by 2050, and signed the final agreement which called for a global “phase down” of coal.

That leaves Australia with two particularly important tasks. First, our power grid – reliant on coal for about half our electricity – must shift to renewable energy. Second, we must dramatically reduce coal exports, which produce about 3% of global CO₂ emissions when burned overseas.

Clearly, Australia needs to have a serious conversation about what the move away from coal means, and how to make it fair. This shift is often called a “just transition”. In our recent study we examined how the idea is understood in Australia.

We found several barriers to a productive conversation about the just transition – not least, an almost complete absence of the federal government in talking about or planning for it. This is a failing the next government must not repeat.

A Tale Of Two Coal Industries

First, it’s important to define “just transition”. Many different definitions are used, but include as a key feature that no-one is left behind when making necessary changes to energy and economic systems.

That means sharing the costs and benefits of the changes fairly, supporting workers with new jobs or retraining, and supporting communities through broader economic changes.

Our research into the just transition in Australia involved reviewing academic research and other literature; interviews with key people from civil society, government and industry; and analysis of hundreds of media articles.

Interviewees reported that the limited discussion in Australia about a just transition has focused on the electricity sector, particularly after the sudden, high-profile closure of Victoria’s Hazelwood Power Station in 2017. Discussion about winding back coal exports was considered too difficult.

Australia’s electricity sector is on the road to decarbonising, and coal-fired power stations are closing faster than expected. In February, for example, Origin Energy announced it would close its massive Eraring Power Station in three years – the soonest timeframe allowed under national rules.

But Australia’s coal mining industry dwarfs the power industry. Some 90% of Australia’s black coal is exported. Most ends up in Asia, either in power stations producing electricity or blast furnaces producing steel. Australian coal contributes more to CO₂ emissions overseas than at home.

Just Transition Is A Toxic Term

Our study revealed how “just transition” is a problematic term in Australia. This is largely driven by parts of the media and some politicians who equate the transition with job losses.

This “jobs versus environment” narrative has been cultivated throughout the so-called “climate wars” plaguing federal politics over the past 15 or so years.

The narrative was exemplified by Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce late last month. Asked if the government planned move away from coal, he said “we’re not going to be saying to people the word ‘transition’ because that equals unemployment”.

The argument resonates in regional communities for two main reasons, according to our interviewees. First, most people calling for a “just transition” are not locals and there is a perception they don’t understand the needs and aspirations of coal towns. And second, many communities have had bad past experiences of economic restructuring programs.

Many interviewees said it’s important to discuss the just transition, but they avoid using the term explicitly because of the negative connotations.

Government Leadership Is Sorely Needed

A just transition is not just something environmental or union campaigners are calling for. Our research revealed almost all key stakeholders are willing to plan for it – from industry to community groups, investors and some state and local governments – even if their motivations differ.

These groups also agreed a lack of government leadership was the biggest barrier to action. In particular, the federal government has been almost completely absent from discussions.

Whichever side wins the May 21 election needs to start talking about, and actively planning, a just transition. That means introducing policies to encourage coal power generation and coal exports to wind down, supporting new industries and helping communities manage the change.

Federal government support is crucial because the transition away from coal affects all of society. Governments can set up the stable, long-term institutions and policy mechanisms to support state and local transition efforts.

How To Have Productive Conversations

Our research highlighted ways the federal government and others can have productive conversations about the just transition away from coal.

Outsiders going to regional communities should listen to people to understand their aspirations and fears.

Explain that the transition away from coal is already underway, and be explicit about what a just transition means: reducing coal production, but increasing other energy sources and diversifying regional economies.

Make clear that the transition is an opportunity for regional people with skills that society needs as our energy systems change. And explain the practical actions available to help communities undergoing major change.

Finally, centre conversations on livelihoods and communities, rather than wages and workers. The transition will only be just if it involves everyone.

Which Way Now?

In the absence of strong government policy, progress towards a just transition has been challenging. Notwithstanding this, we are seeing change.

Australia’s power generation industry is already transitioning away from coal. And Australia’s two largest export-oriented coal miners, Glencore and BHP, also see clear limits on ongoing coal exports.

The shift away from coal is now inevitable. But if not managed effectively, the transition will be disorderly rather than just. This will damage not just coal communities, but Australia’s economy and international standing. ![]()

Gareth Edwards, Associate Professor, University of East Anglia; Robert MacNeil, Lecturer in Environmental Politics, University of Sydney, and Susan M Park, Professor of Global Governance, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How do the major parties rate on climate policies? We asked 5 experts

Poll after poll suggests climate change is one of the most pressing issues for Australian voters. Of the 10,000 people who responded to The Conversation’s #SetTheAgenda poll, more than 60% picked climate change as the issue most impacting their lives.

And yet, climate change has barely been discussed by either major party in this election campaign so far.

Since the last federal election, we’ve watched record-smashing floods, bushfires and heatwaves take lives and destroy livelihoods, corroding our national spirit. Disasters such as these will worsen with every fraction of a degree of global warming. Which town will be hit next? Who will be trapped by rising floodwater, or encroaching flames?

Strong national policies on climate change will help us be better prepared, bring global emissions down, and provide strong leadership in this time of crisis. So how did the major parties’ climate policies stack up? We asked five experts to analyse and grade different aspects of this enormous portfolio.

Here Are Their Detailed Responses:

Coalition

Labor

![]()

Jake Whitehead, E-Mobility Research Fellow, The University of Queensland; Ian Lowe, Emeritus Professor, School of Science, Griffith University; Johanna Nalau, Research Fellow, Climate Adaptation, Griffith University; Matt McDonald, Associate Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland, and Samantha Hepburn, Professor, Deakin Law School, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

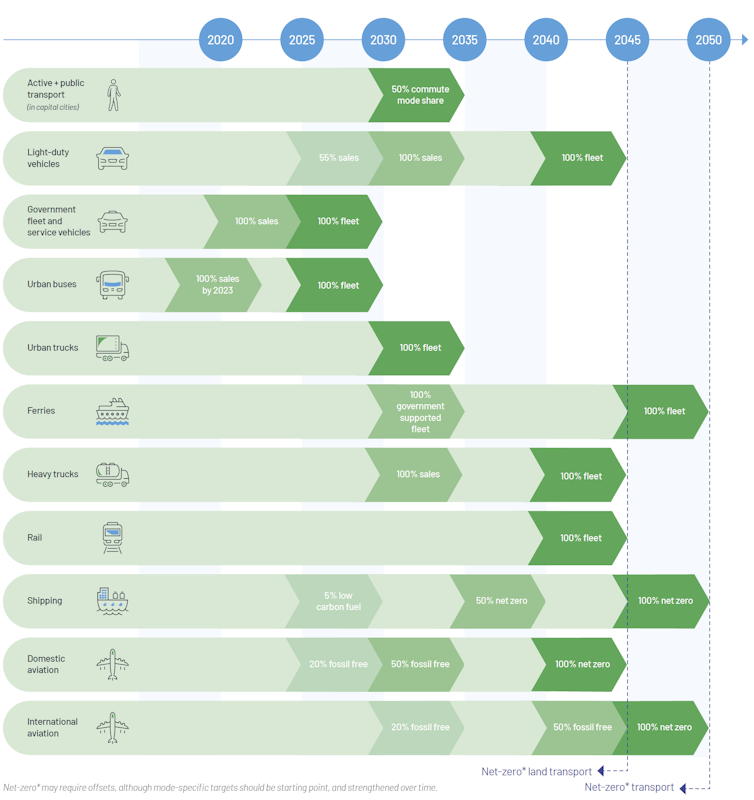

Australia could rapidly shift to clean transport – if we had a strategy. So we put this plan together

Australia has no clear strategy to decarbonise transport. That’s a problem, because without a plan, our take-up of clean technologies like electric cars, trucks and buses is slow. It’s stopping us from meeting our climate commitments. And it leaves us paying exorbitant prices for imported oil at the fuel pump, as well as in the cost of groceries and services.

The good news? Over the last year, 18 transport and energy experts have created this independent, science-based summary of what is now possible in cleaning up land, sea and air transport as well as what will become possible in coming decades.

Our plan gives all levels of Australian government a list of priority policies. Together, these policies would make possible the delivery of a net zero transport system by or before 2050, and see Australia gain major economic, social and environmental benefits from the transition.

The pandemic has shown us how governments and experts can work together to take on wicked challenges. We can do the same here. We can draw on the knowledge of transport and energy experts, engineers, planners, and economists to develop the science-based net zero transport strategy Australia urgently needs.

Why We Must Rapidly Reduce Transport Emissions

Today most of our transport relies on fossil fuels. That makes it one of Australia’s most emission intensive sectors. Worse, transport emissions are forecast keep increasing until at least 2030, during the most critical decade in the fight to slow climate change.

By 2030, transport emissions could grow to a quarter of the country’s domestic emissions. Australia has a high-polluting, inefficient vehicle fleet 90% reliant on imported fuel. These two factors mean many Australians have been hit hard by unprecedented fuel prices.

Shifting to clean transport is a win-win-win – we can slash emissions, cut costs to commuters and boost Australia’s fuel security in a very uncertain geopolitical time.

How Can Australia Reduce Transport Emissions?

To begin this shift, we must have a clear vision for rapid decarbonisation of transport. Our framework has three steps:

avoid: where possible, avoid transport trips and shorten travel distances such as through working from home

shift: for the majority of trips that are unavoidable, shift as many as possible to more efficient transport modes such as e-bikes, public transport and walking

improve: boost Australia’s transport energy efficiency by adopting low and zero emission vehicles, such as electric cars, electric buses and electric trucks.

We must invest in transformative technologies to speed the transition, such as electric vehicles for land transport, and electric, hydrogen, ammonia, sustainable biofuel and synthetic fuel options for shipping and aviation.

This approach is in line with the world’s current best practice. The peak global body for clean transport says the electrification of transport is the single most important technology to decarbonise the sector.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report states electric vehicles offer the largest decarbonisation potential for land transport on a lifecycle basis. The harder challenges will be finding ways to make shipping and planes run without fossil fuels. To do this, we’ll need to invest in finding the solutions.

As if saving the world from the worst of climate change isn’t enough, the economics have shifted enormously. Far from being a long-term cost to Australia, a rapid switch to clean transport could save us nearly half a trillion Australian dollars by 2035. Of this, almost $300 billion is the amount we save the health system by getting killer pollutants out of the air. Australians could also save around $2,000 every year in lower fuel and maintenance costs for electric cars. If all cars in Australia were electric, this would equate to more than $30 billion saved every year.

This may not surprise you to hear, but Australia is woefully behind the rest of the world on this transition. For example, we’re one of the few countries without mandatory fuel efficiency standards, which has given us a dirty and inefficient vehicle fleet.

To date, neither the Coalition or Labor’s current policies go far enough to achieve net zero transport emissions. Our next government must commit to ambitious policy to support the rapid decarbonisation of transport.

Where To From Here? The Road Map To Hit Net Zero Transport By 2050

To reach net zero for land transport by 2045 and all transport by 2050, we need evidence-based strategies.

Given we’re almost starting from scratch, we can only make this shift through ambitious transport policies. These would include:

- clear targets for each transport sector to achieve net zero transport by or before 2050

- new financial incentives to help households and businesses switch to zero emission transport

- new sales mandates and fuel efficiency targets to stimulate innovation and increase the supply of zero emission vehicles

- investing in clean transport manufacturing and recycling industries to allow us to build batteries, produce renewable fuels and build electric vehicles locally by 2030

- infrastructure and policies to support active transport, low emission zones and road pricing reform.

To tackle the harder-to-decarbonise sectors of shipping and aviation, we need:

- research, development and investment into low and zero emission options, coupled with mandates for use of zero emission fuels

- renewable hydrogen clusters to support broader economy decarbonisation and the low and zero emission shipping and aviation.

Luckily for us, we have many resources to draw on to create this better system. We have a natural resource base able to support clean transport not only locally but globally. We will be able to access enormous amounts of cheap, renewable energy, which we can harness to power mining and refining of critical resources, turn water into green hydrogen, manufacture batteries, and build our own zero emission vehicles.

Pipe dream? Hardly. Australia already has one of the world’s top EV charger companies, and we already have companies turning out electric buses.

This is all possible. But time is short. We must move to grasp this opportunity to clean our transport sector while securing new jobs, improving our national security, and cleaning the air we all breathe.

A full list of the 18 co-authors of the FACTS report can be found here, and the FACTS report is available for download here.![]()

Jake Whitehead, E-Mobility Research Fellow, The University of Queensland; Bjorn Sturmberg, Research Leader, Battery Storage & Grid Integration Program, Australian National University; Donna Green, Associate Professor, Investigator for UNSW Digital Grid Futures Institute; Affiliated Investigator NHMRC Centre for Air Pollution, Energy and Health Research, Associate Investigator the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, UNSW Sydney; Emma Rachel Whittlesea, Program Manager - Climate Ready Initiative, Griffith University, and Liz Hanna, Honorary Associate Professor, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia has rich deposits of critical minerals for green technology. But we are not making the most of them … yet

As the transition to clean energy accelerates, we will need huge quantities of critical minerals – the minerals needed to electrify transport, build batteries, manufacture solar panels, wind turbines, consumer electronics and defence technologies.

That’s where Australia can help. We have the world’s largest supply of four critical minerals: nickel, rutile, tantalum and zircon. We’re also in the top five for cobalt, lithium, copper, antimony, niobium and vanadium. Even better, many of these minerals can be produced as a side benefit of mining copper, aluminium-containing bauxite, zinc and iron ores.

But to date, we are not making the most of this opportunity. Many of these vital minerals end up on the pile of discarded tailings. The question is, why are we not mining them? Compared to other major critical mineral suppliers such as China, we are lagging behind.

While the federal government’s new strategy for the sector is a step in the right direction, small-scale miners will need sustained support to help our critical mineral sector grow.

Why Are These Minerals So Important?

Critical minerals are well-named. Lithium, nickel, cobalt and rare earth elements are critical for modern life as well as the industries of the future. But critical also refers to the fact that supply can be hard to secure.

In a time of huge geopolitical uncertainty, securing these minerals has become an ever more critical issue. Soaring demand for these minerals has led to price volatility, commercial risks, geopolitical manoeuvring and disruptions to supply.

As geopolitical tensions grow, many countries are urgently seeking reliable and secure supplies of critical minerals. When China cut off exports of rare earth elements to Japan in 2010 during a dispute, it threatened many of Japan’s high tech companies.

While cobalt, nickel and copper are perhaps the best known, there are dozens of lesser known minerals vital to the modern world.

Different countries and regions require different minerals, with a total of 73 minerals considered critical across 25 separate assessments as of 2020. Some countries are almost entirely dependent on imports of their critical minerals.

Australia Could Be A World Leader In This Area. Why Aren’t We?

Critical minerals represent an enormous opportunity for Australia, given our wealth of these minerals and the soaring demand for green technology minerals like cobalt, lithium and nickel.

To date, however, our production of many critical minerals is well behind other countries when compared to our resources base.

Our large resources of the minerals coupled with high environmental, social and governance standards mean the sector is well placed to respond to demand, especially where we could replace supplies from areas where mining is more destructive or dangerous. Think of the “blood cobalt” often mined by children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In March, the federal government released its plan to grow the sector through boosting onshore processing to create high-wage, high-skill jobs and to offer our trading partners secure supplies of these sought-after minerals. This is a worthwhile goal, particularly the aim to make Australia the “major powerhouse of the world in critical minerals by 2030”.

A plan, however, is one thing and delivery is another. We will need to tackle some key challenges for the mining sector to make us a powerhouse.

Bottlenecks, Tailings And Major Miners

While the demand for critical minerals is growing, there are challenges in production.

Around the world, critical minerals such as cobalt, gallium, molybdenum and germanium are produced as by-products of major commodities such as bauxite, zinc, copper and iron ore.

So why are we discarding most of these critical minerals by dumping them in tailings storage? We can, of course, recover these minerals later, but only if the value exceeds the costs of extraction and processing.

If we were smart about this, we would encourage the extraction of these minerals as a way to add value to existing commodities.

One issue is that while the demand is rising, the overall market size for many of these minerals is small relative to our export giants, iron ore and coal. That’s one reason our major miners have not shown much interest in these minerals.

If the majors aren’t interested, that leaves the door open for small and mid-tier mining and exploration companies such as Cobalt Blue, Iluka, VHM, Australian Vanadium, Australian Strategic Minerals and Critical Minerals Group which have seen the opportunity.

For many smaller miners, however, it can be very difficult to raise capital. That’s where the government’s A$2 billion fund should help, by allowing small and medium miners access to capital to scale up domestic production.

What Else Do We Need To Do?

If we get this right, Australia could play a major role in stabilising the markets for several critical mineral supply chains such as rare earth elements, lithium and cobalt.

For us to create this future-focussed industry, we have to plan ahead. The government should look to policies and programs such as:

● stronger domestic processing and refining sectors for metals like cobalt where our high environmental, social and governance reputation would give us an edge

● introducing incentive schemes to encourage mining companies and smelters to retrofit their facilities so they can produce critical minerals as well as process their main ores

● expand the sector’s proposed $50 million research and development centre and regional hubs to include universities, especially the critical mineral research groups.

Acknowledgements: David Whittle contributed to the research base, and Stuart Walsh, Sue Smethurst and Lilian Khaw reviewed the article.![]()

Mohan Yellishetty, Associate Professor, Resources Engineering, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Analysis of 5,500 apartment developments reveals your new home may not be as energy efficient as you think

Michael Ambrose, CSIROApartment living is booming in Australia. Many people choose apartments for their good energy efficiency, which reduces the need for heating and cooling and leads to lower power bills. But not every apartment is as energy efficient as the development advertises.

All proposed new dwellings, including apartments, require an energy rating certificate. Generally, apartments achieve a higher average energy star rating than houses in the same area.

However, the method used to assess and report the energy efficiency of new developments – averaged across the entire development – could lead some purchasers to believe their new apartment is more energy efficient than it is.

My colleagues and I collected energy rating profiles for more than 5,500 apartment developments across Australia to explore what’s really going on. In many cases, we found clusters of apartments far below the energy star rating for the complex as a whole.

Averages Can Be Misleading

Australia’s home energy star ratings are formally known as the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS). The scheme measures the “thermal performance” of a new home – or how well it remains at a comfortable temperature without artificial heating or cooling.

Last year in New South Wales, 58% of all energy rating certificates issued were for new apartments, reflecting the popularity of this type of dwelling.

In some areas, demand for apartments is skyrocketing. In the ACT, for example, 33% of certificates issued last year were for apartments, up from 7% four years earlier.

For a residential development to comply with the National Construction Code, the average rating across all apartments must be at least 6 stars. The maximum rating is 10 stars. Across Australia last year, the average rating of new apartments was 6.6 stars, compared to an average of 6.2 stars for houses.

This averaging process means some apartments may be above the average and some below. It may also mean some individual apartments don’t meet the minimum 6 star requirement.

In fact, there may be a significant cluster of apartments that rate below 6 stars – for example, west-facing apartments exposed to the afternoon sun that require a lot of cooling.

Conversely, a small number of apartments may rate well above 6 stars. These may be north-facing apartments that are also well insulated by other apartments above, below and on either side. These apartments will pull up the average star rating of the development.

This is a legitimate approach to energy ratings of apartment blocks. But it does raise an important question: do buyers know the energy rating of their individual apartment – especially those apartments with a below-average rating?

Crunching The Numbers

We collected data from NatHERS certificates for more than 5,500 apartment developments across Australia comprising both the certificates for individual apartments and the rating of developments as a whole.

Generally, ratings for individual apartments were close to the average of the entire complex. But in about 19% of apartment developments, at least 10% of apartments rated 5 stars or lower.

The chart below shows the star rating distribution for a development in Melbourne with about 150 apartments. The average star rating for the development was 6.2 stars. However, 47% of apartments rated below 6 stars while 23% rated above 7 stars.

We also examined a large development in Sydney with more than 400 apartments. The development has an average rating of 7 stars. However, as illustrated below, 16% of apartments rate below 6 stars and 1% (five apartments) are below 5 stars.

Those five apartment owners will likely have much higher energy costs than most of their neighbours. But they may not have realised that at the time of purchase, and the sale price may not have reflected this poorer energy performance.

Know What You’re Buying

Energy ratings are mandatory for all new individual dwellings in Australia. However, providing the result to consumers is not.

Recent research has shown most real estate advertisements do not promote a home’s energy rating, and real agents often don’t know what the rating is.

Energy rating certificates could be included as standard in the information provided to someone looking to buy an apartment.

But in the meantime, if you’re planning on buying a new apartment, ask for a copy of the energy rating certificate. Only then will you know what you’re paying for.![]()

Michael Ambrose, Research Team Leader, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Could we learn to love slugs and snails in our gardens?

Before you squash or poison the next slug or snail you see in your garden, consider this: The British Royal Horticultural Society no longer classifies these gastropods as pests. Why on earth would a leading gardening organisation do that, you might wonder. After all, slugs and snails are usually seen as a problem, given their eagerness to devour the plants you’ve lovingly nurtured.

The issue is that they are part of nature. Slugs and snails play a key role in healthy ecosystems, acting to break down organic material as well as providing a source of food for blue-tongued lizards, frogs and kookaburras.

So can we learn to live with slugs and snails? Yes, if we reframe how we see these invertebrates. After all, the definition of “pest” is based on our perception and can change over time. By rejecting the “pest” status of many invertebrates and advocating planet friendly gardening, the horticultural society directly connects the local actions of gardeners to our global biodiversity crisis.

Their principal entomologist, Andrew Salisbury, has argued that “now is the time to gracefully accept, even actively encourage, more of this life into our gardens”.

This doesn’t have to mean letting them destroy your lettuces. Nature can help. Enticing lizards, frogs and birds to your garden can help control slugs and snails and boost biodiversity.

Are These ‘Pests’ Actually Legitimate Garden Inhabitants?

Gardening increased in popularity during the pandemic. With widespread rainy weather across Australia’s east coast, gardeners are more likely to see – and potentially be annoyed by – slugs and snails.

So should Australian gardeners follow the UK’s example? Should we try to welcome all species into the garden? Responses to these questions typically describe slugs and snails as “pests”, invoke the idea of a native/non-native species divide or describe the perceived damage done by invasive species.

Let’s tackle the pest argument first. We define pests based on perception. That means what we think of as a pest can change. The garden snail is a good example. Many gardeners consider them a pest, but they are cherished by snail farmers who breed them for human consumption.

By contrast, many scientists consider the concept of an invasive species to be less subjective. Australia’s environment department defines them as species outside their normal distribution (often representing them as non-native) which “threaten valued environmental, agricultural or other social resources by the damage it causes”. Even this definition, however, is a little rubbery.

In recent decades, researchers in the humanities, social sciences and some natural sciences have shown our ideas of nativeness and invasiveness also undergo change. Is the dingo a native animal, for instance, after being introduced thousands of years ago? Would it still be considered a native if it was introduced to Tasmania where it does not occur?

Despite these questions over their worth, the ideas of “pest” and “invasive species” have proven remarkably persistent in ecological management.

What Exactly Are The Slugs And Snails We Find In Our Gardens?

Australia has a huge diversity of land snails, with many species yet to be described. Many species are in decline, however, due to introduced predators and loss of habitat, and now require conservation efforts.

Does that include our gardens? Well, most snails and slugs found in gardens are considered non-native species which were introduced accidentally. The ability of snails to spread far and wide means these humble gastropods are listed on Australia’s official list of priority pests. We already have biosecurity measures in place to avoid unwanted introduction of new snail species.

The common garden snail, which hails from the Mediterranean, has now spread to every state and territory. But other species are still spreading, such as the Asian tramp snail on the east coast or the green snail, which is currently limited to Western Australia. So if we accept the existence of all kinds of snails and slugs in the garden, we could be undermining efforts to detect and control some of these species.

While slugs and snails don’t usually seriously threaten our home gardens, some species are known agricultural pests. The common garden snail can cause major damage to citrus fruit and young trees, while slugs such as the leopard slug or the grey field slug can devastate fields of seedlings. The damage they can do means farmers and their peak bodies would feel uneasy about changing how we think of these land molluscs.

Some snails can also carry dangerous parasites like the rat lungworm or the trematode worm Brachylaima cribbi. These can hurt us, particularly if a snail is accidentally eaten, or if vegetables in the garden are contaminated. If we let snails move around unhindered, we could increase the number of infections. Pets and children are the most at risk.

So Should We Follow The UK’s Example?

It is not straightforward to rethink how we view and respond to creatures typically considered pests in the garden. But it is worthwhile thinking this through, as it requires appreciating how humans and nonhumans are interdependent. And we can gain a better understanding of how our simple actions in our gardens can scale up to affect human and planetary health and well-being.

The world’s ongoing loss of biodiversity and the steadily changing climate must inform how we relate to and care for the nonhuman life – from mycelium in the soil to gastropods – that enliven our gardens.

This does not mean everything must have an equal opportunity to flourish. But it does require us to pay attention. To observe, to wonder and to be curious about our entangled lives. This kind of attention could help us take a more ethical approach to the everyday life and death decisions we make in our patch.

What does that look like? By understanding gardens as interconnected natural and cultural spaces, we can work to limit our resident slug and snail population and promote biodiversity. A perfect way to start is to design a lizard, frog and bird friendly site.![]()

Bethaney Turner, Associate Professor, Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra and Valerie Caron, Research Scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Smaller Female North Atlantic Right Whales Have Fewer Calves: Declining Body Size May Contribute To Low Birth Rates

- Prey availability

- Climate impacts on the main feeding grounds

- Maternal health

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire