Inbox and environment news: Issue 539

May 22 - 28, 2022: Issue 539

Bush Regeneration Field Day On North Narrabeen Headland

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Annual Whale Migration Makes A Splash

Residents Warned Of Barmah Forest Virus Risk

- Always wear long, loose-fitting clothing to minimise skin exposure

- Choose and apply a repellent that contains either Diethyl Toluamide (DEET), Picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE)

- Be aware of peak mosquito times at dawn and dusk

- Keep your yard free of standing water like containers, birdbaths, kids toys and pot plant trays where the mosquitos can breed.

Sydney Wildlife Rescue And Care Course: June 2022

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Autumn 2022 Newsletter

Cassia Flowering Now: Dispose Of This Weed To Stop The Spread

Darkinjung Plans For 600 Homes On Central Coast's Lake Munmorah Now On Exhibition: Closes May 24

Dendrobium Mine Extension Project: Have Your Say (Again)

Political Stitch Up Over Dendrobium Abandons Community, Climate, And Water, Favours Coal Mining Company Residents State

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

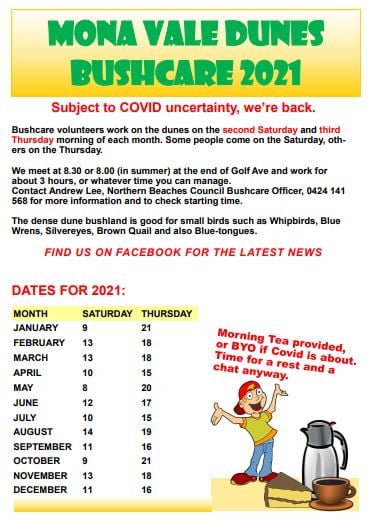

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Community Reminded About Safe Baiting Of Mice

NSW And Denmark Join Forces On Road To Net Zero

First Standard Biodiversity Certification For Yass Valley Housing Development

Search And Rescue Operation For Illawarra's Endangered Plants

Statement On Collection Of Threatened Species From Barrington Tops National Park

Perrottet Government’s Support For Glencore Expansion Untenable After Heritage NSW Admits Ravensworth’s Historical Significance

NSW Government Should Refuse Potentially Unlawful Coal Exploration Applications In The Namoi

- The large size of the two connected exploration licences would breach the government’s own size limit for its so-called “operational allocation” framework, which allows an extension of coal exploration only over a limited area connected to a current mine and;

- An advertisement placed by Whitehaven in the Sydney Morning Herald misled readers because it incorrectly stated “comments received that relate to mining will not be considered in this process”.

NSW Government Takes Water From Coastal Wetlands And Gives To Big Agribusiness

More Security For Coastal Farmers

NSW Leads Discussions For Proposed Changes To Menindee Lakes Operations

The NSW Government will begin discussions immediately with the Murray Darling Basin Authority and Basin jurisdictions on how to improve the way water in the Menindee Lakes is stored and managed.

The NSW Government will begin discussions immediately with the Murray Darling Basin Authority and Basin jurisdictions on how to improve the way water in the Menindee Lakes is stored and managed.Canaries in the coal mine: why birds can tell us so much about the health of Earth

Following a deadly explosion in a Welsh coal mine in 1896, an engineer called John Haldane invented a type of bird cage that allowed canaries to accompany miners into the depths. The small songbirds are much more sensitive than humans to the deadly carbon monoxide gas found underground.

A sudden halt to their singing would warn workers to evacuate the pit – and rescue the canary by closing its cage door and opening a valve to pump oxygen inside. Remarkably, it was only in 1986 that canaries were relieved of their duties detecting noxious gases in UK coal mines.

As rising temperatures and habitat loss degrade the natural world, bird species everywhere play the role of mine canaries for the whole planet. Trends in the size of their populations inform us of the extent and patterns of environmental change, providing a kind of early warning system.

There are a number of reasons why birds are excellent indicators of the status of other wildlife groups and the health of the wider ecosystem. For one, birds are found all over the world, in all countries and in nearly all habitats. From ivory gulls and emperor penguins on the polar ice caps to birds of paradise in tropical rainforests, and from albatrosses cruising the remote open ocean to desert larks in the Sahara.

Birds are found on the highest mountains and some fly to extraordinary heights: a Rüppell’s vulture collided with an aircraft at an altitude of 11,300 metres. Certain seabirds feed at remarkable depths: one emperor penguin was recorded diving to 564 metres where it is almost completely dark and the pressure is 50 times stronger than at the ocean’s surface.

There are enough bird species that the patterns in their distribution and numbers closely reflect variation in the environment, with over 11,000 species in total, and over 400 species on average in each country.

Birds make good indicators because of their biology. Typically feeding towards the top of food webs, bird populations are an eye-catching gauge of changes further down the food chain, such as declines in the abundance of the things they eat. Fewer bug-eating birds like flycatchers may be a tell-tale sign of shrinking insect populations, something more difficult to measure but itself indicative of deteriorating natural habitats.

Birds also tend to move in response to environmental changes, with their local abundance reflecting changes in the climate or how land is used. Bird population trends often mirror those of other species.

For example, other groups of organisms such as butterflies, dung beetles and reptiles (which may be more difficult to study than birds) have mirrored the declines in abundance of farmland birds in the UK since the 1970s. This has been driven largely by the intensification of food production such as the increased use of pesticides.

Similarly, distribution patterns for birds broadly reflect those of many other wildlife groups, meaning that conservation efforts targeted at birds can typically be trusted to benefit a wider array of species.

One Million Records A Month

There are also not so many species as to make identifying birds too difficult. The taxonomy, distribution, ecology and life history of birds are well understood. Over 16,000 scientific papers on bird biology are published each year.

Being relatively large, conspicuous, and generally easy to identify, birds are popular and engage the public. It has been estimated that 20% of people in the US and 30% in the UK watch or feed birds regularly.

An army of birdwatchers worldwide collects data on birds, whether on an ad hoc basis, or as part of more formal surveys and monitoring schemes. The eBird platform, where people can log their bird records, now holds more than one billion observations from over 200 countries, with over one million checklists submitted each month.

And some datasets on bird trends go back many decades, rendering them valuable for tracking environmental trends over time. Birds act as ambassadors for nature, capable of symbolising complex ecological communities while managing to resonate with most people.

Of course, birds tend to be less specialised within very specific types of habitats, such as coastal dunes or lake margins than insects or plants. They are less representative of freshwater and marine habitats than land-based ones, and are scarce or totally absent from some environments, such as the deep ocean or cave systems.

Nevertheless, it is still hard to beat birds as living indicators of environmental change. We must listen to the message they are sending us about the state of nature, and the pressures upon it. Like canaries in the coal mine, they tell us that it is time to act. Our lives may depend upon it.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Stuart Butchart, Chief Scientist, BirdLife International & Honorary Research Fellow, Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New Material Can 'Capture Toxic Pollutants From Air'

Native Plant Gardening For Species Conservation

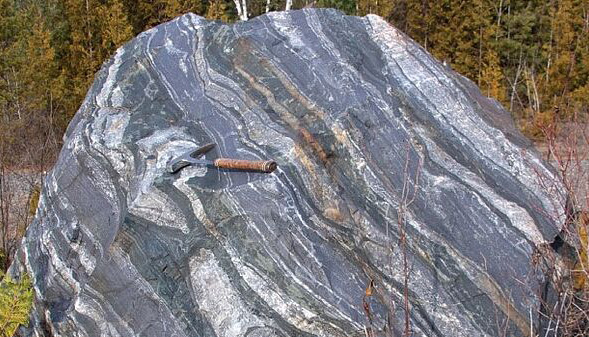

Farm vehicles now weigh almost as much as heaviest dinosaurs – here’s why that’s a problem

What does a modern combine harvester and a Diplodocus have in common? One answer, it seems, may be their big footprints on the soil. A new study led by researchers from Sweden and Switzerland has found that the weight of farming machinery today is approaching that of the largest animals to have ever roamed the Earth – the sauropods.

Depicted as the giant, friendly “veggiesaurus” in the movie Jurassic Park, sauropods were the biggest of the dinosaurs. The heaviest were thought to weigh in at around 60 tonnes – similar to the weight of a fully laden combine harvester. Tractors and other machinery used on farms have grown enormously heavier over the past 60 years as intensive, large-scale agriculture has become widespread. A combine harvester is almost ten times heavier today than it was in the 1960s.

The weight of animals or machines matters because soils can only withstand so much pressure before they become chronically compacted. They may not look it, but soils are ecosystems containing fragile structures – pores and pathways which allow air to circulate and water to reach plant roots and other organisms. Tyres, animal hooves and human feet all apply pressure, squashing the pores, not just at the surface but deeper down too.

Soil compaction can cut plant growth and harvests, and increase the risk of floods as water runs off the land and reaches waterways more quickly. The scientists involved in the new study took a look at how much compaction is being caused by these giant farming machines and compared it with the sauropods who lived over 66 million years ago. They found both to be big culprits of compaction.

Under Pressure

The study points out that as the weight of farm machinery has grown, tyre sizes have ballooned too, adjusting the area of contact between the vehicle with the soil to reduce the pressure on the surface and help avoid sinking. It seems that animals evolved with a similar strategy – increasing foot size with weight to help avoid sinking into the soil.

Overall, pressure at the soil surface has remained fairly constant as farm machinery has gained weight. But the authors suggest that stresses on the soil continue to increase below the surface and penetrate deeper as vehicles (or animals) get heavier. Farm machinery today (and the sauropods of the past) are now so heavy that they irreparably compact soil below the first 20 cm, where it isn’t tilled. Aside from restricting how deep the roots of crops can grow to seek water and nutrients further down in the soil, this can also create low-oxygen conditions that are not good for plants or the organisms they share the soil with.

Where Did The Dinosaurs Go For Dinner?

This creates a “sauropod paradox”, as the researchers call it. The dinosaurs and the loads transmitted through their feet were so large that they would have likely caused significant subsurface damage to soils wherever they roamed, potentially destroying the soil’s ability to support the plants and ecosystems they would have relied on as their food source.

The image of sauropods roaming widely and foraging freely as depicted by Jurassic Park seems unlikely, as they would have had an unsustainable influence on their environment. So how did they survive?

The scientists behind the study speculate that they may have kept to well-trodden paths, limiting their impact while browsing the canopy with their long necks. How exactly a sauropod could live in equilibrium with the soil remains a mystery for now.

Big Food For Thought

A more pressing conundrum is how to reconcile soil compaction by farming vehicles with sustainable food production today. The risk of soil compaction varies with the type of machinery and the way it’s used, as well as the type of soil and the moisture bound up in it.

The study estimates that 20% of croplands globally are at high risk of losing productivity because of subsoil compaction by modern agricultural vehicles, with the highest risks in Europe and North America where it’s relatively moist and there are more large farms using the largest machines. Clearly, this is an issue in arable landscapes, but the problem also extends to grasslands where silage is baled, and urban landscapes where the movement of construction vehicles on green space is not well controlled.

The authors call for design changes to machinery to help maintain the soil’s structure. We suggest another option. To reduce their impact on the soil, we could reduce the need for such large machines in the first place by growing food using smaller machines on smaller parcels of land, particularly in high-risk zones. Finding ways to break up vast monoculture landscapes makes sense for many other reasons. For example, wildflower field margins, hedgerows and trees can help sequester carbon, manage water quality and support biodiversity.

Soil can only withstand so much pressure – whether from compaction or other threats such as continual harvesting, erosion or pollution. Humans must act to reduce pressures on soils, or we risk going the way of the dinosaurs.![]()

Jess Davies, Chair Professor in Sustainability, Lancaster University and John Quinton, Professor of Soil Science, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Lismore faced monster floods all but alone. We must get better at climate adaptation, and fast

Johanna Nalau, Griffith University; Hannah Melville-Rea, New York University, and Mark Howden, Australian National UniversityAustralia is no stranger to disasters like droughts, floods, bushfires and heatwaves. The problem is, they’re going to get worse. And then worse again. As the global temperature ratchets up, these disasters will grow in size, frequency and intensity. We will have to get much better at adapting, and do this even as we phase out fossil fuels to stop climate change getting worse.

Climate adaptation is about working with our new reality, rather than clinging to the way things were done in the past. We must accept our climate and environment has already changed, with more major upheavals on the way. If we don’t, we’ll be caught napping by “unprecedented” events which just keep on coming.

While local and state governments have led the way on climate adaptation to date, we have much more to do, as the worrying lack of preparation for the floods that devastated Lismore makes clear.

Do Both: Climate Adaptation And Emissions Reduction

Many people believe climate adaptation is a red herring, diverting resources and attention away from emissions.

This is simply not true. We must do both. The world has already warmed 1.2℃ since the industrial age began, and is heating up by just under 0.2℃ per decade. There is also a lag time between fossil fuels burned today and the extra warming this causes.

Climate change is already here, and will only intensify. We must urgently slash emissions while also helping our communities be ready. The good news is adaptation often helps lower emissions, and vice versa.

It can be hard to picture what climate adaptation looks like. So take the hard-hit town of Lismore as an example. Official warnings did not reach this Northern Rivers community. When these monster floods hit, these communities were largely left to save themselves. If it hadn’t been for neighbours undertaking rooftop rescues, the death toll would likely have been much higher. In the aftermath, many residents have been living in tents and caravans while struggling to find affordable housing.

To be ready for the next floods, Lismore would benefit from:

- rebuild using flood-resistant designs and materials

- coordinating community preparations

- exploring land-swap or changing land-use planning for high-risk areas

- better coordination between government agencies

- better warnings delivered sooner.

As soon as you consider the problem, it becomes clear there is no silver bullet. We need to plan ahead of time, rather than try to scramble to respond to disasters as they grow in size and frequency. Preparing and planning saves lives and cuts costs.

Drawing on local community strength is vital, as the Northern Rivers has shown Australia. But it is not enough by itself. Movements like Resilient Byron and Resilient Lismore show how locally led adaptation can assist communities. They could do more, with directed long-term investments and support.

What Have We Done So Far?

The knowledge we already have about surviving in the world’s most arid inhabited continent is a start. First Nations communities have a sophisticated understanding of caring for country, while Australian farmers are among the best climate-risk managers globally, after a rocky start.

To date, most government-led climate adaptation happens at local and state levels. Highly innovative approaches have come from local governments, such as a council-led land-swap to get people permanently out of flood plains in the Lockyer Valley. Victoria’s state government has a climate adaptation program to help the natural resources sector prepare for possible futures, while Queensland has a strategy for local governments to find the greatest risks to coastal areas and plan for adaptation.

While these are welcome, we must do much more at a national level. In this area, we seem to be going backwards. In 2007 the federal government invested heavily in climate adaptation, but these initiatives were progressively dismantled after the 2013 election. Today, disaster spending is focused on recovery rather than preparation. While that might be politically rewarding, it is extraordinarily expensive.

On a national scale, our current climate adaptation strategy lacks clear targets and timelines. Not only that, it does not connect the dots between the levels of adaptation required and different scenarios for cutting emissions. We hope the new framework being produced by the National Reconstruction and Recovery Agency will better incorporate adaptation.

What Does Well-Adapted Look Like?

Our political parties differ substantially on climate adaptation efforts. Liberal and National Party policies barely mention climate adaptation. Labor has disaster preparation policies, such as up to A$200 million per year on disaster prevention and recovery, while the Greens are most ambitious with plans to both slash emissions and boost adaptation through initiatives such as making housing better able to cope with floods and cyclones.

Climate adaptation pays dividends – regardless of who takes government. Active climate adaptation would save Australia A$380 billion in gross domestic product over the next 30 years.

We cannot let climate adaptation be the plaything of day-to-day politics. To have any chance of success, we need a robust bipartisan strategy. We should look to countries such as the UK which has laws requiring a national climate risk assessment every five years as well as a program coordinating and reporting adaptation actions across the country.

There is support for these measures in Australia, with 72% of us in favour of introducing national climate risk assessments giving our state and local governments access to up to date information on flood projections, neighbourhoods most vulnerable to heatwaves and expected levels of sea level rise. Crucially, this would let us pick out the best ways we could adapt.

Australia also needs a national climate adaptation hub, a one-stop shop offering advice to all levels of government, communities, non-governmental organisations and the private sector on the adaptation strategies available and ways to scale up the best approaches.

We must act now to make the best of the future coming towards us. We know a great deal about what we’ve set in motion by heating up our planet. Now we must prepare for what this brings. And we have to do it together.![]()

Johanna Nalau, Research Fellow, Climate Adaptation, Griffith University; Hannah Melville-Rea, Research Fellow, Climate Resilience, Environmental Arts & Humanities, New York University, and Mark Howden, Director, ANU Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bucking the trend: Is there a future for ultra long-haul flights in a net zero carbon world?

This year, Qantas announced two plans in direct conflict. In March, Australia’s largest airline group went public with the admirable goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050 and a 25% reduction by 2030 by using new clean fuels, boosting efficiency and using carbon offsets. For the aviation industry, this was a watershed moment, containing world-leading detail and bold links between executive pay and improved sustainability.

But only two months later, Qantas confirmed its order for 12 new Airbus planes capable of ultra long-distance flights, making possible non-stop flights from Sydney and Melbourne to London or New York.

What’s the conflict? These long distance flights must carry substantially more fuel and, as a result, fewer passengers, making them markedly less efficient.

If the aviation industry heads down this route, it will be a backwards step in the fight against climate change. While Qantas intends these flights to be carbon neutral, this will have to involve carbon offsets given there are no other options at present.

As the world gets more serious about climate action, flights like this will come under scrutiny.

Flying The Furthest Comes With A Carbon Cost

For decades, Qantas has hoped to overcome Australia’s tyranny of distance, beginning ultra long-haul test flights as early as 1989. These tests didn’t translate into regular flights, however, leaving the door open to key competitor Singapore Airlines, which currently has the world’s top two ultra long flights.

Qantas seems determined to change that. In 2025, the carrier’s new Sydney-London non-stop flight will cover 17,800km non-stop to become the world’s longest flight.

While it might seem like a single flight would produce less emissions, the opposite is true.

The most efficient flights (based on fuel burned per kilometre) are those between 3,000 and 5,000km, depending on aircraft type. By contrast, non-stop ultra long haul flights produce more carbon emissions than two shorter journeys with a stop-over.

The reason is simple physics. Planes flying ultra long distances must carry lots of fuel, especially at take-off, to cover the later stages of the journey. For the new planes Qantas has ordered, it takes about 0.2kg of fuel to transport a kilo a thousand kilometres.

Given the long distance, this means it’s not a very efficient use of fuel. Not only that, but the high fuel load means there is less space for passengers.

That gives an even less favourable result based on the metric of carbon dioxide emitted per passenger-kilometre. For example, the non-stop flight from Auckland to Dubai of 14,193km produces 876kg of CO2 per person in economy class, whereas the same journey with a stop-over in Singapore would produce 772kg. Exact emission rates may differ due to flight paths, freight weight, and weather, among other issues.

So while a typical A350-900 seats between 300 and 350 passengers, Singapore Airline’s existing marathon flights using these planes can only carry half that, namely 161 passengers. Similarly, the planned Qantas flights would have just 238 passengers, 112 to 172 seats fewer than what Airbus recommends.

As you’d expect, less passengers increases the ticket cost and makes these flights more exclusive, adding to the problem that a small wealthy elite have a disproportionately high environmental impact.

Can Long-Haul Ever Be Low Carbon?

Marathon non-stop flights stand in the way of a wider shift towards a low-emissions world. If airlines are serious about tackling their sector’s growing contribution to fossil fuel emissions, they must look to research into alternative fuels and technologies by programs like the EU’s Clean Sky.

These programs have shown sustainable fuels and new technologies are much better suited to shorter flights. Electric aircraft, for instance, are becoming viable for short flights in the near-term future. In Sydney, electric seaplanes will soon enter the short-hop sector, while hybrid-electric technology has the potential to support flights of up to 1500km, depending on progress in battery technology.

So what about long distance? We have two options. One is hydrogen and the other is sustainable aviation fuels.

While there is a huge amount of hype around clean hydrogen at present, the reality is green hydrogen derived from renewable electricity currently makes up just 1% of all hydrogen we produce. We would need a monumental effort to scale up to fill the demand from aviation.

Another challenge is hydrogen’s low energy density, which will restrict flying range to an estimated maximum of 7,000km by 2040.

That leaves sustainable aviation fuel as the only option for long-haul flights. The airline industry is pinning their hopes on fuels derived either from biological feedstocks (used cooking oils or oil derived from algae) or produced synthetically.

The sustainability of these fuels depends on the feedstock, the production process (which, again, will demand large amounts of renewable energy) and a detailed understanding of impacts on the atmosphere from any gases emitted. That suggests these fuels will likely be expensive, with volumes hard to secure to fully replace fossil fuels. Even so, these fuels will have to be part of aviation’s future.

New Ways Of Travel

The way we think about flying is changing, with climate impact front of mind for many travellers.

In response, some countries have begun to ramp up their focus and infrastructure spending on rail travel, to encourage new travel patterns. The growing regenerative tourism movement – which emphasises deeper engagement with place and people – signals there is real potential to shift mass travel away from far-and-fast destinations to close-and-deep.

The role of flying in tourism is already changing, and it will change more in coming years. You can already glimpse this in the trends towards more climate-friendly travel closer to home. Soon, electric and hybrid planes will encourage shorter flights in a carbon-constrained world.

As for ultra long-haul flights, it is difficult to picture how these are compatible with the goal of net-zero emissions.![]()

Susanne Becken, Professor of Sustainable Tourism and Director, Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University and Paresh Pant, PhD Candidate and Sessional Academic, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Maths The Solution To Future Careers

NSW Health Seizes More Than $1 Million Of Illegal Nicotine Vapes

- For individuals, up to $11,000 for a first offence, and up to $55,000 for a second or subsequent offence;

- For corporations, up to $55,000 for a first offence, and up to $110,000 for a second or subsequent offence.

Major Milestone For Fee-Free Training In NSW

NSW is enjoying a fee-free training boom with more than 200,000 enrolments recorded under JobTrainer, a program helping people get skilled for in-demand jobs.

NSW is enjoying a fee-free training boom with more than 200,000 enrolments recorded under JobTrainer, a program helping people get skilled for in-demand jobs.Dorothea Mackellar Poetry Awards 2022: Entries Close June 30th

There's also a special History page running this Issue for you - the Australian poet Dorothea Mackellar, after whom the Electorate of Mackellar is named, had a house here in Pittwater at Lovett Bay.

“Our poets are encouraged to take inspiration from wherever they may find it, however if they are looking for some direction, competition participants are invited to use this year’s optional theme to inspire their entries.”

In 2022, the Dorothea Mackellar Memorial Society has chosen the theme “In My Opinion.”

As always, it is an optional theme. The Society encourages students to write about topics and experiences that spark their poetic genius (in whatever form they choose.)

HOW TO ENTER

PLEASE SEE HERE FOR A DETAILED PDF ON ENTRY INSTRUCTIONS FOR TEACHERS AND PARENTS.

ONLINE SUBMISSION

Primary school and secondary school entries can be submitted anytime during the competition period. Visit: https://dorothea.com.au/how-to-enter/

Local Women Named In Australian Gridiron Squad

Young Writers’ Competition 2022

Young people across the Northern Beaches are encouraged to enter this year’s Young Writers’ Competition for their chance to be published.

Now in its 13th year, the annual competition is open to students from kindergarten to grade 12 who live or go to school on the Northern Beaches. The theme of this year’s competition is ‘rise’.

“The Northern Beaches is home to some very talented young writers, and I continue to be blown away by the creativity and skill of entrants in our annual Young Writers’ Competition,” Mayor Michael Regan said.

“It’s time for young writers to once again rise and shine and show us what they’ve got. More than 500 stories were submitted in last year’s competition, and we suspect this year will be just as competitive.”

Entrants can write on any topic or theme but must include a derivation of the word ‘rise’. Entries will be grouped by age and judged according to characterisation, originality, plot, and language.

Four finalists will be chosen in each age category and invited to a presentation night on Wednesday 10 August, where a winner, runner-up, and two highly commended prizes are awarded.

Finalists from each category will have their stories published in an eBook which is added to the Northern Beaches Council Library collection.

Entries close Tuesday 31 May 2022. Entrants must be members of the Northern Beaches Council Library Service.

Complete the online entry form and attach your story as a Word document. If your story is hand-written, then a clear, readable photo or scanned PDF can be submitted.

Not a member of the library? Don't worry, Council will use this form to create a membership for you. Just mark 'no' under the library member field in the online form. If you are a member and unsure of your library card number, just mark 'yes' in the library member field in the online form and Council will find your library membership number.

Entries are judged according to characterisation, originality, plot and use of language and arranged into six different age group categories.

Four finalists are chosen in each age category and invited to a presentation night where a winner, runner-up and two highly commended prizes are awarded. Finalists from each category will have their stories published in an eBook that will be added to Council's collection.

For more information visit Council's library.

Word Of The Week: Breathe

The Corrs - Breathless [Official Video]

Air That I Breathe – The Hollies, 1974

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds - Breathless

Jimi Hendrix - The Wind Cries Mary(Live In Stockholm 1967)

Louis Armstrong - What A Wonderful World (Original Spoken Intro Version) ABC Records 1967 - Take A Deep Breath And Just Exhale!

Sydney Pro Junior At Manly Beach: Ellie Harrison And Levi Slawson Win

Cluttercore: Gen Z’s revolt against millennial minimalism is grounded in Victorian excess

Have you heard maximalism is in and minimalism is out? Rooms bursting at the seams with clashing florals, colourful furniture and innumerable knick-knacks, this is what defines the new interiors trend cluttercore (or bricabracomania).

Some say it’s a war between generation Z (born 1997-2012) and minimal millennials (born 1981-1996), symptomatic of bigger differences. Others say it’s a pandemic response, where our domestic prisons became cuddly cocoons, stimulating our senses, connecting us with other people and places. But what really lays behind the choice to clutter or cull?

Why do some people revel in collections of novelty eggcups? Or have so many framed pictures you can barely see the (ferociously busy) wallpaper? And why do those at the other end of the spectrum refuse to have even the essential stuff visible in the home, hiding it behind thousands of pounds’ of incognito cupboards?

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Rihanna and radical pregnancy fashion – how the Victorians made maternity wear boring

William Morris – how a great thinker and poet was overlooked for his wallpaper

One important reason for the clash between minimalism and maximalism is simple: the relentless pendulum swing of fashion. Whatever psychological or cultural rationale pundits may suggest, fashion is always about the love of what strikes us as new or different.

This struggle might seem new but it is just history repeating itself, encapsulated in the interior struggle between less and more that began between class-ridden Victorian commodity culture and modernism’s seemingly healthy and egalitarian dream.

A Lot Of Stuff

Victorians liked stuff that they could put on display. These things communicated their status through solid evidence of capital, connectedness, signs of exotic travel and colonial power. Think inherited antique cabinets and Chinese ivory animals. Then imagine the labour required to not only create, but polish, dust, manage and maintain these myriad possessions.

But this deluge of stuff was made possible for more people as mass-produced commodities – especially those created from synthetic materials – became cheaper.

All this created a novel and lasting problem: how to choose and how to organise a world with so much aesthetic possibility – how to make things “go together”. The 19th and 20th-century guardians of culture and the “public good” were just as concerned about the spiritual chaos of too much clutter as modern “organisational consultants” like Marie Kondo.

In response, they set up design schools and educational showcases, like the Great Exhibition of 1851, the 1930 New York World’s Fair and the Festival of Britain in 1951.

Very Little Stuff

The minimalist mantra “less is more”, courtesy of German art school the Bauhaus was established in the 1920s. For some modernists, “needless decoration” was a sign of an “uncivilised” (read feminine and non-white) mind. They nevertheless also looked to “primitive” cultures for bold aesthetics and authenticity superior to western excess.

Modernists believed that simplicity and elegant functionality, enabled by mass production and cost-effective new materials (like tubular steel and plywood), could promote social equality in interior design. They had a point. Without staff, what working person can, realistically, keep “curated” clutter looking cool (and clean)?

But, what about “cosiness”? That feeling, described in the 1990s as “cocooning or providing a "warm welcome” to guests?

A 1980s American study found that the “homeyness” desired in interiors was achieved by successive circles of stuff – from the white picket fence, to the wisteria on the exterior walls, the wallpaper, pictures and bookshelves lining the interior walls and then furniture arranged also in roughly circular formations.

These layers would then be overlain with decorations and texture, making symbolic entry points as well as enclosures. “Homey” was aesthetically the total opposite of modern minimalism, whose “functionality” was perceived as cold, unsympathetic and unwelcoming.

Despite this popular rejection, modernism was the postwar default for European “good taste”, seen in design HQs and high-end interiors magazines. But wasn’t it all not just uncomfortable, but also a bit boring? And, unfortunately, every bit as unforgiving without a lot of cash and a team of cleaners?

Modernism on the cheap is just depressing (see the concrete blocks of 1960s UK council flats). Sleek built-in cupboards cost a lot. And smooth, unadorned surfaces show every speck of dirt.

Rebelling against modernist mantras, 1980s design sought to put “the fun back into function” for sophisticates. However, ordinary people were always buying fun stuff, from plastic pineapples to granny chic knick knacks.

The Impossibility Of It All

Nowadays, the “safe” and default mainstream option is a broadly-defined “modern” look characterised by Ikea. But it’s not really minimalist. This look encourages an accumulation of stuff that never quite functions or fits together and which still fills a room according to the ethos of homeyness – even though each object may “look modern”.

It fails to tell a convincing story of the self or remain tidy, prompting further purchases of “storage solutions”. Minimalists strip this back to a minimum of objects with a neutral palette. Fewer mistakes equals less chucking out. Less stuff equals less to change when you tire of it.

But minimalism is more difficult than ever. We are powerless against the tides of half-wanted incoming consumer stuff – especially if you have children – which makes achieving minimalism all the more impressive. People who do achieve it frame their shots with care and they chuck a lot of stuff away.

Making a more elastic aesthetic look good is also difficult, maybe more difficult. Clutter lovers range from sub-pathological hoarders, to upper middle-class apers of aristocratic eclecticism, to ethical “keepers”. An aesthetic mess can look like an accidental loss of human control, identity or hope. It takes a lot to make harmony out of all that potential noise – and keep it tidy.

Cluttercore is perfect for now, a vehicle to display the curated self, the “interesting” and “authentic” self so demanded by social media. And it hides behind the idea that anything goes, when in fact, maybe some things must.![]()

Vanessa Brown, Course Leader MA Culture, Style and Fashion, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Loch Ness monster: a modern history

Reports of Loch Ness monster sightings keep coming. The latest report, accompanied by a video, is of a 20-30ft long creature occasionally breaking the water’s surface. Although the video clearly shows a moving v-shaped wake it does not reveal the underlying source. The witnesses certainly saw something, but what?

There have been over 85 theories of what the Loch Ness monster is, ranging from the prosaic (wind slicks, reflections, plant debris and boat wakes) to the zoological implausible (anacondas, killer whales and the ocean sunfish) to the frankly bonkers (ghost dinosaurs). The people who came up with these theories were not necessarily that familiar with the loch.

Many early suggestions by foreign zoologists implied they thought the loch was saltwater, which explains suggestions of sunfishes, whales, sharks and rays. Some theories have been reinvented independently, showing the ingenuity of each generation of Nessie inventors. For example, the idea that the Loch Ness monster was originally a swimming elephant from a visiting circus, resurfaced three times, in 1934, 1979 and 2005. Each time, the person claimed the idea was original.

Nessie The Reptile

However, it was the notion of the Loch Ness monster as a prehistoric reptile that really captured the public’s imagination in the 1930s. Nessie’s modern genesis really started in April 1933. The first eyewitness reports of a strange animal in the loch started in 1930.

Yet it would only be in August of 1933 that witness George Spicer, who saw Nessie on land, first suggested that the creature was a reptile. Until then informed commentators assumed that if there was an animal in the loch, it was some sort of vagrant freshwater animal like a seal that had made its way from the Moray Firth. Spicer just described it as a prehistoric reptile. He claimed it had a long neck which allowed a journalist five days later to suggest it was a plesiosaur, a type of long-necked marine reptile from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. One (but not the only one) popular image of the Loch Ness monster was born.

The fact that the plesiosaur image of Nessie arose in August 1933 casts doubt on Daniel Loxton and Donald Prothero’s (2013) theory Nessie originated with the highly popular 1933 King Kong film with its portrayal of a man-eating, long-necked, swamp-dwelling reptile. It’s more likely that King Kong only influenced rather than created the modern Nessie. The very first sightings of the Loch Ness monster were in 1930 and although there were more sightings in 1933, they started in April before King Kong was screened in Scotland.

She’s Complicated

Most reports of the Loch Ness monster don’t feature long necks. Biochemist (and Nessie investigator) Roy Mackal said in 1976 there were over 10,000 reports of the Loch Ness monster but gave no evidence to back this, and a table in his book Monsters of Loch Ness only contains 251 reports. I know of 1,452 distinct encounters. Only about 20% of the reports mention a neck of any length, so it is not the monster’s normal form. Also less than 1% of creatures in the reports are described as reptilian or scaly. So I think it reasonable to assume that whatever the reported phenomena of the Loch Ness monster is founded on, it is not based on glimpses of a prehistoric reptile.

In reality, the Loch Ness monster has multiple identities. It may not be a walrus, moose, camel or visiting extra-terrestrials, as some have suggested, but could be a myriad of anthropogenic (boats, wakes, debris) and natural (animals, vegetation mats) and physical phenomena (wind effects, reflections). The Loch Ness monster can vary in colour from pink to black, it can be matt or glossy, furry or scaly. It can have humps and manes, it can have horns and travel at great speed or not move at all. No one identity captures the variety of Nessie’s reported features.

This suggests that Nessie is a function of human psychology rather than nature. And perhaps it is human psychology rather than nature that has sustained the idea of Nessie since the 1930s.

So what did the latest witnesses see? The reality is we have too little information to reach a firm conclusion about what was happening in the video footage. The problem with the vast majority of Nessie reports, is that they simply lack details you need to identify an animal. And any details that are reported may be misinterpretations. The fact that the visible wake moves indicates it was an actual animal (rather than snagged vegetation). But was it a 20-30ft animal or some waterfowl or an otter under the water that created a large wake in smooth water? We will simply never know.![]()

Charles Paxton, Research Fellow, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

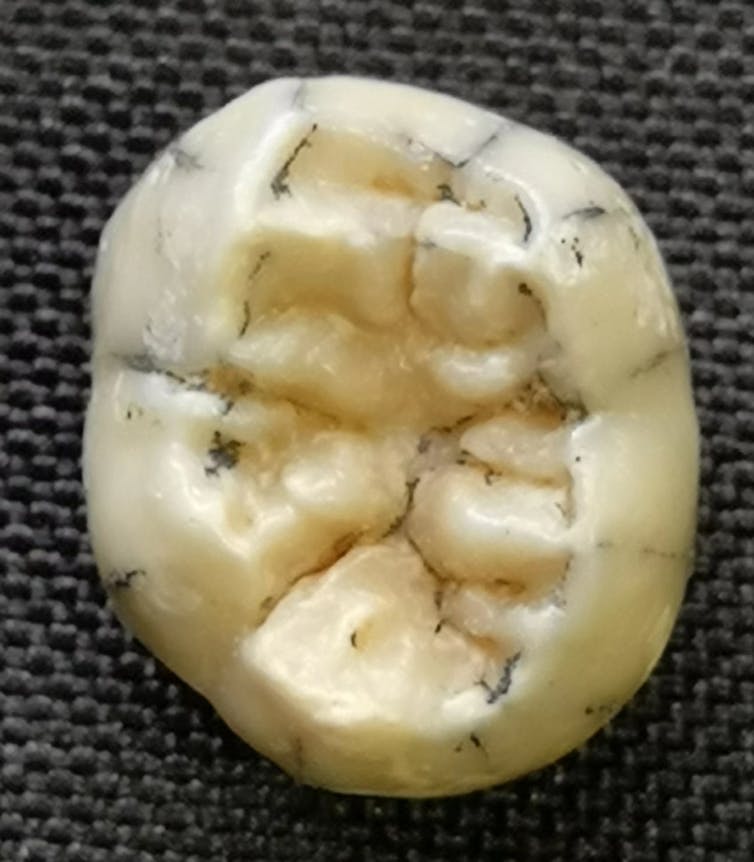

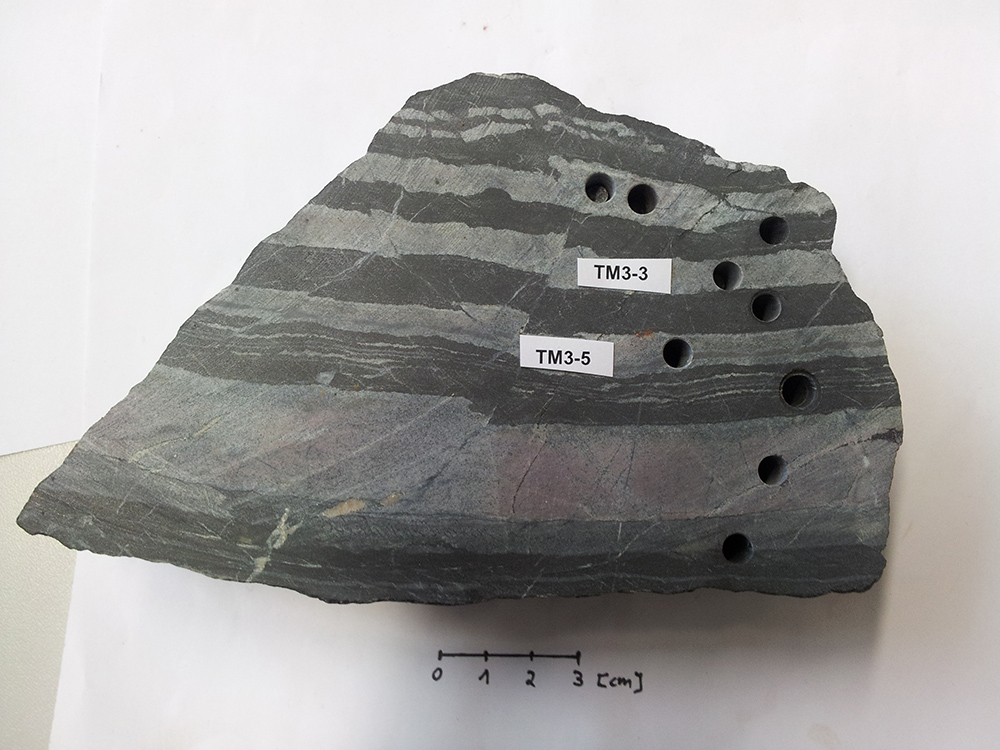

A fossil tooth places enigmatic ancient humans in Southeast Asia

What do a finger bone and some teeth found in the frigid Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai mountains have in common with fossils from the balmy hills of tropical northern Laos?

Not much, until now: in a Laotian cave, an international team of researchers including ourselves has discovered a tooth belonging to an ancient human previously only known from icy northern latitudes – a Denisovan.

The find shows these long-lost relatives of Homo sapiens inhabited a wider area and range of environments than we previously knew, confirming hints found in the DNA of modern human populations from Southeast Asia and Australasia.

Who Were The Denisovans?

Little is known about these distant cousins of modern humans, except that they once lived in Asia, were related to and interacted with the better-known Neanderthals, and are now extinct.

The first traces of Denisovans were only found in 2010, with the discovery of an innocuous finger bone in remote Denisova Cave. The extreme cold of the cave meant some ancient DNA was preserved in the bone – and the DNA revealed the finger had belonged to an unknown species of human.

This discovery changed the course of human evolutionary studies, and the newly discovered humans were named Denisovans after the cave where the fossil was found.

Fossilised teeth from Denisovans were later discovered in the same cave. Two upper and one lower molar were found in sediments that were dated to between 195,000 and 52,000 years ago.

Meanwhile, it was found that genes from Denisovans survived in modern day people from Southeast Asia and Australasia. This implied that the Denisovans had dispersed over a far larger area than anticipated.

The Hunt For More Fossils

The hunt was on to find more evidence of these humans outside Russia, but scientists had no idea what they actually looked like. For the first time in history we knew more about a human’s DNA than their anatomy!

The next twist came when a 160,000-year-old Denisovan jawbone surfaced on the Tibetan Plateau, giving the scientific community a tantalising glimpse of what the bodies of these ancient humans were like and where they lived.

But questions remained: just how far did they spread in Asia, and how did their genetic imprint survive in Southeast Asians and Australasians?

Clearly Denisovans could live in the cold environments of Siberia and Tibet, but could they have also occupied a completely different ecological niche and adapted to a tropical climate?

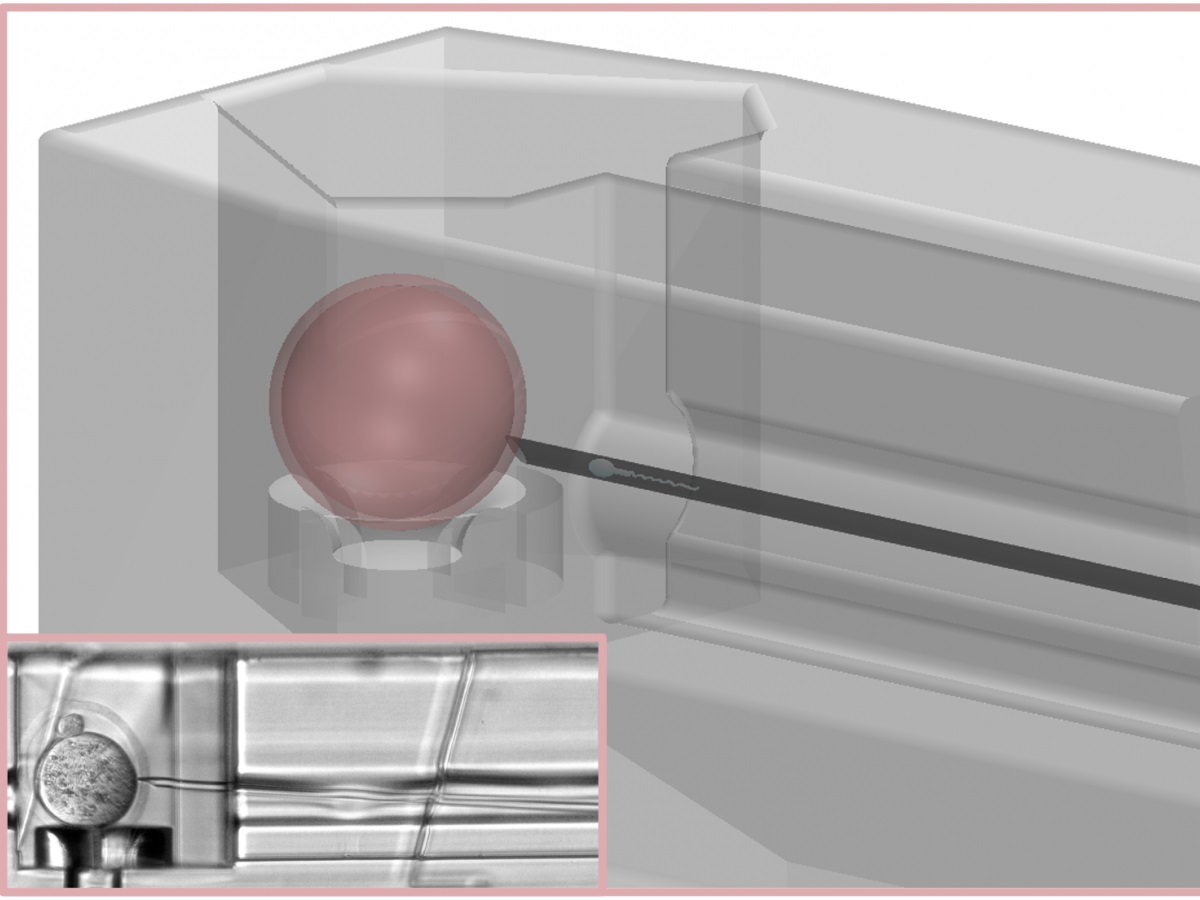

Tam Ngu Hao 2 (Cobra Cave)

Enter a new cave found by an international (Laos–French–American–Australian) team in northern Laos in 2018, close to the famous Tam Pa Ling cave where 70,000-year-old modern human fossils were found.

The site, named Tam Ngu Hao 2 (or Cobra Cave), was found high up in the limestone mountains and contained remnants of old cave sediment packed with fossils.

The cave sediments contained teeth from giant herbivores, such as ancient elephants and rhinos that liked to live in woodland environments. The teeth were likely washed into the cave during a flooding event that deposited the sediments and fossils.

These sediments were covered by a layer of very hard rock called flowstone, which is formed by water flowing over the cave floor. The sediments and fossils were dated by this study to provide an age for the time of deposition in the cave, and by association a minimum age for the death of the animals.

A Young Girl’s Tooth

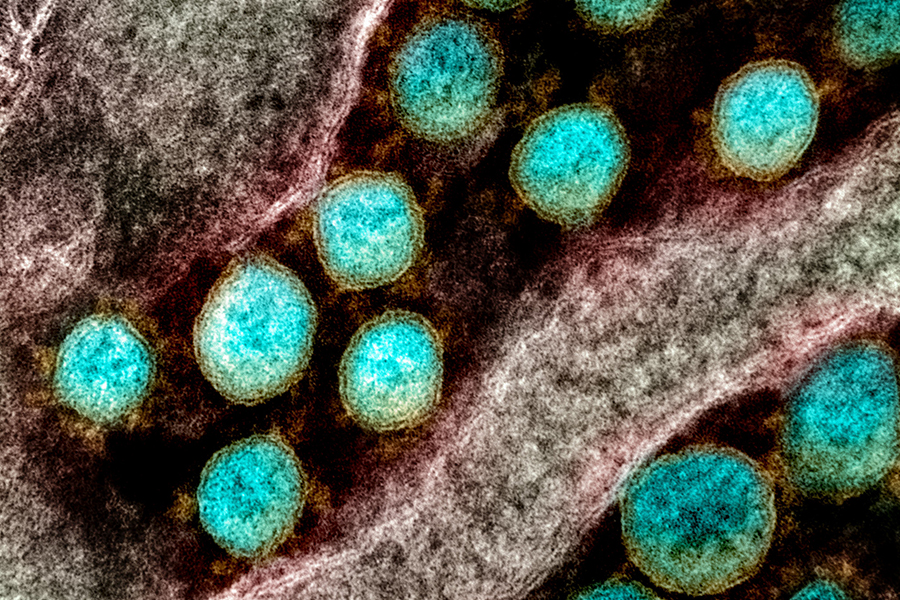

A human tooth (a lower permanent molar) was found in the cave sediments, but we could not initially identify what species of human it came from. The humid conditions in Laos meant that the ancient DNA was not preserved.

We did however find ancient proteins that suggested the tooth came from a young, likely female, human – probably between 3.5 and 8.5 years old.

After very detailed analysis of the shape of this tooth, our team identified many similarities to the Denisovan teeth found on the Tibetan Plateau. This suggested the tooth’s owner was most likely a Denisovan who lived between 164,000 and 131,000 years ago in the warm tropics.

An Ancient Human Hotspot

This fossil represents the first discovery of Denisovans in Southeast Asia, and shows that Denisovans were at least as far south as Laos. This is in agreement with the genetic evidence found in modern day Southeast Asian populations.

They may have been just at home in the balmy tropical climates of Laos as the icy conditions of northern Europe and the high-altitude environments of the Tibetan Plateau. This suggests the Denisovans were very good at adapting to diverse environments.

It would seem that Southeast Asia was a hotspot of diversity for humans. At least five different species set up camp there at different times: Homo erectus, the Denisovans/Neanderthals, Homo floresiensis, Homo luzonensis, and Homo sapiens.

How many of these species overlapped and interacted? Another fossil discovered in the dense network of Southeast Asian caves could provide the next clue to understanding these complex relationships.![]()

Kira Westaway, Associate professor, Macquarie University; Mike W Morley, Associate Professor, Flinders University, and Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Associate Professor, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wrong, Elon Musk: the big problem with free speech on platforms isn’t censorship. It’s the algorithms

Imagine there is a public speaking square in your city, much like the ancient Greek agora. Here you can freely share your ideas without censorship.

But there’s one key difference. Someone decides, for their own economic benefit, who gets to listen to what speech or which speaker. And this isn’t disclosed when you enter, either. You might only get a few listeners when you speak, while someone else with similar ideas has a large audience.

Would this truly be free speech?

This is an important question, because the modern agoras are social media platforms – and this is how they organise speech. Social media platforms don’t just present users with the posts of those they follow, in the order they’re posted.

Rather, algorithms decide what content is shown and in which order. In our research, we’ve termed this “algorithmic audiencing”. And we believe it warrants a closer look in the debate about how free speech is practised online.

Our Understanding Of Free Speech Is Too Limited

The free speech debate has once more been ignited by news of Elon Musk’s plans to take over Twitter, his promise to reduce content moderation (including by restoring Donald Trump’s account) and, more recently, speculation he might pull out of the deal if Twitter can’t prove the platform isn’t inundated with bots.

Musk’s approach to free speech is typical of how this issue is often framed: in terms of content moderation, censorship and matters of deciding what speech can enter and stay on the platform.

But our research reveals this focus misses how platforms systematically interfere with free speech on the audience’s side, rather than the speaker’s side.

Outside the social media debate, free speech is commonly understood as the “free trade of ideas”. Speech is about discourse, not merely the right to speak. Algorithmic interference in who gets to hear which speech serves to directly undermine this free and fair exchange of ideas.

If social media platforms are “the digital equivalent of a town square” committed to defending free speech, as both Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Musk argue, then algorithmic audiencing must be considered for speech to be free.

How It Works

Algorithmic audiencing happens through algorithms that either amplify or curb the reach of each message on a platform. This is done by design, based on a platform’s monetisation logic.

Newsfeed algorithms amplify content that keeps users the most “engaged”, because engagement leads to more user attention on targeted advertising, and more data collection opportunities.

This explains why some users have large audiences while others with similar ideas are barely noticed. Those who speak to the algorithm achieve the widest circulation of their ideas. This is akin to large-scale social engineering.

At the same time, the workings of Facebook’s and Twitter’s algorithms remain largely opaque.

How It Interferes With Free Speech

Algorithmic audiencing has a material effect on public discourse. While content moderation only applies to harmful content (which makes up a tiny fraction of all speech on these platforms), algorithmic audiencing systematically applies to all content.

So far, this kind of interference in free speech has been overlooked, because it’s unprecedented. It was not possible in traditional media.

And it is relatively recent for social media as well. In the early days messages would simply be sent to one’s follower network, rather than subjected to algorithmic distribution. Facebook, for example, only started filling newsfeeds with the help of algorithms that optimise for engagement in 2012, after it was publicly listed and faced increased pressure to monetise.

Only in the past five years has algorithmic audiencing really become a widespread issue. At the same time, the extent of the issue isn’t fully known because it’s almost impossible for researchers to gain access to platform data.

But we do know addressing it is important, since it can drive the proliferation of harmful content such as misinformation and disinformation.

We know such content gets commented on and shared more, attracting further amplification. Facebook’s own research has shown its algorithms can drive users to join extremist groups.

What Can Be Done?

Individually, Twitter users should heed Elon Musk’s recent advice to re-organise their newsfeeds back to chronological order, which would curb the extent of algorithmic audiencing being applied.

You can also do this for Facebook, but not as a default setting – so you’ll have to choose this option every time you use the platform. It’s the same case with Instagram (which is also owned by Facebook’s parent company, Meta).

What’s more, switching to chronological order will only go so far in curbing algorithmic audiencing – because you’ll still get other content (apart from what you directly opt-in to) which will target you based on the platform’s monetisation logic.

And we also know only a fraction of users ever change their default settings. In the end, regulation is required.

While social media platforms are private companies, they enjoy far-ranging privileges to moderate content on their platforms under section 230 of the US’s Communications Decency Act.

In return, the public expects platforms to facilitate a free and fair exchange of their ideas, as these platforms provide the space where public discourse happens. Algorithmic audiencing constitutes a breach of this privilege.

As US legislators contemplate social media regulation, addressing algorithmic audiencing must be on the table. Yet, so far it has hardly part of the debate at all – with the focus squarely on content moderation.

Any serious regulation will need to challenge platforms’ entire business model, since algorithmic audiencing is a direct outcome of surveillance capitalist logic – wherein platforms capture and commodify our content and data to predict (and influence) our behaviour – all to turn a profit.

Until we are regulating this use of algorithms, and the monetisation logic that underpins it, speech on social media will never be free in any genuine sense of the word.![]()

Kai Riemer, Professor of Information Technology and Organisation, University of Sydney and Sandra Peter, Director, Sydney Business Insights, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Stimulating Brain Circuits Promotes Neuron Growth In Adulthood; Improving Cognition And Mood

New Tool To Create Hearing Cells Lost In Aging

Dementia: the quality of your night’s sleep can affect symptoms the next day – new research

We’ve probably all experienced how a poor night’s sleep can make us feel tired, irritable and have difficulty concentrating the next day. But while the odd night of poor sleep has no impact on our health, research shows that prolonged sleep disturbances predict cognitive decline – and are also a risk factor for dementia. Disrupted sleep is also known to be a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, a type of dementia.

But while we know that poor sleep is connected to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease on a long-term scale, until now it was unknown to what extent night-to-night variation of sleep affects dementia symptoms in the short term (such as the following day). This is something we tried to answer in our recently published study.

We found that nightly variations in sleep (such as sleeping too long or waking up in the night) had a greater effect on some aspects of brain function (such as memory and mood) the next day in people with Alzheimer’s disease compared to those with mild cognitive impairment or no cognitive impairment.

Trouble Sleeping

To conduct our study, we looked at 15 participants with Alzheimer’s, eight with mild cognitive impairment and 22 with no signs of cognitive impairment to compare the relationship between sleep and daytime function.

For two weeks, participants reported their sleep quality and how long they slept using a sleep diary. We also used an activity monitor to record objective sleep measures such as how long participants slept during the night or how long it took them to fall asleep.

To see whether the previous night’s sleep had an effect on their cognitive ability, we also phoned participants every morning to test things like their thinking ability and memory. For example, participants were asked to count backwards in sevens (calculation ability), or to recall a list of words (memory).

In addition to this, participants completed daily measures of their mood (such as how alert they were feeling) and whether they’d experienced any memory problems (such as forgetting an appointment) during a daily telephone session. To ensure that none of the participants with cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s forgot to complete these tasks, we invited caregivers to help remind them. Caregivers also documented participants’ daily patterns of behaviour.

We found that greater sleep continuity (waking up fewer times during the night) was generally better for daytime performance. Participants with Alzheimer’s had improved alertness the next evening and made fewer memory errors during the day. Both participants with Alzheimer’s and mild cognitive impairment also had fewer observable behavioural problems (such as crying, aggression or asking repeated questions) the next day following higher sleep continuity.

Surprisingly, we also found that for all participants, regardless of whether they had cognitive impairment or not, greater sleep continuity was actually related to worse calculation ability the next day.

These findings persisted even when we adjusted for other factors that might impact results – such as sex, age and years of education. We also excluded participants with conditions, such as anxiety, depression and sleep disorders, which affect sleep and cognitive ability, and thus could have influenced the results.

A Good Night’s Sleep

Though our study was small, our findings seem to be in line with what other research has shown: that there’s an optimal level of sleep when it comes to some cognitive functions. This optimal level is likely to be different for each person.

Although our study didn’t look at why sleep continuity was important for next day function, one potential mechanism suggested by other research states that sleep helps clear the buildup of amyloid (a type of protein) deposits from the brain. If enough amyloid deposits aren’t removed from the brain by deep, continuous sleep, they can clump together as plaques in brain areas linked with memory and cognitive function. Amyloid plaques are also one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

But it’s still unclear why increased sleep continuity led to poorer performance in the calculation task. It may be that because the task took place in the morning, participants were experiencing sleep inertia (grogginess and cognitive impairment felt immediately after waking). Further research, where assessments are scheduled at different times of day, would need to be conducted to rule out the effects of sleep inertia.

The findings of our study also need to be interpreted with caution, given we only looked at a small number of participants – though the repeated testing if each individual meant that collectively there were about 500 opportunities for collecting data overall. It will be important for larger studies to be conducted to see whether our results can be replicated.

In future, we’d also like to measure brain waves and other physiological signals, such as body temperature and eye movement. This will help us to better identify how long people spend in different sleep stages – such as slow wave and rapid eye movement sleep, which are shown to be important for learning and memory. This will help us better understand exactly what type of sleep is most important for daytime function.

Though it will be important for researchers to continue investigating this, our research makes a first step in showing just how important even a single night’s sleep is when it comes to dementia symptoms. This may very well mean it could be possible to optimise how much time a person living with dementia spends in bed and sleeping to improve their symptoms.![]()

Sara Balouch, Lecturer in Psychology, University of Brighton and Derk-Jan Dijk, Professor of Sleep and Physiology and Director of Surrey Sleep Research Centre, University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ultra-Powerful Brain Scanners Offer Hope For Treating Cognitive Symptoms In Parkinson's Disease

Higher Antioxidant Levels Linked To Lower Dementia Risk

Treating sleep apnoea can improve memory in people with cognitive decline

There is increasing recognition of the important role sleep plays in our brain health. Growing evidence suggests disturbed sleep may increase the risk of developing dementia.

I and University of Sydney colleagues have published a new study showing treating sleep apnoea in older adults with mild cognitive impairment can improve memory, but not other areas of cognition, in the short term.

As there is no current treatment or cure for dementia, increasing efforts have focused on developing novel approaches to slow its progression. Mild cognitive impairment is the stage between the expected cognitive decline of normal ageing and the more serious decline of dementia.

In mild cognitive impairment, the individual, family and friends notice cognitive changes, but the individual can still successfully carry out everyday activities. Mild cognitive impairment is associated with an increased risk of developing dementia in subsequent years.

Researchers believe this is the optimal time to intervene to help prevent a future dementia diagnosis. Finding new ways to slow cognitive decline in those with mild cognitive impairment is therefore important.

How Is Sleep Important For Our Brain Health?

Sleep optimises the ability of our brains to stabilise and consolidate newly learned information and memories. These processes can occur across all the different stages of sleep, with deep sleep (also known as stage 3 or restorative sleep) playing a key role.

We also now know the glymphatic system, or the waste management system of the brain, is highly active during sleep, especially during deep sleep. This process allows waste products, including toxins, our brain has built up during the day to be cleaned out.

Toxins in the brain include beta-amyloid, one of the key proteins in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Disturbing sleep could disrupt this cleaning process and lead to more accumulation of beta-amyloid in the brain.

The important role of sleep in these vital processes has led to the investigation of whether sleep disruption, including sleep disorders, could be associated with changes in our cognition when we age, and a possible link to the development of dementia.

What Is Sleep Apnoea?

Sleep apnoea is estimated to affect 1 billion people worldwide. In Australia, 5-10% of adults are diagnosed with the condition. Sleep apnoea causes the throat (also called the upper airway) to close either completely (an apnoea) or partially (a hypopnoea) during sleep.

These closures or obstructions can range from ten seconds up to one minute and can lead to a drop in blood oxygen levels. To start breathing again, a short awakening occurs without the individual being aware.