inbox and environment news: Issue 540

May 29 - June 4, 2022: Issue 540

Plastic Bag Ban Commences From June 1st In NSW

- single-use plastic straws, stirrers, cutlery, plates, bowls and cotton buds

- expanded polystyrene food ware and cups

- rinse-off personal care products containing plastic microbeads.

Northern Beaches Surfrider Foundation members Brendan Donohoe (middle) with Jesse and Rowan Hanley - who organise Beach Clean Upsand have campaigned for a plastics ban in NSW. A J Guesdon photo.

Bush Regeneration Field Day On North Narrabeen Headland

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Forum: May 2022 - Speaker - Prof. Dennis Foley On The Aboriginal Heritage Of The Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

Annual Whale Migration Makes A Splash

Residents Warned Of Barmah Forest Virus Risk

- Always wear long, loose-fitting clothing to minimise skin exposure

- Choose and apply a repellent that contains either Diethyl Toluamide (DEET), Picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE)

- Be aware of peak mosquito times at dawn and dusk

- Keep your yard free of standing water like containers, birdbaths, kids toys and pot plant trays where the mosquitos can breed.

Sydney Wildlife Rescue And Care Course: June 2022

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

State's First Hydrogen Bus To Hit Central Coast Streets

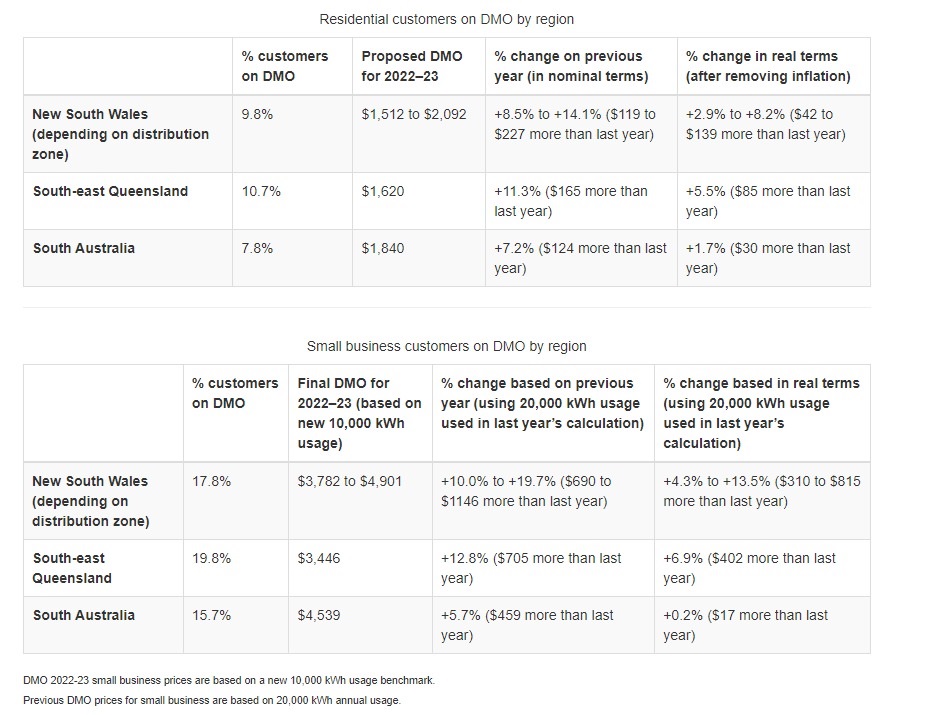

Australian Energy Regulator (AER) Sets Energy Price Cap To Protect Consumers

Renewal Of Final “Zombie” Coal Seam Gas Licence On Eve Of Federal Election Another Cruel Blow To NSW Farmers

May 20, 2022

The decision to quietly raise from the dead 90,000 hectares of the final “zombie” petroleum exploration licence on the eve of the Federal Election exposes the NSW Perrottet Government’s disdain for farmers and desperate attempts to avoid scrutiny, NSW Environment groups state.

Part of the renewed part of PEL 427 sits within Adam Marshall’s electorate and the Moree Plains Shire. Mr Marshall is on the public record opposing coal seam gas in his electorate.

The renewed part of the tenement is owned jointly by Santos and Comet Ridge, and borders Santos’ existing tenement which contains the company’s Pilliga (Narrabri) gas project.

The decision follows the renewal of three other expired petroleum exploration licences (PEL 1, PEL 12, and PEL 238) for coal seam gas in the days before Easter earlier this year.

While the renewal of the 90,000ha has not yet been gazetted, its status has been updated on the NSW Government’s Common Ground website to show it now expires in 2028. It’s believed this change was made in the past 24 hours or less.

Lock the Gate Alliance National Coordinator Georgina Woods said the renewal of the final zombie PEL put farms and groundwater at risk at a time when politicians should be doing everything in their power to protect Australia’s food growing capabilities.

“It’s shocking to see the Perrottet Government continuing to permit coal seam gas exploration on some of the state’s best farmland,” she said.

“In less than a month, the Perrottet Government has put more than one million hectares of NSW land and the groundwater beneath it at the mercy of the polluting coal seam gas industry.

“Coal seam gas is incompatible with a thriving agriculture industry and resilient rural communities.

“The Perrottet Government has given gas companies the green light to pockmark farmland with gas wells and further fuel dangerous climate change, which is in turn making it harder for farmers to grow food and fibre.

“As recent community meetings have shown, locals will not passively accept the renewal of these licences. The Perrottet Government now has one hell of a fight on its hands.”

Koala Endangered Listing In NSW Must Push NSW Government To Protect Habitat

May 20, 2022

Today’s announcement that koalas will be finally listed as Endangered under the Biodiversity Conservation Act is a huge wake up call for protecting koala habitat in New South Wales.

“The devastating endangered listing of koalas comes as no surprise in a state where the government refuses to protect habitat. Koala numbers have been in freefall for years and the NSW Government must act immediately to protect their habitat” Nature Conservation Council Deputy Chief Executive Jacqui Mumford said.

"The reality is koalas are dwindling across New South Wales and we don’t have a proper mechanism to protect their habitat.”

“If you want to save koalas you have to protect their trees. It is not complex. But koala habitat continues to be destroyed because of weak government policy that prioritises land clearance for grazing, agriculture, urbanisation, timber harvesting and mining.”

“The recently released NSW Koala Strategy was inadequate for protecting the species and we are seriously lacking a state-wide mechanism to bring this iconic species back to a healthy population. Any party looking to lead NSW into the future needs to have this as a commitment.”

“We are calling on the NSW Government to immediately:

- Ban the destruction of koala habitat, on both public and private land;

- End native forest logging; and

- Expand the National Parks estate to protect high quality koala habitat including the proposed Great Koala National Park”

The NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee found:

“Human activities including deforestation and land clearance for grazing, agriculture, urbanisation, timber harvesting, mining and other activities have resulted in loss, fragmentation and degradation of koala habitats” (page 3)

“Large areas of forest and woodland within the koala’s range were cleared between 2000 and 2017 (Ward et al. 2019) with clearing for grazing accounting for most of this loss of koala habitat”. “Land clearing continues to impact habitat across the koala’s range” (page 3)

“Clearing of native vegetation’ is listed as a Key Threatening Process under the Act.” (page 4)

“Modelled climatic suitability from 2010 to 2030 indicates a 38-52% reduction in available habitat for the koala and a 62% reduction in koala habitat by 2070 has been forecast” (page 4)

“... it is facing a very high risk of extinction in the near future...” (page 5)

Koalas Exposed To Double Whammy Health Threat

May 25, 2022

An AIDS-like virus plaguing Australia’s koala population is leaving them more vulnerable to chlamydia and other threatening health conditions, University of Queensland research has found.

One of UQ’s leading COVID-19 vaccine researchers, Associate Professor Keith Chappell, has discovered that the chlamydia epidemic plaguing endangered koala populations in Queensland and NSW is linked to a common virus that likely supresses koalas’ immune systems.

Dr Chappell and Dr Michaela Blyton, from UQ’s Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology and School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, made this discovery after studying more than 150 koalas admitted to Currumbin Wildlife Hospital.

Dr Chappell said this study could have far reaching impacts and lead to better protective measures like breeding programs and new anti-viral medications.

“We know Queensland and NSW koala populations are heavily impacted by chlamydia infections and a retrovirus, but until now a clear link between the two has not been conclusively established,” Professor Chappell said.

“Our research has found that the amount of retrovirus circulating within an animal’s blood was strongly associated with chlamydia and symptoms like cystitis and conjunctivitis, as well as overall poor health.

“It’s a double whammy for already-endangered koalas.”

Dr Chappell said they found high levels of the virus increased a koala’s risk of chlamydia by over 200% per cent.

“There is no question that koala retrovirus and chlamydia are connected, and we believe the retrovirus suppresses the koala’s immune system, making them more vulnerable to disease.”

It was previously assumed that a particular subtype of koala retrovirus may be more capable of causing disease, but this research has found that all the subtypes increase disease and has further highlighted the urgent need to stop the virus circulating within koala populations.

Dr Blyton said while these findings highlighted another threat facing endangered koalas, it could also lead to new ways to treat populations and reduce the risk of extinction.

“It is deeply concerning that koalas are facing environmental pressures at the same time as biological threats from a retrovirus and diseases,” Dr Blyton said.

“The findings from this study are important for conservation, especially as the koala is now listed as endangered and wild populations continue to decline in Queensland and NSW.

“Research like this helps us understand how the threats facing koalas are interlinked, so we can help find ways to protect the species going forward and closely examine the success of anti-viral medications and breeding programs.”

The UQ team now intends to study how environmental factors influence the amount of circulating retrovirus and disease in koalas.

Currumbin Wildlife Hospital Senior Veterinarian Michael Pyne said this was an important project and he was excited to have been working alongside the University of Queensland for so many years.

“This is a major step forward in understanding how retroviruses can affect koalas and the link with other disease, and is a perfect example of the importance of research when saving endangered species.”

KOALAS - The Hard Truths

Published May 18, 2022 by Simon Reeve

With this story, I set out to speak to the people who are coping with the trauma and the consequences of our collective apathy around koalas. I don't place myself above the crowd at all, I've been ignorant of what we've been doing to koalas for a very long time.

That is, driving them to extinction in the wild. Not a case of if, but when. These quiet, compassionate people, pick up injured and dead koalas off the roads. They watch trees disappear in their area on private property, for residential and commercial developments and forest logging. If it's fair game pretty much, in time, those trees will disappear.

There are some bright spots out there, but too few. Local, State and Federal Governments come and go, policies chop and change. Koalas meanwhile, go without a voice.

They're held up when we need them ... a visiting dignitary, a Commonwealth or Olympic Games, but backstage the destruction of habitat goes on apace.

So it's left to a handful of organisations and extraordinary, tireless volunteers for the most part, to deal with the fallout.

This takes a huge toll on their lives, physically and emotionally. You feel it when you sit with them.

They're dealing with tremendous loss, week to week. Animals they endeavour not to become attached to, but It's impossible with koalas, with their distinctive personalities and quirks.

Dendrobium Mine Extension Project: Have Your Say (Again)

Political Stitch Up Over Dendrobium Abandons Community, Climate, And Water, Favours Coal Mining Company Residents State

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

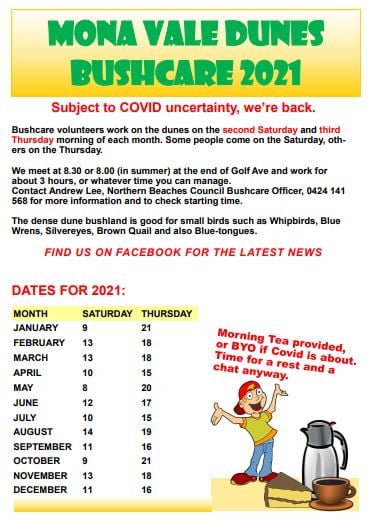

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

BOM Special Climate Statement 76 - Extreme Rainfall And Flooding In South-East Queensland And Eastern New South Wales, February-March 2022

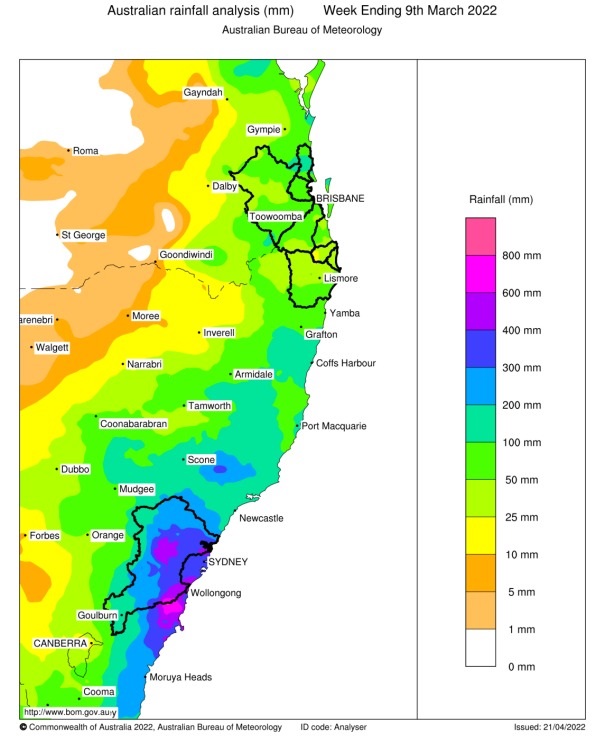

Persistent intense rainfall in Sydney and along the central New South Wales coast caused widespread flash flooding and major riverine flooding, particularly in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley. The already saturated soils, full reservoirs and swollen rivers meant that the severe thunderstorms and persistent rain in the week of 3 to 9 March quickly led to flash flooding. The widespread intense rainfall quickly overwhelmed local stormwater and drainage systems, resulting in significant flash flooding across regional and metropolitan Sydney as well as along the New South Wales coast. Severe weather and major flood warnings were issued, and thousands of people were evacuated from the affected areas.The Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley was impacted by two periods of consecutive heavy rainfall between 27 February and 9 March, with the heaviest falls observed in the Upper Nepean catchment. Moderate to major flooding was recorded along the Upper Nepean, driven by the first period of rain. A second period of heavy rain followed, resulting in renewed increases of already elevated water levels, and higher second peaks at all locations.Figure 3: Map of 7-day rainfall totals for south-eastern Queensland and eastern New South Wales for the week ending 9 March 2022. Black outlines show river catchments where 7-day catchment-average records were exceeded during the 22 February – 9 March period (Table 11). More details of river catchment regions are available at http://www.bom.gov.au/water/about/riverBasinAuxNav.shtml.The Hawkesbury River reached major flood levels from North Richmond downstream to the Wisemans Ferry gauge (Table 12). Warragamba Dam, the largest water storage in the region at over 2 million megalitres, sits at the headwaters of the Hawkesbury River system and was already at 98% of capacity on 22 February. The water in the Hawkesbury River in late February and early March came from heavy rainfall in the catchment, the spilling of Warragamba Dam and from the Nepean River, which also reached major flood levels at both Menangle Bridge and Wallacia Weir (Figure 11). The Nepean River at Menangle Bridge reached a height of 15.92 metres on 8 March, surpassing the March 2021 flood levels by more than 3 metres. The Hawkesbury River also surpassed the flood level reached in March 2021 at Windsor, Sackville, Lower Portland and Wisemans Ferry (Table 12). At Windsor, levels peaked on 9 March at 13.8 metres, nearly 1 metre above the March 2021 floods. At Lower Portland, river levels peaked at 8.64 metres on 9 March, almost 1 metre above the 2021, 1978, and 1964 flood levels (Table 12).There was significant flooding from the central to north coast of New South Wales along the Manning, Macleay and Hunter rivers. Moderate to major flooding occurred in the Hunter River catchment. At Bulga on Wollombi Brook, prolonged major flooding occurred from 7 to 11 March and a major flood peak of 7.37 metres was recorded on 9 March, with levels exceeding the March 2021 floods by over 0.7 metres (Table 13). At Singleton on the Hunter River, a major flood peak of 13.15 metres was recorded around 6pm on 9 March, caused by the floodwaters coming from Wollombi Brook. This was just above the major flood level (13 metres) and exceeded levels during March 2021 floods by nearly 1 metre.

Models indicate increased chance of negative Indian Ocean Dipole for winter

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is currently neutral. However, the IOD index has become more negative over the past fortnight. All climate model outlooks surveyed suggest a negative IOD may develop in the coming months. While model outlooks have low accuracy at this time of year and some caution should be taken with IOD outlooks, there is strong forecast consistency across international models. Outlook accuracy for the IOD begins to significantly improve during June. A negative IOD increases the chances of above average winter–spring rainfall for much of Australia. It also increases the chances of warmer days and nights for northern Australia.The 2021–22 La Niña event continues in the tropical Pacific. Some indicators of La Niña, including tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures and equatorial cloudiness near the Date Line, have seen little change over the past fortnight. However, beneath the surface of the tropical Pacific, waters have continued their gradual warming away from La Niña levels. The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) is easing slowly from its recent very high positive values, while trade winds have been close to average over the past fortnight.Most climate models surveyed by the Bureau indicate a return to neutral ENSO during the southern hemisphere winter. Two of the seven models maintain La Niña conditions through the southern winter. Even if La Niña eases, the forecast sea surface temperature pattern in the tropical Pacific still favours average to above average winter rainfall for eastern Australia.The Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO) has recently weakened. Most climate models indicate the MJO will briefly re-strengthen in just over a week's time over the western Pacific region. This would increase the chance of westerly wind anomalies in the western Pacific, which typically weakens La Niña events.The Southern Annular Mode (SAM) index is currently neutral and is forecast to remain neutral for the coming two weeks, and neutral-to-positive for early June. During autumn SAM typically has a weaker influence on Australian rainfall, but as we approach winter, positive SAM often has a drying influence for parts of south-west and south-east Australia.Climate change continues to influence Australian and global climate. Australia's climate has warmed by around 1.47 °C for the 1910–2020 period. Southern Australia has seen a reduction of 10–20% in cool season (April–October) rainfall in recent decades. There has also been a trend towards a greater proportion of rainfall from high intensity short duration rainfall events, especially across northern Australia.

Irrawong Reserve Flooded Track; March 7, 2022 - Photo by Joe Mills

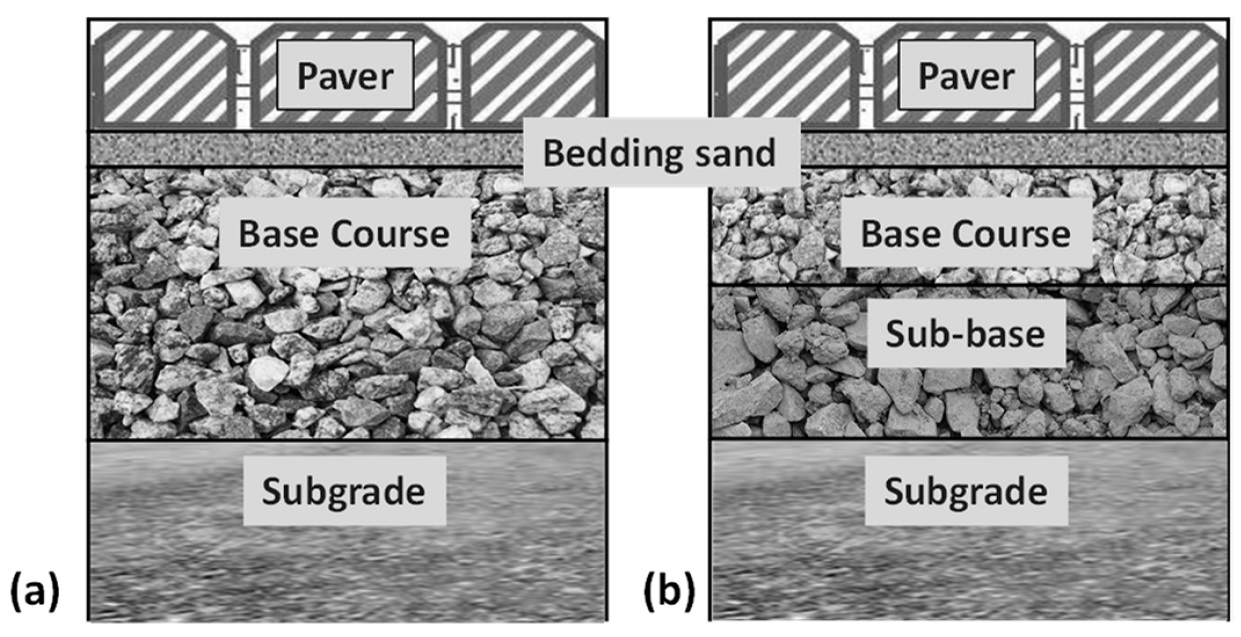

The Road To Success When It Comes To Mitigating Flood Disasters In Australia: Permeable Pavements And Roads

Fin Whale Songs Shed Light On Migration Patterns

.jpg?timestamp=1653510204717)

NSW’s World Class Climate Science Research Expands To WA

$10 Million To Boost Hardwood Timber Supplies

I am a climate scientist – and this is my plea to our newly elected politicians

The 2022 federal election will go down in history as Australia’s climate change election.

Australians resoundingly voted for ambition on climate action, something which has been missing for a decade under a Coalition government, along with integrity and gender equality.

I am a climate scientist who has spent the last two decades studying how our climate is changing and sharing our increasingly urgent and frightening findings with the world.

This is my plea to our newly elected politicians.

Dear Mr Albanese,

Congratulations on becoming the 31st Prime Minister of Australia.

If you wanted a clear mandate that the people are ready for ambitious and immediate climate action, then Australian voters certainly delivered that last Saturday. And how could they not?

Climate change is already impacting every inhabited part of our planet. Over the past few years Australians have suffered devastating bushfires and killer heat, catastrophic off-the-charts flooding, damage along our coasts from relentlessly rising seas, and the drawn-out hardship of droughts.

I spend every day looking at the data that tells us each of those climate extremes will keep getting worse.

Every tonne of carbon dioxide that we emit adds to global warming. And every fraction of a degree of further warming will cause climate impacts to become more frequent and more intense.

So I implore you and the Labor Party to govern like every decision, and every year, matters. Because it really, really does.

You’ll have a chance to prove on the world stage that the Australian Government is serious about climate action at the international climate conference, COP27, in Egypt later this year. You’ve got some work to do, because COP26 last year was an embarrassment for our nation.

We took little more than a three-word slogan to the conference in Glasgow, and came away from those negotiations as a climate villain. The world is waiting for Australia to increase our 2030 commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions at COP27.

Labor’s plan to reduce Australia’s emissions by 43% by 2030 is a good start. Though it will still put us on track to contribute to more than 2℃ of global warming (roughly twice the warming level we’re currently at).

Fortunately, the international climate negotiations framework is designed for ratcheting up ambition over time. This means Australia can still increase our 2030 ambition further and do our fair share to limit warming to 1.5℃, which would be a much safer pathway.

To The Greens,

Well done on your record-high vote. Yours was a campaign with a climate policy aligned to the science of what’s needed from Australia to keep the 1.5℃ warming goal alive. I hope you’re able to push from inside the house and the senate to make that a reality.

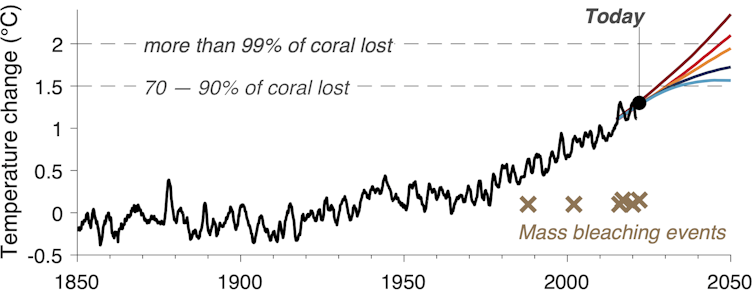

The strength of the Greens vote in Queensland perhaps shouldn’t have been a surprise to me. Nowhere else in Australia would the difference between 1.5℃ and 2℃ of warming be more apparent.

Earlier this year I wrote the saddest research proposal I ever have. A decade ago I could not have imagined having to pen anything like it, but here we are.

I study climate change and its impacts using corals that have grown in the ocean for centuries. These ancient corals faithfully record natural and human-caused changes in the environment around them.

But now those very coral records I use to study the climate are being destroyed by climate change. My proposal is to call for an urgent international effort to recover valuable scientific samples from coral reefs before they’re lost forever.

Amid all of the bluster of this election campaign, the Great Barrier Reef quietly bleached for the fourth time in the last seven years. As scientists we knew to expect this – at 1.5℃ of warming 90% of reefs will have been lost, and at 2℃ the wondrous Great Barrier Reef as we know it today will no longer exist.

This most recent bleaching event hits me hard. Maybe it hit Queensland voters hard this time too?

I wish the elected Greens well as they work inside Parliament to do what’s needed to give the reef a fighting chance.

To The Teal Independents,

Thank you for putting yourselves forward. For seeing the political status quo was not working for the people, and having the courage and conviction to provide Australians with an alternative.

It is well recognised that women need to be at the heart of climate action and solutions. Globally, female representation in politics has been shown to lead to stronger climate policies and better conservation outcomes.

It makes me proud and hopeful to see the Australian people have elected so many strong, talented, independent women to our parliament.

To Every Member Of Our New Parliament,

Its time to get to work. The federal government has squandered the last decade and made the job harder.

But fortunately, Australia’s state governments have made a start while federal government dallied. Australia’s states and territories adopted net-zero targets before the federal government, and together those commitments are estimated to represent defacto national emission reductions of around 37-42% by 2030.

Tackling the climate crisis is going to take a scale of ambition unlike anything we’ve ever seen before. But we have many solutions for decarbonising our energy and transport sectors ready to go. We will have to deploy these as quickly as possible to make the significant cuts to emissions needed this decade.

In future decades we will also need solutions that don’t yet exist. This includes technologies and enhanced nature-based solutions that will help us to draw carbon dioxide back out of the atmosphere. These need to be underpinned by an investment in fundamental science today, so we can forge a pathway to those as-yet-unknown solutions.

People in Australia, and our neighbours in the Pacific, also need your help. Climate extremes are going to worsen and we need investment in the climate science and modelling capabilities to be able to improve adaptation decisions at the local scale.

To paraphrase our new Prime Minister, together you can end the climate wars and seize the abundant opportunities that Australia has to be a climate leader.

Good luck.![]()

Nerilie Abram, Chief Investigator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes; Deputy Director for the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The election showed Australia’s huge appetite for stronger climate action. What levers can the new government pull?

As the polls closed on Saturday night, most election commentary focused on the dispiriting campaign where both major parties avoided any substantial division on policy issues and instead focused on negatively framing the opposing leader.

Even to many seasoned political minds, the most likely outcome seemed to be a reversal of the last parliament, with Labor winning enough seats to form a narrow majority, and one or two more seats falling to independents. As we all now know, the outcome was utterly different. The Liberals lost many of their crown jewels to climate challengers – teal independents and the Greens.

This means the new Labor government now has a different challenge on climate. Rather than trying to keep check on concessions to the cross-bench, Labor must now find ways to pursue more ambitious climate policies. Labor can’t pull the most effective lever available – a carbon price – after the Liberals successfully poisoned the well. But there are other ways to accelerate Australia’s shift to cleaner and greener, such as through public investment in large-scale solar and wind.

The next three years will be challenging economically and politically. But the transformation wrought by the election has opened up the possibility of a similar transformation of climate policy. With bold action, a bright future awaits.

Climate Proved Critical

Labor’s path to victory was unusual. The party taking government will do so despite its primary vote slumping to a postwar low, far below the level of routs seen in 1996 and 1975.

Outside Western Australia (where the result was driven largely by the success of the McGowan government’s Covid policy), Labor barely moved the dial. So far Labor has taken five seats from the Liberals (with some Labor-held seats still in doubt) while losing Fowler to an independent and Griffith to the Greens.

The big shock in this election was the loss of a string of formerly safe Liberal seats to Greens and “teal” independents. All of these candidates campaigned primarily on climate change, an issue the major parties, and most of the mainstream media had agreed should be put to one side as too dangerous and divisive.

During the campaign, the possibility of a hung parliament drew attention. In response, both major parties vowed (not very credibly) that they would never do a deal with Greens or independents to secure office. Realistically, it seemed possible that Labor might offer a slightly more ambitious program on climate policy in order to make minority government easier.

In retrospect, it’s clear that this type of analysis assumed Australia’s long-standing political pattern would continue: a two-party system, with a handful of cross-benchers occasionally playing the role of kingmaker. All of the media commentary leading up to the election took this for granted. The “teal” independents were seen as a possible threat to two or three urban Liberals and the Greens were, for all practical purposes, ignored.

What we have instead is a shock to this system. Australia now has a radically changed political scene in which the assumptions of the two-party system no longer apply. Even if Labor scrapes in with a majority, it is unlikely to be sustained at the next election, given the challenging economic circumstances the incoming government will face. As for the LNP, unless they can regain some of the seats lost to independents and Greens, they have almost no chance of forming a majority government at the next election, even with a big win over Labor in traditionally competitive seats.

Adapting To Political Change

Labor’s challenge now is to adapt to this new world. They will have to find ways of delivering what the electorate clearly wants on climate, after ruling out most of the obvious options in the course of the campaign. The new leader of the LNP will have the unenviable task of winning back lost Liberal heartlands while placating a party room dominated by climate denialists and coal fans.

Having ruled out a carbon price, Labor will need to be much more aggressive with the safeguard mechanism it inherits from the LNP. By itself, this won’t be nearly enough.

The real need is to promote rapid growth in large-scale solar and wind energy, and to push much harder on the transition to to electric vehicles. Some of this could be done through direct public investment, on the model of Queensland’s CleanCo, or through expanded use of concessional finance using the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the new Rewiring the Nation Corporation. The great political appeal of this approach is that all of these agencies are off-budget and therefore won’t count in measures of public debt, which is bound to grow in coming years due to pandemic spending.

Democracy, however imperfect, works through the possibility of renewal and change. What this election has shown us that the political system can change. Now comes the task of applying politics – the art of the possible – to the challenge of switching our energy systems from fossil fuels to clean power. It’s our best chance yet.

Correction: A previous version of this article mentioned Cowper rather than Fowler as the Labor seat lost to an independent.![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We identified the 63 animals most likely to go extinct by 2041. We can’t give up on them yet

It feels a bit strange to publish a paper that we want proved wrong – we have identified the 63 Australian birds, mammals, fish, frogs and reptiles most likely to go extinct in the next 20 years.

Australia’s extinction record is abysmal, and we felt the best way to stop it was to identify the species at greatest risk, as they require the most urgent action.

Leading up to this paper, we worked with conservation biologists and managers from around the country to publish research on the species closest to extinction within each broad group of animals. Birds and mammals came first, followed by fish, reptiles and frogs.

From these we identified the species that need immediate work. Our purpose is to try to ensure our predictions of extinction do not come true. But it won’t be easy.

Animals In Peril

The hardest to save will be five reptiles, four birds, four frogs, two mammals and one fish, for which there are no recent confirmed records of their continued existence.

Four are almost certainly extinct: the Christmas Island shrew, Kangaroo River Macquarie perch, northern gastric brooding frog and Victorian grassland earless dragon. For example, there have only ever been four records of the Christmas Island shrew since it was found in the 1930s, with the most recent in the 1980s.

While some of the 16 species feared extinct may still persist as small, undiscovered populations, none have been found, despite searching. But even for species like the Buff-breasted button-quail, those searching still hold out hope. It is certainly too soon to give up on them entirely.

We know the other 47 highly imperilled animals we looked at still survive, and we ought to be able to save them. These are made up of 21 fish, 12 birds, six mammals, four frogs and four reptiles.

For a start, if all their ranges were combined, they would fit in an area of a little over 4,000 square kilometres – a circle just 74km across.

Nearly half this area is already managed for conservation with less than a quarter of the species living on private land with no conservation management.

More than one-third of the highly imperilled taxa are fish, particularly a group called galaxiids, many of which are now confined to tiny streams in the headwaters of mountain rivers in southeastern Australia.

Genetic research suggests the different galaxiid fish species have been isolated for more than a million years. Most have been gobbled up by introduced trout in little more than a century. They have only been saved from extinction by waterfall barriers the trout cannot jump.

The other highly imperilled animals are scattered around the country or on offshore islands. Their ranges never overlap – even the three highly threatened King Island birds – a thornbill, a scrubtit and the orange-bellied parrot – use different habitats.

Sadly, it is still legal to clear King Island brown thornbill habitat, even though there are hardly any left.

It’s Not All Bad News

Thankfully, work has begun to save some of the species on our list. For a start, 17 are among the 100 species prioritised by the new national Threatened Species Strategy, with 15 of those, such as the Kroombit Tinkerfrog and the Bellinger River Turtle, recently getting new funding to support their conservation.

There is also action on the ground. After the devastating fires of 2019-20, big slugs of sediment were swept into streams when rain saturated the bare burnt hillsides, choking the habitats of freshwater fish.

In response, Victoria’s Snobs Creek hatchery is devoting resources to breeding some of the most affected native fish species in captivity. And in New South Wales, fences have been constructed to stop feral horses eroding the river banks.

Existing programs have also had wins, with more orange-bellied parrots returning from migration than ever. This species is one of seven we identified in our paper – three birds, two frogs and two turtles – to which captive breeding is contributing to conservation.

Ten species – six fish, one bird, one frog, one turtle and Gilbert’s potoroo – are also benefiting from being relocated to new habitats in safer locations.

For example, seven western ground parrots were moved from Cape Arid National Park to another site last April, and are doing so well that more will be moved there next month.

The wet seasons since the 2019-2020 fires have also helped some species. Regent honeyeaters, for example, are having their best year since 2017. Researcher Ross Crates, who has been studying the birds for years, says 100 birds have been found, there are 17 new fledglings and good flocks of wild and newly released captive birds being seen.

In fact, in some places the weather may have been too favourable. While good streamflows helped some galaxiids breed, invasive trout have also benefited. Surveys are underway to check if flows have been large enough to breach trout barriers.

There’s Work Still To Do

The fish hatchery program is only funded for three years, and a shortage of funds and skilled staff mean attempts to ensure populations are safe from trout has been patchy. And one cannot afford to be patchy when species are on the edge.

Some legislation also needs changing. In NSW, for example, freshwater fish are not included under the Biodiversity Conservation Act so are not eligible for Save Our Species funding or in the otherwise laudable commitment to zero extinctions in national parks.

Elsewhere, land clearing continues in scrub-tit and brown thornbill habitat on King Island – none of it necessary given so little native vegetation remains on the island.

Swift parrot habitat in Tasmania continues to be logged. The key reserve of the western swamp tortoise near Perth is surrounded by burgeoning development.

Also, the story we tell here is about the fate of Australian vertebrates. Many more Australian invertebrates are likely to be equally or even more threatened – but so far have largely been neglected.

Nevertheless, our work shows that no more vertebrates should be lost from Australia. The new Labor government has promised funds for recovery plans, koalas and crazy ants. Hopefully, money can also be found to prevent extinctions. There is no excuse for our predictions to come true.![]()

Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University; Hayley Geyle, PhD candidate, Charles Darwin University; John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University, and Mark Lintermans, Associate professor, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

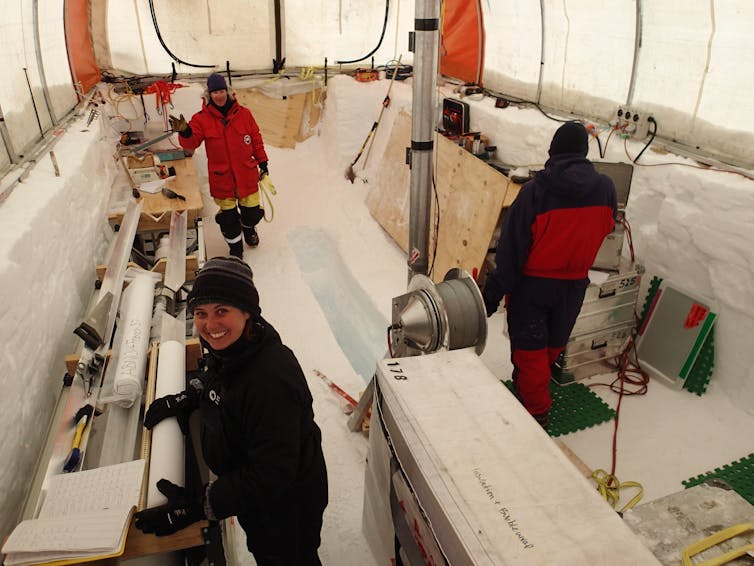

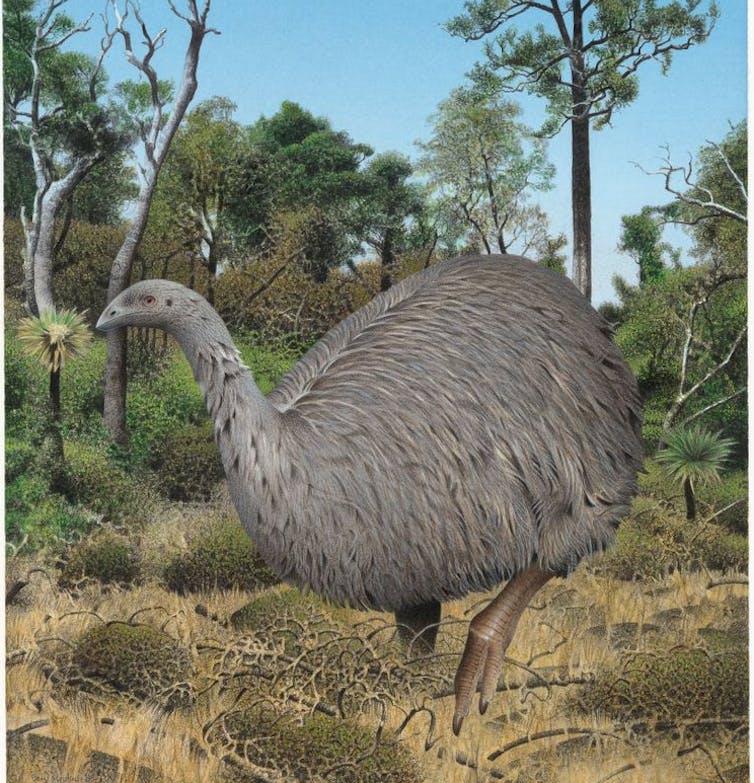

How did ancient moa survive the ice age – and what can they teach us about modern climate change?

One species of iconic moa was almost wiped out during the last ice age, according to recently published research. But a small population survived in a modest patch of forest at the bottom of New Zealand’s South Island, and rapidly spread back up its east coast once the climate began to warm.

What we’re learning about this remarkable survival story has implications for the way we can help living species adapt to climate change, and how we conserve and restore what may be important future habitats.

Growing to around 80kg and up to 1.8 metres tall, the eastern moa was one of the smaller of the nine extinct moa species. It got its name because its fossil bones have been found in sand dunes, swamps, caves and middens all along the eastern parts of the South Island – Southland, Otago, Canterbury and Marlborough.

Eastern moa became extinct from over-hunting and habitat destruction by humans, and possibly predation by kurī (dogs) and kiore (rats). But were eastern moa populations thriving when people arrived, or were they already in trouble due to ancient climate change?

Refuge In The South

Between 29,000 and 19,000 years ago, New Zealand was in the grip of an ice age. Glaciers were much larger and more widespread than they are today, and the distribution of grasslands and forests changed as the climate became colder and drier.

Current climate change threatens the survival of many different species, and the same was true of climate change thousands of years ago. The fossil record hints that the ice age was bad news for eastern moa, as few eastern moa bones from this period have been discovered.

But a lack of fossils doesn’t necessarily mean a species was doing it tough. Perhaps they just avoided the caves and swamps where we might eventually discover their bones.

To find out more, we sequenced DNA from dozens of eastern moa bones to see how their genetic diversity and population size changed over the past 30,000 years.

Large and healthy animal populations tend to have high genetic diversity, while low genetic diversity can be a sign that a population is in decline. We found eastern moa had very low genetic diversity immediately after the last ice age.

So eastern moa didn’t cope well with the ice age climate – but how did they manage to escape extinction? Our study provides a clue: their genetic diversity was highest in the very south of the South Island.

Preserving Future Habitats

During the ice age, grassland replaced wet podocarp forests in many areas. Those forests were the favourite habitat of eastern moa, possibly explaining why they struggled to survive.

Luckily for eastern moa, however, small pockets of forest survived in southern New Zealand during this time. While eastern moa disappeared from most of the country, our study suggests they clung on in remnant forest at the very south of the South Island.

Scientists have a special name for pockets of habitat where species can shelter and endure climate change – “refugia”.

Once the climate began to return to pre-ice age conditions, eastern moa were able to return to parts of the country they had formerly occupied. They bounced back so well that they were the most common moa in some parts of New Zealand at the time of Polynesian arrival.

Ancient DNA from fossils across the world has shown that refugia play an important role in allowing species to adapt to climate change. The story of eastern moa shows this is equally true in New Zealand.

Importantly, though, the eastern moa was affected differently to other moa, showing not all species are affected by climate change in the same way. Our study emphasises the need to conserve and restore a diverse range of habitats for the future, given the places where species are found today may be unsuitable for them in the very near future.

By ensuring that species can continue to find appropriate refugia, we may reduce the number that become extinct as a result of our global impacts on the climate.![]()

Nic Rawlence, Senior Lecturer in Ancient DNA, University of Otago; Alexander Verry, Postdoctoral Researcher, Université de Toulouse III – Paul Sabatier, and Kieren Mitchell, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Zoology, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The teals and Greens will turn up the heat on Labor’s climate policy. Here’s what to expect

Public concern over climate change was a clear factor in the election of Australia’s new Labor government. Incoming Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has committed to action on the issue, declaring on Saturday night: “Together we can take advantage of the opportunity for Australia to be a renewable energy superpower”.

Following Labor’s win, frontbencher Richard Marles said the new government would stick to the climate policies it took to the election. But it’s not yet clear if Labor can form a majority in the lower house, or will rely on support from the teal independents and Greens MPs – all of whom campaigned heavily for stronger climate action.

Independent Monique Ryan, a pro-climate teal MP projected to win Kooyong, on Sunday declared she would work with a minority Labor government if it went further on climate policy – including ramping up its 2030 emissions target. Other crossbenchers are likely to take a similar stance.

Labor’s climate and energy policies provide an important foundation for progress. But there are some sectors of the economy that still need far more focus. So what might the next parliament bring on climate action?

Towards Net-Zero

Saturday’s federal poll was the first where Australia had a national commitment to net-zero emissions. Whoever won government faced the task of normalising the target within government and across the economy, and accelerating rapid real-world emissions cuts.

Under the Morrison government, Australia pledged to reach net-zero by 2050. But our research, conducted with the CSIRO, has shown Australia could get there by 2035.

Such a target would be consistent with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5℃. It would also unlock our competitive advantage in a net-zero world – one where we can be a major player in exporting green energy and other low-emissions commodities.

Labor’s Powering Australia plan would reduce national greenhouse gas emissions by 43% by 2030, based on 2005 levels.

Analysis shows Labor’s proposed target, while far more ambitious than the previous government’s, is consistent with 2℃ of global warming. This is not yet in line with the Paris Agreement goal for “well below” 2℃ warming.

In minority government, Labor would come under pressure from the crossbench to adopt a stronger 2030 goal. Incumbent Warringah independent Zali Steggall, for example, is calling for at least 60% emissions reduction by 2030, and the Greens want even more.

Greens and teal independents are aligned with Labor on legislating Australia’s net-zero emissions target and reinvigorating institutions such as the Climate Change Authority.

A climate change bill, which Steggall and others championed in the last parliament, is more comprehensive. It would provide legislated timeframes for action on climate change, and implement a process ensuring targets are in line with the science.

The teals are likely to support Labor’s plans to standardise company reporting on matters such as climate risk and emissions. The move brings Australia in line with international best practice and will bring substantial benefits.

So too will Labor’s commitment to net-zero emissions in the federal public service by 2030, which will stimulate demand for low-carbon goods and services.

A gap to be addressed by the Labor government is creating roadmaps to net-zero for sectors and key regions. These could be integrated into Labor’s proposed National Reconstruction Fund, and should be devised in collaboration with the states and industry, as well as communities and workers affected by the global shift to net-zero.

The electricity sector produces about one-third of Australia’s emissions. The teals and Labor both went to the election aiming for renewable energy to comprise 80% of the electricity mix by 2030, which is about the pace of change needed.

Two major new Labor policies will be the basis for this:

Rewiring the Nation: includes A$20 billion in new electricity transmission infrastructure. If designed sensibly, the investment will unlock further private investment

Powering the Regions: investment in ultra low-cost solar banks, community batteries and improving energy efficiency in existing industries.

Yet more must be done – for example, more planning and new energy market rules. These should ensure the future energy system is no bigger than it needs to be, and that zero-emissions energy by 2035 is produced at least cost.

Spotlight On Industry

The Greens and teals want to halve emissions from Australia’s industrial sector by 2030. Labor’s current plans for industry aren’t that specific – and a crossbench with the balance of power is likely to pressure Labor in this area.

Labor’s policies on industry emissions comprise two main building blocks:

National Reconstruction Fund: $3 billion from the fund will aid industry’s low-carbon transition, including for manufacturing of green metals such as steel and aluminium

a revised “safeguard mechanism” requiring big polluters to reduce emissions.

Australia’s energy-intensive industries are already planning their response to shifting global markets. Labor must help these industries manage the change at the scale and pace required.

A Broader Transport Plan

In transport, Labor has proposed removing taxes and duties on lower-cost electric vehicles – making them cheaper – and adopting Australia’s first electric vehicle strategy.

The party has already committed to 75% of all new Commonwealth fleet cars being low- or no-emissions by 2025. The teals want 76% of all new vehicle sales to be electric by 2030. The Greens would also push for a far stronger electric vehicle policy.

Labor will also take steps to establish high-speed rail on Australia’s east coast. But its transport policy essentially ends there. It could do more on public and active transport, as well as decarbonising freight and aviation.

A broader transport strategy – especially involving infrastructure planning and investment – would help the transport sector move towards net-zero.

Strip Emissions From Buildings

Labor’s Housing Australia Future Fund is rightly focused on building new social and affordable housing, but is silent on net-zero. All governments have agreed to a zero-carbon buildings trajectory - now it’s time the federal government worked proactively with the states to achieve this.

The forthcoming review of the National Construction Code is a chance to bring in higher energy performance standards for new buildings.

But existing homes and business premises also need attention. A package of funds and regulations to drive electrification and energy performance gains there would bring lower energy bills and better health outcomes to many Australians.

A Sustainable Land Sector

Labor policies will support innovation in agriculture, including reducing methane emissions from livestock and other carbon farming opportunities. There will also be crossbench support for increased tree planting and soil carbon storage, as well as more spending on low-carbon agriculture practices and technologies.

Under Australia’s carbon credit scheme, landholders are granted carbon credits for activities such as retaining and growing vegetation. Serious questions have been raised over the integrity of the scheme, and dealing with these issues should be a priority for the new government.

Many of Australia’s natural systems, such as rivers and other ecosystems, are stressed or near failure. The land sector both contributes to this alarming trend and can be part of the solution, and will be badly affected if the problems are not addressed.

Many farmers have shifted their practices in response to climate and environmental threats. But the new government should create a roadmap to place the land sector in a wider environmental context. This would ensure the sector seizes investment opportunities and plays its part in a sustainable future.

Such a plan would also help Australian agriculture shore up its share of global food exports in a world increasingly demanding low-emissions products.

A Bigger, Bolder Vision Is Needed

The new Labor government has three years to steer Australia in a world that expects – and badly needs – every nation to take rapid climate action across the economy.

Australians have voted for a parliament with a stronger climate action agenda. More will be needed beyond the headline measures.

The onus is on all Australians help shape and implement these changes and ensure the nation not just survives, but thrives in a warmer world.![]()

Anna Skarbek, CEO, Climateworks Centre and Anna Malos, Australia - Country Lead, Climateworks Centre

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

After many false dawns, Australians finally voted for stronger climate action. Here’s why this election was different

Before the 2019 federal election, many people expected Australia would vote for faster climate action. That, of course, didn’t happen. But just three years later, the climate election arrived at last. The question is – what changed?

In short: Reality hit. Over the Morrison government’s term, the east coast was ravaged by the Black Summer of megafires. Then came the devastating floods. These disasters proved to us what scientists have long predicted: climate change isn’t a future threat, it’s here, now.

Since 2019, Australia has been under growing international pressure to do more on climate, given we have (correctly) been seen as a laggard. With Biden replacing Trump, our isolation became clear at the Glasgow summit. Polls showed the result: more and more Australians named climate change as an important issue.

Morrison shrugged off these concerns with a non-binding “goal” of net zero by 2050. As Saturday’s election showed, Australians saw through these half-hearted measures and voted accordingly.

Three Years Of Public Concern And International Pressure

Unexpected wins by the Greens in flood-affected seats along the Brisbane river gave a snapshot of voter sentiment. But earlier images of disaster – pensioners on rooftops in Lismore, overwhelmed firefighters and dying koalas – were hard to shake for many across the country.

In many ways, this election was a perfect storm for the Coalition. Since 2019, the impatience of the international community with Australian delay tactics was clear. Our Pacific neighbours had been consistently critical of Australia’s fossil fuel protectionism, regardless of promises of new funding for the region and the so-called Pacific step-up. Scott Morrison’s speech to a nearly empty room at the climate summit at Glasgow made our isolation clear.

Joe Biden’s victory in the US meant Australians increasingly saw our government as holdouts at the back of the international pack.

These changes came through in growing public concern. Polling in 2021 showed a substantial majority of Australians supported stronger emissions reduction commitments and a commitment to net zero emissions by 2050. Similarly, a YouGov poll in late 2021 found a majority of voters in every Australian seat wanted stronger action on climate change from the government. More than a quarter of voters rated climate change as the most important issue in determining their vote.

A Day Late, A Dollar Short

Despite the pressure and clear signals from voters, the Coalition went to the 2022 election with the emissions reduction targets announced by former Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2015. In addition, they had a non-binding ‘goal’ to reach net zero emissions by 2050, announced only after serious pressure and internal haggling.

The public was sceptical of this promise, due to efforts by segments of the Coalition to immediately walk this back. Outspoken Nationals senator Matt Canavan suggested on election eve the government would consider walking away from its own net zero commitment.

With Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce leading the internal opposition to net zero, there were concerns the Nationals could hold Australia to ransom on climate even after the election.

We Can’t Say It Was All Climate – But It Was A Key Factor

For the Coalition, navigating climate change during the election campaign proved far more challenging than in 2019.

Crucially, they found themselves fighting on multiple fronts. In blue ribbon seats in Sydney and Melbourne the Coalition was confronted and in many cases, beaten, by well-resourced ‘teal’ candidates. These independents appealed to a traditionally conservative electorate concerned about climate change but less likely to switch to a left-leaning party. Liberal candidates in these electorates promised more action on climate, but not much beyond that.

The Greens seemed an easier target for the government. Even so, the concentrated support for the third party in inner-city areas meant attacks by the government didn’t hurt.

Labor’s targets were more ambitious than the Coalition’s, which put them ahead for middle of the road voters concerned about climate change. But stung by their 2019 defeat, Labor actually went to the election with less ambitious emissions reductions targets than they had at the previous election: a 43% reduction by 2030. This made them a smaller target than in 2019 and able to avoid a Coalition scare campaign on costs to jobs and the economy. This might have cost them in inner-city seats like Brisbane’s Griffith with strong Greens campaigns. But it allowed them to hold seats with strong mining constituencies, like Hunter in NSW.

For the Coalition, the changing facts on the ground made it much harder to even run a scare campaign on the costs of climate action. The anticipated declining market for fossil fuels, significant and well-publicised government subsidies for the fossil fuel sector, the plummeting cost of renewables and the ballooning costs of climate change impacts all undermined the power of the narrative that Australia had to choose between economy and jobs or climate action.

Young voters registered to vote in record numbers, while we saw formidable ground campaigns from the Greens and teal independents.

Does This Spell The End Of Toxic Climate Politics?

If 2022 was the long-anticipated climate election, is it also the end of the toxic politics of climate change in Australia?

That depends on how the Coalition deals with the sting of this defeat. Will they seize the chance for a reset on climate? Or will we see a further shift to the right? Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce has already signalled the possibility of abandoning net zero. With moderate Liberal MPs now thin on the ground, there’s no guarantee of bipartisanship.

If the Coalition doubles down on climate delaying tactics, it would ensure its electoral irrelevance and make genuine climate action easier to achieve in Australia, one of the world’s last holdouts.

The Conversation’s #Settheagenda poll of more than 10,000 readers found more than 60% rated climate change as the top concern for them this election![]()

Matt McDonald, Associate Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Good timing and hard work: behind the election’s ‘Greenslide’

Kate Crowley, University of TasmaniaDuring Saturday’s election, 31.5% of the voters deserted the major parties, with a swag of female teal independents tipping Liberal MPs out of their heartland urban seats.

By contrast, the underestimated Greens had a sensational election, surprising many pundits with the strength of their support.

Even though their lower house vote increased by just 1.5% overall, their concentrated support saw the Greens gain two, potentially three, seats in Brisbane. Their traditional strength in the Senate is set to grow, potentially to an all time high of 12 senators. That would give them the balance of power.

So, how did the Greens do it? A combination of good timing and hard work. The climate election arrived at last, Scott Morrison was deeply unpopular, and the third party of Australian politics harnessed support it had been quietly building for years, especially in conservative-leaning Queensland. The only surprise is that many of us weren’t paying attention.

How Did The Greens Do It?

The Greens have hit a new high-water mark in the lower house with 11.9% of the vote. While good, it’s barely better than their 2010 best of 11.76%. Even so, because of the concentration of their support, their leader Adam Bandt will likely be joined by two other Greens in the lower house and possibly one more.

If Labor is unable to secure a majority, the Greens will likely support minority government. Australia’s only other Greenslide election was in 2010, when the Greens shared the balance of power in the lower house, and held it in the Senate. They were on board then with Labor’s reformist agenda and smoothed the passage of its bills.

As a result, the minority government was our most productive government in recent years.

Playing To Party Strengths

Are these results a shock? Not really. The party has played to its strengths by targeting specific seats at least since 2010, when they had the biggest swings to their party across the country. That was when 85% of us wanted climate action, before the climate wars set us back a decade.

Every election since has been about growing the Green vote across the country whilst expanding their inner-city strongholds, with very specific targeting of seats like Melbourne (Adam Bandt’s safe seat), Kooyong, Goldstein, Sydney, MacKellar, Warringah, Brisbane, Curtin and Grayndler.

In March 2021, the Greens released their election strategy in a largely neglected but extremely clear press release. They identified nine priority lower house seats, three additional Senate seats, and the balance of power in both houses as party goals. Notably, their campaigning efforts only overlapped the teal independents in the seat of Kooyong.

It looks like they’ll win the three Queensland seats of Ryan, Griffith and Brisbane from, respectively, the Liberals, Liberal National Party and Labor. Adam Bandt is now confident the Greens are “on the march” in the sunshine state. That’s quite a turnaround from 2019, where Queensland proved critical to Morrison’s miracle victory.

From The Ground Up

Crucially, Green politics is built from the ground up, beginning with participation at local council level and in state parliaments.

In 2020, the party won two state seats, following their gain of a seat on Brisbane City Council, and have continued to build on that momentum into this election with sophisticated grass roots campaigning.

This is a long term effort. In the seat of Ryan, for example, which takes in much of Brisbane’s leafy west and hinterland, the Greens have been slowly building up strength since reaching just under 19% in 2010. On Saturday, Elizabeth Watson-Brown wrested Ryan from the LNP with a primary vote of 31.1% and a two-party-preferred vote of 53.2%.

Traditionally, the Greens have posed more of a threat to Labor. While they have done most damage to the Liberals this election, Labor knows that it is not immune to this rising third force. Adam Bandt’s seat was solidly Labor for over one hundred years.

A Green Mandate

Gaining the balance of power in either or both houses would give the Greens greater leverage to introduce parts of their agenda. The election result was clearly a mandate for strengthened climate action, and they will seek that immediately.

What could this look like? Think of the key achievements of the Gillard minority Labor government, which included Green initiatives such as clean energy legislation, carbon pricing and the establishment of the Climate Change Authority, Renewable Energy Agency and Clean Energy Finance Corporation.

In 2022, Greens preferences to Labor across the country proved vital in unseating Liberal MPs. Despite Labor’s traditional discomfort with Green incursions into “their” seats, this trend is here to stay. Labor will have to deal with it. The Greens back much of the teal independents’ agenda of climate action and political integrity, making them collectively a powerful crossbench for change.

In his post election speech, Bandt made clear what he wants: a principled, stable Labor government, with an end to coal and gas, a just transition for displaced workers, and investment in climate resilience.

By neglecting environmental issues and failing to adequately tackle Australia’s growing inequality, both major parties have created the political space which Green politics fills.

Over the last decade, as climate-linked crises have intensified, public concern has soared. The economic cost of this neglect is already in the billions and climbing.

The Greens and teal independents will likely seek to end fossil fuel subsidies and to ban fossil industry donations to political parties. Had the political parties kept a distance from corrosive fossil fuel influence in the first place, they would not find Greens and teals replacing them.![]()

Kate Crowley, Adjunct Associate Professor, Public and Environmental Policy, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change is killing trees in Queensland’s tropical rainforests

In recent years, the Great Barrier Reef off Australia’s northeast coast has seen multiple events of mass coral bleaching as human-caused global warming has driven sustained high temperatures in the ocean.

Alongside the Coral Sea is another spectacular natural wonder: the rainforests of the World Heritage-listed wet tropics of Queensland.

It turns out the same climate change forces contributing to coral bleaching have also taken a toll on the trees that inhabit these majestic tropical rainforests.

In new research, we and our co-authors found that mortality rates among these trees have doubled since the mid 1980s, most likely due to warmer air with greater drying power. Like coral reefs, these trees provide essential structure, energy and nutrients to their diverse and celebrated ecosystems.

A 50-Year Record

Our study was based on 20 plots of trees in rainforests in northeast Queensland, which were created and monitored in a project begun in 1971 by a forest scientist named Geoff Stocker.

These plots were later incorporated into the Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area, and the monitoring has been carried on by CSIRO scientists based in Atherton, Queensland.

The plots are typically half a hectare (5,000m²) in size. In each plot the species and diameter of all trees larger than 10cm diameter at breast height were recorded.

The plots were revisited at intervals ranging from two to about five years. Tree diameters were recorded again, along with any new trees that had grown into the 10+cm size class, and any trees that had died.

Over the years, a few additional plots were initiated and contributed to our analyses. But these 20 provided a uniquely long record and formed the core of the dataset.

The Lifespan Of Trees

With many plots visited multiple times, and many tree species on each plot, we were able to estimate the average percentage of trees in each species that died in a given year (the “annual mortality rate”). We also examined how this rate has changed over time.

Until about the mid 1980s, the average annual mortality rate was around 1%. This means that any given year, each tree had about a one in 100 chance of dying.

This corresponds to an average tree lifespan of about 100 years.

However, beginning in the mid-1980s, the annual mortality rate began to increase. By the end of our dataset in 2019, the average annual mortality rate had doubled to 2%.

These results match a similar pattern in tree deaths in the Amazon rainforest at the same time, which suggests the increase in tropical tree mortality may be widespread.

A doubled annual mortality rate means that trees are only living half as long as they were, which means they are only storing carbon for half as long.

If the trend we observed is indicative of tropical forests in general, this could have big implications for the capacity of tropical forests to absorb and mitigate carbon dioxide emissions from human activity.

Thirsty Air

What caused the increasing mortality rates of the tropical trees?

A first guess might be temperature stress: the average air temperature of the plots has increased in recent decades.

However, we did not find that temperature directly caused the increasing mortality rates. Instead the mortality rates correlated better with the drying power or “thirstiness” of the air, which scientists call the “air vapour pressure deficit”.

You’re probably familiar with the idea of relative humidity. It tells you how much water vapour there is in the air, as a percentage of the maximum amount the air can hold.

When temperatures rise, the air’s capacity to hold water vapour increases exponentially. Each degree of warming lets the air hold about 7% more water vapour.

So if the air temperature increases, and the relative humidity stays the same, the air will have a bigger capacity to take on more water vapour.

To a first approximation, this is what has happened with global warming. Air temperature has increased, relative humidity has remained approximately constant, and the air has become thirstier.

This means the drying power of the atmosphere (or “evaporative demand”) has increased. This is what we found best explained the increasing mortality rates in Australian tropical trees.

What’s Next

If greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, both the air temperature and the air vapour pressure deficit will continue to increase. Our results suggest that in all likelihood this will cause a further acceleration in the increasing mortality rates of tropical rainforest trees.

Like coral reefs, tropical rainforests may then experience relatively rapid changes in species composition, biodiversity, and three-dimensional structure, threatening these prized Australian ecosystems as we know them. The best way to mitigate this threat is to urgently reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, in order to slow global warming and eventually stabilise the global climate system. ![]()

Lucas Cernusak, Associate professor, James Cook University and Susan Laurance, Professor, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

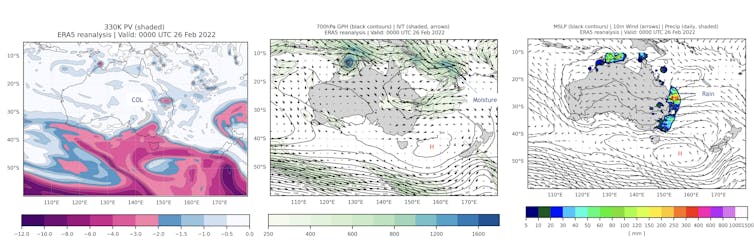

Planetary waves, cut-off lows and blocking highs: what’s behind record floods across the Southern Hemisphere?

Tess Parker, Monash University and Michael Barnes, Monash UniversityFrom February to May 2022, many places in Queensland, New South Wales and Western Australia have seen record-breaking daily and monthly rainfall. Repeated periods of persistent and intense rain have caused devastating and widespread floods.

In Queensland and New South Wales alone, the floods and storms caused an estimated AU$3.35 billion in insured losses, making these the costliest floods in Australia’s history and the fifth most costly natural disaster. More than 20 people lost their lives.

Similar events have occurred around the Southern Hemisphere. Brazil was hit with heavy rain, flash flooding and landslides in February and March, killing more than 200 people. In April and May it was South Africa’s turn, as torrential downpours destroyed homes and infrastructure, resulting in some 400 deaths and US$1.5 billion in property damage.

Behind most of these intense rain events lies a particular combination of weather conditions: a “cut-off low” over the coast, pinned in place by a “blocking high” out to sea. This configuration itself is not uncommon, but this year’s repeated events and their high impact have been unusual.

What Caused The Extreme Rainfall This Year?

Outside the tropics, weather is mainly driven by what are called “Rossby waves” or “planetary waves”. These are wiggles in the jet stream, which is a band of strong winds in the upper atmosphere that goes right around the globe.

When winds are displaced to the north or south by mountains or weather systems, they can push part of the jet stream out of its normal position. This undulation in the jet stream is a Rossby wave.

Rossby waves usually then move eastward, guided by the jet stream. Under the right conditions the waves can amplify and break, just like ocean waves at the shore.

When this happens, the breaking wave can form a region of high pressure air at ground level, which may stay in one place for some time. This high-pressure region can in turn cause other weather systems (such as low-pressure systems bearing rain) to stall over one location.

Stalled weather systems that stay put for a long time can lead to prolonged downpours, but also to lengthy heat waves.

During the flooding on the east coast of Australia, an amplifying Rossby wave formed a high-pressure system over the Tasman Sea, as well as a low-pressure region in the upper atmosphere known as a “cut-off low”.

This setup provided the two ingredients required for rain: a supply of moisture, in the form of easterly winds around the high carrying moist air from the ocean to the land; and a mechanism to lift that moisture, provided by the presence of the cut-off low. As the low moved between southern Queensland and northern New South Wales, so did the rain.

The same fingerprint was also seen during the floods in South Africa and Brazil. For the flood events in south-west Western Australia, the moist onshore flow was boosted by a low between the coast and the high to the west over the Indian Ocean.

What Does Climate Change Mean For These Events?

One of the most difficult challenges for atmospheric scientists is understanding how global warming will change the weather at the regional scale.

Weather forecasts are a crucial tool for mitigating the effects of extreme weather, providing predictions of such events up to a week in advance. Accurate forecasts are vital to afford critical time for response mobilisation, such as warnings, evacuations and deployment of emergency services.

At present, the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, a measure of sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, is in the La Niña phase for the second year in a row. La Niña is associated with rainier-than-normal conditions over north-eastern Australia, south-eastern Africa and northern Brazil.

In addition, global warming is likely to lead to more intense rainfall because warmer air can hold more moisture. However, we still have a lot to learn about where that rain is likely to fall, and how frequent and intense the rainfall is likely to be.

To understand how extreme weather like this year’s Southern Hemisphere deluges will change as the climate warms, we must understand the underlying physical processes responsible for their development.

At present, different climate models show different things about what climate change means for Rossby waves and wave breaking. The models don’t yet have high enough resolution to explicitly include some of the detailed physical processes related to rainfall, jet streams and Rossby waves.

While the models agree that climate change will alter the position and speed of the jet stream winds, they disagree about what will happen to Rossby waves. Investment in the research necessary to answer these questions is therefore imperative.![]()

Tess Parker, Research Fellow, Monash University and Michael Barnes, Research Fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The election shows the conservative culture war on climate change could be nearing its end

Matthew Hornsey, The University of Queensland; Cassandra Chapman, The University of Queensland, and Jacquelyn Humphrey, The University of QueenslandFormer Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s shock loss to an independent running on a climate action platform wasn’t a fluke event. “Teal” independents have ousted five of Frydenberg’s colleagues, all harvesting votes from conservative heartland and all calling for more action on climate change.

Amid the wreckage, Frydenberg was asked whether the Liberals needed to rethink their policies on climate change. His response – that he didn’t believe Australia had been “well served by the culture wars on climate change” – deserves analysis.

Who started the culture war on climate change? And are we nearing its demise? Our research, published this month, provides some clues.

We found that approximately a third of Australians – predominantly conservatives – maintain that climate change is not caused by human activity, but rather by natural environmental fluctuations.

Crucially, however, we also found signs the conservative position against climate science has weakened over time. The election results reinforce this message, with a projection of six teal independents nationwide and two new Green seats in Queensland.

As such, this election may well be remembered as the first cracks in the dam wall of conservative-led climate scepticism.

How Climate Science Became Political

Historically, science has been excluded from “left” and “right” political culture wars. Science, it was agreed, was best left to the scientists.

For example, shortly after definitive evidence emerged that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were eroding the ozone layer, an international treaty committed to phasing them out. The response was swift and apolitical: in the 1980s you couldn’t tell how someone voted from knowing their stance on CFCs.