Inbox and environment news: Issue 541

June 5 -11, 2022: Issue 541

World Environment Day 2022: June 5th + World Oceans Day 2022: June 7th

Long Reef Slump

Sonar Used To Locate Underwater Dangers On Hawkesbury

The NSW EPA has announced an advanced sonar program has started surveying NSW rivers for hazardous submerged debris across the State following this year’s destructive floods with shoreline clean-up crews coming in behind to remove those debris once located.

The NSW EPA has announced an advanced sonar program has started surveying NSW rivers for hazardous submerged debris across the State following this year’s destructive floods with shoreline clean-up crews coming in behind to remove those debris once located.Chemical Clean Out: June 2022 At Mona Vale

Plastic Bag Ban Commences From June 1st In NSW

- single-use plastic straws, stirrers, cutlery, plates, bowls and cotton buds

- expanded polystyrene food ware and cups

- rinse-off personal care products containing plastic microbeads.

Northern Beaches Surfrider Foundation members Brendan Donohoe (middle) with Jesse and Rowan Hanley - who organise Beach Clean Upsand have campaigned for a plastics ban in NSW. A J Guesdon photo.

Sydney Wildlife Rescue And Care Course: June 2022

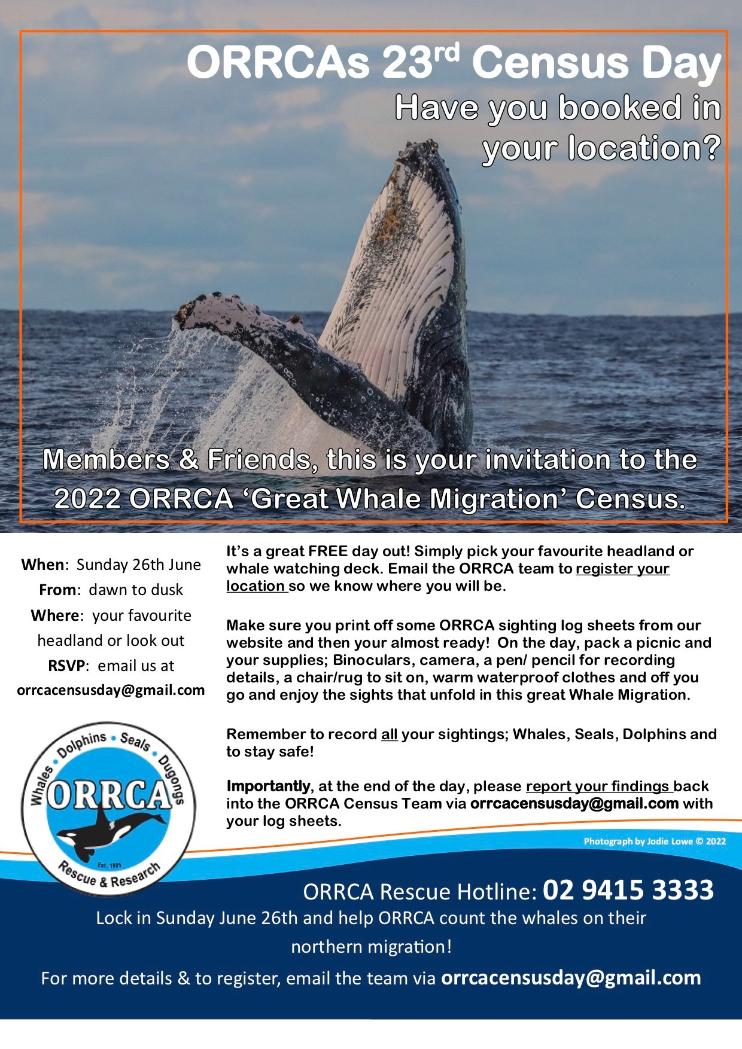

Living Ocean Traditional Welcome To Country For The Southern Humpback Whale Migration: June 24

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Five Year Extension To Wood Supply Agreements

NSW Planning Department’s Latest Coal Mine Recommendation

NSW Must Deliver Robust, Climate-Ready Water Resource Plans As A Matter Of Urgency

New Virus Variant Threatens The Health Of Bees Worldwide

Dendrobium Mine Extension Project: Have Your Say (Again)

Political Stitch Up Over Dendrobium Abandons Community, Climate, And Water, Favours Coal Mining Company Residents State

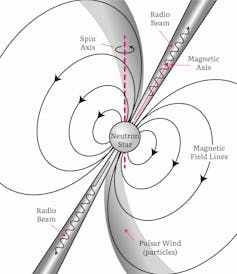

Deep Sea Ears Map Migration Of Fin Whales

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

The ultra-polluting Scarborough-Pluto gas project could blow through Labor’s climate target – and it just got the green light

The Albanese government has this week thrown its support behind what’ll be one of Australia’s most polluting developments: the Scarborough-Pluto gas project in Western Australia.

Our analysis last year found the full Scarborough-Pluto project will emit almost 1.4 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases over its lifetime. That’s over three times Australia’s current annual emissions, and around 14 times WA’s annual emissions.

We calculate that the emissions from this project and all of its related activities will add about 41 megatonnes per year to Australia’s national emissions by 2030. That is a materially relevant number – it’s nearly 7% of our emissions in 2005, which is the year we use as a baseline for emissions targets.

To put it another way, it’s nearly twice as much as the emissions avoided by all the rooftop solar panels in Australia each year.

It comes as the new minister for climate and energy Chris Bowen yesterday reiterated his commitment to Labor’s 2030 climate target of reducing Australia’s emissions by 43% on 2005 levels.

But as Bowen doubled down on this vow, the new resources minister, Madeleine King, was reassuring the gas giants their climate-wrecking projects were here to stay.

Woodside’s Calculations Don’t Tell The Full Story

Ours was the first study that put together the total greenhouse gas implications of the entire Scarborough-Pluto project.

The project is made up of the Scarborough gasfield (located offshore) and the Pluto processing plant (on land).

Woodside Energy projects the offshore Scarborough gasfield expansion will release 878 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent over its lifetime. This projection is derived from its federal government approval assessment.

But this doesn’t tell the full story. State government approvals looked at emissions from the entire project, including the Pluto processing plant and its extension.

We put state and federal numbers together for the first time to find emissions for the whole Scarborough-Pluto project would be nearly 60% larger than Woodside’s reported projections for Scarborough alone.

In a statement to The Conversation, a Woodside Energy spokesperson said its “data is in accepted regulatory approval documents”, which notes that a Environmental Resources Management study from 2020 examined the emissions intensity of Scarborough gas, processed through Pluto, and then used to generate electricity in selected markets.

Our own work, along with a CSIRO report for Woodside, debunks the argument that LNG from this project will reduce emissions globally. The bottom line is that adding the amount of LNG planned from this project is likely to slow down decarbonization in key markets and add significantly to global emissions.

Woodside’s Scarborough-Pluto project is just one of many fossil fuel projects in the pipeline. Overall there are 114.

We added up the emissions of 46 liquefied natural gas and coal mines officially classified as “new projects” by the federal government. By 2030 these would add at least 8-10% to Australia’s projected emissions for 2030.

Including the Scarborough-Pluto project and all its related activities in this mix would add 15-17% to Australia’s 2030 emissions.

We Can’t Lower Emissions Using Gas

It’s difficult to see how Labor can both embrace the gas industry and reduce emissions to its target of 43% by 2030. It could try using controversial carbon offset schemes, but this wouldn’t go down well with the public nor with Labor’s emphasis on restoring integrity and trust in government.

While Australia’s domestic emissions account for 2% of global emissions, we calculate that adding emissions from our fossil fuel exports would increase our total greenhouse gas footprint to around 4-5% of global emissions. And those exports, thanks to the gas (and coal) industry, look set to balloon.

It’s clear the Scarborough-Pluto project is not compatible with the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5℃ this century.

Last year the International Energy Agency (IEA) released a roadmap for bringing global emissions to net zero. It found gas use would need to depend on a large roll-out of carbon capture and storage technologies: 14% of total energy supplied by gas would be captured and stored in 2040, increasing to 30% by 2050.

But carbon capture and storage is flawed. WA’s Gorgon gas project’s attempt at using the technology is testament to that. Gorgon has blown its budget and fallen short of its targets by around 50%.

It should be noted there are no current or proposed plans to utilise carbon capture and storage for Scarborough.

The Woodside spokesperson says IEA modelling shows there’s an important role for oil, gas and hydrogen in the world’s future.

Woodside argues that in the IEA’s net zero emissions scenario, the forecast cumulative global investment in oil and gas needed to meet the world’s energy needs is approximately US$10 trillion by 2050. But this obscures the fact new and additional fossil fuel infrastructure at the scale of Scarborough-Pluto expansions is not consistent with net zero emissions.

The IEA modelling also shows a rapid decline of demand for gas over the next five to ten years. Its net zero roadmap projects the potential for a rapid collapse in Australia’s major liquefied natural gas markets (South Korea, Japan, China) by the mid-2020s, as they implement Paris compatible climate targets.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced the whole world to rethink its relationship with gas, as prices rise here and overseas largely due to sanctions on Russia’s supply.

Woodside claims the shift away from Russian energy sources strengthens the case for Browse – a proposed A$30 billion gas development north of Broome, WA. But phasing out gas, in fact all fossil fuels, is not only a climate question. It is a security matter.

We Must Fully Embrace Renewables

Those who will now fully embrace renewables as a way to ensure energy independence will also be at the forefront of the inevitable global energy transformation, gaining competitive advantage.

And Australia, with such vast renewables resources, could be a world leader in green hydrogen exports.

Gas simply has no place in the fight to stop global warming beyond 1.5℃ this century. The big question is whether the Albanese government, if it wants to be taken seriously on climate change, will take that on board.

Right now, given the high-profile intervention from the resources minister providing “absolute” support for Woodside and gas developments, the jury unfortunately is well and truly out.![]()

Bill Hare, Adjunct Professor, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Caring for Country means tackling the climate crisis with Indigenous leadership: 3 things the new government must do

Bhiamie Williamson, Australian National UniversityThe election of a new Australian government offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity to promote the self-determination of Indigenous peoples to Care for Country.

Indigenous peoples have been leading Australia’s response to the climate crisis, such as by harbouring deep-time knowledge of the land and water, and managing the land through cultural burning. Yet climate change continues to erode our cultural heritage and threatens our ongoing connection to Country.

In its pre-election budget, the former Coalition government committed A$636 million to expand the Indigenous ranger program and Indigenous Protected Areas. The new parliament, with its greater hunger for climate action, can think even bigger and create a new, exciting and just agenda.

I have previously written about ways everyday Australians can support Indigenous people to heal Country. Here, I lay out practical steps and big ideas that expand the realms of possibility in this new parliamentary era.

What Indigenous People Have At Stake

Climate change and industrial development - dams, land clearing, mining, urban development and more - are bringing more native wildlife to the edge of extinction and are degrading the environment they, and we, rely on.

This environmental damage impacts the ability of Indigenous peoples to remain connected to Country, as our ancestors have before us.

Compounding this is the disproportionate impact bushfires, floods and other disasters have on Indigenous peoples.

For example, 6.2% of those affected by the recent flooding in regional areas outside Sydney were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, despite making up just 3.3% of the general population.

Adding to this is damage feral animals, invasive weeds, and unmanaged fire inflict on biodiversity, cultural values, and the overall health of ecosystems.

These crises disrupt Indigenous peoples ways of life. They degrade or destroy our cultural heritage and natural resources such as plants, grasses, native timber, and clean running water, which provide a basis for our peoples to practice culture.

In this way, Indigenous peoples have much at stake in a changing climate, perhaps more so than others, and in ways that are different to all others.

Caring For Country

Indigenous peoples have enormous capacity to make Australia more resilient to the climate crisis, as we have an extraordinary database of cultural knowledge reaching back to ancient climate change events.

In Victoria, Gunditjmara people have kept knowledge of Australia’s last volcanic eruption, estimated to have occurred 37,000 years ago. While off the coast of Western Australia, Aboriginal groups maintain knowledge of camps their ancestors occupied off the continental shelf.

Our peoples continue to draw on and apply this long history of knowledge to manage land and seascapes today.

Contemporary Caring for Country programs – ranger groups, Indigenous Protected Areas, and co-management arrangements – are now key elements in defending Australia’s biodiversity from further degradartion.

This includes developing extensive management plans to protect native species, managing invasive weeds and feral animals, and exploring economic development opportunities such as renewable energy investment.

Aboriginal ranger groups have also had a demonstrable impact in reducing bushfires and protecting biodiversity throughout northern and central Australia using cultural burning. Indeed, Indigenous fire management here is one of Australia’s most effective emissions reduction practices.

And during the 2019-2020 bushfires in western Victoria, Gunditjmara people and local fire authorities worked together to respond to a large bushfire, safeguarding both Gunditjmara and non-Indigenous values.

Where To Now?

The significant increase in funding for Caring for Country programs in the pre-election budget was welcomed by all sides of politics. Now, with a new Labor government, we must ensure this immense and generational opportunity is not squandered.

Caring for Country programs are complex operations. What works for one community, at one point in time, may not work in others. Yet the programs I’ve observed generally share three common pillars:

Environmental management: restoring ecosystems for greater biodiversity and to mitigate against threats

Community development: ensuring we have the infrastructure, skills, capabilities, and funding to implement projects

Indigenous governance: supporting and resourcing groups to come together, discuss important matters, and make and enact decisions

Expanding Caring for Country programs requires the knowledge and skills of these three interrelated pillars. This has traditionally been the strong point of a properly resourced federal environment department, one with collegial relationships with front-line Indigenous land managers.

This work also requires a “two-toolbox” approach: harnessing Indigenous and western science, and working together respectfully and collaboratively. These skills should be front of mind for a federal public service seeking to support Caring for Country.

Time To Think Big

As people uniquely impacted by – and with demonstrable knowledge and practices to mitigate against – climate change, Indigenous peoples must be at the table in all climate change talks.

We cannot allow climate change mitigation and adaptation to become another colonial process of dispossession and disempowerment.

Everyone stands to lose when Indigenous people are locked out of climate change discussions including, for instance, in recent reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Excluding our voices will inevitably mean opportunities will pass us by, or negatively impact us, even when we’re expected to contribute our knowledge and skills to support larger climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Here are three practical ways the new parliament can address climate change and promote Indigenous self-determination and development simulatenously:

Formally recognising Caring for Country as a key pillar in Australia’s response to the climate crisis through policies and legislation

Committing all Australian national parks and protected areas to have some form of joint management with Traditional Owners within ten years

Drawing these and other opportunities together in a National Indigenous Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Strategy.

These changes will take time. But supporting them will lay a foundation of stone and establish a generation of unbridled opportunity.

The door is open for an ambitious parliament to consider climate change and justice as tandem pursuits. Doing so opens opportunities to address climate change, heal Country and, perhaps most importantly, heal the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. ![]()

Bhiamie Williamson, Research Associate & PhD Candidate, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

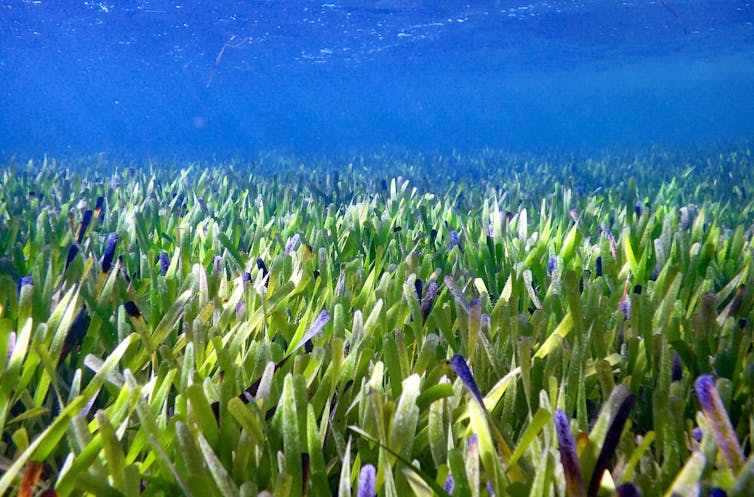

Meet the world’s largest plant: a single seagrass clone stretching 180 km in Western Australia’s Shark Bay

Next time you go diving or snorkelling, have a close look at those wondrously long, bright green ribbons, waving with the ebb and flow of water. They are seagrasses – marine plants which produce flowers, fruit, and seedlings annually, like their land-based relatives.

These underwater seagrass meadows grow in two ways: by sexual reproduction, which helps them generate new gene combinations and genetic diversity, and also by extending their rhizomes, the underground stems from which roots and shoots emerge.

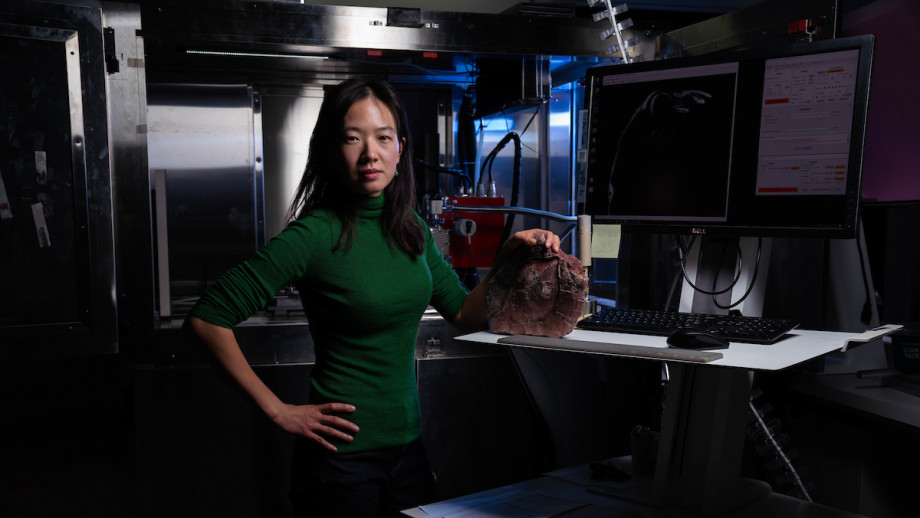

To find out how many different individual plants are growing in a seagrass meadow, you have to test their DNA. We did this for meadows of ribbon weed seagrass called Posidonia australis in the shallow sun-drenched waters of the Shark Bay World Heritage Area, in Western Australia.

The result blew us away: it was all one plant. One single plant has expanded over a stretch of 180 km making it the largest known plant on Earth.

We collected shoot samples from ten seagrass meadows from across Shark Bay, in waters where the salt levels range from normal ocean salinity to almost twice as salty. In all samples, we studied 18,000 genetic markers to show that 200 km² of ribbon weed meadows expanded from a single, colonising seedling.

How Did It Evolve?

What makes this seagrass plant unique from others, other than its enormous size, is that it has twice as many chromosomes as its relatives. This makes it what scientists call a “polyploid”.

Most of the time, a seagrass seedling will inherit half the genome of each of its parents. Polyploids, however, carry the entire genome of each of their parents.

There are many polyploid plant species, such as potatoes, canola, and bananas. In nature they often reside in places with extreme environmental conditions.

Polyploids are often sterile, but can continue to grow indefinitely if left undisturbed. This seagrass has done just that.

How Old Is This Plant?

The sandy dunes of Shark Bay flooded some 8,500 years ago, when the sea level rose after the last ice age. Over the following millennia, the expanding seagrass meadows made shallow coastal banks and sills through creating and capturing sediment, which made the water saltier.

There is also a lot of light in the waters of Shark Bay, as well as low levels of nutrients and large temperature fluctuations. Despite this hostile environment, the plant has been able to thrive and adapt.

It is challenging to determine the exact age of a seagrass meadow, but we estimate the Shark Bay plant is around 4,500 years old, based on its size and growth rate.

Other huge plants have been reported in both marine and land systems, such as a 6,000-tonne quaking aspen in Utah, but this seagrass appears to be the largest to date.

Other huge seagrass plants have also been found, including a closely related Mediterranean seagrass called Posidonia oceanica, which covers more than 15 km and may be around 100,000 years old.

Why Does This Matter?

In the summer of 2010–11, a severe heatwave hit land and sea ecosystems along the Western Australian coastline.

Shark Bay’s seagrass meadows suffered widespread damage in the heatwave. Yet the ribbon weed meadows have started to recover.

This is somewhat surprising, as this seagrass does not appear to reproduce sexually – which would normally be the best way to adapt to changing conditions.

We have observed seagrass flowers in the Shark Bay meadows, which indicates the seagrass are sexually active, but their fruits (the outcome of successful seagrass sex) are rarely seen.

Our single plant may in fact be sterile. This makes its success in the variable waters of Shark Bay quite a conundrum: plants that don’t have sex tend to also have low levels of genetic diversity, which should reduce their ability to deal with changing environments.

However, we suspect that our seagrass in Shark Bay has genes that are extremely well-suited to its local, but variable environment, and perhaps that is why it does not need to have sex to be successful.

Even without successful flowering and seed production, the giant plant appears to be very resilient. It experiences a wide range of water temperatures (from 17℃ to 30℃ in some years) and salt levels.

Despite these variable conditions and the high light levels (which are typically stressful for seagrass), the plant can maintain its physiological processes and thrive. So how does it cope?

We hypothesize that this plant has a small number of somatic mutations (minor genetic changes that are not passed on to offspring) across its 180 km range that help it persist under local conditions.

However, this is just a hunch and we are tackling this hypothesis experimentally. We have set up a series of experiments in Shark Bay to really understand how the plant survives and thrives under such variable conditions.

The Future Of Seagrass

Seagrasses protect our coasts from storm damage, store large amounts of carbon, and provide habitat for a great diversity of wildlife. Conserving and also restoring seagrass meadows has a vital role in climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Seagrasses are not immune from climate change impacts: warming temperatures, ocean acidification and extreme weather events are a significant challenge for them.

However, the detailed picture we now have of the great resilience of the giant seagrass of Shark Bay provides us hope they will be around for many years to come, especially if serious action is taken on climate change.![]()

Elizabeth Sinclair, Senior Research Fellow, The University of Western Australia; Gary Kendrick, Winthrop Professor, Oceans Institute, The University of Western Australia; Jane Edgeloe, PhD candidate (Marine Biology), The University of Western Australia, and Martin Breed, Senior Lecturer in Biology, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wild animals are evolving faster than anybody thought

How fast is evolution? In adaptive evolution, natural selection causes genetic changes in traits that favour the survival and reproduction of individual organisms.

Although Charles Darwin thought the process occurred over geological timescales, we have seen examples of dramatic adaptive evolution over only a handful of generations. The peppered moth changed colour in response to air pollution, poaching has driven some elephants to lose their tusks and fish have evolved resistance to toxic chemicals.

However, it is still hard to tell how fast adaptive evolution is currently occurring. We also don’t know whether it has a hand in the fate of populations challenged by environmental change.

To measure the speed of adaptive evolution in the wild, we studied 19 populations of birds and mammals over several decades. We found they were evolving at twice to four times the speed suggested by earlier work. This shows adaptive evolution may play an important role in how the traits and populations of wild animals change over relatively short periods of time.

The Tools Of The Evolutionary Biologist: Maths And Binoculars

How do we measure how fast adaptive evolution is occurring? According to the “fundamental theorem of natural selection”, the amount of genetic difference in “fitness” to survive and reproduce among individuals across a population also corresponds to the population’s rate of adaptive evolution.

The “fundamental theorem” has been known for 90 years, but it has been difficult to apply in practice. Attempts to use the theorem in wild populations have been rare, and are plagued by statistical problems.

We worked with 27 research institutions to assemble data from 19 wild populations that have been monitored for long periods of time, some since the 1950s. Generations of researchers collected information about the birth, mating, reproduction and death of each individual in these populations.

Together, those data represent around 250,000 animals and 2.6 million hours of field work. The investment may look outrageous, but the data have already been used in thousands of scientific studies and will be used again.

Statistics To The Rescue

We then used quantitative genetic models to apply the “fundamental theorem” to each population. Instead of keeping track of changes in every gene, quantitative genetics uses statistics to capture the net effect emerging from changes in thousands of genes.

We also developed a new statistical method that fits the data better than previous models. Our method captures two key properties of how survival and reproduction are unevenly distributed across populations in the wild.

First, most individuals die before breeding, meaning there are a lot of entries in the “zero offspring” column of the lifetime reproduction record.

Second, whereas most breeders have only a few offspring, some have a disproportionately high number, leading to an asymmetric distribution.

The Rate Of Evolution

Among our 19 populations, we found that, on average, genetic change in response to selection was responsible for an 18.5% increase per generation in the ability of individuals to survive and reproduce.

This means offspring are on average 18.5% “better” than their parents. To put it another way, an average population could survive an 18.5% deterioration in the quality of its environment. (This may change if genetic response to selection is not the only force at play; more on that below.)

Given these rates, we found adaptive evolution could explain most recent changes in wild animal traits (such as size or reproductive timing). Other mechanisms are important too, but this is strong evidence evolution should be considered alongside other explanations.

An Exciting Result For An Uncertain Future

What does this mean for the future? At a time when natural environments are changing dramatically all over the world, due to climate change and other forces, will evolution help animals adapt?

Unfortunately, that is where things get tricky. Our research estimated only genetic changes due to natural selection, but in the context of climate change there are other forces at play.

First, there are other evolutionary forces (such as mutations, random chance and migration).

Second, the environmental change itself is likely a more important driver of population demographics than genetic change. If the environment keeps deteriorating, theory tells us that adaptive evolution will generally be unable to fully compensate.

Finally, adaptive evolution can itself change the environment experienced by future generations. In particular, when individuals compete with each other for a resource (such as food, territory or mates), any genetic improvement will lead to more competition in the population.

Our work alone is insufficient to draw predictions. However, it shows that evolution cannot be discounted if we want to accurately predict the near future of animal populations.

Despite the practical challenges, we are thrilled to witness Darwinian evolution, a process once thought exceedingly slow, acting observably in our lifetimes.![]()

Timothée Bonnet, Researcher in evolutionary biology (DECRA fellow), Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s biggest carbon emitter buckles before Mike Cannon-Brookes – so what now for AGL’s other shareholders?

Mark Humphery-Jenner, UNSW SydneyBillionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes has won a major battle against Australia’s biggest energy company, AGL Energy, thwarting its plan to split up the company’s coal-heavy generation and power distribution assets.

AGL’s board announced it was dumping its demerger proposal this morning. Heads have rolled too. Chief executive Graeme Hunt, chairman Peter Botten and non-executive director Jacqueline Hey have resigned. Another director, Diane Smith-Gander, will go in August.

But it remains to be seen if Cannon-Brookes and his allies can achieve their ultimate goal – to force AGL, Australia’s biggest carbon emitter, to accelerate the closure of its coal and gas-fired power stations.

Cannon-Brookes’ Hard Campaign

The plan to split AGL was due to go to a shareholders vote in mid-June, at which it required 75% support.

Earlier this year, Cannon Brookes – Australia’s third-richest person – led two unsuccessful takeover bids for AGL, with the goal of taking the company private and retiring its fossil fuel generators. He has campaigned hard against the demerger on the basis it would hinder his plan for AGL to lead Australia’s energy transition to renewables.

He strengthened his hand by spending, through his investment company Grok Ventures, about A$650 million to acquire a 11.3% stake in AGL – almost half the shares needed to thwart the demerger vote. This has made him AGL’s single biggest shareholder.

Securing Super Allies

Only 10 days ago, then chief executive Graeme Hunt called Cannon-Brookes’ opposition to the demerger “out-of-touch, undeliverable and irresponsible nonsense”.

But late last week, Cannon Brookes gained a symbolically significant ally in HESTA, the superannuation fund for health and community service workers. It announced it would vote against the demerger “because it will not adequately support economy-wide decarbonisation”. It said a “proactive and orderly transition to net zero emissions” was “in the best financial interests of our members”.

HESTA holds just 0.36% of AGL shares, but its siding with Cannon-Brookes was a sign AGL’s board was losing the war of words over what was best for shareholders.

AGL’s board confirmed that this morning when it withdrew the demerger proposal.

Why Did AGL’s Board Want To Demerge?

The board’s proposal to split (or demerge) AGL into two entities was to increase returns to shareholders.

“AGL Australia” would focus on energy distribution and trading. “Accel Energy” would own AGL’s existing half-dozen fossil-fuel generators – such as the Bayswater black coal-fired plant in NSW, the Loy Yang brown coal-fired station in Victoria and the Torrens Island gas-powered station in South Australia – as well as its wind, solar and hydroelectric assets.

The board argued this was good for shareholders in three key ways.

First, it would create two “pure-play” companies – focusing on only one line of business – which would be more attractive to investors wanting specific assets (such as energy distribution) but not others (such as coal generators). This could lead to a takeover bid offering more money than what Cannon-Brookes and his partners offered.

Second, each company would have focused managements, empowered to pursue strategies and opportunities “based on their unique assets and capabilities”.

Third, shareholders would have the choice to divest from fossil fuels while still keeping their investment in distribution.

The AGL board also argued the demerger could accelerate “decarbonisation beyond what could be achieved” under the existing structure.

This appeared to be based on the new AGL Australia being partly freed from the old AGL’s legacy fossil-fuel generation, and Accel Energy having more focus and better access to capital as a pure-play company.

Why Oppose The Demerger?

Cannon-Brookes (through Grok Ventures) argued three notable objections.

First, splitting and duplicating management structures would cost at least A$260 million, and $35 million a year thereafter.

Second, the two new companies would have more volatile cash flows and be less able to withstand financial shocks. Accel especially would be at “high insolvency risk” due to having so many assets in coal-fired generation.

Third, and most importantly, the demerger would eliminate the benefits of AGL being a vertically integrated electricity generator and distributor. “We believe that retaining vertical integration strategically positions AGL to lead Australia’s energy transition,” Grok Ventures argued.

What Now For AGL?

AGL is now in for a tumultuous period. It’s unclear who will replace Hunt as chief executive or Botten as chair.

Cannon-Brookes has reportedly demanded two board seats. But shareholders cannot merely demand and receive board seats, even if they are the largest or loudest. The board must act for all shareholders – the majority of which may well have supported the demerger.

By law, the board’s primary obligation is to the corporation’s best interests – which means maximising returns to shareholders.

On that basis it had solid ground on which to propose the demerger. Research shows that, on average, demergers, spin-offs and divestitures do benefit shareholders, while mergers and acquisitions tend to destroy shareholder value.

The board cannot adhere to what a minority of shareholders want – no matter how worthy their cause. It should generally not pursue social or policy goals unless they also maximise shareholder wealth.

On the other side of the ledger, the market has turned against fossil fuels. There is declining long-term shareholder value in coal-fired power stations. Banks are reportedly reluctant to lend to AGL given its ownership of coal and gas generators. However, it would seem logical for them to be willing to finance renewable energy investments.

AGL could potentially become a takeover target, though the question is at what price. On Monday, its share price dipped as low as $8.52 – but that’s still more than the $8.25 the Cannon-Brookes-led consortium offered in March. It’s possible, though, that they might revive that bid.

Aside from Cannon-Brookes being positioned to play a larger role, the future is uncertain. AGL has announced another strategic review. But it is not clear what, if anything, this will achieve – given its previous strategic review led to the now scrapped demerger.![]()

Mark Humphery-Jenner, Associate Professor of Finance, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To walk the talk on climate, Labor must come clean about the future for coal and gas

Australia’s climate election has been won. Now comes the harder part. It’s now entirely possible we could see a government committed to domestic climate action, speeding up the exit of coal and gas from our grid and electrifying transport –while still exporting vast quantities of fossil fuels for other countries to burn.

In short, we could fall into what we can call the “Norway trap”: clean at home, dirty abroad. Norway has vigorously pursued clean energy and electric transport at home and is progressing well towards its goal of a 55% reduction in emissions by the end of the decade – while doubling down on exporting its oil and gas reserves, thereby undermining its domestic gains.

In Australia, Labor still believes in supporting and expanding our fossil fuel exports, which are by far our largest contribution to heating the planet. Backing fossil fuels no doubt helped the new government keep coal seats such as Hunter in New South Wales.

To change this situation, we need to urgently reduce the influence of the fossil fuel lobby – and include our exported emissions in the government’s net zero plans plans.

Wasn’t This The Climate Election?

Despite the clear mandate for stronger climate action, both major parties soft-pedalled on exports to woo electorates with substantial coal and gas infrastructure. Seats such as Hunter, and Flynn in Queensland, recorded swings to Labor in a reversal of the 2019 election, when Labor was not seen to be standing up for the interests of coal communities.

This time around, Labor made its support clear, flagging continuation – and even expansion – of our fossil fuel exports. In a speech to the Minerals Council last year, Anthony Albanese said of coal exports, “We will continue to export these commodities.”

That means Australia will go to the next global climate summit trumpeting its increased commitment to slashing emissions while maintaining its dubious role as one of the largest fossil fuel exporters in the world. We could even see ourselves once again aligned with Russia and Saudi Arabia on opposing production cuts.

It’s long been a climate sceptic talking point that Australia’s emissions are just 1.2% of the world’s total – the 15th-highest in the world. But our vast liquefied natural gas (LNG), thermal and metallurgical coal exports are the equivalent of double our domestic emissions. That means exports are by far our biggest contribution to climate change.

Real Change Starts With Taming The Lobbyists

Little about this situation will change while Labor and the Coalition keep listening to the fossil fuel industry – and accepting millions of dollars in donations. Over the past decade the fossil fuel industry has given hundreds of millions of dollars to political parties. Woodside, one of Australia’s largest oil and gas producers, has donated more than A$2 million to political parties.

Without change, the revolving door of politicians and staffers who end up working for fossil fuel companies will continue slowing climate policy.

This election offers us a long overdue reset. What we need is to tackle Australia’s total contribution to climate change. That includes our role as one of the world’s top exporters of government-subsidised fossil fuels. We can’t just aim to get Australia to net zero and say job done if we leave the export industry to just keep growing, with more than 100 fossil fuel projects in the pipeline.

Steps the government should take immediately should include clamping down on fossil fuel lobbyists and the revolving door. It would be simple to ban government employees from joining the fossil fuel industry without a long cool-down period, as well as banning ex-ministers or politicians from taking up lucrative posts in the industry when they leave politics. The government should also end all direct and indirect subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.

Our fossil fuel lobby has had too many wins over the last two decades. We cannot afford to have our government beholden to an industry incompatible with a liveable climate. We can expect lobby groups to lay low for a little while. But the role of these lobbyists is to ensure that nothing actually challenges their ability to export vast quantities of fossil fuels.

We Cannot Ignore Our Role In Heating The Planet

You’ve no doubt heard the argument that if we don’t export fossil fuels, someone else will. This doesn’t stack up.

That’s because the argument ignores the impact leadership in this area would have. If one of the world’s largest fossil fuel exporters began to phase out its exports and bed down a just transition for those affected, it would have a huge impact on fossil fuel finance and signal time really is up for an industry long thought untouchable. Leading on this would show our neighbours in the Pacific that we can change.

This argument is also morally dubious. Just because someone else is doing something unacceptable, that doesn’t give anyone else license to do the same. We cannot let our leaders and fossil fuel companies off the hook just because other fossil fuel exporters exist. If this argument were really true, then Australia should have no qualms about engaging in bribery or corruption to achieve its ends if other countries are likely to do so.

This election result – and especially the climate campaigns of the Greens and teal independents – has given us our first good opportunity in years to make a real dint in our emissions, both local and exported.![]()

Jeremy Moss, Professor of Political Philosophy, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AI could help us spot viruses like monkeypox before they cross over – and help conserve nature

When a new coronavirus emerged from nature in 2019, it changed the world. But COVID-19 won’t be the last disease to jump across from the shrinking wild. Just this weekend, it was announced that Australia, is no longer an onlooker, as Canada, the US and European countries scramble to contain monkeypox, a less dangerous relative of the feared smallpox virus we were able to eradicate at great cost.

As we push nature to the fringes, we make the world less safe for both humans and animals. That’s because environmental destruction forces animals carrying viruses closer to us, or us to them. And when an infectious disease like COVID does jump across, it can easily pose a global health threat given our deeply interconnected world, the ease of travel and our dense and growing cities.

We can no longer ignore that humans are part of the environment, not separate to it. Our health is inextricably linked to the health of animals and the environment. This will not be the last pandemic.

To be better prepared for the next spillover of viruses from animals, we must focus on the connections between human, environmental and animal health. This is known as the One Health approach, endorsed by the World Health Organization and many others.

We believe artificial intelligence can help us better understand this web of connection, and teach us how to keep life in balance.

How Can AI Help Us Ward Off New Pandemics?

Fully 60% of all infectious diseases affecting humans are zoonoses, meaning they came from animals. That includes the lethal Ebola virus, which came from primates, swine flu, from pigs, and the novel coronavirus, most likely from bats. It’s also possible for humans to give animals our diseases, with recent research suggesting transmission of COVID-19 from humans to cats as well as deer.

Early warning of new zoonoses is vital, if we are to be able to tackle viral spillover before it becomes a pandemic. Pandemics such as swine flu (influenza H1N1) and COVID-19 have shown us the enormous potential of AI-enabled prediction and disease surveillance. In the case of monkeypox, the virus has already been circulating in African countries, but has now made the leap internationally.

What does this look like? Think of collecting and analysing real-time data on infection rates. In fact, AI was used to first flag the novel coronavirus as it was becoming a pandemic, with work done by AI company Bluedot and HealthMap at Boston Children’s Hospital.

How? By tracking vast flows of data in ways humans simply cannot do. Healthmap, for instance, uses natural language processing and machine learning to analyse data from government reports, social media, news sites, and other online sources to track the global spread of outbreaks.

We can also use AI to mine social media data to understand where and when the next COVID surge will occur. Other researchers are using AI to examine the genomic sequences of viruses infecting animals in order to predict whether they could potentially jump from their animal hosts into humans.

As climate change alters the earth’s systems, it is also changing the ways disease spreads and their distributions. Here, too, AI can be put to use in new surveillance methods.

Better Conservation Through AI

There are clear links between our destruction of the environment and the emergence of new infectious diseases and zoonotic spillovers. That means protecting and conserving nature also helps our health. By keeping ecosystems healthy and intact, we can prevent future disease outbreaks.

In conservation, too, AI can help. For instance, Wildbook uses computer-vision algorithms to detect individual animals in images, and track them over time. This allows researchers to produce better estimates of population sizes.

Trashing the environment by deforestation or illegal mining can also be spotted by AI, such as through the Trends.Earth project, which monitors satellite imagery and earth observation data for signs of unwelcome change.

Citizen scientists can pitch in as well by helping train machine learning algorithms to get better at identifying endangered plants and animals on platforms like Zooniverse.

AI For The Natural World As Well As Humans

Researchers are beginning to consider the ethics of AI research on animals. If AI is used carelessly, we could actually see worse outcomes for domestic and wild animal species, for example, animal tracking data can be prone to errors if not double-checked by humans on the ground, or even hacked by poachers.

AI is ethically blind. Unless we take steps to embed values into this software, we could end up with a machine which replicates existing biases. For instance, if there are existing inequalities in human access to water resources, these could easily be recreated in AI tools which would maintain this unfairness. That’s why organisations such as the AINowInstitute are focusing on bias and environmental justice in AI.

In 2019, the EU released ethical guidelines for trustworthy AI. The goal was to ensure AI tools are transparent and prioritise human agency and environmental health.

AI tools have real potential to help us tackle the next pandemic by keeping tabs on viruses and helping us keep nature intact. But for this to happen, we will have to widen AI outwards, away from the human-centredness of most AI tools, towards embracing the fullness of the environment we live in and share with other species.

We should do this while embedding our AI tools with principles of transparency, equity and protection of rights for all.![]()

Ann Borda, Associate Professor, Melbourne Medical School, The University of Melbourne; Andreea Molnar, Associate Professor, Swinburne University of Technology; Cristina Neesham, Associate Professor of Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility, Newcastle University, and Prof Patty Kostkova, Professor in Digital Health, Director of UCL Centre of Digital Public Health in Emergencies (dPHE), UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

3 ways the Albanese government can turn Australia into a renewable energy superpower – without leaving anyone behind

Australians will bear yet another blow to our cost of living in July when electricity prices will surge up to 18.3%, which amounts to over A$250 per year in some cases.

This is partly due to geopolitical tensions driving up the cost of generating electricity from coal and gas – costs that are increasingly volatile – leading the Australian Energy Regulator to increase its so-called “default market offers” for electricity retailers in New South Wales, South Australia and Queensland.

If the Albanese government ever needed another reason to turbocharge its efforts on renewable energy and storage, this is it.

Investing in renewables, energy storage, electric vehicles and other clean industries will not only lower power prices, but will also lower emissions, increase our self-sufficiency, create new jobs, and protect us from international price shocks like we’re seeing now.

Fortunately, the Albanese government has a strong mandate for game-changing climate action this decade. The government aims for renewable energy to make up over 80% of Australia’s electricity mix by 2030, but its pledge of $20 billion for new transmission infrastructure means we can aim higher and go faster.

Holding us back, however, is continued investment in the coal industry. Indeed, doubling down on fossil fuels right now would be extraordinarily reckless from a security perspective – as the United Nations climate envoy pointed out this month, “no one owns the wind or the sun”.

So how can Australia transform into a renewable energy powerhouse? Here are three important ways the Albanese government can meet its ambition swiftly and justly.

1. Energy Justice With Community Energy

Communities must be placed at the heart of the energy transition if we’re to see energy justice in Australia. Energy justice is when all members of society are granted access to clean energy, particularly disadvantaged communities such as those without housing security.

One way to make this happen is with community-owned renewable energy and storage, such as wind energy co-operatives. For example, the Hepburn Wind Co-operative is a 4.1 megawatt wind farm owned by more than 2,000 community shareholders. Another example is community-owned social enterprise electricity retailers such as Enova, which has more than 1,600 community shareholders.

Labor has made a great start. Its Powering Australia plan pledges to install 400 community batteries and develop shared solar banks to give renters, people in apartments, and people who can’t afford upfront installation costs access to solar energy.

The next step should be a rapid roll out of a federal community solar scheme, similar to a program in the United States. The US Community Solar scheme is backed by legislation to create a third-party market for communities. It allows communities to own solar panels or a portion of a solar project, or to buy renewable energy with a subscription.

This means lower socio-economic households can benefit from clean, reliable and cheaper electricity from solar when they’re not able to put panels on their rooftop.

Australia needs a dedicated national policy or government body that builds on the work of other bodies, such as the Coalition for Community Energy, to govern community-based energy and enshrine the principles of energy justice.

2. Rapid Uptake Of Offshore Wind

Offshore wind farms represent a key opportunity for Australia’s decarbonisation – the combined capacity of all proposed offshore wind projects would be greater than all Australia’s coal-fired power plants.

But Australia’s offshore wind industry is only in its infancy. And while Labor’s Powering Australia plan targets manufacturing wind turbine components, it lacks policy ambition for offshore wind.

Renewable Energy Zones (a bit like the renewables equivalent of a power station) are currently being rolled out Australia wide. These should encompass offshore wind zones to encourage the rapid uptake of this vast energy source.

For example, in February, the Renewable Energy Zone in the Hunter-Central Coast region had seven offshore wind proposals and attracted over $100 billion in investment. Potential renewable energy projects in this region represent over 100,000 gigawatt hours of energy – the same as the annual output of ten coal-fired power stations.

The federal government should also set an offshore wind target to accelerate uptake. Victoria, for instance, recently announced a target of 2 gigawatts installed by 2032, 4 gigawatts by 2035, and 9 gigawatts by 2040.

Similarly, the United Kingdom recently increased its offshore wind target to 50 gigawatts by 2030 – the equivalent to powering every household in the nation, according to the UK government.

Despite its potential, Australia only introduced federal legislative framework for offshore wind last year – and it needs work. For example, the legislation doesn’t incorporate marine spatial planning, which is a process of coordinating sectors that rely on the ocean, such as marine conservation, the fishing industry, and the government.

3. Just Transitions For Coal Communities

The Australian Energy Market Operator says the National Electricity Market could be 100% powered by renewables by 2025. Further closures of aging and unreliable coal-fired power stations are inevitable.

The government must not leave carbon-intensive regions behind in the transition to new clean industries. If we do this right, generations of Australians could be working in renewable energy, clean manufacturing, renewable hydrogen, and the extraction of critical minerals.

Creating a national coal commission could help produce a roadmap away from fossil fuels, and seize on the opportunity to create clean jobs. This is being done in Germany, where a government-appointed coal commission consulted unions, coal regions, local communities and more to develop a pathway to transition the coal industry by 2038.

We can also see this in Canada, which is developing legislation with principles of a just transition by establishing a body to provide advice on strategies supporting workers and communities.

Strong climate and energy policy will take hard work – let’s hope this truly marks the end of the climate wars and the start of Australia’s turbocharged energy transition.![]()

Madeline Taylor, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tapping mineral wealth in mining waste could offset damage from new green economy mines

To go green, the world will need vast quantities of critical minerals such as manganese, lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements. But to some environmentalists, mining to save the planet is a hard pill to swallow if it leads to damage to pristine areas.

The good news is that in many cases, the mining for these minerals has already been done. After Australia’s major miners dig up iron ore, billions of tonnes of earth and rock are left over. Hidden in these rock piles and tailing dams are minerals vital to high tech industries of today and tomorrow.

In recent years, we have seen a welcome focus on remining – the extraction of valuable minerals and metals from mining waste. While Australia has been slow to adopt this approach, it holds real promise. We don’t necessarily have to mine more. We can mine smarter.

Why Do Critical Minerals Matter?

For our new government to deliver net-zero by 2050, we will have to mine more critical minerals. In Australia, these minerals include lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements, tin, tungsten and indium. These metals are essential for manufacturing the wind turbines and electric vehicles required to transition to a low-carbon economy.

In May, Four Corners explored the potential for critical minerals mining in Australia, such as Western Australia’s major lithium deposits, cobalt resources in New South Wales and Tasmania’s opportunities in tungsten and tin. For nearby communities, new mining can mean socioeconomic rejuvenation.

But some environmentalists are sceptical, with the Bob Brown Foundation calling it a form of “greenwashing”. They point out that increasing mining would mean more damage to the environment, and produce much more waste. Globally, mining produces over 100 billion tonnes of solid waste annually. This waste is usually deposited in tailings dams or waste rock dumps, which both have risks if not done properly. Tailing dams breaking due to geotechnical issues have caused lethal disasters. Another issue is acid mine drainage, when highly acidic water laden with heavy metals escapes containment.

If Australia does want to make the most of its critical minerals, it is important to improve mining methods. If we don’t, we are likely to see extremely high waste to product ratios, as we already do for traditional commodities like gold, copper and iron.

Balancing these concerns is difficult. For instance, the multi-metal Rosebery mine in Tasmania requires a new way to store tailings to continue operations. If it doesn’t, the mine’s operators say they may have to close. But the Bob Brown Foundation is strongly protesting its construction, due to the threat to a rare owl.

One Solution? Mine The Waste

How can we resolve these issues? One approach is to look to circular economy principles. By treating this waste as a source of value, we could reduce the environmental footprint of mining while producing critical minerals and other vital products such as sand.

For instance, at the Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara Aktiebolag mine in Sweden, the tailings from iron ore mining now comprise one of the largest deposits of rare earth elements in Europe. Recognising this, the mine’s owners are planning a circular industrial park to recover these valuable elements.

Similarly, the world’s annual phosphate production is estimated to contain around 100,000 tonnes of rare earth elements, a large proportion of which ends up in waste streams.

Copper deposits are a well-known source of many critical metals such as antimony and bismuth, as well as cobalt and indium.

Even in coal ash – the deposits left after burning coal – we can find valuable minerals such as gallium, scandium, vanadium and rare earth elements.

A Growing Area Of Interest

There is growing interest in extracting minerals from mining waste, with conferences held in the new area of remining in Europe and new prospecting ventures under way in Australia exploring mine waste.

The first to invest in this secondary prospecting was the Queensland government, which has funded sampling across 16 sites. Early results have found cobalt deposits rich enough to draw overseas investment.

New South Wales has recently launched a similar program, while work is under way by Geoscience Australia, the University of Queensland and RMIT to produce the first-ever atlas of mine waste in Australia.

Once complete, this atlas will be a valuable resource for companies keen to position themselves as tailings extraction experts such as New Century Resources.

Major miners are also paying attention. Rio Tinto has invested A$2 million into a new startup, Regeneration, which uses income from mine waste mineral recovery to pay for mining site rehabilitation.

Do We Have The Right Technologies For The Task?

Existing technologies are being put to work to extract manganese from waste from South 32 mines using aqueous solutions.

Another proven technique, gravity separation, is being used to recover tungsten from mine waste at Mt Carbine.

For some deposits, however, we will need more advanced techniques. These might include emerging methods such as fine particle flotation, and even using remarkable plants to mine metal in a process called phytomining.

Given the federal government has committed A$240 million to develop critical mineral processing facilities, we should explore the use of mine waste as feedstock.

Early Days For Re-Mining

Australia’s mineral wealth could see us become a renewable and critical mineral superpower. But to ensure this shift gains widespread support, we must do the best we can to tackle environmental concerns. To spur on this change, we can vote with our wallets. Companies like Volkswagen and Apple are looking for new providers of critical minerals, given ethical and geopolitical concerns around existing supplies.

If we as consumers call for a percentage to be sourced from mine waste, we could drive clean economic growth and reduce the need for new mines, while funding the rehabilitation of Australia’s 50,000 abandoned mine sites.![]()

Anita Parbhakar-Fox, Principal Research Fellow/ Group Leader- MIWATCH, The University of Queensland; Kamini Bhowany, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The University of Queensland; Kristy Guerin, Postdoctoral Research Fellow; Laura Jackson, , The University of Queensland, and Partha Narayan Mishra, , The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Helping Households With Energy Bills

National Seniors Welcomes New Aged Care Ministers

End The ‘Do Nothing’ Decade For Seniors With Disabilities: Joint Statement By Organisations

- A short term funding solution for people with high intensity support needs so they can receive the same standard care and support as other Australians with disabilities, regardless of when they were acquired.

- A fair and transparent consultation process that prioritises the needs, choices and goals of people with disabilities aged over 65.

- A streamlined solution that works for older people with severe disabilities as well as aged care and disability service providers.

- If you acquire a disability after you turn 65, there is no disability support available to fund your care.

- If you were eligible for the NDIS during your life but were not accepted before you turned 65, you are not eligible for any Federal Government disability support.

- People with disabilities over 65 must rely on Home Care Packages that are currently capped at $52,000 each However, the proper care for a 65+ year old person with quadriplegia costs more than $200,000 a year.

- Funding and care shortfalls are currently met by family members who leave their jobs to become carers and sell their homes to fund support.

- The current gap in funding places unbearable pressure on older partners who have their own care and support They now spend their time fighting for funding in a complex system that should empower and support them.

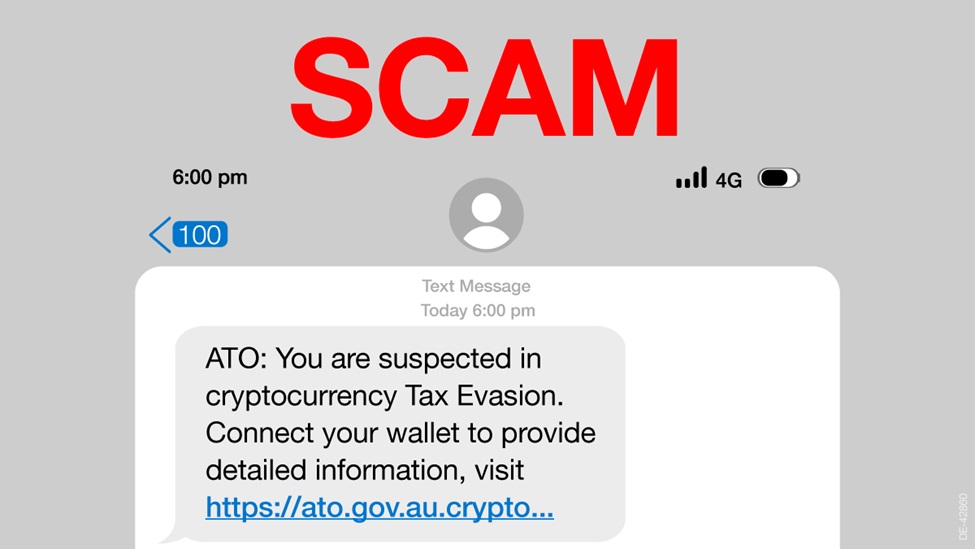

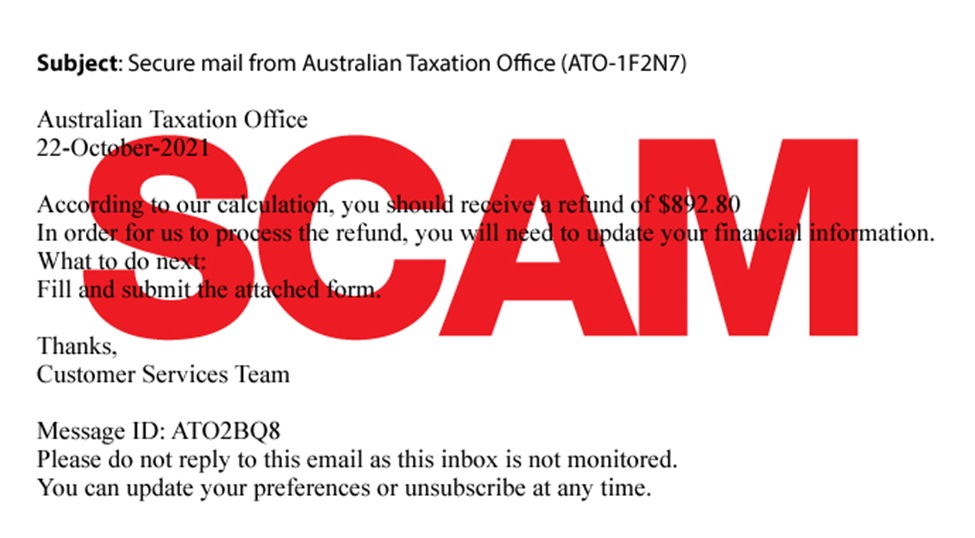

Tax Time Scams And How To Avoid Them

- Contact people you know: Let your friends and family know what's happened.

- Contact your financial institution: If you've provided your bank or credit card details to the scammer, contact your financial institution immediately. They may be able to stop the transaction, perform a 'charge back' to your credit card (reverse the transaction) or close your bank account.

- Recover your stolen identity: If you have had your identity stolen, get in touch with contact IDCARE, a government website that will work with you to plan a response. Visit the IDCARE website or call 1800 595 160. You can also apply for a Commonwealth Victims' Certificate to support your claim that you've been a victim of identity crime and help re-establish credentials.

- Report the scam to authorities: Report scams to the ACCC via the Report a Scam website. Depending on the type of scam, you may also need to report it to the ATO, Centrelink, Medicare, the ACCC, the police, and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. You should also report the scam to your telecommunications provider, email service, and/or the social media platform (depending how you were first contacted).

- Change your online passwords: If any of your online accounts have been compromised, change your password immediately. Most websites will have instructions for how you can recover a hacked account if you're unable to get into it.

- Set up two-factor authentication for online accounts: Two (or three factor) authentication offers an extra layer of protection. Along with your username and password, most two-factor authentication will set up a second step such as entering a code sent to your phone or email. This makes it harder for hackers to access your account without first gaining access to your phone or email. Most websites will have instructions for how to set this up for your online account.

How to complain about aged care and get the result you want

It can be hard to know what to say, or who to talk to, if you notice something isn’t right for you or a loved one in residential aged care.

You might have concerns about personal or medical care, being adequately consulted about changes to care, or be concerned about charges on the latest bill. You could also be concerned about theft, neglect or abuse.

Here’s how you can raise issues with the relevant person or authority to improve care and support for you or your loved one.

Keep Records

You can complain about any aspect of care or service. For instance, if medical care, day-to-day support or financial matters do not meet your needs or expectations, you can complain.

It is best to act as soon as you notice something isn’t right. This may prevent things from escalating. Good communication helps get better results.

Make written notes about what happened, including times and dates, and take photos. Try to focus on facts and events. You can also keep a record of who was involved and their role.

Keep track of how the provider responded or steps taken to resolve the issue. Write notes of conversations and keep copies of emails.

Who Do I Complain To?

Potential criminal matters

If you have concerns about immediate, serious harm of a criminal nature then you should contact the police, and your provider immediately. These types of serious incidents include unreasonable use of force or other serious abuse or neglect, unlawful sexual contact, stealing or unexpected death.

The provider may have already contacted you about this. They are required to report such serious incidents to both the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission within 24 hours, and to the police.

Other matters

For other matters, talk to the care staff involved. Try to find out more detail about what happened and why things went wrong. Think about what you expect in the situation.