Inbox and Environment News: Issue 542

June 12 -18, 2022: Issue 542

Sydney Metropolitan Wildlife Services: Possums In Your Roof

Local Leatherback Turtle Deaths

Pelicans Heading To The Coast Now: Winter Migrations

Central Coast Announced As Location For New Offshore Artificial Reef

Sand Point - Palm Beach: Winter 2022

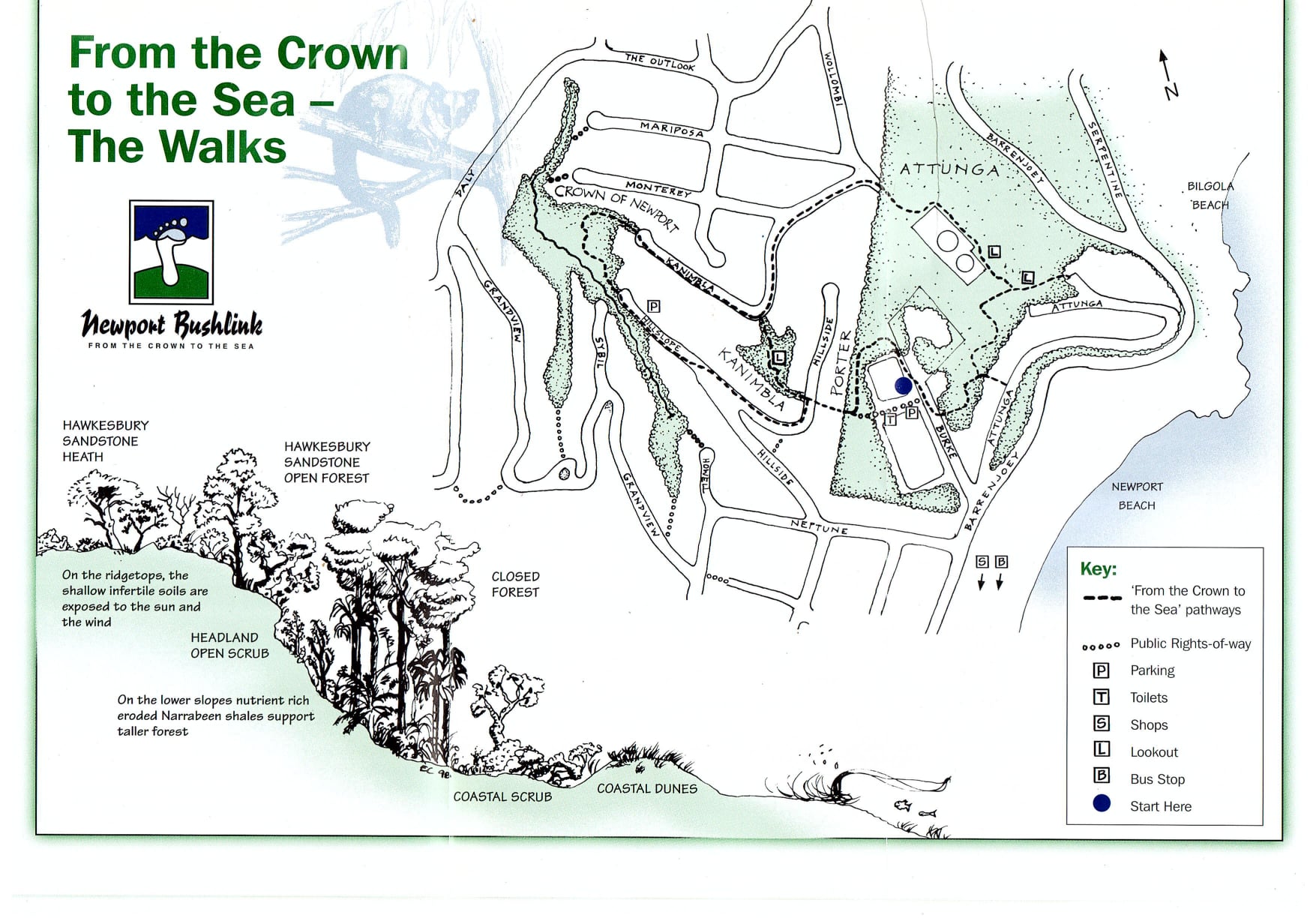

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Walks

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): What’s This Plant? + Microbat

Microbats Of Sydney

Chemical Clean Out: June 2022 At Mona Vale

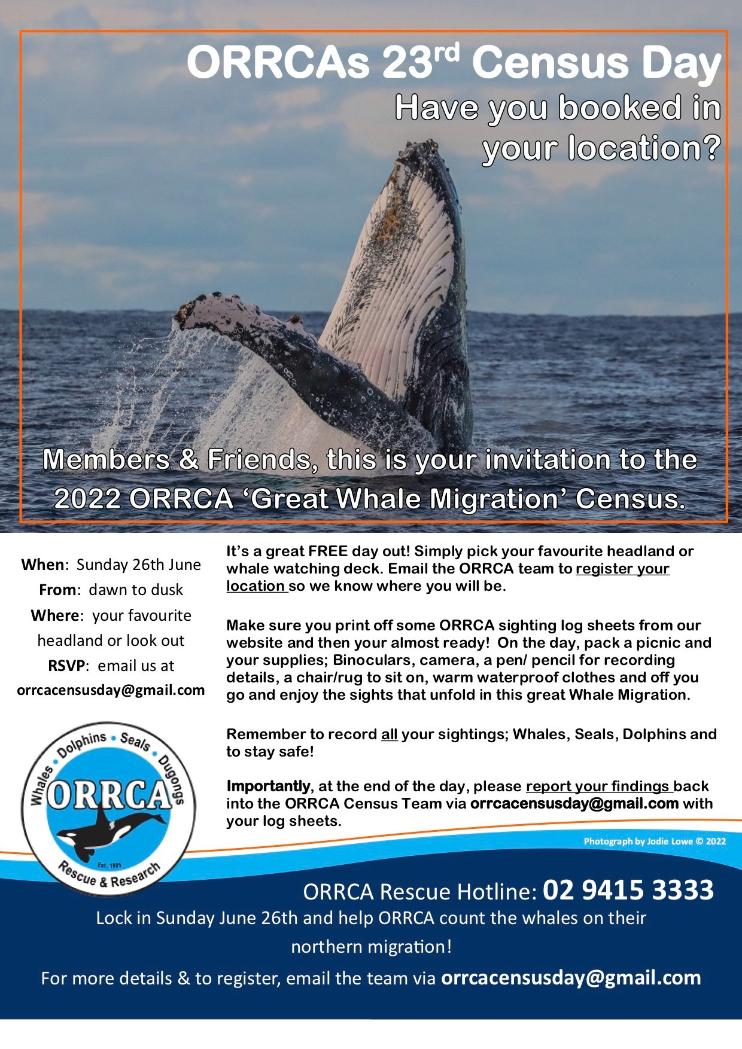

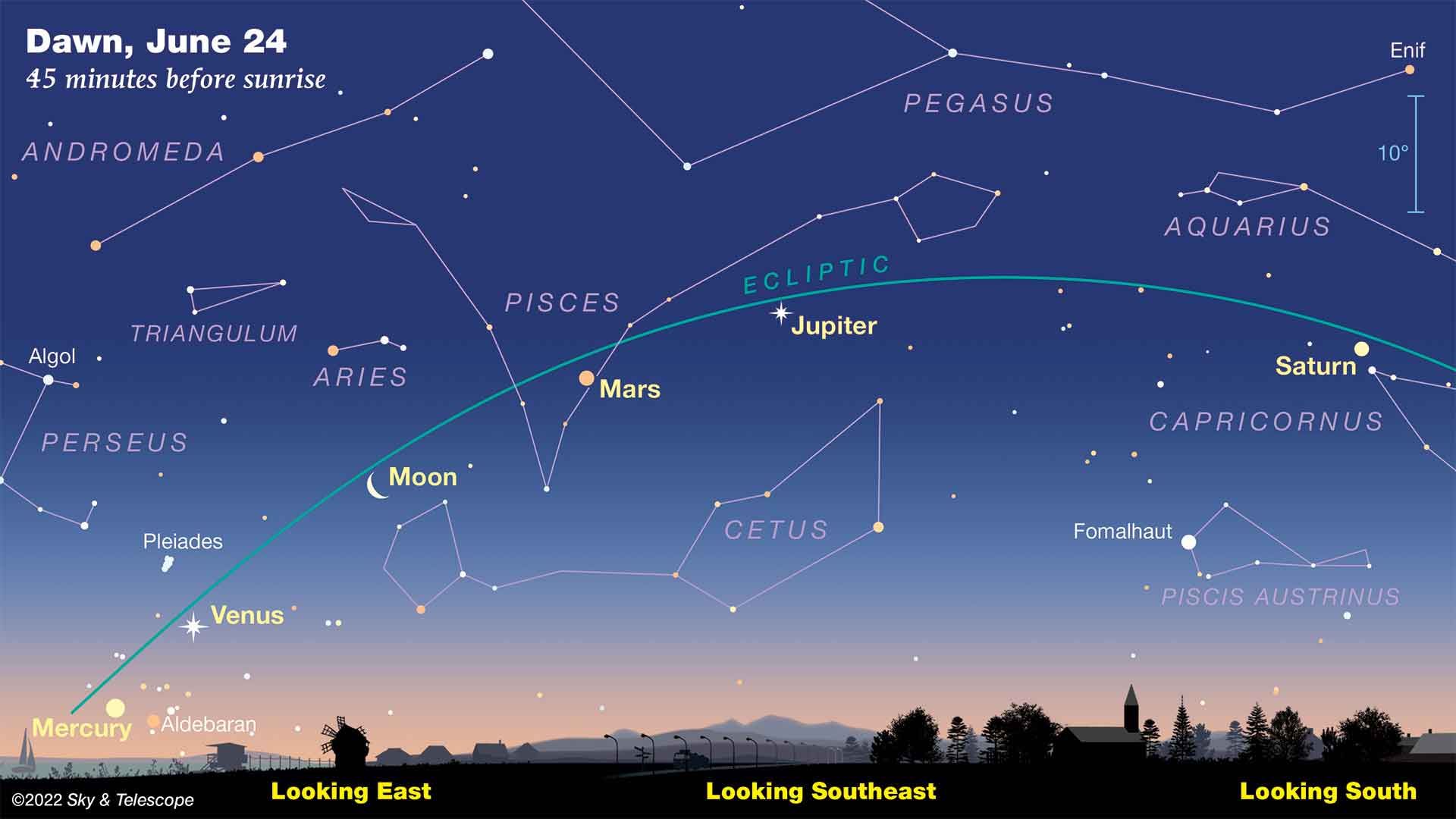

Living Ocean Traditional Welcome To Country For The Southern Humpback Whale Migration: June 24

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Narrabeen - June 26

Barrenjoey Lighthouse Tours

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

New Report Lets Rip On Australia’s Problem With Gassy Coal Mines

- Australia is the world’s 6th largest coal mine methane emitter and on track to become the 3rd worst. Despite this, the government has not signed the Global Methane Pledge and has continued to approve new and expanding coal mines at a rate only behind China and Russia.

- Methane’s short-term climate impact is 82.5 times that of carbon dioxide, making the methane released by coal mines equivalent to 74.3 million tonnes of CO2. This is greater than the 44 million tonnes of CO2 emitted by cars each year.

- But the International Energy Agency estimates that direct methane emissions from Australian coal mines in 2019 were double the reported amount. This would mean coal mines are releasing equivalent to 149Mt of CO2-e.

- Even the IEA’s figure is likely to be conservative, with state of the art satellite data showing some coal mines are releasing ten times the amount officially recorded.

Dendrobium Mine Extension Project: Have Your Say (Again)

Political Stitch Up Over Dendrobium Abandons Community, Climate, And Water, Favours Coal Mining Company Residents State

Golden Re-Entry To NSW National Parks For Extinct Bandicoots

Stunning New Walk Opens In The Snowies

Important Koala Population Discovered In Kosciuszko National Park

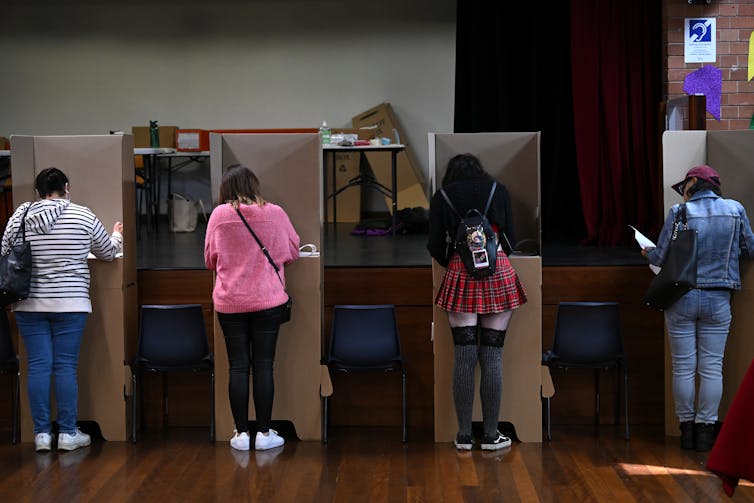

How Australia’s expanding environmental movement is breaking the climate action deadlock in politics

The federal election saw voters’ growing concern about Australia’s laggardly response to climate change finally addressed, with teal independents garnering seats in Liberal heartland and record votes for Greens candidates.

But what caused this seismic shift in Australia’s political landscape? And why now? We believe the rapid growth and diversification of Australia’s environmental movement since 2015 played an important role.

For example, almost a million Australians volunteered for an environmental charity in 2019, whether by planting trees, organising candidate forums or joining a climate strike.

The environmental movement is also increasingly crossing into traditionally conservative areas, with the emergence of groups such as the Coalition for Conservation and Farmers for Climate Action, which has united 7,000 farmers and 1,200 agriculture industry supporters.

Much of this work remains invisible and takes time, despite being punctuated by highly visible uprisings. And after many years, it may be finally precipitating the end of the climate wars.

Challenging Stereotypes

Many Australians will already be familiar with iconic environmental campaigns such as the Franklin Blockade in Tasmania in the early 1980s, which was pivotal in the evolution of Australia’s environmental movement.

More recently, the Extinction Rebellion and School Strike 4 Climate protests have gained substantial public attention in Australia.

Behind these well-known protests is a diversifying and rapidly expanding environmental movement. In recent years, hundreds of new groups have appeared, and many are actively challenging the activist stereotype characterised by labels such as hippies, extremists, or zealots.

Groups such as First Nations Clean Energy Network, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action, and the Investor Group on Climate Change have normalised calls for climate action in new industry sectors, and across regional and remote communities.

Many of these groups are using innovative methods to bring about change. Market Forces, for example, applies financial levers to challenge corporate support for the fossil fuel industry.

Wangan and Jagalingou Traditional Owners have established a sovereignty camp inside the Adani coal mining lease after their native title rights were extinguished.

And Next Economy canvassed regional communities, discovering a strong desire for clear and well-resourced transition plans for a zero emissions economy.

Meanwhile, philanthropic organisations are increasingly prioritising funding for climate activism. Other organisations offer research services, resources, training and fellowships for people demanding social and environmental change.

Building Consensus On Climate Action

Tactics we’ve seen activists use to demand climate action include the 2019 street blockades, die-ins and mass strikes by Extinction Rebellion and School Strike 4 Climate.

These actions put climate change onto the public agenda by generating widespread media attention. But they represent just a fraction of environmental movement activities.

Most environmental movement activity seeks to build consensus on climate change with those who share different values and worldviews.

Our extensive empirical analysis published last year found between 2010 and 2019, environmental groups advertised more than 24,000 events on Facebook alone, such as film screenings, seminars and clean-ups.

Many Australians have now felt impacts of the climate crisis. The 2019-2020 bushfires affected 80% of Australians whether directly or indirectly. Tens of thousands of people were displaced by the recent floods in New South Wales and Queensland.

By sharing heart-wrenching accounts of climate change-related harm, groups such as Bushfire Survivors for Climate Action are able to influence peoples’ opinions and beliefs on climate change .

The diversification of groups has also increased calls for climate action from conservative voices, which have been closely tied to climate scepticism in Australia.

But research from 2021 shows how amplifying these voices within the environmental movement can help normalise climate action within conservative ideology. Conservatives are also more likely to support messages delivered by other conservatives.

We can see these processes playing out in groups such as Farmers for Climate Action. Farmers, traditionally represented by conservative politicians famous for questioning climate science, have become increasingly frustrated about climate inaction.

By championing the economic opportunities and food security benefits delivered by strong climate policy, Farmers for Climate Action have helped connect farmers’ identity to environmental stewardship, while preserving conservative values and outlooks.

More Than One Goal

For many groups, the election is only one way of creating change to adequately tackle climate change in Australia. They continue to take action in different ways.

Some, such as Australian Parents for Climate Action, are building community groups working on local issues. This includes installing solar panels and batteries in schools and early childhood centres.

Original Power, a community-focused Aboriginal organisation, seeks self-determination and recognition that Indigenous rights go hand in hand with climate crisis solutions.

And Better Futures is building an alliance of public and private sector leaders to showcase individual and collaborative climate action across industry sectors and communities.

Groups such as these are organising hundreds of new campaigns every year from local to national scale, many of which are achieving their goals.

What Does This Mean For The New Government?

Entrenched interests seeking to maintain the fossil fuel industry and media-supported climate denial have propped up political inaction on climate change, and perpetuated Australia’s relentless climate wars for decades.

While the Albanese government has set a stronger emissions reduction target and promises to inject more renewables into the grid, it insists on continuing to support the emissions-intensive gas industry.

This year’s election offers a chance for the federal government to chart a new way forward. Whether politicians grasp this opportunity remains to be seen.

Will the government heed the call that voters expect greater climate action? Will Labor forge a path beyond fossil fuels, one that doesn’t leave coal and gas communities behind? And how far will the Greens and teal independents push Labor to rise to the challenge?

The environmental movement is now tightly woven into communities across Australia and its demands are clear. It has achieved demonstrable impact and wields considerable power to affect change. Politicians ignore it at their peril.![]()

Robyn Gulliver, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

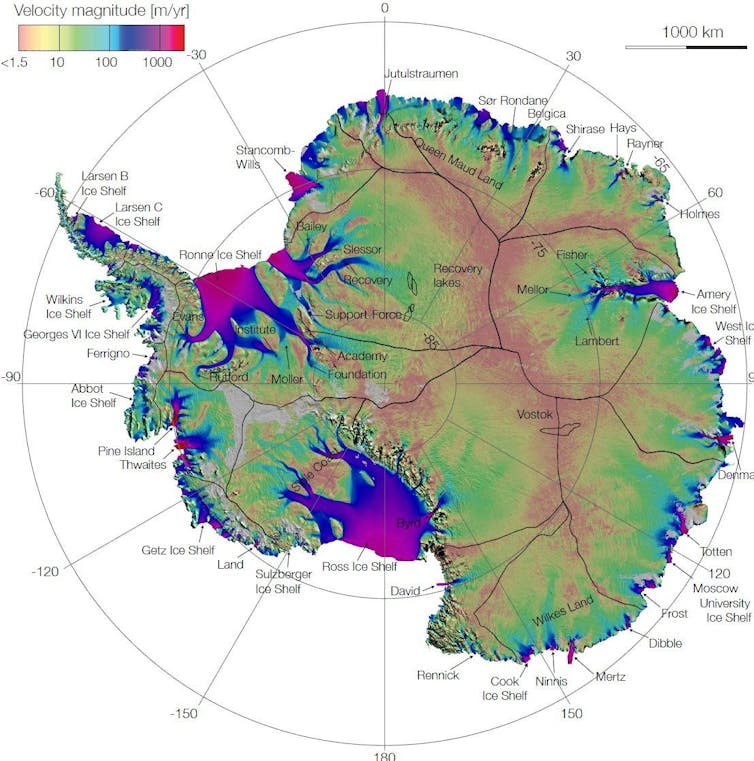

Ice world: Antarctica’s riskiest glacier is under assault from below and losing its grip

Flying over Antarctica, it’s hard to see what all the fuss is about. Like a gigantic wedding cake, the frosting of snow on top of the world’s largest ice sheet looks smooth and unblemished, beautiful and perfectly white. Little swirls of snow dunes cover the surface.

But as you approach the edge of the ice sheet, a sense of tremendous underlying power emerges. Cracks appear in the surface, sometimes organized like a washboard, and sometimes a complete chaos of spires and ridges, revealing the pale blue crystalline heart of the ice below.

As the plane flies lower, the scale of these breaks steadily grows. These are not just cracks, but canyons large enough to swallow a jetliner, or spires the size of monuments. Cliffs and tears, rips in the white blanket emerge, indicating a force that can toss city blocks of ice around like so many wrecked cars in a pileup. It’s a twisted, torn, wrenched landscape. A sense of movement also emerges, in a way that no ice-free part of the Earth can convey – the entire landscape is in motion, and seemingly not very happy about it.

Antarctica is a continent comprising several large islands, one of them the size of Australia, all buried under a 10,000-foot-thick layer of ice. The ice holds enough fresh water to raise sea level by nearly 200 feet.

Its glaciers have always been in motion, but beneath the ice, changes are taking place that are having profound effects on the future of the ice sheet – and on the future of coastal communities around the world.

Breaking, Thinning, Melting, Collapsing

Antarctica is where I work. As a polar scientist I’ve visited most areas of the ice sheet in more than 20 trips to the continent, bringing sensors and weather stations, trekking across glaciers, or measuring the speed, thickness and structure of the ice.

Currently, I’m the U.S. coordinating scientist for a major international research effort on Antarctica’s riskiest glacier – more on that in a moment. I have gingerly crossed crevasses, trodden carefully on hard blue windswept ice, and driven for days over the most monotonous landscape you can imagine.

For most of the past few centuries, the ice sheet has been stable, as far as polar science can tell. Our ability to track how much ice flows out each year, and how much snow falls on top, extends back just a handful of decades, but what we see is an ice sheet that was nearly in balance as recently as the 1980s.

Early on, changes in the ice happened slowly. Icebergs would break away, but the ice was replaced by new outflow. Total snowfall had not changed much in centuries – this we knew from looking at ice cores – and in general the flow of ice and the elevation of the ice sheet seemed so constant that a main goal of early ice research in Antarctica was finding a place, any place, that had changed dramatically.

But now, as the surrounding air and ocean warm, areas of the Antarctic ice sheet that had been stable for thousands of years are breaking, thinning, melting, or in some cases collapsing in a heap. As these edges of the ice react, they send a powerful reminder: If even a small part of the ice sheet were to completely crumble into the sea, the impact for the world’s coasts would be severe.

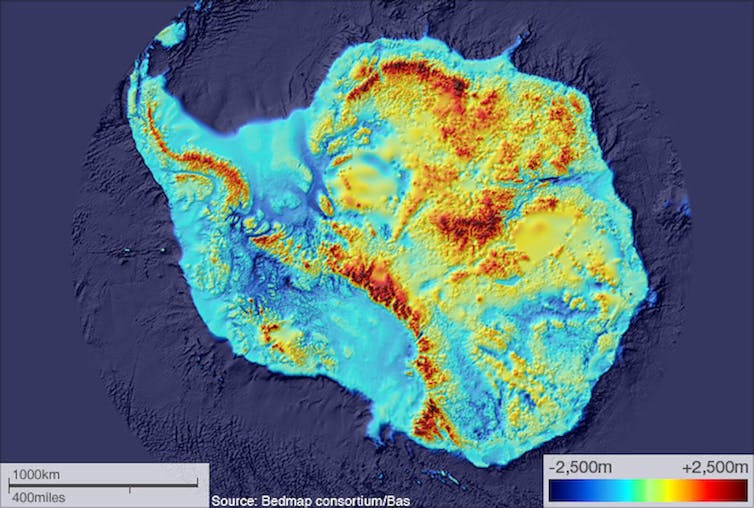

Like many geoscientists, I think about how the Earth looks below the part that we can see. For Antarctica, that means thinking about the landscape below the ice. What does the buried continent look like – and how does that rocky basement shape the future of the ice in a warming world?

Visualizing The World Below The Ice

Recent efforts to combine data from hundreds of airplane and ground-based studies have given us a kind of map of the continent below the ice. It reveals two very different landscapes, divided by the Transantarctic Mountains.

In East Antarctica, the part closer to Australia, the continent is rugged and furrowed, with several small mountain ranges. Some of these have alpine valleys, cut by the very first glaciers that formed on Antarctica 30 million years ago, when its climate resembled Alberta’s or Patagonia’s. Most of East Antarctica’s bedrock sits above sea level. This is where the city-size Conger ice shelf collapsed amid an unusually intense heat wave in March 2022.

In West Antarctica the bedrock is far different, with parts that are far deeper. This area was once the ocean bottom, a region where the continent was stretched and broken into smaller blocks with deep seabed between. Large islands made of volcanic mountain ranges are linked together by the thick blanket of ice. But the ice here is warmer, and moving faster.

As recently as 120,000 years ago, this area was probably an open ocean – and definitely so in the past 2 million years. This is important because our climate today is fast approaching temperatures like those of a few million years ago.

The realization that the West Antarctic ice sheet was gone in the past is the cause of great concern in the global warming era.

Early Stages Of A Large-Scale Retreat

Toward the coast of West Antarctica is a large area of ice called Thwaites Glacier. This is the widest glacier on earth, at 70 miles across, draining an area nearly as large as Idaho.

Satellite data tell us that it is in the early stages of a large-scale retreat. The height of the surface has been dropping by up to 3 feet each year. Huge cracks have formed at the coast, and many large icebergs have been set adrift. The glacier is flowing at over a mile per year, and this speed has nearly doubled in the past three decades.

This area was noted early on as a place where the ice could lose its grip on the bedrock. The region was termed the “weak underbelly” of the ice sheet.

Some of the first measurements of the ice depth, using radio echo-sounding, showed that the center of West Antarctica had bedrock up to a mile and a half below sea level. The coastal area was shallower, with a few mountains and some higher ground; but a wide gap between the mountains lay near the coast. This is where Thwaites Glacier meets the sea.

This pattern, with deeper ice piled high near the center of an ice sheet, and shallower but still low bedrock near the coast, is a recipe for disaster – albeit a very slow-moving disaster.

Ice flows under its own weight – something we learned in high school earth science, but give it a thought now. With very tall and very deep ice near Antarctica’s center, a tremendous potential for faster flow exists. By being shallower near the edges, the flow is held back – grinding on the bedrock as it tries to leave, and having a shorter column of ice at the coast squeezing it outward.

If the ice were to step back far enough, the retreating front would go from “thin” ice – still nearly 3,000 feet thick – to thicker ice toward the center of the continent. At the retreating edge, the ice would flow faster, because the ice is thicker now. By flowing faster, the glacier pulls down the ice behind it, allowing it to float, causing more retreat. This is what’s known as a positive feedback loop – retreat leading to thicker ice at the front of the glacier, making for faster flow, leading to more retreat.

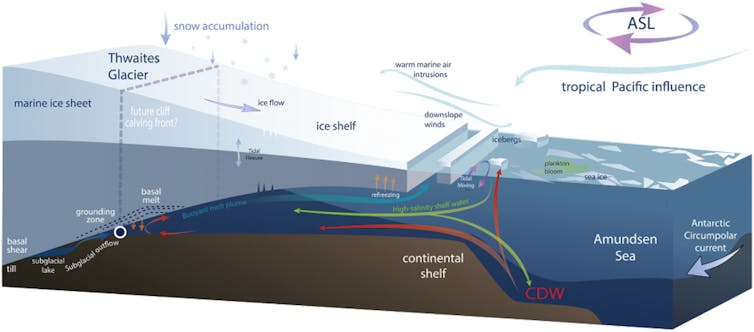

Warming Water: The Assault From Below

But how would this retreat begin? Until recently, Thwaites had not changed a lot since it was first mapped in the 1940s. Early on, scientists thought a retreat would be a result of warmer air and surface melting. But the cause of the changes at Thwaites seen in satellite data is not so easy to spot from the surface.

Beneath the ice, however, at the point where the ice sheet first lifts off the continent and begins to jut out over the ocean as a floating ice shelf, the cause of the retreat becomes evident. Here, ocean water well above the melting point is eroding the base of the ice, erasing it as an ice cube would disappear bobbing in a glass of water.

Water that is capable of melting as much as 50 to 100 feet of ice every year meets the edge of the ice sheet here. This erosion lets the ice flow faster, pushing against the floating ice shelf.

The ice shelf is one of the restraining forces holding the ice sheet back. But pressure from the land ice is slowly breaking this ice plate. Like a board splintering under too much weight, it is developing huge cracks. When it gives way – and mapping of the fractures and speed of flow suggests this is just a few years away – it will be another step that allows the ice to flow faster, feeding the feedback loop.

Up To 10 Feet Of Sea Level Rise

Looking back at the ice-covered continent from our camp this year, it is a sobering view. A huge glacier, flowing toward the coast, and stretching from horizon to horizon, rises up to the middle of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. There is a palpable feeling that the ice is bearing down on the coast.

Ice is still ice – it doesn’t move that fast no matter what is driving it; but this giant area called West Antarctica could soon begin a multicentury decline that would add up to 10 feet to sea level. In the process, the rate of sea level rise would increase severalfold, posing large challenges for people with a stake in coastal cities. Which is pretty much all of us.![]()

Ted Scambos, Senior Research Scientist, CIRES, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shifting seasons: using Indigenous knowledge and western science to help address climate change impacts

Traditional Owners in Australia are the creators of millennia worth of traditional ecological knowledge – an understanding of how to live amid changing environmental conditions. Seasonal calendars are one of the forms of this knowledge best known by non-Indigenous Australians. But as the climate changes, these calendars are being disrupted.

How? Take the example of wattle trees that flower at a specific time of year. That previously indicated the start of the fishing season for particular species. Climate change is causing these plants to flower later. In response, Traditional Owners on Yuku Baja Muliku (YBM) Country near Cooktown are having to adapt their calendars and make new links.

That’s not all. The seasonal timing of cultural burning practices is changing in some areas. Changes to rainfall and temperature alter when high intensity (hot) burns and low intensity (cool) burns are undertaken.

Seasonal connections vital to Traditional Owners’ culture are decoupling.

To systematically document changes, co-author Larissa Hale and her community worked with western scientists to pioneer a Traditional Owner-centred approach to climate impacts on cultural values. This process, published last week, could also help Traditional Owners elsewhere to develop adaptive management for their Indigenous heritage.

Climate Change Threatens First Nations - Their Perspectives Must Be Heard

Australia’s First Nations people face many threats from climate change, ranging from impacts on food availability to health. For instance, rising seas are already flooding islands in the Torres Strait with devastating consequences.

The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on impacts and adaption noted in the Australasia chapter that climate-related impacts on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, their country and cultures are “pervasive, complex and compounding.”

While it is important these impacts are recorded, the dominant source of the data is academic literature based on western science. Impacts and pressures Traditional Owners are seeing and managing on their country must be assessed and managed from their unique perspective.

Traditional Owners have survived and adapted to climatic shifts during their 60,000+ years in Australia. This includes sea-level rise that flooded the area that is now the Great Barrier Reef and extreme rainfall variability. As a result, they have developed a fine-tuned sense of nature’s variability over time.

So What Did We Do?

Worried about the changes they were seeing on their Land and Sea Country around Archer Point in North Queensland, the YBM people worked with scientists from James Cook University to create a new way to assess impacts on cultural values.

To do this, we drew on the values-based, science-driven, and community-focused approach of the climate vulnerability index. It was the first time this index had been used to assess values of significance for Indigenous people.

YBM people responded to key prompts to assess changes to their values, including:

- What did the value look like 100 years ago?

- What does it look like now?

- What do you expect it will look like in the climate future around 2050?

- What management practices relate to that value and will they change?

We then discussed what issues have emerged from these climatic changes.

Using this process, we were able to single out issues directly affecting how YBM people live. For instance, traditional food sources can be affected by climate change. In the past, freshwater mussels in the Annan River were easy to access and collect. Extreme temperature events in the last 10 years have contributed to mass die-offs. Now mussels are much smaller in size and tend to be far fewer in number.

Through the process we also documented that changes to rainfall and temperature have altered the time when some plant foods appear. This is particularly true for plants that depend upon cultural burns to flower or put up shoots. This in turn has meant that the timing of collecting and harvesting has changed.

These climate-linked changes challenge existing bodies of traditional knowledge, altering connections between different species, ecosystems and weather patterns across Land and Sea Country.

A key part of this process was developing a mutually beneficial partnership between traditional ecological knowledge holders and western scientists. It was critical to establish a relationship built on trust and respect.

Walking the country first – seeing rivers, mangroves, beaches, headlands, bush, wetlands, and looking out at Sea Country – helped researchers understand the perspectives of Traditional Owners. Honouring experience and knowledge (especially that held by Elders and Indigenous rangers) was important. Indigenous cultural and intellectual property protocols were recognised and respected throughout the assessment.

Respecting and working collaboratively with Traditional Owners as expert scientists in their own knowledge system was critical for success. Any effort to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge in climate change assessments must protect sensitive traditional knowledge.

As climate change will continue and accelerate, we must work together to minimise resulting impacts on the cultural heritage of First Nations peoples.![]()

Karin Gerhardt, PhD student, James Cook University; Jon C. Day, PSM, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University; Larissa Hale, Yuku Baja Muliku Traditional Owner, Indigenous Knowledge, and Scott F. Heron, Associate Professor in Physics, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A huge Atlantic ocean current is slowing down. If it collapses, La Niña could become the norm for Australia

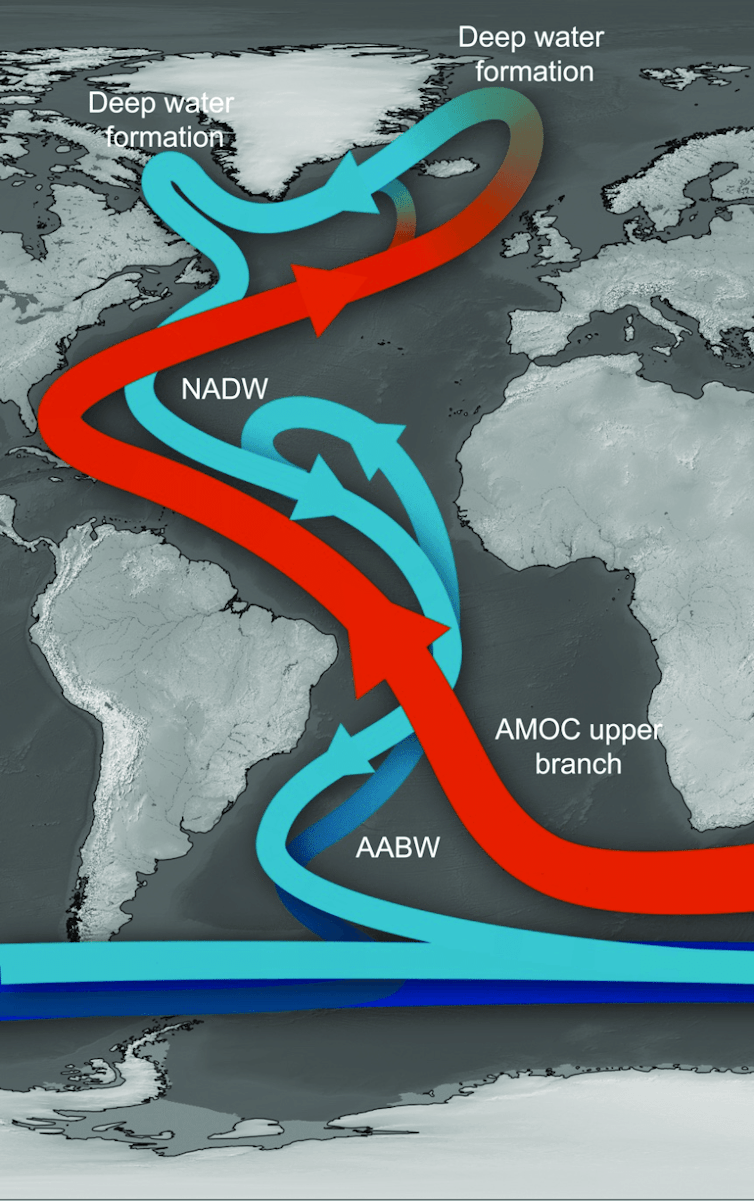

Climate change is slowing down the conveyor belt of ocean currents that brings warm water from the tropics up to the North Atlantic. Our research, published today in Nature Climate Change, looks at the profound consequences to global climate if this Atlantic conveyor collapses entirely.

We found the collapse of this system – called the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation – would shift the Earth’s climate to a more La Niña-like state. This would mean more flooding rains over eastern Australia and worse droughts and bushfire seasons over southwest United States.

East-coast Australians know what unrelenting La Niña feels like. Climate change has loaded our atmosphere with moister air, while two summers of La Niña warmed the ocean north of Australia. Both contributed to some of the wettest conditions ever experienced, with record-breaking floods in New South Wales and Queensland.

Meanwhile, over the southwest of North America, a record drought and severe bushfires have put a huge strain on emergency services and agriculture, with the 2021 fires alone estimated to have cost at least US$70 billion.

Earth’s climate is dynamic, variable, and ever-changing. But our current trajectory of unabated greenhouse gas emissions is giving the whole system a giant kick that’ll have uncertain consequences – consequences that’ll rewrite our textbook description of the planet’s ocean circulation and its impact.

What Is The Atlantic Overturning Meridional Circulation?

The Atlantic overturning circulation comprises a massive flow of warm tropical water to the North Atlantic that helps keep European climate mild, while allowing the tropics a chance to lose excess heat. An equivalent overturning of Antarctic waters can be found in the Southern Hemisphere.

Climate records reaching back 120,000 years reveal the Atlantic overturning circulation has switched off, or dramatically slowed, during ice ages. It switches on and placates European climate during so-called “interglacial periods”, when the Earth’s climate is warmer.

Since human civilisation began around 5,000 years ago, the Atlantic overturning has been relatively stable. But over the past few decades a slowdown has been detected, and this has scientists worried.

Why the slowdown? One unambiguous consequence of global warming is the melting of polar ice caps in Greenland and Antarctica. When these icecaps melt they dump massive amounts of freshwater into the oceans, making water more buoyant and reducing the sinking of dense water at high latitudes.

Around Greenland alone, a massive 5 trillion tonnes of ice has melted in the past 20 years. That’s equivalent to 10,000 Sydney Harbours worth of freshwater. This melt rate is set to increase over the coming decades if global warming continues unabated.

A collapse of the North Atlantic and Antarctic overturning circulations would profoundly alter the anatomy of the world’s oceans. It would make them fresher at depth, deplete them of oxygen, and starve the upper ocean of the upwelling of nutrients provided when deep waters resurface from the ocean abyss. The implications for marine ecosystems would be profound.

With Greenland ice melt already well underway, scientists estimate the Atlantic overturning is at its weakest for at least the last millennium, with predictions of a future collapse on the cards in coming centuries if greenhouse gas emissions go unchecked.

The Ramifications Of A Slowdown

In our study, we used a comprehensive global model to examine what Earth’s climate would look like under such a collapse. We switched the Atlantic overturning off by applying a massive meltwater anomaly to the North Atlantic, and then compared this to an equivalent run with no meltwater applied.

Our focus was to look beyond the well-known regional impacts around Europe and North America, and to check how Earth’s climate would change in remote locations, as far south as Antarctica.

The first thing the model simulations revealed was that without the Atlantic overturning, a massive pile up of heat builds up just south of the Equator.

This excess of tropical Atlantic heat pushes more warm moist air into the upper troposphere (around 10 kilometres into the atmosphere), causing dry air to descend over the east Pacific.

The descending air then strengthens trade winds, which pushes warm water towards the Indonesian seas. And this helps put the tropical Pacific into a La Niña-like state.

Australians may think of La Niña summers as cool and wet. But under the long-term warming trend of climate change, their worst impacts will be flooding rain, especially over the east.

We also show an Atlantic overturning shutdown would be felt as far south as Antarctica. Rising warm air over the West Pacific would trigger wind changes that propagate south to Antarctica. This would deepen the atmospheric low pressure system over the Amundsen Sea, which sits off west Antarctica.

This low pressure system is known to influence ice sheet and ice shelf melt, as well as ocean circulation and sea-ice extent as far west as the Ross Sea.

A New World Order

At no time in Earth’s history, giant meteorites and super-volcanos aside, has our climate system been jolted by changes in atmospheric gas composition like what we are imposing today by our unabated burning of fossil fuels.

The oceans are the flywheel of Earth’s climate, slowing the pace of change by absorbing heat and carbon in vast quantities. But there is payback, with sea level rise, ice melt, and a significant slowdown of the Atlantic overturning circulation projected for this century.

Now we know this slowdown will not just affect the North Atlantic region, but as far away as Australia and Antarctica.

We can prevent these changes from happening by growing a new low-carbon economy. Doing so will change, for the second time in less than a century, the course of Earth’s climate history – this time for the better.![]()

Matthew England, Scientia Professor and Deputy Director of the ARC Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS), UNSW Sydney; Andréa S. Taschetto, Associate Professor, UNSW Sydney, and Bryam Orihuela-Pinto, PhD Candidate, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia has overshot three planetary boundaries based on how we use land

We used to believe the world’s resources were almost limitless. But as we spread out across the planet, we consumed more and more of these resources. For decades, scientists have warned we are approaching the limits of what the environment can tolerate.

In 2009, the influential Stockholm Resilience Centre first published its planetary boundaries framework. The idea is simple: outline the global environmental limits within which humanity could develop and thrive. This concept has become popular as a way to grasp our impact on nature.

For the first time, we have taken these boundaries – which can be hard to visualise on a global scale – and applied them to Australia. We found Australia has already overshot three of these: biodiversity, land-system change and nitrogen and phosphorus flows. We’re also approaching the boundaries for freshwater use and climate change.

The nation’s land use is a key contributor to these trends, with natural systems under increasing pressure as a result of many land management practices. Luckily, we already know many of the solutions for living within our limits, such as waste management, conservation and restoration of natural lands in conjunction with agriculture, and shifts in food production.

What Are Planetary Boundaries?

In 2015, scientists took stock of how humanity was tracking, warning four of nine boundaries had already been crossed.

While such warnings make global headlines, they can also leave people wondering, “What does this actually mean for me?”

This is the question we have sought to answer for Australia and its land use sector. We took five of these global boundaries and calculated what Australia’s “share” of those would be in our new technical report.

We then went one step further, breaking down what these boundaries mean for Australia’s land use industries, such as agriculture and forestry.

These Limits Are Not Abstractions – They’re Real

These are real-world limits. Pushing past them has real-world consequences.

Take nitrogen and phosphorus flows, which refers to the levels of these chemicals in the nation’s waterways.

In around 50% of our river catchments, we already have concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus past the safe level for the health of the environment. These chemicals are applied as fertiliser to cropland and pasture. If there’s too much, it can run off into waterways. Once in our rivers, these chemicals can fuel dangerous algal blooms which can force the closure of popular recreational areas, fill lakes with weeds and hurt fish and other wildlife.

Tackling one environmental issue often has benefits for others. Improving water quality has benefits for biodiversity, because the plants and animals supported by those rivers have better water to live off and in.

Why does biodiversity matter? The diversity of life on our continent plays a critical role in keeping ecosystems stable and sustaining vital services – such as fresh air and water – they provide to wildlife and to us.

It’s well known areas with lower numbers of species and lower genetic diversity prove generally less resilient to shocks. That means these environments are at higher risk of tipping into a state where they can no longer provide the services vital to life.

Different species occupy different niches within ecosystems, meaning the loss of one or two can erode the functioning of the system as a whole.

Protecting and restoring biodiversity is therefore critical to achieving planetary health. Unfortunately, biodiversity is among the boundaries Australia has already overshot. The number of species threatened by our activities is growing, and many of our endangered animals are at risk of extinction.

We Know What We Need To Do

With this report, we contribute to the national conversation about how Australia can stay within its fair share of planetary limits and contribute to the global effort for sustainable development.

Agriculture, forestry and other land use industries also have a critical role to play in reducing emissions and sequestering carbon. But the land use sector is under increasing pressure from growing populations, the impacts of climate change and extreme weather events.

Understanding what sustainability means in practical, measurable terms for Australia’s land use sector is vital to enable humanity to continue to prosper.![]()

Romy Zyngier, Senior Research Manager, Climateworks Centre

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get out and go fungal: why it’s a bumper time to spot our native fungi

When COVID forced Melburnians to isolate during large parts of 2020 and 2021, many took the opportunity to walk around parks, creeks or remnant bush.

In your walks, you may have noticed the wonderful and diverse range of fungal fruiting bodies on display. Victoria’s display of puff balls, bracket fungi and fairy rings has been nothing short of splendid.

The fun’s not over, either. This year has been a particularly good one for fungus too, and here’s why. As you may recall, the harsh 2019-20 summer dried our soils, stressed much of our vegetation and led to major bushfires. In 2021, this switched abruptly to one of the wettest starts to a year on record in many places, courtesy of the La Niña climate pattern.

With the rains, the weather became ideal for fungal reproduction. We had warm, very moist soils and lovely warm and sunny autumnal days, perfect for fungi to send up their reproductive structures (you might know these as mushrooms and toadstools) and spread their spores. Conditions this good may not occur again for years so seize the opportunity to see them.

What You Can See In A Walk In The Park

Fungi are not just for adults. Oh no! They can entertain children for hours.

In 2020, our family group took a walk in Brimbank Park, in Melbourne’s northwest. The five year old leader waved his lucky stick/sword/wand in the air as we entered, declaring, “today we hunt fungus!” He was still doing so two hours later, closely followed by his younger brother.

Their first findings were puff balls, some brown and others like little white pebbles. If you squeeze these puff balls, a fine dust of spores can emerge like a mist. You don’t want to breathe them in but at a distance they are mostly harmless.

We spotted some like ordinary field mushrooms, but when you scratched their light tan surface a bright yellow colour emerged. If you were to eat these yellow-staining mushrooms you would be sick and potentially seriously ill. Some contain very powerful toxins and can prove to be deadly if eaten. Unless you know exactly what fungus you have, don’t even think of eating them. It’s advisable to wash hands well after handling any kind of fungi.

Spores are the means by which fungi reproduce themselves. Most are tiny but they can be dry like powder, damp and sticky, dull or brightly coloured, plain or ornately decorated and sometimes quite smelly. The dry spores can easily be dispersed by even a gentle breeze, but the sticky ones often adhere to an unsuspecting passer-by such as a bird, rabbit, dog or human sock.

We gave the little ones extra points if they looked at the fungus but left it intact, even if they couldn’t resist giving one or two a poke. Their next discovery gained even more points because you had to look up: it was a bracket fungus growing on a dead branch. Some of these are snowy white, but others are yellow or bright orange, almost like traffic lights. Some have an almost velvety outer texture while others appear to be made of woody rings like the tree upon which they are growing.

On dead trees, bracket fungi have the role of recycling old dead wood. Some don’t even wait until the tree dies. They gain access to the old wood at the tree’s centre and begin the decay process while the tree is still living. The fruiting bodies of these fungi look like little shelves on the trunk of the tree and can persist for decades. On some trees, multiple brackets form a veritable stairway to heaven. If you have a large bracket fungus on a large old branch or tree, it’s a good idea to get arboricultural advice about the safety of the tree.

Fairy Rings, Basket Fungus And Symbiotic Relationships

Our little posse of fungal hunters had travelled 100 metres into the park, but in the zigzag pattern of explorers, it had taken us an hour. A brown dried star-like structure was revealed as a dried puff ball, its spores well and truly blown and what was once a ball had peeled back as it dried into a near perfect star. In a section of mown grass, we come across the delicate mushrooms of a fairy ring. Excitement ensues.

Why is it a ring? Where are the fairies? Can you eat them? Not the fairies, the mushrooms! The fairies of course heard us coming and so they are hiding. No, you can’t eat them because they might be poisonous and make you sick.

Fairy rings form into a circle because they came from a single starting point and expanded outward from the centre at more or less the same rate.

Is that a pebble? No it’s a fungus doing a brilliant impression of a pebble. We were camouflage experts now, and it couldn’t hide from us. Then a squeal. What is that? A soccer ball? No, old plastic. No, a dome. It’s a magnificent white basket fungus shaped like an intricate geodesic sphere. We left it for others to discover. With the mighty stick/sword/wand high in the air, we head for home.

Fungi are always there in our soils. Their fine thread structures, called hyphae, lie underfoot all year, but their fruiting bodies only appear under the right conditions. Many of these fungi entwine around the roots of specific plants and in many cases into the plant root cells themselves. The fungus offers water and nutrients to the plants and in return the plants give the fungus some of the carbohydrates they produce from photosynthesis. It’s a marvellously beneficial relationship.

We went a-hunting several more times, and the young ones never tired of the sport. Interacting closely with plants and fungi meets basic physical, mental and psychological needs hailing back to our early travel through natural ecosystems.

Finding and poring over plants and fungi engages all our senses – sight, hearing, smell, touch – and for experts only, taste. It’s no wonder all of us in the hunt feel the better for this purposeful forest bathing.

Spotting fungi above ground is a rare treat. If the weather gets too chilly, or if La Niña gives way to hot and dry El Niño, the fungi will vanish. But if we get a mild, wet winter, the fungal season can just roll on. That’s the thing about fungi, you can never be sure. They play by their own rules. ![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our new environment super-department sounds great in theory. But one department for two ministers is risky

Good news, Australia – the environment is back. Our new government has introduced a new super-department covering climate change, energy, the environment and water.

But while the ministry move sounds great in theory, it’s risky in practice. Having one super-department supporting two ministers – Tanya Plibersek in environment and water, and Chris Bowen for climate change and energy – is likely to stretch the public service too far.

If a policy area is important enough to warrant its own cabinet minister, it also warrants a dedicated secretary and department. This is especially true for the shrunken environment department, which has to rebuild staff and know-how after having over a third of its budget slashed in the early Coalition years.

Supporting two cabinet ministers stretches department secretaries too thinly. It makes it hard for them to engage in the kind of deep policy development we need in such a difficult and fast-moving policy environment.

What Are The Politics Behind This Move?

Tanya Plibersek’s appointment last week as minister for the environment and water was the surprise of the new ministerial lineup.

Even if Plibersek’s move from education in opposition to environment in government was a political demotion for her, as some have suggested, placing the environment portfolio in the hands of someone so senior and well-regarded is a boon for the environment.

Having the environment in the broadest sense represented in Cabinet by two experienced and capable ministers is doubly welcome. It signifies a return to the main stage for our ailing natural world after years of relative neglect under the Coalition government.

It also makes good political sense, given the significant electoral gains made by the Greens on Labor’s left flank. While ‘climate’ rather than ‘environment’ was the word on everybody’s lips, other major environmental issues need urgent attention. Threatened species and declining biodiversity are only one disaster or controversy away from high political urgency.

When released at last, the 2021 State of the Environment Report will make environmental bad news public. Former environment minister Sussan Ley sat on the report for five months, leaving it for her successor to release it.

Now Comes The Avalanche Of Policy

Both ministers have a packed policy agenda, courtesy of Labor’s last minute commitment to creating an environmental protection agency, as well as responding to the urgent calls for change in the sweeping [2020 review] of Australia’s national environmental law (https://epbcactreview.environment.gov.au/resources/final-report).

That’s not half of it. Bowen is also tasked with delivering the government’s high-profile 43% emissions cuts within eight years, which includes the Rewiring the Nation effort to modernise our grid. He will also lead Australia’s bid to host the world’s climate summit, COP29, in 2024, alongside Pacific countries.

Plibersek also has to tackle major water reforms in the Murray Darling basin and develop new Indigenous heritage laws to respond to the parliamentary inquiry into the destruction of ancient rock art site Juukan Gorge by Rio Tinto.

Can One Big Department Cope With This Workload?

Creating a super-department is a bad idea. That’s because the agenda for both ministers is large and challenging. It will be a nightmare job for the department secretary tasked with supporting two ministers. It’s no comfort that the problem will be worse elsewhere, with the infrastructure department supporting four cabinet ministers.

Giving departmental secretaries wide responsibilities crossing lines of ministerial responsibility encourages them to reconcile policy tensions internally rather than putting them up to ministers, as they should.

The tension between large renewable energy projects and threatened species is a prime example of what can go wrong. Last year, environment minister Sussan Ley ruled a $50 billion renewable megaproject in the Pilbara could not proceed because of ‘clearly unacceptable’ impacts on internationally recognised wetlands south of Broome.

Ley’s ‘clearly unacceptable’ finding stopped the project at the first environmental hurdle. That’s despite the fact the very same project was awarded ‘major project’ status by the federal government in 2020.

The problem here is what might have been the right answer on a narrow environmental basis was the wrong answer more broadly.

If Australia is to achieve its potential as a clean energy superpower and as other renewable energy megaprojects move forward, we will need more sophisticated ways of avoiding such conflicts. This will require resolution of deep policy tensions – and that’s best done between ministers rather than between duelling deputy secretaries.

Super-departments also struggle to maintain coherence across the different programs they run. While large departments bring economies of scale, these benefits are more than offset by coordination and culture issues.

An early task for Glyn Davis, the new head of the prime minister’s department, will be to recommend a secretary for this new super-department of climate change, energy, the environment and water. In addition to the ability to absorb a punishing workload, the successful appointee will need high level juggling skills to support Plibersek and Bowen simultaneously.

Ironically, in dividing time between two ministers, she or he will be the least able to accept Plibersek’s call for staff of her new department to be ‘all in’ in turning her decisions into action.![]()

Peter Burnett, Honorary Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This mosquito species from Papua New Guinea was lost for 90 years – until a photographer snapped a picture of it in Australia

There are already plenty of mosquitoes in Australia. They bring pest and public health risks to many parts of the country.

Now a new species of mosquito, Aedes shehzadae, has been discovered 90 years after the first (and only other observation) of it in Papua New Guinea – and it’s thanks to citizen science.

Mosquitoes And Their Health Threats

Mosquitoes are simple creatures, but they pose complex health risks. The recent widespread arrival of Japanese encephalitis virus, which caused dozens of cases of disease and five deaths, is a reminder of the threat mosquitoes pose in Australia.

To address this threat, there are mosquito and mosquito-borne pathogen surveillance programs in states and territories around the country. Our borders are checked by the Department of Agriculture Water and Environment for the arrival of invasive mosquitoes with international travellers, their belongings, or freight.

These programs collect valuable information on local and invasive mosquitoes. But they can’t be everywhere – which is where citizen science can step in.

We can learn more about mosquitoes, and their spread across the country, with the help of volunteer “citizen scientists”. Individuals or groups can participate in projects such as Zika Mozzie Seeker or Mozzie Monitors. Mozzie Monitors has expanded in recent years to become the only national program, primarily focused around the annual Mozzie Month.

Citizen scientists can also upload photographs of mosquitoes to online platforms such as iNaturalist, which provides opportunities to observe the insects in nature. An analysis of more than 2,000 mosquito observations uploaded to iNaturalist revealed an astonishing 57 species observed across Australia.

And one of the most remarkable observations uploaded to iNaturalist in recent years has been a mysterious and distinctive mosquito, Aedes shehzadae.

A Discovery 90 Years In The Making

Aedes shehzadae was first captured in Australia by photographer John Lenagan in 2021, while on the lookout for moths in the Kutini-Payamu National Park (Iron Range) in Queensland’s Cape York.

The photo kicked off a cascade of investigations into mosquito collections held in research institutes and museums across Australia. They even stretched as far as the Natural History Museum in London.

We and our colleagues have detailed the circumstances around this unique discovery in this month’s edition of the Journal of Vector Ecology.

Lenagan’s photo wasn’t just the first time Aedes shehzadae was observed in Australia – it was also only the second time this mosquito had ever been formally recorded. The discovery may have gone unnoticed, had the photograph not been uploaded to iNaturalist and sparked interest.

The only other specimen of this mosquito was collected in Papua New Guinea in 1934, almost 90 years ago. It was collected by a remarkable unpaid entomologist named Lucy Evelyn Cheesman, and stored in the Natural History Museum, until being formally described in 1972 by the Malaria Institute of Pakistan entomologist M. Qutubiddin (first name unconfirmed). He named the mosquito after his daughter.

Cheesman was a tenacious naturalist who collected around 70,000 specimens of insects, plants, and other animals for the Natural History Museum – many during expeditions to the South West Pacific.

We don’t know much about Aedes shehzadae. We’re not even sure whether it’s a new arrival in Australia, or if it had simply not been observed before. In all likelihood it won’t pose a significant threat to our backyards.

But that can’t be said for other exotic and invasive mosquitoes knocking on our door. Mosquitoes such as Aedes albopictus, or the “tiger mosquito”, could be a game-changer for mosquito-borne disease in Australia.

Community Assistance

Much has been said about the potential for citizen science to help health authorities identify exotic and invasive mosquitoes. This has been the case in Europe. And these programs may well be instrumental in tracking newly arrived mosquitoes that have hitched a ride with travellers or freight to the backyards and bushland of Australia.

We’re used to female mosquitoes biting us for blood, but we’re less aware of the flowers they visit to help pollination. We also don’t know a lot about the animals that eat mosquitoes, so perhaps some photographs of them caught in spider webs would be useful too.

There’s no doubt participants in citizen science projects can contribute to our understanding of native and invasive species distribution in meaningful ways. If Aedes shehzadae is anything to go by, anyone with a camera and some curiosity can be the discoverer of a new species, or new mosquito arrival.![]()

Cameron Webb, Clinical Associate Professor and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney; Craig Williams, Professor and Dean of Programs (Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences), University of South Australia; Larissa Braz Sousa, PhD candidate on citizen science and public health, University of South Australia, and Marlene Walter, Masters of Research Student, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

3 key measures in the suite of new reforms to deal with Australia’s energy crisis

Tim Nelson, Griffith University and Joel Gilmore, Griffith UniversityWith electricity prices surging to previously unimaginable levels, state and federal energy ministers met yesterday to consider how to respond to Australia’s energy crisis.

The market is pricing electricity at over A$300 per megawatt hour, more than three times what it traded at the beginning of this year.

In yesterday’s meeting, ministers agreed on 11 actions for lowering gas bills and to ensure a crisis like this doesn’t happen again. Here we take a closer look at three key ones.

None will address prices immediately, so all consumers should look for the best deal on electricity through excellent comparison sites, such as the Energy Made Easy website.

Three Important Measures On The Table

Power bills are set to remain high for months to come. Wholesale electricity makes up one third of a typical household retail bill, and the Australian Energy Regulator recently approved household electricity price rises of up to 20%.

If wholesale prices stay at current levels, Australians will have to pay even more for their electricity during the second half of the year.

So what key measures have the ministers proposed to address this? First, the ministers will allow the market operator to purchase gas and hold it in reserve.

If done well, holding reserves to release in times of supply shortage could smooth out extreme prices. Holding reserves of gas won’t be costless, but the cost of that insurance may be worth it to taxpayers. It will be important to see the detail of how this will be implemented.

The second action is to develop a national plan for growth in renewables, hydrogen, and transmission.

Accelerating new renewables will be key to reducing our exposure to fuel prices. A new wind or solar project can provide energy for $50-80 per megawatt hour, compared to $300-500 per megawatt hour from fossil fuel plants today.

Having a clear plan is a good start, but ministers will need to work out how to deliver it. Expanding the national Renewable Energy Target would be a good first step.

This target, legislated by the Rudd government, currently requires roughly 20% of electricity to come from new renewable energy. This could be increased significantly.

Indeed, state targets in place now could be more efficiently delivered if they were amalgamated into a stronger national target. Ministers could also consider similar targets for green gas or hydrogen.

The third action is the most contested. Ministers have recommended implementing a capacity mechanism that would pay units to be available even if they’re not used, which may be similar to a capacity market. It’s not clear what this proposal will look like in detail or how this proposal would address the current crisis.

The communique doesn’t explicitly rule out coal. But there are reasons to be hopeful that what ministers have actually asked for is a capacity reserve, which will facilitate more renewables accompanied by modern technologies such as battery storage.

What Is A Capacity Market And Why Should It Exclude Coal?

A traditional capacity market is designed to pay all power stations (including existing coal) for being available, even if they’re not used.

This sort of capacity market won’t build the type of capacity we urgently need. Our grid requires generation that can turn on and off quickly, adjusting to consumers’ increasing appetite for installing their own solar panels.

A traditional capacity market that pays inflexible capacity such as coal will delay investment in new flexible capacity such as hydro, batteries, and hydrogen-ready gas peakers. Coal is considered inflexible because it takes hours to ramp up to full production, whereas “flexible” capacity can ramp to full production in seconds or minutes.

Locking in existing inflexible generation can reduce the reliability of the grid, a risk now possible in Western Australia.

Paying coal power stations to stay around longer also exposes Australia to fuel price spikes as we’ve seen recently, as well as continued shortfalls of capacity. This is because, as federal Energy Minister Chris Bowen pointed out, the current crisis is due to an unexpected shortage of coal, not gas.

Paying coal power stations twice – once for their capacity, and again for their energy – means it’s harder to build new, flexible capacity. A capacity market like this wouldn’t have avoided our current crisis or reduced consumers’ bills: the cost of coal and gas would still be high.

Coal is also increasingly unreliable. Currently up to 25% of coal is offline for maintenance, and unplanned outages are rising. Ironically, some coal generators are simultaneously asking to be paid to close their power stations.

Governments also need to consider the very significant financial assistance already paid to coal-fired generators when the Clean Energy Future package was introduced in 2012 and repealed only two years later.

None of the over $5 billion in assistance provided to coal-fired generators was paid back to taxpayers. Asking consumers to pay again for these power stations to “stay in the market” via a capacity market payment doesn’t seem fair or equitable.

So What Should Ministers Do?

Our current market already provides strong signals for investment in the right mix of capacity.

The market operator says there are around 1.2 gigawatts (GW) of new gas, 1.2 GW of battery, and 2.3 GW of hydro projects entering the market in coming years. Total new capacity entering the market is over 11 GW.

With electricity prices as high as they are, investors such as Snowy Hydro say it’s simply incorrect that the existing market doesn’t incentivise new storage such as batteries and pumped hydro.

However, a well designed “capacity reserve” would smooth out the market. New capacity, such as batteries and pumped hydro, could be brought into a “waiting room” and held until it’s needed.

This could be implemented very quickly. The New South Wales roadmap provides a somewhat similar approach - underwriting new investments to ensure they’re built sooner rather than later.

Importantly, ministers make it clear in their communique that they’re only really wanting the mechanism to support new investment in fast-start zero emissions technologies. As such, it may be that the “capacity mechanism” they have in mind is actually more akin to the “capacity reserve” we have articulated here.

In the near-term, governments need to ensure all energy companies are doing their fair share to address costs and reliability.

The government has asked the ACCC to consider this, as we suggested last week.

But for now, the best option to keep warm this winter without breaking the bank is to shop around for the best electricity deals.![]()

Tim Nelson, Associate Professor of Economics, Griffith University and Joel Gilmore, Associate Professor, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How to make your lawn wildlife friendly all year round – tips from an ecologist

Alongside the worrying current fad for plastic grass, a growing number of people are choosing to let their lawns grow wild in order to encourage a more diverse range of plants and insects to live in them.

You may not be convinced of the beauty of a wild and unruly garden, but there is a sweet spot to be found between a rewilded jungle and a sterile green desert which not only looks good but provides a haven for wildlife. This is especially important in the UK, where 97% of semi-natural grassland has been destroyed over the last 80 years.

I’m an ecologist specialised in the study of this kind of habitat, and I want to help you get the most out of it. One simple compromise you can make is to put off when you first get the lawn mower out each year. A campaign by conservation charity Plantlife called #NoMowMay asks people with lawns to hold off the first cut until June, which allows grasses and herbs time to flower and set seed.

But if you want to maintain a wildlife-friendly lawn throughout the year, without letting your garden become completely overgrown, here’s some advice for what else you can do.

To find a happy medium, some mowing may be necessary. This halts the ecological processes which would otherwise transform a grass lawn into a woodland over time. By varying the height at which you mow different areas of your lawn and how often you do it (simulating the effect of different herbivores grazing in the wild), you can create a mix of conditions which benefit a variety of species.

Areas cut short will favour daisies, which flower in profusion and offer a nectar buffet to bees and butterflies. Unkempt areas left uncut for a year suit a wider variety of flowers, tempting a diverse cast of bugs and other creatures into your garden.

In experiments on his own garden in Kent, Charles Darwin recorded that refraining from mowing turf for too long resulted in fewer species overall, because:

the more vigorous plants gradually kill the less vigorous … thus out of 20 species growing on a little plot of turf (three feet by four) nine species perished from the other species being allowed to grow up freely.

Another key thing to think about is the level of nutrients the lawn receives. Even if you have never succumbed to the lawn feed products heavily promoted in most garden centres, your lawn will get a sufficient dose of fertiliser from reactive nitrogen carried on the wind.

The purpose of mowing in a natural grassland should be to mimic grazing by animals. And to do that, you have to remove the clippings otherwise the nutrients they carry will soak back into the soil.

Fungi and bacteria decompose dead plant material and return those nutrients to plants in a lawn through networks of mycorrhizal fungi in the soil. Regular mows which dump the cuttings and overload the soil with nutrients drive a stick through the spokes of this cycle by devaluing the currency of the nitrogen and phosphorus fungi deliver. Clumps of cut grass can also smother small seedlings.

At unnaturally high soil nutrient levels (common in lawns mown and topped with the clippings regularly), the vegetation is dominated by a small number of fast-growing, weedy species. As Darwin found, this prevents a rich community of wildflowers from taking shape. Soil with low nutrient levels favours not only more species, but also healthy soil food webs.

At the Rothamsted Park Grass experiment in Hertfordshire, scientists have studied the effects of annual haycutting since 1860, making it the oldest field experiment in the world. When fertiliser was evenly applied to some plots, it reduced the number of plant species from 40 to fewer than five.

Autumn Fruiting

You also want to consider the time of year. Mow sparingly and leave grass long in summer to create diverse plant and insect communities in the warmest months. A lawn left uncut until late July, as in a traditional hay meadow, will favour the greatest variety of flowers. But cut it short in autumn to foster conditions for mushrooms fruiting as the year winds down.

Soil organisms and their hidden lives are badly neglected in nature conservation. Among the most overlooked are grassland macrofungi, so named because they are large enough to be visible to the naked eye. My favourites are the brightly coloured waxcaps. These film stars of the fungal world are restricted to undisturbed grasslands where soil nutrient concentrations are low.

The British Isles is a global hotspot for these fungi, but they are threatened by habitat loss. 11 species found in the UK were assessed by international experts as vulnerable – the same extinction risk faced by the panda and snow leopard.

A study by my research group showed that waxcaps need the turf to be short (8cm tall at most) in the autumn, but that their most prolific fruiting occurred when the grass was left uncut until mid-July. Waxcaps grow slowly and are long-lived, but with late cuts and the removal of clippings to lower soil nutrient levels, it is likely that the first waxcaps will return within a decade.

To sum up, delay mowing until midsummer, keep your lawn free of clippings and leave patches more unkempt for longer to please butterflies and bees. But give it regular trims from August onwards to encourage globally rare mushrooms. You’ll then see that grasslands are diverse and dynamic habitats just waiting to be unleashed.![]()

Gareth Griffith, Professor of Fungal Ecology, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Making room for wildlife: 4 essential reads

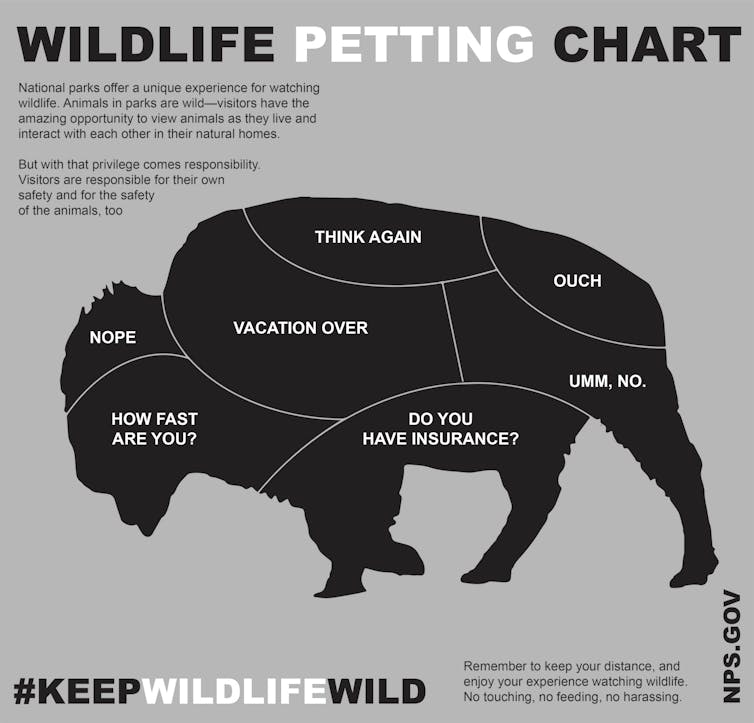

Millions of Americans enjoy observing and photographing wildlife near their homes or on trips. But when people get too close to wild animals, they risk serious injury or even death. It happens regularly, despite the threat of jail time and thousands of dollars in fines.

These four articles from The Conversation’s archive offer insights into how wild animals view humans and how our presence affects nearby animals and birds – plus a scientist’s perspective on what’s wrong with wildlife selfies.

1. They’re Just Not That Into You

In some parts of North America, wild animals that once were hunted to near-extinction have rebounded in recent decades. Wild turkeys, white-tailed deer, beavers and black bears are examples of wild species that have returned to large swaths of their pre-settlement ranges. As human development expands, people and animals are finding themselves in close quarters.

How do the animals react? Conservation researcher Kathy Zeller and her colleagues radio-collared black bears in central and western Massachusetts and found that the bears avoided populated areas, except when their natural food sources were less abundant in spring and fall. During those lean seasons, the bears would visit food sources in developed areas, such as bird feeders and garbage cans – but they foraged at night, contrary to their usual habits, to avoid contact with humans.

“Wild animals are increasing their nocturnal activity in response to development and other human activities, such as hiking, biking and farming,” Zeller reports. “And people who are scared of bears may be comforted to know that most of the time, black bears are just as scared of them.”

2. Wild Animals Turn Up In Unexpected Places

When a recovering species shows up on its old turf or in its former waters, humans aren’t always happy to make room for it. Ecologist Veronica Frans studied sea lions in New Zealand, a formerly endangered species that moves inland from the coast to breed, often showing up on local roads or in backyards.

Frans and her colleagues created a database that they used to find and map potential breeding grounds for sea lions all over the New Zealand mainland. They also identified potential challenges for the animals, such as roads and fences that could block their inland movement.

“When wild species enter new areas, they inevitably will have to adapt, and often will have new kinds of interactions with humans,” Frans writes. “I believe that when communities understand the changes and are involved in planning for them, they can prepare for the unexpected, with coexistence in mind.”

3. Your Presence Has A Big Impact

How close to wildlife is too close? Guidelines vary, but as a starting point, the U.S. National Park Service recommends staying at least 25 yards (23 meters) away from wild animals, and 100 yards (91 meters) from predators such as bears or wolves.

In a review of hundreds of studies, conservation scholars Jeremy Dertien, Courtney Larson and Sarah Reed found that human presence may affect many wild species’ behavior at much longer distances.

“Animals may flee from nearby people, decrease the time they feed and abandon nests or dens,” they report. “Other effects are harder to see, but can have serious consequences for animals’ health and survival. Wild animals that detect humans can experience physiological changes, such as increased heart rates and elevated levels of stress hormones.”

The scholars’ review found that the distance at which human presence starts to affect wildlife varies by species, although large animals generally need more distance. Small mammals and birds may change their behavior when people come within 300 feet (91 meters), while large mammals like elk and moose can be affected by humans up to 3,300 feet (1,006 meters) away – more than half a mile.

4. Don’t Take Wildlife Selfies, Even If You’re A Scientist

There are stories from around the world of people dying in the act of taking selfies. Some involve wildlife, such as a traveler in India who was mauled by an injured bear in 2018 when he stopped to photograph himself with the animal.

Tourists are often the culprits, but they’re not alone. As ocean scientist Christine Ward-Paige explains, scientists who have special permission to handle wild animals as part of their field research sometimes use this opportunity to take personal photos with their subjects.

“I have witnessed the making of many researcher-animal selfies, including photos with restrained animals during scientific study,” Ward-Paige recounts. “In most cases, the animal was only held for an extra fraction of a second while vigilant researchers simply glanced up and smiled for the camera already pointing in their direction.”

“But some incidents have been more intrusive. In one instance, researchers had tied a large shark to a boat with ropes across its tail and gills so that they could measure, biopsy and tag it. Then they kept it restrained for an extra 10 minutes while the scientists took turns hugging it for photos.”

In Ward-Paige’s view, legitimizing wildlife selfies in this way encourages people who don’t have scientific training or understand animal behavior to think that taking them is OK. That undercuts warnings from agencies like the National Park Service and puts both people and animals in danger.

Instead, she urges fellow scientists to “work to show the vulnerability of our animal subjects more clearly” and help guide the public to observe wildlife safely and responsibly.![]()

Jennifer Weeks, Senior Environment + Energy Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

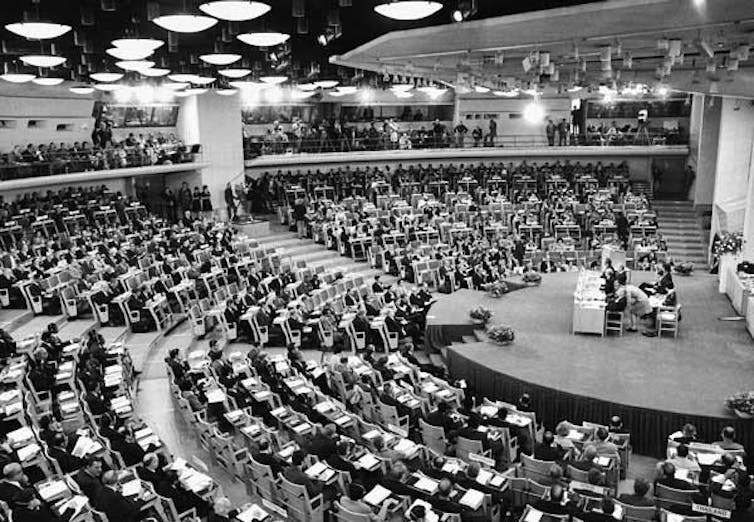

50 years of UN environmental diplomacy: What’s worked and the trends ahead

In 1972, acid rain was destroying trees. Birds were dying from DDT poisoning, and countries were contending with oil spills, contamination from nuclear weapons testing and the environmental harm of the Vietnam War. Air pollution was crossing borders and harming neighboring countries.

At Sweden’s urging, the United Nations brought together representatives from countries around the world to find solutions. That summit – the U.N. Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm 50 years ago on June 5-16, 1972 – marked the first global effort to treat the environment as a worldwide policy issue and define the core principles for its management.

The Stockholm Conference was a turning point in how countries thought about the natural world and the resources that all nations share, like the air.

It led to the creation of the U.N. Environment Program to monitor the state of the environment and coordinate responses to the major environmental problems. It also raised questions that continue to challenge international negotiations to this day, such as who is responsible for cleaning up environmental damage, and how much poorer countries can be expected to do.

On the 50th anniversary of the Stockholm Conference, let’s look at where half a century of environmental diplomacy has led and the issues emerging for the coming decades.

The Stockholm Conference, 1972

From a diplomacy perspective, the Stockholm Conference was a major accomplishment.

It pushed the boundaries for a U.N. system that relied on the concept of state sovereignty and emphasized the importance of joint action for the common good. The conference gathered representatives from 113 countries, as well as from U.N. agencies, and created a tradition of including nonstate actors, such as environmental advocacy groups. It produced a declaration that included principles to guide global environmental management going forward.

The declaration explicitly acknowledged states’ “sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.” An action plan strengthened the U.N.’s role in protecting the environment and established UNEP as the global authority for the environment.

The Stockholm Conference also put global inequality in the spotlight. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi questioned the urgency of prioritizing environmental protection when so many people lived in poverty. Other developing countries shared India’s concerns: Would this new environmental movement prevent impoverished people from using the environment and reinforce their deprivation? And would rich countries that contributed to the environmental damage provide funding and technical assistance?

The Earth Summit, 1992