inbox and environment news: Issue 544

June 26 - July 2, 2022: Issue 544

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Complex Cliff Failure At Long Reef

My Wonder World Of Rocks

Sydney Metropolitan Wildlife Services: Possums In Your Roof

Pelicans Heading To The Coast Now: Winter Migrations

The Story Of Narrabeen Lagoon - Part 2

Barrenjoey Lighthouse Tours

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Midwinter Swim At Mawson

Environmental Assessment Of Illawarra's Mountain Bike Network Released: Have Your Say

Woodside, We'll See You In Court

FCNSW In Court For Alleged Breaches Of 2019/20 Bushfire Harvest Rules

Non-Compliance With Forestry Regulations Costs Forestry Corporation NSW

Budget Boost To Biodiversity

- $598 million over 10 years for National Parks and Wildlife Service to deliver 250 permanent jobs, including 200 firefighters, and critical infrastructure and fleet upgrades

- $286.2 million over 4 years to implement the NSW Waste and Sustainable Materials Strategy 2041 and NSW Plastics Action Plan

- $206.2 million over 10 years in natural capital for a Sustainable Farming Program, rewarding farmers who opt into an accreditation program to improve carbon and biodiversity outcomes

- $148.4 million over 2 years to manage the clean-up and removal of flood and storm-related damage, debris and green waste from the 2022 floods

- $106.7 million over 3 years to increase the supply of biodiversity offset credits through a new Biodiversity Credits Supply Fund

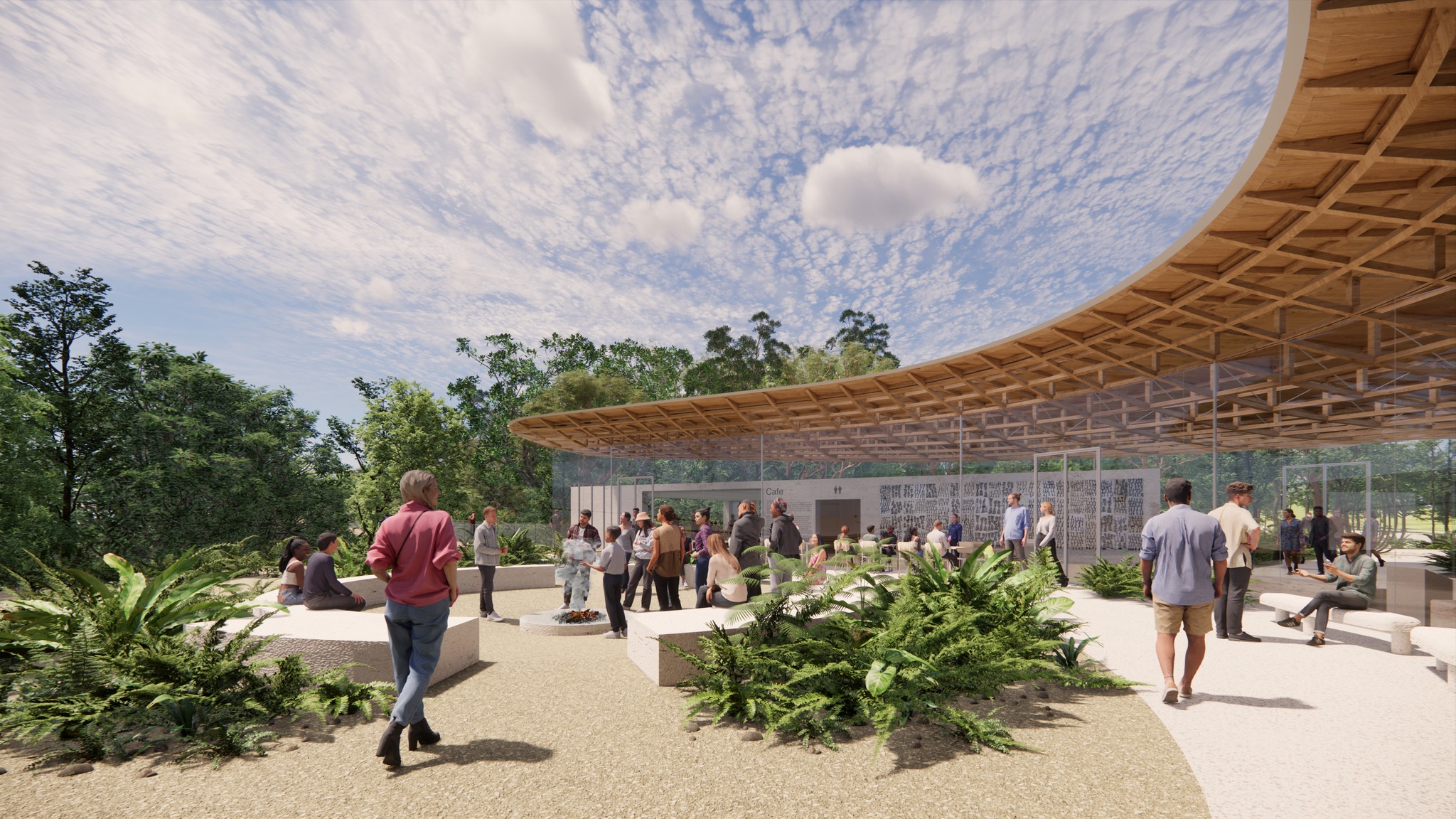

- $56.4 million over 4 years for a new Arc Rainforest Centre and Dorrigo Escarpment Great Walk in the Dorrigo National Park

- $44.8 million over 10 years for a state-wide environmental and air-quality monitoring program

- $42.9 million over 4 years for the Me-Mel (Goat Island) Remediation, paving the way for the transfer of the island to the First Nations communities

- $32.9 million over 4 years to safeguard the future of the World Heritage listed Lord Howe Island by rolling out a biosecurity regime targeting invasive species

- $18.5 million over 10 years to expand Beachwatch to a state-wide program, meeting community demand for water-quality monitoring in NSW swim sites.

Magnificent New Multiday Walk Puts NSW On Global Ecotourism Map

The ancient Gondwana Rainforests on the NSW mid-north coast will host a spectacular new multi-day walk as part of a $56.4 million investment in the NSW Budget.

The ancient Gondwana Rainforests on the NSW mid-north coast will host a spectacular new multi-day walk as part of a $56.4 million investment in the NSW Budget.

Farmers Supported To Build Natural Capital

Farmers around the State will be supported to adopt additional sustainable practices through a groundbreaking $206 million program delivered in the NSW Budget.

Farmers around the State will be supported to adopt additional sustainable practices through a groundbreaking $206 million program delivered in the NSW Budget.NSW Takes The Lead With EV Charger Boost

- $10 million to co-fund 500 kerbside charge points to provide on-street charging in residential streets where private off-street parking is limited.

- $10 million to co-fund around 125 medium and large apartment buildings with more than 100 car parking spaces to make EV charging electrical upgrades.

- $18 million for more EV fast charging grants to speed up the rollout of stations. It will also increase the number of charging points – from the current four to at least 8 – at charging stations located in high density urban areas.

Budget Fails To Tackle Key Threat To Biodiversity — Habitat Destruction

Precious Callala Bay Wildlife Habitat Must Be Protected

Santos’ Raised Zombie To Begin Inflicting Destruction On Liverpool Plains

Support For Santos From New Resources Minister Disrespectful, Ill-Informed

The national electricity market is a failed 1990s experiment. It’s time the grid returned to public hands

A crisis, as the saying has it, combines danger and opportunity. The dangers of the current electricity crisis are obvious. The opportunity it presents is to end to the failed experiment of the national electricity market.

Having suspended the market last week, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) is now directing generators when to supply electricity. It’s also paying them lavish compensation for the financial shortfalls they suffer as a result.

These emergency measures are unsustainable. But they provide the starting point for a restructured electricity supply industry – one that’s better balanced between markets and planning.

Now’s the time to create a national grid that serves the Australian public and meets the challenges of a warming world. A new government-owned and operated body should take control of Australia’s electricity system. And decarbonising the grid, while ensuring reliable and affordable energy, should be its core business.

Privatisation And Poor Design

The National Electricity Market is where energy generators and retailers trade electricity. It was established about 25 years ago after technological advances allowed electricity grids to be connected across all states except Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

Before the market began, each state operated its own electricity industry with only limited interconnection. Back then, electricity companies were publicly owned. Most were also fully integrated, with one company responsible for the entire electricity supply chain, from generation to distribution and billing.

The national grid’s arrival coincided with the peak of enthusiasm for micro-economic reform. So, instead of a unified national enterprise, state utilities were broken up into separate parts – generation, transmission, distribution and retail – with the intention they would be privatised then engage in market competition.

Driving the trend towards privatisation was a widespread view that state-owned electricity enterprises had not performed well – particularly in investing to expand access to electricity.

Reflecting this view, the industry became fully or mostly privatised in Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales. Other states opened electricity generation and retail to competition.

The market was created just as the global need to reduce carbon emissions was being recognised. Despite this, the climate problem was not considered in the design of the market, which was based on a mix of coal and gas plants.

Until AEMO suspended the market last week, bids from generators determined the wholesale price of electricity at five-minute intervals. Retailers supplied electricity to consumers at prices that shielded them from the fluctuations in wholesale prices.

Prices typically sat around A$50 per megawatt hour. But in periods of very high electricity demand, the price can reach the market “price cap”, currently set at $15,100 per megawatt hour.

Meanwhile, electricity distribution – getting the power to homes and businesses using poles, wires and other infrastructure – was handed to a set of regulated monopolies, which were awarded high rates of return on low-risk assets.

What Went Wrong

The designers of the national electricity market hoped it would lead to better efficiency and more rational investment decisions. The market also aimed to lower consumer power bills and promote competitive retail offers tailored to individual needs. But none of this happened.

In fact, consumer electricity prices – after falling for the better part of a century in real terms under public ownership – rose dramatically.

This was partly due to high returns to private electricity distribution companies, and the need for infrastructure investment to improve reliability. A proliferation of highly paid marketers, managers and financiers were also required to run the market.

Over time, the failures of the original design led to an alphabet soup of agencies needed to run the industry. They include AEMO, AEMC, AER, ARENA and a bunch of state-level regulators. Finally, the Turnbull government created the misnamed Energy Security Board (ESB), which sat on top of the whole process.

All this delayed the transition from an old and unreliable coal-based system to its necessary replacement by a combination of solar, wind and storage.

Now, this rickety system has failed to deal with a major supply crisis. The temptation is to slap on another patch and restore “normal” market conditions. The ESB’s proposal to pay coal and gas generators to be on standby if needed is one such quick fix. But much more comprehensive reform is needed.

Where To From Here?

A combination of public and private investment is now needed to secure affordable electricity and transition to renewable energy generation.

The plethora of bodies regulating the market should be replaced by a single government agency that buys wholesale electricity from generators. This organisation could then sell electricity directly to customers or supply it to electricity retailers.

The emergency purchasing arrangements AEMO currently has in place should be replaced by “power purchase agreements”. These are long-term contracts between a buyer and a generator to purchase energy, in which prices, availability and reliability are set.

Within those terms, generators that consistently produce electricity at very low prices are the first to be called on. This dispatch method, known as merit order, has been shown in Germany to lead to lower prices for consumers.

At the same time, the Australian electricity grid should be returned to government ownership and operation. And its guiding principle should be moving to a decarbonised energy system, rather than the “net market benefit” test AEMO currently uses when deciding where to approve investment.

Labor’s Rewiring the Nation policy provides a starting point for reform. It should invest directly in the expanded transmission network needed to support the transition to renewable energy.

Australian energy policy took a wrong turn in the 1990s. It’s time to get back on course.![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Grape growers are adapting to climate shifts early – and their knowledge can help other farmers

It’s commonly assumed Australia’s farmers and cities are divided over climate issues. This is not true. After all, farmers are on the front line and face the realities of our shifting climate on a daily basis.

In regional Australia, our research has found many farmers are already responding to climate change threats and finding ways to adapt.

Wine grape growers are among those who are responding fastest. That’s because their crop is extremely sensitive to weather and climatic shifts. Growers have had to learn quickly how to adapt to safeguard their industry. Think pruning for better canopy management, growing cover crops to keep the ground cooler and promote soil health, and reducing how much water they use in irrigation.

Establishing a vineyard takes a long time – up to five years until the vines produce a full yield. Grape growers have to take a medium to long term perspective to farming, weighing up forecasts about climate change and market trends a decade or more in advance. Successful vignerons recognise the need to work together in a coordinated way to achieve positive outcomes. Maintaining local agency is crucial, and relinquishing this can open up new risks.

Australia’s broader farming community will have to draw on similar adaptations – preparing for less rainfall in some areas, or finding ways to capture the enormous but less frequent rain bursts predicted for other areas.

Why Have Wine Grape Growers Moved Early?

Wine grape growers have had to act early because wine has enormous market differentiation based on variety. In turn, choice of varieties depends heavily on water and soil.

During the 1990s and 2000s, Australian wine exports boomed. The lion’s share of the cheap and cheerful Aussie wines bound for supermarket shelves around the world came from grapes from extensive irrigated vineyards throughout the Murray-Darling Basin, where grapes are grown relatively cheaply with lots of sunshine and lots of water. But the days of water abundance are no longer guaranteed.

Our research in South Australia’s Langhorne Creek wine region has found climate change is having most impact in respect to water.

Historically, this region has relied on groundwater or surface irrigation from seasonal floods along local watercourses. But as groundwater suffered from over-extraction, the aquifers became saltier.

In response, farmers sought to minimise reliance on groundwater. Some vineyards even installed desalination plants to make groundwater usable again. Community leaders spearheaded a push to cut their own allocations and seek supply from nearby Lake Alexandrina, which the Murray and other rivers empty into.

Then came the 2001–2009 Millennium Drought, which led to the shallow lake beginning to dry up through lack of inflow. The crisis of these drought years is seared into regional memory. Without a clear end in sight, many began to wonder if the region had a future.

The community backed a new private-public pipeline drawing directly from the Murray. When the new pipeline opened in 2009, it gave Langhorne Creek an important boost to water security. But it did so at the expense of tying its future directly to that of the Murray Darling Basin.

Now, farming in Langhorne Creek is at the mercy of everything that happens upstream. After two years of La Niña rains, there’s plenty of water in the system. For the time being, things are good – but farmers know better than most that good times don’t last.

In response to the broader shifts, many grape growers have increased plantings of southern Mediterranean varieties such as tempranillo or vermentino, better suited to hotter and drier conditions than traditional mainstays like shiraz and cabernet sauvignon grapes.

To date, Langhorne Creek offers an excellent example of how a strong community can act effectively in the face of environmental threat. As the region becomes integrated into the wider basin, there will be new challenges in navigating basin-wide management policies, a broadening bureaucratisation of decision making, and falling public trust in basin management.

While the technological fix of a new pipeline has helped grape growers overcome an immediate water supply issue, it does not defeat broader climate risk. What it does show is the need for forward thinking. The task for current and future farmers is to remain vigilant in confronting new climate risks, and responding through strong and coordinated local action and political cooperation. ![]()

Bill Skinner, Postdoctoral research associate, University of Adelaide; Douglas Bardsley, Associate professor, University of Adelaide, and Georgina Drew, Associate Professor and Program Director, Stretton Institute, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

After decades of loss, the world’s largest mangrove forests are set for a comeback

Mangroves ring the shores of many of Indonesia’s more than 17,000 islands. But in the most populated areas, the world’s largest mangrove forests have been steadily whittled away, and with them, the ability to store blue carbon.

As the world’s fourth-most populous nation has grown, pressure on the mangroves has too. More than 756,000 hectares of mangroves have been cleared and turned into brackish ponds to farm water shrimp and milkfish.

Every year for the past three decades, another 19,000 hectares has been ripped out for aquaculture and increasingly, for oil palm plantations. As of 2015, an estimated 40% of the country’s mangroves had been degraded or lost.

Is this another predictable bad news story about the environment? No. This is a good news story. That’s because Indonesia’s government is, rising to the challenge of conserving its mangroves – and restoring lost forests.

Government investment in mangroves is rising and the political will is in place. Indonesia’s ambitious goal is to restore almost all of what’s been lost, rehabilitating 600,000 hectares of mangroves by 2024.

Why Have Indonesia’s Mangroves Been Hard Hit?

In a 2012 interview, former Indonesian forestry official Eko Warsito explained why his country’s mangroves were disappearing:

More than 50% of Indonesia’s population lives in coastal areas, and most of them are poor. An ordinary plot of mangroves is worth $84 a hectare. But if it’s cleared and planted with oil palms, it can be worth more than $20,000 a hectare.

Unfortunately, this difference in perceived value has seen mangroves degraded or replaced. You can glimpse the current state of Indonesia’s 3.3 million hectares of mangrove area in the map below, which was released last year by Indonesia’s environment and forestry ministry.

Mangroves are broadly in good condition in the provinces of Papua and West Papua. But in the more populated areas – especially around the densely populated island of Java – mangroves have been largely deforested and degraded.

Recent analysis by the World Bank puts the value of mangrove ecosystems at between A$21,000 to $70,000 per hectare per year. Similarly, a 2020 cost-benefit analysis of mangrove conservation versus conversion to shrimp aquaculture in Indonesia’s Papua province estimated the direct and indirect value of mangroves at A$34,000 per hectare per year.

But these valuations are heavily influenced by the role mangroves play in providing ecosystem services. Without these services, mangroves are worth two orders of magnitude less, at around A$340 per hectare.

Their real value lies in their ability to store large amounts of carbon, averaging almost 4000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents per hectare. Until now, however, policy bottlenecks at the national level have stopped Indonesia from investing in better mangrove management and producing new revenue streams from stemming mangrove losses.

Indonesia’s mangroves have suffered because of this disconnect between their real value and government policies and institutions. Over 20 institutions have some level of responsibility for mangrove management in Indonesia. It’s no wonder their agendas often conflict.

But progress is being made. Two years ago, President Joko Widodo added mangroves to the mandate of the country’s peatland restoration agency, after its success at restoring damaged peatlands. The goal for mangroves is to restore 600,000 hectares of mangroves by 2024.

There Are Alternatives To Aquaculture

You might think it’s too hard to restore mangroves once they’ve been turned into shrimp farms. Previously, this has been true, with an over-reliance on simply planting more seedlings rather than tackling the harder work of social and economic reliance on former mangrove habitat. In response, Indonesia’s government has mapped around 77,000 hectares of the best restoration candidate areas across 300 villages in Sumatra and Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), working in full collaboration with coastal villagers.

To create alternatives to aquaculture, Indonesia’s national farmer field school program will expand to include hundreds of coastal villages. These coastal field schools help local villages improve their management of the coasts and develop alternative sources of income.

These include learning to use Nypah palms alongside mangroves, to allow villagers to harvest the valuable sugar from the sap. This species is the only palm considered a true mangrove. They can produce 800,000 litres of sap per hectare per year, forming a sustainable commodity base for organic palm sugar production as well as bio-ethanol.

Other options include encouraging production of honey, gluten-free flour, tea, juice, jam, and cosmetics. For some villages, eco-tourism could be an option, or shifting to more sustainable aquaculture.

What’s Next?

Indonesia’s government is drafting a new mangrove policy, focused on balancing mangrove protection, sustainable use and restoration. We’re already seeing welcome realignment between the nation’s ministries.

These efforts are being funded by a $A573 million loan from the World Bank and a $A27 million grant for the policy reforms and investment in coastal livelihoods. This loan will be repaid with credits from blue carbon. Indonesia’s government is seeking more financial support from other governments and multilateral organisations to scale up their mangrove management to a national scale.

Indonesia’s work to turn around the fate of their ailing mangroves will be shown on the world stage at the G20 summit in Bali in November. By then, there will be a public dashboard to represent progress captured by field-based and satellite monitoring.

World Bank natural resources expert André Rodrigues de Aquino contributed to the research underlying this article![]()

Benjamin Brown, Postdoctoral research associate, Charles Darwin University and Satyawan Pudyatmoko, Professor of Forestry, Universitas Gadjah Mada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is Migaloo … dead? As climate change transforms the ocean, the iconic white humpback has been missing for two years

Vanessa Pirotta, Macquarie UniversityIt’s that time of year again, when the humpback highway is about to hit peak blubber to blubber as humpback whales migrate up Australia’s east and west coasts from Antarctic waters.

They’re headed to the whale disco – warm breeding waters where males will sing their whale song to attract female company, and pregnant females will birth their calves.

Already this season we’ve seen dolphins dancing with whales, dwarf minke whales with their calves, killer whales and a re-sighting of Curly, the humpback with an unusual curved tail. That’s only just the beginning.

We expect more than 40,000 humpback whales to make this annual journey. I’ll be joining the ABC for their special tonight, Southern Ocean Live, to explore the science around this glorious migration first hand.

But as excitement for the whale season builds, there’s just one whale on the minds of many: the famous white humpback whale named Migaloo.

Who Is Migaloo?

Migaloo is by far one of the world’s most recognisable whales, because he is completely white. Thanks to genetic sampling of Migaloo’s skin, scientists have identified that he’s male, and his albino appearance is a result of a variation in the gene responsible for the colour of his skin.

Simply by looking different, Migaloo has become an icon within Australia’s east coast humpback whale population. Indeed, Migaloo has his own Twitter account with over 10,000 followers, and website where fans can lodge sightings and learn more about humpback whales.

He was first discovered in 1991 off Byron Bay, Australia, and has since played hide and seek for many years, with many not knowing where or when he’ll show up next. He’s even surprised Kiwi fans by showing up in New Zealand waters.

With the last official sighting two years ago, the time has once again come for us to ask: where is Migaloo?

Already this year there have been false sightings, such as a near all white whale spotted off New South Wales. To make things more confusing, regular-looking humpbacks can trick whale watchers when they flip upside down, due to their white bellies.

Migaloo As A Flagship Whale

The annual search for Migaloo connects people with the ocean during the colder months, and is an opportunity to learn more about the important ecological role whales play in the sea.

Migaloo’s popularity has also help drive modern marine citizen science. For example, the Cape Solander Whale Migration study records sightings of Migaloo as part of their 20 year data set. His presence was always a highlight for citizen scientists in the team.

Migaloo also represents the connection whales play between two extreme environments: the Antarctic and the tropics, both of which are vulnerable to climate change.

Earlier this year humpbacks were removed from Australia’s list of threatened species, as populations bounced back significantly after whaling ceased. But climate change poses a new threat, with a paper this year suggesting rising sea surface temperatures may make humpback whale breeding areas too warm.

Other changes to the ocean – such as ocean currents and the distribution of prey – may change where whales are found are when they migrate.

In Australia, for example, we’re already seeing many whales dine out on their migration south. Humpback whales are known to primarily feed once they’re back in Antarctic waters, so scientists are closely watching any new feeding areas off Australia.

Feeding in Australian waters might even become an annual event, and may mean southern NSW waters become an area of importance for migrating humpback whales. This behaviour encourages us to ask more about what’s going on below the surface, and the potential changes in the broader marine ecosystem we just don’t yet know about.

So Where Is He Now? Could He Be Dead?

Migaloo’s presence – or lack thereof – highlights the variations in whale migration. Some whales may choose to migrate early or late, or even elsewhere such as in New Zealand. Others might choose not to migrate at all and remain in the Southern Ocean.

Migaloo’s presence may be driven by several factors. This includes social circumstances, such as interactions with other whales (including moving between different pods) or biological needs (the desire to head north the reproduce).

Environmental conditions, such as currents and water temperature, may also impact when and where Migaloo chooses to swim.

Unfortunately, Migaloo and other whales do face a number of human-caused threats in the ocean every day, such as entanglement in fishing gear or collisions with ships. They also face natural threats, such as predation by killer whales.

Fortunately, Migaloo’s sighting history has shown us he can turn up when we least expect it, or not. So, there’s still hope we might see him yet. After all, being in his mid 30s, he’s likely in the prime of his whale life.

How To Get Involved

The continuing search for Migaloo shows how marine citizen science has become a powerful way to learn about wildlife. Many eyes make science work, as a network of citizen scientists can cover vast areas scientists can’t alone.

A team of 200 citizen science scuba divers, for example, surveyed 2,406 ocean sites in 44 countries over a decade to track how warming oceans impact marine life. They found fish may expand their habitat, pushing out other sea creatures.

But participating in marine citizen science is often as easy as recording wildlife observations on your phone next time you’re at the beach. Opportunities include Happy Whale, RedMap, Wild Sydney Harbour and INaturalist.

This year’s annual migration will last until October or November, so here’s hoping we’ll see Migaloo once again. The power of this unique whale to generate discussion, despite not being seen for years, is true testament to just how curious we are about the mysteries of the deep.![]()

Vanessa Pirotta, Postdoctoral Researcher and Wildlife Scientist, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why including coal in a new ‘capacity mechanism’ will make Australia’s energy crisis worse

Australia’s electricity generators would be paid extra money to be available even if they don’t actually generate any energy, under a new mechanism proposed by the federal government’s Energy Security Board (ESB).

Controversially, the ESB has recommended all generators be eligible for the payment, including ageing coal-fired generators that are increasingly breaking down.

The proposal comes after federal and state ministers last week requested the ESB advance its work on a “capacity mechanism … to bring on renewables and storage”. The ESB says a mix of generators is crucial for the mechanism to be effective, guaranteeing energy supply to the grid.

So will this capacity mechanism lower energy prices for households? Probably not, because it includes unreliable coal-fired power stations, and consumers are likely to pick up the cost when the plants ultimately fail.

The Electricity Market Is In Crisis

Wholesale electricity prices have surged due to two main factors: high coal and gas prices (driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) and roughly one in four coal power stations being out of action at various times in the past few weeks.

The coal stations are unavailable because of maintenance as well as the sudden exit of 3,000 megawatts of power due to breakdowns, with almost all Australian coal-fired power stations now older than their original design life.

The Australian Energy Market Operator has suspended the market in response to the crisis, and it’s unclear when it will restart.

Under the temporary system now in place, generators provide their availability and the market operator tells generators when to run to ensure secure supply. Market prices are then fixed at the past 28-day average for that hour of the day, between A$150 and $300 per megawatt hour.

If generation costs are higher, power station owners can apply for additional compensation, which will be later recovered from consumers. Unfortunately, this means all electricity customers will effectively subsidise the companies that own the unreliable coal generators that caused this crisis.

Would A Capacity Market Have Helped Avoid This Crisis?

The short answer is no. The long answer is actually worse: a capacity market is likely to cause further crises such as the one we’re currently in.

The ESB suggests that selling “capacity certificates” three or four years in advance will mean coal generators will signal when they intend to close. But coal generators are unlikely to face penalties if they don’t turn up when needed - they will just hand back the extra payments they’ve received.

This sort of arrangement is what economists call a “free option” - it costs nothing to participate. If the coal stations fail to deliver, as they have done over the last two months, it will be left to consumers to deal with the consequences.

By including all existing generators (including coal), a traditional capacity market is actually more likely to delay investment in new, fast-start, dispatchable technologies (such as batteries, pumped hydro and hydrogen-ready gas turbines) than accelerate them, as ministers want.

Indeed, ESB’s recommendation is already looking difficult to implement. Federal Energy Minister Chris Bowen says it will be up to the states to choose which generators are eligible, and Victoria has already said fossil fuels will not be.

Most electricity suppliers also say they don’t want coal included.

What’s The Real Problem We’re Trying To Address?

Any capacity mechanism needs to have a solution to unexpected and sudden shortfalls of capacity.

The ESB has noted the biggest risk to consumers is that coal will exit suddenly with little warning because it is old and prone to breaking down. This has been a significant contributing factor to the current crisis.

It also drove higher prices in 2017 when Hazelwood suddenly closed without sufficient time for investment in new capacity to be brought online.

The market operator didn’t foresee any reliability problems less than two months ago - and neither did anyone in the market. The ESB’s proposed capacity market would have implicitly recommended less capacity in the system.

A Capacity Mechanism Needs To Create A Reserve

As older coal power stations are increasingly unreliable, it may be prudent to have new generation in place before coal power stations fail.

Governments should create a capacity reserve market. Effectively, a capacity reserve pays new generators for new capacity until it’s needed, whereas a traditional capacity market (like the ESB is recommending) pays all existing generators that would have been available anyway. This is the key difference between a capacity market and a capacity reserve.

Under a capacity reserve, governments could provide payments only to new, modern, reliable, fast-start, firm capacity such as batteries, hydrogen-ready gas turbines and pumped hydro. This could be brought into a “waiting room” and held until it’s needed.

New generators could be deployed immediately when coal power stations fail, helping prevent the type of crisis we’re going through now.

Importantly, consumers would only be paying for new generation, not coal-fired power stations. This will cost less, and is the only way to provide the insurance the market needs.

We Already Have The Tools In Place

Several years ago, the ESB introduced the Retail Reliability Obligation, which requires retailers to hold contracts with generators for their share of peak electricity demand. This is intended to encourage retailers to plan ahead.

The Retail Reliability Obligation framework could be modified to address situations such as what we’re in now.

If coal-fired generators fail and the market operator is forced to intervene like it did last week, then any costs the market operator incurred could be recovered from the retailers without enough generation or contracts in place to supply all of their customers.

This would be better than today, where the operator’s costs are recovered from all electricity consumers.

By strengthening price signals and building some reserves, we can help prevent future crises and deliver what ministers have rightly requested: a smooth pathway to more renewables and storage.

It’s also worth remembering coal-fired generators received a windfall of up to $5 billion under the Clean Energy Future package in 2012. How much more money do coal generators need from taxpayers and energy consumers to simply do the right thing and make their plant reliable? Or to shut it down with sufficient notice to allow new capacity to be built?![]()

Tim Nelson, Associate Professor of Economics, Griffith University and Joel Gilmore, Associate Professor, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

$3.3 Million To Understand Generational Health Challenges That Influence Dementia Prevalence

Ultimately, we want to be able to help inform planning for services and health policy – and better target preventative strategies against Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. - Professor Henry Brodaty

Eye movements could be the missing link in our understanding of memory

Humans have a fascinating ability to recreate events in the mind’s eye, in exquisite detail. Over 50 years ago, Donald Hebb and Ulrich Neisser, the forefathers of cognitive psychology, theorised that eye movements are vital for our ability to do this. They pointed out we move our eyes not only to receive sensory visual input, but also to bring to mind information stored in memory. Our recent study provides the only academic evidence to date for their theory.

It could help research in everything from human biology to robotics. For instance, it could shed new light on the link between eye movements, mental imagery and dreaming.

We can only process information from a small part of our visual field at a time. We overcome this limitation by constantly shifting our focus of attention through eye movements. Eye movements unfold in sequences of fixations and saccades. Fixations occur three to four times per second and are the brief moments of focus that allow us to sample visual information, and saccades are the rapid movements from one fixation point to another.

Although only a limited amount of information can be processed at each fixation point, a sequence of eye movements binds visual details together (for example, faces and objects). This allows us to encode a memory of what we can see as a whole. Our visual sampling of the world – through our eye movements – determines the content of the memories that our brains store.

A Trip Down Memory Lane

In our study, 60 participants were shown images of scenes and objects, such as a cityscape and vegetables on a kitchen counter. After a short break, they were asked to recall the images as thoroughly as possible while looking at a blank screen. They rated the quality of their recollection and were asked to select the correct image from a set of highly similar images. Using state-of-the-art eye tracking techniques we measured participants’ scanpaths, their eye movement sequences,both when they inspected the images and when they recalled them.

We showed that scanpaths during memory retrieval was connected to the quality of participants’ remembering. When participants’ scanpaths most closely replicated how their eyes moved when they looked at the original image, they performed their best during the recollection. Our results provide evidence that the actual replay of an sequence of eye movements boosts memory reconstruction.

We analysed different features of how participants’ scanpaths progressed over space and time – such as the order of fixations and the direction of saccades. Some scanpath features were more important than others, depending on the nature of the sought-after memory. For example, the direction of eye movements was more important when recalling the details of how pastries were positioned next to each other on a table than when recalling the shape of a rock formation. Such differences can be attributed to different memory demands. Reconstructing the precise arrangement of pastries are more demanding than reconstructing the coarse layout of a rock formation.

Episodic memory allows us to mentally travel in time to relive past experiences. Previous research established that we tend to reproduce gaze patterns from the original event we are trying to call to mind and that gaze locations during memory retrieval have important consequences for what you remember. Those findings all relate to static gaze, not eye movements.

Donald and Ulrich’s 1968 theory was that eye movements are used to organise and assemble “part images” into a whole image visualised during episodic remembering. Our study showed that the way scanpaths unfold over time is critical to recreate experiences in our mind’s eye.

A Step Forwards

The results could be important for cognitive neuroscience and human biology research and in fields as diverse as computing and image processing, robotics, workplace design, as well as clinical psychology. This is because they provide behavioural evidence of a critical link between eye movements and cognitive processing which can be harnessed for treatments such as brain injury rehabilitation. For instance, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) is a well-established psychotherapy treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In this therapy, the patient is focusing on the trauma and engaging in bilateral eye movements, which is associated with a reduction in the vividness and emotion associated with the memory of the trauma. But the underlying mechanisms of the therapy are not yet well understood. Our study shows a direct link between eye movements and the human memory systems, which may provide an essential piece of the puzzle.![]()

Roger Johansson, Associate professor, Lund University and Mikael Johansson, Professor of Psychology, Lund University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Board games: how playing them online can bring grandparents and grandchildren closer together

We’re all familiar with the blissful image of grandma or grandpa playing snakes and ladders with their grandchild – or a large family sat round a table at Christmas over a game of Scrabble, Monopoly or Cluedo.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that the popularity of board games might have waned in favour of the smartphone, tablet or other online gaming. In fact, the market value of board games has been growing considerably in recent years.

While board games were already on the rise pre COVID, lockdown fuelled this trend. A study conducted during the lockdowns suggested nostalgia may have been an important factor in how people coped with isolation, both dusting off board games for solace and watching classic films.

According to a study carried out in Sweden, board games can help children learn about relationships, to become more socially adept and develop their cognitive abilities. Research suggests playing board games can also enhance family togetherness across the generations.

Close But Far

The COVID lockdowns gave us a unique opportunity to study the extent to which families separated by geography managed to maintain that warm glow of togetherness all year round. Suddenly, even relatives who were used to seeing their grandchildren, nieces and nephews on a regular basis were forced to depend upon technology to communicate.

Those with experience of family video calls will know that conversations between older and younger people can often be uncomfortable. Grandparents ask formal questions – how’s school? What’s your favourite subject? – and get monosyllabic responses. The children will then wander away, leaving their parents to continue the conversation.

We wanted to explore how families can use technology to connect and build their relationships, and how game playing, specifically board games, could improve the quality of interactions between grandparents and grandchildren.

Extended family members who lived in different places became more separate than ever during the pandemic and many families struggled to sustain intergenerational relationships. This kind of geographical separation, research suggests, can hinder the development of emotional closeness in the relationships between grandparents and grandchildren.

Our research aimed to address this gap. We know that the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren can be mutually beneficial. It can contribute to children’s development and help grandparents adapt to the ageing process.

Studies have shown that play using technology can help maintain grandparent-grandchild relationships, as well as improving older people’s digital literacy and reducing their social isolation. It may also benefit children’s development and support parents in replacing “bad” screen time.

We gave families something to talk about. We asked pairs of grandchildren and grandparents living in the UK to play the well known board game Articulate, adapted for online play. We interviewed 12 pairs of grandparents and grandchildren together before the game, and then observed their game play during a video call.

We found that it was an overwhelmingly positive experience for grandparents and grandchildren alike. During play, they talked about shared memories relevant to the game and there was much fun and laughter. Grandparents also showed grandchildren love and care through celebrating their game successes. All participants reported that, in contrast to their standard video call, game-playing enabled longer, more enjoyable and meaningful interaction.

We partnered with child development experts Anna Taylor and Amanda Gummer from play consultancy Fundamentally Children for this research. Their face-to-face research on intergenerational play found that grandparents feel pressure to adopt technology for fear of missing out on their grandchild’s lives.

After Lockdown

Children develop impressive expertise in online gaming early in life. Older adults, however, are often less familiar with new technology but are far more experienced in traditional pastimes.

A key barrier to intergenerational play on the video calls in our study was that online board game instructions did not take advantage of children’s expertise. Grandparents looked to grandchildren for help setting up but game instructions are written for adults.

Our findings suggested that intergenerational board game play normally happens on special occasions or holidays, particularly Christmas. Playing games in everyday life is something that children do. But video-calling technologies mean family time is no longer reliant on physically coming together. Technology allows those family dramas over Monopoly to happen anytime, not just at Christmas.![]()

Rose Capdevila, Professor in Psychology, The Open University and Lisa Lazard, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ongoing Support For Seniors In NSW Budget

ACCC Product Safety Priorities Announced At National Consumer Congress

Roadblocks On The Drive Back To Work - New Research

Gold Ribbon Not Necessary: Healthy Brain And Body Function Are The Rewards In This Game

Do optimists really live longer? Here’s what the research says

Do you tend to see the glass as half full, rather than half empty? Are you always looking on the bright side of life? If so, you may be surprised to learn that this tendency could actually be good for your health.

A number of studies have shown that optimists enjoy higher levels of wellbeing, better sleep, lower stress and even better cardiovascular health and immune function. And now, a recent study has shown that being an optimist is linked to longer life.

To conduct their study, researchers tracked the lifespan of nearly 160,000 women aged between 50 to 79 for a period of 26 years. At the beginning of the study, the women completed a self-report measure of optimism. Women with the highest scores on the measure were categorised as optimists. Those with the lowest scores were considered pessimists.

Then, in 2019, the researchers followed up with the participants who were still living. They also looked at the lifespan of participants who had died. What they found was that those who had the highest levels of optimism were more likely to live longer. More importantly, the optimists were also more likely than those who were pessimists to live into their nineties. Researchers refer to this as “exceptional longevity”, considering the average lifespan for women is about 83 years in developed countries.

What makes these findings especially impressive is that the results remained even after accounting for other factors known to predict a long life – including education level and economic status, ethnicity, and whether a person suffered from depression or other chronic health conditions.

But given this study only looked at women, it’s uncertain whether the same would be true for men. However, another study which looked at both men and women also found that people with the highest levels of optimism enjoyed a lifespan that was between 11% and 15% longer than those who were the least optimistic.

The Fountain Of Youth?

So why is it that optimists live longer? At first glance it would seem that it may have to do with their healthier lifestyle.

For example, research from several studies has found that optimism is linked to eating a healthy diet, staying physically active, and being less likely to smoke cigarettes. These healthy behaviours are well known to improve heart health and reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease, which is a leading cause of death globally. Adopting a healthy lifestyle is also important for reducing the risk of other potentially deadly diseases, such as diabetes and cancer.

But having a healthy lifestyle may only be part of the reason optimists live a longer than average life. This latest study found that lifestyle only accounted for 24% of the link between optimism and longevity. This suggests a number of other factors affect longevity for optimists.

Another possible reason could be due to the way optimists manage stress. When faced with a stressful situation, optimists tend to deal with it head-on. They use adaptive coping strategies that help them resolve the source of the stress, or view the situation in a less stressful way. For example, optimists will problem-solve and plan ways to deal with the stressor, call on others for support, or try to find a “silver lining” in the stressful situation.

All of these approaches are well-known to reduce feelings of stress, as well as the biological reactions that occur when we feel stressed. It’s these biological reactions to stress –- such as elevated cortisol (sometimes called the “stress hormone”), increased heart rate and blood pressure, and impaired immune system functioning –- that can take a toll on health over time and increase the risk for developing life-threatening diseases, such as cardiovascular disease. In short, the way optimists cope with stress may help protect them somewhat against its harmful effects.

Looking On The Bright Side

Optimism is typically viewed by researchers as a relatively stable personality trait that is determined by both genetic and early childhood influences (such as having a secure and warm relationship with your parents or caregivers). But if you’re not naturally prone to seeing the glass as half full, there are some ways you can increase your capacity to be optimistic.

Research shows optimism can change over time, and can be cultivated by engaging in simple exercises. For example, visualising and then writing about your “best possible self” (a future version of yourself who has accomplished your goals) is a technique that studies have found can significantly increase optimism, at least temporarily. But for best results, the goals need to be both positive and reasonable, rather than just wishful thinking. Similarly, simply thinking about positive future events can also be effective for boosting optimism.

It’s also crucial to temper any expectations for success with an accurate view of what you can and can’t control. Optimism is reinforced when we experience the positive outcomes that we expect, and can decrease when these outcomes aren’t as we want them to be. Although more research is needed, it’s possible that regularly envisioning yourself as having the best possible outcomes, and taking realistic steps towards achieving them, can help develop an optimistic mindset.

Of course, this might be easier said than done for some. If you’re someone who isn’t naturally optimistic, the best chances to improve your longevity is by living a healthy lifestyle by staying physically active, eating a healthy diet, managing stress, and getting a good night’s sleep. Add to this cultivating a more optimistic mindset and you might further increase your chances for a long life.![]()

Fuschia Sirois, Professor in Social & Health Psychology, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Go glammas! How older people are turning to TikTok to dispel myths about ageing

During lockdown, my 65-year-old mother did something that actually shocked me. She started going on to TikTok so she could watch and follow her favourite “Dancing Dadi” – which means grandmother in Hindi.

I was genuinely taken aback to discover that my mother – who is completely technophobic – had bought an iPad, got a high-speed internet connection and figured out how to create a TikTok account, all just to watch uninterrupted Dancing Dadi.

While I appreciate that few sights are more entertaining than an Indian granny amusing others with her wicked dance moves, there had to be something more than mere amusement converting my mother to technology and the youthful attractions of social media.

As I started to examine the reason behind this transformation, I realised that both my mother and Dancing Dadi herself are trying to bust the negative stereotypes and myths about old age.

While my mother was tearing down the trope of the older person who cannot get to grips with technology or understand social media, Dancing Dadi was shattering the stereotype that older women don’t have the energy to dance or express joy through movement – and was using social media to demonstrate it.

Recent research from the University of Singapore has shown this isn’t as unusual as you might think. Many older people are turning to TikTok – best known as a playground for Gen Z – to reframe the experience of ageing and kick back against age stereotyping.

In my own work as a behavioural data scientist, I explore how humans become biased in the first place. We are all born unbiased but then learn our prejudices from all sorts of sources such as culture, language, society, peers, values and so on. My research is concerned with developing sophisticated AI technologies to mitigate human biases, prejudices and stereotypes.

Both my mother and Dancing Dadi compelled me to ponder these ageist stereotypes – why they still exist and why some people are trying so hard to overcome them using one of world’s most popular social media platforms.

How Stereotypes Work

Stereotypes are beliefs (or associations) about certain social groups or categories. For instance, men are commonly associated with power and career while women are often associated with family and a lack of power. In other words, stereotypes are expectations about a certain group’s ability, preferences and personality type, which are often over-generalised and thus inaccurate.

Along the same lines, older people (those over 60) are stereotypically considered weak, ailing, incapable, boring and useless at technology and social media.

Research has shown that the human mind has cognitive limitations such as bounded rationality, meaning, we seek for good enough decisions rather than the best possible ones. When making decisions, we rely on simple cues which are often formed by our assumptions or stereotypical associations. This is especially true when people don’t have the time or resources to discover new information.

The question is, are these associations correct and should they be relied on during decision making? Many of us might deny we think that way, but how often when making decisions under pressure, do we actually succumb to our cognitive limitations, forming biased opinions? In this way, stereotypes lead to biased perceptions then which can then lead to discriminatory behaviour.

Smashing Biases

The only way to unshackle the mind from our own subconscious biases is to demolish these stereotypes. However, challenging stereotypes, changing society and mitigating subconscious biases that lead to discrimination is not easy.

But those wishing to dispel negative stereotypes of older age have already started a social media revolution on Tiktok’s popular video platform. Smart, funny and generally geared towards youngsters, 41% of TikTok users are under 24 – but around 14.5% of users are over 50.

Increasingly, as the Singapore research has shown, more and more older people are adopting this platform as their social media of choice to provide a glimpse to a youth-centric world what their lives are like, the views they hold and the fun they have.

The researchers compiled TikTok’s most-viewed videos of people over 60 with at least 100,000 followers, resulting in up to 1,382 posts with more than 3.5 billion views. An in-depth analysis then highlighted how older adults are proactively engaging in TikTok to defy the negative stereotypes and challenge socially constructed notions of “old age”.

These revolutionary content creators are users over 60 and creating viral content for their millions of followers. The big hitters are people like Grandma Droniak, who hands out straight-talking advice; Grandad Joe, who makes humorous, non-speaking videos about how he sees things; J-Dog, a nonagenarian who likes to put young people right; Grandpa Chan, who is a whizz at keep-fit dance videos; and Babs aka Nonna, who is now a best-selling cookbook author through her popular TikTok recipe and lifestyle videos.

These people showcase their wisdom, vibrancy, energy and fierceness, proving that granddads can be granfluencers and grandmothers can be glammas – glorious and glamorous.

In using humorous, engaging videos, older people are taking a stand against bias and discrimination, and rejecting the idea that they are invisible. Of course there needs to be greater effort on a variety of fronts to eliminate the stereotyping of older people that goes on in our culture. This includes what I do – designing programmes which can make us aware of our own biases and devising strategies which can challenge them.

Meanwhile, these older TikTok-ers are part of an encouraging and heartening movement that is helping to shift prevailing attitudes. In a world so concerned with inclusion, older people are often at the end of the queue, as we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic. This delightful late-in-life embracing of TikTok serves to remind us all of the value and humanity of a section of society that is so often ignored and sidelined.![]()

Shweta Singh, Assistant Professor, Information Systems and Management, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Art Competition To Remember Our ANZACS

6 Students Score Top Marks To Tour Hiroshima And Pearl Harbour

- Ashley Kim, Tara Anglican School for Girls

- Kathleen Polson, Menai High School

- Elsa McLean, Brigidine College St Ives

- Lucas Hepworth, Ambarvale High School

- Gabriel Fernandez, St Aloysius College Milsons Point

- Caleb Harrison, Clarence Valley Anglican School

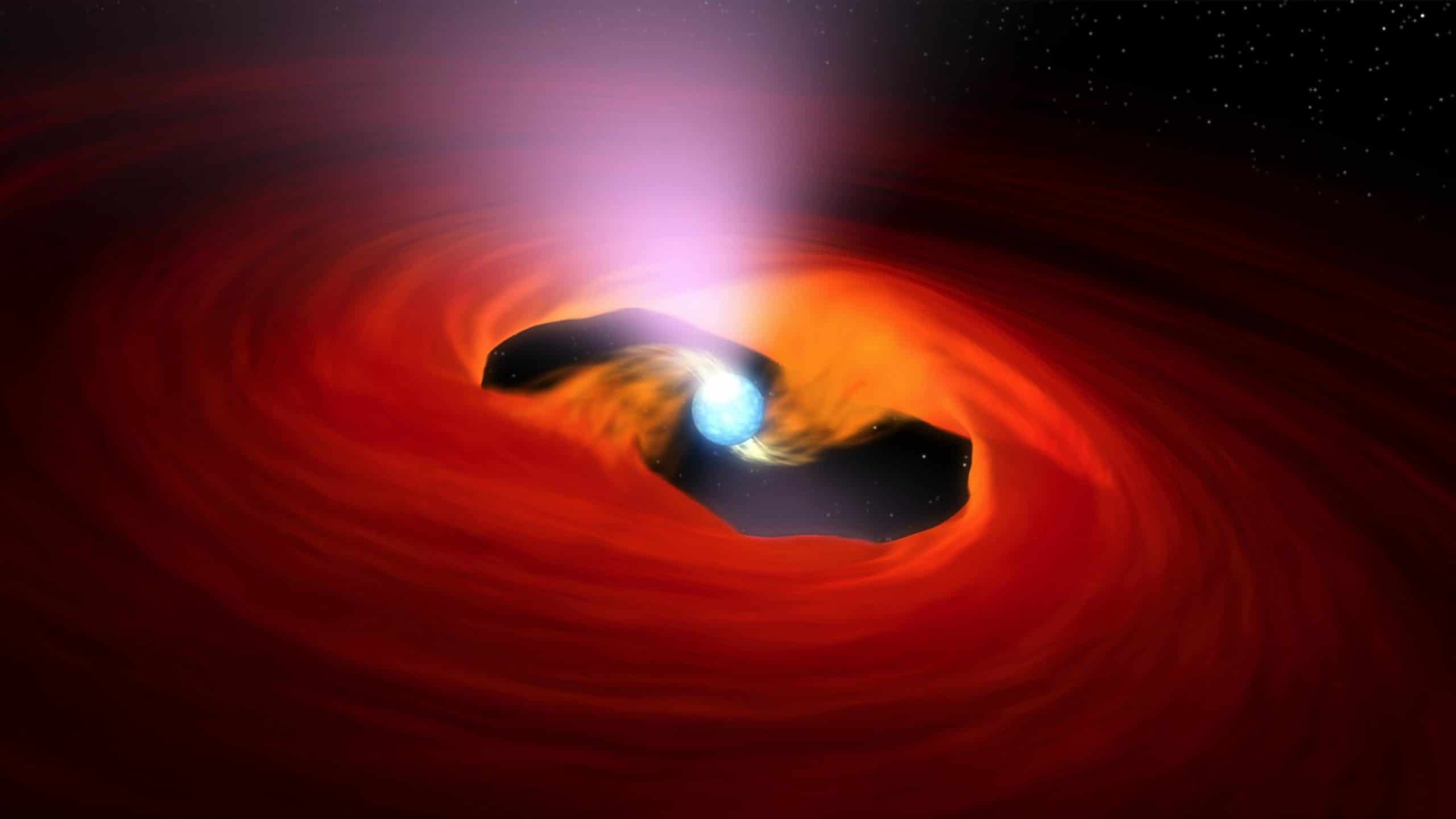

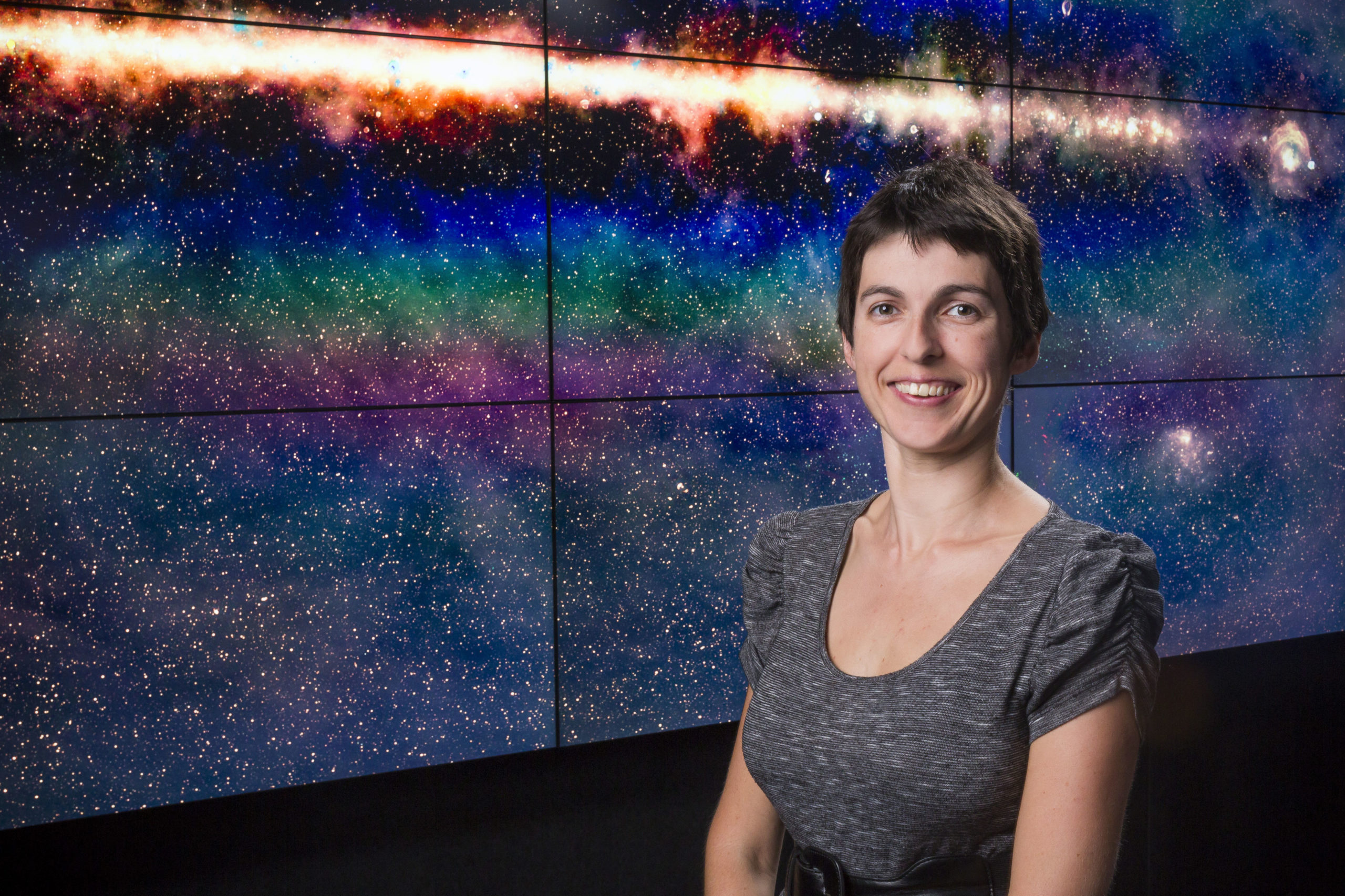

Massive X-Ray Blasts, Thousands Of Black Holes Revealed; A Universe In A Computer And More - Next Generation Astronomers Win National Recognition

- Our Milky Way may just have two arms, says University of Sydney student Maria Djuric.

- A rare X-ray blast a thousand times brighter than the sun was predicted and observed by ICRAR astrophysicist Adelle Goodwin from Monash University and Curtin University.

- Thousands of black holes are pictured in colour by Curtin University/ICRAR radio astronomer Natasha Hurley-Walker.

- The laws of the universe have been manipulated in a supercomputer by University of Western Australia/ICRAR theoretical astrophysicist Adam Stevens.

- A telescope is opening up the sky thanks to CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope team.

- The Astronomical Society of Australia (ASA) will honour the five at its Annual Scientific Meeting in Hobart 27 June – 1 July.

Word Of The Week: Locavore

The term “locavore“ was named the Word of the Year for 2007 in the Oxford American Dictionary. Locavore was coined by a group of women in San Francisco, who encouraged people to eat food produced within a 100-mile radius of where they lived. Runners up for Word of the Year included: cougar: an older woman who romantically pursues younger men and upcycling: the transformation of waste materials into something more useful or valuable.

There are several factors that motivate people to adopt the locavore philosophy. The idea began in the United States with three women: Jessica Prentice, Dede Sampson and Sage Van Wing. Prentice coined the term “locavore” in 2005 and they began a website, challenging people to eat only locally produced food during the month of August.

Locavores reject the idea that any food should be available anywhere, at any time of the year, with fresh produce imported from the other side of the globe. One source estimates that supermarket produce in the USA travels on average 1,300 to 2,000 miles (2,092 to 3,218 kilometres) to reach the consumer, at a considerable carbon cost. The distance the food travels has come to be called “food miles”.

As well as reducing the climate impacts by eating local food in season, locavores recognise that such food is likely to be fresher. In addition, buying it helps support local growers. The locavore movement coincides with the increase in the number of community farms and farmers’ markets as well as a renewed interest in backyard vegetable growing. Even committed locavores tend to stumble when it comes to coffee though.

There are those who point out that local ingredients aren’t always environmentally friendly, saying that raising livestock has a bigger environmental cost than transport. Food processing also has a high environmental impact, although those concentrating on eating locally are likely to avoid highly processed foods.

Fifth Of Global Food-Related Emissions Due To Transport

The world’s affluent must start eating local food to tackle the climate crisis, new research shows

The desire by people in richer countries for a diverse range of out-of-season produce imported from overseas is driving up global greenhouse gas emissions, our new research has found.

It reveals how transporting food across and between countries generates almost one-fifth of greenhouse gas emissions from the food sector – and affluent countries make a disproportionately large contribution to the problem.

Although carbon emissions associated with food production are well documented, this is the most detailed study of its kind. We estimated the carbon footprint of the global trade of food, tracking a range of food commodities along millions of supply chains.

Since 1995, worldwide agricultural and food trade has more than doubled and internationally traded food provides 19% of calories consumed globally. It’s never been clearer that eating local produce is a powerful way to take action on climate change.

A Web Of Food Journeys

The concept of “food miles” is used to measure the distance a food item travels from where it’s produced to where it’s consumed. From that, we can assess the associated environmental impact or “carbon footprint”.

Globally, food is responsible for about 16 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year – or about 30% of total human-produced carbon emissions. The sources of food emissions include transport, land-use change (such as cutting down trees) and the production process.

Our study used an accounting framework we devised in an innovative platform called the FoodLab. It involved an unprecedented level of detail, spanning:

- 74 countries or regions

- 37 economic sectors

- four transport modes - water, rail, road and air

- more than 30 million trade connections: journeys of a single food from one place to another.

Our Results

We found global food miles emissions were about 3 billion tonnes each year, or 19% of total food emissions. This is up to 7.5 times higher than previous estimates.

Some 36% of food transport emissions were caused by the global freight of fruit and vegetables – almost twice the emissions released during their production. Vegetables and fruit require temperature-controlled transport which pushes their food miles emissions higher.

Overall, high-income countries were disproportionate contributors to food miles emissions. They constitute 12.5% of the world’s population yet generate 46% of international food miles emissions.

A number of large and emerging economies dominate the world food trade. China, Japan, the United States and Eastern Europe are large net importers of food miles and emissions – showing food demand there is noticeably higher than what’s produced domestically.

The largest net exporter of food miles was Brazil, followed by Australia, India and Argentina. Australia is a primary producer of a range of fruits and vegetables that are exported to the rest of the world.

In contrast, low-income countries with about half the global population cause only 20% of food transport emissions.

Where To Now?

To date, sustainable food research has largely focused on the emissions associated with meat and other animal-derived foods compared with plant-based foods. But our results indicate that eating food grown and produced locally is also important for mitigating emissions associated with food transport.

Eating locally is generally taken to mean eating food grown within a 161km radius of one’s home.

We acknowledge that some parts of the world cannot be self-sufficient in food supply. International trade can play an important role in providing access to nutritious food and mitigating food insecurity for vulnerable people in low-income countries.

And food miles should not be considered the only indicator of environmental impact. For example, an imported food produced sustainably may have a lower environmental impact than an emissions-intensive local food.