Inbox and Environment News: Issue 545

July 3 - 16, 2022: Issue 545

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Stop It And Swap It This Plastic Free July

To mark the beginning of Plastic Free July, the NSW Government is partnering with 17 organisations to help communities around the state stop using single-use plastic.

To mark the beginning of Plastic Free July, the NSW Government is partnering with 17 organisations to help communities around the state stop using single-use plastic.- Girl Guides NSW

- Green Connect

- Green Music Australia

- KU Children's Services

- Meals on Wheels NSW

- Men’s Shed Association

- NSW Environment & Zoo Education Centres

- OzGreen

- Plastic Free July

- Southern Cross University

- Surfing NSW

- TAFE NSW/Addison Road Community Organisation

- Take 3

- The Great Plastic Rescue

- University of New England

- University of Newcastle

- University of Wollongong

County Road Reserve + Nandi Reserve Finalised Designs: Belrose - Frenchs Forest

Sydney Metropolitan Wildlife Services: Possums In Your Roof

Pelicans Heading To The Coast Now: Winter Migrations

Whale Beach Clean Up: Sunday July 31

Barrenjoey Lighthouse Tours

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

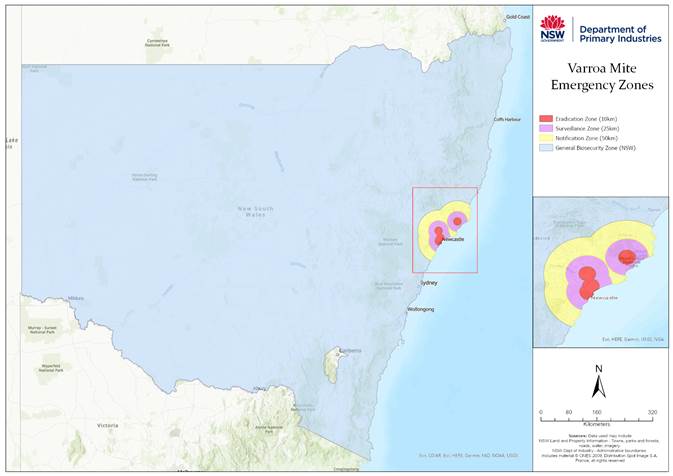

Varroa Mite Incursion Detected In NSW

New Biosecurity Zone Set Up For Varroa Mite

FCNSW To Pay Another $230,000 Following Seven Convictions This Month

Mapping errors in Dampier State Forest near Bodalla, have cost Forestry Corporation of NSW (FCNSW) $230,000 after the Land and Environment Court convicted FCNSW for breaching its approval and carrying out unlawful forestry activities in an exclusion zone.

Mapping errors in Dampier State Forest near Bodalla, have cost Forestry Corporation of NSW (FCNSW) $230,000 after the Land and Environment Court convicted FCNSW for breaching its approval and carrying out unlawful forestry activities in an exclusion zone.Asbestos Dumper To Pay Over $450,000 For Offences In Sydney And Illawarra

- Mr Binos convicted of one charge of failing to comply with a clean-up notice contrary to s 91(5) of the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (POEO Act).

- Mr Binos ordered to:

- pay a fine of $110,000 (the maximum fine that could be imposed by the local court),

- have the waste removed and disposed of lawfully within one year, and

- pay the EPA’s legal costs of $30,000.

- One charge of unlawful disposal of asbestos waste contrary to s 144AAA of the POEO Act,

- and one charge of failing to comply with a clean-up notice contrary to s 91(5) of the POEO Act.

- pay a fine of $110,000 for each offence (total of $220,000),

- remove any contaminated fill at the property within six months of being released from custody,

- compensate the landowner for costs incurred in remediation, totalling $61,192.21,

- and pay the EPA’s legal costs of $30,000.

Boost For Solar Panels Diversion From Landfill

- PV Industries is receiving $2.3 million to scale-up its solar panel recycling technology and build a new solar panel and battery recycling facility in the Bankstown area, which will process up to 8,000 tonnes per year.

- Tes-Amm Australia is receiving $1.9 million to construct a new lithium-ion battery recycling facility in the Fairfield area, processing up to 800 tonnes per year of lithium-ion batteries from solar panel systems.

- Scipher Technologies is receiving $1.7 million to construct a solar panel recycling facility in the Albury area, which aims to process up to 2,000 tonnes per annum, with the recovered materials going back into local markets.

- Blue Tribe is receiving $400,000 to investigate a process to divert serviceable decommissioned solar panels from landfill for reuse in community solar gardens, which has the potential to divert 10,000 tonnes per year of reusable end-of-life solar panels by 2030.

- The University of New South Wales is receiving $1million to complete research and development activities for a prototype recycling technology that can recover valuable metals, glass, and silicon from solar panels.

Environmental Assessment Of Illawarra's Mountain Bike Network Released: Have Your Say

Tender Awarded For New Eurobodalla Dam

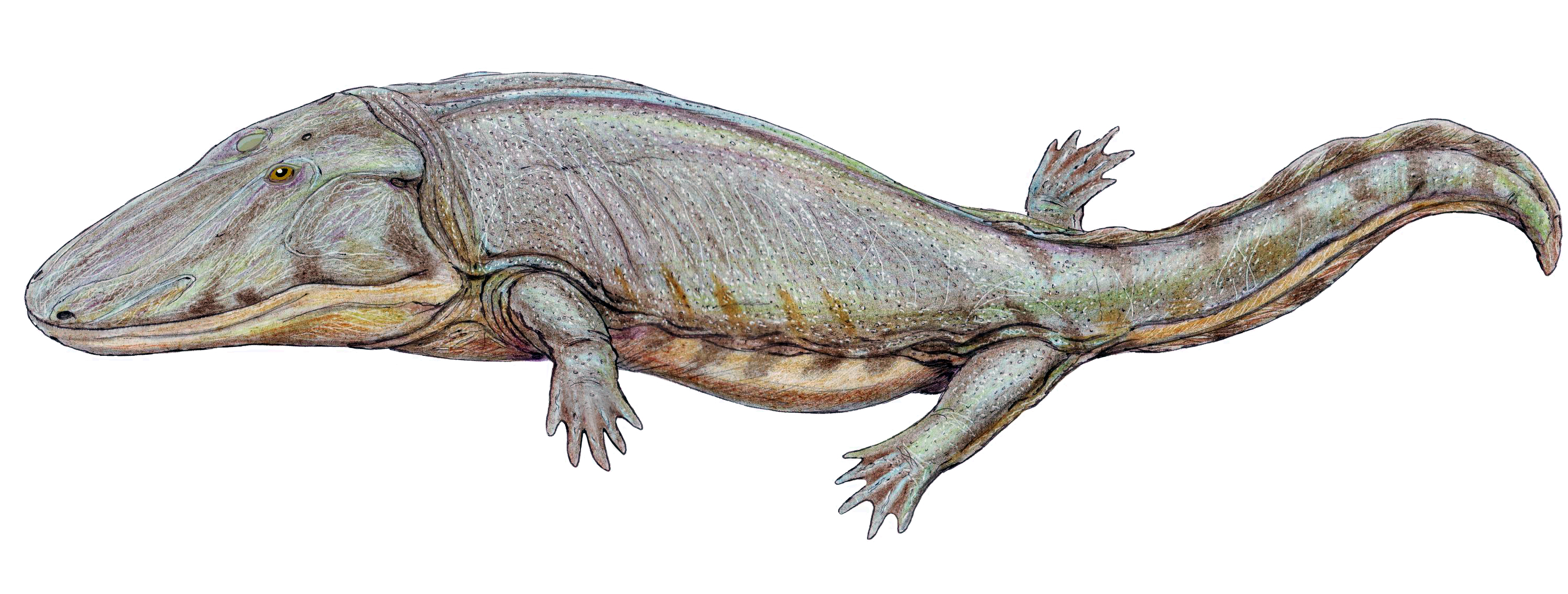

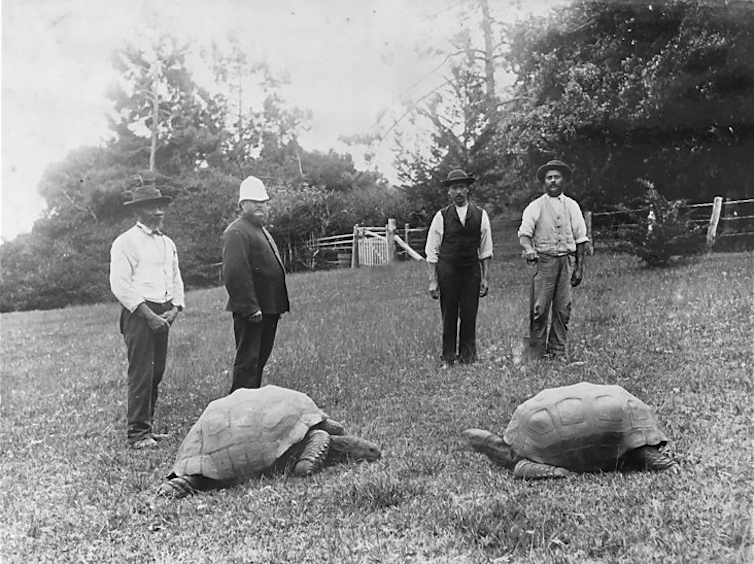

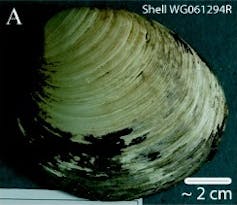

Secrets Of Aging Revealed In Largest Study On Longevity; Aging In Reptiles And Amphibians

Climate Change Is Making Plants More Vulnerable To Disease; New Research Could Help Them Fight Back

Funding For New Frontiers Exploration Program: For Deposits Of Critical Minerals And High-Tech Metals

Support For Developing Countries To Tackle Environment And Climate Change Challenges: United Nations Ocean Conference

Killalea Joins The National Park Estate

Big Blue Carbon Boost To Restore Mangroves, Seagrasses And Tidal Marshes

Pair Of Orcas Deterring Great White Sharks

We blew the whistle on Australia’s central climate policy. Here’s what a new federal government probe must fix

Andrew Macintosh, Australian National University; Don Butler, Australian National University, and Megan C Evans, UNSW SydneyClimate Change Minister Chris Bowen is today expected to announce a much anticipated review of Australia’s carbon credit scheme, known as the Emissions Reduction Fund.

In March, we exposed serious integrity issues with the scheme, labelling it a fraud on taxpayers and the environment. We welcome the federal government’s review. Labor has promised a 43% cut in Australia’s emissions by 2030, and a high-integrity carbon credit market is vital to reaching this goal.

The fund was established by the Abbott government in 2014 and is now worth A$4.5 billion. It provides carbon credits to projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. For the past decade, it has been the centrepiece of Australia’s climate policy.

In this and subsequent articles, we seek to simplify the issues for the Australian public, the new parliament and whoever is appointed to review the Emissions Reduction Fund.

The Background

We are experts in environmental law, markets and policy. The lead author of this article, Andrew Macintosh, is the former chair of the Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee (ERAC), the government-appointed watchdog that oversees the Emissions Reduction Fund’s methods.

Our analysis suggests up to 80% of credits issued under three of the fund’s most popular emissions reduction methods do not represent genuine emissions cuts that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

Our decision to call the scheme a “fraud” was deliberate and considered. In our view, a process that systematically pays for a service that’s not actually provided is fraudulent.

The Clean Energy Regulator (which administers the fund) and the current ERAC reviewed our claims and, earlier this month, dismissed them. We have expressed serious concerns with that review process, which we believe was not transparent and showed a fundamental lack of understanding of the issues.

This week, Bowen said our concerns were “substantial and real” and he took them “very seriously”.

The Conversation contacted the Clean Energy Regulator regarding the authors’ claims. The regulator pointed to its “comprehensive response” to the issues raised and also rejected allegations of fraud. The full statement is included at the end of this article.

The 3 Biggest Problems

Under the fund, projects that reduce emissions are rewarded with carbon credits. These credits can be sold on the carbon market to entities that want to offset their emissions. Each credit is supposed to represent one tonne of carbon abatement.

Buyers include the federal government (using taxpayer funds) and private entities that are required to, or voluntarily choose to, offset their emissions.

Under the scheme, a range of methods lay out the rules for emissions abatement activities. Concerns have been raised about these methods for years.

Our initial criticism focuses on the scheme’s most popular methods, which account for about 75% of carbon credits issued:

human-induced regeneration: projects supposed to regenerate native forests through changes in land management practices, particularly reduced grazing by livestock and feral animals

avoided deforestation: projects supposed to protect native forests in western New South Wales that would otherwise be cleared

landfill gas: projects supposed to capture and destroy methane emitted from solid waste landfills using a flare or electricity generator.

Our analysis found credits have been issued for emissions reductions that were not real or additional, such as:

- protecting forests that were never going to be cleared

- growing trees that were already there

- growing forests in places that will never sustain them permanently

- large landfills operating electricity generators that would have operated anyway.

In forthcoming articles, we will detail the problems with these methods.

However, at a high level, the issues have arisen because the scheme has focused on maximising the number of carbon credits issued, to put downward pressure on carbon credit prices. This has resulted in attempts to use carbon offsets in inappropriate situations.

A Tricky Policy Lever

Designing high integrity methods for calculating carbon credits is hard because it involves:

trying to determine what would happen in the absence of the incentive provided by the carbon credit. For example, would a farmer have cleared a paddock of trees if they weren’t given carbon credits to retain it?

activities where it’s not always clear if carbon abatement was the result of human activity or natural variability. For instance, soil carbon levels can be increased by changing land management practices, but can also happen naturally due to rainfall

activities where it can be hard to measure the emissions outcome. For example, carbon sequestration in vegetation is often measured using models that can be inaccurate when applied at the project scale

dynamic carbon markets with fast-evolving technologies.

These complexities mean mistakes are inevitable; no functional carbon offset scheme can ever get it 100% right. A degree of error must be accepted.

But decisions regarding risk tolerance must consider the consequences of issuing low-integrity credits, including contributing to worsening climate change.

The Dangers Of Sham Credits

The safeguard mechanism places caps on the emissions of major polluters and was originally intended to protect gains achieved through the Emissions Reduction Fund. It applies to about 200 large industrial polluters and requires them to buy carbon credits if their emissions exceed these caps.

When carbon credits used by polluters do not represent real and additional abatement, Australia’s emissions will be higher than they otherwise would be.

To avoid such risks, the legislation governing the Emissions Reduction Fund requires the methods to be “conservative” and supported by “clear and convincing evidence”.

The fund’s main methods do not meet these standards.

An Open And Transparent Process

Carbon credit schemes are, by nature, complex and involve a high risk of error. To maintain integrity, systems to promote transparency are needed.

This includes requiring administrators to not just expect, but actively seek out errors and move quickly to correct them.

To this end, rules are needed to:

force the disclosure of information by the Clean Energy Regulator and ERAC

guarantee disinterested third parties the right to be involved in rule-making

give anybody the right to seek judicial review of decisions made by the Clean Energy Regulator and ERAC

require proponents to move off methods found to contain material errors.

The Emissions Reduction Fund has none of these features and needs urgent reform.

We hope the federal government review will be comprehensive and independent, with the power to compel people to give evidence. Because Australians deserve assurance that our national climate policy operates with the utmost integrity.

The Clean Energy Regulator provided the following statement in response to this article.

The comments made regarding the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) repeat generalised claims that ‘fraud’ is occurring and are rejected. No substantial evidence for claims of fraud has ever been provided. These are serious allegations and the CER is dismayed at the statement that attributes these alleged outcomes to the work done by the CER. We understand that ERAC has the same view.

The claims about lack of additionality and over-crediting are also not new. Prof Macintosh and his colleagues have not engaged with the substance of the ERAC’s comprehensive response papers on human induced regeneration and landfill gas and the CER’s response to the claims on avoided deforestation.

The government has said it will undertake a review of the ERF and details will be announced shortly. We do not wish to pre-empt the scope of the review or its findings. We welcome the review and look forward to engaging substantively with the review process once it commences.![]()

Andrew Macintosh, Professor and Director of Research, ANU Law School, Australian National University; Don Butler, Professor, Australian National University, and Megan C Evans, Senior Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How technology allows us to reveal secrets of Amazonian biodiversity

Tropical forest covers 12% of the planet’s land surface yet hosts around two thirds of all terrestrial species. Amazonia, which spans the vast Amazon River basin and the Guiana Shield in South America, is the largest extent of remaining tropical forest globally, home to more species of animal than any other terrestrial landscape on the planet.

Spotting wildlife in these dark and dense forests teeming with insects and spiny palms is always challenging. This is because of the very nature of biodiversity in Amazonia, where there is a small number of abundant species, and a greater number of rare species which are difficult to survey adequately.

Understanding what species are present and how they relate to their environment is of fundamental importance for ecology and conservation, providing us with essential information on the impacts of human-made disturbances such as climate change, logging or wood burning. In turn, this can also enable us to pick up on sustainable human activities such as selective logging – the practice of removing one or two trees and leaving the rest intact.

As part of BNP’s Bioclimate project, we are deploying a range of technological fixes like camera traps and passive acoustic monitors to overcome these hurdles and refine our understanding of Amazonian wildlife. These devices beat traditional surveys through their ability to continuously gather data without the need for human interference, allowing animals to go about their business undisturbed.

The Eyes Among The Trees

Camera traps are small devices that are triggered by changes of activity in their vicinity, such as animal movements. They have been essential to our field work in the Tapajos National Forest in Para, North West Brazil, allowing us to investigate whether disturbances such as climate change have impacted upon the presence and behaviour of animals that are in turn necessary to natural processes.

Animals’ dispersal of seeds, which enables forest regeneration, is one of such processes. By eating fruits or carrying nuts, they will typically excrete or drop the seeds elsewhere. Our research has shown that at least 85% of all tree species in our plots have their seeds scattered by animals.

We also know that many of these animals are strongly impacted by disturbance. To better grasp the impact of losing these seed-dispersing species, we need to know which ones spread which plants and how far.

We have attempted to look at this by setting up cameras at the foot of fruit-bearing trees on our study site, revealing which species were eating which fruits and thus carrying seeds across the forest.

The survey resulted in over 30,000 hours of footage, and we were able to ascertain that 5,459 videos contained animals. An impressive total of 152 species of birds and mammals were recorded, including rare records of threatened species such as the vulturine parrot (Pyrilia vulturina).

The videos included incredible insights into animal behaviour, such as an ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) hunting a common opossum (Didelphis marsupialis), a giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) carrying an infant on its back, and even a curious female tufted capuchin monkey (Sapajus apella) that checked out a camera and ended up throwing it to the floor.

Importantly, we also recorded 48 species eating fruit, including species considered important seed dispersers, such as the South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris) which is able to scatter large seeds over longer distances due to its size.

Our research demonstrated that bird species such as the white-crested guan (Penelope pileata) and mammals like the silvery marmoset (Mico argentatus) and the Amazonian brown brocket deer (Mazama nemorivaga) are frequent consumers of fruits. Many of these species are overhunted in the study region which may lead to cascading impacts for forest regeneration.

Pulsing Forests

Acoustic recorders, on the other hand, are key to compiling inventories of the species-rich bird community. Indeed although birds are rarely seen in dense forest, their vocalisations reveal their presence.

When ornithologists study tropical birds, they are limited by how often they can conduct counts as it is often logistically challenging to return to individual locations. Consequently traditional surveys are often of quite long duration – between 5 and 15 minutes – with only a limited number of repeat counts at each surveyed site. This means that only a small proportion of the time period in which birds are most active – the two hours after sunrise typically known as the dawn chorus – is able to be surveyed.

Yet birds don’t all sing at the same time: a few species prefer to sing very early in the morning, most wait until it is slightly warmer and the sun is fully up, and a few more rise late. By limiting ourselves to a few surveys, it is difficult to cover the full time period and detect all the species present. Moreover, surveys only conducted on a handful of days mean factors such as the weather or the presence of predators on certain days can completely change which species are detected.

Our research found that by setting autonomous acoustic recorders to take 240 very short 15 second recordings totalling one hour of surveying, we could record 50% more species at each site that we surveyed in comparison to four 15-minute surveys that replicated the duration of human surveys. The extra surveys allowed us to spread our survey period across more days, but most importantly across the whole dawn chorus. We found that there was a small group of species which preferred to sing from 15 minutes before sunrise to 15 minutes after, and we were only really likely to detect if them if we had multiple surveys during that period – something only possible with automated recorders.

These more complete surveys allow us to provide better estimates of the species living in these hyperdiverse regions – but also of the ones that vanish when forests are logged or burnt. Thanks to this method, we were able to detect 224 species of bird across 29 locations with a total of just one hour of surveying at each location.

The species present across intact and disturbed forest also confirmed our previous research that showed that undisturbed, primary forests hold unique bird communities that are lost when forests are damaged by selective logging or wildfires.

Acoustic recorders have also allowed us to gather data over long stretches of time, with over 10,000 hours clocked thus far.

However, collecting data on this scale also means it is not viable for a scientist to listen to all of the recordings. Instead, the new field of ecoacoustics has developed statistical techniques to characterise entire soundscapes. These acoustic indices measure variation in amplitude and frequency to give a metric of just how busy or varied each soundscape is. By doing away with the need to identify individual sounds, these can efficiently process large volumes of acoustic data.

We have used acoustic indices to show undisturbed primary forests have unique soundscapes that can be identified with machine-learning techniques. Such data in turn allows us to contrast soundscapes that have been disturbed by phenomena such as fires or logging and make out the species groups which have been the most impacted.

To conclude, camera traps and acoustic recorders allows us to have eyes and ears in the forest even when our researchers are not there. As technology develops we will continue to use the latest techniques to understand animal behaviour and ecology better, and how to use that to better value and protect the habitats they live in.

We are particularly looking to develop deep-learning models to identify species, and in some cases to differentiate between individuals of the same species. Images and recorded sounds from automated recorders are opening up new ways of understanding animal abundance and behaviour, providing new insights into the secret world of tropical forest fauna.

The research project “Bioclimate” of which this publication is part was supported by the BNP Paribas Foundation as part of the Climate and Biodiversity Initiative program. It is coordinated by the Rede Amazonia Sustentavel (RAS).![]()

Oliver Metcalf, Postdoctoral Research Associate, Manchester Metropolitan University and Liana Chesini Rossi, Invited User, University of São Paulo State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

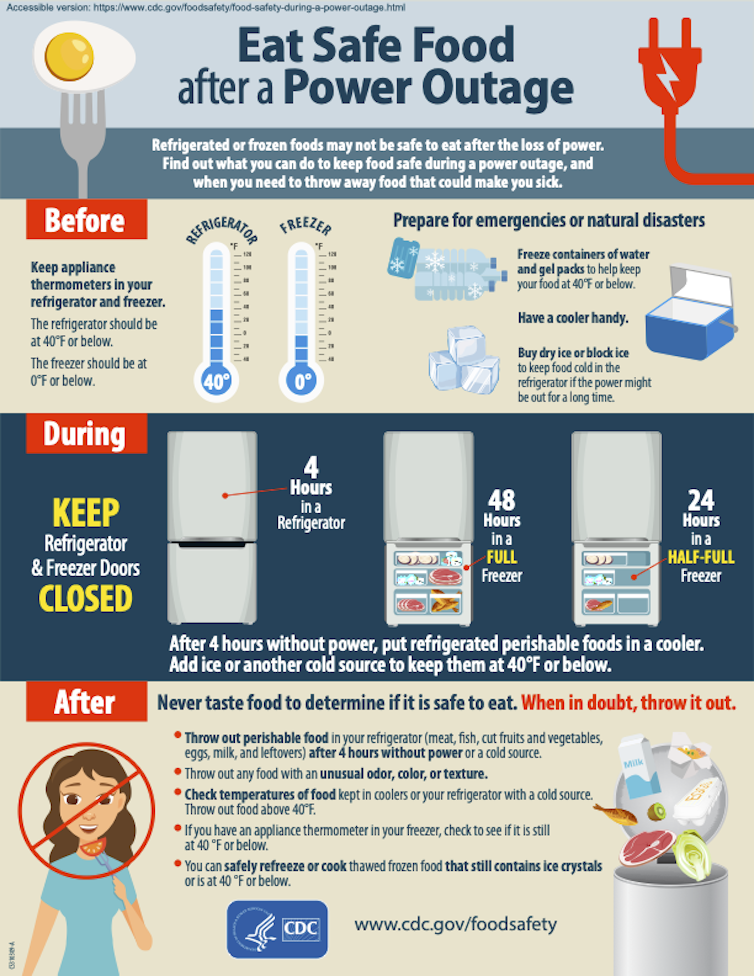

Climate change is putting food safety at risk more often, and not just at picnics and parties

Every year, almost 1 in 6 Americans gets a foodborne illness, and about 3,000 people die from it, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates. Picnics and parties where food sits out for hours are a common source, but heat waves and power outages are another silently growing threat.

As global temperatures rise, the risk of foods going bad during blackouts in homes or stores or during transit in hot weather rises with them. Elena Naumova, an epidemiologist and data scientist at Tufts University, explains the risk and what you need to know to stay safe.

What Does Climate Change Have To Do With Foodborne Illness?

The link between foodborne illness and climate change is quite straightforward: The pathogens that cause many foodborne infections are sensitive to temperature. That’s because warm, wet weather conditions stimulate bacterial growth.

Three main factors govern the spread of foodborne illness: 1) the abundance, growth, range and survival of pathogens in crops, livestock and the environment; 2) the transfer of these pathogens to food; and 3) human exposure to the pathogens.

Safety measures like warning labels and product recalls can help slow the spread of harmful bacteria and parasites, but these measures don’t always evolve rapidly enough to keep pace with the changing risk.

One growing problem is that heat waves, wildfires and severe storms are increasingly triggering power outages, which in turn affect food storage and food handling practices in stores, production and distribution sites and homes. A review of federal data in 2022 found that major U.S. power outages linked to severe weather had doubled over the previous two decades. California often experiences smaller-scale outages during heat waves and periods of high wildfire risk.

This can happen on the hottest and, in some areas, most humid days, creating ideal conditions for bacteria to grow.

Which Causes Of Foodborne Illness Are Increasing With The Heat?

Nationwide, many types of foodborne infection peak in warm summer months.

Cyclospora, a tiny parasite that causes intestinal infections and is transmitted through food or water contaminated with feces, often on imported vegetables and fruits, peaks in early June.

The bacteria Campylobacter, a common cause of diarrhea that’s often linked to undercooked meat; Vibrio, linked to eating raw or undercooked shellfish; Salmonella, which causes diarrhea and is linked to animal feces; and STEC, a common type of E. coli, peak in mid-July. And the parasite Cyptosporidium, germ Listeria and bacteria Shigella peak in mid-August.

Many of these infections cause upset stomach, but they can also lead to severe diarrhea, dehydration, vomiting and even longer-term illnesses, such as meningitis and multiple organ failures.

In our studies, my colleagues and I have also found that food recalls increase during summer months.

Typically, the U.S. sees about 70 foodborne outbreaks per month, with about two of them resulting in a food recall. In summer, the number of outbreaks can exceed 100 per month, and the number of recall-related outbreaks goes up to six per month, increasing from 3% to 6% of all reported and investigated outbreaks nationwide.

The rate of individual infections can also easily double or triple the annual average during summer months.

Precisely estimating infection numbers is very challenging because the vast majority of foodborne illness outbreaks – an estimated 80% of illnesses and 56% of hospitalizations – are not attributed to known pathogens due to insufficient testing, and many foodborne illnesses are not even reported to the health authorities.

What Types Of Food Should People Worry About?

Watch out for perishable products, including meat, poultry, fish, dairy and eggs, along with anything labeled as requiring refrigeration. How warm a food item can get before becoming risky varies, so the simplest rule for keeping food safe is to follow food labels and instructions.

The CDC website emphasizes four basic rules to prevent food poisoning at home: clean, separate, cook and chill.

It also offers some guidelines for when the power goes out, starting with keeping refrigerator and freezer doors closed. “A full freezer will keep food safe for 48 hours (24 hours if half-full) without power if you don’t open the door. Your refrigerator will keep food safe for up to four hours without power if you don’t open the door,” it says.

After four hours without power or a cooling source, the CDC recommends that most meat, dairy, leftovers and cut fruits and vegetables in the refrigerator be thrown out.

Unfortunately, you cannot see, smell or taste many harmful pathogens that cause foodborne illness, so it’s better to be safe than sorry. Rule of thumb: When in doubt, throw it out.

What’s The Best Response If A Person Gets Sick From Food?

If you do get sick, it can be hard to pinpoint the culprit. Harmful bacteria can take anywhere from a few hours to several days to make you sick. And people respond in different ways, so the same food might not make everyone ill.

Check with your doctor if you think you have food poisoning. Get tested so your case will be reported. That helps public health authorities get a better sense of the extent of infections. The full extent of infections is typically vastly underreported.

I recommend checking health department websites, like Washington state’s, for more advice, and check on food recalls during the hot months.![]()

Elena N. Naumova, Professor of Epidemiology and Data Science, Tufts University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Draconian and undemocratic’: why criminalising climate protesters in Australia doesn’t actually work

Robyn Gulliver, The University of QueenslandA man who drove through a climate protest blocking the Harbour Tunnel this week has copped a A$469 fine, while multiple members of the activist group were arrested. The protest was among a series of peak hour rallies in Sydney by Blockade Australia, in an effort to stop “the cogs in the machine that is destroying life on earth”.

Disruptive protests like these make an impact. They form the iconic images of social movements that have delivered many of the rights and freedoms we enjoy today.

They attract extensive media coverage that propel issues onto the national agenda. And, despite media coverage to the contrary, research suggests they don’t reduce public support for climate action.

But disruptive protest also consistently generates one negative response: attempts to criminalise it.

Tasmania, Victoria and New South Wales have all recently proposed or introduced anti-protest bills targeting environmental and climate activists. This wave of anti-protest legislation has been described as draconian and undemocratic.

Let’s take a look at how these laws suppress environmental protesters – and whether criminalisation actually works.

How Do Governments Criminalise Protest?

The criminalisation of environmental protest in Australia isn’t new.

Tasmania provides a compelling example. The Tasmania Workplaces (Protection from Protestors) Act 2014 sought to fine demonstrators up to $10,000 if they “prevent, hinder, or obstruct the carrying out of a business activity”. Described as a breach of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, it was subsequently voted down by the Tasmanian Legislative Council.

The bill was resurrected in 2019, but also voted down, an outcome described by the Human Rights Law Centre as a “win for democracy”.

But yet again in 2022, the freedom to protest in Tasmania is under threat. The Police Offences Amendment (Workplace Protection) Bill 2022 proposes fines of up to $21,625 and 18 months jail for peaceful protest.

Activities such as handing out flyers, holding a placard or sharing a petition could fall within the offences.

Tasmania is not an outlier. After the Port of Botany and Sydney climate blockades in March this year, NSW passed the Roads and Crimes Legislation Amendment Bill 2022.

Almost 40 civil society groups called to scrap the bill, which used vague and broad wording to expand offences with up to two years in jail and a $22,000 fine.

Similarly, the Andrews government in Victoria is introducing the Sustainable Forests Timber Amendment (Timber Harvesting Safety Zones) Bill 2022, which raises penalties on anti-logging protest offences to $21,000 or 12 months imprisonment.

Other Ways Australia Criminalise Protest

Legislation isn’t the only tool in the toolbox of protest criminalisation. The expansion of police and government discretionary powers is also often used. Examples include:

“move-on” orders restricting protesters’ access to public spaces or engagement in particular behaviours

on-the-spot fines, such as for the use of specific lock-on devices defined in Queensland legislation

surveillance, pre-emptive arrests and infiltration of landowners and anti-coal groups, including Blockade Australia

onerous bail conditions, such as restricting travel to CBD areas, banning journalists from mine sites, and unprecedented non-association orders preventing interaction with family

persistent attempts to silence environmental NGOs engaging in advocacy.

Corporations also use discretionary powers. Adani/Bravus coal mining company reportedly used private investigators to restrict Wangan and Jagalingou Traditional Owners’ access to their ceremonial camp.

It also reportedly bankrupted senior spokesperson Adrian Burragubba in 2019, sued one climate activist for intimidation, conspiracy and breaches of contract, surveilled his family, and is pursuing him for $600 million (now reduced to $17m) in damages.

In statements to the ABC and the Guardian, Adani says it is exercising its rights under the law to be protected from individuals and groups who act “unlawfully”.

Another tool for suppressing protest is the use of “othering” language. This language seeks to stigmatise activists, de-legitimise their concerns and frame them as threats to national security or the economy.

We see it frequently after disruptive protest. For example, ministers have recently described Blockade Australia protesters as “bloody idiots”, who should “get a real job”.

The Queensland Premier has described protesters as “extremists”, who were “dangerous, reckless, irresponsible, selfish and stupid”.

Why Do Governments Feel The Need To Implement Harsher Penalties?

Some politicians have argued that anti-protest laws act as a “deterrent” to disruptive protest. Critics have also argued that government powers are used as a shield to protect corporate interests.

In its new report, for example, the Australian Democracy Network shows how corporations can manipulate government powers to harass and punish opponents through a process called “state capture”.

Non-profit organisations have also demonstrated the powerful influence of the fossil fuel industry, particularly in weakening Australian environmentalists’ protest rights.

But it’s not only civil sector groups and protesters sounding the alarm. Increased repression of our rights to engage in non-violent protest have also been voiced by lawyers, scholars and observers such as the United Nations Special Rapporteur.

Does Criminalisation Reduce Protest?

Numerous organisations have highlighted how criminalising protest and silencing charities threaten democratic freedoms that are fundamental to a vibrant, inclusive and innovative society.

But more than that, these strategies don’t appear to work.

Courts have used anti-protest legislation to instead highlight the importance of peaceful protest as a legitimate form of political communication. They have struck down legislation, released activists from remand, overturned unreasonable bail conditions and reduced excessive fines.

Police, too, have refused to remove cultural custodians from their ceremonial grounds.

And in general, research shows the public does not support repressive protest policing.

Indeed, rates of disruptive protest are escalating, while protesters vow to continue despite the risk.

The majority of Australians support more ambitious climate action. Many agree with Blockade Australia’s statement that “urgent broad-scale change” is necessary to address the climate crisis.

Politicians may be better served by focusing their efforts on this message, rather than attacking the messengers.![]()

Robyn Gulliver, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

U.S. Supreme Court Limits U.S. EPA's Power To Curb Carbon Emissions

Statement By President Joe Biden On Supreme Court Ruling On West Virginia V. EPA

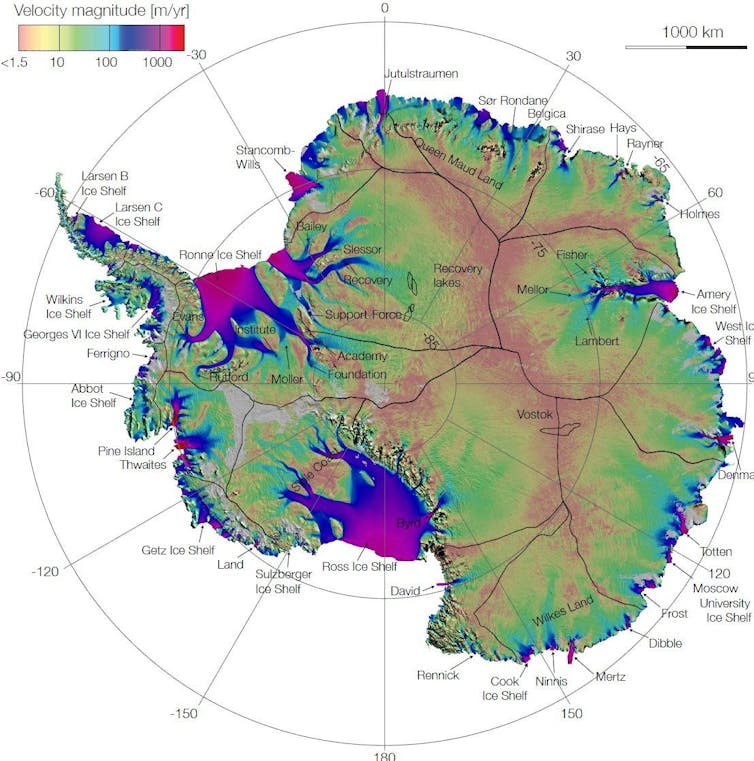

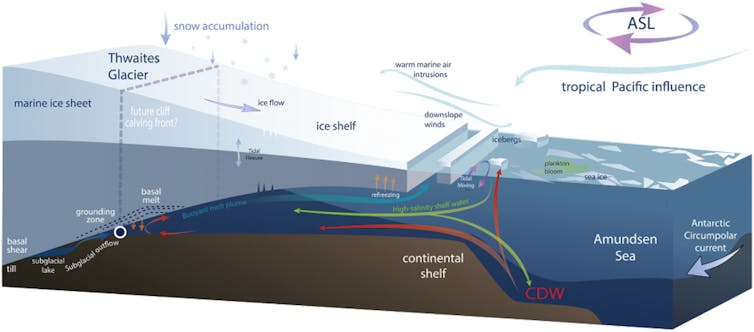

Ice world: Antarctica’s riskiest glacier is under assault from below and losing its grip

Flying over Antarctica, it’s hard to see what all the fuss is about. Like a gigantic wedding cake, the frosting of snow on top of the world’s largest ice sheet looks smooth and unblemished, beautiful and perfectly white. Little swirls of snow dunes cover the surface.

But as you approach the edge of the ice sheet, a sense of tremendous underlying power emerges. Cracks appear in the surface, sometimes organized like a washboard, and sometimes a complete chaos of spires and ridges, revealing the pale blue crystalline heart of the ice below.

As the plane flies lower, the scale of these breaks steadily grows. These are not just cracks, but canyons large enough to swallow a jetliner, or spires the size of monuments. Cliffs and tears, rips in the white blanket emerge, indicating a force that can toss city blocks of ice around like so many wrecked cars in a pileup. It’s a twisted, torn, wrenched landscape. A sense of movement also emerges, in a way that no ice-free part of the Earth can convey – the entire landscape is in motion, and seemingly not very happy about it.

Antarctica is a continent comprising several large islands, one of them the size of Australia, all buried under a 10,000-foot-thick layer of ice. The ice holds enough fresh water to raise sea level by nearly 200 feet.

Its glaciers have always been in motion, but beneath the ice, changes are taking place that are having profound effects on the future of the ice sheet – and on the future of coastal communities around the world.

Breaking, Thinning, Melting, Collapsing

Antarctica is where I work. As a polar scientist I’ve visited most areas of the ice sheet in more than 20 trips to the continent, bringing sensors and weather stations, trekking across glaciers, or measuring the speed, thickness and structure of the ice.

Currently, I’m the U.S. coordinating scientist for a major international research effort on Antarctica’s riskiest glacier – more on that in a moment. I have gingerly crossed crevasses, trodden carefully on hard blue windswept ice, and driven for days over the most monotonous landscape you can imagine.

For most of the past few centuries, the ice sheet has been stable, as far as polar science can tell. Our ability to track how much ice flows out each year, and how much snow falls on top, extends back just a handful of decades, but what we see is an ice sheet that was nearly in balance as recently as the 1980s.

Early on, changes in the ice happened slowly. Icebergs would break away, but the ice was replaced by new outflow. Total snowfall had not changed much in centuries – this we knew from looking at ice cores – and in general the flow of ice and the elevation of the ice sheet seemed so constant that a main goal of early ice research in Antarctica was finding a place, any place, that had changed dramatically.

But now, as the surrounding air and ocean warm, areas of the Antarctic ice sheet that had been stable for thousands of years are breaking, thinning, melting, or in some cases collapsing in a heap. As these edges of the ice react, they send a powerful reminder: If even a small part of the ice sheet were to completely crumble into the sea, the impact for the world’s coasts would be severe.

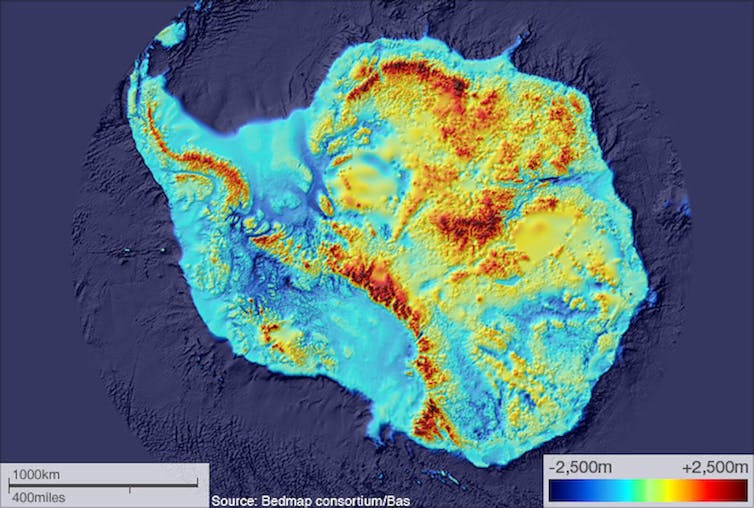

Like many geoscientists, I think about how the Earth looks below the part that we can see. For Antarctica, that means thinking about the landscape below the ice. What does the buried continent look like – and how does that rocky basement shape the future of the ice in a warming world?

Visualizing The World Below The Ice

Recent efforts to combine data from hundreds of airplane and ground-based studies have given us a kind of map of the continent below the ice. It reveals two very different landscapes, divided by the Transantarctic Mountains.

In East Antarctica, the part closer to Australia, the continent is rugged and furrowed, with several small mountain ranges. Some of these have alpine valleys, cut by the very first glaciers that formed on Antarctica 30 million years ago, when its climate resembled Alberta’s or Patagonia’s. Most of East Antarctica’s bedrock sits above sea level. This is where the city-size Conger ice shelf collapsed amid an unusually intense heat wave in March 2022.

In West Antarctica the bedrock is far different, with parts that are far deeper. This area was once the ocean bottom, a region where the continent was stretched and broken into smaller blocks with deep seabed between. Large islands made of volcanic mountain ranges are linked together by the thick blanket of ice. But the ice here is warmer, and moving faster.

As recently as 120,000 years ago, this area was probably an open ocean – and definitely so in the past 2 million years. This is important because our climate today is fast approaching temperatures like those of a few million years ago.

The realization that the West Antarctic ice sheet was gone in the past is the cause of great concern in the global warming era.

Early Stages Of A Large-Scale Retreat

Toward the coast of West Antarctica is a large area of ice called Thwaites Glacier. This is the widest glacier on earth, at 70 miles across, draining an area nearly as large as Idaho.

Satellite data tell us that it is in the early stages of a large-scale retreat. The height of the surface has been dropping by up to 3 feet each year. Huge cracks have formed at the coast, and many large icebergs have been set adrift. The glacier is flowing at over a mile per year, and this speed has nearly doubled in the past three decades.

This area was noted early on as a place where the ice could lose its grip on the bedrock. The region was termed the “weak underbelly” of the ice sheet.

Some of the first measurements of the ice depth, using radio echo-sounding, showed that the center of West Antarctica had bedrock up to a mile and a half below sea level. The coastal area was shallower, with a few mountains and some higher ground; but a wide gap between the mountains lay near the coast. This is where Thwaites Glacier meets the sea.

This pattern, with deeper ice piled high near the center of an ice sheet, and shallower but still low bedrock near the coast, is a recipe for disaster – albeit a very slow-moving disaster.

Ice flows under its own weight – something we learned in high school earth science, but give it a thought now. With very tall and very deep ice near Antarctica’s center, a tremendous potential for faster flow exists. By being shallower near the edges, the flow is held back – grinding on the bedrock as it tries to leave, and having a shorter column of ice at the coast squeezing it outward.

If the ice were to step back far enough, the retreating front would go from “thin” ice – still nearly 3,000 feet thick – to thicker ice toward the center of the continent. At the retreating edge, the ice would flow faster, because the ice is thicker now. By flowing faster, the glacier pulls down the ice behind it, allowing it to float, causing more retreat. This is what’s known as a positive feedback loop – retreat leading to thicker ice at the front of the glacier, making for faster flow, leading to more retreat.

Warming Water: The Assault From Below

But how would this retreat begin? Until recently, Thwaites had not changed a lot since it was first mapped in the 1940s. Early on, scientists thought a retreat would be a result of warmer air and surface melting. But the cause of the changes at Thwaites seen in satellite data is not so easy to spot from the surface.

Beneath the ice, however, at the point where the ice sheet first lifts off the continent and begins to jut out over the ocean as a floating ice shelf, the cause of the retreat becomes evident. Here, ocean water well above the melting point is eroding the base of the ice, erasing it as an ice cube would disappear bobbing in a glass of water.

Water that is capable of melting as much as 50 to 100 feet of ice every year meets the edge of the ice sheet here. This erosion lets the ice flow faster, pushing against the floating ice shelf.

The ice shelf is one of the restraining forces holding the ice sheet back. But pressure from the land ice is slowly breaking this ice plate. Like a board splintering under too much weight, it is developing huge cracks. When it gives way – and mapping of the fractures and speed of flow suggests this is just a few years away – it will be another step that allows the ice to flow faster, feeding the feedback loop.

Up To 10 Feet Of Sea Level Rise

Looking back at the ice-covered continent from our camp this year, it is a sobering view. A huge glacier, flowing toward the coast, and stretching from horizon to horizon, rises up to the middle of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. There is a palpable feeling that the ice is bearing down on the coast.

Ice is still ice – it doesn’t move that fast no matter what is driving it; but this giant area called West Antarctica could soon begin a multicentury decline that would add up to 10 feet to sea level. In the process, the rate of sea level rise would increase severalfold, posing large challenges for people with a stake in coastal cities. Which is pretty much all of us.![]()

Ted Scambos, Senior Research Scientist, CIRES, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Drones and DNA tracking: we show how these high-tech tools are helping nature heal

Technology has undoubtedly contributed to global biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation.

Where forests once stood, artificial lights now illuminate vast urban jungles. Where animals once roamed, huge factories now churn out microchips, computers, and cars. But now, we can also leverage technology to help repair our precious ecosystems.

Here, we discuss our two new research papers published today. They show how drones and genomics (the same technology used to identify COVID strains) can help protect and restore nature.

One paper demonstrates that drones can help safeguard biodiversity and monitor ecosystem restoration activities. They can also help us understand how impacts in one ecosystem may affect another.

Genomics can help identify populations that may be vulnerable to future climate change, and monitor elusive animals such as platypuses, lynx, and newts. Yet, our other paper found ecologists without genomics expertise thought the technology still needed to be tried and tested.

Remote Sensing With Drones

Drones are an increasingly common sight in, for instance, urban parks and weddings. Farmers also use them to assess crop health, and engineers use them to detect damage to bridges and wind turbines.

Drone technology has rapidly advanced over the last decade. Advancements include obstacle avoidance, enhanced flight times, high-definition cameras, and the ability to carry heavier payloads.

But can drones help repair damaged ecosystems? We reviewed the scientific literature from various environmental sectors to explore the existing and emerging uses of drones in restoring degraded ecosystems. The answer, we found, is a resounding “yes”.

We found drones can help map vegetation and collect water, soil, and grassland samples. They can also monitor plant health and wildlife population dynamics. This is essential for understanding whether a restoration intervention is working.

In Australia, for instance, drones have helped researchers identify the habitat requirements for marsupials such as the spotted-tailed quoll and the eastern bettong. Thanks to having the drone’s birds-eye view, researchers and practitioners are gaining a better understanding of what vegetation to restore as well as new approaches to monitor the return of critical habitat.

Famously, drones have recently been used to plant trees by dropping “seed bombs” to help restore forests. While drone-based tree planting has potential, it still requires more research as the survival rate of seedlings is currently poor.

Some researchers have even developed bushfire-fighting drones to protect sensitive ecosystems. This is where one drone detects fire using thermal technology, and another puts it out by dropping fire-extinguishing balls. But controlled wildfires can sometimes be vital to ecosystem restoration, so we can also use drones to drop tiny fireballs, too.

However, there are many pitfalls to consider when using drones. In the wrong hands, drones can be a nuisance and harm wildlife.

Studies have shown flying too close to animals, such as birds and bears can impact their physiology. For example, a 2015 study showed drones flying too close to American black bears caused their heart rates to rise – even for one bear deep in hibernation.

Drone pilots should acquire appropriate licences and follow strict protocols when flying them in sensitive habitats.

Genomics: Valuable, Yet Misunderstood

Genomics is a toolkit jam-packed full of innovative ways of looking at DNA, the blueprint of life on Earth. When scientists talk about genomics, they usually refer to modern DNA sequencing technologies or the analysis of vast collections of DNA.

But despite the potential for genomics to improve ecosystem restoration, our recent study showed restoration scholars without genomics experience were concerned genomics was over-hyped.

We interviewed leading experts in different ecology disciplines and found many called for case studies to demonstrate the benefits of genomics in restoration.

But surprisingly, we found restoration genomics literature included over 70 restoration genomics studies, many of which used environmental DNA to monitor ecosystem health. So, plenty of case studies already exist.

In ecosystem restoration, the two most common genomics applications are population genomics and environmental DNA.

Population genomics studies small differences in an organism’s genome to answer questions such as how much genetic variation exists in a population, how related individuals are, or how landscapes change migration patterns.

Linking changes in DNA sequences to historical climates has become central to modern-day nature conservation and restoration. It allows us to understand how resilient animals, plants and microbes are to future climates.

For example, we have used this approach to select robust tree seeds, such as red ironbark (Eucalyptus tricarpa), for woodland restoration plantings across southeast Australia. Using genomics to select the most resilient seeds gives the trees the best chance of surviving in a changing climate.

Scientists can also gain insights into ecosystems and monitor elusive species using the DNA organisms leave behind in environments, such as soil or water.

This environmental DNA data can help track the presence of species — invasive, endangered, or cryptic — and help measure community health and diversity. This includes pollinators such as bees, other animals and plants and our invisible friends, the microbes.

For instance, in the United Kingdom, ecologists currently use environmental DNA to detect the presence of vulnerable amphibians, such as great crested newts.

Where To From Here?

Greater uptake of remote sensing and genomics in restoration has clear potential to help improve the monumental task of restoring our degraded ecosystems. Our papers outline ways for restoration ecologists to integrate drones and genomics into their toolboxes.

Given humans have caused substantial degradation to global ecosystems, it makes sense to use the technologies now available to restore wildlife and prevent additional biodiversity loss.![]()

Jake M Robinson, Ecologist and Researcher, Flinders University; Jakki Mohr, Professor of Marketing & Innovation, The University of Montana; Martin Breed, Senior Lecturer in Biology, Flinders University; Peter Harrison, Lecturer in Forest Adaptation and Restoration Genetics, University of Tasmania, and Suzanne Mavoa, , The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Research shows tropical cyclones have decreased alongside human-caused global warming – but don’t celebrate yet

The annual number of tropical cyclones forming globally decreased by about 13% during the 20th century compared to the 19th, according to research published today in Nature Climate Change.

Tropical cyclones are massive low-pressure systems that form in tropical waters when the underlying environmental conditions are right. These conditions include (but aren’t limited to) sea surface temperature, and variables such as vertical wind shear, which refers to changes in wind speed and direction with altitude.

Tropical cyclones can cause a lot of damage. They often bring extreme rainfall, intense winds and coastal hazards including erosion, destructive waves, storm surges and estuary flooding.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest report detailed how human emissions have warmed tropical oceans above pre-industrial levels, with most warming happening since around the middle of the 20th century. Such changes in sea surface temperature are expected to intensify storms.

At the same time, global warming over the 20th century led to a weakening of the underlying atmospheric conditions that affect tropical cyclone formation. And our research now provides evidence for a decrease in the frequency of tropical cyclones coinciding with a rise in human-induced global warming.

Reckoning With A Limited Satellite Record

To figure out whether cyclone frequency has increased or decreased over time, we need a reliable record of cyclones. But establishing this historical context is challenging.

Before the introduction of geostationary weather satellites in the 1960s (which stay stationary in respect to the rotating Earth), records were prone to discontinuity and sampling issues.

And although observations improved during the satellite era, changes in satellite technologies and monitoring throughout the first few decades imply global records only became consistently reliable around the 1990s.

So we have a relatively short post-satellite tropical cyclone record. And longer-term weather trends based on a short record can be obscured by natural climate variability. This has led to conflicting assessments of tropical cyclone trends.

Declining Global And Regional Trends

To work around the limits of the tropical cyclone record, our team used the Twentieth Century Reanalysis dataset to reconstruct cyclone numbers to as far back as 1850. This reanalysis project uses detailed metrics to paint a picture of global atmospheric weather conditions since before the use of satellites.

Drawing on a link to the observed weakening of two major atmospheric circulations in the tropics – the Walker and Hadley circulations – our reconstructed record reveals a decrease in the annual number of tropical cyclones since 1850, at both a global and regional scale.

Specifically, the number of storms each year went down by about 13% in the 20th century, compared to the period between 1850 and 1900.

For most tropical cyclone basins (regions where they occur more regularly), including Australia, the decline has accelerated since the 1950s. Importantly, this is when human-induced warming also accelerated.

The only exception to the trend is the North Atlantic basin, where the number of tropical cyclones has increased in recent decades. This may be because the basin is recovering from a decline in numbers during the late 20th century due to aerosol impacts.

But despite this, the annual number of tropical cyclones here is still lower than in pre-industrial times.

It’s A Good Thing, Right?

While our research didn’t look at cyclone activity in the 21st century, our findings complement other studies, which have predicted tropical cyclone frequency will decrease due to global warming.

It may initially seem like good news fewer cyclones are forming now compared to the second half of the 19th century. But it should be noted frequency is only one aspect of risk associated with tropical cyclones.

The geographical distribution of tropical cyclones is shifting. And they’ve been getting more intense in recent decades. In some parts of the world they’re moving closer to coastal areas with growing populations and developments.

These changes – coupled with increasing rain associated with tropical cyclones, and a trend towards hurricanes lasting longer after making landfall – could point to a future where cyclones cause unprecedented damage in tropical regions.

Then again, these other factors weren’t assessed in our study. So we can’t currently make any certain statements regarding future risk.

Moving forward, we hope improvements in climate modelling and data will help us identify how human-induced climate change has affected other metrics, such as cyclone intensity and landfalling activity.![]()

Savin Chand, Senior Lecturer, Applied Mathematics and Statistics, Federation University Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Hear me out – we could use the varroa mite to wipe out feral honey bees, and help Australia’s environment

Patrick O'Connor, University of AdelaideA tiny parasitic mite that lives on the European honeybee (Apis mellifera) has breached Australia’s border quarantine and been detected in managed bee hives in New South Wales.

This is bad news for Australia’s honey industry, with over 300 hives in Newcastle set to be destroyed and biosecurity zones in place. The potential economic impact to the honey industry is estimated at around A$70 million per year, but the broader impacts to agriculture are not yet known.

This is where much of the dialogue on the impact of varroa mite settling in Australia usually stops. But there’s another way to look at this pest: as an effective biocontrol for feral honeybees in Australia’s natural environment.

Honeybees were introduced to Australia almost 200 years ago and out-compete native pollinators, which may have dire flow-on effects for ecosystems. The varroa mite’s arrival in Australia was only a matter of time – and with better planning, we could benefit from one pest fighting another.

Making Trade-Offs

The varroa mite infests hives, parasitises the bees, and can spread viruses and other pathogens. They mainly feed and breed on honeybee larvae and pupae, causing malformation. If left unmanaged, heavy mite infestation can cause colony collapse in some circumstances.

The mite has spread across the world to colonise almost every known location of European honeybees. It has been kept out of Australia thanks to stringent border quarantine measures, but this tiny mite can easily hitchhike on imports, then establish and spread when it reaches a honeybee colony.

So would Australia benefit more from treating the varroa mite as a pest, or an environmental biocontrol? More research is needed to resolutely answer this question, but let’s look at a the potential trade-offs of either option.

Treating the mite as a pest

Treating the mite as a pest would mean chasing down known outbreaks and destroying hives, beefing up border quarantine measures and supporting the beekeeping industry to tide them over the impact and adjustment period.

Beekeepers can stop the mite in its tracks in managed hives with chemical controls, but this comes at a cost, including some loss of productivity. And a loss of productivity in managed hives can have a knock-on effect on the pollination industry, as beekeepers are paid to take their bees to pollinate crops.

Thirty-five agricultural industries in Australia rely entirely or in part on bee pollination, including almonds, apples and cherries. Indeed, the total contribution of honeybees to Australia’s economy is estimated at $14.2 billion.

The potential consequences for industrial beekeeping and agriculture, and increased costs of production, can have unwelcome effects on food prices.

Treating the mite as a biocontrol

Treating the mite as an environmental biocontrol would mean diverting money for eradication and control measures to help industries live with varroa. This could be by, for instance, increasing the use of native pollinators for Australian agriculture.

It could also involve releasing the mite into feral honeybee hives, where we believe a rapid recovery of native pollinators is needed, such as in areas recovering from bushfires. The varroa mite has little impact on native bees because it’s specific to the Apis genus of the introduced bee, though the usual rules for biocontrol release would need to be followed.

Feral European honeybee populations are recognised as a key threatening process to Australia’s native biodiversity, with impacts felt across the country. Feral bees are abundant and efficient pollinators, and compete with native birds, insects and mammals (such as pygmy possums) for nectar from flowers.

Honeybees avoid, or only partially pollinate, some native plants. This means a high concentration of honeybees could shift the make-up of native vegetation in a region. They also pollinate invasive weeds such as gorse, lantana and scotch broom, which are particularly expensive to control in the wake of bushfires.

When the varroa mite breached New Zealand, feral honeybees declined by about 90% within a few years. However, there’s limited information about the ecological benefits of this, because the data was not collected while the focus was on agricultural industry impact.

It’s also worth noting that knocking down feral honeybees could also be good for the honeybee industry, as feral honeybees are a recognised competitor with commercial ones.

Making The Best Decision

Questions about trading-off potential agricultural costs for environmental benefits are difficult to answer. This is, in part, because any environmental benefits gained from reducing a widespread threat are usually indirect, such as flow-on effects of increased ecosystem health.

Another reason is because markets are well established for agricultural products and services, but they’re usually missing or only just forming for ecosystem services (such as flood control, water supply and quality, and cultural values).

To calculate the economic benefit of reducing feral honeybees, we first must put a value on the services natural ecosystems provide.

While some steps have been made, progress on implementation has been slow for the last decade. So far, we’ve predominately put values on ecosystem services from discrete natural assets, such as the Great Barrier Reef, which contributed an estimated $6.4 billion in 2015-2016 to Australia’s economy.

In the case of the varroa mite, we have known the potential for opportunities and costs from a likely invasion for more than a decade. But the focus has been on preventing the invasion to protect agriculture, because we’re mostly concerned about the industry’s direct benefits and impacts.

There have been no estimations of the economic benefits of using the mite as an environmental biocontrol to lower feral honeybee populations, even though our New Zealand friends did suggest, in a paper, we prepare ourselves.

We may successfully eradicate the varroa mite’s recent incursion to the relief of agriculture and beekeepers. But given the near inevitability of the mite establishing in Australia, we must invest in better understanding the holistic economics of keeping a potentially very important biocontrol out of the country.![]()

Patrick O'Connor, Associate Professor, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia can help ensure the biggest mine in PNG’s history won’t leave a toxic legacy

The COVID pandemic slowed mining activity across the Pacific. But as economic activity returns, an Australia-based company is poised to pursue what would be the largest mine in Papua New Guinea’s history.

The vast gold and copper project, known as the Frieda River mine, would also include a hydroelectric plant and a dam with a storage capacity for around 4.6 billion tonnes of mine tailings and waste rock.

The project is awaiting approval by the PNG government. However, locals, conservationists and experts say it could cause catastrophic harm to one of the world’s most important river systems and should not proceed as proposed.

Australia is PNG’s largest development partner. As resource extraction expands across the Pacific, the new Labor government is well placed to help our neighbours ensure mining activity doesn’t harm people or the environment.

Remote, Unstable Terrain

The Frieda River mine is proposed by Brisbane-based, Chinese-owned company Pan Aust.

The project centres on the Frieda River copper-gold deposit located in the tropical mountain ranges of northwest PNG.

The river flows into the Sepik River Basin, one of the world’s great river systems. It’s the largest unpolluted freshwater system in New Guinea and among the largest freshwater basins in the Asia-Pacific.

The Frieda River deposit was discovered in the 1960s. It lies in extremely remote terrain, along the Pacific Ring of Fire which is prone to seismic activity.

The mine would produce tailings (or waste materials) containing sulphide, which turns into sulphuric acid when exposed to oxygen. For this reason, the tailings must be permanently covered by water.

The proposed mine’s location, high in the mountains, means a tailings accident could devastate the entire Sepik River Basin.

About 430,000 people depend on the Sepik River and nearby forests for their livelihood. The proposal has galvanised massive opposition from both locals and others.

Downplaying The Risks

In 2020, ten independent experts including myself, were commissioned by PNG’s Centre for Environmental Law and Community Rights to individually review the project’s “environmental impact statement”. The work was undertaken pro bono.

I’m an experienced gold exploration geologist and environmental scientist. In my review, I found the statement downplayed or obscured the proposal’s extraordinary level of risk.

First, it omitted a report by design engineers that analysed the extreme consequences of dam failure.

Second, the main report failed to mention the dam would need an intensive inspection and maintenance regime “in perpetuity”. In other words, a potentially toxic dam in a remote part of a very poor country requires highly skilled and experienced professionals to maintain it – not just for the 33-year life of the mine, but forever.

Our reports prompted a group of UN Special Rapporteurs to write letters of concern to the governments of PNG, Australia, China and Canada, where companies involved in the joint venture have ties.

The letters said the mine’s development appeared to “disregard the human rights of those affected … given the nature of the project it could undermine the rights of Sepik children to life, health, culture, and a healthy environment, including the rights of unborn generations.”

The Conversation contacted Pan Aust for a response to these claims. In a statement, the company said it was “respectfully engaged in the Government of Papua New Guinea’s approvals process” and as such, it was inappropriate to provide a public comment.

New Safeguards Are Needed

Inadequate consideration of a mine’s social and environmental impact is rife cross the Pacific. And PNG provides many examples of the catastrophes that can result.

Tailings from BHP’s ill-fated Ok-Tedi mine, located in the same mountain range as the proposed Frieda River mine, severely damaged nearby rivers.

And environmental damage from the Panguna copper mine was a key factor in community unrest and the Bougainville civil war.

Recent research into governance of mining in PNG found government agencies were under-resourced, leaving “companies as effectively self-regulating”.

Proponents of mining in PNG frequently cite its contribution to economic development. But for the benefits to be realised, resources must be extracted in a way that is environmentally, socially and economically sustainable.

New laws are needed to ensure resource extraction projects in PNG don’t cause long-lasting social and environmental damage. This should include mandatory, transparent and independent reviews of projects.

Australia has extensive experience with environmental regulation of mining projects and can assist in this regard. Such assistance should be delivered in a way that strengthens relations between Australia and PNG, and empowers and equips the smaller nation.

Sustainable development for our Pacific neighbours is in Australia’s strategic interests. Australian companies often benefit significantly from resource extraction in PNG, creating an extra responsibility to ensure better outcomes.![]()

Michael Main, Visiting Scholar, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Coastal gentrification in Puerto Rico is displacing people and damaging mangroves and wetlands

As world travel rebounds after two years of COVID-19 shutdowns and restrictions, marketers and the media are promoting Puerto Rico as an accessible hot spot destination for continental U.S. travelers. The commonwealth set a visitor record in 2021, and it is expanding tourism-related development to continue wooing travelers away from more exotic destinations.

Tourism income is central to Puerto Rico’s economy, especially in the wake of heavy damage from Hurricane Maria in 2017. But it comes at a cost: destruction of mangroves, wetlands and other coastal areas. Puerto Rico is no stranger to resort construction, but now widespread small-scale projects to meet demand for rentals on platforms like Airbnb are adding to concerns about coastal gentrification and touristification.

As scholars who study anthropology and coastal communities, we believe it is important to understand what Puerto Rico is losing in the quest for ever-increasing tourist business. For the rural coastal communities where we do our research, habitat is tied to residents’ cultural identity and economic well-being.

For the last two decades, we have documented how many rural Puerto Ricans’ lives are inextricably linked to coastal forests and wetland habitats. These communities often are poor, neglected by the state and disproportionately affected by pollution and noxious industries. Decisions about the future of the coast too often are made without accounting for human impacts.

Once-Scorned Areas Are Now In Demand

Estuaries and coastal forests are some of Earth’s most biodiverse and productive ecosystems. Millions of people rely on mangroves and coastal wetlands to make a living.

Around the world, these areas are under stress from climate change, tourism and luxury residential development. But these zones weren’t always prized so highly.

In Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Americas, wetlands historically were seen as undesirable and even dangerous places to live and work. They often were settled by the poor and dispossessed, most notably Afro-descendant people and Indigenous communities, who made livings fishing, foraging, harvesting coconuts, cutting wood and making charcoal.

In the early 20th century, however, tropical coasts started attracting attention from the global leisure class. In 1919, the Vanderbilt Hotel opened in San Juan, followed in 1949 by the massive Caribe Hilton resort – the first Hilton hotel outside the continental U.S., built in partnership with the Puerto Rican government. Many more hotels followed, along with casinos and golf courses.

Today, Puerto Rico’s rural coastal communities have to compete for space and resources against tourism development, gentrification, urbanization, industry and conservation. Often these uses are not compatible with local lifestyles.

For example, people from communities near mangrove forests, like Las Mareas in southern Puerto Rico, are no longer permitted to harvest small amounts of mangrove wood to build traditional fishing boats. At the same time, they see wealthy residents and developers destroying entire tracts of mangrove forest with impunity. Some coastal communities are starting to push back.

Beaches Are For The People

In March 2022, Eliezer Molina, an environmental activist, engineer and 2020 gubernatorial candidate, posted an exposé on YouTube of the illegal cutting and filling of a mangrove shoreline in the Las Mareas neighborhood in Salinas’ Jobos Bay. As Puerto Rico’s second-largest estuary and only Federal Estuarine Reserve, the bay is an important and sensitive habitat for birds, turtles and manatees, and a nursery for many types of fish.

Wealthy Puerto Ricans clandestinely developed this waterfront site for weekend homes. Residents of Las Mareas had been alerting local authorities for well over a decade about destruction of the mangroves, to no avail. Federal authorities and Puerto Rico’s Justice Department are now conducting a criminal investigation of the illegal construction.

This case led to widespread public outrage about similar instances around the archipelago. Puerto Ricans are condemning local government agencies online and in person for what they describe as incompetence, corruption and a lack of monitoring and oversight.

One hot-button issue is privatization and destruction of the Zona Marítimo Terrestre, or Terrestrial Maritime Zone. This area is legally defined as “Puerto Rico’s coastal space that is bordered by the sea’s ebb and flow” – that is, between the low and high tide or up to the highest point of the surf zone. It includes beaches, mangroves and other coastal wetlands, and is publicly owned.

Activists are urging Gov. Pedro Pierluisi to declare a comprehensive moratorium on all coastal construction, a demand the governor calls “excessive.” A popular protest slogan, “Las playas son del pueblo!” (“Beaches belong to the people”), aptly summarizes popular feeling.

Overlooked Value

Coastal development generates a lot of money in Puerto Rico, but what is gained by conserving these areas for use by local communities? In research that we carried out in 2010-2013 and 2016-2021, we found that coastal resources provide many benefits for local residents that are not easily replaced.

Our results show that about one-third of households in these communities rely on coastal goods for at least part of their income, while more than two-thirds rely on them as food sources. Local harvesters supply family-owned seafood restaurants with foods such as land crabs, helping to attract economic activity to the coast.

We also found that residents rely more heavily on local coastal foods during times of severe economic stress, such as recessions and natural disasters. In the aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and María, for example, many residents in the southern towns of Salinas and Santa Isabel harvested unusually abundant land crabs when it was hard to find other foods. Some even saw this abundance as divine restitution for the suffering the storm inflicted on them.

Local economies in these communities consist mainly of small-scale, community-based transactions that include gifting, bartering and selling. Their social and economic impacts often go unnoticed and are underestimated in official economic accounts, so they aren’t reflected in decisions about coastal development. But as our work shows, coastal ecosystems are ecologically, economically and socially productive places.