inbox and environment news: Issue 546

July 17 - 23, 2022: Issue 546

Seabirds Being Blown Off Course

Wildlife Car Rescue Kits Now Available

Seal At Careel Bay

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Stop It And Swap It This Plastic Free July

To mark the beginning of Plastic Free July, the NSW Government is partnering with 17 organisations to help communities around the state stop using single-use plastic.

To mark the beginning of Plastic Free July, the NSW Government is partnering with 17 organisations to help communities around the state stop using single-use plastic.- Girl Guides NSW

- Green Connect

- Green Music Australia

- KU Children's Services

- Meals on Wheels NSW

- Men’s Shed Association

- NSW Environment & Zoo Education Centres

- OzGreen

- Plastic Free July

- Southern Cross University

- Surfing NSW

- TAFE NSW/Addison Road Community Organisation

- Take 3

- The Great Plastic Rescue

- University of New England

- University of Newcastle

- University of Wollongong

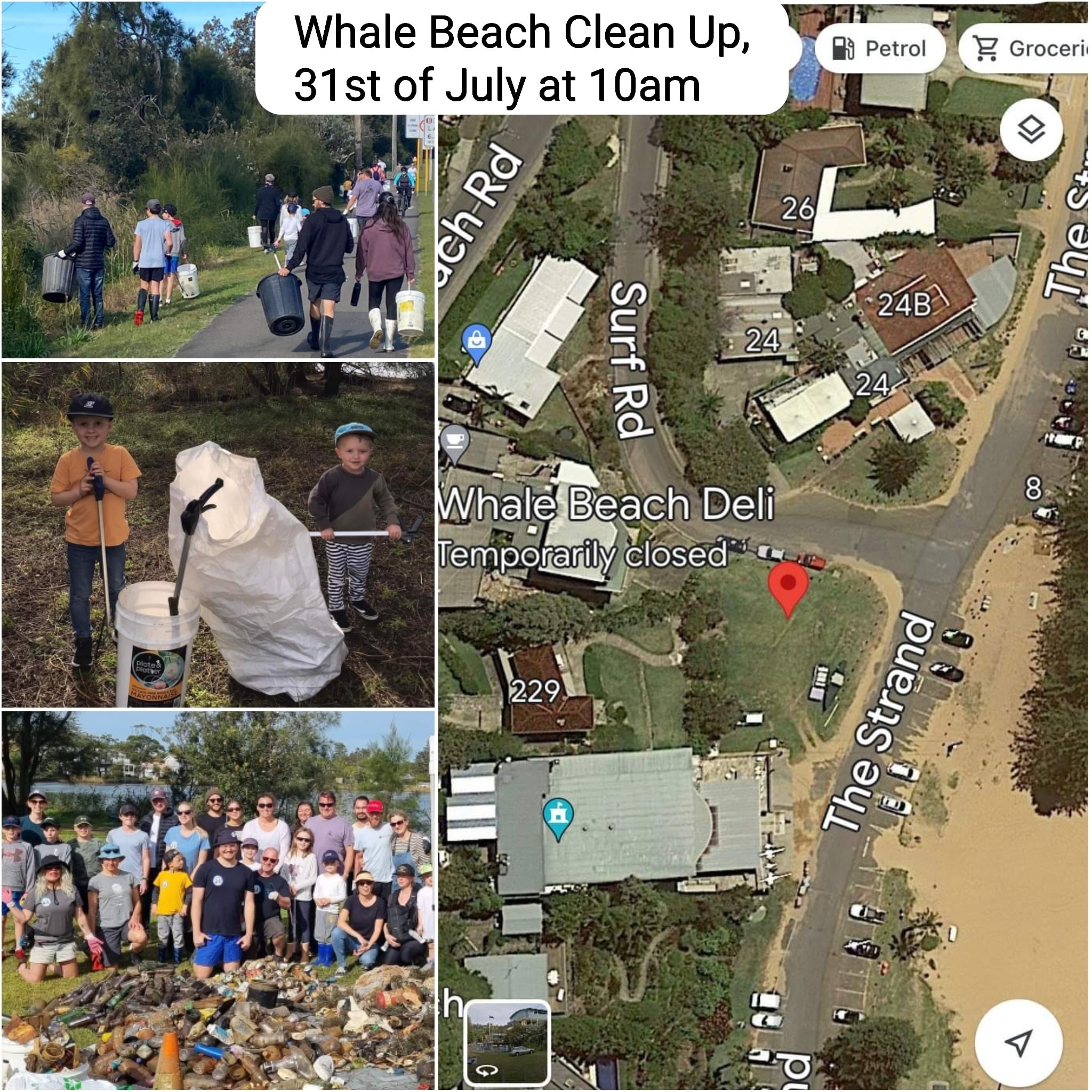

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Whale Beach - Sunday July 31st

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Pelicans Heading To The Coast Now: Winter Migrations

Barrenjoey Lighthouse Tours

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

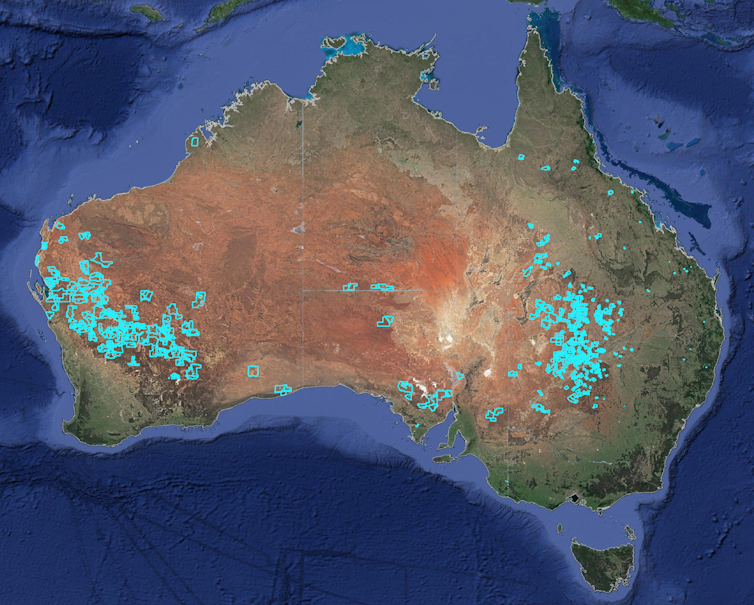

Research reveals fire is pushing 88% of Australia’s threatened land mammals closer to extinction

About 100 of Australia’s unique land mammals face extinction. Of the many threats contributing to the crisis, certain fire regimes are among the most pervasive.

In a new paper, we reveal how “inappropriate” fire patterns put 88% of Australia’s threatened land mammals at greater risk of extinction – from ground-dwelling bandicoots to tree-climbing possums and high-flying microbats.

Our research also identifies what type of fires are most damaging to threatened mammals, and shows some mammals are suffering due to a lack of fire.

A better understanding of how inappropriate fire regimes damage mammal populations is crucial to addressing biodiversity loss and improving conservation efforts.

Understanding Patterns Of Fire

Fire is an important ecological process. Yet human actions – such as global heating, forestry and agriculture – are transforming fire activity in ways that challenge nature’s ability to cope.

“Inappropriate” fire regimes are those with patterns that drive biodiversity decline.

Fire patterns are made up of various components, including frequency, intensity, seasonality and size. But to date, there’s been no Australia-wide assessment of which components make a fire regime inappropriate for threatened species.

Our research set out to close this knowledge gap. It involved a comprehensive review of more than 400 research articles and policy documents on fires and mammals, and taking a close look at the evidence linking the two.

To start, we identified whether land mammals of conservation concern – those listed as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable – were at risk from fire-related threats. We found that fire threatens 88% of these mammals.

Then we assessed the scientific evidence, such as field studies and expert opinion, to find out which fire components were in play. Contributing most to population declines were fires that are: intense and severe; large and extensive; and frequent.

Such a result might be expected. But significantly, we discovered these fire patterns are threatening species across the continent – from the arid interior to temperate forests in the south and tropical savannas to the north.

And our analysis went further, by identifying how these fire patterns may kill individual mammals and drive down populations.

Intense and severe fires usually generate a lot of heat and smoke, which can kill animals immediately or shortly afterwards. Such deaths are probably the cause of a decline in koala populations after intense and severe bushfires in temperate forests, as well as the western ringtail possum and numbat.

Animals may also die in the weeks and months after a fire due to a lack of food and shelter – especially when large and extensive fires destroy habitat over a wide area.

This was likely the case for a species of antechinus – a small mammal reliant on vegetation cover. Populations of swamp antechinus were considered extinct in some places after the large and severe Ash Wednesday fires in 1983 burned 40,000 hectares of heathy woodlands in southeast Australia.

In tropical savannas, frequent and intense fires affect reproduction of northern quolls, by reducing nesting resources and killing young in the pouch.

And some animals can suffer due to a lack of fire. For example, declines in some populations of northern bettongs may be due to long periods without fire which led to a decline in the grasses they eat.

Fires Are Not The Only Threat

But why do fires pose a threat to species that have evolved in a fire-prone landscape such as Australia? We believe it’s because several threatening processes, on their own and in combination, have reduced the size of mammal populations and affected their capacity to cope with fire.

For example, habitat loss and fragmentation means smaller populations of mammals are restricted to increasingly narrow geographic areas. This makes them more likely to be harmed by intense and large fires.

And when fire destroys vegetation cover, native animals are more vulnerable to being hunted by introduced species such as foxes and feral cats.

Climate change, grazing activity and weed invasion can also interact with fire to exacerbate mammal declines.

Importantly, fire regimes are also changing rapidly. The Black Summer fires of 2019-2020 – a disaster intensified by climate change – were unprecedented in terms of size and area severely burnt.

Towards Better Conservation

Linking changes in mammal populations to the characteristics of fire regimes will help develop more effective conservation actions and policies.

For example, restoring Indigenous fire practices is likely to promote cooler, patchier fires that retain habitat refuges and boost food resources for ground-dwelling animals such as bilbies and bettongs.

And controlling foxes and feral cats, particularly in areas burned by large and severe fires, will likely increase mammal survival in post-fire environments.

Other actions will be needed to manage fire for mammal conservation. These include:

- habitat restoration

- strategic planned burning

- rapid recovery teams that assist wildlife after fire

- reintroductions of threatened mammals

- targeted fire suppression

- reducing greenhouse gases.

To explore whether these actions might be effective, models can simulate the impact of management strategies and fire regimes on species and ecosystems.

Finally, our research highlighted considerable uncertainty in the evidence for fire-related declines of many threatened mammals. Fires influence animal survival, reproduction and movement in many ways, and more research into threatened species ecology is needed to address Australia’s biodiversity crisis.

Julianna Santos, PhD candidate, The University of Melbourne; Holly Sitters, Senior Ecologist, The University of Melbourne, and Luke Kelly, Senior Lecturer in Ecology, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Greater gliders are hurtling towards extinction, and the blame lies squarely with Australian governments

Darcy Watchorn, Deakin University and Luke Emerson, Deakin UniversityThe southern and central greater glider, the world’s largest gliding marsupial, was officially listed as “endangered” this week, with the species facing a very high risk of extinction.

In just six years, the number of greater gliders has declined at a staggering rate, going from no conservation listing at all, to “vulnerable”, and now to “endangered”. During this time, the destruction of their forest habitat in eastern Australia has continued.

Greater gliders are among thousands of native species under threat of extinction. Already this year, for example, the yellow-bellied glider was listed as vulnerable nationally, and koala populations across Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory were listed as endangered.

A key reason is that Australia’s environmental laws and practices are outdated and offer little meaningful protection to threatened plants and animals. To avoid a future in which greater gliders are nothing more than a memory, we must immediately stop destroying their habitat.

The Plight Of The Greater Glider

Greater gliders are beautiful, fluffy, cat-sized possums with large ears, long tails and claws. They have fur-covered membranes that enable them to glide up to 100 metres between trees.

Like koalas, greater gliders feed almost exclusively on eucalypt leaves. But, unlike koalas, greater gliders require mature forests with tree hollows to sleep in and rear young.

In 2020, scientists discovered there are actually three species of greater glider: the northern greater glider (now vulnerable), as well as the central and southern greater gliders, although these two are not officially recognised by the federal government as separate species yet.

The conservation advice following this uplisting to endangered indicates an overall rate of population decline exceeding 50% over a 21-year period – that’s just three generations of greater gliders.

Greater gliders were once abundant along Australia’s east coast. However, 200 years of forest clearing and logging has steadily reduced their habitat and numbers. This legacy of disturbance has amplified the impact of recent bushfires on remaining forest and glider populations.

For those who have stood on bare ground in recently logged or burnt forest, you know the silence of a once thriving ecosystem is chilling. The sense of loss is overwhelming.

The Last Six Years

In 2016, before we knew three species existed, the greater glider was listed as “vulnerable” under Australia’s key environment law: the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

The conservation advice back then stated that stopping their decline required a recovery plan, and “existing mechanisms are not adequate to address these needs”. However, no such plan has ever been developed and implemented.

Logging and land clearing continued unabated. In fact, our recent study found that after this listing, destruction of greater glider habitat actually increased in Queensland and NSW, and remained consistently high in Victoria.

Then, in the summer of 2019 and 2020, the catastrophic Black Summer bushfires struck, razing around 30% of greater glider habitat. Still, logging and land clearing continued.

A NSW government report revealed that in 2020, 51,400 hectares of woody vegetation was cleared.

So, it’s not terribly surprising that only six years on from the 2016 “vulnerable” listing, central and southern greater gliders have been nationally listed as endangered.

Controllable Threats Continue

Climate change also poses a considerable threat to the greater glider, in terms of both the increasing risk of fire and rising temperatures, particularly in NSW and Victoria.

While the impacts of these threats will be ongoing and are challenging to mitigate, they can be addressed by urgently and significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Cutting down forests, however, is a threat that could be stopped immediately.

Unfortunately, native forest logging continues in NSW and Victoria. And in Queensland, a new coal mine will destroy thousands of hectares of greater glider and koala habitat.

It’s clear the EPBC Act is ineffective at protecting forest-dwelling species. One reason is due to so-called “regional forest agreements” established in the mid-1990s as a compromise between warring environmentalists and the forestry industry.

Under these agreements, a range of logging operations around Australia are exempt from federal environment laws. They need only comply with state regulations, removing a layer of potential protection for threatened species.

Failure to implement legislation that protects our biodiversity is incredibly shortsighted.

Not only does it mean many essential ecological processes on which we depend will be irreversibly disrupted, but the joy of encountering unique wildlife - shaped by millions of years of evolution - may be lost forever too.

What Needs To Change?

Being listed as endangered does nothing to boost protection for Australian species unless meaningful policies and legislated protection measures are actually implemented in response.

The failure of state governments to act appropriately on the recommendations of the 2016 vulnerable listing is evidence of this.

Often, attempts to conserve greater gliders and other forest mammals take the form of artificial hollow provisioning (including nest boxes) or reforestation. While these measures can be valuable, they are far from silver bullets.

It’s not possible to provide nest boxes across the 5 million hectares of greater glider habitat that burned in the Black Summer fires. Nor can they replace the thousands of hectares of habitat logged each year.

At best, nest boxes are a localised stopgap. At worst, they can be completely ineffective, and can even be used to greenwash environmentally destructive projects or delay appropriate action.

Similarly, reforestation will do little in the short term for a species that depends on old-growth forest. It can take well over 100 years for trees to form hollows in which greater gliders can shelter.

Rather than band-aid solutions that don’t address the cause of decline, meaningful legislated change is required to protect our biodiversity. Australia must strengthen its environment laws and transition towards a timber supply from certified plantations.

Western Australia has already committed to end native forestry by 2024. The Victorian and NSW governments must do better, and end native forest logging immediately, or see more greater gliders, koalas and other endangered forest mammals perish.

We cannot wait until they’re listed as critically endangered to take serious action.

We’ve been lucky enough to share peaceful, cool nights in an ancient forest, surrounded by greater gliders, their bright yellow eyes shining, before they launch into the night and glide out of view. We want future generations to experience this too.

The authors are grateful for the contributions of Kita Ashman, an ecologist at the World Wildlife Fund, to this article.![]()

Darcy Watchorn, PhD Candidate, Deakin University and Luke Emerson, PhD Candidate, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Patently ridiculous’: state government failures have exacerbated Sydney’s flood disaster

Jamie Pittock, Australian National UniversityFor the fourth time in 18 months, floodwaters have inundated homes and businesses in Western Sydney’s Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley. Recent torrential rain is obviously the immediate cause. But poor decisions by successive New South Wales governments have exacerbated the damage.

The town of Windsor, in the Hawkesbury region, has suffered a particularly high toll, with dramatic flood heights of 9.3 metres in February 2020, 12.9m in March 2021 and 13.7m in March this year.

As I write, flood heights at Windsor have reached nearly 14m. This is still considerably lower than the monster flood of 1867, which reached almost 20m. It’s clear that standard flood risk reduction measures, such as raising building floor levels, are not safe enough in this valley.

We’ve known about the risk of floods to the region for a long time. Yet successive state governments have failed to properly mitigate its impact. Indeed, recent urban development policies by the current NSW government will multiply the risk.

We Knew This Was Coming

A 22,000 square kilometre catchment covering the Blue Mountains and Western Sydney drains into the Hawkesbury-Nepean river system. The system faces an extreme flood risk because gorges restrict the river’s seaward flow, often causing water to rapidly fill up the valley after heavy rain.

Governments have known about the flood risks in the valley for more than two centuries. Traditional Owners have known about them for millennia. In 1817, Governor Macquarie lamented:

it is impossible not to feel extremely displeased and Indignant at [colonists] Infatuated Obstinacy in persisting to Continue to reside with their Families, Flocks, Herds, and Grain on those Spots Subject to the Floods, and from whence they have often had their prosperity swept away.

Macquarie’s was the first in a long line of governments to do nothing effective to reduce the risk. The latest in this undistinguished chain is the NSW Planning Minister Anthony Roberts.

In March, Roberts reportedly revoked his predecessor’s directive to better consider flood and other climate risks in planning decisions, to instead favour housing development.

Roberts’ predecessor, Rob Stokes, had required that the Department of Planning, local governments and developers consult Traditional Owners, manage risks from climate change, and make information public on the risks of natural disasters. This could have helped limit development on floodplains.

Why Are We Still Building There?

The Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley is currently home to 134,000 people, a population projected to double by 2050.

The potential economic returns from property development are a key driver of the lack of effective action to reduce flood risk.

In the valley, for example, billionaire Kerry Stokes’ company Seven Group is reportedly a part owner of almost 2,000 hectares at Penrith Lakes by the Nepean River, where a 5,000-home development has been mooted.

Planning in Australia often uses the 1-in-100-year flood return interval as a safety standard. This is not appropriate. Flood risk in the valley is increasing with climate change, and development in the catchment increases the speed of runoff from paved surfaces.

The historical 1-in-100 year safety standard is particularly inappropriate in the valley, because of the extreme risk of rising water cutting off low-lying roads and completely submerging residents cut-off in extreme floods.

What’s more, a “medium” climate change scenario will see a 14.6% increase in rainfall by 2090 west of Sydney. This is projected to increase the 1-in-100 year flood height at Windsor from 17.3m to 18.4m.

The NSW government should impose a much higher standard of flood safety before approving new residential development. In my view, it would be prudent to only allow development that could withstand the 20m height of the 1867 flood.

No Dam Can Control The Biggest Floods

The NSW government’s primary proposal to reduce flood risk is to raise Warragamba Dam by 14m.

There are many reasons this proposal should be questioned. They include the potential inundation not just of cultural sites of the Gundungarra nation, but threatened species populations, and part of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

The cost-benefit analysis used to justify the proposal did not count these costs, nor the benefits of alternative measures such as upgrading escape roads.

Perversely, flood control dams and levee banks often result in higher flood risks. That’s because none of these structures stop the biggest floods, and they provide an illusion of safety that justifies more risky floodplain development.

The current NSW transport minister suggested such development in the valley last year. Similar development occurred with the construction of the Wivenhoe Dam in 1984, which hasn’t prevented extensive flooding in Brisbane in 2011 and 2022.

These are among the reasons the NSW Parliament Select Committee on the Proposal to Raise the Warragamba Dam Wall recommended last October that the state government:

not proceed with the Warragamba Dam wall raising project [and] pursue alternative floodplain management strategies instead.

What The Government Should Do Instead

The NSW government now has an opportunity to overcome two centuries of failed governance.

It could take substantial measures to keep homes off the floodplain and out of harm’s way. We need major new measures including:

- preventing new development

- relocating flood prone residents

- building better evacuation roads

- lowering the water storage level behind Warragamba Dam.

The NSW government should help residents to relocate from the most flood-prone places and restore floodplains. This has been undertaken for many Australian towns and cities, such as Grantham, Brisbane, and along major rivers worldwide.

Relocating residents isn’t easy, and any current Australian buyback and relocation programs are voluntary.

I think it’s in the public interest to go further and, for example, compulsorily acquire or relocate those with destroyed homes, rather than allowing them to rebuild in harm’s way. This approach offers certainty for flood-hit people and lowers community impacts in the longer term.

It is patently ridiculous to rebuild on sites that have been flooded multiple times in two years.

In the case of the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley, there are at least 5,000 homes below the 1-in-100-year flood return interval. This includes roughly 1,000 homes flooded in March.

The NSW government says a buyback program would be too expensive. Yet, the cost would be comparable to the roughly $2 billion needed to raise Warragamba Dam, or the government’s $5 billion WestInvest fund.

An alternative measure to raising the dam is to lower the water storage level in Warragamba Dam by 12m. This would reduce the amount of drinking water stored to supply Sydney, and would provide some flood control space.

The city’s water supply would then need to rely more on the existing desalination plant, a strategy assessed as cost effective and with the added benefit of bolstering drought resilience.

The flood damage seen in NSW this week was entirely predictable. Measures that could significantly lower flood risk are expensive and politically hard. But as flood risks worsen with climate change, they’re well worth it.![]()

Jamie Pittock, Professor, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To stop risky developments in floodplains, we have to tackle the profit motive – and our false sense of security

Brian Robert Cook, The University of Melbourne and Tim Werner, The University of MelbourneIn the aftermath of destructive floods, we often seek out someone to blame. Common targets are the “negligent local council”, the “greedy developer”, “the builder cutting corners”, and the “foolish home owner.” Unfortunately, it’s not that simple, as Sydney’s huge floods make clear.

In flood risk management, there’s a well-known idea called the “levee effect.” Floodplain expert Gilbert White popularised it in 1945 by demonstrating how building flood control measures in the Mississippi catchment contributed to increased flood damage. People felt more secure knowing a levee was nearby, and developers built further into the flood plains. When levees broke or were overtopped, much more development was exposed and the damages were magnified. “Dealing with floods in all their capricious and violent aspects is a problem in part of adjusting human occupance,” White wrote.

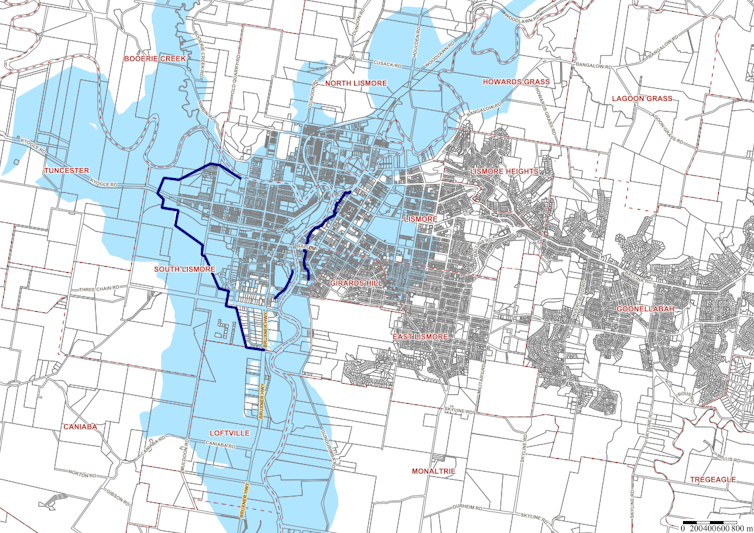

The levee effect shows why it’s so hard to reduce flood risk, even in areas hit hardest by this year’s record-breaking floods. The NSW town of Lismore had a 10 metre levee, experience dealing with many floods, and a flood risk management plan. It was devastated regardless.

To tackle flood risk, we have to respond to the social, political, economic, and environmental factors that drive development and occupation of floodplains.

Social Factors: We Love Living Near Water

Around the world, people like to live near water – even if it might flood. Waterfront properties and those with river views command significantly higher prices. In addition, Australians view home ownership as a rite of passage, a key marker of adulthood as well as an economic investment. People will prioritise home ownership over concerns about living in a floodplain – especially when the house is part of a government approved development.

Political Economy Factors: Money Can Drive Decision Making

Developing flood-prone areas generates profits, not just in monetary terms, but also through social and political capital. When developments are proposed, flood risk is assessed using the 1% annual exceedance probability line. This line, colloquially known as the 100-year flood event, defines land with a 1% chance of experiencing a flood each year.

The act of drawing this line creates more valuable and less valuable lands. Land owners on the boundary have an incentive to argue for change, sometimes based on how the 1% line is modelled. Developers can – and have – argued certain blocks should be acceptable for development. This can be appealing to local councils eager to encourage economic development and expand their tax base. When boundaries shift and less valuable land is converted into residential land, developers are rewarded with higher profits – while communities and future homeowners take a step closer to the next flood.

In some cases, like Lismore, developers building inside the 1% line are permitted to install mitigation measures, such as by infilling land, raising floor levels, building embankments, and installing large pumps. They are usually required to also build an additional 500 mm of freeboard above the 1% flood level.

Job done? Not quite. When a developer successfully argues for the redesignation of ‘flood-prone’ to ‘developable’, this sets a precedent that strengthens future development proposals. More developments create more risk, causing new flood control measures to be proposed, which are justified on the basis of encouraging more investment and development. The cycle continues.

When a developer converts flood-prone land into homes, they own the consequences a flood might bring to them. But when that building is sold, liability for flood damages is transferred to the new owner. It is common to portray such owners as naive or irresponsible, but they’re purchasing a home approved by the council on the basis of expert modelling.

The home owner pays their rates, like everyone else, and has every right to assume professionals have determined the safety of the development. When large-scale floods hit, those owners are as entitled as anyone to government assistance and relief.

This final act of goodwill – extremely difficult for any government to refuse – effectively shifts the costs of disaster mitigation, relief, and recovery to the Australian taxpayer. As John Handmer has argued, “flood risk is characterised by private sector profit while the costs are borne by the public sector, individuals and small business.”

Environmental Factors: Warping Nature Means More Reliance On Engineering

Floods are valuable, natural processes. In many farming regions, a bumper crop follows floods due to additional moisture and deposited nutrients.

But when parts of the environment are turned to concrete, the ability of the land to absorb flood waters drops and engineering protections become even more necessary.

Dams, embankments, storm drains, and pumps which protect developments are only effective to a point. Such structures effectively eliminate small scale floods, which would have otherwise helped to recharge aquifers, raise the level of “green water” stored in soils, deposit sediments, aid soil fertility, and prevent compaction and subsidence.

As a result, engineering solutions stop small-scale flooding and its accompanying benefits, while failing to prevent large-scale floods – and giving a false sense of security to floodplain residents.

What Can Be Done?

To some degree, we’re all implicated in a system encouraging some people to profit by building flood-prone housing. When houses flood, it is the public who subsidises these developments with disaster relief and structural flood mitigation.

As climate change shifts the traditional boundaries of flood-prone areas, we face the pressing need to confront the forces driving us to develop floodplains.

A key first step is to harden boundaries and limit opportunities to ‘nibble’ into floodplains. Holding developers and builders accountable to home owners even after the sale would be beneficial, though such arrangements are virtually unprecedented.

Evacuation or abandonment of floodplains is inevitable. Lismore’s voluntary house purchase scheme is aimed at removing flood-prone structures inside the area prone to 1 in 20 year floods. Despite efforts like this, floodplain withdrawal has only succeeded a handful of times – and those gains are often quickly erased.

For now, Australians living in flood-prone areas should consider making their homes more flood-resilient to limit the impacts of small and medium floods, given these are likely to expand geographically due to climate change.

Nationally, Australia must tackle the hidden incentives causing encroachment if we are to avoid settling in areas where we cannot safely live.![]()

Brian Robert Cook, Associate professor, The University of Melbourne and Tim Werner, ARC DECRA Fellow, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Department Of Planning Approves Plan For Up To 450 In Flood Prone South Kiama - Instructs Kiama Council To Implement Its Plan

- Further master planning

- Preparing a development control plan

- Developing a development application assessment process

EPA Launches Yet Another FCNSW Prosecution For Alleged Forestry Breaches In Koala Habitat

New Plan To Allow Pollination Movements

- Alcohol washing a proportion of their hives and recording the results to prove they are free from varroa mite; and,

- Checking their records are up to date and that none of their hives has been in an eradication, notification or surveillance zone within the past 24 months.

What’s causing Sydney’s monster flood crisis – and 3 ways to stop it from happening again

Again, thousands of residents in Western Sydney face a life-threatening flood disaster. At the time of writing, evacuation orders spanned southwest and northwest Sydney and residents of the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley were being warned the crisis was escalating.

It’s just over a year since the region’s long-suffering residents lived through one of the largest flood events in recent history. And of course, earlier this year floods devastated the Northern NSW town of Lismore.

Right now, attention is rightly focused on helping those immediately affected by the disaster. But as the floodwaters subside, we must urgently act to avert a repeat of this crisis.

Obviously, nature is a major culprit here. But there’s plenty humans can do to plan for major flooding and make sure we’re not sitting in the path of disaster.

So What’s Caused The Current The Flood Problem?

The first driver of this disaster is nature and geography.

For many months now, much of New South Wales has experienced significant rain and associated flooding.

There’s a reason both the Hawkesbury-Nepean and Lismore flood the way they do – geography. Both areas sit in low-lying bowl-like depressions in the landscape.

Lismore sits at the confluence of several large rivers that each drain significant catchments – and so can deliver large floods.

And in the Hawkesbury-Nepean, huge rivers have to pass through a very tight “pinch point” known as the Sackville Bathtub. This slows the flow, causing water to back up across the floodplain.

The NSW government wants to raise the wall of the Warragamba Dam to help alleviate this problem. But as others have argued, this controversial proposal might not work. That’s because raising the wall will control only about half the floodwater, and won’t prevent major floods delivered by other rivers feeding the region.

The second factor making the current floods so bad is the exposure of infrastructure and housing. In the Hawkesbury-Nepean region, lots of stuff people care about – such as homes, businesses and schools – is in the path of floodwaters.

In an ideal world, nothing would be built on a floodplain. But due to Sydney’s growing population and the housing affordability crisis, local governments in Western Sydney have been under pressure to build more and more homes, despite the known flood risk.

In 2018, more than 140,000 people lived or worked on the Hawkesbury-Nepean floodplain. Due to this large population and the region’s geography, the area has the most significant and unmitigated community flood exposure in Australia.

What’s worse, the region’s population is expected to double over the next 30 years. At the same time, climate change will change rainfall patterns and make severe flooding more likely.

Being Prepared

The third contributing factor to this flood disaster is a lack of preparedness.

The NSW government has a strategy to manage the flood risk in the Hawkesbury-Nepean. It includes improved flood warning and emergency response measures, upgraded evacuation routes, recovery planning and a regional floodplain management study.

But given the region’s big, growing population and massive flood exposure, these three bolder and more urgent measures are needed:

1. Get better at urban planning

Local governments, developers and communities must collaborate to agree on smarter land-use zoning – basically, deciding what infrastructure and activities go where. Because let’s be honest: some land just should not be built on.

This is a lesson Lismore has learned the hard way. There’s now a broad-ranging discussion underway about whether the town’s central business district should be moved entirely, and flood-prone riverside land turned over to other uses.

If we must build on flood-exposed land, better building codes and designs are needed. This may mean accepting higher construction costs. It will certainly require tough rules requiring developers and homeowners to comply with planning measures.

And when building new suburbs in flood-prone areas, several best-practice building standards should be adopted. They include:

- raising floor heights above, say, a one in 500 year flood level

- improving drainage

- reducing hard surfaces that don’t absorb water.

2. Prepare infrastructure and people

All too often, flooding cuts off vital access roads and prevents or limits evacuations. More emergency routes in and out of flood-prone areas are needed.

More designated evacuation shelters – accessible to all – are also required.

And it’s crucial people living in flood-exposed areas are aware of, understand and prepare for the risk. This requires community education and engagement – undertaken regularly (such as once a year) and in multiple languages.

For those in the Hawkesbury-Nepean region who want to better understand the flood-risk, check out this valuable resource provided by the NSW State Emergency Service (SES).

Even for those who understand the risks, insuring themselves against the damage may be difficult or impossible. Rising premiums mean insurance is already out of reach for many Australians – and the problem is set to worsen.

3. Equip the SES properly

The SES is responsible for flood and storm response, and it does exceptional work. But like most government agencies, the SES is being asked to do more with ever tighter budgets.

The organisation is largely made up of volunteers – and that workforce is very stretched.

As a society, we must ask how the SES can be better funded and supported to do the job we ask of them. For example, is it still appropriate to rely on a mostly volunteer-run service to provide such a challenging disaster response – especially as climate change worsens? Or should the SES’s paid workforce be greatly expanded?

Looking Ahead

Unfortunately, the wet conditions we’re now seeing may persist for some time. Recent climate modelling suggests Australia may face a third consecutive La Nina this spring and summer.

This extra rain will fall on already soaked landscapes, further increasing the likelihood of flooding. And the ramifications will extend far beyond affected communities.

Disruptions will be felt in agriculture, supply chains, transport routes and broader state and national economies.

In the longer term, of course, climate change is projected to bring far worse extreme rain events than in the past. The current flood crisis will recede, but the need to plan for future flooding disasters has never been more pressing.![]()

Dale Dominey-Howes, Honorary Professor of Hazards and Disaster Risk Sciences, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

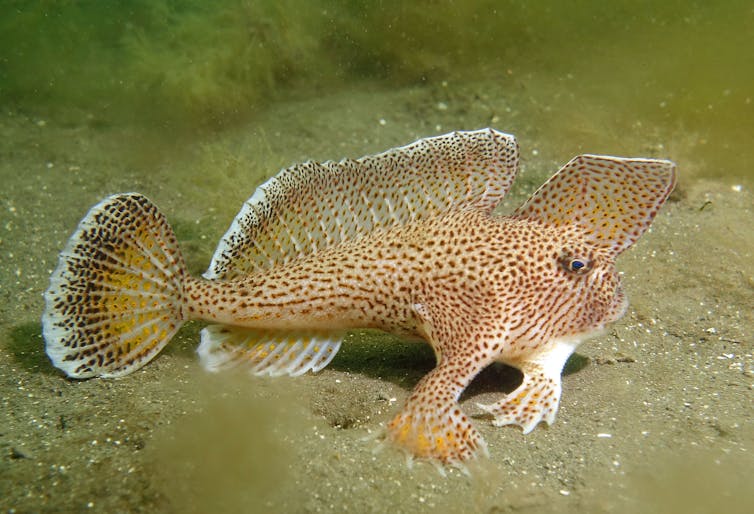

A New South Wales First! New Species Of Legless Lizard Discovered In The Hunter Valley

Climate change is white colonisation of the atmosphere. It’s time to tackle this entrenched racism

“Climate change is racist”. So reads the title of a recent book by British journalist Jeremy Williams. While this title might seem provocative, it’s long been recognised that people of colour suffer disproportionate harms under climate change – and this is likely to worsen in the coming decades.

However, most rich white countries, including Australia, are doing precious little to properly address this inequity. For the most part, they refuse to accept the climate debt they owe to poorer countries and communities.

In so doing, they sentence millions of people to premature death, disability or unnecessary hardship. This includes in Australia, where climate change compounds historical wrongs against First Nations communities in many ways.

This injustice – a type of “atmospheric colonisation” – is a form of deeply entrenched colonial racism that arguably represents the most pressing global equity issue of our time. Several upcoming global talks, including the Pacific Islands Forum this week, offer a chance to urgently elevate climate justice on the global agenda.

‘Not Borne Equally’

The effects of climate change are not borne equally between everyone on the planet, and this problem will only worsen. Black people, people of colour and Indigenous people often face the most dire consequences in a warming world.

For example, research suggests global warming of 2℃ would leave more than half of Africa’s population at risk of undernourishment, due to reduced agricultural production. This is despite Africa having contributed relatively little to greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate injustice also manifests closer to home. The Lowitja Institute, Australia’s national body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research, says climate change:

disrupts cultural and spiritual connections to Country that are central to health and wellbeing. Health services are struggling to operate in extreme weather with increasing demands and a reduced workforce.

All these forces combine to exacerbate already unacceptable levels of ill-health within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

Failure At Bonn

Last month, the continued failure on the part of rich white countries to take responsibility for this injustice was on full display at the United Nations climate meetings in Bonn, Germany.

There, governments failed to make any significant progress towards compensation for “loss and damage”. According to Oxfam, loss and damage collectively refers to:

the consequences and harm caused by climate change where adaptation efforts are either overwhelmed or absent.

At Bonn, the G77 (a coalition of 134 developing countries) and China wanted financing for a so-called “loss and damage facility” put on the official agenda at the COP27 climate conference in Egypt in November this year. This facility would comprise a formal body to deliver funding to developing nations to cope with the consequences of climate change.

But the United States and the European Union opposed the move, fearing they would become liable for billions of dollars in damages.

Concerns around “loss and damage” have been long plagued global climate negotiations.

In 2013, the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage was established at COP19. Climate activists hoped it would usher in a new era of climate justice. But almost a decade on, there’s still no clear path to the financing required.

And rich white countries continue to distance themselves from all language of compensation or reparation for both historic and contemporary emissions.

This refusal continues long histories of European racism, including the deeply racialised processes of large-scale extraction that fuelled and sustained the Industrial Revolution from the outset.

Sugar plantations throughout the Caribbean were worked for generations by Africans who were enslaved, generating massive profits for Europeans that were then invested and reinvested in energy-intensive industrial infrastructure. This infrastructure helped fuel the global emissions that remain in the atmosphere today.

British industrialisation would simply not have been possible without the stolen land and uncompensated labour acquired through colonisation and slavery. Compensation for this plunder was never provided.

And today, the emissions it initiated are doubling back on those whose land and labour made them possible.

Climate Change At The Centre Of Reparations

Calls for reparations for colonialism and slavery have grown rapidly over the past few years – particularly as a result of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US and UK.

Some European states have begun to take responsibility and provide redress for colonial theft, violence and displacement.

These efforts are laudable. But there’s an urgent need to focus this sentiment on climate change – and in particular, to supercharge demands for climate reparations.

The Pacific Islands forum this week provides an opportunity for Australia to undertake climate reparation, by committing new finance for the loss and damage incurred by poorer Pacific nations under climate change.

UN Special Rapporteur Philip Alston recently said the world risks a new era of “climate apartheid”. In this scenario, tens of millions of people will be impoverished, displaced and hungry, while the rich buy their way out of hardship.

Going into COP27 in November, negotiators from the US, the EU and Australia must prioritise loss and damage finance. Failing to do so will only further solidify climate injustice.![]()

Erin Fitz-Henry, Deputy Coordinator - Anthropology, Development Studies & Social Theory, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Global Energy And Climate Leaders Meet In Sydney To Strengthen Clean Energy Technology Supply Chains

- High-level discussions among Ministers from Australia, Japan, India, Indonesia, Samoa, US and other countries are informed by new IEA reports on supply chains for technologies such as solar panels and batteries.

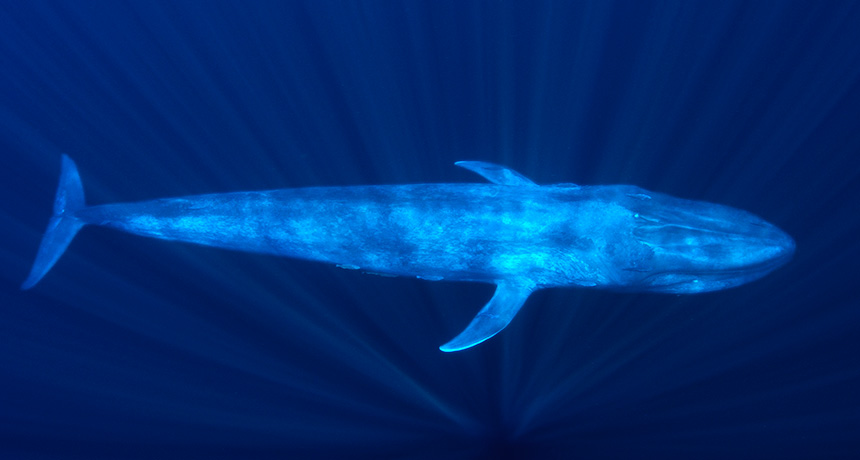

Bomb Detectors Picking Up More Blue Whale Songs In Indian Ocean

New Research Finds Deep-Sea Mining Noise Pollution Will Stretch Hundreds Of Miles

Albanese just laid out a radical new vision for Australia in the region: clean energy exporter and green manufacturer

Gone are the days when the federal government would cheer on Australia’s fossil fuel exports to the exclusion of all else, while seemingly doing everything in its power to hold back the switch to renewables.

Now we have a new government, the clean energy transition is accelerating. Labor is framing the transition not just as decarbonisation but as a green economic boom through manufacture of electrolysers, green steel, green cement and green fertiliser. If successful, this will amount to a green industrial revolution.

This radical new vision was laid out in Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s speech this week to the Sydney Energy Forum. He proposed a new era for Australian energy industries and exports as well as using our wealth of renewables to drive deeper involvement in our region.

It makes good commercial and climate sense for the federal government to target the Indo-Pacific for this green industrial revolution, since the region is already the world’s leader in clean energy investments.

As of 2021, our region accounts for over 80% of the world’s private investment in clean energy. India, China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia and Pacific nations are natural partners for Australia in this new green push as well as leaders creating the market for clean energy and green products.

What Does This Actually Look Like?

For a sign of what’s to come, look to the massive Sun Cable project, launched four years ago with early funding by Australian billionaires Mike Cannon-Brookes of Atlassian and Andrew Forrest of Fortescue Minerals Group.

The project’s ambitious goal is to become the first intercontinental exporter of renewables, by generating massive amounts of energy from solar farms in the Northern Territory and transmitting it to energy-hungry Singapore through a 4,200 km-long high voltage undersea cable. Government backing will help it progress faster.

The project has gained strong support from both territory and federal governments, and is now attracting support from the Indonesian and Singaporean governments. Indonesia’s government has given in principle approval for the cable’s undersea route through its national waters and has approved the undersea survey permit. There will be spillover benefits, such as $A1.5 billion earmarked for a marine repair base in Indonesia.

Sun Cable and other renewable megaprojects, such as Western Australia’s proposed Asian Renewable Energy Hub, show the move away from reliance on fossil fuel exports is actually happening. The Albanese government has signalled its intention to promote clean energy exports as well as green industrial development across the Indo-Pacific.

Our research project on the clean energy shift in north-east Asia has captured the progress made by major regional economies China and Korea in powering ahead with their own green transitions since the 2000s. These ongoing transitions offer major opportunities, such as exporting Australian-made green hydrogen to fuel cars in these countries.

Our Clean And Green Transition Is Bigger Than Just Renewables

Since Labor took office, we’ve heard a lot about our future as a renewables superpower. Often overlooked is the fact this would mean not just generating renewable electricity and green hydrogen at vast scale but also investing in new industries and processes to grasp as many opportunities as we can.

This would mean investing in upstream industries such as solar array fabrication and electrolyser manufacture, as well as downstream industries such as green steel, green cement and green fertiliser. These new green products would be produced using locally generated supplies of green hydrogen and cheap clean renewable power, as economist Ross Garnaut has outlined.

Green energy is no longer a niche concern. Australia’s largest companies are leading the way.

Andrew Forrest’s new spin-off company, Fortescue Future Industries, has begun constructing a $1 billion project building green hydrogen manufacturing components, cabling and renewable generation in central Queensland. This single project is expected to double the global production capacity of green hydrogen. It will make Queensland home to a new green hydrogen fuel and components export industry.

If our new government can pull this off and turn vision to reality, we could embrace a new green growth economy and begin our own green industrial revolution.

Better yet, Australia could finally make full use of its abundant land and renewable resources to fast-track the clean economic development of our Indo-Pacific neighbours.

Green Energy Comes With Security And Geopolitical Benefits

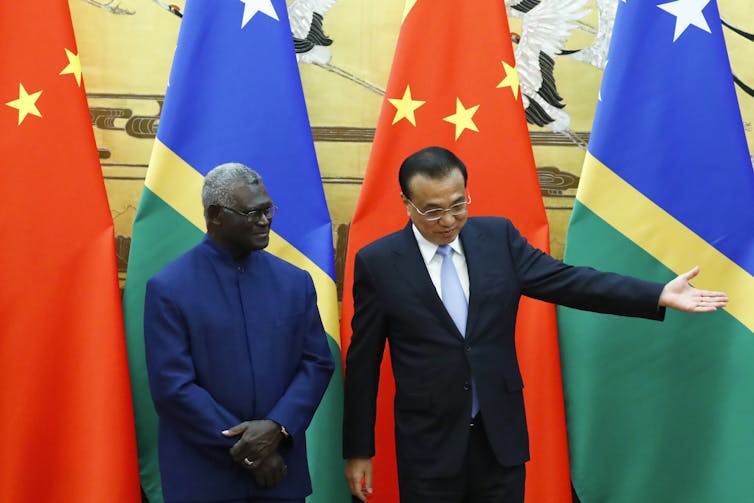

For decades, Pacific nations have seen climate change as the single greatest threat to their people. As a result, Australian investment in exportable renewables will become a key diplomatic tool as geopolitical competition between China and the US intensifies in our region.

China isn’t standing still either. Until recently, China focused its regional aid and investment on traditional infrastructure projects such as airports, roads and stadiums. Now Beijing is ramping up its climate responses to the region, with climate change issues at the top of the agenda at the China-Pacific Islands forum held in 2019.

In light of China’s growing green activism in the Pacific, the Australian government has a lot of ground to make up.

It should start with a major rethink of Australia’s traditional approach to financing energy projects, which has seen us support fossil fuel power in the region.

We can no longer keep propping up fossil fuels, with the costs of this support not only environmental, but geostrategic as well. Partnering with China on Pacific projects, as Pacific minister Pat Conroy has flagged, could also help.

Albanese’s speech this week was promising. He laid out a very different role for Australia in our region – one where our regional engagement policy is in line with a new domestic policy on climate goals, and where renewable energy provides a means of deepening regional cooperation on tangible investment projects. Now comes the hard part: delivery. ![]()

John Mathews, Professor Emeritus, Macquarie Business School, Macquarie University; Elizabeth Thurbon, Scientia Associate Professor in International Relations / International Political Economy, UNSW Sydney; Hao Tan, Associate Professor, Newcastle Business School, University of Newcastle, and Sung-Young Kim, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, Discipline of Politics & International Relations, Macquarie School of Social Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Times have changed: why the environment minister is being forced to reconsider climate-related impacts of pending fossil fuel approvals

A non-profit group is imploring the new federal environment minister Tanya Plibersek to consider the climate change impacts of 19 fossil fuel projects currently pending approval, drawing on a rarely used legal provision that will require her to reconsider the findings of her predecessors.

The minister will be forced to either confirm or revoke previous decisions that the fossil fuel projects – which propose to extract new coal or gas – aren’t likely to have a significant impact on Australia’s protected species and places.

The group that issued the 19 requests, the Environment Council of Central Queensland, argues the projects will contribute to climate change. This will, in turn, harm the threatened and migratory species, wetlands, heritage sites, and marine areas protected under Australia’s environmental law, the EPBC Act.

So what makes this intervention important?

The Environment Is Changing Rapidly

The legal term for the type of request issued by the environment council is a “reconsideration request”. Made under section 78A of the EPBC Act, reconsideration requests depend on “substantial new information”.

Here, this includes the latest climate science and evidence about how Australian species and places are responding to climate change.

For example, the situation for a species like the Eyre Peninsula southern emu-wren, whose habitat has been decimated by bushfire is more dire than it was just a few years ago, making any new impact more significant.

Similarly, the Great Barrier Reef has now suffered its fourth mass bleaching event since 2016. Further climate change could bring this iconic ecosystem closer to collapse.

The environment council and its team argue that essentially all matters protected under the EPBC Act are vulnerable to the effects of fossil fuel projects, not just species and areas next door to mine sites.

Their logic is that every project unearthing new fossil fuels to be extracted and burned over a long period of time will make an important contribution to climate change. As we transition toward net-zero emissions, every tonne of emissions counts.

In turn, climate change will significantly impact Australia’s heritage and biodiversity. The environment council want to make sure this is factored into any final approval decision.

What Happens Now?

Now the requests have been made, the minister is legally obliged to reconsider the projects in light of climate change.

If the minister confirms the previous decisions that there aren’t likely to be significant impacts on protected species and places, despite the new information, she can go ahead and approve or reject the projects based on the information she already had. However, this could then be challenged in the Federal Court.

So, what might the court say? Would it find that climate-related impacts to protected species and places are relevant to fossil fuel approvals?

This depends on the interpretation of key terms “likely”, “significant”, and “impact”.

Under the EPBC Act, the word “likely” means “a real and not remote chance or possibility”. It doesn’t equate to a probability over 50%.

“Impact” can include an indirect impact, which might occur at a different place and time to the project, including in the future. An impact doesn’t have to be wholly caused by a project to be relevant.

That said, there hasn’t yet been an authoritative judicial interpretation of the definition of this term. This means we don’t know if the court would find that climate-related impacts to biodiversity and heritage are impacts of fossil fuel projects. Arguably, it certainly could.

What we do know is that the word “significant” calls for the courts to consider the context of an impact. The context here is an extinction crisis that’s being exacerbated by a climate crisis.

If the minister does decide the projects are likely to significantly impact Australia’s threatened species and protected places, she’ll revoke the original decisions. This would trigger a process to procure sufficient information to better inform a final approval decision.

What Does This Mean For The Law And For Future Approvals?

The EPBC Act came into force more than two decades ago, without any reference to climate change. Yet, it’s the law we’ve got to protect the environment.

Recognising that fossil fuel projects are likely to harm the Australian environment would mean climate change would need to be taken into account for new extraction proposals in future.

Specifically, the plight of threatened species and protected places would be broadly relevant to all final coal and gas approval decisions. The minister could still approve new projects, but she’d have to be mindful of the broad-ranging impacts to biodiversity and heritage.

Whatever the ultimate result, this challenge will help elucidate a potential link between the EPBC Act and climate change.

This includes clarifying the responsibility fossil fuel projects have over climate-related harm to the environment, now climate change is well and truly manifest.![]()

Laura Schuijers, Deputy Director, Australian Centre for Climate and Environmental Law and Lecturer in Law, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Will Australia’s new climate policy be enough to reset relations with Pacific nations?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is hoping his government’s more ambitious climate policy will help reset Pacific relations when he meets with island leaders next week.

Hosted by Fiji, this year’s Pacific Islands Forum will be the first in-person leaders summit since the 2019 Pacific Islands Forum in Tuvalu, which saw Albanese’s predecessor Scott Morrison try to water down a Pacific regional climate declaration. In the aftermath of that bruising summit, Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama told waiting media partnering with China was preferable to working with Morrison.

Since then, geo-strategic competition between China and the United States has intensified. This contest looms over this year’s Pacific Islands Forum. China is seeking new security arrangements with island countries, while the US and its allies are stepping up their engagement with Pacific nations.

But while Australia worries about China, most Pacific nations are more worried about climate change on their doorstep. A new Climate Council report endorsed by a group of prominent Pacific leaders says committing to more ambitious climate action is key to Australia’s claim to be the Pacific’s security partner of choice.

Security Will Be High On The Agenda

Why is security suddenly important? Because the Pacific has become a region of geo-strategic competition for the first time in decades.

China has become more powerful. That’s seen it invest in an ocean-going navy and seek new security arrangements with Pacific countries. Australian security officials have been particularly worried Beijing could use infrastructure loans to secure a Chinese naval base in the Pacific.

In April, Solomon Islands signed a security deal with China which – if it is anything like the draft leaked online – contains provisions that allow for Chinese military presence and ship resupply.

The deal has changed the dynamic of a region long aligned with the West (notwithstanding Pacific concerns about decolonisation and the impact of nuclear testing).

While Solomon Islands leaders say they have no intention of allowing a Chinese base or an ongoing security presence in the country, concerns remain.

Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong – who meets with Pacific foreign ministers today to iron out the final agenda for the forum meeting – wants leaders to discuss the controversial security deal. She says Pacific security should be a matter for the “Pacific family”.

In May, China’s foreign minister Wang Yi toured the Pacific hoping to secure a regional security deal with island countries. The proposal was politely declined by island leaders, who explained there was no regional consensus on the deal. Undeterred, Wang Yi proposed a meeting with Pacific foreign ministers next week, on exactly the same day Albanese meets island leaders at the Pacific Islands Forum.

Tackling The Region’s Key Threat: Climate Change

Pacific island leaders argue growing tension between the US and China does little to address climate change, which they are adamant is the region’s single greatest threat.

For decades, Pacific leaders have called for recognition that climate change is a threat to their nations akin to war. During the first UN Security Council debate on climate change in 2007, Pacific Islands Forum countries argued the impacts of a warming planet for island nations were “no less serious than those faced by nations and peoples threatened by guns and bombs”.

In June this year, Fiji’s defence minister Inia Seruiratu told a regional security dialogue that

machine guns, fighter jets, grey ships and green battalions are not our primary security concern. Waves are crashing at our doorsteps, winds are battering our homes, we are being assaulted by this enemy from many angles.

Today’s report from the Climate Council backs what island leaders are saying: climate change is the single greatest threat to the region.

If the world is to have a reasonable chance of achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, and ensuring the survival of all Pacific island countries, global greenhouse gas emissions must be halved by 2030. A wealthy country like Australia, with high emissions and vast untapped renewable resource, should be aiming to reduce emissions to 75% below 2005 levels by 2030, according to the report.

Optimism And Wariness

Australia’s new climate policies have been met by Pacific island countries with a mixture of optimism and wariness.

Albanese has pledged to cut emissions by 43% by 2030. While this brings Australia closer to the rest of the developed world, this target by no means leads the pack. Most other developed countries have promised to cut emissions by at least 50% this decade. Labor’s 43% cut should be the floor for Australia’s ambition, not a ceiling.

The new Australian government wants to co-host the annual UN climate summit with Pacific island countries, potentially as soon as 2024. While this is a positive sign, Australia cannot assume Pacific leaders will automatically support it.

Pacific island countries want Australia to do more. That includes moving beyond coal and gas and committing new finance to help island countries to deal with the growing impacts of climate change (including unavoidable loss and damage).

Albanese will have the chance to hear Pacific concerns in Suva next week. It will be the start of an ongoing conversation. If the Australian government listens carefully, and takes meaningful action on climate, it will strengthen its claim to be the Pacific’s security partner of choice.![]()

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s finally acknowledged climate change is a national security threat. Here are 5 mistakes to avoid

The climate policies of the former Morrison government were widely panned – largely for a weak commitment to cutting emissions and a slow transition to renewable energy. But amid all the shortcomings, arguably the biggest was the Coalition’s neglect of security threats posed by climate change.

The Albanese government has moved to address this gap. It has launched an urgent review of climate and security risk led by intelligence chief Andrew Shearer, working closely with Defence. The review team now faces a daunting task.

Climate change is a pressing and accelerating threat to global security. It will disrupt trade, displace populations, cause food and energy shortages and drive conflict between nations.

Southeast Asia, on our northern doorstep, is particularly at risk. It’s a global hotspot of overlapping climate hazards such as intensifying cyclones, sea level rise and extreme heat.

What’s more, the region is heavily populated – 275 million people live in Indonesia alone – and its social safety nets cannot support all those displaced by disasters.

The government review is a crucial first step in preparing Australia for the dangers ahead. But to be successful, it must avoid these five pitfalls.

1. Narrow Definition Of National Security

Climate change will no doubt challenge our defence force, threatening military infrastructure and readiness. It will also exacerbate tensions in military hotspots such as the South China Sea, where sea level rise and ocean warming will amplify disputes over maritime boundaries and fisheries.

But the most pressing regional security threats will come from climate change disruptions to social systems. In particular, disruptions to food, water and energy will displace large populations, undermine the legitimacy of governments and cause other social upheaval.

The issues go far beyond traditional national security portfolios such as Defence, Foreign Affairs, Home Affairs and intelligence agencies. A wide range of government departments must be involved in addressing these risks.

2. Focusing Too Much On Overseas Threats

The risk assessment should consider the need to both respond to climate harms within Australia while being prepared to meet overseas threats, such as military instability abroad. This will primarily require personnel to deal with both tasks.

During the election campaign, Labor mooted a new civilian national disaster response force. This force would free Defence to meet intensifying military threats abroad.

A review too heavily focused on overseas threats would miss the need for such measures.

3. Taking A Siloed View

Most analysis of climate damage tends to focus on individual, rather than system-wide, impacts.

For example, a study might examine how rising temperatures will reduce food production, but not the compounding effects of hazards happening at the same time such as floods, drought and increased pests.

It’s difficult to analyse how hazards can trigger cascades of disruptions across society. But unless the review grapples with this reality, it will fundamentally misjudge the scale of the challenge.

4. Underestimating The Urgency

It’s easy to assume the pace of climate impacts we’ve experienced in the recent past is what to expect in future. But in fact, these impacts are now increasing rapidly.

Extreme heat events, for example, have mushroomed 90-fold over the past decade, relative to the previous 30 years. Severe one-in-100-year flood events will soon become annual events in many parts of the world.

These changes are already visible in Southeast Asia where sea levels are rising at the fastest pace globally. Some 75 million Indonesians are now exposed to high flood risk.

So the risk assessment must avoid miscalculating how soon major disruptions to society will be felt.

5. Oversimplifying

Labor wants the review completed urgently (although it will be updated regularly). With time pressures, some shortcuts will be needed. But the assessment team should avoid oversimplifying the process.

It would be unfortunate, for example, if the review involved a series of common questions presented to government departments, with the answers collated to form the final report. This was essentially the approach of the Biden administration in the US. The result was a patchy assessment with little whole-of-government integration.

Ideally, the process should begin with consultation across government to identify the key objectives – many of which will fall within the mandates of multiple government department, such as:

- securing our borders

- ensuring energy security

- tackling transnational organised crime

- countering terrorism and violent extremism.

The objectives would be the reference points for the review, and relevant government agencies would work together to identify the risks and responses.

For example, China’s regional trajectory cannot be understood separately from the risks posed by climate change. Australia must develop a deep and nuanced understanding of how climate change may affect Australian efforts to compete (or cooperate) with China in the region. The review should lay the groundwork for this.

Getting It Right

Climate threats exist all at once in every direction: domestically, regionally, and internationally. This is the core challenge the review must tackle.

It will take exceptionally good judgement and execution to ensure that the risk assessment avoids becoming a platitude or, at the other extreme, mired in complexity.

Our national security, and the safety and well-being of all Australians, depends on getting it right.![]()

Robert Glasser, Honorary Professor, Institute for Climate, Energy & Disaster Solutions, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

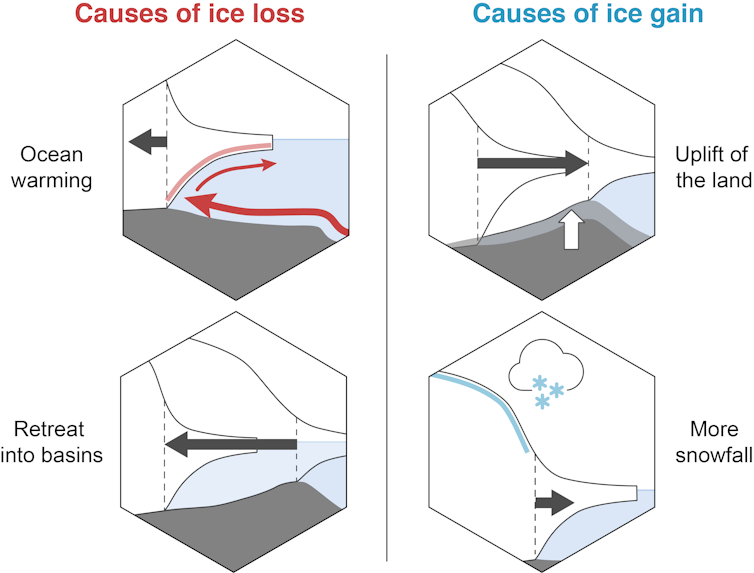

No more excuses: restoring nature is not a silver bullet for global warming, we must cut emissions outright

Restoring degraded environments, such as by planting trees, is often touted as a solution to the climate crisis. But our new research shows this, while important, is no substitute for preventing fossil fuel emissions to limit global warming.

We calculated the maximum potential for responsible nature restoration to absorb carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. And we found that, combined with ending deforestation by 2030, this could reduce global warming 0.18°C by 2100. In comparison, current pledges from countries put us on track for 1.9-2℃ warming.

This is far from what’s needed to mitigate the catastrophic impacts of climate change, and is well above the 1.5℃ goal of the Paris Agreement. And it pours cold water on the idea we can offset our way out of ongoing global warming.

The priority remains rapidly phasing out fossil fuels, which have contributed 86% of all CO₂ emissions in the past decade. Deforestation must also end, with land use, deforestation and forest degradation contributing 11% of global emissions.

The Hype Around Nature Restoration

Growing commitments to net-zero climate targets have seen an increasing focus on nature restoration to remove CO₂ from the atmosphere, based on claims nature can provide over one-third of climate mitigation needed by 2030.

However, the term “nature restoration” often encompasses a wide range of activities, some of which actually degrade nature. This includes monoculture tree plantations, which destroy biodiversity, increase pollution and remove land available for food production.

Indeed, we find the hype around nature restoration tends to obscure the importance of restoring degraded landscapes, and conserving existing forests and other ecosystems already storing carbon.

This is why we applied a “responsible development” framework to nature restoration for our study. Broadly, this means restoration activities must follow ecological principles, respect land rights and minimise changes to land use.

This requires differentiating between activities that restore degraded lands and forests (such as ending native forest harvest or increasing vegetation in grazing lands), compared to planting a new forest.

The distinction matters. Creating new tree plantations means changing the way land is used. This presents risks to biodiversity and has potential trade-offs, such as removing important farmland.

On the other hand, restoring degraded lands does not displace existing land uses. Restoration enhances, rather than changes, biodiversity and existing agriculture.

The Potential Of Nature Restoration

We suggest this presents the maximum “responsible” land restoration potential that’s available for climate mitigation. We found this would result in a median 378 billion tonnes of CO₂ removed from the atmosphere between 2020 and 2100.

That might sound like a lot but, for perspective, global CO₂ equivalent emissions were 59 billion tonnes in 2019 alone. This means the removals we could expect from nature restoration over the rest of the century is the same as just six years worth of current emissions.

Based on this CO₂ removal potential, we assessed the impacts on peak global warming and century-long temperature reduction.

We found nature restoration only marginally lowers global warming – and any climate benefits are dwarfed by the scale of ongoing fossil fuel emissions, which could be over 2,000 billion tonnes of CO₂ between now and 2100, under current policies.

But let’s say we combine this potential with a deep decarbonisation scenario, where renewable energy is scaled up rapidly and we reach net zero emissions globally by 2050.

Then, we calculate the planet would briefly exceed a 1.5℃ temperature rise, before declining to 1.25-1.5℃ by 2100.

Of course, phasing out fossil fuels while restoring degraded lands and forests must also be coupled with ending deforestation. Otherwise, the emissions from deforestation will wipe out any gains from carbon removal.

Given this, we also explored the impact of phasing out ongoing land-use emissions, to reach net-zero in the land sector by 2030.

As with restoration, we found halting deforestation by 2030 has a very small impact on global temperatures, and would reduce warming by only around 0.08℃ over the century. This was largely because our baseline scenario already assumed governments will take some action. Increasing deforestation would lead to much larger warming.

Taken together – nature restoration plus stopping deforestation – end-of-century warming could be reduced by 0.18℃.

Is This Enough?

If we enter a low-emissions pathway to limit global warming to 1.5℃ this century, we expect global temperature rise to peak in the next one to two decades.

As our research shows, nature restoration will unlikely be done quickly enough to offset the fossil emissions and notably reduce these global peak temperatures.

But let us be clear. We are not suggesting nature restoration is fruitless, nor unimportant. In our urgency to mitigate climate change, every fraction of a degree of warming we can prevent counts.

Restoring degraded landscapes is also crucial for planetary health – the idea human health and flourishing natural systems are inextricably linked.

What’s more, protecting existing ecosystems – such as intact forests, peatlands and wetlands – has an important immediate climate benefit, as it avoids releasing the carbon they store.

What our research makes clear is that it’s dangerous to rely on restoring nature to meet our climate targets, rather than effectively and drastically phasing out fossil fuels. We see this reliance in, for instance, carbon offset schemes.

Retaining the possibility of limiting warming to 1.5℃ requires rapid reductions in fossil fuel emissions before 2030 and global net-zero emissions by 2050, with some studies even calling for 2040.

Wealthy nations, such as Australia, should achieve net-zero CO₂ emissions earlier than the global average based on their higher historical emissions.

We now need new international cooperation and agreements to stop expansion of fossil fuels globally and for governments to strengthen their national climate pledges under the Paris Agreements ratcheting mechanism. Promises of carbon dioxide removals via land cannot justify delays in these necessary actions.![]()

Kate Dooley, Research Fellow, Climate & Energy College, The University of Melbourne and Zebedee Nicholls, PhD Researcher at the Climate & Energy College, The University of Melbourne