Inbox and environment news:Issue 547

July 24 - 30, 2022: Issue 547

Flock Of Black Cockatoos Feasting At North Narrabeen

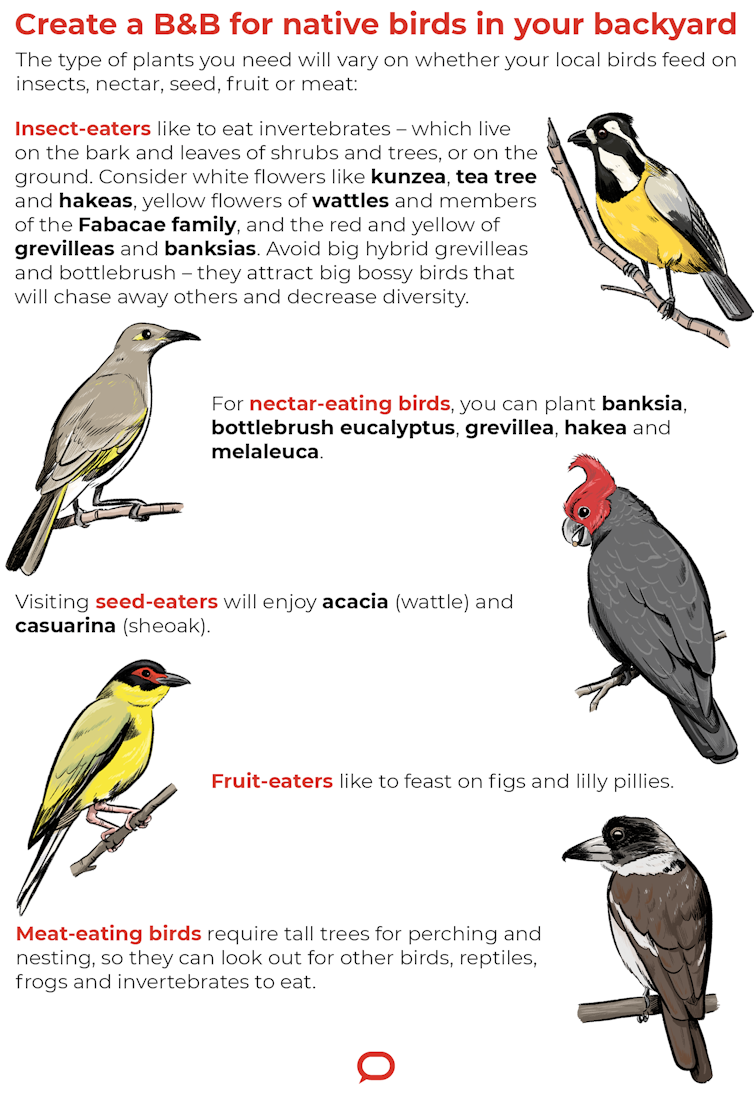

Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoos were once content to feed on the seeds of native shrubs and trees, especially banksias, hakeas and casuarinas, as well as extracting the insect larvae that bore into the branches of wattles. Now, after the establishment of extensive plantations of exotic Monterey Pines, the cockatoos may feed more often by tearing open pine cones to extract the seeds. The population on South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula is now reliant on the seeds of the Aleppo Pine, a noxious weed, as its preferred habitat, Sugar Gum woodlands, has become extensively fragmented.Research featured in the 'State of Australia's Birds 2015' headline and regional reports indicates a significant decline for the Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo (and some other parrot species) in the East Coast.

National Tree Day 2022: July 31

Seabirds Being Blown Off Course

Wildlife Car Rescue Kits Now Available

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Stop It And Swap It This Plastic Free July

To mark the beginning of Plastic Free July, the NSW Government is partnering with 17 organisations to help communities around the state stop using single-use plastic.

To mark the beginning of Plastic Free July, the NSW Government is partnering with 17 organisations to help communities around the state stop using single-use plastic.- Girl Guides NSW

- Green Connect

- Green Music Australia

- KU Children's Services

- Meals on Wheels NSW

- Men’s Shed Association

- NSW Environment & Zoo Education Centres

- OzGreen

- Plastic Free July

- Southern Cross University

- Surfing NSW

- TAFE NSW/Addison Road Community Organisation

- Take 3

- The Great Plastic Rescue

- University of New England

- University of Newcastle

- University of Wollongong

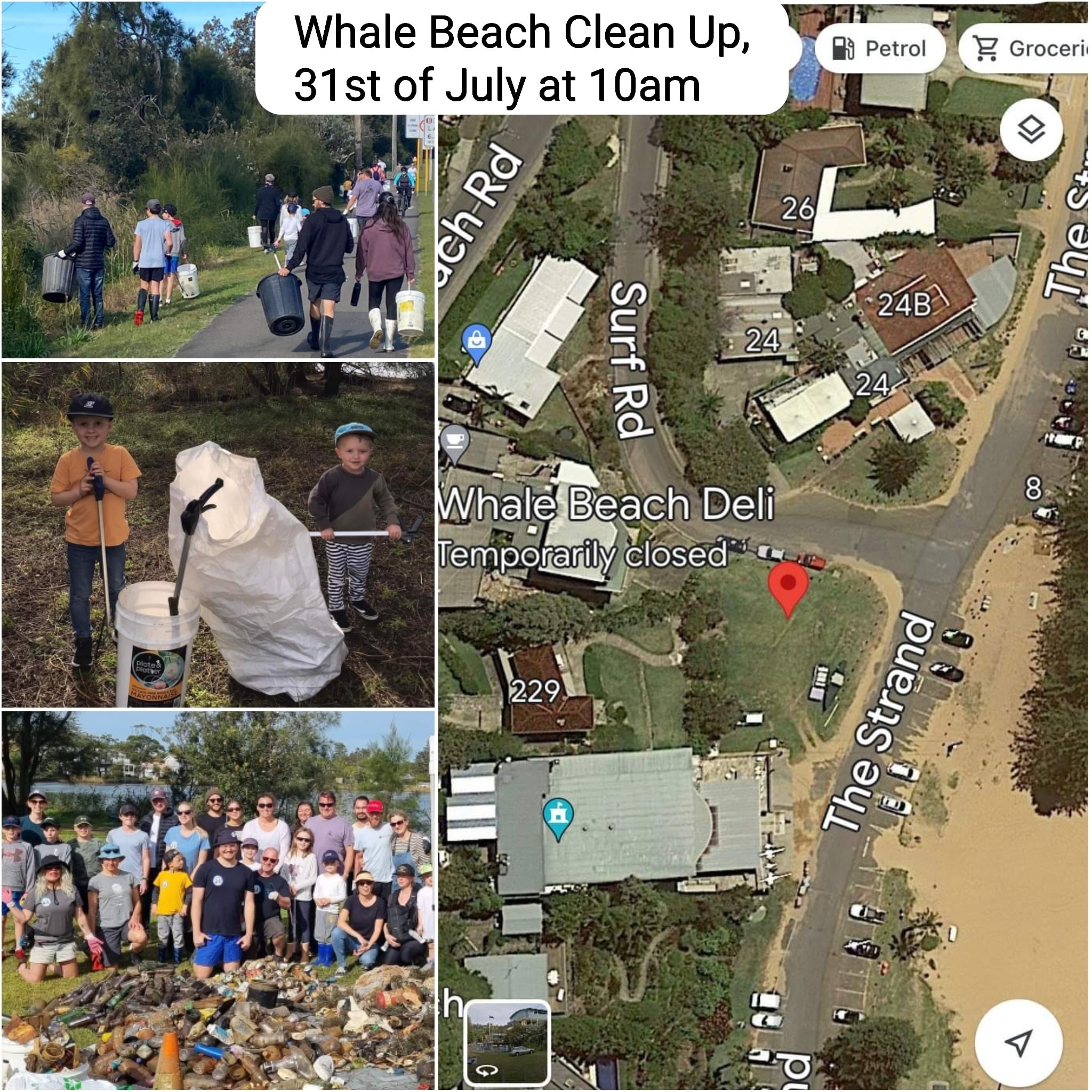

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Whale Beach - Sunday July 31st

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Pelicans Heading To The Coast Now: Winter Migrations

Barrenjoey Lighthouse Tours

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

National Press Club Address: Minister For The Environment And Water Tanya Plibersek

‘The EPBC Act is outdated and requires fundamental reform’.‘The EPBC Act is ineffective. It does not enable the Commonwealth to effectively protect environmental matters that are important for the nation. It is not fit to address current or future environmental challenges.‘The resounding message that I heard through the Review is that Australians do not trust that the Act is delivering for the environment, for business or for the community’.

This is Australia’s most important report on the environment’s deteriorating health: We present its grim findings

Climate change is exacerbating pressures on every Australian ecosystem and Australia now has more foreign plant species than native, according to the highly anticipated State of the Environment Report released today.

The report also found the number of listed threatened species rose 8% since 2016 and more extinctions are expected in the next decades.

The document represents thousands of hours of work over two years by more than 30 experts. It’s a sobering read, but there are some bright spots.

Australia has produced a national state of environment report every five years since 1995. They assess every aspect of Australia’s environment and heritage, covering rivers, oceans, air, ice, land and urban areas. The last report was released in 2017.

This report goes further than its predecessors, by describing how our environment is affecting the health and well-being of Australians. It is also the first to include Indigenous co-authors.

As chief authors of the report, we present its key findings here. They include new chapters dedicated to extreme events and Indigenous voices.

1. Australia’s Environment Is Generally Deteriorating

There have been continued declines in the amount and condition of our natural capital – native vegetation, soil, wetlands, reefs, rivers and biodiversity. Such resources benefit Australians by providing food, clean water, cultural connections and more.

The number of plant and animal species listed as threatened in June 2021 was 1,918, up from 1,774 in 2016. Gang-gang cockatoos and the Woorrentinta (northern hopping-mouse) are among those recently listed as endangered.

Australia’s coasts are also under threat from, for instance, extreme weather events and land-based invasive species.

Our nearshore reefs are in overall poor condition due to poor water quality, invasive species and marine heatwaves. Inland water systems, including in the Murray Darling Basin, are under increasing pressure.

Nationally, land clearing remains high. Extensive areas were cleared in Queensland and New South Wales over the last five years. Clearing native vegetation is a major cause of habitat loss and fragmentation, and has been implicated in the national listing of most Australia’s threatened species.

2. Climate Change Threatens Every Ecosystem

Climate change is compounding ongoing and past damage from land clearing, invasive species, pollution and urban expansion.

The intensity and frequency of extreme weather events are changing. Over the last five years, extreme events such as floods, droughts, wildfires, storms, and heatwaves have affected every part of Australia.

Seasonal fire periods are becoming longer. In NSW, for example, the bushfire season now extends to almost eight months. Extreme events are also affecting ecosystems in ways never before documented.

For example, the downstream effects of the 2019-2020 bushfires introduced a range of contaminants to coastal estuaries, in the first global record of bushfires impacting estuarine habitat quality.

3. Indigenous Knowledge And Management Are Helping Deliver On-Ground Change

This includes traditional fire management, which is being recognised as vital knowledge by land management organisations and government departments.

For example, Indigenous rangers manage 44% of the national protected area estate, and more than 2,000 rangers are funded under the federal government’s Indigenous rangers program.

Work must still be done to empower Indigenous communities and enable Indigenous knowledge systems to improve environmental and social outcomes.

4. Environmental Management Isn’t Well Coordinated

Australia’s investment is not proportional to the grave environmental challenge. The area of land and sea under some form of conservation protection has increased, but the overall level of protection is declining within reserves.

We’re reducing the quantity and quality of native habitat outside protected areas through, for instance, urban expansion on land and over-harvesting in the sea.

The five urban areas with the most significant forest and woodland habitat loss were Brisbane, Gold Coast to Tweed Heads, Townsville, Sunshine Coast and Sydney. Between 2000 and 2017, at least 20,212 hectares were destroyed in these five areas combined, with 12,923 hectares destroyed in Queensland alone.

Australia is also increasingly relying on costly ways to conserve biodiversity. This includes restoration of habitat, reintroducing threatened species, translocation (moving a species from a threatened habitat to a safer one), and ex situ conservation (protecting species in a zoo, botanical garden or by preserving genetic material).

5. Environmental Decline And Destruction Is Harming Our Well-Being

In this report we document the direct effects of environmental damage on human health, for example from bushfire smoke.

The indirect benefits of a healthy environment to mental health and well-being are harder to quantify. But emerging evidence suggests people who manage their environment according to their values and culture have improved well-being, such as for Indigenous rangers and communities.

Environmental destruction also costs our economy billions of dollars, with climate change and biodiversity loss representing both national and global financial risks.

Climate Change Is Hitting Ecosystems Hard

Previous reports mostly spoke of climate change impacts as happening in future. In this report, we document significant climate harms already evident from the tropics to the poles.

As Australia’s east coast emerges from another “unusual” flood, this report introduces a new chapter dedicated to extreme events. Many have been made more intense, widespread and likely due to climate change.

We document the national impacts of extreme floods, droughts, heatwaves, storms and wildfires over the past five years. And while we’ve reported on immediate impacts – millions of animals killed and habitats burnt, enormous areas of reef bleached, and people’s livelihoods and homes lost – many longer-term effects are still to play out.

Extreme conditions put immense stress on species already threatened by habitat loss and invasive species. We expect more species extinctions over the next decades.

An extreme heatwave in 2018, for example, killed some 23,000 spectacled flying foxes. In 2019, the species was uplisted from vulnerable to endangered.

Many Australian ecosystems have evolved to rebound from extreme “natural” events such as bushfires. But the frequency, intensity, and compounding nature of recent events are greater than they’ve experienced throughout their recent evolutionary history.

For example, marine heatwaves caused mass coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016, 2017, 2020 and 2022. Such frequent disturbances leave little time for recovery.

Indeed, ecological theory suggests frequently disturbed ecosystems will shift to a “weedy” state, where only the species that live fast and reproduce quickly will thrive.

This trend will bring profound shifts in ecosystem structure and function. It also means we’ll have to shift how we manage and rely on ecosystems – including how we harvest, hunt and otherwise benefit from them.

Including Indigenous Voices

Indigenous people of Australia have cared for the lands and seas over countless generations and continue to do so today.

In Australia, a complex web of government laws and agreements relate to Indigenous people and the environment. Overall, they are not adequate to deliver the rights Indigenous people seek: responsibility for and stewardship of their Country including lands and seas, plants and animals, and heritage.

For the first time, this report has a separate Indigenous chapter, informed by Indigenous consultation meetings, which highlights the importance of caring for Country.

Including an Indigenous voice has required us to change the previous approach of reporting on the environment separately from people. Instead, we’ve emphasised how Country is connected to people’s well-being, and the interconnectedness of environment and culture.

Failures Of Environmental Management

Australia needs better and entirely new approaches to environmental management. For example, the inclusion of climate change in environmental management and resilience strategies is increasing, but it’s not universal.

As well as climate stresses, habitat loss and degradation remain the main threats to land-based species in Australia, impacting nearly 70% of threatened species.

More than a third of Australia’s eucalypt woodlands have been extensively cleared, and the situation is worse for some other major vegetation groups.

Experts say within 20 years, another seven Australian mammals and ten Australian birds – such as the King Island brown thornbill and the orange-bellied parrot – will be extinct unless management is greatly improved.

Of the 7.7 million hectares of land habitat cleared between 2000 and 2017, 7.1 million hectares (93%) was not referred to the federal government for assessment under the national environment law.

Only 16% (13 of 84) of Australia’s nationally listed threatened ecological communities meet a 30% minimum protection standard in the national reserve system.

Three critically endangered communities, all in NSW, have no habitat protection at all. These are the Hunter Valley weeping myall woodland, the Elderslie banksia scrub forest, and Warkworth sands woodland.

The Bright Spots

The report also highlights where investments and the hard work of many Australians made a difference.

Individuals, non-government organisations and businesses are increasingly purchasing and managing significant tracts of land for conservation. The Australian Wildlife Conservancy, for example, jointly manages some 6.5 million hectares actively conserving many threatened species.

By building on achievements such as these, we can encourage new partnerships and innovations, supported with crucial funding and commitment from government and industry.

We also need more collaboration across governments and non-government sectors, underpinned by greater national leadership. This includes listening and co-developing solutions with Indigenous and local communities, building on and learning from Indigenous and Western scientific knowledge.

And we need more effort and resources to measure progress. This includes consistent monitoring and reporting across all states and territories on the pressures, and the health of our natural and cultural assets.

Such efforts are crucial if we’re to reverse declines and forge a stronger, more resilient country.

Read the full 2022 State of the Environment report here.

![]()

Emma Johnston, Professor and Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research), University of Sydney; Ian Cresswell, Adjunct professor, UNSW Sydney, and Terri Janke, Honorary Associate Professor, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘That patch of bush is gone, and so are the birds’: a scientist reacts to the State of the Environment report

Australia’s State of the Environment Report was finally released today – and its findings are a staggering picture of loss and devastation.

As a conservation scientist, I’ve spent the last decade helping governments, community groups and individuals better manage our environment. But the report reveals things are getting worse.

I’m disappointed, but not surprised. I’ve seen firsthand the devastation wrought by threats such as bushfires and land clearing.

I remain hopeful we can turn the crisis around. But it will take money, government commitment and public support to protect and recover our precious natural places.

New Year’s Day, 2020

Since the last State of the Environment Report report was released in 2016, Australia has experienced record-breaking floods and fires. In fact, my New Year’s Day of 2020 was spent frantically packing precious family items at my mum’s home in rural New South Wales, as smoke from nearby megafires blanketed our property.

We evacuated, nervously watching a fire tracking app, while neighbours’ properties were progressively swallowed by a fire that eventually burned for 74 days, razing half a million hectares.

Thankfully, the fire stopped at a creek down the road. This creek and its adjoining forest is where my family have spent decades hiking, birding and exploring nature.

We’ve watched rare rock warblers dabbling in streams that trickle down sheer sandstone gorges and male lyrebirds singing their hearts out. Multitudes of king parrots, yellow-tail cockatoos and gang-gang cockatoos would visit to gnaw on gum nuts and, to my mum’s eternal anguish, her prize geraniums.

After the fires, I worked with a team to document their devastating impacts on wildlife. Gang gangs lost up to one-fifth of their entire population, and are now endangered.

I can’t imagine visiting the bush without hearing their creaking call, or peering into the branches to spot their telltale flash of red through the leaves.

Australia’s Abysmal Record

As the State of Environment report explains, the 2019-2020 bushfires razed more than eight million hectares of native vegetation. Up to three billion animals were either killed or displaced.

Last year, I contributed to the first global United Nations assessment of wildfire. We found the worldwide risk of devastating fires could increase by up to 57% by the end of the century, primarily because of climate change.

Most of Australia is likely to burn even more. That’s bad news for places such as Australia’s ancient Gondwana rainforests. Historically, these have rarely, if ever, burned. Yet more than 50% was impacted in the 2019-2020 fires.

These rainforests harbour the highest concentrations of threatened species in subtropical southeast Queensland and northern NSW. To recover, they need hundreds of years without fire.

Unfortunately for Australia’s ravaged species and ecosystems, more frequent and intense fires are not the only pressures they face. Australia’s history of managing native vegetation is abysmal.

For example in 2014, almost 40 nations pledged to end natural forest loss and restore 350 million hectares of degraded landscapes and forests by 2030 – but not Australia. Meanwhile, land clearing in NSW and Queensland increased between 2010 and 2018, mostly on farmland.

My research requires driving across large swathes of eastern and central Australia. I’ve watched patches of bush across rural and urban areas thin and, in many places, completely disappear.

One patch I grew to love was home to a very friendly, very noisy family of grey-crowned babblers. It wasn’t a particularly pretty patch of bush, but it was perfectly placed for a night’s rest on the three-day drive to my field sites.

At dawn I would lie in my swag, listening to them chattering away, giving me energy for the day. Now, that patch of bush is gone, and so are the birds.

They may be small, but these patches of bushland are vital for the persistence of already heavily fragmented, degraded ecosystems.

The clearing and thinning of vegetation makes it harder for remaining plants and animals to recover from extreme events such as drought. It also puts native wildlife at greater risk from introduced predators such as cats, and aggressive native birds such as noisy miners.

Most importantly, the cumulative loss of these seemingly insignificant little patches of woodland is a death by a thousand cuts, putting many ecosystems at greater risk of extinction.

Extinctions Aren’t Inevitable

I’m writing this because, despite the dire situation, it’s not too late to do something about it. Here are three ways to start.

First, we need immediate action on climate change. All levels of government must commit to urgently transitioning away from fossil fuels.

Investments and action must be proactive: planning for, preventing and responding to environmental threats. This would help avoid massive costs incurred after a disaster hits.

And crucially, management and conservation actions must respectfully draw from Indigenous knowledge.

Second, vegetation should be restored, not removed, on private land. This requires overhauling vegetation clearing codes and taking action against those who flout the rules.

Finally, the federal government should acknowledge that a substantial increase in funding could, in fact, recover all disappearing species and ecosystems. Extinctions are a choice, not an inevitability.

Australia ranks among the world’s worst when it comes to funding biodiversity conservation. At least six times the current funding is needed to save our threatened species.

Research shows when adequate investment is made in management, threatened populations do recover. The story of the yellow-footed rock wallaby in South Australia shows what’s possible.

Intensive goat and fox control reversed the species’ population decline. It was made possible through long-term state government investment and efforts by non-government conservation organisations and land managers.

Not only did rock-wallaby populations increase, but the pest control meant the western quoll and the common brushtail possum – both historically extinct in the area – could be reintroduced.

But sadly, such success stories are the exception. Today’s report clearly shows that unless we radically change course, we’re heading towards species extinctions, degraded landscapes and a less resilient nation.

All Australians - governments, business, individuals and communities – must commit to restoring our natural environment. Only then will we withstand whatever the future throws at us.

Read the full 2022 State of the Environment report here.![]()

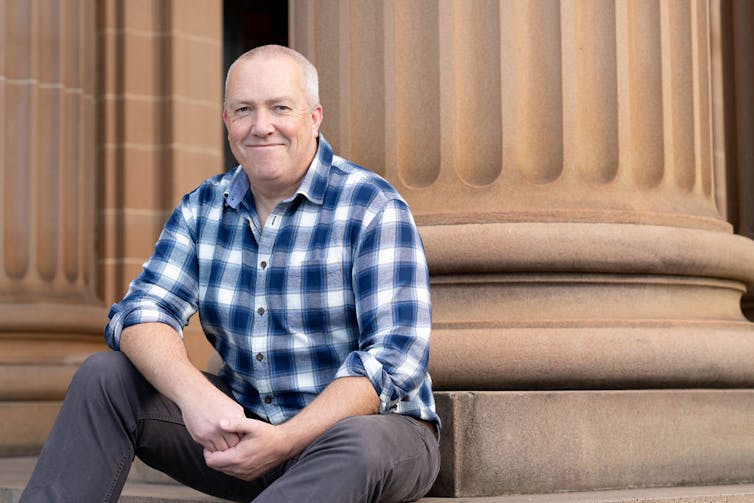

Ayesha Tulloch, ARC Future Fellow, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Yes, the state of the environment is grim, but you can make a difference, right in your own neighbourhood

The newly released State of the Environment report paints a predictably grim picture. Species are in decline, ecosystems are at breaking point, and threats abound. For many of us, it can feel like a problem that’s too big, too complex and too distant to solve.

But this report also shows every Australian can be on the conservation frontline. We can save species in the places we live and work. According to the report, Australia’s cities and towns are home to more than 96% of our population and 46% of threatened species. We have mapped the occurrence of hundreds of threatened species in urban areas.

We share our cities with iconic koalas, charming gang-gang cockatoos and floral wonders like Caley’s grevillea. And, as the report notes, some species are found only in urban areas – our cities and towns are the last chance to save them from extinction. What an incredible opportunity to reconnect Australians with our fantastic natural heritage and protect it at the same time.

Our research shows a huge appetite for saving nature in cities. Councils, industry and community groups all over the country are working to make change.

Here are five things we can think about to improve the state of our city environments.

1. Small But Mighty

Don’t have a lot of space? That’s OK! Whether it’s a small pond, garden strip or solitary gum tree, these often provide a key resource that isn’t found elsewhere in the nearby landscape. This means they pack a punch when it comes to supporting local nature.

And resources like these all add up. Researchers found that a collection of small, urban grassland reserves supported more native plants, and rarer species, than just a few large reserves.

So while making one small change might feel futile, it can make a big difference.

2. Embracing The ‘In Between’

Conservation doesn’t just happen in nature reserves, which is good, because urban areas don’t have many. Backyards are already making huge contributions through “gardens for wildlife” initiatives.

But what about the more unconventional spaces? We found city-dwelling species take advantage of roadsides, schoolyards, carpark gardens, railway stations and rooftops. These are all opportunities for us to make a little more space for nature in cities.

3. Grand Designs For Wildlife

People aren’t the only ones facing a housing crisis – wildlife struggle too. The tree hollows, rock piles and fallen wood that many species call home are often removed in favour of sleek lines and tidy urban spaces.

You can provide valuable real estate for local critters by adding nesting boxes, bee hotels and lizard lounges. And simply leaving a designated “messy patch” in your garden improves the local habitat too.

4. Creative Connections

Moving safely through cities can be risky for wildlife. They have to navigate cars, fences, roaming pets and swathes of concrete.

Many councils and road agencies are looking at creative ways to help wildlife get from A to B. Solutions range from rope bridges for western Sydney’s sugar gliders and tunnels for Melbourne’s bandicoots to forested bridges for Brisbane’s bush birds. Some gardeners in Bunbury even built their own backyard “possum bridges” to help the endangered western ringtail possum in their neighbourhoods.

5. People Power

Having threatened species live close to people is typically seen as bit of “negative’” in the conservation world. But this closeness can be an advantage if the community is aware and engaged.

Orchids like the sunshine diuris and Frankston spider orchid would surely be extinct if not for countless hours of volunteer work, crowd-funding and the passion of the local community.

Get involved through your local council or “Friends of” groups to see how you can support nature in your neck of the woods.

Urban Habitats – Often Small And Scrappy, Always Valuable

There are so many wonderful ways to support nature in cities. Recent examples include conservation goats saving native skinks, floating habitat rafts in city waterways and using flowerpots on concrete sea walls to support marine life. New ideas are being explored and tested all over the country.

Some of the best examples bring all these ideas together. For example, Melbourne’s Pollinator Corridor, led by the Heart Gardening Project, helps individual community members convert their own small urban patch into a bee-friendly garden. When complete, 200 individual gardens will create an 8km pollinator paradise between two of the city’s largest parks.

Right now, efforts to save nature in cities are driven by champions – individuals in our communities, local councils or industry who see an opportunity to make a difference, no matter how small, and fight to make it happen. Imagine what we could achieve if more of us pitched in.

So, look around. Can you add just one small patch? Contact your local council about turning a neglected roadside strip into a pollinator paradise? Or maybe set up a little B&B for wildlife in your backyard? ![]()

Kylie Soanes, Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Existential threat to our survival’: see the 19 Australian ecosystems already collapsing

In 1992, 1,700 scientists warned that human beings and the natural world were “on a collision course”. Seventeen years later, scientists described planetary boundaries within which humans and other life could have a “safe space to operate”. These are environmental thresholds, such as the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and changes in land use.

Crossing such boundaries was considered a risk that would cause environmental changes so profound, they genuinely posed an existential threat to humanity.

This grave reality is what our major research paper, published today, confronts.

In what may be the most comprehensive evaluation of the environmental state of play in Australia, we show major and iconic ecosystems are collapsing across the continent and into Antarctica. These systems sustain life, and evidence of their demise shows we’re exceeding planetary boundaries.

We found 19 Australian ecosystems met our criteria to be classified as “collapsing”. This includes the arid interior, savannas and mangroves of northern Australia, the Great Barrier Reef, Shark Bay, southern Australia’s kelp and alpine ash forests, tundra on Macquarie Island, and moss beds in Antarctica.

We define collapse as the state where ecosystems have changed in a substantial, negative way from their original state – such as species or habitat loss, or reduced vegetation or coral cover – and are unlikely to recover.

The Good And Bad News

Ecosystems consist of living and non-living components, and their interactions. They work like a super-complex engine: when some components are removed or stop working, knock-on consequences can lead to system failure.

Our study is based on measured data and observations, not modelling or predictions for the future. Encouragingly, not all ecosystems we examined have collapsed across their entire range. We still have, for instance, some intact reefs on the Great Barrier Reef, especially in deeper waters. And northern Australia has some of the most intact and least-modified stretches of savanna woodlands on Earth.

Still, collapses are happening, including in regions critical for growing food. This includes the Murray-Darling Basin, which covers around 14% of Australia’s landmass. Its rivers and other freshwater systems support more than 30% of Australia’s food production.

The effects of floods, fires, heatwaves and storms do not stop at farm gates; they’re felt equally in agricultural areas and natural ecosystems. We shouldn’t forget how towns ran out of drinking water during the recent drought.

Drinking water is also at risk when ecosystems collapse in our water catchments. In Victoria, for example, the degradation of giant Mountain Ash forests greatly reduces the amount of water flowing through the Thompson catchment, threatening nearly five million people’s drinking water in Melbourne.

This is a dire wake-up call — not just a warning. Put bluntly, current changes across the continent, and their potential outcomes, pose an existential threat to our survival, and other life we share environments with.

In investigating patterns of collapse, we found most ecosystems experience multiple, concurrent pressures from both global climate change and regional human impacts (such as land clearing). Pressures are often additive and extreme.

Take the last 11 years in Western Australia as an example.

In the summer of 2010 and 2011, a heatwave spanning more than 300,000 square kilometres ravaged both marine and land ecosystems. The extreme heat devastated forests and woodlands, kelp forests, seagrass meadows and coral reefs. This catastrophe was followed by two cyclones.

A record-breaking, marine heatwave in late 2019 dealt a further blow. And another marine heatwave is predicted for this April.

These 19 Ecosystems Are Collapsing: Read About Each

What To Do About It?

Our brains trust comprises 38 experts from 21 universities, CSIRO and the federal Department of Agriculture Water and Environment. Beyond quantifying and reporting more doom and gloom, we asked the question: what can be done?

We devised a simple but tractable scheme called the 3As:

Awareness of what is important

Anticipation of what is coming down the line

Action to stop the pressures or deal with impacts.

In our paper, we identify positive actions to help protect or restore ecosystems. Many are already happening. In some cases, ecosystems might be better left to recover by themselves, such as coral after a cyclone.

In other cases, active human intervention will be required – for example, placing artificial nesting boxes for Carnaby’s black cockatoos in areas where old trees have been removed.

“Future-ready” actions are also vital. This includes reinstating cultural burning practices, which have multiple values and benefits for Aboriginal communities and can help minimise the risk and strength of bushfires.

It might also include replanting banks along the Murray River with species better suited to warmer conditions.

Some actions may be small and localised, but have substantial positive benefits.

For example, billions of migrating Bogong moths, the main summer food for critically endangered mountain pygmy possums, have not arrived in their typical numbers in Australian alpine regions in recent years. This was further exacerbated by the 2019-20 fires. Brilliantly, Zoos Victoria anticipated this pressure and developed supplementary food — Bogong bikkies.

Other more challenging, global or large-scale actions must address the root cause of environmental threats, such as human population growth and per-capita consumption of environmental resources.

We must rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero, remove or suppress invasive species such as feral cats and buffel grass, and stop widespread land clearing and other forms of habitat destruction.

Our Lives Depend On It

The multiple ecosystem collapses we have documented in Australia are a harbinger for environments globally.

The simplicity of the 3As is to show people can do something positive, either at the local level of a landcare group, or at the level of government departments and conservation agencies.

Our lives and those of our children, as well as our economies, societies and cultures, depend on it.

We simply cannot afford any further delay. ![]()

Dana M Bergstrom, Principal Research Scientist, University of Wollongong; Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University; Lesley Hughes, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, and Michael Depledge, Professor and Chair, Environment and Human Health, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Natural systems in Australia are unravelling. If they collapse, human society could too

In the long-delayed State of the Environment report released this week, there is one terrifying sentence: “Environmental degradation is now considered a threat to humanity, which could bring about societal collapses.”

Hyperbole? Sadly not.

Climate change has already warmed Australia 1.4℃ and changed rainfall in some regions. Natural ecosystems are already struggling from land clearing, intensive agriculture, soil degradation and poor water management. Climate changes and related sea level rise are making this worse. It’s a mistake to think this won’t affect us.

It can be easy to live in cities and believe you’re somehow walled off from environmental disaster. This is a fiction. Healthy environments provide clean air, clean food, clean water and a safe place to live – all essential to a healthy life.

Our lives will not be easy if we continue eating away at the ecosystems that prop us up. It is no exaggeration to say societal collapse is a possible outcome.

Why Is The News So Bad?

Every day, we rely on services provided by healthy ecosystems.

The long-delayed report shows the sobering consequences of wilful disregard for environmental protection and focusing on natural resource exploitation. Burning fossil fuels causes climate change and ocean acidification. Land clearing destroys existing ecosystems. Intensive agriculture reduces biodiversity.

Australia’s fragile ecosystems are acutely vulnerable to decades of environmental disregard. Swathes of the continent are increasingly flipping from extreme drought and devastating fires to unprecedented floods under highly variable rainfall patterns. In the last few years, unprecedented bushfires and floods have forced thousands out of their homes. This worsens housing shortages, income insecurity and human health.

Our land temperatures have increased by 1.44°C since 1910. Very high monthly maximum temperatures have increased sixfold over the 60-year period since 1960. These effects have come from a 1.1℃ rise globally. We’re still on track for 3℃. This is highly problematic as humans have limited capacity to withstand heat exposure, and ecosystems suffer in the heat.

4 Things A Well-Functioning Environment Does For Us

1. Clean food

Food systems require intact ecosystems to remain productive, without which crop yields and rural incomes drop. Hunger can ensue. The consequences of food shortages to date in Australia have been small compared with other countries. But with repeated intense droughts, heatwaves, fires and floods these shortages could rapidly escalate. In 2008, we saw riots and social upheaval across multiple continents. A key cause was the global food crisis. This year, food prices have skyrocketed again in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

2. Clean air

Australia has traditionally had some of the cleanest air in the world. But smoke from the megafires over the Black Summer of 2019–2020 caused 417 deaths, as well as thousands of hospital admissions. Health costs were estimated at almost $A2 billion. People lost days at work and at school, and some will have ongoing health problems. Climate change is predicted to steadily worsen our bushfires.

3. Adequate clean water

Water is essential for human life, health and activity, and the healthy functioning of ecosystems. As the driest inhabited continent, Australia’s water is one of our most valuable resources. Unfortunately, it is often poorly managed. Many Indigenous communities do not have clean, healthy drinking water, while dozens of non-Indigenous communities had to truck water in during the last drought.

Land clearing disrupts ecosystems, threatens biodiversity and can alter stream flow and water quality. Run-off from agriculture damages aquatic ecosystems and encourages algal blooms and species loss. Again, this isn’t just pain for the environment.

The Murray–Darling Basin is home to more than 2.2 million people and more than four million people depend on these rivers for their water. Already, the basin’s rivers and catchments are rated as poor or very poor.

4. Liveable climate

Climate change is pushing the south-west of Western Australia into a new normal of near-permanent drought. This has already massively reduced the inflows into Perth’s dams, requiring more use of groundwater and desalination. South-eastern Australia is also drying, stressing plants and animals. We’re already seeing agricultural productivity dropping. As parts of Australia dry out, it’s hard to see how drought-prone towns and regions will remain viable.

What Will Happen If We Don’t Repair The Environment?

Humans can only withstand heat up until a point. After that, exposure to extreme heat leads to damage to tissues and organs, and, eventually damage and death. The same goes for the livestock we rely on, which are at risk of serious health threats from heat. Heat hits weight gain, milk production and reproductive success.

The profitability of broadacre crops such as wheat and barley is an estimated 22% less since 2000 than it would have been if climate change wasn’t happening. In turn, this is leaving many Australians in rural and regional communities facing worsening incomes and health.

Irrigation water is less reliable, while increases in temperature reduce both quantity and quality of fruit and vegetable crops. The nutritional value of foods also declines under extreme heat.

In short, we can no longer pretend we live in a world walled off from nature. Damaging nature damages humans. Think of the cartoon trope where a character cuts off the tree branch they’re sitting on.

We have created these problems collectively. To avoid social upheaval, we have to repair the damage – together.

The federal government’s newly announced Environmental Protection Agency is a good start. It must be adequately resourced and have powers to enforce compliance.

Beyond that, we urgently need coordinated policies, sound supporting science and effective data systems, prioritised actions, commitment and investment and community support. ![]()

Liz Hanna, Honorary Associate Professor, Australian National University and Mark Howden, Director, ANU Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Bad and getting worse’: Labor promises law reform for Australia’s environment. Here’s what you need to know

Laura Schuijers, University of Sydney and Thomas Newsome, University of SydneyFederal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek acknowledges “it’s time to change” after the State of the Environment report revealed a bleak picture of Australia’s natural places.

In a speech on Tuesday, Plibersek foreshadowed a suite of reforms to Australia’s environment policies, including new legislation to go before parliament next year. Plibersek told reporters:

Australia’s environment is bad and getting worse, as this report shows, and much of the destruction outlined in the State of the Environment Report will take years to turn around. Nevertheless, I am optimistic about the steps that we can take over the next three years.

The changes will be informed by the government’s response to Professor Graeme Samuel’s independent review of federal environment law. That review found the law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act, has failed to safeguard Australia’s vulnerable plants, animals, and ecological communities.

Having been in the minister’s chair for only six weeks, Plibersek was hesitant to outline major policy initiatives and said the government would consult widely before making changes. She says overhauling Australia’s environmental protections will be “challenging” and public views on the right policy response will differ wildly.

Our collective expertise spans environmental law and ecosystem processes. Here, we consider whether today’s announcements go far enough to restore and protect Australia’s precious natural assets.

What’s Been Promised?

Plibersek’s speech contained a couple of new announcements, and a reiteration of previous policy pledges. As well as committing to a response to the Samuel review by the end of the year, these include:

setting clear environmental standards with explicit targets

fundamental reform of national environmental laws and a new national level Environmental Protection Agency to enforce them

expanding Australia’s national estate to protect 30% of land and 30% of oceans by 2030

producing better and more shareable environmental data to better track progress and decline

including environmental indicators in the government’s new “wellbeing budget”

supporting investment into blue carbon projects, such as restoring mangroves and seagrasses

doubling the number of Indigenous rangers to 3,800 this decade and increasing funding for Indigenous protected areas.

enshrining a higher national emissions reduction target into law.

These important changes are likely to lead to environmental gains. But the key will be ensuring progress is independently monitored, and that new laws and targets can be amended as needed.

Changes Urgently Needed

The commitment to expand Australia’s national estate may be comforting, but it misses crucial context. As the report notes, the overall level of protection within reserves has fallen.

In fact, in some of our most prized protected areas, threatened species are declining. These include northern quolls, northern brown bandicoots and pale field-rats in Kakadu National Park.

Researchers estimated in 2019 that we spend only 15% of what’s needed to avoid extinctions and recover threatened species. Expanding protected areas means little unless accompanied by adequate funding for species recovery.

The report also recognises invasive species as one of the biggest threats to native biodiversity. In particular, feral and domestic cats have played a leading role in most of Australia’s mammal extinctions since colonisation.

Controlling invasive species such as feral cats will be difficult without developing new management strategies that can be applied at scale. This will require more investment in research and adequate resources to trial, test and monitor approaches.

Rates of land clearing also continue to soar, as Plibersek noted. But we’re yet to see details of how the federal government plans to address this crucial issue.

Nonetheless, Plibersek spoke optimistically about cooperating with state and territory governments, who are primarily responsible for forests in their jurisdictions.

The next five-yearly review of the Regional Forest Agreements – made between federal and state governments – offer an important opportunity. These agreements broadly exempt logging operations from federal environmental law.

Cooperating with the states will be important in addressing the environmental challenges posed by, for instance, native forest logging in Victoria, which has contributed to the greater glider being recently listed as endangered.

New Environmental Law For 2023

Plibersek noted the importance of climate change as a cumulative threat to the pressures already affecting the environment.

While she reinforced her election promise to legislate emissions cuts, she skirted around how climate change’s harms to biodiversity could be incorporated into environmental law. A fundamental issue with the EPBC Act is that there’s no explicit mention of climate change.

This could be a problem if federal support continues to be given to new projects that could also undermine emissions targets. For example, the federal government recently approved Western Australia’s Scarborough-Pluto gas project. It is set to be one of Australia’s most emissions-intensive developments.

Another crucial problem with the EPBC Act, as Professor Graeme Samuel recognised is his review, is that it operates in a piecemeal way.

Instead of protecting the environment holistically, it’s triggered when individual projects are likely to affect specific aspects of the environment, such as a threatened species.

When triggered, the act requires an assessment of a project’s potential impact, but doesn’t require any specific measurable outcomes once the project has gone ahead.

It also focuses on lists of species and places, rather than the interactions within and between environmental systems. It will be impossible for the new government to adequately respond to the Samuel review without acknowledging this major flaw.

The proposal to introduce national environment standards next year will make a positive difference. It needs to operate not as a vague reference point, but as a ceiling.

We Can’t Afford To Fail

Continuing to ignore the damning evidence revealed in the report today will worsen Australia’s biodiversity crisis. Not only will further losses lead to more extinctions, they will also compromise our ecosystems’ ability to support us.

Biodiversity loss has been heralded as one of the top threats to the global economy, ranking third behind climate change and extreme weather events.

Australia’s extinction track record is among the world’s worst. Failing to make the necessary legal and policy reforms could not only represent a missed opportunity to restore past losses, but also lock in further decline for decades.

The report shows the best time to take action has passed. The second best time is now.![]()

Laura Schuijers, Deputy Director, Australian Centre for Climate and Environmental Law and Lecturer in Law, University of Sydney and Thomas Newsome, Academic Fellow, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

CSIRO: State Of The Environment 2021 Report

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Inaugural Gotcha4Life Cup 2022: July 28

Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Confectioner

Confectionery Makers operate machines and perform routine tasks to make and wrap confectionery. Confectioners mix, shape and cook sweeteners and other ingredients to produce confectionery, including chocolate, toffee and other lollies.

To become a confectioner you usually have to complete a traineeship. Entry requirements may vary, but employers generally require Year 10 and a certificate II or III in food processing will be useful.

Duties & Tasks of a Confectioner

Confectioners:

- Examine production schedules to determine confectionery types and quantities to be made

- Check the cleanliness and operation of equipment before beginning production

- Weigh, measure, mix, dissolve and boil ingredients in pans

- Operate equipment that refines and tempers chocolate

- Assist with coating chocolate bars and preparing chocolate products

- Control temperature and pressure in cookers used to make boiled sweets, starch-moulded products, caramels, toffees, nougat and chocolate centres

- Operate equipment to compress sugar mixes into sweets

- Check batch consistency using a stainless steel spatula or measuring equipment such as a refractometer

- Sort and inspect finished or partly finished products.

Tasks

- Weighs, measures, mixes, dissolves and boils ingredients..

- Moves products from production lines into storage and shipping areas..

- Operates machines to process food product..

- Monitors product quality before packaging by inspecting, taking samples and adjusting treatment conditions when necessary.

- Packages products.

- Operates heating, chilling, and similar equipment..

- Cleans equipment, pumps, hoses, storage tanks, vessels and floors, and maintains infestation control programmes..

- Adds materials, such as spices and preservatives, to food.

Working conditions for a Confectioner

Most confectioners work full time. Senior confectioners provide on-the-job training to junior employees and coordinate work in a team environment.

Employment Opportunities for a Confectioner

Most confectioners are employed by confectionery manufacturers and work in factories. With more experience, confectioners can be involved in developing confectionery items with new textures, colours and flavours. With experience, and sometimes further training, it is possible to progress to leading hand, supervisory or management positions.

Candy, also called sweets (British English) or lollies (Australian English, New Zealand English), is a confection that features sugar as a principal ingredient. The category, called sugar confectionery, encompasses any sweet confection, including chocolate, chewing gum, and sugar candy. Vegetables, fruit, or nuts which have been glazed and coated with sugar are said to be candied.

Physically, candy is characterized by the use of a significant amount of sugar or sugar substitutes. Unlike a cake or loaf of bread that would be shared among many people, candies are usually made in smaller pieces. However, the definition of candy also depends upon how people treat the food. Unlike sweet pastries served for a dessert course at the end of a meal, candies are normally eaten casually, often with the fingers, as a snack between meals. Each culture has its own ideas of what constitutes candy rather than dessert. The same food may be a candy in one culture and a dessert in another.

The word candy entered the English language from the Old French çucre candi ("sugar candy"). The French term could have earlier word roots in the Arabic qandi, Persian qand and Sanskrit khanda, all words for sugar.

Candy at a souq in Damascus, Syria. Photo: Elisa Azzali

Sugarcane is indigenous to tropical South and Southeast Asia. Pieces of sugar were produced by boiling sugarcane juice in ancient India and consumed as khanda.] Between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, the Persians, followed by the Greeks, discovered the people in India and their "reeds that produce honey without bees". They adopted and then spread sugar and sugarcane agriculture.

Before sugar was readily available, candy was based on honey. Honey was used in Ancient China, the Middle East, Egypt, Greece and the Roman Empire to coat fruits and flowers to preserve them or to create forms of candy. Candy is still served in this form today, though now it is more typically seen as a type of garnish.

Chocolatier

A chocolatier can be defined as someone who makes and sells confectionery made from chocolate. They may be responsible for the whole process from start to finish, from devising a recipe, through to making the product, and finally packaging, displaying and selling. They may be salaried or self-employed and can become a Master Chocolatier once they have acquired the relevant skills and experience. They may work in a specialist chocolate shop, whether artisanal, independent or part of a worldwide group, or indeed as part of a professional kitchen or at the production facilities of a chocolate manufacturer.

Chocolate is a food product made from roasted and ground cacao seed kernels, that is available as a liquid, solid or paste, on its own or as a flavoring agent in other foods. Cacao has been consumed in some form since at least the Olmec civilization (19th-11th century BCE), and the majority of Mesoamerican people ─ including the Maya and Aztecs ─ made chocolate beverages.

The seeds of the cacao tree have an intense bitter taste and must be fermented to develop the flavour. After fermentation, the seeds are dried, cleaned, and roasted. The shell is removed to produce cocoa nibs, which are then ground to cocoa mass, unadulterated chocolate in rough form. Once the cocoa mass is liquefied by heating, it is called chocolate liquor. The liquor may also be cooled and processed into its two components: cocoa solids and cocoa butter. Baking chocolate, also called bitter chocolate, contains cocoa solids and cocoa butter in varying proportions, without any added sugar. Powdered baking cocoa, which contains more fiber than cocoa butter, can be processed with alkali to produce dutch cocoa. Much of the chocolate consumed today is in the form of sweet chocolate, a combination of cocoa solids, cocoa butter or added vegetable oils, and sugar. Milk chocolate is sweet chocolate that additionally contains milk powder or condensed milk. White chocolate contains cocoa butter, sugar, and milk, but no cocoa solids.

Chocolate is one of the most popular food types and flavours in the world, and many foodstuffs involving chocolate exist, particularly desserts, including cakes, pudding, mousse, chocolate brownies, and chocolate chip cookies. Many candies are filled with or coated with sweetened chocolate. Chocolate bars, either made of solid chocolate or other ingredients coated in chocolate, are eaten as snacks. Gifts of chocolate moulded into different shapes (such as eggs, hearts, coins) are traditional on certain Western holidays, including Christmas, Easter, Valentine's Day, and Hanukkah. Chocolate is also used in cold and hot beverages, such as chocolate milk and hot chocolate, and in some alcoholic drinks, such as crème de cacao.

In 2019 we ran a page about some of the earlier chocolate makers in Australia - you can find that in Old Australian Chocolates Back On The Market: The Cherry Ripe Song. You can also read about the History of Darrell Lea sweets, lollies, liquorice and chocolate on their website at: https://dlea.com.au/our-story/ while the Cadbury factory, in Tasmania, was opened in 1922.

Some of the earliest Confectioners of local lollies were at Manly.

Until the 16th century, no European had ever heard of the popular drink from the Central American peoples. Christopher Columbus and his son Ferdinand encountered the cocoa bean on Columbus's fourth mission to the Americas on 15 August 1502, when he and his crew stole a large native canoe that proved to contain cocoa beans among other goods for trade.

Fry's produced the first chocolate in solid state in 1847, which was then mass-produced as Fry's Chocolate Cream in 1866.

J. S. Fry & Sons, Ltd. better known as Fry's, was a British chocolate company owned by Joseph Storrs Fry and his family. Beginning in Bristol in the 18th century, the business went through several changes of name and ownership, becoming J. S. Fry & Sons in 1822. In 1847, Fry's produced the first solid chocolate bar. The company also created the first filled chocolate sweet, Cream Sticks, in 1853. Fry is most famous for Fry's Chocolate Cream, the first mass-produced chocolate bar, which was launched in 1866, and Fry's Turkish Delight, launched in 1914.

Fry, alongside Cadbury and Rowntree's, was one of the big three British confectionery manufacturers throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and all three companies were founded by Quakers. The company became a division of Cadbury in the early twentieth century.

Confectioner as a job information courtesy The Good Universities Guide, Australia.

Northern Beaches Youth Theatre At Warriewood: Christmas Play

Calling all 12-17 year olds!

Register now to be a part of our hilarious, fun and enchanting modern take on the old Dickens tale of the ghosts of Christmas past, present and future taking an old scrooge on a heartfelt awakening and the resulting realisation of all that makes a person good and wise. Mark Landon Smith's "Christmas Carol High School" is a play (not musical) with a modern take on the timeless classic. It uses a present day setting and a cast of cool, modern characters with throwbacks to old favourites for family-oriented fun.

We welcome any 12-17YO with the slightest, niggling interest in theatre to come along and have a go. There are many parts up for grabs and it's a great opportunity to give theatre a go if you're new, or put something on your resume if you're already honed and experienced. All while being part of an open, inclusive and warm community.

Rehearsals weekly Fridays 430-630pm

Show dates last week of November and first week of December with some extra rehearsals closer to show dates.

Sign up using the form (or bio link): https://form.jotform.com/221797029650865

Find out more at: https://www.facebook.com/NorthernBeachesYouthTheatre

Art Competition To Remember Our ANZACS

Word Of The Week: Sail

noun

1. a piece of material extended on a mast to catch the wind and propel a boat or ship or other vessel; "all the sails were unfurled". 2. a wind-catching apparatus attached to the arm of a windmill.

verb

1. travel in a boat with sails, especially as a sport or recreation. 2. move smoothly and rapidly or in a stately or confident manner.

From: Old English segel (noun), Old English segl "sail, veil, curtain," from Proto-Germanic *seglom (source also of Old Saxon, Swedish segel, Old Norse segl, Old Frisian seil, Dutch zeil, Old High German segal, German Segel), of obscure origin with no known cognates outside Germanic (Irish seol, Welsh hwyl "sail" are Germanic loan-words). In some sources (Klein, OED) referred to PIE root *sek- "to cut," as if meaning "a cut piece of cloth."

Old English segilan (verb) "travel on water in a ship by the action of wind upon sails; equip with a sail," from the same Germanic source as sail (n.); cognate with Old Norse sigla, Middle Dutch seghelen, Dutch zeilen, Middle Low German segelen, German segeln. Later extended to travel over water by steam power or other mechanical agency. The meaning "to set out on a sea voyage, leave port" is from c. 1200. Extended sense of "float through the air; move forward impressively" is by late 14c., as is the sense of "sail over or upon."

Christopher Cross: Sailing (1980)

Most Soothing Sir David Attenborough Moments

By BBC Earth: July 2022

Meeting the world's smallest lemur, watching the miracle of chicks hatching and describing his love for fossils: here are 26 minutes of some of the most soothing Sir David Attenborough moments.

Even if TikTok and other apps are collecting your data, what are the actual consequences?

By now, most of us are aware social media companies collect vast amounts of our information. By doing this, they can target us with ads and monetise our attention. The latest chapter in the data-privacy debate concerns one of the world’s most popular apps among young people – TikTok.

Yet anecdotally it seems the potential risks aren’t really something young people care about. Some were interviewed by The Project this week regarding the risk of their TikTok data being accessed from China.

They said it wouldn’t stop them using the app. “Everyone at the moment has access to everything,” one person said. Another said they didn’t “have much to hide from the Chinese government”.

Are these fair assessments? Or should Australians actually be worried about yet another social media company taking their data?

What’s Happening With TikTok?

In a 2020 Australian parliamentary hearing on foreign interference through social media, TikTok representatives stressed: “TikTok Australia data is stored in the US and Singapore, and the security and privacy of this data are our highest priority.”

But as Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) analyst Fergus Ryan has observed, it’s not about where the data are stored, but who has access.

On June 17, BuzzFeed published a report based on 80 leaked internal TikTok meetings which seemed to confirm access to US TikTok data by Chinese actors. The report refers to multiple examples of data access by TikTok’s parent company ByteDance, which is based in China.

Then in July, TikTok Australia’s director of public policy, Brent Thomas, wrote to the shadow minister for cyber security, James Paterson, regarding China’s access to Australian user data.

Thomas denied having been asked for data from China or having “given data to the Chinese government” – but he also noted access is “based on the need to access data”. So there’s good reason to believe Australian users’ data may be accessed from China.

Is TikTok Worse Than Other Platforms?

TikTok collects rich consumer information, including personal information and behavioural data from people’s activity on the app. In this respect, it’s not different from other social media companies.

They all need oceans of user data to push ads onto us, and run data analytics behind a shiny facade of cute cats and trendy dances.

However, TikTok’s corporate roots extend to authoritarian China – and not the US, where most of our other social media come from. This carries implications for TikTok users.

Hypothetically, since TikTok moderates content according to Beijing’s foreign policy goals, it’s possible TikTok could apply censorship controls over Australian users.

This means users’ feeds would be filtered to omit anything that doesn’t fit the Chinese government’s agenda, such as support for Taiwan’s sovereignty, as an example. In “shadowbanning”, a user’s posts appear to have been published to the user themselves, but are not visible to anyone else.

It’s worth noting this censorship risk isn’t hypothetical. In 2019, information about Hong Kong protests was reported to have been censored not only on Douyin, China’s domestic version of TikTok, but also on TikTok itself.

Then in 2020, ASPI found hashtags related to LGBTQ+ are suppressed in at least eight languages on TikTok. In response to ASPI’s research, a TikTok spokesperson said the hashtags may be restricted as part of the company’s localisation strategy and due to local laws.

In Thailand, keywords such as #acab, #gayArab and anti-monarchy hashtags were found to be shadowbanned.

Within China, Douyin complies with strict national content regulation. This includes censoring information about the religious movement Falun Gong and the Tiananmen massacre, among other examples.

The legal environment in China forces Chinese internet product and service providers to work with government authorities. If Chinese companies disagree, or are unaware of their obligations, they can be slapped with legal and/or financial penalties and be forcefully shut down.

In 2012, another social media product run by the founder of ByteDance, Yiming Zhang, was forced to close. Zhang fell into political line in a public apology. He acknowledged the platform deviated from “public opinion guidance” by not moderating content that goes against “socialist core values”.

Individual TikTok users should seriously consider leaving the app until issues of global censorship are clearly addressed.

But Don’t Forget, It’s Not Just TikTok

Meta products, such as Facebook and Instagram, also measure our interests by the seconds we spend looking at certain posts. They aggregate those behavioural data with our personal information to try to keep us hooked – looking at ads for as long as possible.

Some real cases of targeted advertising on social media have contributed to “digital redlining” – the use of technology to perpetuate social discrimination.

In 2018, Facebook came under fire for showing some employment ads only to men. In 2019, it settled another digital redlining case over discriminatory practices in which housing ads were targeted to certain users on the basis of “race, colour, national origin and religion”.

And in 2021, before the US Capitol breach, military and defence product ads were running alongside conversations about a coup.