inbox and environment news: Issue 548

July 31 - August 6, 2022: Issue 548

National Tree Day 2022: July 31

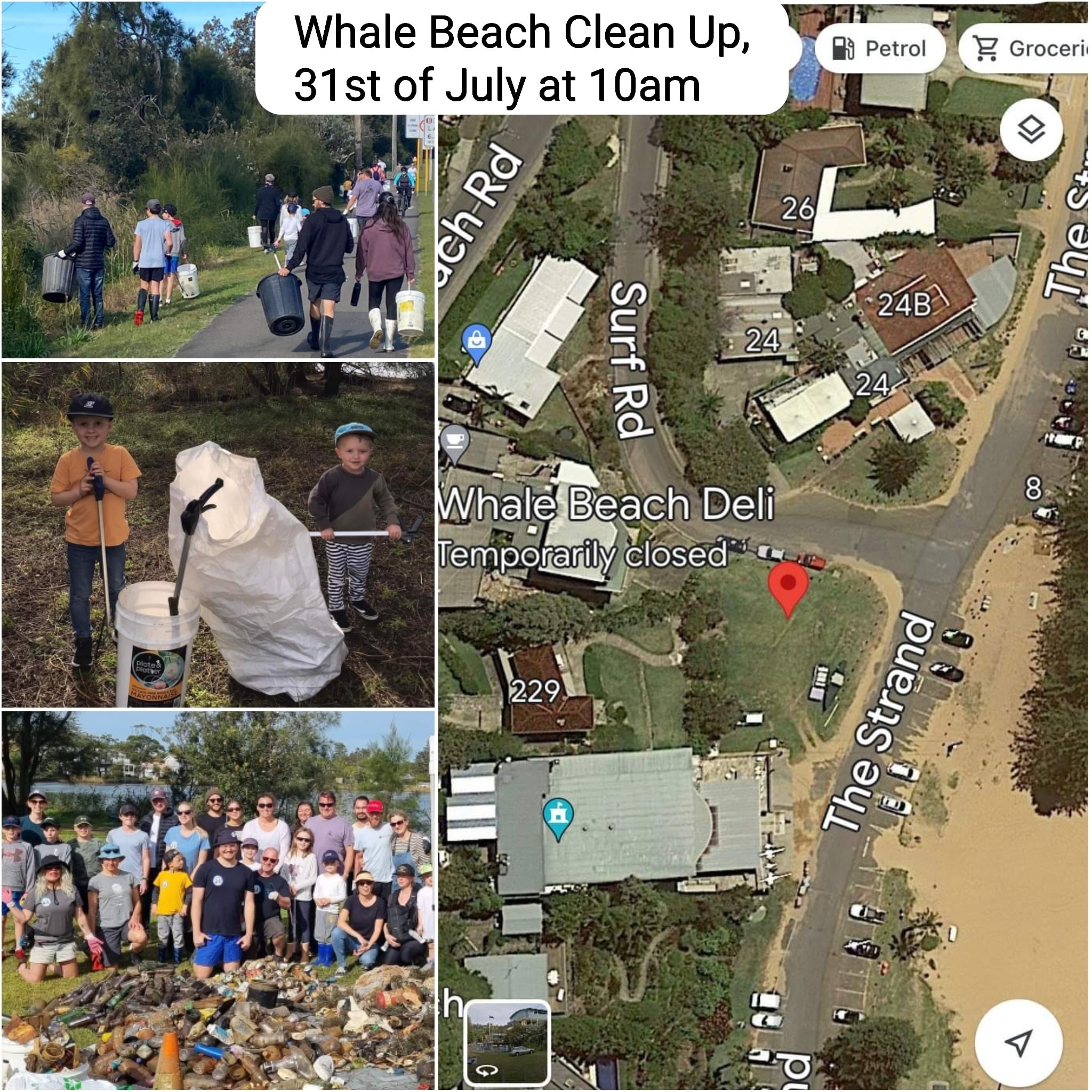

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Whale Beach - Sunday July 31st

Seagull Pair At Turimetta beach: Spring Is In The Air!

Magpie Breeding Season: Avoid The Swoop!

- Try to avoid the area. Do not go back after being swooped. Australian magpies are very intelligent and have a great memory. They will target the same people if you persist on entering their nesting area.

- Be aware of where the bird is. Most will usually swoop from behind. They are much less likely to target you if they think they are being watched. Try drawing eyes on the back of a helmet or hat. You can also hold a long stick in the air to deter swooping.

- Keep calm and do not panic. Walk away quickly but do not run. Running seems to make birds swoop more. Be careful to keep a look out for swooping birds and if you are really concerned, place your folded arms above your head to protect your head and eyes.

- If you are on your bicycle or horse, dismount. Bicycles can irritate the birds and the major cause of accidents following an encounter with a swooping bird, is falling from a bicycle. Calmly walk your bike/horse out of the nesting territory.

- Never harass or provoke nesting birds. A harassed bird will distrust you and as they have a great memory this will ultimately make you a bigger target in future. Do not throw anything at a bird or nest, and never climb a tree and try to remove eggs or chicks.

- Teach children what to do. It is important that children understand and respect native birds. Educating them about the birds and what they can do to avoid being swooped will help them keep calm if they are targeted. Its important children learn to protect their face.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

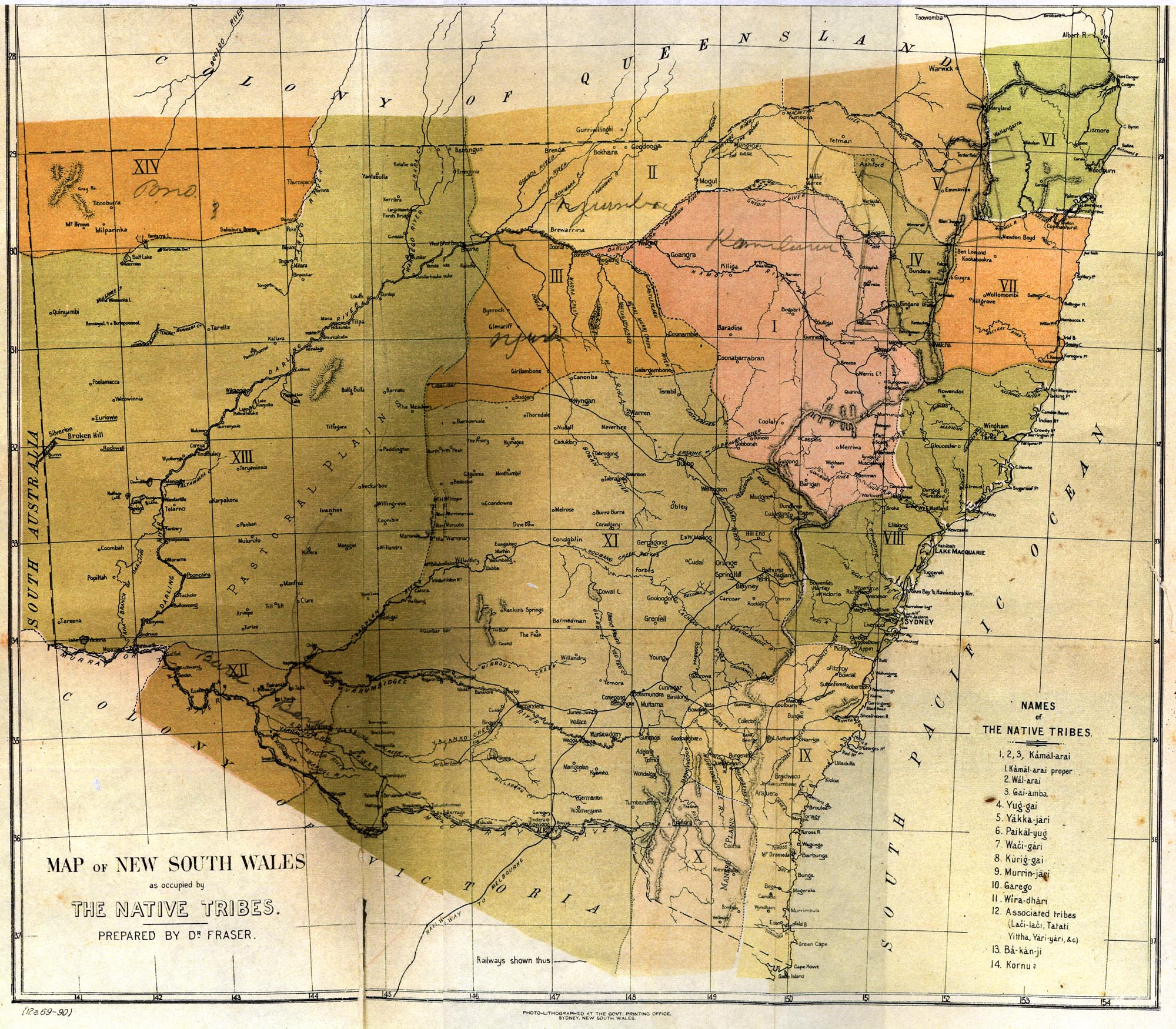

Water Sharing Plans: Farmers And Water Users

- by 1 September, licence holders in the Border Rivers and Gwydir valleys will have their water accounts credited and the floodplain harvesting framework will be fully operational

- licences for the Macquarie, Barwon-Darling and Namoi valleys will be determined and will come into effect later this year and in early 2023.

Eastern Bristlebirds Sent South

Call Out To Improve Coastal Design

Land IQ To Deliver Savings, Speed Up Planning

Healthy Fish, Healthy Rivers And Healthy Farms

NSW farmers and native fish species will benefit from modern fish-protection screens, which will protect aquatic life as well as valuable farming equipment.

NSW farmers and native fish species will benefit from modern fish-protection screens, which will protect aquatic life as well as valuable farming equipment.Reimbursement For Recreational Beekeepers Impacted By Varroa Mite

- They must decontaminate all vehicles that will be used for transporting honey supers, before and after the move.

- The honey super must be cleared of bees and sealed so no bees can enter.

- The honey supers must be taken to an enclosed space for honey extraction.

- Transportation can only take place within the eradication zone and by using the most direct route.

- Beekeepers must not move any part of the brood box.

- Honey must not be extracted until the honey super is stored in a bee proof manner for 21 days or at -20 degrees Celsius for 72 hours.

Biosecurity Blueprint To Safeguard NSW Agriculture

- Set a clear vision for biosecurity and food safety in NSW;

- Map strategy objectives for Government, industry, and the community; and

- Outline key activities that will guide decision-making for farmers.

Labor has introduced its controversial climate bill to parliament. Here’s how to give it real teeth

Earlier today, the federal government introduced its hotly awaited climate change bill to parliament. Despite the attention and controversy it’s attracted, the proposed legislation – as it stands – would be almost entirely symbolic.

Labor has updated Australia’s obligations under the Paris Agreement. So we’re already committed to a 43% emissions reduction by 2030, based on 2005 levels.

Enshrining the target in law might send a message that the new government is committed to reducing emissions. But as I explain below, the law will have little material effect.

Labor needs the support of the Greens and one other crossbencher to get the bill through the Senate. Labor won’t concede to the Greens’ core demands, but a climate “trigger” on new developments could ensure the bill has real force.

New Laws Are Not Needed

Introducing the bill to parliament on Wednesday, Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen said Labor’s emissions reduction target of 43% was “ambitious but achievable”. But in fact, the goal is far from ambitious – and in all likelihood will be easily met.

Even before the election, Australia was on track for a 35% emissions reduction – well above the commitment of the Morrison government. This was mainly due to state government action, and rapid take up of clean energy by households and businesses.

Former prime minister Scott Morrison could not publicly admit this, or adjust the government’s official target accordingly, at the risk of antagonising climate denialists on his own side.

But it means Australia is likely to be well on track to achieve the 43% target by the next election – with a little help from Labor’s modest proposed policy changes, and steep increases in the cost of coal, oil and gas. So legislating the target isn’t really necessary.

Nor does Labor need new laws to prevent a future Coalition government from scaling back the emissions reduction target.

Under the Paris Agreement, there is no process to go backwards. Nations are expected to rachet up their pledges until, it is hoped, global emissions fall to a trajectory consistent with global temperature goals.

Unless Australian withdrew from the agreement altogether – as the Trump administration did in the United States – the 43% commitment is almost impossible to reverse.

Even ignoring our international commitments, the Coalition is unlikely to propose backtracking on the 43% target.

Even if it went to the next election promising no further action on climate change, Australia would still be on track to hit the target. So modifying the target would bring no policy benefit – and would kill off any chance of recapturing seats lost to teal independents and Greens at the last election.

Labor has proposed to tighten the so-called “safeguard mechanism” established by the previous government. But this policy is achievable under existing law and did not require inclusion in the bill now before parliament.

The mechanism is supposed to prevent big industrial polluters from increasing their emissions beyond a certain cap – a move necessary to protect gains in emissions reduction made elsewhere in the economy.

In theory, polluters receive a financial incentive if their emissions fall below a previously established baseline, and incur a financial cost if their emissions exceed it. But under the Coalition, many polluters were allowed to increase their baselines to avoid being penalised.

Labor has proposed to implement the scheme more effectively. This relatively modest policy will proceed regardless of the climate bill’s passage.

Room To Move On A Climate ‘Trigger’

The Greens have made two key demands in exchange for supporting Labor’s climate bill in the Senate: increasing the 43% target and a ban on new coal and gas projects.

There is virtually no chance Labor will agree to a higher target – given both its election commitments, and the political imperative of not being seen to cave in to the Greens.

Nor is the government likely to accept an explicit ban on new coal and gas projects, even though the International Energy Agency says such a ban is needed.

There is, however, room for compromise. The Greens have called for the legislation to incorporate a “climate trigger”, which would mean development proposals are not approved unless their impact on climate change has been considered.

The trigger would mean new coal and gas projects could be rejected on the grounds of potential damage to the climate, without Labor having to commit to such a ban.

Labor did not rule out the trigger before the election, and elements of its grassroots membership are calling for the policy to form part of the government’s planned overhaul of federal environment laws.

Making Real Progress

The election in May of an unprecedented number of independent and Green MPs reflected a groundswell of community feeling on the need for climate action. The federal government must take account of this, if the current parliament is to land on a sustainable climate policy.

The Greens and other crossbenchers should not rubber stamp a purely symbolic statement of Labor’s targets. But for their part, they should seek a sensible compromise on measures to help decarbonise the Australian and global economies.

And what of the Dutton-led opposition? The Coalition’s embrace of climate denialism produced one of its worst electoral defeats in history. Even if it votes against the legislation now before parliament, the Coalition’s political recovery depends on it taking a more constructive climate position in future.![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nature’s deteriorating health is threatening the wellbeing of Australians, the State of the Environment report finds

For the first time, the new State of the Environment report explicitly assessed the dependency of humans on nature. We, as report authors, evaluated trends and changes in the environment’s health for their impact on human society. This is described in terms of “human wellbeing”.

Wellbeing encompasses people’s life quality and satisfaction, and is increasingly being recognised in national policy. It spans our physical and mental health, living standards, sense of community, our safety, freedom and rights, cultural and spiritual fulfilment, and connection to Country.

For example, over 85% of Australians live near the coast, and beach activities – swimming, surfing, walking – are an important part of our coastal lifestyle. Such nature-based activities can relieve stress and connect with our individual and national identities. Healthy coastal ecosystems also provide our seafood and support many businesses.

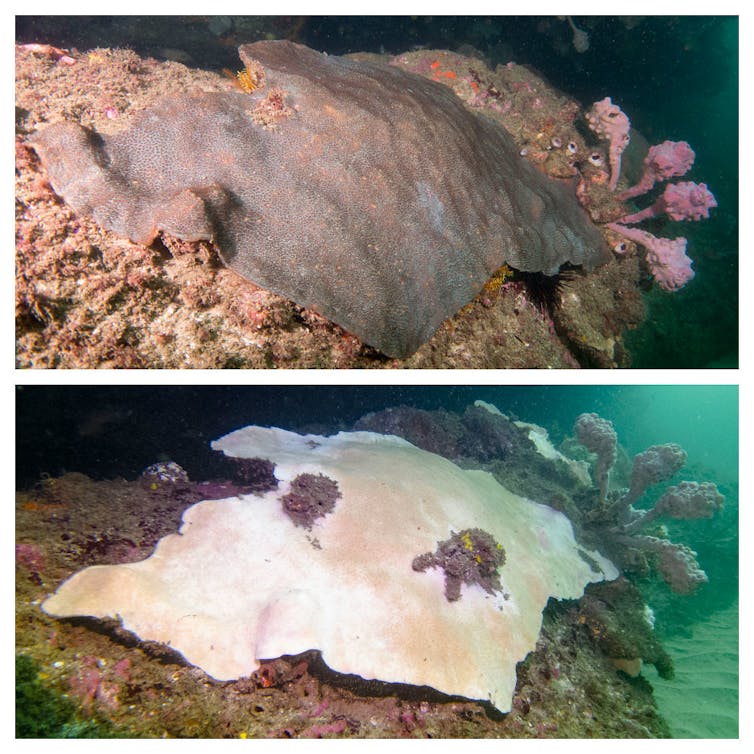

Yet, these ecosystems are under great pressure from human activities. The Great Barrier Reef has suffered four mass bleaching events in the last seven years, kelp forests are in decline in southern Australia, storms are eroding beaches, and coastal fishing pressure is high.

Australia’s ecosystems are collapsing, and our unsustainable actions are threatening our own wellbeing. But there are signs of change, and it’s not too late to make a difference in your own community.

Good, But Deteriorating

The State of the Environment report, released last week, contains several new wellbeing assessments, where data were available.

Overall, wellbeing as determined by the environment is graded as “good but deteriorating”. Examples of such assessments include:

land management: graded partially effective as community participation is improving, but our sense of loss is mounting

extreme events: graded good to date, but deteriorating as climate change impacts accelerate

Antarctica: graded good but deteriorating, as its changing environment will negatively effect marine ecosystems and global climate.

Our urban spaces are ranked well in terms of livability, particularly in Australia’s capital cities. Air and water quality are good most of the time, and Australians can generally access adequate nutrition.

But these conditions are not universal, and they are changing. Remote and rural areas score lower on liveability and some social groups, such as Indigenous people, do not have fair and adequate access to essential resources like fresh water.

Indigenous people in Australia are also disproportionately impacted by extreme events.

Climate Change Is Already Hurting Our Wellbeing

Previous State of Environment Reports warned of future impacts of climate change. The new report documents impacts already here – and getting worse.

This includes many recent extreme events, from the 2019-2020 bushfires to the recent extreme floods. These have measurable impacts on both our environment and our lives.

While cyclones, floods and bushfires directly destroy our homes and landscapes, heatwaves kill more people in Australia than any other extreme event.

Heatwave intensity in Australia has increased by 33% over the last two decades, with at least 350 deaths between 2000 and 2018. And when heatwaves strike, we see flow-on consequences to, for instance, our hospital emergency departments.

Climate change is also exacerbating air quality issues through dust, smoke and emissions. For example, the 2019-2020 bushfires exposed over 80% of the Australian population to smoke. This exposure killed an estimated 417 people.

Other pressures to the environment – industrial pollution, land clearing, unsustainable water consumption, extraction of natural resources – also lower our wellbeing, due to their degradation to nature.

These pressures are, of course, often by-products of producing food, water and wealth. We need to find ways to more effectively monitor, manage and prioritise them to ensure they’re sustainable.

A Sustainable Future

The State of the Environment report, for the first time, links to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, which include good health, quality education, clean energy, and the health of life on land and in the water.

Sustainability means meeting today’s needs without compromising the needs of future generations. It is founded on effective ecosystem protection and environmental stewardship.

The State of the Environment report contains a range of recommendations to tackle our sustainability challenges. Foremost is the need to strengthen and build connections: between people and Country, economics and environment.

Learning from and empowering Indigenous management of Country is a key part of this success, as is greater national leadership, reducing pollution, better monitoring, and long-term reliable funding for the environment.

An important step is the environment minister’s recent announcement that Australia’s proposed wellbeing budget will include environmental factors.

Establishing more protected areas with higher standards of protection is another important part of the solution. The federal government’s recent commitment to expand Australia’s national estate to protect 30% of land and 30% of oceans by 2030 is a good start.

However, we must be careful to ensure this protection is effective and representative of all our precious ecosystems.

What Can You Do?

There’s much we can do at a personal level, too. You can become informed about the urgency of the twin climate and biodiversity crises - and getting familiar with the State of Environment Report is a great place to start.

Immersing yourself in nature, and encouraging children to do so as well, is also essential. Spending time in nature raises our understanding of its plight.

There are also opportunities to make a tangible impact on the wellbeing of our communities by getting involved in nature restoration, citizen science and other community programs.

We don’t lack the knowledge of what needs to be done. What we need now is urgent action by individuals, organisations and government. Our lives, and our environmental life support system, depend on it.![]()

John Turnbull, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Sydney and Emma Johnston, Professor and Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research), University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Urban patchwork is losing its green, making our cities and all who live in them vulnerable

One delight of flying is seeing our familiar landscapes in a new way from above. At low altitude most of us know where things are, but as we ascend it becomes difficult to determine the local details, and we begin to see a bigger picture. Sometimes this bigger picture can be scary.

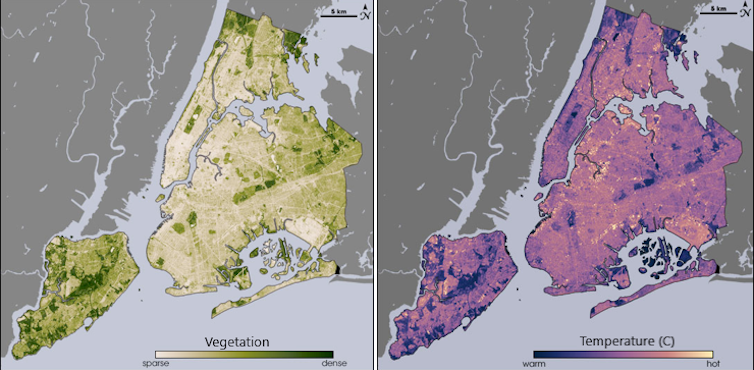

After nearly three years of being unable to fly I have had a couple of recent opportunities to take to the air. My first observation was that in many once-leafy suburbs the green tinge is disappearing under a tsunami of development. You can see this new development on the fringes of towns and cities, as well as redevelopment and infill in the older places. Familiar rows of roadside trees and large old trees that were once suburban landmarks have gone.

As you look from above, it comes as no surprise that the latest State of the Environment report delivered damning findings this week. Vegetation cover in cities is diminishing. So too are the wildlife corridors that once connected now-isolated remnant communities of plants and animals.

Most of you will have heard people describing the view we get from above as being like a patchwork quilt of different colours and land uses, or perhaps like an Indigenous painting that gives us a bird’s eye view of the world below. It shows us a jigsaw puzzle of the disturbed and fragmented environments in which we live.

However, as we soar higher we are reminded that there is only one space, that it is all connected. Each piece of the jigsaw has a place in the big picture.

Cities Can’t Afford To Lose Their Green Cover

Not all green cover has gone in the past few years, but the losses are noticeable. And unless something is done quickly, they will continue. We will reach the point where so many trees are lost that it will jeopardise the capacity of our cities and towns to be resilient, liveable and sustainable in the face of climate change.

No local government can deal with this situation. It is a matter of state and federal planning policy and development regulation.

In most states, for example, developers adopt a scorched-earth policy of removing most, if not all, mature trees from a site before construction begins. State government agencies help deliver treeless sites for development. Expensive government legal teams often fight local community groups opposing tree removals through tribunals and courts.

Vegetation needs to be valued both for the habitat it provides and for the many services it provides to residents of towns and cities. As heatwaves become more intense and frequent, it’s sobering to think the loss of urban trees will result in greater urban heat island effects and more heatwave-related illnesses, hospitalisations and deaths.

Lockdowns Reminded Us Of The Value Of These Spaces

It was fascinating to watch the use of public open space during COVID-19 lockdowns. Concerns about people’s physical health, capacities for coping with stressful situations, increased risks of self-harm and domestic violence, and the learning and development environments of children led to people flocking to their local parks, gardens and riverside reserves.

From the air, though, it becomes painfully obvious that not every suburb or region has many such spaces. It is well known worldwide that people in areas of lower socio-economic status (SES) are disadvantaged by lack of access to treed open space.

This is true of Australia’s cities, regional centres and many country towns where some of the jigsaw pieces seem to be devoid of green. Lack of treed green space is associated with problems such as obesity, poor physical and mental health and social disadvantage.

It’s highly likely people in these areas were further disadvantaged and subjected to greater stress during the lockdowns because of the lack of accessible treed open space. Perhaps this partly explains why some urban areas had lower levels of lockdown compliance than others. There is evidence that the health benefits of access to treed open space are greatest for lower-SES communities.

Public parks and gardens served their purpose admirably during lockdowns. With proper planning, they will do so again in enabling cities to cope with climate change. However, if cities and suburbs keep losing green space and tree cover, their capacity to adapt will be limited. Society as a whole will be the loser.

The mosaic quilt we see from the air reveals just how disconnected the green patches and corridors of our landscapes and urban environments have become. It is astonishing to see developments of large houses on small blocks, which could have been plucked from the new suburbs of any major Australian city, fringing hot, inland towns. There appears to have been no recognition of the effects of a hot Australian summer.

The rapid expansion of Australian cities and towns presents planning challenges in the face of demands to subdivide undeveloped land for housing, countered by demands for connected, treed, public, green space. Providing large and well-connected green space is going to be essential urban infrastructure for increased urban populations facing climate change. It’s not a luxury for a privileged minority, but a vital component of a sustainable economy and environment for all.![]()

Gregory Moore, Senior Research Associate, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Greening the greyfields: how to renew our suburbs for more liveable, net-zero cities

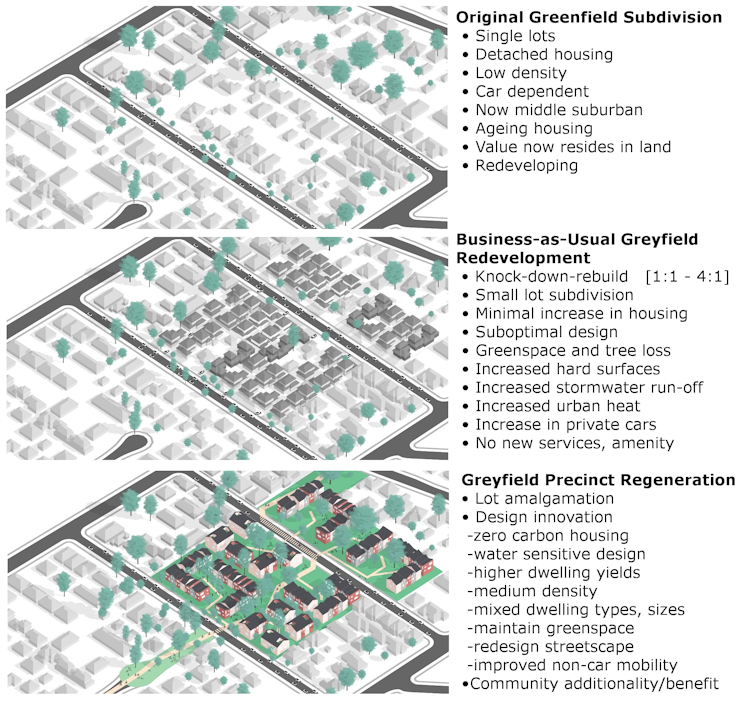

Our ageing cities are badly in need of regeneration. Many established residential areas, the “greyfields”, are becoming physically, technologically and environmentally obsolete. They are typically located in low-density, car-dependent middle suburbs developed in the mid to late 20th century.

Compared to the outer suburbs, these middle suburbs are rich in services, amenities and jobs. But the greyfields also represent economically outdated, failing or undercapitalised real-estate assets. Their location has made them the focus of suburban backyard infill development.

Unfortunately, the current approach typically cuts down all the trees and creates more car traffic as resident numbers grow. A new kind of urban regeneration is needed at the scale of precincts, rather than lot by lot, to transform the greyfields into more liveable and sustainable suburbs. It calls for a collaborative approach by federal, state and local governments.

How Do We Do This?

Our free new e-book, Greening the Greyfields, sets out how to do this. It draws on ten years of research that led to a new model of urban development.

This approach integrates two goals of urban research:

ending the dependence on cars caused by a disconnect between land use and transport

accelerating the supply of more sustainable, medium-density, infill housing to replace the current dysfunctional model of urban regeneration.

Greening greyfields will help our cities make the transition to net zero emissions.

Why Do We Need To Regenerate These Areas?

We need to shrink the unsustainable urban and ecological footprints of “suburban” cities. Neighbourhoods need to become more resilient, sustainable, liveable and equitable for their residents.

Urban regeneration must also allow for the COVID-driven restructuring of the work–residence relationship for city residents. This involves relocalising urban places so they become more self-sufficient as “20-minute neighbourhoods”. Their residents will have access to most of the services they need via low-emission cycling and walking, as well as public transport.

Current attempts to increase residential density and limit sprawl in most Australian cities tend to focus on blanket upzoning in selected growth zones. The resulting backyard infill involves a few small homes, which is all that is allowed on each block. Density increases only marginally, so there are still too few housing options for residents who want to be close to city services and opportunities.

Piecemeal infill redevelopment often degrades the quality of our suburbs. The loss of trees and increase in hard surfaces worsen urban heat island effects and flood risk. And a lack of convenient transport options for the extra residents reinforces car dependence.

We need more strategic models of suburban regeneration.

Greyfield regeneration compared to conventional approaches

Why Do This At The Precinct Scale?

Urban regeneration is best tackled at the scale of precincts. They are the building blocks of cities: greenfield sites continue to be developed, and old brownfield industrial sites are redeveloped, at this scale.

Design-led precinct-scale regeneration can maximise co-ordination of aspects of urban living neglected by piecemeal lot-by-lot redevelopment. Think local health and education services, small shops, social housing, walkable open space, public transport and even regenerated biodiversity.

Model precincts like WGV, in a greyfields suburb of Fremantle, have very successfully demonstrated how regeneration can produce high-quality, medium-density housing and net-zero outcomes. However, this development was on an old school site, so there was no need to combine individual blocks into a precinct-scale site. There were also no residents that needed to be engaged – though WGV became very popular because of its attractive architecture and treed green spaces.

What Are The Key Elements Of This Model?

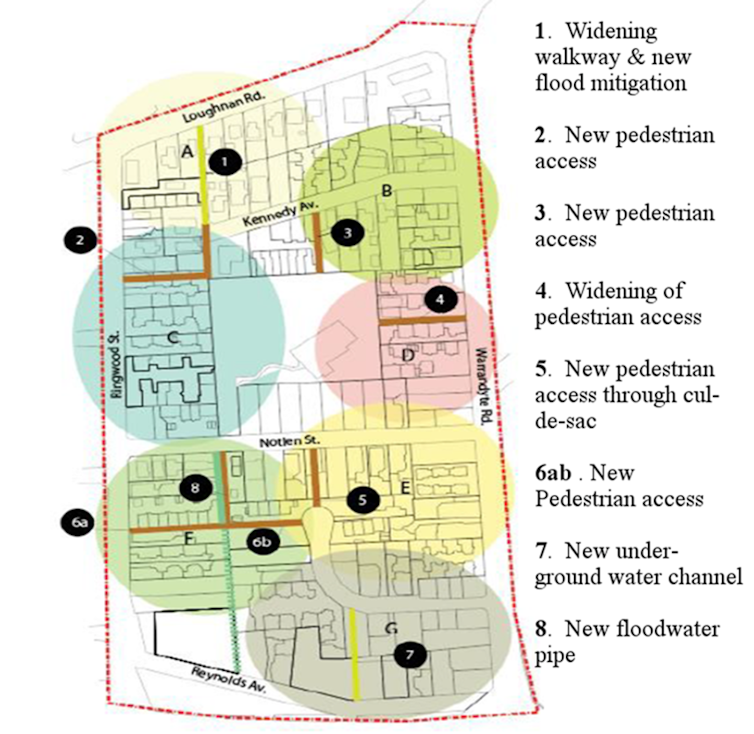

Greyfield precinct regeneration has two sub-models: place-activated and transit-activated. A place-activated precinct may shorten travel distances for residents by providing services and amenities, but does not in itself increase public transport. For transit-activated precincts, good public transport increases land values, which makes these regenerated greyfields even more attractive.

Mid-tier transit like trackless trams is an ideal way to enable precinct developments along main road corridors. Local governments are recognising this around Australia.

Greyfield regeneration can begin with a strategy of district greenlining. Redlining was an American planning tool to exclude people of colour from a neighbourhood. Greenlining is the opposite: it includes the whole community in greening their neighbourhood.

This strategic process would identify neighbourhoods in need of next-generation infrastructure. Projects of this sort require a precinct-scale vision and plan.

State and municipal agencies can do this work. It would include:

physical infrastructure – energy, water, waste and transport

social infrastructure – health and education

green infrastructure – the nature-based services we get from planting and retaining trees and enabling open space and landscaped streets.

The City of Maroondah in Victoria provided an early demonstration of how this can happen. It produced a set of playbooks to show how other municipalities, developers and land owners can replicate the process.

Greening the greyfields will deliver the many benefits associated with more sustainable and liveable communities. However, these outcomes depend on more comprehensive, design-led, integrated land use and transport planning.

Property owners, councils, developers and financiers will have to work together much more closely and effectively than happens with the business-as-usual approach of fragmented, small-lot infill, which is failing dismally. New laws and regulations will be needed to change this approach.

Better Cities 2.0?

Precinct-based projects offer a model for net zero development of our cities.

Greyfield regeneration is an increasingly pervasive and pressing challenge for our cities. It calls for all levels of government to work on a strategic response.

We suggest a Better Cities 2.0 program, led by the federal government, to establish greyfield precinct regeneration authorities in major cities and build partnerships with all major urban stakeholders. It would set us on the path to greening the greyfields.![]()

Peter Newman, Professor of Sustainability, Curtin University; Giles Thomson, Senior Lecturer, Department of Strategic Sustainable Development, Blekinge Institute of Technology; Peter Newton, Emeritus Professor in Sustainable Urbanism, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology, and Stephen Glackin, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Protecting 30% of Australia’s land and sea by 2030 sounds great – but it’s not what it seems

You would have heard Australia’s environment isn’t doing well. A grim story of “crisis and decline” was how Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek described the situation when she launched the State of the Environment Report last week. Climate change, habitat destruction, ocean acidification, extinction, and soil, river and coastal health have all worsened.

In response, Plibersek promised to protect 30% of Australia’s land and waters by 2030. Australia committed to this under the previous government last year, joining 100 other countries that have signed onto this “30 by 30” target.

While this may be a worthy commitment, it’s not a big leap. Indeed, we’ve already gone well past the ocean goal, with 45% protected. And, at present, around 22% of Australia’s land mass is protected in our national reserve system.

To get protected lands up to 30% through the current approach will mean relying on reserves created by non-government organisations and Indigenous people, rather than more public reserves like national parks. This approach will not be sufficient by itself.

The problem is, biodiversity loss and environmental decline in Australia have continued – and accelerated – even as our protected areas have grown significantly in recent decades. After years of underfunding, our protected areas urgently need proper resourcing. Without that, protected area targets don’t mean much on the ground.

What Counts As A Protected Area?

In 1996, the federal government set up the National Reserve System to coordinate our network of protected areas. The goal was to protect a comprehensive, adequate and representative sample of Australia’s rich biodiversity.

Since then, marine reserves have expanded the most, with the government protecting Commonwealth waters such as around Cocos Islands and Christmas Island.

On land, the government has been very hands-off. Progress has been driven by non-government organisations, Indigenous communities and individuals. New types of protected area, offering different levels of protection, have emerged. The Australian Wildlife Conservancy now protects or manages almost 13 million hectares – about twice the size of Tasmania. Bush Heritage Australia protects more than 11 million hectares. While these organisations do not always own the land, they have become influential players in conservation.

Partnerships between Traditional Owners and the federal government have produced 81 Indigenous Protected Areas, mainly on native title land. These cover 85 million hectares – fully 50% of our entire protected land estate. Independent ranger groups are also managing Country outside the Indigenous Protected Area system.

Protected areas have also grown through covenants on private land titles, aided by groups such as Trust for Nature (Victoria) and the Tasmanian Land Conservancy.

In total, public protected areas like national parks have only contributed to around 5% of the expansion of terrestrial protected area since 1996. Non-governmental organisation land purchases, Indigenous Protected Areas and individual private landholders have facilitated 95% of this growth.

The Real Challenge For Protected Areas? Management

So how did non-government organisations become such large players? After the national reserve system was set up, the federal government provided money for NGOs to buy land for conservation, if they could secure some private funding. Protected lands expanded rapidly before the scheme ended in 2012.

Unfortunately, federal funding did not cover the cost of managing these new protected areas. Support for Traditional Owners to manage Indigenous Protected Areas has continued, albeit on erratic short-term cycles and very minimally, to the tune of a few cents per hectare per year.

As a result, NGOs and Traditional Owners have increasingly had to rely on market approaches and philanthropy. Between 2015 and 2020, for example, the Traditional Owner non-profit carbon business Arnhem Land Fire Abatement Limited earned $31 million in the carbon credit market through emissions reductions. This money supports a significant portion of the conservation efforts of member groups.

What does this mean? In short, corporate partnerships and market-based approaches once seen as incompatible with conservation are now a necessity to address the long-term shortfall of government support.

You might think wider investment in conservation is great. But there are risks in relying on NGOs funded by corporations and philanthropists to conserve Australia’s wildlife.

For instance, NGOs may no longer feel able to push for transformative political change in conservation if this doesn’t align with donor interests. There’s also lack of transparent process in how conservation funding is allocated, and for what purpose.

Protection On Paper Isn’t Protection On The Ground

On paper, conservation in Australia looks in good shape. But even as protected areas of land and sea have grown, the health of our environment has plunged. The 2021 State of the Environment Report is a sobering reminder that it’s not enough simply to expand protected areas. It’s what happens next that matters.

If we value these protected lands, we have to fund their management. Without management – which costs money – protected areas can rapidly decline, especially under the impacts of climate change.

We also have to tackle what happens outside protected areas. We can’t simply keep sectioning off more and more poorly funded areas for nature while ignoring the drivers of biodiversity loss, such as land clearing, resource extraction, mismanagement and the dispossession of Indigenous lands.

It’s excellent our new environment minister wants to begin the environmental repair job. But creating protected areas is just the start. Now we have to answer the bigger questions: how we care for ecologies, whose knowledge is valued, who does this work and how will it be funded over the long term.

We also have to go beyond lip service to Indigenous knowledge and Caring for Country to genuinely acknowledge First Nations sovereignty and support self-determination.

On this front, moves by conservation organisations to return land to First Nations suggests a willingness in the conservation community to begin this work.

While our protected area estate is large and set to grow further towards the 30 by 30 goal, lines on a map do not equate to protection. We have long known the funding and capability for actual protection is woefully inadequate. For us to reverse our ongoing environmental collapse, that has to change. ![]()

Benjamin Cooke, Senior lecturer, RMIT University; Aidan Davison, Associate Professor, University of Tasmania; Jamie Kirkpatrick, Professor of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, and Lilian Pearce, Lecturer, Environmental Humanities, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Not waving, drowning: why keeping warming under 1.5℃ is a life-or-death matter for tidal marshes

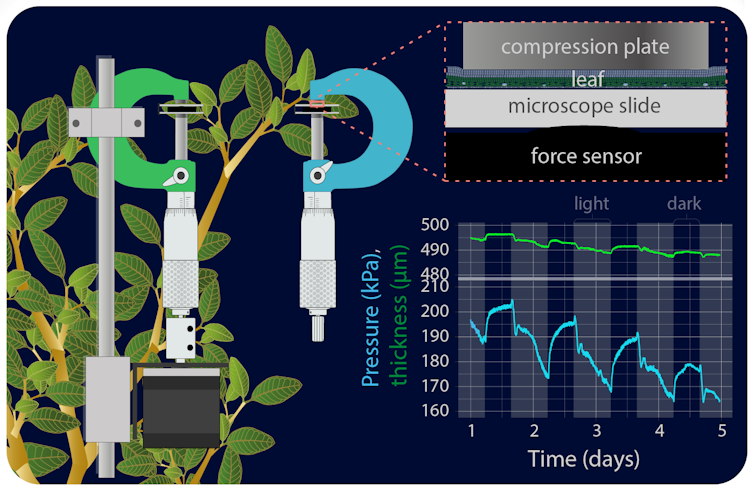

It may not always be clear why global temperature rise must be kept below 1.5℃, compared to 2℃ or 3℃. Research published today in the journal Science shows this apparently small distinction will make all the difference for the world’s tidal marshes.

Tidal marshes fringe most of the world’s coastlines. These coastal wetlands are flooded and drained by salt water brought by tides. They provide valuable habitat for animals, support fisheries that feed millions of people and take carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, storing it in their roots.

New roots build up the marsh soil, while stems trap sediment. Both processes help tidal marshes keep pace with sea-level rise. Indeed, tidal marshes increase the amount of carbon they store as the rate of sea-level rise increases.

This feedback has led scientists to question whether tidal marshes might survive future sea-level rise. Unfortunately, our research shows that’s unlikely if warming exceeds 1.5℃.

A 20-Year Experiment Provides The Answer

I am part of an international team of scientists who embarked on an experiment nearly 20 years ago to test whether tidal marshes were keeping pace with sea-level rise. Nearly 500 devices called “surface elevation tables” were installed in tidal marshes in countries including Australia, the United States, Canada, Belgium, Italy, the United Kingdom and South Africa.

These devices measured the amount of sediment and root material accumulating in the marshes. They also measured changes in the marsh’s surface elevation. Nearby tide gauges measured the rate of sea-level rise. This rate varied across the network.

Some coastlines such as Australia’s have a stable land mass – so the rate of sea-level rise reflects the rise in ocean volume driven by global warming.

On other coastlines, including much of North America, the land may still be sinking or rising after the removal of massive ice sheets at the end of the last ice age. What’s more, extracting oil and water resources from underground can cause local subsidence, increasing “relative” sea-level rise.

The data we gathered provide insights into what might happen to tidal marshes as sea-level rise accelerates.

What Do The Findings Tell Us?

One set of findings was encouraging. These data showed the rate at which material accumulates in tidal marshes around the world corresponds closely to the varying rates of sea-level rise.

Even the marshes experiencing sea-level rise of 7-10mm per year – the rate anticipated globally under high-emissions scenarios – were accumulating sediment and organic matter at a comparable rate.

However, measuring changes in elevation produced a very different picture. Even though marshes under higher rates of sea-level rise were accumulating more sediment, this did not translate into more elevation gain.

The new research suggests a simple explanation for this.

The additional sediment and water accumulating on the surface weigh the marsh down, compressing the sediment below. This is particularly apparent in marshes with high organic content: precisely the type that develops under high rates of sea-level rise.

This insight accords with observations emerging from the paleo record, which also suggest tidal marshes are highly vulnerable to rapidly rising sea levels.

A Story Of Good News And Bad

To protect our tidal marshes, we must try to reduce global carbon emissions that cause global warming and sea-level rise.

Sea level rise has averaged about 3.7mm per year since 2006. Our research shows tidal marshes are capable of keeping up with this on most of the world’s coastlines.

But global sea-level rise is set to increase. Modelling by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects it will reach 7mm per year if warming reaches between 2℃ and 3℃.

Current global commitments put Earth on a trajectory for this level of warming. And once we reach tipping points for sea-level rise, they are locked in for centuries, regardless of subsequent cuts in emissions.

The best hope for preserving the world’s existing tidal marshes is to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming below 2℃ – and if possible 1.5℃.

But we should even now be considering how we might allow for these important ecosystems to shift landwards. This has been their natural adaptation to episodes of high sea-level rise in the past. Countries with large expanses of undeveloped coastal floodplain, such as Australia, are well placed to provide areas to preserve shifting tidal marshes in a warmer future.![]()

Neil Saintilan, Professor, School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4 lessons for the Albanese government in making its climate targets law. We can’t afford to get this wrong

As the new parliament sits for the first time this week, one issue will be in sharpest focus: enshrining a climate target into law. The Albanese government’s pre-election promise was to cut Australia’s emissions 43% on 2005 levels, by 2030.

The government’s commitment to legislate climate targets is welcome and long overdue. Many nations now have climate laws in place to help ensure timely and sufficient emissions reductions.

But not all laws are equal. Our new research explored the impact of Victoria’s Climate Change Act 2017, and similar laws in the United Kingdom and many European countries.

The Albanese government should be guided by lessons from the design and implementation of existing laws such as these, to ensure it follows best practice. Failing to learn from experiences in other jurisdictions would be a missed opportunity Australia – and our warming planet – can hardly afford.

Holding Governments To Account

Labor’s forthcoming legislation is an example of “framework climate legislation”.

Typically, framework climate laws do three things:

- they establish a long-term net zero emissions target

- they require governments to set targets at regular intervals along the pathway to net zero

- they include obligations to develop regulatory and policy measures to meet targets.

These laws rarely include direct emissions reduction measures, such as emission trading, taxation or emissions standards for high emitters like power plants. Instead they establish a cycle of policy development and implementation, providing governments with flexibility to respond to rapidly evolving climate policy, science and technology.

The backbone of laws like these are provisions to hold the government to account. Governments are legally required to set out robust and credible measures to achieve their targets, and to report publicly on their progress.

In many jurisdictions, independent expert bodies advise governments and monitor progress.

Framework climate laws are an important piece of the climate policy puzzle. Long-term policy goals, such as net-zero emissions by 2050, can be easily discounted in the face of competing short-term pressures, such as pandemic recovery. Framework laws are designed to keep governments on track.

Under framework laws in Ireland and the UK, courts have quashed government policies that aren’t specific enough or realistic about how to achieve emissions reduction targets.

This requires governments to commit to more robust, ambitious action.

Labor’s Climate Bill

A draft of the government’s proposed legislation has been shared with the crossbench and leaked to Nine newspapers, but at this point it hasn’t been made public.

We can expect the bill to include Labor’s 2030 emissions reduction target, and a role for the reinstated Climate Change Authority to advise government on future targets.

Newly elected Independents and environment NGOs have highlighted some important concerns with the proposed legislation.

They emphasise the need to ensure that Australia’s targets can be increased over time in line with best available science, and to equip the Climate Change Authority with sufficient resourcing and expertise. These are important features and a failure to address them in the legislation would be disappointing.

Our empirical research on the Victorian Climate Change Act and comparisons with other framework laws highlight four critical lessons for strong, effective climate legislation.

1. Embedding Best Available Science In Targets

Long-term targets should be consistent with Paris Agreement goals and best available science, such as the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports.

Many framework laws, including the Victorian Act, set a long-term target of net zero emissions by 2050. Yet, science is increasingly telling us the world must reach net zero emissions well before 2050, in order to keep Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels this century in reach.

The impacts of global warming will be considerably more severe if we exceed this 1.5℃ threshold.

Instead of a blanket reliance on “net zero by 2050”, framework laws should legislate long term targets referencing the ambitious 1.5℃ Paris Agreement goal, and explicitly allow for any necessary revisions of targets to reflect the science.

2. Requirements For Setting Interim Targets

Clear, detailed requirements for setting interim targets help maximise the benefits of acting sooner rather than later.

Interim targets set under the Victorian Act aim to reduce emissions 28-33% on 2005 levels by 2025, and 45-50% by 2030. Yet these targets have been criticised for deferring significant emissions reductions to later.

Legislation should require governments to prioritise consistency with the best available science. It should require that interim targets are designed to achieve the long-term net zero target in an efficient, effective, equitable manner.

All targets – interim and long-term – must increase in ambition over time. The legislation should prohibit “backsliding” – targets which lower ambition.

This is built into Victoria’s Act and in the Paris Agreement itself.

3. Robust And Enforceable Government Obligations

Framework climate laws should include clearly defined and strategically allocated legal duties for government ministers and agencies. This includes duties to set and achieve long-term and interim targets and to develop policies and actions which will deliver on targets.

And they should be enforceable via the courts as in Ireland and the UK.

4. Transparency Is Vital

Independent expert oversight and public participation are vital for transparency. Regular progress reporting can help drive ambitious implementation and hold governments accountable, but this also depends on public and political scrutiny.

The Victorian Act falls short here by not effectively providing for the participation of independent experts and the public.

What works well in other jurisdictions, such as the UK, is a permanent independent climate commission.

This commission has an ongoing role advising government on target setting and mitigation policy, monitoring progress and facilitating stakeholder engagement and public debate. Proper resourcing is needed to make this work.

A Way Forward

After years of dangerous inaction, Australia desperately needs a framework climate law at the national scale – as well as a raft of ambitious direct measures to rapidly reduce emissions.

But this law needs to do more than just legislate targets and reinstate the Climate Change Authority.

Learning from experience in Victoria and other jurisdictions with similar laws is critical to getting the framework right.![]()

Anita Foerster, Associate professor, Monash University; Alice Bleby, PhD Candidate, UNSW Sydney, and Anne Kallies, Senior Lecturer, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change killed 40 million Australian mangroves in 2015. Here’s why they’ll probably never grow back

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

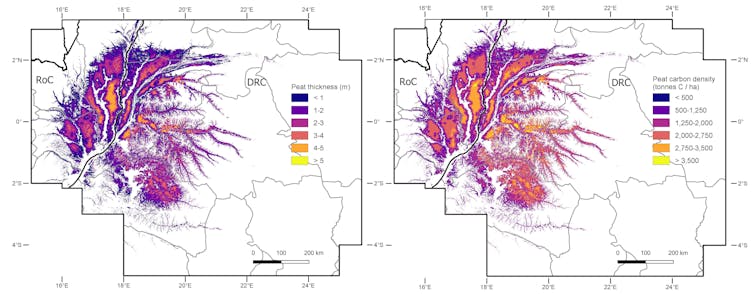

In the summer of 2015-2016, some 40 million mangroves shrivelled up and died across the wild Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia, after extremely dry weather from a severe El Niño event saw coastal water plunge 40 centimetres.

The low water level lasted about six months, and the mangroves died of thirst. Seven years later, they have yet to recover. My new research, published today, is the first to realise the full scale of this catastrophe, and understand why it occurred.

This event, I discovered, is the world’s worst incidence of climate-related mangrove tree deaths in recorded history. Over 76 square kilometres of mangroves were killed, releasing nearly one million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere.

But this event, while unprecedented in scale, is not unique. My research also discovered evidence of another mass die-back of mangroves in the region in 1982 – the same year the Great Barrier Reef suffered its first mass bleaching event.

The mangroves took 15 years to recover. This time, we won’t be so lucky.

Mangroves Are Immensely Important

In Samoa, El Niño-driven sea level drops are called “Taimasa” because of the putrid smell of decaying marine life from long-exposed corals, when sea levels remained low for months on end.

In northern Australia, Taimasa conditions in 2015 left mangroves at higher elevations exposed for at least six months. Without regular flushing and wetting of tides, shoreline mangroves don’t stand a chance.

Mangroves are enormously valuable coastal ecosystems. Healthy mangrove ecosystems not only buffer shorelines against rising sea levels, but they also provide valuable protection against erosion, abundant carbon sinks, shelter for animals, nursery habitat, and food for marine life.

These benefits have cultural and economic value, with widespread significance to local communities.

The mass die-back event of 2015 was widely reported in national and international news, with shocking images emerging from the remote region.

Although the cause was unknown at the time, the implications of such catastrophic damage were immense for local and regional communities, natural coastal ecosystems and the fisheries that depend on them.

Access was difficult and expensive, and environmental records for the region were scarce. But after four years of research , we uncovered evidence this event was indeed a dramatic consequence of climate change.

Why The Mangroves Probably Won’t Recover This Time

Our research reveals the presence of a previously unrecognised “collapse-recovery cycle” of mangroves along Gulf shorelines. The mangroves, damaged in 1982, are now attempting to recover again after the mass-death event in 2015.

But, at least three factors have changed since 1982, leaving recovery less likely.

For one, sea levels have risen dramatically due to climate change, causing erosion. This places escalating pressure on tide-fed wetlands to retreat towards higher land.

Younger trees are essential for future mangrove habitat. But upland, environmental conditions for newly established seedlings can be deadly. Landward pressures of bushfires, feral pigs and weed infestations are made far worse by the catastrophic sudden drops in sea level associated with severe El Niño events.

Two, localised storms, such as tropical cyclones, have become increasingly severe. At least two particularly severe cyclones struck the Gulf of Carpentaria coast: Owen in 2018, and Trevor in 2019. A severe flood event also hit the region in 2019.

The cyclone impacts were notable and extreme. Piles of dead mangrove timber were swept up and driven across tidal areas, bulldozing any newly established trees, as well as sprouting survivors.

And three, the threat of future Taimasa low sea level events appear imminent, as evidence points to a link between climate change and severe El Niño and La Niña events. Indeed, El Niños and La Niñas have become more deadly over the last 50 years, and the long-term damage they inflict are expected to escalate.

Under these circumstances, the potential for the mangroves to recover are understandably low.

Protecting These Vital Ecosystems

These new findings make us more aware of the vulnerability of shoreline ecosystems, and the benefits we’re losing.

A $30 million fishing industry relies on these mangroves, including for redleg banana prawns, mudcrabs and fin fish. When the El Niño of 2015-2016 struck, redleg banana prawn fishers reported their lowest-ever catches.

Mangroves also help stabilise shorelines by buffering otherwise exposed areas from erosion. Such shoreline protection is crucial as sea levels continue to rise rapidly, coupled with increasingly severe storm waves and winds.

Healthy living mangroves are among the world’s most carbon-rich forests, binding and holding considerable carbon reserves both in their woody structure and below ground in peaty sediments.

Losing mangroves in the Gulf released more than 850,000 tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, across both mass dieback events. That’s similar to 1,000 jumbo jets flying return from Sydney to Paris.

It’s critical these buried carbon reserves remain intact, but this will occur only if living vegetation on the surface remains healthy and protected.

Mangroves are also like the kidneys of the coast. Losing them will amplify pollutants in runoff, with excess nutrients, sediments and agricultural chemicals travelling unmitigated into the sea.

They Need Greater Monitoring

Tropical mangroves – as well as saltmarsh-saltpans, the other part of tidal wetlands – need much greater protection, and more effective maintenance with regular health checks from dedicated national shoreline monitoring.

Our aerial surveys of more than 10,000 kilometres of north Australian coastlines have made a start. We’ve recorded environmental conditions and drivers of shoreline change for north-western Australia, eastern Cape York Peninsula, Torres Strait islands and, of course, the Gulf of Carpentaria.

As the climate continues to change, it’s vital to keep a close eye on our changing shoreline wetlands and to ensure we’re better prepared next time another El Niño disaster strikes. ![]()

Norman Duke, Professor of Mangrove Ecology, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Soil abounds with life – and supports all life above it. But Australian soils need urgent repair

Under your feet lies the most biodiverse habitat on Earth. The soil on which we walk supports the majority of life on the planet. Without the life in it, it wouldn’t be soil. Unfortunately, Australia’s soils are not in good shape. The new State of the Environment report rates our soils as “poor” and “deteriorating”.

We’re all familiar with some soil dwellers, such as earthworms. But the lion’s share of life underneath is invisible to the naked eye. Microbiota like bacteria, nematodes, and fungi play vital roles in our environment. These tiny lifeforms break down dead leaves and organic matter, they cycle nutrients, carbon and water. Without them, ecosystems would collapse. Amazingly, most of this wealth of life is unknown to science.

Australia has not undergone the same glacial or volcanic activity as other parts of the world. That’s left most of our soil old and infertile. Our soils are highly sensitive to human pressures, such as contamination, acidification and loss of organic carbon. When we remove communities of plants, this leads to soil erosion. Land clearing also hits underground life hard, causing microbial diversity to decline.

Soil’s lifeforms are also under immense pressure from agriculture, as well as climate change and urban expansion. If we include livestock, more than half of Australia is now being used for farming. If we can improve farming methods, we can bring back soil biodiversity – and use it to produce healthy crops.

Why Does It Matter If We Lose Soil Microbial Diversity?

Australia has many different soil types. Images of each state’s iconic soil demonstrates how much they can differ. Importantly, soils differ greatly in their ability to support industrial crop production. Much of Australia is not naturally suited to this.

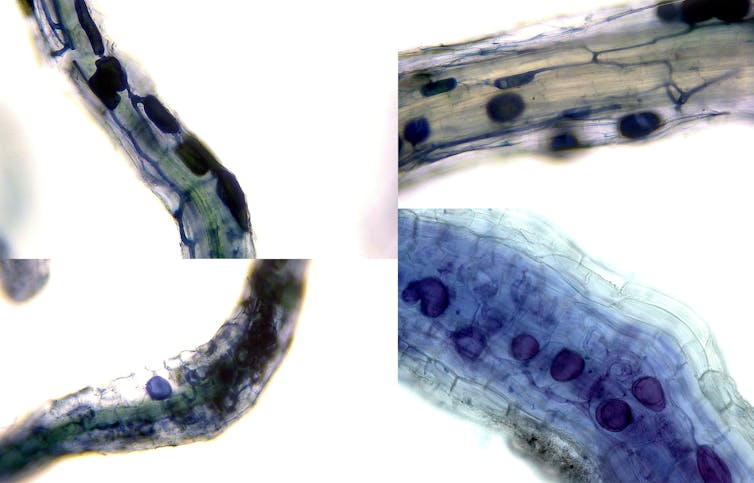

Some intensive farming methods like ploughing, irrigation and the use of fertilisers and pesticides are particularly damaging to the life in our soils. We know these practices reduce the abundance and diversity of a particularly important group of microorganisms, known as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi spread out into vast fungal networks below ground, and colonise the root systems of plants in a symbiotic relationship.

When you look at a field of corn or wheat, you might think all the action is above ground. But what happens in the soil is vital. The plants we rely on to survive rely in turn on strong relationships with these underground fungal networks.

Soil fungi can boost plant uptake of key resources like phosphorus and water and can even improve how plants resist pests. These fungi are also critical to the cycling of nutrients and carbon in our environment, and the networks they form give structure to soil. These relationships go back much further than humans do. Plants and fungi have been cooperating for hundreds of millions of years.

Despite breaking up this relationship in our agriculture, we have achieved ever-increasing yields.

That’s because most crop and pasture production relies on various fertilisers and pesticides for crop nutrition and pest control, rather than fungal networks or soil biology. The continued development of these fertilisers and pesticides have undoubtedly enhanced crop production and allowed millions of people to escape hunger and poverty.

The problem is, relying on pesticides and fertilisers is not sustainable. Many pesticides are under increasing restrictions or bans, and phosphorus fertiliser will only become more expensive as we deplete global phosphate reserves. Critically, their excessive use negatively impacts soil biology and the environment.

If we reduce the diversity of fungi in our soils, we lose the benefits they provide to healthy ecosystems – and to our crops. A soil with less biodiversity erodes more easily, loses its stored carbon quicker and causes disrupted nutrient cycles.

Can We Protect Our Soil Fungi?

Yes – if we change how we manage our soils. By working with our living soils rather than against them, we can meet increasing demand for food and keep farms economically viable.

As you might expect, organic and conservation farming is less damaging to soil fungi compared to conventional farming, due to their limited use of certain fertilisers and most pesticides.

These approaches also involve less ploughing or tilling of the soil, which lets fungal networks remain intact and so benefitting soil structure. This can promote plant protection from pests, and this soil biodiversity also keeps disease-causing microbes in check.

Clearly, changes to our agriculture can’t happen overnight. Sri Lanka’s sudden ban on synthetic fertilisers and pesticides in 2021 caused chaos in their farming sector and continues to threaten their food security. Widespread adoption of more sustainable farming techniques in Australia must be done gradually, with support and incentives from industry and government. But it will have to happen. The status quo can’t last, as our soils continue to deteriorate and fertilisers and pesticides become more expensive and unavailable.

To Care For Our Soils, We Need To Know More About Them

While we know the life permeating our soils is in trouble, we need to know more. One important finding from the State of the Environment report was the need for more data on the biology of our soil to aid sustainable land use.

Why? To date, most of our understanding of how farming impacts soil fungal diversity is based on overseas research. Despite the ecological importance of these microbiota and their potential to accelerate sustainable food production, we still don’t have a clear picture of what’s underneath our fields. For a start, we need to know what mycorrhizal fungi live where.

To overcome this challenge, we have launched Dig Up Dirt, a new nationwide research project designed to let us take stock of our beneficial soil fungi.

Farmers, land managers and citizen scientists can send us soil samples to allow us to map Australia’s networks of soil fungi. The data we collect will also be fed into the international efforts to map fungi globally.

This is a long-overdue step towards learning to work with soil fungi to benefit agriculture – while conserving the life below our feet.![]()

Adam Frew, Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, University of Southern Queensland; Christina Birnbaum, Lecturer, University of Southern Queensland; Eleonora Egidi, Researcher, Western Sydney University, and Meike Katharina Heuck, PhD Candidate, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Artificial light at night can change the behaviour of all animals, not just humans

As the Moon rises on a warm evening in early summer, thousands of baby turtles emerge and begin their precarious journey towards the ocean, while millions of moths and fireflies take to the air to begin the complex process of finding a mate.

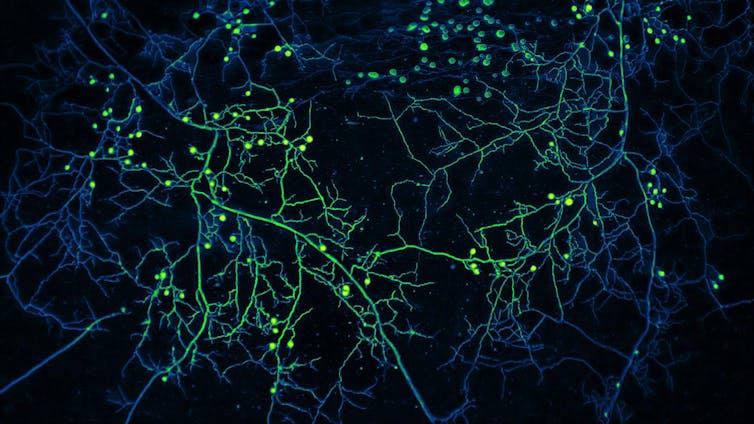

These nocturnal behaviours, and many others like it, evolved to take advantage of the darkness of night. Yet today, they are under a increasing threat from the presence of artificial lighting.

At its core, artificial light at night (such as from street lights) masks natural light cycles. Its presence blurs the transition from day to night and can dampen the natural cycle of the Moon. Increasingly, we are realising this has dramatic physiological and behavioural consequences, including altering hormones associated with day-night cycles of some species and their seasonal reproduction, and changing the timing of daily activities such as sleeping, foraging or mating.

The increasing intensity and spread of artificial light at night (estimates suggest 2-6% per year) makes it one of the fastest-growing global pollutants. Its presence has been linked to changes in the structure of animal communities and declines in biodiversity.

How Animals Are Affected By Artificial Lighting

Light at night can both attract and repel. Animals living alongside urban environments are often attracted to artificial lights. Turtles can turn away from the safety of the oceans and head inland, where they may be run over by a vehicle or drown in a swimming pool. Thousands of moths and other invertebrates become trapped and disoriented around urban lights until they drop to the ground or die without ever finding a mate. Female fireflies produce bioluminescent signals to attract a mate, but this light can’t compete with street lighting, so they too may fail to reproduce.

Each year it is estimated millions of birds are harmed or killed because they are trapped in the beams of bright urban lights. They are disoriented and slam into brightly lit structures, or are drawn away from their natural migration pathways into urban environments with limited resources and food, and more predators.

Other animals, such as bats and small mammals, shy away from lights or may avoid them altogether. This effectively reduces the habitats and resources available for them to live and reproduce. For these species, street lighting is a form of habitat destruction, where a light rather than a road (or perhaps both) cuts through the darkness required for their natural habitat. Unlike humans, who can return to their home and block out the lights, wildlife may have no option but to leave.

For some species, light at night does provide some benefits. Species that are typically only active during the day can extend their foraging time. Nocturnal spiders and geckos frequent areas around lights because they can feast on the multitude of insects they attract. However, while these species may gain on the surface, this doesn’t mean there are no hidden costs. Research with insects and spiders suggests exposure to light at night can affect immune function and health and alter their growth, development and number of offspring.

How Can We Fix This?

There are some real-world examples of effective mitigation strategies. In Florida, many urban beaches use amber-coloured lights (which are less attractive to turtles) and turn off street lights during the turtle nesting season. On Philip Island, Victoria, home to more than a million short-tailed shearwaters, many new street lights are also amber and are turned off along known migration pathways during the fledging period to reduce deaths.

In New York, the Tribute in Light (which consists of 88 vertical searchlights that can be seen nearly 100km away) is turned off for 20-minute periods to allow disoriented birds (and bats) to escape and to reduce the attraction of the structure to migrating animals.

In all cases, these strategies have reduced the ecological impact of night lighting and saved the lives of countless animals.

However, while these targeted measures are effective, they do not solve what might be yet another global biodiversity crisis. Many countries have outdoor lighting standards, and several independent guidelines have been written but these are not always enforceable and often open to interpretation.

As an individual there are things you can do to help, such as:

default to darkness: only light areas for a specific purpose

embrace technology: use sensors and dimmers to manage lighting frequency and intensity

location, location, location: keep lights close to the ground, shield at the rear, and direct light below the horizontal

respect the spectrum: choose low-intensity lights that limit the blue, violet and ultraviolet wavelengths. Wildlife is less sensitive to red, orange and amber light

all that glitters: choose non-reflective finishes for your home. This reduces the scattered light that contributes to sky glow.

In one sense, light pollution is relatively easy to fix – we can simply not turn on the lights and allow the night to be illuminated naturally by moonlight.

Logistically, this is mostly not feasible as lights are deployed for the benefit of humans who are often reluctant to give them up. However, while artificial light allows humans to exploit the night for work, leisure and play, in doing so we catastrophically change the environment for many other species.

In the absence of turning off the lights, there are other management approaches we can take to mitigate their impact. We can limit their number; reduce their intensity and the time they are on; and, potentially change their colour. Animal species differ in their sensitivity to different colours of light and research suggests some colours (ambers and reds) may be less harmful than the blue-rich white lights becoming commonplace around the world.![]()

Therésa Jones, Associate Professor in Evolution and Behaviour, The University of Melbourne and Kathryn McNamara, Post-doctoral research associate, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How likely would Britain’s 40°C heatwave have been without climate change?

Every heatwave occurring today is made more likely and intense by human-caused climate change. Early estimates by the UK Met Office suggest that days over 40°C have become ten times more likely to happen in the UK as a result of the rising global temperature.

But even this may be a significant underestimate, as models have underrated increases in the occurrence of extreme heat events before. And we know that climate change has increased the likelihood of new high-temperature records more than any other extreme weather phenomenon.

July 2022 would have had a few hot days without climate change. But with it, those days were several degrees hotter, which brought 40°C within reach for England for the first time.

Not-So-Great British Bake Off

The heatwave was caused by a low pressure system over the North Atlantic that produced a slingshot effect, firing a plume of hot, dry Saharan air northwards. With little moisture to evaporate and no clouds to block the sun’s rays, the land baked.

There is growing evidence to suggest that these hot weather-generating pressure systems are becoming more frequent for Europe. But even if they continued occurring at the same rate, the air itself is certainly getting hotter.

On a warming planet everywhere gets hotter, but not at the same rate. The land heats up faster than the ocean, especially the driest areas such as the Sahara. The approximately 1.2°C of global warming already experienced has added at least 2°C onto the average UK heatwave day, and even more on to night-time temperatures.

The UK is not prepared for these Mediterranean temperatures. Buildings are poorly insulated and lack air conditioning. Much of the infrastructure cannot cope: train lines are built from steel that is only stress-tested to 27°C. Beyond that, the lines are prone to buckling.

Extreme heat is a killer. Heatwaves in Europe in 2003 and in western Russia in 2010 killed around 70,000 and 55,000 people respectively – two of the deadliest weather disasters in history.

Extremely high temperatures are especially dangerous for the elderly, those with chronic medical conditions, people in cities and pets. That’s partly because it takes a heavy toll on the heart and lungs, especially when a warm night offers little respite. And partly because hot, stagnant air concentrates dangerous pollution like ozone, especially in cities.

Nearly 2,000 excess deaths have already been reported from the beginning of the mid-July heatwave in Spain and Portugal, which also experienced this Saharan plume of hot air. For every person killed, several more require hospital treatment for heat-related illness.

Heat On The Rise

An international team of attribution scientists has conducted several studies on recent heatwaves. The March-May 2022 heatwave in India and Pakistan, which destroyed much of the wheat harvest and is contributing, alongside the Ukraine conflict, to global food price rises, was made 30 times more likely by climate change. Canada’s extreme heat in June 2021 and Siberia’s high temperatures in the first half of 2020 each would have been virtually impossible without it.

The recent heatwave was relatively short, but it was also widespread across western Europe, and very intense. We are confident that climate change made it much more likely because the event stands out in bold against natural variation in the climate, which normally averages out to be unremarkable over such a wide area.

Though there aren’t yet estimates, we know that disruption to travel and the slowing down of work during the heatwave cost European economies dearly. Unprecedented water demand put a heavy strain on systems already running dry. A combination of extreme heat and dryness created exceptional conditions for wildfires to spread rapidly.

This released carbon held in vegetation, warming the planet further. The resulting smoke is also toxic. As the days and nights were several degrees hotter, the effect of climate change cost society on all of these fronts.

The amount by which previous temperature records were smashed is directly linked to the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. The faster carbon dioxide (CO₂) is dumped into the atmosphere, the faster the planet warms and the more regularly new records will be exceeded.

While this crisis plays out, the contest to replace Boris Johnson as Conservative Party leader and UK prime minister has barely covered climate change, and former contenders even pledged to scrap the country’s commitment to reach net zero by 2050.

This is the opposite of what is needed to prevent heatwaves becoming ever hotter and deadlier, which can only be achieved by urgently reducing long-lived greenhouse gas emissions such as CO₂ to zero. Economists widely favour action on climate change as a far cheaper alternative to enduring broken weather records year after year.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Ben Clarke, DPhil Candidate in Environmental Research, University of Oxford; Friederike Otto, Associate Director, Environmental Change Institute, Imperial College London, and Luke Harrington, Senior Lecturer in Climate Change, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New research in Arnhem Land reveals why institutional fire management is inferior to cultural burning

David Bowman, University of Tasmania; Christopher I. Roos, Southern Methodist University, and Fay Johnston, University of TasmaniaOne of the conclusions of this week’s shocking State of the Environment report is that climate change is lengthening Australia’s bushfire seasons and raising the number of days with a fire danger rating of “very high” or above. In New South Wales, for example, the season now extends to almost eight months.

It has never been more important for institutional bushfire management programs to apply the principles and practices of Indigenous fire management, or “cultural burning”. As the report notes, cultural burning reduces the risk of bushfires, supports habitat and improves Indigenous wellbeing. And yet, the report finds:

with significant funding gaps, tenure impediments and policy barriers, Indigenous cultural burning remains underused – it is currently applied over less than 1% of the land area of Australia’s south‐eastern states and territory.

Our recent research in Scientific Reports specifically addressed the question: how do the environmental outcomes from cultural burning compare to mainstream bushfire management practices?

Using the stone country of the Arnhem Land Plateau as a case study, we reveal why institutional fire management is inferior to cultural burning.