inbox and environment news: Issue 549

August 7 - 13, 2022: Issue 549

Newport Coastal Erosion

Why Trees?

Magpie Breeding Season: Avoid The Swoop!

- Try to avoid the area. Do not go back after being swooped. Australian magpies are very intelligent and have a great memory. They will target the same people if you persist on entering their nesting area.

- Be aware of where the bird is. Most will usually swoop from behind. They are much less likely to target you if they think they are being watched. Try drawing eyes on the back of a helmet or hat. You can also hold a long stick in the air to deter swooping.

- Keep calm and do not panic. Walk away quickly but do not run. Running seems to make birds swoop more. Be careful to keep a look out for swooping birds and if you are really concerned, place your folded arms above your head to protect your head and eyes.

- If you are on your bicycle or horse, dismount. Bicycles can irritate the birds and the major cause of accidents following an encounter with a swooping bird, is falling from a bicycle. Calmly walk your bike/horse out of the nesting territory.

- Never harass or provoke nesting birds. A harassed bird will distrust you and as they have a great memory this will ultimately make you a bigger target in future. Do not throw anything at a bird or nest, and never climb a tree and try to remove eggs or chicks.

- Teach children what to do. It is important that children understand and respect native birds. Educating them about the birds and what they can do to avoid being swooped will help them keep calm if they are targeted. Its important children learn to protect their face.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

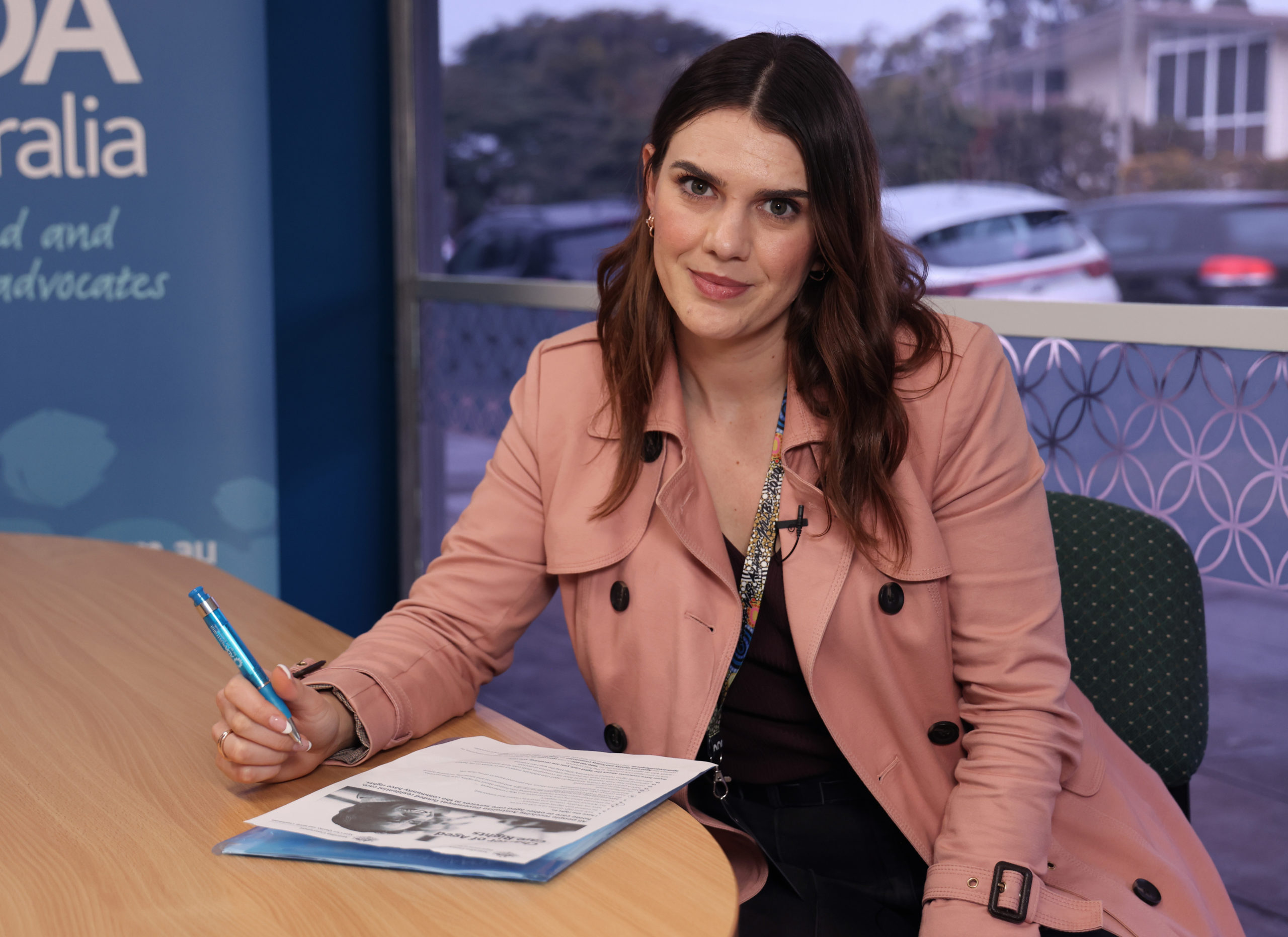

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Release Of Second Water For The Environment Special Account (WESA) Report

“It is not possible to reach the 450 GL target through the current efficiency measures program – the Off Farm Efficiency Program – even if the WESA’s time and budget limits were removed.”“Putting aside program and timing limitations, the estimated cost to recover the full 450GL through [only] efficiency measures is between $3.4 billion and $10.8 billion.”''Only 2.6 GL has been recovered or contracted to be recovered through previous efficiency measures programs.''

20,000 People Force NSW Parliament To Debate Ending Native Forest Logging

- Develop a plan to transition the native forestry industry to 100% sustainable plantations by 2024.

- In the interim, place a moratorium on public native forest logging until the regulatory framework reflects the recommendations of the leaked NRC report.

- Immediately protect high-conservation value forests through gazettal in the National Parks estate.

- Ban use of native forest materials as biomass fuel.

Government Gives Away Billions Of Litres Of Water At The Stroke Of A Pen

Water Sharing Plans: Farmers And Water Users

- by 1 September, licence holders in the Border Rivers and Gwydir valleys will have their water accounts credited and the floodplain harvesting framework will be fully operational

- licences for the Macquarie, Barwon-Darling and Namoi valleys will be determined and will come into effect later this year and in early 2023.

Communities Central To Improving Murray-Darling Basin Health

- Trialling environmental DNA technology that can tell us what fish, frogs and other animals have been active in the water, even if they’re not currently present – working with local citizens to collect water samples. This helps to track changes in biodiversity over time.

- Collecting oral histories that will capture the changes in the Basin experienced by long-term community members over time, ensuring their experiences are incorporated into future plans.

- Working with several First Nations groups to identify cultural flow requirements in the Basin.

- Building a better understanding of the economic contribution of a variety of industries including tourism & recreation and floodplain grazing.

Unlocking The Power Of Offshore Wind

- The Pacific Ocean region off the Hunter in NSW

- The Pacific Ocean region off the Illawarra in NSW

- The Southern Ocean region off Portland in Victoria

- The Bass Strait region off Northern Tasmania

- The Indian Ocean region off Perth/Bunbury, WA.

Call Out To Improve Coastal Design

Government set to legislate its 43% emissions reduction target after Greens announce support

Michelle Grattan, University of CanberraThe government is now assured it will secure its legislation to enshrine its 43% 2030 emissions reduction target, after Greens leader Adam Bandt pledged his party would support it in both houses.

The government has the numbers on its own in the House of Representatives. In the Senate, it only needs one more vote, apart from the Greens. It expects the vote of ACT crossbencher David Pocock. The bill will be voted on in the lower house this week and will go to the Senate next month.

Bandt’s announcement follows long negotiations with the government which, however, refused to budge on the minor party’s demand for a ban on new coal and gas mines.

The Greens’ decision came after it took two party room meetings to reach their position. Bandt said it was a “consensus” decision.

The government doesn’t require legislation to implement its policy, but has been anxious to put the target into law to send a strong signal including to prospective investors.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said after Bandt’s announcement that while the legislation wasn’t necessary, it “locks in” progress.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry said the announcement “is in Australia’s national interest and will provide certainty for business”.

The opposition formally decided this week to vote against the legislation.

Bandt told the National Press Club that Labor’s refusal to stop new mines was “ultimately untenable”.

He said Labor might not get a United Nations climate summit, which it will be seeking, if it was willing to allow new projects.

“We will pull every lever at our disposal,” to make a ban happen, he said.

“Labor is set to undo parliament’s work by opening new coal and gas projects, unless we stop them,” Bandt said.

“Over the next six to 12 months the battle will be fought on a number of fronts. We will comb the entire budget for any public money, any subsidies, hand outs or concessions going to coal and gas corporations and amend the budget to remove them.

"We will push to ensure the safeguard mechanism safeguards our future by stopping new coal and gas projects. We will push for a climate trigger in our environment laws.

"We will continue to fight individual projects around the country, like Beetaloo, Scarborough and Barossa. I call on all Australians to join this battle. This battle to save our country, our communities and indeed our whole civilisation from the climate and environment crisis.”

Meanwhile, one of the Liberal moderates, Warren Entsch, has given strong support to the Coalition decision to inquire into nuclear power as a potential policy. Entsch told Sky that as coal went out of the system, we had to have “something to back up” renewable alternatives.

Territories Legislation Sails Through Lower House

Legislation to allow the ACT and the Northern Territory to make laws on voluntary assisted dying has passed the House of Representatives by 99 to 37.

MPs on both sides had a conscience vote. Leader of the House Tony Burke was among several Labor members to vote against the bill, which overturns a 1997 ban on the territories legislating for euthanasia. Liberal leader Peter Dutton and Nationals leader David Littleproud were both yes votes.

The bill will go to the Senate next month, where it is expected to pass.

UPDATE On Climate Bill – Liberal To Cross Floor

Tasmanian Liberal Bridget Archer told parliament late Wednesday that she will cross the floor and vote for Labor’s climate bill.

“At the end of the day, it’s important to me that when I am back in my own community, I am able to sincerely say that I used the opportunity afforded to me with the power of my vote, to stand up for what they want and need and to move on from this debate.”

She said she had had constructive discussions with Peter Dutton “about my views and that of the party on this issue.

"While there is much we do agree on, he understands why I have made this decision.

"I have respect for him and he has my support as our party formulates our own plan to combat climate change while supporting the Australian economy.

"However, while that happens, it is important that we do move forward and act now and not delay until the eve of the next election.”![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It’s official: the Murray-Darling Basin Plan hasn’t met its promise to our precious rivers. So where to now?

A long-awaited report released on Tuesday found the amount of water promised to river environments under the Murray-Darling Basin Plan “cannot be achieved” under current settings. In short, the plan is failing on a key target.

The water is essential to protecting plants, animals and ecosystems along Australia’s most important river system.

One part of the plan stipulates that by 2024, 450 billion litres of water – a small proportion of the overall target – should be recovered and returned to rivers, wetlands and groundwater systems. This should be achieved through water efficiency programs funded by the Commonwealth.

But just two years out from the deadline, only 2.6 billion litres, or about 0.5% of this water, has actually been delivered. The findings have reignited debate about the Murray-Darling Basin – a running sore for which treatments abound, but seemingly no cure exists.

Before the May election, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese pledged to deliver the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. But yesterday’s report, prepared by independent experts, casts serious doubt on whether that promise can be kept. The basin’s focus on a sustainable future is still a way off, and only political will can fix it.

What’s This All About?

You could be forgiven for not having read Tuesday’s report, which bore the repellent title “Second review of the Water for the Environment Special Account”. It reflects the arcane and impenetrable jargon surrounding water management in the basin which hinders public understanding of this crucial policy area.

The plan involves “water recovery targets” to be met by “efficiency and constraints measures”. But what does that all mean?

Irrigators and other water users extract water from the rivers, streams and aquifers of the Murray-Darling Basin. Over the years, too much water has been extracted, which has left the basin in poor condition.

The A$13 billion Murray-Darling Basin Plan was meant to address this problem. Passed into law in 2012 under the Gillard Labor government, it promised to deliver 3,200 billion litres of water to the environment each year, by buying back water allocated to extractors and retaining it in the river system.

The goal comprised two targets for water to be delivered to the environment each year: 2,750 billion litres as soon as possible, and an additional 450 billion litres later, if it did not cause significant socio-economic impact. To do the latter, the federal government established a $1.8 billion Commonwealth fund to invest in water efficiency projects that would deliver water back to the environment.

Complicating matters, irrigators and others were opposed to water buybacks. In 2015, the Coalition government put a stop to the practice, despite its proven cost-effectiveness compared to alternatives such as subsidising dams and channels under efficiency programs.

Water savings were to come from measures such as improving water efficiency on farms, and funding irrigators to reduce evaporation from dams by building them deeper.

But engineering does not easily replace ecological complexity shaped over millennia. Making water move more quickly down a river produces casualties: the creeks and wetlands and groundwater systems that rely on it.

Major efficiency projects have been exposed as inadequte. They predominantly just move environmental water from one part of the basin to the other, at significant public cost.

So what’s the upshot of all this? According to Tuesday’s report, under current efficiency measures only 60 billion litres of water can be returned to the basin environment by 2024. What’s more, the original target of 2,750 billion litres has not yet been achieved.

Our Rivers Remain In Trouble

After all this effort and debate, the health of the Murray-Darling Basin continues to degrade.

The State of the Environment report released this month found water extraction and drought left water levels at record lows in 2019. Rivers and catchments are mostly in poor condition, and native fish populations fell by more than 90% in the past 150 years.

Who could forget the disaster of late 2018 and early 2019, when millions of fish died at Menindee Lakes? That disaster was associated with low river flows, from the drought exacerbated by over-extraction.

First Nations peoples, river communities and others that rely on healthy rivers have also borne the costs of this policy failure.

Recent rainfall and flooding has bought breathing space, but drought will return, and climate change is projected to make the basin drier.

Other factors are denying rivers the water they need. They include water theft and poor policy – such as the NSW government’s commitment to let water be harvested from floodplains, against warnings by its own advisers.

Finding Political Will

A crucial aspect not covered in the report is the lack of credible information on how much water is actually recovered by water efficiency programs. An independent audit on this is urgently needed.

And there remain opportunities to implement more efficient and cost-effective ways of recovering water for the environment. This could include buying back water from willing irrigators, while recognising the potential local economic effects.

It’s a politically difficult move – sure to attract opposition from the Nationals, as well as the NSW and Victorian governments.

But the health of the Murray-Darling Basin is essential for all Australians. As this latest report shows, our politicians must finally find the will to secure the basin’s future.![]()

Richard Kingsford, Professor, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Record coral cover doesn’t necessarily mean the Great Barrier Reef is in good health (despite what you may have heard)

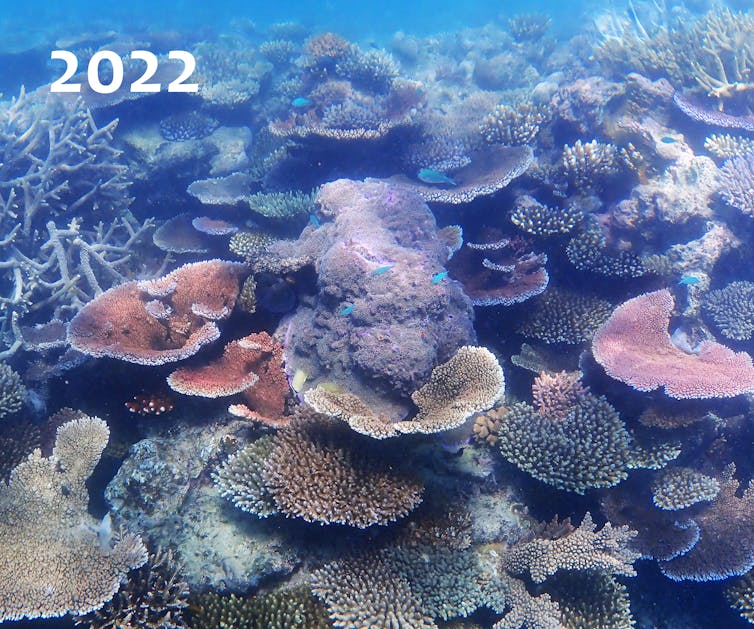

In what seems like excellent news, coral cover in parts of the Great Barrier Reef is at a record high, according to new data from the Australian Institute of Marine Science. But this doesn’t necessarily mean our beloved reef is in good health.

In the north of the reef, coral cover usually fluctuates between 20% and 30%. Currently, it’s at 36%, the highest level recorded since monitoring began more than three decades ago.

This level of coral cover comes hot off the back of a disturbing decade that saw the reef endure six mass coral bleaching events, four severe tropical cyclones, active outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish, and water quality impacts following floods. So what’s going on?

High coral cover findings can be deceptive because they can result from only a few dominant species that grow rapidly after disturbance (such as mass bleaching). These same corals, however, are extremely susceptible to disturbance and are likely to die out within a few years.

The Data Are Robust

The Great Barrier Reef spans 2,300 kilometres, comprising more than 3,000 individual reefs. It is an exceptionally diverse ecosystem that features more than 12,000 animal species, plus many thousand more species of plankton and marine flora.

The reef has been teetering on the edge of receiving an “in-danger” listing from the World Heritage Committee. And it was recently described in the State of the Environment Report as being in a poor and deteriorating state.

To protect the Great Barrier Reef, we need to routinely monitor and report on its condition. The Australian Institute of Marine Science’s long-term monitoring program has been collating and delivering this information since 1985.

Its approach involves surveying a selection of reefs that represent different habitat types (inshore, midshelf, offshore) and management zones. The latest report provides a robust and valuable synopsis of how coral cover has changed at 87 reefs across three sectors (north, central and south) over the past 36 years.

The Results

Overall, the long-term monitoring team found coral cover has increased on most reefs. The level of coral cover on reefs near Cape Grenville and Princess Charlotte Bay in the northern sector has bounced back from bleaching, with two reefs having more than 75% cover.

In the central sector, where coral cover has historically been lower than in the north and south, coral cover is now at a region-wide high, at 33%.

The southern sector has a dynamic coral cover record. In the late 1980s coral cover surpassed 40%, before dropping to a region-wide low of 12% in 2011 after Cyclone Hamish.

The region is currently experiencing outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish. And yet, coral cover in this area is still relatively high at 34%.

Based on this robust data set, which shows increases in coral cover indicative of region-wide recovery, things must be looking up for the Great Barrier Reef – right?

Are We Being Catfished By Coral Cover?

In the Australian Institute of Marine Science’s report, reef recovery relates solely to an increase in coral cover, so let’s unpack this term.

Coral cover is a broad proxy metric that indicates habitat condition. It’s relatively easy data to collect and report on, and is the most widely used monitoring metric on coral reefs.

The finding of high coral cover may signify a reef in good condition, and an increase in coral cover after disturbance may signify a recovering reef.

But in this instance, it’s more likely the reef is being dominated by only few species, as the report states that branching and plating Acropora species have driven the recovery of coral cover.

Acropora coral are renowned for a “boom and bust” life cycle. After disturbances such as a cyclone, Acropora species function as pioneers. They quickly recruit and colonise bare space, and the laterally growing plate-like species can rapidly cover large areas.

Fast-growing Acropora corals tend to dominate during the early phase of recovery after disturbances such as the recent series of mass bleaching events. However, these same corals are often susceptible to wave damage, disease or coral bleaching and tend to go bust within a few years.

Inferring that a reef has recovered by a person being towed behind a boat to obtain a rapid visual estimate of coral cover is like flying in a helicopter and saying a bushfire-hit forest has recovered because the canopy has grown back.

It provides no information about diversity, or the abundance and health of other animals and plants that live in and among the trees, or coral.

Cautious Optimism

My study, published last year, examined 44 years of coral distribution records around Jiigurru, Lizard Island, at the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef.

It suggested that 28 of 368 species of hard coral recorded at that location haven’t been seen for at least a decade, and are at risk of local extinction.

Lizard Island is one location where coral cover has rapidly increased since the devastating 2016-17 bleaching event. Yet, there is still a real risk local extinctions of coral species have occurred.

While there’s no data to prove or disprove it, it’s also probable that extinctions or local declines of coral-affiliated marine life, such as coral-eating fishes, crustaceans and molluscs have also occurred.

Without more information at the level of individual species, it is impossible to understand how much of the Great Barrier Reef has been lost, or recovered, since the last mass bleaching event.

Based on the coral cover data, it’s tempting to be optimistic. But given more frequent and severe heatwaves and cyclones are predicted in the future, it’s wise to be cautious about the reef’s perceived recovery or resilience.![]()

Zoe Richards, Senior Research Fellow, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

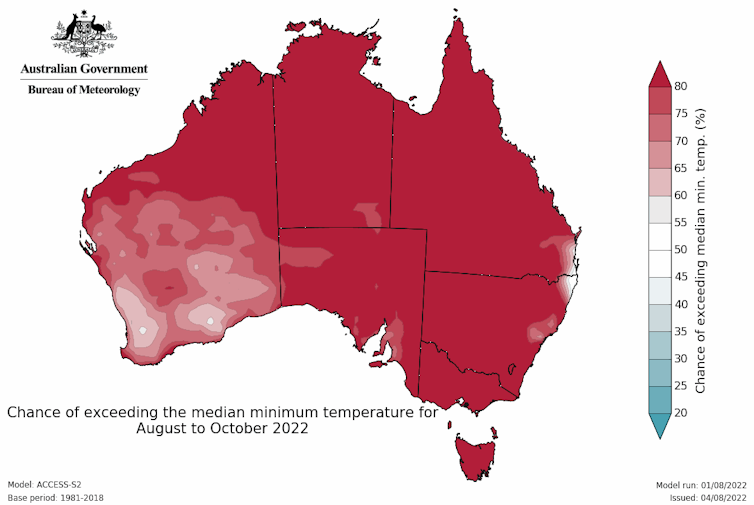

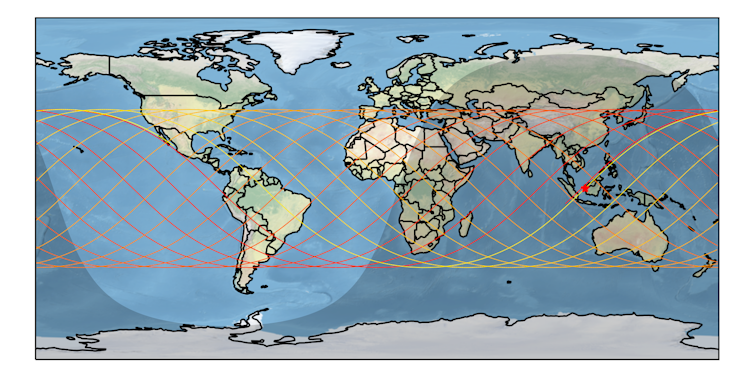

A wet spring: what is a ‘negative Indian Ocean Dipole’ and why does it mean more rain for Australia’s east?

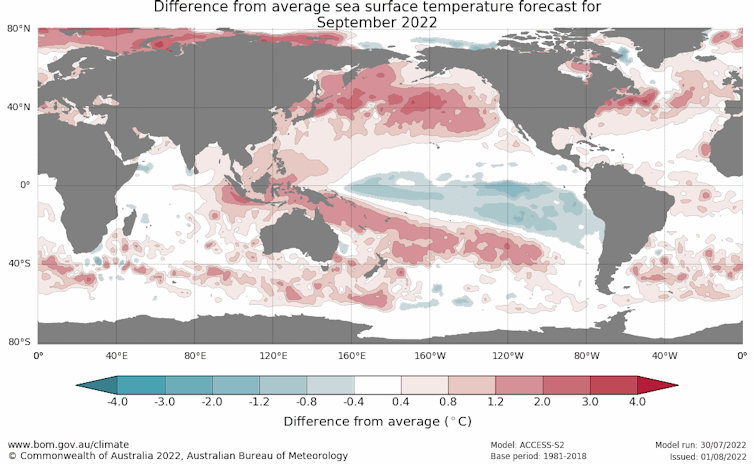

Andrew King, The University of MelbourneThe Bureau of Meteorology recently announced a negative Indian Ocean Dipole event is underway.

But what does that mean and how does it affect Australia’s weather? Will we get a reprieve from the flooding rains of recent months?

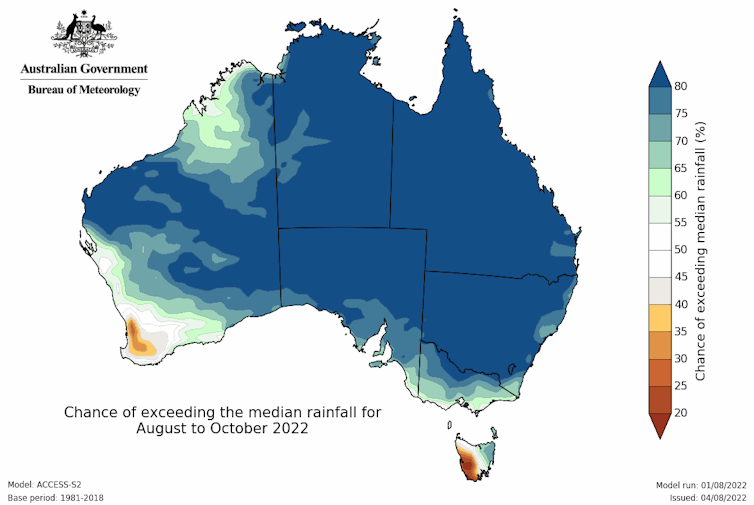

For many places across the east coast, the answer is no. Spring won’t bring a clean break from this year’s very wet winter.

Warmer Waters Around Australia Equals More Rain

The negative Indian Ocean Dipole, or IOD, has been declared because ocean temperatures are warmer in the tropical east Indian Ocean than in the west Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean Dipole is a type of year-to-year climate variability, a bit like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, but in the Indian Ocean rather than the Pacific.

Once it goes into a particular phase, it usually remains in that phase for a few months. This persistence in sea surface temperature patterns results in predictability in Australian climate conditions.

When we have negative Indian Ocean Dipole conditions we tend to see more rain over southern and eastern Australia.

The Indian Ocean Dipole relationship with Australian rainfall is strongest in September and October, so we’re likely to see wet conditions over the next few months at least.

Warm waters in the east Indian Ocean, like we’re seeing at the moment, increase the occurrence of low pressure systems over the southeast of Australia as well as the amount of moisture in the air.

This means there’s a higher likelihood of rain generally and an increased chance of extreme rain events too.

When Will The Rain Stop?

Another wet outlook is alarming for many people in eastern Australia who have suffered through wetter than normal conditions since 2020.

We’ve seen back-to-back La Niña events and a negative Indian Ocean Dipole in 2021’s winter.

The negative Indian Ocean Dipole is showing its influence in the Bureau of Meteorology’s seasonal predictions. Wetter than normal conditions are forecast for the coming months throughout the east of the continent.

This also happens to be the time of year when seasonal outlooks tend to be most skilful. In the summer, more rain falls in storms and small-scale systems that are harder to forecast well in advance. In winter and spring the outlooks tend to be a bit more accurate but are not always perfect.

Unfortunately, after two consecutive La Niña summers it is also looking increasingly likely we’ll see another La Niña form later this year.

Three La Niña events in a row is not unprecedented but it is unusual. The increased chance of another La Niña raises the odds of wetter conditions persisting for a few more months at least.

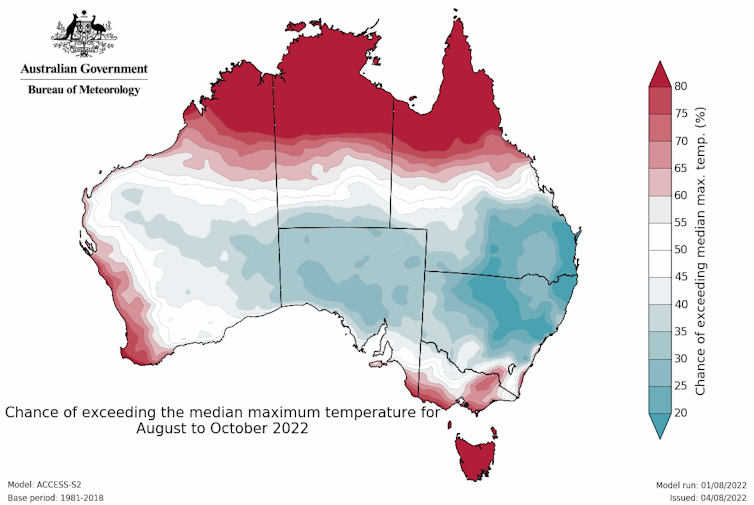

Have We Seen The End Of The Cold Weather?

We saw a cold start to winter in the southeast of Australia. Since then temperatures have been below normal across much of northern Australia.

Nationally, we had the coldest July for a decade, but in the past this would have been an unremarkable event as it was only slightly cooler than historical averages.

As we leave the coldest part of winter behind the temperatures will inevitably rise, although we could still have another cold spell.

The Bureau’s seasonal outlook suggests warmer than average daytime temperatures are likely for the north and southern coastal areas. Other areas may be cooler than normal as increased cloud cover and rain are likely to suppress temperatures.

On the other hand, minimum temperatures are likely to be above normal across the country. Increased cloud cover and rain tends to be associated with warmer nights as the cloud prevents the ground from cooling rapidly overnight. This reduces the chance of frost.

Is The Constant Rain A Result Of Climate Change?

For parts of New South Wales, the news of wet conditions being on the cards could not come at a worse time. Sydney and other areas of the eastern seaboard have already received record-breaking rain totals so far this year, including in July. Catchments remain saturated so further rainfall may well lead to more flooding.

Australia has highly variable rainfall and we have seen multi-year spells of persistent wet conditions before – notably in the mid-1970s and 2010-2012.

There isn’t a strong trend in rainfall in the areas that have been devastated by floods and it’s only three years since we saw the driest year on record in New South Wales.

The jury is still out on how climate change affects rainfall over most of Australia.

It is vital we build a better understanding of rainfall changes under global warming so we can plan better for our future climate.![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The length of Earth’s days has been mysteriously increasing, and scientists don’t know why

Atomic clocks, combined with precise astronomical measurements, have revealed that the length of a day is suddenly getting longer, and scientists don’t know why.

This has critical impacts not just on our timekeeping, but also things like GPS and other technologies that govern our modern life.

Over the past few decades, Earth’s rotation around its axis – which determines how long a day is – has been speeding up. This trend has been making our days shorter; in fact, in June 2022 we set a record for the shortest day over the past half a century or so.

But despite this record, since 2020 that steady speedup has curiously switched to a slowdown – days are getting longer again, and the reason is so far a mystery.

While the clocks in our phones indicate there are exactly 24 hours in a day, the actual time it takes for Earth to complete a single rotation varies ever so slightly. These changes occur over periods of millions of years to almost instantly – even earthquakes and storm events can play a role.

It turns out a day is very rarely exactly the magic number of 86,400 seconds.

The Ever-Changing Planet

Over millions of years, Earth’s rotation has been slowing down due to friction effects associated with the tides driven by the Moon. That process adds about about 2.3 milliseconds to the length of each day every century. A few billion years ago an Earth day was only about 19 hours.

For the past 20,000 years, another process has been working in the opposite direction, speeding up Earth’s rotation. When the last ice age ended, melting polar ice sheets reduced surface pressure, and Earth’s mantle started steadily moving toward the poles.

Just as a ballet dancer spins faster as they bring their arms toward their body – the axis around which they spin – so our planet’s spin rate increases when this mass of mantle moves closer to Earth’s axis. And this process shortens each day by about 0.6 milliseconds each century.

Over decades and longer, the connection between Earth’s interior and surface comes into play too. Major earthquakes can change the length of day, although normally by small amounts. For example, the Great Tōhoku Earthquake of 2011 in Japan, with a magnitude of 8.9, is believed to have sped up Earth’s rotation by a relatively tiny 1.8 microseconds.

Apart from these large-scale changes, over shorter periods weather and climate also have important impacts on Earth’s rotation, causing variations in both directions.

The fortnightly and monthly tidal cycles move mass around the planet, causing changes in the length of day by up to a millisecond in either direction. We can see tidal variations in length-of-day records over periods as long as 18.6 years. The movement of our atmosphere has a particularly strong effect, and ocean currents also play a role. Seasonal snow cover and rainfall, or groundwater extraction, alter things further.

Why Is Earth Suddenly Slowing Down?

Since the 1960s, when operators of radio telescopes around the planet started to devise techniques to simultaneously observe cosmic objects like quasars, we have had very precise estimates of Earth’s rate of rotation.

A comparison between these estimates and an atomic clock has revealed a seemingly ever-shortening length of day over the past few years.

But there’s a surprising reveal once we take away the rotation speed fluctuations we know happen due to the tides and seasonal effects. Despite Earth reaching its shortest day on June 29 2022, the long-term trajectory seems to have shifted from shortening to lengthening since 2020. This change is unprecedented over the past 50 years.

The reason for this change is not clear. It could be due to changes in weather systems, with back-to-back La Niña events, although these have occurred before. It could be increased melting of the ice sheets, although those have not deviated hugely from their steady rate of melt in recent years. Could it be related to the huge volcano explosion in Tonga injecting huge amounts of water into the atmosphere? Probably not, given that occurred in January 2022.

Scientists have speculated this recent, mysterious change in the planet’s rotational speed is related to a phenomenon called the “Chandler wobble” – a small deviation in Earth’s rotation axis with a period of about 430 days. Observations from radio telescopes also show that the wobble has diminished in recent years; the two may be linked.

One final possibility, which we think is plausible, is that nothing specific has changed inside or around Earth. It could just be long-term tidal effects working in parallel with other periodic processes to produce a temporary change in Earth’s rotation rate.

Do We Need A ‘Negative Leap Second’?

Precisely understanding Earth’s rotation rate is crucial for a host of applications – navigation systems such as GPS wouldn’t work without it. Also, every few years timekeepers insert leap seconds into our official timescales to make sure they don’t drift out of sync with our planet.

If Earth were to shift to even longer days, we may need to incorporate a “negative leap second” – this would be unprecedented, and may break the internet.

The need for negative leap seconds is regarded as unlikely right now. For now, we can welcome the news that – at least for a while – we all have a few extra milliseconds each day.![]()

Matt King, Director of the ARC Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science, University of Tasmania and Christopher Watson, Senior Lecturer, School of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Business can no longer ignore extreme heat events – it’s becoming a danger to the bottom line

When record-breaking heatwaves cause train tracks to bend, airport runways to buckle, and roads to melt, as happened in the United Kingdom last month, it is likely that business performance will suffer.

The problem is not going away, either. Businesses will need to better manage extreme heat risk. But are investors sufficiently informed on the economic toll caused by the increasing frequency of extreme weather?

It is becoming clearer that extreme heat can have devastating and costly effects. People are dying, energy grids are struggling to cope, transport is disrupted, and severe drought is straining agriculture and water reserves.

While the frequency of these events is increasing, more worrisome is that heat intensity is also increasing. Clearly, businesses are not immune to the need to adapt, though their silence might make you think otherwise.

Rising Temperatures Affect Everything

Keeping cool, transporting goods, and scheduling flights as runways melted were just some of the challenges people and businesses have faced during the current European summer.

As it became apparent that our workplaces and infrastructure might not be able to cope with extreme heat, we also saw unions call for workers to stay home. But could workers take the day off? The UK’s Health and Safety Executive stated:

There is no maximum temperature for workplaces, but all workers are entitled to an environment where risks to their health and safety are properly controlled.

Are these rules sufficient in this new normal? Some EU countries already have upper limits, but many do not. The Washington Post reported US federal action might be coming due to concerns over extreme heat for workers. Mitigation of these factors will no doubt be costly.

While media reports highlight the toll on workers and businesses, there is little empirical evidence on the financial hit to business. Here is where our research comes into play: how much of an impact does extreme heat have on business profitability?

Heat Hitting The Bottom Line

We focused on the European Union and the UK because the region has a diversity of climate and weather extremes. They are a major economic force, with strong policies on decarbonising their economies, but also rely on coal, gas, and oil for many sectors.

When it’s hot, these countries are forced to burn more fossil fuel to cool overheated populations, contrary to the need and desire to do the opposite.

With detailed records on heat events at a local level, we connected weather data to a large sample of private and public companies in the EU and the UK. We focused on two critical aspects of a firm’s financial performance around a heat spell (at least three consecutive days of excessive heat): the effect on profit margin and the impact on sales. We also examined firms’ stock performance.

We found that businesses do suffer financially, and the effects are wide ranging.

For the average business in our sample, these impacts translate into an annualised loss of sales of about 0.63% and a profit margin decrease of approximately 0.16% for a one degree increase in temperature above a critical level of about 25C.

Aggregated for all firms in our sample, UK and EU businesses lose almost US$614 million (NZ$975 million) in annual sales for every additional degree of excessive temperature.

Impact Bigger Than The Data Shows

We also found the intensity of a heat wave is more important than its duration.

This financial effect might sound small, but remember, this is an average effect across the EU and the UK. The localised effect is much larger for some firms, especially those in more southern latitudes.

The stock market response to extreme heat is also muted, perhaps for the same reason. We find stock prices on average dropped by about 22 basis points in response to a heat spell.

These average annualised effects include businesses’ efforts to recoup lost sales during heat spells. They also include businesses in certain sectors and regions that appear to benefit from critically high heat spell temperatures, such as power companies and firms in northern European countries.

While we show a systematic and robust result, our evidence probably further underestimates the total effects of heat waves. That’s because businesses disclose very little about those effects due to lax disclosure rules and stock exchange regulations relating to extreme weather.

Financial Data Part Of Climate Change

Without a doubt, better disclosure will help untangle these effects.

Ideally, financial data needs to be segmented by climate risk and extreme heat dimensions so investors are better able to price the risk. Regulators need to pay attention here. Investors must be able to price material risk from extreme weather.

A good example is New Zealand, which is about to mandate climate risk disclosures with reporting periods starting in 2023. Such mandates recognise that poor disclosure of climate risk is endemic, and we don’t have the luxury of time.

For those businesses negatively affected, disclosing the number and cost of lost hours and the location of the damage would be helpful. However, it is not yet clear if climate disclosure standards effectively capture these risks, as companies have significant discretion about what to disclose.

It is not necessarily all about cost – some sectors might even benefit. While power companies, for example, might report increased sales from increased energy consumption, they are also constrained by the grid and the increased cost of production.

And our evidence suggests there is little overall benefit to the energy sector. This doesn’t rule out some windfall profits, so we need to understand more about both the positive and negative effects on each industry.

Finally, this July saw temperatures in the United Kingdom soar to 20C above normal. Can businesses cope? Next time you feel the heat, pause to ask if this is also hitting the bottom line of your workplace or investment portfolio.![]()

David Lont, Professor of Accounting and Finance, University of Otago; Martien Lubberink, Associate Professor of Economics, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington, and Paul Griffin, Distinguished Professor of Management, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Good news: highway underpasses for wildlife actually work

Australia’s wildlife is increasingly threatened with extinction. One key driver of this is habitat clearing and fragmentation. An associated factor is the expansion of our road network, particularly the upgrade and duplication of our highways.

Governments expand our major highways in the interests of road safety and traffic flow. But major roads become barriers to wildlife movement, as well as places where cars can hit and kill many animals.

Our new research explores whether highway underpasses help animals safely cross roads. We wanted to know if animals actually use underpasses – and if they had hidden dangers by funnelling animals through a confined space, making it easier for predators.

What Did We Find?

To find out whether underpasses work, we used wildlife cameras to monitor 12 underpasses for more than two years in north-east New South Wales. Five under the Oxley Highway at Port Macquarie and seven under the Pacific Highway south of Grafton.

What we found was quite astounding. Vastly more animals than we expected were using the underpass. We detected over 4,800 medium-large mammals and goannas, while smaller species such as snakes and rodents also used the underpasses but were less reliably detected by our cameras.

Species such as eastern grey kangaroos, swamp wallabies, red-necked wallabies, red-necked pademelons and lace monitors crossed some underpasses more than once a week. Rufous bettongs and echidnas crossed individual underpasses every two to four weeks. These crossing rates suggest animals use underpasses to forage on both sides of the freeways.

We were particularly interested in whether the endangered koala would use the underpasses. They did, occasionally. We found they were not avoiding the underpasses, because they were detected infrequently in the adjoining forest.

Do underpasses with fences reduce or eliminate wildlife roadkill? Anecdotal evidence for our study road at Port Macquarie suggested roadkill rates were very low. Only four roadkills (two eastern grey kangaroos, one red-necked wallaby and one brushtail possum) were reported to the local animal welfare group for this road segment over a three year period encompassing our study. However, we should not be complacent. Roadside fences develop holes and need to be repaired to maintain their value.

Do Underpasses Attract Predators?

Many people believe underpasses increase predator risk. This idea – known as the “prey-trap hypothesis” – suggests predators will be drawn to places where they can easily pick off unsuspecting animals funnelled into the confined space of an underpass.

We detected red foxes, feral cats and dingoes using these underpasses. But of these, only foxes were detected frequently enough to be a potential concern.

We tested the prey-trap hypothesis by testing three predictions. If the hypothesis was correct, foxes should be more common in the underpasses than in the forest, foxes should focus their activity at underpasses where potential prey are more abundant and the timing of use of underpasses by foxes and potential prey should coincide.

What we observed didn’t match these predictions. At Port Macquarie, foxes were detected at three underpasses, while being absent from two. Of the three underpasses used by foxes, one particularly favoured by foxes was not favoured by bandicoots and pademelons, the potential prey.

We expected to detect foxes close in time to prey detection. But on average, there was a gap of over three hours between detecting foxes and bandicoots or pademelons, and over four hours between foxes and wallabies. We also found foxes were less often detected on nights when potential prey were using the underpasses.

These observations suggest potential prey may be avoiding the underpasses when foxes are about.

What Conclusions Can We Draw?

Underpasses are a useful tool to enable wildlife to move across landscapes with roads. Not all ground-dwelling species of wildlife will find underpasses to their liking, but many do.

Could we retrofit underpasses to highways with very high roadkill rates? That depends. The conditions have to be right. For an underpass to be installed, you need the road to be adequately elevated. You also need roadside fences, to prevent animals taking the shorter but much more dangerous path across the highway. These fences don’t work if there are intersections, freeway off ramps or driveways.

What we need is to prioritise areas where underpasses are possible, where threatened species exist and roadkill rates are high. It’s very expensive to retrofit underpasses into existing roads, which is why we have to focus on priority areas.

In the future, it could be possible to use cattle-grid type structures to stop animals like koalas getting around fences and onto the roads. These are currently being trialled.

To figure out how to make underpasses even more effective, we need more publicly available research. At present, there’s a great deal of monitoring sitting in expensive but unpublished reports from consultants.

Underpasses are not a panacea for impacts on wildlife. And we shouldn’t use their effectiveness as a justification to run highways through pristine areas. They’re a tool to minimise impacts of road projects that have wide community support. ![]()

Ross Goldingay, Lecturer in Wildlife Conservation & Biology, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

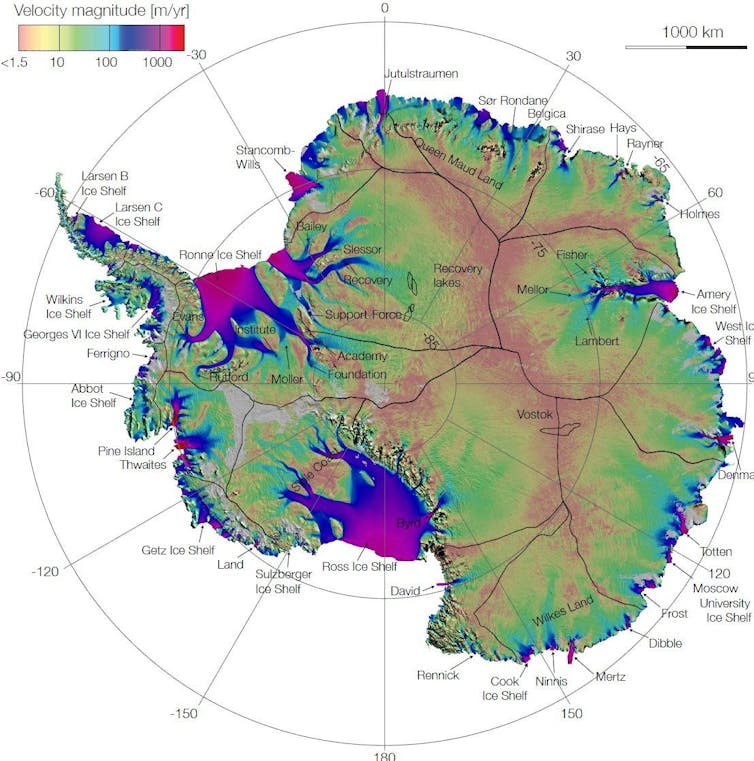

Troubling new research shows warm waters rushing towards the world’s biggest ice sheet in Antarctica

Warmer waters are flowing towards the East Antarctic ice sheet, according to our alarming new research which reveals a potential new driver of global sea-level rise.

The research, published today in Nature Climate Change, shows changing water circulation in the Southern Ocean may be compromising the stability of the East Antarctic ice sheet. The ice sheet, about the size of the United States, is the largest in the world.

The changes in water circulation are caused by shifts in wind patterns, and linked to factors including climate change. The resulting warmer waters and sea-level rise may damage marine life and threaten human coastal settlements.

Our findings underscore the urgency of limiting global warming to below 1.5℃, to avert the most catastrophic climate harms.

Ice Sheets And Climate Change

Ice sheets comprise glacial ice that has accumulated from precipitation over land. Where the sheets extend from the land and float on the ocean, they are known as ice shelves.

It’s well known that the West Antarctic ice sheet is melting and contributing to sea-level rise. But until now, far less was known about its counterpart in the east.

Our research focused offshore a region known as the Aurora Subglacial Basin in the Indian Ocean. This area of frozen sea ice forms part of the East Antarctic ice sheet.

How this basin will respond to climate change is one of the largest uncertainties in projections of sea-level rise this century. If the basin melted fully, global sea levels would rise by 5.1 metres.

Much of the basin is below sea level, making it particularly sensitive to ocean melting. That’s because deep seawater requires lower temperatures to freeze than shallower seawater.

What We Found

We examined 90 years of oceanographic observations off the Aurora Subglacial Basin. We found unequivocal ocean warming at a rate of up to 2℃ to 3℃ since the earlier half of the 20th century. This equates to 0.1℃ to 0.4℃ per decade.

The warming trend has tripled since the 1990s, reaching a rate of 0.3℃ to 0.9℃ each decade.

So how is this warming linked to climate change? The answer relates to a belt of strong westerly winds over the Southern Ocean. Since the 1960s, these winds have been moving south towards Antarctica during years when the Southern Annular Mode, a climate driver, is in a positive phase.

The phenomenon has been partly attributed to increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. As a result, westerly winds are moving closer to Antarctica in summer, bringing warm water with them.

The East Antarctic ice sheet was once thought to be relatively stable and sheltered from warming oceans. That’s in part because it’s surrounded by very cold water known as “dense shelf water”.

Part of our research focused on the Vanderford Glacier in East Antarctica. There, we observed the warm water replacing the colder dense shelf water.

The movement of warm waters towards East Antarctica is expected to worsen throughout the 21st century, further threatening the ice sheet’s stability.

Why This Matters To Marine Life

Previous work on the effects of climate change in the East Antarctic has generally assumed that warming first occurs in the ocean’s surface layers. Our findings – that deeper water is warming first – suggests a need to re-think potential impacts on marine life.

Robust assessment work is required, including investment in monitoring and modelling that can link physical change to complex ecosystem responses. This should include the possible effects of very rapid change, known as tipping points, that may mean the ocean changes far more rapidly than marine life can adapt.

East Antarctic marine ecosystems are likely to be highly vulnerable to warming waters. Antarctic krill, for example, breed by sinking eggs to deep ocean depths. Warming of deeper waters may affect the development of eggs and larvae. This in turn would affect krill populations and dependent predators such as penguins, seals and whales.

Limiting Global Warming Below 1.5℃

We hope our results will inspire global efforts to limit global warming below 1.5℃. To achieve this, global greenhouse gas emissions need to fall by around 43% by 2030 and to near zero by 2050.

Warming above 1.5℃. greatly increases the risk of destabilising the Antarctic ice sheet, leading to substantial sea-level rise.

But staying below 1.5℃ would keep sea-level rise to no more than an additional 0.5 metres by 2100. This would enable greater opportunities for people and ecosystems to adapt.![]()

Laura Herraiz Borreguero, Physical oceanographer, CSIRO; Alberto Naveira Garabato, Professor, National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton, and Jess Melbourne-Thomas, Transdisciplinary Researcher & Knowledge Broker, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Greens’ climate trigger policy could become law. Experts explain how it could help cut emissions – and why we should be cautious

Brendan Sydes, The University of Melbourne; Anita Foerster, Monash University, and Laura Schuijers, University of SydneyAustralia’s freshly elected parliament is hashing out the details of Labor’s Climate Change Bill, which would enshrine an emissions reduction target into federal law. The Greens have the numbers to block the bill in the Senate, and are likely to seek concessions from Labor in return for their support.

Labor has already ruled out the demand to ban new coal and gas projects, saying this would devastate the economy. But Labor did not rule out another Greens policy: introducing a “climate trigger” into Australia’s environment law.

Under that proposal, future projects – such as a new mine or high-emissions industrial plant – would be assessed on the climate harms they’d potentially cause.

Let’s take a closer look at how the climate trigger would work, what it would achieve and, crucially, how it could help Australia reduce emissions.

What Is The Climate Trigger?

To understand the proposed climate trigger, we should first outline the federal government’s role in assessing and approving new projects under Australia’s national environment law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

The government’s role under the act is to assess the impacts of proposed projects on “matters of national environmental significance”. There are nine designated matters, including threatened species, wetlands of international significance and world heritage sites.

If a project is likely to have a significant impact on one of these matters, then the environmental impact assessment and approval scheme is “triggered”.

Surprisingly for legislation intended to protect the environment, climate change is not presently designated as a matter of national environmental significance. This means it’s considered only indirectly, such as how climate change impacts might harm a protected wetland or a threatened species.

The proposed climate trigger would add climate change to the list, and allow it to be dealt with head on.

In practice, this means the impacts of a proposed project on the climate would be thoroughly assessed, and then weighed in the environment minister’s final decision on whether the proposal should be approved.

Past Climate Trigger Proposals

The climate trigger is not a new idea. In fact, when the EPBC Act was first introduced in 1999, the then environment minister sought to develop a greenhouse gas trigger. Nothing eventuated from that commitment.

In 2005, Anthony Albanese, then the shadow environment minister, introduced the Avoiding Dangerous Climate Change (Climate Change Trigger) Bill, but this also did not proceed.

And in 2020, the Greens introduced a climate trigger bill in the Senate which lapsed with the last parliament. The Greens’ new bill will presumably be based on this one.

Meanwhile, a major independent review of the EPBC Act in 2020 by Professor Graeme Samuel did not support a climate trigger on the basis that reducing emissions is best left to other policies and programs.

Professor Samuel did, however, say new projects should fully disclose all potential emissions as part of the assessment process. He did not elaborate on how this should be treated in approval decisions.

What Could It Achieve?

The climate trigger could be defined in terms of an emissions threshold, or by reference to emissions intensive activities, or by some combination of these. It could, for example, require any development likely to produce over 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year to be assessed under the act.

Coal mining and gas extraction are significant contributors to Australia’s domestic emissions.

Approving more of these projects will not only make it harder for Australia to meet its climate targets, but also, is completely contrary to the goals of the Paris Agreement. Limiting global warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels this century means putting a stop to new coal and gas.

Australia is the third largest exporter of fossil fuels, behind Russia and Saudi Arabia. Our fossil fuel exports account for more than double our direct emissions. Labor’s emissions reduction targets do not address these downstream emissions.

A climate trigger would see Australia stepping up to take some responsibility for the total emissions from such fossil fuel export projects, including the emissions from burning coal and gas overseas.

Even if new fossil fuel projects are given the go ahead, requiring proponents to disclose emissions through the assessment process would make it possible to regulate these emissions using conditions on approvals.

This would help to address significant problems with new mine proponents underestimating their emissions.

Depending on how it’s framed, a climate trigger could also play a role in regulating emissions from other sources, such as land clearing.

Why We Should Be Cautious

There are two reasons to be cautious about what a new climate trigger might achieve.

First, a climate trigger would require only projects which trigger the act to be assessed and a decision made on approval. This is well short of demands by Greens and others to halt new fossil fuel extraction projects.

We could expect that the climate trigger would make proponents think carefully about emissions before submitting their projects for approval. But the trigger would not of itself prevent new fossil fuel projects from being proposed and approved.

If the desired result is to stop new coal and gas, there are better and more direct ways to legislate for this result.

Second, the EPBC Act is widely acknowledged as failing to protect matters of national environmental significance. It has failed to protect threatened species, world heritage sites and internationally recognised wetlands – all of which have been “triggers” under the legislation since 1999.

Adding a new climate trigger to an already failing EPBC Act may not achieve very much without additional reforms.

This includes implementing national environmental standards, as recommended by Professor Samuel, and introducing a national Environment Protection Agency to enforce the act, as promised by the Albanese government.

Arguably, proposals for a climate trigger should be dealt with as part of this larger overhaul of the act.

Still, a climate trigger could bring some real teeth to the government’s proposed Climate Change Act, whether introduced as a stand alone amendment to the EPBC Act or as part of wider reforms expected next year.

Perhaps most importantly, a climate trigger would also be a step toward Australia recognising the global harm caused by fossil fuels extracted in Australia, and the need to take greater responsibility for deciding whether these projects should be allowed to proceed.![]()

Brendan Sydes, Honorary Senior Fellow, Melbourne Law Masters, The University of Melbourne; Anita Foerster, Associate professor, Monash University, and Laura Schuijers, Deputy Director, Australian Centre for Climate and Environmental Law and Lecturer in Law, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pacific nations are extraordinarily rich in critical minerals. But mining them may take a terrible toll

Plundering the Pacific for its rich natural resources has a long pedigree. Think of the European companies strip-mining Nauru for its phosphate and leaving behind a moonscape.

There are worrying signs history may be about to repeat, as global demand soars for minerals critical to the clean energy transition. This demand is creating pressure to extract more minerals from the sensitive lands and seabeds across the Pacific. Pacific leaders may be attracted by the prospect of royalties and economic development – but there will be a price to pay in environmental damage.

As our new research shows, this dilemma has often been ignored due to the urgency of the green transition. But if we fail to address the social and environmental costs of extraction, the transition will not be fair.

Trouble In Paradise: Climate Change And Globalisation

Nations across the Pacific now face a double threat: climate change and the consequences of extractive industries. Rising sea levels, more powerful cyclones and droughts threaten low-lying nations, while the legacy of the worst effects of global resource extraction industries lives on.

Now they face a resurgence. You might not associate the small islands of the Pacific with mining, but the region contains enormous deposits of minerals and metals needed for the global energy transition.

Under the soils of New Caledonia lie between 10 and 30 per cent of the world’s known reserves of nickel, a critical component of the lithium-ion batteries which will power electric cars and stabilise renewable-heavy grids. In Papua New Guinea and Fiji there are vast undeveloped copper reserves. It’s estimated cobalt – another key battery component – is found in the deep sea around the Pacific in quantities several times larger than land resources.

Sensing this opportunity, miners from Australia, China and elsewhere are lining up to take advantage of global demand while positioning themselves as vital contributors to climate action.

You might think this is a win-win – the world gets critical minerals, and the Pacific gets royalties. While some Pacific nations like Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia see an opportunity for economic development, the problem is that historically, many Pacific states have struggled to control the excesses of the extractive industries and convert their natural mineral wealth into broad based human development.

Yes, building low-carbon energy systems to power a low-carbon economy will require vast amounts of minerals and metals for new technologies and energy infrastructure.

But supplying these resources shouldn’t come at the expense of communities and environments.

Our research reveals that extractive projects planned or underway in the Pacific are located in some of the world’s most complex and volatile environmental, social and governance conditions in the world.

Think of the historic and current tensions in Solomon Islands or the separatist movement radicalised by mining in Papua New Guinea’s Bougainville region. Increased pressure to mine in combustible regions is risky.

Will This Place Pressure On Pacific Unity?

Pacific leaders understand these risks. At last month’s forum, they endorsed a new 30 year strategy for the Pacific, which speaks to this double bind. The strategy declares the urgent need to act on climate while also calling for careful stewardship of the region’s natural resources to boost socio-economic growth and improve the lives of their citizens.

Tourism campaigns by Pacific nations often show pictures of happy people in lush environments. But the reality is much of the region is chronically unequal.

Many Pacific leaders want development opportunities and resent being told what to do with their natural resources by the leaders of developed nations. Others, however, are concerned about the damage mining may do to their environment.

This emerging divide is why dreams of regional unity remain elusive. Despite calls for a unified Pacific voice, different leaders have very different views about mining.

In recent months, we’ve seen the Federated States of Micronesia join Samoa, Fiji and Palau in calling for a moratorium on deep sea mining, while Nauru, Tonga, Kiribati and Cook Islands have already backed seabed projects.

In February this year, Cook Islands granted three licences to explore for polymetallic nodules – lucrative lumps of multiple metals – in the seas to which they have exclusive economic rights.

You can see the appeal – an estimated 8.9 billion tons of nodules lie strewn around the ocean floor. These deposits are worth an estimated $A14.4 trillion. Trillion, not billion. This is the world’s largest and richest known resource of polymetallic nodules within a sovereign territory, and a massive share of the world’s currently known cobalt resources.

These nodules are so rich in four essential metals needed for batteries (cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese) that they are often called “a battery in a rock”.

Meanwhile the Papua New Guinean government is considering enormous new gold and copper mines which lie in ecologically and socially vulnerable areas. Locals, environmentalists and experts have already sounded warnings over a project planned at the headwaters of the untouched Sepik River. No one wants to see a repeat of the Ok Tedi mining disaster.

Similar debates are raging over whether to reopen the lucrative but disastrous Panguna copper mine on Bougainville Island, as local leaders look for ways to fund their forthcoming independence from Papua New Guinea.

Policymakers Must Pay Attention

To date, Australian policymakers have not considered the risks of huge new mining operations across the Pacific. In part, this is because some of these mines are framed as a key way to tackle climate change, the largest threat to the region.

This has to change. Action on climate change is vital – but the Pacific’s peoples must actually benefit from the mining of their resources. If this mineral rush isn’t done carefully, we could see the profits disappear overseas – and the environmental mess left behind for Pacific nations to deal with.

This challenge comes at a time of heightened geostrategic competition, as China moves into the region seeking influence and raw materials ranging from wood to fish to minerals.

If Australia’s new government is serious about using its sizeable regional influence to tackle climate change in the Pacific, it must ensure it is done justly and fairly. We must focus our policy attentions on the complicated knot of clean energy and intensified mining. ![]()

Nick Bainton, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland and Emilka Skrzypek, Senior Policy Fellow, University of St Andrews

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Laid awake and wept’: destruction of nature takes a toll on the human psyche. Here’s one way to cope

Predictions of catastrophic climate change seem endless – and already, its effects are hard to ignore. Events such as bushfires, floods and species loss generate feelings of sadness, anxiety and grief in many people. But this toll on the human psyche is often overlooked.

Our research has investigated the negative emotions that emerge in Australians in response to the destruction of nature, and how we can process them. We’ve found being in nature is crucial.

Our latest research examined an eco-tourism enterprise in Australia. There, visitors’ emotional states were often connected to nature’s cycles of decay and regeneration. As nature renews, so does human hope.

As our climate changes, humans will inhabit and know the world differently. Our findings suggest nature is both the trigger for, and answer to, the grief that will increasingly be with us.

Emotions Of Climate Distress

Our research has previously examined how acknowledging and processing emotions can help humans heal in a time of significant planetary change. This healing can often come about through social, collective approaches involving connection with the Earth’s natural systems.

Eco-tourism experiences offer opportunities to connect with nature. Our recent research examined the experiences of tourists who had recently stayed at Mount Barney Lodge in Queensland’s Scenic Rim region.

The eco-tourism business is located on Minjelha Dhagun Country, next to the World Heritage-listed Mount Barney National Park. The region was badly affected by the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-2020.

Through an online questionnaire conducted last year, we sought to understand visitors’ psychological experiences and responses while at the lodge.

Seventy-two participants were recruited via an information sheet and flyer placed in the lodge reception. The youngest was aged 18, the oldest was 78 and the average age was 46. Some 71% were female and 29% were male.

We found 78% of respondents experienced sadness, anger, anxiety and other grieving emotions in response to current pressures on the Earth’s life supporting systems.

One reflected on how they “have laid awake at night thinking about all the biodiversity loss [and] climate change and wept” and another said they felt “so sad for the animals” in the face of bushfires or urban sprawl.

Another participant spoke of their sadness following bushfires in the Snowy Mountains fires of New South Wales:

This area is where I [spent] much of my youth, so it was really sad to see it perish. I felt like I was experiencing the same hurt that the environment (trees, wildlife) was – as my memories were embedded in that location.

This response reflects how nature can give people a sense of place and identity – and how damage to that environment can erode their wellbeing.

But grief can also emerge in anticipation of a loss that has not yet occurred. One visitor told us:

When I was little, I thought of the world as kind of guaranteed – it would always be there – and having that certainty taken away […] knowing that the world might not be survivable for a lot of people by the time I’m a grown-up – it’s grief, and anger, and fear of how much grief is still to come.

Anger and frustration towards the then-federal government were also prominent. Participants spoke of a “lack of leadership” and the “government’s inability to commit to a decent climate policy”. They also expressed frustration at “business profits being put ahead of environmental protection”.

Participants also said “it feels like we can’t do anything to stop [climate change]” and “anything we do try, and change is never going to be enough”.

Healing Through Immersion In Nature

Emotions such as ecological grief and eco-anxiety are perfectly rational responses to environmental change. But we must engage with and process them if their transformative potential is to be realised.

There is increasing evidence of nature’s ability to help people sit with and process complex emotional states – improving their mood, and becoming happier and more satisfied with life.

Participants in our study described how being in natural areas such as Mount Barney helped them deal with heavy emotions triggered by nature’s demise.

Participants were variously “retreating to nature as much as possible”, “appreciating the bush more” and “spending as much time outside [so] that I can hear trees, plants, and animals”.

Participants explained how “being in nature is important to mental wellbeing”, is “healing and rejuvenating” and “always gives me a sense of spiritual coherence and connection with the natural world”.

For some, this rejuvenation is what’s needed to continue fighting. One participant said:

If we don’t see the places, we forget what we’re fighting for, and we’re more likely to get burned out trying to protect the world.

Similarly, one participant spoke of observing the resilience and healing of nature itself after devastation:

[I] find peace and some confidence in its [nature’s] ability to regenerate if given a chance.

The Call Back To Nature

Our findings suggest immersing ourselves in nature more frequently will help us process emotions linked to ecological and climate breakdown – and thus find hope.

Eco-tourism sites promote opportunities for what’s known as eutierria – a powerful state that arises when one experiences a sense of oneness and symbiosis with Earth and her life-supporting systems.

Through this powerful state, it’s possible for one to undertake the courageous acts needed to advocate on behalf of nature. This is essential for the transformations Earth desperately needs.![]()

Ross Westoby, Research Fellow, Griffith University; Karen E McNamara, Associate professor, The University of Queensland, and Rachel Clissold, Researcher, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Women are turning the tide on climate policy worldwide, and may launch a new era for Australia

Jacqueline Peel, The University of Melbourne; Annabelle Workman, The University of Melbourne; Kathryn Bowen, The University of Melbourne, and Rebekkah Markey-Towler, The University of MelbourneWhen the new federal parliament opened last week, a record number of female politicians took their seats: 38% in the House of Representatives and 57% in the Senate. This changing of the guard, with women at the forefront, brings an opportunity to accelerate Australia’s efforts on climate change.

The major parties were virtually silent on the issues of gender equity and climate change throughout the 2022 election campaign. Yet, both issues proved to be turning points for the Australian electorate.

Climate change – one of the key platforms on which the teal candidates successfully campaigned - is central to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s parliamentary agenda. A bill to enshrine a climate target into Australian law was among the first introduced to parliament last week.

Women are on the front line of climate change impacts, which makes our experiences and leadership critical at decision-making tables. From Barbados to Finland, we’ve seen women’s leadership on climate bring fair, innovative and ambitious policies. We hope a new era in Australian climate policy is upon us, too.

Women And Climate Change

Women around the world are disproportionately impacted by climate change due to existing systemic inequalities. For example in Africa, when disaster strikes, women may find it more difficult to evacuate their homes as primary caregivers, be unable to read written warnings, or be overlooked in rescue attempts in favour of men.

Australia’s experience is no exception. For example, researchers note sharp surges in domestic violence in the wake of disasters, such as bushfires.

Women also have a critical role to play in achieving ambitious and innovative climate action. As the Women’s Leadership statement at last year’s Glasgow climate summit noted:

Despite increased vulnerability to climate impacts, we recognise that women and girls have been creating and leading innovative climate solutions at all levels.

There are scores of examples of female climate leadership and the benefits that follow when women and girls are afforded the opportunity to take a lead on climate action, throughout recent history.

Notable examples include Christiana Figueres, who steered international climate negotiations to a successful outcome in 2015, with the adoption of the Paris Agreement.

Greta Thunberg’s vigil to sit outside the Swedish Parliament every Friday protesting inadequate climate action inspired a youth climate protest movement.

Other young women such as National Director of Seed Mob Amelia Telford in Australia, and Pacific Climate Warriors founding member Brianna Fruean are at the forefront of First Nations’ climate advocacy efforts.

An OECD Working Paper released this year notes that women’s participation in decision-making often leads to the development of comparatively strong and sustainable climate policies and goals.

Case in point, Finland, under leadership of progressive Prime Minister Sanna Marin, recently committed to one of the most ambitious climate targets, legislating net zero by 2035 and carbon negative by 2040.

Meanwhile, Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley aims to phase out fossil fuels by 2030 and is a passionate advocate for developing nations vulnerable to climate change.

In the private sector, women’s participation is also crucial. The OECD cites evidence that when women occupy at least 30% of board seats they bring about change to climate governance within companies.

An End To Australia’s Climate Wars?

The Australian government’s sharp focus on climate change is a far cry from the “climate wars” that have been a roadblock to meaningful climate policy in this country for the past decade.

But Australia wasn’t always a problem country in international climate negotiations. At times, we’ve been a climate leader.

Under Julia Gillard’s Labor government, for example, Australia was one of the first countries to introduce a national legislated carbon price in 2011. This changed in 2013, when the newly elected Prime Minister Tony Abbott swiftly repealed this landmark law. Almost a decade of inaction on climate change by the federal government followed.

Signs of progress on climate change began to take shape at the 2019 federal election, when conservative but green Independent MP Zali Steggall ousted Tony Abbott from his long-held seat of Warringah.

The May election then brought a teal wave of female independents, along with gains for Greens and Labor women candidates. These women – such as Kate Chaney, Zoe Daniels, Monique Ryan, Sophie Scamps, Kylea Tink, Zali Steggall and Allegra Spender – are set to play a transformative role in our politics and society.

They campaigned on a climate and integrity platform, calling for stronger 2030 climate targets, increased renewable energy generation and passing a Climate Change Act to legislate and lock in emissions reduction targets.

Labor’s Climate Change Bill was one of the first pieces of legislation to be introduced to the new parliament, and negotiations are now well underway between Labor, the Greens and the female independents to pass it.

An early success borne from these negotiations has been establishing that Labor’s current target – 43% emissions reduction by 2030 – is a floor, not a ceiling, for ambition.