inbox and environment news: Issue 550

August 14 - 20, 2022: Issue 550

Public Meeting On Northern Beaches Aboriginal Lands Approval By State Government

Bushfire Affected Species Listed As Threatened

Glossy Black-Cockatoos Added To Federal Threatened List

Vale Peter Higgins

1959–2022

Tasmanian Birdlife Cull

Careel Creek Birds Seen This Week

Magpie Breeding Season: Avoid The Swoop!

- Try to avoid the area. Do not go back after being swooped. Australian magpies are very intelligent and have a great memory. They will target the same people if you persist on entering their nesting area.

- Be aware of where the bird is. Most will usually swoop from behind. They are much less likely to target you if they think they are being watched. Try drawing eyes on the back of a helmet or hat. You can also hold a long stick in the air to deter swooping.

- Keep calm and do not panic. Walk away quickly but do not run. Running seems to make birds swoop more. Be careful to keep a look out for swooping birds and if you are really concerned, place your folded arms above your head to protect your head and eyes.

- If you are on your bicycle or horse, dismount. Bicycles can irritate the birds and the major cause of accidents following an encounter with a swooping bird, is falling from a bicycle. Calmly walk your bike/horse out of the nesting territory.

- Never harass or provoke nesting birds. A harassed bird will distrust you and as they have a great memory this will ultimately make you a bigger target in future. Do not throw anything at a bird or nest, and never climb a tree and try to remove eggs or chicks.

- Teach children what to do. It is important that children understand and respect native birds. Educating them about the birds and what they can do to avoid being swooped will help them keep calm if they are targeted. Its important children learn to protect their face.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

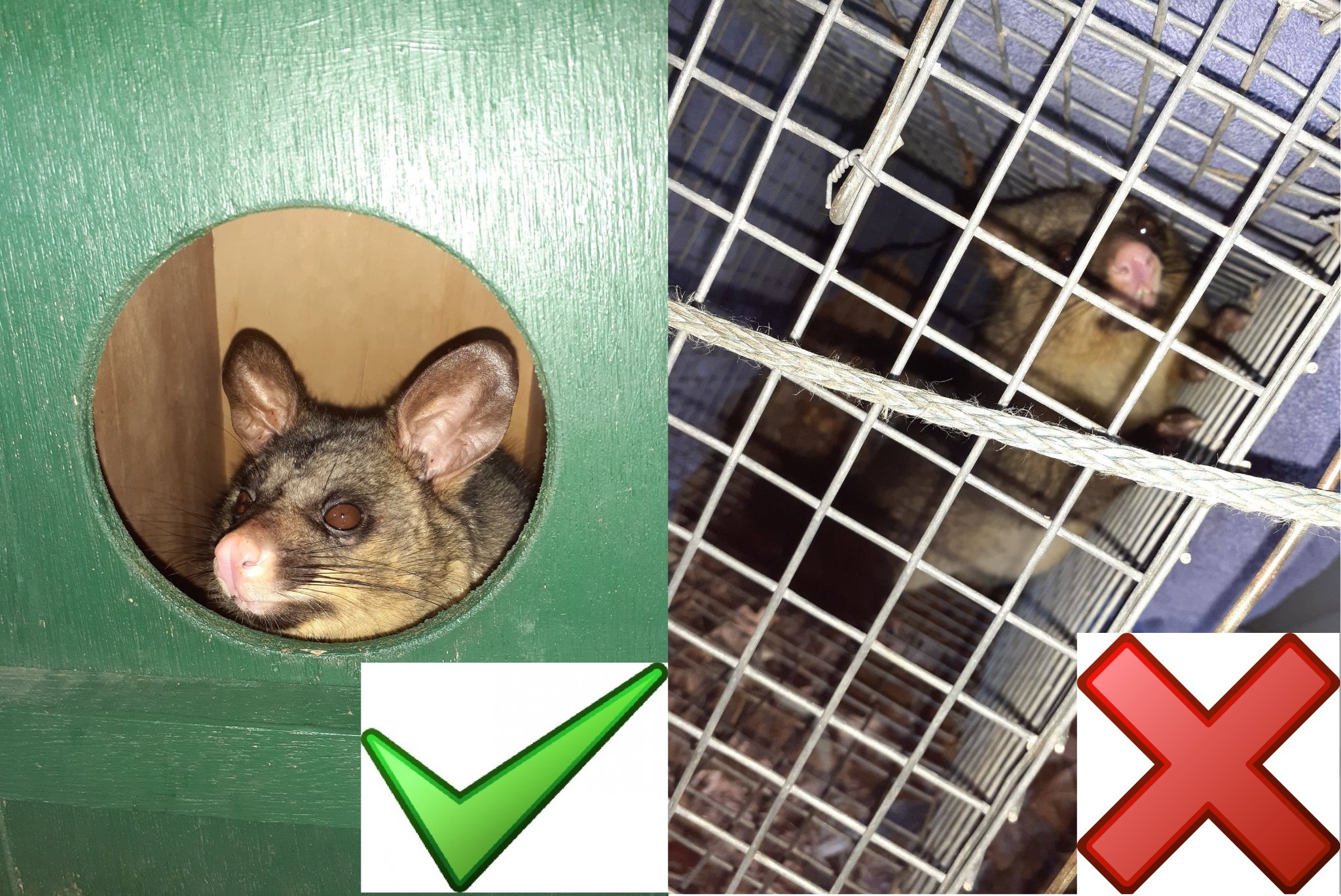

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

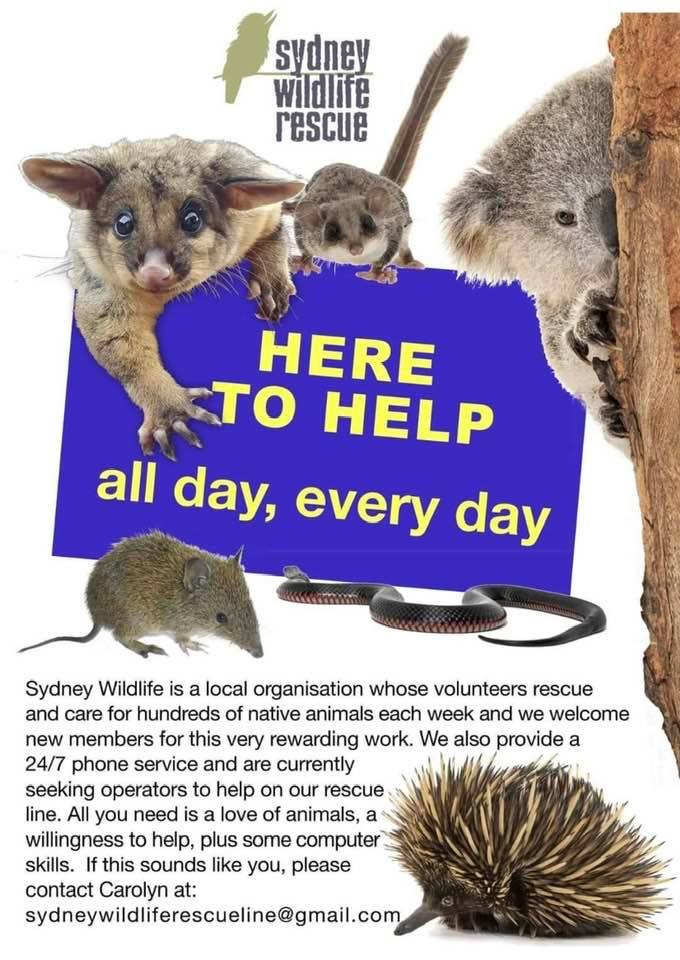

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

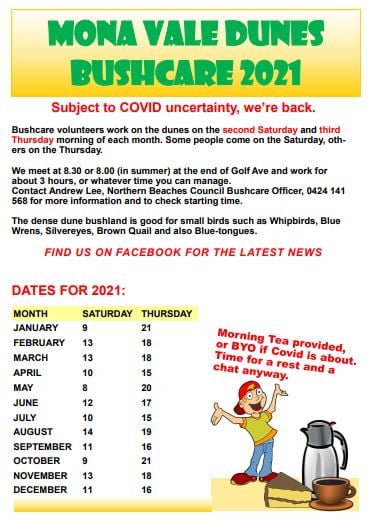

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

National Parks And Wildlife Amendment (Reservations) Bill 2022 Passes NSW Parliament

- about 23 hectares in the Blue Mountains National Park

- about 21.41 hectares in the Conjola National Park

- about 0.3 hectares in the Corramy Regional Park

- about 3.56 hectares in the Hartley Historic Site

- about 2.35 hectares in the Limeburners Creek National Park and

- about 3.68 hectares in the Parma Creek Nature Reserve

NSW Department Of Planning Announces New Chief Executive Secured For NSW Land And Housing Corporation

Applications Now Open For 2022 Gone Fishing Day Grants

Minister Officially Opens Koala Hospital

$1.27 Million To Bolster Energy Storage In The Hunter

Queensland's Renewable Energy Sector Gets $160m Boost

Santos’ Pipeline Purchase Faces Massive Hurdles As Landholders Line Up Against It

QLD Farmers Given Just Days To Respond To Massive Gas Threat

Historic new deal puts emissions reduction at the heart of Australia’s energy sector

Australia’s energy ministers on Friday voted to make emissions reduction a key national energy goal, in a major step forward in the clean energy transition.

Federal, state and territory energy ministers agreed to include emissions in what’s known as the “national energy objectives”. The objectives guide rule-making and other decisions concerning electricity, retail energy and gas.

Announcing the deal on Friday, Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen said it was the first change to the objectives in 15 years. He added:

This is important, it sends a very clear direction to our energy market operators, that they must include emissions reductions in the work that they do … Australia is determined to reduce emissions, and we welcome investment to achieve it and we will provide a stable and certain policy framework.

The agreement comes not a moment too soon. To meet Australia’s net-zero goals, variable renewable energy capacity must increase nine-fold by 2050. That means doubling Australia’s renewables capacity every decade. So let’s take a closer look at what the deal means.

Prioritising Emissions Reduction

A body called the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) makes the rules for the electricity and gas market. It must refer to the national energy objectives to guide the formation of these rules.

The exclusion of emissions from the objectives meant the commission did not have to consider the long-term climate implications of the rules it set. Instead, the objectives mostly meant the commission considered the price, quality, safety, reliability and security of energy.

This limited scope meant some investment decisions by the commission were based on short-term economic grounds. For example, these old regulations required a transmission company to maintain diesel generators rather than build a world-first clean energy mini-grid near Broken Hill, New South Wales.

Other jurisdictions worldwide already include sustainability objectives in electricity laws.

For example, a principal objective of the United Kingdom’s Electricity Act 1989 requires officials to protect the interests of existing and future consumers. The first listed priority is the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from electricity supply.

What Has Its Exclusion Meant For Projects?

The environment used to be included in the objectives, but the Howard government removed it more than two decades ago. The move was a major setback for climate action and the transition to renewable energy.

The energy market operator may consider the environmental or energy policies of participating jurisdictions to identify effects on the power system. But Friday’s deal means consideration of emissions would no longer be optional for the commission.

The traditional principles of efficiency and reliability are, of course, still crucial to energy systems. Yet, the ongoing energy crisis shows we must invest in a suite of technologies to reach net-zero goals while assuring future energy security.

Ensuring The Transition Is Fair

Including emissions in investment decisions is crucial for planning the future of the National Electricity Market. Some states are making excellent progress.

For example, New South Wales has mapped five “renewable energy zones” to replace ageing coal-fired generators. The roadmap’s objectives explicitly include improving “the affordability, reliability, security and sustainability of electricity supply”.

A successful energy transition must also consider society’s values. This includes consulting with landholders and communities about developing renewable energy projects on their land.

Making sure Australia’s transition is fair for everyone means prioritising people and their involvement. It also means getting a social licence for energy industry decisions.

The requirement to consider emissions in energy investment decisions may create further incentives for energy bodies to consider societal impacts. This is also reflected in Friday’s ministerial commitment to work on a co-designed First Nations clean energy strategy.

Considering climate impacts in energy financing and planning decisions is also crucial to the resilience of our energy systems. It will help ensure we don’t see a repeat of the Black Summer bushfires in 2019-2020, when entire sections of the national grid were destroyed.

Aligning With Our Long-Term Interests

This is a momentous period for Australia’s energy policy. The new federal government recently established Australia’s first offshore wind zone and is close to enshrining an emissions target in legislation. All this signals a long-needed embrace of the energy transition towards net zero.

This latest change increases this momentum. Importantly, it sends a direct signal for more investment net-zero technologies.

The international COP27 climate conference is due in November and Australia wants to co-host COP29 in 2024 with our Pacific Island neighbours. With that in mind, our regulation must reflect our commitment to the energy transition – and this new deal is a crucially important step.![]()

Madeline Taylor, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Beyond net-zero: we should, if we can, cool the planet back to pre-industrial levels

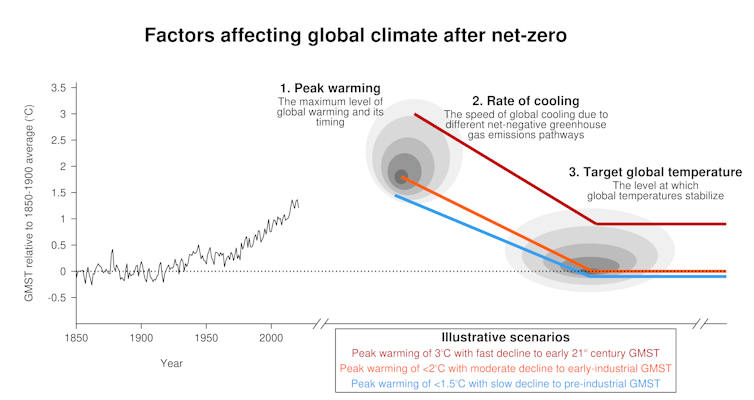

The world’s focus is sharply fixed on achieving net-zero emissions, yet surprisingly little thought has been given to what comes afterwards. In our new paper, published today in Nature Climate Change, we discuss the big unknowns in a post net-zero world.

It’s vital that we understand the consequences of our choices when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions and what comes next. The pathways we choose before and after reaching global net-zero emissions might mean the difference between a planet that remains habitable and one where many parts become inhospitable.

At the moment, human activities have a warming effect on the planet. But achieving our climate policy goals would take humanity into the uncharted territory of being able to cool the planet.

Being able to cool the planet raises a number of questions. Principally, how fast would we want the planet to cool, and what global average temperature should we aim for?

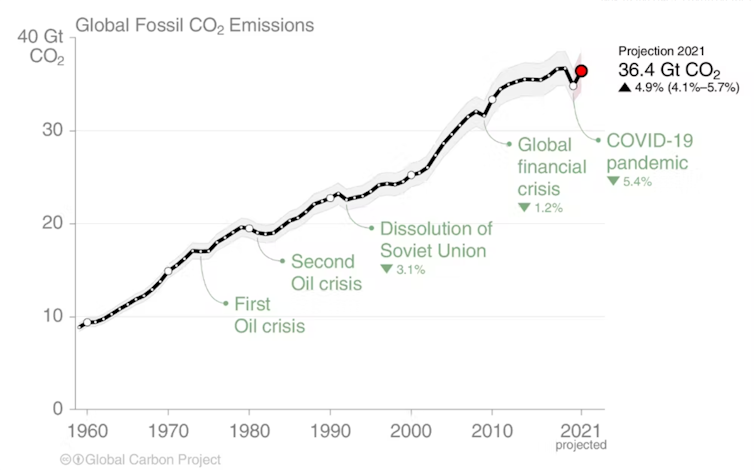

How Are Our Emissions Changing?

Our collective greenhouse gas emissions have warmed the planet about 1.2℃, relative to pre-industrial temperatures. In fact, despite all the talk about reducing emissions, global carbon dioxide emissions are at near-record levels.

Some countries have successfully reduced their greenhouse gas emissions in recent years, such as the United Kingdom which has halved greenhouse gas emissions relative to 1990.

There is also greater push from major emitters such as the United States and the European Union – as well as countries that emit less but already experience climate change impacts – to take stronger steps to limit the damage we are doing to the climate.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reaching net-zero are humanity’s greatest challenges. As long as greenhouse gas emissions remain substantially above net-zero we will continue to warm the planet.

To be in line with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to well below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels this century, we need to drastically reduce our emissions.

We also need to increase our uptake of carbon from the atmosphere through developing and implementing drawdown technology.

What Will Come After Net-Zero?

Net-zero emissions will be reached when humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere are balanced by their removal from the atmosphere. We would likely need to reach global net-zero well within the next 50 years to keep global warming well below 2℃.

If we achieve this, we could continue the process of decarbonisation to reach net-negative greenhouse gas emissions – where more of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions are removed from the atmosphere than released into it.

This would need to be achieved through a combination of “negative emissions” technologies, likely including some not invented yet, and land use changes such as reforestation.

Continued net-negative emissions will cause the planet to cool as greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere fall. This is because the greenhouse effect, where gases such as carbon dioxide absorb radiation from Earth and warm the atmosphere, would weaken.

Currently, there’s almost no focus from governments, or indeed scientists, on the consequences of meeting our policy goals and going beyond net-zero. But this would be a turning point as the world would begin to cool.

Land would cool faster than the ocean. Indeed, some people may experience substantial cooling over their lifetimes – an unfamiliar concept to grasp in our warming climate.

These changes would be accompanied by effects on weather extremes and impacts to weather and climate-sensitive industries. While there’s not much research on this yet, we could, for example, see shipping routes close up as ice regrows in polar regions.

In the long-term, the best target global temperature for the planet might be something akin to a pre-industrial climate, with the human effect on Earth’s climate receding.

In our paper we call for a new set of climate model experiments that allow us to understand the range of possible future climates after net-zero.

Any decisions must be informed by an understanding of the consequences of different choices for a post net-zero climate. For example, competing interests between countries and industries may make global agreements more challenging in a post net-zero world.

Why Does This Matter Now?

Reading this article, you may feel we’re getting ahead of ourselves. After all, as highlighted, global greenhouse gas emissions remain at near-record highs.

A key factor that will affect the behaviour of the climate system after net-zero emissions would be the maximum level of global warming that we peak at. This is dictated by our current and near-future emissions.

If we fail to meet the Paris Agreement and peak global warming reaches 2℃ or more, then future generations will endure the effects of higher sea levels and other possible disastrous climate changes for many centuries to come.

Our understanding of post net-zero impacts of different peak levels of global warming is extremely limited.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions through decarbonisation remains our key priority. The more we can suppress global warming by reaching net-zero emissions as early as possible, the more we limit potential disastrous effects and the need to cool the planet in a post net-zero world. ![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne; Celia McMichael, Senior Lecturer in Geography, The University of Melbourne; Harry McClelland, Lecturer in Geomicrobiology, The University of Melbourne; Jacqueline Peel, Director, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne; Kale Sniderman, Senior Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Kathryn Bowen, Professor - Environment, Climate and Global Health at Melbourne Climate Futures and Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, The University of Melbourne; Tilo Ziehn, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO, and Zebedee Nicholls, Research Fellow at The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

These unusual moths migrate over thousands of kilometres. We tracked them to reveal their secret navigational skills

Migratory insects number in the trillions. They’re a major part of global ecosystems, helping to transport nutrients and pollen across continents – and often travelling thousands of kilometres in the process.

It had long been thought migrating insects largely go wherever the wind blows. But there’s mounting evidence they’re actually great navigators and can select favourable conditions to undertake their journeys.

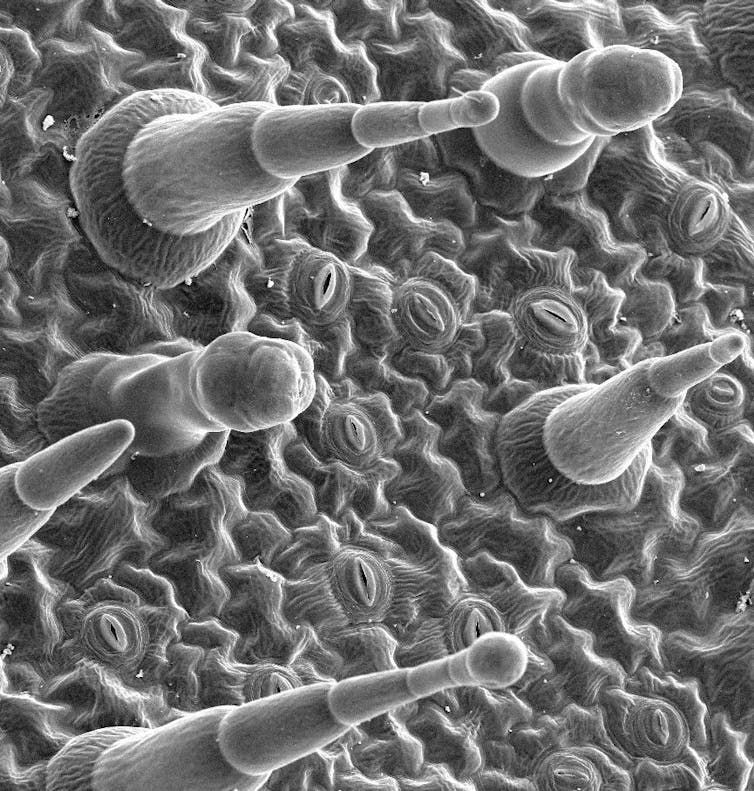

One outstanding question for experts has been how they react to varying wind conditions while en route. In research published today in Science, we show one migratory insect species, the death’s-head hawkmoth, can maintain a perfectly straight flight path. These moths are able to adjust their trajectory to compensate for rough wind conditions.

Tiny Transmitters

Much of our knowledge of insect migration comes from direct observations. These include observations made using radar, or studies of population processes, such as using genetic methods, or measuring ratios of isotopes in tissues (which can reveal insects’ food and water sources and provide information on where they come from).

How individual insects behave, and the paths they take, during migration has been relatively difficult to study, mostly due to their small size and the sheer number of them. But recent advances in tracking technology have helped produce transmitters small enough to be carried by larger insects.

These transmitters weigh less than a gram and can be attached to individual insects. This allows us to track them directly as they migrate and learn what this process involves.

Migratory Moths

Our study focused on the death’s-head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos), an enigmatic moth found in Europe and Africa. The species is well known for the unusual skull-like marking on its thorax. When disturbed, it also has the habit of squeaking and flashing its bright-yellow abdomen.

The moth feeds on honey it steals from honeybee hives, entering the hive and piercing the honeycomb with its stout proboscis (its feeding tube).

While we know this species occurs in Europe, little is understood about its migratory behaviour and where it spends the winter. Adult moths tend to appear in Europe during spring (May to June), and the next generation of adults sets out in autumn (August to October) – likely making its way to the Mediterranean or North Africa, and perhaps as far as south of the Sahara.

It’s thought the species is unable to spend winter north of the Alps, so its migration is probably driven by low temperature and resource availability.

Tracking In The Dark

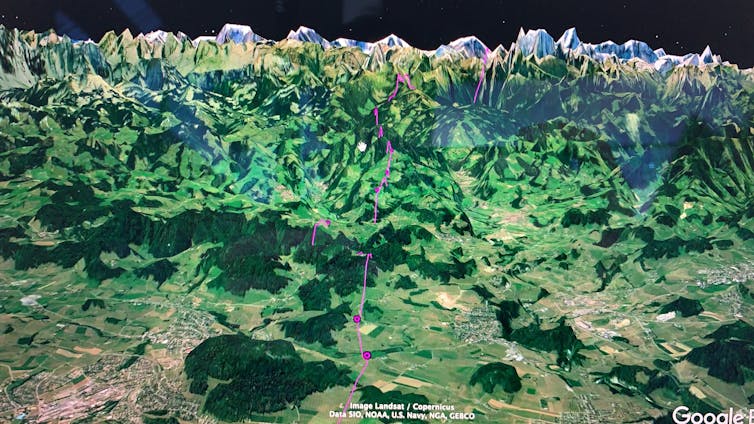

For our research, we tracked 14 moths for up to four hours each – a stretch of time long enough to be considered migratory flight.

We fitted each individual with a tiny radio transmitter, weighing less than 0.3g, before releasing them. A Cessna aeroplane with receiving antennas flew after them as they migrated, detecting their precise location every five to 15 minutes. This method gave us in-depth insight into their flight behaviour.

Radio tracking has successfully been used to investigate the migration of some day-flying insects, such as the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and green darner dragonfly (Anax junius). However, it has never been used on nocturnal insects in the wild, or at this resolution.

In fact, our research marks the longest distance any insect has ever been continuously tracked in the field.

Making A Bee-Line

So what do moths do on migration? To our surprise, we found they flew along very straight paths, effectively making a bee-line for their destination. Some of the longest tracks reached nearly 90km over a period of four hours. This is a fascinating finding as such straight tracks are very uncommon in long-range migratory animals.

The moths also showed distinct strategies to deal with different wind conditions. When there were favourable tailwinds (winds going in the same direction as them) they flew downwind and were propelled towards their destination, or offset their heading slightly to maintain control of their trajectory.

In unfavourable conditions, such as headwinds (coming from the front) and crosswinds (from the side), the moths flew low to the ground and directly into the headwinds, adjusting their trajectory to avoid drifting off course. They also increased their speed to stay in control.

This remarkable ability to stay on course, even in unfavourable conditions, indicates the death’s-head hawkmoth has sophisticated compass mechanisms.

Where To Next?

We’ve shown insects are capable of being expert navigators, on par with birds, and aren’t at the whim of the winds as we once thought. This is an important discovery in migration science.

That said, there’s still a huge amount we don’t know about how insects migrate and where they go. The next step will be to understand exactly what mechanisms these moths use to stay on their path. For instance, are they following the Earth’s magnetic field? Or perhaps relying heavily on visual cues?

The more we understand, the closer we can get to being able to predict the phenomena of insect migration. And this would have broad implications – from managing threatened species and species with agricultural benefits, to having better control over agricultural pests. ![]()

Myles Menz, Lecturer, Zoology and Ecology, James Cook University and Martin Wikelski, , Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thousands more species at risk of extinction than currently recorded, suggests new study

New research suggests the extinction crisis may be even worse than we thought. More than half of species that have so far evaded any official conservation assessment are threatened with extinction, according to predictions by researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Conservation resources are limited and it is not feasible or logical to protect every square kilometre of land and sea. So to mitigate the rapid loss of biodiversity, where should our conservation resources go? To answer this question we first need to know which species to protect.

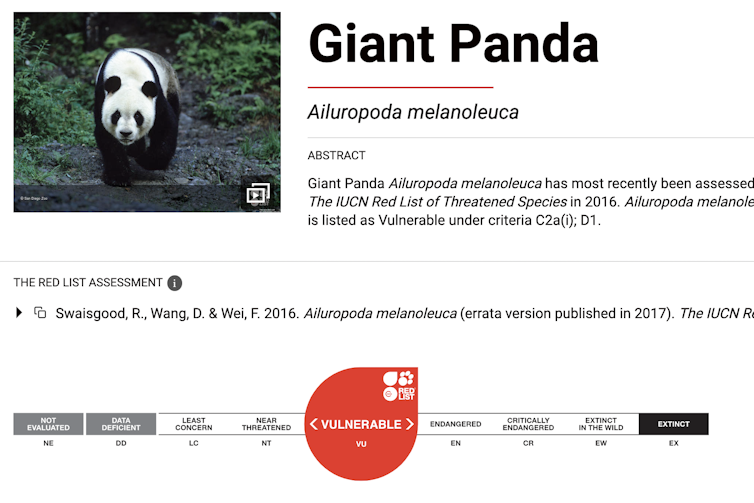

The International Union for Conservation of Nature coordinates a network of scientists who have assessed biological information available for all sorts of species worldwide for more than 50 years, publishing their findings in the Red List of Threatened Species. Its goal has been to identify species that need protection with an assigned conservation category of extinction risk.

It’s the Red List that confirmed tigers are officially endangered, for instance, or that giant panda populations have recovered enough to move from endangered to merely vulnerable.

However, while species like pandas and tigers are well studied, researchers don’t know enough about some species to properly assess their conservation status. These “data deficient” species make up around 17% of the nearly 150,000 species currently assessed.

When analysing conservation data it is common for researchers to remove or underestimate assumptions of threat for these species, in order to control for unknown variations or misjudgements. Now, these researchers in Norway have tried to shed light on the black hole of unknown extinction risk by designing a machine learning model that predicts the threat of extinction for these data deficient species.

Machine Learning For Extinction Assessment

When thinking of artificial intelligence and machine learning it is easy to imagine robots, computer-simulations and facial recognition. In reality, at least in ecological science, machine learning is simply an analytical tool used to run thousands of calculations to best represent the real-world data we have.

In this case, the Norwegian researchers simplified the Red List extinction categories into a “binary classifier” model to predict a probability of whether data deficient species are likely “threatened” or “not threatened” by extinction. The model algorithm has “learned” from mathematical patterns found in biological and bioclimatic data of those species with an already assigned conservation category on the Red List.

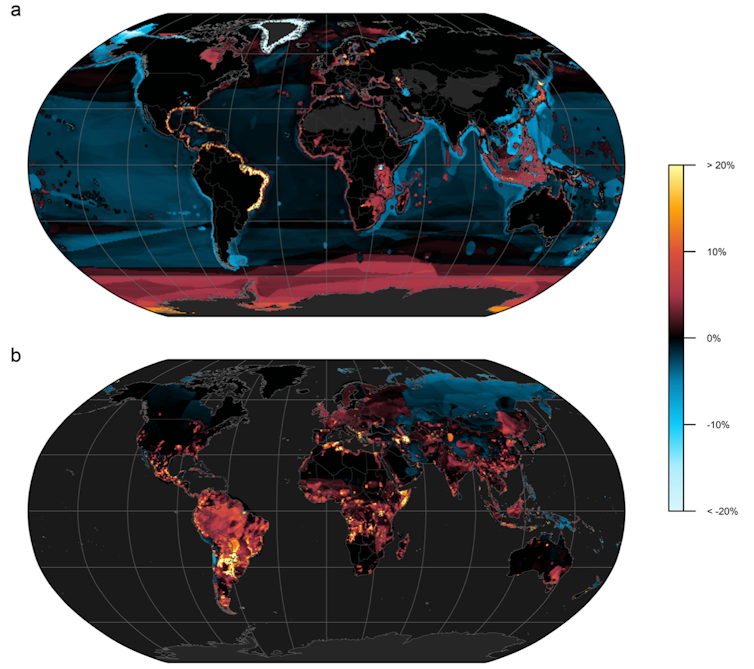

They found more than half (56%) of the data deficient species are predicted to be threatened, which is double the 28% of total species currently evaluated as threatened in Red List. This reinforces the concern that data deficient species are not only under-researched, but are at risk of being lost forever.

On land, these likely threatened terrestrial species are found across all continents, but live in small geographically restricted areas. This finding supports previous research with similar conclusions that species with small range sizes are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic habitat degradation, such as deforestation or urbanisation.

At Risk Amphibians

Amphibians are the most at-risk group, with 85% of those data deficient species predicted as threatened (compared to 41% of those currently evaluated on the Red List). Amphibians are already a poster-child for the extinction crisis and are a key indicator for ecological health, as they depend on both land and water. We don’t know enough about what causes such catastrophic extinction of amphibians, and I am part of a science initiative trying to address the problem.

It’s a slightly different, but still tragic, story at sea. Data deficient marine species that are predicted to be facing extinction are concentrated along coasts, particularly in south-eastern Asia, the eastern Atlantic coastline and in the Mediterranean. When data deficient species are combined with fully-assessed species on the Red List, there is a 20% increase in the probability of extinction along the eastern coastlines of tropical Latin America.

What This Means For Global Conservation

Though it is likely that the need for conservation has actually been underestimated worldwide these probability predictions are highly variable across different areas and groups of species, so don’t be fooled into overgeneralising these findings. But these broad results do highlight why it is so important to further investigate data deficient species.

The use of machine learning tools can be a time-and-cost-effective way to enhance the Red List and help overcome the challenging decision of where and what to protect, aiding targeted conservation action and expanding protected areas in these black holes of biodiversity.![]()

Lilly P. Harvey, PhD Researcher, Environmental Science, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How centuries of self-isolation turned Japan into one of the most sustainable societies on Earth

At the start of the 1600s, Japan’s rulers feared that Christianity – which had recently been introduced to the southern parts of the country by European missionaries – would spread. In response, they effectively sealed the islands off from the outside world in 1603, with Japanese people not allowed to leave and very few foreigners allowed in. This became known as Japan’s Edo period, and the borders remained closed for almost three centuries until 1868.

This allowed the country’s unique culture, customs and ways of life to flourish in isolation, much of which was recorded in art forms that remain alive today such as haiku poetry or kabuki theatre. It also meant that Japanese people, living under a system of heavy trade restrictions, had to rely totally on the materials already present within the country which created a thriving economy of reuse and recycling). In fact, Japan was self-sufficient in resources, energy and food and sustained a population of up to 30 million, all without the use of fossil fuels or chemical fertilisers.

The people of the Edo period lived according to what is now known as the “slow life”, a sustainable set of lifestyle practices based around wasting as little as possible. Even light didn’t go to waste – daily activities started at sunrise and ended at sunset.

Clothes were mended and reused many times until they ended up as tattered rags. Human ashes and excrement were reused as fertiliser, leading to a thriving business for traders who went door to door collecting these precious substances to sell on to farmers. We could call this an early circular economy.

Another characteristic of the slow life was its use of seasonal time, meaning that ways of measuring time shifted along with the seasons. In pre-modern China and Japan, the 12 zodiac signs (known in Japanese as juni-shiki) were used to divide the day into 12 sections of about two hours each. The length of these sections varied depending on changing sunrise and sunset times.

During the Edo period, a similar system was used to divide the time between sunrise and sunset into six parts. As a result, an “hour” differed hugely depending on whether it was measured during summer, winter, night or day. The idea of regulating life by unchanging time units like minutes and seconds simply didn’t exist.

Instead, Edo people – who wouldn’t have owned clocks – judged time by the sound of bells installed in castles and temples. Allowing the natural world to dictate life in this way gave rise to a sensitivity to the seasons and their abundant natural riches, helping to develop an environmentally friendly set of cultural values.

Working With Nature

From the mid-Edo period onwards, rural industries – including cotton cloth and oil production, silkworm farming, paper-making and sake and miso paste production – began to flourish. People held seasonal festivals with a rich and diverse range of local foods, wishing for fertility during cherry blossom season and commemorating the harvests of the autumn.

This unique, eco-friendly social system came about partly due to necessity, but also due to the profound cultural experience of living in close harmony with nature. This needs to be recaptured in the modern age in order to achieve a more sustainable culture – and there are some modern-day activities that can help.

For instance zazen, or “sitting meditation”, is a practice from Buddhism that can help people carve out a space of peace and quiet to experience the sensations of nature. These days, a number of urban temples offer zazen sessions.

The second example is “forest bathing”, a term coined by the director general of Japan’s forestry agency in 1982. There are many different styles of forest bathing, but the most popular form involves spending screen-free time immersed in the peace of a forest environment. Activities like these can help develop an appreciation for the rhythms of nature that can in turn lead us towards a more sustainable lifestyle – one which residents of Edo Japan might appreciate.

In an age when the need for more sustainable lifestyles has become a global issue, we should respect the wisdom of the Edo people who lived with time as it changed with the seasons, who cherished materials and used the wisdom of reuse as a matter of course, and who realised a recycling-oriented lifestyle for many years. Learning from their way of life could provide us with effective guidelines for the future.![]()

Hiroko Oe, Principal Academic, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The world’s biggest ice sheet is more vulnerable to global warming than scientists previously thought

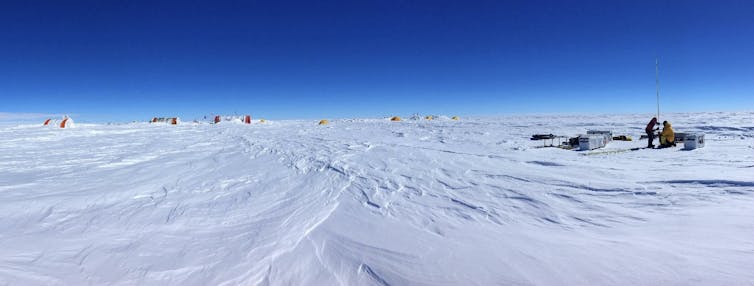

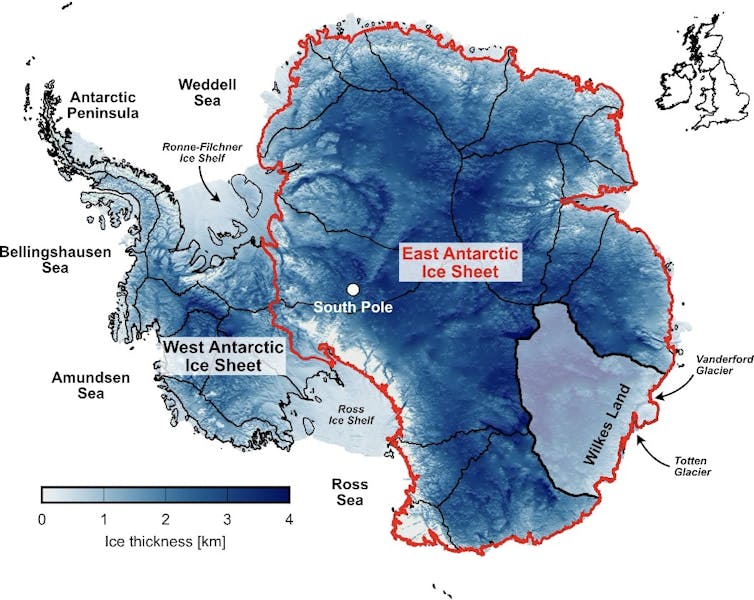

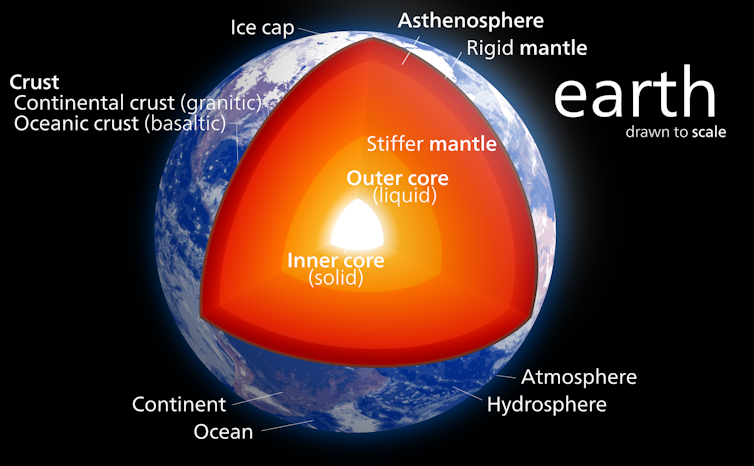

The eastern two thirds of Antarctica is covered by an ice sheet so large that if it melted the sea would rise by 52 metres. Most scientists had once thought this ice sheet was largely invulnerable to climate change, but not any more. And our new research, published in Nature, reveals the dire consequences if we were to awaken Antarctica’s sleeping giant.

Almost 70% of the Earth’s fresh water is frozen in vast continental ice sheets that cover Greenland and Antarctica. Together, they store the equivalent of around 65 metres of sea level rise. Hence, even relatively small changes in the volume of these remote polar ice sheets will have a global impact. An estimated 1 billion people live within 10 metres of sea level, including 230 million within 1 metre.

Scientists measure changes in the volume of these ice sheets by estimating the mass input, mostly via snowfall, and the mass output, mostly melting snow and ice along with icebergs that break off and float away. The difference between input and output is known as the ice sheet’s “mass balance”, which is highly sensitive to climate change.

The most recent efforts to measure ice sheet mass balance paint a very worrying picture. The Greenland Ice Sheet, which contains around 7.4 metres of sea level rise, lost 3,900 billion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2018, causing global sea level to increase by 11 millimetres over this period. A similar story emerges from the western part of Antarctica, known as the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. It holds around 5.3 metres of sea level and lost more than 2,000 billion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2017, adding around 6 mm to the sea level.

More Sensitive Than We Thought

Perhaps surprisingly, much less work has focused on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, which is by far the world’s largest but was thought to be a lot less vulnerable to global warming. This is because large parts of the ice sheet have persisted through “natural” climate changes across millions of years, and because recent measurements indicate that it has been in equilibrium or has maybe even gained mass (a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, which means more snow). In fact, the ice sheet may have even slightly reduced sea level rise over the past century.

However, over the past two decades or so, observations suggest that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet may be far more sensitive to climate warming than previously thought. Major outlet glaciers like the Totten and Vanderford are thinning and retreating. And there are clear signals of mass loss in Wilkes Land, the ice sheet’s “weak underbelly”, so-called because it rests on “land” that lies well below sea-level and so is particularly unstable.

Lessons From The Past

There is also evidence that parts of East Antarctica retreated quite dramatically during warm periods in the past, when carbon dioxide concentrations and atmospheric temperatures were only slightly higher than present.

It is likely that East Antarctica contributed several metres to global sea level during the mid-Pliocene warm period, around 3 million years ago, with ice loss concentrated in Wilkes Land. Recent work has also suggested that ice in Wilkes Land retreated 700 km inland from its present position around 400,000 years ago, when global temperatures were only 1 or 2℃ higher than present. A key lesson from the past, therefore, is that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is highly sensitive to relatively modest warming, even if it is currently stable.

Don’t Wake A Sleeping Giant

So what will actually happen over the next few decades and centuries? We recently analysed projections from various computer simulations to answer this question. Our results were alarming, but also offered some encouragement.

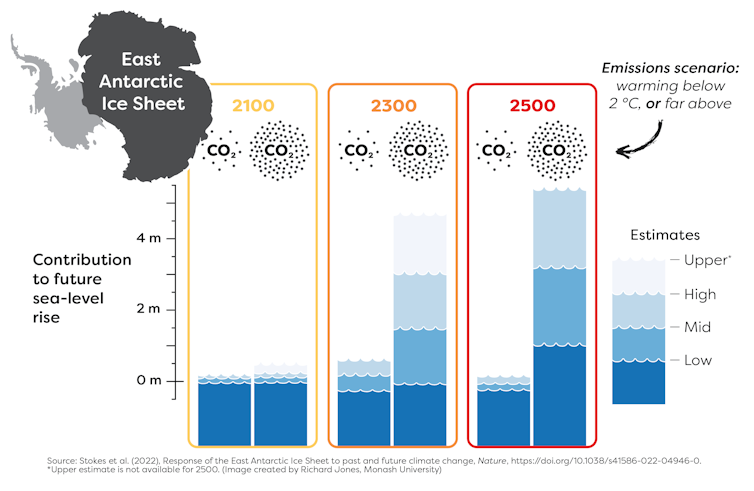

We found the ice sheet will probably remain broadly in balance in the short-term, because any mass loss due to global warming will be offset by increased snowfall. Although there are large uncertainties, we concluded that the ice sheet will only raise the sea level by about 2cm by the year 2100, which is much less than the contribution projected from melting ice in Greenland or West Antarctica.

Over the next few centuries, however, the sea-level contribution from East Antarctica will depend critically on whether we manage to curb our emissions. If warming continues beyond 2100, sustained by high emissions, then East Antarctica could contribute around 1 to 3 metres by 2300 and around 2 to 5 metres by 2500, adding to the substantial contributions from Greenland and West Antarctica and threatening millions of people who inhabit coastal areas.

Crucially, however, our analysis suggests that if the Paris Agreement to limit warming to well below 2℃ is satisfied, then East Antarctica’s sea-level contribution would remain below 0.5 metres, even five centuries from now.

The fate of the world’s largest ice sheet remains in our hands.![]()

Chris Stokes, Professor in the Department of Geography, Durham University and Guy Paxman, Assistant Professor (Research), Department of Geography, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ice shelves hold back Antarctica’s glaciers from adding to sea levels – but they’re crumbling

As Antarctica’s slow rivers of ice hit the sea, they float, forming ice shelves. These shelves extend the glaciers into the ocean until they calve into icebergs.

But they also play a crucial role in maintaining the world as we know it, by acting as a brake on how fast the glaciers can flow into the ocean. If they weren’t there, the glaciers would flow faster into the sea and melt, causing sea levels to rise.

Unfortunately, Antarctica’s ice shelves are not what they were. In research published today in Nature, we show these ice shelves have significantly reduced in area over the last 25 years due to more and more icebergs breaking off. Overall, the net loss of ice is about 6,000 billion tonnes since 1997.

Previous estimates of ice shelf loss come from satellite measurements, which captured ice shelves gradually thinning in recent years. We tracked how much extra ice had been lost as icebergs calve away from the retreating edge of the continent. We found Antarctica’s ice shelves have lost twice as much mass as previous studies suggested.

Ice shelves are now weaker than at any time since at least the 1990s. This has led Antarctica’s glaciers to begin adding more water to the oceans, and more quickly. To date, much of the concern about the cryosphere – the world’s frozen parts – has focused on the fast-melting Arctic sea ice. But as climate change intensifies, Antarctica will begin melting in earnest, contributing more to sea level rise.

What We Measured

We built numerical models to figure out what ice shelf thinning and loss of area mean for the ability of ice shelves to resist new ice being pushed in from upstream glaciers.

Our work shows the drop in ice shelf area has led to more ice flowing into the sea since 2007, as calving has weakened ice shelves and allowed some of the world’s largest glaciers to accelerate.

We found the Pine Island Glacier and the so-called “Doomsday” Thwaites Glacier – which could destabilise the entire West Antarctic ice sheet if it melts – are highly sensitive to calving, and are already increasing their contribution to sea level rise as their protective ice shelves crumbled.

Iceberg calving is a natural process. In any climate, we expect to see massive flat-top icebergs periodically break off and float away. So while no single calving event should be taken as cause for alarm, the long term trend is concerning. We found a majority of Antarctica’s ice shelves have lost mass since the late 1990s.

Why are Antarctic ice shelves shrinking? There’s no single answer. Some ice shelves such as the Wilkins Ice Shelf have already seen catastrophic disintegration, while others are retreating slowly and some are even advancing. But overall, these ice shelves are shrinking.

We know one cause of ice shelf retreat is the thinning of ice shelves, which is largely caused by relatively warm seawater eroding the base of these shelves.

We also know iceberg calving increases whenever Antarctica’s protective ring of sea ice weakens. This year, Antarctica saw the lowest sea ice extent ever recorded since measurements began in the 1970s. We’ve also seen entire ice shelves collapse when warmer air temperatures create surface meltwater that can cut through hundreds of metres of ice shelf.

Four Giant Ice Shelves Are Still In Good Shape

Antarctica’s four largest ice shelves are the Ross, Ronne, Filchner, and Amery. These vast floating sheets of ice tend to calve off giant icebergs once every few decades.

All four are on track for major calving events in the next 10 to 15 years, and none would normally be cause for alarm. The problem is calving will come on top of steady ice shelf loss. When the major ice shelves do calve off huge icebergs, they will leave the Antarctic Ice Sheet smaller than we’ve ever seen it.

But while we’re not yet seeing any abnormal behaviour in these four major ice shelves, the overlooked losses from all the smaller ice shelves fringing the continent are adding up. Earlier this year, one smaller ice shelf collapsed entirely.

The most troubling changes of the past few decades are less photogenic than sudden ice shelf collapse. Bit-by-bit, West Antarctica’s Thwaites ice shelf has retreated.

Each calving event has left the ice shelf weaker and allowed the Thwaites Glacier behind it – the size of the state of Victoria – to flow faster into the ocean. While the Thwaites ice shelf is relatively small, it is vital. Until now, it has acted like a plug. If it keeps retreating, it could potentially destabilise the entire West Antarctic ice sheet and unlock several metres of sea level rise.

Climate Change Is The Big Picture

Our warming atmosphere and ocean are the root cause. Given the long lag time between greenhouse gases trapping heat and actual warming, it stands to reason that what we’re seeing in Antarctica right now is at least partly a response to warming gases dumped into the atmosphere decades or even a century ago. That means we’re already locked into more ice shelf retreat, as emissions have continued rising.

Antarctica holds around 30 million cubic kilometres of ice, a truly enormous figure. That represents around 90% of the world’s surface fresh water. If it all melted, seas would rise almost 60 metres. Humanity’s decisions will shape what Antarctica will look like in decades to come, and how much ice will remain.![]()

Alexander Fraser, Senior Researcher in Antarctic Remote Sensing, University of Tasmania and Chad Greene, Scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The US has finally passed a huge climate bill. Australia needs to keep up

If politics moves slowly, climate politics often feels like it doesn’t move at all.

Yet at the weekend, US senators worked through the night to accomplish something they have failed to do since NASA scientist James Hansen first warned them about the dangers of climate change almost 35 years ago. They passed a major climate bill.

And not just any bill. The A$530 billion of clean energy initiatives in the larger Inflation Reduction Act represent the largest single investment to slow global heating in US history. It means the world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases will become a global leader on climate change.

Initial modelling suggests the bill could be enough to cut US emissions by around 40% by 2030, relative to a 2005 baseline. That won’t meet President Joe Biden’s goal of halving emissions by 2030, but it gives America a fighting chance.

What does it mean for Australia? After the go-slow years of Coalition government and Trump’s fossil-fuel-friendly presidency, the times finally favour action. There is a clean energy race on, and Australia needs to keep up.

It’s Been A Hard Road

When the bill passed, senators broke down in tears. Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer spoke of “a long, tough and winding road. But at last, at last we have arrived.”

The bill looked dead in the water as recently as July, when controversial Democratic senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia pulled his crucial vote for climate legislation.

That led many to despair, believing the window for climate action had shut again given Republican disinterest in climate action. But then Manchin cut a deal. It was the last chance to act before November’s midterm elections, which Republicans are expected to win – although the Supreme Court’s seismic decision on abortion may change this.

I remember being in Washington DC, studying climate policy, the last time the US got this close. In the summer of 2009, the US House of Representatives passed a bill designed to institute a nationwide carbon price. With chants of “yes we can” still ringing in many ears after President Barack Obama’s arrival in the White House, it seemed climate politics was moving. But the Senate killed that bill, and with it any hope for legislative action on climate change.

America had to wait more than a decade for the next opportunity. The weekend’s vote was close, with Vice President Kamala Harris casting the decider.

What was lost in the intervening years was more than time. In the past decade, climate impacts have become more frequent and deadly. Just ask the flood victims of Lismore in New South Wales, or the citizens of Mallacoota in Victoria after the bushfires.

Most of Europe is now in drought. Stories of unprecedented heatwaves and flooding come in weekly from China, India, the Middle East and South America. The western US is in megadrought, the worst in at least 1,200 years, with reservoirs at dangerous lows.

What Does The Bill Actually Contain?

When climate action is deliberately stalled by political parties, the price is paid by communities, families and the natural world.

That’s why the US bill is momentous. Senate approval of the A$530 billion in spending will directly advance clean energy. This includes billions of dollars in tax credits for solar panels, wind turbines, batteries and geothermal plants, among other technologies.

This comes through around A$13 billion in rebates for Americans to electrify their homes, tax credits of almost A$11,000 to electrify their cars, and billions more to establish a “green bank”, target agricultural emissions and help disadvantaged communities.

Even better, these billions in public money will crowd in private investment, accelerating the speed at which the US economy can decarbonise.

What Should Australia Take From This?

There are several lessons for Australia.

The first is legislating a target as Labor has done is a start, but only a start. The world is set for a clean energy race, given China is also investing huge amounts in clean energy while European nations are trying to wean themselves off Russian gas.

The Albanese government should follow the US with historic investments in clean energy, using renewable jobs as an incentive. Key features of the US bill aim to turbocharge local clean energy manufacturing, such as requiring battery components be made in the US. As it stands, America’s geopolitical rival China has cornered the market in many areas of clean tech, such as solar panels.

Second, fossil fuel industries will fight tooth and nail against change. Manchin has received more money from the oil and gas industry than any other member of Congress – and has personal interests in coal. His interventions mean the bill has rewards for the oil and gas industries, such as requiring the federal government to auction new offshore oil and gas leases. There is likely more devil in the detail.

For decades, fossil fuel industries have had an outsized influence on climate policy in Australia. It’s folly to think they’ll just give up. This week we found out the car industry has already launched a secret PR campaign to slow electric vehicle uptake.

Against these entrenched interests stand the growing throngs of people involved in climate movements. This is what has kept climate politics moving. Countless Americans, from political activists to schoolkids, mobilised to pressure Congress to act.

The same has happened here. Arid and sparsely populated Australia is already being hit by intensifying natural disasters. As the May election result showed, people have had enough of political delays and inaction.

We must keep moving. Climate science does not stand still, and neither should the politics.![]()

Christian Downie, Associate Professor, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Backyard hens’ eggs contain 40 times more lead on average than shop eggs, research finds

There’s nothing like the fresh eggs from your own hens, the more than 400,000 Australians who keep backyard chooks will tell you. Unfortunately, it’s often not just freshness and flavour that set their eggs apart from those in the shops.

Our newly published research found backyard hens’ eggs contain, on average, more than 40 times the lead levels of commercially produced eggs. Almost one in two hens in our Sydney study had significant lead levels in their blood. Similarly, about half the eggs analysed contained lead at levels that may pose a health concern for consumers.

Even low levels of lead exposure are considered harmful to human health, including among other effects cardiovascular disease and decreased IQ and kidney function. Indeed, the World Health Organization has stated there is no safe level of lead exposure.

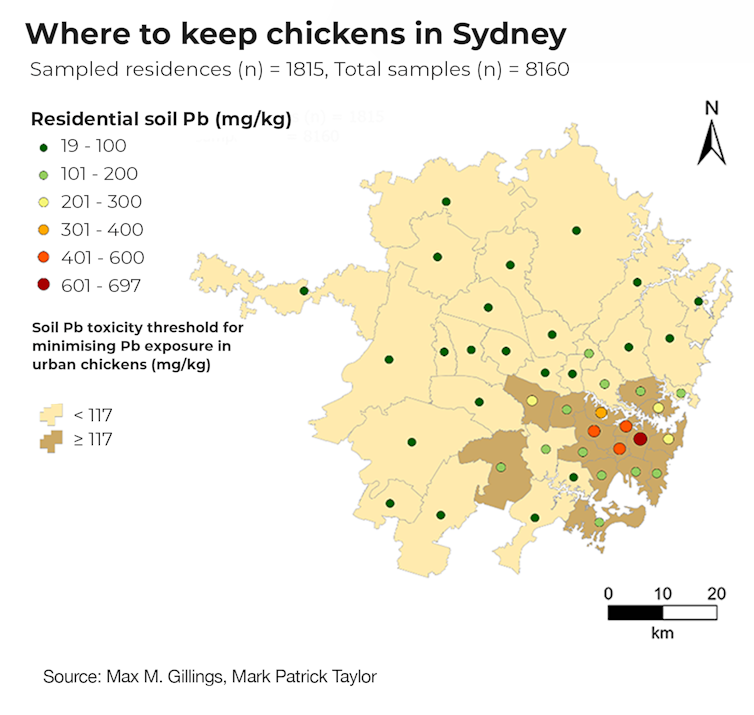

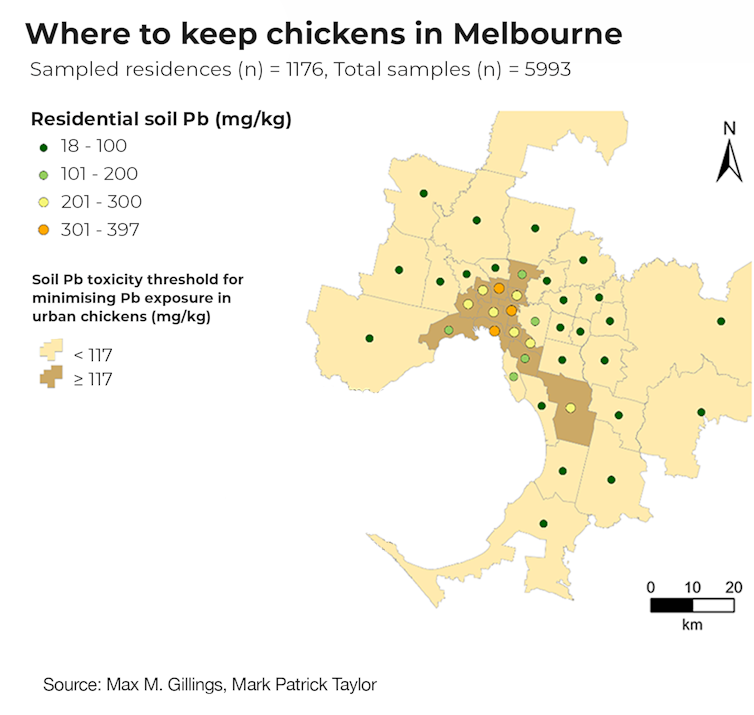

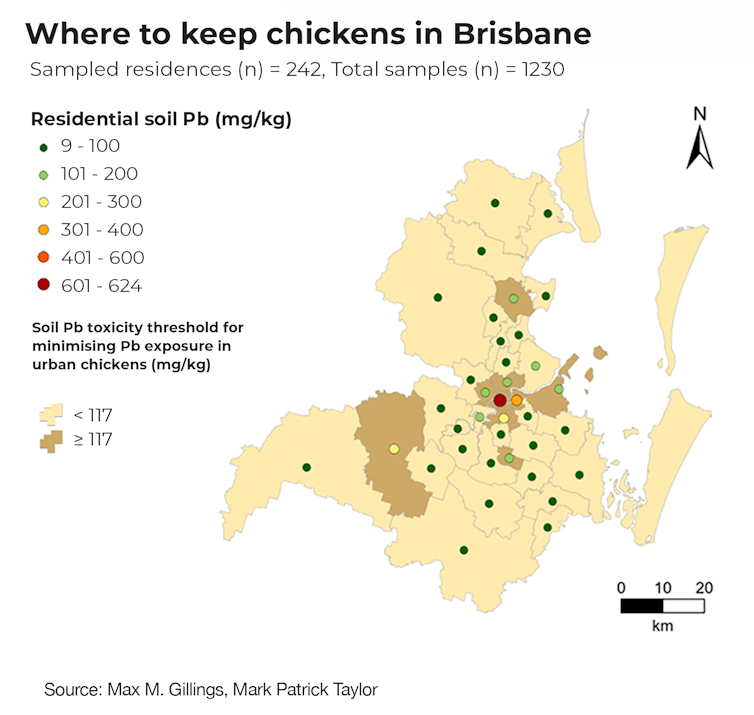

So how do you know whether this is a likely problem in the eggs you’re getting from backyard hens? It depends on lead levels in your soil, which vary across our cities. We mapped the areas of high and low risk for hens and their eggs in our biggest cities – Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane – and present these maps here.

Our research details lead poisoning of backyard chickens and explains what this means for urban gardening and food production. In older homes close to city centres, contaminated soils can greatly increase people’s exposure to lead through eating eggs from backyard hens.

What Did The Study Find?

Most lead gets into the hens as they scratch in the dirt and peck food from the ground.

We assessed trace metal contamination in backyard chickens and their eggs from garden soils across 55 Sydney homes. We also explored other possible sources of contamination such as animal drinking water and chicken feed.

Our data confirmed what we had anticipated from our analysis of more than 25,000 garden samples from Australia gardens collected via the VegeSafe program. Lead is the contaminant of most concern.

The amount of lead in the soil was significantly associated with lead concentrations in chicken blood and eggs. We found potential contamination from drinking water and commercial feed supplies in some samples but it is not a significant source of exposure.

Unlike for humans, there are no guidelines for blood lead levels for chickens or other birds. Veterinary assessments and research indicate levels of 20 micrograms per decilitre (µg/dL) or more may harm their health. Our analysis of 69 backyard chickens across the 55 participants’ homes showed 45% had blood lead levels above 20µg/dL.

We analysed eggs from the same birds. There are no food standards for trace metals in eggs in Australia or globally. However, in the 19th Australian Total Diet Study, lead levels were less than 5µg/kg in a small sample of shop-bought eggs.

The average level of lead in eggs from the backyard chickens in our study was 301µg/kg. By comparison, it was 7.2µg/kg in the nine commercial free-range eggs we analysed.

International research indicates that eating one egg a day with a lead level of less than 100µg/kg would result in an estimated blood lead increase of less than 1μg/dL in children. That’s around the level found in Australian children not living in areas affected by lead mines or smelters. The level of concern used in Australia for investigating exposure sources is 5µg/dL.

Some 51% of the eggs we analysed exceeded the 100µg/kg “food safety” threshold. To keep egg lead below 100μg/kg, our modelling of the relationship between lead in soil, chickens and eggs showed soil lead needs to be under 117mg/kg. This is much lower than the Australian residential guideline for soils of 300mg/kg.

To protect chicken health and keep their blood lead below 20µg/kg, soil concentrations need to be under 166mg/kg. Again, this is much lower than the guideline.

How Did We Map The Risks Across Cities?

We used our garden soil trace metal database (more than 7,000 homes and 25,000 samples) to map the locations in Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne most at risk from high lead values.

Deeper analysis of the data showed older homes were much more likely to have high lead levels across soils, chickens and their eggs. This finding matches other studies that found older homes are most at risk of legacy contamination from the former use of lead-based paints, leaded petrol and lead pipes.

What Can Backyard Producers Do About It?

These findings will come as a shock to many people who have turned to backyard food production. It has been on the rise over the past decade, spurred on recently by soaring grocery prices.

People are turning to home-grown produce for other reasons, too. They want to know where their food came from, enjoy the security of producing food with no added chemicals, and feel the closer connection to nature.

While urban gardening is a hugely important activity and should be encouraged, previous studies of contamination of Australian home garden soils and trace metal uptake into plants show it needs to be undertaken with caution.

Contaminants have built up in soils over the many years of our cities’ history. These legacy contaminants can enter our food chain via vegetables, honey bees and chickens.

Urban gardening exposure risks have typically focused on vegetables and fruits. Limited attention has been paid to backyard chickens. The challenge of sampling and finding participants meant many previous studies have been smaller and have not always analysed all possible exposure routes.

Mapping the risks of contamination in soils enables backyard gardeners and chicken keepers to consider what the findings may mean for them.

Particularly in older, inner-city locations, it would be prudent to get their soils tested. People can do this at VegeSafe or through a commercial laboratory. Soils identified as a problem can be replaced and chickens kept to areas of known clean soil.![]()

Mark Patrick Taylor, Chief Environmental Scientist, EPA Victoria; Honorary Professor, Macquarie University; Dorrit E. Jacob, Professor, Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University, and Vladimir Strezov, Professor, School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Once the fish factories and ‘kidneys’ of colder seas, Australia’s decimated shellfish reefs are coming back

Australia once had vast oyster and mussel reefs, which anchored marine ecosystems and provided a key food source for coastal First Nations people. But after colonisation, Europeans harvested them for their meat and shells and pushed oyster and mussel reefs almost to extinction. Because the damage was done early – and largely underwater – the destruction of these reefs was all but forgotten.

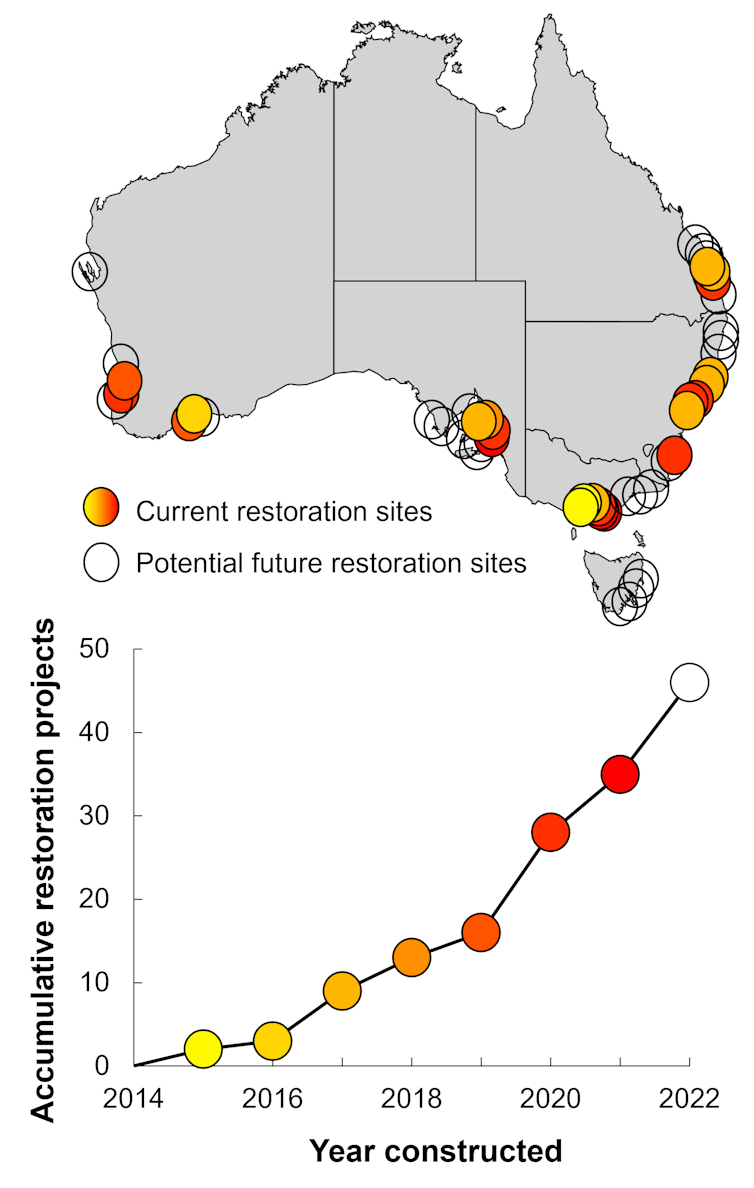

No longer. We have learned how to restore these vital reef systems. After a successful pilot in 2015, there are now 46 shellfish reef restorations underway – Australia’s largest marine restoration program ever undertaken. It’s not a moment too soon. There’s just one natural reef remaining for the Australian flat oyster, which is teetering on extinction.

How did shellfish reefs go from forgotten to frontline? Our new research shows how this historical amnesia was overcome through a national community of researchers, conservationists, and government and fisheries managers.

This matters, because oysters and mussels are ecological superheroes. As we restore these reefs, we give local marine life a real boost and support human livelihoods reliant on healthy seas. These cold-water reefs play a similar role to coral in tropical seas. They give hiding places and food to baby fish, filter seawater and defend coastlines against erosion from waves.

What Killed Our Original Shellfish Reefs?

Just 200 years ago, shellfish reefs carpeted Australia’s temperate regions, filling up sheltered bays and estuaries around over 7,000 kilometres of coastline.

Archaeological research from Queensland shows First Nations people were sustainably harvesting local shellfish reefs over at least 5,000 years, replenishing oyster populations by building reefs with stone and shell.

This ended as Europeans took the lands and waters from Traditional Owners. Shellfish became one of colonial Australia’s first fisheries. Oysters were fished extensively for food, while their shells were burnt to manufacture lime for fertiliser and cement. If you walk past a colonial-era building, look at the mortar. Chances are, a lot of oyster shells went into it.

Even though the wild fishery ended a century ago, these shellfish weren’t able to return. That’s because they can’t just grow on bare sand. Their preferred substrate is the shells of their ancestors, left behind on the sea bottom. Once substrate was scraped by dredge or smothered by sediment, there was nowhere for baby oysters and mussels to settle and grow.

Today, there’s just one small natural flat oyster reef (Ostrea angasi) and six remnant Sydney Rock oyster (Saccostrea glomerata) reefs remaining, across all Australian waters.

How To Kick-Start Shellfish Reef Restoration

Shellfish can’t recover by themselves. But it turns out with a little human help, they can. Think of it as making up for our unsustainable use.

For a decade before the first large-scale restoration, recreational fishing groups and community groups worked on smaller projects, sometimes with government backing.

To begin larger-scale restoration work, we first had to remember how it used to be. Because the ecological collapse of Australia’s shellfish reefs was so profound, they were almost lost to human memory. Historical records guided us as to what a restored ecosystem should look like, and where these reefs used to be.

Our job was made easier because of the huge benefits shellfish reefs provide to marine life. Intact oyster and mussel reefs are natural fish factories providing nursery habitats for economically important fish species like bream and whiting.

Even better, these filter-feeding shellfish are the kidneys of the coast, cleaning water cloudy with sediment or overloaded with nutrients. A single oyster can filter 100 litres of water a day. Shellfish reefs also act as living defences against the energy of waves, store carbon in their shells and help protect intertidal communities from the warming climate through shade and moisture at low tide.

People working on reef restoration turned to our thriving oyster and mussel farming industry to understand their life cycles and what they needed to thrive. The fact these farms are successful indicated many areas remained suitable for shellfish reefs.

Environmental NGO The Nature Conservancy connected the emerging reef restoration community as well as bringing practical experience from longer-running shellfish restoration projects in America. Reef restoration work is now being led by conservation NGOs, local and state governments, and, increasingly, by community groups.

So does it work? Yes. It’s as if the oysters have been waiting for this opportunity. Many human-made reefs have been settled by millions of baby oysters within months of construction, such as the largest project to date, the 20 hectare Windara Reef in South Australia. Some restored reefs are closing in on oyster densities in line with natural reefs.

Looking Forward

We hope the rapid rise of shellfish reef restoration is the beginning of a new era for large-scale marine restoration in Australia.

Today, community-led restorations are growing in scale and number, and public support for shellfish restoration is widespread.

It is an impressive story. This is a national program of recovery showing significant successes with a relatively modest investment. These restoration efforts show large-scale action to repair nature can work – and work quickly – when experts from a range of disciplines work with communities towards a common goal.

As the restored oyster and mussel reefs mature, we will see more fish in our seas and more recreation and tourism opportunities emerging. That, in turn, could give more communities the idea to restore their own shellfish reefs. Together, we can bring back the reefs which lived in our cooler seas for millennia. ![]()

Dominic McAfee, Postdoctoral researcher, marine ecology, University of Adelaide; Chris Gillies, Adjunct Associate Professor in marine ecology, James Cook University; Christine Crawford, Senior research fellow in marine biology, University of Tasmania; Ian McLeod, Professorial Research Fellow in Marine Biology, James Cook University, and Sean Connell, Professor, Program Director of Stretton Institute, Program Director of Environment Insitute, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Unacceptable costs’: savanna burning under Australia’s carbon credit scheme is harming human health

Savanna burning projects in northern Australia provide economic benefits to Indigenous communities and claim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But our research suggests smoke from these projects is harming human health.

Northern Australia’s savannas cover about 25% of Australia’s land mass. They’re among the most flammable regions in the world and comprise 70% of Australia’s fire-affected area each year.

Savanna fire management involves strategically burning grasslands early in the dry season, purportedly to reduce the chance of large, intense, more carbon-intensive fires later in the season. Under Australia’s Emissions Reduction Fund, land managers who undertake savanna burning receive financial rewards in the form of carbon credits.

But our research, focused on Darwin, has shown savanna burning under the fund is making air pollution worse. A review of the fund now underway must consider these unacceptable costs to human health.

The Top End’s Smoke Problem

Savanna fire management is currently a topic of substantial global interest – much of it stemming from its potential to reduce carbon emissions.

The underlying premise is that early dry season burning releases fewer emissions than late dry season burning. This is because the fuel is moister and weather conditions milder — hence fires will be less extensive, less fuel will combust and less carbon will be released.

In Australia, savanna burning programs for carbon abatement were developed in the mid-2000s and integrated into the carbon market. Land managers are offered financial incentives to burn large amounts of savanna before the end of July each year.

The scheme has proved popular: registered projects now cover some 25% of Australia’s 1.2 million km² tropical savannas, including 55% of land within 500km of Darwin.

Australia now touts itself as a world leader in savanna burning. We are sharing the practice with other regions around the world, and savanna burning programs linked to carbon markets have been proposed elsewhere.

Yet the smoke pollution consequences of such programs are rarely considered. In Australia’s Top End, for example, thick and prolonged smoke blankets communities every dry season. Darwin, a city of 158,000 people, regularly exceeds the Australian air quality standard for particulate matter.

In Darwin, smoky days bring more hospital admissions for lung and heart disease, and more emergency department presentations for asthma. These impacts disproportionately affect Indigenous people.

Almost all Darwin’s particulate pollution is caused by landscape fires. In the early dry season, almost all of this is generated by prescribed burning - and there’s been a marked increase in burning in recent years linked to carbon abatement schemes.

What Our Research Found

Our research considered the relationship between prescribed burning and smoke pollution in Darwin from 2004 to 2019.

We first assessed the very small particles found in smoke known as PM2.5. We then analysed fire activity within a 500km radius, and assessed the links between pollution, weather and fire.

The results showed air quality worsened in Darwin in the early dry season (particularly in June and July), with an increase in the annual number of severely polluted days.

Perhaps surprisingly, air quality did not change substantially in other seasons. In other words, shifting savanna burning to the early dry season did not appear to lead to better air quality later in the season.

Our findings highlight a complex story. Despite a substantial expansion of savanna burning for carbon abatement over our study period, net annual PM2.5 concentrations in Darwin did not decline. In fact, there was an increase in the number of times the national air quality standard was exceeded.

So what’s driving these results? One important factor involves large areas of savanna burned for carbon abatement to the southeast of Darwin in the early dry season. At that time of year, a steady south-easterly trade wind hits Darwin, bringing much of the smoke from these fires with it.

Fuel dynamics may also be at play. Native and non-native grasses which are highly flammable in the early dry season have been expanding on frequently burned savannas. Higher temperatures may be drying fuel out earlier in the dry season. These factors may make early dry season fires as extensive and intense as savannas burnt later in the season.

Our research comes with caveats. For example, we drew only broad inferences about the geographic sources of smoke over Darwin. Notwithstanding this, our results clearly demonstrate Darwin’s already significant air quality problem is worsening, rather than improving, in association with increased early dry season burning.

A Balancing Act

None of this means savanna burning should cease, nor that traditional owners should not be paid to manage fire on country. But it does mean policies should be designed so unintended harm is minimised and the benefits are maximised.

Policymakers must consider how to regulate burning to avoid smoke pollution exposure. In Darwin, particular attention may be needed in locations southeast of the city. One solution may be to regulate how much smoke can be released in a specific area on a given day.

Other factors should be considered too. For example, savanna burning in Australia may risk harming biodiversity.

But the Emissions Reduction Fund is a blunt tool which doesn’t consider these hidden costs and other nuances.

The new Labor government has ordered an independent review of the fund. For this review to fulfil its brief, all unintended harms must be taken into account. ![]()

Penelope Jones, Research Fellow in Environmental Health, University of Tasmania; David Bowman, Professor of Pyrogeography and Fire Science, University of Tasmania, and Fay Johnston, Professor, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Southern conifers: meet this vast group of ancient trees with mysteries still unsolved

When you think of “conifers”, tall, conical shaped trees often found in public parks or front yards may spring to mind. But these impressive trees are far more fascinating than you may have realised, as they represent just one piece of an unsolved botanical puzzle.

These popular garden trees are from the northern hemisphere. But we also have conifers in the southern hemisphere, called “southern conifers”, found largely in Australia, South America, New Zealand and New Caledonia.

A little detective work reveals that southern conifers evolved in Gondwana, and long ago separated from coniferous relatives in the northern hemisphere.

They appeared around 200 million years ago, before the first flowering plants evolved, sharing land with the dinosaurs. One example is the Wollemi pine, which was famously saved in a secret firefighting operation during the 2019-2020 bushfires.

Unlike the introduced conifer garden trees, southern conifers are neither as well-known nor as popular with Australians as they should be. So let me help you get to know them a little better.

Famous ‘Living Fossils’

Northern conifers are mostly evergreen, woody trees with needle-like leaves, while southern conifers tend to have broad leaves like flowering trees.

Trees in the genus Araucaria, including the monkey puzzle, bunya bunya, hoop pine and Norfolk Island pine, are southern conifers. As are most members of the Podocarp family (Huon pine, celery top pine and plum pine) and 22 species of Agathis (including the majestic Queensland and New Zealand Kauri trees).

Southern conifers often possess cones, such as the Araucaria and Agathis species. Sometimes, these cones are very large and heavy that can cause serious injury if they fall from high in the tree onto an unsuspecting passerby.

Some southern conifers can be over 30 metres high. Others, such as the Kauri and Huon pine, are renowned for their longevity. They can live for centuries or, for the Huon pine, perhaps over an astonishing ten millennia.

While all species of southern conifers are of ancient origin, the Wollemi pine is famous for its status as a “living fossil”. Of course, this is a contradiction in terms – a fossil is any evidence of past life.

But in this context, the term refers to organisms that appeared in the fossil record long ago, were then thought to be extinct, before a living version was discovered. We are curious as to how they successfully hid for so long and may imagine a link with a distant, different past.

So, the question botanists have yet to answer is: how distant are the north and south relatives?

When Flowering Plants Evolved

Many southern conifers show little resemblance to the “true conifers” of the northern hemisphere, such as pine, cedar, spruce and juniper.

All conifers are gymnosperms, which means they have naked seeds and cones. They evolved from an ancient group of seed ferns, before the fragmentation of the super continent Pangaea.

These seed ferns were a diverse group. As Pangaea divided into Gondwana in the south and Laurasia in the north, the seed ferns began to diversify, giving rise to northern and southern seed ferns.

Botanists have long known that northern conifers and other gymnosperms evolved from these northern seed ferns. But what of the southern seed ferns? They remained a bit of a mystery until the 1970s.

One group of southern seed ferns constituted what’s now called the Glossopteris flora, which was of Gondwanan origin. From this diverse group of Glossopterids, flowering plants in all their variety evolved.

This solved one of the great riddles of botany – the origin of the flowering plants which had puzzled scientists, particularly in the northern hemisphere until the early 1980s.

It’s likely southern conifers also evolved from these southern seed ferns. Some may have arisen from other members of the Glossopteris group, too, or perhaps their relatives.

If this was the case, then the southern conifers would be more closely related to flowering plants than to the true conifers of the north.

When The Trees Were In Fashion

After millions of years of evolution, southern conifers became fashionable with gardeners in the 1800s.

Their novelty and striking form captured the interest of the educated and wealthy landowners of Europe and they were planted as status symbols on estates and in public gardens.

In Australia they were planted in large private gardens and in many public parks from the mid 1800s to World War 1, after which their popularity waned.

You can see many of these fine trees growing still in large gardens and public parks across Australia, such as botanic gardens in most Australian states, as well as in smaller public parks and gardens of older suburbs and inland towns. Their striking, almost geometrical, form catches the eye.

Southern conifers are known for their resilience, are rarely affected by pests or disease and, despite their large size, cause few problems with paths, roads, buildings and other urban infrastructure. Probably because they were given plenty of space to grow when first planted.

We Still Have Much To Learn

It takes time to solve some of these botanical puzzles. Evolution is a sophisticated process that has led to very complex relationships between plant groups.

In future we may well recognise that southern conifers are not really conifers at all. Perhaps, the links between the two groups go so far back in time, the relationship is too distant for both southern and true conifers to be called conifers at all.

In any case, these mysterious trees have persisted through vast periods of time and changing environments – they have much to teach us about plant responses to climate change.![]()

Gregory Moore, Senior Research Associate, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Who’s holding back electric cars in Australia? We’ve long known the answer – and it’s time to clear the road

New analysis this week found strong fuel efficiency standards would have saved Australia A$5.9 billion in fuel costs and emissions equal to a year’s worth of domestic flights if the policy was adopted in 2015.

The finding, by think-tank the Australia Institute, puts further pressure on the new federal government to bring our fuel efficiency standards in line with Europe and other developed nations.

Unlike other comparable countries, Australia does not have fuel efficiency standards for motor vehicles. On the face of it this is puzzling; aside from lower costs for motorists and fewer emissions, the policy would also decrease our reliance on imported oil.

But opposition from vested interests – including oil refineries and the car dealership industry – has held Australia back. The onus is now on the Albanese government to enact this obvious and long overdue policy which is crucial to the electric vehicle transition.

Long Road, Little Progress

So how would a fuel efficiency standard work?

Under a likely model, the government would set a national limit, averaged across all new cars sold, stipulating grams of CO₂ that can be emitted for each kilometre driven. This measure depends on fuel-efficiency: that is, the amount of fuel burnt per kilometre.

The limit would not apply to individual cars. Instead, each supplier of new light vehicles to Australia would have to make sure the mix of vehicles does not exceed the limit. Low-efficiency vehicles could still be sold, but car dealers would have to balance this out by selling enough high-efficiency vehicles.

Because electric vehicles don’t use fuel (or use less, in the case of hybrids), a fuel efficiency standard would give suppliers an incentive to include electric vehicles in the mix of vehicles they supply.

The prospect of fuel efficiency standards on light vehicles has regularly hit the national agenda in recent years.

In 2014, the Climate Change Authority prepared a detailed plan for a standard and estimated the likely economic savings. The plan seemed well timed. Australia has traditionally produced large, fuel-guzzling cars like the Holden Commodore and Ford Falcon. At the time of the plan’s release, however, the last remaining domestic car manufacturers had just announced plans to close, removing the most likely source of political resistance.