inbox and environment news: Issue 552

August 28 - September 3, 2022: Issue 552

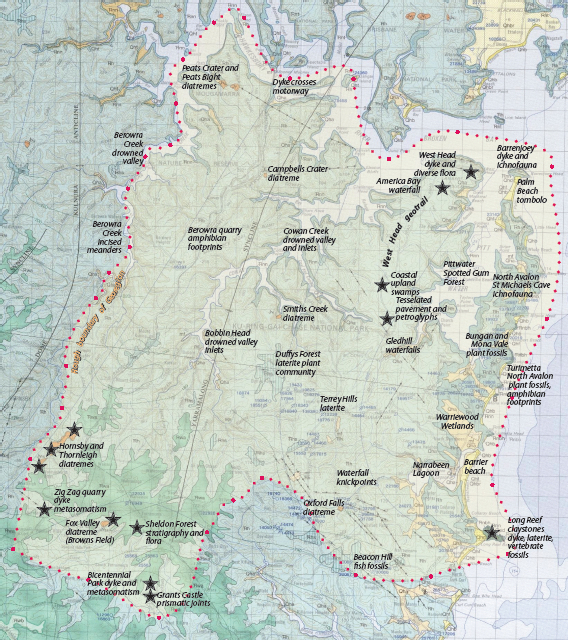

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment August Forum: Ku-Ring-Gai GeoRegion Project

Warriewood Creeklines Works Delayed Due To Rains

So-Called Biodiversity Certificates Scheme Another False Solution To Tackling Environmental Crisis Researcher States

Biodiversity Certificates To Increase Native Habitat And Support Australian Landholders

Nap Nap Water Recovery Project Announced

- Access points for the Rural Fire Service.

- Provide economic benefits to the local economy through local purchasing and employment opportunities from the investment in the project.

- Increasing drought resilience and preparedness of Nap Nap Station.

- Improve the conditions for animals on the property improving both their wellbeing and health outcomes.

Measuring Benefits Of Blue Carbon Ecosystems

Planning Decisions For Aboriginal Communities: Two New Groups Formed By NSW Department Of Planning

Australian Teachers Want Support To Embrace Nature Play In Primary Education

- better mental health (98%)

- improved cognitive development (96%)

- learning about risk-taking (96%)

- spending time outdoors/in nature (96%).

- limited knowledge and confidence about how to incorporate into learning or how to operate the class outside (68%)

- a crowded curriculum restricted their ability to adopt new learning (64%)

- a lack of understanding/support from others in the school (38%).

Bringing Sea Horses And Kelp Forests Back To World's Most Iconic Harbour: Seabirds To Seascapes

- restoring Sydney Harbour's marine ecosystems by installing Living Seawalls, and replanting seagrass meadows and kelp forests

- supporting the future of little penguins in New South Wales by conducting the first ever statewide little penguin census to better understand their population size and how they're responding to threats such as climate change

- helping fur seals thrive as a species by conducting a seal survey to identify their preferred habitat, breeding grounds, diet and key threats.

Leopard Seal Visitor

.jpg?timestamp=1660590847423)

Echidna 'Love Train' Season Commences

Dogs Off-Leash On Beaches Open For Feedback

- Do You Want Pittwater Leashed? Let The Council Know Why!

- Calls For Council To Address Dogs Offleash Everywhere After Two Serious Dog Attacks On Local Beaches In Same Week - owner has still not come forward or been identified as of Saturday August 6, 2022

- Sydney Dog Attack Victim Awarded $225, 000: July 2022

- Council Push For Dogs Off Leash On Family Beaches Among Wildlife Habitat

White faced heron landing at north Palm Beach, March 7th, 2022 during storm event. All native birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals (except the dingo) are protected in New South Wales by the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act).

Magpie Breeding Season: Avoid The Swoop!

- Try to avoid the area. Do not go back after being swooped. Australian magpies are very intelligent and have a great memory. They will target the same people if you persist on entering their nesting area.

- Be aware of where the bird is. Most will usually swoop from behind. They are much less likely to target you if they think they are being watched. Try drawing eyes on the back of a helmet or hat. You can also hold a long stick in the air to deter swooping.

- Keep calm and do not panic. Walk away quickly but do not run. Running seems to make birds swoop more. Be careful to keep a look out for swooping birds and if you are really concerned, place your folded arms above your head to protect your head and eyes.

- If you are on your bicycle or horse, dismount. Bicycles can irritate the birds and the major cause of accidents following an encounter with a swooping bird, is falling from a bicycle. Calmly walk your bike/horse out of the nesting territory.

- Never harass or provoke nesting birds. A harassed bird will distrust you and as they have a great memory this will ultimately make you a bigger target in future. Do not throw anything at a bird or nest, and never climb a tree and try to remove eggs or chicks.

- Teach children what to do. It is important that children understand and respect native birds. Educating them about the birds and what they can do to avoid being swooped will help them keep calm if they are targeted. Its important children learn to protect their face.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

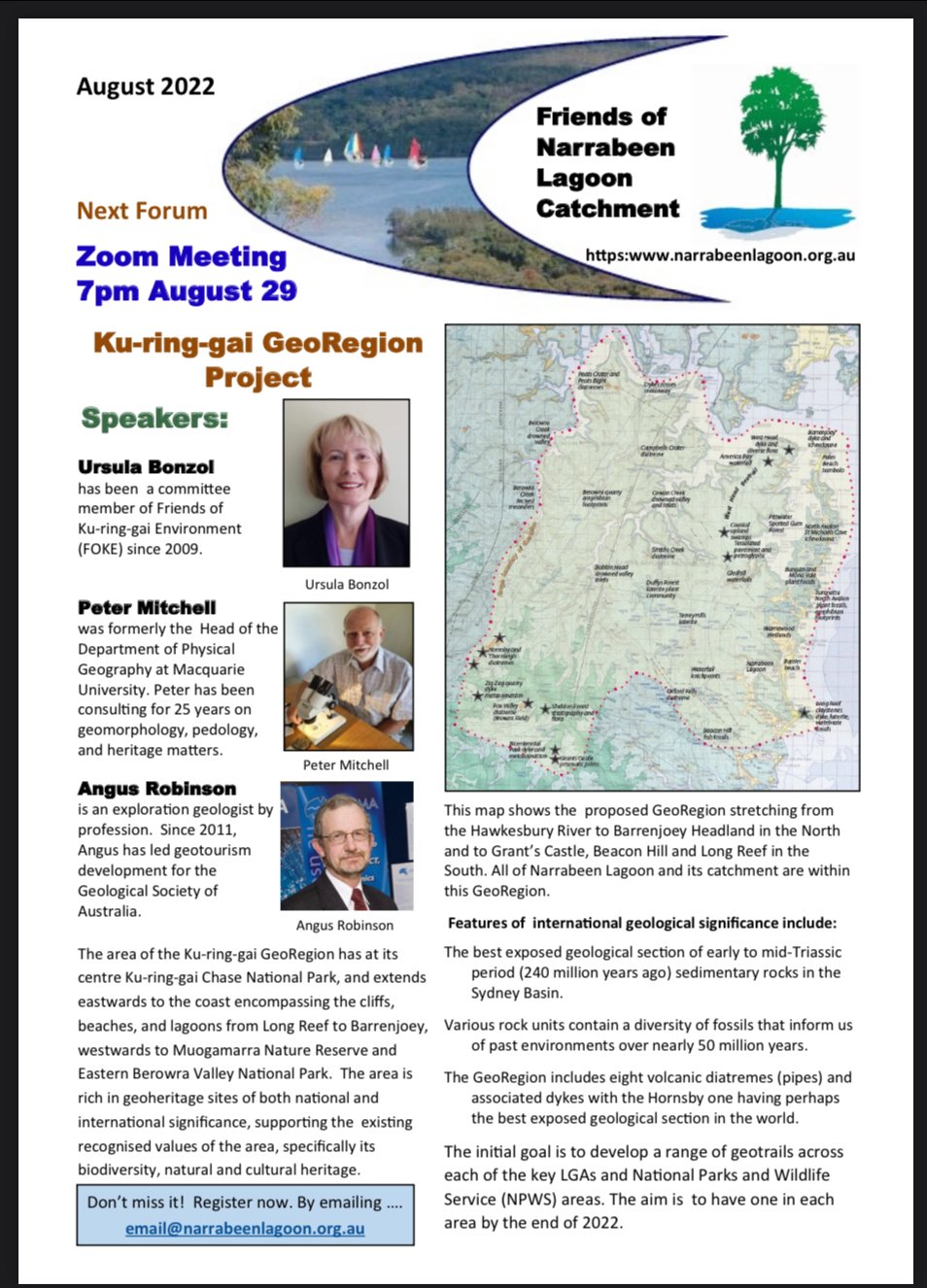

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

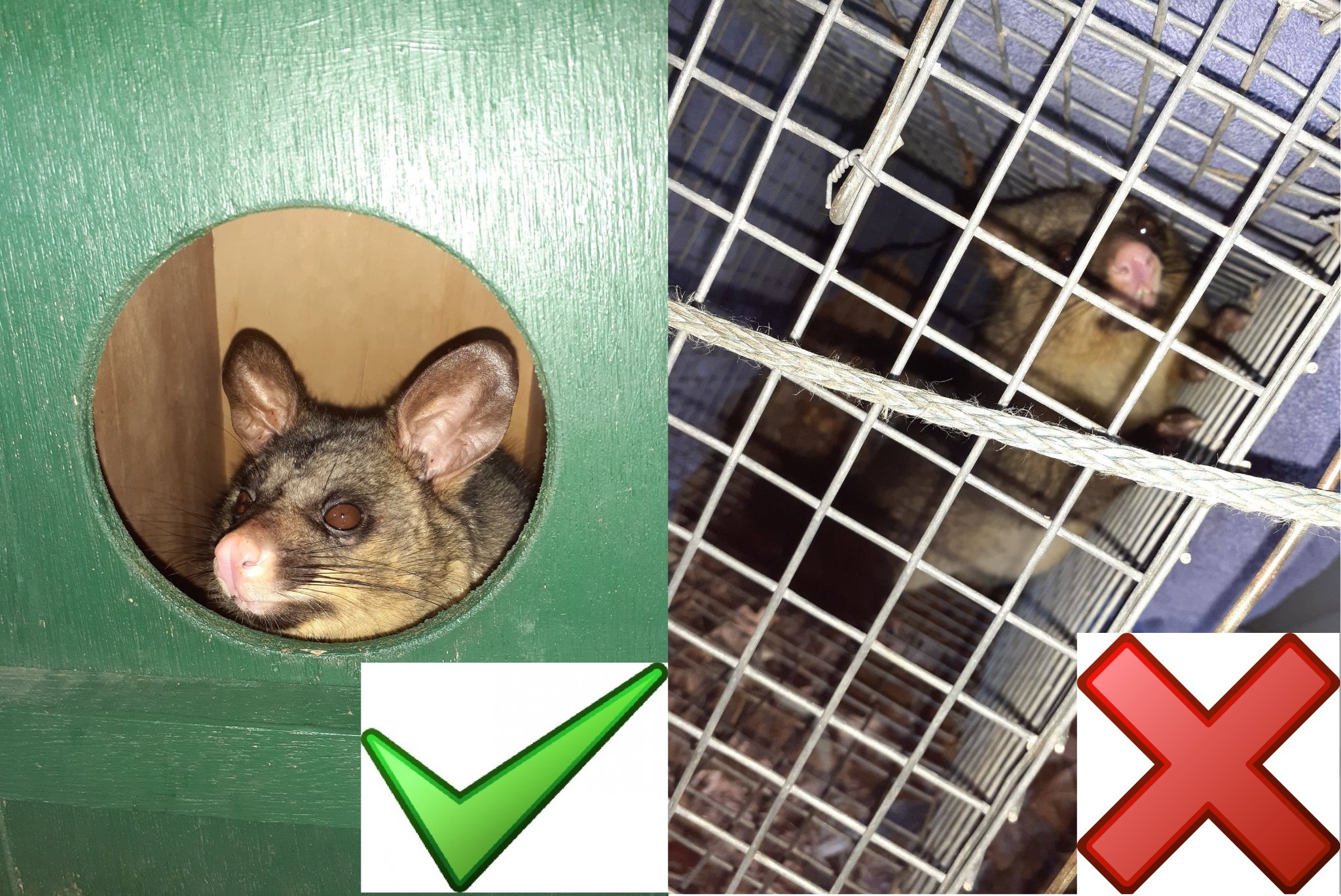

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

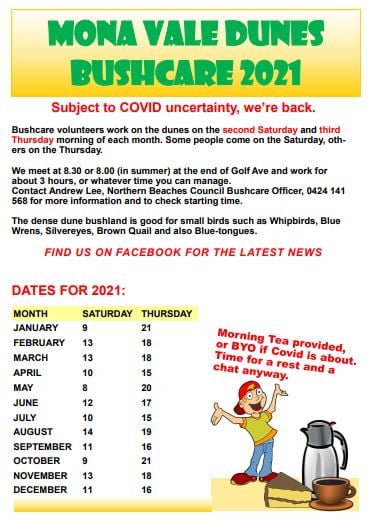

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Opening 10 new oil and gas sites is a win for fossil fuel companies – but a staggering loss for the rest of Australia

Federal Resources Minister Madeleine King yesterday handed Australia’s fossil fuel industry two significant wins.

The minister announced oil and gas exploration will be allowed at ten new Australian ocean sites – comprising almost 47,000 square kilometres. And she approved two new offshore greenhouse gas storage areas off Western Australia and the Northern Territory, to explore the potential of “carbon capture and storage” (CCS) technology.

The minister said the new oil and gas permits will bolster energy security in Australia and beyond, and ultimately aid the transition to renewables. King also said controversial carbon-capture and storage was necessary to meet Australia’s net-zero emissions targets.

The world’s energy market is going through a period of disruption, largely due to Russian sanctions and the Ukrainian war. But expanding carbon-intensive fossil fuel projects is flawed reasoning that will lead to greater global insecurity.

Research shows 90% of coal and 60% of oil and gas reserves must stay in the ground if we’re to have half a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5℃ this century.

Ignoring The Facts

The new sites for offshore gas and oil exploration comprise ten areas off the coasts of the NT, WA, Victoria, and the Ashmore and Cartier Islands. King’s announcement came at a resources conference in Darwin, where she said:

Gas enables greater use of renewables domestically by providing energy security. Australian [liquefied natural gas] is also a force for regional energy security and helps our trading partners meet their own decarbonisation goals.

The problem with this assessment is that it ignores two things.

First, Australia exports nearly 90% of domestically produced gas and lacks robust export controls to moderate this. Without these controls, increasing domestic production will not improve Australia’s energy security.

Second, gas can only enable greater use of renewables domestically and provide energy security where it is “decarbonised” through the use of carbon-capture and storage. If it isn’t decarbonised, using gas undermines energy security by risking further global warming.

However the deployment of CCS technology is complex, expensive and faces many barriers. To date it has a history of over-promising and under-delivering.

Carbon-capture and storage typically involves capturing carbon dioxide at the source (such as a coal-fired power station), sending it to a remote location and storing it underground.

Offshore CCS involves injecting and storing CO₂ in suitable rock formations. Doing so safely requires robust monitoring and verification, but challenging ocean conditions can make this extremely difficult.

For example, Chevron allegedly failed to capture and store CO₂ at its huge offshore Gorgon gas project, after the WA government approved the project on the condition the company sequester 80% of the project’s emissions in its first five years.

A report in February suggested the project emitted 16 million tonnes more than anticipated due to injection failure. King calls CCS a “proven” technology, but Chevron’s experience indicates this is far from the case.

King did say the federal government won’t rely entirely on CCS, adding “it’s one of the many means of getting to net-zero” and renewable energy remained central to Australia’s emissions reduction efforts.

But critics labelled the technology a “smokescreen” behind which fossil fuel companies can continue to pollute.

Fossil Fuels Are Not The Future

Putting gas in competition with renewable energy will end badly for the fossil fuel industry. As renewable energy’s market share expands, fossil fuels will become uneconomic due to their environmental impacts and higher costs.

Eventually, natural gas will be used only during periods of peak demand or when wind and solar are not producing electricity – in other words, when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. It will not provide the steady, constant electricity supply that makes up our baseload power system. This reality will significantly reduce gas demand and negate the need for carbon-capture and storage.

Opening up new gas and oil exploration is a reactive and dangerous move that does not support Australia’s long-term energy future. Many of our international peers already acknowledge this.

The United Kingdom, for example, now generates 33% of its electricity from renewable sources such as onshore and offshore wind, solar and biomass. The subsequent decline of fossil fuels means the UK has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by more than 50% on 1990 levels.

Gas in the UK is valuable for its ability to provide rapid, flexible power supply during peak periods, to integrate with other renewable technologies and to improve system flexibility. During periods of high demand, storage devices can discharge into the grid and maintain security of supply.

Wrong Way, Go Back

Clearly, Australia is heading in the wrong direction by opening up new fossil fuel exploration.

The move will damage our longer-term security and undermine our climate imperatives. It ignores the glaring economic realities that will eventually push gas out of the market.

And opening new gas fields while carbon-capture remains uncertain is dangerous for the planet. ![]()

Samantha Hepburn, Professor, Deakin Law School, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Suspected Poisoning Of Shoalhaven Flying-Foxes

South32 Cancels Water-Draining Dendrobium Coal Mine Expansion Plan

Newly Discovered Legless Lizard To Be Considered In Final IPC Decision On Mount Pleasant Coal Mine

In a letter dated 12 August 2022, the Department wrote to the IPC, advising that:

‘MACH Energy Australia Pty Ltd (MACH) [the applicant for the Project] has provided the Department with a research paper … confirming that the Legless Lizard recorded at Mount Pleasant is not the Striped Legless Lizard (Delma impar) as previously thought, but is in fact a new species not previously identified. Importantly, this species is not yet listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act).’

The Panel has since heard from stakeholders in relation to this issue and has revised its position of 19 August 2022. The Panel considers that it would be assisted by public submissions on the DPE letter and its attachments regarding the identification of the Legless Lizard, linked here.Public submissions may be made only on this new material and must be received via email (ipcn@ipcn.nsw.gov.au) by 5pm AEST Tuesday, 30 August 2022.

Santos Wants To Dump 61,500 Bull Elephants Worth Of Coal Seam Gas Waste In Western Sydney Or The Headwaters Of The Murray-Darling

- WeKando, Chinchilla, Queensland (on the banks of a tributary of the Murray-Darling)

- A landfill facility at Kemps Creek in Western Sydney

- A landfill facility at Jackson, Queensland (500km from Narrabri)

Chlamydia Vaccine Trial For Koalas In South-West Sydney

Climate Change Predicted To Reduce Kelp Forests' Capacity To Trap And Store Carbon

.jpg?timestamp=1661476788801)

It’ll be impossible to replace fossil fuels with renewables by 2050, unless we cut our energy consumption

Energy consumption – whether its heating your home, driving, oil refining or liquefying natural gas – is responsible for around 82% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Unless Australia reduces its energy consumption, my recent study finds it’ll be almost impossible for renewable energy to replace fossil fuels by 2050. This is what’s required to reach our net-zero emissions target.

Yet, as the nation’s economy recovers from the pandemic, Australia’s energy consumption is likely to return to its pre-pandemic growth. The study identifies two principal justifications for reducing energy consumption (or “energy descent”):

- the likely slow rate of electrifying transport and heating

- that renewable energy will be chasing a retreating target if energy consumption grows.

Energy descent isn’t an impossible task. Indeed, in 1979, Australia’s total final energy consumption was about half that in 2021. Key to success will be transitioning to an ecologically sustainable, steady-state economy, with greener technologies and industries.

What’s Slowing Down Growth In Renewables?

To transition to sustainable energy, Australia must electrify transport and combustion heating, while replacing all fossil-fuelled electricity with energy efficiency and renewables, which are the cheapest energy technologies.

Renewables can be rolled out rapidly: wind and solar farms can be built in just a few years and residential rooftop solar can be installed in a single day.

But rapid growth in wind and solar is slowed by three critical infrastructural and institutional requirements of the electricity industry:

- to establish Renewable Energy Zones (a cluster of wind and solar farms and storage)

- to build new transmission lines and medium-term energy storage such as pumped hydro

- to reform electricity market rules to make them more suitable for renewable electricity.

These take longer than building solar and wind farms and much longer than installing rooftop solar and batteries. Nevertheless, they could be fully implemented within a decade.

In fact, transitioning existing fossil-fuelled electricity generation, such as coal-fired power stations, to 100% renewables could possibly be completed by the early 2030s.

But optimistic calculations based on how quickly we can build solar and wind farms and their infrastructure ignore the fact that the growth of renewable electricity is limited by electricity demand.

When existing coal-fired power stations have been replaced by renewables, electricity demand will be determined by how rapidly we can electrify transport and combustion heating. These are the principal tasks that will limit the future growth rate of renewable electricity. They will likely be implemented slowly, despite the urgency of climate change.

Households and industries have big investments in petrol/diesel vehicles and combustion heating. They may be reluctant to replace these working technologies, without substantial government incentives.

So far, effective federal government policies are almost non-existent for transitioning transport and heating, which are together responsible for 38% of Australia’s emissions.

This month’s announcement of a future “consultation” on fleet fuel efficiency standards is the government’s tentative first step.

Chasing A Retreating Target

If we look at only percentage growth rates, the task of renewable electricity looks misleadingly easy. From 2015 to 2019, Australia’s renewable electricity grew by 62% – an excellent achievement.

But, it was starting from a small base. This means its increase in energy production over that period was only slightly bigger than the growth of total final energy consumption – comprising electricity, transport and heating – which is still mostly fossil fuelled.

On the global scale, the situation is even worse. As a result of growth in total final energy consumption, the share of fossil fuels was the same in 2019 as in 2000: namely around 80%.

The challenge for renewable energy is like a runner trying to break a record while officials are striding away down the track with the finishing tape.

This situation is not the fault of renewable energy technologies. Nuclear energy, for example, would grow much more slowly and would take even longer to catch up with growing consumption.

In one of the scenarios I explore in my study, Australia’s total final energy consumption grows linearly at the pre-pandemic rate from 2021 to 2050. Then, renewable electricity would have to grow at 7.6 times its pre-pandemic rate to catch up by 2050.

Alternatively, if renewable electricity growth is exponential, it would have to double every 6.8 years until 2050.

Considering that future growth in renewable electricity will be limited by the rate of electrifying transport and combustion heating, both the required linear and exponential growth rates appear impossible.

Possible Solutions

Both the International Energy Agency and modelling done for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change avoid the problem by assuming large-scale carbon dioxide capture and storage or directly capturing CO₂ from the air will become commercially available.

But relying on these unproven technologies is speculative and risky. Therefore, we need a Plan B: reducing our energy consumption.

My study shows if we could halve 2021 energy consumption by 2050, the transition may be possible. That is, if raw materials (such as lithium and other critical minerals) are available and local manufacturing could be greatly increased.

For example, if the total final energy consumption declines linearly and renewable electricity grows linearly, the latter would only have to grow at about three times its 2015–2019 rate to replace all fossil energy by 2050. For exponential growth, the doubling time is 9.4 years.

Improvements in energy efficiency would help, such as home insulation, efficient electrical appliances, and solar and heat pump hot water systems. However, the International Energy Agency shows such improvements will be unlikely to reduce demand sufficiently.

We need behavioural changes encouraged by socioeconomic policies, as well as technical.

Implications Of Energy Descent

To reduce our energy consumption, we would need public debate followed by policies to encourage greener technologies and industries, and to make socioeconomic changes.

This need not involve deprivation of key technologies, but rather a planned reduction to a sustainable level of prosperity.

It would be characterised by greater emphasis on improving and expanding public transport, bicycle paths, pedestrian areas, parks and national parks, public health centres, public education, and public housing.

This approach of providing universal basic services reduces the need for high incomes and its associated high consumption. As research in 2020 pointed out, the world’s wealthiest 40 million people are responsible for 14% of lifestyle-related greenhouse gas emissions.

And on a global scale, energy descent could be financed by the rich countries, including Australia. Most people would experience a better quality of life. Energy descent is a key part of the pathway to an ecologically sustainable, socially just society.![]()

Mark Diesendorf, Honorary Associate Professor, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

10 images show just how attractive Australian shopping strips can be without cars

Think of a typical Australian shopping street: parked cars occupy the prime public space in front of the shops. But we could instead create a place that’s good for business and is beautiful too. It would attract customers while being good for our physical, mental and social health.

This isn’t a new idea. Realising they can make better use of the space next to businesses to boost sales, shopping centres design places to attract people. That’s why they provide seats, air-conditioning, music, artwork, cafes and plants outside their shops.

Online shopping is even comfier, but it lacks human contact.

We know what works to create people-friendly local shopping streets. Safer speeds, improving lighting, replacing parking with “parklets”, planting street trees and widening pavements — these are just some of the ways.

Below we’ll discuss four reasons to reallocate parking space next to shops. But first, we’ve re-imagined ten car-centric Australian streets to illustrate the benefits of reallocating space to people … to shoppers, diners, riders, children, prams and the mobility-impaired.

Transforming 10 Car-Centric Shopping Streets

These re-imagined streets show thriving liveable communities, supporting friends and families to meet, creating local jobs and providing access to fresh food. (Click on and move the sliders to compare the actual and re-imagined streets.)

1. Chapel Street, Windsor, Melbourne, Victoria

2. Beaumont Street, Hamilton, Newcastle, New South Wales

3. Darby Street, Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

4. Hall Street, Bondi, Sydney, NSW

5. Princes Highway, Woonona, Wollongong, NSW

6. Belvidere Street, Belmont, Perth, Western Australia

7. Oxford Street, Leederville, Perth, WA

8a. Parklet, South Terrace, Fremantle, Perth, WA

8b. South Terrace, Fremantle, Perth, WA

9. Musk Avenue, Kelvin Grove, Brisbane, Queensland

The Elephant In The Room

Typically a car transports just one or two customers. A parked car occupies about 13 square metres. That’s about the size of an elephant lying down.

In the same space, 20 shoppers can be walking, 12 diners can sit outside a cafe, or 12 customers can park their bikes.

Before re-imagining the streets, we calculated that car parking (27%) and travel lanes (46%) took up nearly three-quarters of the street space, comparable to other research.

Reducing car parking and travel lanes allowed us to increase green space (up 18%), seating (up 17%) and footpaths (up 6%) in our re-imagined streets.

Creating beautiful and healthy shopping streets that provide safe and equitable access is key to attracting more business.

Encouraging motorists to park on neighbouring side streets or in off-street car parks can free up space for people. In any case, motorists rarely find parking right out the front of a shop — the (rising) number and size of cars makes that impossible.

4 Reasons To Redesign Shopping Streets

1: Local businesses benefit

Just this week, Perth’s lord mayor proposed ripping out a pedestrian mall in the CBD and opening it to cars. But this logic doesn’t stack up to get more customers.

It’s important to remember: cars don’t buy things from shops, people do. Shopping streets that prioritise people and beauty over cars will attract higher sales, higher retail rental values and reduced shop vacancy rates.

But where will shoppers park? Shoppers are already used to walking short distances from parking on side streets and in off-street car parks.

Switching to other modes of transport for short journeys to the shops is another option.

2. More attractive for COVID-19 dining

We now know that COVID-19 is airborne — meaning we can inhale the virus. Improving ventilation is key to reducing the spread, but this can be a challenge indoors.

The evidence suggests gathering outdoors is safer than indoors.

Almost half of Australians have a family dog, so being able to have a coffee outside opens up further business benefits of outdoor dining space.

Trialling more people-friendly streets can be a great way to demonstrate their benefits. NSW has already run trials of “streets as shared spaces” encouraging outdoor dining.

3: For kids and families

Great streets are enjoyable and safe places for kids and their families. Streets like this make it easier to get active and have fun.

We should listen to kids’ ideas when it comes to building healthy streets — they want their local streets to be active and fun places to meet their friends.

Shopping streets should make everyone feel welcome. By this we mean streets that:

- are safe and easy to cross

- have shade and shelter

- provide rest stops and benches

- are quiet, walkable and rideable

- have interesting things to see and do

- are relaxing

- have fresh, clean air.

4: Boost our physical activity and mental health

More than half of city car journeys are shorter than 5km — and many are even shorter. Ongoing under-investment in safe walking and cycling means Australians feel forced into driving short distances, even though they might prefer to walk or cycle.

Increasing walking is a cost-effective investment to boost Australia’s physical activity levels. It would reduce the one in ten deaths and A$15.6 billion-a-year burden of inactivity.

Riding or walking to the shops can be a relaxing and enjoyable experience, and shopping streets can be destinations that people enjoy walking around, staying a while and spending more.

When Australians have better access to local destinations, they walk more.

More people on the streets builds a sense of community, essential for optimal mental health.

Take-Home Message

For shopping streets to compete with larger shopping centres, they need to be more beautiful places to visit, which provide safe and inclusive access for people to spend money locally.

Towns and cities around the world are realising this. Tens of thousands of on-street car parking spaces are being reallocated to people, including in Auckland, Stockholm, Paris, Amsterdam, Milan. Australia can learn from their successes.

The authors encourage the open access reuse of the re-imagined streets. They are freely available to download in multiple formats.![]()

Matthew Mclaughlin, Research Fellow, Telethon Kids Institute, The University of Western Australia; Hayley Christian, Associate Professor, School of Population and Global Health, The University of Western Australia; Jasper Schipperijn, Professor of Active Living Environment, University of Southern Denmark, and Trevor Shilton, Adjunct Professor, School of Public Health, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

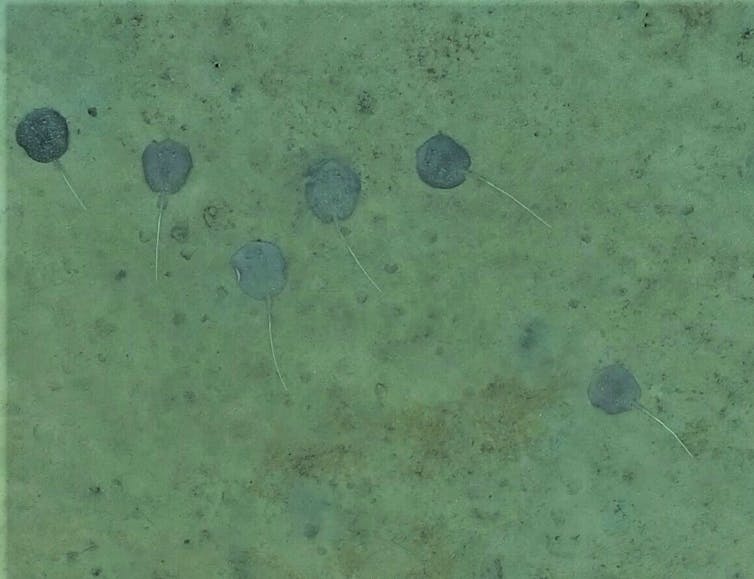

‘I will miss them if they are gone’: stingrays are underrated sharks we don’t know enough about

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s series introducing you to unloved Australian animals that need our help.

Have you ever done the “stingray shuffle”? If you live by the coast, you’ve probably taken this precaution to frighten off any buried stingrays as you wade into the water. Breath easy – your chances of getting stuck with a nasty barb are slim.

Any thoughts we have about stingrays usually end once danger is averted, but these fascinating creatures are much more than an inconvenience for beachgoers.

Stingrays are flat-bodied sharks that live in almost all marine environments worldwide. In fact, there are over 600 recognised species – most of which we know very little about. Even in the research world, we struggle to answer simple questions such as: which areas are most valuable for stingray populations and why?

The mangrove whipray (Urogymnus granulatus) is one such species. Aptly named, mangrove whiprays feel at home gliding through submerged mangrove roots in the tropical coastal regions of the Indo-Pacific and Northeast Australia. Unfortunately, they are at risk of decline and localised extinctions.

As a scientist who studies them, I attest these rather ordinary, mud-covered stingrays are beautiful, and I never tire of watching them. We have to ask ourselves: would it make any difference if these rays were here or not? How relevant are they for ecosystem health?

The Situation At Hand

Sharks and rays are experiencing some of the most drastic declines of any animal group inhabiting our oceans today due to fishing pressure and habitat loss, and coastal species are particularly vulnerable.

Stingrays are occasionally preyed upon by their toothy relatives, such as formidable Carcharhinid or hammerhead sharks. However, the shark-eat-shark world isn’t all to blame for losses of abundance and species becoming red-listed.

Most stingrays depend on shallow tidal habitats for feeding and protection, especially during their first years of life, but many of these areas worldwide are being lost and degraded. This is a big threat to the survival of mangrove whiprays.

Coastal development is a major contributor to the destruction of mangroves as we replace these seaside forests with marinas, agricultural land, factory ports, ocean-view hotels, homes, and other structures.

A recent global assessment of tidal wetlands found that compared to other coastal environment types, mangroves experienced some of the greatest losses due to human activities, with 3,700 square kilometres lost worldwide between 1999-2019.

Worsening drought conditions due to climate change may also threaten mangrove forests. For example, recent research suggests climate change contributed to the deaths of 40 million Northern Australian mangroves in the summer of 2015 and 2016.

We can only expect that with the loss of pristine mangrove environments, mangrove whiprays will diminish along with them. As this threat continues into the future, this little stingray remains at risk.

Why They Matter

Mangrove whiprays do much more than lay buried in the sand. While they’re not high profile apex predators, they fill an important niche as intermediate predators. Essentially, they are the glue that connects higher and lower levels of the food chain.

Since they’re usually seen from above, it’s hard to notice the small, suction-like mouth underneath, which they use to extract buried invertebrate prey. Combined with vigorous flapping of their winged pectoral fins, their feeding can stir up hefty clouds of sediment.

Through this intense excavation, they recirculate buried nutrients and small food items back into the water column. This, in turn, can be important for creating feeding opportunities for other organisms. My personal observations of foraging mangrove whiprays have revealed that small fishes often linger nearby to snack on stray food particles.

As both predator and prey, these rays also help transfer nutrients beyond where they feed across a broader range of ecosystems. This can occur at small scales when they creep in and out of intertidal areas with the tide and at larger scales when juveniles transition to deeper waters as adults.

This strengthens ecosystem connectivity, which is a critical component of overall health and stability of coastal environments.

So, under the category “ecosystem functions”, coastal stingrays like the mangrove whipray have an impressive resume worthy of our attention. The next big question regarding their conservation is: what can we do for them?

What We Can Do

Realistically, we cannot snap our fingers and stop all human activities from threatening the coastal mangroves they call home. What we can do is achieve a better understanding of where they are highly abundant and why, so we can identify pieces of critical habitat.

This way, conservation efforts can be designed to protect the areas they rely on the most.

An improved understanding on how mangrove whiprays participate in coastal food chains would also help us determine if declining populations threaten the welfare of coastal mangrove forests.

But the campaign for action doesn’t stop at mangrove whiprays. This species represents just one of many creeping into the bubble of conservation concern, and more may join the list if we continue without vital knowledge that can support their protection.

Examples of other vulnerable species that have been documented sharing habitats with mangrove whiprays are the pink whipray (Pateobatus fai) and giant guitarfish (Glaucostegus typus). Therefore, in areas where these different ray species live together, conservation strategies for one may have positive outcomes for all.

It’s up to scientists to fill the existing gaps on stingray ecology, but the average bystander can also help by spreading awareness for stingrays so their plight won’t drag on without any media headlines to lament it.

They may not warm our hearts with their cuddly cuteness (me excluded), but the wellbeing of our coastal ecosystems may just depend on these remarkable flat-bodied sharks. I know I will miss them if they are gone.![]()

Jaelen Nicole Myers, PhD Candidate, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The road to new fuel efficiency rules is filled with potholes. Here’s how Australia can avoid them

Last week, federal Climate and Energy Minister Chris Bowen officially put fuel efficiency standards on the national agenda, saying the measure would reduce transport emissions and encourage electric vehicle uptake.

Fuel efficiency standards are applied to car manufacturers and indirectly set limits on how much CO₂ can on average be emitted from a new vehicle. Such standards lead to lower fuel costs for motorists and could help Australia meet its targets under the Paris climate agreement.

Importantly, Bowen noted any new rules must be ambitious and designed specifically for Australia. But implementing effective standards is easier said than done – and there are many potholes to avoid.

Without a robust set of mandatory transport emissions standards, Australia’s dependence on fossil fuels will deepen, and reaching our emissions reduction goals will become harder.

Standards Must Be Mandatory

Road vehicles vary in the efficiency with which they use fossil fuels such as petrol and diesel. For example, large SUVs are usually less fuel efficient than smaller, lighter cars. And of course, electric vehicles operate without any fossil fuels at all (although the energy source used to charge their batteries determines how “green” they are).

Stringent fuel efficiency standards will encourage the auto industry to bring more electric vehicles to Australia, and reduce how many polluting vehicles it imports.

Australia is the only country in the OECD without mandatory fuel efficiency standards for road transport vehicles. Voluntary fuel economy targets were adopted for new petrol cars in 1978, but were not achieved in 2010. In 2020, Australia’s automotive industry announced a new voluntary reporting system for CO₂ emissions reduction of 3-4% per year this decade.

These rules are not mandatory, and the target probably falls short of what’s needed. Yet, the industry is promoting these standards as a template for Australia’s new fuel efficiency rules.

Mandatory fuel efficiency standards are at the core of energy and transport policies around the world. So this should be the first guiding principle of any new system pursued by the federal government.

Real-World Driving Patterns

Second, the standards must be based on real-world fuel consumption.

Setting fuel efficiency standards first requires selecting a specific “driving pattern” that includes vehicle speed, acceleration, deceleration and power usage, and are used to determine a vehicle’s fuel use and emissions.

The patterns also take into account local road type (such as residential, arterial or motorway) and driving conditions (such as free-flow or morning peak).

The voluntary industry standards now in place in Australia are based on a driving pattern called the “New European Drive Cycle” or NEDC. Among its shortcomings, the cycle assumes mild accelerations and constant speeds that don’t reflect modern-day driving.

This has led to substantial deviations between the NEDC assumptions about fuel use and real-world consumption.

Our recent research measured emissions from five SUVs driving around Sydney. After comparing our measurements with the Green Vehicle Guide, we found fuel use was 16% to 65% higher than NEDC values, depending on the vehicle and driving conditions.

And research in 2019 suggested that, contrary to official figures using the NEDC, the rate of CO₂ emissions for new Australian passenger vehicles was not falling – and may actually have increased since 2015.

Why? It’s likely due to an increase in sales of bigger, heavier vehicles in Australia, such as SUVs, as well as a shift towards more 4WD and diesel cars.

So it’s crucial that we drop the NEDC – and base the new Australian standards on a drive pattern that represents real-world conditions. This could be similar to the pattern adopted by the European Union, or a real-world Australian drive cycle.

Other Things To Consider

The federal government should implement a single standard for all passenger vehicles – including all SUVs, without exception.

Australia’s voluntary system allows large road-based SUVs to fall into the same category as light commercial vehicles. This means they’re subject to less stringent fuel efficiency standards than cars.

This may inadvertently promote sales of heavy SUVs and, as a result, significantly increase real-world fuel consumption and associated emissions.

And Australia’s standards must also eliminate loopholes that could allow companies to comply with regulations but not actually improve fuel efficiency to the extent intended.

The considerations listed above are by no means exhaustive. And new fuel efficiency standards must be supported by other policy measures, such as reducing our reliance on private cars, and promoting public transport, walking and cycling.

Transport is Australia’s third-biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions, and federal government moves to tackle this problem are welcome. But if fuel efficiency standards are not carefully designed, the sector will continue to let down motorists, and the planet.![]()

Robin Smit, Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Technology Sydney; Hussein Dia, Professor of Future Urban Mobility, Swinburne University of Technology, and Nic Surawski, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Engineering, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Frozen in time, we’ve become blind to ways to build sustainability into our urban heritage

It was hard to keep up with all the bad news coming out of the recent Australia State of the Environment report. The dire state of natural places and First Nations heritage rightly attracted attention. However, one important finding was overlooked: the poor state of Australia’s so-called historic heritage.

The report found this heritage is at risk on many fronts. It’s under pressure from land development, resource extraction, poorly managed tourism, climate change and inadequate management and protections.

In a familiar framing, the report points the finger at urban development and other changes. However, this mindset itself is actually an obstacle to protecting our urban heritage.

Change in our cities, and to our heritage, is both inevitable and necessary. Our relationships to neighbourhoods and places constantly evolve, as we learnt during COVID-19 lockdowns.

Policy ideas framed by sustainability, such as adaptive management that encourages heritage places to change and evolve, are more sensible. Flexible and creative responses to heritage places should be allowed.

An example of embracing change is the Walsh Bay Arts Precinct in Sydney. The project has reimagined maritime heritage for culture and the arts.

Adopting new perspectives won’t only preserve our historic buildings and places by enabling us to shape them for today’s needs. It will also mean urban heritage can contribute to cities becoming more socially, economically and environmentally sustainable.

A Problem Of Definitions

The historic heritage that the report finds is deteriorating refers to places, buildings and structures dating from 1788 onwards. But the very idea of “historic heritage” is out-of-date.

The term originally contrasted colonial built heritage with so-called “pre-history”. Indigenous heritage was generally seen as being in the past rather than continuing into the present or having a future.

A more precise term, “cultural heritage”, embraces the diverse historical and societal values that shape cities and historic environments. It better recognises that our urban cultural heritage is a product of colonisation and dispossession and located on Indigenous Country.

On the ground, we see a few examples of more progressive activities. The deeply researched City of Melbourne Hoddle Grid Review embraced Indigenous perspectives, social values and modern buildings. But this is an unusual case of innovation.

A Problem Of Knowledge

For heritage to contribute more to social sustainability, by ensuring places reflect and strengthen diverse communities, we need more robust knowledge about existing protections.

We simply lack that data. Australia has no heritage reporting mechanisms across national, state and local heritage jurisdictions.

As a result, the State of the Environment report was unable to provide a fuller picture of the state of urban heritage: what is protected, why and how it is protected, nor its values and condition. The report was not funded for this kind of comprehensive data collection, nor for widespread site visits.

We cannot identify which Australian communities and histories – whether First Nations, colonial or multicultural stories – are represented within heritage lists. The five-year report identifies only six targeted projects exploring gaps in state heritage registers. Only one of these studies foregrounds social value.

Centralising community perspectives in heritage remains a challenge. For example, when the City of Ballarat collaborated with residents to identify places of importance, the insights could not be translated into protections because planning laws don’t adequately recognise community heritage expertise. Work needs to be done to integrate heritage management and social sustainability.

A Problem Of Adaptation

Expanding the scope of urban heritage enables new perspectives on how it can contribute to economic and environmental sustainability. Economic development can threaten heritage, but also rescue it from decay. Leading heritage projects treat existing physical and social spaces as significant but underutilised resources.

The regeneration of Sydney’s Kings Cross, for example, seeks to return glitz and glamour to the area, albeit minus its gritty and subversive character. Heritage and communities are both enhanced and diminished through development and investment.

The report rightly identifies climate change as a threat to heritage places. Yet, across jurisdictions, inadequate emphasis is placed on heritage as a driver of climate adaptation. Reworking existing environments, buildings and structures, whether or not they are heritage-listed, is a sustainability trend.

Indeed, the report encourages the retention of existing buildings for their embodied energy due to the resources that have gone into constructing and maintaining them. But it maintains the premise that development tends to undermines conservation.

This longstanding mindset stands in the way of widespread adaptive reuse. Adopting broader perspectives and new approaches empowers heritage for sustainability agendas.

Although not heritage-listed, Broadmeadows Town Hall (1964) in Melbourne has been conserved and transformed in a sophisticated and functional way. At Melbourne’s Southbank, the listed Robur Tea House may soon finally be revitalised. Reworking the 1880s industrial building with a skyscraper above may well be the best way forward.

What’s Stopping Us From Doing Better?

With clear parallels to today, the Inquiry into the National Estate reported in 1974 that Australia’s heritage had been “downgraded, disregarded, and neglected”. The Commonwealth government took dramatic action by establishing the independent and innovative Australian Heritage Commission (1975–2004).

In recent times, however, the Commonwealth has greatly reduced its involvement in conserving urban heritage. Every state and local government now has its own approaches, resulting in fragmented governance arrangements. The lack of national leadership, co-ordination and innovation has led to us falling behind international approaches.

Urban heritage can strengthen communities and help foster an inclusive and democratic society only by engaging with a diversity of places and stories. Widespread adaptation and reuse of both listed and non-listed heritage places can support economic and environmental sustainability.

New and radical perspectives are needed to keep heritage relevant and thriving in cities.

James Lesh’s book Values in Cities: Urban Heritage in Twentieth-Century Australia will be launched at the Robin Boyd Foundation in Melbourne on August 24 2022.![]()

James Lesh, Lecturer in Cultural Heritage and Museum Studies, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

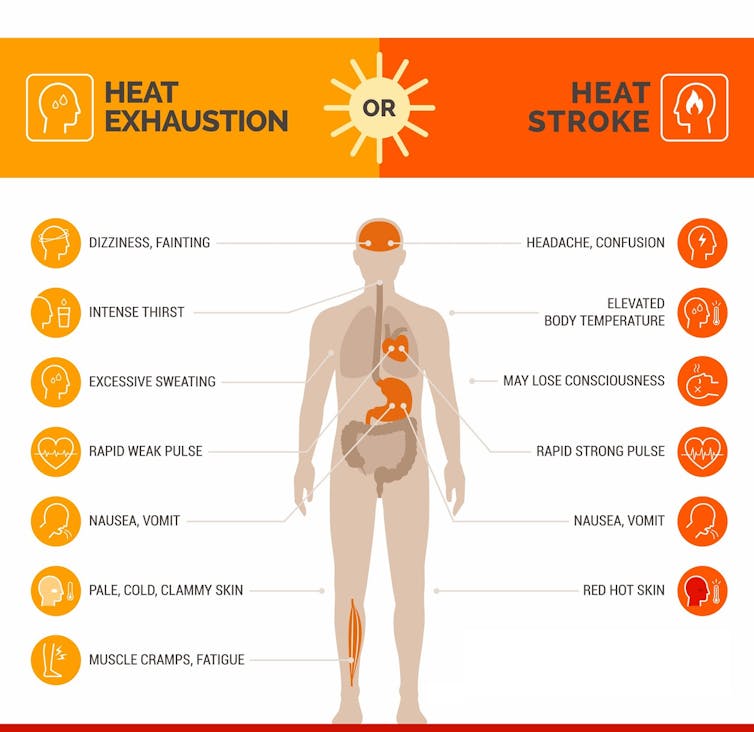

If you thought this summer’s heat waves were bad, a new study has some disturbing news about dangerous heat in the future

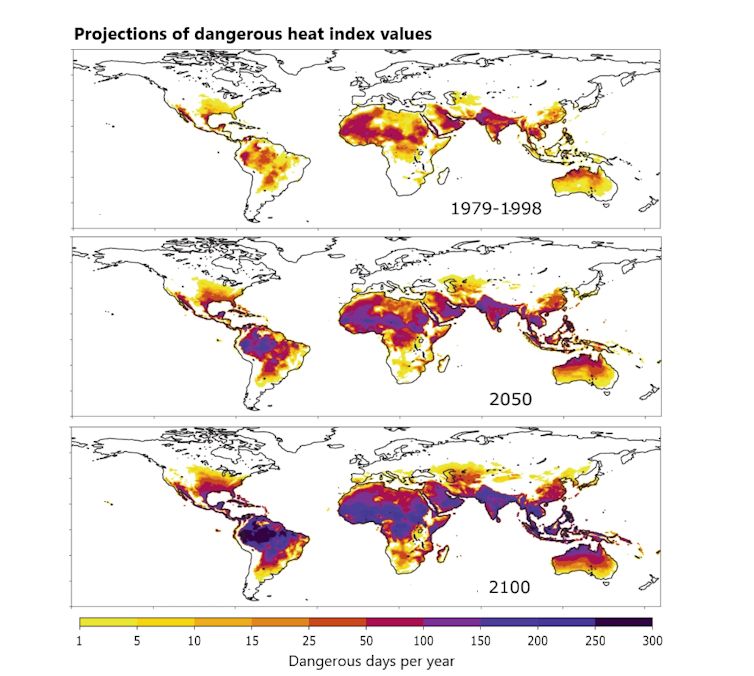

As global temperatures rise, people in the tropics, including places like India and Africa’s Sahel region, will likely face dangerously hot conditions almost daily by the end of the century – even as the world reduces its greenhouse gas emissions, a new study shows.

The mid-latitudes, including the U.S., will also face increasing risks. There, the number of dangerously hot days, marked by temperatures and humidity high enough to cause heat exhaustion, is projected to double by the 2050s and continue to rise.

In the study, scientists looked at population growth, economic development patterns, energy choices and climate models to project how heat index levels – the combination of heat and humidity – will change over time. We asked University of Washington atmospheric scientist David Battisti, a co-author of the study, published Aug. 25, 2022, to explain the findings and what they mean for humans around the world.

What Does The New Study Tell Us About Heat Waves In The Future, And Importantly The Impact On People?

There are two sources of uncertainty when it comes to future temperature. One is how much carbon dioxide humans are going to emit – that depends on things like population, energy choices and how much the economy grows. The other is how much warming those greenhouse gas emissions will cause.

In both, scientists have a really good sense of the likelihood of various scenarios. For this study, we combined those estimates to get a likelihood in the future of having dangerous and life-threatening temperatures.

We looked at what these “dangerously high” and “extremely dangerous” levels on the heat index would mean for daily life in both the tropics and in the mid-latitudes.

“Dangerous” in this case refers to the likelihood of heat exhaustion. Heat exhaustion won’t kill you if you’re able to stop and slow down – it’s characterized by fatigue, nausea, a slowed heartbeat, possibly fainting. But you really can’t work under these conditions.

The heat index indicates when a person is likely to reach that threshold. The National Weather Service defines “dangerous” as a heat index of 103 F (39.4 C), and “extremely dangerous” as 125 F (51.7 C). If a person gets to “extremely dangerous” temperatures, that can lead to heat stroke. At that level, you have a few hours to get medical attention to cool your body down, or you die.

“Extremely dangerous” heat index conditions are almost unheard of today. They happen in a few locations near the Gulf of Oman, for example, for maybe a few days in a decade.

But the odds of the number of “dangerous” days are increasing as the planet warms. We’ll likely have about the same weather variability as today, but it’s all happening on top of a higher average temperature. So, the likelihood of extremely hot conditions increases.

What Does Your Study Show For Each Region?

In the mid-latitudes by 2050, we’ll see the number of dangerous heat days double in the most likely future scenario – even under modest greenhouse gas emissions that would meet the Paris climate agreement target of keeping warming under 2 C (3.6 F).

In the Southeastern U.S., the most likely scenario is that people will experience a month or two of dangerous heat days every year. The same is likely in parts of China, where some regions have been sweating through a summer 2022 heat wave for over two straight months.

We found that by the end of the century, most places in the mid-latitudes will see a three- to tenfold increase in the number of dangerous days.

In the tropics, such as parts of India, the heat index right now can exceed the dangerous level for a few weeks a year. It’s been like that for the past 20 to 30 years. By 2050, those conditions are likely to occur over several months each year, we found. And by the end of the century, many places will see those conditions most of the year.

What that means in practice is if you’re a rich country like the U.S., most people can afford or find air conditioning. But if you’re in the tropics, where about half the world’s population lives and poverty is higher, the heat is a more serious problem for a good part of the year. And a large percentage of people there work outside in agriculture.

As we get toward the end of the century, we’ll start exceeding “extremely dangerous” conditions in several places, primarily in the tropics.

Northern India could see over a month per year in extremely dangerous conditions. Africa’s Sahel region, where poverty is widespread, could see a few weeks of extremely dangerous conditions per year.

Can Humans Adapt To What Sounds Like A Dystopian Future?

If you’re a rich country, you can build cooling facilities and generate electricity to run air conditioners – hopefully they won’t be powered with fossil fuels, which would further warm the planet.

If you’re a developing country, a very large fraction of people work outdoors in agriculture to earn money to buy food. There, if you think about it, there aren’t a lot of options.

Migrant workers in the U.S. also face more difficult conditions. A farm might be able to provide cooling facilities, but farmers’ margins are pretty small and migrant workers are often paid by volume, so when they aren’t picking, they aren’t paid.

Eventually, conditions will get to the point that more workers are overheating and dying.

The heat will be a problem for crops, too. We expect most of the major grains to be less productive in the future because of heat stress. In the mid-latitudes right now, we’re close to optimal temperatures for growing grains. But as temperatures increase, grain yield goes down. In the tropics, that could be anywhere between a 10% to 15% reduction per degree Celsius increase. That’s a pretty big hit.

What Can Be Done To Avoid These Risks?

Part of our work in this study was determining the odds that the world will actually meet the Paris agreement. We found that to be around 0.1%. Basically, it’s not going to happen.

By the end of the century, we found the most likely scenario is that the planet will see 5.4 F (3 C) of warming globally compared to pre-industrial times. Land warms faster than ocean, so that translates to about a 7 F (3.9 C) increase for places where we live, work and play – and you can get a sense of the future.

The faster renewable energy comes online and fossil fuel use is shut down, the better the chances of avoiding that.![]()

David Battisti, Professor of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Hunger is increasing worldwide but women bear the brunt of food insecurity

Recent UN data on food insecurity paints a bleak picture of a growing international problem: global hunger is not only growing but it disproportionately affects women. Similarly, the international humanitarian aid organisation, CARE, estimates that 150 million more women than men went hungry in 2021.

Despite gains in global food security since 2015, food security has gone backwards, with an increase of 150 million people experiencing hunger since 2019.

The UN reports that globally, 2.3 billion people were food insecure in 2021 with 276 million (12%) facing severe food insecurity. This rapid and sustained increase in hunger over a short time is highly concerning. So too, is the growing gender gap, with 32% of women compared to 27.5% of men going hungry.

Why Are Women More Affected By Food Insecurity Than Men?

To answer this question, the global food system needs to be understood as a mirror of society. It reflects income inequalities and the uneven distribution of goods and services and, as such, is likely to show the same underlying structural inequalities as society at large.

The causes of food insecurity are complex and multi-dimensional. However, two important dimensions are the availability of food (is there enough food?) and the accessibility of food (is it affordable?).

Recently, the availability of food has been challenged by climate crises, conflicts, and disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, cost of living pressures have pushed the accessibility of food beyond the means of many people in both developed and developing countries.

On official measures of gender equality, women tend to experience a lower socio-economic status than men. Globally, 388 million women and girls live in extreme poverty right now, compared to 372 million men and boys. Oxfam reports that women earn 24% less than men, work longer hours, have more precarious work and do at least twice as much unpaid work.

The Impact Of Other Forms Of Inequality

Income disparities are also important to consider. Even when food is in abundance, with a few exceptions, it cannot be accessed without money. Accordingly, a bigger gender gap in income equality also means women have fewer means to purchase food.

The disadvantage of women has also been described in terms of their lack of agency to change their circumstances. In developing countries where subsistence farming is a key means of food provision, structural inequalities in land tenure and access to credit undermine women’s ability to generate income. Women make up 43% of the agricultural workforce, yet own less than 15% of land.

Improved women’s agency is strongly correlated with a reduction in poverty and has been recognised by the Higher Level Panel of Experts on Food Security as a critical dimension of food security.

Australia Also Has Severe Food Insecurity, But Women Aren’t Counted

Despite being the “lucky country,” Australia does not have a food security policy, nor does it collect the data necessary for an informed and targeted response.

In fact, the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry argues that concerns about food security are “understandable, yet misplaced” because Australia “[…] produces substantially more food than it consumes.”

The narrative might work in terms of availability of food but overlooks key issues regarding its accessibility, including gender dimensions, the difference between individual, household and domestic food security, and the link between poverty and food insecurity.

Some of these data gaps have been filled by Food Bank, a food relief organisation, that conducts annual surveys on food insecurity in Australia. Their recent data reveals 17% of Australian adults are “severely” food insecure. While the data is not segregated by gender, we can surmise a food insecurity gap if we use income as a proxy.

Indeed, the Australian parliament reports that women’s median weekly earnings were 25% lower than men’s in 2019, suggesting women may also have reduced access to food. We may also expect a “food security gap” with other marginalised groups such as the aged, people with disabilities, sole parents, and Indigenous populations.

Future Responses

Severe levels of food insecurity are currently increasing in all regions of the world, and women are faring worse than men. Gender inequality worldwide intensifies the lack of access to food for women.

Recognising that women’s food security cannot be separated from broader concerns of agency, policies must consider the specific issues of gender equality, women’s rights and empowerment.

To do this, governments must also institute funded, systematic data collection, segregated by gender. Improved knowledge and transparency is central to policies aiming to strengthen women’s agency, lift women out of poverty and ensure the food security gender gap does not widen.![]()

Carol Richards, Associate professor, Queensland University of Technology and Rudolf Messner, Postdoctoral research fellow, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What the High Court decision on filming animals in farms and abattoirs really means

What do farm animals have to do with the Australian Constitution?

Should the public know what happens in abattoirs and farms? Do we have the right to publish footage of what happens to animals in slaughterhouses? Should governments be able to make laws criminalising it? How do we best protect the privacy of farmers and prevent trespass?

The High Court considered these issues in Farm Transparency v New South Wales, handing down its judgment this month. This case concerned sections 11 and 12 of the Surveillance Devices Act 2007 (NSW): section 11 prohibits the publication or communication of footage or photographs of “private activities”, including intensive farming and slaughtering operations, with penalties of up to five years in prison. Section 12 criminalises the possession of such recordings.

In 2015, Farm Transparency Project’s director, Chris Delforce, was charged with publishing footage and photos depicting lawful practices at piggeries. The footage related to the use of carbon dioxide gas as a means of slaughtering animals.

While the charges were eventually dismissed, animal welfare organisations are concerned the legislation will obstruct legitimate whistleblowing (and public access to information) about the agricultural industry. There are also concerns the legislation may dampen the willingness of media to grapple with these issues. In turn, this may limit the ability of the Australian consumer to make informed choices about what they eat, and hinder public discussions about animal welfare due to a lack of information.

In that context, Farm Transparency took legal action arguing that the Surveillance Devices Act was in breach of the “freedom of political communication” implicitly protected by the Australian Constitution. In doing so, they turned an animal welfare and consumer rights issue into a constitutional issue.

What Is The Implied Freedom Of Political Communication?

Australia, unlike all other western democracies, does not have a federal bill of rights. This means there is no stand-alone right to free expression or speech.

However, freedom of political communication is implied from sections 7 and 24 of the Australian Constitution, which require that elected representatives be “chosen by the people”.

The courts have held previously that this implies laws should not limit our communication on political matters because that influences our choice of representative. This means state or federal laws that disproportionately “burden” communication about political matters can be struck down as unconstitutional.

The High Court has repeatedly emphasised that the freedom of political communication is not absolute, nor is it a personal right. Rather, laws directed at a legitimate objective that are reasonable and adapted to that objective will still be valid.

In this case, the question before the court was whether the Surveillance Devices Act 2007 is “suitable”, “necessary” and “balanced” in pursuing a legitimate objective. These questions have also been considered before by the court in relation to, for example, protesting, tweeting, political donations, bail conditions, and media reporting.

What Did The High Court Decide?

Four members of the court (Kiefel CJ, and Keane, Edelman, and Steward JJ) held that while the legislation did burden political communication, it also has a legitimate purpose of privacy. They also held that the offence provisions were proportionate to that purpose. Another judge (Gordon J) “read down” the reach of the provisions, which meant she thought they had limited scope and couldn’t be enforced to restrict publication of political communication.

Notably, two judges disagreed with the majority view (Gageler and Gleeson JJ), and found that the legislation was invalid. In their view, sections 11 and 12 impose blanket prohibitions and do so indiscriminately. In particular, Gageler J thought “The prohibitions are too blunt; their price is too high”.

However, ultimately the majority view was that sections 11 and 12 are constitutionally valid.

Of significance to those interested in animal welfare is that Kiefel CJ and Keane J accepted it was “a legitimate matter of governmental and political concern”. However, in their views, the relevant provisions in this case were not directed at restricting the content of the communications, but to the manner (such as trespass) in which they were obtained.

Why Does This Matter?

This decision means improved conditions for farm animals needs to be achieved by legislative and policy reform. Concerned consumers must convince parliaments to improve legal protections for non-human animals.

The issue is unlikely to go away. Animal welfare groups are increasingly concerned about standards of care and the manner in which animals are raised and slaughtered. Consumers are savvier in the information age and prefer choice.

The recognition of animal sentience and animal rights may eventually curtail the ability to engage in large-scale factory farming. This in turn will contribute to overall efforts to mitigate climate change and other environmental effects.

There is also the overarching issue of the legal protection offered to whistleblowers generally and the inherent problem in restricting information necessary for meaningful public debate.

Individuals and organisations do have legitimate expectations of privacy. However, disclosing reasonable concerns about conduct is an important tool in maintaining good governance and advancing accountability. Protections for whistleblowers are limited in Australia and there is space for legislative reform on this.![]()

Danielle Ireland-Piper, Associate Professor of Constitutional and International Law, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Not all of us have access to safe drinking water. This clever rainwater collector can change that

Access to clean drinking water is fundamental to our health and wellbeing, and a universal human right. But almost 200,000 Australians are still forced to use water contaminated with unsafe levels of various chemicals and bacteria. The situation is especially dire in remote areas.

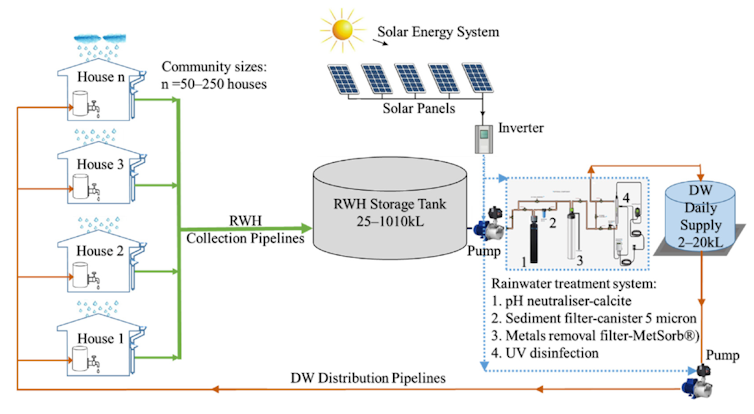

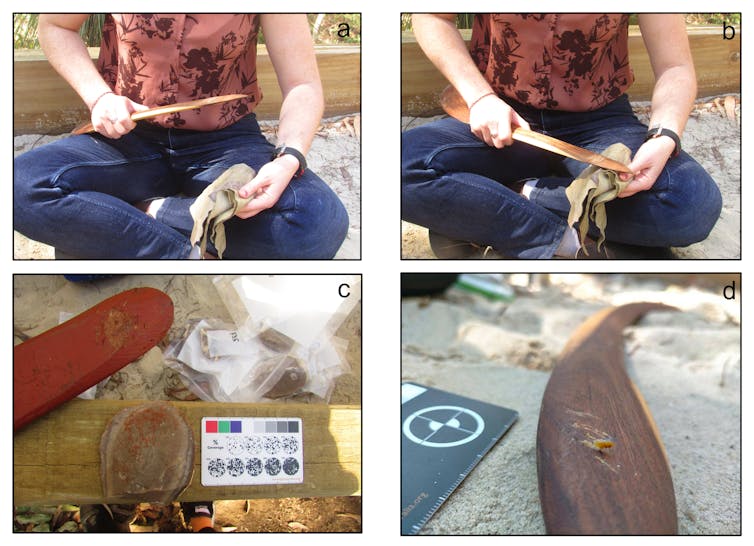

To tackle this issue, we have developed an integrated rainwater harvesting unit at Western Sydney University (WSU).

This simple system can produce safe drinking water for households and communities in remote areas. It’s cheap, easy to use, and could improve the lives of thousands of people.

Far From City Life

In large Australian cities, we are used to turning on the tap – clean, plentiful water is always there, coming from the central water supply. We also take for granted the use of potable water for other uses, such as car washing, gardening and laundry.

But in rural and remote Australia, communities must develop private water supply systems to get safe drinking water from other sources. These can be rainwater, groundwater, surface water and “carted water” – treated water from a supplier.

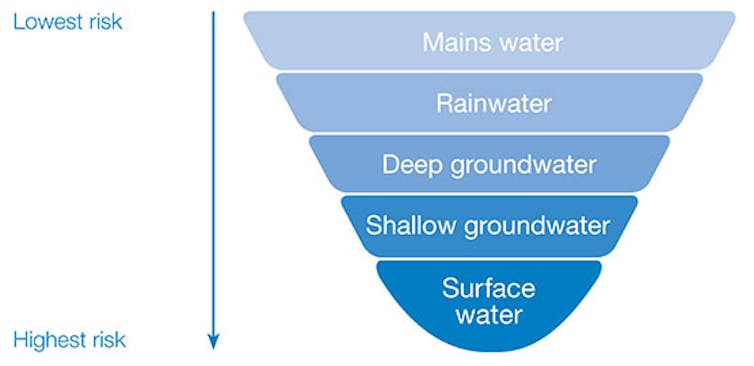

Among these sources, harvested rainwater is considered to be the second-safest option after mains supply, according to the private water supply risk hierarchy chart. So, many residents in rural and remote Australia are using rainwater for their needs.

But rainwater isn’t always safe to drink without adequate treatment, as it can be contaminated from various sources, including air pollution, runoff chemicals, animal droppings, and more.

Unknown Water Quality

In Australia, roughly 400 remote or regional communities don’t have access to good quality drinking water, and 40% of those are Indigenous communities.

According to a 2022 drinking water quality report by Australian National University researchers, at least 627,736 people in 408 rural locations have drinking water that doesn’t meet at least one of the standards set by the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines.

Although the 2022 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals progress report declares that 100% of the Australian population has access to safe and affordable drinking water, it seems this report excluded about 8% of the population living in regional and remote areas.

The issue could be even more widespread due to lack of adequate testing.

Better Options Are Available

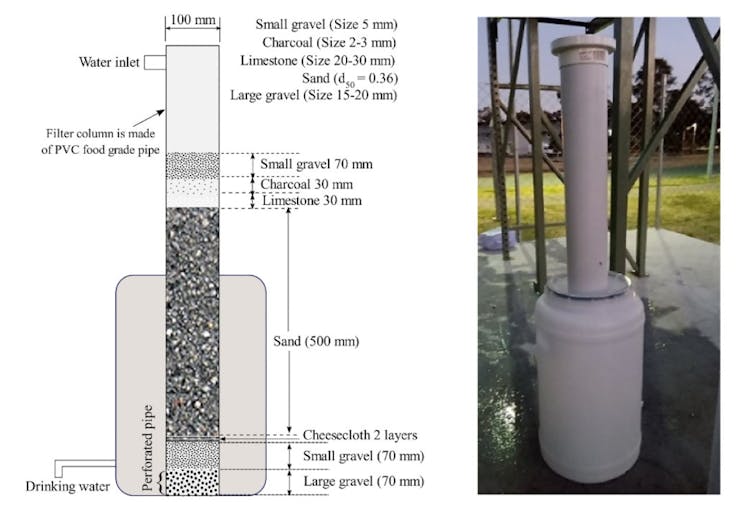

Our low-cost rainwater harvesting unit can produce safe drinking water that meets Australian guidelines, particularly maintaining Escherichia coli and nitrate levels below the recommended limits.

Most importantly, the system is integrated, which means it both collects rainwater, and treats it to be safe for household use.

The system is sustainable, uses locally available materials (such as gravel, sand, charcoal, limestone and stainless steel wire mesh or even cheesecloth), needs minimal maintenance, and is simple to operate. Communities can be trained to use these water systems regardless of technological skill level.

It’s also affordable. The cost of the drinking water produced through this system would be just over 1 cent per litre, according to a recent technical and financial feasibility analysis.

Ready To Use, With Improvements On The Way

Despite their simplicity, these rainwater filter systems don’t even have to be confined to individual households – we can scale them up so entire communities can benefit.

A case study has proved this in both developed and developing countries. Our collaborators in Bangladesh made the first move to adopt this technology, supplying safe drinking water to student accommodation at the Khulna University of Engineering & Technology.

We are also working on improvements. For example, we are building an automated system that can monitor the water quality from the unit regularly and adjust disinfectant dosing to keep it safe for drinking. We’re also developing a method for the system to sense when the filter materials need cleaning, and even start this process automatically.

In Australia, there is a clear need to improve water quality in remote communities. Adopting our simple rainwater filtering system would help communities to produce safe drinking water at minimum cost, and the WSU team is ready to work with local shire councils and groups from different remote communities to transfer the knowledge.![]()

Md Abdul Alim, Associate lecturer, Western Sydney University; Ataur Rahman, Professor, Western Sydney University, and Zhong Tao, Professor, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

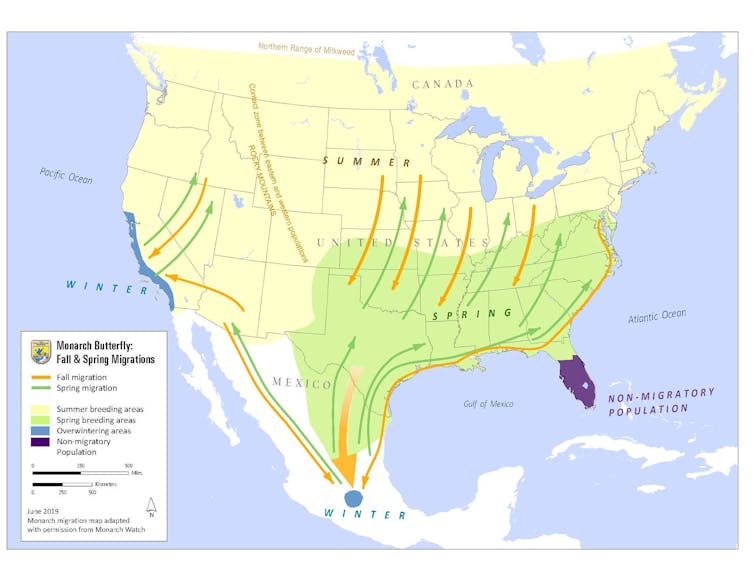

The survival of the endangered monarch butterfly depends on conservation beyond borders

The iconic North American monarch butterfly Danaus plexippus plexippus was recently listed in the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, signalling that its ongoing decline could lead to extinction. The compounding effects of habitat degradation, insufficient food and water and climate change have led to these dwindling numbers.

This tiny, almost weightless, butterfly can travel thousands of kilometres across natural and human-made borders with ease. It can survive harsh weather during its long-distance flights across Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. And it has developed, over millennia, these movements in a delicate relationship with its milkweed host plant.

Despite their remarkable adaptations and ongoing conservation efforts, things have gone downhill for these monarchs. Why? Part of the answer lies in our misguided approach to protecting them.

As a social anthropologist, I have followed this butterfly across North America over the past decade. I document how monarchs are natural crossers, uniting people, fields of expertise and countries. What is at risk of disappearing with them, I argue, is the wonder of a natural connector. And we need to unite to truly protect them.

Monarch Butterflies Need People

Most monarch conservation initiatives are grounded in a false separation of nature and society. Monarch conservation reserves are based on a western ideal of pristine nature, fenced off from humans.

National parks that protect monarchs removed — sometimes forcefully — local people, including Indigenous groups who have long lived sustainably with these insects. This separation caused the monarchs to suffer from that disconnection from the communities which followed agricultural practices that protected them.

In Mexico, forest extensions that used to be community commons (later a Biosphere Reserve to protect monarchs) have been converted into avocado plantations. In Canada, the emblematic Point Pelee National Park that hosts monarchs at their fall migration also substituted monarch habitat with wooded areas that are not suitable for monarchs. Creating this National Park entailed evicting the Caldwell First Nation from their ancestral land.

Borders Affect Monarch Conservation

Monarchs are negatively affected by national borders. The U.S., Canada and Mexico have different environmental laws and political priorities.

Monarchs are protected when they spend the winter in the cool and humid forests of central Mexico, but the migratory route is still not fully integrated into the conservation plan. In Canada, monarchs are listed as endangered but protected differently across provinces and in the United States, monarchs are still not listed as endangered.

These protective measures keep changing and political and economic motivations can take precedence over the genuine need to care for monarch habitat trans-nationally. For example, a butterfly enthusiast can freely collect and rear monarchs in captivity in most of the U.S., but not in Ontario.

Monocrop Displaces Milkweed And Monarchs

Monarchs live in an unequal North America — a region that is integrated economically and geographically, but marked by inequality based on race, class and citizenship. The fates of marginalized residents are closely tied to those of the monarch.

This is seen in monocrop agriculture, which has displaced Indigenous people and destroyed habitats for monarchs and other pollinators by changing the native landscape.

Meanwhile, agribusiness, which is both a push and pull factor in the precarious migration of Mexican farmers, has also displaced the milkweed in what is known as the Canadian and U.S. corn belt.

Rethinking Conservation Strategies

Monarchs’ migrating behaviour entails crossing nature and human-made barriers despite the added difficulties of this journey.

Instead of more fragmentation and boundaries (around countries, parks and people), what monarchs need to survive is for us to emulate their “crossing” behaviour. We must ask: how can we create more and better crossings?

To enable more crossings, we need to de-centre the role of conservation experts as leaders of monarch protection policies. Actions to save the monarch butterfly should be planned with — not merely in consultation with — Indigenous peoples who have ancestrally lived with this insect.

We also need to begin democratizing monarch knowledge. This would include accounting for the role of citizen scientists in monarch protection. They should be viewed not merely as amateurs or “helpers” in scientific research, but as knowledge producers and, ideally, policy-makers in their own right.

Despite the harsh reality of its path to extinction, we should see the latest monarch listing as an opportunity. We have a short, but potential window to redirect our conservation efforts by connecting crossing fields and boundaries to ensure the survival of this insect and, perhaps, secure a better future for us as well.

We need to move beyond the goal of saving a beloved butterfly to learning from it about how to safeguard our collective futures.![]()

Columba González-Duarte, Assistant Professor, Sociology & Anthropology, Mount Saint Vincent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach