Inbox and environment news: Issue 555

September 18 - 24, 2022: Issue 555

Channel-Billed Cuckoos Return

Weed Alert: Corky Passionflower At Mona Vale + Narrabeen Creek

.jpg?timestamp=1663392221562)

La Nina Event Declared - Above Average Rainfall Likely For Eastern Australia

Flood Warning - Peel And Namoi Rivers

Wakehurst Parkway Closed Due To Flooding

''OXFORD FALLS: Both directions closed on the Wakehurst Pkwy between the Academy Of Sport & Dreadnought Rd due to flooding. Use Pittwater and Warringah Rds instead.

6:56am: UPDATE: Wakehurst Pkwy has reopened in both directions following earlier flooding.

Manly Lagoon Friends September Clean Up Nets A Heap Of Rubbish

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Clontarf September 25

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary Open

Ku-Ring-Gai Sculpture Trail For 2022 Eco Festival

Sydney Cockatoos And Humans Are In An Arms Race Over Garbage Access

September 12, 2022

Residents of southern Sydney, Australia have been in a long-term battle over garbage -- humans want to throw it out, and cockatoos want to eat it. The sulphur-crested cockatoos that call the area home have a knack for getting into garbage bins, and people have been using inventive devices to keep them out. Researchers detail the techniques used by both people and parrots in a study publishing on September 12 in the journal Current Biology.

"When I first saw a video of the cockatoos opening the bins I thought it was such an interesting and unique behaviour and I knew we needed to look into it," says lead author Barbara Klump, a behavioural ecologist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behaviour.

The cockatoos' motivation is food waste. "They really like bread," she says. "Once one gets a bin open all the cockatoos in the vicinity will come and try to get something nice to eat."

The birds typically pry the bins open with their beaks and then manoeuvre themselves onto a small rim and flip the lid open. It's a community affair. "We could actually show that this is a cultural trait," says Klump. "The cockatoos learn the behaviour from observing other cockatoos and within each group they sort of have their own special technique, so across a wide geographic range the techniques are more dissimilar."

Human residents trying to keep the cockatoos out can't simply secure the bin lids completely closed because the lids need to open when tipped by an automated arm on the garbage truck. A survey given by the researchers found that people put bricks and stones on their bin lids, strap water bottles to the top, rig ropes to prevent the lid from flipping, use sticks to block the hinges, and switch tactics once the cockatoos figure them out. "There are even commercially available cockatoo locks for bins," says Klump.

"It's not just a social learning on the cockatoo side, but it's also social learning on the human side," she says. "People come up with new protection methods on their own, but a lot of people actually learn it from their neighbours or people on their street, so they get their inspiration from someone else."

Klump won't say who she expects to win the race for control of the bins, but she and her colleagues plan to look at how the cockatoos' behaviour varies from season to season.

Klump expects we will see more of these kinds of human-wildlife interactions in the future. "As cities expand, we will have more interactions with wildlife," she says. "I'm hoping that there will be a better understanding and more tolerance for the animals that we share our lives with."

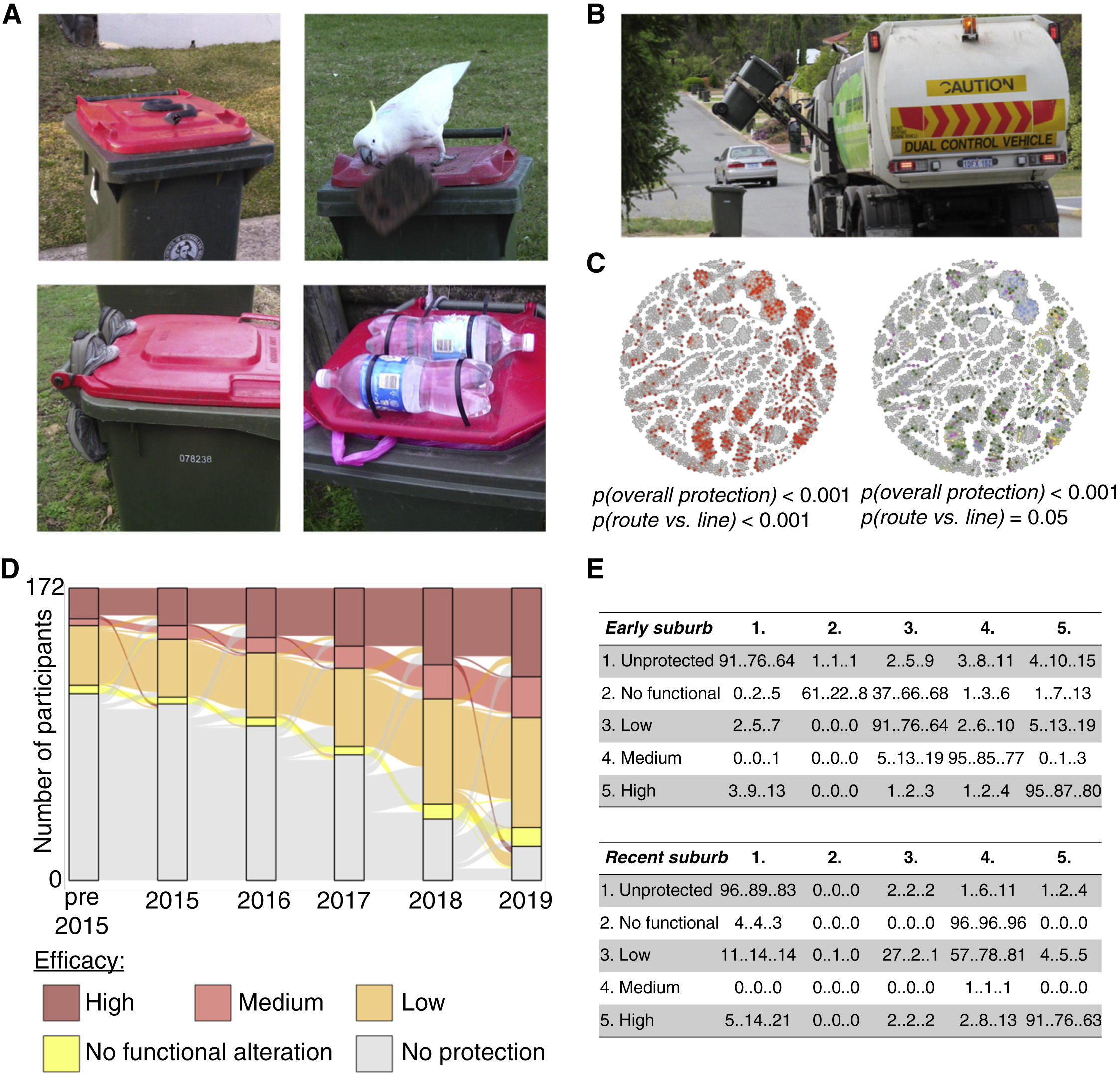

(A) Examples of protection devices (left to right, top to bottom): a snake to scare away cockatoos (level 2 – no functional alteration to the bin), a cockatoo removing a brick from a general household waste bin (level 3 – unfixed object to prevent lifting; low efficacy), shoes between hinges to avoid full flipping of the lid (level 4 – object to prevent flipping; medium efficacy), full water bottles tied to the lid (level 5 – fixed alteration to prevent opening; high efficacy). (B) A household waste bin being emptied by a garbage truck. Photo: Andrew Owens/Wikicommons (CC-BY-SA.3.0). (C) Spatial distribution of bin-protection devices in Helensburgh (protection level: 33%, n = 1312) based on: (i) overall protection: binary yes (red)/ no (grey), (ii) clusters (for colour scheme see Figure S1). Given are p-values for assortment and for comparison of street vs. direct line-of-sight distance (route vs. line). For results from all four suburbs see Figure S1. (D) Change in efficacy of bin-protection devices over time. Of 1134 survey participants, 172 protected their bins at some point and are displayed here. (E) Changes in transition probabilities across the five levels of bin protection over 1, 3 and 5 years for each area (represented by the first, second and third number in each cell, respectively). Top shows transition probabilities for ‘early’ suburbs where cockatoos already opened bins for at least 3 years, bottom shows ‘recent’ suburb where bin-opening has emerged in the last 3 months).

Barbara C. Klump, Richard E. Major, Damien R. Farine, John M. Martin, Lucy M. Aplin. Is bin-opening in cockatoos leading to an innovation arms race with humans? Current Biology, 2022; 32 (17): R910 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.08.008

Dust Off Your Picnic Blankets For The First Ever Statewide Picnic For Nature

Echidna 'Love Train' Season Commences

EPA Releases Climate Change Policy And Action Plan

September 8, 2022

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is taking action to protect the environment and community from the impacts of climate change, today releasing its new draft Climate Change Policy and Action Plan which works with industry, experts and the community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support resilience.

NSW EPA Chief Executive Officer Tony Chappel said the EPA has proposed a set of robust actions to achieve a 50 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (from 2005 levels), ensure net zero emissions by 2050, and improve resilience to climate change impacts.

“NSW has ambitious targets that align with the world’s best scientific advice and the Paris commitments, to limit global warming to an average of 1.5 degrees in order to avoid severe impacts on ecosystems,” Mr Chappel said.

“Over the past few years we have seen first-hand just how destructive the impacts of climate change are becoming, not only for our environment, but for NSW communities too.

“We know the EPA has a critical role to play in achieving the NSW Government’s net-zero targets and responding to the increasing threat of climate change induced weather events.

“Equally, acting on climate presents major economic opportunities for NSW in new industries such as clean energy, hydrogen, green metals, circular manufacturing, natural capital and regenerative agriculture.

“This draft Policy sends a clear signal to regulated industries that we will be working with them to support and drive cost-effective decarbonisation while implementing adaptation initiatives that build resilience to climate change risks.

“Our draft plan proposes a staged approach that ensures the actions the EPA takes are deliberate, well informed and complement government and industry actions on climate change. These actions will support industry and allow reasonable time for businesses to plan for and meet any new targets or requirements.

“Climate change is an issue that we all face so it’s important that we take this journey together and all play our part in protecting our environment and communities for generations to come.”

Actions include:

- working with industry, government and experts to improve the evidence base on climate change

- supporting licensees prepare, implement and report on climate change mitigation and adaptation plans

- partnering with NSW Government agencies to address climate change during the planning and assessment process for activities the EPA regulates

- establishing cost-effective emission reduction targets for key industry sectors

- providing industry best-practice guidelines to support them to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

- phasing in the introduction of greenhouse gas emission limits on environment protection licences for key industry sectors

- developing and implementing resilience programs, best-practice adaptation guidance and harnessing citizen science and education programs

- working with EPA Aboriginal and Youth Advisory Committees to improve the EPA’s evolving climate change response

EPA Acting Chair Carolyn Walsh said the EPA is a partner in supporting and building on the NSW Government’s work to address climate change for the people of NSW.

“The draft Policy and Action Plan adopts, supports and builds on the strong foundations that have been set by the NSW Government through the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework, Net Zero Plan and Climate Change Adaptation Strategy,” Ms Walsh said.

The EPA will work with stakeholders, including licensees, councils, other government agencies, and the community to help implement the actions.

The draft EPA Climate Change Policy and Action Plan is available at https://yoursay.epa.nsw.gov.au/ and comments are open until 3 November 2022.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Great Artesian Basin At Risk As Perrottet Government Approves New Coal Exploration

- Part of the recharge area of the Great Artesian Basin

- Several creek systems that flow into the Namoi River and areas of alluvial aquifers on the Namoi River floodplain used for irrigation

- 182 waterbores used for general water supply, irrigation, or stock and domestic.

- A formally listed Aboriginal Heritage site

- 12 threatened species including three endangered species - the Black-striped Wallaby, Koala, and Five-clawed Worm-skink

- 13,502.5 ha of native vegetation in the north eastern section of the Pilliga Forest including four four threatened ecological communities

Transition To Plantation Timber Would Be A Win For The Nature And Industry

Ever heard of ocean forests? They’re larger than the Amazon and more productive than we thought

Amazon, Borneo, Congo, Daintree. We know the names of many of the world’s largest or most famous rainforests. And many of us know about the world’s largest span of forests, the boreal forests stretching from Russia to Canada.

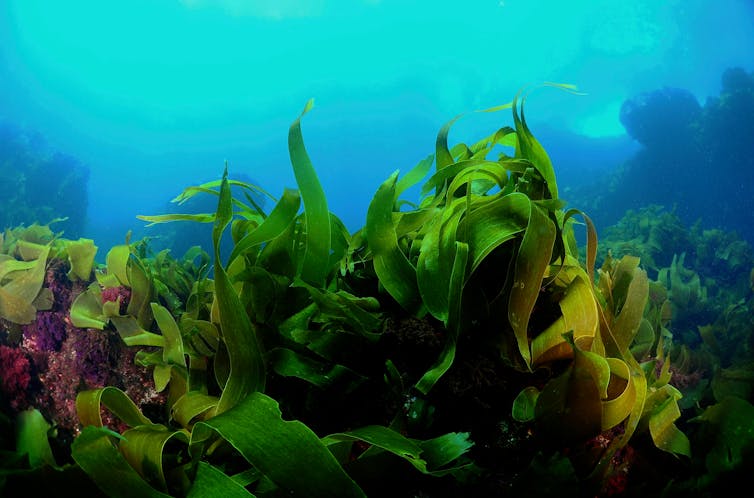

But how many of us could name an underwater forest? Hidden underwater are huge kelp and seaweed forests, stretching much further than we previously realised. Few are even named. But their lush canopies are home to huge numbers of marine species.

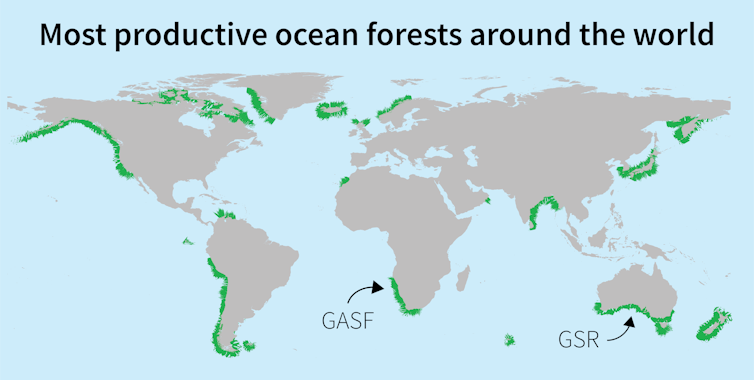

Off the coastline of southern Africa lies the Great African Seaforest, while Australia boasts the Great Southern Reef around its southern reaches. There are many more vast but unnamed underwater forests all over the world.

Our new research has discovered just how extensive and productive they are. The world’s ocean forests, we found, cover an area twice the size of India.

These seaweed forests face threats from marine heatwaves and climate change. But they may also hold part of the answer, with their ability to grow quickly and sequester carbon.

What Are Ocean Forests?

Underwater forests are formed by seaweeds, which are types of algae. Like other plants, seaweeds grow by capturing the Sun’s energy and carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. The largest species grow tens of metres high, forming forest canopies that sway in a never-ending dance as swells move through. To swim through one is to see dappled light and shadow and a sense of constant movement.

Just like trees on land, these seaweeds offer habitat, food and shelter to a wide variety of marine organisms. Large species such as sea-bamboo and giant kelp have gas-filled structures that work like little balloons and help them create vast floating canopies. Other species relies on strong stems to stay upright and support their photosynthetic blades. Others again, like golden kelp on Australia’s Great Southern Reef, drape over seafloor.

How Extensive Are These Forests And How Fast Do They Grow?

Seaweeds have long been known to be among the fastest growing plants on the planet. But to date, it’s been very challenging to estimate how large an area their forests cover.

On land, you can now easily measure forests by satellite. Underwater, it’s much more complicated. Most satellites cannot take measurements at the depths where underwater forests are found.

To overcome this challenge, we relied on millions of underwater records from scientific literature, online repositories, local herbaria and citizen science initiatives.

With this information, we modelled the global distribution of ocean forests, finding they cover between 6 million and 7.2 million square kilometres. That’s larger than the Amazon.

Next, we assessed how productive these ocean forests are – that is, how much they grow. Once again, there were no unified global records. We had to go through hundreds of individual experimental studies from across the globe where seaweed growth rates had been measured by scuba divers.

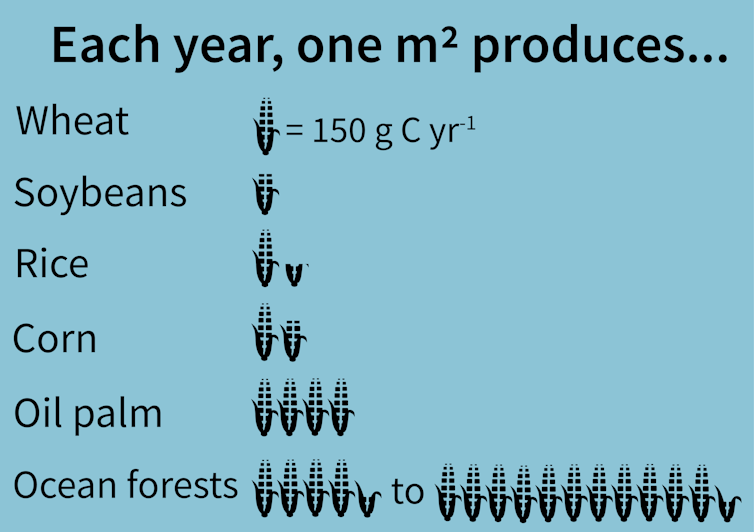

We found ocean forests are even more productive than many intensely farmed crops such as wheat, rice and corn. Productivity was highest in temperate regions, which are usually bathed in cool, nutrient-rich water. Every year, on average, ocean forests in these regions produce 2 to 11 times more biomass per area than these crops.

What Do Our Findings Mean For The Challenges We Face?

These findings are encouraging. We could harness this immense productivity to help meet the world’s future food security. Seaweed farms can supplement food production on land and boost sustainable development.

These fast growth rates also mean seaweeds are hungry for carbon dioxide. As they grow, they pull large quantities of carbon from seawater and the atmosphere. Globally, ocean forests may take up as much carbon as the Amazon.

This suggests they could play a role in mitigating climate change. However, not all that carbon may end up sequestered, as this requires seaweed carbon to be locked away from the atmosphere for relatively long periods of time. First estimates suggest that a sizeable proportion of seaweed could be sequestered in sediments or the deep sea. But exactly how much seaweed carbon ends up sequestered naturally is an area of intense research.

Hard Times For Ocean Forests

Almost all of the extra heat trapped by the 2,400 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases we have emitted so far has gone into our oceans.

This means ocean forests are facing very difficult conditions. Large expanses of ocean forests have recently disappeared off Western Australia, eastern Canada and California, resulting in the loss of habitat and carbon sequestration potential.

Conversely, as sea ice melts and water temperatures warm, some Arctic regions are expected to see expansion of their ocean forests.

These overlooked forests play an crucial, largely unseen role off our coasts. The majority of the world’s underwater forests are unrecognised, unexplored and uncharted.

Without substantial efforts to improve our knowledge, it will not be possible to ensure their protection and conservation – let alone harness the full potential of the many opportunities they provide.![]()

Albert Pessarrodona Silvestre, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The University of Western Australia; Karen Filbee-Dexter, Research Fellow, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, and Thomas Wernberg, Professor, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nearly 30% of Australia’s emissions come from industry. Tougher rules for big polluters is a no-brainer

Rebecca Pearse, Australian National UniversityAustralia’s historic climate law passed the Senate last week and enshrined an economy-wide target to reduce emissions. But an important measure to reduce Australia’s industrial emissions is still up for debate: the “safeguard mechanism”.

Introduced by the Abbott government in 2014, the safeguard mechanism is supposed to stop Australia’s largest greenhouse gas polluters from emitting over a certain threshold. But the policy has been frequently criticised for lacking teeth. The Labor government has promised to strengthen the mechanism, and is currently reviewing it.

Industry has raised concerns over any toughening of the policy. Meanwhile, the Greens will push Labor to strengthen it further.

The safeguard mechanism covers the grid-connected power stations with a sectoral target. It also applies to 215 of Australia’s largest industrial emitters. Together, these 215 facilities produce almost 30% of Australia’s total annual emissions. So a stringent policy to curb this pollution is crucial to climate action.

Wait, What’s The Safeguard Mechanism?

The safeguard mechanism works by setting a limit on the emissions individual enterprises can produce in a year. This limit is put into place with “baselines” that get set in a number of different ways, depending on the type of company involved. Such companies might include a mining company, aluminium smelter, steelworks or airline.

If the company emits beyond their limit, they can buy carbon credits to compensate for, or “offset”, the excess emissions.

The mechanism covers hard-to-abate industries which are regulated on an individual basis, such as new coal, oil and gas projects, steel, aluminium, manufacturing and transport. These include Woodside’s Northwest Shelf gas project, Qantas, Chevron’s Gorgon gas project, Port Kembla steelworks, and AngloAmerican coal mines in central Queensland.

Coal fired power remains our biggest industrial source of emissions, but is regulated separately. A “sectoral baseline” has been set for all electricity generators connected to the national grid at 198 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent each year.

Rubbery Baseline Emissions

Historically, the safeguard mechanism hasn’t put strong obligations on industrial emitters to reduce their emissions. Indeed, industrial emissions have increased since the mechanism began in 2016.

Imposing a genuine carbon limit on high-emitting companies requires a clear definition and enforcement of the baselines. But the safeguard mechanism provides enormous scope for expanded production and, therefore, expanded emissions.

The government’s review paper identifies a major problem with how baselines have been set in the past. Namely, many facilities have been allowed to set their baseline emissions well above their actual emissions.

Baselines for each facilities’ emissions are currently measured according to “production-adjusted” emissions intensity. So, for example, a coal mine’s baseline is measured per tonne of coal commodity produced. This means over time, baselines rise or fall in proportion to a company’s expected production.

The government’s consultation paper reports that in the 2020-21 financial year the combined baseline emissions recorded for non-electricity grid emissions under the safeguard mechanism was estimated at 180 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent.

But actual emissions in the same period were 137 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent.

It should also be noted that research suggests up to one in five fossil fuel projects are underestimating their actual emissions. But regardless, the high baselines mean there’s no regulatory pressure for companies to reduce their emissions.

The current review paper seeks feedback on these issues. Removing the head room for facilities with baselines well above their actual emissions is on the cards.

Carbon Credit Questions

The government is poised to propose significantly expanding carbon credit trading under the safeguard mechanism.

Carbon credits are granted to projects that reduce, store or avoid greenhouse gas emissions. These credits can be sold to the federal government or to private companies to offset a project’s own emissions.

Under the current safeguard mechanism, if a company exceeds its baseline emissions, then it can purchase Australian carbon credits to offset this.

These carbon offsets, however, are plagued with credibility problems. In fact, another federal government review is underway to examine the issues.

There are calls to strongly limit or remove questionable offsets linked to the safeguard mechanism.

For instance, climate science professor Mark Howden argued recently that offsets should not be used to give big emitters a “free ride” to continue polluting if they invest in carbon sequestration projects, at this stage. Instead, the immediate priorities should be limiting fossil fuel combustion burning, and making concrete plans for other industries to transition.

Despite this, the federal government is considering expanding trade in these and potentially other types of carbon credits.

The government is proposing a new type of carbon credit for companies emitting below their baseline. For instance, if an aluminium smelter reduced its emissions over 2024 and 2025, it could be granted credits to sell to others in the carbon market.

The government is also considering allowing companies to trade carbon credits on an international level, pending reforms to address integrity issues in safeguard mechanism like the baseline headroom problem.

The international trade in carbon credits has been plagued with problems for 20 years. A 2021 literature review found little evidence demonstrating causal effect of carbon trading markets on emissions reduction.

It puts a strong case forward against linking carbon markets internationally, after Europe, Quebec and California case studies show linking carbon markets has led to price crashes and volatility – not stability.

The Risk Of A Weak Carbon Trading Market

We can expect industry to continue to lobby for a weak safeguard mechanism and carbon credit rules. But if the Labor government is genuine about wanting to reduce Australia’s emissions, our biggest polluters cannot be allowed to carry on emitting as usual.

And there is no role for a carbon trading policy that excuses big emitters from making clean energy transition plans.

Labor may need the numerous pro-climate independent senators or the Greens to make changes signalled in the safeguard consultation paper. They are unlikely to be satisfied with a weak carbon trading scheme.

Any proposed changes that undermine Australia’s emissions reduction goals will not easily be passed.![]()

Rebecca Pearse, Lecturer, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Too hard to get to work’: climate change is making workers’ lives more difficult

Lauren Rickards, RMIT University and Todd Denham, RMIT University“Work” – broadly defined – is what allows society to function. Like other old certainties, it is under threat from climate change.

A key reason climate-related stresses and disruptions can have such a big impact is precisely because of their effect on the work we do and on the wider system of work we rely on. But little attention has been given to the urgent need to adapt work to climate change.

Our new report on climate impacts at work, released today, documents emerging serious risks.

A female professional told us: “there were days where I simply had to use up sick leave because it was too hot to get safely to work”.

One male sales worker told us about working during the Black Summer of 2019/2020:

Smoke from bushfires two years ago was intolerable. The heat also was horrific at times. During the smokiest days temperatures often shot up to over 40 degrees. It was like the planet Venus. My employer … provided no masks at all at that time, despite numerous requests, even pleadings.

Australia is already 1.4℃ warmer than it was in 1910. Climatic extremes and events like the 2022 floods and Black Summer – as well as many less visible disruptions – are already undermining our capacity to work across different organisations, industries and sectors.

We will have to get better at adapting to our changed climate – and quickly.

What Did We Find?

We found the effects of climate change on workers reach more widely than than previously thought.

In short, no one is immune to climate harms, whether indoor or outdoor, junior or senior. Given we rely on each others’ work, that means climate change impacts are likely to increasingly “cascade” through society, as the 2022 IPCC report on Australasia details.

Our research comes from a survey of 1,165 workers across ten industries undertaken in the first half of 2022, assisted by six unions. The sample is not representative of the workforce as a whole and is skewed towards types of workers not typically considered on harms from climate change, such as professionals and community and personal service workers.

Previous research has documented the serious ways heat affects workers, especially those outdoors or in poorly cooled spaces. Other studies have found outdoor council workers and delivery cyclists in Sydney are already having to use coping mechanisms such as extra breaks, lighter duties and temporarily stopping work to try to avoid heat stress.

Our data similarly points to heat’s health impacts. Outdoor workers were especially likely to report being tired and fatigued, dehydrated and less productive. They were also more likely to sweat excessively and be sunburnt.

Less recognised is that indoor workers are also being affected by heat and smoke.

These health impacts are serious. Close to 450 people died from the effects of smoke inhalation over the Black Summer. These issues were compounded by the COVID pandemic, notably for those workers who have to had to wear personal protective equipment or work from poorly cooled houses during heatwave conditions.

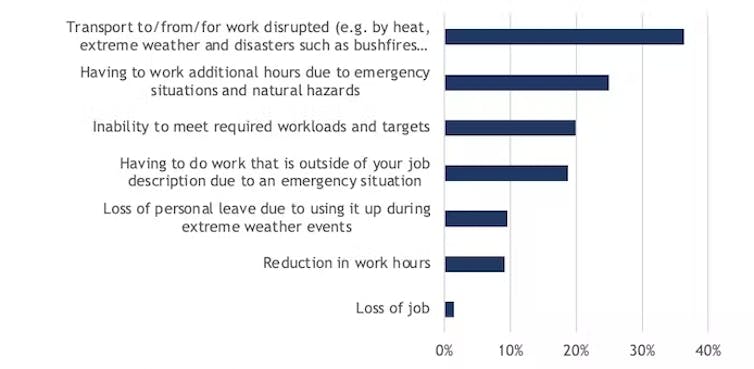

Climate change can undermine people’s capacity to work in other ways. Some workers reported impacts on the amount and focus of their work. For example, some had to take on new tasks to cover for colleagues who were overwhelmed or furloughed due to the Black Summer fires. A quarter reported having to work additional hours due to emergency situations such as the floods, while others reported they had lost hours, had to take personal leave or even lost their job as a result of climatic events.

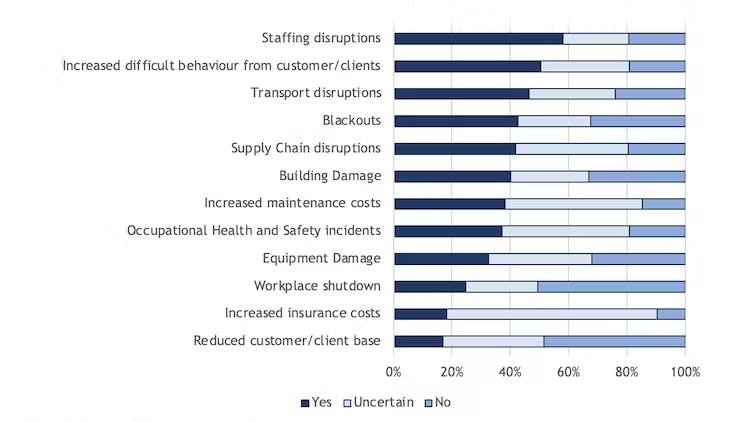

There are even impacts from climatic effects on the wider public. Half of the survey respondents reported having to manage angrier customers, while 60% said climatic events had led to staffing disruptions. Some reported extreme weather was causing supply chain disruption.

One male professional said:

The frequency of storm events has noticeably increased, and these storms are often more severe with higher wind speeds and rates of precipitation than in the past. […] Our workload has increased accordingly and risk to people and property has also increased.

Management are struggling to come to terms with the frequency and severity of storm events and this is leading to anxiety and conflict with management in relation to the perceived need to close the site, or part of it, during severe weather events. Site closure protects individuals from harm […] but is bad for revenue raising for the many businesses that operate on our site.

Our capacity to work often relies on intricate systems of settlements, infrastructure and services that consist of workplaces and support others. When any of these workplaces are affected, there are flow-on effects.

Our survey found more than a third of workers had not been able to travel to work due to climatic factors. If trains don’t run or roads are blocked, it can bring many workplaces to a halt.

We are now enmeshed in a different climate to the one we grew up in – and it will change more.

To make our societies and systems resilient to climate change, we will have to adapt how, where, when we work, who “we” is, what we work on, and why. This adaptation work is urgent. No one is immune.

Friends of the Earth contributed to this research![]()

Lauren Rickards, Professor, RMIT University and Todd Denham, Research officer, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

La Niña, 3 years in a row: a climate scientist on what flood-weary Australians can expect this summer

After weeks of anticipation, it’s finally official: the Bureau of Meteorology has declared another La Niña is underway. This means Australia’s east coast will likely endure yet another wet, and relatively cool, spring and summer.

It’s the third La Niña event in a row. This is rare, but not unheard of. Triple La Niñas have also occurred in, for example, 1973–1976 and 1998–2001.

The past two La Niñas mean water catchments are already full, and soils are sodden from Noosa in the north through to Lismore and the Hunter Valley in the south. It means more flood events are likely in the coming months.

The bureau’s declaration will be unwelcome news to many people – especially those in parts of New South Wales and Queensland still recovering from recent floods. So what else can flood-weary Australians expect in the coming months? And is a fourth La Niña on the cards?

A Potentially Mild La Niña

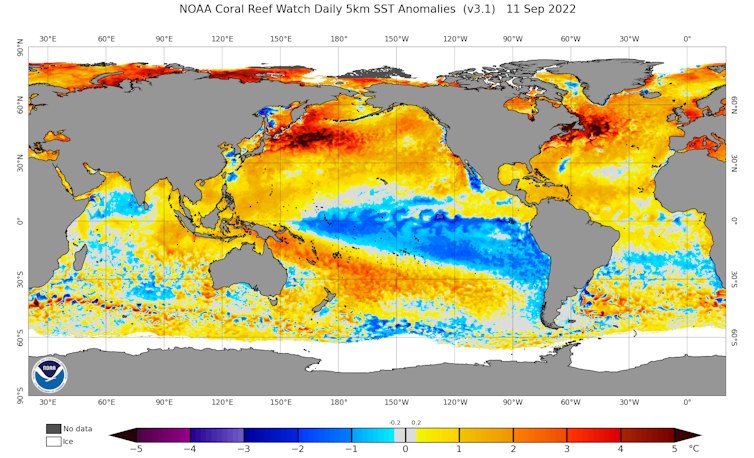

La Niña is part of a natural climate cycle over the tropical Pacific Ocean. Sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific vary between being warmer than average (El Niño) and cooler than average (La Niña).

This variability has worldwide effects as it shifts weather patterns – bringing droughts to some regions and floods to others.

For most of Australia, La Niña raises the chance of rain. It has contributed to some of Australia’s wettest ever conditions, and some of the driest in the southern United States across the Pacific Ocean.

The Bureau of Meteorology says this La Niña may peak during spring, and return to neutral conditions early in 2023. Most seasonal prediction models are suggesting this La Niña event will be weaker and shorter-lived than the last two.

Typically, stronger La Niña seasons are associated with more extreme rainfall in eastern Australia. So hopefully a mild La Niña comes to pass and flood-hit regions avoid the worst of the summertime rain, at least.

La Niña is a part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, a natural phenomenon. We know these events have occurred in the past – before large-scale greenhouse gas emissions from human activities.

We don’t yet know how La Niña may change as the planet continues to warm, but evidence suggests climate change may make La Niña (and its counterpart El Niño) events more frequent and intense.

And research from earlier this year suggests relationships between La Niña and regional climate may become stronger over many parts of the world, including much of Australia. This could mean Australia feels the force of La Niña and El Niño events more in future as the planet continues to heat.

Three Climate Forces At Work

It’s not just La Niña affecting Australia’s climate at the moment. Two other natural climate forces are also in play: the Indian Ocean Dipole and the Southern Annular Mode.

The Indian Ocean Dipole is characterised by variable sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean, and the Southern Annular Mode by the positioning of winds and weather systems to Australia’s south.

We’re currently in a “negative” Indian Ocean Dipole and a “positive” phase of the Southern Annular Mode.

These all have different effects on the Australian climate. In springtime, these conditions – in combination with La Niña – are conducive to more rain in eastern Australia.

We saw all three of these phenomena occur simultaneously in the spring of 2010, when eastern Australia experienced record high rainfall.

It’s too early to say where exactly in Australia is most likely to experience flooding this spring. While La Niña, the negative Indian Ocean Dipole and positive Southern Annular Mode raise the chances of rainfall, individual weather systems and their trajectories will determine where the worst is located.

What Does La Niña Mean For Drought And Bushfire?

One positive aspect of La Niña is it keeps drought out of the picture for the time being. Some of Australia’s worst droughts are characterised by a lack of La Niña or negative Indian Ocean Dipole conditions over several years. Eastern Australia is unlikely to experience severe drought in the near future.

The La Niña conditions also reduce the likelihood that we’ll see a bad bushfire season in eastern Australia this coming summer.

But it isn’t all good news. La Niña and the other climate influences raise the chances of plant growth and greening in eastern Australia. And this could provide fuel for future fires once conditions dry out again.

Historically, major bushfire seasons in eastern Australia have often followed La Niña events. In 2011, after a La Niña and very wet conditions, we saw some of the biggest fires on record.

A background trend towards hotter, drier weather due to climate change could spell trouble down the track.

Another effect of the triple La Niña is that we haven’t seen record high global-average temperatures since 2016 (noting that 2020 and 2016 are almost tied). This is despite our continued very high greenhouse gas emissions, which have rebounded since the pandemic-associated dip.

La Niña typically reduces global-mean temperatures slightly by cooling a large area of the Pacific Ocean – but this is a temporary effect. Record high global-average temperatures will come again soon, and are more likely when the next El Niño occurs.

Could We Have A Fourth La Niña?

Many Australians hoping La Niña was behind us for a few years now have to contend with a third in a row.

While we’ve seen triple La Niña events before, we have never seen quadruple La Niña in the historical record. This doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen. In fact, the 2001-2002 season that followed the 1998-2001 triple La Niña wasn’t a long way off from being yet another La Niña.

For now, we must prepare for a wet spring and possibly another wet summer to come.

Severe flooding is more likely than usual in already flood-hit zones, so lessons learnt from the devastation caused by the recent floods should be put in place. ![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We may be underestimating just how bad carbon-belching SUVs are for the climate – and for our health

Robin Smit, University of Technology Sydney and Nic Surawski, University of Technology SydneyAustralia’s love for fuel-hungry and fuel-inefficient SUVs is hampering our ability to bring transport emissions down. SUVs make up half of all new car sales last year, a National Transport Commission report revealed this week – up from a quarter of all sales a decade ago.

As a result, the carbon emitted by all new cars sold in Australia dropped only 2% in 2021, the report found. Sales of battery electric vehicles tripled last year, but still make up just 0.23% of all cars and light commercial vehicles on our roads.

In internationally peer-reviewed research earlier this year, we measured the emissions of five SUVs driving around Sydney, and our findings suggest the situation may actually be worse than the new report finds.

The National Transport Commission’s numbers are based on the “New European Drive Cycle” (NEDC) emissions test. Our research found the real-world emissions of SUVs are, on average, about 30% higher than the NEDC values. This means we are not reducing fleet average emissions by a few percent per year, but actually probably increasing them by a few percent every year.

What The Report Found

The transport sector is responsible for almost 20% of Australia’s emissions, ranking third behind the electricity and agriculture sector. The first year of the COVID pandemic only reduced transport carbon dioxide emissions by about 7%, compared to 2019 emission levels.

Overall, Australia’s pride in carbon-belching transport is evident by the fact transport CO₂ emissions have risen 14% between 2005 and 2020.

SUVs are generally larger and heavier than other passenger cars, which means they need quite a bit more energy and fuel per kilometre of driving when compared with smaller, lighter cars.

Although SUV sales are rising globally, the Australian fleet is unique due to its large portion of SUVs in the on-road fleet, often with four-wheel-drive capability.

According to the National Transport Commission report, sales of four-wheel-drives and utes surged by more than 43,000 in 2021, while large SUV sales rose by around 25,000.

Rapidly shifting to electric cars is an important way to bring emissions down. But the report found in 2021, just 2.8% of Australia’s car sales were electric. Compare this to 17% in Europe, 16% in China and 5% in the United States.

In Australia, there is still no option to buy an electric ute, and electric vehicles remain prohibitively expensive.

Measuring SUV Emissions In Sydney

There are a range of methods scientists use to measure vehicle emissions.

One popular method worldwide uses so-called “on-board portable emission monitoring systems”. These systems are effective because they enable second-by-second emissions testing under a variety of real-world driving conditions on the road.

On the other hand, the New European Drive Cycle (NEDC) emissions test is conducted in the laboratory. It was also developed in the early 1970s and reflects unrealistic driving behaviour, because test facilities at the time could not deal with significant changes in speed.

We fitted five SUVs with a portable emission monitoring system and drove them a little over 100 kilometres around Sydney in various situations, such as in the city and on the freeway.

We then compared our measurements with the Green Vehicle Guide – the national guide to vehicle fuel consumption and environmental performance, which is also based on the NEDC test.

Our measurements of fuel consumption and CO₂ emissions were consistently higher. This varied from 16% to 65% higher than NEDC values, depending on the actual car and driving conditions.

On average, real-world fuel consumption and CO₂ emissions were both 27% higher than NEDC values. Importantly, this gap has increased substantially from about 10% in 2008.

Indeed, previous research from 2019 found fleet average greenhouse gas emissions for new Australian cars and SUVs has probably been increasing by 2-3% percent per year since 2015, rather than the reported annual reduction by, for instance, the National Transport Commission.

This detailed analysis showed a sustained increase in vehicle weight and a shift to the sale of more four-wheel-drive cars (in other words, SUVs) are probably the main factors contributing to this change.

More Bad News For SUVs

We also recently summarised the results of various emission measurement campaigns conducted in Australia and compared them with international studies. These include results from a study of vehicle emissions in a tunnel, and a study of vehicle emissions measured on the road with remote sensing.

We found modern diesel SUVs and cars or diesel light commercial vehicles (such as utes) in Australia and New Zealand have relatively high emissions of nitrogen oxides and soot – both important air pollutants.

Around 2,600 deaths are attributed to fine-particle air pollution in Australia each year. Transport and industrial activities (such as mining) are the main sources of this.

And in 2015, an estimated 1,715 deaths were attributed to vehicle exhaust emissions – 42% more than the road toll that year.

The remote sensing emissions data suggest 1% of one to two-year-old diesel SUVs and 2% of one-to-two year old diesel light commercial vehicles have issues with their particulate filters, leading to high soot emissions.

These percentages are high when compared with a similar study conducted in the United Kingdom, which could not find any clear evidence of filter issues.

Three Ways To Move Forward

Ever increasing SUVs sales are a drag on successfully reducing Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions. So what should we do?

Of course there are several things to consider, but in terms of fuel efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions, we believe there are three main points.

First, we need to make sure we have realistic fuel use and emissions data. This means the National Transport Commission and Green Vehicle Guide should stop using the NEDC values and shift to more realistic emissions data. We acknowledge this is not a simple matter and it requires a lot more testing.

Second, we need to electrify transport as fast as we can, wherever we can. This is crucial, but not the whole solution.

To ensure Australia meets its net-zero emissions target, we also need to seriously consider energy and fuel efficiency in transport. This could be by promoting the sales of smaller and lightweight vehicles, thereby optimising transport for energy efficiency.

In all of this, it will be essential for car manufacturers to take responsibility for their increasing contributions to climate change. From this perspective, they should move away from marketing profitable fossil-fueled SUVs that clog up our roads, and instead offer and promote lighter, smaller and electric vehicles.![]()

Robin Smit, Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Technology Sydney and Nic Surawski, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Engineering, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

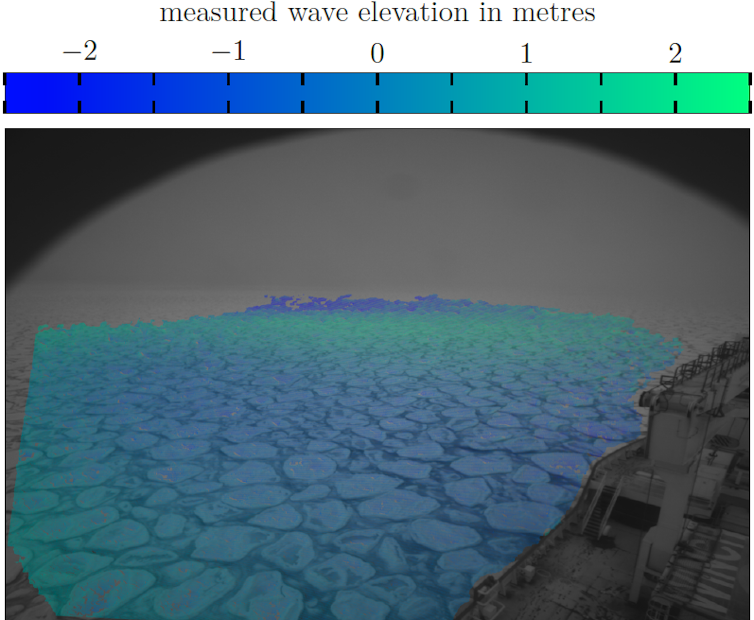

Scientists are divining the future of Earth’s ice-covered oceans at their harsh fringes

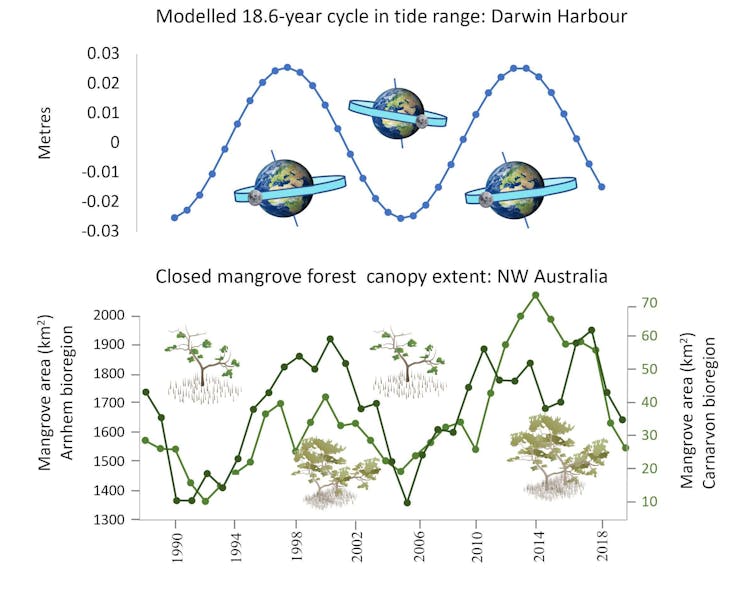

One of the harshest and most dynamic regions on Earth is the marginal ice zone – the place where ocean waves meet sea ice, which is formed by freezing of the ocean’s surface.

Published today, a themed issue of the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A reviews the rapid progress researchers have made over the past decade in understanding and modelling this challenging environment.

This research is vital for us to better understand the complex interactions of Earth’s climate systems. That’s because the marginal ice zone plays a role in the seasonal freezing and thawing of the oceans.

A Harsh Place To Study

In the Arctic and Antarctic, surface ocean temperatures are persistently below -2℃ – cold enough to freeze, forming a layer of sea ice.

At the highest latitudes closer to the poles, sea ice forms a solid, several-metre-thick lid on the ocean that reflects the Sun’s rays, cooling the region and driving cool water around the oceans. This makes sea ice a key component of the climate system.

But at lower latitudes, as the ice-covered ocean transitions to the open ocean, sea ice forms into smaller, much more mobile chunks called “floes” that are separated by water or a slurry of ice crystals.

This marginal ice zone interacts with the atmosphere above and ocean below in a very different way to ice cover closer to the poles.

It’s a challenging environment for scientists to work in, with a voyage into the marginal ice zone around Antarctica in 2017 experiencing winds over 90km/h and waves over 6.5m high. It is also difficult to observe remotely because the floes are smaller than what most satellites can see.

Crushed By Waves

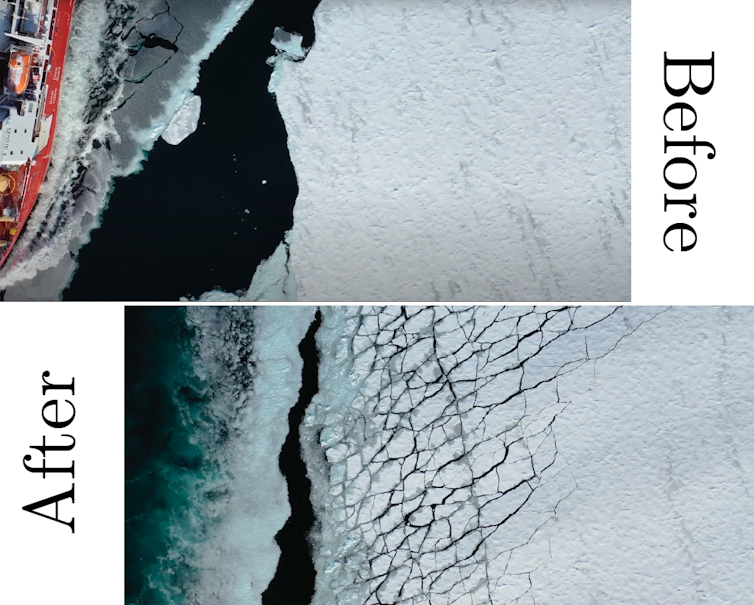

The marginal ice zone also interacts with the open ocean via surface waves, which travel from the open waters into the zone, impacting the ice. The waves can have a destructive effect on the ice cover, by breaking up large floes and leaving them more susceptible to melt during summer.

By contrast, during winter, waves can promote the formation of “pancake” floes, so called because they are thin disks of sea ice (you can see them in the image above).

But wave energy itself is lost during interactions with floes, so that waves gradually become weaker as they travel deeper into the marginal ice zone. This produces wave–ice feedback mechanisms driving sea ice evolution in a changing climate.

For example, a trend for warmer temperatures will weaken the ice cover, allowing waves to travel deeper into ice-covered oceans and cause more breakup, which further weakens the ice cover – and so on.

Scientists studying marginal ice zone dynamics aim to improve our understanding of the zone’s role in the dramatic and often perplexing changes the world’s sea ice is undergoing in response to climate change.

For instance, in the Arctic Ocean, sea ice cover has “has dropped by roughly half since the 1980s”. In the Antarctic, the sea ice cover has recently had both one of its largest and smallest recorded extents, with the marginal ice zone being one source of year-to-year variability.

Our progress in better understanding these harsh regions has revolved around large international research programs, run by the United States’ Office of Naval Research and others. These programs involve earth scientists, geophysicists, oceanographers, engineers and even applied mathematicians (like us).

Recent efforts have produced innovative observation techniques, such as a method to 3D-image wave and floe dynamics in the marginal ice zone from onboard an icebreaker and capture waves-in-ice from satellite images.

They have also resulted in new models capable of simulating the interaction of waves and ice from the level of individual floes to the overall behaviour of entire oceans. The advances have motivated an Australian led multi-month experiment in the Antarctic marginal ice zone, on the new $500M icebreaker RSV Nuyina, which is expected next year.

The marginal ice zone will be an increasingly important component of the world’s sea ice cover in the future, as temperatures rise and waves become more extreme.

Despite the rapid progress, there is still some way to go before the understanding of feedback processes in the marginal ice zone translates into improved climate predictions used by, for example, the International Panel on Climate Change Assessment Reports.

Including the marginal ice zone in climate models has been described as the “holy grail” for the field by one of its leading figures, and the theme issue points to closer ties with the broader climate community as the next major direction for the field.![]()

Jordan Peter Anthony Pitt, Post-Doctoral Researcher, University of Adelaide and Luke Bennetts, Lecturer in applied mathematics, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Where is your seafood really from? We’re using ‘chemical fingerprinting’ to fight seafood fraud and illegal fishing

Fake foods are invading our supermarkets, as foods we love are substituted or adulterated with lower value or unethical goods.

Food fraud threatens human health but is also bad news for industry and sustainable food production. Seafood is one of most traded food products in the world and reliant on convoluted supply chains that leave the the door wide open for seafood fraud.

Our new study, published in the journal Fish and Fisheries, showcases a new approach for determining the provenance or “origin” of many seafood species.

By identifying provenance, we can detect fraud and empower authorities and businesses to stop it. This makes it more likely that the food you buy is, in fact, the food you truly want to eat.

Illegal Fishing And Seafood Fraud

Wild-caught seafood is vulnerable to illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing can have a devastating impact on the marine environment because:

it is a major cause of overfishing, constituting an estimated one-fifth of seafood

it can destroy marine habitats, such coral reefs, through destructive fishing methods such as blast bombing and cyanide fishing

it can significantly harm wildlife, such as albatross and turtles, which are caught as by-catch.

So how is illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing connected to seafood fraud?

Seafood fraud allows this kind of fishing to flourish as illegal products are laundered through legitimate supply chains.

A recent study in the United States found when seafood is mislabelled, it is more likely to be substituted for a product from less healthy fisheries with management policies that are less likely to reduce the environmental impacts of fishing.

One review of mislabelled seafood in the US found that out of 180 substituted species, 25 were considered threatened, endangered, or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

Illegal fishing and seafood fraud also has a human cost. It can:

adversely affect the livelihoods of law-abiding fishers and seafood businesses

threaten food security

facilitate human rights abuses such as forced labour and piracy

increase risk of exposure to pathogens, drugs, and other banned substances in seafood.

The Chemical Fingerprints In Shells And Bones

A vast range of marine animals are harvested for food every year, including fish, molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms.

However, traditional food provenance methods are typically designed to identify one species at a time.

That might benefit the species and industry in question, but it is expensive and time consuming. As such, current methods are restricted to a relatively small number of species.

In our study, we described a broader, universal method to identify provenance and detect fraud.

How? We harnessed natural chemical markers imprinted in the shells and bones of marine animals. These markers reflect an animal’s environment and can identify where they are from.

We focused on a chemical marker that is similar across many different marine animals. This specific chemical marker, known as “oxygen isotopes”, is determined by ocean composition and temperature rather than an animal’s biology.

Exploiting this commonality and how it relates to the local environment, we constructed a global ocean map of oxygen isotopes that helps researchers understand where a marine animal may be from (by matching the oxygen isotope value in shells and bones to the oxygen isotope value in the map).

After rigorous testing, we demonstrated this global map (or “isoscape”) can be used to correctly identify the origins of a wide range of marine animals living in different latitudes.

For example, we saw up to 90% success in classifying fish, cephalopods, and shellfish between the tropical waters of Southeast Asia and the cooler waters of southern Australia.

What Next?

Oxygen isotopes, as a universal marker, worked well on a range of animals collected from different latitudes and across broad geographic areas.

Our next step is to integrate oxygen isotopes with other universal chemical markers to gives clues on longitude and refine our approach.

Working out the provenance of seafood is a large and complex challenge. No single approach is a silver bullet for all species, fisheries or industries.

But our approach represents a step towards a more inclusive, global system for validating seafood provenance and fighting seafood fraud.

Hopefully, this will mean ensure fewer marine species are left behind and more consumer confidence in the products we buy.

Dr Jasmin Martino, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, contributed to this research and article.![]()

Zoe Doubleday, Marine Ecologist and ARC Future Fellow, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The climate crisis is real – but overusing terms like ‘crisis’ and ‘emergency’ comes with risk

Noel Castree, University of Technology Sydney“Crisis” is an incredibly potent word, so it’s interesting to witness the way the phrase “climate crisis” has become part of the lingua franca.

Once associated only with a few “outspoken” scientists and activists, the phrase has now gone mainstream.

But what do people understand by the term “climate crisis”? And why does it matter?

The Mainstreaming Of Crisis-Talk

It’s not only activists or scientists sounding the alarm.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres now routinely employs dramatic phrases like “digging our own graves” when discussing climate. Bill Gates advises us to avoid “climate disaster”.

This linguistic mainstreaming marks redrawn battle lines in the “climate wars”.

Denialism is in retreat. The climate change debate now is about what is to be done and by whom?

Scientists, using the full authority of their profession, have been key to changing the discourse. The lead authors of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports now pull no punches, talking openly about mass starvation, extinctions and disasters.

These public figures clearly hope to jolt citizens, businesses and governments into radical climate action.

But for many ordinary folks, climate change can seem remote from everyday life. It’s not a “crisis” in the immediate way the pandemic has been.

Of course, many believe climate experts have understated the problem for too long.

And yet the new ubiquity of siren terms like climate “crisis”, “emergency”, “disaster”, “breakdown” and “calamity” does not guarantee any shared, let alone credible, understanding of their possible meaning.

This matters because such terms tend to polarise.

Few now doubt the reality of climate change. But how we describe its implications can easily repeat earlier stand-offs between “believers” and “sceptics”; “realists’ and "scare-mongerers”. The result is yet more political inertia and gridlock.

We will need to do better.

Four Ideas For A New Way Forward

Terms like “climate crisis” are here to stay. But scientists, teachers and politicians need to be savvy. A keen awareness of what other people may think when they hear us shout “crisis!” can lead to better communication.

Here are four ideas to keep in mind.

1. We must challenge dystopian and salvation narratives

A crisis is when things fall apart. We see news reports of crises daily – floods in Pakistan, economic collapse in Sri Lanka, famine in parts of Africa.

But “climate crisis” signifies something that feels beyond the range of ordinary experience, especially to the wealthy. People quickly reach for culturally available ideas to fill the vacuum.

One is the notion of an all-encompassing societal break down, where only a few survive. Cormac McCarthy’s bleak book The Road is one example.

Central to many apocalyptic narratives is the idea technology and a few brave people (usually men) can save the day in the nick of time, as in films like Interstellar.

The problem, of course, is these (often fanciful) depictions aren’t suitable ways to interpret what climate scientists have been warning people about. The world is far more complicated.

2. We must bring the climate crisis home and make it present now

Even if they’re willing to acknowledge it as a looming crisis, many think climate change impacts will be predominantly felt elsewhere or in the distant future.

The disappearance of Tuvalu as sea levels rise is an existential crisis for its citizens but may seem a remote, albeit tragic, problem to people in Chicago, Oslo or Cape Town.

But the recent floods in eastern Australia and the heatwave in Europe allow a powerful point to be made: no place is immune from extreme weather as the planet heats up.

There won’t be a one-size-fits-all global climate crisis as per many Hollywood movies. Instead, people must understand global warming will trigger myriad local-to-regional scale crises.

Many will be on the doorstep, many will last for years or decades. Most will be made worse if we don’t act now. Getting people to understand this is crucial.

3. We must explain: a crisis in relation to what?

The climate wars showed us value disputes get transposed into arguments about scientific evidence and its interpretation.

A crisis occurs when events are judged in light of certain values, such as people’s right to adequate food, healthcare and shelter.

Pronouncements of crisis need to explain the values that underpin judgements about unacceptable risk, harm and loss.

Historians, philosophers, legal scholars and others help us to think clearly about our values and what exactly we mean when we say “crisis”.

4. We must appreciate other crises and challenges matter more to many people

Some are tempted to occupy the moral high ground and imply the climate crisis is so grand as to eclipse all others. This is understandable but imprudent.

It’s important to respect other perspectives and negotiate a way forward. Consider, for example, the way author Bjørn Lomborg has questioned the climate emergency by arguing it’s not the main threat.

Lomborg was widely pilloried. But his arguments resonated with many. We may disagree with him, but his views are not irrational.

We must seek to understand how and why this kind of argument makes sense to so many people.

Words matter. It’s vital terms like “crisis” and “calamity” don’t become rhetorical devices devoid of real content as we argue about what climate action to take.![]()

Noel Castree, Professor of Society & Environment, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Now, we begin: 10 simple ways to make Australia’s climate game truly next-level

Australia last week moved to tackle the climate crisis when federal parliament passed Labor’s climate bill. But the new law is just the first step. Over the next eight years to 2030, we must get on a steep trajectory of emissions reductions.

The law set a national target to cut emissions by 43% this decade, based on 2005 levels. While this brings Australia closer to the international consensus, we should be aiming to go much further, much faster.

When Prime Minister Anthony Albanese informed the United Nations of Australia’s new target, he wrote of his government’s aspiration for “even greater emission reductions in the coming decade”. But how will Australia go beyond a 43% cut to emissions? And what policies should the government implement and fund first?

A roadmap released today by the Climate Council charts the way forward. It sets out key goals Australia should be chasing this decade, and ten climate policy “game-changers” to help get us there.

100% Renewables By 2030

Australia’s energy grid is responsible for 33% of our national emissions. Today, 59% of our electricity comes from coal-fired power plants.

Renewables are not just a clean form of energy – they are also the cheapest form of new energy. Our analysis suggests Australia should aim to achieve 100% renewables by 2030.

We must also increase overall power generation by around 40% this decade to make steep inroads into electrifying other sectors of the economy.

Here’s how to do it:

1. Enable transmission infrastructure: the federal government has promised A$20 billion for transmission infrastructure. This is crucial. To connect renewables to the grid, we need new transmission lines, and lots of them. The total length of transmission will need to be about 24 times what it is now.

2. Boost storage: to support grid security, we’ll need lots of electricity storage – think grid-scale batteries and pumped-hydro. To encourage greater investment the federal government should set a mandatory Renewable Energy Storage target, with specific goals for additional storage each year to 2030.

3. Upskill Australians: a new energy system will need skilled workers. The federal government must help workers upskill for clean trades through new investment in TAFE courses and electrical apprenticeships.

4. Establish a National Energy Transition Authority: this new organisation should set closure dates and develop transition plans for all coal-fired power stations by 2024, and support communities through the process.

Clean Up Transport

Australia’s transport sector is responsible for 19% of national greenhouse gas emissions. By the end of this decade, transport emissions should be halved. Almost all new cars in Australia will need to be zero-emissions vehicles, and we’ll need major improvements in public and active transport infrastructure and use.

How do we get there?

5. Fuel efficiency: the federal government should implement mandatory fuel efficiency standards. Already common across the developed world, these standards encourage auto companies to supply more low and zero-emissions vehicles to the market.

The standards can be made more stringent over time, ensuring an orderly shift to zero-emissions vehicles. Without them, Australia risks becoming a dumping ground for polluting older-model cars – while the rest of the world charges ahead.

6. Ditch dirty diesel: Governments – both state and federal – need to invest in cleaner and more convenient public transport. A key first step is replacing diesel buses with a renewable electric fleet.

Net-Zero Buildings

Some 20% of Australia’s emissions are created by the building sector. (It should be noted, this figure includes electricity consumed in buildings, which is also counted as emissions from the energy sector). To reach our climate goals we’ll need to change the way our homes, businesses and other buildings are constructed and run.

This should be done by:

7. Tightening building rules: The National Construction Code must be tightened so all new homes are net-zero emissions – through energy efficient design, rooftop solar and all-electric appliances.

By 2025 gas connections should be banned for new homes, and new gas appliances should be banned for established homes. This would ensure the move to cheaper and cleaner forms of heating and cooking.

Households will also need government support to refit their homes with electric appliances, through incentive programs and concessional finance. As Australians switch energy-efficient renewables-powered homes, they’ll save on bills.

Overhaul Industry

Australia’s industrial sector creates 34% of our national emissions – and that’s excluding electricity use. These emissions must be halved, by increasing energy efficiency, electrifying processes where possible, switching fuels and phasing out fossil fuel extraction.

At the same time, we must seize new economic opportunities for industry in a future low-carbon world.

Reaching this goal will require:

8. Proper rules for big polluters: The federal government must reform what’s known as the “safeguard mechanism” to ensure big polluters do their fair share to cut emissions. This includes government incentives to drive the steepest emissions reduction possible.

Redirect Public Spending

Public spending must be aligned with the net-zero goal. That means:

9. No more handouts: federal and state governments spent an estimated $11.6 billion on subsidies for the fossil fuel industry last financial year, up $1.3 billion on the previous year. These handouts, such as fuel tax credits, must stop.

10. Create a climate and energy investment plan: the federal government should introduce climate budget statements outlining how taxpayer investment is aligned with the goal of rapidly reducing emissions.

Time To Get Started

Australia has already warmed by around 1.4℃ since pre-industrial times. We’re suffering significant losses from accelerating climate change, and worse is on the way.

The passing of the climate bill into law has set the floor for action. Now, we must immediately build our cleaner future – because waiting until the 2030s will be much too late.![]()

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘The most significant environmentalist in history’ is now king. Two Australian researchers tell of Charles’ fascination with nature

The natural world is close to the heart of Britain’s new King Charles III. For decades, he’s campaigned on environmental issues such as sustainability, climate change and conservation – often championing causes well before they were mainstream concerns.

In fact, Charles was this week hailed as “possibly most significant environmentalist in history”. Upon his elevation to the throne, the new king is expected to be less outspoken on environmental issues. But his advocacy work have helped create a momentum that will continue regardless.

As Prince of Wales, Charles regularly met scientists and other experts to learn more about environmental research in Britain and abroad. Here, two Australian researchers recall encounters with the new monarch that left an indelible impression.

Nerilie Abram, Australian National University

In 2008, I was a climate scientist working on ice cores at the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge. On one memorable day, Prince Charles visited the facility – and I was tasked with giving him a tour.

At the time, I’d just returned from James Ross Island, near the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. There, at one of the fastest warming regions on Earth, I’d helped collect a 364-metre-long ice core.

Ice cores are cylinders of ice drilled out of an ice sheet or glacier. They’re an exceptional record of past climate. In particular, they contain small bubbles of air trapped in the ice over thousands of years, telling us the past concentration of atmospheric gases.

We started the tour by showing Prince Charles a video of how we collect ice cores. We then ventured into the -20℃ freezer and held a slice of ice core up to the lights to see the tiny, trapped bubbles of ancient atmosphere.

Outside the freezer, we listened to the popping noises as the ice melted and the bubbles of ancient air were released into the atmosphere of the lab.

Holding a piece of Antarctic ice is a profound experience. With a bit of imagination, you can cast your mind back to what was happening in human history when the air inside was last circulating.

Prince Charles embraced this idea during the tour, making a connection back to the British monarch that would have been on the throne at the time.

All this led into a discussion about climate change. Ice cores show us the natural rhythm of Earth’s climate, and the unprecedented magnitude and speed of the changes humans are now causing.

At the time of the 2008 visit, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere had reached 385 parts per million - around 100 parts per million higher than before the Industrial Revolution. Today we are at 417 parts per million, and still rising each year.

In 2017, Prince Charles co-authored a book on climate change. It includes a section on ice cores, featuring the same carbon dioxide data I showed him a decade earlier.

Last year, the royal urged Australia’s then Prime Minister Scott Morrison to attend the COP26 climate summit at Glasgow, warning of a “catastrophic” impact to the planet if the talks did not lead to rapid action.

And in March this year, the prince sent a message of support to people devastated by floods in Queensland and New South Wales, and said:

“Climate change is not just about rising temperatures. It is also about the increased frequency and intensity of dangerous weather events, once considered rare.”

As prince, Charles used his position to highlight the urgency of climate change action. His efforts have helped to bring those messages to many: from young children to business people and world leaders.

He may no longer speak as loudly on these issues as king. But his legacy will continue to drive the climate action our planet needs.

Peter Newman, Curtin University

In the 1970s, being an environmentalist was lonely work. It meant years of standing up for something that people thought was a bit marginal. But even back then Prince Charles – now King Charles III – was an environmental hero, advocating on what we needed to do.

I met the Prince of Wales in 2015. He and Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, visited Perth on the last leg of their Australia tour. I was among a group of Order of Australia recipients asked to meet the prince at Government House. I spoke to him about my lifelong passion – sustainability, including regenerative agriculture.

I knew earlier in their trip, Charles had toured the orchard at Oranje Tractor Wine, an organic and sustainable wine producer on Western Australia’s south coast. The vineyard is run by my friend Murray Gomm and his partner, Pam Lincoln, and I’d encouraged them over the years. They’d started winning awards, and it became even more special when the prince came down and blessed it!

The Oranje Tractor is now a net-zero-emissions venture: the carbon dioxide it sucks up from the atmosphere and into the soil is well above that emitted from its operations.

Charles’ eyes really lit up when I mentioned the Oranje Tractor. He was trying to do similar things in his gardening and at his farms – avoiding pesticides and sucking carbon from the atmosphere back into the soil.

Charles has that same knack the Queen had – an extraordinary ability to really listen and engage. To meet him, and see he’s been involved in sustainability as long as I have, it was validating and inspirational.

Now he’s king, Charles will be a little more constrained in his comments about environment issues. But I don’t think you can change who you are. He will just be more subtle about how he goes about it.

Climate change is now at the forefront of the global agenda. But the world needs to accelerate its emissions reduction commitments. If we don’t move fast enough, King Charles will no doubt raise a royal eyebrow – and that’s enough.![]()

Nicole Hasham, Energy + Environment Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

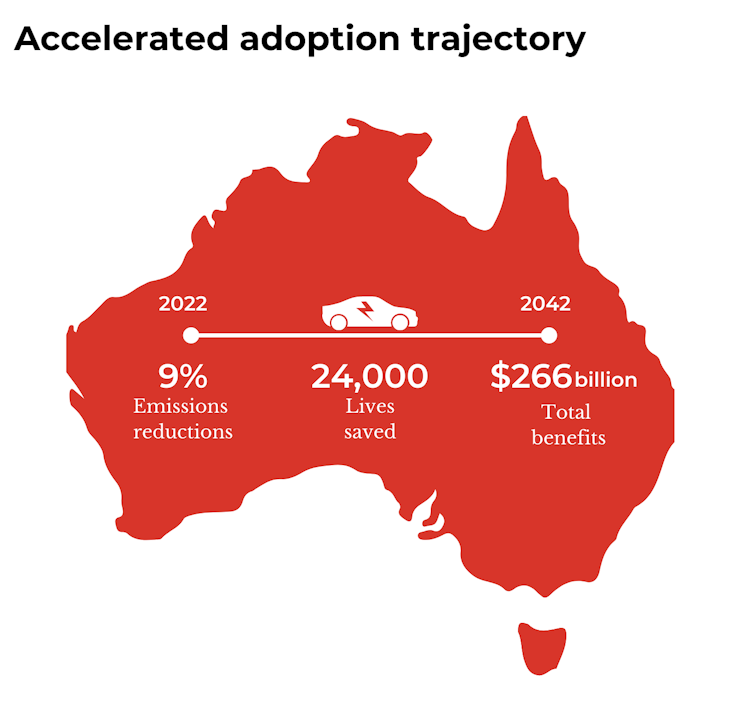

A rapid shift to electric vehicles can save 24,000 lives and leave us $148bn better off over the next 2 decades

Reducing air pollution from road transport will save thousands of lives and improve the health of millions of Australians. One of the quickest ways to do this is to accelerate the current slow transition to electric vehicles.

Our newly published research evaluated the costs and benefits of a rapid transition. In one scenario, Australia matches the pace of transition of world leaders such as Norway. Our modelling estimates this would save around 24,000 lives by 2042. The resulting greenhouse emission reductions over this time would almost equal Australia’s current total annual emissions from all sources.

We also calculated the total costs and benefits through to 2042. Australia would be about A$148 billion better off overall with a rapid transition.

Air Pollution Causes Thousands Of Deaths

Every year, around 2,600 deaths in Australia are attributed to fine-particle air pollution. The main sources of this pollution are transport and industrial activities such as mining and energy generation.

An estimated 1,715 deaths were attributed to vehicle exhaust emissions in 2015. This was 42% more than the road toll that year.

Vehicle emissions increase respiratory infections as well, particularly in young children. Transport pollution contributes to many diseases, including lung cancer, heart disease, pneumonia, asthma and diabetes. It has also been linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

A 2019 study by the Electric Vehicle Council and Asthma Australia found vehicle emissions had 21,000 serious health impacts each year in New South Wales alone.

A Grattan Institute study last month showed exhaust-pipe pollutants from trucks kill more than 400 Australians every year.

The Benefits Greatly Outweigh The Costs

Our new Swinburne University of Technology research evaluated the benefits of a transition to electric vehicles by considering public health, household and emissions reductions savings. We compared the benefits with costs, including charging infrastructure outlay, higher purchase prices for electric vehicles and green energy package costs – for household solar panels, battery storage and charging points.

Each electric vehicle was considered to have been bought along with a green energy package. The package minimises emissions and demands on electricity grid capacity, while increasing the benefits for households.

The study explored three scenarios:

slow scenario – business-as-usual, with electric vehicle sales increasing slowly from the current rate (a 5% increase in the first year, followed by a 10% yearly increase)

accelerated market-based scenario – aligns with the highest rates of adoption around the world like those in Norway (where 64% of new vehicles sold in 2021 were battery-powered), increasing by 5% every year

aggressive regulatory scenario – assumes all new vehicle sales would be electric in the base year as a result of government regulation.

The main differences between the scenarios are the rate of electric vehicle uptake (once consumers decide to retire their current vehicles) and the degree of government intervention.

The research found the business-as-usual scenario undermines national efforts to reduce the loss of life and cut emissions. It also found the aggressive strategy would have to overcome massive barriers given Australia trails many other countries in adopting electric vehicles.

The accelerated adoption strategy, however, is well aligned with uptake in other nations. Their example shows it can be achieved using progressive policies and incentives.

If implemented, the accelerated scenario could reduce the loss of life by around 24,000 by 2042. The reduction in emissions over this time would be 444 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, or 91% of Australia’s emissions from all sources in 2021. The cost would be around $118 billion, less than half of the total benefits of $266 billion.

Putting Us On Track For Emissions Targets