inbox and environment news: Issue 556

September 25 - October 1, 2022: Issue 556

100 Trees For 100 Years Of Avalon Beach

Above are some of the 100 trees that have been planted in and around the Avalon Beach village centre over the past few months to celebrate the Avalon Beach Centenary.

An Avalon 100 Centenary wildlife talk is scheduled for Sunday 16th October at 11am in the Avalon RSL.

Roger Treagus of the Avalon 100 Committee states;

''One of the important features of Avalon life is its wildlife. We will have three speakers at the event - John Dengate will talk about the general scene and is keen to answer lots of questions that residents may have. Then Andrew Gregory, famed wildlife photographer will show his stunning pictures of the powerful owl. Finally we have Merinda Air from WIRES to explain what to do when encountering injured wildlife.''

Australian water dragon, Intellagama lesueurii, catching some afternoon sun at Careel Creek, Avalon Beach. Photos: A J Guesdon

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

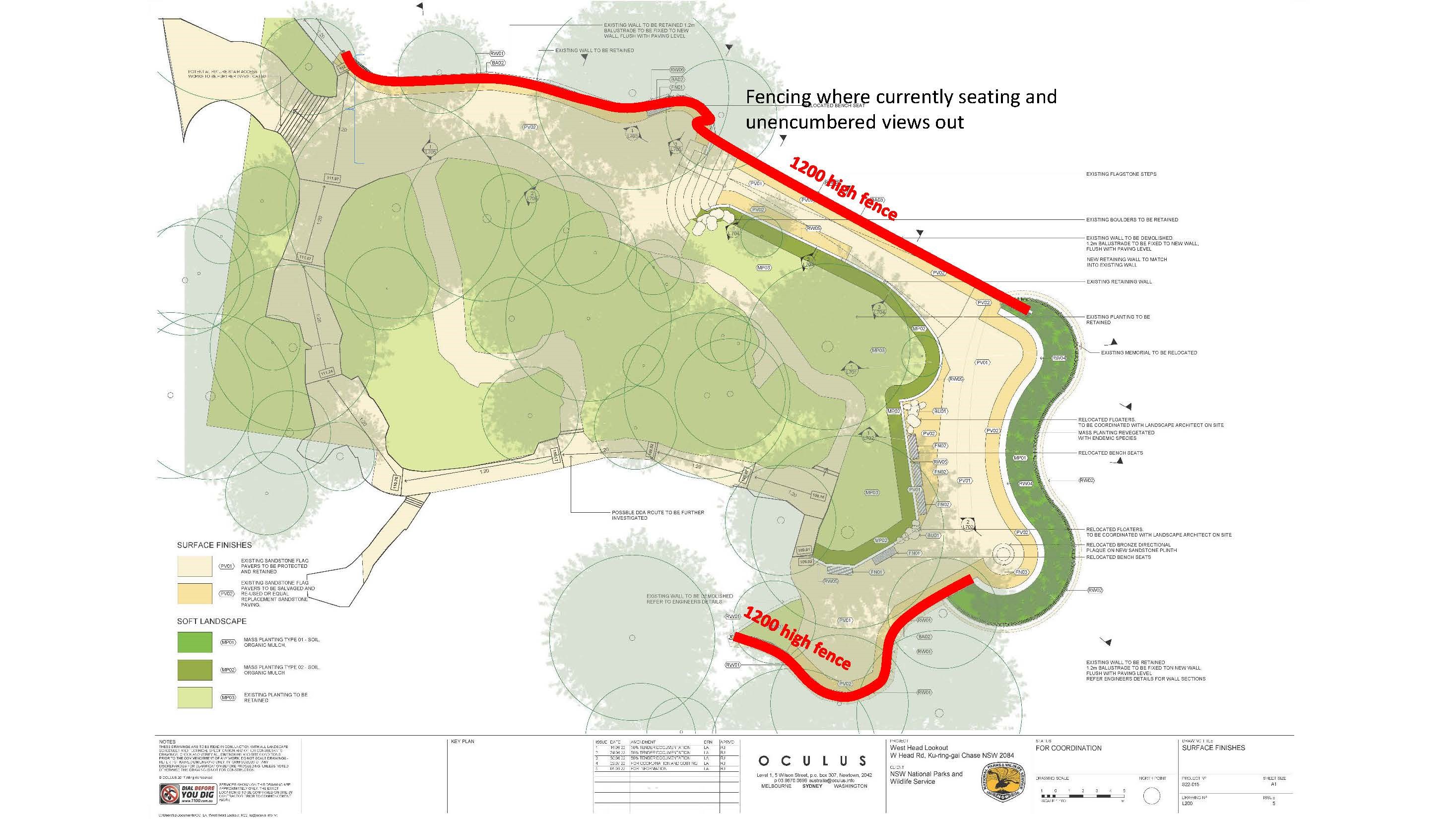

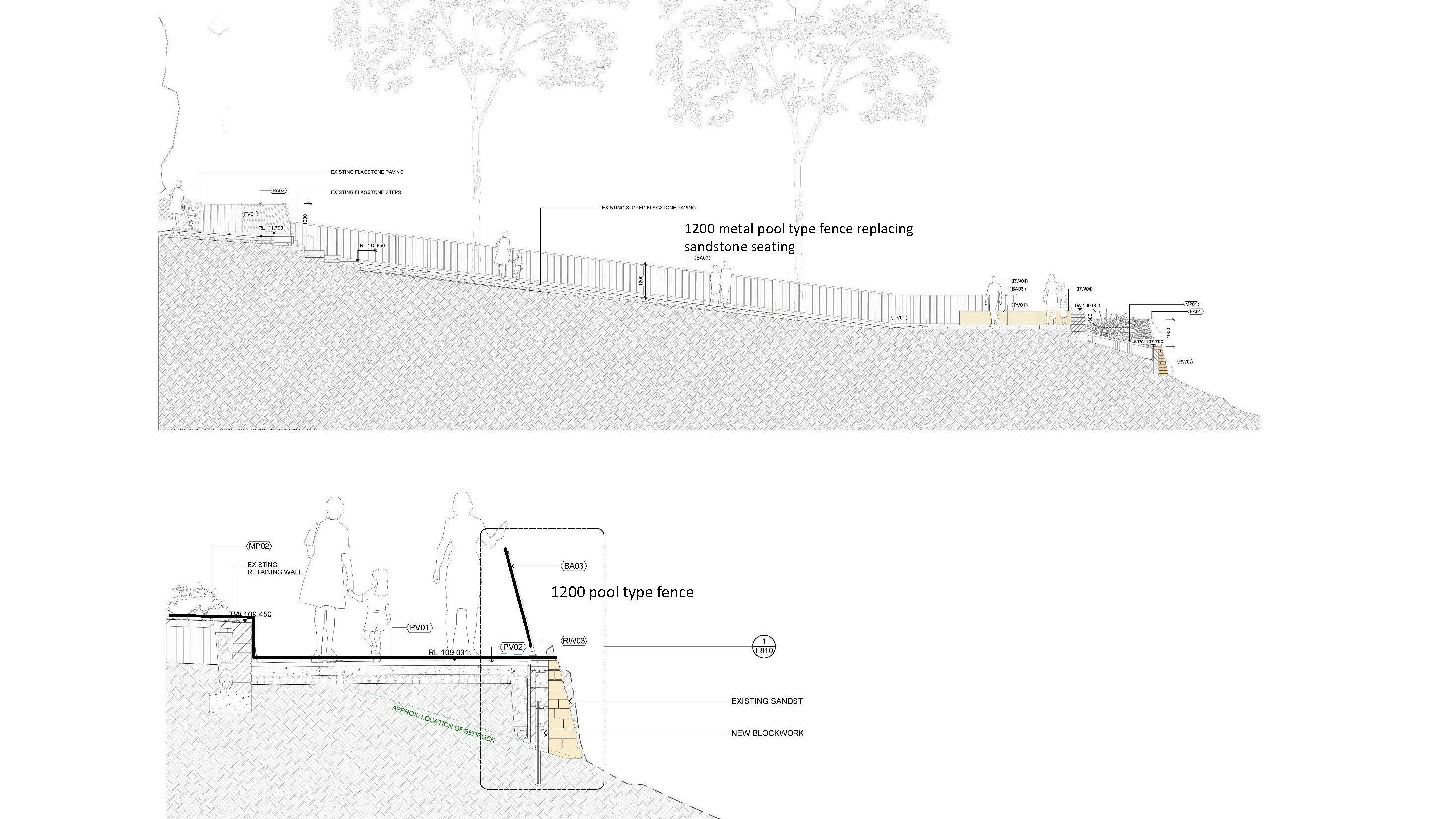

West Head Lookout Upgrade

- The area of outlook unencumbered by fencing has been substantially reduced yet the information email highlights a cross section through this area. In fact most of the site will be affected by a crude metal perimeter fence similar to a pool fence - see red highlight on plan below.

- The scheme is represented as a concept design whereas it is in fact part of a tender set presumably advanced to call tenders for construction. This is a barrier to addressing any design concerns raised.

- The site is widely recognised as an exceptional example of landscape architecture within a national park. The National Trust is similarly concerned with developments proposed for this location.

- It appears the concerns originally raised by so many in the community either have not been heard or appreciated. These relate to the lookout serving as a place where the public have been able to enjoy unimpeded views over Pittwater and North to Bouddhi. The lookout has been a quiet place of contemplation as well as a place for small numbers of people to stop for impromptu picnics. The imposition of a 1200 high crude metal fence will impact the enjoyment currently experienced. The proposal as it stands is a regressive step and detracts from the experience of visiting this exceptional site.

Over A Hectare Of Crown Land At Belrose To Be Sold: Transferred Public Lands

Residents have contacted Pittwater Online regarding the transfer of over one hectare of Crown Land at Blackbutts road Belrose to Aruma (formerly House With No Steps).

Residents have contacted Pittwater Online regarding the transfer of over one hectare of Crown Land at Blackbutts road Belrose to Aruma (formerly House With No Steps). Scotland Island Spring Garden Festival

Weed Alert: Corky Passionflower At Mona Vale + Narrabeen Creek

.jpg?timestamp=1663392221562)

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Clontarf September 25

Want noisy miners to be less despotic? Think twice before filling your garden with nectar-rich flowers

Noisy miners are complicated creatures. These Australian native honeyeaters live in large cooperative groups, use alarm calls to target specific predators, and sometimes help raise the young of other miners. But they’re perhaps best known for their aggressive and coordinated attacks on other birds – a behaviour known as “mobbing”.

We conducted a study investigating some of the possible factors that influence mobbing. We were interested in whether access to human food left on plates at cafes, or a high nectar supply thanks to planted gardens, might give urban miners extra energy and time to mob other species more often. We also examined whether miners were more aggressive towards some species over others.

Our study, published in the journal Emu - Austral Ornithology, found it wasn’t cafes with access to sugar-rich food that led to more miner aggression. In fact, gardens were where we recorded the highest amount of aggressive behaviour.

Understanding mobbing is important, because this behaviour can drive out other birds and reduce diversity. Smaller birds with a similar diet to noisy miners are particularly vulnerable.

What We Did

The noisy miner’s preferred habitat is along the edges of open eucalypt forest, including cleared land and urban fringes. Their numbers have grown in recent decades, presenting a significant conservation problem.

We know from previous research that urban noisy miners tend to be more aggressive compared with rural populations.

But to examine mobbing behaviour more closely, we placed museum taxidermies (stuffed animals) of different species of birds in three different types of habitat around Canberra:

urban cafes with lots of food leftovers

urban gardens that had higher-than-usual supplies of nectar

bush areas more typical of “natural” miner habitat.

For each habitat, we then presented the resident noisy miners with three different types of museum taxidermy models of birds:

food competitors with a similar diet to miners, both of the same size (musk lorikeets) and a much smaller species (spotted pardalote)

potential predators, including a dangerous species that preys on miners (brown goshawk) and a species that robs nests but poses less of a risk to adult miners (pied currawong)

neutral species, meaning a bird that does not prey upon nor compete with miners for food (in our study, we used a model of an eastern rosella).

We wanted to see how miners responded to these “intruders” in various settings. We also set up a speaker nearby to broadcast alarm calls, to see how miners reacted.

What We Found

We found interesting differences in how miners responded to our taxidermy models and the broadcasted alarm calls.

Noisy miners exhibited aggressive behaviours for a much longer time in gardens and cafés in comparison to natural bush areas.

Surprisingly, however, access to sugar-rich food from cafes didn’t yield the most aggressive behaviour. Rather, we recorded the highest levels of aggressive behaviour near garden sites.

Nectar-rich plants (such as grevilleas and bottlebrushes) are attractive to birds with a sweet tooth, and miners are no exception. Newer cultivars flower for longer, meaning miners living in our gardens may have access to an almost year-round source of food.

Ready access to these flowering shrubs may affect aggression by providing more time, energy or reward to noisy miners defending these uber-rich resources.

The type of model presented also impacted miner response.

More miners were attracted to an area and mobbed the subject for longer when the model was of a predator.

Miners showed even greater aggression to food competitor models, however. They were more likely to physically strike food competitor models with a peck or swoop compared to predator models.

What Can Gardeners Do With These Findings?

Our research shows the importance of considering how gardens – whether in back yards, in parks or new housing estates – can affect local ecosystems, including bird behaviour. Previous studies have drawn a link between the types of plants humans choose to plant and the local mix of bird species.

To reduce the risk of creating a perfect habitat for despotic miners in your garden, aim to:

plant multi-layered levels in your garden – that means including ground cover, small shrubs, medium shrubs and trees to provide shelter at different heights for various birds and animals

consider planting plenty of dense shrubs with small flowers to attract insects and provide shelter for small birds

use a mix of nectar-rich and non-flowering shrubs and grasses (instead of focusing too heavily on flowering plants)

try to avoid planting too many exotic species; opt instead for native plants local to your area and suited to the climate, as these benefit native plants and animals whilst minimising benefits to aggressive noisy miners.

Jade Fountain, PhD Student, University of Adelaide and Paul McDonald, Professor of Animal Behaviour, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sydney Pig And Cattle Feed Check Helps Protect Livestock Industries

Hunter Residents Encouraged To Be On The Lookout For Toxic Cane Toads

New Research Facilities To Put NSW Seafood Industry In Box Seat

- Double marine finfish fingerling production capacity over the next five years;

- Support the oyster industry with continued selective breeding, while assisting the emergence of new industries based on seaweeds and microalgae;

- Attract an additional three new research partnerships in the next three years; and,

- Ensure the continuity of spat and fingerling supply for existing and developing aquaculture, and for marine fish stocking exercises, including Mulloway and Dusky Flathead.

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary Open

Ku-Ring-Gai Sculpture Trail For 2022 Eco Festival

Dust Off Your Picnic Blankets For The First Ever Statewide Picnic For Nature

Echidna 'Love Train' Season Commences

EPA Releases Climate Change Policy And Action Plan

September 8, 2022

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is taking action to protect the environment and community from the impacts of climate change, today releasing its new draft Climate Change Policy and Action Plan which works with industry, experts and the community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support resilience.

NSW EPA Chief Executive Officer Tony Chappel said the EPA has proposed a set of robust actions to achieve a 50 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (from 2005 levels), ensure net zero emissions by 2050, and improve resilience to climate change impacts.

“NSW has ambitious targets that align with the world’s best scientific advice and the Paris commitments, to limit global warming to an average of 1.5 degrees in order to avoid severe impacts on ecosystems,” Mr Chappel said.

“Over the past few years we have seen first-hand just how destructive the impacts of climate change are becoming, not only for our environment, but for NSW communities too.

“We know the EPA has a critical role to play in achieving the NSW Government’s net-zero targets and responding to the increasing threat of climate change induced weather events.

“Equally, acting on climate presents major economic opportunities for NSW in new industries such as clean energy, hydrogen, green metals, circular manufacturing, natural capital and regenerative agriculture.

“This draft Policy sends a clear signal to regulated industries that we will be working with them to support and drive cost-effective decarbonisation while implementing adaptation initiatives that build resilience to climate change risks.

“Our draft plan proposes a staged approach that ensures the actions the EPA takes are deliberate, well informed and complement government and industry actions on climate change. These actions will support industry and allow reasonable time for businesses to plan for and meet any new targets or requirements.

“Climate change is an issue that we all face so it’s important that we take this journey together and all play our part in protecting our environment and communities for generations to come.”

Actions include:

- working with industry, government and experts to improve the evidence base on climate change

- supporting licensees prepare, implement and report on climate change mitigation and adaptation plans

- partnering with NSW Government agencies to address climate change during the planning and assessment process for activities the EPA regulates

- establishing cost-effective emission reduction targets for key industry sectors

- providing industry best-practice guidelines to support them to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

- phasing in the introduction of greenhouse gas emission limits on environment protection licences for key industry sectors

- developing and implementing resilience programs, best-practice adaptation guidance and harnessing citizen science and education programs

- working with EPA Aboriginal and Youth Advisory Committees to improve the EPA’s evolving climate change response

EPA Acting Chair Carolyn Walsh said the EPA is a partner in supporting and building on the NSW Government’s work to address climate change for the people of NSW.

“The draft Policy and Action Plan adopts, supports and builds on the strong foundations that have been set by the NSW Government through the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework, Net Zero Plan and Climate Change Adaptation Strategy,” Ms Walsh said.

The EPA will work with stakeholders, including licensees, councils, other government agencies, and the community to help implement the actions.

The draft EPA Climate Change Policy and Action Plan is available at https://yoursay.epa.nsw.gov.au/ and comments are open until 3 November 2022.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Sneezing with hay fever? Native plants aren’t usually the culprit

Hay fever is a downside of springtime around the world. As temperatures increase, plant growth resumes and flowers start appearing.

But while native flowering plants such as wattle often get the blame when the seasonal sneezes strike, hay fever in Australia is typically caused by introduced plant species often pollinated by the wind.

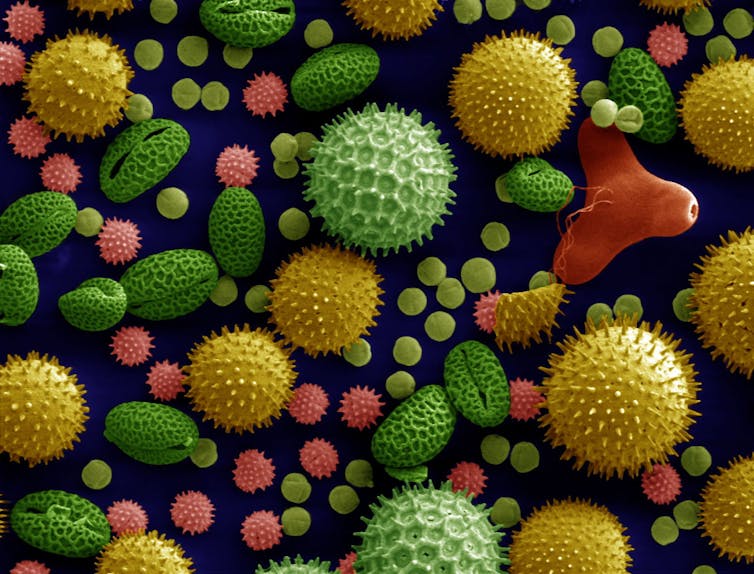

A Closer Look At Pollen

Pollen grains are the tiny reproductive structures that move genetic material between flower parts, individual flowers on the same plant or a nearby member of the same species. They are typically lightweight structures easily carried on wind currents or are sticky and picked up in clumps on the feathers of a honeyeater or the fur of a fruit bat or possum.

Hay fever is when the human immune system overreacts to allergens in the air. It is not only caused by pollen grains but fungal spores, non-flowering plant spores, mites and even pet hair.

The classic symptoms of hay fever are sneezing, runny noses, red, itchy, and watery eyes, swelling around the eyes and scratchy ears and throat.

The problem with pollen grains is when they land on the skin around our eyes, in our nose and mouth, the proteins found in the wall of these tiny structures leak out and are recognised as foreign by the body and trigger a reaction from the immune system.

So What Plants Are The Worst Culprits For Causing Hay Fever?

Grasses, trees, and herbaceous weeds such as plantain are the main problem species as their pollen is usually scattered by wind. In Australia, the main grass offenders are exotic species including rye grass and couch grass (a commonly used lawn species).

Weed species that cause hay fever problems include introduced ragweed, Paterson’s curse, parthenium weed and plantain. The problematic tree species are also exotic in origin and include liquid amber, Chinese elm, maple, cypress, ash, birch, poplar, and plane trees.

Although there are some native plants that have wind-spread pollen such as she-oaks and white cypress pine, and which can induce hay fever, these species are exceptional in the Australian flora. Many Australian plants are not wind pollinated and use animals to move their clumped pollen around.

For example, yellow-coloured flowers such as wattles and peas are pollinated by insect such as bees. Red- and orange-coloured flowers are usually visited by birds such as honeyeaters. Large, dull-coloured flowers with copious nectar (the reward for pollination) are visited by nocturnal mammals including bats and possums. Obviously Australian plant pollen can still potentially cause the immune system to overreact, but these structures are less likely to reach the mucous membranes of humans.

What Can We Do To Prevent Hay Fever Attacks At This Time Of The Year?

With all of this in mind, here are some strategies to prevent the affects of hay fever:

- stay inside and keep the house closed up on warm, windy days when more pollen is in the air

- if you must go outside, wear sunglasses and a face mask

- when you return indoors gently rinse (and don’t rub) your eyes with running water, change your clothes and shower to remove pollen grains from hair and skin

- try to avoid mowing the lawn in spring particularly when grasses are in flower (the multi-pronged spiked flowers of couch grass are distinctive)

- when working in the garden, wear gloves and facial coverings particularly when handling flowers

- consider converting your garden to a native one. Grevilleas are a great alternative to rose bushes. Coastal rosemary are a fabulous native replacement for lavender. Why not replace your liquid amber tree with a fast growing, evergreen and low-allergenic lilly pilly tree?

If You Do Suffer A Hay Fever Attack

Sometimes even with our best efforts, or if it’s not always possible to stay at home, hay fever can still creep up on us. If this happens:

- antihistamines will reduce sneezing and itching symptoms

- corticosteroid nasal sprays are very effective at reducing inflammation and clearing blocked noses

- decongestants provide quick and temporary relief by drying runny noses but should not be used by those with high blood pressure

- salt water is a good way to remove excessive mucous from the nasal passages.

Behavioural changes on warm, windy spring days are a good way of avoiding a hay fever attack.

An awareness of the plants around us and their basic reproductive biology is also useful in preventing our immune systems from overreacting to pollen proteins that they are not used to encountering.![]()

John Dearnaley, Associate Professor, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UN Committee Finds Australia Violated Torres Strait Islanders’ Rights To Enjoy Culture And Family Life: Impacts Of Climate Change

- Climate change was indeed currently impacting the claimants’ daily lives;

- To the extent that their rights are being violated; and,

- That Australia was breaching its human rights obligations to the people of the Torres Strait by failing to cut its greenhouse gas emissions quickly enough.

Climate change threatens up to 100% of trees in Australian cities, and most urban species worldwide

To anyone who has stepped off a hot pavement into a shady park, it will come as little surprise that trees (and shrubs) have a big cooling effect on cities.

Our study published today in Nature Climate Change found climate change will put 90-100% of the trees and shrubs planted in Australian capital cities at risk by 2050. Without action, two-thirds of trees and shrubs in cities worldwide will be at potential risk from climate change.

Increasing city temperatures mean their trees are becoming more important than ever. More than just shade umbrellas, the natural air-conditioning magic of trees happens as water moves up from the soil through their roots and evaporates out of their leaves into the air.

But how will the trees themselves cope with climate change as conditions shift beyond their natural tolerance limits for high temperatures or lack of water? Our team of scientists from Australia and France examined the impacts of temperature and rainfall changes projected for coming decades on 3,129 tree and shrub species planted in 164 cities across 78 countries.

About half of these urban tree and shrub species are already experiencing climate conditions beyond their natural tolerance limits.

These findings sound bleak – but read on. We have also identified steps people can take to help their local trees survive, thrive and keep on cooling.

Risks In Australia Are Higher

In Australia, reduced rainfall will be the most common stress on urban trees, but increasing temperatures will also be a major factor, especially in Darwin.

By 2050, the proportion of urban tree species that might be at risk of projected temperature increases in Australian cities is very high. Among the major cities with inventories of urban plantings, those with high percentages at risk include: Cairns 82%, Melbourne 93%, Perth 95%, Hobart 95%, Sydney 96%, Canberra 98% and Darwin 100%.

Common native species, including manna gum, swamp gum, yellow box, narrow-leaved peppermint, blackwood and brush box, and well-loved introduced species, such as jacaranda, oaks, elms, poplars and silver birch, are among the trees that could be at risk in Australia.

By at risk, we mean these species might be experiencing stressful climatic conditions that could affect their health and performance. However, we could buffer the risk for these species by providing water or creating other microclimate conditions. Also, urban trees may exhibit plasticity in traits that govern survival, growth and environmental tolerance, which can help them to adapt to local environmental conditions.

More Than 1,000 Tree Species At Risk Globally

Worldwide, we found common species of cherry plums, oaks, maples, poplars, elms, pines, lindens, wattles, eucalypts and chestnuts are among more than 1,000 species that have been flagged at risk due to climate change in most cities where they occur.

Even more worryingly, the number of species affected, and the scale of the impacts, will increase markedly by 2050 as temperatures increase. These trends jeopardise the health and longevity of urban forests and the benefits they provide to society.

The United Nations predicts the world’s population will grow to around 8.5 billion by 2030, with more than half of those people living in cities. Climate change will further heat up the urban heat islands created by millions of people, vehicles and industries generating heat that’s retained among buildings and other infrastructure.

Urban trees have a vital role to play in keeping cities liveable. As they cool their surroundings, they reduce our electricity use for air conditioning, while also absorbing carbon dioxide, purifying the air, reducing city noise and providing wildlife habitat. They are also inherently beautiful, living things that underpin much of the biodiversity on Earth.

Being around their natural greenness also improves our mental health and well-being. Trees have helped us through stressful times such as pandemics.

However, when climatic conditions exceed the natural tolerance of trees, not only can this lead to poor tree health and limited growth, but it can also reduce their cooling effect and eventually lead to tree dieback. During drought or heat stress, trees can stop releasing water vapour from their leaves or shed leaves to reduce tissue damage. This means that at a time when we most need their natural air conditioning, they are more likely to be switching off.

What Can We Do To Protect Our Trees?

Increasing the number of trees and shrubs in our cities, collectively called urban forests, is a key climate change adaptation and liveability strategy being used around the world. Until now, though, little information was available on whether or not current climatic conditions exceed what urban forests can stand, or how these conditions compare with projected changes in temperature and precipitation (drought, rain and snow) around the world.

Our study provides guidance to urban forest managers in 164 cities about which species might be at risk and should be monitored. It also identifies which species are likely to be resilient to climate change and so suitable for future plantings.

People can help urban forests to survive and keep providing their many benefits in a few simple ways:

1) reduced rainfall and soil moisture are a big threat to many species, so you can help rain soak into the ground to ensure precious water is not wasted down the drain – consider diverting water from your downpipe to a raingarden or a rainwater tank that trickle-feeds the garden (this also helps your local creek).

2) plant even more trees and shrubs, which helps to keep city temperatures comfortable for them and us – get advice from your local council or horticulturalists about suitable climate-resilient species for your area.

3) leave trees and shrubs in place – think twice before cutting down trees and shrubs, as they are providing you with more benefits than you realise.![]()

Manuel Esperon-Rodriguez, Lecturer and Research Fellow, Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Jonathan Lenoir, Senior Researcher in Ecology & Biostatistics (CNRS), Université de Picardie Jules Verne (UPJV); Mark G Tjoelker, Professor and Associate Director, Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University, and Rachael Gallagher, Associate Professor, Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

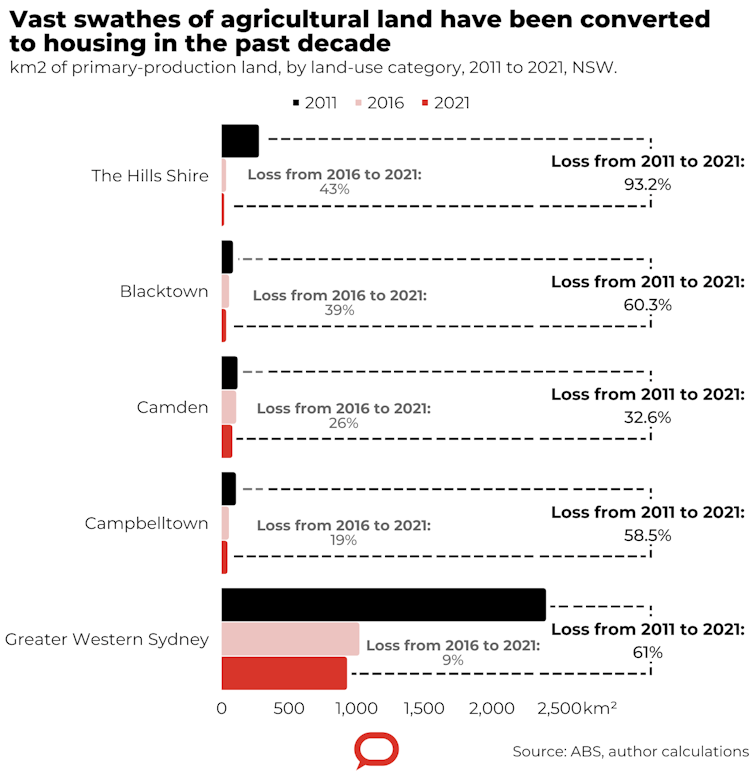

Half of Western Sydney foodbowl land may have been lost to development in just 10 years

Nicky Morrison, Western Sydney University and Awais Piracha, Western Sydney UniversityMore and more farming land is being lost to other land uses such as housing on the outskirts of our cities. But how much land is being lost? And why does it matter?

Our newly published research used the Western Sydney region as a case study of land lost since the 2011 census, and newly released Australian Bureau of Statistic (ABS) data allowed us to update our findings. While changes in ABS land-use definitions make precise comparisons difficult, Western Sydney may have lost as much as 60% of its agricultural land over the past ten years.

The significance of these losses is that Western Sydney has long been seen as the foodbowl of Greater Sydney. It produces more than three-quarters of the total value of agricultural produce in the metropolitan region. The city relies heavily on Western Sydney for livestock, vegetables, eggs, grapes and nuts.

We also interviewed people from different tiers of government working in Western Sydney. Our study highlights growing tensions between the New South Wales government and its attempts to manage population growth and housing pressures, and local councils and their efforts to protect food production on the city outskirts. The loss of productive land around our major cities is an increasingly urgent issue for our food security.

Food Systems Under Pressure

Like many cities, Sydney is being hit by many shocks and stresses – drought, bushfires, storms, floods and the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on supply chains. This rapid succession of shocks tests the resilience of local food security. Communities face soaring food prices as part of a broader surge in costs of living.

A lack of political will, short-term election cycles with shifting priorities, and low public awareness have meant the importance of retaining farming land close to the city isn’t well understood. Perishable foods grown close to urban markets not only reduce transport and energy costs, and emissions, but also improve a city’s food security.

Our study quantifies the loss of land categorised as agricultural or primary production in Western Sydney over time. Based on ABS data for land use by mesh blocks (the smallest geographic areas defined by the ABS), we estimate Western Sydney lost 9% of its primary production land from 2016 to 2021. The worst-affected council areas over this period, The Hills Shire, Blacktown, Camden and Campbelltown, lost 43%, 39%, 26% and 19% respectively.

Changes in ABS mesh block land-use definitions (from “agriculture” in 2011 to “primary production” in 2016 and 2021), as well as changes to mapping standards, make it difficult to accurately calculate the loss of land between 2011 and 2021. However, if these land-use categories in 2011, 2016 and 2021 are assumed to be broadly comparable, we can estimate that Western Sydney lost roughly 60% of its farming land over the past ten years.

The Pressures Of Growth

The NSW government has historically looked to Western Sydney to accommodate Greater Sydney’s growing population.

The population in Western Sydney is estimated to increase from 2.4 million residents in 2016 to 4.1 million in 2041. The Department of Planning and Environment’s latest housing supply forecast predicts the region will supply roughly 60% of Greater Sydney’s new dwellings in the period 2021-2025.

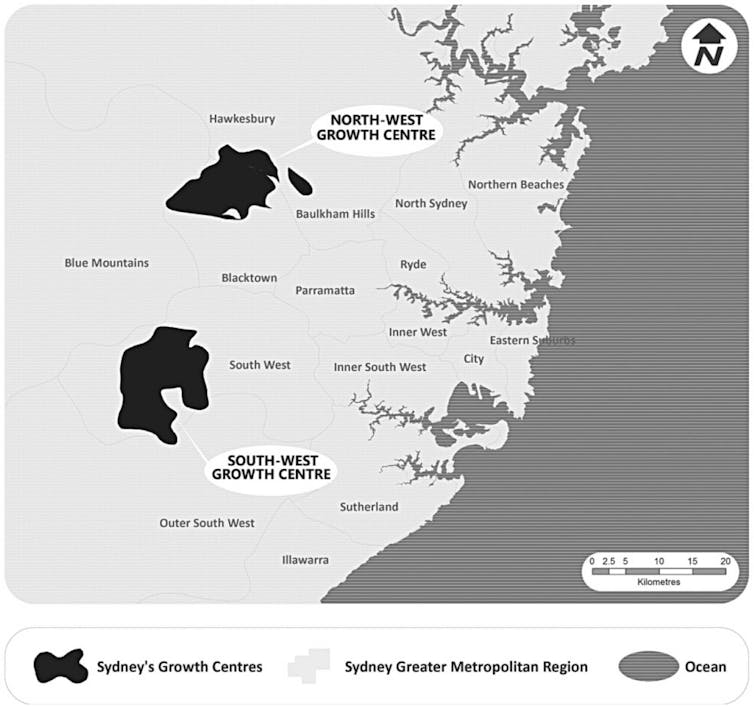

Attempts have been made to concentrate new development in two designated growth areas – the North-West and South-West – from 2006 onwards. These locations used to contain swathes of undeveloped greenfield land. But local council policies to retain productive farmland have been put aside to accommodate state government growth plans.

The Greater Sydney Commission (now the Greater Cities Commission) introduced the concept of Metropolitan Rural Areas (MRAs) to help preserve the remaining peri-urban rural land. The MRA is defined as the land uses outside the established and planned urban areas of Greater Sydney. It broadly comprises rural towns and villages, farmland, floodplains, defence land, national parks and wilderness areas.

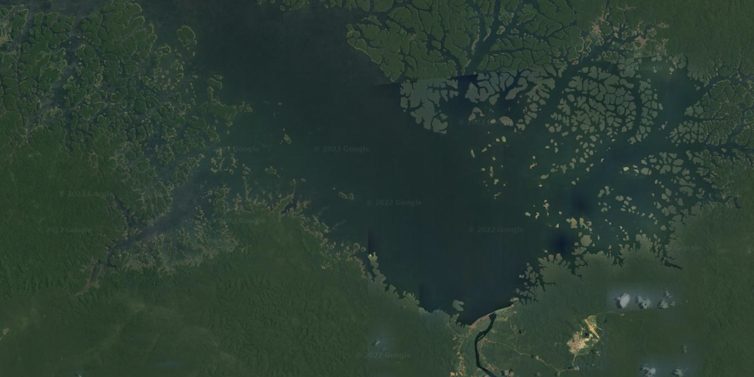

Satellite imagery from our research reveals a slow but steady housing sprawl into surrounding rural land. Is the MRA concept too late to stem urban encroachment?

Why Are Farmers Selling Up?

Why is farming land disappearing? Part of the answer lies in the cost-price squeezes farmers face. Costs of farming inputs have risen, while farmgate prices have fallen because of pressure from major retailers and competition.

As the cost of land and farming costs increase, low returns mean many farmers consider selling up to capitalise on land speculation. We estimate price differences between rural and residential land plots of up to 200% in Western Sydney (using the NSW Valuer General online tools).

The potential value uplift is a big incentive for farmers to approach the council and seek land rezoning to convert their rural holdings to more profitable land uses, such as housing and other urban uses. It makes financial sense. Who can blame them?

Local Food Production Has Been Undervalued

Our study suggests some questioning of a pro-urban growth agenda has begun. There is growing recognition of the importance of preserving agricultural and rural land on the outskirts of our major cities to help us withstand and recover from crises.

We are seeing shortages of essential items, supply-chain disruptions and rises in the prices of foods affected by climate-related events. These developments highlight the need to reduce dependence on distant food supplies.

Australian cities must find ways to maximise the sustainable use of available natural resources for more localised food production. We should also consider more carefully the role that farming land plays in other land-use functions, including flood mitigation.

Amy Lawton, consultant in the advisory team at the Institute for Public Policy and Governance at UTS, was a co-author of this article, and of the journal publication while at WESTIR Ltd.![]()

Nicky Morrison, Professor of Planning and Director of Urban Transformations Research Centre, Western Sydney University and Awais Piracha, Associate Professor of Urban Planning, Director Academic Programs, Geography Tourism and Urban Planning, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We helped fill a major climate change knowledge gap, thanks to 130,000-year-old sediment in Sydney lakes

Plants capture around half the carbon we emit by burning fossil fuels, making them a crucial part of mitigating climate change. But carbon is often released back into the atmosphere when plants die, decompose and eventually turn into dirt.

Carbon is only permanently removed from the atmosphere if it’s stored in sediments that accumulate at the bottom of oceans, lakes, reservoirs, or in peat bogs.

Our latest research on the Thirlmere Lakes near Sydney aimed to find out how trees, shrubs and soils in Australia’s eastern tablelands responded to climate changes over the last 130,000 years. The key question we sought to answer was whether carbon stored in Australia’s trees, shrubs, and soils contribute to the pool of carbon stored safely in lake sediment.

The answer, we determined, depends on a number of crucial factors, and erosion plays an essential, previously neglected, part.

Erosion is like a conveyer belt for carbon – it transports carbon to the lake from nearby hills where plants die. We found when the climate near Sydney was warm and wet, then trees and shrubs flourished and erosion was reduced. So while more carbon was stored in plants, it took longer for carbon in soil to be safely buried in the lake.

Previous research has shown ignoring the impact of erosion on carbon burial has caused Australia to overestimate the amount of carbon emitted into the atmosphere over the last 50 years, by a staggering 40%.

The Cycle Of Carbon

Plants capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during photosynthesis, and store carbon in their tissue. So what happens when plants die?

The equation is easier for the oceans: dead phytoplankton (tiny algae floating close to the surface) sinks to seafloor, where most of its captured carbon is stored safely far away from the atmosphere. On land things are more complex.

When trees and shrubs die, they cover the surface, decompose and become part of the soil. In fact, 80% of carbon on land is stored in soils. Decomposition releases some of the captured carbon back into the atmosphere, unless they’re buried deep.

In Australia, much more carbon is stored when weather conditions are wetter. During the strong La Niña event of 2010-2012, large areas of the Australia’s dry interior and temperate landscape experienced significant “greening”.

Research shows 20% more carbon was captured from the Earth’s atmosphere during this La-Niña event due to increasing plant growth. Australia contributed more than half of this.

The Last 130,000 Years

The story is even more dramatic if you look back at the last 130,000 years. During this time, the planet experienced cycles of two climate phenomena: glacial periods and interglacial periods.

A “glacial” period is characterised by much colder and drier conditions, when wide parts of northern Europe, Eurasia, and America were covered by ice kilometres thick. The last time it peaked was around 21,000 years ago.

Australia endured warmer and wetter conditions during “interglacial” periods, which peaked around 125,000 years ago and again over the last 11,600 years.

For our research, we drilled deep into Sydney’s Thirlmere Lake mud, and pulled up long columns of sediment containing traces of vegetation, climate, and erosion from the last 130,000 years. We observed significant changes in the types of vegetation growing in the catchment over this time.

Shrubs and large trees such as eucalypts flourished during warmer and wetter interglacial periods. They were less abundant when it was colder and dry during glacial periods, when grass and herbs became more common.

Large trees capture more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than grasses and herbs. And this captured carbon then accumulates in the surface of soils when the plant dies.

But how is the soil-carbon transported from the slopes where the trees and shrubs grow, to the bottom of the lake?

Soil Erosion

Erosion – whether gravity, water or wind - forms our landscape and is essential for the accumulation of soil carbon in lakes, reservoirs and the oceans.

The deeper the carbon is buried in the sediments of these reservoirs, the more efficiently it is locked away from the atmosphere. In contrast, the longer it remains on the slopes and in soils close to the surface, the more it decomposes, and carbon dioxide is released back into the atmosphere.

For the wider Sydney region, more plant growth occurred during the interglacial period, which take up vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But this may be offset by decreased erosion. And indeed, our data suggests decreased erosion during interglacial periods.

This decreased erosion is because of the protection of trees which, for example, stabilise the soil with their roots. Indeed, we found tree cover slows the rate that soil carbon moves from slope to lake by nearly 10 times.

This means there’s much more time for soils to decompose on the slope, and to release carbon back into the atmosphere.

Nevertheless, we still recorded significantly higher carbon storage in lake sediments during warmer and wetter periods, thanks largely to the greater growth of trees and shrubs compared to grasses, which are more abundant during interglacial periods. This compensates for the reduced erosion.

We also found the lake transformed into a productive wetland during warm periods. This means more carbon is also captured by plants growing in the lake.

What Will Happen Under Climate Change?

The interplay between climate, vegetation, and erosion is difficult to quantify. Our research fills a critical gap in knowledge, as climate models currently don’t account for soil-carbon erosion.

Those models assume all soil-carbon is eventually emitted back into the atmosphere, introducing uncertainties into climate predictions.

Future climate change may raise the risk of the Thirlmere Lakes drying out, which means the sediments will be exposed, which promotes decomposition. This means the previously stored carbon will be emitted back into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

Extreme aridity may also reduce terrestrial plant growth, as it did during the millennium drought.

Further, destruction of vegetation by severe bushfires reduce biomass yield to the wetlands. Preserving Australia’s unique native terrestrial vegetation and wetlands is therefore essential to sustain the continent’s role in the global carbon cycle.![]()

Alexander Francke, Research Fellow, University of Adelaide; Anthony Dosseto, Professor, University of Wollongong; Haidee Cadd, Research associate, University of Wollongong, and Tim Cohen, Associate Professor and ARC Future Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In a win for Traditional Owners, Origin is walking away from the Beetaloo Basin. But the fight against fracking is not over

What a difference six months makes. Before the federal election, the Beetaloo Basin in the Northern Territory was to have spearheaded Australia’s “gas-led recovery”. But Origin Energy this week announced it would sell its share of the basin project ahead of a wider exit from new gas ventures.

The Beetaloo Basin holds a truly enormous amount of fossil carbon – prompting Greens leader Adam Bandt to describe it as a “climate bomb”.

Origin’s exit is not a killing blow to the controversial project. But it shows increasing corporate jitters about investing in gas. And the announcement came as major iron miner Fortescue announced plans to eliminate fossil fuel use within eight years.

Origin’s exit is a major win for the region’s Traditional Owners, many of whom feared the fracking would cause large-scale environmental damage, as well as harming the climate. But Origin has sold its rights to frack Beetaloo – so the fight is far from over.

What Is This Basin And Why Does It Matter?

Oil and gas are usually found in geological basins – large, low-lying areas filled with rocks and sediment. The Beetaloo Basin covers 28,000 square kilometres and lies around 500 kilometres south-east of Darwin. Origin’s former exploration area lies near the town of Daly Waters.

Fracking the basin has been planned since 2004. The former Morrison Coalition government planned a so-called “gas led recovery” to accelerate its development, fuelled by large amounts of taxpayer money to encourage the fossil fuel industry to frack the remote area.

The move was unpopular with the region’s Traditional Owners, with fracking described by Traditional Owner Ned Jampijinpa Hargraves as “digging up my body, breaking my Tjukurpa (Dreaming)” in a government inquiry.

Local Traditional Owners formed the Nurrdalinji Native Title Aboriginal Corporation to fight fracking, in partnership with local pastoralists.

Origin’s statement makes no mention of these tensions in its decision. Indeed, it talks of “strong support” from the local community, including native title holders.

Despite this rhetoric, the work by Traditional Owners and pastoralists created enormous pressure for Origin to back out of the project.

This win demonstrates yet again how Indigenous people around the world are playing a key role in warding off the worst of the climate crisis.

This occurs not only when Indigenous people oppose fossil fuel projects on their land, but through their management of 38 million square kilometres of land across 87 countries.

This is an enormous estate – one quarter of the Earth’s land surface – and often covers land rich in biodiversity.

Australia’s First Nations peoples hold rights and interests in land covering about 40% of the continent, again land that has been sustainably managed by First Nations peoples for thousands of years and is therefore highly environmentally valuable.

Land management is central to combating climate change, through nature-based solutions such as storing carbon in trees, soils and mangroves and seagrass meadows. First Nations communities have at least 60,000 years of knowledge of how to care for Country in ways which can aid climate adaptation, mitigation and repair.

What Next?

Origin has sold its rights to a company half-owned by Tamboran Resources Limited.

Under the previous Coalition government, Tamboran subsidiary Sweetpea Petroleum received A$7.5 million of public money to drill exploration wells in the Beetaloo. Tamboran and Sweetpea refused to appear at a 2021 Senate inquiry into oil and gas activities in the Beetaloo Basin – a move the Senate committee declared was “unacceptable”.

Tamboran is now trying to raise $133 million to pay Origin for the rights and invest the rest in developing the project.

As the International Energy Agency has warned, we cannot open new fossil fuel projects if we hope to limit global temperature rise to the crucial 1.5℃ threshold.

For more than a decade, climate activists have called on institutions to divest themselves of their fossil fuel holdings. Origin has divested itself of Beetaloo and BHP is divesting its oil and gas portfolio.

But these are not true victories for the climate if the fossil fuel assets are sold to be extracted and burned by another company.

Keeping It In The Ground

If we are serious about saving our planet we need to legislate to close down fossil fuel assets and force shareholders and investors to cop the losses.

In selling its share, Origin has taken an estimated loss of up to $90 million. But the fight against fracking in the Beetaloo is not over.

Still, it’s important to recognise what’s been achieved. As Johnny Wilson, Chair of Nurrdalinji Corporation said:

We hope this is the start of more companies turning their back on gas production where we live. Fracking is not what we want … The government should give up backing the industry with taxpayers’ money and invest in health, education and clean energy from the sun because that’s what will keep our future strong.

Lily O'Neill, Senior Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne and Ben Neville, A/Prof and Deputy Director of Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dugongs and turtles are starving to death in Queensland seas – and La Niña’s floods are to blame

Kathy Ann Townsend, University of the Sunshine CoastTo rescue a turtle, University of the Sunshine Coast PhD candidate Caitlin Smith half-swam, half-crawled across mud on an inner tube. She tied a harness around its chest and front flippers, so the rest of the team could carefully pull it to safety. It was just one of 15 sick green turtles our team discovered in recent weeks in the Great Sandy Strait near Queensland’s Hervey Bay.

It’s not just turtles struggling at the moment. A dead dugong was found nearby, while another emaciated dugong was found still alive up the Noosa River.

They’re starving. Huge rains and floods have washed large quantities of sediment out to sea, where it smothers the seagrass these marine creatures rely on. There’s no relief in sight, as we enter our third wet year of La Niña.

Why Is This Happening?

Most of the sick sea turtles we found – as well as those found by Queensland’s Department of Environment and Science team – showed signs of starvation and illness, including the newly identified soft shell disease.

What lies behind these deaths are the rains and floods brought by La Nina.

Like much of New South Wales and Queensland, the Great Sandy Strait has been heavily hit by flooding this year, with three major floods engorging the Mary River. Floodwaters have carried huge amounts of sediment into Hervey Bay, reducing the water quality and flushing pollutants into sea turtle and dugong habitat.

In normal years, sediment from rivers brings a flush of nutrients, which can actually cause a seagrass boom once the water quality improves. The problem is, there’s been just too much sediment. With one La Niña after another, it’s been harder for seagrass to recover or regrow.

As sediment from the floods spread out over the shallow seas, it made the water murkier. Soon, sunlight couldn’t penetrate the gloom to reach the seagrass meadows. Worse, floods release a cocktail of chemicals, including pesticides and herbicides, unintentionally washed down from farms and inundated townships.

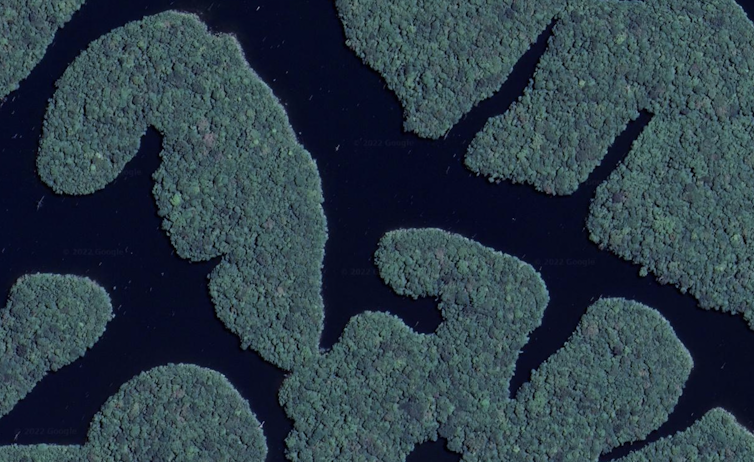

The result has been widespread devastation in the Great Sandy Straits region. In May this year, a James Cook University team surveyed 2,300 square kilometres across the region and found almost no seagrass left in waters ranging from 1 metre to 17 metres.

Green sea turtles and dugongs are the grazers of the Australian seas and rely heavily on seagrass. In good years, they drift over these lush meadows of seagrass – which resemble grassy fields on land – eating as they go.

Summers are when our seagrass meadows usually flourish, letting turtles and dugong fatten up for the winter. During winter, seagrass naturally dies back. This year, local sea turtles and dugongs went into winter in poor condition, having missed out on fattening up during the summer season.

That’s why we’re seeing so many sick or dying animals. From January 1 to August 31 this year, volunteers from Turtles in Trouble Rescue have taken 91 sea turtles from the region to the nearest wildlife hospital, 300 kilometres away. By contrast, in 2019, before the La Niña cycle began, the group had only 12 transports.

Is There Nowhere Else They Can Get Food From?

In flood-affected areas, turtles and dugongs have only two choices: move away, or try eating something else.

During the large 2010 floods, dugongs from Hervey Bay were found more than 200 kilometres south in Moreton Bay, offshore from Brisbane. Unfortunately, their migration didn’t leave them much better off – the seagrass in Moreton Bay had been hit by Brisbane River sediment. But we do know some survived.

Others were found dead, washed up 900 kilometres south after trying to find food and failing. Turtles can migrate too, but they’re often so weak from starvation that disease and parasites that they die before finding an alternative food source.

What about finding something else to eat? When our team analysed the stomachs of dead sea turtles from the Hervey Bay region, we found many were full of mangrove leaves.

Unfortunately, these trees have a range of natural toxins designed to stop animals eating them, such as the toxic sap of the milky mangrove. Worse, as the “kidneys of the coast”, mangroves use their leaves to store concentrated salt and toxins such as heavy metals. In short, this diet is no substitute.

Is This Part Of A Natural Cycle Of Boom And Bust?

While turtles and dugongs do have natural variation in their populations over time – and often due to food availability – there are limits. Turtles and dugongs cannot respond to climate-induced pressures the same way fast-breeding mice can.

Female green sea turtles have to be 30 to 40 years old before they can begin to reproduce. They only undertake their long migrations to breed every three to eight years. They lay over 1,000 eggs in the hope just one hatchling will survive the perilous seas long enough to hit reproductive age.

Dugongs, meanwhile, only raise a single calf every three to seven years. These reproductive strategies make it very difficult to respond to fast changes to their environments.

Successive lean years caused by back-to-back La Niña events will hit both the survival rate and reproductive ability of these animals.

Sea turtles in poor condition will not be able to migrate successfully, which means they’re heading for a poor nesting season. Dugongs, too, will struggle. Without stores of fat, the females won’t be able to support their calves through to weaning stage. That will make it harder to replenish the population and recover from losses from starvation or relocation. We won’t know the full impact of this event until years from now.

In response to the crisis, local volunteers have stepped up. The Turtles in Trouble Rescue group has gone from five to 50 trained members, and are working with the University of the Sunshine Coast to create a sea turtle rehabilitation centre in the area. We’ll be better prepared for the next flooding event. ![]()

Kathy Ann Townsend, Senior Lecturer in Animal Ecology, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Young cold-blooded animals are suffering the most as Earth heats up, research finds

Climate change is making heatwaves worse. Many people have already noticed the difference – and so too have other animals.

Sadly, research by myself and colleagues has found young animals, in particular, are struggling to keep up with rising temperatures, likely making them more vulnerable to climate change than adults of their species.

The study focused on “ectotherms”, or cold-blooded animals, which comprise more than 99% of animals on Earth. They include fish, reptiles, amphibians and insects. The body temperature of these animals reflects outside temperatures – so they can get dangerously hot during heat waves.

In a warming world, a species’ ability to adapt or acclimatise to temperatures is crucial. Our study found that young ectotherms, in particular, can struggle to handle more heat as their habitat warms up. That may have dramatic consequences for biodiversity as climate change worsens.

Our findings are yet more evidence of the need to urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions to prevent catastrophic global heating. Humans must also provide and retain cool spaces to help animals navigate a warmer future.

Tolerating Heat In A Changing Climate

The body temperature of ectotherms is extremely variable. As they move through their habitat, their body temperature varies according to the outside conditions.

However, there’s only so much heat these animals can tolerate. Heat tolerance is defined as the maximum body temperature ectotherms can handle before they lose functions such as the ability to walk or swim. During heat waves, their body temperature gets so high they can die.

Species, including ectotherms, can adapt to challenges in their environment over time by evolving across generations. But the rate at which global temperatures are rising means in many cases, this adaptation is not happening fast enough. That’s why we need to understand how animals acclimatise to rising temperatures within a single lifetime.

Unfortunately, some young animals have little to no ability to move and seek cooler temperatures. For example, baby lizards inside eggs cannot move elsewhere. And owing to their small size, juvenile ectotherms cannot move great distances.

This suggests young animals may be particularly vulnerable during intense heat waves. But we know very little about how young animals acclimatise to high temperatures. Our research sought to find out more.

Young Animals At Risk

Our study drew on 60 years of research into 138 ectotherm species from around the world.

Overall, we found the heat tolerance of embryos and juvenile ectotherms increased very little in response to rising temperatures. For each degree of warming, the heat tolerance of young ectotherms only increased by an average 0.13℃.

The physiology of heat acclimatisation in animals is very complex and poorly understood. It appears linked to a number of factors such as metabolic activity and proteins produced by cells in response to stress.

Our research showed young land-based animals were worse at acclimatising to heat than aquatic animals. This may be because moving to a cooler temperature on land is easier than in an aquatic environment, so land-based animals may not have developed the same ability to acclimatise to heat.

Heat tolerance can vary within a species. It can depend on what temperatures an animal has experienced during its lifetime and, as such, the extent to which it has acclimatised. But surprisingly, our research found past exposure to high temperatures does not necessarily help a young animal withstand future high temperatures.

Take, for example, Lesueur’s velvet gecko which is found mostly along Australia’s east coast. Research shows juveniles from eggs incubated in cooler nests (23.2℃) tolerated temperatures up to 40.2℃. In contrast, juveniles from warmer nests (27℃) only tolerated temperatures up to 38.7℃.

Those patterns can persist through adulthood. For example, adult male mosquito fish from eggs incubated to 32℃ were less tolerant to heat than adult males that experienced 26℃ during incubation.

These results show embryos are especially vulnerable to extreme heat. Instead of getting better at handling heat, warmer eggs tend to produce juveniles and adults less capable of withstanding a warmer future.

Overall, our findings suggest young cold-blooded animals are already struggling to cope with rising temperatures – and conditions during early life can have lifelong consequences.

What’s Next?

To date, most studies on the impacts of climate change have focused on adults. Our research suggests animals may be harmed by heatwaves long before they reach adulthood – perhaps even before they’re born.

Alarmingly, this means we may have underestimated the damage climate change will cause to biodiversity.

Clearly, it’s vitally important to limit global greenhouse gas emissions to the extent required by the Paris Agreement.

But we can also act to protect species at a finer scale – by conserving habitats that allow animals to find shade and shelter during heatwaves. Such habitats include trees, shrubs, burrows, ponds, caves, logs and rocks. These places must be created, restored and preserved to help animals prosper in a warming world.![]()

Patrice Pottier, PhD Candidate in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pando In Pieces: Understanding The New Breach In The World's Largest Living Thing

From crumbling rock art to exposed ancestral remains, climate change is ravaging our precious Indigenous heritage

Climate change is rapidly intensifying. Amid the chaos and damage it wreaks, many precious Indigenous heritage sites in Australia and around the world are being destroyed at an alarming rate.

Sea-level rise, flooding, worsening bushfires and other human-caused climate events put many archaeological and heritage sites at risk. Already, culturally significant Indigenous sites have been lost or are gravely threatened.

For example, in Northern Australia, rock art tens of thousands of years old has been destroyed by cyclones, bushfires and other extreme weather events.

And as we outline below, ancestral remains in the Torres Strait were last year almost washed away by king tides and storm surge.

These examples of loss are just the beginning, unless we act. By combining Indigenous Traditional Knowledge with Western scientific approaches, communities can prioritise what heritage to save.

Indigenous Heritage On The Brink

Indigenous Australians are one of the longest living cultures on Earth. They have maintained their cultural and sacred sites for millennia.

In July, Traditional Owners from across Australia attended a workshop on disaster risk management at Flinders University. The participants, who work on Country as cultural heritage managers and rangers, hailed from as far afield as the Torres Strait Islands and Tasmania.

Here, three of these Traditional Owners describe cultural heritage losses they’ve witnessed, or fear will occur in the near future.

- Enid Tom, Kaurareg Elder and a director of Kaurareg Native Title Aboriginal Corporation:

Coastal erosion and seawater inundation have long threatened the Torres Strait. But now efforts to deal with the problem have taken on new urgency.

In February last year, king tides and a storm surge eroded parts of a beach on Muralug (or Prince of Wales) Island. Aboriginal custodians and archaeologists rushed to one site where a female ancestor was buried. They excavated the skeletal remains and reburied them at a safe location.

It was the first time such a site had been excavated at the island. Kaurareg Elders now worry coastal erosion will uncover and potentially destroy more burial sites.

- Marcus Lacey, Senior Gumurr Marthakal Indigenous Ranger:

The Marthakal Indigenous Protected Area covers remote islands and coastal mainland areas in the Northern Territory’s North Eastern Arnhem Land. It has an average elevation of just one metre above sea level, and is highly vulnerable to climate change-related hazards such as severe tropical cyclones and sea level rise.

The area is the last remnant of the ancient land bridge joining Australia with Southeast Asia. As such, it can provide valuable information about the first colonisation of Australia by First Nations people.

It is also an important place for understanding contact history between Aboriginal Australians and the Indonesian Maccassans, dating back some 400 years.

What’s more, the area provides insights into Australia’s colonial history, such as Indigenous rock art depicting the ships of British navigator Matthew Flinders. Sea level rise and king tides mean this valuable piece of Australia’s history is now being eroded.

- Shawnee Gorringe, operations administrator at Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation:

On Mithaka land, in remote Queensland, lie important Indigenous heritage sites such as stone circles, fireplaces and examples of traditional First Nations water management infrastructure.

But repeated drought risks destroying these sites – a threat compounded by erosion from over-grazing.

To help solve these issues, we desperately need Indigenous leadership and participation in decision-making at local, state and federal levels. This is the only way to achieve a sustainable future for environmental and heritage protection.

Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation general manager Joshua Gorringe has been invited to the United Nations’ COP27 climate conference in Egypt in November. This is a step in the right direction.

So What Now?

The loss of Indigenous heritage to climate change requires immediate action. This should involve rigorous assessment of threatened sites, prioritising those most at risk, and taking steps to mitigate damage.

This work should be undertaken not only by scientists, engineers and heritage workers, but first and foremost by the Indigenous communities themselves, using Traditional Knowledge.

Last year’s COP26 global climate conference included a climate heritage agenda. This allowed global Indigenous voices to be heard. But unfortunately, Indigenous heritage is often excluded from discussions about climate change.

Addressing this requires doing away with the usual “top down” Western, neo-colonial approach which many Indigenous communities see as exclusive and ineffective. Instead, a “bottom up” approach should be adopted through inclusive and long-term initiatives such as Caring for Country.

This approach should draw on Indigenous knowledge – often passed down orally – of how to manage risk. This should be combined with Western climate science, as well as the expertise of governments and other organisations.

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge into cultural heritage policies and procedures will not just improve heritage protection. It would empower Indigenous communities in the face of the growing climate emergency.![]()

Anna M. Kotarba-Morley, Senior Lecturer in Archaeology, Flinders University; Enid Tom, Kaurareg Elder and director of Kaurareg Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, Indigenous Knowledge; Marcus Lacey, Senior Gumurr Marthakal Indigenous ranger, Indigenous Knowledge, and Shawnee Gorringe, Manager at Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What if carbon border taxes applied to all carbon – fossil fuels, too?

The European Union is embarking on an experiment that will expand its climate policies to imports for the first time. It’s called a carbon border adjustment, and it aims to level the playing field for the EU’s domestic producers by taxing energy-intensive imports like steel and cement that are high in greenhouse gas emissions but aren’t already covered by climate policies in their home countries.

If the border adjustment works as planned, it could encourage the spread of climate policies around the world. But the EU plan, as well as most attempts to evaluate the impact of such policies, is missing an important source of cross-border carbon flows: trade in fossil fuels themselves.

As energy analysts, we decided to take a closer look at what including fossil fuels would mean.

In a newly released paper, we analyzed the impact and found that including fossil fuels in carbon border adjustments would significantly alter the balance of cross-border carbon flows.

For example, China is a major exporter of carbon-intensive manufactured goods, and its industries will face higher costs under the EU border adjustment if China doesn’t set sufficient climate policies for those industries. But when fossil fuels are considered, China becomes a net carbon importer, so setting its own comprehensive border adjustment could be to its energy producers’ benefit.

The U.S., on the other hand, could see harm to its domestic fuel producers if other countries imposed carbon border adjustments on fossil fuels. But the U.S. would still be a net carbon importer, and adding a border adjustment could help its domestic manufacturers.

What Is A Carbon Border Adjustment?

Carbon border adjustments are trade policies designed to avoid “carbon leakage” – the phenomenon in which manufacturers relocate their production to other countries to get around environmental regulations.

The idea is to impose a carbon “tax” on imports that is commensurate with the costs domestic companies face related to a country’s climate policy. The carbon border adjustment is imposed on imports from countries that do not have similar climate policies. In addition, countries can give rebates to exports to ensure domestic manufacturers remain competitive in the global market.

This is all still in the future. The EU plan phases in starting in 2023 but currently isn’t scheduled to fully go into effect until 2026. However, other countries are closely watching as they consider their own policies, including some members of the U.S. Congress who are considering carbon border adjustment legislation.

Capturing All Cross-Border Carbon Flows

One issue is that current discussions of carbon border taxes focus on “embodied” carbon – the carbon associated with the production of a good. For example, the EU proposal covers cement, aluminum, fertilizers, power generation, iron and steel.

But a comprehensive border adjustment, in theory, should seek to address all cross-border carbon flows. All the major analyses to date, however, leave out the carbon content of fossil fuels trade, which we refer to as “explicit” carbon.

In our analysis, we show that when only manufactured goods are considered, the U.S. and EU are portrayed as carbon importers because of their “embodied” carbon balance – they import a lot of high-carbon manufactured goods – while China is portrayed as a carbon exporter. That changes when fossil fuels are included.

The Impact Of Including Fossil Fuels

By assessing the impact of a carbon border adjustment based only on embodied carbon flows, those involving manufactured goods, policymakers are missing a significant part of total carbon traded across their borders – in many cases, the largest part.

In the EU, our findings largely reinforce the current motivation behind a carbon border adjustment, since the bloc is an importer of both explicit carbon and embodied carbon.

For the U.S., however, the results are mixed. A carbon border adjustment could protect domestic manufacturers but harm the international competitiveness of domestic fossil fuels, and at a time when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is placing renewed importance on the U.S. as a global energy supplier.

The Chinese economy, as an exporter of embodied carbon in manufactured goods, would suffer if its trading partners imposed a carbon border adjustment on China’s products. On the other hand, a Chinese domestic border adjustment could benefit Chinese domestic energy producers at the expense of foreign competitors who fail to adopt similar policies.

Interestingly, our analysis suggests that, by including explicit carbon flows, the U.S., EU and China are all net importers of carbon. All three key players could be on the same side of the discussion, which could improve the prospects for future climate negotiations – if all parties recognize their common interests.![]()

Joonha Kim, Graduate fellow, Baker Institute, Rice University and Mark Finley, Fellow in Energy and Global Oil, Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How you can help protect sharks – and what doesn’t work

Sharks are some of the most ecologically important and most threatened animals on Earth. Recent reports show that up to one-third of all known species of sharks and their relatives, rays, are threatened with extinction. Unsustainable overfishing is the biggest threat by far.

Losing sharks can disrupt coastal food webs that billions of people depend on for food. When food chains lose their top predators, the rest can unravel as smaller prey species multiply.

In my years of talking with the public about sharks and ocean conservation, I’ve found that many people care about sharks and want to help but don’t know how. The solutions can be quite technical, and it’s challenging to understand and appreciate the scale and scope of some of the threats.

At the same time, there is an enormous amount of oversimplification and even misinformation about these important topics, which can lead well-intentioned people to support policies that experts know won’t work.

I am a marine conservation biologist and have sought to improve this situation by surveying shark researchers and helping scientists identify research topics that can advance conservation. I’ve also written a book, “Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive With the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator.” Here are three ways that anyone can make a difference for sharks and avoid taking steps that are ineffective or even harmful.

Don’t Eat Unsustainable Seafood

The No. 1 threat to sharks and rays – and arguably, to marine biodiversity in general – is unsustainable overfishing. Some fishing methods are incredibly destructive to marine life and habitats.

They can also produce high rates of bycatch – the unintended catch of nontarget species. For example, fishermen pursuing tuna may accidentally catch sea turtles or sharks swimming near the tuna.

The single most effective thing that individual consumers can do is to avoid seafood produced using these harmful methods. This does not mean completely avoiding seafood, as some advocates urge. Seafood is healthy, delicious and culturally important, and there are environmentally friendly ways of catching it sustainably. There are even sustainable fisheries for sharks.

Reputable organizations such as California’s Monterey Bay Aquarium publish sustainable seafood guides that rate different types of seafood based on how they are caught or raised. While experts may quibble over details of some of these rankings, consumers can follow these guidelines and know that they are helping to protect sharks and ocean life in general.

Support Reputable Environmental Nonprofits, Not Harmful Extremists

Lots of great environmental nonprofit organizations work on shark issues and offer opportunities to get involved, such as donating money and communicating with elected officials and other decision-makers. In my book, I describe the work of many of these groups, including my favorite, Shark Advocates International.

Unfortunately, some organizations promote pseudoscience that doesn’t help anyone or anything. In a 2021 study, colleagues and I surveyed employees of 78 nonprofits that work on shark conservation issues to understand whether and how these organizations engaged with the science of shark conservation.

We found that a small but vocal minority had never read scientific reports or spoken with scientists, and held blatantly incorrect and harmful views that cannot help sharks. For example, some organizations are trying to get certain airlines to stop carrying shark products like dried fins, without acknowledging that well over 95% of fins are shipped by sea or that sustainable sources of these fins exist.

One of my particular pet peeves is amateur online petitions that may not reflect actual conditions. For example, in the spring of 2022, some 60,000 people signed a petition calling for Florida to ban the practice of shark finning – without recognizing that Florida had banned shark finning in the early 1990s. As I explain in my book, it is essential to identify organizations that use science in support of worthwhile conservation goals and avoid promoting others that do not.

Look To Experts

Many ocean science, management and conservation experts are active on social media. Following them is a great way to learn about fascinating new scientific discoveries and conservation issues.

Unfortunately, sharks also get a lot of sensational coverage in the media, and well-intentioned but uninformed people often spread misinformation on social media. For example, you may have seen posts celebrating Hawaii for banning shark fishing in its waters – but these posts don’t note that about 99% of fishing in Hawaii occurs in federal waters.

Don’t take the bait. By getting your information from reliable sources, you can help other people learn more about these fascinating, ecologically important animals, why they need humans’ help and the most effective steps to take.![]()

David Shiffman, Post-Doctoral and Research Scholar in Marine Biology, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Patagonia’s founder has given his company away to fight climate change and advance conservation: 5 questions answered

Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, his wife and their two adult children have irrevocably transferred their ownership of the outdoor apparel company to a set of trusts and nonprofit organizations.

From now on, the corporation’s profits will fund efforts to deal with climate change, as well as protect wilderness areas. It will, however, remain a privately held enterprise. According to initial reports about this unusual approach to philanthropy that ran on Sept. 14, 2022, Patagonia is worth about US$3 billion and its profits that will be donated in perpetuity could total $100 million every year.

The Conversation U.S. asked Indiana University’s Ash Enrici – a scholar who studies how philanthropy affects the environment – to explain why this arrangement is so significant.

1. Is This Move Part Of A Trend?

The biggest donors, those giving away billions of dollars, are increasingly making climate change a priority. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, for example, announced in 2020 that he was putting $10 billion into his Earth Fund, and Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, said in 2021 that she would devote $3.5 billion of her fortune to fighting climate change.

Likewise, big donors are increasing their funding of conservation efforts.

In September 2021, the Earth Fund joined with eight other philanthropic powerhouses to pledge $5 billion to “support the creation, expansion, management and monitoring of protected and conserved areas of land, inland water and sea” around the world. This initiative aims to conserve 30% of Earth by 2030.

Within days of Chouinard’s announcement, another splashy climate gift emerged, setting a similar precedent. Filmmaker Adam McKay said he will donate $4 million he made from the movie “Don’t Look Up,” which he wrote, co-produced and directed. Those proceeds from his satirical film, which was a metaphor regarding climate inaction, will fund a climate activism group.

No matter how frequently these donations occur, it’s important to keep in mind that the cost of meeting the world’s environmental challenges is enormous and will cost trillions of dollars. So while all of these gifts are certainly significant in their scale, donors and governments will need to do and spend much more.

2. What Makes It Stand Out?