inbox and environment news: Issue 557

October 2 - 15, 2022: Issue 557

Arnies Recon Will Recycle Your Electronics For Free: Drop Off At Cromer-North Narrabeen-Manly Vale-Avalon Beach This October

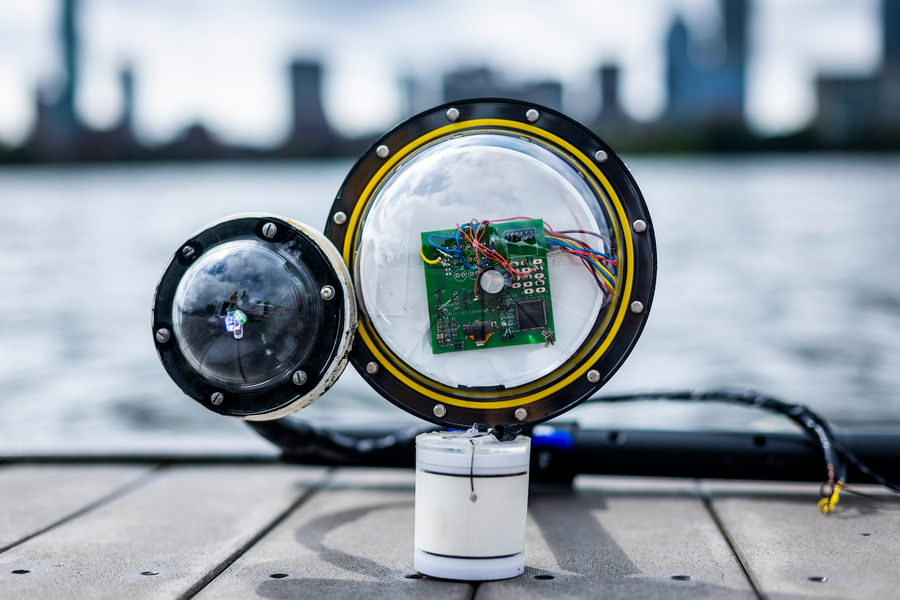

Adrian and Lisa Saunders founded Arnies Recon in 2019 as a self-funded social enterprise to reimagine the approach to dealing with electronic waste. Their services are free to households, business and government.

Adrian and Lisa Saunders founded Arnies Recon in 2019 as a self-funded social enterprise to reimagine the approach to dealing with electronic waste. Their services are free to households, business and government. - 4 October - Cromer: 7:00 - 9:00am at Cromer Community Centre Car Park, Fisher Road North

- 6 October - North Narrabeen: 7:00 - 9:00am at Lake Park Car Park, Lake Park Road

- 12 October - Manly Vale: 7:00 - 9:00am at Miller's Reserve, Campbell Parade

- 13 October - Avalon Beach: 7:00am - 9:00am at Hitchcock Park, Barrenjoey Road

- Arnies try to find buyers for the items as they are. If we can safely provide the item to a collector or refurbisher, we can recycle with the lowest footprint possible.

- Arnies find people who refurbish and reuse the items as they are or as parts to make whole units.

- Arnies locate collectors in Australia and overseas who are excited by retro electronics and want to own or restore old items that have nostalgic value.

- Disassemble items and sell individual items are parts

- Donate items for use in community and/or arts projects

- Break down computers for precious and valuable metals recovery

- Recycle any items that we are unable to sell with safety for metals and precious metals

- Constantly seek better ways to recycle

100 Trees For 100 Years Of Avalon Beach: Avalon 100 Centenrary Wildlife Talk

Above are some of the 100 trees that have been planted in and around the Avalon Beach village centre over the past few months to celebrate the Avalon Beach Centenary.

An Avalon 100 Centenary wildlife talk is scheduled for Sunday 16th October at 11am in the Avalon RSL.

Roger Treagus of the Avalon 100 Committee states;

''One of the important features of Avalon life is its wildlife. We will have three speakers at the event - John Dengate will talk about the general scene and is keen to answer lots of questions that residents may have. Then Andrew Gregory, famed wildlife photographer will show his stunning pictures of the powerful owl. Finally we have Merinda Air from WIRES to explain what to do when encountering injured wildlife.''

Australian water dragon, Intellagama lesueurii, catching some afternoon sun at Careel Creek, Avalon Beach. Photos: A J Guesdon

National Bird Week + Aussie Bird Count 2022

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Take Someone Under Your Wing This World Migratory Bird Day: October 8 2022

- A priority when birdwatching should always be to ensure minimal disturbance to birds and their habitats, and their wellbeing should never be compromised to get a good sighting or photograph. Don’t get too close, never disturb their nests, and avoid blocking their route back to the nest. This can prevent parents from returning to their chicks, leaving them hungry and at greater risk of predation. Also, try to stay on roads and paths when possible, so as not to trample vegetation or ground nests.

- You don’t need to travel far to enjoy birdwatching as one of the many incredible things about birds is that we can see them everywhere! You can head out to a forest or nature reserve, or just watch out from your kitchen window. No matter where you see a bird, submitting your sightings is always useful information, whether it’s at a National Park or your local bus stop.

- Birds are easily startled by loud noises, so to increase your chances of exciting sightings you need to be as quiet as possible and avoid sudden movements. This way, you’re more likely to hear their songs and calls too. Patience is also key, so don’t be disheartened if you don’t immediately spot lots of species – persevering will pay off!

- Identifying birds takes practice. There are thousands of different species of bird, so don’t pressure yourself to know them all! Use a guidebook to help with your identification or take a photo if you can and ask a friend to help to figure out the species.

Magpies, curlews, peregrine falcons: how birds adapt to our cities, bringing wonder, joy and conflict

For all the vastness of our Outback and bush, most Australians live in urban areas. In cities, we live within an orderly landscape, moulded and manufactured by us to suit our needs. But other species also live in this modified environment.

Review: Curlews on Vulture Street: cities, birds, people & me – Darryl Jones (NewSouth)

In many cases, this cohabitation is peaceful, benign or even mutually beneficial. Part of Darryl Jones’ Curlews on Vulture Street: cities, birds, people & me documents the surprising variety of bird life in our cities and towns. Many of these birds are native species, finding a way to live – and sometimes to flourish – in a human-dominated system.

Lorikeets, honeyeaters, cockatoos, crows, currawongs, silver gulls, peregrine falcons, and even (in some Australian cities) curlews and brush-turkeys have cracked the code, adapting to the resources we inadvertently provide, or intentionally create, for them – such as native plants in our gardens. They survive or thrive notwithstanding the cars, cats, concrete, dogs, noise and pollution.

Many of us appreciate these birds, they add colour, joy and wildness to our lives. As witness to their fascination, thousands of Australians meticulously record the birds in our backyards every year, chuffed at every novelty, casually competing with other backyard observers.

Jones notes that many of us also feed birds, to seek closer interactions with them, and to provide some restitution for the damage our species has done to their natural environment. Urban life can be alienating, lonely; birds can connect us to the wellspring of nature.

However, in some cases, cohabitation with other species is problematic: we come into conflict with those other lives.

Much of the content of this book describes such situations: aggressive dive-bombing magpies, brush-turkeys re-arranging what were once meticulously neat gardens, bin-chickens (white ibis) snatching food from our lunch tables and picnics, and hooligan sulphur-crested cockatoos ripping up our verandahs.

Many of us love these birds; some of us hate them. These are challenging conflicts to resolve, and Jones carefully describes various cases and how he goes about finding solutions.

Happy to admit his initial assumptions are often proven entirely wrong, Jones articulates the need for carefully planned and implemented – and often highly innovative – research in order to understand why these “troublesome” birds are behaving as they do.

He also shows that at least some of these problems, and their solutions, have more to do with human attitudes and behaviours than with the wayward intentions of birds. So, if we stressed less about the orderliness of our gardens, we may enjoy the landscaping chaos that comes with sharing our yards with industrious brush-turkeys. If we can admire the pluck and fierce paternal protective drive of magpies, we may better tolerate their brief seasonal bouts of aggression, or shift our walking or cycling routes to avoid them.

Solving The Swoop

Most Australians have been swooped by magpies, some terrified and long-scarred by the sometimes spectacular experience. It is an acute case of courageous, untamed nature fighting back within our domain.

Jones shows that many magpies do not swoop, that the swooping birds are most always the males, that the behaviour occurs when there are eggs in the nest, and that many swooping birds specialise in their targets. Some birds swoop only cyclists, others pedestrians, and some just one or two individual humans.

Swooping is an exaggerated form of defence of the clutch against what the magpie perceives to be a potential predator. Whereas many such issues were once addressed simply by shooting, Jones uses careful experimentation to show that the problem can be at least temporarily resolved by capturing the magpie and moving it at least 30 kilometres away: any closer and it may swiftly return.

His studies also show that other male magpies may replace the transported male and help raise his young, an altruism that may return longer-term benefits.

But this book is more than simply an account of urban birds and wildlife management problems. It is part autobiography, part mystery, part reflective celebration of the beauty, vitality and value of our wildlife.

Jones’ fascination with nature, and particularly with birds, is the current that shapes his career and his life. And the stories in this book infect the reader with this fascination. This engagement is further reinforced by wonderful, evocative illustrations by Kathleen Jennings.

Childhood Events

Some childhood events shape us, embed enduring values, open the pathways that we may follow all our lives. For Jones, the wonder in his life starts with noticing something different in his solitary youth – this particular wonder as prosaic as a single introduced blackbird in the backyard of his house in rural New South Wales, far from the Australian city centres where it was “meant” to be. (Nature is fluid; we cannot presume too much.)

The first mystery solved by Jones is its identification, a more complex challenge then – in the 1960s – when bird books were crude. Knowing the name of things proves to be a gateway to understanding. The second mystery, also triggered by early experience, is a much larger one, and it permeates this book: how does nature live with us; and how do we live with nature?

Another childhood event is traumatic. Jones describes the brutal killing by other boys of a beloved pet magpie. It reinforces his feeling for birds, and a desire to help conserve them; and it reminds us that we can’t assume that all people share such sympathies.

Jones honed his youthful interest in birds through tertiary education. He is generous in recognising the mentors who guided him on this pathway, and the characters who later helped him understand and develop practical solutions to urban wildlife issues. Over time, he returns the favour: mentoring – and admiring the expertise of – many students.

The subject of this book is a tricky one. We should all appreciate the variety of wildlife that can live within our cities, and we should help to maintain and enhance it. But of course, across much of the world, including much of Australia, biodiversity is in steep decline, and it is particularly those native species that are dependent upon unmodified natural environments that are most suffering.

Jones at least notes this broader context. We should not be so beguiled by the wildlife in our cities, and even the increases in that wildlife, into presuming that nature is resilient and can cope with the way we mess with this world.

But we should also be grateful: even in our cities and suburbs, we live in a wonderful world, full of small mysteries, surrounded by the lives of many other animals. Our lives become better, richer, less selfish if we can see and try to understand that wonder. This book helps guide us there.![]()

John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

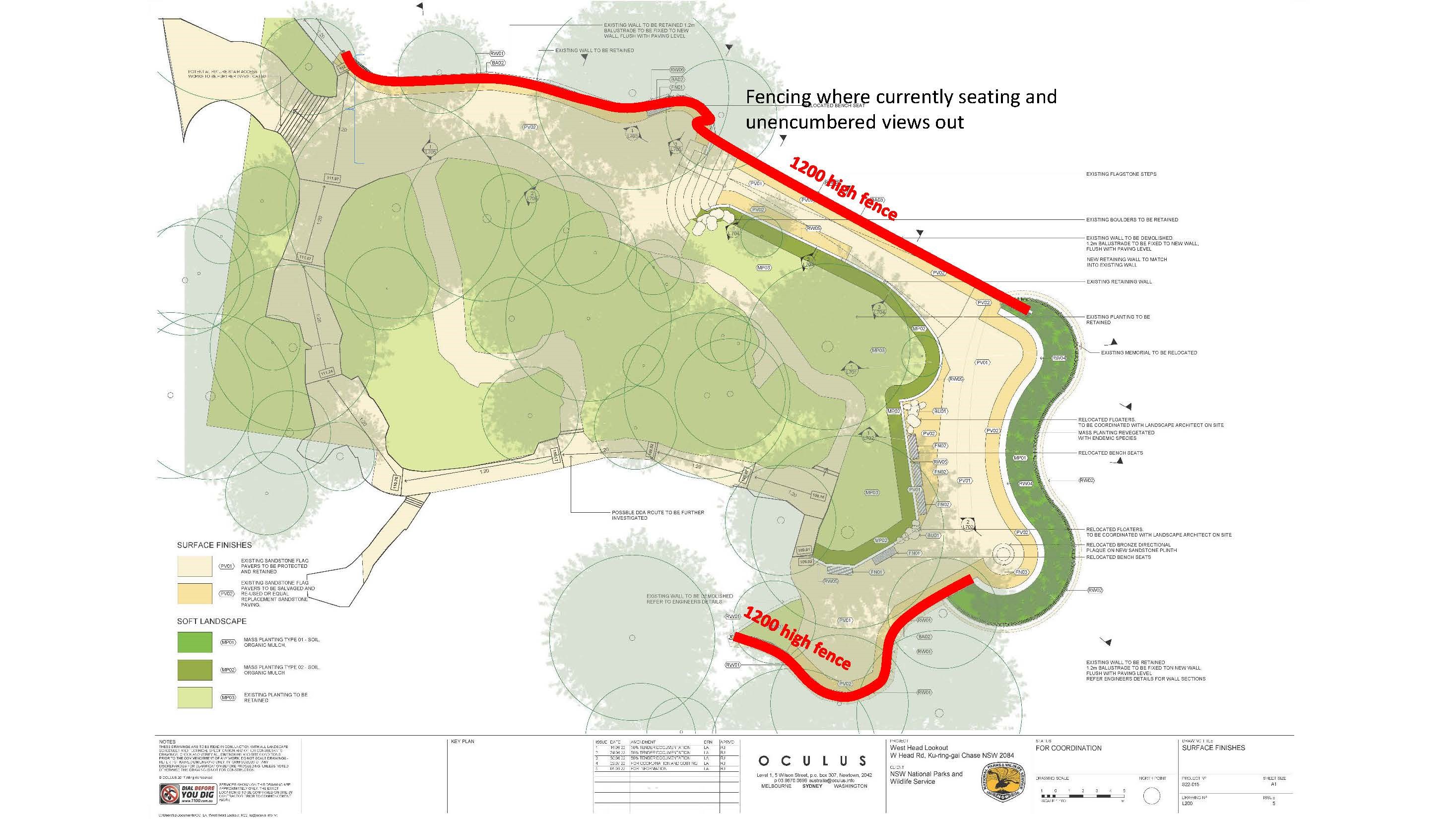

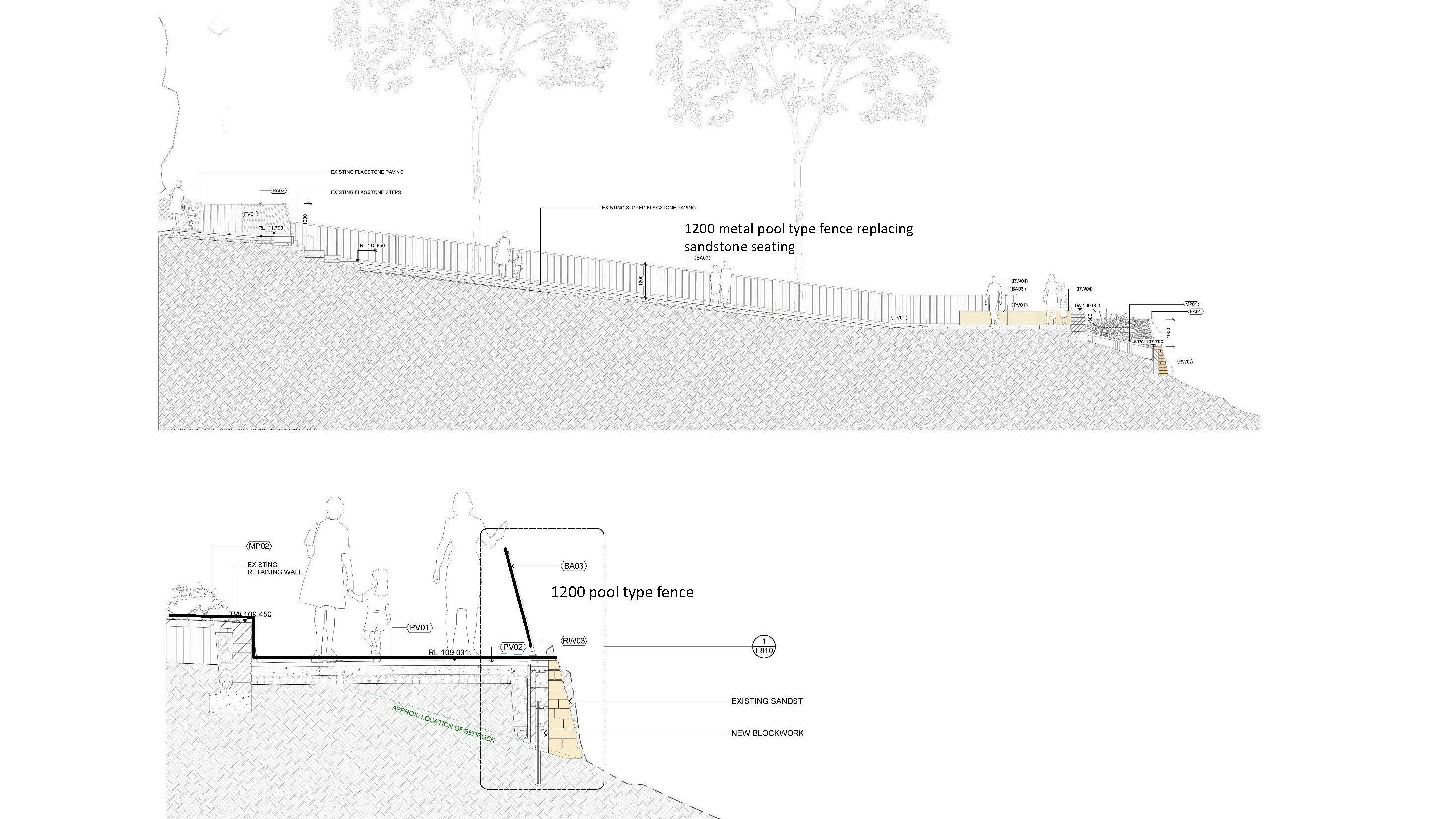

West Head Lookout Upgrade

- The area of outlook unencumbered by fencing has been substantially reduced yet the information email highlights a cross section through this area. In fact most of the site will be affected by a crude metal perimeter fence similar to a pool fence - see red highlight on plan below.

- The scheme is represented as a concept design whereas it is in fact part of a tender set presumably advanced to call tenders for construction. This is a barrier to addressing any design concerns raised.

- The site is widely recognised as an exceptional example of landscape architecture within a national park. The National Trust is similarly concerned with developments proposed for this location.

- It appears the concerns originally raised by so many in the community either have not been heard or appreciated. These relate to the lookout serving as a place where the public have been able to enjoy unimpeded views over Pittwater and North to Bouddhi. The lookout has been a quiet place of contemplation as well as a place for small numbers of people to stop for impromptu picnics. The imposition of a 1200 high crude metal fence will impact the enjoyment currently experienced. The proposal as it stands is a regressive step and detracts from the experience of visiting this exceptional site.

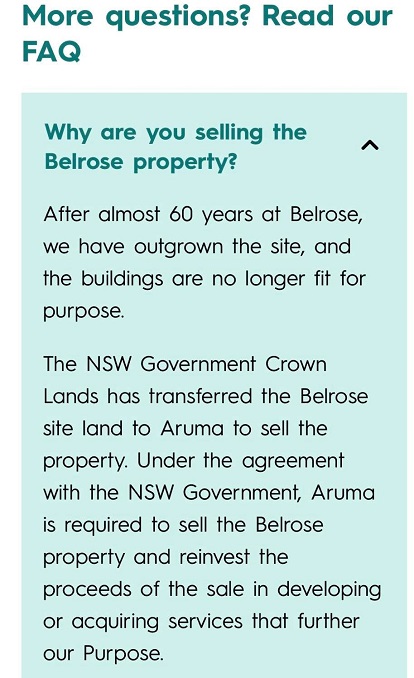

Over A Hectare Of Crown Land At Belrose To Be Sold: Transferred Public Lands

Residents have contacted Pittwater Online regarding the transfer of over one hectare of Crown Land at Blackbutts road Belrose to Aruma (formerly House With No Steps).

Residents have contacted Pittwater Online regarding the transfer of over one hectare of Crown Land at Blackbutts road Belrose to Aruma (formerly House With No Steps). Scotland Island Spring Garden Festival

Weed Alert: Corky Passionflower At Mona Vale + Narrabeen Creek

.jpg?timestamp=1663392221562)

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary Open

Ku-Ring-Gai Sculpture Trail For 2022 Eco Festival

Dust Off Your Picnic Blankets For The First Ever Statewide Picnic For Nature

EPA Releases Climate Change Policy And Action Plan

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is taking action to protect the environment and community from the impacts of climate change, today releasing its new draft Climate Change Policy and Action Plan which works with industry, experts and the community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support resilience.

NSW EPA Chief Executive Officer Tony Chappel said the EPA has proposed a set of robust actions to achieve a 50 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (from 2005 levels), ensure net zero emissions by 2050, and improve resilience to climate change impacts.

“NSW has ambitious targets that align with the world’s best scientific advice and the Paris commitments, to limit global warming to an average of 1.5 degrees in order to avoid severe impacts on ecosystems,” Mr Chappel said.

“Over the past few years we have seen first-hand just how destructive the impacts of climate change are becoming, not only for our environment, but for NSW communities too.

“We know the EPA has a critical role to play in achieving the NSW Government’s net-zero targets and responding to the increasing threat of climate change induced weather events.

“Equally, acting on climate presents major economic opportunities for NSW in new industries such as clean energy, hydrogen, green metals, circular manufacturing, natural capital and regenerative agriculture.

“This draft Policy sends a clear signal to regulated industries that we will be working with them to support and drive cost-effective decarbonisation while implementing adaptation initiatives that build resilience to climate change risks.

“Our draft plan proposes a staged approach that ensures the actions the EPA takes are deliberate, well informed and complement government and industry actions on climate change. These actions will support industry and allow reasonable time for businesses to plan for and meet any new targets or requirements.

“Climate change is an issue that we all face so it’s important that we take this journey together and all play our part in protecting our environment and communities for generations to come.”

Actions include:

- working with industry, government and experts to improve the evidence base on climate change

- supporting licensees prepare, implement and report on climate change mitigation and adaptation plans

- partnering with NSW Government agencies to address climate change during the planning and assessment process for activities the EPA regulates

- establishing cost-effective emission reduction targets for key industry sectors

- providing industry best-practice guidelines to support them to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

- phasing in the introduction of greenhouse gas emission limits on environment protection licences for key industry sectors

- developing and implementing resilience programs, best-practice adaptation guidance and harnessing citizen science and education programs

- working with EPA Aboriginal and Youth Advisory Committees to improve the EPA’s evolving climate change response

EPA Acting Chair Carolyn Walsh said the EPA is a partner in supporting and building on the NSW Government’s work to address climate change for the people of NSW.

“The draft Policy and Action Plan adopts, supports and builds on the strong foundations that have been set by the NSW Government through the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework, Net Zero Plan and Climate Change Adaptation Strategy,” Ms Walsh said.

The EPA will work with stakeholders, including licensees, councils, other government agencies, and the community to help implement the actions.

The draft EPA Climate Change Policy and Action Plan is available at https://yoursay.epa.nsw.gov.au/ and comments are open until 3 November 2022.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

‘Sad and distressing’: massive numbers of bird deaths in Australian heatwaves reveal a profound loss is looming

This article contains images that some readers may find upsetting.

Heatwaves linked to climate change have already led to mass deaths of birds and other wildlife around the world. To stem the loss of biodiversity as the climate warms, we need to better understand how birds respond.

Our new study set out to fill this knowledge gap by examining Australian birds. Alarmingly, we found birds at our study sites died at a rate three times greater during a very hot summer compared to a mild summer.

And the news gets worse. Under a pessimistic emissions scenario, just 11% of birds at the sites would survive.

The findings have profound implications for our bird life in a warming world – and underscore the urgent need to both reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and help animals find cool places to shelter.

Feeling The Heat

The study examined native birds in two parts of semi-arid New South Wales: Weddin Mountains National Park near Grenfell and Charcoal Tank Nature Reserve near West Wyalong. At both locations, citizen scientists have been catching, marking and releasing birds regularly since 1986.

This has produced data for 22,000 individual birds spanning 37 species. They include honeyeaters, thornbills, fairy-wrens, whistlers, treecreepers, finches and doves.

Data from the past 30-odd years showed cold winters led only to a relatively small drop in survival rates. But it was a far starker picture in summer.

During a mild summer with no days above 38℃, 86% of the birds survived. But in a hot summer with 30 days above 38℃, just 59% survived.

We then used these real-life findings to model future survival, to the end of the century, for birds at our study sites.

Worryingly, climate projections for the sites we studied show the number of days above 38℃ will at least double by the end of the century (or the year 2104). Meanwhile, days below 0℃ will disappear during this time.

These projections are broadly similar for all arid and semi-arid regions across Australia.

As winters warm, we predict bird survival in winter would increase slightly by the end of this century. But this would not offset the many more birds killed by extreme heat as summers warm.

But to what extent will populations decline? To answer this question, we considered an optimistic scenario of rapid emissions reduction – resulting in about 1℃ warming compared to pre-industrial levels. Under this scenario, we predict annual survival will fall by one-third, from 63% to 43%.

Under a pessimistic scenario, involving very little emissions reduction and 3.7℃ warming this century, the survival rate falls to a shocking 11%.

Other lab-based studies around the world have made similar projections for bird populations. But our projections are unusual because they’re based on actual survival rates in wild populations measured over decades.

What Happens To Birds In Heatwaves?

Some birds do manage to survive extreme heat. We then wondered: how does a bird protect itself from soaring temperatures? And can its habitat offer life-saving shelter?

We addressed these questions in a complementary study led by zoologist Lynda Sharpe. It involved comparing the behaviour of individual birds on mild and hot days.

We chose as our subject the Jacky Winter, a small robin common across Australia. Between 2018 and 2021 we followed the fates of 40 breeding pairs living in semi-arid mallee woodland in South Australia. There, the annual number of days above 42℃ has more than doubled over the past 25 years.

As heat escalated, Jacky Winters showed a broad range of behavioural responses. This included adjusting their posture, activity levels and habitat use to avoid gaining heat and to increase heat dissipation.

As air temperatures approached 35℃, birds moved to the top of the highest trees where greater wind speeds cooled their bodies. The birds also began to pant, which can lead to fatal dehydration.

Once air temperatures climbed above 40℃, exceeding the birds’ body temperature, they moved to the ground to shelter in tree-base hollows and crevices. They remained in these “thermal refuges” for as long as it took for air temperatures to drop to about 38℃ – sometimes for up to eight hours. But this made foraging impossible and the birds lost body mass.

We then examined what parts of the birds’ habitat offered the coolest place to shelter on extremely hot days. Hollows in tree bases were significantly cooler than all other locations we measured. The best of these cool hollows were rare and found only in the largest eucalypt mallees.

Even with their flexible behaviour, the ability of Jacky Winters to survive heatwaves was finite – and apparently dependent on whether large trees were available. Some 29% percent of adults we studied disappeared (and were presumed dead) within 24 hours of air temperatures reaching a record-breaking 49℃ in 2019.

Similarly, during two months of heatwaves in 2018, 20% of adults studied were lost, compared with only 6% in the two months prior.

Eggs and nestlings were even more susceptible to heat. All 41 egg clutches and 21 broods exposed to air temperatures above 42℃ died.

We found it distressing to witness such losses among birds we had followed for months and years. And it was deeply sad to see the breeding failures after the parent birds had invested so much effort in caring for eggs and tending to young.

We Need To Act

Our studies show extremely high temperatures are already killing troubling numbers of birds in Australia’s arid and semi-arid regions. These regions comprise 70% of the Australian continent and 40% of the global landmass.

Such losses will only worsen as climate change escalates. This has profound implications for biodiversity in Australia and more broadly.

Obviously, humanity must urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming. But we must also better manage our biodiversity as the climate changes.

Key to this is identifying and protecting thermal refuges such as tree hollows by, for example, managing fire to reduce the loss of large trees.

The authors wish to acknowledge our colleagues, especially Lynda Sharpe and Tim Bonnet, for their important contributions to the research upon which this article is based.![]()

Janet Gardner, Adjunct Research Scientist, CSIRO and Suzanne Prober, Senior Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

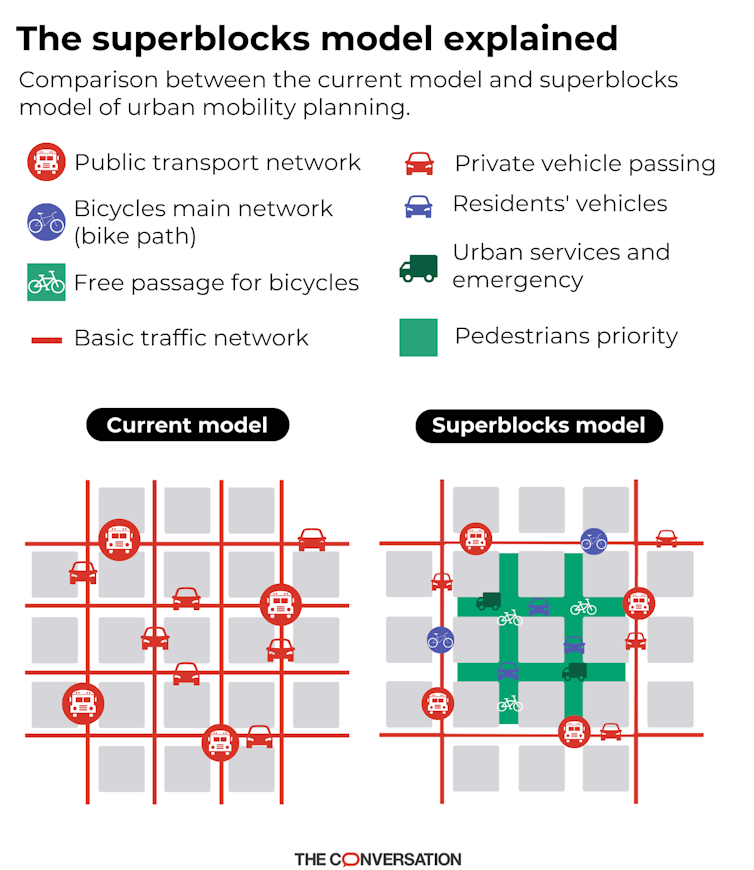

Cars have taken over our neighbourhoods. Kid-friendly superblocks are a way for residents to reclaim their streets

You might remember your time as a child playing outdoors with friends and walking to school. These activities had tremendous benefits for our health and development.

Today, parents report barriers to letting their kids play, walk and ride in their neighbourhood. The safety of local streets is a major concern.

One way to boost communities is to create “superblocks for kids”. Pioneered in cities like Barcelona, a superblock covers several neighbourhood blocks reserved for shared use by cyclists, walkers and residents who simply want to use the street space. Superblocks allow low-speed access for residents’ cars, but exclude through-traffic.

Superblocks have evolved from concepts dating back to the 1970s. Retrofitted and planned examples of more liveable and safer streets can be found from Melbourne to Perth, where there are interesting alternative designs in Willetton and Crestwood.

Transforming neighbourhoods in this way enables us to once again enjoy the public space right on our doorsteps – the street.

Superblocks For Kids Are A Low-Cost Fix

Superblocks are a low-cost solution to the problem of the residential “stroad” – a street-road hybrid that drivers use to avoid congested main roads, many at unsafe speeds.

These stroads are a troubled mix of two different functions: roads are through routes, and streets connect neighbourhoods socially and physically. Streets connect houses to local parks, shops and through routes, but are also public places themselves. The dual role of stroads comes at the expense of residents and their children.

Superblocks for kids can be retrofitted to existing suburbs to create safer, quieter and more play-friendly streets. They are typically about a square kilometre in area, bounded by main roads and features such as rivers. Ideally, superblocks are clustered together to provide safe access to local amenities and public transport hubs.

Everyone can still drive to their home in a superblock, but they might have to take a slightly longer, more circular route. This can reduce traffic by nudging residents to walk and cycle short journeys within their superblock.

Various low-cost “filters” exclude through traffic. These filters include:

pocket parks – small areas of community green space

modal filters – bollards, gates or planters exclude cars but allow access for walkers and cyclists

diagonal filters – used at four-way intersections

end-of-street filters – open cul-de-sacs to walkers and cyclists

bus gates – automatic numberplate recognition or rising bollards allow bus access

The resulting superblocks are places where kids play on the streets, which are quiet and easy to cross. There’s shade and shelter, places to stop and rest, things to see and do, and the air is clean. People feel safe and relaxed. Neighbourhoods like this promote public health and community camaraderie.

Four examples of streets that could be transformed in this way are shown below:

Lyall Street, Redcliffe, Perth

A pocket park breaks up a rat run to the airport.

The Avenue, Mount St Thomas, Wollongong

Plantings and bollards eliminate a known rat run.

Lithgow Street, Abbotsford, Melbourne

Wider kerbs make school drop-offs and pick-ups safer.

Meymot Street, Banyo, Brisbane

A pocket park and residents-only car access create a safer and quieter street.

Rat-Running Is A Big Problem

Almost twice as many cars are on Australian roads today as 20 years ago. Coupled with the rise of satellite navigation technology, this has led to more drivers using residential streets as rat runs to avoid congested main roads.

Decades of prioritising cars in Australian communities have created a serious safety issue. Overall, serious road injuries are on the rise. Despite small declines in road deaths, deaths on local streets haven’t fallen.

People feel less safe on their local streets, but we know what we can do to improve safety. Preventing rat-running leads to cleaner air, less noise, safer streets and more walking, riding, wheelchairs and mobility scooters. These results all promote stronger communities.

Everyone Benefits From Kid-Friendly Neighbourhoods

A remarkable feature of building neighbourhoods for kids is how quickly residents reoccupy their streets. People emerge from their houses to talk, their voices no longer drowned by vehicle noise. Thoroughfares become communities. Children come out to play.

As physical activity researchers, we know that getting children to move more is an urgent issue. Australian kids score a D- for overall physical activity levels on international ratings. Australian adults also have low levels of physical activity.

Neighbourhoods for kids help everyone enjoy the benefits of becoming more active. For kids, the street can connect them to nature and help them develop movement and independent travel skills for life.

Increasing neighbourhood liveability also boosts house prices and reduces noise pollution.

Leaving The Car At Home For Short Local Trips

Superblocks make it easier for families to choose the “right tool for the job” for small local trips — a bicycle over a car. This saves money and improves health.

All these small trips add up. For example, two-thirds (2.8 million) of daily car trips in Perth are under 5km — a 20-minute bike ride or less. In Melbourne, 41% of trips are under 3km, but 58% of these are by car. That’s 3.6 million car trips a day.

Where Should Australia Start?

Our research highlights the need to listen to communities, and kids in particular, when designing neighbourhoods.

In the vast majority of cases, any initial opposition to creating kid-friendly neighbourhoods soon dissipates. Residents see the benefits of safer and more pleasant streets for themselves and their families.

Two-thirds of Australians support improving their neighbourhood to help them be more active. We should start by creating neighbourhoods for the communities that need it most — those with the poorest access to green space and public transport, most through traffic and crashes, and highest levels of childhood obesity.

Get your community talking again! You can start by hosting a temporary play street! Demonstrating its success will help when asking your council for permanent changes.

The authors encourage the reuse of the re-imagined streets. They are freely available to download in multiple open-access formats.![]()

Matthew Mclaughlin, Research Fellow, Telethon Kids Institute, The University of Western Australia; Hayley Christian, Associate Professor, School of Population and Global Health, The University of Western Australia; Jasper Schipperijn, Professor of Active Living Environment, University of Southern Denmark, and Trevor Shilton, Adjunct Professor, School of Public Health, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW Government Offers Multi-Million Dollar Support For Critical Minerals Projects

Impact Of New Energy Efficient Streetlights On Insects Revealed

Songbirds with unique colours are more likely to be traded as pets – new research

People like beautiful things. This comes as no surprise: beauty underpins highly profitable businesses, from cosmetics and art to the illegal wildlife trade, which reaps up to US$23 billion (£20 billion) annually according to some estimates.

Tigers and pandas show that aesthetic value can be an asset to wildlife conservation, attracting public support and funding. On the flip side, anything that you might want to preserve in the wild so you can look at it, somebody else will probably want to own for the same reason.

The unsustainable trade in plants and animals can rapidly deplete wild populations and put species at risk of going extinct in certain areas, or even globally.

Songbirds (birds in the order Passeriformes) are an interesting case study. This group contains the greatest number of bird species, many of which are traded and many of which are threatened with extinction.

Canaries, for example, were originally sought as pets for the beautiful music they sing. But we need only look at their striking yellow feathers to see that colour – and beauty – also play a role in the popularity of songbirds.

Recent research I conducted with colleagues at the University of Florida in the US, the Centre for the Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity in France and Massey University in New Zealand, showed the colour of a songbird’s plumage predicts the likelihood of it being traded as a pet and its risk of extinction.

Colour By Numbers

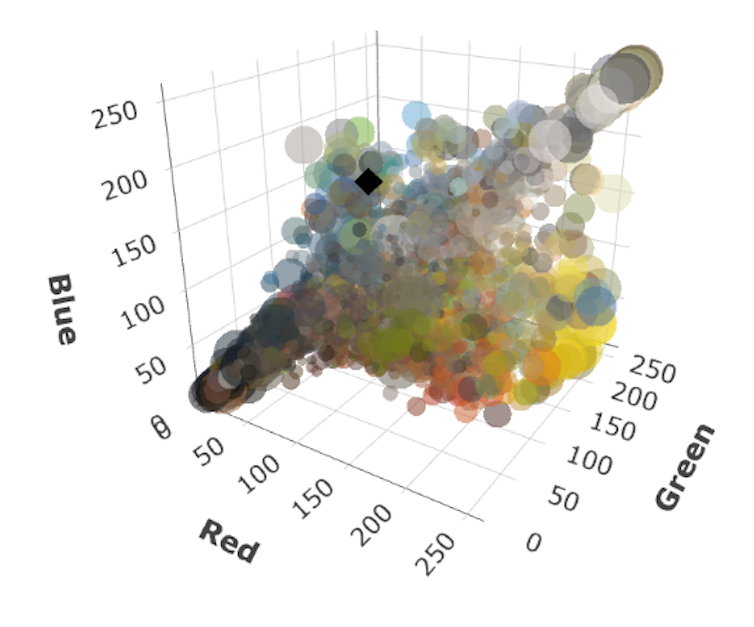

How do you quantify colour? We started off using data on the red, green and blue values of the colours that make up each species’ plumage. This is a standard way to quantify colour, which readers might be familiar with from television screens, for example.

Each primary colour of red, green and blue takes a value ranging from the minimum of zero to the maximum of 255. And these so-called RGB values together denote a specific colour. For example, a bird with 255 red, 204 green, and 255 blue would appear pale pink.

Unfortunately, you cannot easily identify and classify colours using these RGB values, so we converted them into colour categories using some simple maths. We used 15 categories, including the primary colours (red, green, blue), secondary colours (yellow, cyan, magenta), tertiary colours (orange, chartreuse green, spring green, azure, violet, rose), and the additional categories of brown, light (including white) and dark (including black).

Using a 3D graph with one axis for red, one for green and one for blue, we plotted every species according to the colour of its plumage. This allows you to see how rare the colours of different species are, based on how far away their colour is from others in the 3D space.

For the entire community of birds occurring in a given location, you can also look at how many colours are represented by those species based on how much of the 3D space they occupy. This we refer to as colour diversity.

Species At Risk

Our results showed certain colour categories, such as azure and yellow, are more likely to be found on species that are traded than those that are not.

We believe that yellow is a common colour in the illegal wildlife trade partly because there are simply lots of species that are yellow. Azure, in contrast, is a colour found on far fewer species, but when it does occur it seems that it is highly likely to be on species that are heavily traded.

Other colours, such as brown, are less likely to be found on traded species compared with those that aren’t traded. Species with more unique colouration, such as pure white, have a generally higher probability of being traded.

What does this all mean for biodiversity? We identified nearly 500 additional species that are not currently traded but are at risk of being traded in future based on their colour and how closely related they are to currently traded species.

Since the tropics contain the greatest diversity of colours, in terms of both the range of colours exhibited by songbirds and the number of colourful species, this is where most colours would be lost if all currently traded species went extinct. The loss of these species would mute nature’s colour palette, leading to generally drabber bird communities with less colour variety globally.

This is just the first step in understanding the aesthetic value that underlies the trade in songbirds. A better understanding of what motivates this trade can help identify species that could benefit from monitoring and trade regulation.

Equally, identifying, celebrating and conserving hotspots of colour diversity has the best chance of conserving the aesthetic value of colour, as well as the overall biodiversity boasted by the tropics.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Rebecca Senior, Assistant Professor of Conservation Science, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Backcountry visitors are leaving poo piles in the Australian Alps – and it’s a problem

Pascal Scherrer, Southern Cross University; Isabelle Wolf, University of Wollongong, and Jen Smart, University of WollongongSpring has arrived in Australia’s Snowy Mountains. The snow is starting to melt. Wildflowers are emerging in a variety of colours: blues, yellows, whites … hang on. Those aren’t white flowers. They’re scrunched up bits of toilet paper left behind by skiers, boarders and snow-shoers.

When you think of backcountry snow adventures, you think of pristine wilderness. But unfortunately, there’s a problem: what to do with your poo. Many backcountry adventurers just squat, drop and don’t stop. The result, as we saw ourselves on an overnight ski trip, is a surprisingly large amount of poo and toilet paper. It’s become a bigger problem in recent years, as backcountry trips have boomed in places like the Main Range section of the Snowy Mountains.

Our new research explores this issue to find out how to better protect these wild areas. We surveyed backcountry visitors to Kosciuszko National Park in New South Wales and found a minority of visitors were carrying out their waste from overnight trips, as recommended. To combat the alpine poo scourge, we recommend building more toilets in strategic locations, making their location readily known, and giving out poo transport bags at entry points and gear shops.

If you’re sceptical, take heart – it wasn’t so long ago many people believed dog owners would never agree to scoop up their pet’s poo and bin it. But for the most part, they did.

So What Are You Meant To Do With Snow Poo?

You might wonder why this matters. After all, aren’t our snow-covered mountains full of possums, wombats and wallabies, all of which poo? And can’t you bury your poo, like you can in other parts of Australia? The problem here is the snow. Human poo deposited in winter won’t decompose until spring. In popular areas, poo and toilet paper can pile up, which is an unpleasant visual for other visitors. And as the snow melts, it can carry poo into creeks, depositing cold-resistant viruses, bacteria like E. coli, and parasites such as giardia. If another skier eats contaminated snow or drinks the stream water, they can be infected.

That’s why backcountry visitors to Kosciuszko National Park are urged to carry out their poo in biodegradable bags or a home made poo tube (basically a sealable plastic pipe).

This, our survey of 258 visitors found, is not hugely popular. Only a third of highly experienced skiers on multi-day trips carry their poo out, while only a fifth of less experienced visitors did the same.

The options our multi-day skiers preferred were using a toilet at a hut, if available, or burying poo in the snow. This is not ideal – if you can’t carry it out, it’s preferable to bury it in exposed soil (ideally, at least 50 metres away from any water courses). Some visitors reported covering their waste with rocks.

Day visitors largely used toilets at the entry and exit points or at a resort, though around 10% reported burying their poo in the snow or using toilets at huts.

This means overall compliance with the carry-it-out policy is low.

But as one longtime backcountry visitor points out, it’s not actually hard – or disgusting – to carry it out:

It was easy. It was the most satisfying experience I have had, knowing that I had left no trace for the entire journey; the view, the ground, the creeks, the plants had been left unspoilt. No-one would have ever known I had been there. Carrying and taking it out went without mishap and finally disposing of my waste was not a problem.

What Can Be Done?

People prefer toilets as a tried and true method of removing poo. Installing new toilets is the most effective way to prevent open defecation. The problem is where to put them. Installing toilets in remote areas is a delicate matter, as many visitors may see them as taking away from the natural experience which is the major drawcard for backcountry visitors. It’s also expensive to maintain toilets in the snow, as they require helicopters or trucks to pump out the waste.

Other options include digging pit latrines, disposing of it into crevasses, burying in soil, snow or rocks, leaving it on the ground, burning it, or carrying it out in poo tubes or biodegradable bags. You can see why park authorities prefer carrying it out.

So how can we make it more inviting for visitors to pack their poo? Clearly, the present messaging isn’t fully effective. It’s time for a new approach, especially given the numbers of people heading to the backcountry is growing.

We recommend a two-pronged approach: better communication and targeted infrastructure at entry points.

Friends, websites and outdoor recreation clubs are important sources of information about how to undertake a backcountry trip. To harness these sources, parks authorities could work with the wider backcountry community on the issue, with simple, targeted messages.

By itself, messaging won’t be enough. That’s why we need more and improved toilets – and bins – at key locations, to make it as easy as possible for visitors to do the right thing with their poo.

Authorities should also make these locations clearly known on visitor maps and online, as well as making biodegradable bags or poo tubes available at entry points, information centres and gear shops.

If we get this right, backcountry skiers will once again be able to enjoy the wildflowers. Let’s aim for spring has sprung – not spring has dung. ![]()

Pascal Scherrer, Senior Lecturer, School of Business and Tourism, Southern Cross University; Isabelle Wolf, Vice Chancellor Senior Research Fellow, University of Wollongong, and Jen Smart, PhD student, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

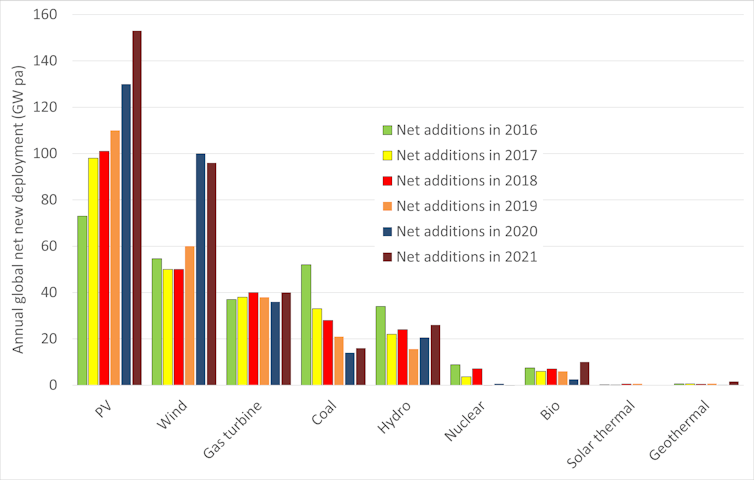

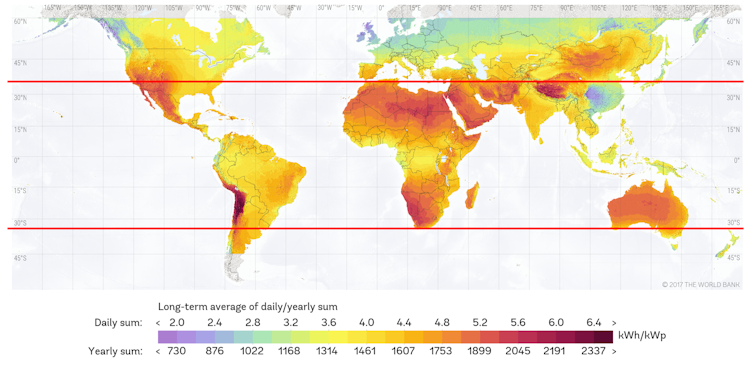

There’s a huge surge in solar production under way – and Australia could show the world how to use it

You might feel despondent after reading news reports about countries doubling down on fossil fuels to cope with energy price spikes.

Don’t. It’s a blip. While the Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to a temporary fossil fuel resurgence, it also accelerated Europe’s renewable ambitions. And the United States and Australia have finally passed climate bills. This week, federal energy minister Chris Bowen announced “Australia is back” on climate action.

There’s better news too. In March this year, the world hit one terawatt of installed solar. By 2025, the world’s polysilicon factories are predicted to bounce back from supply shortages and churn out enough high-purity silicon for almost one terawatt of solar panels every year.

Coupled with major growth in wind, pumped hydro, energy storage, grid batteries and electric vehicles, the solar boom puts zero global emissions within reach before 2050.

Best of all – Australia could show the world how to add solar to their grid. You might not suspect it, but we’re the global leaders in finding straightforward solutions to the variability of solar power and wind. We’re showing that it’s easier to get carbon emissions out of electricity generation than many predicted.

Rapid, Deep And Cheap Emissions Reductions

This surge in the renewable supply chain allows sustained exponential growth that is already disrupting fossil fuel markets in some countries, notably Australia.

This year, global fossil fuel prices have skyrocketed in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In turn, that’s generated intense interest in solar and wind energy to boost domestic energy security, particularly in Europe, which needs to wean itself off Russian gas.

While fossil fuels are concentrated in countries such as Russia, Saudi Arabia and Australia, solar and wind resources are widely distributed. Most countries can generate all their own energy from the sun and wind.

Europe could readily become energy independent, harnessing its enormous North Sea offshore wind resources and solar in the south. Even densely populated countries such as Japan and Indonesia have far more solar and wind resources than they need.

Solar and wind now provide the cheapest new electricity generation in most markets. As a bonus, the widespread uptake of solar and wind will eliminate many of our worst air pollutants and improve our health.

Why Are Solar And Wind Winning?

In a word, cost. Solar and wind have won the race for the energy of the future because they are cheap. Once built, the fuel is free, and does not need to be imported or dug up.

Wind and solar are being built three times faster than everything else combined. It follows they will dominate future energy markets as existing fossil fuel generators retire and electricity use grows rapidly.

Nuclear generation hasn’t grown in the past decade. Coal and gas plants able to capture and store carbon have not got traction in the energy market. Hydroelectricity can’t expand much further. There will, however, be a huge market for off-river pumped hydro energy storage.

There are no serious technical, environmental or material constraints to solar power on any scale. However, solar has been hit by supply chain issues in recent months, with major price spikes in polysilicon. These are common to any rapidly growing industry, and should resolve as more suppliers see the opportunity and enter the market.

There Is Enough Land

Most of the world’s population live at moderate latitudes with good sunshine on most days. Here, solar is effectively unlimited. Those further north have abundant wind energy (particularly offshore wind) to offset weaker solar in winter.

Sceptics point out you need more land or sea to produce the same amount of electricity as fossil fuel plants. While true, solar farms can happily coexist with livestock and cropping to create a double income for farmers. The solar electricity needed to power the world and eliminate all fossil fuels can be generated from about 1% of the land area devoted to agriculture.

Once we have cheap clean electricity, we can use it to eliminate the use of fossil fuels altogether by electrifying nearly everything: transport, heating, industry and chemical production. This could reduce emissions by three quarters.

Global electricity production will need to rise sevenfold to about 200,000 terawatt-hours a year to give everyone the energy needed to reach developed nation living standards. But this is not all that hard over the next 30 years. And the alternative – keep pumping warming pollutants into the atmosphere – will make the lives of our children harder and harder.

Together, solar and wind have passed two terawatts of installed capacity. That means we’re about 2% of the way to reaching the almost 100 terawatts of solar and wind required to decarbonise the world, while raising living standards.

Annual solar deployment needs to double every four years to get the job done by 2050–60 – similar to the global growth rate achieved over the past decade.

Australia Can Show The Way

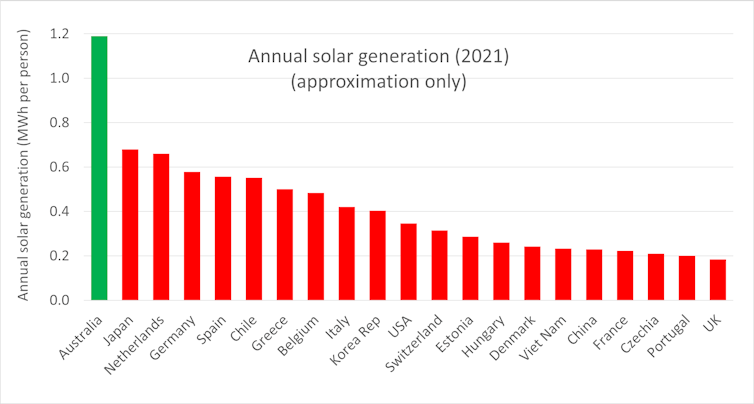

You might not think it, given the decade of political climate wars, but Australia is the world leader in terms of solar electricity produced per person.

In Australia, solar and wind are booming while coal is rapidly falling. We’re already on track to reach 80-90% renewables by 2030. Remarkably, our per capita solar generation is twice as large as the second placed countries (Germany, Japan and the Netherlands) and far ahead of China and the USA.

Australia is quietly demonstrating how to accommodate huge new flows of cheap, clean electricity. The world will soon follow suit. ![]()

Andrew Blakers, Professor of Engineering, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

After the Voice, climate change commitments should be the next urgent constitutional reforms

Ron Levy, Australian National UniversityAfter decades of foot-dragging on climate change, Australia has finally put significant commitments in national legislation. It joins other countries such as Canada and the United States that also recently took big new legal steps.

The new laws may still not be enough, but they mark real progress. Yet, will such progress last or be short-lived?

As we saw with Australia’s carbon price law, which passed in 2011, a change of government can lead to a change in direction. And that direction may be broadly backwards.

For this reason I have, in recent research, called for a new kind of commitment to climate change mitigation: a set of clear numeric targets entrenched in our highest laws, namely our constitutions. Constitutions spell out our most sacrosanct commitments. They are hard to budge once enacted.

At the moment, the focus of constitutional change in Australia is on the recognition of Indigenous people in the First Nations Voice to Parliament – as it should be.

But we must also look over the horizon to the next challenges. After the Voice, climate change commitments should be the next urgent constitutional reform. The republic can wait; climate change cannot.

What Would It Look Like?

An ongoing emergency like climate change calls for an unwavering set of policy solutions well into the future. But a long-term policy – such as a target year for net-zero emissions – may struggle in a democratic system that can promise only occasional and precarious environmental protection.

Entrenching such policies in our national, state or territorial constitutions may help firm up our commitments to resolute action. But that depends on what constitutional climate action looks like.

Ideally it should specify a carbon emissions reduction target – as a minimum or “floor” – and a process for ratcheting up the target over time (similar to the international Paris Agreement). There should also be new enforcement bodies to review the carbon budgets of Australian governments.

On the one hand, if we took these constitutional steps we would be in good company. A majority of national constitutions already protect the environment. On the other, what I suggest here goes beyond most past examples. Most have been decidedly vague.

South Africa’s Bill of Rights, for instance, guarantees everyone the “right (a) to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being; and (b) to have the environment protected”.

Elsewhere, we see rights to a “healthy” environment, or obligations to “protect and improve” the environment.

Unfortunately, these constitutional laws reflect only broad aspirations. They don’t always lead to meaningful environmental protection. This is largely because short-term, myopic economic concerns often act as counterweights blocking effective environmental action. South Africa itself provides one example where courts balance environmental ideals in the constitution against economic factors.

What I call “fixed constitutional commitments” are precise constitutional guarantees, like carbon reduction targets. Since they fix a specific quantity of commitment, they can be resistant to the judicial balancing that usually neuters environmental constitutional clauses.

Precedents Abroad, And Even In Australia

While this idea is largely novel, it has some precedents. Bhutan, Kenya and New York State each specify a minimum amount of forest coverage. On this, New York was the trailblazer: the state’s constitutional protections for forests date back to 1894.

Just last year in Australia, Victoria constitutionally entrenched a ban on fracking. To do this Victoria used a simple legislative process for constitutional entrenchment available to each state under the Australia Act 1986.

This makes Victoria one of a handful of jurisdictions that have also set precise environmental targets in constitutional law. In this case, a commitment to zero fracking.

After the Victorian constitutional reform, one opposition member raised an important objection: that putting environmental policy in the constitution takes it out of the democratic sphere.

This is true to an extent. But there are important responses.

First, fixed constitutional commitments may correct failures of democracy. Elected representatives often represent the preferences of citizens on the environment weakly, at best.

And despite overwhelming popular support for a strong response to the climate emergency, many politicians worldwide oppose such responses – and not because they know better. Many believe their real constituents to be the businesses and other interests that underwrite electoral campaigns.

Moreover, the “climate wars” have long held Australia in legal limbo. We can’t take significant action on the climate as long as politicians can’t agree for long about what actions to take.

Before a community can begin to hash out new policy, it has to settle its basic policy priorities – such as net-zero carbon emissions by a given year. A democracy that’s stuck at the priority-setting stage can’t go on to work out the details of policy. And deliberation about policy details is where most of our democratic activity generally lies.

Fixing Democratic Failures On The Environment

There has been much talk in recent years about whether the world’s remaining democracies are too prone to division, and too weak to take action against long-term problems.

Can democratic systems still adequately address challenges – such as climate change – almost tailor-made for disinformation, political polarisation and gridlock? Or do we need new tools to avoid the policymaking quagmires that have so often kept democracies from tackling complex problems?

The best solutions will invent new ways of getting things done while preserving, and even improving, democracy. Fixed constitutional commitments on climate change may demonstrate a democratic society can indeed remain responsive to our most complex and urgent problems. ![]()

Ron Levy, Associate professor, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Seagull Pair At Turimetta Beach: Spring Is In The Air!

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

Stony Range Regional Botanical Garden: Some History On How A Reserve Became An Australian Plant Park

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Topham Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP, August 2022 by Joe Mills and Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Spring School Holidays 2022

We hope all of you who have been part of Year 12 Graduation ceremonies and Formals this week have had a great time

We also hop you all have a wonderful school holidays break. We will run another Issue next Sunday, October 2nd, and then have No Issue on Sunday October 9th so we can spend some time with our own youngsters in the week leading up to that Sunday. We've loaded up your page with some fun stuff this week and will do so again next week; some of your regular sections will stay as is until the break. We will get back to more serious subjects after the Spring School Holidays. Have a great break!

Year 12 Performance Showcase 2022

School Leavers Support

- Download or explore the SLIK here to help guide Your Career.

- School Leavers Information Kit (PDF 5.2MB).

- School Leavers Information Kit (DOCX 0.9MB).

- The SLIK has also been translated into additional languages.

- Download our information booklets if you are rural, regional and remote, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or living with disability.

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (DOCX 1.1MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (PDF 2MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Download the Parents and Guardian’s Guide for School Leavers, which summarises the resources and information available to help you explore all the education, training, and work options available to your young person.

School Leavers Information Service

- navigate the School Leavers Information Kit (SLIK),

- access and use the Your Career website and tools; and

- find relevant support services if needed.

National Bird Week + Aussie Bird Count 2022

HSC Online Help Guides

Stay Healthy - Stay Active: HSC 2022

Preparing for exam season: 10 practical insights from psychology to help teens get through

Exam season is fast approaching for many senior students in New Zealand and Australia. At the best of times, adolescents may struggle with ambition and drive, let alone after two-and-a-half years of COVID-induced disruption and uncertainty.

But parents can still nurture their teens’ motivation to do what they need to do.

Behind the scenes, the adolescent period is one of huge developmental change, and not only physically. Teens are developing their sense of identity and refining their own values. Their autonomy and individuation is emerging while they still remain somewhat dependent on the family system.

Parents may expect their young people to be intrinsically motivated when it comes to exams. The importance of studying is obvious to many adults. But even the most diligent among us can easily identify behaviours we know we should be doing, but aren’t.

Clearly, knowing that something is important may not be enough to generate the desired behaviour.

Understanding Human Behaviour

According to clinical psychologist Susan Michie and her colleagues at University College London, three factors interact to produce any human behaviour, whether it’s studying or surfing: capability, opportunity and motivation.

Michie’s team developed the “COM-B” model, which forms the basis for behavioural interventions relating to everything from hand washing to our own efforts to support clinicians to use evidence-based treatments.

Capability (both physical and psychological), opportunity (physical and social) and motivation come together to influence behaviour in an interactive way.

For example, if a young person is very capable (or believes themselves to be very capable) at solving maths equations, those around them are supportive or encouraging (social opportunity), and they have the practical resources they need (physical opportunity), they’re likely to want to do maths homework (be motivated).

Conversely, imagine a young person who starts the school term really motivated to study for two hours online every night, but only has access to the laptop at school (limited physical opportunity), still has fatigue after an illness (limited physical capability), and is surrounded by friends who have other priorities (low social opportunity). Herculean motivation may be required in this situation.

How Parents Can Support Their Teen To Study

Put simply, parents should “zoom out”. Motivation can’t be produced magically out of thin air, and attempts to force it can have the opposite effect. But parents can support and encourage their young person’s capability and opportunity to study.

1. Motivation fluctuates

Motivation is not something that is simply present or absent. It fluctuates from hour to hour, day to day. So rather than “how can I make him be motivated today?”, a more useful question is “how can I create an environment where he’ll be a bit more motivated than he was last night?”

2. Good foundations

Remember the basics, for teens and parents alike – sleep, exercise and balanced nutrition. If these are in place, it’ll help both physical and psychological capability.

3. Balanced thinking promotes capability

A sense of mastery or capability is important. Stressed teens can fall into black and white thinking traps. “I’m useless at maths” fuels feeling overwhelmed and a sense of futility.

Instinctively, it’s tempting to reply with “no you’re not, you’re amazing!” But that’ll likely bounce right off. Instead, try to encourage your teen’s balanced thinking. “Stats is hard, but I’m okay at algebra and geometry”.

4. Focusing on what teens can control

Praise effort over achievement. Persisting with an hour a day of English revision for six weeks deserves as much acknowledgement as winning the English prize (and unlike the prize, it is within your teen’s control).

5. Reinforcing their worth, no matter what

Likewise, be sure to separate your teen’s attributes (who they are) from their behaviour (what they do). They’re not a “lazy” person, but there are particular behaviours they may need to do more (or do less).

6. Behaviour as communication

If young people are irritable or snappy, try to hold in mind that this anger or irritation is likely to be secondary to other emotions, like anxiety, hopelessness or overwhelm. It’s probably not about you.

7. Worry might have a purpose

Lots of anxiety may be incapacitating, but some anxiety in this season makes sense, and a little bit can actually enhance preparation and performance. Paradoxically, perfectionism isn’t always useful.

8. Validate what you can

Try to validate the emotion, even if the behaviour can’t be justified. Perhaps reflect that it makes perfect sense that things feel overwhelming, many people would feel that way in that situation, and then pause.

It’s tempting to rush to solve the problem, or rapidly fire questions. But often young people just need to be given permission to feel the feeling, and they can sometimes figure out the solution themselves.

9. Collaborating to solve problems

Similarly, try to avoid doing “to” (or “for”), instead aiming to do “with”. Collaborating to solve problems (if they want input) may develop or enhance future independent problem-solving abilities. It also communicates your belief in their capability to do so.

10. Acknowledge to create habits

Parents might consider using targeted, short-term incentives (we don’t see these as bribes, but recognition of hard work or effort) to create new habits or reinforce emerging behaviours.

Finally, try to hold a longer-term view. One exam, one assessment, won’t make or break things. Families and cultures may hold a range of values around what a successful life looks like, but it usually involves more than just exam success.

Good health, connection with others, and meaning or purpose are fundamental to success in life. Try to keep this in mind over the next few months, even if the going gets tough.![]()

Melanie Woodfield, Clinical Psychologist, Te Whatu Ora | HRC Clinical Research Training Fellow, University of Auckland, University of Auckland and Jin Russell, Community and Developmental Paediatrician, University of Auckland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

2023 Year 12 School Scholarship Program Now Open: DYRSL

Securing A Brighter Future For Disadvantaged Youth

The Unique Power Of Australian Seaweed

By BBC newsreel

Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Marine Electrician - New Subject After School Holidays

- Troubleshoot wiring and other electrical systems on marine equipment and make repairs

- Test low and high-voltage circuit systems for safety

- Work on power generators or other alternative sources of energy, like solar or wind power

- Wire and test the alarm and communication systems

- Monitor for potential electrical voltage threats

- Design and update bonding systems to protect the ship against weather elements

- Protect the boat's equipment using drip loops and heat shrinks

- Interpret and write technical reports and estimate repair costs

- Install wiring and electrical equipment when building new ships

- Install and configure generators