Inbox and environment news: Issue 558

October 16 - 22, 2022: Issue 558

Impacting Pittwater - Have Your Say:

Conservation Zones Review Has Potential To Facilitate Medium Density In Previously 'Environmental Living' Zones: Community Groups Forum for Residents on October 16, 4pm, Mona Vale Memorial Hall

Proposal For Barrenjoey Lighthouse Cottages To Be Used For Tourist Accommodation Open For Feedback - Again - feedback closes November 22nd

Scotland Island Spring Garden Festival

- Midday - Craig Burton - renowned landscape architect - Scotland Island - What was here what mistakes have been made and making the best of we've got moving forward.

- Weed Warrior Game! Fun Game for kids finding weeds in the Park! lots of prizes.

- Cafe Open till 2pm, Barista Coffee with Artisan Cakes and Pastries | Sausage Sizzle.

- Open Gardens

- Special Harpist Performance on the lawn of Yamba.

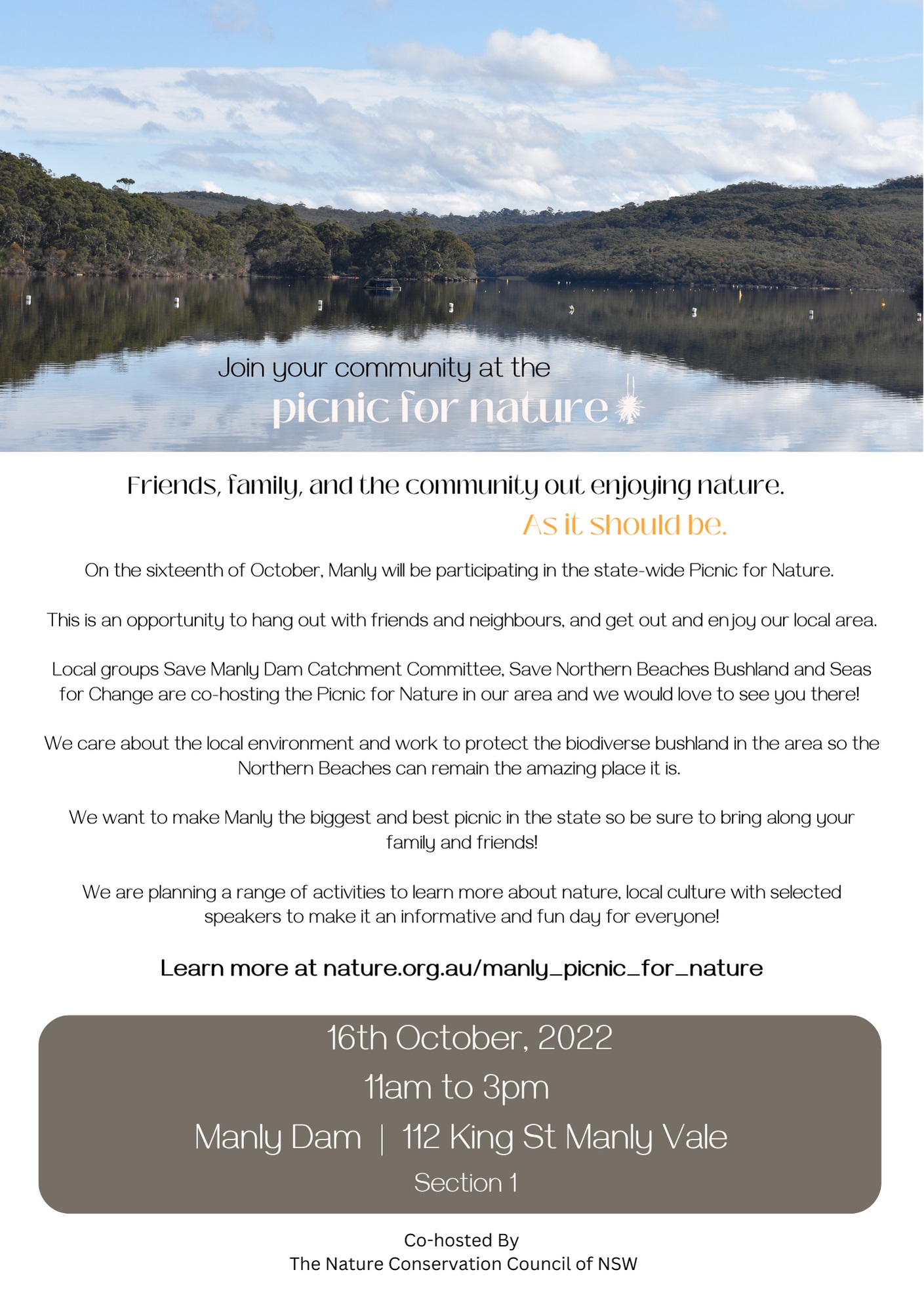

Dust Off Your Picnic Blankets For The First Ever Statewide Picnic For Nature

National Bird Week + Aussie Bird Count 2022

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

TALK & BOOK LAUNCH

Book Your Free Ticket To: Developing Sustainable Communities

Weed Alert: Corky Passionflower At Mona Vale + Narrabeen Creek

.jpg?timestamp=1663392221562)

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary Open

EPA Releases Climate Change Policy And Action Plan

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is taking action to protect the environment and community from the impacts of climate change, today releasing its new draft Climate Change Policy and Action Plan which works with industry, experts and the community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support resilience.

NSW EPA Chief Executive Officer Tony Chappel said the EPA has proposed a set of robust actions to achieve a 50 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (from 2005 levels), ensure net zero emissions by 2050, and improve resilience to climate change impacts.

“NSW has ambitious targets that align with the world’s best scientific advice and the Paris commitments, to limit global warming to an average of 1.5 degrees in order to avoid severe impacts on ecosystems,” Mr Chappel said.

“Over the past few years we have seen first-hand just how destructive the impacts of climate change are becoming, not only for our environment, but for NSW communities too.

“We know the EPA has a critical role to play in achieving the NSW Government’s net-zero targets and responding to the increasing threat of climate change induced weather events.

“Equally, acting on climate presents major economic opportunities for NSW in new industries such as clean energy, hydrogen, green metals, circular manufacturing, natural capital and regenerative agriculture.

“This draft Policy sends a clear signal to regulated industries that we will be working with them to support and drive cost-effective decarbonisation while implementing adaptation initiatives that build resilience to climate change risks.

“Our draft plan proposes a staged approach that ensures the actions the EPA takes are deliberate, well informed and complement government and industry actions on climate change. These actions will support industry and allow reasonable time for businesses to plan for and meet any new targets or requirements.

“Climate change is an issue that we all face so it’s important that we take this journey together and all play our part in protecting our environment and communities for generations to come.”

Actions include:

- working with industry, government and experts to improve the evidence base on climate change

- supporting licensees prepare, implement and report on climate change mitigation and adaptation plans

- partnering with NSW Government agencies to address climate change during the planning and assessment process for activities the EPA regulates

- establishing cost-effective emission reduction targets for key industry sectors

- providing industry best-practice guidelines to support them to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

- phasing in the introduction of greenhouse gas emission limits on environment protection licences for key industry sectors

- developing and implementing resilience programs, best-practice adaptation guidance and harnessing citizen science and education programs

- working with EPA Aboriginal and Youth Advisory Committees to improve the EPA’s evolving climate change response

EPA Acting Chair Carolyn Walsh said the EPA is a partner in supporting and building on the NSW Government’s work to address climate change for the people of NSW.

“The draft Policy and Action Plan adopts, supports and builds on the strong foundations that have been set by the NSW Government through the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework, Net Zero Plan and Climate Change Adaptation Strategy,” Ms Walsh said.

The EPA will work with stakeholders, including licensees, councils, other government agencies, and the community to help implement the actions.

The draft EPA Climate Change Policy and Action Plan is available at https://yoursay.epa.nsw.gov.au/ and comments are open until 3 November 2022.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Toondah Harbour Proposal Will Undermine Global Protection Of Wetlands: BirdLife Australia Vehemently Opposes The Proposal

Eastern Curlew at Careel Bay foreshore in October 2011 - A J Guesdon photo

Raising Warragamba Dam Wall Threatens Birds On The Edge: Regents Threatened By Floods Upstream Of Megadam

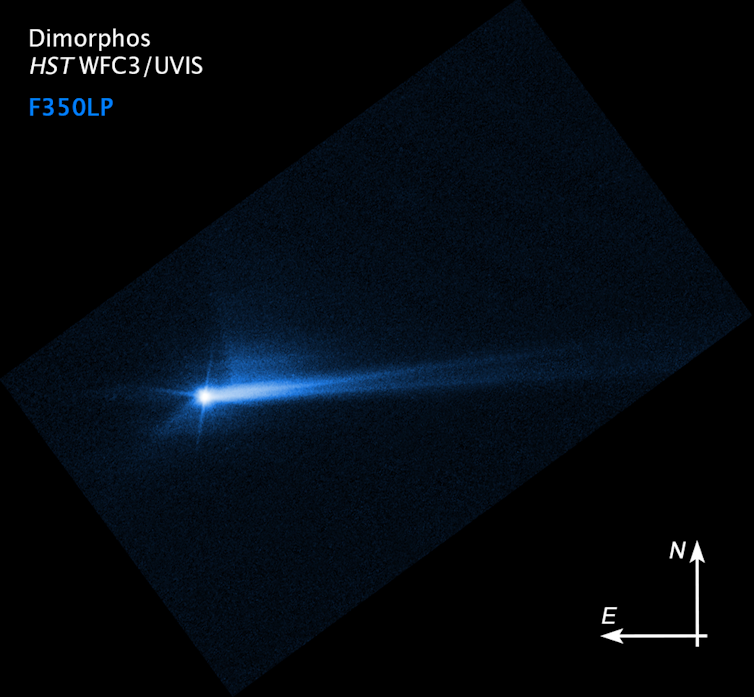

Touch Down!

The wild weather of La Niña could wipe out vast stretches of Australia’s beaches and sand dunes

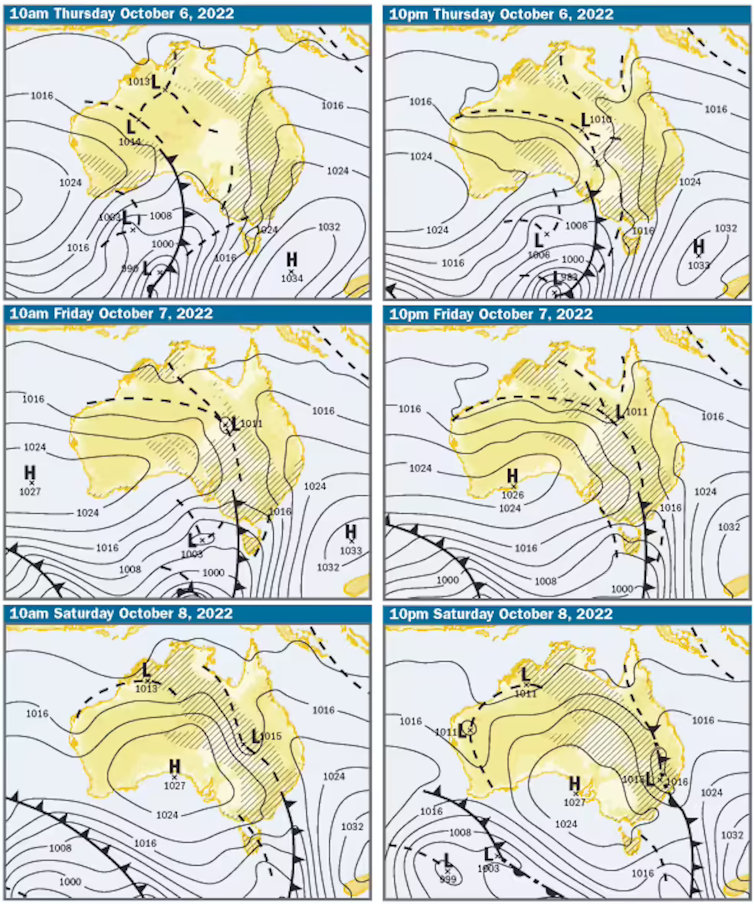

Javier Leon, University of the Sunshine CoastAustralians along the east cost are bracing for yet another round of heavy rainfall this weekend, after a band of stormy weather soaked most of the continent this week.

The Bureau of Meteorology has alerted southern inland Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria and northern Tasmania to ongoing flood risks, as the rain falls on already flooded or saturated catchments.

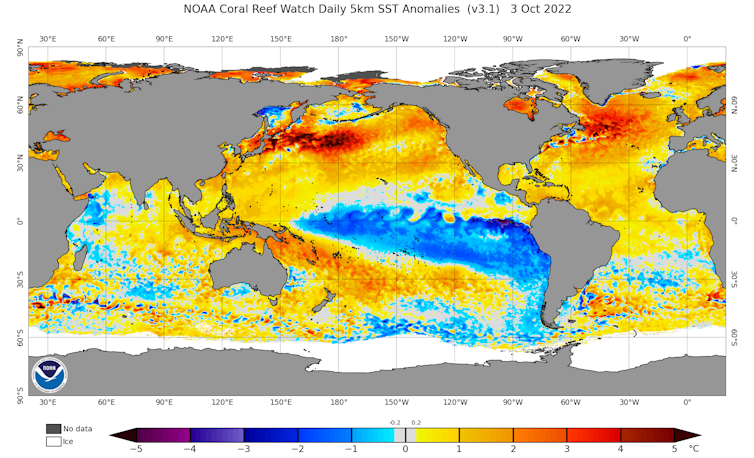

This widespread wet weather heralds Australia’s rare third back-to-back La Niña, which goes hand-in-hand with heavy rain. There is, however, another pressing issue arising from La Niña events: coastal erosion.

The wild weather associated with La Niña will drive more erosion along Australia’s east coast – enough to wipe out entire stretches of beaches and dunes, if all factors align. So, it’s important we heed lessons from past storms and plan ahead, as climate change will only exacerbate future coastal disasters.

How La Niña Batters Coastlines

La Niña is associated with warmer waters in the western Pacific Ocean, which increase storminess off Australia’s east coast. Chances of a higher number of tropical cyclones increase, as do the chances of cyclones travelling further south and further inland, and of more frequent passages of east coast lows.

Australians had a taste of this in 1967, when the Gold Coast was hit by the largest storm cluster on record, made up of four cyclones and three east coast lows within six months. 1967 wasn’t even an official La Niña year, with the index just below the La Niña threshold.

Such frequency didn’t allow beaches to recover between storms, and the overall erosion was unprecedented. It forced many local residents to use anything on hand, even cars, to protect their properties and other infrastructure.

Official La Niña events occurred soon after. This included a double-dip La Niña between 1970 and 1972, followed by a triple-dip La Niña between 1973 and 1976.

These events fuelled two cyclones in 1972, two in 1974 and one in 1976, wreaking havoc along the entire east coast of Australia. Indeed, 1967 and 1974 are considered record years for storm-induced coastal erosion.

Studies show the extreme erosion of 1974 was caused by a combination of large waves coinciding with above-average high tides. It took over ten years for the sand to come back to the beach and for dunes to recover. However, recent studies also show single extreme storms can bring back considerable amounts of sand from deeper waters.

La Niña also modifies the direction of waves along the east coast, resulting in waves approaching from a more easterly direction (anticlockwise).

This subtle change has huge implications when it comes to erosion of otherwise more sheltered north-facing beaches. We saw this during the recent, and relatively weaker, double La Niña of 2016-18.

In 2016, an east coast low of only moderate intensity produced extreme erosion, similar to that of 1974. Scenes of destruction along NSW – including a collapsed backyard pool on Collaroy Beach – are now iconic.

This is largely because wave direction deviated from the average by 45 degrees anticlockwise, during winter solstice spring tides when water levels are higher.

All Ducks Aligned?

The current triple-dip La Niña started in 2020. Based on Australia’s limited record since 1900, we know the final events in such sequences tend to be the weakest.

However, when it comes to coastal hazards, history tells us smaller but more frequent storms can cause as much or more erosion than one large event. This is mostly about the combination of storm direction, sequencing and high water levels.

For example, Bribie Island in Queensland was hit by relatively large easterly waves from ex-Tropical Cyclone Seth earlier this year, coinciding with above-average high tides. This caused the island to split in two and form a 300-metre wide passage of seawater.

Further, the prolonged period of easterly waves since 2020 has already taken a toll on beaches and dunes in Australia.

Traditionally, spring is the season when sand is transported onshore under fair-weather waves, building back wide beaches and tall dunes nearest to the sea. However, beaches haven’t had time to fully recover from the previous two years, which makes them more vulnerable to future erosion.

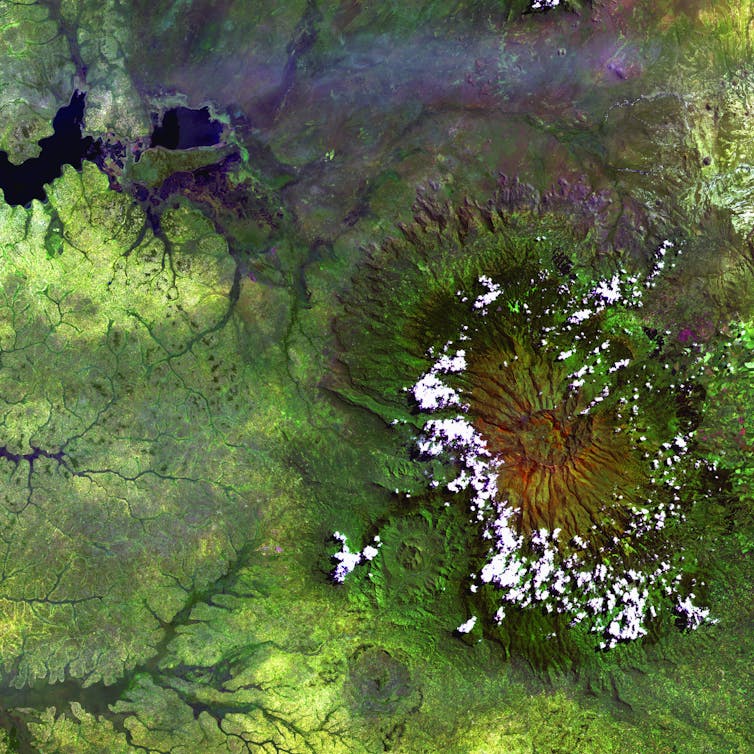

Repeated elevation measurements by our team and citizen scientists along beaches in the Sunshine Coast and Noosa show shorelines have eroded more than 10m landwards since the beginning of this year. As the photo below shows, 2-3m high erosion scarps (which look like small cliffs) have formed along dunes due to frequent heavy rainfalls and waves.

On the other hand, we can also see that the wet weather has led to greater growth of vegetation on dunes, such as native spinifex and dune bean.

Experiments in laboratory settings show dune vegetation can dissipate up to 40-50% of the water level reached as a result of waves, and reduce erosion. But whether this increase in dune vegetation mitigates further erosion remains to be seen.

A Challenging Future

The chances of witnessing coastal hazards similar to those in 1967 or 1974 in the coming season are real and, in the unfortunate case they materialise, we should be ready to act. Councils and communities need to prepare ahead and work together towards recovery if disaster strikes using, for example, sand nourishment and sandbags.

Looking ahead, it remains essential to further our understanding about coastal dynamics – especially in a changing climate – so we can better manage densely populated coastal regions.

After all, much of what we know about the dynamics of Australia’s east coast has been supported by coastal monitoring programs, which were implemented along Queensland and NSW after the 1967 and 1974 storms.

Scientists predict that La Niña conditions along the east coast of Australia – such as warmer waters, higher sea levels, stronger waves and more waves coming from the east – will become the norm under climate change.

It’s crucial we start having a serious conversation about coastal adaptation strategies, including implementing a managed retreat. The longer we take, the higher the costs will be.![]()

Javier Leon, Senior lecturer, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

On our wettest days, stormclouds can dump 30 trillion litres of water across Australia

This week, rain has drenched almost all of Australia – even the arid interior. The heaviest falls have hit the continent’s southeast, where the huge deluge has just propelled Sydney past its annual rainfall record of 2.2 metres with three months to go until year’s end.

Other parts of the eastern seaboard are bracing for yet more flooding in coming days. So what’s actually causing all this rain?

It all started last week, when unusually warm seas off northwest Australia gave off vast volumes of moist air. This air rose to form huge clouds which, propelled by winds, carried billions of tonnes of water across the continent.

Clouds might look fluffy and insubstantial, but they actually carry truly gigantic quantities of water. Let’s take the nearly 100 millimetres of rain that’s fallen so far this week on Sydney’s inner city – about 25 square kilometres. That’s about 2.5 billion litres of water!

On the wettest days, we can accumulate more than 4mm of rain on average across the whole continent. This equates to about 30 trillion litres of water. Or, to use the colloquial Australian measurement, 60 Sydney Harbour’s worth (1 Sydharb = 500 gigalitres).

Why Do We Get Rain In The First Place?

Major rain events need two main ingredients: moisture and rising motion in the atmosphere. Most of that moisture comes from evaporation from oceans but some comes from evaporation from the land, especially when it’s wet.

We get rising motion with surface heating or when air is forced to go up over obstacles (like mountains), or when we have weather systems that cause the air to ascend.

A blob of moist air rising from the surface will expand as it moves higher up in the atmosphere, since air pressure drops quickly with height. This is why balloons eventually pop when they go up in the sky. We can’t see this blob as it rises – it hasn’t turned white and fluffy yet.

The expansion of this moist air blob requires work, so energy has to be found from somewhere. The energy is taken from the movement of air and water molecules within the blob, and since temperature is a measure of the movement of molecules, the air cools.

As the air cools and the water molecules slow down, they stick together more easily, forming droplets. This is the process of condensation and it results in clouds forming. Clouds range in sizes but the biggest cumulonimbus – towering dark storm clouds – can reach more than 10km above the surface.

Even small clouds contain a lot of water. A single cloud covering one cubic kilometre would hold around 500 tonnes of water. You might wonder why this weight doesn’t bring the whole cloud down immediately. The answer is the moisture is very spread out throughout the cloud, and the air beneath the cloud is denser.

At a certain point, enough water has condensed and come together into droplets for gravity to win out and pull the water to the ground as rain.

So Why’s It Raining So Much Right Now?

Right now, we have abundant moisture in the air. The weather is primed to move moisture up through the atmosphere, via low pressure systems and cold fronts moving from west to east.

Low pressure systems mean air pressure is lower than the surrounding areas. Because nature likes to even things out, air at the surface moves in to try and cancel out differences in pressure, although the rotation of the Earth forces the air to spiral in rather than moving directly in. This creates winds which move in towards the low pressure centre and then have to move upwards, carrying moisture with them. That’s why low pressure systems are associated with winds and rain.

Cold fronts are characterised by rising masses of air because they mark divisions between colder and warmer air. The warmer air is less dense and forced to rise over the colder air.

Why is there so much moisture in the air? That’s linked to warmer sea temperatures off northern Australia, which cause more water to evaporate from the sea surface.

La Niña conditions – which we’re experiencing for the third year running – brings cooler seas in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean near the equator and above-average sea surface temperatures in the western Pacific, including around Australia.

But La Niña has company. We also have what’s called a negative Indian Ocean Dipole, where westerly winds intensify, warming the waters around Indonesia and Australia’s northwest.

With these two climate cycles intersecting, we get more and more moisture in the air around Australia. When low pressure systems emerge, they draw the moisture over the continent and cause the air to rise and form heavily-laden clouds.

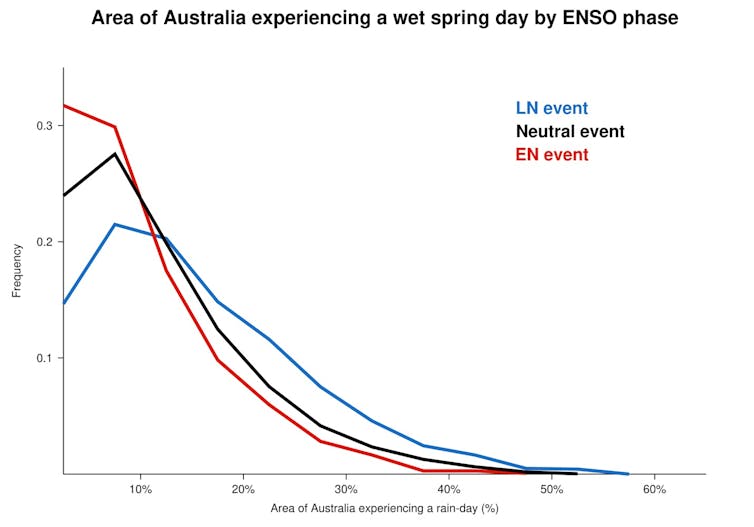

We can get heavy rains without La Niña, but La Niña loads the dice, making it more likely we get heavier and more widespread rain events. For example, the chance of having a wet day across a third of Australia more than doubles during La Niña compared to neutral conditions – and is more than five times more likely than in an El Niño event.

During most spring days, only a small percentage of Australia has a day with more than 1mm of rain. But occasionally, we can have days when a third or more of the continent experiences rain – just as we’ve seen this week.

Rain, Rain, Go Away

With the devastating floods of February and March still fresh in our memories, most Australians will be hoping for the rain to stop.

But the deluge isn’t done with us yet.

As La Niña continues, we can expect more widespread heavy rain events. And since eastern Australia’s soils are saturated in many areas, there’s a renewed chance of flooding.

By the start of next year, most forecast models predict a weakening La Niña. But it will most likely be a wet summer. Keep your eye on the horizon – and look for the clouds. ![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Labor’s plan to save threatened species is an improvement – but it’s still well short of what we need

Euan Ritchie, Deakin University; Megan C Evans, UNSW Sydney, and Yung En Chee, The University of MelbourneAustralia’s dire and shameful conservation record is well established. The world’s highest number of recent mammal extinctions – 39 since colonisation. Ecosystems collapsing from the north to the south, across our lands and waters. Even species that have survived so far are at risk, as the sad list of threatened species and ecological communities continues to grow.

During the election campaign, Labor pledged to turn this around. On Tuesday, federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek announced what this would look like: a new action plan for 110 threatened species. The goal: no new extinctions. “Our current approach has not been working. If we keep doing what we’ve been doing, we’ll keep getting the same results,” Plibersek said.

But is this really a step change? Let’s be clear. This plan is a welcome improvement – especially the focus on First Nations rangers and Indigenous knowledge, clearer targets, better monitoring and the goal of protecting 30% of Australia’s lands and seas within five years.

But the funding is wholly inadequate. The A$225 million committed is an order of magnitude less than what we need to actually bring these threatened species back from oblivion. The grim reality is this plan is nowhere near enough to halt the extinctions. Here’s why.

There’s Nowhere Near Enough Funding

Conservation costs money. Recovering threatened species takes effort. Tackling the threats that are pushing them over the edge, from feral cats to land clearing, is expensive. “Measures of last resort”, such as captive breeding, creation of safe havens and translocations, takes more still.

How much is enough? Estimates put it at A$1.7 billion per year. This is around one-seventh of the money Australian governments spent on fossil fuel subsidies last financial year. If there’s funding for that, there should be funding for wildlife.

Make no mistake – starving conservation of adequate funding is a choice. For decades, Australia’s unique environment and wildlife have been thrown consolation crumbs of funding – even though they are our collective natural heritage, fundamental to human survival, wellbeing and economic prosperity, and a major draw card for tourists and locals. You can see the results for yourself: more extinctions and many more threatened species.

Picking Winners Means Many Species Will Lose

Labor’s plan is focused on arresting the decline of 110 species, and 20 places such as the Australian Alps, Bruny Island and Kakadu and West Arnhem Land.

Unfortunately, that’s a drop in the ocean. Combined, we now have more than 2,000 species and ecological communities listed as threatened. Picking species to survive betrays our remarkable, diverse and largely unique plants, animals and ecosystems. It suggests – wrongly – that we have to choose winners and losers, when in fact we could save them all.

The plan assumes recovering priority species may help conserve other threatened species in the same areas and habitats. This is questionable, given only around 6% of listed threatened species are slated to receive priority funding, and how much the needs of different species can vary even in the same habitats and ecosystems. Different species respond very differently to fire regimes, for instance.

Policies And Laws Are Essential

Funding by itself isn’t enough. Unless all levels of governments enact and enforce effective policies aimed at conserving species and their homes, the situation will worsen. Australians are still waiting to see what reforms actually emerge from Graeme Samuel’s sweeping review of the main laws governing biodiversity and environmental protection.

Alignment of policies is vital. What’s the point of saving a rare finch from land clearing if you’re simultaneously opening up huge areas to fracking, polluting groundwater and adding yet more emissions to our overheated atmosphere? Despite Labor’s rhetoric on threatened species and climate change, they are still committed to more coal and gas.

Similarly, native vegetation clearing and habitat loss is barely mentioned in the threatened species plan. Yet these are leading causes of environmental degradation, as the 2021 State of the Environment Report makes clear.

If you want to save the critically endangered western ringtail possum and endangered black cockatoos, why would you approve the clearing of habitat vital to their existence? The Labor government did just that in July.

Conserving More Land Isn’t A Panacea

Protecting 30% of Australia’s lands and oceans by 2030 sounds great. But protecting degraded farmland is not the same as protecting a biodiverse grassland or wetland. And establishing protected areas is not the same as effective management.

To get this right, the new areas must add to our existing conservation estates by adding species and ecological communities with little or no representation. They must help species move as they would have before European colonisation, by connecting protected areas separated by human settlement or farms. And there must be enough money to actually look after the land. There’s no point protecting ever-larger tracts of degraded, weed-infested, rabbit, deer, horse, pig, fox and cat-filled land.

The 50 million hectares of land and sea to be added by 2027 is supposed to come almost entirely from Indigenous Protected Areas. But again, where’s the funding? Right now, these land and sea areas get a pittance – a few cents per hectare per year.

It’s also important to support conservation on private land, where many threatened species live and where significant gains can be made. Maintaining wildlife on private land can also help farmers and landholders through pollination and seed dispersal as well as broader ecosystem health.

We Need Laws With Teeth

If you liked it, you should have put a law around it. If the federal government is serious about ending extinctions, it should be enshrined in legislation. As it stands, “zero extinctions” is a promise with no clear way for us to see who is responsible or how the promise will be kept.

Too cynical? Alas, there’s a very real trend here. Successive governments have avoided accountability for losing species doing exactly this. They release strategies on glossy paper which note we all have a role to play in conservation – but strangely omit the part about who is responsible when a species dies out. If you want to save species, make human careers depend on species staying alive.

We know strong legislation and billions rather than millions of dollars are needed to stop extinctions. So far, the new government has announced inadequate funding, a non-binding strategy with an aspirational goal, and a seemingly rushed idea of a biodiversity market, dubbed “green Wall Street”, which made conservationists including the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists very concerned.

Tossing breadcrumbs to conservation is what we’ve done for decades. It’s a major reason why our unique species are in this mess. Time’s up.![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University; Megan C Evans, Senior Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW Sydney, and Yung En Chee, Senior Research Fellow, Environmental Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia has hundreds of mammal species. We want to find them all – before they’re gone

Andrew M. Baker, Queensland University of Technology; Diana Fisher, The University of Queensland; Greta Frankham, Australian Museum; Kenny Travouillon, Western Australian Museum; Linette Umbrello, Western Australian Museum; Mark Eldridge, Australian Museum; Sally Potter, Macquarie University, and Stephen Jackson, Australian MuseumLife on Earth is undergoing a period of mass extinction – the sixth in history, and the first caused by humans. As species disappear at an alarming rate, we have learned that we understand only a fraction of Earth’s variety of life.

The task of describing this biodiversity before it is lost relies on the discipline of taxonomy, the scientific practice of classifying and naming organisms.

But taxonomy is far more than just naming things. It underpins an enormous range of human activities, including biology (via health and conservation management), the economy (via agriculture and biosecurity) and many other areas of endeavour.

Unfortunately, taxonomy is suffering globally from reduced support and funding. This is an area of ongoing concern recognised in Australia’s State of the Environment report released in July this year. The workforce of taxonomists has declined when it is needed most.

Taxonomists Unite

So, what is being done?

Communities of taxonomists in Australia and the world over are making a concerted effort to face the challenge of naming and understanding Earth’s unknown species.

Australian taxonomists are garnering support to achieve the goal of documenting all Australian species by 2050.

This ambitious plan requires not just government and other external support but also co-ordination of our taxonomists. Success will mean bringing together those who study lesser-known groups, such as insects, spiders and fungi, with those who work on more familiar groups such as vertebrates, including mammals.

Mammals Under Threat

Mammals are perhaps the best known and cherished group of species on the planet. Even so, many mammals remain undiscovered.

Mammals are also among the most threatened animal groups globally. And because it has contributed the most species to the list, Australia has the worst modern mammal extinction record of any country, along with one of the most distinctive mammal faunas on Earth: about 90% of our terrestrial mammals live nowhere else.

More than 100 species that lived only in Australia are recognised as having become extinct since 1788.

Thirty-nine of these extinct species are mammals. Most recently, this includes the Bramble Cay melomys (Melomys rubicola), a native rodent declared extinct in 2016, and the first known mammal extinction due at least in part to human-induced climate change.

In the face of an avalanche of human-mediated threats, including climate warming, land-use change and introduction of pest species, are the host of hidden mammal species destined for extinction before they are even discovered, described and known to humanity?

The Australasian Mammal Taxonomy Consortium

To help address this existential threat, and in response to the call to arms within Australian taxonomy, we have formed the Australasian Mammal Taxonomy Consortium (AMTC), a group affiliated with the Australian Mammal Society.

The consortium aims to promote stability and consensus, provide advice and guidance, and promote the cause and importance of Australasian mammal taxonomy to both scientists and the broader public.

We have recently introduced the aspirations and aims of our group in a review paper and published our first list of species, covering Australian mammals.

We recognise 404 Australian mammal species, including 2 monotremes (platypus and short-beaked echidna), 175 marsupials (such as the Tasmanian devil, the numbat, the koala, kangaroos and so on) and 227 placentals (such as rodents, bats, seals, whales and dolphins). The list includes 11 species, and numerous subspecies, that have only been discovered and formally named in the past decade.

A suite of other recognised variable forms, new species-in-waiting, need study and description.

The Australian mammal species list will be updated annually to incorporate new species names. In the future, working with research groups throughout the region, we will produce lists of mammal species found elsewhere in Australasia.

A New Launching Point

We hope this will standardise the use of mammal species names, highlight groups where further taxonomic work is required, and provide a launching point for this work.

In the past decade, rapid DNA sequencing has revolutionised our ability to understand biodiversity, even while species loss to extinction at the hands of humanity is at an all-time high. This juxtaposition makes it both an exciting and critically important time for taxonomy.

We hope the Australasian Mammal Taxonomy Consortium can do its part to help grow and focus an interest to better understand and conserve our precious Australasian mammals before it is too late.

The authors comprise a steering committee representing the broader Australasian Mammal Taxonomy Consortium working group, which includes more than 30 members.![]()

Andrew M. Baker, Senior Lecturer in Ecology and Environmental Science, Queensland University of Technology; Diana Fisher, Associate Professor, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland; Greta Frankham, Scientific Officer, Australian Centre for Wildlife Genomics, Australian Museum; Kenny Travouillon, Curator of Mammals, Western Australian Museum; Linette Umbrello, Research Associate – Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum; Mark Eldridge, Principal Research Scientist, Terrestrial Vertebrates, Australian Museum; Sally Potter, Australian Research Council Future Fellow, School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University, and Stephen Jackson, Associate Director, Collection Enhancement Project, Australian Museum

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

740,000km of fishing line and 14 billion hooks: we reveal just how much fishing gear is lost at sea each year

Two per cent of all fishing gear used worldwide ends up polluting the oceans, our new research finds. To put that into perspective, the amount of longline fishing gear littering the ocean each year can circle the Earth more than 18 times.

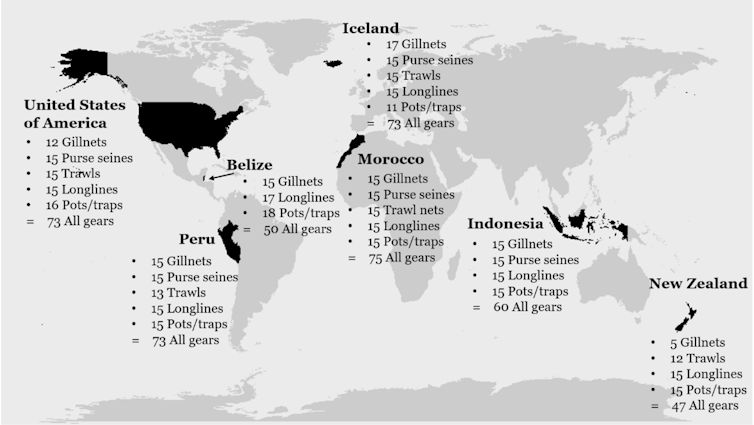

We interviewed 450 fishers from seven of the world’s biggest fishing countries including Peru, Indonesia, Morocco and the United States, to find out just how much gear enters the global ocean. We found at current loss rates, in 65 years there would be enough fishing nets littering the sea to cover the entire planet.

This lost fishing equipment, known as ghost gear, can cause heavy social, economic and environmental damage. Hundreds of thousands of animals are estimated to die each year from unintentional capture in fishing nets. Derelict nets can continue to fish indiscriminately for decades.

Our research findings help highlight where to focus efforts to stem the tide of fishing pollution. It can also help inform fisheries management and policy interventions from local to global scales.

14 Billion Longline Hooks Litter The Sea Each Year

The data we collected came directly from fishers themselves. They experience this issue firsthand and are best poised to inform our understanding of fishing gear losses.

We surveyed fishers using five major gear types: gillnets, longlines, purse seine nets, trawl nets, and pots and traps.

We asked how much fishing gear they used and lost annually, and what gear and vessel characteristics could be making the problem worse. This included vessel and gear size, whether the gear contacts the seafloor, and the total amount of gear used by the vessel.

We coupled these surveys with information on global fishing effort data from commercial fisheries.

Fishers use different types of nets to catch different types of fish. Our research found the amount of nets littering the ocean each year include:

- 740,000 kilometres of longline mainlines

- nearly 3,000 square kilometres of gill nets

- 218 square kilometres of trawl nets

- 75,000 square kilometres of purse seine nets

In addition, fishers lose over 25 million pots and traps and nearly 14 billion longline hooks each year.

These estimates cover only commercial fisheries, and don’t include the amount of fishing line and other gear lost by recreational fishers.

We also estimate that between 1.7% and 4.6% of all land-based plastic waste travels into the sea. This amount likely exceeds lost fishing gear.

However, fishing gear is designed to catch animals and so is generally understood as the most environmentally damaging type of plastic pollution in research to date.

Harming Fishers And Marine Life

Nearly 700 species of marine life are known to interact with marine debris, many of which are near threatened. Australian and US research in 2016 found fishing gear poses the biggest entanglement threats to marine fauna such as sea turtles, marine mammals, seabirds and whales.

Other marine wildlife including sawfish, dugong, hammerhead sharks and crocodiles are also known to get entangled in fishing gear. Other key problematic items include balloons and plastic bags.

Lost fishing gear is not only an environmental risk, but it also has an economic impact for the fishers themselves. Every metre of lost net or line is a cost to the fisher – not only to replace the gear but also in its potential catch.

Additionally, many fisheries have already gone through significant reforms to reduce their environmental impact and improve the sustainability of their operations.

Some losses are attributable to how gear is operated. For instance, bottom trawl nets – which can get caught on reefs – are lost more often that nets that don’t make contact with the sea floor.

The conditions of the ocean can also make a significant difference. For example, fishers commonly reported that bad weather and overcrowding contributes to gear losses. Conflicts between gears coming into contact can also result in gear losses, such as when towed nets cross drifting longlines or gillnets.

Where fish are depleted, fishers must expend more effort, operate in worse conditions or locations, and are more likely to come in contact with others’ gear. All these features increase losses.

What Do We Do About It?

We actually found lower levels of fishing gear losses in our current study than in a previous review of the historical literature on the topic. Technological improvements, such as better weather forecasts and improved marking and tracking of fishing gear may be reducing loss rates.

Incentives can further reduce losses resulting in ghost gear. This could include buyback programs for end-of-life fishing gear, reduced cost loans for net replacement, and waste receptacles in ports to encourage fishers to return used fishing gear.

Technological improvements and management interventions could also make a difference, such as requirements to mark and track gear, as well as regular gear maintenance and repairs.

Developing effective fishing management systems can improve food security, leave us with a healthier environment, and create more profitable businesses for the fishers who operate in it.![]()

Britta Denise Hardesty, Senior Principal Research Scientist, Oceans and Atmosphere, CSIRO; Chris Wilcox, Senior Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO; Joanna Vince, Associate professor, University of Tasmania, and Kelsey Richardson, PhD Candidate, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Megadroughts helped topple ancient empires. We’ve found their traces in Australia’s past, and expect more to come

Kathryn Allen, University of Tasmania; Alison O'Donnell, The University of Western Australia; Benjamin I. Cook, Columbia University; Jonathan Palmer, UNSW Sydney, and Pauline Grierson, The University of Western AustraliaMost Australians have known drought in their lifetimes, and have memories of cracked earth and empty streams, paddocks of dust and stories of city reservoirs with only a few weeks’ storage. But our new research finds over the last 1,000 years, Australia has suffered longer, larger and more severe droughts than those recorded over the last century.

These are called “megadroughts”, and they’re likely to occur again in coming decades. Megadroughts can last multiple decades – or even centuries – with occasional wet years offering only brief relief. Megadroughts can also be shorter periods of very extreme conditions.

We show megadroughts have occurred several times across every inhabited continent over the last two millennia. They’ve dealt profound damage to agriculture and water supplies, increased fire risk, and have even contributed to toppling civilisations.

Unless we incorporate the full potential of Australian drought into our planning, management and design, their impacts on society and the environment will likely worsen in coming decades.

The Role Of Climate Change

Instrumental records only go back so far. In Australia, they cover only the last 120 years or so. Scientists can gauge local, yearly climate further back in time, by deciphering clues written in tree rings, corals, and buried ice (known as ice cores), among other archives.

To look at previous occurrences of megadroughts, we consolidated findings drawn from such datasets and a range of other long-term records.

Historically, droughts have been defined by rainfall deficits, and these deficits can be largely attributed to complex interactions between oceans and the atmosphere over a long time. For example, decades-long La Niña conditions have been linked to medieval droughts in North and South America.

In contrast, research suggests human-caused climate change is now playing a more important role in amplifying drought conditions, as rising global temperatures increase evaporation.

There is some uncertainty in climate models about the effect of climate change on rainfall at local and regional scales. However, climate change is putting places that have previously endured megadroughts – such as Australia – at an increased risk of megadroughts in future.

Megadroughts And Collapsing Civilisations

Currently, parts of the United States – including Arizona, Nevada and Utah – are in the throes of a megadrought, lasting some two decades. Historically, megadroughts have profoundly impacted societies and environments.

In the American southwest, megadroughts in the late 1200s likely contributed to the desertion of the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings. Likewise, the Hohokam peoples relied heavily on a canal system, and this dependence in a time of severe and extended drought may have contributed to their decline over the 14th and 15th Centuries.

In Central America, a megadrought between 1149 and 1167 likely brought instability to the Toltec state. And a megadrought between 1514-1539 weakened the Aztec state just prior to Spanish conquest.

Europe and Asia have had their share of megadroughts, too. Research shows severe megadroughts in Asia in the 1300s and early 1400s quite likely helped cause the collapse of Cambodia’s vast Khmer Empire.

Megadroughts In Australia

While many Australians may remember the severity of the Millennium Drought between 1997 and 2009, we found this drought wasn’t actually particularly unusual. Megadroughts of the same or greater severity have occurred over the past 1,000 years across several parts of Australia, and were relatively common over much of eastern Australia.

This includes megadroughts between 1500 and the 1520s, and between the 1820s and 1840s. And while relatively short, a dry period between 1789 and 1795, coinciding with European invasion, included several years of severe drought. The year 1792 in particular was extremely dry over almost all of eastern Australia.

Western Australia’s wheat belt is currently experiencing a decline in rainfall. This, too, isn’t unusual compared to droughts there in the past. Tree rings in the region reveal that longer, more severe droughts occurred there six times in the last 700 years, including the years 1393-1407, 1755-1785, and 1889-1908.

Even in Tasmania, evidence suggests prolonged dry periods occurred in the latter part of the 16th Century, with a shorter but more severe downturn from 1670-1704.

We Need To Be Better Prepared

Water management in Australia has relied on short instrumental data. These do not capture the full range of variability in our rainfall.

This means, for example, that Australia’s infrastructure may be inadequately designed or managed to cope with major flood events or prolonged dry conditions.

Now, even relatively short but very dry periods can lead to major problems. We saw this recently in Tasmania in the summer of 2015 and 2016 when, after a dry winter and spring, water levels in major catchments were minimal and fires raged in the west. The Basslink cable, which connects Tasmania to the national grid, broke, resulting in the use of diesel power generation to keep power on in the state.

Future megadroughts will amplify the pressures on already degraded Australian ecosystems. We know from Australia’s recent past the harm relatively smaller droughts can impose on the environment, the economy, and our mental and physical health.

We must carefully consider whether current management regimes and water infrastructure are fit-for-purpose, given the projected increased frequency of megadroughts.

It’s difficult to plan effectively without fully understanding even natural variability. And this means better appreciating the data we have from archives such as tree rings, corals and ice cores – crucial windows to our distant past.![]()

Kathryn Allen, ARC Future Fellow, University of Tasmania; Alison O'Donnell, Adjunct Research Fellow, The University of Western Australia; Benjamin I. Cook, Climate Scientist, Columbia University; Jonathan Palmer, Research Fellow, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences., UNSW Sydney, and Pauline Grierson, Director, West Australian Biogeochemistry Centre; Professor School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A secretive legal system lets fossil fuel investors sue countries over policies to keep oil and gas in the ground – podcast

A new barrier to climate action is opening up in an obscure and secretive part of international trade law, which fossil fuel investors are using to sue countries if policy decisions go against them.

In this episode of The Conversation Weekly podcast, we speak to experts about the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism and how it works. Many are worried that these clauses in international trade deals could jeopardise global efforts to save the climate – costing countries billions of dollars in the process.

ISDS clauses were first introduced into international trade agreements in the post-colonial period. Most of these treaties were between a developed and a developing country. “It was really intended in the first instance to protect the interests of multinational companies from the global north when they were operating in these newly decolonised parts of the world,” explains Kyla Tienhaara, an expert in ISDS and environmental governance at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada.

Yet Tienhaara says the use of ISDS has “morphed beyond all recognition” of the treaties’ original intentions, due to what she calls “creative lawyering” and the fact the system is stacked in favour of investors and against governments.

A looming concern is the chilling effect these clauses could have on countries’ decisions to phase out fossil fuels or take other action to protect the environment if investors decide to sue for compensation. In April, a summary report by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change singled out ISDS clauses saying that they may “limit countries’ ability to adopt trade-related climate policies” and stick to their commitments under the 2015 Paris agreement.

In a recent study, Tienhaara and her colleagues estimated that countries could face up to US$340 billion in financial and legal risk from cancelling fossil fuel projects covered by ISDS clauses.

Some countries are more vulnerable than others because of the nature of the contracts they’ve entered into. Mozambique, with its large gas and coal reserves, is particularly so, explains Lea Di Salvatore, a PhD candidate at Nottingham University in the UK.

She analysed 29 of the country’s mega-projects for gas, coal and hydrocarbons and found that the vast majority are covered by ISDS clauses. This means that “the company can directly go and initiate an arbitration against Mozambique”, she says, if it feels a government policy has negatively affected its investment.

We hear what it’s like inside one of these arbitration rooms from Emilia Onyema, a professor of international commercial law at SOAS, University of London in the UK. “It’s a private process,” she explains. “The parties determine who the arbitrator is. They appoint the arbitrator. They pay the arbitrator. So they have more powers over the process than they would have in litigation.”

And we tell the story of one ISDS case launched against Italy by the British oil company, Rockhopper Exploration. In 2016, Italy banned oil drilling 12 nautical miles off its coast, which blocked Rockhopper’s exploration of the offshore Ombrina Mare field in the Adriatic Sea. Maria-Rita D'Orsogna, a US-based mathematician and leading campaigner against oil exploration in Abruzzo, explains what was at stake and what happened next.

Listen to the whole episode on The Conversation Weekly to find out about the fight back against ISDS, including moves to reform a big international trade treaty covering the fossil fuel industry and what countries are doing to limit their risk from ISDS climate arbitration.

This episode was produced by Gemma Ware and Mend Mariwany, with sound design by Eloise Stevens. The executive producer was Gemma Ware. Our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also sign up to The Conversation’s free daily email here. A transcript of this episode will be available soon.

You can listen to “The Conversation Weekly” via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed, or find out how else to listen here.![]()

Gemma Ware, Editor and Co-Host, The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation and Daniel Merino, Assistant Science Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

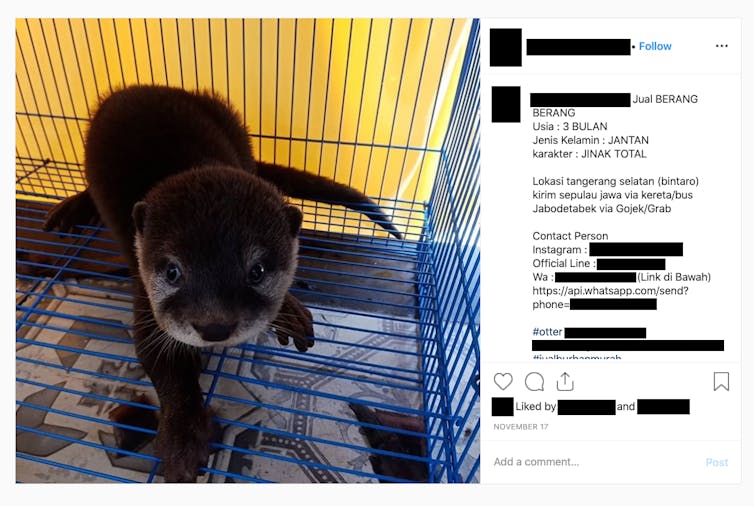

‘Astonishing’: global demand for exotic pets is driving a massive trade in unprotected wildlife

Global demand for exotic pets is increasing, a trend partly caused by social media and a shift from physical pet stores to online marketplaces.

The United States is one of the biggest markets for the wildlife trade. And our new research has identified an astonishing number of unregulated wild-caught animals being brought into the US – at a rate 11 times greater than animals regulated and protected under the relevant global convention.

Wildlife trade can have major negative consequences. It can threaten the wild populations from which animals and plants are harvested, and introduce novel invasive species to new environments. It can also lead to diseases transmitted from wildlife to humans and threaten the welfare of trafficked animals.

Tackling this problem requires an international effort – particularly by rich nations where the demand for exotic pets is greatest.

Shining A Light On The Pet Market

Most live animals transported through the wildlife trade are destined for the global, multi-billion dollar exotic pet market. Captive breeding supplies a portion of this market, but many species are collected from the wild – often illegally.

Animals such as otters, slow lorises and galagos or “bushbabies” are frequently depicted on social media as cute, and with human-like feelings and behaviours. This helps create demand for such species as pets which drives both the illegal and legal wildlife trades.

Non-native animals frequently smuggled into Australia in the past, include the corn snake, leopard gecko and red-eared slider turtle. Reptiles and birds are among the most commonly trafficked species because they can be easily transported.

Species deemed at risk from international trade are regulated through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). It aims to ensure sustainable and traceable legal international trade.

But the convention lists less than 10% of all described plants and terrestrial vertebrates, and less than 1% of all fish and invertebrate species. No international regulatory framework exists to monitor the trade of the many unlisted species.

Australia has rigorous regulations for exotic pet ownership and trade. Broadly, our native wildlife cannot be commercially exported.

However, Australia’s fauna is poached from the wild and illegally exported for the international pet market. Once the animal is smuggled out of Australia, its trade in recipient countries is often not monitored or restricted.

For example, research last year showed four subspecies of Australia’s shingleback lizard – one of which is endangered – were being illegally extracted from the wild and smuggled out of the country, to be sold across Asia, Europe and North America.

This lack of overseas regulation prompted the former Morrison government to push for 127 native reptile species targeted by international wildlife smugglers to be listed under CITES. They include blue tongue skinks and numerous gecko species.

But in the meantime, the global illegal wildlife trade continues. Our new research analysed the extent of this, by focusing on the movement of unlisted species to and from the US.

What We Found

The US is one of the few countries that maintains detailed records of all declared wildlife trade, including species not listed under CITES.

We examined a decade of data on wild-harvested, live vertebrate animals entering the US. Most would have been headed for the pet trade. We found 3.6 times the number of unlisted species in US imports compared with CITES-listed species – 1,356 versus 378 species.

Overall, 8.84 million animals from unlisted species were imported – about 11 times more than animals from CITES-listed species. More than a quarter of unlisted species faced conservation threats – including those with declining populations and those threatened with extinction.

For example, we found a substantial trade of the unlisted Asian water dragon. These bright green lizards are native to Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Burma and southern China, and are considered vulnerable.

In the decade to 2018, more than 575,000 Asian water dragons were imported to the US from Vietnam. The species has been proposed for inclusion in CITES. But decades of unregulated global trade poses a major threat to the survival of native populations.

How Do We Fix This?

Our study highlights the urgent need to monitor all traded wildlife species, not just those listed under CITES.

The biodiversity of life on Earth is under enormous pressure. Given this, and the other harms caused by the wildlife trade, this lack of regulation and monitoring is unacceptable.

For a species to be considered for listing under CITES, a national government must demonstrate that regulation is needed to prevent trade-related declines. But if trade in the species has never been monitored, how can that need be proven?

Sadly, the trade of many species is not formally regulated until it’s too late for their wild populations. Clearly, tighter regulation is needed to prevent this decline.

Traded wildlife predominantly flows from lower-income to higher-income countries. Many source countries do not possess the frameworks needed to monitor the harvest and export of unlisted species.

So what should be done? First, all nations should follow the lead of the US and record species-level data for all wildlife imported and exported. This information should be gathered as part of a standardised data management system.

Such a system would increase compliance with the rules and make the origin of wildlife easier to trace It would allow trade data to be shared and integrated between countries and allow timely assessment of species which may need further protection.

And second, affluent countries – where demand for exotic pets is largest – must take the lead on sustainable trade practices. This should include supporting supply countries and pushing for better data collection.

Such measures are vital to protecting both wildlife and human wellbeing.![]()

Freyja Watters, PhD candidate, University of Adelaide and Phill Cassey, Assoc Prof in Invasion Biogeography and Biosecurity, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dramatic Decline In Adelie Penguins Near Mawson

Commission For The Conservation Of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) 2022 Meeting

A deadly disease has driven 7 Australian frogs to extinction – but this endangered frog is fighting back

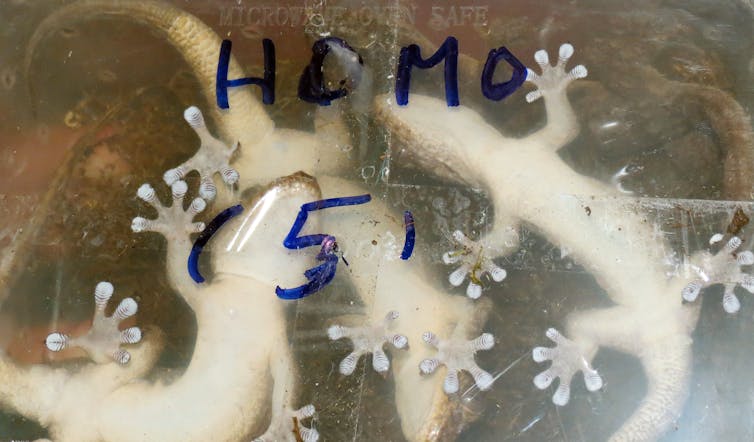

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

Frogs are among the world’s most imperilled animals, and much of the blame lies with a deadly frog disease called the amphibian chytrid fungus. The chytrid fungus has caused populations of over 500 frog species worldwide to plummet, and rendered seven Australian frogs extinct.

Our new research, however, has identified an endangered frog species that seems to have developed a natural resistance to the disease, after having previously succumbed to it in prior decades: Fleay’s barred frog (Mixophyes fleayi).

Fleay’s barred frog grows up to 9 centimetres long, and lives near gravelly streams in the rainforests of northern New South Wales and southeast Queensland. It is not the only frog species largely resistant to the disease, with a precious few others also known to survive it, such as common mistfrogs and cascade treefrogs.

We speculate that other frog species worldwide may be on a similar trajectory. There is currently no cure for the chytrid fungus, but understanding how Fleay’s barred frog and others are fighting back may prove instrumental in helping us bring more species back from the brink.

The Killer Fungus

The amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) causes a skin disease and breached Australian borders in the 1970s. Since then, the disease has caused populations of dozens of species to severely decline, and has driven seven to extinction, including the gastric brooding frogs and southern day frogs.

It wasn’t until 1998 that two independent research teams discovered the fungal pathogen was to blame. This unfortunately meant much of the damage was already done prior to its discovery.

Similarly, Fleay’s barred frog wasn’t distinguished as being a separate species of barred frog before the chytrid fungus caused its populations to decline across its range in the 1980s. It became extinct in at least three places it once lived.

But our research suggests the Fleay’s barred frog is bouncing back. Over four years, we conducted intensive field research at several rainforest streams in northern New South Wales to investigate the prevalence and intensity of infection within Fleay’s barred frog populations.

We found while some frogs with high-level infections died, most seemed capable of clearing their infections.

Frogs Are Fighting Back

Surveys in the late 1990s detected up to 15 Fleay’s barred frogs at the sites we studied. But during our investigations, we regularly found close to 100. Moreover, other researchers have noted that these frogs are relatively common across many rainforest streams, suggesting populations of Fleay’s barred frog have recovered.

We implanted 686 frogs with microchips and tested frogs for the chytrid fungus via a skin swab every time they were captured. This allowed us to follow these frogs over four years to learn about the population’s death rates and infection dynamics.

Fortunately, male Fleay’s barred frogs don’t travel far from home and are readily recaptured – we located some frogs more than 20 times.

We confirmed the prevalence of the chytrid fungus and the intensity of its infection was influenced by environmental conditions. Specifically, it was greatest with lower temperatures and higher rainfall.

This may help explain why we have witnessed mass death events in Australian frogs during recent wet winters along the eastern seaboard.

In addition to investigating the deadliness of a chytrid fungus infection, we also estimated the rates with which individuals were gaining and clearing infections.

We found infections were poor predictors of death. Only the highest pathogen loads were associated with an increase in rate of deaths, but frogs were very rarely infected with such high burdens.

Instead, frogs were much more likely to clear their infections than to gain them, ultimately leading to a low infection prevalence in the populations. On average, just one in five frogs were likely to be infected at any given time.

For those infected, pathogen loads were among the lowest we observed in rainforest frog communities. Some of the other species, such as the cascade treefrog, stony creek frog and giant barred frog, carried loads that were 30% higher.

How This Could Help Save Frogs

So why can the frogs now deal with a disease that decimated populations just a few decades ago? This question is unfortunately still hard to answer.

Given their low pathogen loads and high rates of clearing them, we believe Fleay’s barred frogs have developed natural resistance against the chytrid fungus, meaning their immune systems are actively combating infections. We further speculate that other species worldwide may be doing the same.

A promising avenue of conservation research is to use the genetic information of some species to help others survive threats in the wild, such as disease or climate change. Fleay’s barred frogs may carry just the genes we’re looking for.

We now hope to use these resistant frogs for a reintroduction program in nearby Wollumbin (Mount Warning) in NSW, where the species disappeared from in the 1990s. This approach may help the ecosystem of this iconic World Heritage site to thrive.![]()

Matthijs Hollanders, PhD candidate, Southern Cross University and David Newell, Senior Lecturer, School of Environment, Science & Engineering, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

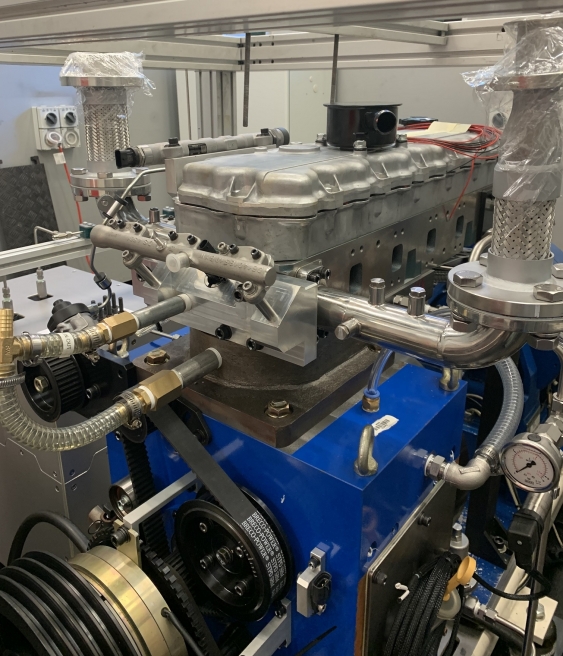

The Nord Stream breaches are a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities in undersea infrastructure

Claudio Bozzi, Deakin UniversityOn the night of September 26, near the end of the calm season on the Baltic, a broiling kilometre-wide circle disturbed the face of the sea and a huge mass of methane erupted into the air. The gas formed a cloud that crossed Europe, in what’s considered the greatest single release of this potent greenhouse gas ever recorded.

It was caused by four breaches of Russia’s Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines, located in or near the territorial seas of Denmark and Sweden. Seismologists detected explosions at a depth of 70-90 metres on the seabed. These were not earthquakes.

Danish, Swedish and German authorities have reported that the explosions were a deliberate act, equivalent to the use of 500 kilograms of TNT.

The bubbling surface of the Baltic is a stark visual image of fossil fuel consumption changing the world’s climate. Methane has over 25 times the global warming effect of the equivalent amount of carbon dioxide, and is a crucial target for combating climate change.

It also highlights the vulnerability of undersea pipelines and undersea infrastructure in general, of which Australia has a significant network.

Wasted Emissions

The explosions have had no direct economic or energy consequences. Nord Stream 1 stopped operating at the beginning of September following gradual supply reductions during the summer.

Nord Stream 2 was never launched as Germany refused to certify it following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Europe was not counting on the resumption of supplies from either pipeline.

While the pipelines were not transmitting gas, they contained methane gas to maintain pressure.

The amount of gas released is hard to quantify. Estimates suggest that roughly 300,000 tonnes of methane (or the equivalent of 7.5 million tonnes of carbon) has probably been released into the atmosphere, making it the largest release of methane in a single event (and over twice as large as the 2015 Aliso Canyon leak in California).

That tonnage represents around 10% of Germany’s annual methane output, or one third of Denmark’s total annual gas emissions, or the equivalent of the annual carbon emissions of one million cars. Nord Stream, however, is a wasted emission without either social benefit or productivity gains.

The leak is a reminder of the problem of “fugitive” methane, which comprises the leak, loss, escape and emission of gas from active or abandoned industrial sites.

While emissions from beef and rice production are the main culprits of fugitive emissions, oil and gas facilities also leak a significant amount of methane, as do activities such as fracking, coal mining and oil extraction. CSIRO estimates global oil and gas industries emit between 69 and 88 million tonnes of methane each year.

Australia’s Undersea Infrastructure Network

Critical undersea infrastructure plays a vital role in the global economy. For example, the fibre-optic cable network is the unseen lifeblood of globalisation, consisting of around 1.1 million kilometres of cables carrying 99% of global data.

When we talk about data flows and digital commodities we are, in fact, referring to the transmission of communications through these undersea cables. The stability of the global economy and the wealth of multi-national corporations depend on the integrity of these cables and on the uninterrupted connectivity they provide.

Undersea pipelines delivering oil and gas from one country or state to another form the material basis of energy markets. Australia’s offshore energy pipelines include the 740km-long Tasmanian Gas Pipeline, 300km of which is sub-sea, as well as the Gorgon (140km), Scarborough (280km), Pluto (180km), Browse (400km), and numerous others.

Undersea power cables are a rapidly developing infrastructure. The proposed undersea and underground Marinus power cable link will connect Tasmania and Victoria.

Harnessing the potential of offshore wind (now one of the largest energy investments globally) is being realised in Australian projects such as Star of the South. Meanwhile, Sun Cable aims to supply renewable energy produced in Australia to Singapore via 4,200km subacqueous cable.

While speculative, such projects represent aspects of the green power revolution which will drive emissions reductions, and which are likely to become more common. Ensuring the resilience of these systems against malicious digital and physical threats is a priority.

System Failures And Hostile Agents

The dependence of society and the economy on the reliability of this infrastructure is underappreciated.

The integration between cables and pipelines and the national and international markets they service is so tight, even the slightest disruption could inflict disproportionate economic damage.

These systems are so complex and closely integrated that their failures have consequences that traverse physical and national borders. This represents a significant challenge to ocean infrastructure governance.

System failure may occur because cables and pipelines are prone to accidental damage by ships’ anchors, trawl net fishing, and other undersea activities such as dredging. As the Nord Stream pipeline incident shows, they are also vulnerable to intentional hostile attack – both physical and cyber.

Hostile agents may exploit the fact that the sea is an opaque realm, one that’s difficult to operate in and defend. It, therefore, provides an effective shield against detection and subsequent prosecution.

Nord Stream was attacked in one of the busiest and the most surveilled seas in the world – the Baltic, in close proximity to the Danish military base of Bornholm Island. This clearly exposes the vulnerabilities of undersea infrastructure: it enables attackers to get close to targets undetected.

Cables and pipelines are governed by both national and international law. However, there are security gaps in international waters, where responsibility is ambiguously shared between corporations and government.

The lack of clarity gives companies little incentive to invest in security, or cooperate with government, increasing their vulnerability to attack.

The privatisation of cables and pipelines has resulted in cost-effective practices being adopted to reduce operating costs. But this has been achieved by reducing maintenance and surveillance.

Undersea infrastructure will continue to be vital to world trade and social cohesion. The growing demand for bandwidth and the need for energy security makes cables and pipelines both more crucial and vulnerable. Nord Stream highlights the need for resilient systems to limit the risk of accidents, and has given greater impetus to transition from fossil to renewable energy.![]()

Claudio Bozzi, Lecturer in Law, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

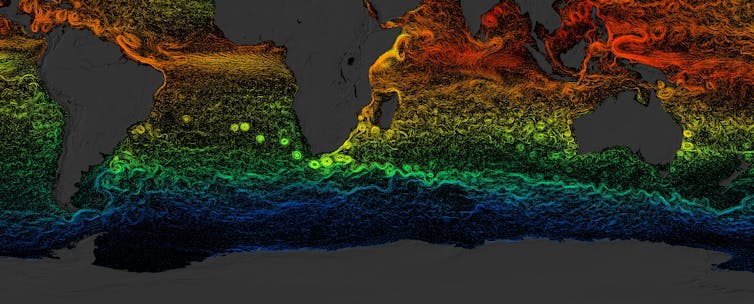

Shifting ocean currents are pushing more and more heat into the Southern Hemisphere’s cooler waters

The oceans absorb more than 90% of all extra heat trapped by the emissions we’ve produced by burning fossil fuels. This heat is enormous. It’s as if we exploded an atom bomb underwater, every second of every day.

The ocean isn’t warming at the same rate everywhere. We know the heat is concentrated in the fast, narrow currents that flow along the east coasts of the world’s continents and funnel warm water from the tropics down towards the poles.

In the Southern Hemisphere, these currents – known as the western boundary currents – are warming faster than the global average at their southern limits, creating ocean warming hotspots.

Until now, we haven’t known exactly why. These western boundary currents are particularly important in the Southern Hemisphere, which is more than 80% ocean compared to just 60% for the Northern Hemisphere.

Our new research has found a vital part of the puzzle: strong easterly winds in the mid-latitudes are moving south, driving the western boundary currents further south and leading to faster ocean warming in these areas.

What Are These Currents And Why Do They Matter?

These streams of warm water are like fast-flowing rivers in the oceans. They flow rapidly in a narrow band along the western side of the world’s major ocean basins, passing densely populated coastlines in South Africa, Australia and Brazil where hundreds of millions of people live.

These currents often play a role in regulating local climates. Think of the most well known of these currents, the Northern Hemisphere’s Gulf Stream, which has for millennia ensured Europe is much warmer than it would otherwise be given its latitude.

In the Southern Hemisphere, we have three major sub-tropical western boundary currents, the Agulhas Current in the Indian Ocean, the East Australian Current in the Pacific Ocean and the Brazil Current in the Atlantic Ocean.

In recent decades, these currents have become hotspots for ocean warming, carrying larger and larger amounts of heat south. Since 1993, the East Australian Current has moved southward at around 33 kilometres per decade, while the Brazil Current is moving south by around 46 kilometres per decade. The currents send heat and moisture into the atmosphere as they flow. In their southernmost reaches, the heat they carry displaces the colder ocean and warms it rapidly. These areas of the ocean are warming two to three times faster than the global average.

As the currents carry more heat energy, they also generate more ocean eddies – large rotating spirals of water spinning off from the main current. If you’ve looked closely at the way a fast flowing stream flows, you’ll see small eddies forming and dissolving all the time.

Why do these eddies matter? Because they’re the way heat actually ends up in the cold seas. As the eddies get faster and more loaded with heat, they act as path-breakers, carrying heat further south and eventually into the deep ocean. This is why NASA is soon to launch a new satellite to track these eddies, responsible for up to half of all heat transfer to the deep.

Our team have a research cruise planned for September next year aboard RV Investigator, Australia’s research vessel, to explore eddies under the path of this new satellite. This will shed new light on eddy processes in the warming ocean.

How Do The Winds Fit In?

Western boundary currents are driven by large-scale winds blowing across ocean basins.

You might have heard of the trade winds. These are the winds traders and mariners used for centuries to go from east to west, taking advantage of winds blowing constantly from the southeast across the tropics and subtropics.

Further south, the strongest winds are the prevailing westerlies, better known by sailors as the Roaring Forties. These westerly winds carry cold fronts and rain, and often stray north to dump rain over Australia.

These westerlies can change track over time, shifting northwards and southwards, depending on a pattern known as the Southern Annular Mode.

At present, this belt of strong westerly winds has strengthened and moved southward in what’s known as the mode’s positive phase. Since 1940, this climate pattern has increasingly favoured this positive phase, which tends to bring drier conditions to Australia.

When we analysed changes in the tropical trade winds over the past three decades, we found they too had shifted poleward 18 km per decade since 1993.

So what does this mean? The trade winds have been pushed further south while the Southern Annual Mode is increasing. As they move south, they drive the western boundary currents further southward.

Even though these currents are carrying ever-warmer water southwards from the tropics, they have not actually become stronger. Rather, they’ve become less stable in their southern regions as they’ve elongated. As the currents are pushed south, they transfer heat energy into the cold seas through chaotic eddies mixing the warmer water with the cold. These eddies aren’t small – they’re between 20 and 200 kilometres wide.

What Does This Mean For People And Nature?

Western boundary currents have long played a key role in stabilising our climate, by carrying heat southwards and moderating coastal climates. As these currents warp and become less predictable, they will change how heat is distributed, how gases are dissolved in seawater, and how nutrients are spread across the oceans. In turn, this will mean major changes to local weather patterns and marine ecosystems.

More intense eddies are likely to warm our coastal oceans, too, by moving warm waters closer to shore.

For many people, these currents are out of sight, out of mind. They won’t stay that way. As these vital currents change, they will change the lives and livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people who live along the coasts of South Africa, Australia and Brazil. ![]()

Moninya Roughan, Professor in Oceanography, UNSW Sydney and Junde Li, Postdoctoral research associate

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

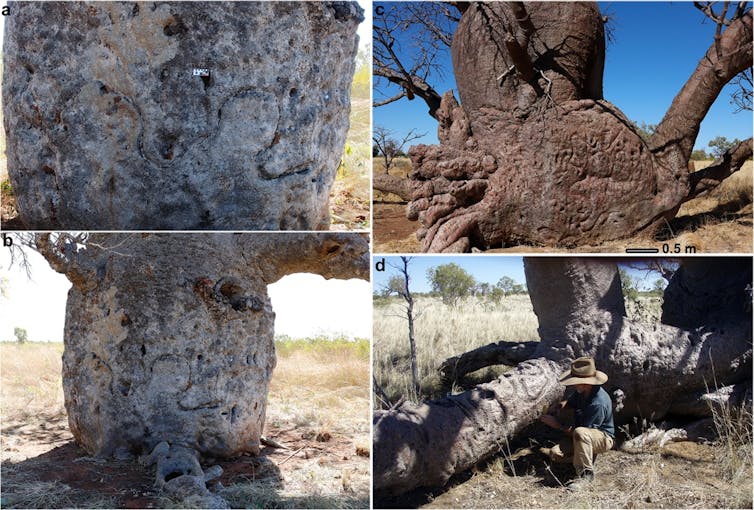

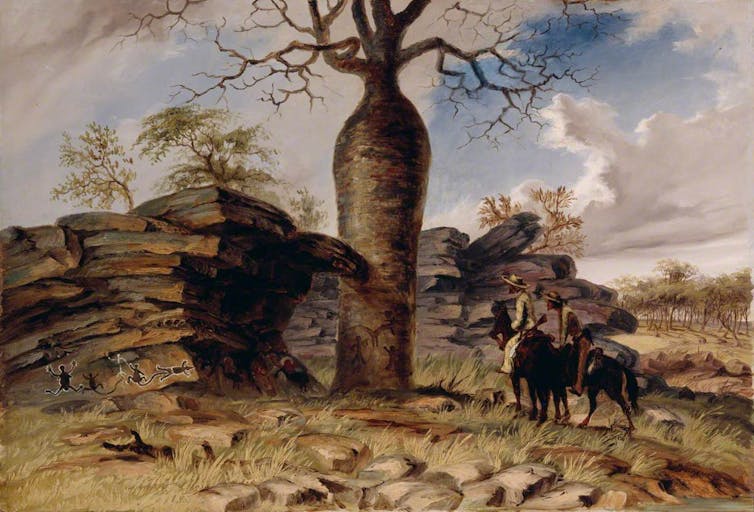

The boab trees of the remote Tanami desert are carved with centuries of Indigenous history – and they’re under threat

Australia’s Tanami desert is one of the most isolated and arid places on Earth. It’s a hard place to access and an even harder place to survive.