inbox and environment news: Issue 559

October 23 - 29, 2022: Issue 559

Impacting Pittwater - Have Your Say + Discussions + new works:

Conservation Zones Review Residents Forum: Resolutions Call For Shift In Criteria Applied, For Keeping Pittwater's Green-Blue Wings Intact, For State Election Candidates To Declare Their Position On Pittwater Community's Stated Expectations - feedback closes December 2nd

Motion To Have Fauna Management Plans In Local Council Comply With The NSW Code Of Practice For Injured, Sick And Orphaned Protected Fauna To Be Presented At LGNSW 2022 Conference - Some FMP's Passed Allow For Wildlife To Be Killed Where Their Homes Are Felled

Proposal For Barrenjoey Lighthouse Cottages To Be Used For Tourist Accommodation Open For Feedback - Again - feedback closes November 22nd

Avalon Beach Village Shared Space Timeline For Works Made Available - works commenced

World Kangaroo Day: Manly Beach October 24

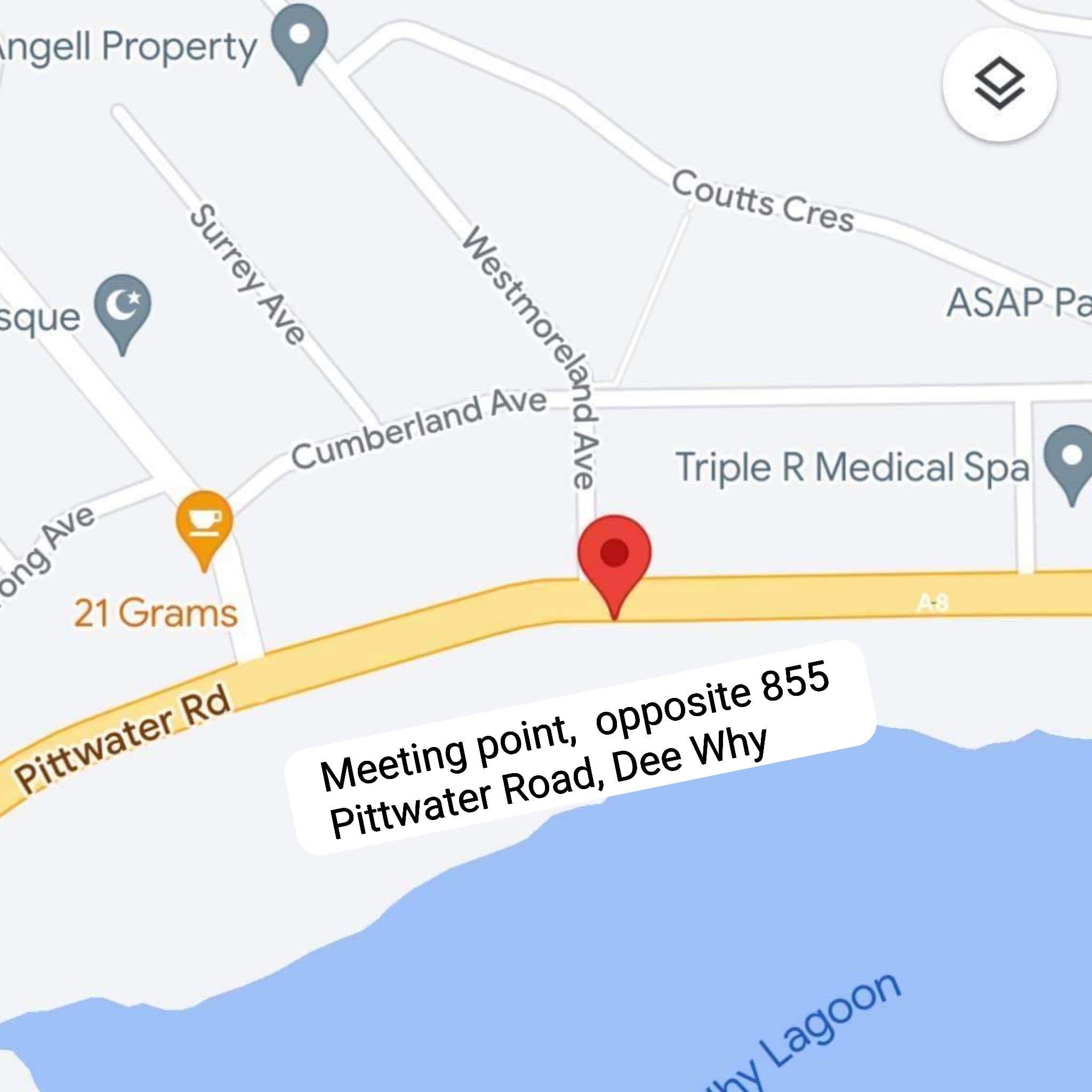

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Dee Why Lagoon Clean Up: October 30, 2022

- - You'll most likely get muddy

- - You'll most likely get wet

- - You'll walk a bush trail inside the lagoon

- - You'll see plenty of plastic bottles

- - getting in the reeds and getting muddy

- - carrying bags back to the tarp “bag runners”

- - sorting the rubbish on the tarps (we will have tarps for plastic bottles, glass bottles, etc)

Weed Small-Leafed Privet Flowering Now; Cut Flower Heads To Prevent Seeding

Single-Use Plastics Ban In NSW Commences November 1st, 2022

- serving utensils such as salad servers or tongs

- items that are an integrated part of the packaging used to seal or contain food or beverages, or are included within or attached to that packaging, through an automated process (such as a straw attached to a juice box).

- meat or produce trays

- packaging, including consumer and business-to-business packaging and transport containers

- food service items that are an integrated part of the packaging used to seal or contain food or beverages, or are including within or attached to that packaging, through an automated process (such as an EPS noodle cup).

- polyethylene (PE)

- polypropylene (PP)

- polyethylene terephthalate (PET)

- polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)

- nylon (PA).

- carrying on an activity for commercial purposes. For example:

- retail businesses like a restaurant, café, bar, takeaway food shop, party supply store, discount store, supermarket, market stall, online store, and packaging supplier and distributor, and any other retailer that provides these items to consumers.

- a manufacturer, supplier, distributor or wholesaler of a prohibited item

- carrying on an activity for charitable, sporting, education or community purposes. For example, a community group, not-for-profit organisation or charity, including those that use a banned item as part of a service, for daily activities or during fundraising events.

From 1 June 2022 The Following Was Banned:

- barrier bags such as bin liners, human or animal waste bags

- produce bags and deli bags

- bags used to contain medical items (excluding bags provided by a retailer to a consumer used to transport medical items from the retailer).

Help Needed To Save Sea Turtle Nests As Third La Nina Summer Looms

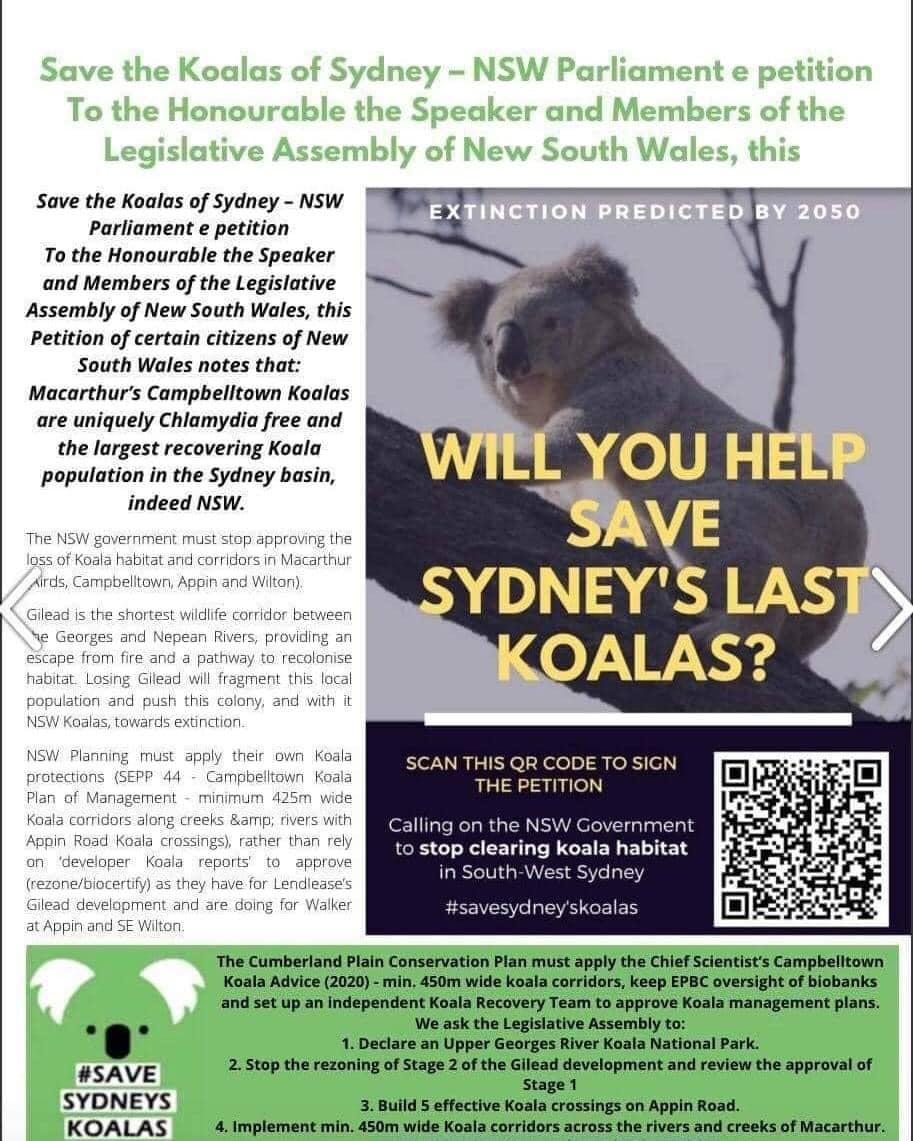

Save Sydney's Koalas Petition

National Bird Week + Aussie Bird Count 2022

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

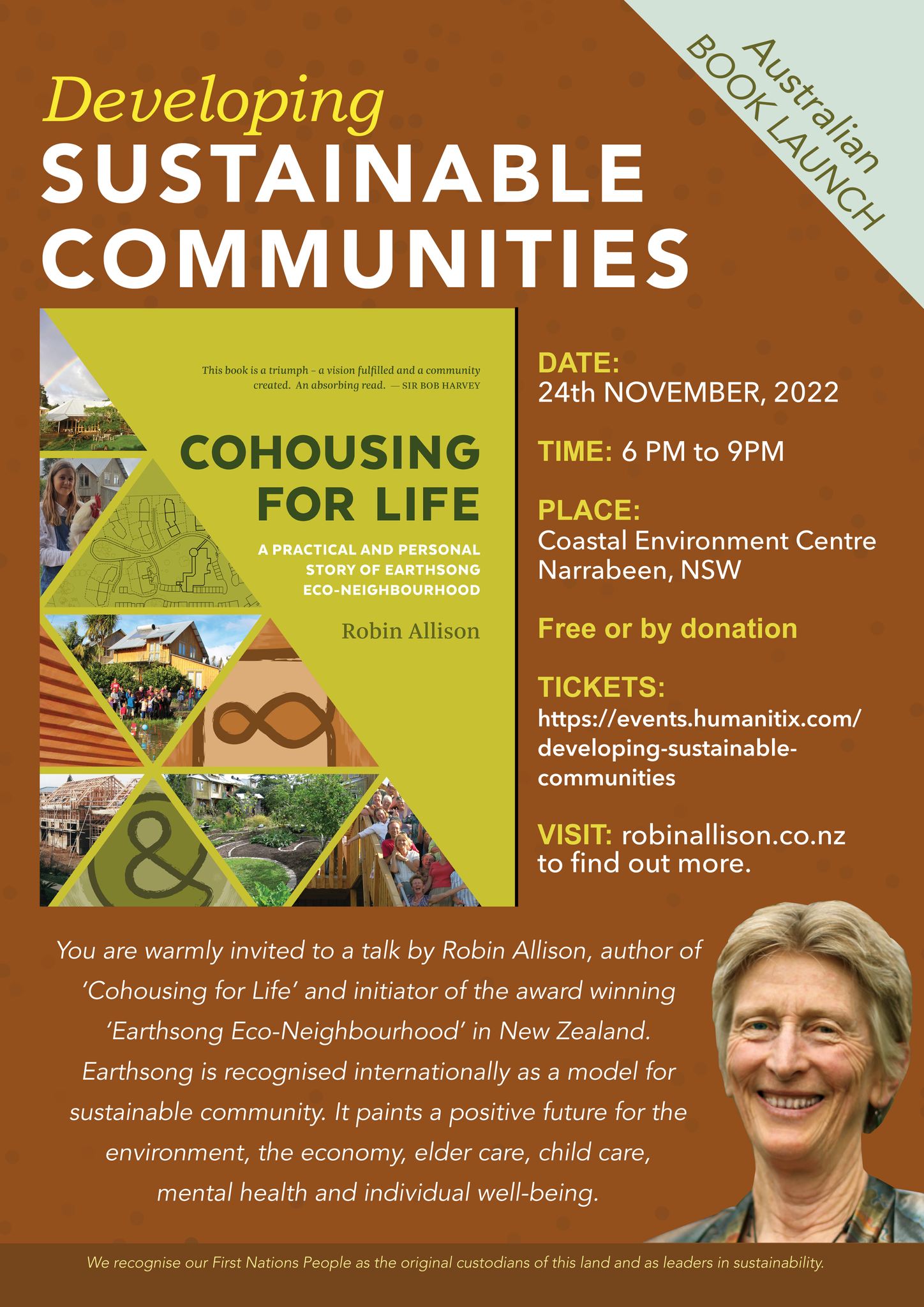

TALK & BOOK LAUNCH

Book Your Free Ticket To: Developing Sustainable Communities

Weed Alert: Corky Passionflower At Mona Vale + Narrabeen Creek

.jpg?timestamp=1663392221562)

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary Open

EPA Releases Climate Change Policy And Action Plan

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is taking action to protect the environment and community from the impacts of climate change, today releasing its new draft Climate Change Policy and Action Plan which works with industry, experts and the community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support resilience.

NSW EPA Chief Executive Officer Tony Chappel said the EPA has proposed a set of robust actions to achieve a 50 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (from 2005 levels), ensure net zero emissions by 2050, and improve resilience to climate change impacts.

“NSW has ambitious targets that align with the world’s best scientific advice and the Paris commitments, to limit global warming to an average of 1.5 degrees in order to avoid severe impacts on ecosystems,” Mr Chappel said.

“Over the past few years we have seen first-hand just how destructive the impacts of climate change are becoming, not only for our environment, but for NSW communities too.

“We know the EPA has a critical role to play in achieving the NSW Government’s net-zero targets and responding to the increasing threat of climate change induced weather events.

“Equally, acting on climate presents major economic opportunities for NSW in new industries such as clean energy, hydrogen, green metals, circular manufacturing, natural capital and regenerative agriculture.

“This draft Policy sends a clear signal to regulated industries that we will be working with them to support and drive cost-effective decarbonisation while implementing adaptation initiatives that build resilience to climate change risks.

“Our draft plan proposes a staged approach that ensures the actions the EPA takes are deliberate, well informed and complement government and industry actions on climate change. These actions will support industry and allow reasonable time for businesses to plan for and meet any new targets or requirements.

“Climate change is an issue that we all face so it’s important that we take this journey together and all play our part in protecting our environment and communities for generations to come.”

Actions include:

- working with industry, government and experts to improve the evidence base on climate change

- supporting licensees prepare, implement and report on climate change mitigation and adaptation plans

- partnering with NSW Government agencies to address climate change during the planning and assessment process for activities the EPA regulates

- establishing cost-effective emission reduction targets for key industry sectors

- providing industry best-practice guidelines to support them to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

- phasing in the introduction of greenhouse gas emission limits on environment protection licences for key industry sectors

- developing and implementing resilience programs, best-practice adaptation guidance and harnessing citizen science and education programs

- working with EPA Aboriginal and Youth Advisory Committees to improve the EPA’s evolving climate change response

EPA Acting Chair Carolyn Walsh said the EPA is a partner in supporting and building on the NSW Government’s work to address climate change for the people of NSW.

“The draft Policy and Action Plan adopts, supports and builds on the strong foundations that have been set by the NSW Government through the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework, Net Zero Plan and Climate Change Adaptation Strategy,” Ms Walsh said.

The EPA will work with stakeholders, including licensees, councils, other government agencies, and the community to help implement the actions.

The draft EPA Climate Change Policy and Action Plan is available at https://yoursay.epa.nsw.gov.au/ and comments are open until 3 November 2022.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

‘Gut-wrenching and infuriating’: why Australia is the world leader in mammal extinctions, and what to do about it

In fewer than 250 years, the ravages of colonisation have eroded the evolutionary splendour forged in this continent’s relative isolation. Australia has suffered a horrific demise of arguably the world’s most remarkable mammal assemblage, around 87% of which is found nowhere else.

Being an Australian native mammal is perilous. Thirty-eight native mammal species have been driven to extinction since colonisation and possibly seven subspecies. These include:

- Yirratji (northern pig-footed bandicoot)

- Parroo (white-footed rabbit-rat)

- Kuluwarri (central hare-wallaby)

- Yallara (lesser bilby)

- Tjooyalpi (lesser stick-nest rat)

- Tjawalpa (crescent nailtail wallaby)

- Yoontoo (short-tailed hopping-mouse)

- Walilya (desert bandicoot)

- toolache wallaby

- thylacine

This makes us the world leader of mammal species extinctions in recent centuries. But this is far from just an historical tragedy.

A further 52 mammal species are classified as either critically endangered or endangered, such as the southern bent-wing bat, which was recently crowned the 2022 Australian Mammal of the Year. Fifty-eight mammal species are classed as vulnerable.

Many once-abundant species, some spread over large expanses of Australia, have greatly diminished and the distributions of their populations have become disjointed. Such mammals include the Mala (rufous hare-wallaby), Yaminon (northern hairy-nosed wombat), Woylie (brush-tailed bettong) and the Numbat.

This means their populations are more susceptible to being wiped out by chance events and changes – such as fires, floods, disease, invasive predators – and genetic issues. The ongoing existence of many species depends greatly upon predator-free fenced sanctuaries and offshore islands.

Without substantial and rapid change, Australia’s list of extinct mammal species is almost certain to grow. So what exactly has gone so horribly wrong? What can and should be done to prevent further casualties and turn things around?

Up To Two Mammal Species Gone Per Decade

Australia’s post-colonisation mammal extinctions may have begun as early as the 1840s, when it’s believed the Noompa and Payi (large-eared and Darling Downs hopping mice, respectively) and the Liverpool Plains striped bandicoot went extinct.

Many extinct species were ground dwellers, and within the so-called “critical weight range” of between 35 grams and 5.5 kilograms. This means they’re especially vulnerable to predation by cats and foxes.

Small macropods (such as bettongs, potoroos and hare wallabies) and rodents have suffered most extinctions – 13 species each, nearly 70% of all Australia’s mammal extinctions.

Eight bilby and bandicoot species and three bats species are also extinct, making up 21% and 8% of extinctions, respectively.

The most recent fatalities are thought to be the Christmas Island pipistrelle and Bramble Cay melomys, the last known record for both species was 2009. The Bramble Cay melomys is perhaps the first mammal species driven to extinction by climate change.

Overall, research estimates that since 1788, about one to two land-based mammal species have been driven to extinction each decade.

When Mammals Re-Emerge

It’s hard to be certain about the timing of extinction events and, in some cases, even if they’re actually extinct.

For example, Ngilkat (Gilbert’s potoroo), the mountain pygmy possum, Antina (the central rock rat), and Leadbeater’s possum were once thought extinct, but were eventually rediscovered. Such species are often called Lazarus species.

Our confidence in determining whether a species is extinct largely depends on how extensively and for how long we’ve searched for evidence of their persistence or absence.

Modern approaches to wildlife survey such as camera traps, audio recorders, conservation dogs and environmental DNA, make the task of searching much easier than it once was.

But sadly, ongoing examination and analysis of museum specimens also means that we’re still discovering species not known to Western science and that tragically are already extinct.

What’s Driving Their Demise?

Following colonisation, Australia’s landscapes have suffered extensive, severe, sustained and often compounding blows. These include:

- widespread habitat modification and destruction

- the introduction of invasive predators, such as feral cats, red foxes and herbivores (European rabbits, feral horses, goats, deer, water buffalo, donkeys)

- toxic “prey” (cane toads)

- intense livestock grazing

- changed fire patterns associated with the forced displacement of First Nations peoples and cultural practices

- climate change

- hunting

- disease.

And importantly, the ongoing persecution of Australia’s largest land-based predator: the dingo. In some circumstances, dingoes may help reduce the activity and abundance of large herbivores and invasive predators. But in others, they may threaten native species with small and restricted distributions.

Through widespread land clearing, urbanisation, livestock grazing and fire, some habitats have been obliterated and others dramatically altered and reduced, often resulting in less diverse and more open vegetation. Such simplified habitats can be fertile hunting grounds for red foxes and feral cats to find and kill native mammals.

To make matters worse, European rabbits compete with native mammals for food and space. Their grazing reduces vegetation and cover, endangering many native plant species in the process. And they are prey to cats and foxes, sustaining their populations.

While cats and foxes, fire, and habitat modification and destruction are often cited as key threats to native mammals, it’s important to recognise how these threats and others may interact. They must be managed together accordingly.

For instance, reducing both overgrazing and preventing frequent, large and intense fires may help maintain vegetation cover and complexity. In turn, this will make it harder for invasive predators to hunt native prey.

What Must Change?

Above all else, we genuinely need to care about what’s transpiring, and to act swiftly and substantially to prevent further damage.

As a mammalogist of some 30 years, the continuing demise of Australia’s mammals is gut-wrenching and infuriating. We have the expertise and solutions at hand, but the frequent warnings and calls for change continue to be met with mediocre responses. At other times, a seemingly apathetic shrug of shoulders.

So many species are now gone, probably forever, but so many more are hurtling down the extinction highway because of sheer and utter neglect.

Encouragingly, when we care for and invest in species, we can turn things around. Increasing numbers of Numbats, Yaminon and eastern-barred bandicoots provide three celebrated examples.

Improving the prognosis for mammals is eminently achievable but conditional on political will. Broadly speaking, we must:

- minimise or remove their key threats

- align policies (such as energy sources, resource use, and biodiversity conservation)

- strengthen and enforce environmental laws

- listen to, learn from and work with First Nations peoples as part of healing Country

- invest what’s actually required – billions, not breadcrumbs.

The recently announced Threatened Species Action plan sets an ambitious objective of preventing new extinctions. Of the 110 species considered a “priority” to save, 21 are mammals. The plan, however, is not fit for purpose and is highly unlikely to succeed.

Political commitments appear wafer thin when the same politicians continue to approve the destruction of the homes critically endangered species depend upon. What’s more, greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets are far below what climate scientists say are essential and extremely urgent.

There’s simply no time for platitudes and further dithering. Australia’s remaining mammals deserve far better, they deserve secure futures.![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Gas Grants For Middle Arm Announcement Astounds Community

The magnificent Lake Eyre Basin is threatened by 831 oil and gas wells – and more are planned. Is that what Australians really want?

Richard Kingsford, UNSW SydneyThe heart-shaped Lake Eyre Basin covers about one-sixth of Australia. It contains one of the few remaining pristine river systems in the world.

But new research shows oil and gas activity is extending its tentacles into these fragile environments. Its wells, pads, roads and dams threaten to change water flows and pollute this magnificent ecosystem.

The study, by myself and colleague Amy Walburn, investigated current and future oil and gas production and exploration on the floodplains of the Lake Eyre Basin. We found 831 oil and gas wells across the basin – and this number is set to grow. What’s more, state and Commonwealth legislation has largely failed to control this development.

State and national governments are promoting massive gas development to kickstart Australia’s economy. But as we show, this risks significant damage to the Lake Eyre Basin and its rivers.

A Precious Natural Wonder

The Lake Eyre Basin is probably the last major free-flowing river system on Earth – meaning no major dams or irrigation diversions stem the rivers’ flow.

This country has been looked after for tens of thousands of year by First Nations people, including the Arrernte, Dieri, Mithaka and Wangkangurru. This care continues today.

The biggest rivers feeding the basin – the Diamantina, Georgina and Cooper – originate in western Queensland and flow to South Australia where they pour into Kathi Thanda-Lake Eyre.

As they wind south, the rivers dissect deserts and inundate floodplains, lakes and wetlands – including 33 wetlands of national importance.

This natural phenomenon has happened for millennia. It supports incredible natural booms of plants, fish and birds, as well as tourism and livestock grazing. But our new research shows oil and gas development threatens this precious natural wonder.

Massive Industrial Creep

Our analysis used satellite imagery to map the locations of oil and gas development in the Lake Eyre Basin since the first oil wells were established in late 1950s.

We found 831 oil and gas production and exploration wells exist on the floodplains of the Lake Eyre Basin – almost 99% of them on the Cooper Creek floodplains. The wells go under the river and its floodplains into the geological Cooper Basin, considered to have the most important onshore petroleum and natural gas deposits in Australia.

Our research also shows how quickly oil and gas mining in the Lake Eyre Basin is set to grow. We identified licensing approvals or applications covering 4.5 million hectares of floodplains in the Lake Eyre Basin, across South Australia and Queensland.

The CSIRO recently examined likely scenarios of 1,000 to 1,500 additional unconventional gas wells in the Cooper Basin in the next 50 years. It predicted these wells would built be on “pads” – areas occupied by mining equipment or facilities – about 4 kilometres apart. They would typically access gas using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

Fracking is the process of extracting so-called “unconventional gas”. It involves using water and chemicals to fracture deep rocks to extract the gas. This polluted water, known to be toxic to fish, is brought back to the surface and stored in dams.

Two locations we focused on were in South Australia at the protected, Ramsar-listed Coongie Lakes site, which was recognised as internationally significant in 1987. The other site was in Queensland’s channel country, also on the Cooper floodplain.

In total across the Coongie Lakes sites, we found a three-fold increase in wells: from 95 in 1987 to 296 last year. We also identified 869 kilometres of roads and 316 hectares of storage pits, such as those that hold water.

Some of these dams could potentially hold polluted fracking water and become submerged by flooding, particularly at Coongie Lakes.

A Disaster Waiting To Happen?

Examples from around the world already show oil and gas exploration and development can reduce water quality by interrupting sediments and leading to elevated chemical concentrations. Production waste can also degrade floodplain vegetation.

The CSIRO says risks associated with oil and gas development in the Cooper Basin include:

- dust and emissions from machinery that may cause habitat loss, including changes to air quality, noise and light pollution

- disposal and storage of site materials that may contaminate soil, surface water and/or groundwater through accidental spills, leaks and leaching

- unplanned fracking and drilling into underground faults, unintended geological layers or abandoned wells

- gas and fluids contaminating soil, surface water, groundwater and air

- changes to groundwater pressures could potentially reactivate underground faults and induce earthquakes.

Fracking for unconventional gas also requires drawing large amounts of water from rivers and groundwater.

The Laws Have Failed

Our findings raise significant questions for Australian governments and the community.

Are we prepared to accept industrialisation of the Lake Eyre Basin, and the associated risk of pollution and other environmental damage? Have the companies involved earned a social licence for these activities? Where do the profits end up, and who will bear the social, environmental and financial costs of such intense development?

Clearly, state and federal environmental protections have failed to stop unfettered development of the basin.

These policies include the Lake Eyre Basin Agreement, signed by the states, the Commonwealth and the Northern Territory, which has been in place since 2000.

Australia’s federal environment law – the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act – is supposed to protect nationally important areas such as Ramsar wetlands. Yet our research identified that just eight developments in the basin were referred to the Commonwealth government for approval and with only one deemed significant enough for assessment. This legislation does not deal adequately with the cumulative impacts of development.

And finally, gas extraction and production is associated with substantial “fugitive” emissions - greenhouse gases which escape into the atmosphere. This undermines Australia’s emissions reduction efforts under the Paris Agreement.

The governments of South Australia and Queensland should restrict mining development in the Lake Eyre Basin. And stronger federal oversight of this nationally significant natural treasure is urgently needed.

In response to this article, Chief executive of the Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association, Samantha McCulloch, said in a statement:

The oil and gas industry takes its responsibilities to the environment and to local communities seriously and it is one of the most heavily regulated sectors in Australia. The industry has been operating in Queensland for more than a decade and the gas produced in Queensland plays an important role in Australia’s energy security.

Richard Kingsford, Professor, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tasmanian Fast-Tracked Rezoning Laws For Development Alongside Critically-Endangered Forty-Spotted Pardalote Gets Federal Approval - Bird Week 2022

Release Of Environment Ministers' Meeting Communique

- To work collectively to achieve a national target to protect and conserve 30% of Australia’s landmass and 30% of Australia’s marine areas by 2030.

- To note the Commonwealths’ intention to establish a national nature repair market and agreed to work together to make nature positive investments easier, focusing on a consistent way to measure and track biodiversity.

- To work with the private sector to design out waste and pollution, keep materials in use and foster markets to achieve a circular economy by 2030.

NSW Continues To Lead On A Better, Cleaner Environment: NSW Minister For Environment James Griffin

Scotts Head Development Withdrawal A Win For Community Power: Greens

Calling All Slug Sleuths

How to ensure the world’s largest pumped-hydro dam isn’t a disaster for Queensland’s environment

To quit coal and move to renewables, we need large-scale energy storage. That’s where pumped hydro comes in. Queensland’s ambitious new plan involves shifting from a coal-dominated electricity grid to 80% renewables within 13 years, using 22 gigawatts of new wind and solar. The plan relies on two massive new pumped hydro developments to store electricity, including the biggest proposed in the world.

While it sounds high-tech, it’s very simple: take two dams at different elevations. Pump water to the top dam when cheap renewables are flooding the grid. Run the water down the slope and through turbines to make power at night or when the wind isn’t blowing.

When dams are built badly, however, they can trash the environment. For two decades, I’ve pointed out the environmental destruction conventional dams can cause. But now we urgently need more pumped hydro dams to enable Australia’s transition to fully renewable power.

Queensland Is Getting Pumped

Queensland’s huge new renewable energy plan relies heavily on two massive pumped hydro projects. Inland from the Sunshine Coast is Borumba Dam, which could deliver two gigawatts of 24-hour storage by 2030. This was first proposed last year. The new proposal is Pioneer-Burdekin, west of Mackay, which is intended to store five gigawatts of 24-hour storage from the 2030s. It would involve relocating residents of the small town of Netherdale, which would be inundated.

For consumers, this means energy reliability. Each gigawatt of stored power could supply around two million homes – and Queensland has around two million households.

Environmentally, the good news is we can learn from previous mistakes and build this vital infrastructure carefully to minimise local environmental damage and maximise the broader environmental benefit of quitting coal power.

Why Is Pumped Hydro So Important To The Energy Transition?

Solar and wind power can produce vast quantities of cheap power – but not all the time. Pumped hydro is one way to store renewable energy when it’s being generated and releasing it later when needed.

While grid-scale batteries such as Victoria’s Big Battery have drawn plenty of media coverage, they are better at storing smaller amounts of electricity and releasing it quickly. Pumped hydro is slightly slower to start feeding back to the grid, but big facilities can keep generating power for days.

Renewable fuels such as green hydrogen and ammonia may be available in the future, but not now. Nuclear energy is very expensive and would take decades to build. Batteries cannot meet supply gaps longer than a few hours, and come with environmental costs from the mining of raw materials, manufacture, and recycling and disposal of toxic materials.

That leaves pumped hydro as a vital option – especially on cold, still and overcast days in winter when solar and wind produce very little electricity.

So Why Is Pumped Hydro A Better Environmental Prospect?

Conventional hydropower dams destroy river ecosystems and flood forests, towns and prime farm land. Globally, the hydropower industry anticipates expanding by 60% by 2050 to provide renewable electricity and storage.

I’m less worried about pumped hydro, for three reasons.

First, the two reservoirs can be built away from rivers. This alone greatly reduces the damage done by damming rivers and flooding fertile valleys.

Second, the area flooded is generally an order of magnitude smaller than conventional hydropower. This is because the great elevation difference between the two reservoirs may enable more power to be generated from limited water.

And third, pumped hydro doesn’t need much extra water once filled, as the water cycles around. A little topping up to replace losses from evaporation and seepage is all that’s needed.

More than 3,000 potential sites for pumped hydro have been identified in Australia. Importantly, these are all outside formal nature reserves and mostly located along the Great Dividing Range. We’d only need around 20 of these sites to be developed to store power for the nation. That’s around the same number currently planned, built or under construction in Tasmania, South Australia, New South Wales and Queensland.

Nearly all large renewable energy developments meet local opposition based on non-financial values. Opponents of big pumped hydro developments such as Snowy 2.0 have called for other sites to be developed instead.

If we took this approach, however, we could multiply the environmental disruption. That’s because Snowy 2.0, as well as the proposed Borumba and Pioneer-Burdekin projects in Queensland are huge. They could each generate up to ten times more power than most of the other projects being planned elsewhere.

Shifting elsewhere could mean many more smaller projects, which means more roads, transmission lines and reservoirs.

Avoiding The Mistakes Of The Past

Environmental disruption from pumped hydro differs greatly depending on the site.

At the site selection stage, it’s vital to avoid areas of high conservation and Indigenous cultural value.

We can limit environmental damage by using existing dams, as we’re seeing at Snowy 2.0. Old mines in the right locations can have a second life as pumped hydro, as the Kidston project in Queensland demonstrates.

By using existing dams or mines, we can actually begin repairing past damage, such as by improving old dams to boost environmental flows.

That’s not to say damage won’t be done. Pumped hydro has been linked to the introduction of diseases affecting wildlife, as well as invasive plant and animal species.

Roads and transmission lines are one of the biggest impacts on the natural world. For example, nine kilometres of new overhead transmission lines are proposed to access the Snowy 2.0 project, which involves clearing forest in Kosciuszko National Park.

We could dramatically reduce environmental damage and visual clutter by putting the lines underground, or building close to existing power lines.

So, the choice is ours. While pumped hydro is a lot less damaging than traditional hydroelectricity, it will cause some environmental damage.

That’s why pumped hydro developers must choose sites and build carefully, to minimise environmental damage and maximise the benefits of storage. After all, this technology offers the enormous environmental good of freeing ourselves from the need to burn coal, gas and oil every hour of every day.

This article has been corrected. It originally suggested more habitat would be cleared for new Snowy 2.0 transmission lines than for the project’s new roads and pipelines.![]()

Jamie Pittock, Professor, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rewiring The Nation Supports Its First Two Transmission Projects

NSW Government Pushes Ahead With Dungowan Dam - EIS Now On Display - Despite Infrastructure Australia Stating Is Not On Priority List

''The New Dungowan Dam and Pipeline aims to increase town water supply for Tamworth and maintain water reliability for agricultural production in the Peel Valley. The proposal was developed in response to long periods of drought and water restrictions. At a time in 2019, Tamworth was 12 months away from running out of water from its primary water source, the Chaffey Dam.The project has a capital cost of more than $1 billion and a benefit cost-ratio of just 0.09. Although it offers sustainability and resilience benefits, our assessment found that similar community benefits could be achieved through a combination of lower cost build and non-build options.This includes increasing the amount of water from Chaffey Dam that is available for urban use, along with policy changes such as demand management and water use efficiency measures.We would welcome a revised business case for an investment solution that better aligns to the identified problems and opportunities for providing increased water security to the Tamworth region.'' Infrastructure Australia, the federal arm, stated.

NSW Government Announces Supplementary Water For Murray Irrigators

Chasm Opens Up Around Liverpool Plains Gas Pipeline

Mining Lobbyists Weakens Well-Intentioned Queensland Environmental Laws Once Again

- Updating environmental conditions for older coal and gas projects operating under conditions that are not up to modern standards.

- Requiring a condition about the scale and intensity of an activity

- Introducing uniform conditions to similar Environmental Authorities.

- All major amendments to Environmental Authorities will now be publicly notified, giving local communities a say.

- The public interest of projects will be assessed by a pool of independent assessors.

- Companies will have to progress their projects or withdraw from the assessment process, mitigating a problem where communities faced years of heartache and limbo while waiting to see if a project would go ahead.

Our environmental responses are often piecemeal and ineffective. Next week’s wellbeing budget is a chance to act

Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ federal budget next week will for the first time include a section on wellbeing, which aims to measure how well Australians are doing in life.

The wellbeing budget will, among other things, assess the state of our natural places using a set of environmental indicators. But what indicators? And what environmental information should be used?

Getting meaningful environmental measures into the wellbeing budget won’t be easy. And tokenism won’t do.

We need a system providing comprehensive, regular and up-to-date information that can genuinely inform environmental and economic decisions.

An Information ‘Grab Bag’

Australia has, for too long, relied on the five-yearly State of the Environment reports for updates on how our environment is faring, using a grab-bag of information. As the latest report noted:

Australia currently lacks a framework that delivers holistic environmental management to integrate our disconnected legislative and institutional national, state and territory systems, and break down existing barriers to stimulate new models and partnerships for innovative environmental management and financing.

In other words, we cannot get our environmental act together. Our responses to problems are often piecemeal and ineffective. We do not even have the information we need to fix them.

We’re yet to see what environmental information is included in next week’s wellbeing budget.

The Nine newspapers on Wednesday reported that no indicators have been agreed upon as yet, but the budget papers will contain a chapter on methods used in other jurisdictions, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s long-running wellbeing framework.

Given the dearth of good information, the government must resist the temptation to rely on partial, uninformative or misleading environmental statistics.

These might include the number of listed threatened species (which would be larger if the environment department had been better-resourced) or the extent of the network of protected areas (which is large but significantly under-represents many ecosystems).

There’s no problem starting with what we have. But we must get to what we need.

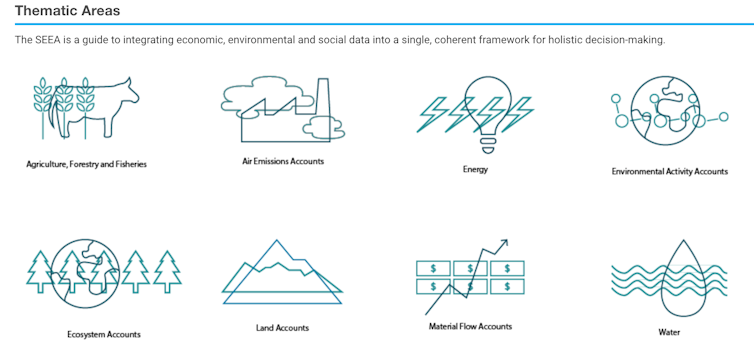

We could draw inspiration from the giant information and policy apparatus in the public service that helps us track economic progress, and use a United Nations framework called the System of Environmental Economic Accounting (sometimes shortened to SEEA).

The Giant Information And Policy Apparatus

Every day, thousands of public servants work to gauge what the economy is doing and figure out what it means for industry, the government and the public.

Gross domestic product is measured, reported and debated. The Australian Bureau of Statistics releases it to a set schedule, without needing ministerial approval. Good or bad, the data comes out.

Officials from treasury, the finance department and the Reserve Bank pore over the figures. Their analyses and advice are sent to the treasurer, prime minister and cabinet.

If growth is too strong, the Reserve Bank might increase interest rates. If the economy is weak, the government might stimulate it with infrastructure spending.

Compare this to what we have for the environment.

A five-yearly State of the Environment report. In between reports, environmental problems are identified by scientists, environment groups and concerned citizens. Environmental laws are largely reactive. The agencies tasked with responding have limited funding and information.

The result? We consume the environment salami, one slice at a time, without knowing how much is left.

One example is the box-gum grassy woodlands once common across much of southeast Australia. These woodlands were protected under Australia’s most significant environmental law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

A recovery plan was prepared. But there’s no evidence the plan was delivered and the ecosystem is still no better off.

In his 2020 review of the EPBC Act, Professor Graeme Samuel recommended an overhaul, saying

National Environmental Standards should be immediately developed and implemented to provide clear rules and improved decision-making.

Recognising this couldn’t happen without a system of comprehensive environmental information, Samuel recommended building one including national environmental-economic accounts.

These should be tabled annually in parliament alongside traditional budget reporting.

Samuel’s approach strongly resembles the way governments manage the economy: use regular information to adjust policy settings to stay on trajectory towards desired outcomes.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has hinted she is inclined to follow Samuel, describing his review as “thorough”.

So if environmental management is going to emulate economic management and be informed by the accounts Samuel envisioned, then just what are they?

What Is Environmental-Economic Accounting And What’s The UN-Backed System?

Environmental-economic accounting is an information system blueprint.

SEEA-based accounts are ready-made to provide information for environmental decision-making, just as the national accounts inform economic decision-making.

This UN-backed system was only completed in 2021, so real-world examples remain few. But one Victorian study shows the potential.

The accounts in the study showed the economic benefit of harvesting Central Highlands native forests for timber were far outweighed by the economic benefit of maintaining the forests for carbon storage and water supply. In other words, the forest is more valuable if you just leave it alone.

Ceasing harvesting would also bring major biodiversity gains. An assessment of all regional forest agreement areas in Victoria gave similar results.

On paper, Australia’s governments in 2018 endorsed the SEEA and adopted a national strategy to implement it.

In practice however, these governments are yet to produce the vision or political will to build a such a system that will actually inform environmental decisions.

Overseas, change is underway. The US, previously a laggard, now has an ambitious strategy to build environmental-economic accounts into their national information system.

An Urgent Need

Establishing a comprehensive set of environmental-economic accounts is the first step in delivering integrated environmental and economic management.

The United Nation’s System of Environmental-Economic Accounting offers a way forward. Graeme Samuel recommended it. Now government must deliver it. But it will take time and it won’t be cheap.

Early signs are positive but can Plibersek and Chalmers stay the course? Our future depends on it.![]()

Michael Vardon, Associate Professor at the Fenner School, Australian National University and Peter Burnett, Honorary Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

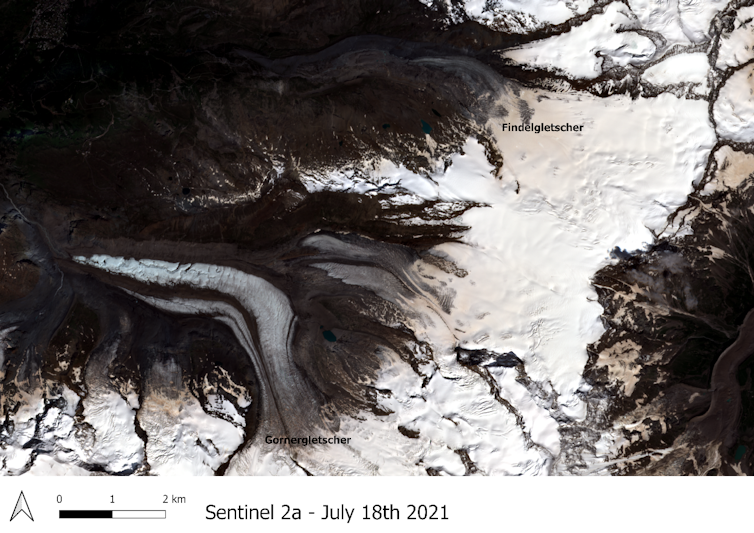

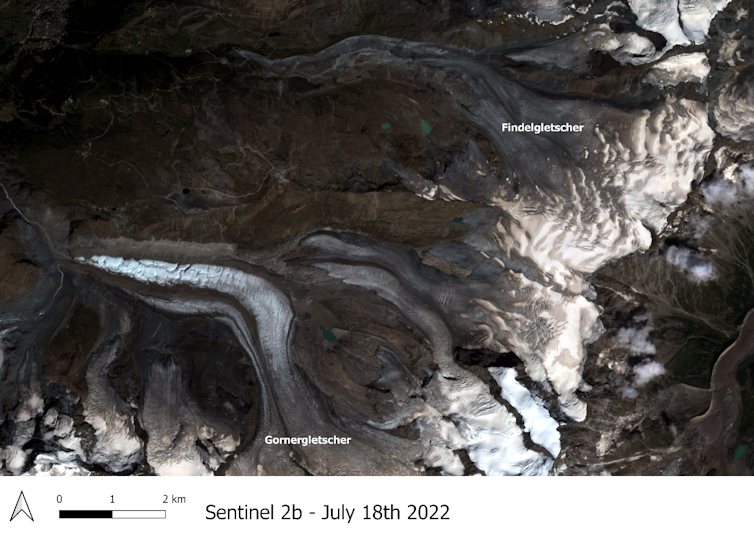

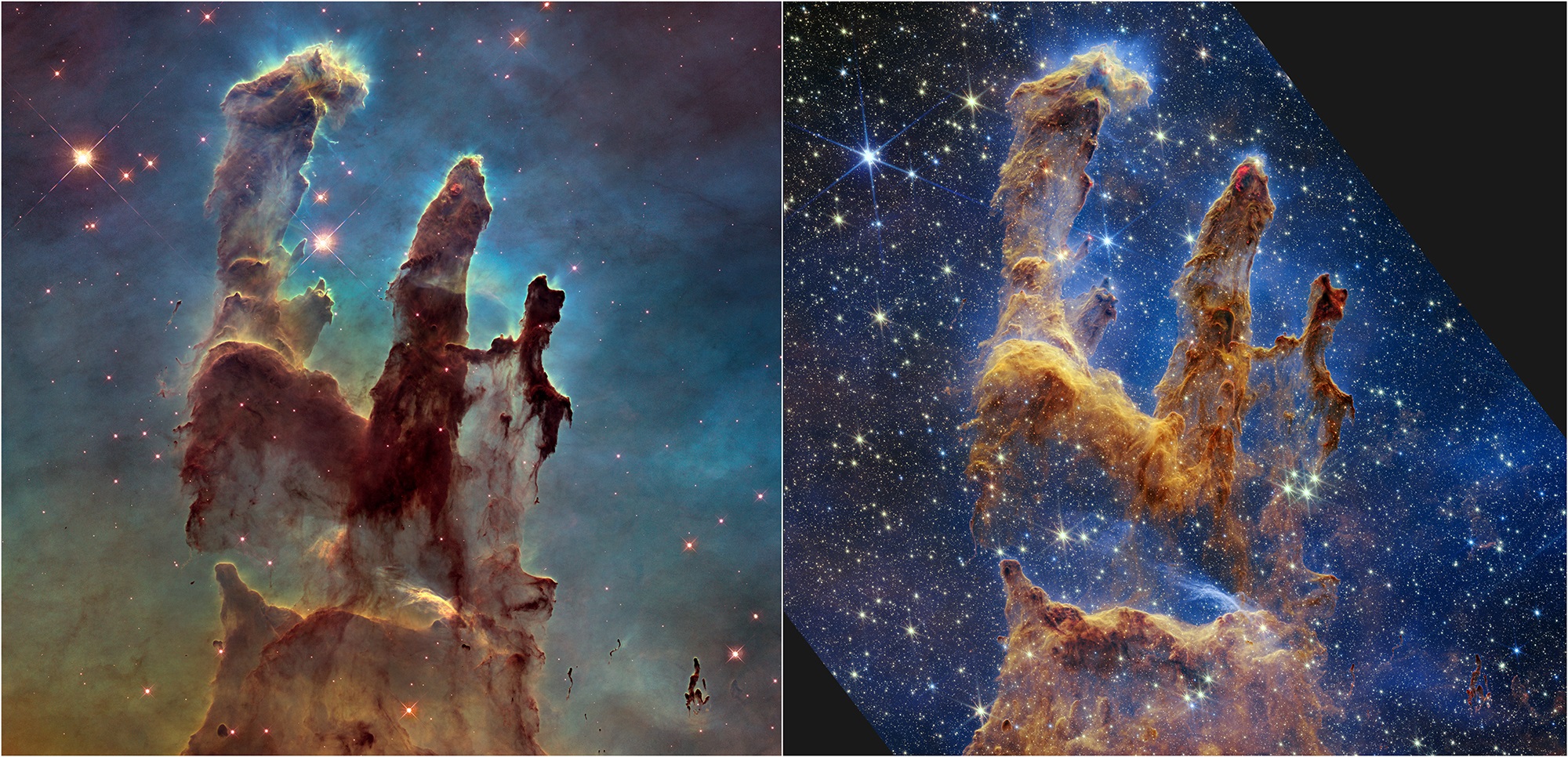

Glaciers in the Alps are melting faster than ever – and 2022 was their worst summer yet

Finally, after what was arguably the worst summer on record for glaciers, snow has begun to fall in the European Alps. It is much needed. Over the 19 years that I have visited and studied the glaciers in Switzerland, I have not seen a summer like 2022. The scale of change is staggering.

Glaciologists like me used to use the word “extreme” to describe annual ice loss of around 2% of a glacier’s overall volume. This year Switzerland’s glaciers have lost an average of 6.2% of their ice – extreme indeed.

The new flurries of snow will form a protective blanket to shield and reflect 90% of the sun’s radiation back into the atmosphere and limits the warming and melting of the ice beneath. When snow falls over the winter, and then subsequently doesn’t melt over the summer, it adds to the mass of a glacier. Over a few similar years, gravity would take over and glaciers would start to advance downhill.

However over the past century, that has not been the case. The protective layers of snow have not been thick enough to offset the warming summer temperatures and on average glaciers around the world have been wasting away since the end of the little ice age in the mid-late 1800s.

Saharan Sand And A Huge Heatwave

Back to this summer. Across the Alps, the preceding winter had very limited snowfall and therefore glaciers were not well insulated against the forthcoming summer melt season.

Spring was particularly harsh as natural atmospheric weather patterns carried Saharan dust to Europe and blanketed the Alpine landscape. Since dust absorbs more solar energy than snow (which is white and therefore more reflective), the now orange-tinted snow melted faster than ever.

Then a major heatwave saw temperature records smashed across Europe, with parts of the UK reaching 40°C for the first time. The Alps were not spared. For instance Zermatt, a famous car-free Swiss village in the shadow of the Matterhorn, recorded temperatures up to 33°C despite being 1,620 meters above sea level.

Glaciers in particular took a beating. By July, the Alps looked like they normally look in September: snow free, with snow and ice-fed rivers flowing at their peak. This was not normal.

The last time glaciers had an extreme melt season was in 2003 when, again, temperatures were very high across Europe, and a heatwave killed at least 30,000 people (more than 14,000 in France alone). That calendar year, 3.8% of glacier ice melted across Switzerland.

This year, for the first time ever, Zermatt closed its summer skiing. Guides stopped leading high mountain expeditions as permafrost – the frozen ground that binds rocks together – was thawing and causing almost constant rockfalls. Mont Blanc was closed.

50 Years Of Data

We are able to put this in historical context thanks in part to work by the charitable organisation Alpine Glacier Project which was established in 1972 and, along with the University of Salford where I work, has led scientific expeditions to glaciers near Zermatt every summer for 50 years.

Scores of students have helped to observe the effect of our warming climate through chemically monitoring changes in meltwater, topographically surveying the landscape and by taking photos from the same position over the years. Over the project’s five decades, Gorner Glacier and Findel Glacier have retreated 1,385 metres and 1,655 metres respectively.

In Switzerland these glacial meltwaters are used for hydropower. In fact, water falling on 93% of Switzerland ultimately passes through at least one electric power plant before even leaving the country. So one consequence is that melting glaciers help to compensate for low rainfall in times of drought, filling reservoirs to supply the nations energy supply.

You could argue that not all glaciers were equally affected by this summer’s catastrophic retreat and ice loss. In part, this is true. The extent to which a glacier has melted does depend on the altitude at which it is located, how steep the glacier tongue is, and how heavily it is covered with debris. There may too be localised climate factors.

However, research just published has shown that Austrian glaciers have also lost more glacial ice in 2022 than they have in 70 years of observations and therefore it is quite clear that severe melt has been the norm in 2022.

Visiting and viewing the geography of high mountain environments is a breathtaking experience, but my fear is that the continued ice melt and extreme temperatures seen this year are not an anomaly. Many more glaciers could be lost entirely within a generation.![]()

Neil Entwistle, Professor of River Science and Climate Resilience, University of Salford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Farm floods will hit food supplies and drive up prices. Farmers need help to adapt as weather extremes worsen

Some of Victoria’s most important agricultural regions are among the areas worst hit by severe floods inundating the state this week.

This may lead to food shortages and higher supermarket prices for milk, fruit, vegetables and other farm products. Indeed, about 20% of Victoria’s milk is produced in flood-affected regions, and millions of litres now may be lost.

For farmers, the floods will certainly be devastating. Over the last five years, Australian farm businesses have faced a relentless string of extreme events, from drought to unprecedented bushfires.

Now, floods are destroying crops, drowning livestock or damaging equipment and infrastructure. Indirect impacts also flow from road closures and electricity outages that can severely interrupt farm operations, damaging products and harming animal welfare.

Farmers face a multitude of challenges in future. Climate change is projected to lead to more frequent severe floods, as well as other climate extremes such as heatwaves and drought. How do farmers adapt to these changes and how can governments support them?

How Floods Damage Farms

Some of the areas hardest-hit by current flooding are in northern Victoria, including Shepparton, Rochester and Echuca – some of Victoria’s most important growing regions.

The damage floods inflict on farms can last long after the water has receded. Farm activities may be interrupted by water-logged soils for days or weeks. Fertile topsoil also can be lost due to water erosion, potentially leading to long-term yield declines.

Livestock can also be harmed. For example, the 2019 flood in Queensland killed hundreds of thousands of cows. Surviving, flood-affected livestock can suffer long-term health conditions, including parasites and bacterial infections, and this has big implications for animal welfare and farm productivity.

The indirect impacts of flooding on farm businesses can be equally harmful. For example, when roads are blocked, agricultural products cannot be transported to processing facilities or retailers.

Power outages also mean many Victorian farmers cannot milk their cows, or must dispose of milk that cannot be transported to processing sites in time. This may lead to large losses for producers and higher supermarket prices for consumers.

Farms And Climate Change

Floods are just the beginning. Farmers face a range of climate extremes, which are becoming more frequent and severe with time. Over recent decades, global warming has shifted Australia’s climate towards higher temperatures and lower winter rainfall, posing significant challenges for farmers.

According to the Bureau of Meteorology, winter rainfall in the southeast of Australia has declined by 12% since the late 1990s, and 16% since 1970 in the southwest of Australia. Combined with streamflow declines across southern Australia, this has reduced soil moisture and the amount of water available for irrigation.

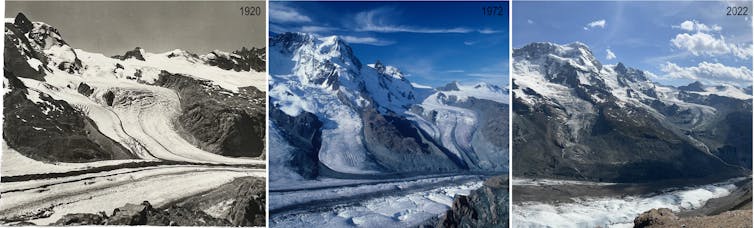

In fact, changes in climate between 2001 and 2020 (relative to 1950 to 2000) have reduced annual average farm profits by an estimated 23%, according to modelling by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES). The most severe impacts have been seen in south-western and south-eastern Australia.

Even more challenging have been the observed changes in climate variability and extremes, such as increases in the risk of bushfires or severe flooding. These are less predictable and more difficult to adapt to than relatively gradual changes.

One of the biggest challenges for agricultural businesses and the Australian community are increasing risks of compounding climate extremes. These involve multiple climate hazards happening at the same time, in the same location or in connected regions – or multiple climate extremes happening in short succession.

Such compounding events can overwhelm the capacity for farmers, emergency services and the broader community to cope.

The extremes of the last five years are a clear example. Severe drought in 2017-2019 was followed by the devastating bushfires in 2019-2020, before three consecutive flooding years due to La Niña.

The drought, for instance, caused wheat production in 2018-2019 to drop to its lowest level since 2008 (down by 16% compared to the previous financial year), and rice and cotton production were down by 90% and 56%.

Climate change is projected to further increase the severity and frequency of many types of climate extremes, depending on global greenhouse gas emissions. Australia will be particularly affected, as hotter temperatures and less rainfall will make parts of Australia more arid.

It’s important to note that such extremes poses significant threats to the mental health of farmers and rural communities.

Research this year, for example, investigated drought and mental health in Australia’s rural communities. It found that each year on average, 1.8% of suicides among rural working-age men could be attributed to drought. Under the driest future climate change scenario, this will increase to 3.3%.

What Can Farmers Do To Adapt?

Australian farmers are experienced in managing climate variability and extremes, and continuously adapt to changes by modifying current farm management practices to reduce risks. These strategies include:

- adjusting planting and harvest dates

- modifying their use of irrigation, such as by upgrading irrigation equipment to more efficient systems

- using minimum tillage practices (soil turnover) to reduce soil erosion and increase water retention

- adjusted livestock management, such as providing shade and cooling for livestock during heatwaves

- optimising the application of fertilisers.

Farmers also adapt by diversifying their farms. For example, they might transition from purely cropping to mixed crop-livestock farming.

Another important way farmers can adapt to extremes is by using forecasting information. Farmers make use of a wide range of weather and commodity price forecasts to prepare for the season ahead. This includes the Bureau of Meteorology’s seasonal climate and water outlooks, ABARES’ agricultural outlook and forecasting information provided by state departments and agricultural consultancies.

New climate information services that are more specific to the needs of agricultural managers have become available. Still, more research is needed to further improve and tailor forecasts, to help farmers make better decisions and manage the risks of climate extremes.

Government support is also crucial to help Australian farmers adapt to climate change. Another important area where governments can provide valuable support is by funding research and development into adapting agricultural production and supply chains.

A good example is the Future Drought Fund, which supports research and innovation to enhance drought preparedness in the agricultural sector.

But ultimately, the most important way to cope with future climate change is by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Until we reach net-zero emissions globally, the planet will continue to warm and climate extremes will become more likely and more severe in many regions.![]()

Elisabeth Vogel, Postdoctoral research fellow, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The air we breathe: how I have been observing atmospheric change through art and science

Overlooking the Bass Strait on the remote and windy northwest tip of Lutruwita/Tasmania is the Kennaook/Cape Grim Baseline Air Pollution Station.

The air that arrives at Kennaook has travelled thousands of kilometres. It hasn’t touched land for many days, weeks or even months. It is said to be some of the cleanest in the world.

The powerful westerly winds – the “roaring forties” – carry air masses across the Southern Ocean, reaching land well-mixed and uncontaminated by recent human activity.

Considered “baseline”, this air is representative of true background atmospheric conditions, and grants us insight into the driving forces behind human-driven climate change.

When I arrived at Kennaook in mid-April, it was late afternoon and a storm was brewing. The wind was blowing from the southwest at a steady 54 kilometres an hour – baseline conditions – and the carbon dioxide levels were 413.5 parts per million.

More than 40 years ago, scientists warned CO₂ levels like these would create catastrophic and irreversible environmental damage and species collapse.

I climbed the stairs to the top deck, set up my camera and tripod, and started filming.

Making Invisible Visible

Much of my work has been about the ongoing human and environmental harm caused by uranium mining and atomic testing programs. The invisibility of both the harm and the substances has continued to challenge me creatively.

How do you make visible the invisible? How do you communicate imperceptible change?

Discovering there is a place that captures, archives and measures the air and these imperceptible changes presented me with an opportunity to do just that.

I have since based my creative-practice PhD on the work done at Kennaook/Cape Grim, working alongside the scientists from the Bureau of Meteorology and the CSIRO.

As an artist whose projects have a documentary basis, I use photography, video and sound to respond to place through story, and expand out from there to go beyond what is simply before me.

I believe art has the capacity to reach us in ways other forms of information cannot, revealing the imperceptible hidden in the everyday. In this case: what stories are we breathing?

Sarah Sentilles wrote in The Griffith Review that art shows us “the world is made and can be unmade and remade”.

In troubled times, we are collectively searching for ways to unmake and remake the world around us. Art is one way to unlock that capacity.

The Present Emergency

For this project, titled The Smallest Measure, I have taken an intentionally slow, observational approach, using “slow cinema” techniques to respond to the slow science carried out on site and to the “slow violence” of climate change.

Slow cinema, says writer Matthew Flanagan, “compels us to retreat from a culture of speed […] and physically attune to a more deliberate rhythm”.

Slow violence is described by environmental literature professor Rob Nixon as “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight […] an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all."

This kind of violence is so embedded within daily life, connected to commonplace activities and daily rituals we don’t see it at all, let alone regard it as an emergency. In using slow aesthetic techniques, myself and the viewer use our own capacities to observe and pay attention to the damage within the everyday.

On the top deck of the station, as I watch the storm roll across the ocean, I wonder where the air has come from, who else has breathed it, what is inside of it and how long it has been on its journey.

While at Kennaook, I film and record the landscape and science working together, in constant conversation.

Inside the station, the scientists and technicians are at work. A day is spent cleaning one of the instruments, tubes are flushed and reflushed, tests are run. All the while the air is flowing in from the outside through pipes and into different machines, registering numbers and building graphs, telling us what gases are contained within it and which direction it may have come from.

If there is a sudden spike, it has come from a car outside the station. If it is a more consistent patch of dirty contaminants, the air is probably coming from the north, from Melbourne.

Meanwhile, outside the station, the landscape is working too. The ocean currents ebb and flow, the waves crash onto the rocks below, the wind keeps on blowing, making patterns across the grass, sometimes with such force it is destabilising.

My work doesn’t show dramatic scenes or spectacularly catastrophic events. Instead, through slow visual, aural and scientific processes of attention and observation it shows the emergency is already here. We are entangled within it.

If we really want to, we have the capacity to respond. ![]()

Jessie Boylan, PhD student, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Facing the dual threat of climate change and human disturbance, Mumbai – and the world – should listen to its fishing communities

Coastal cities and settlements are at the forefront of climate disruption. Rising sea levels, warmer seas and changes in rainfall patterns are together creating conditions that mean misery for coastal dwellers.

Disasters triggered by extreme weather often make headlines, but many problems linked to the climate are harder to see. These include the effects of warmer sea temperatures on marine ecosystems, the encroachment of seawater into once-fertile land, and coastal erosion.

Climate risks vary for coastal cities around the world. But according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, people living in coastal settlements with high social inequality are particularly at risk. This includes cities with a high proportion of informal settlements and those built near river deltas.

The Koli people are one such community. As the original inhabitants of Mumbai, they are spread across a number of historic fishing villages on the city’s coast. But they have steadily been marginalised. Mumbai’s official development plan ignores the role of the Koli, and the ecosystems they depend on, in reducing the climate risks facing the city.

This has forced the community to take risk mitigation into their own hands. Through our work with the Koli community, we have seen how their response to human threats has the potential to create a city more resilient to environmental change.

Mumbai’s Environmental Problem

In Mumbai, enormous wealth co-exists with poverty. Largely built on reclaimed land, the city has undergone rapid development.

Poor waste management, property development and increasingly frequent extreme weather have reduced mangrove cover and polluted the city’s coastal waters. Mangroves are important breeding grounds for a diverse range of aquatic species. Many of these species, such as the Bombay Duck and Pomfret, are vital sources of income for Koli fishers and are key to mangrove biodiversity.

But fish stocks are disappearing fast. Environmental degradation combined with intensive trawling has led to declining catches for traditional fishers. This has affected livelihoods, with Koli women feeling the impact particularly strongly due to their prominent role in processing and selling fish.

Studies have also shown that mangrove forests protect coastal areas from storm surges and coastal erosion. Reduced mangrove cover means extreme weather events now inflict severe damage to fishing infrastructure. Cyclone Tauktae in 2021 inflicted losses of 10 billion rupees (£109,000) to coastal fishers – damage to fishing boats alone was worth 250,000 rupees (£2,700).

Taking The Initiative

Following Cyclone Tauktae, the Koli produced reports documenting the changing frequency and intensity of cyclones affecting the region. These reports, supplemented by media coverage, have raised awareness of the community’s vulnerability towards climate change.

This has allowed the Koli to collaborate with various groups to reduce their vulnerability. We have been working with the Koli community through our own research project, Tapestry. Our research has involved creating photographs and maps with the community to build a more comprehensive understanding of the consequences of climate change and environmental degradation for the region. This has highlighted the importance of mangroves for marine biodiversity and flooding protection.

The efforts of the Conservation Action Trust, a Mumbai-based non-profit organisation that aims to protect forests and wildlife, have also been key in protecting mangroves. They found that mangroves were being cleared to make way for golf courses, residential buildings, rubbish dumps and transport infrastructure. They were instrumental in the development of the Mangrove Cell, a government agency that monitors efforts to conserve and enhance mangrove cover in India’s western Maharashtra state.

Addressing water pollution also emerged as a priority through discussions with the Koli community. Our project partner Bombay61 has since implemented measures to improve water quality. Over three days, a pilot trial of net filters collected around 500kg of waste from a single creek. This initiative also challenges the perception of creeks as “drains” or “sewers”.

Engagement between the Koli community, environmental organisations, government officials and local public events and exhibitions has allowed more equitable solutions to human threats to be explored. These highlight the importance of local communities to resource governance and urban planning, and could help dissuade the government from destructive future development plans.

The lessons from the Koli experience extend beyond just Mumbai. While each coast and city will face different threats, the seeds of responses can be found in the people who know and understand the environments in which they live. Working with grassroots methods and groups can reveal how action can respond to local needs and address more than just physical climate risks.

If local strategies can be scaled up, they could transform urban planning and climate change mitigation. These strategies must address the need to adapt to climate change and minimise human disturbance. Paying attention to local people’s struggles and harnessing their ideas can be an essential part of creating cities that are more resilient to future threats.![]()

Lyla Mehta, Professorial Fellow, Institute of Development Studies; D Parthasarathy, Professor of Sociology, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, and Shibaji Bose, PhD Student in Community Voices, National Institute of Technology Durgapur

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Eels are some of nature’s weirdest creatures. Here are 5 reasons why they’re such cool little freaks

It’s the question that baffled scientists for hundreds years – where on Earth do eels come from?

Aristotle’s best guess was that they spontaneously generated. Danish biologist Johannes Schmidt was pretty sure they spawned in the Sargasso Sea – right near the Bermuda Triangle, for a little extra mystery. His extensive biological surveys over 100 years ago found lots of young eels in this area, leading him to conclude they must hatch somewhere nearby.

But eggs or adult eels breeding were never seen anywhere nearby. So the question remained unanswered … until now.

Last week, a team of researchers were able to confirm that yes, the 1-metre long European eel people knew from their local river really did come from a sub-tropical sea up to 10,000 kilometres away. This team had something history’s biggest thinkers didn’t: cool tech.

Pop-up Satellite Archival Tags are a relatively new type of tracking device that allows scientists to map the movements of marine creatures in a way that simply wasn’t possible before. The tags record where the animals travel, how fast they move, and even how deep they dive. Then, the tags detach and float to the surface where they can transmit data back into the hands of eager scientists.

The European eel’s migration is impressive, but they are still shrouded in mystery. All the eels on the mainland come from the same spawning place – yes, even the eels in backyard ponds, which can slither along land to the sea after only a little rain. Eels can even climb up enormous dam walls! But how do they know where to go? How do they decide when?

Australia, too, has its own illustrious eels. They generally keep to themselves, so much so that most of us wouldn’t even know they’re there. But with all this rain and flooding, there’s a chance you might stumble across one soon.

So I thought this was a good time to share five things you might not know about eels, including in Australia.

1. We Have Our Own Marvellous Migration Story In Australia

While not quite as long as the European eel’s journey, Australia’s short-finned eels undertake a massive migration.

In research published last year, researchers from the Arthur Rylah Institute and Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owner Aboriginal Corporation used satellite tracking tags to map the path of 16 eels from Port Phillip Bay off Melbourne, to the Coral Sea outside the Great Barrier Reef. Some travelled almost 3000km in just five months.

It’s an arduous journey. The tags showed some eels dive to depths of almost 1,000m below the ocean surface, taking advantage of currents and dodging predators. Not all were successful though - at least five of the tracked eels were eaten by sharks or whales.

2. Eels Are Obstacle Course Masters

When you stop to think about it, there are more than a few obstacles between inland fresh waters and the ocean. Many of the swamps and wetlands that would traditionally have offered safe passage have been filled in, replaced by farms, dams and cities.

And yet, eels find a way. One key feature is their ability to breathe through their skin, meaning even the shallowest drain or puddle-soaked lawn is enough water for them to move through.

According to urban legends, eels have been seen slithering through urban gutters, sports ovals, or over university campus fountains, following ancient pathways back out to sea.

3. Eels Are Expert Transformers

Imagine if you had to go through puberty four or five times, with each bodily change more dramatic than the last. Then you’d have a pretty good understanding of what it’s like to be an eel.

Migrating eels have to go from being a saltwater fish to a freshwater fish and back again, which means they have incredible life cycles. They start out as as tiny larva out in the ocean in the Sargasso or Coral Sea where they spawn, before morphing into translucent “glass eels”.

After that, they shape-shift into darker “elvers” at about one year old as they make their way back to fresh water, where they eventually mature into the adult eels that live in our rives, lakes and dams.

When the time comes, they make their final transformation into lean, mean, migrating machines – known as silver eels.

Their eyes grow larger and their heads becomes pointed and streamlined. They also stop eating, as their stomachs shrink to make way for bigger gonads (all the better to spawn with).

4. Sigmund Freud Was An Eel Fan, Too

Speaking of gonads, Sigmund Freud (yes, that Freud) spent the early years of his research career trying to understand the sexual anatomy of eels.

Unfortunately for Freud, and the eels, the only way to tell if an eel is male or female is to dissect it to observe it’s internal reproductive organs.

Despite performing hundreds of dissections, Freud rarely found male eels. Turns out, this is because eels don’t develop reproductive parts until later in life – usually not until they’re at least ten years old.

5) Eels Can Live Very Long Lives

Yes, these long fish have long lives, with some eels living to be more than 50 years old.

One man in Sweden claimed his backyard eel lived to 155, while another eel reportedly lived to 85 in a Swedish Aquarium.

Eels spend the first few years of life getting from their spawning grounds back to fresh water, and the last few making the return journey out to sea. They only make this spawning once – after that, they die.

Why Is This Kind Of Research Important?

There’s still so much we don’t understand about eels around the world. But satellite research such as that published this week, takes us a step closer to pulling all the pieces together.

This has real implications for how we look after eel populations. The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) is critically endangered, with the species experiencing declines of up to 95% in the last 50 years.

We don’t really know how well Australian eels are tracking. If we understand where animals breed and how they get there, it means we can find ways to help, rather than hinder their journey, and protect the places that are important.

The Conversation is grateful for the contribution of Australia’s number 1 eel enthusiast, Dr Emily Finch, whose twitter thread inspired this article![]()

Kylie Soanes, Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Right now, more adult incontinence products than baby nappies go to landfill. By 2030, it could be ten times higher

Many parents worry about the waste created by disposable nappies.

But while baby nappy waste is well known, there’s a hidden waste stream that our research has found is actually a bigger issue. More adult incontinence products go to landfill than baby nappies in Australia.

Adult incontinence is often underreported and undertreated. The social stigma and lack of access to affordable health support may stop people seeking treatment and instead rely on incontinence products.

As Australia’s population ages, this issue will grow. By 2030, we predict adult incontinence waste will be four to ten times greater than baby nappies. We’ll need to get much better at dealing with the waste issues associated with these products.

Adult Incontinence Is Common And Long-Lasting

The reason these products will soon outstrip baby nappies is because infants usually only need nappies for a couple of years. By contrast, adult incontinence can stay with you for a lot longer – and it can emerge in many different ways.

How common is adult incontinence? It varies widely. The risk of urinary incontinence increases with age, and women experience higher levels of incontinence compared to men across all age groups. Women over 60 experience the biggest issues, with an estimated 30% to 63% of women over 65 living with some degree of urinary incontinence.

It’s common for people to manage their incontinence with single-use absorbent hygiene products, an umbrella term for incontinence products for both babies and adults.

Like baby nappies, adult incontinence products are usually made from a combination of natural fibres, plastics, glues and synthetic absorbent materials.

What happens to these products after use varies around the world, and can range from illegal dumping, to landfill, composting or burning in a waste-to-energy plant.

In Australia, both infant and adult products typically end up in landfill. The problem is, when you deposit organic waste in landfill, it gives off biogas (a mix of methane and carbon dioxide) and leachate, a polluted liquid that can leak through the lining at the bottom of landfills.

Some landfills in Australia are equipped with collection systems for leachate and biogas – but not all. Biogas emissions and leachate leaks can still occur even if there are collection systems in place.

Food and garden waste are the main source of biogas and organic contaminants in leachate. While councils look to remove food and garden waste from landfills, our ageing population will contribute more incontinence product waste to them.

Could We Divert Adult Incontinence Products From Landfill?

Right now, we estimate about half of all adult incontinence products used in Australia end up in landfills without biogas collection.

The European Union has moved to ban disposal of untreated organic waste – including these products – to landfill. Because adult incontinence products usually contain plastics, the EU requires them to be incinerated where possible rather than biodegraded. Australia has no such laws for this waste.

Could biodegradable incontinence products tackle the waste issue? Only if there are systems in place to manage the waste and recover the resources.

A recycling pathway for biodegradable incontinence products could include anaerobic digestion – systems that harness bacteria to take our waste and make useful products such as renewable natural gas and biofertiliser. This waste stream could also be composted, if the temperature rises high enough to kill off any pathogens and recover the resources.

Problem Solving

This is only part of the solution. Tackling the stigma around incontinence and ensuring access to affordable treatment options could cut the waste stream.