Inbox and Environment News: Issue 560

October 30 - November 5, 2022: Issue 560

Impacting Pittwater - Have Your Say + Discussions + New Works:

Conservation Zones Review Residents Forum: Resolutions Call For Shift In Criteria Applied, For Keeping Pittwater's Green-Blue Wings Intact, For State Election Candidates To Declare Their Position On Pittwater Community's Stated Expectations - feedback closes December 2nd

Residents Opposed To Rezoning Proposal For 15-17 Mona Street Mona Vale

Narrabeen Education Campus DA Available On Council's Website For Feedback - For Narrabeen Sports High School + Narrabeen North Public School - submissions open until November 21

Aquatics: Manly's Little Penguins: Warden Program Update by Taylor Springett, 2022 Eco Achievement Award - Youth Winner - Manly's Little Penguin population of breeding pairs is now just 27, falling below the number needed to sustain the population. The volunteers are trying to ascertain of they have moved elsewhere - have you seen Little Penguins trying to nest on the harbour or in our area? Please contact Taylor if you have - details run this week.

$86,668 For Northern Beaches Scoping Study Allocated Under The Coastal Management Program

Proposal For Barrenjoey Lighthouse Cottages To Be Used For Tourist Accommodation Open For Feedback - Again - feedback open until November 22nd

Avalon Beach Village Shared Space Timeline For Works Made Available - works commenced

Motion To Have Fauna Management Plans In Local Council Comply With The NSW Code Of Practice For Injured, Sick And Orphaned Protected Fauna To Be Presented At LGNSW 2022 Conference - Some FMP's Passed Allow For Wildlife To Be Killed Where Their Homes Are Felled - this passed unopposed at 2022 LGNSW Conference

Kangaroo Day Protest At Manly

Every year, over the winter months, ratepayers fund the ACT Government to send hired guns to stalk Canberra nature reserves at night.Over 12 years, across 11,400 hectares of the Canberra Nature Park, 27,950 kangaroos have been killed.Thousands more pouch joeys have been bludgeoned to death or decapitated.Thousands more dependent at-foot joeys have been orphaned to slower death from hunger, thirst, cold and myopathy (a particularly painful and deadly form of stress).Many Canberra residents feel their own lives have been placed at risk, because shooting often occurs near people, next to roads, reserve fences, off-reserve walking trails, or back fences of homes.The reserves themselves are also affected by the reduction in kangaroo populations, their keystone native grazers, and from the impact of shooters’ vehicles which churn up the ground, killing native species and seeding exotic weeds.Many reserves are now covered in thistles and rank grassy weeds. These weeds will be suburban fire traps in summers to come.Culling began in 2009 without any scientific baseline research on the ACT’s kangaroo populations. Since then, no plausible evidence has been produced to demonstrate any benefits from killing kangaroos. Every government attempt to justify this slaughter has been debunked. Independent research, and even research funded by the government itself, provides no evidence that kangaroo grazing has ever harmed any other native species or ecosystem.During 2021-22, a citizen science project conducted a “direct observational count” of kangaroos in all 37 of Canberra’s accessible nature reserves. This research has confirmed that the Environment Directorate’s claims of an overabundance of kangaroos is demonstrably unfounded.This project’s findings are corroborated by a Farrer resident, who has walked on Farrer Ridge Reserve for decades. She reports that, until last year, the kangaroo population there had remained stable for 40 years, reducing during drought. Last year was the first year Farrer Ridge was included in the government’s slaughter, and almost the entire population was wiped out.The ACT Environment Directorate itself confirmed, on April 13, 2022, that the kangaroo population of the ACT is unknown – but that it intends to kill another 1500 kangaroos this year, anyway.This is not conservation. This is extermination.The Kangaroo Management Plan, which mandates killing kangaroos, and the Code of Practice, which mandates the bludgeoning of joeys, are legislative instruments.Each and every member of the Legislative Assembly is therefore personally responsible for this tragedy. Please stop it before any more damage is done.

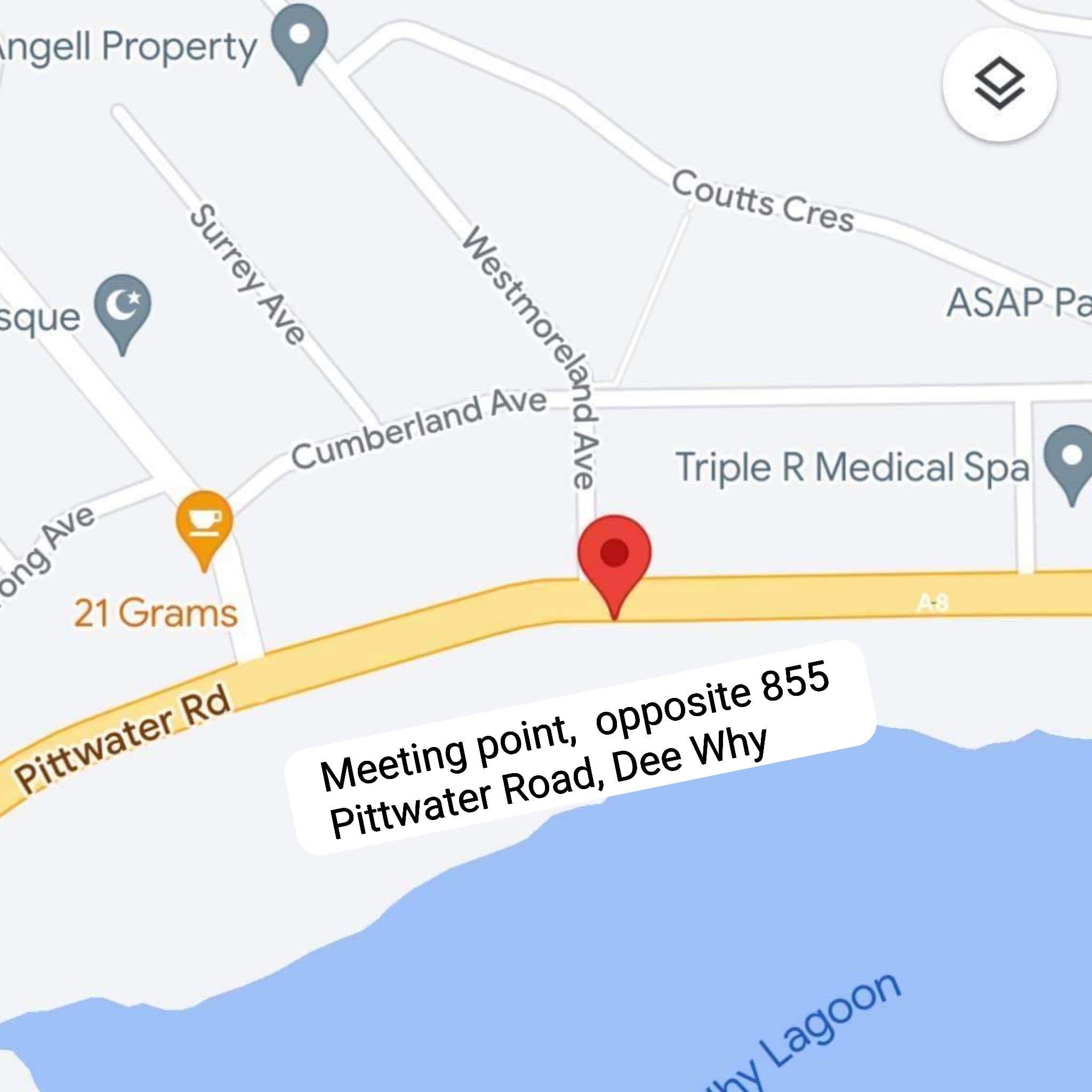

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Dee Why Lagoon Clean Up: October 30, 2022

- - You'll most likely get muddy

- - You'll most likely get wet

- - You'll walk a bush trail inside the lagoon

- - You'll see plenty of plastic bottles

- - getting in the reeds and getting muddy

- - carrying bags back to the tarp “bag runners”

- - sorting the rubbish on the tarps (we will have tarps for plastic bottles, glass bottles, etc)

Community Invited To Have A Say On Draft Management Plan For Flying-Foxes

Thursday, 27 October 2022

Northern Beaches Council has released a draft plan for the management of flying-foxes in colonies in Balgowlah, Avalon and Warriewood and is encouraging the community to have their say.

The 5-year draft management plan sets out a three-tiered management approach with a focus on:

- routine reserve maintenance (e.g. mowing, path maintenance, revegetation, weed control, hazardous tree management)

- support for affected residents

- community education

- maintenance of existing buffers between properties and flying-foxes

- habitat restoration in less populated areas.

CEO Ray Brownlee said the draft strategy sought to balance the need to protect flying-foxes as a threatened species while reducing their impact on residents who live near the camps.

“As a species in decline across Australia and listed as threatened by the State and Federal governments, we have an obligation to ensure they are protected.

“This species plays an important role in pollinating our forests, so it's crucial we do our bit.

“However, we recognise that there can be impacts on people living near flying-fox camps.

“The draft plan seeks to minimise those impacts by maintaining buffer zones, offering support to residents and providing alternative habitat in less populated areas.

“We welcome feedback on the draft plan and encourage residents to have their say.”

The draft plan will be on exhibition until Sunday 20 November 2022. Residents can learn more, book a meeting with a Council officer, or attend the online information session on 10 November, and make a submission here: https://yoursay.northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au/flying-fox-camp-management-plan

Mickey Mouse Plant Flowering In Warriewood Wetlands

Residents have reported this week that the Mickey mouse plant, Ochna serrulata (commonly known as the small-leaved plane, bird's eye bush, Mickey mouse plant or Mickey Mouse bush due to the plant's ripe blackfruit, which upside down resembles the ears of Mickey Mouse, and bright-red sepals, which resembles his trousers) has been seen flowering in Warriewood wetlands.

This plant is a weed when seen locally.

The plant is native to the forest areas of South Africa. It occurs throughout the country, from Cape Town in the south, along the east coast as far as Kwazulu-Natal, and inland through Eswatini and Gauteng. This tough, adaptable shrub grows in sunny, open positions as well as in the shade of deep forest.

It has been widely cultivated outside of South Africa as an ornamental garden plant, and has become a weed in New South Wales and southern Queensland in eastern Australia, where it is found near human habitation in and around large towns and cities.

Ochna comes into flower in Spring. Once established, Ochna plants are extremely difficult to kill, and produce copious numbers of shiny black berries which are spread prolifically by birds, foxes and other pests and wildlife.

Once Ochnas finish flowering, the yellow petals fall off, revealing the calyx and berries. The calyx turns bright red, and the berries ripen from light green to glossy black.

It is best to hand-pull seedlings, though this is notoriously hard to do from a surprisingly small size. Ochna plants grow with a tough, kinked root that snaps off, leaving the taproot in the ground to re-grow.

When Ochnas are too difficult to pull out, the most effective way to control them is to "scrape and paint" the stem with herbicide.

First, collect any berries from the plant and dispose of them in the bin.

Then, using a sharp knife, scrape the top layer of the bark away, exposing the green stem below. This should be done along the stem, as far down the root and up the main stem as possible.

photo: Ochna serrulata with fruits and the bright-red sepals that resemble the ears and trousers of Mickey Mouse. Photo: C T Johansson.

Weed Small-Leafed Privet Flowering Now; Cut Flower Heads To Prevent Seeding

Single-Use Plastics Ban In NSW Commences November 1st, 2022

- serving utensils such as salad servers or tongs

- items that are an integrated part of the packaging used to seal or contain food or beverages, or are included within or attached to that packaging, through an automated process (such as a straw attached to a juice box).

- meat or produce trays

- packaging, including consumer and business-to-business packaging and transport containers

- food service items that are an integrated part of the packaging used to seal or contain food or beverages, or are including within or attached to that packaging, through an automated process (such as an EPS noodle cup).

- polyethylene (PE)

- polypropylene (PP)

- polyethylene terephthalate (PET)

- polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)

- nylon (PA).

- carrying on an activity for commercial purposes. For example:

- retail businesses like a restaurant, café, bar, takeaway food shop, party supply store, discount store, supermarket, market stall, online store, and packaging supplier and distributor, and any other retailer that provides these items to consumers.

- a manufacturer, supplier, distributor or wholesaler of a prohibited item

- carrying on an activity for charitable, sporting, education or community purposes. For example, a community group, not-for-profit organisation or charity, including those that use a banned item as part of a service, for daily activities or during fundraising events.

From 1 June 2022 The Following Was Banned:

- barrier bags such as bin liners, human or animal waste bags

- produce bags and deli bags

- bags used to contain medical items (excluding bags provided by a retailer to a consumer used to transport medical items from the retailer).

Help Needed To Save Sea Turtle Nests As Third La Nina Summer Looms

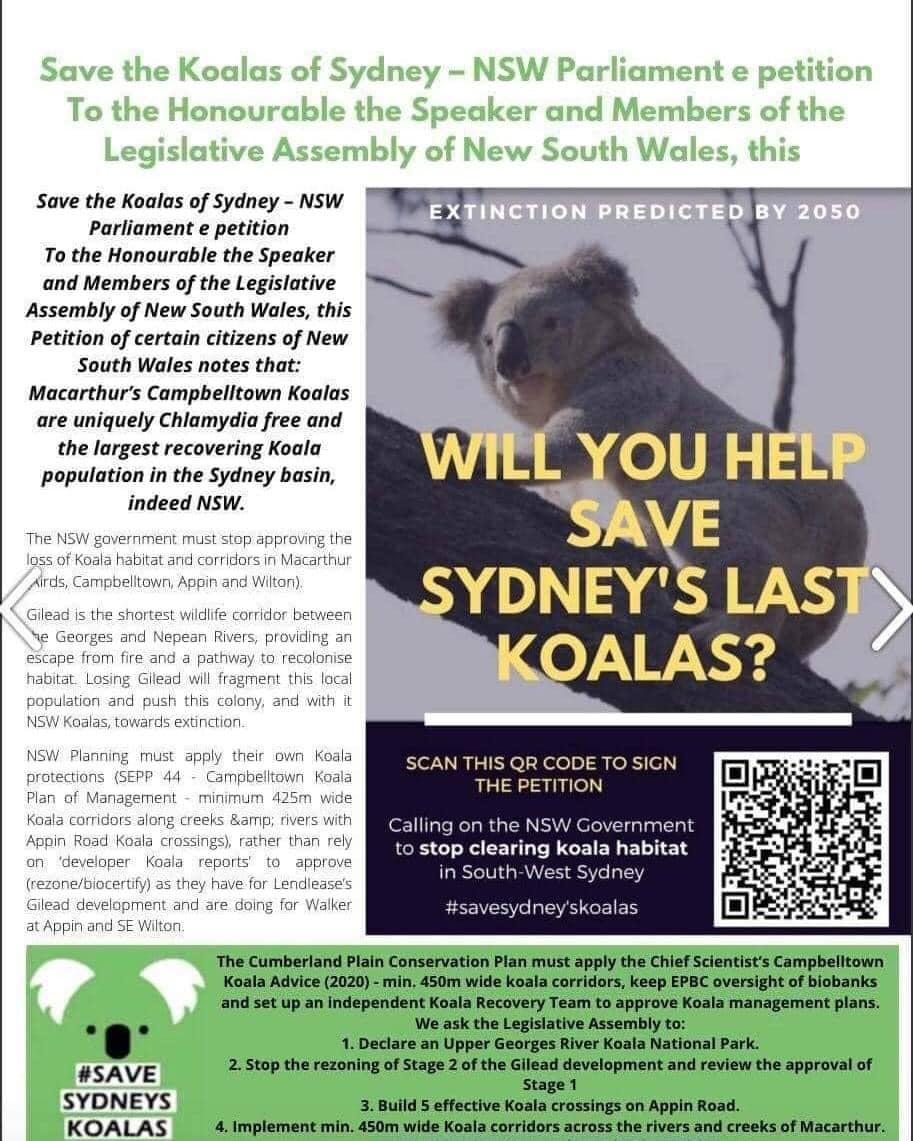

Save Sydney's Koalas Petition

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

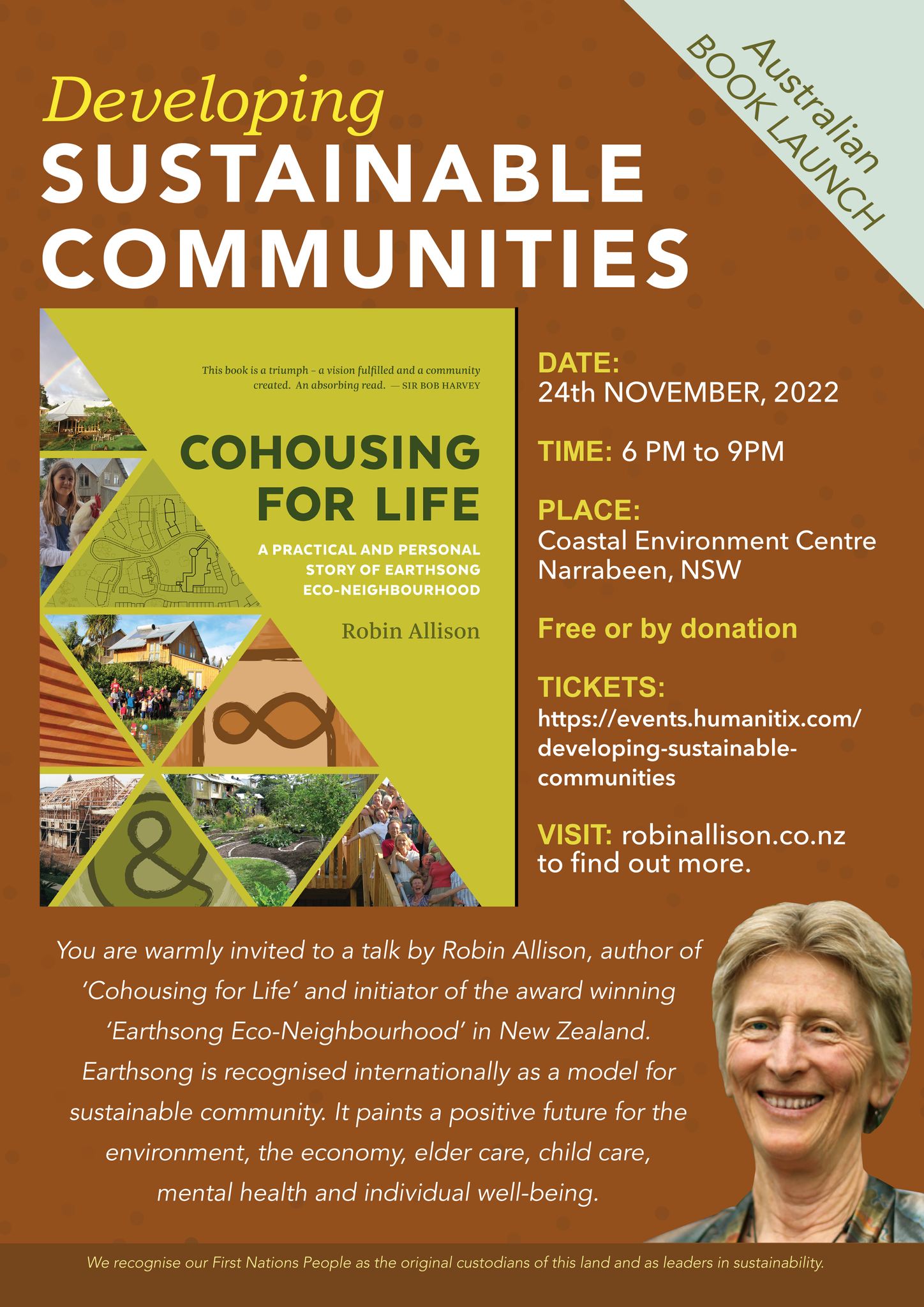

TALK & BOOK LAUNCH

Book Your Free Ticket To: Developing Sustainable Communities

Weed Alert: Corky Passionflower At Mona Vale + Narrabeen Creek

.jpg?timestamp=1663392221562)

EPA Releases Climate Change Policy And Action Plan

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is taking action to protect the environment and community from the impacts of climate change, today releasing its new draft Climate Change Policy and Action Plan which works with industry, experts and the community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support resilience.

NSW EPA Chief Executive Officer Tony Chappel said the EPA has proposed a set of robust actions to achieve a 50 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (from 2005 levels), ensure net zero emissions by 2050, and improve resilience to climate change impacts.

“NSW has ambitious targets that align with the world’s best scientific advice and the Paris commitments, to limit global warming to an average of 1.5 degrees in order to avoid severe impacts on ecosystems,” Mr Chappel said.

“Over the past few years we have seen first-hand just how destructive the impacts of climate change are becoming, not only for our environment, but for NSW communities too.

“We know the EPA has a critical role to play in achieving the NSW Government’s net-zero targets and responding to the increasing threat of climate change induced weather events.

“Equally, acting on climate presents major economic opportunities for NSW in new industries such as clean energy, hydrogen, green metals, circular manufacturing, natural capital and regenerative agriculture.

“This draft Policy sends a clear signal to regulated industries that we will be working with them to support and drive cost-effective decarbonisation while implementing adaptation initiatives that build resilience to climate change risks.

“Our draft plan proposes a staged approach that ensures the actions the EPA takes are deliberate, well informed and complement government and industry actions on climate change. These actions will support industry and allow reasonable time for businesses to plan for and meet any new targets or requirements.

“Climate change is an issue that we all face so it’s important that we take this journey together and all play our part in protecting our environment and communities for generations to come.”

Actions include:

- working with industry, government and experts to improve the evidence base on climate change

- supporting licensees prepare, implement and report on climate change mitigation and adaptation plans

- partnering with NSW Government agencies to address climate change during the planning and assessment process for activities the EPA regulates

- establishing cost-effective emission reduction targets for key industry sectors

- providing industry best-practice guidelines to support them to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

- phasing in the introduction of greenhouse gas emission limits on environment protection licences for key industry sectors

- developing and implementing resilience programs, best-practice adaptation guidance and harnessing citizen science and education programs

- working with EPA Aboriginal and Youth Advisory Committees to improve the EPA’s evolving climate change response

EPA Acting Chair Carolyn Walsh said the EPA is a partner in supporting and building on the NSW Government’s work to address climate change for the people of NSW.

“The draft Policy and Action Plan adopts, supports and builds on the strong foundations that have been set by the NSW Government through the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework, Net Zero Plan and Climate Change Adaptation Strategy,” Ms Walsh said.

The EPA will work with stakeholders, including licensees, councils, other government agencies, and the community to help implement the actions.

The draft EPA Climate Change Policy and Action Plan is available at https://yoursay.epa.nsw.gov.au/ and comments are open until 3 November 2022.

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Some councils still rely on outdated paper maps as supercharged storms make a mockery of flood planning

Mark Ellis, Bond UniversityWhole towns and cities are seemingly locked into more frequent and severe flooding. Business-as-usual development continues despite extreme weather and sea-level rises due to climate change. While some local councils have online mapping, others are still using outdated paper maps.

Repeated floods across eastern Australia have prompted the Planning Institute of Australia to call for a framework to update flood mapping to take climate change into account.

A flood map shows areas to be inundated based on risk modelling and past weather data. As well as identifying at-risk areas for land-use planning, these maps are needed for flood responses. The problem with static flood maps is they don’t show critical details of the hazard a flood will present.

Councils have a duty of care to provide flood maps that accurately identify areas at risk, as well as those that are safe. Yet existing information on riverine and coastal flood risks was “patchy and outdated”, the institute said.

[…] there is a patchwork of datasets gathered and applied inconsistently by councils and water authorities, who often do not have the budgets to pay for the necessary modelling, or the political authority to apply controls at a local level. This means that new housing and development can occur in flood-prone areas […]

For many flooded communities, the immediate priority is to deal with the emergency. However, we should not lose sight of how urban planning has affected them, nor of the urgent need for planning frameworks to catch up with climate change impacts.

Who’s Responsible?

The floods have highlighted the glacial pace of adaptation to climate change by planning frameworks at all levels of government.

For example, the New South Wales government direction on flood-prone land that took effect in July 2021 still adheres to the principles in the state’s floodplain development manual from 2005, which advocates for development on floodplains.

The dysfunctional relationships between the different levels of government also continue. Victorian Premier Dan Andrews said flood mapping was mainly “a matter for local government”. NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet ran the nature-versus-people debate in announcing the wall of Warragamba Dam, Sydney’s biggest, will be raised.

Those on the front line of the flooding see things differently. The mayor of Wollondilly, southwest of Sydney, said:

Raising Warragamba Dam is not in the interests of Western Sydney, potentially costing over $2 billion and enabling developers to cover rural floodplains with housing, as well as the possibility of creating a sense of complacency from those still at risk of catastrophic flooding.

The National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy, based on a 2012 Council of Australian Government (COAG) report, outlines the roles and responsibilities for adaptation of the three levels of government. The strategy states: “Local governments are on the frontline in dealing with the impacts of climate change.”

So local councils are seen to have a crucial role in adaptation at a local level. But how are underfunded councils to manage the ongoing damage to infrastructure, and the legacy of development in areas hit by supercharged weather systems?

It’s a legacy that led to $7 billion in insurance claims from floods, storms and cyclones in the past 18 months.

The Politics Of Flood Mapping

The flood-mapping issue is complicated by a level of political entrenchment related to property rights. Councils are wary of upsetting voters and ratepayers who see their assets devalued by a flood rating. When Gold Coast Council released updated flood maps in 2018, for example, they caused a stir among residents.

On the NSW Central Coast, the local council completed a flood study that concluded a majority of the housing lots would be flooded as a result of rising sea levels in coming decades. Yet the council removed the option of retreat or property buyouts under pressure from residents. They preferred adaptations such as levees, walls and raising their buildings. Councils would need to secure additional funding to cover the costs of such measures.

On the other hand, there was community opposition to a planned levee in Seymour, because of concerns about the loss of river views, access and habitat. This led the local council to abandon the levee to protect homes and businesses that have now been flooded.

We Must Plan For The Long Term

Current approaches to flood mitigation are not a viable long-term strategy. More development on floodplains means more property damage when the floods come. Increasing populations also put added strain on emergency services and escape routes.

Even before the latest floods, the Insurance Council of Australia issued a statement, Building a More Resilient Australia, which said:

“[…] it’s imperative that governments at state and federal level commit to a significant increase in investment in programs to lessen the impact of future events. We also need to plan better so we no longer build homes in harm’s way [and] make buildings more resilient to the impacts of extreme weather”.

If the insurance industry gets it, why are governments still allowing new development in high-risk areas? Some see developing these areas as necessary to solve the ongoing affordable housing crisis. Others consider it entwined with development industry lobbying. And some councils want the rate revenue and fear costly court actions over refused development applications.

So to the greater question: how are governments addressing the climate risk of flooding and urban development within the planning frameworks? Regional and state plans take a long time to draft, put out for public consultation, redraft and get approved.

A New Era Demands A New Approach

Climate change presents vexing problems for communities, governments and urban planning. As ice sheets melt, sea levels rise and climate drivers change, more extreme weather patterns are increasingly a threat to the fabric of our society.

Planning frameworks must adapt to the climate crisis. This requires land-use approaches that direct people and property away from hazardous floodplains. As the Planning Institute of Australia has warned:

“The decisions planners make now have a lasting impact, and our profession is key to responding to a changing climate.”

Mark Ellis, PhD Candidate in Planning, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Toxic Algae Blooms Detected On NSW Coastline: Broken Bay Affected

- numbness and a tingling (prickly feeling) around the mouth, face, and extremities (hands and feet)

- difficulty swallowing or breathing

- dizziness and headache

- nausea and vomiting

- diarrhoea

- paralysis and respiratory failure and in severe cases, death.

- The waters of the Hawkesbury River downstream of the Brooklyn railway bridge;

- Brisbane Water downstream of the Rip Bridge; and

- The waters of Twofold Bay.

World Headed For Climate Catastrophe Without Urgent Action: UN Secretary-General

Murray Cray Rescue Operation

Nestling Birds Recognise Their Local Song 'Dialect'

We spoke to the exhausted flood-response teams in the Hunter Valley. Here’s what they need when the next floods strike

Iftekhar Ahmed, University of Newcastle and Thomas Johnson, University of NewcastlePeople living in the Hunter region of New South Wales know all too well the devastation disasters can bring. After enduring the 2019-2020 horror bushfire season, La Niña settled in for three wet summers and residents experienced back-to-back floods.

Since early October, we’ve conducted nine in-depth interviews with members of flood-response teams in the Hunter for our ongoing qualitative research into how prepared these communities are for future floods. Many people in the Hunter are living in temporary accommodation. A councillor we spoke to pointed out, “there are still people living in caravans, and they’ll be in caravans for quite some time”.

For the Northern Rivers region, which was ravaged by record-breaking floods in February and March this year, some relief is coming.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet today announced a A$800 million buyback scheme for residents in seven areas – including Lismore, Ballina and Tweed – where “major flooding would pose a catastrophic risk to life”. Some 2,000 homeowners will be eligible for funding to sell their homes, repair damage, or make their homes more resilient.

More flooding is expected across eastern Australia in coming weeks, as La Niña conditions are set to persist until early 2023. This is a time to take stock of the lessons gained from the previous spate of floods, and to assess how agencies and communities are heeding these lessons to manage coming floods.

Floods In The Hunter

Overall it seems regular warnings are being provided and agencies have actively stepped up their operations. Still, some Australian communities currently experiencing floods, such as in Victoria, remain vulnerable.

For example, this month many people have become marooned in places where flood defences were inadequate and it was too late to evacuate.

Our research focuses on the Hunter region’s experience of recent floods as they relate to climate change. We want to find out how local communities can improve their resilience and capacity to adapt to floods.

In the Hunter, floods have severely impacted businesses. Cumulative losses in businesses across the region caused a significant economic setback, at a time when many were still struggling with the economic impacts of COVID.

For example, a pub in the centre of Wollombi was submerged to its roof last July. And a vineyard and resort owner we spoke to explained: “We were trapped here for nearly a week in July, including some resort guests”.

Towns such as Broke, Gillieston Heights, Maitland and Singleton were completely isolated, as road networks became inundated. This made evacuations difficult or even impossible.

A police officer said people were trapped in recent floods and he expected the same if another flood strikes, adding: “We need to put in place better evacuation systems.”

Great demands are placed on volunteers of the State Emergency Services (SES). As one volunteer said: “I just joined the SES early this year and since then it has been a very busy time!”

Other volunteers mentioned the potential for “burnout” after dealing with so many floods over a long time, including this month.

Mixed Messages

The biggest problem to be solved, according to our interviews, is inadequate communication.

A local police officer told us: “The focus should be on early warning and communication. There were mixed messages [to residents] from the services on the ground”. This was in regards to when exactly residents should evacuate.

These mixed messages not only hampered timely evacuation operations, but also strained the communication between the regional Emergency Management Centre and on-ground staff, as well as between emergency services and communities.

He also pointed out the challenge of local complacency to heed warnings, encapsulated in the typical “She’ll be right” mentality.

Research shows social media offers communication opportunities during disasters, but it’s also evident that the potential for misinformation on social media can hinder effective communication. Lack of internet access and language barriers can also make effective communication difficult.

Another police officer said: “Communication is something that I am always thinking of. It’s not just us getting the messages out but getting [communities] to hear our messages and respond to them appropriately”.

The importance of emergency communications has been highlighted in Australian research on disaster risk management. For example, a 2016 paper found around 20% of all emergency management problems since 2010 were linked to communicating with communities.

As agencies and communities grapple with frequent flooding, it seems preparedness measures may indeed be improving. For example, in anticipation of Victoria’s floods this month, we saw the rapid deployment of sandbags and even the building of a new levee in Echuca.

Across towns in the Hunter regions, our research participants told us of efforts to improve, for instance, equipment supply and inter-agency coordination. For example, the NSW SES have, in recent years, initiated “Flood Forums” to gather together, plan and coordinate different emergency agencies, in response to communications issues.

What Next?

Another key area that deserves attention is to understand the multi-hazard scenario confronting Australian agencies and communities, as we face back-to-back bushfires, floods, and storms under climate change.

One way to tackle this is by bringing together agencies, such as the Rural Fire Service and the SES, into coordination to address multiple hazards, perhaps even as a single entity.

Interestingly, this was suggested by both SES and Rural Fire Service volunteers in our research interviews. They told us that combining the agencies into a single entity would lead to, for instance, less competition for recruiting volunteers.

As soil remains sodden and catchments are saturated, towns across Australia should be wary of more floods in the coming weeks. We hope being awareness of the urgent need for disaster management agencies to communicate better will lead to tangible improvements.![]()

Iftekhar Ahmed, Associate Professor, University of Newcastle and Thomas Johnson, Associate Lecturer, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Money for dams dries up as good water management finally makes it into a federal budget

A story from the early days of the Abbott government still circulates in the halls of Parliament House.

The government’s Expenditure Review Committee apparently supported then Minister for Agriculture Barnaby Joyce’s first A$500 million budget funding for the National Party’s dam-building plans, over then Treasurer Joe Hockey’s objections. Hockey reputedly said to Joyce “good luck with that, I don’t think you’ll build one of them”. If true then Joe, take a cigar.

In our land of drought and flooding rains, better water management should feature in every federal budget. Thankfully, the budget handed down by Treasurer Jim Chalmers on Tuesday delivers it.

It slashes spending on big dams and elevates the role of science in water decision-making. It also positions Labor to undertake further reform in the Murray-Darling Basin by buying back more water from farmers to improve the health of the rivers, and manage the impacts of climate change.

These measures promise to deliver more sustainable use of water in Australia’s most economically important and exploited river system. But they also buy a fight with some quarters of the farming community, and the New South Wales and Victorian governments.

Nationals Set About Building Dams

Dams are a talisman for Australians who believe development and the conquest of nature is essential to nation-building.

The National Party arguably exemplifies this ideology. It gained control of the water portfolios in the former federal government and current NSW government and set about trying to build dams, especially in the Murray-Darling Basin.

The Liberal Party has conceded to National Party demands on water even though the National Water Initiative, established by the Coalition in 2004, stipulates:

proposals for investment in new or refurbished water infrastructure […] be assessed as economically viable and ecologically sustainable prior to the investment occurring.

This week’s budget wields a long overdue axe to dam proposals from Coalition governments, saving $1.7 billion over four years. Two of the most controversial dam proposals in the Murray-Darling Basin are among those axed or indefinitely postponed.

First is the $1.27 billion Dungowan proposal near Tamworth in NSW. It was slammed by the Productivity Commission as excessively expensive and the leading example of poor water infrastructure decision making.

Second is the hugely expensive - up to $2.1 billion at last estimate - raising of Wyangala Dam, near Cowra. In 2021 a NSW parliamentary inquiry found the proposal was “yet to demonstrate the cost effectiveness and water yield benefits of the project”.

Further, $153.8 million of unallocated funding in former “water efficiency” projects in the basin has been (somewhat ambiguously) “re-profiled”. These efficiency projects have been criticised as double-counting water at the expense of the environment, being very expensive and subsidising irrigators.

Importantly, Labor has quietly sought to lock a commitment to better governance with transparent environmental and socio-economic assessment standards in a new National Water Grid Investment Framework.

Science And The Murray-Darling Basin

Labor has allocated $51.9 million over five years to strengthen the Murray-Darling Basin Plan “by updating the science to account for the impacts of climate change and restore trust and transparency in water management”.

This spending is timely. The past decade and more has seen risk-averse government agencies commission water research through narrow briefs to the government-owned CSIRO and other contractors. In one instance, the South Australian Royal Commission into the Murray-Darling Basin described this research as “improperly pressured” and representing “maladministration”.

The situation worsened when the research program into better water management commissioned by the independent National Water Commission was axed under Abbott in 2014.

This has resulted in science that may not be independently peer-reviewed and often doesn’t address the big questions.

For instance, after allocating around $13 billion for water management reforms in the basin since 2008, governments still can’t tell the public:

why water inflows into South Australia are about 22% lower than basin modelling projected (excluding climatic variability)

the area and types of wetlands watered each year

if threatened species populations are recovering.

Further, water institutions in the basin do not currently adequately address the threat of climate change.

Returning Water To The Rivers

Measures to implement the basin plan are meant to be complete in mid-2024. Consequently, allocated funding for all Basin water reforms was due to decline markedly after this point. Yet, major and expensive elements of the plan have still not been implemented.

In just one example, the Victorian and NSW governments were supposed to reach agreements and pay over 3,300 riverside land owners to fill river channels and allow water to spill safely onto the lower-most floodplains. This would conserve nearly 375,000 hectares of wetlands, and maximise conservation of flora and fauna with the limited volume of available environmental water.

However, since 2013 the state governments have failed to make a single agreement with land owners.

Hundreds of billions of litres of water that were supposed to have been reallocated to the environment are still missing. The latest federal budget describes the lack of water recovery for the environment as an unquantified “fiscal risk”.

Waving a big stick, Labor has allocated initial funding for meeting the environmental water targets in the plan. The amount of the funding has not been disclosed. It could involve purchasing water entitlements from farmers who volunteer to sell them – a move deeply opposed by the state governments and the irrigation industry.

The budget also funds repairs to other broken elements of the basin’s water governance. After a decade of cuts, the now Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water will have funding restored to, among other goals, improve “the health of our rivers and freshwater ecosystems”.

There is also money to start work on re-establishing a National Water Commission, and to reform the much criticised water trading markets to make them more transparent and robust.

Finally, the budget allocates $40 million to begin addressing the appalling dispossession of water from Indigenous peoples, who now hold just 0.17% of surface water entitlements in the basin. It’s a small but important first step for water justice.![]()

Jamie Pittock, Professor, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dead crustaceans washing up on England’s north-east coast may be victims of the green industrial revolution

Thousands of dead and dying crabs and lobsters washed up along a 50km stretch of England’s north-east coast last autumn. Observers reported seeing the animals experience peculiar behaviours including convulsions, before suffering paralysis and death.

An initial investigation conducted by the Department of Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, concluded that a harmful algal bloom was most likely responsible for the deaths. Autumnal phytoplankton blooms are a normal part of temperate marine ecosystems and can produce potent toxins that attack an animal’s central nervous system. But such blooms typically don’t lead to deaths on the scale seen.

The government’s explanation has been contested by local fishermen. They believe recent intensive dredging has released industrial toxins, including pyridine, from the sediment of the River Tees.

As an industrial solvent, pyridine is used in a wide range of manufacturing processes. It is also a by-product of coking coal, a crucial input for steel production. The Tees area was home to both steel and chemical industries and the discharge of contaminated effluent into the river and surrounding wetlands has been common practice, often with minimal or no treatment.

Attempts to understand what caused these deaths has set traditional coastal industries on a collision course with the region’s green growth aspirations.

I took part in efforts to determine what actually happened and whether pyridine could have caused the death of these crabs and lobsters. Using standard ecotoxicology methods, my research involved monitoring the behaviour, physiology and survival of the crustaceans in carefully controlled pyridine solutions. It became clear to me that pyridine may have played a major role in the death of these animals.

The Redevelopment Of Teesside

As one of the UK’s industrial heartlands, Teesside has been designated as a special economic zone, or freeport. The region will play a key role in the government’s Levelling Up programme and Clean Growth Strategy, including hosting the UK’s first hydrogen transport hub.

To facilitate this, the region’s major sea port is undergoing redevelopment. Teesport’s shipping canal has been widened and deepened and the South Bank quay is being reconstructed. This required dredging. Taking place last autumn, almost 150,000 tonnes of sediment has been displaced from the Tees estuary as part of the project.

The onset of the marine deaths coincided with this dredging campaign. This prompted the Environment Agency to undertake chemical analysis of the dead crabs. Pyridine levels recorded in the dead crabs were substantially higher than in those from outside the impacted area. But there was no existing toxicological data on the impact of pyridine on crabs and other large crustaceans.

My research concluded that pyridine is acutely toxic to crabs at concentrations well below those measured in the dead crabs. Even surviving crabs with very low pyridine doses behaved as if they were partially anaesthetised. A single droplet of pyridine per litre of seawater would be sufficient to kill half of the crab population exposed to it.

Further analysis of biochemical markers showed major spikes in the production of reactive oxygen species in the muscle tissue. This means that the animal’s muscle cells have experienced major stress, with the potential for damage to DNA, proteins and cell membranes, which could lead to cell death.

However, although pyridine was detected in the crabs examined by the government investigation, it was not detected in water samples. As a result, pyridine’s involvement in the deaths has been dismissed by the Environment Agency.

Why Has Pyridine Gone Undetected?

Pyridine is highly water soluble, very volatile and vulnerable to attack and destruction by oxygen. By the time water samples are taken, any pyridine could have been heavily diluted, lost to the atmosphere or destroyed.

Despite this, earlier this year researchers at the University of York still measured trace levels of pyridine in surface sediments both along the River Tees estuary and in the spoil grounds – the areas of the sea where dredged material is deposited. Given the volatility and instability of pyridine in the presence of oxygen, this implies a large pyridine reservoir deep in the sediment of the Tees that is percolating steadily up to the surface.

My colleague at Newcastle University has also undertaken a range of computer simulations. They show that this reservoir, once disturbed by dredging, could have released enough pyridine (among many other chemical contaminants) to account for mortalities on the scale and range of those recorded last autumn. The size of the pyridine reservoir still needs to be verified to ground the models in real-world data.

Research has so far not prevented additional dredging work for the new South Bank quay. But the sediment there contains high levels of long-lasting pollutants, including heavy metals and various industrial chemicals. Should these sediments be dumped at sea, it could render England’s northeast coastline toxic for generations.

Teesside is undergoing rapid redevelopment to hasten the green industrial revolution. But in so doing we have been forced to reconcile with the region’s industrial legacy. It will take a change in current working practises and in the disposal of dredged sediment to ensure this redevelopment can continue without causing more damage to the marine ecosystem.![]()

Gary Caldwell, Senior Lecturer in Applied Biology, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Indigenous defenders stand between illegal roads and survival of the Amazon rainforest – Brazil’s runoff election Sunday could be a turning point

Leer en español ou em português

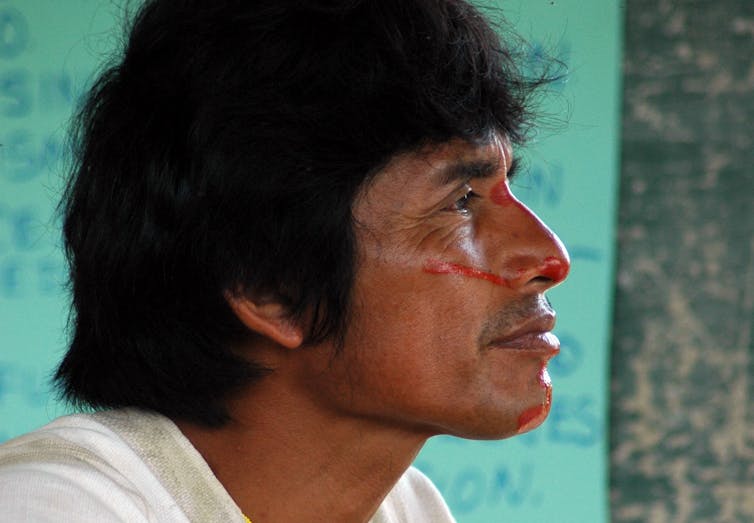

The Ashéninka woman with the painted face radiated a calm, patient confidence as she stood on the sandy banks of the Amonia River and faced the loggers threatening her Amazonian community.

The loggers had bulldozed a trail over the mahogany and cedar saplings she had planted, and blocked the creeks her community relied on for drinking water and fish. Now, the outsiders wanted to widen the trail into a road to access the towering rainforests that unite the Peruvian and Brazilian border along the Juruá River.

María Elena Paredes, as head of the Sawawo Hito 40 monitoring committee, said no, and her community stood by her.

She knew she represented not just her community and the other Peruvian Indigenous communities, but also her Brazilian cousins downstream who also rely on these forests, waters and fish.

The Indigenous residents of the Amazon borderlands understand that the loggers and their tractors and chainsaws are the sharp point of a road allowing coca growers, land traffickers and others access to traditional Indigenous territories and resources. They also realize that their Indigenous communities may be all that stands in defense of the forest and stops invaders and road builders.

The 2022 elections could be a turning point away from deforestation, unsustainable road building and the targeting of Indigenous lands – or the election results could continue to escalate the pressure. After a closer than expected first-round vote, Brazil’s presidential race is headed for a runoff on Oct. 30.

Explosive Growth Of Illegal Roads As Government Pulled Back

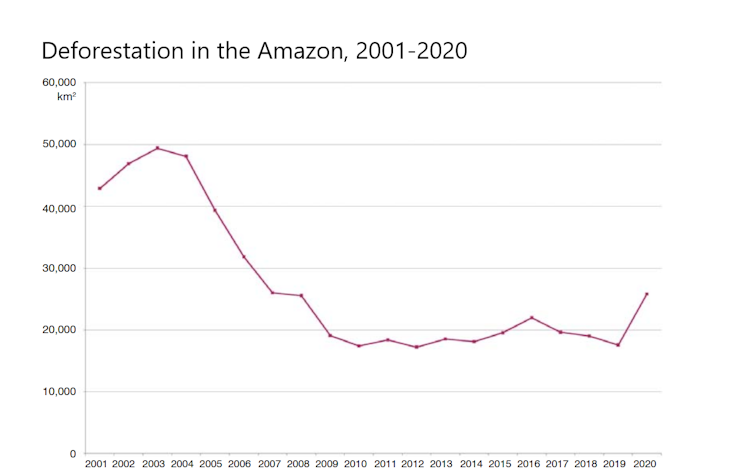

During Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency in Brazil and the COVID-19 pandemic, the Amazon rainforest has witnessed explosive growth in informal and illegal roads.

The Amazonian departments of Ucayali, Loreto and Madre de Dios, Peru, saw road expansion increase by 25% from 2019 to 2020 and 16% from 2020 to 2021. In the Brazilian Amazon, roads are being built at such a rapid pace that researchers are turning to artificial intelligence to map the expansion.

Roads are the most damaging infrastructure in the tropical rainforest, bringing deforestation and a host of related cultural and environmental impacts.

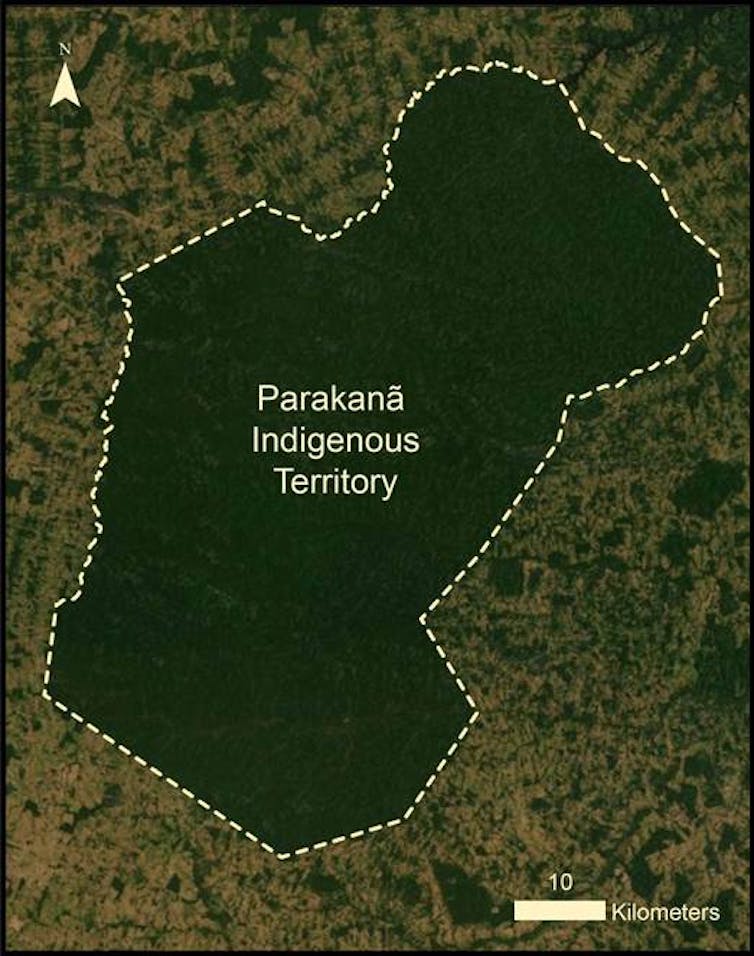

Research shows that Indigenous lands are crucial to safeguarding the forest ecosystems and immense carbon stores. These territories, covering about a third of the Amazon region, act as a buffer against road expansion, reducing both deforestation and fires.

But the Indigenous communities near the border between Peru and Brazil are experiencing an onslaught on their homelands.

When the pandemic forced governments to reduce monitoring and law enforcement in the remote rainforests, the illegal road builders, loggers, miners and traffickers increased their presence and work rate. The state’s absence gave them a relative respite from law enforcement, and in Brazil, they were goaded on by Bolsonaro’s anti-environment, anti-Indigenous and anti-science rhetoric.

A combination of road-building, climate change-induced forest heating and drying, and related deforestation is pushing the Amazon rainforest toward a tipping point that could turn the world’s largest rainforest and reserve of terrestrial biodiversity into a sparsely wooded savanna in just a few decades.

Elections Could Turn The Tide

A few hours downriver from where she confronted the loggers, Paredes and other Peruvian Indigenous leaders met with their Brazilian counterparts in September 2022 to discuss strategies to stop the invasions. The Brazilian leaders included Francisco Piyako and Isaac Piyako, two Indigenous Ashéninka brothers who ran for election at the federal and state levels but lost amid the southern Amazon’s conservative turn toward agribusiness.

While Brazil’s election included more Indigenous candidates than any in Brazilian history, with the 186 candidates representing a 40% increase over 2018, few of those candidates won.

Two Indigenous women with strong anti-Bolsonaro platforms emerged from the election as federal deputies: Sônia Guajajara in São Paulo state and Célia Xakriabá in Minas Gerais. Marina Silva, a former environment minister and past Green Party presidential candidate, also won election as a federal deputy in São Paulo state. Seven other self-declared indigenous candidates won at various levels, but most didn’t run on pro-Indigenous rights or environment platforms.

These results place the future of the Amazon very much in the hands of Brazil’s national election.

On one side of the presidential election stands Bolsonaro, a populist who has derided Indigenous people, environmentalists and science while weakening environmental and Indigenous agencies and inciting miners, loggers, ranchers and agribusiness leaders to cut down the forest.

On the other side is Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – commonly called Lula – a former Brazilian president who is arguing for zero deforestation. Da Silva had 48.4% of the first-round vote to Bolsonaro’s 43.2%.

Peru also held elections on Oct. 2 at the regional and municipal levels. In the Ucayali region, 37% of the candidates were Indigenous. But the elected governors in Peru’s Amazonian departments – a coca farmer in Ucayali, a miner in Madre de Dios and a doctor in Loreto who is under investigation by prosecutors – are not Indigenous.

In Maria Elena Paredes’ home district, Yurúa, pro-conservation Indigenous residents did win, providing one of few positive signs for the environment in the Amazon.

Without adequate pro-environment and Indigenous representation, the roads and extractive development will march forward, making the Peruvian side of the forest even more vulnerable. A victory for sustainability, conservation and culture in Brazil could resonate across political borders into Peru and the other seven countries that share the Amazon, just as Paredes’ intervention in Peru stopped the tractors from ruining the forests and streams that flow into Brazil.

A Dangerous Job: Defending The Amazon

As leaders like Paredes and others defend their forests and people, they are also targets for violence.

In the Amazon borderlands, danger threatens from multiple sides, and justice is rarely served. The killing of journalist Dom Phillips and activist Bruno Pereira in June 2022 was just the latest high-profile attack. Global Witness reported that 200 land and environmental defenders were killed in 2021.

Fifteen years ago, the legendary Indigenous leader Edwin Chota protested the road that Paredes and her community are blocking today. He and three colleagues were later gunned down in 2014 after receiving death threats from loggers and traffickers. The killers remain free in the borderlands.

This summer, I visited Chota’s grave with over 20 of the surviving family and community members of the four slain defenders. Most of these families are afraid to return to their beautiful forests in the borderland community of Saweto, and instead remain on the outskirts of the city of Pucallpa, squeezed into dilapidated houses with intermittent electricity and clean water.

Far from their village, the children cannot build their cultural and environmental knowledge in the forest.

Five participants from Saweto were among the 120 Indigenous representatives from 13 ethnicities in the Amazon borderlands who joined our NASA workshop to discuss how they can use satellite imagery to monitor changes to the forest and climate. By integrating Indigenous ecological knowledge and geospatial analysis of the Amazon rainforest and climate, scientists and Indigenous groups can both better track the changing Amazon.

The Indigenous mothers, fathers and children told us they want training and education that will help them to protect their territory, adapt to climate change and build a sustainable future. Our NASA SERVIR project is creating mapping platforms based on satellite imagery analysis that the Indigenous communities, nongovernment organizations and government agencies can use to monitor roads, deforestation and climate change.

Indigenous Defense Is Crucial

All of humanity is feeling the effects of climate change. Our Indigenous colleagues recognize the changes in temperature, the water cycle and the seasons already happening in their communities.

Environmental land defenders like Paredes are working to keep the world’s largest forest standing tall in the face of threats that don’t just harm the Amazon. If the Amazon rainforest becomes a savanna, there will be reverberations in the climates of South America, the Caribbean, North America and across the globe.

Everyone loses if the Indigenous defenders of the Amazon do not have the support and educational opportunities needed to be safe, prosperous and empowered to protect their rainforest home.

This article was updated Oct. 11, 2022, with additional election results.![]()

David S. Salisbury, Associate Professor of Geography, Environment, and Sustainability, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Orangutans: could ‘half-Earth’ conservation save the red ape?

Half-Earth is a proposal by the late naturalist and “father of biodiversity”, EO Wilson. In its original context, it proposes that half of the Earth’s surface should be designated a human-free nature reserve to preserve biodiversity.

The proposal of course raises some pretty big questions. What happens to the people that happen to live in the areas designated to become human free? Would we give up on biodiversity in the other half of Earth? And whose half should be chosen and who decides? Would richer countries continue on their current path and tell poorer nations, especially those in the tropics with relatively intact forests and marine systems, that their part of the world will from now on only be for nature?

Perhaps not unexpectedly, the grand idea of half-Earth has attracted a lot of criticism as being unethical and infeasible. It has even led to a distinct counter-proposal: whole-Earth. Sometimes known as sharing the planet, this proposal focuses on things like equitable land management or finance, as its advocates argue that conservation will only ever work if we change the political and economic systems that are driving today’s crises.

It is difficult to judge the merits of half and whole-Earth without testing what either would mean on the ground. This is what we recently set out to do by applying our interpretations of these two options to the conservation of an animal we have studied for decades – the orangutan.

Expert Predictions

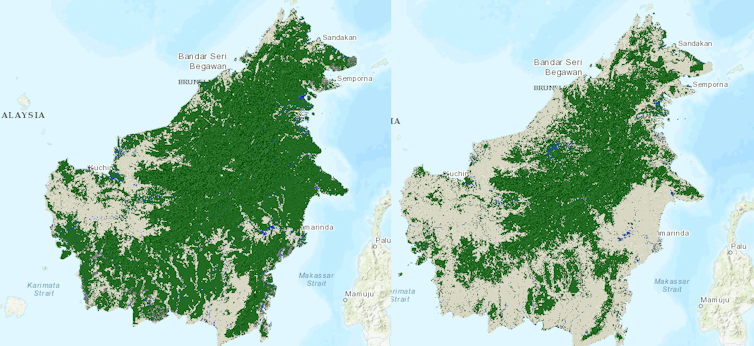

We focused on Borneo, the world’s third largest island (only Greenland is significantly larger) and home of most orangutans. The Bornean orangutan is listed as “critically endangered” as its habitat is being destroyed and many are killed for food, for profit or simply because people fear them (direct killing remains a major problem on a par with deforestation).

We gathered a group of 33 other experts, mostly scientists with a specific track record of estimating orangutan population sizes. They were then asked (confidentially) what would happen to Bornean orangutans in the next decade under half- and whole-Earth conditions (translated as half and whole-Borneo) compared to continuing business-as-usual conservation practices. Our results are now published in the conservation journal Oryx.

The experts predicted that business-as-usual would mean the total population of orangutans on Borneo would decline by around 27% between now and 2032. That is clearly not sufficient to support the protection of the species.

Half-Earth was predicted to strongly reduce orangutan declines. The experts, in fact, concluded that it would be comparatively easy to achieve and would reduce population decline by at least half compared to current management.

However, the experts thought whole-Earth would lead to greater forest loss and ape killing and a 56% population decline within the next decade. Whole-Earth approaches are valuable but may not be workable for the short-term orangutan conservation needs, because of political and economic realities on the ground.

The good news is that the experts predicted that, if orangutan killing and habitat loss were stopped, populations could rebound and reach 148% of their current size by 2122.

Despite more than 100,000 orangutans lost over the past two decades, the experts now see glimmers of hope. Indonesian and Malaysian deforestation rates are down, as are expansion rates of oil palm and other crops. How should orangutan conservation proceed from here? What are the best strategies?

Protections – On Paper

Interestingly, both the Indonesian and Malaysian governments had more or less reached the objective of legally designating half of the land mass as protected in their respective states of Kalimantan and Sabah.

With 67.1% of Indonesian Borneo designated as state forest, Indonesia already exceeds the half-Earth goal of locking in 50%. Malaysian Sabah has also exceeded the half-Earth goal, with 65% of the state remaining forested.

This is all on paper though, and a lot of effective conservation investment and management would be needed to ensure that these orangutan habitats would indeed remain permanently forested, and that the other key threat – killing – is effectively addressed.

This is where elements of the whole-Earth approach are helpful, as it might prompt a more sensitive and equitable engagement with rural communities. Communities need to be given responsibility for coexisting with orangutans and there must be incentives to protect orangutans and their habitats. And companies – logging, mining, or plantations – need to be made legally responsible for ensuring that the protected orangutan can survive and thrive on the lands that they manage. Ultimately, we need to protect both orangutans and humans’ rights and access to their customary lands.

In the case of orangutans, half-Earth seems to be a good idea in the short term, especially with regard to habitat loss. Whole Earth-type approaches might be needed in the longer term to ultimately ensure a reduction in the number of orangutans who are killed or have to be captured and relocated.

Neither approach is likely to provide a silver bullet. Every conservation context is going to be different and will require its own specific solution. It is therefore also important to just get on with conservation and not spend too much time thinking about ideal solutions.

It is not an easy path ahead, but solutions exist that can ensure the long-term survival and even recovery of the Asian red ape.![]()

Erik Meijaard, Adjunct Professor of Conservation, University of Kent and Serge Wich, Professor of Primate Biology, Liverpool John Moores University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Playing sea soundscapes can summon thousands of baby oysters – and help regrow oyster reefs

Imagine you’re in a food court and spoilt for choice. How will you choose where to eat? It might be the look of the food, the smell, or even the chatter of satisfied customers.

Marine animals do the same thing when choosing a good place to live. Even seemingly simple creatures such as marine larvae use sight, smell and sound as navigational cues. Once we understand these cues, we can use them to help nature recover faster than it would on its own.

In our new research, we amplified the natural sounds of the sea through underwater speakers. We were testing if sound cues would draw baby oysters to swim to the locations where we are trying to regrow oyster reefs. It worked better than we’d hoped. Many thousands more larvae swam to our locations than control areas and settled on the bare rocks.

Why Can’t These Reefs Return Naturally?

Oyster reef restoration is gaining momentum in Australia and globally as a way to restore healthy ecosystems. Reefs of shellfish filter and clean vast volumes of water as they feed, while their shell piles provide habitat for fish. Oysters are also food for many marine species.

These highly productive shellfish reefs once spanned thousands of kilometres of Australian waters, but more than 90% were dredged up for food and or to use their shells as lime for cement during the early colonial years.

When we try to restore these reefs, however, we hit a problem. Free-swimming baby oysters need to find the boulders we drop onto sandy seafloors at our restoration sites.

That’s where our siren songs come in. Many marine animals use sound like we use sight on land. Think of whalesong, which lets whales communicate over long distances. Sound is more useful than sight or smell underwater because it can carry information a long way – much further than you can see – and without getting pushed about by ocean currents.

If you’ve snorkelled on a coral or rocky reef, you’ll know healthy reefs are surprisingly noisy. As you float over the reef, you hear a cacophony of sound: crackles and pops from fish as they feed and invertebrates like snapping shrimp.

If this soundscape is present, it tells oyster larvae it’s a healthy habitat. And because sound travels so well, the soundscapes are broadcast a decent distance. That’s why it’s such a useful cue if you’re a baby oyster looking for a rock to settle on and begin growing your shell.

To test if this works outside the laboratory, we recorded sounds from the healthy Port Noarlunga Reef in South Australia. Then we played these sounds underwater near two large reef restoration sites offshore from Adelaide and the Yorke Peninsula.

This attracted up to 17,000 more oysters per square metre to our restoration sites. Not only that, but over the next five months, close to four times more large oysters grew in our test areas, which accelerated habitat growth. By contrast, the areas where we played ambient sound from oyster-free areas produced only stunted habitat with few oysters settling.

Hang On, Oysters Can Hear?

The way we hear is based on the pressure of soundwaves hitting our eardrums. Marine mammals like seals and dolphins hear this way too. But fish and marine invertebrates such as oysters are different.

Oyster larvae are brainless and earless, but they are certainly not clueless. Like fish, they hear by detecting and interpreting the movement of water particles stirred up by soundwaves as they pass. Soundwaves alternately squish and stretch water particles, sending vibrations in the direction the soundwave is moving. Oysters sense this motion with tiny sensory hairs, or with statocysts, sensory organs used for balance and orientation.

Despite being only the width of a human hair themselves, larval oysters use these organs to follow these vibrations back towards the healthy reef producing the sound. In adult oysters, the tiny statocyst is near impossible to find. But swimming oyster larvae project their statocysts out in front of them, presumably to improve navigation and interpret marine sounds.

The Reefs Are Alive With The Sound Of Music

Researchers and community groups around the world are launching restoration efforts to repair some of the damage we’ve done. In Queensland, for instance, fishing communities in Moreton Bay offshore from Brisbane plan to restore 100 hectares of oyster reef over the next decade.

While exciting, success isn’t guaranteed. It can be hard to restore ecosystems which haven’t existed for a century. And it can be expensive to get large stocks of larvae.

This technique – and others like it – could help improve how many baby oysters or other keystone species actually make it to their new homes and start the great task of reef-building.

Researchers have discovered fish can be attracted to coral reef sites by playing healthy reef noises, and it has long been known that birds can be drawn to specific nesting sites by playing their social calls.

In science, there’s no such thing as a silver bullet and there are potential downsides. It wouldn’t help if we drew all larval oysters to our sites at the expense of others – or if we attracted predators in large numbers.

But if we do this carefully, these techniques could help re-establish the invisible acoustic highways of the sea – and turn the deathly quiet of many coastal waters back into vibrant, noisy and healthy oyster reefs. ![]()

Dominic McAfee, Postdoctoral researcher, marine ecology, University of Adelaide; Brittany Williams, PhD Candidate, University of Adelaide; Lachlan McLeod, PhD Candidate, University of Adelaide, and Sean Connell, Professor, Program Director of Stretton Institute, Program Director of Environment Insitute, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Labor’s ‘sensible’ budget leaves Australians short-changed on climate action. Here’s where it went wrong

Treasurer Jim Chalmers last night delivered a budget he declared was “solid, sensible and suitable to the times”. But what does a sensible budget look like in a world that is fast running out of time on climate change?

Lowy Institute polling this year suggests most Australians believe immediate and substantial action on climate change is eminently sensible. Some 60% agreed global warming was a serious and pressing problem for which “we should begin taking steps now even if this involves significant costs”. A further 29% want mitigation to occur gradually.

Chalmers unveiled his budget in a precarious economic environment and amid fears of a looming global recession. But while the national conversation is focused on short-term economic pressures, the world is entering unprecedented territory of climate disruption.

This federal budget was Labor’s first opportunity to establish its economic vision for emissions reduction. Even as Chalmers prepared his speech, parts of Australia’s east coast were battling floods, and the summer rain outlook looks grim.

The budget earmarked a suite of worthwhile climate-related measures, but many are relatively piecemeal. As extreme weather events occur at a record-breaking frequency and severity, federal spending on climate action still falls well short.

Where’s The Tangible Action?

Over the past few months, Labor has generated significant headlines on climate change.

It’s Climate Change Bill passed parliament last month. It means Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions must fall by 43% (relative to 2005 levels) by 2030, and emissions must reach net-zero by 2050.

Labor on Sunday also announced Australia will sign a global pledge to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

But setting these targets is just the first step. Limiting climate change to 1.5℃ degrees – the goal of the Paris Agreement – requires immediately reversing the upward trend in global emissions and making significant cuts over the next two decades. That means tangible actions must occur right now.

But looking at the budget papers released last night, it’s hard to see how Australia’s climate targets will be met.

What’s In The Budget For Climate?

Most budget measures related to climate change and the environment formed part of Labor’s pre-election platform. They include:

A$224 million over four years to fund 400 community batteries, and $100 million for community solar banks

the Rewiring the Nation plan: $20 billion of low-cost finance to improve Australia’s transmission network, and new investments in renewable electricity generation which aren’t yet detailed

Also worth noting are measures to mitigate the future impact of climate change:

the Disaster Ready Fund to support adaptation measures such as flood levees, sea walls, fire breaks and evacuation centres

$225 million over four years to implement the Threatened Species Action Plan and funding to establish Indigenous Protection Areas and protect heritage places

increased funding to preserve and restore the Great Barrier Reef.

These initiatives are, in part, funded by a $747 million reduction in environment spending over the next four years. The cancelled spending includes projects for gas and carbon capture and storage, funding earmarked for the Murray Darling Basin, and other Morrison government measures.

The budget also contained subsidies and infrastructure investment to support the uptake of electric vehicles. This includes 117 electric vehicle charging stations on highways, exempting electric cars from the fringe benefits tax and removing custom duties on electric car imports.

Electric cars will reduce Australia’s dependence on international oil markets made volatile by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But whether electric cars significantly reduce Australia’s transport emissions depends on the extent to which renewables power the electricity grid. Until coal and gas are phased out, many electric cars in Australia will be powered by fossil fuels.

Is It Enough? No

Chalmers said the budget drives investment in renewable energy and delivers thousands of new jobs. But what’s lacking are mechanisms that encourage or compel companies to reduce their emissions in line with nationally legislated targets.

Of course, it’s hardly the present government’s fault that such mechanisms are not in place. The former Coalition government’s decision to axe Labor’s carbon price left a gaping policy hole that put Australia at the back of the global pack on climate action.

The initiatives outlined in this budget should be applauded. But many Australians who voted for Labor, the Greens or the Teal independents wanted significant action on climate change – and they’re still waiting.

So what climate measures should the government be taking?

Many of the policies at its disposal would require new legislation and would not necessarily appear in the budget. They include ending logging of old-growth forest to reduce forestry emissions, and changes to the safeguard mechanism.

The government has flagged reforms to this policy, a legacy of the previous government that purports to set limits on emissions from big industrial polluters.

Given a price on carbon is politically challenging in Australia, the safeguard mechanism appears the most likely means through which industrial emissions reductions will be curbed.

Hopefully other initiatives appear in future budgets, in good haste. They should include:

larger capital investments in renewable electricity generation and battery storage

a very significant funding boost for science and engineering research to produce further technological breakthroughs in low-carbon manufacturing and green steel production

electric vehicle charging stations powered by 100% renewable energy in every city and major highway

taxes on the worst climate offenders such as the beef and dairy industries and other sources of methane emissions.

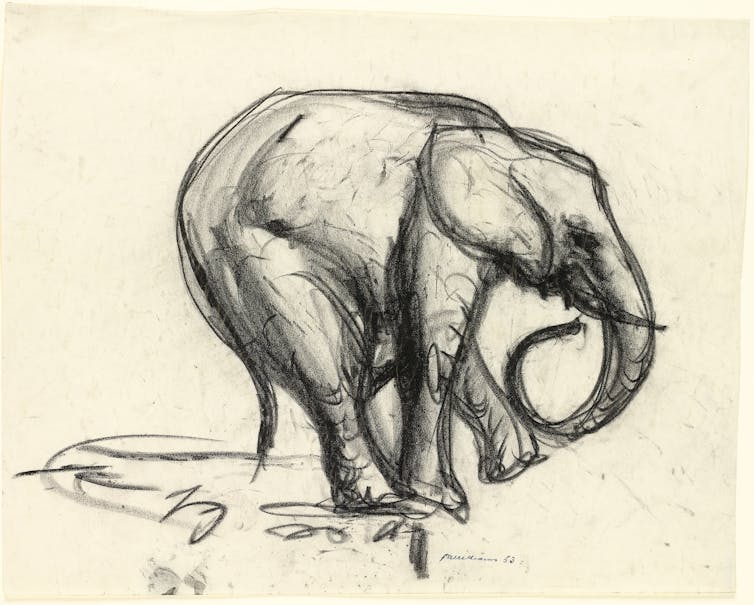

And then we come to the elephant in the room: the emissions created when Australia exports fossil fuels to countries where it’s burned for energy.

Domestically, Australia is responsible for about 1.5% of global emissions. But factor in our fossil fuel exports and that rises to about 5% – and may jump to up to 12% by 2030.

So perhaps the most significant decisions Labor will make for the climate change aren’t budget initiatives at all – but rather, what fossil fuel exploitation the government allows in coming years.

Let’s Get Started

This budget included, for the first time, a statement on the fiscal impact of climate change.

It outlined the damage climate change can cause to government budgets including the cost of “responding to extreme weather events, which are likely to increase in severity and frequency”.

One thing is clear: Australia must reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and transition away from its reliance on fossil fuel exports. It’s in the nation’s best economic interests – and there’s no better time than now to begin this work in earnest.![]()

Timothy Neal, Senior research fellow in the Department of Economics, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Out of bounds: how much does greenwashing cost fossil-fuel sponsors of Australian sport?

High-profile Australian athletes and supporters across sports such as cricket, netball and Australian Rules football have recently called for their sports to reconsider their partnerships with fossil fuel or mining companies.

Our report, released today, is the first research to quantify the number and value of fossil-fuel sponsorships in Australian sport. It reveals coal, gas and oil companies spend A$14 million to A$18 million each year sponsoring 14 high-profile leagues and sports in Australia.

We identified 51 such partnerships. The major fossil-fuel sponsors of sport include companies such as Santos, Alinta, BHP and Woodside.

The money these sponsors spend on sport is at least partly an investment in “greenwashing” their images. Fossil fuel corporations are major sources of the emissions that drive climate change, but through sports sponsorship they leverage the positive image of sport and fan loyalty associated with teams.

The association of these sponsors’ names and logos with popular sports and athletes can sanitise the image of fossil fuel companies. When sports embrace high-polluting brands, they help normalise those companies’ contributions to the climate crisis.

But many Australian sport organisations are starting to take action to reduce their carbon footprint. They are also leveraging their media profiles to promote environmentally positive behaviours. As they do so, coal, oil and gas sponsorships and partnerships are coming under increasing public scrutiny.

Why Does This Matter For Sport?

Sport is part of the Australian cultural identity. Millions of Australians watch and play sport. Hundreds of thousands volunteer every week to do the work needed to bring community sport to life.

Sport is integral to the social fabric of communities. It provides well-documented mental and physical health benefits as well as social benefits for participants. Sport also contributes around $50 billion a year to the Australian economy.

However, climate change is both an immediate and future threat to sport in Australia.

Increasing heat as a result of climate change is a problem for sport. The viability of iconic sporting events such as cricket’s MCG Boxing Day Test and the Australian Open tennis could be threatened by heatwaves reaching highs of 50℃ by 2040. Extreme heat poses a risk for community sport too.

Higher temperatures are also driving longer and more intense bushfire seasons, exposing athletes and spectators to dangerous air pollution.

In this context, accepting sponsorship from coal, gas and oil corporations creates reputational risks for Australian sport.

Which Sports Are Favoured?

Our report, Out of bounds: coal, gas and oil sponsorship of Australian sports, was prepared by Swinburne University of Technology’s Sport Innovation Research Group for the Australian Conservation Foundation. We identified 51 partnerships (3.5% of all partnerships) between 14 top-tier sporting organisations and coal, gas and oil companies. We found oil and gas companies tend to sponsor Australian Rules football, rugby union and rugby league, while fossil-fuel energy retailers favour partnerships with cricket, soccer and netball.

While not a small level of investment, we suggest these 14 sports could, over time, replace the $14 million to $18 million they receive each year.

The benefits that associating with sport provides to these corporations would be much more difficult for them to replace.

What Can Sports Do?

There is a solution to this challenge for the Australian sport industry. Sport organisations have a history of having to move away from corporate sponsors due to growing public concern about their impact on individual and community health and wellbeing. Tobacco, alcohol and gambling are just some industries that have faced regulation to control their involvement with sport as a promotional platform.

Cricket Australia has already announced it is parting ways with Alinta Energy when its nearly $40 million, five-year sponsorship deal ends in 2023.

The road away from coal, oil and gas company sponsorship of sport, as well as wider environmental approaches, can be either direct or indirect. Directly, organisations or brands can end or reject coal, oil and gas sponsorship. They can also actively advocate or illustrate sports’ role in a more sustainable future.