inbox and environment news: Issue 562

November 13 - 19, 2022: Issue 562

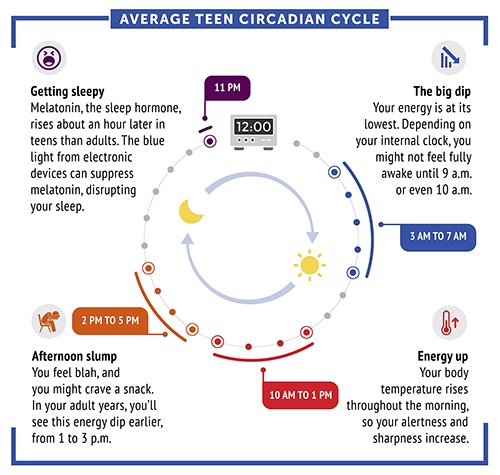

Circadian Rhythms

- Create a sleep schedule. One of the easiest ways to improve your circadian rhythm is to go to bed at the same time every night. After you have done this for a while you will find your body wants to go to sleep at that time.

- Limit stimuli. Make sure your room is dark and quiet when you're ready to sleep.

- Exercise earlier in the day - doing the 'hard yards' type of exercise earlier and having a swim or some form of less strenuous 'stretch' exercises later in the day eases sore muscles and sets you up for a good sleep.

- Avoid caffeine after 10am.

- Make breakfast and lunch your bigger meals for the day and have only a light dinner. A diet focused on carbohydrates and protein for breakfast will give you lots of energy for the day ahead. If you are still getting mid-morning or mid-afternoon cravings, reach for a handful of nuts mixed with chia and pumpkin seeds or an apple/banana and some real Greek yoghurt.

- Limit screen time in the hours before sleep.

Lunar Eclipse: November 8, 2022

Manly Warringah Vawdon Cup 2022 Champions – Touch

NSW Touch - Vawdon Cup Results 2022

School Leavers Support

- Download or explore the SLIK here to help guide Your Career.

- School Leavers Information Kit (PDF 5.2MB).

- School Leavers Information Kit (DOCX 0.9MB).

- The SLIK has also been translated into additional languages.

- Download our information booklets if you are rural, regional and remote, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or living with disability.

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (DOCX 1.1MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (PDF 2MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Download the Parents and Guardian’s Guide for School Leavers, which summarises the resources and information available to help you explore all the education, training, and work options available to your young person.

School Leavers Information Service

- navigate the School Leavers Information Kit (SLIK),

- access and use the Your Career website and tools; and

- find relevant support services if needed.

New Courses To Strengthen Digital Workforce

November 9, 2022

An army of cyber security, cloud computing and artificial intelligence experts will be trained at the State’s first revolutionary Institute of Applied Technology (IAT) with the NSW Government today unveiling of a suite of 19 new digital-focused courses.

The new facility, located at Meadowbank, is a partnership between TAFE NSW, Microsoft, the University of Technology Sydney and Macquarie University, and will focus on turbocharging the take-up of digital skills to strengthen our State’s workforce.

Minister for Skills and Training Alister Henskens said the new IAT, which opens in February next year, is now taking enrolments in courses spanning artificial intelligence, cyber security, cloud computing, machine learning and data analytics.

“These courses have been developed hand-in-glove with industry to meet current and emerging skill needs,” Mr Henskens said.

“At a time when cyberattacks are on the rise, this training will allow people to quickly build the skills we need for a strong and safe digital economy.

“With Australia needing another 17,000 cyber professionals by 2026, now is the time for people to enroll in courses at our new IAT and get the skills they need for jobs in cyber security, digital forensics, data engineering, machine learning, and more.”

To meet this increasing industry demand, the IAT will offer a combination of flexible microskills and microcredentials to cater for new learners as well as current industry workers who require upskilling to maintain pace with the rapidly evolving sector.

Member for Ryde and Minister for Customer Service and Digital Government Victor Dominello said learners can stack multiple microcredentials to create a nationally recognised certification, such as a diploma, or advanced diploma, or count towards a degree with participating education partners.

“Ryde is being transformed into an education and employment powerhouse, and this revolutionary new training facility will help attract, retain and upskill local workers, which is a fantastic win for our community,” Mr Dominello said.

In addition to the 19 programs now available, the IAT will release another 16 courses in time for Semester 2, 2023. For more information, visit the Institute of Applied Technology

Local Students And Support Staff Have Opportunity To Train As Teachers

November 6, 2022

Classroom support staff in NSW public schools will be guaranteed a permanent teaching job once they finish their training under a new Teacher Supply Strategy program to grow the teaching workforce.

The Grow Your Own Teacher Training program will initially support up to 100 School Learning Support Officers (SLSOs) to upskill and study teaching degrees while working in local schools.

Deputy Premier and Minister for Regional NSW Paul Toole said the program recognises the outstanding contribution SLSOs make in classrooms across the State and helps remove barriers to a teaching career.

“We have generous financial incentives, including housing, to encourage teachers to work in our regional schools, but we're also committed to fostering local talent,” Mr Toole said.

“Our regional SLSOs have strong ties to their local community and are already doing fantastic work in our schools. We want to do all we can to support them to upskill and progress their careers without having to travel away from home.”

Minister for Education and Early Learning Sarah Mitchell said the Grow Your Own Teacher Training program is complemented by another Grow Your Own stream that will encourage year 12 students and community members living in rural and regional areas to explore a career in teaching.

“The Grow Your Own Community Entry Pathway is about supporting school leavers who are interested in becoming teachers to stay at their local school and gain hands-on experience as SLSOs or classroom teacher support officers,” Ms Mitchell said.

“Through both Grow Your Own streams we are building new pathways to teaching careers that encourage and support young people into this rewarding profession.”

The NSW Department of Education has partnered with Charles Sturt University and Western Sydney University to deliver the Grow Your Own Teacher Training pilot program.

Participants will commence their studies in early 2023 and remain employed as an SLSO in their current school while studying. They receive $10,000 training allowance per year (up to $30,000 for the degree) and can work part-time as an educational paraprofessional in their final four semesters of study.

Applications opened this week, with a focus on rural, regional schools and high-demand metropolitan areas.

To support schools to introduce a Community Entry Pathway model, an online toolkit is rolling out to provide resources and information on how to identify and recruit year 12 students and community members.

For more information visit: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teach-nsw/become-a-teacher/grow-your-own

Be The Boss: I Want To Be An Electronic Repair Technician

- develops, constructs and tests electronic equipment and associated circuitry in accordance with technical manuals and instructions of Electronics Engineers and Engineering Technologists

- estimates material costs and quantities of electronic circuitry and equipment

- evaluates performance of electronic equipment

- inspects designs and finished products for compliance with specifications, drawings, contracts and regulations

- installs, repairs and modifies electronic equipment.

- Fabricate, assemble and dismantle electrical equipment and devices

- Solve technical issues in analogue and digital electronic and communications circuits and systems

- Use industry-relevant computer applications

- Implement safe work practices and regulations

- Gain practical experience and develop specialist skills that give you an advantage in the job market.

- Experience in applying key electronic principles to a range of real world industry challenges

- The skills to build and test electronic circuits using different electronics components and devices

- Techniques to install, set-up, test, repair and maintain electronic equipment and devices at a component/sub-assembly level

- Drawing on environmentally-minded electronic practices and procedures

- A strong pathway to continue your study and enhance your career opportunities

Summer Skills Fee Free Courses

Summer Skills is a fee-free* short course program to support school leavers, aged between 15 – 24 years, obtain job-ready skills over the summer months.

Whether you plan to attend TAFE NSW, university, have a gap year or are still undecided, we have a course that can give you the skills for a brighter future.

Priority industry areas have been identified under Skilling for Recovery and include short courses in Early Childhood Care, Aged Care, Disability, Hospitality, Construction, Agriculture, Business and Administration, IT and Digital, Retail, Transport and Logistics, Manufacturing/Engineering and Sport and Recreation.

For example - starting November 23, 2022 at Ryde: STATEMENT OF ATTAINMENT IN COMMERCIAL COOKERY BASICS

Or starting November 24th at Ryde: STATEMENT OF ATTAINMENT IN ESPRESSO COFFEE

Find out more at: https://www.tafensw.edu.au/summer-skills

Also Available:

- Be the Boss: I Want To Be A Baker

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be An Information Technology Administrator

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be An Architect

- Be The Boss: I Want to Be a Marine Electrician

- Be The Boss: I want To Be A Cabinet Maker

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be An Automotive Mechanic

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Biotechnologist

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Pilot

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Music Producer

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Gardener

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Builder

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Confectioner

- Be The Boss: I Want To Be A Ship's Captain

Word Of The Week: Shambolic

adjective; "chaotic, disorderly," 1961, derived from 'shamble' in the sense "disorder"

shamble; verb; (of a person) move with a slow, shuffling, awkward gait. noun; a slow, shuffling, awkward gait.

compare shambles (noun); A scene of great disorder or ruin. A great mess or clutter.

A scene of bloodshed, carnage or devastation. A slaughterhouse. (archaic) A butcher's shop.

From "meat or fish market," early 15c., from schamil "table, stall for vending" (c. 1300), from Old English scamol, scomul "stool, footstool" (also figurative); "bench or stall in a market on which goods are exposed for sale, table for vending." Compare Old Saxon skamel "stool," Middle Dutch schamel, Old High German scamel, German schemel, Danish skammel "footstool." All these represent an early Proto-Germanic borrowing from Latin scamillus "low stool, a little bench," which is ultimately a diminutive of scamnum "stool, bench," from a word root skmbh- "to prop up, support."

In English, the sense evolved from "place where meat is sold" to "slaughterhouse" (1540s), then figuratively "place of butchery" (1590s), and, generally, "confusion, mess" (1901, usually in plural).

York: The Shambles, 1965. Geograph Image: Ben Brookshank

The Church - Under The Milky Way

Hoodoo Gurus - Come Anytime

Split Enz - Message To My Girl

Goanna - Solid Rock (Sacred Ground)

Yothu Yindi - Djapana

Christine Anu My Island Home

I Am, You Are, We Are Australian

Why Maradona’s ‘Hand of God’ goal is priceless – and unforgettable

Football has “The Catch,” baseball has “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” and basketball has “The Block.”

For soccer, it is Diego Maradona’s “Hand of God” – a sporting moment captured in time, the mere mention of which can conjure up strong emotions among supporters.

Such is its legacy, that some 36 years after bouncing into the back of the net, the soccer ball involved is set to be sold at auction on Nov. 16, 2022, at an expected price of up to US$3.3 million.

So why does this goal, which should not even have been a goal, carry so much significance? As an economist who studies sport, I’ve long believed that you have to grasp the cultural significance to understand the financial dimension of sports. This goal was one of soccer’s most iconic events for a number of reasons.

1. It’s About The Controversy

The goal in question was scored by Argentinian great Maradona against England in the quarterfinals of the 1986 World Cup. It was the second half, no goals had been scored, and Argentina’s team was passing the ball around the edge of the England penalty box.

England midfielder Steve Hodge tried to clear the ball but only succeeded in kicking high above the goalkeeper. Normally one would expect the goalkeeper to catch it, especially against the 5-foot-5-inch Maradona. But somehow the ball ended up in the back of the net.

At first, it seemed that Maradona had headed the ball, but replays clearly showed him steering the ball with his clenched fist. This was three decades before the use of video assistant referee, or VAR, in soccer. There was no way to review. The referee’s vision was blocked, and he looked to the linesman for guidance – but the linesman saw nothing wrong, and the goal was allowed to stand.

Speaking after the game, Maradona told reporters that the goal was scored “un poco con la cabeza de Maradona y otro poco con la mano de Dios,” or in the English translation, “a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God.” The phrase stuck, and with it the legend of the goal.

2. It’s Really About That Second Goal

The Argentina team of 1986 was not a great team. Rather, it was an average team combined with the greatest player in the world at the time, and many would say the most talented footballer ever to grace a pitch.

England were probably a better team if you took Maradona out of the game. So that is what England’s defenders tried to do: shut him out by fair means or foul. England’s plan was to make it the responsibility of almost every player on the field to track him and try to stop him from advancing. They tried, but it was impossible.

Four minutes after the first goal, Maradona took the ball and at lightning pace skipped past three defenders and the England goalkeeper to score again. The goal was voted “the goal of the [20th] century” in a 2002 FIFA poll.

Argentina would go on to win the final in what is still known as “Maradona’s World Cup.”

3. No, It’s All About Argentina’s Revenge!

There was no escaping the political context of the game – or the goal. In 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, or Las Malvinas – the name you use determines your allegiance – a British overseas territory some 300 miles off the Argentinian coast.

The islands had been occupied by the British since 1833, and former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher cemented her image as “The Iron Lady” by sending a military task force 8,000 miles across the Atlantic to recapture the islands. The U.K. claimed its primary motivation was respecting the self-determination of the islanders, but valuable fishing rights and a seat at the table in the administration of the Antarctic were also at stake. Among the neutrals, there was considerable sympathy for the Argentine cause in what seemed like an anachronistic act of colonial imperialism by the British.

The humiliation for Argentinian generals likely hastened the end of the military dictatorship and the restoration of democracy in Argentina. But it bred resentment against the English – Argentinians believe in their heart that Las Malvinas belong to them, not to Britain – and that colored the build-up to the 1986 game, as Maradona later recalled in his memoir “Yo Soy El Diego,” or “I Am The Diego:”

“Somehow we blamed the English players for everything that had happened, for everything that the Argentinian people had suffered … we were defending our flag, the dead kids, the survivors.”

4. OK, It’s Because Diego Maradona Really Is The GOAT

Few players have stamped their presence on a World Cup quite like Maradona. His performance in the England game stands as a memorial to his greatness, and the phrase “Hand of God” neatly puts his name in the same sentence as divinity. It wasn’t a one-off – the entire tournament became a showground for his outrageous skill – and he fittingly raised the trophy at the end.

But Maradona – who died in 2020 at age 60 – was also a troubled genius. A child of the slums of Buenos Aires, he never lost the anxiety that he would not receive his due. He became addicted to drugs – potentially as a result of all the painkillers he needed to keep playing in an era in which defenders were prone to bone-crunching tackles – and struggled with cocaine.

He was frequently abusive toward the media, was accused of assaulting one girlfriend, and he was alleged to have close connections to the mafia.

But for most soccer enthusiasts, none of this really detracts from his greatness as a player.

There are simply some players – a very small number indeed – whose story transcends right and wrong and whose acts are forever remembered like the heroes of ancient Greek epics. Maradona is one such player. Like Achilles or Odysseus, his name will live on, remembered in the “Hand of God” goal![]()

Stefan Szymanski, Professor of Sport Management, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why do I remember embarrassing things I’ve said or done in the past and feel ashamed all over again?

We’ve all done it – you’re walking around going about your business and suddenly you’re thinking about that time in high school you said something really stupid you would never say now.

Or that time a few years ago when you made a social gaffe.

You cringe and just want to die of shame.

Why do these negative memories seem to just pop into our heads? And why do we feel so embarrassed still, when the occasion is long past?

How Do Memories Come Into Our Awareness?

The current thinking is there are two ways in which we recall experiences from our past. One way is purposeful and voluntary. For example, if you try to remember what you did at work yesterday, or what you had for lunch last Saturday. This involves a deliberate and effortful process during which we search for the memory in our minds.

The second way is unintended and spontaneous. These are memories that just seem to “pop” into our minds and can even be unwanted or intrusive. So, where does this second type of memory come from?

Part of the answer lays in how memories are connected to each other. The current understanding is our past experiences are represented in connected networks of cells that reside in our brain, called neurons.

These neurons grow physical connections with each other through the overlapping information in these representations. For example, memories might share a type of context (different beaches you’ve been to, restaurants you’ve eaten at), occur at similar periods of life (childhood, high school years), or have emotional and thematic overlap (times we have loved or argued with others).

An initial activation of a memory could be triggered by an external stimuli from the environment (sights, sounds, tastes, smells) or internal stimuli (thoughts, feelings, physical sensations). Once neurons containing these memories are activated, associated memories are then more likely to be recalled into conscious awareness.

An example might be walking past a bakery, smelling fresh bread, and having a spontaneous thought of last weekend when you cooked a meal for a friend. This might then lead to a memory of when toast was burned and there was smoke in the house. Not all activation will lead to a conscious memory, and at times the associations between memories might not be entirely clear to us.

Why Do Memories Make Us Feel?

When memories come to mind, we often experience emotional responses to them. In fact, involuntary memories tend to be more negative than voluntary memories. Negative memories also tend to have a stronger emotional tone than positive memories.

Humans are more motivated to avoid bad outcomes, bad situations, and bad definitions of ourselves than to seek out good ones. This is likely due to the pressing need for survival in the world: physically, mentally, and socially.

So involuntary memories can make us feel acutely sad, anxious, and even ashamed of ourselves. For example, a memory involving embarrassment or shame might indicate to us we have done something others might find to be distasteful or negative, or in some way we have violated social norms.

These emotions are important for us to feel, and we learn from our memories and these emotional responses to manage future situations differently.

Does This Happen To Some People More Than Others?

This is all well and good, and mostly we’re able to remember our past and experience the emotions without too much distress. But it may happen for some people more than others, and with stronger emotions attached.

One clue as to why comes from research on mood-congruent memory. This is the tendency to be more likely to recall memories which are consistent with our current mood.

So, if you’re feeling sad, well, you’re more likely to recall memories related to disappointments, loss or shame. Feeling anxious or bad about yourself? You’re more likely to recall times when you felt scared or unsure.

In some mental health disorders, such as major depression, people more often recall memories that evoke negative feelings, the negative feelings are relatively stronger, and these feelings of shame or sadness are perceived as facts about themselves. That is, feelings become facts.

Another thing that is more likely in some mental health disorders is rumination. When we ruminate, we repetitively think about negative past experiences and how we feel or felt about them.

On the surface, the function of rumination is to try and “work out” what happened and learn something or problem-solve so these experiences do not happen again. While this is good idea in theory, when we ruminate we become stuck in the past and re-experience negative emotions without much benefit.

Not only that, but it means those memories in our neural networks become more strongly connected with other information, and are even more likely to then be recalled involuntarily.

Can We Stop The Negative Feelings?

The good news is memories are very adaptable. When we recall a memory we can elaborate on it and change our thoughts, feelings, and appraisals of past experiences.

In a process referred to as “reconsolidation”, changes can be made so the next time that memory is recalled it is different to what it once was and has a changed emotional tone.

For example, we might remember a time when we felt anxious about a test or a job interview that didn’t go so well and feel sad or ashamed. Reflecting, elaborating and reframing that memory might involve remembering some aspects of it that did go well, integrating it with the idea that you stepped up to a challenge even though it was hard, and reminding yourself it’s okay to feel anxious or disappointed about difficult things and it does not make us a failure or a bad person.

Through this process of rewriting experiences in a way that is reasonable and self-compassionate, their prominence in our life and self-concept can be reduced, and our well-being can improve.

As for rumination, one evidenced-based strategy is to recognise when it is happening and try to shift attention onto something absorbing and sensorial (for example doing something with your hands or focusing on sights or sounds). This attention shifting can short circuit rumination and get you doing something more valued.

Overall, remember that even though our brain will give us little reminders of our experiences, we don’t have to be stuck in the past.![]()

David John Hallford, Senior Lecturer and Clinical Psychologist, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why Meta’s share price collapse is good news for the future of social media

Facebook may not be the original social media platform but it has stood the test of time – until recently. Meta, the company that owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, saw its value plummet by around $80 billion (£69 billion) in just one day at the end of October, after its third-quarter profits halved amid the global slowdown. Meta is now valued at around $270 billion compared with more than $1 trillion last year.

Several issues have caused investors to turn away from the social media giant, including falling advertising revenue, a conflict with Apple over its app store charging policy, and competition for younger audiences from newer platforms such as TikTok.

Meta’s chief-executive Mark Zuckerberg has also used his majority control to double down on his ambitions for the “metaverse”, a virtual reality project on which he has already spent more than $100 billion – with questionable results according to initial investor and media reaction. Zuckerberg has promised even more investment in the metaverse next year.

It’s tempting to describe this spending spree as a billionaire’s “insane fantasy”, but there is a simpler explanation. As dominant platforms compete for a limited amount of advertising revenue, regulation – particularly when it differs between countries or regions – has created space for more competitors. This is good news for new social media companies, but it also means that the only way Meta is likely to be able to keep its dominant position is by placing a massive bet on the technology of the future. Zuckerberg believes that means the metaverse, but this remains to be seen.

Tech’s Changing Fortunes

Even with its recent troubles, Meta owns the largest social network in the world. Those recent results that caused investors to flee in their droves still showed total revenues of $27 billion and profits of $4.4 billion.

To maintain its position as market leader in the past, Meta has typically bought its most promising competitors as early as possible. Integrating these newly acquired startups into the company’s ecosystem helped to maximise advertising revenue and preclude competition.

Research shows that digital markets are typically dominated by a single firm, but also that these firms tend to be much more specialised than the major companies of the past. Meta is only active in social media and makes money almost exclusively by selling advertising.

Attempts by such firms to expand into other areas typically fail – know anyone with a Facebook phone? And while you may not remember Google’s attempt at social media, iPhone users are probably at least aware of Apple’s maps app.

So Facebook relies on consumers using devices produced by other tech companies to make money. But as global social media advertising revenue slows down, this is becoming more difficult. Apple has begun charging Meta for the revenue it makes from iPhone users, for example. And research shows that, when two companies compete to make money from the same captive source, their successive markups not only push prices higher for consumers but also keep profits lower for both firms.

Global Domination Fail

Meta’s strategy has, until recently, allowed it to rule social media in western markets – but not in China, a country of more than 300 million social media users. Since 2009, Facebook has been blocked by the country’s “great firewall”, the largest and most sophisticated system of censorship in the world.

Reported attempts to adapt Facebook to suit Chinese government media control have never been successful. And so, Chinese company ByteDance was able to launch a news platform called Toutiao in 2012 without having to compete with a dominant social network. In 2016, ByteDance launched Douyin, a social media platform for publishing short videos which was subsequently released to the rest of the world in 2018 as TikTok.

Despite not being profitable, ByteDance’s market capitalisation is now estimated at around $300 billion – versus Meta’s current £270 billion valuation. It is also popular among younger users that tend to be much more avid social media users.

Meta cannot simply buy TikTok: it is too big, not publicly traded and under tight control by the Chinese government. Zuckerberg’s firm has instead tried to compete by launching similar features on Instagram. Ironically, the only large market where this strategy is really working is India, a country that banned TikTok in 2021 due to a military conflict with China.

Fair Competition

At the same time that TikTok has been expanding beyond Meta’s reach, western regulators have also started to examine the impact of the lack of competition in digital markets on innovation. While research shows that the winner-take-all nature of highly innovative markets is typically good for consumers, this is only true when all companies get a fair chance to become dominant.

In addition to recent rulings against tech company dominance by its highest court, the European Union also recently introduced the Digital Markets Act. This outlaws many practices used by dominant firms to preserve their status in a market.

Similar legislation is expected from the US after the November midterm elections, while the UK has forced Meta to sell gif library Giphy to ensure it doesn’t decrease competition in the online advertising sector.

All of this means that, for Facebook to remain dominant, Meta needs to invest in its own products. To be the market leader of tomorrow, the company cannot simply count on buying up promising startups.

But its metaverse is a nebulous project and an odd bet. After all, Google has already failed to drum up interest in Google Glass, even though the technology behind it was successful. What has changed to convince normal people to regularly wear virtual reality headsets?

The only alternative for Meta may be to find a better idea in which to invest. In the meantime, regulation continues to protect potential competitors. This is great news for consumers and creators alike: now might be the best moment to launch an innovative social media format that can actually compete with giants like Meta to become the market leader.

Renaud Foucart, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Lancaster University Management School, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How early failure can lead to success later in creative careers

Failing early in our careers can make us question whether we are on the right path. We may look at people who have succeeded from the outset and wonder why it doesn’t come so easily to us. Classical violinist Nigel Kennedy, actor Natalie Portman and painter Pablo Picasso are examples of young geniuses who were successful early on.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

But for some of us, failure at the beginning of our careers is important to later success. For many creatives, how we deal with those moments when things aren’t going right or you’ve received yet another rejection letter can make or break us.

The author and self-improvement lecturer Dale Carnegie maintained that inaction breeds doubt and fear; action creates confidence and courage, which inevitably ends up helping a person to succeed. This chimes with what American psychologist Carol Dweck outlines in her 2006 book Mindset.

Dweck discusses the concept of people with a “fixed mindset” versus a “growth mindset”. The former is a way of thinking where there is a lack of self belief and a negative persona while the latter is where no challenge or task is too large to take on board. Which mindset you have dictates how you will interpret failure and success and how well you approach everyday life.

This article is part of Fail Better, a series for those of us in our 20s and 30s about navigating the moments when things aren’t quite going as planned. Many of us are tuned into the highlight reel of social media, where our peers share their successes in relationships, careers and family. When you feel like you’re not measuring up, the pieces in this special Quarter Life series will help you learn how to cope with, and even grow from, failure.

A passion for learning and a desire to improve upon failure creates opportunities to learn and challenge yourself. This mentality is a boon to creatives. While yes, there are the Picassos and Portmans of the world, there are also a few famous creatives who had to overcome failure early on in their careers. These individuals demonstrate the “growth mindset”.

Rejection Doesn’t Have To Kill Dreams

A young schoolteacher from Maine, US, was a passionate part-time writer who worked tirelessly trying to get his novels published (unsuccessfully) in the late 1960s. He continued to believe in himself and chase the dream of becoming a successful author. But sometimes the reality of failure gets the better of a person and after 30 rejections he famously threw his fourth attempt at a novel away.

Fortunately, the manuscript was saved by his wife who, having confidence in his work, persuaded him to continue trying. Eventually, the novel was sold for an advance of £2000, a nice bonus for a schoolteacher. The publishing rights were ultimately purchased for an additional £200,000 and the novel Carrie turned Stephen King into a household name.

Dreams can propel us forward but they can also be crushed by rejection. The composer Johnathon Larson spent years working on his 1991 musical Superbia only for it to be turned down by theatre producers. He was told by his agent to “go away and write something you know about”.

This was a crushing moment for Larson. Eight years of work rejected. However, he listened to the advice and his next muscial Rent premiered on Broadway in 1996, becoming a box office sensation. The semi-autobiographical Tick, Tick Boom, which Larson began performing as a one-man show in 1990, went on to also be a hit when it premiered in 2001. It has recently been turned into a major motion picture directed by Lin-Manuel Miranda (creator of Hamilton).

Larson’s secret was to learn from failure and take on the advice given to him. He used that experience to propel himself forward. Sadly, Larson never witnessed his triumph, he died on the eve of Rent’s Broadway premier in 1996 from an aortic dissection. But his life, including his failures, made him successful. His roadblocks became his inspiration. Both of his successful productions tell the stories of larger-than-life characters struggling with their failings while trying to achieve a degree of success.

Overcoming Difficult Circumstances

There are situations in life that conspire to make us fail. However, adversity can often act as a springboard of determination to succeed. My turning point as a youngster was failing my grade five music theory exam. That one singular event, although heartbreaking, made me determined to succeed in music and become a composer and producer of Scottish Musicals.

Others deal with much more difficult circumstances. Imagine being homeless, penniless with partial facial paralysis, yet dreaming of an acting career. Never-ending rejection from talent scouts and agents, hours of waiting for appointments that never materialise, such a life would be demoralising. However, the realisation of personal failure can become the catalyst for success.

This real-life scenario eventually earned Sylvester Stallone over £178 million and catapulted his writing and acting career to stardom. He didn’t let these circumstances, which led to failure, stop him. The key here is that he believed in his ability and that drove him onward. Continual failure reinforced his resolve to succeed.

Steven Spielberg had poor high school grades and was rejected three times from film school. He battled through his early career failures before eventually directing 51 films and winning three Oscars. Again, it was his perseverance and self belief that drove his determination to succeed.

We might never become the next Spielberg, King or Larson but the lesson learnt from their experiences is a sharp reminder of the mantra of playwright Samuel Beckett:

Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

Failure is not damaging, it is part of a proactive progression and once we learn to accept that we might be unstoppable. I eventually passed my grade five theory exam and went on to get two degrees and a PhD in musical theatre, the rest is history … my personal history began with a failure for which I am very proud.

Quarter Life is a series about issues affecting those of us in our 20s and 30s.![]()

Stephen Langston, Senior Lecturer and Programme Leader for Performance, University of the West of Scotland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How the philosophy behind the Japanese art form of kintsugi can help us navigate failure

In our 20s and 30s, there can be immense pressure to measure up to the expectations of society, our families, our friends and even those we have for ourselves. Many people look back and feel disappointed that they hadn’t taken the opportunity to travel more. Others might have envisioned that they would be further along in their careers or personal relationships. In reality, life is hard and we might face setbacks (big and small) that can shatter our dreams, leaving us with fragments we perceive as worthless.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

Feelings of failure can take a long-lasting mental toll but they don’t have to stop you in your tracks. There are many teachings, practices and philosophies that can help you deal with disappointment, embrace imperfection and remain optimistic.

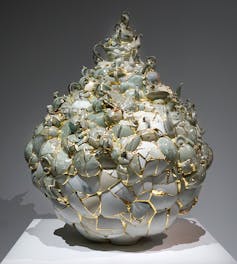

One such practice is the Japanese art form of kintsugi, which means joining with gold. It has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years as both an art technique, a worldview and metaphor for how we can live life.

Many forms of Japanese art have been influenced by Zen and Mahayana philosophies, which champion the concepts of acceptance and contemplation of imperfection, as well as the constant flux and impermanence of all things.

This article is part of Fail Better, a series for those of us in our 20s and 30s about navigating the moments when things aren’t quite going as planned. Many of us are tuned into the highlight reel of social media, where our peers share their successes in relationships, careers and family. When you feel like you’re not measuring up, the pieces in this special Quarter Life series will help you learn how to cope with, and even grow from, failure.

Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery. If a bowl is broken, rather than discarding the pieces, the fragments are put back together with a glue-like tree sap and the cracks are adorned with gold. There are no attempts to hide the damage, instead, it is highlighted. The practice has come to represent the idea that beauty can be found in imperfection. The breakage is an opportunity and applying this kind of thinking to instances of failure in our own lives can be helpful.

A Technique To Repair Broken Pots

Kintsugi was fairly widespread in Japan around the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The origins of this aesthetic go back hundreds of years to the Muromachi period (approximately 1336 to 1573). The third ruling Shogun (leader) of that era, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408), is said to have broken his favourite tea bowl. The bowl was unique and could not be replaced.

So, instead of throwing it away, he sent it to China for a replacement or repair. The bowl returned repaired with its pieces held in place by metal staples. Staple repair was a common technique in China as well as in parts of Europe at the time for particularly valuable pieces. However, the Shogun considered it to be neither functional nor beautiful.

Instead, the Shogun had his own artisans resolve the situation by finding a method to make something beautiful from the broken, damaged object, but without disguising the damage. And so, kintsugi came to be.

Finding The Beauty In Imperfection

Kintsugi makes something new from a broken pot, which is transformed to possess a different sort of beauty. The imperfection, the golden cracks, are what make the new object unique. They are there every time you look at it and they welcome contemplation of the object’s past and of the moment of “failure” that it and its owner has overcome.

The art of kintsugi is inextricably linked to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi: a worldview centred on the acceptance of transience, imperfection and the beauty found in simplicity. Wabi-sabi is also an appreciation of both natural objects and the forces of nature that remind us that nothing stays the same forever.

Wabi-sabi can also be incorporated into contemplating something and seeing it grow more beautiful as time passes. As a craft and an art form, kintsugi challenges expectations. This is because the technique goes further than repairing an object but actually transforms and intentionally changes its appearance.

In an age of mass production and conformity, learning to accept and celebrate imperfect things, as kintsugi demonstrates, can be powerful. Whether it’s reeling from a breakup or being turned down for a promotion, the fragments of our disappointment can be transformed into something new.

That new thing might not be perfect or be how you had envisioned it would be, but it is beautiful. Rather than try to disguise the flaws, the kintsugi technique highlights and draws attention to them. The philosophy of kintsugi, as an approach to life, can help encourage us when we face failure. We can try to pick up the pieces, and if we manage to do that we can put them back together. The result might not seem beautiful straight away but as wabi-sabi teaches, as time passes, we may be able to appreciate the beauty of those imperfections.

The bowl may seem broken, the pieces scattered, but this is an opportunity to put it back together with seams of gold. It will be something new, unique and strong.

Quarter Life is a series about issues affecting those of us in our 20s and 30s.![]()

Ella Tennant, Lecturer, Language and Culture, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Girls are held up as figureheads of political change, but they don’t want to do it alone

Girls are at the centre of global movements for indigenous rights, climate justice, gender equality and civil rights. Educational activist Malala Yousafzai was awarded the Nobel peace prize at 17.

Greta Thunberg has inspired millions of her peers to campaign for climate action: she began a series of school strikes when she was 15. Iranian and Afghan girls are taking to the streets to demand their rights to an education and basic freedoms.

But our understanding of girls’ involvement in politics is still limited, and their opportunities to participate are all too often tokenistic.

Girls have historically been excluded from most political institutions and movements because of both their age and their gender. While all children and young people are excluded from voting in elections and standing for government, girls and young women have to deal with the additional barrier that politics is still seen by many as a “man’s game”.

Around the world, women still make up just 21% of government ministers and 26% of parliamentarians. Perhaps that is why research shows that girls and young women who are already involved in community organising and activism are reluctant to describe themselves as “political”.

But girls are leading political change – whether on the world stage or in their own communities. In research with girls across nine different countries, my co-authors and I found that girls are taking part in everyday acts of resistance, winning a bit more freedom for themselves and their friends as they navigate their way through childhood.

Girls Lead Movements

Girls push back against inequalities in their communities, challenge unfair rules that stop them from doing everything their male peers are able to and demand fairer treatment from parents and elders.

They set up girls’ rights or feminist clubs in schools and take action on issues they care about, even though they often experience stigma for doing so. And, of course, girls take part in, or even lead, global political movements.

One 2019 study found that daughters were particularly good at convincing their parents of the evidence that our climate is changing as a result of human activity. The increase in climate concern was most dramatic among fathers and conservative parents. So, we know that girls are not just politically active, but that they are also effective political communicators.

But UK media coverage of girls’ activism still often misses the mark. I analysed UK media representations of Malala Yousafzai in the aftermath of her shooting by the Pakistani Taliban. I found that she was often portrayed as younger than she was and as a helpless victim of forces beyond her control.

Despite the fact that Yousafzai had been campaigning and blogging for some time, speaking out even after threats to her life, almost nine times out of ten, the newspapers in this study quoted somebody else’s words in explaining her story and its significance.

Help – Not Hope

While there is also plenty of positive media coverage of girl activists, it often risks presenting the issues they are campaigning on as already solved. Greta Thunberg is calling for adults to urgently address climate change, but media coverage of her activism can adopt a reassuring tone, focusing on Thunberg herself and her amazing qualities, or her ability to inspire millions of other youth activists like her.

As she raises the alarm about the need for urgent action, many adults see her as evidence that everything is going to be OK. As Thunberg said in a 2019 appearance at the UN: “You all come to us young people for hope? How dare you?”

For more than two decades now, we’ve seen international institutions, governments, NGOs and transnational corporations embrace the idea of girl power. Everyone from Nike to the World Bank has been keen to tell us of the importance of investing in girls, so that they can fulfil their spectacular potential.

The narrative goes that if you educate and empower a girl, she will go on to use that education for the better of humanity. Girls, we are told, will save the world.

But girls don’t want to save the world all by themselves. Nor should they have to. The issues they care most about are not problems of their making.

Girls need more meaningful opportunities to participate in decision-making, and they need adults to resist the temptation to feel reassured that young people have got the most important issues under control. They need support in their efforts at organising, because they still face so many barriers in terms of funds and platforms to speak from.

As has been shown in Iran and Afghanistan in recent weeks, girls are phenomenally brave in standing up to the injustices they face. But they shouldn’t have to do it alone.![]()

Rosie Walters, Lecturer in International Relations, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Landmark

Have Your Say On The Future Of Help At Home

- ensuring flexibility to respond to changing needs

- care management and self-management

- funding to cover the cost of care and provide value for money

- increasing early support for independence at home.

Seniors Welcome New Concession Card Limits

Pensioner's Concessions: Council Rates

- Half of the total of your ordinary rates and domestic waste management service charge, up to a maximum of $250.

- Half of your water rates or charges, up to a maximum of $87.50.

- Half of your sewerage rates or charges, up to a maximum of $87.50.

Freshie Masters Carnival - Saturday 19 November

Have Your Say On Strengthening Quality In Aged Care

Attacks on Dan Andrews are part of News Corporation’s long abuse of power

Sane people trying to fathom the Herald Sun’s bizarre coverage of Victorian Premier Dan Andrews over the past few days might be helped by some insights from the founding of News Limited, the company on which Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation empire has been built and of which the Herald Sun is part.

The main insight is that journalism is not, and never has been, the purpose of News Corporation. Its purpose, its reason for existence, is to provide the means by which three generations of the Murdoch family accumulate wealth and exert power.

In her magisterial history of Australian newspaper empires, Paper Emperors, Sally Young tells what she calls the real story of the birth of News Limited.

The company’s own creation myth is that its first newspaper, the Adelaide News, was the work of a couple of rugged individuals, a “miner” called Gerald Mussen, who was in fact an industrial consultant to Broken Hill Associated Smelters, and a former editor of the Melbourne Herald, J. E. Davidson.

As Young makes clear, these two had long worked as collaborating propagandists for the Herald and Weekly Times, of which Keith Murdoch was managing director, and its associated mining interests in Broken Hill and Port Pirie. The evidence indicates that Mussen and Davidson were financed into the newspaper start-up by these interests for the purpose of continuing the propagandising.

Keith Murdoch later acquired the paper in his own right and bequeathed it to Rupert.

Propagandising was News’s original sin, and it has never been redeemed. Instead it has broadened out to beat-ups, misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories.

Of course, along the way it has done plenty of journalism, some of it very high quality. In 1959, the Adelaide News, under the editorship of Rohan Rivett, played a large role in securing a judicial review of the Rupert Max Stuart case. Stuart had been sentenced to hang for the rape and murder of a nine-year-old girl, after a trial that caused much public disquiet. His conviction was never conclusively overturned but he was released after 14 years in prison.

More recently, Hedley Thomas’s exposés of the wrong done to Dr Mohamed Haneef and the inadequacies of the police investigation into the murder of Lynette Dawson, for which her husband Chris was recently convicted, have been instances of public-interest journalism at its best.

However, this function of doing journalism – the “what” – is to be distinguished from the “why”. The journalism is done in pursuit of the organisation’s primary purpose, the empowerment and enrichment of the Murdochs, while every now and again also serving the public interest.

The coverage of Daniel Andrews needs to be seen in this light.

The starting point is that the Murdochs – Lachlan or Rupert or both – clearly prefer a non-Labor government, and the continuance in office of a Labor administration in Victoria is an offence against their wishes.

So we saw in the 2018 election campaign a racist scare campaign against so-called African gangs, pushed along by Peter Dutton, now leader of the Liberal-National opposition in federal parliament, and turbo-charged by the Herald Sun.

It backfired spectacularly, and Andrews won in a landslide. That simply aggravated the offence.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Herald Sun promoted increasingly shrill criticisms of the Andrews lockdowns, particularly by the former Liberal federal treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, who subsequently lost his Melbourne seat of Kooyong in the May federal election. More aggravation.

Most recently, on November 4, 22 days before the 2022 Victorian state election, there was yet further offence. Newspoll showed the Liberal Party trailing Labor 46-54% in two-party-preferred terms. Landslide territory again.

This succession of rebuffs shows that the capacity of the Murdoch media to influence electoral outcomes is weaker than it once was, adding insult to injury.

Time for some mud-chucking in the hope that enough will stick.

First, the Herald Sun resurrects a nine-year-old motor accident involving not Andrews himself but his wife. It publishes online a video-taped interview with the cyclist involved in the collision, and his father.

The interview is long on innuendo and short on facts. It is insinuated that in some undefined way, Andrews improperly used his power to deny the young man justice and that the legal system let him down.

Time, too, to resurrect a conspiracy theory.

On March 9 2021, Andrews slipped on some outside stairs at a holiday house he and his family had rented on the Mornington Peninsula, injuring his back and ribs.

As The Guardian has reported, an anonymous post about what had allegedly “really” happened appeared first on an encrypted messaging app favoured by far-right activists and conspiracy theorists, then moved to a fringe website promoting QAnon and Port Arthur massacre misinformation.

The conspiracy theory asserted that Andrews’ injuries had been sustained in dark circumstances.

For reasons best known to herself, the Liberals’ then Shadow Treasurer Louise Staley, decided this was a fire worth throwing fuel on, so she published a list of 12 questions she said Andrews needed to answer about the incident.

The list was predicated on so much misinformation and disinformation that Ambulance Victoria, whose crew had taken Andrews to hospital, and the chief commissioner of police both felt it necessary to issue statements setting out the facts.

This had the effect of killing off the conspiracy theory, and when Matthew Guy took over as leader of the Liberal Party a few months later, he demoted Staley to shadow minister for scrutiny of government.

Yet on November 6, the Sunday Herald Sun devoted many hundreds of words to a rehash of the conspiracy theory. This time it included a photograph of the steps, noting that the house had been repainted since the incident. What might have been covered up by a fresh coat of paint, the reader is implicitly invited to ask.

News Corporation is cradled in conflict of interest, overt and covert influence-peddling and propaganda, all for the purpose of advancing the Murdoch family’s interests. Abuse of media power is baked into its culture.

This does not excuse what the Herald Sun is doing, but helps explain it.![]()

Denis Muller, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Advancing Journalism, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It’s after-hours and I need to see a doctor. What are my options?

There are times when medical care can’t wait until 9am or first thing Monday. Perhaps your COVID has worsened and you’re becoming short of breath. Or your baby has a fever that’s worrying you. Or your elderly parent’s pain can’t be relieved with over-the-counter medications.

When last asked in 2020, two-thirds of Australians had accessed after-hours health services in the previous five years. But how do you access health care on weekends and after 5pm in 2022?

Many GP Super Clinics continue to operate beyond business hours, accept walk-ins and provide access to onsite pharmacy services. You can find their locations here, though opening hours and costs vary between clinics.

Search engines such as HotDoc and Healthdirect can help you find local health services such as GPs, COVID testing clinics, emergency departments, and allied health services. You can filter search results by “open now”, bulk-billing and accessibility requirements such as building access ramps.

The COVID pandemic accelerated investment in virtual care for non-life-threatening emergencies, which can be less stressful for patients and families than attending an emergency department.

Here are some options for in-person and virtual after-hours care.

Nurse Helplines

If you’re not sure whether you need medical care, or if you need basic information or advice, a useful starting point is to call a free nursing helpline such as Nurse-on-Call in Victoria, 13HEALTH in Queensland, or Healthdirect in other states.

In some cases, nurses may offer a call-back from a GP using phone or video consultation.

Getting A Doctor To Visit You At Home

The National Home Doctor service, which can be booked using telephone (13 74 25) or its mobile app, provides bulk-billed doctor home visits.

Telehealth consultations can also be booked through this service, though they may incur a fee.

Video Consultation With A GP

A range of companies offer GP telehealth consultation after hours, for a fee. It doesn’t have to be an emergency, and can be used for things like last-minute repeat prescriptions.

Search engines HotDoc and Healthdirect can direct you to these services through the “accepts telehealth” or “telehealth capable” options.

Virtual Emergency Departments

Virtual emergency departments in Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia allow people in these states to virtually connect with emergency doctors and nurse practitioners for treatment and advice on non-life-threatening emergencies.

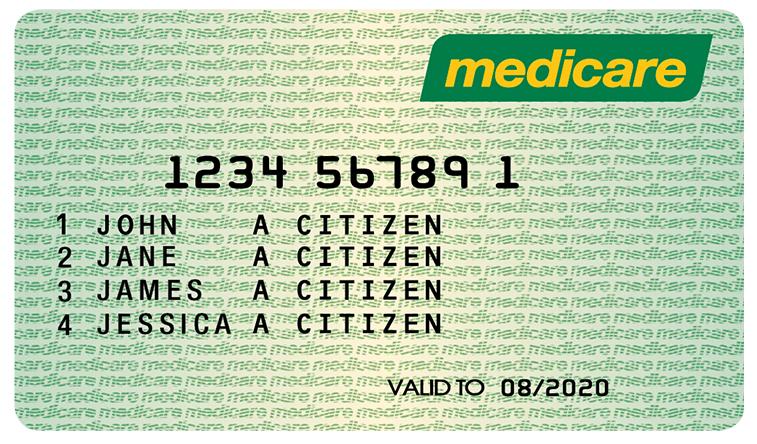

In Victoria, the establishment of the virtual ED program has decreased wait times, with an easy-to-use platform, triage and waiting room. After the consultation, instructions can be emailed, or e-scripts sent to your local pharmacy. This service is currently covered by Medicare with no out-of-pocket costs, though that may change in the future.

My Emergency Doctor is a private service with a hotline and web-based consultations with expert emergency doctors, for patients across Australia. Typically consultations cost A$250-$280, however people living in certain Primary Health Networks can receive free after-hours telehealth consultations through this platform.

Children’s Health Services

In South Australia, free paediatric emergency services are available through the Women’s and Children’s Hospital’s Child and Adolescent Virtual Urgent Care Service, though similar services aren’t available across the country.

However, on-demand services such as KidsDocOnCall and Cub Care provide telehealth paediatric services after-hours to people in all states and territories, for a fee.

Pharmacies

If you need to see a pharmacist or buy medicine after-hours, the Pharmacy Guild of Australia and National Home Nurse pharmacy finders might be helpful.

In Victoria, Supercare Pharmacies are also open 24/7, with nurses available from 6pm to 10pm.

Under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Continued Dispensing Arrangements, approved pharmacists may supply eligible medicines to a person in time of immediate need, when the prescribing doctor can not be contacted, once in a 12-month period.

Medical Chests In Remote Areas

The Royal Flying Doctor service runs a Medical Chest program, to provide emergency and non-emergency, pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatments for people in remote areas, such as antibiotics, pain relief and first-aid.

Medical chests are provided for communities which are located more than 80 kilometres from professional medical services and maintained by a designated local medical chest custodian.

Mental Health Support

Some mental health supports are available after-hours. Free options include:

You can also access paid psychologist services via platforms such as Virtual Psychologist and MyMirror.

Indigenous Health And Wellbeing

Yarning SafeNStrong is a free, confidential, culturally suitable counselling service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This service offers support with social and emotional wellbeing, financial wellbeing, medical support including COVID testing, drug and alcohol counselling and rehabilitation services.

Other Indigenous health services include 13YARN, Support Act, and Brother to Brother.

For People With Communication Needs

Access to after-hours care is often dependent on people’s ability to communicate over a phone.

The National Relay Service can assist hearing- or speech-impaired people with changing voice to text or English to AUSLAN.

Non-English speaking people can access interpreter assistance for telehealth via the National Translating and Interpreting Service. This service is typically free of charge, covers 150 languages, and can be accessed after-hours.

Life-Threatening Emergencies

Of course, none of the options above should replace the Triple Zero (000) service for life-threatening emergencies such as difficulty breathing, unconsciousness and severe bleeding.

This handy infographic shows some of your options for after-hours care. Click on the hand icon on top right to activate interactive elements. Then press the + button to learn more:

We would like to acknowledge the following people for their input to this article: Dr Loren Sher (Director of Victorian Virtual ED at the Northern Hospital), A/Prof Michael Ben-Meir (Director of Emergency Department, Austin Health), Ms Karen Bryant (Senior Aboriginal Liaison Officer, Northern Health) and Dr Kim Hansen (Director of Emergency, St Andrew’s War Memorial Hospital).![]()

Mahima Kalla, Digital Health Transformation Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Feby Savira, Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Deakin University; Kara Burns, Digital Health Program Manager at the Centre for Digital Transformation of Health, The University of Melbourne, and Sathana Dushyanthen, Academic Specialist & Lecturer in Cancer Sciences & Digital Health, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fermented foods and fibre may lower stress levels – new study

When it comes to dealing with stress, we’re often told the best things we can do are exercise, make time for our favourite activities or try meditation or mindfulness.

But the kinds of foods we eat may also be an effective way of dealing with stress, according to research published by me and other members of APC Microbiome Ireland. Our latest study has shown that eating more fermented foods and fibre daily for just four weeks had a significant effect on lowering perceived stress levels.

Over the last decade, a growing body of research has shown that diet can have a huge impact on our mental health. In fact, a healthy diet may even reduce the risk of many common mental illnesses.

The mechanisms underpinning the effect of diet on mental health are still not fully understood. But one explanation for this link could be via the relationship between our brain and our microbiome (the trillions of bacteria that live in our gut). Known as the gut-brain axis, this allows the brain and gut to be in constant communication with each other, allowing essential body functions such as digestion and appetite to happen. It also means that the emotional and cognitive centres in our brain are closely connected to our gut.

While previous research has shown stress and behaviour are also linked to our microbiome, it has been unclear until now whether changing diet (and therefore our microbiome) could have a distinct effect on stress levels.

This is what our study set out to do. To test this, we recruited 45 healthy people with relatively low-fibre diets, aged 18–59 years. More than half were women. The participants were split into two groups and randomly assigned a diet to follow for the four-week duration of the study.

Around half were assigned a diet designed by nutritionist Dr Kirsten Berding, which would increase the amount of prebiotic and fermented foods they ate. This is known as a “psychobiotic” diet, as it included foods that have been linked to better mental health.

This group was given a one-on-one education session with a dietitian at both the start and halfway through the study. They were told they should aim to include 6-8 servings daily of fruits and vegetables high in prebiotic fibres (such as onions, leeks, cabbage, apples, bananas and oats), 5-8 servings of grains per day, and 3-4 servings of legumes per week. They were also told to include 2-3 servings of fermented foods daily (such as sauerkraut, kefir and kombucha). Participants on the control diet only received general dietary advice, based on the healthy eating food pyramid.

Less Stress

Intriguingly, those who followed the psychobiotic diet reported they felt less stressed compared with those who followed the control diet. There was also a direct correlation between how strictly participants followed the diet and their perceived stress levels, with those who ate more psychobiotic foods during the four-week period reporting the greatest reduction in perceived stress levels.

Interestingly, the quality of sleep improved in both groups – though those on the psychobiotic diet reported greater improvements in sleep. Other studies have also shown that gut microbes are implicated in sleep processes, which may explain this link.

The psychobiotic diet only caused subtle changes in the composition and function of microbes in the gut. However, we observed significant changes in the level of certain key chemicals produced by these gut microbes. Some of these chemicals have been linked to mental health, which could potentially explain why participants on the diet reported feeling less stressed.

Our results suggest specific diets can be used to reduce perceived stress levels. This kind of diet may also help to protect mental health in the long run as it targets the microbes in the gut.

While these results are encouraging, our study is not without its limitations. First, the sample size is small due to the pandemic restricting recruitment. Second, the short duration of the study could have limited the changes we observed – and it’s unclear how long they would last. As such, long-term studies will be needed.

Third, while participants recorded their daily diet, this form of measurement can be susceptible to error and bias, especially when estimating food intake. And while we did our best to ensure participants didn’t know what group they’d been assigned to, they may have been able to guess based on the nutrition advice they were given. This may have affected the responses they gave at the end of the study. Finally, our study only looked at people who were already healthy. This means we don’t understand what effect this diet could have on someone who may not be as healthy.

Still, our study offers exciting evidence that an effective way to reduce stress may be through diet. It will be interesting to know if these results can also be replicated in people suffering from stress-related disorders, such as anxiety and depression. It also adds further evidence to this field of research, showing evidence of an association between diet, our microbiome and our mental health.

So the next time you’re feeling particularly stressed, perhaps you’ll want to think more carefully about what you plan on eating for lunch or dinner. Including more fibre and fermented foods for a few weeks may just help you feel a little less stressed out.![]()

John Cryan, Vice President for Research & Innovation, University College Cork

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What’s it like being a young person with long COVID? You might feel like a failure (but you’re not)

Imagine you’re young, healthy and active. Then, one day, the rug is pulled out from under you. You initially have symptoms akin to a cold, so you take a lateral flow test, which shows you have COVID. But it’s nothing that stops you from getting on with things, at least from a distance.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

A few weeks later, or perhaps months, you start to have strange symptoms. You feel unwell after exercising, and you’re exhausted after a trip to the shops or meeting a friend. Your chest becomes heavy when you load the dishwasher.

You go to the doctor and they run some tests. None come back with anything out of the ordinary. Your doctor tells you: “You might have long COVID, but we still don’t know much about it.”

This article is part of Fail Better, a series for those of us in our 20s and 30s about navigating the moments when things aren’t quite going as planned. Many of us are tuned into the highlight reel of social media, where our peers share their successes in relationships, careers and family. When you feel like you’re not measuring up, the pieces in this special Quarter Life series will help you learn how to cope with, and even grow from, failure.

Suddenly words like “rest” and “slowing down” become commonplace in your life. These words are not compatible with the life you want to lead, but your body gives you little choice. You feel shocked by this turn of events and you may even feel like a failure.

You’re not, of course. But living with a chronic medical condition like long COVID, when only months ago you were fit and healthy, can mean you feel that way.

Young People And Long COVID

Many might assume otherwise, but young, healthy people can develop long COVID. Data shows that 2.7% of people aged 17-24 and 3.6% of those aged 25-34 have symptoms at least four weeks after an infection. Even athletes are not immune.

Long COVID is still poorly understood, yet it can be life altering. Although symptoms and their severity vary from person to person, debilitating fatigue is common. Many sufferers are no longer able to do exercise, and even struggle with ordinary daily tasks.

People facing cognitive symptoms like problems with memory and concentration (“brain fog”) might see the quality and quantity of their output at work decline. This may be particularly worrying for young adults only just starting out in their careers.

Long COVID can be episodic and unpredictable. Energy can fluctuate from week to week, day to day, and hour to hour. Physical, mental or emotional exertion can also exacerbate symptoms. Over time, you may feel you are gradually improving. But just as you think you’re reaching the end, your symptoms can hit you hard again.

For people with long COVID, while improvement is possible, there’s a degree of uncertainty about the course their illness might take. This can cast doubt over all sorts of plans a young person might have, from work, to study, to travel, to starting a family.

People with other chronic and poorly understood medical conditions, such as Lyme disease and ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome), frequently struggle with feelings of identity loss. Research on people with long COVID is still emerging, but it’s not difficult to see how it could lead to an identity crisis. The way a person saw themselves before getting sick – as a healthy and able-bodied professional, friend, partner, for example – is challenged when they’re no longer able to carry out these roles like they once could.

Seeking Support For An ‘Invisible’ Illness

Unfortunately, for people with “invisible” medical conditions like long COVID, seeking understanding from others can be fraught. Some may have their experiences discredited or dismissed as psychological by friends, family or even health professionals, which is sometimes called medical gaslighting.

This can be doubly so for people from certain groups, such as women and ethnic minorities, who are sadly at increased risk of having their experiences trivialised or discredited in a healthcare context.

In the face of all these challenges, it’s important to have social support. Research shows that belonging to social groups and maintaining connections benefits our health and wellbeing.

Unfortunately, people with chronic conditions can face shrinking social circles. Others may not understand the reality of living with chronic ill health, and so are not flexible about regularly cancelled plans, for example. Feeling guilty for missing social events is yet another aspect of chronic illness that can take an emotional toll.

However, people with long COVID can develop new communities of others who understand what they’re going through. These connections can help them rebuild their identity and adjust to their new normal. They can also help them face challenges in how their new health status is accepted at work by sharing experiences and resources.

For people living with long COVID, it’s worthwhile seeking out supportive social networks. Online groups may be particularly beneficial when symptoms make it hard to travel.

Even though there’s much ground still to cover in long COVID research, the evidence is rapidly evolving and, with it, hopefully we’ll see more enlightened attitudes and better treatments.

Our advice is to listen to your body and trust that you know its needs better than anyone else. Be your own best support, but at the same time, stay connected and seek out understanding people. If health professionals are unhelpful, remember you can seek second opinions and, in the meantime, pace yourself, rest and respect your body’s limits.

Regressing after a period of good health may be particularly difficult. Know that it’s normal to feel frustrated with the illness and with yourself, wondering if you’re doing anything to trigger these symptoms. But try to be as compassionate with yourself as you can. It’s not your fault, and long COVID does not make you a failure. Remember you’re doing the best you can under the circumstances.

Quarter Life is a series about issues affecting those of us in our 20s and 30s.![]()

Ana Leite, Associate Professor in Social and Organisational Psychology, Durham University; Damien Ridge, Professor of Health Studies, University of Westminster, and Nisreen Alwan, Associate Professor in Public Health, University of Southampton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Aged Care Council Of Elders

- aged care quality and safety

- the needs of older Australians and their families and carers

- the rights and dignity of older Australians.

- call for written submissions and surveys

- hold public meetings and workshops

- facilitate focus groups and individual interviews

- engage in online consultations, including webinars.

- Minister for Health and Aged Care

- Minister for Aged Care

- Department of Health.

New COVID-19 Variant Leads To Increase In Cases

Amendment To Pension Work Bonus Welcomed

A Pay Rise For Aged Care Workers

More Ways For Seniors To Stay Connected

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 50 years and over

- Seniors from culturally and linguistically diverse (CaLD) backgrounds

- Seniors who are carers

- Seniors from culturally and linguistically diverse (CaLD) backgrounds

- Seniors living with disability, dementia, chronic disease or mental illness

- Seniors from culturally and linguistically diverse (CaLD) backgrounds

- Seniors living with disability, dementia, chronic disease or mental illness

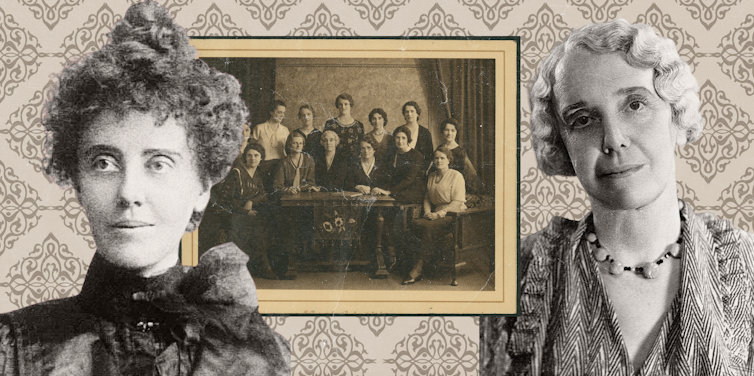

Hidden women of history: Kate Cocks, the pioneering policewoman who fought crime and ran a home for babies – but was no saint

In 1915, an unmarried, 40-year-old woman by the name of Fanny Kate Boadicea Cocks was hand-picked for the role of South Australia’s first policewoman. A small number of others had taken up similar roles globally, amid growing fears for the morality of young women enjoying ever more independence in a rapidly changing world.

But Kate Cocks, as she called herself, was the first woman in the British Empire to enjoy the same salary as her male counterparts, and to receive the same powers of arrest. Asked if she wanted six additional policewomen in her tiny office in Adelaide’s Victoria Square, she replied: “No, give me one woman. I don’t even know what I am going to do yet.”

Most of the time, Cocks walked the beat, patrolling railway stations, beaches and parklands for 60 hours a week in prim neck-to-ankle civilian outfits and one-and-a-half-inch heels. But Cocks was instrumental in solving several major crimes, too.

She received six honorary mentions (and ultimately an MBE) for resolving cases including the poisoning of children in a country town, abortion rackets, drug smuggling and a controversial sodomy case involving a prominent Adelaide hotelier and politician.

The staunch Methodist was known to hold all-night vigils with desperate mothers outside houses where their daughters were “living in sin”. She strode into opium dens to frogmarch young women out. And she regularly arrested “callous” fortune tellers “preying” on the wives and mothers of soldiers during World War I.

A Childhood Of Drought And Debt

Three short biographies, drawing primarily on a series of interviews with Cocks for Adelaide’s The Advertiser after her 1935 retirement, paint the policewoman as highly empathetic – almost saintly (although she was in fact far more complex than that). They trace that empathy to a childhood of poverty, dislocation and faith.