inbox and environment news: Issue 563

November 20 - 26, 2022: Issue 563

The Ku-Ring-Gai GeoRegion UNESCO Proposal

Pittwater’s zonings have been critical to protecting this spectacular and precious area. Large swathes of our suburbs were classified as Environmental Zones - later redefined by the NSW government as Conservation zones. Much of Pittwater’s residential areas are currently zoned C4 (Environmental Living).

Conservation zones, such as C4, are applied to properties with significant environmental values - which may be ecological, scientific or aesthetic - and to those potentially exposed to significant hazards such as bushfires, flooding and landslides. The zones help determine what owners are allowed to do on their land.

- Cliffs, beaches, and lagoons from Long Reef to Barrenjoey.

- Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park.

- Muogamarra Nature Reserve.

- Northern Garigal National Park.

- Berowra Valley National Park.

- Numerous geological sites, including several sites of international significance. Currently more than 45 key geosites have been identified across the area.

- Extensive rare and threatened flora and fauna

- Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park was registered on the National Heritage List in 2006, with the following assessment:

‘Summary of Significance: Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park and Long Island, Lion Island, and Spectacle Island Nature Reserves contain an exceptional representation of the Sydney region biota, a region which is recognised as a nationally outstanding centre of biodiversity. The place contains a complex pattern of 24 plant communities, including heathland, woodland, open forest, swamps and warm temperate rainforest, with a high native plant species richness of over 1000 species and an outstanding diversity of bird and other animal species. The place is an outstanding example of a centre of biodiversity.’

- The area provides a vast array of Aboriginal heritage sites including rock engravings, cave art sites, grinding grooves, shell middens, occupational deposits, stone arrangements and burials. It is one of Australia’s most dense areas for Aboriginal sites. Over 570 sites recorded, some with multiple site traits.

- The proposed ‘Ku-ring-gai’ GeoRegion reveals the best exposed geological section of early to mid-Triassic period (240 million years ago) sedimentary rocks in the Sydney Basin.

- The sediments were deposited in Gondwana adjacent to a high latitude coast under a cold climate in fluvial, lacustrine, and shallow marine environments. Various rock units contain a diversity of fossils that inform us of past environments over nearly 50 million years.

- The GeoRegion includes eight volcanic diatremes (pipes) and associated dykes with the Hornsby diatreme having perhaps the best known exposed geological section in NSW, if not in all Australia.

Ku-Ring-Gai GeoRegion: A New Concept In Landscape Conservation

Help Guide Future Decisions For Manly Dam

The Council are calling for expressions of interest from the community to sit on the advisory committee that will guide decisions about how Manly Dam is managed over the next four years.

Officially known as the Manly Warringah War Memorial State Park, we’re seeking to appoint three community members to the Advisory Committee including:

- an environment representative

- a recreational representative

- a community representative.

Manly Dam is a popular spot for enjoying picnics, bushwalking, mountain biking, swimming, and water-skiing. Loved by locals and visitors, this dedicated war memorial and State Park is home to a wide variety of significant ecological communities and flora and fauna.

This is your opportunity to have your say on how this beautiful park is managed over the next four years.

The Manly Warringah War Memorial State Park Advisory Committee includes three community members, and representatives from Council and the NSW Government.

If you’re interested in a position, submit your expression of interest on the council website before 11 December 2022

Orchid at Manly Dam. Photo: Selena Griffith

Mozzies are everywhere right now – including giant ones and those that make us sick. Here’s what you need to know

Like all insects, mosquitoes thrive in warmer weather. But what they really need is water. La Niña rainfall and flooding are providing the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, with numbers exploding in recent weeks.

People are also seeing giant mosquitoes, tiny mosquitoes, and species they haven’t noticed before. Some of these mosquitoes are around every season but their numbers are booming, thanks to the favourable conditions.

Australia has around 300 species of mosquito. So which do you need to look out for?

First, let’s go over some mozzie basics.

Mozzies Live For Around 3 Weeks

The mosquito life cycle is complex. Eggs are laid on or around water. When immature mosquitoes hatch, they’re completely reliant on being in water.

During the warmer months, it may take as little as a week for an adult mosquito to emerge from the water to start buzzing and biting.

Adult mosquitoes only live for about three weeks.

Only Females Bite

As well as water and warmth, mosquitoes also need blood. But only female mosquitoes bite, as they need the extra nutritional hit to help develop eggs.

Mosquitoes don’t just bite people. They will bite a wide range of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. They can even bite earthworms, mudskippers (amphibious fish) and maybe even whales.

What Are ‘Giant’ Mosquitoes?

One mosquito in Australia that doesn’t bite at all is Toxorhynchites speciosus, a “giant” mosquito, common in eastern Australia.

The mosquito is predatory: their “wrigglers” often eat those of other pest mosquitoes. Closely related mosquitoes have even been used for mosquito control in other counties.

But it isn’t these “friendly” mosquitoes causing all the problems after flooding.

Other mosquitoes, commonly known as “floodwater mosquitoes”, can bite and are found in large swarms following flooding. They’re a serious nuisance. Examples of these mosquitoes include Aedes sagax, Aedes vittiger, and Aedes aculeatus. They often disappear as quickly as they appear.

Mosquito surveillance programs, such as the NSW Arbovirus Surveillance and Mosquito Monitoring Program, are picking up these mosquitoes (and lots of smaller species) already this season. Perhaps the most famous of them all is the large, sandy-coloured mosquito Aedes alternans. Commonly known as the Hexham Grey, this mosquito has had poems written about it and there is even a “big mozzie” in Hexham, NSW.

Which Mosquitoes Make Us Sick?

Despite the diversity of mosquitoes in Australia, only a few pose a serious public health threat.

Aedes notoscriptus mosquitoes have given up their natural habitat and adapted to life in water-filled containers around our homes. They’ve proven to nuisance-biting pests as well as transmitting viruses that make us sick.

In coastal regions of Australia, Aedes vigilax (commonly known as the saltmarsh mosquito) and Aedes camptorhynchus (commonly known as the southern saltmarsh mosquito) are found in estuarine wetlands. These include mangrove and saltmarsh habitats where water is often brought in with “king tides”. The mosquitoes tolerate the salty conditions. These mosquitoes can emerge in huge numbers in summer, are aggressive biters, and can fly many kilometres from wetlands. They are also the mosquito most likely to be causing outbreaks of mosquito-borne disease in coastal regions due to their ability to spread Ross River virus.

There are a number of pest mosquitoes found in freshwater wetlands. The biggest pest is Culex annulirostris (commonly known as the banded freshwater mosquito). This mosquito is found in a range of habitats, from wetlands to stagnant puddles. The banded freshwater mosquito is probably the most important species when it comes to spreading pathogens such as Ross River virus, Murray Valley encephalitis virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus.

How Can We Beat Their Bites?

After three years of above average rainfall, and recently flooding, most of eastern Australia is just one giant mosquito habitat. While some efforts to use insecticides to control mosquitoes may be effective, the reality is the task of adequately controlling mosquito numbers is insurmountable.

There are some steps you can take to protect yourself and family from mosquito bites. When outdoors, wear a loose-fitting long sleeved shirt, long pants, and covered shoes. You can even treat your clothing with chemicals such as permethrin or transfluthrin.

Insect repellents also provide protection. Products that contain deet, picaridin, or lemon eucalyptus oil will provide the longest-lasting protection but ensure you cover all exposed areas of skin.

Mosquito coils and other products may help when paired with repellents.

Now the bad news. The floods may pass quickly but the water is going to remain in pools and puddles across much of eastern Australia for most of the summer. That is great news for mosquitoes but not so good for those of us already nursing arms and legs full of itchy red mosquito bites.![]()

Cameron Webb, Clinical Associate Professor and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Flowering Now

The Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) tell us Bottlebrushes are done, and now it’s time for Melaleucas.

They have fluffy flowers because their many stamens grow five bundles on each flower. Photos; Small tree Snow in Summer aka Melaleuca linariifolia is white, flowers attracting lots of insects, in Warriewood Rd, and Etival St Avalon. Hillock Bush aka Melaleuca hypericifolia a sprawling shrub is dusty red.

Also Flowering Now

PON staff photos

Misty Morning At Turimetta Beach

photos taken by Joe Mills, Monday November 14th, 2022

Gardening With Brush Turkeys: November 24 At Narrabeen - PNB End Of Year Event

THURSDAY, 24 NOVEMBER 2022 FROM 19:30-21:00

Hosted by Permaculture Northern Beaches

At: Tramshed Arts and Community Centre

Spring is well and truly here and so are the brush turkeys. We are very lucky to have turkey expert, Dr Ann Goeth, author of “Mound Builders”, deliver this month’s PNB talk. Ann will provide her unique insights into the life of brush turkeys and help us uncover fascinating facts about their foraging habits, breeding, and why they build such large mounds. She will also give tips on how to deal with them in the garden.

Come and see and hear a different side of one of our most common garden visitors.

This is our last meeting for the year for PNB and we will be celebrating all that has gone before us in 2022 and welcoming in 2023. If you would like to bring some snacks and non-alcoholic drinks to share with other members on the night for our end-of-year gathering.

Entry is by donation to help pay for room hire.

Photo: Joe Mills

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew South Curl Curl Beach Clean Up: Sunday November 27

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew, meets the last Sunday of every month at 10am on Sydney's northern beaches. We update our location every month. Come and join us for our South Curl Curl clean up. It will be our last clean up this year, because the last Sunday in December falls on Christmas Day. We'll meet in the grass area, close to the beach - see the map on our website or social media. For exact meeting point look at the map or type in "75 Carrington Parade, Curl Curl in NSW" - we'll be at opposite that address.

We have clean and washed gloves, bags and buckets. We'll clean up the surrounding area and the beach, to try and catch the litter before it hits the beach, trying to remove as much plastic, cigarette butts and rubbish as possible.

The ones in the crew that are certified wildlife rescuers will also look for an entangled seagull that has been reported needing help.

We're a friendly group of people and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event (just leave political, religious and business messages at home so everyone feel welcome). It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time. Send us a message if you are lost - email or on our social media. Please invite family and friends and share this event.

We meet at 10am for a briefing. Then we generally clean between 60-90 minutes. After that, we sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to litter research. We normally finish around 12.30 when we go to lunch together (at own cost). Please note, we completely understand if you cannot stay for the whole event. We are just grateful for any help we can get. No booking required. Just show up on the day. Looking forward to meeting you at South Curl Curl beach.

Help Needed To Save Sea Turtle Nests As Third La Nina Summer Looms

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

TALK & BOOK LAUNCH

Book Your Free Ticket To: Developing Sustainable Communities

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

As New South Wales reels, many are asking why it’s flooding in places where it’s never flooded before

Mark Gibbs, Queensland University of TechnologyOn Monday, residents of Eugowra in New South Wales had to flee for their lives. They had only minutes to get to higher ground – or their rooftops – to escape what’s been dubbed an “inland tsunami” of water. This week, many other towns across western NSW faced renewed floods. For many people affected, the real shock is how unexpected it was – and how fast the water came. Their houses and land had never flooded, as far as they knew. What had changed?

This is an important question with a number of answers. When we make these assessments, we’re drawing on two sources: local knowledge and, increasingly, what flood maps tell us.

While tremendously useful, local knowledge has limits. Human memory is fallible and written records do not stretch back far. Flood maps also have constraints. That’s because floods can differ greatly depending on where the rain falls, at what intensity, and over what period of time. We will also have to redraw flood maps more often, as climate change brings more extreme weather. As climate change progresses, the atmosphere can hold more water. This supercharges atmospheric rivers – huge torrents of water carried above our heads.

The result? You might think you’re safe if you drew on local knowledge and flood maps when choosing where to live. The reality is there always have been gaps in our knowledge, and homes built on floodplains once thought safe may not be any more.

This doesn’t mean we should ignore credible sources of information. But it does mean we have to remember every information source has some uncertainty.

What Are The Limits Of Our Knowledge?

Local knowledge held by long-term residents, historical records and hearsay are tremendously useful sources.

But these only reach back a short way in terms of the history of flooding. Indigenous knowledge of flooding reaches back far further, with oral stories of the flooding of Port Phillip Bay and many other locations passed down over many generations.

Australia’s floodplains have periodically flooded for millennia, renewing ecosystems.

What’s new are the towns and cities built along their banks. Early European settlers were often taken by surprise by the size of the floods, and a number of rescues were undertaken by Indigenous peoples.

In our time, communities are increasingly turning to flood maps produced by local and state governments to take stock of their vulnerability. This is broadly a good thing, as these maps can drill down to which streets are more vulnerable.

But they aren’t perfect – and they’re mostly only updated every few years. Some councils are still relying on outdated maps.

Flood maps are generated from computer flood models and simulate how floods develop and spread. To do this, you need to consider a range of variables. How much rain falls? When? Where? For how long? Is the ground sodden already, or dry as a bone? What has changed in the catchment since the last flood modelling study that may alter the overland flows of water?

Rain doesn’t fall evenly across catchment areas. Intense rain can carpet some areas and leave others all but untouched. In the devastating 2011 floods in South East Queensland, huge volumes of rain fell in the upper catchment of the Brisbane River, across foothills of the Great Dividing Range. Flash floods hit communities like Toowoomba and Grantham hard, while bayside Brisbane was experiencing light rain and sunshine – and had more time to prepare.

Many of this year’s floods, by contrast, have come from heavy rain falling on lower catchment areas, with repeated soaking priming the area for near-instant floods. That’s partly why cities like Forbes have been taken by surprise, with the worst floods in decades.

In short, every intense or extreme rainfall event is different – and that, in turn, means the resulting floods can differ dramatically.

What Information Should We Rely On?

You can see the challenge for flood modellers. Which events do you model? You can’t model all of them, as it’s impractical to model all possible combinations of rainfall, location and so on. So you model the most likely combinations.

This is a major reason why major floods may not actually flood all of the houses in a designated flood zone in every flood, as it depends in part on where the rain is falling in the catchment.

In turn, this leads to confusion. People in affected communities may believe the flood models and warnings are wrong.

It’s been long understood this kind of information can be complicated and confusing for the people relying on it. Does the Annual Exceedance Probability mean the chance of a 1 in 100 year flood, or not? And if so, how can it flood twice in quick succession? There’s jargon galore.

When vital information is hard to understand, many people may give up and ignore the information. Others may make decisions based on their own interpretation or with social media.

It is hard to sift through complex information. We will need to continue to find ways to make clearer the likely risk for prospective home-owners as well as the danger from the more severe floods we can expect as the world warms.

For now, we need to stay as vigilant as possible on flood risk when choosing where to live. And we need to heed official warnings issued months ahead as seasonal outlooks as well as in the lead up to major rains. It hasn’t flooded here before? Unfortunately, it may be more accurate to say it hasn’t flooded here yet. ![]()

Mark Gibbs, Adjunct Professor, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To stop new viruses jumping across to humans, we must protect and restore bat habitat. Here’s why

Bats have lived with coronaviruses for millennia. Details are still hazy about how one of these viruses evolved into SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID in humans. Did it go directly from bats to humans or via another animal species? When? And why? If we can’t answer these questions for this now-infamous virus, we have little hope of preventing the next pandemic.

Some bat species are hosts for other viruses lethal to humans, from rabies to Nipah to Hendra. But their supercharged immune systems allow them to co-exist with these viruses without appearing sick.

So what can we do to prevent these viruses emerging in the first place? We found one surprisingly simple answer in our new research on flying foxes in Australia: protect and restore native bat habitat to boost natural protection.

When we destroy native forests, we force nectar-eating flying foxes into survival mode. They shift from primarily nomadic animals following eucalypt flowering and forming large roosts to less mobile animals living in a large number of small roosts near agricultural land where they may come in contact with horses.

Hendra virus is carried by bats and can spill over to horses. It doesn’t often spread from horses to humans, but when it does, it’s extremely dangerous. Two-thirds of Hendra cases in horses have occurred in heavily cleared areas of northern New South Wales and south-east Queensland. That’s not a coincidence.

Now we know how habitat destruction and spillover are linked, we can act. Protecting the eucalyptus species flying foxes rely on will reduce the risk of the virus spreading to horses and then humans. The data we gathered also makes it possible to predict times of heightened Hendra virus risk – up to two years in advance.

What Did We Find Out?

Many Australians are fond of flying foxes. Our largest flying mammal is often seen framed against summer night skies in cities.

These nectar-loving bats play a vital ecosystem role in pollinating Australia’s native trees. (Pollination in Australia isn’t limited to bees – flies, moths, birds and bats do it as well). Over winter, they rely on nectar from a few tree species such as forest red gums (Eucalyptus tereticornis) found mostly in southeast Queensland and northeast NSW. Unfortunately, most of this habitat has been cleared for agriculture or towns.

Flying foxes are typically nomadic, flying vast distances across the landscape. When eucalypts burst into flower in specific areas, these bats will descend on the abundant food and congregate in lively roosts, often over 100,000 strong.

But Australia is a harsh land. During the severe droughts brought by El Niño, eucalyptus trees may stop producing nectar. To survive, flying foxes must change their behaviour. Gone are the large roosts. Instead, bats spread in many directions, seeking other food sources, like introduced fruits. This response typically only lasts a few weeks. When eucalypt flowering resumes, the bats come back to again feed in native forests.

But what happens if there are not enough forests to come back to?

Between 1996 and 2020, we found large winter roosts of nomadic bats in southeast Queensland became increasingly rare. Instead, flying foxes were forming small roosts in rural areas they would normally have ignored and feeding on introduced plants like privet, camphor laurel and citrus fruit. This has brought them into closer contact with horses.

In related research published last month, we found the smaller roosts forming in these rural areas also had higher detection rates of Hendra virus – especially in winters after a climate-driven nectar shortage.

An Early Warning System For Hendra Virus

Our models confirmed strong El Niño events caused nectar shortages for flying foxes, splintering their large nomadic populations into many small populations in urban and agricultural areas.

Importantly, the models showed a strong link between food shortages and clusters of Hendra virus spillovers from these new roosts in the following year.

This means by tracking drought conditions and food shortages for flying foxes, we can get crucial early warning of riskier times for Hendra virus – up to two years in advance.

Biosecurity, veterinary health and human health authorities could use this information to warn horse owners of the risk. Horse owners can then ensure their horses are protected with the vaccine.

How Can We Stop The Virus Jumping Species?

Conservationists have long pointed out human health depends on a healthy environment. This is a very clear example. We found Hendra virus never jumped from flying foxes to horses when there was abundant winter nectar.

Protecting and restoring bat habitat and replanting key tree species well away from horse paddocks will boost bat health – and keep us safer.

Flying foxes leave roosts in cities or rural areas when there are abundant flowering gums elsewhere. It doesn’t take too long – trees planted today could start drawing bats within a decade.

SARS-CoV-2 won’t be the last bat virus to jump species and upend the world. As experts plan ways to better respond to next pandemic and work on human vaccines built on the equine Hendra vaccines, we can help too.

How? By restoring and protecting the natural barriers which for so long kept us safe from bat-borne viruses. It is far better to prevent viruses from spilling over in the first place than to scramble to stop a possible pandemic once it’s begun.

Planting trees can help stop dangerous new viruses reaching us. It really is as simple as that. ![]()

Alison Peel, Senior Research Fellow in Wildlife Disease Ecology, Griffith University; Peggy Eby, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, Centre for Ecosystem Science, UNSW Sydney, and Raina Plowright, Professor, Cornell University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New electric cars for under $45,000? They’re finally coming to Australia – but the battle isn’t over

If you’re shopping for an electric vehicle in Australia at the moment, your options are limited. Of more than 300 electric vehicle models on sale globally, only about 30 are available here.

What’s more, waiting lists for vehicles are long and the purchase cost is still higher than many consumers are willing to pay.

Australia might now have a federal government with stronger climate ambition than the last. But major new policies are still needed to accelerate the road transport transition.

There’s good news, however: Australian motorists have been promised more choice soon. So let’s take a look at the cars we might be driving in the next few years.

Why Make The Switch?

Transport is Australia’s third-largest – and fastest growing – source of greenhouse gas emissions. Cars are responsible for the greatest share of these emissions.

Most of Australia’s vehicle fleet uses polluting fossil fuels. A switch to electric vehicles, coupled with a transition to renewable energy, is vital if Australia is to meet its commitments to tackle climate change.

Electric vehicles are also cheaper to run than their traditional counterparts, and don’t rely on expensive imported fuel.

Despite all the benefits, electric vehicle uptake in Australia is still low. They accounted for just 3.39% of new vehicle sales (or 26,356 cars in total) to September this year, according to the Electric Vehicle Council of Australia.

It’s an increase on last year, but still well below other nations. In the UK, for example, 19% of new cars sold are electric.

The ACT buys the most electric vehicles (9.5% of new vehicles) followed by New South Wales (3.7%), Victoria (3.4%), Queensland (3.3%), Tasmania (3.3%), Western Australia (2.8%), South Australia (2.3%) and the Northern Territory (0.8%).

Which Electric Vehicles Are We Buying?

Almost 40% of new battery electric vehicle sales this year were Tesla Model 3 (8,647 sales) and 25% were Tesla Model Y (5,376 sales). Other top-selling models include the Hyundai Kona (897 sales), MG ZS EV (858 sales) and Polestar 2 (779 sales).

Less than 20% of vehicles sold had a purchase price below $65,000.

The Porsche Taycan, one of the most expensive electric vehicles on the market, was in 11th place with 401 sales. Its price ranges from $156,000 to more than $350,000, depending on the model grade.

Some buyers are yet to receive the cars they purchased. Supply shortages mean consumers can wait 11 months for their vehicle.

But despite the frequent delays, consumers keep placing orders. Hyundai recently offered 200 of its Ioniq 5 electric SUVs for sale online; they were snapped up within 15 minutes.

Price Is A Sticking Point

Clearly, some Australians are willing to buy an electric vehicle despite the price tag. But the purchase cost remains a big concern for others.

In a recent survey, more than half of Australian respondents preferred electric vehicles over fossil fuel cars – but 67% said price was the main barrier preventing them from making the switch.

Only 13% were willing to spend between $45,000 and $54,999 on an electric car.

In another survey of around 1,000 Australians, about 72% said they would budget less than $40,000 for their next car purchase.

But few battery electric vehicles cost less than $55,000, and many cost more than twice this. Others are nearly 60% more expensive than their petrol-powered counterparts.

Choice Coming Soon

Carmakers have promised a suite of new battery electric vehicles will soon be available in Australia.

Two are expected to be the among the cheapest new battery electric vehicles available here: the Atto 3 by carmaker BYD and MG’s updated ZS compact SUV.

Both will be available for less than $50,000 including on-road costs. The MG model is the cheaper of the two, at $44,990 for the Excite variant.

Other models expected to arrive in the next two years include the Aiways U5 SUV, Fiat 500e, Kia Soul, Peugeot e-2008, Skoda Enyaq, Toyota bZ4x and Volkswagen ID series.

The Chinese LDV electric ute is already on sale in New Zealand and may be on Australian roads by the end of this year. It remains to be seen, however, if electric utes and vans will be embraced by Australia’s tradespeople.

What Policy Settings Are Needed?

Clearly, Australia needs more affordable mid- and low-end electric vehicles. But one key policy setting is holding us back: the lack of mandatory fuel efficiency standards for road transport vehicles.

Australia is the only country in the OECD without such a policy. The standards help drive demand for low-emissions vehicles – so electric vehicle manufacturers often prefer to sell into those markets.

Car importers also tend to promote top-end models first because they have higher profit margins.

Meanwhile globally, competition between manufacturers of cheaper battery electric vehicles is expected to intensifying. Multinational automakers in China have been gearing up. Their lineup of new models is already selling in international markets.

Heavy trucks are also ripe for electrification, and progress has been rapid in recent years. Broad deployment in Australia will accelerate emissions cuts and improve air quality.

The Road Ahead

Electric vehicles are not the total solution to cutting transport emissions. We also need strategies to change our travel behaviour, reduce the number of cars on the roads and improve walkability and access to public transport.

But electric vehicles are a crucial piece of the puzzle. To improve their uptake in Australia, policymakers can draw from a range of effective electric vehicle policies that can be adapted from other nations. They include investment in charging stations and providing financial incentives to buy and run electric vehicles.

Australians want to drive electric vehicles, and governments must respond. Without a variety of affordable electric vehicles, Australia’s dependence on fossil fuels will deepen, and reaching our emissions reduction goals will become harder.![]()

Hussein Dia, Professor of Future Urban Mobility, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

REDcycle’s collapse is more proof that plastic recycling is a broken system

This week the federal government joined an international agreement to recycle or reuse 100% of plastic waste by 2040, putting an end to plastic pollution. But major obstacles stand in the way.

The most recent is the collapse of Australia’s largest soft plastic recycling program, REDcycle. The program was suspended after it was revealed soft plastic items collected at Woolworths and Coles had been stockpiled for months in warehouses and not recycled.

The abrupt halt to the soft plastics recycling scheme has left many consumers deeply disappointed, and the sense of betrayal is understandable. Recycling, with its familiar “chasing arrows” symbol, has been portrayed by the plastics industry as the answer to the single-use plastics problem for years.

But recycling is not a silver bullet. Most single-use plastics produced worldwide since the 1970s have ended up in landfills and the natural environment. Plastics can also be found in the food we eat, and at the bottom of the deepest oceans.

The recent collapse of the soft plastics recycling scheme is further proof that plastic recycling is a broken system. Australia cannot achieve its new target if the focus is on the collection, recycling and disposal alone. Systemic change is urgently needed.

Recycling Is A Market

Australia has joined the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution, a group of more than 30 countries co-led by Norway and Rwanda, and also including the United Kingdom, Canada and France.

It aims to deliver a global treaty banning plastic pollution by setting global rules and obligations for the full life cycle of plastic. This includes setting standards to reduce plastic production, consumption and waste. It would also enable a circular economy, where plastic is reduced, reused or recycled.

The idea behind recycling is simple. By reprocessing items into new products, we can conserve natural resources and reduce pollution.

Unfortunately, the recycling process is much more complex and entwined in the economic system. Recycling is a commodities market. Who buys what is usually determined by the quality of the plastic.

Sitting in the middle of the chasing arrow symbol is a number. If it’s a one or a two, it’s high value and will most likely be sold on the commodities market and recycled. Numbers three to seven indicate mixed plastics, such as soft plastics, which are considered low value.

Sadly, it often costs more to recycle most plastics than to just throw them away. Up until 2018, low value plastics were exported to China. The reliance on the global waste trade for decades precluded many countries, including Australia, from developing advanced domestic recycling infrastructure.

What Are The Biggest Problems?

One of the biggest problems with plastics recycling is the massive diversity of plastics that end up in the waste stream – foils, foams, sachets, numerous varieties of flexible plastic, and different additives that further alter plastic properties.

Most plastics can only be recycled in pure and consistent form, and only a limited number of times. What’s more, municipal plastic waste streams are very difficult to sort.

Achieving high levels of recycling in the current system requires the mixed plastic waste stream to be sorted into hundreds of different parts. This is unrealistic and particularly challenging for remote, low-income communities, which are typically far away from a recycling facility.

For example, throughout the developing world, single-use “sachet” size products are often directed towards low socio-economic communities and low-income families, who may buy most of their food in small daily portions.

Waste from small single-use packaging is notoriously difficult to recycle and is particularly prevalent in remote and rural communities which have less sophisticated waste management infrastructure.

Furthermore, high transportation costs associated with shipping plastic waste to a reprocessing facility make recycling a difficult issue for remote communities everywhere, including Outback Australia.

Failing Corporate Responsibility

Worldwide production and consumption of plastic per capita continues to increase, and is expected to triple by 2060. For many consumer-packaged goods companies, recycling remains the dominant narrative in addressing the issue.

For example, a study this year examined how companies in the food and beverage sector address plastic packaging as part of their wider, pro-active, sustainability agenda. It found the sector’s transition to sustainable packaging is “slow and inconsistent”, and in their corporate sustainability reports most companies focus on recyclable content and post-consumer initiatives rather than solutions at the source.

Although producer responsibility is growing, most companies in the fast-moving consumer goods sector are doing very little to reduce single-use plastic packaging. Special consideration should be given to products sold in regions lacking waste management infrastructure, such as in emerging economies.

Like A Band Aid On A Bullet Wound

The Australian government’s new goal to end plastic pollution by 2040 is encouraging to see. But putting the onus on recycling, consumer behaviour, and post-consumer “quick fix” solutions will only perpetuate the problem.

In the context of the global plastic crisis, focusing on recycled content is like putting a band aid on a bullet wound. We need better and more innovative solutions to turn off the plastic tap. This includes stronger legislation to address plastic waste and promote sustainable packaging.

One such approach is to establish “extended producer responsibility” (EPR). This involves laws and regulations requiring plastics producers and manufacturers to pay for the recycling and disposal of their products.

For example, in 2021, Maine became the first US state to adopt an EPR law for plastic packaging. Maine’s EPR policy shifts recycling costs from taxpayers and local government to packaging producers and manufacturers. Companies that want to sell products in plastic packaging must pay a fee based on their packaging choices and provide easily recyclable product options.

Currently, the burden of managing plastic disposal typically lies with local councils and municipalities. As a result, many municipalities worldwide are championing EPR schemes.

It’s the responsibility of everyone in the value chain to limit the use of single-use plastic and provide sustainable packaging alternatives for consumers. We need better product design and prevention through legislation.

The exciting thing is that businesses transitioning towards a more sustainable way of producing, distributing, and re-using goods are more likely to improve their competitive position.![]()

Anya Phelan, Lecturer, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change will clearly disrupt El Niño and La Niña this decade – 40 years earlier than we thought

You’ve probably heard a lot about La Niña lately. This cool weather pattern is the main driver of heavy rain and flooding that has devastated much of Australia’s southeast in recent months.

You may also have heard of El Niño, which alternates with La Niña every few years. El Niño typically brings drier conditions to much of Australia.

Together, the two phases are known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation – the strongest and most consequential factor driving Earth’s weather. And in recent years there has been much scientific interest in how climate change will influence this global weather-maker.

Our new research, released today, sheds light on the question. It found climate change will clearly influence the El Niño-Southern Oscillation by 2030 – in just eight years’ time. This has big implications for how Australians prepare for extreme weather events.

A Complex Weather Puzzle

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation occurs across the tropical Pacific, and involves complex interplays between the atmosphere and the ocean. It can be in one of three phases: El Niño, La Niña or neutral.

During an El Niño phase, the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean warms significantly. This causes a major shift in cloud formation and weather patterns across the Pacific, typically leading to dry conditions in eastern Australia.

During a La Niña phase, which is occurring now, waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean are cooler than average. The associated changes in weather patterns include higher than average rainfall over much of Australia.

When the oscillation is in the neutral phase, weather conditions hover around the long-term average.

Previous research has suggested El Niño and La Niña events may vary depending on where in the tropical Pacific the warm or cold ocean temperatures are located.

But climate change is also affecting ocean temperatures. So how might this play into El Niño and La Niña events? And where might the resulting change in weather patterns be detected? These are the questions our research sought to answer.

What We Found

We examined 70 years of data on the El Niño–Southern Oscillation since 1950, and combined it with 58 of the most advanced climate models available.

We found the influence of climate change on El Niño and La Niña events, in the form of ocean surface temperature changes in the eastern Pacific, will be detectable by 2030. This is four decades earlier than previously thought.

Scientists already knew climate change was affecting the El Niño–Southern Oscillation. But because the oscillation is itself so complex and variable, it’s been hard to identify where the change is occurring most strongly.

However, our study shows the effect of climate change, manifesting as changes in ocean surface temperature in the tropical eastern Pacific, will be obvious and unambiguous within about eight years.

So what does all this mean for Australia? Warming of the eastern Pacific Ocean, fuelled by climate change, will cause stronger El Niño events. When this happens, rain bands are drawn away from the western Pacific where Australia is located. That’s likely to mean more droughts and dry conditions in Australia.

It’s also likely to bring more rain to the eastern Pacific, which spans the Pacific coast of Central America from southern Mexico to northern Peru.

Strong El Niño events are often followed by strong and prolonged La Niñas. So that will mean cooling of the eastern Pacific Ocean, bringing the rain band back towards Australia – potentially leading to more heavy rain and flooding of the kind we’ve seen in recent months.

What Now?

Weather associated with El Niño and La Niña has huge implications. It can affect human health, food production, energy and water supply, and economies around the world.

Our research suggests Australians, in particular, must prepare for more floods and droughts as climate change disrupts the natural weather patterns of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation.

Our findings should be incorporated into policies and strategies to adapt to climate change. And crucially, they add to the weight of evidence pointing to the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to stabilise Earth’s climate.![]()

Wenju Cai, Chief Research Scientist, Oceans and Atmosphere, CSIRO, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Urban planning is now on the front line of the climate crisis. This is what it means for our cities and towns

Barbara Norman, University of CanberraInternational climate talks in Egypt known as COP27 are into their second week. Thursday is Solutions Day at the summit. Recognising that urban planning is now a front-line response to climate change, discussions will focus on sustainable cities and transport, green buildings and resilient infrastructure.

The COP26 Glasgow Pact expects countries to update planning at all levels of government to take climate change and adaptations into account. Urban planning is also included in the most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The Australian Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements similarly reinforced the urgency of planning for climate change. Its report recommended making it mandatory for land-use planning decisions to consider natural disaster risks.

Australian communities have been through a series of recent disasters. We have had extremes of drought, bushfires and now storms and floods. Some towns have been evacuated repeatedly.

Land-use planning needs to be updated to respond to a changing climate. This means working with nature, involving communities and, importantly, including the tools needed to plan for risk and uncertainty. Examples include scenario planning, carbon assessments of developments, water-sensitive urban design and factoring in the latest climate science into everyday decisions on land use.

We Can’t Avoid The Issue Of Resettlement

Climate-driven resettlement, in my view, will be one of the most significant social challenges of this century. The IPCC estimates that “3.3 to 3.6 billion people live in contexts that are highly vulnerable to climate change […] unsustainable development patterns are increasing exposure of ecosystems and people to climate hazards”.

The costs are staggering. The OECD estimates, for example, that in the past two decades alone, the cost of storms reached US$1.4 trillion globally.

In my review of recent climate-induced resettlement around the world, two important lessons are:

it must actively involve the community

it takes time.

The relocation of houses in Grantham, Queensland, is a positive example of resettlement. The repeated floods across eastern Australia – and the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20 – show why a national conversation with urban and regional communities on this very challenging issue needs to start very soon.

What Are The Essential Actions For Planning?

Based in part on interviews with urban leaders around the world for my new book, Urban Planning for Climate Change, I have put forward ten essential actions. Particularly relevant to Australia are the following actions:

map the climate risks and overlay these on existing and future urban zones to identify the “hot spots” – then publicly share the data

make it mandatory to consider natural disaster and climate risks in all land-use planning decisions for new development and redevelopment

plan for the cumulative impacts of climate change on communities and their consequences – this includes planning resettlement with those at risk

provide an inclusive platform for community conversations about carbon-neutral development and adaptation options – such as climate-resilient housing and smart local renewable energy hubs – together with up-to-date, accessible information on predicted climate risks so communities and industry can make informed decisions

invest in strategic planning that integrates action on carbon-neutral development and climate adaptation. Do not build housing any more on flood-prone land or areas of extreme fire risk.

The outcome must be that policymakers and the public have a clear understanding of where the risks are, where to build, where not to build, and the range of options in between.

For example, not building on the coastal edge does not mean quarantining that land. It means allowing activities, such as recreation, that can withstand increasing coastal flooding, as well as coastal-dependent uses such as fisheries and coastal landscapes designed to absorb storm surges.

What Are The Next Steps For Australia?

Architects, engineers, planners and builders around the world are working with communities to make development more sustainable. They need support from all levels of government.

To better plan for climate change, we in Australia can take a few key steps:

1. Update the 2011 National Urban Policy

An updated national policy should incorporate the latest climate science, national emission targets, energy policies and adaptation plans. This will help ensure new development, redevelopment and critical infrastructure are designed and built to be carbon-neutral and adapt to a changing climate.

2. Audit planning at all levels to ensure it considers climate change

The federal government should host a meeting of state and territory planning and infrastructure ministers as soon as possible after COP27. Climate change needs to be a mandatory consideration in all future land-use planning. The ministers should commission an audit of all planning legislation and major city and regional centre plans to ensure this happens.

Engagement with wider industry will be important to ensure effective implementation. Partnering in demonstration projects that showcase affordable, climate-resilient urban development can help promote the uptake of leading practice. Examples range from affordable retrofitting of housing with renewable energy solutions to recycled building materials and heat-reducing landscaping.

Extending this approach to whole neighbourhoods and suburbs is the next step.

3. Engage with the region

The federal government should continue its positive first steps on climate change with our regional neighbours, including Indonesia, New Zealand and Pacific Island nations. This long-term work needs to include support for developing climate-resilient towns and cities, as well as for resettlement.

We can learn from each other on this challenging pathway, which will connect us more than ever as a region.

4. Ensure all levels of government work together on strategic funding

Funding is needed to develop climate-resilient plans for communities across Australia. This will help minimise future impacts and ensure we are building back better now and for future generations.

Most of the developments being approved today will still be here in 2050. This means these developments must factor in climate change now.

We now have a national government that is committed to action on climate change, thank goodness. Much is being done on renewable energy and electrification of the transport system. It is time to turn our attention to making our built environment more climate-resilient.![]()

Barbara Norman, Emeritus Professor of Urban & Regional Planning, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

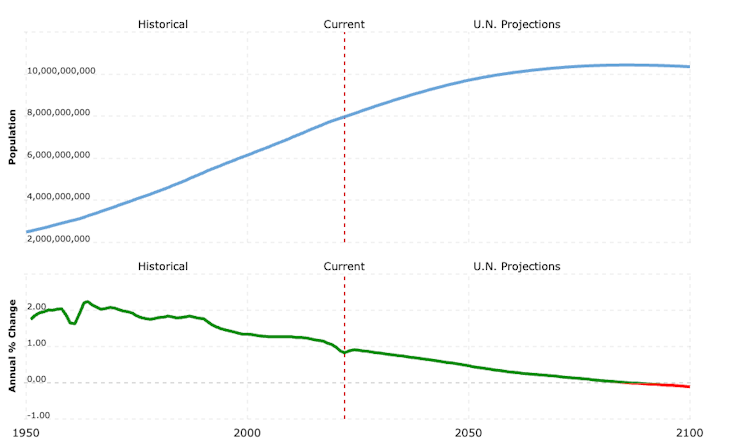

You are now one of 8 billion humans alive today. Let’s talk overpopulation – and why low income countries aren’t the issue

Today is the Day of Eight Billion, according to the United Nations.

That’s an incredible number of humans, considering our population was around 2.5 billion in 1950. Watching our numbers tick over milestones can provoke anxiety. Do we have enough food? What does this mean for nature? Are more humans a catastrophe for climate change?

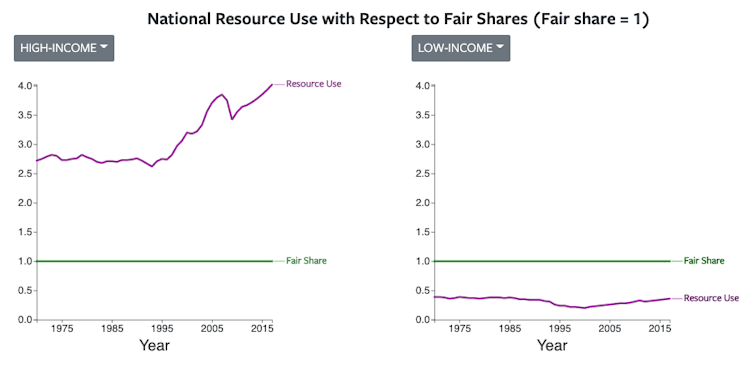

The answers are counterintuitive. Because rich countries use vastly more resources and energy, greening and reducing consumption in these countries is more effective and equitable than calling for population control in low income nations. Fertility rates in most of the world have fallen sharply. As countries get richer, they tend to have fewer children.

We can choose to adequately and equitably feed a population of 10 billion by 2050 – even as we reduce or eliminate global greenhouse gas emissions and staunch biodiversity loss.

Why Is The World’s Population Still Growing?

We hit 7 billion people just 11 years ago, in October 2011, and 6 billion in October 1999. And we’re still growing – the UN predicts 9.7 billion humans by 2050 before potentially topping out at 10.3 billion at the end of the century. But modelling by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation predicts the population peak much earlier, in 2064, and falling below 9 billion by century’s end.

Why is it still growing? Momentum. The number of women entering child-bearing age is growing, even as the average number of children each woman is having falls. Plus, we are generally living longer.

In 1950, the world’s population was growing at almost 2% a year. That growth rate is now less than 1%, and predicted to keep falling. There’s little we can do to change population trends. Researchers have found even if we introduced harsh one-child policies worldwide, our population trajectories would not change markedly.

In many ways, the story of population growth is evidence of improvement. Better farming techniques and better medicine made the population boom possible. And slowing population growth has come from falling rates of poverty, as well as better health and education systems, especially for women.

Increased gender equality and women’s empowerment have also helped. Put simply, if women can choose their own paths, they still have children – just fewer of them. That’s why climate solutions group Project Drawdown ranks female education and family planning as one of the top ways to tackle climate change.

Should We Worry About Overpopulation At All?

You are now one of 8,000,000,000 humans alive today. How should we feel about this?

The modern fear of overpopulation has old roots. In 1798, Reverend Thomas Malthus warned population grows exponentially while food supply does not. Close to two centuries later, Paul and Anne Erlich’s 1968 book The Population Bomb triggered a new wave of concern. As our numbers skyrocketed, they argued, we would inevitably hit a Malthusian cliff and run out of food. Famine and war would follow. It didn’t happen.

What resulted was inhumane population control policies. The book – replete with racially charged passages about a crowded Delhi “slum” – directly influenced India’s 1970s forced sterilisation policies. China’s notorious one-child policy emerged from similar concerns.

Low- or middle-income countries are most often called on to tackle overpopulation. And the people calling for action tend to be from high-income, high-consumption countries. Even David Attenborough is concerned.

Recent calls by Western conservation researchers to tackle environmental degradation by slowing population growth repeat the same issue, focusing on the parts of the world where populations are still growing strongly – sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and some Asian countries.

People from lower income countries reject these calls. Pakistani academic Adil Najam has observed these countries are “weary of international population policy in the name of the environment.”

Overall, the world’s wealthiest 1% account for 15% of the world’s carbon emissions. That’s more than double the emissions of the poorest 50% of the planet – who are the most vulnerable to climate change.

Prince William, for instance, has linked African population growth to wildlife loss – even though he has three children and comes from a family with a carbon footprint almost 1,600 times higher than the average Nigerian family.

What about saving wildlife? Again, a mirror may be useful here. It turns out demand from rich countries is the single largest driver of biodiversity loss globally. How? Your beef burger may have been made possible by burning the Amazon for pasture for cows, as well as many other global supply chain issues. Rich countries like Australia are also notoriously bad at protecting their own wildlife from agriculture and land clearing.

This is not to say population growth in lower income countries isn’t worth discussing. While many countries have seen their populations taper off naturally as they get wealthier, countries like Nigeria are showing signs of strain from very fast population growth. Many young Nigerians move to cities seeking opportunities, but infrastructure and job creation has not kept pace.

For Western environmentalists and policymakers, however, it would be better to shift away from a blame mentality and tackle drivers of inequality between and within nations. These include support for family planning, removing barriers to girls’ education, better regulation of global financial markets, reduced transaction costs for global remittances, and safe migration for people seeking work or refuge in higher income countries.

As we pass the eight billion mark, let’s reconsider our reaction. Blaming low-consumption, high-population growth countries for environmental issues ignores our role. Worse, it takes our attention away from the real work ahead of transforming society and reducing our collective impact on the planet. ![]()

Matthew Selinske, Senior research fellow, RMIT University; Leejiah Dorward, Postdoctoral research associate, Bangor University; Paul Barnes, Visiting researcher, UCL, and Stephanie Brittain, Conservation scientist, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4 signs of progress at the UN climate change summit

Something significant is happening in the desert in Egypt as countries meet at COP27, the United Nations summit on climate change.

Despite frustrating sclerosis in the negotiating halls, the pathway forward for ramping up climate finance to help low-income countries adapt to climate change and transition to clean energy is becoming clearer.

I spent a large part of my career working on international finance at the World Bank and the United Nations and now advise public development and private funds and teach climate diplomacy focusing on finance. Climate finance has been one of the thorniest issues in global climate negotiations for decades, but I’m seeing four promising signs of progress at COP27.

Getting To Net Zero – Without Greenwashing

First, the goal – getting the world to net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 to stop global warming – is clearer.

The last climate conference, COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, nearly fell apart over frustration that international finance wasn’t flowing to developing countries and that corporations and financial institutions were greenwashing – making claims they couldn’t back up. One year on, something is stirring.

In 2021, the financial sector arrived at COP26 in full force for the first time. Private banks, insurers and institutional investors representing US$130 trillion said they would align their investments with the goal of keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius – a pledge to net zero. That would increase funding for green growth and clean energy transitions, and reduce investments in fossil fuels. It was an apparent breakthrough. But many observers cried foul and accused the financial institutions of greenwashing.

In the year since then, a U.N. commission has put a red line around greenwashing, delineating what a company or institution must do to make a credible claim about its net-zero goals. Its checklist isn’t mandatory, but it sets a high bar based on science and will help hold companies and investors to account.

Reforming International Financial Institutions

Second, how international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank are working is getting much-needed attention.

Over the past 12 months, frustration has grown with the international financial system, especially with the World Bank Group’s leadership. Low-income countries have long complained about having to borrow to finance resilience to climate impacts they didn’t cause, and they have called for development banks to take more risk and leverage more private investment for much-needed projects, including expanding renewable energy.

That frustration has culminated in pressure for World Bank President David Malpass to step down. Malpass, nominated by the Trump administration in 2019, has clung on for now, but he is under pressure from the U.S., Europe and others to bring forward a new road map for the World Bank’s response to climate change this year.

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, a leading voice for reform, and others have called for $1 trillion already in the international financial system to be redirected to climate resilience projects to help vulnerable countries protect themselves from future climate disasters.

At COP27, French President Emmanuel Macron supported Mottley’s call for a shake-up in how international finance works, and together they have agreed to set up a group to suggest changes at the next meeting of the IMF and World Bank governors in spring 2023.

Meanwhile, regional development banks have been reinventing themselves to better address their countries’ needs. The Inter-American Development Bank, focused on Latin America and the Caribbean, is considering shifting its business model to take more risk and crowd in more private sector investment. The Asian Development Bank has launched an entirely new operating model designed to achieve greater climate results and leverage private financing more effectively.

Getting Private Finance Flowing

Third, more public-private partnerships are being developed to speed decarbonization and power the clean energy transition.

The first of these “Just Energy Transition Partnerships,” announced in 2021, was designed to support South Africa’s transition away from coal power. It relies on a mix of grants, loans and investments, as well as risk sharing to help bring in more private sector finance. Indonesia announced a similar partnership at the G-20 summit in November worth $20 billion. Vietnam is working on another, and Egypt announced a major new partnership at COP27.

However, the public funding has been hard to lock in. Developed countries’ coffers are dwindling, with governments including the U.S. unable or unwilling to maintain commitments. Now, pressure from the war in Ukraine and economic crises is adding to their problems.

The lack of public funds was the impetus behind U.S. Special Climate Envoy John Kerry’s proposal to use a new form of carbon offsets to pay for green energy investments in countries transitioning from coal. The idea, loosely sketched out, is that countries dependent on coal could sell carbon credits to companies, with the revenue going to fund clean energy projects. The country would speed its exit from coal and lower its emissions, and the private company could then claim that reduction in its own accounting toward net zero emissions.

Globally, voluntary carbon markets for these offsets have grown from $300 million to $2 billion since 2019, but they are still relatively small and fragile and need more robust rules.

Kerry’s proposal drew criticism, pending the fine print, for fear of swamping the market with industrial credits, collapsing prices and potentially allowing companies in the developed world to greenwash their own claims by retiring coal in the developing world.

New Rules To Strengthen Carbon Markets

Fourth, new rules are emerging to strengthen those voluntary carbon markets.

A new set of “high-integrity carbon credit principles” is expected in 2023. A code of conduct for how corporations can use voluntary carbon markets to meet their net zero claims has already been issued, and standards for ensuring that a company’s plans meet the Paris Agreement’s goals are evolving.

Incredibly, all this progress is outside the Paris Agreement, which simply calls for governments to make “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.”

Negotiators seem reluctant to mention this widespread reform movement in the formal text being negotiated at COP27, but walking through the halls here, they cannot ignore it. It’s been too slow in coming, but change in the financial system is on the way.

This article was updated Nov. 15, 2022, with Indonesia’s climate finance deal announced.![]()

Rachel Kyte, Dean of the Fletcher School, Tufts University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

At least 700,000 years ago, the world’s largest sand island emerged as the barrier that helped the Great Barrier Reef form

Scientists had always been puzzled why the Great Barrier Reef formed long after Australia had conditions suitable for reef growth. It turns out the answer might be K'gari (Fraser Island).

K’gari, the world’s largest sand island and a UNESCO World Heritage Area, juts out from the Australian coastline where the continent extends furthest east. It lies at the northern end of one of the world’s largest and longest longshore drift systems. If not for the presence of K’gari, the sand carried by this system would continue to migrate northward directly into the area of the Great Barrier Reef, which starts a little north of the island.

The volumes of sand carried along the coast are immense. It is estimated 500,000 cubic metres of sand moves north past each metre of shoreline every year.

K’gari plays a key role in delivering this sand to the deep ocean. Sand moving along its eastern beaches is directed across the continental shelf and into the deep immediately north of the island. The dominant south-easterly trades would drive sand all the way into the full tropics if K’gari did not direct it off the shelf.

Our research, published today, has established the age of K'gari as being older than the Greater Barrier Reef. This suggests the reef became established only after the island protected it from the northward drift of sand.

Why Does The Reef Depend On The Island?

The southern limit of the Great Barrier Reef is not a result of the climate being too cool further south. Corals can and do grow many hundreds of kilometres further south in places like Moreton Bay (Brisbane) and Lord Howe Island.

The main limiting factor for the southern extent of the reef is the drowning of corals by the rivers of sand going north. The corals in places like Moreton Bay occur where they have a hard substrate to grow on and are sheltered from sediment inundation.

The sand comes from sediment delivered to the Tasman Sea via the Hawkesbury and Hunter rivers in mid-New South Wales. Prevailing south-easterly breezes and their associated coastal wave systems sweep these sediments north for more than 1,000 kilometres.

The geological setting of eastern Australia is rather stable, so this longshore drift system should have been in operation for many millions of years. The Great Barrier Reef corals could not have survived without some protection from this northward flow of sand.

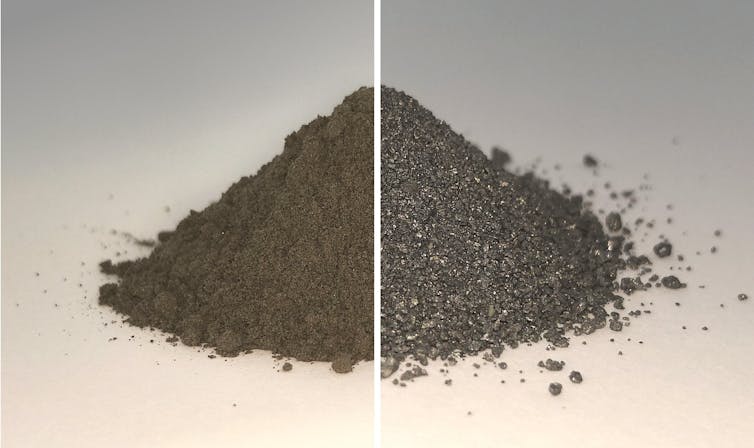

The techniques we used to establish the age of the coastal dune fields of K’gari and the adjacent Cooloola Sand Mass on the mainland south of K’gari show the first coastal dunes date to about 1 million years ago. The modern dune fields were established by 700,000-800,000 years ago. Prior to 1 million years and definitely prior to 700,000-800,000 years ago, sand would have drifted north into the region of the modern barrier reef.

Why Did K'gari Form At That Time?

This timing coincides with a major geo-astronomical event, the Mid-Pleistocene Transition. At this time Earth’s glacial cycles changed from a period of about 40,000 years to about 100,000 years. This change had a major impact on global sea levels because the longer cycles supported the growth of larger ice caps during cold periods.

Prior to this transition, global sea levels went up and down about 70 metres between warm (interglacial) and cold (glacial) periods. Afterwards, the range increased to 120-130m.

Under a longshore drift system some sediment “leaks” out into deeper water where currents and waves are not strong enough to move it. A drop of 70m would still leave the South-East Queensland coastline on the continental shelf. So, before the Mid-Pleistocene Transition, sand moving north would be gradually stored on the outer parts of the continental shelf, potentially accumulating over millions of years.

Once the first 100,000-year cycle occurred, sea levels would have dropped to the outer edge of the continental shelf. During the start of the next warm period, rising sea levels would erode the accumulated sands and transport it shoreward. This would drive a major period of dune building along the coast.

This was a major event because sediment accumulated over millions of years was added back into the sedimentary system. The very different dune types associated with plentiful sand are recorded in the oldest parts of the cliff sections at Cooloola and K’gari.

Again, remnants of dunes formed when sea levels were low are preserved directly off this coastline. We have shown a major pulse of sand was released into the dune systems formed during the earliest high sea-level periods of the 100,000-year climate cycles.

How Does That Line Up With The Age Of The Reef?

K’gari was constructed in its “modern” form between about 1 million and 700,000 years ago. Once it was in place, any further sand driven up the coast during interglacial high sea levels was lost to deep water off the north of K’gari.

The last piece of the puzzle is the age of the Great Barrier Reef. For a heavily investigated natural wonder, this is remarkably poorly defined, but the oldest evidence dates the reef to about 650,000 years ago.

In short, coral reef development appears to not have started until sediment drift from the south was blocked off. In this way the whole of the east coast of Australia is linked together as a single story and K’gari has played a key role in the formation and protection of the Great Barrier Reef.![]()

James Shulmeister, Adjunct Professor, University of Queensland, and Professor and Head of School of Earth and Environment, University of Canterbury and Daniel Ellerton, Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If you care about nature in Victoria, this is your essential state election guide

If we learnt anything from the past federal election, it’s that Australians care about climate change and nature. A survey released this week suggests the same dynamic is at play as we head into the Victorian state election.

The poll, prepared for the Victorian National Parks Association, found 36% of Victorians say their vote would be influenced by policy announcements regarding saving threatened species and stopping extinction.

The Victorian government’s own surveys have highlighted the enormous number of people who value nature. And research this year for the Australian Conservation Foundation found 95% of Australians agree it’s important to protect nature for future generations.

Despite the weight of public concern, Victoria is failing its wildlife. Last year the Victorian Auditor General’s Office handed down a damning report on biodiversity protection. It concluded that about a third of Victoria’s land-based plants, animals and ecological communities face extinction, their continued decline will likely have dire consequences for the state, and funding to protect them is grossly inadequate.

We know what’s primarily behind Australia’s extinction crisis: land clearing, invasive species and climate change-induced impacts such as extreme bushfires.

So, what have the different political parties promised in the lead up to the Victorian election, and how do they stack up? Here’s a brief guide to what’s on offer.

Funding And Policy Commitments

Let’s start with one of the key shortfalls discussed by the Auditor General – funding for biodiversity conservation. Labor has announced:

a $10 million nature fund to match biodiversity projects proposed by private or philanthropic groups

$2.8 million for Trust for Nature

$7.35 million for six large-scale conservation projects to reduce the impact of pests, predators and invasive weeds

$773,000 to extend Victoria’s Icon Species Program for another year

$160,000 for platypus conservation.

These funds don’t come close to the estimated annual shortfall of $38 million in ongoing funding needed for the government to deliver its biodiversity strategy, as identified by the Auditor General.

The Victorian Liberals have denounced Labor’s relatively dismal promises and their record of under-funding biodiversity. But, so far, new Liberal-National Coalition announcements have been limited. They include:

$20 million to increase canopy cover in metropolitan Melbourne from 15% to 35% by 2050 (it’s unclear whether this will benefit biodiversity)

$200,000 in environmental grants for Dandenong Creek, its catchments and wetlands

$1 million to rehabilitate and protect wetlands in Mount Eliza.

But the Coalition has also announced anti-environmental commitments, such as ending feral horse culling and $10 million to dredge Mordialloc Creek.

The Greens plan is to create an ongoing, $1 billion per year “zero extinction” fund to support a Save our Species program.

This would double the funding for national parks and create a program to restore land, including through a First Nations Caring for Country investment. It would also fund Trust for Natures’s work to protect and restore private land and urban biodiversity.

The Greens also commit to reforming nature laws and to offer First Nations people greater rights and control over land, water and oceans.

Teal candidate Melissa Lowe supports significant investment towards reforestation and the rehabilitation of native habitats.

Response To Native Forest Harvesting

Native forest timber harvesting continues to be a prickly issue in Victoria. This month the Supreme Court ruled state-owned logging company VicForests broke the law by failing to protect threatened species. Despite this, an ABC investigation this week found old growth forests continue to be cleared.

Greater gliders, Leadbeater’s possums and other forest-dwelling animals are facing a greater risk of extinction, and logging is one of the key threats. Without a significant change in protection, their numbers will continue to decline.

Labor’s policy is to phase out native forest logging by 2030 – but this leaves plenty of time for a lot of damage to be done. Labor also hasn’t legislated this phase-out, nor has it responded to VicForests’ failure to protect biodiversity.

Other election commitments relating to forestry include increasing fines to protesters who disrupt native forest logging.

The Liberal-Nationals have pledged to immediately reverse both of the Andrews government’s 2019 decisions to end old-growth forest logging and to phase-out native forest logging by 2030. This would take us backwards in terms of biodiversity protection.

The Greens have committed to legislating an end to native forest logging in 2023. This includes a transition plan to move workers into new jobs and a shift towards greater use of plantations.

The Reason Party and two Teal candidates have also articulated commitments for an immediate end to native forest logging.

How About Land Clearing From Other Causes?