inbox and environment news: Issue 564

November 27 - December 3, 2022: Issue 564

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew South Curl Curl Beach Clean Up: Sunday November 27

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew, meets the last Sunday of every month at 10am on Sydney's northern beaches. We update our location every month. Come and join us for our South Curl Curl clean up. It will be our last clean up this year, because the last Sunday in December falls on Christmas Day. We'll meet in the grass area, close to the beach - see the map on our website or social media. For exact meeting point look at the map or type in "75 Carrington Parade, Curl Curl in NSW" - we'll be at opposite that address.

We have clean and washed gloves, bags and buckets. We'll clean up the surrounding area and the beach, to try and catch the litter before it hits the beach, trying to remove as much plastic, cigarette butts and rubbish as possible.

The ones in the crew that are certified wildlife rescuers will also look for an entangled seagull that has been reported needing help.

We're a friendly group of people and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event (just leave political, religious and business messages at home so everyone feel welcome). It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time. Send us a message if you are lost - email or on our social media. Please invite family and friends and share this event.

We meet at 10am for a briefing. Then we generally clean between 60-90 minutes. After that, we sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to litter research. We normally finish around 12.30 when we go to lunch together (at own cost). Please note, we completely understand if you cannot stay for the whole event. We are just grateful for any help we can get. No booking required. Just show up on the day. Looking forward to meeting you at South Curl Curl beach.

Help Guide Future Decisions For Manly Dam

The Council are calling for expressions of interest from the community to sit on the advisory committee that will guide decisions about how Manly Dam is managed over the next four years.

Officially known as the Manly Warringah War Memorial State Park, we’re seeking to appoint three community members to the Advisory Committee including:

- an environment representative

- a recreational representative

- a community representative.

Manly Dam is a popular spot for enjoying picnics, bushwalking, mountain biking, swimming, and water-skiing. Loved by locals and visitors, this dedicated war memorial and State Park is home to a wide variety of significant ecological communities and flora and fauna.

This is your opportunity to have your say on how this beautiful park is managed over the next four years.

The Manly Warringah War Memorial State Park Advisory Committee includes three community members, and representatives from Council and the NSW Government.

If you’re interested in a position, submit your expression of interest on the council website before 11 December 2022

Orchid at Manly Dam. Photo: Selena Griffith

Gilead Stage 2 Development

''no longer required to assess impacts to ‘biodiversity values’ as these have already been addressed by the Minister and ‘conservation areas’ will be required to be managed in perpetuity for conservation''.

Land Court In Queensland Recommends Against Clive Palmer’s Coal Mine

BirdLife Australia Photography Awards 2022 Winners Announced

Regent Honeyeaters Being Helped To Find Their Songs Again

Help Needed To Save Sea Turtle Nests As Third La Nina Summer Looms

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

They might not have a spine, but invertebrates are the backbone of our ecosystems. Let’s help them out

Peter Contos, La Trobe University and Heloise Gibb, La Trobe UniversityMany of Australia’s natural places are in a poor state. While important work is being done to protect particular species, we must also take a broader approach to returning entire ecosystems to their former glory – a strategy known as “rewilding”.

Rewilding aims to restore the complex interactions that make up a functioning ecosystem. It involves reintroducing long-lost plants and animals to both conserve those species and restore an area’s natural processes.

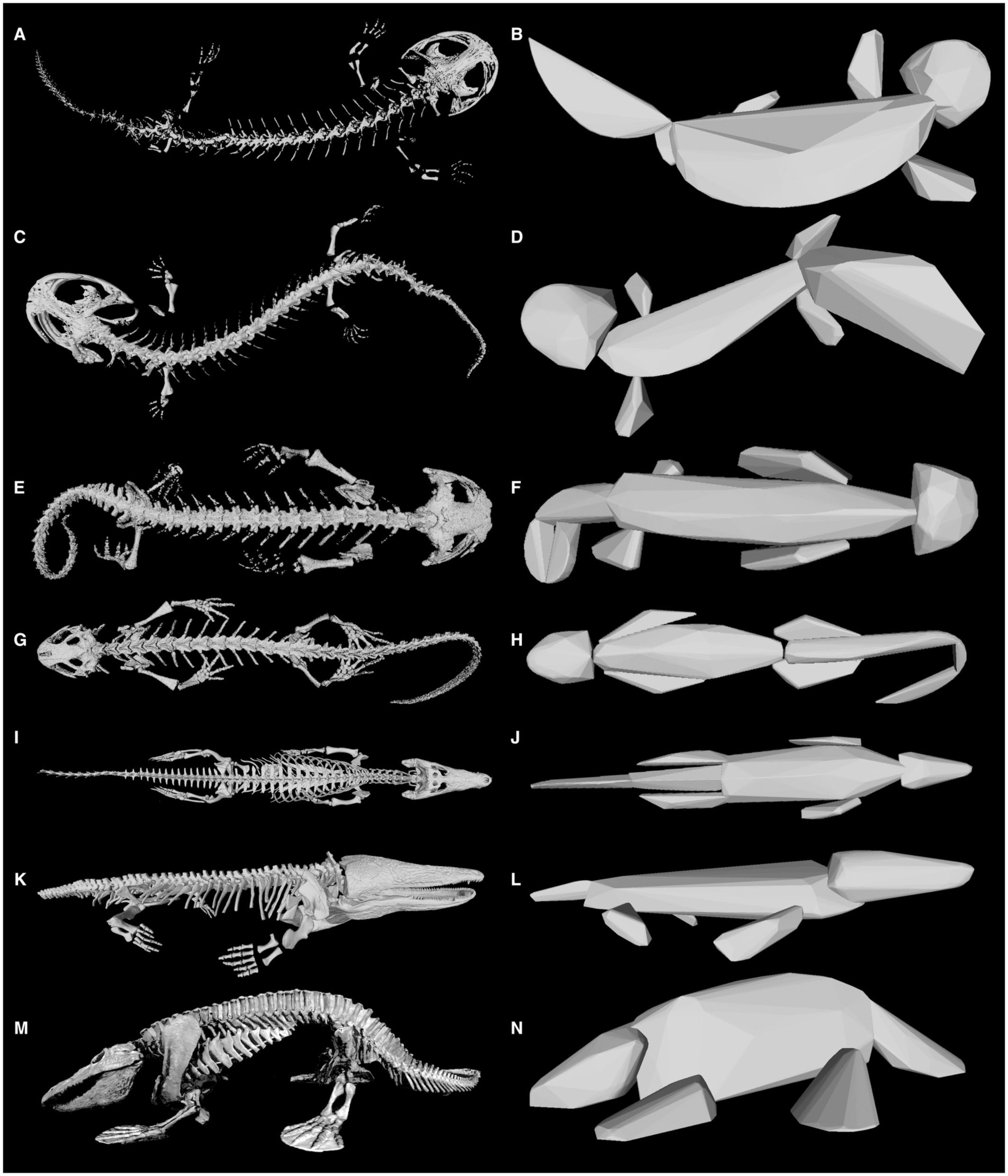

You might imagine this involves an ecologist releasing cute, furry bilbies, or an endangered songbird. This is a logical assumption. Research shows a marked bias in reintroduction programs towards vertebrates, especially birds and mammals.

Meanwhile, invertebrates are often overlooked. But our new research shows rewilding with invertebrates – insects, worms, spiders and the like – can go a long way in bringing our degraded landscapes back to life.

A Shocking Decline

Invertebrates make up 97% of animal life and drive key processes such as pollination and cycling nutrients. But they’re the focus of just 3% of reintroduction projects.

This reflects a taxonomic bias in conservation. Overseas, this has led to rewilding projects centred on large keystone mammals that alter ecosystems on a broad scale, such as wolves and bison.

Of course, traditional vertebrate rewilding projects are very important for ecosystem restoration. In Australia, for example, they are vital in restoring mammal communities decimated by cats and foxes.

But invertebrate species are declining at shocking rates around the world, especially as climate change worsens. They also need our help to re-colonise new areas.

No Beetle Is An Island

Picture an island in the middle of the ocean. The further from shore it is, the more animals on the mainland will struggle to reach it – especially if they’re tiny and wingless, like many invertebrates.

My colleagues and I built our study around this analogy.

Instead of islands, our research involved six isolated patches of revegetated land on farms. And instead of an ocean, invertebrates had to cross a sea of pasture which, for many litter-dwelling invertebrates, is a barren, unsheltered wasteland.

The farm sites were “biologically poor”. That is, despite the habitat quality improving following revegetation, they contained lower-than-expected invertebrate biodiversity.

We surmised that invertebrates from surrounding “biologically rich” national parks were struggling to reach and recolonise the isolated revegetation patches.

Our study involved giving invertebrates a hand to find new homes. We moved leaf litter – and more than 300 invertebrates species hiding in it – from national park sites into six revegetated farm sites in central Victoria.

We moved litter samples several times between 2018 and 2020, over different seasons. Sites were “paired”, so a national park site was paired with a revegetated one that would have been similar had degradation had not occurred.

The litter community of invertebrates is incredibly complex and can be broken into three groups: macroinvertebrates (more than 5 mm), mesoinvertebrates (less than 5 mm) and microbes. We focused on mesoinvertebrates, which mostly comprise mites, ticks, ants, beetles and springtails (small, wingless arthropods).

We found among this group, beetles were most likely to survive and thrive in their new habitat, which was much drier than the one they left. Rove beetles did particularly well.

Beetles are hardy little things with strong exoskeletons that protect them from drying out. In fact, as early as seven months after being moved, beetle numbers at the new sites reached levels similar to that in pristine national parks that we sourced leaf litter from.

We did not have the same success with other types of invertebrates. For example, springtails are a massive component of leaf litter communities in national parks. But they’re soft-bodied and dry out easily, so were more likely to die when moved to a new, drier environment.

Understanding why some groups are more likely to survive leaf litter transplants than others is a vital step in the development of invertebrate rewilding. Nonetheless, our results show the relatively simple act of moving leaf litter can lead to comparatively large increases in species richness in a short time.

Loving Our Creepy Crawlies

Our study showed how a simple method of rewilding with invertebrates can effectively reintroduce multiple species at once. This is an important finding.

More research into the method is needed across different types of sites and over longer timeframes. However, our method has the potential to be applied widely in the fight against global invertebrate declines.

The method is cheap and easy. In contrast, rewilding projects involving vertebrates can be hard to execute and expensive, and often require breeding animals for release.

Invertebrates are the bulk of terrestrial diversity and the backbone for proper ecosystem functioning. We need to start putting them at the centre of rewilding projects.

Our results are just one small piece in the puzzle. Many other invertebrate communities will need safeguarding and restoring in the future.

Recent research has challenged the assumption that humans naturally find vertebrates more engaging than invertebrates. We might be pleasantly surprised to find the public is as engaged with invertebrate rewilding projects as those focused on cute and cuddly critters.![]()

Peter Contos, PhD Candidate, La Trobe University and Heloise Gibb, Professor, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

That siren-imitating lyrebird at Taronga Zoo? He lost his song culture – and absorbed some of ours

Alex Maisey, La Trobe UniversityA fortnight after five lions escaped at Sydney’s Taronga Zoo, an amused zoo visitor captured footage of Echo the superb lyrebird as he mimicked alarm sirens and evacuation calls with astonishing accuracy.

News outlets were quick to link the lyrebird’s alarm impersonation with the lion’s great escape. But while this tale made for a great headline, the truth of this story is far more interesting.

Superb lyrebirds are arguably the bird world’s greatest mimics. Using their phenomenal voiceboxes, males will sing elaborate songs and perfectly imitate sounds made by other birds to impress prospective mates.

Not only this, they share songs in a form of cultural transmission. In the wild, some songs become more popular while others wane. Think of it as pop charts for the bush.

But Echo was bred in captivity. He wasn’t exposed to wild song culture. Instead, he learned from what he was exposed to – and that includes “songs” like the alarm call. Echo had been practising this call for years to get it that good – not just the two weeks after the lions escaped.

The ability of these birds to imitate sounds is rightly world-famous. But for their song culture to continue, we need healthy wild populations. Otherwise, they could face a future like critically endangered regent honeyeaters, which are now borrowing mating songs from other birds.

Why Do Lyrebirds Learn Human-Made Sounds And Songs?

Many of us are familiar with the famous sequence in David Attenborough’s Life of Birds where a lyrebird accurately imitates camera clicks, a chainsaw motor and construction sounds.

But most watchers wouldn’t have guessed the bird’s secret – it was bred in captivity. That’s why it was so good at imitating our sounds.

Similarly, Echo of Taronga Zoo was also captive-bred. Mimicking a human-origin sound such as the alarm is a behaviour not commonly seen in the wild, other than in heavily visited areas such as in Victoria’s Dandenong Ranges where wild lyrebirds may hear, say, human voices every day.

That’s because lyrebirds seem to learn which songs to sing by listening to their peers, rather than simply soaking up sounds around them like a sponge.

In Victoria’s Sherbrooke Forest, lyrebirds mimic the familiar melodic whip-crack of the whipbird above all other mimicked sounds. But in Kinglake forest just 60 kilometres north, the whipbird’s call was only the 12th most popular for local lyrebirds, while the calls of the grey shrike-thrush and laughing kookaburra took top billing.

This is culture – the songs and sounds are passed from one bird to the next, between generations, and undergo change over time.

But How Do They Do It?

It’s not magic – it’s a complicated organ. Our voicebox – the larynx – is in our throats. But birds have theirs – the syrinx – further down, at the bottom of their windpipes. As they breathe out, they pass air through the syrinx to make their calls and songs.

Remarkably, many songbirds can control airflow from each lung, meaning they can produce sound in mono or stereo and have greater control over the types of sound they can make. They can use one side of the syrinx, both together, or switch back and forth.

Lyrebirds take it a step further again. They have fewer pairs of muscles around their syrinx, but the ones they do have are extremely well adapted to the job of making sound. Some lyrebird researchers believe this may be the reason they can produce such an extraordinary range of sounds, but this has yet to be conclusively shown.

Even so, they’re not born superstars. Young lyrebirds struggle to reproduce mimicked sounds as perfectly as adult lyrebirds can. This suggests a lyrebird’s voice improves over years of practice.

Added to that is the dancing. Male courtship displays involve dance moves accompanying their song. That’s a cognitively challenging task, which is why not all of us are capable of being K-Pop stars.

To combine song and dance needs a large and well-developed brain. And that, after all, may be the point – the male’s ability to coordinate and song with dance is thought to be the key selection criteria for females choosing their mates.

So for Echo to perfect his fire alarm song, he had to practice and practice and practice to get it to the point where we can recognise it. Like humans practising a language or a musical instrument, lyrebirds must work at their songs.

Why Does Bird Culture Matter?

Imagine if Echo was inspired by the lions and escaped. How would he fare in the wild? It’s unlikely he’d ever manage to impress a mate with his “evacuate now” mimicry and siren song. It’s as if a human was raised by wolves – it would be all but impossible to reintegrate.

The reason why we watch videos of Echo and find them amusing is because we are instinctively drawn to animal behaviour we can make sense of through our own. Animals acting like humans is amusing and appealing for us. But, alas, there’s a serious point here.

Take the critically endangered regent honeyeater, which once flew through box-ironbark forests in dense, raucous flocks. Now there are only 300 or so left in the wild.

With a population this low, the species loses not only genetic diversity but culture as well. Regent honeyeaters are losing their courtship songs, because the young birds simply don’t have enough peers to listen to and learn from. Without peers, some males only sing the songs of other species.

While lyrebirds are good survivors during natural disasters, there’s no room for complacency. The Black Summer fires put the superb lyrebird at real risk from habitat loss as well as introduced predators. If we’re not careful, the lyrebird too, could lose its culture and its songs. ![]()

Alex Maisey, Postdoctoral research fellow, Research Centre for Future Landscapes, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Stripping carbon from the atmosphere might be needed to avoid dangerous warming – but it remains a deeply uncertain prospect

Australia’s latest State of the Climate Report offers grim reading. As if recent floods weren’t bad enough, the report warns of worsening fire seasons, more drought years and, when rain comes, more intense downpours. It begs the question: is it too late to avoid dangerous warming?

At the COP27 climate summit in Egypt some states began to question whether the target to limit global warming to 1.5℃ this century should be dropped. The commitment was ultimately retained, but it remains unlikely we’ll meet it.

This means attention is turning to other options for climate action, including large-scale carbon removal.

Carbon removal refers to human activities that take carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it (ideally permanently) – in rock formations, land or ocean reservoirs. The more common, and least controversial, forms of carbon removal are tree-planting, mangrove restoration and enhancing soil carbon.

All forms of carbon removal - including natural and high-tech measures - are defined as forms of geoengineering. All are increasingly part of the global climate discussion.

Proponents argue carbon removal is required at a massive scale to avoid dangerous warming. But the practice is fraught. Successfully stripping carbon from the atmosphere at the scale our planet requires is a deeply uncertain prospect.

Limiting Global Warming To 1.5℃ Is Getting Harder

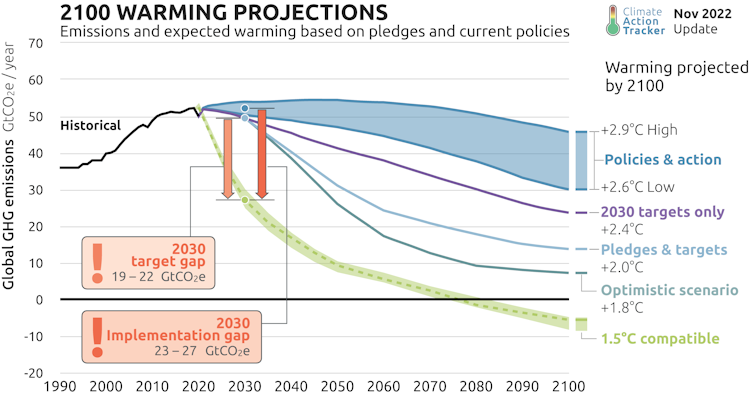

In 2015 the international community set a goal of limiting warming to well below 2℃, and preferably to 1.5℃ this century, compared to pre-industrial levels. Seven years later, global emissions are not on track to achieve this.

The State of the Climate Report released this week found Australia has already warmed by 1.47℃. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says the planet overall has heated by 1.09℃.

Renewable energy is growing rapidly, but so too is the use of oil and coal. The emissions “budget” that would limit warming to 1.5℃ is almost spent.

The IPCC said in a report this year that large-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal was “unavoidable” if the world is to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

It followed an IPCC report in 2018 containing scenarios in which warming could be limited to 1.5℃. These scenarios required significant emission reductions along with carbon removal of between 100–1,000 billion tonnes of CO₂ by 2100. For context, global annual energy emissions are now approximately 31 billion tonnes of CO₂.

Today, policy planners often assume large-scale carbon removal will become necessary. Meanwhile, critics worry that the promise of carbon removal will delay other actions to mitigate climate change.

Indeed, some critics question if large-scale removal will ever be feasible, saying it’s unlikely to be developed in time nor work effectively.

What Does Carbon Removal Look Like?

Cramming centuries of carbon pollution into the biosphere won’t be easy. One key challenge is making the storage permanent.

Consider trees. While forests store a lot of carbon, if they burn then the carbon goes straight back into the atmosphere. What’s more, there’s not enough land for forests to deliver negative emissions on the scales we require to limit global warming.

Carbon removal by planting new forests (afforestation) can also create social injustices. In some cases Indigenous communities have lost control of homelands appropriated for carbon storage.

As a result, some experts and civil society groups are calling for more complex methods of carbon removal. Two widely discussed examples include “direct air capture and storage” (use fans to force air through carbon-capturing filters) and “bioenergy, carbon capture and storage” (grow forests, burn them for electricity, capture and store the carbon).

In each case, the goal is to permanently sequester captured carbon in underground geologic formations. This will likely offer more permanent carbon removal than “natural solutions” such as planting trees. Their lower land requirements mean they should also be easier to scale.

However, these higher-tech methods are also more expensive and often lack public support. Consider plans for the Sizewell Nuclear Power Station in the United Kingdom to power “direct air capture” of carbon dioxide. Sizewell is promising carbon negative electricity, but nuclear-powered negative emissions are unlikely to be popular or cheap.

One Australian start-up has plans for solar-powered direct air capture of CO₂. However, this project’s costs are prohibitively high.

Much social learning will be needed before large-scale carbon removal of any type can become a thing. For now, we need to democratically review which, if any, carbon removal methods are actually a good idea.

Carbon Removal Credits Could Be Dodgy

As governments begin to grasp the difficulties in decarbonising sectors such as agriculture and aviation, they have begun to look to carbon removal technologies to meet their net-zero emissions pledges.

For example, in the United States, the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction and CHIPS Acts promise massive new carbon removal programs.

At COP27, negotiators considered how carbon removals should be defined internationally. At stake is which carbon removal projects will be able to generate “tradeable” offsets.

Most decisions at COP27 ended up being delayed or referred to working groups. Nevertheless, civil society observers worried that dodgy carbon removal credits might undermine the Paris Agreement’s integrity.

When credits are awarded to projects that don’t really capture carbon or do so only temporarily, then carbon reduction schemes lose all credibility.

How To Avoid Integrity Issues

Assessing the material and social impacts of carbon removal – whether via a “natural solution” or a new technology – will first require small-scale deployment.

To avoid integrity issues, the world will need robust regulations on how carbon removal is conducted. This includes:

agreed standards to measure carbon removal in ways that rule out dodgy or temporary carbon removal

more advanced carbon removal technologies that bring down the cost and reduce land and energy requirements

more sophisticated ways of aligning carbon removal with social justice so that sovereignty and humanity rights are prioritised over carbon markets

a system of incentives to encourage carbon removal. States, companies and other actors should be rewarded for their climate restoration work, but these efforts must be additional to actual emissions reduction.

Of course, the best thing to do is to stop emitting carbon. However, preserving a safe climate will likely require us to go further. It’s time to start a democratic discussion about carbon removal.![]()

Jonathan Symons, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie School of Social Sciences, Macquarie University and Matt McDonald, Associate Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

State of the climate: what Australians need to know about major new report

The latest State of the Climate report is out, and there’s not much good news for Australians.

Our climate has warmed by an average 1.47℃ since national records began, bringing the continent close to the 1.5℃ limit the Paris Agreement hoped would never be breached. When global average warming reaches this milestone, some of Earth’s natural systems are predicted to suffer catastrophic damage.

The report, released today, paints a concerning picture of ongoing and worsening climate change. In Australia, associated impacts such as extreme heat, bushfires, drought, heavy rainfall, and coastal inundation threaten our people and our environment.

The report is a comprehensive biennial snapshot of the latest trends in climate, with a focus on Australia. It’s compiled by the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, drawing on the latest national and international climate research.

It synthesises the latest science about Australia’s climate and builds on the previous 2020 report by including, for example, information from the most recent assessment report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

And the take home message? Climate change continues unabated. The world is warming, sea levels are rising, ice is melting, fire weather is worsening, flooding rains are becoming more frequent – and the list goes on.

What follows is a summary of major findings in three key categories – and an explanation of what it all means.

1. Warming, Heat Extremes And Bushfire

The 2020 report said Australia’s climate has warmed on average by 1.44℃ since national records began in 1910. That warming has now increased to 1.47℃. This mirrors trends across the world’s land areas, and brings with it more frequent extreme heat events.

The year 2019 was Australia’s warmest on record. The eight years from 2013 to 2020 are all among the ten warmest ever measured. Warming is happening both by day and by night, and across all months.

Since the 1950s, extreme fire weather has increased and the fire season has lengthened across much of the country. It’s resulted in bigger and more frequent fires, especially in southern Australia.

2. Rain, Floods And Snow

In Australia’s southwest, May to July rainfall has fallen by 19% since 1970. In the southeast of Australia, April to October rainfall has fallen by 10% since the late 1990s.

This will come as somewhat of a surprise given the relatively wet conditions across eastern Australia over the past few years. But don’t confuse longer term trends with year-to-year variability.

Lower rainfall has led to reduced streamflow; some 60% of water gauges around Australia show a declining trend.

At the same time, heavy rainfall events are becoming more intense – a fact not lost on flood-stricken residents in Australia’s eastern states in recent months. The intensity of extreme rainfall events lasting an hour has increased by about 10% or more in some regions in recent decades. This often brings flash flooding, especially in urban environments. The costs to society are enormous.

Warm air can hold more water vapour than cooler air. That’s why global warming makes heavy rainfall events more likely, even in places where average rainfall is expected to decline.

Also since the 1950s, snow depth and cover, and the number of snow days, have decreased in alpine regions. The largest declines are happening in spring and at lower altitudes.

Extremely cold days and nights are generally becoming less frequent across the continent. And while parts of southeast and southwest Australia have recently experienced very cold nights, that’s because cool seasons have become drier and winter nights clearer there, leading to more overnight heat loss.

Any camper will tell you how chilly it can get on a clear starry night, without the warm blanket of cloud cover.

3. Oceans And Sea Levels

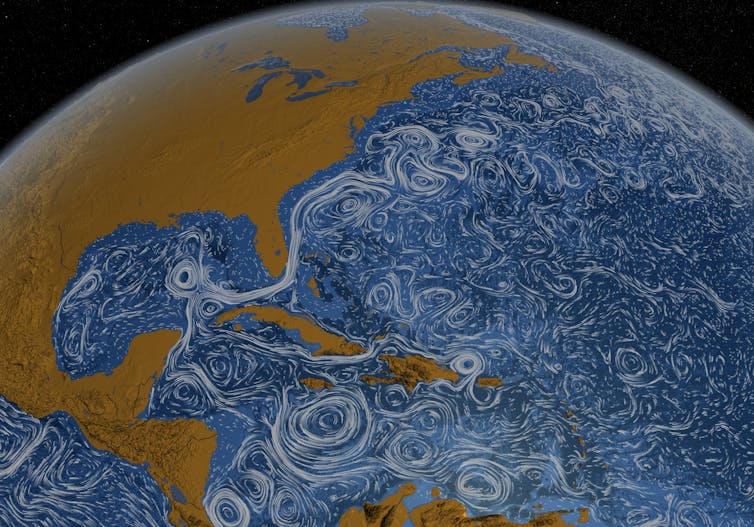

Sea surface temperatures around the continent have increased by an average 1.05℃ since 1900. The greatest ocean warming since 1970 has occurred off southeast Australia and Tasmania. In the Tasman Sea, the warming rate is now twice the global average.

Ongoing ocean warming has also contributed to longer and more frequent marine heatwaves. Marine heatwaves are particularly damaging to ecosystems, including the Great Barrier Reef, which is at perilous risk of ruin if nothing is done to address surging greenhouse gas emissions.

Oceans around Australia have also become more acidic, and this damage is accelerating. The greatest change is occurring in temperate and cooler waters to the south.

Sea levels are rising globally and around Australia. This is driven by both ocean warming and melting ice. Ice loss from Greenland, Antarctica and glaciers is increasing, and only set to get worse.

Around Australia, the largest sea level rise has been observed to the north and southeast of the continent. This is increasing the risk of inundation and damage to coastal infrastructure and communities.

What’s Causing This?

All this is happening because concentrations of greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere continue to rise. The principal driver of these gases is human burning of fossil fuels. These long-lived gases form a “blanket” in the atmosphere that makes it harder for Earth to radiate the Sun’s heat back into space. And so, the planet warms, with very costly impacts to society.

The report confirmed carbon dioxide (CO₂) has been accumulating in the atmosphere at an increasing rate in recent decades. Worryingly, over the past two years, levels of methane and nitrous oxide have also grown very rapidly.

What Comes Next?

None of these problems are going away. Australia’s weather and climate will continue to change in coming decades.

As the report states, these climate changes are increasingly affecting the lives and livelihoods of all Australians. It goes on:

Australia needs to plan for, and adapt to, the changing nature of climate risk now and in the decades ahead. The severity of impacts on Australians and our environment will depend on the speed at which global greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced.

This point is particularly confronting, given the abject failure of the recent COP27 climate talks in Egypt to build on commitments from Glasgow only a year earlier to phase out fossil fuels.

It’s no surprise, then, that the insurance sector is getting nervous about issuing new policies to people living at the front-line of climate extremes.

While the urgency for action has never been more pressing, we still hold the future in our hands - the choices we make today will decide our future for generations to come. Every 0.1℃ of warming we can avoid will make a big difference.

But it’s not all bad news. Re-engineering our energy and transport systems to be carbon neutral will create a whole new economy and jobs growth - with the added bonus of a safer climate future.

Do nothing, and these State of the Climate reports will continue to make for grim reading. ![]()

Matthew England, Scientia Professor and Deputy Director of the ARC Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS), UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP27: how the fossil fuel lobby crowded out calls for climate justice

Alix Dietzel, University of BristolCOP27 has just wrapped up. Despite much excitement over a new fund to address “loss and damage” caused by climate change, there is also anger about perceived backsliding on commitments to lower emissions and phase out fossil fuels.

As an academic expert in climate justice who went along this year, hoping to make a difference, I share this anger.

“Together for Implementation” was the message as COP27 got underway on November 6 and some 30,000 people descended on the Egyptian resort town of Sharm El Sheik. The UNFCCC strictly regulates who can attend negotiations. Parties (country negotiation teams), the media and observers (NGOs, IGOs and UN special agencies) must all be pre-approved.

I went along as an NGO observer, to represent the University of Bristol Cabot Institute for the Environment. Observers have access to the main plenaries and ceremonies, the pavilion exhibition spaces and side events. The negotiation rooms, however, are largely off limits. Most of the day is spent listening to speeches, networking and asking questions at side-events.

The main role of observers, then, is to apply indirect pressure on negotiators, report on what is happening and network. Meaningful impact on and participation in negotiations seems out of reach for many of the passionate people I met.

Who Does – And Doesn’t – Get A Say

It has long been known that who gets a say in climate change governance is skewed. As someone working on fair decision making as part of a just transition to less carbon-intensive lifestyles and a climate change-adapted society, it is clear that only the most powerful voices are reflected in treaties such as the Paris Agreement. At last year’s COP26, men spoke 74% of the time, indigenous communities faced language barriers and racism and those who could not obtain visas were excluded entirely.

Despite being advertised as “Africa’s COP”, COP27 further hampered inclusion. The run up was dogged by accusations of inflated hotel prices and concerns over surveillance, and warnings about Egypt’s brutal police state. The right to protest was limited, with campaigners complaining of intimidation and censorship.

Arriving in Sharm El Sheik, there was an air of intimidation starting at the airport, where military personnel scrutinised passports. Police roadblocks featured heavily on our way to the hotel and military officials surrounded the COP venue the next morning.

Inside the venue, there were rumours we were being watched and observers were urged not to download the official app. More minor issues included voices literally not being heard due to unreliable microphones and the constant drone of aeroplanes overhead, and a scarcity of food with queues sometimes taking an hour or more. Sponsored by Coca Cola, it was also difficult to access water to refill our bottles. We were sold soft drinks instead.

Outside of the venue, unless I was with a male colleague, I faced near constant sexual harassment, hampering my ability to come and go from the summit. All these issues, major and minor, affect who is able to contribute at COP.

Fossil Fuel Interests Dominated

In terms of numbers, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) registered the largest party delegation with more than 1,000 people. The oil and gas-rich nation of just 9 million people had a delegation almost twice the size of the next biggest, Brazil. More troublingly, the oil and gas lobby representatives were registered in the national delegations of 29 different countries and were larger than any single national delegation (outside of the UAE). According to one NGO, at least 636 of those attending COP27 were lobbyists for the fossil-fuel industry.

Despite the promise that COP27 would foreground African interests, the fossil lobby outnumbers any delegation from Africa. These numbers give a sense of who has power and say at these negotiations, and who does not.

Protecting The Petrostates

The main outcomes of COP27 are a good illustration of the power dynamics at play. There is some good news on loss and damage, which was added to the agenda at the last moment. Nearly 200 countries agreed that a fund for loss and damage, which would pay out to rescue and rebuild the physical and social infrastructure of countries ravaged by extreme weather events, should be set up within the next year. However, there is no agreement yet on how much money should be paid in, by whom, and on what basis.

Much more worryingly, there had been a push to phase out all fossil fuels by countries including some of the biggest producers: the EU, Australia, India, Canada, the US and Norway. However, with China, Russia, Brazil, Saudi Arabia and Iran pushing back, several commitments made at COP26 in Glasgow were dropped, including a target for global emissions to peak by 2025. The outcome was widely judged a failure on efforts to cut emissions: the final agreed text from the summit makes no mention of phasing out fossil fuels and scant reference to the 1.5℃ target.

Laurence Tubiana, one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, blamed the host country, Egypt, for allowing its regional alliances to sway the final decision, producing a text that clearly protects oil and gas petrostates and the fossil fuel industries.

The final outcomes demonstrate that, despite the thousands who were there to advocate for climate justice, it was the fossil fuel lobby that had most influence. As a climate justice scholar, I am deeply worried about the processes at COPs, especially given next year’s destination: Dubai. It remains to be seen what happens with the loss and damage fund, but time is running out and watered down commitments on emissions are at this stage deeply unjust and frankly dangerous.![]()

Alix Dietzel, Senior Lecturer in Climate Justice, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

After COP27, all signs point to world blowing past the 1.5 degrees global warming limit – here’s what we can still do about it

The world could still, theoretically, meet its goal of keeping global warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius, a level many scientists consider a dangerous threshold. Realistically, that’s unlikely to happen.

Part of the problem was evident at COP27, the United Nations climate conference in Egypt.

While nations’ climate negotiators were successfully fighting to “keep 1.5 alive” as the global goal in the official agreement, reached Nov. 20, 2022, some of their countries were negotiating new fossil fuel deals, driven in part by the global energy crisis. Any expansion of fossil fuels – the primary driver of climate change – makes keeping warming under 1.5 C (2.7 Fahrenheit) compared to pre-industrial times much harder.

Attempts at the climate talks to get all countries to agree to phase out coal, oil, natural gas and all fossil fuel subsidies failed. And countries have done little to strengthen their commitments to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the past year.

There have been positive moves, including advances in technology, falling prices for renewable energy and countries committing to cut their methane emissions.

But all signs now point toward a scenario in which the world will overshoot the 1.5 C limit, likely by a large amount. The World Meteorological Organization estimates global temperatures have a 50-50 chance of reaching 1.5C of warming, at least temporarily, in the next five years.

That doesn’t mean humanity can just give up.

Why 1.5 Degrees?

During the last quarter of the 20th century, climate change due to human activities became an issue of survival for the future of life on the planet. Since at least the 1980s, scientific evidence for global warming has been increasingly firm , and scientists have established limits of global warming that cannot be exceeded to avoid moving from a global climate crisis to a planetary-scale climate catastrophe.

There is consensus among climate scientists, myself included, that 1.5 C of global warming is a threshold beyond which humankind would dangerously interfere with the climate system.

We know from the reconstruction of historical climate records that, over the past 12,000 years, life was able to thrive on Earth at a global annual average temperature of around 14 C (57 F). As one would expect from the behavior of a complex system, the temperatures varied, but they never warmed by more than about 1.5 C during this relatively stable climate regime.

Today, with the world 1.2 C warmer than pre-industrial times, people are already experiencing the effects of climate change in more locations, more forms and at higher frequencies and amplitudes.

Climate model projections clearly show that warming beyond 1.5 C will dramatically increase the risk of extreme weather events, more frequent wildfires with higher intensity, sea level rise, and changes in flood and drought patterns with implications for food systems collapse, among other adverse impacts. And there can be abrupt transitions, the impacts of which will result in major challenges on local to global scales.

Steep Reductions And Negative Emissions

Meeting the 1.5 goal at this point will require steep reductions in carbon dioxide emissions, but that alone isn’t enough. It will also require “negative emissions” to reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide that human activities have already put into the atmosphere.

Carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for decades to centuries, so just stopping emissions doesn’t stop its warming effect. Technology exists that can pull carbon dioxide out of the air and lock it away. It’s still only operating at a very small scale, but corporate agreements like Microsoft’s 10-year commitment to pay for carbon removed could help scale it up.

A report in 2018 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change determined that meeting the 1.5 C goal would require cutting carbon dioxide emissions by 50% globally by 2030 – plus significant negative emissions from both technology and natural sources by 2050 up to about half of present-day emissions.

Can We Still Hold Warming To 1.5 C?

Since the Paris climate agreement was signed in 2015, countries have made some progress in their pledges to reduce emissions, but at a pace that is way too slow to keep warming below 1.5 C. Carbon dioxide emissions are still rising, as are carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere.

A recent report by the United Nations Environment Program highlights the shortfalls. The world is on track to produce 58 gigatons of carbon dioxide-equivalent greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 – more than twice where it should be for the path to 1.5 C. The result would be an average global temperature increase of 2.7 C (4.9 F) in this century, nearly double the 1.5 C target.

Given the gap between countries’ actual commitments and the emissions cuts required to keep temperatures to 1.5 C, it appears practically impossible to stay within the 1.5 C goal.

Global emissions aren’t close to plateauing, and with the amount of carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere, it is very likely that the world will reach the 1.5 C warming level within the next five to 10 years.

How large the overshoot will be and for how long it will exist critically hinges on accelerating emissions cuts and scaling up negative emissions solutions, including carbon capture technology.

At this point, nothing short of an extraordinary and unprecedented effort to cut emissions will save the 1.5 C goal. We know what can be done – the question is whether people are ready for a radical and immediate change of the actions that lead to climate change, primarily a transformation away from a fossil fuel-based energy system.![]()

Peter Schlosser, Vice President and Vice Provost of the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP27 flinched on phasing out ‘all fossil fuels’. What’s next for the fight to keep them in the ground?

Fergus Green, UCL and Harro van Asselt, Stockholm Environment InstituteThe latest UN climate change summit (COP27) concluded, once again, with a tussle over the place of fossil fuels in the global economy.

An agreement by the world’s governments to phase out all fossil fuels would have been a welcome progression from last year’s Glasgow climate pact. It called on countries to “[accelerate] efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”, making it the first UN treaty to acknowledge the need to do something about the main source of greenhouse gas emissions.

But at COP27, widespread anxieties about the cost and availability of energy made many governments cautious about expressing a clear intention to phase out all fossil fuels in the resulting agreement. The COP27 text reiterated the COP26 decision but failed to broaden it to encompass oil and gas, despite a proposal by India to that end (a move that would have helped take the emphasis off coal, of which it is a major consumer).

Still, growing support for such an extension is evident. More than 80 countries (including the EU and US) supported India’s proposal. Many nations are building international agreements outside of the UN negotiation process. After the failure of COP27, the question is what should happen next in the fight against continued fossil fuel use.

There is no doubt that, to preserve a liveable climate, the extraction and burning of coal, oil and gas must be rapidly reduced and, depending on how optimistic you are about carbon capture technologies, phased out altogether.

Despite large planned increases in fossil fuel production, recent research (released just before COP27) found, for the first time, that global demand for each of the fossil fuels will peak or plateau in all scenarios within 15 years. This is partly due to attempts to reduce energy use and increase renewables in the wake of the gas shortage created by sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

As the dangers of extracting and burning fossil fuels have become increasingly apparent, many experts, campaigners, international organisations and, increasingly, governments have contested the moral legitimacy of these activities. In a recent journal article, we argued that the Glasgow agreement represented a breakthrough (albeit a modest one) in the emergence of international anti-fossil fuel norms.

An international norm is a morally appropriate standard of behaviour among states (for example, prevailing norms prohibit foreign aggression, piracy, or the testing and use of nuclear weapons). International conferences such as COP27 catalyse emerging norms by specifying them in formal declarations.

COP decisions are not binding and the language on fossil fuels at COP26 was watered down during negotiations. But the Glasgow text reflected a growing sense among governments that certain activities relating to fossil fuels (like generating electricity from coal without capturing the CO₂ and policies which make fossil fuels cheaper to extract and consume) are becoming illegitimate.

The lack of progress on fossil fuels reflects the upheavals in the energy sector as well as the constraints of the climate negotiations themselves, which operate by consensus. This often produces decisions that reflect the lowest common denominator among nearly 200 countries with diverse energy profiles and interests, and COP27 was no exception.

Large oil and gas producers are profiting handsomely from current market prices and have lobbied governments to permit them to explore and drill for yet more oil and gas. At COP27, there were more oil and gas industry lobbyists than the combined number of delegates from the ten countries most affected by climate change. Little wonder COP27 did not yield consensus on phasing down all fossil fuels.

Other international initiatives are not bound by such procedural constraints, and there was more progress on the sidelines of COP27. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (Boga), an initiative launched around the time of COP26 by Denmark and Costa Rica that aims to phase out oil and gas production, attracted new members Chile, Fiji and the US state of Washington, with Portugal upgraded to “core member” status.

Emulating a deal between South Africa and several wealthy countries from a year earlier, a new just energy transition partnership was launched between Indonesia and Japan, Canada, the US, Denmark and others, to help Indonesia transition from coal to renewables.

What More Can Be Done?

In the coming years, there will be growing civil society and diplomatic pressure for a phase-out of all fossil fuels in a COP decision. But independent initiatives among states, like Boga, must be nurtured in parallel, and the high-level pledges made in these initiatives must be implemented.

For instance, a group of nations pledged at COP26 to end public finance for fossil fuels by the end of 2022. While some countries are on track to meet this goal, others are not following through.

Countries should also develop an international agreement to restrict and phase out fossil fuels. Building on a global campaign for such an agreement, the small island nations of Tuvalu and Vanuatu have called for a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty. We suggest two ways to advance these efforts which draw on our recent research.

First, Tuvalu and Vanuatu could encourage their Pacific Island counterparts to create a regional fossil free zone treaty that prohibits the extraction and transportation of fossil fuels throughout the territories and territorial waters of members.

Second, more must be done to name and shame governments, especially rich ones, who are expanding how much fossil fuel they extract and burn. This effort demands greater transparency around government activities. A new global registry of fossil fuels is helping to catalogue this information. But governments should also disclose all fossil fuel infrastructure that is being planned or considered on their territory, or with their support.

The COP27 outcome is a timely reminder that curbing the growth in fossil fuels will not come about through consensus-oriented negotiations among governments that include those corrupted by the fossil fuel industry. It will require social movements pressuring leaders to legislate a managed phase out of fossil fuels, while ensuring a just transition for affected workers and communities. And it will require pioneering governments to work together internationally to forge new alliances that accelerate this goal.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Fergus Green, Lecturer in Political Theory and Public Policy, UCL and Harro van Asselt, Professor of Climate Law and Policy, University of Eastern Finland, Visiting Researcher, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University & Affiliated Researcher, Stockholm Environment Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Adapting to a hotter planet has never been more important, and progress edged forward at COP27

Johanna Nalau, Griffith UniversityAs the COP27 climate summit drew to a close over the weekend, it’s important to acknowledge that progress was made on climate adaptation – even if more can be done.

“Climate adaptation” is a term for how countries adapt to the impacts of climate change. It could be, for instance, by strengthening infrastructure to better withstand disasters, moving towns out of floodplains, or transforming the agriculture sector to minimise food insecurity.

As the costs of disasters climb, working out who will finance climate adaptation has become increasingly urgent for developing nations. For decades, they’ve called upon wealthy countries – largely responsible for causing the climate crisis in the first place – to foot the bill.

So let’s explore what COP27 achieved, how these achievements might translate into tangible commitments, and what must happen now to give everyone a fighting chance to survive on a hotter planet.

A Thorny Issue

The thorniest issues at climate change negotiations are about finance: who is giving, who is receiving, how is the money received and what kind of finance is made available.

Developed countries don’t have a good track record on this. In 2009, they committed to mobilising US$100 billion per year of climate finance by 2020 – a target that remains unmet.

What’s more, most climate finance so far has been directed towards helping developing nations mitigate their emissions, rather than for adaptation.

As Dina Saleh, the Regional Director of the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development, explained during the conference, failing to help rural populations adapt could lead to more poverty, migrations and conflict. She said:

We are calling on world leaders from developed nations to honour their pledge to provide the $100 billion a year in climate finance to developing nations and to channel half of that [for] climate adaptation.

Adaptation Finance Still Falls Short

The United Nations has established different funds to channel adaptation finance, including the Least Developing Countries Fund, Special Climate Change Fund and Adaptation Fund.

At COP27, eight countries pledged US$105.6 million for adaptation via the Least Developing Countries Fund and Special Climate Change Fund, including Sweden, Germany and Ireland. Others, such as the United States and Canada, expressed potential future financial commitments.

These funds are in addition to the US$413 million promised at COP26 in Glasgow last year, via the Least Developing Countries Fund. The money will target the most urgently needed adaptation efforts, such as strengthening infrastructure, social safety nets and diversifying livelihoods.

There is also a specific new funding for small-island developing states. While this development has been welcomed by the Alliance of Small Island States, it also says faster processes are needed to make the money available.

Small island nations such as Tuvalu are already experiencing severe climate impacts, and the projections are dire. For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found some atoll islands are likely to experience coral bleaching every year by 2040.

These islands are also particularly vulnerable to tropical cyclones. One single large event can set development back years. For example, in 2016 tropical cyclone Winston took out over a third of Fiji’s GDP in about 36 hours.

Similarly, other highly vulnerable nations across Africa and Asia are asking for easier access to adaptation finance. The Adaptation Fund included an innovation that gave countries easier access to money, and ensured it responds directly to each country’s needs.

At COP27, this fund received over US$230 million in new pledges. However, it currently has unfunded adaptation projects worth US$380 million in the pipeline, signalling the urgent need to ramp up finance.

Progress Is Edging Forward

The Paris Agreement in 2015 set the “global goal on adaptation” to drive collective progress on climate adaptation worldwide. At COP27, countries agreed to develop a framework for this goal in 2023. This includes gender-responsive approaches, and science-based metrics and targets to track progress.

Another big-ticket item is the “global stocktake” on adaptation, which measures progress at the national level on fulfilling Paris Agreement obligations.

At COP27, it was noted only 40 countries so far have submitted their national adaptation plans, which identify adaptation priorities and strategies for reducing climate vulnerability. Questions remain about how to accelerate the planning, implementation and financing of these plans.

The Sharm-el-Seikh Adaptation Agenda was also launched by the two UN-appointed High-Level Climate Champions. These seek to engage non-state actors, such as cities, businesses and investors, to boost ambition for climate adaptation.

The agenda’s ultimate aim is to help 4 billion people become more resilient to climate change impacts by 2030. It has 30 adaptation outcomes to aim for, including:

protecting 3 billion people from disasters by installing smart and early warning systems in the most vulnerable communities

investing US$4 billion to secure the future of 15 million hectares of mangroves worldwide

mobilising US$140-300 billion across both public and private finance sources for adaptation.

What Now?

Many pledges on adaptation finance have been made in COP26 and COP27, and the next step is to get the money where it is most urgently needed.

As climate impacts are already unfolding rapidly, communities worldwide must develop the capacity to plan for climate adaptation. This requires action at every level, and shouldn’t be left to local communities alone.

Making progress on climate adaptation in the coming years is crucial. Early action and planning can save thousands of dollars, but only if we have robust processes in place to make decisions before impacts occur. This calls for more planning, investments and collaboration across local, regional, state and international levels.

But most important is the willingness to change our mindset. We must stop operating in a business-as-usual model and push for a more sustainable world in this changing climate. ![]()

Johanna Nalau, Research Fellow, Climate Adaptation, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wildfires often lead to dust storms – and they’re getting bigger

Wildfires affect large areas of the Earth’s surface and many of their effects occur at an alarming speed. The fires that consumed half of Australia’s Kangaroo Island in 2019 left a trail of animal corpses in their wake. In 2021, wildfires burned over 2.5 million acres of land in California.

But wildfires have other harmful effects that are slower to materialise. Wildfires reduce vegetation cover and can damage soil to the extent that it retains less moisture. As wind blows over the scarred landscape this can lead to the increased release of dust made from fine mineral grains (often less than 0.01 mm in diameter).

The wind lifts the dust emissions into the air where they can find themselves suspended in a global atmospheric process that transfers them around the world. Dust events can therefore affect areas far from the land close to a wildfire.

Scientists have long established that concentrations of atmospheric dust increase following large wildfires. But the global extent of post-fire dust events has been an underresearched aspect of the study into the impact of wildfires. Now researchers from Peking and Princeton universities have identified that the duration and scale of post-fire atmospheric dust storms may be far greater than previously understood.

Larger Dust Storms

Using two decades of satellite observations, the researchers found that over 150,000 large wildfires had occurred worldwide between 2003 and 2020. At least 20 1km by 1km squares within an area of approximately 100km² had to include detectable fires for at least seven consecutive days for a fire event to be defined as a large wildfire.

Over half of the large wildfires identified were followed by dust events. In these events, the concentration of atmospheric dust in the area surrounding the fire-affected region increased more than threefold on average.

Most of the dust storms continued for a few days after a fire. But in 10% of the events occurring in savannah and grassland areas, dust concentrations were still exceptionally high ten days later and occasionally more than three weeks after the fire.

Across the period of study, the researchers found that the duration of post-fire dust events increased significantly. A dust event that occurred in 2020 lasted 24 hours longer on average than it did in 2003.

Should We Be Concerned?

Atmospheric dust storms can have serious impacts on ecology and human health.

Dust emissions are rich in chemical nutrients including phosphorus, nitrogen and iron. Nutrients such as these are key elements of soil productivity. As the nutrient-rich top layer of soil is removed by wind, soil quality in the area affected by a fire is depleted.

But dust can also be transported vast distances via the global dust cycle. When deposited, nutrient-rich dust emissions can fertilise soils and oceans far from the affected area.

Research has linked Australia’s wildfires in 2019–2020 to extensive phytoplankton blooms in the Southern Ocean. Dust emissions can provide phytoplankton with the nutrients needed for rapid growth, leading to the formation of blooms. Such blooms can harm local marine ecosystems by reducing the oxygen content of the water.

Smoke is an obvious health concern associated with wildfires. Small, inhalable, coarse particles within smoke can cause respiratory damage. Research links airborne particulate matter to over two million deaths worldwide each year.

Fine dust particles are even smaller (2.5 micrometres in diameter) and pose a similar threat. The researchers suggest that the risks posed by large wildfires to human health may extend well beyond the immediate plume of smoke and may continue long after the smoke has cleared.

Does Climate Change Have A Role?

It might be tempting to ascribe the observed increase in the duration of post-fire dust events to our warming climate. Climate change can make hot and dry weather conditions more common and create the conditions for dangerous wildfires.

Yet the researchers are cautious to adopt this explanation. They note only that enhanced dust emissions correlate with the number of previous fires at a given location.

Fire is a natural part of many ecosystems and evidence for increasing wildfire frequency is complex. Savannah ecosystems, which the study identifies as the landscape most prone to post-fire dust emissions, owe their existence to the presence of fire. Regular fires remove young trees and return the grassland community to its original state.

Determining whether a wildfire has been caused by direct human actions or climate change is also difficult. Just as for climate change, human actions can influence wildfire activity. The use of fire to burn farming or logging residue, for example, increases the risk of wildfire.

Scientists increasingly understand that wildfires are a feature of the natural world. But their impacts can be dangerous and extend well beyond the margins of the fire itself.![]()

Matt Telfer, Associate Professor of Physical Geography, University of Plymouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How to design clean energy subsidies that work – without wasting money on free riders

The planet is heating up as greenhouse gas emissions rise, contributing to extreme heat waves and once-unimaginable flooding. Yet despite the risks, countries’ policies are not on track to keep global warming in check.

The problem isn’t a lack of technology. The International Energy Agency recently released a detailed analysis of the clean energy technology needed to lower greenhouse gas emissions to net zero globally by 2050. What’s needed, the IEA says, is significant government support to boost solar and wind power, electric vehicles, heat pumps and a variety of other technologies for a rapid energy transition.

One politically popular tool for providing that government support is the subsidy. The U.S. government’s new Inflation Reduction Act is a multibillion-dollar example, packed with financial incentives to encourage people to buy electric vehicles, solar panels and more.

But just how big do governments’ clean energy subsidies need to be to meet their goals, and how long are they needed?

Our research points to three important answers for any government considering clean energy subsidies – and for citizens keeping an eye on their progress.

Why Subsidize At All?

An obvious first question is: Why should governments subsidize clean energy at all?

The most direct answer is that clean energy helps to reduce harmful emissions – both of gases that cause local pollution and of those that warm the planet.

Reducing emissions helps to lower both public health costs and damage from climate change, which justifies government spending. Reports have estimated that the U.S. spends US$820 billion a year just on health costs associated with air pollution and climate change. Globally, the World Health Organization estimated that the costs reached $5.1 trillion in 2018. Taxing and regulating polluting industries can also cut emissions, but carrots are often more politically popular than sticks.

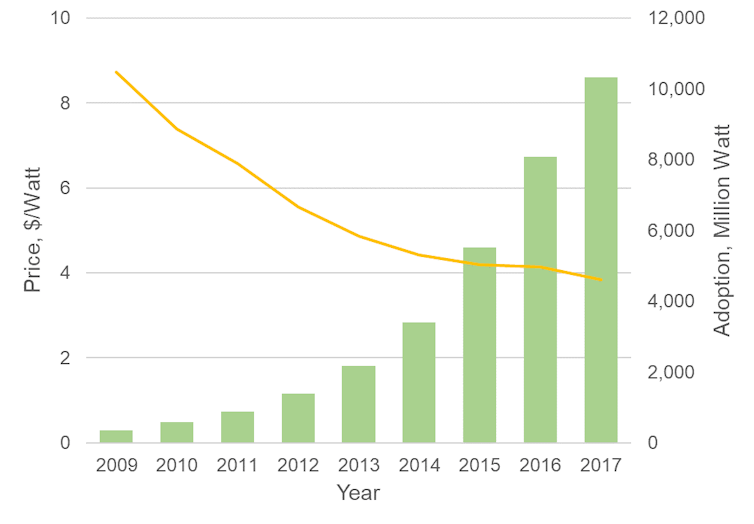

A less obvious reason for subsidies is that government support can help a new and initially expensive technology become competitive in the market.

Governments have been central to the development of many technologies that are pervasive today, including microchips, the internet, solar panels and GPS. Microchips were fantastically expensive when first developed in the 1950s. Demand from the U.S. military and NASA, which could pay the high price, fueled the growth of the industry, and costs eventually dropped enough that they’re now found in everything from cars to toasters.

Government support has also helped to bring down the cost of solar power. Rooftop solar system costs fell 64% from 2010 to 2020 in the U.S. because cells became more efficient and higher volumes drove prices down.

How Much Money?

So, subsidies can work, but what’s the right amount?

Too low, and a subsidy has no effect. Giving everyone a coupon for $1 off an electric car won’t change anyone’s buying plans. But subsidies can also be set too high.

The government doesn’t need to spend money persuading consumers who already plan to buy an electric car and can afford one, yet studies show clean energy subsidies disproportionately go to richer people. When people who would have purchased the item anyway receive subsidies, they’re known as “free riders.”

The ideal subsidy attracts new buyers while avoiding free riders and overspending on people who are already convinced. The subsidy can only work when it convinces a previously uninterested consumer to buy a product.

How Long Should Subsidies Last?

Timing is also important when thinking about the size of subsidies. When a promising technology is new and expensive, free riders are less of an issue. A large subsidy may be needed to attract even a few buyers, build out the emerging market and support the industry’s growth.

Solar power is a good example: In 2005, solar was several times more expensive than traditional electricity sources. Subsidies, like the 30% Investment Tax Credit established that year, helped lower the cost, and today’s solar is about one-tenth the price and cost-competitive with other electricity sources.

Once a clean technology is competitive, subsidies can still play an important role in speeding up the energy transition, but at a lower level than in the past.

In our research on residential solar panels, we estimate that the ideal subsidy for rooftop solar should have been initially higher than the actual federal tax credit but fall more quickly, declining to zero after 14 years from its start date.

By starting the subsidy about 20% higher, our models found that it would have boosted production faster, which would cut costs faster and reduce the need for high future subsidies.

Should Subsidies Eventually Disappear?

It makes sense for subsidies to disappear altogether once a technology is sufficiently cost-competitive. However, even if a technology is competitive, it might be worth further subsidy if the speed of adoption is important.

The argument for continuing a subsidy depends on whether the additional adoption it stimulates is cost-effective in reducing emissions. Wind power is cheaper than fossil fuel power in many parts of the country. Even so, we found that continuing subsidies for wind power would lead to valuable emission benefits.

That said, sometimes subsidies stick around when they shouldn’t.

Fossil fuels have been heavily subsidized for decades, despite their harm to human health, the environment and the climate, all of which raise public costs. Governments globally spent almost $700 billion on fossil fuel subsidies in 2021. The U.S. government, in recent years, has spent more on renewable energy tax credits than fossil fuels, which is a promising transition of government support.

Global Impact

While the U.S. was the focus of our solar subsidy research, this way of thinking – balancing the costs and benefits of subsidies – can be applied in other nations to design better subsidies for clean energy technologies.

The subsidy is just one policy tool, but it is an important one for both stimulating early-stage technologies and accelerating deployment of more competitive options. As the world attempts the fastest energy transition in history, today’s energy subsidy decisions will affect its ability to succeed.![]()

Eric Hittinger, Associate Professor of Public Policy, Rochester Institute of Technology; Eric Williams, Professor of Sustainability, Rochester Institute of Technology; Qing Miao, Associate Professor of Public Policy, Rochester Institute of Technology, and Tiruwork B. Tibebu, Ph.D. Student, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What planting tomatoes shows us about climate change

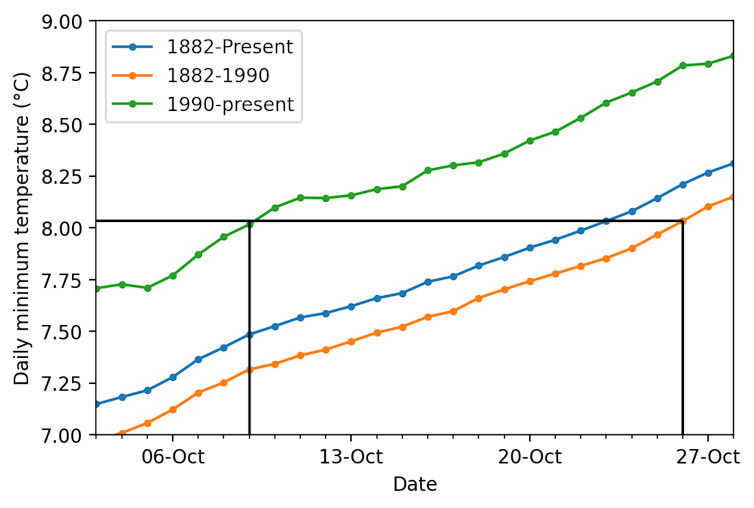

There’s a piece of gardening lore in my hometown which has been passed down for generations: never plant your tomatoes before Show Day, which, in Tasmania, is the fourth Saturday in October. If you’re foolhardy enough to plant them earlier, your tomato seedlings will suffer during the cold nights and won’t grow.

But does this kind of seasonal wisdom still work as the climate warps? We often talk about climate change in large-scale ways – how much the global average surface temperature will increase.

Nations are trying to keep the temperature rise well under 2℃. Taken as an average, that sounds tiny – after all, the temperature varies much more than that when day gives way to night. But remember – before the industrial revolution, the world’s average surface temperature was 12.1℃. Now it’s almost a degree hotter – and could be up to 3℃ hotter by the end of the century if high emissions continue.

For many of us, climate change can seem abstract. But the natural world is very sensitive to temperature change. Wherever we look, we can see that the seasons are changing. Gardening lore no longer holds. Flowering may happen earlier. Many species have to move or die. Here’s what you might notice.

Spring Is Coming Earlier

Warmer temperatures mean spring is arriving earlier and earlier. In Australia, it’s also now five days shorter than the 1950–1969 period, according to Australia Institute research. Trees and plants put out new leaves days earlier.

For some Australian plants, earlier spring means early flowering and fruiting – an average of 9.7 days earlier per decade.

Japan’s famous spring cherry blossoms are blooming earlier than they have in centuries. The cherry blossom peak last year was the earliest recorded bloom in a data record going back to the year 812.

Not only are flowers blooming earlier, birds are also migrating earlier, and may also be delaying their autumn migrations.

Summer Is Getting Hotter And Longer

A hotter planet means hotter and longer summers.

It might not feel like it this year with all the rain, but the overall trend is clear. In turn, this means bushfire risk is growing year on year, with more days of high to catastrophic fire danger. Every year for the last three decades, an extra 48,000 hectares of forest has burnt across Australia.

Longer fire seasons are making it harder to schedule fuel reduction burns, and reducing the amount of time for firefighters to rest and recover between fire seasons.

Hotter temperatures are already posing challenges for salmon farmers in Tasmania. Atlantic salmon grow best in cold water and climate change has already pushed ocean temperatures up. In summers now, the waters around Tasmania are close to the fish’s limit. Warmer summers will be a substantial challenge for salmon farmers in the future.

Hotter water has also killed off almost all Tasmania’s giant kelp, and made it possible for warm-water fish to migrate south.

For millennia, the North Pole has been covered by sea ice. This, too, is changing. Arctic sea ice is melting earlier in summer and freezing later in winter. As warming intensifies, the central Arctic is likely to go from permanent ice cover to ice free over summer by 2100.

Autumn Is Falling Behind

At the beginning of autumn, the leaves of nothofagus, Australia’s only temperate deciduous tree, change colour and fall to the ground, just as many Northern Hemisphere trees do.

Here, too, we can see the climate changing. Around the world, warmer temperatures and rising atmospheric carbon dioxide are delaying the arrival of autumn colours by up to a month.

Winter Is Disappearing

Alpine species such as the mountain pygmy possum have life cycles built around winter snow, while many of the world’s cities rely on snow melt for their water supply. In Australia, snowfall has been decreasing in recent decades.

In a warmer world, there’s less snow and ice. That’s posing major challenges for cities like Santiago in Chile, as well as semi-arid areas in the United States which have relied on snowmelt.

Species Are On The Move

What else might you notice? Different animals, birds, fish and plants. Not only are the seasons changing, but many species are now found in areas they could never have survived before.

Tropical corals have now been found happily growing near Sydney. Coral reef fish, too, are heading south to areas well outside their historic range.

You can see some of the surprising new finds on the citizen science project Redmap, such as sightings of the tropical yellow bellied sea snake in Tasmanian waters.

For First Australians, climate change brings a different upheaval. The seasonal link between, say, a wattle flowering and the arrival of fish species is breaking down.

Changes Everywhere

Climate change really does mean change – both large scale and small. From extreme weather to ecosystems changing all the way through to the time when you can plant tomatoes.

For gardeners, this means accepted wisdom no longer holds. In Tasmania, you can now safely plant tomatoes 18 days earlier than you could in the 1900s. That’s because minimum temperatures in October are now about 1℃ warmer than they were in 1910.

Climate change is altering our seasons and changing our world in both obvious and subtle ways.

So while planting tomatoes may seem like a trivial example, it’s yet another sign of the climate changing all around us. It’s no longer a problem for the far-off future. It’s our problem, now.![]()

Edward Doddridge, Research Associate in Physical Oceanography, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Remaking our suburbs’ 1960s apartment blocks: a subtle and greener way to increase housing density

As cities grow, new buildings gradually replace the older ones. Ideally, the new buildings are higher quality, more sustainable and better suited to today’s needs. But there’s a risk current approaches to urban renewal will produce poorer amenities and buildings that are less flexible and more environmentally damaging than those they replace.

Take, for example, the 1960s walk-up apartment block. These ageing buildings are often derided for being unattractive, utilitarian and cheap.