inbox and environment news: Issue 565

December 4 - 10, 2022: Issue 565

Carp In Careel Creek

Help Guide Future Decisions For Manly Dam

The Council are calling for expressions of interest from the community to sit on the advisory committee that will guide decisions about how Manly Dam is managed over the next four years.

Officially known as the Manly Warringah War Memorial State Park, we’re seeking to appoint three community members to the Advisory Committee including:

- an environment representative

- a recreational representative

- a community representative.

Manly Dam is a popular spot for enjoying picnics, bushwalking, mountain biking, swimming, and water-skiing. Loved by locals and visitors, this dedicated war memorial and State Park is home to a wide variety of significant ecological communities and flora and fauna.

This is your opportunity to have your say on how this beautiful park is managed over the next four years.

The Manly Warringah War Memorial State Park Advisory Committee includes three community members, and representatives from Council and the NSW Government.

If you’re interested in a position, submit your expression of interest on the council website before 11 December 2022

Orchid at Manly Dam. Photo: Selena Griffith

Gilead Stage 2 Development

''no longer required to assess impacts to ‘biodiversity values’ as these have already been addressed by the Minister and ‘conservation areas’ will be required to be managed in perpetuity for conservation''.

Help Needed To Save Sea Turtle Nests As Third La Nina Summer Looms

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Magnetic Material Mops Up Microplastics In Water: RMIT

Mangroves: Environmental Guardians Of Our Coastline

- Globally, mangrove forest, tidal marshes and seagrass meadows store more than 30,000 teragrams (or 30 trillion kilograms) of carbon across 185 million hectares, potentially reducing around three per cent of global carbon emissions.

- In 1992, an oil spill from the Era, at Port Bonython, released 300 tonnes of bunker fuel was released into Spencer Gulf, with a small slick of condensate getting into the mangroves south of Port Pirie. Mangroves do very badly in oil spills, and you can still see the scars of where the oil landed to this day.

Coastal property prices and climate risks are both soaring. We must pull our heads out of the sand

Tayanah O'Donnell, Australian National University and Eleanor Robson, Western Sydney UniversityAustralians’ well-documented affinity with the sun, surf and sand continues to fuel coastal property market growth. This growth defies rising interest rates and growing evidence of the impacts of climate change on people living in vulnerable coastal locations.

People in these areas are finding it harder to insure their properties against these risks. Insurers view the Australian market as sensitive to climate risks, as climate change impacts can trigger large insurance payouts. They are pricing their products accordingly.

Clearly, there is a vast disconnect between the coastal property market and climate change impacts such as increasingly severe storms, tidal surges, coastal erosion and flooding. There is no shortage of reports, studies and analyses confirming the climate risks we are already living with. Yet another alarming State of the Climate report was released last week.

We keep talking about reaching global net-zero emissions. But this “blah blah blah” masks the fact that climate impacts are already with us. Even if we make deeper, faster cuts to emissions, as we must, our world is now warmer. Australians will feel the effects of that warming.

We ultimately cannot afford the price of business as usual, as embodied by so many coastal developments.

Risks Are Worrying Banks And Insurers

In Australia, the disasters and the environmental collapse we are experiencing will get worse. While a range of businesses see this as opening up new market and product frontiers, the fact is climate change is creating a fundamentally uncertain, unstable and difficult world.

Banks have a central role in addressing climate risks. They are exposed to climate risk through residential lending on properties that are vulnerable to climate impacts and now face insurance pressures.

One in 25 Australian homes are projected to be uninsurable by 2030. The Australian government risks bearing the large costs of supporting the underinsured or uninsured – otherwise known as being “the insurer of last resort”.

This costly legacy shows why planning decisions made now must take account of climate change impacts, and not just in the wake of disasters.

The rapidly escalating impacts and risks across sectors demand that we undertake mitigation and adaptation at the same time, urgently and on a large scale. This means reducing emissions to negative levels – not just reaching net zero and transitioning our energy sector, but also actively removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

We must also respond to climate change risks already locked into the system. We have to make substantial changes in how we think about, treat, price and act on these risks.

As The Climate Shifts, So Must Our Coastal Dream

The consequences of a warming climate, including reaching and crossing tipping points in the Earth’s weather systems, are occurring sooner than anticipated. The required behavioural, institutional and structural changes are vast and challenging.

People are often attached to places based on historical knowledge of them. These lived experiences, while important, inform a worldview based on an understanding of our environment before the rapid onset of climate change. This can skew our climate risk responses, but compounding climate impacts are outpacing our ability to adapt as we might have in the past.

Institutional signalling, such as warnings by the Reserve Bank, support greater public awareness of climate impacts and risks.

When buying a property, people need to consider these factors more seriously than, say, having an extra bathroom. Obligatory disclosure of regional climate change impacts could inform buyers’ decision-making. The data and models used would have to be clear on the validity and limitations of their scenarios.

Nature-Based And Equitable Solutions

In recent years there has been an increasing focus on nature-based solutions. This approach uses natural systems and tools for tackling societal issues such as the enormous and complex risks posed by climate change. Indeed, many Indigenous peoples, communities and ways of knowing have long recognised the fundamental role of nature in making good and safe lives possible for people.

Nature-based solutions provide a suite of valuable tools for remedying issues we’re already facing on coasts. For example, in many contexts, building hard seawalls is often a temporary solution, which instils a false sense of security. Planting soft barriers such as mangroves and dense, deep-rooting vegetation can provide a more enduring solution. It also restores fish habitat, purifies water and eases floods.

Acknowledging the well-being of people and nature as interconnected has important implications for decisions about relocating people from high-risk areas. Effective planned retreat strategies must not only get people out of harm’s way, but account for where they will move and how precious ecosystems will be protected as demand for land supply shifts. Nature-based solutions must be built into retreat policies too.

As the Australian Academy of Science’s Strategy for Just Adaptation explains, effective adaptation also embeds equity and justice in the process. Research on historic retreat strategies has shown that a failure to properly consider and respect people’s choices, resources and histories can further entrench inequities. Giving people moving to a new home as much choice as possible helps them work through an emotional and highly political process.

We all need to find the courage to have difficult conversations, to seek information to make prudent choices, and to do all we can to respond to the growing climate risks that confront us. As climate activist Greta Thunburg says:

“Hope is not passive. Hope is not blah blah blah. Hope is telling the truth. Hope is taking action. And hope always comes from the people.”

Acting on this kind of hope can put us on an altogether different and more positive path.![]()

Tayanah O'Donnell, Honorary Associate Professor, Australian National University and Eleanor Robson, PhD Candidate, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

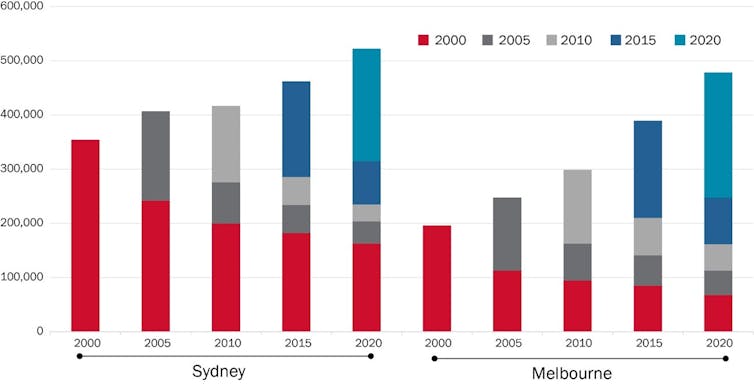

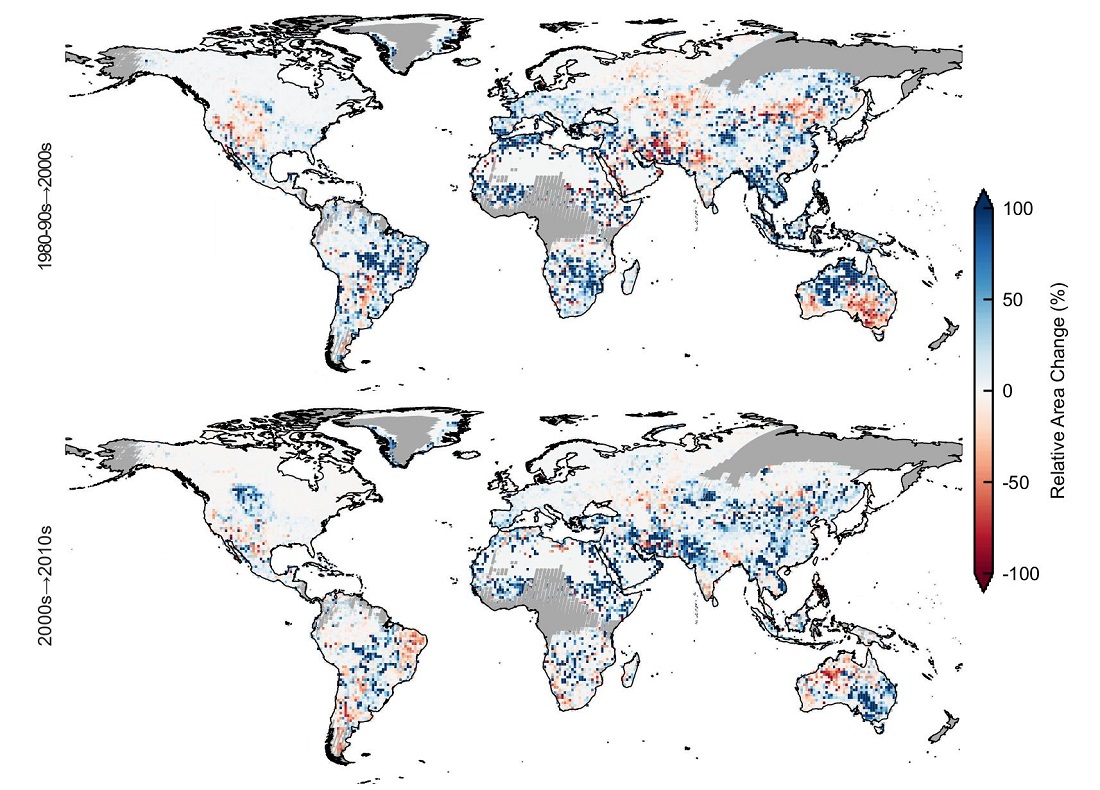

Many forests will become highly flammable for at least 30 extra days per year unless we cut emissions, research finds

Hamish Clarke, The University of Melbourne; Anne Griebel, Western Sydney University; Matthias Boer, Western Sydney University; Rachael Helene Nolan, Western Sydney University, and Víctor Resco de Dios, Universitat de LleidaWithout strong climate action, forests on every continent will be highly flammable for at least 30 extra days per year by the end of the century – and this fire threat is far greater for some forests including the Amazon, according to our new study.

Our research in Nature Communications looked at 20 years of global satellite data to test the link between wildfires and “vapour pressure deficit” – a measure of the atmosphere’s power to suck moisture out of living and dead plants. It can also be thought of as how “thirsty” the air is.

Our results show that forest fire becomes much more likely above a certain threshold of vapour pressure deficit in many regions. This threshold depends on the type of forest.

Alarmingly, climate change is increasing the number of days the planet passes these crucial thresholds. But by urgently bringing global emissions down, we can minimise the number of extra wildfire days.

How A Forest Becomes Flammable

Wildfire is an ancient, highly diverse phenomenon. Four key conditions for a fire are:

fuel: the leaves, branches, twigs and everything else that can catch alight in a forest

fuel moisture: whether fuel is dry enough to burn

ignition: the spark to set things off, such as a lightning strike

weather: conditions such as strong winds and high temperatures, which can aid a fire’s spread.

These four processes act as switches. All must be in the “on” position for a fire to take hold.

The drying out of fuel is particularly crucial for making a forest dangerously flammable. Indeed, many researchers are finding links between vapour pressure deficit (VPD) and fire activity.

VPD describes the difference between how much moisture is in the air and how much moisture the air can hold when it’s saturated. Once air becomes saturated, water will condense to form clouds or dew on leaves.

Importantly, warmer air can hold more water, which means VPD increases. We refer to the air being “thirsty” when the gap between full and empty air becomes bigger, meaning there’s a greater demand (thirst) for the water to come out of living and dead plant material, drying it out.

This is a serious issue as climate change leads to rising global temperatures.

Climate Change And Fire Days

We analysed more than 30 million satellite records and a global climate dataset to find the maximum daily VPD, for each time and place a fire was detected.

We then measured the strength of the relationship between VPD and fire activity for different forest types in each continent. And we showed, for the first time, that in many forests there is a strong link between fire activity and VPD on any given day.

Our results show certain VPD thresholds beyond which forest fire becomes more likely than not.

For example, in boreal forests (predominantly northern European and American coniferous forests), this threshold is 0.7-1.4 kilopascals (a unit of pressure). In subtropical and tropical forests such as the Amazon, the threshold rises dramatically to 1.5-4.0 kilopascals. This means the air must be a lot thirstier to spark fire in the tropical forests of Borneo and Sumatra than in the spruce, pine and larch of Canada.

We looked at both low- and high-emissions scenarios and found the risks are much greater if we fail to curb emissions.

If humanity continues to release greenhouse gas emissions unabated, the planet is expected to warm by around 3.7℃ by the end of the century. Under this high-emissions scenario, our study finds there are forests on every continent that will experience at least 30 extra days per year above critical flammability thresholds.

Under a lower-emissions scenario where global warming is limited to around 1.8℃, each continent will still see at least an extra 15 days per year crossing the threshold.

Parts of tropical South America including the Amazon will see the greatest increases in both scenarios by the end of the century: at least 90 additional days in a low-emissions scenario, and at least 150 extra days in a high-emissions scenario.

What Are The Risks?

Increasing forest fires will have serious consequences. This includes potentially destabilising patterns of fire and regrowth and disrupting the carbon storage we rely on forests for. Indeed, research last year showed the role of the Amazon rainforest as a “carbon sink” (which absorbs more CO₂ that it releases) may already be in decline.

We can also expect increasing harms to human health from wildfire smoke. It is estimated that around the world, more than 330,000 people die each year from smoke inhalation. This number could increase notably by the turn of the century, particularly in the most populated areas of South Asia and East Africa.

Our next research project will explore the links between fire, VPD and climate change in more detail in Australia, our home country. We’re also interested in the forests and regions where VPD doesn’t seem to be the main driver of fire, such as in Japan and Scandinavia.

Our discovery of reliable links between atmospheric dryness and forest fire risk in many regions means we can now develop better fire predictions, at both seasonal and near-term scales. This could bring significant benefits to those on the frontlines of fighting, managing and coexisting with wildfire.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Shiva Khanal from Western Sydney University to this article.![]()

Hamish Clarke, Senior Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Anne Griebel, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Western Sydney University; Matthias Boer, Professor, Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University; Rachael Helene Nolan, Senior research fellow, Western Sydney University, and Víctor Resco de Dios, Profesor de ingeniería forestal y cambio global, Universitat de Lleida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We all know the Great Barrier Reef is in danger – the UN has just confirmed it. Again

You might be forgiven for thinking it’s Groundhog Day reading headlines about the Great Barrier Reef potentially being listed on the World Heritage “in danger” list. After all, there have been similar calls in 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2017.

Successive federal governments have lobbied hard to keep the largest coral reef in the world off the high-profile list kept by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Only last year, former environment minister Sussan Ley jetted around the world in a successful effort to stave off the inevitable, pointing to hundreds of millions of dollars spent on issues such as water quality. The new minister, Tanya Plibersek, also wants to avoid having the reef “singled out” in this way.

The question is, what does in-danger mean? Everyone knows the reef is in trouble. An in-danger listing is not a sanction or punishment. Rather, it’s a call to the international community that a World Heritage property is under threat, requiring actions to protect it for future generations. In-danger listing is not permanent, nor does it mean the Reef will be permanently removed from the World Heritage list.

The reef faces a multitude of threats. The most significant threats are coral bleaching worsened by climate change, poor water quality from land-based runoff, and unsustainable fishing and coastal development. We already have regulations to tackle many of them – but we need more effective enforcement to ensure compliance.

What Just Happened?

The Great Barrier Reef has been World Heritage listed since 1981. This means it’s considered an area of outstanding value to humanity. Covering an area the size of Italy, this iconic area includes some 3,000 separate reefs, over 1,000 islands and a variety of other significant habitats.

The latest UN mission has just reported back, finding the reef’s condition is worsening and recommending it be listed as “in danger”. It also offered practical solutions.

Previous governments have fought to ensure the reef is not listed as in-danger despite their own five-yearly reviews demonstrating an obvious decline. In 2009, the reef’s condition was rated poor and declining. In 2014 it was poor and declining and in 2019, very poor and declining.

So the government knows the reef is in danger. We know, and the tourism industry knows. While some tourism operators worry about their business, the opposite appears to be true: more people go, thinking it might be their last chance to see it. And already, operators are adapting by taking tourists to areas still in good condition.

Federal governments just don’t want the reef on the list because of the hit to their international reputation – and to their domestic standing.

If the reef is officially listed as “in danger” next year, it will draw a much greater focus to the reef’s plight. And that may help galvanise effective national and global action.

Take the case of the famous coral reefs of Belize in Central America. When these reefs were listed, the government banned nearby oil exploration and protected mangroves. Belize’s reefs have now been taken off the in-danger list.

So What Has To Be Done?

The mission’s report lays out what needs to be done for the major issues.

Australia already has a long-term plan aimed at ensuring the reef’s sustainability. There are regulations governing, say, sediment and water quality in run off from agriculture and towns. We have some targets too, particularly around water quality.

The problem is delivery. There is a need to scale up efforts and improve compliance. Regulations mean very little if there’s ineffective enforcement. For example, while most farmers have taken on board the rules around fertiliser use, erosion and run-off, those flouting the rules get only a slap on the wrist. As the state government notes, enforcement is a “last resort”.

The UN mission has called on Australia to improve in four key areas:

1. Look after land and water

When native vegetation is cleared, it makes erosion more likely. Eroded soils are washed downstream and out to sea, where they can settle on coral and seagrass, smothering them. In Queensland, native vegetation is still being cleared at unsustainable levels.

2. Phase out gillnets

These long nets catch fish by their gills. But they also catch dugongs, dolphins and turtles, which then die. The UN mission made a very strong recommendation: phase out gillnets in the marine park.

3. More effective disposal of dredge spoil

Dredging shipping channels and ports produces a lot of silt and sand. If this is dumped in shallow areas, it can also spread to nearby corals and seagrass beds already under stress from climate change. A previous government policy ended the dumping of capital dredge spoil (dredging previously undisturbed areas). But maintenance dredge spoil is still being dumped at sea or used for reclamation, both causing adverse impacts.

4. Tackle climate change

This month, the northern reefs are sweltering in record water temperatures – raising the chance of further bleaching events. The UN report makes it clear that climate change is the biggest threat. Climate change heats up tropical waters, causing coral bleaching and potentially coral death. Australia, as one of the world’s top exporters of fossil fuels gas and coal, has long tried to go slow on climate action. The new government has moved to legislate a stronger 2030 emissions reduction target, but the UN report calls for even more ambition to keep warming under 1.5℃ as this is widely accepted as the critical threshold for reef survival.

The report doesn’t make reference to the impacts of shipping on nearby coral and seagrass areas, such as sediment churned up by propellers of large ships and tankers.

Death By A Thousand Cuts

If you dive the reef for the first time this year, you might wonder if there really is a problem. After all, there are still fish and coral. When I first dove on the reef more than 35 years ago, it was in much better condition. What you see now may seem okay – but it’s a pale shadow of what it could or should be. It’s death by a thousand cuts.

As reef expert Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg has said:

The reef is in dire trouble, but it’s decades away before it’s no longer worth visiting. That’s the truth. But unless we wake up and deal with climate change sincerely and deeply then we really will have a Great Barrier Reef not worth visiting.

We’re never going to restore the reef to its pre-European conditions. But unless we take real action, future generations will wonder how and why we failed them so badly. We don’t need to wait for the World Heritage Committee to make in-danger listing to know the reef is in real trouble. ![]()

Jon C. Day, PSM, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP27 was disappointing, but 2022 remains an historic year for international climate policy

This year’s global climate negotiations at the COP27 in Egypt were disappointing. In particular, the international commitment to limit planetary warming to 1.5℃ remains on “life support”.

But hope is not lost. In fact, 2022 was an historic year for international climate policy. It marked a shift in how the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters – China, the United States, the European Union and India – deal with climate change when faced with economic and energy shocks.

In the past, climate action has been pushed to the back-burner when governments devise policy responses to global crises. But this year, amid Russia’s war on Ukraine, spiralling inflation and energy shortages, tackling climate change has been central to recovery plans.

It signals climate action and economic stability are no longer seen as competing priorities – instead, national governments realise they go hand-in-hand. As European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has noted, this represents a major turning point in global climate policy and a “leap into the future”.

A Global Turning Point

Russia’s illegal war on Ukraine has destabilised the global energy market and caused sharp rises in food and commodity prices, worsening global inflation.

In the past, such shocks would have prompted governments to enact a fairly blinkered policy response.

During the 1970s global oil crisis, for example, governments brought in massive fossil fuel subsidies and eased environmental rules for the petroleum industry, rather than reduce oil dependency.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008, government responses were often similarly short-sighted. Low-interest loans to banks and other institutions, for example, perpetuated a business-as-usual economic system of high emissions.

This was coupled with years of austerity which derailed funding and investment for climate action.

Hearteningly, 2022 has seen a very different approach.

The United States, European Union, China and India have all prioritised climate change in their response to global economic crises, as I outline below.

Why? Public support for climate action is ever-growing and climate-related disasters are becoming worse. What’s more, renewable energy costs continue to fall, and energy security and global competitiveness remain big concerns.

The EU And US Step Up

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU made a “dash for gas” to replace Russian supply. Germany made deals to purchase gas from African countries, Australia, the US and Middle East, triggering fears climate action would be delayed.

But the EU has since made climate change action a central priority. Its RePowerEU plan, released in May, presents clean energy as the solution to the so-called energy trilemma of costs, security and environmental sustainability.

Among other measures, the plan involves:

- ramped-up targets for renewable energy and energy efficiency

- substantial home and business electrification measures including electric vehicles and heat pumps

- ambitious targets for green hydrogen.

The plan intends to eliminate reliance on Russian gas by 2027 and almost halve overall gas use by 2030.

The US took similar action this year. Its historic Inflation Reduction Act puts clean energy investment at the forefront of plans to address the cost-of-living crisis.

At least US$369 billion will be spent on clean energy initiatives to reduce energy bills. Clean energy will be embedded in measures across the economy through tax incentives, subsidies and grants. The investment prompted one observer to predict “the climate economy is about to explode”.

By aligning climate change with economic policy, the government has shifted the business narrative from risk to opportunity.

This month the Biden administration went further, with a proposal for major government suppliers to disclose greenhouse gas emissions and set science-based emissions reduction targets. Climate change is also being considered in US pension plans and company reporting requirements.

By embedding climate change in existing systems, trillions of dollars will shift into clean energy. This is likely to change the US economy forever and accelerate emissions reduction.

Progress In China And India

So what about the developing economies of China and India?

In China, coal use increased in the short-term over winter this year. However, China’s government has released plans for specific sectors coupling economic and energy security, and low-carbon growth.

In July, the government released an emissions reduction blueprint for urbanisation and rural development. It includes ambitious measures to increase the energy efficiency of buildings, electrify buildings and transport (including huge deployment of electric vehicle charging stations) and mandate rooftop solar on new factories and public buildings.

The government has also worked closely with provincial governments on targets to more than double the installed capacity of wind and solar by 2025.

In India, a National Electricity Plan released by the central government this year has clean energy at its core. It means renewables capacity is set to soar by 250% over the next decade.

India’s government has also introduced policies to favour electrification in buildings and transport – a departure from a previous policy in which gas played a significant role in future energy supply.

Change Is Afoot

Analysis suggests the systemic changes outlined above could mean the EU, China and India exceed their current commitments under the Paris Agreement.

This is good news – but the world still has a long way to go. Climate action must be embedded deeply in the government policies of all nations, as well as in existing economic and energy systems. This is no small task – but it’s necessary to achieve the transformation required to address the climate crisis.

Of course, 2022 was also a big year for climate action in Australia. The Albanese Labor government was elected in May, and has set about implementing a climate action agenda far stronger than that of the previous Coalition government.

Australia still lags behind other comparable nations. But recent developments in the EU and US offer lessons on the way forward.![]()

Katherine Lake, Research Associate at the Centre for Resources, Energy and Environmental Law, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘This case has made legal history’: young Australians just won a human rights case against an enormous coal mine

Justine Bell-James, The University of QueenslandIn a historic ruling today, a Queensland court has said the massive Clive Palmer-owned Galilee Basin coal project should not go ahead because of its contribution to climate change, its environmental impacts, and because it would erode human rights.

The case was mounted in 2020 by a First Nations-led group of young people aged 13 to 30 called Youth Verdict. It was the first time human rights arguments were used in a climate change case in Australia.

The link between human rights and climate change is being increasingly recognised overseas. In September this year, for example, a United Nations committee decided that by failing to adequately address the climate crisis, Australia’s Coalition government violated the human rights of Torres Strait Islanders.

Youth Verdict’s success today builds on this momentum. It heralds a new era for climate change cases in Australia by youth activists, who have been frustrated with the absence of meaningful federal government policy.

1.58 Billion Tonnes Of Emissions

The Waratah Coal mine operation proposes to extract up to 40 million tonnes of coal from the Galilee Basin each year, over the next 25 years. This would produce 1.58 billion tonnes of carbon emissions, and is four times more coal extraction than Adani’s operation.

While the project has already received approval at the federal government level, it also needs a state government mining lease and environmental authority to go ahead. Today, Queensland land court President Fleur Kingham has recommended to the state government that both entitlements be refused.

In making this recommendation, Kingham reflected on how the global landscape has changed since the Paris Agreement in 2015, and since the last major challenge to a mine in Queensland in 2016: Adani’s Carmichael mine.

She drew a clear link between the mining of this coal, its ultimate burning by a third party overseas, and the project’s material contribution to global emissions. She concluded that the project poses “unacceptable” climate change risks to people and property in Queensland.

The Queensland Human Rights Act requires a decision-maker to weigh up whether there is any justifiable reason for limiting a human right, which could incorporate a consideration of new jobs. Kingham decided the importance of preserving the human rights outweighed the potential A$2.5 billion of economic benefits of the proposed mine.

From a legal perspective, I believe there are four reasons in particular this case is so significant.

1. Rejecting An Entrenched Assumption

A major barrier to climate change litigation in Queensland has been the “market substitution assumption”, also known as the “perfect substitution argument”. This is the assertion that a particular mine’s contribution to climate change is net zero, because if that mine doesn’t supply coal, then another will.

Kingham rejected this argument. She noted that the economic benefits of the proposed project are uncertain with long-term global demand for thermal coal set to decline. She observed that there’s a real prospect the mine might not be viable for its projected life, rebutting the market substitution assumption.

This is an enormous victory for environmental litigants as this was a previously entrenched argument in Australia’s legal system and policy debate.

2. Evidence From First Nations People

It was also the first time the court took on-Country evidence from First Nations people in accordance with their traditional protocols. Kingham and legal counsel travelled to Gimuy (around Cairns) and Traditional Owners showed how climate change has directly harmed their Country.

As Youth Verdict co-director and First Nations lead Murrawah Johnson put it:

We are taking this case against Clive Palmer’s Waratah Coal mine because climate change threatens all of our futures. For First Nations peoples, climate change is taking away our connection to Country and robbing us of our cultures which are grounded in our relationship to our homelands.

Climate change will prevent us from educating our young people in their responsibilities to protect Country and deny them their birth rights to their cultures, law, lands and waters.

This decision reflects the court’s deep engagement with First Nations’ arguments, in considering the impacts of climate change on First Nations people.

3. The Human Rights Implications

In yet another Australian first, the court heard submissions on the human rights implications of the mine.

The Land Court of Queensland has a unique jurisdiction in these matters, because it makes a recommendation, rather than a final judgment. This recommendation must be taken into account by the final decision-makers – in this case, the Queensland resources minister, and the state Department of Environment and Science.

In an earlier proceeding, Kingham found the land court itself is subject to obligations under Queensland’s Human Rights Act. This means she must properly consider whether a decision to approve the mine would limit human rights and if so, whether limits to those human rights can be demonstrably justified.

Kingham found approving the mine would contribute to climate change impacts, which would limit:

- the right to life

- the cultural rights of First Nations peoples

- the rights of children

- the right to property and to privacy and home

- the right to enjoy human rights equally.

Internationally, there are clear links made between climate change and human rights. For example, climate change is worsening heatwaves, risking a greater number of deaths, thereby affecting the right to life.

4. A Victory For A Nature Refuge

Kingham also considered the environmental impacts of the proposed mine on the Bimblebox Nature Refuge – 8,000 hectares semi-arid woodland, home to a recorded 176 bird species, in the Galilee Basin.

She deemed these impacts unacceptable, as “the ecological values of Bimblebox [could be] seriously and possibly irreversibly damaged”.

She also observed that the costs of climate change to people in Queensland have not been fully accounted for, nor have the costs of mining on the Bimblebox Nature Refuge. Further, she found the mine would violate Bimblebox Alliance’s right to family and home.

Making History

This case has made legal history. It is the first time a Queensland court has recommended refusal of a coal mine on climate change grounds, and the first case linking human rights and climate change in Australia. As Kingham concluded:

Approving the application would risk disproportionate burdens for future generations, which does not give effect to the goal of intergenerational equity.

The future of the project remains unclear. But in a year marked by climate-related disasters, the land court’s decision offers a ray of hope that Queensland may start to leave coal in the ground.![]()

Justine Bell-James, Associate Professor, TC Beirne School of Law, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Victoria faces a grave climate and energy crisis. The new government’s policies must be far bolder

Ariel Liebman, Monash UniversityThe Andrews Labor government has been returned in Victoria. It must now reckon with two particularly crucial challenges: runaway climate change and wartime-scale energy costs.

Victorians are still reeling from rare major flooding in which the state’s largest dam, Dartmouth, spilled over. Meanwhile, electricity prices in Victoria are rising dramatically.

The Andrews government has signalled a major shakeup of Victoria’s energy sector. Its pre-election commitments – a 95% renewable electricity target by 2035 and net-zero emissions by 2045 – are definite moves in the right direction.

And plans to reinstate the State Electricity Commission, including a constitutional amendment to cement this change permanently, speaks to the government’s intention to regain control of the electricity market and skyrocketing energy prices.

These are significant pledges and daunting tasks to accomplish. But the Victorian government must go further to secure the energy sector and take stronger climate action.

Reducing Energy Costs

Today’s high energy costs are driven primarily by fossil fuel supply constraints. The reduction in gas supply due to sanctions on Russia has exposed the delicate balance of supply and demand, and the fragility of the global fossil-based energy system.

For more than a decade, specialists have known the long-term solution to reduce electricity prices and cost volatility: a large-scale shift to renewable sources of energy.

This would shield us from short-term supply and demand shocks because the cost of renewables-produced wholesale energy is fixed at construction, with no variable costs such as fuel.

Shifting to renewables would also make electricity cheaper than coal and gas in countries with major wind and sun advantages, such as Australia and Indonesia. And it would decouple electricity production from strongly geographically concentrated sources of fossil fuels such as in the middle east.

But realistically, in the next two years or so the Victorian and Australian governments can only manage energy prices by curbing the worst excesses of an unfettered free market operation in natural gas and retail electricity.

We are still working with precisely the same market frameworks as when deregulation started in 1998. Victoria, and the other states, need to accept that this framework has failed to produce benefits to consumers, particularly for households.

For example, in the decade to June 2013, electricity prices for Australian households increased by an average 72% in real terms.

We must go back to the drawing board to determine what the energy market should look like. In the meantime, Australian states and territories must consider reimposing price caps on energy retailers.

An immediate relief measure would be to delink Australia’s natural gas market from global markets for a limited period.

The only sure way to do this is by implementing a domestic gas reservation policy, which entails reserving a portion of Australian gas for domestic use, rather than exporting it. This must be nationally coordinated, as we have a strongly interconnected national gas market.

Western Australia uses its own isolated energy system and put a gas reservation policy in place years ago, which seeks to make the equivalent of 15% of gas exports available for people in WA. This policy has helped mitigate price shocks.

Since winning the election, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews has continued to urge the federal government to impose such a policy Australia wide. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese should heed these calls.

Steps To Reduce Emissions

Our energy futures are intrinsically intertwined with addressing climate change.

The world has only eight years left for global warming to be limited to 1.5℃. This means accelerating the switch to renewable energy without any further delays.

Our first step must be to make all electricity renewable by 2035 in Victoria (and, indeed, in the rest of Australia).

Second, we need a transition to electric vehicles across all transport systems as fast as possible and well before 2040. The Andrews government is investing $100 million to decarbonise the state’s road transport sector, but the transition won’t be complete until 2050.

Third, hard-to-abate sectors – such as certain manufacturing operations, shipping and aviation – need ongoing technological development.

They require significant government support to progress clean fuels, likely based on the renewable hydrogen to ammonia pathway. Victoria has a range of hydrogen and ammonia related industry development policies that show the government recognises this sector’s importance.

Ultimately, the incoming Victorian government’s promises address the first issue well, while making some headway on the second and third.

The Victorian Government Must Be Brave

We can’t rely on the rest of the world for innovation. Governments in Australia must play a more prominent role in infrastructure investment, technology research and development, energy industry development and significant market reform.

Tackling all these challenges isn’t really a job for a single state, particularly given Australia has one major east coast electricity grid and one national energy framework.

The Victorian government cannot achieve any significant changes without working closely with other states and the federal government. In this, state governments must be brave and go against the past three decades of hands-off government approaches to essential energy infrastructure.

This isn’t a time for leaving things to the market to resolve. The Victorian government must take immediate and giant leaps to ensure a stable and climate-friendly energy sector.![]()

Ariel Liebman, Ariel Liebman Director, Monash Energy Institute and Professor of Sustainable Energy Systems, Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is China ready to lead on protecting nature? At the upcoming UN biodiversity conference, it will preside and set the tone

As the world parses what was achieved at the U.N. climate change conference in Egypt, negotiators are convening in Montreal to set goals for curbing Earth’s other crisis: loss of living species.

Starting on Dec. 7, 2022, 196 nations that have ratified the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity will hold their 15th Conference of the Parties, or COP15. The convention, which was adopted at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, is designed to promote sustainable development by protecting biodiversity – the variety of life on Earth, from genes up to entire ecosystems.

Today, experts widely agree that biodiversity is at risk. Because of human activities – especially overhunting, overfishing and altering land – species are disappearing from the planet at 50 to 100 times the historic rate. The United Nations calls this decline a “nature crisis.”

This meeting was originally scheduled to take place in Kunming, China, in 2020 but was rescheduled because of the COVID-19 pandemic, with some negotiations held online. China will lead the deliberations in Montreal and will set the agenda and tone. This is the first time that Beijing has presided over a major intergovernmental meeting on the environment. As a wildlife ecologist, I am eager to see China step into a global leadership role.

Biodiversity In China

If you ask people where on Earth the greatest concentrations of wild species are found, many will assume it’s in rainforests or tropical coral reefs. In fact, China also is rich in nature. It is home to nearly 38,000 higher plant species – essentially, trees, shrubs and ferns; more than 8,100 species of vertebrate animals; over 1,400 bird species; and 20% of the world’s fish species.

Many of China’s wild species are endemic, meaning that they are found nowhere else in the world. China contains parts of four of the world’s global biodiversity hot spots – places that have large numbers of endemic species and also are seriously at risk. Indo-Burma, the Mountains of Southwest China, Eastern Himalaya and the Mountains of Central Asia are home to species such as the giant panda, Asiatic black bear, the endangered Sichuan partridge, Xizang alpine toad, Sichuan lancehead and golden pheasant.

China’s Conservation Record

Western media coverage of environmental issues in China often focuses on the nation’s severe urban air pollution and its role as the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter. But China has a vision for protecting nature, and it has made progress since the last global biodiversity conference in 2018.

In that year, Chinese leaders coined the term “ecological civilization” and wrote it into the nation’s constitution. This signaled a recognition that development should consider environmental impacts as well as economic goals.

At that point, China had already created over 2,750 protected areas, covering nearly 15% of its total land area. Protected areas are places where there is dedicated funding and management in place to conserve ecosystems, while also allowing for some human activities in designated zones within them.

In 2021 President Xi Jinping announced that China was formally augmenting this system with a network of five national parks covering 88,000 square miles (227,000 square kilometers) – the largest such system in the world.

China also has the fastest-expanding forest area in the world. From 2013 to 2017 alone, China reforested 825 million acres (334 million hectares) of bare or cultivated land – an area four times as large as the entire U.S. national forest system.

At least 10 of China’s notable endangered species are on the path to recovery, including the giant panda, Asian crested ibis and Elliot’s pheasant.

More To Do

Still, China has major areas for improvement. It has underperformed on four of the original Aichi Targets – goals that members of the Convention on Biodiversity adopted for 2011-2020 – including promoting sustainable fisheries, preventing extinctions, controlling invasive alien species and protecting vulnerable ecosystems.

For example, nearly 50% of amphibians in China are threatened. Notable species have been declared extinct, including the Chinese dugong, the Chinese paddlefish and Yangtze sturgeon, and the white-handed gibbon.

The COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted China’s central role in legal and illegal wildlife trade, which threatens many endangered mammals, fish, reptiles and birds. In response, China updated its Wildlife Protection Law, originally enacted in 1989.

On Feb. 24, 2020, the law was expanded to impose a near-total ban on trading wildlife for use as food. Now, however, the ban is being revised in ways that could weaken it, such as easing restrictions on captive breeding.

Around 90% of China’s grasslands are degraded, as are 53% of its coastal wetlands. China has lost 80% of its coral reefs and 73% of its mangroves since 1950. These challenges highlight the need for aggressive action to protect the nation’s remaining biodiversity strongholds.

Goals For COP15

The central goal of the Montreal conference is adopting a post-2020 global biodiversity framework. This road map expands on frameworks put forth in past meetings, including the 2010 Aichi Targets. As the U.N. has reported, nations failed to meet any of the Aichi Targets by 2020, although six goals were partially achieved.

The proposed new framework includes 22 targets to meet by 2030 and four key long-term goals to meet by 2050. They include conserving ecosystems; enhancing the variety of benefits that nature provides to people; ensuring fairness in the sharing of genetic resources, such as digital DNA sequencing data; and solidifying funding commitments.

Many people will be watching to see whether China can successfully lead the negotiations and promote collaboration and consensus. One central challenge is how to pay for the ambitious efforts that the new framework lays out. Environmental advocates are urging wealthy countries to provide up to US$60 billion annually to help lower-income nations pay for conservation projects and curb illegal wildlife trafficking.

China moved in this direction in 2021 when it launched the Kunming Biodiversity Fund and contributed $230 million to it. Pledges from other countries currently total some $5.2 billion per year, mainly from France, the United Kingdom, Japan and the European Union.

China is likely to face questions about its Belt and Road Initiative, a massive infrastructure project that is building railways, pipelines and highways across more than 60 countries. Critics say it is causing deforestation, flooding and other harmful environmental impacts – including in global biodiversity hot spots like Southeast Asia’s Coral Triangle, which contains one of the world’s most important reef systems.

China has pledged to “green” the Belt and Road Initiative going forward, and in 2021, Xi announced a ban on financing new coal power plants overseas, which so far has led to cancellation of 26 plants. This is a start, but China has more to do in addressing Belt and Road’s global impacts.

As home to 18% of Earth’s population and the producer of 18.4% of global GDP, China has a key role to play in protecting nature. I hope to see it provide bold leadership in Montreal and in the years ahead.![]()

Vanessa Hull, Assistant Professor of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Even weak tropical cyclones have grown more intense worldwide – we tracked 30 years of them using currents

Tropical cyclones have been growing stronger worldwide over the past 30 years, and not just the big ones that you hear about. Our new research finds that weak tropical cyclones have gotten at least 15% more intense in ocean basins where they occur around the world.

That means storms that might have caused minimal damage a few decades ago are growing more dangerous as the planet warms.

Warmer oceans provide more energy for storms to intensify, and theory and climate models point to powerful storms growing stronger, but intensity isn’t easy to document. We found a way to measure intensity by using the ocean currents beneath the storms – with the help of thousands of floating beachball-sized labs called drifters that beam back measurements from around the world.

Why It’s Been Tough To Measure Intensity

Tropical cyclones are large storms with rotating winds and clouds that form over warm ocean water. They are known as tropical storms or hurricanes in the Atlantic and typhoons in the Northwest Pacific.

A tropical cyclone’s intensity is one of the most important factors for determining the damage the storm is likely to cause. However, it’s difficult to accurately estimate intensity from satellite observations alone.

Intensity is often based on maximum sustained surface wind speed at about 33 feet (10 meters) above the surface over a period of one, two or 10 minutes, depending on the meteorological agency doing the measuring. During a hurricane, that region of the storm is nearly impossible to reach.

For some storms, NOAA meteorologists will fly specialized aircraft into the cyclone and drop measuring devices to gather detailed intensity data as the devices fall. But there are many more storms that don’t get measured that way, particularly in more remote basins.

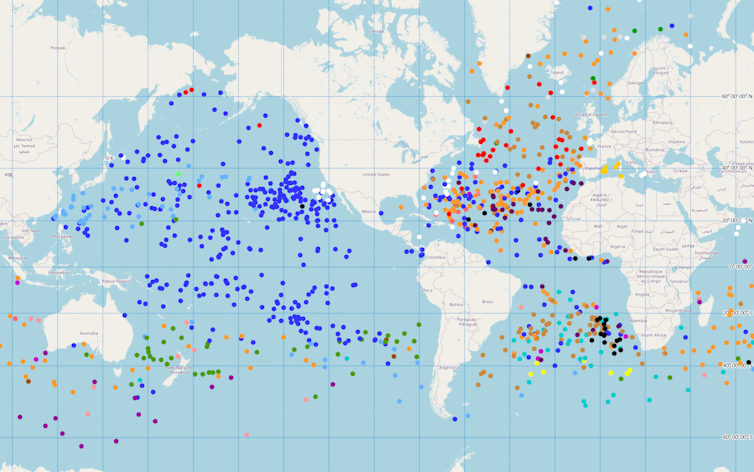

Our study, published in the journal Nature in November 2022, describes a new method to infer tropical cyclone intensity from ocean currents, which are already being measured by an army of drifters.

How Drifters Work

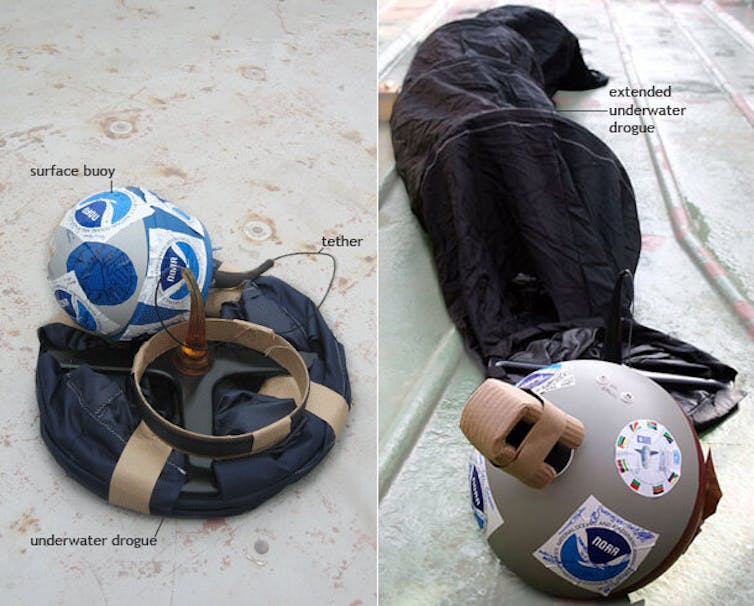

A drifter is a floating ball with sensors and batteries inside and an attached “drogue” that looks like a windsock trailing under the water beneath it to help stabilize it. The drifter moves with the currents and regularly transmits data to a satellite, including water temperature and location. The location data can be used to measure the speed of currents.

Since NOAA launched its Global Drifter Program in 1979, more than 25,000 drifters have been deployed in global oceans. Those devices have provided about 36 million records over time. Of those records, more than 85,000 are associated with weak tropical cyclones – those that are tropical storms or Category 1 hurricanes or typhoons – and about 5,800 that are associated with stronger tropical cyclones.

That isn’t enough data to analyze strong cyclones globally, but we can find trends in the intensity of the weak tropical cyclones.

Here’s how: Winds transfer momentum into the surface ocean water through frictional force, driving water currents. The relationship between wind speed and ocean current, known as Ekman theory, provides a theoretical foundation for our method of deriving wind speeds from the drifter-measured ocean currents.

Our derived wind speeds are consistent with wind speeds directly measured by nearby buoy arrays, justifying the new method to estimate tropical cyclone intensity from drifter measurements.

Evidence Beneath The Storms

In analyzing those records, we found that the ocean currents induced by weak tropical cyclones became stronger globally during the 1991-2020 period. We calculated that the increase in ocean currents corresponds to a 15% to 21% increase in the intensity of weak tropical cyclones, and that intensification occurred in all ocean basins.

In the Northwest Pacific, an area including China, Korea and Japan, a relatively large amount of available drifter data also shows a consistent upward trend in the intensity of strong tropical cyclones.

We also found evidence of increasing intensity in the changes in water temperatures measured by satellites. When a tropical cyclone travels through the ocean, it draws energy from the warm surface water and churns the water layers below, leaving a footprint of colder water in its wake. Stronger tropical cyclones bring more cold water from the subsurface to the surface ocean, leading to a stronger cooling in the ocean surface.

It’s important to remember that even weak tropical cyclones can have devastating impacts. Tropical Storm Megi, called Agaton in the Philippines, triggered landslides and was blamed for 214 deaths in the Philippines in April 2022. Early estimates suggest Hurricane Nicole caused over $500 million in damage in Volusia County alone when it hit Florida as a Category 1 storm in November 2022.

The 2022 Atlantic hurricane season officially ends on Nov. 30, after 14 named storms and eight hurricanes. It isn’t clear how rising global temperatures will effect the number of tropical cyclones that form, but our findings suggest that coastal communities need to be better prepared for increased intensity in those that do form and a concurrent rise in sea level in the future.![]()

Wei Mei, Assistant Professor of Earth, Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Shang-Ping Xie, Roger Revelle Professor of Climate Science, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To fight the climate crisis, we need to stop expanding offshore drilling for oil and gas

Environmental disaster struck the shores of Peru on Jan. 15, 2022, when Spanish energy company Repsol spilled 12,000 barrels of crude oil into the Bay of Lima after its tanker ruptured. The spill endangered 180,000 birds and destroyed the livelihoods of 5,000 families.

Although this disaster was the largest-ever oil spill in Peru, it is only the most recent of the dozens of large spills that occurred worldwide. In fact, 39 million litres of oil from offshore drilling — enough to fill 16 Olympic-sized swimming pools — pollute our seas every year.

Time and time again, offshore oil and gas activities have jeopardized coastal environments, human health and local economies. At the same time, global reliance on fossil fuels — 30 per cent of which is extracted from beneath the seabed — continues to drive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions towards the planetary tipping point.

A way out of this mess, according to new analysis conducted by conservation non-profit Oceana, is to halt the expansion of offshore oil and gas extraction, while ramping down future production. This is a critical step towards reducing global emissions.

Offshore Drilling’s Immense Carbon Footprint

Offshore oil and gas emits vast amounts of GHG, starting during the exploration and extraction below the seabed, continuing through intensive processing and refining onshore, and right up until the fuels are finally burned.

Drilling operations are dirty too. Oil extraction vents unusable and wasted gas that must be burned on the spot. This intentional flaring — burning of gas — blasts not only methane and carbon dioxide (CO2), but also toxic air pollutants into the atmosphere.

At the current rate, these lifecycle-emissions from offshore oil and gas are estimated to reach 8.4 billion tons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e, which includes CO2 and other GHG) by 2050.

Ocean Solutions Are Climate Solutions

Ocean-based climate solutions envision a healthy ocean that provides both nature- and technology-based opportunities to limit the worst impacts of climate change.

Simply by existing, the ocean acts as a buffer against the impacts of climate change. It absorbs more than two-thirds of human-produced CO2 and 90 per cent of the excess heat trapped by GHG pollution. Connecting science with concrete policy actions, however, is needed to drastically cut emissions and achieve global climate targets.

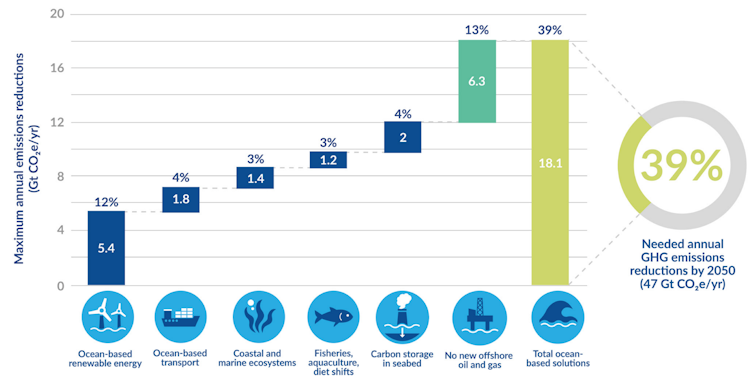

Experts previously examined the potential of five ocean-based solutions — ocean-based renewable energy, ocean-based transport, coastal and marine ecosystems, fisheries and marine aquaculture and seabed carbon storage — to mitigate global emissions.

Scaling up offshore renewable energy could significantly cut the need to burn coal for electricity. Meanwhile, co-ordinated efforts are already underway to decarbonize global shipping fleets. Seabed carbon injection remains a contested option to directly capture CO2, as concerns about its risks and scalability persist.

The nature-based solutions hold promise as well. Protecting and restoring coastal ecosystems like mangroves, seagrasses and saltmarshes will amplify their ability to drawdown and lock carbon away. Replacing emissions-intensive food options with climate-smart seafood protein ensures better climate and nutrition outcomes.

Ocean-Based Solutions Can Cut Emissions

For the first time in UN Climate Conference history, earlier this month, leaders at COP27 in Egypt were mandated to prioritize national ocean climate actions under the Paris Agreement.

But after a week of negotiations, COP27 ended with a whimper as delegates failed to agree to a phase down of fossil fuels. In fact, fossil fuel industry delegates in Egypt outnumbered those from the ten countries most affected by climate change. Without collective opposition, fossil fuel interests will continue to deliberately thwart policy plans to reduce emissions.

The Oceana study put a number on GHG emissions that could be averted if countries cancelled their inactive offshore drilling leases and prevented tapping into any new fields. Instead of continuing investments in dirty and dangerous offshore oil and gas, their funds should support renewable energy development to meet our future energy demands.

The International Energy Agency modelled future oil and gas production under exactly those conditions. The net-zero emissions by 2050 scenario predicts that ambitious investments in renewable energy will go hand-in-hand with the gradually declining offshore fossil fuel production. By 2050, the annual emissions averted — 6.3 billion tons of CO2e — would be equivalent to taking 1.4 billion cars off the road.

Combined with the other ocean climate solutions, stopping new offshore drilling would close nearly 40 per cent of the emissions gap needed to meet the Paris Agreement.

But without immediate policy interventions, more untouched oil and gas reserves from the sea will be extracted, burned and generate planet-warming CO2.

When Ocean Conservation Meets Climate Priorities

So is it actually feasible to halt expansion of all new offshore drilling?

Currently, only 10 countries dominate 65 per cent of the offshore oil and gas market. By 2025, around 355 new offshore oil and gas projects across 48 countries are slated to start operating. At COP27, some coastal African nations expressed intentions to tap into fossil fuels to improve energy access.

But locking in more offshore drilling leases will not ensure energy security or necessarily lower fuel prices. Oil companies continue to rake in record profits. New drilling will, however, trap coastal communities in an unsustainable industry that threatens to pollute waters, harm their health and heat our planet.

Several countries are already taking the lead in plugging this pipeline for good. Since 2017, countries like Costa Rica, Belize, Denmark, Ireland and New Zealand have stopped granting licenses for offshore oil and gas exploration.

Others pledged to ban extraction altogether, while the European Union, India and multiple island nations called for a phase down of all fossil fuel production in this year’s UN climate agreement. A new global emissions data tool released at COP27 can further help governments hold the biggest fossil fuel polluters accountable.

We are also seeing benefits of regional transitions to clean energy. In the U.S., for instance, the offshore wind industry could support 80,000 new jobs by 2030. And new markets in the Global South, like Vietnam and India, are also shifting away from offshore oil and gas.

The outcomes of COP27 fell short of the ambition needed to limit emissions on track with our climate goals. More than ever, we need our nations’ leaders to prioritize the well-being of their citizens over the wallets of the fossil fuel industry. A future with less offshore drilling is the only future compatible with clean energy access, a healthy ocean and liveable climate for all.![]()

Daniel Skerritt, Affiliated Researcher, Fisheries Economics Research Unit, University of British Columbia and Claire Huang, Master of Environmental Management, Duke University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Beware of ‘Shark Week’: Scientists watched 202 episodes and found them filled with junk science, misinformation and white male ‘experts’ named Mike

The Discovery Channel’s annual Shark Week is the longest-running cable television series in history, filling screens with sharky content every summer since 1988. It causes one of the largest temporary increases in U.S. viewers’ attention to any science or conservation topic.

It’s also the largest stage in marine biology, giving scientists who appear on it access to an audience of millions. Being featured by high-profile media outlets can help researchers attract attention and funding that can help super-charge their careers.

Unfortunately, Shark Week is also a missed opportunity. As scientists and conservationists have long argued, it is a major source of misinformation and nonsense about sharks, the scientists who study them, and how people can help protect endangered species from extinction.

I am a marine biologist who recently worked with five colleagues to scientifically analyze the content of Shark Week episodes. We tracked down copies of 202 episodes, watched them all and coded their content based on more than 15 variables, including locations, which experts were interviewed, which shark species were mentioned, what scientific research tools were used, whether the episodes mentioned shark conservation and how sharks were portrayed.

Even as longtime Shark Week critics, we were staggered by our findings. The episodes that we reviewed were full of incorrect information and provided a wildly misleading picture of the field of shark research. Some episodes glorified wildlife harassment, and many missed countless chances to teach a massive audience about shark conservation.

Spotlight Real Solutions

First, some facts. Sharks and their relatives, such as rays and skates, are among the most threatened vertebrate animals on Earth. About one-third of all known species are at risk of extinction, thanks mainly to overfishing.

Many policy solutions, such as setting fishing quotas, creating protected species lists and delineating no-fishing zones, are enacted nationally or internationally. But there also are countless situations in which increased public attention can help move the conservation needle. For instance, consumers can avoid buying seafood produced using unsustainable fishing methods that may accidentally catch sharks.

Conversely, focusing on the wrong problems does not lead to useful solutions. As one example, enacting a ban on shark fin sales in the U.S. would have little effect on global shark deaths, since the U.S. is only involved in about 1% of the global fin trade, and could undermine sustainable U.S. shark fisheries.

The Discovery Channel claims that by attracting massive audiences, Shark Week helps educate the public about shark conservation. But most of the shows we reviewed didn’t mention conservation at all, beyond vague statements that sharks need help, without describing the threats they face or how to address them.

Out of 202 episodes that we examined, just six contained any actionable tips. Half of those simply advised against eating shark fin soup, a traditional Asian delicacy. Demand for shark fin soup can contribute to the gruesome practice of “finning” – cutting fins off live sharks and throwing the mutilated fish overboard to die. But finning is not the biggest threat to sharks, and most U.S.-based Shark Week viewers don’t eat shark fin soup.

Spotlighting Divers, Not Research

When we analyzed episodes by the type of scientific research they featured, the most frequent answer was “no scientific research at all,” followed by what we charitably called “other.” This category included nonsense like building a submarine that looks like a shark, or a “high tech” custom shark cage to observe some aspect of shark behavior. These episodes focused on alleged risk to the scuba divers shown on camera, especially when the devices inevitably failed, but failed to address any research questions.

Such framing is not representative of actual shark research, which uses methods ranging from tracking tagged sharks via satellite to genetic and paleontological studies conducted entirely in labs. Such work may not be as exciting on camera as divers surrounded by schooling sharks, but it generates much more useful data.

Who’s On Camera

We also were troubled by the “experts” interviewed on many Shark Week shows. The most-featured source, underwater photographer Andy Casagrande, is an award-winning cameraman, and episodes when he stays behind the camera can be great. But given the chance to speak, he regularly claims the mantle of science while making dubious assertions – for example, that shark diving while taking LSD is a great way to learn about these animals – or presents well-known shark behaviors as new discoveries that he made, while misrepresenting what those behaviors mean.

Nor does Shark Week accurately represent experts in this field. One issue is ethnicity: Three of the five most-featured locations on Shark Week are Mexico, South Africa and the Bahamas, but we could count on one hand the number of non-white scientists who we saw featured in shows about their own countries. It was far more common for Discovery to fly a white male halfway around the world than to feature a local scientist.

Moreover, while more than half of U.S. shark scientists are female, you wouldn’t know this from watching Shark Week. Among people who we saw featured in more than one episode, there were more white male non-scientists named Mike than women of any profession or name.

In contrast, the Discovery Channel’s chief competitor, National Geographic, is partnering with the professional organization Minorities in Shark Sciences to feature diverse experts on its shows.

More Substance And Better Representation

How could Shark Week improve? Our paper makes several recommendations, and we recently participated in a workshop, highlighting diverse voices in our field from all over the world, that focused on improving representation of scientists in shark-focused media

First, we believe that not every documentary needs to be a dry, boring science lecture, but that the information shared on marine biology’s biggest stage should be factually correct and useful. Gimmicky concepts like Discovery’s “Naked and Afraid of Sharks 2” – an endurance contest with entrants wearing masks, fins and snorkels, but no clothes – show that people will watch anything with sharks in it. So why not try to make something good?

We also suggest that more scientists seek out media training so they can take advantage of opportunities like Shark Week without being taken advantage of. Similarly, it would be great to have a “Yelp”-like service that scientists could use to rate their experiences with media companies. Producers who want to feature appropriately diverse scientists can turn to databases like 500 Women Scientists and Diversify EEB.

For a decade, concerned scientists and conservationists have reached out to the Discovery Channel about our concerns with Shark Week. As our article recounts, Discovery has pledged in the past to present programming during Shark Week that puts more emphasis on science and less on entertainment – and some episodes have shown improvement.

But our findings show that many Shark Week depictions of sharks are still problematic, pseudoscientific, nonsensical or unhelpful. We hope that our analysis will motivate the network to use its massive audience to help sharks and elevate the scientists who study them.

Editor’s note: The Conversation US contacted Warner Brothers Discovery by phone and email for comment on the study described in this article. The network did not immediately respond or offer comment.![]()

David Shiffman, Post-Doctoral and Research Scholar in Marine Biology, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve