Inbox and environment news: Issue 566

December 11 2022 - January 14 2023: Issue 566

The Good, The Bad, The Ugly 2022

The good remains those volunteers who have toiled all year at local bushcare sites and shared knowledge of our local plants and seasons and how to look after and restore these places. There are many great examples, everywhere you look. New volunteers always welcome.

The bad is the amount of tree loss our area is sustaining, and the loss of wildlife that follows.

The ugly is the destruction of all that work, over many decades, sometimes due to not knowing the impact such activities have on our special environment, along with the growing number of over the top developments or even incremental height increases for housing developments that are passed and block razings of everything on a site, as well as carving out a chunk of the hillside.

This is occurring across the Sydney Basin, where habitat for listed critically endangered species is being destroyed or removed, and all that lives in it in the form of wildlife killed, under the direction, policy and changing laws of the incumbent state government.

We still, too, have those who are poisoning protected trees, for views.

Who Owns The Beach?

The Australian Coastal Society (ACS) is proud to present the podcast “Let’s Talk Coast” a short series that brings you conversations on coastal issues and projects from around Australia.

Episode 1 – Who owns the beach?

In our very first episode of “Let’s Talk Coast”, Emeritus Professor Bruce Thom and coastal engineer, Angus Gordon, explore issues around beach management, beach access, private ownership and coastal policy.

Known as the founding father of the Australian Coastal Society, Professor Bruce Thom is Emeritus Professor at the University of Sydney and a member of the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists. In 2010, Bruce was awarded a member of the Order of Australia for his services to the environment and advocacy for the ecological management of the coastal zone and as a contributor to a public debate on natural resource policy. Bruce regularly writes blogs for ACS, which can be found here.

Angus Gordon is a coastal engineer and former General Manager of Pittwater Council. Angus has worked on coastal engineering, coastal zone management and planning projects across Australia and the globe, and in 2018 he received an Order of Australia for his services to the environment planning and the community. You can read more about Angus Gordon here.

Both guests bring a wealth of knowledge to the discussion around the question of “Who owns the beach?” and suggest a way forward in protecting Australians right to the beach through national standards.

This podcast is an Australian Coastal Society podcast, produced and hosted by Gretchen Miller.

If you would like further information about this episode, contact us at admin@australiancoastalsociety.org.au

Let’s Talk Coast, was created through the financial support of our donors over the years.

To become a member and find out more about membership benefits, follow this link: https://australiancoastalsociety.org.au/membership-account/acs-membership/

To make a tax-deductible donation and help us continue to be a voice for the coast, follow this link: https://australiancoastalsociety.org.au/get-involved/donate/

This episode was recorded on the lands of the Garigal or Caregal people.

Australian Shorebird Monitoring Program: Critically Endangered Eastern Curlew Chased Out Of Port Hacking - Saturday December 10, 2022 - NSW Dept. Of Environment Responds With Mission Statements Only

The Eastern curlew is listed as critically endangered in Australia, with global populations estimated to have declined by 80% in the last 30 years. As a wading bird that travels across our earth, they rely on intertidal mudflats for food and habitat.

Australia is a signatory of the East Asian – Australasian Flyway. The East Asia/Australasia Flyway extends from Arctic Russia and North America to the southern limits of Australia and New Zealand. It aims to protect migratory waterbirds, their habitats and the livelihoods of people dependent upon them.

On Saturday December 10, jetskis and people disturbed this group of Eastern curlews at Port Hacking. One of the monitors that works as a volunteer to protect this bird when it visits our shores filmed the following. This bird comes to Careel Bay too - where people are frequently seen taking dogs in a 'no dogs' area for this very reason.

The volunteer tells us ;

''Yesterday the Port Hacking eastern curlews put up with 6 hours of disturbance in order to get an afternoon feed. This morning after 1 hr and 4 disturbances they decided the energy needed to stay was too great, so flew out to Botany Bay. I had asked these 2 charmers if they wouldn’t mind turning around rather than walk to end of beach to avoid disturbing the roosting curlews. They had already walked almost 2 km having left their kayaks at the other end of the Spit, surely they wouldn't mind giving up the last 100m. Rude response and on they walked.''

Pittwater Online News forwarded this to the Office of James Griffin, NSW Environment Minister for a response - Monday, December 12, 2022.

Late on Friday December 16th a Department of Planning and Environment spokesperson replied with the statement so readily found on the OEH webpages, nothing specific about addressing what is occurring to these critically endangered birds at Port Hacking was broached.

The statement reads:

''Remember to keep your distance. If shorebirds take off or run away as you approach, you are too close.

Eastern Curlews fly thousands of kilometres to get here, typically from Russia and north-eastern China

Every unnecessary flight uses energy and potentially affects their ability to fly home.

There is a saying: Birds in sight – don’t make them take flight!

Migratory shorebirds have travelled a long way so it’s really important they are allowed to roost and feed in peace, to build up their fat reserves before they migrate north.

There are four ways you can help protect our shorebirds -

1. Pay attention to signs or fences

2. Leash your dog whenever you’re on the beach, and only walk dogs on designated beaches

3. Stick to the wet sand and leave the birds space

4. Respect beach-closure signs and beach-driving rules. Only drive on designated beaches

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Within Australia, the Eastern Curlew has a primarily coastal distribution, and in NSW is mainly found in estuaries such as the Hunter River, Port Stephens, Clarence River, Richmond River and the south coast.

The Eastern Curlew breeds in Russia and north-eastern China but its distribution is poorly known. During the non-breeding season a few birds occur in southern Korea and China, but most spend the non-breeding season in north, east and south-east Australia.''

Gilead Stage 2 Development

''no longer required to assess impacts to ‘biodiversity values’ as these have already been addressed by the Minister and ‘conservation areas’ will be required to be managed in perpetuity for conservation''.

Nature Positive Plan: Better For The Environment, Better For Business

December 8, 2022

Statement By The Hon Tanya Plibersek MP, Minister for the Environment and Water

Australia’s environment laws are broken.

Professor Graeme Samuel’s 2019 review into the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act found that “the EPBC Act is outdated and requires fundamental reform… Australians do not trust that the Act is delivering for the environment, for business or for the community”.

Nature is being destroyed. Businesses are waiting too long for decisions. That’s bad for everyone. Things have to change.

Labor is today delivering on our promise by responding to Professor Samuel’s review and announcing our Nature Positive Plan: better for the environment, better for business.

We want an economy that is nature positive – to halt decline and repair nature.

We will build our legislation on three basic principles: clear national standards of environmental protection, improving and speeding up decisions, and building trust and integrity.

Our Nature Positive Plan will be better for the environment by delivering:

- Stronger laws designed to repair nature, to protect precious plants, animals and places. For the first time, our laws will introduce standards that decisions must meet. Standards describe the environmental outcomes we want to achieve. This will ensure decisions made will protect our threatened species and ecosystems.

- A new Environment Protection Agency to make development decisions and properly enforce them.

Our Nature Positive Plan will be better for business by delivering:

- More certainty – saving time and money with faster, clearer decisions about developments including housing and energy. Regional plans will identify the areas we want to protect, areas for fast-tracked development and where development can proceed with caution.

- Less red tape – easier paperwork and less duplication. Streamlining and consolidating the project assessment process.

Our Nature Positive Plan is a win-win: a win for the environment and a win for business.

I look forward to working with environment, business, community and First Nations groups to deliver it.

Our reforms are seeking to turn the tide in this country – from nature destruction to nature repair.

And they match what we’ve already begun in our first six months in office.

A stronger emissions reduction target, with a clear path to net zero.

A target of zero new extinctions on this continent.

A commitment to protecting thirty percent of Australia’s land and oceans by 2030.

A new nature repair market.

Reducing waste and building an economy focussed on recycling, re-use and repair.

Campaigning on the world stage, to protect our oceans, to support the Pacific, and to reduce plastic waste.

And $1.8 billion in the recent Budget –

- to protect the Great Barrier Reef

- to save our native species

- to employ 1,000 new Landcare Rangers.

- to support new Indigenous Protected Areas

- to fund the Environmental Defenders Office, for the first time in nine years

- And to clean up our urban rivers and waterways.

The legislation will be released as an exposure draft prior to being introduced into the Parliament before the end of 2023.

The Government’s full response to the Samuel Review can be found here: EPBC Act reform - DCCEEW

New Marine Wildlife Group Launched On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Help Needed To Save Sea Turtle Nests As Third La Nina Summer Looms

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Local Wildlife Rescuers And Carers State That Ongoing Heavy Rains Are Tough For Us But Can Be Tougher For Our Wildlife:

- Birds and possums can be washed out of trees, or the tree comes down, nests can disintegrate or hollows fill with water

- Ground dwelling animals can be flooded out of their burrows or hiding places and they need to seek higher ground

- They are at risk crossing roads as people can't see them and sudden braking causes accidents

- The food may disappear - insects, seeds and pollens are washed away, nectar is diluted and animals can be starving

- They are vulnerable in open areas to predators, including our pets

- They can't dry out and may get hypothermia or pneumonia

- Animals may seek shelter in your home or garage.

You can help by:

- Keeping your pets indoors

- Assessing for wounds or parasites

- Putting out towels or shelters like boxes to provide a place to hide

- Drive to conditions and call a rescue group if you see an animal hit (or do a pouch check or get to a vet if you can stop)

- If you are concerned take a photo and talk to a rescue group or wildlife carer

There are 2 rescue groups in the Northern Beaches:

Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300

WIRES: 1300 094 737

Please be patient as there could be a few enquiries regarding the wildlife.

Generally Sydney Wildlife do not recommend offering food but it may help in some cases. Please ensure you know what they generally eat and any offerings will not make them sick. You can read more on feeding wildlife here

Information courtesy Ed Laginestra, Sydney Wildlife volunteer. Photo: Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Helpers Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Our laws fail nature. The government’s plan to overhaul them looks good, but crucial detail is yet to come

The Albanese government has just released its long-awaited response to a scathing independent review of Australia’s environment protection law. The 2020 review ultimately found the laws were flawed, outdated and, without fundamental reform, would continue to see plants and animals go extinct.

The extent to which the government implements the review’s 38 recommendations to strengthen the laws will determine the fate of many species and ecosystems – so, how did it go?

As biodiversity conservation experts, we find the plan to be promising. For example, federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek pledged to establish an independent environmental protection agency to be “a tough cop on the beat”.

But some uncertainty remains, and there is also a lot of important detail still to be worked through.

Australia’s Extinction Crisis

Australia has the world’s worst track record for mammal extinctions. The national threatened species list comprises more than 1,700 species and over 100 threatened ecological communities, and more are added every year.

Extraordinary species such as mountain pygmy possums, northern hairy-nosed wombats and regent honeyeaters are hanging on by a thread. Others, such as the white-footed rabbit-rat and the central hare-wallaby, are already lost forever. Previously abundant animals such as bogong moths, which the mountain pygmy possum relies on for food, have become rare.

Australia’s environment law – the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act – is ostensibly wildlife’s best defence against a range of threats to their habitat, such as urban development, mining and land clearing.

But this defence has failed, time and again. In just one example, the extinction threat facing the iconic koala has become worse, not better, since it was “protected” under the EPBC Act.

What The Plan Got Right

We note a few standout positives in the government’s response today. One is the promise to rapidly prepare and implement conservation plans – with strong regulatory standing – for each nationally listed threatened species and ecological community.

There is strong merit in this. We encourage a similar emphasis on developing plans to abate threats such as such as feral cats, foxes, deer, and rabbits, that should also have strong regulatory standing.

We’re also pleased to see confirmation of the formation of the environmental protection agency (EPA). This addresses one of the review’s top criticisms on the lack of resourcing and independent enforcement of the EPBC Act.

The model could be a game-changer: undertaking assessments and making decisions about development proposals at arm’s length from government. The EPA will have its own budget and mandatory tabling of an annual report in parliament.

Another big plus is the government’s pledge to deliver on national environmental standards, overseen by the newly formed EPA. These standards describe the environmental outcomes that must be achieved. For example, the standards could require that decisions result in no further population decline of threatened species.

Crucially, these standards will apply to “regional forest agreements”. These agreements are controversial because they effectively exempt forest logging from scrutiny under the EPBC Act. However, the timeline for imposing the standards on regional forest agreements is uncertain, and currently “subject to further consultation with stakeholders”.

Finally, a regional planning approach will be used to identify environmentally valuable and sensitive areas in which new developments pose too great a risk, as well as places that are more-or-less available for new development. The critical detail of how those zones are determined is yet to be negotiated.

A Major Uncertainty: Offsets

Perhaps the biggest concern we have about the federal government’s approach relates to environmental offsets. Offsets can be imposed by the government as a way to compensate for environmental destruction by improving nature in other places.

Evidence shows offsets have so far been largely ineffective, in part because existing policy is not properly implemented and rules not enforced. They may even facilitate more biodiversity loss by removing ethical roadblocks to destroying ecosystems and habitat for threatened species.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek on Thursday emphasised a move away from simply protecting habitat that already exists in exchange for habitat loss elsewhere (so-called “avoided loss offsets”), and instead focusing on restoration. This is a welcome improvement to how offsets are delivered.

However, the government will accept payments into a fund when offsetting is too difficult: for example, when there’s no like-for-like habitat available. This is worrying. If offsets for a threatened species are hard to find, it’s an important signal that we’re reaching the limit of habitat we can lose.

Imagine if a developer cleared cassowary habitat in a Queensland rainforest, and compensated for that by paying for koala tree planting in another part of Australia. Nice for the koala, but we have guaranteed a further decline for the cassowary.

The government’s plan points to the New South Wales Biodiversity Conservation Trust as an example of how these offset payments could be managed. Yet the auditor-general of NSW recently discredited the way this scheme handles offsets, saying it doesn’t lead to enough biodiversity gains compared to the losses and impacts from development in the state.

The national system would need to be very different to the NSW one if it’s to support the federal government’s goal of zero extinctions by 2030. In practice, this would mean avoiding the use of offsets to compensate for the destruction of habitats that aren’t replaceable or cannot be readily recreated elsewhere.

National environmental standards for environmental offsets haven’t yet been finalised. The detail included in these will be crucial to the success of the scheme.

Show Us The Money

Much of the federal government’s overhaul is to be welcomed. But we won’t prevent new extinctions unless it’s supported by serious investment to develop and implement plans, and enforce laws. Increased funding to recover endangered species is also urgently needed, to the tune of A$2 billion per year.

This is nowhere near as much as we spend on, for instance, submarines or even caring for our cats and dogs.

But it’s an order of magnitude more than our current spend on targeted threatened species recovery actions.

By and large, the proposed plan looks set to make a positive difference to Australia’s threatened plants and animals. But a lot of detail remains to be worked through. Getting that detail right could mean the difference between a species surviving, or disappearing forever.![]()

Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Science, School of Ecosystem and Forest Science, The University of Melbourne; Martine Maron, Professor of Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, and Sarah Bekessy, Professor in Sustainability and Urban Planning, Leader, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Repairing gullies: the quickest way to improve Great Barrier Reef water quality

Back-to-back bleaching events have highlighted the critical threat that climate change poses to the Great Barrier Reef. But few people are aware of the network of gullies pumping out about half the sediment that is polluting reef water quality and threatening its World Heritage status.

These gully networks are like miniature Grand Canyons, some with walls up to 20 metres high. They make a spectacular sight but are a disaster for the land, the reef and the rivers that connect them.

In the UNESCO delegation’s latest report on the reef, dramatically scaling up gully repair efforts is the top recommendation.

Along with global warming, degraded water quality is a key threat to the reef. But as the world continues to debate how to combat climate change, the report recognises that fixing gullies will give the reef a fighting chance to survive warming oceans. This is something Australia can do right now.

Over more than a century, land use changes have disturbed fragile soils in grazing country. The unearthed fine sediment from below the surface dissolves like a Berocca tablet when it rains, creating a gully. Left alone, this process will continue for hundreds of years and keep eating into the landscape.

Our team at Griffith university have been researching gullies since 2005. Over the last decade we’ve developed the tools to identify and target the highest priority gullies, and helped design ways to fix them.

Through detailed mapping we’ve found we can identify and target just a few percent of the tens of thousands of gullies to achieve a massive, cost-effective water quality improvement.

More Than 400,000 Dump Trucks Of Sediment A Year

As the planet warms, Australia is already experiencing record heat. For our team working in Queensland’s gullies, temperatures can reach over 50℃ in the midday sun.

Field work in these conditions usually feels about as comfortable as working on the surface of Mars. Nonetheless, our team of scientists keep returning because of the staggering implications of the data we’ve been collecting.

Each wet season, the exposed soils in these gullies turn to a yoghurt-like consistency. Their chemistry primes them to readily erode, which they do with every raindrop that falls on them.

In fact, an individual gully can produce thousands of tonnes of fine sediment each year from just a few hectares of land. If you look at the total flow of sediment from all gullies, on average over 400,000 truckloads are dumped across the reef every year, mostly within the inner lagoon.

As sediment and nutrients travel freely down the rivers, they pollute fragile ecosystems, filling water holes, clouding the water and reducing biodiversity. Once they reach the reef lagoon, they smother corals and seagrasses, which struggle to survive.

As the UNESCO report identifies, degraded water quality severely affects the resilience of the reef, limiting its ability to recover from bleaching and cyclones, and to withstand the changes caused by global warming.

The Most Effective Solution For Improving Water Quality

Stabilising gullied landscapes requires an approach akin to mine site rehabilitation. In 2016, we demonstrated that if you reshape (with major earthworks), recap (with rock, soil and mulch) and revegetate the gullies, you can rapidly repair them. Our research has shown that erosion from priority gullies can be reduced by 98% within a space of one to two years.

We’ve now mapped more than 25,000 individual gullies in three hot spot areas in the Normanby, Burdekin and Fitzroy River catchments.

Remarkably, we discovered that only a small proportion of the mapped gullies in each area are contributing a large proportion of the sediment pollution.

For example, in the Burdekin hot spot, we found only about 2% of the gullies contribute 30% of the sediment load to the reef. Targeting these gullies provides the best and quickest way to improve the reef’s water quality.

But the number of gullies repaired to date is a drop in the ocean compared to what still needs to be done.

So far, our method of identifying priority gullies for repair has been implemented across only 1% of the 44-million-hectare reef catchment. The urgent task, as the UNESCO report notes, is to identify other hot spot areas and rapidly roll out the prioritisation mapping to enable targeted remediation to get under way.

What Needs To Happen Now

UNESCO highlights the critical need to speed up effective action, recommending:

there is a need to secure a greater reduction of [sediment and nutrient] pollutants in the next three years than has been achieved since 2009.

The good news is the research has already been done. The data demonstrates it is possible to achieve this ambitious goal. The implementation of on-ground gully repair works with economies of scale is the quickest and most cost-effective way to do it.

Since 2008, Australian governments have set sediment reduction targets and invested considerable funds to improve reef water quality. The federal government intends to spend an additional A$580 million over nine years, and a further $270 million has been committed by the Queensland government.

Importantly, rapid progress can be made given the current funds earmarked for reef water quality. There are also proven working relationships already in place between our Griffith team, Traditional Owners , government and other stakeholders.

The challenge ahead is delivery. The next step requires a coordinated program to develop a pipeline of targeted gully projects.

The pieces of the puzzle are now all in place and there is no reason for delay.![]()

Andrew Brooks, Principal Research Fellow - Fluvial Geomorphologist - specialising in catchment erosion research, Griffith University and James Daley, Research Fellow, Coastal and Marine Research Centre, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Should we protect nature for its own sake? For its economic value? Because it makes us happy? Yes

Extinction is part of life on Earth. Through much of our planet’s history, species have been forming, evolving and eventually disappearing. Today, however, human activities have dramatically sped up the process. The Earth is losing animals, birds, reptiles and other living things so fast that some scientists believe the planet is entering the sixth mass extinction in its history.

On Dec. 7, 2022, the United Nations will convene governments from around the world in Montreal for a 10-day conference that aims to establish new goals for protecting Earth’s ecosystems and their biodiversity – the variety of life at all levels, from genes to ecosystems. There’s broad agreement that there is a biodiversity crisis, but there are many different views about why protecting it is important.

Some people, cultures and nations believe biodiversity is worth conserving because ecosystems provide many services that support human prosperity, health and well-being. Others assert that all living things have a right to exist, regardless of their usefulness to humans. Today, there’s also growing understanding that nature enriches our lives by providing opportunities for us to connect with each other and the places we care about.

As a conservation biologist, I’ve been part of the effort to value biodiversity for years. Here’s how thinking in this field has evolved, and why I’ve come to believe that there are many equally valid reasons for protecting nature.

Defending Every Species

Conservation biology is a scientific field with a mission: protecting and restoring biodiversity around the world. It came of age in the 1980s, as humans’ impact on the Earth was becoming alarmingly clear.

In a 1985 essay, Michael Soulé, one of the field’s founders, described what he saw as the core principles of conservation biology. Soulé argued that biological diversity is inherently good and should be conserved because it has intrinsic value. He also proposed that conservation biologists should act to save biodiversity even if sound science isn’t available to inform decisions.

To critics, Soulé’s principles sounded more like environmental activism than science. What’s more, not everyone agreed then or now that biodiversity is inherently good.

After all, wild animals can destroy crops and endanger human lives. Contact with nature can lead to disease. And some conservation initiatives have displaced people from their land or prevented development that might otherwise improve people’s lives.

Valuing Nature’s Services

Soulé’s essay spurred many researchers to push for a more science-driven approach to conservation. They sought to directly quantify the value of ecosystems and the roles species played in them. Some scholars focused on calculating the value of ecosystems to humans.

They reached a preliminary conclusion that the total economic value of the world’s ecosystems was worth an average US$33 trillion per year in 1997 dollars. At the time, this was nearly twice the global value of the entire world’s financial markets.

This estimate included services such as predators controlling pests that would otherwise ruin crops; pollinators helping to produce fruits and vegetables; wetlands, mangroves and other natural systems buffering coasts against storms and flooding; oceans providing fish for food; and forests providing lumber and other building materials.

Researchers have refined their estimates of what these benefits are worth, but their central conclusion remains the same: Nature has shockingly high economic value that existing financial markets don’t account for.

A second group began to quantify the nonmonetary value of nature for human health, happiness and well-being. Studies typically had people take part in outdoor activities, such as strolling through a green space, hiking in the woods or canoeing on a lake. Later, they measured the subjects’ physical or emotional health.

This research found that spending time in nature tended to reduce blood pressure, lower hormones related to stress and anxiety, decrease the probability of depression and improve cognitive function and certain immune functions. People exposed to nature fared better than others who took part in similar activities in nonnatural settings, such as walking through a city.

Losing Species Weakens Ecosystems

A third line of research asked a different question: When ecosystems lose species, can they still function and provide services? This work was driven mainly by experiments where researchers directly manipulated the diversity of different types of organisms in settings ranging from laboratory cultures to greenhouses, plots in fields, forests and coastal areas.

By 2010, scientists had published more than 600 experiments, manipulating over 500 groups of organisms in freshwater, marine and land ecosystems. In a 2012 review of these experiments, colleagues and I found unequivocal evidence that when ecosystems lose biodiversity, they become less efficient, less productive and less stable. And they are less able to deliver many of the services that underlie human well-being.

For example, we found strong evidence that loss of genetic diversity reduced crop yields, and loss of tree diversity reduced the amount of wood that forests produced. We also found evidence that oceans with fewer fish species produced less-reliable catches, and that ecosystems with lower plant diversity were more prone to invasive pests and diseases.

We also showed that it was possible to develop robust mathematical models that could predict reasonably well how biodiversity loss would affect certain types of valuable services from ecosystems.

Many Motives For Protecting Nature

For years, I believed that this work had established the value of ecosystems and quantified how biodiversity provided ecosystem services. But I’ve come to realize that other arguments for protecting nature are just as valid, and often more convincing for many people.

I have worked with many people who donate money or land to support conservation. But I’ve never heard anyone say they were doing it because of the economic value of biodiversity or its role in sustaining ecosystem services.

Instead, they’ve shared stories about how they grew up fishing with their father, held family gatherings at a cabin or canoed with someone who was important to them. They wanted to pass on those experiences to their children and grandchildren to preserve familial relationships. Researchers increasingly recognize that such relational values – connections to communities and to specific places – are one of the most common reasons why people choose to conserve nature.

I also know many people who hold deep religious beliefs and are rarely swayed by scientific arguments for conservation. But when Pope Francis published his 2015 encyclical Laudato si’: On Care for Our Common Home and said God’s followers had a moral responsibility to care for his creation, my religious relatives, friends and colleagues suddenly wanted to know about biodiversity loss and what they might do about it.

Surveys show that 85% of the world’s population identifies with a major religion. Leaders of every major religion have published declarations similar to Pope Francis’ encyclical, calling on their followers to be better stewards of Earth. Undoubtedly, a large portion of humanity assigns moral value to nature.

Research clearly shows that nature provides humanity with enormous value. But some people simply believe that other species have a right to exist, or that their religion tells them to be good stewards of Earth. As I see it, embracing these diverse perspectives is the best way to get global buy-in for conserving Earth’s ecosystems and living creatures for the good of all.![]()

Bradley J. Cardinale, Department Head, Ecosystem Science and Management, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

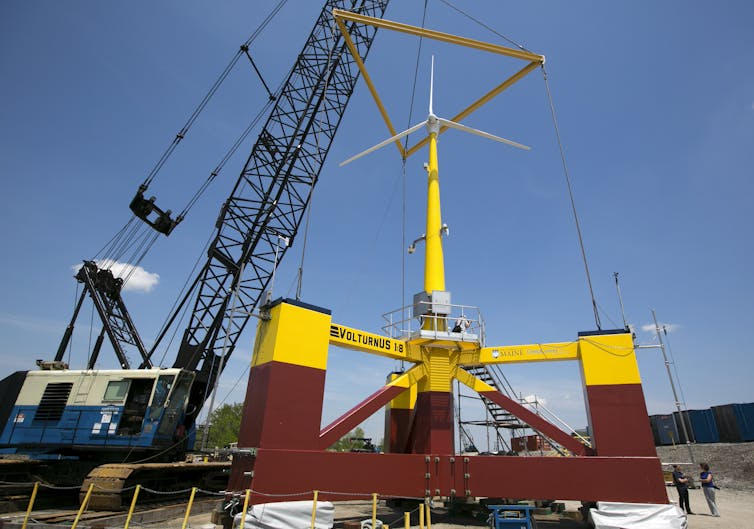

How do floating wind turbines work? 5 companies just won the first US leases for building them off California’s coast

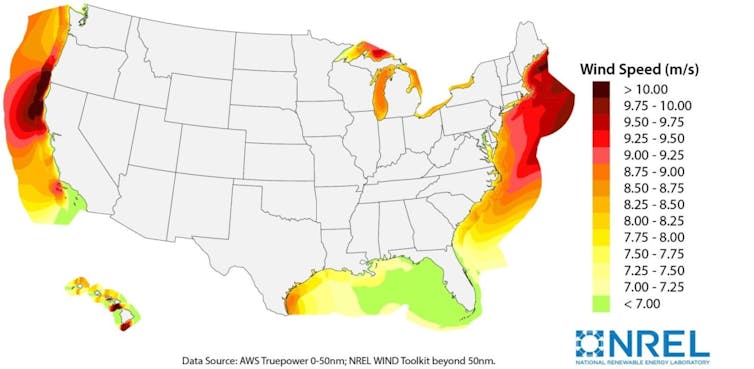

Matthew Lackner, UMass AmherstNorthern California has some of the strongest offshore winds in the U.S., with immense potential to produce clean energy. But it also has a problem. Its continental shelf drops off quickly, making building traditional wind turbines directly on the seafloor costly if not impossible.

Once water gets more than about 200 feet deep – roughly the height of an 18-story building – these “monopile” structures are pretty much out of the question.

A solution has emerged that’s being tested in several locations around the world: wind turbines that float.

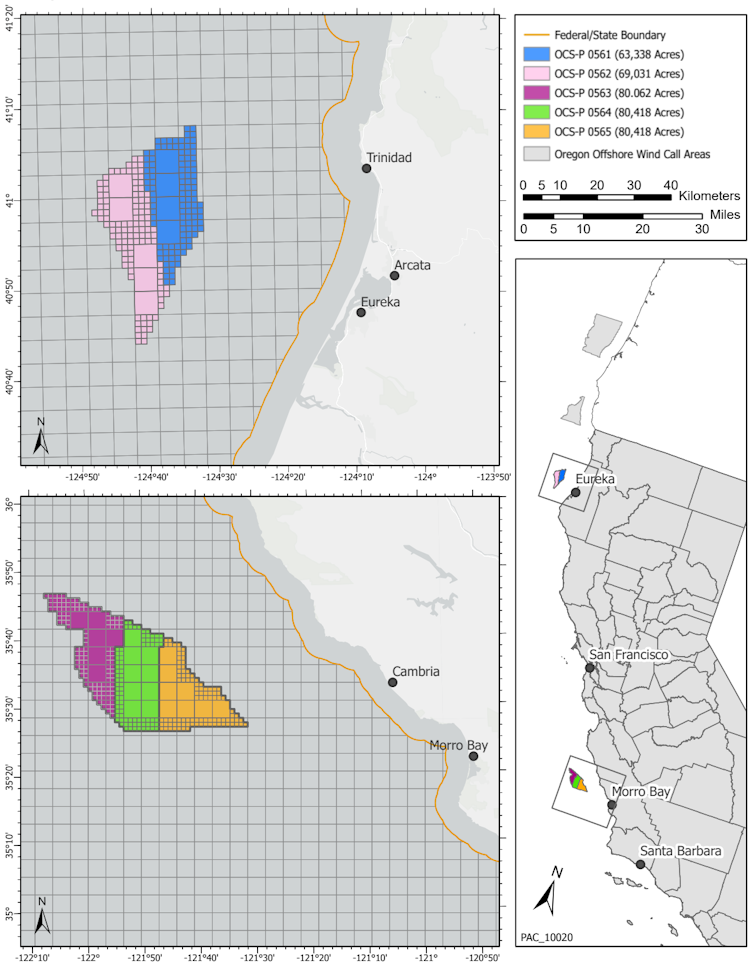

In California, where drought has put pressure on the hydropower supply, the state is moving forward on a plan to develop the nation’s first floating offshore wind farms. On Dec. 7, 2022, the federal government auctioned off five lease areas about 20 miles off the California coast to companies with plans to develop floating wind farms. The bids were lower than recent leases off the Atlantic coast, where wind farms can be anchored to the seafloor, but still significant, together exceeding US$757 million.

So, how do floating wind farms work?

Three Main Ways To Float A Turbine

A floating wind turbine works just like other wind turbines – wind pushes on the blades, causing the rotor to turn, which drives a generator that creates electricity. But instead of having its tower embedded directly into the ground or the seafloor, a floating wind turbine sits on a platform with mooring lines, such as chains or ropes, that connect to anchors in the seabed below.

These mooring lines hold the turbine in place against the wind and keep it connected to the cable that sends its electricity back to shore.

Most of the stability is provided by the floating platform itself. The trick is to design the platform so the turbine doesn’t tip too far in strong winds or storms.

There are three main types of platforms:

A spar buoy platform is a long hollow cylinder that extends downward from the turbine tower. It floats vertically in deep water, weighted with ballast in the bottom of the cylinder to lower its center of gravity. It’s then anchored in place, but with slack lines that allow it to move with the water to avoid damage. Spar buoys have been used by the oil and gas industry for years for offshore operations.

Semisubmersible platforms have large floating hulls that spread out from the tower, also anchored to prevent drifting. Designers have been experimenting with multiple turbines on some of these hulls.

Tension leg platforms have smaller platforms with taut lines running straight to the floor below. These are lighter but more vulnerable to earthquakes or tsunamis because they rely more on the mooring lines and anchors for stability.

Each platform must support the weight of the turbine and remain stable while the turbine operates. It can do this in part because the hollow platform, often made of large steel or concrete structures, provides buoyancy to support the turbine. Since some can be fully assembled in port and towed out for installation, they might be far cheaper than fixed-bottom structures, which require specialty vessels for installation on site.

Floating platforms can support wind turbines that can produce 10 megawatts or more of power – that’s similar in size to other offshore wind turbines and several times larger than the capacity of a typical onshore wind turbine you might see in a field.

Why Do We Need Floating Turbines?

Some of the strongest wind resources are away from shore in locations with hundreds of feet of water below, such as off the U.S. West Coast, the Great Lakes, the Mediterranean Sea and the coast of Japan.

The U.S. lease areas auctioned off in early December cover about 583 square miles in two regions – one off central California’s Morro Bay and the other near the Oregon state line. The water off California gets deep quickly, so any wind farm that is even a few miles from shore will require floating turbines.

Once built, wind farms in those five areas could provide about 4.6 gigawatts of clean electricity, enough to power 1.5 million homes, according to government estimates. The winning companies suggested they could produce even more power.

But getting actual wind turbines on the water will take time. The winners of the lease auction will undergo a Justice Department anti-trust review and then a long planning, permitting and environmental review process that typically takes several years.

Globally, several full-scale demonstration projects with floating wind turbines are already operating in Europe and Asia. The Hywind Scotland project became the first commercial-scale offshore floating wind farm in 2017, with five 6-megawatt turbines supported by spar buoys designed by the Norwegian energy company Equinor.

Equinor Wind US had one of the winning bids off Central California. Another winning bidder was RWE Offshore Wind Holdings. RWE operates wind farms in Europe and has three floating wind turbine demonstration projects. The other companies involved – Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, Invenergy and Ocean Winds – have Atlantic Coast leases or existing offshore wind farms.

While floating offshore wind farms are becoming a commercial technology, there are still technical challenges that need to be solved. The platform motion may cause higher forces on the blades and tower, and more complicated and unsteady aerodynamics. Also, as water depths get very deep, the cost of the mooring lines, anchors and electrical cabling may become very high, so cheaper but still reliable technologies will be needed.

But we can expect to see more offshore turbines supported by floating structures in the near future.

This article was updated with the first lease sale.![]()

Matthew Lackner, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, UMass Amherst

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

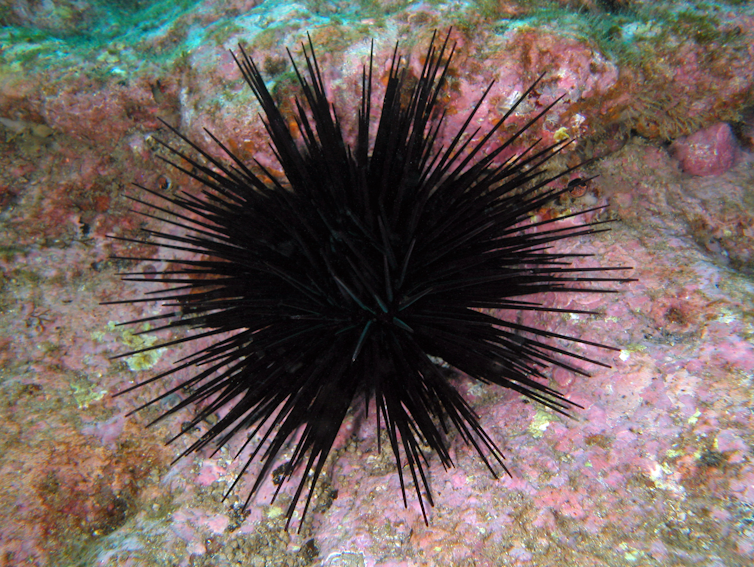

Sea urchins have invaded Tasmania and Victoria, but we can’t work out what to do with them

While crown-of-thorns starfish on the Great Barrier Reef have long been ecological villains in the popular imagination, sea urchins have mostly crawled under the national radar – until now.

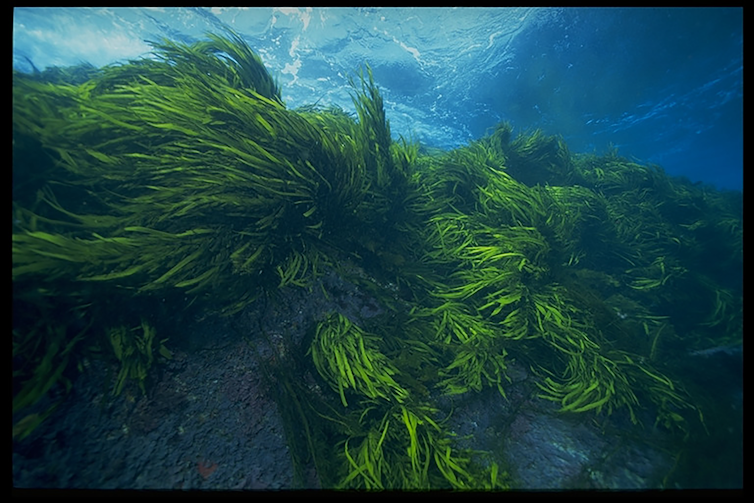

Long-spined sea urchins (Centrostephanus rodgersii) have invaded Tasmania and Victoria from their historical range in New South Wales. Where it occurs, this species dominates near-shore reefs to create “barrens habitat”. This is where at high densities sea urchins remove all large brown algae (kelp), and few abalone and other important species for fishers remain.

Both climate change and over-fishing of its main predators have been blamed for the urchin’s southward extension.

This is a central issue in the ongoing Senate inquiry into climate-related marine invasive species, which has brought the challenges and contradictions of managing the marine estate into sharp relief. The inquiry received over 40 diverse and often contradictory submissions.

It’s clear there is little national consensus about the nature of the sea urchin problem, its causes, or what to do about it. In Tasmania and Victoria, policy directions are clear and being implemented. But managing barrens within New South Wales seascapes isn’t as clear cut. Although a single solution may not be clear now, there is a path forward.

Meet The Long-Spined Sea Urchin

Long-spined sea urchins defend themselves with a menacing armoury of long, hollow spines. By day they are found in crevices or aggregated on the reef, and emerge to forage at night. As with many sea urchins, their roe (unfertilised fish eggs and sperm) is edible and the species is harvested in all three southeastern states.

They begin their lives as minute larvae. Ocean currents carry the larvae to reefs where they settle and grow. Understanding the relative importance of processes that limit them as larvae and as grazing urchins on reefs is crucial to discerning what controls their populations.

In Tasmania and Victoria, the larval supply horse has bolted. Over the last half century, the East Australian Current has pushed further south more often as it eddies into the Tasman Sea. This incursion of warmer water into cooler, southern seas has been attributed to climate change.

Urchin larvae can tolerate a wide temperature range and survive when food is limited, making the species a good coloniser.

Still, in 2009 researchers concluded larval supply was not a sufficient explanation for urchin numbers rising in Tasmania. Rather, they argued the population boomed because a predator, the southern rock lobster (Jasus edwardsii) has been overfished.

More recent research published this year has challenged the notion that southern rock lobster predation limits long-spined sea urchin numbers.

Sea urchins in Tasmania and Victoria are currently managed with a patchwork of diver culling, subsidised sea urchin fisheries and marine reserves. Despite local successes, Centrostephanus populations continue to boom and to expand their geographic spread.

Sea Urchins In NSW

Although it waxes and wanes on local scales, the total area of barrens habitat in NSW has been a relatively stable and prominent feature of reefs for more than 60 years.

But it’s not clear whether the extent of barrens habitat in NSW is “natural” or a long-term artefact of overfishing.

For example, a different lobster, the eastern rock lobster (Sagmariasus verreauxi), has been cited as a missing predator, along with the fabulous eastern blue groper (Achoerodus viridis). Certainly, both lobster and groper eat sea urchins and have historically been overfished, but the evidence for them acting as a controlling influence is weak.

Strong opinions notwithstanding, predatory control of sea urchins in NSW remains an unresolved question for now.

Innovative and committed mitigation programs can make a difference locally. Nevertheless, fishing and/or culling sea urchins has not successfully reduced overall populations in NSW where the geographic range is so large.

Sea urchins, for their part, have just got on with being good echinoderms – colonising, eating and reproducing.

The Stories We Tell Ourselves And Others

If we can’t settle on what’s driving the long-spined sea urchin boom in Victoria, Tasmania and NSW, then it’s no surprise we’re struggling to agree on how to manage them. As in many fields, this is classically a wicked problem.

If you prioritise conservation values, livelihoods, commercial fisheries or, more fundamentally, First Nations communities’ rights and aspirations, you see the problem differently. And so be guided toward different solutions.

For Traditional Owners and abalone divers, sea urchins impinge on a range of economic, cultural and social values. For others, black sea urchins are a natural and important element of the ecosystem.

Along with diverse and incompatible views, legal instruments to manage the marine estate, First Nations rights, and fisheries overlap, further defying simple solutions.

For example, the NSW Fisheries Management Act has traditionally focused on the sustainability of fisheries, while the NSW Marine Estate Management Act has a much broader focus than harvesting marine species.

The urchins may be seen as a symptom rather than a cause of a suite of ecological, institutional and political problems. These larger issues include climate change, marginalisation and lack of voice, conflicting worldviews, and institutional paralysis.

A Way Forward For NSW

The Senate inquiry should prompt new ways to manage the marine estate. We need a form of transparent, flexible and inclusive governance, consistent with fisheries and other legislation.

Structured management experiments to manage the marine estate, including sea urchins, should be implemented in small zones to learn how reefs respond to different management.

A diverse range of people should be brought together to design and implement such experiments. As examples of what may be considered as interventions:

the urchin fishery should be co-managed with abalone to optimise yields, maximising profitability rather than environmental sustainability

the abalone industry should be enabled and supported to cull sea urchins and otherwise fish in ways that boost productivity

First Nations communities should be enabled and supported to manage Sea Country

and Marine Sanctuary Zones should be monitored, not fished.

Shifting the centre of gravity of managing the issue to those most affected and with the greatest experience creates an opportunity for collaboration. This means marine estate managers, industry, and First Nations peoples need to be at the forefront. Researchers have important, but secondary roles, in monitoring and evaluation.

Although solutions may not be clear now, they will emerge as shared understanding evolves into common purpose. This is difficult work, but in a quote Sir Peter Medawar ascribes to philosopher Thomas Hobbes, “there can be no contentment but in proceeding”.![]()

Neil Andrew, Professor of fisheries and international development, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP15: three visions for protecting nature on the table at the UN biodiversity conference

With the dust still settling on the UN climate change summit in Egypt, another round of international talks is beginning in Montreal, Canada. The UN biodiversity conference, otherwise known as COP15, will assemble world leaders to agree on new targets for protecting nature.

The loss of biodiversity – the dizzying variety of life forms from microscopic viruses, bacteria and fungi to towering trees and enormous whales – is accelerating. The last agreement in 2010 yielded the 20 Aichi targets which included halving the rate at which species were being lost and expanding protected habitats on land and in the sea by 2020. Governments failed to meet a single one.

A global assessment in 2019 showed that nature was declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history. The forces driving more and more species towards extinction – climate change, habitat destruction and pollution – are all trending in the wrong direction. Nothing less than a transformation of how societies work and the relationship between people and the rest of nature will get us on track.

After two years of delay due to the pandemic and difficulties negotiating a new venue with the country that holds the conference presidency, China, many are relieved that COP15 is happening at all. That relief may prove short-lived as there is much to be done in these two short weeks. The grand objective is the approval of a new global biodiversity framework, essentially a plan for how the world’s nations expect to halt the loss of biodiversity and ensure that, by 2050, society is living in harmony with nature.

30% By 2030

One debate which has dominated discussions so far is how much land and sea should be set aside for conservation. The current text aims for 30% by 2030. Some scientists believe this is insufficient, and that preserving half the Earth for nature is necessary. Others are wary of reviving failed ideas which have tried to boost wildlife by expelling people and erecting walls to keep them out.

Negotiators will debate whether a 30x30 target should be met at the national level or globally. The former would mean each country meeting this standard within its own borders. The latter would prioritise Earth’s most important areas of biodiversity (such as tropical rainforests) but oblige countries with large remaining wildernesses (overwhelmingly in developing countries) to shoulder the lion’s share of conservation work. Many poorer countries foresee this stopping their economic development.

There is also disagreement over what level of protection should be given to these areas and how the rights of people living within them should be recognised. These plans would require a doubling of protected areas on land and perhaps as much as a tenfold increase in the oceans. But they could exclude indigenous people and those who make their living from cultivation, forestry and fishing.

Less Emissions, Less Meat, Less Waste

Instead of concentrating on the total area reserved for nature, recent research highlights the importance of addressing the underlying causes of extinctions and habitat loss, such as greenhouse gas emissions, meat consumption and plastic pollution.

Targeting the processes driving biodiversity loss would shift attention away from where nature is being destroyed to the places where these processes are guided and sustained: boardrooms, trading floors, local planning offices and supermarkets.

The framework under negotiation includes several targets that would restrain the destruction, from eliminating policies subsidising the conversion of forest to cow pasture to halving food waste. These have failed to attract the momentum behind flashier goals like the 30x30 target. Changing how economies and societies function is more contentious and asks more from rich countries with more influence over the drivers of biodiversity loss.

Safeguard Nature’s Services

Yet another approach would safeguard the services nature generates, including flood protection, wood fuel, climate regulation and food provision. And it would identify the natural assets (wetlands, forests, coral reefs and mangroves to name a few) that must endure for these services to continue. This would mean protecting nature close to where it is most needed. A staggering 6.1 billion people live within one hour of such assets.

Good COP Or Bad COP?

While everyone gathering in Montreal agrees that a breakthrough is needed, there are different ideas about what that should look like. For many seasoned conservationists, a good outcome will mean more stringent targets for protecting and restoring nature and more expansive protected areas, plus the money and other resources necessary to enforce them.

Businesses, investors, cities, regional governments and the communities they represent want an agreement that mobilises the whole of society. Some companies have asked that all businesses be forced to report the impacts their activities have on nature. Cities and regions have their own pledges and have asked COP15 to formally recognise their role in delivering national plans.

This could bring the protection and restoration of nature into mainstream thinking around how economies develop and societies are organised, and make the case that much of what is important about nature is not to be found on the other side of a fence. This trend is evident in growing enthusiasm around nature-based solutions to climate change.

The recent UN climate summit in Egypt heralded the potential of such solutions, which include restoring peatlands and seagrass beds. These actions tackle the climate and biodiversity crisis together by expanding refuge for wildlife and drawing carbon from the air. Cities, businesses and investors smell an opportunity to meet multiple measures of sustainable development at once.

Some conservationists worry these supposed solutions are greenwashing and allow companies to exploit indigenous people and communities. Other experts argue that, with the right safeguards in place, these fears can be put to rest.

With much at stake, in seeking to straddle different agendas, COP15 risks achieving none.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Harriet Bulkeley, Professor of Geography, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Loss, decay and bleaching: why sponges may be the ‘canary in the coal mine’ for impacts of marine heatwaves

Marine sponges were thought to be more resilient to ocean warming than other organisms. But earlier this year, New Zealand recorded the largest-ever sponge bleaching event off its southern coastline.

While only one species, the cup sponge Cymbastella lamellata, was affected, a prolonged marine heatwave turned millions of the normally dark brown sponges bright white.

Subsequently, we reported tissue loss, decay and death of other sponge species across the northern coastline of New Zealand, with an estimated impact on hundreds of thousands of specimens. In contrast, we didn’t observe any bleaching or tissue loss in central areas of New Zealand’s coastline, despite extensive surveys.

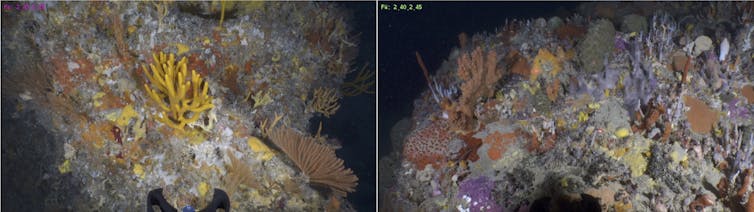

Our latest research shows the most severe impacts on sponges occurred in areas where the marine heatwave was most intense. The loss of sponges may have major repercussions for the whole ecosystem.

Why Should We Care About Sponges?

Sponges are among the most ancient and abundant animals on rocky reefs across the world. In New Zealand, they occupy up to 70% of the available seafloor, particularly in so-called mesophotic ecosystems at depths of 30-150m.

They serve a number of important ecological functions. They filter large quantities of water, capturing small food particles and moving carbon from the water column to the seafloor where it can be eaten by bottom-dwelling invertebrates. These invertebrates in turn are consumed by organisms further up the food chain, including commercially and culturally important fish species.

Sponges also add three-dimensional complexity to the sea floor, which provides habitat for a range of other species such as crabs, shrimps and starfish.

Sponge Bleaching, Tissue Loss And Decay

Like corals, sponges contain symbiotic organisms thought to be critical to their survival. Cymbastella lamellata is unusual in that it hosts dense populations of diatoms, small single-celled photosynthetic plants that give the sponge its brown colour.

These diatoms live within the sponge tissue, exchanging food for protection. When the sponge bleaches, it expels the diatoms, leaving the sponge skeleton exposed.

Tissue loss occurs when sponges are stressed and either have to invest more energy into cell repair or when their food source is depleted and they reabsorb their own tissue to reduce body volume and reallocate resources.

Tissue decay or necrosis on the other hand is generally associated with changes in the microbial communities living within sponges and growth of pathogenic bacteria.

Bleaching, tissue loss and decay in sponges have all previously been associated with heat stress, but didn’t necessarily result in sponge death. In other places where such impacts have been observed, they were much more localised, compared to what we saw in New Zealand.

The Impact Of Marine Heat Waves

Marine heatwaves are defined as unusual periods of warming that last for five consecutive days or longer. Some can last from weeks to several months and extend over hundreds or thousands of kilometres of coastline.

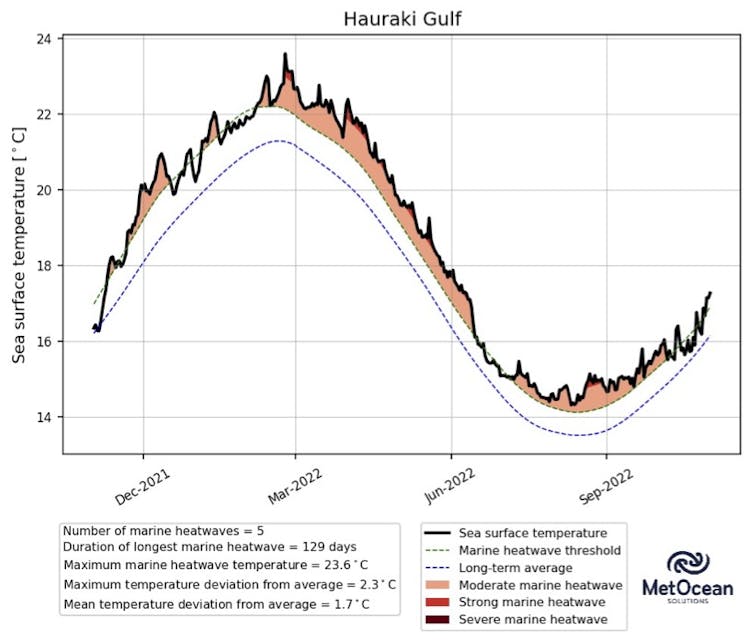

The sponge bleaching and tissue loss or decay in New Zealand matched the duration and intensity of marine heatwaves to the north and south of New Zealand during the summer of 2021/2022. The Hauraki Gulf, where sponge necrosis and decay was reported, was in a continuous marine heatwave for 29 weeks from November 2021 to the end of May 2022, with a maximum intensity of 3.77℃ above normal.

In Fiordland, a prolonged marine heatwave developed in early February 2022 and persisted for more than 16 weeks into May, with a maximum intensity of 4.85℃ above normal temperatures. In contrast, the Wellington and Marlborough Sounds regions experienced only short (weeks) marine heatwaves with a lower intensity and we did not observe any impacts on sponges.

These extreme heat events can result from a combination of changes in the heat exchange between the air and the sea, wind patterns and ocean currents. Their likelihood is also influenced by large-scale climate patterns such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

What The Future May Hold

Most global research on climate change impacts has focused on experimental studies exposing organism to temperatures predicted for 2100, often 2-4℃ higher than current temperatures. But the occurrence of marine heatwaves means organisms are already experiencing these temperatures, sometimes for several weeks or months. By 2100, marine heatwaves will become even more extreme.

For bleached Cymbastella, recent anecdotal reports suggest many sponges have recovered their colour, which is good news. However, observations immediately after the bleaching indicate many sponges were being eaten by fish, possibly because their symbionts may provide chemical defences against predation.

For bleached corals, studies have shown impacts on spawning success for many years after the event, likely because their energy reserves have been depleted.

We don’t yet know if this is the case for sponges. For sponges with decayed tissue the outlook is even less clear, as many probably died.

Sponges are not the only species to be affected by marine heatwaves New Zealand experienced in 2021/2022. There were reports of seaweed die-offs and changes to normal distribution patterns of tuna and other ecologically and commercially important fish species.

Marine heatwaves should be front of mind when thinking about climate impacts. They are happening now, not in 50 years, and we don’t know enough yet to determine if sponges may be the canary in the coal mine.

This is especially important because New Zealand’s northern coastlines are already experiencing almost continuous marine heatwave conditions, with the ongoing event forecast to extend into the coming summer.![]()

James Bell, Professor of Marine Biology, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Nick Shears, Associate Professor in Marine Science, University of Auckland, and Robert Smith, Lecturer, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A China-backed dam in Indonesia threatens a rare great ape – and that’s just the tip of the iceberg

In 2017, scientists described a new species of great apes – the Tapanuli orangutan. The species, found in the Batang Toru ecosystem of North Sumatara, Indonesia was listed as critically endangered soon after.

The population of the species has declined by 83% over the past 75 years, largely due to hunting and habitat loss. Just 800 Tapanuli orangutans remain – and their last known habitat is threatened by a slew of infrastructure projects.

Chief among them is the Chinese-funded Batang Toru hydropower dam, which threatens to fragment and submerge a large chunk of the orangutan’s habitat. The project is just one of a staggering 49 hydropower dams China is funding: mostly across Southeast Asia, but also in Africa and Latin America.

In new research, my colleagues and I show the substantial risk to biodiversity posed by the sheer number of Chinese-funded dams. And yet, environmental regulation of these projects has serious flaws.

Big Dams, Big Risks

Hydropower is expected to be an important part of the global renewable energy transition. But the technology brings environmental risks. Dams disrupt the flow of rivers, altering species’ habitat. And dam reservoirs inundate and fragment habitats on land.

Traditionally, financing of hydropower projects in low-income countries was the preserve of Western-backed multilateral development banks. China has now emerged as the biggest international financier of hydropower under its overseas infrastructure investment program, the Belt and Road Initiative.

Yet little is known about the scale of China’s hydropower financing or the biodiversity risks it brings. Whether adequate safeguards are applied to the projects by Chinese and host country regulators is also poorly understood. Our research attempted to remedy this.

We found China is funding 49 hydropower dams in 18 countries including Myanmar, Laos and Pakistan.

The dams are likely to impede the flow of 14 free-flowing rivers, imperilling the species they harbour. The first dam on a free-flowing river is akin to the proverbial “first cut” of a road into an intact forest ecosystem, causing disproportionate harms to biodiversity.

We also found Chinese-funded dams overlap with the geographic ranges of 12 critically endangered freshwater fish species, including the iconic Mekong Giant Catfish and the world’s largest carp species, the Giant Barb. The dams exacerbate the threats to these species and may push them closer to extinction.

Almost 135 square kilometres of critical habitat on land is also likely to be inundated and fragmented by the dams and their reservoirs.

Lax Environmental Rules

Despite the biodiversity risks, we found serious gaps in the environmental rules applied to Chinese-funded dams.

A previous analysis found six Chinese state-owned banks – which together contribute most financing for Belt and Road projects – had no safeguard standards to limit biodiversity damage.

Complementing this analysis, our investigation found Chinese regulators also did not require hydropower projects to mitigate environmental damage. Some regulator policies, however, contained non-binding guidelines.

A number of Chinese government policies defer to host country laws on environmental protection. But our investigation found in most countries where the dams are being built, regulation to limit environmental harms was absent or still developing.

This poor governance leaves species and ecosystems in these countries vulnerable to environmental damage from dams.

A Spotlight On Sumatra

The Batang Toru dam aims to bolster North Sumatra’s energy supplies. Its proponents say the dam uses environmentally-friendly technology that requires only a small area to be flooded.

Two multilateral development banks, however, distanced themselves from the project after concerns were raised about potential impact on the Tapanuli orangutan. The Chinese state-owned Bank of China also withdrew its finance offer after international protests. Chinese financier SDIC Power Holdings then stepped in to fund it.

Habitat destruction has confined the few remaining Tapanuli orangutans to a fragmented 1,400 square kilometre tract of rainforest in North Sumatra. Scientists say the Batang Toru dam further threatens this habitat.

Constructing the dam requires digging a tunnel in an area where most Tapanuli orangutans live. Experts also say the project will permanently isolate sub-populations of the species, increasing the risk of extinction.

The case illustrates the potential destruction hydropower projects can cause in the absence of appropriate planning and safeguards.

Need For Holistic Planning

The sheer number of Chinese-funded dams presents significant biodiversity risks. It also presents an opportunity.

China is funding several hydropower projects in single river basins. This puts it in an advantageous position to carry out “basin-scale planning”.

This involves making decisions about dams not based solely on an individual project, but by considering it in the context of other projects within the basin, as well as in the broader context of communities and the environment.

This type of planning also means dams can be configured to have the least impact on critically endangered species, and other irreplaceable and vulnerable biodiversity elements.

Such “system scale” planning is a key recommendation of international initiatives such as the World Commission on Dams and the European Union’s Water Framework Directive.

It also involves determining whether a proposed dam is the best way to meet energy needs, or if alternatives – such as wind or solar – could do so with lower environmental risks.

In the case of the Batang Toru dam, a 2020 report by a leading international consulting firm found the dam would not “materially improve access to nor the regularity of power supply” in North Sumatra, which in fact had a power surplus.

Given the huge damage dams can cause to biodiversity, it is crucial that only those dams that are really needed get built – and any associated damage is minimised.

The many Chinese-funded dams on the horizon must undergo rigorous vetting if serious biodiversity damage is to be averted. ![]()

Divya Narain, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Clashing laws need to be fixed if we want to live in bushfire-prone areas

Phillipa McCormack, University of AdelaideIt’s almost bushfire season. Yes, even though floods are still racing through parts of eastern Australia. Fire conditions are above average including in inland New South Wales and Queensland.

When we switch back to a neutral or El Niño climate cycle, our fire risk will likely intensify, given the huge vegetation growth during these rainy years.

As we prepare for the next major fire season, it’s vital we take a close look at our laws. Why? Because these laws can clash in ways that make it harder for us to prepare.

Governments have always struggled to balance laws protecting nature with laws protecting us from bushfire.

In recent years, planning laws have been changed to make it easier to fell trees and clear vegetation to keep our homes safe. Some of these came out of the review of Victoria’s catastrophic 2009 Black Saturday fires, where many houses nestled in bush burned. But these changes to the rules about clearing native vegetation can also make it harder for us to preserve habitat – and can give us a false sense of security, encouraging us to settle deeper and deeper into the fire-prone bush.

Why Do Laws Matter For Bushfire Preparation?

My colleagues and I recently mapped out Australia’s legal “anatomy” for fire. By anatomy, we mean all the different parts of the legal framework, including those that affect fire preparation.

Why? To optimise our system of laws to be ready for the ever-more-intense fires expected as the world heats up.

Here’s what a clash looks like. It’s now common to undertake prescribed burns and burn vegetation to reduce fuel loads and reduce the chances of a major bushfire.

But prescribed fires cause smoke. Fire agencies must comply with smoke pollution laws designed to keep vulnerable people safe. These two different risks – bushfire, and smoke-related illness – are managed under two different areas of law. Finding the balance is really hard.

We already know our environmental laws are failing to adequately protect nature.

Bushfires add to this as a serious and growing threat to our distinctive wildlife and ecosystems. The Black Summer megafires of 2019–20 killed huge numbers of animals and pushed many species closer to extinction, including mountain pygmy possums, native bees and rare frogs.

As fire seasons worsen and get longer over coming decades, fire agencies and local governments will be called on to clear and manage fuel loads – essentially, trees, plants and leaf litter – close to communities in the bush.

You can see the issue. Bushfire fuel is also habitat. Our international and domestic obligations to protect threatened species and habitats will come into increasing conflict with the need to preserve our settlements and farms.

Better, clearer laws would help balance these issues. Last year, the Victorian government announced plans to make bushfire planning provisions clearer and more understandable. Reviews like this should clarify where homes can and can’t be safely built, as well as preventing development in sensitive habitat.

Laws Around Fire Need To Be Considered Separately

Emergency planners often group floods, storms and bushfires under the blanket term “all hazards”. This is done to help emergency services to plan efficient and coordinated responses to all kinds of extreme events.

We believe laws about fire also deserve specific attention, particularly in Australia, where many of our ecosystems have evolved alongside fire. Not all fire is equal and not all fires are emergencies.

In fact, laws governing protected areas in some states actually require parks agencies to use fire as a conservation tool. Using fire carefully is front and centre in the new plan to look after Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area.

Not only that, but some areas need small fires lit in a mosaic pattern. Why? To encourage moorland plants to put out the flowers and seeds the critically endangered orange-bellied parrot relies on.

Or take the growing importance of cultural fire management and traditional land management. Victoria’s cultural fire strategy describes cultural burning as a “responsibility” and an example of “living knowledge”, but not as an emergency.

Some laws, like arson, only apply to fire. There’s no equivalent crime for floods. Improving arson prevention could help cut the estimated A$1.6 billion in damages annually from fires being lit deliberately.

While arson is not as common as it used to be, cutting arson further will reduce the number of fires Australian firefighters have to respond to.

We Have To Make Laws Intersect Better

In the wake of destructive and lethal fires come the reviews and inquiries, which often recommend changes to emergency management laws.

These post-disaster inquiries also often recommend streamlining rules around native vegetation, to let landholders clear more trees and shrubs around their houses. That’s understandable, because these inquiries are intended to find lessons.

But if we look across the whole range of laws governing or touching on fire, we might find new ways to help us adapt.

Over the last century, Australian governments have launched hundreds of inquiries and commissions after major bushfires.

We don’t need to wait for the next fire and inquiry. We can find ways of optimising our web of intersecting laws right now – and prepare ourselves and nature for what is to come.

My co-authors Professors Jan McDonald and David Bowman, Associate Professor Michael Eburn, Dr Stuart Little and Dr Rebecca Harris contributed to the research on which this article is based.![]()

Phillipa McCormack, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New food technologies could release 80% of the world’s farmland back to nature

Here’s the basic problem for conservation at a global level: food production, biodiversity and carbon storage in ecosystems are competing for the same land. As humans demand more food, so more forests and other natural ecosystems are cleared, and farms intensify and become less hospitable to many wild animals and plants. Therefore global conservation, currently focused on the COP15 summit in Montreal, will fail unless it addresses the underlying issue of food production.

Fortunately, a whole raft of new technologies is being developed that make a system-wide revolution in food production feasible. According to recent research by one of us (Chris), this transformation could meet increased global food demands by a growing human population on less than 20% of the world’s existing farmland. Or in other words, these technologies could release at least 80% of existing farmland from agriculture in about a century.

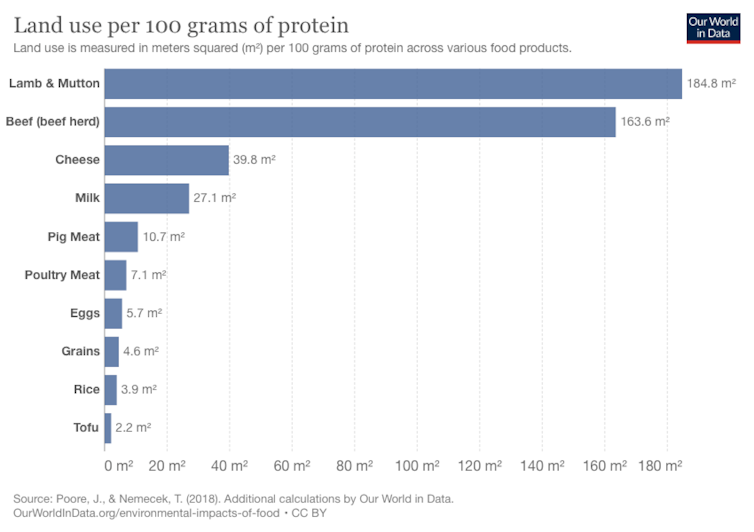

Around four-fifths of the land used for human food production is allocated to meat and dairy, including both range lands and crops specifically grown to feed livestock. Add up the whole of India, South Africa, France and Spain and you have the amount of land devoted to crops that are then fed to livestock.

Despite growing numbers of vegetarians and vegans in some countries, global meat consumption has increased by more than 50% in the past 20 years and is set to double this century. As things stand, producing all that extra meat will mean either converting even more land into farms, or cramming even more cows, chickens and pigs into existing land. Neither option is good for biodiversity.