inbox and environment news: Issue 567

January 15 - 21 2023: Issue 567

The Plastic In Our Waters + The Balloons Killing Wildlife: Local Petition Calls On Council & Surf Life Saving Clubs To Implement A Balloon Ban

Petition: Call For Northern Beaches Council & Surf Life Saving Clubs To Implement A Balloon Ban

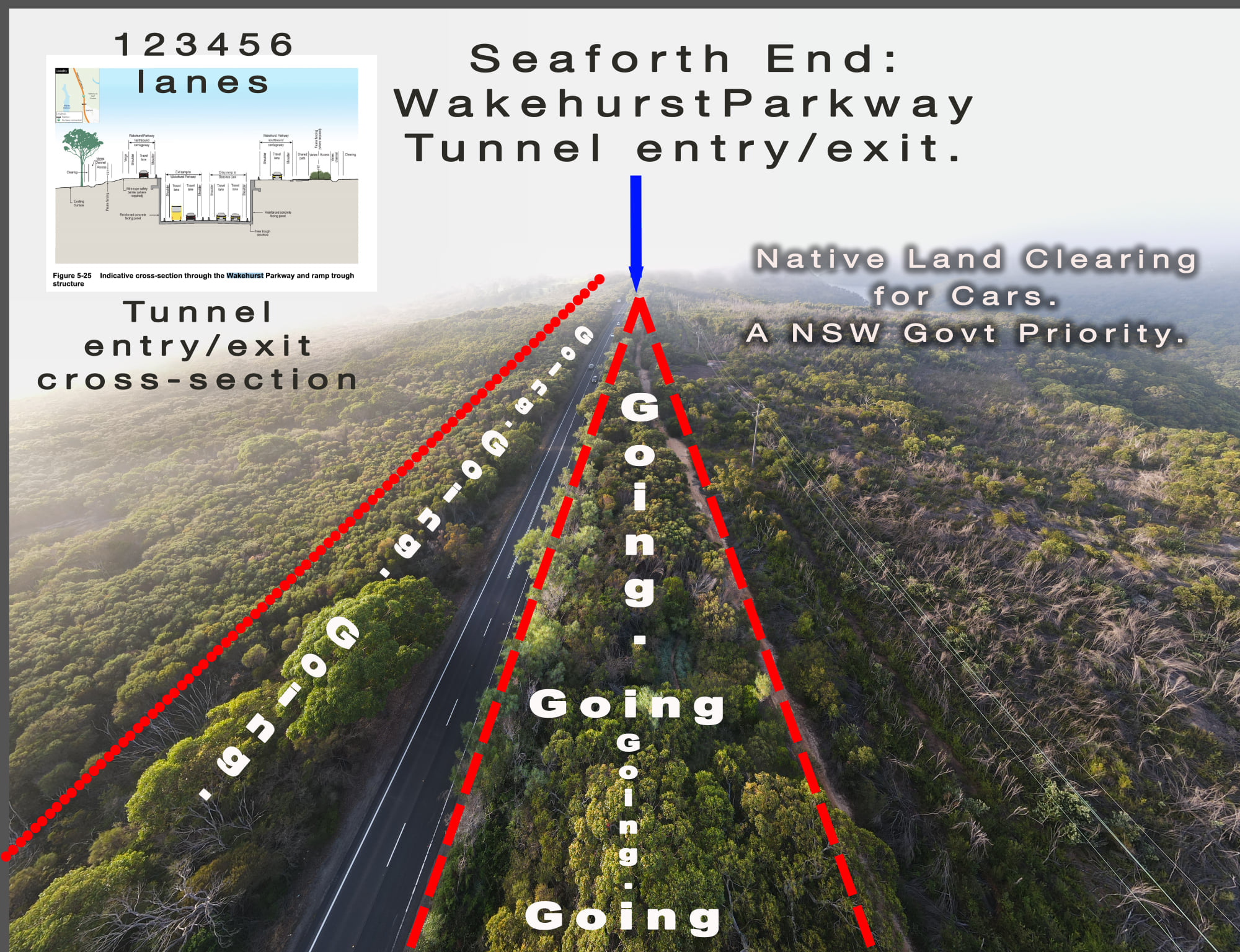

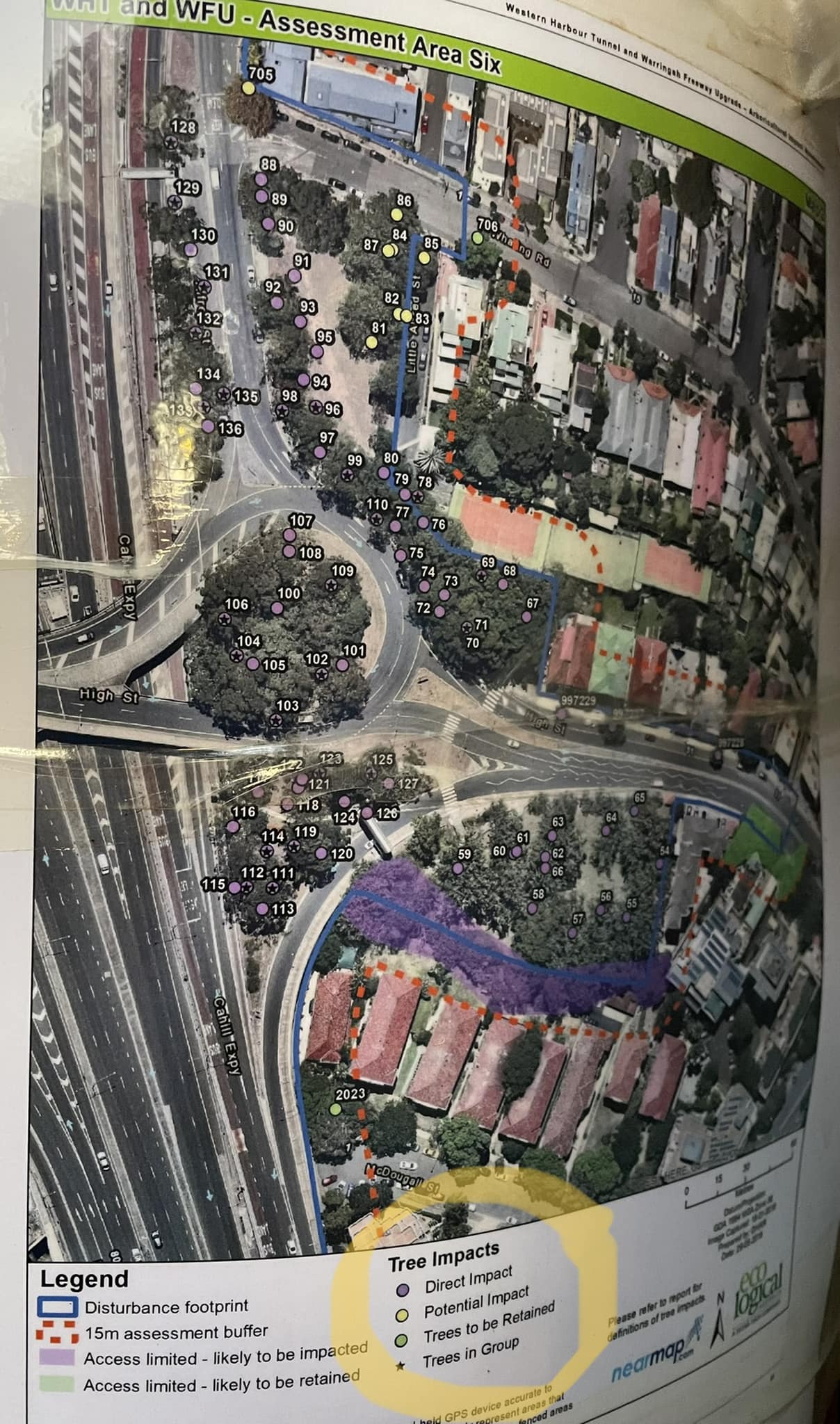

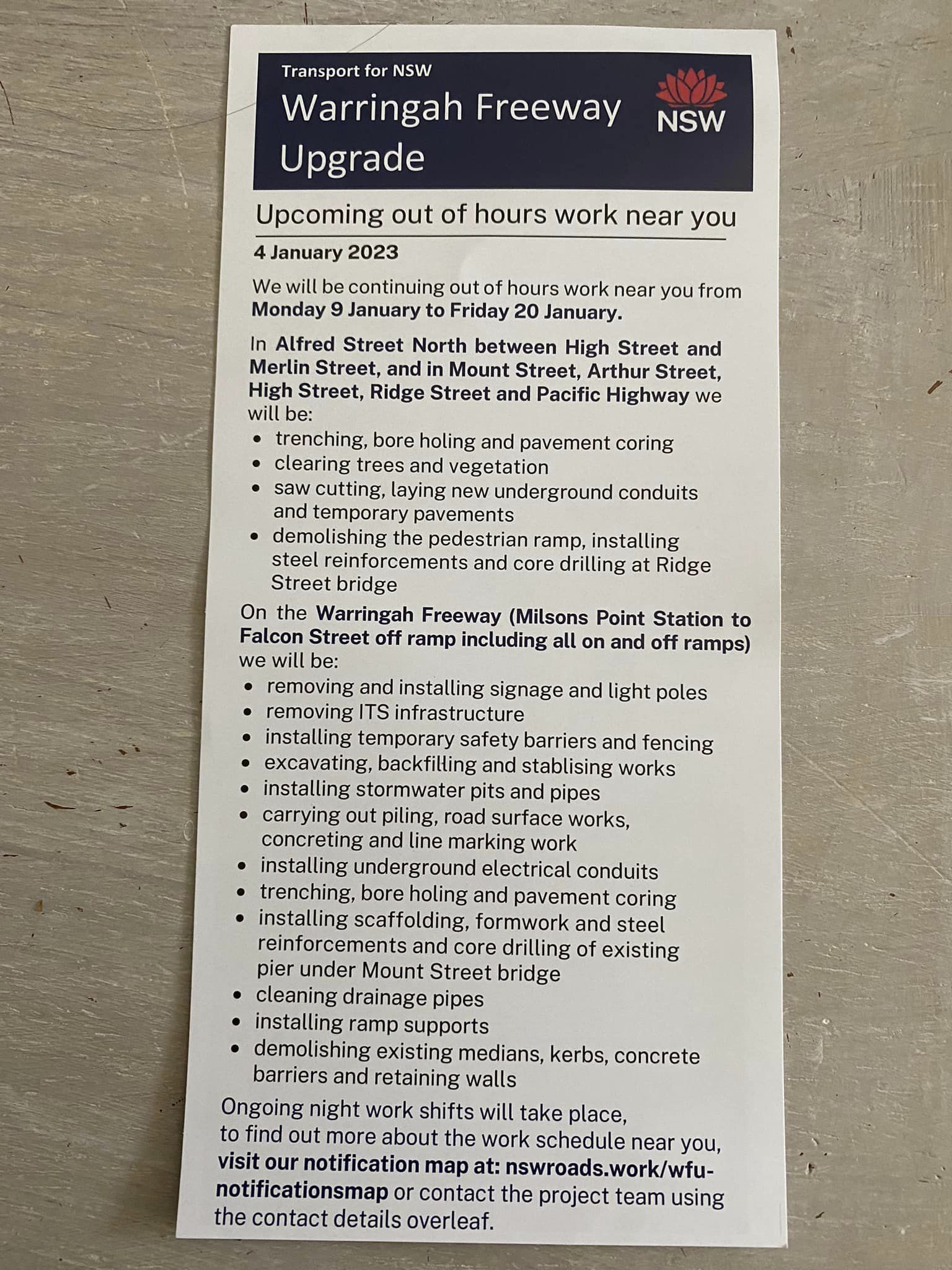

Warringah Freeway Upgrade: Future Beaches Link Tunnel Environment Destruction Apparent In Cammeray Local Residents/Groups State - Just Two Trees To Be 'Retained'

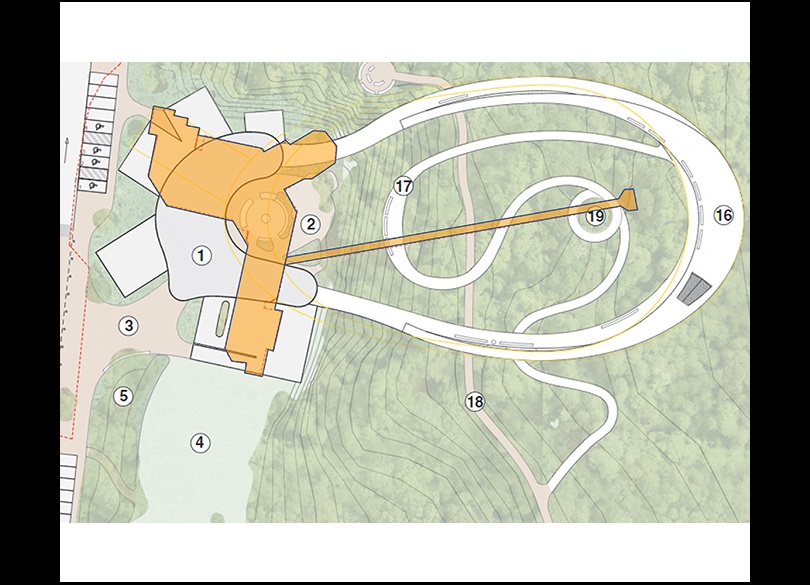

The Upper House Public Works Committee released its report on the impact of the Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link on Monday December 5th 2022.

Chair of the Committee, the Hon Daniel Mookhey MLC, commented: 'This inquiry examined government plans to build two under-harbour motorways in Sydney—the Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link.

'These are large projects, with large price tags, and significant impact on communities they interact with.

The community responded strongly to the committee’s inquiry, contributing more than 575 submissions, with the vast majority opposed to the projects.'

Mr Mookhey continued, 'The committee identified various issues with the planning and justification of the Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link, including that the government failed to adequately consider public transport options, that procurement processes led to delays and extra costs, and that there was a lack of transparency regarding project planning.

The committee makes various recommendations to improve transparency around the projects, noting the importance of properly informing the public ahead of the March 2023 election.'

'Importantly, the committee recommends the government not proceed with Beaches Link, as there has not been an adequate explanation of what its benefits and costs are for the NSW community.

'The committee also makes several recommendations on the impacts of the Projects on air and water quality, and recommendations on managing the impacts of the Projects on three Sydney regions that would be directly affected by construction and operation—the Inner West, Lower North Shore and Northern Beaches.'

The Chair concluded, 'I note that at the time of writing enabling works for the Western Harbour Tunnel have begun, and that the government has recently announced major changes to the way the Tunnel itself is constructed. I put on record my hope that the recommendations of this inquiry and the contributions of its stakeholders are appropriately considered in any decisions the government makes.'

Information about the inquiry, including the committee's report, is available on the committee's website: www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/committees/inquiries/Pages/inquiry-details.aspx?pk=2767

Northern Beaches Council supported the Project, listing it would address high levels of traffic congestion on Northern Beaches, provide a direct connection to the Sydney motorway network, support growth in the Northern Beaches, ′unlock′ parts of the Council′s Hospital Precinct Structure Plan for Frenchs Forest and support additional growth in Brookvale as its reasons for support.

Council expressed its satisfaction with stakeholder and community engagement around the Projects through to the EIS exhibition.

However, St Cecilia's Catholic School Advisory Committee and Northern Beaches Secondary College Balgowlah Boys Campus Parents & Citizens Association expressed dissatisfaction with consultation and planning processes, noting their schools were omitted in the EIS. Northern Beaches Secondary College Balgowlah Boys Campus Parents & Citizens Association further claimed to be ′ignored during preparation of the EIS′ due to the proposal not being substantially changed in response to their concerns and the school not be contacted during EIS preparation.

Environmental impacts in the Northern Beaches were a common theme for stakeholders. Organisations from our area highlighted impacts of Beaches Link on parks, biodiversity, specific flora and fauna, established trees, and waterways either as reasons to oppose Beaches Link or as impacts that need to be addressed.

There are all concerns persisting around the health impacts of air pollution.

The Inquiry was a result the community lobbied for after a 11,000 strong petition to Parliament was effectively dismissed by the government in 2020.

‘’The community have been asking for transparency and real consultation around these multi-billion dollar toll road investments for some time given their extreme impacts and planning documents which simply don't pass the pub test. Many of the major findings reflect what we identified in planning documents 5 years ago and have been lobbying government members to look into for years.’’ one community group has stated

A public campaign championed by Greens MP Jamie Parker, Member for Balmain, has seen the government change its plan to dredge Sydney Harbour between Birchgrove and Waverton and committed to continue boring underground.

The original plan was to dig up thousands of tonnes of toxic sludge from the bed of Sydney Harbour just off Yurulbin Point in Birchgrove. This contaminated sediment, marine biologists warned, was likely to pollute the harbour and threaten up to 70 marine species including seahorses, sea dragons, dolphins, little penguins and seagrasses.

Residents anticipate the same may occur in Middle Harbour.

The Beaches Link tunnel construction is to include two cofferdams to allow construction of the interface structures where driven tunnels will meet immersed tube tunnels. According to the environmental impact statement for Beaches Link the cofferdams will be ′constructed at each end of the Middle Harbour crossing and within the harbour off the shore at Northbridge to the south and Seaforth to the north′. Middle Harbour will be dredged between the two cofferdams to allow a gravel bed and immersed tube tunnels to be placed in the resulting trench.

NSW Opposition Leader Chris Minns stated in October 2021 a Labor government would scrap plans for the $10 billion Beaches Link toll road tunnel and redirected the money into public transport infrastructure for Western Sydney.

"Parramatta's population is set to increase by 204,000, Camden by 227,000, Liverpool by 229,000 and Blacktown by 264,000 over the next two decades," he said.

"Meanwhile, the northern beaches will grow by just 31,000 and Mosman by just 1,000 people over the same period." he told the annual state conference of the Labor party

On December 1st, 2022 the State Government announced that Sydney’s third harbour crossing had reached a major milestone with the $4.24 billion contract to deliver stage two of the project awarded to ACCIONA.

Premier Dominic Perrottet said the new Western Harbour Tunnel would provide a western bypass of the CBD, taking pressure off other major roads across the city and helping commuters move around more easily.

However the City of Sydney Council, in it's October 2022 Submission to Western Distributor Network Improvements proposal, stated the Transport for NSW Western Distributor road network improvements proposal will have substantial negative impacts on people, place and safety in Pyrmont and Ultimo.

'The impacts will also hinder the NSW Government’s ability to achieve its vision and planning aspirations. The proposal: conflicts with NSW Government policy and planning, will permanently increase traffic in Pyrmont and Ultimo, will negatively impact the safety of people in Pyrmont and Ultimo, requires removal of 71 trees, up to 10% of trees across the study area, will impact local communities and public transport during construction and into the future.

The Western Harbour Tunnel will connect to WestConnex at the Rozelle Interchange, cross underneath Sydney Harbour between Birchgrove and Waverton, and connect with the Warringah Freeway near North Sydney via a 6.5 kilometre tunnel with three lanes in each direction.

Minister for Metropolitan Roads Natalie Ward said the new tunnel would be constructed underground with Tunnel Boring Machines instead of being an Immersed Tube Tunnel.

“We’ve collaborated with industry to come up with the best outcome for the local community and the environment, which involves tunnelling underneath the harbour seabed rather than building a tunnel on top of the seabed,” Mrs Ward said.

“We know our population is growing and this is how we make sure our infrastructure keeps pace, supporting a strong economy and a brighter future for everyone in NSW, not just those who use this tunnel.”

Member for North Shore Felicity Wilson said her community would enjoy significant benefits from the project, which will redirect traffic off rat runs on local streets and see the delivery of more green open space.

“Tunnelling means we no longer need construction sites at Balls Head and Berrys Bay in Waverton,” Ms Wilson said.

“I’m enormously excited to be able to return Berrys Bay to the local community and deliver them 1.9 hectares of beautiful foreshore parkland and public space, even earlier than planned.”

The government states that once complete, the Western Harbour Tunnel will cut traffic by 35 per cent in the Western Distributor, 20 per cent in the Sydney Harbour Tunnel and 17 per cent on the Harbour Bridge.

Construction of stage one is already underway. Further community consultation will take place next year ahead of the commencement of major work on stage two in late 2023.

The timing of the State Government's announcement, when it would have been aware the Inquiry report was due for release, has also caused concern, given that the contract to bring the tunnel into Camera was signed off prior to their assessing and responding to what the Inquiry found.

''This inquiry was one of the best submitted to inquiries in recent history with quality submissions from hundreds of community members and well qualified experts (ie Marine Scientists, Asthma Australia, Dr's etc). All committees are headed by various members of parliament under terms of reference - the governments weak argument that the findings are politically biased simply does not hold water as findings are very well evidenced.

In light of the findings a Halt and Reassessment of the plan for the Western Harbour Tunnel post March 23 is absolutely necessary - the extensive further planning required should not be rushed through given the complexity of this project and extent of it's issues. A new cabinet needs to ensure that this project is done right and that we do not bear any further unnecessary risk.

It is time now to cancel the Beaches Link outright - clearly the Environmental Impact Assessment does not satisfy the terms of the Secretaries Environmental Assessment Requirements (SEARS) and there is no business case or public/active transport consideration. The Beaches Link doesn't just need a few amendments it needs to go back to the drawing board with public transport alternatives at it's heart.

Tearing down thousands of additional trees, digging up contaminated Flat Rock Gully and dredging Middle Harbour is not an option worth considering for an unjustified project which simply delivers more traffic into the Northern Beaches.

By rights the Western Harbour Tunnel should likewise be completely re-assessed and re-designed with a new business case produced independent of the pressure of politically timed contracts. How a project can be deemed to have a positive cost benefit ratio with such a fundamental part of the projects design (the harbour crossing and therefore alignment) is almost impossible to understand. The costs of bringing all construction up from Waverton into North Sydney and the loss of some benefits of the original design will have a considerable impact on the BCR.

Fiscal accountability and public transparency around these projects is extremely limited and a great deal of community time has gone into giving feedback over the difficult Covid years. It's time the government showed the community some good faith and proceeded as they should have 5 years ago - with some objectivity and transparency around the need for these toll roads.'' one of the local residents groups has stated.

Another shared this:

Open Letter To Tim James MP

Western Harbour Tunnel Statement From North Sydney Mayor:

North Sydney Council: When Will The Destruction End?

North Sydney Council:A sad update on this story: three of the ducklings have died. Mama duck remains lost, so the other two ducklings have been re-homed in Lane Cove under the care of another duck.With the significant loss of canopy created by the Western Harbour Tunnel project, it’s more important than ever for us to protect the bushland we have left and our native fauna. The tunnels impact register describes the risk to fauna as ‘low’. They are required to rescue fauna during tree clearing.

Who Owns The Beach?

The Australian Coastal Society (ACS) is proud to present the podcast “Let’s Talk Coast” a short series that brings you conversations on coastal issues and projects from around Australia.

Episode 1 – Who owns the beach?

In our very first episode of “Let’s Talk Coast”, Emeritus Professor Bruce Thom and coastal engineer, Angus Gordon, explore issues around beach management, beach access, private ownership and coastal policy.

Known as the founding father of the Australian Coastal Society, Professor Bruce Thom is Emeritus Professor at the University of Sydney and a member of the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists. In 2010, Bruce was awarded a member of the Order of Australia for his services to the environment and advocacy for the ecological management of the coastal zone and as a contributor to a public debate on natural resource policy. Bruce regularly writes blogs for ACS, which can be found here.

Angus Gordon is a coastal engineer and former General Manager of Pittwater Council. Angus has worked on coastal engineering, coastal zone management and planning projects across Australia and the globe, and in 2018 he received an Order of Australia for his services to the environment planning and the community. You can read more about Angus Gordon here.

Both guests bring a wealth of knowledge to the discussion around the question of “Who owns the beach?” and suggest a way forward in protecting Australians right to the beach through national standards.

This podcast is an Australian Coastal Society podcast, produced and hosted by Gretchen Miller.

If you would like further information about this episode, contact us at admin@australiancoastalsociety.org.au

Let’s Talk Coast, was created through the financial support of our donors over the years.

To become a member and find out more about membership benefits, follow this link: https://australiancoastalsociety.org.au/membership-account/acs-membership/

To make a tax-deductible donation and help us continue to be a voice for the coast, follow this link: https://australiancoastalsociety.org.au/get-involved/donate/

This episode was recorded on the lands of the Garigal or Caregal people.

Ringtail Posse 2023: The Generation Witnessing An Extinction Of Urban Wildlife

Australian Shorebird Monitoring Program: Critically Endangered Eastern Curlew Chased Out Of Port Hacking On December 10, 2022 + January 12 2023 - Occurs In Our LGA As Well

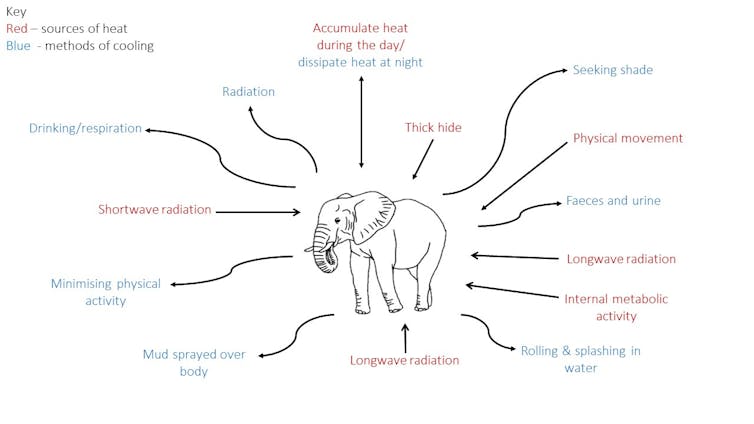

The Eastern Curlew is listed as critically endangered in Australia, with global populations estimated to have declined by 80% in the last 30 years. As a wading bird that travels across our earth, they rely on intertidal mudflats for food and habitat.

Australia is a signatory of the East Asian – Australasian Flyway. The East Asia/Australasia Flyway extends from Arctic Russia and North America to the southern limits of Australia and New Zealand. It aims to protect migratory waterbirds, their habitats and the livelihoods of people dependent upon them.

On Saturday December 10, jetskis and people disturbed this group of Eastern curlews at Port Hacking. One of the monitors that works as a volunteer to protect this bird when it visits our shores filmed the following. This bird comes to Careel Bay too - where people are frequently seen taking dogs in a 'no dogs' area for this very reason.

The volunteer tells us ;

''Yesterday the Port Hacking eastern curlews put up with 6 hours of disturbance in order to get an afternoon feed. This morning after 1 hr and 4 disturbances they decided the energy needed to stay was too great, so flew out to Botany Bay. I had asked these 2 charmers if they wouldn’t mind turning around rather than walk to end of beach to avoid disturbing the roosting curlews. They had already walked almost 2 km having left their kayaks at the other end of the Spit, surely they wouldn't mind giving up the last 100m. Rude response and on they walked.''

Pittwater Online News forwarded this to the Office of James Griffin, NSW Environment Minister for a response - Monday, December 12, 2022.

Late on Friday December 16th a Department of Planning and Environment spokesperson replied with the statement so readily found on the OEH webpages, nothing specific about addressing what is occurring to these critically endangered birds at Port Hacking was broached.

The statement reads:

''Remember to keep your distance. If shorebirds take off or run away as you approach, you are too close.

Eastern Curlews fly thousands of kilometres to get here, typically from Russia and north-eastern China

Every unnecessary flight uses energy and potentially affects their ability to fly home.

There is a saying: Birds in sight – don’t make them take flight!

Migratory shorebirds have travelled a long way so it’s really important they are allowed to roost and feed in peace, to build up their fat reserves before they migrate north.

There are four ways you can help protect our shorebirds -

1. Pay attention to signs or fences

2. Leash your dog whenever you’re on the beach, and only walk dogs on designated beaches

3. Stick to the wet sand and leave the birds space

4. Respect beach-closure signs and beach-driving rules. Only drive on designated beaches

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Within Australia, the Eastern Curlew has a primarily coastal distribution, and in NSW is mainly found in estuaries such as the Hunter River, Port Stephens, Clarence River, Richmond River and the south coast.

The Eastern Curlew breeds in Russia and north-eastern China but its distribution is poorly known. During the non-breeding season a few birds occur in southern Korea and China, but most spend the non-breeding season in north, east and south-east Australia.''

It could have been a very expensive day out for these people had Sutherland Shire Council rangers been there. Once again these critically endangered birds were chased from their feeding and resting area, this time by a dog whose owners deemed themselves a part of that growing pack of humans to whom the law does not apply.

An Australian Shorebird Monitoring volunteer points out for this January 12th 2023 incident they witnessed:

1. Dog in dog prohibited area.

2. Dog off leash in public space that is not a declared off-leash area.

3. Dog rushing at wildlife.

Not shown in this clip:

4. People pointing at birds encouraging dog to “get the birdie”.

The Eastern curlew is listed as critically endangered in Australia, with global populations estimated to have declined by 80% in the last 30 years. As a wading bird that travels across our earth, they rely on intertidal mudflats for food and habitat.

Australia is a signatory of the East Asian – Australasian Flyway. The East Asia/Australasia Flyway extends from Arctic Russia and North America to the southern limits of Australia and New Zealand. It aims to protect migratory waterbirds, their habitats and the livelihoods of people dependent upon them.

These birds are now in a critical phase as they are preparing for the approx. 10 day non-stop flight towards their breeding grounds. Breeding plumage is starting to appear. They are trying to put on weight. This type of behaviour, causing birds to fly, puts their lives at risk. They are using up energy rather than stacking on the weight needed to sustain them during their long flight. They don’t stop along the way to eat. It is only the weight they are carrying that can keep them alive. It’s easy to point fingers at developers or forestry but we also need to consider our own personal behaviour and the impact we are having on wildlife. If we don’t start looking after our wildlife, we are going to lose it.

SECTION 16: COMPANION ANIMALS ACT: DOG ATTACKS

16(1) Dog attacks generally

There is a maximum penalty of $11,000 for owner’s of dogs that rush at, attack, bite, harass or chase an animal (other than vermin) whether or not any injury is caused.

SECTION 17: ENCOURAGING DOG TO ATTACK

17(1) Encouraging a dog to attack generally

There is a maximum penalty of $22,000 for anyone who ‘sets on or urges a dog’ to attack, bite, harass or chase any person or animal (other than vermin).

Section 23(2)(c) gives the Court power to disqualify a guilty person from owning a dog for a specified period of time.

Video: Australian Shorebird Monitoring volunteer, JK

A Failure To Protect Local Wildlife

There is a local context here as well.Careel Bay is a WPA (Wildlife Protected Area) and also part of or one of the places where the Eastern Curlew will land and feed during its Summer sojourn in Pittwater.

Eastern Curlew at Careel Bay foreshore in October 2011 - A J Guesdon photo

Unfortunately, here too, people report the same people doing the same things and their same pet dogs chasing off the wildlife at the same time - for months in a row - with little or no actions taken - again for months in a row. - and despite these being 'no dogs' areas.

People have witnessed owners setting their dogs on wildlife - in WPA's, in creeks, on playing fields that are not offleash areas.

The belief now is the Northern Beaches Council simply does not have enough rangers tasked with curtailing what has become a growing problem.

Rangers will turn up at a place where this is occurring for an hour after months of reports and then be absent again for months in a row. The 'above the law' followers are back within hours, the same day.

As a consequence our area is losing its wildlife.

As another consequence this Council is not honouring its part of Australia being a signatory of the East Asian – Australasian Flyway.

Not only the critically endangered are impacted. The Pacific Black Duck, which has a traditional songline running through our area, going back thousands of years, is being destroyed under this Council's watch by dog attacks on ducklings - on babies - every Spring and every Summer.

These birds are bringing their young along the 'old ways' - the playing fields or drains where creeks once ran - and meet, once again, dogs offleash where they are banned and the same people doing the same thing at the same time - for months on end, unchallenged, or if challenged, threatening physical violence or online and physical stalking and threats of violence.

''People just want these public spaces back.'' the parents of children who have been chased in these areas state.

''We are distressed by the amount of wildlife we are rescuing after a dog has attacked. Many of these we are unable to save.'' wildlife rescuers state. ''There has been so much lately, so many 'rescues'.''

''We did not have this problem under Pittwater Council.'' another states ''They knew where people were doing the wrong thing and made daily patrols to look after residents and wildlife. They made sure they had enough people doing this work. The problem has occurred under the council which was imposed on us and which makes the right noises, those the dog lobbyists like.''

The Ringtail Posse

The critically endangered Eastern Curlew being chased by dogs, along with the thousands of residents who have contacted Pittwater Online News about dogs offleash where they are not meant to be has led to what will be one of the 'subject' series this Community News Service will run in 2023.

This has been named the 'Ringtail Posse' as what is called the 'Common Ringtail Possum' is not so common in this LGA anymore, and a core group of volunteers are collating data, penning insights, saving wildlife, taking photographs, investigating local, state and federal laws and much more.

Residents state that we are, alike those still alive who witnessed the extinction of local koalas, the people witnessing the extinctions of all our urban wildlife.

There has been generation after generation of humans living alongside and with wildlife, until this one.

There is a growing silence at night for those species that forage for food then - owls, wallabies, bandicoots. The same is occurring for those that are active during daylight.

The impacts are not just dog attacks due to irresponsible owners. There is what is termed the 'inconvenient possum' in a roof or garden shed, because its home tree has been cut down. These are caught by those hired, some of whom have little knowledge or scruples, and release them into areas out of their home range - a death sentence for that possum as this species is territorial, along with requiring certain food trees in order to eat, to survive.

There is predation by other introduced species - readers regularly send in photos and videos of foxes or cats roaming and killing at night.

There are roadkill black spots, places where wallabies or turtles or possums used to cross the area where a road has been cut through and a speed limit that means death for wildlife. There are no 'speed humps' in place, and no plan at a local, state or federal government level to do so. Residents and wildlife rescuers have reported some drivers 'aiming straight for' a stricken animal.

There is the razing of blocks of land for development prior to any required assessment of the environment taking place to circumvent those requirements so a report can state 'nothing present'. There is nothing present because its habitat has been cleared or the wildlife killed by these actions.

At the 2021 LGNSW a Motion to address the same was passed - but has not, as yet, been ratified at NSW State Government level. In fact, the incumbent government is still passing approvals to raze Listed critically endangered woodlands and species - such as Sydney's Koalas.

An overview of that long overdue structure is available in the October 2022 report:

Coupled with those who will illegally or legally kill trees that 'block their view' this generation is witnessing local extinctions, and a possibly permanent silence.

Our area already has thousands of local wildlife impacted annually and that number has risen from around 4000 each year to over 5000.

Data to 30 June 2021 lists of the 5, 235 animals rescued during that 2020 to 2021 period just 1,573 were released. There have been thousands more rescued since then, the bulk of which are not re-released.

As a result of those thousands of resident voices Pittwater Online News is finalising that series of Reports/Profiles that will run. At present we would like to hear from anyone who knows they have bandicoots still living in or visiting their yard.

Please email us if you do, we would like to hear from and talk to you - pittwateronlinenews@bigpond.com - Thank you very much in advance.

There's some background on our local bandicoots, also now seldom heard, in Bandicoots: Friends Or Foes? - a 2016 report by one of our local wildlife rescuers and carers.

Long-nosed Bandicoot, Northern Beaches, New South Wales. Photo: J J Harrison.

Prune Viburnum Hedge Agapanthus Flowers To Prevent Spread Into Bush Reserves

PNHA: January 11, 2023

Now is the time to prune the berries off the Viburnum hedge and dehead those old Agapanthus flowers. Put these prunings into your green waste bin. Both are now weeds of bushland as their seeds travel.

Photos: Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA)

Sydney Wildlife (Sydney Metropolitan Wildlife Services): Rescue Care Course - February 2023

Our next course starts on the 4th of February. It runs for 3 weeks in a self-paced format online and then a 1 day practical session at the end on the 26th February. Both sessions must be passed to join Sydney Wildlife Rescue and rescue and care for our native wildlife.

Visit the sign on page for full details: https://smws.wildapricot.org/RCC-Trainee-Application-Form

The cost of the course is $120 and you will receive membership, manuals and equipment to help you. All new members are fully supported with a mentor when they join. Join us and make a difference to the wildlife in your area.

Summer Visitors: Scaly-Breasted Lorikeet Pair

The Scaly-breasted lorikeet, Trichoglossus chlorolepidotus, was first described by German zoologist Heinrich Kuhl in 1820. Other names this bird is known by include the gold and green lorikeet, greenie, green lorikeet, green and yellow lorikeet, and green leaf. It is often colloquially referred to as a "scaly''. Their specific epithet is derived from the Ancient Greek root khlōros 'green, yellow', and lepidōtos 'scaly'. Sexes appear the same, with green upper-wings and body, marked with yellow 'scales' on the breast and neck. In flight, Scaly-breasted Lorikeets have two-tone, red-orange underwings with grey trailing edges. They are much shorter-tailed than Rainbow Lorikeet. Their call is similar to Rainbow Lorikeet, but smoother and less squawky.

Scaly-breasted Lorikeets feed in flocks, sometimes joining flocks of Rainbow Lorikeets. They feed on nectar and pollen that they harvest with their brush-tongues, mostly from eucalypts, but also from shrubs such as melaleucas, callistemons and banksias.

Scaly-breasted Lorikeet females lay their eggs on a bed of decayed wood in a hollow limb, or where a branch has broken from the trunk of a eucalypt tree, at a height of between 3 m and 25 m above the ground. Both the male and female modify the nest hollow by chewing off pieces of wood, and this can take six weeks. Only the female incubates the eggs, but the male feeds her on the nest. Both sexes feed the young.

Information: BirdLife Australia. Photos: A J Guesdon/Pittwater Online News, taken PON yard 7.15am January 11, 2023

New Marine Wildlife Group Launched On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Updated Report On Koala Response To Timber Harvesting Released By NSW Government's Natural Resources Commission: States Logging Does Not Impact Koala Density

On December 22nd 2022 the NSW Government's Natural Resources Commission released the final updated report on koala response to harvesting in NSW north coast state forests. This report includes new findings from recently completed DNA diet analysis for koalas and additional advice on implications for management and recommendations.

The authors of The 'Koala response to harvesting in NSW north coast state forests' - Final report (updated) December 2022, state the overall research findings and their substantive advice outlined in the previous version of the report (2021) have not changed.

''The research found selective harvesting did not adversely impact koala density, nor the nutritional quality of koala habitat. This suggests the koala protections and wider landscape protections codified the Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval (Coastal IFOA) are effectively mitigating the risks from selective harvesting to date at the research sites.'' their statement reads

Research insights included that koala density was higher than anticipated in the surveyed forests and, as noted above was not reduced by selective harvesting according to the authors

the report states koala density was mostly similar between state forest and national park sites, selective harvesting at the treatment sites did not significantly change canopy tree species composition and, therefore, is not expected to impact on nutritional quality of koala habitat, and tree species composition is the key determinant of habitat nutritional quality for koalas

Tallowwood (Eucalyptus microcorys) and small-fruited grey gum (E. propinqua) were confirmed to be important diet species, in alignment with the Coastal IFOA koala browse tree list

Spotted gum (Corymbia maculata) and ironbarks (E. paniculata, E. siderophloia), while not included on the Coastal IFOA browse tree list were browsed by koalas to a considerable extent.

The report recommends opportunities to improve outcomes for koalas, including reviewing koala browse trees listed under the Coastal IFOA.

The 2021 version was met with scorn by the North East Forest Alliance (NEFA) which stated that the assertion by the Natural Resources Commission (NRC) report that logging of koala feed trees doesn’t have any impact on koalas is ‘dangerous propaganda’.

‘It further threatens their survival by denying koalas the increased protection they urgently need,’ said NEFA said spokesperson Dailan Pugh.

NEFA explained that the use of koala recordings that indicate the presence of a koala somewhere in the vicinity is not appropriate for detecting the impact of logging on koalas. They said they do not accept the NRC claim from DPI Forestry’s fundamentally flawed study that ‘the Coastal IFOA conditions and protocols did not adversely impact koala density’.

‘This is contrary to the EPA’s 2016 study that found “areas of higher activity positively correlated with greater abundance and diversity of local koala feed trees, trees and forest structure of a more mature size class, and areas of least disturbance”,’ said Mr Pugh.

‘The NRC’s pretence that the Forestry Corporation can log the large trees that koala’s are preferentially feeding on and have no impact on koalas maintains a dangerous fallacy. That fallacy is one of the reasons why koala populations on the north coast had declined by 50 per cent in the 20 years before the 2019/20 fires.’'

The significant impact on koalas of the 2019/20 fires was confirmed by the NRC, however, Mr Pugh said the NRC failed to propose anything ‘to mitigate impacts’ of logging on those areas.

‘It is particularly concerning that the NRC has not reconsidered its decision in 2016 to over-ride the advice of the EPA and the government’s Expert Fauna Panel that minimum retentions of koala feed trees should be 15–25 feed trees/ha greater than 25cm diameter at breast height (DBH) in modelled habitat.

‘The NRC intervention to reduce the retentions to 5–10 feed trees/ha and sizes to 20cm DBH is not supported by this study.

‘Strangely the NRC have not released results from this study on koala preferences for tree sizes, instead stating their results are “consistent with previous studies at sites in northern NSW and the Sydney region that found koalas use trees ranging from 30 to 80 centimetres DBH”. This is far greater than 20cm trees.

‘This study reaffirms that koalas chose certain tree species for food, and then individual trees with relatively low amounts of toxic compounds, emphasising the need to retain all individuals of preferred feed species rather than the arbitrary 5–10 feed species per hectare specified by NRC (2016).

‘The study also identifies that koalas use Flooded Gum as a feed tree and Turpentine as a roost tree, yet the NRC makes no attempt to add these to the species requiring retention for Koalas.

‘The NRC were meant to review the adequacy of the existing logging prescriptions, but instead have relied upon a fundamentally flawed assessment by DPI Forestry to claim that logging has no impact on Koalas to justify not reviewing the clearly inadequate logging rules. Even though NRC admitted the impacts of the fires it similarly failed to recommend any changes to account for them. The NRC have failed koalas in their time of greatest need,’ Mr Pugh said.

In its 2022 updated version the Commission recommends that the Committee should review the Coastal IFOA koala browse tree list, with support from experts for the upper and lower north-east subregion, to ensure that the highest value browse species are retained and to advise on whether to list ironbarks (particularly E. paniculata and possibly E. siderophloia), flooded gum (E. grandis) and spotted gum (C. maculata) as secondary browse species and elevate small-fruited grey gum (E. propinqua) from a secondary to primary browse species.

Further, the Committee should analyse the potential impacts to wood supply and other environmental risks of such adjustments to the Coastal IFOA koala browse tree list.

Current regulations to retain clumps of habitat that provide a mix of species and tree size classes for both food and shelter throughout the landscape should be maintained, taking habitat connectivity into consideration.

After consideration by the Committee, the Commission will advise the Chief Executive Officer of the NSW Environmental Protection Authority and the Director General of NSW Department of Primary Industries to inform the NSW Government’s five yearly review of the Coastal IFOA.

The Commission also recommends that the EPA and DPI request the Coastal IFOA monitoring program undertake further analysis of nutritional value and contribution to koala diet of New England blackbutt (E. andrewsii) and other potentially low-use koala species (including: narrow-leaved peppermint, E. radiata; ribbon gum, E. nobilis and E. viminalis; messmate stringybark, E. obliqua; snow gum, E. pauciflora; mountain gum, E. dalrympleana; New England blackbutt, E. campanulata) with the view of improving the Coastal IFOA koala browse tree list.

The 2022 updated report is available to download at: https://www.nrc.nsw.gov.au/koala-research

Photo: WWF

NEFA Campaigner Susie Russell Arrested At Save Bulga Forest Protest: Protest Spreads To Lorne Forest As Well

In related koala and NSW Forestry Corporation news, long-time forest campaigner and North East Forest Alliance (NEFA) spokesperson, Susie Russell, was arrested on Monday January 9th at Bulga State Forest, and given bail conditions prohibiting her from entering into any part of the Bulga Forest.

The arrest came as the Save Bulga Forest community ramped up their campaign of civil disobedience calling for an end to logging native forests and in particular the Bulga Forest.

“It was clear I was singled out for arrest”, Ms Russell said. “There were about 30 people on site supporting the young tripod-sitter. I was there, but diligently keeping outside the boundary of the closed area, which was tricky because the distance that was closed was not specified in the closure notice, so I erred on the side of caution.

“Police arrived on the scene just after 7am and spent half and hour walking around talking to different participants. They then went back to their vehicles for a huddle, presumably discussing how they were going to approach the situation. During that time the forest protectors were milling around and chatting in small groups.

“I left the area near my vehicle and walked the 30 odd meters to make sure the tripod-sitter was ok. When I got there, there was a child hugging an adult size koala. I took a couple of photos and then walked back around to my vehicle. The whole exercise took about 5 minutes.

“Almost immediately afterwards the police inspector approached me by name and said I was under arrest for entering a prohibited area. This while there were plenty of people making merry in the “prohibited” area and several colleagues in a similar situation to mine, freely moved backwards and forwards to chat.

“I have no doubt I was arrested in order to try and limit my involvement in the campaign. It has however, made my resolve stronger.

“I have watched the forests of my region being steadily degraded over three decades. In the 1990’s a spotlighting trip through these forests would reveal dozens of Greater Gliders. Now we are lucky to see one. There is nothing ecologically sustainable about this logging. It is smash and grab and runs at a loss. These forests will take centuries to recover.

“I feel I owe it to young people and to those lives without voice, to not stand by in silence while the destruction continues. I will continue to speak for the trees,” Ms Russell said.

Susie Russell at Bulga Forest. Image supplied.

The Bulga Forest is found between the Biriwal Bulga National Park, Tapin tops National Park and The Cottan-Bimbang National Park.

The Save Bulga Forest group states that logging forests where surviving koalas are seeking refuge, forests that didn’t burn as fast and hot as the surrounding area, makes absolutely no sense.

On Thursday January 12th the members released the following:

Forest Action Spreads To Lorne Forest

Media Release January 12, 2022

At 5am this morning, access to the logging machines that have been actively munching their way through Lorne State Forest, on the mid north coast, was blocked by a forest protector on a tree platform suspended over the road.

Barry, a Lorne local, doesn’t want to give his surname, but his neighbour, Jane McIntyre, was the spokesperson for the action. She said there was a growing concern among Lorne locals about the destruction happening in the forests, and that she could no longer stand by and see their local forest and water catchment security, heading down the road on trucks.

Jane McIntyre has lived in Lorne for 14 years. She has lived adjacent to state forests since 1980, and has witnessed the escalating industrialisation of the logging industry, and the simultaneous degradation of the forests to young regrowth without habitat trees to support wildlife.

Now retired, Jane has worked as a science educator and community development coordinator. This grandmother of 3 small children fears that they will grow up in a world without healthy forests that shelter wildlife such as quolls, gliders and koalas.

She is determined to do all she can to prevent that. “Yes, of course we need wood “, she says, “but instead of clearfelling our remaining native forests, we should be leaving them alone and growing genuine plantation on marginal farmland. These forests have been hit by unprecedented droughts, fires and floods- and now the survivors are being intensively logged. Trees are the best known way of drawing down carbon in our climate emergency. Even the NSW Government’s own Natural Resources Commission states that native forest logging is uneconomical and unsustainable. It’s time to stop now, before we lose more species.”

“Inspired by the action of the Elands community standing up for the Bulga Forest, we reached out for some assistance to enable us to do the same, and make a public statement that we will no longer stand idly by and watch the daily destruction.

“We know that a majority of people in NSW, think that the ongoing logging of our publicly owned forests is sheer madness. The time is now. It has to stop".

Background

On February 21st 2018 the NSW Dept. of Primary Industries announced the NSW Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) were undergoing a review and renewal process, which included an opportunity to update and improve the content to capture emerging issues.

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) Group Director, Forestry, Nick Milham, said then stakeholder feedback is imperative at this stage and views will help shape the renewed agreements.

“The consultation is a genuine chance to influence what form the NSW RFAs take for the sustainable management of our native forests for decades to come,” he said.

Mr Milham said they and the then coalition federal governments had conducted in-person stakeholder meetings and public drop in sessions in Lismore, Coffs Harbour, Bulahdelah, Eden, Batemans Bay, Tumut and Sydney throughout February.

“In the sessions, we have heard from many environmental groups, industry members, local governments, the community and recreational forest users – providing a great insight into the key priorities and opinions of each group,” he said.

“Feedback, questions, criticisms and endorsements have been welcomed throughout the sessions and it has been great to hear the community’s views first-hand.

“The NSW Government has the difficult role of balancing the economic, social and environmental demands on forests, but there is sound logic, underpinned by peer-reviewed, internationally published science, to renew RFAs.

“The only decisions that have been made so far are that the RFAs will be renewed and that their objectives and geographical regions will remain unchanged – the rest is on the table.”

At that time the NSW Nature Conservation Council stated the Berejiklian government was putting threatened forest wildlife and an historic 20-year peace deal at risk by pushing ahead with a sham consultation process designed to lock in unsustainable logging indefinitely.

- Consider whether the RFAs are a suitable model for forest management.

- Complete the RFA 10- and 15-year reviews before beginning negotiations on the RFA renewal.

- Complete a socioeconomic assessment of all land-use options that considers, among other things, climate change impacts and the potential use of forests for carbon capture and storage.

- Establish a fair process for RFA renewal negotiations, with balanced representation and moderation by a credible, independent third party.

- Guarantee there would be no pre-emptive decisions (i.e., no new Wood Supply Contracts) before the end of the process.

January 12th, 2023. Photo: Save Bulga Forest on Biripi Country 2429

January 12th, 2023. Photo: Save Bulga Forest on Biripi Country 2429

Gloucester Knitting Nannas at Save BulgaForest Falls Camp, January 12th, 2023. Photo: Save Bulga Forest on Biripi Country 2429

Kurri Kurri Lateral Pipeline Approved By NSW State Government

December 27, 2022

The NSW Government has granted planning approval for a new pipeline to deliver natural gas to the future 660 mega-watt gas-fired power station in Kurri Kurri.

Minister for Planning and Minister for Homes Anthony Roberts said the underground pipeline was the crucial link to deliver natural gas from the transmission network to the Hunter Power Project.

“This pipeline will enable the Hunter Power Project to improve energy reliability and security in the National Energy Market, supporting the surge of renewable energy projects,” Mr Roberts said. “The power station will provide on-demand energy when the grid needs it, and will operate on average two percent over a year.”

Snowy Hydro Acting CEO Roger Whitby said the project, coupled with the Hunter Power Project, would be a huge win for the region.

“Together, this pipeline and the Hunter Power Project equate to more than $800 million in spending and 650 construction jobs,” Mr Whitby said.

APA CEO Adam Watson welcomed the NSW Government’s approval of the Environmental Impact Statement.

“As coal is withdrawn across the National Electricity Market at ever increasing rates, gas and gas infrastructure will continue to play an important role in our energy mix by complementing renewables and helping to underpin the energy transition,” Mr Watson said.

“The approval follows a thorough review of the EIS which addresses how the pipeline will be built and operated safely, and how APA plans to continue to work collaboratively with landholders and the community.” Mr Watson stated

The pipeline will provide natural gas to the Hunter Power Project at Kurri Kurri via a connection to the existing gas transmission network at Lenaghan. The power station is being built on part of the site of the former Kurri Kurri Aluminium Smelter, which ceased operations in 2012, and has since been demolished.

However, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis had stated the Kurri Kurri Gas Lateral Pipeline project should have been rejected.

''The Kurri Kurri Lateral Pipeline project – Environmental Impact Statement points to a vastly different project to the Kurri Kurri Gas Power project that was approved by the Independent Planning Commission.'' the Institute said in May 2022

''Snowy Hydro maintained that the Kurri Kurri gas power project would cost $600m with a further $100m for the gas lateral. The budget has blown out by $164m to $600m for the power plant and $264m for the gas lateral and storage system. Snowy Hydro will lease the gas lateral and storage system off APA. The $264m cost for the gas lateral understates the true cost to Snowy Hydro as it is before financing costs and a profit margin for APA, the owner of the asset.''

Further, ''The Kurri Kurri Gas power project is not “hydrogen ready” for even the smallest percentages of hydrogen blends as the gas storage system proposed in the Kurri Kurri Lateral pipeline EIS is not hydrogen compatible.''

The Kurri Kurri Lateral Pipeline project is a plan to develop a ~21 km underground gas pipeline from the existing Sydney to Newcastle pipeline to the Hunter Power Project near Kurri Kurri, a compressor station and a 24 km underground gas storage pipeline and ancillary infrastructure.

The application, Environmental Impact Statement and accompanying documents were on exhibition from Wednesday 13 April 2022 until Tuesday 10 May 2022 and the project was listed as 'State Significant Infrastructure' by the Liberal-Nationals Government.

The project will now be submitted to the Commonwealth for final approval, which if granted, with the State Government stating they expected to allow construction to begin in the following months.

For more information, visit the NSW Planning Department's For more information, visit the NSW Planning Portal Kurri Kurri Lateral Pipeline Project webpage.

NSW Government Lists 99-Year Lease For Historic Cadman's Cottage Consultation During End Of Year Break: Closes Same First Week Of New Year

The NSW Government's Department of Environment and Heritage listed historic Cadman's Cottage as open for a 99 year lease on December 14th, 2022, with public submissions on their proposal closing on January 4th 2023, a 21 day 'consultation' period.

The webpage listing the 'Have your say' details states;

'Pursuant to Section 151 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974, the Minister administering the National Parks and Wildlife Act proposes to grant Place Management NSW ABN: 51 437 725 177 (PMNSW) a lease to use Cadmans Cottage Historic Site for the purposes of:

- heritage interpretation

- provision of tourist information for the lessee and lessor

- use as a museum

- use as an Aboriginal cultural centre

- provision of food and beverage facilities and amenities for visitors and tourists

- event activation

- provision of facilities to enable the hosting of conferences or functions ancillary to facilities and amenities for visitors and tourists in accordance with all applicable building codes, safety regulations and laws

- any purpose that enables the adaptive reuse of an existing building or structure or the use of a modified natural area as mutually agreed between the parties in writing.

The proposed term of the lease is 99 years.'

Opponents of the proposal state this is just another example of the Liberal-National Government excising a public owned property from the public, and point to the timing of the consultation as flawed and yet another instance of the incumbent government making announcements or conducting consultations when the community has effectively 'clocked off' from politics and politicians for the year.

''Yet another 'done deal' snuck through by this government under their usual tick a box modus operandi, and as usual, it wouldn't matter how many people oppose this, they will push it through anyway ''.

Cadmans Cottage or Cadman's Cottage is a heritage-listed former water police station and sailor's home and now visitor attraction located at 110 George Street in the inner city Sydney suburb of The Rocks in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. The property is overseen by the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, an agency of the Government of New South Wales. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

Free guided tours of the grounds and bottom level of the house were available. They ran on the 1st and 3rd Sunday of each month from 9.45am to 10.15am, excluding public holidays.

However, NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service advises on their Cadmans Cottage webpage that these are currently suspended and will resume later in 2023.

Place Management NSW is a State Government Entity. Place Management NSW (part of Place Design & Public Spaces) is responsible for managing Sydney’s most historically and culturally significant waterfront locations, including Sydney’s heritage and cultural precincts at The Rocks and Darling Harbour.

Place Management NSW was also responsible for the management of the Public-Private Partnership delivering the new ICC Sydney convention, exhibition and entertainment venues in Darling Harbour.

Front view of Cadman's Cottage at The Rocks. Photo: Julioenrekei

A 20+ Years Of Excluding The Public From A Public Asset?: Gardens Of Stone Leases To Privatise Yet Another NSW National Park 'Consult' Listed Over Christmas-New Years Break By State Government - Same Announces Tourism Company For 'Lost City' Tourist Accommodation In Gardens Of Stone

The new Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area Plan of Management was adopted by the Minister for Environment and Heritage, Manly MP James Griffin on 7 November 2022 - this included 'proposed' Commercial activities of a lease of 4 of the 5 areas identified as supported accommodation AND the development and operation of elevated walkways, zip-lines (the 'longest one in Australia'), rope swings, high ropes, via ferrata and flying-fox infrastructure in the Lost City adventure activity precinct.

On December 21st 2022 the incumbent State Government listed a 'Have your Say' page Notice of intention to grant a 20 year lease to Wild Bush Luxury Pty Ltd and Trees Adventure Holdings for what was in that PoM ticked off just weeks before. The 'consultation' closes January 18th 2023 - while residents of NSW are coming back from having clocked off.

Under the National Parks and Wildlife Regulation 2019, section 24 'Commercial activities', (1) A person must not in a park—

(c) compete with or hinder the commercial operations of any person, business or corporate body possessing a lease, licence, occupancy or franchise from the Minister or the Secretary for a specific purpose or purposes

This instance points to the 'step by step' process of those following the incumbent government's policies, as instructed, and shows what could/or is planned to happen at Barrenjoey. That too lists 'Commercial Activities' for the Barrenjoey Headland precinct.

In November 2021, the Liberal-National Government declared 31,500 hectares of the Gardens of Stone north of Lithgow would become a state conservation area, with Premier Dominic Perrottet stating their plan the "most important environmental announcement this government has ever made".

The new reserve were established by legislation introduced that same month by

- Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area (total 28,944 ha) created by the transfer of Newnes, Ben Bullen and Wolgan State forests and Crown land

- additions to Gardens of Stone National Park (342 ha) from Crown land

- additions to Wollemi National Park (2259 ha) from Newnes State Forest.

The coalition government's plans differed from what had originally been proposed by the group, called the Gardens of Stone Alliance, which wanted low-impact eco-tourism ventures, like bushwalking and camping. In a bid to campaign for the full protection of the Gardens of Stone The Blue Mountains Conservation Society has joined forces with two other prominent environmental organisations, Colong Foundation for Wilderness and Lithgow Environment Group.

"[The government] is thinking that will generate more people, more money into the area at a quicker rate," Julie Favell from the Lithgow Environment Group told the ABC

Listed as critically endangered koalas, spotted-tailed quolls and regent honeyeaters are some species which call the area home.

The Gardens of Stone Alliance is asking NSW residents to object to these lease proposals, stating:

''When the Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area was announced on November 13, 2021, the NSW Government also announced an adventure theme park at Lost City and exclusive accommodation in association with a Great Walk.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service is seeking public comments on its intention to grant 20 year leases for these two proposals in parts of the Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area. The period for comments is in the holiday period closing on 18 January. The parent company involved with these proposals is Experience Co, the same company that has plans to develop the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.

[we ask people to ]Object to these leases, that will privatise parts of this conservation reserve, [and this being done so] before the public has an opportunity to comment on the details of these developments.

The proposed locations and extent of the accommodation are only approximate and not clearly defined on the simple map provided. Likewise the location of “ziplines, via ferrata and suspension bridges” and other requirements for the Lost City Adventure Precinct. This means that the possible environmental impacts of the proposed lease are hard to identify, let alone avoid them and protect the area.'' the group states

''Ticking the consultation box without information is a sham process. Very limited information is available in the public exhibition of the notice to grant leases.

[Please] Express your concerns about the development threat to this important Blue Mountains reserve before close of business, 18 January 2023.

For more information and assistance with making a submission, go to the gardensofstone.org.au website''. the Gardens of Stone Alliance states

You can provide your written submission via email to: Commercial.Enquiries@environment.nsw.gov.au

On November 16th 2022 the State Government announced it had adopted its Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area (SCA)Plan of Management. This includes drive-in camping facilities in the former Forest Camp, including 100 plus tent sites, toilets, camp kitchen shelter, access to adjoining walking and a MTB track network.

It also includes 'parking and a varied range of other facilities (toilets, picnic tables) at relevant trailheads, to 'Improve facilities to lookout points generally', NSW's first Via Ferrata rock-climbing opportunity, a protected climbing route employing steel cables, rungs or ladders fixed to the rock, Australia's longest zipline and an elevated canyon walk'.

On December 21st 2022 the coalition government announced the Lost City precinct was now ready to move forward through a partnership between the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and Experience Co.

The government states ''the partnership follows a competitive Expressions of Interest (EOI) process which will see Experience Co working with NPWS to bring to life plans for the park's new multi-day walk including overnight accommodation and the Lost City zipline adventure experience.''

Head of NSW National Parks Atticus Fleming said the 31,500 hectare Gardens of Stone reserve will deliver diverse experiences catering for all visitors, alongside dedicated conservation programs to protect the exceptional values of the new reserve.

"Thanks to a $50 million dollar investment from the NSW Government, the new reserve will host an array of nature-based options including accessible family-friendly camping areas, bushwalks, lookouts and four-wheel driving routes.

"There will be something for everyone as the reserve will also feature a network of mountain bike tracks catering for all abilities, canyoning and rock climbing.

"The Gardens of Stone's ancient sandstone pagoda formations and canyons will be showcased by the Great Walk, which will link the new State Conservation Area to Wollemi National Park, providing visitors an opportunity to take in outstanding views of this special place, which is home to over 80 rare and threatened species, including koalas and regent honeyeaters."

The first stages of the multi-day walk will be open in mid-2024, the government states.

The zip line and via ferrata experiences at Lost City are projected to open in December 2023.

The planned 'low impact eco-accommodation and public campsites' are also part of this announced private-government partnership.

Experience Co Chief Executive Officer John O'Sullivan said the company was delighted to be selected to partner with NPWS to help deliver 2 exciting new tourism experiences.

"Building on our expertise developing sustainable tourism products in sensitive locations, we are looking forward to creating new experiences that elevate the region and engage with this unique area of NSW as well as recognise the importance of this ancient landscape to Wiradjuri people," he said.

The Government states the Gardens of Stone SCA is expected to attract up to 200,000 new visitors, create around 190 local jobs and generate up to $30 million in regional economic activity each year.

It also states all visitor infrastructure will be subject to rigorous environmental and cultural approvals to ensure effective protection of ecological and cultural values.

The '$50 million dollar investment from the NSW Government' is, of course, from the pockets of taxpayers, despite these announcements keyed to sound as though the government has given the money from the pockets of the politicians who make these announcements.

One resident of the area has stated, ''This is an environmental disaster in the making. All the result of grubby political deals done behind closed doors. The government should hang its head in shame if this is what it calls protecting the unique conservation values of this special place.''

In Tasmania, the only state or territory other than NSW where a Liberal government is still in power, there has been widespread opposition to that incumbent government's privatisation of National Parks.

On June 8th 2022 the Wilderness Society coolly welcomed proposed minor changes by the Tasmanian Government to its discredited ‘tourism expressions of interest’ process that lets commercial tourism developers into the national parks there.

“Given the near-universal unpopularity of and widespread public opposition to the Hodgman, Gutwein and now Rockliff Government’s continued parks privatisation push, business as usual wasn’t really tenable although these changes don’t go far enough,” said Tom Allen, Tasmanian campaign manager for the Wilderness Society.

“Thanks to the public standing up for their public national parks, these proposed changes are the result of strong, sustained and near-universal public opposition to the parks privatisation push and show the need for stronger Community Rights.

“While everyone else has to abide by the state planning laws and environmental assessment requirements, the tourism EOI process creates a low-bar loophole, through which can waltz commercial tourism operators to exploit some of the most ecologically-important lands anywhere, with minimal obligations or oversight. This makes a mockery of the Tasmanian Government’s aspirations to be a global ‘ecotourism’ leader. They should be raising not lowering the bar for these special places.

“It continues to be unacceptable that the Tasmanian Government solicits commercial tourism proposals that breach the Statutory Management Plan for the world’s highest-rated World Heritage wilderness.

“As Experience Co/Wild Bush Luxury’s current plans to commercialise the South Coast Track show, until the Rockliff Government takes the parks privatisation policy and the tourism EOI ‘process’ off the table, the threat to the ecological integrity – and to that of palawa/Aboriginal cultural values – of national parks and World Heritage wilderness remains,” said Mr Allen.

The privatisation and excluding the NSW public from the Gardens of Stone is not the only 'development' proposed of NSW National Parks. On June 19th 2022 the State Government announced upgrades to Dorrigo National Park which will encompass a brand-new Arc Rainforest Centre featuring a huge boardwalk and a new multi-day walk along the escarpment edge through Gondwana World Heritage rainforests, with hut and camping accommodation.

The November 4th 2022 update on same announces 'Planning has commenced on a new multi-day walk and a spectacular new visitor centre as part of a $56 million investment on Gumbaynggirr Country in Dorrigo National Park.'

The Dorrigo Escarpment Great Walk project webpage states it proposes 2 main components to be constructed in stages:

The Dorrigo Arc Rainforest Centre – a new visitor centre and treetop walkway on the footprint of the existing Dorrigo Rainforest Centre, that will provide an improved rainforest experience and accessible access to the existing Balaminda welcome platform and Wonga Walk.

The Dorrigo Escarpment Great Walk – a 46-kilometre multi-day walk ''with 4 purpose-built communal low impact walkers' huts and camping areas'', including a number of additional shorter walking options.

Artistic render of draft plan for the proposed Arc Rainforest Centre. Credit: Studio Hollenstein

Concept drawing for the proposed new Dorrigo Arc Rainforest Centre, with an overlay of the footprint of the existing rainforest centre existing footprint Credit: DPE

Artistic render of proposed Arc Rainforest Centre with elevated lookout platform. Credit: Studio Hollenstein

Preparation of a new plan of management for Dorrigo National Park, Bindarri National Park and Bindarri State Conservation Area is underway, the NSW Department of Environment states. Once a draft plan of management has been prepared, it will be placed on public exhibition for community feedback.

''We will keep you informed of an opportunity to 'have your say' on the draft plan of management, with public exhibition planned for 2023. We are also planning to exhibit the draft project master plans with the draft plan of management.''

An August 29, 2022 article 'Stealth privatisation’ in iconic national parks threatens public access to nature’s health boost' by Ralf Buckley, International Chair in Ecotourism Research, Griffith University and Alienor Chauvenet, Senior Lecturer, Griffith University stated;

'The public almost always opposes permanent accommodation in parks, whoever owns it, based on the belief private lodges and camps should be on private land.

But state governments in New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and South Australia have enabled this regardless. Think of the pristine Ben Boyd National Park near Eden in NSW, slated for eco-tourism cabins at the expense of campers.

The examples go on: ecotourism cabins in Main Range National Park in Queensland, Tasmania’s private Three Capes walk in Tasman national park and a resort in Freycinet National Park, as well as Kangaroo Island in South Australia.

Private developments exclude the wider public, both physically and financially.'

Visit:

Residents Call On Everyone In Sydney To Join Community Protest Against The Commercialisation Of Barrenjoey Headland - January 2023 report

Plan To Commercialise Barrenjoey Lighthouse Precinct On Timetable To Be Pushed Through Prior To 2023 State Election - December 2022 report

Proposal For Barrenjoey Lighthouse Cottages To Be Used For Tourist Accommodation Open For Feedback - Again - October 2022 report

The second Barrenjoey Rally takes place on Sunday January 22nd alongside Station Beach, where the first occurred in 2013.

2013 Barrenjoey Rally. Photo: Pittwater Online News

Heritage Listed Walka Water Works To Provide Tourist Accommodation State Government Announces

On January 11, 2022 the Liberal-National Government announced the historic Crown land reserve at Maitland, Walka Water Works, will receive a $10 million boost via Round Two of the NSW Government’s Regional Tourism Activation Fund.

Parliamentary Secretary for the Hunter Taylor Martin said Maitland City Council, Reflections Holiday Parks and Crown Lands had partnered on a joint bid for the funding.

“Walka Water Works is one of the state’s most unique public sites serving the Hunter since 1887 as a source of water, then power and now recreation and heritage,” Mr Martin said.

“This plan aims to restore Walka Water Works to its former glory and invest in additional improvements that can make it a tourism magnet for the Hunter Valley.”

CEO of Reflections Holiday Parks Nick Baker said Reflections would also contribute a further $1.6 million to the project.

"Reflections is excited to partner with Maitland City Council on this successful grant application which will deliver new accommodation options for visitors to Maitland, while enhancing community access and amenity,” Mr Baker said.

“We look forward to working with Council and the community to develop plans for a mix of accommodation offerings, including cabins and powered caravan and camping sites.''

Reflections is a Crown Land Manager and Australia’s only social enterprise holiday park group, reinvesting profit into Crown Land across New South Wales.

Walka Water Works is a heritage-listed 19th-century pumping station at 55 Scobies Lane, Oakhampton Heights, City of Maitland. Originally built in 1887 to supply water to Newcastle and the lower Hunter Valley, it has since been restored and preserved and is part of Maitland City Council's Walka Recreation and Wildlife Reserve.

It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

The complex had been classified by the National Trust in 1976.

Walka Water Works, West Maitland, NSW, Australia [c1893], courtesy University of Newcastle Living Histories node

Presently the area is open as a free public reserve, with barbecues, picnics areas, a playground, walking trails and a 7 1/4 inch gauge miniature railway that operates passenger rides each Sunday.

The reservoir and surrounding bush make it a unique environment for birds and animals in the area.

The proposed works include:

- Restoring the 1885 pumphouse building and chimney back to their original condition to preserve their heritage and allow tourism and hospitality businesses to flourish, such as an interpretive centre, cafés, restaurants, craft brewery or distillery, and event functions.

- Establishing overnight visitor accommodation starting with 10 eco-cabins, 12 glamping tents and 40 powered caravan sites, as well as a camp kitchen and barbecue area.

- Upgrading the Eastern Lawn with landscaping and infrastructure for weddings and other events.

- Redeveloping the miniature train railway station as an improved visitor experience.

- Upgrading walking trails to improve accessibility and include interpretive information.

- Developing a centralised amenities building, upgrading car parking to meet accessibility standards, and other infrastructure improvements.

Clean-Up Notice Issued For Flat Rock Creek Fish Kill At Naremburn And Cammeray

December 22, 2022

The NSW EPA, with the help of Department of Planning and Environment (DPE) scientists, has been sampling and monitoring Flat Rock Creek to better understand the impacts of a recent pollution incident which caused a fish kill.

On 6 December 2022, the EPA received reports of a fish kill and pollution incident in Flat Rock Creek in Naremburn and Cammeray.

The EPA, with the help of DPE, has been sampling and monitoring Flat Rock Creek during and after clean-up of the pollution incident to understand the cause of the fish kill.

This includes sampling to test for contaminants and continuing to monitor dissolved oxygen levels in Flat Rock Creek.

Water quality monitoring has shown a general trend of improvement in dissolved oxygen levels in some parts of Flat Rock Creek.

However, full results are required to determine the cause of the fish kill as there are a number of factors that may have contributed.

The EPA will continue to keep the community informed as the investigation progresses.

Clean-up and advice

As a precautionary measure, residents are advised to be cautious around the creek and keep pets out of the water until investigations are finalised.

The EPA has issued a Clean-Up Notice to Cleanaway Pty Ltd requiring sampling of Flat Rock Creek on a weekly basis until further notice to inform ongoing clean-up efforts.

This follows a fire at Cleanaway’s Artarmon waste storage facility on 5 December 2022 which the EPA believes may have caused a pollution incident at the creek.

The EPA will continue to work with Willoughby Council to monitor the condition of Flat Rock Creek.

Failure To Do Rehabilitation Work Leads To $320,000 In Fines For Central Coast Petrol Station

December 20, 2022

A company has been convicted and fined $320,000 in the Land and Environment Court for failing to comply with a contaminated land Management Order issued by the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) in relation to a petrol station in Kanwal on the Central Coast.

Zoya Investments Pty Ltd plead guilty to the offence, which occurred when it failed to undertake rectification works on its underground petrol storage system and provide a report to the EPA detailing those works.

EPA Executive Director Steve Beaman said the site had been declared significantly contaminated following an assessment by the EPA in 2018.

“The EPA found the soil and groundwater beneath the site was contaminated by petrol and had potential to impact human health and the surrounding environment,” Mr Beaman said.

“We have a high standard for protecting local communities and by not rectifying the identified problems, Zoya Investments has fallen short of this standard.”

The Court found that Zoya Investments had breached the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997 and issued a fine of $180,000 and a further penalty of $140,000 for the time it took for Zoya Investments to ultimately comply with the Management Order.

Mr Beaman said the severity of the fine, particularly the additional cost for not complying with the Management Order for approximately a year, served as a strong deterrent to other operators.

“The EPA expects timely responses to environmental issues and the punishments are severe when companies ignore orders and continue to put the environment and human health at risk.