inbox and environment news: Issue 569

January 29 - February 4 2023: Issue 569

Avian Flu Could Decimate Australian Black Swans

Black Swans on Narrabeen Lagoon - Photo by Michael Mannington OAM

Prune Viburnum Hedge Agapanthus Flowers To Prevent Spread Into Bush Reserves

PNHA: January 11, 2023

Now is the time to prune the berries off the Viburnum hedge and dehead those old Agapanthus flowers. Put these prunings into your green waste bin. Both are now weeds of bushland as their seeds travel.

Photos: Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA)

Sydney Wildlife (Sydney Metropolitan Wildlife Services): Rescue Care Course - February 2023

Our next course starts on the 4th of February. It runs for 3 weeks in a self-paced format online and then a 1 day practical session at the end on the 26th February. Both sessions must be passed to join Sydney Wildlife Rescue and rescue and care for our native wildlife.

Visit the sign on page for full details: https://smws.wildapricot.org/RCC-Trainee-Application-Form

The cost of the course is $120 and you will receive membership, manuals and equipment to help you. All new members are fully supported with a mentor when they join. Join us and make a difference to the wildlife in your area.

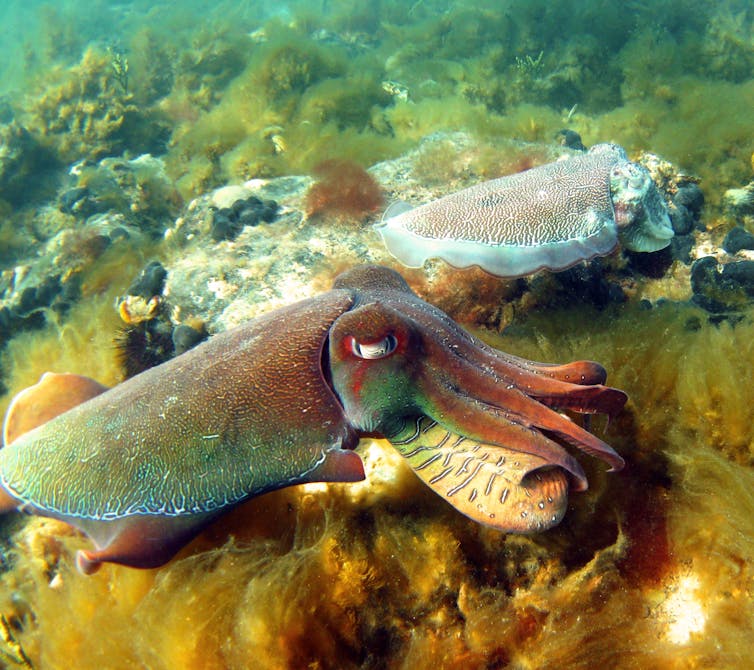

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group Launched On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

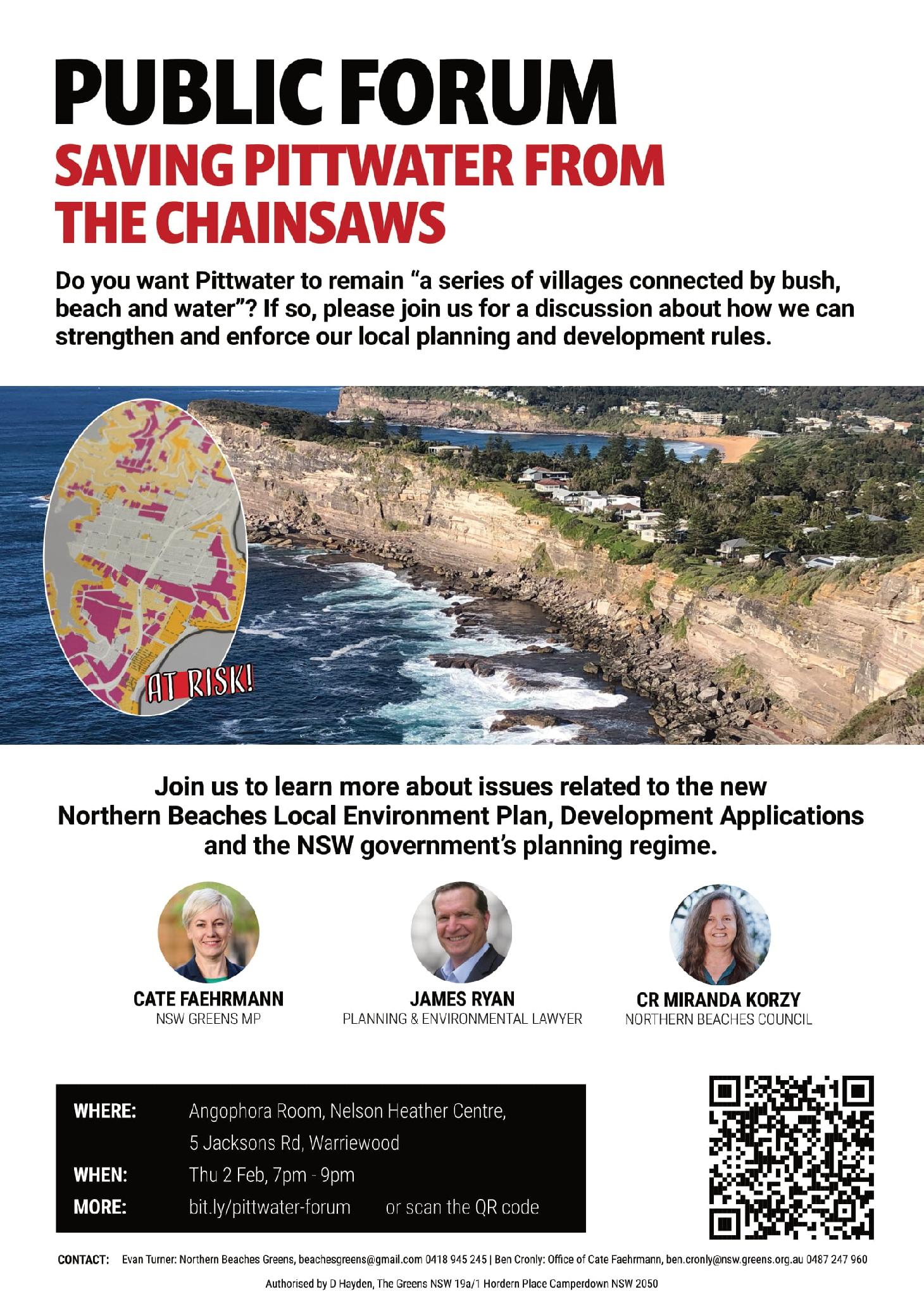

Environment Law Fails To Protect Threatened Species In Australia

January 23, 2023

Federal environmental laws are failing to mitigate against Australia's extinction crisis, according to University of Queensland research. UQ PhD candidate Natalya Maitz led a collaborative project which analysed potential habitat loss in Queensland and New South Wales and found the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation 1999 (EPBC) Act is not protecting threatened species.

"The system designed to classify development projects according to their environmental impact is more or less worthless," Ms Maitz said.

"There's no statistically significant difference between the amount of threatened habitat destroyed under projects deemed 'significant' or 'not significant' by the national biodiversity regulator."

Under the EPBC Act, individuals or organisations looking to commence projects with a potentially 'significant impact' on protected species must seek further federal review and approval.

Developments deemed unlikely to have a significant impact don't require further commonwealth approval.

"But as the law is currently applied, significant impact projects are clearing just as much species habitat as projects considered low risk," Ms Maitz said.

"If the legislation were effectively protecting threatened habitats, we would expect less environmentally sensitive habitat cleared under the projects classified as unlikely to have a big impact."

The research examined vegetation cleared for projects in areas which provided habitat for threatened species, migratory species and threatened ecological communities in Queensland and New South Wales -- a global deforestation hotspot.

Co-author, Dr Martin Taylor, said that the regulator's 'significant' classification appeared to have no consistent, quantitative basis in decision-making by the regulator.

"Neither the Act itself, nor the regulator, have been able to provide clear, scientifically robust thresholds for what constitutes a significant impact, such as x hectares of habitat for species y destroyed," Dr Taylor said.

"Numerous species have lost a majority of their referred habitat to projects deemed 'non-significant'.

"For example, the tiger quoll lost 82 per cent of its total referred habitat to projects considered unlikely to have a significant impact, while the grey-headed flying-fox lost 72 per cent.

"These species are well on their way to extinction, and the government will not achieve its zero extinctions goal unless these threats are stopped."

Dr Taylor said the research highlights what appears to be inconsistencies in the referral decision-making process, a concern raised in the 2020 Independent Review of the EPBC Act by Graeme Samuel.

"These findings emphasise the importance of considering cumulative impacts and the need to develop scientifically robust thresholds that are applied rigorously and consistently -- factors that need to be considered when drafting the upcoming reforms in order to give Australia's irreplaceable biodiversity a fighting chance," Dr Taylor said.

The Australian Government announced that major reforms will be made to the legislation.

Natalya M. Maitz, Martin F. J. Taylor, Michelle S. Ward, Hugh P. Possingham. Assessing the impact of referred actions on protected matters under Australia's national environmental legislation. Conservation Science and Practice, 2022; 5 (1) DOI: 10.1111/csp2.12860

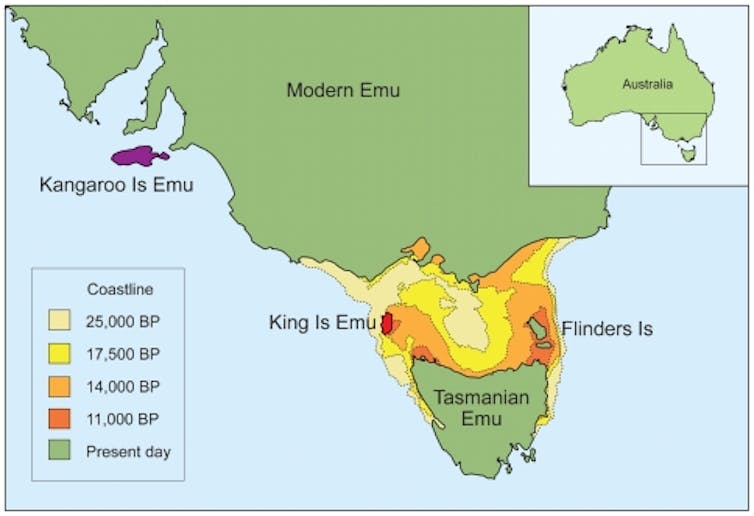

They’re on our coat of arms but extinct in Tasmania. Rewilding with emus will be good for the island state’s ecosystems

The emu is iconically Australian, appearing on cans, coins, cricket bats and our national coat of arms, as well as that of the Tasmanian capital, Hobart. However, most people don’t realise emus once also roamed Tasmania but are now extinct there.

Where did these Tasmanian emus live? Why did they go extinct? And should we reintroduce them?

Our newly published research combined historical records with population models to find out. We found emus lived across most of eastern Tasmania, including near Hobart, Launceston, Devonport, the Midlands and the east coast. However, in the early days of British occupation, colonists hunting with purpose-bred dogs slaughtered so many emus that the population crashed.

It’s not all bad news, though. Those areas still provide enough good, safe emu habitat to make reintroducing emus from the Australian mainland to Tasmania a realistic option.

Large animals, such as bison, wolves and giant tortoises are already part of global efforts to repair and maintain ecosystems and prevent more extinctions, through the conservation movement known as “rewilding”.

In Tasmania, rewilding with emus might help native plants to cope with a changing climate. As our world warms, the places where conditions are just right for particular plant species are shifting. Those plants must disperse far and fast to keep up. Introducing emus, which disperse many plant seeds in their droppings, could help.

Emus Were Tasmania’s Biggest Herbivores

Emus are the biggest birds in Australia. The females weigh up to a whopping 37 kilograms. But when European sealers and explorers arrived on Australia’s southern islands, they found smaller, shorter emus. According to one estimate, Kangaroo Island emus averaged 24-27kg and King Island emus a mere 20-23kg.

Contrary to local folklore, Tasmanian emus were actually more similar to their mainland cousins. They weighed about 30-34kg (but sometimes up to 40kg).

Along with eastern grey kangaroos, known locally as “foresters”, emus were the biggest herbivores in Tasmania.

What Are The Likely Impacts On Ecosystems?

Large herbivores play important roles in ecosystems around the world. By chewing on plants, pushing through vegetation and churning up soil, large animals can create a mosaic of habitat types for other, smaller creatures. They move seeds and nutrients across the landscape and shape the frequency and intensity of fires.

Exactly how emus help ecosystems is a bit of a mystery because so few researchers have looked into it. But we do know emus are very good at seed dispersal. Emus live anywhere, eat anything and swallow their food whole. They walk miles and miles while seeds slowly pass through their gut, to be ejected in a ready-made batch of compost.

Without emus, some plant populations won’t be able to disperse quickly enough to escape the local effects of global warming.

How Did Tasmania Lose Its Emus?

We know colonists hunted emus and kangaroos in Tasmania. Emus were rarely seen on the island after 1845. But was hunting by a few hungry settlers enough to take out the whole population?

To find out, we recreated the emu population using computer simulations. Then we turned up the hunting pressure.

The signal was clear. Tasmania’s emu population could not sustain a harvest of more than about 1,500 adults per year. This limit was probably exceeded within a decade or two, which makes over-hunting the most likely cause of extinction.

Interestingly, the results of the simulation imply the island’s Indigenous people hunted adult emus at very low rates, less than one per person per year.

Where Can We Reintroduce Emus?

To find safe places for reintroductions, we overlapped emu habitat with current land use. We found large parts of the state that have both good emu habitat and a healthy distance from areas with higher risk of human-emu conflict.

Small-scale, trial introductions could be done in fenced enclosures to learn more about the emus’ needs and their ecological roles.

Indigenous voices are particularly important in conversations about reintroductions, because of the roles such animals play in living traditional cultures. For example, emus have featured in Tasmanian Aboriginal story, dance, song and art for generations. Pakana and Palawa still perform emu dances today.

Such conversations must be had with care, because many Indigenous people are wary of terms such as “rewilding” and “wilderness”. These terms can carry the implication of a land without people, when in fact Australian landscapes have a long and rich history of Indigenous people caring for Country. Even the concept of “wildness” can imply too strong a separation between humans and our non-human kin, and a lack of reciprocity and responsibility.

Australia Has Just Begun Rewilding

Landscapes all over the world have lost large animals that would otherwise be keeping ecosystems healthy and dynamic. European and American conservationists have responded by reintroducing large animals for their ecological and cultural functions.

Rewilding Europe, for example, has reintroduced bison to the Carpathian mountains and primitive horses to Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria and Ukraine. These efforts are placing prehistoric grazing regimes back into a rich cultural landscape.

On islands in the Indian Ocean, giant tortoises have been introduced to replace their extinct cousins. Those tortoises graze down weeds and give native plants a better chance of recovery.

In Siberia, the Pleistocene Park project aims to re-create a rich steppe ecosystem by reintroducing bactrian camels, musk oxen and American plains bison. One benefit is this will increase the amount of carbon stored in that landscape.

In Australia, most of our animal reintroduction programs are focused on conserving individual species. In a few cases, like the Marna Banggara project, ecological engineers like bettongs are being introduced to kick-start ecosystem restoration, but this is happening behind fences and on islands.

We need solutions like rewilding for our open landscapes. Reintroducing emus to Tasmania would be a good first step.![]()

Tristan Derham, Research Associate, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH) Policy Hub – Training and Education, University of Tasmania; Christopher Johnson, Professor of Wildlife Conservation, University of Tasmania, and Matthew Fielding, Research Associate / Teaching Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH), University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Exploding carp numbers are ‘like a house of horrors’ for our rivers. Is it time to unleash carp herpes?

With widespread La Niña flooding in the Murray-Darling Basin, common carp (Cyprinus carpio) populations are having a boom year. Videos of writhing masses of both adult and young fish illustrate that all is not well in our rivers. Carp now account for up to 90% of live fish mass in some rivers.

Concerned communities are wondering whether it is, at last, time for Australia to unleash the carp herpes virus to control populations – but the conversation among scientists, conservationists, communities and government bodies is only just beginning.

Globally, the carp virus has been detected in more than 30 countries but never in Australia. There are valid concerns to any future Australian release, including cleaning up dead carp, and potential significant reductions of water quality and native fish.

As river scientists and native fish lovers, let’s weigh the benefits of releasing the virus against the risks, set within a context of a greater vision of river recovery.

A House Of Horrors For Rivers

Carp are a pest in Australia. They cause dramatic ecological damage both here and in many countries. Carp were first introduced in the 1800s but it was only with “the Boolarra strain” that populations exploded in the basin in the early 1970s.

Assisted by flooding in the 1970s, carp have since invaded 92% of all rivers and wetlands in their present geographic range. There have been estimates of up to 357 million fish during flood conditions. This year, this estimate may even be exceeded.

Carp are super-abundant right now because floods give them access to floodplain habitats. There, each large female can spawn millions of eggs and young have high survival rates. While numbers will decline as the floods subside, the number of juveniles presently entering back into rivers will be stupendous and may last years.

The impacts of carp are like a house of horrors for our rivers. They cause massive degradation of aquatic plants, riverbanks and riverbeds when they feed. They alter the habitat critical for small native fish, such as southern pygmy perch. And they can make the bed of many rivers look like the surface of golf balls – denuded and dimpled, devoid of any habitat.

Most strikingly, this feeding behaviour contributes to turbid rivers, reducing sunlight penetration and productivity for native plants, fish and broader aquatic communities.

Carp truly are formidable “ecosystem engineers”, which means they directly modify their environment, much like rabbits. Their design leads to aquatic destruction of waterways.

We know when their “impact threshold” exceeds 88 kilograms per hectare of adult carp, we see declines in aquatic plant health, water quality, native fish numbers and other aquatic values. At present, we expect carp to far exceed this impact threshold. For river managers, the challenge is to keep numbers below that level.

The Carp Herpes Virus

The carp virus (Cyprinid herpesvirus 3) represents one of the only landscape-scale carp control options, although there are some exciting genetic modification technologies also emerging.

Mathematical modelling suggests the carp virus could cause a 40-60% knockdown for at least ten years, which may help tip the balance in favour of native fish. Certainly, there have been some well documented virus outbreaks in the United States resulting in large-scale carp deaths.

The risks and benefits of a potential Australian release of a carp virus are transparently addressed under the federal government’s National Carp Control Plan, released last year. This plan provides some sorely needed leadership in the carp management space.

Risks the plan identifies include:

- major logistic challenges in cleaning up dead carp

- potentially serious short-term deterioration in water quality

- potential native fish deaths due to poor water quality.

On the other hand, the benefits of releasing the virus include:

- recovery of aquatic biodiversity populations – fish, plants and invertebrates

- major long-term improvements to water quality

- improved social amenity of inland waterways.

As carp continue to destroy Australia’s riverine heritage, it’s time to lay our cards on the table and have a serious conversation about the carp virus. Managing expectations is a key and the confidence of stakeholders and the community is vital for its success.

Like rabbits and other vertebrate pests, carp are emblematic of our inability to deal with entrenched pest animals. There are no silver bullets.

How Else Can We Manage Carp?

Rolling out the carp virus is only one potential pathway away from carp. If we truly want to reduce carp numbers and impacts in the long-term then we need to examine all the roles humans play supporting them.

For example, the series of weir pools in the lower Murray create perfect conditions for carp because they give fish access to floodplains year round.

Strategically lowering and removing weir pools to re-create flowing water habitats would be one solution to help Murray cod and other flowing water specialists, such as silver perch, river snails and Murray crays. This is one of many integrated actions that could help tip the balance against carp.

Also, floodplain structures (which create artificial “floods”) generate static, warm-bathtub conditions that carp, being from Central Asia, prefer, contributing to huge numbers especially in dry years. Few medium or large native fish benefit from these conditions.

Another pathway is to seek guidance from increasingly sophisticated environmental modelling, which can identify optimal population trajectories for native fish over carp.

Now the floods have returned, we need to move away from local decisions at the site-scale and instead manage ecosystems across the entire Murray-Darling Basin.

The present flooding also reminds us of the huge potential increases in the numbers of golden perch, frogs, yabbies and water birds. Animals that eat carp (Murray cod, golden perch, pelicans, cormorants) should all be as fat as can be.

Looking Beyond Carp

Just like the huge numbers of dead native fish from the Darling River fish kills in 2018-2019, the huge numbers of carp is a big wake-up call on the poor state of rivers in the Murray-Darling Basin and how we’re managing them.

Perhaps what has been missing from the whole conversation is a vision for what our rivers should look like in ten or 20 years time. We don’t want to leave a legacy of degraded rivers for future Australians.

River health is an issue all Australian’s, country and city, need to engage with. If we don’t identify a common purpose, then we will likely continue to remain in lock-step with the great armies of carp and rivers of fish kills for generations to come. We need to do better than this. The future of our rivers depends on it.![]()

Ivor Stuart, Fisheries ecologist, Charles Sturt University; John Koehn, Freshwater fish ecologist, Charles Sturt University; Katie Doyle, Freshwater Ecologist, Charles Sturt University, and Lee Baumgartner, Professor of Fisheries and River Management, Institute for Land, Water, and Society, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t kill the curl grubs in your garden – they could be native beetle babies

Have you ever been in the garden and found a large, white, C-shaped grub with a distinctive brown head and six legs clustered near the head?

If so, you’ve had an encounter with the larva of a scarab beetle (family: Scarabaeidae) also known as a “curl grub”.

Many gardeners worry these large larvae might damage plants.

So what are curl grubs? And should you be concerned if you discover them in your garden?

What Are Curl Grubs?

Curl grubs turn into scarab beetles.

There are more than 30,000 species of scarab beetles worldwide. Australia is home to at least 2,300 of these species, including iridescent Christmas beetles (Anoplognathus), spectacularly horned rhinoceros beetles (Dynastinae), and the beautifully patterned flower chafers (Cetoniinae).

While the adults might be the most conspicuous life stage, scarabs spend most of their lives as larvae, living underground or in rotting wood.

Scarab Larvae Can Help The Environment

Soil-dwelling scarab larvae can aerate soils and help disperse seeds.

Species that eat decaying matter help recycle nutrients and keep soils healthy.

Most scarab larvae are large and full of protein and fat. They make an excellent meal for hungry birds.

Besides being important for ecosystems, scarabs also play a role in cultural celebrations.

For example, the ancient Egyptians famously worshipped the sun through the symbol of the ball-rolling dung beetle.

In Australia, colourful Christmas beetles traditionally heralded the arrival of the holiday season.

Sadly, Christmas beetle numbers have declined over the last few decades, likely due to habitat loss.

Are The Curl Grubs In My Garden Harming My Plants?

Most scarab larvae feed on grass roots, and this can cause damage to plants when there’s a lot of them.

In Australia, the Argentine lawn scarab and the African black beetle are invasive pest species that cause significant damage to pastures and lawns.

Native scarab species can also be pests under the right circumstances.

For example, when Europeans began planting sugar cane (a type of grass) and converting native grasslands to pastures, many native Australian scarab species found an abundant new food source and were subsequently classified as pests.

Unfortunately, we know little about the feeding habits of many native scarab larvae, including those found in gardens.

Some common garden species, like the beautifully patterned fiddler beetle (Eupoecila australasiae), feed on decaying wood and are unlikely to harm garden plants.

Even species that consume roots are likely not a problem under normal conditions.

Plants are surprisingly resilient, and most can handle losing a small number of their roots to beetle larvae. Even while damaging plants, curl grubs may be helping keep soil healthy by providing aeration and nutrient mixing.

How Do I Know If I Have ‘Good’ Or ‘Bad’ Beetle Larvae In My Garden?

Unfortunately, identifying scarab larvae species is challenging. Many of the features we use to tell groups apart are difficult to see without magnification. While there are identification guides for scarabs larvae found in pastures, there are currently no such identification resources for the scarabs found in household gardens.

Since identification may not be possible, the best guide to whether or not scarab larvae are a problem in your garden is the health of your plants. Plants with damaged roots may wilt or turn yellow.

Since most root-feeding scarabs prefer grass roots, lawn turf is most at risk and damage is usually caused by exotic scarab species.

What Should I Do If I Find Curl Grubs In My Garden?

Seeing suspiciously plump curl grubs amongst the roots of prized garden plants can be alarming, but please don’t automatically reach for insecticides.

The chemicals used to control curl grubs will harm all scarab larvae, regardless of whether or not they are pests.

Many of the most common treatments for curl grubs contain chemicals called “anthranilic diamides”, which are also toxic to butterflies, moths and aquatic invertebrates.

And by disrupting soil ecosystems, using insecticides might do more harm than good and could kill harmless native beetle larvae.

So what to do instead?

Larvae found in decaying wood or mulch are wood feeders and are useful composters; they will not harm your plants and should be left where they are.

Larvae found in compost bins are helping to break down wastes and should also be left alone.

If you find larvae in your garden soil, use your plant’s health as a guide. If your plants appear otherwise healthy, consider simply leaving curl grubs where they are. Scarab larvae are part of the soil ecosystem and are unlikely to do damage if they are not present in high numbers.

If your plants appear yellow or wilted and you’ve ruled out other causes, such as under-watering or nutrient deficiencies, consider feeding grubs to the birds or squishing them. It’s not nice, but it’s better than insecticides.

Lawns are particularly susceptible to attack by the larvae of non-native scarabs. Consider replacing lawns with native ground covers. This increases biodiversity and lowers the chances of damage from non-native scarab larvae.

Scarab beetles are beautiful and fascinating insects that help keep our soils healthy and our wildlife well fed.![]()

Tanya Latty, Associate professor, University of Sydney and Chris Reid, Adjunct Associate Professor in Zoology, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

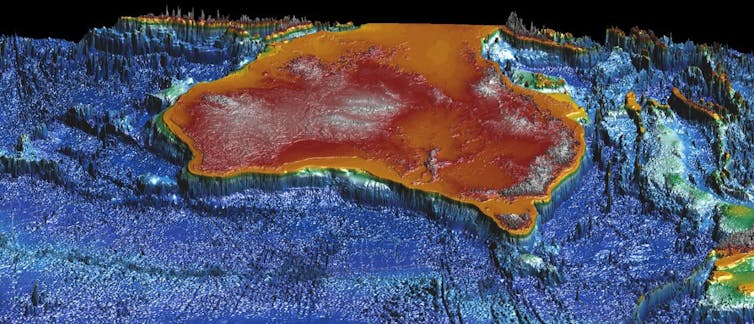

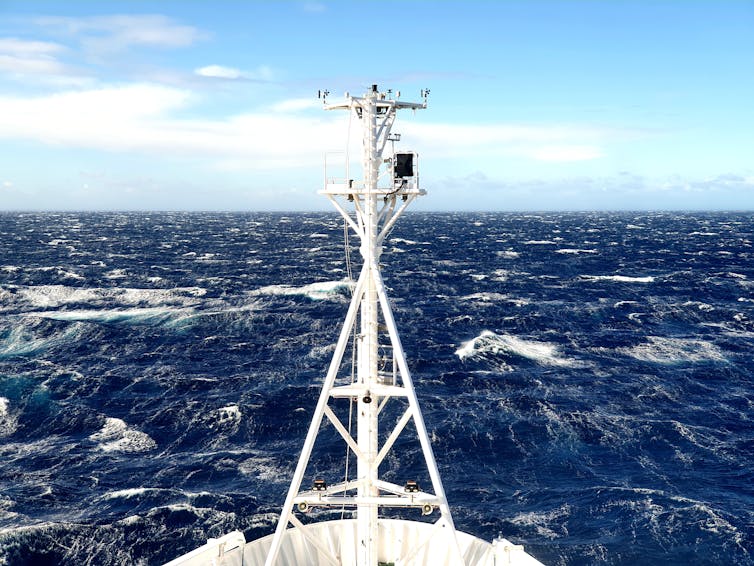

Photos from the field: our voyage investigating Australia’s submarine landslides and deep-marine canyons

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

We gathered at the edge of the ship deck, awaiting the return of our sediment corer that had been lowered 4.5 kilometres – half the height of Mount Everest – to the seafloor. Our team of 53 people nervously shuffled together like penguins as we speculated about what we’d find.

It was July 2022. We’d been at sea for 36 days on CSIRO’s Research Vessel Investigator to explore the edges of our continent and learn how it evolved through time. While we’re all familiar with the shape of modern Australia, our continental mass actually extends well beyond our shorelines.

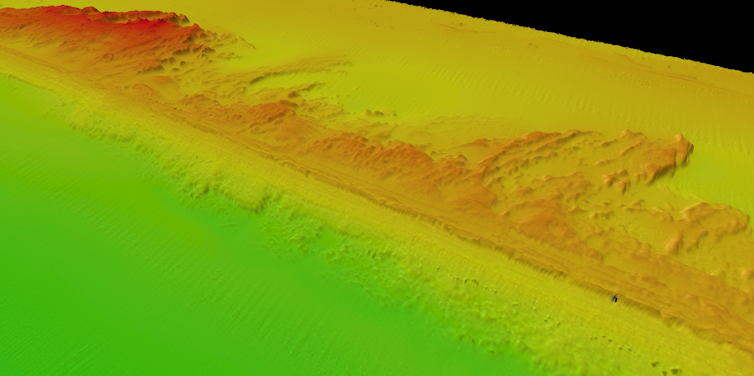

Over the 36 days of our voyage, we mapped more than 40,000 square kilometres of the seafloor from as shallow as 22 metres to depths of over 4.8km. And we’ve created 3D visualisations of features never seen before.

The steel corer emerged from the deep glistening like pirate treasure. It marks just one of many samples we collected at sea. Analysing them all will probably take years, but we can still share exciting new maps of the seafloor and what they may reveal – from the threat of tsunami in Australia to evidence of ancient beaches and dunes.

The Threat Of Tsunami

Our research voyage aimed to investigate how mud and sand flows from our continent into the deep oceans. Along the way, these different sediments can travel down submarine canyons and form large landslides.

Sometimes, these submarine landslides are large enough to trigger a tsunami – so we’re also working to understand what the local tsunami risk is for Australia’s eastern seaboard communities.

A big part of understanding the potential threat of tsunami is learning how the material from the submarine landslides along the eastern seaboard has moved down into the deep ocean. For example, does it go as a single, large slab of sediment, failing all at once? Or does it slowly break apart, with smaller pieces heading down slope one at a time as a slurry of sediment and water?

While Australia has a relatively low tsunami risk compared to other places around the world, we are still exposed and so should heed warnings from emergency services.

A recent tsunami to hit Australia was caused by the underwater volcanic explosion in Tonga in January last year. This brought waves of more than 80 centimetres to the Gold Coast, which could knock you off your feet.

Mapping The Seafloor Surface

We mapped areas of the seafloor with a level of precision not available to previous generations of hydrographers and map-makers in Australia. Some areas were nearly 5km deep and over 100 nautical miles from the coast.

To do this, we use a multibeam system. This involves sending out sound waves from the bottom of the ship in a wide cone-shape. These sound waves bounce off the seafloor back to the ship, giving us information about the depth of the seafloor and allowing us to map any features on its surface.

One feature we remapped was an area of the continental slope offshore of Yamba, New South Wales. Here we see cliffs up to a few hundred metres high – evidence of slope failure and sliding.

We also remapped the scar from the Bulli submarine landslide, which is the biggest submarine landslide identified on the Australian continental margin to date. At over 25km long and over 10km wide, the Bulli landslide off Wollongong in NSW removed 40 cubic kilometres of sediment from the edge of our continent.

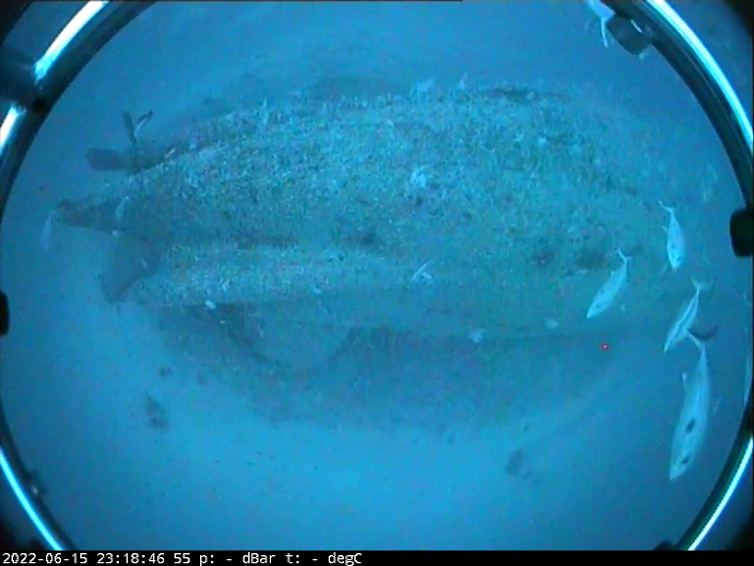

But to get a true feel for the multibeam system’s capabilities, we also mapped the wreck of the Limerick, a ship sunk by Japanese submarines off Australia’s east coast near Cape Byron in 1943. This also supported efforts to understand the current state of the famous shipwreck.

The wreck sits upside down in about 80m of water. To get a better view, we also lowered a camera to the torpedo hole in the side that sunk the ship.

Beneath The Seafloor

Understanding what’s on the surface of the seafloor tells us a lot about what has happened over the last few hundreds of thousands of years.

But looking below the surface at the sediment layers beneath can tell us how the seafloor has evolved over millions of years.

To do this, we use techniques that send out pulses of sound that can penetrate the seafloor. These pulses then listen for return signals that bounce off interfaces of different types of sediments and rocks.

Through these sub-surface imaging techniques, we have identified a range of interesting features. These include extinct river channels that were previously above the sea surface when sea levels were much lower in the past.

But to really tie things down we need physical samples of the seafloor and the sediment beneath it. Doing this is a challenge when you’re floating kilometres above the seafloor you want to sample.

So we use deep sea sediment corers and dredges, lowered down on winches with kilometres of cable. Corers punch into the seafloor and bring us back a column of sediment, while dredges drag along the bottom pulling up bits of mud and rocks, bringing them on board in big chain baskets.

Once on board, these samples are carefully analysed to look for key features that will help us piece together the puzzle of the continental margin’s evolution. Further work, such as radiocarbon dating and isotope analysis, is conducted in the months to years after the voyage to complete the analysis.

We’ve collected some fascinating new data that will keep us busy for years to come, but we also had time for table tennis competitions, a few movie nights, and a daily debate on which of the many delicious meals onboard was the favourite.

And we can’t forget the many spectacular sunrises and sunsets!![]()

Hannah Power, Associate Professor in Coastal and Marine Science, University of Newcastle; Kendall Mollison, Postdoctoral researcher, University of Newcastle; Michael Kinsela, Lecturer in Coastal and Ocean Geoscience, University of Newcastle, and Tom Hubble, Associate Professor, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

A Walk Around The Cromer Side Of Narrabeen Lake by Joe Mills

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Seagull Pair At Turimetta Beach: Spring Is In The Air!

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

Stony Range Regional Botanical Garden: Some History On How A Reserve Became An Australian Plant Park

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Topham Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP, August 2022 by Joe Mills and Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

RACGP Cautions Medicare Reforms Must Support GP Stewardship Of Patient Care

- improving access to care by tripling bulk billing incentives, increasing Medicare rebates for longer, complex consultations by 20%, funding enhanced primary care services for people over 65, with mental health conditions and disability, and funding patients to see their GP after an unplanned hospital visit.

- boosting the GP workforce by fast-tracking entry for international doctors, re-instating the subsidy for their training, supporting junior doctors to intern in general practice, and introducing payroll tax exemption for independent tenant GPs to prevent more practices closing.

- Long-term reforms based on the RACGP Vision to build the role of GPs as the stewards of patient care in multidisciplinary teams, with serious investment to improve the health of Australians and reduce spending on expensive hospital care.

ACCC Social Media Sweep Targets Influencers

January 27, 2023

The ACCC has this week started a sweep to identify misleading testimonials and endorsements by social media influencers. It will also look at more than 100 influencers mentioned in over 150 tip-offs from consumers who responded to the ACCC’s Facebook post asking for information.

Most of the tip-offs from members of the public were about influencers in beauty and lifestyle, as well as parenting and fashion, failing to disclose their affiliation with the product or company they are promoting.

“The number of tip-offs reflects the community concern about the ever-increasing number of manipulative marketing techniques on social media, designed to exploit or pressure consumers into purchasing goods or services,” ACCC Chair Gina Cass-Gottlieb said.

“We want to thank the community for letting us know which influencers they believe might not be doing the right thing,” Ms Cass-Gottlieb said.

“Already, we are hearing some law firms and industry bodies have informed their clients about the ACCC’s sweep, and reminded them of their advertising disclosure requirements,” Ms Cass-Gottlieb said.

The sweep is being run over the coming weeks as part of the ACCC’s compliance and enforcement priorities for 2022/23, with the broad aim of identifying deceptive marketing practices across the digital economy.

As part of the sweep, the ACCC team is reviewing a range of social media platforms including Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, YouTube and Facebook, and livestreaming service, Twitch. The sweep is targeting sectors where influencer marketing is particularly widespread including fashion, beauty and cosmetics, food and beverage, travel, health fitness and wellbeing, parenting, gaming and technology.

In conducting the sweep, the ACCC is also considering the role of other parties such as advertisers, marketers, brands and social media platforms in facilitating misconduct.

“With more Australians choosing to shop online, consumers often rely on reviews and testimonials when making purchases, but misleading endorsements can be very harmful,” Ms Cass-Gottlieb said.

“It is important social media influencers are clear if there are any commercial motivations behind their posts. This includes those posts that are incentivised and presented as impartial but are not. The ACCC will not hesitate to take action where we see consumers are at risk of being misled or deceived by a testimonial, and there is potential for significant harm.

This action may include following up misconduct with compliance, education and potential enforcement activities as appropriate.”

Many consumers are aware that influencers receive a financial benefit for promoting products and services. However, the ACCC remains concerned that influencers, advertisers and brands try to hide this fact from consumers, which prevents them from making informed choices. This can particularly apply to micro influencers with smaller followings, as they can build and maintain a more seemingly authentic relationship with followers to add legitimacy to hidden advertising posts. The ACCC is therefore monitoring a mix of small and larger influencers in the sweep.

This sweep follows a similar initiative carried out in 2022, which focused on identifying misleading online reviews and testimonials posted on business’ websites, their social media pages and third-party review platforms. A report outlining the findings from 2022 will be published in the coming months.

“Online markets need to function well to support the modern economy. Part of that is ensuring consumers have the confidence they need to make more informed purchasing decisions,” Ms Cass-Gottlieb said.

The ACCC will publish the findings of this sweep once the results have been analysed.

Background

Each year, the ACCC announces a list of Compliance and Enforcement priorities. These priorities outline the areas of focus for the ACCC’s compliance and enforcement activities for the following year. As part of the 2022/23 Compliance and Enforcement Priorities, the ACCC is prioritising both consumer and fair-trading issues in relation to issues relating to manipulative or deceptive advertising and marketing practices in the digital economy.

The ACCC is also conducting the Digital Platform Services Inquiry that is focused on the provision of social media services, including sponsored posts and influencer advertising on social media platforms. We will provide the sixth interim report on social media services to the Treasurer by 31 March 2023.

There are also industry led practices and guidelines which provide a standard for Australian influencer businesses and advertisers. For example, the Australian Association of National Advertisers provides guidance on what can be considered clearly distinguishable advertising. The Australian Influencer Marketing Code of Practice also outlines best practice for companies engaging in influencer marketing, including in disclosing advertisements.

Other regulators such as the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the Therapeutic Goods Administration and the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Authority are also responsible for regulating influencer conduct in their areas of jurisdiction. The ACCC engages with these regulators to determine which is best placed to take action in relation to any misleading or deceptive conduct.

Free Menstrual Hygiene Products For All NSW Students

January 25, 2023

NSW public school students will have access to free menstrual hygiene products from the start of the school year.

More than 4600 dispensers have been installed in public schools across the state to support young women overcome barriers in accessing menstrual hygiene products.

Minister for Education and Early Learning Sarah Mitchell celebrated the rollout of this program for the start of the 2023 school year.

“Getting your period should not be a barrier to education. We have installed 4600 sanitary product dispensers in NSW schools to ensure students can participate in all aspects of school life,” Ms Mitchell said.

“I want our young women to feel comfortable in knowing they have access to free sanitary products when they need, in their school.

“Evidence shows that providing sanitary items has a very positive impact on educational engagement and attainment, so we know this program is going to make a huge difference for our students’ education.”

The NSW Government is also supporting delivery of the Periods, Pain and Endometriosis Program (PPEP-Talk), developed by the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia (PPFA) and co-funded by the Australian Government.

The PPEP-Talk, an age-appropriate program to help students, parents and schools understand endometriosis and pelvic pain and early intervention strategies, will be delivered at select public schools in NSW.

“These PPEP-Talks will allow for both male and female students to be able to discuss women’s health in a respectful way that reduces the stigma that can come around women's health,” Ms Mitchell said.

Northern Composure Band Competition 2023

Due to the pandemic, Council have had the 20th anniversary on hold but pleased to say that the competition is open and running again.

Northern Composure is the largest and longest-running youth band competition in the area and offers musicians local exposure as well as invaluable stage experience. Bands compete in heats, semi finals and the grand final for a total prize pool of over $15,000.

Over the past 20 years we have had many success stories and now is your chance to join bands such as:

- Ocean Alley

- Lime Cordiale

- Dear Seattle

- What So Not

- The Rions

- Winston Surfshirt

- Crocodylus

And even a Triple J announcer plus a wide range of industry professionals

About the Competition

In 2023, the comp looks a little different.

All bands are invited to enter our heats which will be exclusively run online and voted on by your peers and community by registering below and uploading a video of one song of your choice. (if you are doing a cover, please make sure to credit the original band) We are counting on you to spread the word and get your friends, family, teachers voting for you!

The top 8-12 bands will move on through to our live semi finals with a winner from each moving on to the grand final held during National Youth Week. Not only that but we have raised the age range from 19 to 21 for all those musicians who may have missed out over the past two years.

Key dates

- Voting open for heats: Mon 13 Feb – Sun 26 Feb

- Band Briefing: Mon 6 March, Dee Why PCYC

- Semi 1: Sat 18 March Mona Vale Memorial Hall

- Semi 2: Sat 25 March, YOYOs, Frenchs Forest

- Grand Final: Fri 28 April, Dee Why PCYC

For more information contact Youth Development at youth@northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au or call 8495 5104

Stay in the loop and follow Northern Composure Unplugged on KALOF Facebook.

School Leavers Support

- Download or explore the SLIK here to help guide Your Career.

- School Leavers Information Kit (PDF 5.2MB).

- School Leavers Information Kit (DOCX 0.9MB).

- The SLIK has also been translated into additional languages.

- Download our information booklets if you are rural, regional and remote, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or living with disability.

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (DOCX 1.1MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (PDF 2MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Download the Parents and Guardian’s Guide for School Leavers, which summarises the resources and information available to help you explore all the education, training, and work options available to your young person.

School Leavers Information Service

- navigate the School Leavers Information Kit (SLIK),

- access and use the Your Career website and tools; and

- find relevant support services if needed.

Word Of The Week: School

noun

1. an organisation that provides instruction: such as an institution for the teaching of children, acollege or university, a group of scholars and teachers pursuing knowledge together that with similar groups constituted a medieval university. 2. the process of teaching or learning especially at a school. 3. source of knowledge. 4. a group of persons who hold a common doctrine or follow the same teacher (as in philosophy, theology, or medicine). 5. the regulations governing military drill of individuals or units.

The word school derives from Greek scholē, originally meaning "leisure" and also "that in which leisure is employed", but later "a group to whom lectures were given, school". Middle English scole, from Old English scōl, from Latin schola, from Greek scholē leisure, discussion, lecture, school.

Plato's academy, mosaic from Pompeii

Molly Meldrum at 80: how the ‘artfully incoherent’ presenter changed Australian music – and Australian music journalism

Liz Giuffre, University of Technology SydneyIan Alexander “Molly” Meldrum is 80 on January 29 2023.

The Australian music industry would not be where it is today without his work as a talent scout, DJ, record producer, journalist, broadcaster and professional fan.

His legacy has been acknowledged by the ARIAs, APRA, the Logies, an Order of Australia and even a mini-series.

Just a couple of weeks ago, Meldrum made headlines again for an appearance at Elton John’s farewell concert in Melbourne when he “mooned” the crowd in a playful display of rock and roll rebellion. He later apologised to the audience and old friend Elton, keen to make sure no one else was blamed.

It was an irreverence typical of Meldrum’s long career. But his legacy is not just in the musical acts he supported. It is also in the taste makers who followed in his footsteps.

‘Artfully Incoherent’

A journalist at pioneering music magazine Go-Set, a presenter and record producer, Meldrum became a household name with the ABC TV music show Countdown (1974-87). Countdown was a weekly touchstone for the industry and fans, promoting local acts alongside the best in the world.

Meldrum’s approach to interviewing and commentary is legendary. ABC historian Ken Inglis called his interviewing style “artfully incoherent”.

Importantly, his charm put artists and fans at ease.

Meldrum is not a slick player, but a fan. This fandom is felt so deeply that, at times, he became overwhelmed.

One of Meldrum’s most famous interviews was in 1977 when the then Prince Of Wales appeared on Countdown to launch a charity record and event. The presenter became increasingly flustered.

Even now, watching back, it’s hard not to side with Meldrum rather than his famous guest. Pomp, ceremony and hierarchy really didn’t make sense in this rock and pop oasis.

In another interview, Meldrum spoke to David Bowie on a tennis court. Both men casually talked and smoked (it was the ‘70s!), talking seriously about the work but not much else.

As Meldrum handed Bowie a tennis racket to demonstrate how the iconic track, Fame (with John Lennon) was born, the Starman was given space to be hilariously human.

When meeting a sedate Stevie Nicks, Meldrum met her on her level.

Nicks told Meldrum she was only happy “sometimes”, and rather than probing, he just listened. When Meldrum asked about the dog Nicks had in her lap, she opened up:

I got her way before I had any money, I didn’t have near enough money to buy her […] She’s one of the things I’ve had to give up for Fleetwood Mac, because you’re not home.

Meldrum approached this, and all his guests, with humanity. This is how his insights into the reality of rock royalty are effortlessly uncovered.

New Taste Makers

A country boy who came to the city, Meldrum studied music and the growing local industry much more attentively than his law degree. He passionately supported (and continues to support) Australian popular music – and Australian music fans.

He speaks a love language for music that musicians and fans share, and a language which has continued in other presenters.

Following in Meldrum’s footsteps we have seen distinct critical voices like Myf Warhurst, Julia Zemiro and Zan Rowe.

Each of these women have approached the music industry with charm like Meldrum, but also their own perspectives: Zemiro with a love of international influence; Warhurst with pop as a language to connect us to the everyday; Rowe with a way to connect audiences and musicians through conversations about their own processes and passions.

Our best music critics, and musicians, have embraced an unapologetic energy Meldrum made acceptable.

Meldrum is also a pioneer in the LGBTQ+ community, weathering the storms of prejudice during his early career. Today, members of the media and musical community have greater protection from the prejudice common when his career began.

The Music, Of Course, The Music

The Australian music industry would not be what it is had Molly Meldrum gone on to be a lawyer.

Through the pages of Go-Set and on Countdown he worked to promote new talent, believing in and developing acts like AC/DC, Split Enz, Paul Kelly, Do Re Mi, Australian Crawl and Kylie Minogue before the rest of the industry knew what to do with them.

He did the same for international artists. ABBA, Elton John, KISS, Madonna and many other now mega-names were first presented to Australian audiences via Meldrum’s wonderful ear.

Today, Australian music encompasses pop, dance, electro and hip hop, and artists from all walks of life. Meldrum’s willingness to listen has contributed to this, and he encouraged others to do the same.

Meldrum remains revered not just for nostalgia but as an example of what putting energy into the local scene can achieve.

Most importantly, Meldrum continues to be a music fan. He loves the mainstream, the place where the majority of the audience also resides. He has never bought into the idea of a “guilty” pleasure – if it works, it works, no music snobbery here.

His catch-cry – “do yourself a favour” – really does sum up the importance of music. It is not a luxury, but something to really keep us going. ![]()

Liz Giuffre, Senior Lecturer in Communication, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Let’s dance! How dance classes can lift your mood and help boost your social life

If your new year’s resolutions include getting healthier, exercising more and lifting your mood, dance might be for you.

By dance, we don’t mean watching other people dance on TikTok, as much fun as this can be. We mean taking a dance class, or even better, a few.

A growing body of research shows the benefits of dance, regardless of the type (for example, classes or social dancing) or the style (hip hop, ballroom, ballet). Dance boosts our wellbeing as it improves our emotional and physical health, makes us feel less stressed and more socially connected.

Here’s what to consider if you think dance might be for you.

The Benefits Of Dance

Dance is an engaging and fun way of exercising, learning and meeting people. A review of the evidence shows taking part in dance classes or dancing socially improves your health and wellbeing regardless of your age, gender or fitness.

Another review focuses more specifically on benefits of dance across the lifespan. It shows dance classes and dancing socially at any age improves participants’ sense of self, confidence and creativity.

Researchers have also looked at specific dance programs.

One UK-based dance program for young people aged 14 shows one class a week for three months increased students’ fitness level and self-esteem. This was due to a combination of factors including physical exercise, a stimulating learning environment, positive engagement with peers, and creativity.

Another community-based program for adults in hospital shows weekly dance sessions led to positive feelings, enriches social engagement and reduced stress related to being in hospital.

If you want to know how much dance is needed to develop some of these positive effects, we have good news for you.

A useful hint comes from a study that looked exactly at how much creative or arts engagement is needed for good mental health – 100 or more hours a year, or two or more hours a week, in most cases.

Dance Is Social

But dance is more than physical activity. It is also a community ritual. Humans have always danced. We still do so to mark and celebrate transitory periods in life. Think of how weddings prompt non-dancers to move rhythmically to music. Some cultures dance to celebrate childbirth. Many dance to celebrate religious and cultural holidays.

This is what inspired French sociologist Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) to explore how dance affects societies and cultures.

Durkheim saw collective dance as a societal glue – a social practice that cultivates what he called “collective effervescence”, a feeling of dynamism, vitality and community.

He observed how dance held cultures together by creating communal feelings that were difficult to cultivate otherwise, for example a feeling of uplifting togetherness or powerful unity.

It’s that uplifting feeling you might experience when dancing at a concert and even for a brief moment forgetting yourself while moving in synchrony with the rest of the crowd.

Synchronous collective activities, such as dance, provide a pleasurable way to foster social bonding. This is due to feelings Durkheim noticed that we now know as transcendental emotions – such as joy, awe and temporary dissolution of a sense of self (“losing yourself”). These can lead to feeling a part of something bigger than ourselves and help us experience social connectedness.

For those of us still experiencing social anxiety or feelings of loneliness due to the COVID pandemic, dance can be a way of (re)building social connections and belonging.

Whether you join an online dance program and invite a few friends, go to an in-person dance class, or go to a concert or dance club, dance can give temporary respite from the everyday and help lift your mood.

Keen To Try Out Dance?

Here’s what to consider:

if you have not exercised for a while, start with a program tailored to beginners or the specific fitness level that suits you

if you have physical injuries, check in with your GP first

if public dance classes are unappealing, consider joining an online dance program, or going to a dance-friendly venue or concert

to make the most of social aspect of dance, invite your friends and family to join you

social dance classes are a better choice for meeting new people

beginner performance dance classes will improve your physical health, dance skills and self-esteem

most importantly, remember, it is not so much about how good your dancing is, dance is more about joy, fun and social connectedness.

In the words of one participant in our (yet-to-be published) research on dance and wellbeing, dance for adults is a rare gateway into fun:

There’s so much joy, there’s so much play in dancing. And play isn’t always that easy to access as an adult; and yet, it’s just such a joyful experience. I feel so happy to be able to dance.

Tamara Borovica, Research assistant and early career researcher, Critical Mental Health research group, RMIT University and Renata Kokanovic, Professor and Lead of Critical Mental Health, Social and Global Studies Centre, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Asteroid 2023 BU just passed a few thousand kilometres from Earth. Here’s why that’s exciting

There are hundreds of millions of asteroids in our Solar System, which means new asteroids are discovered quite frequently. It also means close encounters between asteroids and Earth are fairly common.

Some of these close encounters end up with the asteroid impacting Earth, occasionally with severe consequences.

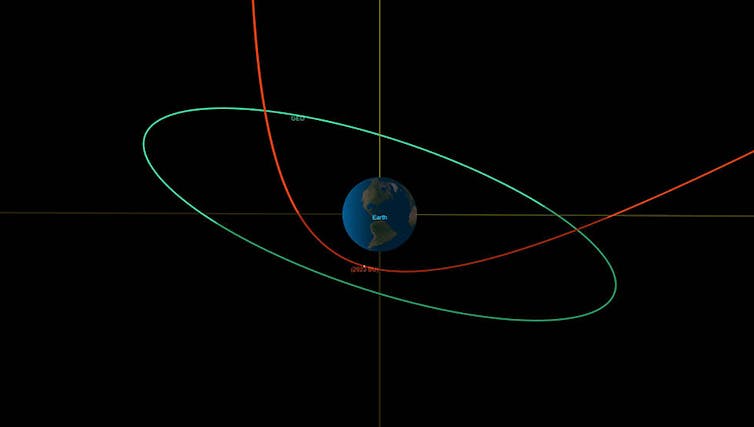

A recently discovered asteroid, named 2023 BU, has made the news because today it passed very close to Earth. Discovered on Saturday January 21 by amateur astronomer Gennadiy Borisov in Crimea, 2023 BU passed only about 3,600km from the surface of Earth (near the southern tip of South America) six days later on January 27.

That distance is just slightly farther than the distance between Perth and Sydney, and is only about 1% the distance between Earth and our Moon.

The asteroid also passed through the region of space that contains a significant proportion of the human-made satellites orbiting Earth.

All this makes 2023 BU the fourth-closest known asteroid encounter with Earth, ignoring those that have actually impacted the planet or our atmosphere.

How Does 2023 BU Rate As An Asteroid And A Threat?

2023 BU is unremarkable, other than that it passed so close to Earth. The diameter of the asteroid is estimated to be just 4–8 metres, which is on the small end of the range of asteroid sizes.

There are likely hundreds of millions of such objects in our Solar System, and it is possible 2023 BU has come close to Earth many times before over the millennia. Until now, we have been oblivious to the fact.

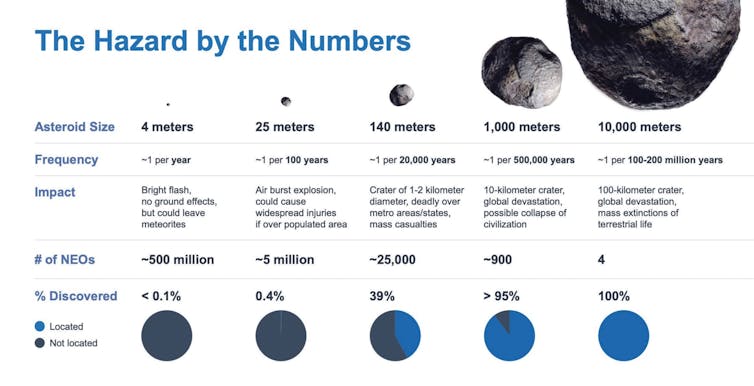

In context, on average a 4-metre-diameter asteroid will impact Earth every year and an 8-metre-diameter asteroid every five years or so (see the infographic below).

Asteroids of this size pose little risk to life on Earth when they hit, because they largely break up in the atmosphere. They produce spectacular fireballs, and some of the asteroid may make it to the ground as meteorites.

Now that 2023 BU has been discovered, its orbit around the Sun can be estimated and future visits to Earth predicted. It is estimated there is a 1 in 10,000 chance 2023 BU will impact Earth sometime between 2077 and 2123.

So, we have little to fear from 2023 BU or any of the many millions of similar objects in the Solar System.

Asteroids need to be greater than 25 metres in diameter to pose any significant risk to life in a collision with Earth; to challenge the existence of civilisation, they’d need to be at least a kilometre in diameter.

It is estimated there are fewer than 1,000 such asteroids in the Solar System, and could impact Earth every 500,000 years. We know about more than 95% of these objects.

Will There Be More Close Asteroid Passes?

2023 BU was the fourth closest pass by an asteroid ever recorded. The three closer passes were by very small asteroids discovered in 2020 and 2021 (2021 UA, 2020 QG and 2020 VT).

Asteroid 2023 BU and countless other asteroids have passed very close to Earth during the nearly five billion years of the Solar System’s existence, and this situation will continue into the future.

What has changed in recent years is our ability to detect asteroids of this size, such that any threats can be characterised. That an object roughly five metres in size can be detected many thousands of kilometres away by a very dedicated amateur astronomer shows that the technology for making significant astronomical discoveries is within reach of the general public. This is very exciting.

Amateurs and professionals can together continue to discover and categorise objects, so threat analyses can be done. Another very exciting recent development came last year, by the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which successfully collided a spacecraft into an asteroid and changed its direction.

DART makes plausible the concept of redirecting an asteroid away from a collision course with Earth, if a threat analysis identifies a serious risk with enough warning.![]()

Steven Tingay, John Curtin Distinguished Professor (Radio Astronomy), Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is ‘Toadzilla’ a sign of enormous cane toads to come? It’s possible – toads grow as large as their environment allows

Last week, the world met “Toadzilla”, a cane toad the size of a football and six times larger than average. The rangers who found her – female toads are bigger than male – were stunned. Weighing in at 2.7 kilograms, Toadzilla may be the largest cane toad ever recorded.

Is this a sign Australia’s cane toads are getting bigger? Not necessarily. Like all other “cold-blooded” or ectothermic animals, cane toads don’t have a limit to their body size like mammals and birds do. They can keep growing their entire lives. Researchers have found toads at the front of the invasion wave get bigger quicker due to more prey.

But there’s another possibility too. Last year, we found toads in urban areas have smaller parotid (toxin) glands than those in rural areas. That might be because bush toads experience higher predation, selecting for more toxins. In nature, an easy way to select for larger toxin glands is to make the whole animal bigger.

Given many native animals, reptiles and birds have now figured out how to eat these toads, we may possibly see more Toadzilla contenders in future.

Wait, Cane Toads Have Predators In Australia?

When you think of cane toads in Australia, you might think of an unstoppable army hopping across the countryside, killing endangered animals, such as quolls, with their poison. There’s some truth to this – a large cane toad would appear to be a delectable package of protein for everything from freshwater crocodiles to goannas to birds of prey.

To survive, they have evolved large poison glands on their shoulders. When attacked, toads can pump out lethal bufotoxin. Worse, the eggs, tadpoles and toadlets are all poisonous as well.

In the South American savannas where they evolved, cane toads have many predators, which can consume them in spite of the poison.

While Australia has no native toads, we have frogs with poisonous skins and glands, for example red-crowned toadlets and corroboree frogs, so the concept of a toxic amphibian is not entirely new to our fauna.

Not only that, but many of our birds’ ancestors may have originated in Asia, where they were exposed to other poisonous amphibians. Our native rats, too, have some tolerance of these toxins from their more recent overseas ancestry. And colubrid snakes such as keelbacks can also eat cane toads.

Some species susceptible to the toxin have figured out ways to defeat it. Our famous “bin chickens” – the white ibis – have figured out how to eat cane toads, by flicking them about to make them produce their toxin and then washing them at a nearby creek. Rakali – the large water rat known as Australia’s otter – learned how to eat cane toads. They flip them over and eat their organs, avoiding the glands.

Overall, though, cane toads are bad news for many native species. Even with predator pressure, their populations keep growing and they keep moving into new areas.

How Do Water-Loving Toads Thrive In Dry Australia?

The difference between a toad and a frog isn’t whether they can live out of water. Australia has dozens of native treefrog species which have far better ways of holding onto their water than do cane toads. Desert tree frogs, for instance, can live in semi-arid regions, while burrowing frogs can live in true deserts. (The real difference is more obscure – toads have sternums in two cartilaginous parts instead of one, possibly an adaptation to walking or jumping).

So how did they become one of Australia’s most notorious introduced species? One answer: they were introduced purposely and vigorously, with thousands of toads bred up and introduced in many locations.

The plan was for the toads to eat native cane beetles plaguing Queensland’s sugarcane plantations. Before the 1935 introduction, the fantastically named entomologist Walter Froggatt pleaded with authorities not to release them. “This great toad, immune from enemies, omnivorous in its habits, and breeding all year round, may become as great a pest as the rabbit or cactus,” he wrote.

But farmers won, the toads arrived, the beetles proved too hard to catch and the toads began eating everything else. Soon, they began to spread. Each female can lay 20,000 eggs a year. (Cane beetles were brought under control only a few years later, when an effective pesticide was discovered).

Another reason these toads now number in the hundreds of millions is their sheer adaptability. They are incredibly good at finding hidden sources of water, even in semi-arid parts of the country. During the dry season, toads tend to stay very close to water. When the wet season comes and soaks the ground, they begin to move.

You might have come across research suggesting toads at the front of the invading wave are evolving longer legs. This isn’t natural selection – it’s spatial selection, where longer-legged toads naturally get to the front and breed with other longer-legged toads.

But we are seeing signs cane toads may be adapting to local conditions by getting better at retaining water. And, remarkably, they’ve become cannibals.

Are Cane Toads Unstoppable?

They’re formidable opponents, but cane toads have limits.

These toads eat everything they can catch – even if it has a sting or bite. They eat giant centipedes up to 16cm long. Beekeepers hate them because they’ll sit in front of hives and eat bee after bee.

Despite their poison glands, fecundity and adaptability, there’s one thing they can’t beat. Most amphibians can’t live in very arid conditions. That means toads will probably never infiltrate central Australia’s deserts.

Modelling has shown they’re unlikely to get past the arid middle coastline of Western Australia, and we think they’ll never make it to Melbourne because it’s too cold. Researchers have suggested protecting southern Western Australia from toads by converting cattle dams to tanks.