inbox and environment news: Issue 571

February 12 - 18 2023: Issue 571

Stop PEP11 & Protect Our Coast Bill 2023 To Be Tabled In Federal Parliament This Week By Warringah MP - Will Be Seconded By Mackellar MP

Mackellar MP Dr. Sophie Scamps has stated she will be seconding Warringah MP Zali Steggall's Stop PEP11 and Protect Our Coast Bill 2023 on Monday February 13th when Parliament returns.

''The Northern Beaches is united on this - we will never accept drilling for oil and gas off our beaches!'' Dr. Scamps has stated

''Zali's Bill will rule out any consideration of an application to drill for oil and gas off our coast and protect our oceans and our coastline for good.

It's time for the Albanese Government to do what the Morrison Government couldn't, and that's kill off PEP-11 for good and start investing in the future - clean, cheap and reliable renewables backed by storage technology.''

More in: Agreement To End PEP-11 Litigation Revives Applicants' Licence Extension Process - Issue 570

Plastic Boardwalk Through Manly Warringah War Memorial Park: 'We Can Do Better!' States Save Manly Dam Bushland Group

WE CAN DO BETTER !!

Boardwalk Empire from Malcolm Fisher on Vimeo.

Pittwater: Urban Wallabies

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Avalon Dunes Bushcare Returns Sunday March 5th

Next will be on March 5, meeting at 8.30 in the parking area off Tasman Rd south.

We work until 11.30 but any time you can spare is wonderful.

We always find interesting insects and other wildlife. We can see the progress happening as we work in this corner of the 4.5ha dunes.

Call in to say hello or phone 0420 817 574 if you can't see us there.

New helpers very welcome, and there's always something yummy for morning tea.

Our bushcare area is within the red lines. We can work in the shade in summer, or in sun in winter. Barrenjoey High school is to the north.

Morning tea with good company and cake.

The egg case or ootheca of a Praying Mantis. Each ootheca contains a number of eggs, up to 200 with some species. Mantis eggs can take anywhere from 40 days to around five months to hatch. On hatching, the baby mantises are about as big as a large ant. The tiny holes on this one suggest the eggs have hatched.

This Leaf Beetle in the genus Paropsisterna. It has been feeding on Eucalypt or Acacia foliage. It is one of Australia's many beetles. The total species number is estimated to be in the range of 80,000 to 100,000.

A long-legged Dancing Fly pauses on a leaf of Snake Vine.

Photos; PNHA

Ocean Street Narrabeen Bridge Works

Juvenile Rainbow Lorikeet Pair

.jpg?timestamp=1675965948553)

.jpg?timestamp=1675965974397)

Black Swans On DY Lagoon

Collins Beach Clean Up

Prune Viburnum Hedge Agapanthus Flowers To Prevent Spread Into Bush Reserves

PNHA: January 11, 2023

Now is the time to prune the berries off the Viburnum hedge and dehead those old Agapanthus flowers. Put these prunings into your green waste bin. Both are now weeds of bushland as their seeds travel.

Photos: Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA)

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group Launched On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

200 experts dissected the Black Summer bushfires in unprecedented detail. Here are 6 lessons to heed

The Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20 were cataclysmic: a landmark in Australia’s environmental history. They burnt more than 10 million hectares, mostly forests in southeast Australia. Many of our most distinctive, ancient and vulnerable species were worst affected.

A new book released today, titled Australia’s Megafires, synthesises the extent of the losses. The work involved contributions from more than 200 scientists and experts. It provides the most comprehensive assessment yet of how the fires affected biodiversity and Indigenous cultural values, and how nature has recovered.

The work reveals a picture of almost unfathomable destruction. More than 1,600 native species had at least half their range burnt. And hundreds of species and ecosystems became nationally threatened for the first time, or were pushed closer to extinction.

We must use Black Summer as an opportunity to learn – and make fundamental changes. Here, we outline six lessons to heed.

1. Natural Systems Are Already Stressed

Problem: Even before Black Summer, most Australian ecosystems were already struggling due to multiple threats.

The threatened alpine bog communities in the Australian Capital Territory, for example, were already being damaged by climate change, weeds and feral animals. Then the Black Summer fires came through and burnt 86% of known sites.

Put all these threats together, and recovery for these ecosystems – which are slow to develop – will not be easy. They may be lost altogether, along with threatened animals that call the bogs home, such as the broad-toothed rat.

Solution: Managing crises such as fires is not enough on its own. Our natural systems must be made more resilient. More effective legislation and management is needed to control all threats that degrade nature. And in some cases, threatened species may need to be relocated to put them out of harm’s way.

2. We Don’t Know What, Or Where, All Species Are

Problem: Thousands of Australian species are not (or barely) known to science. It’s very hard to protect a species if we don’t know it exists, where it lives or how it responds to fire.

For example, it’s likely that the Black Summer fires sent many invertebrate species – such as insects and spiders - to extinction. But we’ll never know because they were never described by Western science, and their distributions were never traced.

Only about 30% of Australia’s estimated 320,000 invertebrate species have been described by taxonomists. Of those that are described, most are known from only one or two records, which provides only limited insight. Information is similarly poor for fungi.

Solution: We need to gather more information about how species and environments respond to fires, and to what extent conservation efforts after fires are working. This is especially true for poorly known species groups. And the data should be made accessible to all who seek it.

3. Emergency Responders Don’t Have Enough Information

Problem: Emergency responders told us that during the fires, they didn’t have the information to prioritise the most important areas for conservation.

We found across 13 agencies, just two threatened species were covered by a specific and accessible emergency plan: the Wollemi pine and the eastern bristlebird. These plans told emergency responders what rescue action was needed.

For example, a plan was in place to protect the only known natural stand of Wollemi pines, in New South Wales. This prompted an extraordinary firefighting effort during the Black Summer fires. The effort was successful.

Solution: More than 1,800 of Australia’s plant and animal species are at risk of extinction. We must identify which are a priority, where they are, and how to protect them from bushfires. This information must be communicated to emergency responders and incorporated into regional fire management plans.

4. Biodiversity Usually Comes Last

Problem: Traditionally, the hierarchy of what to protect in disasters goes like this: first human life, then infrastructure, and finally biodiversity. If this hierarchy continues, some of our most significant species and natural environments will be lost.

In one example recounted to the book’s researchers, fire authorities decided to prioritise saving a few farm sheds over 5,000 hectares of national park.

Solution: There are cases, such as avoiding extinctions, where protecting nature is more important than saving infrastructure. Community priorities should be surveyed, and the information used to inform planning and policy.

Legal obligations to protect biodiversity in fires are few. The current re-working of federal environment laws provides an opportunity to change this.

5. Conservation Funding Is Grossly Insufficient

Problem: Decades of sustained management effort is needed to recover many species and environments affected by fire. Unfortunately, funding for the task is short-term and inadequate.

For example, both state and federal governments invested heavily in controlling feral herbivores, such as deer, in the months after the fires. This was done to protect unburnt and regenerating vegetation. Yet, eventually the funding dries up and feral populations rebound.

Extra funding for some short-term recovery projects flowed in the wake of the Black Summer fires – from governments, the private sector and the community. But for many species, recovery will be a long-term proposition – if it happens at all.

Solution: Governments must stop seeing spending on the environment as optional. It’s as fundamental to our society and well-being as health and education – and funding levels should reflect this.

6. First Nations Knowledge Has Been Sidelined

Problem: First Nations people have used fire to manage forested landscapes for millenia. Yet their knowledge and perspectives have not been incorporated into forest fire management and recovery.

So how has this come about? Barriers identified in the book include inadequate employment and training opportunities for First Nations people to undertake cultural burning activities. Also, First Nations people are frequently denied access to Country to rekindle and develop their land management skills, and lack the legal authority to undertake cultural burning.

And as the book shows, cross-cultural challenges mean non-Indigenous fire officers can have limited appreciation or knowledge of Indigenous cultural burning protocols.

Solution: Indigenous people should be supported to rekindle cultural fire practices in forests. And non-Indigenous fire managers should, with consent from First Nations people, incorporate these practices into policies governing fire management and recovery.

What’s more, species and sites that are culturally important to First Nations people should be prioritised for protection and recovery.

Harnessing Our Grief

The Black Summer fires showed people care. The disaster triggered an outpouring of grief from Australia and around the world. We understood one thing clearly: we were losing what enriches our lives.

But protecting our precious natural assets requires a fundamental reset of Australia’s fire management.

More broadly, the Black Summer fires kickstarted a huge collaborative recovery effort from governments, conservation and research organisations, and First Nations groups. If we’re to be better prepared for future megafires, this impetus must continue.

Libby Rumpff, Senior Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Science, School of Ecosystem and Forest Science, The University of Melbourne; John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University; Sarah Legge, Professor, Australian National University, and Stephen van Leeuwen, Indigenous Chair of Biodiversity & Environmental Science, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

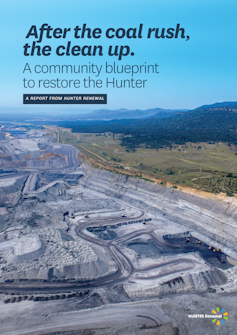

‘We need to restore the land’: as coal mines close, here’s a community blueprint to sustain the Hunter Valley

The decline of the coal industry means 17 mines in the New South Wales Hunter Valley will close over the next two decades. More than 130,000 hectares of mining land — nearly two-thirds of the valley floor between Broke and Muswellbrook — will become available for new uses.

Restoring and reusing this land could contribute billions of dollars to the Hunter economy, create thousands of full-time jobs and make the region a world leader in industries such as renewable energy and regenerative agriculture that improves soil and water quality and increases biodiversity and resilience. But to unlock these future opportunities, we must first clean up the legacy of the past.

Last year community organisation Hunter Renewal asked people across the Hunter Valley about their priorities. They told us they want the Hunter to become a thriving natural environment, a more vibrant and attractive place to live with connected communities, and a diverse and resilient economy.

These community priorities, and their implications for land use planning, are outlined in a report published by Hunter Renewal today: After the coal rush, the clean-up. A community blueprint to restore the Hunter. This blueprint could be a model for other Australian communities planning their transition away from fossil fuels.

How Were Priorities Identified?

We began by analysing more than 170 documents from government, academia and industry about post-mining land use, planning and related issues. From this, a first draft of principles and recommendations for action was created.

The draft was put to a panel of ecological, social and technical experts from the University of Newcastle. Wanaruah/Wonnorua Elders and other First Nations peoples also advised on this draft.

Hunter community members then reviewed and revised a second draft through a series of workshops, interviews and an online survey. They included land holders, students, business owners, mine rehabilitation experts, Indigenous knowledge holders and renewable energy workers.

Rehabilitation And Restoration

Hunter residents want mined lands to be restored to support biodiversity and clean industries such as regenerative farming, renewable energy, and other industries that regenerate rather than extract.

To ensure this restoration happens, stronger legal obligations would ensure mining companies cannot walk away from their obligations, leaving voids in the landscape that become a perpetual hazard to human and environmental health. As one resident said:

Mining companies shouldn’t be allowed to have a free pass at everything and get as much funding via subsidies as they do from the government.

Planning And Governance

People said that for the Hunter landscape to be restored at the scale required, planning and policy mechanisms will have to be well co-ordinated. An independent and locally based Hunter Rehabilitation and Restoration Commission could do this. It could work alongside the already proposed Hunter Valley Transition Authority.

The community suggested increasing coal-mining royalties to pay for this co-ordinated work. Mining companies would then be the ones that foot the clean-up bill.

In NSW, the royalty rate for open-cut coal is just 8.2% of the resale value. That’s too low for what is required. As another resident said:

We shouldn’t underestimate the size of the task and true cost and effort of rehabilitation of multiple large mines over decades. This is an opportunity to repurpose the land and the physical and social infrastructure.

Community Involvement

Successful mine closure and relinquishment requires that affected communities and stakeholders are meaningfully involved at every stage of planning and implementation. Yet true involvement is rare

People in the Hunter want to see greater community involvement mandated to ensure new developments benefit their communities for the long term. As one Hunter resident said:

The mines have privatised all the profits and socialised all the costs […] We want to be involved from the beginning as equals.

First Nations

In Australia all mines are on Indigenous land and over 60% of mines are near to Indigenous communities. Yet Indigenous people are less likely to benefit economically from mining operations than non-Indigenous people.

Hunter residents said this needs to change. One way to do this is to return mining land to Traditional Owners, especially unmined buffer lands.

Making decisions with First Nations people from the outset for new projects will help to overcome the systemic disadvantage in Australia since colonisation. It will also build a knowledge base for change. As one Hunter resident said:

There is so much to be gained in recognising and understanding the land management practices of the local Aboriginal people, based on 60,000 years of observation and science dealing with the oldest continent on the planet.

Climate And Environment

Plants and animals need connected ecosystems that allow them to move, adapt and survive. People in the Hunter want a region-wide system of biodiversity corridors. The transition from coal is an opportunity to set up a system that will give the region’s native species a fighting chance in a warming world.

As one resident told us:

Rehabilitating the land to ensure biodiversity is restored is the most important thing to ensure the native plant species can grow back and allow the native animals to return. We need to restore the land to try and reverse the human impacts on the site as much as possible.

Dawn Of A Cleaner Future

The coal industry has had it pretty good in this region for generations. We need a focus now on cleaning up the mess so a new, cleaner future can emerge. This requires a new approach to planning and development in partnership with local communities.

The consultative approach behind the Hunter community blueprint demonstrates the value of including a wide range of perspectives in planning for a post-coal future.

What this set of prioritised recommendations shows is that the people of the Hunter understand the complexity of the task and want to be part of planning it. It will require new laws and well-resourced public agencies capable of managing restoration and ensuring coal companies pay their dues and clean up after themselves.![]()

Kimberley Crofts, Doctoral Student, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney and Liam Phelan, Senior Lecturer, School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tanya Plibersek killed off Clive Palmer’s coal mine. It’s an Australian first – but it may never happen again

Justine Bell-James, The University of QueenslandFederal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has formally rejected mining magnate Clive Palmer’s proposed Central Queensland Coal Project. Her decision was based on the risk of damage to the Great Barrier Reef, freshwater creeks and groundwater.

The 20-year open-cut mine project would have extracted up to 10 million tonnes of metallurgical coal – used to make steel – each year.

Plibersek’s decision is significant. It’s the first time a coal mine has been refused in the two decades our federal environment law has been in place. But those hoping the decision sets a precedent for other mine proposals are likely to be disappointed.

Palmer’s mine was not refused on climate change grounds. Objectors to coal mines will still need to persuade the federal government of the link between future coal mine developments and global warming.

A Rare Decision Indeed

Australia’s federal environment law is known as the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. It came into force in 2000 to provide federal oversight of large projects.

Under the law, proponents must refer a proposal to federal environment authorities if it’s likely to significantly impact so-called “matters of national environmental significance”. These matters include the Great Barrier Reef.

But it’s extremely rare that any development is refused under the EPBC Act. As of July last year, more than 7,000 projects had been referred to the federal government under the law, for assessment of the proposal’s impacts. Just 13 were ultimately refused.

So why did Palmer’s proposed mine cross this exceptional hurdle for refusal? Largely because of its location. The proposed site was just ten kilometres from the Great Barrier Reef world heritage area.

Explaining the decision on Wednesday, Plibersek said:

[…] risks to the Great Barrier Reef, freshwater creeks and groundwater are too great. Freshwater creeks run into the Great Barrier Reef and onto seagrass meadows that feed dugongs and provide breeding grounds for fish.

The Thin End Of The Wedge?

Plibersek’s decision has triggered calls for the federal government to reject other fossil fuel projects.

For example, Greens environment spokeswoman Sarah Hanson-Young on Wednesday described Plibersek’s decision as “the thin edge of the wedge”. She went on:

There [were] 118 new coal and gas projects in the pipeline. One down, 117 to go.

From Narrabri’s double-whammy new coal and gas projects, Woodside’s North West Shelf offshore gas extension, billionaire miner Gina Rinehart’s proposed CSG expansion in the Surat Basin, or the Mount Pleasant coal project extension in the Hunter, the Minister has many projects left to rule out.

Approving more coal and gas in the midst of a climate crisis is reckless and dangerous.

However, persuading the federal minister to reject these mines will not be easy. That’s because the law contains no explicit requirement for the minister to consider the climate change impacts of a proposal.

This certainly hasn’t stopped litigants from challenging projects on climate grounds. But to date, none have succeeded.

Other legal objections – such as one brought by the Australian Conservation Foundation against the Adani mine – have taken a different tack. They’ve sought to show the carbon emissions resulting from burning coal from a mine would harm a matter of national environmental significance.

The ACF argued the Adani mine was inconsistent with Australia’s international obligations to protect the Great Barrier Reef. But the challenge was unsuccessful.

Such arguments are difficult to run. That’s partly because they string together a number of causal links. In other words, they rest on the assumption that one action is definitively responsible for another, and so on down the chain.

Such links may be possible to show in cases such as the Palmer mine, when a development is close to the coast and its direct operation might pollute waterways. But it’s harder to show that coal from a single mine, burnt by a third party, will damage the Great Barrier Reef.

Room For Hope

Plibersek’s decision is unlikely to set a precedent for federal mine approvals.

The EPBC Act could, in theory, be strengthened to give the minister more power to reject a proposal on climate grounds. But unfortunately, the Albanese government’s promised reforms of the law fail to do so.

First, the reforms failed to include a “climate trigger” – a mechanism by which development proposals are not approved unless their climate impact has been considered.

Second, the reforms fail to make so-called “scope 3 emissions” a mandatory consideration in environmental approvals. These types of emissions are produced indirectly – such as when a company’s coal is burned for energy.

There is room for hope, however. The federal government’s Climate Change Act enshrines in law Australia’s goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. Under this policy position, the approval of large coal mines will become increasingly difficult to reconcile.

And in recent years, some state courts have been convinced by causal arguments linking mines to climate change. So future federal decisions are unlikely to be immune from further challenge.

What’s Next For Clive Palmer?

Plibersek’s decision comes during a bad few months for Palmer. In November last year, Queensland’s Land Court recommended Palmer’s proposed Waratah coal project in Queensland also be rejected due to its likely contribution to climate change, and subsequent erosion of human rights.

Palmer can seek a judicial review of the latest decision. But success would rest on whether it could be shown Plibersek’s decision involved a legal error. These types of challenges are notoriously difficult – so there’s a good chance this proposed mine has reached the end of the road. ![]()

Justine Bell-James, Associate Professor, TC Beirne School of Law, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The coal whack-a-mole: getting rid of coal power will make prices fall and demand rise elsewhere

The fight against climate change is full of inconvenient truths. The latest? Coal is going to be harder to get rid of than we had hoped. Every victory like the rejection of Clive Palmer’s proposed Rockhampton coal mine seems to be offset by coal’s gains elsewhere.

Potsdam Institute experts this week published research suggesting we have less than 5% chance of actually ending coal use by 2050. That would make the Paris Agreement goal of keeping global heating under 1.5℃ all but impossible.

Why? Supply and demand coupled with domestic policies and priorities. While coal power is likely to drop sharply, coal use will rebound in other sectors, according to the research. Why? As some countries move to clean energy, the price of coal will fall. Once coal is cheaper, other countries or domestic sectors such as steelmaking are likely to seize the opportunity and buy more. The researchers estimate for every 100 joules of coal not burned in power plants, an extra 54 joules will be burned in other sectors, in a trend they dub “coal leakage”.

Leakage poses a new challenge, just as the world seems set to accelerate climate action. The only answer? Accelerate even faster.

Fossil Fuels Are Extraordinarily Resilient

What this study tells us is our current efforts won’t be enough – even with the current tailwinds of Europe’s gas crisis and plunging renewable costs.

In 2017, nations at the annual United Nations climate talks launched the Powering Past Coal Alliance in an effort to speed up action. But according to the Potsdam research, efforts by the 48 nations and 49 sub-national regions involved could be counterproductive.

That’s because members of this alliance haven’t taken steps to avoid the risk of rebound coal use – even elsewhere in their own economies.

Depressingly, this is part of a trend. The fossil fuel sector is proving powerfully resistant to change. The world keeps on burning more fossil fuels despite the COVID lockdown drop in 2020. Coal burning increased by 6.3% in 2021, and the International Energy Agency estimates this figure will have increased again by 1.2% in 2022 to reach a historic high.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine saw coal use soar, as Europe weaned itself off Russian gas. Germany had to delay its plans to quit coal power within 15 years and fire up coal plants again over the winter, while Japan’s reliance on coal has only grown in recent years.

In developing countries, coal is seen as a cheap, convenient and proven way to power the economy. China is far and away the world’s largest coal user – and producer. The downside has been terrible air pollution. That forced the government to force millions of households to replace coal with natural gas or electricity for heating, while supercharging its renewable sector, which now produces almost 30% of its electricity.

But as China’s economy slows and energy shortages increase, the government has backtracked and approved 300 million tonnes of new coal production capacity in 2022, on top of 220 million tons of capacity added in 2021. That’s more than all the coal Australia produced in 2021 (478 million tonnes).

New coal power projects have also been boosted, with 65 gigawatts of new coal power projects approved by the Chinese government in the first 11 months of 2022 – more than three times the capacity approved in 2021.

It’s no wonder coal and other fossil fuel producers are enjoying windfall profits. Australian coal exporters earned A$45 billion over 2021–22 thanks to soaring prices in the international market.

What About The Huge Investment In Renewables?

You might read this with your heart sinking and think – wait, wasn’t 2022 the first year the world invested more than US$1 trillion (A$1.44 trillion) in clean energy? How can coal rebound while we switch to clean energy?

Yes, we’ve seen stunning and welcome growth in green energy technologies and related industries. This has been driven by government policies, corporate demand for clean energy and the ever-increasing market competitiveness of solar, wind and offshore wind.

Unfortunately, what this new research tells us is that both are true. Renewables are racing ahead. But the world’s demand for energy grows and grows as nations get richer and the population grows. To phase out fossil fuels remains the hardest challenge we face. The solutions will have to be hashed out politically.

After all, we now have almost all the technologies we need to stop burning fossil fuels. (Aviation, cargo ships and steelmaking are some of the hardest sectors to clean up.)

What Do We Do?

Put simply, we’re almost out of time. Any delay in ending our reliance on coal and keeping those carbon-dioxide dense rocks safely stored in the ground is extremely dangerous.

Sustained political effort does work. Even though Germany had to reopen some coal plants, their reliance on coal for electricity fell from 60% in 1985 to below 30% in 2020.

To end coal means clamping down on free-riders. Australia is a good case study. The companies which own our doddering old coal stations are heading for the exit as quickly as they can. Even the newest coal power stations are expected to have shorter lifetimes than anticipated. But to date, there’s been little effort to ensure coal doesn’t simply get burned in, say, steelworks.

Internationally, developed countries should offer greater financial incentives to help developing countries switch to renewables. In 2021, rich countries offered billions to South Africa to quit coal. Last year, they made a similar offer to Indonesia. This is welcome – but we need more.

Worldwide, 770 million people still live without access to electricity. For years, China used this as a justification for funding coal plants overseas. But in 2021, President Xi Jinping announced this would end.

Moves like this are essential. We can’t simply expect markets to end the burning of coal as quickly as we need. That means we’ll need policies to do the work.

To nail down the coffin on fossil fuels, we have to embrace what economists call “creative destruction” – the ability for technologies to disrupt the old and create the new. Coal and oil ended centuries of reliance on horses for transport. Now it’s time to end our reliance on fossil fuels – to destroy the old and make room for the new. ![]()

Hao Tan, Associate Professor, Newcastle Business School, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The new climate denial? Using wealth to insulate yourself from discomfort and change

While the days of overt climate denial are mostly over, there’s a distinct form of denial emerging in its stead. You may have experienced it and not even realised. It’s called implicatory denial, and it happens when you consciously recognise climate change as a serious threat without making significant changes to your everyday behaviour in response.

Much research has focused on how we intellectually distance ourselves from the unpleasant realities happening around us. What requires greater attention is how we may engage in climate denial by seeking out spaces of sensory comfort and using them to shield ourselves as the world unravels outside our window.

Denial, thought of in this way, is entirely sensible. My colleagues and I asked residents around the Western Sydney suburb of Penrith – famously the hottest place on Earth during the Black Summer of 2019-20 – about their experiences during heatwave conditions. Unsurprisingly, sensory denial is central to how they cope with extremes – primarily by using air conditioning.

Those without access to aircon resorted to wetting towels, or using fans and spray bottles. While these low-cost strategies are actually more sustainable than aircon, people don’t like them as much. Given the opportunity, we’re likely to engage in sensory climate denial as a way to insulate ourselves from experiences of climate change.

Why Do Our Senses Matter When It Comes To Climate Denial?

We tend to think of climate denial as a delaying tactic used by fossil fuel advocates. This is not wrong, given climate denial was strategically created and fostered by politicians and coal, oil and gas companies with vested interests in stalling action and deflecting responsibility.

Researchers have historically linked climate denial to inadequate knowledge, sociopolitical biases or emotional defence. Other researchers have focused on beliefs, psychological barriers, and moral disengagement.

But focusing on how and why we think overlooks the main way we actually respond to our environments: our bodies. The role of our senses and their influence on our everyday behaviour tends to be overlooked in social and political thought. Reckoning with climate change inaction demands we return to our senses. Here, we find climate denial is more than just a political tool.

Within our communities, it’s the way in which different segments of society are able to maintain a physical sense of normalcy and comfort, while others bear the brunt of climate disasters.

A heatwave in Western Sydney in 2016-17 reflects this clear divide, as colleagues and I found in earlier research.

People who lived in households without aircon were hit hard by the heat. It affected their bodies and emotions, making them fatigued, sometimes nauseous, anxious and stressed. It was hard for them to do anything other than swelter or seek out spaces of relief where possible. In contrast, people with aircon were far less affected, or even unbothered by the heat. They knew there was a heatwave, but it didn’t directly affect them.

One resident told us of trying to sleep without aircon:

If you only get maybe three or four hours sleep – and it’s not good sleep – … it’s like, “I can cope today.” (By) the third sleep, it’s like, “Please keep away from me” … And every day after that just gets worse and worse.

Another resident told us of the relief she felt at being able to leave her overheated house, taking her kids and staying at a friend’s house with both air conditioning and a pool. “It was like a holiday,” she said.

Both groups were being entirely rational in seeking relief from the overwhelming heat in whatever ways they could. Those without aircon longed for the relief it would bring.

For those with aircon, their main concern was the cost of running it. While this is a burden, the fact this was their main worry indicates aircon worked. Their relative wealth shielded them.

Why Does This Matter?

If we use technologies like aircon to avoid dealing with the root causes of climate change, we are in denial.

As the world heats up, demand for air conditioning has skyrocketed. The International Energy Agency has estimated that by 2050, up to two-thirds of the world’s households will have installed aircon, particularly in China, India and Indonesia.

As a privatised answer to a public problem, aircon reliance has been normalised to the point of invisibility. When we use our air conditioners to fend off a heatwave, we can overwhelm the power grid and trigger local blackouts. Worse, with today’s energy sources, our need for sensory comfort causes yet more emissions to be pumped into the atmosphere. On a street level, air conditioners make your house colder and the outside air warmer still.

This pattern of sensory comfort for wealthier people is systemically reinforced in for-profit housing developments, while lower-income rentals and public housing are legally and financially excluded. These residents are forced to rely instead on evacuation shelters or spending hours in airconditioned shopping centres.

This kind of denial, then, is tied to forms of privilege. To be able to literally shut out climate disruption and pretend everything is normal speaks to our universal desire to live in comfort and without pain. But as the climate warps, this is possible only for some.

If you had the opportunity, of course you would shut yourself and your loved ones away from the disruption, discomfort and danger of heatwaves, floods and bushfires.

The risk is we anaesthetise ourselves to what’s really going on. Inequality is rampant in Australia and worldwide, and people without the means to insulate themselves will suffer the most.

To tackle sensory climate denial means understanding that immunity to climate disruption is a temporary fantasy. As our ecosystems and climatic stability crumble, this kind of denial will inevitably vanish. ![]()

Hannah Della Bosca, PhD Candidate and Research Assistant at Sydney Environment Institute, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Plastic Debris In The Arctic Comes From All Around The World

How Waste-Eating Bacteria Digest Complex Carbons: New Information Could Lead To Bacteria-Based Platforms That Recycle Plastic And Plant Waste

Earth has lost one-fifth of its wetlands since 1700 – but most could still be saved

Like so many of the planet’s natural habitats, wetlands have been systematically destroyed over the past 300 years. Bogs, fens, marshes and swamps have disappeared from maps and memory, having been drained, dug up and built on.

Being close to a reliable source of water and generally flat, wetlands were always prime targets for building towns and farms. Draining their waterlogged soils has produced some of the most fertile farmland available.

But wetlands also offer some of the best natural solutions to modern crises. They can clean water by removing and filtering pollutants, displace floodwater, shelter wildlife, improve our mental and physical wellbeing and capture climate-changing amounts of carbon.

Peatlands, a particular type of wetland, store at least twice the carbon of all the world’s forests.

How much of the Earth’s precious wetlands have been lost since 1700 was recently addressed by a major new study published in Nature. Previously, it was feared that as much as 50% of our wetlands might have been wiped out. However, the latest research suggests that the figure is actually closer to 21% - an area the size of India.

Some countries have seen much higher losses, with Ireland losing more than 90% of its wetlands. The main reason for these global losses has been the drainage of wetlands for growing crops.

Wetlands Are Not Wastelands

This is the most thorough investigation of its kind. The researchers used historical records and the latest maps to monitor land use on a global scale.

Despite this, the new paper highlights some of the scientific and cultural barriers to studying and managing wetlands. For instance, even identifying what is and isn’t a wetland is harder than for other habitats.

The defining characteristic of a wetland – being wet – is not always easily identified in each region and season. How much is the right amount of wetness? Some classification systems list coral reefs as wetlands, while others argue this is too wet.

And for centuries, wetlands were seen as unproductive wastelands ripe for converting to cropland. This makes records of where these ecosystems used to be sketchy at best.

The report shows clearly that the removal of wetlands is not spread evenly around the globe. Some regions have lost more than average. Around half of the wetlands in Europe have gone, with the UK losing 75% of its original area.

The US, central Asia, India, China, Japan and south-east Asia are also reported to have lost 50% of their original wetlands. It is these regional differences which promoted the idea that half of all the world’s wetlands had disappeared.

This disparity is somewhat hopeful, as it suggests there are still plenty of wetlands which haven’t been destroyed – particularly the vast northern peatlands of Siberia and Canada.

An Ecological Tonic

Losing a wetland a few acres in size may not sound much on a global or even national scale, but it’s very serious for the nearby town that now floods when it rains and is catastrophic for the specialised animals and plants, like curlews and swallowtail butterflies, living there.

Fortunately, countries and international organisations are beginning to understand how important wetlands are locally and globally, with some adopting “no-net-loss” policies that oblige developers to restore any habitats they destroy. The UK has promised to ban the sale of peat-based composts for amateur growers by 2024.

Wetland habitats are being conserved around the world, often at huge expense. Over US$10 billion (£8.2 billion) has been spent on a 35-year plan to restore the Florida Everglades, a unique network of subtropical wetlands, making it the largest and most expensive ecological restoration project in the world.

The creation of new wetlands is also underway in many places. The reintroduction of beavers to enclosures across Britain is expected to increase the nation’s wetland coverage, bringing with it all the advantages of these habitats.

Beaver dams and the wetlands they create reduce the effects of flooding by up to 60% and can boost the area’s wildlife. One study showed the number of local mammal species shot up by 86% thanks to these furry engineers.

Even the sustainable drainage system ponds developers create on the fringes of new housing estates could see pocket wetlands appearing in towns and cities across the UK. By mimicking natural drainage regimes instead of removing surface water with pipes and sewers, sustainable drainage systems can create areas of plants and water that have been shown to increase biodiversity, especially invertebrates.

Whether the total global loss of wetlands is 20% or 50% doesn’t really matter. What does matter is that people stop looking at wetlands as wastelands, there for us to drain and turn into “useful” land.

As the UN recently pointed out, an estimated 40% of Earth’s species live and breed in wetlands and a billion people depend on them for their livelihoods. Conserving and restoring these vital habitats is key to achieving a sustainable future.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Christian Dunn, Senior Lecturer in Natural Sciences, Bangor University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

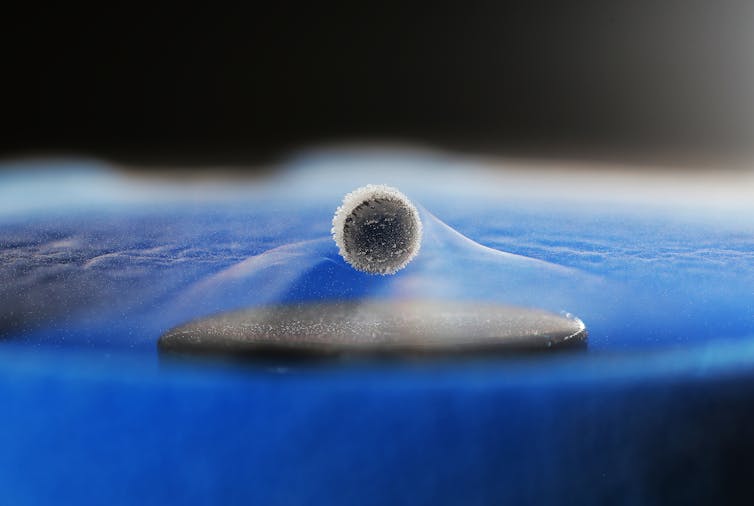

A tenth of all electricity is lost in the grid. Superconducting cables can help

For most of us, transmitting power is an invisible part of modern life. You flick the switch and the light goes on.

But the way we transport electricity is vital. For us to quit fossil fuels, we will need a better grid, connecting renewable energy in the regions with cities.

Electricity grids are big, complex systems. Building new high-voltage transmission lines often spurs backlash from communities worried about the visual impact of the towers. And our 20th century grid loses around 10% of the power generated as heat.

One solution? Use superconducting cables for key sections of the grid. A single 17-centimetre cable can carry the entire output of several nuclear plants. Cities and regions around the world have done this to cut emissions, increase efficiency, protect key infrastructure against disasters and run powerlines underground. As Australia prepares to modernise its grid, it should follow suit. It’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

What’s Wrong With Our Tried-And-True Technology?

Plenty.

The main advantage of high voltage transmission lines is they’re relatively cheap.

But cheap to build comes with hidden costs later. A survey of 140 countries found the electricity currently wasted in transmission accounts for a staggering half-billion tonnes of carbon dioxide – each year.

These unnecessary emissions are higher than the exhaust from all the world’s trucks, or from all the methane burned off at oil rigs.

Inefficient power transmission also means countries have to build extra power plants to compensate for losses on the grid.

Labor has pledged A$20 billion to make the grid ready for clean energy. This includes an extra 10,000 kilometres of transmission lines. But what type of lines? At present, the plans are for the conventional high voltage overhead cables you see dotting the countryside.

System planning by Australia’s energy market operator shows many grid-modernising projects will use last century’s technologies, the conventional high voltage overhead cables. If these plans proceed without considering superconductors, it will be a huge missed opportunity.

How Could Superconducting Cables Help?

Superconduction is where electrons can flow without resistance or loss. Built into power cables, it holds out the promise of lossless electricity transfer, over both long and short distances. That’s important, given Australia’s remarkable wind and solar resources are often located far from energy users in the cities.

High voltage superconducting cables would allow us to deliver power with minimal losses from heat or electrical resistance and with footprints at least 100 times smaller than a conventional copper cable for the same power output.

And they are far more resilient to disasters and extreme weather, as they are located underground.

Even more important, a typical superconducting cable can deliver the same or greater power at a much lower voltage than a conventional transmission cable. That means the space needed for transformers and grid connections falls from the size of a large gym to only a double garage.

Bringing these technologies into our power grid offers social, environmental, commercial and efficiency dividends.

Unfortunately, while superconductors are commonplace in Australia’s medical community (where they are routinely used in MRI machines and diagnostic instruments) they have not yet found their home in our power sector.

One reason is that superconductors must be cooled to work. But rapid progress in cryogenics means you no longer have to lower their temperature almost to absolute zero (-273℃). Modern “high temperature” superconductors only need to be cooled to -200℃, which can be done with liquid nitrogen – a cheap, readily available substance.

Overseas, however, they are proving themselves daily. Perhaps the most well-known example to date is in Germany’s city of Essen. In 2014, engineers installed a 10 kilovolt (kV) superconducting cable in the dense city centre. Even though it was only one kilometre long, it avoided the higher cost of building a third substation in an area where there was very limited space for infrastructure. Essen’s cable is unobtrusive in a metre-wide easement and only 70cm below ground.

Superconducting cables can be laid underground with a minimal footprint and cost-effectively. They need vastly less land.

A conventional high voltage overhead cable requires an easement of about 130 metres wide, with pylons up to 80 metres high to allow for safety. By contrast, an underground superconducting cable would take up an easement of six metres wide, and up to 2 metres deep.

This has another benefit: overcoming community scepticism. At present, many locals are concerned about the vulnerability of high voltage overhead cables in bushfire-prone and environmentally sensitive regions, as well as the visual impact of the large towers and lines. Communities and farmers in some regions are vocally against plans for new 85-metre high towers and power lines running through or near their land.

Climate extremes, unprecedented windstorms, excessive rainfall and lightning strikes can disrupt power supply networks, as the Victorian town of Moorabool discovered in 2021.

What about cost? This is hard to pin down, as it depends on the scale, nature and complexity of the task. But consider this – the Essen cable cost around $20m in 2014. Replacing the six 500kV towers destroyed by windstorms near Moorabool in January 2020 cost $26 million.

While superconducting cables will cost more up front, you save by avoiding large easements, requiring fewer substations (as the power is at a lower voltage), and streamlining approvals.

Where Would Superconductors Have Most Effect?

Queensland. The sunshine state is planning four new high-voltage transmission projects, to be built by the mid-2030s. The goal is to link clean energy production in the north of the state with the population centres of the south.

Right now, there are major congestion issues between southern and central Queensland. Strategically locating superconducting cables here would be the best location, serving to future-proof infrastructure, reduce emissions and avoid power loss. ![]()

Ian Mackinnon, Professor and Director, Centre for Clean Energy Technologies and Practices, Queensland University of Technology and Richard Taylor, Principal research fellow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bacteria use life’s original energy source to thrive in the ocean’s lightless depths

There are more than a billion bacteria in just one litre of seawater. How do all of these organisms find the energy and nutrients they need to survive?

In the nutrient-rich waters near the surface of the ocean, the primary energy source is sunlight, which drives photosynthesis, the transformation of light energy into chemical energy. In much of the open ocean, however, a lack of nutrients limits photosynthesis, and in the deep ocean it ceases altogether as there is no sunlight.

Despite this, microbes have found a way to live throughout the vast and dark ocean. How do they do it?

As we report in Nature Microbiology, many ocean bacteria in fact gain energy from two dissolved gases, hydrogen and carbon monoxide, in a process called chemosynthesis. This hidden but ancient process helps maintain the diversity and productivity of our oceans.

When The Lights Go Out, Chemosynthesis Prevails

We aimed to identify the preferred energy sources of microbes in the world’s oceans.

Humans and other animals depend on eating organic foods, while plants rely on photosynthesis. In contrast, microbes use a myriad of energy sources: solar, organic, and inorganic.

Many eat high-energy gases such as hydrogen and even carbon monoxide, which is poisonous to us. They do so by using special enzymes called hydrogenases and carbon monoxide dehydrogenases.

The world’s oceans contain quite a lot of dissolved hydrogen and carbon monoxide due to various biological and geological processes. Given this, we predicted these gases would be key energy sources for oceanic microbes.

During our five-year study, we surveyed the capabilities and activities of the microbes present in the world’s oceans. We sampled seawater from diverse sites, spanning tropical islands to subantarctic waters. Public data from the global Tara Oceans study were also analysed.

Using a technique called metagenomic sequencing, we discovered the genetic blueprints of all the microbes in our ocean samples. We also took chemical measurements during the expeditions, analysed bacterial cultures, and used mathematical modelling to understand how the bacteria were getting their energy.

In all the samples we analysed, microbes were using enzymes to gain energy from hydrogen and carbon monoxide. As we expected, photosynthesis was the main source of energy in coastal surface waters – but gas-eating microbes grew more common further away from shore and in the deeper ocean.

In nutrient-poor waters, chemosynthesis may be the main strategy for obtaining energy.

Eight distantly related groups, or phyla, of bacteria made the enzymes to use hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Clearly chemosynthesis is a far more widespread strategy in the oceans than previously thought!

Hydrogen and carbon monoxide aren’t the only chemical energy sources supporting ocean bacteria. Building on previous work by others, we found ammonia, sulfide and thiosulfate were also widely used.

Together, all these inorganic energy sources allow diverse microbes to prosper even in the darkest and most nutrient-poor regions of the ocean. As we have previously reported, chemosynthesis even allows a “microbial jungle” to form beneath the ice sheets of Antarctica.

An Ancient Trait That Remains Surprisingly Widespread Today

Chemosynthesis is less well known than photosynthesis, but it has much more ancient roots. Leading theories on the origin of life suggest hydrogen – produced in hydrothermal vents devoid of sunlight – was the first energy source for life. Photosynthesis likely evolved much later, providing the oxygen in the atmosphere that supports human life.

Some ecosystems still exist today that are primarily driven by chemosynthesis, most notably “black smokers”. Here, inorganic energy sources released from underwater volcanoes support complex microbially driven ecosystems, which include giant tube worms (you might have seen these on David Attenborough’s Blue Planet). But it’s conventionally thought that most ecosystems today are either directly or indirectly driven by photosynthesis.

Our findings suggest the situation is more complicated. By presenting the first report of hydrogen consumption in open oceans, we reveal unexpected similarities of marine microorganisms today to their ancient ancestors.

Chemosynthesis remains highly active today and provides a lifeline for oceanic microbes when photosynthesis is low.

The hydrogenases that modern marine bacteria use to consume hydrogen appear to be directly descended from the ancient catalysts that supported the first life. But through billions of years of evolution, they’ve adapted to the lower hydrogen and higher oxygen levels of today.

Interestingly, hydrogen and carbon monoxide appear to have distinct roles for ocean bacteria.

Hydrogen-consuming microbes grow using the slow, steady feed of energy provided by this gas. These bacteria are often ultrasmall and adapted to life with minimal energy, as reflected by our experiments with the polar bacterium Sphingopyxis alaskensis.

In contrast, carbon monoxide is primarily a “last resort” energy source for bacteria lacking light or organic carbon. It provides enough energy to survive until a better meal, but doesn’t allow for much growth. This agrees with previous work showing carbon monoxide dehydrogenase supports survival, but not growth, of various bacteria.

Bacterial Survival In A Changing World

Through our studies of the oceans and many other environments, it’s now clear that chemosynthesis is a universal process and microbes are actually quite flexible in their diets. Such insights improve our understanding of how ocean microbes survive, produce and consume nutrients, and adapt to their environment.

In turn, we are better able to predict how they may respond to a changing climate and other pressures. The deep ocean, often considered Earth’s “final frontier”, no doubt holds many other secrets big and small.![]()

Chris Greening, Professor, Microbiology, Monash University; Rachael Lappan, Group Leader and ARC DECRA Fellow, Monash University, and Zahra F. Islam, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Environment plan for England asks farmers to restore nature – but changes are likely to be superficial

The UK government’s environment improvement plan pledges to restore 500,000 hectares (1.2 million acres) of wildlife-rich habitat, create or expand 25 national parks, invest in the recovery of hedgehogs and red squirrels, tackle rising sewage pollution and improve access to green spaces in England over the next five years.

Since 69% of land in England is farmed, much of the plan’s success in improving nature will hinge on its reform of the country’s agricultural sector. Farming is implicated in the extinction risk of 86% of threatened species globally, and accounts for roughly one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change, not to mention soil erosion and river pollution.

The government has described the plan as an “ambitious road map” to a cleaner, greener country. Some of the targets certainly are ambitious. For example, the plan aims to bring 40% of farmland soils into sustainable management by 2028.

This would be a monumental shift in how soil is cared for in England. Intensive agriculture has slashed the amount of carbon soils store by 60% and put 6 million hectares across England and Wales at risk of erosion or compaction, costing an estimated £1.2 billion a year.

But the plan doesn’t actually explain how sustainable management will be expanded. The only action proposed is to create a “baseline map” of soil health in England by 2028.

The plan also aims for 65%-80% of landowners and farmers to adopt nature-friendly farming by 2030. “Nature-friendly farming” is not defined, nor is it based on any internationally recognised principles, making it impossible to assess the government’s progress.

The plan only aims for this to be adopted on 10%-15% of farmers’ land too, which would amount to a mere 6%–12% of England’s farmland overall. Research shows that protecting small pockets of land won’t benefit biodiversity if the majority of farming in the surrounding landscape is ecologically destructive.

All Carrots, No Sticks

The main instrument the government has chosen to shake up agriculture is the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) scheme. SFIs are payments to farmers based on actions which benefit the environment. For example, a farmer could receive up to £40 a hectare for their efforts to improve soils on arable fields.

An integrated strategy for converting farmland to more sustainable management would mean increasing the diversity of crops grown, helping healthy soils regenerate and eliminating pesticides, all at the same time. Instead, SFI payments reward farmers for making standalone changes.

This might mean putting out seeds for birds in winter or leaving a grassy strip on an unused section of land to provide habitat for insects, though it could also mean significantly cutting down on pesticides. This system offers flexibility for landowners, but research shows that farmers are more likely to choose environmental improvements which don’t require significant changes to how they farm.

This is the fatal flaw in the government’s flagship farming reform. Farmers can continue doing things which harm soils and wildlife on the (majority) productive parts of their land while receiving benefits for sprinkling pro-environment measures around the edges.

Wildflower margins which are planted around pesticide-soaked crops under the pretence of supporting pollinators offer a common example. Not only is the continued use of pesticide on the crop harmful in itself, the wildflowers actually accumulate the chemical residue, sometimes in higher concentrations than in the crops themselves. This renders the wildflower pollen harmful, rather than beneficial, to bees, butterflies and other bugs.

The environment improvement plan heavily relies on voluntary participation in lieu of regulation, not only through SFIs but quality assurance schemes such as Red Tractor. For example, fertilisers and slurries (semi-liquid manures) emit ammonia, a greenhouse gas which is bad for human health. Rather than regulate this, the plan favours an “industry led” approach with Red Tractor certifications.

Red Tractor is yet another voluntary scheme, and has been criticised as ineffectual for encouraging improvements to the environment and animal welfare on farms. The plan has only suggested that it will consider regulating dairy and intensive beef farms in the same way that it regulates intensive poultry and pig farms.

Even if regulations were to be expanded, environmental regulators visit farms so rarely and superficially that it might not make a difference. On average, it is estimated that English farms can expect an environmental inspection once every 263 years. Despite being regulated, intensive poultry and pig operations are a major cause of river pollution.

Beyond England’s Borders

In post-Brexit policy discussions, some landowners and consumers worried that payments for environmental improvements would outweigh income from food production, meaning less homegrown fare. Government discourse has since emphasised that farmers will receive support to deliver on environmental outcomes “alongside” food production. Nothing in the plan ensures this.

Other countries have a food policy which guides farmers to grow produce necessary for healthy diets and determines how much should be imported or exported. Responsibility for food in England is divided between 16 different departments, with no overarching framework or body.

SFIs and the new plan do very little to stem the environmental consequences of food produced beyond England’s borders. The aggregate ammonia emissions from crops and livestock imported into England are significantly higher than those stemming from domestic production.

And despite its favourable growing conditions, the majority of fruit and vegetables eaten in England are imported, contributing to water scarcity and pollution in other countries. Preserving the environment at home while polluting and degrading environments abroad is nonsensical, as all ecosystems are interconnected. But it is also shameful to shift the environmental burden of English diets onto other people.

If the government and citizens are serious about improving the environment, then policies must require that ecological principles are integrated into food production. At present, voluntary measures and weak regulation are all that is offered.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Elise Wach, Research Advisor, Institute of Development Studies

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Loopholes wide enough to ‘drive a diesel truck through’ – how to tell if a business is really net zero

Ian Thomson, University of BirminghamThe science is clear: greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions must peak before 2025 to prevent planetary warming exceeding 1.5℃. The solution is simple: stop doing and investing in things that emit GHGs and instead protect the natural systems that remove them from the atmosphere.

Disclosure of a company’s emissions should then let consumers and investors make informed decisions. But businesses are rarely required to disclose all of the emissions generated in their full “lifecycle”.

For example, the UK’s Cumbria coal mine, which was approved in December, will produce 2.8 million tonnes of coking coal each year for the steelmaking industry without accounting for the emissions produced when this coal is burned. These emissions instead represent the responsibility of the steel industry.

The Cumbria coal mine has made no claims regarding net zero. But other fossil fuel companies have used this reporting ambiguity to claim they are on target to becoming net zero despite the use of their products being responsible for almost three-quarters of global GHG emissions. Consumers or investors will then probably make decisions that result in emissions being generated at unsustainable levels. Since joining the United Nations (UN) Net Zero Banking Alliance, 56 banks have provided US$270 billion (£221 billion) worth of finance to fossil fuel companies.

But the actions of the UK government and several large businesses offer promise. The government now requires firms competing for major government contracts to report their full lifecycle emissions.

Understanding This Absurdity

An organisation’s climate impact can be made immediately clear by separating their GHG emissions into four groups or scopes.

Scope 1 refers to GHG emissions generated directly by business activities up to point of sale. Scope 2 refers to the emissions related to the generation of the energy purchased by a business. The emissions generated in the production and delivery of a business’s resources are called scope 3 upstream, and scope 3 downstream accounts for all emissions after a product or service has been sold.

Current guidance only requires a business, like the operator of the Cumbrian coke mine, to report their scope 1 and 2 emissions. Yet a report conducted in 2020 by global management consultant McKinsey found that these emissions only account for between 14% and 25% of the coal sector’s total emissions. The majority of the GHG emissions associated with coal mining are therefore not disclosed.

Calculating Scope 3 Emissions

But these emissions are essential for determining the carbon footprint of an organisation and are relatively straight forward to calculate.

The UN has published a standard called the Greenhouse Gas Protocol that details how to calculate scope 3 emissions. And most of the goods, services, materials and equipment used by businesses have readily available GHG conversion factors.

These factors allow us to convert activities like driving into their associated GHG emissions. The GHG conversion factor for driving the average car for a kilometre is 0.171 kg of CO₂e. By driving a car 100 km, we would emit 171 kg of CO₂e.

In the case of burning coking coal, we can rely on the laws of physics and chemistry. Burning coal involves a combustion process where the carbon in the coal reacts with oxygen to produce CO₂. Using the government’s GHG conversion factors, we know that burning a tonne of coking coal produces 3.14 tonnes of CO₂, regardless of what you use it for or where it is used.

By multiplying this conversion factor by the total amount of coking coal extracted from the Cumbria plant (2.8 million tonnes), we obtain a reliable measure of the emissions generated by burning the plant’s coal – 8.8 million tonnes of CO₂. Roughly the same amount of emissions would be produced by driving a car 1.3 million times around the Earth. These are scope 3 emissions that are largely ignored when determining whether a coal mine is net zero.

Applying This In Practise

Companies are best placed to estimate the future GHG emissions that arise from the use of their products. Car manufacturers, for example, have the data necessary to predict the future emissions generated by their vehicles. They know the expected lifetime mileage of their models sold and the fuel type that their vehicles use.

Some organisations already calculate their scope 3 emissions and provide this information willingly. Microsoft have a tool that measures the GHG emissions of your cloud software that runs off the internet usage and estimates the emissions avoided by using the cloud. And global chemical producer BASF publish publicly available information on the GHG emissions associated with their products along their full lifecycle.

This should allow consumers and investors to make more informed decisions.

The future emissions of other activities, such as land use change, are more difficult to measure. Yet from 2010 to 2019, deforestation is estimated to have caused between 5.9 and 9.5% of total GHG emissions. Initiatives like the UN Land Sector and Removals Guidance, which is set for publication in 2023, will produce GHG conversion factors for land use change and will enable a more accurate evaluation of the climate impact of these activities.

At the latest UN climate change summit (COP27), Secretary-General António Guterres criticised the current criteria for net zero commitments for having loopholes wide enough to “drive a diesel truck through”. Measuring scope 3 emissions is crucial to accurately assess how far an organisation is progressing towards net zero. To prevent climate breakdown, more businesses must be required to disclose what many of them already know.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Ian Thomson, Director of the Centre for Responsible Business, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

A Walk Around The Cromer Side Of Narrabeen Lake by Joe Mills

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways; Bungan Beach and Bungan Head Reserves: A Headland Garden

Pittwater Reserves, The Green Ways: Clareville Wharf and Taylor's Point Jetty

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways; Hordern, Wilshire Parks, McKay Reserve: From Beach to Estuary

Pittwater Reserves - The Green Ways: Mona Vale's Village Greens a Map of the Historic Crown Lands Ethos Realised in The Village, Kitchener and Beeby Parks

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways Bilgola Beach - The Cabbage Tree Gardens and Camping Grounds - Includes Bilgola - The Story Of A Politician, A Pilot and An Epicure by Tony Dawson and Anne Spencer

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Seagull Pair At Turimetta Beach: Spring Is In The Air!

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

Stony Range Regional Botanical Garden: Some History On How A Reserve Became An Australian Plant Park

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray