Inbox and Environment news: Issue 572

February 19 - 25 2023: Issue 572

Word Of The Week: Wildlife

noun

1. wild animals collectively; the native fauna (and sometimes flora) of a region. 2. animals that live independently of people, in natural conditions.

Wildlife refers to undomesticated animal species, but has come to include all organisms that grow or live wild in an area without being introduced by humans. Wildlife was also synonymous to game: those birds and mammals that were hunted for sport. Wildlife can be found in all ecosystems. Deserts, plains, grasslands, woodlands, forests, and other areas, including the most developed urban areas, all have distinct forms of wildlife. While the term in popular culture usually refers to animals that are untouched by human factors, most scientists agree that much wildlife is affected by human activities.

Global wildlife populations have decreased by 68% since 1970 as a result of human activity, particularly overconsumption, population growth, habitat destruction and intensive farming, according to a 2020 World Wildlife Fund's Living Planet Report and the Zoological Society of London's Living Planet Index measure, which is further evidence that humans have unleashed a sixth mass extinction event. According to CITES, it has been estimated that annually the international wildlife trade amounts to billions of dollars and it affects hundreds of millions of animal and plant specimen.

The habitat of any given species is considered its preferred area or territory. Many processes associated with human habitation of an area cause loss of this area and decrease the carrying capacity of the land for that species. In many cases these changes in land use cause a patchy break-up of the wild landscape. Agricultural land frequently displays this type of extremely fragmented, or relictual, habitat. Farms sprawl across the landscape with patches of uncleared woodland or forest dotted in-between occasional paddocks.

Examples of habitat destruction include grazing of bushland by farmed animals, changes to natural fire regimes, forest clearing for timber production and wetland draining for city expansion.

All wild populations of living things have many complex intertwining links with other living things around them. Large herbivorous animals such as the hippopotamus have populations of insectivorous birds that feed off the many parasitic insects that grow on the hippo. Should the hippo die out, so too will these groups of birds, leading to further destruction as other species dependent on the birds are affected. Also referred to as a domino effect, this series of chain reactions is by far the most destructive process that can occur in any ecological community.

Another example is the black drongos and the cattle egrets found in India. These birds feed on insects on the back of cattle, which helps to keep them disease-free. Destroying the nesting habitats of these birds would cause a decrease in the cattle population because of the spread of insect-borne diseases.

From wild + life

Compare - Fauna - noun; the animals of a particular region, habitat, or geological period.

From late 18th century: modern Latin application of Fauna, the name of a rural goddess, sister of Faunus. Fauna comes from the name Fauna, a Roman goddess of earth and fertility, the Roman god Faunus, and the related forest spirits called Fauns. All three words are cognates of the name of the Greek god Pan, and panis is the Greek equivalent of fauna.

Originally fauns of Roman mythology were spirits (genii) of rustic places, lesser versions of their chief, the god Faunus. Before their conflation with Greek satyrs, they and Faunus were represented as nude men (e.g. the Barberini Faun). Later fauns became copies of the satyrs of Greek mythology, who themselves were originally shown as part-horse rather than part-goat. By Renaissance times fauns were depicted as bipedal creatures with the horns, legs, and tail of a goat and the head, torso, and arms of a human; they are often depicted with pointed ears. These late-form mythological creatures borrowed their appearance from the satyrs, who in turn borrowed their appearance from the god Pan of the Greek pantheon. They were symbols of peace and fertility, and their Greek chieftain, Silenus, was a minor deity of Greek mythology.

.jpg?timestamp=1676518344292)

Australian and New Zealand fauna. This image was likely first published in the first edition (1876–1899) of the Nordisk familjebok.

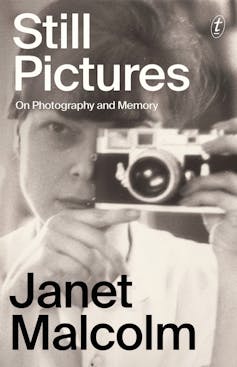

‘The unlooked-for and idiosyncratic was her stock-in-trade’: last words from the unclassifiable Janet Malcolm

Janet Malcolm, who died in 2021 at the age of 86, left her readers this “memoir”, Still Pictures, an apt and fascinating coda to a celebrated and provocative life’s work.

As a young girl, Malcolm fled Nazism with her Czech-Jewish family on one of the last boats to sail for America. Her father was a psychiatrist, her mother a lawyer, and her work is filled with the kind of attention to people, language and the “truth” that a child might inherit from such professionals, with their specific personal history.

Malcolm’s writing is sui generis. During her 58-year relationship with the New Yorker and over the course of 13 books, she covered psychoanalysis, literature, photography, art, archives and – notoriously – journalism and biography. Her huge subjects – life and truth, their representations in art and in person – were accessed via her attention to the minutest details of a subject’s dress or gesture, a slip of the tongue, and her persistent revisiting of contradictions.

Review: Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory – Janet Malcolm (Text Publishing).

Malcolm’s shifting examination of her own premises, and her awareness of the poses and self-deceptions involved in our dealings with one another, led her works of literary journalism and biography to become commentaries on the forms themselves. The Silent Woman, a study of the “afterlives” of Sylvia Plath, and The Journalist and the Murderer, on the ethics of journalism, are famous examples.

To read a “memoir” from Malcolm, then, is to enter a realm where the very idea of memoir will be treated with mistrust.

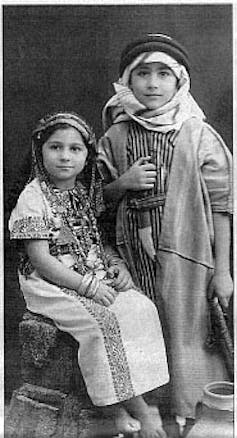

Resistant to autobiography’s false claims and its “passion for the tedious”, Still Pictures uses photographs as imperfect and contradictory aide-memoirs. The result is Malcolmesque: fragmentary, restless and extraordinarily vivid.

I Don’t Think Of The Child As Me

Still Pictures opens with a photograph of Malcolm as an impish toddler, which she uses to access her biography. But she resists the urge to use archives as evidence that substantiates memory. Disavowing connection with this lovely girl, she writes:

I don’t think of the child as me. No feeling of identification stirs as I look at her round face and thin arms and her incongruously assertive pose.

Real memory begins offstage, with a procession of girls in white dresses scattering rose petals. Wanting to join them, little Janet is given peony petals by a kind aunt, but she knows these are inferior, and the flavour of disappointment lingers across a lifetime. “I have carried this memory around with me all my life,” Malcolm writes, “but never looked at it very hard.”

But then she does. What follows is an analysis of her disappointment according to the relative merits – aesthetic, sensory, culturally bestowed – of rose and peony petals. Partial but illuminative self-knowledge is achieved via oblique enquiry. Malcolm at last begins to identify with her childhood self.

Along the way, the writing “I” invites you to question the nature of the self and its means of access to its own story.

The Pose

The photograph that opens out this enquiry does not stand alone. Incongruously, it appears alongside a portrait by Ingres of Louis-François Bertin, a French journalist of the 19th century: “a powerfully bulky man in his sixties […] who sits with both hands assertively planted on his thighs as he engages the viewer with a look of determination touched with irony”.

Ingres, so the story goes, despaired of creating a successful representation of his subject, until he spied Bertin in public, sitting in “The Pose”.

The echoed pose brings the two images together. The young Janet appears to be copying him. But what both subjects are doing, observes Malcolm, is unconsciously drawing on “the repertoire of stereotypical poses with which nature has endowed all creatures, and which we tend to notice less in our own species than we do in, say, cats and squirrels and marmosets”.

Malcolm employs ways of seeing and reading that bring to light the dynamic between individual and group that guides our actions and gives them meaning. She makes them endlessly open to interpretation by those with a watchful eye and the instruments to decode their messages.

Meaningful Gestures

Early in Still Pictures, Malcolm approaches memories of her mother, Hanka, via a picture of Hanka as a girl, with her sister Jiřina, and their mother Klara. In the photograph, Hanka is pushing her palm into Klara’s thigh.

As in the story of the pose and the memory of scattering petals, Malcolm interprets the gesture, “of mushing or squishing something”, through the connecting portals of memory. In her first language, Czech, the gesture, known as patlat, becomes upatlaný, or food that has been “over-meddled with”. It is a gesture she knows straight away. She recalls her mother performing it as a grown woman.

“I am not ready to write about my mother yet,” Malcolm states. So she broaches the subject of her mother indirectly, via her aunt’s family. The paths of memory are associative, and it is Malcolm’s uncle – Jiřina’s husband – who becomes the focus of the essay. He exposes the gradations of class between the sisters’ families.

Her own family, Malcolm realises now, were the poor relations, always visiting, never hosting, and it is another examined gesture that brings this dynamic to life, in the figure of her Uncle Paul:

I remember the deliberation with which he chewed his food, the assurance and self-confidence the working of his jaws seemed to express.

The image is superseded by the revelation that Malcolm’s family considered themselves, with their interest in art and literature, to be “vastly superior” to her aunt’s, for whom money and business were central.

But Wait A Minute

The essay is characteristic of her method. Malcolm begins with an image, then follows the nudges and connections of memory. She lingers on details that conjure a slice of a world in its interpersonal and social dynamics, before reversing, changing tack, advancing in a new direction.

She employs the bait-and-switch technique that is a central feature of her writing, and perhaps the key to how her writing always becomes about writing – its forms, methods and assumptions. Helen Garner, a great admirer, describes the way Malcolm always pushes beyond first readings, “undercutting the certainty she has just reasoned you into accepting”.

Malcolm wonders whether we can ever “write about our parents without perpetrating a fraud”. She undermines her own enterprise before tugging you further into it. Employing a metaphor, she asks whether “the lock on the bedroom door” protects our parents from scrutiny. “But wait a minute,” she says – then picks apart the metaphor and its supposed aptness.

That move, the swiping away of assuredness, occurs continually. It creates a compelling narrative quality. What more is there to know about this? What has been missed?

‘Old Not Good Photos’

Malcolm was an accomplished photographer, but bad photographs – she discusses one she finds in a box labelled “Old Not Good Photos” – can yield particular rewards.

In an essay titled “Lovesick”, she compares photographs to dreams. Some are memorable, asking for interpretation.

However, as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams […] that sometimes bear the most important messages from the inner life. So, too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.

So begins an interwoven account of the habits of love in youth, adolescent reading, and an explanation of Freud’s theory of transference.

The theory contains a key to Malcolm’s methods. Transference, for Freud, described the ways in which we see each other imperfectly, “through a haze of associations with early family figures”, who play out the same old dramas. The psychoanalyst reveals what is unnoticed and proposes “an alternative script”.

In reading photographs, people and memories, Malcolm is ever alert to what goes unremarked. She opens up the possibilities we miss the first time around.

In Still Pictures, she covers a range of compelling subjects. The topics include, among many others, her parents, the delineations of class via humour and, amazingly, the story of how she took speech lessons to defend herself in court.

What we learn, as Malcolm guides us into her memories via the clues and opacities of photographs and their associated memories, is that nothing is ever finished. There is always the possibility of new meaning if we take another look.

In an Afterword, Malcolm’s daughter Anne tells us that Still Pictures was supposed to have one last chapter on Malcolm’s “lifelong interest in taking pictures”. There is no use trying to second-guess what it might have covered. As Anne observes of her mother, “the unlooked-for and idiosyncratic was her stock-in-trade”.

As much as we might feel the loss of this chapter, the knowledge of its existence as a glimmer in Malcolm’s mind is a gift. Her great and enduring interest in her subjects – “the intense pleasure she gets from looking and thinking,” as Garner describes it – makes her work come alive in the inner world of the reader. It is gratifying to learn that, right to the end, the quality of attention that so enlivened the world, for her and for us, remained undiminished.![]()

Belinda Castles, Lecturer in Creative Writing, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The rise of ChatGPT shows why we need a clearer approach to technology in schools

ChatGPT and its powerful capacity to generate original text has taken the education sector by surprise. Not only are universities hurrying to adapt to it, schools are also grappling with this new technology.

NSW and most other states blocked the tool in public schools, to protect students from possible misinformation and curb cheating. But South Australia has allowed use of ChatGPT, in part so students can better learn and understand the potential and risks of artificial intelligence.

The range of responses to ChatGPT shows how education has yet to figure out the best way to use such tools.

ChatGPT is also just the latest example of technology coming into classrooms. Education technology (or “edtech)” is a common – and rapidly growing – part of day-to-day learning. But we need to understand it better.

Edtech In Australian Schools

The global edtech market is estimated to be worth about US$300 billion (A$432 billion). More than one billion students globally are expected to use edtech by 2025. Google and Microsoft are major players, but investment is also increasingly fueled by China, India and the European Union.

Edtech includes teaching support platforms, with sample lesson plans, tasks, games and tests. It also includes AI-backed personalised learning tools to help with maths, literacy and other school subjects. As of 2019, Australian teachers were using an estimated 250 different types of edtech, although there is no reliable number of how many use AI.

We already know some of these edtech tools are having positive results, including in disadvantaged areas. Studies suggest adaptive tutoring, which adjusts to the precise needs and level of the individual student, is especially promising.

Edtech also allows for more personalised assessment. As students move through a lesson answering questions, they can automatically get feedback, find additional instruction and branch into easier or harder content as needs be. Most importantly, teachers get detailed insight to student progress that allows them to adjust their teaching to better match what students need.

But despite these advancements, we also know edtech delivers the best results when the tools are based on proven teaching techniques. Poorly designed tools also can undermine education. In the United States, national funding laws now push school districts to make sure edtech and other teaching tools are independently evaluated for positive impact.

There are significant risks to these tools as well, especially around privacy and the marketing of student and teacher data collected when they use the tech. These risks increase if autonomous AI is behind the tool.

How Can We Prepare For More Edtech In Schools?

With a rapidly expanding edtech market, it’s easy for teachers and parents to be confused about what’s on offer, how to use it and whether it will help students learn.

ChatGPT highlights quickly products are emerging and how quickly education systems will need to respond. We need governments to be shaping what and how technology is used in classrooms to ensure high quality, safe products and avoid being caught by surprise.

Globally, some steps are underway. The EU has adopted a comprehensive digital education plan, the US has created a dedicated national edtech office, and the United Kingdom and Singapore want to use edtech to tackle specific learning needs.

What Australia Needs To Do

Australia also needs to ramp up government leadership in managing the opportunities and risks that come with this edtech. This includes:

quality requirements for the tech itself – including evidence it is based on education research

professional learning and support for schools and teachers using it

regulation and transparency around how student data will be collected, stored and used.

Independent websites in the US are also helping schools and families find high-quality learning resources (including digital tools). For example, EdReports assists teachers to evaluate curriculum materials, while Evidence for ESSA reviews the quality of research behind claimed edtech impact.

What Next

A growing body of research shows that high-quality education technology can be a powerful tool to improve student outcomes, particularly for students facing education disadvantage.

But not all edtech tools work well and much depends on how schools use them.

The most important impact of ChatGPT may be to galvanise governments and education systems to ensure Australian schooling can proactively and properly use edtech in our classrooms.

The next National School Reform Agreement offers the perfect opportunity to do this. This agreement ties federal, state, and territory funding mechanisms to lifting student learning outcomes. It is currently being negotiated and is due in December 2024.

It is important we use the opportunities provided by edtech, rather than edtech using us. ![]()

Leslie Loble, Industry Professor & Paul Ramsay Foundation Fellow, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The largest structures in the Universe are still glowing with the shock of their creation

On the largest scales, the Universe is ordered into a web-like pattern: galaxies are pulled together into clusters, which are connected by filaments and separated by voids. These clusters and filaments contain dark matter, as well as regular matter like gas and galaxies.

We call this the “cosmic web”, and we can see it by mapping the locations and densities of galaxies from large surveys made with optical telescopes.

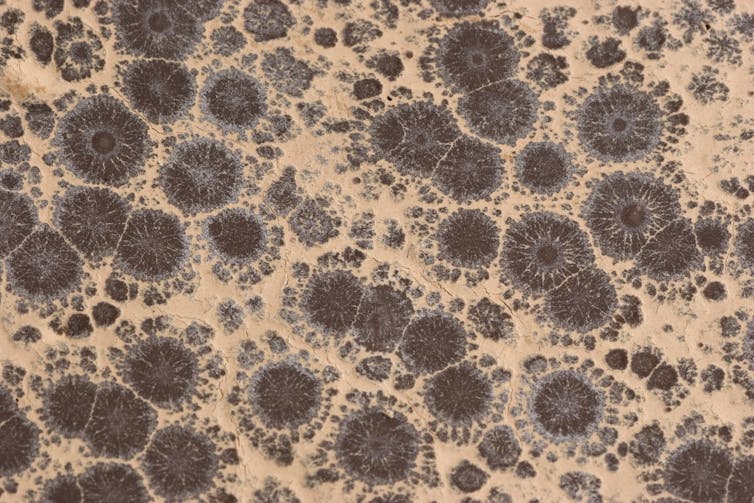

We think the cosmic web is also permeated by magnetic fields, which are created by energetic particles in motion and in turn guide the movement of those particles. Our theories predict that, as gravity draws a filament together, it will cause shockwaves that make the magnetic field stronger and create a glow that can be seen with a radio telescope.

In new research published in Science Advances, we have for the first time observed these shockwaves around pairs of galaxy clusters and the filaments that connect them.

In the past, we have only ever observed these radio shockwaves directly from collisions between galaxy clusters. However, we believe they exist around small groups of galaxies, as well as in cosmic filaments.

There are still gaps in our knowledge of these magnetic fields, such as how strong they are, how have they evolved, and what their role is in the formation of this cosmic web.

Detecting and studying this glow could not only confirm our theories for how the large-scale structure of the Universe has formed, but help answer questions about cosmic magnetic fields and their significance.

Digging Into The Noise

We expect this radio glow to be both very faint and spread over large areas, which means it is very challenging to detect it directly.

What’s more, the galaxies themselves are much brighter and can hide these faint cosmic signals. To make it even more difficult, the noise from our telescopes is usually many times larger than the expected radio glow.

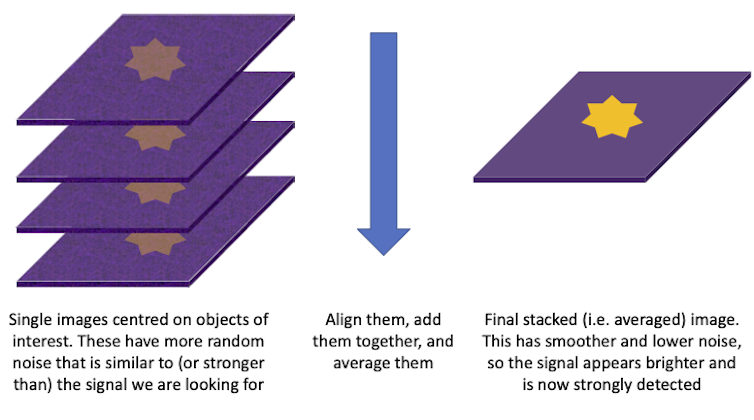

For these reasons, rather than directly observing these radio shockwaves, we had to get creative, using a technique known as stacking. This is when you average together images of many objects too faint to see individually, which decreases the noise, or rather enhances the average signal above the noise.

So what did we stack? We found more than 600,000 pairs of galaxy clusters that are near each other in space, and so are likely to be connected by filaments. We then aligned our images of them so that any radio signal from the clusters or the region between them – where we expect the shockwaves to be – would add together.

We first used this method in a paper published in 2021 with data from two radio telescopes: the Murchison Widefield Array in Western Australia and the Owens Valley Radio Observatory Long Wavelength Array in New Mexico. These were chosen not only because they covered nearly all the sky but also because they operated at low radio frequencies where this signal is expected to be brighter.

In the first project, we made an exciting discovery: we found a glow between the pairs of clusters! However, because it was an average of many clusters, all containing many galaxies, it was difficult to say for sure the signal was coming from the cosmic magnetic fields, rather than other sources like galaxies.

A ‘Shocking’ Revelation

Normally the magnetic fields in clusters are jumbled up due to turbulence. However, these shock waves force the magnetic fields into order, which means the radio glow they emit is highly polarised.

We decided to try the stacking experiment on maps of polarised radio light. This has the advantage of helping to determine what is causing the signal.

Signals from regular galaxies are only 5% polarised or less, while signals from shockwaves can be 30% polarised or more.

In our new work, we used radio data from the Global Magneto Ionic Medium Survey as well as the Planck satellite to repeat the experiment. These surveys cover almost the entire sky and have both polarised and regular radio maps.

We detected very clear rings of polarised light surrounding cluster pairs. This means the centres of the clusters are depolarised, which is expected as they are very turbulent environments.

However, on the edges of the clusters the magnetic fields are put in order thanks to the shockwaves, meaning we see this ring of polarised light.

We also found an excess of highly polarised light between the clusters, much more than you would expect from just galaxies. We can interpret this as light from the shocks in the connecting filaments. This is the first time such emission has been found in this kind of environment.

We compared our results with state-of-the-art cosmological simulations, the first of their kind to predict not just the total signal of the radio emission but the polarised signal as well. Our data agreed very well with these simulations, and by combining them we are able to understand the magnetic field signal left over from the early Universe.

In future we would like to repeat this detection for different times over the history of the Universe. We still do not know the origin of these cosmic magnetic fields, but further observations like this can help us to figure out where they came from and how they have evolved. ![]()

Tessa Vernstrom, Senior research fellow, The University of Western Australia and Christopher Riseley, Research Fellow, Università di Bologna

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Reade him, therefore; and againe, and againe’. It’s the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folio, a monumental project put together by his friends

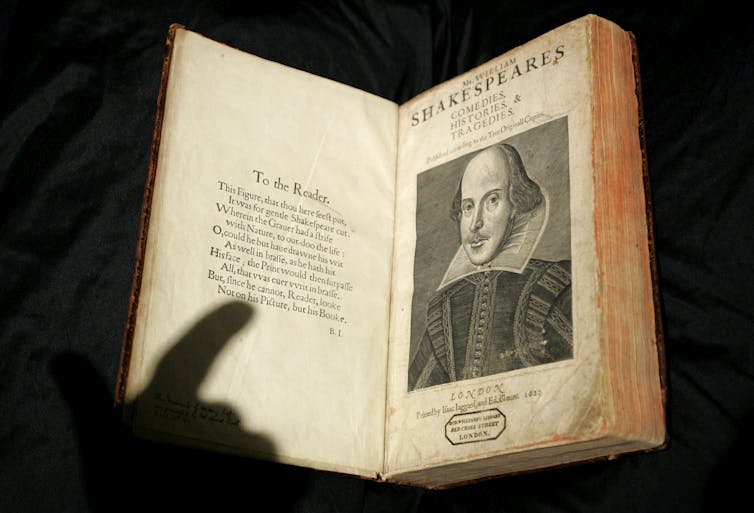

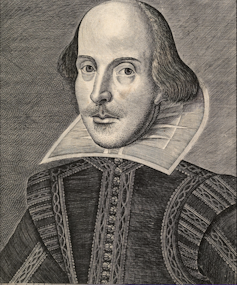

Shakespeare’s First Folio – more accurately known as Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies – was published 400 years ago this November.

It is the book that gave us Martin Droeshout’s famous engraved portrait of Shakespeare, and playwright Ben Jonson’s equally famous praise describing him as “not of an age, but for all time”. It remains one of the most iconic and recognisable books in English, with copies sometimes selling for around US$10 million.

The folio contains 36 Shakespeare plays – 18 of which had never been published before – along with two poems by Jonson that have significantly shaped Shakespeare’s reputation.

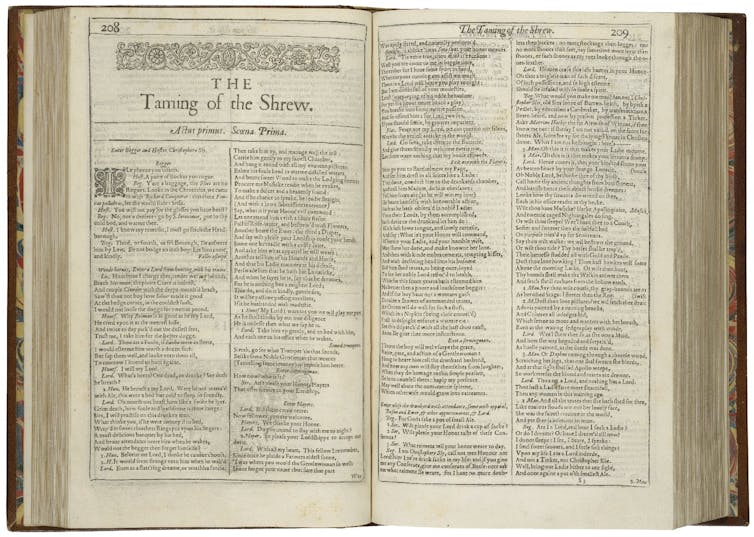

The first published collection of Shakespeare’s plays, it was put together by his fellow actors John Heminge and Henry Condell, seven years after Shakespeare’s death. Plays published here for the first time included Macbeth, The Taming of the Shrew, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus, The Tempest, Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar and As You Like It.

Despite the hefty price tag, the folio is not a rare book. Of the conjectured 750 copies printed, hundreds still survive. A popular estimate is 235 extant copies, though the Shakespeare Census project more specifically lists the locations of 228 substantively complete copies and a further 155 fragments (that is, copies with fewer than half their original leaves).

Of these, a staggering 82 copies were collected by the American businessman Henry Folger and his wife Emily in the early 20th century. These are held by the library they built for this purpose as a gift to the public – the Folger Shakespeare Library – in Washington, DC.

Meisei University in Japan holds 12 copies, and around 20 copies remain in private hands. “New” copies turn up regularly, if not frequently: in 2006, 2014, and twice in 2016, for example. Oxford’s Bodleian Library discarded its copy of the First Folio sometime in the 17th century, but in 1905 it was promptly snapped up again by its original owner!

So if it’s not a rare book, what makes a First Folio so special? The way the book was presented provides some clues.

‘What Ever You Do, Buy’

Heminge and Condell composed two prefatory notes that frame the book rather differently.

In the first – the dedication to two of Shakespeare’s patrons, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke and Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery – Heminge and Condell refer humbly to Shakespeare’s plays as “trifles”. They urge the dedicatees to patronise the plays as they patronised their author, likening the plays to “Orphanes” in need of “Guardians”.

The pair are at pains to emphasise the lowly quality of their offering, likening the plays to the “leavened Cake” offered to the gods of many nations “that had not gummes & incense”. Seen thus, with the implication that the plays will be made precious through this offering to the earls, the folio cements Shakespeare’s reputation by virtue of endorsement by its patrons.

In their second address, Heminge and Condell invoke the commercial imperative, urging people to “read and censure” the book of plays if they will, but to “buy it first”. “What ever you do, Buy”.

They style themselves as collectors and gatherers of Shakespeare’s plays: they assembled the works and brought the plays together for the first time. And of course, as one would expect of a sales pitch, they dismiss earlier publications as “stolne, and surreptitious copies, maimed, and deformed”.

By contrast, the folio they assembled offers plays “cur’d, and perfect of their limbes, and all the rest, absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them”. (Subsequent scholarship has demonstrated how false such claims often were; the quality of the versions of the plays in the folio is far from uniform.) Here, it’s the publishing industry that seemingly secures Shakespeare’s posthumous reputation.

Common to both epistles is the notion that the reader will have experienced the plays previously – on stage or in allegedly inferior published form – and that the folio marks a turning point.

The plays presented here are to be read and understood in the context of Shakespeare’s career:

Reade him, therefore; and againe, and againe: And if then you doe not like him, surely you are in some manifest danger, not to understand him.

Such sentiments remind me of the biting comment Ben Jonson makes in Every Man Out of His Humour (1599): “Art hath an enemy called Ignorance”.

A Shift In Thinking

It’s worth noting that the folio imposes the classical five-act structure onto plays that were generally conceived with only scenes in mind.

Between around 1590, when the public amphitheatre venues in London really took off, and 1608, when Shakespeare’s company began performing in the indoors Blackfriars playhouse (in addition to its outdoor Globe playhouse), English commercial plays didn’t typically use a five-act structure. (With its regular Choruses, Henry V – and to a lesser extent Romeo and Juliet – is exceptional in the Shakespeare canon in this regard.)

The generation of “university wits” who dominated the 1580s theatrical scene had all been raised on classical drama and therefore emulated its style. But Shakespeare did not go to university as far as we know, and it wasn’t until his company began performing at an indoor playhouse, where candles needed to be trimmed at regular intervals during performance, that it began to deliberately include act breaks.

The folio editors, however, attempt to impose them on Shakespeare’s plays, so they look more like the classical drama that was deemed worthy of serious consideration.

By the time of his death in 1616, around half of Shakespeare’s plays had appeared in print in single-text editions, typically in quarto format. (The term “quarto” refers to a sheet of paper being folded twice to produce four “leaves” – that is, eight pages – of a book; a “folio” results from folding the sheet just once, to yield two leaves and thus four pages.)

Modern fans of Shakespeare can be surprised by which plays were published and reprinted in this way, and which plays were not: Titus Andronicus appeared in quarto three times, Richard II five times, and Pericles three times before Shakespeare died. Othello, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra did not appear in print during the author’s lifetime.

Scholars have argued about what inherent quality made a play like Titus appeal to stationers as a sound publishing investment. We still don’t entirely know how such decisions were made, but the folio represents a shift in thinking: rather than speculating about an individual play’s worthiness or otherwise for print, the priority was gathering Shakespeare’s plays together.

A play like Timon of Athens that not only hadn’t appeared by itself in quarto, but wasn’t even originally planned for inclusion in the folio, could eventually find a home in the volume because it was contributing to the greater project, and the reasons for printing it were independent of any perceived commercial value it may have held on its own.

Lost Forever? Perhaps Not

A piece of received wisdom about the folio that most cling to is probably not true: it’s unlikely that unpublished masterpieces such as The Tempest, Twelfth Night and Julius Caesar would have been lost forever had they not been published in 1623.

The fact that copies of these plays were still available to the folio editors seven years after Shakespeare’s death and ten years after his retirement from the stage suggests that they were still accessible or even in use.

Presumably, like The Two Noble Kinsmen, a collaboration between Shakespeare and John Fletcher that came out in quarto in 1634, many or even all of these 18 plays would have eventually found their way into the world in standalone quartos or as augmentations to subsequent folios.

Fortunately we don’t have to wonder “what if”, because the folio did bring together 36 of Shakespeare’s plays in a single volume, the sum greater than the parts. Only two Shakespeare plays that didn’t appear in the First Folio (Love’s Labour’s Won and the Fletcher collaboration, Cardenio) are known to have been lost.

Literally a monumental project, the folio’s appeals to patronage and commerce, combined with its praise of the playwright’s wit, formed a multi-pronged approach to ensuring Shakespeare’s genius would receive the appreciation his friends thought it deserved.

400 years later, we continue to appreciate Heminge and Condell’s labours.![]()

David McInnis, Associate Professor of Shakespeare and Early Modern Drama, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I treat people with gambling disorder – and I’m starting to see more and more young men who are betting on sports

As a therapist who treats people with gambling problems, I’ve noticed a shift over the past few years – not only in the profile of the typical clients I treat, but also in the way their gambling problems develop.

In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court made the landmark decision to allow states to legalize sports wagering. Tennessee, where I am studying clinical psychology, took advantage of this ruling, and in late 2020, the state legalized online and mobile sports betting.

With most sportsbooks offering betting apps, my clients are finding it more difficult to quit gambling than ever before. Unlike other forms of gambling, such as playing roulette or slots at a casino, these apps are on their phones and in their pockets, accompanying them wherever they go.

This availability makes it that much harder to resist any urges that might arise – and presents unique challenges for helping clients reduce their gambling.

A New Type Of Client Emerges

When I first started treating people for gambling disorder in 2019, my clients were usually older and gambled in casinos, with slot machines and card games among their favorite forms of gambling. They also tended to be poorer and often talked about how they began gambling to make some side money, viewing it as a second job. Many of them had retired and would say things like, “Going to the casino gets me out of the house” or “The casino is like my ‘Cheers’” – a nod to the popular watering hole in the eponymous sitcom.

That all changed when sports betting was legalized in Tennessee in November 2020.

Since then, I’ve noticed that my average client has started to look different. I’m now providing therapy to younger men, mostly in their 20s, who are seeking treatment for problems with sports betting. These clients tend to earn more money and be wealthier than my previous clients – a pattern that sports betting researchers have observed.

Several of them reported being avid sports fans or having a competitive streak. And they thought they could “beat the system” due to their extensive sports knowledge.

Many of them started betting on sports after hearing promotions for various betting companies. Even if you’re a casual sports fan with no interest in betting, you can’t miss these ads, which regularly air during televised sporting events. For example, some ads for FanDuel, one of the more popular sports betting apps, highlight a “No Sweat First Bet,” with new users eligible for a risk-free bet of up to $1,000.

There’s also a social element to sports betting. One client talked about betting on sports as a way to bond with relatives who also gambled. Similarly, a few college students I have treated told me that they started betting because they wanted to fit in with their fraternity brothers.

The Apps Don’t Make It Easy To Set Limits

But once gambling issues begin, it can be hard for these clients to stop. Most of them started by placing smaller bets on a single outcome. Over time, they start to bet more to recoup their losses. Before they knew it, their bets had increased, with many not realizing how this change even happened.

Betting apps are available on any smartphone and are connected to clients’ bank accounts, making it quick and easy to deposit more funds. This often leads clients to lose track of how much money they have lost. As one client told me, “It’s easier to spend money on these apps because you never really see it. The transactions are all done electronically.”

These apps do not make it easy for those with gambling problems to sign up for cool-off periods or self-exclusion. Cool-off periods allow the user to set a time frame – from a few hours to several months – where they will be unable to log into their betting account. Self-exclusion allows the user to ban themselves from the app for longer periods of time. Specific exclusion lengths differ by state. In Tennessee, there are one-year, five-year and lifetime ban options.

While many apps have these features, my clients often have to search online for this information, and even when they do find it, they can’t figure out how to put these guardrails in place. If they wish to set a cool-off period or ban themselves from all sports betting apps, they must do so from each app, one at a time, which can be tedious.

It’s Impossible To Avoid Sports And Smartphones

Sports betting presents unique challenges for treating gambling problems.

In addiction treatment, therapists, like me, often encourage clients to fill their time with activities that aren’t connected to gambling or to avoid situations where they may be likely to gamble. But when gambling is available at the touch of a button, it becomes harder to determine what situations may lead to gambling, which makes it harder to figure out what to avoid.

Before the apps, clients had to make plans for how and when to gamble. Now, all they have to do is pick up their phone and open an app. It is also incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to ask a client to stop using their smartphone or stop watching sports.

This is why I often tailor treatment to each client’s needs and circumstances. Some may wish to quit altogether, while others may simply want to cut back on their gambling. This has forced me to consider other possible alternatives, such as showing them how to set screen time limits for sportsbook apps or talking about strategies to watch less sports.

Most people who bet on sports don’t develop gambling problems. But with so few regulations in place – advertising or otherwise – those who are the most at risk are especially vulnerable to developing problems.![]()

Tori Horn, PhD Student in Clinical Psychology, University of Memphis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Chocolate chemistry – a food scientist explains how the beloved treat gets its flavor, texture and tricky reputation as an ingredient

Whether it is enjoyed as creamy milk chocolate truffles, baked in a devilishly dark chocolate cake or even poured as hot cocoa, Americans on average consume almost 20 pounds (9 kilograms) of chocolate in a year. People have been enjoying chocolate for at least 4,000 years, starting with Mesoamericans who brewed a drink from the seeds of cacao trees. In the 16th and 17th centuries, both the trees and the beverage spread across the world, and chocolate today is a trillion-dollar global industry.

As a food scientist, I’ve conducted research on the volatile molecules that make chocolate taste good. I also developed and taught a very popular college course on the science of chocolate. Here are the answers to some of the most frequent questions I hear about this unique and complex food.

How Does Chocolate Get Its Characteristic Flavor?

Chocolate starts out as a rather dull-tasting bean, packed into a pod that grows on a cacao tree. Developing the characteristic flavor of chocolate requires two key steps: fermentation and roasting.

Immediately after harvest, the beans are piled under leaves and left to ferment for several days. Bacteria create the chemicals, called precursors, needed for the next step: roasting.

The flavor you know as chocolate is formed during roasting by something chemists call the Maillard reaction. It requires two types of chemicals – sugar and protein – both of which are present in the fermented cacao beans. Roasting brings them together under high heat, which causes the sugar and protein to react and form that wonderful aroma.

Roasting is something of an art form. Different temperatures and times will produce different flavors. If you sample a few chocolate bars on the market, you will quickly realize that some companies roast at a much higher temperature than others. Lower temperatures maximize the floral and fruity notes, while higher temperatures create more caramel and coffee notes. Which is better is really a matter of personal preference.

Interestingly, the Maillard reaction is also what creates the flavor of freshly baked bread, roasted meat and coffee. The similarity between chocolate and coffee may seem fairly obvious, but bread and meat? The reason those foods all smell so different is that the flavor chemicals that get formed depend on the exact types of sugar and protein. Bread and chocolate contain different types, so even if you roasted them in exactly the same manner, you wouldn’t get the same flavor. This specificity is part of the reason it’s so hard to make a good artificial chocolate flavor.

How Long Can You Store Chocolate?

Once the beans are roasted, that wonderful aroma has been created. The longer you wait to consume it, the more of the volatile compounds responsible for the smell evaporate and the less flavor is left for you to enjoy. Generally you have about a year to eat milk chocolate and two years for dark chocolate. It’s not a good idea to store it in the refrigerator, because it picks up moisture and odors from the other things in there, but you can store it tightly sealed in the freezer.

What’s Different About Hot Chocolate?

To make powdered hot chocolate, the beans are soaked in alkali to increase their pH before roasting. Raising the pH to be more basic helps make the powdered cocoa more soluble in water. But when the beans are at a higher pH during roasting, it changes the Maillard reaction so that different flavors are formed.

The flavor of hot chocolate is described by experts as a smooth and mellow flavor with earthy, woodsy notes, while regular chocolate flavor is sharp, with an almost citrus fruit finish.

What Creates The Texture Of A Chocolate Bar?

Historically, chocolate was consumed as a drink because the ground beans are very gritty – far from the smooth, creamy texture people can create today.

After removing the shells and grinding the beans, modern chocolate makers add additional cocoa butter. Cocoa butter is the fat that occurs in the cacao beans. But there isn’t enough fat naturally in the beans to make a smooth texture, so chocolate makers add extra.

Next the cacao beans and cocoa butter undergo a process called conching. When the process was first invented, it took a team of horses a week walking in a circle, pulling a large grinding stone, to pulverize the particles small enough. Today machines can do this grinding and mixing in about eight hours. This process creates a smooth texture, and also drives off some of the undesirable odors.

Why Is Chocolate So Difficult To Cook With?

The chocolate you buy in a store has been tempered. Tempering is a process of heating up the chocolate to just the right temperature during production, before letting it cool to a solid. This step is necessary because of the fat.

Cocoa butter’s fat can naturally exist in six different crystal forms when it is a solid. Five of these are unstable and want to convert into the most stable, sixth form. Unfortunately, that sixth form is white in appearance, gritty in texture and is commonly called “bloom.” If you see a chocolate bar with white spots on it, it has bloomed, which means the fat has rearranged itself into that sixth crystal form. It is still edible but doesn’t taste as good.

You can’t prevent bloom from happening, but you can slow it down by heating and cooling the chocolate through a series of temperature cycles. This process causes all the fat to crystallize into the second-most stable form. It takes a long time for this form to rearrange itself into the white, gritty sixth form.

When you melt chocolate at home, you break the temper. The day after you’ve created your confection, the chocolate usually blooms with an unattractive gray or white surface.

Is Chocolate An Aphrodisiac Or Antidepressant?

The short answer is, sorry, no. Eating chocolate may make you feel happier, but that’s because it tastes so good, not because it is chemically changing your brain.![]()

Sheryl Barringer, Professor of Food Science and Technology, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Orientalism: Edward Said’s ground-breaking book explained

Whether you’re conscious of it or not, you likely have a vivid mental image of what the Middle East looks and sounds like. You might envision a sparse landscape, the air warped by heat and yellowed with flurries of sand. You might hear the plucking of an oud, or a haunting voice singing in a double harmonic scale.

This viral TikTok video captures just how salient these tropes are in our collective awareness and in popular media. Here, TikTokers collaboratively satirise features commonly found in Hollywood films about the Middle East, such as Beirut (2018), American Sniper (2014), and Argo (2012).

The video spoofs “the yellow filter”, a colour-grading style used when depicting places perceived as impoverished or rife with conflict. We also hear a crude rendition of “Arabic” music, and someone poses as a “lady in lots of fabric staring at the camera”, parodying the unsettling mystique attributed to Middle Eastern women.

These tropes form a part of what Palestinian-American intellectual and activist Edward Said called Orientalism. His seminal 1978 book of the same name explores the ways Western experts, or “Orientalists”, have come to understand and represent the Middle East.

Said analyses a vast, organised body of knowledge on the Middle East, starting with Napoléon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, for which a legion of scholars, writers and scientists were enlisted to collect as much information about Egypt as they could. Orientalism peels back the supposedly neutral veneer of scientific interest and discovery attached to such projects.

Said shows how Orientalist writings and ideologies actively shape the world they describe, and how they perpetuate views of Middle Eastern people as inferior, subservient, and in need of saving. As a result, these often racist or romanticised stereotypes create a worldview that justifies Western colonialism and imperialism.

What Is “The Orient”?

According to Said, the Orient is a “semi-mythical construct” imposed on a set of countries east of Europe. While the term has been used to describe countries in East and South Asia, Said mainly focuses on how it’s used in relation to Southwest Asia and North Africa, or the Middle East.

Indeed, the Orient doesn’t have a stable set of geographical bounds. Orientalists might write about countries as varied as Lebanon, Turkey and Iraq with little distinction. Consequently, the geographical vagueness of “the Orient” works to conflate a vast and diverse array of landscapes, peoples and cultures into a single, unchanging unit.

Orientalists often describe parts of Southwest Asia and North Africa with the intention of representing the entire Orient, and a wide range of moral attitudes, religions, languages, cultures and political structures are folded into one.

As such, the idea of the Orient functions more as an abstract antithesis the West defines itself against than as an accurate descriptor of a region.

Who Are “The Orientals”?

The term “Oriental” was often used to describe any person or group of people east of Europe, usually from Arab and/or Islamic countries. Like “the Orient”, this term reduces a variety of peoples to a discrete set of traits and temperaments.

In his book, Said observes a spate of harmful and sometimes contradictory stereotypes of so-called Oriental peoples, who are described as lazy, suspicious, gullible, mysterious or untruthful.

Said argues that by minimising the rich diversity of Southwest Asian and North African peoples, Orientalists turn them into a “contrasting image” against which the West seems culturally superior.

The peoples of the Middle East are often portrayed as weak, barbaric and irrational. Westerners, in comparison, are made to seem strong, progressive and rational. This style of thinking, in which East and West, or Orient and Occident, are placed into a mutually exclusive binary, is central to Orientalist thought.

What Is An “Orientalist”?

Said mounts much of his study of Orientalism on analyses of academic research. In his book, Said mainly focuses on academics working in philology and anthropology: those who wrote about the languages and cultures of Southwest Asia and North Africa.

He shows how these researchers fashioned their highly selective, biased observations into supposedly “scientific” findings, thus positioning themselves as objective authorities on Southwest Asia and North Africa.

But Orientalists aren’t exclusively tucked away in ivory towers. Said also explores the work of authors, poets, painters, philosophers and politicians, citing figures as varied as Arthur Balfour, Victor Hugo and Eugène Delacroix.

More Than “A Mere Collection Of Lies”

It’s important to note that, for Said, Orientalism isn’t just a set of myths. He understood it as an interconnected system of institutions, policies, narratives and ideas.

Said referred to this as the interaction between “latent Orientalism” (the system of implicit ideas and beliefs about Southwest Asia and North Africa) and “manifest Orientalism” (explicit policies and ideologies acted upon by institutions).

What keeps Orientalism flourishing and relevant is its consistent and active traffic between a variety of fields. Findings in academia inform foreign and domestic policies. Portrayals in popular culture influence the framing of news about Southwest Asia and North Africa, and vice versa. Seeing the links between culture, knowledge and power is fundamental to understanding the reach of Orientalism.

What Does Orientalism Do?

Orientalism served as an ideological basis for French and British colonial rule. But Orientalist perceptions didn’t simply disappear after the colonial period. In fact, they continue to be used as justification for contemporary foreign and domestic policies.

And this, Said stresses, is how Orientalism sustains its power: through repetition. Orientalist ideas, stereotypes and approaches have been renewed and reiterated over the past two centuries, and we can still see them in circulation today.

For instance, we can see them at work in the ways the United States and European Union have endowed themselves with the authority to impose what a 2022 UN report called “suffocating” economic sanctions against Syria.

While the US Department of State has justified the unilateral sanctions as a means to “deprive [Bashar al-Assad’s] regime of the resources it needs to continue violence against civilians”, the sanctions have disproportionately affected the civilian population in Syria.

What’s more, these justifications contain the central assumption Said critiques in his book: that Southwest Asian and North African peoples need to be saved from themselves. The price of this so-called salvation is the agency and self-determination of these populations.

A Note On Context

Many scholars note that Said’s lived experience offered him a unique perspective in writing “Orientalism”. Said himself acknowledged this. In his 2003 preface, he wrote, “much of the personal investment in this study derives from my awareness of being an ‘Oriental’ as a child growing up in two British colonies”.

His family was exiled from Mandate Palestine during the 1948 Nakba, and he went on to live in Lebanon, Egypt and the United States. Educated in British colonial schools and elite US universities, Said linked the experience of being at once an insider and an outsider to the disparity he felt between his own identity as a Palestinian Arab and how Arabs are represented by the West.

Why Is Orientalism Important?

The impact of “Orientalism” is monumental. Said is often credited with founding the field known as postcolonial studies, and his work has significantly influenced fields across the humanities: including cultural studies, anthropology, comparative literature and political science.

We can also attribute the growing awareness of Orientalist tropes to his book’s vast popularity. “Orientalism” has been translated into 36 languages (as of 2003) and remains a classic available in most bookstores.

While media literacy about Orientalism is increasing, these tropes remain as relevant as ever in the Western popular imagination. We should continue to challenge the ways Orientalism shapes our perception of Southwest Asia and North Africa countries and peoples.![]()

Cyma Hibri, PhD, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A rose by any other name – how roses and cut flowers became a symbol of love and luxury

Before the creation of international systems of cultivation and the ability to move goods by air freight, flowers matched the pattern of the seasons. Roses on Saint Valentine’s Day were something unexpected, and very expensive.

In very old age, in 1989, the late Queen Mother wrote a letter about her youth:

I remember dancing with a nice young American at Lady Powis’ ball in Berkeley Square (aged 17) and the amazement and thrill when the next day a huge bunch of red roses arrived! In those days flowers were very rare!

Where does the tradition of flower gifts come from and do they pose risks for an ecologically aware world today?

Roses In Culture And Society

A Roman murdered for his religion on February 14, AD 269, St Valentine was promoted by Geoffrey Chaucer in the 14th century as a figure of courtly romance. The red rose therefore signals blood and sacrifice as well as devotion. The tradition of flowers having anything to do with love came to the West much later than the classical world.

Many of our beautiful roses descend from enormously tall, single-petalled specimens originally found in south central and northern China. Simple versions are also found in Europe and North Africa. They required crossings and hybridisation to produce the many lush varieties we enjoy today. We could say the flower that we call natural has been for centuries a product of conquest and commerce.

The rose – so spectacular for its thorny beauty – was all over early floral decorations. In Greek mythology it was woven into the fabric that Andromache made for Hector at the time of his death in Troy.

Commercial trade in flowers began as early as Hellenistic times. Egypt grew mass-produced blooms and shipped them long-distance for ritual, including wearing garland crowns.

Early Christians Were Suspicious Of Flowers

Greek and Roman men and women wore floral crowns later presented as offerings to the dead. This was too pagan for the early Christian Church. St Jerome and St Ambrose were suspicious about flowers on tombs. They raised concerns of luxury. The rose was doubly suspect as it was linked to the Crown of Thorns worn at the Crucifixion. The evil Roman Emperor Heliogabalus was said to have smothered his diners with roses and violets released from a false glass ceiling. Exotic flowers were about decadence, not virtue.

The foundations of botany emerged within both ancient China and Greece. Knowledge of plants plummeted after the fall of the classical world in the West. Islam and the Near East were less disrupted by the decline of cities and had rich traditions of cultivation and botanical trade, notably in the 8th and 9th centuries AD. The rose appears stylised in the famous Persian carpets.

China, called by plant collectors the “flowering land”, had one of the most diverse floral resources, a result of its geology and great horticultural expertise encouraged by the literati class. From China came the azalea, the camellia, chrysanthemum, magnolia and new types of rose.

In China flowers were uniformly positive. “Hua” can mean a blossom, a firework, a decorative border or a cotton print, or it can refer to women and courtesans. Han ladies wore large flowers in their hair, either fresh or artificial, and their make-up included flowers and petals. Courtesans, some of whom worked on flower-filled barges, were named after blooms.

Roses were rehabilitated in the Christian West in the 12th century. Within Gothic art, the stained-glass rose window of the cathedral itself resembled that flower.

Men Liked Flowers As Much As Women

Thirteenth-century French romances describe young men wearing clothes embroidered with flowers, and during this period the Paris guild of hatters produced hats for men decorated with peacock feathers and fresh flowers. Young men decorating their straw hats with flowers in summer remains a tradition at the famous English school Eton.

Flower painting emerges as an independent European form in the Ghent-Bruges School of manuscript decorators after 1475. Many Flemish painters specialised in paintings of the Virgin surrounded by a garland or wreath. The inclusion of bees, butterflies, insects and worms was a reminder of the transience of life, a memento mori.

Flowers underlined the contrast between internal and external beauty typical of classical sources. Sixth-century Roman philosopher Boethius wrote:

The beauty of things is fleet and swift, more fugitive than the passing of flowers in Spring". Here is the explanation why we are so fascinated by flowers, they are about life, but at the same time, death and decay.

By the 17th century, flowering plants were established as essential luxuries for rulers and merchants. Collectors and patrons travelled between notable botanical centres including Prague, London, Leiden, Brussels, Antwerp, Middleburg, Milan and Paris to engage with this new science and form of collecting. This, the ethnologist Jack Goody claims, was an expert system that led to floriography – the European language of flowers. The red rose is love, the white rose devotion.

‘Too True, Too Perfect’: Nineteenth-Century Fashion And Flowers

In 19th-century Paris the flower market expanded to a twice-weekly format with corner booths, spiced with the erotic charms of the flower sellers who worked the streets.

Large blooms such as lilacs, Easter lilies and the large, perfumed Bourbon roses were the height of luxury. Flowers had shorter seasons and were scarcer than now, although the rich endeavoured to force plants in their private hothouses. The cult of flowers was significant. There were 100 florists in St Petersburg in 1912 – trains carried out-of-season blooms up on the St Petersburg-Paris-Nice express.

Mature women were not to use real flowers, the prerogative of youth, but rather artificial ones dispersed in their textiles and made in ornamental fabrics.

Today, flowers can be purchased at corner supermarkets every day. Most of what you see in stores is not grown locally. Much of it has been grown in South America or South Africa, shipped up to the Dutch wholesale markets, then flown back to the southern hemisphere. Flower cultivation uses large amounts of water and pesticides and often proceeds with low-paid labour in the developing world. Many of us could grow a few flowers ourselves, and get back to the simplicity of our grandparents’ generation, when flowers were scarce and also cherished.

If your flowers have not arrived for Valentines’ Day, remember this: Mizza Bricard, who worked for Christian Dior in the 1950s, once noted:

when a man asks who is your favourite florist, say my florist is Cartier.

Peter McNeil, Distinguished Professor of Design History, UTS, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Meet The Stars Of The First Coin Of 2023: CSIRO's Creatures Of The Deep

CSIRO have worked with the Royal Australian Mint (the Mint) to develop their 2023 collector coin program, Creatures of the Deep.

The coin showcases the CSIRO research vessel (RV) Investigator and the deep towed camera technology. It features rarely seen deep sea creatures like gold coral, brittle star and the king crab.

This program continues the Mint’s focus on the natural world. Creatures of the Deep was chosen as the 2023 theme to continue showcasing Australia’s unique flora and fauna.

The coin collection features deep sea creatures discovered during several voyages on RV Investigator along Australia’s southern and eastern coastline.

These voyages of discovery reached some of Australia’s deepest habitats, including the abyss. This is one of the largest and least explored areas on the planet.

Researchers used a deep sea camera developed by us to capture information on environments and life in the deep sea.

The camera can withstand the high pressures of the deep sea environment. When deployed on the RV Investigator, a fibre optic cable is used to relay video and data in real time to scientists on the ship. Impressively, this can be broadcasted from depths of up to 4km deep.

The new coin collection highlights these collaborative research voyages and the significant contribution they’ve made to better understanding life in our oceans.

One of RV Investigator’s recent voyages, Sampling the Abyss, travelled 3500km along Australia’s eastern coastline, studying life in the darkest and deepest parts of the ocean.

This voyage was led by Museums Victoria and supported by CSIRO, National Environmental Science Programme Marine Biodiversity Hub and Parks Australia, as well as Australian and international museums and research institutes.

The other voyages surveyed life and seabed habitats in the deep ocean of the Great Australian Bight and seamounts off the coast of Tasmania. They uncovered many new and fascinating deep-sea species.

Stars of the deep sea

The deep sea creatures showcased as part of the Creatures of the Deep coin program include:

- Blobfish, known for their grumpy and forlorn faces, and crowned the ‘world’s ugliest animal’

- Bigfin squid, known for their large fins and extremely long, slender arm and tentacle filaments. We saw a big fin squid for the first time in Australian waters in 2017, 2km below the ocean surface.

- Gold coral, which are octocorals. They have polyps with eight tentacles used to capture food particles floating in the water

- King crab, which is the largest of the 12 species from Australia. King crabs are adorned with sharp spines to provide protection from predators, and can reach a size of up to 20cm.

- Tripodfish, which prop themselves off the seafloor with stilt-like fins. Tripodfish are hermaphrodites, meaning they have both male and female sexual organs, so don’t need to find a mate.

- Dumbo octopus, which are nicknamed on account of their two fins. These can be large in some species and resemble the ears of Disney’s Dumbo the Flying Elephant. They use their fins and webbed arms to to glide gracefully through the water.

- Brittle star, many of which live on the branches of large coral colonies. This is so they can access drifting food particles. In exchange, the brittle stars keep the coral clean and free of debris.

- Cactus urchins, which occur in groups, perched on coral heads, or on hard, rocky bottoms. They can be short and round, or long and narrow. They are thought to be filter feeders, which extract food from the water.

Blobfish, known for their grumpy and forlorn faces and being the ‘world’s ugliest animal’. Credit: Museums Victoria / Rob Zugaro

Tripodfish: Credit Rob Zugaro, Museums Victoria

Get your hands on a coin

The 2023 ‘C’ Mintmark Gallery Press coin is an Australian legal tender, officially approved by the Currency Determination and minted by the Royal Australian Mint.

If you’re visiting Canberra between 1 January and 31 December 2023, you can press your very own coin at the Royal Australian Mint. This means you’ll have the chance to hold a piece of history in your hands!

And if you’re not able to visit Canberra, you can still get your hands on the rest of the Mintmark suite by purchasing it online from the Royal Australian Mint.

On the other side of these coins, you’ll find an image of Queen Elizabeth II, featuring the dates of her reign from 1952 to 2022.

This Is The Life. Australia And Your Future No 2.: Working Women In 1947

From the Film Australia Collection of the National Film and Sound Archive.

Made by the National Film Board 1947. Directed by Catherine Duncan. This is the Life describes the daily lives of single working women employed in industry in Australia in the 1940s. Young women are shown beginning the day in their homes, then cycling or taking a tram to the Returned Soldiers Mill in Geelong, Victoria - a thriving textile centre. We see them in the mill environment then, work done, enjoying their leisure - dancing, playing sport, hiking and shopping. The film also outlines the pay, sick leave and holiday conditions to which the women are entitled.

How does the stuff in a fire extinguisher stop a fire?

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Let’s talk fire! And extinguishers.

You need three ingredients to make fire: fuel (like wood or gasoline), oxygen and heat.

Fire is a chemical reaction between oxygen and the fuel. If you want to put out a fire, just get rid of one of those three things – fuel, oxygen or heat. Removing the fuel is easy when the fire is controlled. For example, when you shut off the gas valve on a propane grill, the fuel stops flowing and the fire goes out.

I teach chemistry and know from lab experiments that removing the heat or spark is harder to do. Once the fire starts, it provides heat and keeps burning. That is why throwing water on a fire puts it out. When water hits fire it boils, turns to steam and floats away, taking some heat with it. It also prevents oxygen from reaching the fuel.

Most fire extinguishers work by separating the fuel from the oxygen. The oxygen comes from the air. It is the same oxygen we breathe. Since the oxygen has to be in contact with the fuel, if you can coat the fuel with something that keeps the oxygen away, the fire will go out.

Cool Gas

Water isn’t the only chemical that can put out fires. You want something that won’t burn, is light and easy to spread. One common choice: carbon dioxide.

Carbon dioxide is an odorless, colorless gas that is present in the air. People and animals breathe in oxygen from the air and exhale carbon dioxide.

That’s exactly what happens when wood burns. The fire uses oxygen and expels carbon dioxide. So, carbon dioxide is sort of already burned – it won’t burn if you throw it on a fire.

Since carbon dioxide is a gas, it is easy to store and distribute. If squeezed into a steel canister, the gas streams out as you open the nozzle.

Carbon dioxide is denser than oxygen. So when you spray the carbon dioxide on fire, it sinks under the oxygen, separating the fire from oxygen. No oxygen, no fire.

Hidden Danger

Carbon dioxide has several big advantages. Because the gas is squished into a canister, when it comes out it is super cold – at least minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit – removing heat from the fire.

And when sprayed on a fire, carbon dioxide just floats away. That means no cleanup. When tossed on a fire, water will flow along the floor. This means water can spread the fire if the fuel is light enough to be carried. So carbon dioxide removes two out of the three things you need to have a fire.

And, unlike water, carbon dioxide doesn’t conduct electricity, so it is good for electrical fires.

The biggest danger in using carbon dioxide is suffocation in enclosed spaces. In the same way that carbon dioxide puts out a fire by robbing it of oxygen, the gas can do the same to a human.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Joseph Lanzafame, Senior Lecturer of Chemistry and Materials Science, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why are planets round?

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why are planets round? – Daniel B., La Crosse, Wisconsin

The ancient Greeks proved over 2,000 years ago that the Earth was round and figured out how big it was by using simple observations of the Sun.

But how do people know this today? When you drop anything, gravity causes it to fall directly toward the center of the Earth, at least until it hits the ground. Gravity is a force that is caused by nearly everything that has mass. Mass is a measure of how much material there is in anything. It could be in the form of rocks, water, metal, people – anything. Everything material has mass, and therefore everything causes gravity. Gravity always pulls toward the center of mass.

The Earth and all planets are round because when the planets formed, they were composed of molten material – essentially very hot liquid. Since gravity always points toward the center of a mass, it squeezed the stuff the Earth is made of equally in all directions and formed a ball. When the Earth cooled down and became a solid, it was a round ball. If the Earth didn’t spin, then it would have been a perfectly round planet. Scientists call something that is perfectly round in all directions a “sphere.”

The gas cloud that the Earth was made from was slowly rotating in one direction around an axis. The top and bottom of this axis are the north and south poles of Earth.

Now, hold out your right hand. Point your thumb on your right hand straight up, and curl your fingers around the direction of rotation. Your thumb is pointing toward the North pole. The equator is defined as the plane, halfway between the North and South Poles.

If you ever played on a merry-go-round, you know that the spinning merry-go-round tends to throw you off. The faster it spins, the harder it is to stay on. This tendency to be flung off is called centrifugal force and pushes the mass on the equator outward. This makes the planet bulge at the equator.

The faster the spin, the more unround it becomes. Then, when it cools and hardens, it retains that shape. If a molten planet starts off spinning faster, it would be less round and have a bigger bulge.

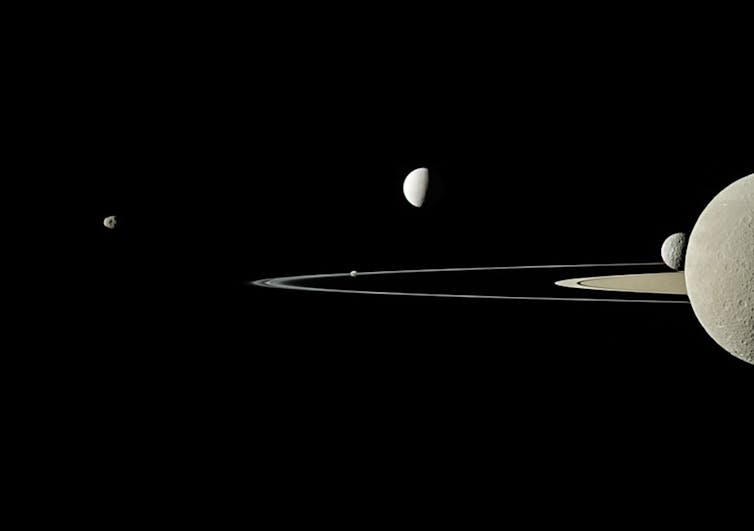

The planet Saturn is very oblate – non-spherical – because it rotates very fast. Because of gravity, all planets are round, and because they rotate at different rates, some have fatter equators than their poles. So the shape of the planet and the speed and direction that it rotates depends on the initial condition of the material out of which it forms.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

James Webb, Professor and Director, Stocker AstroScience Center for Physics; Stocker AstroScience Center, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why does the Earth spin?

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why does the Earth spin? Sara H., age 5, New Paltz, New York

A globe was the first thing I ever bought with my own money. I was maybe 5 years old, and I was really excited to take it home. As I quickly discovered, you can spin it in the direction that the earth actually spins.

There’s an imaginary line between the North Pole and the South Pole. We call it the rotation axis. For the Earth, the rotation axis points toward a bright star, Polaris, which is visible on clear nights in the Northern Hemisphere.

If you want to know which way to spin your globe, make the goofy “thumbs-up” sign with your right hand. Imagine your thumb is the Earth’s rotation axis, pointing to the North Pole. Your fingers will naturally curl around your hand, and the direction those fingers are pointing is the way Earth spins.

Every 24 hours, the Earth makes a full rotation, spinning west to east, which is why the sun rises in the east and sets in the west and the stars at night appear to move across the sky.

To understand why this happens, let’s see what we can learn from other bodies in space.

Everything Spins

The Sun also spins. In fact, it spins in the same direction the Earth does.

Not only that, the Earth orbits the Sun in the same direction, as do all the other planets and more than a million asteroids and dwarf planets.

Most are spinning in the same direction, too. Jupiter and Saturn spin quite a bit faster than Earth, taking only about 10 hours to rotate. Saturn’s spin is a little bit tilted, so we get to see changing views of its rings over time.

There are two funky exceptions: Uranus appears to have been tipped over on its side. Nobody knows exactly how. Maybe it collided with another planet. Venus is also odd – it spins backward. We don’t know for sure whether it formed that way or got knocked over. Most scientists now think its spin has been reversed over time by tidal forces involving the Sun and Venus’ thick atmosphere.

All that leads astronomers like me to wonder: Is there something about how the solar system formed that kind of “baked in” that direction of spin?

Birth Of A Star

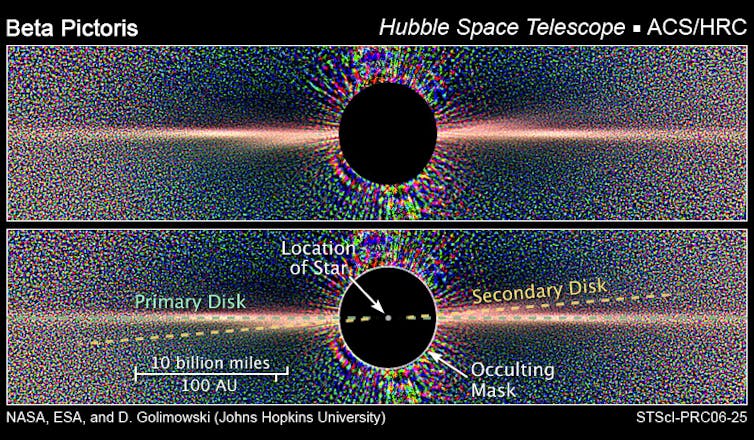

For more clues, we can look at a young star, one that is just forming its system of planets.

A famous one is called Beta Pictoris. It is surrounded by a thin disk of dust, gas and little bits called planetesimals; they range in size from a grain of sand to rocks maybe up to the size of a mountain. Astronomers are pretty sure the disk formed from material left over when the star was born.

Every star is born from a cloud of gas and dust that moves through space surrounded by other similar clouds. The force of gravity causes these clouds to tug on one another as they pass, which makes them slowly rotate.

Even when one of these clouds collapses to form a star, it continues to rotate. The star forms, spinning at the center of a flat pancake of rotating gas and dust called a protoplanetary disk. All of it – the star, the gas, the dust – is spinning in the same direction.

Astronomers think that our solar system looked a lot like Beta Pictoris in its early years.

We think that inside the disk, the gas and dust can stick together in a process called accretion. As a baby planet starts to grow, it gets heavier, and its gravity attracts more and more little pieces.

When the baby planet gets massive enough, the force of gravity begins crushing it, making it denser. Because of that, like an ice skater drawing in her arms to spin, the planet spins faster. Rising pressure in the core causes the core to melt. Denser materials sink toward the core, and lighter materials float to the planet’s surface. We end up with a planet with an iron core surrounded by rock, and maybe on the outer parts stuff like water and ice.

That’s what we see in our solar system.

What If Earth Didn’t Spin?

Earth’s spin is important for life. It causes day and night. It’s also important for ocean tides. Without the daily ebb and flow of water, it’s possible life would never have emerged from the sea onto land.

So, astronomers believe Earth spins because the entire solar system was already rotating when Earth formed – but there are still a lot of questions about how planets’ spins change over time, and how spin affects the evolution of life. With more than 5,000 planets now known beyond the solar system, future scientists are going to be busy exploring.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to remove the reference to Mercury.![]()

Silas Laycock, Professor of Astronomy, UMass Lowell