inbox and environment news: Issue 573

February 26 - March 4 2023: Issue 573

Little Penguin Released Back Into Ocean At Palm Beach After Lifesaving Care At Taronga Wildlife Hospital

A Little Penguin is now back in the ocean after having made a full recovery from life-threatening injuries. The female bird had been treated at Taronga Wildlife Hospital in Sydney for seven weeks, but was relaxed and healthy when the hospital team released her off Sydney’s Palm Beach on Monday February 20th 2023.

“Nothing beats the feeling of being able to release a fully recovered Little Penguin back into the wild,” Taronga Wildlife Hospital Rescue and Rehabilitation Coordinator Libby Hall said.

The penguin was found lying lethargic with deep wounds on its back by a member of the public on Newcastle Beach on 1 January. Local wildlife group Hunter Wildlife Rescue brought the injured bird to Taronga Wildlife Hospital for specialist care.

Upon admission, the hospital team determined the penguin had three deep, rake-like wounds on her back, a gash on her belly and an injured right leg. She was examined under anaesthetic and x-rays were taken to ensure no other injuries were present.

“Although it is difficult to know exactly what has happened, judging by the pattern of the wounds she could have been attacked by another animal - potentially a sea eagle or even a dog,” Taronga Wildlife Hospital Veterinary Officer Frances Hulst said.

The penguin received full supportive care and pain relief, as well as regular wound care at the Taronga Wildlife Hospital during her stay. She also spent several weeks in the hospital’s dedicated rehabilitation area, where she was able to swim and exercise to regain her fitness and strength.

“We decided to release her off Palm Beach because there is a Little Penguin colony nearby, and we suspect she may have temporarily been travelling further up the coast when she sustained her injuries,” Taronga Wildlife Hospital Rescue and Rehabilitation Coordinator Libby Hall said.

However, the danger isn’t over for this Little Penguin. Moulting season takes place around March for Little Penguins in NSW, during which they replace their entire set of feathers with new ones.

During this time, they remain out of the water and are unable to feed and can lose up to 50 percent of their body weight which makes them weak and vulnerable to predators on land.

“The moulting season is the most vulnerable time of the year for Little Penguins, and that’s when we see an increase in injured penguins being treated in our wildlife hospital,” Libby explained.

“We urge people to keep your dog on a leash where there may be wildlife, but this is more important than ever during the entire month of March for penguins in NSW. Little Penguins may be hiding in a cave near the beach while they moult, so you might not be able to see them with the human eye, but your dog will be able to smell them,” she added.

The Little Penguin is the world’s smallest penguin species, and it’s the only penguin to breed in Australia. Every year, 1500 animals are admitted to Taronga Wildlife Hospitals, and Taronga is the leading contributor to veterinary services in wildlife treatment and rehabilitation in NSW.

Taronga’s strategic priority is to increase its capacity to assist wildlife in need, which is why work is underway to build a new world-class wildlife hospital in Sydney.

The new Taronga Wildlife Hospital in Sydney – set to open in 2025 – will increase the hospital’s capacity to hold and care for injured wildlife including turtles, koalas and platypus and other native animals by 400 percent.

The project is a joint philanthropic project between Taronga and the NSW State Government, with the NSW State Government matching philanthropic donations to Taronga up to $40 million.

.jpg?timestamp=1677117696224)

Photos: Little penguin being fed while in care and Taronga Wildlife Hospital Veterinary-Officer-Frances Hulst checking up on penguin. Images: Taronga Wildlife Hospital

Lerp On Angophora And Corymbia Spp. At Present

Residents are reporting 'tree dandruff' at present falling from Angophora and Corymbia spp. trees. This is what is known as 'lerp'. Lerps are the shell or covering that some psyllid insects make during their juvenile stage. Psyllids are sap sucking insects usually only a few millimetres long and are easily overlooked. However the lerps are quite visible being up to 1cm long and with distinctive designs.

Each lerp is made from the waste excretion of a juvenile psyllid. As with many other sap sucking insects this waste is high in sugars and is sometimes called ‘honeydew’. It’s thought the lerp shell provides protection against the weather and predators. Ants can often be seen around the lerps collecting the sugary honeydew and fighting off predatory insects. You will also see birds feeding on them.

A large outbreak of lerps on a tree often indicates that the tree is under stress for other reasons. Psyllids can be a problem on a broad range of plants but the species that create lerps seem to only attack gum trees. This includes our local Eucalyptus, Angophora and Corymbia spp.

How To Organically Control Lerps:

Wipe leaves clean with a damp cloth or cut off infested sections. Restrict ant access by applying a band of horticultural glue around the main trunk.

Weekly doses of OCP eco-seaweed to help reduce plant stress.

You can also improve plant heath by assessing the growing conditions and make the necessary corrections. Ask yourself questions like: Is the soil compacted? What is the soil pH? Are the watering and fertilising levels correct? Does the tree get enough light?

Information courtesy Eco Organic Garden and PNHA. Photos: AJG/PON

.jpg?timestamp=1676928286158)

.jpg?timestamp=1676928315296)

Thunderstorms Close Wakehurst Parkway - Local SES Units Respond To Calls For Help - White Slug Comes Out To Feast After The Rains

This slug (Triboniophorus graeffei) feeds on microscopic algae on smooth bark eucalypts, and algae on other smooth surfaces, leaving a narrow wiggly track. The Red Triangle Slug is Australia's largest native land slug. The distinctive red triangle on its back contains the breathing pore. This one was photographed in the Pittwater Online backyard this morning, Wednesday February 22nd, amid all the rain we've had overnight.

.jpg?timestamp=1677016447101)

The NSW State Emergency Service - Operational Statistics Update for February 22nd, 2023

Severe thunderstorms impacted Sydney Metropolitan, Central West and Southern Tablelands yesterday.

In total, NSW SES received 377 (227 Sydney Metro) incidents in the last 24 hours (to 5am). 12 (11 Sydney Metro) Flood Rescues (Mainly involving cars driving into floodwater).

Focus areas:

- Warringah Pittwater (and Manly Unit) – 51

- Orange – 42

- Queanbeyan – 33

- Ku-ring-gai – 21

- Sutherland – 17

The NSW SES Warringah / Pittwater Unit reported it had been a busy night for Warringah/Pittwater and NSW SES Manly Units:

''We currently have 4 of our vehicles attending to jobs, along with NSW SES Manly Unit, and several RFS units assisting us. In addition to this we have our Flood Rescue team along with Flood Rescue Teams from Manly and NSW SES Ku-Ring-Gai Unit

There has been 44 Requests for Assistance tonight, including 4 Flood Rescues.

We had 60mm of rain in a 1 hour period, which caused multiple roads to flood. There is more rain expected over night. So please take care.''

If you need emergency assistance due to flood/storm damage, call NSW SES on 132 500. If life threatening, call 000.

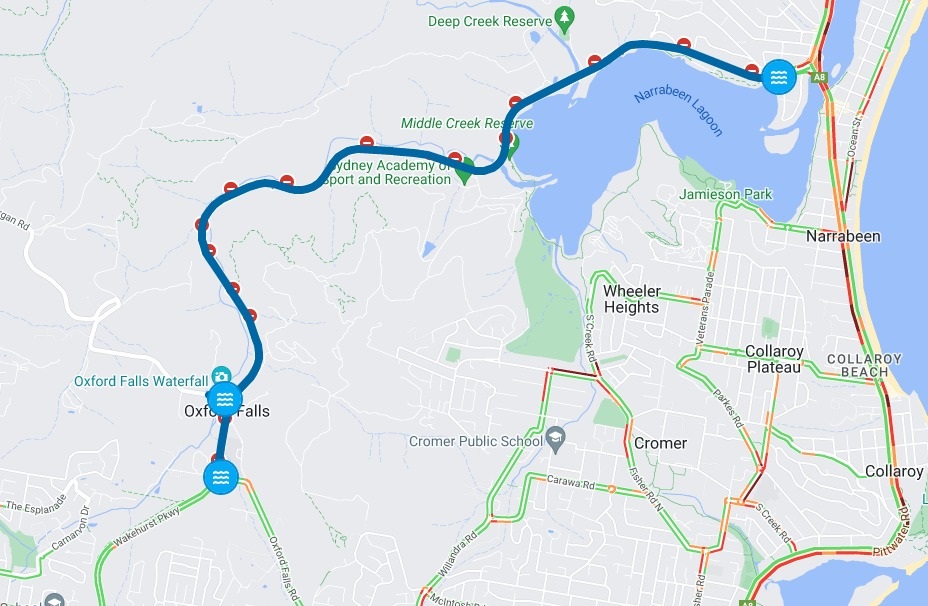

Parkway floods along multiple points

Live Traffic reported that the Wakehurst Parkway closed at 8:26pm on Tuesday February 21st 2023 - it had not reopened 12 hours later - 8:27am Wednesday February 22nd 2023. The map from Live Traffic shows the Parkway has flooded at three places along its length, between Dreadnought Road at Frenchs Forest and Wimbledon Avenue at North Narrabeen:

Plastic Boardwalk Through Manly Warringah War Memorial Park: 'We Can Do Better!' States Save Manly Dam Bushland Group

WE CAN DO BETTER !!

Boardwalk Empire from Malcolm Fisher on Vimeo.

Australia’s Hotly Contested Eucalypt Of The Year Voting Opens Today!

Australia’s much loved - and hotly contested - Eucalypt of the Year voting is now open. Passionate gumtree lovers across the country are invited to vote for their favourite gum, now in its sixth consecutive year. There are ~850 species of eucalypt across the continent and they are an unmistakable feature of living where we do.

“After running for five years, there are still hundreds of eucalypts that haven’t had their time in the sun as Eucalypt of the Year. We’ve whittled down the species to a shortlist of 25 that represent a diverse range of ecological features and geographical spread to make it easier for you to vote. Last year’s winner - the mighty Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans) is not eligible. Now is the time to cast your vote for your personal favourite,” says Linda Baird, CEO of Eucalypt Australia.

People can vote for their favourite eucalypt until 19th March at www.eucalyptaustralia.org.au

The winning eucalypt will be announced on National Eucalypt Day, Thursday March 23. National Eucalypt Day is Australia’s biggest annual celebration of eucalypts held every year to celebrate and promote Australia’s eucalypts and what they mean to our lives and hearts.

Tell the organisers how you voted on social media by tagging @EucalyptAus using the hashtag #EucalyptoftheYear. The 25 shortlisted species are:

- Angophora costata (Sydney Red Gum)

- Angophora hispida (Dwarf Apple)

- Corymbia aparrerinja (Ghost Gum)

- Corymbia citriodora (Lemon-scented Gum)

- Corymbia ficifolia (Red-flowering Gum)

- Corymbia opaca (Desert Bloodwood)

- Corymbia ptychocarpa (Swamp Bloodwood)

- Eucalyptus caesia (Silver Princess)

- Eucalyptus cinerea (Argyle Apple)

- Eucalyptus cneorifolia (Kangaroo Island Narrow-leaved Mallee)

- Eucalyptus lansdowneana (Crimson mallee)

- Eucalyptus platyphylla - (Poplar Gum)

- Eucalyptus leucoxylon - (Yellow Gum or South Australian Blue Gum)

- Eucalyptus macrandra (River Yate)

- Eucalyptus marginata (Jarrah)

- Eucalyptus miniata (Darwin Woollybutt)

- Eucalyptus perriniana (Tasmanian Spinning Gum)

- Eucalyptus radiata (Narrow-leaved Peppermint)

- Eucalyptus rhodantha (Rose Mallee)

- Eucalyptus rubida (Candlebark)

- Eucalyptus salmonophloia (Salmon Gum)

- Eucalyptus oleosa (Giant Mallee)

- Eucalyptus synandra (Jingymia Mallee)

- Eucalyptus tetraptera (Square-fruited Mallee or Four-winged Mallee)

- Eucalyptus vernicosa (Varnished Gum)

Angophora costata (Sydney Red Gum), McKay Reserve Palm Beach. Photo: A J Guesdon

Tasmanian Spinning Gum Eucalyptus perriniana. Photo: Remember The Wild, Catherine Cavallo, Instagram handle rememberthewild

Varnished Mallee Eucalyptus vernicosa. Photo: Dean Nicolle

Red Flowering Gum Corymbia ficifolia. Photo: Melanie Cooper, Instagram handle maxxle5

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Ticks And Mosquitos In Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment

A Friends of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment meeting Monday 27th February 7pm

A Friends of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment meeting Monday 27th February 7pm

Avalon Dunes Bushcare Returns Sunday March 5th

Next will be on March 5, meeting at 8.30 in the parking area off Tasman Rd south.

We work until 11.30 but any time you can spare is wonderful.

We always find interesting insects and other wildlife. We can see the progress happening as we work in this corner of the 4.5ha dunes.

Call in to say hello or phone 0420 817 574 if you can't see us there.

New helpers very welcome, and there's always something yummy for morning tea.

Our bushcare area is within the red lines. We can work in the shade in summer, or in sun in winter. Barrenjoey High school is to the north.

Morning tea with good company and cake.

The egg case or ootheca of a Praying Mantis. Each ootheca contains a number of eggs, up to 200 with some species. Mantis eggs can take anywhere from 40 days to around five months to hatch. On hatching, the baby mantises are about as big as a large ant. The tiny holes on this one suggest the eggs have hatched.

This Leaf Beetle in the genus Paropsisterna. It has been feeding on Eucalypt or Acacia foliage. It is one of Australia's many beetles. The total species number is estimated to be in the range of 80,000 to 100,000.

A long-legged Dancing Fly pauses on a leaf of Snake Vine.

Photos; PNHA

Ocean Street Narrabeen Bridge Works

Collins Beach Clean Up

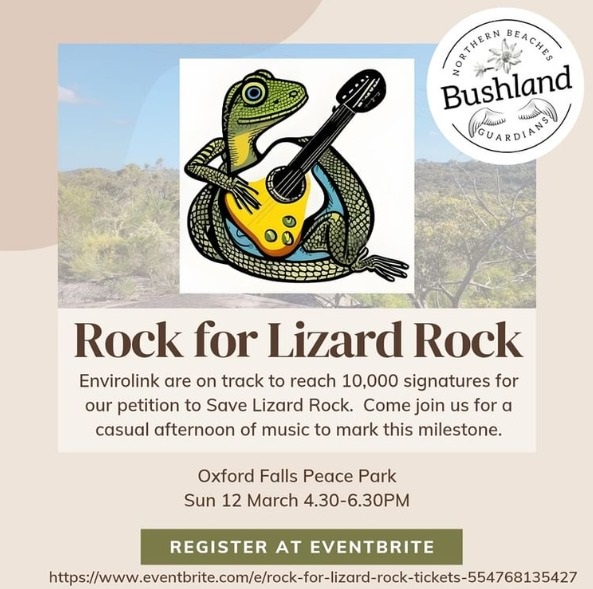

Concert: Rock For Lizard Rock

FREE. Register at: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/rock-for-lizard-rock-tickets-554768135427

Create A Spit To Seaforth Oval Walk: The Missing Link - Petition

There is approx. 20,000 square metres of land situated between Rignold Street and Castle Circuit, Seaforth. The largest block is now FOR SALE. There is currently contracts out to overseas investors and developers.

The land is separated by conservation land that joins Garigal National Park. This land should be purchased and returned to the community for all to enjoy and wildlife to be given a fighting chance at survival.

This is a thriving riparian zone that should be made a wildlife corridor. It is currently the wildlife corridor that connects existing corridors to Garigal National Park .Running through the middle of the land is a permanent water source that attracts and aids the survival of many animals. Currently there are wallabies, echidnas, powerful owls, lyrebirds, monitor lizards, water dragons, numerous species of small birds and insects such as a large variety of dragonflies.

The Powerful Owl is listed as vulnerable in NSW and there is talk of changing the lyrebird's status to threatened in light of the recent loss of habitats due the devastating fire season of last summer. The Seaforth Mint Bush is listed as critically endangered. The Angophora's are a protected species.

The loss of hollow bearing trees is a key threatening process in determining whether or not these vulnerable and threatened species will survive.

Given the conservation status of this flora and fauna I am asking for this land be bought back to create a wildlife corridor to join the land that was saved behind Dalwood homes. At present the land is made up of two privately owned properties, one is owned by a Chinese consortium and the other is owned by an American family. Both parcels have derelict houses that are falling down, leaving shattered glass, asbestos and building rubble spread through the bush. One property has no street access and is only accessible by water.

Thank you to all who have read this far and thank you in anticipation of your signatures helping to protect this very unique area.

Petition at: https://www.change.org/p/create-a-spit-to-seaforth-oval-walk

THIS IS THE MISSING LINK TO CREATING A FORESHORE WALK THROUGH SEAFORTH.

Prune Viburnum Hedge Agapanthus Flowers To Prevent Spread Into Bush Reserves

PNHA: January 11, 2023

Now is the time to prune the berries off the Viburnum hedge and dehead those old Agapanthus flowers. Put these prunings into your green waste bin. Both are now weeds of bushland as their seeds travel.

Photos: Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA)

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

NSW Still Holding The Murray Darling Basin Plan Back

The Murray Darling Basin Authority has released a six-monthly report card on the progress of the Murray Darling Basin Plan, highlighting yet again that when it comes to the Basin Plan, NSW continues to have the hand brake on.

The law requires all Water Resource Plans to have been approved by July 2019, however NSW have only today (February 14) resubmitted the critical documents. It is yet to be seen if these overdue NSW Water Resource Plans are sound enough to be accredited.

Nature Conservation Council (NCC) Chief Executive Officer Jacqui Mumford says NSW had since 2012 to get twenty Water Resource Plans written by the 2019 deadline, but has dragged its feet while still taking the lion’s share of water from the Basin.

“We’ve seen successive NSW Coalition Water Ministers duck and weave, avoiding their responsibilities to the rivers of the Murray Darling Basin, and are now almost four years late with their homework," said Ms Mumford.

“For almost four years, there has been no way for the Commonwealth to determine if water extraction in NSW is over the legal limits.

“NSW has the biggest contribution to make to the implementation of the Murray Darling Basin Plan, because we’ve been the biggest water users. The enormous wealth created for a privileged few by excessive water take has come at huge cost to First Nations communities and the environment.

“The balance between industry and the environment when it comes to water sharing has been heavily skewed to favour industry for over a hundred years. Clawing back some water for the health of the rivers under the Basin Plan still falls a long way short of that elusive concept of balance.” said Ms Mumford.

NCC is extremely concerned that NSW is actively working against the principles of the Basin Plan by issuing an environmentally unsustainable volume of floodplain harvesting entitlements.

“NSW is driving water management backwards – instead of working with the Commonwealth and other states to return water to inland rivers, it’s handing out billions of litres of brand-new water entitlements to privileged floodplain harvesting irrigation corporations” said Ms Mumford.

Related:

NSW Government Shows Contempt For Democratic Process With 5th Introduction Of Floodplain Harvesting Regulations

Basin Plan Report Card Paints Clearer Picture As 2024 Deadline Nears

February 14, 2023

The latest assessment of progress to implement the Murray–Darling Basin Plan has found only minor movement in the past 6 months, with important elements at risk or unlikely to be achieved by the June 2024 deadline.

Chief Executive of the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, Andrew McConville said progress in some areas was overshadowed by lack of advancement in others.

"The Basin Plan needs to be fully implemented if it’s to achieve the outcomes we’re seeking for a healthy and sustainable Basin for all communities. It is becoming clear what will and won’t be achieved by June next year," Mr McConville said.

In line with the MDBA's commitment to transparency, the ninth report card provides a clear picture of the status and progress on five areas of the Basin Plan: water resource plans, water recovery, Sustainable Diversion Limit (SDL) adjustment mechanism measures, Northern Basin initiatives and the delivery of water for the environment.

"Since the July 2022 report card, we have seen some progress with 4 New South Wales water resource plans accredited for groundwater resources. However, the dial remains firmly on the red because there is still a way to go to get all the WRPs accredited," Mr McConville said.

"The dial for some projects under the Sustainable Diversion Limit adjustment mechanism also remains on red. Of the 36 supply and constraints projects, 22 are likely to be operable, 8 are on the cusp of delivery and 6 will not be delivered as originally proposed by 30 June 2024.

"We’ve seen positive outcomes from good planning and delivery of environmental water across the Basin – this is critically important and underpins the very foundation of the Basin Plan to support the health of rivers, floodplains and wetlands. The focus of the past 6 months has been to support bird breeding events and to improve water quality where floods have resulted in low oxygen levels."

Mr McConville said some of the northern Basin toolkit measures in the northern Murray–Darling Basin were running behind schedule, with one measure in particular highly unlikely to be delivered on time.

"These important initiatives are intended to protect water for the environment, improve compliance with water laws and create opportunities for local communities, including First Nations People. It is in everyone’s interest that greater headway is made towards completing the northern Basin toolkit measures."

The Basin Plan Report Card is available on the MDBA website at: https://www.mdba.gov.au/publications/mdba-reports/basin-plan-report-card

Background

The Basin Plan was agreed by the Australian Government and the governments of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory. It is a major reform agenda that was created to improve and protect the health of the rivers for future generations, while continuing to support farming and other industries, for the benefit of the Australian community.

The Murray–Darling Basin Plan is being implemented over a transition period to 2024 to allow time for Basin states, communities and the Australian Government to work together to manage the changes required for a healthy working Basin. The Basin Plan is an ongoing commitment. In accordance with legislative requirements, the Plan will be formally evaluated in 2025 and reviewed in 2026 by the MDBA.

Herding cats: councils’ efforts to protect wildlife from roaming pets are hampered by state laws

How we manage pet cats in our suburbs is in the spotlight. As the estimated number of pet cats in Australia passes 5 million, people are increasingly aware of the damage cats do to wildlife.

One-third of owners already keep their cats securely contained 24 hours a day. This has major benefits for cat welfare and prevents cats killing and disturbing wildlife. But that leaves the other 3.5 million or so pet cats free to roam for at least part of the day or night.

In Australia, local government is responsible for regulating our feline pets, but little is known about how this works in practice. We sent a survey to every local council in Australia to understand their approaches to managing pet cats and how these could be improved. We received responses from 240 councils (45%).

Councils across Australia reported managing pet cats is a challenge. But many are adopting regulations that to help protect local wildlife and improve the wellbeing of pet cats. However, state laws, especially in Western Australia and New South Wales, are making it difficult for local councils to manage pet cats well.

Cats Kill More Than Their Owners Realise

Why the big deal? Many cat owners think their moggy is blameless. “I don’t think my cat goes out that much and I never see any dead animals,” they often say. This is largely untrue.

Research shows the impact of pet cats is much bigger than people realise. Many cats don’t bring home what they kill, or bring back only a very small proportion (15% on average), so their owners aren’t aware of the majority of the wildlife toll. Radio-tracking studies have shown a large proportion of cats are out on adventures when their owners thought they were inside.

On average, each roaming, hunting pet cat in Australia kills 40 native reptiles, 38 native birds and 32 native mammals per year.

Our suburbs are now home to around 55 cats per square kilometre. That adds up to about 6,000 native animals killed per square kilometre per year in our suburbs alone. The national wildlife death toll from pet cats is well over 300 million native animals per year.

Even when roaming cats don’t kill animals, they have negative impacts on wildlife by spreading diseases and because wildlife must spend more time hiding or escaping instead of feeding and caring for young.

As well as hunting wildlife, roaming pet cats can increase feral cat populations if unwanted litters are abandoned.

Seeing wildlife, like blue-tongued lizards and fairywrens, in our gardens and local parks is something we all cherish. How we manage pet cats can either jeopardise our co-existing wildlife or help to safeguard it. So we set out to examine how pet cats are being managed across the country.

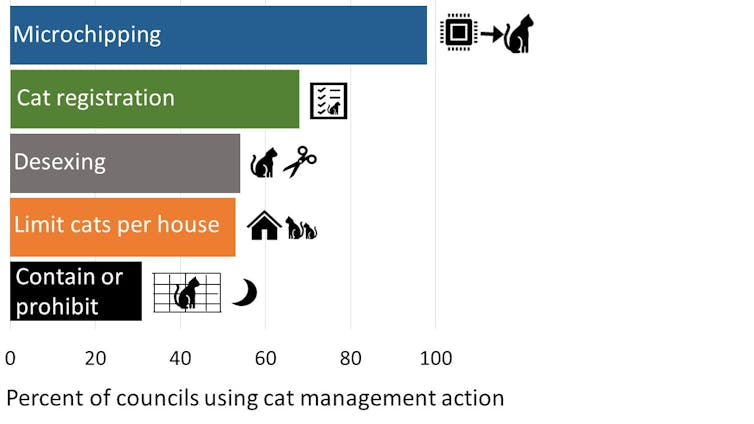

What Are Councils Doing About It?

Our survey found almost all local councils require pet cats to be microchipped. Three-quarters require them to be registered. Just over half require desexing and limit the number of cats that can be kept per household.

These approaches are very important to manage pet cats and constrain their numbers and should be extended to all local government areas. However, these measures do not prevent pet cats roaming.

Concern about the impacts of roaming cats has led almost one-third of councils to introduce cat-free areas, cat curfews and containment requirements at all or some places in their local government area. Where adequately policed, these measures appear to be working.

These approaches are most common in city areas of the ACT, Victoria and South Australia, and on some islands. The number of local government areas using this approach has grown markedly over the past five years, partly in response to growing awareness of the impacts of pet cats on wildlife.

For example, Adelaide Hills Council (SA) and Victoria’s Knox City Council brought in 24-hour containment last year. There are plans to do the same on Phillip Island (Victoria) later this year. Bruny Island (Tasmania) and Kangaroo Island (SA) both require cats to be contained. In NSW, Tweed Shire has designated some recently built and future suburbs, which are next to bushland with high conservation value, as cat-free.

Christmas Island has gone further. All pet cats are desexed and the community has agreed not to bring in any more, so their numbers on the island are gradually dwindling.

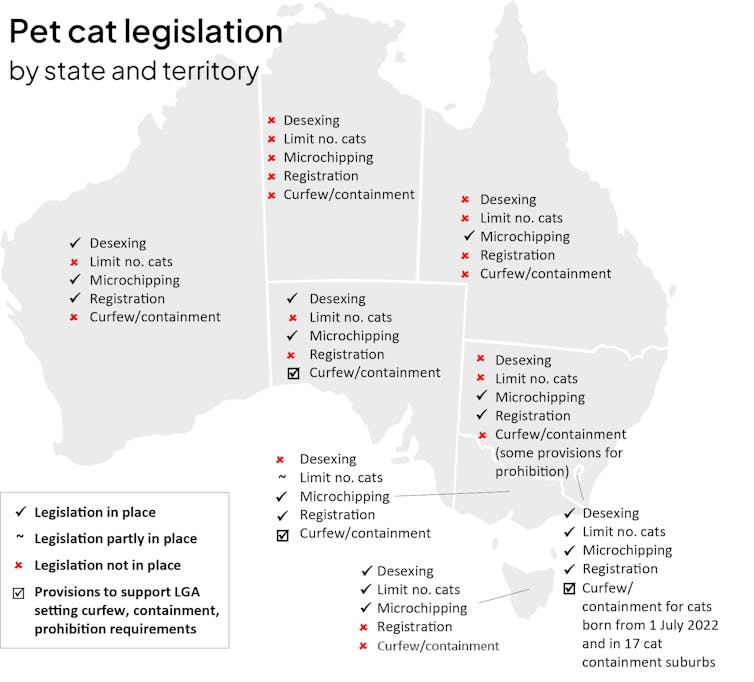

Some State Laws Stand In The Way Of Better Protection

Many local councils would also like to adopt containment regulations and no-cat areas as part of strategies to protect local wildlife. However, the overarching laws on domestic animal management are set at the state level. If these laws don’t allow local government to set and then police cat containment bylaws, then the local councils can be hamstrung.

Local councils in WA and NSW complained most often about this situation. They want changes to state laws to make it easier for them to set and police local rules about cat containment or cat prohibition.

In SA, local governments noted inconsistencies in cat containment provisions between councils make implementation and enforcement challenging. A statewide approach using the SA Dog and Cat Management Act would be more effective.

To support fair and effective management of pet cats we recommend all states and territories adopt strong and nationally consistent legislation to enable responsible pet cat management.

This should be supported by enhanced community awareness programs and support for owners and their pets to make the transition to a new, contained lifestyle. Outcomes for local wildlife and for cat welfare and health should also be monitored.

Protecting wildlife and caring for our delightful pets can both be achieved if we rethink what it is to be a cat owner and support local government to manage these issues for the whole community.![]()

Sarah Legge, Professor of Wildlife Ecology, Australian National University; Georgia Garrard, Senior Lecturer, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; John Woinarski, Professor of Conservation Biology, Charles Darwin University, and Tida Nou, Project Officer, School of Earth and Environmental Science, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Flooded Home Buyback scheme helps wash away the pain for Queenslanders

It’s almost a year since floods devastated parts of Ipswich in Southeast Queensland.

Over the course of four days (February 25-28 2022), Ipswich received 682 millimetres of rain and the Bremer River rose to 16.72m in the centre of the city. Parts of the city were inundated, and almost 600 homes were damaged, many severely.

Many of these houses had flooded before, as recently as 2011, because they were built in areas of high flood risk. On previous occasions, when the water subsided, these houses were simply patched up and left vulnerable to flooding.

But this time was different. The early success of Queensland’s Voluntary Home Buyback Program shows we can learn from history and avoid repeating our mistakes. It offers an example for other states to follow.

Introducing A Buyback Scheme

Implementing a buyback scheme in areas vulnerable to regular flooding was a recommendation of the Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry.

A $741 million Resilient Homes Fund was created in May 2022 with Commonwealth and State Disaster Recovery funds to be administered by the Queensland Reconstruction Authority. Of this, $350 million was allocated for buybacks, expected to buy 500 homes, and would be distributed among eight Queensland councils.

Ipswich City Council was keen to be involved. Fortuitously, just two days before the flood, on February 24, the council adopted the Ipswich Integrated Catchment Plan that identified 36,380 buildings exposed to flooding (17% in the highest flood risk categories). Among the report’s 47 recommendations was the need to remove the home with the highest flood risk. So when the buyback scheme run by the Queensland Reconstruction Authority was announced, Ipswich had its list of vulnerable homes ready in priority order, and seized the opportunity.

House owners register for the scheme and then the Queensland Reconstruction Authority organises a valuation, negotiates with the owner, develops the sale documentation and sells the property to the Council. Pre-flood valuations were offered to homeowners so they could afford to move. The land is rezoned as “non-habitable” use – no home can be built there in future.

The authority insists that the program is voluntary, people can refuse, in recognition that homeowners are in a sensitive state and must not feel pressured into making a life-changing decision.

Homeowners Welcome Buybacks

There has been a strong public response. By January 2023 more than 5,700 Queensland homeowners had registered for the Resilient Homes Fund. The first group of houses selected in Ipswich were in Goodna, those with the highest flood risk, and in January 2023 the first three houses were demolished. Less than a year since the floods, more than 40 homes have been accepted for the buyback program, with 160 valuations completed.

Not all have accepted the offer, with others publicly declaring a sense of relief. Paul Harding, whose Goodna house flooded halfway up its second storey in 2022, was one of the first to accept a buyback contract. He says when he heard the contract was signed he was “doing cartwheels down the street” as he thought he’d be “stuck with the house”, with no chance of selling. He says the offer was extremely fair and as he knows floods will come again, his family faces a happier future.

Both the number of registered homeowners and vulnerable properties are well beyond the capacity of the fund. Homeowners that do not qualify for the scheme are able to apply for the $741 million Flood Resilient Homes Fund that may fund house raising or resilient reconstruction, but the reality is that many will miss out.

A Hopeful Sign Of Things To Come

The program is currently scheduled to end in June 2023, by which time it is hoped that at least 150 homes will have been demolished in Ipswich, the land never to be occupied by a home in the future. Let’s hope future funding is forthcoming.

It is an encouraging start, demonstrating what needs to happen. As Murray Watt, the Federal Minister for Emergency Management, has said: “Every property we can buy back through this program is a win for disaster resilience … These Queenslanders, once vulnerable, can now look towards a brighter future without fear of rising flood waters.”

The 2022 floods revealed that Australia has many homes in flood-prone areas that should be removed. This home buyback model needs to be replicated up and down the eastern seaboard.![]()

Margaret Cook, Research Fellow, Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For developing world to quit coal, rich countries must eliminate oil and gas faster – new study

James Price, UCL and Steve Pye, UCLLimiting how much coal countries can burn is considered an urgent priority for restraining global heating. After all, coal is the most carbon-rich of all fossil fuels and its combustion has contributed the most to planetary warming. For the first time in international talks, negotiators agreed to “phase down” coal use to prevent global temperature rise exceeding 1.5°C in the 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact.

Coal’s primacy in climate negotiations is partly because of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which has devised pathways to halting warming at 1.5°C. These scientific assessments prioritise the rapid phasing out of coal burning not only for the fuel’s carbon intensity and the need to head off CO₂ accumulation in the atmosphere, but also because cost-competitive alternatives are available in the form of solar and wind farms.

Researchers also stress the importance of decarbonising the power sector early in the green transition to enable other sectors, such as transport and industry, to run on clean electricity from the grid.

This puts the onus on certain nations to reduce emissions faster than others. The majority of global coal use can be found in emerging and developing countries, such as China and India. Here, large fleets of power stations and factories rely on coal which is cheap and abundant compared to other fossil fuels. By framing the solution to climate change as one in which coal is removed first, it is these countries that must commit to rapidly decarbonising in the next decade.

In our new paper, we highlight two problems with most published pathways to avoiding catastrophic climate change. First, it is unlikely that coal-dependent countries will be able to ditch the fuel as rapidly as these pathways set out.

And second, as this is the case, other fossil fuels, namely oil and gas, must be phased out more rapidly to compensate for coal’s slower exit. This would shift responsibility for mitigating climate change towards developed countries.

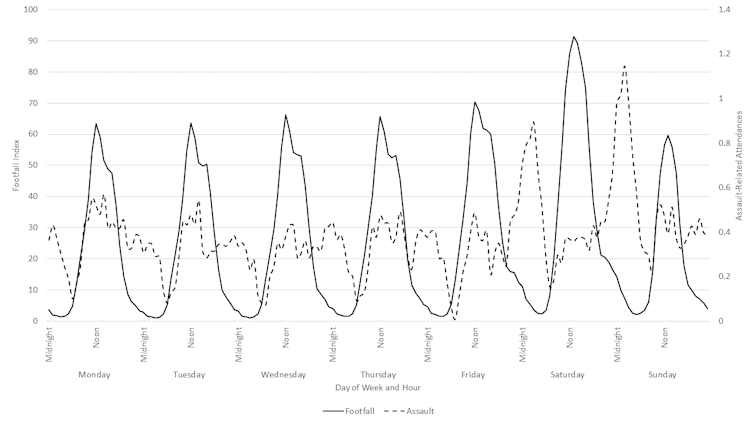

The Speed Limit On Phasing Out Coal

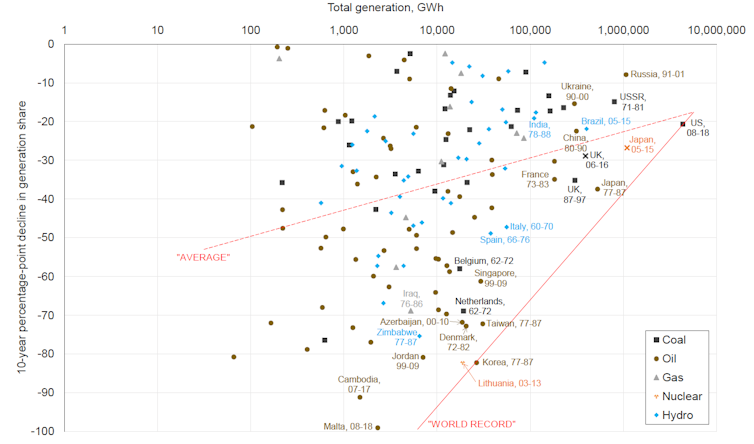

We compared how much coal use is expected to fall in modelled pathways to 1.5°C with the fastest power transitions that have taken place over the last 50 years, with all fuels and in all countries.

These transitions are shown in the figure below, and reflect a range of drivers, such as policy responses to the 1970s oil price crisis and political events such as wars, sanctions and the collapse of the Soviet Union. The red line labelled “world record” indicates the fastest pace that could be feasible with the political will to enact ambitious policies.

Based on modelled pathways from the IPCC, we estimate that coal power will have to be phased out in India, China and South Africa more than twice as fast as any historical power transition for electricity systems of comparable size. This is unlikely to be achievable or acceptable in any major coal-dependent developing country.

A more feasible pathway to eliminating coal might use the targets set out by the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA), an international coalition of countries established in 2017. The PPCA favour a differentiated timeline for exiting coal power, with rich countries going first by 2030 and the rest of the world by 2050.

These targets reflect how developing countries are more dependent on coal and have less money to invest in the green transition, but bear less historical responsibility for causing climate change.

This differentiated pace would put several countries, including China, at the speed limit of historical transitions. In other words, it would offer them a pathway to decarbonisation that is difficult, but possible. This trajectory would see developed countries reducing carbon emissions roughly 50% faster compared to pathways without the fairer distribution of efforts proposed by the PPCA.

This inverts the narrative from successive climate summits: developed, not developing, countries are the ones that must do more in the short-term to limit warming.

It also has important consequences for oil and gas. In all countries, oil and gas production must fall even in published pathways to 1.5°C, rather than increasing as most countries plan.

But when the world phases out coal at the PPCA pace, oil and gas must be phased out correspondingly faster. This has a different impact on different countries. For example, cumulative oil production by the US from 2020 to 2050 is 20% lower than in a 1.5°C pathway without the differentiated efforts proposed by the PPCA.

Limiting climate change requires phasing out all three fossil fuels: coal, oil and gas. Our research finds that climate models and policy debates rely too much on winding down coal, especially in coal-dependent developing countries.

Instead, a fairer and more realistic balance of mitigation efforts is needed, which means more emphasis on eliminating oil and gas. It also means greater effort by the global north, even while all countries, including those in the global south, end coal power as quickly as possible.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

James Price, Senior Research Associate in Energy, UCL and Steve Pye, Associate Professor in Energy Systems, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What Australia learned from recent devastating floods – and how New Zealand can apply those lessons now

Australia and New Zealand have both faced a series of devastating floods triggered by climate change and the return of the La Niña weather pattern. So it makes sense that Australia has now sent disaster crews to help with the aftermath of Cyclone Gabrielle.

With five serious floods in the space of 19 months in 2021-2022, Australia’s experiences – and how people responded – offer New Zealand a guide for recovering and rebuilding after an extreme weather event.

The flooding events in both countries share two key common elements. First, the floods broke previous records and were the largest in recent history. Second, there were also repeat flood events.

In Auckland, there were two massive floods within five days, while Cyclone Gabrielle became the Coromandel’s fifth severe weather event for 2023 and devastated other parts of the North Island.

The other common factor is urbanisation. Auckland’s population has been growing, resulting in the increasing development of the built environment. Intensifying urban development places pressure on existing drainage systems – parts of which are no longer fit for purpose.

Extensive built-up and paved areas with hard, impermeable surfaces can also cause rapid run-off during heavy rain, with the water unable to be absorbed into the ground as it would be in soft, vegetated areas.

Working With The Community

Our recent research in the Hunter Valley in Australia – one of the areas affected by those five successive floods – identified similar factors contributing to the flooding events, including a rapidly growing regional population.

Two of our research sites – the Cessnock and Singleton local government areas – had growing urban centres that reflected a similar development trajectory to Auckland, albeit in a smaller scale.

Our research in the Hunter Valley established the importance of identifying existing community resilience and gaps. We also observed the need to involve the community at all levels. This included having early warning systems and evacuation protocols in place to improve community access to information and warnings.

The State Emergency Services (SES) is the main agency in New South Wales responsible for flood response and management. Supported by community volunteers, the SES has a clear focus at the local level.

This community focus is evident with its “door-knocking kit”, which is based on a community-level vulnerability assessment. The SES has a list of those in the community who are most at risk, such as the elderly and people with disabilities. When a flood risk becomes evident, SES volunteers go knocking on doors to check their preparedness and provide evacuation support.

The equivalent of SES in New Zealand, Auckland Emergency Management, could learn from this community-based approach and include it within its Community Group Support initiative, so that future disaster responses can be more closely tailored to the community.

In the recent floods in Auckland, communication was an issue. Relaying directives and information through multiple institutional layers led to confusion, which could have been avoided through a closer community-based approach.

Building A Volunteer Army

Another key factor in Australia is the large cadre of SES volunteers – around 9,000 in New South Wales, a state with a population of just over eight million. This is a significant form of social capital, without which the current approach to flood response and management would not be possible.

While there are initiatives in New Zealand to attract and engage volunteers, more needs to be done. Civil defence needs to conduct a structural review of the existing volunteer organisations that work in the disaster and emergency response field to identify ways to improve the recruitment and retention.

We also found evidence of volunteer “burn-out”, meaning there’s a need to support volunteers emotionally and financially during extended periods of disaster response and recovery.

While there is a large number of SES volunteers in Australia, more are needed as climate change drives more frequent, extensive and intense disasters. Given the similar nature of repeat climate-related disaster events in New Zealand, provisions for a large cadre of well-supported and well-trained volunteers is necessary.

A review of existing volunteer agencies and community organisations should be undertaken to identify ways they can be harmonised to avoid competing pressures for resources. As well, there’s a need to nurture collaboration between agencies to help with sharing skills, training, data and resource management.

The Need For Resilience

Perhaps the key lesson for New Zealand, and also Australia, is the need to think beyond emergency management to building long-term resilience within agencies and communities.

As climate-related disasters become more common, we need to think about how our cities grow and how we can incorporate flood resilience by retaining green areas and vegetation, improved drainage and transportation links.

But both countries also need to focus on being ready for a disaster, instead of managing it after it happens. In doing so, the pressures of managing the disaster when it arrives would be less – and so would the long-term impacts on people and the economy.![]()

Iftekhar Ahmed, Associate Professor, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Would a nature repair market really work? Evidence suggests it’s highly unlikely

Why should governments do all of the heavy lifting to arrest the steep decline of many ecosystems? Endangered species live on private land too – so why not give farmers and landholders incentives to look after them and restore habitat?

Framed like this, it’s easy to see the appeal of nature repair markets. Harness private money and direct it towards rescuing nature. No wonder the Albanese government is forging ahead with its nature repair market bill and seeking public submissions. If it becomes law, landholders will be able to gain tradeable biodiversity certificates for projects that protect, manage and restore nature.

Why do we need it? According to the government, actually reversing the decades of decline in Australia’s environment is so expensive it’s beyond government and individual landholders.

It sounds beautiful in theory – carbon credits, but for nature. But the idea has a poor track record in practice. Other offset markets have been easily gamed. Ensuring integrity is costly. Policies with teeth – banning land clearing, stronger environmental laws – are much more likely to work.

Where Did This Idea Come From?

It’s not wholly new. Labor’s plan is based on a repackaged and expanded Morrison government biodiversity stewardship program, originally targeted at farmers.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has claimed the market is a response to demand. “Businesses tell me all the time that they want to invest in nature because their shareholders, customers and staff are demanding it,” she has said.

Consultants paint glowing futures where markets in nature balloon in size. McKinsey estimates the current value of global nature credit markets is around A$7 billion a year. If the forecasts of PricewaterhouseCoopers are correct, that could vastly increase to $137 billion in Australia by 2050.

Enthusiasm for voluntary nature markets is at an all time high. In the last two years, we’ve seen many plans and initiatives, from Nature Finance to the Taskforce on Nature Markets to the Biodiversity Credit Alliance.

So why the scepticism? In short, it’s harder than it looks to unlock private capital and direct it to pro-nature interventions.

If they are to succeed, these kinds of schemes must be legitimate. To make these credits worthy of investment and tradeable, you need a governance framework, measurement systems, certification, registration, contracting, trading, monitoring, reporting, accounting, auditing, and a bureaucracy for administering, consulting and advising on all of it.

3 Reasons For Scepticism: Money, Demand And Effectiveness

1. Money

If the reason for turning to the private sector is funding, how can we reconcile this with the Stage 3 tax cuts, set to slash government revenues by $300 billion?

Crying poor is not a credible excuse. As economists repeatedly point out, countries with their own sovereign currency can create money to spend on priorities they care about.

2. Demand

You would think a policy aimed at the private sector would be based on credible market data. But demand for these voluntary credits is “untested and likely overestimated”.

Almost three-quarters of the current global biodiversity market is based on compliance. Companies aren’t plowing money in because they want to. They do it because they have to. Australia’s nature repair scheme, by contrast, is voluntary. No other country has launched a large-scale voluntary biodiversity credit scheme.

In showcasing two decades of practice of voluntary biodiversity credits, the World Economic Forum only mustered four examples. None of them have detail on scale, value or improvement to the environment.

3. Effectiveness

To date, we have little evidence market-based regulatory measures, such as compulsory biodiversity and carbon offsets, actually do what they promise to do. In short, it is very unclear that these tools make things better relative to a baseline.

Of Australia’s states, Victoria has arguably the best-developed and most technically sophisticated biodiversity offset scheme. Even so, the Victorian Auditor-General has found the scheme cannot show results. Their report found Victoria “is not achieving no net biodiversity loss from native vegetation clearing on private land”.

In New South Wales, the deficiencies are even more severe. Our most populous state has a scheme which lacks a clearly defined objective to measure success against.

Among the scheme’s many problems are non-delivery, double-dipping, conflicts of interest and potential insider trading.

Why Use A Market To Deliver A Public Good?

Functioning ecosystems produce clean water, breathable air, nutrient recycling, fertile soil, food, fibre and many other benefits.

So why are we turning to markets to deliver complex public goods like biodiversity?

The natural world is multifaceted, interconnected and complex. Developing market infrastructure to deliver desired natural outcomes is extremely difficult.

Victoria and NSW’s biodiversity offset schemes show us there’s no guarantee advocates of voluntary markets can design and produce tangible, low fraud risk biodiversity credits.

Even if they can, the cost of credibility and good governance will mean these credits will have high transaction costs in conflict with the competitive returns sought by investors.

Consider the challenges faced by the far more straightforward schemes aimed at preserving forests for carbon offsets or credits. These schemes have been plagued by issues, such as human rights violations, questions over credibility of offsets and leakage of environmental damage to other areas.

In these schemes, failure is common and success is rare. It’s time to end the catchcry of “let’s not allow the perfect to become the enemy of the good”.

After 30 years of experience, we can now conclude these schemes have done a great deal more harm than good.

Repairing Nature? Use Sticks, Not Carrots

If we want to reverse Australia’s environmental decline, we know what we have to do.

We have to end land clearing to salvage as much habitat as possible.

We have to end unsustainable water extraction.

We have to rapidly cut emissions to limit further climate damage.

We have to put public money into conservation and environmental management.

And we need environmental laws with teeth to act as a more direct and effective method of ending the damage.

Turning nature around is hard. We’ve left it late. But markets are not the answer – they’re a band-aid solution. Time to rip it off. ![]()

Yung En Chee, Senior Research Fellow, Environmental Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

From the dingo to the Tasmanian devil - why we should be rewilding carnivores

No matter where you live, apex predators and large carnivores inspire awe as well as instil fear.

Large predators have been heavily persecuted and removed from areas where they once lived because of conflict with livestock graziers.

Beyond their large teeth, sharp claws and iconic status, research is finding they are crucially important in ecosystems. So there is considerable interest in returning large carnivores to areas where they once lived, as part of a shift towards rewilding.

Bringing back carnivores is not without risk, but it’s a potentially powerful conservation tool.

Rewilding dingoes and Tasmanian devils in Australia could benefit many of our troubled ecosystems, by keeping herbivore numbers down, keeping feral cats and foxes fearful, and triggering a rebound in vegetation and small animal populations.

Predators Vs Prey

Predators can affect their prey’s behaviour. When prey species know a predator is around and perceive risk to their survival, they change how they behave.

The landscape of fear predators create can make it harder for prey species to survive.

That’s often good for ecosystems. The effect of dingoes in reducing, say, kangaroo and wallaby populations and changing their behaviour, can actually help bring back plants and smaller animals through a “trophic cascade”. For example, wolves chasing, eating and scaring deer can lead to an increase in the growth of plants, which can benefit other species.

Predators also affect other predators. If humans poison, shoot, trap and exclude top predators like dingoes, smaller predators can increase in number and get bolder, in a phenomenon called mesopredator release. In California, when coyotes disappeared due to habitat destruction, populations of smaller predators such as cats grew and songbird numbers fell.

How Is It Done?

Rewilding can occur passively, by changing laws to stop the exclusion or killing of large carnivores and making areas more favourable for carnivores to live. When this happens, species often move back by themselves. Encouragingly, this is happening in many parts of the world, including a recent sighting of a wolf in Brandenburg, Germany.

In other cases, rewilding may need a more active approach, such as physically moving animals to an area. The return of wolves to Yellowstone National Park and the ecological transformation that followed is a famous example of this, although in recent times the details of this story have been questioned.

When does rewilding work best? Recent research shows wild-born animals fare better than captive-born animals, though the results are far from conclusive. Wild-born animals may have an edge due to their skills in hunting and defending territories critically important for survival.

Rewilding In Australia Means Bringing Back Dingoes

Once carnivores are killed or fenced off from an area, the ecosystem changes. Will we restore nature by bringing them back? Potentially – but it’s not guaranteed. Australia’s controversial canine, the dingo, is a perfect example. Aside from humans, dingoes are Australia’s only living land predator over 15 kilograms.

Dingoes have a vital role in Australian ecosystems, such as keeping populations of kangaroos and emus under control. They can also take down feral goats. Their natural control of herbivores means plants can bounce back, as well as making room for smaller animals. Their effect on plant life may even affect the height and shape of sand dunes.

In some parts of Australia, kangaroo populations have exploded. Land clearing for pasture favours kangaroos, as do the dams and water troughs for livestock, the killing off of dingoes and the ending of First Nations Peoples’ cultural practices and hunting.

At times, these population booms have led to sudden crashes, with widespread starvation in droughts. Harvesting kangaroos is one response, but this is often controversial and unpopular. Bringing dingoes back would help reduce kangaroo numbers in a way more palatable to many people.

When present, dingoes also keep a lid on our worst introduced predators, feral cats and foxes, either by eating them or forcing them to alter their behaviour. If cats and foxes have to be more careful, it may benefit their smaller prey.

We could rewild dingoes very easily by removing large barriers like the dingo fence. This, of course, would trigger pushback from livestock graziers worried about attacks on their stock.

It doesn’t have to be this way though. We’ve learned a lot about ways to reduce conflict between farmers and predators. It’s now entirely possible for livestock producers and top predators to coexist. Western Australian farmers are already using guardian animals such as Maremma dogs to protect livestock.

So Should We Do It?

Australia has been slow to support and attempt large carnivore rewilding. But we can learn valuable lessons from the relocation of Tasmanian devils to an offshore haven, Maria Island.

Devils were introduced to safeguard the species against the severe population decline from devil facial tumour disease. These predators were not native to Maria Island, but they’ve flourished. One unexpected side effect was the devastating impact on the island’s little penguin population.

Rewilding comes with risks. But it also comes with major benefits, which may help our collapsing ecosystems and threatened species.

Time is short. Conservation must take calculated and informed risks to achieve better outcomes. Rewilding attempts are valuable, even when things don’t go entirely as planned.

What else could we do? Discussions over the carefully planned reintroduction of Tasmanian devils to mainland Australia continue. If the devils come back to the mainland for the first time in thousands of years, they might help to manage herbivore and feral cat populations.

Rewilding is not about recreating the mythical idea of wilderness. Humans have shaped ecosystems for millennia.

If rewilding and ecological restoration is to succeed, communities and their values, including First Nations groups, must be involved.![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

A Walk Around The Cromer Side Of Narrabeen Lake by Joe Mills

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways; Bungan Beach and Bungan Head Reserves: A Headland Garden

Pittwater Reserves, The Green Ways: Clareville Wharf and Taylor's Point Jetty

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways; Hordern, Wilshire Parks, McKay Reserve: From Beach to Estuary

Pittwater Reserves - The Green Ways: Mona Vale's Village Greens a Map of the Historic Crown Lands Ethos Realised in The Village, Kitchener and Beeby Parks

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways Bilgola Beach - The Cabbage Tree Gardens and Camping Grounds - Includes Bilgola - The Story Of A Politician, A Pilot and An Epicure by Tony Dawson and Anne Spencer

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Seagull Pair At Turimetta Beach: Spring Is In The Air!

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

Stony Range Regional Botanical Garden: Some History On How A Reserve Became An Australian Plant Park

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Topham Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP, August 2022 by Joe Mills and Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Mushrooms Magnify Memory By Boosting Nerve Growth

Pets Create ‘Pawsitive’ Change For People In Aged Care

Applications Now Open For Inaugural $10,000 Military History Prize

Don’t Lose Your Money Donating To A Fake Earthquake Appeal

- Who benefits from the charity’s work

- Where it operates

- Who is running it

- Whether it is meeting its financial reporting obligations.

- Look for established, registered charities running verified appeals.

- Check the Charity Register to see details about a charity’s main work.

- Don’t click on links in unsolicited emails and social media posts which may take you to a fake, scam website. Find the charity’s website in a search engine or on the Charity Register.

- Don’t give your credit card and bank account details on social media and be cautious if you do so online.

- If you get a call claiming to be from a charity, say you’ll call back. Search the Charity Register and call back on the number shown there.

- Always ask for identification from collectors at a shopping centre, on the street or at your front door.

Should private schools share their facilities with public students?

There is a new push for private schools to open their grounds and facilities to the broader community. North Sydney mayor Zoe Baker, wants to ask top private schools in her area to share their green spaces and other facilities.

For so much of the year, schools sit unused and most campuses close at 4pm. We should search for opportunities where space can be shared where it is suitable.

Along with opening up space for the public, she also suggests public school students could use the playing fields, halls and performing arts centres after-hours.

Amid headlines about private schools building plunge pools and A$125 million sports centres and a widening gap in results between students between high and low socioeconomic backgrounds, could this be a way to make the education system fairer and improve outcomes for all students?

The Idea Isn’t New

The idea to open up grounds and facilities is not new.

In 2018, former New South Wales education minister Rob Stokes said both public and private schools should be opened up to the community as they were “public spaces”.

We pay for them, I feel the same way about private schools as well, a lot of money goes into them and a way they can get a social licence to operate in the local community is to let the community utilise them.

The NSW government also introduced a Share Our Space program where schools received a grant to upgrade their facilities for both community and school use during the school holidays.

In Victoria, schools have been encouraged to consider partnerships with other school sectors to improve education and opportunities for students since 2016.

However, partnerships are only formed in an ad hoc way, relying on schools to develop their own relationships. Current sharing arrangements between public and private schools mainly focus on infrastructure. This includes access to sporting grounds, theatre spaces, and specialist learning environments, such as STEM centres.

Could Sharing Be Expanded?

So far, this debate has underestimated what government schools could bring to the equation. The traffic tends to be one way from private to public.

Public schools could also share their teaching expertise, professional learning opportunities and curriculum resources with nearby private schools. As a result, more subject areas and elective options could be offered.

This could equally include partnering with other public schools to expand opportunities for their students. It is interesting to consider how this approach may have better supported schools and teachers throughout pandemic lockdowns.

The Victorian government has begun some work in this area. It has a toolkit which highlights the possibilities of sharing teaching and curriculum ideas. But again, this continues to be ad hoc and more formalised mechanisms are needed to build partnerships.

Is This A Good Idea?

Firstly, care must be taken to not overestimate the value of private schooling on learning. While access to state-of-the-art facilities is understandably attractive, research suggests there is little evidence a private school education ultimately makes a difference to students academically, once socio-economic status is taken into account.

A possible sticking point in any sharing arrangements is that existing partnership models have traditionally involved payment. Arguably if one school is simply paying another a fee to use their resources or facilities it may not really be classified as “sharing”.

If sharing occurred between schools, rather than just public students using private schools’ facilities, it may be possible to rethink this approach. Thinking needs to move from a focus on physical resources and facilities to include the sharing of curriculum and teaching expertise in both directions.

While there may be some resistance from school communities where parents are paying large school fees, the benefit for private schools is building local goodwill which may prove useful in seeking to expand their brand in the community.

Of course, we are still left with the issue of why some private schools have the facilities they have in comparison with other schools and the funding system that allows this to happen.

This debate is a vexed one. But there is an opportunity here if school communities are prepared to work together to share their strengths and resources.![]()

Ange Fitzgerald, Professor, Associate Dean (Education) and Director (Initial Teacher Education), RMIT University and Thembi Mason, Lecturer, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jimmy Carter’s lasting Cold War legacy: Human rights focus helped dismantle the Soviet Union

Former President Jimmy Carter, who has entered hospice care at age 98 at his home in Plains, Georgia, was a dark horse Democratic presidential candidate with little national recognition when he beat Republican incumbent Gerald Ford in 1976.

The introspective former peanut farmer pledged a new era of honesty and forthrightness at home and abroad, a promise that resonated with voters eager for change following the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War.