inbox and environment news: Issue 575

March 12 - 18 2023: Issue 575

Large Leatherback Turtle Found On Whale Beach: Deceased

Further:

- Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2021/22 Annual Performance Report - Data Shows Vulnerable, Endangered and Critically Endangered Species Being Found Dead In Nets Off Our Beaches - August 2022

- Pittwater's Turtles Impacted By Boat Strikes In The Pittwater Estuary: 4 Knots Speed Limit/Distance To Shore Being Ignored - April 2022, Issue 533

- Shark Listening Stations + Drumlines Have Been Installed Off Our Beaches - May 2022 Update

- New Fleet Of Shark-Spotting Drones For New South Wales - July 2020

- NSW Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2020/21 Annual Performance Report: 90% Of Northern Beaches Marine Animals Entangled Were Not Targeted Sharks, Included are Threatened or Protected Species Mortalities

- NSW DPI's Shark Meshing 2019/20 Performance Report Released

- DPI Shark Meshing 2018/19 Performance Report: Local Nets Catch Turtles, a Few Sharks + Alternatives Being Tested + Historical Insights

Avalon Dunes Bushcare: A Great Weeds Out Morning In March

Swamp Wallaby At Palm Beach

Cat Owners Encouraged To Keep Their Pets Safe At Home

Wednesday, 1 March 2023

Northern Beaches residents are being encouraged to keep their pets safe at home as part of a new animal protection campaign.

According to RSPCA NSW, two out of three cat owners have lost a cat to a roaming-related accident, and one in three to a car accident. Northern Beaches Council is proud to be one of 11 councils partnering with RSPCA NSW as part of the Keeping Cats Safe at Home project.

Promoting responsible ownership, the new campaign goes beyond desexing and micro chipping of beloved cats and asks owners to consider keeping their cats at home.

Northern Beaches CEO Ray Brownlee said there’s a dual benefit to cats and local wildlife that flows directly from promoting responsible ownership of domesticated cats.

“Northern Beaches residents love their pets, but they’re also passionate about protecting the local environment,” Mr Brownlee said.

“Because pet cats occupy a special place in our hearts we need to educate the community on how have them microchip and desexed to keep them safe. This initiative has an educational focus. It aims to protect tiny native species like lizards, mammals, baby birds and frogs, while also preventing domesticated cats from falling prey to road accidents.”

In 2021, the NSW Government awarded a $2.5 million grant from the NSW Environmental Trust to RSPCA NSW to deliver the project.

To help promote the campaign, Council is asking cat-lovers living on the Northern Beaches to submit a photo of their cat or kitten living their best life at home and go in the draw to win one of 10 $1000 vouchers for a deluxe outdoor cat enclosure from Catnets. The competition opens on March 1st and closes on Sunday April 9th 2023. Finalists will be published in an online gallery.

For competition details visit www.northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au/environment/non-native-animals/cats/competition-keeping-cats-safe-home

Learn more about keeping cats safe at www.rspcansw.org.au/keeping-cats-safe

Photo: Greg Hume

Protest For Koalas: Manly - Sunday March 12

We are taking a stand for koalas in NSW Environment Minister James Griffin’s Manly Electorate.

Koalas need forests.

The continual loss of habitat is contributing to the decline of koalas — and if we don’t end native forest logging they are on track to becoming extinct by 2050.

Join in showing your support in Manly to stand against the senseless devastation of koala habitat in NSW forests.

Environment Minister James Griffin is sitting on his hands on koalas.

It’s time we protect koalas by saving their habitat.

Speakers to be announced.

Event by Bob Brown Foundation

Manly Beach Promenade at the Corso: Sunday 12 March at 10am

Concert: Rock For Lizard Rock

FREE. Register at: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/rock-for-lizard-rock-tickets-554768135427

Black Summer Vigil For Wildlife: April 2nd

The New South Wales Wildlife Council invites all wildlife carers, wildlife vets, vet nurses, first responders and supporters to the upcoming Black Summer Vigil for Wildlife on Sunday April 2nd 2023 starting at 2pm.

Please join us for the Black Summer Vigil, a three-year anniversary memorial service for the three billion animals who lost their lives in the fires – “one of the worst wildlife disasters in modern history”.

Attend online or in-person at Camperdown Memorial Rest Park (Sydney).

RSVP at: blacksummervigil.com

You’ll hear personal stories from the NSW Wildlife Council, Southern Cross Wildlife Care and other first responders across wildlife rescue, rural fire service, photojournalism, Aboriginal custodianship, veterinary medicine, ecology and more.

+ Performance and Ceremony by Jannawi Dance Clan, sharing a Dharug cultural perspective to honour the Ancestors and bring the spirit of the animals into our midst.

Join us to honour the animals who perished – and in doing so, celebrate the unique and extraordinary wildlife of these lands.

Speakers include:

Greg Mullins, Former Commissioner, Fire and Rescue NSW; Climate Councillor and founder, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action. Greg warned Australia's then–Prime Minister in April 2019 that a bushfire catastrophe was coming. He pleaded for support and was ignored, then risked his life dealing with the ramifications on the ground. “You couldn’t see very far because of the orange smoke. Everything was dark. It was probably 2 o’clock in the afternoon but it was like night. Then I saw something moving on the side of the road and I walked closer. It was a mob of kangaroos. The speed of that fire with its pyroconvective storm driving it in every direction, they had nowhere to go. They came out of the forest, on fire, and dropped dead on the road. I’ve never seen that. Kangaroos know what to do in a fire. They’re fast animals. Climate change, driven by the burning of coal, oil, and gas is driving worsening bushfires across Australia, and putting our precious, irreplaceable wildlife in danger.”

Internationally recognised ecologist and WWF board member, Professor Christopher Dickman oversaw the work calculating the animal deaths from Black Summer. A Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science, Professor Dickman already wore the heavy task of being an ecologist during the sixth mass extinction, in the country that has the worst rate of mammalian extinction in the world. On 8 January 2020 media around the world shared his finding that Black Summer fires had killed one billion animals. Sadly, the fires continued for two more months, and his team's final count was three billion. This does not include invertebrates: it is estimated 240 trillion beetles, moths, spiders, yabbies and other invertebrates died in the fires.

Coming up from the South Coast, owner of Wild2Free Kangaroo Sanctuary Rae Harvey, as seen in The Bond and The Fire. She is in the sad position of having personally known and cared for a number of Black Summer's victims: many of the orphaned joeys she cared for were killed in the fires. (She nearly died herself too.) For three years, she has been unable to even speak their names. Now, for the first time, she will tell the story of the joeys she lost.

Cultural burning practitioner and Southern NSW Regional Coordinator with Firesticks Alliance, Djiringanj-Yuin Custodian Dan Morgan. Dan practises using Aboriginal knowledge to heal Country. He has worked for 18 years with the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and is on the board of management for the Biamanga National Park, a sacred area home to the last surviving koalas on the NSW south coast – which was partly destroyed by the fires of Black Summer. “The animals that live on our sacred sites are our Ancestors, it's our Cultural obligation to protect them. We have evolved with our Country over thousands of years, nourishing and protecting all living species. Our Country represents our people. So when the fires came, it was devastating to see the aftermath, and the feeling of helplessness was truly traumatising for our people, due to the denial of our Cultural right to manage Country as our Ancestors did for thousands of years prior to colonisation. Australia needs to make legislative changes that allow us to heal Country and our community through the fire knowledge and to stop incinerating ecosystems with destructive 'hazard-reduction' burns."

Head of Programs & Disaster Response at Humane Society International (HSI), Evan Quartermain was one of the first responders on Kangaroo Island where nearly 40% of the island burnt at high severity: “Those were some of the toughest scenes I’d ever witnessed as an animal rescuer: the bodies of charred animals as far as the eye can see. Every time we found an animal alive it felt like a miracle.” As a result of this firsthand experience, HSI commissioned a report into the state of Australia's disaster response for wildlife, which we'll also hear about.

+ More to come.

The Black Summer Vigil is brought to you by the Department of Animals, Animals Australia, the NSW Wildlife Council, World Animal Protection, Humane Society International and Defend the Wild, with support from WIRES, Firesticks Alliance, Nature Conservation Council of NSW, Wild2Free Kangaroo Rescue, Four Paws, Friends of the Koala and Kangaroos Alive.

Permaculture Northern Beaches - Upcoming Events

- Learn about Permaculture design

- Caring for and raising chickens

- Native bees and bee hotels

- Living Skills - soap making

- AND Live Music!

Australia’s Hotly Contested Eucalypt Of The Year Voting Now Open

Australia’s much loved - and hotly contested - Eucalypt of the Year voting is now open. Passionate gumtree lovers across the country are invited to vote for their favourite gum, now in its sixth consecutive year. There are ~850 species of eucalypt across the continent and they are an unmistakable feature of living where we do.

“After running for five years, there are still hundreds of eucalypts that haven’t had their time in the sun as Eucalypt of the Year. We’ve whittled down the species to a shortlist of 25 that represent a diverse range of ecological features and geographical spread to make it easier for you to vote. Last year’s winner - the mighty Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans) is not eligible. Now is the time to cast your vote for your personal favourite,” says Linda Baird, CEO of Eucalypt Australia.

People can vote for their favourite eucalypt until 19th March at www.eucalyptaustralia.org.au

The winning eucalypt will be announced on National Eucalypt Day, Thursday March 23. National Eucalypt Day is Australia’s biggest annual celebration of eucalypts held every year to celebrate and promote Australia’s eucalypts and what they mean to our lives and hearts.

Tell the organisers how you voted on social media by tagging @EucalyptAus using the hashtag #EucalyptoftheYear. The 25 shortlisted species are:

- Angophora costata (Sydney Red Gum)

- Angophora hispida (Dwarf Apple)

- Corymbia aparrerinja (Ghost Gum)

- Corymbia citriodora (Lemon-scented Gum)

- Corymbia ficifolia (Red-flowering Gum)

- Corymbia opaca (Desert Bloodwood)

- Corymbia ptychocarpa (Swamp Bloodwood)

- Eucalyptus caesia (Silver Princess)

- Eucalyptus cinerea (Argyle Apple)

- Eucalyptus cneorifolia (Kangaroo Island Narrow-leaved Mallee)

- Eucalyptus lansdowneana (Crimson mallee)

- Eucalyptus platyphylla - (Poplar Gum)

- Eucalyptus leucoxylon - (Yellow Gum or South Australian Blue Gum)

- Eucalyptus macrandra (River Yate)

- Eucalyptus marginata (Jarrah)

- Eucalyptus miniata (Darwin Woollybutt)

- Eucalyptus perriniana (Tasmanian Spinning Gum)

- Eucalyptus radiata (Narrow-leaved Peppermint)

- Eucalyptus rhodantha (Rose Mallee)

- Eucalyptus rubida (Candlebark)

- Eucalyptus salmonophloia (Salmon Gum)

- Eucalyptus oleosa (Giant Mallee)

- Eucalyptus synandra (Jingymia Mallee)

- Eucalyptus tetraptera (Square-fruited Mallee or Four-winged Mallee)

- Eucalyptus vernicosa (Varnished Gum)

Angophora costata (Sydney Red Gum), McKay Reserve Palm Beach. Photo: A J Guesdon

Tasmanian Spinning Gum Eucalyptus perriniana. Photo: Remember The Wild, Catherine Cavallo, Instagram handle rememberthewild

Varnished Mallee Eucalyptus vernicosa. Photo: Dean Nicolle

Red Flowering Gum Corymbia ficifolia. Photo: Melanie Cooper, Instagram handle maxxle5

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Weed Of The Week: Cassia - Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

Create A Spit To Seaforth Oval Walk: The Missing Link - Petition

There is approx. 20,000 square metres of land situated between Rignold Street and Castle Circuit, Seaforth. The largest block is now FOR SALE. There is currently contracts out to overseas investors and developers.

The land is separated by conservation land that joins Garigal National Park. This land should be purchased and returned to the community for all to enjoy and wildlife to be given a fighting chance at survival.

This is a thriving riparian zone that should be made a wildlife corridor. It is currently the wildlife corridor that connects existing corridors to Garigal National Park .Running through the middle of the land is a permanent water source that attracts and aids the survival of many animals. Currently there are wallabies, echidnas, powerful owls, lyrebirds, monitor lizards, water dragons, numerous species of small birds and insects such as a large variety of dragonflies.

The Powerful Owl is listed as vulnerable in NSW and there is talk of changing the lyrebird's status to threatened in light of the recent loss of habitats due the devastating fire season of last summer. The Seaforth Mint Bush is listed as critically endangered. The Angophora's are a protected species.

The loss of hollow bearing trees is a key threatening process in determining whether or not these vulnerable and threatened species will survive.

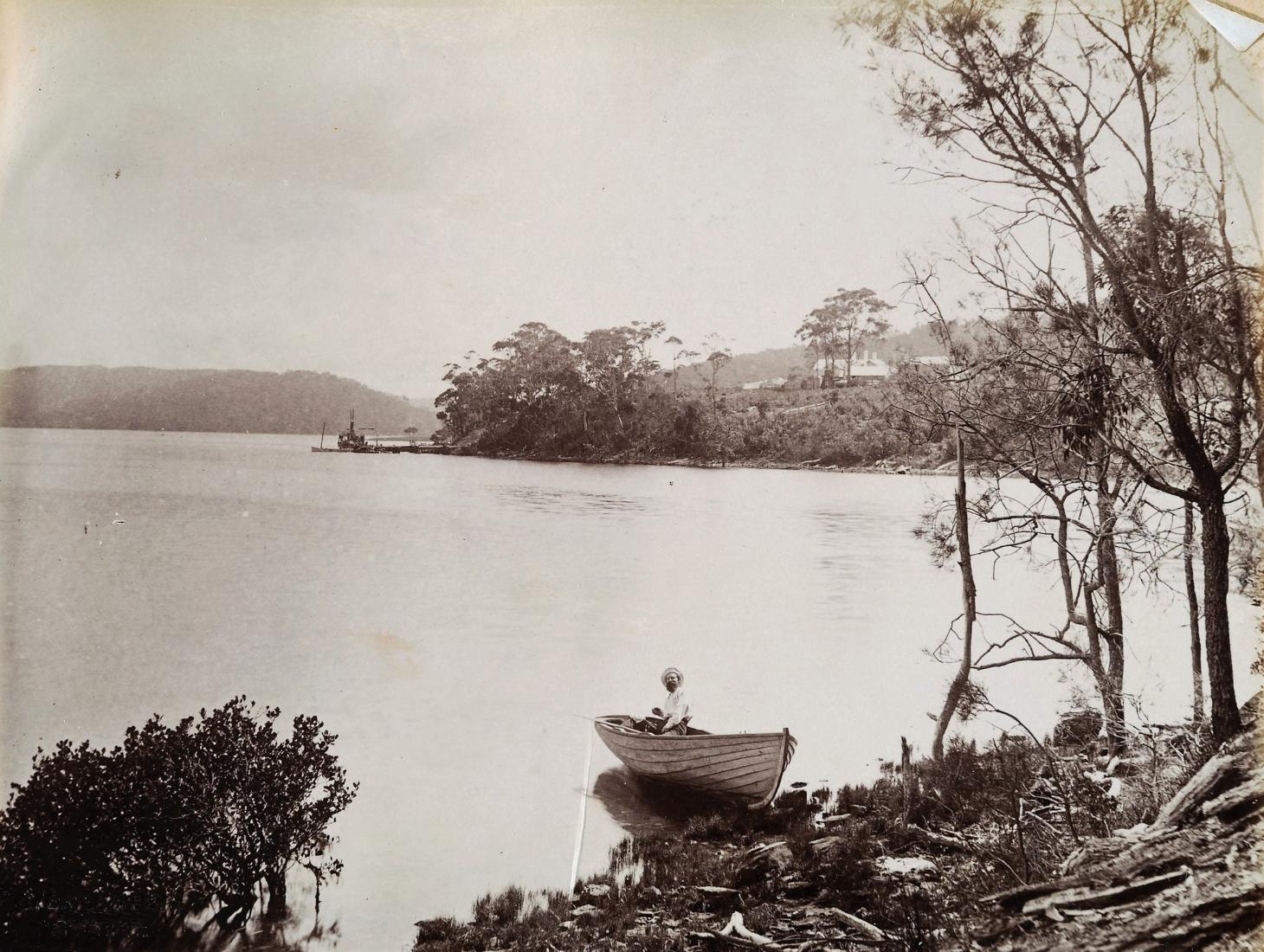

Given the conservation status of this flora and fauna I am asking for this land be bought back to create a wildlife corridor to join the land that was saved behind Dalwood homes. At present the land is made up of two privately owned properties, one is owned by a Chinese consortium and the other is owned by an American family. Both parcels have derelict houses that are falling down, leaving shattered glass, asbestos and building rubble spread through the bush. One property has no street access and is only accessible by water.

Thank you to all who have read this far and thank you in anticipation of your signatures helping to protect this very unique area.

Petition at: https://www.change.org/p/create-a-spit-to-seaforth-oval-walk

THIS IS THE MISSING LINK TO CREATING A FORESHORE WALK THROUGH SEAFORTH.

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

We now have a treaty governing the high seas. Can it protect the Wild West of the oceans?

Delegates gave a jubilant cheer at United Nations Headquarters in New York on Saturday night, as nations reached an agreement on ways to protect marine life in the high seas and the international seabed area.

It has been a long time coming, debated for almost two decades. It took nine years of discussions by an Informal Working Group, four sessions of a Preparatory Committee, five meetings of an Intergovernmental Conference and a 36-hour marathon final push to reach agreement.

So why was it so hard to achieve? And what does it do?

In short, the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction agreement paves the way for the establishment of more high seas marine protected areas. Only 1% of the high seas are currently fully protected, so the new agreement is a vital step towards achieving the recently adopted Kunming-Montreal biodiversity pact, which pledges to protect 30% of terrestrial and marine habitats by 2030.

In turn, the designation of more high seas marine protected areas could assist in curbing fishing activities in these waters. At present, distant water fleets can scoop up almost everything that swims or scuttles thousands of kilometres from their home country. As the high seas are also teeming with marine life, the new agreement also ensures this genetic wealth is shared fairly and equitably among the international community.

It’s not too much to say this agreement marks a significant turning point in the protection of our deep oceans.

Where Are We Talking About?

Nations have rights to marine resources out to 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) from their coastline. After that? It’s almost completely unregulated, much like the Wild West. It’s a huge area, representing over 60% of our oceans.

But this agreement doesn’t just cover what lives in the high seas water column. It also covers the seabed, ocean floor and subsoil beyond a coastal country’s continental shelf.

Major discoveries on the ocean floor have dispelled the long perceived myth that the deep seabed is a barren desert and featureless plain. One important breakthrough has been the discovery of hydrothermal vents and their rich biological community. These seabed habitats, have been labelled one of the richest nurseries of life on Earth and harbour unique organisms of particular interest to science and industry alike. These organisms may offer a limitless catalogue of medical, pharmaceutical and industrial applications. They may even hold the cure for cancer.

Isolation Is No Longer Protection

Due to their remote nature, the high seas were long considered protected from human impact. But only 13% of the ocean is now classified as marine wilderness, completely free from human disturbance, with most being located in the high seas.

International law, as it stands, is not up to the task of protecting this region. Regulations and rules are haphazard, with some regions and resources (like marine genetic resources) not protected at all. Enforcement is weak, and cooperation lacking, as I have found in my research.

Without adequate regulation, the high seas are being heavily exploited with 34% of all fished species now overfished. Illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing is also a serious problem on the high seas.

There is also growing interest in deep-sea mineral resources. The International Seabed Authority has entered into contracts with companies to mine deep-seabed areas, but the long term impacts of this mining activity are difficult to predict and its effects could have irreversible consequences for marine ecosystems. Marine pollution is also a growing problem with approximately 6.4 million tonnes of litter entering our oceans every year.

What Solutions Does This Agreement Offer?

Under this agreement, the door is open to establish marine parks and sanctuaries covering key areas of the high seas. Fishing could be banned or heavily restricted in these areas along with other activities that could have a detrimental impact on marine life.

You might have expected fishing to be a key reason for the long delay in getting this agreement across the line. However, one of the main stumbling blocks was how to share the genetic wealth of the high seas. Under the agreement, all countries will have to share benefits – financial and otherwise – from efforts to harness the benefits to be derived from these resources. Think of the possible new cancer treatments coming from compounds in sponges and starfish.

Why was this a challenge? It was difficult to find common ground on how to share benefits from this genetic wealth, with a clear divide between developed and developing nations. But it was achieved and now data, samples and research advances will need to be shared with the world.

What’s Next?

Reaching agreement has been achieved. To make it legally binding, it must be adopted and ratified by countries. Will the world’s nations sign up? We’ll need as close to universal participation as possible to make this work. The first part is done. But getting States to sign on, ratify and follow the agreement is likely to be a harder task. ![]()

Dr Sarah Lothian, Lecturer and Academic Barrister, Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security, University of Wollongong, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The high seas are supposed to belong to everyone – a new UN treaty aims to make it law

It may come as a surprise to fellow land-dwellers, but the ocean actually accounts for most of the habitable space on our planet. Yet a big chunk of it has been left largely unmanaged. It’s a vast global common resource, and the focus of a new treaty called the biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ) agreement.

For 15 years, UN member states have been negotiating rules that will apply to the ocean lying more than 200 nautical miles from coastlines, including the seabed and the air space above, referred to as the “high seas”.

Covering nearly half the Earth’s surface, the high seas are shared by all nations under international law, with equal rights to navigate, fish and conduct scientific research. Until now, only a small number of states have taken advantage of these opportunities.

This new agreement is supposed to help more countries get involved by creating rules for more fairly sharing the rewards from new fields of scientific discovery. This includes assisting developing countries with research funding and the transfer of technology.

Countries that join the treaty must also ensure that they properly assess and mitigate any environmental impacts from vessels or aircraft in the high seas under their jurisdiction. This will be especially relevant for novel activities like removing plastic.

Once at least 60 states have ratified the agreement (this may take three years or more), it will be possible to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) in high sea locations of special value.

This could protect unique ecosystems like the Sargasso Sea: a refuge of floating seaweed bounded by ocean currents in the north Atlantic which offers breeding habitat for countless rare species. By restricting what can happen at these sites, MPAs can help marine life persevere against climate change, acidification, pollution and fishing.

There are obstacles to all nations participating in the shared enjoyment and protection of the high seas, even with this new treaty. Nations joining the new agreement will need to work with existing global organisations such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO), which regulates shipping, as well as regional fisheries management organisations.

The new treaty encourages consultation and cooperation with existing bodies, but states will need to balance their commitments with those made under other agreements. Already, some departments within governments work against each other when implementing broad, international treaties. For example, one division may chafe at greenhouse gas pollution regulations imposed at the IMO while a sister agency advocates for more stringent climate change measures elsewhere.

A New Research Frontier

A key element of the new treaty addresses the disproportionate ability of developed countries to benefit from the scientific knowledge and commercial products derived from genetic samples taken from the high seas. More than 40 years ago, when the law of the sea convention was being negotiated, the same issue arose over seabed minerals in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Industrialised nations had the technology to explore and intended to eventually mine these minerals, while developing countries did not. At that time, nations agreed that these resources were part of the “common heritage of humankind” and created the International Seabed Authority to manage a shared regime for exploiting them.

The extreme conditions for life in the open ocean have nurtured a rich diversity of survival strategies, from the bacteria that thrive in the extremely hot hydrothermal vents of the deep sea to icefish that breed in the intense cold of the Southern Ocean off Antarctica. These life forms carry potentially valuable information in their genes, known as marine genetic resources.

This new agreement provides developing states, whether coastal or landlocked, with rights to the benefits of marine genetic resources. It does not establish an administrative body comparable to that created for seabed mining, however. Instead, non-monetary benefits, such as access to samples and digital sequence information, will be shared and researchers from all countries will be able to study them for free.

Economic inequality between countries will still determine who can access these samples to a large extent, and sharing DNA sequencing data will be further complicated by the convention on biological diversity, another global treaty. The BBNJ agreement will establish a financial mechanism for sharing the monetary benefits of marine genetic resources, though experts involved in the negotiations are still parsing what it will eventually look like.

The best hope for robust marine protected areas and equitable use of marine genetic resources lies in rapid implementation of the BBNJ agreement. But making it effective will depend on how its provisions are interpreted in each country and what rules of procedure are established. In many ways, the hard work is beginning.

Although areas beyond national jurisdiction are remote for most people they generate the air you breathe, the food you eat and moderate the climate. Life exists throughout the ocean, from the surface to the seabed. Ensuring it benefits everyone living today, as well as future generations, will depend on this next phase of implementing the historic treaty.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Cymie Payne, Associate Professor of Human Ecology and Law, Rutgers University and Robert Blasiak, Research Fellow in Ocean Management, Stockholm University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

When is a nature reserve not a nature reserve? When it’s already been burned and logged

David Lindenmayer, Australian National University and Chris Taylor, Australian National UniversityAustralia has the world’s worst mammal extinction record, with nearly 40 native mammal species lost since European colonisation. By contrast, the United States has lost three.

Last year, the federal Labor government made a welcome commitment to stop further extinctions. One essential tool to do this is protecting habitat in dedicated conservation reserves.

Reserves can and do work – especially when well designed and then well managed. By some estimates, a quarter of the world’s bird species have been saved from extinction because of conservation reserves. Here too, the government is to be commended for plans to conserve 30% of the continent by 2030.

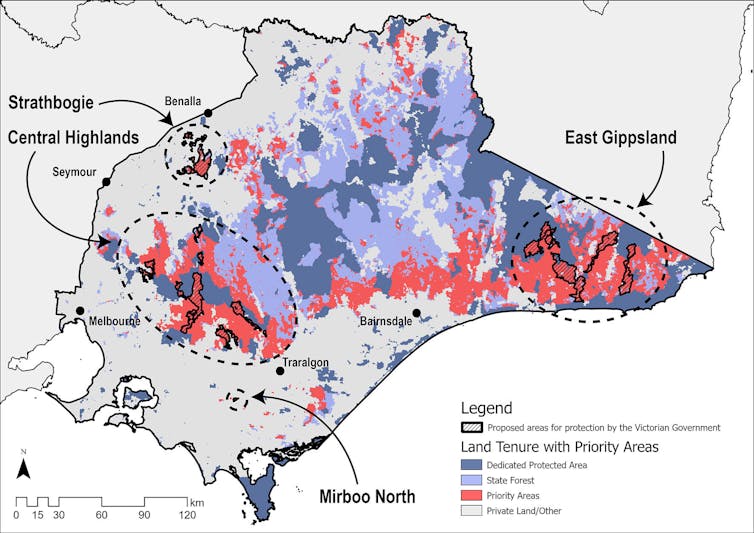

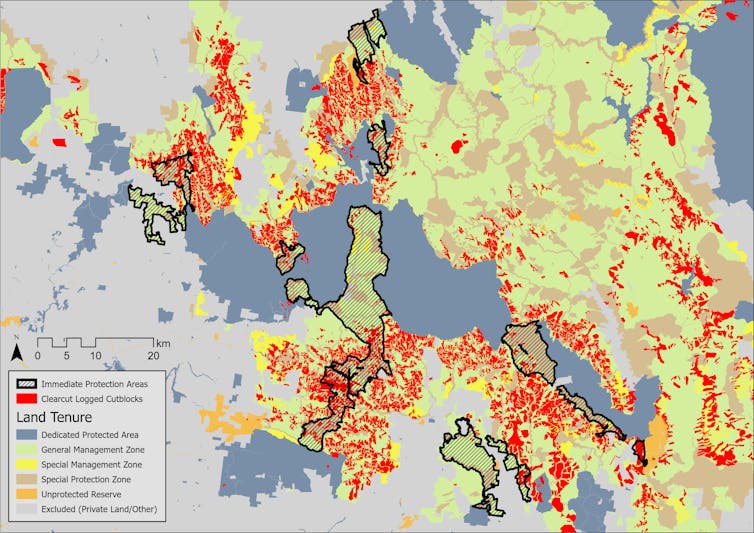

In light of this, we analysed Victoria’s newest conservation reserves - called Immediate Protection Areas - designed to conserve forest biodiversity in Victoria as the state prepares to phase out native forest logging by 2030.

We found Immediate Protection Areas didn’t do what they were supposed to do. The protected areas were small, and well short of the area needed to adequately conserve threatened species. Many Immediate Protection Areas were established in forests already burned, logged, or both, meaning their value as habitat was limited. Some areas even appeared to have been chosen because they were no longer needed for logging, rather than for their conservation value.

As we accelerate plans to protect more Australian habitat, we must watch for problems like this. Land with high conservation value must be prioritised for protection.

What Were These New Conservation Reserves Meant To Do?

Victoria’s state government has pledged to conserve biodiversity. This includes measures such as protecting the critically endangered Leadbeater’s Possum, ambitious investments to protect the Southern Greater Glider, and ending native forest logging by 2030.

As a prelude, the government established Immediate Protection Areas to better protect forest species from the impacts of logging.

We compared the known and mapped ranges of threatened species against the new conservation reserve areas. We wanted to see where 53 threatened species – including animals such as Leadbeater’s Possum and Southern Greater Glider – were most likely to occur. We also examined what had happened to these areas previously, to determine their habitat value. Had they been logged or burned?

The results were sobering. The Immediate Protection Areas, combined with Victoria’s existing set of formal conservation reserves, fell well short of adequately protecting remaining areas of habitat for 23 of the 53 species analysed, such as the Southern Greater Glider, Leadbeater’s Possum, and Barred Galaxias.

This wouldn’t matter so much if the forests outside Victoria’s existing parks and reserves weren’t under pressure from continued industrial-scale logging of native forests by the state-owned forestry business, VicForests.

But they are. And worse, areas of highest conservation value for threatened forest-dependent species, such as the Central Highlands north east of Melbourne, and East Gippsland in the far east of Victoria, will actually be targeted for logging under the Timber Release Plan.

These high conservation value areas are important because they provide critical habitat for rare and threatened species, including endemic species found nowhere else.

Even as native forest logging is supposedly winding down, a major conflict between logging and conservation remains.

VicForests is legally bound to supply 350,000 cubic metres of logs from native forests to industry until 2030. This is the same year the Victorian government intends to cease native forest logging in Victoria.

In 2020, VicForest’s senior legal counsel testified in court that VicForests would have to shut down all its operations in the Central Highlands if it couldn’t continue to log threatened species’ habitat.

This is at at odds with both federal and state governments’ commitment to stop extinctions. Logging the remaining high conservation value habitat is going to accelerate rather than prevent extinctions.

Protect All Remaining Habitat For Species On The Edge

An outsider might wonder why there has to be conflict. Aren’t there enough native forests to sustain seven more years of logging, especially now these Immediate Protection Areas have been established?

For many species, the answer is no. The number of sites occupied by species teetering on the edge of extinction, such as Leadbeater’s Possum, has fallen by half in the last 25 years. Logging is a major driver of its decline.

Protecting all Mountain and Alpine Ash forests where Leadbeater’s Possum occur should not be controversial. The federal government’s Threatened Species Scientific Committee declared in 2015 that the most effective way to prevent further decline and rebuild the possum population was to cease logging in Mountain Ash and Alpine Ash forests of the Central Highlands.

But this isn’t just a cautionary tale about logging in Victoria. Unless we’re careful, we’ll see the same story again and again.

Protecting 30% of Australian land by 2030, as the government intends, means rapidly protecting large areas of land. At present, around 20% of our land is protected in some way. Increasing this by half again in seven years is fast.

The danger is that governments will look for ways to rapidly boost the percentage of land area under protection without determining whether the land is effective for conservation.

As important as the size of the areas of land protected is what lives on it, and the ecosystem services it provides. To prevent extinctions in Australia, some ecosystems will need total protection of every fragment remaining, especially those under significant threat where key species are in marked decline. ![]()

David Lindenmayer, Professor, The Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University and Chris Taylor, Research Fellow, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Study Into Global Daily Air Pollution Shows Almost Nowhere On Earth Is Safe

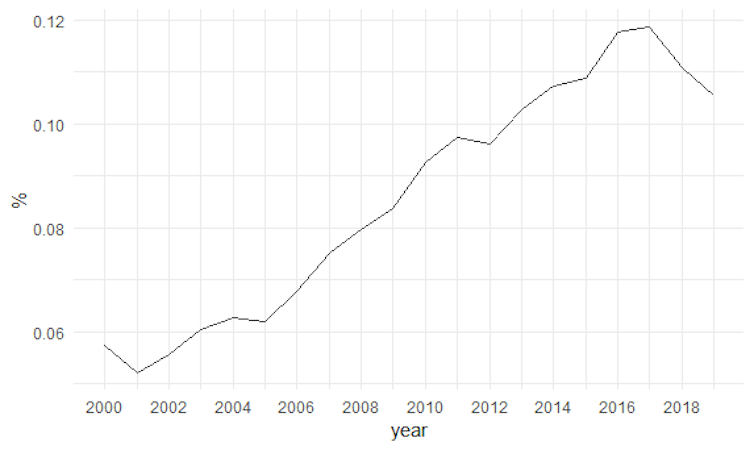

- Despite a slight decrease in high PM2.5 exposed days globally, by 2019 more than 70% of days still had PM2.5 concentrations higher than 15 μg/m³.

- In southern Asia and eastern Asia, more than 90% of days had daily PM2.5 concentrations higher than 15 μg/m³.

- Australia and New Zealand had a marked increase in the number of days with high PM2.5 concentrations in 2019.

- Globally, the annual average PM2.5 from 2000 to 2019 was 32.8 µg/m3.

- The highest PM2.5 concentrations were distributed in the regions of Eastern Asia (50.0 µg/m3) and Southern Asia (37.2 µg/m3), followed by northern Africa (30.1 µg/m3).

- Australia and New Zealand (8.5 μg/m³), other regions in Oceania (12.6 μg/m³), and southern America (15.6 μg/m³) had the lowest annual PM2.5 concentrations.

- Based on the new 2021 WHO guideline limit, only 0.18% of the global land area and 0.001% of the global population were exposed to an annual exposure lower than this guideline limit (annual average of 5 μg/m³) in 2019.

Drones Detect Moss Beds And Changes To Antarctica Climate

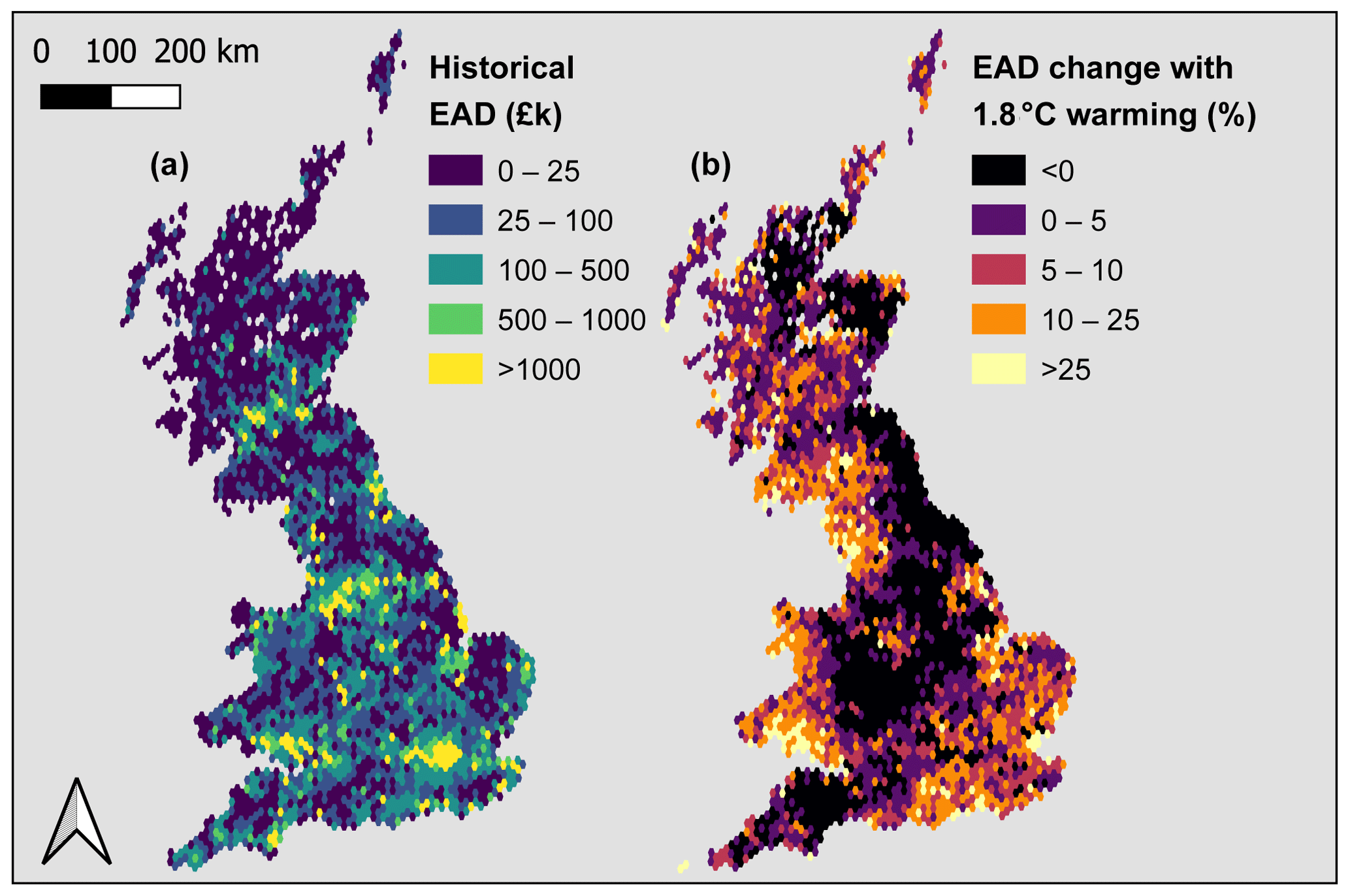

Pioneering Study Shows Flood Risks Can Still Be Considerably Reduced If All Global Promises To Cut Carbon Emissions Are Kept

Solar power can cut living costs, but it’s not an option for many people – they need better support

As the cost of living soars, many Australian households are turning to rooftop solar to cut their energy costs. A Pulse of the Nation survey last month showed about 29% of Australians have installed or are considering installing solar panels on their homes.

The same survey shows one in five Australians can’t afford to adequately heat or cool their homes. Many are also unable to install energy-saving options such as solar panels or insulation because of the upfront costs or because they are renters who cannot make changes to the dwelling. Among those who are financially stressed, earn less than A$50,000 or are between the ages of 18 and 34, a large majority do not intend to install energy-saving options, largely because they cannot afford them.

Renewable energy is not just critical for saving on energy bills, but also for mitigating climate change and fostering sustainable development. However, the reality is access to solar power is not equitable for all Australians. Our new research shows without better government support, many people will miss out on its benefits.

What Does Equity In Rooftop Solar Uptake Look Like?

Our research focuses on how to make access to rooftop solar more equitable.

It is important to distinguish between equity and equality. Equality means every household will be given the same resources or opportunities. For example, every household would receive the same subsidy to install solar panels.

Equity refers to fairness. The idea of equity recognises not all households start from the same place. Instead, adjustments to imbalances might be required.

In the context of solar adoption, equity would mean every Australian can benefit from solar power. Any subsidies or other support would be adjusted based on individual circumstances.

To better understand how it affects the adoption of solar panels, we looked at several aspects of inequity. These include financial situation, renting status, gender, education and ethnicity.

For our study, we collected 167 studies worldwide on household solar panel adoption to determine what we know about how it’s affected by these aspects of inequity.

Solar Power Equity Has Been Neglected

Our findings show there is very limited in-depth data and research on this issue in Australia. Australian studies on residential solar uptake account for 20 (12%) of the 167 studies.

Research in Australia tends to focus on equity related to income. Of the 20 Australian studies, six find a positive link between income and solar panel adoption, four find a negative link, five show inconclusive results and five omit income altogether.

These mixed results can be explained, in part, by the fact that a range of factors impact whether a household can afford solar power. For example, a somewhat higher household income does not automatically mean that a household has less bill stress and enough accumulated wealth to afford the upfront cost of installing solar power.

Few studies offer a deeper analysis of variables such as education or ethnicity. For Australia, only five studies looked at education and only one at ethnicity. There is a lack of data on solar uptake among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

This limited research does not allow for definite conclusions about how these variables impact rooftop solar uptake.

Energy-saving installations in investment properties have also received limited attention. Many Australian renters report their dwellings have extremely poor insulation. This leads to hot indoor temperatures in summer and cold conditions in winter.

Renters typically have limited ways to fix these problems. The only available options for many renters are air conditioning and portable heaters powered by traditional energy sources, which increases electricity bills.

What Policies Can Improve Solar Equity?

Policies that could improve equity in rooftop solar access include:

direct financial support for low-income households that otherwise could not afford solar power

a variety of other financial incentives such as solar rebates

community solar programs that allow households to share the benefits.

Some programs are in place to help home owners on low incomes to install solar systems. For example, New South Wales has a “Solar for low-income households” program. Eligible individuals can get a free 3-kilowatt solar system in return for giving up the Low-Income Household Rebate for ten years. South Australia had a “Switch for Solar” trial, for which applications closed on August 31 2022.

However, to access these schemes Australians must first overcome one difficult hurdle: home ownership.

In addition, a focus on income alone can be problematic. Directing subsidies to low-income households alone misses households with low wealth that are above an income threshold.

The Australian government has promised new policy approaches. Its Powering Australia Plan pledged $102.2 million for community solar banks. These are community-owned projects to improve access for those currently locked out of solar power. Households can lease or buy a plot in these solar banks, instead of using their own rooftops.

The success of such projects will depend on whether they are accessible to and affordable for everyone.

More data collection is needed to identify priorities for policy action on energy equity. This can include a new Household Energy Consumption Survey (the Australian Bureau of Statistics conducted such a survey until a decade ago), broader analysis by researchers to consider equity dimensions, and collaboration between researchers and policymakers to trial new policies.![]()

Martina Linnenluecke, Professor of Environmental Finance at UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney; Mauricio Marrone, Associate Professor, Department of Actuarial Studies and Business Analytics, Macquarie University, and Rohan Best, Senior Lecturer, Department of Economics, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

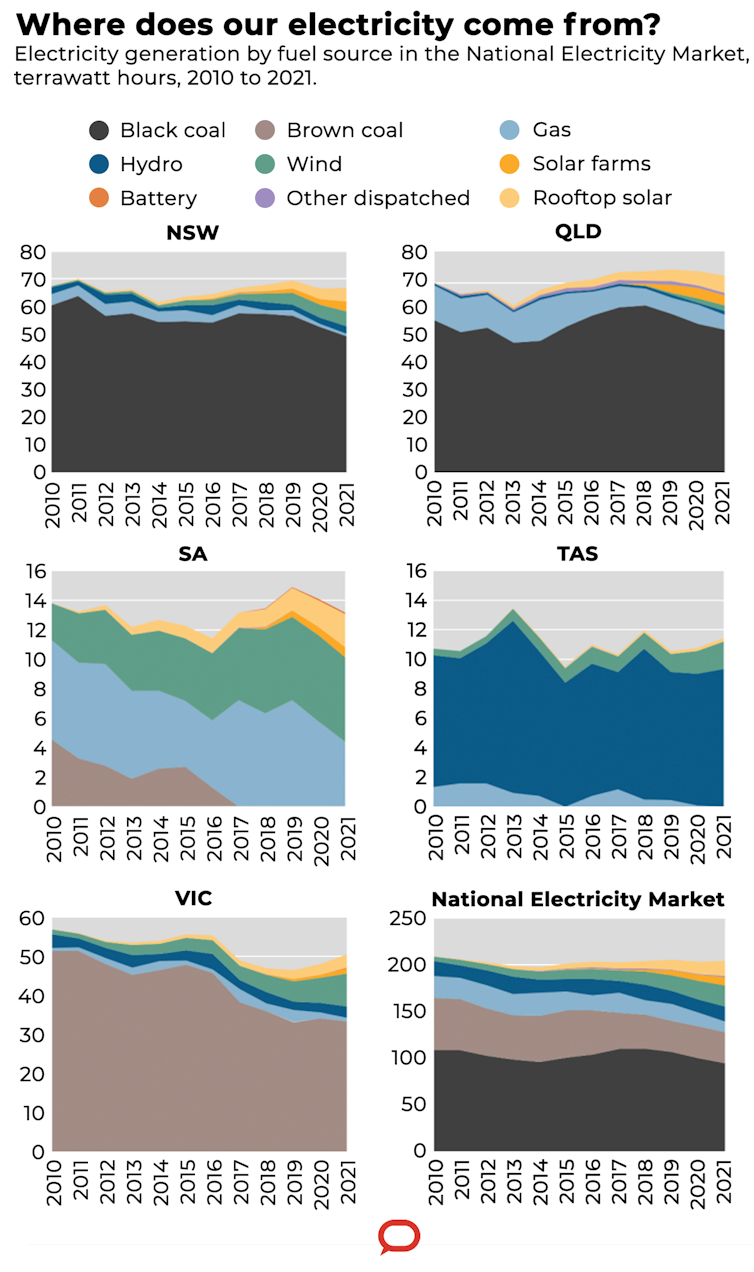

First look at the new settlement rule of Australia’s electricity market, has it worked?

You might not realise this when you flick your switch at home, but Australian electricity generators are forever locked in a bidding war. They compete for the right to supply electricity on the spot market. The cheapest bids win and electricity from those generators is supplied, or “dispatched”, to the grid in five-minute intervals.

This means that every five minutes, the electricity grid is rebalanced to ensure supply meets demand. Too little supply causes blackouts; too much causes tripping (and more blackouts).

But until recently, the price paid for wholesale electricity (the settlement price) on the Australian National Electricity Market (NEM) was averaged over six five-minute intervals (30 minutes). (Australia is unusual in this regard. Many grids elsewhere such as in Europe operate forward or day-ahead markets, where supply is planned in advance.)

That worked fine in the early days, but when supply started to fluctuate more wildly with the advent of intermittent renewable energy, so did the bidding war. Some generators starting gaming the system, pushing prices sky-high. Retailers complained.

So when the NEM finally introduced five-minute settlement in October 2021, it was a big deal. There was a great deal of excitement. Most commentators expected wholesale electricity prices to settle down, coal to lose market share, and batteries to boom. That’s mainly because the new system would be more efficient, rewarding cheap, nimble and flexible generators including batteries.

But what actually happened? Our analysis reveals the average spot price went up, not down, in Tasmania, Queensland, and New South Wales. Black coal-fired generators made more money on the spot market, not less. Flexible generators, especially batteries, did well too. (In the other NEM states, South Australia and Victoria, there was no significant change).

We argue further changes are needed to achieve the desired effects. These include increasing competition in the market (reducing the power of the three biggest electricity generators), building the infrastructure needed to support a green grid, and investing in more flexible and fuel-efficient technologies.

Greening The Grid

The NEM opened in 1998. The market adopted a 30-minute settlement rule at the time, because five-minute settlement would have pushed the limits of metering and data-processing capabilities.

But as the share of renewable energy grew, it became increasingly apparent that more flexible technology would be needed to cope with intermittent solar and wind power.

Problems included frequent price spikes, blackouts, power tripping, and “gaming” behaviours by major generators.

Energy retailers became frustrated by this gaming behaviour in particular, and complained to the authorities, prompting the rule change. Previously, coal and gas generators could send dispatch prices through the roof in one interval, so that when prices were averaged over the 30 minutes, it made the final trading price high. One way of doing this was to create artificial scarcity of supply, by withdrawing generation to raise spot prices.

When a price spike occurred, generators would then pile in by offering a lower price for the remainder of the 30-minute settlement period.

Five-minute settlement aimed to resolve these issues and better support the integration of wind and solar power into the electricity grid, ultimately making electricity more affordable for customers.

The new rule would also encourage investment in faster response technologies such as batteries.

Our study adds to the understanding of early effects of this regulatory change in the NEM. This will support the transition to clean energy generation, and inform policy for future electricity markets that offer stability, security and lower prices. We also propose courses of action to facilitate more effective adaptation to the rule change.

Did The New Rule Work?

The market had four years to prepare for the rule change, allowing generators to adjust their operations.

When five-minute settlement came in on October 1 2021, there was no substantial immediate effect.

However, within the first eight months of the change, the market started to adjust. We found that five-minute settlement led to an average spot price increase (not decrease) in Tasmania, Queensland and New South Wales.

That’s because generators no longer had a financial incentive to rebid at a very low price after a price spike, as they had done in a 30-minute trading interval. That was a strategy that caused significant fluctuation in the spot price.

Promisingly, the implementation of five-minute settlement had no measurable impact on the intensity of electricity price fluctuations. That suggests the new rule may have been effective in maintaining price stability.

So, in these early stages of the rule change, wholesale electricity customers are actually paying more, but the price has been more stable.

The impact on retail prices remains uncertain. The retailers’ costs of buying electricity and managing price risks are one component of what costumers pay in their energy bills. In 2020–21, it accounted for about a third of their bill. So if these effects persist, there is a possibility these higher prices will be passed on to consumers as well.

We also found that variable and flexible generators, especially batteries, took advantage of their flexibility to capture more revenue from the spot market. Gas generators’ revenue barely changed, but that could be because less flexible gas generators are lumped in together with highly flexible gas generators.

Surprisingly, the revenue earned by black coal-fired generators also increased. We suspect generators changed their operations and bidding strategies to align with the five-minute settlement rule. However, revenue for coal-fired generators is still likely to fall over the medium to long term.

Three Ways To Improve Five-Minute Settlement

It will take time to see the full effect of the rule change on the wholesale and retail electricity markets. However, we think the following changes are needed to fully realise the benefits of five-minute settlement:

Market concentration. The NEM is a concentrated market. The three largest generators, AGL Energy, Origin Energy and Energy Australia, hold a substantial market share. Together, they supply about 80% of the generated energy. Policies that promote competition are key to realising the benefits of five-minute settlement.

Supporting infrastructure. Five-minute settlement is expected to increase the operational cost of generating coal-fired power. That’s because ageing power plants would need to be upgraded to be able to compete during periods of fluctuating demand. Renewable generators, on the other hand, have extremely low operating costs, largely due to having no fuel costs. Coal-fired generators are likely to lose revenue and leave the market much earlier than expected. Firming and flexible demand technologies such as energy storage systems (pumped hydro, batteries or solar thermal) can effectively respond to the new market conditions and fill the gap.

Fuel-efficient and flexible technologies. Technologies such as batteries, pumped hydro and aero-derivative gas turbines operate more effectively in a five-minute settlement design. The recent rise in gas prices also necessitates investment in flexible and fuel-efficient technologies, such as reciprocating gas engines.

Without policies to address these three areas, we believe five-minute settlement is unlikely to offer substantial benefits to the market.![]()

Christina Nikitopoulos, Associate professor, Finance Discipline Group, University of Technology Sydney and Muthe Mwampashi, PhD Candidate, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Buildings used iron from sunken ships centuries ago. The use of recycled materials should be business as usual by now

At Fremantle Prison in the 1850s, when metal was scarce, the prison gate and handrails were made from iron recovered from sunken ships. As I toured the prison recently, I reflected on how similar the situation was when COVID-19 disrupted building supply chains across Australia. The shortage of materials such as steel, which is still an issue, turned heads to using recycled steel, which would otherwise be exported overseas for full recovery.

Do we really needed material shortages for the construction industry to get serious about using products with recycled content? When resources are depleted, does it only then mean it’s time to go sustainable?

It is encouraging to see many state initiatives to recycle construction materials, such as Roads to Reuse in Western Australia. It offers a $5 per tonne incentive to use recycled materials such as road base and drainage rock for construction projects.

Are such programs enough to ensure the supply of construction materials is sustainable? No, and if you look back at the examples of the past two centuries, industry-wide reuse of such materials should have been business as usual by now.

What Is The Next Step?

As awareness of waste recycling benefits has risen, recovery rates have improved. The National Waste Report 2022 shows Australia now has an 80% recovery rate for construction and demolition waste. That waste, 29 million tonnes of it, comprises 38% of all waste produced in Australia.

These recycled materials are becoming increasingly available to the market, but it isn’t being widely used.

The next challenge is to increase the use of these products across the construction sector. But how? That’s the focus of our recently completed research project.

Showcasing The Use Of Recycled Materials

We conducted four case studies in Victoria and Western Australia. The two states produce about 46% of Australia’s construction and demolition waste.

The case studies are Burwood Brickworks Shopping Centre and Mordialloc Freeway in Victoria and the Tonkin Gap Project and OneOneFive Hamilton Hill in WA. They comprise two road projects, a shopping centre and a housing development. One goal of these projects is to showcase the possibilities for using recycled materials in the construction industry.

Brickworks Shopping Centre was completed in 2019 and has won numerous awards for its demonstration of sustainability. The project achieved full accreditation under the rigorous criteria of the Living Building Challenge.

The large amounts of recycled materials used in the project include crushed concrete in a sub-base of bitumen, salvaged timber for ceiling cladding, and recycled brick for the floor and as a finish on the building façade.

The head contractor explained the use of recycled products for these architectural features:

The end user, who’s the consumer at Burwood Brickworks, they can see it and it’s front of mind that, hey, we can reuse these things.

The Mordialloc project created a 9km freeway link between Dingley Bypass and Mornington Peninsula Freeway. Dubbed “Australia’s greenest freeway”, it was completed in 2021.

The project saved more than 300,000 tonnes of waste from going to landfill (or 3 hectares of land would have been needed for stockpiling). It used 675 tonnes of plastic waste in noise walls and drainage pipes and 21,000 tonnes of reclaimed asphalt in pavements.

A member of the project’s design team said:

It was a good example of taking a design and […] looking at ways where you could improve it in terms of using recycled materials. So I know it’s got a tagline as Australia’s greenest freeway at the moment, but I’m sure it’s just setting a precedent now. And almost all, if not all, future road projects will incorporate an increasing amount of recycled materials in them.

The Tonkin Gap Project is upgrading the Tonkin Highway east of Perth with extra lanes, new interchanges, bridges and a shared cycling and walking path.

By July 2022, the project had used 430,000 tonnes of recycled materials including:

296,000 tonnes of sand

105,000 tonnes of treated spoil

27,000 tonnes of crushed recycled concrete

1,200 tonnes of reclaimed asphalt pavement.

A Main Roads WA representative said:

The culture comes down to a lot of experience. You need to make sure that there’s a positive experience using the [recycled] product, and make sure that there’s enough training and education and awareness that can be delivered to the industry on using the product and what they need to do to use it safely.

OneOneFive Hamilton Hill redeveloped an old high school and neighbouring lands (11.9 hectares) as a residential estate. It was one of DevelopmentWA’s Innovation Through Demonstration projects to showcase sustainability in the built environment. It was recognised as a sustainable project by the national EnviroDevelopment initiative.

Recycled materials in this project included:

salvaged timber in landscaping features such as shade structures and seating

40,000 clay bricks and roof tiles reused as aggregates under the drainage infrastructure

old bricks in brick walls and a toilet block

crushed brick, tiles and concrete in the road sub-base

2,425 cubic metres of recycled concrete in retaining walls

400 tonnes of other recycled products in various constructions including temporary access roads.

The project’s client representative said:

We want to be showing that we’re pushing the boundaries and trying to, I suppose, provide demonstration projects that show what can be done within a normal commercial environment.

What Are The Barriers And How Do We Overcome Them?

Case study participants said the major barriers to optimal industry use of recycled materials include:

unsupportive regulations

limited availability of quality recycled materials

lack of expertise and understanding of their applications

inconsistency in recycled materials quality and performance.

They said education, investigation and demonstration activities together with effective project management planning could help overcome these barriers.

We thank our collaborators in the research Professor Tim Ryley (Griffith University), Dr Savindi Caldera (University of Sunshine Coast), Associate Professor Atiq Zaman (Curtin University) and Professor Peter S.P. Wong (RMIT University).![]()

Salman Shooshtarian, Lecturer, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University and Tayyab Maqsood, Associate Dean and Head of of Project Management, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Let’s get real’: scientists discover a new way climate change threatens cold-blooded animals

All animals need energy to live. They use it to breathe, circulate blood, digest food and move. Young animals use energy to grow, and later in life, to reproduce.

Increased body temperature increases the rate at which an animal uses energy. Because cold-blooded animals rely on the thermal conditions of their environment to regulate their body temperature, they’re expected to need more energy as the planet warms.

However, our new research, published today in Nature Climate Change, suggests temperature is not the only environmental factor affecting the future energy needs of cold-blooded animals. How they interact with other species will also play a role.

Our findings suggest cold-blooded animals will need even more energy in a warmer world than previously thought. This may increase their extinction risk.

What We Already Know

The amount of energy animals use in a given amount of time is called their metabolic rate.

Metabolic rate is influenced by a variety of factors, including body size and activity levels. Larger animals have higher metabolic rates than smaller animals, and active animals have higher metabolic rates than inactive animals.

Metabolic rate also depends on body temperature. This is because temperature affects the rate at which the biochemical reactions involved in energy metabolism proceed. Generally, if an animal’s body temperature increases, its metabolic rate will accelerate exponentially.

Most animals alive today are cold-blooded, or “ectotherms”. Insects, worms, fish, crustaceans, amphibians and reptiles – basically all creatures except mammals and birds – are ectotherms.

As human-induced climate change raises global temperatures, the body temperatures of cold-blooded animals are also expected to rise.

Researchers say the metabolic rate of some land-based ectotherms may have already increased by between 3.5% and 12% due to climate warming that’s already occurred. But this prediction doesn’t account for the animals’ capacity to physiologically “acclimate” to warmer temperatures.

Acclimation refers to an animal’s ability to remodel its physiology to cope with a change in its environment.

But rarely can acclimation fully negate the effect of temperature on metabolic processes. For this reason, by the end of the century land-based ectotherms are still predicted to have metabolic rates about 20% to 30% higher than they are now.

Having a higher metabolic rate means that animals will need more food. This means they might starve if more food is not available, and leaves them less energy to find a mate and reproduce.

Our Research

Previous research attempts to understand the energetic costs of climate warming for ectotherms were limited in one important respect. They predominantly used animals studied in relatively simple laboratory environments where the only challenge they faced was a change in temperature.

However, animals face many other challenges in nature. This includes interacting with other species, such as competing for food and predator-prey relationships.

Even though species interact all the time in nature, we rarely study how this affects metabolic rates.

We wanted to examine how species interactions might alter predictions about the energetic costs of climate warming for cold-blooded animals. To do this, we turned to the fruit fly (from the genus Drosophila).

Fruit fly species lay their eggs in rotting plant material. The larvae that hatch from these eggs interact and compete for food.

Our study involved rearing fruit fly species alone or together at different temperatures. We found when two species of fruit fly larvae compete for food at warmer temperatures, they were more active as adults than adults that didn’t compete with other species as larvae. This means they also used more energy.

From this, we used modelling to deduce that species interactions at warmer global temperatures increase the future energy needs of fruit flies by between 3% and 16%.

These findings suggest previous studies have underestimated the energetic cost of climate warming for ectotherms. That means purely physiological approaches to understanding the consequences of climate change for cold-blooded animals are likely to be insufficient.

Let’s Get Real

Understanding the energy needs of animals is important for understanding how they’ll survive, reproduce and evolve in challenging environments.

In a warmer world, hotter ectotherms will need more energy to survive and reproduce. If there is not enough food to meet their bodies’ energy demands, their extinction risk may increase.

Clearly, we must more accurately predict how climate warming will threaten biodiversity. This means studying the responses of animals to temperature change under more realistic conditions.![]()

Lesley Alton, Research Fellow, Monash University and Vanessa Kellermann, Research fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Crocodiles are uniquely protected against fungal infections. This might one day help human medicine too

Over the millions of years crocodiles and their relatives have roamed our planet, they have evolved robust immune systems to help combat the potentially harmful microbes in the swamps and waterways they call home.

Our study, recently published in Nature Communications, takes a closer look at antimicrobial proteins called defensins, found in saltwater crocodiles. These proteins play a key role in the reptiles’ first line of defence against infectious disease.

As the threat of antibiotic-resistant microbes grows, so does our need for new and effective treatments. Could the defensins of these beasts hold the answers to help create a new wave of life-saving therapeutics?

What Are Defensins?

Defensins are small proteins produced by all plants and animals. In plants, defensins are usually made in the flowers and leaves, whereas animal defensins are made by white blood cells and in mucous membranes (for example in the lungs and intestines). Their role is to protect the host by killing infectious organisms.

Research into the defensins of different plant and animal species has found they can target a broad range of disease-causing pathogens. These include bacteria, fungi, viruses and even cancer cells.

The most common way defensins kill these pathogens is by attaching themselves to the outer membrane – the layer that holds the cell together. Once there, defensins create holes in the membrane, causing the cell contents to leak out, killing the cell in the process.

What’s Special About Crocodile Defensins?

Despite living in dirty water, crocodiles rarely develop infections even though they often get wounded while hunting and fighting for territory. This suggests crocodiles have a potent immune system. We wanted to better understand how their defensins have adapted over time to protect them in these harsh environments.

By searching through the genome of the saltwater crocodile, we found that one particular defensin, named CpoBD13, was effective at killing the fungus Candida albicans – the leading cause of human fungal infections worldwide. Although some plant and animal defensins have previously been shown to target Candida albicans, the mechanism behind CpoBD13’s antifungal activity is what makes it unique.

That’s because CpoBD13 can self-regulate its activity based on the pH of the surrounding environment. At neutral pH (for example, in the blood) the defensin is inactive. However, when it reaches a site of infection which has a lower, acidic pH, the defensin is activated and can help clear the infection. This is the first time this mechanism has been observed in a defensin.

Our team discovered this mechanism by revealing the structure of CpoBD13 using a process called X-ray crystallography. This involves “shooting” lab-grown protein crystals with high-powered X-rays, which we were able to do at the Australian Synchrotron.

Are Fungi Really A Threat To Human Health?

In comparison to bacterial and viral infections, fungal infections are often not seen as serious. After all, pandemics throughout human history have only ever been caused by the former. Indeed, fungi are most commonly known in the general public for causing athlete’s foot and toenail infections – hardly life-threating conditions.

But fungi can pose severe problems to human health, particularly in people with impaired immune systems. Globally, approximately 1.5 million deaths per year are attributed to fungal infections.

Our current arsenal of antifungals is limited to only a handful of drugs. Furthermore, we haven’t had a new class of antifungal treatments since the early 2000s. To make matters even worse, overuse of the antifungal medicines we do have has led to some drug-resistant fungal strains.

Rising global temperatures have also made once cooler regions more hospitable to pathogenic fungi. Climate change has even been linked with the emergence of new drug-resistant species, such as Candida auris.

A Long Way From Crocs To The Clinic

In the hunt for new medicines, our study and those like it are important for finding potential future antibiotics. By characterising the defensins of crocodiles, we have provided the groundwork needed to develop CpoBD13 into an effective antifungal. However, undertaking clinic trials is a long and costly process. From the initial discovery, it can take between five and 20 years to get a new drug approved.

Currently, protein-based treatments can sometimes unintentionally harm a person’s healthy cells. By using our knowledge of the crocodile’s defensins, we could potentially engineer other proteins to take on CpoBD13’s pH-sensing mechanism. Thus, they would only “turn on” upon reaching the infection.

Although there is much work to do before we see crocodile defensins in the clinic, we hope to one day harness the unique primal power of the crocodile’s immune system to aid in the global fight against infectious disease.![]()

Scott Williams, PhD Candidate in Biochemistry, La Trobe University and Mark Hulett, Professor and Head of Department, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How we discovered flamingos form cliques, just like humans

As social animals we have an innate understanding of the joy a good friendship can bring. So it’s unsurprising humans delight in seeing such closeness between animals. We can see ourselves reflected in the behaviour of cuddling chimpanzees, but a new wave of research is showing less relatable animals have pals too.

Our team’s new research found that while flamingos appear to live in a very different world to humans, they form cliques much like human ones. Like us, flamingos have a need to be social, are long lived (sometimes into their 80s) and form enduring friendships. Paul Rose’s previous work indicates captive flamingos are as picky about their friends as we are. They spend their time with preferred companions and depend on them for support during squabbles with rivals.

A flamingo’s inner circle can include their breeding partner plus several friends. Flamingos will form both platonic and maybe even sexual bonds with birds of the same sex and can form mixed sexed trios and quartets. These relationships can last for decades.

Wise humans know you can’t be friends with everyone. Paul was keen to learn why the flamingos formed friendships with some birds but not others. Animals choose their companions according to all sort of rules. Some of them do it by body length, for example guppies, others by age, such as in albatrosses. Personality impacts friend choice in many species such as chimpanzees (and, of course, humans).

Throughout his project studying long term flamingo friendships, Paul noticed flamingos living on Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT) reserves (and indeed those that live in zoos) formed cliques not unlike children in a playground. There were the popular kids, the bullies, the quiet ones in the corner… always the same birds and nearly always together. This provided a perfect opportunity to test if these personality cues might help explain how flamingos find their friendship groups.

Fionnuala McCully was recruited to address this question as part of her masters in animal behaviour. She set about documenting the dramatic lives of the Chilean and Caribbean flamingos housed at WWT Slimbridge in Gloucestershire, south-west England. Each bird carried a leg ring with a unique code, which she used to tell them apart and establish who was spending time with who. Working out these friendship groups took a lot of observation – four months to be exact.

By scrutinising the birds’ behaviour over the days and months, Fionnuala built a personality profile for every flamingo in each flock. Aggressive birds would often be spotted intimidating their flock mates, while submissive birds avoided conflict. Then, we used a technique called social network analysis to investigate the relationships within each flock, and whether personality could explain the friendships.

The answer was yes. The flamingos in both flocks tended to have friends who where similar in personality. In the Caribbean flock, the importance of personality ran deeper. Aggressive, outgoing birds had more friends compared to quieter flockmates. These confident cliques also spent more time in each other’s company than less outgoing groups. Caribbean flamingos were more willing to start fights and enter a fray to defend their friends. In contrast, there was no evidence to suggest outgoing Chilean flamingos had more friends, nor were they more willing to aid their buddies during rows. This shows that what is true for one species may not be true for the others, even when they are closely related. Caribbean and Chilean flamingos, for example, both have the same body structure and foraging behaviour.

Our work demonstrates how flamingos need space and time to choose and maintain their own friendships. When a flock is large enough for all different personality types to be represented, each flamingo has the opportunity to find a social partner of its liking. Keeping flamingos within the same flock across several breeding seasons helps them work out “who is who” and get better at forming compatible relationships once they have worked out the social dimensions of the group. Flamingo breeding is a numbers game - the more birds, the greater the chance of success. So understanding choosy flamingo friendships can help staff take good care of captive flamingos and manage populations.

As behaviour scientists, we are discouraged from comparing animals directly to humans as it can increase the risk of biasing our work with human values. But sometimes we can’t help ourselves. For example, the king and queen of the Caribbean flock were a particularly outgoing mated pair who Fionnuala affectionately nicknamed “the Beckhams”.

More and more studies are revealing the complexity of animals’ social lives, which makes it harder to ignore our reflections in research findings. Using human behaviour as a blueprint might give us valuable clues into what animals need to be happy. This is applied more easily to some species (such as primates) than others. However it is critical that science doesn’t neglect the social needs of animals simply because they are considered less “clever” or “relatable” than other species in the zoo. If humans require friendships to be happy, is it really such a great leap to think that flamingos might need the same?![]()

Fionnuala McCully, PhD candidate in behavioural ecology, University of Liverpool and Paul Rose, Lecturer, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

A Stroll Through Warriewood Wetlands by Joe Mills February 2023

A Walk Around The Cromer Side Of Narrabeen Lake by Joe Mills

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park