inbox and environment news: Issue 576

March 19 - 25 2023: Issue 576

Mona Vale Woolworths Front Entrance Gets Garden Upgrade: A Few Notes On The Site's History

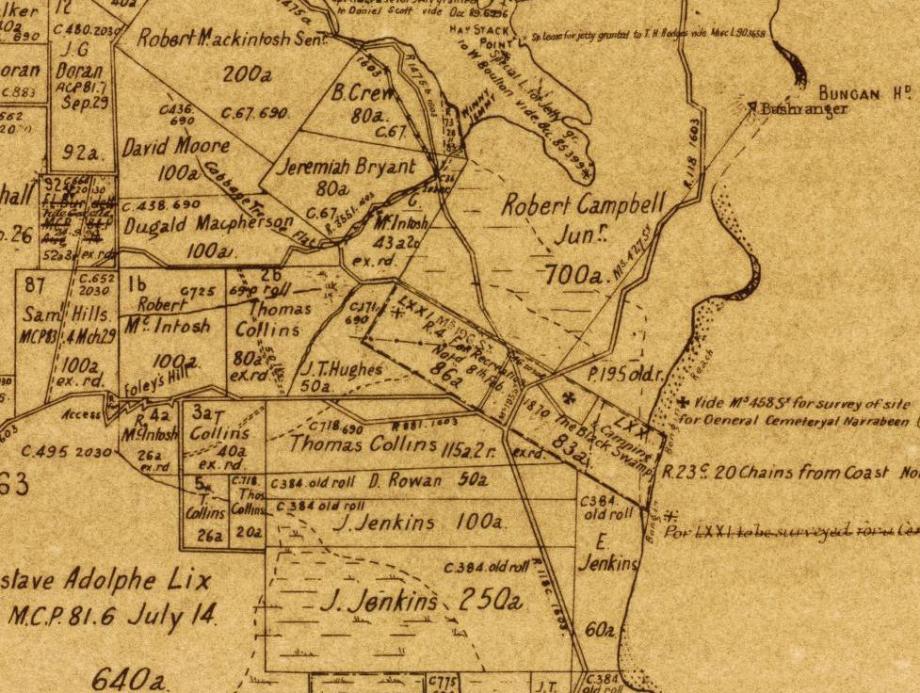

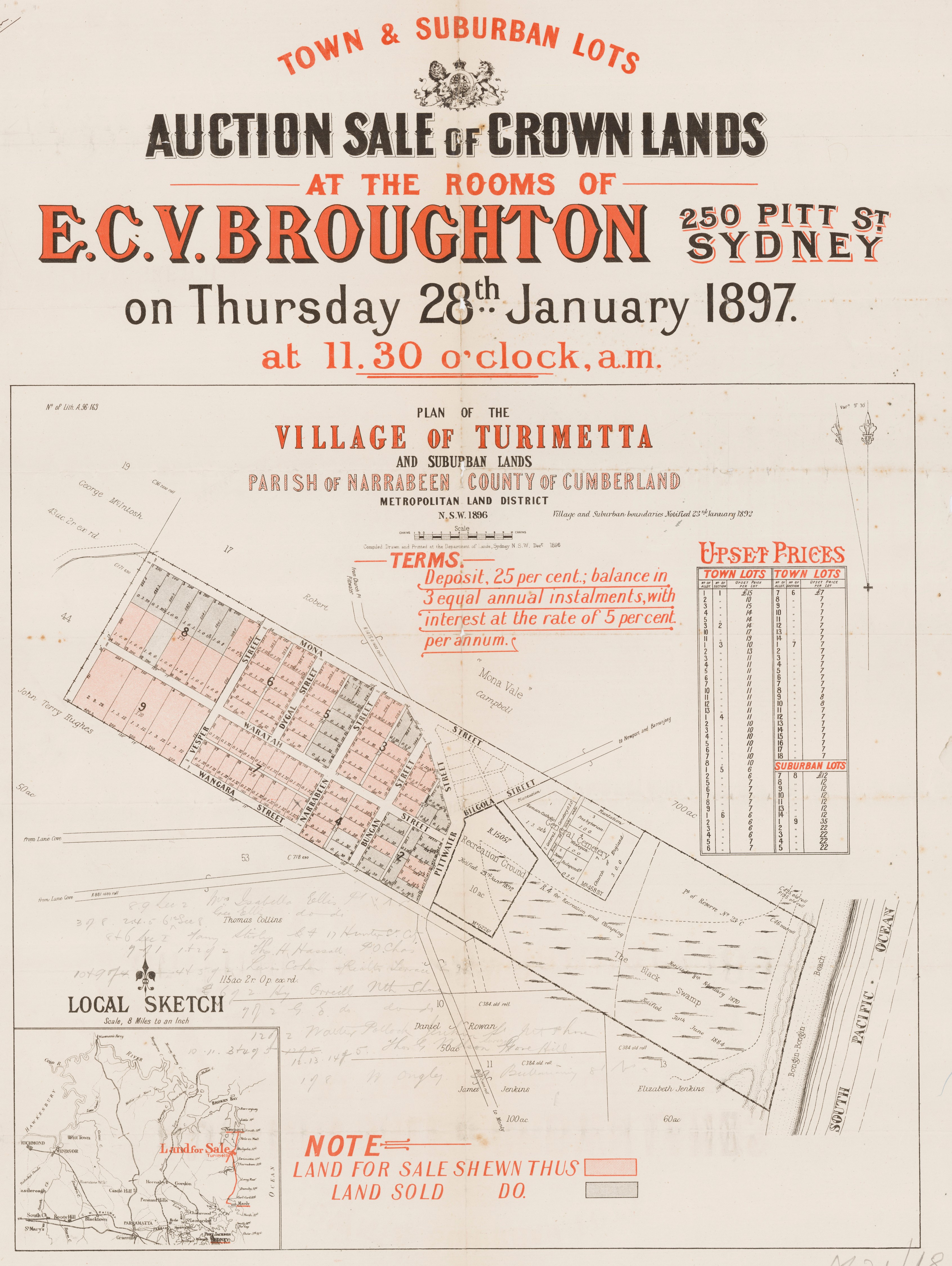

Parish of Narrabeen, County of Cumberland [cartographic material] : Metropolitan Land District, Eastern Division N.S.W. 1886. MAPG8971.G46 svar (Copy 1). Courtesy National Library of Australia

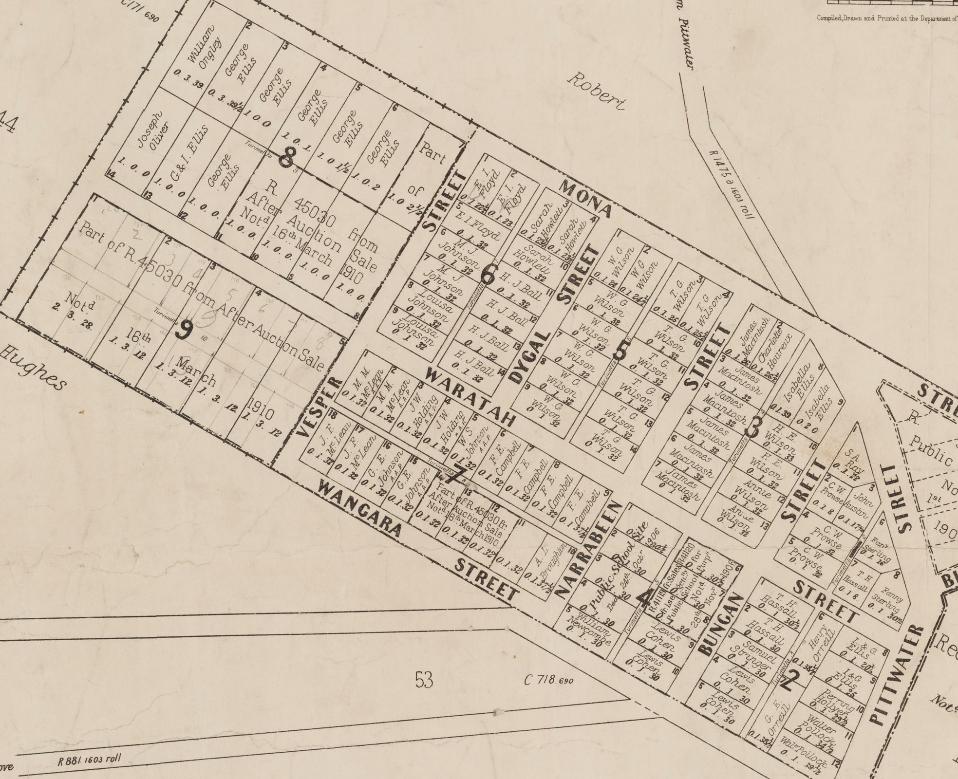

Prior to then an 1886 Land map indicates previous names for this 'Recreation Area' and that 86 acres and 83 acres were set aside on February 8th 1870 and it was envisioned people would go camping in a 'black swamp'. The water was black as there is peat under much of present day Mona Vale Golf Course. Creeks from the west, south west and south fed into the reserve to fill undulations in the landscape.

.jpg?timestamp=1679139660330)

.jpg?timestamp=1679139769220)

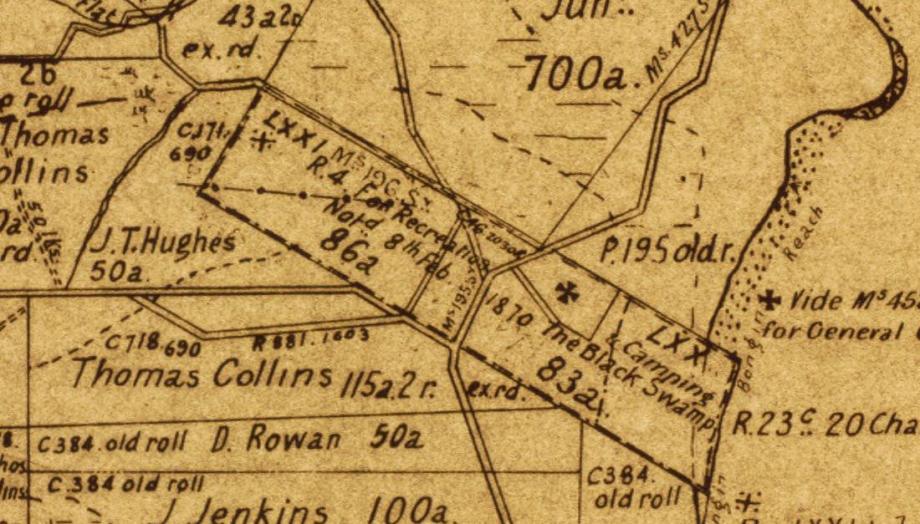

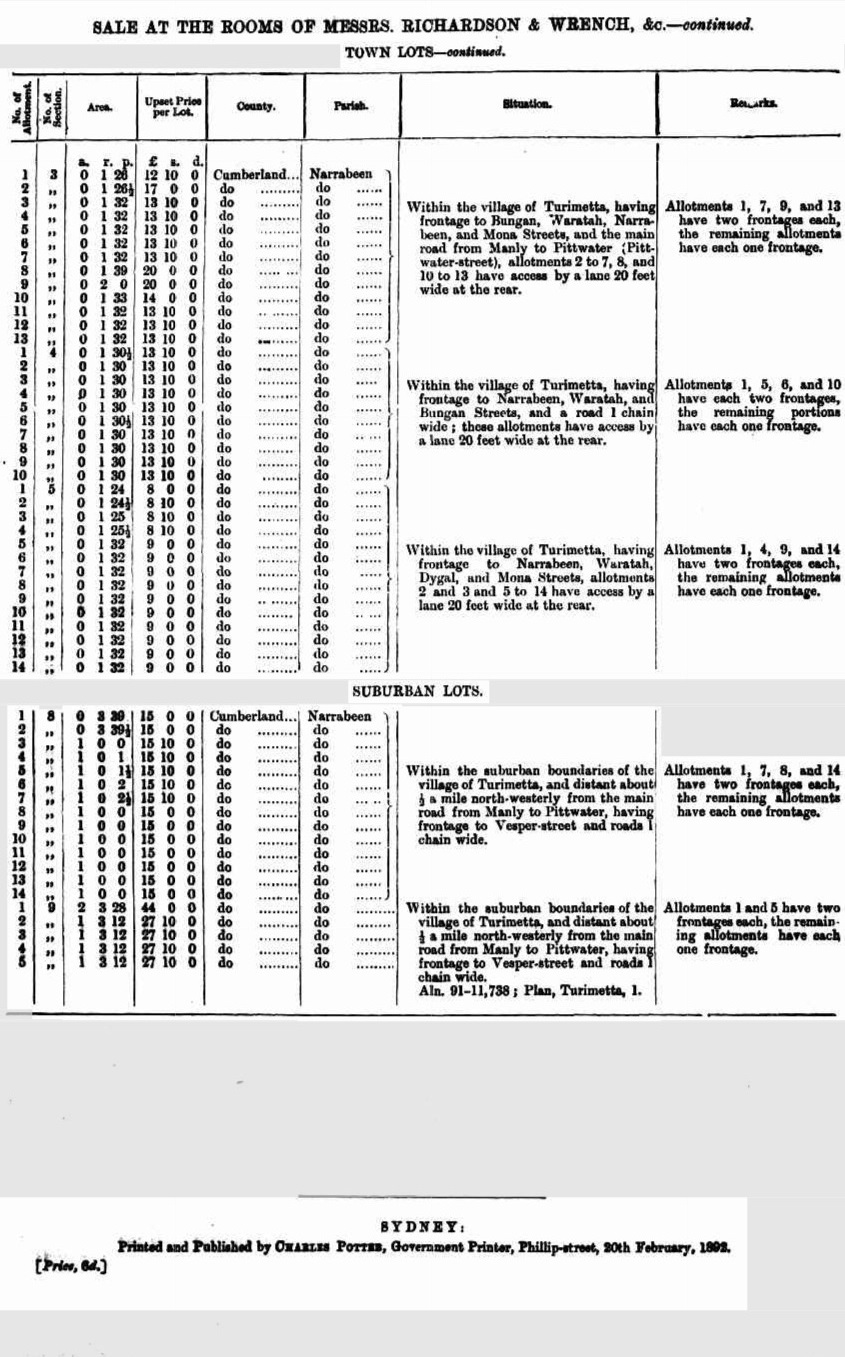

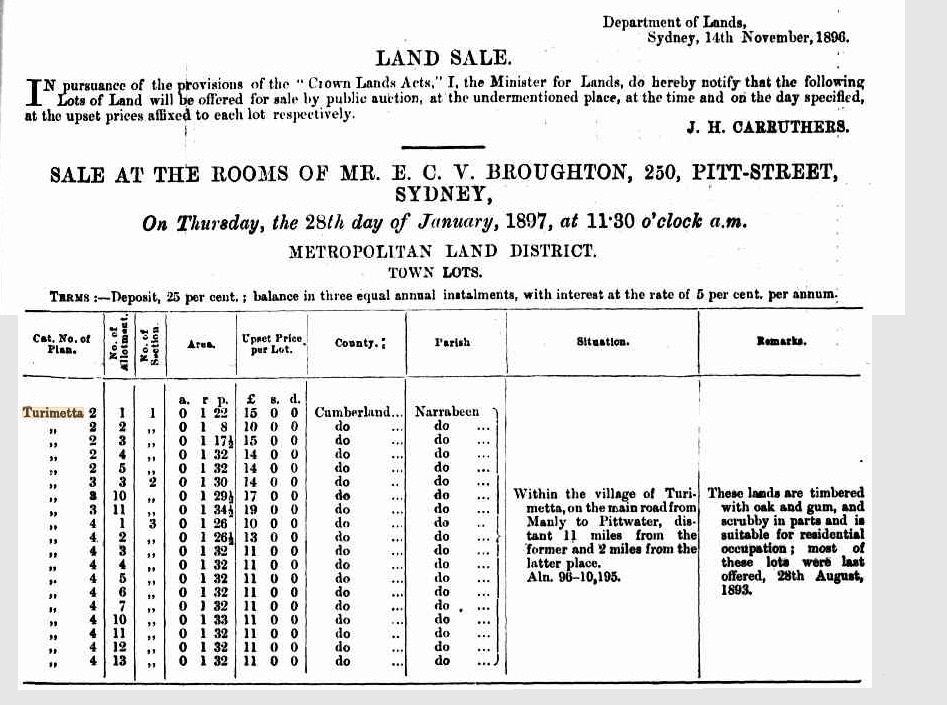

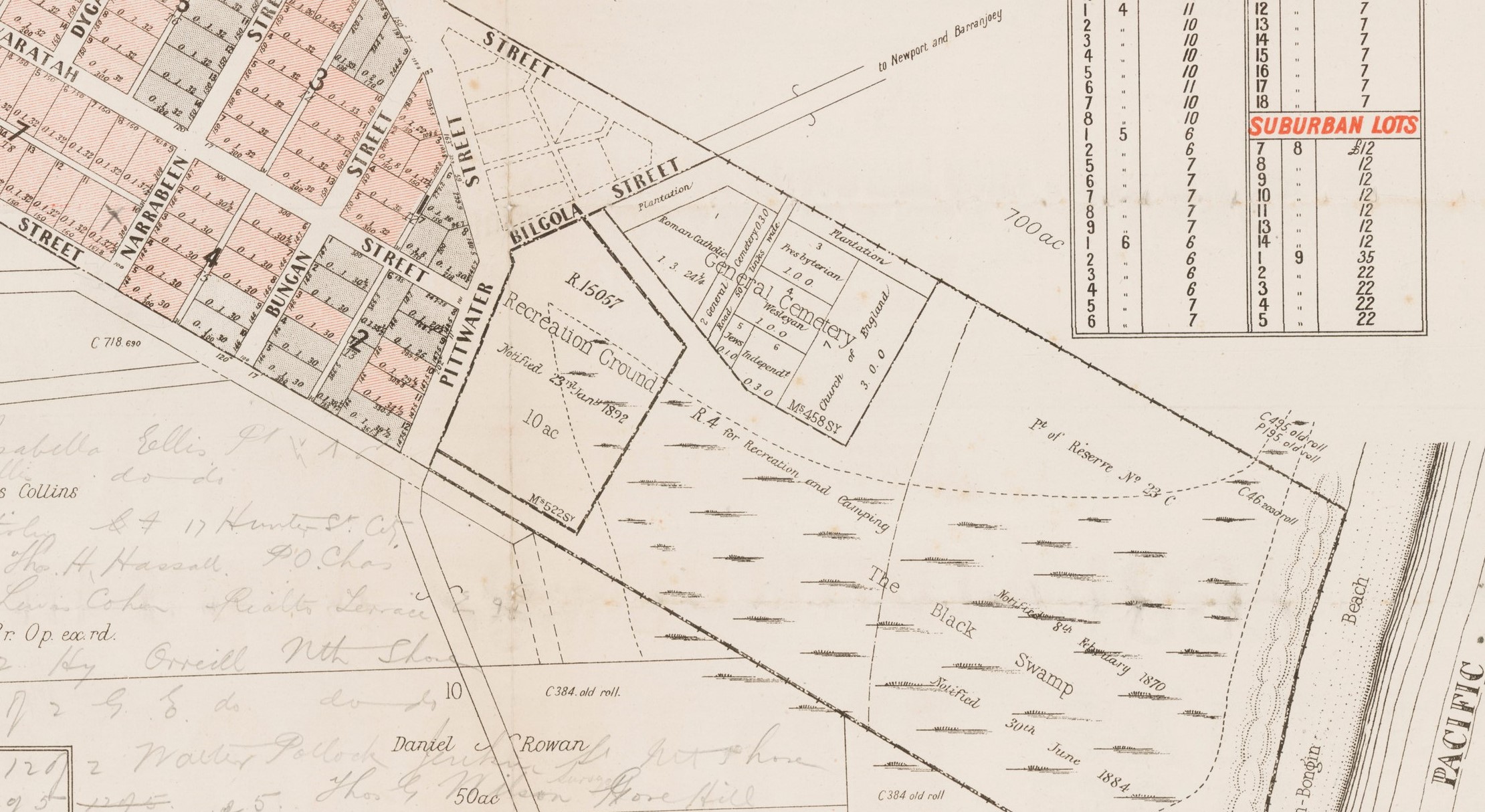

Plan of the Village of Turimetta and Suburban Lands - Parish of Narrabeen - Vesper St, Mona Street, Allen St, Pittwater St, Wangara St, 1897 “Village of Turimetta” with cemetery. Note the site of the farm known as “Mona Vale”, a name given to this place by early resident David Foley according to family records. Item c046820016, from Pittwater Subdivision records, courtesy State Library of NSW

Land sales:

Interesting to note that the now Woolworths land area were selling for £11 per Lot in 1897, cheaper than those down around current day Mona Vale Village Park where it would flood. One pound in 1897 equates to around $3 417.77 Australian dollars in 2023, or around $37,595.47 per Lot - a substantial increase but nowhere near what units built on single Lots of land are selling for in Mona Vale presently. All up Mr. Macintosh's 6 Lots would command $225,572.82 at that scale.

Further, an The Australian Jewish News report from 1999 tells us:

Compare this sale with that of the Woolworths supermarket in Mona Vale sold to a Sydney investor for $16 million on a yield of 6.25 per cent. Launceston sale at $5.85 m (1999, September 10). The Australian Jewish News (Melbourne, Vic. : 1935 - 1999), p. 9 (Property and Investment). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article260923135

Woolworths record sale

AMP Henderson Global Investments has just completed a record sale of the freestanding Woolworths supermarket in Queanbeyan NSW. The property was part of the GIO portfolio and was sold off-market by Burgess Rawson & Associates Pty Ltd to a private investor from Melbourne.

The supermarket sold for $13.35 million on a yield of 8.4%. This is the biggest sale in value terms in Australia, outside Melbourne and Sydney and ranks as the third largest sale ever (Safeway Fitzroy sold last year for $13.55 million and Mona Vale in Sydney for $16 million two years ago).

According to Chris Burgess who acted for AMP Henderson in negotiating the sale... "the reasons for the record price are twofold; the successful turnover growth of the store, particularly in the last 3 years has resulted in high annual rental by way of a flat 2%; the low interest rate environment together with the general economic uncertainty has increased the demand for supermarkets where a large proportion of turnover is non-discretionary - rather than discretionary or non-essential spending and therefore immune from an economic downturn "

The deal was negotiated off market to a private investor, however, there was considerable competition from the institutional market resulting in a price considerably above AMP's book value.

Located at 27 Antill Street, Queanbeyan, NSW the store has competition from a new Aldi and an existing Coles. The site area is 1.346 Ha and the store has a GLA of 4,133 m2 with 208 on-grade car spaces.

The 20-year lease expires on 22 March 2002 and Woolworths have taken up the second last of its two 5-year options. Woolworths pay all outgoings making the yield a true net return. Woolworths record sale (2002, February 8). The Australian Jewish News (Sydney, NSW : 1990 - 2008), p. 2 (Property Review Weekly). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article262899467

Narrabeen Creek Bird Gathering: Curious Juvenile Swamp Hen On Warriewood Boardwalk + Dusky Moorhens + Buff Banded Rails - Notes About Our Local Waterhens

Buff-banded Rail pair (Gallirallus philippensis) - Careel Creek, December 2012. Photos: AJG

In December 2012 a pair of Buff-banded Rails and a single tiny black fluffy black chick were spotted on Careel Creek. While at first unconcerned about the presence of the bird-watcher, alarmed peeps came from who is obviously the mum of the pair when the baby began stumbling and so a quiet retreat was in order while making soothing noises. These pictures were snapped quickly so as not to alarm the pair or baby.

The sight of these birds, kindly identified for us by Marita Macrae of PNHA, has not occurred outside of the Warriewood wetlands or the Royal Botanic Gardens for some time. Thus our chant; please keep your dogs on their leashes when walking through or beside the habitat of these ground dwelling beautiful birds - and remember that Warriewood is a WPA (Wildlife Preservation Area) where no dogs are allowed.

These birds live ere, people just visit these places.

Their nests are usually situated in dense grassy or reedy vegetation close to water, with a clutch size of 3-4. Seeing only one chick with this pair, and their alarm at being seen, indicates something may have killed the others.

A pair has since been seen closer to the bay at Careel Bay itself.

The Buff-banded Rail is a distinctively coloured, highly dispersive, medium-sized rail of the family Rallidae. This species comprises several subspecies found throughout much of Australasia and the south-west Pacific region, including the Philippines(where it is known as Tikling), New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand (where it is known as the Banded Rail or Moho-pereru in Māori)

They feed on snails, crabs, spiders, beetles and worms, feeding at dawn, dusk and after high tide. They can run at great speed but seldom take to flight.

Swamp Wallaby At Palm Beach

Urgent Action Needed To Avert Ecosystem Collapse Following Darling-Baaka Fish Kill: Greens

March 19, 2023

Cate Faehrmann, Greens MP and water spokesperson, is calling on the NSW and Federal Governments to take emergency action to remove the millions of dead fish from the river before they decompose and cause an ecological disaster.

Millions of fish have died and are currently choking the lower Darling-Baake river near Menindee, this situation is more severe than any of the large scale fish kill events that have occurred in recent times and represents an existential threat to the river’s health and community water security.

“This is categorically a catastrophe, regardless of whether this is a consequence of receding floods or water mismanagement, the NSW and Federal Governments should be acting now to clean up the millions of rotting fish which are spanning kilometres of the river,” said Cate Faehrmann

“We are experiencing a natural disaster in the Darling-Baaka river right now and government departments and agencies are ducking responsibility and writing this off as a natural event - that is utter nonsense and is doing nothing to help.

“Right now, every natural aspect of the river and the communities that rely on it for water are threatened with cascading collapse and these millions of fish that are rotting away are a harmful tragedy and will further degrade the system and quality of the water.

“The NSW and Federal Governments should be mobilising their considerable resources to avert the ecosystem harm that this fish kill will lead to. The State Emergency Service, the Army Reserve - whatever it takes to clean the Darling-Baaka needs to be happening right now. To suggest the scale is too difficult to deal with is unacceptable. We must get to work, like we would in any state emergency.

“While Dominic Perrottet is making Tik Toks in Sydney, the Murray Darling Basin is in a crisis of unprecedented proportions. Both levels of Government need to pull their fingers out and get these millions of dead fish out of the river before we are facing a compounding disaster that will reverberate along the entire river," said Cate Faehrmann

NSW DPI Fisheries released the following statement on Saturday March 18, 2023:

DPI is aware of a developing large-scale fish death event on the Lower Darling-Baaka below Menindee Main Weir through to Weir 32, adjacent to the Menindee township. It is estimated that millions of fish, predominantly Bony Herring (Bony Bream) have been affected, as well as smaller numbers of other large-bodied species such as Murray Cod, Golden Perch, Silver Perch and Carp.

This event is ongoing as a heatwave across western NSW continues to put further stress on a system that has experienced extreme conditions from wide-scale flooding.

NSW DPI understands that fish death events are distressing to the local community, particularly on the Lower Darling-Baaka.

The Bony Herring species typically booms and busts over time. It ‘booms’ in population numbers during flood times and can then experience significant mortalities or ‘busts’ when flows return to more normal levels. They can also be more susceptible to environmental stresses like low oxygen levels especially during extreme conditions such as increased temperatures currently being experienced in the area.

These fish deaths are related to low oxygen levels in the water (hypoxia) as flood waters recede. Significant volumes of fish including Carp and Bony Herring, nutrients and organic matter from the floodplain are being concentrated back into the river channel. The current hot weather in the region is also exacerbating hypoxia, as warmer water holds less oxygen than cold water, and fish have higher oxygen needs at warmer temperatures.

Multiple agencies across NSW and Commonwealth are continuing to work together on the response.

Community members are encouraged to report any fish deaths or observations through the Fishers Watch phoneline on 1800 043 536.

For more information on fish kills please visit: www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/habitat/threats/fish-kills

Not The First Time Millions Of Fish Have Died In This System

In January 2019, just before the state headed into one of the largest broad scale bushfire seasons in a generation, with fires commencing in July and culminating in the November to February 2020 disasters, NSW DPI were investigating another large fish kill at Menindee. The statement released then reads:

The NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) and WaterNSW are investigating a large fish kill at Menindee in Western NSW.

In recent weeks fish kills have occurred in the Namoi River below Keepit Dam, the Lachlan River at Wyangala Dam and also in the the Darling River at Menindee in a separate event in December.

DPI Senior Fisheries Manager, Anthony Townsend, said fisheries officers have visited the affected area downstream of Menindee today and are investigating the incident.

“The ongoing drought conditions across western NSW have resulted in fish kills in a number of waterways recently and today our fisheries officers have confirmed a major fish kill event in the Darling River at Menindee affecting hundreds of thousands of fish, including Golden Perch, Murray Cod and Bony Herring,” Mr Townsend said.

“After a very hot period, a sharp cool change hit the Menindee region over the weekend, with large temperature drops experienced.

“This sudden drop in temperature may have disrupted an existing algal bloom at Menindee, killing the algae and resulting in the depletion of dissolved oxygen.”

The incident follows an earlier fish kill in December, after intense rainfall events following hot weather, which disrupted algal blooms resulting in low dissolved oxygen levels conditions that exacerbated water quality for already stressed fish.

During the December event investigations by District Fisheries Officers from DPI revealed over 10,000 fish mortalities along a 40km stretch of the Darling River, including numerous Murray Cod, Golden Perch and Silver Perch, and native Bony Herring.

Mr Townsend said preliminary investigations by DPI into the current fish kill event suggest that hundreds of thousands of native fish have been impacted in the same stretch of waterway and further downstream.

“As a result of this incident, DPI will take this opportunity to learn more about our native fish to help improve their future management,” Mr Townsend said.

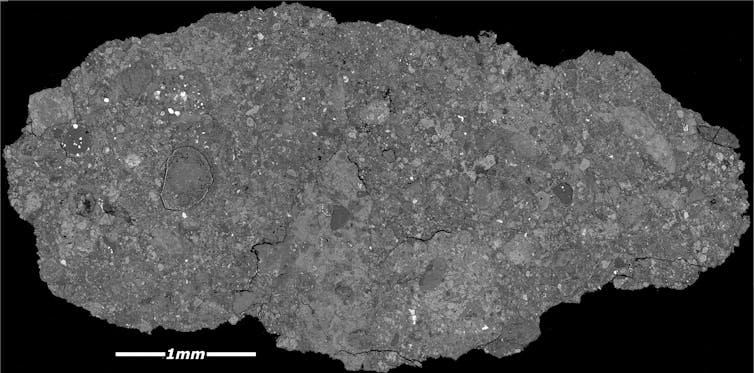

“Our fisheries experts are extracting otoliths (or the ear bone) from some of the Murray Cod killed during the event to improve our knowledge of the species.

“Otoliths allow us to work out how old a fish is and can be used to help establish age and length/weight relationships, as well as potentially unearth other secrets including where the fish was born and spent its life through microchemistry work.

“All of this new knowledge will help improve how we manage waterways and the fishery across the entire Murray-Darling Basin to help protect and improve native fish populations when conditions improve.

“Fisheries staff would like to thank local anglers and residents who have provided information.

“The current low flows and warming temperatures are likely to pose an ongoing threat to native fish throughout the summer.”

WaterNSW is continuing to monitor water quality throughout the dams and river systems.

Adrian Langdon, WaterNSW executive manager of systems operations said regional NSW is experiencing intense drought conditions, with the state’s Central West, Far West and North West regions the worst affected.

“Algal alerts have been in place for several weeks in the Menindee region and linked to this, low dissolved oxygen levels are likely to occur within slow flowing or no flow sections of the river,” Mr Langdon said.

“It is almost certain these impacts will persist and possibly increase further as summer proceeds if we don’t receive significant rainfall to generate replenishment flows.”

However, the locals, in a report run by The Land in January 2019 report, stated it was a disaster made by the MDBA and NSW Coalition government through over allocation of water from the river to a few. They were furious fish that were estimated to be around 100 years old were dead, furious this was being perpetuated and stated the policies of the then incumbent Federal and NSW State government were killing the river system, stating you could tell just by looking at the colour of the water that the rivers were ill.

An independent panel determined there were three main causes for the fish deaths in the Lower Darling in 2018 and 2019.

- not enough water flowing in the river

- poor water quality

- a sudden change in temperature.

The The Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) conducted an investigation which stated that between December 2018 and January 2019, three mass fish death events happened in the Lower Darling. Although this is often described as the Menindee Lakes fish kill, the events covered a 40km stretch of the Darling River, downstream of Menindee Lakes.

The exact number of fish deaths is unknown, but an independent panel chaired by Professor Rob Vertessy concluded that over a million fish may have died in the fish death events.

The main native fish that were affected were:

- bony herring

- Murray cod

- silver perch

- golden perch

The mass death events in the Lower Darling were caused by a combination of several factors, including:

- an extended period of very hot weather leading to layering of the water, with a layer of cooler water with very low oxygen levels near the bed of the river

- sudden temperature drop aided by other weather conditions caused this low oxygen water to mix depleting oxygen throughout the water below the threshold fish needed to breathe

- the lack of water flowing into the northern rivers due to low rainfall and high evaporation rates

- over-allocation of water resources in the Basin for many years.

When the Menindee lakes are full they are used by some native species as major 'nursery habitats' (areas which support young fish).

Heavy rainfall and flooding in 2012 and 2016 led to an increase in the numbers of fish living in the Barwon-Darling. By 2018, there were extremely high numbers of young and mature fish in the Menindee Lakes system and in the river.

However, from 2016 there were extended hot and dry weather conditions. The lack of water coming into the lakes (‘low inflows’) and reduced amounts of water being released from the lakes into the lower Darling River, resulted in poor water quality. By 2019 the remaining water in the Menindee Lakes and lower Darling River had dropped significantly and was of poor quality and so could not sustain high numbers of fish.

The Panel’s reports on the fish deaths are available here: www.mdba.gov.au/publications/mdba-reports/response-fish-deaths-lower-darling

In March 2019 Pittwater Online ran a new study out of the ANU which found billions of dollars are being wasted in water recovery subsidies to increase irrigation efficiency across the Murray-Darling Basin.

- An unprecedented breeding program, utilising government and private hatcheries, to ensure the long-term sustainability of the iconic Murray Cod and other native species, such as Trout Cod and Golden Perch;

- Artificial aeration, oxygenation and chemical treatments to support water quality and fish survival across river systems;

- Extra dedicated fish teams to conduct rescue operations during fish kill events ;

- A $4 million expansion of the Department of Primary Industries’ flagship Fisheries Hatchery and Research Centre in Narrandera, as well as other facilities, which will house many of the rescued fish; and

- The State’s largest restocking program in history of rescued and bred native fish once normal water conditions return.

- Environmental water. Inadequate protection of held environmental water especially in sub-catchments of the Upper Darling River. Current Water Sharing Plans on exhibition for public comment, as part of the Water Resource Plan consultation, have no rules to protect publicly owned environmental water from extraction.

- Drought of record. Water allocation decisions that are currently based on worst inflow records prior to 2004. This has resulted in over allocation of water resources in inland NSW causing water shortages in this current severe drought.

- Flood plain harvesting. The continued failure of government agencies to fully quantify and assess the environmental impact of floodplain water harvesting as part of the Healthy Floodplains Project.

- NSW SDL adjustment projects. The lack of substantial business cases for NSW Sustainable Diversion Limit adjustment mechanism projects (supply measure projects).

On the afternoon of February 3rd 2023 the NSW Government gazetted regulations to license floodplain harvesting after previous regulations were voted down for the 4th time by the NSW Legislative Council in September 2022. The timing meant the NSW Parliament would not have an opportunity to consider the regulations until after the NSW state election on 25 March.

The NSW Water Minister’s introduction of the floodplain harvesting regulations for a fifth time shortly before an election showed complete and utter contempt for the voters of NSW, Cate Faehrmann, Greens MP and water spokesperson, stated.

“This just shows complete contempt for the voters of NSW and for the traditional owners, downstream communities and farmers who have raised the alarm about these regulations for the entire last term of parliament,” says Ms Faehrmann.

“The National Party has effectively hamstrung the will of the parliament by introducing these regulations now knowing that we will have no opportunity to vote on them until well after the election.

“After each disallowance, I've called on the Water Minister to sit down and negotiate with the community instead of trying to shove the same laws down their throats again, but each time he’s done exactly that.

“These regulations are just about ensuring the National Party’s big irrigator mates in the north get handed $1 billion in water rights for free.

“We all want to see floodplain harvesting licensed, metered and measured, but it needs to be ecologically sustainable and within existing legal limits,” Cate Faehrmann said

Video posted on FB by Graeme McCrabb, who stated; ''Unbelievable!! Menindee NSW! 17/03/2023. Nearly all native dead fish. - Bonnie Bream, Golden perch, Silver Perch, Carp but not many.

Cat Owners Encouraged To Keep Their Pets Safe At Home

Wednesday, 1 March 2023

Northern Beaches residents are being encouraged to keep their pets safe at home as part of a new animal protection campaign.

According to RSPCA NSW, two out of three cat owners have lost a cat to a roaming-related accident, and one in three to a car accident. Northern Beaches Council is proud to be one of 11 councils partnering with RSPCA NSW as part of the Keeping Cats Safe at Home project.

Promoting responsible ownership, the new campaign goes beyond desexing and micro chipping of beloved cats and asks owners to consider keeping their cats at home.

Northern Beaches CEO Ray Brownlee said there’s a dual benefit to cats and local wildlife that flows directly from promoting responsible ownership of domesticated cats.

“Northern Beaches residents love their pets, but they’re also passionate about protecting the local environment,” Mr Brownlee said.

“Because pet cats occupy a special place in our hearts we need to educate the community on how have them microchip and desexed to keep them safe. This initiative has an educational focus. It aims to protect tiny native species like lizards, mammals, baby birds and frogs, while also preventing domesticated cats from falling prey to road accidents.”

In 2021, the NSW Government awarded a $2.5 million grant from the NSW Environmental Trust to RSPCA NSW to deliver the project.

To help promote the campaign, Council is asking cat-lovers living on the Northern Beaches to submit a photo of their cat or kitten living their best life at home and go in the draw to win one of 10 $1000 vouchers for a deluxe outdoor cat enclosure from Catnets. The competition opens on March 1st and closes on Sunday April 9th 2023. Finalists will be published in an online gallery.

For competition details visit www.northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au/environment/non-native-animals/cats/competition-keeping-cats-safe-home

Learn more about keeping cats safe at www.rspcansw.org.au/keeping-cats-safe

Photo: Greg Hume

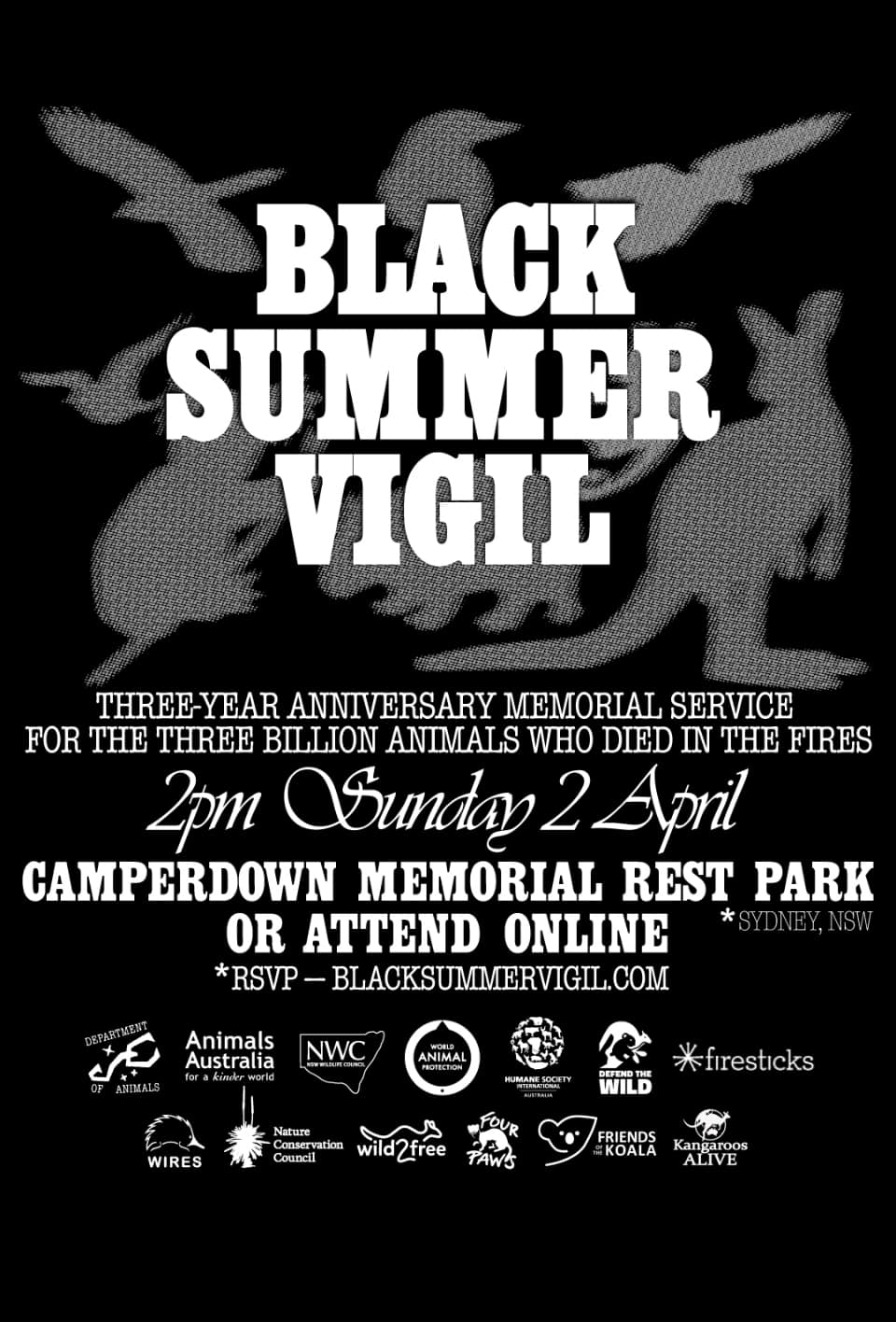

Black Summer Vigil For Wildlife: April 2nd

The New South Wales Wildlife Council invites all wildlife carers, wildlife vets, vet nurses, first responders and supporters to the upcoming Black Summer Vigil for Wildlife on Sunday April 2nd 2023 starting at 2pm.

Please join us for the Black Summer Vigil, a three-year anniversary memorial service for the three billion animals who lost their lives in the fires – “one of the worst wildlife disasters in modern history”.

Attend online or in-person at Camperdown Memorial Rest Park (Sydney).

RSVP at: blacksummervigil.com

You’ll hear personal stories from the NSW Wildlife Council, Southern Cross Wildlife Care and other first responders across wildlife rescue, rural fire service, photojournalism, Aboriginal custodianship, veterinary medicine, ecology and more.

+ Performance and Ceremony by Jannawi Dance Clan, sharing a Dharug cultural perspective to honour the Ancestors and bring the spirit of the animals into our midst.

Join us to honour the animals who perished – and in doing so, celebrate the unique and extraordinary wildlife of these lands.

Speakers include:

Greg Mullins, Former Commissioner, Fire and Rescue NSW; Climate Councillor and founder, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action. Greg warned Australia's then–Prime Minister in April 2019 that a bushfire catastrophe was coming. He pleaded for support and was ignored, then risked his life dealing with the ramifications on the ground. “You couldn’t see very far because of the orange smoke. Everything was dark. It was probably 2 o’clock in the afternoon but it was like night. Then I saw something moving on the side of the road and I walked closer. It was a mob of kangaroos. The speed of that fire with its pyroconvective storm driving it in every direction, they had nowhere to go. They came out of the forest, on fire, and dropped dead on the road. I’ve never seen that. Kangaroos know what to do in a fire. They’re fast animals. Climate change, driven by the burning of coal, oil, and gas is driving worsening bushfires across Australia, and putting our precious, irreplaceable wildlife in danger.”

Internationally recognised ecologist and WWF board member, Professor Christopher Dickman oversaw the work calculating the animal deaths from Black Summer. A Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science, Professor Dickman already wore the heavy task of being an ecologist during the sixth mass extinction, in the country that has the worst rate of mammalian extinction in the world. On 8 January 2020 media around the world shared his finding that Black Summer fires had killed one billion animals. Sadly, the fires continued for two more months, and his team's final count was three billion. This does not include invertebrates: it is estimated 240 trillion beetles, moths, spiders, yabbies and other invertebrates died in the fires.

Coming up from the South Coast, owner of Wild2Free Kangaroo Sanctuary Rae Harvey, as seen in The Bond and The Fire. She is in the sad position of having personally known and cared for a number of Black Summer's victims: many of the orphaned joeys she cared for were killed in the fires. (She nearly died herself too.) For three years, she has been unable to even speak their names. Now, for the first time, she will tell the story of the joeys she lost.

Cultural burning practitioner and Southern NSW Regional Coordinator with Firesticks Alliance, Djiringanj-Yuin Custodian Dan Morgan. Dan practises using Aboriginal knowledge to heal Country. He has worked for 18 years with the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and is on the board of management for the Biamanga National Park, a sacred area home to the last surviving koalas on the NSW south coast – which was partly destroyed by the fires of Black Summer. “The animals that live on our sacred sites are our Ancestors, it's our Cultural obligation to protect them. We have evolved with our Country over thousands of years, nourishing and protecting all living species. Our Country represents our people. So when the fires came, it was devastating to see the aftermath, and the feeling of helplessness was truly traumatising for our people, due to the denial of our Cultural right to manage Country as our Ancestors did for thousands of years prior to colonisation. Australia needs to make legislative changes that allow us to heal Country and our community through the fire knowledge and to stop incinerating ecosystems with destructive 'hazard-reduction' burns."

Head of Programs & Disaster Response at Humane Society International (HSI), Evan Quartermain was one of the first responders on Kangaroo Island where nearly 40% of the island burnt at high severity: “Those were some of the toughest scenes I’d ever witnessed as an animal rescuer: the bodies of charred animals as far as the eye can see. Every time we found an animal alive it felt like a miracle.” As a result of this firsthand experience, HSI commissioned a report into the state of Australia's disaster response for wildlife, which we'll also hear about.

+ More to come.

The Black Summer Vigil is brought to you by the Department of Animals, Animals Australia, the NSW Wildlife Council, World Animal Protection, Humane Society International and Defend the Wild, with support from WIRES, Firesticks Alliance, Nature Conservation Council of NSW, Wild2Free Kangaroo Rescue, Four Paws, Friends of the Koala and Kangaroos Alive.

Permaculture Northern Beaches - Upcoming Events

- Learn about Permaculture design

- Caring for and raising chickens

- Native bees and bee hotels

- Living Skills - soap making

- AND Live Music!

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Weed Of The Week: Cassia - Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Federal Government States It Is Using Every Tool In The Box To Conserve More Of Our Iconic Landscapes; Invites Feedback On Framework

- A geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed

- in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in-situ conservation

- of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable,

- cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values.

Thousands of our native plants have no public photographs available. Here’s why that matters

For hundreds of years, botanists have collected plants to describe species and keep in herbaria across the world. But while physical plant specimens are irreplaceable, photographs of plants are also an invaluable resource for botanical research, conservation and education.

Photographs of plants capture information that can be lost from dead, dried plants, such as flower colour. They also provide ecological context and form the cornerstone of many field guides and education resources.

All plant species known to science have samples preserved in at least one herbarium. Under the scientific rules for naming species, a species is not recognised unless there is at least one specimen officially stored in a collection somewhere in the world.

Unfortunately, and perhaps surprisingly, many plants have never been photographed in the field. Just 53% of the 125,000 known plant species in the Americas have field photographs in major online databases.

Given almost 40% of the world’s plant species are threatened with extinction, there’s a strong impetus to photograph as many of these as possible before they disappear forever. Without photographs of these species in the field, many could go extinct without us even realising.

How Does Australia Compare?

We were interested in how the Australian flora stacks up, so in our research, published today, we surveyed 33 major online databases. Most of these were resources created and maintained by professional botanists, such as New South Wales’ state herbarium portal PlantNET, but we also included some citizen science platforms such as iNaturalist.

Out of roughly 21,000 native Australian vascular plant species, a surprisingly large 3,715 (or 18%) did not have a single field photograph we could track down across our surveyed databases.

While most species across the southeastern states are well-photographed, Western Australia is the great frontier for unphotographed plants: 52% of all unphotographed species can be found in WA. The most incomplete plant family was Poaceae, the grasses, with 343 unphotographed species.

We identified three major “hotspots” for unphotographed Australian plants:

northern Australia, from the Kimberley to Arnhem Land

Queensland’s Wet Tropics World Heritage Area

the Stirling Range and Fitzgerald River National Park in southwestern WA.

All three regions are characterised by remote environments that are often difficult to access.

Just as some animals receive less research and conservation attention than others because they aren’t as charismatic, there is also a similar charisma deficit for some types of plants. Many groups of Australian shrubs or trees with spectacular floral displays have comprehensive, or even complete, photographic records. For example, all 176 of Australia’s Banksia species have been photographed.

Conversely, small herbs, plants with tiny or dull flowers, or groups such as grasses or sedges tend to miss out on being photographed – some of them for a very long time indeed. Schoenus lanatus, for example, is a small sedge that grows across a vast stretch of coastal WA, from Perth all the way to the South Australian border. It was described in 1805 yet, more than two centuries later, it is still unphotographed in the field!

Although botanists and taxonomists take many photographs of plants, citizen scientists also have a crucial role to play in the documentation of our native flora, with organisations such as Desert Discovery at the forefront. During last year’s expedition to Yeo Lake Nature Reserve at the remote western edge of the Great Victoria Desert, the Desert Discovery team photographed hundreds of native plants, including five species on our unphotographed list.

One example is the daisy bush Olearia eremaea, which is only found in WA’s arid interior. First described in 1990 and illustrated with black-and-white line drawings, it was not until more than 30 years later that this species was first photographed, at Yeo Lake, a remote nature reserve roughly 200km northeast of Laverton.

Of course, some of the species on our unphotographed list have in fact been photographed, but the images are not available in any of the 33 major databases we surveyed. These photographs may be slides in someone’s desk drawer or hard drive somewhere, appear in possibly out-of-print field guides and books, be behind paywalls in the scientific literature, or are not currently identified due to a lack of other comparison photos. This lack of discoverability is a problem, because these photos are very unlikely to be found by someone in the field trying to identify the species.

We have produced a searchable list of Australian native plants lacking photographs. We hope this work stimulates both professional and citizen scientists to track down these species and add photographs to public, discoverable repositories such as iNaturalist.

But be warned: these aren’t easy treasure hunts. These species are a mix of very remote and often overlooked species – they are typically not famous or eyecatching. Finding them will take determination, botanical know-how, and a sturdy off-road vehicle.

But the pay-off would be well worth it – successful pictures would make their way into identification guides, allowing both citizen and professional scientists to identify, monitor and conserve these species into the future.![]()

Thomas Mesaglio, PhD candidate, UNSW Sydney; Hervé Sauquet, Senior Research Scientist, Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney and Adjunct Associate Professor, UNSW Sydney, and Will Cornwell, Associate Professor in Ecology and Evolution, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

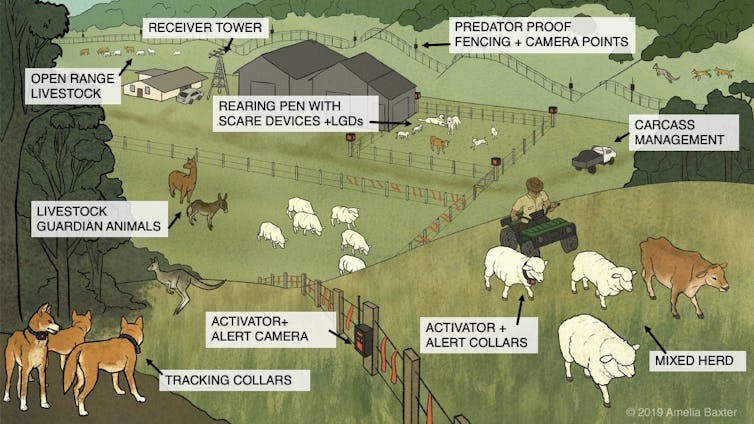

Cultural burning is safer for koalas and better for people too

Koalas are an iconic endangered species living in a fire-prone environment. This makes them an ideal subject when investigating solutions to wildfires.

We explored how koalas fared before and after cultural burns on Minjerribah island (also known as North Stradbroke Island), near Brisbane on Quandamooka Country.

We used heat-seeking drones to assess population density and collected koala droppings to check hormone levels. We found cultural burns had no detectable effect on these parameters.

The project also found the benefits of cultural burns extended far beyond landscape management. We hope this research further highlights the practice of cultural burning as a strategy to help us manage the risk of wildfire in a warming world.

Menacing Megafires

The Australian Black Summer bushfires shocked the world. But nothing brought home the terrifying ferocity of the megafires - and our vulnerability to them - more than scenes of dead, dying or distressed koalas in an apocalyptic landscape.

Unfortunately, there’s overwhelming evidence that megafires are part of the new normal. Climate change will continue to create the exceptionally dry fuel loads and dangerous fire weather that lead to catastrophic events. So we need to find ways to minimise the damage.

Ancestral practices of cultural burning hold great promise all over the world. The California Fire Science Consortium says fire fuel control, such as that derived from cultural burning, can limit the severity of future wildfires.

Minjerribah is a haven for wildlife. Half of the land is already national park and there are plans to increase the protected area.

Cultural burns have been a significant part of Minjerribah’s history. However, in recent times, large and intense fires have swept across the island, causing considerable damage to property, ecosystems and cultural resources. A megafire on Minjerribah in January 2014 burned more than 70% of the island - the largest fire in memory there.

Living On The Edge

There is scant research on wildfires and koalas. That’s largely because wildfires are dangerous and unpredictable, making them difficult to study. And when monitored koalas happen to be in the path of a wildfire, researchers tend to try to save them.

Koalas are particularly vulnerable, suffering long after the fire has passed. They have limited energy reserves and require continuous access to food.

That’s a problem when trees lose their edible leaves. These trees typically require months to produce enough new foliage. After a fire, koalas are also vulnerable to overheating, because they rely on shade and cooling from healthy trees with thick canopies to regulate their body temperature.

The koalas on Minjerribah are virtually disease-free, making this a rare and precious population in southeast Queensland. Wildfires pose the greatest threat to their survival, according to the Quandamooka Native Title rights administrators, Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation (QYAC). It is hoped restoring cultural fire practices will reduce the occurrence of large bushfires.

Cultural Burning On Quandamooka Country

If cultural burning was a person, one might describe her as patient, slow-moving, calm and quiet. A cultural burn will snake slowly through a site, missing some patches. This creates a burn mosaic.

The fire is not too hot and does not burn high into the tree canopy.

Use of fire in the landscape varied across Australia, between different First Nations groups. Uses for fire can include: fuel and hazard reduction, regeneration of habitat, generation of and management of particular sources of food, fibre and medicines, facilitation of access and movement, protection of cultural and natural assets, or healing Country’s spirit.

Quandamooka people have the oldest published archaeological occupation site on the east coast of Australia. Their use of fire is a deliberate and integral part of caring for Country. That includes burning and prevention of burning.

As leaders and practitioners of cultural burns on Minjerribah, the Quandamooka people wanted to establish standard practices for wildlife management during burning – specifically, whether thermal imaging drones could establish where koalas and other animals are present in areas to be burnt. This could inform actions to reduce risk.

Studying Koalas And Cultural Burning

Koalas are difficult to study, as they are exceptionally good at hiding. That has prompted researchers to find more innovative survey methods.

We used heat-seeking drones to establish koala density, and koala droppings to study their hormone levels. We established a baseline of both measures through repeat surveys prior to the burns.

We also compared sites with and without cultural burns, accounting for seasonal variations that are not due to the burns. We found cultural burns had no detectable impact on either koala density, or hormone levels.

Multiple Benefits Of More Feet On Country

A perfect cultural burn is lit the right way, at the right place and time of year. Some years, only some places can be burnt, based on the fire interval and soil moisture levels. This requires local knowledge and constant observation all year round, not just during a single pre-burn site visit.

Having people on Country throughout the year also improves social connections between generations, and protects stories and sacred sites on Country. Other benefits include:

- employment

- reducing the risk of megafires

- supporting low-carbon economies

- improving biodiversity

- increasing water protection

- improving forest resilience and adaptation to climate change

- reducing air pollution

- fostering reconciliation.

Of course, this needs to be financially supported and done right – following the guiding principles of Responsibility, Respect and Recognition. It’s crucial that First Nations people of the specific land are involved. The process should also be embedded within contemporary natural resource management and supported by government agencies.

Teamwork Vital To Success

As the world warms, we must become increasingly resilient and work together to find solutions. We can draw on past successes as we shape new and better ways of managing landscapes.

Compassion will play an important role, including the need to listen and respect all contributions even as the world around us is increasingly stressful, so we can create a better future for all.![]()

Romane H. Cristescu, Researcher in Koala, Detection Dogs, Conservation Genetics and Ecology, University of the Sunshine Coast; Darren Burns, Community Land & Sea manager at Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation, Indigenous Knowledge, and Kye McDonald, PhD Candidate, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A tonne of fossil carbon isn’t the same as a tonne of new trees: why offsets can’t save us

This week, the Albanese government is attempting to reform the safeguard mechanism to try to make it actually cut emissions from our highest polluting industrial facilities.

Experts and commentators see Labor’s plan as a cautious, incremental change that doesn’t yet rise to the urgency of the intensifying climate crisis. But it could generate momentum after a wasted decade of climate denial and delay under the previous government. Done right, it could set our biggest industrial polluters on a pathway to cut their emissions and be a springboard for more ambitious changes.

But there’s one glaring problem. Under the government’s proposed rules, there is still no requirement for polluters to actually cut their emissions at the sites where they are released into the atmosphere. Instead, companies can choose to buy carbon credits or offsets to meet their obligations. Incredibly, there would be no limit on the number of offsets companies can use.

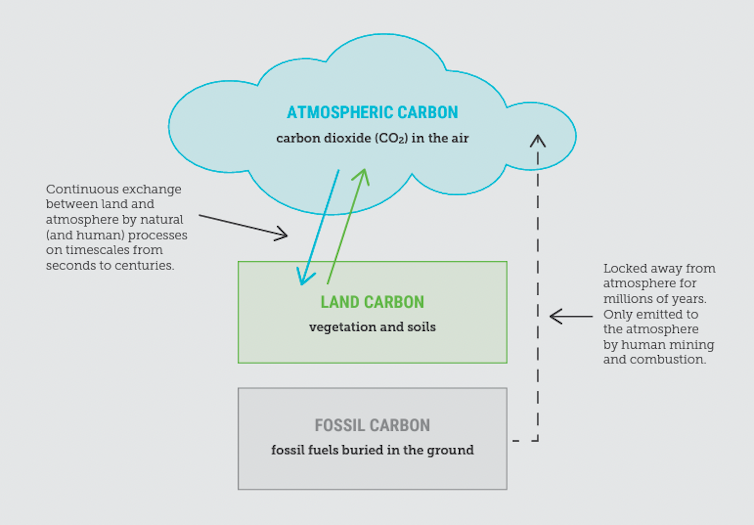

You’ve probably heard about Australia’s rubbery offset schemes and questions of integrity. But there’s an even more fundamental problem. One tonne of carbon dioxide pumped into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels is not the same as one tonne of carbon stored in the tree trunks of a newly planted forest.

The carbon in coal, gas and oil has been safely stored underground for extraordinary lengths of time. But when trees take carbon dioxide back out of the atmosphere, they may only store it for a short period.

There is simply no way around it. Avoiding the worst of climate change means stopping the extraction and burning of fossil fuels. Offsets will not save us. In fact, unlimited use of offsets could see even more emissions, if coal and gas companies “offset” emissions and ramp up exports.

Why Can’t We Rely On Nature To Pull Carbon Dioxide From The Air?

In 2023, many policymakers still believe we can adequately offset emissions. It would certainly be easier if we could keep burning fossil fuels and offsetting them by planting forests. But it doesn’t work. It’s simply not possible to fully “offset” billions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions from burning of coal, oil and gas by regrowing forests, increasing the amount of carbon in soils or other measures.

That’s because the carbon dioxide released by burning fossil fuels is fundamentally different to the way carbon is stored above ground in trees, wetlands and in the soil.

Carbon is everywhere on Earth — in the atmosphere, the ocean, in soils, in all living things, and in rocks and sediments. It is constantly being cycled through these different parts. Carbon is also being continually exchanged between the atmosphere and the ocean’s surface. Together these processes make up the earth’s “active” carbon cycle.

When we burn fossil fuels, we release carbon locked away for millions of years (hence “fossil” fuels), pumping vast new volumes of carbon into the active carbon cycle. This is very clearly altering the balance of carbon in the Earth system and faster than ever recorded in the Earth’s geological history. Planting trees does not lock carbon away again deep underground. Instead, the introduced fossil carbon remains part of the active carbon cycle.

To compound the problem, much of the carbon stored in land-based offsets does not stay stored. Forests can easily be destroyed by fire, disease, floods and droughts, all of which are increasing with climate change.

Offsets Are A Last Resort – Nothing More

Despite these issues, offsets will still have a small role. Some emissions cannot be avoided or reduced at present, given low-emissions technologies for industries like steelmaking are still scaling up. But these offsets must be strictly limited and set to progressively decline over time, as opportunities for genuine emissions reductions – at the source – are developed and rapidly scaled.

Unfortunately, paying for offsets is the first and only thing many large companies are doing about their harmful emissions.

If we allow fossil fuel companies to offset their emissions without limit, they will keep along a business as usual track or even expand their operations. That, in turn, will mean significantly more emissions when Australian fossil fuels are burned overseas.

Our Leaders Must Avoid The Offset Trap

It’s taken Australia decades too long, but we’re finally past climate denial, perhaps due to unprecedented fire and floods. Our leaders tell us it’s now about finding solutions. Well, offsets are not a solution. There is no substitute to actually ending the routine burning of fossil fuels.

We all want our comfortable lives to continue with a minimum of change. Offsets seem to deliver that. But all they really do is offset our guilt and responsibility. They cannot solve the central problem which is that every year, we add another 33 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels.

The atmosphere doesn’t respond to good intentions or clever schemes. All it responds to is the volume of greenhouse gases which trap ever more heat.

If Labor is to make the safeguard mechanism fit for purpose, it must focus on genuine emissions reductions at the source.

What Australia does matters a great deal to the world’s efforts to tackle the climate crisis. If Australia became the first major fossil fuel exporter to embrace a future as a clean energy superpower, it will demonstrate it is possible – and that it comes with benefits like new industries, cleaner air and energy security.

First, though, we have to give up on offset pipe dreams. The only thing that matters is cutting emissions. ![]()

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Orange-bellied parrot shows there’s more to saving endangered species than captive breeding

Dejan Stojanovic, Australian National University; Carolyn Hogg, University of Sydney, and Rob Heinsohn, Australian National UniversityCaptive breeding of threatened species for release into the wild is an important conservation tool. But where threats to wild populations remain unresolved, this tool may not guarantee population recovery in the long term.

Our new research on one of the most endangered birds in the world shows we need to tackle underlying threats to survival if we are to save species from extinction in the wild.

Captive breeding and release is sustaining the population of orange-bellied parrots, holding extinction at bay. But most of the young born into the population each year die during their migration and winter.

Our modelling shows that if captive breeding and release stopped tomorrow, orange-bellied parrots would soon become extinct. The natural birth rate is too low to compensate for the high death rates of juveniles. So we’re locked into releasing captive-bred parrots until we can solve the underlying problems afflicting the wild population. Unfortunately, it’s not clear exactly what those problems are.

No Guarantees When Threats Remain

Globally, captive breeding has prevented the extinction of iconic species such as the California condor.

However, despite the benefits of captive breeding, success is not guaranteed. This is especially so when captive-bred animals are released into habitats where threats remain unresolved. In such cases, captive-bred animals will succumb to the same threats as their wild counterparts.

For some species, identifying and correcting threats is straightforward. For example, removing introduced predators from islands may be a way to eliminate a threat and optimise the benefit of releases from captivity.

But the exact nature of threats is often not clear-cut, especially for species that move over large areas. This can create uncertainty about what the threats are, where they occur, and how to resolve them.

Inability to mitigate threats may result in lost opportunities for released animals to learn crucial behaviours such as migration or song, and ultimately, the decline of wild populations.

Conservationists may sometimes need to “buy time” and prevent extinction in the wild by releasing animals to ensure the continuity of animal cultures in landscapes where threats persist.

Locked Into A Cycle Of Dependency

The orange-bellied parrot is one of the most endangered birds in the world. In 2016, just four females returned to Tasmania from migration, and only one of them produced a surviving descendant. (The species migrates from its summer breeding ground in southwestern Tasmania to the coasts of southeastern mainland Australia, but these movements take a toll on the population.)

Fortunately, despite ongoing uncertainty about reducing threats, intensive conservation efforts have grown the population. More than 30 females have returned from migration annually over the past two years. Despite this success, most juvenile parrots (both captive-bred and wild-born) that leave Tasmania on their northward migration die.

Overcoming the unresolved threats that drive this high mortality is crucial for making this population self-sustaining. Unfortunately due to the practical limitations of studying a small, scattered population across remote areas, it is unlikely that this knowledge gap can be addressed in the short term. In the meantime, there are several options available.

We used simulations to compare the benefits of different management scenarios on the orange-bellied parrot. We showed that of all the potential intervention options available to the recovery project, releasing captive juveniles in autumn – to learn from wild adults, and increase the size of migrating flocks – was the most beneficial.

However, none of the interventions available to managers can directly address the underlying problem of high juvenile mortality, so their benefits were temporary. When we simulated stopping captive releases, the populations rapidly went extinct. Without addressing the underlying threats faced by the species, we found the natural birth rate too low to compensate for high juvenile mortality rates.

Until a solution is found for high migration and winter mortality rates, orange-bellied parrots will remain dependent on captive breeding and release to prevent extinction and grow the population.

Lulled Into A False Sense Of Security

Orange-bellied parrots provide a stark reminder that there is no “quick fix” for most threatened species. Although captive breeding for release can effectively prevent extinction in the short term, long-term self-sustaining populations in the wild depend on finding solutions for the threats that caused their decline in the first place. Until solutions can be found, management agencies may be locked into a cycle of conservation dependency aimed at preventing extinction, but struggle to address the threats that cause the underlying problems.

Given the global popularity and visibility of captive breeding programs, it is easy to be lulled into a false sense of security that they are a quick fix for the extinction crisis. However, identifying the threats to wild populations early is crucial because re-establishing “extinct in the wild” species from captivity is extremely difficult, albeit not impossible.

In the case of the orange-bellied parrot, we hope preventing extinction of the wild population through releases of captive-bred birds may buy enough time to identify and mitigate the causes of high juvenile migration/winter mortality. But we also hope our study is a reminder to policymakers that conservation of wild populations should focus on identifying and preventing threats, negating the need for captive breeding in the first place. ![]()

Dejan Stojanovic, Postdoctoral Fellow, Australian National University; Carolyn Hogg, Senior Research Manager, University of Sydney, and Rob Heinsohn, Professor of Evolutionary and Conservation Biology, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What can we expect from the final UN climate report? And what is the IPCC anyway?

After all the talk on the need for climate action, it’s time for a reality check. On Monday the world will receive the latest United Nations climate report. And it’s a big one.

Hundreds of scientists, forming what’s known as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), have been working hard behind the scenes. They’ve produced a series of reports in the latest round, which began in 2015. But on Monday it all comes together in what’s called the Synthesis Report.

It will explain how greenhouse gas emissions are warming the planet, then delve into the consequences. There’s a focus on where we are most vulnerable, as well as efforts to adapt. And then, how we’re acting to reduce emissions and mitigate climate change.

Gathering all the evidence, from every corner of the globe, is an enormous undertaking, let alone reviewing the science to achieve consensus. It’s a process that has been repeated several times since it began, more than three decades ago.

This is the sixth round of reports. And it won’t be the last. But this is a crucial moment, because the chance to limit warming and avert dangerous climate change is slipping away.

What Is The IPCC And Why Do We Need It?

The IPCC is comprised of 195 member countries charged with producing comprehensive and objective assessments of the scientific evidence for climate change.

The World Economic Forum ranks climate action failure as the number-one risk on a global scale over the next decade. And several other top-ten global risks – extreme weather, biodiversity loss, human environment damage and natural resource crises – are made worse by climate change.

Governments, industries and communities are becoming increasingly aware of the need to tackle climate change, especially as predictions become reality.

The scientific effort to understand the causes, effects and solutions is vast and growing. Every year tens of thousands of new peer-reviewed scientific studies on climate change are published. There has to be a way to identify key messages across this enormous body of scientific evidence, and use this information to make better decisions. This is what IPCC reports do.

The IPCC process also provides a framework for the scientific community to organise and coordinate their efforts. Each reporting cycle is matched with an international scientific effort, where standardised experiments are run to test the reliability of current climate models.

The experiments include multiple possible scenarios for how atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations could change in the future, depending on choices made today. The range of results produced by different models across these sets of experiments helps to determine how confident we are in the climate change impacts expected in the future.

A key aspect of IPCC reports is that they are co-produced between scientists and governments. The summary of each report is negotiated and approved line by line, with consensus from all of the IPCC member governments. This process ensures the reports remain true to the underlying scientific evidence, but also pull out the key information governments need.

What Can We Expect From Monday’s Report?

The Synthesis Report will draw on all six reports released in the current cycle.

They include three so-called “working group reports” on:

the physical science basis of climate change

impacts, adaptation and vulnerability

mitigation.

In addition, three special reports cut across these working groups and tackled focused topics, where governments requested rapid assessments to aid in their decision making. They covered:

global warming of 1.5℃

climate change and land

the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate.

The headline statements from this cycle of IPCC reports have been clearer than ever. They leave absolutely no room for disputing human-caused warming and the need for urgent reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, this decade. We can expect similarly strong and clear headlines from Monday’s report.

How Have IPCC Reports Changed?

Looking back over IPCC reports from the past 33 years demonstrates how our understanding of climate change has improved. The first report in 1990 stated: “the unequivocal detection of the enhanced greenhouse effect from observations is not likely for more than a decade”. Fast forward to 2021 and the equivalent assessment now states: “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land”.

In some cases, the pace of change has dramatically exceeded expectations. In 1990 West Antarctica was a region of concern but not expected to lose major amounts of ice in the next century. But by 2019 our observations show glaciers in West Antarctica retreating rapidly. This has contributed to an accelerating rise in global sea level.

There are also emerging concerns for the stability of parts of the East Antarctic ice sheet once thought to be protected from human-caused climate warming.

This demonstrates the tendency for IPCC assessments to understate the scientific evidence. Climate science is often accused of being alarmist – particularly by those trying to delay climate change action – but in fact the opposite is true.

The production of IPCC reports by consensus with governments means that statements that appear in the report summaries are justified by multiple lines of scientific evidence. This can lag behind current climate science discoveries.

What’s Next?

Plans are already underway for the next assessment cycle of the IPCC, which is to begin in July this year. It’s hoped the next round of reports will be produced in time to inform the Global Stocktake in 2028, where progress towards the Paris Agreement will be assessed.

The current (sixth assessment) cycle has been gruelling. Scientists have stepped up their commitment to work with governments to provide the clear and robust information required.

Writing and approving reports amid a global pandemic added to the challenges. So too did the inclusion of three special reports in addition to the usual three working group reports.

The evidence for human-caused climate change is now unequivocal. This has prompted calls for future IPCC reports to more efficiently assess rapidly changing areas of science and cut across the working groups. This would bring together assessments of the causes, impacts and solutions for key aspects of climate change in one report, rather than always separating them into individual working group reports.

The establishment of the IPCC signalled climate change was an important global problem. Despite this recognition more than three decades ago, and the increasingly concerning reports produced by the IPCC in this time, global greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise year-on-year.

However, there is some hope we may be nearing the peak in global emissions. By the time the next IPCC reports are released, global climate action may have finally started to move the world onto a more sustainable pathway.

Time will tell. Let’s hope policy makers will stand with the science on the right side of history. ![]()

Nerilie Abram, Chief Investigator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes; Deputy Director for the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The flap of a butterfly’s wings: why autumn is not a good time to predict if El Niño is coming

Remember the butterfly effect? It was a popular summary of chaos theory suggesting a butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon could cause a tornado in Texas.

Right now, a version of this is making it hard for us to predict whether an El Niño event is coming.

After three consecutive La Niña years, that part of the cycle is officially over. But it’s not certain an El Niño will replace it. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology this week announced an El Niño watch – a “wait and see” forecast giving us a 50% chance of an El Niño forming later this year. Other climate forecasting agencies around the world are sending a similar message to the Bureau of Meteorology’s, that we are on an El Niño watch.

While the conditions seem right for El Niño to form and likely bring hotter, drier weather to Australia, the world’s chaotic climate system is in a very unpredictable state. Fast forward three months, and our models will be much more certain about whether El Niño really is coming – or whether the system will remain in a neutral, or near-normal, state.

Why Can’t We Predict What’s Going To Happen?

At this time of year, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle is at its most susceptible to change. Right now, the subsurface waters of the equatorial western Pacific are warmer than usual. If this water rises from deeper down to the surface of the ocean, it will interact with the atmosphere. This usually leads to more rain and floods for Chile, drier, hotter weather for Australia, and a variety of other effects worldwide.

But this isn’t inevitable. Let’s say a sudden burst of wind strikes, forcing warmer water to stay down deeper. This can disturb the whole cycle. Unexpected windbursts at this time of year can even tip the system into a different mode, ending up neutral or as a La Niña event.

Among climate scientists, this is known as the predictability barrier – and it’s why we can’t say for certain an El Niño is coming until later in the year.

Have We Seen Unexpected Swings In The Cycle Before?

Yes, most recently in 2014. Early that year, climate models were predicting a truly enormous El Niño was set to begin.

But the monster El Niño didn’t happen. Cooler water flowed into the south-eastern Pacific at a critical time of year, while the unusual timing of westerly windbursts kept the warmer water down deeper.

The end result was that the whole system was nudged into a different configuration of a weak El Niño. It took another year for a full El Niño to develop. This time, it was very strong.

Could we really see a fourth La Niña? It could happen but it would be very unusual, given we’ve never seen four years of successive La Niña conditions. At present, the heat build-up under the surface of the equatorial Pacific suggests an El Niño is coming, but it’s not a given.

Why Do We Get These Cycles Anyway?

We believe the El Niño-La Niña cycle has a very long history, dating back to the formation of the Pacific Ocean about 190 million years ago.

That’s because this ocean basin is the largest on Earth – and has a lot of seawater sitting along the equator. In our models, we can see the El Niño cycle forming out of the fluid dynamics, as warmer or cooler water moves across the ocean.

The Atlantic has a smaller version, named the Atlantic Niño. Why is it smaller? Because there’s much less water along the equator in the Atlantic. As a result, the Atlantic Niño has much less of an effect on weather globally.

So When Will We Know For Sure?

El Niño and La Niña are at their strongest over December and January, though the effects and their timing can differ in Australia depending on where in the country you are. These cycles usually end some time between February and May.

The popular understanding of the butterfly effect and chaos science often gets one thing wrong. Chaotic systems like the world’s weather are not always unpredictable, but can be more or less sensitive to small changes at different times. Between March and May, it can take just a small nudge to flip the system. Later in the year, as either an El Niño, neutral phase or La Niña gathers pace, it is much harder to change course.

It’s like a ball poised on top of a high hill. A very tiny push is enough to send the ball rolling down either one side of the hill or another. The push might even be so tiny you can’t measure it accurately.

That’s why it’s so difficult to predict what’s going to happen, even though we understand the physics behind these events fairly well. The Pacific Ocean and the air overhead are extremely sensitive to “pushes” in any direction from March to May.

But once the ball rolls down one side rather than another, it’s much easier to predict which way it will keep rolling. By June or July, the ball is already rolling down the hill on whichever side it’s going to go, and there’s a lot more confidence and clarity in our predictions. Stay tuned. ![]()

Nandini Ramesh, Senior Research Scientist, Data61, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

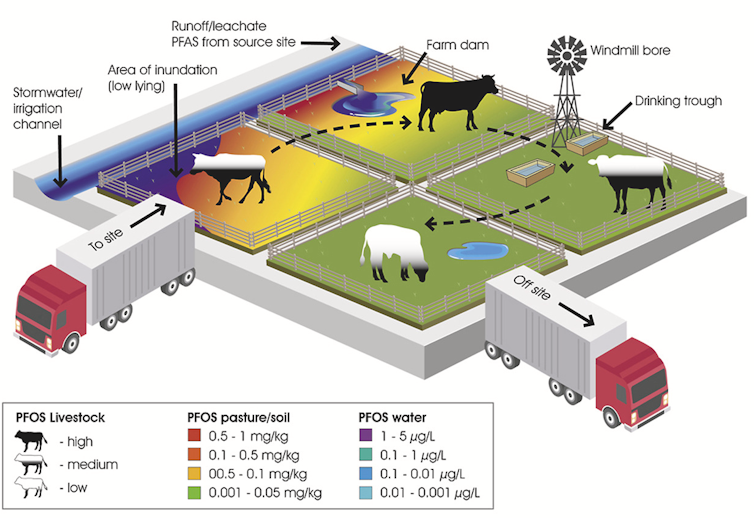

PFAS for dinner? Study of ‘forever chemicals’ build-up in cattle points to ways to reduce risks

PFAS, known as “forever chemicals”, have been found just about everywhere on Earth, including in toilet paper.

These chemicals are a group of artificial compounds based on carbon and fluorine – per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. They comprise thousands of individual chemicals with hundreds of documented uses, including water proofing and fire suppression. It is likely every household has products or textiles that contain or were treated with a product that contained PFAS (including some non-stick cookware and stain-resistant fabrics).

Studies have shown most people have one or more PFAS compounds in their blood. We live in a world full of chemicals, so why do we care about these ones? Well, some PFAS have been associated with a wide range of adverse human health effects, such as cancer and immune problems. However, there is limited evidence of human disease resulting from environmental exposures.

Our study investigated the uptake of PFAS into livestock at ten PFAS-impacted farms in Victoria. Our analysis also shows how risks can be reduced.

Our findings show the land and livestock can be managed to reduce PFAS levels in the animals before they enter the food chain. This means good management practices can protect food quality and reduce consumer exposure.

How Do PFAS Get In Your Blood?

Exposure to household dust and consumption of contaminated food or water are major contributors to human exposure to PFAS. It then accumulates in our blood.

As the name would suggest, forever chemicals persist in the environment. As a result, when released into the environment, they disperse and over time can contaminate surrounding areas.

Firefighting and training activities have historically resulted in large releases of PFAS into the environment. This includes farming areas.

As livestock feed and drink from contaminated sources, this leads to PFAS accumulation in tissues. From there, PFAS can be transferred into the food chain, including products we eat such as meat and milk.

The causal links and what levels of PFAS exposure are harmful are still being investigated. The scientific community has yet to reach a consensus on how “bad” these compounds are, or conversely what the safe exposure levels are.

In the meantime, it is important to limit exposure through regulation. Australia has adopted environmental and health-based guideline values for three PFAS of concern: perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS).

Australian food quality is high. In a 2021 study, scientists tested for 30 different PFAS in a broad range of Australian foods and beverages. Only one specific PFAS (PFOS) was detectable. It was found in just five out of 112 commonly consumed foods and beverages at levels below concern.

These findings would suggest PFAS contamination is not an issue at most farms in Australia. The risks are likely to be higher from food produced at PFAS-contaminated sites. At such locations, PFAS can affect a range of foods, including eggs, vegetables and livestock.

What Did The Study Investigate?

We collated data from environmental investigations at ten PFAS-impacted farms in Victoria. This included testing about 1,000 samples of soil, water, pasture and livestock blood for concentrations of 28 types of PFAS. Our analysis also included information about farm practices, including livestock rotation, access to clean pasture and water.

We found:

two specific PFAS compounds (PFOS and PFHxS) made up more than 98% of total PFAS detected in livestock blood

PFAS concentrations in water were correlated to concentrations in livestock blood, implying water was a critical exposure pathway, while the relationships between livestock and PFAS levels for soil and pasture were weaker

livestock exposure to PFAS varies over time and across paddocks. Seasonal patterns in PFAS blood concentrations were linked to seasonal grazing behaviours and the animals’ need for drinking water.

What’s The Next Step?

Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA) is leading research and policy to understand how environmental PFAS risks can be better managed. In this regard, EPA along with research partners, is working to develop predictive models to estimate PFAS accumulation in livestock over their lifetime. This research will help determine when a site is too contaminated for livestock production and which ones to prioritise for PFAS remediation in soil and water.

Ultimately, this will allow more effective management of PFAS accumulation and reduce the likelihood of having PFAS for dinner.![]()

Antti Mikkonen, Principal Health Risk Advisor – Chemicals, EPA Victoria, and PhD Candidate, School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, University of South Australia and Mark Patrick Taylor, Victoria's Chief Environmental Scientist, EPA Victoria; Honorary Professor, School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia hasn’t figured out low-level nuclear waste storage yet – let alone high-level waste from submarines

Ian Lowe, Griffith UniversityWithin ten years, Australia could be in possession of three American-made Virginia-class nuclear submarines under the AUKUS agreement with the United States and United Kingdom. The following decade, we plan to build five next-generation nuclear submarines.

To date, criticism of the deal has largely focused on whether our unstable geopolitical environment and China’s military investment means it’s worth spending up to A$368 billion on eight submarines as a deterrent.

But nuclear submarines mean nuclear waste. And for decades, Australia has failed to find a suitable place for the long-term storage of our small quantities of low and intermediate level nuclear waste from medical isotopes and the Lucas Heights research reactor.

With this deal, we have committed ourselves to managing highly radioactive reactor waste when these submarines are decommissioned – and guarding it, given the fuel for these submarines is weapons-grade uranium.

Where will it be stored? The government says it will be on defence land, making the most likely site Woomera in South Australia.

What Nuclear Waste Will We Have To Deal With?

Under this deal, Australia will not manufacture nuclear reactors. The US and later the UK will give Australia “complete, welded power units” which do not require refuelling over the lifetime of the submarine.

In this, we’re following the US model, where each submarine is powered by a reactor with fuel built in. When nuclear subs are decommissioned, the reactor is pulled out as a complete unit and treated as waste.

An official fact sheet about this deal states Australia “has committed to managing all radioactive waste generated through its nuclear-powered submarine program, including spent nuclear fuel, in Australia”.

What does this waste look like? When Virginia-class submarines are decommissioned, you have to pull out the “small” reactor and dispose of it. Small, in this context, is relative. It’s small compared to nuclear power plants. But it weighs over 100 tonnes, and contains around 200 kilograms of highly enriched uranium, which is nuclear weapons-grade material.

So, when our first three subs are at the end of their lives – which, according to defence minister Richard Marles, will be in about 30 years time – we will have 600kg of so-called “spent fuel” and potentially tonnes of irradiated material from the reactor and its protective walls. Because the fuel is weapons-grade material, it will need military-scale security.

Australia Has No Long-Term Storage Facility

There’s one line in the fact sheet which stands out. The UK and US “will assist Australia in developing this capability, leveraging Australia’s decades of safely and securely managing radioactive waste domestically”.