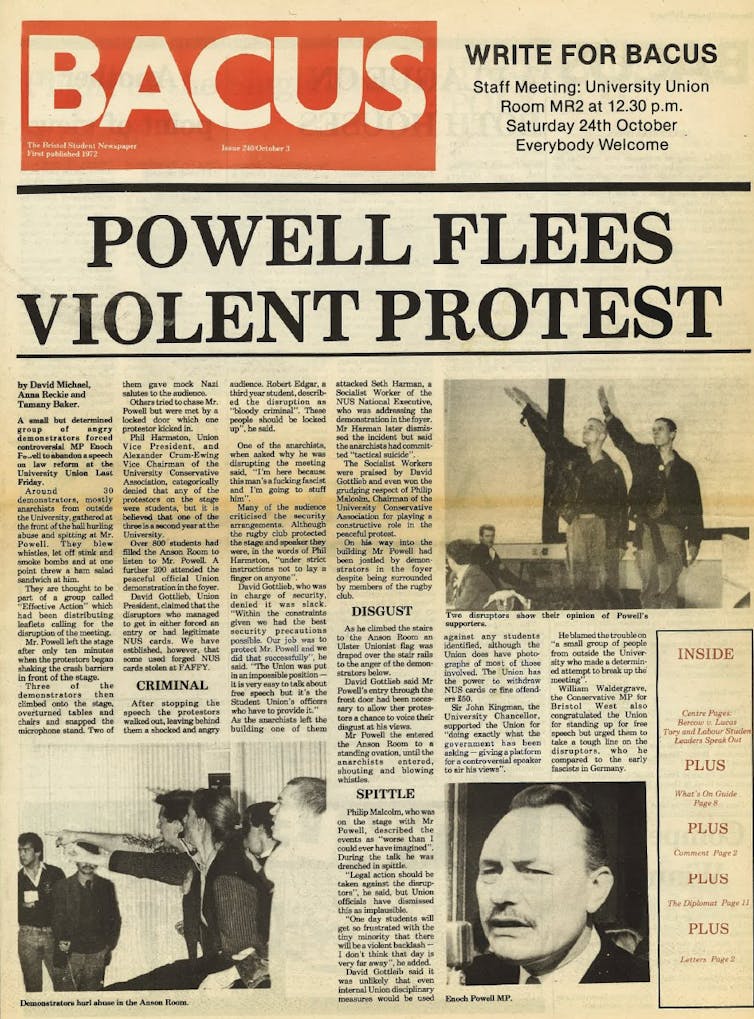

inbox and environment News: Issue 578

April 2 - 15 2023: Issue 578

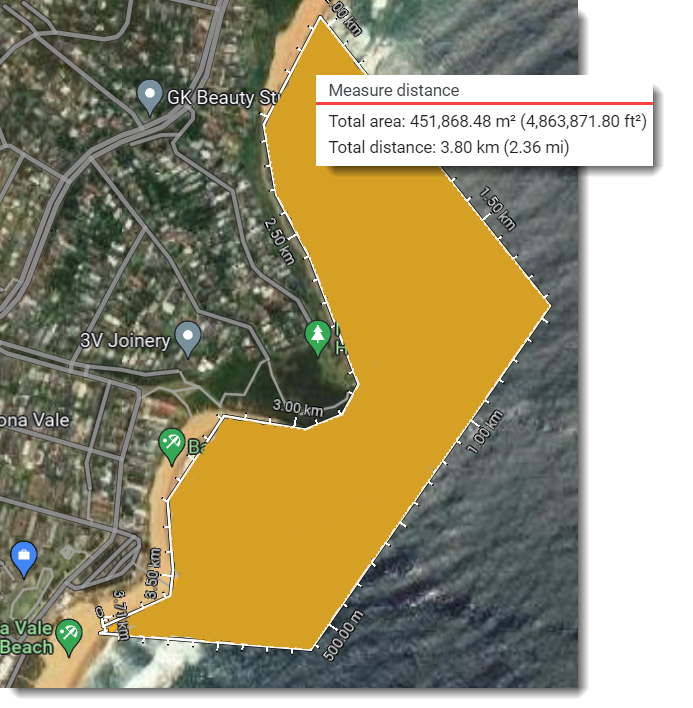

Protect Mona Vale's Bongin Bongin Bay - Establish An Aquatic Reserve

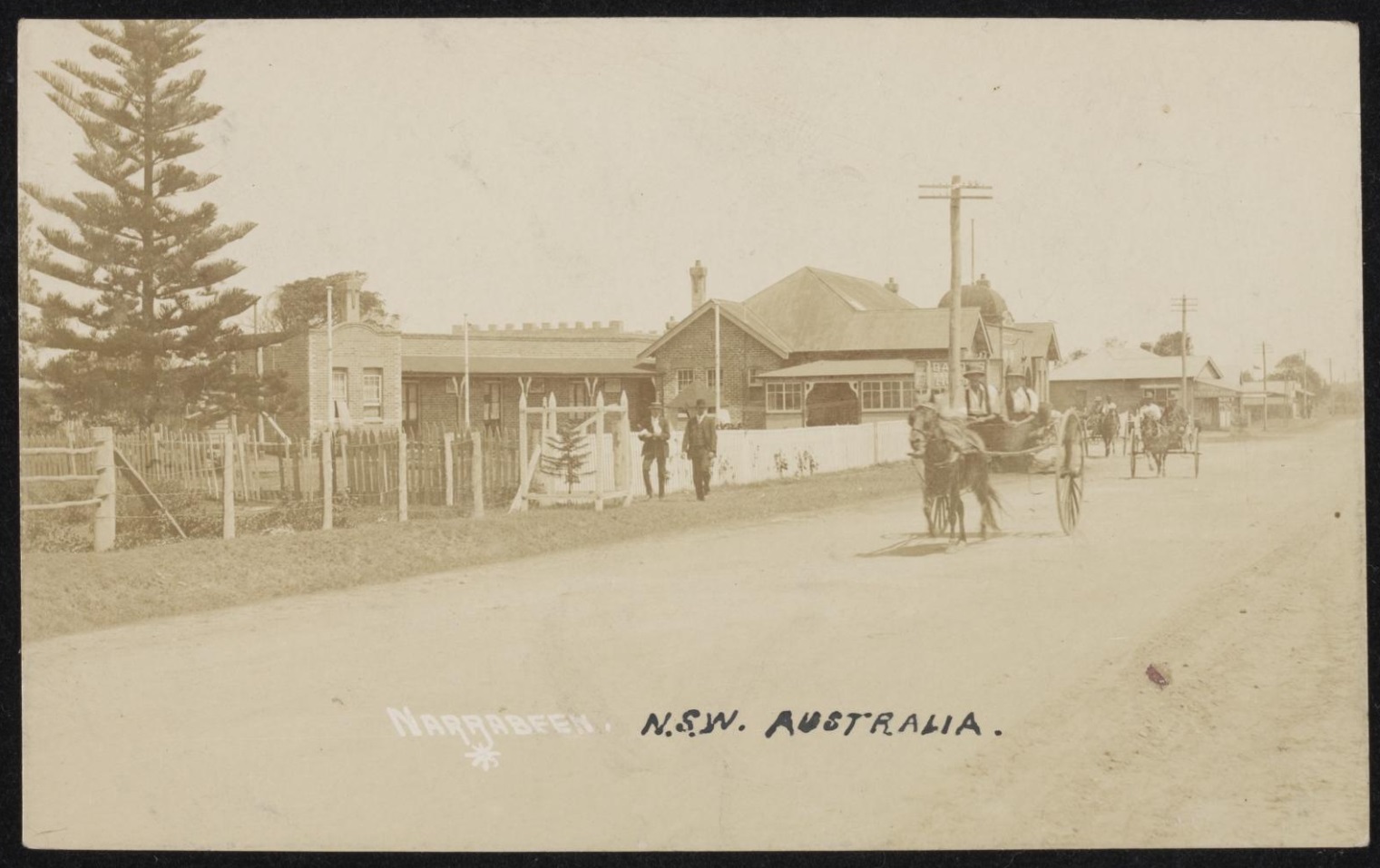

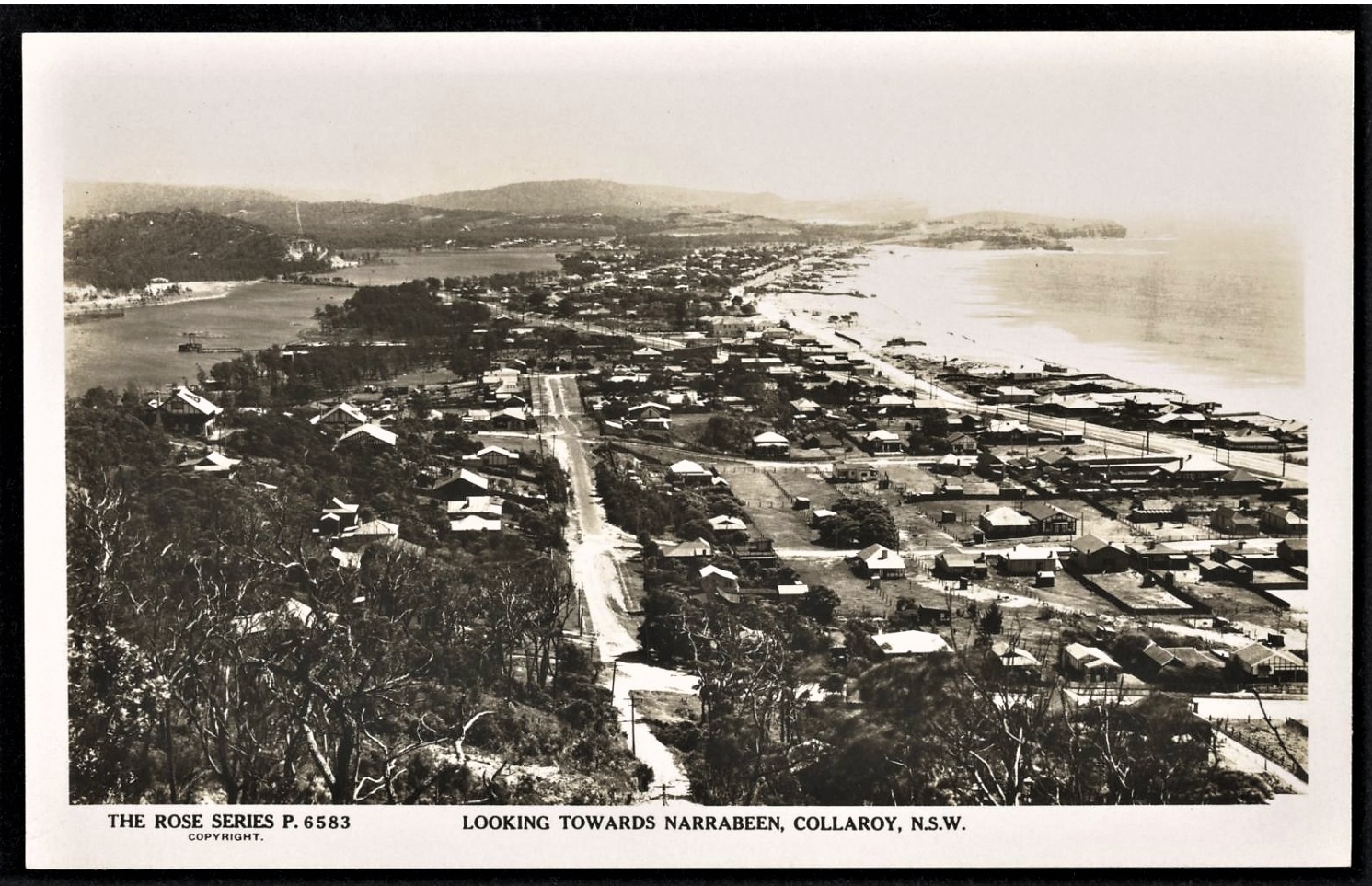

More Runoff Pollution - Narrabeen- Collaroy Beachfront

March 30, 2023: Oily muck oozing out of a drain at Frazer Street, Collaroy - Narrabeen beach.

Council informed - water flow was stopped.

Photo: Surfrider Foundation Northern Beaches

Rainbow Lorikeet Pair Feasting On Palm Flowers

Careel Bay, March 30 2023

Photos: AJG

.jpg?timestamp=1680382887182)

.jpg?timestamp=1680293666288)

New Handrail Installed At North Avalon Beach

Swamp Wallaby At Palm Beach

Westleigh Park - Critically Endangered Forest - POM Open For Feedback By Hornsby Council Until April 8

Purchased from Sydney Water in 2016, the 36-hectare Westleigh Park, Hornsby Council states, will play a key role in recreational provision for the district including a diverse range of provisions for formal sports, passive recreation (e.g. picnics, walking, playground), mountain biking and ancillary facilities (including internal roads, carparks, amenities buildings, shared paths and water management).

At its 8 March 2023 Council Meeting, Hornsby Council endorsed a revised draft Master Plan for Westleigh Park to be published for comment as part of the exhibition of the draft Plan of Management (read the Business Papers and Minutes).

The revised draft Master Plan seeks to provide a conceptual framework for ongoing planning on the site.

The draft Plan of Management establishes an appropriate character and scale for the development and management for Westleigh Park. It will enable the construction of new open space facilities at Westleigh Park to commence and will help identify a program of development and ongoing maintenance works.

Closes April 9, 2023

Visit: https://yoursay.hornsby.nsw.gov.au/westleigh-park-plan-management

Video published March 24, 2023 by Wild Bush Solutions

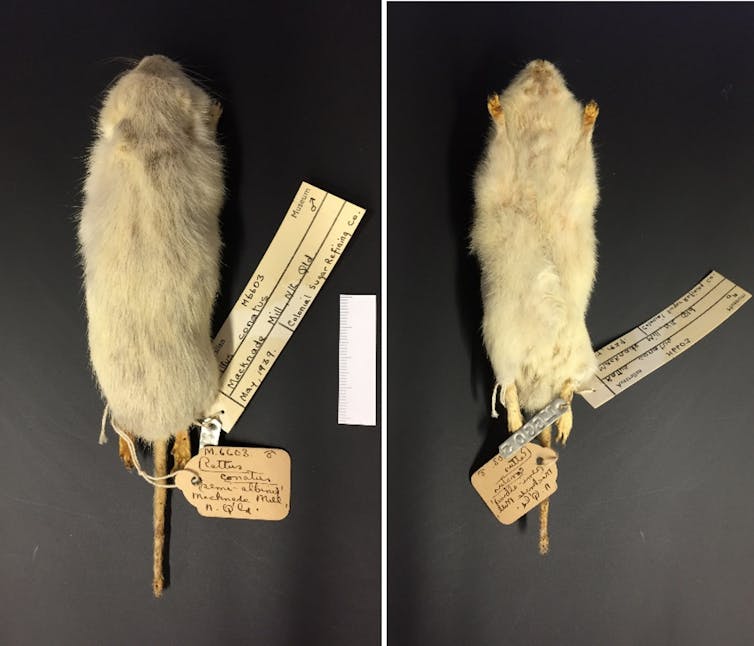

Calling All Citizen Scientists: Hunt For Shark Egg Cases Launches In Australia

March 20, 2023: CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency, is calling on citizen scientists to find and record egg cases washing up on Australian coasts, so researchers can better-understand oviparous chondrichthyans: egg-laying sharks, skates and chimaeras.

The Great Eggcase Hunt, an initiative of United Kingdom-based charity The Shark Trust, has launched in Australia in partnership with CSIRO to help provide new data for scientists studying the taxonomy and distribution of oviparous chondrichthyans.

Helen O’Neill, CSIRO Australian National Fish Collection biologist, said recording sightings of egg cases on beaches and coastlines would help scientists discover what the egg cases of different chondrichthyans look like, with some species still unknown.

“Egg cases are important for understanding the basic biology of oviparous chondrichthyans, as well as revealing valuable information such as where different species live and where their nurseries are located,” Ms O’Neill said.

Cat Gordon, Senior Conservation Officer at The Shark Trust, said the Great Eggcase Hunt began in the United Kingdom 20 years ago and has since recorded more than 380,000 individual egg cases from around the world.

“We’re really excited to be partnering with CSIRO to officially launch this citizen science project in Australia and to be able to expand the Shark Trust’s eggcase identification resources," Ms Gordon said.

"There’s such a diversity of species to be found around the Australian coastline, and with a tailored identification guide created for each state, they really showcase the different catsharks, skate, horn sharks, carpetsharks and chimaera eggcases that can be found washed ashore or seen while diving,” she said.

Also known as mermaids’ purses, egg cases come in many different shapes and colours, ranging from cream and butterscotch to deep amber and black. They range in size from approximately 4 to 25 centimetres.

Some egg cases have a smooth and simple appearance, while others have ridges, keels or curling tendrils that anchor them to kelp or coral. Port Jackson sharks have corkscrew-shaped egg cases that they wedge into rocks.

Each different species' egg case has a unique morphology that is helpful in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species.

“At the Australian National Fish Collection, we are matching egg cases to the species that laid them,” Ms O’Neill said.

“We borrow egg cases from other collections, museums and aquariums around the world and use our own specimens collected from fish markets and surveys at sea or extracted from the ovaries of preserved specimens in our collection,” she said.

Chondrichthyans have the most diverse reproduction strategies found among vertebrates, encompassing parthenogenesis (no father), multiple paternity (more than one father of the litter), adelphophagy (baby sharks predating each other in the womb) and various modes of egg laying.

Egg cases found on beaches rarely contain live embryos, whose incubation times range from a few months up to three years, depending on the species.

“Egg cases found washed up on beaches have likely already hatched, died prematurely due to being washed ashore or been predated on by creatures like sea snails, who bore a hole in the egg case and suck out the contents,” Ms O’Neill said.

The Shark Trust is a United-Kingdom-based charity dedicated to safeguarding the future of sharks, skates, rays, and chimaera through positive change. The Trust achieves this through science, education, influence and action.

To get involved in the Great Eggcase Hunt, you can record sightings via the Shark Trust citizen science mobile phone app or through the project website: www.sharktrust.org/greateggcasehunt

Photo: Port Jackson shark egg on Station Beach at Pittwater. Image PON/AJG

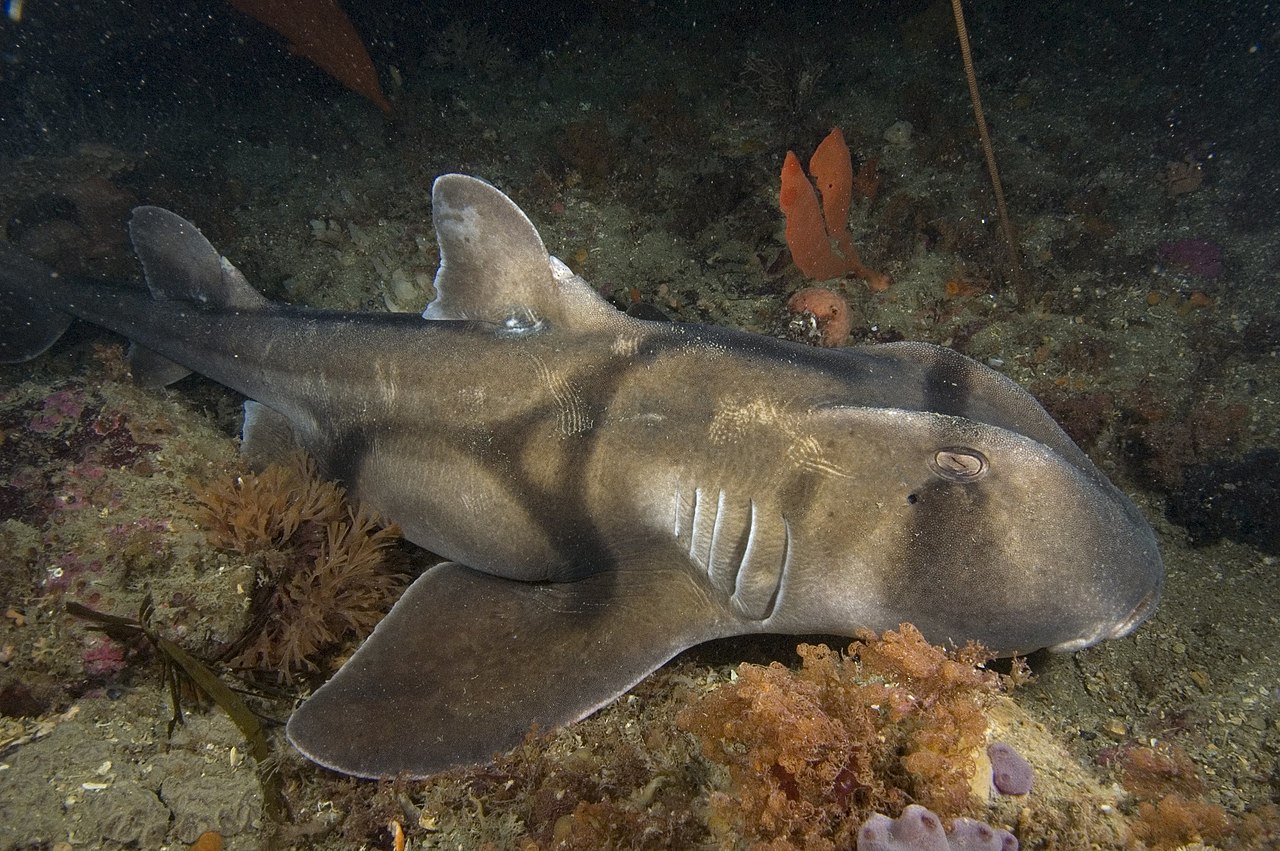

The Port Jackson shark (Heterodontus portusjacksoni) is a nocturnal, oviparous (egg laying) type of bullhead shark of the family Heterodontidae, found in the coastal region of southern Australia, including the waters off Port Jackson. It has a large, blunt head with prominent forehead ridges and dark brown harness-like markings on a lighter grey-brown body, and can grow up to 1.65 metres (5.5 ft) long. They are the largest in the genus Heterodontus.

The Port Jackson shark is a migratory species, traveling south in the summer and returning north to breed in the winter. It feeds on hard-shelled mollusks, crustaceans, sea urchins, and fish. Identification of this species is very easy due to the pattern of harness-like markings that cross the eyes, run along the back to the first dorsal fin, then cross the side of the body, in addition to the spine in front of both dorsal fins.

These sharks are are oviparous, meaning that they lay eggs rather than give live birth to their young. The species has an annual breeding cycle which begins in late August and continues until the middle of November. During this time, the female lays pairs of eggs every 8-17 days. As many as eight pairs can be laid during this period. The eggs mature for 10–11 months before the hatchlings, known as neonates, can break out of the egg capsule.

Port Jackson shark adults are often seen resting in caves in groups, and prefer to associate with specific sharks based on sex and size. Juvenile Port Jackson sharks, on the other hand, do not appear to be social. A captive study showed that these juveniles did not prefer to spend time next to other sharks, even when they were familiar with each other (i.e. tank mates). Juvenile Port Jackson sharks have unique personality traits, just like humans. Some were bolder than others when exploring a novel environment and they also reacted differently to a stressful situation (in choosing a freeze or flight response).

Juvenile Port Jackson sharks are also capable of learning to associate bubbles, LED lights, or sounds with receiving a food reward, can distinguish different quantities (i.e. count), and can learn by watching what other sharks are doing.

At least in some of these lab experiments males are shyer than females and boldness increases with consecutive trials of the same experiment. In experiments with different music genres, none of the sharks tested learned to discriminate between a jazz and a classical music stimulus.

Port Jackson Sharks are considered harmless to humans, although the teeth, whilst not large or sharp, can give a painful bite.

Heterodontus portusjacksoni. Photo: Mark Norman, Museums Victoria

Cat Owners Encouraged To Keep Their Pets Safe At Home

Wednesday, 1 March 2023

Northern Beaches residents are being encouraged to keep their pets safe at home as part of a new animal protection campaign.

According to RSPCA NSW, two out of three cat owners have lost a cat to a roaming-related accident, and one in three to a car accident. Northern Beaches Council is proud to be one of 11 councils partnering with RSPCA NSW as part of the Keeping Cats Safe at Home project.

Promoting responsible ownership, the new campaign goes beyond desexing and micro chipping of beloved cats and asks owners to consider keeping their cats at home.

Northern Beaches CEO Ray Brownlee said there’s a dual benefit to cats and local wildlife that flows directly from promoting responsible ownership of domesticated cats.

“Northern Beaches residents love their pets, but they’re also passionate about protecting the local environment,” Mr Brownlee said.

“Because pet cats occupy a special place in our hearts we need to educate the community on how have them microchip and desexed to keep them safe. This initiative has an educational focus. It aims to protect tiny native species like lizards, mammals, baby birds and frogs, while also preventing domesticated cats from falling prey to road accidents.”

In 2021, the NSW Government awarded a $2.5 million grant from the NSW Environmental Trust to RSPCA NSW to deliver the project.

To help promote the campaign, Council is asking cat-lovers living on the Northern Beaches to submit a photo of their cat or kitten living their best life at home and go in the draw to win one of 10 $1000 vouchers for a deluxe outdoor cat enclosure from Catnets. The competition opens on March 1st and closes on Sunday April 9th 2023. Finalists will be published in an online gallery.

For competition details visit www.northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au/environment/non-native-animals/cats/competition-keeping-cats-safe-home

Learn more about keeping cats safe at www.rspcansw.org.au/keeping-cats-safe

Photo: Greg Hume

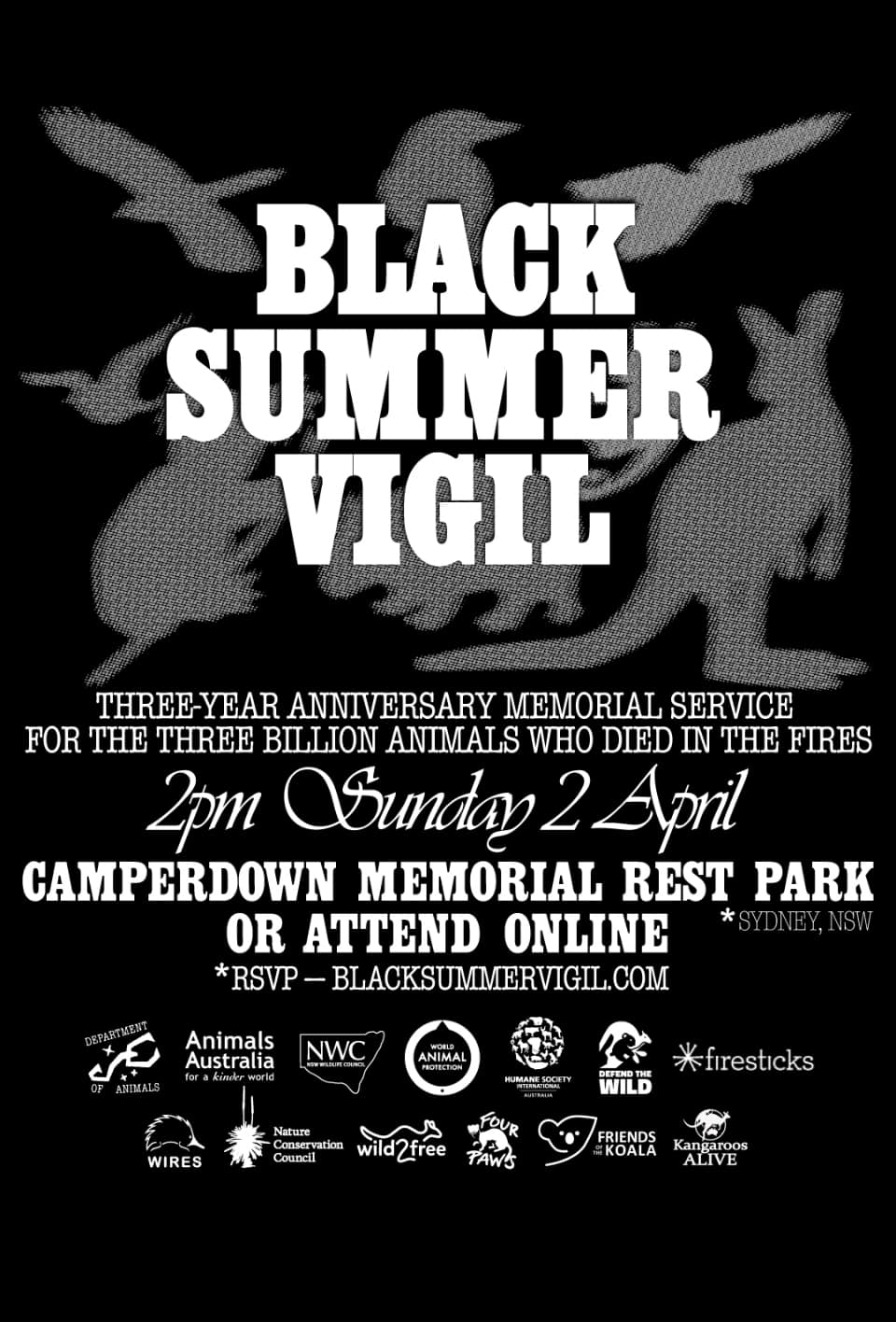

Black Summer Vigil For Wildlife: April 2nd

The New South Wales Wildlife Council invites all wildlife carers, wildlife vets, vet nurses, first responders and supporters to the upcoming Black Summer Vigil for Wildlife on Sunday April 2nd 2023 starting at 2pm.

Please join us for the Black Summer Vigil, a three-year anniversary memorial service for the three billion animals who lost their lives in the fires – “one of the worst wildlife disasters in modern history”.

Attend online or in-person at Camperdown Memorial Rest Park (Sydney).

RSVP at: blacksummervigil.com

You’ll hear personal stories from the NSW Wildlife Council, Southern Cross Wildlife Care and other first responders across wildlife rescue, rural fire service, photojournalism, Aboriginal custodianship, veterinary medicine, ecology and more.

+ Performance and Ceremony by Jannawi Dance Clan, sharing a Dharug cultural perspective to honour the Ancestors and bring the spirit of the animals into our midst.

Join us to honour the animals who perished – and in doing so, celebrate the unique and extraordinary wildlife of these lands.

Speakers include:

Greg Mullins, Former Commissioner, Fire and Rescue NSW; Climate Councillor and founder, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action. Greg warned Australia's then–Prime Minister in April 2019 that a bushfire catastrophe was coming. He pleaded for support and was ignored, then risked his life dealing with the ramifications on the ground. “You couldn’t see very far because of the orange smoke. Everything was dark. It was probably 2 o’clock in the afternoon but it was like night. Then I saw something moving on the side of the road and I walked closer. It was a mob of kangaroos. The speed of that fire with its pyroconvective storm driving it in every direction, they had nowhere to go. They came out of the forest, on fire, and dropped dead on the road. I’ve never seen that. Kangaroos know what to do in a fire. They’re fast animals. Climate change, driven by the burning of coal, oil, and gas is driving worsening bushfires across Australia, and putting our precious, irreplaceable wildlife in danger.”

Internationally recognised ecologist and WWF board member, Professor Christopher Dickman oversaw the work calculating the animal deaths from Black Summer. A Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science, Professor Dickman already wore the heavy task of being an ecologist during the sixth mass extinction, in the country that has the worst rate of mammalian extinction in the world. On 8 January 2020 media around the world shared his finding that Black Summer fires had killed one billion animals. Sadly, the fires continued for two more months, and his team's final count was three billion. This does not include invertebrates: it is estimated 240 trillion beetles, moths, spiders, yabbies and other invertebrates died in the fires.

Coming up from the South Coast, owner of Wild2Free Kangaroo Sanctuary Rae Harvey, as seen in The Bond and The Fire. She is in the sad position of having personally known and cared for a number of Black Summer's victims: many of the orphaned joeys she cared for were killed in the fires. (She nearly died herself too.) For three years, she has been unable to even speak their names. Now, for the first time, she will tell the story of the joeys she lost.

Cultural burning practitioner and Southern NSW Regional Coordinator with Firesticks Alliance, Djiringanj-Yuin Custodian Dan Morgan. Dan practises using Aboriginal knowledge to heal Country. He has worked for 18 years with the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and is on the board of management for the Biamanga National Park, a sacred area home to the last surviving koalas on the NSW south coast – which was partly destroyed by the fires of Black Summer. “The animals that live on our sacred sites are our Ancestors, it's our Cultural obligation to protect them. We have evolved with our Country over thousands of years, nourishing and protecting all living species. Our Country represents our people. So when the fires came, it was devastating to see the aftermath, and the feeling of helplessness was truly traumatising for our people, due to the denial of our Cultural right to manage Country as our Ancestors did for thousands of years prior to colonisation. Australia needs to make legislative changes that allow us to heal Country and our community through the fire knowledge and to stop incinerating ecosystems with destructive 'hazard-reduction' burns."

Head of Programs & Disaster Response at Humane Society International (HSI), Evan Quartermain was one of the first responders on Kangaroo Island where nearly 40% of the island burnt at high severity: “Those were some of the toughest scenes I’d ever witnessed as an animal rescuer: the bodies of charred animals as far as the eye can see. Every time we found an animal alive it felt like a miracle.” As a result of this firsthand experience, HSI commissioned a report into the state of Australia's disaster response for wildlife, which we'll also hear about.

+ More to come.

The Black Summer Vigil is brought to you by the Department of Animals, Animals Australia, the NSW Wildlife Council, World Animal Protection, Humane Society International and Defend the Wild, with support from WIRES, Firesticks Alliance, Nature Conservation Council of NSW, Wild2Free Kangaroo Rescue, Four Paws, Friends of the Koala and Kangaroos Alive.

Permaculture Northern Beaches - Upcoming Events

- Learn about Permaculture design

- Caring for and raising chickens

- Native bees and bee hotels

- Living Skills - soap making

- AND Live Music!

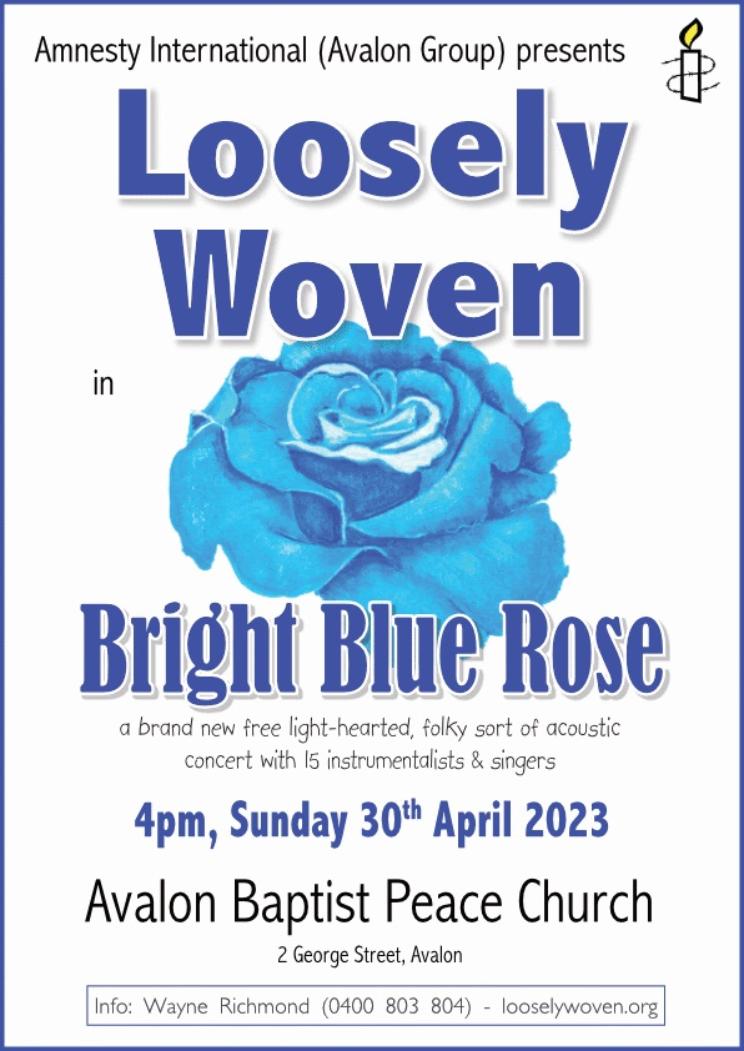

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Avalon Beach April 30

Come and join us for our family friendly April clean up, close to Avalon Surf Lifesaving Club (558 Barrenjoey road, Avalon) on the 30th at 10am.

We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the ocean. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the beach and even clean up in the water (at own risk). We will clean up until around 11.20, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time. For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages. There is a council carpark, but it is often busy on Sundays, so check streets close by as well if it's full or please consider using public transport.

Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost. All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too!

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Weed Of The Week: Cassia - Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Federal Government States It Is Using Every Tool In The Box To Conserve More Of Our Iconic Landscapes; Invites Feedback On Framework

- A geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed

- in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in-situ conservation

- of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable,

- cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values.

Australia’s safeguard mechanism deal is only a half-win for the Greens, and for the climate

Kate Crowley, University of TasmaniaLabor and the Greens on Monday announced a deal to strengthen a key climate policy, the safeguard mechanism, by introducing a hard cap on industrial sector emissions.

But the Greens failed in their bid to force Labor to ban new coal and gas projects.

Labor did give ground in setting a hard cap on emissions which should – if it works – make many new fossil fuel projects unviable.

This isn’t the end of the climate wars – but the politics are changing. Denial and inaction are over. Now we’re seeing a tussle between the urgency of the Greens, Teals who want to ban fossil fuels and the Labor government as it balances demands from industry, climate voters and the unions.

All the while, our carbon budget is shrinking and the time available to act on climate change is disappearing.

How Did We Get Here?

In May last year, the Coalition government lost office after almost a decade of climate policy failures.

Labor won government. But the balance of power changed in other ways too. Seven Climate 200-backed Teal independent MPs were elected. The Greens had a record four members elected to the House of Representatives and gained the balance of power in the Senate.

Labor immediately set a new goal of cutting emissions 43% by the end of the decade. To do it, they pledged to strengthen the Coalition’s questionable safeguard mechanism. This scheme’s emissions allowances had been set too high, and there were too many exemptions, meaning it wouldn’t have cut the promised 200 million tonnes of emissions by 2030.

Labor promised to fix these problems. The Greens and Teals were extremely sceptical. The resulting negotiations have lasted months, and left many disillusioned about how ambitious Labor will really be on climate.

But we do have something. Yesterday, a deal was announced and Labor’s reformed plan passed the lower house en route to the Senate. The Liberal and National parties voted against the reforms, even though it is their own – indeed their only – climate policy.

Were The Negotiations Worth It?

Hopefully. But it hasn’t been smooth sailing to secure Green and Teal support.

From the outset the Greens tried to drive a hard bargain by seeking an end to all new coal and gas projects. This, the government made clear, was not going to happen, and it didn’t.

Relations deteriorated rapidly as the government looked set to keep backing new coal and gas projects. Even so, the Greens kept negotiating. This produced an early win – the government ruled out using its new A$15 billion National Reconstruction Fund to invest in coal, gas or logging native forests.

Labor did not give ground on no new coal and gas. But the Greens did secure a legislated cap on the total industrial emissions covered by Australia’s 215 largest polluters covered by the safeguard mechanism – essentially, fossil fuel industries and manufacturers.

Greens leader Adam Bandt says the cap will mean only half of the 116 proposed coal and gas projects can proceed. But this isn’t guaranteed. Some projects would not have been viable regardless. And laws can be readily changed.

It remains to be seen how the concessions won by the Greens will work in practice.

What About The Teals?

The Teals have been less visible in this process, but they haven’t been sitting idle. Both the Teal independents and independent senator David Pocock have called for an absolute cap on industrial emissions.

Indeed, founding Teal Zali Steggall was the first to call for a UK-style “climate budget”, which proved palatable for that country’s conservative government.

Besides an emission cap, the Teals have called for restraint around the use of offsets and increased legitimacy on the use of controversial carbon offsets to ensure emissions are actually cut, not just offset. They advocate stronger oversight by the Climate Change Authority and other regulators.

Teal Sophie Scamps has proposed a means of ending the revolving door between the fossil fuel industry and government positions which influence government’s climate policy.

Teal Kylea Tink proposes expanding the safeguard mechanism to cover more of the economy. At present, the mechanism only covers about 30% of Australia’s emissions and is limited to industrial facilities emitting over 100,000 tonnes a year. Tink wants this to be lowered to 25,000 tonnes.

In the Senate, Labor needs David Pocock’s vote as well as the Greens to pass the bill. Pocock’s constituents are worried about the effect of new fossil fuel projects on our shrinking carbon budget. But as a pragmatist wanting action rather than inaction, he has given his support.

Where To Next?

Attention will remain on the Greens, given they hold the balance of power in the Senate. They have capitalised on this, making sure to capture the media narrative by claiming the win – and flagging political fights to come over new fossil fuel projects.

But the Greens have also taken some friendly fire. Many environmentalists have been privately and publicly critical of a deal struck which does not rule out continued fossil fuel expansion in one of the world’s largest suppliers. Greens senator Nick McKim hit back at those in the movement he claim had undermined negotiations.

Greens founder Bob Brown dubbed Labor’s rejection of no new coal and gas a “colossal mistake”. He warned if climate minister Chris Bowen moves to weaken the hard cap on emissions, “it will bring the house down.”

We’ve seen this kind of backlash before, and it can be dangerous. Similar outrage helped kill the Rudd Labor government’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme.

This is just the start. Having achieved a hard emissions cap, the Greens must ensure the cap actually caps emissions. That it’s set at the right level. And that it can’t be dodged or gamed. Stopping half of the mooted 116 fossil projects is hypothetical right now. Their voters will want them to deliver. ![]()

Kate Crowley, Adjunct Associate Professor, Public and Environmental Policy, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Greens will back Labor’s safeguard mechanism without a ban on new coal and gas. That’s a good outcome

Labor and the Greens have reached a compromise on the safeguard mechanism after months of tense negotiations, giving the government the numbers it needs to pass the bill into law.

Greens leader Adam Bandt on Monday announced his party had secured a hard cap on emissions from polluters covered by the scheme. The cap will potentially affect new or expanding fossil fuel projects. But it falls short of the main concession the Greens originally demanded from Labor – an outright ban on new gas and coal projects.

The safeguard mechanism aims to curb emissions from about 215 of Australia’s biggest polluters. Labor’s tightening of the policy is crucial if Australia is to meet its emissions reduction target of 43% by 2030.

Building a hard emissions cap into the safeguard mechanism will go some way to giving this policy teeth. By limiting emissions to 140 million tonnes – the current emissions from industries covered by the scheme – it will make it harder for new fossil fuel projects to be viable.

How Will The Hard Cap Work?

Under the hard cap, the energy minister of the day will decide whether to permit a new fossil fuel project. The decision will be based on advice from the Climate Change Authority on projected gross emissions – meaning without carbon offsets being used.

The carbon budget for the sector will ensure Australia’s net emissions are in line with the central objective of the policy.

While the cap doesn’t prevent new projects, it does give us a level of confidence that any future projects can’t emit past a certain level.

Some 116 fossil fuel projects are being planned in Australia. Bandt says the cap means half of them will no longer proceed – and projects further along, such as fracking in the Northern Territory’s Beetaloo Basin, may no longer be feasible.

Bandt says Labor “still wants to open the rest” of the 116 projects in the pipeline, adding: “now there is going to be a fight for every new project that the government wants to open”. In reality, history suggests many of these projects would not have proceeded anyway, so we shouldn’t put too much weight on Labor’s concession.

No New Fossil Fuels Was A Hard Sell

From the outset of negotiations, Labor would not budge on the Greens’ demand to ban new coal and gas projects. On Monday, Bandt said trying to strike a deal with Labor was:

like negotiating with the political wing of the coal and gas corporations. Labor seems more afraid of the coal and gas corporations than climate collapse. Labor seems more afraid of Woodside than global warming.

But banning new coal and gas projects is a hard sell.

Fossil fuel projects in Australia have traditionally enjoyed bipartisan support. The Coalition likes them because they support corporations and exports. And many in Labor’s union base like the well-paid, reliable work the mines offer.

And then there’s the simple fact of supply and demand. Right now, the world is still 81% powered by fossil fuels. We have not yet built enough clean alternatives.

Right now, we ship large volumes of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and coal to countries in our region such as China, Japan and South Korea. If Australia banned new gas projects, these exports would be at risk. Our Asian trading partners would probably have to find new suppliers once the long-term contracts ended.

For these reasons and more, the odds were stacked against the Greens and their demands.

Where To Now?

Bandt has rightly pointed to the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which makes it clear the world must stop opening coal and gas mines if it wants to avert the worst damage from climate change.

But for the next few decades, the world is likely to keep using fossil fuels alongside renewables and other clean options. So what options does Australia have to make a significant dent in global emissions?

It should publicly plan to for a future without fossil fuel exports – and work with our fossil fuel customers in Asia to offer them green alternatives.

Australia is well placed to explore industries such as green cement, critical minerals such as cobalt, green iron ore and green hydrogen. If we can ramp these industries up as demand for legacy fossil fuels wanes, we could find a sweet spot.

We should take punts on technologies and products which may – or may not – become vitally important. Not every clean tech development will succeed. But some will.

We want companies such as Nippon Steel to invest in green steel in Australia. We need business leaders to invest in green hydrogen exports – even though there’s a chance of failure.

United States President Joe Biden has embraced this logic. Environmentalists have condemned his approval of new fossil fuel projects. But the Biden administration last year passed a A$530 billion bill to pump huge funds into heat pumps, solar, wind and other clean technologies. If we don’t tackle demand, there will be no way to stop supply.

And Australia must also reduce its own fossil fuel demand, by shifting to zero-emissions in power and transport sectors as quickly as possible.

Do We Now Have A Legitimate Emissions Policy?

The policy outcome announced on Monday will make a major contribution to meeting Australia’s emissions reduction targets, and marks a major jump in climate ambition.

But as ever, the devil can be in the detail. We must wait to see how the reformed scheme, with its new conditions, will work. ![]()

Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia will have a carbon price for industry – and it may infuse greater climate action across the economy

Frank Jotzo, Australian National UniversityAustralia is about to take a big, constructive step on climate change policy: we will have a carbon price for the industry sector, under the safeguard mechanism.

It comes nine years after the Abbott Coalition government abolished Labor’s carbon price. The safeguard mechanism lay as a sleeper for many years – legislated in large parts under the Coalition government, but kept ineffective due to how it was implemented.

The mechanism will become effective as a so-called “baseline and credit scheme”, putting a price signal on about 30% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. It will create a sizeable financial incentive to cut emissions in industry, even though it also relies on land-based carbon offsets.

Under the parliamentary compromise this week between Labor, the Greens and some crossbenchers, the legislation will prescribe that overall emissions from industrial facilities covered by the scheme cannot rise over time.

Implementation of the safeguard mechanism bodes well for future climate policy in Australia. The policy does not have bipartisan support but the Dutton opposition is not vocal about it.

It could be a basis from which to expand sensible economic climate policy instruments to other parts of the Australian economy and infuse greater climate policy ambition throughout.

How The Safeguard Mechanism Will Work

The safeguard mechanism applies to 215 of Australia’s largest greenhouse gas emitters. It requires them to keep their net emissions below a set limit, known as a baseline.

Facilities under the scheme include gas extraction and processing coal mines, factories producing steel, aluminium and cement, and more. Importantly, the electricity generation sector is excluded from the scheme.

The safeguard mechanism covers a smaller share of the economy than the Gillard government’s carbon pricing scheme, which operated from 2012 to 2014. That scheme also covered the electricity sector and some other emissions.

But the trading price of emissions credits under the safeguard mechanism will likely be much higher than under the earlier scheme. It will be capped at A$75 a tonne, with that cap rising over time.

The higher the price, the stronger the financial incentive to cut emissions, such as by investing in low-emissions processes and equipment.

Under the scheme, a facility’s baseline is set depending on the emissions-intensity of the goods they produce and the amount of product they make.

New facilities will get low baselines, reflecting international best-practice in production. The federal government will issue credits to facilities that remain below their baseline emissions. If a facility exceeds its baseline, it must cover the excess by purchasing carbon credits – either from other facilities, or from outside the scheme.

The credits trade at a market price. That creates the financial incentive for everyone in the scheme to cut emissions – either to save money or to make money. In that way, it works like an emissions trading scheme.

But the scheme will not be a source of revenue for government. That has been seen as a political necessity, but it’s also a lost fiscal opportunity.

A Big Role For Offsets

Emissions baselines under the safeguards mechanism will decline by nearly 5% each year. The resulting net emissions by facilities under the scheme is estimated to decline from the current 143 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent to 100 million tonnes in 2030. It is a suitably steep reduction rate, considering industry emissions have been slowly rising.

But facilities will be allowed to emit above the declining baselines, if they offset the excess by buying Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs). These carbon credits are generated by projects in agriculture, forestry and land use. The idea is that emissions reductions that cannot be achieved in industry will be achieved in the land sector and paid for by industry.

There is no limit on how many offset credits industry can use to comply with their baselines. This is unusual for carbon trading schemes internationally. It provides maximum flexibility but also makes for a vulnerability. It is possible that a sizeable share of the overall targeted emissions reductions will come from offset credits.

Australia’s carbon credit system has been accused of not delivering genuine reductions in greenhouses gas emissions in some cases. For example, some offset projects might be granted credits for outcomes such as native vegetation growth that might have happened anyway.

The carbon credit scheme will be tightened following the recommendations of the Chubb review. But doubts will unavoidably remain about whether all credits represent real emissions reductions.

The revised safeguard mechanism will create new demand from industry for offset credits. This will encourage new offset projects, possibly at higher prices.

Nevertheless the ACCU mechanism invariably excludes many emissions reduction options. Additional policy efforts to cut emissions in agriculture and forestry will be needed – as well as in transport, the building sector and electricity.

The Future Of Coal And Gas

The Greens had sought a ban on new coal and gas projects in exchange for supporting the safeguard mechanism bill. So will the policy achieve this? No, though it will make the investment case harder for some fossil fuel projects.

For coal and gas production projects, the mechanism applies only to emissions that arise during the mining of coal and the extraction and processing of gas. It does not apply to the emissions produced when the fuel is burnt for energy, except when the fuel is used by another facility under the mechanism.

So the policy will create a financial disincentive for fossil fuel projects that produce a lot of emissions on site – for example, gassy coal mines and leaky gas extraction. But it does not penalise the fact that fossil fuel is produced.

So what about the amendments negotiated by the Greens – in particular, the “hard cap” on emissions? It means total emissions covered by the mechanism must, by law, fall over time, assessed over rolling five-year periods. The minister will need to be satisfied that the overall emissions objective in the legislation will be met, and may need to change the rules in future if needed.

This is a kind of safeguard on the safeguard mechanism. But it does not amount to a stop to new coal mining and gas production. It will only tend to limit new coal mines and gas fields that have high production emissions – and these face financial disincentives under the safeguards mechanism anyway.

In any case, expansion of coal and gas production is unlikely. Coal demand will decline sharply in Australia as coal power plants get replaced by wind and solar, and the international coal demand outlook is declining. No expansion of Australia’s gas export industry is on the cards; the question is mostly about replacing gas fields that run out.

A question remains how to prepare for the inevitable long-term demise of fossil fuel industries, including whether Australia should in some way constrain fossil fuel production for export. The safeguard mechanism, however, is not the policy to deal with that.

Looking Ahead

The safeguard mechanism will create strong incentives for large industrial emitters to cut emissions. It lays the foundations for a cleaner and more efficient industry sector in Australia.

It positions Australia for future international industrial competitiveness. It will help avoid trade penalties for imports from countries without a comparable carbon policy. It will give advantage to low-emissions production – the only kind viable in a world that acts on climate change.

The safeguard mechanism may also pave the way for carbon pricing beyond the industry sector – possibly with money flowing to government, rather than as a revenue-neutral scheme. More federal level policy effort will be needed right across the economy to complete Australia’s transition to net-zero emissions.![]()

Frank Jotzo, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy and Head of Energy, Institute for Climate Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why Western Sydney is feeling the heat from climate change more than the rest of the city

Milton Speer, University of Technology Sydney; Anjali Gupta, University of Technology Sydney; Joanna Wang, University of Technology Sydney; Joshua Hartigan, University of Technology Sydney, and Lance M Leslie, University of Technology SydneyGlobal warming has led to higher summer temperatures across Sydney over the past 30 years. However, our data analysis shows very hot summer days are becoming much more common in Western Sydney than in coastal Sydney. These hotter summers are also getting longer.

Although January and February are usually the warmest months, Greater Sydney summers now extend from December to March. For example, the city’s record-setting March has been the hottest month this summer. Summers are expanding and winters shrinking across subtropical and temperate Australia.

Our newly published analysis of temperature data from 1962-2021 shows one in ten days in summer reached temperatures of 35.4℃ or more in Western Sydney. That’s a full 5℃ hotter than near the coast, where one in ten days exceeded 30.4℃. One in 20 days reached 37.8℃ or more in the west – the equivalent figure near the coast was 33.6℃.

Furthermore, very hot days have become more common over the past 30 years in Western Sydney, but not near the coast. The difference in maximum temperatures between the regions can be as much as 10℃.

So what explains the startling difference between two parts of the same city? In our research, we show the influence of four climate drivers: El Niño-La Niña, Southern Annular Mode, global temperatures and local Tasman Sea temperatures.

Extreme Heat Is Getting Worse In The West

In our study, we calculated the threshold values for the top 10% and top 5% of summer maximum temperatures (the 90th and 95th percentiles) recorded for coastal Sydney (at Observatory Hill) and Western Sydney (at Richmond, about 50km to the north-west) over the 60 years from 1962-2021.

Comparing the first 30-year period, 1962-1991, to the second 30-year period, 1992-2021, revealed a stark difference in maximum temperature trends in Sydney’s west and nearer the coast.

In Richmond, the number of days with temperatures above 35.4℃ and 37.8℃ increased by 120 days and 64 days, respectively. In contrast, Observatory Hill recorded decreases of 4 and 52 days in days above the 90th and 95th percentiles (over 30.4℃ and 33.6℃).

What Explains These Differences?

Poorly planned development in the west and its distance from coastal sea breezes explains part of the disparity between inland and coastal Sydney. But we also found the increase in extreme heat in Western Sydney is due to Australian climate drivers being amplified by increased global and Tasman Sea temperatures.

Using machine-learning techniques, we were able to attribute temperature differences to the influences of these climate drivers and their interactions with each other. The results show common, highly influential climate drivers for both regions:

the Niño3.4, (an indicator of sea-surface temperatures in the tropical central Pacific Ocean, which drive El Niño and La Niña events)

the Indian Ocean Dipole (the difference in ocean temperatures between the eastern and western sides of the Indian Ocean)

the combination of the Southern Annular Mode (the movement of winds and weather systems to Australia’s south) with the Southern Oscillation (large-scale changes in sea-level air pressure between Tahiti and Darwin)

the combination of global temperature with the Southern Annular Mode.

Tasman Sea and global sea surface temperatures have had far more influence on coastal Sydney than on inland Western Sydney.

Despite the importance of rising temperatures in Sydney and particularly in Western Sydney, there has been little focus on their links with large-scale climate drivers. Our findings underline the worsening situation in Western Sydney compared with coastal Sydney.

Studies that employ machine-learning techniques or comparative analyses are typically done in regions of smaller populations. Western Sydney is home to more than 2.5 million people.

Its economic development and fast-growing population have led to higher concentrations of buildings and man-made surfaces, which absorb and retain more heat. Known as the urban heat island effect, it compounds the impacts of climate change. Development on this scale also presents complex challenges for policy planning and resource management.

What Does This Mean For The People Of Western Sydney?

Identifying the climate drivers that most influence maximum temperatures is crucial for Sydney’s planning. It matters for infrastructure development, health and socioeconomic wellbeing in Western Sydney in particular.

Two-thirds of Sydney’s population growth by 2036 is projected to be in Western Sydney. By then an estimated 3.5 million residents will be exposed to more extreme summer heat.

The escalating climate crisis is widening Sydney’s health and socioeconomic divide. Western Sydney has higher unemployment and a larger proportion of lower-income families than the rest of the city.

It’s imperative to understand how Western Sydney differs from near-coastal Sydney, and to plan accordingly. Some local councils in the west, such as Blacktown, are already trialling heat refuges to reduce the growing risks for residents.

Longer and more intense summers are driving longer heatwaves and droughts. It’s leading to more bushfires of greater intensity, such as the 2019-20 bushfires.

The economic burden of dealing with these disastrous events is increasing. According to the Climate Council, the costs associated with extreme weather events in Australia have more than doubled since the 1970s. Australians are now five times more likely to be displaced by such events than people living in Europe.

The urban heat island effect already permeates Western Sydney. Recent extreme temperatures have been close to the limits of human endurance. The human body’s ability to cool itself declines above 35℃, especially in humid conditions.

The impacts of more frequent extreme heat, compounded by heat island effects, are greatest for vulnerable populations such as children in classrooms without air conditioning or low-income family households. Their situation is in stark contrast to the experience of residents of cooler coastal areas. ![]()

Milton Speer, Visiting Fellow, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney; Anjali Gupta, Lecturer, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, and Researcher, Centre for Forensic Science, University of Technology Sydney; Joanna Wang, Senior Lecturer, School of Mathematics and Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney; Joshua Hartigan, PhD Candidate, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, and Lance M Leslie, Professor, School of Mathematical And Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

2022 was a good year for nature in Australia – but three nasty problems remain

A new report card on Australia’s environment reveals 2022 was a bumper year for our rivers and vegetation – but it wasn’t enough to reverse the long-term decline in plant and animal species.

The analysis was drawn from many millions of measurements of weather, biodiversity, water availability, river flows and the condition of soil and vegetation. The data is gathered from satellites and field stations and processed by a supercomputer.

From the data, we calculate a score between 0 and 10 to determine the overall condition of Australia’s environment.

In 2022, a third and very wet La Niña year brought a strong improvement in several key indicators, leading to a national score of 8.7 out of 10. This is the best score since 2011. But unfortunately, three wicked problems remain.

First, The Good News

By some measures, 2022 was the best year for water availability and plant growth since our national score system began 23 years ago.

New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT enjoyed the highest environmental scores since before 2000. South Australia and Queensland also improved.

Scores for rainfall, river flows and the extent of floodplain inundation were the highest since before 2000 in many parts of eastern Australia. The water supplies of all eastern capital cities all rose and several reached capacity.

Wetland area and waterbird breeding were well above the long-term average. Vegetation density, growth rates and tree cover in NSW and Queensland were the best since before 2000.

It was a bumper year for dryland farmers. Average national growth rates in dryland cropping were a massive 49% better than average conditions. The many full or filling reservoirs are also good news for irrigators.

What About The Losers?

Some regions missed out on the rainfall bonanza, and many environmental indicators declined. They include the Top End in the Northern Territory, southern inland Western Australia and western Tasmania.

Across the NT, low rainfall and high temperatures meant environmental scores once more declined to the low values seen before 2021.

And in areas where rainfall was high, not everyone benefited. Many homes and businesses flooded, and some farmers lost crops or stock.

At the end of 2022, reports emerged that floodwaters were causing so-called “blackwater events” and fish kills in the Murray River. Murky floodwaters also ran into the ocean and smothered seagrass meadows, leading dugongs and sea turtles to starve.

The ocean around Australia was the warmest on record in 2022. The Great Barrier Reef suffered the fourth mass bleaching event in seven years – and alarmingly, the first to occur during a La Niña year, which is usually cooler.

Fortunately, conditions for the remainder of the year favoured coral recovery.

Chronic Ailments

Despite many positive indicators, three severe, chronic and untreated problems continue to weaken our environment: habitat destruction, invasive species and climate change.

The rate of habitat destruction shows little sign of improvement. Much vegetation continues to be removed for new housing, mining and agriculture. Fire activity in 2022 was low, but climate change means bushfires will be back soon, and become more frequent and severe over time.

La Niña is already on the way out, although it will probably take more than one hot and dry year before we experience megafires such as those in the Black Summer of 2019-20.

The scorecard also shows Australia is still struggling to combat pest species. They include fungi, invasive weeds, carp, cane toads, rats, rabbits, goats, pigs, foxes and cats. Every year, about eight million feral cats and foxes kill 1.5 billion native reptiles, birds and mammals.

Climate change remains a huge problem. La Niña normally brings cool conditions and the average temperature last year in Australia was the coolest since 2012. But it was still relatively warm, at 0.5℃ above the long-term average.

The combination of habitat destruction, invasive species and climate change has already decimated many Australian species. In 2022, 30 plants and animals were added to the official list of threatened species.

That’s a 43% increase since 2000, bringing the total number to 1,973. Most species added last year were affected by the Black Summer fires.

Our analysis drew on the Threatened Species Index, which reports with a three-year time lag. In 2019 the index showed a steady decline of about 3% in the abundance of threatened species each year. This is an overall decline of 62% since 2000.

Threatened plants showed the worst decline (72%), followed by birds (62%) and mammals (33%).

We Can Avoid The Worst

Amid the gloom, there are glimmers of hope. Many species feared impacted by the fires proved resilient. Some large new national park areas have been added. Active management is recovering – or at least slowing – the decline of some threatened species, albeit sometimes within the narrow confines of reserves.

Also in 2022, humpback whales were one of the few species in Australian history to be taken off the threatened species list due to a population increase. The species has staged a remarkable recovery since the global moratorium on whaling.

Sadly, there is no fast solution to climate change. Greenhouse gases will linger in the atmosphere for decades to come and further warming is unavoidable. But we can still prevent worse outcomes, by dramatically curbing global emissions.

Australia’s emissions are not falling anywhere near fast enough. They were almost the same in 2022 as in the previous year. And our national emissions remain among the highest in the world per person.

Decisive action is needed. Slowing down habitat destruction, invasive species and climate change is key to preserving our natural resources and species for future generations. ![]()

Albert Van Dijk, Professor, Water and Landscape Dynamics, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University; Geoff Heard, , The University of Queensland; Mark Grant, Ecosystem Science Programs Lead, Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network, The University of Queensland, and Shoshana Rapley, Research assistant, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Torrents of Antarctic meltwater are slowing the currents that drive our vital ocean ‘overturning’ – and threaten its collapse

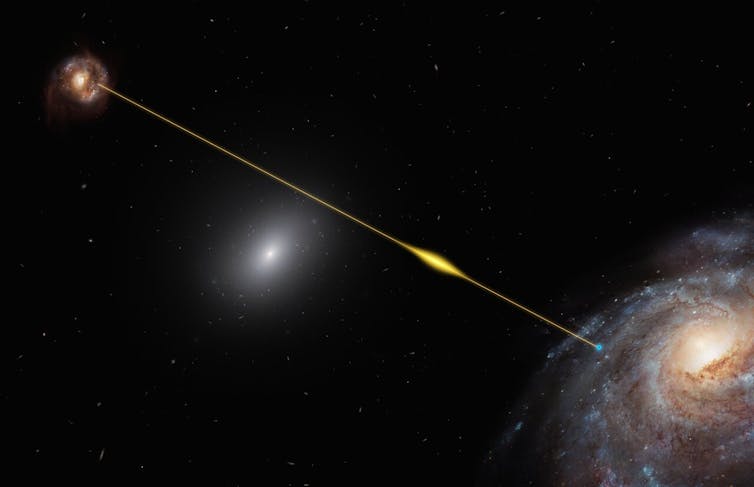

Off the coast of Antarctica, trillions of tonnes of cold salty water sink to great depths. As the water sinks, it drives the deepest flows of the “overturning” circulation – a network of strong currents spanning the world’s oceans. The overturning circulation carries heat, carbon, oxygen and nutrients around the globe, and fundamentally influences climate, sea level and the productivity of marine ecosystems.

But there are worrying signs these currents are slowing down. They may even collapse. If this happens, it would deprive the deep ocean of oxygen, limit the return of nutrients back to the sea surface, and potentially cause further melt back of ice as water near the ice shelves warms in response. There would be major global ramifications for ocean ecosystems, climate, and sea-level rise.

Our new research, published today in the journal Nature, uses new ocean model projections to look at changes in the deep ocean out to the year 2050. Our projections show a slowing of the Antarctic overturning circulation and deep ocean warming over the next few decades. Physical measurements confirm these changes are already well underway.

Climate change is to blame. As Antarctica melts, more freshwater flows into the oceans. This disrupts the sinking of cold, salty, oxygen-rich water to the bottom of the ocean. From there this water normally spreads northwards to ventilate the far reaches of the deep Indian, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. But that could all come to an end soon. In our lifetimes.

Why Does This Matter?

As part of this overturning, about 250 trillion tonnes of icy cold Antarctic surface water sinks to the ocean abyss each year. The sinking near Antarctica is balanced by upwelling at other latitudes. The resulting overturning circulation carries oxygen to the deep ocean and eventually returns nutrients to the sea surface, where they are available to support marine life.

If the Antarctic overturning slows down, nutrient-rich seawater will build up on the seafloor, five kilometres below the surface. These nutrients will be lost to marine ecosystems at or near the surface, damaging fisheries.

Changes in the overturning circulation could also mean more heat gets to the ice, particularly around West Antarctica, the area with the greatest rate of ice mass loss over the past few decades. This would accelerate global sea-level rise.

An overturning slowdown would also reduce the ocean’s ability to take up carbon dioxide, leaving more greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere. And more greenhouse gases means more warming, making matters worse.

Meltwater-induced weakening of the Antarctic overturning circulation could also shift tropical rainfall bands around a thousand kilometres to the north.

Put simply, a slowing or collapse of the overturning circulation would change our climate and marine environment in profound and potentially irreversible ways.

Signs Of Worrying Change

The remote reaches of the oceans that surround Antarctica are some of the toughest regions to plan and undertake field campaigns. Voyages are long, weather can be brutal, and sea ice limits access for much of the year.

This means there are few measurements to track how the Antarctic margin is changing. But where sufficient data exist, we can see clear signs of increased transport of warm waters toward Antarctica, which in turn causes ice melt at key locations.

Indeed, the signs of melting around the edges of Antarctica are very clear, with increasingly large volumes of freshwater flowing into the ocean and making nearby waters less salty and therefore less dense. And that’s all that’s needed to slow the overturning circulation. Denser water sinks, lighter water does not.

How Did We Find This Out?

Apart from sparse measurements, incomplete models have limited our understanding of ocean circulation around Antarctica.

For example, the latest set of global coupled model projections analysed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change exhibit biases in the region. This limits the ability of these models in projecting the future fate of the Antarctic overturning circulation.

To explore future changes, we took a high resolution global ocean model that realistically represents the formation and sinking of dense water near Antarctica.

We ran three different experiments, one where conditions remained unchanged from the 1990s; a second forced by projected changes in temperature and wind; and a third run also including projected changes in meltwater from Antarctica and Greenland.

In this way we could separate the effects of changes in winds and warming, from changes due to ice melt.

The findings were striking. The model projects the overturning circulation around Antarctica will slow by more than 40% over the next three decades, driven almost entirely by pulses of meltwater.

Over the same period, our modelling also predicts a 20% weakening of the famous North Atlantic overturning circulation which keeps Europe’s climate mild. Both changes would dramatically reduce the renewal and overturning of the ocean interior.

We’ve long known the North Atlantic overturning currents are vulnerable, with observations suggesting a slowdown is already well underway, and projections of a tipping point coming soon. Our results suggest Antarctica looks poised to match its northern hemisphere counterpart – and then some.

What Next?

Much of the abyssal ocean has warmed in recent decades, with the most rapid trends detected near Antarctica, in a pattern very similar to our model simulations.

Our projections extend out only to 2050. Beyond 2050, in the absence of strong emissions reductions, the climate will continue to warm and the ice sheets will continue to melt. If so, we anticipate the Southern Ocean overturning will continue to slow to the end of the century and beyond.

The projected slowdown of Antarctic overturning is a direct response to input of freshwater from melting ice. Meltwater flows are directly linked to how much the planet warms, which in turn depends on the greenhouse gases we emit.

Our study shows continuing ice melt will not only raise sea-levels, but also change the massive overturning circulation currents which can drive further ice melt and hence more sea level rise, and damage climate and ecosystems worldwide. It’s yet another reason to address the climate crisis – and fast.![]()

Matthew England, Scientia Professor and Deputy Director of the ARC Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS), UNSW Sydney; Adele Morrison, Research Fellow, Australian National University; Andy Hogg, Professor, Australian National University; Qian Li, , Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Steve Rintoul, CSIRO Fellow, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Indigenous knowledge offers solutions, but its use must be based on meaningful collaboration with Indigenous communities

As global environmental challenges grow, people and societies are increasingly looking to Indigenous knowledge for solutions.

Indigenous knowledge is particularly appealing for addressing climate change because it includes long histories and guidance on how to live with, and as part of, nature. It is also based on a holistic understanding of interactions between living and non-living aspects of the environment.

However, without meaningful collaborations with Indigenous communities, the use of Indigenous knowledge can be tokenistic, extractive and harmful.

Our newly published work explores the concept of kaitiakitanga. This is often translated as guardianship, stewardship or the “principle and practices of inter-generational sustainability”.

We want to encourage Western-trained scientists to work in partnership with Māori and meaningfully acknowledge Māori values and knowledge in their work in conservation and resource management.

Kaitiakitanga Is More Than Guardianship

Indigenous knowledge includes innovations, observations, and oral and written histories that have been developed by Indigenous peoples across the world for millennia.

This knowledge is living, dynamic and evolving. In Aotearoa New Zealand, mātauranga Māori is the distinct knowledge developed by Māori. It includes culture, values and world view.

The concept of kaitiakitanga is often (mis)used in the context of conservation and resource management in Aotearoa. In our work, we highlight how kaitiakitanga is inherently linked to other concepts. It is difficult to translate these concepts directly but they include tikanga (Māori customs), whakapapa (genealogy), rangatiratanga (sovereignty) and much more.

One of the key conceptual differences between kaitiakitanga and conservation is that for kaitiakitanga, we consider being part of te taiao (the environment) and manage our relationships accordingly. Conservation is characterised by humans managing the environment as if they were separate from it.

The Honourable Justice Joe Williams describes kaitiakitanga as “the obligation to care for one’s own”, indicating the intrinsic link between people and the environment.

We caution against simplistic definitions of kaitiakitanga. They often divorce it from its cultural context. Simplistic definitions reduce the richness of the concept and also fail to recognise the differences in how kaitiakitanga is conceptualised and practised.

Instead, we encourage Western-trained researchers to gain a deeper understanding of concepts that underpin kaitiakitanga and work with mana whenua to further develop understanding.

Kaitiakitanga And Conservation In Practice

There is a growing number of examples of successful collaborations between mana whenua and researchers. Exploring these projects will allow researchers to gain insights into how to contribute in an effective and respectful way.

For instance, a study of the traditional harvest and management of sooty shearwater in the Marlborough Sounds shows the importance of including cultural harvest in species conservation management.

Similarly, putting Indigenous knowledge at the centre of the translocation of rare species improves conservation outcomes.

Rāhui In Conservation

Rāhui is a customary process that can be used by mana whenua to restrict access to a certain resource or area of land to allow recovery. It includes an holistic understanding of the environmental problem, and social and political control.

Rāhui has been used to reduce the spread of kauri dieback disease in the Waitakere Ranges. It has also been used to protect kaimoana (including scallops, mussels, crayfish and pāua) on Waiheke Island.

Other examples include rāhui covering forests, lakes, beaches and marine areas for durations from days to decades. Rāhui are widely used but highly specific to local conditions. For iwi to be able to implement rāhui, they need to have rangatiratanga, as kaitiakitanga is both an affirmation and manifestation of rangatiratanga.

An Effective Way Forward

Empowering Māori researchers and communities is central to worthwhile collaborations. We encourage non-Māori researchers to approach partnership with an awareness of the limits of their training and knowledge.

Embracing a mindset of intellectual humility will more likely create conditions for meaningful co-created work. While establishing and maintaining collaborations can be time-consuming, our collective experience is that taking time to develop trust and understanding is essential for successful outcomes.

We hope our work will provide some inspiration and guidance for established practitioners and students alike.

There are a number of other examples of how mātauranga and ecology can work together. The New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research has dedicated a special issue to mātauranga Māori and how it is shaping marine conservation. Others have explored how respectful collaborations can support better teaching of science and better research outcomes.![]()

Tara McAllister, Research Fellow, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Cate Macinnis-Ng, Associate Professor in Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, and Dan C H Hikuroa, Senior Lecturer in Māori Studies, University of Auckland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

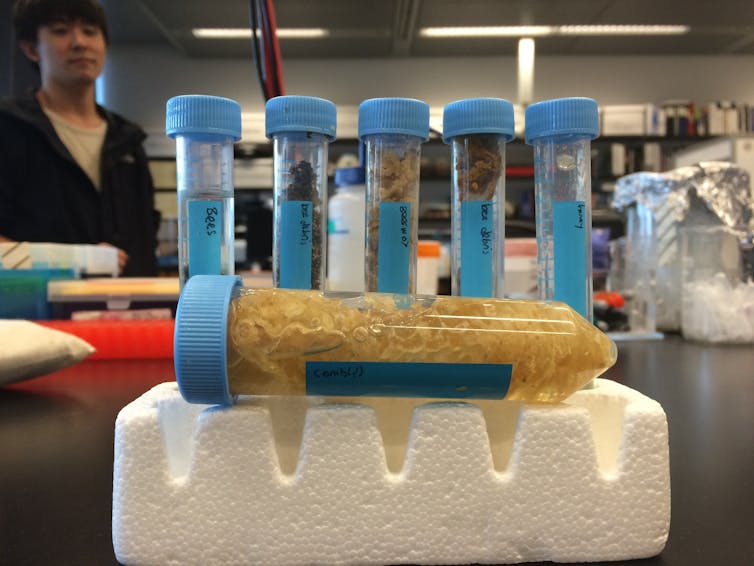

What can’t bees do? Unique study of urban beehives reveals the secrets of several cities around the world

Bees provide myriad benefits to humanity, including pollination services, honey production, food security and crop pollination, artistic inspiration and even career opportunities.

But what if bees could also provide insights into human and city health? A new study published today in Environmental Microbiome shows how honeybee hives reveal information about human health, pathogens, plant life and the environment of different cities.

Our Living Cities

The United Nations predicts nearly 70% of the human population will reside in cities by 2050.

While cities are planned and built with humans in mind, they also act as complex, adaptive ecosystems hosting a diversity of other living organisms. Human health and wellbeing in urban areas can be affected by our interactions with the many invisible things we share our cities with.

It is therefore important to understand what biotic (living organisms such as plants, animals, and bacteria) and abiotic (non-living components such as soil, water and the atmosphere) parts make up our cities. However, to collect such samples from across the city, we need lots of volunteers, time and intensive labour.

Honeybee hives maintained by urban beekeepers could provide a new, more efficient way to sample the urban microbiome – a collection of the local microbes, such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and their genes.

Honeybees As Collaborators

Honeybees often live in hives of 60,000–80,000 individuals. When a bee reaches a certain age in the hive (roughly 21 days), they become a forager. Foragers leave the hive in search of nectar, pollen and other resources.

Researchers enlisted the help of honeybees as data collectors in five cities: New York in the United States, Tokyo in Japan, Venice in Italy, and Melbourne and Sydney. In urban areas, honeybee foragers typically travel approximately 1.5km from the hive to visit flowers.

During these flights they can interact with many biotic and abiotic components of the environment, carrying traces of these interactions back to the hive. In each city, the team took samples of one or more of the following: hive materials including honey, bee bodies, hive debris (accumulation of material under or at the bottom of the hive) and swabs of the hive itself.

The ‘Genetic Signature’ Of A City

The researchers found some unexpected materials in the hives, alongside less surprising results. Hive materials showed plant DNA that varied between cities. In Melbourne, the sample was dominated by eucalyptus, while samples from Tokyo contained plant DNA from lotus and wild soybean, as well as the soy sauce fermenting yeast Zygosaccharomyces rouxii.

Samples from Venice were dominated by fungi related to wood rot and date palm DNA. The samples also contained bee-related microorganisms, indicating both healthy hives and hives with pathogens or parasites, such as Varroa destructor.

The more surprising discoveries included genetic data in the Sydney sample from a bacterial species that degrades rubber, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans. DNA from a pathogen spread to humans via cat fleas called Rickettsia felis was also found in samples, and showed up in Tokyo hives over time.

How Do We Interpret These Results?

The study offers a new and interesting use of honeybee hives in cities – the potential to monitor human health and urban pollution. However, there were some limitations to the work. The differences in microbiomes across cities were based on small sample sizes – one hive in Venice, three in New York, two in Melbourne, two in Sydney and 12 in Tokyo.

Due to these constraints, differences between cities could potentially be attributed to variation in hives and their genetics. Future work using longer-term studies with more hives would help to uncover whether the unique genetic signatures were due to differences amongst cities or between hives or even time periods.

The authors have suggested that honeybee hive debris could provide a snapshot of the microbial landscape of cities. In the future, they argue such methods could even help to monitor antibiotic resistance and the spread viral diseases, but much more sampling and validation will be needed to achieve these goals.![]()

Scarlett Howard, Lecturer, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Attention plant killers: new research shows your plants could be silently screaming at you

If you’re like me, you’ve managed to kill even the hardiest of indoor plants (yes, despite a doctorate in plant biology). But imagine a world where your plants actually told you exactly when they needed watering. This thought, as it turns out, may not be so silly after all.

You might be familiar with the growing body of work that provides evidence for plants being able to sense sounds around them. Now, new research suggests they can also generate airborne sounds in response to stress (such as from drought, or being cut).

A team led by experts at Tel Aviv University has shown tomato and tobacco plants, among others, not only make sounds, but do so loudly enough for other creatures to hear. Their findings, published today in the journal Cell, are helping us tune into the rich acoustic world of plants – one that plays out all round us, yet never quite within human earshot.

Plants Can Listen, But Now They Can Talk!

Plants are “sessile” organisms. They can’t run away from stressors such as herbivores or drought.

Instead, they’ve evolved complex biochemical responses and the ability to dynamically alter their growth (and regrow body parts) in response to environmental signals including light, gravity, temperature, touch, and volatile chemicals produced by surrounding organisms.

These signals help them maximise their growth and reproductive success, prepare for and resist stress, and form mutually beneficial relationships with other organisms such as fungi and bacteria.

In 2019, researchers showed the buzzing of bees can cause plants to produce sweeter nectar. Others have shown white noise played to Arabidopsis, a flowering plant in the mustard family, can trigger a drought response.

Now, a team led by Lilach Hadany, who also led the aforementioned bee-nectar study, has recorded airborne sounds produced by tomato and tobacco plants, and five other species (grapevine, henbit deadnettle, pincushion cactus, maize and wheat). These sounds were ultrasonic, in the range of 20-100 kilohertz, and therefore can’t be detected by human ears.

Stressed Plants Chatter More

To carry out their research, the team placed microphones 10cm from plant stems that were either exposed to drought (less than 5% soil moisture) or had been severed near the soil. They then compared the recorded sounds to those of unstressed plants, as well as empty pots, and found stressed plants emitted significantly more sounds than unstressed plants.

In a cool addition to their paper, they also included a soundbite of a recording, downsampled to an audible range and sped up. The result is a distinguishable “pop” sound.

The number of pops increased as drought stress increased (before starting to decline as the plant dried up). Moreover, the sounds could be detected from a distance of 3-5 metres – suggesting potential for long-range communication.

But What Actually Causes These Sounds?

While this remains unconfirmed, the team’s findings suggest that “cavitation” may be at least partially responsible for the sounds. Cavitation is the process through which air bubbles expand and burst inside a plant’s water-conducting tissue, or “xylem”. This explanation makes sense if we consider that drought stress and cutting will both alter the water dynamics in a plant stem.

Regardless of the mechanism, it seems the sounds produced by stressed plants were informative. Using machine learning algorithms, the researchers could distinguish not only which species produced the sound, but also what type of stress it was suffering from.

It remains to be seen whether and how these sound signals might be involved in plant-to-plant communication or plant-to-environment communication.

The research has so far failed to detect any sounds from the woody stems of woody species (which includes many tree species), although they could detect sounds from non-woody parts of a grapevine (a woody species).

What Could It Mean For Ecology, And Us?

It’s temping to speculate these airborne sounds could help plants communicate their stress more widely. Could this form of communication help plants, and perhaps wider ecosystems, adapt better to change?

Or perhaps the sounds are used by other organisms to detect a plant’s health status. Moths, for example, hear within the ultrasonic range and lay their eggs on leaves, as the researchers point out.

Then there’s the question of whether such findings could help with future food production. The global demand for food will only rise. Tailoring water use to target individual plants or sections of field making the most “noise” could help us more sustainably intensify production and minimise waste.

For me personally, if someone could give a microphone to my neglected veggie patch and have the notifications sent to my phone, that would be much appreciated! ![]()

Alice Hayward, Molecular Biologist, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is ‘climate anxiety’ a clinical diagnosis? Should it be?