Inbox and environment news: Issue 579

April 16 - 22 2023: Issue 579

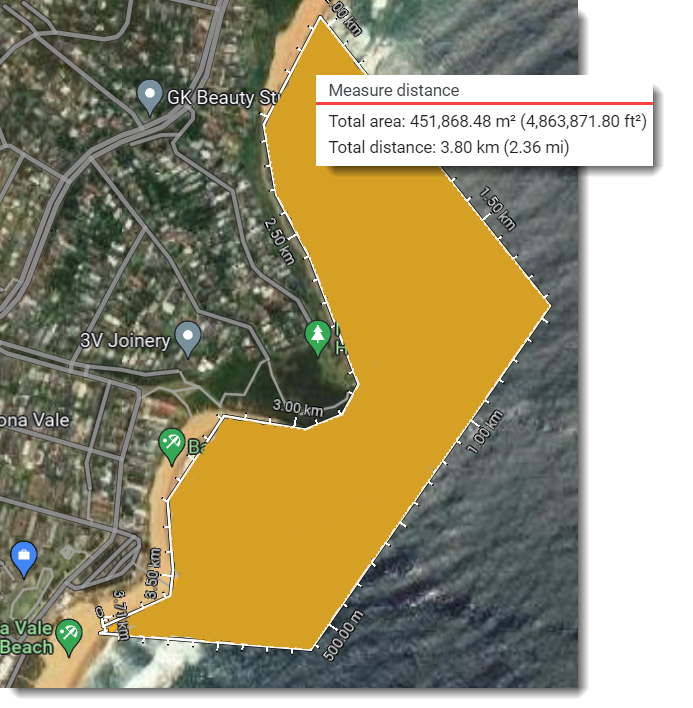

Protect Mona Vale's Bongin Bongin Bay - Establish An Aquatic Reserve

Autumn: Gum Blossom - Fungi Time

'Nature Prescriptions' Can Improve Physical And Mental Health: Study

Environmental Impact Reports Hugely Underestimate Consequences For Wildlife

April 2023

Research shows that environmental impact reports hugely underestimate the consequences of new developments for wildlife. This is because they don't take into account how birds and other animals move around between different sites. The research shows how a planned airport development in Portugal could affect more than 10 times the number of Black-tailed Godwits estimated in a previous Environmental Impact Assessment. The team have been studying these Godwits across Europe for over 30 years but they say that any species that moves around is likely to be under-represented by such reports.

Environmental Impact Assessments may hugely underestimate the effect that new developments have on wildlife, according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

This is because they don't take into account how birds and other animals move around between different sites.

A study published today, April 6th 2023, shows how a new airport development planned in Portugal could affect more than 10 times the number of Black-tailed Godwits estimated in a previous Environmental Impact Assessment.

The research team have been studying these Godwits across Europe for over 30 years but they say that any species that moves around is likely to be under-represented by such reports.

Here in the UK, the environmental impact of a planned tidal barrage across the Wash estuary could similarly be much worse than predicted for wild birds and England's largest common seal colony.

Prof Jenny Gill from UEA's School of Biological Sciences said: "Environmental Impact Assessments are carried out when developments are planned for sites where wildlife is protected.

"But the methods used to produce these reports seldom consider how species move around between different sites. This can drastically underestimate the number of animals impacted and this is particularly relevant for species that are very mobile, like birds."

Josh Nightingale, a PhD researcher in UEA's School of Biological Sciences and from the University of Aveiro in Portugal, said: "We studied the Tagus Estuary in Portugal, an enormous coastal wetland where a new airport is currently planned and has already been issued an environmental license.

"This area is Portugal's most important wetland for waterbirds, and contains areas legally protected for conservation.

"But it faces the threat of having a new international airport operating at its heart, with low-altitude flightpaths overlapping the protected area.

"Black-tailed Godwits are one of several wading birds that we see in large numbers on the Tagus.

"The new airport's Environmental Impact Assessment estimated that under six per cent of the Godwit population will be affected by the plans.

"However, by tracking movements of individual Godwits to and from the affected area, we found that the more than 68 per cent of Godwits in the Tagus estuary would in fact be exposed to disturbance from aeroplanes."

The research team have been studying individual Black-tailed Godwits for three decades, by fitting them with uniquely identifiable combinations of coloured leg-rings.

With the help of a network of birdwatchers across Europe, they have recorded the whereabouts of individual Godwits throughout the birds' lives.

"Many of these Godwits spend the winter on the Tagus Estuary," said Dr José Alves, a researcher at the University of Aveiro and visiting academic at UEA's School of Biological Sciences.

"So we used local sightings of colour-ringed birds to calculate how many of them use sites that are projected to be affected by airplanes. We were then able to predict the airport's impact on future Godwit movements across the whole estuary.

"This method of calculating the footprint of environmental impact could be applied to assess many other proposed developments in the UK, particularly those affecting waterbirds and coastal habitats where tracking data is available.

"Eight environmental NGOs together with Client Earth have already taken the Portuguese government to court to contest the approval of this airport development. We hope our findings will help strengthen the case by showing the magnitude of the impacts, which substantially surpass those quantified in the developer's Environmental Impact Assessment," he added.

Conservation beyond Boundaries: Using animal movement networks in Protected Area assessment' Is published in the journal Animal Conservation.

Nightingale, Josh, Gill, Jennifer A., Þórisson, Böðvar, Potts, Peter M., Gunnarsson, Tomas and Alves, Jose. Conservation beyond Boundaries: Using animal movement networks in Protected Area assessment. Animal Conservation (in press), 2023 DOI: 10.1111/acv.12868

Black-tailed Godwit. Photo: Andreas Trepte

The Black-tailed Godwit is a migratory wading bird that breeds in Mongolia and Eastern Siberia and flies to Australia for the southern Summer. In NSW, it is most frequently recorded at Kooragang Island (Hunter River estuary), with occasional records elsewhere along the coast, including the Sydney basin, and inland. Records in western NSW indicate that a regular inland passage is used by the species, as it may occur around any of the large lakes in the western areas during Summer, when the muddy shores are exposed. The species has been recorded within the Murray-Darling Basin, on the western slopes of the Northern Tablelands and in the far north-western corner of the state.

The black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa) is a large, long-legged, long-billed shorebird first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. It is a member of the godwit genus, Limosa. There are four subspecies, all with orange head, neck and chest in breeding plumage and dull grey-brown winter coloration, and distinctive black and white wingbar at all times.

A large sandpiper reaching 44 cm long, with a wingspan of 63 - 75 cm. It has a distinctive long, straight bill that is pink with a black tip. The wing has a white wing-bar across the dark flight feathers, and white underwing coverts. There is a sharp demarcation between the white rump and the black tail. Legs are greenish-black, long and trailing. The non-breeding plumage, observed in Australia, is greyish-brown above and white below, and a grey breast. There is a broad white stripe on the underwing. The iris is brown. Most readily mistaken for the similar and more common Bar-tailed Godwits Limosa lapponica. Distinguishing features of the Black-tailed Godwit include the black tail in flight; longer, more pink, non-upturned bill; and non-streaked breast. Grey to rufous-chestnut coloured breeding plumage may be visible in some Australian birds just after arrival in spring, or prior to departure in autumn, and in some over-wintering birds.

It is listed as Vulnerable in NSW and Threatened throughout the world. It comes to Australia to feed and rest prior to the northern breeding season.

Activities to assist this species

- Raise visitor awareness about the presence of this and other threatened shorebird species; provide information on how visitors' actions will affect the species' survival.

- Searches for the species should be conducted in suitable habitat in proposed development areas in appropriate time of the year.

- Manage estuaries and inland waterbodies and the surrounding landscape, to ensure the natural hydrological regimes are maintained.

- Protect and maintain known or potential habitats; implement protection zones around known habitat sites and recent records.

- Assess the importance of sites to the species' survival; include the linkages the site provides for the species between ecological resources across the landscape.

We rely on expert predictions to guide conservation. But even experts have biases and blind spots

When faced with uncertainty, we often look for predictions by experts: from election result forecasts, to the likely outcomes of medical treatment. In nature conservation, we turn to expert opinion to assess extinction risk, or predict the long-term responses of plant species to fire management.

But how reliable are these predictions? There’s a well known saying, “Prediction is difficult, particularly when it involves the future”.

In our new research, we put this to the test. We asked eight experienced ornithologists to predict how bird species respond when farmland is revegetated – a common conservation practice.

The result? There was a surprising amount of variation among experts. And there were consistent biases, such as favouring birds commonly seen on farms while underestimating small woodland species. However, when we combined their responses, we got better outcomes.

Does this mean we shouldn’t use such expertise? No. Expert knowledge has a vital role in conservation decisions.

But like anything, it has limitations we should recognise. We should treat expert knowledge as a guide, rather than a source of truth.

How Do You Put Experts To The Test?

Expert knowledge is commonly used for making decisions in conservation, yet it is seldom tested.

We asked our expert ornithologists to predict which bird species would be found at 20 revegetation sites on farms in western Victoria, which were spread across an area of more than 1,400 square kilometres.

We gave each expert detailed information about the sites, including a map, the size of the revegetation plot and when it was planted, the number of tree species planted, and management at the site.

Our experts then had to make judgements about how likely specific bird species were to be detected there. This was based on a list of more than 100 species for each site, which had been recorded in the surrounding district.

Then we compared their predictions with data from bird surveys of the sites – undertaken by different experienced ornithologists – as well as a random selection of bird species.

What did we find? A lot of variation between our experts.

Across the eight ornithologists, the average number of species they considered likely to be detected at sites ranged from 15 to 45. The average recorded from bird surveys was 19.

The predicted composition of the bird community at each site also varied between experts. Some were closer in their predictions than others, but all differed significantly from the community of bird species actually observed.

We All Have Biases – And Experts Are Not Immune

You might wonder if there were similarities in what the experts got wrong. There were.

By and large, our experts overestimated how likely common farmland species – like the galah, eastern rosella, willie wagtail and magpie-lark – would be. They also overestimated the likelihood of larger species that can occur in open country with scattered trees, such as the laughing kookaburra and black-faced cuckoo-shrike.

Why might this be? These species are very visible and common in farm landscapes, but they also range widely and are hence less likely to occur at a particular site while it was being surveyed.

By contrast, our experts tended to underestimate the presence of small woodland birds, such as the brown thornbill, superb fairy-wren, silvereye and grey fantail.

When we combined the expertise of our eight ornithologists, we saw less variability. When grouped, our experts performed much better than a random selection of bird species. Even so, their predictions still differed strongly from those actually observed.

Why does this matter? The loss of woodland birds in farmland areas of southern Australia is a major conservation concern. Revegetation helps restore wooded habitats for such species. These biases could lead to conservation managers discounting the benefits of revegetation for conservation.

The task we gave our experts was not easy. To make reliable predictions is complex. For each species, they had to make multiple judgements. How common is the species in this region? Was the revegetated area likely to provide suitable habitat? How might this species be influenced by the age of the planting and the diversity of tree species? Would it be a resident species, or a visitor? Regular or irregular?

Some of the variation we found is likely due to differing levels of familiarity with the birds of western Victoria. Our experts also had different levels of experience in carrying out surveys and studying birds in revegetated habitats.

What Does This Mean For Our Reliance On Expertise?

Expert knowledge may be the best – or only – source of information for decision making when we need to rely on predictions, where knowledge has to be applied in novel circumstances, or where management involves complex interacting factors.

So how can we improve the accuracy and reliability of expert predictions, given we all have biases and gaps in our knowledge?

Carefully selecting experts based on relevant experience, using a structured protocol to draw out information, and combining knowledge from multiple experts can help.

Where possible, we should seize the opportunity to test expert predictions and identify potential biases. At present, this kind of testing is rare.

Good conservation management benefits from the wealth of knowledge held by experts, but it also depends on evidence from well-designed empirical studies.

Expert predictions are only as good as the data – and the experience – on which their judgements are based. ![]()

Andrew Bennett, Adjunct Professor in Ecology, La Trobe University; Angie Haslem, Research Fellow, La Trobe University; Jim Thomson, Senior Scientist, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, and Tracey Hollings, Associate Research Scientist, Ecological Modelling, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nature is in crisis. Here are 10 easy ways you can make a difference

Last month, Sir David Attenborough called on United Kingdom residents to “go wild once per week”. By this, he meant taking actions which help rather than harm the natural world, such as planting wildflowers for bees and eating more plant-based foods.

Australia should follow suit. We love our natural environment. But we have almost 10 times more species threatened with extinction than the UK. How we act can accelerate these declines – or help stop them.

We worked with 22 conservation experts to identify 10 actions which actually do help nature.

Why Do We Need To Act For Nature?

If you go for a bushwalk, you might wonder what the problem is. Gums, wattles, cockatoos, honeyeaters, possums – everything is normal, right? Alas, we don’t notice what’s no longer there. Many areas have only a few of the native species once present in large numbers.

We are losing nature, nation-wide. Our threatened birds are declining very rapidly. On average, there are now less than half (48%) as many of each threatened bird species than in 1985. Threatened plants have fared even worse, with average declines of over three quarters (77%).

Biodiversity loss will have far-reaching consequences and is one of the greatest risks to human societies, according to the OECD.

The small choices we all make accumulate to either help or harm nature.

Our Top Ten Actions To Help Biodiversity

1. Choose marine stewardship council certified seafood products

Why? Overfishing is devastating for fish species. By-catch means even non-food species can die in the process.

Where to start: Look for the blue tick of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) or the green tick of the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) approval on seafood products where you shop, or use the Australia’s Sustainable Seafood Guide. Certified products are caught or farmed sustainably.

2. Keep your dog on a leash in natural areas – including beaches

Why? Off-leash dogs scare and can attack native wildlife. When animals and birds have to spend time and energy fleeing, they miss out on time to eat, rest and feed their young.

Where to start: Look for local off-leash areas and keep your dog leashed everywhere else.

3. Cut back on beef and lamb

Why? Producing beef and lamb often involves destroying or overgrazing natural habitat, as well as culling native predators like dingoes.

Where to start: Eat red meat less often and eat smaller portions when you do. Switch to poultry, sustainable seafood and more plant-based foods like beans and nuts. Suggest a meatless Monday campaign in your friend and family group chat to help wildlife – and your own health.

4. Donate to land protection organisations.

Why? These organisations protect land in perpetuity. Donations help them expand and do important on-ground biodiversity management.

Where to start: Check out organisations such as the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, Bush Heritage Australia, Trust for Nature, and Tasmanian Land Conservancy.

5. Make your investments biodiversity-friendly

Why? Many funds include companies whose business model relies on exploiting the natural environment. Your money could be contributing. Looking for biodiversity-positive investments can nudge funds and companies to do better.

Where to start: Look at the approach your superannuation fund takes to sustainability and consider switching if you aren’t impressed. You could also explore the growing range of biodiversity-friendly investment funds.

6. Donate to threatened species and ecosystem advocacy organisations

Why? These groups rely on donations to fund biodiversity advocacy, helping to create better planning and policy outcomes for our species.

Where to start: Look into advocacy groups like WWF Australia, Birdlife Australia, Biodiversity Council, Environment Centre NT, and the Environmental Defenders Office.

7. Plant and maintain a wildlife garden wherever you have space

Why? Our cities aren’t just concrete jungles – they’re important habitat for many threatened species. Gardening with wildlife in mind increases habitat and connections between green space in suburbs.

Where to start: Your council or native nursery is often a great source of resources and advice. Find out if you have a threatened local species such as a butterfly or possum you could help by growing plants, but remember that non-threatened species also need help.

8. Vote for political candidates with strong environmental policies

Why? Electing pro-environment candidates changes the game. Once inside the tent, environmental candidates can shape public investment, planning, policy and programs.

Where to start: Look into local candidate and party policies at every election. Consider talking to your current MP about environmental issues.

9. Desex your cat and keep it inside or in a cat run

Why? Research shows every pet cat kept inside saves the lives of 110 native animals every year, on average. Desexing cats avoids unexpected litters and helps to keep the feral cat population down.

Where to start: Keep your cat inside, or set up a secure cat run to protect wildlife from your cute but lethal pet. It’s entirely possible to have happy and healthy indoor cats. Indoor cats also live longer and healthier lives.

10. Push for better control of pest animals

Why? Pest species like feral horses, pigs, cats, foxes and rabbits are hugely destructive. Even native species can become destructive, such as when wallaby populations balloon when dingoes are killed off.

Where to start: Look into the damage these species do and tell your friends. Public support for better control is essential, as these issues often fly under the radar.

Making A Difference

Conservation efforts may seem far away. In fact, our daily choices and actions have a considerable effect.

Talking openly about issues and actions can help these behaviours and habits spread. If we all do a small part of the work and support others to do the same, we will see an enormous effect.![]()

Matthew Selinske, Senior Research Fellow, RMIT University; Georgia Garrard, Senior Lecturer, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University, and Sarah Bekessy, Professor in Sustainability and Urban Planning, Leader, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Scientists Show How We Can Anticipate Rather Than React To Extinction In Mammals

April 10, 2023

Most conservation efforts are reactive. Typically, a species must reach threatened status before action is taken to prevent extinction, such as establishing protected areas. A new study published in the journal Current Biology on April 10 shows that we can use existing conservation data to predict which currently unthreatened species could become threatened and take proactive action to prevent their decline before it is too late.

"Conservation funding is really limited," says lead author Marcel Cardillo of Australian National University. "Ideally, what we need is some way of anticipating species that may not be threatened at the moment but have a high chance of becoming threatened in the future. Prevention is better than cure."

To predict "over-the-horizon" extinction risk, Cardillo and colleagues looked at three aspects of global change -- climate change, human population growth, and the rate of change in land use -- together with intrinsic biological features that could make some species more vulnerable. The team predicts that up to 20% of land mammals will have a combination of two or more of these risk factors by the year 2100.

"Globally, the percentage of terrestrial mammal species that our models predict will have at least one of the four future risk factors by 2100 ranges from 40% under a middle-of-the-road emissions scenario with broad species dispersal to 58% under a fossil-fueled development scenario with no dispersal," say the authors.

"There's a congruence of multiple future risk factors in Sub-Saharan African and southeastern Australia: climate change (which is expected to be particularly severe in Africa), human population growth, and changes in land use," says Cardillo. "And there are a lot of large mammal species that are likely to be more sensitive to these things. It's pretty much the perfect storm."

Larger mammals in particular, like elephants, rhinos, giraffes, and kangaroos, are often more susceptible to population decline since their reproductive patterns influence how quickly their populations can bounce back from disturbances. Compared to smaller mammals, such as rodents, which reproduce quickly and in larger numbers, bigger mammals, such as elephants, have long gestational periods and produce fewer offspring at a time.

"Traditionally, conservation has relied heavily on declaring protected areas," says Cardillo. "The basic idea is that you remove or mitigate what is causing the species to become threatened."

"But increasingly, it's being recognized that that's very much a Western view of conservation because it dictates separating people from nature," says Cardillo. "It's a sort of view of nature where humans don't play a role, and that's something that doesn't sit well with a lot of cultures in many parts of the world."

In preventing animal extinction, the researchers say we must also be aware of how conservation impacts Indigenous communities. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to many Indigenous populations, and Western ideas of conservation, although well-intended, may have negative impacts.

Australia has already begun tackling this issue by establishing Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs), which are owned by Indigenous peoples and operate with the help of rangers from local communities. In these regions, humans and animals can coexist, as established through collaboration between governments and private landowners outside of these protected areas.

"There's an important part to play for broad-scale modeling studies because they can provide a broad framework and context for planning," says Cardillo. "But science is only a very small part of the mix. We hope our model acts as a catalyst for bringing about some kind of change in the outlook for conservation."

Marcel Cardillo, Alexander Skeels, Russell Dinnage. Priorities for conserving the world’s terrestrial mammals based on over-the-horizon extinction risk. Current Biology, 2023; 33 (7): 1381 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.063

Swamp Wallaby At Palm Beach

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Avalon Beach April 30

Come and join us for our family friendly April clean up, close to Avalon Surf Lifesaving Club (558 Barrenjoey road, Avalon) on the 30th at 10am.

We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the ocean. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the beach and even clean up in the water (at own risk). We will clean up until around 11.20, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time. For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages. There is a council carpark, but it is often busy on Sundays, so check streets close by as well if it's full or please consider using public transport.

Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost. All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too!

Permaculture Northern Beaches - Upcoming Events

- Learn about Permaculture design

- Caring for and raising chickens

- Native bees and bee hotels

- Living Skills - soap making

- AND Live Music!

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Weed Of The Season: Cassia - Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Can a ‘nature repair market’ really save Australia’s environment? It’s not perfect, but it’s worth a shot

Australia has embarked on an experiment to create a market for biodiversity. No, we’re not talking about buying and selling wildlife, although, sadly, there is a black market for that. This is about repairing and restoring landscapes, providing habitat for threatened species and getting business and philanthropy to help pay for it.

When Environment and Water Minister Tanya Plibersek introduced the Nature Repair Market Bill to parliament last week, she said:

Just because something is difficult, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do it. It means we should do it properly.

I agree. We have been publishing research on this topic for decades, discussing the issue with scientists, social scientists and economists. Now as chief scientist at the not for profit environmental accounting organisation Accounting for Nature and chief councillor at the Biodiversity Council, we are working hard to help turn the theory into reality.

There is, rightfully, a lot of concern about the integrity of biodiversity markets. However, with appropriate processes in place from governments, including independent authorities that verify biodiversity outcomes, and vigilance from the community, there is potential to create a well-behaved, net-positive biodiversity market in Australia.

What Does A Biodiversity Market Look Like?

Australia has signed up to the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity, which commits us to protecting and restoring 30% of the land for nature. This means 30% of every kind of habitat – it can’t just be deserts and salt lakes, for example.

That’s a big task, and governments can’t do it alone. It’s going to have to be the entire community, every single individual. This isn’t just about protection, a lot will be habitat restoration which needs serious investment.

The general public is increasingly concerned about the decline of nature in their local parks and backyards. One example is a nationwide concern about the disappearance of willie wagtails, a bird many Australians have grown up with. The loss of nature affects everyone, and can harm our mental health. It is not just about threatened species.

Concern for the cassowarry in the wet tropics region of far north Queensland prompted environmental management organisation Terrain NRM (natural resource management) to create a new biodiversity market scheme called Cassowary Credits. Terrain NRM says this is:

a mechanism that enables investors such as governments, philanthropists or corporates to pay landholders and land managers to undertake habitat restoration activities.

Australia has well over half a million different species, and about a third of them have a name. You can’t run a market for that many species – so the challenge will be to develop ways of quantifying biodiversity that are credible and simple.

Trial And Error

A credible market needs a credible biodiversity currency (let’s call it a token). Such a token requires many attributes to make it work. The token should be awarded for measurable outcomes, like an increase in the abundance of hooded robins (a recently listed threatened woodland bird and one of my favourites) on your property, or an improvement in the extent and quality of native vegetation.

These outcomes need to be “additional”, outcomes that would not have otherwise happened without the investment. Ideally outcomes are permanent, and above and beyond what would have happened if we did nothing.

And finally, someone has to want to buy them – there is no point in creating a product when there is no demand. Making a trusted and valuable biodiversity currency is going to take time.

Almost 3,000 years ago the Lydians invented a currency based on metal coins with a ruler’s face stamped on it. That’s still roughly how it works, even with most of our money now being digital, rather than physical in coins and notes. However, even after 3,000 years, money is not yet perfect. Its value constantly changes, and it can collapse, too. There’s still fraud and scams – despite a global army of accountants, financial advisors, mathematicians and lawyers paid to assure integrity.

By comparison, creating a biodiversity market is more complex than stamping a face on a coin. Turning a million-dimensional object – the biodiversity of Australia – into a market will require biodiversity accountants, and biodiversity auditors, and strong laws to govern the new biodiversity markets. However, too much is at stake, and too many species will continue to disappear if we don’t try.

Rivers Of Gold

The government points to a 2022 PricewaterhouseCoopers report that found a biodiversity market could unlock A$137 billion to repair and protect Australia’s environment by 2050.

It sounds fanciful but it could be even bigger than that. The demand is there, internationally, and it’s growing. Can we bring this investment to Australia?

The idea is companies who want to prove they’re “nature positive” will pay for the privilege; some investment could also come from philanthropy. (Notably this is not about “biodiversity offsetting” where people are forced to compensate for the damage they cause.)

The most important issue is integrity – it is transparent proof that actions have delivered additional permanent outcomes – much like biting a coin in 500 BCE to check it is really gold. And that’s the system we’re still struggling to create.

We’re getting there. A lot of smart people in the finance sector and the ecology sector are coming together to resolve some of these issues. I find it both exciting and uncertain.

Time To Be Bold

The federal government’s nature repair bill is not perfect. Many submissions have pointed out problems. But it’s a bold effort. And we need bold efforts like this to start taking off.

When you get down to it, everybody really does care a lot - about huge trees, cassowaries and coral reefs, the nature that inspires them, every single day. We all love willie wagtails and want to make a contribution. While governments still need to massively increase investments to repair landscapes and restore habitat for Australian native species, biodiversity markets could be a big part of a zero extinction Australia. So there’s every reason to give biodiversity markets a go.

Editor’s Note: This article has been adapted from an interview with the author published today on the Eco Futurists podcast.![]()

Hugh Possingham, Professor, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s main iron ore exports may not work with green steelmaking. Here’s what we must do to prepare

Making steel was responsible for about 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. That’s because steelmakers in countries like China, Japan and South Korea have long relied on fossil fuels like coal to make steel in blast furnaces.

But change is coming, as the world works to decarbonise. Researchers and steelmakers are exploring new ways of making steel without using coal.

If the move to green steel gathers speed, Australia could be left behind. That’s because even though we’re the world’s largest exporter of iron ore, some of the new techniques rely on ore with a higher purity than we currently export. Coal exporters could also lose income, as we’re the largest exporter of the coking coal burnt in furnaces using current technology.

To avoid this, we should plan for a green steel future. Our recent report on opportunities for Australian industry to decarbonise suggests this is possible. Australia can make the transition to green steel and remain a major global player.

Why Would Australia Be Affected By A Shift To Green Steel?

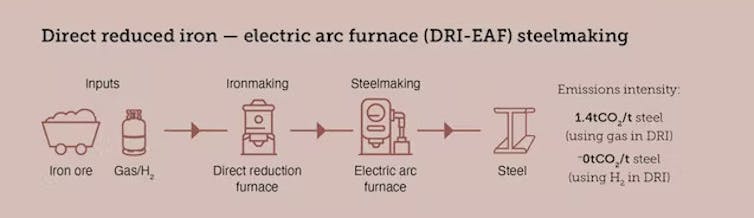

Emerging steelmaking technologies are well along the path to development. Sweden produced the first batch of steel made without coal in 2021.

This steel was made using a direct reduced iron-electric arc furnace process, which can be powered with renewable energy and green hydrogen. While the pilot schemes are promising, this technology could take until the late 2030s to be available at scale.

The problem for Australia is this approach needs high purity ore. At present, the bulk of our iron ore exports would simply not be compatible, as there are too many impurities.

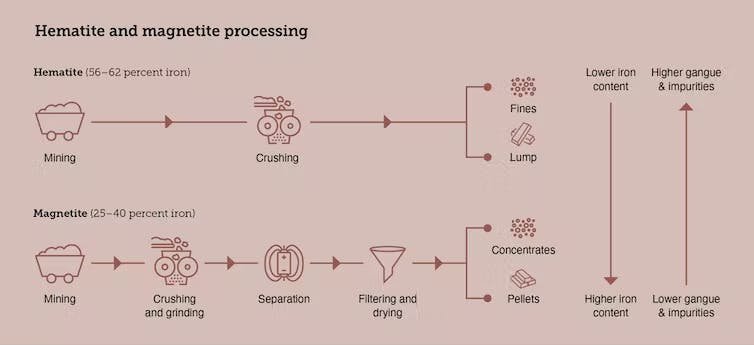

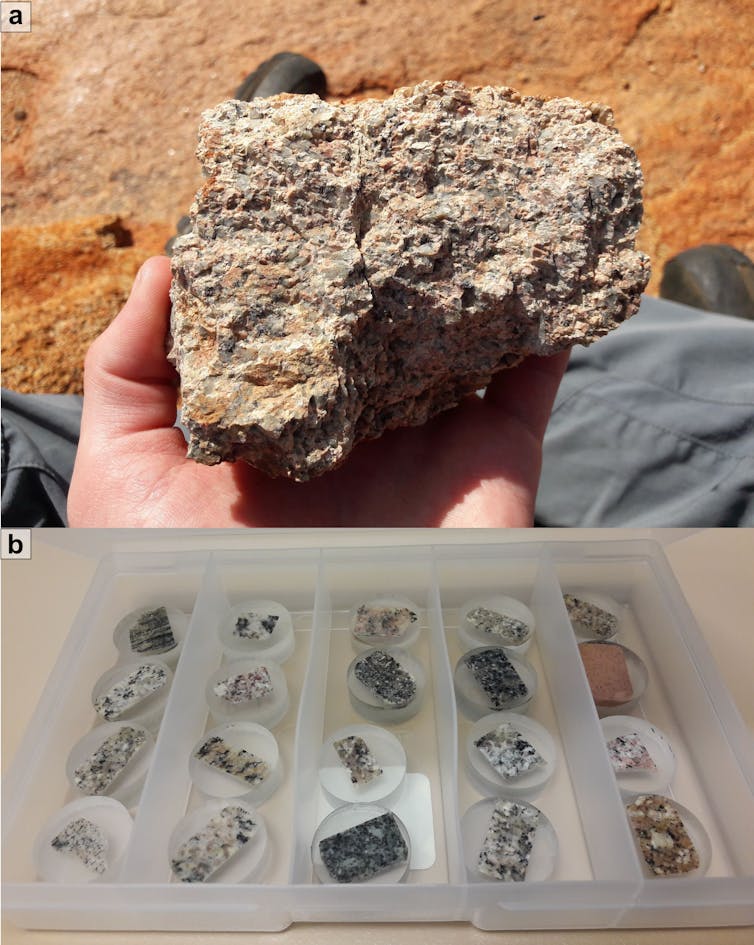

Australia exports two main types of iron ore: hematite and magnetite.

Hematite is mined in Western Australia’s Pilbara. It’s a naturally higher-grade ore (56–62% iron) and makes up almost all (96%) of our exports.

Magnetite is a lower grade ore (25-40% iron) which needs extra processing. This processing, however, produces ore with more iron content, fewer impurities and less waste rock (known as gangue) than hematite.

It’s also, as the name suggests, magnetic. That makes it possible to efficiently separate iron from waste rock using magnets.

Why does this matter? Because this processing converts lower grade iron ore into a product compatible with direct reduced iron-electric arc furnace technology.

You might wonder why it’s important to get rid of waste rock. Doesn’t it slough off in the furnace? In a traditional blast furnace, this is true. But in the direct reduction process, the iron ore doesn’t actually melt. And the next step – the electric arc furnace – can’t handle too many contaminants.

Hematite Or Magnetite?

This leaves us with a predicament.

Our major iron ore export, hematite, won’t be able to supply green steelmakers using one of the leading technologies. But our much smaller ore type, magnetite, could.

If we develop new methods of processing hematite to allow it to be used in green steelmaking, we could keep current mines open and preserve existing markets. But it would mean significant research and development to make possible commercially viable methods.

The other option is to accelerate mining of magnetite, because processing this kind of ore is well understood.

Some Australian miners are already heading down this path. Fortescue’s Iron Bridge magnetite project in the Pilbara is scheduled to begin production this quarter.

Magnetite is also recognised as an opportunity in South Australia, given it makes up 90% of the state’s ore body. The state government has set a target of 50 million tonnes per year by 2030.

To ensure expanded mining of magnetite is sustainable, we need strong benchmarks to limit emissions and broader environmental impacts from new mine facilities.

That’s because the actual mining of iron ore is an emissions-intensive industry, given it relies on heavy machinery. But our modelling shows there are pathways to progress here too, with electrification and fuel switching.

Are Other Green Steel Techniques Better Suited To Pilbara Ore?

The direct reduction method being pioneered in Sweden isn’t the only way to clean up steelmaking.

We looked at a range of potential low-emissions steelmaking techniques, some of which could make use of Australia’s existing hematite exports.

Australian steelmaker Bluescope and multinational miner Rio Tinto are exploring another method, using direct reduction to get rid of oxygen, melting the ore to remove impurities, and then using a basic oxygen furnace to make steel. This, they hope, will let them keep using Pilbara hematite ore.

Other emerging steelmaking techniques, such as electrolytic steelmaking, should also be developed to ensure there are plenty of options for the use of hematite in zero emissions steelmaking in the future.

Fortescue Future Industries recently announced they have succeeded in producing zero carbon iron using an electrolyser and a membrane, but so far have not provided details of the process.

It’s hard to give concrete timelines for these changes, as a transformation at this scale will require coordinated effort. Each of these technologies requires significant investment and a massive build-up of reliable, cost-competitive renewable energy and green hydrogen production.

Planning And Action Is Needed Now

As you would imagine, steelmaking companies plan for their plants to last decades. This timeframe means decisions being made now will affect emissions in the future.

It’s vital Australia is prepared for the shift to green steel. We’ll need a national strategy to futureproof iron ore production, and iron and steel supply chain roadmaps to get suppliers, finance, consumers and decision-makers on the same page in working to take the fossil fuels out of industries.![]()

Tessa Leach, Senior Analyst at Climateworks, Monash University and Tyra Horngren, Senior Analyst (Industry System), Climateworks Centre

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dingo attacks are rare – but here’s what you need to know about dingo safety

Australia has an ambivalent relationship with dingoes – to some they are almost magical representations of our arid landscapes, responsible for holding back a tide of foxes and feral cats, as found in some studies.

To others they are pests, dangerous marauders of our cattle and sheep. We even argue about what to call them. They also loom large in our national conscience as potential killers of children, as shown by a recent dingo attack on a child on K'gari (Fraser Island).

Why Do Dingoes Attack?

Dingo attacks on humans are very rare, and in most cases where humans have been attacked, the dingoes have become habituated to humans and have perhaps lost some fear of them.

This is usually because they have come to associate people with food, though not necessarily as food. This kind of habituation is seen in many animals across the world, including large carnivores such as bears and coyotes in North America, and even spotted hyaenas in Ethiopia.

The recent attack on K’gari has another facet, though. The child was attacked while sitting in shallow water at the beach, and the event highlights that dingoes can be predators. There is no indication the dingo was trying to take food from the child; it’s possible it was tentatively seeing if the child was suitable as prey.

Children As Prey

A 2017 study of dingo attacks on K’gari showed most of the dingoes involved were young ones, and children who were some distance from an adult were often the recipients of attacks.

In 2001, a nine-year-old boy was tragically killed by two dingoes on K’gari when he was standing some distance away from the rest of his family and tripped and fell over. A five-year-old boy who was badly bitten by dingoes on K’gari in 2022 was attacked when his elder brother walked away from him.

In all these cases, although there were other people nearby, the dingoes selected the smallest and most separated person. This suggests that a hunting response was triggered – a child is not much bigger than normal dingo prey (such as wallabies). The dingoes involved were perhaps young and exploratory.

In fact, you can often see such reactions in zoo animals – lions, tigers and other big cats often ignore adult humans looking at them, but become excited when they see a child; the smaller size seems to trigger a predatory response.

How Can You Stay Safe From Dingoes?

The bottom line is dingoes are wild animals and can sometimes act as predators towards us, especially the smallest humans.

Dingoes are found across Australia, though they are less common in pastoral areas where lethal control occurs. They tend to avoid people wherever possible. K'gari dingoes are protected for their high conservation value, because they show little evidence of inbreeding with domestic dogs. As a result, these island dingoes are much bolder. Visitors need to treat them with respect.

So how do we stay safe? We should always be on high alert around such animals, especially in places where dingoes are more common and bolder. As with any wildlife, we should leave dingoes alone as much as possible, and keep a respectful distance. We also should avoid leaving food around, which could attract attention in the first place.

But if you do encounter a dingo (or several), here’s what to do:

- stay alert and keep a safe distance

- avoid being alone or, if in a group, don’t spread too far out

- stay close to any children in your group

- don’t run or turn your back on the dingo, as this may trigger an attack.

People often feel they should not act aggressively if approached by a carnivore, but studies on wolves and pumas suggest that shouting and throwing things is actually more likely to prevent an attack – don’t be afraid to resort to this if you feel threatened.

Anything that makes you, or the people with you, seem less like prey – less enticing – is good. Stay safe, but most importantly, respect these animals for the wild creatures they are.![]()

Bill Bateman, Associate professor, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pragmatism versus idealism? Behind the split between environmental groups and the Greens on the safeguard mechanism

Rebecca Pearse, Australian National UniversityOld tensions emerged between green groups en route to the hard-fought Labor-Greens deal over the safeguard mechanism industrial emissions policy.

At the height of negotiations, the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) started lobbying the Greens to accept a deal. Greens Senator Nick McKim accused the ACF of undermining the Greens’ negotiating strategy and ultimately the legislative outcome, saying:

The environment and climate movement needs to collectively get its shit together. There is a desperate need for a new model of change and the clock is ticking loudly.

These splits are not uncommon, especially when there’s a rare opportunity to actually improve environmental protection.

But why do Australia’s environmental groups disagree over reform?

Who’s Part Of Australia’s Environment Movement, Anyway?

In the late nineteenth century, the nascent green movement was led by naturalists, bushwalkers, adventurers, and government-appointed botanists. They led the first campaigns for national parks and wise use of resources, particularly forestry.

As urban pollution problems escalated into the next century, other reformers led campaigns for better living conditions. We forget now, but it wasn’t that long ago our major rivers were filled with run-off from tanneries and abattoirs and dangerous chemical waste. Epidemics of diptheria, scarlet fever and typhoid spread through growing cities like Melbourne and Sydney.

As development intensified after the second world war, popular environmental campaigns focused on unsustainable resource extraction or destructive forms of development, such as sand mining on Stradbroke Island/Minjerribah and proposed uranium mining in Kakadu. The Greens emerged as a political force from Tasmanian battles such as the plan to dam the pristine Franklin River.

Historically, environmentalists have been members of the professional class. The “social base” of the movement is made up of people with a lot of formal education and jobs such as lawyers, doctors, scientists, public servants and teachers. And today, environmental campaigning is itself a profession.

Many people in the environmental movement are conservative in both senses, wanting to conserve nature as well as maintain current patterns of wealth and privilege. Other environmentalists are progressive, coupling environmental concern with a commitment to social justice and reconciliation. There have also been attempts at green trade unionism like the Green Bans used in conflicts over Sydney’s development in the 1970s.

Pricing Carbon, Dividing Green Groups

The green movement has now split twice over carbon pricing.

In 2009, a group of Australia’s largest environment groups including the ACF and World Wildlife Fund for Nature formed a coalition to try and influence the Rudd government’s carbon pollution reduction scheme.

Ahead of parliamentary debate, these groups came out in support of the scheme. They saw the issue as a trade-off. The movement would agree to lower targets and weaker carbon market rules in return for gaining a framework for carbon regulation. Something was better than nothing, they argued.

But this led to a difficult split. While the largest environmental groups backed the government’s reforms, mid-sized organisations such as Greenpeace disagreed, as did groups like GetUp!, the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, Friends of the Earth and more. They did not want to settle for what they saw as a weak carbon target and flimsy rules for the carbon market.

At the time, the Greens declared the scheme was “worse than doing nothing”.

Sound familiar? We’ve seen a version of this play out in the debate over the safeguard mechanism in 2023. A Labor government, a proposal to cut emissions, environmental group criticism over the weakness of the plan, a push by the Greens party for much more, and a split in the movement.

Just as in 2009, bigger environmental groups such as ACF took the pragmatic view: take what you can get. This is what the Greens have seen as betrayal – and worse, undercutting their ability to negotiate a better deal. But there’s more to it. The groups who backed the carbon market reforms in 2009 have historically been close to Labor or to both major parties.

For their part, the Greens point to their best-ever democratic mandate as evidence of their right to negotiate for a stronger deal on behalf of the movement.

Disputes Are More About Strategy Than Ideology

In their excellent history of Australia’s environment movement, Greens activists Drew Hutton and Libby Connors show the most heated fights are over short- and long-term strategy rather than ideology or political affiliation.

We can see this in the carbon price debate. Since 2011, green groups have been drawn into debate over the design of carbon market instruments. But the economic ideology of solving climate change with market mechanisms is not the main point of debate between groups.

Though ideology and political affiliations certainly shape the situation, most green campaigners identify as pragmatists who simply want the best climate outcome possible.

Today, the broader movement is less torn by the carbon price debates. But the strategic tensions between groups like the ACF and the Greens remain.

Are These Tensions Constructive Or Not?

The environment movement’s current model is pluralist, meaning conservative and progressive campaigners can work alongside one another most of the time. They avoid tensions by focusing on different areas. On climate change, the environment movement works across three distinct arenas: negotiating expansion of renewable energy markets, resisting fossil fuel expansion, and climate policy.

But when a rare chance for large-scale reform emerges, these differences can no longer be avoided.

Bigger groups like ACF and their associated experts are clearly pinning their hopes on winning slow, steady improvements to carbon market regulations over time. By contrast, the Greens and their younger, action-focused supporters have been trying to push hard for tough rules laid down in law rather than regulations, which are easier to change.

So What’s The Solution?

While these groups at times form or disband coalitions around specific debates, it’s fairly ad hoc. By contrast, the longer-established trade union movement deals with frequent ideological, factional and personal differences through caucusing (forming alliances and committees among like-minded people) in order to influence open debate about movement policy.

If green groups negotiate more formally and openly over strategy, it may open up space to become more ambitious.

After all, green groups have much in common. But too often, each group is fighting on its own when they may well be stronger together.![]()

Rebecca Pearse, Lecturer, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Seven ways to recycle heat and reduce carbon emissions

Amin Al-Habaibeh, Nottingham Trent UniversityHeating of space and water in buildings accounts for about 44% of all energy consumed globally according to the International Energy Agency. This heat is still overwhelmingly generated by burning fossil fuels, making it an enormous source of the carbon emissions driving climate change. But you might be surprised to learn just how much heat is wasted each day. Finding ways to recover and recycle it could drastically reduce emissions.

Consider a standard petrol or diesel car. The engine provides the momentum and produces excess heat that a radiator removes. This heat is largely wasted, except in winter when it warms the windscreen and passengers. Generators that supply electricity to the grid work in a similar way – their excess heat could be diverted to heat buildings instead. In the UK, there are many gas engines on standby to supply the power grid when needed. I was part of the team that linked the heat from a gas power generator to a building central heating system.

The idea of combined heat and power is nothing new. In Nottingham, the energy for the city’s district heating network and some electricity comes from a waste incinerator. This also reduces the amount of rubbish sent to landfill. But once you realise just how much heat is out there, waiting to be reused, the problem of decarbonising heating doesn’t seem so mighty. Here are seven examples.

1. Data Centres

Computers processing data get hot – just feel the bottom of a laptop. Data centres are rooms filled with computers that may house the IT servers for an entire office building. The heat they generate is extracted and dumped, usually by energy-hungry air conditioners.

Elsewhere, data centres have been used as “digital boilers” to heat swimming pools. In many cases, cold water runs through pipes between the two buildings where it helps to cool the data centre servers. The heated water is then pumped back to warm the pool.

2. Ice Rinks

Believe it or not, any artificially cooled ice rink produces lots of heat. This is because of the refrigeration cycle that keeps the water you skate on frozen. Think about this process as you would your freezer at home. When you put something at room temperature in the freezer, like a water tray for making ice cubes, the heat is extracted to freeze the water and pumped outside of the fridge. You can feel the side or the back of the freezer getting warmer as this happens.

Similar to data centres, this heat can be captured by circulating water and distributing it via pipes to other parts of the building or buildings nearby.

3. Kitchens And Bathrooms

In most homes, extraction fans and windows remove steam from kitchens and bathrooms. Certain types of ventilation systems can recover the heat from this humid air instead, reducing how much energy is needed for heating. It’s estimated that this could save between 23 and 56% of the cost of an energy bill when combined with other energy-saving measures, such as wall and loft insulation.

4. Wastewater Treatment Plants

Sewage and water treatment plants produce a lot of heat, which is generated from the composting of organic material in sludge (temperatures can reach 70°C). This excess heat can be reused directly or via heat pumps.

5. River And Sea Water

A heat pump works in a similar way to a kitchen fridge, in which the heat is extracted from the food and drink inside and released outside. The temperature of river and sea water changes less between days and seasons than the air, and heat pumps can use these stable water temperatures as a source of heating in winter and cooling during summer. Think about the water bottle inside the fridge as the river water, and the heat pumped outside the fridge as the source of heating for a house.

6. Flooded Coal Mines

The water in coal mines offers an even more efficient solution. Ground temperatures do not change much deeper than 1 metre. At much lower depths, temperatures actually increase. Abandoned coal mines tend to fill with lukewarm water from rain and the water table, and the UK has the equivalent of 400,000 Olympic swimming pools stored in these mines, all at a fairly stable temperature. In winter, when the weather is very cold, this warm water is a suitable source of heat that can be transferred to buildings via heat pumps.

7. You

The average human body emits around 100 watts of heat at rest. When exercising, that heat can reach 1,000 watts: enough to boil one litre of water in six minutes.

When people gather indoors, the heat they emit starts to accumulate. Crowded public places can be used to heat other parts of the same building or adjacent buildings.

Infrared imaging reveals how much heat is typically lost from the buildings we spend much of our lives in. Combined with insulation and some of the technologies discussed here, humanity could meet much of its heating needs without additional sources – and cut one of the biggest sources of climate-warming emissions.![]()

Amin Al-Habaibeh, Professor of Intelligent Engineering Systems, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

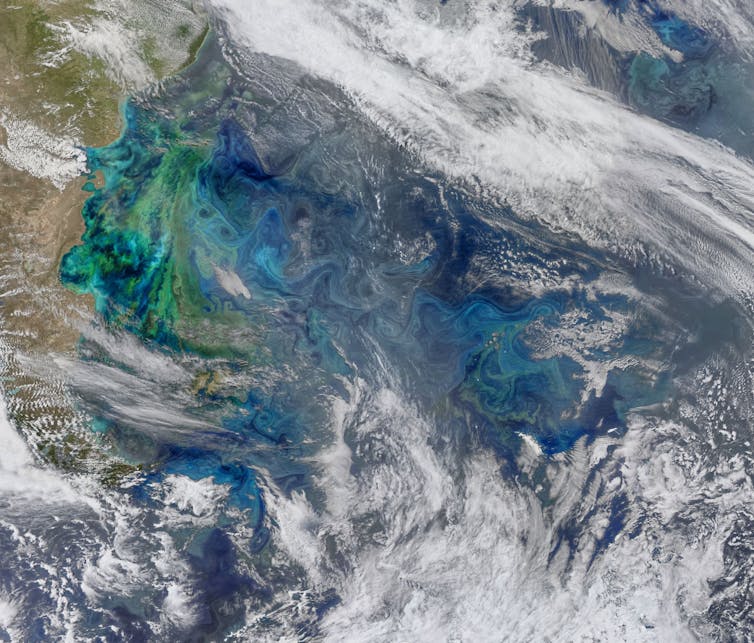

Monsters or masters of the deep sea? Why the deepest of deep-sea fish aren’t as scary as you might think

How deep can fish live in the ocean? That question has captivated me for more than a decade. But my research team’s discovery of the deepest sea fish, announced this week, might not be the final answer. There may be more. How deep – and how strange – remains open for debate.

Last year, my colleagues and I went on an expedition to the deep trenches around Japan. Having already found the Mariana snailfish in 2014 – thought to be the deepest ever – we had a hunch that with more exploration and a better understanding of things like temperature, the Japanese trenches would host a fish at even greater depths.

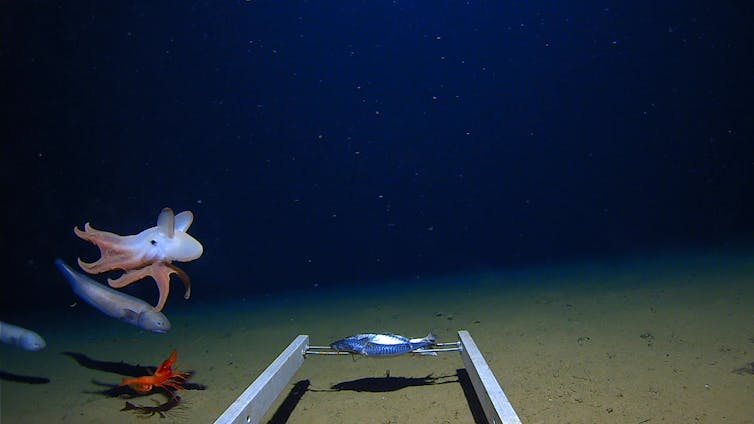

After another 63 deployments of our deep-sea cameras, bringing our total to about 250 across the globe, we hit the jackpot.

We found what is likely a new species of fish in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench and filmed it many times at depths between 6,500 and 8,000 metres. Then, at a staggering 8,336m, a rather unassuming little juvenile slowly swam past the camera, oblivious to the fact it had just become the deepest fish on record.

Much More Than Monsters

If you ask someone what the deepest fish in the world looks like, they will probably conjure up an image of a scaly, black, stealthy creature with bioluminescent lures, large fangs, spiny fins and demonic eyes lurking in the depths waiting to strike at unsuspecting victims. It would be nothing like the shallow-water fish we eat, keep as pets, or pay to see in aquariums. It would be more the stuff of nightmares.

While these sorts of visually striking creatures do exist, they are often not that deep, or that big. Hatchet fish, fangtooth, lanternfish, dragonfish, viperfish and angler fish inhabit the mid-waters of the twilight zone (less than 1,000m deep). Many of these classically spooky monsters are actually very small and are simply enlarged in our imagination, in the absence of any sense of physical scale.

The black body, big eyes, bioluminescent lures and unfamiliar fins and textures are all adaptations to stealthy but efficient living in low-light conditions.

At deeper levels, where low-light adaptations are no longer required (because there’s a total absence of light), marine life takes on different, less dramatic forms. Adaptations to depth, or rather high pressure, are not usually things we can see, but rather changes at the level of cells or body tissues, to enable life at depth.

If we take, for example, the deepest fish, the deepest prawn, the deepest jellyfish, the deepest anemone and the deepest octopus, we find them at depths of 8,336m, 7,703m, 10,000m, 10,900m and 7,000m, respectively (between 4.3 and 6.8 miles deep).

The Deepest Of The Deep

The deepest fish in the world isn’t really a deep-sea fish. They are snailfish in the family of ray-finned fishes called Liparidae. There are more than 400 species of snailfish, and most are found in shallow waters, or even estuaries in some cases. This family of fish has adapted to an array of different environmental settings and habitats, including the deepest.

We found the deepest of all in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench at 8,336m, but this fish does not conform to any preconceived visual impression of what the deepest dweller should look like. They are in fact small, translucent pink, quirky little fish that swim like tadpoles and would not look out of place in a sunlit lagoon.

Similarly, if we look at the deepest of the big crustaceans, which happen to be penaeid prawns (Benthesicymus), there is nothing all that unfamiliar about them. The can be up to a foot long, strikingly red in colour, and swim and behave in exactly the way one would expect a prawn to swim and behave in our coastal regions. It would not look out of place at the local fish market.

The deepest jellyfish looks like a normal jellyfish. The deepest anemones can be found attached to rocks at the very bottom of the Challenger Deep, the deepest place on Earth. These as yet unknown species are attached to rocks that filter food out of the water. They appear more plant-like, resembling delicate and beautiful flowers swaying in the wind.

And then there is the octopus, an animal that has haunted sailors for centuries. In contrast, the newly discovered species of Dumbo octopus (Grimpoteuthis) is a small and cute little cephalopod with fins that resemble big ears (as in Dumbo the elephant). The species was filmed nearly 2,000 metres deeper than any other octopus or squid at a depth of nearly 7,000m.

The True Masters

Essentially, dark-sea creatures in the upper ocean detract from the real deep-sea creatures, giving us a false impression of the natural aesthetic of this community.

While the dark-sea animals have adapted to low light in a way that jars our imagination, the true deep-sea animals represent more of a case of where the wild things aren’t.

The snailfish are the true masters of the deep, not monsters of the deep. If we are to ever truly understand the ocean, and appreciate it as the largest habitat on Earth, we should retrain our brains and realise that even thousands of metres underwater, there are populations of little fish just going about their daily business.![]()

Alan Jamieson, Founding Professor of the Minderoo-UWA Deep-Sea Research centre, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ice Sheets Can Collapse Faster Than Previously Thought Possible

April 2023

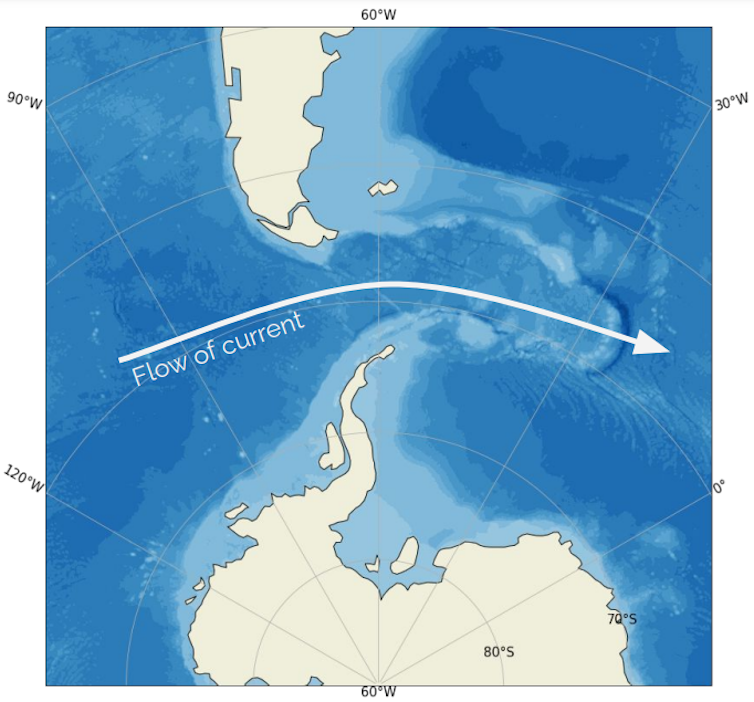

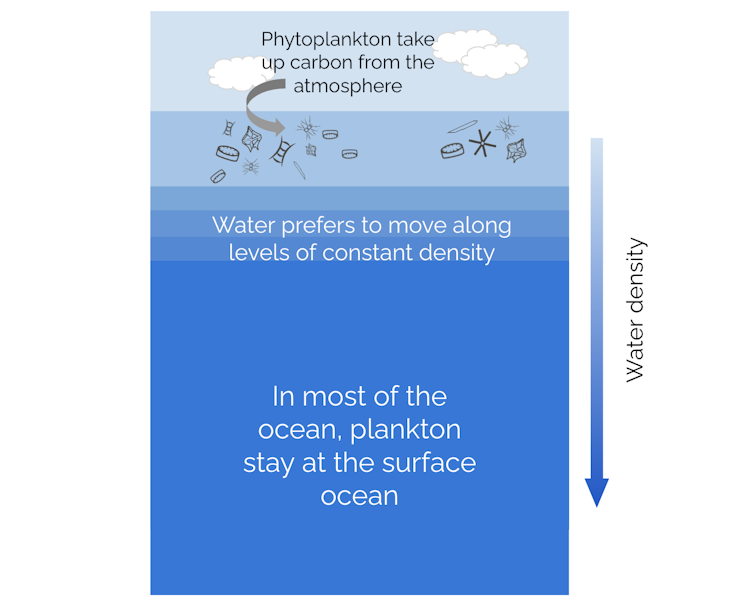

Ice sheets can retreat up to 600 metres a day during periods of climate warming, 20 times faster than the highest rate of retreat previously measured.

An international team of researchers, led by Dr Christine Batchelor of Newcastle University, UK, used high-resolution imagery of the seafloor to reveal just how quickly a former ice sheet that extended from Norway retreated at the end of the last Ice Age, about 20,000 years ago.

The team, which also included researchers from the universities of Cambridge and Loughborough in the UK and the Geological Survey of Norway, mapped more than 7,600 small-scale landforms called 'corrugation ridges' across the seafloor. The ridges are less than 2.5 m high and are spaced between about 25 and 300 metres apart.

These landforms are understood to have formed when the ice sheet's retreating margin moved up and down with the tides, pushing seafloor sediments into a ridge every low tide. Given that two ridges would have been produced each day (under two tidal cycles per day), the researchers were able to calculate how quickly the ice sheet retreated.

Their results, reported in the journal Nature, show the former ice sheet underwent pulses of rapid retreat at a speed of 50 to 600 metres per day.

This is much faster than any ice sheet retreat rate that has been observed from satellites or inferred from similar landforms in Antarctica.

"Our research provides a warning from the past about the speeds that ice sheets are physically capable of retreating at," said Dr Batchelor. "Our results show that pulses of rapid retreat can be far quicker than anything we've seen so far."

Information about how ice sheets behaved during past periods of climate warming is important to inform computer simulations that predict future ice-sheet and sea-level change.

"This study shows the value of acquiring high-resolution imagery about the glaciated landscapes that are preserved on the seafloor," said study co-author Dr. Dag Ottesen from the Geological Survey of Norway, who is involved in the MAREANO seafloor mapping programme that collected the data.

The new research suggests that periods of such rapid ice-sheet retreat may only last for short periods of time (days to months).

"This shows how rates of ice-sheet retreat averaged over several years or longer can conceal shorter episodes of more rapid retreat," said study co-author Professor Julian Dowdeswell of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge. "It is important that computer simulations are able to reproduce this 'pulsed' ice-sheet behaviour."

The seafloor landforms also shed light into the mechanism by which such rapid retreat can occur. Dr Batchelor and colleagues noted that the former ice sheet had retreated fastest across the flattest parts of its bed.

"An ice margin can unground from the seafloor and retreat near-instantly when it becomes buoyant," explained co-author Dr Frazer Christie, also of the Scott Polar Research Institute. "This style of retreat only occurs across relatively flat beds, where less melting is required to thin the overlying ice to the point where it starts to float."

The researchers conclude that pulses of similarly rapid retreat could soon be observed in parts of Antarctica. This includes at West Antarctica's vast Thwaites Glacier, which is the subject of considerable international research due to its potential susceptibility to unstable retreat. The authors of this new study suggest that Thwaites Glacier could undergo a pulse of rapid retreat because it has recently retreated close to a flat area of its bed.

"Our findings suggest that present-day rates of melting are sufficient to cause short pulses of rapid retreat across flat-bedded areas of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, including at Thwaites," said Dr. Batchelor. "Satellites may well detect this style of ice-sheet retreat in the near-future, especially if we continue our current trend of climate warming."

Other co-authors are Dr. Aleksandr Montelli and Evelyn Dowdeswell at the Scott Polar Research Institute of the University of Cambridge, Dr. Jeffrey Evans at Loughborough University, and Dr. Lilja Bjarnadóttir at the Geological Survey of Norway. The study was supported by the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Newcastle University, Peterhouse College at the University of Cambridge, the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, and the Geological Survey of Norway.

Christine L. Batchelor, Frazer D. W. Christie, Dag Ottesen, Aleksandr Montelli, Jeffrey Evans, Evelyn K. Dowdeswell, Lilja R. Bjarnadóttir, Julian A. Dowdeswell. Rapid, buoyancy-driven ice-sheet retreat of hundreds of metres per day. Nature, 2023; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05876-1

The Fimbul Ice Shelf in East Antarctica. Christine Batchelor, Author provided

New research shows how rapidly ice sheets can retreat – and what it could mean for Antarctic melting

The Antarctic Ice Sheet, which covers an area greater than the US and Mexico combined, holds enough water to raise global sea level by more than 57 metres if melted completely. This would flood hundreds of cities worldwide. And evidence suggests it is melting fast. Satellite observations have revealed that grounded ice (ice that is in contact with the bed beneath it) in coastal areas of West Antarctica has been lost at a rate of up to 30 metres per day in recent years.

But the satellite record of ice sheet change is relatively short as there are only 50 years’ worth of observations. This limits our understanding of how ice sheets have evolved over longer periods of time, including the maximum speed at which they can retreat and the parts that are most vulnerable to melting.

So, we set out to investigate how ice sheets responded during a previous period of climatic warming – the last “deglaciation”. This climate shift occurred between roughly 20,000 and 11,000 years ago and spanned Earth’s transition from a glacial period, when ice sheets covered large parts of Europe and North America, to the period in which we currently live (called the Holocene interglacial period).

During the last deglaciation, rates of temperature and sea-level rise were broadly comparable to today. So, studying the changes to ice sheets in this period has allowed us to estimate how Earth’s two remaining ice sheets (Greenland and Antarctica) might respond to an even warmer climate in the future.

Our recently published results show that ice sheets are capable of retreating in bursts of up to 600 metres per day. This is much faster than has been observed so far from space.

Pulses Of Rapid Retreat

Our research used high-resolution maps of the Norwegian seafloor to identify small landforms called “corrugation ridges”. These 1–2 metre high ridges were produced when a former ice sheet retreated during the last deglaciation.

Tides lifted the ice sheet up and down. At low tide, the ice sheet rested on the seafloor, which pushed the sediment at the edge of the ice sheet upwards into ridges. Given that there are two low tides each day off Norway, two separate ridges were produced daily. Measuring the space between these ridges enabled us to calculate the pace of the ice sheet’s retreat.

During the last deglaciation, the Scandinavian Ice Sheet that we studied underwent pulses of extremely rapid retreat – at rates between 50 and 600 metres per day. These rates are up to 20 times faster than the highest rate of ice sheet retreat that has so far been measured in Antarctica from satellites.

The highest rates of ice sheet retreat occurred across the flattest areas of the ice sheet’s bed. In flat-bedded areas, only a relatively small amount of melting, of around half a metre per day, is required to instigate a pulse of rapid retreat. Ice sheets in these regions are very lightly attached to their beds and therefore require only minimal amounts of melting to become fully buoyant, which can result in almost instantaneous retreat.

However, rapid “buoyancy-driven” retreat such as this is probably only sustained over short periods of time – from days to months – before a change in the ice sheet bed or ice surface slope farther inland puts the brakes on retreat. This demonstrates how nonlinear, or “pulsed”, the nature of ice sheet retreat was in the past.

This will likely also be the case in the future.

A Warning From The Past

Our findings reveal how quickly ice sheets are capable of retreating during periods of climate warming. We suggest that pulses of very rapid retreat, from tens to hundreds of metres per day, could take place across flat-bedded parts of the Antarctic Ice Sheet even under current rates of melting.

This has implications for the vast and potentially unstable Thwaites Glacier of West Antarctica. Since scientists began observing ice sheet changes via satellites, Thwaites Glacier has experienced considerable retreat and is now only 4km away from a flat area of its bed. Thwaites Glacier could therefore suffer pulses of rapid retreat in the near future.

Ice losses resulting from retreat across this flat region could accelerate the rate at which ice in the rest of the Thwaites drainage basin collapses into the ocean. The Thwaites drainage basin contains enough ice to raise global sea levels by approximately 65cm.

Our results shed new light on how ice sheets interact with their beds over different timescales. High rates of retreat can occur over decades to centuries where the bed of an ice sheet deepens inland. But we found that ice sheets on flat regions are most vulnerable to extremely rapid retreat over much shorter timescales.

Together with data about the shape of ice sheet beds, incorporating this short-term mechanism of retreat into computer simulations will be critical for accurately predicting rates of ice sheet change and sea-level rise in the future.![]()

Christine Batchelor, Lecturer in Physical Geography, Newcastle University and Frazer Christie, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Cambridge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The UN is asking the International Court of Justice for its opinion on states’ climate obligations. What does this mean?

The United Nations has just backed a landmark resolution on climate justice.

Last week, the UN General Assembly supported a Pacific-led resolution asking the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to provide an advisory opinion on a country’s climate obligations.

This has been hailed as a “turning point in climate justice” and a victory for the Pacific youth who spearheaded the campaign.

But what does this UN decision actually mean? Does an advisory opinion from the ICJ have any teeth? And what might be the legal consequences for rich countries, like Australia, that have contributed the most to the climate problem?

What Is An ICJ Advisory Opinion?

The ICJ is the world court and the leading global authority on international law. It generally hears disputes between countries known as “contentious cases” such as the 2010 case brought by Australia against Japan over whaling in the Southern Ocean. In that case, the court ruled in Australia’s favour.

However, the ICJ can also issue advisory opinions. This is a kind of general advice on the status of international law on a particular topic. Opinions must be requested by one of the organs or specialised agencies of the UN, such as the General Assembly.

On March 29 2023, the UN General Assembly resolved to seek an ICJ advisory opinion on the obligations of states with respect to climate change. That was based on draft text put forward by the tiny Pacific nation of Vanuatu.

Significantly, this resolution was co-sponsored by 105 states, including Australia. It’s the first time the General Assembly has requested an advisory opinion from the ICJ with unanimous state support.

The question put to the ICJ asks whether countries have an obligation to protect the global climate system. It also seeks advice on the “legal consequences” when countries’ actions or omissions cause significant climate harm to small island states and future generations in particular.

The UN will communicate the resolution to the ICJ in coming weeks and the court will then organise hearings over the next few months. It’s expected an advisory opinion will be issued six to 12 months later.

A Win For The Pacific

The adoption of the advisory opinion resolution represents an important milestone in a long-running fight by Pacific small island nations and youth activists to secure climate justice.

For these communities, climate change is already causing or exacerbating harm to natural and human systems. Indeed, only a few weeks before the UN General Assembly decision, a rare double cyclone event ripped through Vanuatu.