Inbox and environment news: Issue 580

April 23 - 29 2023: Issue 580

Autumn In Pittwater

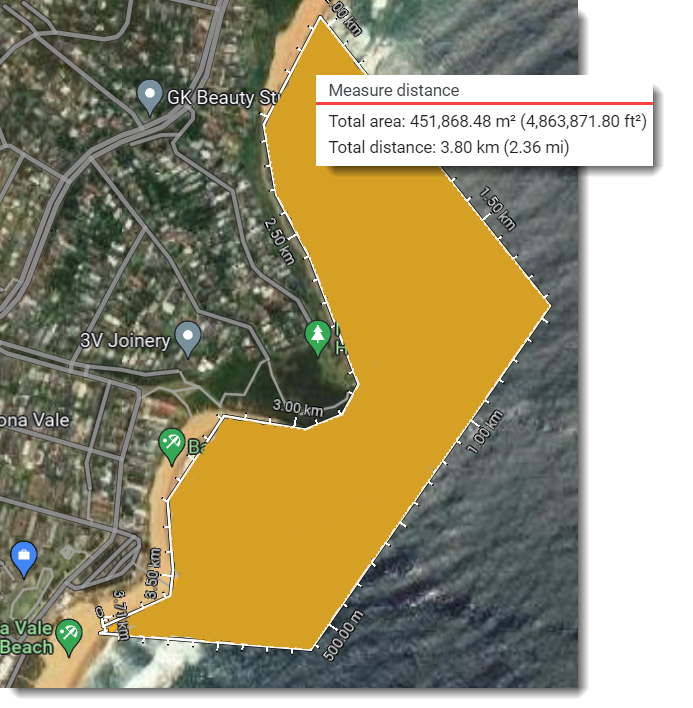

Protect Mona Vale's Bongin Bongin Bay - Establish An Aquatic Reserve

Deep Creek Reserve

April 18, 2023: video by All World Music

Deep Creek Reserve is located along Wakehurst Parkway and is one of the Northern Beaches highest conservation reserves. The reserve contains a small freshwater wetland on the lower section of the reserve which is a form of Sydney Freshwater Wetlands, listed as a Threatened Ecological Community in NSW. This reserve contributes to a regional corridor providing movement for an abundance of native animals including threatened pygmy possums (Cercartetus nanus), powerful owls (Ninox strenua) and heath monitors (Varanus rosengergi).

Sulphur Crested Cockatoo Fledglings Update

The parent bird was feeding the same 2 it has been helping for last few weeks on Tuesday April 18, afternoon - by Wednesday April 19 4pm one has 'flown the nest' and become part of the bigger 'crew' that ranges from Careel Bay to South Avalon Beach and Clareville each day. Just one of the annual stories you get to witness when you keep the trees ;

this one has stayed with parent bird (to right)

the twins

the twins and parent bird

A forgotten and neglected ecosystem covers a third of Earth’s coastlines, with a collective value of $500 billion

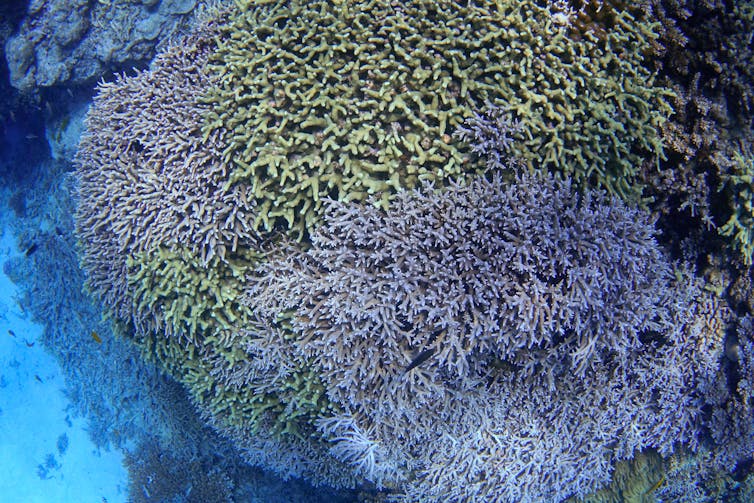

Underwater forests known as kelp have been sustaining people and cultures for millennia. However, most of us are only vaguely aware of the vibrant masses of seaweed hugging the ocean shores around Earth. Furthermore, we don’t realise how valuable and necessary they really are.

In a new study published today in Nature Communications, we have produced the first global estimate of the economic value of kelp forests – revealing they provide hundreds of billions of dollars in value to humans across the world.

A Human History Of Kelp

Along the Pacific, kelp harvest has long played an important role in Asian societies. In Japan, seaweed was among the marine products people could use to pay taxes, according to a law code from the year 701.

In Medieval Europe, kelp was used to fertilise soil and increase crop yields, to treat goitre, and was used to fortify building materials for centuries. In the 21st century kelp forests have become the main source for alginate, a common food and medical additive.

And throughout this time, kelps have supported teeming ecosystems and important fisheries of abalone, lobsters and many different types of fishes. Through their prolific productivity, kelp forests draw carbon from the atmosphere, exude oxygen, and help reduce nutrient pollution in our oceans.

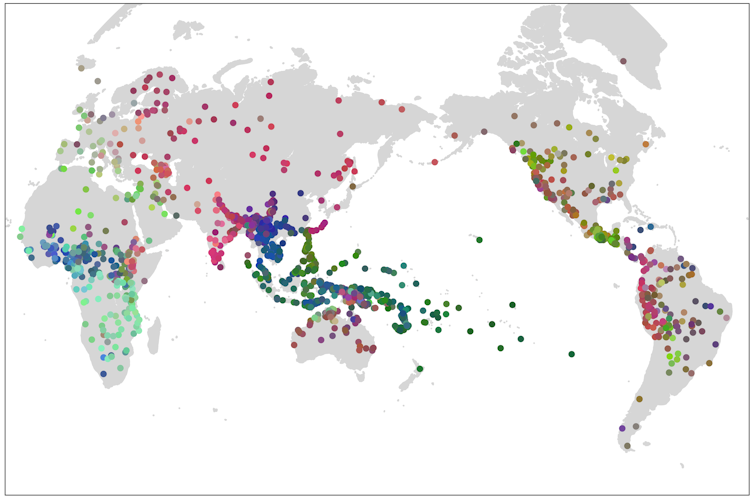

A marine marvel, hidden kelp forests spread across almost one third of our world’s coastlines and lie within 50km of 740 million people. If you live in London, Tokyo, New York, Vancouver, Santiago, Cape Town, Los Angeles or Lisbon, you have one of these ecosystems on your doorstep.

Yet they tend to be forgotten or misunderstood. People often aren’t even aware of a kelp forest, and if they are, they might be most familiar with a pile of decomposing seaweed on the beach after a storm.

This disconnect has real-world implications. Despite sitting next to some of the biggest research centres on the planet and likely covering more seafloor than any other biotic habitat, research and conservation of kelp forests is terribly behind other ecosystems.

This knowledge gap impedes desperately needed action and conservation. Kelp populations in northern California, Tasmania, and the Salish Sea have all but disappeared in living memory. Elsewhere, kelp populations have been continually declining over the last 50 years.

What we value and how we value it is actually quite a complicated process. And despite the fact we make value judgements over and over each day, we have a really poor understanding of something’s value if it doesn’t have a price tag on it.

Our natural world is perhaps the ultimate value provider – everything we do in our societies is ultimately tied to nature, ecosystems, and a healthy planet. But because these processes and benefits happen with or without humans, they are often taken for granted.

So, What Is The ‘Value’ Of A Kelp Forest?

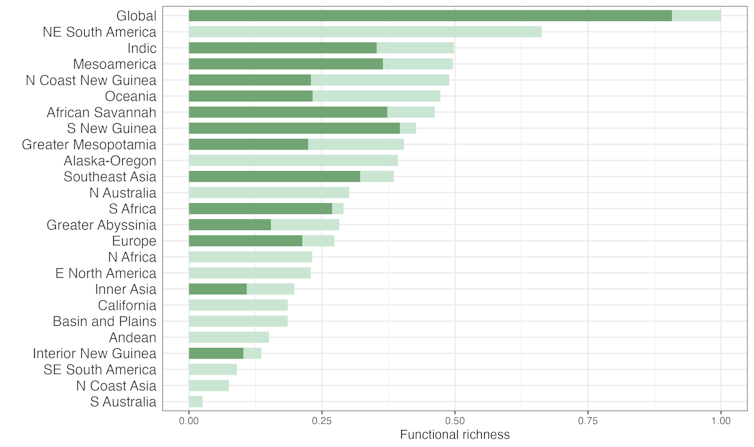

Our research has brought together data from all across our oceans to produce a global estimate of the economic value of kelp forest ecosystems. Looking at six key genera of kelp – Macrocystis, Nereocystis, Laminaria, Saccharina, Ecklonia, and Lessonia – and the potential economic value of the fisheries they support, the carbon they pull from the atmosphere, and the nutrient pollution they remove from the water, we found that kelp forests are valued at US$500 billion per year.

The highest of these values was the removal of excess nitrogen from the water, which can trigger blooms of algae, reduced water quality, and ultimately oxygen-depleted dead zones.

A close second was the fisheries values – kelp forests support some of our most iconic fisheries, including lobster and abalone.

Lastly, despite finding the carbon sequestration of kelp forests was comparable to other terrestrial and marine ecosystems, the economic value was much lower, as society has yet to place a high price on carbon. This finding suggests that carbon credits may not be an economic driver of kelp conservation, but kelp forests still play an important role in the blue carbon cycle.

The Future Of Kelp

When nature is treated as a freebie, where we can take what we want and not pay for the damages, this attitude has direct consequences; people and the environment suffer.

First, it can mean that people and government don’t see the value in protecting and restoring ecosystems. Second, development projects are able to destroy nature without compensating for those damages.

Lastly, it leads to poor management. How can we manage something if we cannot quantify it? Imagine if you didn’t know where your bank account was, or how much money was in it.

The battle to save our kelp forests is just getting started, and we need greater action to protect these intrinsically and economically valuable marine ecosystems.

That is why researchers like me have started the not-for-profit Kelp Forest Alliance, and have now launched the Kelp Forest Challenge, a global call to protect and restore 4 million hectares of kelp forest by 2040. This is a call for governments to meet their commitments to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and act now to save these ecosystems and #HelpTheKelp.![]()

Aaron Eger, Postdoctoral research fellow, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Swamp Wallaby At Palm Beach

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Avalon Beach April 30

Come and join us for our family friendly April clean up, close to Avalon Surf Lifesaving Club (558 Barrenjoey road, Avalon) on the 30th at 10am.

We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the ocean. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the beach and even clean up in the water (at own risk). We will clean up until around 11.20, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time. For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages. There is a council carpark, but it is often busy on Sundays, so check streets close by as well if it's full or please consider using public transport.

Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost. All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too!

Permaculture Northern Beaches - Upcoming Events

- Learn about Permaculture design

- Caring for and raising chickens

- Native bees and bee hotels

- Living Skills - soap making

- AND Live Music!

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Weed Of The Season: Cassia - Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

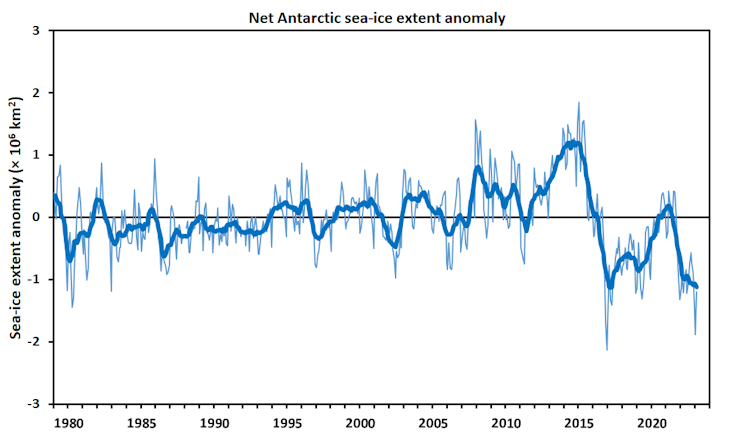

Antarctica’s heart of ice has skipped a beat. Time to take our medicine

The rhythmic expansion and contraction of Antarctic sea ice is like a heartbeat.

But lately, there’s been a skip in the beat. During each of the last two summers, the ice around Antarctica has retreated farther than ever before.

And just as a change in our heartbeat affects our whole body, a change to sea ice around Antarctica affects the whole world.

Today, researchers at the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP) and the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS) have joined forces to release a science briefing for policy makers, On Thin Ice.

Together we call for rapid cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, to slow the rate of global heating. We also need to step up research in the field, to get a grip on sea-ice science before it’s too late.

The Shrinking White Cap On Our Blue Planet

One of the largest seasonal cycles on Earth happens in the ocean around Antarctica. During autumn and winter the surface of the ocean freezes as sea ice advances northwards, and then in the spring the ice melts as the sunlight returns.

We’ve been able to measure sea ice from satellites since the late 1970s. In that time we’ve seen a regular cycle of freezing and melting. At the winter maximum, sea ice covers an area more than twice the size of Australia (roughly 20 million square kilometres), and during summer it retreats to cover less than a fifth of that area (about 3 million square km).

In 2022 the summer minimum was less than 2 million square km for the first time since satellite records began. This summer, the minimum was even lower – just 1.7 million square km.

The annual freeze pumps cold salty water down into the deep ocean abyss. The water then flows northwards. About 40% of the global ocean can be traced back to the Antarctic coastline.

By exchanging water between the surface ocean and the abyss, sea ice formation helps to sequester heat and carbon dioxide in the deep ocean. It also helps to bring long-lost nutrients back up to the surface, supporting ocean life around the world.

Not only does sea ice play a crucial role in pumping seawater across the planet, it insulates the ocean underneath. During the long days of the Antarctic summer, sunlight usually hits the bright white surface of the sea ice and is reflected back into space.

This year, there is less sea ice than normal and so the ocean, which is dark by comparison, is absorbing much more solar energy than normal. This will accelerate ocean warming and will likely impede the wintertime growth of sea ice.

Headed For Stormy Seas

The Southern Ocean is a stormy place; the epithets “Roaring Forties” and “Furious Fifties” are well deserved. When there is less ice, the coastline is more exposed to storms. Waves pound on coastlines and ice shelves that are normally sheltered behind a broad expanse of sea ice. This battering can lead to the collapse of ice shelves and an increase in the rate of sea level rise as ice sheets slide off the land into the ocean more rapidly.

Sea ice supports many levels of the food web. When sea ice melts it releases iron, which promotes phytoplankton growth. In the spring we see phytoplankton blooms that follow the retreating sea ice edge. If less ice forms, there will be less iron released in the spring, and less phytoplankton growth.

Krill, the small crustaceans that provide food to whales, seals, and penguins, need sea ice. Many larger species such as penguins and seals rely on sea ice to breed. The impact of changes to the sea ice on these larger animals varies dramatically between species, but they are all intimately tied to the rhythm of ice formation and melt. Changes to the sea-ice heartbeat will disrupt the finely balanced ecosystems of the Southern Ocean.

A Diagnosis For Policy Makers

Long term measurements show the subsurface Southern Ocean is getting warmer. This warming is caused by our greenhouse gas emissions. We don’t yet know if this ocean warming directly caused the record lows seen in recent summers, but it is a likely culprit.

As scientists in Australia and around the world work to understand these recent events, new evidence will come to light for a clearer understanding of what is causing the sea ice around Antarctica to melt.

If you noticed a change in your heartbeat, you’d likely see a doctor. Just as doctors run tests and gather information, climate scientists undertake fieldwork, gather observations, and run simulations to better understand the health of our planet.

This crucial work requires specialised icebreakers with sophisticated observational equipment, powerful computers, and high-tech satellites. International cooperation, data sharing, and government support are the only ways to provide the resources required.

After noticing the first signs of heart trouble, a doctor might recommend more exercise or switching to a low-fat diet. Maintaining the health of our planet requires the same sort of intervention – we must rapidly cut our consumption of fossil fuels and improve our scientific capabilities.![]()

Edward Doddridge, Research Associate in Physical Oceanography, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

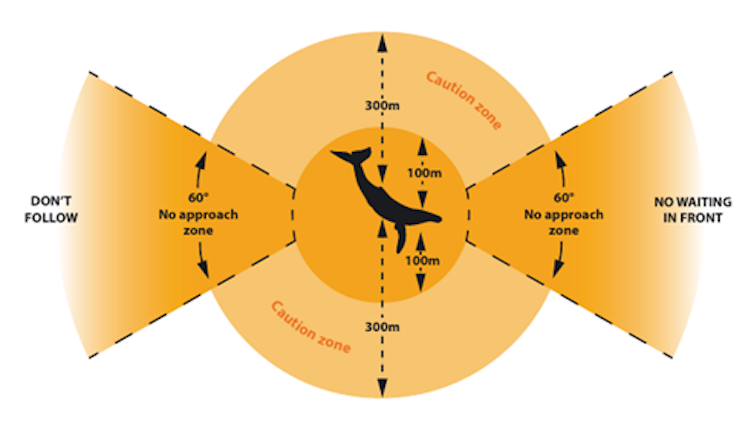

Whale-watching guidelines don’t include boat noise. It’s time they did

Imagine … eco-tourists enjoying views of undisturbed whales and dolphins, watching them doing what comes naturally.

This is ultimately what we all wish to see when spending time in nature watching animals. We can achieve this by using quieter boats.

But why do we need quieter boats? Whales and dolphins primarily use hearing to sense their surroundings (rather than sight like humans do). Sound travels almost five times faster underwater than it does in the air, so it’s an important sense for whales. They rely on sounds to communicate, navigate, feed and detect predators.

Our new research confirms noise from a boat watching whales at a distance of 300 metres can still disturb them. And watching whales involves a lot of boats and millions of tourists each year. This multi-billion-dollar industry is active in waters off more than 100 countries. The Australian whale-watching industry is one of the biggest in the world.

Because the industry actively seeks out whales and dolphins, using quieter boats should be a priority. Yet current whale-watching guidelines, including Australia’s, do not include noise levels. They should.

As the whale-watching season begins in Australia for humpback whales and southern right whales, we offer tips here for individual operators to reduce noise from their boats.

How Does Noise Affect Whales And Dolphins?

Besides income for local communities, whale watching has education and conservation benefits if tourists are inspired to care for the environment.

Despite these benefits, watching whales from a motorised boat and swimming with whales can disturb their natural behaviour. For example, it might prevent them from resting or feeding, or change their breathing, swimming and dive patterns. These impacts are especially important for whales with young.

If the cumulative effects of these short-term impacts are not considered, they can lead to long-term consequences for the animals, such as population declines or leaving an area altogether.

Such outcomes are not only negative for the animals, but also for the whale-watching industry that depends on them.

Whale-Watching Guidelines Overlook Noise Impacts

Many countries have guidelines on the boat’s minimum distance from the animals (typically around 100 metres), the speed at which it passes (typically below wake speed) and the approaching angle (typically from the side-rear). Guidelines, however, do not consider the noise level of the boat’s engine. A very loud boat is, in effect, considered to have the same impact on the animals as a very quiet boat.

Research confirms louder boat noise disturbs whales more than quiet boat noise. Boats should be as quiet as possible.

We recommend a noise threshold be added to whale-watching regulations, ideally around the volume of the natural underwater background noise. At this level, boat noise is perhaps audible to the whales but with a low perceived loudness. This change to the guidelines will help minimise disturbance to whales and dolphins.

You can see how humpback whales change their behaviour in response to low, medium and high underwater boat noise in this video from our study.

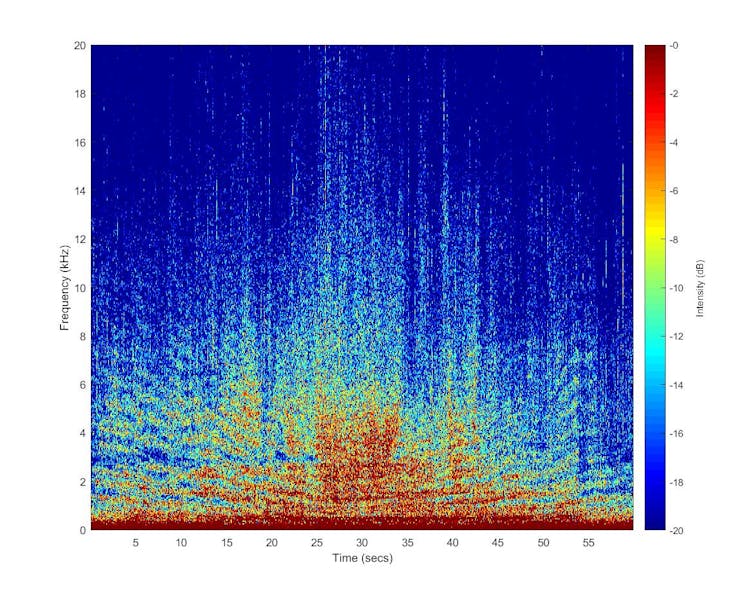

What Do Whale-Watching Boats Sound Like Underwater?

A range of different boats are used for whale watching worldwide. We have calculated the underwater noise level of whale-watching boats operating at low speeds. The quietest boat was a hybrid boat using its electric engines.

The vessel with the quieter electric engines was later used in an experiment with short-finned pilot whales. This study compared the whales’ responses to the boat’s quieter electric engines and its louder petrol engines.

What was the result? The louder engines did indeed disturb the behaviour of short-finned pilot whales compared to the quieter engines. Notably, resting and nursing of young decreased.

Ultimately, some vessels are better designed to minimise noise emissions. You can hear the quieter electric-engined boat in this recording from the study. This makes this boat more appropriate for whale watching.

Noise When Arriving And Departing Matters Too

Having a quiet boat will reduce the disturbance to animals. However, even when a whale-watch operator adheres to current best-practice guidelines, there may still be disturbance.

This is because as a vessel increases in speed to leave the whales, it produces higher underwater noise levels. Our research shows this is likely to disturb whales. So we recommend boats maintain a slow speed when approaching and departing whales – say, less than 10 knots within 1km of the whales.

We know it is exciting to zoom off towards a breaching whale, leaving a sleeping whale behind, but the sudden increase in boat speed and noise may then disturb that sleeping whale.

5 Tips To Reduce Boat Noise

On an individual level, boat operators can easily reduce disturbance to whales and dolphins by considering the following five factors.

Speed increases noise from the propeller, so lower the speed, even when arriving/departing.

Distance: the closer a vessel is the greater the peak in noise, so keep to the regulated distance.

Gear shifts cause high-level noise changes, so minimise shifting.

Approach type to the animals can cause disturbance – driving in front of their path, for example, so drive in parallel to their path.

Movements of a boat, such as fast and erratic movements, can disturb animals, so drive consistently.

To further reduce noise, whale-watching companies can use larger, slower-moving propellers (to minimise the water disturbance that creates noise), quieter/electric engines and/or install noise absorption gear.

Both the industry and the whales will benefit from companies using quieter whale-watch boats and approaches.![]()

Kate Sprogis, Adjunct Research Fellow, UWA Oceans Institute, The University of Western Australia; Fredrik Christiansen, Senior Researcher in Marine Biology, Aarhus University, and Patricia Arranz Alonso, Researcher in Marine Biology, Universidad de La Laguna

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Victoria’s plans for engineered wetlands on the Murray are environmentally dubious. Here’s a better option

Governments love the idea of a win-win – even when it doesn’t exist. That’s why Victoria has been spending millions on planning “red gum irrigation ponds” – essentially, engineered wetlands along the River Murray. These wetlands are designed to save some red gum ecosystems, leave many others to decline, and redirect billions of litres of water promised to the environment to farmers.

Controversy has followed these projects. Now, Victoria appears to have blinked, with the state’s water minister, Harriet Shing, halting the development of four of nine projects.

Victory for environmental water? Not quite. Victoria has spent around A$54 million just on planning these projects. By halting four of them, it sets the scene for a larger-scale federal buyback of water for the environment. This could signal a resumption of the Murray-Darling Basin water wars, with Victoria the last holdout. National Irrigators’ Council chair Jeremy Morton predicted “riot” if further water buybacks went ahead.

What Was Victoria Trying To Do?

Historically, flooding covered 6.3 million hectares of red gum, black box and coolibah forests, lakes and billabongs in the Murray-Darling Basin. These forests rely on regular floods to survive.

But the basin is also home to most of our thirsty crops, from rice to cotton to orchards. The demand for irrigation alongside the long-term drying trend from climate change means something has had to give. You guessed it: it’s the wetlands, which are drying out and dying.

In 2012, state and federal governments launched the Murray-Darling Basin Plan in a bid to solve longstanding tussles over water. The plan was intended to preserve environmental flows while allocating set volumes of water to farmers.

But it’s not working properly. As our research shows, only 2% of the basin’s wetlands have received managed environmental flows each year since.

To keep wetlands alive with less water, there are two basic options: use pulsed flows from dams to flood a larger area, or build floodplain infrastructure to maintain some wetlands while abandoning others.

Victoria has pursued infrastructure. As originally planned, these projects would have meant building $320 million of dams, pumps, levees and roads in conservation reserves to artificially pond water – while leaving less water in the main river channels. Similar projects were proposed in New South Wales at Menindee Lakes, but these are unlikely to proceed.

These projects are greenwashed as “environmental works”. Victoria brazenly calls its plan a “floodplain restoration project”.

It is not. Since the plan began, irrigators have been credited with 605 billion litres of water for 36 largely unimplemented projects under the sustainable diversion mechanism. In November 2022, basin authority chief Andrew McConville laid out the problem:

The credit has been banked, but the payment still needs to be delivered. The payment is in the form of the [wetland] projects being in operation by 30 June 2024.

Water has been credited to irrigators before the wetland projects were built. As a result, actual environmental flows are 19% lower than the Basin Plan target of 3,200 billion litres per year.

Building Wetland Infrastructure Is Unprecedented

Around the world, nations are going the other way to Victoria and removing floodplain infrastructure. In China, across Europe and in the United States, efforts are under way to reconnect rivers to their floodplains. Why? To reduce flood impacts (levees intensify floods downstream), improve water quality, restore flood-dependent ecosystems, make river systems more recreation-friendly and diversify local economies.

Only in the Murray-Darling Basin are we seeing governments building infrastructure for environmental water offsetting on such a huge scale.

And just as controversies have dogged Australia’s attempts to offset biodiversity losses and carbon emissions, there are major problems with water offsetting.

The reason for this offsetting is political, not ecological. In 2012, Victoria’s then water minister, Peter Walsh, stated the plan was meant to:

stop irrigation water being stripped from rural communities and food and fibre producers, and to achieve better environmental outcomes.

In fact, these projects are environmentally dubious. Ponding water on floodplains may meet some ecological targets, but it cannot replicate unconstrained natural floods. Worse, it risks harming ecosystems by upending aquatic food webs and leading to lower native fish populations and worse water quality.

Victoria’s very expensive projects would water only 14,000 hectares of wetlands. By contrast, safe flood pulse releases from existing dams would water 27 times that area – 375,000 hectares.

In his royal commission report into how the Murray-Darling water-sharing system works, Commissioner Brett Walker found there was “real doubt” over whether projects like this were based on the best scientific knowledge.

Our research backs his conclusions. We have found flaws in how these projects are evaluated, which mean their environmental benefits are overstated.

What’s Likely To Happen Now?

Four down – but what about the remaining five projects?

There’s a better option. In 2013, the basin’s governments agreed to a strategy that would allow pulsed releases from existing dams to fill river channels and spill onto the floodplains.

Under this strategy, the Commonwealth would pay for roads and bridges to be removed or raised to make way for restoration of natural floods, and for compensation to landowners.

Our research shows this approach would reduce flood damage by moving infrastructure off floodplains, and allow floods to spread out more, lowering water height and speed. It would also water a much larger wetland area at far less cost. But the strategy has not yet been implemented.

Next month, federal and state water ministers will meet to discuss the failing basin plan. If the new NSW water minister, Rose Jackson, backs her federal Labor colleagues, it will leave Victoria as the last state objecting to water purchases for river restoration.

The federal water minister, Tanya Plibersek, shows every indication of implementing Labor’s 2022 election policy of buying back the remaining water needed to meet the 3,200 billion litre environmental restoration target under the plan. (The federal government has bought back around 2,100 billion litres since 2008.)

The stage is set: will Plibersek prevail and finally achieve long-sought environmental restoration goals under the basin plan, or will Victoria hold out?![]()

Jamie Pittock, Professor, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University and Matthew Colloff, Honorary Senior Lecturer, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Floods of nutrients from fertilisers and wastewater trash our rivers. Could offsetting help?

The rivers running through the hearts of Australia’s major cities and towns are often carrying heavy loads of nutrients and sediments.

This is a problem. While nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus are essential to life in small quantities, in large quantities they become destructive to river and ocean ecosystems.

When rivers are pumped too full of nutrients washing out from farms or from wastewater treatment, bacteria and algae numbers soar. We see the effects in dangerous blue-green algal blooms and in oxygen levels dropping so low that millions of fish can die, as we saw recently in Menindee, New South Wales.

Fixing the problem can be expensive and difficult for landholders. That’s where a new idea could help: nutrient offsetting. Here, large wastewater plants can meet stringent requirements to keep nutrient levels low by fixing eroded riverbanks and gullies upstream, creating wetlands, and preventing fertiliser runoff. The end result: cleaner rivers.

While offsetting schemes for carbon have come under significant scrutiny, nutrient offsetting is a simpler market, with fewer participants and clear ways of measuring success.

Early trials in southeast Queensland by water utilities have proven it can work, as our new report shows.

Why Are Our Rivers Too Full Of Nutrients?

In the early industrial period, rivers around the world were seen as dumping grounds, from factory chemicals to tannery waste. Since then, many countries have worked hard to clean up their waterways, with major successes including the UK’s Thames river.

It’s comparatively easy to stop the dumping of chemicals. You can see the pipes and pinpoint who’s doing it. But nutrient overloading is a harder problem, which is why we’re still wrestling with it.

Our cities and towns are growing. Almost seven million more people live in Australia now compared to the year 2000. As our population grows, we need more food, and we create more human waste. Our agriculture sector has also boomed and is exporting more and more food. To make our famously poor soils fertile requires fertiliser. When too much fertiliser is applied, heavy rains can wash it into rivers. Erosion on riverbanks and in gullies make the problem worse.

Some rivers, estuaries and coastal waters are in real trouble, such as parts of the Murray-Darling, and some urban creeks in our capital cities. We’ve hit their natural limit to handle nutrient loads and gone past it. This can cause algal blooms, fish kills and water too disgusting to drink without expensive treatment.

Why Do We Need Offsetting At All?

Chemical dumping can be solved with laws and enforcement. But while we can fix degraded river catchments to reduce nutrient loads, this is rarely done. That’s because the costs are too high to be borne by any one sector, such as farmers.

By contrast, regulations on nutrients discharged by sewage treatment plants place limits of how much can be released into rivers and estuaries. The costs of further upgrades to sewage treatment plants to reduce nutrients to the required low levels is prohibitively expensive, because ratepayers would end up paying much more for water treatment.

That’s why offsetting can be useful, as it offers a win-win. Urban polluters like wastewater treatment plants can meet their regulatory requirements by restoring eroded and degraded catchment areas upstream to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus flows from farmland. Better, this can be done reasonably cheaply when done at scale. Depending on the available sites, this can be done along rivers and creeks on rural properties, or on council owned land in cities and towns.

Making this viable means using a market. Polluters looking for low-cost ways to comply with regulation of nutrient flows are linked with landholders upstream with degraded land.

This is an emerging solution, but early trials show it has promise. Population-dense south east Queensland has large waterways like the Brisbane and Logan Rivers. Wastewater plant operators such as Logan Water, Urban Utilities and Unity Water have replanted shrubs, grasses and trees along riverbanks, as well as undertaking engineering work to stabilise eroding banks.

This led to significant cost savings. Urban Utilities avoided spending A$8 million in upgrading a sewage treatment plant to cut nutrients and got the same result by spending $800,000 in erosion control and revegetation upriver, which prevented five tonnes of nitrogen entering waterways. Operational costs were also much lower, saving $5 million over ten years.

Controlling erosion keeps nutrients in the soil to help crops and grasses to grow, benefiting farmers, rather than having it washed downstream. Healthier riverbanks create better habitat for birds, reptiles and mammals and makes rivers healthier for fish and other species.

What’s Next?

Nutrient offsetting is still new in Australia. For it to gain traction across Australia means working to make sure the systems and science are mature.

To maximise benefits and give participants certainty, we’ll need to shift from a piecemeal trial approach to a coordinated trading scheme. Successful overseas examples typically have a third party coordinating buying and selling, and ensure there’s a robust structure to set up and assess these projects.

Canada has seen successes here, such as the South Nation River trading program which has reduced phosphorus in the river, while America has examples such as the nutrient credit trading program in Chesapeake Bay. In Australia, a voluntary reef trading scheme is underway in the catchments of rivers flowing into the waters of the Great Barrier Reef, involving farmers and a range of investors.

To make sure this works, we need detailed scientific knowledge on comparing nutrient pollution from different sources. Catchment runoff nutrients are mostly bound to soil particles, while sewage treatment plants have much more dissolved nutrients. As yet we don’t know how these sources differ.

We also need to know what methods of land management are best suited to stopping nutrients from washing into rivers, to ensure the best outcome for the money spent.

Creative Solutions Are Necessary

Despite our efforts in cleaning up many of our rivers, traditional approaches haven’t been enough to stop nutrient pollution. It’s time to explore creative new approaches to make our rivers and reefs healthier.![]()

Michele Burford, Professor - Australian Rivers Institute, and Dean - Research Infrastructure, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Plastic action or distraction? As climate change bears down, calls to reduce plastic pollution are not wasted

Climate change, pollution and overfishing are just a few problems that need addressing to maintain a healthy blue planet. Everyone must get involved – but it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and unsure where to start.

Of course we can start with the obvious - making sure we reduce, reuse and recycle. Yet, given the scale of the challenge, these small, relatively simple steps are not enough. So, how can we encourage people to do more?

There is controversy about the best approach. Some argue focusing on easy actions is distracting and can lead people to overestimate their positive impact, reducing the chance they will do more.

However, our new research found promoting small and relatively easy actions, such as reducing plastic use, can be a useful entry point for engaging in other, potentially more effective actions around climate change.

The Plastic Distraction Debate

Marine plastic pollution is set to quadruple by 2050 and efforts to reduce this have received a lot of attention. In this arena, Australia is making significant progress.

For example, last year scientists discovered the amount of plastic litter found on Australian coasts had reduced by 30% since 2012-13. Seven out of eight Australian states and territories have also committed to ban single-use plastics.

Yet, some scientists are concerned all this fuss about plastic distracts us from addressing the more pressing issue of climate change, which is degrading marine ecosystems at an alarming rate and making oceans hotter than ever before.

For example, without an urgent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, coral reefs could lose more than 90% coral cover within the next decade. This includes our very own Great Barrier Reef.

When it comes to climate action, Australia is behind. Many Australians are also unsure which actions to take. For example, a 2020 study asked more than 4,000 Australians what actions were needed to help the Great Barrier Reef. The most common response (25.6%) involved reducing plastic pollution. Only 4.1% of people mentioned a specific action to mitigate climate change.

‘Spillover’ Behaviour

We ran an experiment to test whether we could shift this preference for action on plastic into action on climate change.

Our experiment was based on a theory known as “behavioural spillover”. This theory assumes the actions we take in the present influence the actions we take in future.

For example, deciding to go to the gym in the morning may influence what you decide to eat in the afternoon.

Some experts argue focusing on reducing plastic use – a relatively simple action – can help build momentum and open the door for other environmental actions in the future. This is known as positive spillover.

Conversely, those in the “plastic distraction” camp argue if people reduce their plastic use, they might feel they have done enough and become less likely to engage in additional actions. This is known as negative spillover.

Experimenting With Spillover From Plastic To Climate

To test whether we could encourage spillover behaviour in the context of the Great Barrier Reef, we conducted an online experiment with representative sample of 581 Australians.

Participants were randomly allocated to one of three experimental groups or a control group. The first group received information about plastic pollution on the reef along with prompts to remind them of their efforts to tackle the problem in the past week (a “behaviour primer”). The second group received the reef plastic information only. The third group received information about the reef and climate change. The control group received general information about World Heritage sites, with no call to action or mention of the Great Barrier Reef.

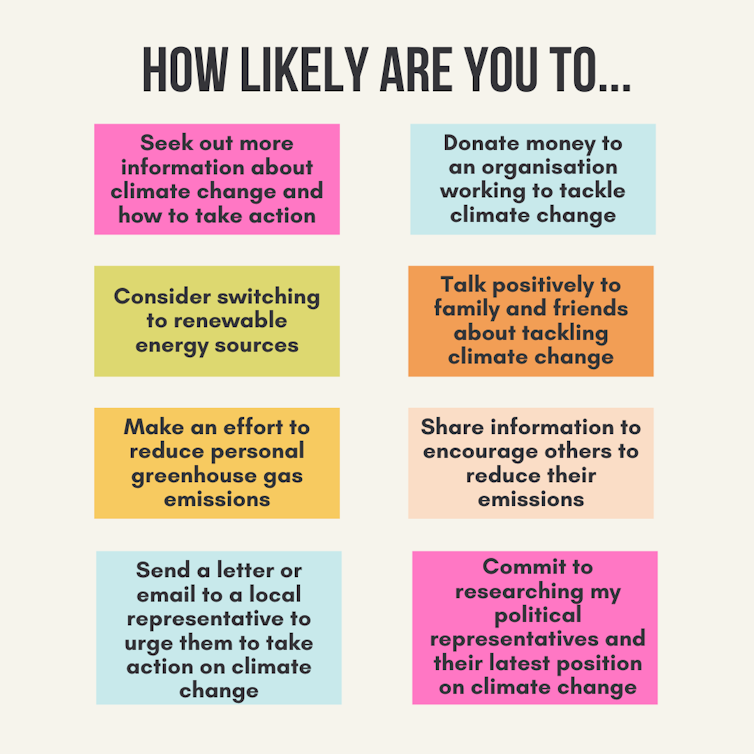

Participants were then asked whether they would be likely to take a range of climate actions, such as reducing personal greenhouse gas emissions and talking to others about climate change. They also had the opportunity to “click” on a few actions embedded within the survey such as signing an online petition for climate action.

Compared to the control group, those provided with information about plastic pollution were more willing to engage with climate actions, particularly when they were reminded of positive past behaviours. Whereas those provided with information about climate change showed no significant difference.

Plastic messages also had a stronger positive effect on climate action for those who were politically conservative, compared to those more politically progressive.

But the approach didn’t work for everyone. We repeated the experiment with 572 self-identified ocean advocates, many of whom already engaged with marine conservation issues. For this audience, talking about plastic and their past efforts made them less likely to engage with climate action compared to the control group.

So What Does All This Mean?

Our results suggest it’s possible to motivate climate action for the reef without slipping back into conversations about plastic. Here are four ways to help achieve this:

Remind people of the small actions they already take: reminding people of their positive contributions and making them feel like they are capable of doing more can open the gateway to further action.

Connect the dots between plastic and climate: plastics are primarily derived from fossil fuels and production alone accounts for billions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year. Making it clear that a fight against fossil fuels is a fight against both plastic and climate can help guide people towards those extra climate actions.

Provide clear calls to (climate) action: research shows most people are unable to identify climate actions on their own. As a result, they tend to get stuck on common behaviours such as recycling. Giving people clear advice on how they can contribute to mitigating climate change is crucial.

Know your audience: spillover from plastic to climate is more likely in a general audience. If your network is full of ocean advocates, it might be better to skip the plastic conversation and dive straight into conversations about climate change actions.

It’s important to remember that people’s first steps don’t have to be their only steps. Sometimes, they just need a little guidance for the journey ahead.![]()

Yolanda Lee Waters, PhD Candidate and Research Assistant, The University of Queensland and Angela Dean, Lecturer, School of Agriculture and Food Science & Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We need a National Energy Transition Authority to help fossil fuel workers adjust

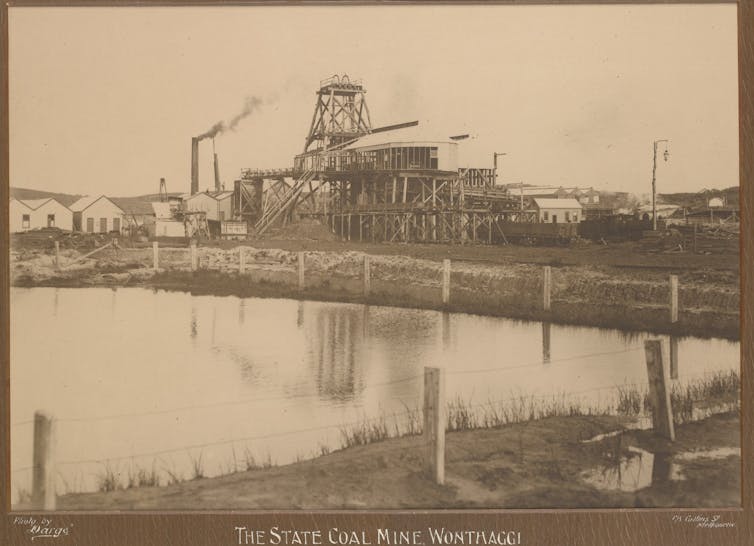

Fergus Green, UCLAustralia’s coal-fired power stations are exiting the grid. This transition is already well underway, as cheaper renewables displace coal and older generators close. Australia’s oldest coal plant, Liddell, is about to close. Eleven coal-fired power plants closed between 2013 and 2020, and at least seven others are slated to close between now and 2030.

Closing a power station sounds bloodless. But if it’s not done well, it can be devastating for affected workers and their families, and economically and socially disruptive to the communities in which they are based. Many towns grew up around coal mines and power plants. We cannot simply leave it to the market to smooth the transition.

To better manage the vital human part of our transition to a low-carbon electricity system, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) recently proposed a solution. It called on the federal government to establish an independent National Energy Transition Authority.

This is an excellent idea, and well overdue given the rate at which our coal plants are closing. Countries that have embraced this approach, such as Spain, have seen the benefits, economic, social – and even political.

What Would This Authority Do?

An energy transition authority, as envisaged by the ACTU, would have three main functions:

develop schemes to support affected workers, including through redeployment into similar facilities, or retraining and recruitment into sustainable industries

support, coordinate and partly finance plans to develop new industries in coal-dependent regions such as Gippsland in Victoria and the Hunter Valley in New South Wales, including attracting federal and state investment and incentives to drive investment in local sustainable industries

ensure education and training programs and infrastructure are in place to support industrial diversification in these regions.

Do We Actually Need A New Authority?

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen proposals for authorities like this. The union movement has proposed several variants in the past, and Labor backed a similar initiative before the 2022 federal election.

After it won government, Labor set up a net zero economy taskforce aimed at advising on how to best support regional communities during the low-carbon transition.

The Greens have also proposed an expanded version of this authority, which would take on extra advisory and law-reform functions. An inquiry into the Greens’ proposed bill by a Labor-majority committee last month described the measure as “premature”, given the government’s taskforce is exploring options to help regions.

Labor, of course, would prefer its own version gets up. That’s entirely possible – the proposed authority has broad support beyond the labour movement.

But some have been critical, with Australian Energy Council experts questioning whether such an authority would be needed, given regional development programs already exist.

Regional industrial transitions are complex, requiring sustained governance over long periods. Australia’s existing programs are not enough, and are often fragmented across a patchwork of federal, state and local government departments.

A new federal authority would help coordinate existing programs across all levels of government, bring the additional capabilities of the federal government, and take a sustained, long-term focus to the challenging task of regional transition.

In a few weeks, we’ll find out whether the Albanese government decides to fund such a body in its May budget.

The Moral Case For A Transition Authority

An authority dedicated to smoothing the path of the energy transition is, in my view, justified on moral grounds. It would elevate the voices of workers and regional communities who are most affected by the low-carbon transition, helping to ensure the benefits and burdens of the transition are fairly shared.

Those whose jobs are at risk have a moral claim to government support to help them adjust to these changes. But so do residents in these regions who never enjoyed the benefits of highly paid unionised jobs in the fossil fuel industry in the first place. They, too, should share in the benefits.

That’s why the ACTU is right to propose a wider, community-level mandate for the authority, to spur regional development that’s not only more environmentally sustainable but also more socially diverse.

The Political Case

Residents of coal and gas regions are often sceptical of the low-carbon transition, and may view it as a threat. An authority like this could build local support by demonstrating what comes next.

In Spain, for instance, the incumbent Spanish Socialist Party is reaping the political benefits of the “just transition agreement” it negotiated with unions, employers and community representatives in coal regions in 2018.

This agreement made clear coal-mining would be phased out by the end of 2019. In return, the government agreed to provide €250 million (A$407 million) in support for workers and community-level investment over the next eight years.

At the April 2019 national election, the incumbents won. Interestingly, our research found their vote share in coal-mining regions covered by the agreement increased relative to comparable rural areas not covered.

Spain and Australia obviously have different political contexts. But our research does suggest there are potential political benefits – not just costs – on offer to governments that provide climate leadership grounded in a just-transition strategy.

An Australian transition authority will only be politically successful if it works with local bodies with similar mandates, such as the Latrobe Valley Authority and the Collie Delivery Unit – or helps establish them.

Working with locally supported groups is common sense. It is also backed up by research showing that fossil fuel communities do not like the idea of having their futures dictated to them by Canberra. But if they feel heard and see their concerns tackled in the transition, they are more likely to be supportive.

For years, organisations such as The Next Economy and the Real Deal project have been working on the energy transition in communities like Gladstone, one of the Queensland towns most reliant on gas and coal. This community-building expertise would be vital for the authority to draw on.

From The Power Stations To The Mines?

If Australia creates an energy transition authority, the immediate task is to help catalyse just and politically smooth transitions in coal power-generating regions.

But there’s a bigger task lying ahead. Australia’s domestic emissions are dwarfed by the emissions from its coal and gas exports. If the authority proves itself, it could begin to support workers and communities to wind down Australia’s export-oriented coal mines and fossil-gas production industries.![]()

Fergus Green, Lecturer in Political Theory and Public Policy, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

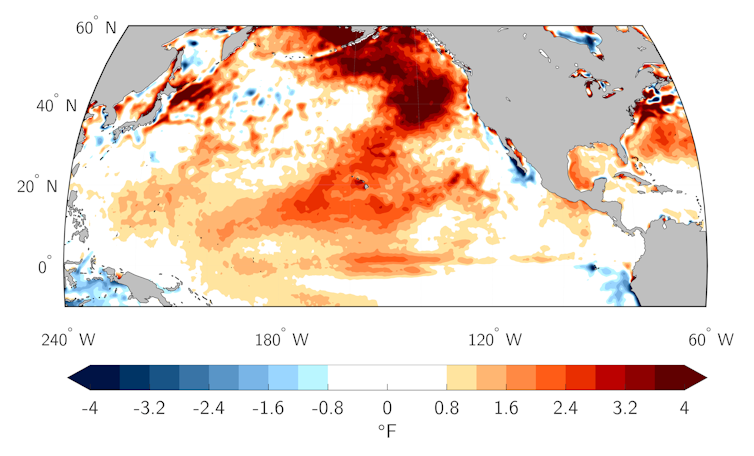

El Niño is coming, and ocean temps are already at record highs – that can spell disaster for fish and corals

It’s coming. Winds are weakening along the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Heat is building beneath the ocean surface. By July, most forecast models agree that the climate system’s biggest player – El Niño – will return for the first time in nearly four years.

El Niño is one side of the climatic coin called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. It’s the heads to La Niña’s tails.

During El Niño, a swath of ocean stretching 6,000 miles (about 10,000 kilometers) westward off the coast of Ecuador warms for months on end, typically by 2 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit (about 1 to 2 degrees Celsius). A few degrees may not seem like much, but in that part of the world, it’s more than enough to completely reorganize wind, rainfall and temperature patterns all over the planet.

I’m a climate scientist who studies the oceans. After three years of La Niña, it’s time to start preparing for what El Niño may have in store.

How El Niño Affects The Planet

No two El Niño events are exactly alike, though we’ve seen enough of them that forecasters have a pretty good idea of what’s likely to happen.

People tend to focus on El Niño’s impact on land, justifiably. The warm water affects air currents that leave areas wetter or drier than usual. It can ramp up storms in some areas, like the southern U.S., while tending to tamp down Atlantic hurricane activity.

El Niño can also wreak havoc on the many marine ecosystems that support the world’s fishing industries, including coral reefs and seagrass meadows.

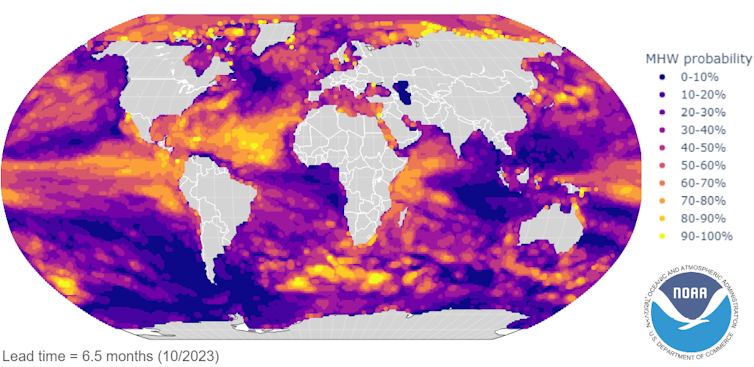

Specifically, El Niño tends to trigger intense and widespread periods of extreme ocean warming known as marine heat waves.

Global ocean temperatures are already at record highs, so El Niño-induced marine heat waves could push many sensitive fisheries to a breaking point.

The Problem With Marine Heat Waves

A marine heat wave is just that: a “wave” of extreme heat in the ocean, not dissimilar to an atmospheric heat wave on land.

At their smallest, marine heat waves can inundate local bays and coves with hotter-than-normal water for a few days or weeks. At their largest, marine heat waves like the Northeast Pacific Warm Blob of 2013-2014 can grow to gargantuan proportions, with regions three times the size of Texas experiencing ocean temperatures 4 to 6 F (about 2 to 3 C) above average for months or even years.

Warm water might not seem like a big deal, especially to surfers hoping to leave their wetsuits at home. But for many marine organisms that are highly adapted to specific water temperatures, marine heat waves can make living in the ocean feel like running a marathon.

For example, some fish increase their metabolism in warm waters by so much that they burn energy faster than they can eat, and they can die. Pacific cod declined by 70% in the Gulf of Alaska in response to a marine heat wave. Other impacts include bleached corals, widespread harmful algal blooms, decimated seaweeds and increased marine mammal strandings. All told, billions of U.S. dollars are lost to marine heat waves each year.

Marine heat waves flare up for a variety of reasons. Sometimes ocean currents shift warm water around. Sometimes surface winds are weaker than normal, leading to less evaporation over the ocean and warmer waters. Sometimes cloudy places just aren’t as cloudy for a few months, which lets more sunlight in and heats up the ocean. Sometimes both weaker winds and fewer clouds happen at the same time, producing record-breaking marine heat waves.

Where El Niño Fits In

In the climate system, El Niño is king. When it dons its fiery crown, the entire planet takes notice, and the oceans are no exception. But the likelihood of increased marine heat wave activity during El Niño depends on where you are.

Along the U.S. West Coast during El Niño, surface winds that normally blow from the north tend to subside. This weakens evaporation and slows upwelling of colder, deeper water. That increases the chances of coastal marine heat waves.

Peruvian fishers have for centuries weathered periods of extreme ocean warming that drive fish away. It wasn’t until the 1920s that scientists realized that these South American marine heat waves were related to the Pacificwide ENSO.

In the Bay of Bengal east of India, interactions between El Niño and a tropical air flow pattern known as the Walker Circulation elevate the risk for marine heat waves.

Seafloor Heat Waves Are Another Risk

Even if marine heat waves aren’t more obvious at the ocean surface this year, it doesn’t mean all is well down below.

In a recent study, my colleagues and I showed that marine heat waves also unfold along the seafloor of coastal regions. In fact, these “bottom marine heat waves” are sometimes more intense than their surface counterparts. They can also persist much longer. For example, a 1997-1998 bottom marine heat wave off the U.S. West Coast lasted an extra four to five months after surface ocean temperatures had already cooled.

Events like this can be related to El Niño and put a lot of stress on bottom-dwelling species. Bering Sea snow crab landings were down 84% in 2018 after a marine heat wave reached the seafloor.

We’re In (For) Hot Water

With El Niño on the horizon, what can we expect for this year?

The good news is seasonal forecast models can skillfully predict marine heat waves three to six months in advance, depending on the region. And forecasts tend to be most accurate during El Niño years.

The latest forecast predicts several active marine heat waves to persist into June-August, including in the North Pacific, off the coast of Peru, southeast of New Zealand and in the tropical North Atlantic.

The same forecasts predict El Niño to ramp up over the next six to nine months, increasing marine heat wave risk in January to March of 2024 for the U.S. West Coast, the western Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal, and the tropical North Atlantic.

That said, these predictions are far enough out that things could change. Time will tell whether they hold (hot) water, but we would do well to prepare. El Niño is coming.![]()

Dillon Amaya, Climate Research Scientist, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

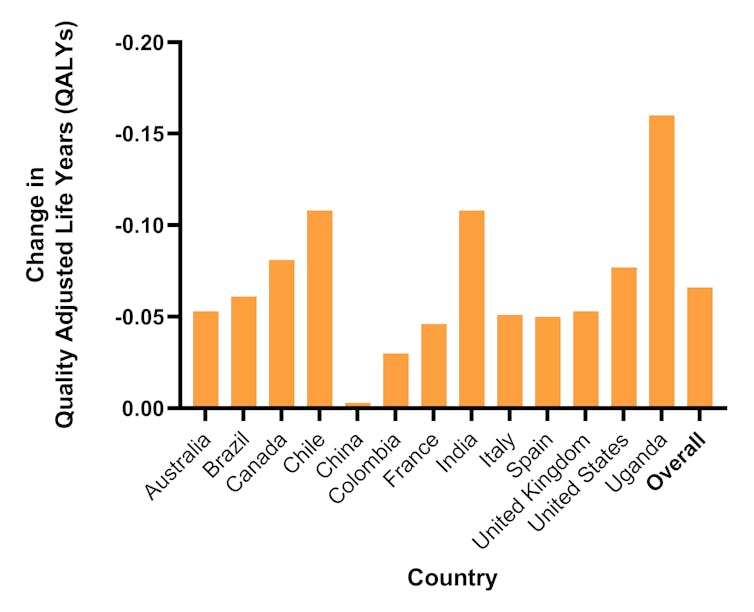

Poorer countries must be compensated for climate damage. But how exactly do we crunch the numbers?

As the planet warms, a key concern in international climate negotiations is to compensate developing nations for the damage they suffer. But which nations should receive money? And which extreme weather events were influenced by climate change?

Most nations last year signed up to an agreement to establish a so-called “loss and damage” fund. It would provide a means for developed nations – which are disproportionately responsible for greenhouse gas emissions – to provide money to vulnerable nations dealing with the effects of climate change.

Part of the fund would help developing nations recover from catastrophic extreme weather. For example, it might be used to rebuild homes and hospitals after a floods or provide food and emergency cash transfers after a cyclone.

Some experts have suggested the science of “event attribution” could be used to determine how the funds are distributed. Event attribution attempts to determine the causes of extreme weather events – in particular, whether human-caused climate change played a part.

But as our new paper sets out, event attribution is not yet a good way to calculate compensation for nations vulnerable to climate change. An alternative strategy is needed.

What Is Event Attribution?

Extreme weather events are complex and caused by multiple factors. The science of extreme event attribution primarily seeks to work out whether either human-caused climate change or natural variability in the climate contributed to these events.

For example, a recent study found the extreme rain that triggered New Zealand’s February flooding was up to 30% more intense due to human influence on the climate system.

Attribution science is progressing quickly. It’s increasingly focused on extreme rain events, which in the past have been tricky to study. But it’s still not a consistent and robust way to estimate the costs and impacts of extreme events.

Why Can’t We Use It?

Event attribution science draws on both observational weather data and climate model simulations.

Most commonly, two types of climate model simulations are used: those that include the effects of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, and those that exclude them. Comparing the two types of simulations allows scientists to estimate how climate change influences the likelihood and severity of extreme events.

But climate models primarily simulate processes in the atmosphere and ocean. They don’t directly simulate the damage caused by an extreme weather event - such as how many people died due to a heatwave or infrastructure loss during a flood.

To directly simulate the effects of an extreme event, we need to know the exact extent to which weather components such as temperature and rainfall caused damage. In some cases, this can be determined. But it requires high-quality data, such as hospital admissions, that’s rarely available in most parts of the world.

Also, climate models are not good at simulating some extreme events, such as thunderstorms or extreme winds. That’s because such events are sporadic and tend to occur across small areas. This makes them harder to model than, say, a heatwave that affects a large area.

So if “loss and damage” funding decisions relied too much on event attribution, then a low-income nation hit by a heatwave may receive more support than a nation damaged by storms or high winds, relative to the damage caused.

What’s more, event attribution is not yet able to estimate how climate change causes damage associated with so-called “compound” extreme events.

Compound events refer to cases where more than one extreme event occurs simultaneously in neighbouring regions, or consecutively in a single region. Examples include a drought followed by a heatwave, or sea level rise which makes damage from a tsunami even worse.

How Do We Move Forward?

Event attribution is not yet advanced enough to calculate “loss and damage” from climate change.

Instead, our paper suggests “loss and damage” funds are used alongside foreign aid spending to support recovery in low-income nations following any extreme events where human-caused climate change may have played a role.

We also present four major recommendations for using event attribution to estimate “loss and damage” in future. These are:

Help developing countries use event attribution techniques: to date, event attribution has largely been conducted by wealthy countries in their own regions

Address more types of extreme events: tornadoes, hailstorms and lightning are largely beyond the capability of climate models used in event attribution because they are localised and complex. New techniques to examine these events should be attempted

More research into the impacts and costs of extreme events: few studies have attempted to attribute the costs of extreme events to climate change. Further efforts are needed, especially in low-income nations

Combine event attribution with other knowledge: scientists and experts in aid and policymaking must collaborate on a strategy for using event attribution information. Better understanding of the needs of policymakers and the limitations of event attribution science could lead to more useful studies.

A Growing Burden

Low-income nations have contributed relatively little to global emissions. Compensation from richer nations is vital to helping them manage the growing burden of climate harms.

But distributing these funds in a fair way is challenging. Until the field of event attribution advances, putting too much reliance on event attribution is a risky strategy.

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Izidine Pinto to the research underpinning this article.![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne; Joyce Kimutai, Climate Scientist, University of Cape Town; Luke Harrington, Senior Lecturer in Climate Change, University of Waikato, and Michael Grose, Climate projections scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A dive into the deep past reveals Indigenous burning helped suppress bushfires 10,000 years ago

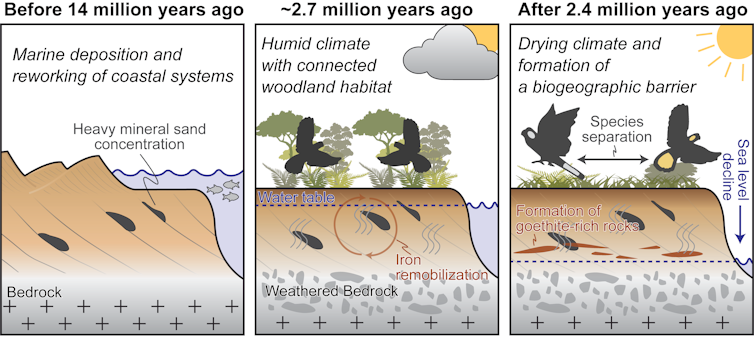

Indigenous Australians have conducted cultural burning for at least ten millenia and the practice helped reduce bushfire risk in the past, our new research shows.

The study provides more evidence of the very long history of cultural burning in southeast Australia. While the burning was probably not specifically used to manage bushfires, our data suggest it nonetheless reduced fire extremes.

Indigenous cultural burning involves applying frequent, small and low-intensity or “cool” fires to clean out grasses and undergrowth. But the scientific evidence for when in history Indigenous Australians used cultural burning, and what they were seeking to achieve, is unclear.

Our findings suggest Indigenous cultural burning in the past may have helped reduce the intensity of bushfires. These findings are important because evidence suggests cultural burning can assist modern land management as climate change worsens.

When Did Cultural Burning Start In Australia?

Some experts suggest cultural burning was adopted in the Pleistocene period, about 50,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Increases in charcoal in sediments have been linked to the arrival of humans, and subsequent vegetation change, on the Atherton Tablelands in northeast Queensland from about 45,000 years ago.

However, similar changes occurred on some Pacific Islands at times when humans were not present. This has cast doubt on whether past fires in Australia were the result of human activity.

Another point of view suggests cultural burning was adopted only in the last few thousand years.

Some current cultural burning programs in Australia were only established or re-established in the second half of the 20th Century. But they mostly take place in arid and tropical environments, and it’s not certain whether they can be readily applied to temperate regions.

Our research sought to shed light on when cultural burning in southeast Australia began, and what effect it had. We focused on a site in the Illawarra region of New South Wales. In particular, we examined sediments from the bed of Lake Courijdah in the Thirlmere Lakes National Park, which holds a unique record into the past.

A Spotlight On Charcoal

Sediments in Lake Courijdah cover two time periods: one before Aboriginal people are thought to have arrived in Australia, and one after.

The older sediments, from about 135,000 to 105,000 years ago, included a period known as the Last Interglacial. This climatic period was very similar to today’s and would have produced similar environmental conditions. Importantly, humans were not present at this time.

Above this layer were deposits dating to the last 18,000 years, extending from the end of a cool and probably arid period known as the Last Glacial Maximum up to about 500 years ago.

It’s well-documented that in this time period, Indigenous people were living across the Sydney Basin, including the Illawarra region.

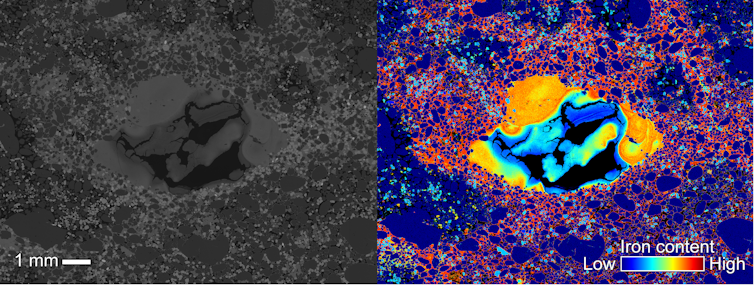

From these sediments, we examined the accumulation of charcoal – a common method used to determine the frequency and relative size of bushfires. We also used a new method known as “Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy”. It determines bushfire severity based on the chemical composition of the charcoal produced.

Using this new method is important. Recent research by our UNSW lab showed how traditional charcoal techniques may mask evidence of human fire use (in the form of cool fires).

Our Results

So what did we find? During both periods, climatic change was the main driver of fire activity. This suggests human-caused climate change will continue to influence overall fire conditions in future.

But we found a marked difference between the two time periods when looking at the severity of fire. Despite significant climatic change over the last 18,000 years, fire severity remained lower, when compared to the earlier period without humans.

As such, we conclude that Indigenous cultural burning practices undertaken around Thirlmere Lakes from about 10,000 years ago may have suppressed extreme wildfires.

Cultural burning in the region may have begun earlier than this. However, data from before 10,000 years ago is variable – probably as a result of sea-level change – so we can’t say for sure.

Indigenous people using cultural burning were probably not focused on wildfire suppression. Early explorer records, and even more recent work, suggests burning improved hunting prospects and the diversity of resources. However, cultural burning nonetheless appears to have reduced wildfires in this case.

Looking Ahead

El Niño conditions are predicted to return to Australia this year. Inevitably, thoughts return to the massive Black Summer bushfire season of 2019-2020 and how to prevent such disasters in future.

Our findings suggest when it comes to future fire management in eastern Australia, traditional practices by Indigenous people should be taken into account in policy and decision-making.

Adopting cultural burning as part of our toolkit is likely to minimise wildfires and help keep people safe. ![]()

Alan N Williams, Associate Investigator, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, UNSW Sydney; Mark Constantine IV, Researcher, UNSW Sydney, and Scott Mooney, Associate professor, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Surprising Science Behind Long-Distance Bird Migration

April 17, 2023

Scientists have recently made a surprising discovery, with the help of a wind tunnel and a flock of birds. Songbirds, many of which make twice-yearly, non-stop flights of more than 1,000 miles to get from breeding range to wintering range, fuel themselves by burning lots of fat and a surprising amount of the protein making up lean body mass, including muscle, early in the flight. This flips the conventional wisdom on its head, which had assumed that migrating birds only ramped up protein consumption at the very end of their journeys, because they would need to use every ounce of muscle for wing-flapping, not fuel.

"Birds are amazing animals," says Cory Elowe, the paper's lead author and a postdoctoral researcher in biology at UMass Amherst, where he received his Ph.D. "They are extreme endurance athletes; a bird that weighs half an ounce can fly, non-stop, flapping for 100 hours at a time, from Canada to South America. How is this possible? How do they fuel their flight?"

For a very long time, biologists assumed that birds fuelled such feats of endurance by burning fat reserves. And indeed, fat is an important part of migratory birds' secret mix. "The birds in our tests burned fat at a consistent rate throughout their flights," says Elowe. "But we also found that they burn protein at an extremely high rate very early in their flights, and that the rate at which they burn protein tapers off as the duration of the flight increases."

"This is a new insight," says Alexander Gerson, associate professor of biology at UMass Amherst and the paper's senior author. "No one has been able to measure protein burn to this extent in birds before."

"We knew that birds burned protein, but not at this rate, and not so early in their flights," continues Gerson. "What's more, these small songbirds can burn 20% of their muscle mass and then build it all back in a matter of days."

A blakpoll warbler. Photo: University of Massachusetts Amherst

To make this breakthrough, Elowe had help from the bird banding operators at Long Point Bird Observatory, in Ontario, along the northern shore of Lake Erie. Every fall, millions of birds gather near the observatory on their journey to their wintering grounds -- including the blackpoll warbler, a small songbird that travels thousands of miles during its migration. After capturing 20 blackpolls and 44 yellow-rumped warblers -- a shorter distance migrant -- using mist nets, Elowe and his colleagues then transported the birds to the Advanced Facility for Avian Research at Western University, which has a specialized wind tunnel built specifically for observing birds in flight.

Elowe measured the birds' fat and lean body mass pre-flight, then, when the sun set, let the birds free in the wind tunnel. Because the birds naturally migrate at night, Elowe and his colleagues would then stay awake -- at one point, for 28 hours -- watching for when a bird would decide to rest. At that point, the researchers would collect the bird and again measure its fat and lean body mass content, comparing them with the pre-flight measurements.

"One of the biggest surprises was that every bird still had plenty of fat left when it chose to end its flight," says Elowe. "But their muscles were emaciated. Protein, not fat, seems to be a limiting factor in determining how far birds can fly."

The researchers still don't quite know why the birds are burning such vast stores of protein so early in their journeys, but the possible answers open up a wide range of future research avenues.

"How exactly is it possible to burn up your muscles and internal organs, and then rebuild them as quickly as these birds do," wonders Gerson. "What insights into the evolution of metabolism might these birds yield?"

Elowe is curious about shivering -- nonmigratory birds that overwinter in cold areas keep themselves warm by shivering. "This is also a feat of endurance," says Elowe. "Do birds fuel their winter shivering spells the same way? And as the world warms, which method of coping with the cold -- shivering or migrating -- might be the better option for survival?"

Cory R. Elowe, Derrick J. E. Groom, Julia Slezacek, Alexander R. Gerson. Long-duration wind tunnel flights reveal exponential declines in protein catabolism over time in short- and long-distance migratory warblers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2023; 120 (17) DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2216016120

Coastal Species Persist On High Seas On Floating Plastic Debris

April 17, 2023

The high seas have been colonised by a surprising number of coastal marine invertebrate species, which can now survive and reproduce in the open ocean, contributing strongly to the floating community composition. This finding was published today in Nature Ecology and Evolutionby a team of researchers led by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) and the University of Hawai'i (UH) at Manoa.

The researchers found coastal species, representing diverse taxonomic groups and life history traits, in the eastern North Pacific Subtropical Gyre on over 70 percent of the plastic debris they examined. Further, the debris carried more coastal species than open ocean species.

"This discovery suggests that past biogeographical boundaries among marine ecosystems -- established for millions of years -- are rapidly changing due to floating plastic pollution accumulating in the subtropical gyres," said lead author Linsey Haram, research associate at SERC.

These researchers only recently discovered the existence of these "neopelagic communities," or floating communities in deep ocean waters. To understand the ecological and physical processes that govern communities on floating marine debris, SERC and UH Manoa formed a multi-disciplinary Floating Ocean Ecosystem (FloatEco) team. UH Manoa led the assessment of physical oceanography and SERC evaluated biological and ecological dimensions of the study.

For this study, the FloatEco team analysed 105 plastic samples collected by The Ocean Cleanup during their 2018 and 2019 expeditions in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, which occupies most of the northern Pacific Ocean. The field work relied on participation of both individual volunteers and non-governmental organisations.

"We were extremely surprised to find 37 different invertebrate species that normally live in coastal waters, over triple the number of species we found that live in open waters, not only surviving on the plastic but also reproducing," said Haram. "We were also impressed by how easily coastal species colonized new floating items, including our own instruments -- an observation we're looking into further."

"Our results suggest coastal organisms now are able to reproduce, grow, and persist in the open ocean -- creating a novel community that did not previously exist, being sustained by the vast and expanding sea of plastic debris," said co-author Gregory Ruiz, senior scientist at SERC. "This is a paradigm shift in what we consider to be barriers to the distribution and dispersal of coastal invertebrates."

While scientists already knew organisms, including some coastal species, colonized marine plastic debris, scientists were unaware until now that established coastal communities could persist in the open ocean. These findings identify a new human-caused impact on the ocean, documenting the scale and potential consequences that were not previously understood.

"The Hawaiian Islands are neighboured in the northeast by the North Pacific garbage patch," said Nikolai Maximenko, co-author and senior researcher at the UH Manoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. "Debris that breaks off from this patch constitutes the majority of debris arriving on Hawaiian beaches and reefs. In the past, the fragile marine ecosystems of the islands were protected by the very long distances from coastal communities of Asia and North America. The presence of coastal species persisting in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre near Hawai'i is a game changer that indicates that the islands are at an increased risk of colonization by invasive species."

"Our study underscores the large knowledge gap and still limited understanding of rapidly changing open ocean ecosystems," said Ruiz. "This highlights the need for dramatic enhancement of the high-seas observing systems, including biological, physical and marine debris measurements."