Inbox and environment news: Issue 581

April 30 - May 6 2023: Issue 581

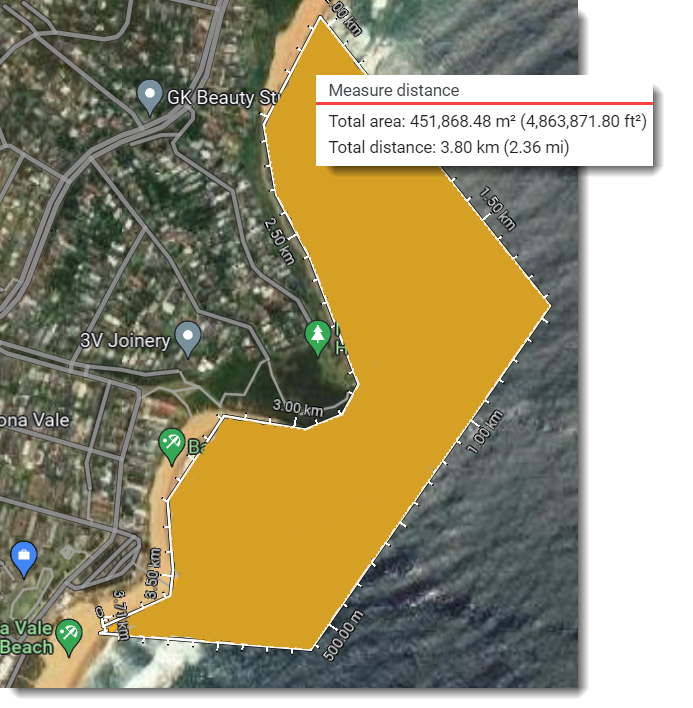

Protect Mona Vale's Bongin Bongin Bay - Establish An Aquatic Reserve

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Avalon Beach April 30

Come and join us for our family friendly April clean up, close to Avalon Surf Lifesaving Club (558 Barrenjoey road, Avalon) on the 30th at 10am.

We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the ocean. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the beach and even clean up in the water (at own risk). We will clean up until around 11.20, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time. For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages. There is a council carpark, but it is often busy on Sundays, so check streets close by as well if it's full or please consider using public transport.

Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost. All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too!

Permaculture Northern Beaches - Upcoming Events

- Learn about Permaculture design

- Caring for and raising chickens

- Native bees and bee hotels

- Living Skills - soap making

- AND Live Music!

NSW Reconstruction Authority Regulation: Have Your Say

- to prescribe actions in relation to which the NSW Reconstruction Authority may direct relevant entities

- to require relevant entities and the NSW Reconstruction Authority to have regard to the State disaster mitigation plan and any relevant disaster adaptation plan in exercising prescribed functions

- to prescribe exceptional circumstances in which the Minister may authorise the undertaking of development without consent or assessment under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979

- to provide for the determination and payment of fees under the NSW Reconstruction Authority Act 2022launch.

Trout Spawning Stream Rules Now In Place In Thredbo And Eucumbene Rivers

April 26, 2023

Recreational fishers are reminded that the annual trout fishing spawning stream rules commence from Monday 1 May 2023 in the region’s two declared spawning streams.

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) Deputy Director General Fisheries, Sean Sloan said the annual trout spawning stream fishing rules apply to the Thredbo River and its tributaries and the Eucumbene River and its tributaries (upstream of the backed-up waters of Lake Eucumbene and including Providence Portal).

“While this is a great opportunity to target trophy trout in the Thredbo and Eucumbene rivers, there are some special rules in place to provide protection for spawning trout,” Mr Sloan said.

"A minimum size limit of 50cm, daily bag limit of one and possession limit of two trout applies to the Thredbo and Eucumbene rivers from 1 May to the end of the King’s Birthday long weekend on Monday, June 12, 2023.

“Fishers can only use one rod and line at a time, rigged with up to two artificial flies or lures and they can possess up to three rods, rigged with artificial flies or lures, however the use and possession of handlines is not permitted, and any fishing gear rigged for bait fishing is also prohibited.

“DPI Fisheries Officers will be patrolling the Thredbo and Eucumbene rivers to ensure that fishers abide by the rules and fishers are encouraged to respect each other and be sure to leave the area as pristine as it was found.”

The public is urged to report illegal or suspected illegal fishing activities to the Fishers Watch Phoneline on 1800 043 536 or via the online report form.

For more information on fishing rules and bag limits, please visit the DPI website.

Australian Bass And Estuary Perch Closure Commences 1 May

April 27, 2023

Recreational fishers are reminded that the annual fishing closure for Australian Bass and Estuary Perch in all coastal rivers and estuaries in NSW will commence on Monday 1 May 2023.

NSW Department Primary Industries (DPI) Fisheries Deputy Director General, Sean Sloan said the zero-bag limit over this four-month period helps protect the native fish species while they spawn over the winter period.

“During winter, these popular native sportfish species form large groups and migrate to parts of estuaries with the right salinity to trigger spawning,” Mr Sloan said.

“It is important that fishers respect this closure from 1 May through to 31 August, as the spawning period is key for the survival of these iconic species.

“This closure protects the fish during this spawning period to ensure they can remain a popular catch with recreational fishers for many generations to come.

“Australian Bass and Estuary Perch are a commercially protected species and as such commercial fishers are prohibited from retaining or selling Australian Bass and Estuary Perch.”

Mr Sloan said that the zero-bag limit does not apply to Australian Bass and Estuary Perch caught in freshwater dams or in rivers above impoundments, as the fish do not breed in these areas.

“All fish in freshwater impoundments, like Glenbawn Dam and Glennies Creek Dam in the Hunter Valley, Brogo Dam near Bega and Clarrie Hall and Toonumbar Dams in the northeast, are stocked fisheries, meaning we physically replace fish stocks annually, with fingerlings bred in our hatcheries, therefore anglers may continue to fish for these species in these waters all year round,” Mr Sloan said.

“However, any Australian Bass or Estuary Perch caught in estuaries and in rivers below dams during the closure must be returned to the water immediately with the least possible harm to the fish.

“The zero-bag limit for these species does not close any waters to fishing and does not affect anglers fishing for other estuarine species, such as bream or flathead during the colder months.

“Our DPI Fisheries Officers will be out in full force during this time to ensure that these rules are being followed."

If any suspected illegal activity is witnessed, the public are urged to contact the Fishers Watch Phoneline on 1800 043 536 or via the online report form here.

For more information regarding the annual closure, visit the DPI website.

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Weed Of The Season: Cassia - Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

In hot water: here’s why ocean temperatures are the hottest on record

Large swathes of the world’s oceans are warm. Unusually warm. The heat this year is likely to break records. Since mid-March, the global average sea surface temperature is over 21℃ – the highest since satellite records began.

What’s going on? Climate change is the big picture – nine-tenths of all heat trapped by greenhouse gases goes into the oceans. But there’s an immediate cause too: the rare triple-dip La Niña is over. During this cycle, cooler water from deep in the ocean upwells to the surface. It’s like the Pacific Ocean’s air conditioner is running. But now the air conditioner is turned off. It’s likely we’re set for an El Niño, which tends to bring hotter, dryer weather to Australia.

When you run your air conditioner, you’re masking the heat outside. It’s the same for our oceans. La Niña brought three years of cooler conditions, while global warming continued apace.

Now we’re likely to see the heat roar back. If El Niño develops, climatologists estimate it could add an extra 0.2℃ to global temperatures, which would nudge some areas past 1.5℃ of warming for the first time.

What Are We Seeing?

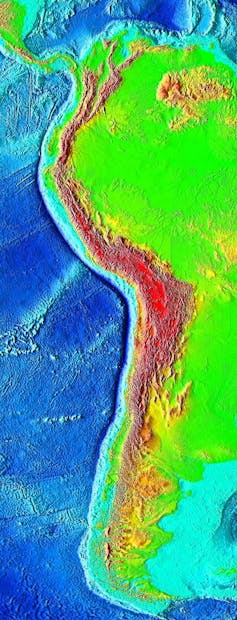

Wind patterns are changing over the eastern Pacific near Chile. These winds have stopped the upwelling of deep colder waters from cooling the surface. That’s why you can see temperatures much higher than average in that area.

This is often the start of an El Niño cycle, which usually brings Australia fire weather – dry and hot – while damaging fisheries in Ecuador and Peru and bringing torrential rain to parts of South America.

But the age-old El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle is happening amid climate change. That’s why it’s so hot across swathes of the world’s oceans.

Why Do The Oceans Matter So Much?

Ocean currents are a major carrier of heat around the globe, alongside atmospheric convection. Sun doesn’t pour down at the same rate everywhere. At the poles, it’s easier for sunlight to glance off, which is why they are colder. But the equator gets the full force of the sun, heating up air and water.

Ocean and air currents move this heat towards the poles. As the currents move south, heat mixes into the surrounding water. The East Australian Current carries warm water from the tropics southwards, distributing heat along south-eastern Australia. By the time the current reaches Hobart, it is typically a lot cooler.

Water can hold much more heat than air can. In fact, just the top few metres of the ocean store as much heat as Earth’s entire atmosphere. The oceans are slower to warm up, and slower to cool down. By contrast, the temperature of our atmosphere is much more mercurial and can change rapidly.

Heat gets into the ocean at the surface, as you’d expect, as that’s where sunlight warms water directly as well as warm winds transferring heat. Over time, this heat is mixed with the rest of the ocean. Most of the extra heat is going into the top two kilometres of seawater, but there’s warming all down the water column. On average, the oceans are four kilometres deep.

How much energy? A startling study suggests the earth system trapped roughly 380 zettajoules of extra heat from 1971-2020 – with the oceans taking up 90% of that. That’s a truly enormous number, the equivalent of 25 billion nuclear bombs.

Our research has found warmer currents – where heat is concentrated – are pushing further south, towards Antarctica.

Is That Why My Ocean Swims Are So Warm This Month?

Surprisingly, the answer is “not necessarily”. Local dynamics always play a role. And so do our own expectations.

In Sydney, many people have been surprised by how warm the water has felt when they dare a dip this month. The long-term trend of warming oceans plays a role. But more important is how long water can hold heat.

That warm Sydney dip is due to the oceans holding their heat from summer and autumn. Air temperatures might fall to 22℃ while the ocean is at 21℃. But that’s actually quite common in April – cooler air and warmer water. For a person swimming the contrast makes the ocean feel warm compared to the air, particularly if a breeze is blowing.

This is partly why global warming is hard to grasp. We experience the weather and climate directly, by our lived experience. What matters more is the big picture we are seeing. And that, based on the intense heating off Latin America, is a real worry. ![]()

Moninya Roughan, Professor in Oceanography, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

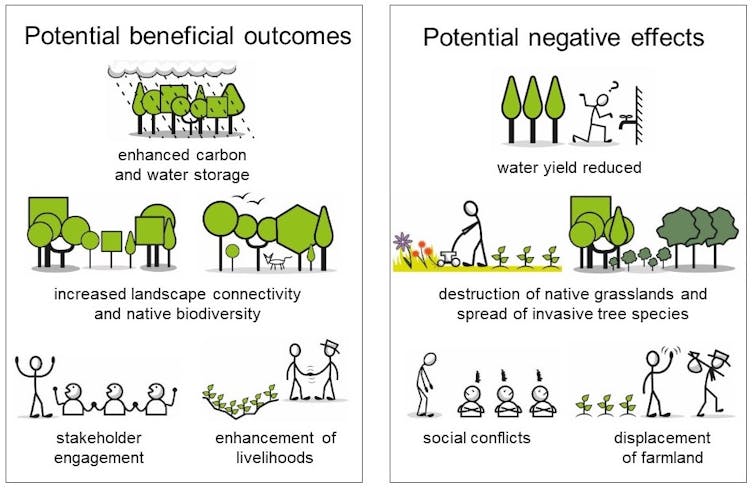

Restoring forests often falls to landholders. Here’s how to do it cheaply and well

From the outside, planting trees seems simple. Seedlings want to grow – pop them in the soil, water them and walk away.

But Australia has never seriously invested in restoration and has barely monitored outcomes when it has been done. Recent research into the replanting of 20 million trees nationwide found little impact on the threatened species these trees were meant to support.

This matters, because Australia is a major global deforester. Efforts to preserve forests are important, but the remnants that remain are highly fragmented. Before 1788, forest covered an estimated 30% of the continent. Only half of Australia’s forest coverage has survived colonisation.

For a little over a decade, we’ve experimented with different planting methods on our own land in Queensland’s wet tropics. In our recent research, we collated what works well and cheaply. Use a planter spade, make sure both sapling and soil are wet, gently press the seedling into the hole, and only spray weedkiller where needed.

Australia Still Isn’t Serious About Restoration

Forests support most of life on Earth. But in just the last century, the world has lost as much forest as it had in the previous 9,000 years. Today half of the Earth’s land previously covered by trees has been cleared. Of the forests remaining only 40% have high ecosystem integrity.

Under First Nations stewardship, around 30% of Australia was originally covered with forest.

Australia remains one of the world’s top deforesters – the only developed nation on the list.

All climate action pathways limiting warming to 1.5℃ rely on intact forests. But we still lack basic information on how to do restoration best. Most native species have not been tested for their survival and growth rates.

Globally, improving seedling survival has proved difficult because of lack of evidence of best practices. The evidence we do have shows seedling mortality can be as high as 30-40%.

Landscape-scale restoration now relies largely on private investment, often done at small scale on bush blocks owned by individuals and small groups.

A major problem is money. Community restoration in the wet tropics, for instance, has been estimated to cost over A$60,000 a hectare for densely planted native seedlings. This cannot stretch to the scale of restoration desperately needed across Australia’s iconic landscapes.

But there’s good news – since 2011, we’ve been experimenting with how to restore land effectively and for much, much less money.

Restoring Forests Means Mastering Replanting

Eighteen years ago, we bought Thiaki – 180 hectares of land on the Atherton Tablelands, in Queensland’s wet tropics. Covering just 0.3% of Australia, this biome supports more species diversity than anywhere else, including cassowaries, tree kangaroos, striped and lemuroid possums.

Much was cleared early on for dairy. But since the 1940s, many farmers have left the industry due to new economic realities. This has provided new opportunities for restoration.

We bought a patch of forest and set it up as a research project looking at cost-effective restoration for carbon and biodiversity using native species.

While the immediate challenge was cost, there were other challenges. Which trees do you plant, where do you plant them and what time of year? How do you plant them quickly and cost-effectively?

Here’s What Works

In our latest research, we tested many combinations of technique, spacing and planting care across three landscape-scale experiments. What we found sounds simple. But recreating a forest relies on doing these things right.

Here are five tips:

Use a spade: Using a two-person tree planting auger made no difference to survival versus a simple planter spade. But the humble planter spade was four times cheaper and four times faster, which substantially reduces costs of restoration.

Saturate the seedling and the soil. This sounds like common sense, but it’s often overlooked, particularly when plantings are scheduled for drier months. When we planted seedlings into drying soil, we lost up to 40% in the first four months.

Treat saplings with care. Damaging roots by yanking a seedling out of the tube or kicking them instead of closing the soil gently with the toe of your boot can cut survival by 20%.

Don’t lose sleep over spacing. We found the distance between plants had little impact on survival. It didn’t matter whether we planted six or 24 different species.

Don’t blanket the area with weedkiller. In places like the wet tropics, fast-growing grasses can make it impossible for trees to establish. But spraying weedkiller across an entire area isn’t necessary. We found just spraying the rows where seedlings will be planted gave the same survival rates. This cuts costs, reduces erosion and protects soil biodiversity.

What Else Did We Learn?

It’s vital to maximise survival in the first months. Boosting survival rates by 10% in the first four months of a planting program proved to be an indicator of up to 40% better survival rate 18-20 months later.

Many restoration programs plant species expecting them to grow as they do in intact forests. Their behaviour in the wild, however, does not necessarily translate to saplings in restoration projects. So it’s also important to take on board experience of sapling survival in other plantings, and nursery experience and provenance.

We kept a close record of costs, and found it was possible to slash restoration costs more than seven-fold, to below $8,000 a hectare – even in areas where costs are usually higher. When you bring the cost down this low, it makes carbon farming worthwhile in agricultural landscapes (if prices are above $37/tonne of CO₂).

Some of these tips may not be as important in every ecosystem. But caring for saplings will be true everywhere.

To help Australians at work restoring their bush blocks, it would be useful to have regional best-practice guidance documents – particularly around cost-effective planting, monitoring, species selection and case studies.

While the work of individual landowners is laudable, it won’t be enough – even if carbon farming and biodiversity markets take off.

Ideally, governments would knuckle down and help restore these denuded landscapes at scale. But if they prefer to stand back, the only option will be to set prices for carbon and biodiversity to reflect the true value of bringing our forests back. ![]()

Penny van Oosterzee, Adjunct Associate Professor James Cook University and University Fellow Charles Darwin University, James Cook University and Noel D Preece, Adjunct Asssociate Professor, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dozens of woodland bird species are threatened, and we still don’t know what works best to bring them back

Australia’s woodland birds include colourful parrots, flitting honeyeaters, bright blue fairywrens and the unassuming “little brown birds”. Some, such as willie wagtails, laughing kookaburras and rosellas are found in urban gardens. Others, such as swift parrots and regent honeyeaters, are exceptional rarities for which bird enthusiasts spend days or weeks searching.

There are other woodland birds you might never have noticed, such as pardalotes, thornbills, treecreepers, gerygones and nightjars. Forty woodland bird species are listed as threatened and several others are declining.

And just this month another six woodland birds were added to the national threatened list.

Efforts to help these species recover are being made. Common actions include replanting trees and installing nest boxes. But it is important we know which efforts are making the biggest difference. We can then ensure we are doing enough to recover these birds and directing resources to actions that work best.

Our systematic review collated all the published research we could find that tested the effectiveness of 26 conservation actions for woodland bird communities. And yet we found little evidence about exactly how effective most of these actions are.

Why Don’t We Know More About What Works?

Australian woodland birds are a well-studied group of species. However, the research on management effectiveness for this ecological community is sparse. This limits our ability to develop general, evidence-based recommendations.

Some actions are certainly beneficial. For example, we know replanting trees and shrubs helps recover woodland birds. Leaving large pieces of dead wood on the ground helps too – birds like robins and treecreepers appreciate it.

However, many of the studies we reviewed didn’t compare sites where a conservation action was done with “control” sites – otherwise similar areas where that action hadn’t occurred. That made it difficult to compare the effectiveness of different actions. Because of this, we simply can’t be sure which actions work best in different contexts, and how large their effect is.

We found surprisingly few actions had been the subject of studies that used control sites, where birds were studied in similar sites where no action had been taken. This was true even for common actions, like control of weeds, feral herbivores (goats, pigs, deer) and predators (cats and foxes), or nest box installation.

All these actions probably have at least some benefits. Without more studies and appropriate controls, though, we can’t say how large the benefits are, or which action makes the biggest difference.

Where The Evidence Exists, Results Are Mixed

Interestingly, four actions for which we could collate some clear evidence had mixed results. These actions were grazing management, prescribed burning, noisy miner control and habitat protection. The evidence shows their effects on birds depend on the site and management context.

Reducing livestock grazing had mixed results for woodland birds. Sometimes the effects were positive, sometimes negative, and sometimes it had no effect.

Prescribed burning was unlikely to boost woodland bird numbers, with some studies showing no effect, and others negative effects.

These contradictory results could be due to differences in the bird communities, the severity of threats, or differences in the habitat or climatic conditions of the site, as well as in the landscapes surrounding the study sites.

They could also be explained by differences in how the management actions were implemented (such as intensity, frequency, method) and monitored (for example, time since the action took place). But because there was only a handful of studies, we couldn’t tease apart these reasons.

Despite declines of Australian woodland birds and ongoing investment in their conservation, we were unable to make generalised conclusions about the overall effectiveness of 26 conservation actions for these species. We still don’t know which management actions are most effective for this well-loved bird community. This knowledge gap is likely to be worse for less-studied taxonomic groups.

So What Can We Do To Fill In The Gaps?

To give us concrete answers, there are two key messages for conservation practitioners and researchers.

First, we need to do more research designed to test the effectiveness of management actions, and understand the context in which different results occur. These studies need rigorous study designs, appropriate controls and careful statistical reporting.

Second, we encourage practitioners to tap into the online database of existing studies that we did collate and the accompanying annotated bibliography. These provide a wealth of detailed practical information about each management action. These resources are a comprehensive collation of the best available evidence to help support management decisions for woodland birds.

We also encourage collaborations among practitioners and researchers to build the evidence base by evaluating management actions that are being implemented or soon to be trialled.

Unfortunately, these conclusions of “we need more research” and “it depends on the context” are not novel. However, we now have a clear understanding of the knowledge gaps.

In the meantime, avoiding damage and loss of habitat in the first place is the most important thing we can do.![]()

Jessica Walsh, Lecturer in Conservation Science, Monash University; Martine Maron, Professor of Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, and Michelle Gibson, Research Fellow, Bird Ecology and Fire Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

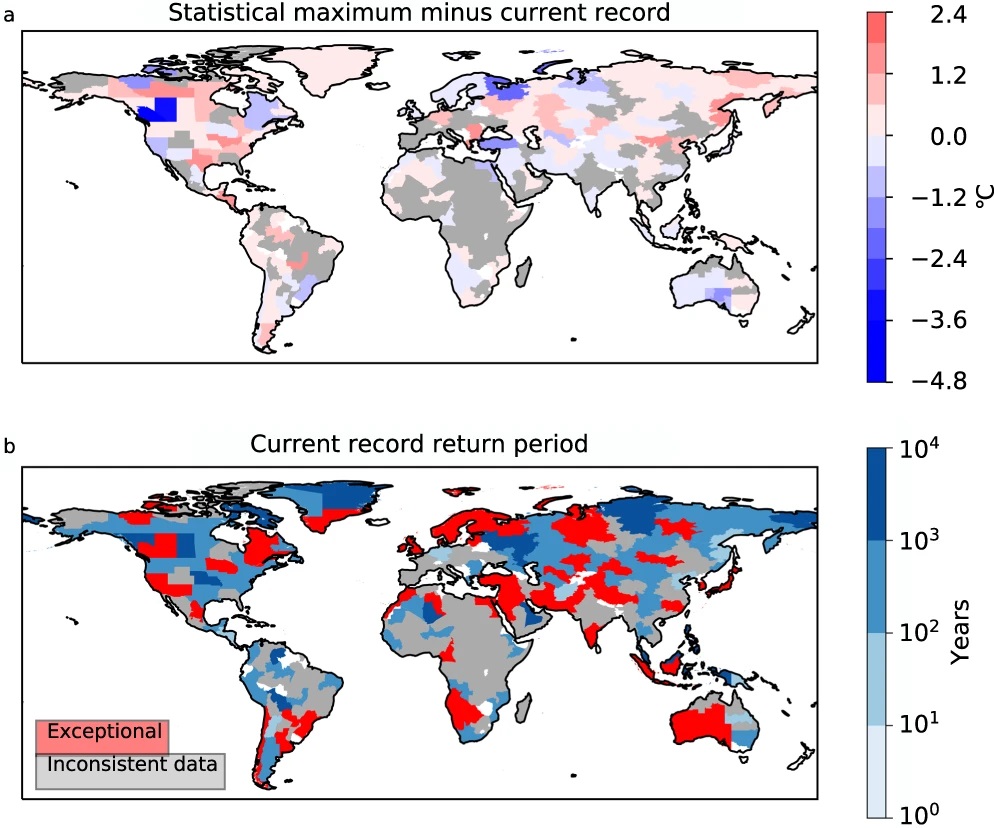

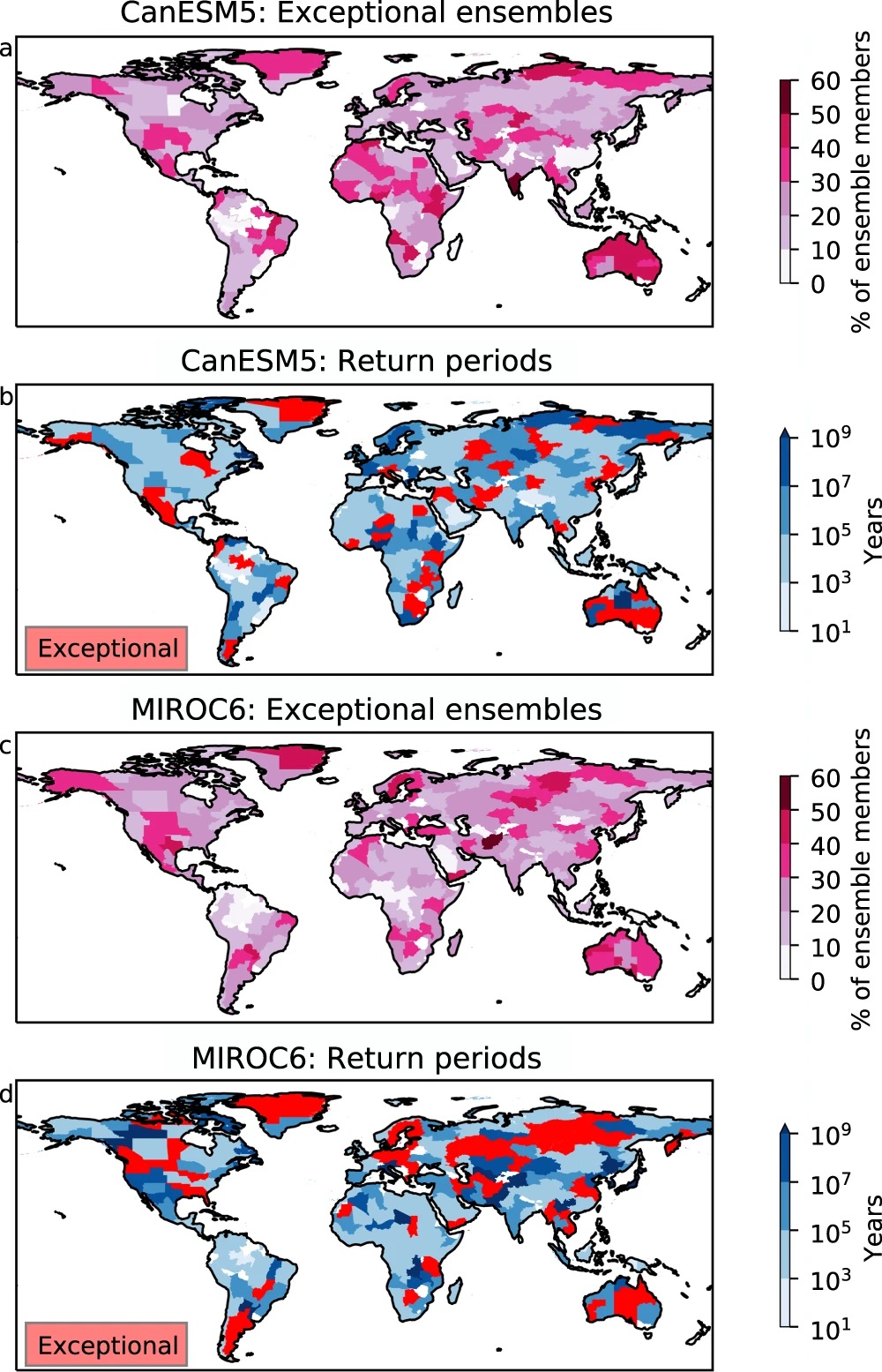

‘Statistically impossible’ heat extremes are here – we identified the regions most at risk

In the summer of 2021, Canada’s all-time temperature record was smashed by almost 5℃. Its new record of 49.6℃ is hotter than anything ever recorded in Spain, Turkey or indeed anywhere in Europe.

The record was set in Lytton, a small village a few hours’ drive from Vancouver, in a part of the world that doesn’t really look like it should experience such temperatures.

Lytton was the peak of a heatwave that hit the Pacific Northwest of the US and Canada that summer and left many scientists shocked. From a purely statistical point of view, it should have been impossible.

I’m part of a team of climate scientists who wanted to find out if the Pacific Northwest heatwave was unique, or whether any other regions had experienced such statistically implausible events. And we wanted to assess which regions were most at risk in future. Our results are now published in the journal Nature Communications.

Tracking these outlier heatwaves is important not just because the heatwaves themselves are dangerous, but because countries tend to prepare to around the level of the most extreme event within collective memory. An unprecedented heatwave can therefore provoke policy responses to reduce the impact of future heat.

For instance, a severe heatwave in Europe in 2003 is estimated to have caused 50,000-70,000 excess deaths. Although there have been more intense heatwaves since, none have resulted in such a high death toll, due to management plans implemented in the wake of 2003.

One of the most important questions when studying these extreme heatwaves is “how long do we have to wait until we experience another similarly intense event?”. This is a challenging question but, fortunately, there is a branch of statistics, called extreme value theory, that provides ways in which we can answer that exact question using past events.

But the Pacific Northwest heatwave is one of several recent events that have challenged this method and should not have been possible according to extreme value theory. This “breakdown” of statistics is caused by conventional extreme value theory not taking into account the specific combination of physical mechanisms, which may not exist in the events contained in the historical record.

Implausible Heat Is Everywhere

Looking at historical data from 1959 to 2021, we found that 31% of Earth’s land surface has already experienced such statistically implausible heat (though the Pacific Northwest heatwave is exceptional even among these events). These regions are spread all across the globe with no clear spatial pattern.

We also drew similar conclusions when we analysed “large ensemble” data produced by climate models, which involve computers simulating the global climate many times over. These simulations are extremely useful for us, since the effective length of this simulated “historical record” is far larger and thus they produce many more examples of rare events.

However, while this analysis of the most exceptional events is interesting, and cautions against using purely statistical approaches for assessing the limits to physical extremes, the most important conclusions of our work come from the other end of the spectrum – regions that have not experienced particularly extreme events before.

Some Places Have Got Lucky – So Far

We identified a number of regions, again spread across the globe, that have not experienced especially extreme heat over the past six decades (relative to their “expected” climate). As a result, these regions are more likely to see a record-breaking event in the near future. And with no experience of such a huge outlier, and less incentive to prepare for one, they may be particularly harmed by a record heatwave.

Socioeconomic factors, including population size, population growth and level of development will exacerbate these impacts. As a result, we factor in population and economic development projections in our assessment of the regions that are most at risk globally.

Our at-risk regions include Afghanistan, several countries in Central America and far eastern Russia among others. These regions may be surprising, since they are not those people typically think of when considering extreme heat impacts of climate change like India or the Persian Gulf. But those countries have recently experienced severe heatwaves and so are already doing what they can to prepare.

Central Europe and several provinces in China, including the area around Beijing, also appear to be vulnerable when considering the extremeness of the record and population size, but as more developed areas they are likely to already have plans to mitigate severe impacts.

Overall, our work raises two important points:

The first is that statistically implausible heatwaves can occur anywhere on the Earth, and we must be very cautious about using the historical record in isolation to estimate the “maximum” heatwave possible. Policymakers across the globe should prepare for exceptional heatwaves that would be deemed implausible based on current records.

The second is that there are a number of regions whose historical record is not exceptional, and therefore is more likely to be broken. These regions have been lucky so far, but as a result, are likely to be less well prepared for an unprecedented heatwave in the near future. It is especially important that these regions prepare for more intense heatwaves than they have already experienced.![]()

Nicholas Leach, Postdoctoral Researcher, Climate Science, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The public history, climate change present, and possible future of Australia’s botanic gardens

Can we justify maintaining water-hungry botanic gardens in an age of climate change and rising water prices?

Perhaps such gardens are no longer suited to Australia’s changing climate – if they ever were.

It is easy to argue Australian botanic gardens are imperial remnants full of European plants, an increasingly uncomfortable reminder of British colonisation.

But gardens, and their gardeners, aren’t static. They are intrinsically changing entities.

A Brief History

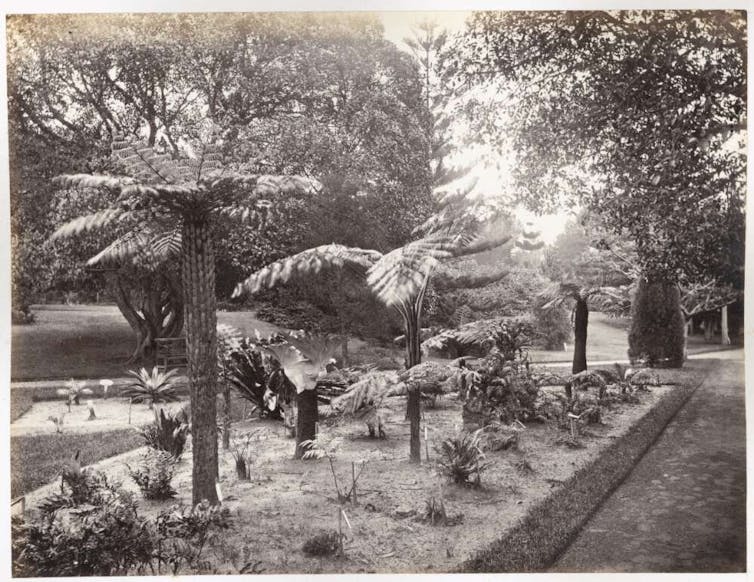

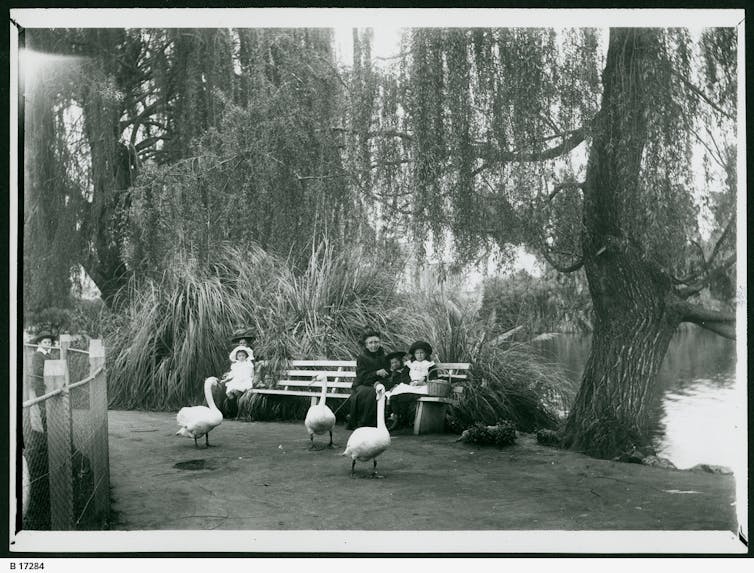

Most Australian botanic gardens were established in the 19th century, starting with the garden in the Sydney Domain around 1816.

The earliest gardens served multiple functions.

They were food gardens. They were test gardens used to establish the suitability of crops and vegetables introduced from Europe and other colonies.

Nostalgia, European ideas of beauty and the desire to test introduced varieties meant botanic gardens were planted with trees familiar to British visitors. Oaks, elms and conifers were all planted, along with the kinds of flowers and shrubs naturalised in British private and public gardens.

Introduced plants and trees were distributed to settlers as part of acclimatisation – the introduction of exotic plants intended to transform the Australian landscape to a more familiar one and make it “productive”.

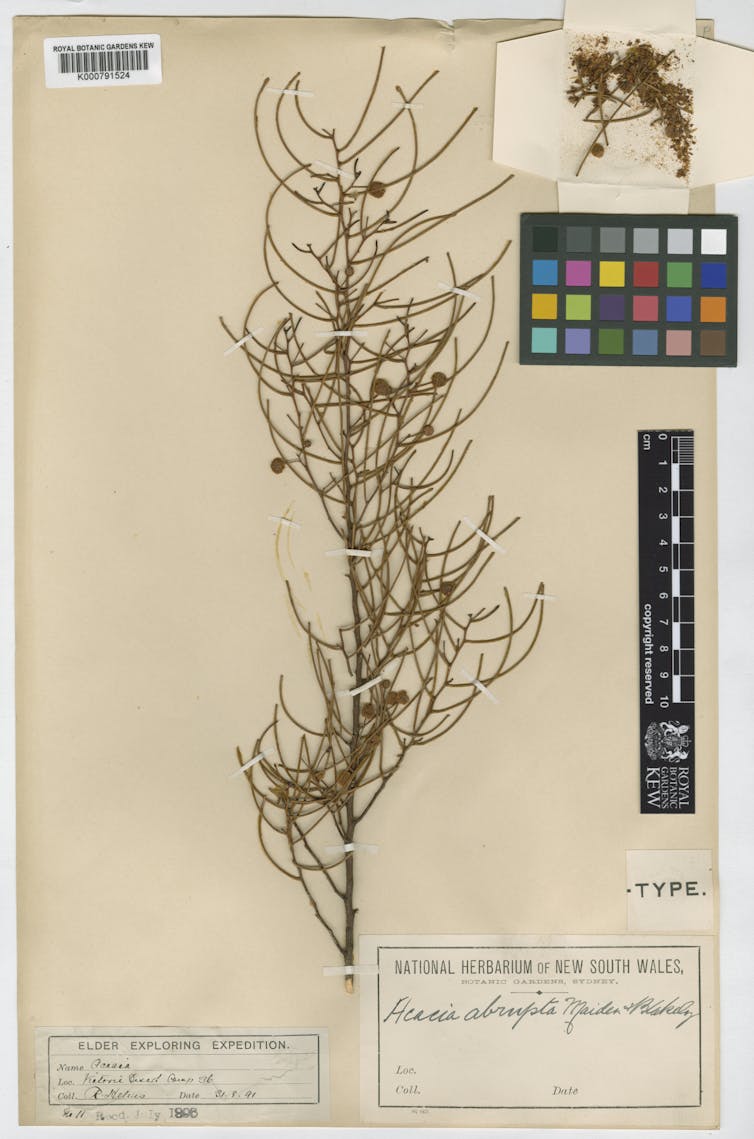

Botanic gardens also reversed this exchange by collecting, cultivating and internationally distributing Australian native plants deemed potentially useful or beautiful.

Finally, and most controversially, they were public spaces.

Australian public gardens drew on then new ideas from European social reformers and progressive politicians. These gardens were seen as providing healthy air for the citizens of increasingly crowded cities. They were also built on older ideas about commons and provision of shared public space for the recreation of the poorer classes.

These different uses sometimes clashed. Ferdinand Mueller, director of the Melbourne Botanic Gardens, was arguably displaced from his role because his vision of the garden was as an instructional botanical nursery. Public demand had shifted to a desire for a more aesthetic and usable garden.

Facing The Climate Emergency

Water for trees and decorative plants drawn from very different climates were always an issue for these gardens.

As early as 1885, Richard Schomburgk in his role of director of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens told Nature about the drought affecting that city and the drastic impact it was having “upon many of the trees and shrubs in the Botanic Garden, natives of cooler countries”.

As the climate has shifted, droughts, changes in water table and climate change uncertainty have foregrounded the plight of these thirsty trees, and some have died.

The Geelong Botanic Gardens, established in 1851, provide an example of water demand and the work done to retain historic trees, using wastewater to maintain these plantings. The garden also now has a “21st-Century Garden” focused on sustainability, containing hardy natives including acacias, eremophila, saltbush and grasses.

Today’s botanic gardens are still test gardens, and are now important sites for global climate change research. They demonstrate what not to plant, but also that not all introduced plants are unsuited to Australian conditions.

Adelaide Botanic Gardens offer a plant selection guide where residents can check whether a plant is suited to their local conditions.

The Melbourne Royal Botanic Gardens have a “climate ready” rose display, a reframing of the decimated species rose collection, which adjusts exotic planting to climate change, without throwing the baby out with the (diminishing) bath water.

Some European, Mediterranean, North and South American plants are exactly suited to Australian climates, or are robust enough to adapt to changes which include increased drying and heat in many areas, but also the possibility of increased humidity in formerly arid zones.

Colonial Memorials

There has been a recent trend to erase reminders of our colonial past.

Do the best lessons come from removing colonial memorials, or from rewriting their meaning? Pull out the giant trees and exotic gardens, or use them to demonstrate and examine the assumptions and mistakes of the past, as well as to design the future?

Various garden exhibitions, such as the touring Garden Variety photography exhibition, do the latter, foregrounding the problematic history as well as the future possibilities of the space.

Many gardens also now include Indigenous acknowledgement and content: heritage walks, tours, and talks by Indigenous owners to demonstrate the long history, naming and uses of local plants which overturn their colonial positioning.

Shifting Landscapes

Australia’s botanic gardens have changed a lot over the past 200 years.

Botanic gardens are adapting to climate change, replacing dying and stressed trees and outdated gardens with hardier varieties and new possibilities, conserving endangered species and acting as proving grounds for climate impacts.

For decades, state and national gardens like the Western Australian Botanic Garden and regional gardens like Mildura’s Inland Botanic Gardens have installed indigenous, native or climate-focused gardens, as well as or instead of the traditional heritage European style.

Botanic Gardens Australia and New Zealand offers a landscape succession toolkit: a guide for mapping out what is doomed, what most needs preserving and what adaptations are most pertinent for our botanic gardens of the future.

Finally, we don’t need to rip out non-hardy introduced trees: climate change will progressively remove them for us.![]()

Susan K Martin, Emeritus Professor in English, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We found long-banned pollutants in the very deepest part of the ocean

I was part of a team that recently discovered human-made pollutants in one of the deepest and most remote places on Earth – the Atacama Trench, which goes down to a depth of 8,000 meters in the Pacific Ocean. The presence of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in such a remote location emphasises a crucial fact: no place on Earth is free from pollution.

PCBs were produced in large quantities from the 1930s to the 1970s, mostly in the northern hemisphere, and were used in electrical equipment, paints, coolants and lots of other products. In the 1960s, it became clear they were harming marine life, leading to an almost global ban on their use in the mid-1970s.

However, because they take decades to break down, PCBs can travel long distances and spread to places far from where they were first used, and they continue to circulate through ocean currents, winds and rivers.

Our study took place in the Atacama Trench, which tracks the coast of South America for almost 6,000km. Its deepest point is roughly as deep as the Himalayas are high.

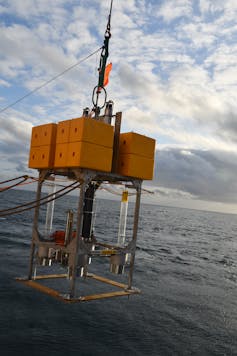

We collected sediment from five sites in the trench at different depths ranging from 2,500m to 8,085m. We sliced each sample into five layers, from surface sediment to deeper mud layers, and found PCBs in all of them.

Pollutants Stick To Dead Plankton

In that part of the world, ocean currents bring cold and nutrient-rich waters to the surface, which means lots of plankton – the tiny organisms at the bottom of the food web in the oceans. When plankton die, their cells sink to the bottom, carrying with them pollutants such as PCBs. But PCBs don’t dissolve well in water and instead prefer to bind to tissues rich in fat and other bits of living or dead organisms, such as plankton.

Since seabed sediment contains a lot of remnants of dead plants and animals, it serves as an important sink for pollutants such as PCBs. About 60% of PCBs released during the 20th century are stored in deep ocean sediment.

A deep trench like the Atacama acts like a funnel that collects bits of dead plants and animals (what scientists refer to as “organic carbon”) that come falling down through the water. There is a lot of life in the trench, and microbes then degrade the organic carbon in the seafloor mud.

We found that the organic carbon at the deepest locations in the Atacama Trench was more degraded than at shallower places. At the greatest depths, there were also higher concentrations of PCB per gram of organic carbon in the sediment. The organic carbon in the mud is more easily degraded than the PCBs, which remain and can accumulate in the trench.

A Look Into The Past

The storage of pollutants means ocean sediment can be used as a rear-view mirror on the past. It is possible to determine when a sediment layer accumulated on the seafloor, and by analysing pollutants in different layers we can gain information about their concentrations over time.

The sediment archive in the Atacama Trench surprised us. PCB concentrations were highest in the surface sediment, which contrasts to what we usually find in lakes and seas. Typically, the highest concentrations are found in lower layers of sediment that were deposited in the 1970s through to the 1990s, followed by a decrease in concentrations towards the surface, reflecting the ban and reduced emissions of PCBs.

For now, we still don’t understand why the Atacama would be different. It is possible that we didn’t look at the sediment closely enough to detect small variations in PCBs, or that concentrations have not yet peaked in this deep trench.

These concentrations are still quite low, hundreds of times lower than in areas close to human pollution sources such as the Baltic Sea. But the fact we have found any pollution whatsoever shows the magnitude of humanity’s influence on the environment.

What we can say for sure is that the more than 350,000 chemicals currently in use globally come at a cost of polluting the environment and ourselves. Pollutants have now been found buried below the bottom of one of the world’s deepest ocean trenches – and they’re not going anywhere.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Anna Sobek, Professor of Environmental Chemistry and Head of Department of Environmental Sciences, Stockholm University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate isn’t a distraction from the military’s job of war fighting. It’s front and centre

Matt McDonald, The University of QueenslandIt was pitched as the “most significant” shift in Australia’s armed forces in decades. And among the headline announcements, climate change was recognised as an issue of national security.

But the strategic review of Australia’s military released yesterday doesn’t go a lot further than that when it comes to the climate crisis. The review devotes just over one of its 100 pages to what climate change means for defence.

And while overseas analysts and militaries seriously address the strategic effects of climate change and the role for defence, the Australian review focused more on climate change as a potential distraction from the military’s core business of war fighting. As our armed forces are increasingly called to respond to natural disasters, the review reports, they are less ready to fight a war.

This focus is too narrow. It’s also a long way from what the research is telling us, and a long way from what our allies are doing.

What’s The Link Between Climate Change And National Security?

At a fundamental level, security doesn’t mean much if it doesn’t extend to conditions of survival. The climate emergency has been described as a direct threat to both human and ecological security.

But climate change also hangs over the traditional security agenda, which is to defend against any attacks. Forward-thinking militaries around the world have begun to prepare for these effects.

Climate change could make armed conflict more likely by acting as a “threat multiplier”.

Climate-driven droughts, desertification, changing rainfall patterns and the loss of arable land could lead to the collapse of governments or a fleeing population.

Former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon and some analysts have pointed to the role of climate change in contributing to armed conflict in Sudan’s Darfur region and Syria’s civil war.

Unchecked climate change is likely to trigger more demand for armed forces to respond to natural disasters, predicted to increase in intensity and frequency on a hotter planet.

Yesterday’s strategic review focuses on this demand, and for good reason – it’s already happening.

Increasingly, the army and air force are being called on to respond to Australia’s tide of “unprecedented disasters” like the floods of the last three years, and the summer of fire in 2019–20. Navy ships evacuated hundreds from the beach at Mallacoota in Victoria, under eerie light.

And then there’s the world. The demand for army-backed humanitarian help is rising. Our neighbours are among the most vulnerable in the world to the effects of natural disasters.

Beyond responses to refugees, conflict and natural disasters, there’s the question of how militaries are equipped, trained and resourced.

Higher temperatures, rising seas and natural disasters could threaten defence infrastructure and bases. Australia’s defence department is the largest landholder in the country, much of it in exposed coastal areas.

Our military has a substantial “carbon bootprint”, given it relies heavily on machines which burn fossil fuels, from destroyers to tanks. Ensuring these have enough fuel in the future is a concern, especially if the substantial military contribution to greenhouse gas emissions comes under more scrutiny.

In this sense it was good to see the review note the importance of the military accelerating a transition to clean energy. But the urgency of the climate crisis suggests our military should also be factoring climate change into procurement considerations and equipment management now. To date, there’s little evidence Australia has done so.

What Are Other Countries Doing?

Key partners like America, the UK and many other countries are well ahead of us. In my ongoing research, I’ve analysed climate responses and interviewed policymakers from other nations. This suggests we’re lagging well behind.

The US military began analysing what climate change would mean for it back in the 1990s. Biden’s government has given climate change greater priority in its National Security Council and firmly linked climate and security in what one interviewee told me was a “game changer”.

The UK has an expert body within its defence ministry examining the security implications of climate change. In 2021, it produced a strategic document with emissions cut goals for its armed forces, as well as investment to make the transition possible.

New Zealand has gone beyond reactive responses and embraced an active role for its military in responding to natural disasters at home and in the region. One interviewee told me this was central to the military’s “social licence”.

New Zealand’s position has been strongly influenced by the concerns of its Pacific neighbours. Wellington decision makers also decided defence will not be exempt from government-mandated goals to get to net zero.

France has taken a similar position on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief focused on its overseas territories and the wider Francophone world. These operations are presented not as a distraction but as a core commitment.

Sweden and Germany used their time on the UN Security Council in recent years to push for a resolution on the organisation’s role in addressing the international security implications of climate change. And when Sweden joins NATO, it’s likely to push for more military preparation for climate change given recent NATO commitments on this front.

Can Australia Catch Up?

Yes. But the first step is to recognise where we are – and where the world is heading.

Australia’s defence sector must seriously engage with what climate change will bring, not least given our region’s acute vulnerabilities and the existential concerns of our Pacific neighbours.

Unfortunately, yesterday’s review suggests our defence establishment does not wholly share these concerns. ![]()

Matt McDonald, Associate Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New exposé of Australia’s exotic pet trade shows an alarming proliferation of alien, threatened and illegal species

Australia has a global reputation for being tough on biosecurity. There are strict rules around the import and export of both native and exotic species. Security is tight, and advanced screening technology commonplace at ports of entry and mail centres.

But it’s a different story within the country, with plenty of movement of wildlife across state borders.

Our research published today in the journal Biological Conservation uncovers the surprising scale and diversity of the domestic online pet trade in Australia. Threatened species, invasive pests, banned imports, and animals not yet known to science are all for sale.

Over a 14-week period, prior to the commencement of Australian COVID-19 restrictions, we detected the trade of more than 100,000 individual live animals. This included more than 60,000 separate advertisements and a total of 1,192 species, including 81 threatened species, 667 alien (non-native) species, and 279 species that are not allowed to be imported into Australia.

We hope our results, from the first systematic survey of exotic vertebrate pets (this includes non-domesticated reptiles, amphibians, fish and birds) traded in Australia, will help biosecurity agencies identify high-risk and potentially illegal species.

What’s The Problem With Trading Exotic Pets?

Unregulated wildlife trade poses serious threats to animal welfare, conservation, human health and biosecurity.

As well as the conservation threat of unsustainably harvesting live animals from the wild, wildlife trade is a source of novel invasive species and their diseases. When exotic species escape from captivity they can become pests. An infamous example is the Burmese pythons of Everglades National Park in the United States, which continue to eat through the native wildlife at an unparalleled rate.

These issues are not lost on Australian biosecurity and conservation agencies. A recent crackdown on reptile smuggling, establishing additional international protection for 127 native species, shows a recognition of the need for more stringent regulation and surveillance. Although low prosecution rates and weak penalties continue to be a barrier to effective enforcement.

Australia goes well beyond its international obligations and prohibits the commercial import of most live animals. Yet audits of alien cagebird and ornamental fish trades show they are thriving within Australia.

Booming Online Trade

Traditionally, pets have been sold from brick and mortar stores or traded between informal networks of keepers and breeders. But now, thanks to online marketplaces, pet trade has largely shifted to the internet.

E-commerce trading sites reach more potential customers across a wider area than previously possible. They also offer a degree of anonymity, meaning that blatantly illegal activity can sometimes occur openly on websites and social media platforms.

To investigate if this was also happening in Australia, we identified 12 of the most prominent online platforms that sold exotic pets. We were able to rapidly monitor thousands of daily advertisements using an automated tool known as webscraping.

To our surprise and alarm, 56% of the trade involved alien species (over 600 species in total). Many of these are illegal to import into Australia or are known to be invasive overseas.

Not Everything Is Clearly Illegal

But these are not all clear-cut examples of illegal activity. The reality is more ambiguous: Australia’s import ban of most animals only came into effect in the early 1980s. So some exotic pets may have arrived in Australia before the ban and have been bred in captivity ever since.

This provides an element of plausible deniability. Traders can declare their animals to be captive-bred within Australia, even if some have been smuggled into the country at a later stage. We found this issue was especially prominent for ornamental fish, with 279 illegal-to-import species being traded in an unregulated manner.

What’s worse is some traders are specialising in animals that are not yet known to science, meaning they haven’t been formally classified, named or described. The presence of undescribed species in Australia, mostly freshwater catfish and African cichlids, can only be explained by illegal smuggling or the exploitation of trade loopholes.

Is Greater Oversight Needed?

It is clear Australia’s exotic pet trade is far more prevalent and less regulated than previously understood. Some researchers call for e-commerce platforms such as Facebook to take greater responsibility by policing wildlife trade. This would reduce opportunities for non-compliant activity occurring on their sites. Meta, the parent company of Facebook, was recently fined for failing to remove illegal trade.

Regardless of how future trade is managed, we are now left with the question of how to deal with thousands of live animals already present that should never have been brought to Australia.

The immediate prohibition of these pets is not feasible. The social licence to euthanise so many animals does not exist and there are no facilities large enough to house them all. Bans, when ineffectively communicated and enforced, can also bolster illegal trade and organised crime.

Permit systems are sometimes used to regulate native pets. A permit is harder to acquire if the species in question poses a greater threat. Recent evidence shows that this can reduce the number of captive animals, and potentially fewer escapees.

Whether such systems can be introduced for these problematic alien species remains to be seen, but new approaches are urgently needed if Australia is to tackle its pet trade problem.![]()

Adam Toomes, Ph.D. student at the Invasion Science & Wildlife Ecology Group, University of Adelaide and Phill Cassey, Head, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We want more climate ambition in our foreign policy – here’s how we can do it

Wesley Morgan, Griffith University and James Bowen, The University of Western AustraliaLast week, foreign minister Penny Wong laid out the strategic challenges facing Australia in a major speech.

Wong described great power competition involving China, America and Russia. She warned of the risk of conflict in our region as China expands its sphere of influence. And she defended the AUKUS nuclear submarine deal with the United States and United Kingdom.

But these are traditional challenges: nation against nation. Australia needs a similar declaration of the catastrophic security implications of climate change.

While Wong did mention climate change, it was secondary, set in the context of regional outreach.

As the climate crisis worsens, we must do more. Climate change is a threat. Maybe even the threat. We need to use every tool we have to tackle it – including our diplomats.

Climate Change Threatens Our Neighbours – And Us

Australia is a big fish in a big, sparsely populated pond. Our neighbours in the Pacific see sea-level rise and ocean acidification as existential threats. For island nations, this is the big one – well above geostrategic competition.

To Wong’s credit, she understands this.

But climate damage isn’t restricted to island nations. Countries across South and Southeast Asia are also on the front line of warming, as this month’s record-breaking heatwaves show.

Just this weekend, people in Bangkok were warned not to go outside due to extreme heat. The apparent temperature - what the temperature feels like when combined with humidity – hit a record 54℃.

In our region, governments typically avoid close alignment with great powers and blocs. Yet there is no doubt rising temperatures are a key threat to all countries. Australia might have a tougher time remaining a credible partner to the region without a greater climate focus here too.

Back Up Words With Serious Action

Under Labor, our political and financial climate commitments have certainly increased.

Despite this, our domestic emissions trajectory is still not compatible with keeping global warming to 1.5℃ this century.

And, as of 2022, Australia was paying just a tenth of its fair contribution to the climate fund set up at the 2009 UN conference in Copenhagen.

Contrast this to the vast sum of money we have committed to spending on traditional security threats, especially the nuclear submarine deal which could cost up to A$368 billion.

Australians want to see more foreign policy ambition on climate front. A United States Studies Centre poll last year found 75% of us want climate action at the heart of our alliance with America. By contrast, only 52% of survey respondents felt the nuclear subs deal was a good idea.

What Should Australia Do?

It’s hard to imagine Australia – or any other country – financing climate action at a level on par with traditional security threats.

But there are actions we could take to help close the gap. We could rejoin and boost funding to the UN-aligned Green Climate Fund, which the previous Australian government left in 2018.

We should also retool our export credit and development finance to invest in climate-friendly assets and stop them funding more fossil fuel extraction.

At the same time, Australia could signal our serious climate commitments by continuing to strengthen domestic policies to ensure the reformed safeguard mechanism actually leads to genuine emission cuts. This would mean closing glaring loopholes, such as allowing major emitters to keep pumping out carbon pollution by purchasing carbon offsets.

As the global energy transition gathers pace, the federal government should do more to support clean energy exports. Australia is well placed to provide critical minerals and the green metals, fertiliser and transport fuels that the rest of the world needs. But we must act fast to secure lucrative opportunities –and to tell the world we are open for green business.

The way we communicate progress to the world is critical. For years, we have been seen as laggards and hold-outs, one of the few developed nations resisting the change which must come. It’s time for us to lead.![]()

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University and James Bowen, Policy Fellow, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most people already think climate change is ‘here and now’, despite what we’ve been told

A quick search on the internet for “climate change images” readily yields the familiar photograph of a lone polar bear on a shrinking block of ice. Despite signifying an impending crisis, such images make climate change seem abstract – happening a long way off (for most of us), to animals we’ve probably never encountered.

The idea that climate change is perceived as “psychologically distant” – happening in the future, in distant places, to other people or animals – has long been presented as a major barrier to action on climate change.

Despite the intuitive appeal of this idea, new research published today in the journal One Earth by behavioural scientists at the University of Groningen now challenges it. The authors argue the psychological distance of climate change has been overestimated – according to their results, most people view climate change as “psychologically close”.

A Review Of The Evidence

To investigate how prevalent psychological distance to climate change really is – and whether it might prevent climate action – the researchers systematically reviewed the available evidence.

First, they analysed data from 27 public opinion polls from around the world – including China, the US, UK, Australia and the EU – finding that most people perceive climate change as happening now and nearby. And this was not just in recent polls. Data from as far back as 1997 indicated almost half of US respondents believed climate change was already occurring.

Second, based on an analysis of past studies, they found people who perceive climate change as more distant do not necessarily engage in less climate action. Indeed, some studies have shown the opposite pattern. People who perceived climate change as affecting people in far-away locations were more motivated to support climate action.

In short, the evidence for the idea that psychological distance is preventing us from climate action is very mixed.

Third, after examining 30 studies, the team found very little evidence that experiments aimed at changing people’s perception of the psychological distance of climate change actually increase their climate action. For example, studies where people watch videos about the impacts of climate change in local versus distant locations do not show these people having different intentions to engage in environmental behaviour.

As I’ve written in an article on the new study, these results remind us that evidence should always trump intuition when it comes to applying psychological theory. The conclusions also echo earlier calls by me and colleagues to be cautious about the relevance of psychological distance when it comes to climate action.

How Should We Communicate About The Climate, Then?

Climate communication strategies and guidelines from a host of different organisations have popularised the idea that climate change is perceived as psychologically distant.

Our own Australian Psychological Society recommends reducing psychological distance by making the local impacts of climate change more salient. For example, highlighting the increase in the number of extreme heat days in one’s town or region.

But if the aim here is to increase climate action, is this good advice?

There is a trade-off between using psychological distance to capture attention, and the idea that it provides a scientific explanation for why people aren’t doing something.

I’ve often used the idea of psychological distance in talks, and spoken to journalists about it, because it starts a conversation and can be a good way to engage otherwise hard-to-reach audiences. But there is a risk of mixing up the narrative appeal with the scientific support.

At worst, repeating ideas about psychological distance could lead people to overestimate the extent to which others think climate change is psychologically distant. In turn, this might demotivate action. If everyone else thinks this is a problem for the future, why should I do something about it now?

We Already Know It’s Here, Now Let’s Act

Another implication is that advocacy groups and governments could be wasting effort on information campaigns that focus on reducing the psychological distance of climate change. If people know that climate change is near and now, why do we need to reinforce that idea?

Our efforts might be better spent increasing people’s belief in being able to take climate action (“self-efficacy”), and that those actions will be effective (“response-efficacy”).

This implies a need to make pro-environmental actions like driving less or eating more plant-based foods easier and cheaper. But it also highlights the need for structural and societal changes that incentivise behavioural change: from offering subsidies for electric vehicles or renewable energy installation, to international agreements on carbon emissions.

There is also a need to remind people of the moral imperative of taking action.

Climate Change Hasn’t Moved ‘Closer’

There is no doubt climate change is becoming more “real” and more concerning for most of us. From 2018 to 2022, the number of Australians “very concerned” about climate change has nearly doubled, from 24% to 42%.

These changes in attitude are almost certainly linked to the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20. But does explaining this shift as a reduction of psychological distance add anything to our scientific understanding?

The results of this new study strongly suggest the answer is no. It is time we moved on from considering psychological distance as an impediment to action.

We know climate change is affecting polar bears, but we also know it is affecting us right now. Our efforts now must be focused on changing behaviour at both the societal and individual level.![]()

Ben Newell, Professor of Cognitive Psychology and Director of the UNSW Institute for Climate Risk and Response, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

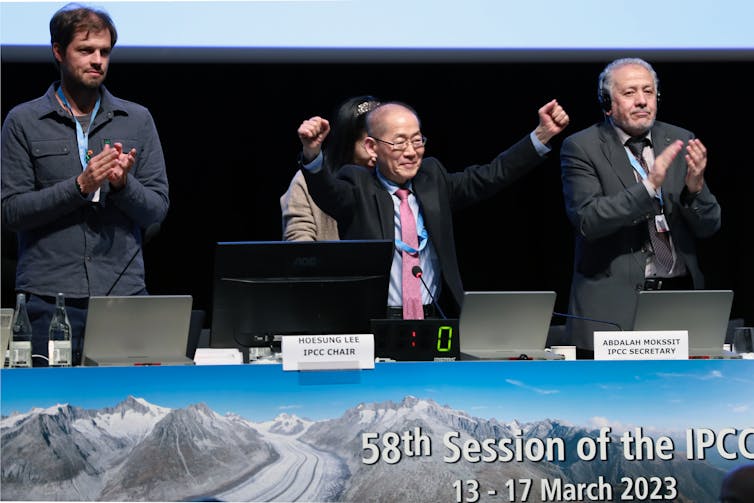

The IPCC’s calls for emissions cuts have gone unheeded for too long – should it change the way it reports on climate change?

Emissions from human activities are substantially increasing the atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gases CO₂, methane, CFCs and nitrous oxide. These increases will enhance the greenhouse effect, resulting on average in an additional warming of the Earth’s surface.

Long-lived gases would require immediate reductions in emissions from human activities of over 60% to stabilise their concentrations at today’s levels.

These are not statements from the latest report released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). They come from its first assessment in 1990.

Back then, the IPCC acknowledged there were uncertainties in the predictions due to incomplete scientific understanding of sources and sinks of greenhouse gases. But what has actually happened in the 30 years since largely matches the predictions:

an average rate of global sea level rise of 30-100mm per decade due to the thermal expansion of the oceans and the melting of some land ice

an increase of global mean temperature of about 0.3℃ per decade under business as usual.

The IPCC also predicted the rise in temperature would slow as we ramped up efforts to cut emissions, but this scenario hasn’t been tested because emissions reductions never happened.

In 1990, the IPCC also presented the first warnings about potential climate change impacts. It then repeated them in one form or another in the following five assessment reports. But emissions continued to rise each year, resulting in a global temperature increase of 1.1-1.2℃.

We Know How To Reduce Emissions

On a more positive note, annual emissions from 18 countries have peaked during the past decades – but not always as a result of climate policies. For example, the UK’s manufacturing capacity reduced significantly as companies moved off-shore. Nevertheless, global emissions kept rising.

Chapters in IPCC reports covering agriculture, land-use change, energy supply, transport, buildings, industry and urban settlements repeatedly provided clear guidance on emissions cuts, such as this section from 2001:

Hundreds of technologies and practices for end-use energy efficiency in buildings, transport and manufacturing industries account for more than half of the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Details of how to reduce emissions from improved energy efficiency in all sectors have been repeated in all six IPCC assessments. But many opportunities to reduce energy demand, and save costs, have not been implemented. Although scientific knowledge has advanced since 1990 and a range of low-carbon technologies have evolved and improved, the key IPCC messages have remained the same.

Given the many repeated warnings, why have global greenhouse gas emissions continued to rise? Typical answers include population growth, the rise of the middle classes in many developing countries, increased consumerism, greater tourism, lobbying by the fossil fuel industry and higher consumption of animal proteins.

National and local governments have also struggled to implement strong climate policies because the majority of their citizens and businesses remain unwilling to change their behaviour. This is even the case when co-benefits are clearly evident, including improved health, reduced traffic congestion and lower costs.

A Possible Future For The IPCC

Having assessed thousands of published research papers over 33 years, what has the IPCC actually achieved since its inception in 1988? And what should be its future role given that many of its strong messages have largely gone unheeded?

Arguably, present and future climate impacts would have been even worse without the IPCC’s work. With each report, the urgency to act on both mitigation and adaptation increased. Few climate deniers now remain. More people want their governments to act.

Although total global emissions continue to rise, energy-related carbon dioxide emissions may be reaching a plateau. According to the International Energy Agency, these emissions rose by under 1% in 2022 – less than initially feared after the COVID dip – largely because of the growth of solar, wind, electric vehicles, heat pumps and improved energy efficiency measures.

So there is hope. But after 25 years of personal involvement with six IPCC reports, my view is that it’s time to review the role of the IPCC and its three main working groups before the next assessment cycle begins.

Since climate science continues to evolve, the IPCC’s Working Group One on the science of the climate system should continue to assess and present the latest knowledge every five to six years.

The need for adaptation and resilience is finally receiving greater attention, mainly as a result of more extreme climate impacts and growing insurance claims. Therefore, Working Group Two should continue but report every two years so that both scientific analyses and local real-world experiences can be shared quickly between local and national governments.

Measures to cut emissions have evolved as newer technologies have been developed and refined. The present understanding of the policies and solutions to reducing emissions across all sectors is similar to 1990 knowledge – we just need to get on with implementing solutions by removing remaining barriers through regulation and advice.

Research to reduce and capture carbon dioxide emissions will continue, but given the urgency, it is too risky to hope that new low-carbon technologies and systems will one day prove to be commercially successful. Overall, the IPCC’s Working Group Three on mitigation has done its job and should be replaced by a new working group on changing human behaviour.

Behavioural science has been included in various chapters within more recent IPCC reports. Without significant social change in the near term, the emissions curve will not bend downwards. Renewed emphasis on how to best achieve societal change across cultures as a matter of urgency is crucial.![]()

Ralph Sims, Emeritus Professor, Energy and Climate Mitigation, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s adoption of electric vehicles has been maddeningly slow, but we’re well placed to catch up fast

Scott Dwyer, University of Technology SydneyAustralia has long had a love affair with the internal combustion engine. Its first petrol-powered car was developed in 1901. (Admittedly, the engine was imported from Germany.)

Roll forward 122 years and there’s now a registered motor vehicle for every one of the 20 million people of driving age in Australia. And fossil fuels power 99.9% of these vehicles.

The slow pace at which Australia has adopted electric vehicles is maddening to many. But the transition to electric vehicles is changing gear in Australia, driven by both consumers and government.

The early signs of this shift can be seen in the latest quarterly vehicle sales data. Two-thirds of medium-sized cars sold were electric.

Also this week, the National Electric Vehicle Strategy filled a glaring hole in federal policy. All the states and territories and many local governments had for some time taken steps to boost the uptake of electric vehicles.

Electrifying the vehicle fleet is going to be one of Australia’s biggest challenges this century. But what makes Australia different from other countries? And why does it make sense to embrace a position as a fast follower?

A Country Wedded To The Car

You can see why cars are so popular in a country like Australia. We’re the sixth-largest country in the world, but the 55th-most-populous. With only around three people per square kilometre, we regularly travel large distances through sparsely populated areas.

Australia also had a burgeoning automotive industry, which spawned fierce loyalties among fans of domestic brands. Its long decline began in the 1940s, with the last vehicle manufacturer shutting up shop in 2017.

Globally, too, the time of internal combustion engine manufacturing seems to have passed. The impacts of human-induced climate change are intensifying, with the transport sector responsible for a large share of global emissions that stubbornly refuses to decline.

The electrification of transport offers a route to decarbonise this sector. It will also bring a host of other benefits such as improved health through reduced local air pollution.

Electric vehicles aren’t new. The first cars were electric but were eventually outcompeted by their fossil-fuelled counterparts. It wasn’t until the start of the last decade that upstarts such as Tesla began disrupting the automotive sector with fully electric offerings.

Not long after this Australia began a series of electric vehicle demonstration projects. The first was a Western Australian trial way back in 2010. However, sales and model availability remained stubbornly low. This was largely due to weak policies.

We Have The Resources To Go Electric

Adding to the frustration of EV advocates is Australia’s wealth of resources that can enhance the benefits electric vehicles offer.

Australia has some of the best wind energy resources in the world with an estimated 5 terawatts of potential. It also has the world’s highest rooftop solar capacity per person. Over 3 million households can power their homes (and potentially vehicles) for free when the sun is shining. There are also 180,000 residential batteries, helping households store the sun’s energy for later use.

The “lucky country” also boasts huge deposits of the minerals needed for making renewable energy technology like solar panels, wind turbines and batteries. Australia produces over 50% of the world’s lithium and 20% of its cobalt, as well as aluminium (27%), nickel (23%) and copper (11%).

And There’s Expertise To Accelerate The Transition

While the new national strategy makes all the right noises, the main critique emerging is that it lacks real teeth. In particular, the specifics of a badly needed fuel-efficiency standard are still being developed.

However, there is still plenty in the strategy to offer promise. It identifies the need for:

- better infrastructure planning and deployment

- training and attracting a workforce with the necessary skills

- product stewardship for end-of-life EV batteries

- better access to charging for apartment residents

- funding for more guidance and demonstrations.