Inbox and environment news: Issue 588

June 18-24 2023: Issue 588

Watching Whales Within Safe Limits: Please Give Them A Safe Passage By Sticking To The Rules

June 13, 2023

With the annual whale migration season in full swing along the south coast, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service is reminding all boaties and those on the water to respectfully watch these creatures from afar.

NPWS Area Manager Jo Issaverdis said this reminder comes after an incident where a small boat purposely approached a whale off Burrewarra Point, north of Broulee.

'While we are looking into this incident, our key message is one of education and awareness,' Ms Issaverdis said.

'We urge boaties, surfers, swimmers and everyone on the water to please give the whales space, and stay at least 100 meters away in all directions.

'This rule is in place to keep both the whales safe and the community safe.

'Adult humpbacks can weigh up to 35 tonnes and if frightened or threatened, can cause serious damage to vessels, passengers and swimmers.

'We understand why people want to get a closer look at these majestic creatures, but the reality is that interfering with the whale migration and getting too close is risky and unsafe for all.

'There are so many great vantage points from the coast where people can watch one of world’s great migrations, and with more than 35,000 humpbacks expected to pass the coast this season, you're guaranteed to see some,' Ms Issaverdis said.

Under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Regulation 2017 all watercraft, including boats, surfboards, surf skis and kayaks must stay at least 100 m from a whale, and at least 300 m if a calf is present.

Restrictions also apply to swimmers, snorkellers, divers and those in the water, who must stay at least 30 m from a whale. There are also restrictions for aircraft, including drones.

From May to November each year, humpback whales make the annual migration from Antarctic waters to Queensland to calve, while southern right whales tend to stay in NSW’s protected bays and beaches to nurture their young.

Signs of disturbance

Disturbed whales, dolphins, dugongs and seals react with a sudden change of behaviour, including:

- hastily diving

- vocalising

- changes in breathing patterns

- sudden change in body posture or positioning

- a sudden change in direction

- a change in swimming speed

- aggressive behaviour such as tail splashing, head lunges and charging

- protectively moving between you and their young.

If you see someone intentionally harming, touching, harassing, chasing, trying to restrict the path of a marine mammal, or getting too close, please report the illegal activity to National Parks and Wildlife on 13000PARKS (1300 072 757).

Approach distance

An approach distance is the closest you can lawfully go to a whale, dolphin, dugong or seal to watch it safely and without disturbing or harassing them, so they can live naturally and without interference.

Scientists, including veterinarians, helped to develop the Biodiversity Conservation Regulation 2017, which outlines the approach distances for New South Wales. These are based on The Australian National Guidelines for Whale and Dolphin Watching 2017 and also includes seals.

Remember, if a marine mammal approaches you, slowly move back to at least the minimum approach distance. Never chase it; try to touch it or restrict its path. On a rare occasion, a National Parks and Wildlife Service officer may ask you to move back beyond the minimum approach distance if they see an animal is still distressed and behaving as if it is disturbed.

By observing the following approach distances, you can have a safe and enjoyable time while helping to keep our wildlife wild.

Whales, dolphins dugongs

The approach distance is determined by the activity you are doing, either in the air, or in or on water, the type of animal and if there is a calf present.

The exception is when a whale, dolphin or dugong that is mostly white in colour is present. You must always stay at least 500 metres from them.

Approaching when in the water – swimmers, snorkelers and divers

If you are a swimmer, snorkeler or diver, to observe a marine mammal, you may enter the water at a minimum distance of:

- 100 metres away from a whale

- 50 metres from a dolphin or dugong.

If you are in the water, you must keep at least:

- 30 metres from a whale, dolphin or dugong, including a calf.

For reference, 30 metres in length is approximately the same length as:

- an official basketball court

- 2 public transport buses lined up end to end.

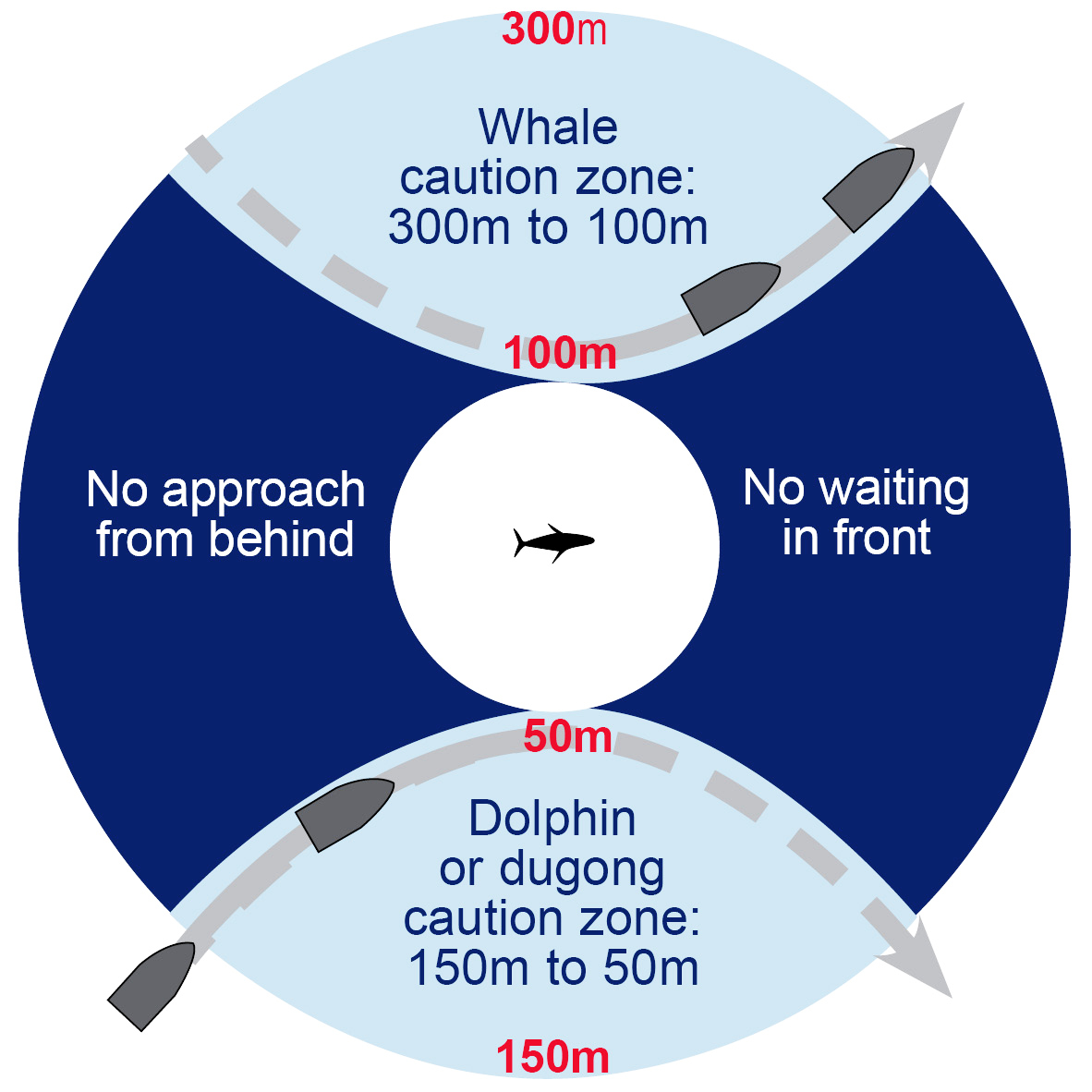

Approaching on the water – boats and surfboards

A vessel is watercraft that can be used as transport, including motorised or non-motorised boats, surfboards, surf skis and kayaks.

If you are on the water in a vessel you are not permitted to approach a marine mammal from behind or wait in front of it.

If a calf is present, you are not permitted to enter the caution zone for closer viewing. The caution zone boundary is 300 metres for whales and 150 metres for dolphins and dugongs.

You must comply with the following approach rules:

A vessel is in the caution zone when it is:

- 300 metres from a whale

- 150 metres from a dolphin or dugong.

A vessel can move no closer than:

- 100 metres to a whale

- 50 metres to a dolphin or dugong.

In the caution zone the skipper must:

- post a lookout if 2 or more people are on board

- not position the vessel ahead of the animal to wait for it

- approach from the side at least 30 degrees to its direction of travel

- move at a constant slow speed with negligible wake – when the waves created by the movement of the prohibited vessel are so small that if there was a boat nearby it would not move

- only 3 vessels are permitted to be in the entire caution zone at any one time – other vessels must wait their turn, regardless of size and not drift closer.

If dolphins are bow-riding, you must maintain course and speed.

If a whale approaches, slow down to minimal wash speed, move away or disengage gears and do not make sudden movements.

Approaching on the water – prohibited vessels

Prohibited vessels include personal motorised watercraft (jet skis), parasail boats, hovercraft, hydrofoils, wing-in-ground effect craft, remotely operated craft or motorised diving aids like underwater scooters.

These vessels are prohibited because they can make fast and erratic movements and not much noise underwater, so there is more chance they may collide with a marine mammal.

If you are approaching a marine mammal using a jet ski or other prohibited vessel you must have negligible wake and stay at least 300 metres from a whale, dolphin or dugong.

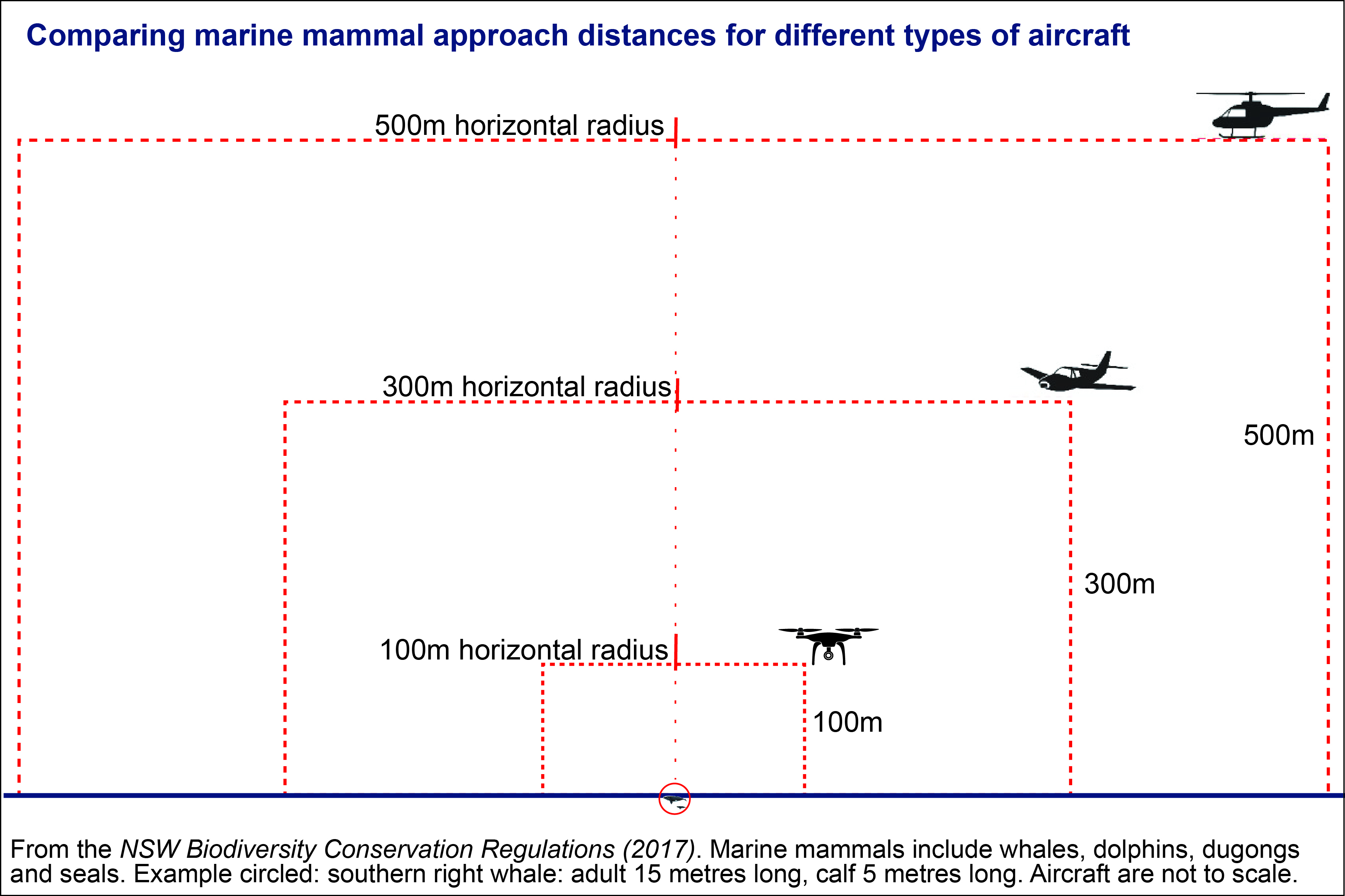

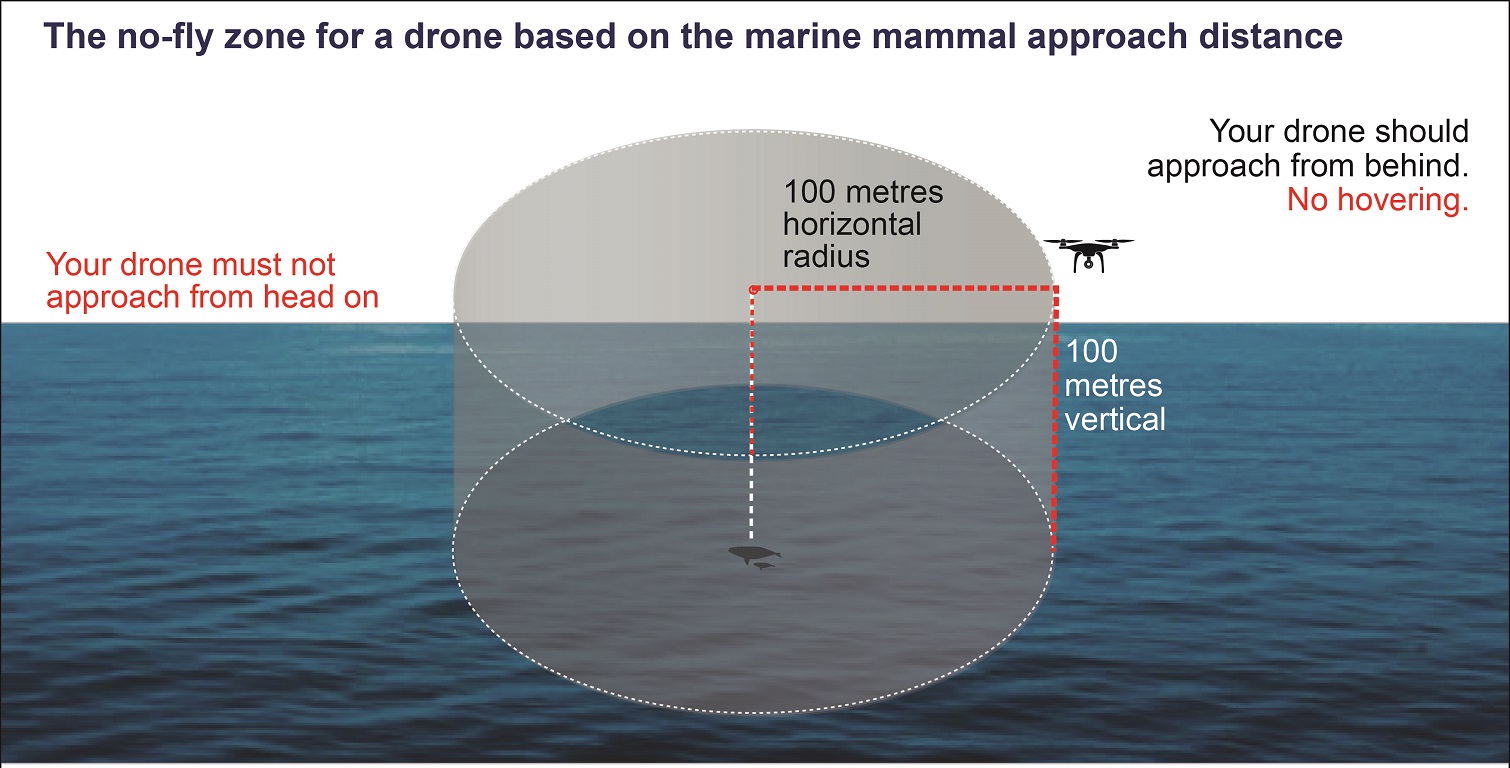

Approaching from the air – aircraft including drones

To observe a marine mammal from the air, you must approach it from behind, not hover over it and not land on the water to observe it. The pilot must also comply with Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) requirements.

The approach distances for different types of aircraft are:

- 100 metres for drones (also known as RPAs and UAVs)

- 300 metres for fixed-wing aircraft

- 500 metres for helicopters and gyrocopters.

The approach distance for aircraft is the height above a marine mammal and the horizontal distance away from it.

If you go closer than the approach distance, you have entered the no-fly zone. The no-fly zone for aircraft over a marine mammal can be imagined as an approach distance cylinder.

The 'no-fly zone' is shaped like a cylinder and moves with the whale, dolphin, dugong or seal. A drone can fly a minimum of 100 metres vertically over, and 100 metres horizontally around a marine mammal. A drone is not permitted to cut through the no-fly space. The aircraft is not to scale. Based on NSW Biodiversity Conservation Regulations (2017).

A drone pilot needs skill, understanding of the regulations and environmental awareness to lawfully approach a marine mammal. The drone pilot must always be in visual line of sight with the drone, not create any hazards and not cause harm to wildlife.

Listen for wildlife distress calls. If birds are disturbed, the pilot is advised to abandon the flight for 5 minutes, land and consider an alternate launch site or wait until birds of prey have left the area, or nesting birds have resettled, then try again.

Seek permission to launch from the landholder or land manager and follow all instructions. Do not launch from or fly over a national park without permission.

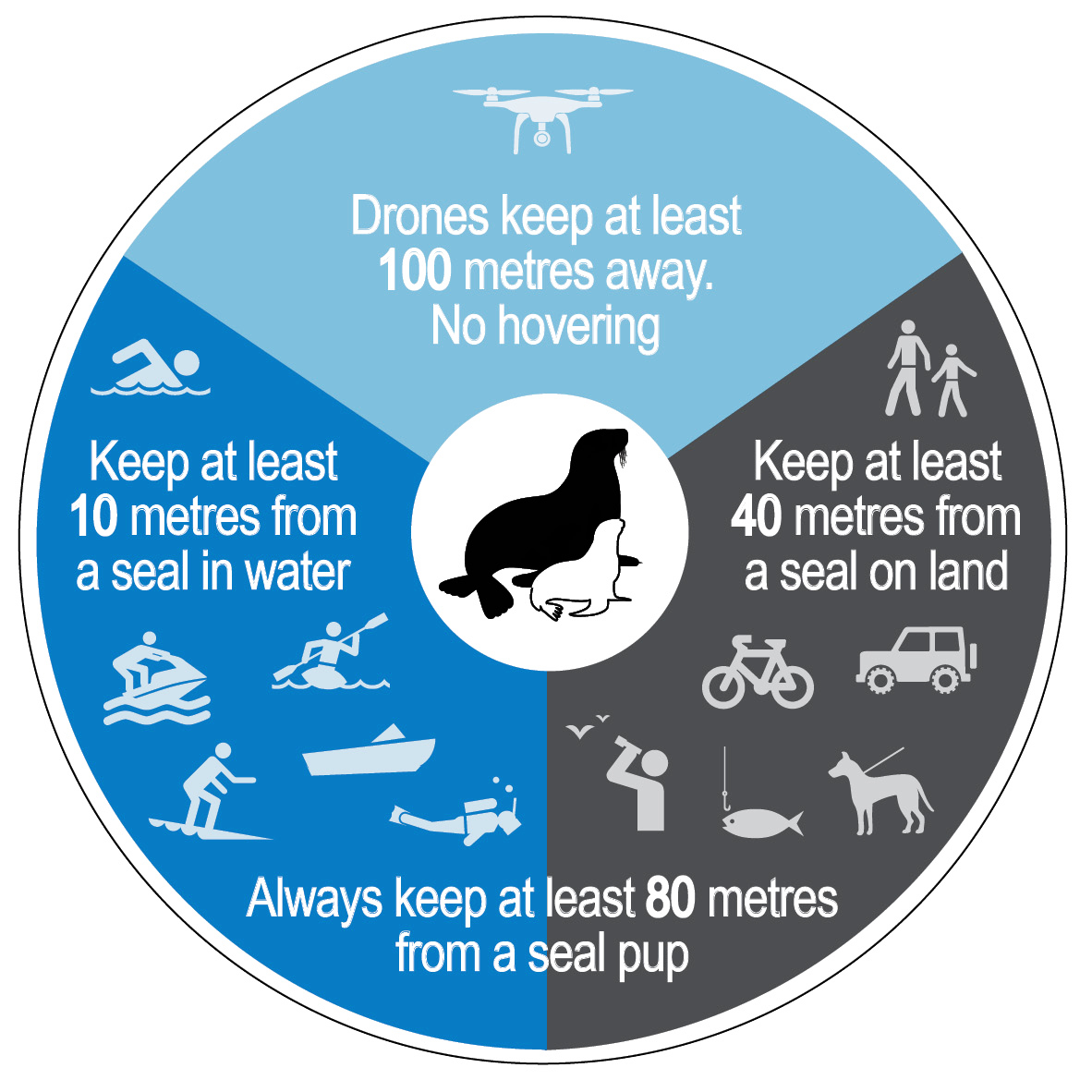

Seals

A seal may look like it is yawning but is actually baring its teeth as a warning sign.

Approach distances for seals are based on where the seal is located and if a pup is present. A seal is considered a pup if it is up to half the length of the adult.

If a seal comes towards you, you must move back to the minimum approach distance.

Approaching a seal when it is in the water

Seals are agile swimmers with strong flippers. When a seal is in the water you must keep at least:

- 10 metres away from the seal

- 80 metres from a seal pup

- 100 metres for a drone.

If you are also in or on the water and a seal approaches you, stay calm and move away slowly. If bitten or scratched, seek immediate medical advice.

Approaching a seal when it is hauled out on land

Seals haul out to rest after foraging at sea.

If a seal feels threatened, it may show aggression by yawning, waving its front flipper or head, or calling out. Seals are very agile and can move fast on land, using all 4 limbs to run. When a seal is hauled out on the land you must keep at least:

- 40 metres away from the seal

- 80 metres from a seal pup

- 100 metres away from the seal for a drone.

Seals can often have injuries that look quite alarming but will heal well without needing veterinary assistance.

If you are concerned call National Parks and Wildlife on 13000 PARKS (1300 072 757), or Organisation for the Rescue and Research of Cetaceans in Australia on 02 9415 3333 for the animal to be checked and monitored.

Vessels watching seals resting on the rocky shore must also keep back 40 metres or 80 metres if a pup is present. Limit the time you spend watching because it can be stressful for them. It is likely you are not the only vessel to approach them that day.

For more information on approach distances, please visit the NSW Environment website.

For information on whale watching vantage points along the South Coast’s National Parks and Reserves, visit the NPWS website.

Keep your dog restrained

With marine mammal populations slowly recovering in New South Wales, there is an increased chance that you will come across one when walking on a break wall or jetty. Keep your dog on a leash to avoid an unexpected encounter. This will reduce stress for the animal and reduce the chance of your dog being bitten. Dogs can transfer diseases to seals and vice versa.

A reminder that it is illegal to take dogs into National Parks.

Entangled whale, dolphin or seal

If you see an entangled animal:

- Watch from a distance, do not approach or enter the water or attempt to disentangle it.

- Immediately report it to:

- National Parks and Wildlife on 13000 PARKS (1300 072 757)

- Organisation for the Rescue and Research of Cetaceans in Australia on 02 9415 3333

Note the time, your location, the whale's direction of travel and speed.

Observe from a safe distance to:

- look for injuries and identifying marks

- take photographs of the entangling material to help rescuers bring the most suitable gear to remove it

- try to keep watch until help arrives.

Images/infographics: DPE/PON

Liquid Amber Seed Pod/Fruits On Roads + Verges At Present: Please Clear These To Prevent Bird Road Deaths - Australian Wildlife Now Eating Fruits - Seeds Of Imported Species

Residents have asked that everyone be aware that the north American liquid amber tree is shedding its seed pod/fruits at present and our native galahs, pigeons and the rainbow lorikeet will descend on these as a flock to eat them. When these trees have been planted on verges the seed pods attract large numbers of these other local residents into roads where they will sit there eating and be susceptible to car strikes. Each year we lose numerous local birds due to this.

To help reduce the mortalities, please sweep the seed pods from the road if you have these outside your place.

American sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) is a deciduous tree in the genus Liquidambar native to warm temperate areas of eastern North America and tropical montane regions of Mexico and Central America. Sweetgum is one of the main valuable forest trees in the southeastern United States, and is a popular ornamental tree in temperate climates. The distinctive compound fruit is hard, dry, and globose, 25–40 mm (1–1+1⁄2 in) in diameter, composed of numerous (40–60) capsules.[14] Each capsule, containing one to two small seeds, has a pair of terminal spikes (for a total of 80–120 spikes). When the fruit opens and the seeds are released, each capsule is associated with a small hole (40–60 of these) in the compound fruit.

_--_Liquidambar_styraciflua.jpg?timestamp=1686254086507)

American sweetgum tree ball (spiny seed pod). Photo: Jim Evans

It is one of a those imported trees that produces seeds and fruits that Australian native birds have taken to eating.

People with olive trees report these being favoured by local parrots, including former Bayview and Narrabeen resident Ken 'Sava' Lloyd:

''I Interrupted this Mallee Ringneck Parrot from eating my olives, and she is not happy. All Types of Parrots are here at Gunnedah eating my Olives.'' - Ken Sava Lloyd, June 3, 2023

The Australian ringneck (Barnardius zonarius) is a parrot native to Australia. Except for extreme tropical and highland areas, the species has adapted to all conditions. Treatments of genus Barnardius have previously recognised two species, the Port Lincoln parrot (Barnardius zonarius) and the mallee ringneck (Barnardius barnardi) but due to these readily interbreeding at the contact zone they are usually regarded as a single species B. zonarius with subspecific descriptions. Currently, four subspecies are recognised, each with a distinct range. The Mallee Ringneck Parrot inhabits central and western New South Wales west of Dubbo, the southwestern corner Queensland west of St George, eastern South Australia and northwestern Victoria.

Mallee ringneck (Barnardius zonarius barnardi), Patchewollock Conservation Reserve, Victoria, Australia. Photo: JJ Harrison

The May 2023 round of the Ringtail Posse saw Nicole Romain, Founder Save The Northern Beaches Bushlands (Lizard Rock), choose the Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoos Calyptorhynchus funereus as her favourite local wildlife species.

Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoos were once content to feed on the seeds of native shrubs and trees, especially banksias, hakeas and casuarinas, as well as extracting the insect larvae that bore into the branches of wattles. Now, after the establishment of extensive plantations of exotic Monterey Pines, the cockatoos may feed more often by tearing open pine cones to extract the seeds in states further south where their preferred habitat and food trees have been destroyed. The population on South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula is now reliant on the seeds of the Aleppo Pine, a noxious weed, as its preferred habitat, as its Sugar Gum woodlands has become extensively fragmented.

Yellow-tailed black cockatoos are one of two species of black cockatoos found in NSW. The other is the much less common south-eastern glossy black cockatoo, a species in decline, particularly after losing crucial habitat during the severe bushfires of 2019/2020, and listed as vulnerable nationally in August 2022.

The south-eastern glossy black cockatoo is a specialist eater and feeds on she oaks, which is why we will sometimes see them in Pittwater and why we need to stop cutting down their food; the trees.

Glossy Black-cockatoo, Calyptohynchus lathami, at Clareville - photo by Paul Wheeler, this species also visits McKay Reserve, Palm Beach, annually to feed on these trees

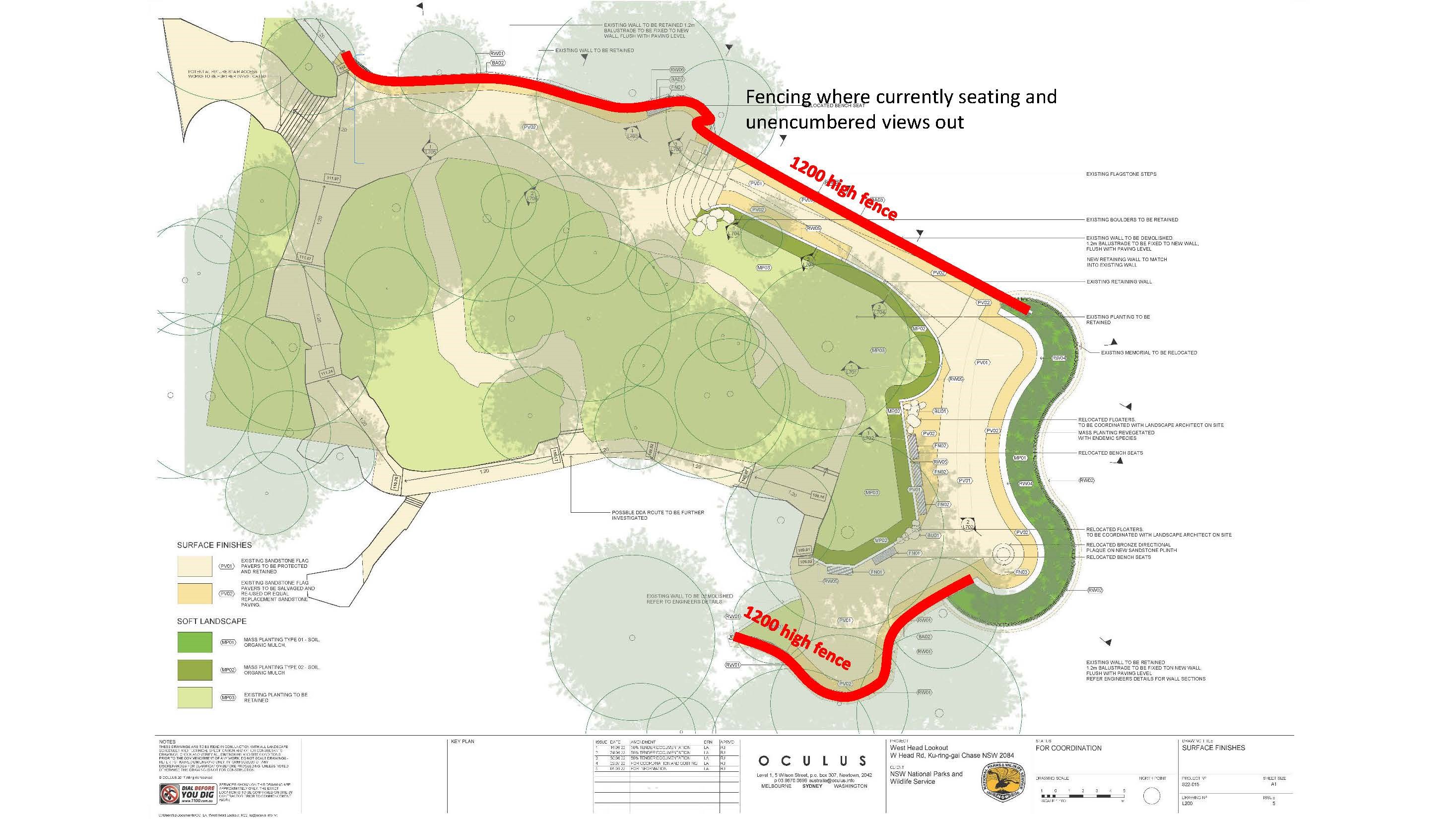

Areas Closed For West Head Lookout Upgrades

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

- West Head lookout

- The loop section of West Head Road

- West Head Army track.

Vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians will have access to the Resolute picnic area and public toilets. Access is restricted past this point.

The following walking tracks remain open:

- Red Hands track

- Aboriginal Heritage track

- Resolute track, including access to Resolute Beach and West Head Beach

- Mackeral Beach track

- Koolewong track.

The West Head lookout cannot be accessed from any of these tracks.

Image: Visualisation of upcoming works, looking east from the ramp towards Barrenjoey Head Credit: DPE

Avalon Dunes Bushcare: July 2023

Join us on Sunday July 2 for another satisfying morning making a difference while being in nature.

We meet on the first Sunday of each month at 8.30am

Facebook page for Avalon Dunes Bushcare where you can keep up to date with progress and find out how to get involved.

Visit: www.facebook.com/AvalonDunesBushcare

Photo: Salt tolerant tree Coast Banksia is in flower now. Unlike most Banksias, it sheds its seeds every summer, not relying on fire to open its seed capsules.

Time Of Burrugin

Cold and frosty; June-July

Echidna seeking mates - Burringoa flowering - Shellfish forbidden

This is the time when the male Burrugin (echidnas) form lines of up to ten as they follow the female through the woodlands in an effort to wear her down and mate with her. It is also the time when the Burringoa (Eucalyptus tereticornis) starts to produce flowers, indicating that it is time to collect the nectar of certain plants for the ceremonies which will begin to take place during the next season. It is also a warning not to eat shellfish again until the Boo'kerrikin (Acacia decurrens, commonly known as black wattle or early green wattle) blooms.

Eucalyptus tereticornis, commonly known as forest red gum, blue gum or red irongum, is a species of tree that is native to eastern Australia and southern New Guinea. It has smooth bark, lance-shaped to curved adult leaves, flower buds in groups of seven, nine or eleven, white flowers and hemispherical fruit.

Eucalyptus tereticornis was first formally described 1795 by James Edward Smith in A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland from specimens collected in 1793 from Port Jackson by First Fleet surgeon and naturalist John White. The specific epithet (tereticornis) is from the Latin words teres (becoming tereti- in the combined form) meaning "terete" and cornu meaning "horn", in reference to the horn-shaped operculum.

Habitat tree: Sclerophyll Forest.

Food tree: Natural stands are an important food tree for koalas and a wide variety of nectar-eating birds, fruit bats and possums.

Eucalyptus tereticornis buds, capsules, flowers and foliage, Rockhampton, Queensland. Photo: Ethel Aardvark

Shelly Beach Echidna

Photos by Kevin Murray, taken late May 2023 who said, ''he/she was waddling across the road on the Shelly Beach headland, being harassed not so much by the bemused tourists, but by the Brush Turkeys who are plentiful there.''

Shelly Beach is located in Manly and forms part of Cabbage Tree Bay, a protected marine reserve which lies adjacent to North Head and Fairy Bower.

From the D'harawal calendar, BOM

D'harawal

The D'harawal Country and language area extends from the southern shores of Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) to the northern shores of the Shoalhaven River, and from the eastern shores of the Wollondilly River system to the eastern seaboard.

Winter Solstice In New South Wales: June 22 2023

This year: Thursday, June 22, 2023 12:57 AM. In terms of daylight, this day is 4 hours, 31 minutes shorter than the December solstice. In locations south of the equator, the shortest day of the year is around this date. The earliest sunset is on 12 June or 13 June. The latest sunrise is on 30 June or 1 July.

The December solstice (summer solstice) in Sydney is at 2:27 pm on Friday, December 22, 2023.

The winter solstice is the day of the year that has the least daylight hours of any in the year and usually occurs on 22 June but can occur between 21 and 23 June.

An interesting idiosyncrasy relating to the summer solstice is that it does not feature the day with the earliest sunrise and latest sunset as is commonly expected. Similarly, on the winter solstice, the sunrise is not the latest and the sunset is not the earliest. However, this day does have the least amount of daylight hours.

Because the path of the Earth around the Sun is an ellipse, not a circle, and because the Earth is off-centre on its axis, these combined phenomena can create up to several minutes difference between solar and mean time. Around the date of summer solstice, these effects make the Sun appear to move slightly slower than expected when measured by a watch or clock. As a result, the earliest sunrise occurs before the date of the summer solstice, and the latest sunset happens after the summer solstice. For the same reasons, around the winter solstice, the time of sunrise continues to get later in the days after the solstice. - from/by Geoscience Australia

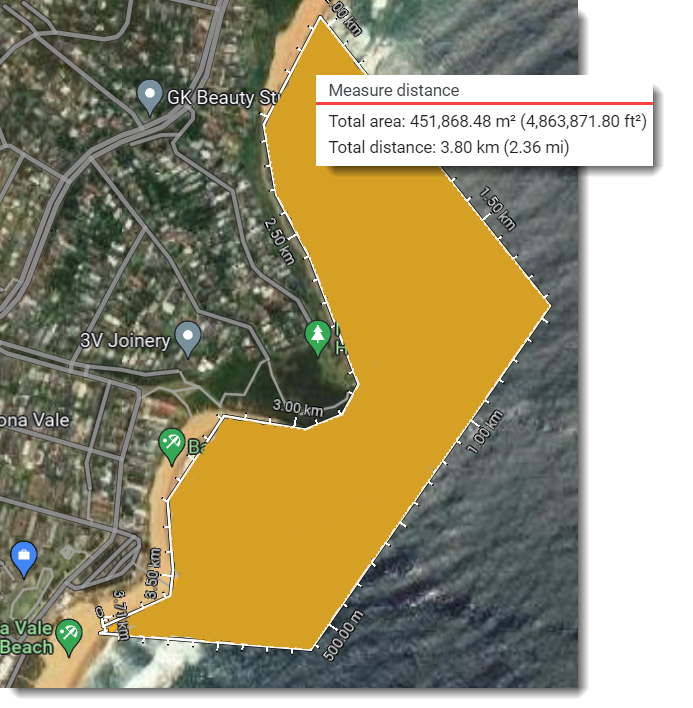

Protect Mona Vale's Bongin Bongin Bay - Establish An Aquatic Reserve

STONY RANGE BOTANIC GARDEN SATURDAY AFTERNOON BUSHCRAFT

STONY RANGE BOTANIC GARDEN SATURDAY AFTERNOON BUSHCRAFT

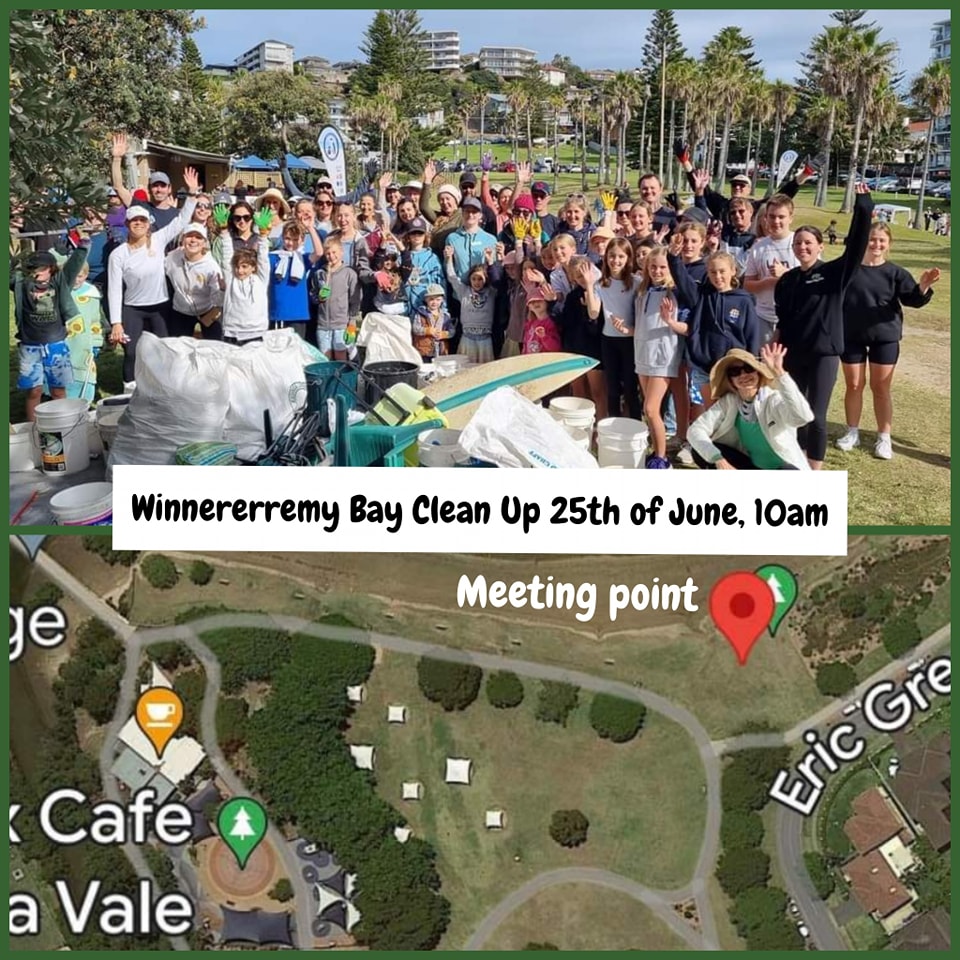

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: June 25 Winnererremy Bay, Mona Vale

Come and join us for our family friendly June clean up, in Winnererremy Bay on the Sunday June 25th at 10am. We meet in the grass area close to 7 Eric Green Drive. We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the water. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the water and even clean up in the water (at own risk).

We will clean up until around 11.15, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day - we will be there no matter what weather. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time. For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages. Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost.

All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too!

All details in our Facebook event or on our website.

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew Facebook page: www.facebook.com/NorthernBeachesCleanUpCrew

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew website: www.northernbeachescleanupcrew.com

Freshwater Beach And Surrounds Clean Up

Done on Sunday May 28 2023

A huge thank you to everyone and cleaned up Freshwater Beach today. More than 100 people came and we are so happy and grateful to everyone who cares and helps making our beaches and local environment a better and cleaner place for all beings.

We had thousands of Styrofoam balls, about 30 single use coffee cups, nearly 90 plastic bottles, 164 glass bottles, 146 aluminium cans, 11 kilos of cardboard/paper, several surf boards, 127 cigarette butts, 3 broken plastic chairs, thousands of pieces of soft plastic and 22 balls among many of the items that we picked up.

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

Sunday June 25: Birdwatching and Bushland along Mullet Creek in Ingleside Chase Reserve

Swamp forest and coastal wetlands are rich habitat for fauna such as Swamp Wallaby and Diamond Python. Over 150 bird species have been recorded for the area. Red-Browed Finch is one.

Bring your binoculars and keep your ears pricked for bird calls. The track is mostly level, but with an optional steep climb near the Irrawong waterfall.

Meet: 8.30am near 31 Irrawong Rd North Narrabeen. Ends about 10.30.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Chemical CleanOut: June 2023

Mona Vale Beach Car Park: Sat 24, Sun 25 June 2023 - 9am-3:30pm

Surfview Road, Mona Vale

Only household quantities accepted. Maximum container size of 20kg or 20L per item.

*Up to 100L of paint (in 20L containers) now accepted at all Sydney, Hunter and Illawarra events.

Accepted:

Fluoro globes and tubes, Gas bottles and fire extinguishers, Household cleaners, Batteries, Paint*, Oils, Garden chemicals, Poisons, Smoke detectors.

Permaculture NB: June To July 2023 Events

Permaculture Northern Beaches (PNB) is an active local group on Sydney's Northern Beaches working for ecological integrity and assisting you on a pathway to sustainability.

PNB holds monthly permaculture-related public meetings on the last Thursday of each month at the Narrabeen Tramshed Community & Arts Centre, Lakeview Room, 1395A Pittwater Road, Narrabeen. Buses stop directly at the centre and there is also car parking nearby. Doors open at 7:15 pm and meetings take place monthly from February to November.

Everyone is welcome!

We also hold a range of workshops, short courses, film and soup nights, practical garden tours, permabees (working bees), beehive installations, eco-product making sessions and much more.

CELEBRATING WORLD OCEANS DAY

Thursday, June 29, 2023: 7:30pm – 9:00pm

Narrabeen Tramshed Arts and Community Centre, Lakeview Room

1395A Pittwater Road, Narrabeen

Join us in World Oceans’ month to learn more about the Blue planet we live on.

Two great speakers will tell us the wonders and threats facing our oceans.

Australia Marine Conservation Society works on the big issues that risk our ocean wildlife - protecting critical ocean ecosystems with marine reserves around the nation, including Ningaloo and the Great Barrier Reef. As well as issues such as over-fishing and supertrawlers, and protecting threatened and endangered species like the Australian Sea Lion.

Surfrider Foundation is actively working to stop drilling and exploration for oil and gas off our coast (PEP2). The organisation works to protect our oceans, beaches and waves through a powerful activist network.

$5 entry by donation to pay for room hire. Organic teas and coffee are available at the night + swap table - bring plants, seeds, food, books and permaculture items to swap and share.

SEED SAVING CIRCLE

Saturday, July 8, 2023: 11:00am – 1:00pm

Balgowlah Community Garden

100 Griffiths Street, Balgowlah

Gather your seeds in winter for the coming spring. Share and swap seeds that are grown organically and locally. These seeds will be the best adapted you can find for the Northern Beaches climate and soils as many have been grown over generations.

Tap into the knowledge and the databank of seeds at Balgowlah Community Garden and PNB + share permaculture knowledge. This is an invaluable resource for the local community. Be part of the change - grow your own seeds and food.

Bring your non-alcoholic drinks and food to share on the day. The seed circle will be outdoors but under cover so dress weather-wise.

PLASTIC FREE JULY

Saturday, July 1, 2023 – Monday, July 31, 2023

Permaculture Northern Beaches is a part of the Plastic Free July challenge - Join Us!

The plastic bottles, bags and takeaway containers that we use for just a few minutes use a material that is designed to last forever. Every bit of plastic ever made still exists!

These plastics:

- Break up, not break down – becoming permanent pollution

- Are mostly made into low-grade products for just one more use or sent to a landfill

- End up in waterways and the ocean – where scientists predict there will be more tons of plastic than tons of fish by 2050

- Transfer to the food chain – carrying pollutants with them

- Increase our eco-footprint – plastic manufacturing consumes 6% of the world’s fossil fuels

Be part of the solution, by taking up these habits:

- Refusing plastic bags and packaging (choose your own alternatives)

- Reducing packaging where possible (opt for refills, remember your reusable shopping bags)

- Refusing plastics that escape as litter (e.g. straws, takeaway cups, utensils, balloons)

- Recycling what cannot be avoided by the use of alternatives.

Register to join 100,000 Australians and a million+ people worldwide stepping up in Plastic Free July www.plasticfreejuly.org

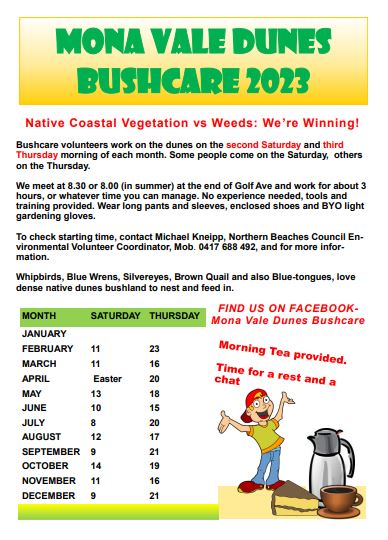

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

New Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Rare Bitterns Boom In Barmah-Millewa Forest

June 13, 2023

The endangered Australasian bittern is being heard in near-record numbers in the Barmah-Millewa Forest, giving hope for the species' long-term survival.

Around 30% of the nation's remaining bittern population is estimated to live in reedy wetland habitats in Barmah and Millewa. With only 1,300 individuals estimated to remain, this elusive night-calling, well-camouflaged bird is nationally endangered.

Impacts to wetlands due to changed watering regimes have contributed to their decline.

As part of The Living Murray (TLM) program, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) along with Victorian partners, have monitored the Barmah–Millewa Forest bittern population for the past seven years. Monitoring depends on identifying the series of deep growls or booms of males that travel across the wetlands when they're in search of a mate.

NPWS Project Officer Brady Cronin said the number of male bitterns calling this year was among the highest ever recorded.

"Monitoring data has identified changes in the timing of the bittern calling as a result of the 2022–23 flood, one of the largest of the decade, where water levels rose and dropped by around 3 to 4 metres in the Barmah–Millewa Forest," Mr Cronin said.

The NSW Government's Water for the Environment program is playing a critical role in supporting Australasian bittern population recovery within the inland wetland systems.

Senior Environmental Water Management Officer, Paul Childs, said the NSW Department of Planning and Environment's environmental water managers work with river operators to deliver water for the environment annually into sites where bitterns are known to breed.

"These flows are designed and timed to mimic the natural flow regime and provide ideal conditions for a range of other waterbirds and wetland-dependent plants and animals too."

Recent research conducted by Dr Elizabeth Znidersic and her team from the Gulbali Institute at Charles Sturt University has provided insight into the secretive life of the Australasian bittern by deploying sound recorders throughout the forest.

"The research shows that male Australasian bitterns started their breeding calls before the peak of the flood, stopped during the peak month, then resumed calling after flood waters slightly receded, and nesting habitat became available again." said Dr Znidersic.

To ensure bittern chicks successfully fledged so late in the season, additional water for the environment was delivered into the wetlands.

"This outcome highlights the importance of long-term monitoring that helps to inform the adaptive management of environmental water and site-based management activities such as predator control, which are essential components for building Australasian bittern populations" Mr Childs said.

The NPWS and Parks Victoria bittern project is funded by the Murray–Darling Basin Authority TLM program and the Victorian Government Sustainability Fund Community Action for Biodiversity (Icon Species) project.

Australasian bittern, Botaurus poiciloptilus, wrestling with an eel. Photo: Imogen Warren

Community Ideas To Deliver The Murray-Darling Basin Plan

May 29, 2023

The Australian Government is inviting communities to share their views about how to best deliver the Murray-Darling Basin Plan.

The Government is committed to delivering the Plan in full, including 450 GL to enhance environmental outcomes. But we know communities and industry have previously felt left out of the conversation.

Delivering the plan includes achieving all water recovery targets. It means putting our rivers on a healthier and more sustainable path, while continuing to support Basin communities who help feed our nation.

The Government is working with Basin states and territories to do this.

Individuals and groups are welcome to make a submission that considers questions including:

- What ideas or concepts can help fully implement the Murray–Darling Basin Plan?

- Will these ideas recover water and deliver environmental outcomes?

- Are there ideas that will make a particular difference to your community?

- What are the challenges or risks to implementing these ideas?

To have your say, and find out more about the Plan, visit the consultation webpage: https://consult.dcceew.gov.au/ideas-to-deliver-the-basin-plan

The consultation closes July 3rd 2023

Minister for the Environment and Water Tanya Plibersek stated;

“We know that climate change has made the implementation of the Plan more important than ever.

“The Albanese Labor Government is committed to delivering the Murray–Darling Basin Plan in full. I’m pleased that all Basin states and territories are also committed to doing this.

“After years of delay and sabotage by the Liberals and Nationals, we want to get this right.

“I’ve said all options are on the table to deliver the Plan. I welcome innovative and practical ideas for how we can deliver a sustainable Basin for the communities, farmers, businesses and First Nations groups who rely on it.”

Many urban waterways were once waste dumps. Restoration efforts have made great strides – but there’s more to do to bring nature back

In the 19th century, many of Australia’s urban creeks and rivers were in poor shape. Melbourne’s major river, the Maribyrnong, was full of waste from abattoirs, tanneries and factories.

I live near Darebin Creek in Melbourne’s north, which was next to a tip and often polluted until cleanup efforts began in the 70s. Now many creatures have returned.

But while many waterways have been cleaned up, others have languished. As late as 2011, Sydney’s notoriously polluted Cooks River was so full of industrial waste and sewage it was dubbed an “open sewer”. Now, it’s starting to improve.

Here’s what the restoration of Darebin Creek shows us about the successes and challenges of bringing life back to our urban waterways.

Rivers Or Rubbish Dumps?

Many of us, like Mole from Wind in the Willows, find ourselves “intoxicated with the sparkle, the ripple, the scents and the sounds…” of our waterways.

But we don’t always treat them very well. European settlement had a big effect on creeks and rivers, we’ve often used them as convenient waste dumps. Pump industrial waste, chemicals or sewage into them and watch it float away. Once we might have thought “problem solved”. Now we know differently. Treating rivers as dumps can (unsurprisingly) damage or even wipe out the life in it.

In Victoria, their fate started to improve when the state government passed the Environment Protection Act in 1970 (since superseded by the the Environment Protection Amendment Act 2018). Since then, community groups, government agencies, and Melbourne Water have started the repair job.

Now, we’re starting to see the benefits. My local waterway, Darebin Creek, is typical of many urban creeks and I love spending time here. Running in the morning, I pass ducks, swans, and moorhens. Kookaburras laugh in the trees, insects buzz in the morning light. It’s beautiful.

In the creek itself live frogs, invertebrates and fish. Endangered species like the growling grass frog and matted flax-lily can now be found.

There are even platypus sightings, which means there’s food there for them like insect larvae and yabbies.

What is now the expansive Darebin Parklands was once was used as a farm, then a quarry, then a tip earmarked for a freeway, and the creek was little more than a stormwater drain. Even today, leachate from the old tip seeps out.

The creek’s transformation – especially in its southern reaches – is due in large part to one determined woman, Sue Course, who was rightly recognised for her work in the 2021 Australia Day honours.

In the 1970s, Sue and her husband Laurie formed a residents’ group and lobbied successfully for the land to be given to the public. The group spent decades removing weeds and rubbish and planting trees.

Many urban waterways in Victoria are now in reasonable health, providing habitat for more than 1,800 species of native plants and 600 species of native animals. But not all. Rivers such as the Ovens and the Murray, and even the Yarra in places, are in poorer condition with low flows and high sediment and salt levels major issues.

Improvements are often connected to community efforts to revegetate, as well as watching for chemicals or other pollutants pumped into the stream. These efforts have to be ongoing. As recently as 2016, eels and other fish died in Darebin Creek due to insecticide being washed into the water.

And the wildlife of the creek has not fully recovered, as the local council points out. The remarkable plains-wanderer once roamed the creekline, but the last sighting was in 1972.

How Do We Fully Restore Our City Waterways?

Native species reliant on our city waterways still face threats. These include:

catchment pollution. A catchment is an area of land where water collects when it rains and then flows to a low point (such as a stream). Pollution in a creek or river’s catchment upstream can affect the whole waterway. A recent study on pesticides found the major source was residential use, meaning the chemicals were washed into the wetlands. A similar project used GPS to track plastic bottles down Melbourne’s creeks. They found bottles could travel many kilometres downstream, or get stuck and break down locally.

organic micropollutants. The way we live means we use a large range of chemicals, including cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, fertilisers, and artificial sweeteners. A detailed study of the Yarra, Sydney and Brisbane River estuaries found traces of these chemicals in the water, including drugs, medication, personal care products, pesticides, and even food additives. Even though they are present in very low concentrations they can still be a worry. A recent study from Monash University showed that concentrations of pharmaceuticals in rivers, though far below the therapeutic dose can still affect fish behaviour.

stormwater. When rain runs off hard surfaces like roofs, driveways, and roads, it runs into storm drains and creeks, carrying debris, bacteria, soil, oil, grease, pesticides and other pollutants with it. In 2016 it was estimated that 95% of litter on Victorian beaches was transported there from suburban areas through stormwater drains.

nutrients. Fertiliser runoff from farms and wastewater spills in urban areas can bring too many nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus into waterways. Overloads of nutrients can trigger sudden plant and algae growth. These block light and reduce oxygen levels, leading to the death of fish and other aquatic animals. Some algae and cyanoabacteria (that also grow in these conditions) produce toxins that can make us sick too.

invasive species. Many invasive species have been introduced into Australian waters including the infamous carp and mosquito fish. These prey on or outcompete native species, damage habitat, and carry diseases and parasites. Careful management to reduce their impact will likely be needed for some time.

How Can We Help Bring Life Back?

If there’s a lesson in the restoration work done so far, it’s that we can’t expect life just to bounce back. Making our waterways healthy again takes effort, ranging from making sure rubbish doesn’t escape into them through to joining your local waterway organisation – or starting one.

Join a local Waterwatch program to monitor river health, or join the national waterbug blitz to learn more about invertebrate life. You can even get involved in efforts to restore riparian vegetation as natural flood dampening measures.

Above all, let’s appreciate our urban creeks and rivers for what they are – and for what they can become, so the next generation will have the same chance to enjoy them as we have.![]()

Oliver A.H. Jones, Professor, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

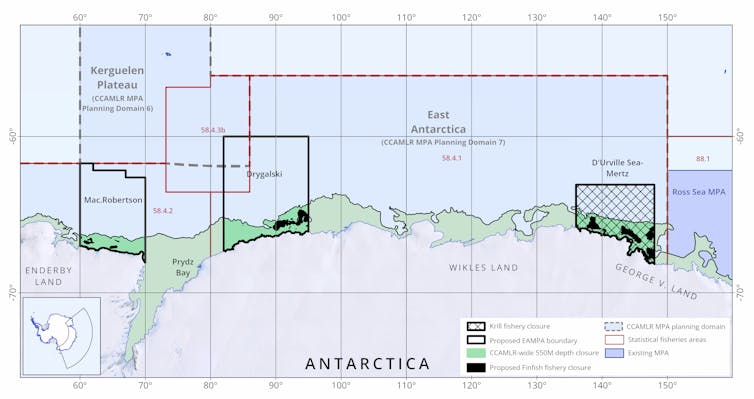

Can next week’s special meeting in Chile break the deadlock over East Antarctica’s marine park proposal?

Amid the challenges of climate change, resource extraction and pollution, the survival of species and ecosystems depends on setting aside protected areas. But plans to establish marine protected areas in East Antarctica have stalled.

Next week, the 27-member Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources will gather at a special meeting in Santiago, Chile, to try to break the deadlock. There’s much at stake, given the seemingly implacable opposition from China and Russia. China appears more concerned about fishing for krill than conservation, while Russia’s objections are less clear.

The need for Antarctic marine protected areas was first discussed in response to the 2002 United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development. The formal plan was adopted three years later, in 2005. While China had not yet joined the commission at that time, it was a member when the commission reaffirmed this commitment in 2011.

These areas were meant to protect a representative suite of Antarctic marine environments, such as unique seafloor communities, deepwater canyons, and highly productive coastal and oceanic food webs. They were to be developed, assessed and agreed on the basis of the best available science.

Slow Progress On Antarctica’s Marine Parks

So far, two marine protected areas have been agreed by the commission: South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf in 2009; and the Ross Sea Region in 2016. Since then, the commission has been unable to agree on any further proposals, including the East Antarctic Region marine protected area. This was first proposed by Australia in 2011. It’s the oldest of those proposed but not yet agreed. The commission has also been unable to adopt the research and monitoring plans or the reviews of the existing marine protected areas.

This year, the United Nations agreed to a treaty on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. This treaty will be up for adoption at a final conference session on June 19-20, 2023.

This treaty sets a global target of 30% of the global oceans to be in marine protected areas by 2030. This will be the likely yardstick against which the Commission’s future performance will be measured. So far, the commission’s marine protected area achievement is just 4.7% of the area of Southern Ocean that it is responsible for.

Of the 27 member countries of the commission, 21 have formally committed their support for the East Antarctic Region marine protected area. Only China and Russia have repeatedly opposed this and other proposals. They are now challenging the commission’s consensus agreement to establish the marine protected area network in Antarctica.

The Shrinking East Antarctic Region Marine Protected Area

The proposed East Antarctic Region marine protected area initially consisted of seven distinct areas designed to protect the diversity of environments in the region. Since then, Australia and its partners, now numbering 17, have granted many compromises in the quest for consensus. The number of distinct areas has been reduced to three and fishing is allowed unless explicitly excluded.

To specifically accommodate China’s concerns about future krill fishing, Australia sacrificed the unique and special Prydz Bay region. That’s despite the fact China’s krill fishing aspirations could be more than adequately met from the rest of the region. Nonetheless, Russia and China continue to withhold consensus on this proposal.

Increasingly, the rhetoric opposing marine protected areas is centred around an argument that invokes a “balance” between “conservation” (in this case, the establishment of marine protected areas), and “rational use” (in this case the right to fish). On both legal and practical grounds, the conservation versus rational use argument centres on the very core of the international agreement that covers the oceans of the region, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

The convention was agreed in 1980 to protect all Antarctic species from potential over exploitation. Its objective was – and remains – clearly centred on conservation in the region. Fishing is allowed, as long as the species and ecosystems of the region are conserved. The convention states that its objective “is the conservation of Antarctic marine living resources”. It identifies those resources as “populations of fin fish, molluscs, crustaceans and all other species of living organisms, including birds” and clarifies that “conservation” includes “rational use”, if such rational use can be conducted with minimal impact on the ecosystem.

In recent years, Russia and China have both argued that there is too much emphasis on conservation. They state that there needs to be a re-balancing between fishing and conservation. In constructing this argument, they are engaging in a wilful reinterpretation of the convention – and ignoring the significant time dedicated by the commission to fisheries management.

A Reliance On Consensus

The commission, like the rest of the Antarctic Treaty System, makes decisions on the basis of consensus. This means that some decisions may take quite some time to be agreed, but the strength of consensus is that all parties are then committed to the final result.

Consensus is built on trust and good faith. But consensus will be undermined when agreement is withheld in bad faith, or used as a means to achieve other objectives. The actions of one or a few that withhold consensus, or who negotiate in bad faith, could, if not confronted, undermine all decision-making in the commission, including decisions on sustainable fisheries.

Now Is Not The Time For Endless Compromise

We must not continue compromising for an apparent “quick win”. The East Antarctic Region marine protected area has been evaluated by the commission’s scientific committee, and the commission has repeatedly reached the point where only Russia and China withhold agreement. It is this behaviour that needs to be explicitly challenged, not the marine protected area proposal itself.

These nations need to explain their specific concerns, and in the spirit of consensus, provide workable alternatives that meet their obligations under the conventions and accommodate the aspirations of all members.

Australia has held many discussions with China and Russia over the years to help resolve their issues. With China, these discussions have been thorough and cordial, and it is clear this nation has a deep and comprehensive understanding of the marine protected area proposal. Several bilateral meetings have also been held with Russia; however, it remains unclear what their specific objections are, particularly as they are no longer fishing.

There are no obstacles to China agreeing to the East Antarctic Region marine protected area proposal now. They have agreed to two large Antarctic marine protected areas in the past. The East Antarctic marine protected area poses no substantive obstacle to China’s aspirations in the region, including their stated desire to harvest krill.

There is much at stake at this upcoming special meeting, including the reputation of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. The protection of the Antarctic requires that a way forward on marine protected areas be found.![]()

Lynda Goldsworthy, Research Associate, University of Tasmania; Marcus Haward, Professor, and Tony Press, Adjunct Professor, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

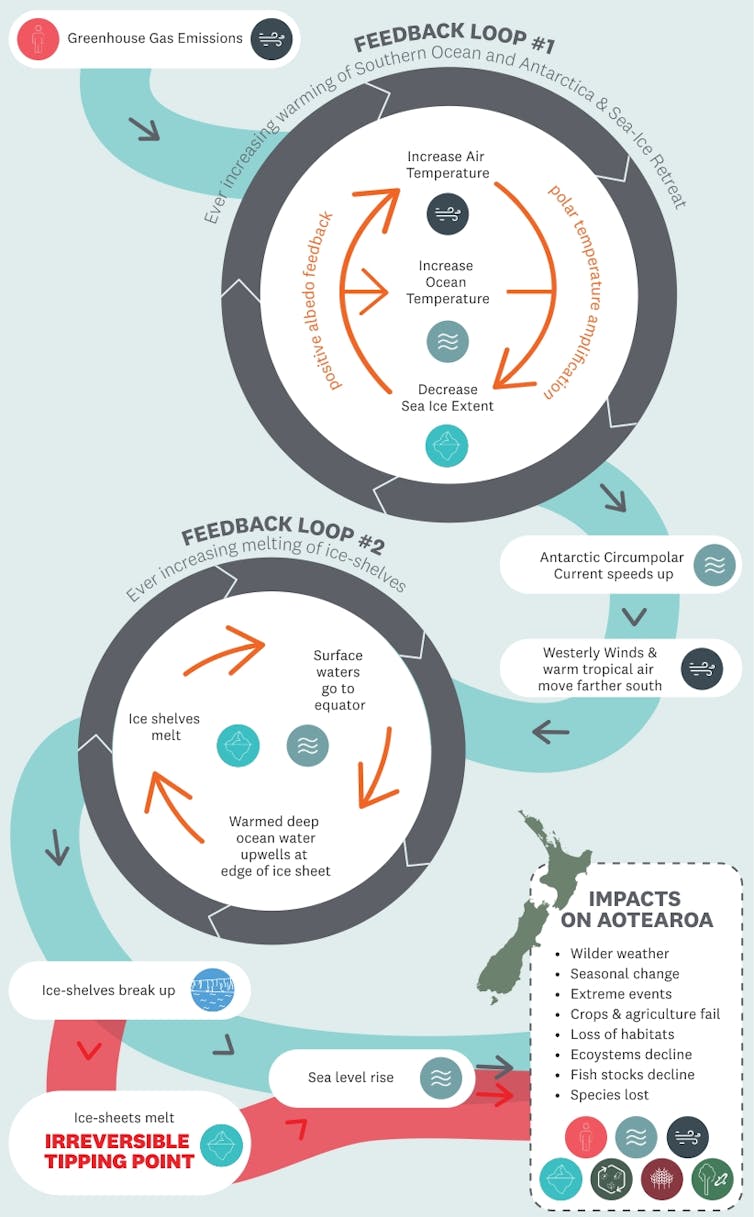

Antarctic tipping points: the irreversible changes to come if we fail to keep warming below 2℃

The slow-down of the Southern Ocean circulation, a dramatic drop in the extent of sea ice and unprecedented heatwaves are all raising concerns that Antarctica may be approaching tipping points.

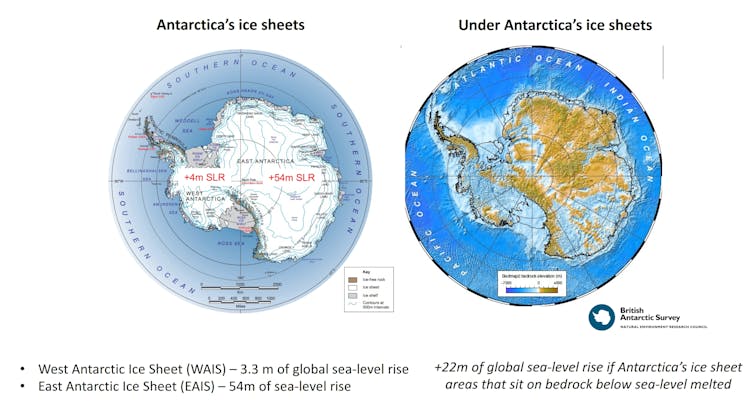

The world has now warmed by 1.2℃ above pre-industrial levels (defined as the average temperature between 1805 and 1900) and has experienced 20cm of global sea-level rise.

Significantly higher sea-level rise and more frequent extreme climate events will happen if we overshoot the Paris Agreement target to keep warming well below 2℃. Currently, we are on track to average global warming of 3-4℃ by 2100.

While the recent Antarctic extremes are not necessarily tipping points, ongoing warming will accelerate ice loss and ocean warming, pushing Antarctica towards thresholds which, once crossed, would lead to irreversible changes – with global long-term, multi-generational repercussions and major consequences for people and the environment.

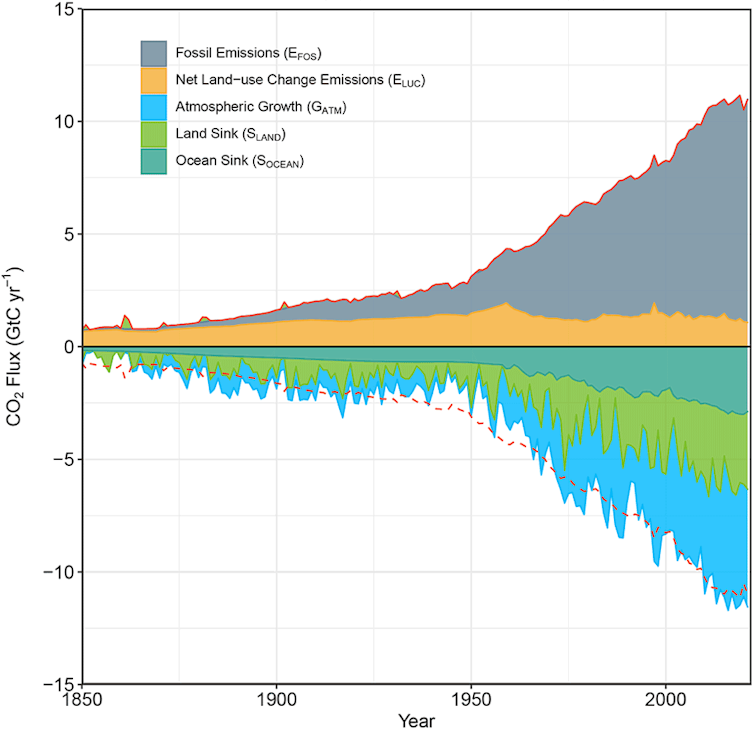

The Earth system is designed to reach equilibrium (come into balance) in response to climate heating, but the last time atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide (CO₂) were as high as they are today (423ppm) was three million years ago.

It took a millennium for the world’s climate to adjust to this. When it did, Earth’s surface was 2℃ warmer and global sea-levels were 20m higher due to Antarctic ice-sheet melting. Back then, even our earliest human ancestors were yet to evolve.

The evolution of humankind could only begin after CO₂ levels dropped below 300ppm, about 2.7 million years ago. Since then, Earth’s average temperature has fluctuated between 10℃ during ice ages and 14℃ during warmer inter-glacial periods.

During the past 10,000 years of our present inter-glacial period, Earth’s greenhouse gas thermostat has been set at 300ppm of CO₂, maintaining a pleasant average temperature of 14℃. A goldilocks climate – not too hot, not too cold – but just right for human civilisation to flourish.

The Earth System Is Interconnected

Current global heating is taking the Earth system across a threshold humans have never experienced, into a climate where Antarctica’s ice shelves and marine ice sheets can no longer exist and one billion people, currently living near the coast, will be drowned by rising seas.

This will be a world where wildfires, heatwaves, atmospheric rivers, extreme rainfalls and droughts – such as those we have seen globally last summer – become commonplace.

The Earth system (oceans, atmosphere, cryosphere, ecosystems etc) is interconnected. This allows energy flow, enabling physical and ecological systems to remain in balance, or to regain balance. But connections can also mean dependencies, leading to reactions, amplifying feedbacks and consequences. Changes have roll-on effects, much like toppling dominoes.

Feedback loops – cyclical chain reactions that repeat again and again – can make the effects of climate change stronger or weaker, sometimes stabilising the system, but more often amplifying a response with adverse impacts.

Change is also not always linear. It can be abrupt and irreversible on human timescales if a threshold or tipping point is crossed.

Here, we outline one sequence of changes and consequences, including feedback loops and thresholds, using the example of global heating melting Antarctica’s ice sheets and the resulting sea-level rise.

We take a 50-year view into the future, as this is relevant for today’s policy makers but also sets in place much longer multi-generational consequences. While we focus on this example, there are many other Antarctic tipping points, including the effects of freshwater from ice-sheet melt on marine ecosystems and the effects of Antarctic change on Aotearoa’s temperature and rainfall patterns.

Antarctica In A Warming World

Unless we change our current emissions trajectory, this is what to expect.

By 2070, the climate over Antarctica (Te Tiri o te Moana) will warm by more than 3℃ above pre-industrial temperatures. The Southern Ocean (Te Moana-tāpokopoko-a-Tāwhaki) will be 2℃ warmer.

As a consequence, more than 45% of summer sea ice will be lost, causing the surface ocean and atmosphere over Antarctica to warm even faster as dark ocean replaces white sea ice, absorbing more solar radiation and re-emitting it as heat. This allows warm, moist air in atmospheric rivers from the tropics to penetrate further south.

This accelerated warming of the Antarctic climate is a phenomenon known as polar amplification. This is already happening in the Arctic, which is warming two to three times faster than the global average of 1.2℃, with dramatic consequences for the permanent loss of sea ice and melting of Greenland’s ice sheet.

Antarctic Tipping Points

The warmed waters melt the ice shelves, which are floating tongues of ice that stabilise the Antarctic ice sheet, slowing down the flow of ice into the ocean.

Ice shelves can pass a tipping point when local ocean temperature thresholds are crossed, causing them to thin and float in places where they were once held in place by contact with the seabed. Melting at the surface also weakens ice shelves. In some cases, water on the surface fills up cracks in the ice and can then cause large areas to disintegrate catastrophically.

By 2070, heat in the ocean and atmosphere will have caused many ice shelves to break up into icebergs that will melt and release a quarter of their volume into the ocean as freshwater. By 2100, 50% of ice shelves will be gone. By 2150, all will have melted.

Without ice shelves holding back the ice sheet, glaciers will discharge at an even faster rate under gravity into the ocean. Large parts of the East Antarctic ice sheet and almost the entire West Antarctic ice sheet sit on rock in deep depressions below sea level.

They are vulnerable to an irreversible process called marine ice sheet instability (MISI). As the edges of the ice retreat into the deep basins, driven by the ongoing encroachment of warm ocean waters, the loss of ice becomes self-sustaining at an accelerating rate until it is all gone.

Another positive feedback, called marine ice cliff instability (MICI), means cliffs at the margins of the retreating ice sheet become unstable and topple over, exposing even taller cliffs that collapse under their own weight continuously like dominoes.

If global heating is not held below 2℃, ice-sheet models show global sea-levels will rise at at an accelerating rate up to 3m per century. Future generations will be committed to unstoppable retreat of the Greenland and marine sections of the Antarctic ice sheets, causing as much as 24m of global sea-level rise.

These changes highlight the urgency for immediate and deep cuts to emissions. Antarctica has to remain a stable ice-covered continent to avoid the worst impacts of rising seas.

Programmes around the world, including the Antarctic Science Platform, are prioritising research about future changes to the Antarctic ice sheet. Even if the news is not great, there is still time to act.

Mel Climo, Sandy Morrison and Nancy Bertler from the Antarctic Science Platform are acknowledged for their input and support.![]()

Timothy Naish, Professor in Earth Sciences, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The case for compost: why recycling food waste is so much better than sending it to landfill

Most food and garden waste in Australia comes from homes. Australian households waste 3.1 million tonnes of food each year. That’s more than five kilograms each household per week.

Over half of all household waste is food organics and garden organics, also known as “FOGO”. These scraps and clippings take up space in landfill and, when they rot, emit dangerous greenhouse gases.

The federal government’s National Waste Policy Action Plan aims to increase the organic waste recycling rate from 47% to 80% by 2030 and halve the amount sent to landfill. This won’t happen on its own - we need investment and action.

Food and garden waste can be captured and turned into compost. Composting is no longer just the domain of the home gardener or eco-warrior. It’s happening at commercial scale, through services such as council collection from homes.

A federal government fund is building new composting facilities and supporting other food and garden organics recycling projects. The South Australian government has invested in council trials of weekly green bin collection and fortnightly rubbish collection.

But more must be done. Recycling food waste into high-quality compost is a win-win solution, for people and the planet. Here, we explain why.

Compost Is A Winner For The Climate

When food rots in landfill, in the absence of oxygen, the process releases a potent greenhouse gas called methane.

Composting is different because the microbes can breathe. In the presence of oxygen, they transform waste into valuable organic matter without producing methane. They recycle organic carbon and nutrients into compost, which can be used to improve soil health and productivity.

This process also captures and stores carbon in the soil, rather than releasing it as carbon dioxide (CO₂) to the atmosphere.

In Australia, organics recycling (including food and garden organics, biosolids and tree wastes) saves an estimated 3.8 million tonnes of CO₂ from entering the atmosphere each year. That’s equivalent to planting 5.7 million trees or taking 877,000 cars off the road.

Soils can profit from compost because globally an estimated 116 billion tonnes of organic carbon has been lost from agricultural soils. This has contributed to rising CO₂ levels in the atmosphere.

Promisingly, compost can restore soil organic carbon while also boosting health and fertility. Compost improves soil structure and water retention. It’s also a source of essential nutrients that reduces the demand for costly fertilisers.

The opportunity presented by soils to draw down atmospheric CO₂ levels was brought to global awareness in the 2015 global Paris Agreement, via the “4-per-mille” initiative.

Translated from French, it means increasing the organic carbon stored in global soils by 0.04% each year (4 per 1000) would neutralise increases in atmospheric CO₂. In other words, CO₂ would remain constant rather than continue to increase. That would make a substantial contribution to mitigating climate change.

Farming With Precision

Our research has investigated how compost can benefit global agriculture.

We found that in most cases where compost is applied as a generic product to agricultural land, the benefits are not fully realised. But if suitable composts and application methods were aligned with target crops and growth environments, crop yields can be increased and organic carbon in soils replenished.

We call this a “precision compost strategy”. Using a data-driven approach, we estimate global application of this strategy has potential to increase the production of major cereal crops by 96.3 million tonnes annually. This is 4% of current global production and twice Australia’s annual cereal harvest.

Of great relevance for Australia’s farms, precision compost has the strongest effects in dry and warm climates, boosting yield by up to 40%. We now need to develop this strategy for the specific needs of farms.

Compost has the potential to restore 19.5 billion tonnes carbon in cropland topsoil, equivalent to 26.5% of current topsoil soil organic carbon stocks in the top 20 cm.

Give FOGO A Go-Go

The amount of food and garden waste in Australia is growing at a rate six times faster than Australia’s population and 2.5 times faster than GDP.

But less than a third of Australian households have access to food waste collection services. A national rollout has been pushed back from 2023 to the end of this decade so there is time to overcome some roadblocks. This includes uptake by community and high quality composting.

This waste stream offers a huge opportunity for landfill diversion and compost production. The cost benefit alone is compelling: councils can save up to A$4.2 million a year on landfill levies by diverting 30,000 tonnes of waste (based on A$74 to 140 per tonne of waste, with levies increasing).

Preventing food in the home from being wasted should be top priority. But for unavoidable food waste, turning it into high-quality compost makes perfect sense.

us![]()

Susanne Schmidt, Professor - School of Agriculture and Food Science, The University of Queensland and Nicole Robinson, Research Fellow, School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Imagine the outcry if factories killed as many people as wood heaters

Imagine a fleet of ageing factories operating in neighbourhoods across Australia.

On most days the smoke from their stacks is hardly noticed. But on cold days when the smog settles in the densely populated valleys and towns, doctors notice unusually high numbers of people suffering from a range of problems, especially asthma.

Air-quality researchers are called in to study the problem in more detail. They confirm that neighbourhoods with these old factories have higher concentrations of fine particles, which are toxic air pollutants.

Invisible to the naked eye, particles are inhaled deep into the lungs, enter the bloodstream and cause a range of harms throughout the body. This air pollution is linked to higher rates of heart and lung diseases, strokes, dementia and some cancers. It also increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes and poorer learning outcomes in children.

The researchers calculate that each year pollution from the factories causes 269 premature deaths in Sydney, 69 in Tasmania and 14 in Armidale, New South Wales.

While the factories are supposed to be built, maintained and operated to certain standards, the regulations are rarely if ever enforced. There isn’t even a central register to tell authorities how many of these factories exist, how old they are, and where they are located.

As news of this research is made public, how would the affected communities react? What might they demand of government?

Would it matter if they knew we were not talking about factories, but wood heaters?

Heaters Produce Much Of Our Air Pollution

Every sentence of this story is true if you replace the word “factory” with “wood heater”.

Less than 10% of households own a wood heater, but burning wood for heating is the largest source of air pollution in many Australian cities and towns. While vehicle manufacturers and industry have greatly reduced emissions following tightened government regulations, domestic heating technology has not kept pace.

Today you would have to drive a diesel truck 500 kilometres to emit as much air pollution as a wood heater does in a single day. And that figure is for a wood heater that meets the current regulatory standards in Australia. Most do not.

Furthermore, wood heater pollution can be many times more severe when owners leave logs to smoulder overnight, burn poorly seasoned wood, or close down the air intake immediately after loading more wood.

Of course, particulate pollution is not all that wood heaters emit. When firewood is sourced from land clearing and illegal wood hooking, wood heaters add to net carbon dioxide and methane emissions in much the same as burning coal does because the carbon is no longer locked away in forests.

The best estimates are that less than a quarter of firewood is sourced from sustainable plantation suppliers. Even from those sources, the carbon emissions take many years to be sequestered into growing trees.

One study estimated that, if we stopped burning wood and clearing forest for heating, Australia would reduce its annual greenhouse gas emissions by 8.7 million tonnes. That’s about one-fifth of Australia’s car emissions.

The Benefits Of Electrification

Inevitably, as Australia moves towards a zero-carbon future, the electrification of domestic heating will bring widespread health and economic benefits. It will prevent hundreds of premature deaths each year.

Hospitals will benefit from a reprieve in the cooler months, enabling doctors and nurses to better cope with seasonal pneumonia and COVID-19 outbreaks. And even those outbreaks will be less severe with reduced air pollution.

Besides being healthier, Australians will enjoy much lower heating costs as a result of using technologies such as reverse-cycle air conditioners (heat pumps). Remarkably, heat pumps are up to 600% efficient. That means, for every unit of energy they consume, they generate up to six units of heating energy.

Making The Switch

As people learn about the impacts of wood heaters on their neighbours, friends and relatives — on pregnant women, young children and the elderly — many will make the switch.

Governments need to ensure safe and affordable heating technology is available to everyone regardless of their income.

Already, governments in the Australian Capital Territory, Tasmania and New Zealand have programs that reimburse households for the cost of replacing their wood heaters.

Buy-back schemes, home efficiency subsidies, regulation and enforcement, including property market regulation (ensuring wood heaters are removed prior to sale), and restrictions on new installations all have a role to play.

We are conducting economic modelling to determine the most cost-effective policy settings for maximising the benefits of policies to manage the problem of wood heaters.

Fire and smoke will remain important experiences for Australians. They can be savoured primarily outside the city, under bright stars, in open deserts and rugged coastlines, in beach shacks and farm cottages, and as part of Indigenous cultural practices.

One day we will look back in amazement that we once tolerated wood heaters in our cities, right next to schools, homes and hospitals. We’ll regard them in much the same way that we think of polluting factories today.![]()

Bill Dodd, Knowledge Broker, Centre for Safe Air (NHMRC CRE), University of Tasmania; Bin Jalaludin, Conjoint Professor, School of Population Health, UNSW Sydney, and Fay Johnston, Professor, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Help, bees have colonised the walls of my house! Why are they there and what should I do?

Have you spotted a swarm of flying insects emerging from a wall? Or noticed a buzzing noise coming from inside the house?

If this sounds familiar, a colony of European honeybees (Apis mellifera) may be making their home in your walls.

Why does this happen, and what should you do?

Are They Honeybees?

First, work out who these house guests really are. Honeybees are often the culprits, but European wasps (Vespula germanica) also occasionally build their nests inside human-made structures. Their nests have a papery appearance and are made from chewed-up plant fibres.

European wasps are a more dramatic yellow and black, and have narrower waists. Honeybees have less slender waists, appear furrier, and are a duller orange-brown colour.

If they are inside homes or high-traffic areas, both honeybees and European wasps will usually need to be removed by a professional.

Depending on where you live, other social bees such as stingless bees and bumblebees may occasionally build colonies in human-built structures, but they rarely cause any serious problems.

Solitary native bees such as carpenter bees, blue banded bees and teddy bear bees do not live in colonies. However, they sometimes build their individual nests close to one another. These insects are rarely aggressive and can often be left alone.

How Did They Get There?

When a honeybee colony outgrows its current dwelling, the bees embark on a quest to find a new home.

In preparation, the queen bee lays eggs in special cells known as “queen cells”. The larvae in these cells are fed with royal jelly, which helps them develop into new queens.

Once the new queens emerge, the old queen leaves the hive accompanied by a substantial number of worker bees.

Now homeless, the house-hunting bees gather together in a tight cluster called a “swarm ball” on a nearby object. From this temporary base of operations, the bees send out scouts to find potential nesting sites.

When a scout discovers a suitable location, she returns to the swarm ball and performs an extraordinary routine known as a “waggle dance”.

Astonishingly, this dance communicates the location of the potential new home to other scouts, who then venture out to inspect the advertised site. If they agree with its suitability, they return to the hive and do their own waggle dance.

Once enough scouts agree on the suitability of the new home, the entire swarm soars through the air to their new home.

Unfortunately, the bees occasionally choose to settle in human-made structures. Once inside, they produce wax to build the hexagonal cells that make up the nest. Some cells are used as nurseries for larvae, while others are used to store pollen and honey.

The most obvious sign is usually a steady stream of bees flying in and out of the hive, usually from a small hole or gap in the wall.

You might also hear a buzzing sound.

What Will The Honeybees Do To My House?

The honey and wax produced by bees can melt when the colony dies or during hot weather. This leads to stains and damage to walls, while the lingering honey may draw in rodents. The growing weight of a colony can also cause structural damage over time.

While honeybees are generally not aggressive, they will sting in self-defence, particularly near their colony.

Moving slowly and avoiding swatting can lower the chance of getting stung.

Dealing With Honeybees In The Home

If honeybees have taken up residence in your home, ask a professional, such as a beekeeper, to remove them.

Do not attempt to remove the bees yourself; this could be dangerous. Spraying insecticides or repellents into your walls may not kill all the bees and could trigger aggression.

Even if the insecticide does kill the colony, the dead bees, wax and honey will decay and melt, creating a bigger mess and attracting pests.

Not all beekeepers are equipped to remove bees from homes. Look for beekeepers who advertise “bee removal” or “bee rescue” services.

You can also try contacting amateur beekeeping associations, which may maintain a list of experienced bee removers. If there are no appropriate beekeepers in your area, or the colony is not easy to access, you may need to contact a pest controller.

Sometimes, colonies can be removed alive and relocated but this is not always possible. Your options will depend on the size of the colony, whether or not the beekeeper can access the colony, their level of experience and how long the colony has been there.

If you live in certain regions of New South Wales, it’s very important you report honeybee swarms or wild colonies to the Department of Primary Industries.

Wild colonies may harbour invasive Varroa mites, which are a deadly honeybee parasite. Varroa mites are currently subject to an eradication program. Varroa mite is only in NSW at the moment.

Prevention Is Key

Try to prevent bees getting in your house in the first place. Seal cracks or holes in exterior walls and put fly screen mesh over outdoor vents.

Beekeepers can prevent swarms happening in the first place by making sure they manage their hives appropriately. Joining a local beekeeping club is an excellent way to learn about bee care.

While honeybees are important pollinators and honey producers, they can also be a nuisance in your home.![]()

Tanya Latty, Associate professor, University of Sydney and Nadine Chapman, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bad break-up in warm waters: why marine sponges suffer with rising temperatures