inbox and environment news: Issue 590

July 16-22 2023: Issue 590

Weeds: A Round Table Discussion: Narrabeen - July 21

Conny Harris has organised this Round Table to discuss the problems with weeds in our area, which are a serious threat to our biodiversity.

You might enjoy this event if you battle with weeds in your garden, work in a Bushcare group, or just tire of seeing weeds along roadsides everywhere.

The Agenda is below, with some reading for you before the event.

Another attachment (also below) explains just what is a priority weed.

We will have weed specimens to help the discussions, and PNHA Cards will be for sale.

All Welcome

Weeds Round Table on July 21, PLEASE RSVP to Conny Harris if you would like to attend. Her email: conny.harris@gmail.com

Conny is providing Pumpkin soup and sourdough bread for supper.

Weeds: A Round Table Discussion

The Tramshed, Pittwater Rd Narrabeen, Friday July 21, 6-8pm

Conny Harris has organised this event because many of us are concerned about weeds increasing in the Northern Beaches area.

What can be done?

Agenda

1. acknowledgement of country

2. introduction of attendees

3. focus - why this forum?

4. presentation by Sonja Elwood, Coordinator, Invasive Species Northern Beaches Council (as per questions sent earlier)

5. discussion within the group about our experience with new or particular strongly emerging weeds.

6. conclusions/ recommendations

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

In advance of the Roundtable discussion, Council staff have provided answers to the following questions asked by Conny in a recent email.

1) Priority weeds for Council and their management:

Council's priority weeds are listed in Council's Local Priority Weed Management Plan. Weeds are managed in accordance with the requirements of the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015.

2) Where are these priority weeds predominantly?

Priority weeds may be found in a variety of locations including private lands and gardens, bushland reserves, creek lines, major roadways and/or degraded building or development sites.

3) How does the Council care for areas with very high biodiversity?

Council objectives for managing land with very high biodiversity are identified in Council’s Bushland and Biodiversity Policy. Council has limited powers over conservation and management (of weeds) of land that is private land or land that is not under our care and control. Funding for management of weeds is limited to land under Council’s care and control. Management of weeds in Council’s reserves is guided by Council policy which states “The restoration and enhancement of public bushland will be prioritised based on both conservation significance and the level of public interest”. Areas of conservations significance within individual reserves are determined by the relevant bushland management officer and based on Council mapping and local expert knowledge. In many instances, management is also guided by relevant Plans of Management.

4) What coordination is in place between roadside maintenance crews and your department?

Council Teams collaborate when carrying out works in sensitive areas such as Bushland and Endangered Ecological Communities (EEC's). The majority of the Parks road side maintenance involves cutting back vegetation from around 1 - 2m in from the road edge to maintain sight lines and safe road access for pedestrians and other road users. Council uses experienced contractors who have been carrying out road side maintenance in most of the bushland areas of Terry Hills, McCarrs Creek, Elanora Heights, Belrose and Ingleside for many years and are well aware of areas of EEC or threatened ecological communities.

5) What coordination is in place with RFS for planned burns?

Council has identified 42 burns for the 23/24 Annual Hazard Reduction Burn Program throughout various reserves and parks which not only contribute towards reducing bush fire risk, but also work towards maintaining diversity and ecological goals.

Council works closely with the relevant fire agency (NSW Rural Fire Service or Fire & Rescue NSW) to plan, prepare and implement Council proposed burns as weather and operational opportunities allow prioritised on risk.

Other land managers such as the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service or the BFMC sometimes propose burns that may involve areas of Council land. Council works closely with these agencies through the BFMC to review any such proposals and provide appropriate permissions as required.

The BFMC is currently working towards renewing the two existing Bush Fire Risk Management Plans. The committee has recently publicly exhibited a new draft Bush Fire Risk Management Plan. The plan is on exhibition until 17th July after which time the BFMC will be working to reviewing any community and agencies comments prior to finalising and adopting the new plan.

6) What responsibility for weed control do the Parks and recreation department, and the department in charge of road maintenance have?

Council Teams collaborate when carrying out all proposed works, in particular our teams work extensively with Pamela Bateman our Weed Management Officer to ensure that we address weed outbreaks.

Also: Northern Beaches Draft Bush Fire Risk Management Plan (open for submissions until 17 July 2023)

| DPI Primefact What is and what is not a priority weed Biosecurity Act JUN2023 (1).pdf Size : 532.84 Kb Type : pdf |

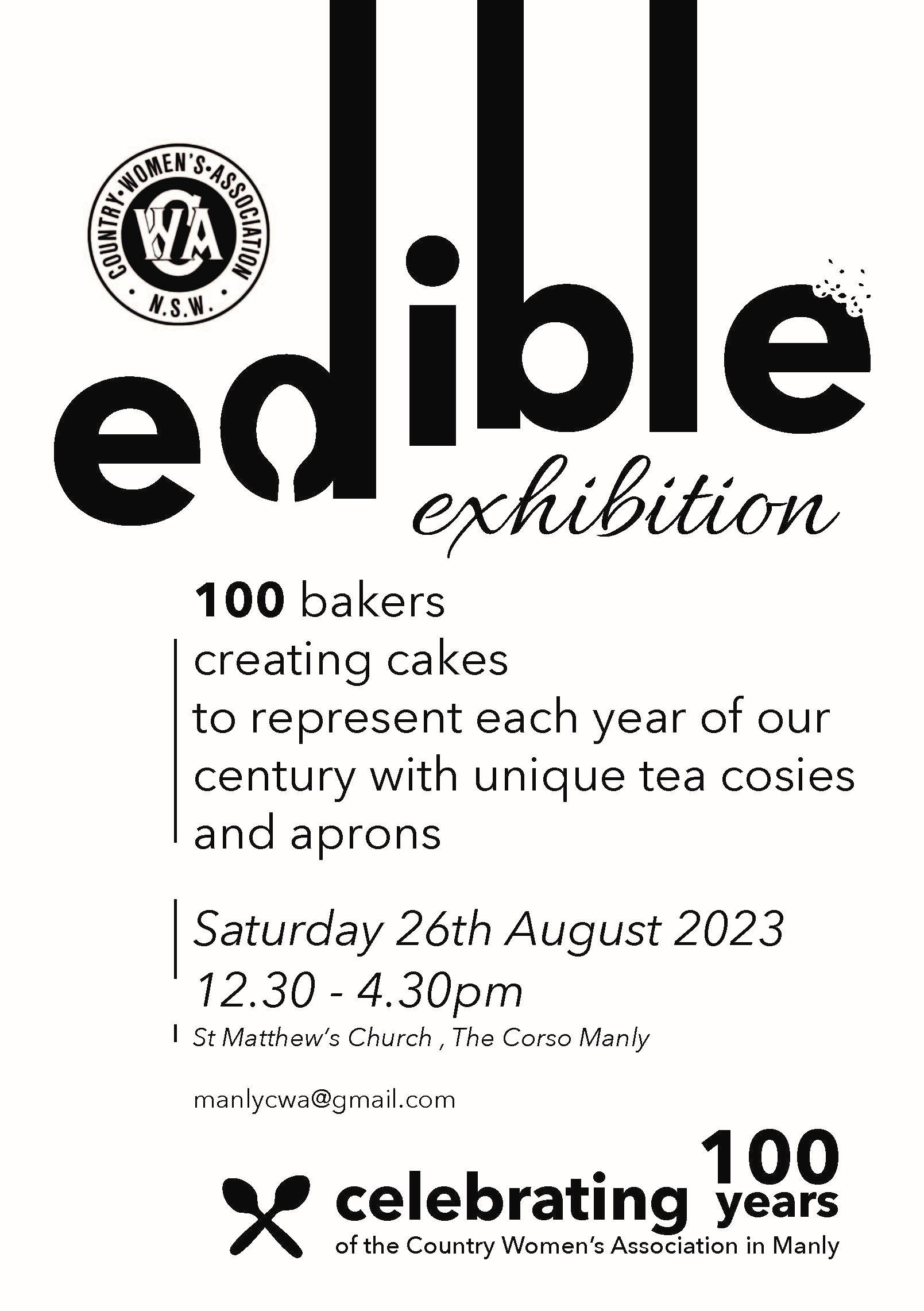

Spring + Summer 2023 Ringtail Posse Membership Now Open - Please Email Us To Express 'I'm In'!

Although there have been calls to open the Ringtail Posse across the Sydney Basin, the founders will leave this up to local wildlife carer groups and councils at present - 2024 will see an expansion and we will persist in sharing local members insights. At present we are seeking residents who want to become part of the Spring and Summer rounds for our LGA.

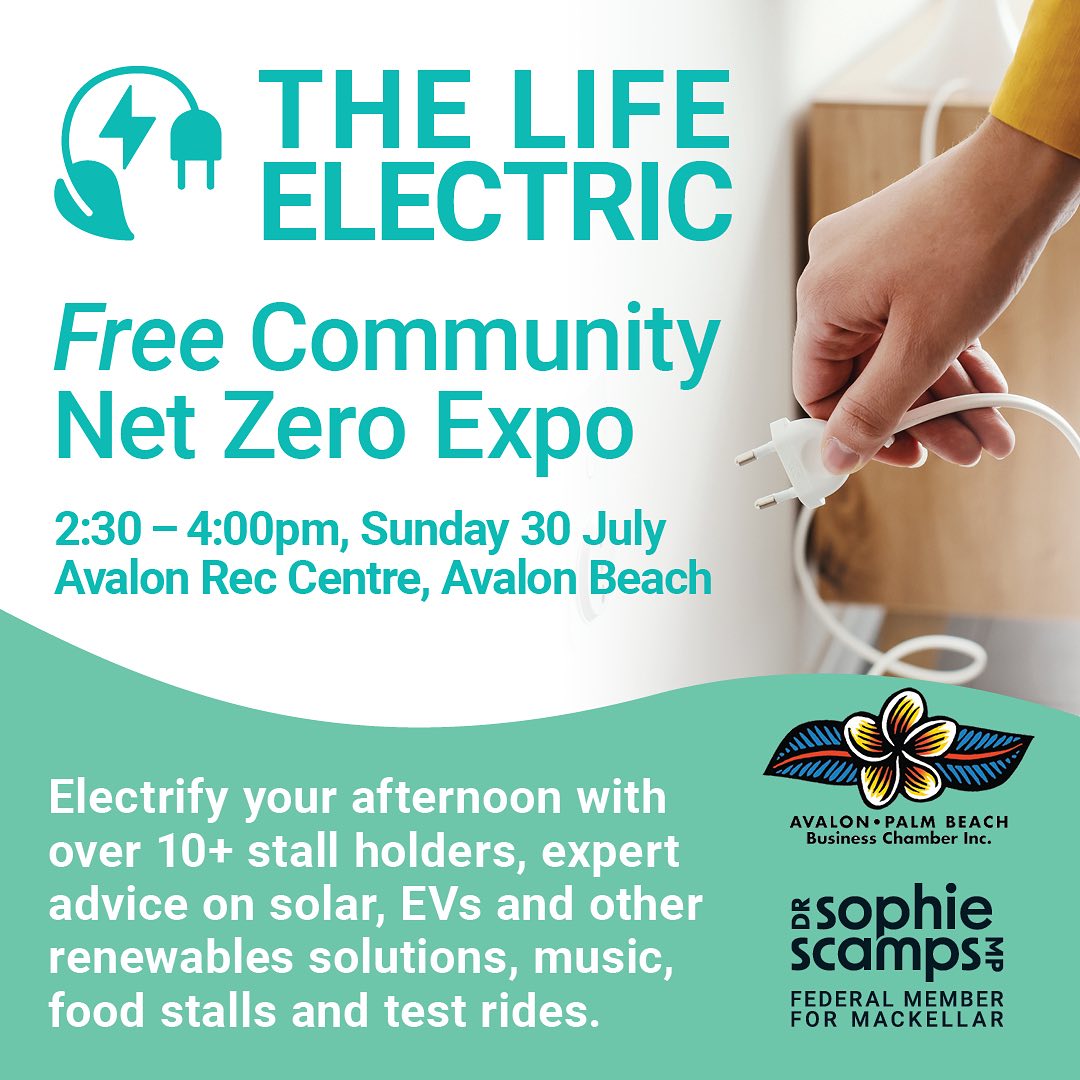

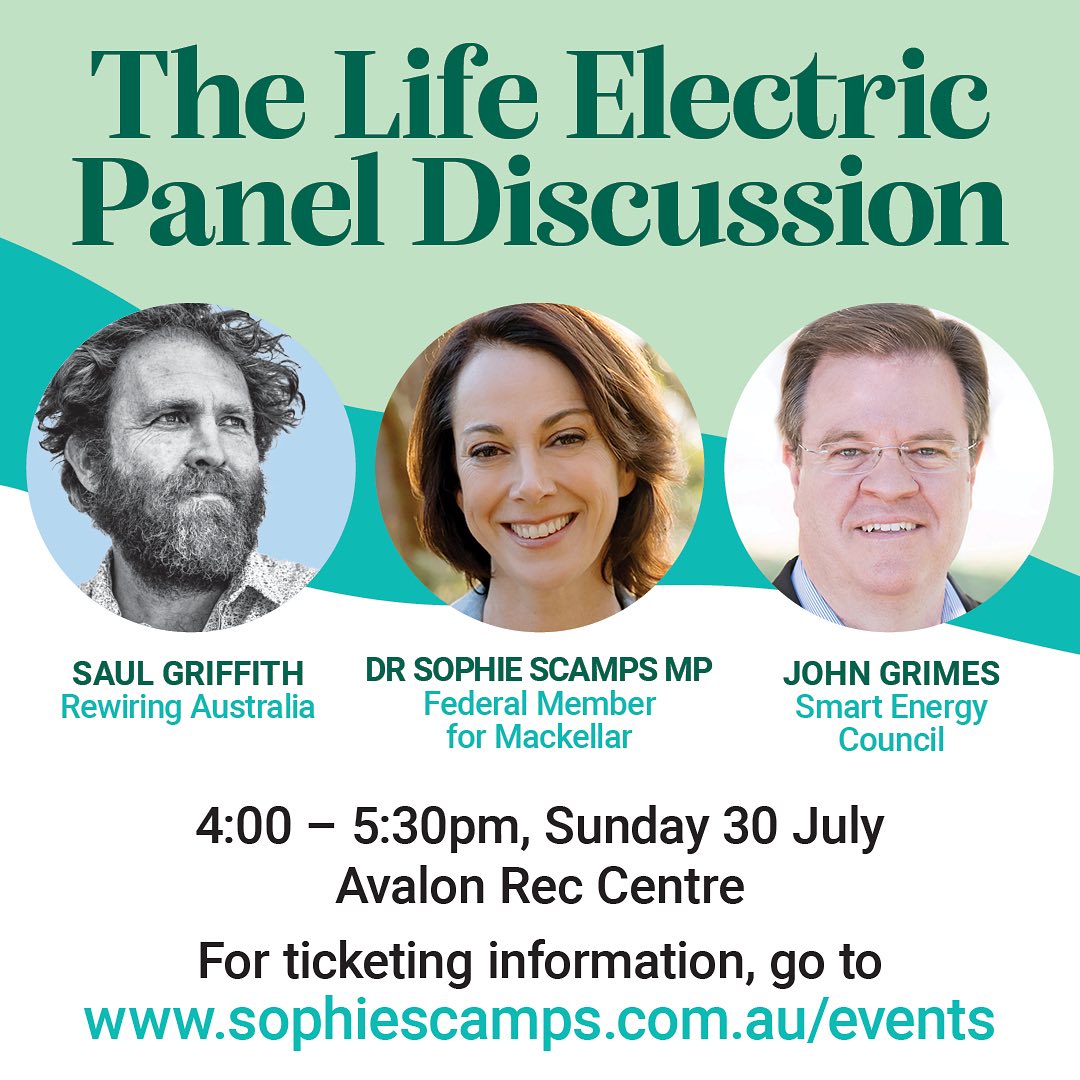

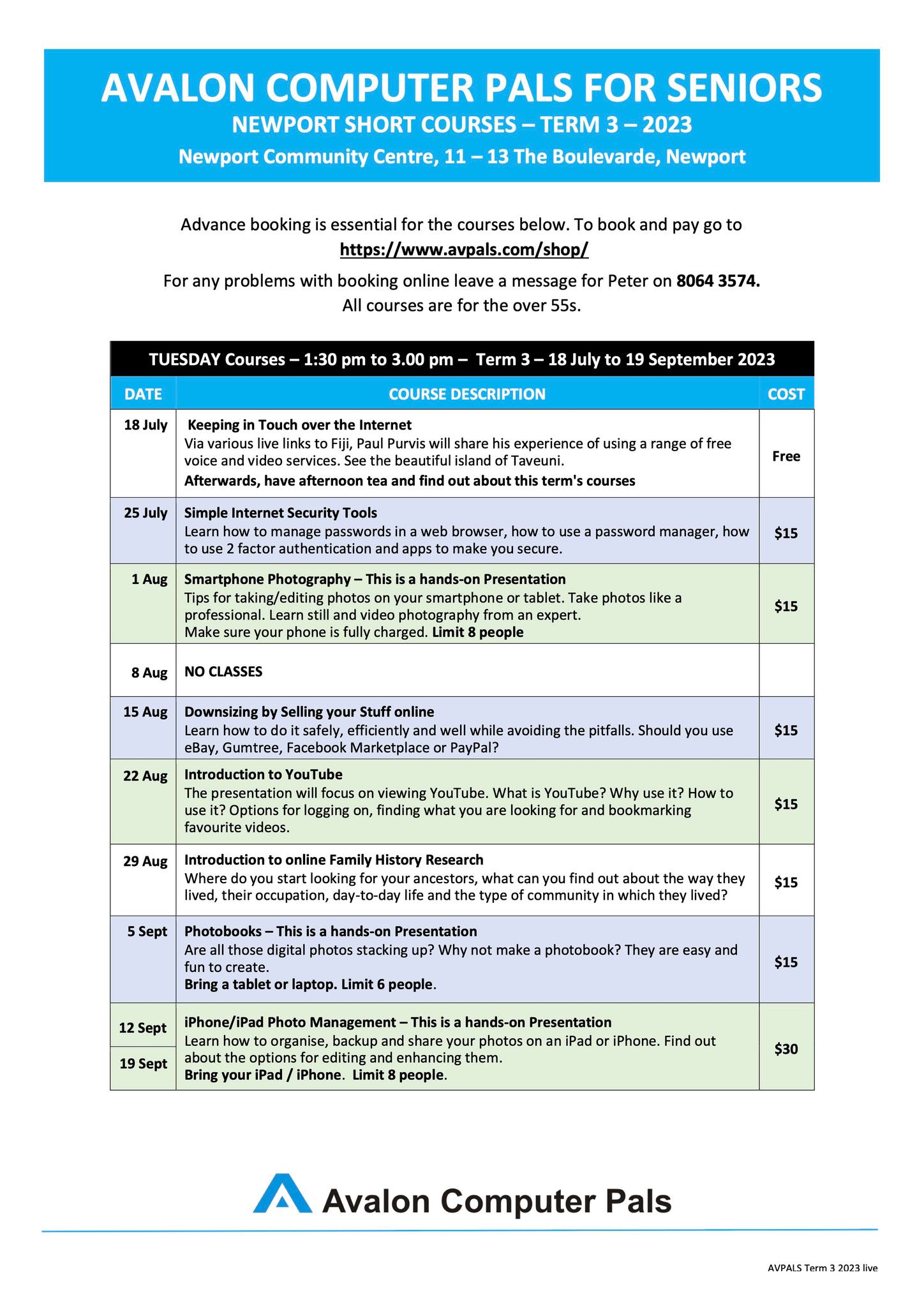

Although there have been calls to open the Ringtail Posse across the Sydney Basin, the founders will leave this up to local wildlife carer groups and councils at present - 2024 will see an expansion and we will persist in sharing local members insights. At present we are seeking residents who want to become part of the Spring and Summer rounds for our LGA.The Life Electric Expo And Forum: July 30th At Avalon Rec. Centre

The Life Electric Community Expo is hosted by Avalon Palm Beach Business Chamber Inc. Entry is free with 10+ stalls, expert advice, food, music and test rides. You can also purchase tickets to the live panel featuring Saul Griffith and John Grimes.

Book your tickets ($10) at the link here: https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1076483

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Dee Why Lagoon Beach Side Clean Up, 30th Of July, 2023, At 10am

Come and join us for our family friendly July clean up, in Dee Why Lagoon on the 30th at 10am. We meet in the grass area close to the council car park, and the surf life saving club at the north end of Dee Why. Please note that this is a different meeting point to where we were last time.

We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the water. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the water and even clean up in the water (at own risk). We will clean up until around 11.15, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day - we will be there no matter what weather. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time.

For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages.

Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost. All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too! All details in our Facebook event, Instagram or on our website.

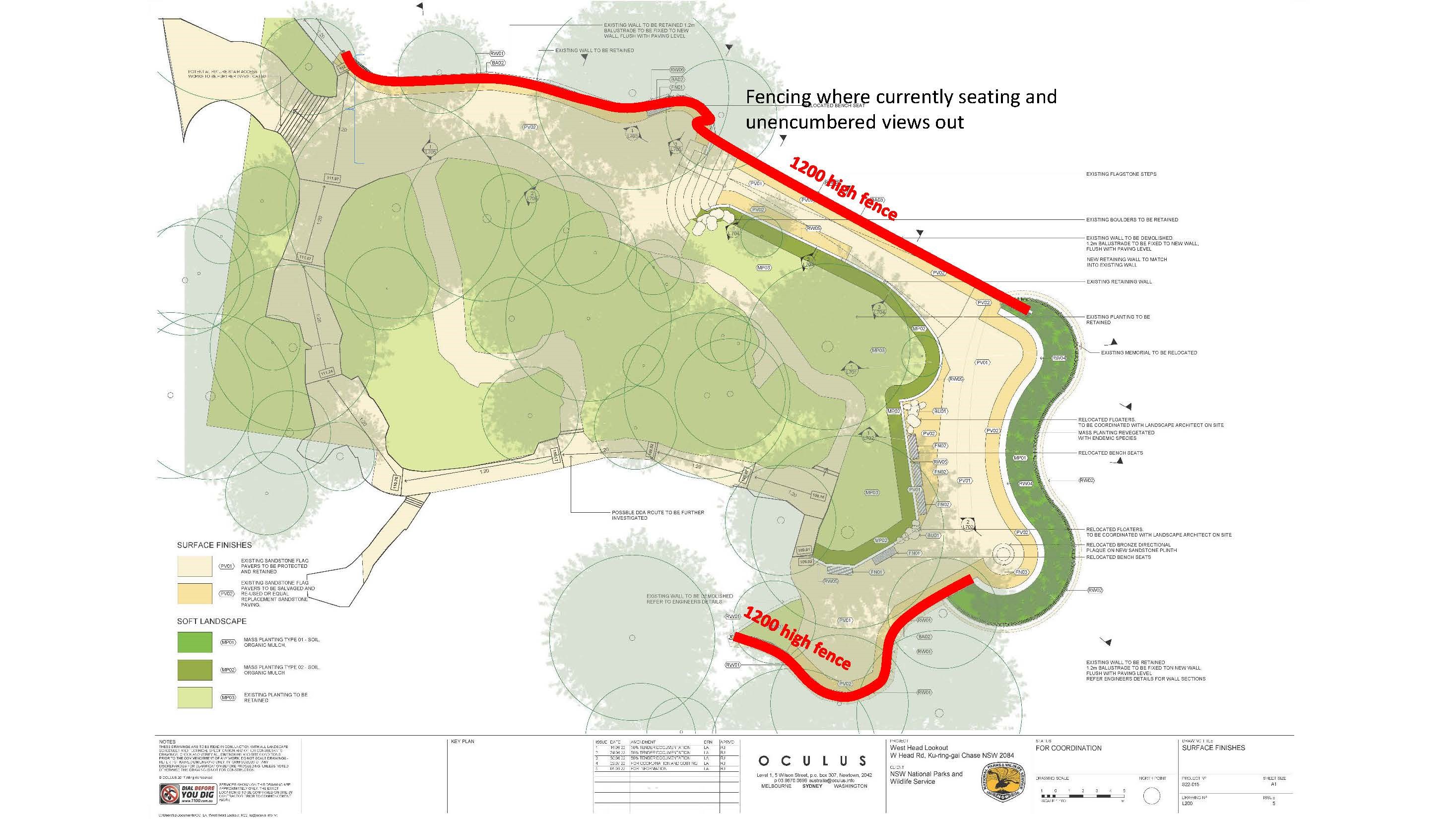

Areas Closed For West Head Lookout Upgrades

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

- West Head lookout

- The loop section of West Head Road

- West Head Army track.

Vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians will have access to the Resolute picnic area and public toilets. Access is restricted past this point.

The following walking tracks remain open:

- Red Hands track

- Aboriginal Heritage track

- Resolute track, including access to Resolute Beach and West Head Beach

- Mackeral Beach track

- Koolewong track.

The West Head lookout cannot be accessed from any of these tracks.

Image: Visualisation of upcoming works, looking east from the ramp towards Barrenjoey Head Credit: DPE

Time Of Burrugin

Cold and frosty; June-July

Echidna seeking mates - Burringoa flowering - Shellfish forbidden

This is the time when the male Burrugin (echidnas) form lines of up to ten as they follow the female through the woodlands in an effort to wear her down and mate with her. It is also the time when the Burringoa (Eucalyptus tereticornis) starts to produce flowers, indicating that it is time to collect the nectar of certain plants for the ceremonies which will begin to take place during the next season. It is also a warning not to eat shellfish again until the Boo'kerrikin (Acacia decurrens, commonly known as black wattle or early green wattle) blooms.

Eucalyptus tereticornis, commonly known as forest red gum, blue gum or red irongum, is a species of tree that is native to eastern Australia and southern New Guinea. It has smooth bark, lance-shaped to curved adult leaves, flower buds in groups of seven, nine or eleven, white flowers and hemispherical fruit.

Eucalyptus tereticornis was first formally described 1795 by James Edward Smith in A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland from specimens collected in 1793 from Port Jackson by First Fleet surgeon and naturalist John White. The specific epithet (tereticornis) is from the Latin words teres (becoming tereti- in the combined form) meaning "terete" and cornu meaning "horn", in reference to the horn-shaped operculum.

Habitat tree: Sclerophyll Forest.

Food tree: Natural stands are an important food tree for koalas and a wide variety of nectar-eating birds, fruit bats and possums.

Eucalyptus tereticornis buds, capsules, flowers and foliage, Rockhampton, Queensland. Photo: Ethel Aardvark

Shelly Beach Echidna

Photos by Kevin Murray, taken late May 2023 who said, ''he/she was waddling across the road on the Shelly Beach headland, being harassed not so much by the bemused tourists, but by the Brush Turkeys who are plentiful there.''

Shelly Beach is located in Manly and forms part of Cabbage Tree Bay, a protected marine reserve which lies adjacent to North Head and Fairy Bower.

From the D'harawal calendar, BOM

D'harawal

The D'harawal Country and language area extends from the southern shores of Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) to the northern shores of the Shoalhaven River, and from the eastern shores of the Wollondilly River system to the eastern seaboard.

Bush Turkeys: Backyard Buddies Breeding Time Commences In August - BIG Tick Eaters - Ringtail Posse Insights

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew : 50 Year Old Soft Drink Can Found In Narrabeen Lagoon

July 8 2023

Rubbish can definitely be around for a very long time. We regularly see evidence of it. Today, a can of Coke was found in Narrabeen Lagoon. It's been there for over 50 years.

Please always be mindful of your rubbish, and remember it is always best to try and avoid as much single use products as possible.

North Narrabeen Lagoon On A Winter Sunday Afternoon

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

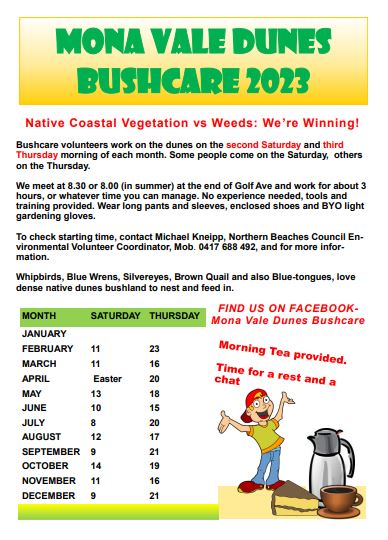

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

MR Vales Point Extension A Line In The Sand, Says Climate Groups

Record Fine For Illegal Water Take Proof Mining Has No Place In Sydney Water Catchment: Greens

Net Zero Economy Agency; Australian Government

July 3, 2023

The Net Zero Economy Agency is responsible for promoting orderly and positive economic transformation across Australia as the world decarbonises, to ensure Australia, its regions and workers realise and share the benefits of the net zero economy.

The agency will engage with a variety of stakeholders including communities, regional bodies, industry, investors and First Nations groups to support a positive transition to a net zero economy. The work of the Net Zero Economy Agency is a precursor to the establishment of a legislated Net Zero Authority, following Parliamentary processes.

It will kick-start the work of the Net Zero Authority by:

- helping investors and companies to engage with net zero transformation opportunities

- coordinating programs and policies across government to support regions and communities to attract and take advantage of new clean energy industries and set those industries up for success

- supporting workers in emissions-intensive sectors to access new employment, skills and support as the net zero transformation continues.

The Hon Greg Combet AM is chair of the Net Zero Economy Agency. As chair, Mr Combet will guide the agency to ensure that the workers, industries and communities that have powered Australia for generations, can seize the opportunities of the net zero transformation. The chair is supported by an advisory board to design and establish the legislated Net Zero Authority.

Me-Mel (Goat Island) To Be Transferred To Aboriginal Community

July 1, 2023

The NSW Government has today taken a significant step in the process for transferring Me-Mel (Goat Island) to Aboriginal ownership by signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Me-Mel Transfer Committee.

$43 million is committed to remediate and restore Me-Mel and pave the way for the transfer back to the Aboriginal community, the NSW Government said in an issued statement

The committee will identify options for the transfer, develop recommendations for cultural, tourism and public uses of the site, and provide advice on the management of the site.

It will also develop a strategic business case to be considered by the NSW Government.

The Committee is made up of key Aboriginal representatives, along with NSW Government representatives from the Cabinet Office, Aboriginal Affairs NSW and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

A wide range of engagement activities and consultation will be undertaken with the Aboriginal community, the broader public and other stakeholders on the plans for future ownership and management options.

Committee members have given unanimous support to a Registered Aboriginal Owners research project which aims to identify Aboriginal Owners of Me-Mel.

This research will be independently undertaken by the Office of the Registrar of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (ORALRA) and is due to commence in the second half of 2023.

To prepare for the transfer of the island, National Parks and Wildlife Service is also undertaking a large-scale remediation and conservation program of the island’s built assets.

The 14-member committee includes:

- Aboriginal community representatives including Shane Phillips, Amanda Reynolds, Elizabeth Tierney and Ash Walker

- Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council representatives include Allan Murray, Nathan Moran, Eunice Roberts and Jennah Dungay

- NSW Aboriginal Land Council representatives include Heidi Hardy and Abie Wright

- NSW Government members include Angie Stringer, Director Aboriginal Partnerships, Planning and Heritage and Deon van Rensburg, Director Greater Sydney Branch, National Parks and Wildlife Service; Nikki Williams, Director for Economic Policy Branch, The Cabinet Office; and Jonathon Captain-Webb, Director, Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, Land and Economy for Aboriginal Affairs NSW.

Iconic South Coast Island Nature Reserve Dual Named In Recognition Of Cultural Significance

July 4, 2023

The NSW Government has officially given Montague Island Nature Reserve a dual Aboriginal name, in honour of the cultural significance of the island to the Yuin people.

Barunguba Montague Island Nature Reserve, off Narooma on the NSW south coast, is valued as a significant ceremonial area and resource gathering place.

In addition to its Aboriginal cultural values and state-listed European lighthouse heritage, the nature reserve protects several seabird species including the endangered Gould's petrel, one of the largest little penguin colonies in New South Wales, and Australian and New Zealand fur seals.

The island is recognised in the international Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Green List of Protected Areas, for its excellence in protected area management. Visitors can experience the island's wildlife by day trip or staying in historic lighthouse accommodation.

The process of renaming Barunguba Montague Island Nature Reserve was initiated by the Aboriginal traditional owners to recognise the cultural heritage of the site.

Further information: Barunguba is pronounced [bar-an-goo-ba]

Yuin Elder Uncle Bunja Smith said:

"From Mother mountain Gulaga, came the 2 sons. Najanuka and Barunguba. We know this because it is in our stories and our songs.

"As an Aboriginal Man and a Yuin Elder, I am filled with emotion to be standing here today with the ministers and our local member, to hear the word 'Barunguba' sounded out as it should be!

"I know this will delight all our Elders and Tribes people past, present and emerging.

"I pray that the spirit of this scared place touches the hearts of the wider south coast community and all visitors who may come. May we always say yes to reconciliation, as it always was and always will be Aboriginal land, Walawanni."

NSW Environment Minister Penny Sharpe said:

"I am delighted to be in this stunning location to officially announce the dual name of Barunguba Montague Island Nature Reserve.

"The cultural significance of Barunguba has been passed down by ancestors to the traditional Yuin custodians of the Far South Coast and I acknowledge the effort of the traditional owners in leading this name change.

"The Aboriginal name will sit alongside the non-Aboriginal name and I look forward to seeing Barunguba Montague Island Nature Reserve become widely and commonly used."

Penny Sharpe MLC: Today with Dr Michael Holland MP - Member for Bega I was able to be part of the ceremony to rename Barunguba Montague Island Nature Reserve. A place of deep cultural significance & beauty. Ready to be better understood & shared. Thanks to Aunties Vivienne, Roslyn, Lynette, Jacqueline & Uncles Bunja, Graham & Bruce & all the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service staff who have worked so hard make this happen. Photos: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service/NSW Government

Eastern Bettongs Return To NSW After 100-Year Absence In Historic Wildlife Reintroduction Project

Broad-Toothed Rat Population Discovered In Victoria

Developers aren’t paying enough to offset impacts on koalas and other endangered species

Developers are commonly required to “offset” their impacts on biodiversity. They can do this in two ways.

They can compensate directly for the biodiversity loss their development causes by taking action to improve habitat and biodiversity elsewhere. It is common, though, for developers to make payments in lieu of creating the required biodiversity offsets themselves. It’s the same idea as when you pay to offset your flight’s carbon emissions.

In Queensland and New South Wales developers settle almost all biodiversity offsets required of them by making payments into an offset fund. These funds are used to create the required biodiversity gains on the developer’s behalf. In NSW, for example, the Biodiversity Conservation Trust does this work.

But what are the pros and cons of allowing developers simply to buy their way out of their offset obligations? Research published today shows these so-called “financial settlement offsets” could be highly problematic. They might even worsen the decline of threatened species.

What Did The Study Find?

Researchers from The University of Queensland and Griffith University analysed the impacts of the Queensland government’s environmental offsets policy on koalas in the state’s south-east. This policy requires every koala habitat tree removed for development to be offset by planting and protecting three new habitat trees elsewhere. The developers can do this themselves or make a payment into a state-managed offset fund.

Our study assessed the likely impacts of financial settlement offsets on koala habitat and koala numbers under different future urban growth scenarios.

First the good news: these offsets can work in some cases. The payments can be used to invest strategically in planting trees in areas that lead to the greatest increase in koala habitat or koala numbers. For example, this could be done in areas that improve connections between areas of suitable habitat or are close to important koala populations.

Developers could do this offset work themselves. However, their priority is usually to minimise cost. This means they are unlikely to act strategically to deliver the maximum benefits for habitats and species.

As a result, our study shows financial settlement offsets could deliver 50-100% greater gains in habitat area and koala numbers than offsets delivered by developers.

Lack Of Suitable Offset Sites Is A Big Problem

Unfortunately, these gains depend on there being enough offset sites available for koala habitat restoration. An offset site must be ecologically suitable and able to be protected, habitat restoration must be feasible and the landholder must agree.

All these factors mean suitable sites are usually hard to find. In such cases, we found payments by developers weren’t enough to achieve the amount of restoration needed to offset their impacts.

If less than one in four of all ecologically suitable locations are available for offsets, the performance of financial settlement offsets falls dramatically. But if only one in 100 of all ecologically suitable locations are available, payments from developers are never enough to cover the cost of the required restoration.

According to the Queensland Offsets Register only 5.2% (0.7 hectares of 13.4ha) of all financial settlement offsets for koala habitat since 2018 have been delivered so far through on-ground activities by the state government. This shows how hard it is to find offset sites.

In Queensland, increasing the supply of offset sites has been identified as a priority.

Unfortunately, the shortage is a common problem across Australia.

In NSW, 90% of demand for offsets cannot be met through offset “credits”. These tradeable credits are created when biodiversity gains are generated at a site. Their supply to offset developer impacts is very low, indicating few suitable sites are available.

Potential offset sites are also increasingly scarce at the federal level. The shortage is expected to increase the use of financial settlement offsets.

A lack of sites can be due to the availability of ecologically suitable sites, but the offset price, transaction costs, regulatory constraints (such as requiring offset sites to be within a certain distance from impact sites) and social and economic influences on the land market are also key factors.

Developers Should Pay The Full Cost Of Offsets

Our study highlights the importance of ensuring developers pay the true cost of offsetting their impacts. By making payments in lieu of delivering offsets themselves, developers essentially transfer their financial risk to the state.

If there aren’t enough funds to deliver the required offset, the state is left with two options. Either it makes up the shortfall (taxpayers essentially subsidise developers’ environmental costs), or it falls short of delivering the full offset, leading to increased pressure on species. Both of these are poor outcomes.

The methods for calculating developer financial contributions have increasingly been called into question. It’s essential to ensure these calculators properly consider the availability and costs of offset sites.

The alternative jeopardises the delivery of offsets and adds to the pressure on threatened species such as the koala.![]()

Jonathan Rhodes, Professor of Ecology, The University of Queensland and Shantala Brisbane, PhD Candidate, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australian Plastics Feeding Climate Crisis: Emissions To Double By 2050

July 10, 2023

- New research shows the plastics Australians consume in one year produce as much greenhouse gas as 5.7 million cars on our roads annually

- Australia’s plastic emissions will more than double by 2050 if we continue on current path

- Recycling alone won’t solve this problem – we must cut plastic use and stop using virgin plastic made from fossil fuels

- We can cut plastic emissions by up to 70% by cutting plastic use by just 10%, improving recycling rates and using renewable energy

The plastic consumed in Australia in just one year produces more greenhouse gas emissions than one third of our car fleet creates annually, according to groundbreaking research into the climate costs of Australia’s plastic addiction.

The report, produced by environmental consultants Blue Environment for the Australian Marine Conservation Society and WWF-Australia, shows that in 2020 Australia’s emissions from plastics created more than 16 million metric tonnes of greenhouse gases – equivalent to the emissions produced by 5.7 million cars on Australia’s roads annually.

If we continue on our current path of accelerating plastic consumption, the emissions from Australia’s plastics will more than double to 42.5 million tonnes annually by 2050 – the year Australia has legislated to reach net-zero emissions. The Center for International Environmental Law estimates plastics could account for up to 15% of the world’s carbon budget by 2050 if decisive action is not taken.

The report, Carbon emissions assessment of Australian plastics consumption, is the first major study to model the emissions associated with the production and disposal of plastics, including recycling, and what Australia can do to cut those emissions. The report shows that plastics produce significant emissions, and virgin plastics made from fossil fuels were the most emissions intensive to produce, creating more than double the emissions of any other plastic.

In Australia, we generate more single-use plastic waste per person than any other country except Singapore. The good news is that we can cut plastic consumption by 30% by 2040 through such approaches as banning plastic or increasing the use of reusables, before needing to substitute plastics with other materials.

AMCS Plastics Campaign Manager Shane Cucow said: “The findings are shockingly clear. We already knew runaway plastic use is creating mountains of waste and pollution, killing millions of animals every year through entanglement or ingestion. Now we have clear evidence it is also fuelling global warming, which is endangering our entire marine ecosystem.

“We must use less plastic, stop using fossil fuels to make it, and stop using fossil fuels as an energy source for plastic production and recycling. If we don’t, the emissions from plastic will only increase and exacerbate climate change.”

WWF-Australia No Plastics in Nature Policy Manager Kate Noble said: “We can’t rely on recycling solely to get us out of this mess; we need to drastically cut our plastic use and stop using virgin plastic made from fossil fuels. Even if we recycle 100% of the plastic we use, we’ll still see emissions double to more than 34 million tonnes annually by 2050.

“The good news is that we can reduce plastic waste and cut down the emissions from plastic at the same time. Reducing plastic consumption, combined with better design, using it longer, and managing it more responsibly, is the only way to bring our plastic addiction under control, and reduce the climate impacts of plastics at the same time.”

Cutting plastics emissions

The report modelled various scenarios including reducing plastics use, decoupling plastic production from fossil fuels, decarbonising energy systems globally, and significantly increasing recycling rates. Simply capping plastic production at current levels results in nearly a 40% fall in carbon emissions by 2050 relative to business as usual. Scenarios that solely rely on increasing recycling rates perform only marginally better than business as usual. Scenarios using renewable energy perform moderately well, and this is a key contributor to the combined scenarios that achieve high reductions in carbon emissions relative to BAU. Overall, the study findings strongly indicate that multiple complementary system level changes are required to significantly reduce the carbon emissions relating to plastics use.

Under a combined scenario, Australia could reduce the total emissions from its plastic use by up to 70% by 2050, with the greatest impact achieved by cutting plastics consumption by just 10%. We need to:

- use plastics more efficiently and cut total consumption by at least 10%,

- rapidly increase plastic recovery and recycling to 100%

- fully power plastics production and recycling with 100% renewable energy, and

- move away from virgin fossil-fuel based plastic entirely.

While these are ambitious goals that Australia is not currently equipped to meet, the report highlights the need for strong action on plastic consumption and waste management now, to avoid the growing waste, pollution and climate costs caused by skyrocketing plastic consumption.

Further findings

Greenhouse gas emissions from plastic production are higher than previously thought, due to substantive new research that indicates that methane from gas extraction and processing is at least 25-40% higher than estimates used by governments globally, which has been averaged to 32.5% for this report. This is likely to be an underestimate, with recent figures from the International Energy Agency putting the discrepancy at 70% higher than former estimates.

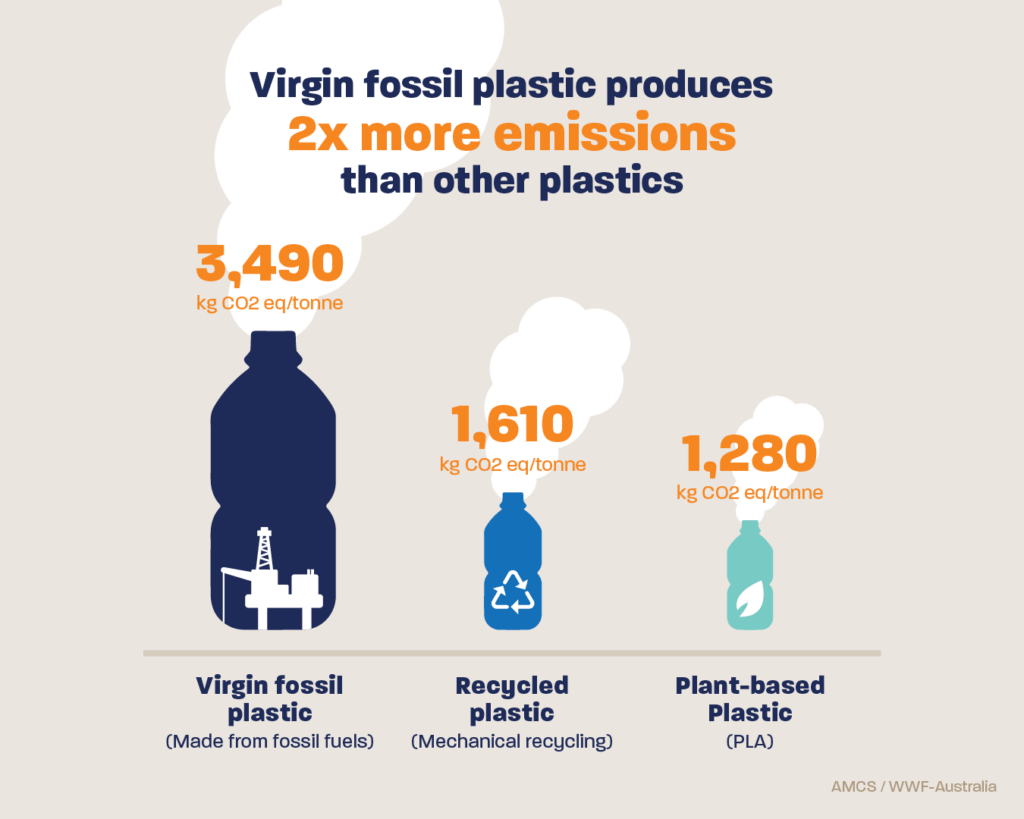

Manufacturing virgin fossil-fuel based plastics produces on average 3,490kg CO2e per tonne, more than double the emissions of producing new plastics through mechanical recycling (1,610kg CO2e/t) – 2.2 times the global warming potential (GWP) over GWP 20 years.

Fossil-fuel based plastics produce nearly three times the emissions to manufacture than plant-based plastics (1,280kg CO2e/t –2.7 times over GWP 20-year basis)

Incineration and burning plastics to produce energy are the most emissions intensive disposable methods for plastics.

Chemical recycling of plastics – where plastic waste is chemically treated to produce oil that can be used as fuel or remanufactured into plastic – is more emissions intensive than mechanical recycling, producing 67% more emissions than mechanical recycling.

Note: The emissions reduction scenarios modelled only refer to plastic emissions and do not consider the emissions of substituted products or other environmental harms caused by plastics. They are indicative projections only and further work is needed to identify technical pathways for reducing plastics consumption and increasing recovery.

The full report and report summary can be found at plasticemissions.org.au

Full report: Carbon emissions assessment of Australian plastics consumption – Project report

Summary report: Climate impacts of plastic consumption in Australia

Hungry Caterpillars: Synthetic Biology Holds The Key To Infinite Plastic Recycling

July 10, 2023

The powerful combination of a unique caterpillar research facility and Macquarie's synthetic biology expertise may be key to a novel method of recycling plastic.

When recycling business REDcycle wound up in November 2022, it emerged that 11,000 tonnes of plastics consumers had returned to supermarkets to be recycled were instead put into storage, due to a lack of recycling capacity.

Australians consume 1 million tonnes of single use plastic each year, with 90 per cent sent to landfill, and approximately 130,000 tonnes leaking into the marine environment. Unless something changes, by 2050, it is estimated that plastic in the oceans will outweigh fish.

But research underway at Macquarie University may hold the key to solving Australia’s growing plastic waste problem.

Microbiologist and ARC Future Fellow Associate Professor Amy Cain is collaborating with partners, including startup Samsara Eco, to develop an innovative approach to tackling plastic waste. She was awarded almost $675,000 in the latest funding round of the Australian Research Council’s Linkage Projects scheme to tackle polyurethane (PU) recycling.

“PU is ubiquitous in our lives, from lacquer coatings and elastane clothing to durable foam padding in car seats, cushions and mattresses,” Associate Professor Cain says.

“There are currently few avenues for recycling and much ends up in landfill.”

A single mattress, for example, produces 15-20 kilograms of PU foam waste.

“Currently, the only way of recycling the PU in mattresses, like the polyethylene in plastic bags, is to ‘upcycle’ them into limited products like benches. This can also only be done once as it downgrades the plastic integrity,” she says.

Fortunately, biodegradation of PU can occur naturally via various microbial means and from insects, such as Galleria mellonella (greater wax moth ) larvae.

When we fed household foams to caterpillars in the lab they munched through 95 per cent in under three days.

Associate Professor Cain is working with enviro-tech company Samsara Eco to understand plastic biodegradation and re-design and improve biologically active enzymes to break down the polymers in PU foams and sustainably recycle them into a variety of virgin plastics or biofuels.

“This process, which translates nature’s solutions into flexible and efficient synthetic enzyme technologies, will allow plastics to be infinitely recycled.”

The very hungry caterpillars

Associate Professor Cain’s research uses a mix of molecular discovery, microbe bioprospecting and synthetic biology.

“In recent years, bacteria have been identified in oil spills and other extreme environments, forced by evolution to develop the capacity to break down long carbon chains,” she says. More recently, a few insects, including wax moth caterpillars, have been identified as plastivores.

Macquarie University’s Applied Biosciences laboratories are home to Australia’s only fully-functional research facility for Galleria.

“Galleria caterpillars attack beehives in Europe and eat the wax which has a similar chemical structure to polyurethane, Associate Professor Cain explains.

“We are figuring out how they do what they do, picking out the relevant enzymes then creating platforms – in this case synthetic microbes – that eat the plastic more efficiently than the original.”

By working closely with the Centre of Excellence in Synthetic Biology, and with its director Distinguished Professor Ian Paulsen as a chief investigator on the linkage grant, the waste products of the process – carbon dioxide and water – are used as feedstock for other processes.

Sort it out: Associate Professor Amy Cain (pictured) says Australians are passionate recyclers but need to improve on separating plastic bottle tops and rings from bottles as these are different types of plastic.

Another priority research area is tackling polyurethane foams. Used in mattresses, car seats and cushions it is designed to be tough and is not currently recyclable, with a single mattress containing as much as 15 to 20 kilograms of foam.

“When we fed household foams to caterpillars in the lab they munched through 95 per cent in under three days," Associate Professor Cain says.

“The caterpillars’ appetite for plastics is so great that they will even eat right through plastic cages, and have to be kept under lock and key in glass and metal enclosures.

"Once we fully understand how they are doing this, we will take out the active component and create a safe, synthetic microbe that can be scaled up to become industrially relevant.”

More bins, less landfill

The great thing about these technologies is that they are more scalable than current industrial methods, she says.

Recycling aluminium for example, requires a lot of energy and significant carbon input. The process uses large plants that can’t be scaled down.

“Enzyme technologies, however, don’t need to melt anything – they will attack any plastic, as long as it’s clean, meaning they can be used on an industrial scale or in a benchtop bucket at home.

“Australians are very passionate about recycling, but we need to get better at sorting – for example separating plastic bottle tops and rings from bottles as these are different types of plastic.”

In Switzerland, she says, there are 17 different recycling bins, which leads to very efficient recycling.

“We still have a long way to go before we reach that.”

Associate Professor Cain has been working on plastics recycling for four years and says the field has recently become much more active, supported by government policy and consumer priority.

“Samsara Eco is a great case study of how the appetite for change and technology have come together. The company began in 2020 as a startup and, following a $54 million grant, is building a plastics recycling factory in Melbourne.

“In 2022 Samsara Eco recycled all of the water bottles used in the Australian Open, and is now partnering with Woolworths, as well as Macquarie, on infinite recycling.”

Microbiologist and ARC Future Fellow Amy Cain is an Associate Professor in the School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University.

Galleria mellonella, the greater wax moth or honeycomb moth, is a moth of the family Pyralidae. G. mellonella is found throughout the world. It is one of two species of wax moths, with the other being the lesser wax moth. G. mellonella eggs are laid in the spring, and they have four life stages. Males are able to generate ultrasonic sound pulses, which, along with pheromones, are used in mating. The larvae of G. mellonella are also often used as a model organism in research.

The greater wax moth is well known for its parasitisation of honeybees and their hives. Because of the economic loss caused by this species, several control methods including heat treatment and chemical fumigants such as carbon dioxide have been used.

The caterpillar of G. mellonella has attracted interest for its ability to degrade polyethylene plastic.

Drones are disturbing critically endangered shorebirds in Moreton Bay, creating a domino effect

Drones are increasingly swarming our skies, capturing images, managing crops and soon, delivering packages. But what do the birds make of this invasion of their territory?

With strict animal ethics approval, we flew drones towards flocks of birds in Queensland’s Moreton Bay. We found many species were not disturbed, provided the drone was small and flew above 60m.

The exception was the critically endangered eastern curlew, which became alarmed and flew away – even when a tiny drone approached at the maximum legal altitude of 120m. But when the eastern curlew took flight, other nearby species were often startled, creating a domino effect that eventually caused the whole flock to take flight.

Drone disturbance can interrupt birds as they rest or feed. It can even cause them to avoid some locations altogether. If birds are consistently interrupted or scared away from their preferred habitats, they may find it difficult to eat and rest enough to survive and reproduce. This is particularly concerning for species such as the eastern curlew, which migrate thousands of kilometres to breed.

Yet Another Threat To Shorebirds

We studied a diverse group of birds typically found along coastlines, known as shorebirds. Heartbreakingly, their global population has plummeted as they continue to battle habitat destruction, sea level rise, disturbance and hunting.

The last few decades have been bleak for the eastern curlew, which is the world’s largest migratory shorebird. Research in 2011 indicated a population decline of 80% over three generations.

While drones are unlikely to have played a major role in shorebird decline so far, our results, combined with the increasing presence of drones along our coastline, indicate they could become yet another source of disturbance for these birds, many of which are already endangered.

Use With Care

At the same time, drones have proven to be a valuable tool. They’ve been used to plant trees, deliver healthcare in developing countries, and have even proven useful for bird conservation.

Drones can observe birds in places that are hard to reach on foot, such as birds of prey nesting in tree tops, or seabirds feeding on tidal inlets. In some cases, they can even be more accurate compared to traditional ground-based survey methods.

Shorebirds spread out across vast mudflats to feed, making it very difficult to survey them on foot and identify critical foraging habitats. Our research has shown that, for certain species, drones may overcome this barrier, providing information that may be pivotal in arresting shorebird population declines.

Drones can be beneficial in many ways, but we must identify when and how drones can be used to minimise potential harm. In some locations, such as some Australian national parks, drone use is already prohibited or restricted. But managers need to understand how drones affect wildlife to inform these regulations.

Our findings provide clear-cut parameters around how much space to give birds to keep drone disturbance to a minimum. In most cases this is about 60m, but it can vary significantly between species. For the eastern curlew, we don’t recommend approaches within 250m, even with small drones.

The Moreton Bay Marine Park, where this research was undertaken, is the single most important site in Australia for the eastern curlew. Disturbing shorebirds within the marine park is an offence that can result in fines. The Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service has already used our findings to place conditions on research projects and media activities involving drones.

Sharing The Skies

We recommend organisations with influence on this issue, such as the Civil Aviation Safety Authority and national parks authorities, regulate drone use near bird flocks – especially those containing at-risk and highly sensitive species.

We also encourage those researchers considering adding drones to their conservation toolkit to carefully evaluate the risk of disturbance before using them to conduct wildlife surveys.

By understanding how shorebirds react to drones, we can inform effective and efficient management actions. Regulating drone use near critical shorebird habitats will help us to avoid exacerbating population declines, while still allowing the use of a valuable tool, where appropriate.

Hopefully, through small steps like this we can arrest the decline of shorebird populations, ensuring we can continue to share our shorelines with these beautiful birds for generations to come.

This research was supported by The Moreton Bay Foundation and the Queensland Wader Study Group. It was conducted under strict ethical clearance with the purpose of benefiting the birds with the knowledge gained.![]()

Joshua Wilson, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Human-Made Materials In Nests Can Bring Both Risks And Benefit For Birds

July 9, 2023

We all discard a huge amount of plastic and other human-made materials into the environment, and these are often picked up by birds. New research has shown that 176 bird species around the world are now known to include a wide range of anthropogenic materials in their nests. All over the world, birds are using our left-over or discarded materials. Seabirds in Australia incorporate fishing nets into their nests, ospreys in North America include baler twine, birds living in cities in South America add cigarette butts, and common blackbirds in Europe pick up plastic bags to add to their nests.

This material found in birds' nests can be beneficial say researchers. For example, cigarette butts retain nicotine and other compounds that repel ectoparasites that attach themselves to nestling bird's skin and suck blood from them. Meanwhile, there are suggestions that harder human-made materials may help to provide structural support for birds' nests, while plastic films could help provide insulation and keep offspring warm. Despite such potential benefits, it is important to remember that such anthropogenic material can also be harmful to birds.

This research was published in a special issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B on "The evolutionary ecology of nests: a cross-taxon approach." The special issue was jointly organised by Mark Mainwaring, a Lecturer in Global Change Biology in the School of Natural Sciences at Bangor University.

Mark Mainwaring said, "The special issue highlights that the nests of a wide range of taxa -- from birds to mammals to fish to reptiles -- allow them to adapt to human-induced pressures. Those pressures range from the inclusion of anthropogenic materials into their nests through to providing parents and offspring with a place to protect themselves from increasingly hot temperatures in a changing climate."

Anthropogenic materials sometimes harm birds. Parents and offspring sometimes become fatally entangled in baler twine. Meanwhile, offspring sometimes ingest anthropogenic material after mistaking it for natural prey items. Finally, the inclusion of colourful anthropogenic materials into nests attracts predators to those nests who then prey upon the eggs or nestlings. This means that we need to reduce the amount of plastic and other anthropogenic material that we discard.

This stork chick has its foot caught in plastic rope in the nest. Photo Credit: Zuzanna Jagiello

The lead author of the study, Zuzanna Jagiełło who is based at the Poznań University of Life Sciences in Poland, added, "A wide variety of bird species included anthropogenic materials into their nests. This is worrying because it is becoming increasingly apparent that such materials can harm nestlings and even adult birds."

The second author of the study, Jim Reynolds, a researcher in the Centre for Ornithology at the University of Birmingham in the UK, remarked,

"In a rapidly urbanising world which we share with many different animal taxa, it is not surprising that birds use our discarded materials in their nests. Although much needs to be understood about how plastics, for example, impact birds, it is exciting that birds, through their high mobility and breeding biology, may prove to be potent biomonitors of environmental anthropogenic material pollution."

Zuzanna Jagiello, S. James Reynolds, Jenő Nagy, Mark C. Mainwaring, Juan D. Ibáñez-Álamo. Why do some bird species incorporate more anthropogenic materials into their nests than others? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2023; 378 (1884) DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0156

Beak Shape Can Predict Nest Material Use In The World's Birds

July 9, 2023

The material a bird selects for its nest depends on the dimensions of its beak, according to researchers.

Using data on nest materials for nearly 6,000 species of birds, a team based at the University of Bristol and the University of St Andrews utilised random forest models, a type of machine learning algorithm, to take data from bird beaks and try to predict what nest materials that species might use.

They found a surprisingly strong correlation. Using only information on beak shape and size, they were able to correctly predict broad nest material use in 60% of species, rising to 97% in some cases.

These findings, published today in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, include a careful exploration of these models, investigating the ecological and evolutionary context behind these relationships. For example, not every species has the same access to all nest material types, which also affects these results.

A Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata) handling nest material. A Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) building a nest. Photos credit: Shoko Sugasawa

The study's lead author, Dr Catherine Sheard of Bristol's School of Earth Sciences said: "We know a lot about primate hands, but not as much about how other animals use their limbs and mouths to manipulate objects. We've very excited about the potential applications of our findings, to further explore how beak shape may have co-evolved with other aspects of nest building or other functions."

Dr Shoko Sugasawa, senior author of the study, based at the University of St Andrews, added: "Most animals, including birds, do not have hands like ours, but manipulating objects like nest material and food is such a crucial part of their lives. Our finding is the first step to reveal possible interactions between the evolution of beaks and manipulation like nest building, and helps us better understand how animals evolved to interact with the world with or without hands."

The team are now working on a project documenting anthropogenic nest material in the world's birds, trying to understand what type of birds put human-made material (like plastic, wire, or cigarette butts) in their nests. They are in particular looking to see whether this would be linked to urban-dwelling birds.

"I'm also interested in how beak shape relates to other properties of the nest, including overall nest structure," added Dr Sheard, "such as whether birds build nests with walls, or a roof."

Catherine Sheard, Sally E. Street, Caitlin Evans, Kevin N. Lala, Susan D. Healy, Shoko Sugasawa. Beak shape and nest material use in birds. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2023; 378 (1884) DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0147

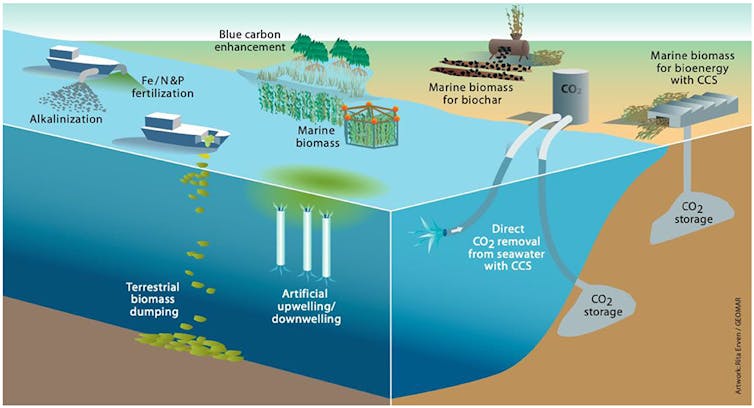

New Australian laws for ‘engineering’ the ocean must balance environment protection and responsible research

The Australian Labor government has introduced a bill to regulate “marine geoengineering” – methods to combat climate change by intervening in the ocean environment.

The bill would prohibit listed marine geoengineering activities without a permit.

Scientists are already experimenting with ways to store more carbon in the ocean or shield vulnerable ecosystems. They include ocean fertilisation and marine cloud brightening. But these proposals are yet to be deployed beyond small-scale outdoor tests. Further research is needed.

These technologies offer huge potential to combat climate change. But large-scale marine geoengineering could also cause harm. Targeted laws are needed to both enable crucial research and protect the marine environment. So does the bill to amend the Sea Dumping Act strike the right balance?

Getting To Grips With Marine Geoengineering

Interest in marine geoengineering has grown over several decades as the climate crisis has worsened. Removing CO₂ from the atmosphere is now necessary to achieve “net-zero” emissions and limit global warming to 1.5℃. But marine geoengineering proposals also present risks to the marine environment.

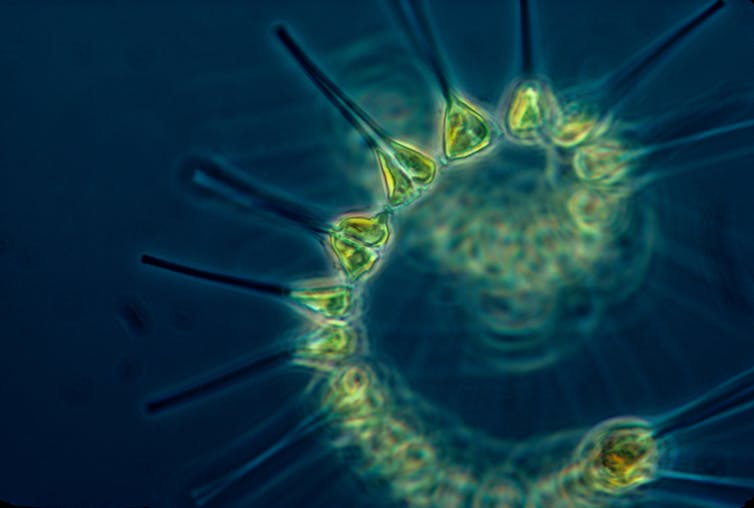

The Southern Ocean – which extends from Australia’s southern coast to Antarctica – has been identified as a suitable location for ocean fertilisation. This involves feeding iron dust to marine algae. Through the process of photosynthesis, the algae pull CO₂ from the atmosphere, which is potentially stored in the deep ocean.

Another proposal is modifying acidity in oceans. Oceans naturally absorb large amounts of CO₂, which is making the water more acidic. Ocean acidification harms marine life, especially animals with shells. It also limits the amount of CO₂ that can be stored. A technology that essentially adds “antacids” to the ocean“ could help counteract this and enable the oceans to store more.

Other proposals seek to reduce the damage from marine heatwaves. "Marine cloud brightening” seeks to limit coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef, by spraying sea-salt particles into clouds. The idea is to make the clouds whiter, to better reflect sunlight away from the ocean and limit further warming of the water.

With help, the oceans could play an even bigger role in stabilising the climate. But there are concerns about unintended consequences of deliberately intervening. For example, ocean fertilisation could decrease water oxygen levels and “rob” neighbouring waters of nutrients, reducing marine productivity.

Marine geoengineering could also distract from efforts to cut emissions at source.

Strong Rules To Protect The Marine Environment

With this new bill, the Australian government has taken an important first step towards regulating marine geoengineering.

The bill involves proposed amendments to the Environment Protection (Sea Dumping) Act. It would introduce a permit system for legitimate scientific research activities.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has said of the bill:

Regulating this type of activity, though a robust application, assessment and approval permitting process, would ensure that only legitimate scientific research activities exploring options to reduce atmospheric CO₂ can proceed. This amendment also provides for regulating other potentially harmful marine geoengineering research activities should they emerge in the future.

The bill implements Australia’s international obligations under the London Protocol, a marine pollution treaty that prohibits the dumping of waste at sea without a permit.

It follows a parliamentary inquiry that recommended Australia ratify these international rules. Australia’s support may encourage other countries to adopt these rules and make them legally binding.

Countries negotiated these rules in response to plans by private companies in the 2000s to conduct ocean fertilisation for profit. They decided new international rules were needed to protect the ocean. Currently, only ocean fertilisation is listed, and hence regulated, under these rules. But other activities may be listed in future.

The bill makes it an offence to place matter into the ocean for marine geoengineering without a permit. Permits may only be granted for scientific research activities. At present, these rules apply just to ocean fertilisation, as it is the only activity listed under the London Protocol.

If the bill is passed as it currently stands, commercial deployment of marine geoengineering cannot be conducted either in Australian waters or from Australian vessels.

Harsh criminal penalties will apply to people who conduct marine geoengineering without a permit. Offenders face 12 months imprisonment and/or a fine of up to $68,750.

The bill also establishes offences for loading and exporting material to be used for marine geoengineering without a permit.

Rules Limit Financial Incentives For Research

Prohibiting marine geoengineering deployment may be appropriate now. But without future prospects for deployment there may be little incentive to invest in research.

The treaty rules ban ocean-based research directly leading to financial and/or economic gain. This protection is important for building public trust and advancing the public interest. But broad prohibition could hamper marine geoengineering research for economic purposes such as eventual carbon crediting and trading. It could also call into question government subsidies and tax incentives encouraging private research investment.

The parliamentary inquiry did not consider the implications of the new rules for Australia’s carbon markets, or on research to save the Great Barrier Reef.

Changes Could Affect Research To Save The Reef

Since 2019, the Australian government has invested in marine cloud brightening and other interventions to protect the reef from heat stress and coral bleaching. The first outdoor experiments were conducted in 2020.

The effectiveness of marine cloud brightening is yet to be demonstrated at scale. But modelling suggests a combination of marine cloud brightening and crown-of-thorns starfish control could help protect the reef until 2040.

The treaty rules do not currently apply to marine cloud brightening. However, countries are currently considering adding marine cloud brightening to the list of regulated activities. This could allow research but prohibit deployment. The government should evaluate how this could affect its investment in marine cloud brightening research and associated programs.

Australia’s marine environment is already suffering from warming and acidification. Appropriately-managed marine geoengineering activities may help reduce the damage and/or mitigate climate change.

The treaty’s environmental safeguards are important to ensure the risks from ocean fertilisation activities are rigorously evaluated.

The current bill favours risk management, which is appropriate at the early stages of research and development. But by ruling out future deployment, Australia may undermine incentives to advance research. ![]()

Kerryn Brent, Senior Lecturer, Adelaide Law School, University of Adelaide; Jan McDonald, Professor of Environmental Law, University of Tasmania, and Manon Simon, Research Fellow, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Small ocean critters use their poo to help seaweeds have sex

Finding a good partner in life is a tricky endeavour, so imagine how much more difficult this task becomes when you’re rooted in the ground.

For most land plants, the inability to move means they have to find clever ways of transporting fertile material to suitable mates. In the millions of years it took for land plants to evolve, they developed intricate and unique relationships with animals that have allowed them to successfully colonise almost every landmass on the planet.

Think of flowers luring in pollinators with the sweet scent of nectar, bristly seedpods travelling on the fur of passing animals, or seeds passing through the digestive tracts of birds and grazers to germinate in their poo.

These animal-plant interactions are often mutually beneficial, or “mutualistic”. The animal gets a reward in the form of fruit or nectar, while the plant gets to disperse its pollen or seeds over a much greater distance than it would have achieved alone.

Mutualism between plants and the animals that eat them was thought to be a unique adaptation to life on land. Underwater, movement from currents and buoyancy take care of the dispersal and fertilisation of seaweeds and marine plants. Seaweeds don’t need animals to spread their seed far and wide – or so it was thought.

Our new research challenges this assumption by showing examples of mutualism among seaweeds and animals. It adds to a growing body of evidence that suggests the ability to use animals to fertilise, and spread fertile material, may not be exclusive to land plants.

From Spore To Kelp

Last year, researchers at the Sorbonne University found that isopods (marine invertebrates about 2-4cm in length) can increase fertilisation success in the red seaweed Gracilaria.

As the isopods feed on small algae growing on the red seaweed, seaweed sperm attaches to their bodies. They then carry this sperm to female seaweeds, which can fertilise exposed eggs. In return, the isopods get a meal and protection from predators.

This year, our team found several examples of how much larger seaweeds have sex with the help of tiny animals.

Kelps are the largest seaweeds in our coastal environments. They provide habitat and shelter for many other species – but their reproduction has been somewhat of a mystery.

They have what is called a biphasic life cycle, where two separate living organisms alternate to complete the life cycle. The organisms that form their reproductive life stage are called gametophytes.

Gametophytes grow from spores released by adults. Male and female gametophytes make sperm and eggs, and when they fertilise they produce baby kelp that develop into adults.

However, gametophytes are microscopic in size (about 0.5mm). Being this small, you might imagine finding another gametophyte to fertilise would require incredible luck. After all, the ocean is very large, and gametophytes need to be as close as 1mm to fertilise successfully.

It has been assumed gametophytes must exist in high densities in the ocean, and this is why successful fertilisation occurs.

Fertilisation Through Poo

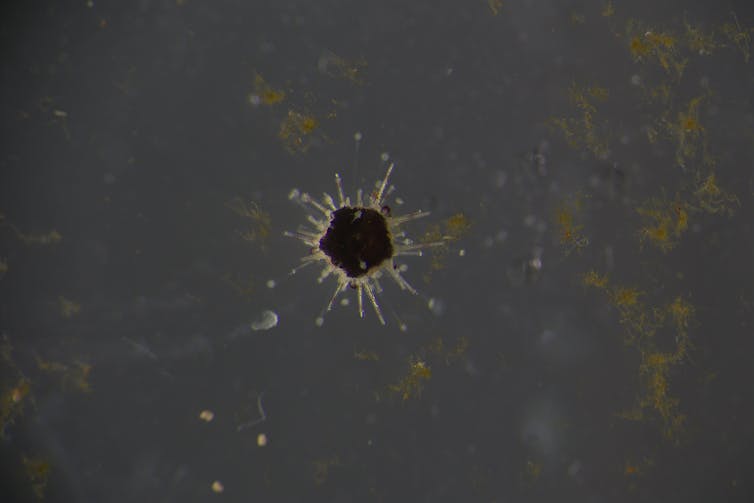

Initially, our team was curious about whether tiny grazers would suppress fertilisation success in kelps by eating gametophytes.

Adult invertebrate grazers, such as snails and urchins, can drastically damage kelp forests. So we wanted to find out if juveniles played a similar role. To our surprise, we found the opposite.

For our research, we fed gametophytes to juveniles of two urchin species, Tripneustes gratilla and Centrostephanus rodgersii, as well as the micro-snail Anachis atkinsoni.

We found the gametophytes could survive through the grazers’ intestinal tracts. We kept the pooed-out gametophytes for a few weeks, and eventually noticed lots of baby kelps growing from the the poo of Tripneustes gratilla and Anachis atkinsoni. We’re not sure why there were no baby kelps growing from the poo of Centrostephanus rodgersii (a species that overgrazes kelps in Tasmania).

Moreover, none of the gametophytes kept outside of the poo were fertilised. This means being eaten by tiny critters, and ending up in their poo, is somehow beneficial for kelp sex.

We don’t know exactly why this is. We think it may be due to increased proximity of gametophytes through ingestion, or the effect of some chemical cue from the poo itself.

Where Did Animal-Mediated Reproduction Begin?

Finding repeated examples of animal-mediated fertilisation in the ocean indicates this process might have originated underwater and not, as previously thought, on land.

In evolutionary terms, seaweeds are a lot older than land plants. So perhaps the unique relationship between animals and seaweed reproductive biology was passed on to land plants.

Alternatively, it could be animal-mediated fertilisation independently evolved multiple times throughout plant evolution, both on land and underwater.

In either case, our findings are changing the way we look at seaweed-herbivore interactions. Seaweed grazers often get a bad rap for causing devastating loss in kelp and seaweed habitats.

Here, we highlight a positive impact: a grazer-seaweed story with a happy ending! Small grazers may fulfil an important role in seaweed reproduction, by making sure microscopic gametophytes in the big ocean can find each other and make babies.

In the end, it’s all about sex! Seaweed sex, that is …![]()

Reina Veenhof, PhD Candidate in kelp ecology, Southern Cross University; Curtis Champion, Research Scientist, Southern Cross University; Melinda Coleman, Adjunct Professor, Southern Cross University and Associate Professor, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, and Symon Dworjanyn, Professor of Marine Ecology and Aquaculture, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why are so many climate records breaking all at once?

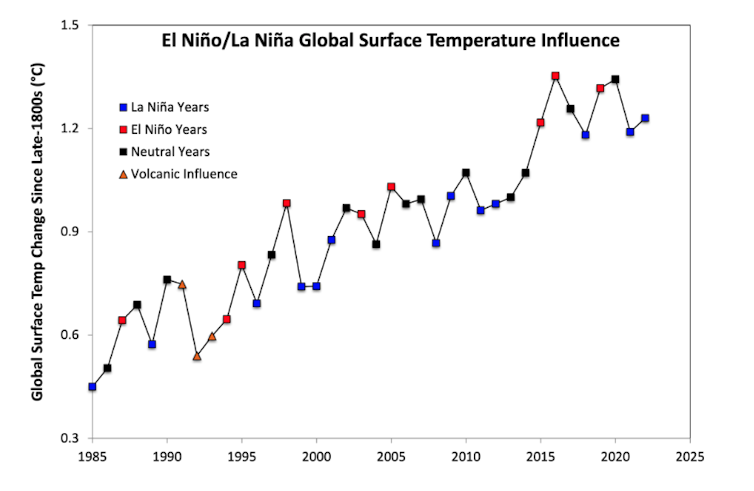

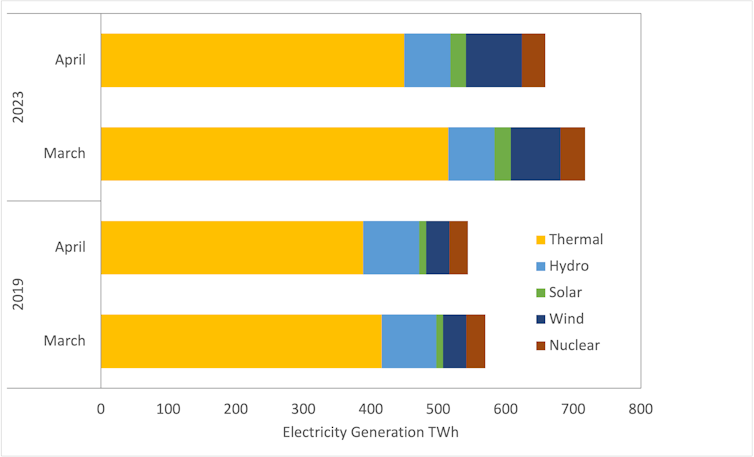

In the past few weeks, climate records have shattered across the globe. July 4 was the hottest global average day on record, breaking the new record set the previous day. Average sea surface temperatures have been the highest ever recorded and Antarctic sea ice extent the lowest on record.

Also on July 4, the World Meteorological Organization declared El Niño had begun, “setting the stage for a likely surge in global temperatures and disruptive weather and climate patterns”.

So what’s going on with the climate, and why are we seeing all these records tumbling at once?

Against the backdrop of global warming, El Niño conditions have an additive effect, pushing temperatures to record highs. This has combined with a reduction in aerosols, which are small particles that can deflect incoming solar radiation. So these two factors are most likely to blame for the record-breaking heat, in the atmosphere and in the oceans.

It’s Not Just Climate Change

The extreme warming we are witnessing is in large part due to the El Niño now occurring, which comes on top of the warming trend caused by humans emitting greenhouse gases.

El Niño is declared when the sea surface temperature in large parts of the tropical Pacific Ocean warms significantly. These warmer-than-average temperatures at the surface of the ocean contribute to above-average temperatures over land.

The last strong El Niño was in 2016, but we have released 240 billion tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere since then.

El Niño doesn’t create extra heat but redistributes the existing heat from the ocean to the atmosphere.

The ocean is massive. Water covers 70% of the planet and is able to store vast amounts of heat due to its high specific heat capacity. This is why your hot water bottle stays warm longer than your wheat pack. And, why 90% of the excess heat from global warming has been absorbed by the ocean.

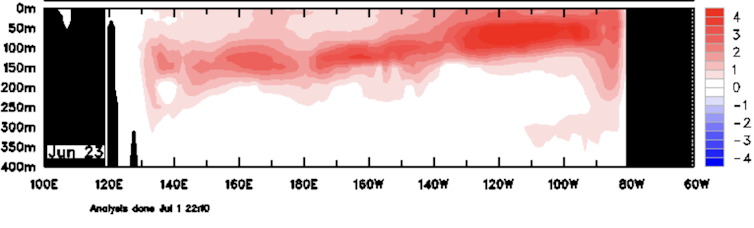

Ocean currents circulate heat between the Earth’s surface, where we live, and the deep ocean. During an El Niño, the trade winds over the Pacific Ocean weaken, and the upwelling of cold water along the Pacific coast of South America is reduced. This leads to warming of the upper layers of the ocean.

Higher than usual ocean temperatures along the equator were recorded in the first 400m of the Pacific Ocean throughout June 2023. Since cold water is more dense than warm water, this layer of warm water prevents colder ocean waters from penetrating to the surface. Warm ocean waters over the Pacific also lead to increased thunderstorms, which further release more heat into the atmosphere via a process called latent heating.

This means that the build up of heat from global warming that had been hiding in the ocean during the past La Niña years is now rising to the surface and demolishing records in its wake.

An Absence Of Aerosols Across The Atlantic

Another factor likely contributing to the unusual warmth is a reduction in aerosols.

Aerosols are small particles that can deflect incoming solar radiation. Pumping aerosols into the stratosphere is one of the potential geoengineering methods that humanity could invoke to lessen the impacts of global warming. Although stopping greenhouse gas emissions would be much better.

But the absence of aerosols can also increase temperatures. A 2008 study concluded that 35% of year-to-year sea surface temperature changes over the Atlantic Ocean in Northern Hemisphere summer could be explained by changes in Saharan dust.

Saharan dust levels over the Atlantic Ocean have been unusually low lately.

On a similar note, new international regulations of sulphur particles in shipping fuels were introduced in 2020, leading to a global reduction in sulphur dioxide emissions (and aerosols) over the ocean. But the long-term benefits of reducing shipping emissions far outweighs the relatively small warming effect.

This combination of factors is why global average surface temperature records are tumbling.

Are We At The Point Of No Return?

In May this year, the World Meteorological Organization declared a 66% chance of global average temperatures temporarily exceeding 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels within the next five years.

This prediction reflected the developing El Niño. That probability is likely higher now, since El Niño has developed.

It is worth noting that temporarily exceeding 1.5℃ does not mean we have reached 1.5℃ by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change standards. The latter describes a sustained average global temperature anomaly of 1.5℃, rather than a single year, and is likely to occur in the 2030s.

This temporary exceedance of 1.5℃ will give us an unfortunate preview of what our planet will be like in the coming decades. Although, younger generations may find themselves dreaming of a balmy 1.5℃ given current greenhouse emissions policies put us on track for 2.7℃ warming by the end of the century.

So we are not at the point of no return. But the window of time to avert dangerous climate change is rapidly shrinking, and the only way to avert it is by severing our reliance on fossil fuels.![]()

Kimberley Reid, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Atmospheric Sciences, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change threatens to cause ‘synchronised harvest failures’ across the globe, with implications for Australia’s food security

New research shows scientists have underestimated the climate risk to agriculture and global food production. Blind spots in climate models meant “high-impact but deeply-uncertain hazards” were ignored. But now that the threat of “synchronised harvest failures” has been revealed, we cannot ignore the prospect of global famine.

Climate change models for North America and Europe had previously suggested global warming would increase crop yields in the short term. Those regional increases were expected to buffer losses elsewhere in global food supply.

But new evidence suggests climate-related changes to fast flowing winds in the upper atmosphere (the jet stream) could trigger simultaneous extreme weather events in multiple locations, with serious implications for global food security.

I have been examining opportunities to manage agricultural risk for 25 years. Much of that work involves learning how agricultural systems can be made more resilient, not only to climate change but to all shocks. This involves understanding the latest science as well as working with farmers and decision-makers to make appropriate adjustments. As the evidence on climate risk mounts, it’s clear Australia must urgently adapt and rethink our approach to global trade and food security.

Building Resilience To Shocks

Unfortunately, the global food system is not resilient to shocks at the moment. Only a few countries such as Australia, the US, Canada, Russia and those in the European Union produce large food surpluses for international trade. Many other countries are dependent on imports for food security.

So, if production declines rapidly and simultaneously across big exporting countries, supply will decrease and prices will increase. Many more people will struggle to afford food.

The prospect of such synchronised harvest failures across major crop-producing regions emerges during northern hemisphere summers featuring “meandering” jet streams. When the path of these fast flowing winds in the upper atmosphere shifts in a certain way, the likelihood of extreme events such as droughts or floods increases.

The researchers studied five key crop regions that account for a large part of global maize and wheat production. They compared historical events and weather to modelling. Yield losses were mostly underestimated in standard climate models, exposing “high-impact blind spots”. They conclude that their research “manifests the urgency of rapid emission reductions, lest climate extremes and their complex interactions […] become unmanageable”.

Free Trade Or Food Sovereignty

Australia has been a big advocate for free trade, reducing barriers to trade such as tariffs and quotas. But the new research revealing the climate risk to food security should trigger a change in policy.

We have already experienced the limitations of an over-reliance on trade to access food. The system has wobbled during the COVID pandemic and the global financial crisis of 2008, when millions of people were thrown back into food insecurity and poverty.

Encouraging free trade in agriculture has not significantly improved global food security. In 1995, the World Trade Organisation implemented the Agreement on Agriculture to liberalise agricultural trade. That agreement constrained the ability of national governments to protect their agricultural industries, and many more people have become food insecure since its introduction.

Australia needs to reconsider its short-term focus on the advantages of selling goods internationally. Conceptualising food more as a human right than a commodity might initiate such a shift.

The global poor do not have the buying power to influence market demand and increase food supply for their benefit. As they face hardship, many are becoming angry, sparking conflict and undermining food security further.