inbox and environment news: Issue 591

July 23 - 29 2023: Issue 591

Unusual Markings On Southern Right Whale Off Bilgola-Avalon

photo taken from A J Small Lookout - Bilgola/Avalon beach headland, Friday July 21 2023, 3.00pm.

The Southern Right Whale (Eubalaena australis) is a large black stocky whale that has a number of features making identification relatively easy. It is the only large whale that lacks a dorsal fin. It has short blunt paddle-shaped flippers and the broad head carries a number of white callosities (raised rough patches of skin) that form individual identifiable pattern. This latter feature enables researchers to gather vital life history information on this species.

The Southern Right Whale may grow to 18 m in length and is black, dark brown or grey, with some individuals having white patches on their head and back. Newborn calves travel alongside the mother and are white or grey. Individuals can be recognised by the patches of raised warty skin (callosities) on the top of their head and chin.

There are two main types of whale - baleen whales and toothed whales. The Southern Right Whale is a baleen whale. All baleen whales have two blowholes.

The Southern Right Whale inhabits the southern and sub-Antarctic oceans except during the winter breeding season. During this breeding season the whales migrate to warmer temperate waters around the southern parts of the African, South American and Australian land masses.

The Southern Right Whale was once abundant in the waters of southern Australia but numbers were drastically reduced during intensive whaling in the 1800s. It was called a 'right whale' as it was the right whale to catch because of its meat and high oil content. Its habit of lingering in bays and sheltered coastal areas made it an easy target so much so that it had virtually disappeared by the beginning of the 20th century.

Whaling continued in Australia until 1978 and a world moratorium on whaling was declared in 1986. All marine mammals in Australia are protected and the Southern Right Whale has made a slow recovery. Fortunately, with strong protection, its numbers are gradually increasing and the species is returning to most of its former range. - Info from Australian Museum

Photo supplied.

Stony Range Regional Botanic Garden To Be Permanently Overshadowed By Approved Development: A Death Knell For Dee Why's Bush Reserve

- Demolition of all structures, including existing commercial buildings and carparking areas

- Removal of 59 trees

- Bulk excavation of the site

- 334 car parking spaces (258 residential, 44 visitor and 32 commercial) in two basement levels

- Vehicular access, loading dock and waste collection from Delmar Parade

- Two main buildings, with varying heights, including five, six and seven storeys

- 219 apartments; comprising 122 units in the Delmar Parade building (being 44 x 1 bed, 8 x 1 bed+, 30 x 2 bed, 16 x 2 bed+, 21 x 3 bed, and 3 x 3 bed+) and 97 units in the Pittwater Road building (being 35 x 1 bed, 6 x 1 bed+, 35 x 2 bed, 6 x 2 bed+, 12 x 3 bed, and 3 x 3 bed+) – so 384 car spaces potentially required, 258 allowed for residential parking leaves a shortfall of 126 spaces

- Four (4) commercial tenancies, two facing Pittwater Road and two facing Delmar Parade

- 2,011m2 of communal open space, including ground floor level and roof top terraces

- Relocated stormwater infrastructure and Overland Flow Path

- New landscaping

“The panel will help council to recognise outstanding and innovative design, and provide practical means of understanding when improvements should be made,” Cr Regan said then.

'''Council is committed to improving the design quality of buildings in the Local Government Area and establishing a ‘design excellence’ system that ensure buildings and the public domain are well designed, and that a process is put in place during the development application process to achieve design excellence as an outcome. As part of this, Northern Beaches Council is establishing a Design and Sustainability Advisory Panel to provide high level independent expert advice on urban design, architecture, landscape architecture and sustainability for significant applications and planning proposals.' the statement from Council read.

.jpg?timestamp=1661596321010)

Church Point Cemetery 'A Disgrace': Neglect Of God's Acre Disappoints Community

In October 2017 Member for Pittwater Rob Stokes announced $100,000 for heritage improvements at the historic Church Point Cemetery.

The funding was provided to Northern Beaches Council as part of the NSW Government’s Heritage Near Me grant program. Improvements were to include; 'an upgrade to the street access and pathway, landscaping, and the installation of a viewing platform, seating and heritage information signage to improve amenity' and increase visitation.

Pittwater Online can report there is NO improvement to the steps, pathway or access up to this 'God's Acre' - they're as they were last time this cemetery was visited. There is NO viewing platform or seating. The 'heritage signage' is as shown in one photo.

In August 2019 Northern Beaches Council stated that ''weathered timbers from a recent upgrade of the Church Point Cargo Wharf have been re-purposed and put to good use in a local historical cemetery nearby.

''Northern Beaches Council staff have teamed up with volunteers from local monumental masons firm Northern Memorials to use the timber to mount plaques displaying a transcription of information on the eroding headstones.

Headstone names, dates and epitaphs appear on each plaque mounted on its own solid wooden block sitting discreetly at the foot of every grave.''

Council stated in their media release that the Cargo Wharf upgrade was a $1,460,000 spend.

The wooden blocks have been installed at the foot of the graves, which are overgrown with weeds and cannot be seen in some cases.

Worth noting from ''OUTCOME OF PUBLIC EXHIBITION - DRAFT DELIVERY PROGRAM 2023-2027, OPERATIONAL PLAN 2023/24 AND LONG-TERM FINANCIAL PLAN 2023-2033'' - June 2023 Council Meeting:

''An internal loan of $4.6 million from the Mona Vale Cemetery Internal Cash Reserve is proposed to part fund the Enterprise Resource Planning system replacement. The anticipated drawdown is $2.2 million in 2023/24 and $2.4 million in 2024/25. The loan will be repaid to the Reserve over six years with the equivalent interest the funds would have earned over the same period.''

This budget was passed by Councillors, as recommended by Council, with only Crs. Korzy and De Luca voting against this budget.

Enterprise resource planning (ERP) is a type of software system that helps organisations automate and manage core business processes for optimal performance.

Those who called Pittwater Online News to 'come have a look at this Disgrace! (at Church Point Cemetery)', have stated that since the forced amalgamation:

- Your councillor representation has reduced to 1-in-87,000 from the former 1-in-5,000.

- Your say on your local area has dropped from 100% to 10% or less.

- The 'localness' you had has disappeared.

- Pittwater and Manly residents have footed the bill for Warringah Council’s large infrastructure backlog.

Another resident, on the same subject, expressed 'extreme disappointment' that these pioneers, some of whom did a lot for the community, and this acre given to the community, have been treated with such disrespect.

Yet another, almost in tears, stated, ''Imagine this was a member of your family - no one looking after them. You can't even see some of the graves anymore, there are so many weeds.''

Photos taken Saturday July 22, 2023; weeds in and over all graves - grass clippings left in place:

REDMAN.— At his residence, Pittwater, John Redman, in his 75th year. Family Notices (1888, April 26). The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW : 1887 - 1909), p. 4 (FIRST EDITION). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article229943738

In the Supreme Court of New South. Wales. ECCLESIASTICAL JURISDICTION.

In the will of John Redman, late of Pittwater, near Sydney, in the Colony of New South Wales, Esquire, deceased.

NOTICE is hereby given that after the expiration of fourteen days from the publication hereof in the New South. Wales Government Gazette, application will be made to this Honorable Court, in its Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction, tbat probate of the last will and testament of the abovenamed deceased, who died on or about the 24th day of April, 1888, may be granted to Benjamin James, of Sydney, Esquire, and John Redman, of the same place, gentleman, the two executors in the said will named.—Dated this 1st day of May, a.d. 1888.

STEPHEN, JAQUES, & STEPHEN,

Proctors for the said Executors,

81, New Pitt-street, Sydney. ECCLESIASTICAL JURISDICTION. (1888, May 4). New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 - 1900), p. 3195. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article222760791

Carrington Centennial Hospital.

We have received from the secretaries of the above institution a letter, with a printed circular enclosed, soliciting our aid in making known its origin and objects. We have previously done this to the best of our opportunities ; and the splendid gift of Mr. Paling, together with the salient features of his "noble and patriotic movement," have by other means been so prominently placed before the reading public, that they must already be tolerably familiar with them, and the result will no doubt be, as the joint hon. secretaries desire, "a warm and generous support to the institution by the public."

A few important facts, however, which we gather from the circular-letter referred to, will be of interest:—The Alpha Cottage, on the Grasmere Estate, which was furnished and provisioned by Mrs. Paling and her daughters, is already occupied by convalescent patients; and the committee have received and accepted an offer from the late John Redman, Esq., to erect a cottage at a cost of £500. It has been determined to proceed at once with the erection of a Convalescent Hospital for one hundred patients, and the building committee are at present engaged with the architect in the preparation of plans. The building committee have also been instructed to prepare plans showing the sites which will be available for the erection of cottages by institutions, private benefactors, or associated bodies. Carrington Centennial Hospital. (1888, August 8). Bowral Free Press and Berrima District Intelligencer (NSW : 1884 - 1901), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118274714

In 2014:

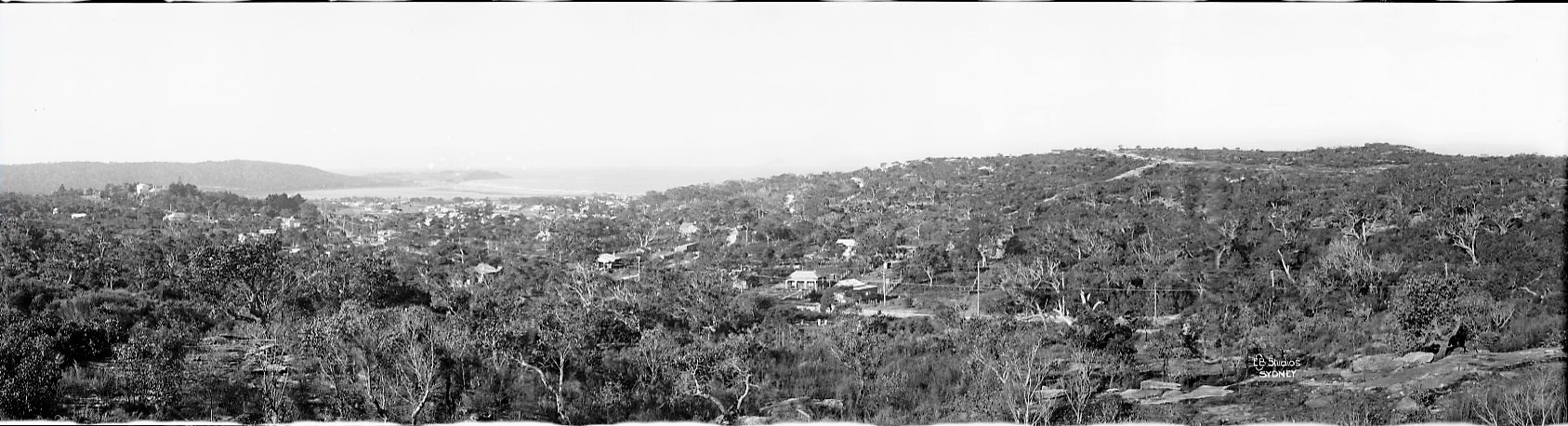

Above: 'Church Point, Pitt Water - 20 minutes from Sydney' by A. J. Vogan (Arthur James), 1859-1948, [circa. 1910 - ca. 1915]. Courtesy State Library of Victoria. Image H82.254/8/29 - showing the chapel; Church Point was named for.

The little church was erected on this land in the year 1872 for the sum of £60, and the point derives its name from this little wooden house of worship (Church Point though in many early records is spoken of as Chapel Point). In the cemetery lie many pioneers who passed away about half a century ago, and such a place enkindles in one's memory the lines of Gray's "Elegy" -

The little church was erected on this land in the year 1872 for the sum of £60, and the point derives its name from this little wooden house of worship (Church Point though in many early records is spoken of as Chapel Point). In the cemetery lie many pioneers who passed away about half a century ago, and such a place enkindles in one's memory the lines of Gray's "Elegy" -

"Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep "

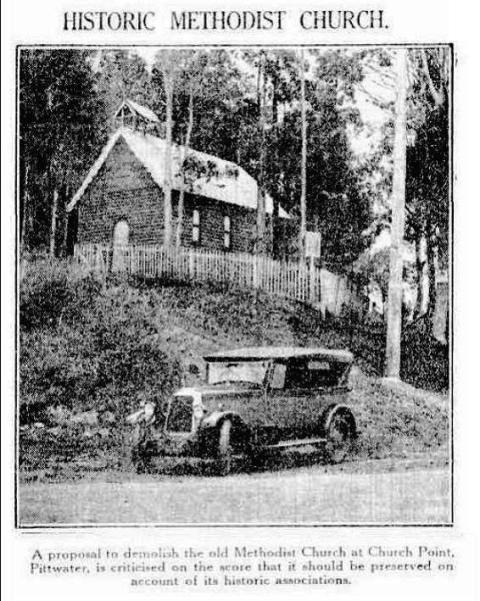

Right: HISTORIC METHODIST CHURCH. (1930, March 19). The Sydney Morning Herald(NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 16. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16634674

The statement of "JEC" that the minister could only visit this church about once a quarter accounts for the burials in this God's Acre being taken by the Rev R S Willis, M.A. Incumbent of St Matthew's Church of England, Manly, up to 1890, and therefore the records of these burials are contained in the Church of England burial register at Manly. This church was used in the week days from May, 1884, until 1888 as a Public school, and known as the Pittwater Public School under the charge of Mr S Morrison, who now resides at Manly. It was on July 19, 1887, that the late Sir Henry Parkes paid a visit to the school in this church building and signed the school's visitors' book. It is to be trusted that the demolition of this church will not be proceeded with, but that it will be restored, and again used for public worship, as the population is growing, and the nearest church is three miles away. This will save this historic place from going into oblivion. I have approached the church authorities with the hope that something may be done at the eleventh hour; even five members of my society (the Manly, Warringah and Pittwater Historical Society) having approached me to the effect that they are willing to spend a few Saturdays, if a conveyance can be provided to help to restore this building. I close with the following appropriate words of Scripture -"Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set." AN HISTORIC CHURCH. (1930, April 5). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16639396

Samuel Morrison was not the first teacher at Church Point, in THE SCHOOLS at Church Point, by Peter Altona and Sue Gould, Mr. Morrison is stated to be the third with the first commencing in early 1881.

The first was a Miss Martha Perry, who, having completed her training at Richmond Public School and being appointed to the small school at Pittwater by the Department of Instruction, begins at the Pittwater Provisional School in the church premises on 23 March 1881.

The Inspector’s Report upon Miss Martha Perry, Richmond, dated 18 Sept 1880 states: 20 years, unmarried, ability to Read and Write – Very Fair, Miss Perry gives promise of becoming a very useful Teacher of a Small School. (NSW State Records) [1.]

The second teacher was Matilda Cannan, born 1862 in Newtown, a young lady who was teaching at Concord Provisional school in 1880, where her family resided. The eldest daughter of Henry Dexter Cannan, a Clerk at what was then called the 'Lunacy Department', had a one year tenure, before returning to more 'urban' places - marrying a few years later and having children of her own:

PUBLIC SCHOOL TEACHERS The undermentioned teachers have been appointed to the Public and Provisional schools specified in connection with their respective names- Provisional Schools – Matilda Cannan, Pittwater PUBLIC SCHOOL TEACHERS. (1883, May 26). Freeman's Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1932), , p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110557837

Matilda resigns on March 31st, 1884. A day later, April 1st 1884, the school is declared a Public one.

Samuel Morrison began teaching in the little church on May 1st, 1884, describing his arrival in "Early Pittwater Reminiscences" Manly, Warringah & Pittwater Historical Society, 16th May 1929, as:

"I was appointed teacher at Pittwater Public School on 1st May, 1884. The coach which was run by W. Boulton, Newport, was timed to leave Bagnall’s Hotel, The Corso, Manly at 4 pm on Sunday for Newport. The men employed at Von Beren’s Powder Works were returning by that coach which collected passengers at the livery stable behind the Steyne Hotel and although the driver had promised to pick me up, he went off as soon as the coach was crowded, thus leaving me no alternative but to walk to Pittwater – a distance of thirteen miles.

After passing the Manly Lagoon, I met no one, and passed only two houses that were occupied – Mrs Malcolm’s at Brookvale and Miss Jenkins at Collaroy. On nearing Narrabeen Lagoon I was overtaken by a man in a spring cart, whom I stopped to make inquiries as to the whereabouts of Pittwater. He told me that he was going that way and would give me a lift. This man was Johnny Collins, an old identity of the district, who kept a boarding house at Newport where Miss Scott now caters for the public.

Next morning Mr Collins rowed me over the Bay, and landed me where Bayview Wharf now stands. I had a walk of one and a half miles to Church Point, where the school was held in the little wooden church."

Mr. Samuel Morrison, Teacher, Provisional School, Pittwater. Government Gazette Appointments and Employment (1884, May 27). New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 - 1900), , p. 3425. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221672305

Church Point at this time was becoming busier - the Prospector powder hulk was soon to be moved to a place just off Woody Point in 1884 and a Post Office had been opened in the Roche store at Bayview in 1882.

The following tenders have been accepted by the Government :-Turner and Collins, contract 31M. M'Gurr's Creek, road Pittwater, Government Gazette. (1884, January 5). Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907), , p. 14. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71007271

THE following tenders were opened by the Tender Board at the Public Works Department yesterday: Wharf at Church Point, Pittwater.NEWS OF THE DAY. (1884, December 10). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 9. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13581494

Accepted tenders: William Boulton, construction of wharf at Church Point, Pittwater. GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. (1884, December 31).The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 6. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13578833

The completion of the Government wharf at Church Point, Pittwater, will prove a great benefit to the residents in that district. The wharf is a substantial wooden structure, and boats drawing 11 feet of water will be able to come alongside at high tide. The population in the neighbourhood of Pittwater is rapidly increasing, and it is understood that the Government intend building a Public school to accommodate 50 pupils. Fruit-growing promises to be the leading industry in that locality. A considerable area of land is being planted with fruit trees.NEWS OF THE DAY. (1885, July 4). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13592258

The above reference to the construction of a new premises for the school follows on from another letter, of August 1884 (signatories; H. McCulloch, Frederick Chave, Charles Johnson, J. Bens, Mrs J. Baker, Thomas Wilson, James Shaw, William Baker, Thomas Oliver, Albert Black, Friedrich Fahl, J. Carrio and A. Wood.) and another in June 1886. This 'News of the Day' appears a few months after the time Albert Black, Coastwaiter of the Broken Bay Customs Station at Barrenjoey, who had children, sells one acre of his land for the purpose of having a schoolhouse and premises for the schoolteacher - his offer was accepted May 7th, 1885.

A few insights from two students who attended the school in the chapel:

Pittwater, Broken Bay.-I am a little boy 11 years old. I come to school in a boat. I have plenty of school-mates, and we have fine fun. My amusements in the evening are playing about and boat sailing. I have a nice little schooner, and she sails very well. This is a very nice place down here, and I would not like to leave it. . -ALFRED.

[Your writing is very good.]

Pittwater, Broken Bay.- I am only a child, but I must write you a letter, and I have seen none from Pittwater yet. We have a public school. The school is held in the church. I believe we shall have a new one. I have a young pet opossum; he will climb up your back, over your shoulders, as he is very tame. It is funny to see him hang by his tail. My father has a large orchard, and we have fruit nearly all the year round. GRACE. The Children's Letter Box. (1886, July 3).Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907), , p. 30. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71064727

Church Point, Pittwater, was on the 9th instant the scene of unusual festivity, the occasion being the distribution of prizes to the children attending the Public School. Upwards of 150 of the residents were present, also visitors from Manly and Sydney. Dr. Tibbetts of Manly, undertook the office of distributing the prizes, which were numerous and valuable. After the prizes were distributed, the children indulged in the usual games – cricket, foot-racing, and rounders, which were continued till evening when a most pleasant day was concluded with the usual loyal cheers, three hearty cheers also being given in honour of the family of Mr Chave, of Pittwater, whose efforts mainly contributed to the successful carrying out of the day’s programme.” NEWS OF THE DAY. (1886, November 12). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), , p. 7. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13620170

Nil Bill Solar

Update On Minerals Legislation Amendment (Offshore Drilling And Associated Infrastructure Prohibition) Bill 2023

When this Bill came before NSW Parliament on Friday June 29 2023, Independent Alex Greenwich moved that the Bill be referred to a Committee for further investigation into some genuine legal concerns raised by the Bill. The Labor NSW Government supported this, with member after member pointing out that it is the will of the House that the Bill go to the Legislative Assembly Standing Committee on Environment and Planning.

Specifically Mr Greenwich moved that

(1)the Minerals Legislation Amendment (Offshore Drilling and Associated Infrastructure Prohibition) Bill 2023 be referred to the Legislative Assembly Standing Committee on Environment and Planning for consideration and report, for the purpose of inquiring into:

(a)any constitutional issues or unintended consequences raised by the bill, and whether any amendments may address those;

(b)whether there are other ways to achieve the intended outcomes of the proposed bill including through the New South Wales Government offshore exploration and mining policy;

(c)enforcement and compliance issues raised by the bill;

(d)environmental impacts of offshore drilling; and

(e)any other related matter.

(2)The committee may seek independent legal advice.

(3)The committee report by 21 November 2023.

(4)The resumption of the debate on the second reading of the bill be restored to the Business Paper on the tabling of the committee's report.

Due diligence and robust legislation to protect our coast was expressed as the intent across the board during the debate about the referral.

Wakehurst MP Michael Regan stated; ''Speaking to the referral, I acknowledge the concerns raised by the Government about the potential unintended consequences of the bill, particularly while a Federal decision is pending on the PEP 11 licence. I understand some legal ambiguity remains in relation to the bill's constitutional validity. I absolutely support the intent of the bill. It must be the best possible bill. After the uncertainty and setback created by the administrative bungle at the Federal level over the PEP 11 exploration licence, the last thing we want to do is pass legislation that is vulnerable to legal challenge; hence why I say that I am annoyed by and conflicted on this referral.''

When the vote came, local MP's Michael Regan, Wakehurst, James Griffin, Manly, and Rory Amon, Pittwater, all voted against the referral.

However, there were 51 Ayes to refer it for examination, and 34 Noes.

What was clear from these activities in NSW Parliament, is that there is genuine desire to prohibit offshore fossil fuel mining, including what the community has experienced throughout the PEP11 extensions, seismic tests and now new mooted plans to drill, for well over a decade now.

The response from the Committee is due by November 21st 2023, as stated above.

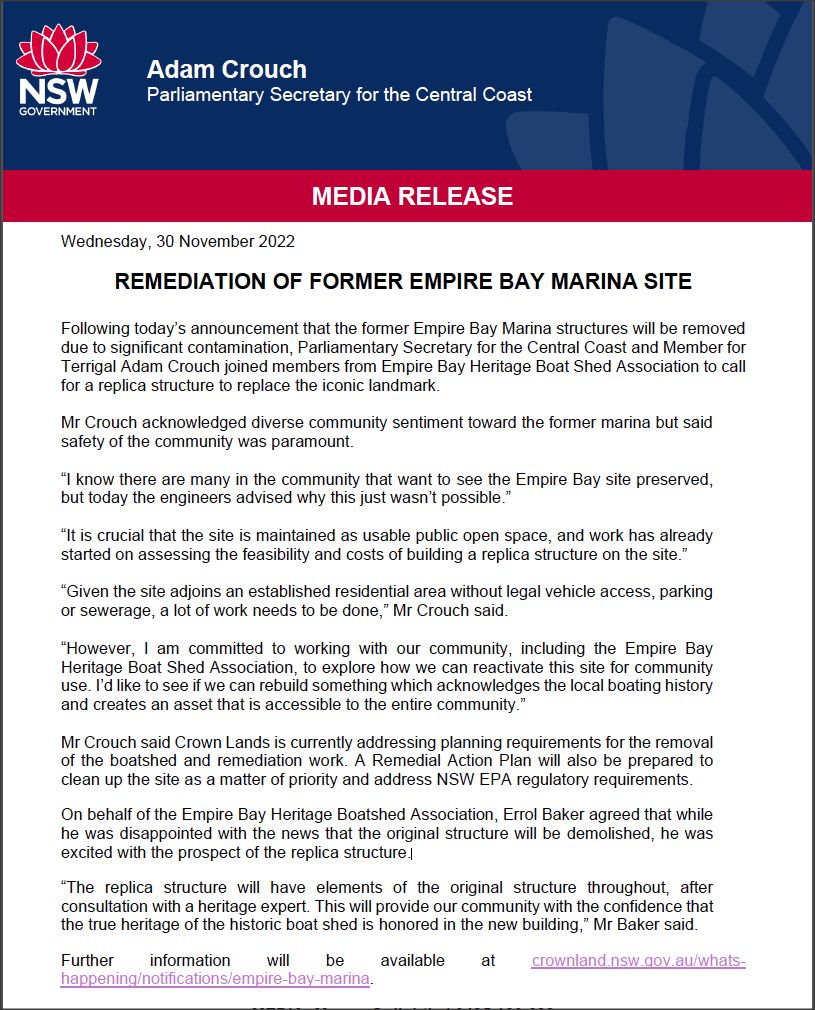

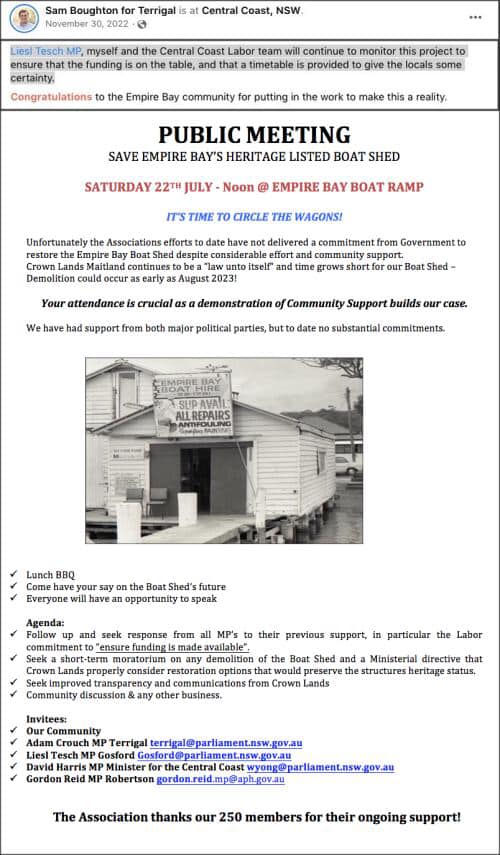

Cleanup Of Empire Bay Marina Site Includes Demolition Of Historic Boatshed

National Tree Day 2023: 3 Sites For Our Area This Year - Planting Out Takes Place Sunday July 30 At Avalon Beach, Duffys Forest, Curl Curl

.jpg?timestamp=1679635455680)

Photo: A J Guesdon

Council and Planet Ark are inviting local residents to dig in and do something good for nature and their community as part of National Tree Day 2023.

National Tree Day is a great opportunity to maintain and enhance our beautiful environment for our local wildlife as well as ensuring the region continues to be a great place to live and getting all the benefits that come from spending time outdoors..

Over 26 million trees have been planted by volunteers since 1996 as part of the program and we are excited for the community to support the goal of getting another million native plants in the ground this year.

Schools Tree Day (July 28) and National Tree Day (July 30) are Australia’s largest annual tree-planting and nature care events, with plantings taking place across the country on the last weekend of July. Each year, around 300,000 people volunteer their time to engage in activities that encourage greater understanding of the natural world and how we can protect it.

National Tree Day event is taking place in three locations in our area on Sunday July 30th. Native trees, shrubs and grasses will be planted at the sites. Residents can register to volunteer at the event via the National Tree Day website at treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/.

Details of each run below

“Our research clearly shows the many benefits that time outdoors in nature has for our physical and mental health, our children’s development, the liveability of our communities and the robustness of local ecosystems,” said Planet Ark co-CEO Rebecca Gilling.

“With the simple action of planting a tree you can help cool the climate, provide homes for native wildlife and make your local community a happier and healthier place to live.”

National Tree Day is an initiative organised by Planet Ark in partnership with major sponsor Toyota Australia and its Dealer Network. For more information and to find events in your local area, please visit treeday.planetark.org.

National Tree Day 2023: Local sites

Avalon Beach: Palmgrove Road

In the grass area between Dress Circle Road and Bellevue Ave, Avalon

DATE & TIME: Sunday, 30 July 2023, 10:00am to 2:00pmSite Organiser: Michael Kneipp

RSVP Contact: Michael Kneipp, 1300 434 434

Suitable for Children: Yes

Accessible for Wheelchairs: No

VOLUNTEER INFORMATION: Please wear long pants, long sleeve shirt, sturdy shoes, gloves and a hat. Everyone is invited to help us regenerate this important wildlife corridor with native plants. Make Avalon a cooler, greener and more connected place for our community and wildlife.

WHAT'S PROVIDED?: Gloves, Tools and equipment for planting, Watering cans / buckets, Refreshments, BBQ

Volunteer at this site: https://treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/volunteer/10028078

Duffys Forest Residents Association

DATE & TIME: Sunday, 30 July 2023, 9:00am to 1:00pm

LOCATION: 13 Namba Road, Duffys Forest

Site Organiser: Jennifer Harris

RSVP Contact: Jennifer Harris, 0408512060

Suitable for Children: Yes

Accessible for Wheelchairs: Yes

DIRECTIONS: You can enter the site at the end of Namba road. Proceed through two large metal gates, to picnic area to sign on for the event.

VOLUNTEER INFORMATION: Volunteers must wear suitable clothing & protective gear including covered shoes, gloves and a hat. It is proposed that volunteers plant up to 600 indigenous native tube stock in degraded areas of the park to create additional canopy species, establish ground cover, reduce weed invasion and to improve biodiversity & wildlife habitat. The activity is located in an iconic park, formerly known as Waratah Park, the home of "Skippy". The event will be supervised by a qualified bush regenerator & aims to inspire & educate participants to become custodians and actively care for our unique environment. Last year we planted over 450 tube stock with 35 volunteers in just over 3 hours. These tube stock have thrived due to ongoing maintenance and watering by volunteers.

WHAT'S PROVIDED?: Gloves, Tools and equipment for planting, Watering cans / buckets, Snacks, Refreshments, BBQ

Volunteer at this site: https://treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/volunteer/10027702

Curl Curl

DATE & TIME: Sunday, 30 July 2023, 10:00am to 2:00pm

Location: Griffin Road, North Curl Curl

VOLUNTEER INFORMATION: Please wear long pants, long sleeve shirt , sturdy shoes, gloves and a hat. There are also public transport and cycling options. Everyone is invited to help us regenerate this important wildlife corridor with native plants. Make Curl Curl a cooler, greener and more connected place for our community and wildlife. Please wear long pants, long sleeve shirt , sturdy shoes, gloves and a hat.

Enter via the car park or footpath on the Southern side of the Greendale Creek bridge. Look for our Northern Beaches Council Marquees.

Site Organiser: Michael Kneipp

RSVP Contact: Michael Kneipp, 1300 434 434

Suitable for Children: Yes

Accessible for Wheelchairs: No

Volunteer at this site: https://treeday.planetark.org/find-a-site/volunteer/10028073

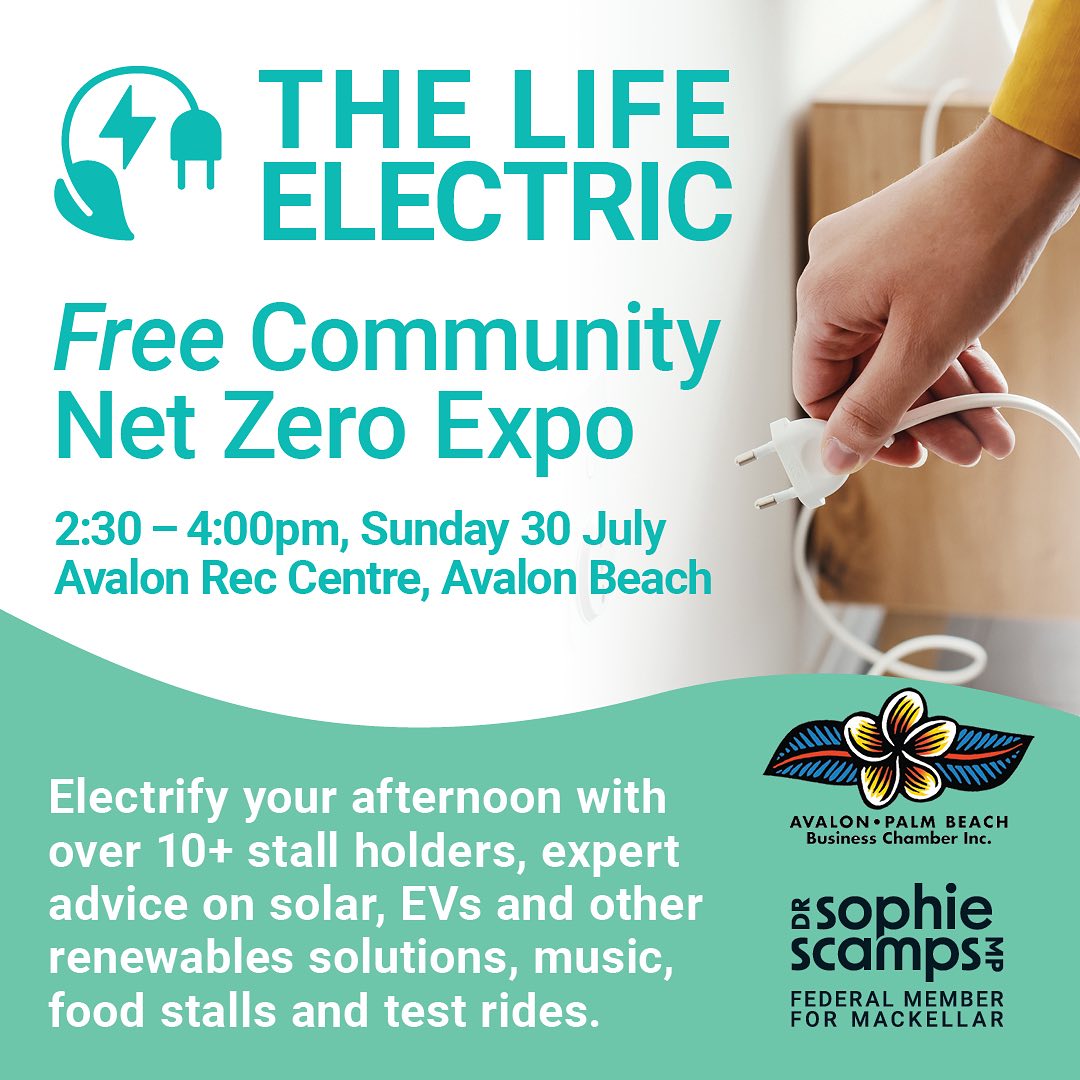

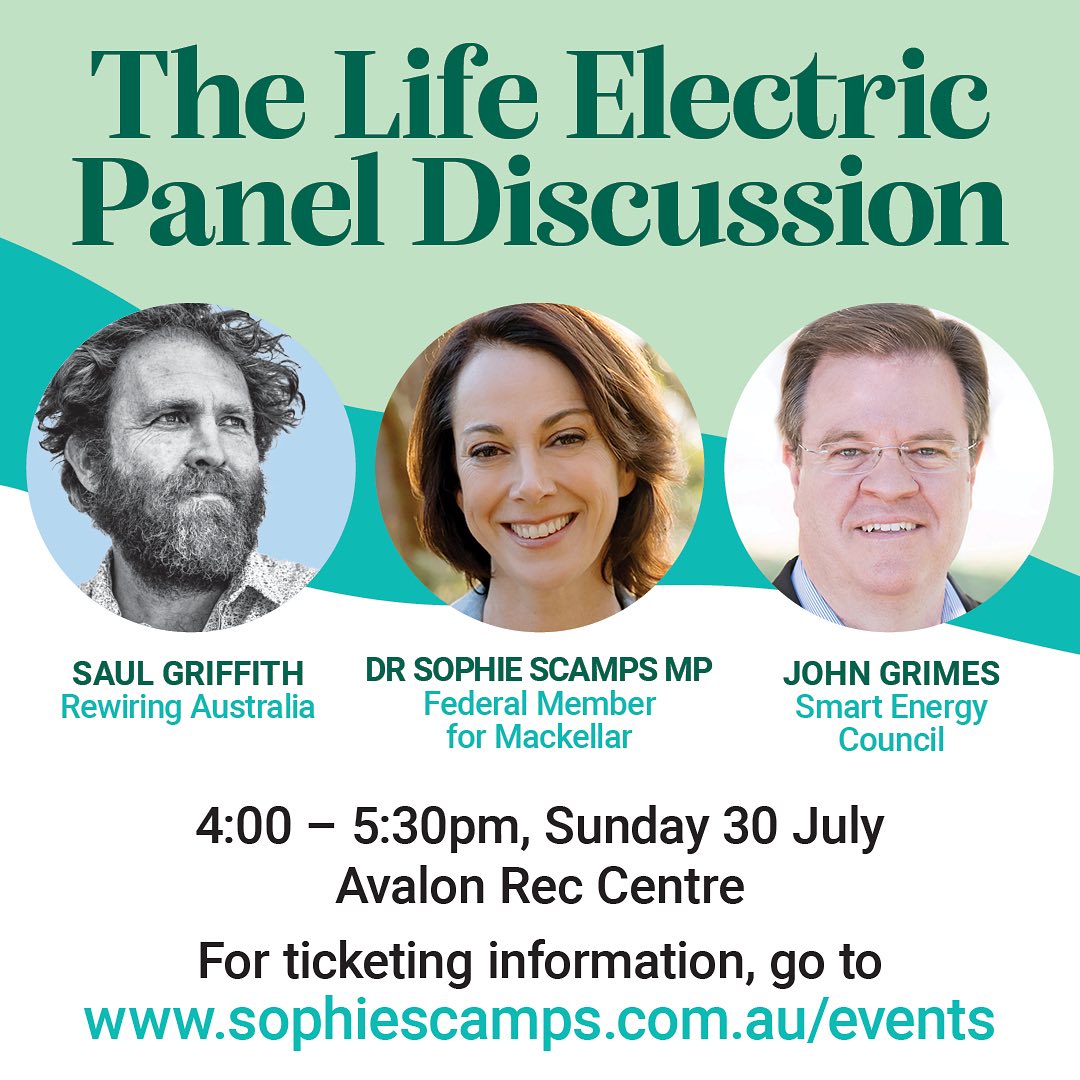

The Life Electric Expo And Forum: July 30th At Avalon Rec. Centre

The Life Electric Community Expo is hosted by Avalon Palm Beach Business Chamber Inc. Entry is free with 10+ stalls, expert advice, food, music and test rides. You can also purchase tickets to the live panel featuring Saul Griffith and John Grimes.

Book your tickets ($10) at the link here: https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1076483

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Dee Why Lagoon Beach Side Clean Up, 30th Of July, 2023, At 10am

Come and join us for our family friendly July clean up, in Dee Why Lagoon on the 30th at 10am. We meet in the grass area close to the council car park, and the surf life saving club at the north end of Dee Why. Please note that this is a different meeting point to where we were last time.

We have gloves, bags, and buckets, and grabbers. We're trying to remove as much plastic and rubbish as possible before it enters the water. Some of us can focus on the bush area and sandy/rocky areas, and others can walk along the water and even clean up in the water (at own risk). We will clean up until around 11.15, and after that, we will sort and count the rubbish so we can contribute to research by entering it into a marine debris database. The sorting and counting is normally finished around noon, and we'll often go for lunch together at our own expense. We understand if you cannot stay for this part, but are grateful if you can. We appreciate any help we can get, no matter how small or big.

No booking required - just show up on the day - we will be there no matter what weather. We're a friendly group of people, and everyone is welcome to this family friendly event. It's a nice community - make some new friends and do a good deed for the planet at the same time.

For everyone to feel welcome, please leave political and religious messages at home - this includes t-shirts with political campaign messages.

Message us on our social media or send us an email if you are lost. All welcome - the more the merrier. Please invite your friends too! All details in our Facebook event, Instagram or on our website.

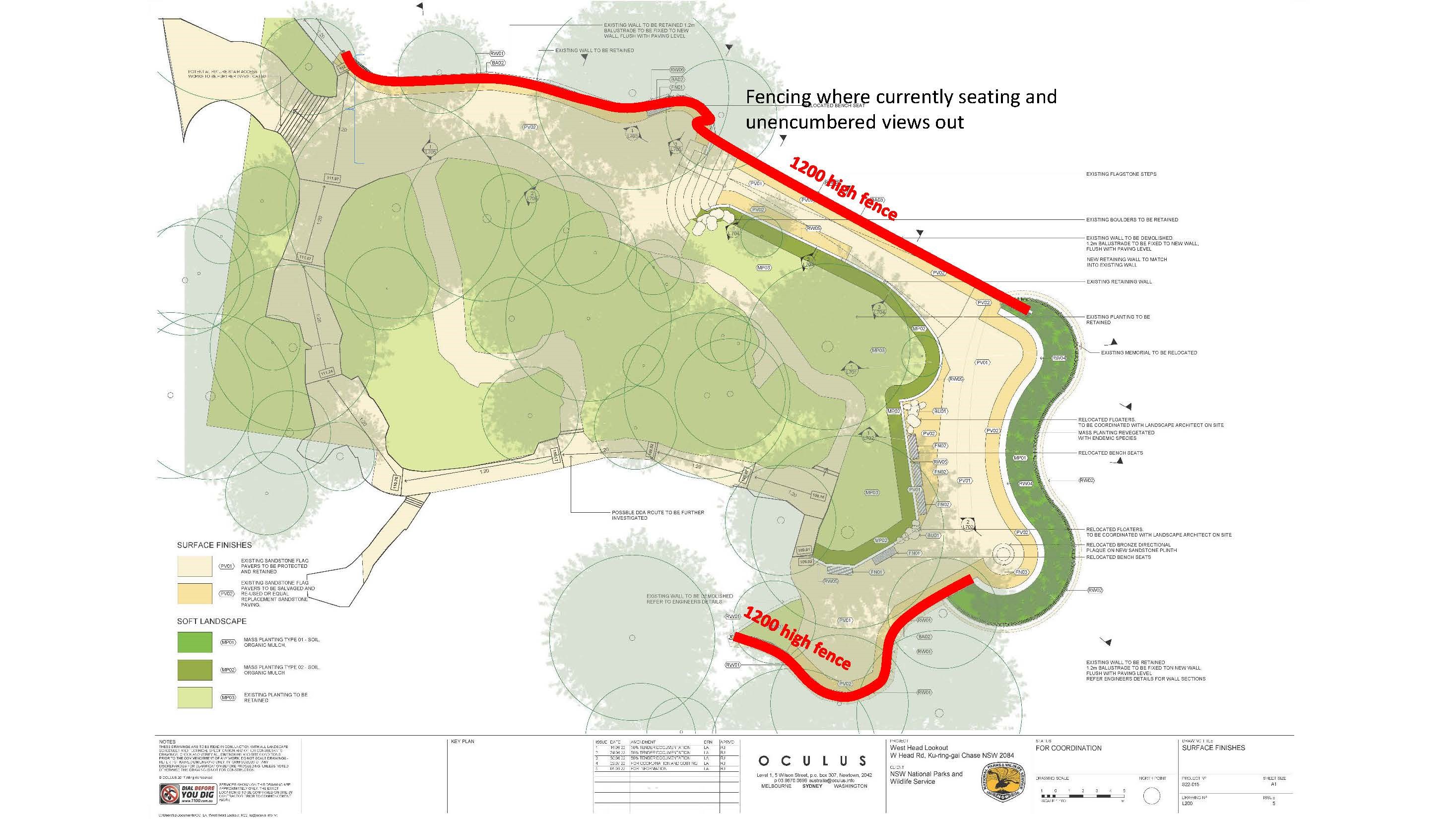

Areas Closed For West Head Lookout Upgrades

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

- West Head lookout

- The loop section of West Head Road

- West Head Army track.

Vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians will have access to the Resolute picnic area and public toilets. Access is restricted past this point.

The following walking tracks remain open:

- Red Hands track

- Aboriginal Heritage track

- Resolute track, including access to Resolute Beach and West Head Beach

- Mackeral Beach track

- Koolewong track.

The West Head lookout cannot be accessed from any of these tracks.

Image: Visualisation of upcoming works, looking east from the ramp towards Barrenjoey Head Credit: DPE

Time Of Burrugin

Cold and frosty; June-July

Echidna seeking mates - Burringoa flowering - Shellfish forbidden

This is the time when the male Burrugin (echidnas) form lines of up to ten as they follow the female through the woodlands in an effort to wear her down and mate with her. It is also the time when the Burringoa (Eucalyptus tereticornis) starts to produce flowers, indicating that it is time to collect the nectar of certain plants for the ceremonies which will begin to take place during the next season. It is also a warning not to eat shellfish again until the Boo'kerrikin (Acacia decurrens, commonly known as black wattle or early green wattle) blooms.

Eucalyptus tereticornis, commonly known as forest red gum, blue gum or red irongum, is a species of tree that is native to eastern Australia and southern New Guinea. It has smooth bark, lance-shaped to curved adult leaves, flower buds in groups of seven, nine or eleven, white flowers and hemispherical fruit.

Eucalyptus tereticornis was first formally described 1795 by James Edward Smith in A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland from specimens collected in 1793 from Port Jackson by First Fleet surgeon and naturalist John White. The specific epithet (tereticornis) is from the Latin words teres (becoming tereti- in the combined form) meaning "terete" and cornu meaning "horn", in reference to the horn-shaped operculum.

Habitat tree: Sclerophyll Forest.

Food tree: Natural stands are an important food tree for koalas and a wide variety of nectar-eating birds, fruit bats and possums.

Eucalyptus tereticornis buds, capsules, flowers and foliage, Rockhampton, Queensland. Photo: Ethel Aardvark

Shelly Beach Echidna

Photos by Kevin Murray, taken late May 2023 who said, ''he/she was waddling across the road on the Shelly Beach headland, being harassed not so much by the bemused tourists, but by the Brush Turkeys who are plentiful there.''

Shelly Beach is located in Manly and forms part of Cabbage Tree Bay, a protected marine reserve which lies adjacent to North Head and Fairy Bower.

From the D'harawal calendar, BOM

D'harawal

The D'harawal Country and language area extends from the southern shores of Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) to the northern shores of the Shoalhaven River, and from the eastern shores of the Wollondilly River system to the eastern seaboard.

Bush Turkeys: Backyard Buddies Breeding Time Commences In August - BIG Tick Eaters - Ringtail Posse Insights

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

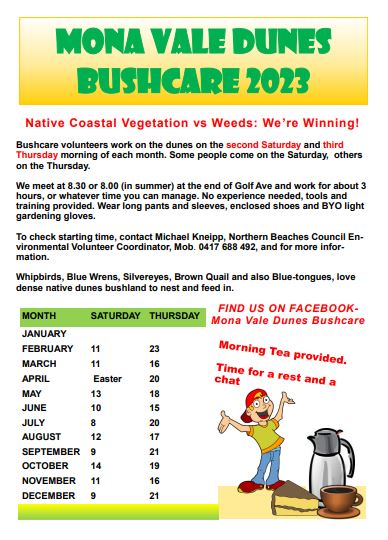

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

With less than a year to go, the Murray-Darling Basin Plan is in a dreadful mess. These 5 steps are needed to fix it

The Murray Darling Basin Plan is an historic deal between state and federal governments to save Australia’s most important river system. The A$13 billion plan, inked over a decade ago, was supposed to rein in the water extracted by farmers and communities, and make sure the environment got the water it needed.

But now, less than a year out from the plan’s deadline, it’s in a dreadful mess. Projects have not been delivered. Governments cannot agree on who gets the water, or how. All the while, water in the Murray-Darling Basin will become scarcer as climate change worsens.

The Albanese government was elected on a promise to uphold the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. But earlier this month, Environment and Water Minister Tanya Plibersek conceded the plan is “too far behind” and needs a “course correction”.

I have studied and promoted sustainability measures in the Murray-Darling Basin for 35 years. Here, I outline the five steps needed now to ensure the health of the river system and the people who depend on it.

A Refresher: What Is The Murray-Darling Basin Plan?

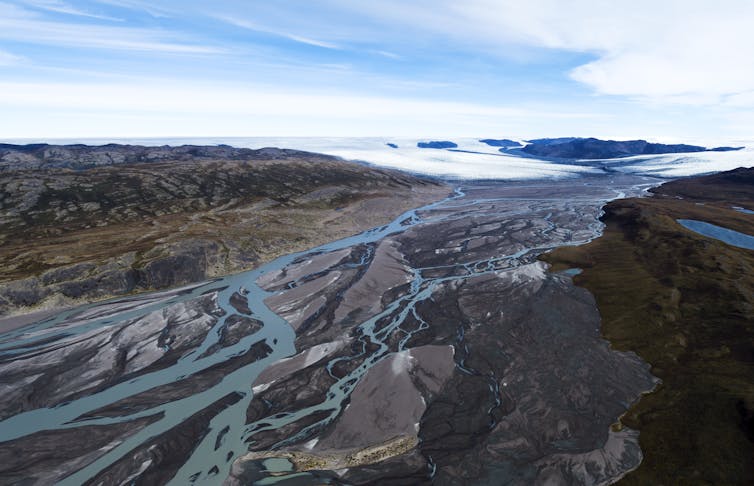

The Murray-Darling Basin covers about a seventh of the Australian land mass: most of New South Wales, parts of Queensland, South Australia and Victoria, and all of the Australian Capital Territory. It includes the Murray River and Darling River/Baarka and their tributaries.

These lands and waters are the traditional lands of more than 40 Indigenous nations. Around 5% of the basin consists of floodplain forests, lakes, rivers and other wetland habitats. Vast amounts of water are extracted from the rivers to supply around three million Australians, including irrigating farms.

The Murray-Darling Basin Plan became law in 2012, under the Labor government. It is due to be fully implemented and audited by the end of June 2024.

The plan limits the amount of water extracted from the basin. It aims to both improve the condition of freshwater ecosystems and maintain the social and economic benefits of irrigated agriculture.

Under the plan, 3,200 billion litres a year would be returned to rivers – about 14% of total surface water in the basin.

The water was largely to be recovered by buying back water entitlements from farmers. Some 450 billion litres would be retrieved through water efficiency projects.

The plan has twice been amended to reduce the amount of water taken from farmers. The first change, made on questionable grounds, reduced the water recovery target by 70 billion litres a year. The second reduced it by 605 billion litres, with the water to instead be recovered through 36 water-saving offset projects.

Further, the Victorian and NSW governments committed to reaching agreements with farmers to enable water for the environment to safely spill out of river channels and across privately owned floodplains, to replenish more wetlands.

So How’s The Plan Going?

Things are not going well. As of November last year, the offset projects were likely to deliver between 290 and 415 billion litres of the 605 billion litres required. And very little water is getting to floodplains.

And of the 450 billion litres to be retrieved through water-efficiency projects, only 26 billion litres has been recovered.

It means of the 3,200 billion litres of water a year to be returned to the environment, only 2,100 billion litres was being achieved as of March this year – plus the small amount of projected water from offset projects, if it’s delivered.

At a meeting in February this year, the nation’s water ministers failed to agree on how to meet the plan’s deadline.

As governments quibble, the rivers and floodplains of the Murray-Darling suffer. In the past decade, millions of fish have perished in mass die-offs. Toxic algae has bloomed, wildife and waterbirds have declined in numbers and wetlands have dried up. These are all signs that too much water is still being taken from the system.

So how do we get the basin plan back on track? Below, I identify the top five priorities.

1. NSW Must Get Its Act Together On Water Plans

Integral to implementing the broader basin plan are 33 “water resource plans” devised by the states. These plans bring the basin plan into legal force and detail how much water can be taken from the system and how it is divided between users such as farmers, communities and the environment.

NSW must produce 20 plans. To date, just five are in place. At least seven plans by NSW were recently withdrawn to be re-drafted.

Until they’re finalised, key measures of the basin plan cannot be implemented. The new NSW Minns government must prioritise the remaining water resource plans and have them accredited by the Commonwealth government.

2. Federal Water Buybacks Must Ramp Up

The Albanese government is taking steps to improve water recovery under the plan, such as consulting stakeholders and restarting water buybacks. But it must do more.

Both NSW and Victoria will almost certainly miss the 2024 deadline for delivering all infrastructure projects they promised to offset 605 billion litres of water.

The federal government is legally obliged to – and should – purchase additional water from farmers to cover any gap. It must also acquire more than 400 billion litres of water to make up for the shortfall in water efficiency projects.

For this to occur, a Coalition-era cap must be lifted from 1,500 billion litres to enable more federal government water purchases from farmers.

3. Abandon Questionable Water-Saving Projects

At least six water-saving projects look unlikely to meet the deadline.

They include a large project proposed by the former NSW government to reduce evaporation at Menindee Lakes, which appears doomed.

Another project at Yanco Creek in NSW has also fallen behind, and four of the nine Victorian projects have been paused.

What’s more, the ecological merit of these projects are contested – as is the scientific rigour of the proposed auditing method. These projects should be abandoned in favour of reconnecting rivers to their floodplain.

4. Reconnect Rivers And Floodplains

For floodplain wetlands to function, they must be regularly inundated with water. To date, just 2% of these parts of the basin are inundated each year by managed flows (or in other words, intentional water releases by authorities).

The federal government holds water for this purpose. Delivering the water requires compensation for the owners of inundated properties, as well as upgraded roads, bridges and levee banks. Managed inundation can benefit landholders, such as by reducing the impacts of natural floods. But governments must do a better job of communicating these benefits to win support.

The federal government needs NSW and Victoria to help implement their agreement for watering floodplains, but this cooperation has been extremely slow.

5. Make Information Transparent

The data and modelling used to manage water in the basin is complex and is often not publicly available.

In its final report in 2019, a South Australian royal commission into the Murray-Darling Basin was highly critical of the Murray-Darling Basin Authority. The report found the authority failed to act on “the best available science” when determining how much water could be returned to the environment, and withheld modelling and other information that should have been made public.

Making such information freely available is crucial for accountability and to build public trust.

Time For Tough Decisions

Each key element of the basin plan has encountered trouble at the implementation stage. The five steps I’ve outlined are essential to rectifying this.

Attention must now also turn to a review of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, which is legally required in 2026. As well as addressing the problems detailed above, it must address two big issues essentially ignored in the plan to date: the lack of Indigenous rights over water, and water losses due to global warming and other environmental change.

If the Albanese government is to uphold its election promise to deliver the plan, hard decisions – and trade-offs – will be required. ![]()

Jamie Pittock, Professor, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A climate expert explains the Northern Hemisphere’s weird, wild summer – and what it means for Australia

Andrew King, The University of MelbourneThe Northern Hemisphere summer has brought one extreme event after another – from heatwaves to wildfires and floods. It comes as the world likely heads into an El Niño pattern, which brings a higher chance of hot, dry weather in much of Australia.

So is the weird northern summer a portent of what Australia can expect in a few months?

The extremes in the Northern Hemisphere are linked to persistent weather patterns which allow heat to build in some places and rain to continue in others. On top of this, human-caused climate change is raising temperatures to new heights.

It’s too early to say whether Australia is in for a scorching summer. The predicted El Niño is a worry, but doesn’t guarantee the record-smashing heat we’re seeing in parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

Having said that, continued global warming will bring more record-high temperatures in Australia. So we must remain on high-alert – and ramp up reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Extreme Weather Across The World

Wild weather in the Northern Hemisphere at this time of year is to be expected. However, recent extremes are off the charts.

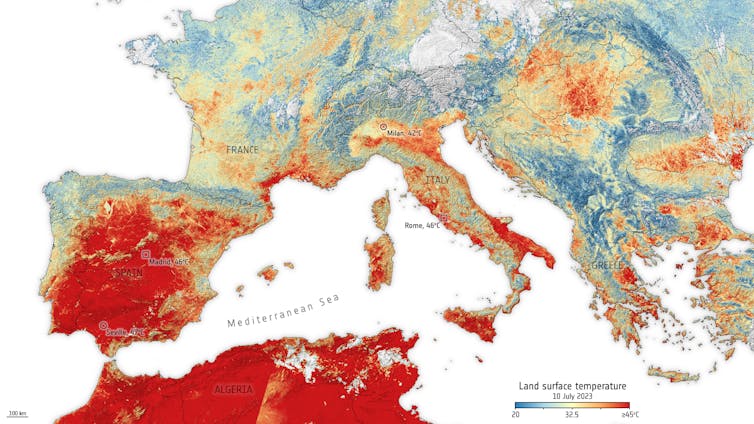

Major heatwaves are underway in North America, Europe, North Africa and Asia. In California’s Death Valley, temperatures on Sunday reached 53.3℃. Parts of Italy were expected to reach 45℃ on Tuesday, and later in the week could approach Europe’s hottest temperature on record: 48.8℃.

China provisionally reached 52.2℃ on Sunday, shattering the previous record for the country by more than 1.5℃.

Meanwhile, wildfires are tearing through Canada, Greece and Spain, destroying properties and forcing evacuations.

So what’s causing these simultaneous heatwaves across multiple regions? They’re all linked to high-pressure weather systems that are “blocking” or deflecting oncoming low-pressure systems (and associated clouds and rain).

These low-pressure systems have moved to other areas and caused extreme rainfall and flooding. Flooding in South Korea has left 40 people dead and destroyed critical infrastructure. Vermont, in the northeast United States, was also flooded after up to two months of rain fell in a few days.

Alarmingly, the atmospheric patterns driving the extremes in the Northern Hemisphere appear to be getting more common under climate change. On top of this, human-caused global warming is greatly increasing the chance of record-breaking extreme heat events and concurrent heatwaves across many regions.

What This Means For Australia

All this begs the question of what might be coming Australia’s way this summer.

There’s one factor working in our favour: the particular atmospheric pattern bringing extremes to the Northern Hemisphere isn’t replicated in the Southern Hemisphere, because we have more ocean and less land.

However, Australia does experience its own “blocking” high pressure patterns which also bring major heatwaves and extreme rain events. Unfortunately we can’t predict these months in advance.

El Niño is a little more easily predicted. Currently, the tropical Pacific Ocean is trending towards El Niño conditions, as waters off the west coast of Ecuador and Peru continue to warm.

El Niño is part of a natural fluctuation in the Earth’s climate system which typically lasts for the best part of a year. It raises the chance of a warmer and drier spring in Australia.

Some meteorological agencies say an El Niño has already arrived. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology is holding off on a declaration, for now. That’s because while the Pacific has fallen into an El Niño pattern, the atmosphere hasn’t yet followed.

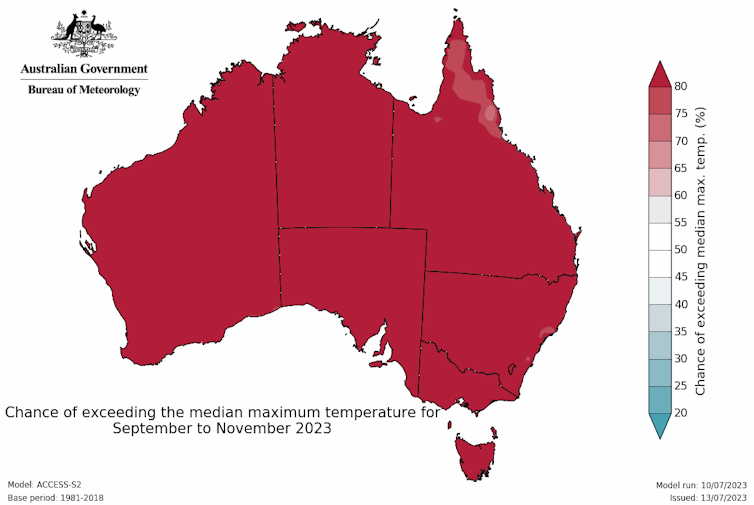

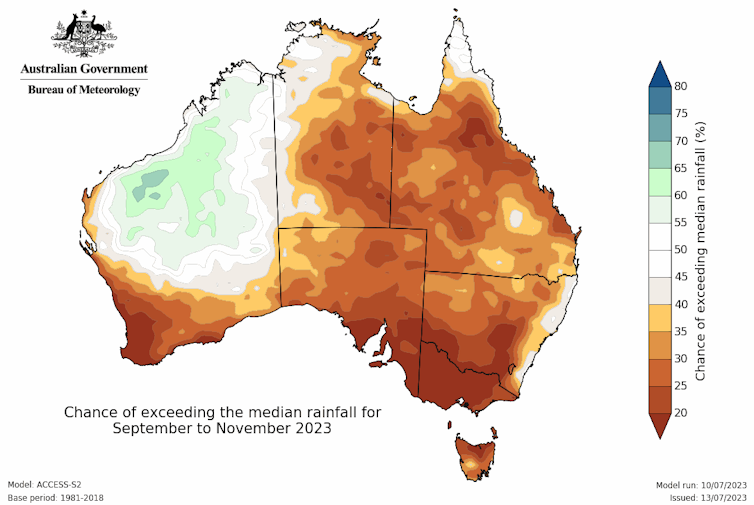

But the bureau still puts the likelihood of an El Niño at 70%, and forecasts warmer and drier conditions across much of Australia from August to November.

The extreme weather in the Northern Hemisphere isn’t strongly related to the developing El Niño. But by the time Australia’s summer arrives, we’ll likely see El Niño’s effects in the weather.

What’s more, another driver of Australia’s climate, the Indian Ocean Dipole, is likely to enter a positive phase in coming months.

This phase is associated with warmer seas in the west Indian Ocean. This leads to fewer low pressure systems, on average, over southeast Australia and less atmospheric moisture over most of the continent. This would likely suppress winter and spring rainfall over much of Australia and exacerbate an El Niño’s drying effect.

Not all El Niño and positive Indian Ocean Dipole events bring warm, dry weather. And there isn’t a strong relationship between the magnitude of an El Niño and the lack of rain in Australia. But these background climate conditions raise the chance of a warmer and drier spring.

We can’t yet predict if Australia will swelter this summer. But an El Niño increases the chance of hotter and drier summer conditions, with more heatwaves and a greater frequency of weather conducive to fire spread.

Australia In A Warming World

Of course, all this comes on top of human-driven global warming. In Australia, land areas have already warmed by 1.4℃ over the past century, and the cool summers common before 1980 are now far less likely.

In fact, even if global warming is limited to well below 2℃, historically hot summers in Australia will become common.

The Northern Hemisphere’s current extreme weather, and predictions of hotter summers in Australia, are all evidence of humanity’s fingerprints on Earth’s climate. This should spur urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Because if global warming continues, Australia is certain to be hit by more record-breaking heat events – and that is not something we want to experience. ![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

European heatwave: what’s causing it and is climate change to blame?

Europe is currently in the midst of a heatwave. Italy, in particular, is expected to face blistering heat, with temperatures projected to reach 40℃ to 45℃. There’s even a chance that the current European temperature record of 48.8℃, set in Sicily in 2021, could be surpassed.

Searing temperatures have spread to other countries in southern and eastern Europe, including France, Spain, Poland and Greece. The heat will complicate the travel plans of those heading to popular holiday destinations across the region.

Heatwaves, which are defined as prolonged periods of exceptionally hot weather in a specific location, can be extremely dangerous. Europe has experienced its fair share of devastating heatwaves in the past.

In 2003, a heatwave swept across Europe, claiming the lives of over 70,000 people. Then, in 2022, another heatwave hit Europe, resulting in the deaths of almost 62,000 people.

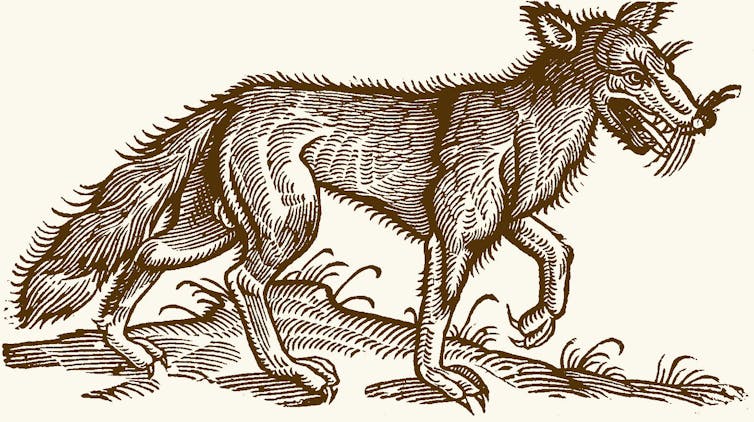

The current heatwave is being caused by an anticyclone named Cerberus after the three-headed monster-dog that guards the gates of the underworld in Greek mythology. An anticyclone – or high-pressure system – is a normal meteorological phenomenon in which sinking air from the upper atmosphere brings about a period of dry and settled weather with limited cloud formation and little wind.

High-pressure systems tend to be slow moving, which is why they persist for days, or even weeks at a time. They often become semi-permanent features over large areas of land. When high pressure systems form over hot land, in regions like the Sahara, the stability of the system generates even hotter temperatures because the already warm air is heated even more.

Eventually, the anticyclone will weaken or break down and the heatwave will come to an end. According to the Italian Meteorological Society, the Cerberus heatwave is expected to persist for around two weeks.

What Role Does Climate Change Play?

High pressure systems, like the one currently affecting Europe, have been expanding northwards in recent years. It’s difficult to ascribe a single event, such as a heatwave, directly to climate change. But as temperatures continue to warm, we are seeing changes in atmospheric circulation patterns that can lead to increased occurrences of extreme temperatures and drought in Europe.

Research by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change confirms this trend. Its data shows an increase in the frequency and magnitude of extreme weather events since the 1950s. A separate analysis of European heatwaves revealed an increasing severity of such events over the past two decades.

In the summer of 2022, southern Europe experienced higher temperatures than usual for that time of the year. Spain, France and Italy saw daily maximum temperatures exceed 40°C. The EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service attributed these unusually hot conditions to climate change and suggested that such events are likely to become more frequent, intense and last longer in the future – indicating a concerning trend that may continue this year.

The Dangers Of Extreme Heat

Heatwaves and extreme temperatures impact human health in a number of ways. These conditions can cause heatstroke, leading to symptoms like headaches and dizziness. Dehydration resulting from the heat can also affect respiratory and cardiovascular performance.

There have already been reports of heat-related health incidents in Europe during the ongoing heatwave. An Italian road worker died, and there have been numerous cases of heatstroke reported across Spain and Italy.

The Italian Ministry of Health has advised residents and visitors in affected areas to take precautions like staying out of the sun during the hottest part of the day, remaining hydrated and to avoid alcohol consumption.

But the effects of heatwaves go beyond individual health. They have broader social and economic consequences too. Extreme heat can damage road surfaces and even cause railway tracks to buckle.

Heatwaves can also lead to reduced water availability, affecting electricity production, crop irrigation and drinking water supply. In 2022, scorching heat meant French nuclear plants were unable to run at full capacity as higher river temperatures and low water levels affected their cooling ability. Research indicates that extreme heat has already had a negative impact on economic growth in Europe, lowering it by up to 0.5% over the past decade.

As temperatures continue to rise, heatwaves will become more severe. It’s crucial that governments worldwide take swift and decisive action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions immediately.

However, it’s important to note that even if we were to completely halt global greenhouse gas emissions today, the climate would still continue to warm. This is due to the heat that is already absorbed and retained by the oceans. While we can slow down the rate of global warming, the effects of climate change will continue to be experienced in the future.![]()

Emma Hill, Associate Professor in Energy & Environmental Management, Coventry University and Ben Vivian, Assistant Professor in Sustainability & Environmental Management, Coventry University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Mining the seabed for clean-tech minerals could destroy ecosystems. Will it get the green light?

A little-known organisation is meeting this week in a conference centre in Jamaica. The rules the International Seabed Authority (ISA) are drafting could have immense impact.

That’s because this United Nations body has the power to permit – or deny – mining on the deep seabed, outside any nation’s exclusive economic zones. Boosters say the billions of tonnes of critical minerals like nickel, manganese, copper and cobalt lying in metal-dense nodules on the seabed could unlock faster decarbonisation and avoid supply shortages.

Developing Pacific nation Nauru has led the charge to open up the seabed for mining, seeing it as a new source of income. (Ironically, Nauru itself was strip-mined for guano, leaving a moonscape and few resources.)

But researchers warn the mining could trash entire ecosystems, by ripping up the sea floor or covering creatures with sediment. Early indications from trial mining efforts suggest the process is worse than expected, with long-lasting impact on sealife.

Almost 20 governments are calling for a moratorium or slowdown on mining. But China, Russia and South Korea are pushing for mining to begin.

The ISA has already missed its July 9 deadline to produce regulations governing seabed mining. That could mean we’re heading for a deep-sea free-for-all.

Why Mine The Deep Sea At All?

Because no one owns it, and because parts of it are rich in easily accessible metals (once you get to the bottom, that is). Land-based mining usually involves processing vast volumes of rock, taking out the minerals you want and leaving the tailings behind. But on the seabed, things are different.

The main area prospectors are eyeing off is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an abyssal plain 4,000–5,000 metres deep east of Hawaii. Here, plate tectonics and underwater volcanoes have produced huge numbers of polymetallic nodules, accretions of minerals about 10-15 centimetres wide. They grow glacially slowly, about one centimetre every million years. But there are a lot of them – an estimated 21 billion tonnes in this zone alone, according to the ISA.

By 2050, demand for nickel and cobalt to make electric vehicle batteries could grow by up to 500%, according to the World Bank. That’s why companies like Nauru’s partner, The Metals Company, are investing in this type of mining.

Seabed mining, they argue, is an environmentally better option than expanding land-based mining into more challenging locations, mining low-grade ore bodies and risking contaminating waterways.

Boosters say seabed mining in international waters avoids the risk of dominance by a few countries or suppliers. For instance, the Ukraine-Russia war has hit battery grade nickel availability, as Russia is the primary global supplier.

But What About The Environment?

This is the sticking point. The seabed in question is a pristine environment. While fishing trawlers already tear up large areas of seafloor to devastating effect, mining would open up even more of the seabed.

Opposition has come from many conservation organisations, civil society representatives, governments like Canada, Germany, Fiji and Papua New Guinea. They want a moratorium on seabed mining based on the precautionary principle – not acting until we know what impact it will have. They argue we lack the technology to monitor the seabed and knowledge of the ecosystems of the deep, meaning we cannot be certain seabed mining can proceed without causing serious and long lasting harm. Early research shows this type of mining can be destructive.

Should The ISA Have The Power To Decide This?

It took 25 years for the UN to negotiate the law of the sea treaty. The treaty is clear about how we should protect and use the seabed, as part of the “common heritage of mankind”. The ISA was created to steward these commons, with the power to make rules in international waters. These cover two-thirds of the world’s oceans and 90% of known polymetallic nodule deposits.

The problem is many governments and organisations don’t think it’s fit for purpose.

The ISA is, like some other UN bodies, a complex bureaucracy and has been criticised for lacking transparency. Even though all 167 nations which signed the law of the sea treaty are automatically ISA members, critical decisions can be made with far fewer.

Applications to mine the seabed are approved or denied by the ISA’s council, which has 36 members. Council decisions stem from recommendations by a legal and technical commission, made up of 30 members appointed by the council. Dominated by lawyers and geologists, this commission, according to NGOs and governments, has ignored comments and critique. Only a handful of the members have environmental expertise.

The council is also geared towards mineral extraction, with many members elected on the basis they already export minerals like nickel and manganese, have invested heavily in seabed mining technology, and already use significant volumes of these minerals.

The ISA’s secretary general Michael Lodge was earlier this year criticised by the German government for allegedly pushing to permit mining, an accusation Lodge rejected.

So Is It A Done Deal?

Ideally, the authority would have more time to develop rigorous rules based on good environmental assessments.

But time is up. Two years ago, Nauru triggered a clause giving the ISA two years to produce a mining code and rules – a feat it had not previously managed. Those two years were up on July 9th and the code isn’t out. That means it’s now legally possible to lodge mining applications.

So because of the delays, we may be heading for a future where seabed mining becomes legal by default – without rules to govern it at all. ![]()

Claudio Bozzi, Lecturer in Law, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Northern Territory does not have a crocodile problem – and ‘salties’ do not need culling

Last week, a 67-year-old man was bitten on the arm by a saltwater crocodile at a waterhole in the Northern Territory’s Top End. Predictably, the incident has prompted debate over whether a crocodile cull is needed.

The incident occurred in Litchfield National Park at Wangi Falls, a popular tourist spot. The man was hospitalised with non-life threatening injuries. Authorities later removed and killed the 2.4 metre crocodile responsible for the attack.

Fatal crocodile attacks in the NT peaked in 2014 when four people died. The last fatal incident in the territory occurred in 2018 when an Indigenous ranger was killed while fishing with her family.

Despite the low number of fatal attacks in recent years, NT Chief Minister Natasha Fyles said last week the territory’s crocodile population had risen dramatically in recent decades and “it’s time for us to consider” if culling should be reintroduced.

This is an over-reaction to a fairly isolated incident. Data suggest the saltwater crocodile population in the NT does not need to be culled and their management does not need changing.

Getting To Grips With ‘Salties’

Saltwater crocodiles, fondly known in Australia as “salties”, are the largest in the crocodilian order of reptiles and can grow to six metres.

Hundreds of saltwater crocodile attacks on humans are reported globally each year. This, as well as demand for crocodile skins, has resulted in the species being eradicated from much of its former range.

The saltwater crocodile was once found widely across the Indo-Pacific region. Now, there are no saltwater crocodiles in several countries including Cambodia, China, Seychelles, Thailand and Vietnam.

Elsewhere, saltwater crocodile populations declined dramatically last century. In the Northern Territory, crocodile numbers dropped to about 5,000 before a culling ban was introduced in 1971. The species’ numbers have since rebounded to more than 100,000.

In some areas, recovering crocodile populations come into conflict with humans. This can occur when, for example, humans destroy the species’ habitat or their prey becomes scarce due human activity such as overfishing and poaching. This can force the species to relocate, bringing them closer to people.

Saltwater crocodiles have long been known to enter Wangi Falls during the wet season, when the location is closed to the public. In fact, a 3.4 metre crocodile was captured there in January this year.

It’s never 100% safe to swim at locations within the natural range of saltwater crocodiles. However, Wangi Falls is considered reasonably safe for swimming during the dry season (May to October) because park officials survey and remove crocodiles before it opens to the public each year.

So what went wrong in this case? We don’t know for sure. The crocodile in question was relatively small: perhaps it wasn’t spotted during surveys. Or it could have just arrived after surveys were conducted.

The Current Approach Works

Following last week’s crocodile attack, Fyles said culling may be needed, telling the media:

I think it’s time for us to consider: do we need to go back to culling considering the significant increase in the crocodile population, and the impact it’s happening, not just on our tourists and visitors, but also locals?

These comments are surprising. Recent data for the Top End suggests crocodile populations are stabilising. And the rarity of fatal attacks on humans indicates the territory’s crocodile management plan is effective.

The plan involves, among other measures, removing problem crocodiles, raising public awareness around safely co-existing with the animals, and monitoring their impact.

Since 2018, the NT has experienced one fatal saltwater crocodile attack while Queensland has experienced two. That’s despite an average saltwater crocodile density in the territory of 5.3 individuals per kilometre – three times more than in Queensland.

This, coupled with data from outside Australia, suggests the frequency of crocodile attacks depends more on human behaviour and population density than how many crocodiles are in a given area.

In Indonesia, crocodiles killed at least 71 people last year alone. Yet the crocodile population there is likely small and recovering, based on the limited number of surveys conducted.

In the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara, for example, crocodiles killed at least 60 people between 2009 and 2018. Yet surveys suggest their average density is only 0.4 per kilometre. The situation is similar on the island of Sumatra, as well as parts of Malaysia.

The Downsides Of Culling Crocs

Culling saltwater crocodiles isn’t just bad for the species. It can also have negative consequences for humans.

The public could be lulled into a false sense of security and think a location is safe for swimming, even though crocodiles remain.

And seeing saltwater crocodiles in the wild is important to the NT’s economy. Culling them could damage the NT’s reputation as an ecotourism destination.

Lastly, culling dominant male crocodiles can be dangerous. Saltwater crocodiles are the most territorial of all crocodilians. When one is removed, other large crocodiles begin to compete for the newly available territory. This can present a threat to public safety.

The crocodile population in the NT does not need to be culled. Indeed, the territory’s current crocodile management plan is an example of large predator conservation done right.![]()

Brandon Michael Sideleau, PhD student studying human-saltwater crocodile conflict, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How a surfing sea otter revealed the dark side of human nature

Surfers often talk about how the sport helps them reconnect with nature, but a recent episode involving an otter with a love for surfboards shows just how brittle our love for wildlife really is.

The authorities are trying to capture and remove said otter from her native environment for climbing onto a man’s surfboard in Santa Cruz, California. In a video of the incident published on Twitter, the otter is seen clambering onto the surfer’s board where she appears to play with it. Wildlife officials described the otter’s behaviour as aggressive.

People have joked that the otter has joined the orca uprising, referring to the killer whale attacks on boats off the coast of Spain. A researcher said the orcas are attacking sailboats for an “adrenaline shot”.

If you watch the video, you will notice that the otter remains at the opposite end of the board to the surfer. But the language used by the media, and the authorities they quote, is far more telling than the otter’s behaviour.

War On Nature

We often use the language of combat to describe unusual events and to make sense of what seems like an imbalance in the world. Words like “conflict” and “clash” fit into an oppositional narrative, which is a simpler way to tell stories than, say, “unusual interaction”. Often, as storytellers in all fields, we humans describe the world, our local environment and to whom they “belong”, as a kind of fight – for example: “force of nature” and “triumph of civilisation”.

Any number of things could explain the Santa Cruz otter’s behaviour, including fear, anxiety, protective territorialism, curiosity and perhaps even aggression. People blame the otter, without stopping to think what our use of this space – their home – may mean to otters. This particular otter may go through the trauma of being trapped, torn from her home and relocated. Yet it is the otter that is considered the aggressor.

The physicist and ecological philosopher Karen Barad urges us to rethink our interactions with the ecological world not as one of ownership or dominion, but entanglement. She wrote that existence is not an individual affair and that people don’t exist separately from their interactions with other beings. Individuals of any species live as part of an entangled existence with other living creatures.

Our Connection To The Natural World

Both otters and humans live in this watery coastal space in ways that are unique but intertwined. When our entanglement with nature becomes conflict, there will be casualties, which tend overwhelmingly to be the animals.

We impose human character traits, such as anger, onto animals without applying sensitivity to their motives. We reduce their complex experiences, feelings and cognition to a single action if they don’t behave how we think they should (otters must be cute).

Think of clichés, such as “stubborn as a mule”. Who wouldn’t be stubborn under threat of whipping or while carrying a huge load? We also borrow from nature for insults such as bitch, dozy cow and pig. We’ll use these words to describe human qualities. But we don’t stop to question the motivation behind animals’ behaviour.

If we reverse the language in the news stories about the sea otter we could say the sea otter had her home invaded by a large, aggressive animal. And that animal’s kin now wants to kidnap and incarcerate her.

The language of combat works for neither party. It doesn’t work for the humans who impose it, because when you flip the language you ignore the fact humans are scared too, and confused because this animal they think of as cute and cuddly is turning against them.

People love otters, but western representation of otters has disconnected us from the random and varied complexities of their behaviour in nature.

We need to learn to share the Earth. And for that we need to change both our language and behaviour. Combat metaphors must be replaced with language about sharing and opening space for the animal.

This story reminds me of the childhood trauma of an entire generation who watched the beautiful film Ring of Bright Water (1969), where an otter is the star. This film is an interesting portrayal of the individuality of animals and how that conflicts with the way we reduce them to pests or nuisances.

Films and stories often use a distinctive animal or human character to remind us that each of Earth’s occupants are individuals. Categorising animals as a species or other mass groupings is what makes us feel as though we can destroy them as “vermin” or “pests”.

Are humans not pests to many animals just trying to thrive? The Evening Standard article ends with this quote from a marine expert: “They’re actually pretty aggressive animals. They’re not as cute and cuddly as people tend to think.”

He could easily have been talking about humans.![]()

Patricia MacCormack, Professor of Continental Philosophy, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wildlife wonders of Britain and Ireland before the industrial revolution – my research reveals all the biodiversity we’ve lost

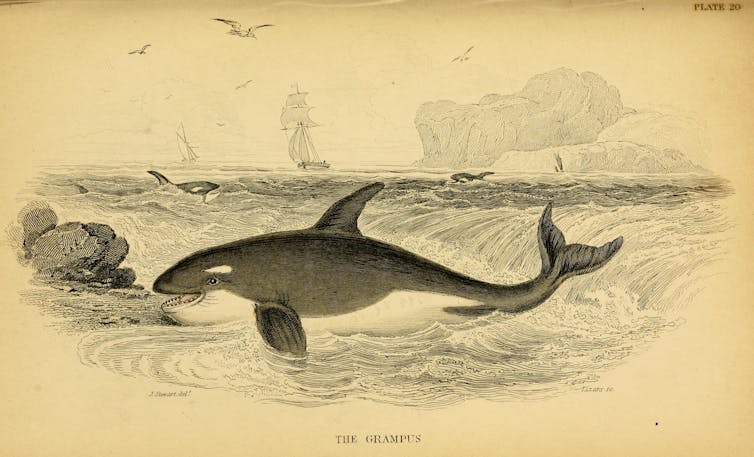

Travel back with me a few hundred years to before the industrial revolution, and the wildlife of Britain and Ireland looks very different indeed. Take orcas: while there are now less than ten left in Britain’s only permanent (and non-breeding) resident population, around 250 years ago the English cleric and naturalist John Wallis gave this extraordinary account of a mass stranding of orcas on the north Northumberland coast:

Sixty-three of them came on shore at Shorestone, 29th July 1734, about noon – 60 of which were between 14 and 19 feet long, and the other three about eight feet. They were all alive when they came on shore and made a hideous noise, but they were soon killed by the country people, who removed them one by one with six oxen and two horses, and made about ten pounds by their blubber. The same kind of noise was heard in the sea the night before by the shepherds in the fields, when it is supposed they were sensible of [the orcas’] distress in shoal-water.

If this record is reliable, then more orcas were stranded on this beach south of the Farne Islands on one day in 1734 than are probably ever present in British and Irish waters today. In his natural history of Northumberland, Wallis describes the orca as a “great enemy to the whale” and waging fierce battles with common thresher sharks, which use their long tails as weapons.

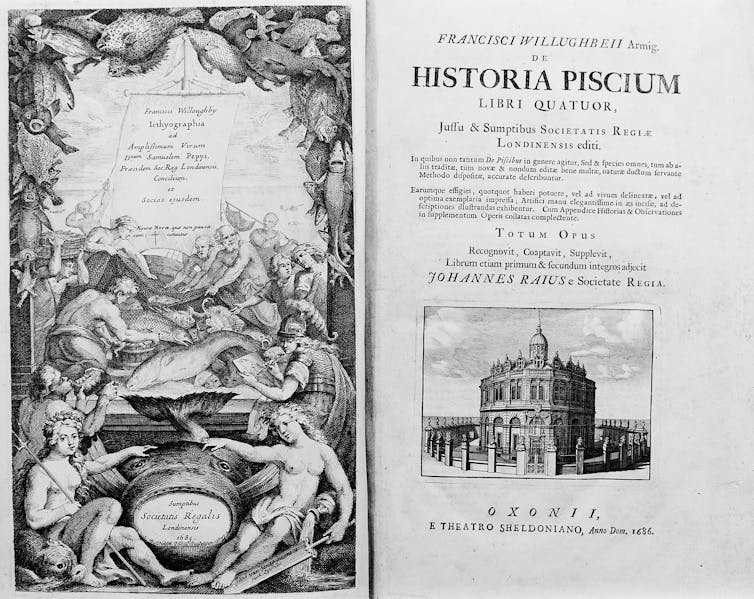

Other careful naturalists from this period observed orcas around the coasts of Cornwall, Norfolk and Suffolk. I have spent the last five years tracking down more than 10,000 records of wildlife recorded between 1529 and 1772 by naturalists, travellers, historians and antiquarians throughout Britain and Ireland, in order to reevaluate the prevalence and habits of more than 150 species for my new book, The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife.

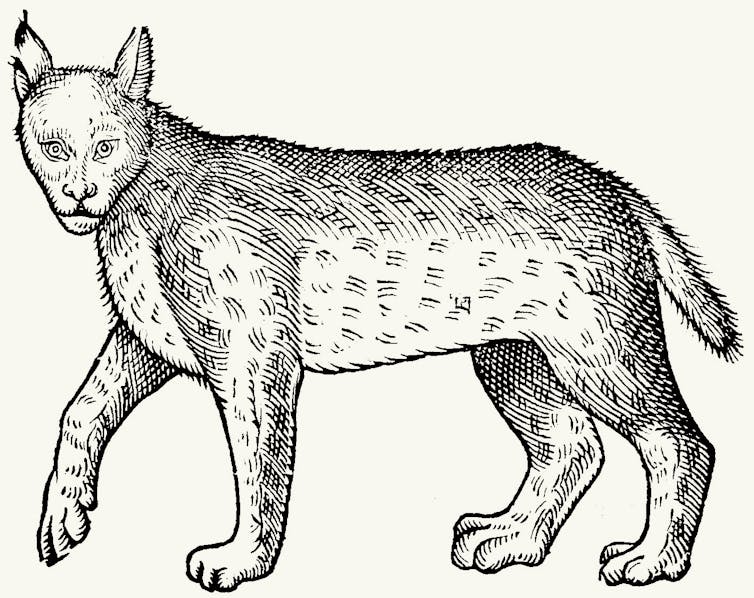

In the early modern period, wolves, beavers and probably some lynxes still survived in regions of Scotland and Ireland. By this point, wolves in particular seem to have become re-imagined as monsters, looming around every corner in the imaginations of writers such as Robert Gordon of Gordonstoun: